DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00653-w

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-14

حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي: مراجعة منهجية للأدبيات

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

الملخص

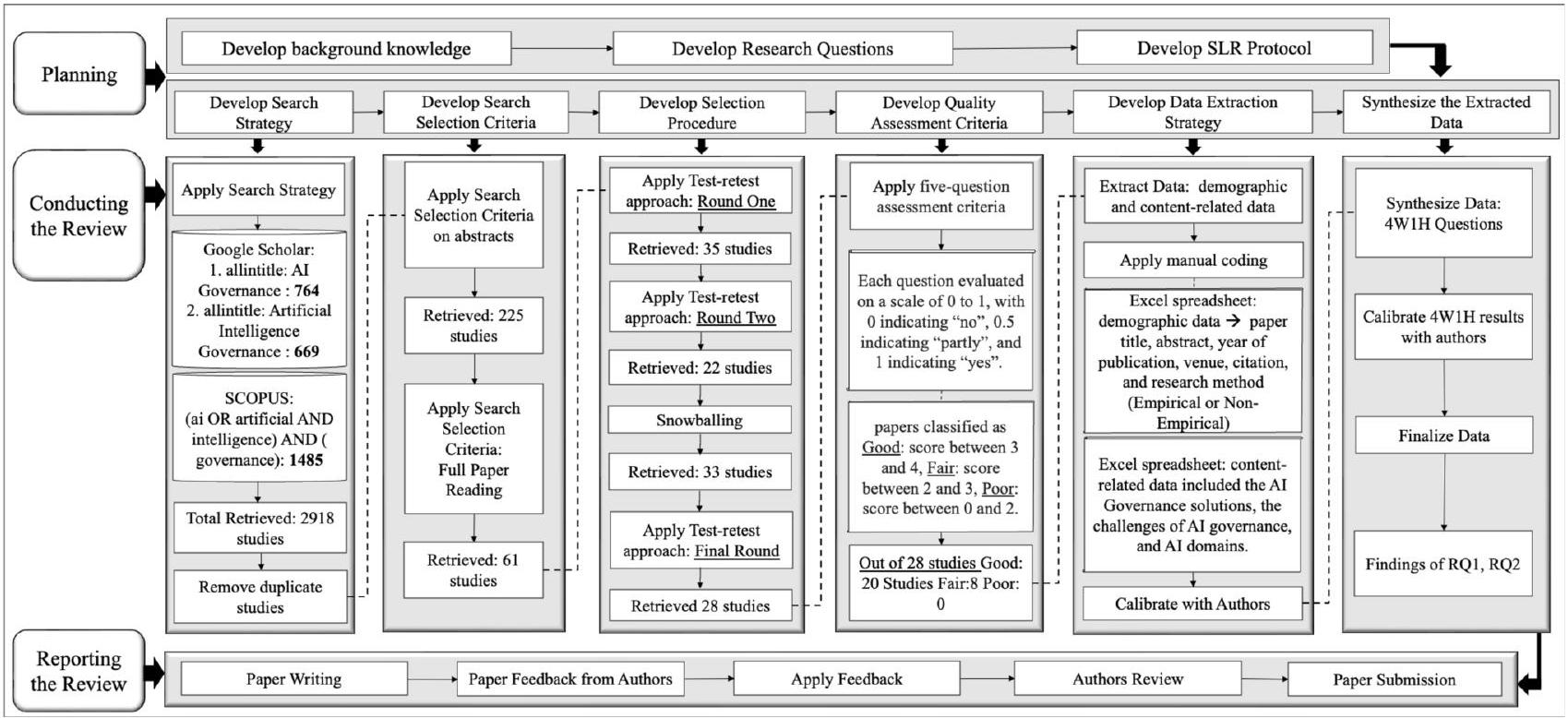

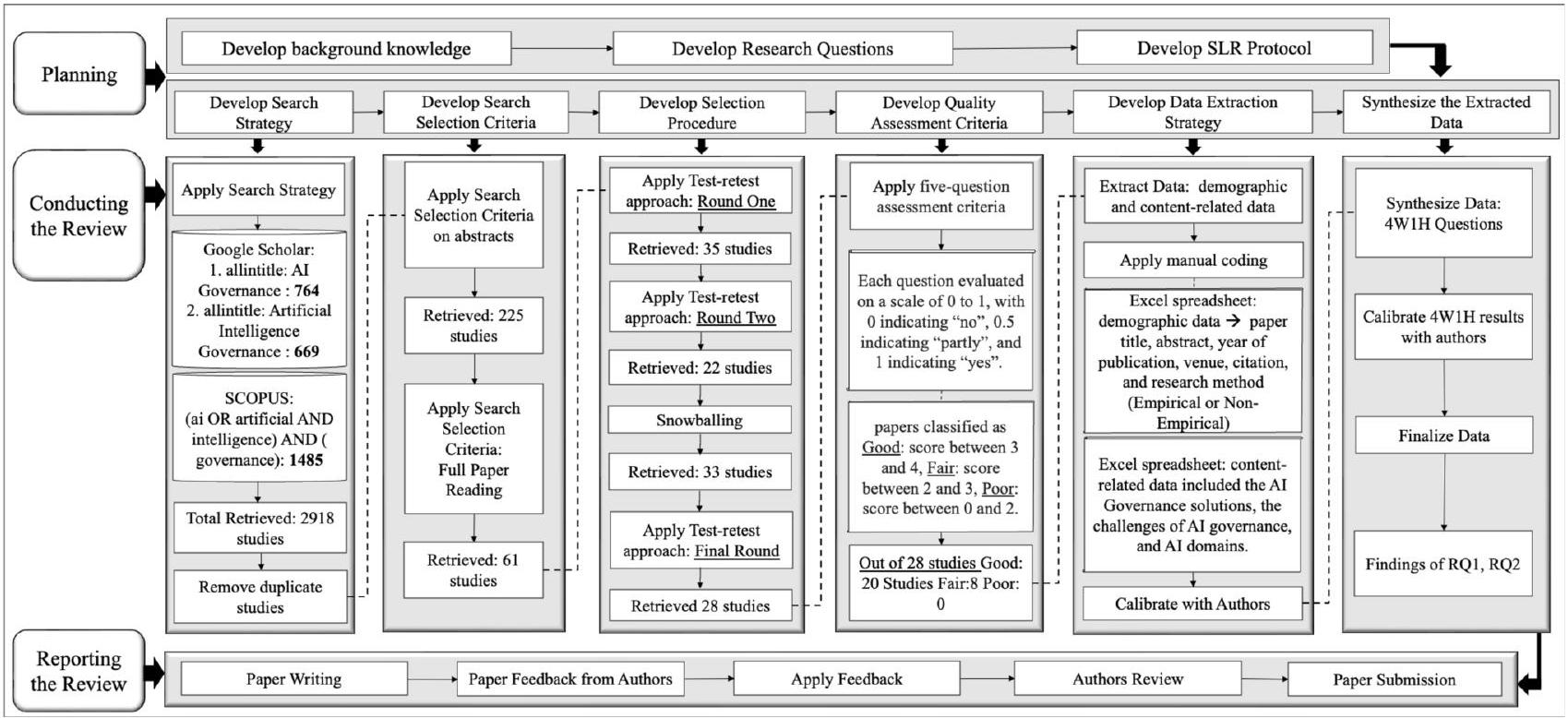

بينما تحول الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) مجموعة واسعة من القطاعات وتدفع الابتكار، فإنه يقدم أيضًا أنواعًا مختلفة من المخاطر التي يجب تحديدها وتقييمها وتخفيفها. تم إصدار العديد من أطر حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي مؤخرًا من قبل الحكومات والمنظمات والشركات لتخفيف المخاطر المرتبطة بالذكاء الاصطناعي. ومع ذلك، قد يكون من الصعب على المعنيين بالذكاء الاصطناعي الحصول على صورة واضحة عن أطر حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي المتاحة، أو الأدوات، أو النماذج وتحليل الأنسب لنظام الذكاء الاصطناعي الخاص بهم. لسد هذه الفجوة، نقدم الأدبيات للإجابة على أسئلة رئيسية: من المسؤول عن حوكمة أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي، ما هي العناصر التي يتم حوكمتها، متى تحدث الحوكمة ضمن دورة حياة تطوير الذكاء الاصطناعي، وكيف يتم تنفيذها من خلال الأطر، أو الأدوات، أو السياسات، أو النماذج. من خلال اعتماد منهجية مراجعة الأدبيات المنهجية (SLR)، بحثت هذه الدراسة بدقة، واختارت، وحللت 28 مقالة، مقدمة أساسًا لفهم جوانب مختلفة من حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي. تم تعزيز التحليل بشكل أكبر من خلال تصنيف عناصر حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي تحت حوكمة على مستوى الفريق، حوكمة على مستوى المنظمة، حوكمة على مستوى الصناعة، حوكمة على المستوى الوطني، وحوكمة على المستوى الدولي. يمكن أن تساعد نتائج هذه الدراسة حول حلول حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الحالية المجتمعات البحثية في اقتراح ممارسات شاملة لحوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي.

1 المقدمة

وتتوافق نشر تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي مع استراتيجياتها ومبادئها وأهدافها [8]. وبالتالي، فإن المنظمات الحكومية والدولية، بما في ذلك قانون الذكاء الاصطناعي في الاتحاد الأوروبي،

- تحليل شامل لـ 28 ورقة بحثية مختارة من الأدبيات الأكاديمية.

- استكشاف التحديات والقيود التي تواجه حلول حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الحالية.

- تصنيف العناصر الرئيسية المقدمة تحت خمسة مستويات من الحوكمة. تم تنظيم هذه الورقة على النحو التالي: القسم 2 يقدم الخلفية والأعمال ذات الصلة. القسم 3 يقدم منهجية البحث مع أسئلة البحث واستخراج البيانات. القسم 4 يقدم تحليل البيانات الذي تم إجراؤه على 28 دراسة مختارة وتصنيف حلول حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي تحت خمسة مستويات من حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي. القسم 5 يقدم المناقشة والقسم 6 يقدم التهديدات لصحة الدراسة وقيودها. القسم 7 يختتم الدراسة مع العمل المستقبلي.

2 الخلفية والأعمال ذات الصلة

مقالة باستخدام منهجية PRISMA. قاموا بتصنيف المقالات إلى أربعة مستويات: فردية، عائلية، مجتمعية، وحوكمة. قدمت الدراسة إطارًا مفاهيميًا يربط بين طبقة الذكاء الاصطناعي-التكنولوجية، وطبقة الذكاء الاصطناعي-الأخلاقية، وطبقة الذكاء الاصطناعي-التنظيمية، وطبقة الذكاء الاصطناعي-التنفيذ، بهدف تعزيز مرونة الأطفال، ورفاهيتهم، والخدمات العامة.

- تركيز المراجعة: في هذه المراجعة الأدبية المنهجية (SLR)، تم تقديم تحليل شامل لعناصر حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي باستخدام 4 أسئلة محددة (من، ماذا، متى، كيف) لاستخراج بيانات غنية حول حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي.

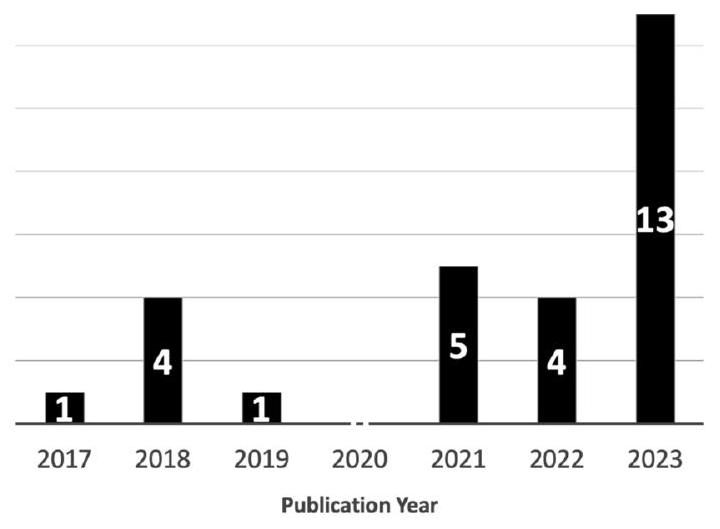

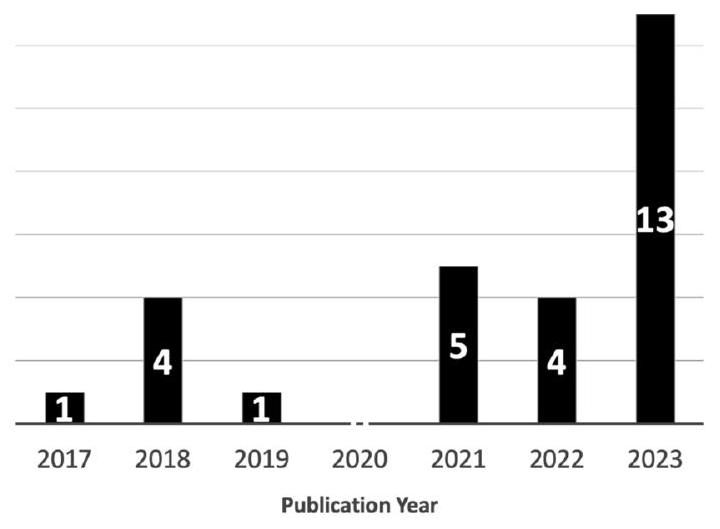

- جدول زمني للمراجعة: تغطي هذه المراجعة الأدبية المنهجية (SLR) المنشورات من 2013 إلى 2023 (10 سنوات).

- نوع الدراسات المشمولة: اتبعت هذه المراجعة الأدبية المنهجية (SLR) الإرشادات الخاصة بالمراجعة الأدبية المنهجية التي وضعتها كيتشام وآخرون [24].

- نطاق مجال الموضوع: توفر هذه المراجعة الأدبية المنهجية (SLR) استكشافًا شاملاً لقطاعات متنوعة مثل الإعلام والاتصالات، والرعاية الصحية، والنقل، والروبوتات، والأكاديمية، والصناعة، إلخ. ركزت المراجعات الحالية بشكل خاص على مجال واحد، إما الرعاية الصحية [25، 26]، أو الروبوتات [27]، أو قطاع الطاقة [28].

- تصنيف حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي وأصحاب المصلحة: قامت هذه المراجعة الأدبية المنهجية (SLR) بتصنيف حلول حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التي تم تحديدها من السؤال كيف يتم الحكم عليها وأصحاب المصلحة الذين تم العثور عليهم من الأسئلة من الذي يحكم إلى مستويات مختلفة، أي فريق، منظمة، صناعة، وطنية، ودولية. الأدبيات الحالية

3 منهجية المراجعة المنهجية

3.1 التخطيط

- RQ1: ما هي الأطر، والنماذج، والأدوات، والسياسات (مبادئ الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقية، والإرشادات، والسياسات) لحوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي المقدمة في الأدبيات؟

- RQ2: ما هي القيود والتحديات المتعلقة بحوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التي تم مناقشتها في الأدبيات؟

| قاعدة البيانات | سلسلة البحث | البحث ضمن | الإطار الزمني | وقت البحث | عدد الأوراق المسترجعة |

| SCOPUS | (AI OR artificial AND intelligence) AND (governance) | العنوان والملخص | 20132023 | 10/07/2023 (10:00 صباحًا) | 1485 |

| Google scholar | Allintitle: AI governance | العنوان فقط | 20132023 | 21/07/2023 (9:00 صباحًا) | 764 |

| Google scholar | Allintitle: Artificial intelligence governance | العنوان فقط | 20132023 | 21/07/2023 (9:00 صباحًا) | 669 |

| الإجمالي: 2918 |

3.2 استراتيجية البحث

وكانت المصادر غير الأكاديمية (مثل أوراق المؤتمرات والمطبوعات السابقة) مفيدة للحصول على منظور أوسع.

3.3 تقييم الجودة

3.4 استخراج البيانات

4 تجميع البيانات وتحليلها

الدولي. يحتوي الملحق ب على المصطلحات لتعريف المصطلحات المستخدمة في هذا الاستعراض المنهجي.

4.1 التحليل

- من الذي يحكم؟: يركز على أصحاب المصلحة (الأدوار الرئيسية في الإشراف على الذكاء الاصطناعي) الذين يجب أن يكونوا مشاركين في الحكم لمراقبة ما إذا كان الذكاء الاصطناعي يتوافق مع المعايير أو اللوائح للذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقي والمسؤول.

- ما الذي يتم الحكم عليه؟: يركز على البيانات والنظام لضمان أي عنصر سواء كان بيانات أو/و نظام يتم الحكم عليه في حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي. يبرز عنصر البيانات أهمية الحصول على البيانات ومعالجتها واستخدامها بشكل مسؤول [30]. تتطلب حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الفعالة التركيز على جودة البيانات والخصوصية والأمان للتخفيف من التحيزات وتعزيز اتخاذ قرارات الذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل عادل وشفاف [30]. يشمل النظام أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي، التي يجب أن تُحكم مع مراعاة قوتها وقابليتها للتفسير ومسؤوليتها.

| البشر (المعنيون) | ||

| من يحكم؟ | ||

| رقم التعريف الشخصي | أدوار الإشراف الرئيسية | مستويات |

| A2 | لجان أخلاقيات الذكاء الاصطناعي من قبل الحكومة | المستوى الوطني |

| A3 | لجنة تنسيق الحوكمة العالمية | المستوى الدولي |

| أ11 | لجنة توجيه متعددة التخصصات بالإضافة إلى لجان فرعية محددة للمشاريع | مستوى المنظمة والفريق |

| أ13 | المديرون العموميون | مستوى المنظمة |

| A23 | أعضاء منظمة الصحة العالمية والاتحاد الدولي للاتصالات | المستوى الدولي |

| A28 | مديرو المستشفيات | مستوى المنظمة |

- متى يتم الحكم عليه؟: يمثل المراحل الثلاث لتطوير الذكاء الاصطناعي التي يجب تطبيق الحلول الحوكمة الخاصة عليها [30]. المراحل الثلاث لتطوير الذكاء الاصطناعي هي مرحلة ما قبل التطوير (التخطيط، الموافقة، وجمع البيانات)، ومرحلة التطوير (التصميم، بناء النماذج، التحقق، والتأكيد)، وما بعد التطوير (المراقبة، والاستخدام)، بما يتماشى مع الأطر والإرشادات المعمول بها من منظمات مثل NIST [32]، OECD [33].

- كيف يتم الحكم عليه؟: يستكشف آثار حلول الحوكمة للذكاء الاصطناعي، مثل السياسات الأخلاقية، والمبادئ والإرشادات، والأدوات، والأطر، والنماذج.

4.1.1 تحليل شامل للأسئلة

ومنع التمييز، بما يتماشى مع المبادئ الأخلاقية بينما تعزز الابتكار [39]. تعكس هذه الاختلافات الإقليمية التحيزات الجيوسياسية الأساسية، حيث تعطي أوروبا الأولوية للمعايير الأخلاقية، وتركز الولايات المتحدة على الابتكار وحرية السوق، وتوازن دول APAC بين السيطرة الحكومية والتنمية الاقتصادية. يوفر إطار أستراليا، الذي يبرز كل من المعايير الأخلاقية والابتكار، أرضية وسطى. إن فهم هذه الفروق الجغرافية يضيف عمقًا إلى تحليل “من” يحكم الذكاء الاصطناعي وكيف تتشكل هياكل الحوكمة من خلال الأهداف الإقليمية.

القضايا، وخاصة الشفافية في أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي، أمر أساسي، ويمكن تحقيق ذلك من خلال إدارة أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي باستخدام آليات حوكمة مختلفة مثل اعتبارات أخلاقية وتحديات خوارزميات التعلم (ECCOLA)، وهي أداة لحوكمة أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقية والموثوقة. بشكل عام، ركزت هذه الدراسات على المخاطر المختلفة المرتبطة بالذكاء الاصطناعي، مما أكد على أن إدارة نظام الذكاء الاصطناعي أمر ضروري.

| عملية | ||

| ما قبل التطوير | أثناء التطوير | ما بعد التنمية |

| A2 | A2 | A2 |

| – | أ7 | – |

| أ11 | – | أ11 |

| أ12 | أ12 | أ12 |

| – | أ13 | – |

| A19 | A19 | A19 |

| A23 | A23 | A23 |

| A25 | A25 | A25 |

| رقم التعريف الشخصي | إطار/نماذج/أدوات/أخلاقيات (مبادئ، سياسات، إرشادات) | نوع | |||||

| A2 | حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقية: القيم الأخلاقية (على المستوى الأعلى) تؤدي إلى المبادئ الأخلاقية التي توجه المعايير الأخلاقية | المبادئ الأخلاقية | |||||

| أ12 | حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي من خلال السياسات: سياسات مرحلة التصميم، سياسات الاختبار والتحقق، سياسات النشر | سياسات أخلاقية | |||||

| أ11، أ13 |

|

إرشادات أخلاقية | |||||

| أ1 | إطار حوكمة الإعلام والذكاء الاصطناعي: إطار متعدد المستويات: أتمتة معالجة البيانات والتقاطها، أتمتة إنشاء المحتوى، أتمتة تعديل المحتوى، وأتمتة التواصل | إطار عمل | |||||

| A20 | إطار حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي النظري | إطار عمل | |||||

| A10 | نموذج حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي البُعدي: أبعاد الذكاء الاصطناعي: هيكلية، وعلاقية، وإجرائية | نموذج | |||||

| A19 | تمديد ECCOLA – أداة تم تطويرها لدمج أخلاقيات الذكاء الاصطناعي | أداة | |||||

| A25 | ECCOLA: أداة تم تطويرها لدمج أخلاقيات الذكاء الاصطناعي | أداة |

مراحل دورة حياة الذكاء الاصطناعي ضمن الشراكة العالمية للصحة الرقمية. تشمل هذه السياسات؛ سياسات مرحلة التصميم: لتقديم آليات حوكمة صارمة. سياسات الاختبار والتحقق: يجب أن تكون مرنة ومناسبة وقابلة للتكيف لإثبات فعالية التقنيات المدفوعة بالذكاء الاصطناعي. سياسات النشر: تركز على تطوير السياسات لمعالجة الفجوات في تحويل البحث إلى الممارسة السريرية. إجراءات المراقبة والإشراف: لتعزيز إجراءات الإشراف الوطنية لتحسين الذكاء الجماعي على المستوى الدولي.

المعيارية المناسبة لسياقات هندسة البرمجيات المتنوعة، وأن تكون قابلة للتكيف مع عمليات التطوير السريعة لتطوير الذكاء الاصطناعي. سلطت الدراسة [A19] الضوء على فجوة في ECCOLA أي، نقص في قوة المعلومات، مما يتطلب الحاجة إلى تدابير حوكمة إضافية لحوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل فعال. بسبب ذلك، اقترحت الدراسة مواءمتها مع مبادئ حفظ السجلات المقبولة عمومًا (GARP) وممارسات حوكمة المعلومات (IG). كشفت تحليل الدراسة أن ECCOLA بالتوافق مع ممارسات GARP IG يحسن من قابليتها للتكيف ويقلل الفجوات في قوة المعلومات.

4.2 مستويات حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي

الحوكمة على المستوى الدولي

- حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي من خلال السياسات لدعم الدول الأعضاء في GDHP في التغلب على حواجز حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي [A12]

الحوكمة على مستوى الصناعة

- إطار حوكمة الإعلام والذكاء الاصطناعي [A1]

الحوكمة على مستوى المنظمة

- تطوير ECCOLA: [A19]

- الإصدار الموسع من ECCOLA [A25]

- نموذج حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي البُعدي [A10]

- إطار حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي النظري [A20]

- حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي من خلال الإرشادات [A11]، [A13]

- حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقية [A2]

| معرف المنتج | حلول حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي | المبادئ |

| A2 | حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقية | العدالة والخصوصية والأمان |

| A12 | حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي من خلال السياسات | غير محدد |

| A11، A13 | حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي من خلال الإرشادات | قابلية التفسير، الدقة، والعدالة |

| A1 | إطار حوكمة الإعلام والذكاء الاصطناعي | الشفافية |

| A20 | إطار حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي النظري | العدالة |

| A10 | نموذج حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي البُعدي | غير محدد |

| A19 | تمديد ECCOLA | الخصوصية والقوة |

| A25 | تطوير ECCOLA | القوة |

5 المناقشة

RQ1: ما هي أطر الحوكمة، والنماذج، والأدوات، والسياسات (السياسات الأخلاقية، والإرشادات، والمبادئ) للذكاء الاصطناعي المقدمة في الأدبيات؟

RQ2: ما هي القيود والتحديات المتعلقة بحوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي التي تم مناقشتها في الأدبيات؟

- قلة الاهتمام بالمبادئ الأخلاقية والمسؤولة للذكاء الاصطناعي: تشير الأدبيات إلى نقص ملحوظ في الاهتمام الممنوح للمبادئ الأخلاقية والمسؤولة للذكاء الاصطناعي في جهود الحوكمة الحالية. تعطي العديد من أطر الحوكمة الحالية الأولوية للامتثال وإدارة المخاطر، وغالبًا ما تركز على الجوانب التقنية والتشغيلية مثل الأداء، والدقة، وقابلية التوسع. ومع ذلك، يمكن أن يطغى هذا التركيز الفني على القضايا الأخلاقية الأساسية مثل العدالة، والشفافية، والشمولية. على سبيل المثال، في بعض الحالات، تكون الإرشادات الأخلاقية مجرد “اقتراحات” بدون لوائح قابلة للتنفيذ لضمان الامتثال، مما يؤدي إلى تجاهل المبادئ الأخلاقية أو دمجها بشكل سيء في أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن نقص نهج موحد ومعياري

إن التوجه نحو الذكاء الاصطناعي المسؤول عبر مختلف القطاعات والمناطق يجعل من الصعب تبني مبادئ الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقي بشكل عالمي. هذه التباينات تخلق فجوات، حيث قد تلتزم المنظمات بالحد الأدنى من المتطلبات القانونية لكنها تفشل في تنفيذ معايير أخلاقية أكثر صرامة، مما قد يؤدي إلى التحيز أو التمييز أو انتهاكات الخصوصية. إن غياب المعايير الأخلاقية القابلة للتنفيذ يسمح للشركات بتجاوز هذه المبادئ، لا سيما في الأسواق التنافسية حيث يتم إعطاء الأولوية لسرعة الوصول إلى السوق والربحية على الاعتبارات الأخلاقية. - نقص المشاركة البشرية:: يُعتبر نقص المشاركة البشرية في أساليب حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الحالية تحديًا يجعل هذه الأساليب أقل تركيزًا على الإنسان. تركز العديد من أطر حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي على أتمتة عمليات اتخاذ القرار، مما يؤدي غالبًا إلى تهميش دور الحكم البشري والمساءلة في هذه القرارات. مع تزايد اعتماد أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي على التعامل مع مهام حساسة وعالية المخاطر، مثل التوظيف، وإنفاذ القانون، والرعاية الصحية، يمكن أن يؤدي غياب الإشراف البشري إلى نتائج غير مقصودة وضارة. علاوة على ذلك، فإن المشاركة البشرية ضرورية لضمان بقاء أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي قابلة للتكيف واستجابة للسياقات الأخلاقية والاجتماعية والقانونية المتغيرة. بدون وجود البشر في الحلقة، قد تتبع أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي قواعد وخوارزميات صارمة، والتي قد تكون غير مناسبة أو ضارة عند تطبيقها على مواقف العالم الحقيقي المتطورة.

- عدم كفاية الأساليب الحالية للحكم: تشير بعض الدراسات إلى أن الأطر الحالية لحوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي قد تكون غير كافية لمعالجة جميع القضايا الأخلاقية المتعلقة بالذكاء الاصطناعي. بينما تركز بعض الأطر على إدارة المخاطر والامتثال التنظيمي، فإنها غالبًا ما تفشل في معالجة القضايا الأوسع المتعلقة بالثقة والخصوصية والمساءلة. يمكن أن تؤدي هذه الغموض إلى نماذج “صندوق أسود” حيث تكون المنطق وراء قرارات الذكاء الاصطناعي غير متاحة، مما يقوض الثقة في أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يتم تطوير تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي ونشرها عبر الحدود، ولكن لا يوجد معيار أو اتفاق عالمي حول كيفية حكم أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل أخلاقي. تجعل هذه الفجوة من الصعب إنشاء نظام حوكمة شامل يمكنه التخفيف من المخاطر التي تطرحها الذكاء الاصطناعي عبر مناطق وصناعات مختلفة. من خلال تسليط الضوء على هذه التحديات، يصبح من الواضح أن حلول حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي يجب أن تستند أساسًا إلى مبادئ الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقي والمسؤول لتعزيز الثقة، ومعالجة القضايا المجتمعية، وضمان النجاح على المدى الطويل لتقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي. مع استمرار دمج الذكاء الاصطناعي في مجالات ذات مخاطر عالية مثل الرعاية الصحية، وإنفاذ القانون، والتوظيف، يجب أن تتطور أطر الحوكمة لت prioritizing المبادئ الأخلاقية مثل العدالة والشفافية و

المسؤولية، التي يتم التعامل معها حالياً بشكل غير كاف. على سبيل المثال، قانون الذكاء الاصطناعي في الاتحاد الأوروبي، الذي يسعى إلى تصنيف أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي بناءً على مستويات المخاطر وفرض تنظيمات صارمة على التطبيقات عالية المخاطر، يمثل هذه الحركة نحو بيئة ذكاء اصطناعي أكثر مسؤولية. من المتوقع أن تركز الأطر مثل هذه بشكل متزايد على الإشراف البشري، مما يضمن أن أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي لا تفي فقط بالمعايير الفنية ولكن تتماشى أيضاً مع القيم المجتمعية. في النهاية، يمكن أن يتضمن مستقبل حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي تحقيق التوازن بين الابتكار والمسؤولية، مع أطر قابلة للتكيف يمكن أن تستجيب لتطورات تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي مع الحفاظ على المبادئ الأخلاقية.

6 تهديدات للصلاحية والقيود

6.1 القيود

6.2 الصلاحية الداخلية

ويمكن أن يُعزى ذلك إلى الدراسات الأساسية التي تم مراجعتها، مما يعزز الصلاحية الداخلية لمراجعتنا المنهجية.

6.3 الصلاحية الخارجية

7 الخاتمة والأعمال المستقبلية

الملحق أ: قائمة بـ 28 دراسة مشمولة

أ2: تشانغ، ج. وتشينغ، ز.م.، 2023. أخلاقيات وحوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الطبي الموثوق. مجلة BMC للمعلوماتية الطبية واتخاذ القرار، 23(1)، ص. 7.

أ4: آرثر، ك.ن.أ. وأوين، ر.، 2022. دراسة ميكرو-إثنوغرافية للابتكار القائم على البيانات الضخمة في قطاع الخدمات المالية: الحوكمة والأخلاقيات والممارسات التنظيمية. في الأعمال والتداعيات الأخلاقية للتكنولوجيا (ص. 57-69). شتوتغارت: سبرينغر ناتشر سويسرا.

أ5: تان، س.ي. وتايهاغ، أ.، 2021. إدارة اعتماد الروبوتات والأنظمة المستقلة في الرعاية طويلة الأمد في سنغافورة. السياسة والمجتمع، 40(2)، ص. 211-231.

ديكنسون، إتش، سميث، سي، كاري، إن وكاري، جي، 2021. استكشاف توترات الحوكمة للتقنيات الم disruptive: حالة الروبوتات المساعدة في أستراليا ونيوزيلندا. السياسة والمجتمع، 40(2)، الصفحات 232-249.

A7: كوتور، ف.، روي، م.س.، داز، إ.، لابيرل، س. وبيليسل-بيبون، ج.س.، 2023. الآثار الأخلاقية للذكاء الاصطناعي في صحة السكان ودور الجمهور في حوكمة ذلك: وجهات نظر من لجنة المواطنين والخبراء. مجلة أبحاث الإنترنت الطبية، 25، ص.e44357.

أ9: أوشاوغنسّي، م.ر.، شيف، د.س.، فارشني، ل.ر.، روزيل، س.ج. ودافنبورت، م.أ.، 2023. ما الذي يحكم المواقف تجاه اعتماد الذكاء الاصطناعي وحوكمته؟. العلوم والسياسة العامة، 50(2)، ص. 161-176.

A10: باباجيانيديس، إ.، إنهولم، إ.م.، دريمل، ج.، ميكاليف، ب. وكروغستي، ج.، 2023. نحو حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي: تحديد أفضل الممارسات والحواجز والنتائج المحتملة. حدود نظم المعلومات، 25(1)، ص. 123-141.

أ11: لياو، ف.، أدلاين، س.، أفشار، م. وباترسون، ب. و، 2022. حوكمة تطبيقات الذكاء الاصطناعي السريري لـ

تسهيل النشر الآمن والعادل في نظام صحي كبير: العناصر الرئيسية والنجاحات المبكرة. الحدود في الصحة الرقمية، 4، ص. 931439.

أ12: مورلي، ج.، مورفي، ل.، ميشرا، أ.، جوشي، I. وكارباتاكيس، ك.، 2022. إدارة البيانات والذكاء الاصطناعي للرعاية الصحية: تطوير فهم دولي. أبحاث JMIR التكوينية، 6(1)، ص.e31623.

أ13: صن، ت. ك. و ميداجليا، ر.، 2019. رسم تحديات الذكاء الاصطناعي في القطاع العام: أدلة من الرعاية الصحية العامة. ربع سنوية معلومات الحكومة، 36(2)، ص.368-383.

أوكُن، س.، هانجر، م.، براون-جيمس، ل.، مونتغومري، ت.، رافالوف، ج. وفان ديلدن، ج.ج.، 2023. الالتزامات تجاه المصادر الأخلاقية المسؤولة، واستخدام وإعادة استخدام بيانات المرضى في العصر الرقمي: عملية التعاون. مجلة أبحاث الإنترنت الطبية، 25، ص.e41095.

أ16: براتون، ب.، 2021. الذكاء الاصطناعي في الحضرية: إطار تصميم للحكم، والبرامج، وإدراك المنصات. الذكاء الاصطناعي والمجتمع، 36(4)، ص. 1307-1312.

أ17: الزعابي، ك.، الحمادي، ك.أ. و الخطيب، م.، 2023. تسليط الضوء على حوكمة البرامج من خلال الذكاء الاصطناعي و البلوك تشين. المجلة الدولية لتحليلات الأعمال والأمن (IJBAS)، 3(1)، ص. 92-102.

A18: شيفر، م.، شنايدر، ج.، دريشلار، ك. وفوم بروك، ج.، 2022. حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي: هل هناك حاجة إلى مسؤولي الذكاء الاصطناعي ورؤساء مخاطر الذكاء الاصطناعي؟. في ECIS.

A19: أغبيسي، م.، ألانين، هـ.ك.، أنتيكاينن، ج.، إريكا، هـ.، إيسوماكي، هـ.، يانتونن، م.، كيميل، ك.ك.، روسي، ر.، فايينو-بيكا، هـ. وفاكوري، ف.، 2023. الحوكمة في أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقية والموثوقة: توسيع طريقة ECCOLA لحوكمة أخلاقيات الذكاء الاصطناعي باستخدام GARP. مجلة e-Informatica للهندسة البرمجية، 17(1).

ماليك، ن.، كار، أ.ك.، تريباتي، س.ن. وغوبتا، س.، 2023. استكشاف تأثير عدالة الروبوتات الاجتماعية على تجربة المستخدم. التنبؤ التكنولوجي والتغيير الاجتماعي، 197، ص. 122913.

أ21: تان، إ.، جان، م.ب.، سيمونوفسكي، أ.، تومبال، ت.، كليزن، ب.، سابي، م.، بيشوك، ل. وويليم، ب.، 2023. الذكاء الاصطناعي والقرارات الخوارزمية في كشف الاحتيال: نموذج هيكلي تفسيري. البيانات والسياسة، 5، ص.e25.

أ22: هاينتس، ف.، تشاجكي، س.، برنارديني، ف.، ودوب، ر.، 2023. حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الموثوق – مناقشة لجنة. وقائع ورشة عمل CEUR، المجلد 3449، 2023 مشترك من الأبحاث الجارية، الممارسين، الملصقات، ورش العمل، والمشاريع في EGOV-CeDEM-ePart،

A23: سالاثيه، م.، ويغاند، ت. ووينزل، م.، 2018. مجموعة تركيز حول الذكاء الاصطناعي للصحة. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.04797.

A24: كاث، سي.، 2018. إدارة الذكاء الاصطناعي: الفرص والتحديات الأخلاقية والقانونية والتقنية. المعاملات الفلسفية للجمعية الملكية A: العلوم الرياضية والفيزيائية والهندسية، 376(2133)، ص.20180080.

A25: فاكوري، ف.، كيميل، ك.ك.، يانتونين، م.، هالم، إ. وأبراهامسون، ب.، 2021. إيكولا – طريقة لتنفيذ أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي المتوافقة أخلاقياً. مجلة الأنظمة والبرمجيات، 182، ص. 111067.

أ26: أرورا، أ.، ألدرمان، ج.إ.، بالمر، ج.، غاناباثي، س.، لووز، إ.، مكرايدن، م.د.، أوكدن-راينر، ل.، بفول، س.ر.، غاسمي، م.، مكاي، ف. وتريانونر، د.، 2023. قيمة المعايير لمجموعات البيانات الصحية في التطبيقات المعتمدة على الذكاء الاصطناعي. ناتشر ميديسن، 29(11)، ص. 2929-2938.

أ27: داناهير، ج.، هوغان، م.ج.، نون، ج.، كينيدي، ر.، بيهان، أ.، دي باور، أ.، فيلزمان، هـ.، هاكلاي، م.، خُو، س.م.، موريزون، ج. ومورفي، م.هـ.، 2017. الحوكمة الخوارزمية: تطوير أجندة بحثية من خلال قوة الذكاء الجماعي. البيانات الضخمة والمجتمع، 4(2)، ص.2053951717726554.

أ28: جونسون، م.، البزري، أ. وهارفوش، أ.، 2023. الذكاء الاصطناعي المسؤول في الرعاية الصحية: التنبؤ ومنع رفض مطالبات التأمين من أجل الرفاهية الاقتصادية والاجتماعية. حدود نظم المعلومات، 25(6)، ص. 2179-2195.

الملحق ب: المصطلحات

- إطار حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي: في هذه الورقة، يشير إطار حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي إلى الأساليب المنظمة المصممة لتوجيه تطوير ونشر وإدارة أنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي بشكل منهجي، مع معالجة الاعتبارات الأخلاقية والتنظيمية والتشغيلية.

- نموذج حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي: في هذه المراجعة المنهجية، يمثل نموذج حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي مجموعة من الخطوات للإشراف على وإدارة الجوانب الأخلاقية والقانونية والتشغيلية لأنظمة الذكاء الاصطناعي.

- أداة حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي: في هذه الورقة، تشير أداة حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي إلى مجموعة من الأدوات المتخصصة، أو مجموعة منظمة من الخطوات، تم تطويرها لتقييم ومراقبة و

تعزيز الاستخدام الأخلاقي والمسؤول للذكاء الاصطناعي (AI). - حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقية والمسؤولة: في هذه الدراسة، تمثل حوكمة الذكاء الاصطناعي الأخلاقية والمسؤولة مجموعة أساسية من القيم والإرشادات التي تهدف إلى توجيه تطوير ونشر واستخدام تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي بطريقة تتماشى مع الاعتبارات الاجتماعية والأخلاقية والقانونية. تضمن هذه المبادئ ممارسات الذكاء الاصطناعي المسؤولة والأخلاقية، مع التأكيد على الشفافية والمساءلة والعدالة وحماية حقوق الأفراد.

الإقرارات

References

- Lu, Q., Zhu, L., Xu, X., Whittle, J., Zowghi, D., Jacquet, A.: Responsible AI pattern catalogue: a collection of best practices for AI governance and engineering. ACM Comput. Surv. 56, 1-35 (2022)

- Shams, R.A., Zowghi, D., Bano, M.: Ai and the quest for diversity and inclusion: a systematic literature review. AI and Ethics, 1-28 (2023)

- Lütge, C., Poszler, F., Acosta, A.J., Danks, D., Gottehrer, G., Mihet-Popa, L., Naseer, A.: Ai4people: ethical guidelines for the automotive sector-fundamental requirements and practical recommendations. Int. J. Technoethics (IJT) 12(1), 101-125 (2021)

- Reddy, S., Allan, S., Coghlan, S., Cooper, P.: A governance model for the application of AI in health care. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 27(3), 491-497 (2020)

- Lee, J.: Access to finance for artificial intelligence regulation in the financial services industry. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 21, 731-757 (2020)

- Bano, M., Zowghi, D., Shea, P., Ibarra, G.: Investigating responsible AI for scientific research: an empirical study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.09561 (2023)

- Jobin, A., Ienca, M., Vayena, E.: The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1(9), 389-399 (2019)

- Mäntymäki, M., Minkkinen, M., Birkstedt, T., Viljanen, M.: Putting ai ethics into practice: the hourglass model of organizational ai governance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.00335 (2022)

- Koene, A., Smith, A.L., Egawa, T., Mandalh, S., Hatada, Y.: Ieee p70xx, establishing standards for ethical technology. In: Proceedings of KDD, ExCeL London UK (2018)

- Fjeld, J., Achten, N., Hilligoss, H., Nagy, A., Srikumar, M.: Principled artificial intelligence: mapping consensus in ethical and rights-based approaches to principles for AI. Berkman Klein Center Research Publication (2020-1) (2020)

- Attard-Frost, B., Brandusescu, A., Lyons, K.: The governance of artificial intelligence in Canada: findings and opportunities from a review of 84 AI governance initiatives. Gov. Inf. Q. 41(2), 101929 (2024)

- Maas, M.M.: Concepts in advanced AI governance: a literature review of key terms and definitions (2023)

- Kluge Corrêa, N., Galvão, C., Santos, J.W., Del Pino, C., Pontes Pinto, E., Barbosa, C., Massmann, D., Mambrini, R., Galvão, L., Terem, E.: Worldwide AI ethics: a review of 200 guidelines and recommendations for ai governance. arXiv e-prints, 2206 (2022)

- Zhang, J., Zhang, Z.-M.: Ethics and governance of trustworthy medical artificial intelligence. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Making 23(1), 7 (2023)

- Pierson, J., Kerr, A., Robinson, C., Fanni, R., Steinkogler, V., Milan, S., Zampedri, G.: Governing artificial intelligence in the media and communications sector. Internet Policy Rev. 12(1), 28 (2023)

- Wang, X., Oussalah, M., Niemilä, M., Ristikari, T., Petri, V.: Towards AI-governance in psychosocial care: a systematic literature review analysis. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 9, 100157 (2023)

- Corrêa, N.K., Galvão, C., Santos, J.W., Del Pino, C., Pinto, E.P., Barbosa, C., Massmann, D., Mambrini, R., Galvão, L., Terem, E., et al.: Worldwide AI ethics: a review of 200 guidelines and recommendations for AI governance. Patterns 4(10), 100857 (2023)

- Laux, J.: Institutionalised distrust and human oversight of artificial intelligence: towards a democratic design of ai governance under the European Union AI act. AI Soc., 1-14 (2023)

- Paz, J.V., Rodríguez-Picón, L.A., Morales-Rocha, V., TorresArgüelles, S.V.: A systematic review of risk management methodologies for complex organizations in industry 4.0 and 5.0. Systems 11(5), 218 (2023)

- Kreutz, H., Jahankhani, H.: Impact of artificial intelligence on enterprise information security management in the context of iso 27001 and 27002: A tertiary systematic review and comparative analysis. Cybersecur. Artif. Intell. Transf. Strategies Disrupt. Innov., 1-34 (2024)

- Alsaigh, R., Mehmood, R., Katib, I.: Ai explainability and governance in smart energy systems: a review. Front. Energy Res. 11, 1071291 (2023)

- Stogiannos, N., Malik, R., Kumar, A., Barnes, A., Pogose, M., Harvey, H., McEntee, M.F., Malamateniou, C.: Black box no more: a scoping review of AI governance frameworks to guide

procurement and adoption of AI in medical imaging and radiotherapy in the UK. Br. J. Radiol. 96(1152), 20221157 (2023) - Abbas, A., Mahrishi, M., Mishra, D.: Artificial intelligence (ai) governance in higher education: a meta-analytic systematic review. Available at SSRN 4657675 (2023)

- Kitchenham, B., Brereton, O.P., Budgen, D., Turner, M., Bailey, J., Linkman, S.: Systematic literature reviews in software engi-neering-a systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 51(1), 7-15 (2009)

- Guan, J.: Artificial intelligence in healthcare and medicine: promises, ethical challenges and governance. Chin. Med. Sci. J. 34(2), 76-83 (2019)

- Ho, C., Soon, D., Caals, K., Kapur, J.: Governance of automated image analysis and artificial intelligence analytics in healthcare. Clin. Radiol. 74(5), 329-337 (2019)

- Fontes, C., Corrigan, C., Lütge, C.: Governing AI during a pandemic crisis: initiatives at the EU level. Technol. Soc. 72, 102204 (2023)

- Niet, I., Est, R., Veraart, F.: Governing AI in electricity systems: Reflections on the EU artificial intelligence bill. Front. Artif. Intell. 4, 690237 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2021.690237

- Liu, Y., Lu, Q., Zhu, L., Paik, H.-Y., Staples, M.: A systematic literature review on blockchain governance. J. Syst. Softw. 197, 111576 (2023)

- Zowghi, D., Rimini, F.: Diversity and inclusion in artificial intelligence. In: Lu, Q., et al. (eds.) Responsible AI: Best Practices for Creating Trustworthy AI Systems. Addi-son-Wesley, Sydney (2023). https://research.csiro.au/ss/ guidelines-for-diversity-and-inclusion-in-artificial-intelligence/

- European Union: High-Level Summary of the Artificial Intelligence Act. Accessed: 2024-10-22 (2024). https://artificialintelli-genceact.eu/high-level-summary/

- AI, N.: Artificial intelligence risk management framework (ai rmf 1.0) (2023)

- OECD: Artificial Intelligence in Society. Accessed: December 10, 2023. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/ artificial-intelligence-in-society_eedfee77-en

- Wallach, W., Marchant, G.E.: An agile ethical/legal model for the international and national governance of ai and robotics. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (2018)

- Salathé, M., Wiegand, T., Wenzel, M.: Focus group on artificial intelligence for health. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.04797 (2018)

- GDPR: What is GDPR? https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/. Accessed: 2024-07-10 (2018)

- AI RMF Knowledge Base. https://airc.nist.gov/AI_RMF_Knowledge_Base/AI_RMF. Accessed: December 10, 2023

- (PDPC), P.D.P.C.: Model AI Governance Framework. Accessed: 2024-07-03 (2020). https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/-/media/Files/ PDPC/PDF-Files/Resource-for-Organisation/AI/SGMode1AIGovFramework2.pdf

- Australia’s National Artificial Intelligence Centre: Responsible AI. https://www.csiro.au/en/work-with-us/industries/technology/ national-ai-centre. Accessed: November 2023 (2023)

- Liebig, L., Güttel, L., Jobin, A., Katzenbach, C.: Subnational AI policy: shaping AI in a multi-level governance system. AI Soc. 39, 1477-1490 (2022)

- Sidorova, A., Saeed, K.: Incorporating stakeholder enfranchisement, risks, gains, and AI decisions in AI governance framework (2022)

- Wirtz, B.W., Weyerer, J.C., Sturm, B.J.: The dark sides of artificial intelligence: an integrated AI governance framework for public administration. Int. J. Public Adm. 43(9), 818-829 (2020)

- Knight, S., Shibani, A., Vincent, N.: Ethical AI governance: mapping a research ecosystem. AI and Ethics, 1-22 (2024)

- Amna Batool

amna.batool@data61.csiro.au

Didar Zowghi

didar.zowghi@data61.csiro.au

Muneera Bano

muneera.bano@data61.csiro.au

1 CSIRO’s Data61, Melbourne, Australia https://www.ey.com/en_ch/forensic-integrity-services/the-eu-ai-ac t-what-it-means-for-your-business.

https://oecd.ai/en/ai-principles.

https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/australias-artificial-intelli gence-ethics-framework/australias-ai-ethics-principles.

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.100-1.pdf.

https://www.iso.org/standard/81230.html. https://www.ey.com/en_ch/forensic-integrity-services/the-eu-ai-ac t-what-it-means-for-your-business.

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.100-1.pdf. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1GsHUo84XwjP1Oa4ne2d7 E18G84VS1_g4/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=106380959154063406110&r tpof=true&sd=true.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00653-w

Publication Date: 2025-01-14

Al governance: a systematic literature review

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

As artificial intelligence (AI) transforms a wide range of sectors and drives innovation, it also introduces different types of risks that should be identified, assessed, and mitigated. Various AI governance frameworks have been released recently by governments, organizations, and companies to mitigate risks associated with AI. However, it can be challenging for AI stakeholders to have a clear picture of the available AI governance frameworks, tools, or models and analyze the most suitable one for their AI system. To fill the gap, we present the literature to answer key questions: WHO is accountable for AI systems’ governance, WHAT elements are being governed, WHEN governance occurs within the AI development life cycle, and HOW it is implemented through frameworks, tools, policies, or models. Adopting the systematic literature review (SLR) methodology, this study meticulously searched, selected, and analyzed 28 articles, offering a foundation for understanding different facets of AI governance. The analysis is further enhanced by categorizing artifacts of AI governance under team-level governance, organization-level governance, industry-level governance, national-level governance, and international-level governance. The findings of this study on existing AI governance solutions can assist research communities in proposing comprehensive AI governance practices.

1 Introduction

and deployment of AI technologies align with its strategies, principles, and goals [8]. Consequently, governmental and international organizations, including the European Union AI Act,

- A comprehensive analysis of 28 research papers selected from the academic literature.

- An exploration of the challenges and limitations of existing AI governance solutions.

- The categorization of key elements presented under five levels of governance.This paper is organized as follows Sect. 2 presents the background and related work. Section 3 presents the research methodology along with research questions and data extraction. Section 4 presents the data analysis carried out on 28 selected studies and the categorization of AI governance solutions under five AI governance levels. Section 5 presents the discussion and Sect. 6 presents the threats to validity and study limitations. Section 7 concludes the study with future work.

2 Background and related work

articles using the PRISMA methodology. They categorized articles into four levels: individual, family, community, and governance. The study presented a conceptual framework that interlinks the AI-Technological layer, AI-Ethics layer, AI-Regulatory layer, and AI-Implementation layer, aiming to enhance child resilience, well-being, and public services.

- Focus of review: In this systematic literature review (SLR), an extensive analysis of AI governance elements has been presented using 4 specific questions (Who, What, When, How) to extract rich data about AI governance.

- Review timeline: This SLR covers publications from 2013 to 2023 (10 years).

- Type of included studies: This SLR followed the guidelines for the Systematic Literature Review established by Kitchenham et al. [24].

- Scope of subject domain: This SLR provides a comprehensive exploration of diverse sectors like media and communication, healthcare, transportation, robotics, academia, industry, etc. The existing reviews particularly focused on a single domain, either healthcare [25, 26], robotics [27], or energy sector [28].

- AI Governance and Stakeholders Classification: This SLR has classified the AI governance solutions identified from the question How it is being governed and the stakeholders found from the questions Who is governing into different levels, i.e., team, organization, industry, national, and international. The existing literature

3 Systematic review methodology

3.1 Planning

- RQ1: What frameworks, models, tools, and policies (ethical AI principles, guidelines, policies) for AI governance are offered in the literature?

- RQ2: What are the limitations and challenges of AI governance discussed in the literature?

| Database | Search string | Search within | Time frame | Search time | No of papers returned |

| SCOPUS | (AI OR artificial AND intelligence) AND (governance) | Title and abstract | 20132023 | 10/07/2023 (10:00 am) | 1485 |

| Google scholar | Allintitle: AI governance | Title only | 20132023 | 21/07/2023 (9:00 am) | 764 |

| Google scholar | Allintitle: Artificial intelligence governance | Title only | 20132023 | 21/07/2023 (9:00 am) | 669 |

| Total: 2918 |

3.2 Search strategy

and non-academic sources (like conference papers and preprints) was useful for obtaining a wider perspective.

3.3 Quality assessment

3.4 Data extraction

4 Data synthesis and analysis

international. Appendix B has the terminology to define the terms used in this SLR.

4.1 Analysis

- Who is governing?: focuses on the stakeholders (key AI oversight roles) who should be involved in governing to oversee if AI complies with standards or regulations for ethical and responsible AI.

- What is being governed?: focuses on data and system to ensure what element either data or/and system is being governed in AI governance. The data element emphasizes the importance of responsible data acquisition, processing, and utilization [30]. Effective AI governance requires a focus on data quality, privacy, and security to mitigate biases and promote fair and transparent AI decision-making [30]. The system encompasses the AI systems, which should be governed in consideration of their robustness, interpretability, and accountability to

| Humans (Stakeholders) | ||

| Who is governing? | ||

| P-ID | Key oversight roles | Levels |

| A2 | AI ethics committees by government | National level |

| A3 | A global governance coordinating committee GGCC | International level |

| A11 | Multi-disciplinary steering committee along with project-specific sub-committees | Organization and team level |

| A13 | Public managers | Organization level |

| A23 | World Health Organization and International Telecommunication Union state members | International level |

| A28 | Hospital administrators | Organization level |

- When is it being governed?: represents the three development stages of AI to which the particular governance solutions should be applied [30]. The three stages of AI development are the pre-development (planning, approval, and data collection), during-development (design, build models, verify, and validate), and postdevelopment (monitor, and use), in alignment with established frameworks and guidelines from organizations such as NIST [32], OECD [33].

- How is it governed?: explores the artifacts of governance solutions for AI, such as ethical policies, principles and guidelines, tools, frameworks, and models.

4.1.1 Comprehensive analysis of questions

preventing discrimination, aligning with ethical principles while promoting innovation [39]. These regional differences reflect underlying geopolitical biases, with Europe prioritizing ethical standards, the U.S. focusing on innovation and market freedom, and APAC countries balancing state control and economic development. Australia’s framework, which emphasizes both ethical standards and innovation, offers a middle ground. Understanding these geographical nuances adds depth to the analysis of “who” governs AI and how governance structures are shaped by regional objectives.

issues especially the transparency in AI systems is essential and this can be done by governing AI systems using different governance mechanisms such as Ethical Considerations and Challenges of Learning Algorithms (ECCOLA) a tool for the governance of ethical and trustworthy AI systems. Overall, these studies focused on various risks associated with AI which emphasized that governing AI system is essential.

| Process | ||

| Pre-development | During development | Post-development |

| A2 | A2 | A2 |

| – | A7 | – |

| A11 | – | A11 |

| A12 | A12 | A12 |

| – | A13 | – |

| A19 | A19 | A19 |

| A23 | A23 | A23 |

| A25 | A25 | A25 |

| P-ID | Framework/models/tools/ethics (principles, policies, guidelines) | Type | |||||

| A2 | Ethical AI Governance: Ethical values (toplevel) lead to Ethical Principles which guide the Ethical Norms | Ethical principles | |||||

| A12 | AI Governance through Policies: Design Phase Policies, Testing and Validation Policies, Deployment Policies | Ethical policie | |||||

| A11, A13 |

|

Ethical guidelines | |||||

| A1 | Media-AI Governance Framework: Multilevel framework: automating data processing and capture, automating content creation, automating content moderation, and automating communication | Framework | |||||

| A20 | Theoretical AI Governance Framework | Framework | |||||

| A10 | Dimensional AI Governance Model: AI dimensions: structural, relational, and procedural | Model | |||||

| A19 | Extension of ECCOLA – A tool developed to embed AI Ethics | Tool | |||||

| A25 | ECCOLA: A tool developed to embed AI Ethics | Tool |

phases of the AI life cycle within the Global Digital Health Partnership. These policies include; Design Phase Policies: to introduce hard governance mechanisms. Testing and Validation Policies: should be flexible, appropriate, and adaptable for proving the efficacy of AI-driven technologies. Deployment Policies: focusing on policy development to address gaps in translating research into clinical practice. Monitoring and Oversight Procedures: to enhance national oversight procedures to improve collective intelligence at an international level.

modular method suitable for diverse Software Engineering contexts, and be adaptable to agile development processes for the development of AI. The study [A19] highlighted a gap in ECCOLA i.e., lack of information robustness, requiring the need for additional governance measures to govern AI effectively. Due to this, the study suggested aligning it with Generally Accepted Recordkeeping principles (GARP) information governance (IG) practices. The analysis of the study revealed that ECCOLA in alignment with GARP IG practices improves its adaptability and reduces the gaps in information robustness.

4.2 Al governance levels

International-Level Governance

- AI Governance through Policies to Support GDHP Member Countries in Overcoming AI Governance Barriers [A12]

Industry-Level Governance

- Media-AI Governance Framework [A1]

Organization-Level Governance

- ECCOLA development: [A19]

- ECCOLA extended version [A25]

- Dimensional AI governance model [A10]

- Theoretical AI governance Framework [A20]

- AI governance through guidelines [A11], [A13]

- Ethical AI Governance [A2]

| P-ID | AI governance solutions | Principles |

| A2 | Ethical AI Governance | Fairness privacy and security |

| A12 | AI Governance through policies | Not specified |

| A11, A13 | AI Governance through guidelines | Interpretability, accuracy, and fairness |

| A1 | Media-AI Governance framework | Transparency |

| A20 | Theoretical AI Governance framework | Fairness |

| A10 | Dimensional AI Governance model | Not specified |

| A19 | Extension of ECCOLA | Privacy and robustness |

| A25 | ECCOLA development | Robustness |

5 Discussion

RQ1: What governance frameworks, models, tools, and policies (ethical policies, guidelines, principles) for AI are offered in the literature?

RQ2: What are the limitations and challenges of AI governance discussed in the literature?

- Less attention to ethical and responsible AI principles: The literature notes a perceived lack of attention given to ethical and responsible AI principles in existing governance efforts. Many existing governance frameworks prioritize compliance and risk management, often focusing on technical and operational aspects such as performance, accuracy, and scalability. However, this technical focus can overshadow essential ethical concerns like fairness, transparency, and inclusiveness. For example, in some cases, ethical guidelines are merely “suggestions” with no enforceable regulations to ensure compliance, leading to ethical principles being either overlooked or poorly integrated into AI systems. Additionally, the lack of a unified, standardized approach

to responsible AI across different sectors and regions makes it challenging to adopt ethical AI principles universally. This inconsistency creates gaps, where organizations might adhere to the minimal legal requirements but fail to implement more robust ethical standards, potentially leading to bias, discrimination, or violations of privacy. The absence of enforceable ethical norms allows companies to bypass these principles, particularly in competitive markets where time-to-market and profitability are prioritized over ethical considerations [A2, A6, A15, A22, A24]. - Lack of human involvement:: The lack of human involvement in current AI governance approaches is discussed as a challenge that makes these approaches less human-centric. Many AI governance frameworks focus on automating decision-making processes, often sidelining the role of human judgment and accountability in these decisions. As AI systems increasingly handle sensitive and high-stakes tasks, such as hiring, law enforcement, and healthcare, the absence of human oversight can lead to unintended and harmful outcomes. Furthermore, human involvement is crucial to ensure that AI systems remain adaptable and responsive to changing ethical, social, and legal contexts. Without humans in the loop, AI systems might follow rigid rules and algorithms, which could be inappropriate or harmful when applied to evolving real-world situations [A6A7, A24].

- Inadequacy of current governance approaches: Some studies suggest that current AI governance frameworks may be insufficient to address all AI ethical concerns. While some frameworks emphasize risk management and regulatory compliance, they often fall short in addressing broader concerns related to trust, privacy, and accountability. This opacity can lead to “black box” models where the logic behind AI decisions is inaccessible, undermining trust in AI systems. Additionally, AI technologies are developed and deployed across borders, but there is no global standard or agreement on how to govern AI systems ethically. This lack of coherence makes it difficult to establish a comprehensive governance system that can mitigate the risks posed by AI across different regions and industries [A6, A24, A15, A22].By highlighting these challenges, it becomes evident that AI governance solutions should be fundamentally based on ethical and responsible AI principles for fostering trust, addressing societal concerns, and ensuring the long-term success of AI technologies [41-43]. As AI continues to integrate into high-stakes areas like healthcare, law enforcement, and employment, governance frameworks must evolve to prioritize ethical principles such as fairness, transparency, and

accountability, which are currently under-addressed. For instance, the EU AI Act, which seeks to classify AI systems based on risk levels and impose strict regulations on high-risk applications, exemplifies this movement toward a more responsible AI landscape [31]. It is anticipated that frameworks like these will increasingly focus on human oversight, ensuring that AI systems not only meet technical standards but also align with societal values. Ultimately, the future of AI governance can involve balancing innovation with responsibility, with adaptable frameworks that can respond to evolving AI technologies while safeguarding ethical principles.

6 Threats to validity and limitations

6.1 Limitations

6.2 Internal validity

and attributable to the primary studies reviewed, thereby enhancing the internal validity of our SLR.

6.3 External validity

7 Conclusion and future work

Appendix A: List of 28 included studies

A2: Zhang, J. and Zhang, Z.M., 2023. Ethics and governance of trustworthy medical artificial intelligence. BMC medical informatics and decision making, 23(1), p.7.

A4: Arthur, K.N.A. and Owen, R., 2022. A micro-ethnographic study of big data-based innovation in the financial services sector: Governance, ethics and organisational practices. In Business and the ethical implications of technology (pp. 57-69). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

A5: Tan, S.Y. and Taeihagh, A., 2021. Governing the adoption of robotics and autonomous systems in long-term care in Singapore. Policy and society, 40(2), pp.211-231.

A6: Dickinson, H., Smith, C., Carey, N. and Carey, G., 2021. Exploring governance tensions of disruptive technologies: the case of care robots in Australia and New Zealand. Policy and Society, 40(2), pp.232-249.

A7: Couture, V., Roy, M.C., Dez, E., Laperle, S. and Bé-lisle-Pipon, J.C., 2023. Ethical implications of artificial intelligence in population health and the public’s role in its governance: perspectives from a citizen and expert panel. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, p.e44357.

A9: O’Shaughnessy, M.R., Schiff, D.S., Varshney, L.R., Rozell, C.J. and Davenport, M.A., 2023. What governs attitudes toward artificial intelligence adoption and governance?. Science and Public Policy, 50(2), pp.161-176.

A10: Papagiannidis, E., Enholm, I.M., Dremel, C., Mikalef, P. and Krogstie, J., 2023. Toward AI governance: Identifying best practices and potential barriers and outcomes. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(1), pp.123-141.

A11: Liao, F., Adelaine, S., Afshar, M. and Patterson, B.W., 2022. Governance of Clinical AI applications to

facilitate safe and equitable deployment in a large health system: Key elements and early successes. Frontiers in Digital Health, 4, p. 931439.

A12: Morley, J., Murphy, L., Mishra, A., Joshi, I. and Karpathakis, K., 2022. Governing data and artificial intelligence for health care: developing an international understanding. JMIR formative research, 6(1), p.e31623.

A13: Sun, T.Q. and Medaglia, R., 2019. Mapping the challenges of Artificial Intelligence in the public sector: Evidence from public healthcare. Government Information Quarterly, 36(2), pp.368-383.

A14: Okun, S., Hanger, M., Browne-James, L., Montgomery, T., Rafaloff, G. and van Delden, J.J., 2023. Commitments for Ethically Responsible Sourcing, Use, and Reuse of Patient Data in the Digital Age: Cocreation Process. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, p.e41095.

A16: Bratton, B., 2021. AI urbanism: a design framework for governance, program, and platform cognition. AI and SOCIETY, 36(4), pp.1307-1312.

A17: Al Zaabi, K., Hammadi, K.A. and El Khatib, M., 2023. Highlights on Program Governance through AI and Blockchain. International Journal of Business Analytics and Security (IJBAS), 3(1), pp.92-102.

A18: SchÃafer, M., Schneider, J., Drechsler, K. and vom Brocke, J., 2022. AI Governance: Are Chief AI Officers and AI Risk Officers needed?. In ECIS.

A19: Agbese, M., Alanen, H.K., Antikainen, J., Erika, H., Isomaki, H., Jantunen, M., Kemell, K.K., Rousi, R., Vainio-Pekka, H. and Vakkuri, V., 2023. Governance in ethical and trustworthy AI systems: Extension of the ECCOLA method for AI ethics governance using GARP. e-Informatica Software Engineering Journal, 17(1).

A20: Malik, N., Kar, A.K., Tripathi, S.N. and Gupta, S., 2023. Exploring the impact of fairness of social bots on user experience. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 197, p. 122913.

A21: Tan, E., Jean, M.P., Simonofski, A., Tombal, T., Kleizen, B., Sabbe, M., Bechoux, L. and Willem, P., 2023. Artificial intelligence and algorithmic decisions in fraud detection: An interpretive structural model. Data and policy, 5, p.e25.

A22: Heintz, F., CsÃjki, C., Bernardini, F., and Dobbe, R., 2023. Trustworthy AI Governance – Panel Discussion. CEUR Workshop Proceedings, vol. 3449, 2023 Joint of Ongoing Research, Practitioners, Posters, Workshops, and Projects at EGOV-CeDEM-ePart,

A23: Salathé, M., Wiegand, T. and Wenzel, M., 2018. Focus group on artificial intelligence for health. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.04797.

A24: Cath, C., 2018. Governing artificial intelligence: ethical, legal and technical opportunities and challenges. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 376(2133), p.20180080.

A25: Vakkuri, V., Kemell, K.K., Jantunen, M., Halme, E. and Abrahamsson, P., 2021. ECCOLA-A method for implementing ethically aligned AI systems. Journal of Systems and Software, 182, p. 111067.

A26: Arora, A., Alderman, J.E., Palmer, J., Ganapathi, S., Laws, E., McCradden, M.D., Oakden-Rayner, L., Pfohl, S.R., Ghassemi, M., McKay, F. and Treanor, D., 2023. The value of standards for health datasets in artificial in-telligence-based applications. Nature Medicine, 29(11), pp.2929-2938.

A27: Danaher, J., Hogan, M.J., Noone, C., Kennedy, R., Behan, A., De Paor, A., Felzmann, H., Haklay, M., Khoo, S.M., Morison, J. and Murphy, M.H., 2017. Algorithmic governance: Developing a research agenda through the power of collective intelligence. Big data and society, 4(2), p.2053951717726554.

A28: Johnson, M., Albizri, A. and Harfouche, A., 2023. Responsible artificial intelligence in healthcare: Predicting and preventing insurance claim denials for economic and social wellbeing. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(6), pp.2179-2195.

Appendix B: Terminology

- AI Governance Framework: In this paper, an AI governance framework refers to structured approaches designed to systematically guide the development, deployment, and management of artificial intelligence systems, addressing ethical, regulatory, and operational considerations.

- AI Governance Model: In this SLR, an AI governance model, represents a set of steps for overseeing and managing the ethical, legal, and operational aspects of artificial intelligence (AI) systems.

- AI Governance Tool: In this paper, an AI governance tool refers to a set of specialized instruments, or structured set of steps, developed to assess, monitor, and

enhance the ethical and responsible use of artificial intelligence (AI). - Ethical and Responsible AI Governance: In this study, Ethical and responsible AI governance represents a foundational set of values, and guidelines intended to guide the development, deployment, and utilization of artificial intelligence technologies in a manner that aligns with societal, moral, and legal considerations. These principles ensure responsible and ethical AI practices, emphasizing transparency, accountability, fairness, and the protection of individual rights.

Declarations

References

- Lu, Q., Zhu, L., Xu, X., Whittle, J., Zowghi, D., Jacquet, A.: Responsible AI pattern catalogue: a collection of best practices for AI governance and engineering. ACM Comput. Surv. 56, 1-35 (2022)

- Shams, R.A., Zowghi, D., Bano, M.: Ai and the quest for diversity and inclusion: a systematic literature review. AI and Ethics, 1-28 (2023)

- Lütge, C., Poszler, F., Acosta, A.J., Danks, D., Gottehrer, G., Mihet-Popa, L., Naseer, A.: Ai4people: ethical guidelines for the automotive sector-fundamental requirements and practical recommendations. Int. J. Technoethics (IJT) 12(1), 101-125 (2021)

- Reddy, S., Allan, S., Coghlan, S., Cooper, P.: A governance model for the application of AI in health care. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 27(3), 491-497 (2020)

- Lee, J.: Access to finance for artificial intelligence regulation in the financial services industry. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 21, 731-757 (2020)

- Bano, M., Zowghi, D., Shea, P., Ibarra, G.: Investigating responsible AI for scientific research: an empirical study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.09561 (2023)

- Jobin, A., Ienca, M., Vayena, E.: The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1(9), 389-399 (2019)

- Mäntymäki, M., Minkkinen, M., Birkstedt, T., Viljanen, M.: Putting ai ethics into practice: the hourglass model of organizational ai governance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.00335 (2022)

- Koene, A., Smith, A.L., Egawa, T., Mandalh, S., Hatada, Y.: Ieee p70xx, establishing standards for ethical technology. In: Proceedings of KDD, ExCeL London UK (2018)

- Fjeld, J., Achten, N., Hilligoss, H., Nagy, A., Srikumar, M.: Principled artificial intelligence: mapping consensus in ethical and rights-based approaches to principles for AI. Berkman Klein Center Research Publication (2020-1) (2020)

- Attard-Frost, B., Brandusescu, A., Lyons, K.: The governance of artificial intelligence in Canada: findings and opportunities from a review of 84 AI governance initiatives. Gov. Inf. Q. 41(2), 101929 (2024)

- Maas, M.M.: Concepts in advanced AI governance: a literature review of key terms and definitions (2023)

- Kluge Corrêa, N., Galvão, C., Santos, J.W., Del Pino, C., Pontes Pinto, E., Barbosa, C., Massmann, D., Mambrini, R., Galvão, L., Terem, E.: Worldwide AI ethics: a review of 200 guidelines and recommendations for ai governance. arXiv e-prints, 2206 (2022)

- Zhang, J., Zhang, Z.-M.: Ethics and governance of trustworthy medical artificial intelligence. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Making 23(1), 7 (2023)

- Pierson, J., Kerr, A., Robinson, C., Fanni, R., Steinkogler, V., Milan, S., Zampedri, G.: Governing artificial intelligence in the media and communications sector. Internet Policy Rev. 12(1), 28 (2023)

- Wang, X., Oussalah, M., Niemilä, M., Ristikari, T., Petri, V.: Towards AI-governance in psychosocial care: a systematic literature review analysis. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 9, 100157 (2023)

- Corrêa, N.K., Galvão, C., Santos, J.W., Del Pino, C., Pinto, E.P., Barbosa, C., Massmann, D., Mambrini, R., Galvão, L., Terem, E., et al.: Worldwide AI ethics: a review of 200 guidelines and recommendations for AI governance. Patterns 4(10), 100857 (2023)

- Laux, J.: Institutionalised distrust and human oversight of artificial intelligence: towards a democratic design of ai governance under the European Union AI act. AI Soc., 1-14 (2023)

- Paz, J.V., Rodríguez-Picón, L.A., Morales-Rocha, V., TorresArgüelles, S.V.: A systematic review of risk management methodologies for complex organizations in industry 4.0 and 5.0. Systems 11(5), 218 (2023)

- Kreutz, H., Jahankhani, H.: Impact of artificial intelligence on enterprise information security management in the context of iso 27001 and 27002: A tertiary systematic review and comparative analysis. Cybersecur. Artif. Intell. Transf. Strategies Disrupt. Innov., 1-34 (2024)

- Alsaigh, R., Mehmood, R., Katib, I.: Ai explainability and governance in smart energy systems: a review. Front. Energy Res. 11, 1071291 (2023)

- Stogiannos, N., Malik, R., Kumar, A., Barnes, A., Pogose, M., Harvey, H., McEntee, M.F., Malamateniou, C.: Black box no more: a scoping review of AI governance frameworks to guide

procurement and adoption of AI in medical imaging and radiotherapy in the UK. Br. J. Radiol. 96(1152), 20221157 (2023) - Abbas, A., Mahrishi, M., Mishra, D.: Artificial intelligence (ai) governance in higher education: a meta-analytic systematic review. Available at SSRN 4657675 (2023)

- Kitchenham, B., Brereton, O.P., Budgen, D., Turner, M., Bailey, J., Linkman, S.: Systematic literature reviews in software engi-neering-a systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 51(1), 7-15 (2009)

- Guan, J.: Artificial intelligence in healthcare and medicine: promises, ethical challenges and governance. Chin. Med. Sci. J. 34(2), 76-83 (2019)

- Ho, C., Soon, D., Caals, K., Kapur, J.: Governance of automated image analysis and artificial intelligence analytics in healthcare. Clin. Radiol. 74(5), 329-337 (2019)

- Fontes, C., Corrigan, C., Lütge, C.: Governing AI during a pandemic crisis: initiatives at the EU level. Technol. Soc. 72, 102204 (2023)

- Niet, I., Est, R., Veraart, F.: Governing AI in electricity systems: Reflections on the EU artificial intelligence bill. Front. Artif. Intell. 4, 690237 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2021.690237

- Liu, Y., Lu, Q., Zhu, L., Paik, H.-Y., Staples, M.: A systematic literature review on blockchain governance. J. Syst. Softw. 197, 111576 (2023)

- Zowghi, D., Rimini, F.: Diversity and inclusion in artificial intelligence. In: Lu, Q., et al. (eds.) Responsible AI: Best Practices for Creating Trustworthy AI Systems. Addi-son-Wesley, Sydney (2023). https://research.csiro.au/ss/ guidelines-for-diversity-and-inclusion-in-artificial-intelligence/

- European Union: High-Level Summary of the Artificial Intelligence Act. Accessed: 2024-10-22 (2024). https://artificialintelli-genceact.eu/high-level-summary/

- AI, N.: Artificial intelligence risk management framework (ai rmf 1.0) (2023)

- OECD: Artificial Intelligence in Society. Accessed: December 10, 2023. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/ artificial-intelligence-in-society_eedfee77-en

- Wallach, W., Marchant, G.E.: An agile ethical/legal model for the international and national governance of ai and robotics. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (2018)

- Salathé, M., Wiegand, T., Wenzel, M.: Focus group on artificial intelligence for health. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.04797 (2018)

- GDPR: What is GDPR? https://gdpr.eu/what-is-gdpr/. Accessed: 2024-07-10 (2018)

- AI RMF Knowledge Base. https://airc.nist.gov/AI_RMF_Knowledge_Base/AI_RMF. Accessed: December 10, 2023

- (PDPC), P.D.P.C.: Model AI Governance Framework. Accessed: 2024-07-03 (2020). https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/-/media/Files/ PDPC/PDF-Files/Resource-for-Organisation/AI/SGMode1AIGovFramework2.pdf

- Australia’s National Artificial Intelligence Centre: Responsible AI. https://www.csiro.au/en/work-with-us/industries/technology/ national-ai-centre. Accessed: November 2023 (2023)

- Liebig, L., Güttel, L., Jobin, A., Katzenbach, C.: Subnational AI policy: shaping AI in a multi-level governance system. AI Soc. 39, 1477-1490 (2022)

- Sidorova, A., Saeed, K.: Incorporating stakeholder enfranchisement, risks, gains, and AI decisions in AI governance framework (2022)

- Wirtz, B.W., Weyerer, J.C., Sturm, B.J.: The dark sides of artificial intelligence: an integrated AI governance framework for public administration. Int. J. Public Adm. 43(9), 818-829 (2020)

- Knight, S., Shibani, A., Vincent, N.: Ethical AI governance: mapping a research ecosystem. AI and Ethics, 1-22 (2024)

- Amna Batool

amna.batool@data61.csiro.au

Didar Zowghi

didar.zowghi@data61.csiro.au

Muneera Bano

muneera.bano@data61.csiro.au

1 CSIRO’s Data61, Melbourne, Australia https://www.ey.com/en_ch/forensic-integrity-services/the-eu-ai-ac t-what-it-means-for-your-business.

https://oecd.ai/en/ai-principles.

https://www.industry.gov.au/publications/australias-artificial-intelli gence-ethics-framework/australias-ai-ethics-principles.

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.100-1.pdf.

https://www.iso.org/standard/81230.html. https://www.ey.com/en_ch/forensic-integrity-services/the-eu-ai-ac t-what-it-means-for-your-business.

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.100-1.pdf. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1GsHUo84XwjP1Oa4ne2d7 E18G84VS1_g4/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=106380959154063406110&r tpof=true&sd=true.