DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04399-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38907185

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-21

جزيئات نانوية من أكسيد الزنك المغلفة بالبيبرين تستهدف الأغشية الحيوية وتسبب موت الخلايا المبرمج في سرطان الفم عبر مسار BCl-2/BAX/P53

الملخص

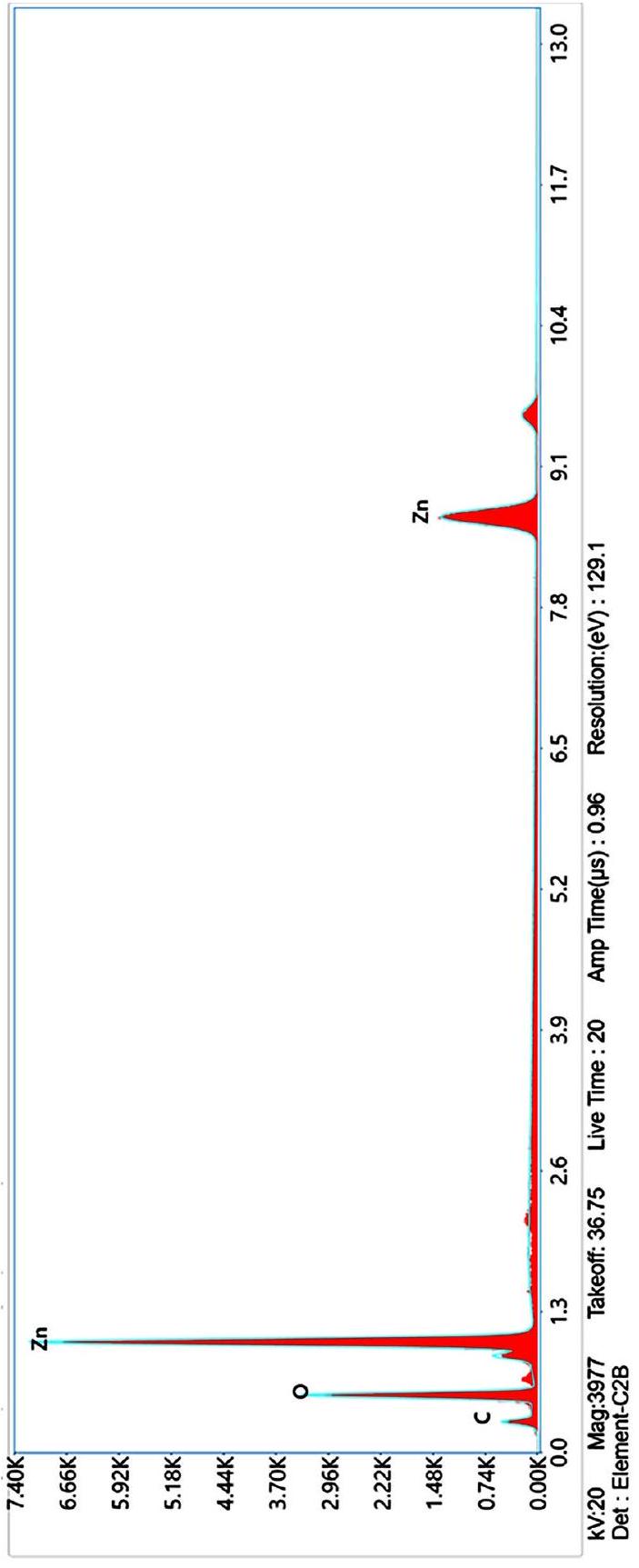

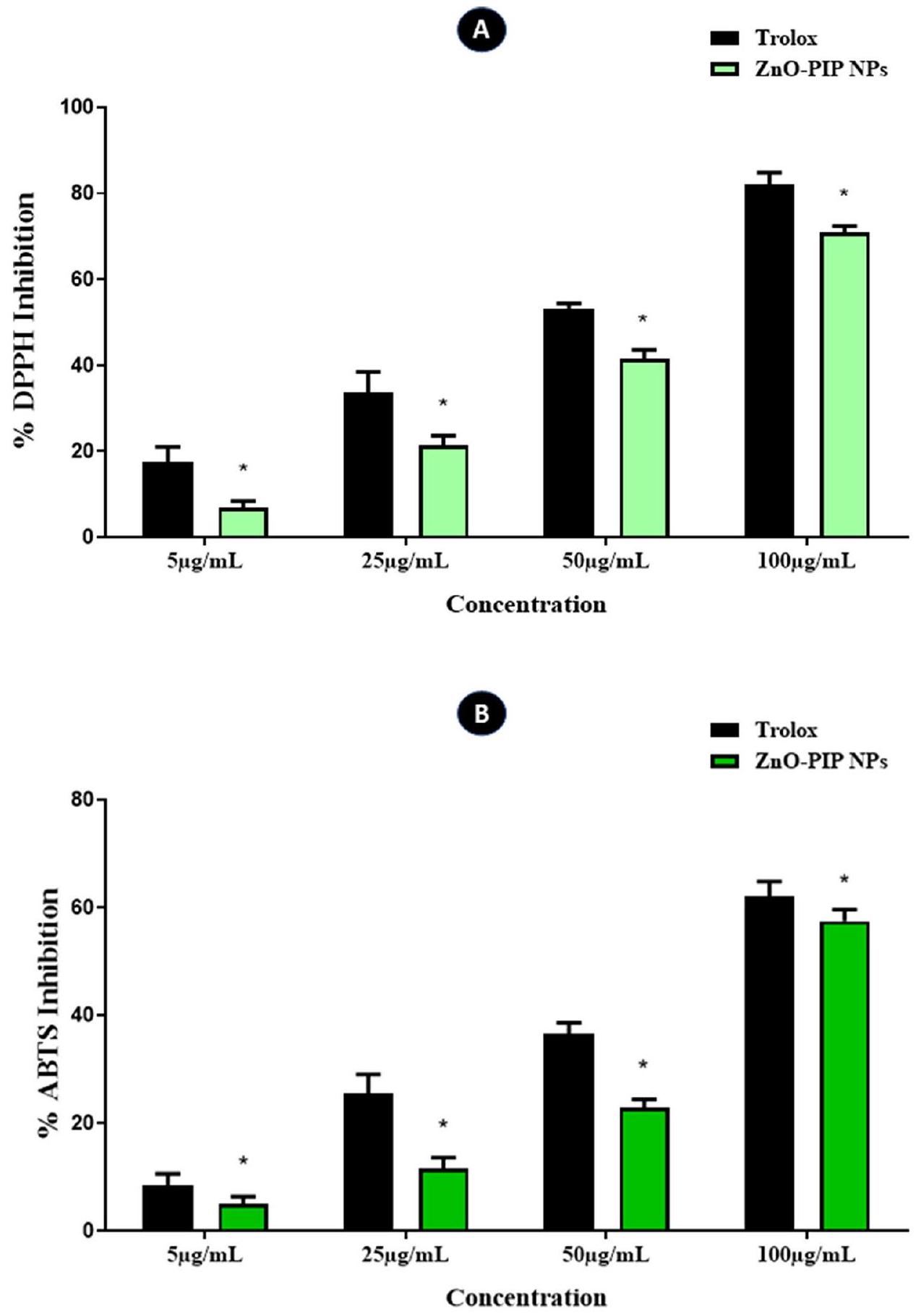

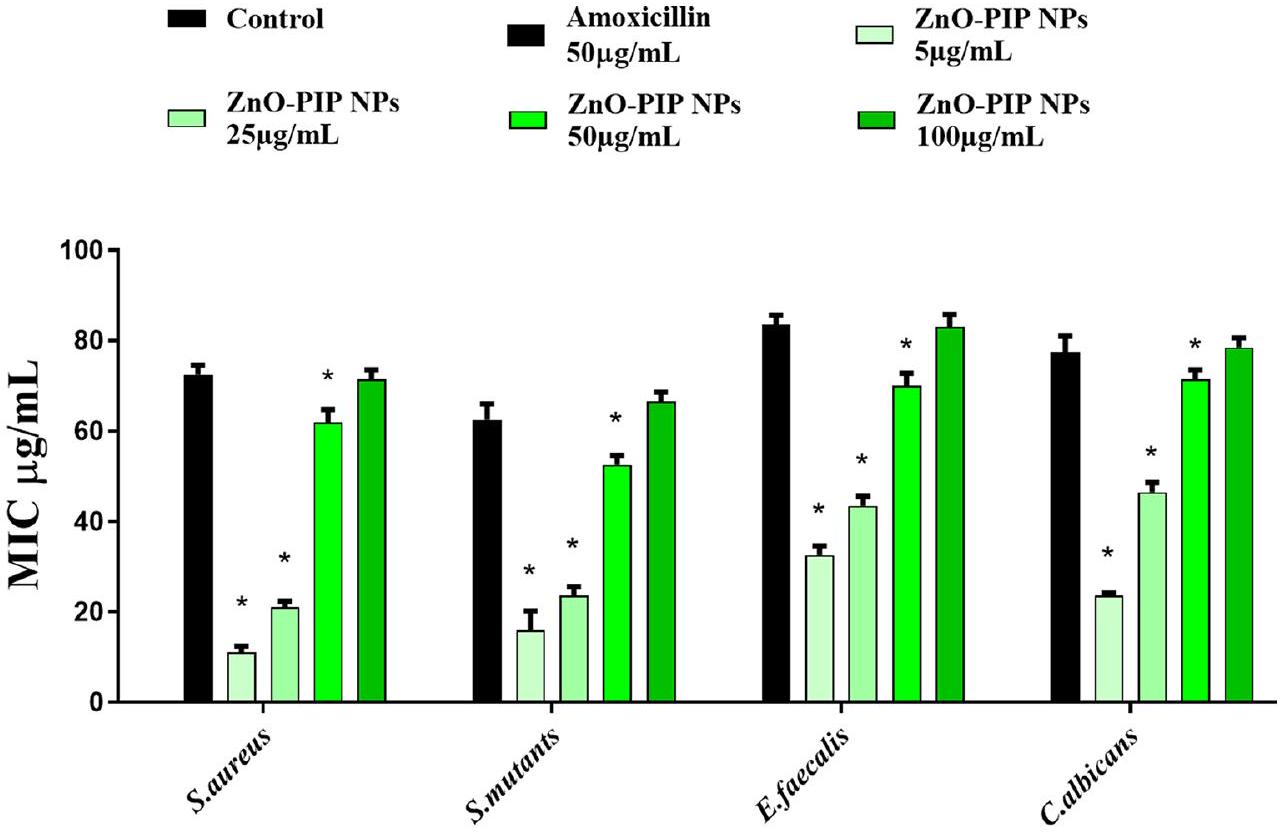

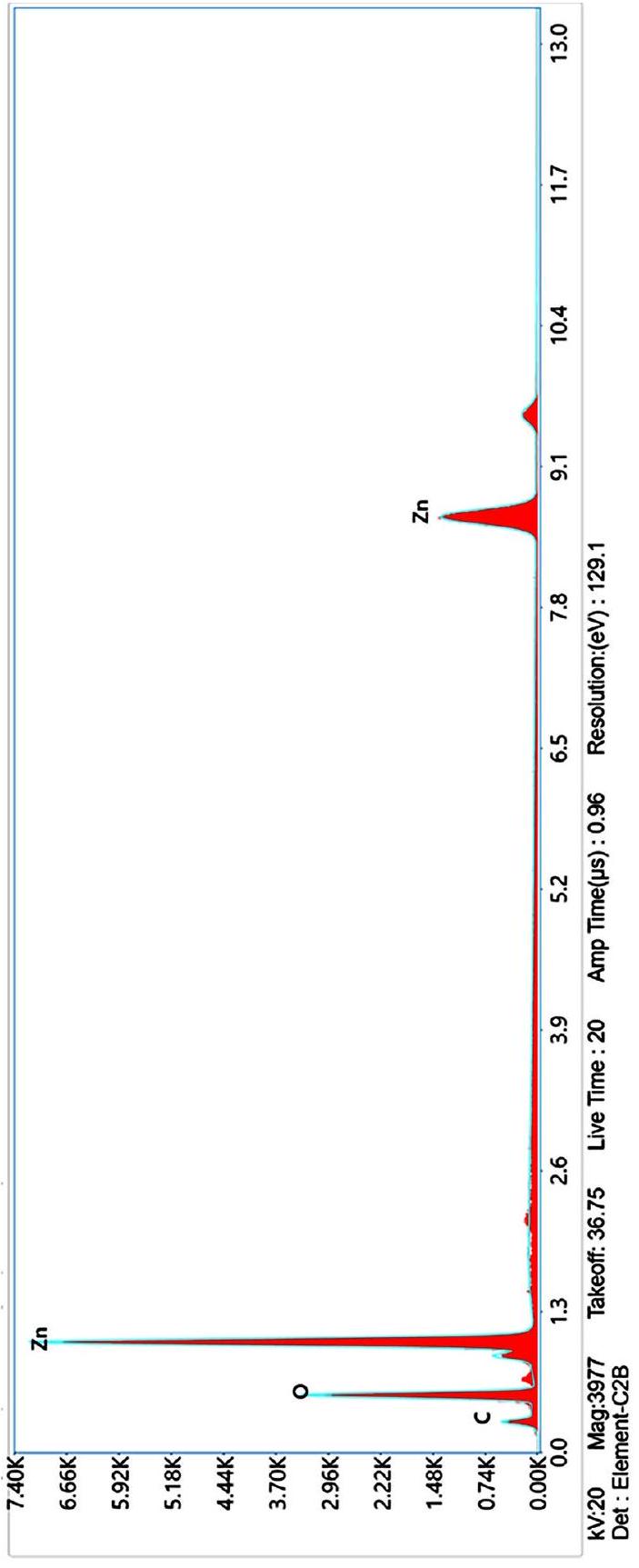

الخلفية تلعب مسببات الأمراض السنية دورًا حاسمًا في مشاكل صحة الفم، بما في ذلك تسوس الأسنان، وأمراض اللثة، والعدوى الفموية، وتشير الأبحاث الحديثة إلى وجود صلة بين هذه المسببات وبدء وتقدم سرطان الفم. هناك حاجة إلى أساليب علاجية مبتكرة بسبب مخاوف مقاومة المضادات الحيوية وقيود العلاج. الطرق قمنا بتخليق وتحليل جزيئات نانوية من أكسيد الزنك المغلفة بالبيبيرين (ZnO-PIP NPs) باستخدام طيف الأشعة فوق البنفسجية، والميكروسكوب الإلكتروني الماسح، وتحليل حيود الأشعة السينية، وطيف الأشعة تحت الحمراء، وتحليل الطاقة المشتتة. تم تقييم الفعالية المضادة للأكسدة والمضادة للميكروبات من خلال اختبارات DPPH وABTS وMIC، بينما تم تقييم الخصائص المضادة للسرطان على خلايا سرطان الخلايا الحرشفية الفموية KB. النتائج أظهرت ZnO-PIP NPs نشاطًا مضادًا للأكسدة ملحوظًا وMIC قدره

مقدمة

موقع الورم ولكن قد تشمل الجراحة، العلاج الإشعاعي، العلاج الكيميائي، العلاج المستهدف، والعلاج المناعي. غالبًا ما تكون هناك حاجة إلى نهج متعددة التخصصات تشمل أطباء الأورام، الجراحين، أطباء الأسنان، وغيرهم من المتخصصين في الرعاية الصحية لتقديم رعاية شاملة للمرضى المصابين بسرطان الفم.

المواد والأساليب

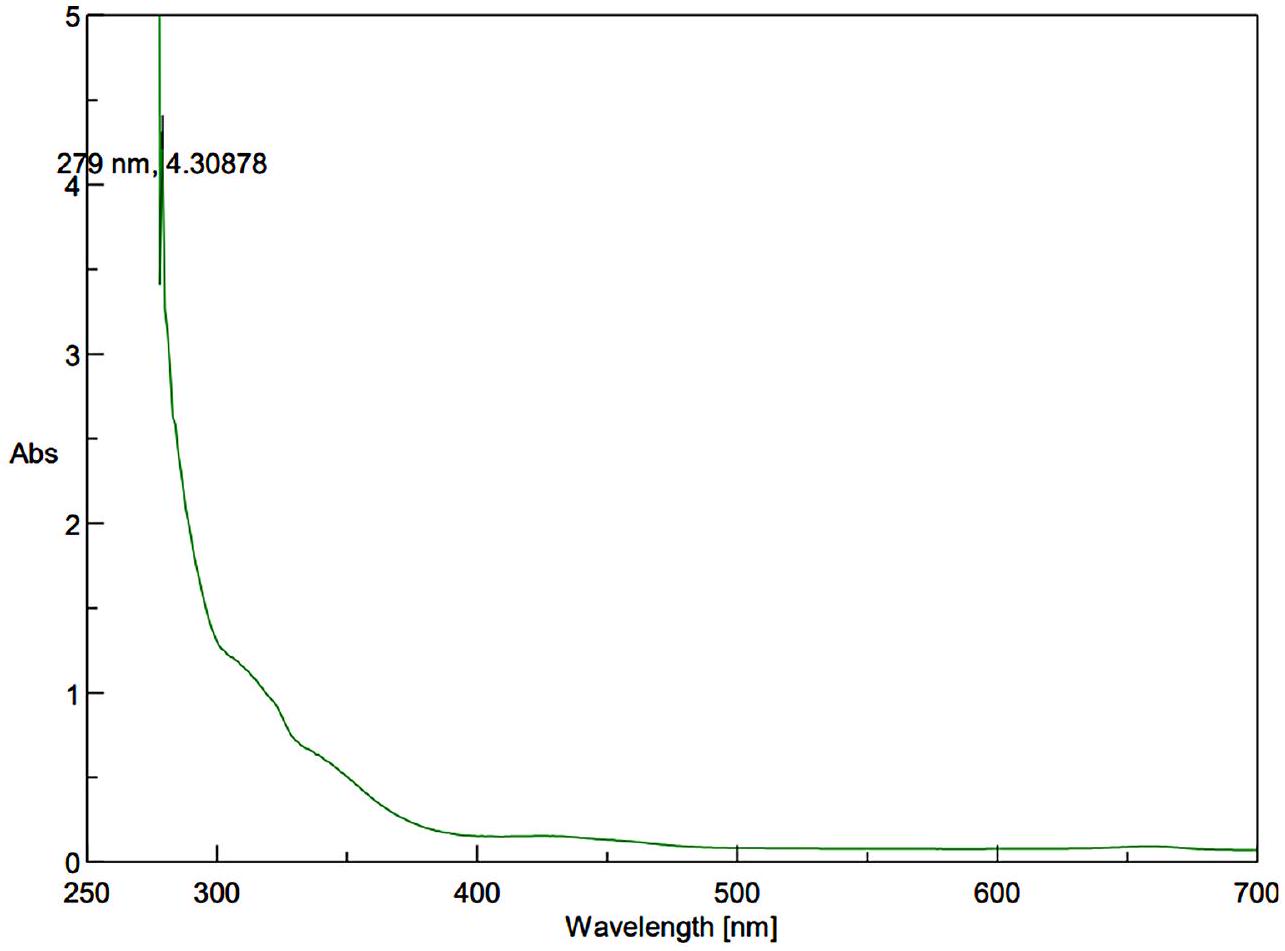

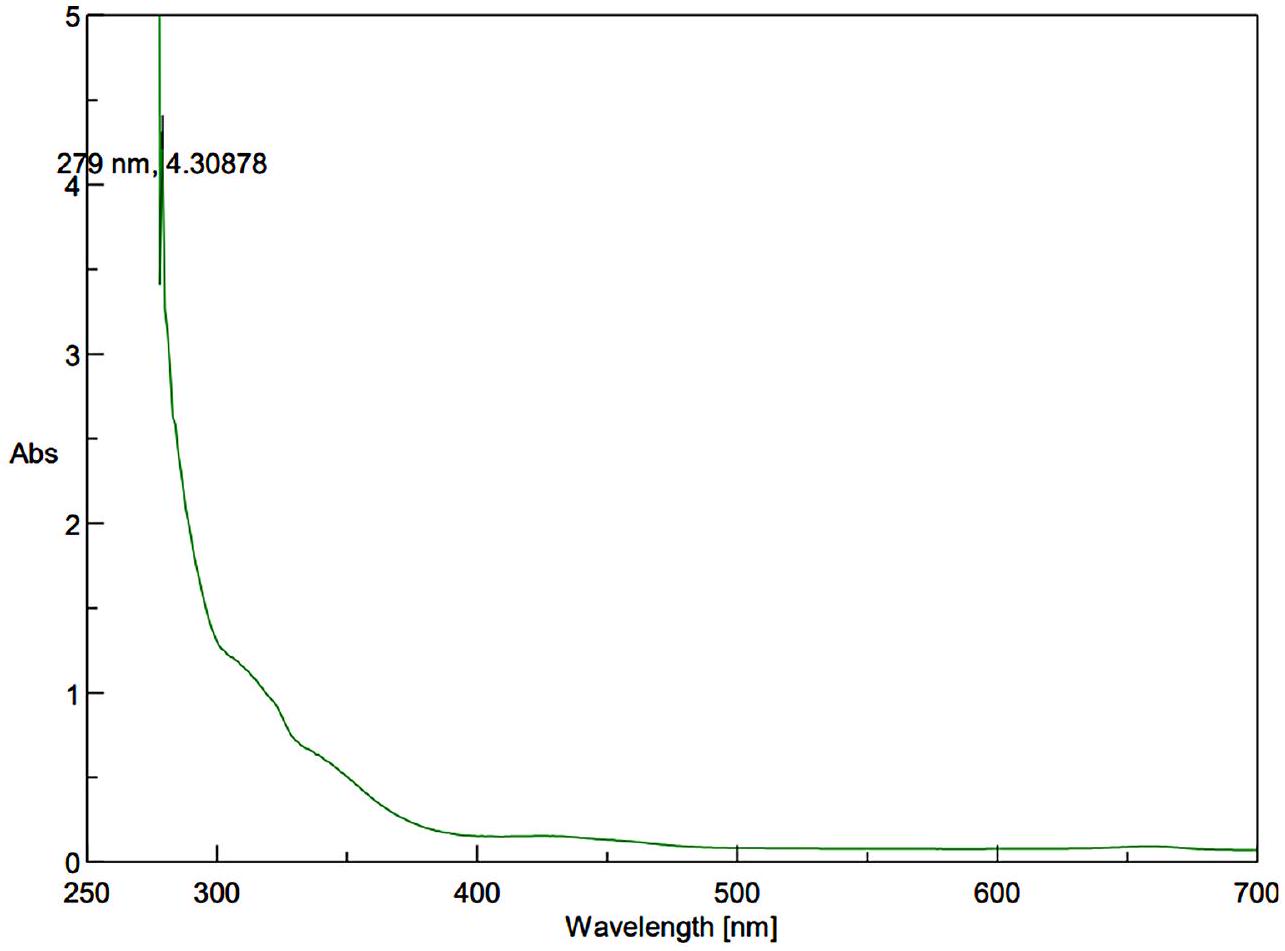

تركيب وتوصيف جزيئات ZnO-PIP النانوية

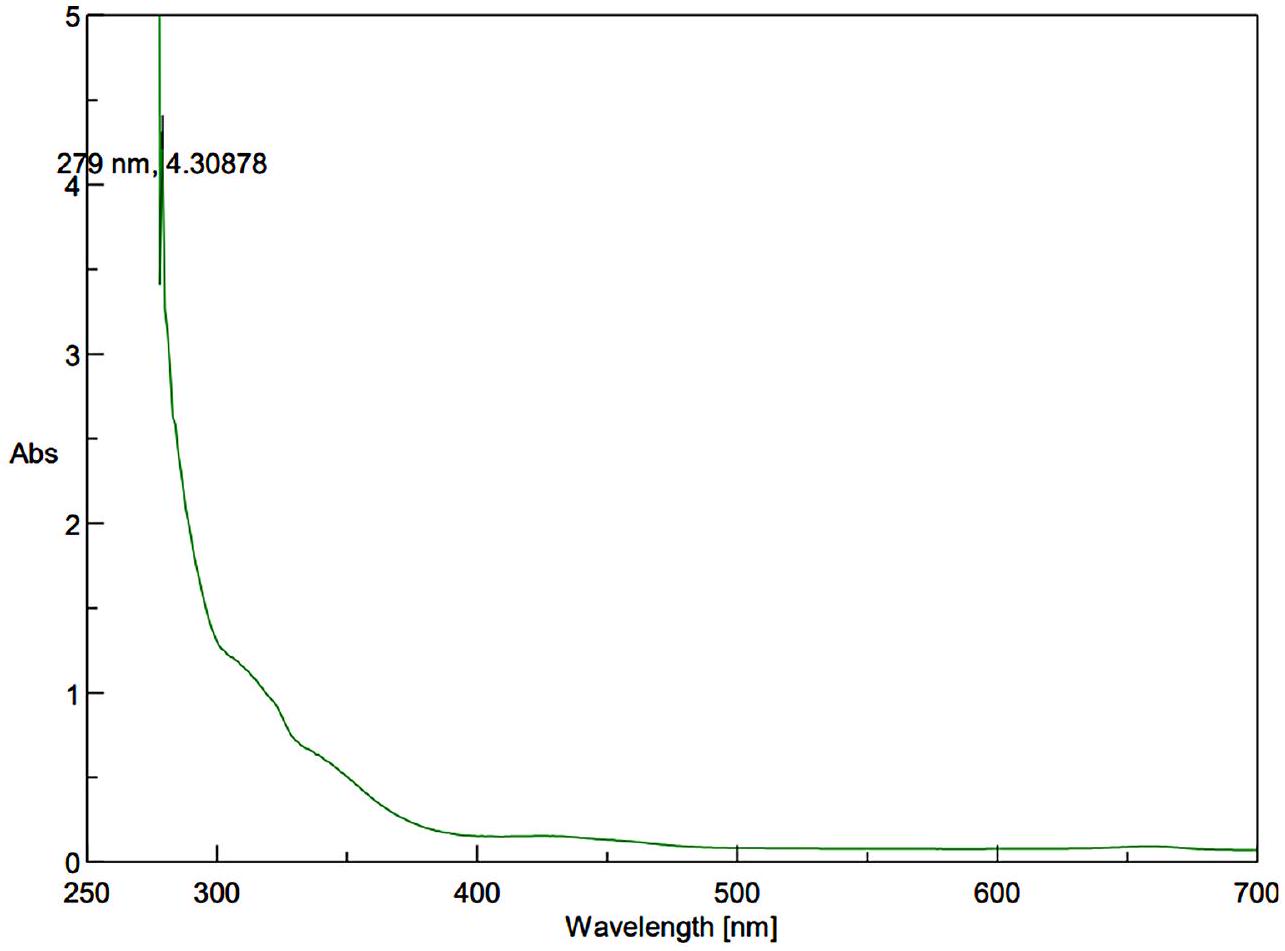

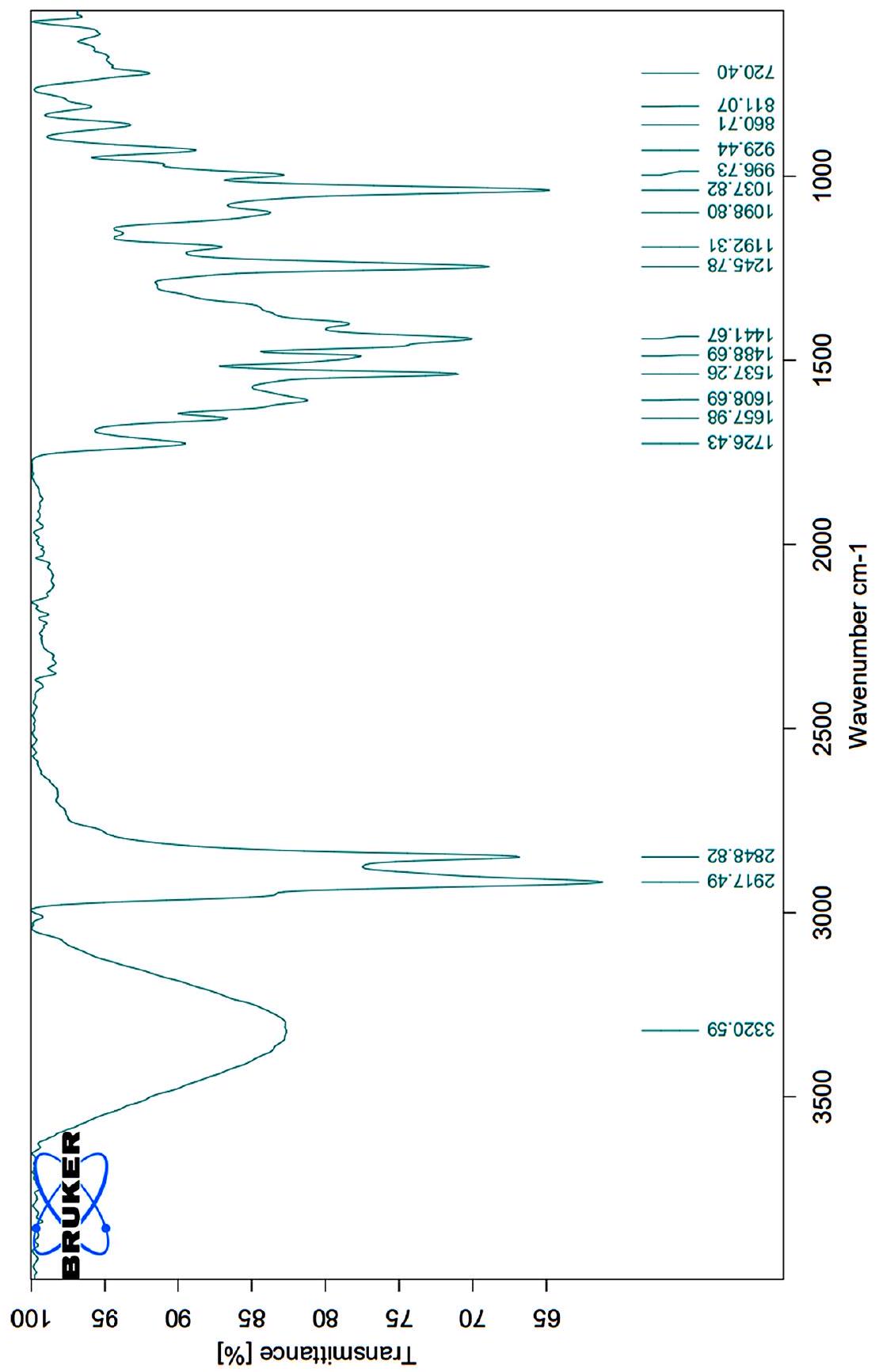

تحت الفراغ. تم مسح تعليقات الجسيمات النانوية في الماء المقطر في نطاق الطول الموجي من

2,2-ثنائي الفينيل-1-بيكريل هيدرازيل (DPPH)

2,2′-أزينو-بيس-(3-إيثيل بنزوتيازولين-6-سلفونيك) (ABTS)

تم القياس عند 734 نانومتر باستخدام مطياف الأشعة فوق البنفسجية والمرئية [23].

اختبار التركيز المثبط الأدنى (MIC)

طريقة انتشار الآبار لمنطقة التثبيط

دراسات الارتباط

اختبار مضاد للسرطان

تعبير جينات الموت الخلوي

الماء. تم تقييم جودة وكمية RNA باستخدام مقياس الطيف الضوئي. تم إجراء تخليق cDNA من الشريط الأول باستخدام مجموعة النسخ العكسية وفقًا لبروتوكول الشركة المصنعة. باختصار، تم حضانة عينات RNA مع خليط يحتوي على إنزيم النسخ العكسي، وبرايمرات عشوائية، وdNTPs، ومثبط RNase في

التحليل الإحصائي

النتائج

تركيب وتوصيف جزيئات ZnO-PIP النانوية

| جين | البرايمر الأمامي (5′-3′) | البرايمر العكسي (5′-3′) | مرجع |

| جابي | جي سي سي إيه إيه إيه جي جي تي سي إيه تي سي إيه تي سي تي جي سي | جي جي تي سي إيه سي جي إيه جي تي سي سي تي تي سي إيه سي جي إيه تي إيه سي | [28] |

| BCL-2 | GACGACTTCTCCCGCCGCTAC | CGGTTCAGGTACTCAGTCATCCAC | [28] |

| باكس | AGGTCTTTTTCCGAGTGGCAG | GCGTCCCAAAGTAGGAGAGGAG | [28] |

| P53 | ACATGACGGAGGTTGTGAGG | TGTGATGATGGTGAGGATGG | [29] |

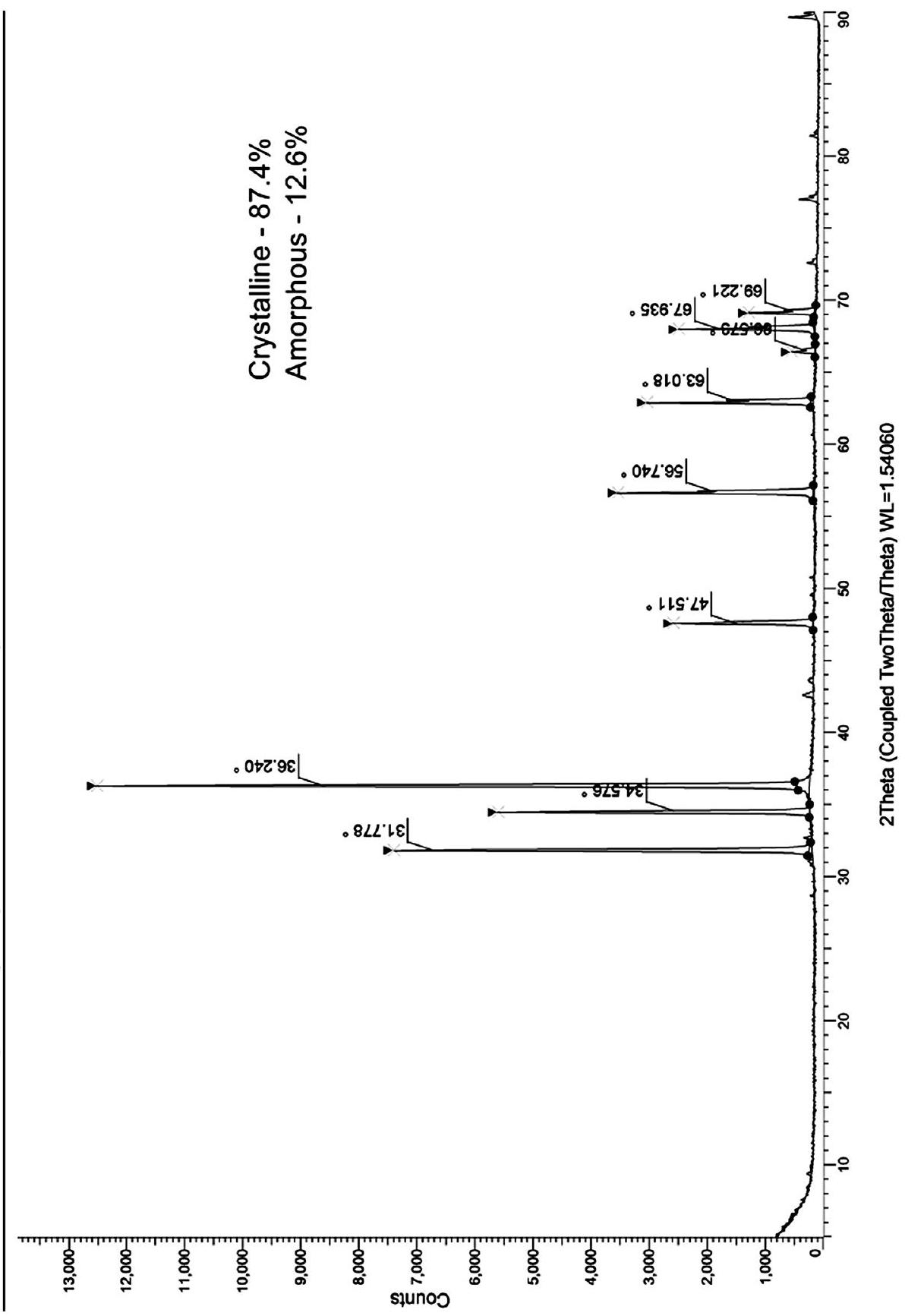

مرحلة بلورية تتكون من

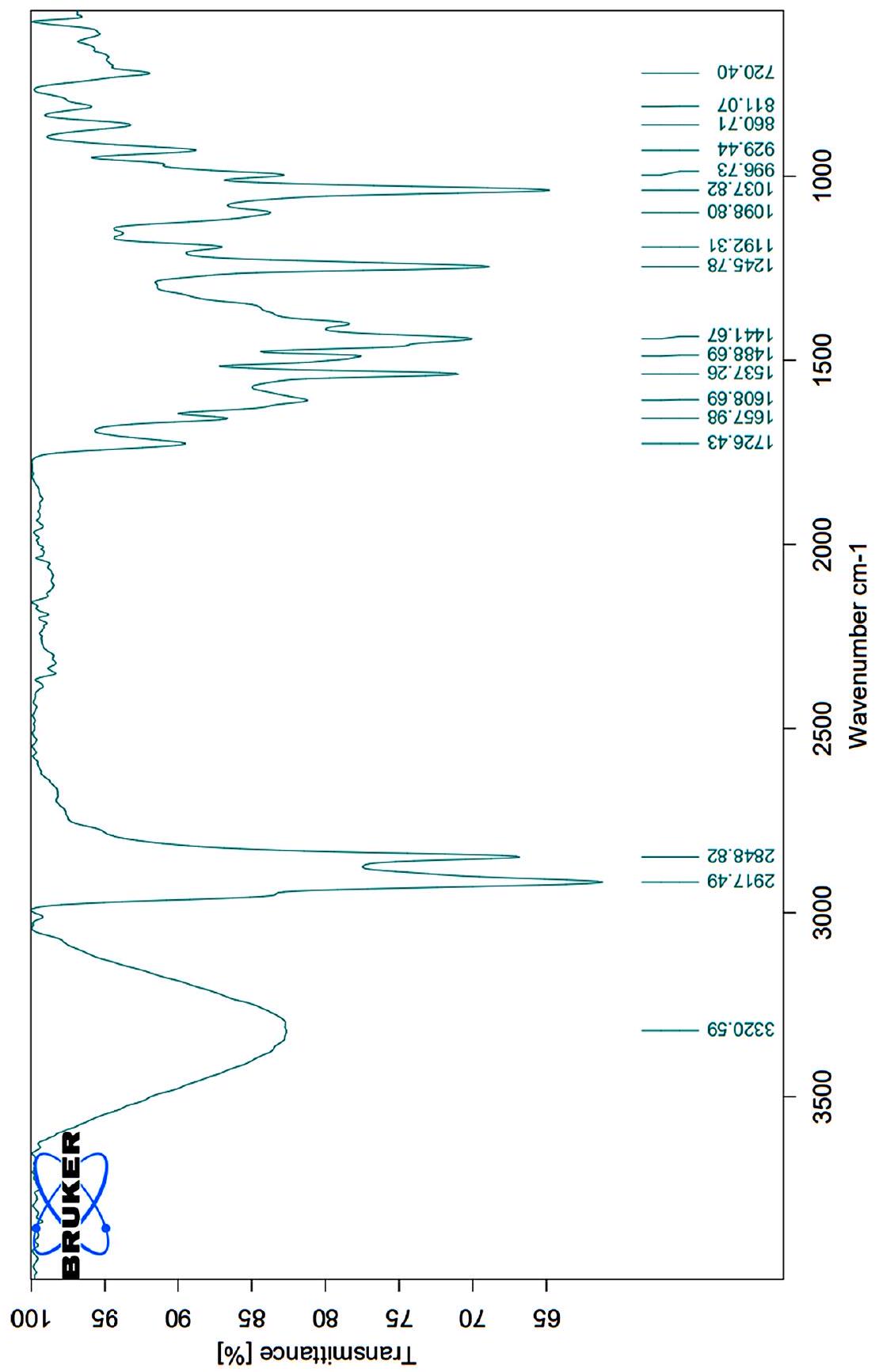

على التوالي. تشير وجود القمم المحددة جيدًا إلى العلوية البلورية العالية والنقاء لجزيئات ZnO النانوية، مع وجود الحد الأدنى من الشوائب أو المراحل غير المتبلورة. تم ملاحظة القمم في FTIR عند

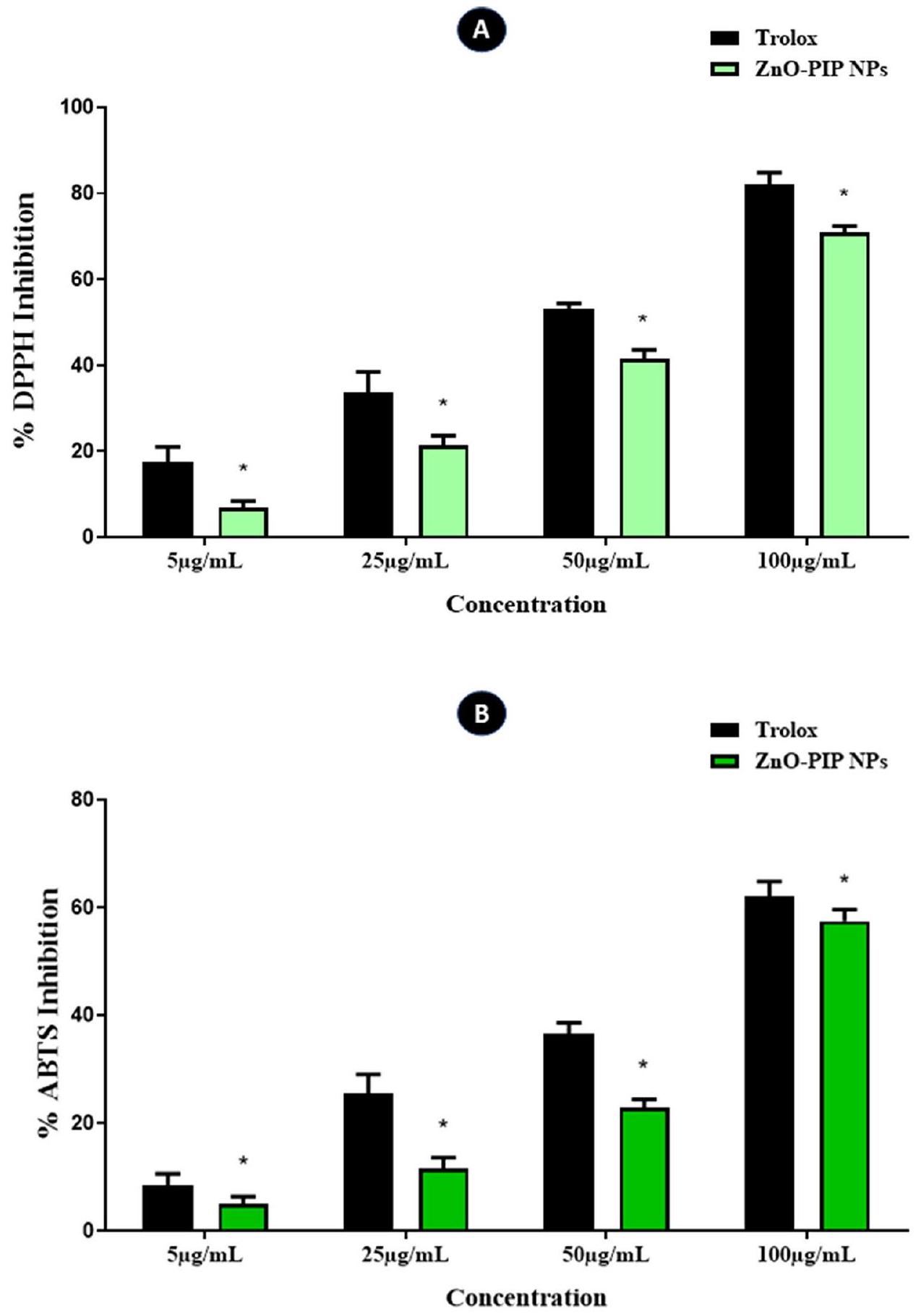

نشاط مضادات الأكسدة لجزيئات ZnO-PIP النانوية

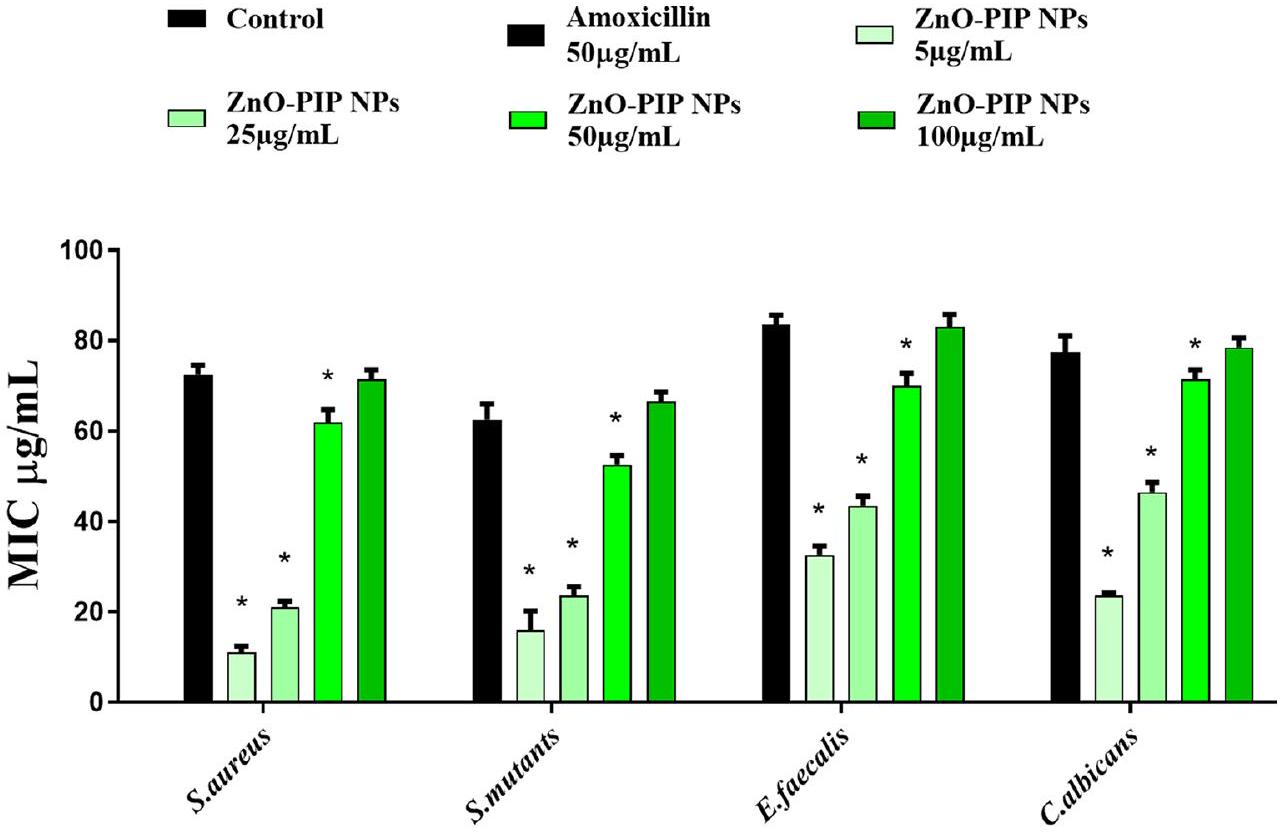

النشاط المضاد للميكروبات لجزيئات ZnO-PIP النانوية ضد مسببات الأمراض السنية

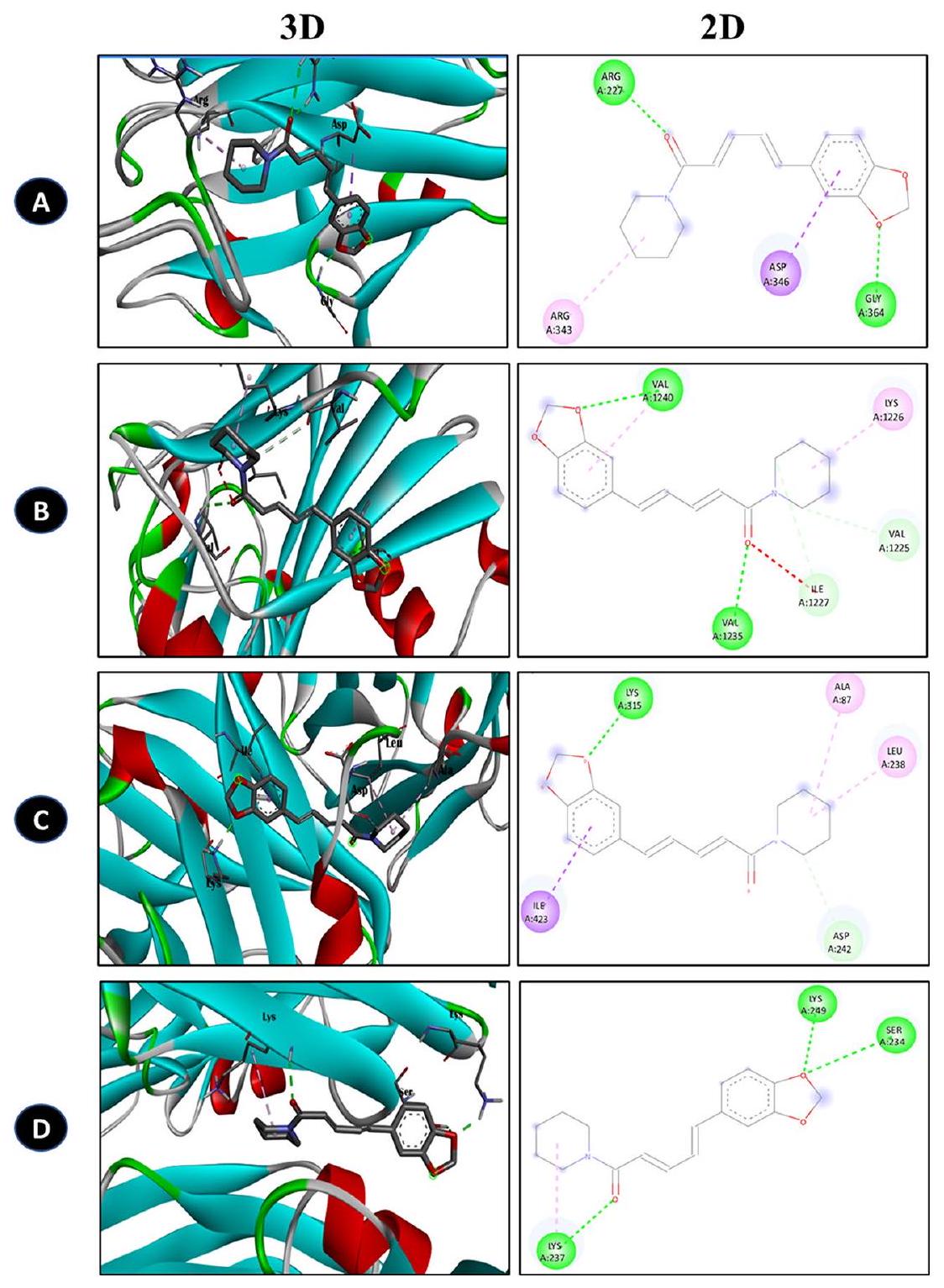

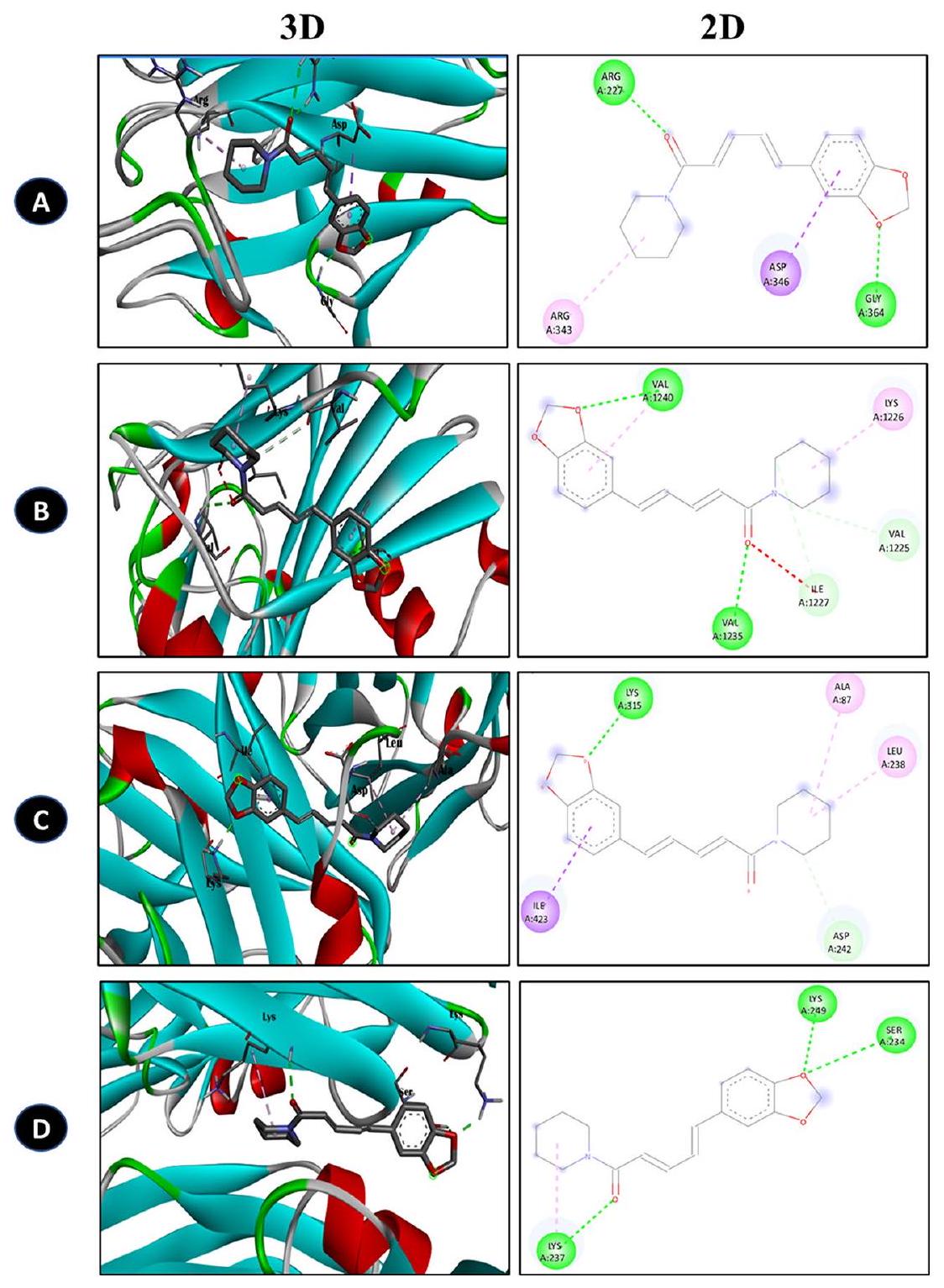

تفاعل PIP مع مستقبلات الأغشية الحيوية لجراثيم الأسنان

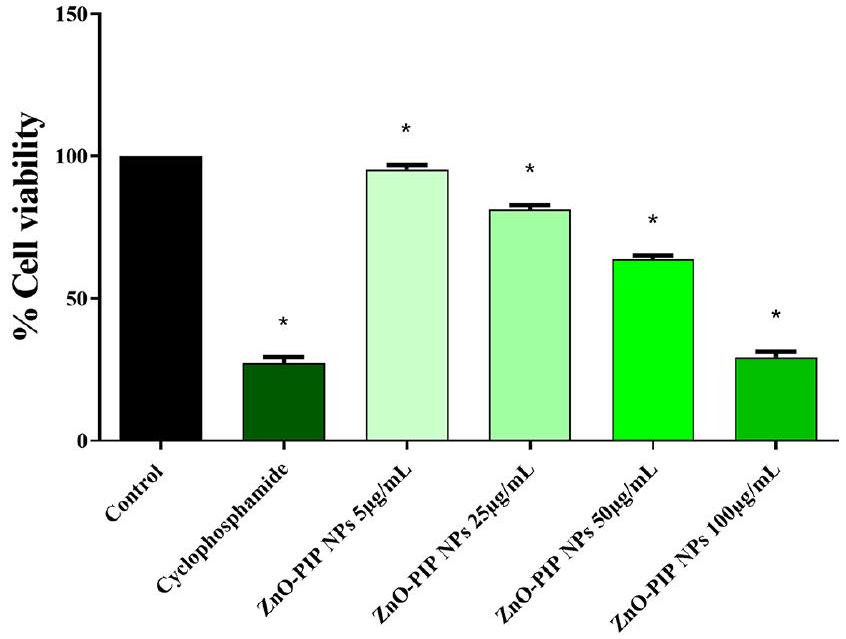

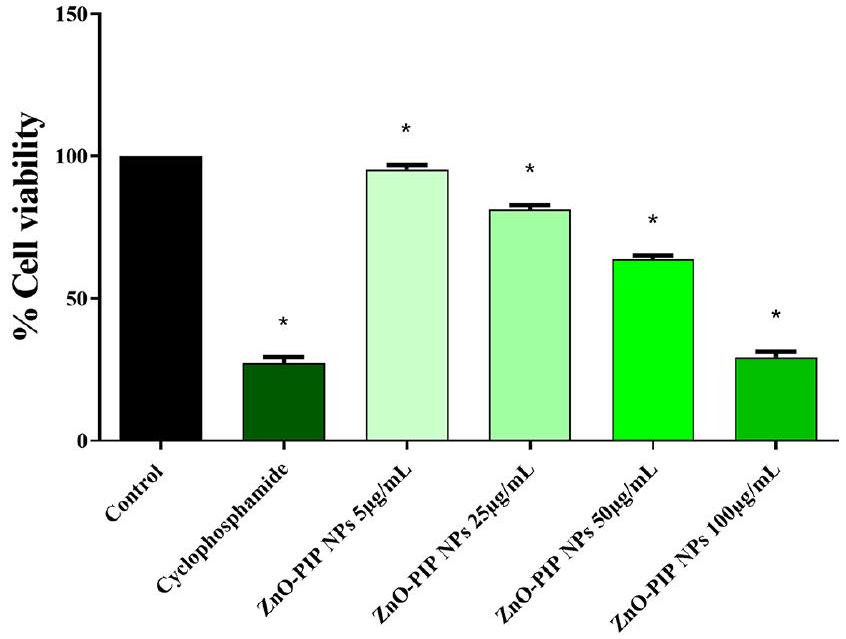

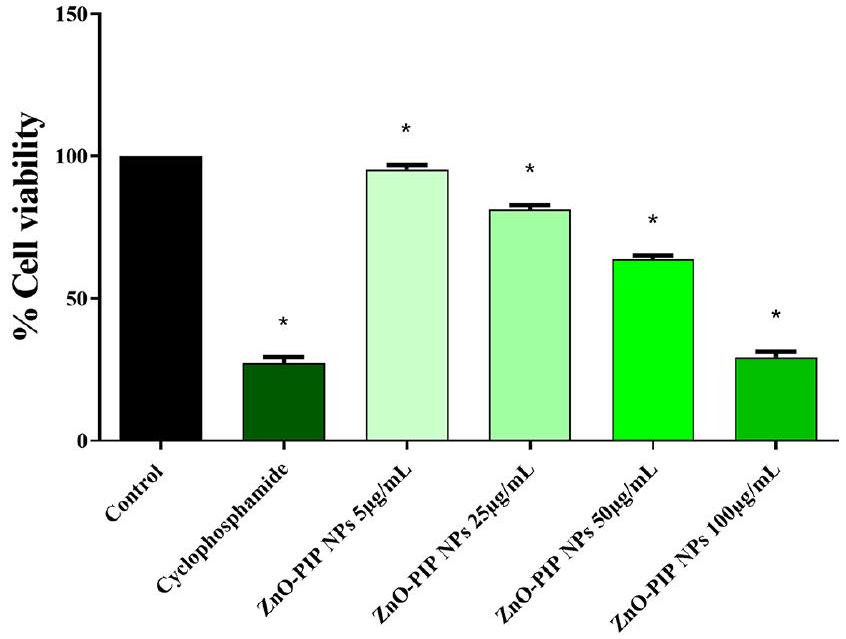

النشاط المضاد للسرطان لجزيئات ZnO-PIP النانوية

في بقاء الخلايا، ينخفض إلى

| منطقة التثبيط (مم) | ||||

| سلالة بكتيرية | تحكم | أموكسيسيلين | زنك أكسيد – بولي إيزوبوتيلين | زنك أكسيد – بولي إيميد |

|

|

|

|

||

| المكورات العنقودية الذهبية | – | 16 | ٨ | 15 |

| ستربتوكوكوس موتانس | – | 15 | ٧ | 14 |

| إنتيروكوكوس فاسياليس | – | 17 | 12 | ١٨ |

| كانديدا ألبيكانس | – | 15 | 11 | 16 |

تنظيم مسارات إشارات الموت الخلوي في سرطان الفم

نقاش

تتعرض تجويف الفم للإجهاد التأكسدي بسبب عوامل مختلفة مثل العدوى البكتيرية، الالتهاب، والتعرض للجذور الحرة للأكسجين (ROS) الناتجة عن العمليات الأيضية. تساعد مضادات الأكسدة في تحييد الجذور الحرة، مما يحمي الأنسجة الفموية من الضرر التأكسدي. يمكن دمج مضادات الأكسدة في المواد السنية مثل المركبات، الأسمنت، والمواد السدادة لتحسين استقرارها، متانتها، وتوافقها الحيوي. يمكن أن يطيل ذلك من عمر الترميمات السنية.

| المستقبل (معرّف PDB) | ليغاند | الارتباط الجزيئي

|

تفاعل الأحماض الأمينية | |

| 1. | المكورات العنقودية الذهبية: بروتين السطح للمكورات العنقودية الذهبية G (7SMH) | بيبرين | -6.7 | أرج، أسب، جلايسين، وأرج |

| 2. | S. mutans: نهاية الكربوكسيل لمستضد I/II (3QE5) | بيبرين | -6.1 | فال، فال، ليس، إيل، وفال |

| 3. | E. faecalis: بروتين سطح الإنتيروكوكوس (6ORI) | بيبرين | -8.2 | إيل، ليس، ألانين، وليوسين |

| ٤ | ك. ألبيكانز: ALS3 (4LEE) | بيبرين | -7.6 | ليس، ليس، وسير |

القدرة على تثبيط أو تحييد الجذور الحرة وأنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية بشكل فعال. علاوة على ذلك، فإنه يؤثر بشكل إيجابي على حالة الثيول الخلوية، وجزيئات مضادات الأكسدة، وإنزيمات مضادات الأكسدة عند دراستها في

النظام، مما يجعله مقاومًا للعلاجات المضادة للميكروبات ويعزز مقاومة العلاج. قدرة هذه المسببات على تشكيل أغشية حيوية قوية ومرنة تسلط الضوء على التحديات في إدارة العدوى السنية وتبرز أهمية تطوير استراتيجيات لتعطيل تشكيل الأغشية الحيوية لعلاج فعال والوقاية من الأمراض الفموية [37]. أظهرت الدراسات الحديثة أن PIP يظهر فعالية ملحوظة ضد الأغشية الحيوية ضد

الميكروبيوم الفموي، يستخدم مادة Als3 اللاصقة لتشكيل الأغشية الحيوية وتفاقم مشاكل الأسنان. تلعب Als3 دورًا محوريًا في الالتصاق الأولي لـ C. albicans بالأسطح الفموية، بما في ذلك مينا الأسنان والأنسجة المخاطية، من خلال الارتباط بمستقبلات خلايا المضيف مثل E-cadherin وfibronectin. بمجرد الالتصاق، تفرز C. albicans مكونات المصفوفة خارج الخلوية، بما في ذلك البروتينات، والسكريات المتعددة، وDNA خارج الخلوي، مما يشكل بنية أغشية حيوية قوية. توفر هذه الأغشية الحيوية حماية ضد استجابات المناعة المضيفة وعوامل مضادة للفطريات، مما يعزز الاستعمار المستمر ويساهم في الأمراض الفموية مثل التهاب الفم الناتج عن الأطقم وداء المبيضات الفموي [44]. تم تقييم التفاعل المحتمل بين PIP والمستقبلات المعنية في تشكيل الأغشية الحيوية بين مختلف مسببات الأمراض السنية. كشفت نتائج الدراسة أن PIP أظهر ميلًا ملحوظًا تجاه جميع المستقبلات التي تم التحقيق فيها. تدعم هذه النتيجة النتائج التي تم الحصول عليها من اختبارات منطقة التثبيط واختبارات تثبيط الأغشية الحيوية. أظهرت النتائج أن PIP قام بتثبيط نمو مسببات الأمراض السنية بفعالية وقلل بشكل كبير من تشكيل الأغشية الحيوية. تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن PIP يمكن أن يكون مرشحًا واعدًا لتطوير عوامل علاجية تهدف إلى تعطيل تشكيل الأغشية الحيوية ومكافحة العدوى السنية التي تسببها مسببات الأمراض مثل S. mutans وS. aureus وE. faecalis وC. albicans. علاوة على ذلك، فإن قدرة PIP على استهداف مستقبلات متعددة مرتبطة بتشكيل الأغشية الحيوية تسلط الضوء على إمكاناته كعامل مضاد للميكروبات واسع الطيف لتطبيقات العناية بالأسنان.

يمكن أن تسهم العدوى بواسطة مسببات الأمراض السنية في تطوير سرطان الفم من خلال آليات مختلفة. يمكن أن تؤدي الالتهابات المزمنة الناتجة عن وجود هذه المسببات ومنتجاتها الثانوية إلى استجابات مناعية مستمرة، مما يعزز تلف الأنسجة وتغيرات جينية تسهل حدوث السرطان [13]. على سبيل المثال، تنتج S. mutans حمض اللبنيك كمنتج ثانوي لتمثيل السكر، مما يخلق بيئة ميكروبية حمضية يمكن أن تلحق الضرر بخلايا الظهارة الفموية وتعزز تحولها الخبيث [45]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن لبعض المسببات مثل C. albicans إنتاج مركبات مسرطنة أو سموم، مما يسهم في العمليات المسرطنة. علاوة على ذلك، غالبًا ما توجد هذه المسببات داخل الأغشية الحيوية، التي لا تحميها فقط من استجابات المناعة المضيفة ولكن أيضًا تعزز غزو الأنسجة المحلية والنقائل، مما يسهل انتشار الخلايا الخبيثة. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تؤدي العدوى المزمنة إلى تعطيل توازن الميكروبيوم الفموي، مما يؤدي إلى اختلال التوازن الميكروبي، والذي ارتبط بزيادة خطر الإصابة بسرطان الفم. بشكل جماعي، يمكن أن تبدأ التفاعلات بين مسببات الأمراض السنية وأنسجة المضيف وتستمر في خلق بيئة مؤيدة للالتهابات ومؤيدة للسرطان داخل تجويف الفم، مما يعرض الأفراد في النهاية لتطوير سرطان الفم [46]. ZnO-PIP NPs، المعروفة بنشاطها المضاد للميكروبات القوي ضد الأسنان

تمت دراسة مسببات الأمراض بشكل أعمق من أجل آثارها المحتملة المضادة للسرطان التي تستهدف بشكل خاص سرطان الفم. كشفت نتائج الدراسة عن نشاط مضاد للسرطان واعد، حيث أظهرت انخفاضًا كبيرًا في حيوية خلايا KB، وهي خط خلايا سرطان الفم البشري. تشير هذه النتيجة إلى أن ZnO-PIP NPs تمتلك وظيفة مزدوجة، حيث تظهر خصائص مضادة للميكروبات ومضادة للسرطان. تعتبر BCL2 وBAX وP53 من المنظمين الرئيسيين لعملية موت الخلايا المبرمج، وهي عملية مركزية في تطور السرطان وتقدمه. في سرطان الفم، يمكن أن تؤدي عدم تنظيم الجينات المرتبطة بموت الخلايا مثل BCL2، الذي يثبط موت الخلايا، وBAX، الذي يعزز موت الخلايا، إلى تعطيل التوازن الدقيق بين تكاثر الخلايا وموت الخلايا، مما يؤدي إلى نمو الورم غير المنضبط. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يلعب P53، وهو جين مثبط للورم، دورًا حاسمًا في تنسيق استجابات الخلايا لتلف الحمض النووي والإجهاد الخلوي، بما في ذلك تحفيز موت الخلايا في الخلايا التالفة أو الشاذة. نظرًا لأدوارها الحاسمة في تنظيم قرارات مصير الخلايا، يمكن أن تؤثر التغيرات في التعبير أو النشاط لهذه الجينات بشكل كبير على التطور والتقدم والاستجابة للعلاج في سرطان الفم. لذلك، فإن دراسة مستويات التعبير ونشاط BCL2 وBAX وP53 استجابةً لعلاج ZnO-PIP NPs توفر رؤى قيمة حول الآليات الأساسية لآثارها المضادة للسرطان وتوضح الأهداف العلاجية المحتملة لمكافحة سرطان الفم. في الدراسة التي تحقق في النشاط المضاد للسرطان لـ ZnO-PIP NPs في خلايا KB، كشفت النتائج عن تغييرات كبيرة في مستويات التعبير للجينات الرئيسية المرتبطة بموت الخلايا، بما في ذلك BCL2 وBAX وP53. أدى العلاج بـ ZnO-PIP NPs إلى تقليل ملحوظ في BCL2، وهو بروتين مضاد لموت الخلايا معروف بأنه يثبط موت الخلايا، مما يحول التوازن نحو تحفيز موت الخلايا. في الوقت نفسه، كان هناك زيادة في BAX، وهو بروتين مؤيد لموت الخلايا يعزز موت الخلايا من خلال تسهيل نفاذية الغشاء الخارجي للميتوكوندريا وإطلاق السيتوكروم ج، مما يعزز استجابة الموت الخلوي في خلايا KB. علاوة على ذلك، أدى علاج ZnO-PIP NPs إلى زيادة P53، وهو جين مثبط للورم حاسم في تنسيق استجابات الخلايا لتلف الحمض النووي والإجهاد. من المحتمل أن تكون زيادة P53 قد ساهمت في تنشيط مسارات الموت الخلوي اللاحقة، بما في ذلك التنظيم النسخي للجينات المؤيدة لموت الخلايا وتحفيز توقف دورة الخلية، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى تثبيط تكاثر خلايا KB وتعزيز موت الخلايا. بشكل جماعي، تشير هذه النتائج إلى أن النشاط المضاد للسرطان لـ ZnO PIP NPs في خلايا KB يتم من خلال تعديل مستويات التعبير لـ BCL2 وBAX وP53، مما يبرز إمكانياتها كعوامل علاجية واعدة لعلاج سرطان الفم من خلال استهداف مسارات الموت الخلوي الرئيسية.

ملف التعريف والتوافق الحيوي لـ ZnO-PIP NPs أمر ضروري لاستخدامها السريري. سيكون من الضروري إجراء دراسات قبل سريرية شاملة، بما في ذلك تقييمات السمية في الجسم الحي ودراسات التحلل الحيوي، لضمان سلامة وتحمل هذه الجسيمات النانوية في التطبيقات الفموية. علاوة على ذلك، فإن استكشاف طرق توصيل بديلة لـ ZnO-PIP NPs، مثل الجل الموضعي، وغسولات الفم، أو زراعة الأسنان المغلفة بـ ZnO-PIP NPs، يمكن أن يعزز من وصولها وفعاليتها في البيئات السريرية. سيكون من الضروري التحقيق في استقرار وإطلاق ZnO-PIP NPs من هذه الأنظمة التوصيلية لتحسين نتائجها العلاجية. بالإضافة إلى خصائصها المضادة للميكروبات والمضادة للسرطان، فإن النشاط المضاد للأكسدة لـ ZnO-PIP NPs يقدم فرصًا لتخفيف الأمراض الفموية المرتبطة بالإجهاد التأكسدي، بما في ذلك تسوس الأسنان وأمراض اللثة. يمكن أن تركز الأبحاث المستقبلية على تقييم إمكانيات ZnO-PIP NPs في تعزيز تجديد الأنسجة الفموية وشفاء الجروح، خاصة في سياق علاج اللثة وجراحة الفم.

الخاتمة

معلومات إضافية

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

الموافقة الأخلاقية

الموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم الاستلام: 26 فبراير 2024 / تم القبول: 22 مايو 2024

References

- Thanvi J, Bumb D. Impact of dental considerations on the quality of life of oral cancer patients. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2014;35:66-70. https://doi. org/10.4103/0971-5851.133724.

- Coll PP, Lindsay A, Meng J, Gopalakrishna A, Raghavendra S, Bysani P, et al. The Prevention of infections in older adults: oral health. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:411-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs. 16154.

- Borse V, Konwar AN, Buragohain P. Oral cancer diagnosis and perspectives in India. Sens Int. 2020;1:100046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sintl.2020.100046.

- Xiu W, Shan J, Yang K, Xiao H, Yuwen L, Wang L. Recent development of nanomedicine for the treatment of bacterial biofilm infections. VIEW. 2021;2. https://doi.org/10.1002/NIW. 20200065.

- Gao Z, Chen X, Wang C, Song J, Xu J, Liu X, et al. New strategies and mechanisms for targeting Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation to prevent dental caries: a review. Microbiol Res. 2024;278:127526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. micres.2023.127526.

- Wong J, Manoil D, Näsman P, Belibasakis GN, Neelakantan P. Microbiological aspects of Root Canal infections and Disinfection Strategies: an Update Review on the current knowledge and challenges. Front Oral Heal. 2021;2. https://doi.org/10.3389/froh.2021.672887.

- Talapko J, Juzbašić M, Matijević T, Pustijanac E, Bekić S, Kotris I, et al. Candida albicans-the virulence factors and clinical manifestations of infection. J Fungi. 2021;7:79. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7020079.

- Perera M, Perera I, Tilakaratne WM. Oral microbiome and oral Cancer. Immunol Dent. 2023;79-99. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119893035.ch7.

- Khalil AA, Sarkis SA. Immunohistochemical expressions of AKT, ATM and Cyclin E in oral squamous cell Carcinom. J Baghdad Coll Dent. 2016;28:44-51. https://doi.org/10.12816/0031107.

- Khalil AA, Enezei HH, Aldelaimi TN, Mohammed KA. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2024;35:e204-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000009959.

- Aldelaimi TN, Khalil AA. Clinical application of Diode Laser (980 nm) in Maxillofacial Surgical procedures. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:1220-3. https://doi. org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000001727.

- Sarkis SA, Khalil AA. An immunohistochemical expressions of BAD, MDM2 and P21 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Baghdad Coll Dent. 2016;28:34-9. https://doi.org/10.12816/0028211.

- Li T-J, Hao Y, Tang Y, Liang X. Periodontal pathogens: a crucial link between Periodontal diseases and oral Cancer. Front Microbiol. 2022;13. https://doi. org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.919633.

- Stasiewicz M, Karpiński TM. The oral microbiota and its role in carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86:633-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. semcancer.2021.11.002.

- Abati S, Bramati C, Bondi S, Lissoni A, Trimarchi M. Oral Cancer and precancer: a narrative review on the relevance of early diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249160.

- Sachdeva A, Dhawan D, Jain GK, Yerer MB, Collignon TE, Tewari D, et al. Novel strategies for the bioavailability augmentation and efficacy improvement of Natural products in oral Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;15:268. https://doi. org/10.3390/cancers15010268.

- Mitra S, Anand U, Jha NK, Shekhawat MS, Saha SC, Nongdam P, et al. Anticancer Applications and Pharmacological properties of Piperidine and Piperine: a Comprehensive Review on Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Front Pharmacol. 2022;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.772418.

- Zhang T, Du E, Liu Y, Cheng J, Zhang Z, Xu Y et al. Anticancer effects of Zinc Oxide nanoparticles through altering the methylation status of histone on bladder Cancer cells. Int J Nanomed 2020;Volume 15:1457-68. https://doi. org/10.2147/IJN.S228839.

- Ravikumar OV, Marunganathan V, Kumar MSK, Mohan M, Shaik MR, Shaik B, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles functionalized with cinnamic acid for targeting dental pathogens receptor and modulating apoptotic genes in human oral epidermal carcinoma KB cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51:352. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11033-024-09289-9.

- Tayyeb JZ, Priya M, Guru A, Kishore Kumar MS, Giri J, Garg A, et al. Multifunctional curcumin mediated zinc oxide nanoparticle enhancing biofilm inhibition and targeting apoptotic specific pathway in oral squamous carcinoma cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51:423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-024-09407-7.

- Marunganathan V, Kumar MSK, Kari ZA, Giri J, Shaik MR, Shaik B, et al. Marinederived k-carrageenan-coated zinc oxide nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery and apoptosis induction in oral cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51:89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-023-09146-1.

- Prabha N, Guru A, Harikrishnan R, Gatasheh MK, Hatamleh AA, Juliet A, et al. Neuroprotective and antioxidant capability of RW20 peptide from histone acetyltransferases caused by oxidative stress-induced neurotoxicity in in vivo zebrafish larval model. J King Saud Univ – Sci. 2022;34:101861. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.101861.

- Haridevamuthu B, Guru A, Murugan R, Sudhakaran G, Pachaiappan R, Almutairi MH, et al. Neuroprotective effect of Biochanin a against Bisphenol A-induced prenatal neurotoxicity in zebrafish by modulating oxidative stress and locomotory defects. Neurosci Lett. 2022;790:136889. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136889.

- Murugan R, Rajesh R, Seenivasan B, Haridevamuthu B, Sudhakaran G, Guru

, et al. Withaferin a targets the membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and mitigates the inflammation in zebrafish larvae; an in vitro and in vivo approach. Microb Pathog. 2022;172:105778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. micpath.2022.105778. - Siddhu NSS, Guru A, Satish Kumar RC, Almutairi BO, Almutairi MH, Juliet A, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokine molecules from Boswellia serrate suppresses lipopolysaccharides induced inflammation demonstrated in an in-vivo zebrafish larval model. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49:7425-35. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11033-022-07544-5.

- Velayutham M, Guru A, Gatasheh MK, Hatamleh AA, Juliet A, Arockiaraj J. Molecular Docking of SA11, RF13 and DI14 peptides from Vacuolar Protein Sorting Associated Protein 26B against Cancer proteins and in vitro

investigation of its Anticancer Potency in Hep-2 cells. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2022;28:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10989-022-10395-0. - Guru A, Sudhakaran G, Velayutham M, Murugan R, Pachaiappan R, Mothana RA, et al. Daidzein normalized gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity and associated pro-inflammatory cytokines in MDCK and zebrafish: possible mechanism of nephroprotection. Comp Biochem Physiol Part – C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2022;258:109364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2022.109364.

- Heidari M, Doosti A. Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin type B (SEB) and alpha-toxin induced apoptosis in KB cell line. J Med Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023;11:96-102. https://doi.org/10.52547/JoMMID.11.2.96.

- Hong JM, Kim JE, Min SK, Kim KH, Han SJ, Yim JH, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Antarctic Lichen Umbilicaria antarctica methanol extract in Lipo-polysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells and zebrafish model. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8812090.

- Abdelghafar A, Yousef N, Askoura M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles reduce biofilm formation, synergize antibiotics action and attenuate Staphylococcus aureus virulence in host; an important message to clinicians. BMC Microbiol. 2022;22:244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-022-02658-z.

- Alves FS, Cruz JN, de Farias Ramos IN, DL do Nascimento Brandão, RN Queiroz, GV da Silva, et al. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity effects of extracts of Piper nigrum L. and Piperine. Separations. 2022;10:21. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10010021.

- Malcangi G, Patano A, Ciocia AM, Netti A, Viapiano F, Palumbo I, et al. Benefits Nat Antioxid Oral Health Antioxid. 2023;12:1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/ antiox12061309.

- Nari-Ratih D, Widyastuti A. Effect of antioxidants on the shear bond strength of composite resin to enamel following extra-coronal bleaching. J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;e126-32. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.55359.

- Magaña-Barajas E, Buitimea-Cantúa GV, Hernández-Morales A, Torres-Pelayo V, del R, Vázquez-Martínez J, Buitimea-Cantúa NE. In vitro a- amylase and a-glucosidase enzyme inhibition and antioxidant activity by capsaicin and piperine from Capsicum chinense and Piper nigrum fruits. J Environ Sci Heal Part B. 2021;56:282-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601234.2020.1869477.

- Bürgers R, Hahnel S, Reichert TE, Rosentritt M, Behr M, Gerlach T, et al. Adhesion of Candida albicans to various dental implant surfaces and the influence of salivary pellicle proteins. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2307-13. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.actbio.2009.11.003.

- Minkiewicz-Zochniak A, Jarzynka S, Iwańska A, Strom K, Iwańczyk B, Bartel M, et al. Biofilm formation on Dental Implant Biomaterials by Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from patients with cystic fibrosis. Mater (Basel). 2021;14:2030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14082030.

- Funk B, Kirmayer D, Sahar-Heft S, Gati I, Friedman M, Steinberg D. Efficacy and potential use of novel sustained release fillers as intracanal medicaments against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm in vitro. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0879-1.

- Das

, Paul P, Chatterjee , Chakraborty P, Sarker RK, Das A, et al. Piperine exhibits promising antibiofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus by accumulating reactive oxygen species (ROS). Arch Microbiol. 2022;204:59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-021-02642-7. - Marsh PD. Dental plaque as a biofilm and a microbial community – implications for health and disease. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6:S14. https://doi. org/10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S14.

- Corrigan RM, Rigby D, Handley P, Foster TJ. The role of Staphylococcus aureus surface protein SasG in adherence and biofilm formation. Microbiology. 2007;153:2435-46. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.2007/006676-0.

- Manzer HS, Nobbs AH, Doran KS. The multifaceted nature of Streptococcal Antigen I/II proteins in colonization and Disease Pathogenesis. Front Microbiol. 2020;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.602305.

- Matsumoto-Nakano M. Role of Streptococcus mutans surface proteins for biofilm formation. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2018;54:22-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jdsr.2017.08.002.

- Elashiry MM, Bergeron BE, Tay FR. Enterococcus faecalis in secondary apical periodontitis: mechanisms of bacterial survival and disease persistence. Microb Pathog. 2023;183:106337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. micpath.2023.106337.

- Todd OA, Peters BM. Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus Pathogenicity and Polymicrobial interactions: lessons beyond Koch’s postulates. J Fungi. 2019;5:81. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof5030081.

- Tsai M-S, Chen Y-Y, Chen W-C, Chen M-F. Streptococcus mutans promotes tumor progression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer. 2022;13:335867. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.73310.

- Di Cosola M, Cazzolla AP, Charitos IA, Ballini A, Inchingolo F, Santacroce L. Candida albicans and oral carcinogenesis. Brief Rev J Fungi. 2021;7:476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7060476.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

أجاى جورو

ajayguru.sdc@saveetha.com

سوراف مالك

sauravmtech2@gmail.com; smallik@hsph.harvard.edu

محمد عاصف شاه

drmohdasifshah@kdu.edu.et

جيسو أروكياراج

jesuaroa@srmist.edu.in

القائمة الكاملة لمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقال

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04399-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38907185

Publication Date: 2024-06-21

Piperine-coated zinc oxide nanoparticles target biofilms and induce oral cancer apoptosis via BCl-2/BAX/P53 pathway

Abstract

Background Dental pathogens play a crucial role in oral health issues, including tooth decay, gum disease, and oral infections, and recent research suggests a link between these pathogens and oral cancer initiation and progression. Innovative therapeutic approaches are needed due to antibiotic resistance concerns and treatment limitations. Methods We synthesized and analyzed piperine-coated zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-PIP NPs) using UV spectroscopy, SEM, XRD, FTIR, and EDAX. Antioxidant and antimicrobial effectiveness were evaluated through DPPH, ABTS, and MIC assays, while the anticancer properties were assessed on KB oral squamous carcinoma cells. Results ZnO-PIP NPs exhibited significant antioxidant activity and a MIC of

Introduction

location of the tumor but may include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy [16]. Multidisciplinary approaches involving oncologists, surgeons, dentists, and other healthcare professionals are often necessary to provide comprehensive care to patients with oral cancer.

Materials and methods

Synthesis and characterization of ZnO-PIP NPs

under vacuum. NPs suspensions in distilled water were scanned in the wavelength range of

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH)

2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic) (ABTS)

measured at 734 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer [23].

Minimal inhibitory concentration (mic) assay

Well diffusion method for zone of inhibition

Docking studies

Anticancer assay

Apoptosis gene expression

water. The quality and quantity of RNA were assessed using a spectrophotometer. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using a reverse transcription kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, RNA samples were incubated with a mixture containing reverse transcriptase enzyme, random primers, dNTPs, and RNase inhibitor at

Statistical analysis

Results

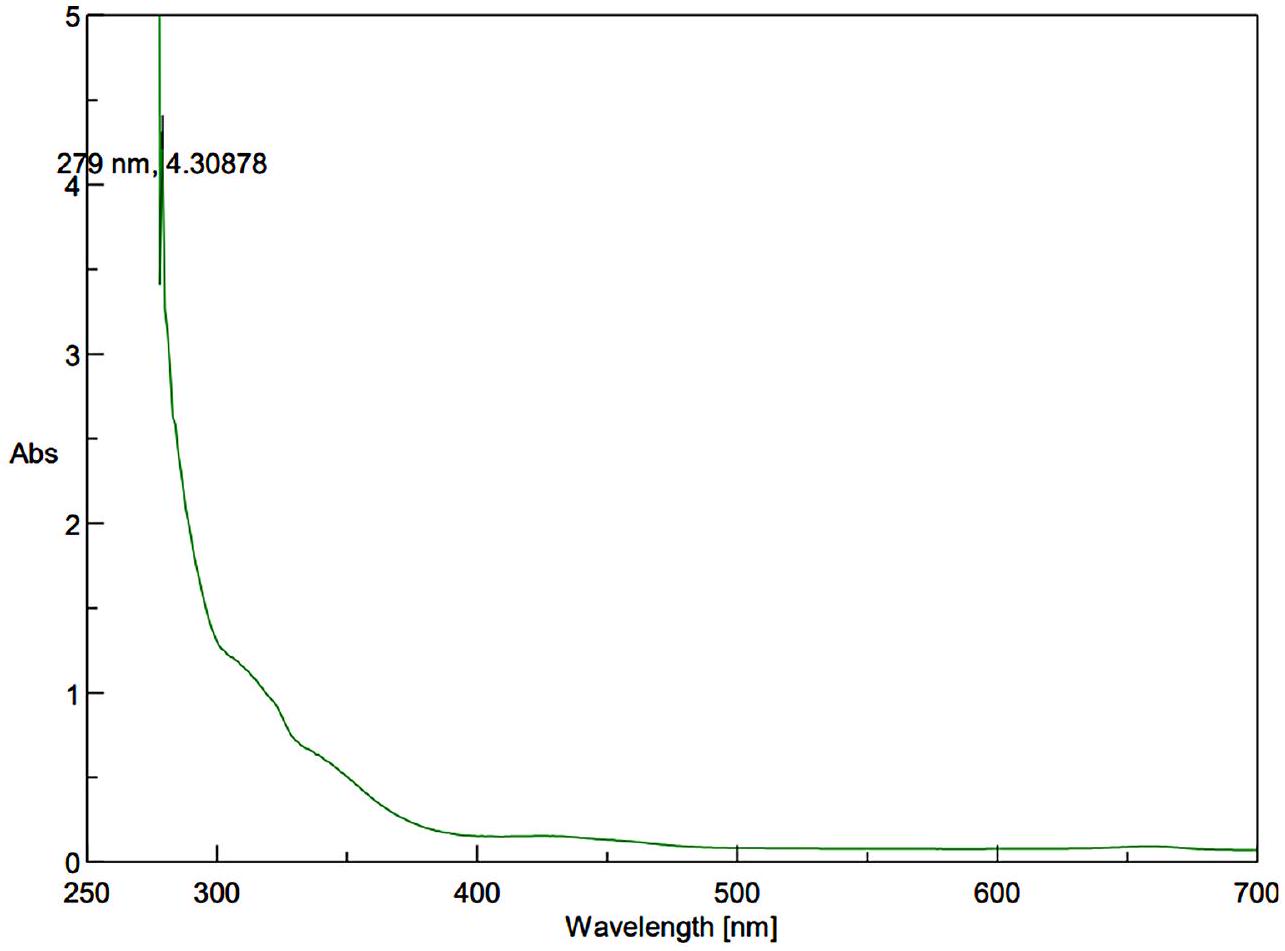

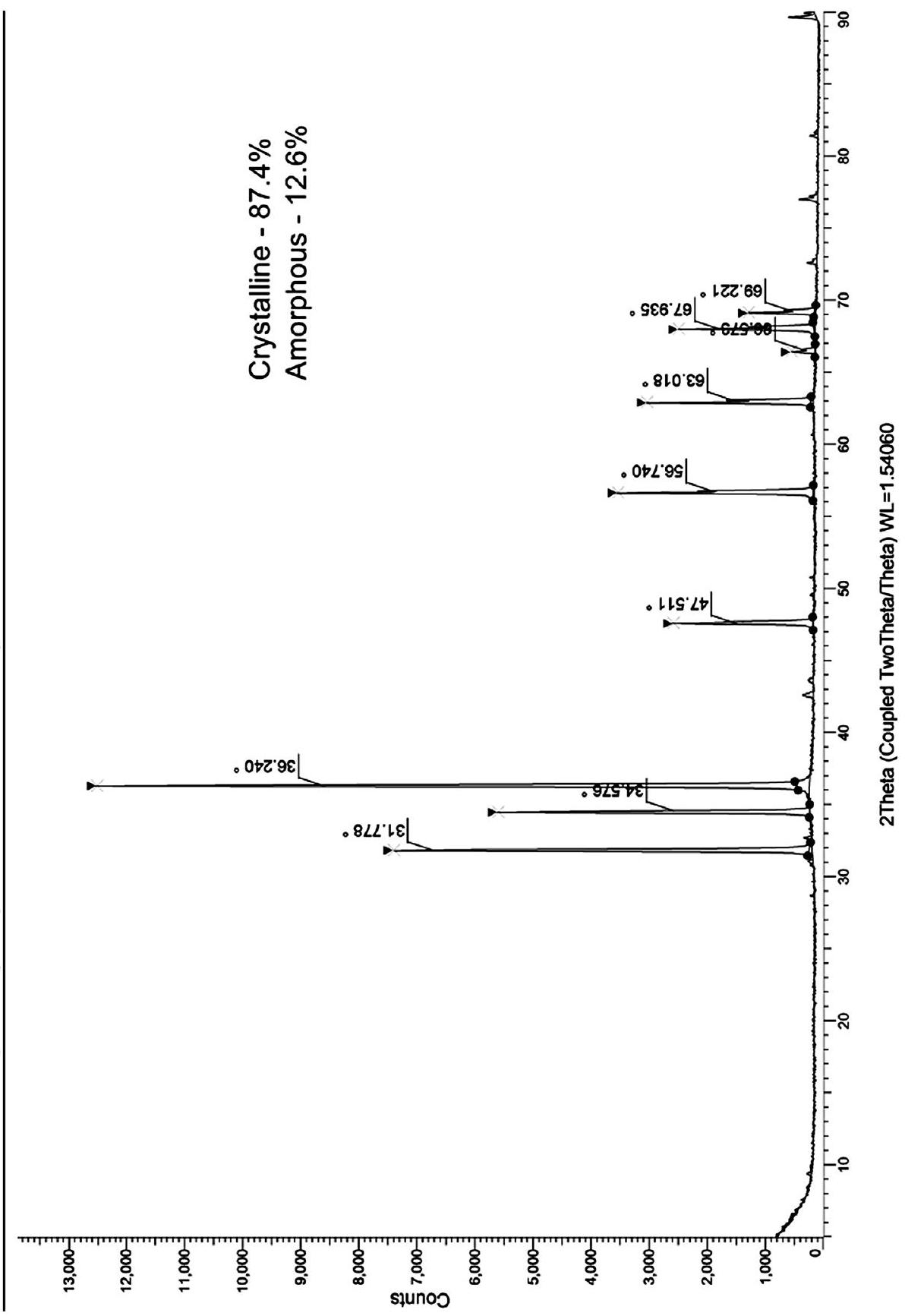

Synthesis and characterization of ZnO-PIP NPs

| Gene | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) | Reference |

| GAPDH | GCCAAAAGGGTCATCATCTCTGC | GGTCACGAGTCCTTCCACGATAC | [28] |

| BCL-2 | GACGACTTCTCCCGCCGCTAC | CGGTTCAGGTACTCAGTCATCCAC | [28] |

| BAX | AGGTCTTTTTCCGAGTGGCAG | GCGTCCCAAAGTAGGAGAGGAG | [28] |

| P53 | ACATGACGGAGGTTGTGAGG | TGTGATGATGGTGAGGATGG | [29] |

crystalline phase comprising

respectively. The presence of well-defined peaks indicates the high crystallinity and purity of the ZnO NPs, with minimal presence of impurities or amorphous phases. The FTIR observed peaks at

Antioxidant activity activity of ZnO-PIP NPs

Antimicrobial activity of ZnO-PIP NPs against dental pathogens

PIP interaction with dental pathogen biofilm receptor

Anticancer activity of ZnO-PIP NPs

in cell viability, dropping to

| Zone of Inhibition (mm) | ||||

| Bacterial Strain | Control | Amoxicillin | ZnO-PIP | ZnO-PIP |

|

|

|

|

||

| Staphylococcus aureus | – | 16 | 8 | 15 |

| Streptococcus mutans | – | 15 | 7 | 14 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | – | 17 | 12 | 18 |

| Candida albicans | – | 15 | 11 | 16 |

Regulating apoptosis signaling pathways in oral cancer

Discussion

The oral cavity is subject to oxidative stress due to various factors such as bacterial infections, inflammation, and exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during metabolic processes. Antioxidants help neutralize ROS, thus protecting oral tissues from oxidative damage [32]. Antioxidants can be incorporated into dental materials such as composites, cements, and sealants to improve their stability, durability, and biocompatibility. This can extend the lifespan of dental restorations

| Receptor (PDB ID) | Ligand | Binding affinity (

|

Amino acid interaction | |

| 1. | S. aureus: Staphylococcus aureus surface protein G (7SMH) | Piperine | -6.7 | ARG, ASP, GLY, and ARG |

| 2. | S. mutans: Antigen I/II carboxy-terminus (3QE5) | Piperine | -6.1 | VAL, VAL, LYS, ILE, and VAL |

| 3. | E. faecalis: Enterococcal surface protein (6ORI) | Piperine | -8.2 | ILE, LYS, ALA, and LEU |

| 4. | C. albicans: ALS3 (4LEE) | Piperine | -7.6 | LYS, LYS, and SER |

the ability to effectively inhibit or neutralize free radicals and reactive oxygen species. Furthermore, it exerts a positive influence on cellular thiol status, antioxidant molecules, and antioxidant enzymes when studied in

system, rendering it resistant to antimicrobial therapies and promoting treatment resistance. These pathogens’ ability to form robust and resilient biofilms underscores the challenges in managing dental infections and highlights the importance of developing strategies to disrupt biofilm formation for effective treatment and prevention of oral diseases [37]. Recent studies have showed that PIP displays notable antibiofilm efficacy against

microbiota, employs its Als3 adhesin to form biofilms and exacerbate dental problems. Als3 plays a pivotal role in the initial attachment of C. albicans to oral surfaces, including tooth enamel and mucosal tissues, by binding to host cell receptors such as E-cadherin and fibronectin. Once adhered, C. albicans secretes extracellular matrix components, including proteins, polysaccharides, and extracellular DNA, forming a robust biofilm structure. This biofilm provides protection against host immune responses and antifungal agents, promoting persistent colonization and contributing to oral diseases such as denture stomatitis and oral candidiasis [44]. The potential interaction between PIP and the receptors involved in biofilm formation among various dental pathogens was evaluated. The results of the study revealed that PIP exhibited a notable affinity towards all the receptors investigated. This finding supports the results obtained from the zone of inhibition assays and biofilm inhibition assays. The outcomes demonstrated that PIP effectively inhibited the growth of dental pathogens and significantly reduced biofilm formation. These results suggest that PIP could be a promising candidate for developing therapeutic agents aimed at disrupting biofilm formation and combating dental infections caused by pathogens such as S. mutans, S. aureus, E. faecalis, and C. albicans. Moreover, the ability of PIP to target multiple receptors associated with biofilm formation underscores its potential as a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent for dental care applications.

The infection by dental pathogens can potentially contribute to the development of oral cancer through various mechanisms. Chronic inflammation triggered by these pathogens’ presence and their byproducts can lead to sustained immune responses, promoting tissue damage and genetic alterations conducive to carcinogenesis [13]. For instance, S. mutans produces lactic acid as a byproduct of sugar metabolism, creating an acidic microenvironment that can damage oral epithelial cells and promote their malignant transformation [45]. Additionally, certain pathogens like C. albicans can produce carcinogenic compounds or toxins, contributing to oncogenic processes. Moreover, these pathogens are often found within biofilms, which not only shield them from host immune responses but also promote local tissue invasion and metastasis, facilitating the spread of malignant cells. Furthermore, chronic infections can disrupt the oral microbiota balance, leading to dysbiosis, which has been associated with an increased risk of oral cancer. Collectively, the interactions between dental pathogens and host tissues can initiate and perpetuate a pro-inflammatory and pro-carcinogenic milieu within the oral cavity, ultimately predisposing individuals to the development of oral cancer [46]. ZnO-PIP NPs, known for their potent antimicrobial activity against dental

pathogens, were further investigated for their potential anticancer effects specifically targeting oral cancer. The results of the study revealed promising anticancer activity, demonstrating a significant reduction in the viability of KB cells, a human oral cancer cell line. This finding suggests that ZnO-PIP NPs possess dual functionality, exhibiting both antimicrobial and anticancer properties. BCL2, BAX, and P53 are pivotal regulators of cellular apoptosis, a process central to cancer development and progression. In oral cancer, dysregulation of apoptosisrelated genes such as BCL2, which inhibits apoptosis, and BAX, which promotes apoptosis, can disrupt the delicate balance between cell proliferation and cell death, leading to uncontrolled tumor growth. Additionally, P53, a tumor suppressor gene, plays a crucial role in orchestrating cellular responses to DNA damage and cellular stress, including the induction of apoptosis in damaged or aberrant cells. Given their critical roles in regulating cell fate decisions, alterations in the expression or activity of these genes can significantly influence the development, progression, and response to therapy in oral cancer. Therefore, studying the expression levels and activity of BCL2, BAX, and P53 in response to ZnO-PIP NPs treatment provides valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of their anticancer effects and elucidates potential therapeutic targets for combating oral cancer. In the study investigating the anticancer activity of ZnO-PIP NPs in KB cells, the results revealed significant alterations in the expression levels of key apoptosisrelated genes, including BCL2, BAX, and P53. Treatment with ZnO-PIP NPs resulted in a remarkable downregulation of BCL2, an anti-apoptotic protein known to inhibit cell death, thereby shifting the balance towards apoptosis induction. Concurrently, there was an upregulation of BAX, a pro-apoptotic protein that promotes apoptosis by facilitating mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and subsequent cytochrome c release, further enhancing the apoptotic response in KB cells. Moreover, ZnO-PIP NPs treatment led to the upregulation of P53, a tumor suppressor gene crucial for orchestrating cellular responses to DNA damage and stress. The upregulation of P53 likely contributed to the activation of downstream apoptotic pathways, including the transcriptional regulation of pro-apoptotic genes and the induction of cell cycle arrest, ultimately leading to the inhibition of KB cell proliferation and the promotion of cell death. Collectively, these results suggest that the anticancer activity of ZnO PIP NPs in KB cells is mediated through the modulation of BCL2, BAX, and P53 expression levels, highlighting their potential as promising therapeutic agents for oral cancer treatment by targeting key apoptotic pathways.

profile and biocompatibility of ZnO-PIP NPs is essential for their clinical use. Conducting comprehensive preclinical studies, including in vivo toxicity assessments and biodegradation studies, will be crucial to ensure the safety and tolerability of these nanoparticles in oral applications. Furthermore, exploring alternative delivery methods for ZnO-PIP NPs, such as topical gels, mouthwashes, or dental implants coated with ZnO-PIP NPs, could enhance their accessibility and efficacy in clinical settings. Investigating the stability and release kinetics of ZnO-PIP NPs from these delivery systems will be imperative to optimize their therapeutic outcomes. In addition to their antimicrobial and anticancer properties, the antioxidant activity of ZnO-PIP NPs presents opportunities for mitigating oxidative stress-related oral diseases, including dental caries and periodontal diseases. Future research could focus on evaluating the potential of ZnO-PIP NPs in promoting oral tissue regeneration and wound healing, particularly in the context of periodontal therapy and oral surgery.

Conclusion

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethical approval

Consent to participate

Consent to publish

Competing interests

Author details

Received: 26 February 2024 / Accepted: 22 May 2024

References

- Thanvi J, Bumb D. Impact of dental considerations on the quality of life of oral cancer patients. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2014;35:66-70. https://doi. org/10.4103/0971-5851.133724.

- Coll PP, Lindsay A, Meng J, Gopalakrishna A, Raghavendra S, Bysani P, et al. The Prevention of infections in older adults: oral health. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:411-6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs. 16154.

- Borse V, Konwar AN, Buragohain P. Oral cancer diagnosis and perspectives in India. Sens Int. 2020;1:100046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sintl.2020.100046.

- Xiu W, Shan J, Yang K, Xiao H, Yuwen L, Wang L. Recent development of nanomedicine for the treatment of bacterial biofilm infections. VIEW. 2021;2. https://doi.org/10.1002/NIW. 20200065.

- Gao Z, Chen X, Wang C, Song J, Xu J, Liu X, et al. New strategies and mechanisms for targeting Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation to prevent dental caries: a review. Microbiol Res. 2024;278:127526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. micres.2023.127526.

- Wong J, Manoil D, Näsman P, Belibasakis GN, Neelakantan P. Microbiological aspects of Root Canal infections and Disinfection Strategies: an Update Review on the current knowledge and challenges. Front Oral Heal. 2021;2. https://doi.org/10.3389/froh.2021.672887.

- Talapko J, Juzbašić M, Matijević T, Pustijanac E, Bekić S, Kotris I, et al. Candida albicans-the virulence factors and clinical manifestations of infection. J Fungi. 2021;7:79. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7020079.

- Perera M, Perera I, Tilakaratne WM. Oral microbiome and oral Cancer. Immunol Dent. 2023;79-99. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119893035.ch7.

- Khalil AA, Sarkis SA. Immunohistochemical expressions of AKT, ATM and Cyclin E in oral squamous cell Carcinom. J Baghdad Coll Dent. 2016;28:44-51. https://doi.org/10.12816/0031107.

- Khalil AA, Enezei HH, Aldelaimi TN, Mohammed KA. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2024;35:e204-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000009959.

- Aldelaimi TN, Khalil AA. Clinical application of Diode Laser (980 nm) in Maxillofacial Surgical procedures. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:1220-3. https://doi. org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000001727.

- Sarkis SA, Khalil AA. An immunohistochemical expressions of BAD, MDM2 and P21 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Baghdad Coll Dent. 2016;28:34-9. https://doi.org/10.12816/0028211.

- Li T-J, Hao Y, Tang Y, Liang X. Periodontal pathogens: a crucial link between Periodontal diseases and oral Cancer. Front Microbiol. 2022;13. https://doi. org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.919633.

- Stasiewicz M, Karpiński TM. The oral microbiota and its role in carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86:633-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. semcancer.2021.11.002.

- Abati S, Bramati C, Bondi S, Lissoni A, Trimarchi M. Oral Cancer and precancer: a narrative review on the relevance of early diagnosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249160.

- Sachdeva A, Dhawan D, Jain GK, Yerer MB, Collignon TE, Tewari D, et al. Novel strategies for the bioavailability augmentation and efficacy improvement of Natural products in oral Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;15:268. https://doi. org/10.3390/cancers15010268.

- Mitra S, Anand U, Jha NK, Shekhawat MS, Saha SC, Nongdam P, et al. Anticancer Applications and Pharmacological properties of Piperidine and Piperine: a Comprehensive Review on Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Front Pharmacol. 2022;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2021.772418.

- Zhang T, Du E, Liu Y, Cheng J, Zhang Z, Xu Y et al. Anticancer effects of Zinc Oxide nanoparticles through altering the methylation status of histone on bladder Cancer cells. Int J Nanomed 2020;Volume 15:1457-68. https://doi. org/10.2147/IJN.S228839.

- Ravikumar OV, Marunganathan V, Kumar MSK, Mohan M, Shaik MR, Shaik B, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles functionalized with cinnamic acid for targeting dental pathogens receptor and modulating apoptotic genes in human oral epidermal carcinoma KB cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51:352. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11033-024-09289-9.

- Tayyeb JZ, Priya M, Guru A, Kishore Kumar MS, Giri J, Garg A, et al. Multifunctional curcumin mediated zinc oxide nanoparticle enhancing biofilm inhibition and targeting apoptotic specific pathway in oral squamous carcinoma cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51:423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-024-09407-7.

- Marunganathan V, Kumar MSK, Kari ZA, Giri J, Shaik MR, Shaik B, et al. Marinederived k-carrageenan-coated zinc oxide nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery and apoptosis induction in oral cancer. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51:89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-023-09146-1.

- Prabha N, Guru A, Harikrishnan R, Gatasheh MK, Hatamleh AA, Juliet A, et al. Neuroprotective and antioxidant capability of RW20 peptide from histone acetyltransferases caused by oxidative stress-induced neurotoxicity in in vivo zebrafish larval model. J King Saud Univ – Sci. 2022;34:101861. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.101861.

- Haridevamuthu B, Guru A, Murugan R, Sudhakaran G, Pachaiappan R, Almutairi MH, et al. Neuroprotective effect of Biochanin a against Bisphenol A-induced prenatal neurotoxicity in zebrafish by modulating oxidative stress and locomotory defects. Neurosci Lett. 2022;790:136889. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.neulet.2022.136889.

- Murugan R, Rajesh R, Seenivasan B, Haridevamuthu B, Sudhakaran G, Guru

, et al. Withaferin a targets the membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and mitigates the inflammation in zebrafish larvae; an in vitro and in vivo approach. Microb Pathog. 2022;172:105778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. micpath.2022.105778. - Siddhu NSS, Guru A, Satish Kumar RC, Almutairi BO, Almutairi MH, Juliet A, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokine molecules from Boswellia serrate suppresses lipopolysaccharides induced inflammation demonstrated in an in-vivo zebrafish larval model. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49:7425-35. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11033-022-07544-5.

- Velayutham M, Guru A, Gatasheh MK, Hatamleh AA, Juliet A, Arockiaraj J. Molecular Docking of SA11, RF13 and DI14 peptides from Vacuolar Protein Sorting Associated Protein 26B against Cancer proteins and in vitro

investigation of its Anticancer Potency in Hep-2 cells. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2022;28:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10989-022-10395-0. - Guru A, Sudhakaran G, Velayutham M, Murugan R, Pachaiappan R, Mothana RA, et al. Daidzein normalized gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity and associated pro-inflammatory cytokines in MDCK and zebrafish: possible mechanism of nephroprotection. Comp Biochem Physiol Part – C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2022;258:109364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2022.109364.

- Heidari M, Doosti A. Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin type B (SEB) and alpha-toxin induced apoptosis in KB cell line. J Med Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023;11:96-102. https://doi.org/10.52547/JoMMID.11.2.96.

- Hong JM, Kim JE, Min SK, Kim KH, Han SJ, Yim JH, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Antarctic Lichen Umbilicaria antarctica methanol extract in Lipo-polysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells and zebrafish model. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8812090.

- Abdelghafar A, Yousef N, Askoura M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles reduce biofilm formation, synergize antibiotics action and attenuate Staphylococcus aureus virulence in host; an important message to clinicians. BMC Microbiol. 2022;22:244. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-022-02658-z.

- Alves FS, Cruz JN, de Farias Ramos IN, DL do Nascimento Brandão, RN Queiroz, GV da Silva, et al. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity effects of extracts of Piper nigrum L. and Piperine. Separations. 2022;10:21. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10010021.

- Malcangi G, Patano A, Ciocia AM, Netti A, Viapiano F, Palumbo I, et al. Benefits Nat Antioxid Oral Health Antioxid. 2023;12:1309. https://doi.org/10.3390/ antiox12061309.

- Nari-Ratih D, Widyastuti A. Effect of antioxidants on the shear bond strength of composite resin to enamel following extra-coronal bleaching. J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;e126-32. https://doi.org/10.4317/jced.55359.

- Magaña-Barajas E, Buitimea-Cantúa GV, Hernández-Morales A, Torres-Pelayo V, del R, Vázquez-Martínez J, Buitimea-Cantúa NE. In vitro a- amylase and a-glucosidase enzyme inhibition and antioxidant activity by capsaicin and piperine from Capsicum chinense and Piper nigrum fruits. J Environ Sci Heal Part B. 2021;56:282-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601234.2020.1869477.

- Bürgers R, Hahnel S, Reichert TE, Rosentritt M, Behr M, Gerlach T, et al. Adhesion of Candida albicans to various dental implant surfaces and the influence of salivary pellicle proteins. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2307-13. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.actbio.2009.11.003.

- Minkiewicz-Zochniak A, Jarzynka S, Iwańska A, Strom K, Iwańczyk B, Bartel M, et al. Biofilm formation on Dental Implant Biomaterials by Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from patients with cystic fibrosis. Mater (Basel). 2021;14:2030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14082030.

- Funk B, Kirmayer D, Sahar-Heft S, Gati I, Friedman M, Steinberg D. Efficacy and potential use of novel sustained release fillers as intracanal medicaments against Enterococcus faecalis biofilm in vitro. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0879-1.

- Das

, Paul P, Chatterjee , Chakraborty P, Sarker RK, Das A, et al. Piperine exhibits promising antibiofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus by accumulating reactive oxygen species (ROS). Arch Microbiol. 2022;204:59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-021-02642-7. - Marsh PD. Dental plaque as a biofilm and a microbial community – implications for health and disease. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6:S14. https://doi. org/10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S14.

- Corrigan RM, Rigby D, Handley P, Foster TJ. The role of Staphylococcus aureus surface protein SasG in adherence and biofilm formation. Microbiology. 2007;153:2435-46. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.2007/006676-0.

- Manzer HS, Nobbs AH, Doran KS. The multifaceted nature of Streptococcal Antigen I/II proteins in colonization and Disease Pathogenesis. Front Microbiol. 2020;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.602305.

- Matsumoto-Nakano M. Role of Streptococcus mutans surface proteins for biofilm formation. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2018;54:22-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jdsr.2017.08.002.

- Elashiry MM, Bergeron BE, Tay FR. Enterococcus faecalis in secondary apical periodontitis: mechanisms of bacterial survival and disease persistence. Microb Pathog. 2023;183:106337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. micpath.2023.106337.

- Todd OA, Peters BM. Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus Pathogenicity and Polymicrobial interactions: lessons beyond Koch’s postulates. J Fungi. 2019;5:81. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof5030081.

- Tsai M-S, Chen Y-Y, Chen W-C, Chen M-F. Streptococcus mutans promotes tumor progression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer. 2022;13:335867. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.73310.

- Di Cosola M, Cazzolla AP, Charitos IA, Ballini A, Inchingolo F, Santacroce L. Candida albicans and oral carcinogenesis. Brief Rev J Fungi. 2021;7:476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7060476.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Ajay Guru

ajayguru.sdc@saveetha.com

Saurav Mallik

sauravmtech2@gmail.com; smallik@hsph.harvard.edu

Mohd Asif Shah

drmohdasifshah@kdu.edu.et

Jesu Arockiaraj

jesuaroa@srmist.edu.in

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article