DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01687-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38177104

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-05

دور الأجسام الالتهابية في الأمراض البشرية وإمكانيتها كأهداف علاجية

الملخص

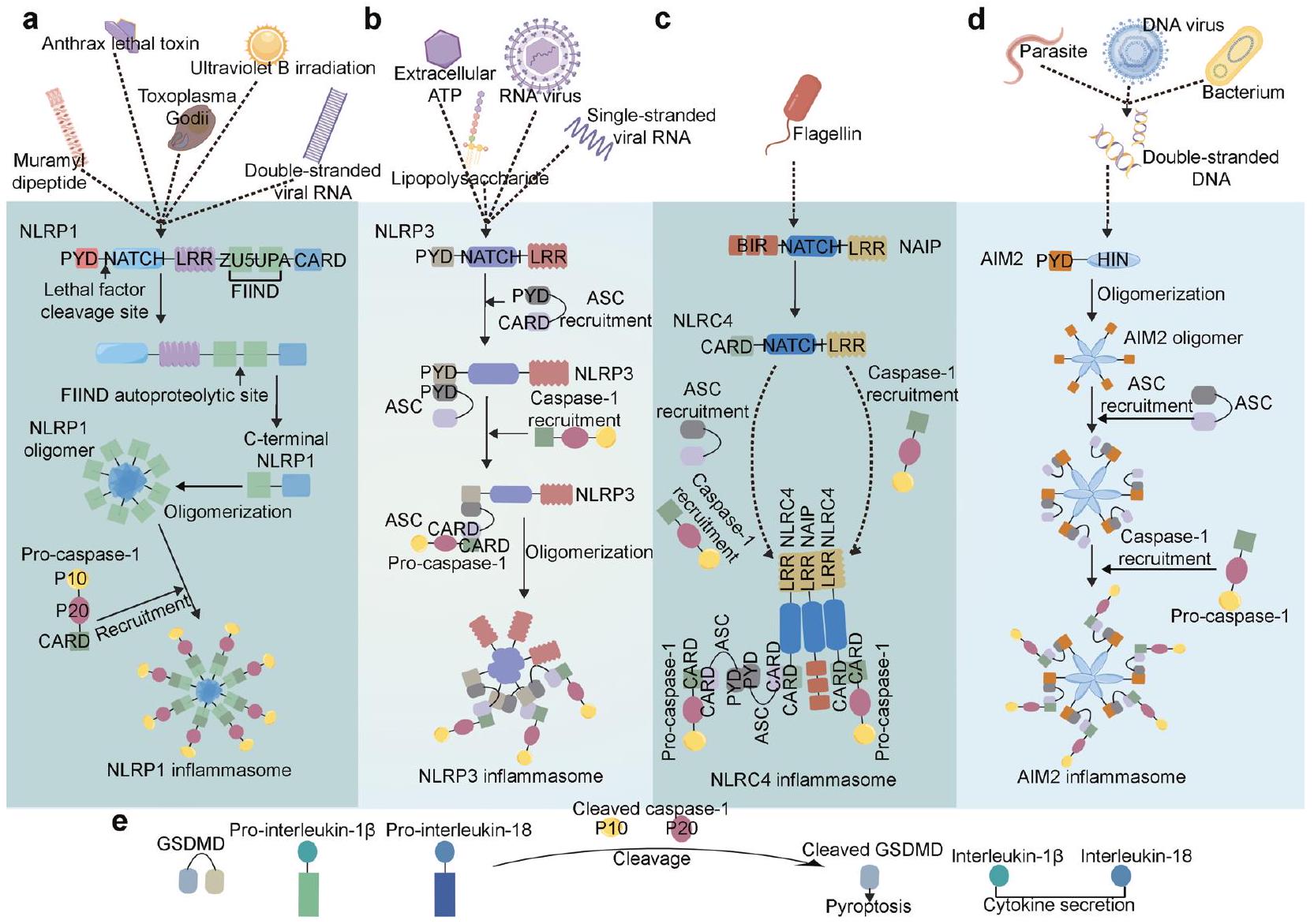

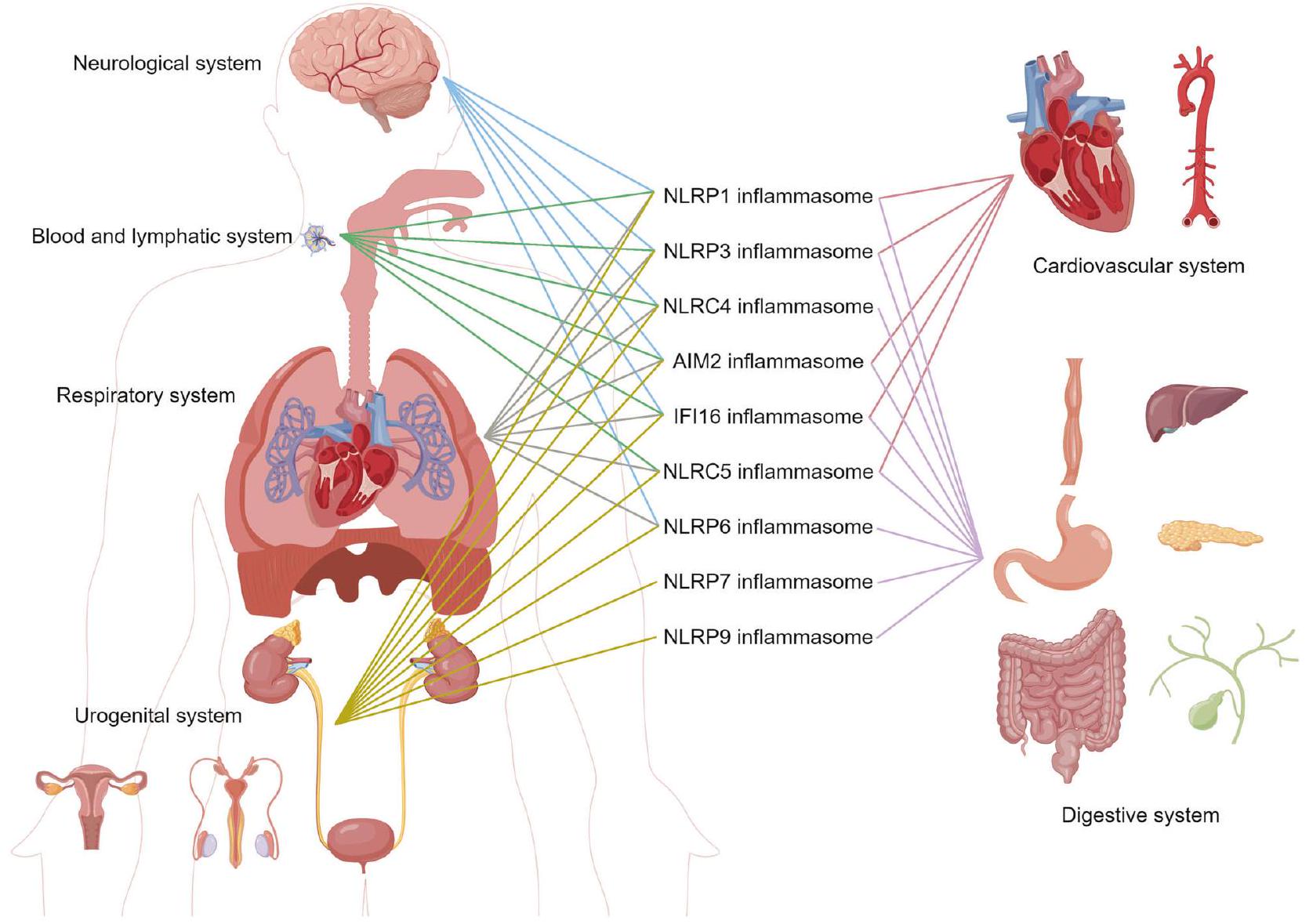

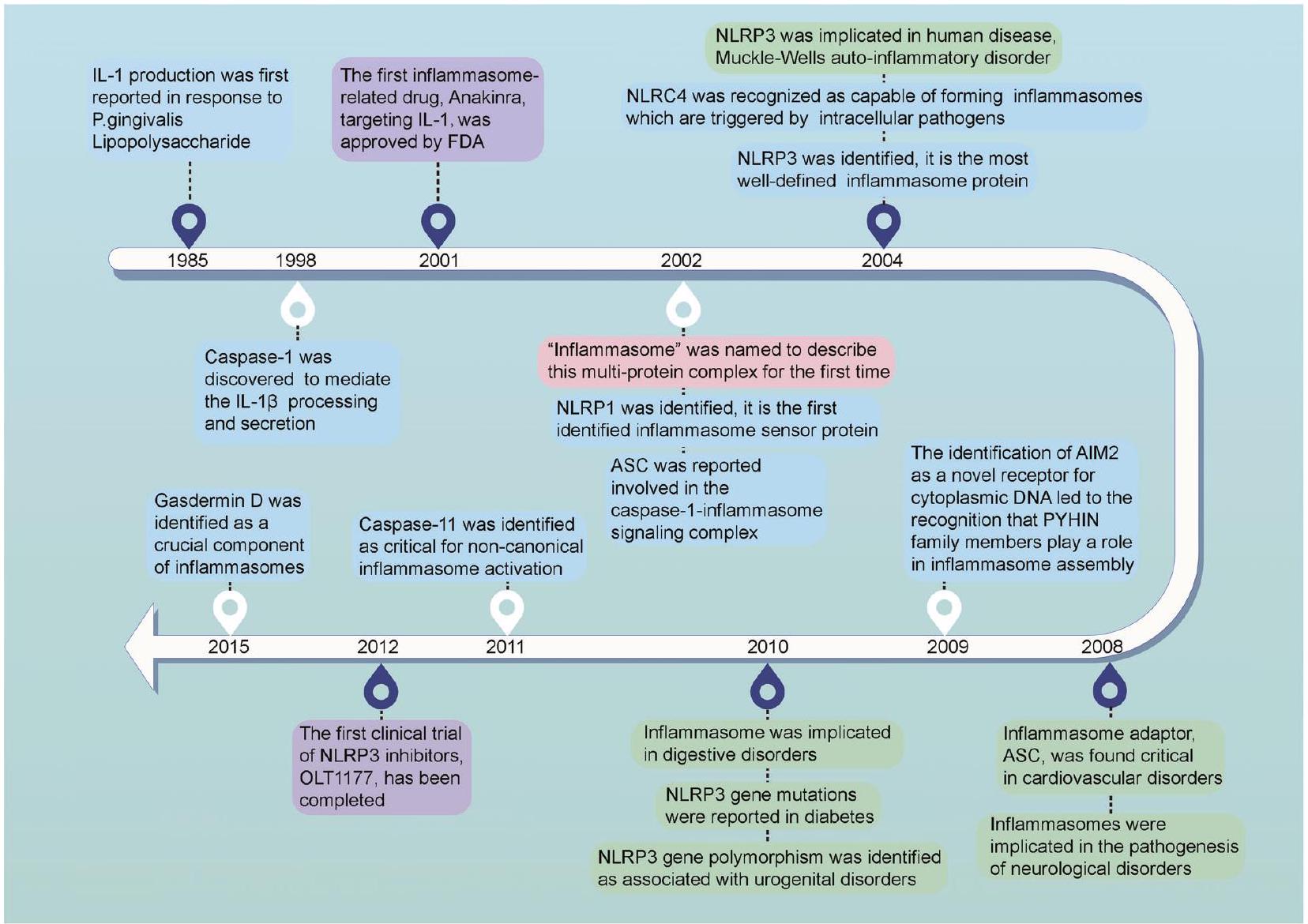

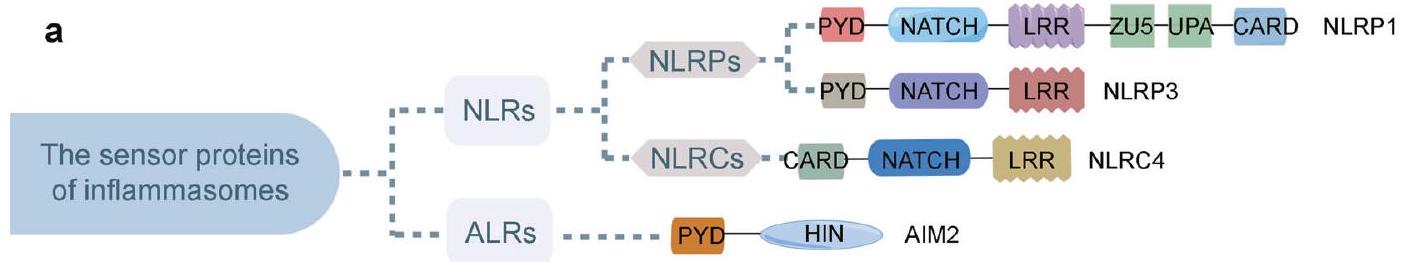

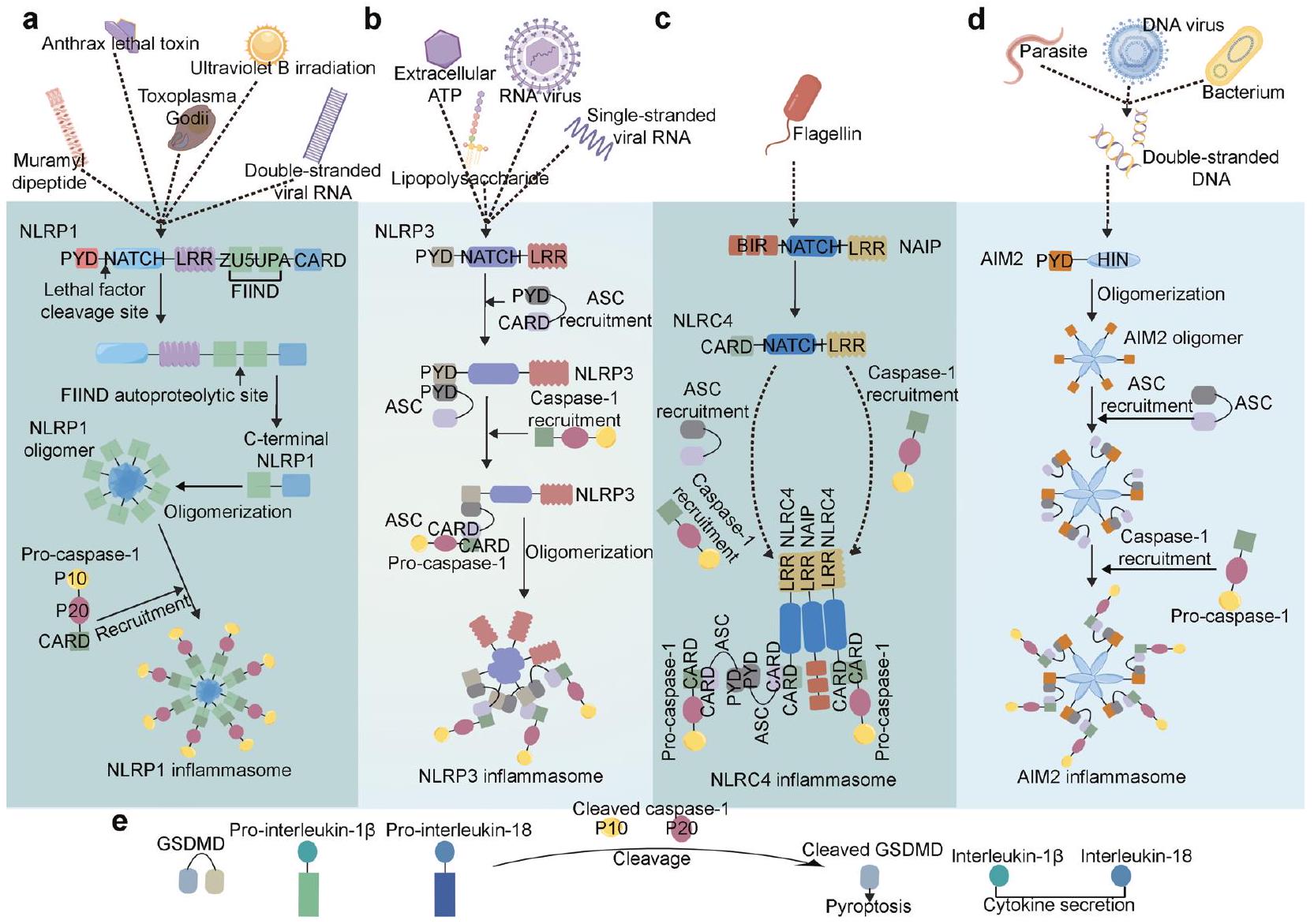

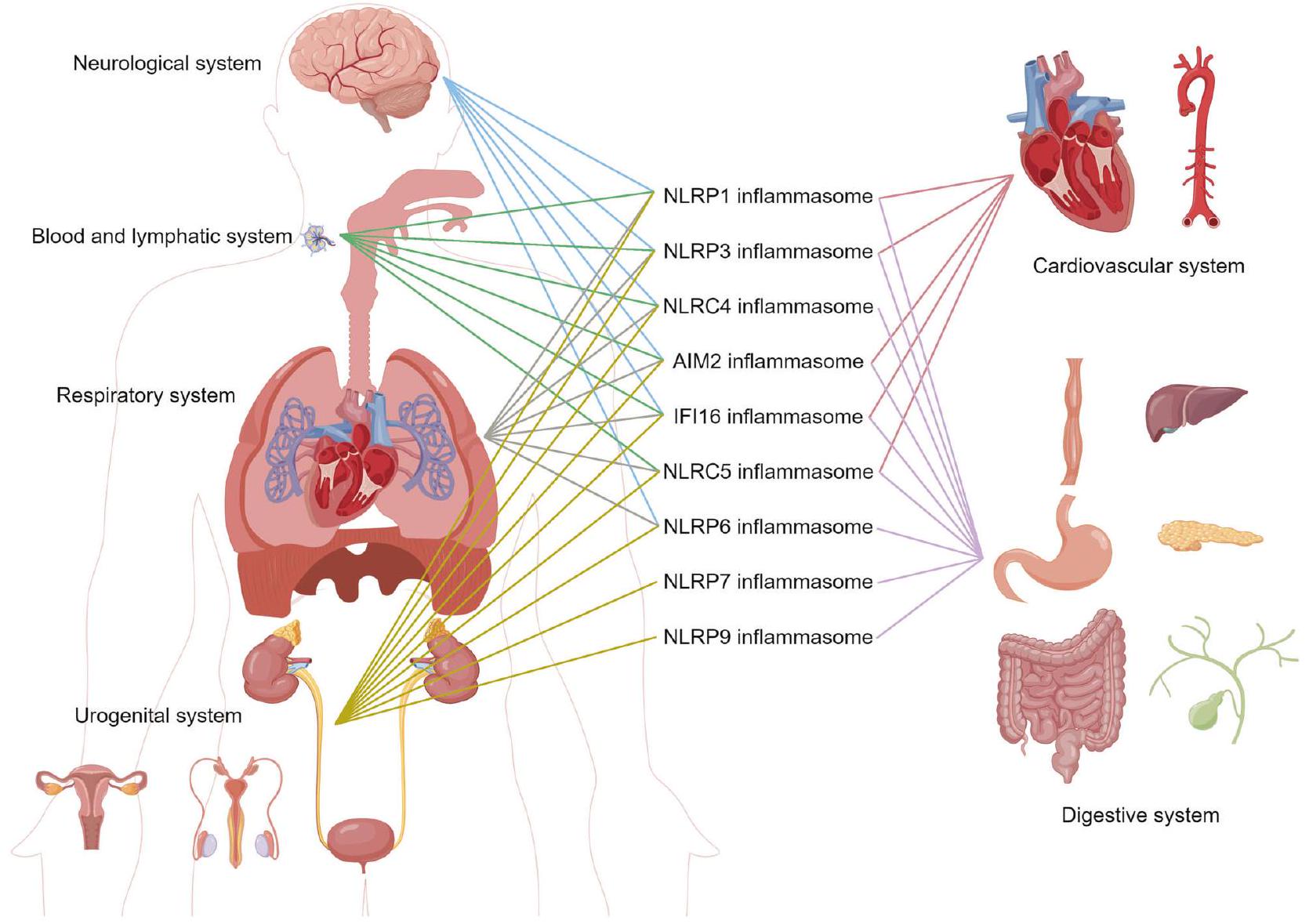

تعتبر الإنفلامازومات مجمعات بروتينية كبيرة تلعب دورًا رئيسيًا في استشعار الإشارات الالتهابية وتحفيز الاستجابة المناعية الفطرية. يتكون كل مجمع إنفلامازوم من ثلاثة مكونات رئيسية: جزيء استشعار علوي مرتبط ببروتين فعّال سفلي مثل كاسبيز-1 من خلال بروتين موصل يُعرف باسم ASC. عادةً ما يحدث تشكيل الإنفلامازوم استجابةً للعوامل المعدية أو الأضرار الخلوية. ثم يقوم الإنفلامازوم النشط بتحفيز تنشيط كاسبيز-1، يليه إفراز السيتوكينات المؤيدة للالتهاب وموت الخلايا النخرية. تساهم تنشيط الإنفلامازوم غير الطبيعي ونشاطه في تطور مرض السكري والسرطان والعديد من الاضطرابات القلبية الوعائية والعصبية التنكسية. نتيجة لذلك، تركز الأبحاث الحديثة بشكل متزايد على دراسة الآليات التي تنظم تجميع وتنشيط الإنفلامازومات، بالإضافة إلى إمكانية استهداف الإنفلامازومات لعلاج أمراض مختلفة. حاليًا، تجري العديد من التجارب السريرية لتقييم الإمكانات العلاجية لعدة علاجات تستهدف الإنفلامازومات. لذلك، قد يكون لفهم كيفية مساهمة الإنفلامازومات المختلفة في علم الأمراض تأثيرات كبيرة على تطوير استراتيجيات علاجية جديدة. في هذه المقالة، نقدم ملخصًا للأدوار البيولوجية والمرضية للإنفلامازومات في الصحة والمرض. كما نبرز الأدلة الرئيسية التي تشير إلى أن استهداف الإنفلامازومات قد يكون استراتيجية جديدة لتطوير علاجات معدلة للأمراض قد تكون فعالة في عدة حالات.

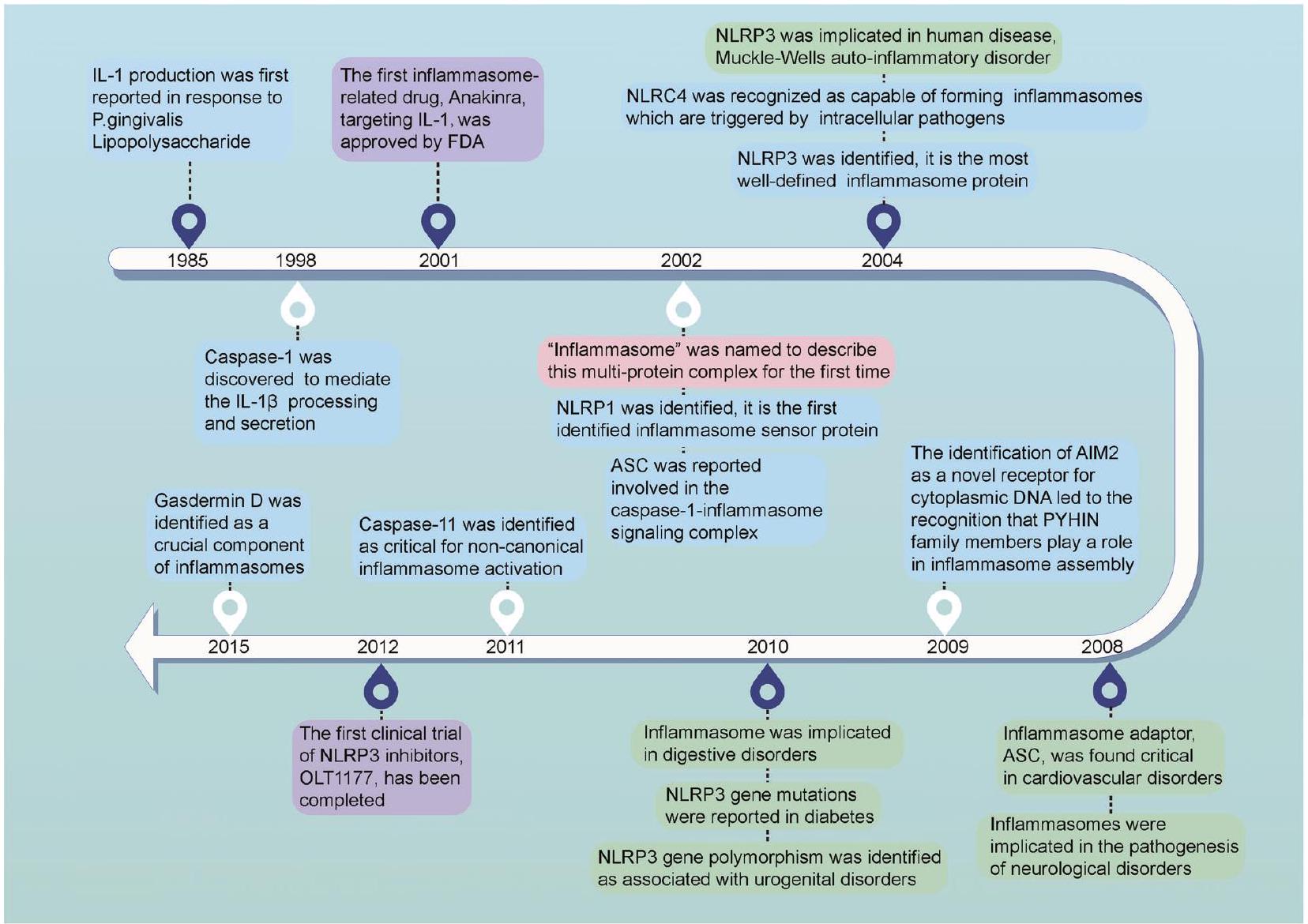

مقدمة

تم تحديد العديد من الإنفلامسومات، كل منها له وظائف مناعية وأدوار فريدة.

نُشر على الإنترنت: 05 يناير 2024

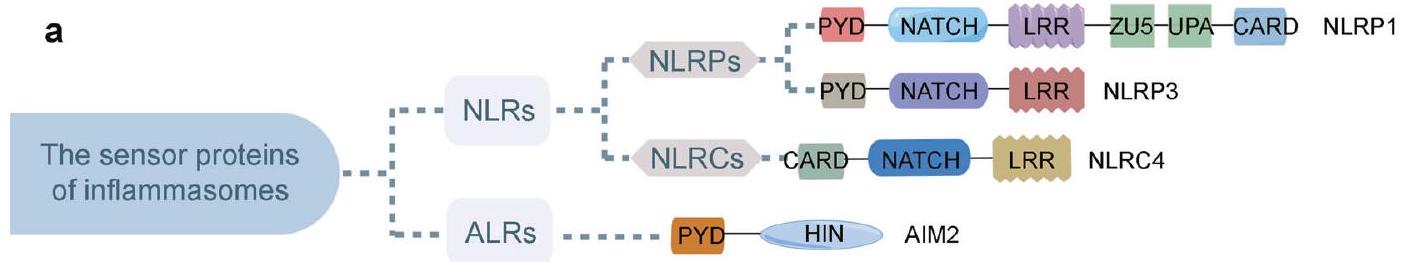

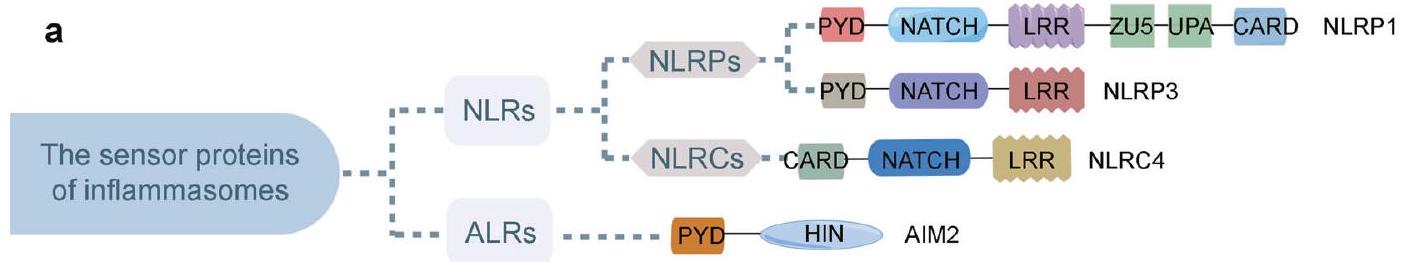

الغياب في الميلانوما 2 (AIM2) و IFI16 هما العضوان المعروفان بقدرتهما على تنشيط الكاسبيز-1.

هيكل مستشعرات الالتهاب

هيكل إنزيمات NLRP1 الالتهابية

سطح.

هيكل إنزيمات NLRP3 الالتهابية

تم ترميزها بواسطة النسخة المتغيرة 4 من NLRP3، بينما يتم ترميز الشكل المتغير d بواسطة النسخة المتغيرة 5 من NLRP3. تحتوي هذه الأشكال المتغيرة على مقاطع داخلية أقصر ولكنها مختلفة في مجال LRR_RI مقارنة بالشكل المتغير e، حيث تفتقر النسخة المتغيرة 2 إلى اثنين من الإكسونات في الإطار، وتفتقر النسخة المتغيرة 4/5 إلى إكسون واحد في الإطار.

هيكل إنزيمات NLRC4 الالتهابية

هيكل inflammasomes AIM2

hام للانخفاض الذاتي لـ AIM2. وجد الباحثون أن مجال AIM2 HIN يمكن أن يتعرف على الحمض النووي مزدوج الشريطة (dsDNA)، مثل البكتيريا والفيروسات.

هيكل inflammasomes الأخرى

تفعيل الإنفلامازومات

تنشيط إنزيم NLRP3

عامل-

يستجيب للعامل الممرض. على سبيل المثال، يؤدي تنشيط قناة الأيونات المرتبطة بـ ATP P2X purinoceptor 7 (P2X7) إلى

أظهرت أن تنشيط إنزيم NLRP3 يمكن أن يحدث دون إشارة التحفيز في أحادية النواة البشرية.

تنشيط إنزيم NLRP1

تنشيط إنزيم NLRC4

تنشيط إنفلامازوم AIM2

خلايا ناقلة فارغة عند معالجتها بـ LPS. بشكل متسق، أظهر المرضى الذين يعانون من ورم هيداتي خلال الحمل والذين لديهم طفرات في NLRP7 ونسخ نادرة مستويات منخفضة من IL

أدوار الإنفلامازومات في الأمراض المختلفة

اضطرابات القلب والأوعية الدموية

الانقباضات الأذينية المبكرة العفوية.

اضطرابات عصبية

تنشيط و IL-

تطوير أدوية تستهدف أنواع خلايا معينة أو مسارات إشارات الإنفلامازوم. يمكن أن توفر هذه الأبحاث رؤى قيمة حول كيفية مساهمة الإنفلامازومات في علم الأمراض في مختلف الاضطرابات التنكسية العصبية. قد تكون لهذه الأدوية إمكانيات علاجية كبيرة ويجب استكشافها بشكل أكبر.

اضطرابات الجهاز التنفسي

المشتقة من الفيروس بواسطة TLR3 و TLR7، مما يؤدي إلى ارتفاع مستويات pro-IL-1

اضطرابات الجهاز الهضمي

(HP). تشير بعض الأبحاث إلى أن تنشيط المركب الالتهابي قد يكون عاملًا مساهمًا في شدة عدوى HP. على سبيل المثال، وجدت دراسة أن مستويات NLRP3 و GSDMD كانت أعلى بشكل ملحوظ في الأنسجة المعدية للأفراد المصابين بـ HP مقارنةً بالضوابط الصحية.

التهاب البنكرياس، والتهاب البنكرياس المزمن. يلعب NLRP3 دورًا حاسمًا في التهاب أنسجة البنكرياس. NLRP3، كاسبيز-1، برو-IL-1

التهاب البنكرياس، والتهاب البنكرياس المزمن. يلعب NLRP3 دورًا حاسمًا في التهاب أنسجة البنكرياس. NLRP3، كاسبيز-1، برو-IL-1

اضطرابات الجهاز البولي التناسلي

الظاهرة ووفاة الخلايا. يجب إجراء مزيد من التحقيقات لتوضيح الدور الدقيق لجهاز الالتهاب NLRP3 في اعتلال الكلى IgA.

اضطرابات نظام الدم واللمف

في مسببات الأورام النقوية المفرطة. تصف متلازمات خلل التنسج النقوي مجموعة من الأورام الخبيثة قبل اللوكيميا الناتجة عن تكوين دم غير طبيعي وغير فعال. تم اقتراح تنشيط إنزيم NLRP3 كعامل مساهم في متلازمات خلل التنسج النقوي. يمكن أن يؤدي الألارمين S100A9 إلى توليد ROS، مما ينشط بعد ذلك إنزيم NLRP3، مما يؤدي إلى IL-

يميل الأشخاص الذين يعانون من الذئبة الحمامية الجهازية (SLE) إلى أن يكون لديهم مستويات أعلى من mRNA AIM2 في كبدهم، وخلايا الدم البيضاء المحيطية، والطحال مقارنة بالأفراد الأصحاء. كما وُجد أن AIM2 يساعد أيضًا في منع إشارات IFN المستحثة بواسطة الحمض النووي التي تثبط SLE.

اضطرابات أخرى

هرمون، بولي ببتيد أميلويد الجزر، يتم إفرازه بواسطة

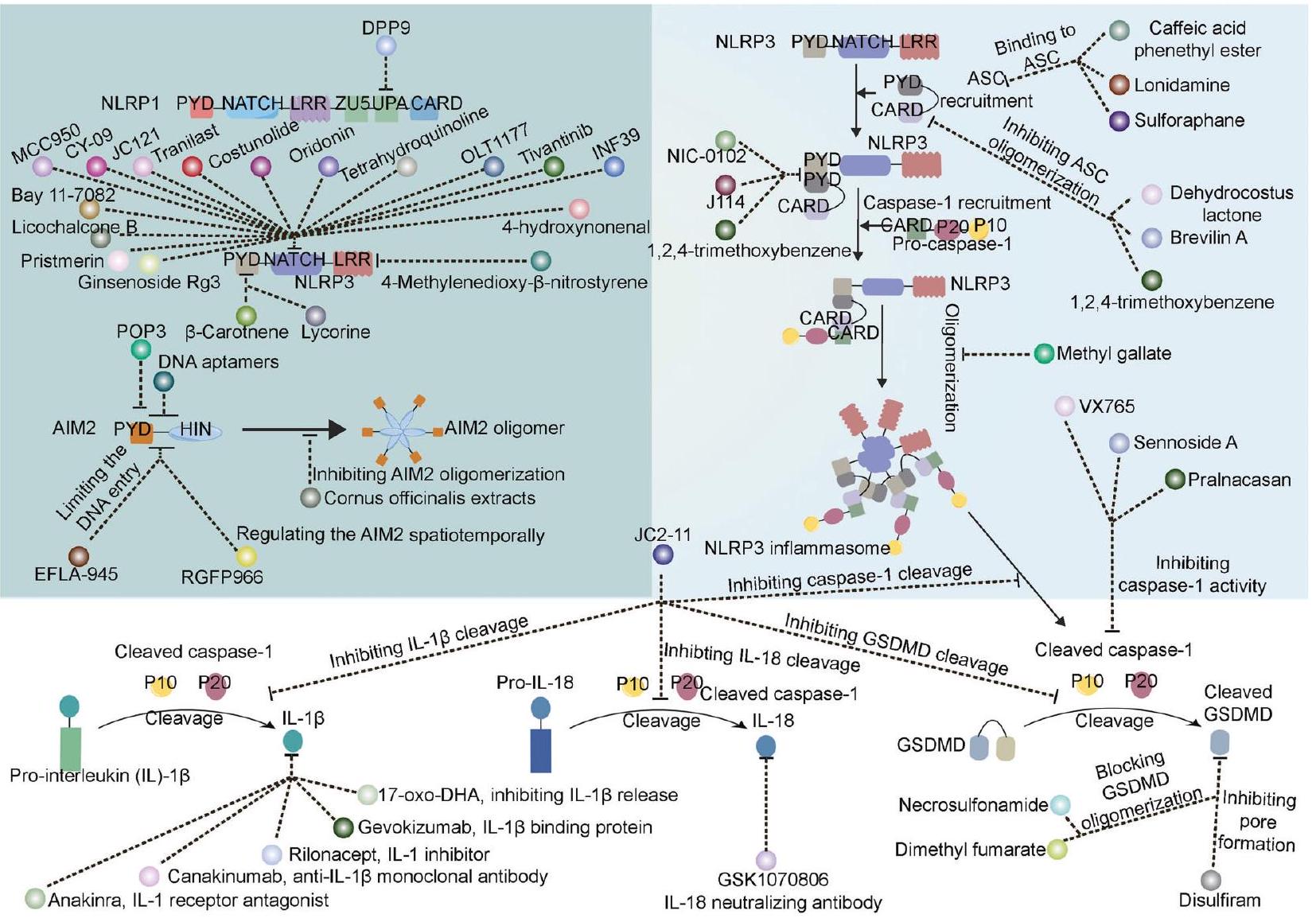

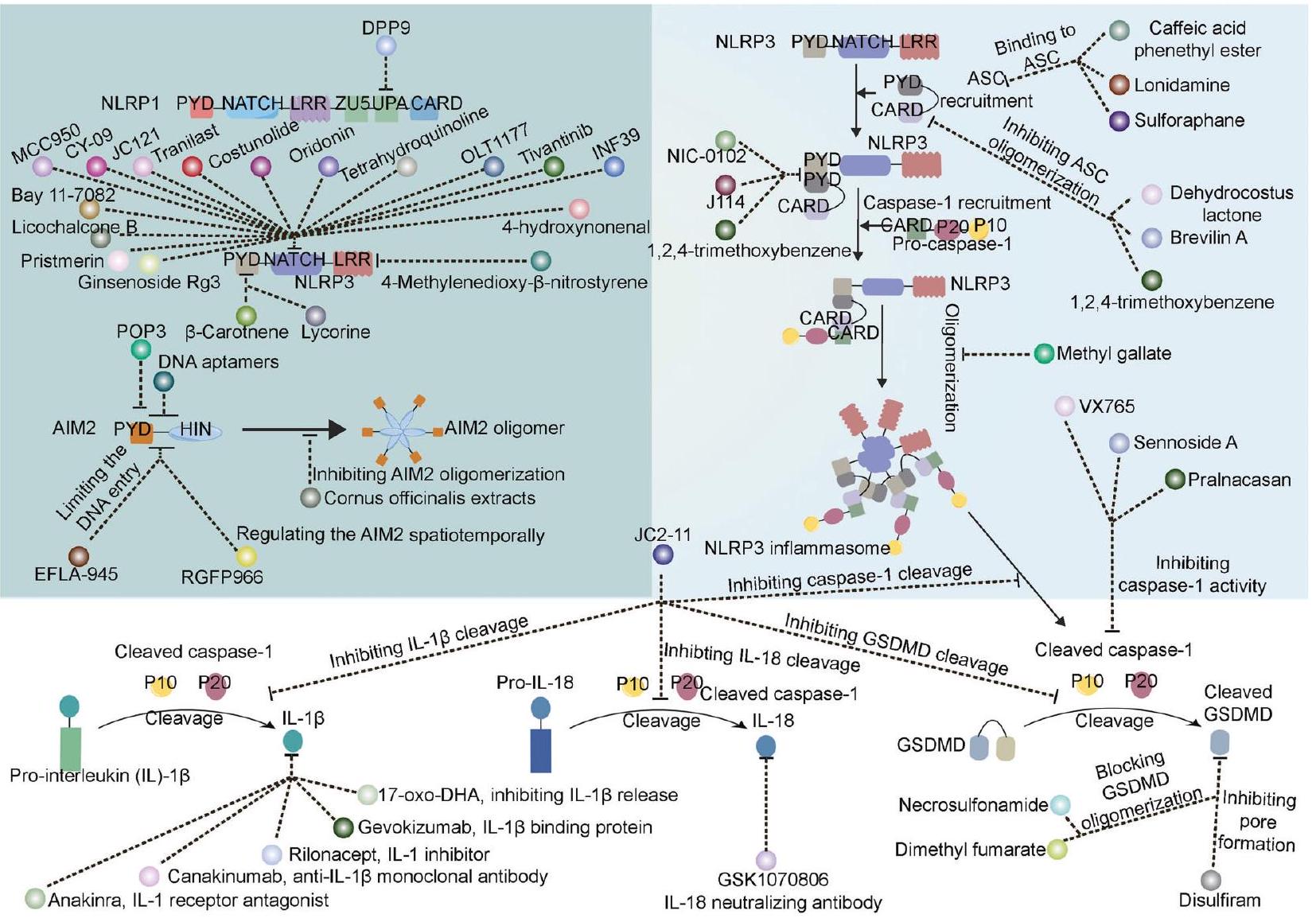

علاج مستهدف للإنفلامازوم

تعديل بروتين المستشعر

| الجدول 1. الأدوية المعتمدة من إدارة الغذاء والدواء المتعلقة بالإنفلامازوم وتطبيقاتها | ||||||

| اسم الدواء | هدف | سنة | التطبيقات الأولية | التطبيقات الحديثة | أكثر التفاعلات السلبية شيوعًا | بلا |

| أنكينرا | IL-1 | 2001 | را | كابس، ديرا | رد فعل في موقع الحقن، تفاقم التهاب المفاصل الروماتويدي، عدوى في الجهاز التنفسي العلوي، صداع، غثيان، إسهال، التهاب الجيوب الأنفية، ألم مفاصل، أعراض شبيهة بالإنفلونزا، وألم في البطن (حدوث

|

١٠٣٩٥٠ |

| ريلوناسيبت | IL-1 | 2008 | كابز | FCAS، MWS | ردود فعل في موقع الحقن والتهابات الجهاز التنفسي العلوي | ١٢٥٢٤٩ |

| كاناكينوماب | IL-1

|

2009 | كابز | FCAS، MWS | التهاب البلعوم، الإسهال، الإنفلونزا، الصداع، والغثيان | ١٢٥٣١٩ |

| RA التهاب المفاصل الروماتويدي، CAPS متلازمات دورية مرتبطة بالكريوبيرين، DIRA نقص مضاد مستقبلات الإنترلوكين-1، FCAS متلازمة الالتهاب الذاتي البارد العائلية، MWS متلازمة موكل-ويلز | ||||||

تعديل ASC

تعديل الكاسبيز

التهاب المفاصل العظمي.

معدلات IL-1/IL-18

معدلات GSDMD

معدلات أخرى

| رقم NCT | اسم الدواء | هدف | الشروط | نوع الدراسة و/أو المرحلة | التسجيل | أسلحة | تاريخ إكمال الدراسة | |||||

| NCT05658575 | OLT1177 | NLRP3 | نوبة النقرس الحادة، هجوم النقرس، تفجر النقرس، التهاب المفاصل النقرسي، التهاب المفاصل الناتج عن النقرس، ألم المفاصل | تداخلي، المرحلة 2/3 | ٣٠٠ |

|

2023-10 | |||||

| NCT04540120 | OLT1177 | NLRP3 | كوفيد-19، متلازمة إطلاق السيتوكينات | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | ٤٩ |

|

٢٠٢٢-٠٧ | |||||

| NCT03595371 | OLT1177 | NLRP3 | متلازمة شنيتزلر | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | 10 |

|

فبراير 2023 | |||||

| NCT02104050 | OLT1177 | NLRP3 | التهاب المفاصل العظمي، الألم | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | ٢٠٢ |

|

2015-08 | |||||

| NCT01768975 | OLT1177 | NLRP3 | التهاب المفاصل العظمي في الركبة | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | 79 |

|

2013-08 | |||||

| NCT03534297 | OLT1177 | NLRP3 | فشل القلب الانقباضي | تجريبي، المرحلة 1 | 30 |

|

2019-11 | |||||

| NCT02134964 | OLT1177 | NLRP3 | صحي | تجريبي، المرحلة 1 | ٣٥ |

|

2014-12 | |||||

| NCT01636141 | OLT1177 | NLRP3 | صحي | تجريبي، المرحلة 1 | ٣٦ |

|

2012-08 | |||||

| NCT05130892 | الكولشيسين، الترانيلست، والأوريدونين | NLRP3 | NLRP3، بروتين سي التفاعلي عالي الحساسية، التدخل التاجي عبر الجلد | تداخلي، المرحلة الرابعة | 132 |

|

فبراير 2023 | |||||

| NCT05855746 | كولشيسين | NLRP3 | التهاب عضلة القلب الحاد | تجريبي، المرحلة 3 | ٣٠٠ |

|

يونيو 2027 | |||||

| NCT05734612 | كولشيسين | NLRP3 | إصابة إعادة التروية، عضلة القلب | تجريبي، المرحلة 3 | ٨٠ |

|

مارس 2023 | |||||

| NCT04322565 | كولشيسين | NLRP3 | عدوى فيروس كورونا، التهاب رئوي فيروسي | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | 193 |

|

2021-10 | |||||

| NCT04867226 | كولشيسين | عدوى فيروس كورونا | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | 100 |

|

يونيو 2021 | ||||||

| NCT05118737 | كولشيسين | التهاب رئوي COVID-19 | تدخلية، المرحلة المبكرة 1 | ٢٣٠ |

|

2022-08 | ||||||

| NCT03923140 | ترانيلست | متلازمات دورية مرتبطة بالكريوبيرين | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | 71 | أ: ترانيلست | ٢٠٢٤-١٠ | ||||||

| NCT01109121 | ترانيلست | النقرس المعتدل إلى الشديد، فرط حمض اليوريك | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | ١١٢ |

|

2011-01 | ||||||

| NCT04047095 |

|

جراحة القلب | تداخلي | ٥٥ |

|

2021-10 | ||||||

| NCT03005496 |

|

الولادة المبكرة | تداخلي، المرحلة الرابعة | ٥٦ | يونيو 2017 | |||||||

| NCT03842709 | براميبيكسول | ألم مزمن NLRP3 |

|

|||||||||

| تدخلية، المرحلة المبكرة 1 | ٤٥ |

|

فبراير 2021 | |||||||||

| NCT02375685 | جيفوكزيماب | IL-1

|

التهاب القزحية المزمن | تدخلية، المرحلة المبكرة 3 | 71 | أ: جفوكزيماب | 2015-11 | |||||

| NCT01965145 | جيفوكزيماب | IL-1

|

التهاب القزحية الناتج عن بهجت | تجريبي، المرحلة 3 | 84 |

|

2015-09 | |||||

| NCT01835132 | جيفوكزيماب | IL-1

|

التهاب الصلبة | تداخلي، المرحلة 1/2 | ٨ | أ: جفوكزيماب | فبراير 2016 | |||||

| NCT01211977 | جيفوكزيماب | IL-1

|

متلازمة موكل ويلز، التهاب ذاتي، مرض بهجت | تداخلي، المرحلة 1/2 | 21 | غير متوفر | 2011-04 | |||||

| NCT02723786 | GSK1070806 | IL-18 | زراعة الكلى | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | ٧ | أ: GSK1070806

|

مارس 2018 | |||||

| NCT01648153 | GSK1070806 | IL-18 | داء السكري | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | 37 |

|

يناير 2014 | |||||

| NCT03522662 | GSK1070806 | IL-18 | مرض بهجت | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | 12 | أ: GSK1070806 | ٢٠٢٠-٠٤ | |||||

| NCT05590338 | GSK1070806 | IL-18 | التهاب الجلد التأتبي | تجريبي، المرحلة 1 | ٣٨ |

|

2023-12 | |||||

| NCT01035645 | GSK1070806 | IL-18 | أمراض الأمعاء الالتهابية | تجريبي، المرحلة 1 | 78 |

|

2012-07 | |||||

| NCT04485130 | ديisulfiram | IL-18 | كوفيد-19 | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | 11 |

|

فبراير 2022 | |||||

| NCT02561481 | سولفورافان | مسار تنشيط إنزيم NLRP3 | اضطراب طيف التوحد | تداخلي، المرحلة 1/2 | 60 |

|

٢٠٢٠-٠١ | |||||

| NCT04972188 | ZYIL1 | مسار inflammasome NLRP3 | صحي | تجريبي، المرحلة 1 | ١٨ | كبسولة ZYIL1 | 2021-10 | |||||

| NCT04731324 | ZYIL1 | مسار inflammasome NLRP3 | صحي | تجريبي، المرحلة 1 | 30 | كبسولة ZYIL1 | يونيو 2021 | |||||

| NCT04409522 | الميلاتونين | مسار inflammasome NLRP3 | كوفيد-19 | تداخلي | ٥٥ |

|

2020-09 | |||||

| NCT05567068 | أتورفاستاتين | مسار mTOR/NLRP3 inflammasome | أمراض الأمعاء الالتهابية | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | ٤٤ |

|

٢٠٢٧-٠٩ | |||||

| NCT05781698 | فينوفيبرات | مسار mTOR/NLRP3 inflammasome | أمراض الأمعاء الالتهابية | تجريبي، المرحلة الثانية | 60 |

|

2024-06 | |||||

| NCT 05276895 | جليكيريزين | تنشيط إنزيم NLRP3 والتهاب NF-

|

التهاب المفاصل العظمي | تداخلي | 60 |

|

2024-12 | |||||

الاستنتاجات

تجميع معقد الالتهاب وتنشيط الكاسبيز-1 اللاحق. يتم تحفيز المسار غير التقليدي لتنشيط الالتهاب بواسطة تنشيط الكاسبيز-4 أو -5 (الكاسبيز-11 في الفئران) استجابةً لـ LPS السيتوزولي من البكتيريا سالبة الجرام. الكاسبيز-

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

معلومات إضافية

٢٢

REFERENCES

- Taguchi, T. & Mukai, K. Innate immunity signalling and membrane trafficking. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 59, 1-7 (2019).

- Hanazawa, S. et al. Functional role of interleukin 1 in periodontal disease: induction of interleukin 1 production by Bacteroides gingivalis lipopolysaccharide in peritoneal macrophages from

and mice. Infect. Immun. 50, 262-270 (1985). - Martinon, F., Burns, K. & Tschopp, J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proll-beta. Mol. Cell 10, 417-426 (2002).

- Watson, R. W., Rotstein, O. D., Parodo, J., Bitar, R. & Marshall, J. C. The IL-1 betaconverting enzyme (caspase-1) inhibits apoptosis of inflammatory neutrophils through activation of IL-1 beta. J. Immunol. 161, 957-962 (1998).

- Dinarello, C. A. Unraveling the NALP-3/IL-1beta inflammasome: a big lesson from a small mutation. Immunity 20, 243-244 (2004).

- Inohara, N. et al. Nod1, an Apaf-1-like activator of caspase-9 and nuclear factorkappaB. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 14560-14567 (1999).

- Ogura, Y. et al. Nod2, a Nod1/Apaf-1 family member that is restricted to monocytes and activates NF-kappaB. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4812-4818 (2001).

- Wagner, R. N., Proell, M., Kufer, T. A. & Schwarzenbacher, R. Evaluation of Nodlike receptor (NLR) effector domain interactions. PLoS One 4, e4931 (2009).

- Hornung, V. et al. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature 458, 514-518 (2009).

- Roberts, T. L. et al. HIN-200 proteins regulate caspase activation in response to foreign cytoplasmic DNA. Science 323, 1057-1060 (2009).

- Cartwright, N. et al. Selective NOD1 agonists cause shock and organ injury/ dysfunction in vivo. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175, 595-603 (2007).

- Proell, M., Riedl, S. J., Fritz, J. H., Rojas, A. M. & Schwarzenbacher, R. The Nod-like receptor (NLR) family: a tale of similarities and differences. PLoS One 3, e2119 (2008).

- Sutterwala, F. S. et al. Immune recognition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mediated by the IPAF/NLRC4 inflammasome. J. Exp. Med 204, 3235-3245 (2007).

- Agostini, L. et al. NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle-Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity 20, 319-325 (2004).

- Elinav, E. et al. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell 145, 745-757 (2011).

- Khare, S. et al. An NLRP7-containing inflammasome mediates recognition of microbial lipopeptides in human macrophages. Immunity 36, 464-476 (2012).

- Zhu, S. et al. Nlrp9b inflammasome restricts rotavirus infection in intestinal epithelial cells. Nature 546, 667-670 (2017).

- Maharana, J. Elucidating the interfaces involved in CARD-CARD interactions mediated by NLRP1 and Caspase-1 using molecular dynamics simulation. J. Mol. Graph Model 80, 7-14 (2018).

- Mayor, A., Martinon, F., De Smedt, T., Petrilli, V. & Tschopp, J. A crucial function of SGT1 and HSP90 in inflammasome activity links mammalian and plant innate immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 8, 497-503 (2007).

- de Alba, E. Structure and interdomain dynamics of apoptosis-associated specklike protein containing a CARD (ASC). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32932-32941 (2009).

- Lu, A. et al. Unified polymerization mechanism for the assembly of ASCdependent inflammasomes. Cell 156, 1193-1206 (2014).

- Kostura, M. J. et al. Identification of a monocyte specific pre-interleukin 1 beta convertase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 5227-5231 (1989).

- He, W. T. et al. Gasdermin D is an executor of pyroptosis and required for interleukin-1beta secretion. Cell Res 25, 1285-1298 (2015).

- Albrecht, M., Choubey, D. & Lengauer, T. The HIN domain of IFI-200 proteins consists of two OB folds. Biochem. Biophys. Res Commun. 327, 679-687 (2005).

- Fernandes-Alnemri, T., Yu, J. W., Datta, P., Wu, J. & Alnemri, E. S. AIM2 activates the inflammasome and cell death in response to cytoplasmic DNA. Nature 458, 509-513 (2009).

- Veeranki, S., Duan, X., Panchanathan, R., Liu, H. & Choubey, D. IFI16 protein mediates the anti-inflammatory actions of the type-l interferons through suppression of activation of caspase-1 by inflammasomes. PLoS One 6, e27040 (2011).

- Damiano, J. S., Newman, R. M. & Reed, J. C. Multiple roles of CLAN (caspaseassociated recruitment domain, leucine-rich repeat, and NAIP CIIA HET-E, and TP1-containing protein) in the mammalian innate immune response. J. Immunol. 173, 6338-6345 (2004).

- Choubey, D. et al. Interferon-inducible p200-family proteins as novel sensors of cytoplasmic DNA: role in inflammation and autoimmunity. J. Interferon Cytokine Res 30, 371-380 (2010).

- Davis, B. K. et al. Cutting edge: NLRC5-dependent activation of the inflammasome. J. Immunol. 186, 1333-1337 (2011).

- Kempster, S. L. et al. Developmental control of the Nlrp6 inflammasome and a substrate, IL-18, in mammalian intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 300, G253-263, (2011).

- Marleaux, M., Anand, K., Latz, E. & Geyer, M. Crystal structure of the human NLRP9 pyrin domain suggests a distinct mode of inflammasome assembly. FEBS Lett. 594, 2383-2395 (2020).

- Hiller, S. et al. NMR structure of the apoptosis- and inflammation-related NALP1 pyrin domain. Structure 11, 1199-1205 (2003).

- Finger, J. N. et al. Autolytic proteolysis within the function to find domain (FIIND) is required for NLRP1 inflammasome activity. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 25030-25037 (2012).

- Jin, T., Curry, J., Smith, P., Jiang, J. & Xiao, T. S. Structure of the NLRP1 caspase recruitment domain suggests potential mechanisms for its association with procaspase-1. Proteins 81, 1266-1270 (2013).

- Robert Hollingsworth, L. et al. Mechanism of filament formation in UPApromoted CARD8 and NLRP1 inflammasomes. Nat. Commun. 12, 189 (2021).

- Gong, Q. et al. Structural basis for distinct inflammasome complex assembly by human NLRP1 and CARD8. Nat. Commun. 12, 188 (2021).

- Xu, Z. et al. Homotypic CARD-CARD interaction is critical for the activation of NLRP1 inflammasome. Cell Death Dis. 12, 57 (2021).

- D’Osualdo, A. et al. CARD8 and NLRP1 undergo autoproteolytic processing through a ZU5-like domain. PLoS One 6, e27396 (2011).

- Huang, M. et al. Structural and biochemical mechanisms of NLRP1 inhibition by DPP9. Nature 592, 773-777 (2021).

- Moecking, J. et al. NLRP1 variant M1184V decreases inflammasome activation in the context of DPP9 inhibition and asthma severity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 147, 2134-2145.e2120 (2021).

- Moecking, J. et al. Inflammasome sensor NLRP1 disease variant M1184V promotes autoproteolysis and DPP9 complex formation by stabilizing the FIIND domain. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 102645 (2022).

- Rahman, T. et al. NLRP3 sensing of diverse inflammatory stimuli requires distinct structural features. Front Immunol. 11, 1828 (2020).

- Sahoo, B. R. et al. A conformational analysis of mouse Nalp3 domain structures by molecular dynamics simulations, and binding site analysis. Mol. Biosyst. 10, 1104-1116 (2014).

- Brinkschulte, R. et al. ATP-binding and hydrolysis of human NLRP3. Commun. Biol. 5, 1176 (2022).

- Samson, J. M. et al. Computational Modeling of NLRP3 Identifies Enhanced ATP Binding and Multimerization in Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic Syndromes. Front Immunol. 11, 584364 (2020).

- Bae, J. Y. & Park, H. H. Crystal structure of NALP3 protein pyrin domain (PYD) and its implications in inflammasome assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 39528-39536 (2011).

- Oroz, J., Barrera-Vilarmau, S., Alfonso, C., Rivas, G. & de Alba, E. ASC pyrin domain self-associates and binds NLRP3 protein using equivalent binding interfaces. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 19487-19501 (2016).

- Hochheiser, I. V. & Geyer, M. An assay for the seeding of homotypic pyrin domain filament transitions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2523, 197-207 (2022).

- Isazadeh, M. et al. Split-luciferase complementary assay of NLRP3 PYD-PYD interaction indicates inflammasome formation during inflammation. Anal. Biochem 638, 114510 (2022).

- Hochheiser, I. V. et al. Directionality of PYD filament growth determined by the transition of NLRP3 nucleation seeds to ASC elongation. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn7583 (2022).

- Tapia-Abellan, A. et al. Sensing low intracellular potassium by NLRP3 results in a stable open structure that promotes inflammasome activation. Sci. Adv. 7, eabf4468 (2021).

- Andreeva, L. et al. NLRP3 cages revealed by full-length mouse NLRP3 structure control pathway activation. Cell 184, 6299-6312.e6222 (2021).

- Ohto, U. et al. Structural basis for the oligomerization-mediated regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2121353119 (2022).

- Hoss, F. et al. Alternative splicing regulates stochastic NLRP3 activity. Nat. Commun. 10, 3238 (2019).

- Ehtesham, N. et al. Three functional variants in the NLRP3 gene are associated with susceptibility and clinical characteristics of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 30, 1273-1282 (2021).

- Zhou, L. et al. Excessive deubiquitination of NLRP3-R779C variant contributes to very-early-onset inflammatory bowel disease development. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 147, 267-279 (2021).

- Dessing, M. C. et al. Donor and recipient genetic variants in NLRP3 associate with early acute rejection following kidney transplantation. Sci. Rep. 6, 36315 (2016).

- Ozturk, K. H. & Unal, G. O. Novel splice-site variants c.393G>A, c.278_2A>G in exon 2 and Q705K variant in exon 3 of NLRP3 gene are associated with bipolar I disorder. Mol. Med. Rep. 26, 293 (2022).

- Chauhan, D. et al. GSDMD drives canonical inflammasome-induced neutrophil pyroptosis and is dispensable for NETosis. EMBO Rep. 23, e54277 (2022).

- Hu, Z. et al. Crystal structure of NLRC4 reveals its autoinhibition mechanism. Science 341, 172-175 (2013).

- Poyet, J. L. et al. Identification of Ipaf, a human caspase-1-activating protein related to Apaf-1. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28309-28313 (2001).

- Yang, J. et al. Sequence determinants of specific pattern-recognition of bacterial ligands by the NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasome. Cell Discov. 4, 22 (2018).

- Yang, X. et al. Structural basis for specific flagellin recognition by the NLR protein NAIP5. Cell Res. 28, 35-47 (2018).

- Paidimuddala, B. et al. Mechanism of NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasome activation revealed by cryo-EM structure of unliganded NAIP5. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 159-166 (2023).

- Tenthorey, J. L., Kofoed, E. M., Daugherty, M. D., Malik, H. S. & Vance, R. E. Molecular basis for specific recognition of bacterial ligands by NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasomes. Mol. Cell 54, 17-29 (2014).

- Kofoed, E. M. & Vance, R. E. Innate immune recognition of bacterial ligands by NAIPs determines inflammasome specificity. Nature 477, 592-595 (2011).

- Zhang, L. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the activated NAIP2-NLRC4 inflammasome reveals nucleated polymerization. Science 350, 404-409 (2015).

- Hu, Z. et al. Structural and biochemical basis for induced self-propagation of NLRC4. Science 350, 399-404 (2015).

- Halff, E. F. et al. Formation and structure of a NAIP5-NLRC4 inflammasome induced by direct interactions with conserved N – and C-terminal regions of flagellin. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 38460-38472 (2012).

- Diebolder, C. A., Halff, E. F., Koster, A. J., Huizinga, E. G. & Koning, R. I. Cryoelectron tomography of the NAIP5/NLRC4 inflammasome: Implications for NLR activation. Structure 23, 2349-2357 (2015).

- Li, Y. et al. Cryo-EM structures of ASC and NLRC4 CARD filaments reveal a unified mechanism of nucleation and activation of caspase-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 10845-10852 (2018).

- Lu, A. et al. Molecular basis of caspase-1 polymerization and its inhibition by a new capping mechanism. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 416-425 (2016).

- Matyszewski, M. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the NLRC4(CARD) filament provides insights into how symmetric and asymmetric supramolecular structures drive inflammasome assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 20240-20248 (2018).

- Wang, L. et al. A novel mutation in the NBD domain of NLRC4 causes mild autoinflammation with recurrent urticaria. Front Immunol. 12, 674808 (2021).

- Canna, S. W. et al. An activating NLRC4 inflammasome mutation causes autoinflammation with recurrent macrophage activation syndrome. Nat. Genet 46, 1140-1146 (2014).

- Chear, C. T. et al. A novel de novo NLRC4 mutation reinforces the likely pathogenicity of specific LRR domain mutation. Clin. Immunol. 211, 108328 (2020).

- Ionescu, D. et al. First description of late-onset autoinflammatory disease due to somatic NLRC4 mosaicism. Arthritis Rheumatol. 74, 692-699 (2022).

- Moghaddas, F. et al. Autoinflammatory mutation in NLRC4 reveals a leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-LRR oligomerization interface. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142, 1956-1967.e1956 (2018).

- Steiner, A. et al. Recessive NLRC4-autoinflammatory disease reveals an ulcerative colitis locus. J. Clin. Immunol. 42, 325-335 (2022).

- Raghawan, A. K., Ramaswamy, R., Radha, V. & Swarup, G. HSC70 regulates coldinduced caspase-1 hyperactivation by an autoinflammation-causing mutant of cytoplasmic immune receptor NLRC4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 21694-21703 (2019).

- Lu, A., Kabaleeswaran, V., Fu, T., Magupalli, V. G. & Wu, H. Crystal structure of the F27G AIM2 PYD mutant and similarities of its self-association to DED/DED interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 1420-1427 (2014).

- Jin, T. et al. Structures of the HIN domain:DNA complexes reveal ligand binding and activation mechanisms of the AIM2 inflammasome and IFI16 receptor. Immunity 36, 561-571 (2012).

- Matyszewski, M. et al. Distinct axial and lateral interactions within homologous filaments dictate the signaling specificity and order of the AIM2-ASC inflammasome. Nat. Commun. 12, 2735 (2021).

- Wang, H., Yang, L. & Niu, X. Conformation switching of AIM2 PYD domain revealed by NMR relaxation and MD simulation. Biochem Biophys. Res Commun. 473, 636-641 (2016).

- Morrone, S. R. et al. Assembly-driven activation of the AIM2 foreign-dsDNA sensor provides a polymerization template for downstream ASC. Nat. Commun. 6, 7827 (2015).

- Lu, A. et al. Plasticity in PYD assembly revealed by cryo-EM structure of the PYD filament of AIM2. Cell Discov. 1, 15013 (2015).

- Liao, J. C. et al. Interferon-inducible protein 16: insight into the interaction with tumor suppressor p53. Structure 19, 418-429 (2011).

- Ni, X. et al. New insights into the structural basis of DNA recognition by HINa and HINb domains of IFI16. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 51-61 (2016).

- Fan, X. et al. Structural mechanism of DNA recognition by the p204 HIN domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 2959-2972 (2021).

- Trapani, J. A., Dawson, M., Apostolidis, V. A. & Browne, K. A. Genomic organization of IFI16, an interferon-inducible gene whose expression is associated with human myeloid cell differentiation: correlation of predicted protein domains with exon organization. Immunogenetics 40, 415-424 (1994).

- Liu, Z., Zheng, X., Wang, Y. & Song, H. Bacterial expression of the HINab domain of IFI16: purification, characterization of DNA binding activity, and cocrystallization with viral dsDNA. Protein Expr. Purif. 102, 13-19 (2014).

- Tian, Y. & Yin, Q. Structural analysis of the HIN1 domain of interferon-inducible protein 204. Acta Crystallogr F. Struct. Biol. Commun. 75, 455-460 (2019).

- Li, T., Diner, B. A., Chen, J. & Cristea, I. M. Acetylation modulates cellular distribution and DNA sensing ability of interferon-inducible protein IFI16. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10558-10563 (2012).

- Motyan, J. A., Bagossi, P., Benko, S. & Tozser, J. A molecular model of the fulllength human NOD-like receptor family CARD domain containing 5 (NLRC5) protein. BMC Bioinforma. 14, 275 (2013).

- Neerincx, A. et al. The N-terminal domain of NLRC5 confers transcriptional activity for MHC class I and II gene expression. J. Immunol. 193, 3090-3100 (2014).

- Cui, J. et al. NLRC5 negatively regulates the NF-kappaB and type I interferon signaling pathways. Cell 141, 483-496 (2010).

- Gutte, P. G., Jurt, S., Grutter, M. G. & Zerbe, O. Unusual structural features revealed by the solution NMR structure of the NLRC5 caspase recruitment domain. Biochemistry 53, 3106-3117 (2014).

- Leng, F. et al. NLRP6 self-assembles into a linear molecular platform following LPS binding and ATP stimulation. Sci. Rep. 10, 198 (2020).

- Shen, C. et al. Molecular mechanism for NLRP6 inflammasome assembly and activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 2052-2057 (2019).

- de Sa Pinheiro, A. et al. Backbone and sidechain (1)H, (15)N and (13)C assignments of the NLRP7 pyrin domain. Biomol. NMR Assign. 3, 207-209 (2009).

- Pinheiro, A. S. et al. Three-dimensional structure of the NLRP7 pyrin domain: insight into pyrin-pyrin-mediated effector domain signaling in innate immunity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27402-27410 (2010).

- Singer, H. et al. NLRP7 inter-domain interactions: the NACHT-associated domain is the physical mediator for oligomeric assembly. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 20, 990-1001 (2014).

- Radian, A. D., Khare, S., Chu, L. H., Dorfleutner, A. & Stehlik, C. ATP binding by NLRP7 is required for inflammasome activation in response to bacterial lipopeptides. Mol. Immunol. 67, 294-302 (2015).

- Ha, H. J. & Park, H. H. Crystal structure of the human NLRP9 pyrin domain reveals a bent N-terminal loop that may regulate inflammasome assembly. FEBS Lett. 594, 2396-2405 (2020).

- Chen, S. et al. Novel Role for Tranilast in Regulating NLRP3 Ubiquitination, Vascular Inflammation, and Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e015513 (2020).

- Py, B. F., Kim, M. S., Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg, H. & Yuan, J. Deubiquitination of NLRP3 by BRCC3 critically regulates inflammasome activity. Mol. Cell 49, 331-338 (2013).

- Ren, G. et al. ABRO1 promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation through regulation of NLRP3 deubiquitination. EMBO J. 38, e100376 (2019).

- Mezzasoma, L., Talesa, V. N., Romani, R. & Bellezza, I. ANP and BNP Exert AntiInflammatory Action via NPR-1/cGMP axis by interfering with canonical, noncanonical, and alternative routes of inflammasome activation in human THP1 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 24 (2020).

- Zhang, Z. et al. Protein kinase D at the Golgi controls NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Exp. Med. 214, 2671-2693 (2017).

- Song, N. et al. NLRP3 phosphorylation is an essential priming event for inflammasome activation. Mol. Cell 68, 185-197.e186 (2017).

- Yaron, J. R. et al.

regulates to drive inflammasome signaling: dynamic visualization of ion flux in live cells. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1954 (2015). - Green, J. P. et al. Chloride regulates dynamic NLRP3-dependent ASC oligomerization and inflammasome priming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E9371-E9380 (2018).

- Hornung, V. et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat. Immunol. 9, 847-856 (2008).

- Chen, J. & Chen, Z. J. Ptdlns4P on dispersed trans-Golgi network mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 564, 71-76 (2018).

- Li, L. et al. CB1R-stabilized NLRP3 inflammasome drives antipsychotics cardiotoxicity. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 190 (2022).

- Kayagaki, N. et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479, 117-121 (2011).

- Kayagaki, N. et al. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature 526, 666-671 (2015).

- Yamamoto, M. et al. ASC is essential for LPS-induced activation of procaspase-1 independently of TLR-associated signal adaptor molecules. Genes Cells 9, 1055-1067 (2004).

24

119. Aachoui, Y. et al. Caspase-11 protects against bacteria that escape the vacuole. Science 339, 975-978 (2013).

120. Tong, W. et al. Resveratrol inhibits LPS-induced inflammation through suppressing the signaling cascades of TLR4-NF-kappaB/MAPKs/IRF3. Exp. Ther. Med 19, 1824-1834 (2020).

121. Simoes, D. C. M., Paschalidis, N., Kourepini, E. & Panoutsakopoulou, V. An integrin axis induces IFN-beta production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Cell Biol. 221, e202102055 (2022).

122. Igbe, I. et al. Dietary quercetin potentiates the antiproliferative effect of interferon-alpha in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through activation of JAK/ STAT pathway signaling by inhibition of SHP2 phosphatase. Oncotarget 8, 113734-113748 (2017).

123. Flood, B. et al. Caspase-11 regulates the tumour suppressor function of STAT1 in a murine model of colitis-associated carcinogenesis. Oncogene 38, 2658-2674 (2019).

124. Aizawa, E. et al. GSDME-dependent incomplete pyroptosis permits selective IL1alpha release under caspase-1 inhibition. iScience 23, 101070 (2020).

125. Compan, V. et al. Cell volume regulation modulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Immunity 37, 487-500 (2012).

126. Gritsenko, A. et al. Priming is dispensable for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human monocytes in vitro. Front Immunol. 11, 565924 (2020).

127. Ming, S. L. et al. The human-specific STING agonist G10 activates Type I interferon and the NLRP3 inflammasome in porcine cells. Front Immunol. 11, 575818 (2020).

128. Zhou, B. & Abbott, D. W. Gasdermin E permits interleukin-1 beta release in distinct sublytic and pyroptotic phases. Cell Rep. 35, 108998 (2021).

129. Robinson, K. S. et al. ZAKalpha-driven ribotoxic stress response activates the human NLRP1 inflammasome. Science 377, 328-335 (2022).

130. Langorgen, J., Williksen, J. H., Johannesen, K. & Erichsen, H. G. [Tissue adhesives versus conventional skin closure]. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen 107, 2944-2945 (1987).

131. Chui, A. J. et al. N-terminal degradation activates the NLRP1B inflammasome. Science 364, 82-85 (2019).

132. Saresella, M. et al. The NLRP3 and NLRP1 inflammasomes are activated in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 11, 23 (2016).

133. Zwicker, S. et al. Th17 micro-milieu regulates NLRP1-dependent caspase-5 activity in skin autoinflammation. PLoS One 12, e0175153 (2017).

134. Zhang, B. et al. Chronic glucocorticoid exposure activates BK-NLRP1 signal involving in hippocampal neuron damage. J. Neuroinflammation 14, 139 (2017).

135. Planes, R. et al. Human NLRP1 is a sensor of pathogenic coronavirus 3CL proteases in lung epithelial cells. Mol. Cell 82, 2385-2400.e2389 (2022).

136. Mariathasan, S. et al. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature 430, 213-218 (2004).

137. Reyes Ruiz, V. M. et al. Broad detection of bacterial type III secretion system and flagellin proteins by the human NAIP/NLRC4 inflammasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 13242-13247 (2017).

138. Miao, E. A. et al. Innate immune detection of the type III secretion apparatus through the NLRC4 inflammasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3076-3080 (2010).

139. Zhao, Y. et al. The NLRC4 inflammasome receptors for bacterial flagellin and type III secretion apparatus. Nature 477, 596-600 (2011).

140. Lage, S. L. et al. Cytosolic flagellin-induced lysosomal pathway regulates inflammasome-dependent and -independent macrophage responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, E3321-E3330 (2013).

141. Gram, A. M. et al. Salmonella flagellin activates NAIP/NLRC4 and canonical NLRP3 inflammasomes in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 206, 631-640 (2021).

142. Pereira, M. S. et al. Activation of NLRC4 by flagellated bacteria triggers caspase-1-dependent and -independent responses to restrict Legionella pneumophila replication in macrophages and in vivo. J. Immunol. 187, 6447-6455 (2011).

143. Mohamed, M. F. et al. Crkll/Abl phosphorylation cascade is critical for NLRC4 inflammasome activity and is blocked by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT. Nat. Commun. 13, 1295 (2022).

144. Arlehamn, C. S., Petrilli, V., Gross, O., Tschopp, J. & Evans, T. J. The role of potassium in inflammasome activation by bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 10508-10518 (2010).

145. Naseer, N. et al. Human NAIP/NLRC4 and NLRP3 inflammasomes detect Salmonella type III secretion system activities to restrict intracellular bacterial replication. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1009718 (2022).

146. Eibl, C. et al. Structural and functional analysis of the NLRP4 pyrin domain. Biochemistry 51, 7330-7341 (2012).

147. Case, C. L. & Roy, C. R. Asc modulates the function of NLRC4 in response to infection of macrophages by Legionella pneumophila. mBio 2, (2011).

148. Van Opdenbosch, N. et al. Caspase-1 Engagement and TLR-Induced c-FLIP Expression Suppress ASC/Caspase-8-Dependent Apoptosis by Inflammasome Sensors NLRP1b and NLRC4. Cell Rep. 21, 3427-3444 (2017).

149. Fernandes-Alnemri, T. et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is critical for innate immunity to Francisella tularensis. Nat. Immunol. 11, 385-393 (2010).

150. Rathinam, V. A. et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nat. Immunol. 11, 395-402 (2010).

151. Lee, S. et al. AIM2 forms a complex with pyrin and ZBP1 to drive PANoptosis and host defence. Nature 597, 415-419 (2021).

152. Zhou, Q. et al. Pseudorabies virus infection activates the TLR-NF-kappaB axis and AIM2 inflammasome to enhance inflammatory responses in mice. J. Virol. 97, e0000323 (2023).

153. Dawson, M. J., Elwood, N. J., Johnstone, R. W. & Trapani, J. A. The IFN-inducible nucleoprotein IFI 16 is expressed in cells of the monocyte lineage, but is rapidly and markedly down-regulated in other myeloid precursor populations. J. Leukoc. Biol. 64, 546-554 (1998).

154. Gariglio, M. et al. Immunohistochemical expression analysis of the human interferon-inducible gene IFI16, a member of the HIN200 family, not restricted to hematopoietic cells. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 22, 815-821 (2002).

155. Wei, W. et al. Expression of IFI 16 in epithelial cells and lymphoid tissues. Histochem Cell Biol. 119, 45-54 (2003).

156. Kerur, N. et al. IFI16 acts as a nuclear pathogen sensor to induce the inflammasome in response to Kaposi Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection. Cell Host Microbe 9, 363-375 (2011).

157. Roy, A. et al. Nuclear innate immune DNA sensor IFI16 Is Degraded during Lytic Reactivation of Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus (KSHV): Role of IFI16 in Maintenance of KSHV Latency. J. Virol. 90, 8822-8841 (2016).

158. Jiang, Z. et al. IFI16 directly senses viral RNA and enhances RIG-I transcription and activation to restrict influenza virus infection. Nat. Microbiol 6, 932-945 (2021).

159. Unterholzner, L. et al. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nat. Immunol. 11, 997-1004 (2010).

160. Kumar, H. et al. NLRC5 deficiency does not influence cytokine induction by virus and bacteria infections. J. Immunol. 186, 994-1000 (2011).

161. Janowski, A. M., Kolb, R., Zhang, W. & Sutterwala, F. S. Beneficial and detrimental roles of NLRs in carcinogenesis. Front Immunol. 4, 370 (2013).

162. Wlodarska, M. et al. NLRP6 inflammasome orchestrates the colonic hostmicrobial interface by regulating goblet cell mucus secretion. Cell 156, 1045-1059 (2014).

163. Kinoshita, T., Wang, Y., Hasegawa, M., Imamura, R. & Suda, T. PYPAF3, a PYRINcontaining APAF-1-like protein, is a feedback regulator of caspase-1-dependent interleukin-1beta secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21720-21725 (2005).

164. Messaed, C. et al. NLRP7, a nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptor protein, is required for normal cytokine secretion and co-localizes with Golgi and the microtubule-organizing center. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 43313-43323 (2011).

165. Luo, Y. et al. Macrophagic CD146 promotes foam cell formation and retention during atherosclerosis. Cell Res 27, 352-372 (2017).

166. Liu, W. et al. Erythroid lineage Jak2V617F expression promotes atherosclerosis through erythrophagocytosis and macrophage ferroptosis. J. Clin. Invest 132, e155724 (2022).

167. Yvan-Charvet, L. et al. Combined deficiency of ABCA1 and ABCG1 promotes foam cell accumulation and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest 117, 3900-3908 (2007).

168. Buono, C. et al. T-bet deficiency reduces atherosclerosis and alters plaque antigen-specific immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 1596-1601 (2005).

169. Zhang, Z. et al. Evidence that cathelicidin peptide LL-37 may act as a functional ligand for CXCR2 on human neutrophils. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 3181-3194 (2009).

170. Duewell, P. et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464, 1357-1361 (2010).

171. Elhage, R. et al. Reduced atherosclerosis in interleukin-18 deficient apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Cardiovasc Res 59, 234-240 (2003).

172. Chang, P. Y., Chang, S. F., Chang, T. Y., Su, H. M. & Lu, S. C. Synergistic effects of electronegative-LDL- and palmitic-acid-triggered IL-1beta production in macrophages via LOX-1- and voltage-gated-potassium-channel-dependent pathways. J. Nutr. Biochem 97, 108767 (2021).

173. Sheedy, F. J. et al. CD36 coordinates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by facilitating intracellular nucleation of soluble ligands into particulate ligands in sterile inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 14, 812-820 (2013).

174. Grace, N. D. Prevention of recurrent variceal bleeding-is surgical rescue the answer? Ann. Intern Med. 112, 242-244, (1990).

175. Kirii, H. et al. Lack of interleukin-1beta decreases the severity of atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23, 656-660 (2003).

176. Alexander, M. R. et al. Genetic inactivation of IL-1 signaling enhances atherosclerotic plaque instability and reduces outward vessel remodeling in advanced atherosclerosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest 122, 70-79 (2012).

177. Sun, H. J. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation contributes to VSMC phenotypic transformation and proliferation in hypertension. Cell Death Dis. 8, e3074 (2017).

178. Al-Qazazi, R. et al. Macrophage-NLRP3 Activation Promotes Right Ventricle Failure in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 206, 608-624 (2022).

179. Suetomi, T. et al. Inflammation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation initiated in response to pressure overload by

180. Liu, C. et al. Cathepsin B deteriorates diabetic cardiomyopathy induced by streptozotocin via promoting NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 30, 198-207 (2022).

181. Zhang, Y. et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis promotes age-related atrial fibrillation by lipopolysaccharide and glucose-induced activation of NLRP3-inflammasome. Cardiovasc Res 118, 785-797 (2022).

182. Yao, C. et al. Enhanced cardiomyocyte NLRP3 inflammasome signaling promotes atrial fibrillation. Circulation 138, 2227-2242 (2018).

183. Zeng, C. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated pyroptosis contributes to the pathogenesis of non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Redox Biol. 34, 101523 (2020).

184. Sun, X. et al. Colchicine ameliorates dilated cardiomyopathy Via SIRT2-mediated suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e025266 (2022).

185. Toldo, S. et al. Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome limits the inflammatory injury following myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in the mouse. Int J. Cardiol. 209, 215-220 (2016).

186. Wang, S. H. et al. GSK-3beta-mediated activation of NLRP3 inflammasome leads to pyroptosis and apoptosis of rat cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts. Eur. J. Pharm. 920, 174830 (2022).

187. de Almeida Oliveira, N. C. et al. Multicellular regulation of miR-196a-5p and miR-425-5 from adipose stem cell-derived exosomes and cardiac repair. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 136, 1281-1301 (2022).

188. Bao, J., Sun, T., Yue, Y. & Xiong, S. Macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome activated by CVB3 capsid proteins contributes to the development of viral myocarditis. Mol. Immunol. 114, 41-48 (2019).

189. Liu, X. et al. Mitochondrial calpain-1 activates NLRP3 inflammasome by cleaving ATP5A1 and inducing mitochondrial ROS in CVB3-induced myocarditis. Basic Res Cardiol. 117, 40 (2022).

190. Wang, Y. et al. Cathepsin B aggravates coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis through activating the inflammasome and promoting pyroptosis. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006872 (2018).

191. Chu, C. et al. miR-513c-5p suppression aggravates pyroptosis of endothelial cell in deep venous thrombosis by promoting caspase-1. Front Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 838785 (2022).

192. Folco, E. J., Sukhova, G. K., Quillard, T. & Libby, P. Moderate hypoxia potentiates interleukin-1beta production in activated human macrophages. Circ. Res 115, 875-883 (2014).

193. Zhang, Y. et al. Inflammasome activation promotes venous thrombosis through pyroptosis. Blood Adv. 5, 2619-2623 (2021).

194. Kong, C. Y. et al. Underlying the mechanisms of doxorubicin-induced acute cardiotoxicity: Oxidative stress and cell death. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 18, 760-770 (2022).

195. Li, X. Q., Tang, X. R. & Li, L. L. Antipsychotics cardiotoxicity: What’s known and what’s next. World J. Psychiatry 11, 736-753 (2021).

196. Sun, Z. et al. SIRT3 attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome via autophagy. Biochem Pharm. 207, 115354 (2023).

197. Li, S. et al. Microglial NLRP3 inflammasome activates neurotoxic astrocytes in depression-like mice. Cell Rep. 41, 111532 (2022).

198. Gustin, A. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome is expressed and functional in mouse brain microglia but not in astrocytes. PLoS One 10, e0130624 (2015).

199. Johann, S. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome is expressed by astrocytes in the SOD1 mouse model of ALS and in human sporadic ALS patients. Glia 63, 2260-2273 (2015).

200. Liu, D. et al. Melatonin Attenuates White Matter Injury via Reducing Oligodendrocyte Apoptosis After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Mice. Turk. Neurosurg. 30, 685-692 (2020).

201. Yao, J., Wang, Z., Song, W. & Zhang, Y. Targeting NLRP3 inflammasome for neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02239-0, (2023).

202. Yan, J. et al. CCR5 activation promotes NLRP1-dependent neuronal pyroptosis via CCR5/PKA/CREB pathway after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 52, 4021-4032 (2021).

203. Wang, L. Q. et al. LncRNA-Fendrr protects against the ubiquitination and degradation of NLRC4 protein through HERC2 to regulate the pyroptosis of microglia. Mol. Med 27, 39 (2021).

204. Ma, C. et al. AIM2 controls microglial inflammation to prevent experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 218, e20201796 (2021).

205. Zhang, Y., Chen, H., Li, R., Sterling, K. & Song, W. Amyloid beta-based therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: challenges, successes and future. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 8, 248 (2023).

206. Moloney, C. M., Lowe, V. J. & Murray, M. E. Visualization of neurofibrillary tangle maturity in Alzheimer’s disease: A clinicopathologic perspective for biomarker research. Alzheimers Dement 17, 1554-1574 (2021).

207. Head, E. et al. Amyloid-beta peptide and oligomers in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of aged canines. J. Alzheimers Dis. 20, 637-646 (2010).

208. Jie, F. et al. Stigmasterol attenuates inflammatory response of microglia via NFkappaB and NLRP3 signaling by AMPK activation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 153, 113317 (2022).

209. Luciunaite, A. et al. Soluble Abeta oligomers and protofibrils induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia. J. Neurochem 155, 650-661 (2020).

210. Yang, Y. et al. Sulforaphane attenuates microglia-mediated neuronal damage by down-regulating the ROS/autophagy/NLRP3 signal axis in fibrillar Abetaactivated microglia. Brain Res 1801, 148206 (2023).

211. Schnaars, M., Beckert, H. & Halle, A. Assessing beta-amyloid-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in primary microglia. Methods Mol. Biol. 1040, 1-8 (2013).

212. Chaturvedi, S., Naseem, Z., El-Khamisy, S. F. & Wahajuddin, M. Nanomedicines targeting the inflammasome as a promising therapeutic approach for cell senescence. Semin Cancer Biol. 86, 46-53 (2022).

213. Couturier, J. et al. Activation of phagocytic activity in astrocytes by reduced expression of the inflammasome component ASC and its implication in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Neuroinflammation 13, 20 (2016).

214. Liu, L. & Chan, C. IPAF inflammasome is involved in interleukin-1beta production from astrocytes, induced by palmitate; implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 309-321 (2014).

215. Heneka, M. T. et al. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 493, 674-678 (2013).

216. Friker, L. L. et al. beta-amyloid clustering around ASC fibrils boosts its toxicity in microglia. Cell Rep. 30, 3743-3754.e3746 (2020).

217. Hulse, J. & Bhaskar, K. Crosstalk between the NLRP3 inflammasome/ASC speck and amyloid protein aggregates drives disease progression in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. Front Mol. Neurosci. 15, 805169 (2022).

218. Spanic, E., Langer Horvat, L., Ilic, K., Hof, P. R. & Simic, G. NLRP1 Inflammasome activation in the hippocampal formation in Alzheimer’s disease: Correlation with neuropathological changes and unbiasedly estimated neuronal loss. Cells 11, 2223 (2022).

219. Tan, M. S. et al. Amyloid-beta induces NLRP1-dependent neuronal pyroptosis in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1382 (2014).

220. Wu, P. J., Hung, Y. F., Liu, H. Y. & Hsueh, Y. P. Deletion of the inflammasome sensor Aim2 mitigates abeta deposition and microglial activation but increases inflammatory cytokine expression in an Alzheimer Disease Mouse Model. Neuroimmunomodulation 24, 29-39 (2017).

221. Pike, A. F. et al. alpha-Synuclein evokes NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL1beta secretion from primary human microglia. Glia 69, 1413-1428 (2021).

222. Freeman, D. et al. Alpha-synuclein induces lysosomal rupture and cathepsin dependent reactive oxygen species following endocytosis. PLoS One 8, e62143 (2013).

223. Konstantin Nissen, S. et al. Changes in CD163+, CD11b+, and CCR2+ peripheral monocytes relate to Parkinson’s disease and cognition. Brain Behav. Immun. 101, 182-193 (2022).

224. Yan, Y. et al. Dopamine controls systemic inflammation through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell 160, 62-73 (2015).

225. Lee, E. et al. MPTP-driven NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia plays a central role in dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Cell Death Differ. 26, 213-228 (2019).

226. Kitada, T. et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature 392, 605-608 (1998).

227. Panicker, N. et al. Neuronal NLRP3 is a parkin substrate that drives neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 110, 2422-2437.e2429 (2022).

228. Coyne, A. N. et al. Nuclear accumulation of CHMP7 initiates nuclear pore complex injury and subsequent TDP-43 dysfunction in sporadic and familial ALS. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabe1923 (2021).

229. Debye, B. et al. Neurodegeneration and NLRP3 inflammasome expression in the anterior thalamus of SOD1(G93A) ALS mice. Brain Pathol. 28, 14-27 (2018).

230. Bellezza, I. et al. Peroxynitrite activates the NLRP3 inflammasome cascade in SOD1(G93A) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol. Neurobiol. 55, 2350-2361 (2018).

231. Meissner, F., Molawi, K. & Zychlinsky, A. Mutant superoxide dismutase 1-induced IL-1beta accelerates ALS pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 13046-13050 (2010).

232. Cihankaya, H., Theiss, C. & Matschke, V. Little helpers or mean rogue-role of microglia in animal models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 993 (2021).

233. Moreno-Garcia, L. et al. Inflammasome in ALS skeletal muscle: NLRP3 as a potential biomarker. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 2523 (2021).

234. McKenzie, B. A. et al. Caspase-1 inhibition prevents glial inflammasome activation and pyroptosis in models of multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E6065-E6074 (2018).

235. Huang, W. X., Huang, P. & Hillert, J. Increased expression of caspase-1 and interleukin-18 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 10, 482-487 (2004).

236. Inoue, M., Williams, K. L., Gunn, M. D. & Shinohara, M. L. NLRP3 inflammasome induces chemotactic immune cell migration to the CNS in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10480-10485 (2012).

237. Peng, Y. et al. NLRP3 level in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: Increased levels and association with disease severity. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 39, 101888 (2019).

238. Elmahdy, M. K., Abdelaziz, R. R., Elmahdi, H. S. & Suddek, G. M. Effect of Agmatine on a mouse model of allergic airway inflammation: A comparative study. Autoimmunity 55, 608-619 (2022).

239. Wood, L. G. et al. Saturated fatty acids, obesity, and the nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in asthmatic patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 143, 305-315 (2019).

240. Kim, R. Y. et al. Role for NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated, IL-1 beta-dependent responses in severe, steroid-resistant asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 196, 283-297 (2017).

241. Wang, Y. et al. FSTL1 aggravates OVA-induced inflammatory responses by activating the NLRP3/IL-1 beta signaling pathway in mice and macrophages. Inflamm. Res 70, 777-787 (2021).

242. Chaly, Y. et al. Follistatin-like protein 1 enhances NLRP3 inflammasomemediated IL-1beta secretion from monocytes and macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 1467-1479 (2014).

243. Wang, H. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome involves in the acute exacerbation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Inflammation 41, 1321-1333 (2018).

244. Mo, R., Zhang, J., Chen, Y. & Ding, Y. Nicotine promotes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease via inducing pyroptosis activation in bronchial epithelial cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 25, 92 (2022).

245. Buscetta, M. et al. Cigarette smoke inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome and leads to caspase-1 activation via the TLR4-TRIF-caspase-8 axis in human macrophages. FASEB J. 34, 1819-1832 (2020).

246. Zhang, M. Y. et al. Cigarette smoke extract induces pyroptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells through the ROS/NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway. Life Sci. 269, 119090 (2021).

247. Tien, C. P. et al. Ambient particulate matter attenuates Sirtuin1 and augments SREBP1-PIR axis to induce human pulmonary fibroblast inflammation: molecular mechanism of microenvironment associated with COPD. Aging (Albany NY) 11, 4654-4671 (2019).

248. Wang, C. et al. Oxidative stress activates the TRPM2-Ca(2+)-NLRP3 axis to promote PM(2.5)-induced lung injury of mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 130, 110481 (2020).

249. Sanche, S. et al. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26, 1470-1477 (2020).

250. Gholaminejhad, M. et al. Formation and activity of NLRP3 inflammasome and histopathological changes in the lung of corpses with COVID-19. J. Mol. Histol. 53, 883-890 (2022).

251. Bortolotti, D. et al. TLR3 and TLR7 RNA sensor activation during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Microorganisms 9, 1820 (2021).

252. Pan, P. et al. SARS-CoV-2 N protein promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation to induce hyperinflammation. Nat. Commun. 12, 4664 (2021).

253. Yong, S. J. et al. Inflammatory and vascular biomarkers in post-COVID-19 syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of over 20 biomarkers. Rev. Med. Virol. 33, e2424 (2023).

254. Abd El-Ghani, S. E. et al. Serum interleukin 1beta and sP-selectin as biomarkers of inflammation and thrombosis, could they be predictors of disease severity in COVID 19 Egyptian patients? (a cross-sectional study). Thromb. J. 20, 77 (2022).

255. Suzuki, S. et al. Serum gasdermin D levels are associated with the chest computed tomography findings and severity of COVID-19. Respir. Investig. 60, 750-761 (2022).

256. Sefik, E. et al. Inflammasome activation in infected macrophages drives COVID19 pathology. Nature 606, 585-593 (2022).

257. Sefik, E. et al. Inflammasome activation in infected macrophages drives COVID19 pathology. bioRxiv, the preprint server for biology, https://doi.org/10.1101/ 2021.09.27.461948 (2022).

258. Albornoz, E. A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 drives NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human microglia through spike protein. Mol. Psych. advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01831-0 (2022).

259. Radermacher, P., Maggiore, S. M. & Mercat, A. Fifty years of research in ARDS. Gas exchange in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 196, 964-984 (2017).

260. Zhang, T. et al. CaMK4 promotes acute lung injury through NLRP3 inflammasome activation in type II alveolar epithelial cell. Front Immunol. 13, 890710 (2022).

261. He, X. et al. TLR4-upregulated IL-1 beta and IL-1RI promote alveolar macrophage pyroptosis and lung inflammation through an autocrine mechanism. Sci. Rep. 6, 31663 (2016).

262. Jiang, P. et al. Extracellular histones aggravate inflammation in ARDS by promoting alveolar macrophage pyroptosis. Mol. Immunol. 135, 53-61 (2021).

263. Song, C. et al. Fluorofenidone attenuates pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis via inhibiting the activation of NALP3 inflammasome and IL-1beta/IL-1R1/ MyD88/NF-kappaB pathway. J. Cell Mol. Med. 20, 2064-2077 (2016).

264. Galliher-Beckley, A. J., Lan, L. Q., Aono, S., Wang, L. & Shi, J. Caspase-1 activation and mature interleukin-1beta release are uncoupled events in monocytes. World J. Biol. Chem. 4, 30-34 (2013).

265. Kolb, M., Margetts, P. J., Anthony, D. C., Pitossi, F. & Gauldie, J. Transient expression of IL-1 beta induces acute lung injury and chronic repair leading to pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest 107, 1529-1536 (2001).

266. Liu, W., Han, X., Li, Q., Sun, L. & Wang, J. Iguratimod ameliorates bleomycininduced pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting the EMT process and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 153, 113460 (2022).

267. Yang, W. et al. Pyroptosis impacts the prognosis and treatment response in gastric cancer via immune system modulation. Am. J. Cancer Res. 12, 1511-1534 (2022).

268. Jang, A. R. et al. Unveiling the crucial role of type IV secretion system and motility of helicobacter pylori in IL-1beta production via NLRP3 inflammasome activation in neutrophils. Front Immunol. 11, 1121 (2020).

269. Pachathundikandi, S. K., Blaser, N., Bruns, H. & Backert, S. Helicobacter pylori Avoids the Critical Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated production of oncogenic mature IL-1beta in human immune cells. Cancers (Basel) 12, 803 (2020).

270. Pan, X. et al. Human hepatocytes express absent in melanoma 2 and respond to hepatitis B virus with interleukin-18 expression. Virus Genes 52, 445-452 (2016).

271. Li, Z. & Jiang, J. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates liver failure by activating procaspase-1 and pro-IL-1 beta and regulating downstream CD40-CD40L signaling. J. Int. Med. Res. 49, 3000605211036845 (2021).

272. Xie, W. H. et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein promotes liver cell pyroptosis under oxidative stress through NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Inflamm. Res 69, 683-696 (2020).

273. Negash, A. A. et al. IL-1 beta production through the NLRP3 inflammasome by hepatic macrophages links hepatitis

274. Daussy, C. F. et al. The Inflammasome Components NLRP3 and ASC act in concert with IRGM to rearrange the golgi apparatus during Hepatitis C virus infection. J. Virol 95, e00826-20 (2021).

275. Dixon, L. J., Berk, M., Thapaliya, S., Papouchado, B. G. & Feldstein, A. E. Caspase-1mediated regulation of fibrogenesis in diet-induced steatohepatitis. Lab Invest 92, 713-723 (2012).

276. L’Homme, L. et al. Unsaturated fatty acids prevent activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in human monocytes/macrophages. J. Lipid Res. 54, 2998-3008 (2013).

277. Li, Q. et al. Irisin alleviates LPS-induced liver injury and inflammation through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-kappaB signaling. J. Recept Signal Transduct. Res 41, 294-303 (2021).

278. Ruan, S. et al. Antcin A alleviates pyroptosis and inflammatory response in Kupffercells of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by targeting NLRP3. Int Immunopharmacol. 100, 108126 (2021).

279. Pierantonelli, I. et al. Lack of NLRP3-inflammasome leads to gut-liver axis derangement, gut dysbiosis and a worsened phenotype in a mouse model of NAFLD. Sci. Rep. 7, 12200 (2017).

280. Gallego, P., Castejon-Vega, B., Del Campo, J. A. & Cordero, M. D. The Absence of NLRP3-inflammasome modulates hepatic fibrosis progression, lipid metabolism, and inflammation in KO NLRP3 mice during aging. Cells 9, 2148 (2020).

281. Yen, I. C. et al. 4-Acetylantroquinonol B ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by suppression of ER stress and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 138, 111504 (2021).

282. Rampanelli, E. et al. Metabolic injury-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation dampens phospholipid degradation. Sci. Rep. 7, 2861 (2017).

283. Lippai, D. et al. Alcohol-induced IL-1beta in the brain is mediated by NLRP3/ASC inflammasome activation that amplifies neuroinflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 94, 171-182 (2013).

284. DeSantis, D. A. et al. Alcohol-induced liver injury is modulated by NIrp3 and NIrc4 inflammasomes in mice. Mediators Inflamm. 2013, 751374 (2013).

285. Iracheta-Vellve, A. et al. Inhibition of sterile danger signals, uric acid and ATP, prevents inflammasome activation and protects from alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. J. Hepatol. 63, 1147-1155 (2015).

286. Kim, S. K., Choe, J. Y. & Park, K. Y. Ethanol augments monosodium urate-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation via regulation of AhR and TXNIP in human macrophages. Yonsei Med. J. 61, 533-541 (2020).

287. Wang, J. et al. Cathepsin B aggravates acute pancreatitis by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome and promoting the caspase-1-induced pyroptosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 94, 107496 (2021).

288. Zhang, G. X. et al. P2X7R blockade prevents NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pancreatic fibrosis in a mouse model of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas 46, 1327-1335 (2017).

289. Cui, L. et al. Saikosaponin A inhibits the activation of pancreatic stellate cells by suppressing autophagy and the NLRP3 inflammasome via the AMPK/mTOR pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 128, 110216 (2020).

290. Li, F. et al. Pachymic acid alleviates experimental pancreatic fibrosis through repressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 86, 1497-1505 (2022).

291. Hoque, R. et al. TLR9 and the NLRP3 inflammasome link acinar cell death with inflammation in acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 141, 358-369 (2011).

292. Sendler, M. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome regulates development of systemic inflammatory response and compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndromes in mice with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 158, 253-269.e214 (2020).

293. Ananthakrishnan, A. N. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (N. Y) 9, 367-374 (2013).

294. Ranson, N. et al. NLRP3-Dependent and -Independent Processing of Interleukin (IL)-1 beta in Active Ulcerative Colitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 57 (2018).

295. Wang, S. L. et al. Inhibition of NLRP3 attenuates sodium dextran sulfate-induced inflammatory bowel disease through gut microbiota regulation. Biomed. J. 46, 100580 (2023).

296. He, R. et al. L-Fucose ameliorates DSS-induced acute colitis via inhibiting macrophage M1 polarization and inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-kB activation. Int Immunopharmacol. 73, 379-388 (2019).

297. Hirota, S. A. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome plays a key role in the regulation of intestinal homeostasis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 17, 1359-1372 (2011).

298. Zaki, M. H. et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome protects against loss of epithelial integrity and mortality during experimental colitis. Immunity 32, 379-391 (2010).

299. Zaki, M. H., Lamkanfi, M. & Kanneganti, T. D. The Nlrp3 inflammasome: contributions to intestinal homeostasis. Trends Immunol. 32, 171-179 (2011).

300. Bai, Y. J. et al. Effects of IL-1beta and IL-18 induced by NLRP3 inflammasome activation on myocardial reperfusion injury after PCI. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 23, 10101-10106 (2019).

301. Wen, Y. et al. mROS-TXNIP axis activates NLRP3 inflammasome to mediate renal injury during ischemic AKI. Int J. Biochem Cell Biol. 98, 43-53 (2018).

302. Gong, W. et al. NLRP3 deletion protects against renal fibrosis and attenuates mitochondrial abnormality in mouse with 5/6 nephrectomy. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 310, F1081-1088, (2016).

303. Xiao, C. et al. Tisp40 induces tubular epithelial cell GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury via NF-kappaB signaling. Front Physiol. 11, 906 (2020).

304. Kim, H. J. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome knockout mice are protected against ischemic but not cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 346, 465-472 (2013).

305. Qian, Y. et al. P2X7 receptor signaling promotes inflammation in renal parenchymal cells suffering from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Death Dis. 12, 132 (2021).

306. Pan, L. L. et al. Cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide protects against ischaemia reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury in mice. Br. J. Pharm. 177, 2726-2742 (2020).

307. Valino-Rivas, L. et al. Loss of NLRP6 expression increases the severity of acute kidney injury. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 35, 587-598 (2020).

308. Cuarental, L. et al. The transcription factor Fosl1 preserves Klotho expression and protects from acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 103, 686-701 (2023).

309. Guo, Y., Zhang, J., Lai, X., Chen, M. & Guo, Y. Tim-3 exacerbates kidney ischaemia/reperfusion injury through the TLR-4/NF-kappaB signalling pathway and an NLR-C4 inflammasome activation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 193, 113-129 (2018).

310. Li, Q. et al. NLRC5 deficiency protects against acute kidney injury in mice by mediating carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 signaling. Kidney Int 94, 551-566 (2018).

311. Lichtnekert, J. et al. Anti-GBM glomerulonephritis involves IL-1 but is independent of NLRP3/ASC inflammasome-mediated activation of caspase-1. PLoS One 6, e26778 (2011).

312. Wu, M. et al. NLRP3 deficiency ameliorates renal inflammation and fibrosis in diabetic mice. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 478, 115-125 (2018).

313. Pulskens, W. P. et al. Nlrp3 prevents early renal interstitial edema and vascular permeability in unilateral ureteral obstruction. PLoS One 9, e85775 (2014).

314. Wang, W. et al. Aliskiren restores renal AQP2 expression during unilateral ureteral obstruction by inhibiting the inflammasome. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 308, F910-922, (2015).

315. Fu, R. et al. Podocyte Activation of NLRP3 Inflammasomes Contributes to the Development of Proteinuria in Lupus Nephritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 69, 1636-1646 (2017).

316. Lv, F. et al. CD36 aggravates podocyte injury by activating NLRP3 inflammasome and inhibiting autophagy in lupus nephritis. Cell Death Dis. 13, 729 (2022).

317. Hu, H., Li, M., Chen, B., Guo, C. & Yang, N. Activation of necroptosis pathway in podocyte contributes to the pathogenesis of focal segmental glomerular sclerosis. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 26, 1055-1066 (2022).

318. Zhao, J. et al. Lupus nephritis: glycogen synthase kinase 3beta promotion of renal damage through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in lupus-prone mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 67, 1036-1044 (2015).

319. Wu, C. Y. et al. Tris DBA Ameliorates Accelerated and Severe Lupus Nephritis in Mice by Activating Regulatory T Cells and Autophagy and Inhibiting the NLRP3 Inflammasome. J. Immunol. 204, 1448-1461 (2020).

320. Peng, W., Pei, G. Q., Tang, Y., Tan, L. & Qin, W. IgA1 deposition may induce NLRP3 expression and macrophage transdifferentiation of podocyte in IgA nephropathy. J. Transl. Med 17, 406 (2019).

321. Yang, S. M. et al. Antroquinonol mitigates an accelerated and progressive IgA nephropathy model in mice by activating the Nrf2 pathway and inhibiting T cells and NLRP3 inflammasome. Free Radic. Biol. Med 61, 285-297 (2013).

322. Tsai, Y. L. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome: Pathogenic role and potential therapeutic target for IgA nephropathy. Sci. Rep. 7, 41123 (2017).

323. Chun, J. et al. NLRP3 localizes to the tubular epithelium in human kidney and correlates with outcome in IgA nephropathy. Sci. Rep. 6, 24667 (2016).

324. Demirel, I. et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway by uropathogenic escherichia coli is virulence factor-dependent and influences colonization of bladder epithelial cells. Front Cell Infect. Microbiol 8, 81 (2018).

325. Harper, S. N., Leidig, P. D., Hughes, F. M. Jr., Jin, H. & Purves, J. T. Calcium pyrophosphate and monosodium urate activate The NLRP3 inflammasome within bladder urothelium via reactive oxygen species and TXNIP. Res Rep. Urol. 11, 319-325 (2019).

326. Hughes, F. M. Jr. et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates inflammation produced by bladder outlet obstruction. J. Urol. 195, 1598-1605 (2016).

327. Hughes, F. M. Jr., Sexton, S. J., Jin, H., Govada, V. & Purves, J. T. Bladder fibrosis during outlet obstruction is triggered through the NLRP3 inflammasome and the production of IL-1beta. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 313, F603-F610 (2017).

328. Lu, J. et al. Rapamycin-induced autophagy attenuates hormone-imba-lance-induced chronic non-bacterial prostatitis in rats via the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammation. Mol. Med Rep. 19, 221-230 (2019).

329. Gu, N. Y. et al. Trichomonas vaginalis induces IL-1beta production in a human prostate epithelial cell line by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome via reactive oxygen species and potassium ion efflux. Prostate 76, 885-896 (2016).

330. Lai, Y. et al. Elevated levels of follicular fatty acids induce ovarian inflammation via ERK1/2 and inflammasome activation in PCOS. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107, 2307-2317 (2022).

331. Wang, D. et al. Exposure to hyperandrogen drives ovarian dysfunction and fibrosis by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome in mice. Sci. Total Environ. 745, 141049 (2020).

332. Refaie, M. M. M., El-Hussieny, M. & Abdelraheem, W. M. Diacerein ameliorates induced polycystic ovary in female rats via modulation of inflammasome/caspase1/IL1beta and Bax/Bcl2 pathways. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharm. 395, 295-304 (2022).

333. Navarro-Pando, J. M. et al. Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome prevents ovarian aging. Sci. Adv. 7, eabc7409 (2021).

334. Murakami, M. et al. Effectiveness of NLRP3 Inhibitor as a Non-Hormonal Treatment for ovarian endometriosis. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 20, 58 (2022).

335. Carey, A. et al. Identification of interleukin-1 by functional screening as a key mediator of cellular expansion and disease progression in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Rep. 18, 3204-3218 (2017).

336. Hamarsheh, S. et al. Oncogenic Kras(G12D) causes myeloproliferation via NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat. Commun. 11, 1659 (2020).

337. Jia, Y. et al. Aberrant NLRP3 inflammasome associated with aryl hydrocarbon receptor potentially contributes to the imbalance of T-helper cells in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol. Lett. 14, 7031-7044 (2017).

338. Paugh, S. et al. NALP3 inflammasome upregulation and CASP1 cleavage of the glucocorticoid receptor cause glucocorticoid resistance in leukemia cells. Nat. Genet. 47, 607-614 (2015).

339. Salaro, E. et al. Involvement of the P2X7-NLRP3 axis in leukemic cell proliferation and death. Sci. Rep. 6, 26280 (2016).

340. Zhou, Y. et al. Curcumin activates NLRC4, AIM2, and IFI16 inflammasomes and induces pyroptosis by up-regulated ISG3 transcript factor in acute myeloid leukemia cell lines. Cancer Biol. Ther. 23, 328-335 (2022).

341. Cominal, J. G. et al. Bone Marrow Soluble Mediator Signatures of Patients With Philadelphia Chromosome-Negative Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. Front Oncol. 11, 665037 (2021).

342. Rai, S. et al. Inhibition of interleukin-1beta reduces myelofibrosis and osteosclerosis in mice with JAK2-V617F driven myeloproliferative neoplasm. Nat. Commun. 13, 5346 (2022).

343. Liew, E. L. et al. Identification of AIM2 as a downstream target of JAK2V617F. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 5, 2 (2015).

344. Shi, L. et al. Cellular senescence induced by S100A9 in mesenchymal stromal cells through NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Aging (Albany NY) 11, 9626-9642 (2019).

345. Zhao, X. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation plays a carcinogenic role through effector cytokine IL-18 in lymphoma. Oncotarget 8, 108571-108583 (2017).

346. Lu, F. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome upregulates PD-L1 expression and contributes to immune suppression in lymphoma. Cancer Lett. 497, 178-189 (2021).

347. Baldini, C., Santini, E., Rossi, C., Donati, V. & Solini, A. The P2X7 receptor-NLRP3 inflammasome complex predicts the development of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Sjogren’s syndrome: a prospective, observational, single-centre study. J. Intern Med. 282, 175-186 (2017).

348. Bostan, E., Gokoz, O. & Atakan, N. The role of NLRP1 and NLRP3 inflammasomes in the etiopathogeneses of pityriasis lichenoides chronica and mycosis fungoides: an immunohistochemical study. Arch. Dermatol Res. 315, 231-239 (2023).

349. Huanosta-Murillo, E. et al. NLRP3 regulates IL-4 expression in TOX(+) CD4(+) T cells of cutaneous T cell lymphoma to potentially promote disease progression. Front Immunol. 12, 668369 (2021).

350. Singh, V. V. et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency in endothelial and

351. Liu, Z. H. et al. Genetic Polymorphisms in NLRP3 Inflammasome-Associated Genes in Patients with B-Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. J. Inflamm. Res. 14, 5687-5697 (2021).

352. Yu, Y. et al. Leptin facilitates the differentiation of Th17 cells from MRL/Mp-Fas Ipr lupus mice by activating NLRP3 inflammasome. Innate Immun. 26, 294-300 (2020).

353. Shin, M. S. et al. Self double-stranded (ds)DNA induces IL-1beta production from human monocytes by activating NLRP3 inflammasome in the presence of antidsDNA antibodies. J. Immunol. 190, 1407-1415 (2013).

354. Zhang, H. et al. Anti-dsDNA antibodies bind to TLR4 and activate NLRP3 inflammasome in lupus monocytes/macrophages. J. Transl. Med. 14, 156 (2016).

355. Yang, M. et al. AIM2 deficiency in B cells ameliorates systemic lupus erythematosus by regulating Blimp-1-Bcl-6 axis-mediated B-cell differentiation. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 6, 341 (2021).

356. Leite, J. A. et al. The DNA sensor AIM2 protects against streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes by regulating intestinal homeostasis via the IL-18 Pathway. Cells 9, 959 (2020).

357. Wu, H. et al. The IL-21-TET2-AIM2-c-MAF pathway drives the T follicular helper cell response in lupus-like disease. Clin. Transl. Med 12, e781 (2022).

358. Choulaki, C. et al. Enhanced activity of NLRP3 inflammasome in peripheral blood cells of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 17, 257 (2015).

359. Meloni, F. et al. Cytokine profile of bronchoalveolar lavage in systemic sclerosis with interstitial lung disease: comparison with usual interstitial pneumonia. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 63, 892-894 (2004).

360. Zhao, C., Gu, Y., Zeng, X. & Wang, J. NLRP3 inflammasome regulates Th17 differentiation in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Immunol. 197, 154-160 (2018).

361. D’Espessailles, A., Mora, Y. A., Fuentes, C. & Cifuentes, M. Calcium-sensing receptor activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in LS14 preadipocytes mediated by ERK1/2 signaling. J. Cell Physiol. 233, 6232-6240 (2018).

362. Wu, X. Y. et al. Complement C1q synergizes with PTX3 in promoting NLRP3 inflammasome over-activation and pyroptosis in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Autoimmun. 106, 102336 (2020).

363. Chen, Y. et al. Expression of AIM2 in rheumatoid arthritis and its role on fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 1693730 (2020).

364. Hajizadeh, S., DeGroot, J., TeKoppele, J. M., Tarkowski, A. & Collins, L. V. Extracellular mitochondrial DNA and oxidatively damaged DNA in synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 5, R234-R240 (2003).

365. Li, F. et al. Inhibition of P2X4 suppresses joint inflammation and damage in collagen-induced arthritis. Inflammation 37, 146-153 (2014).

366. Delgado-Arevalo, C. et al. NLRC4-mediated activation of CD1c+ DC contributes to perpetuation of synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis. JCI Insight 7, e152886 (2022).

367. Zhou, Y. et al. Lipoxin A4 attenuates MSU-crystal-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation through suppressing Nrf2 thereby increasing TXNRD2. Front Immunol. 13, 1060441 (2022).

368. Amaral, F. A. et al. NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neutrophil recruitment and hypernociception depend on leukotriene

369. Fujita, Y. et al. Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (CIRP) potentiates uric acidinduced IL-1beta production. Arthritis Res. Ther. 23, 128 (2021).

370. Gonzalez-Cabello, R., Perl, A., Kalmar, L. & Gergely, P. Short-term stimulation of lymphocyte proliferation by indomethacin in vitro and in vivo. Acta Physiol. Hung. 70, 25-30 (1987).

371. Lee, H. M. et al. Upregulated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 62, 194-204 (2013).

372. Youm, Y. H. et al. Elimination of the NLRP3-ASC inflammasome protects against chronic obesity-induced pancreatic damage. Endocrinology 152, 4039-4045 (2011).

373. Chiazza, F. et al. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome to reduce diet-induced metabolic abnormalities in mice. Mol. Med 21, 1025-1037 (2016).

374. Tomita, T. Islet amyloid polypeptide in pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetic subjects. Islets 4, 223-232 (2012).

375. Jourdan, T. et al. Activation of the NIrp3 inflammasome in infiltrating macrophages by endocannabinoids mediates beta cell loss in type 2 diabetes. Nat. Med 19, 1132-1140 (2013).

376. Gianfrancesco, M. A. et al. Saturated fatty acids induce NLRP3 activation in human macrophages through

377. Camell, C. D. et al. Macrophage-specific de novo synthesis of ceramide is dispensable for inflammasome-driven inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 29402-29413 (2015).

378. Stienstra, R. et al. The inflammasome-mediated caspase-1 activation controls adipocyte differentiation and insulin sensitivity. Cell Metab. 12, 593-605 (2010).

379. van Diepen, J. A. et al. Caspase-1 deficiency in mice reduces intestinal triglyceride absorption and hepatic triglyceride secretion. J. Lipid Res. 54, 448-456 (2013).

380. Stienstra, R. et al. Inflammasome is a central player in the induction of obesity and insulin resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 15324-15329 (2011).

381. Zorrilla, E. P. & Conti, B. Interleukin-18 null mutation increases weight and food intake and reduces energy expenditure and lipid substrate utilization in high-fat diet fed mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 37, 45-53 (2014).

382. Hollingsworth, L. R. et al. DPP9 sequesters the C terminus of NLRP1 to repress inflammasome activation. Nature 592, 778-783 (2021).

383. Sharif, H. et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 9 sets a threshold for CARD8 inflammasome formation by sequestering its active C-terminal fragment. Immunity 54, 1392-1404.e1310 (2021).

384. Coll, R. C. et al. MCC950 directly targets the NLRP3 ATP-hydrolysis motif for inflammasome inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 556-559 (2019).