DOI: https://doi.org/10.26443/seismica.v3i1.1009

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-22

دراسة التحقق من انخفاض الضغط المجتمعي SCEC/USGS باستخدام تسلسل زلازل ريدجكريست 2019

الملخص

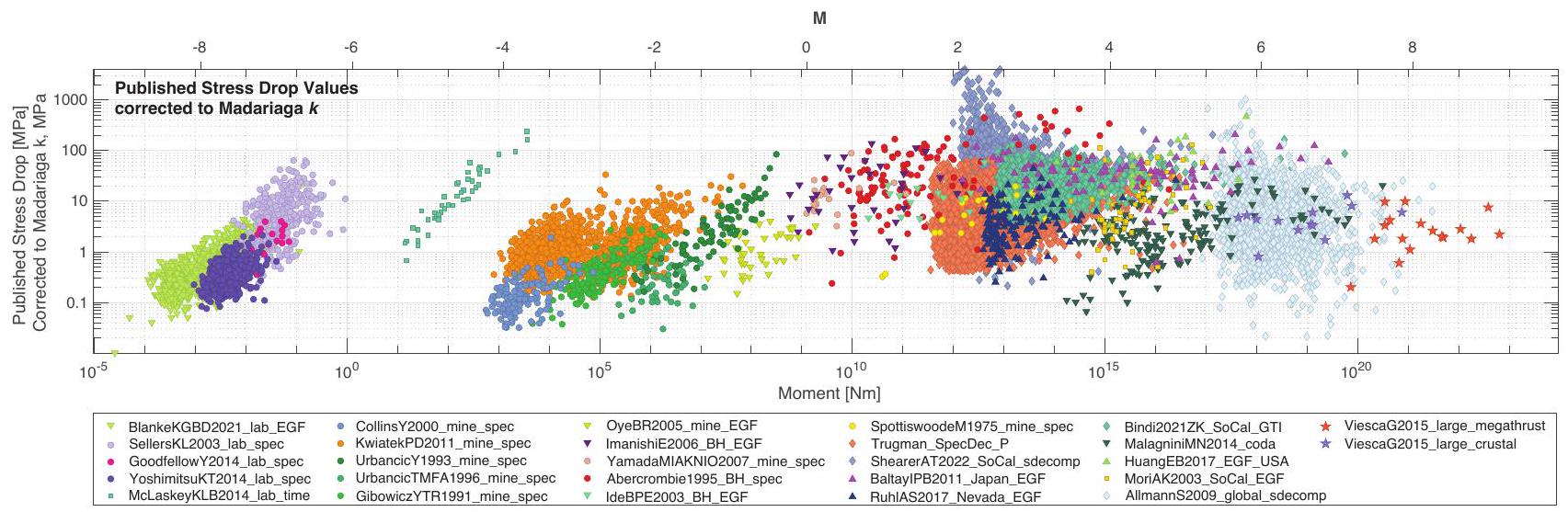

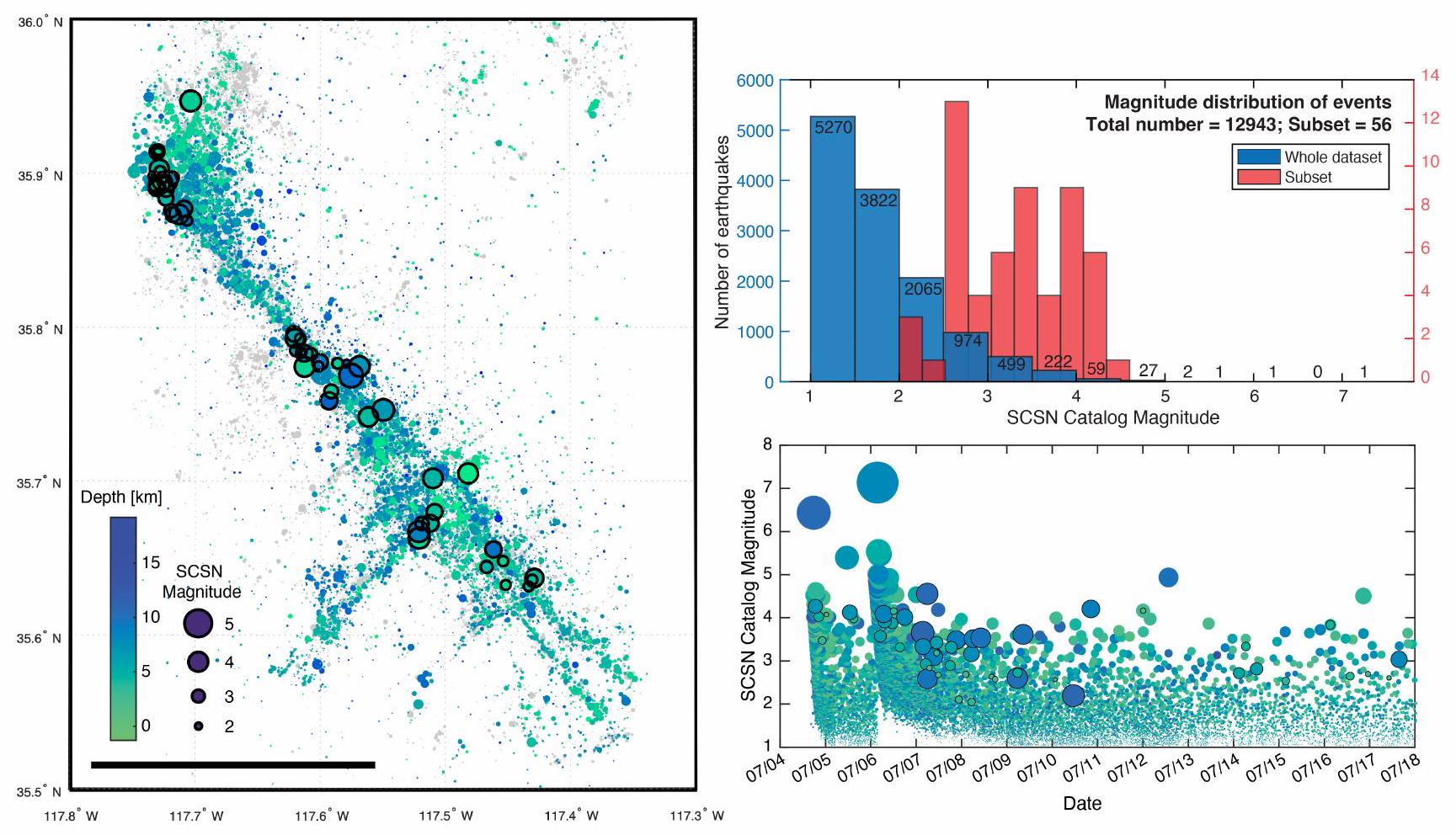

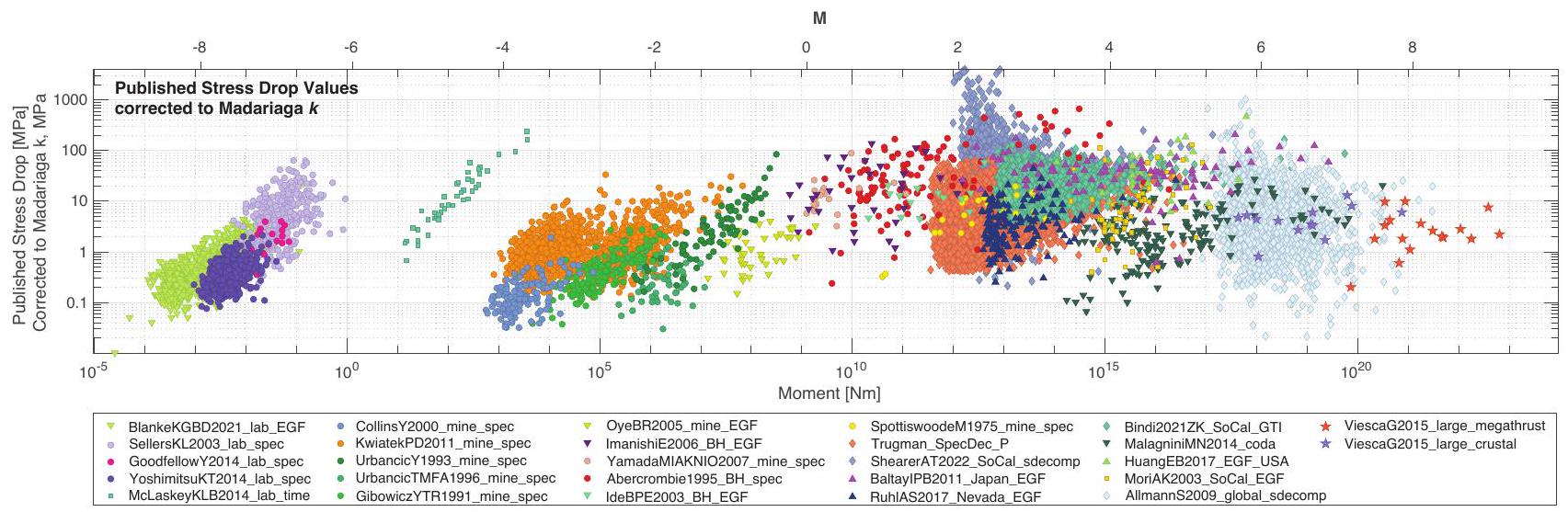

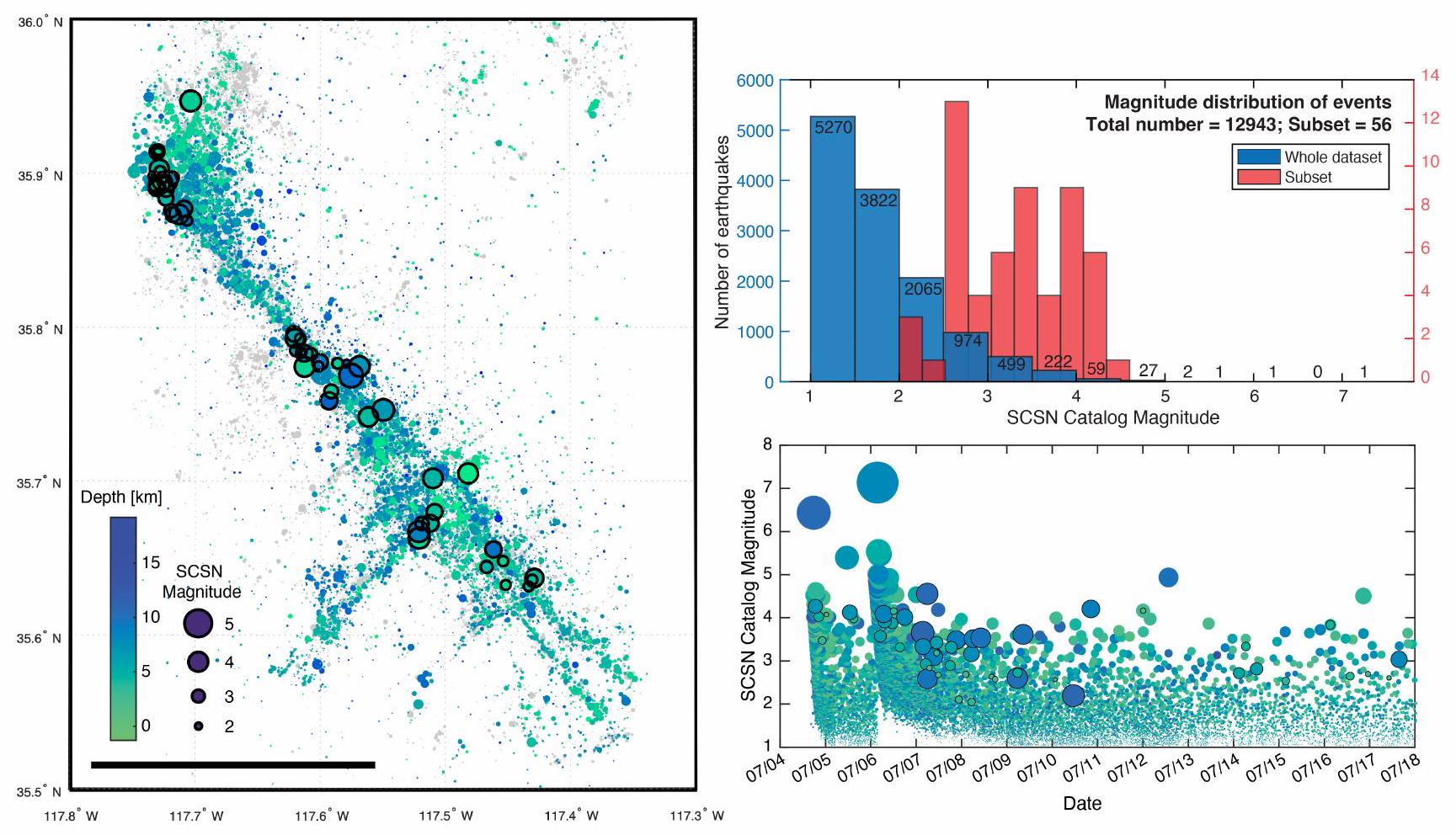

نقدم دراسة تحقق من انخفاض الضغط المجتمعي باستخدام تسلسل زلزال ريدجكريست 2019 في كاليفورنيا، حيث يُدعى الباحثون لاستخدام مجموعة بيانات مشتركة لتقدير قياسات قابلة للمقارنة بشكل مستقل باستخدام مجموعة متنوعة من الطرق. انخفاض الضغط هو التغير في متوسط الضغط القصي على صدع أثناء تمزق الزلزال، وكما هو الحال، فهو معلمة رئيسية في العديد من مشاكل الحركة الأرضية، ومحاكاة التمزق، وفيزياء المصدر في علم الزلازل. يتم تقدير انخفاض الضغط الطيفي عادةً من خلال ملاءمة شكل طيف الطاقة المشعة، ومع ذلك، يمكن أن تختلف التقديرات لزلزال فردي تم إجراؤها من قبل دراسات مختلفة بشكل كبير. في هذه الدراسة المجتمعية، التي تم رعايتها بشكل مشترك من قبل المسح الجيولوجي الأمريكي ومركز الزلازل في كاليفورنيا الجنوبية/الولاية، نسعى لفهم مصادر التباين وعدم اليقين في انخفاض ضغط الزلزال من خلال المقارنة الكمية لانخفاضات الضغط المقدمة. تتكون مجموعة البيانات المتاحة للجمهور من ما يقرب من 13,000 زلزال من M1 إلى 7 من أسبوعين من تسلسل ريدجكريست 2019 المسجل على محطات ضمن درجة واحدة. كدراسة مجتمعية، يتم مشاركة النتائج من خلال ورش العمل والاجتماعات، ويدعى الجميع للانضمام في أي وقت، على أي مستوى من الاهتمام.

ملخص غير تقني: يوفر تحرير الضغط (أو انخفاض الضغط) أثناء الزلزال معلومات حول كيفية تحويل القوى الجيولوجية إلى طاقة زلزالية مشعة عندما يتمزق صدع، والظروف التي سيستمر فيها الزلزال في الزيادة في الحجم أو يحفز الزلازل القريبة. يعد انخفاض الضغط أيضًا عنصرًا مهمًا في رسم خرائط المخاطر الزلزالية وتصميم المباني، حيث إن الزلازل ذات انخفاض الضغط العالي تشع المزيد من الطاقة عالية التردد، مما يؤدي إلى اهتزاز أرضي أقوى. للأسف، فإن تقديرات انخفاض الضغط التي تم إجراؤها في دراسات مختلفة تحتوي على اختلافات منهجية وعشوائية كبيرة، مما يعني أنها ليست موثوقة كما نحتاج لاستخدامها في توقع الحركة الأرضية وأبحاث فيزياء مصدر الزلزال. نقدم دراسة تحقق من انخفاض الضغط المجتمعي حيث ندعو جميع العلماء المهتمين من المجتمع الدولي لتحليل نفس الزلازل ومقارنة نتائجهم. نستخدم مجموعة بيانات عامة من تسجيلات الهزات الارتدادية لزلزال ريدجكريست 2019 في كاليفورنيا. هدفنا هو فهم من أين تأتي الاختلافات والتشابهات في انخفاض الضغط، ثم العمل مع المجتمع الأوسع من المستخدمين لتطوير طرق محسنة لوصف تمزق الزلزال والحركات الأرضية الناتجة لتوقعات مخاطر زلزالية أكثر موثوقية ووعياً.

1 المقدمة

تحديد العوامل التي تتحكم في نشوء تمزق الزلزال، وانتشاره ووقفه، نحتاج إلى فهم التباين الحقيقي في انخفاض ضغط الزلزال (انظر أبركرومبي، 2021).

الانخفاض الطيفي في الضغط وتأثيرات المسار الأخرى. هذه القياسات صعبة بشكل خاص عند الترددات العالية المطلوبة لتحديد الطاقة المشعة للزلازل الصغيرة (مثل Abercrombie، 1995؛ Ide و Beroza، 2001؛ Abercrombie، 2021). هذا الانخفاض الطيفي في الضغط هو متوسط انخفاض الضغط خلال تمزق الزلزال، والعلاقة بين هذا المتوسط والانخفاض المتغير في الضغط مع الزمن والمكان على صدع ليست دائمًا واضحة جيدًا (Noda et al.، 2013). وبالمثل، فإن تفاصيل العلاقة بين هذا الانخفاض الطيفي في الضغط الزلزالي والإفراج الفعلي عن الضغط على صدع أو المحاكاة العددية غير مفهومة جيدًا (مثل Kaneko و Shearer، 2015؛ Ji et al.، 2022). قبل أن نتمكن من محاولة ربط كل هذه المعلمات، نحتاج أولاً إلى التأكد من أن تقديرنا لانخفاض الضغط الطيفي موثوق وقابل للتكرار؛ هذا هو هدف الدراسة المجتمعية.

تأتي الاختلافات الرئيسية من الافتراضات المبسطة ومعايرة النموذج، بالإضافة إلى الجودة والكمية المحدودة من البيانات. إن تحديد الأساليب الأكثر موثوقية لحساب انخفاض الإجهاد، وتقديرات أكثر تمثيلاً لعدم اليقين، يتجاوز قدرات أي مجموعة فردية.

2 أولويات البحث والتنظيم

2.1 أولويات البحث

- افهم كيف تؤدي الطرق والافتراضات المختلفة إلى تباينات في تقدير انخفاض الإجهاد والإشعاع عالي التردد المتوقع. هل تبرز بعض الطرق جوانب ترددية مختلفة من المصدر؟ كيف تؤثر عملية اختيار البيانات والمعالجة المسبقة على النتائج؟ كيف يقوم محللون مختلفون بتنفيذ الطرق؟

- حدد كيف تعكس التغيرات في تقديرات انخفاض الإجهاد الطيفي التغيرات الفيزيائية في عمليات مصدر الزلزال أو خصائص المواد. هل تؤدي الأحداث الأبسط أو الأكثر سلاسة إلى توافق أكبر بين تقديرات انخفاض الإجهاد بينما تظهر الأحداث المعقدة مزيدًا من التباين؟ كيف تعتمد تقديرات انخفاض الإجهاد هذه على الحجم الفيزيائي، العمق، الموقع أو الإعداد التكتوني للزلزال؟

- تطوير أفضل الممارسات لتقدير مقياس انخفاض الإجهاد الطيفي الذي يمكن استخدامه بشكل موثوق في نمذجة الحركة الأرضية والمخاطر، ومن قبل المجتمع الواسع الذي يسعى لفهم فيزياء مصدر الزلازل وعمليات الانكسار الديناميكي (بما في ذلك العمل في المختبر والنمذجة العددية).

في النهاية، قد تختلف أفضل طريقة لتقدير انخفاض الضغط بين الأحداث اعتمادًا على عوامل مثل الإعداد التكتوني، والخصائص اللزجة المستنتجة، وسلوك الانكسار، ولكن هل يمكننا تطوير طريقة أساسية تكون متسقة لنوع معين من الزلازل؟

2.2 تنظيم الدراسة

3 دراسة التحقق الحالية: سلسلة زلازل ريدجكريست 2019

3.1 بيانات شكل الموجة

3.2 البيانات الوصفية

- فهرس الزلازل. فهرس كامل للزلازل مع مقاييس SCSN وإعادة تحديد المواقع من ترغمان (2020).

- اختيارات مرحلة الموجات P و S. اختيارات مرحلة الموجات P و S الأولية لكل سجل (على الرغم من أنه إذا كانت الطريقة تتطلب تحسين الاختيارات، يمكن للمشاركين تعديل أو إعادة اختيار البيانات) من خلال طريقتين: الأولى هي اختيارات مرحلة SCEDC، التي لا تتوفر لجميع الأحداث أو جميع المحطات؛ والثانية هي حسابات زمن السفر النظرية باستخدام نموذج سرعة أحادي الأبعاد. تم تضمين كلا مجموعتي اختيارات المرحلة في ملفات .tar مع الموجات.

-

تقديرات المحطة. متوسط سرعة الموجة القصيرة الزمنية في الجزء العلوي لكل محطة. الـ تُقاس القيم بشكل تفضيلي، كما أبلغ عنه يونغ وآخرون (2013)؛ إذا لم تكن القياسات المباشرة متاحة، فإن يتم تقديره استنادًا إلى نموذج الموزاييك لهيث وآخرون (2020). - نموذج السرعة 1D في ريدجكريست. نموذج سرعة 1D بسيط لأولئك الذين يرغبون في تصحيح سرعة الانكسار المعتمد على العمق، تم تطويره بواسطة وايت (2021)، من خلال دمج وتفكيك النماذج من لين.

نت وآخرون (2007) (الوزن)، تشانغ ولين (2014) ( الوزن) ووايت وآخرون (2021) ( الوزن).

تحليل انخفاض إجهاد الزلزال 4

4.1 تحليل انخفاض الضغط الفردي

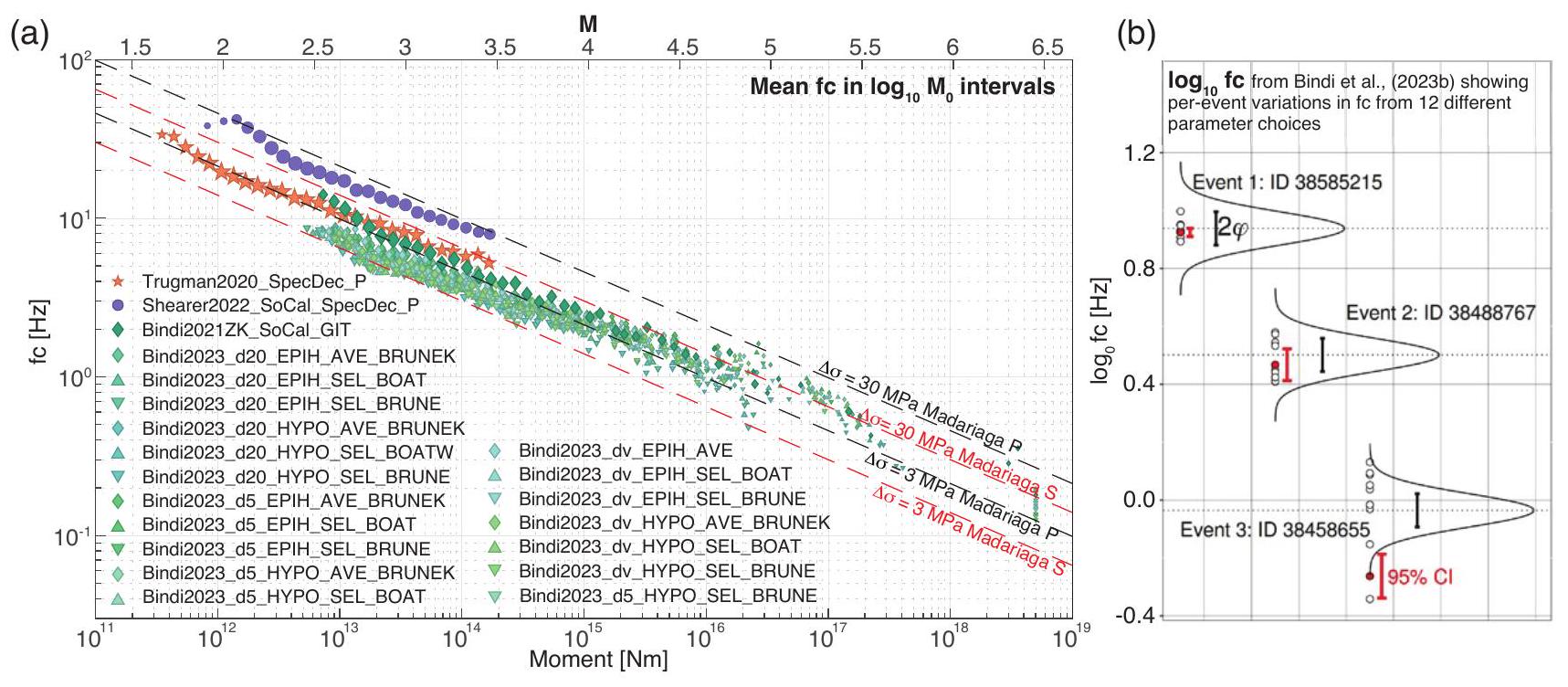

الطريقة الأصلية والأبسط لتناسب طيف الزلازل الفردية لتحديد المصدر والطريق والموقع (على سبيل المثال، ثاتشر وهانكس، 1973) لا تزال قيد الاستخدام (على سبيل المثال، كيمنا وآخرون، 2021) لكنها أثبتت أنها غير محددة بشكل جيد (على سبيل المثال، كو وآخرون، 2012). عندما تتوفر كمية ونوعية كافية من التسجيلات، فإن التعديلات على نهجين متميزين تفضل حاليًا لعزل المصدر، وتقدير تردد الزاوية، ومدة المصدر أو انخفاض الضغط، وكلاهما يمكن أن يستخدم موجات الجسم أو موجات الكودا (انظر أبركرومبي، 2021). تم استخدام التعديلات والتركيبات من هذه الطرق من قبل المشاركين في الدراسة المجتمعية حتى الآن، وقد قدم المؤلفون المذكورون أدناه جميعًا نتائج أولية في وقت كتابة هذا النص.

- تحليل الطيف / الانعكاس العام: يتم الآن استخدام مجموعة من استراتيجيات الانعكاس المختلفة، المعروفة عادةً باسم تقنيات تحليل الطيف أو تقنيات الانعكاس العام (GIT)، على سبيل المثال، شيرر وآخرون (2006)، تشين وشيرر (2011)، بينينغتون وآخرون (2021)، ترغمان (2020)، بيندي وآخرون (2021)، ديفين وآخرون (2021)، فانديفيرت وآخرون (2022). تقوم هذه الانعكاسات بعكس أعداد كبيرة من الزلازل والمحطات في وقت واحد من أجل الاستقرار للحصول على قيم متوسطة لمحطة واحدة. يتطلب الحصول على قيم مطلقة لمعايير المصدر، بما في ذلك شدة الزلزال، افتراض نموذج مصدر (عادةً طيف من نوع برون) أو قيد على تأثير الموقع المتوسط، على سبيل المثال، افتراض استجابة مسطحة في موقع صخري مرجعي. تتضمن هذه الانعكاسات أيضًا هيكل تضعيف مستقل عن الاتجاه، والذي يُفترض أن يكون إما متجانسًا (ثابتًا) أو دالة بسيطة لزمن السفر.

- تحليل دالة جرين التجريبية (EGF): في هذا النهج التجريبي، يتم استخدام زلزال صغير متواجد في نفس الموقع كدالة جرين التجريبية لإزالة تأثيرات المسار والموقع من الطيف أو السجل الزلزالي لزلزال أكبر مستهدف. لا تتطلب عملية فك التداخل افتراضات حول تأثيرات المسار أو الموقع، ويمكن تطبيقها على أزواج فردية من الأحداث، في محطات فردية لتمكين التحقيق في التباين الزاوي في إشعاع المصدر وتأثيرات المسار. يتطلب تقديرًا مستقلًا للحظة الزلزالية لأحد الأحداث أو كليهما، ونموذج مصدر يتناسب مع ترددات الزاوية (يمكن أن يكون واحدًا كما هو موضح في المعادلة 1 أو افتراض أن حدث EGF مسطح بالنسبة للإزاحة في النطاق الترددي المعني)، ويعتمد على توفر زلزال EGF مناسب ومُسجل بشكل جيد، مما يحد بشكل كبير من عدد الأحداث التي يمكن دراستها باستخدام هذه الطريقة. تعتمد النتائج أيضًا على صحة افتراض EGF، ولا يزال البحث في تأثيرات اختيار EGF جاريًا (على سبيل المثال، Abercrombie وآخرون، 2016). عادةً ما يتم حساب النسب الطيفية عن طريق القسمة المباشرة لطيف السعة، ولكن يمكن حساب دوال زمن المصدر إما عن طريق القسمة الطيفية المعقدة أو عن طريق الانعكاس في مجال الزمن. للحصول على معلمات المصدر، يتم ملاءمة النسب الطيفية مع نموذج مصدر برون بسيط (على سبيل المثال، Abercrombie وآخرون، 2020؛ Kemna وآخرون، 2021؛ Liu وآخرون، 2020؛ Ruhl وآخرون، 2017؛

بويد وآخرون، 2017؛ تشين وشيرر، 2011؛ مايدا وآخرون، 2007). بدلاً من ذلك، يمكن استخدام خطأ محدود أو عكس آخر لنمذجة دوال زمن المصدر (على سبيل المثال، دريجر وآخرون، 2021؛ فان وآخرون، 2022).

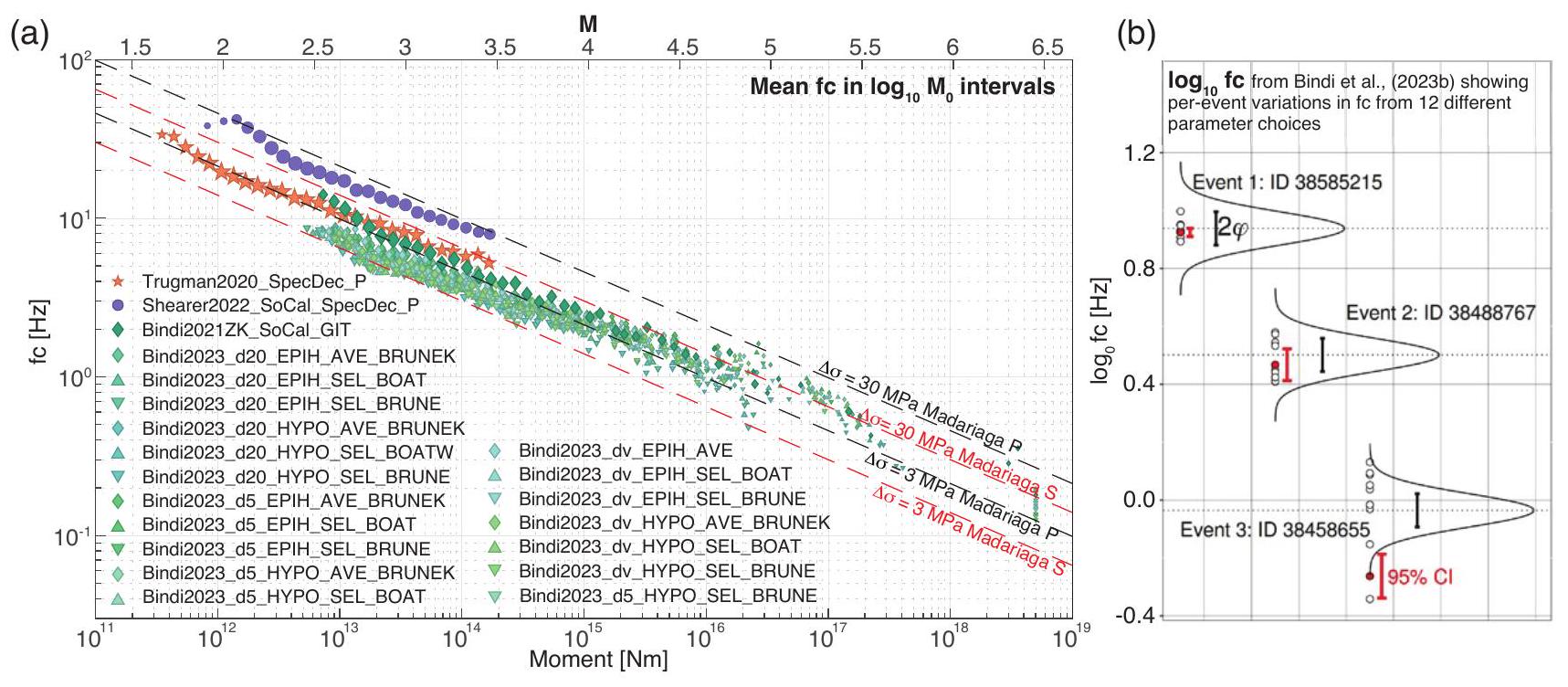

4.2 النتائج الأولية والتحليل الشامل

تباين التكرارات المختلفة وأحيانًا لا، مما يعني أن خيارات الطرق والافتراضات يمكن أن تؤدي إلى تباين أوسع من الأخطاء الرسمية في نهج مفضل واحد، والتي عادة ما يتم نشرها. يبقى أن نرى إذا كانت هناك مؤشرات مادية أو تعقيد قد تشير إلى متى ستتفق الترددات الزاوية المقدرة أم لا.

5 آفاق

الشكر

كل مجتمع SCEC لدعمهم. نشكر ستيف هيكمان، جيرمان بريتو والمحرر ستيفن هيكس على مراجعاتهم الدقيقة لهذه المخطوطة. يشكر R.E. Abercrombie هيئة المسح الجيولوجي الأمريكية على التمويل لدعم هذا الجهد. يشكر S. Chu شركة غاز المحيط الهادئ والكهرباء على دعم هذا العمل. تم دعم هذا البحث من قبل SCEC (الجوائز 21083، 21114، 22101، 22042، 23107 و23108 بما في ذلك دعم الرواتب لـ T. Taira والدعم المالي لورشة العمل في سبتمبر 2022). يتم تمويل SCEC من قبل NSF Cooperative Agreement EAR-1600087 و USGS Cooperative Agreement G17AC00047. مساهمة SCEC #13444. أي استخدام لأسماء التجارة أو الشركات أو المنتجات لا يعني تأييد الحكومة الأمريكية.

توفر البيانات والرموز

المصالح المتنافسة

References

Abercrombie, R. E. Comparison of direct and coda wave stress drop measurements for the Wells, Nevada, earthquake sequence. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 118(4):1458-1470, Apr. 2013. doi: 10.1029/2012jb009638.

Abercrombie, R. E. Investigating uncertainties in empirical Green’s function analysis of earthquake source parameters. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 120(6):4263-4277, June 2015. doi: 10.1002/2015jb011984.

Abercrombie, R. E., Chen, X., and Zhang, J. Repeating Earthquakes With Remarkably Repeatable Ruptures on the San Andreas Fault at Parkfield. Geophysical Research Letters, 47(23), Dec. 2020. doi: 10.1029/2020gl089820.

Abercrombie, R. E., Trugman, D. T., Shearer, P. M., Chen, X., Zhang, J., Pennington, C. N., Hardebeck, J. L., Goebel, T. H. W., and Ruhl, C. J. Does Earthquake Stress Drop Increase With Depth in the Crust? Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 126(10), Oct. 2021. doi: 10.1029/2021jb022314.

Aki, K. Scaling law of seismic spectrum. Journal of Geophysical Research, 72(4):1217-1231, Feb. 1967. doi: 10.1029/jz072i004p01217.

Allmann, B. P. and Shearer, P. M. Global variations of stress drop for moderate to large earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 114(B1), Jan. 2009. doi: 10.1029/2008jb005821.

Baltay, A., Ide, S., Prieto, G., and Beroza, G. Variability in earthquake stress drop and apparent stress. Geophysical Research Letters, 38(6), Mar. 2011. doi: 10.1029/2011gl046698.

Baltay, A., Ellsworth, W., Schoenball, M., and Beroza, G. Proposed Community Stress Drop Validation Experiment. In SCEC Annual Meeting, Palm Springs, CA, 2017.

Baltay, A. S., Hanks, T. C., and Abrahamson, N. A. Earthquake Stress Drop and Arias Intensity. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 124(4):3838-3852, Apr. 2019. doi: 10.1029/2018jb016753.

Beeler, N., Kilgore, B., McGarr, A., Fletcher, J., Evans, J., and Baker, S. R. Observed source parameters for dynamic rupture with non-uniform initial stress and relatively high fracture energy. Journal of Structural Geology, 38:77-89, May 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jsg.2011.11.013.

10.1785/0120200126.

Bindi, D., Spallarossa, D., Picozzi, M., Oth, A., Morasca, P., and Mayeda, K. The Community Stress-Drop Validation Study-Part II: Uncertainties of the Source Parameters and Stress Drop Analysis. Seismological Research Letters, May 2023a. doi: 10.1785/0220230020.

Boyd, O. S., McNamara, D. E., Hartzell, S., and Choy, G. Influence of Lithostatic Stress on Earthquake Stress Drops in North America. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 107(2):856-868, Feb. 2017. doi: 10.1785/0120160219.

Brune, J. N. Tectonic stress and the spectra of seismic shear waves from earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research, 75(26): 4997-5009, Sept. 1970. doi: 10.1029/jb075i026p04997.

California Geological Survey. California Strong Motion Instrumentation Program, 1972. doi: 10.7914/B34Q-BB70.

California Institute of Technology and United States Geological Survey Pasadena. CI, International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks, 1926. doi: 10.7914/SN/CI.

Chen, X. and Abercrombie, R. E. Improved approach for stress drop estimation and its application to an induced earthquake sequence in Oklahoma. Geophysical Journal International, 223 (1):233-253, June 2020. doi: 10.1093/gji/ggaa316.

Collins, D. and Young, R. Lithological Controls on Seismicity in Granitic Rocks. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 90(3):709-723, June 2000. doi: 10.1785/0119990142.

Cotton, F., Archuleta, R., and Causse, M. What is Sigma of the Stress Drop? Seismological Research Letters, 84(1):42-48, Jan. 2013. doi: 10.1785/0220120087.

Denolle, M. A. and Shearer, P. M. New perspectives on selfsimilarity for shallow thrust earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 121(9):6533-6565, Sept. 2016. doi: 10.1002/2016jb013105.

Dreger, D., Malagnini, L., Magana, J., and Taira, T. Comparing Finite-Source and Corner Frequency Based Stress Drop for the

E.C.G.S. Workshop. Earthquake source physics on various scales, 2012. http://www.ecgs.lu/source2012.

Fan, W., Meng, H., Trugman, D., McGuire, J., and Cochran, E. Finitesource Attributes of M4 to 5.5 Ridgecrest, California Earthquakes. In AGU 2022 Fall Meeting, 11-15, December, Chicago, IL, abstract S15C-0209, 2022.

Gibowicz, S., Young, R., Talebi, S., and Rawlence, D. Source parameters of seismic events at the Underground Research Laboratory in Manitoba, Canada: Scaling relations for events with moment magnitude smaller than -2 . Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 81(4):1157-1182, 1991. doi: 10.1785/BSSA0810041157.

Goertz-Allmann, B. P. and Edwards, B. Constraints on crustal attenuation and three-dimensional spatial distribution of stress drop in Switzerland. Geophysical Journal International, 196(1): 493-509, Oct. 2013. doi: 10.1093/gji/ggt384.

Goodfellow, S. D. and Young, R. P. A laboratory acoustic emission experiment under in situ conditions. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(10):3422-3430, May 2014. doi: 10.1002/2014gl059965.

Hanks, T. and Boore, D. Moment-magnitude relations in theory and practice. Journal of Geophysical Research, 89(B7), 1984. doi: 10.1029/JB089iB07p06229.

Ide, S., Beroza, G. C., Prejean, S. G., and Ellsworth, W. L. Apparent break in earthquake scaling due to path and site effects on deep borehole recordings. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 108(B5), May 2003. doi: 10.1029/2001jb001617.

Imanishi, K. and Ellsworth, W. L. Source scaling relationships of microearthquakes at Parkfield, CA, determined using the SAFOD Pilot Hole Seismic Array, page 81-90. American Geophysical Union, 2006. doi: 10.1029/170gm10.

Kaneko, Y. and Shearer, P. M. Variability of seismic source spectra, estimated stress drop, and radiated energy, derived from cohesive-zone models of symmetrical and asymmetrical circular and elliptical ruptures. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 120(2):1053-1079, Feb. 2015. doi: 10.1002/2014jb011642.

Ko, Y., Kuo, B., and Hung, S. Robust determination of earthquake source parameters and mantle attenuation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 117(B4), Apr. 2012. doi: 10.1029/2011jb008759.

Malagnini, L., Mayeda, K., Nielsen, S., Yoo, S.-H., Munafo’, I., Rawles, C., and Boschi, E. Scaling Transition in Earthquake Sources: A Possible Link Between Seismic and Laboratory Measurements. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 171(10):2685-2707, Dec. 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00024-013-0749-8.

Mayeda, K., Hofstetter, A., O’Boyle, J., and Walter, W. Stable and Transportable Regional Magnitudes Based on Coda-Derived Moment-Rate Spectra. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 93(1):224-239, Feb. 2003. doi: 10.1785/0120020020.

Mayeda, K., Malagnini, L., and Walter, W. R. A new spectral ratio method using narrow band coda envelopes: Evidence for non-self-similarity in the Hector Mine sequence. Geophysical Research Letters, 34(11), June 2007. doi: 10.1029/2007gl030041.

McLaskey, G., Kilgore, B., Lockner, D., and Beeler, N. Laboratory generated M-6 earthquakes. Pure and Applied Geophyics, 171, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00024-013-0772-9.

nia, earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 108(B11), Nov. 2003. doi: 10.1029/2001jb000474.

Nielsen, S., Spagnuolo, E., Smith, S. A. F., Violay, M., Di Toro, G., and Bistacchi, A. Scaling in natural and laboratory earthquakes. Geophysical Research Letters, 43(4):1504-1510, Feb. 2016. doi: 10.1002/2015gl067490.

Pennington, C. N., Chen, X., Abercrombie, R. E., and Wu, Q. Cross Validation of Stress Drop Estimates and Interpretations for the 2011 Prague, OK, Earthquake Sequence Using Multiple Methods. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 126(3), Mar. 2021. doi: 10.1029/2020jb020888.

Ruhl, C. J., Abercrombie, R. E., and Smith, K. D. Spatiotemporal Variation of Stress Drop During the 2008 Mogul, Nevada, Earthquake Swarm. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 122 (10):8163-8180, Oct. 2017. doi: 10.1002/2017jb014601.

SCEDC. Southern California Earthquake Data Center, 2013. doi: 10.7909/C3WD3XH1.

Shearer, P. M., Prieto, G. A., and Hauksson, E. Comprehensive analysis of earthquake source spectra in southern California. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 111(B6), June 2006. doi: 10.1029/2005jb003979.

Shearer, P. M., Abercrombie, R. E., Trugman, D. T., and Wang, W. Comparing EGF Methods for Estimating Corner Frequency and Stress Drop From P Wave Spectra. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 124(4):3966-3986, Apr. 2019. doi: 10.1029/2018jb016957.

Shible, H., Hollender, F., Bindi, D., Traversa, P., Oth, A., Edwards, B., Klin, P., Kawase, H., Grendas, I., Castro, R. R., Theodoulidis, N., and Gueguen, P. GITEC: A Generalized Inversion Technique Benchmark. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 112 (2):850-877, Feb. 2022. doi: 10.1785/0120210242.

Supino, M., Festa, G., and Zollo, A. A probabilistic method for the estimation of earthquake source parameters from spectral inversion: application to the 2016-2017 Central Italy seismic se-

quence. Geophysical Journal International, 218(2):988-1007, May 2019. doi: 10.1093/gji/ggz206.

Thatcher, W. and Hanks, T. C. Source parameters of southern California earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research, 78(35): 8547-8576, Dec. 1973. doi: 10.1029/jb078i035p08547.

Trugman, D. T. Stress-Drop and Source Scaling of the 2019 Ridgecrest, California, Earthquake Sequence. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 110(4):1859-1871, May 2020. doi: 10.1785/0120200009.

University of Nevada, Reno. SN Great Basin Network [Data set], 1992. doi:

U.S. Geological Survey. United States National Strong-Motion Network, 1931. doi: 10.7914/SN/NP.

Vandevert, I., Shearer, P., and Fan, W. Earthquake Source Spectra Estimates Obtained from S-Wave Maximum Amplitudes: Application to the 2019 Ridgecrest Sequence. In AGU 2022 Fall Meeting, 11-15, December, Chicago, IL, abstract S25A-06, 2022.

Viesca, R. C. and Garagash, D. I. Ubiquitous weakening of faults due to thermal pressurization. Nature Geoscience, 8(11):875-879, Oct. 2015. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2554.

White, M. Ridgecrest 1D velocity model developed by Malcolm White, 2021. https://service.scedc.caltech.edu/ftp/stressdropridgecrest/Ridgecrest_velocity_model.docx.

White, M. C. A., Fang, H., Catchings, R. D., Goldman, M. R., Steidl, J. H., and Ben-Zion, Y. Detailed traveltime tomography and seismic catalogue around the 2019 Mw7.1 Ridgecrest, California, earthquake using dense rapid-response seismic data. Geophysical Journal International, 227(1):204-227, June 2021. doi: 10.1093/gji/ggab224.

Yong, A., Martin, A., Stokoe, K., and Diehl, J. ARRA-funded VS30 measurements using multi-technique approach at strongmotion stations in California and central-eastern United States. 2013. doi: 10.3133/ofr20131102.

Zhang, Q. and Lin, G. Three-dimensional Vp and Vp/Vs models in the Coso geothermal area, California: Seismic characterization of the magmatic system. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 119(6):4907-4922, June 2014. doi: 10.1002/2014jb010992.

- *Corresponding author: abaltay@usgs.gov

DOI: https://doi.org/10.26443/seismica.v3i1.1009

Publication Date: 2024-05-22

The SCEC/USGS Community Stress Drop Validation Study Using the 2019 Ridgecrest Earthquake Sequence

Abstract

We introduce a community stress drop validation study using the 2019 Ridgecrest, California, earthquake sequence, in which researchers are invited to use a common dataset to independently estimate comparable measurements using a variety of methods. Stress drop is the change in average shear stress on a fault during earthquake rupture, and as such is a key parameter in many ground motion, rupture simulation, and source physics problems in earthquake science. Spectral stress drop is commonly estimated by fitting the shape of the radiated energy spectrum, yet estimates for an individual earthquake made by different studies can vary hugely. In this community study, sponsored jointly by the U. S. Geological Survey and Southern/Statewide California Earthquake Center, we seek to understand the sources of variability and uncertainty in earthquake stress drop through quantitative comparison of submitted stress drops. The publicly available dataset consists of nearly 13,000 earthquakes of M1 to 7 from two weeks of the 2019 Ridgecrest sequence recorded on stations within 1-degree. As a community study, findings are shared through workshops and meetings and all are invited to join at any time, at any interest level.

Non-technical summary The stress release (or stress drop) during an earthquake provides information on how geologic forces are converted to radiated seismic energy when a fault ruptures, and the conditions under which an earthquake will continue to increase in size or trigger earthquakes nearby. Stress drop is also an important element of seismic hazard mapping and building design, since high stress drop earthquakes radiate more high frequency energy, resulting in stronger ground shaking. Unfortunately, stress drop estimates made in different studies have large systematic and random differences, implying that they are not as reliable as we need for use in ground motion prediction and earthquake source physics research. We introduce a Community Stress Drop Validation Study in which we invite all interested scientists from the international community to analyze the same earthquakes and compare and contrast their results. We use a public dataset of recordings of aftershocks of the 2019 Ridgecrest, California earthquake. Our aim is to understand where the differences and similarities in stress drop come from, and then work with the wider user community to develop improved methods for characterizing earthquake rupture and the resulting ground motions for more reliable and informed earthquake hazard forecasts.

1 Introduction

termine the factors that control earthquake rupture nucleation, propagation and arrest, we need to understand the real variation in earthquake stress drop (see Abercrombie, 2021).

attenuation and other path effects. These measurements are especially difficult at the higher frequencies required to quantify radiated energy of smaller earthquakes (e.g. Abercrombie, 1995; Ide and Beroza, 2001; Abercrombie, 2021). This spectral stress drop is an average stress drop over an earthquake rupture, and the relationship between that average and time- and spacevarying stress drop on a fault is not always well resolved (Noda et al., 2013). Similarly, the details of the relationship between this seismological spectral stress drop and the actual stress release on a fault or numerical simulations are poorly understood (e.g., Kaneko and Shearer, 2015; Ji et al., 2022). Before we can attempt to connect all these parameters, we need to first ensure our estimate of the spectral stress drop is reliable and reproducible; this is the aim of the community study.

atic biases, the main differences come from the simplifying assumptions and model parameterization, and the limited quality and quantity of the data. Objectively determining the most reliable approaches for calculating stress drop, and more representative estimates of uncertainties, is beyond the abilities of any individual group.

2 Research priorities and organization

2.1 Research priorities

- Understand how different methods and assumptions lead to variations in estimated stress drop and predicted high frequency radiation. Do certain methods highlight different frequency aspects of the source? How do data selection and preprocessing affect the results? How are different analysts implementing methods?

- Determine how variations in the estimated spectral stress drops reflect physical variations in earthquake source processes or material properties. Do simpler or smoother events yield more agreement between stress drop estimates while complex events show more variability? How do these stress drop estimates depend on the physical size, depth, location or tectonic setting of the earthquake?

- Develop best practices for estimating a measure of spectral stress drop that can reliably be used in ground motion and hazard modeling, and by the wide community seeking to understand earthquake source physics and dynamic rupture processes (including laboratory work and numerical

modeling). Ultimately, the best way to estimate stress drop may vary between events depending on factors such as its tectonic setting, inferred rheological properties and rupture behavior, but can we develop a baseline method that is consistent for a particular type of earthquake?

2.2 Study organization

3 Current validation study: 2019 Ridgecrest earthquake sequence

3.1 Waveform data

3.2 Metadata

- Earthquake Catalog. Full earthquake catalog with SCSN magnitudes and relocations from Trugman (2020).

- P- and S-wave phase picks. Initial P- and S-wave phase picks for each record (although if a method requires improved picks, participants are free to adjust or repick the data) through two methods: The first are the SCEDC phase picks, which are not available for all events or all stations; the second are theoretical travel time calculations using a 1D velocity model. Both sets of phase-picks are included batched into the .tar files with the waveforms.

-

station estimates. Time-averaged shear-wave velocity in the upper for each station. The values are preferentially measured, as reported by Yong et al. (2013); if direct measurements are not available then is estimated based on the mosaic proxy of Heath et al. (2020). - Ridgecrest 1D velocity model. A simple 1D velocity model for those wanting depth-dependent rupture velocity correction, developed by White (2021), by combining and discretizing the models from Lin

et al. (2007) (weight), Zhang and Lin (2014) ( weight) and White et al. (2021) ( weight).

4 Earthquake stress drop analysis

4.1 Individual stress drop analysis

bie (2021). The original, simplest method of fitting individual earthquake spectra to determine source, path and site (e.g., Thatcher and Hanks, 1973) is still in use (e.g., Kemna et al., 2021) but has proven to be poorly constrained (e.g., Ko et al., 2012). When sufficient quantity and quality of recordings are available, variations on two distinct approaches are currently preferred to isolate the source, and estimate corner frequency, source duration or stress drop, and they both can use body or coda waves (see Abercrombie, 2021). Variations and combinations of these have been used by participants in the Community Study to date, and the authors cited below have all submitted preliminary results at the time of writing.

- Spectral Decomposition / Generalized Inversion: A range of different inversion strategies are now in use, commonly known as spectral decomposition or generalized inversion techniques (GIT), for example, Shearer et al. (2006), Chen and Shearer (2011), Pennington et al. (2021), Trugman (2020), Bindi et al. (2021), Devin et al. (2021), Vandevert et al. (2022). These inversions simultaneously invert large numbers of earthquakes and stations for stability to obtain single, station-averaged values. Obtaining absolute values of source parameters, including earthquake magnitude, requires assumption of a source model (typically a Brune-type spectrum) or a constraint on the average site effect, for example, assuming a flat response at a reference rock site. These inversions also incorporate an azimuthally independent attenuation structure, which is assumed to be either homogeneous (constant) or a simple function of travel time.

- Empirical Green’s Function (EGF) Analysis: In this empirical approach, a small, co-located earthquake is used as an EGF to remove path and site effects from the spectrum or seismogram of a larger target earthquake. The deconvolution requires no assumptions about path or site effects, and can be applied to individual pairs of events, at individual stations to enable investigation of azimuthal variation in the source radiation and path effects. It requires an independent estimate of seismic moment of one or both events, a source model with which to fit the corner frequencies (could be one as given in Eq. 1 or an assumption that the EGF event is flat to displacement in the relevant frequency range), and depends on the availability of an appropriate, well-recorded EGF earthquake, which significantly limits the number of events that can be studied using this method. The results also depend on the correctness of the EGF assumption, and research into the effects of EGF choice is ongoing (e.g., Abercrombie et al., 2016). Spectral ratios are usually calculated by direct division of the amplitude spectra, but the source time functions can be calculated either by complex spectral division or by time-domain inversion. To obtain source parameters, the spectral ratios are fit with a simple Brune-source model (e.g., Abercrombie et al., 2020; Kemna et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020; Ruhl et al., 2017;

Boyd et al., 2017; Chen and Shearer, 2011; Mayeda et al., 2007). Alternatively, a finite fault or other inversion can be used to model the source time functions (e.g., Dreger et al., 2021; Fan et al., 2022).

4.2 Initial results and meta analysis

variability of the various iterations and sometimes does not, implying that method choices and assumptions can lead to wider variation than the formal errors in a single preferred approach, that are typically published. It remains to be seen if there are physical predictors or complexity that might indicate when estimated corner frequencies will agree or not.

5 Outlook

Acknowledgements

whole SCEC community for their support. We thank Steve Hickman, German Prieto and editor Stephen Hicks for their thorough reviews of this manuscript. R.E. Abercrombie thanks the U.S. Geological Survey for funding to support this effort. S. Chu thanks Pacific Gas and Electric for support for this work. This research was supported by SCEC (awards 21083, 21114, 22101, 22042, 23107 and 23108 including salary support for T. Taira and financial support for the 2022 September workshop). SCEC is funded by NSF Cooperative Agreement EAR-1600087 & USGS Cooperative Agreement G17AC00047. SCEC Contribution #13444. Any use of trade, firm, or product names does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Data and code availability

Competing interests

References

Abercrombie, R. E. Comparison of direct and coda wave stress drop measurements for the Wells, Nevada, earthquake sequence. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 118(4):1458-1470, Apr. 2013. doi: 10.1029/2012jb009638.

Abercrombie, R. E. Investigating uncertainties in empirical Green’s function analysis of earthquake source parameters. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 120(6):4263-4277, June 2015. doi: 10.1002/2015jb011984.

Abercrombie, R. E., Chen, X., and Zhang, J. Repeating Earthquakes With Remarkably Repeatable Ruptures on the San Andreas Fault at Parkfield. Geophysical Research Letters, 47(23), Dec. 2020. doi: 10.1029/2020gl089820.

Abercrombie, R. E., Trugman, D. T., Shearer, P. M., Chen, X., Zhang, J., Pennington, C. N., Hardebeck, J. L., Goebel, T. H. W., and Ruhl, C. J. Does Earthquake Stress Drop Increase With Depth in the Crust? Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 126(10), Oct. 2021. doi: 10.1029/2021jb022314.

Aki, K. Scaling law of seismic spectrum. Journal of Geophysical Research, 72(4):1217-1231, Feb. 1967. doi: 10.1029/jz072i004p01217.

Allmann, B. P. and Shearer, P. M. Global variations of stress drop for moderate to large earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 114(B1), Jan. 2009. doi: 10.1029/2008jb005821.

Baltay, A., Ide, S., Prieto, G., and Beroza, G. Variability in earthquake stress drop and apparent stress. Geophysical Research Letters, 38(6), Mar. 2011. doi: 10.1029/2011gl046698.

Baltay, A., Ellsworth, W., Schoenball, M., and Beroza, G. Proposed Community Stress Drop Validation Experiment. In SCEC Annual Meeting, Palm Springs, CA, 2017.

Baltay, A. S., Hanks, T. C., and Abrahamson, N. A. Earthquake Stress Drop and Arias Intensity. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 124(4):3838-3852, Apr. 2019. doi: 10.1029/2018jb016753.

Beeler, N., Kilgore, B., McGarr, A., Fletcher, J., Evans, J., and Baker, S. R. Observed source parameters for dynamic rupture with non-uniform initial stress and relatively high fracture energy. Journal of Structural Geology, 38:77-89, May 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jsg.2011.11.013.

10.1785/0120200126.

Bindi, D., Spallarossa, D., Picozzi, M., Oth, A., Morasca, P., and Mayeda, K. The Community Stress-Drop Validation Study-Part II: Uncertainties of the Source Parameters and Stress Drop Analysis. Seismological Research Letters, May 2023a. doi: 10.1785/0220230020.

Boyd, O. S., McNamara, D. E., Hartzell, S., and Choy, G. Influence of Lithostatic Stress on Earthquake Stress Drops in North America. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 107(2):856-868, Feb. 2017. doi: 10.1785/0120160219.

Brune, J. N. Tectonic stress and the spectra of seismic shear waves from earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research, 75(26): 4997-5009, Sept. 1970. doi: 10.1029/jb075i026p04997.

California Geological Survey. California Strong Motion Instrumentation Program, 1972. doi: 10.7914/B34Q-BB70.

California Institute of Technology and United States Geological Survey Pasadena. CI, International Federation of Digital Seismograph Networks, 1926. doi: 10.7914/SN/CI.

Chen, X. and Abercrombie, R. E. Improved approach for stress drop estimation and its application to an induced earthquake sequence in Oklahoma. Geophysical Journal International, 223 (1):233-253, June 2020. doi: 10.1093/gji/ggaa316.

Collins, D. and Young, R. Lithological Controls on Seismicity in Granitic Rocks. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 90(3):709-723, June 2000. doi: 10.1785/0119990142.

Cotton, F., Archuleta, R., and Causse, M. What is Sigma of the Stress Drop? Seismological Research Letters, 84(1):42-48, Jan. 2013. doi: 10.1785/0220120087.

Denolle, M. A. and Shearer, P. M. New perspectives on selfsimilarity for shallow thrust earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 121(9):6533-6565, Sept. 2016. doi: 10.1002/2016jb013105.

Dreger, D., Malagnini, L., Magana, J., and Taira, T. Comparing Finite-Source and Corner Frequency Based Stress Drop for the

E.C.G.S. Workshop. Earthquake source physics on various scales, 2012. http://www.ecgs.lu/source2012.

Fan, W., Meng, H., Trugman, D., McGuire, J., and Cochran, E. Finitesource Attributes of M4 to 5.5 Ridgecrest, California Earthquakes. In AGU 2022 Fall Meeting, 11-15, December, Chicago, IL, abstract S15C-0209, 2022.

Gibowicz, S., Young, R., Talebi, S., and Rawlence, D. Source parameters of seismic events at the Underground Research Laboratory in Manitoba, Canada: Scaling relations for events with moment magnitude smaller than -2 . Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 81(4):1157-1182, 1991. doi: 10.1785/BSSA0810041157.

Goertz-Allmann, B. P. and Edwards, B. Constraints on crustal attenuation and three-dimensional spatial distribution of stress drop in Switzerland. Geophysical Journal International, 196(1): 493-509, Oct. 2013. doi: 10.1093/gji/ggt384.

Goodfellow, S. D. and Young, R. P. A laboratory acoustic emission experiment under in situ conditions. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(10):3422-3430, May 2014. doi: 10.1002/2014gl059965.

Hanks, T. and Boore, D. Moment-magnitude relations in theory and practice. Journal of Geophysical Research, 89(B7), 1984. doi: 10.1029/JB089iB07p06229.

Ide, S., Beroza, G. C., Prejean, S. G., and Ellsworth, W. L. Apparent break in earthquake scaling due to path and site effects on deep borehole recordings. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 108(B5), May 2003. doi: 10.1029/2001jb001617.

Imanishi, K. and Ellsworth, W. L. Source scaling relationships of microearthquakes at Parkfield, CA, determined using the SAFOD Pilot Hole Seismic Array, page 81-90. American Geophysical Union, 2006. doi: 10.1029/170gm10.

Kaneko, Y. and Shearer, P. M. Variability of seismic source spectra, estimated stress drop, and radiated energy, derived from cohesive-zone models of symmetrical and asymmetrical circular and elliptical ruptures. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 120(2):1053-1079, Feb. 2015. doi: 10.1002/2014jb011642.

Ko, Y., Kuo, B., and Hung, S. Robust determination of earthquake source parameters and mantle attenuation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 117(B4), Apr. 2012. doi: 10.1029/2011jb008759.

Malagnini, L., Mayeda, K., Nielsen, S., Yoo, S.-H., Munafo’, I., Rawles, C., and Boschi, E. Scaling Transition in Earthquake Sources: A Possible Link Between Seismic and Laboratory Measurements. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 171(10):2685-2707, Dec. 2013. doi: 10.1007/s00024-013-0749-8.

Mayeda, K., Hofstetter, A., O’Boyle, J., and Walter, W. Stable and Transportable Regional Magnitudes Based on Coda-Derived Moment-Rate Spectra. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 93(1):224-239, Feb. 2003. doi: 10.1785/0120020020.

Mayeda, K., Malagnini, L., and Walter, W. R. A new spectral ratio method using narrow band coda envelopes: Evidence for non-self-similarity in the Hector Mine sequence. Geophysical Research Letters, 34(11), June 2007. doi: 10.1029/2007gl030041.

McLaskey, G., Kilgore, B., Lockner, D., and Beeler, N. Laboratory generated M-6 earthquakes. Pure and Applied Geophyics, 171, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00024-013-0772-9.

nia, earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 108(B11), Nov. 2003. doi: 10.1029/2001jb000474.

Nielsen, S., Spagnuolo, E., Smith, S. A. F., Violay, M., Di Toro, G., and Bistacchi, A. Scaling in natural and laboratory earthquakes. Geophysical Research Letters, 43(4):1504-1510, Feb. 2016. doi: 10.1002/2015gl067490.

Pennington, C. N., Chen, X., Abercrombie, R. E., and Wu, Q. Cross Validation of Stress Drop Estimates and Interpretations for the 2011 Prague, OK, Earthquake Sequence Using Multiple Methods. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 126(3), Mar. 2021. doi: 10.1029/2020jb020888.

Ruhl, C. J., Abercrombie, R. E., and Smith, K. D. Spatiotemporal Variation of Stress Drop During the 2008 Mogul, Nevada, Earthquake Swarm. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 122 (10):8163-8180, Oct. 2017. doi: 10.1002/2017jb014601.

SCEDC. Southern California Earthquake Data Center, 2013. doi: 10.7909/C3WD3XH1.

Shearer, P. M., Prieto, G. A., and Hauksson, E. Comprehensive analysis of earthquake source spectra in southern California. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 111(B6), June 2006. doi: 10.1029/2005jb003979.

Shearer, P. M., Abercrombie, R. E., Trugman, D. T., and Wang, W. Comparing EGF Methods for Estimating Corner Frequency and Stress Drop From P Wave Spectra. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 124(4):3966-3986, Apr. 2019. doi: 10.1029/2018jb016957.

Shible, H., Hollender, F., Bindi, D., Traversa, P., Oth, A., Edwards, B., Klin, P., Kawase, H., Grendas, I., Castro, R. R., Theodoulidis, N., and Gueguen, P. GITEC: A Generalized Inversion Technique Benchmark. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 112 (2):850-877, Feb. 2022. doi: 10.1785/0120210242.

Supino, M., Festa, G., and Zollo, A. A probabilistic method for the estimation of earthquake source parameters from spectral inversion: application to the 2016-2017 Central Italy seismic se-

quence. Geophysical Journal International, 218(2):988-1007, May 2019. doi: 10.1093/gji/ggz206.

Thatcher, W. and Hanks, T. C. Source parameters of southern California earthquakes. Journal of Geophysical Research, 78(35): 8547-8576, Dec. 1973. doi: 10.1029/jb078i035p08547.

Trugman, D. T. Stress-Drop and Source Scaling of the 2019 Ridgecrest, California, Earthquake Sequence. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 110(4):1859-1871, May 2020. doi: 10.1785/0120200009.

University of Nevada, Reno. SN Great Basin Network [Data set], 1992. doi:

U.S. Geological Survey. United States National Strong-Motion Network, 1931. doi: 10.7914/SN/NP.

Vandevert, I., Shearer, P., and Fan, W. Earthquake Source Spectra Estimates Obtained from S-Wave Maximum Amplitudes: Application to the 2019 Ridgecrest Sequence. In AGU 2022 Fall Meeting, 11-15, December, Chicago, IL, abstract S25A-06, 2022.

Viesca, R. C. and Garagash, D. I. Ubiquitous weakening of faults due to thermal pressurization. Nature Geoscience, 8(11):875-879, Oct. 2015. doi: 10.1038/ngeo2554.

White, M. Ridgecrest 1D velocity model developed by Malcolm White, 2021. https://service.scedc.caltech.edu/ftp/stressdropridgecrest/Ridgecrest_velocity_model.docx.

White, M. C. A., Fang, H., Catchings, R. D., Goldman, M. R., Steidl, J. H., and Ben-Zion, Y. Detailed traveltime tomography and seismic catalogue around the 2019 Mw7.1 Ridgecrest, California, earthquake using dense rapid-response seismic data. Geophysical Journal International, 227(1):204-227, June 2021. doi: 10.1093/gji/ggab224.

Yong, A., Martin, A., Stokoe, K., and Diehl, J. ARRA-funded VS30 measurements using multi-technique approach at strongmotion stations in California and central-eastern United States. 2013. doi: 10.3133/ofr20131102.

Zhang, Q. and Lin, G. Three-dimensional Vp and Vp/Vs models in the Coso geothermal area, California: Seismic characterization of the magmatic system. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 119(6):4907-4922, June 2014. doi: 10.1002/2014jb010992.

- *Corresponding author: abaltay@usgs.gov