DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-023-01596-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38177345

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-04

دراسة ارتباط جينومي واسعة النطاق متعددة الأنساب للاكتئاب الشديد تساعد في اكتشاف المواقع، التحديد الدقيق، ترتيب الأولويات الجينية والاستدلال السببي

تم القبول: 26 أكتوبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 4 يناير 2024

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

تظهر قائمة المؤلفين وانتماءاتهم في نهاية الورقة

الملخص

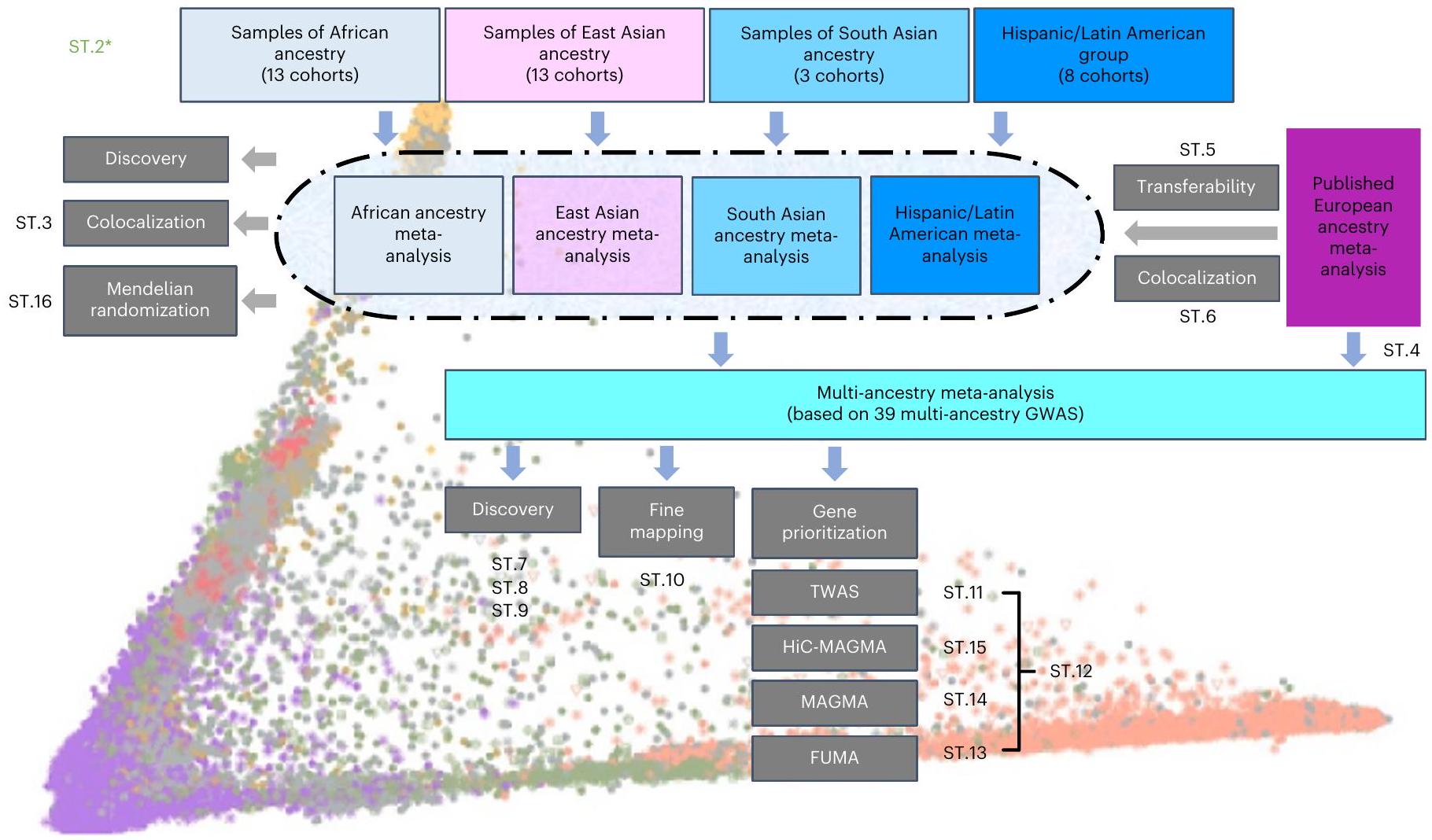

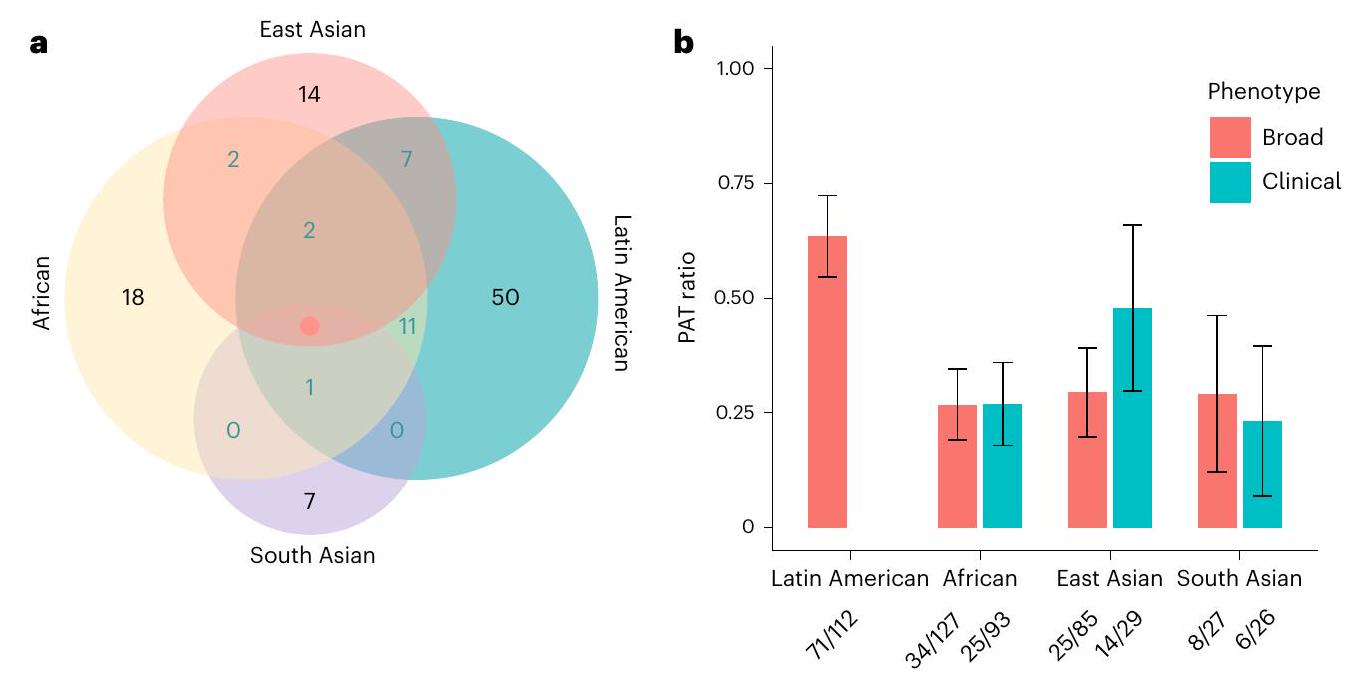

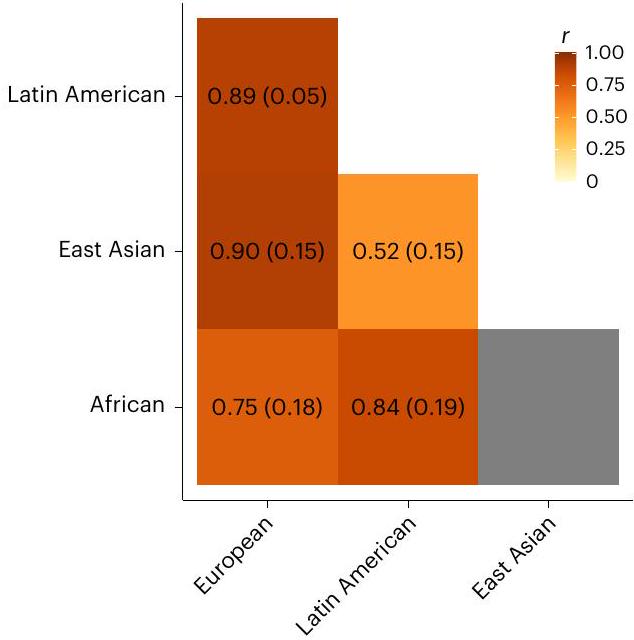

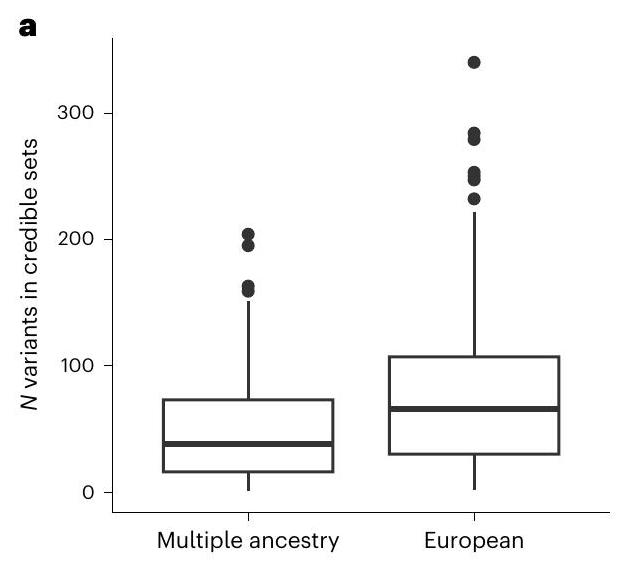

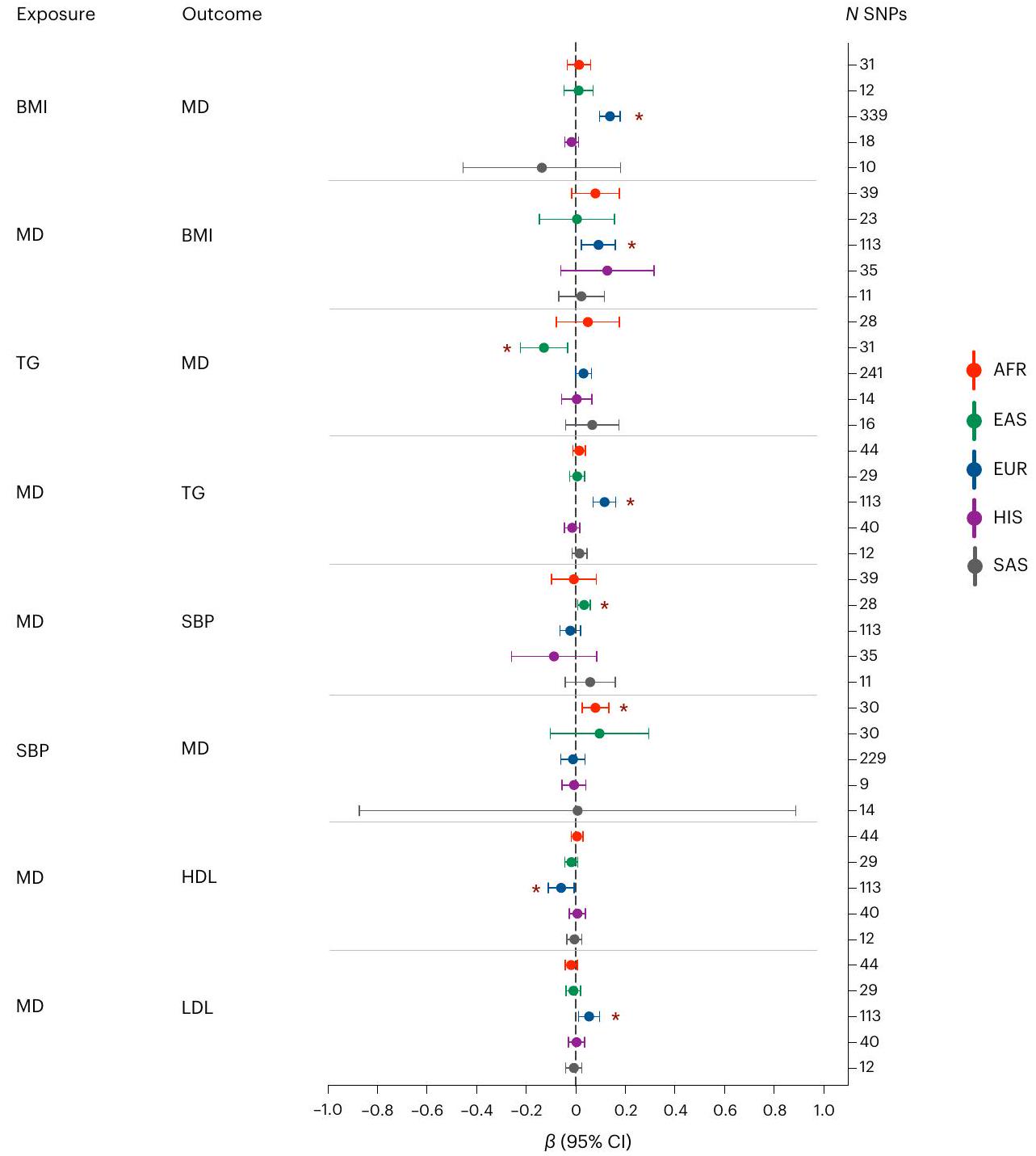

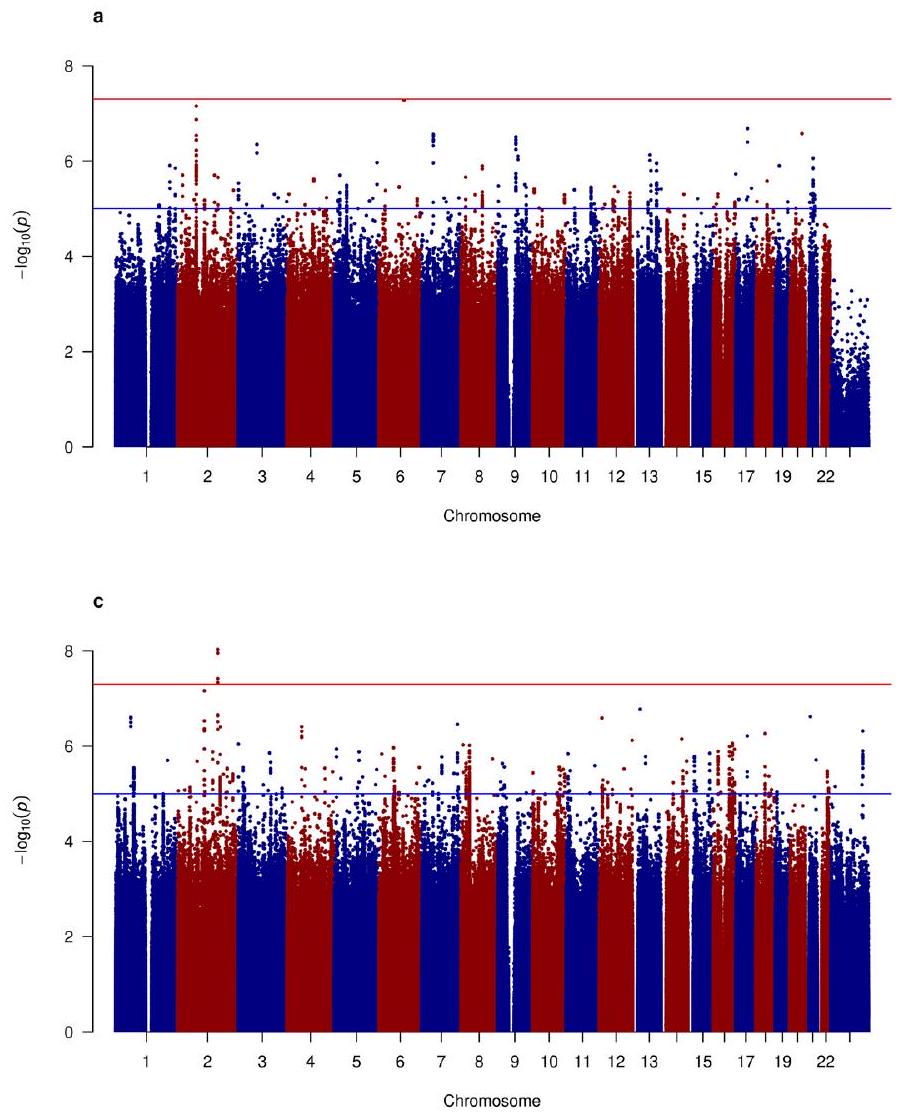

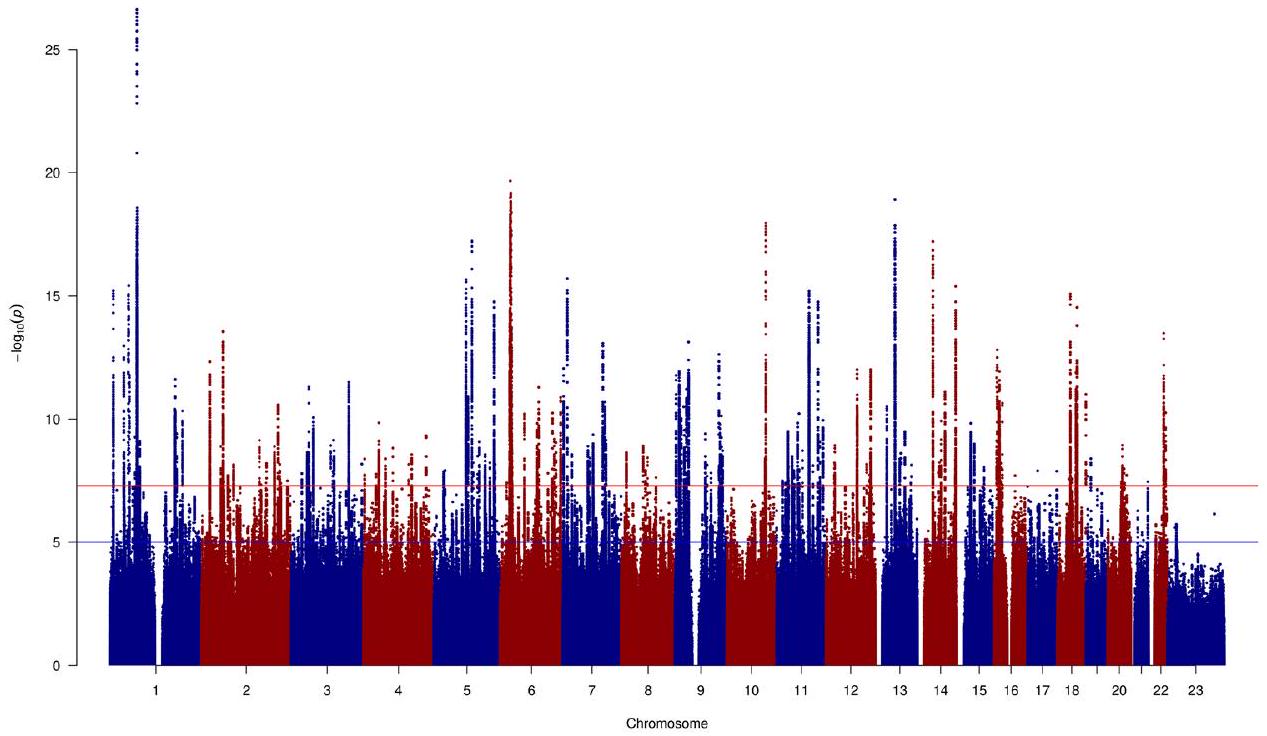

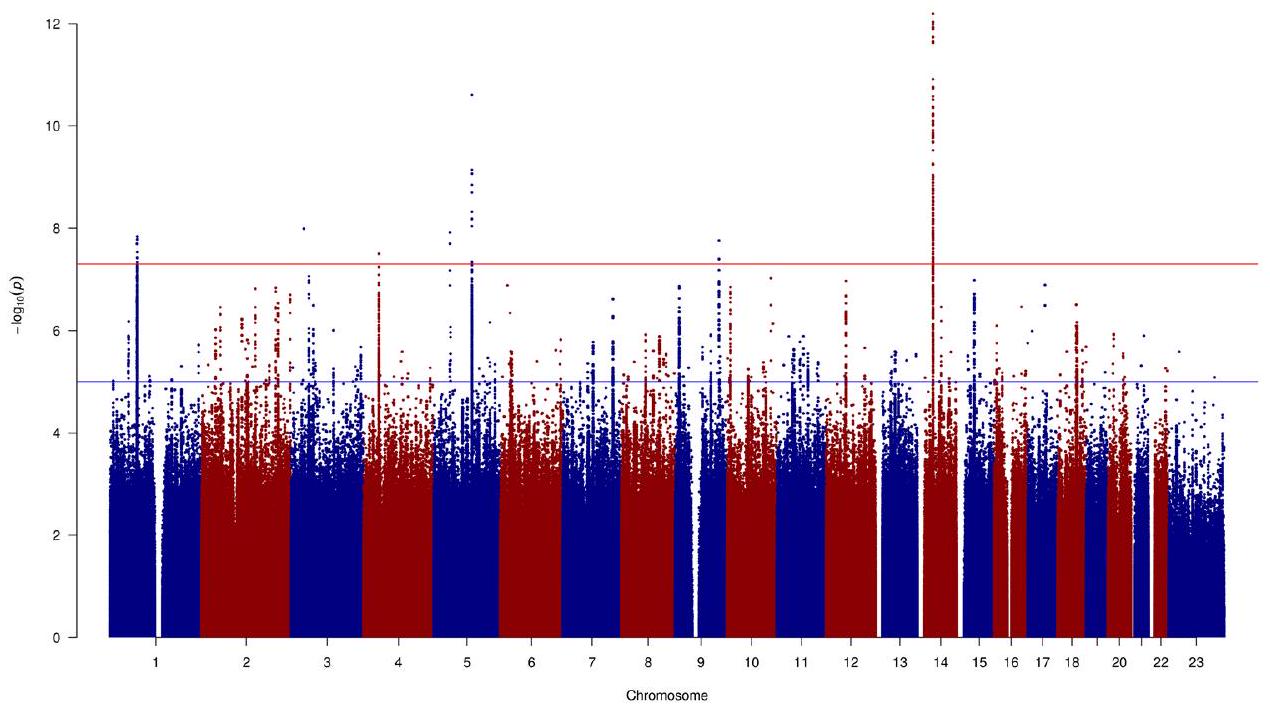

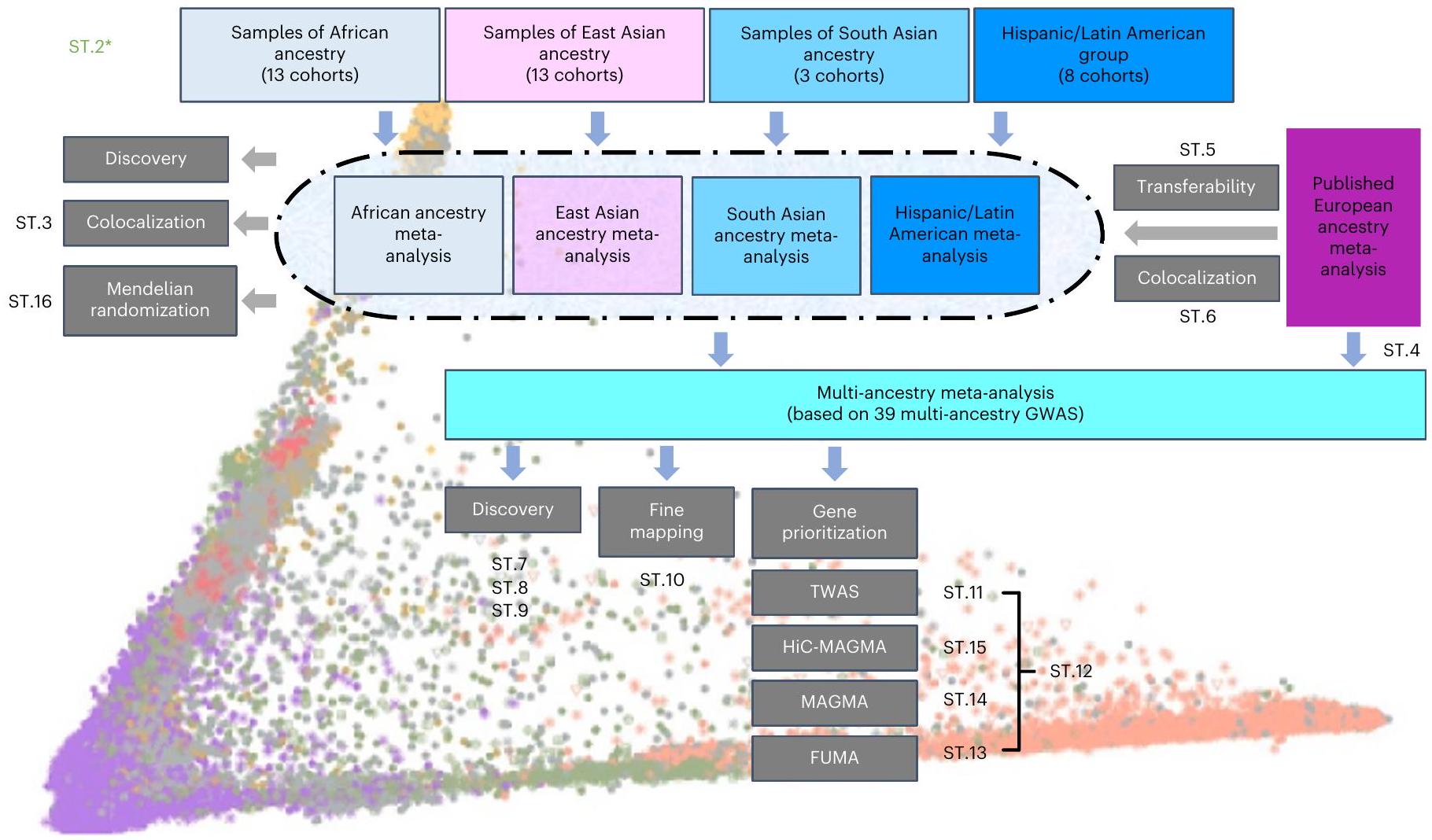

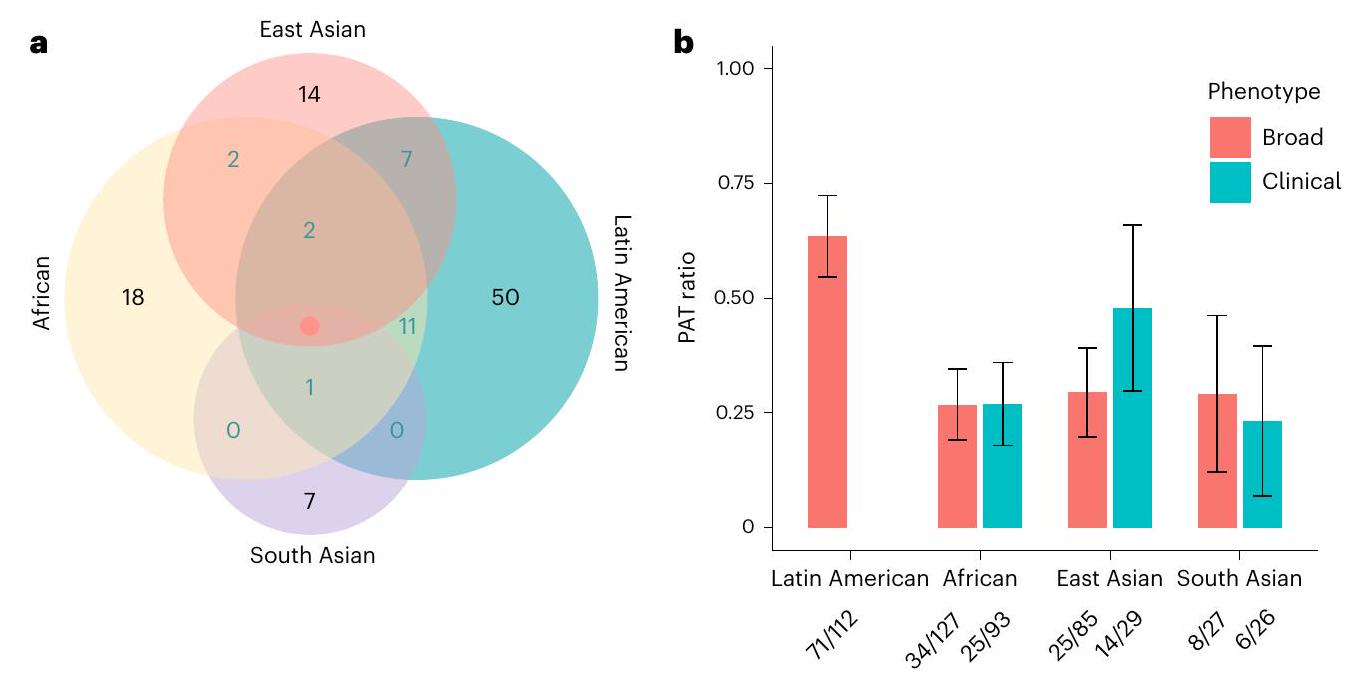

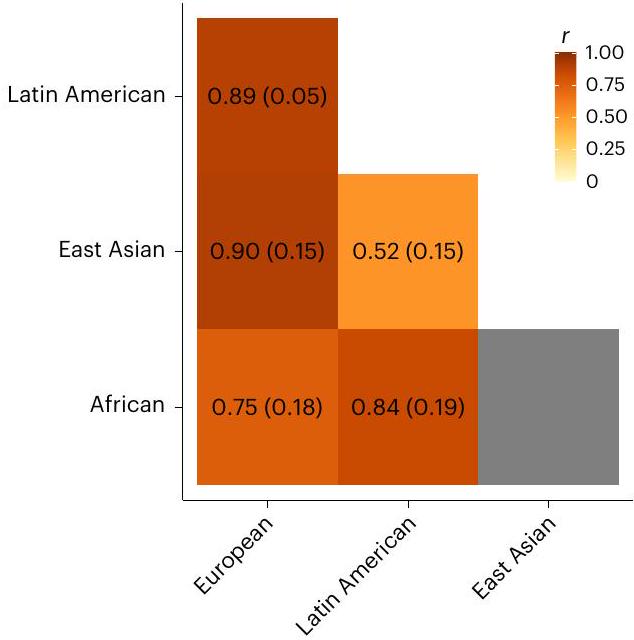

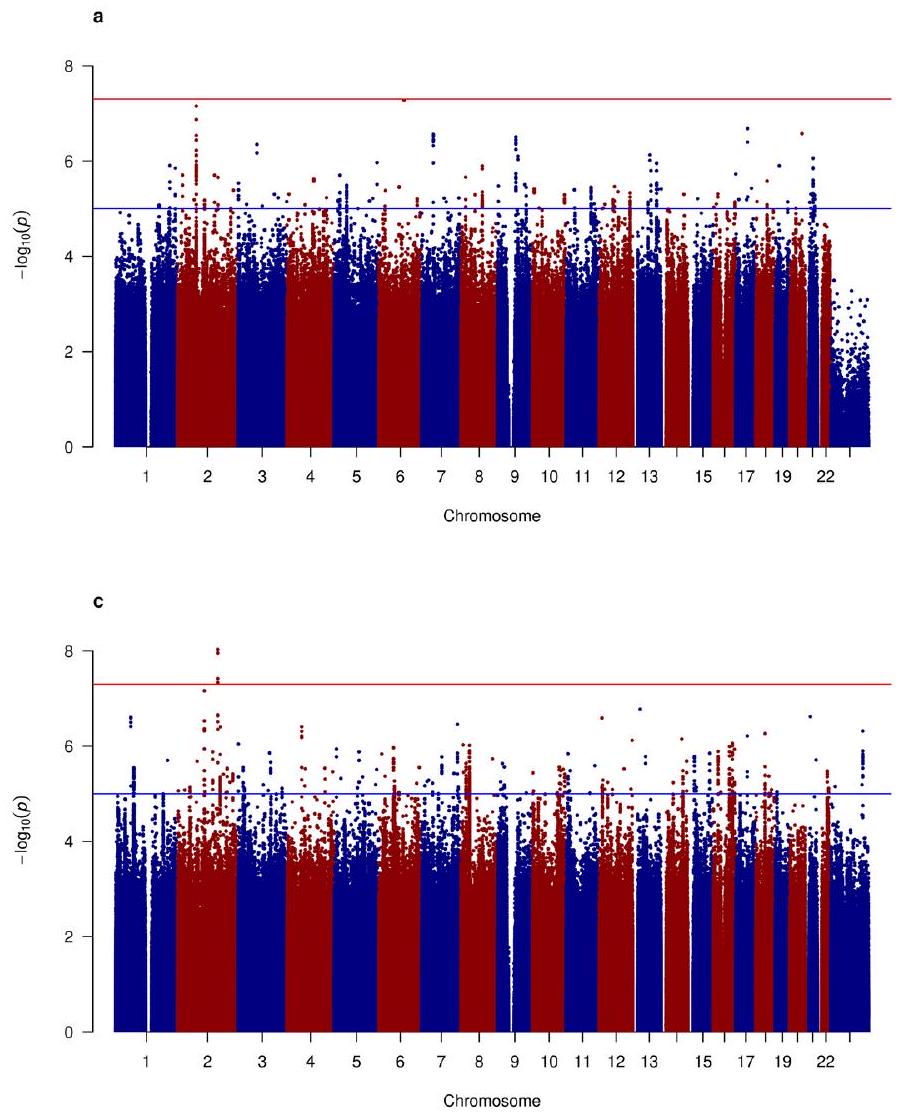

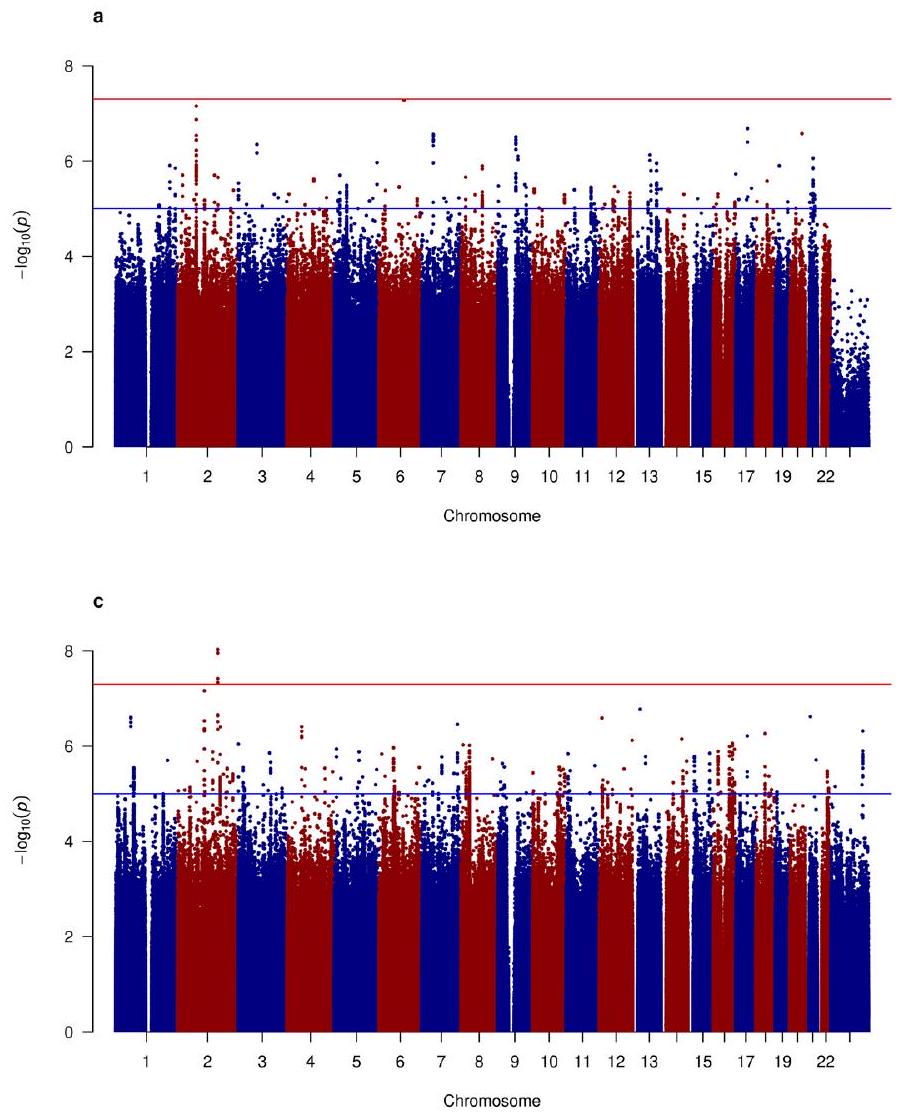

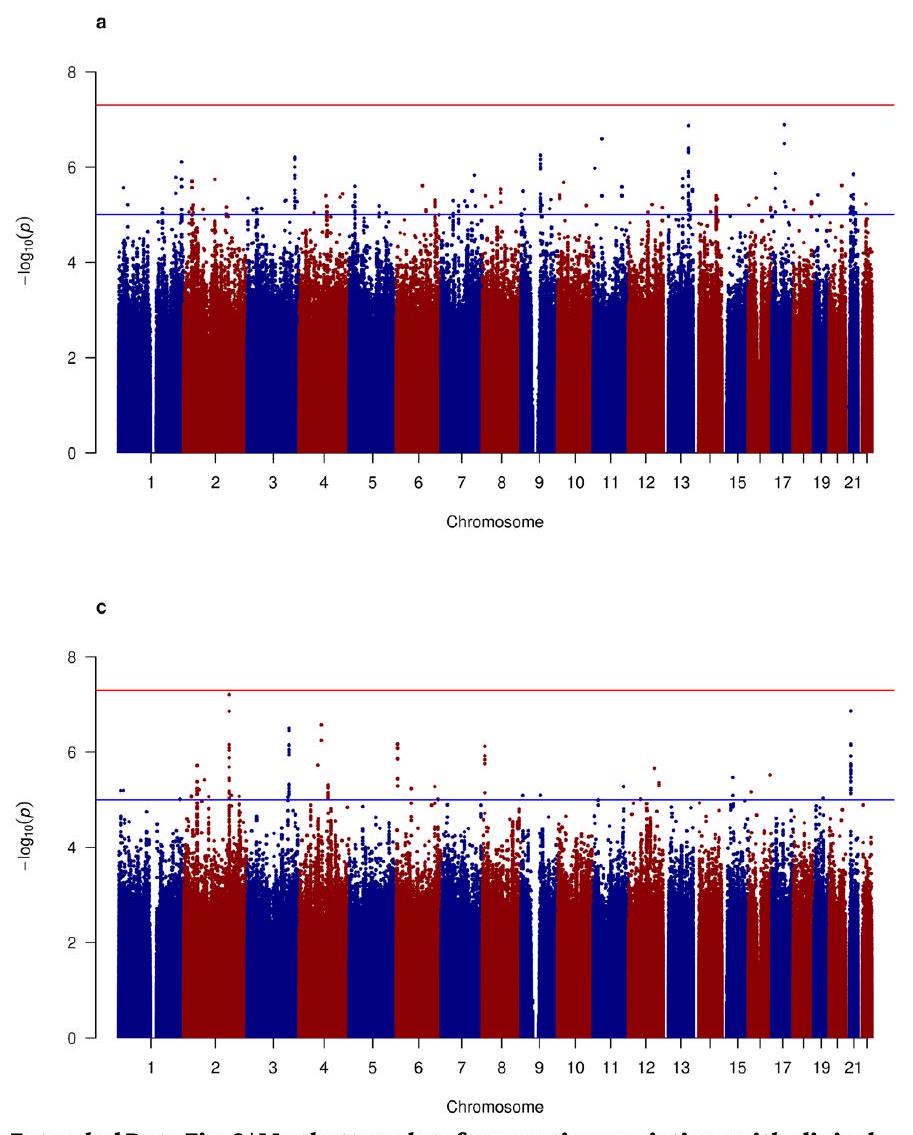

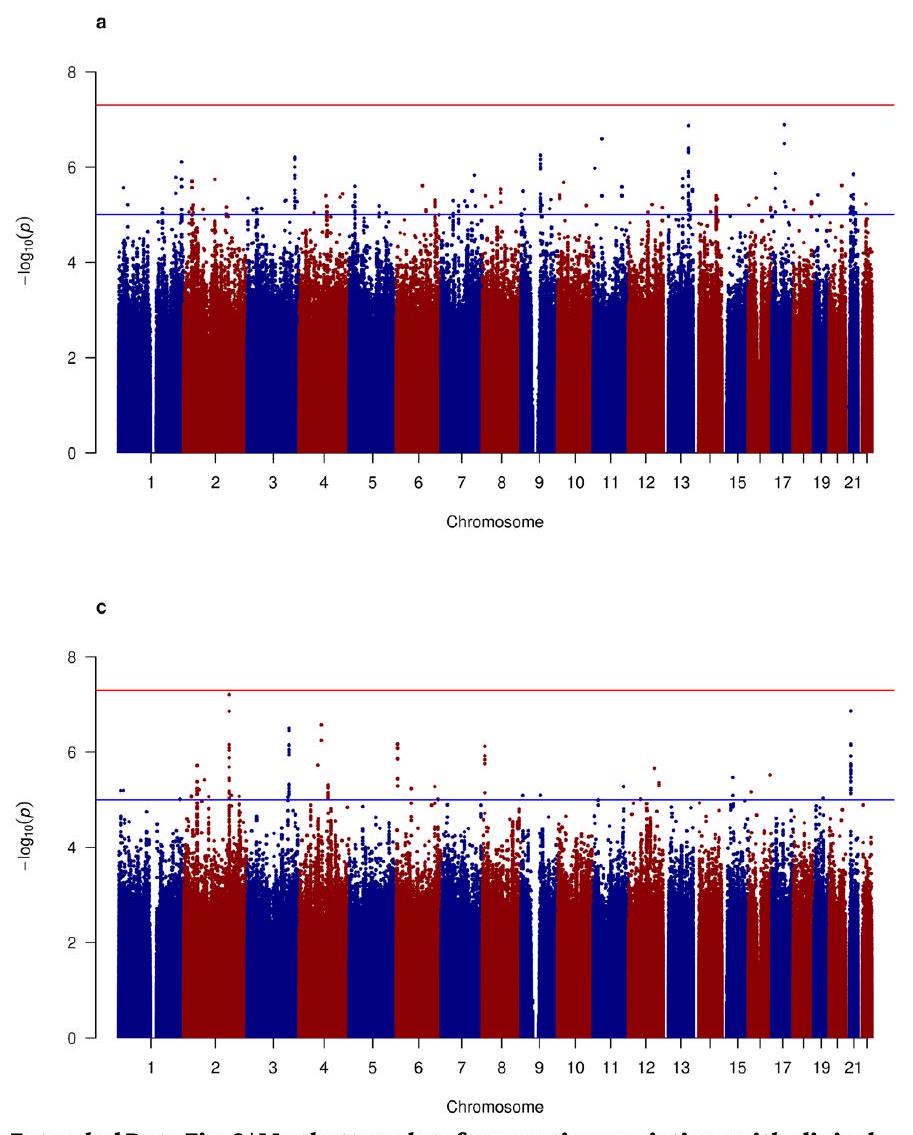

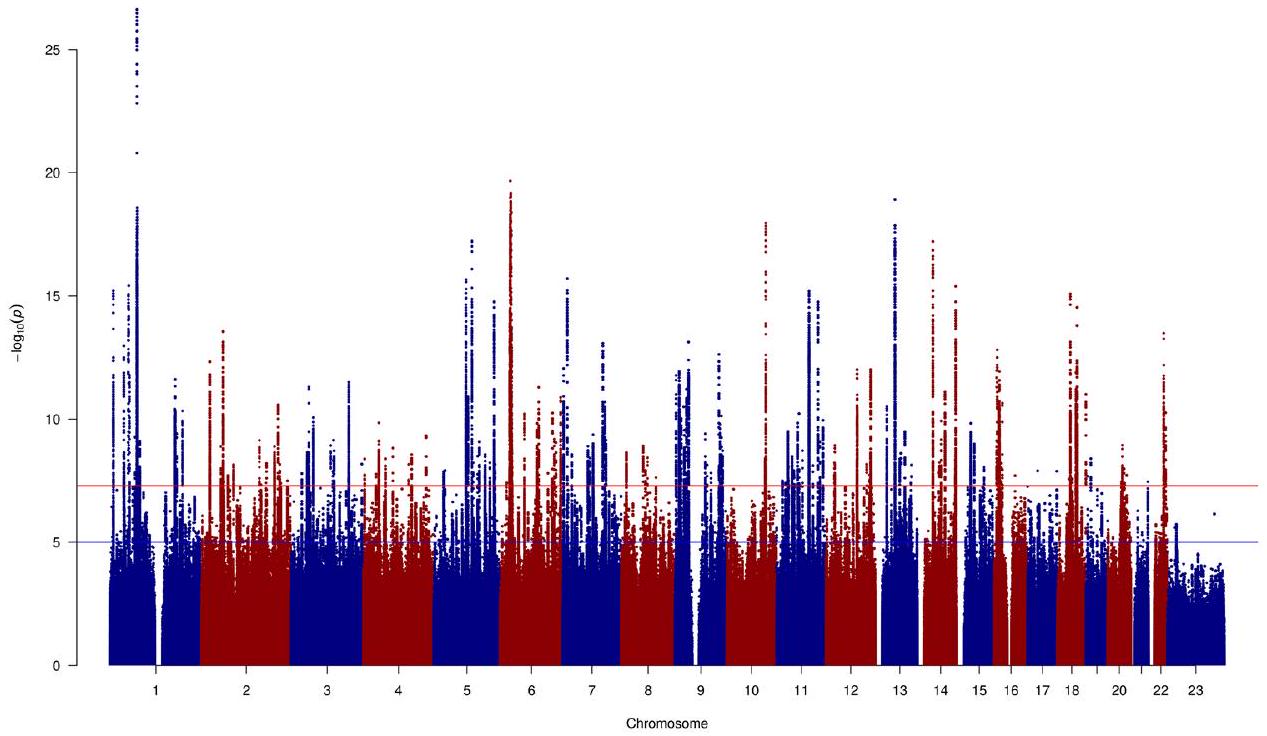

أُجريت معظم دراسات الارتباط الجينومي الواسع النطاق (GWAS) للاكتئاب الرئيسي (MD) على عينات من أصول أوروبية. هنا نبلغ عن دراسة GWAS متعددة الأنساب للاكتئاب الرئيسي، مضيفين بيانات من 21 مجموعة تضم 88,316 حالة اكتئاب رئيسي و902,757 ضابطًا إلى البيانات التي تم الإبلاغ عنها سابقًا. استخدم هذا التحليل مجموعة من المقاييس لتعريف الاكتئاب الرئيسي وشمل عينات من أصول أفريقية (36% من حجم العينة الفعّال)، وشرق آسيوية (26%)، وجنوب آسيوية (6%)، ومشاركين من أصول إسبانية/لاتينية أمريكية (32%). حددت دراسة GWAS متعددة الأنساب 53 موقعًا جينيًا جديدًا مرتبطًا بشكل كبير. بالنسبة للمواقع الجينية من دراسات GWAS على عينات من أصول أوروبية، كان عدد المواقع التي يمكن نقلها إلى مجموعات أنساب أخرى أقل من المتوقع. استفاد التحديد الدقيق من تنوع العينة الإضافي. حددت دراسة الارتباط عبر النسخ الجيني 205 جينات جديدة مرتبطة بشكل كبير. تشير هذه النتائج إلى أنه بالنسبة للاكتئاب الرئيسي، قد يكون زيادة التنوع العرقي والعالمي في الدراسات الجينية أمرًا مهمًا بشكل خاص لضمان اكتشاف الجينات الأساسية ولتوفير معلومات حول إمكانية نقل النتائج.

النتائج

دراسات الارتباط الجيني الواسعة النطاق (GWAS) في عينات من أصول أفريقية وشرق آسيوية وجنوب آسيوية وأمريكية لاتينية/هسبانية

وتحديد النقاط الفاصلة لتعيين المشاركين. ومع ذلك، فإن إنشاء مثل هذه المجموعات مكننا من البحث عن الارتباطات الخاصة بالمجموعات وتقييم قابلية نقل المواقع المحددة سابقًا. استخدمت الدراسات المدرجة في التحليلات التلوية المقاييس التالية لتعريف الاكتئاب الرئيسي: المقابلات السريرية المنظمة، سجلات الرعاية الصحية الطبية، استبيانات الأعراض، والاستطلاعات التي يملأها المشاركون بأنفسهم (الجدول التكميلي 1 والملاحظة التكميلية).

تم اعتبار المتغيرات المختلفة ولكن المرتبطة (الفرضية (H)3) أو متغير سببي واحد (H4) كمتزامنة في الموقع. لاحظنا تزامنًا مهمًا في الموقع لـ DPP4 وRBMS1 وTANK. اختبرنا eQTLs الخاصة بالأصل من الدم ولاحظنا RBMS1 (H3: احتمال التوافق (الهسباني/الأمريكي اللاتيني) 99.12%) وTANK (H3: احتمال التوافق (الأوروبي) 97.85%; H3: احتمال التوافق (الهسباني/الأمريكي اللاتيني)

قابلية نقل ارتباطات MD عبر مجموعات الأنساب

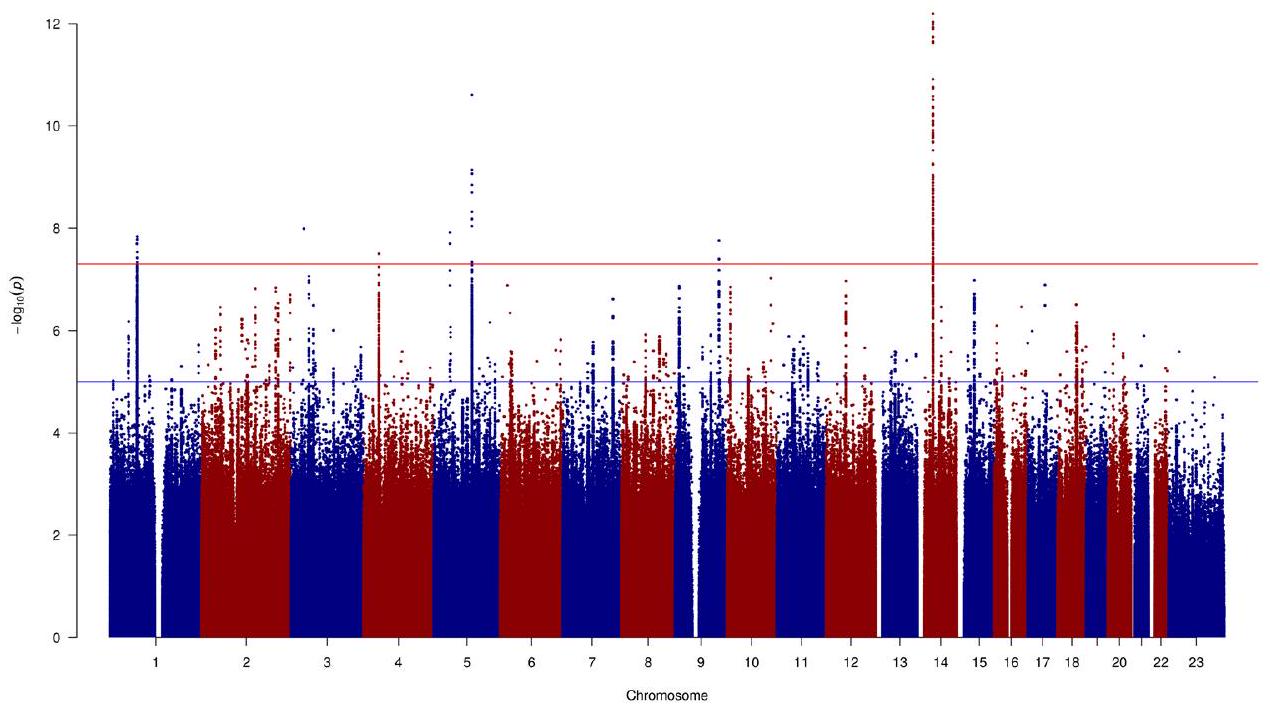

التحليل التلوي متعدد الأنساب

(حالات و214,415 ضوابط في المجموع) (الشكل البياني الموسع 4 والأشكال التكميلية 19 و20). حدد هذا التحليل سبعة مواقع ذات دلالة جينومية واسعة النطاق، اثنان منها جديدان (rs2085224 عند 3p22.3 وrs78676209 عند 5p12) (الجدول التكميلي 8).

التحديد الدقيق متعدد الأنساب

تحديد أولوية جينات TWAS

مع MD موضحة باللون الرمادي. تشير الخطوط الحمراء إلى عتبة الدلالة (

و TMEM106B. كان الكادهرين-9 (CDH9) والبروتوكادهرينات (PCDHA1، PCDHA2 و PCDHA3) أيضًا من بين الجينات ذات الثقة العالية (الجدول التكميلي 12). وأخيرًا، 25 من الجينات ذات الثقة العالية ترمز لأهداف أدوية معروفة، مثل السيمفاستاتين (RHOA). قد تشير هذه إلى فرص لإعادة استخدام الأدوية.

السيد

تم ملاحظة العلاقة ذات الاتجاهين حصريًا في عينات من الأصول الأوروبية (

| جين

|

دواء

|

فوما

|

ماجما

|

هاي-سيماجما

|

كان ت | رواية

|

مجموعة موثوقة

|

| الجينات المرتبطة في TWAS و Hi-C MAGMA | |||||||

| NDUFAF3 | ميتفورمين، ناداه | لا | 1.00 | 0.004 |

|

نعم | ٩ |

| PBRM1 | ألبرازولام، دورفالوماب، إيفيروليموس | لا | 0.10 | 0.017 |

|

نعم | – |

| TBCA | – | لا | 0.16 | 0.042 |

|

نعم | – |

| BTN2A3P | – | لا | 1.00 |

|

|

نعم | – |

| ZNF204P | – | لا | 1.00 | 0.014 |

|

لا | – |

| HLA-B | ثاليدوميد، تيكلوبيدين، فينوباربيتال، كاربامازيبين، كلوزابين، لاموتريجين | لا | 0.46 |

|

|

لا | – |

| RABGAP1 | – | لا | 1.00 | 0.001 |

|

نعم | – |

| جولغا1 | – | لا | 1.00 | 0.020 |

|

نعم | – |

| فرات2 | – | لا | 0.78 | 0.017 |

|

نعم | – |

| ENSG00000278376 | – | لا | ٠٫٠٦ | 0.004 |

|

– | ٦٢ |

| TRHDE-AS1 | – | لا | ٠٫١٤ | 0.048 |

|

نعم | – |

| INSYN1-AS1 | – | لا | ٠٫٢٥ | 0.014 |

|

نعم | ٢٥ |

| الجينات المرتبطة عبر جميع الطرق الأربع | |||||||

| إعادة القراءة | – | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | ٤٥ |

| نيجر1 | – | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | – |

| ZNF638 | سيتيدين | نعم | 0.003 | 0.004 |

|

لا | ٦١ |

| RFTN2 | ليبopolysaccharide (ليبopolysaccharide) | نعم | 0.003 |

|

|

لا | ٢٠٤ |

| ZNF445 | – | نعم |

|

0.001 |

|

لا | ١٣٨ |

| ZNF197 | – | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | ١٣٨ |

| CCDC71 | – | نعم |

|

0.039 |

|

نعم | ٩ |

| ENSG00000225399 | – | نعم | 0.010 | 0.003 |

|

– | ٩ |

| آر إتش أو إيه | سيمفاستاتين، برافاستاتين، أتورفاستاتين، ماغنيسيوم، CCG-1423 | نعم | 0.031 | 0.019 |

|

لا | ٩ |

| CDH9 | الكالسيوم | نعم | 0.003 | 0.002 |

|

لا | ٩٥ |

| TMEM161B | كروفيلمر | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | – |

| PFDN1 | – | نعم | 0.025 |

|

|

نعم | ٦٧ |

| SLC4A9 | بيكربونات الصوديوم | نعم | 0.029 | 0.002 |

|

لا | ٦٧ |

| HARS1 | أدينوسين فوسفات، بيروفوسفات، فوسفات، هستيدين | نعم | 0.024 | 0.017 |

|

نعم | ١٤١ |

| HARS2 | أدينوسين فوسفات، بيروفوسفات، فوسفات، هستيدين | نعم | 0.019 | 0.044 |

|

لا | ١٤١ |

| ZMAT2 | – | نعم | 0.014 | 0.005 |

|

لا | ١٤١ |

| PCDHA1 | الكالسيوم | نعم | 0.015 | 0.005 |

|

لا | ١٤١ |

| PCDHA2 | الكالسيوم | نعم | 0.031 | 0.010 |

|

لا | ١٤١ |

| PCDHA3 | الكالسيوم | نعم | 0.043 | 0.004 |

|

لا | ١٤١ |

| TMEM106B | كروفيلمر | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | 1 |

| زد إتش إتش سي 21 | إنزيم مساعد أ، بالميتيل-إنزيم مساعد أ | نعم | 0.002 | 0.036 |

|

لا | ٤٢ |

| SORCS3 | – | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | ١٦ |

| MYBPC3 | – | نعم | 0.004 | 0.012 |

|

لا | ٤٨ |

| SLC39A13 | كلوريد الزنك، كبريتات الزنك | نعم | 0.007 | 0.003 |

|

نعم | ٤٨ |

| CTNND1 | – | نعم | 0.002 | 0.010 |

|

لا | ٦٠ |

| ANKK1 | الميثادون، نالتريكسون، فوساماتينيب | نعم | 0.011 |

|

|

لا | – |

| DRD2 | كابيرجولين، روبينيرول، سولبيريد | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | – |

| MLEC | – | نعم | 0.013 |

|

|

نعم | – |

| SPPL3 | – | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | – |

| LRFN5 | – | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | 10 |

| AREL1 | – | نعم | 0.007 |

|

|

لا | ١٤٣ |

| جين

|

دواء

|

فوما

|

ماجما

|

هاي-سيماجما

|

كان ت | رواية

|

مجموعة موثوقة

|

| دي إل إس تي | حمض الليبويك سوكسينيل-كوإنزيم أ، كوإنزيم أ، ديهيدروليبوأميد (S)-سوكسينيلديهيدروليبوأميد | نعم |

|

0.001 |

|

لا | ١٤٣ |

| مارك3 | فوستاماتينيب، ألسترباولون | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | ١١ |

| KLC1 | فلورويوراسيل، إيرينوتيكان، لوكوفورين | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | ١١ |

| XRCC3 | فلورويوراسيل، إيرينوتيكان، لوكوفورين | نعم | 0.004 |

|

|

لا | ١١ |

| ZFYVE21 | إينوزيتول 1،3-بيسفوسفات | نعم |

|

|

|

نعم | ١١ |

| سيلف4 | إيلوبيريدون | نعم |

|

|

|

لا | ٨ |

| RAB27B | جوانوزين-5′-ثنائي الفوسفات | نعم |

|

0.042 |

|

لا | – |

| إميليين3 | – | نعم | 0.039 | 0.001 |

|

لا | ٦٤ |

| CHD6 | الفوسفات، أدينوسين ثلاثي الفوسفات (ATP)، أدينوسين ثنائي الفوسفات (ADP) | نعم | 0.001 | 0.001 |

|

لا | ٦٤ |

| EP300 | أسيتيل-كوإنزيم أ، عامل نمو التحول بيتا (TGF-)

|

نعم |

|

|

|

لا | ١٦ |

| رانجاب1 | – | نعم |

|

0.003 |

|

لا | ١٦ |

| ZC3H7B | – | نعم | 0.001 |

|

|

لا | ١٦ |

مناقشة

نسب لعدة صفات أخرى ووجدوا تباينًا بين الصفات، لكن التقديرات لـ MD كانت في القاع

لم تكن هناك ارتباطات ذات دلالة إحصائية.

متغير وذو احتمال بيولوجي عالي

وجدت (UKB) ارتباطات بين NDUFAF3 وتقلب المزاج، مما يشير إلى أن اضطراب الطاقة قد يلعب دورًا مهمًا في فسيولوجيا تقلب المزاج.

المحتوى الإلكتروني

References

- GBD 2017 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1859-1922 (2018).

- Wray, N. R. et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 50, 668-681 (2018).

- CONVERGE Consortium. Sparse whole-genome sequencing identifies two loci for major depressive disorder. Nature 523, 588-591 (2015).

- Zhang, Y., Qi, G., Park, J.-H. & Chatterjee, N. Estimation of complex effect-size distributions using summary-level statistics from genome-wide association studies across 32 complex traits. Nat. Genet. 50, 1318-1326 (2018).

- Flint, J. & Kendler, K. S. The genetics of major depression. Neuron 81, 1214 (2014).

- Cai, N. et al. Minimal phenotyping yields genome-wide association signals of low specificity for major depression. Nat. Genet. 52, 437-447 (2020).

- Blokland, G. A. M. et al. Sex-dependent shared and nonshared genetic architecture across mood and psychotic disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 91, 102-117 (2022).

- Martin, J. et al. Examining sex-differentiated genetic effects across neuropsychiatric and behavioral traits. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 1127-1137 (2021).

- Kang, H.-J. et al. Sex differences in the genetic architecture of depression. Sci. Rep. 10, 9927 (2020).

- Arnau-Soler, A. et al. A validation of the diathesis-stress model for depression in Generation Scotland. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 25 (2019).

- Van der Auwera, S. et al. Genome-wide gene-environment interaction in depression: a systematic evaluation of candidate genes: the childhood trauma working-group of PGC-MDD. Am. J. Med. Genet. B 177, 40-49 (2018).

- Peterson, R. E. et al. Molecular genetic analysis subdivided by adversity exposure suggests etiologic heterogeneity in major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 545-554 (2018).

- Howard, D. M. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 343-352 (2019).

- Mitchell, B. L. et al. The Australian Genetics of Depression Study: new risk loci and dissecting heterogeneity between subtypes. Biol. Psychiatry 92, 227-235 (2022).

- Levey, D. F. et al. Bi-ancestral depression GWAS in the Million Veteran Program and meta-analysis in

million individuals highlight new therapeutic directions. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 954-963 (2021). - Dunn, E. C. et al. Genome-wide association study of depressive symptoms in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J. Psychiatr. Res. 99, 167-176 (2018).

- Dunn, E. C. et al. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) and genome-wide by environment interaction study (GWEIS) of depressive symptoms in African American and Hispanic/Latina women. Depress. Anxiety 33, 265-280 (2016).

- Bigdeli, T. B. et al. Genetic effects influencing risk for major depressive disorder in China and Europe. Transl. Psychiatry 7, e1074 (2017).

- Giannakopoulou, O. et al. The genetic architecture of depression in individuals of East Asian ancestry: a genome-wide association study. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 1258-1269 (2021).

- Torgersen, K. et al. Shared genetic loci between depression and cardiometabolic traits. PLoS Genet. 18, e1010161 (2022).

- O’Loughlin, J. et al. Mendelian randomisation study of body composition and depression in people of East Asian ancestry highlights potential setting-specific causality. BMC Med. 21, 37 (2023).

- Fatumo, S. et al. A roadmap to increase diversity in genomic studies. Nat. Med. 28, 243-250 (2022).

- Bailey, R. K., Mokonogho, J. & Kumar, A. Racial and ethnic differences in depression: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 15, 603-609 (2019).

- Hunter-Zinck, H. et al. Genotyping array design and data quality control in the Million Veteran Program. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 106, 535-548 (2020).

- Stein, M. B. et al. Genome-wide association studies of posttraumatic stress disorder in 2 cohorts of US Army soldiers. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 695-704 (2016).

- Shen, H. et al. Polygenic prediction and GWAS of depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideation/self-harm in a Peruvian cohort. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 1595-1602 (2020).

- Zeng, B. et al. Multi-ancestry eQTL meta-analysis of human brain identifies candidate causal variants for brain-related traits. Nat. Genet. 54, 161-169 (2022).

- Huang, Q. Q. et al. Transferability of genetic loci and polygenic scores for cardiometabolic traits in British Pakistani and Bangladeshi individuals. Nat. Commun. 13, 4664 (2022).

- Brown, B. C., Asian Genetic Epidemiology Network Type 2 Diabetes Consortium, Ye, C. J., Price, A. L. & Zaitlen, N. Transethnic genetic-correlation estimates from summary statistics. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 76-88 (2016).

- Lam, M. et al. Comparative genetic architectures of schizophrenia in East Asian and European populations. Nat. Genet. 51, 1670-1678 (2019).

- McLaren, W. et al. The Ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 122 (2016).

- Sherry, S. T., Ward, M. & Sirotkin, K. dbSNP-database for single nucleotide polymorphisms and other classes of minor genetic variation. Genome Res. 9, 677-679 (1999).

- Dall’Aglio, L., Lewis, C. M. & Pain, O. Delineating the genetic component of gene expression in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 627-636 (2021).

- Guyon, A., Conductier, G., Rovere, C., Enfissi, A. & Nahon, J.-L. Melanin-concentrating hormone producing neurons: activities and modulations. Peptides 30, 2031-2039 (2009).

- Hispanic Community Health Study – Study of Latinos. National Institutes of Health https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/ cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000810.v1.p1 (2015).

- Resource for Genetic Epidemiology Research on Aging. National Institutes of Health https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000674.v3.p3 (2018).

- Maître, J.-L. & Heisenberg, C.-P. Three functions of cadherins in cell adhesion. Curr. Biol. 23, R626-R633 (2013).

- Lutz, M. W., Sprague, D., Barrera, J. & Chiba-Falek, O. Shared genetic etiology underlying Alzheimer’s disease and major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 88 (2020).

- Chang, H. et al. The protocadherin 17 gene affects cognition, personality, amygdala structure and function, synapse development and risk of major mood disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 400-412 (2018).

- Xiao, X. et al. The gene encoding protocadherin 9 (PCDH9), a novel risk factor for major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 43, 1128-1137 (2018).

- Pernicova, I. & Korbonits, M. Metformin-mode of action and clinical implications for diabetes and cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10, 143-156 (2014).

- Zemdegs, J. et al. Metformin promotes anxiolytic and antidepressant-like responses in insulin-resistant mice by decreasing circulating branched-chain amino acids. J. Neurosci. 39, 5935-5948 (2019).

- Ward, J. et al. The genomic basis of mood instability: identification of 46 loci in 363,705 UK Biobank participants, genetic correlation with psychiatric disorders, and association with gene expression and function. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 3091-3099 (2020).

- Tyrrell, J. et al. Using genetics to understand the causal influence of higher BMI on depression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 48, 834-848 (2019).

- van den Broek, N. et al. Causal associations between body mass index and mental health: a Mendelian randomisation study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 72, 708-710 (2018).

- Speed, M. S., Jefsen, O. H., Børglum, A. D., Speed, D. & Østergaard, S. D. Investigating the association between body fat and depression via Mendelian randomization. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 184 (2019).

- So, H.-C., Chau, C. K.-L., Cheng, Y.-Y. & Sham, P. C. Causal relationships between blood lipids and depression phenotypes: a Mendelian randomisation analysis. Psychol. Med. 51, 2357-2369 (2021).

- Perry, B. I., Oltean, B. P., Jones, P. B. & Khandaker, G. M. Cardiometabolic risk in young adults with depression and evidence of inflammation: a birth cohort study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 116, 104682 (2020).

- Hagenaars, S. P. et al. Genetic comorbidity between major depression and cardio-metabolic traits, stratified by age at onset of major depression. Am. J. Med. Genet. B 183, 309-330 (2020).

- Valkovskaya, M. et al. Study protocol of DIVERGE, the first genetic epidemiological study of major depressive disorder in Pakistan. Psychiatr. Genet. 33, 69-78 (2023).

- Breeze, C. E., Beck, S., Berndt, S. I. & Franceschini, N. The missing diversity in human epigenomic studies. Nat. Genet. 54, 737-739 (2022).

- Long, E. et al. The case for increasing diversity in tissue-based functional genomics datasets to understand human disease susceptibility. Nat. Commun. 13, 2907 (2022).

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell 179, 1469-1482.e11 (2019).

© The Author(s) 2024

مجموعة عمل اضطراب الاكتئاب الكبير التابعة لـ PGC

مجموعة التعاون في بنك كادوري الحيوي في الصين

كوانغ لين

فريق أبحاث 23andMe

يونشوان جيانغ

فريق أبحاث الجينات والصحة

ديفيد أ. فان هيل

مشروع بنك الأحياء الياباني

الطرق

المجموعات المشاركة

تحليلات الارتباط الجيني على مستوى الدراسة

تم استلام الإحصاءات من متعاونينا لجميع الدراسات الأخرى. تم إجراء تحليلات الانحدار اللوجستي ذات التأثير الإضافي من قبل شركة 23 and Me Inc، ودراسة تايوان-الاكتئاب، وMVP، وBBJ، وRabinowitz، وMAMHS، وPrOMIS، وBioVU. تم تضمين العمر، الجنس، المكونات الرئيسية والمتغيرات الأخرى ذات الصلة بمستوى الدراسة كمتغيرات ضابطة.

التحليلات التلوية

تم إنشاء مخططات تكبير الموقع المحددة بواسطة خوارزمية GCTA للمنطقة الممتدة 250 كيلوبازا للأمام والخلف. ثم قمنا بفحص كل من هذه المخططات يدويًا وأزلنا أي إشارات ثانوية من قائمتنا حيث كان هناك فصل غير واضح في الترابط الوراثي، أي أن بعض المتغيرات القريبة من الضربة الثانوية كانت مرتبطة وراثيًا بالمتغير الرئيسي.

التحديد الدقيق

تم تصنيف المواقع التي تم تحديدها بدقة على أنها قوية إذا لم تكن هناك متغيرات شاذة.

تحليل التموقع المشترك

تقييم قابلية انتقال المواقع المرتبطة بمرض السكري من النوع الثاني

الارتباطات الجينية عبر الأنساب

تعليق الجينات

تحليل الارتباط عبر كامل النسخ الجينية ورسم خرائط الأدوية

تم اشتقاقه باستخدام إجراء قائم على التبديل، والذي يقدر عتبة الدلالة بناءً على عدد الميزات المختبرة

السيد

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

مشاركة إحصائيات ملخص الجينوم على مستوى الجينوم الكامل. سيتم توفير إحصائيات ملخص GWAS الكاملة لمجموعة بيانات الاكتشاف 23andMe من خلال 23andMe للباحثين المؤهلين بموجب اتفاقية مع 23andMe تحمي خصوصية المشاركين في 23andMe. يرجى زيارةhttps://research.23andme.com/collaborate/#dataset-access/لمزيد من المعلومات وللتقدم بطلب للوصول إلى البيانات. يمكن للباحثين التقدم بطلب للوصول إلى WHI وJHS عبر dbGaP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/gap/). استخدمت الدراسة الحالية بيانات من دراسات dbGaP بموجب الطلب رقم 18933.

توفر الشفرة البرمجية

References

- Zhou, W. et al. Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 50, 1335-1341 (2018).

- Gogartsen, S. M. et al. Genetic association testing using the GENESIS R/Bioconductor package. Bioinformatics 35, 5346-5348 (2019).

- Cook, J. P., Mahajan, A. & Morris, A. P. Guidance for the utility of linear models in meta-analysis of genetic association studies of binary phenotypes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25, 240-245 (2017).

- Willer, C. J., Li, Y. & Abecasis, G. R. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 26, 2190-2191 (2010).

- Gen-ABEL project. GitHub https://github.com/GenABEL-Project/ GenABEL (2022).

- Yang, J. et al. Genomic inflation factors under polygenic inheritance. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19, 807-812 (2011).

- Freedman, M. L. et al. Assessing the impact of population stratification on genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 36, 388-393 (2004).

- Pan-UK Biobank. Broad Institute https://pan.ukbb.broadinstitute. org (2020).

- Bulik-Sullivan, B. K. et al. LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 47, 291-295 (2015).

- Yang, J., Lee, S. H., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76-82 (2011).

- Yang, J. et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat. Genet. 44, 369-375 (2012).

-

Development Core Team. : a language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017). - Wickham, H. in ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (ed. Wickham, H.) 241-253 (Springer International, 2016).

- Turner, D. S. qqman: an R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and manhattan plots. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 731 (2018).

- Kassambara, A. Ggpubr:’ggplot2′ based publication ready plots, R package version 0.6.0 (2023).

- Gormley, P. et al. Meta-analysis of 375,000 individuals identifies 38 susceptibility loci for migraine. Nat. Genet. 48, 856-866 (2016).

- Kanai, M. et al. Meta-analysis fine-mapping is often miscalibrated at single-variant resolution. Cell Genomics 14, 100210 (2022).

- Chen, W. et al. Improved analyses of GWAS summary statistics by reducing data heterogeneity and errors. Nat. Commun. 12, 7117 (2021).

- Giambartolomei, C. et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004383 (2014).

- Schubert, R. et al. Protein prediction for trait mapping in diverse populations. PLoS ONE 17, e0264341 (2022).

- Shang, L. et al. Genetic architecture of gene expression in European and African Americans: an eQTL mapping study in GENOA. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 106, 496-512 (2020).

- Zhang, J. et al. Plasma proteome analyses in individuals of European and African ancestry identify cis-pQTLs and models for proteome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 54, 593-602 (2022).

- Võsa, U. et al. Large-scale cis- and trans-eQTL analyses identify thousands of genetic loci and polygenic scores that regulate blood gene expression. Nat. Genet. 53, 1300-1310 (2021).

- Zhang, H. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 32 novel breast cancer susceptibility loci from overall and subtype-specific analyses. Nat. Genet. 52, 572-581 (2020).

- Mägi, R. et al. Trans-ethnic meta-regression of genome-wide association studies accounting for ancestry increases power for discovery and improves fine-mapping resolution. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 3639-3650 (2017).

- Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8, 1826 (2017).

- de Leeuw, C. A., Mooij, J. M., Heskes, T. & Posthuma, D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004219 (2015).

- Sey, N. Y. A. et al. A computational tool (H-MAGMA) for improved prediction of brain-disorder risk genes by incorporating brain chromatin interaction profiles. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 583-593 (2020).

- Gusev, A. et al. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 48, 245-252 (2016).

- TWAS/FUSION project. Gusev Lab http://gusevlab.org/projects/ fusion/ (2022).

- Dataset summary of analysis samples. GTEx Portal https:// gtexportal.org/home/tissueSummaryPage (2019).

- Gaspar, H. A. et al. Using genetic drug-target networks to develop new drug hypotheses for major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 117 (2019).

- Gerring, Z. F., Gamazon, E. R. & Derks, E. M., Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. A gene co-expression network-based analysis of multiple brain tissues reveals novel genes and molecular pathways underlying major depression. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008245 (2019).

- Pain, O. TWAS-plotter: R script to make Manhattan-style plot for TWAS. GitHub ().

- GeneCards. The GeneCards Human Gene Database https://www. genecards.org/ (2023)

- ChEMBL database. European Bioinformatics Institute https://www. ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ (2023).

- Wishart, D. S. in Principles of Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics (eds. Altman, R. B., Flockhart, D. & Goldstein, D. B.) 55-65 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

- Mendelian randomization with GWAS summary data. GitHub https://mrcieu.github.io/TwoSampleMR/index.html (2020).

- Hemani, G. et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. eLife 7, e34408 (2018).

- Turcot, V. et al. Protein-altering variants associated with body mass index implicate pathways that control energy intake and expenditure in obesity. Nat. Genet. 50, 26-41 (2018).

- Chen, J. et al. The trans-ancestral genomic architecture of glycemic traits. Nat. Genet. 53, 840-860 (2021).

- Graham, S. E. et al. The power of genetic diversity in genome-wide association studies of lipids. Nature 600, 675-679 (2021).

- Sakaue, S. et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 53, 1415-1424 (2021).

- Bowden, J. et al. A framework for the investigation of pleiotropy in two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization. Stat. Med. 36, 1783-1802 (2017).

- Verbanck, M., Chen, C.-Y., Neale, B. & Do, R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet. 50, 693-698 (2018).

الشكر والتقدير

إي. كونغ، ج. مارشيني، هـ. يانغ، ج. وانغ، س. شي، ر. موت، ك. شو، ج. وانغ، ك. س. كيندلر وج. فلينت. تعرب AGDS عن امتنانها لجميع المشاركين الذين منحوا وقتهم للمساهمة في هذه الدراسة. نشكر جميع الأشخاص الذين ساعدوا في التصور والتنفيذ وحملة الإعلام وتنظيف البيانات. نشكر ر. باركر، س. كروس ول. سوليفان على عملهم القيم في تنسيق جميع الجوانب الإدارية والتشغيلية لمشروع AGDS. تشكر دراسة 23andMe المشاركين في البحث وموظفي 23andMe لجعل هذا العمل ممكنًا. تشكر Genes and Health منظمة Social Action for Health، ومركز Cell، وأعضاء مجموعة الاستشارات المجتمعية، والموظفين الذين قاموا بتجنيد وجمع البيانات من المتطوعين. نشكر المركز الوطني للعينات البيولوجية التابع لـ NIHR (UK Biocentre)، ومركز الطب النفسي الاجتماعي والتنموي الوراثي (كلية كينغز لندن)، ومعهد ويلكوم سانجر، ومعهد برود على معالجة العينات، والتصنيف الجيني، والتسلسل، وتوصيف المتغيرات. نشكر مؤسسة Barts Health NHS Trust، ومجموعات تفويض الخدمات السريرية NHS (City and Hackney، Waltham Forest، Tower Hamlets، Newham، Redbridge، Havering، Barking and Dagenham)، ومؤسسة East London NHS Foundation Trust، ومستشفيات Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust، والصحة العامة في إنجلترا (وخاصة د. وايلي)، وخدمة بيانات الاكتشاف/مؤسسة Endeavour Health الخيرية (وخاصة د. ستابلز) لمشاركة البيانات المتوافقة مع اللائحة العامة لحماية البيانات بدعم من الموافقة الخطية الفردية المستنيرة. وقبل كل شيء، نشكر جميع المتطوعين المشاركين في Genes and Health. تحتوي الجداول التكميلية 17-21 على القائمة الكاملة لأعضاء مجموعة عمل PGC-MDD، وفريق أبحاث 23andMe، وفريق أبحاث Genes and Health، ومجموعة التعاون في بنك الصين كادوري، ومشروع BioBank اليابان. هذه الدراسة جزء من مشروع تلقى تمويلاً من المجلس الأوروبي للأبحاث ضمن برنامج أفق 2020 للبحث والابتكار التابع للاتحاد الأوروبي (اتفاقية المنحة رقم 948561) ومن مؤسسة ويلكوم (212360/Z/18/Z). تم دعم الحوسبة من قبل مجلس أبحاث التكنولوجيا الحيوية والعلوم البيولوجية (BB/R01356X/1). يدعم D.K. زمالة MSCA الفردية، المفوضية الأوروبية (101028810). يدعم G.N. مجلس أبحاث التكنولوجيا الحيوية والعلوم البيولوجية، رقم المنحة BB/MOO9513/1. يدعم R.P. منح من المعاهد الوطنية للصحة NIH (R33 DA047527؛ R21 DC018098) وجائزة One Mind Rising Star. يدعم G.A.P. برنامج تدريب العلوم البيولوجية في جامعة ييل (T32 MH014276). يدعم P.-H.K. مشروع وزارة العلوم والتكنولوجيا (MOST 108-2314-B-002-136-MY3)، ومشروع المعاهد الوطنية للصحة (NHRI-EX106-10627NI)، ومشروع تطوير المسيرة المهنية في جامعة تايوان الوطنية (109L7860). يدعم A.M.M. منح من مؤسسة ويلكوم (226770/Z/22/Z، 223165/Z/21/Z، 220857/Z/20/Z و216767/Z/19/Z)، والابتكار والبحوث في المملكة المتحدة (MR/SO35818/1 وMR/WO14386/1)، والمعاهد الوطنية للصحة الأمريكية NIH (R01MH124873)، وبرنامج أفق 2020 للاتحاد الأوروبي (اتفاقية المنحة 847776). يدعم M.J.A. منح من مؤسسة ويلكوم (104036/Z/14/Z و220857/Z/20/Z). تم تمويل AGDS بشكل أساسي من قبل المجلس الوطني للصحة والبحوث الطبية في أستراليا NHMRC، منحة رقم 1086683. تم دعم هذا العمل أيضًا بمنح NHMRC 1145645، 1078901، 1113400 و1087889 والمعهد الوطني للصحة النفسية NIMH. تم تمويل دراسة QSkin من قبل NHMRC (أرقام المنح 1073898، 1058522 و1123248). يدعم N.G.M. منحة باحث NHMRC رقم 1172990. يدعم W.E. منحة المعهد الوطني لتعاطي المخدرات R01DA009897. تم تمويل CONVERGE من قبل مؤسسة ويلكوم (WT090532/Z/09/Z، WT083573/Z/07/Z وWT089269/Z/09/Z) ومنحة NIH رقم MH100549. تم دعم K.S.K. من قبل NIMH R01MH125938 وR21MH126358. تم دعم R.E.P. من قبل NIMH R01MH125938، R21MH126358 ومؤسسة أبحاث الدماغ والسلوك NARSAD منحة 28632P&S Fund. يدعم L.K.D. تمويل R01 MH118223. يدعم R.J.U.، R.C.K. وM.B.S. وزارة الدفاع الأمريكية. تم دعم J.G. ودراسة MVP من قبل مكتب شؤون المحاربين القدامى للبحوث والتطوير بمنحة MVP رقم CX001849-01 (MVP025) و…

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-023-01596-4.

نيتشر بورتفوليو

كارولين كوشنبايكر

آخر تحديث بواسطة المؤلف(ين): 27 سبتمبر 2023

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

تم التأكيد

بيان حول ما إذا كانت القياسات قد أُخذت من عينات مميزة أو ما إذا تم قياس نفس العينة مرارًا وتكرارًا

يجب وصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ وصف التقنيات الأكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

وصف لجميع المتغيرات المشتركة التي تم اختبارها

وصف لأي افتراضات أو تصحيحات، مثل اختبارات التوزيع الطبيعي والتعديل للمقارنات المتعددة

وصف كامل للمعلمات الإحصائية بما في ذلك الاتجاه المركزي (مثل المتوسطات) أو التقديرات الأساسية الأخرى (مثل معامل الانحدار) والتباين (مثل الانحراف المعياري) أو التقديرات المرتبطة بعدم اليقين (مثل فترات الثقة)

مجموعتنا على الويب حول الإحصاءات لعلماء الأحياء تحتوي على مقالات حول العديد من النقاط المذكورة أعلاه.

البرمجيات والرمز البرمجي

معلومات السياسة حول توفر شفرة الكمبيوتر

تحليل البيانات

قمنا بتنفيذ تحليلات تلويّة بتأثير ثابت موزونة بالعكس باستخدام METAL (الإصدار 2011-03-25) وتحليل ميتا متعدد الأنساب باستخدام MR-MEGA (الإصدار 0.2).

لتحديد إشارات الارتباط المستقلة، تم تطبيق عملية الاختيار الأمامي والإقصاء الخلفي في برنامج GCTA (الإصدار 1.92.0 بيتا 2) (الأمر ‘cojo-slt’) باستخدام الإحصائيات الملخصة من التحليل التلوي متعدد الأنساب، مع لوحة مرجعية لتغاير الارتباط متعددة الأنساب.

أجرينا التموقع المشترك بين الارتباطات الجينية مع الاكتئاب الرئيسي وتعبير الجينات في أنسجة الدماغ والدم من عينات ذات أصول أوروبية وأفريقية والمشاركين من أصل إسباني/لاتيني باستخدام حزمة coloc في لغة R (الإصدار).

تم أولاً توضيح إحصائية الملخص من التحليل التلوي متعدد الأنساب باستخدام FUMA (الإصدار 1.3.7).

تم تنفيذ تحليلات الارتباط المعتمدة على الجينات باستخدام تحليل التعدد العلامي للتعليقات الجينومية (MAGMA، الإصدار 1.08) وMAGMA المرتبط بتقنية Hi-C (H-MAGMA).

لإجراء دراسة ارتباط عبر النسخ الجيني (TWAS)، تم استخدام برنامج FUSION.

قمنا بإجراء تحليل MR ثنائي الاتجاه لعينة مزدوجة باستخدام حزمة TwoSampleMR في لغة R (الإصدار 0.5.6،https://mrcieu.github.io/TwoSampleMR/index.html).

قمنا بتقدير الارتباطات الجينية عبر الأنساب باستخدام برنامج POPCORN الإصدار 1.029,55,64. تم حساب الارتباطات الزوجية بين كل

البيانات

معلومات السياسة حول توفر البيانات

- رموز الوصول، المعرفات الفريدة، أو روابط الويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتوافق مع سياستنا

المشاركون في البحوث البشرية

| التقارير عن الجنس والنوع الاجتماعي | استخدمنا الجنس البيولوجي في الدراسة. تم تحديده بناءً على النمط الجيني للمشاركين. | |||||||||||||||||||

| خصائص السكان |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| التوظيف | نقدم أوصافًا مفصلة للمجموعات الـ 21 المشمولة في هذه الدراسة في المواد التكميلية. | |||||||||||||||||||

| الرقابة الأخلاقية | تمت الموافقة على كل مجموعة من المجموعات المشمولة من قبل لجنة مراجعة أخلاقيات ذات صلة وقد قمنا بإدراج التفاصيل في المخطوطة. |

التقارير المتخصصة بالمجال

علوم الحياة

العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية

العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

للحصول على نسخة مرجعية من الوثيقة مع جميع الأقسام، انظر إلىnature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

تصميم دراسة علوم الحياة

| حجم العينة | لتحديد حجم العينة، جمعنا عدد المشاركين في كل دراسة تم تضمينها في التحليل المعني. | ||

| استثناءات البيانات | قمنا بتقييد التحليل اللاحق على المتغيرات الجينية التي لديها درجة دقة التقدير (imputation accuracy info score) بمقدار 0.7 أو أعلى وعدد الأليل الفعال (2ماف(1-مف)نR2) بقيمة 50 أو أكثر. بالنسبة للدراسة ذات حجم العينة الصغيرة، طلبنا بدلاً من ذلك تردد الأليل الطفيف لا يقل عن 0.05. تم إعادة ترميز الأليلات للانديلز كـ “I” للأليل الأطول و “D” للأليل الأقصر. تم إزالة الانديلز ذات الأنماط المختلفة في نفس الموضع. | ||

| التكرار |

|

||

| العشوائية | كانت هذه دراسة ارتباط جيني. التوزيع حسب النمط الجيني. | ||

| مُعمٍ | كانت هذه دراسة ارتباط جيني، أي تصميم رصدي. لذلك لم يتم استخدام التعمية. |

التقارير الخاصة بالمواد والأنظمة والأساليب المحددة

| المواد والأنظمة التجريبية | الطرق | ||

| غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة | غير متوفر | مشارك في الدراسة |

|

|

|

تسلسل ربط البروتين بالحمض النووي (ChIP-seq) |

|

خطوط الخلايا حقيقية النواة |  |

|

|

علم الحفريات والآثار |  |

|

|

الحيوانات والكائنات الأخرى | ||

|

البيانات السريرية | ||

|

البحوث ذات الاستخدام المزدوج المقلقة | ||

- البريد الإلكتروني:k.kuchenbaecker@ucl.ac.uk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-023-01596-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38177345

Publication Date: 2024-01-04

Multi-ancestry genome-wide association study of major depression aids locus discovery, fine mapping, gene prioritization and causal inference

Accepted: 26 October 2023

Published online: 4 January 2024

(A) Check for updates

A list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper

Abstract

Most genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of major depression (MD) have been conducted in samples of European ancestry. Here we report a multi-ancestry GWAS of MD, adding data from 21 cohorts with 88,316 MD cases and 902,757 controls to previously reported data. This analysis used a range of measures to define MD and included samples of African (36% of effective sample size), East Asian (26%) and South Asian (6%) ancestry and Hispanic/Latin American participants (32%). The multi-ancestry GWAS identified 53 significantly associated novel loci. For loci from GWAS in European ancestry samples, fewer than expected were transferable to other ancestry groups. Fine mapping benefited from additional sample diversity. A transcriptome-wide association study identified 205 significantly associated novel genes. These findings suggest that, for MD, increasing ancestral and global diversity in genetic studies may be particularly important to ensure discovery of core genes and inform about transferability of findings.

Results

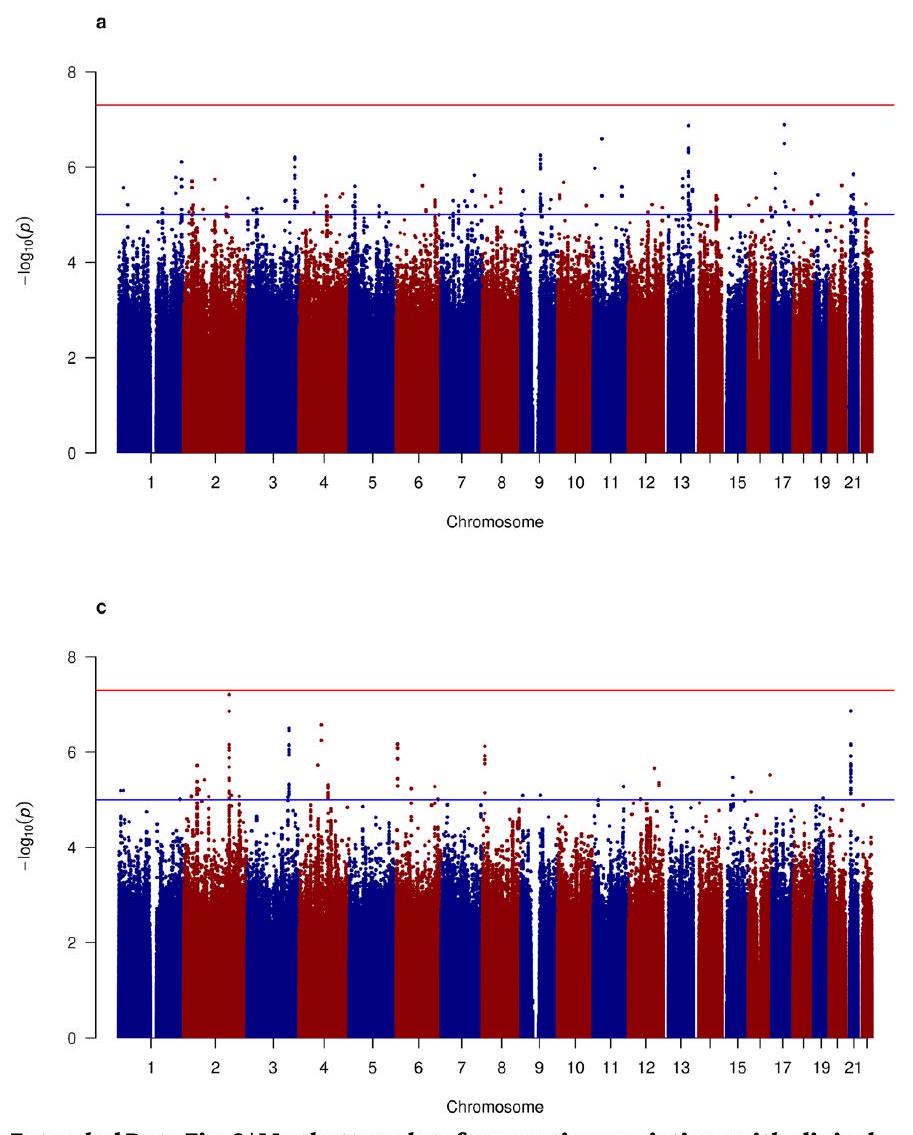

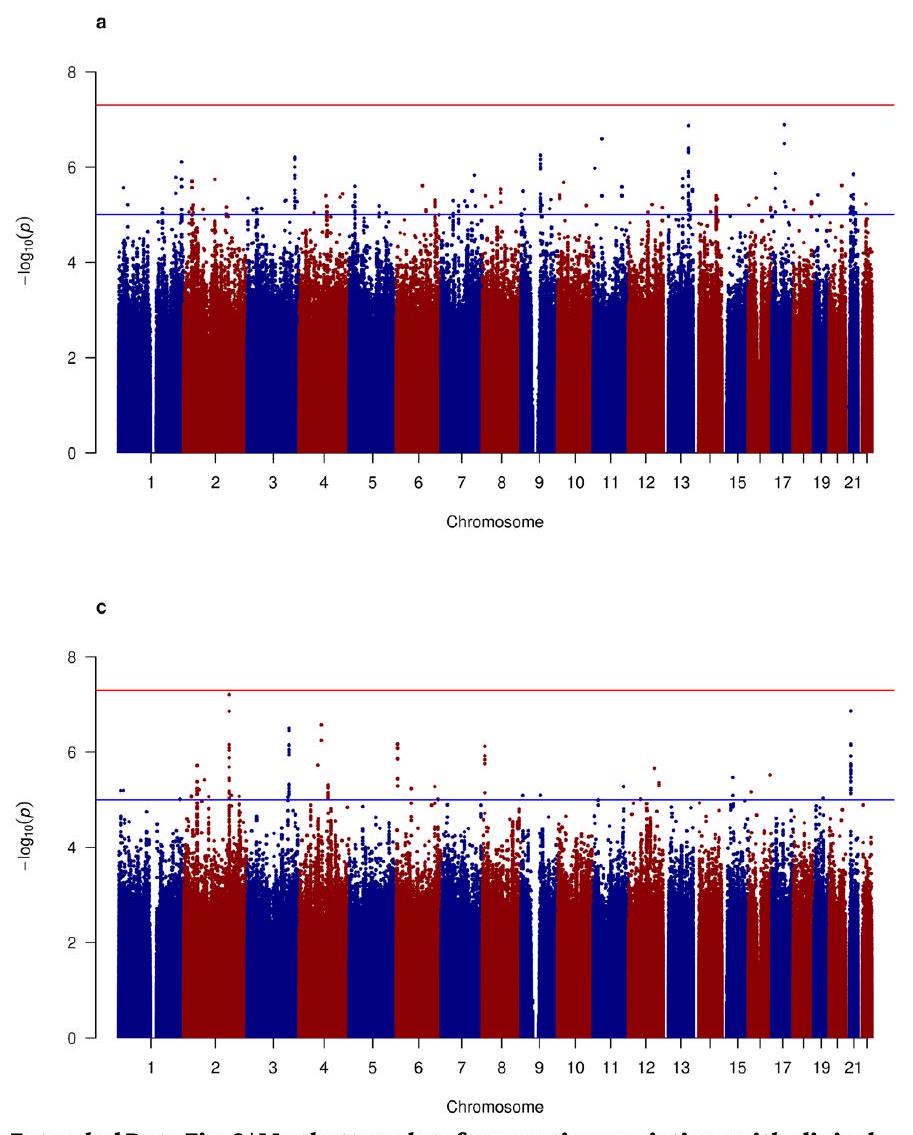

GWAS in African, East Asian and South Asian ancestry and Hispanic/Latin American samples

and cut-offs to assign participants. However, creating such groups enabled us to look for associations that are specific to groups and to assess the transferability of previously identified loci. The studies included in the meta-analyses used the following measures to define MD: structured clinical interviews, medical healthcare records, symptoms questionnaires and self-completed surveys (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note).

different but linked variants (hypothesis (H)3) or a single causal variant (H4) were considered as colocalized. We observed significant colocalization for DPP4, RBMS1 and TANK. We tested ancestry-specific eQTLs from blood and observed RBMS1 (H3: PP (Hispanic/Latin American) 99.12%) and TANK (H3: PP (European) 97.85%; H3: PP (Hispanic/Latin American)

Transferability of MD associations across ancestry groups

Multi-ancestry meta-analysis

cases and 214,415 controls in total) (Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20). This analysis identified seven genome-wide significant loci, two of which were novel (rs2085224 at 3p22.3 and rs78676209 at 5p12) (Supplementary Table 8).

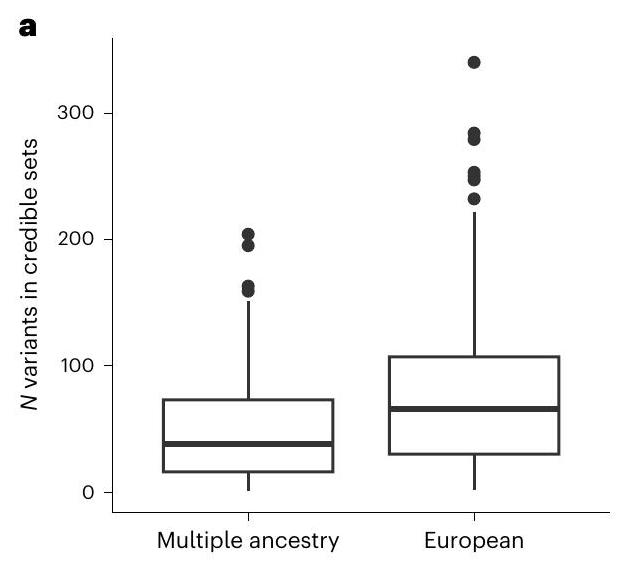

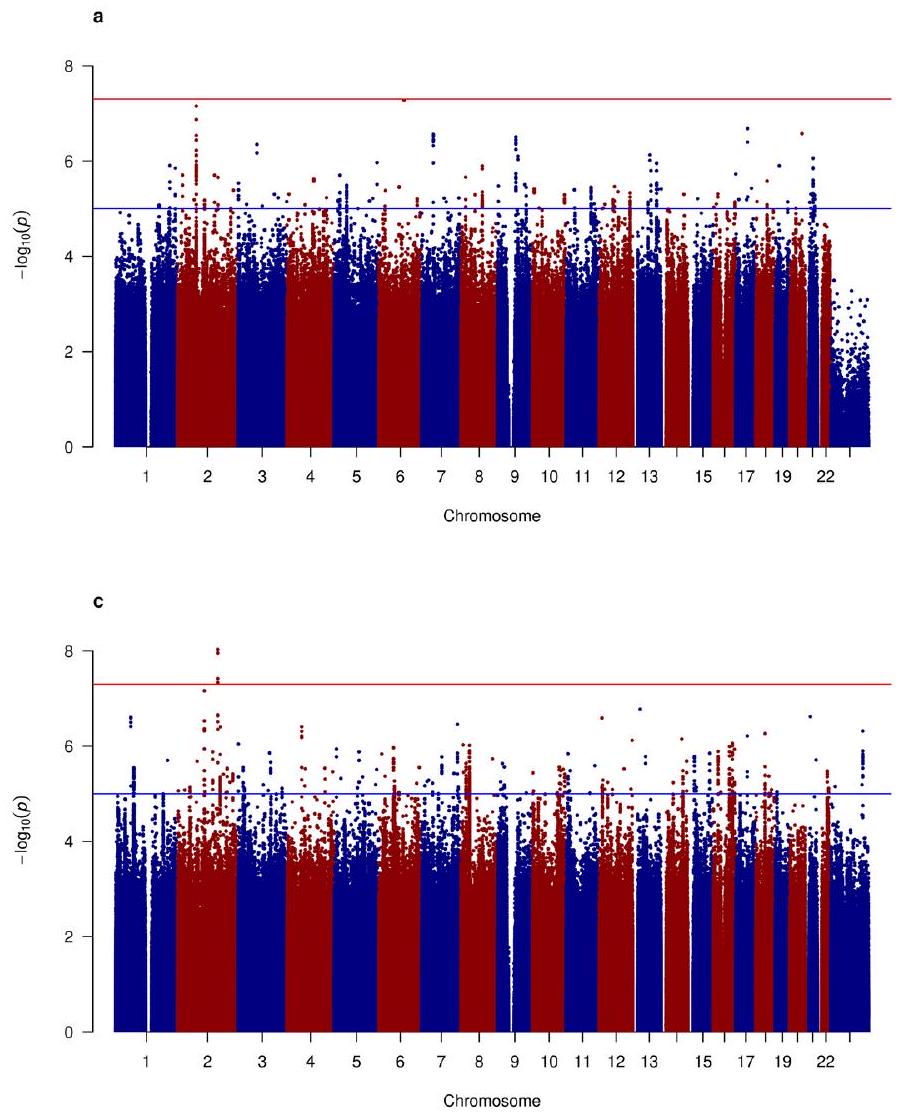

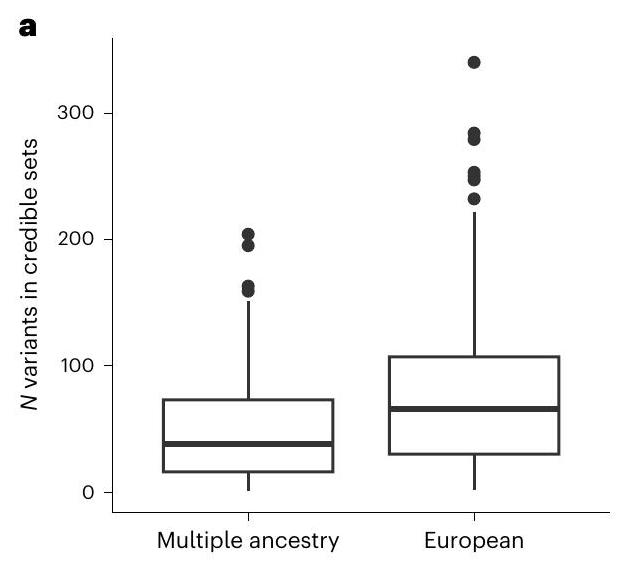

Multi-ancestry fine mapping

TWAS and gene prioritization

with MD are shown in gray. The red lines indicate the significance threshold (

and TMEM106B. Cadherin-9 (CDH9) and protocadherins (PCDHA1, PCDHA2 and PCDHA3) were also among the high-confidence genes (Supplementary Table 12). Finally, 25 of the high-confidence genes encode targets of established drugs, such as simvastatin (RHOA). These may indicate opportunities for drug repurposing.

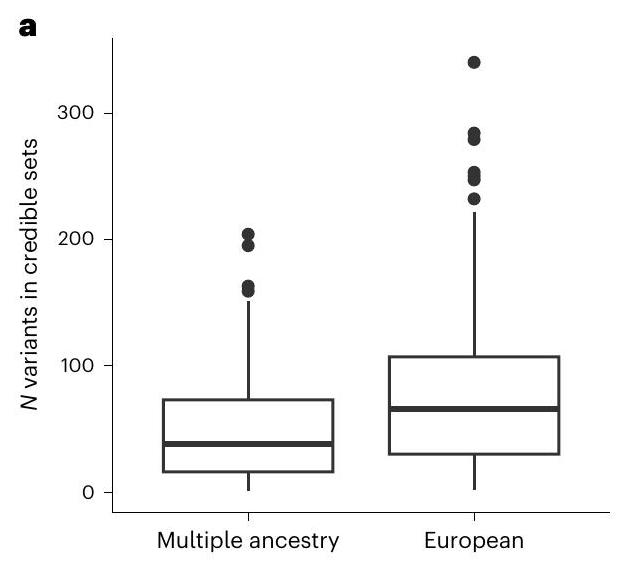

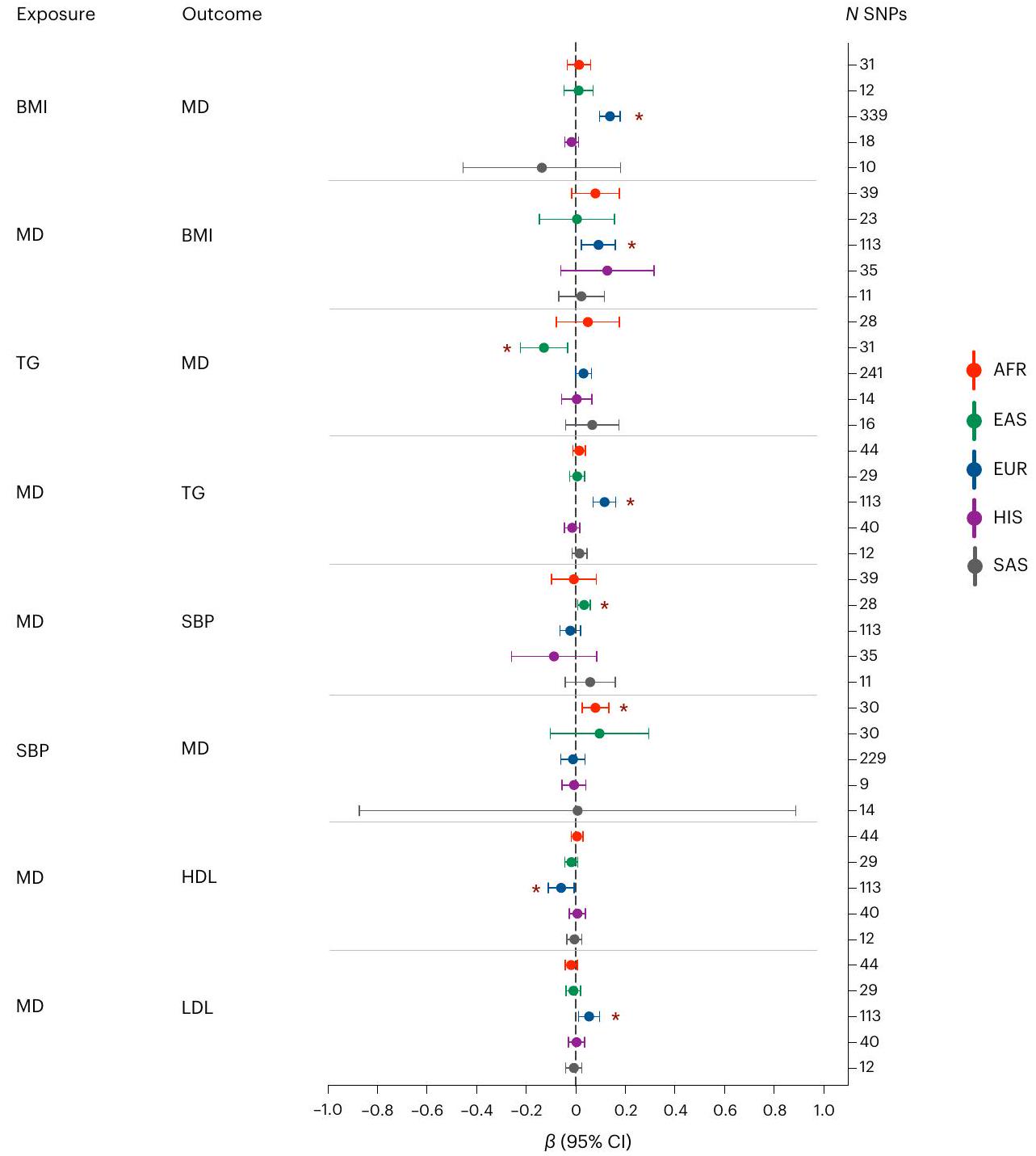

MR

bi-directional relationship was exclusively observed in samples of European ancestry (

| Gene

|

Drug

|

FUMA

|

MAGMA

|

Hi-CMAGMA

|

TWAS P | Novel

|

Credible set

|

| Genes associated in TWAS and Hi-C MAGMA | |||||||

| NDUFAF3 | Metformin, NADH | No | 1.00 | 0.004 |

|

Yes | 9 |

| PBRM1 | Alprazolam, durvalumab, everolimus | No | 0.10 | 0.017 |

|

Yes | – |

| TBCA | – | No | 0.16 | 0.042 |

|

Yes | – |

| BTN2A3P | – | No | 1.00 |

|

|

Yes | – |

| ZNF204P | – | No | 1.00 | 0.014 |

|

No | – |

| HLA-B | Thalidomide, ticlopidine, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, clozapine, lamotrigine | No | 0.46 |

|

|

No | – |

| RABGAP1 | – | No | 1.00 | 0.001 |

|

Yes | – |

| GOLGA1 | – | No | 1.00 | 0.020 |

|

Yes | – |

| FRAT2 | – | No | 0.78 | 0.017 |

|

Yes | – |

| ENSG00000278376 | – | No | 0.06 | 0.004 |

|

– | 62 |

| TRHDE-AS1 | – | No | 0.14 | 0.048 |

|

Yes | – |

| INSYN1-AS1 | – | No | 0.25 | 0.014 |

|

Yes | 25 |

| Genes associated across all four methods | |||||||

| RERE | – | Yes |

|

|

|

No | 45 |

| NEGR1 | – | Yes |

|

|

|

No | – |

| ZNF638 | Cytidine | Yes | 0.003 | 0.004 |

|

No | 61 |

| RFTN2 | Lipopolysaccharide | Yes | 0.003 |

|

|

No | 204 |

| ZNF445 | – | Yes |

|

0.001 |

|

No | 138 |

| ZNF197 | – | Yes |

|

|

|

No | 138 |

| CCDC71 | – | Yes |

|

0.039 |

|

Yes | 9 |

| ENSG00000225399 | – | Yes | 0.010 | 0.003 |

|

– | 9 |

| RHOA | Simvastatin, pravastatin, atorvastatin, magnesium, CCG-1423 | Yes | 0.031 | 0.019 |

|

No | 9 |

| CDH9 | Calcium | Yes | 0.003 | 0.002 |

|

No | 95 |

| TMEM161B | Crofelemer | Yes |

|

|

|

No | – |

| PFDN1 | – | Yes | 0.025 |

|

|

Yes | 67 |

| SLC4A9 | Sodium bicarbonate | Yes | 0.029 | 0.002 |

|

No | 67 |

| HARS1 | Adenosine phosphate, pyrophosphate, phosphate, histidine | Yes | 0.024 | 0.017 |

|

Yes | 141 |

| HARS2 | Adenosine phosphate, pyrophosphate, phosphate, histidine | Yes | 0.019 | 0.044 |

|

No | 141 |

| ZMAT2 | – | Yes | 0.014 | 0.005 |

|

No | 141 |

| PCDHA1 | Calcium | Yes | 0.015 | 0.005 |

|

No | 141 |

| PCDHA2 | Calcium | Yes | 0.031 | 0.010 |

|

No | 141 |

| PCDHA3 | Calcium | Yes | 0.043 | 0.004 |

|

No | 141 |

| TMEM106B | Crofelemer | Yes |

|

|

|

No | 1 |

| ZDHHC21 | Coenzyme A, palmityl-CoA | Yes | 0.002 | 0.036 |

|

No | 42 |

| SORCS3 | – | Yes |

|

|

|

No | 16 |

| MYBPC3 | – | Yes | 0.004 | 0.012 |

|

No | 48 |

| SLC39A13 | Zinc chloride, zinc sulfate | Yes | 0.007 | 0.003 |

|

Yes | 48 |

| CTNND1 | – | Yes | 0.002 | 0.010 |

|

No | 60 |

| ANKK1 | Methadone, naltrexone, fostamatinib | Yes | 0.011 |

|

|

No | – |

| DRD2 | Cabergoline, ropinirole, sulpiride | Yes |

|

|

|

No | – |

| MLEC | – | Yes | 0.013 |

|

|

Yes | – |

| SPPL3 | – | Yes |

|

|

|

No | – |

| LRFN5 | – | Yes |

|

|

|

No | 10 |

| AREL1 | – | Yes | 0.007 |

|

|

No | 143 |

| Gene

|

Drug

|

FUMA

|

MAGMA

|

Hi-CMAGMA

|

TWAS P | Novel

|

Credible set

|

| DLST | Lipoic acid succinyl-CoA, coenzyme A, dihydrolipoamide (S)-succinyldihydrolipoamide | Yes |

|

0.001 |

|

No | 143 |

| MARK3 | Fostamatinib, alsterpaullone | Yes |

|

|

|

No | 11 |

| KLC1 | Fluorouracil, irinotecan, leucovorin | Yes |

|

|

|

No | 11 |

| XRCC3 | Fluorouracil, irinotecan, leucovorin | Yes | 0.004 |

|

|

No | 11 |

| ZFYVE21 | Inositol 1,3-bisphosphate | Yes |

|

|

|

Yes | 11 |

| CELF4 | Iloperidone | Yes |

|

|

|

No | 8 |

| RAB27B | Guanosine-5′-diphosphate | Yes |

|

0.042 |

|

No | – |

| EMILIN3 | – | Yes | 0.039 | 0.001 |

|

No | 64 |

| CHD6 | Phosphate, ATP, ADP | Yes | 0.001 | 0.001 |

|

No | 64 |

| EP300 | Acetyl-CoA, TGF-

|

Yes |

|

|

|

No | 16 |

| RANGAP1 | – | Yes |

|

0.003 |

|

No | 16 |

| ZC3H7B | – | Yes | 0.001 |

|

|

No | 16 |

Discussion

ratios for several other traits and found variation between traits, but the estimates for MD were at the bottom

were no significant associations.

variant and having high biological plausibility

(UKB) found associations between NDUFAF3 and mood instability, suggesting that energy dysregulation may play an important role in the physiology of mood instability

Online content

References

- GBD 2017 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1859-1922 (2018).

- Wray, N. R. et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 50, 668-681 (2018).

- CONVERGE Consortium. Sparse whole-genome sequencing identifies two loci for major depressive disorder. Nature 523, 588-591 (2015).

- Zhang, Y., Qi, G., Park, J.-H. & Chatterjee, N. Estimation of complex effect-size distributions using summary-level statistics from genome-wide association studies across 32 complex traits. Nat. Genet. 50, 1318-1326 (2018).

- Flint, J. & Kendler, K. S. The genetics of major depression. Neuron 81, 1214 (2014).

- Cai, N. et al. Minimal phenotyping yields genome-wide association signals of low specificity for major depression. Nat. Genet. 52, 437-447 (2020).

- Blokland, G. A. M. et al. Sex-dependent shared and nonshared genetic architecture across mood and psychotic disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 91, 102-117 (2022).

- Martin, J. et al. Examining sex-differentiated genetic effects across neuropsychiatric and behavioral traits. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 1127-1137 (2021).

- Kang, H.-J. et al. Sex differences in the genetic architecture of depression. Sci. Rep. 10, 9927 (2020).

- Arnau-Soler, A. et al. A validation of the diathesis-stress model for depression in Generation Scotland. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 25 (2019).

- Van der Auwera, S. et al. Genome-wide gene-environment interaction in depression: a systematic evaluation of candidate genes: the childhood trauma working-group of PGC-MDD. Am. J. Med. Genet. B 177, 40-49 (2018).

- Peterson, R. E. et al. Molecular genetic analysis subdivided by adversity exposure suggests etiologic heterogeneity in major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 175, 545-554 (2018).

- Howard, D. M. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 343-352 (2019).

- Mitchell, B. L. et al. The Australian Genetics of Depression Study: new risk loci and dissecting heterogeneity between subtypes. Biol. Psychiatry 92, 227-235 (2022).

- Levey, D. F. et al. Bi-ancestral depression GWAS in the Million Veteran Program and meta-analysis in

million individuals highlight new therapeutic directions. Nat. Neurosci. 24, 954-963 (2021). - Dunn, E. C. et al. Genome-wide association study of depressive symptoms in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J. Psychiatr. Res. 99, 167-176 (2018).

- Dunn, E. C. et al. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) and genome-wide by environment interaction study (GWEIS) of depressive symptoms in African American and Hispanic/Latina women. Depress. Anxiety 33, 265-280 (2016).

- Bigdeli, T. B. et al. Genetic effects influencing risk for major depressive disorder in China and Europe. Transl. Psychiatry 7, e1074 (2017).

- Giannakopoulou, O. et al. The genetic architecture of depression in individuals of East Asian ancestry: a genome-wide association study. JAMA Psychiatry 78, 1258-1269 (2021).

- Torgersen, K. et al. Shared genetic loci between depression and cardiometabolic traits. PLoS Genet. 18, e1010161 (2022).

- O’Loughlin, J. et al. Mendelian randomisation study of body composition and depression in people of East Asian ancestry highlights potential setting-specific causality. BMC Med. 21, 37 (2023).

- Fatumo, S. et al. A roadmap to increase diversity in genomic studies. Nat. Med. 28, 243-250 (2022).

- Bailey, R. K., Mokonogho, J. & Kumar, A. Racial and ethnic differences in depression: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 15, 603-609 (2019).

- Hunter-Zinck, H. et al. Genotyping array design and data quality control in the Million Veteran Program. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 106, 535-548 (2020).

- Stein, M. B. et al. Genome-wide association studies of posttraumatic stress disorder in 2 cohorts of US Army soldiers. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 695-704 (2016).

- Shen, H. et al. Polygenic prediction and GWAS of depression, PTSD, and suicidal ideation/self-harm in a Peruvian cohort. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 1595-1602 (2020).

- Zeng, B. et al. Multi-ancestry eQTL meta-analysis of human brain identifies candidate causal variants for brain-related traits. Nat. Genet. 54, 161-169 (2022).

- Huang, Q. Q. et al. Transferability of genetic loci and polygenic scores for cardiometabolic traits in British Pakistani and Bangladeshi individuals. Nat. Commun. 13, 4664 (2022).

- Brown, B. C., Asian Genetic Epidemiology Network Type 2 Diabetes Consortium, Ye, C. J., Price, A. L. & Zaitlen, N. Transethnic genetic-correlation estimates from summary statistics. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 76-88 (2016).

- Lam, M. et al. Comparative genetic architectures of schizophrenia in East Asian and European populations. Nat. Genet. 51, 1670-1678 (2019).

- McLaren, W. et al. The Ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 122 (2016).

- Sherry, S. T., Ward, M. & Sirotkin, K. dbSNP-database for single nucleotide polymorphisms and other classes of minor genetic variation. Genome Res. 9, 677-679 (1999).

- Dall’Aglio, L., Lewis, C. M. & Pain, O. Delineating the genetic component of gene expression in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 627-636 (2021).

- Guyon, A., Conductier, G., Rovere, C., Enfissi, A. & Nahon, J.-L. Melanin-concentrating hormone producing neurons: activities and modulations. Peptides 30, 2031-2039 (2009).

- Hispanic Community Health Study – Study of Latinos. National Institutes of Health https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/ cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000810.v1.p1 (2015).

- Resource for Genetic Epidemiology Research on Aging. National Institutes of Health https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000674.v3.p3 (2018).

- Maître, J.-L. & Heisenberg, C.-P. Three functions of cadherins in cell adhesion. Curr. Biol. 23, R626-R633 (2013).

- Lutz, M. W., Sprague, D., Barrera, J. & Chiba-Falek, O. Shared genetic etiology underlying Alzheimer’s disease and major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 88 (2020).

- Chang, H. et al. The protocadherin 17 gene affects cognition, personality, amygdala structure and function, synapse development and risk of major mood disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 400-412 (2018).

- Xiao, X. et al. The gene encoding protocadherin 9 (PCDH9), a novel risk factor for major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 43, 1128-1137 (2018).

- Pernicova, I. & Korbonits, M. Metformin-mode of action and clinical implications for diabetes and cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10, 143-156 (2014).

- Zemdegs, J. et al. Metformin promotes anxiolytic and antidepressant-like responses in insulin-resistant mice by decreasing circulating branched-chain amino acids. J. Neurosci. 39, 5935-5948 (2019).

- Ward, J. et al. The genomic basis of mood instability: identification of 46 loci in 363,705 UK Biobank participants, genetic correlation with psychiatric disorders, and association with gene expression and function. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 3091-3099 (2020).

- Tyrrell, J. et al. Using genetics to understand the causal influence of higher BMI on depression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 48, 834-848 (2019).

- van den Broek, N. et al. Causal associations between body mass index and mental health: a Mendelian randomisation study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 72, 708-710 (2018).

- Speed, M. S., Jefsen, O. H., Børglum, A. D., Speed, D. & Østergaard, S. D. Investigating the association between body fat and depression via Mendelian randomization. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 184 (2019).

- So, H.-C., Chau, C. K.-L., Cheng, Y.-Y. & Sham, P. C. Causal relationships between blood lipids and depression phenotypes: a Mendelian randomisation analysis. Psychol. Med. 51, 2357-2369 (2021).

- Perry, B. I., Oltean, B. P., Jones, P. B. & Khandaker, G. M. Cardiometabolic risk in young adults with depression and evidence of inflammation: a birth cohort study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 116, 104682 (2020).

- Hagenaars, S. P. et al. Genetic comorbidity between major depression and cardio-metabolic traits, stratified by age at onset of major depression. Am. J. Med. Genet. B 183, 309-330 (2020).

- Valkovskaya, M. et al. Study protocol of DIVERGE, the first genetic epidemiological study of major depressive disorder in Pakistan. Psychiatr. Genet. 33, 69-78 (2023).

- Breeze, C. E., Beck, S., Berndt, S. I. & Franceschini, N. The missing diversity in human epigenomic studies. Nat. Genet. 54, 737-739 (2022).

- Long, E. et al. The case for increasing diversity in tissue-based functional genomics datasets to understand human disease susceptibility. Nat. Commun. 13, 2907 (2022).

- Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell 179, 1469-1482.e11 (2019).

© The Author(s) 2024

PGC-MDD Working Group

China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group

Kuang Lin

the 23andMe Research Team

YunxuanJiang

Genes and Health Research Team

David A. van Heel

BioBank Japan Project

Methods

Participating cohorts

Study-level genetic association analyses

statistics were received from our collaborators for all other studies. Additive-effect logistic regressions were conducted by the 23 and Me Inc, Taiwan-MDD study, MVP, BBJ, Rabinowitz, MAMHS, PrOMIS and BioVU.Age, sex, principal components and other relevant study-level covariates were included as covariates.

Meta-analyses

defined by the GCTA algorithm, locus zoom plots were generated for the 250 kb upstream and downstream region. We then inspected each of these plots manually and removed any secondary signals from our list where there was unclear LD separation, that is, some of the variants close to the secondary hit were in LD with the lead variant.

Fine mapping

as outliers. Fine-mapped loci were classified as robust if there were no outlying variants.

Colocalization analysis

Assessment of transferability of MD-associated loci

Trans-ancestry genetic correlations

Gene annotation

Transcriptome-wide association analysis and drug mapping

derived using a permutation-based procedure, which estimates a significance threshold based on the number of features tested

MR

Reporting summary

Data availability

sharing of genome-wide summary statistics. The full GWAS summary statistics for the 23andMe discovery dataset will be made available through 23andMe to qualified researchers under an agreement with 23 and Me that protects the privacy of the 23andMe participants. Please visit https://research.23andme.com/collaborate/#dataset-access/ for more information and to apply to access the data. Investigators can apply for access to WHI and JHS via dbGaP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/gap/). The current study utilized data from dbGaP studies under application #18933.

Code availability

References

- Zhou, W. et al. Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 50, 1335-1341 (2018).

- Gogartsen, S. M. et al. Genetic association testing using the GENESIS R/Bioconductor package. Bioinformatics 35, 5346-5348 (2019).

- Cook, J. P., Mahajan, A. & Morris, A. P. Guidance for the utility of linear models in meta-analysis of genetic association studies of binary phenotypes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25, 240-245 (2017).

- Willer, C. J., Li, Y. & Abecasis, G. R. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 26, 2190-2191 (2010).

- Gen-ABEL project. GitHub https://github.com/GenABEL-Project/ GenABEL (2022).

- Yang, J. et al. Genomic inflation factors under polygenic inheritance. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19, 807-812 (2011).

- Freedman, M. L. et al. Assessing the impact of population stratification on genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 36, 388-393 (2004).

- Pan-UK Biobank. Broad Institute https://pan.ukbb.broadinstitute. org (2020).

- Bulik-Sullivan, B. K. et al. LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 47, 291-295 (2015).

- Yang, J., Lee, S. H., Goddard, M. E. & Visscher, P. M. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88, 76-82 (2011).

- Yang, J. et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat. Genet. 44, 369-375 (2012).

-

Development Core Team. : a language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017). - Wickham, H. in ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (ed. Wickham, H.) 241-253 (Springer International, 2016).

- Turner, D. S. qqman: an R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and manhattan plots. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 731 (2018).

- Kassambara, A. Ggpubr:’ggplot2′ based publication ready plots, R package version 0.6.0 (2023).

- Gormley, P. et al. Meta-analysis of 375,000 individuals identifies 38 susceptibility loci for migraine. Nat. Genet. 48, 856-866 (2016).

- Kanai, M. et al. Meta-analysis fine-mapping is often miscalibrated at single-variant resolution. Cell Genomics 14, 100210 (2022).

- Chen, W. et al. Improved analyses of GWAS summary statistics by reducing data heterogeneity and errors. Nat. Commun. 12, 7117 (2021).

- Giambartolomei, C. et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004383 (2014).

- Schubert, R. et al. Protein prediction for trait mapping in diverse populations. PLoS ONE 17, e0264341 (2022).

- Shang, L. et al. Genetic architecture of gene expression in European and African Americans: an eQTL mapping study in GENOA. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 106, 496-512 (2020).

- Zhang, J. et al. Plasma proteome analyses in individuals of European and African ancestry identify cis-pQTLs and models for proteome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 54, 593-602 (2022).

- Võsa, U. et al. Large-scale cis- and trans-eQTL analyses identify thousands of genetic loci and polygenic scores that regulate blood gene expression. Nat. Genet. 53, 1300-1310 (2021).

- Zhang, H. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 32 novel breast cancer susceptibility loci from overall and subtype-specific analyses. Nat. Genet. 52, 572-581 (2020).

- Mägi, R. et al. Trans-ethnic meta-regression of genome-wide association studies accounting for ancestry increases power for discovery and improves fine-mapping resolution. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 3639-3650 (2017).

- Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8, 1826 (2017).

- de Leeuw, C. A., Mooij, J. M., Heskes, T. & Posthuma, D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004219 (2015).

- Sey, N. Y. A. et al. A computational tool (H-MAGMA) for improved prediction of brain-disorder risk genes by incorporating brain chromatin interaction profiles. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 583-593 (2020).

- Gusev, A. et al. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 48, 245-252 (2016).

- TWAS/FUSION project. Gusev Lab http://gusevlab.org/projects/ fusion/ (2022).

- Dataset summary of analysis samples. GTEx Portal https:// gtexportal.org/home/tissueSummaryPage (2019).

- Gaspar, H. A. et al. Using genetic drug-target networks to develop new drug hypotheses for major depressive disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 117 (2019).

- Gerring, Z. F., Gamazon, E. R. & Derks, E. M., Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. A gene co-expression network-based analysis of multiple brain tissues reveals novel genes and molecular pathways underlying major depression. PLoS Genet. 15, e1008245 (2019).

- Pain, O. TWAS-plotter: R script to make Manhattan-style plot for TWAS. GitHub ().

- GeneCards. The GeneCards Human Gene Database https://www. genecards.org/ (2023)

- ChEMBL database. European Bioinformatics Institute https://www. ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ (2023).

- Wishart, D. S. in Principles of Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics (eds. Altman, R. B., Flockhart, D. & Goldstein, D. B.) 55-65 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

- Mendelian randomization with GWAS summary data. GitHub https://mrcieu.github.io/TwoSampleMR/index.html (2020).

- Hemani, G. et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. eLife 7, e34408 (2018).

- Turcot, V. et al. Protein-altering variants associated with body mass index implicate pathways that control energy intake and expenditure in obesity. Nat. Genet. 50, 26-41 (2018).

- Chen, J. et al. The trans-ancestral genomic architecture of glycemic traits. Nat. Genet. 53, 840-860 (2021).

- Graham, S. E. et al. The power of genetic diversity in genome-wide association studies of lipids. Nature 600, 675-679 (2021).

- Sakaue, S. et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 53, 1415-1424 (2021).

- Bowden, J. et al. A framework for the investigation of pleiotropy in two-sample summary data Mendelian randomization. Stat. Med. 36, 1783-1802 (2017).

- Verbanck, M., Chen, C.-Y., Neale, B. & Do, R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet. 50, 693-698 (2018).

Acknowledgements

E. Cong, J. Marchini, H. Yang, J. Wang, S. Shi, R. Mott, Q. Xu, J. Wang, K. S. Kendler and J. Flint. The AGDS is indebted to all of the participants for giving their time to contribute to this study. We thank all the people who helped in the conception, implementation, media campaign and data cleaning. We thank R. Parker, S. Cross and L. Sullivan for their valuable work coordinating all the administrative and operational aspects of the AGDS project. The 23andMe Study thanks the research participants and employees of 23andMe for making this work possible. Genes and Health thanks Social Action for Health, Centre of the Cell, members of our Community Advisory Group, and staff who have recruited and collected data from volunteers. We thank the NIHR National Biosample Centre (UK Biocentre), the Social Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre (King’s College London), Wellcome Sanger Institute and the Broad Institute for sample processing, genotyping, sequencing and variant annotation. We thank Barts Health NHS Trust, NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups (City and Hackney, Waltham Forest, Tower Hamlets, Newham, Redbridge, Havering, Barking and Dagenham), East London NHS Foundation Trust, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Public Health England (especially D. Wyllie), Discovery Data Service/Endeavour Health Charitable Trust (especially D. Stables) for General Data Protection Regulation compliant data sharing backed by individual written informed consent. Most of all we thank all of the volunteers participating in Genes and Health. Supplementary Tables 17-21 contain the complete list of members of the PGC-MDD Working Group, the 23andMe Research Team, the Genes and Health Research Team, the China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group and the BioBank Japan Project. This study is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement no. 948561) and from Wellcome (212360/Z/18/Z). Computing was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/ R01356X/1). D.K. is supported by the MSCA Individual Fellowship, European Commission (101028810). G.N. is supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, grant number BB/MOO9513/1. R.P. is supported by grants from the NIH (R33 DA047527; R21 DC018098) and One Mind Rising Star Award. G.A.P. is supported by the Yale Biological Sciences Training Program (T32 MH014276). P.-H.K. is supported by The Ministry of Science and Technology Project (MOST 108-2314-B-002-136-MY3), the National Health Research Institutes Project (NHRI-EX106-10627NI) and the National Taiwan University Career Development Project (109L7860). A.M.M. is supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust (226770/Z/22/Z, 223165/Z/21/Z, 220857/Z/20/Z and 216767/Z/19/Z), UK Research and Innovation (MR/SO35818/1 and MR/WO14386/1), the United States NIH (R01MH124873) and the European Union Horizon 2020 scheme (grant agreement 847776). M.J.A. is supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust (104036/Z/14/Z and 220857/Z/20/Z). The AGDS was primarily funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia grant 1086683. This work was further supported by NHMRC grants 1145645, 1078901, 1113400 and 1087889 and NIMH. The QSkin study was funded by the NHMRC (grant numbers 1073898, 1058522 and 1123248). N.G.M. is supported through NHMRC investigator grant 1172990. W.E. is supported by National Institute of Drug Abuse grant R01DA009897. CONVERGE was funded by the Wellcome Trust (WT090532/Z/09/Z, WT083573/ Z/07/Z and WT089269/Z/09/Z) and by NIH grant MH100549. K.S.K. was supported by NIMH R01MH125938 and R21MH126358. R.E.P. was supported by NIMH R01MH125938, R21MH126358 and The Brain & Behavior Research Foundation NARSAD grant 28632P&S Fund. L.K.D. is supported by funding R01 MH118223. R.J.U., R.C.K. and M.B.S. are supported by the US Department of Defense. J.G. and the MVP study were supported by funding from the Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development MVP grant CX001849-01 (MVP025) and

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-023-01596-4.

natureportfolio

Karoline Kuchenbaecker

Last updated by author(s): Sep 27, 2023

Reporting Summary

Statistics

Confirmed

A statement on whether measurements were taken from distinct samples or whether the same sample was measured repeatedly

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

A description of all covariates tested

A description of any assumptions or corrections, such as tests of normality and adjustment for multiple comparisons

A full description of the statistical parameters including central tendency (e.g. means) or other basic estimates (e.g. regression coefficient) AND variation (e.g. standard deviation) or associated estimates of uncertainty (e.g. confidence intervals)

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Software and code

Policy information about availability of computer code

Data analysis

We implemented inverse-variance weighted fixed-effect meta-analyses using METAL (version 2011-03-25) and a multi ancestry metaregression using MR-MEGA (v.0.2).

To identify independent association signals, the GCTA (version 1.92 .0 beta2) forward selection and backward elimination process (command ‘cojo-slt’) were applied using the summary statistics from the multi-ancestry meta-analysis, with a multi ancestry LD reference panel.

We performed colocalization between genetic associations with MD and gene expression in brain and blood tissues from samples of European and African ancestry and Hispanic/Latinx participants using coloc R package (version).

The summary statistic from the multi-ancestry meta-analysis was first annotated with FUMA (v1.3.7).

Gene-based association analyses were implemented using Multi-marker Analysis of GenoMic Annotation (MAGMA, v1.08) and Hi-C coupled MAGMA (H-MAGMA).

To perform a transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS), the FUSION software was used.

We performed a bi-directional two-sample MR analysis using the TwoSampleMR R package (v0.5.6, https://mrcieu.github.io/TwoSampleMR/ index.html).

We estimated trans-ancestry genetic correlations using POPCORN v1.029,55,64. Pairwise correlations were calculated between each

Data

Policy information about availability of data

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

Human research participants

| Reporting on sex and gender | We used biological sex in the study. It was determined based on the participants’ genotypes. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Population characteristics |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Recruitment | We provide detailed descriptions of the 21 cohorts included in this study in the supplementary material. | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ethics oversight | Each of the cohorts included was approved by a relevant ethics review board and we have listed the details in the manuscript. |

Field-specific reporting

Life sciences

Behavioural & social sciences

Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences

For a reference copy of the document with all sections, see nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

Life sciences study design

| Sample size | To determine sample size we added up the number of participants of each study that was included in a given analysis. | ||

| Data exclusions | We restricted the downstream analysis to genetic variants with imputation accuracy info score of 0.7 or higher and effective allele count (2maf(1-maf)NR2) of 50 or higher. For study of small sample size, we instead required a minor allele frequency of no less than 0.05 . The alleles for indels were re-coded as “I” for the longer allele and “D” for the shorter one. Indels of different patterns at the same position were removed. | ||

| Replication |

|

||

| Randomization | This was a genetic association study. Allocation by genotype. | ||

| Blinding | This was a genetic association study, ie observational design. So no blinding was used. |

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

| Materials & experimental systems | Methods | ||

| n/a | Involved in the study | n/a | Involved in the study |

|

|

|

ChIP-seq |

|

Eukaryotic cell lines |  |

|

|

Palaeontology and archaeology |  |

|

|

Animals and other organisms | ||

|

Clinical data | ||

|

Dual use research of concern | ||

- e-mail: k.kuchenbaecker@ucl.ac.uk