DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-024-05777-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38713256

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-07

مراجعة

دور البلعميات المرتبطة بالورم في التهرب المناعي للورم

© المؤلفون 2024

الملخص

خلفية: يرتبط نمو الورم ارتباطًا وثيقًا بأنشطة خلايا مختلفة في بيئة الورم الدقيقة (TME)، وخاصة الخلايا المناعية. خلال تقدم الورم، يتم استقطاب المونوسيتات والبلعميات المتداولة، مما يغير TME ويسرع النمو. تقوم هذه البلعميات بتعديل وظائفها استجابة للإشارات من خلايا الورم والستروما. تعتبر البلعميات المرتبطة بالورم (TAMs)، مشابهة للبلعميات M2، من المنظمين الرئيسيين في TME. الطرق: نستعرض أصول وخصائص ووظائف TAMs داخل TME. تتضمن هذه التحليل الآليات التي تسهل من خلالها TAMs التهرب المناعي وتعزز من انتشار الورم. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، نستكشف استراتيجيات علاجية محتملة تستهدف TAMs. النتائج: تلعب TAMs دورًا حيويًا في التوسط في التهرب المناعي للورم والسلوكيات الخبيثة. تطلق السيتوكينات التي تثبط خلايا المناعة الفعالة وتجذب خلايا مناعية مثبطة إضافية إلى TME. تستهدف TAMs بشكل أساسي خلايا T الفعالة، مما يؤدي إلى الإرهاق مباشرة، أو يؤثر على النشاط بشكل غير مباشر من خلال التفاعلات الخلوية، أو يثبط من خلال نقاط التفتيش المناعية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تشارك TAMs بشكل مباشر في تكاثر الورم، وتكوين الأوعية الدموية، والغزو، والانتشار. الملخص: تطوير علاجات مبتكرة تستهدف الورم واستراتيجيات المناعية هو حاليًا محور واعد في علم الأورام. نظرًا للدور المحوري لـ TAMs في التهرب المناعي، تم وضع عدة نهج علاجية تستهدفها. تشمل هذه الاستراتيجيات الاستفادة من علم الوراثة اللاجينية، وإعادة برمجة الأيض، والهندسة الخلوية لإعادة قطبية TAMs، وتثبيط استقطابها ونشاطها، واستخدام TAMs كوسائل توصيل للأدوية. على الرغم من أن بعض هذه الاستراتيجيات لا تزال بعيدة عن التطبيق السريري، نعتقد أن العلاجات المستقبلية التي تستهدف TAMs ستقدم فوائد كبيرة لمرضى السرطان.

مقدمة

نظرة عامة على TME

المواد تشجع على توسيع الورم وتغير المصفوفة خارج الخلوية المحيطة، مما يساعد على غزو وانتشار خلايا الورم.

مفهوم وأهمية التهرب المناعي في السرطان

نظرة عامة على TAMs

في علم الأمراض السريرية إلى أن تراكم TAMs داخل الأورام مرتبط بنتائج سريرية غير مواتية. تتماشى هذه النتائج مع مجموعة من الدراسات التجريبية ونماذج الحيوانات التي دعمت الفكرة بأن TAMs قد تساهم في خلق بيئة مواتية لكل من ظهور الأورام وتقدمها. يتم تعزيز هذا المفهوم من خلال الملاحظات عبر أنواع مختلفة من الأبحاث، مما يبرز التأثير المحتمل لـ TAMs على ديناميات الورم (تشانمي وآخرون 2014).

أصل TAMs

نسبة وأهمية TAMs في TME

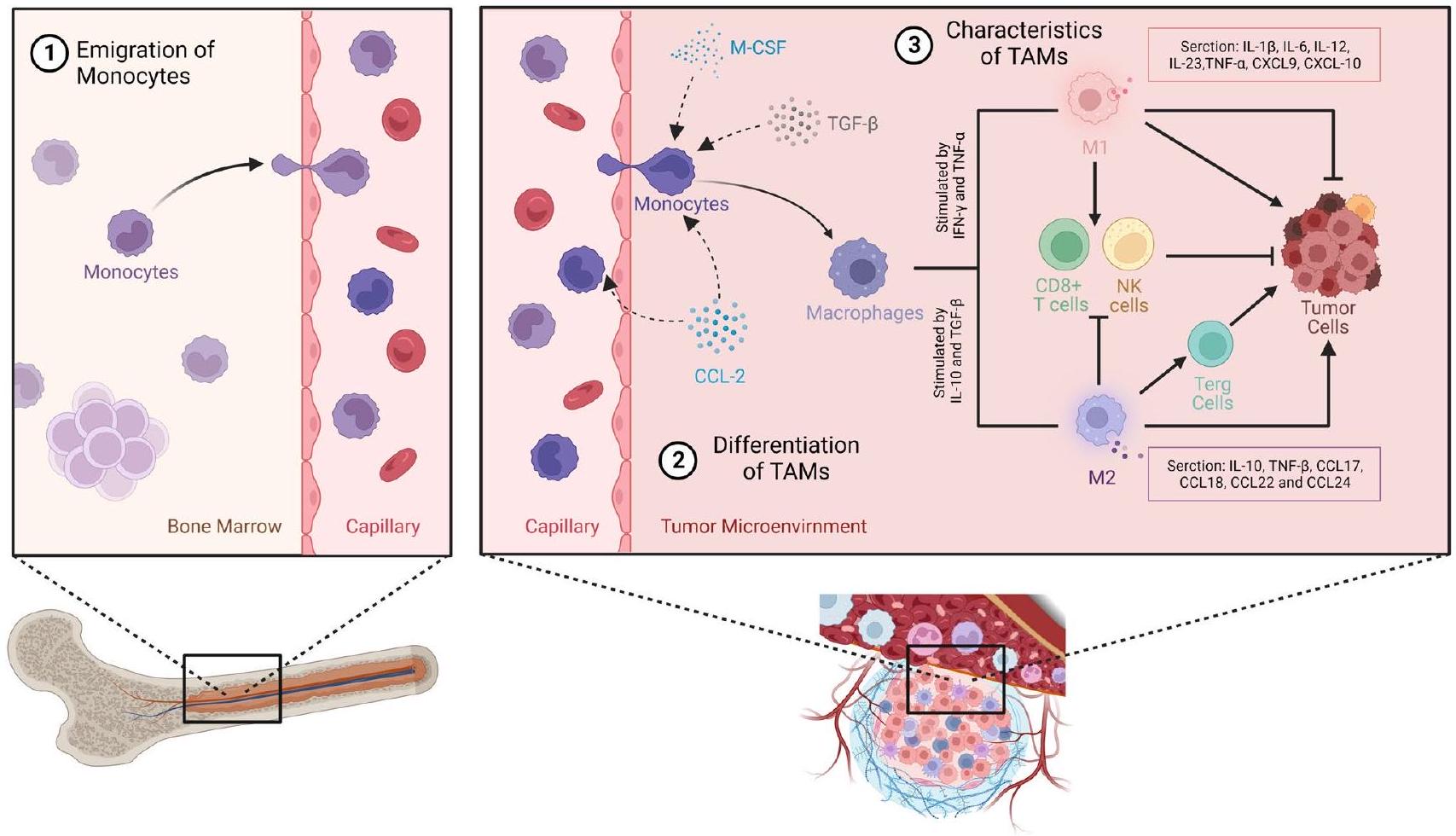

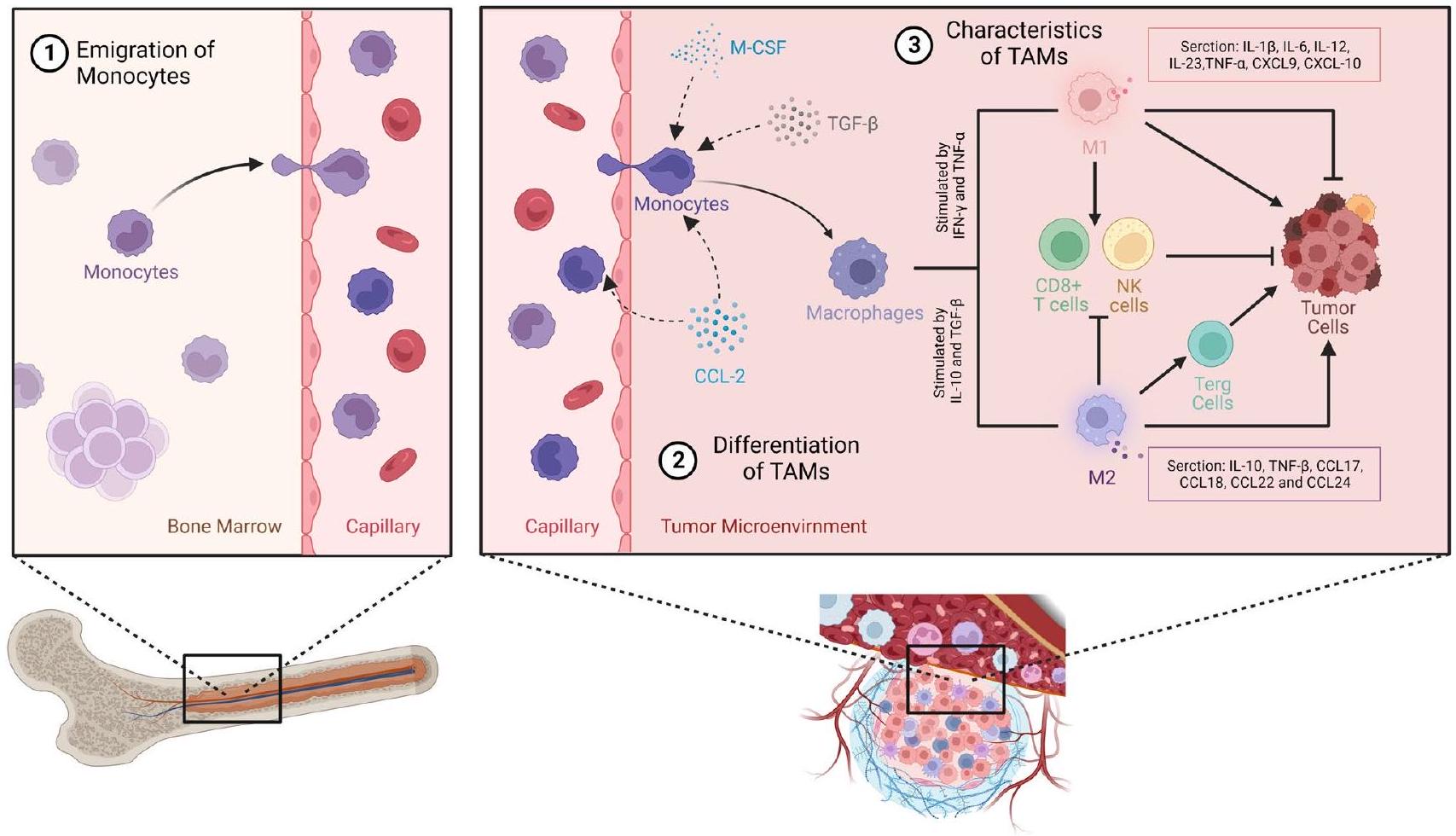

تتباين إلى نمطين ظاهريين، M1 وM2، يتم تحفيزهما بواسطة المزيد من السيتوكينات في TME، وفي النهاية تمارس تأثيرات محددة على خلايا الورم وخلايا المناعة الأخرى داخل TME. تم إنشاء الصورة باستخدامhttps://www.biorender.com/

خطط العلاج (تشو وآخرون 2020a، b، c). علاوة على ذلك، تم ربط TAMs بمقاومة الأدوية، وهي سمة تميز دورها في التهرب من العلاج وتبرز التحديات في علاج السرطان (بان وآخرون 2020). تظهر TAMs درجة ملحوظة من المرونة الوظيفية، تتجلى من خلال استقطابها إلى TAMs الشبيهة بـ M1 وM2. تلعب هذه التنوع الوظيفي دورًا حاسمًا في تحديد المشهد المناعي لـ TME. إن القدرة على تغيير نمطها الوظيفي تقدم أيضًا طريقًا محتملاً للتدخلات العلاجية التي تستهدف إعادة استقطاب TAMs. على سبيل المثال، ساعد عكس بيئة نقص الأكسجين الورمي في إعادة استقطاب TAMs، مما يشير إلى إمكانية تطوير استراتيجيات علاجية جديدة تستهدف TAMs (يانغ وآخرون 2020a، b). لقد حفز الفهم الواسع لدور وأهمية TAMs داخل TME استكشاف العلاجات المناعية المستهدفة لـ TAMs. على الرغم من التقدم الواعد، لا تزال التحديات قائمة في تحسين مثل هذه الاستراتيجيات لزيادة الفعالية السريرية. علاوة على ذلك، يوضح التعبير عن مجموعة متنوعة من الوسائط الجزيئية بواسطة TAMs، بما في ذلك السيتوكينات، الكيموكينات، وعوامل النمو، أدوارها الأساسية في تقدم الورم وتعديل المناعة (تشو وآخرون 2022).

التعديلات الجينية لـ TAMs

تنشيط. ينظم الميثيلين المدفوع بواسطة METTL3 تنشيط البلعميات بشكل إيجابي من خلال تسريع تدهور نسخ IRKAM التي تثبط إشارات TLR (تونغ وآخرون 2021). علاوة على ذلك، يعزز METTL3 استقطاب البلعميات من نوع M1 من خلال تعزيز التعبير عن STAT1 بواسطة m6A. يحافظ METTL14 على التحكم في التغذية الراجعة السلبية لإشارات TLR4/NF-

أنواع TAMs وخصائصها البيولوجية

المرض. بشكل عام، تعتبر البلعميات M1 ضرورية في دفع الاستجابات الالتهابية ومحاربة الأورام، بينما تعزز البلعميات M2 التأثيرات المضادة للالتهابات وتدعم نمو الورم (شانمي وآخرون 2014). ومع ذلك، فإن دور TAMs في أنسجة الأورام المختلفة معقد، حيث تتميز TAMs بعلامات مختلفة تؤثر على جوانب متنوعة مثل تصنيف السرطان، والتصنيف السريري، والتنبؤ، إلخ. هنا، نقوم بتلخيص النمط والوظيفة لـ TAMs في بعض أنواع الأورام الشائعة (الجدول 1).

خصائص ووظائف البلعميات M1

خصائص ووظائف البلعميات M2

تعبير الجزيئات المضادة للالتهابات وتنظيم المناعة

إصلاح الأنسجة والشفاء

| أنواع السرطان | علامات TAMs | وظيفة TAMs | المراجع | |||||||||||

| سرطان الثدي |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| سرطان القولون |

|

|

(إدين وآخرون 2012؛ ناكاياما وآخرون 2002؛ سيكرت وآخرون 2005؛ كافنار وآخرون 2017؛ شابو وآخرون 2009) | |||||||||||

| سرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا |

|

|

(المطرودي وآخرون 2016؛ ركاوي وآخرون 2019؛ زانغ وآخرون 2011؛ يوسن وآخرون 2018؛ لي وآخرون 2018؛ يانغ وآخرون 2015؛ لا فلور وآخرون 2018) | |||||||||||

| سرطان المبيض |

|

|

(لان وآخرون 2013؛ نو وآخرون 2013؛ يين وآخرون 2016) | |||||||||||

| سرطان البروستاتا |

|

|

(لوند هولم وآخرون 2015؛ تاكاياما وآخرون 2009) |

إعادة تشكيل المصفوفة خارج الخلوية

الحركة الاتجاهية لخلايا السرطان (Liguori et al. 2011). يقومون بإعادة تشكيل المصفوفة خارج الخلوية (ECM) من خلال تكسير المصفوفة بشكل واسع وإنتاج بروتينات المصفوفة خارج الخلوية. إن نقص الخلايا المناعية المرتبطة بالورم (TAMs) يقلل بشكل ملحوظ من كثافة وترابط الكولاجين، مما يقلل بشكل خاص من تعبير أنواع الكولاجين I و XIV في الخلايا الليفية المرتبطة بالسرطان (CAFs) (Afik et al. 2016). إن تجميع المصفوفة خارج الخلوية هو خطوة حاسمة ومراقبة بشكل كبير في عملية إصلاح الأنسجة. عندما تتعرض مجموعة المصفوفة خارج الخلوية للتلف، غالبًا ما يؤدي ذلك إلى التليف، وهو مصدر قلق صحي كبير يساهم في ارتفاع معدلات المرض والوفيات (Yoshimura 2024; Zhao et al. 2022). يمكن أن يؤثر التليف على العديد من الأنسجة، بما في ذلك الكبد، والكلى، والرئتين، والقلب، والجلد. وفقًا للأبحاث السائدة، تُعتبر البلعميات M1 عمومًا بمثابة المبادرين لعملية الشفاء، بينما تُعتبر البلعميات M2 تسهل حل الشفاء (Spiller and Koh 2017). في الحالات التي تستمر فيها عملية شفاء الجروح لفترة طويلة أو لا تنتهي بشكل صحيح، يُعتقد عمومًا أن شكلًا مرضيًا من التليف، المدفوع باستجابات Th2 والمُدار بواسطة البلعميات M2، يحدث (Wynn and Barron 2010). تعزز البلعميات M2 إعادة تشكيل الأنسجة وتكوين الأوعية الدموية داخل البيئة المجهرية للورم (TME)، مما يساهم في تقدم الورم (Liu et al. 2022). يمكنهم إعادة تشكيل البيئة المجهرية للورم من خلال التفاعلات مع خلايا أخرى، مما يؤثر على عددها ونشاطها ونمطها المرتبط بمقاومة الأدوية (Wang et al. 2021). تعبر البلعميات M2 عن MARCO، الذي يحفز إعادة تشكيل متسلسلة للمصفوفة الوعائية-البينية، مما يشكل مكانًا مسبقًا للنقائل في البيئة المجهرية للورم (Cendrowicz et al. 2021). كما تعبر البلعميات M2 عن إنزيمات مثل MMP-2 و MMP-7 و MMP-9 و MMP-11 و MMP-12 وcyclooxygenase-2، التي تشارك في إعادة تشكيل المصفوفة وتنظيم تكوين الأوعية الدموية (Egawa et al. 2013; Hao et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2021). تلعب إفرازات MMPs من البلعميات M2، وخاصة التعبير العالي عن MMP-11، دورًا حاسمًا في تسهيل نقائل خلايا سرطان الثدي HER2 +، مع زيادة التعبير عن MMP-11 في البلعميات M2 (Saeidi et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2016). تزيد هذه الزيادة من تجنيد وحيدات النواة وتعزز هجرة خلايا سرطان الثدي HER2 + عبر مسار CCL2/CCR2/MAPK، مما يبرز التأثير الكبير لـ MMP-11 المشتق من TAM على تقدم وإمكانات نقائل سرطان الثدي (Kang et al. 2022).

إعادة برمجة الأيض لخلايا المناعة المرتبطة بالورم

خصائص استقلاب الجلوكوز في TAMs

استجابات خلوية لمستويات الأكسجين المنخفضة، تعزز بنشاط التحول نحو مسارات إنتاج الطاقة الجليكوليتي (سيمينزا 2003). علاوة على ذلك، HIF-1

خصائص استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية والدهون في TAMs

تغذية دورة TCA ودعم OXPHOS، مما يولد المزيد من الطاقة لـ TAMs (هوانغ وآخرون 2014). بعد الاستقطاب M2، يتم تنظيم الجينات المعنية بامتصاص الأحماض الدهنية، وتحلل الدهون، وتخليق الأحماض الدهنية بشكل متزايد. يدعم FAO الإمكانيات المؤيدة للورم لـ TAMs، حيث إن تثبيط FAO قد يمنع تكوين الأورام من خلال تعزيز الخصائص المضادة للورم لـ TAMs (نيو وآخرون 2017).

التوازن بين M1 و M2 وتأثيره على الأورام

أنه يحفز تأثيرًا مثبطًا للورم، مما يبرز الإمكانات العلاجية لتعديل استقطاب الماكروفاج في علاج السرطان (دوان ولو 2021؛ تشو وآخرون 2020أ، ب، ج). يمكن أن يؤدي هذا الانتقال إلى نتائج سريرية أكثر ملاءمة، وترتبط جينات معينة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بماكروفاج M1، مما يظهر أساسًا جزيئيًا محتملاً للمناعة المضادة للورم المرتبطة بالماكروفاج (شو وآخرون 2022أ، ب، ج).

التمييزات بين TAMs البشرية والفأرية

(إنجرسول وآخرون 2010؛ مارتينيز وآخرون 2013). العلامات النموذجية لخلايا M1 وM2 الفأرية هي سينثاز أكسيد النيتريك القابل للتحفيز وتعبير Arg1، ولا يتم التعبير عن أي منهما في ماكروفاج البشر (رايس وآخرون 2005). علاوة على ذلك، فإن معظم الجينات التي تميز خلايا M1 وM2 الفأرية لها وظائف غير معروفة، مما يعقد استنتاج أدوارها في الأورام. دعمًا لهذه النتائج، أظهر زيلونيس وآخرون بفعالية أن TAMs في أورام الرئة تعرض ملفات تعريف مميزة بناءً على نوعها، مما يبرز الحاجة الملحة لدراسة ماكروفاج البشر مباشرة بدلاً من إجراء افتراضات بناءً على بيانات الفئران (زيلونيس وآخرون 2019).

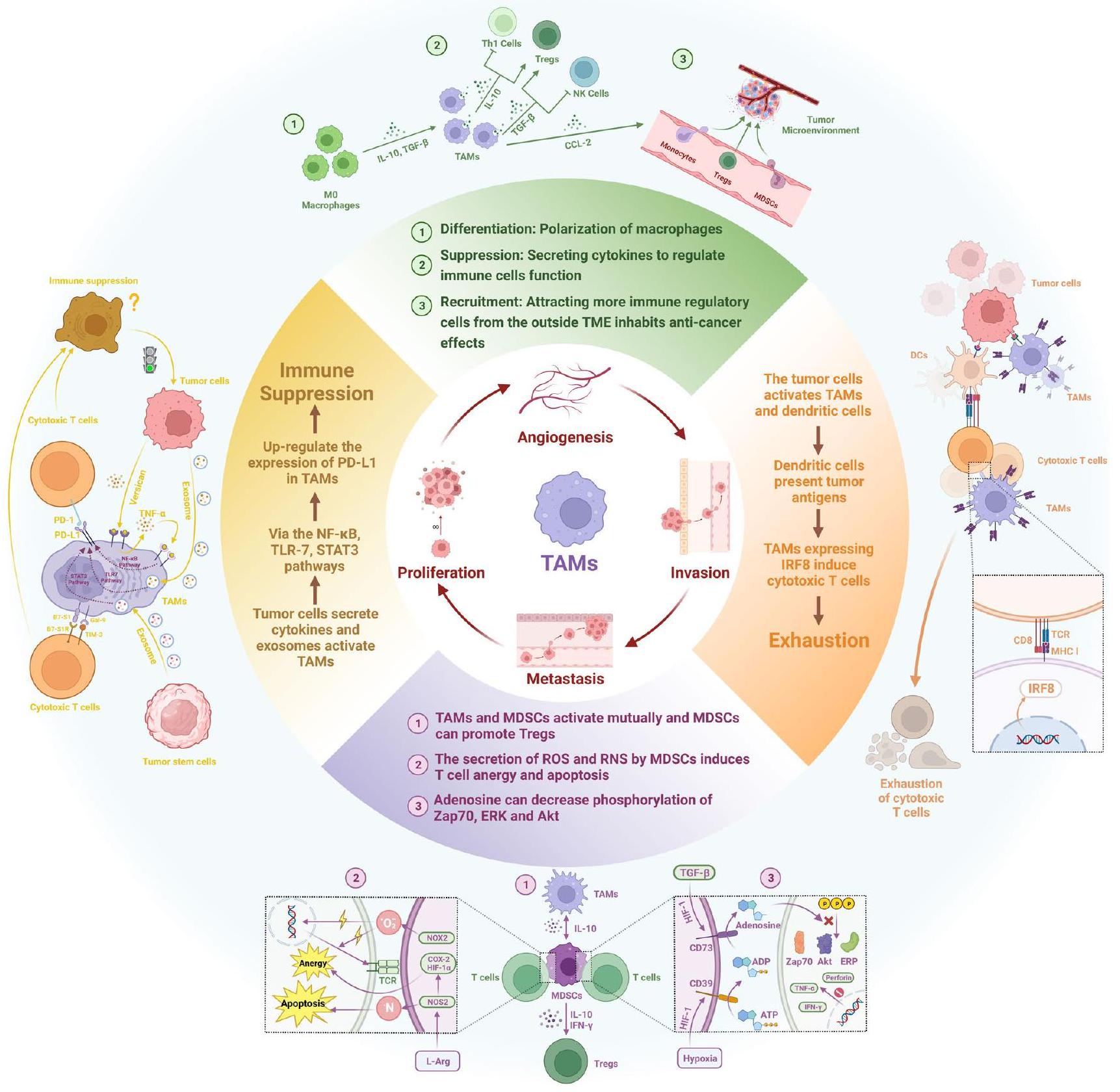

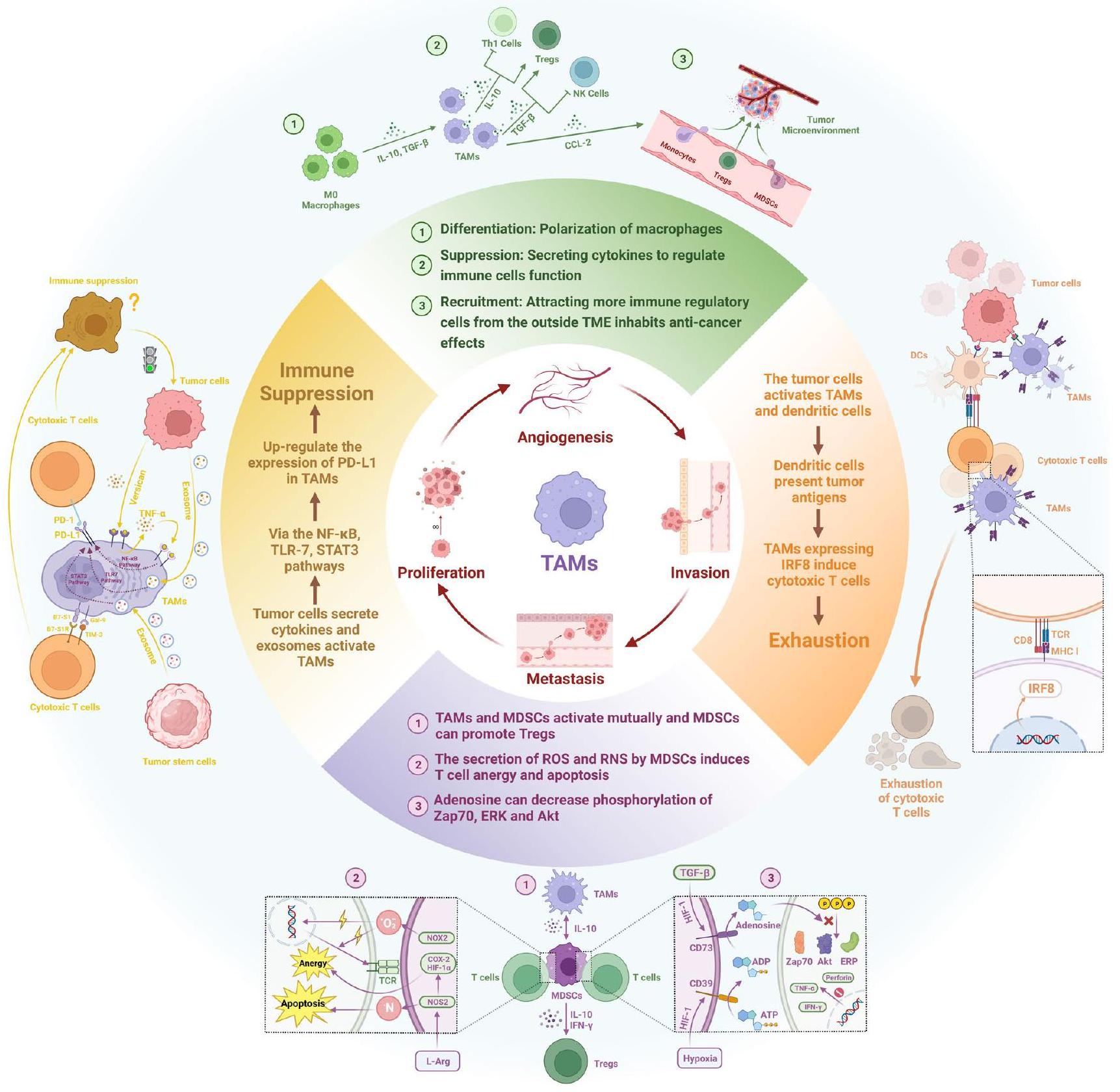

دور TAMs في التهرب المناعي

كيف تتفاعل مع أنواع خلايا مثبطة للمناعة الأخرى وعلاقتها بنقاط التفتيش المناعية للورم لتسهيل التهرب المناعي.

العوامل المثبطة للمناعة المفرزة وآثارها

يوفر درعًا واقيًا لخلايا الورم ضد الهجمات المناعية.

تثبيط وإرهاق وظائف خلايا T

الوعد في الحدود العلاجية. على سبيل المثال، تم ملاحظة أن استهداف TREM2 على TAMs أو تثبيط NEK2 يقلل من TAMs ويخفف من إرهاق خلايا T، مما يعزز استجابة الجهاز المناعي لمكافحة السرطان (Binnewies et al. 2021؛ Lischer & Bruns 2023). علاوة على ذلك، تكشف الديناميات الزمانية والمكانية بين TAMs وخلايا T عن تفاعل معقد في بيئة الورم. إن الفهم الشامل لهذه الديناميات أمر ضروري لتطوير استراتيجيات علاجية فعالة. يمكن أن يُعزى التباين في استجابة المرضى للعلاجات، على الأقل جزئيًا، إلى تأثير TAMs. وهذا يبرز أهمية التحقيق بشكل أعمق في التفاعلات بين TAMs وخلايا T ضمن علم المناعة الورمي (Lubitz & Brody 2022).

تعزيز أدوار الخلايا المثبطة للمناعة الأخرى

الأدوار المتداخلة لهذه المجموعات الخلوية المثبطة للمناعة داخل بيئة الورم (هاست وآخرون 2021).

العلاقة بين TAMs ونقاط التفتيش المناعية للورم

وإنتاج الجذور الحرة للأكسجين (مولون وآخرون 2011؛ موفاهيدي وآخرون 2010). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تساهم TAMs في تثبيط خلايا T من خلال زيادة مستويات ligand الموت المبرمج 1 (PD-L1) وعرض جزيئات تنظيمية مختلفة على سطحها (نومان وآخرون 2012). تشمل هذه الجزيئات PD-L1 و PD-L2، والروابط لـ CTLA-4 (B7-1 و B7-2)، و Ig المناعي لخلايا T ومجال الميوسين المحتوي على 3 (Tim-3)، و CD47، ومثبط Ig من نوع V لتنشيط خلايا T (VISTA)، و B7-H4 (كالابريسي وآخرون 2020؛ مانتوفاني وآخرون 2017؛ سوبودا وسالمان 2020). ترتبط هذه المجموعة من الجزيئات بإرهاق خلايا T، وTME المثبط، ونتائج غير مواتية في الإعدادات السريرية.

ارتباط TAMs بتقدم الورم

التكاثر

الغزو

الانتقال

تكوين الأوعية الدموية

(فو وآخرون 2020). إن العلاقة بين TAMs وتكوين الأوعية الدموية لها تأثير عميق على نمو الورم وتمتد أيضًا إلى ميول الأورام للانتقال (كاسيتا وبولارد 2023).

استراتيجيات علاجية محتملة تستهدف TAMs

تثبيط المناعة، يمكن أن يؤدي وضع استراتيجيات لتعديل نشاط TAM أو استغلال وظائفها إلى زيادة فعالية العلاجات السرطانية بشكل كبير.

إعادة استقطاب أنماط TAMs

إعادة استقطاب TAMs من خلال التدخلات الجينية

إعادة استقطاب TAMs من خلال إعادة برمجة الأيض

التمايز من خلال زيادة مستويات الجلوتامين. يؤدي إزالة GS إلى إعادة برمجة تشبه M1 في TAMs ويؤدي إلى تراكم CTL (بالمييري وآخرون 2017). تظهر الدراسات أن تثبيط GS بواسطة ميثيونين سلفوكسيمين (MSO) يميل بالماكروفاجات M2 نحو نمط ظاهري يشبه M1 في الماكروفاجات المعالجة بـ IL10 (بالمييري وآخرون 2017). يؤدي تثبيط GS إلى إعادة توصيل الأيض مما ينطوي على تحويل الجلوكوز إلى دورة TCA وتراكم السكسينات. مستوى منخفض

إعادة برمجة TAMs باستخدام CAR-M

تثبيط تجنيد وتفعيل TAMs

تثبيط تجنيد TAMs وتحفيز إرهاق TAMs، بما في ذلك تثبيط CSF-1R، وحجب CCL2/CCR2، واستهداف CD40، من بين أمور أخرى (Zhu et al. 2021). يشمل استهداف TAMs لعلاج السرطان تعزيز البلعمة لـ TAMs تجاه خلايا الورم. على الرغم من أن مثبط CSF-1R PLX3397 يمارس تأثيرات مضادة للسرطان من خلال تثبيط تجنيد TAMs، إلا أن الإشارات تنظم أيضًا تكاثر وتنشيط البلعميات (Li et al. 2022). تشمل الاستراتيجيات الأخرى في هذا المجال الحد من تجنيد وحيدات النوى، واستهداف تنشيط TAMs، وإعادة برمجة TAMs إلى نشاط مضاد للورم، واستهداف علامات محددة لـ TAMs (Pan et al. 2020). تنقسم الطرق الحالية بشكل رئيسي إلى نوعين: تثبيط TAMs المؤيدة للورم، بما في ذلك تثبيط تجنيد TAMs واستنفاد TAMs، وتنشيط TAMs المضادة للورم، والتي تشير إلى إعادة برمجة البلعميات المؤيدة للورم إلى بلعميات مضادة للورم (Zhang et al. 2020). على الرغم من أن استراتيجيات استهداف TAMs التي تركزت على استنفاد البلعميات وتثبيط تجنيدها أظهرت فعالية علاجية محدودة، إلا أن التجارب لا تزال جارية مع العلاجات المركبة (Lopez-Yrigoyen et al. 2021).

استخدام TAMs كوسائط لتوصيل الأدوية

الخاتمة وآفاق المستقبل

تلعب دورًا كبيرًا في تعزيز هروب الورم من المناعة. تشكل خلايا السرطان وTAMs وخلايا T مثلثًا تفاعليًا. من ناحية، تقوم TAMs بقمع خلايا المناعة بشكل غير مباشر أو تنشيط خلايا تنظيم المناعة، مما يثبط وظيفة خلايا T السامة في قتل خلايا السرطان. من ناحية أخرى، بعد تلقي إشارات من خلايا الورم، تقوم TAMs بإيقاف تشغيل خلايا T عن طريق تثبيط نقاط التفتيش المناعية الخاصة بها. كما تعزز TAMs عمليات بيولوجية متنوعة في تطور الورم. كان استهداف TAMs نقطة محورية في البحث في العلاج المناعي للورم. على وجه التحديد، يُنظر إلى إعادة استقطاب TAMs على أنها نهج واعد، حيث من كل من المنظور الجيني والأيضي، هناك إمكانية لتحويل TAMs نحو نمط M1 أو عكس نمط M2، مما يحسن في النهاية TME المثبط للمناعة. في السنوات الأخيرة، ظهرت علاجات جديدة، مثل علاج CAR-M باستخدام هندسة الخلايا لتعديل البلعميات، والتي تعتبر واعدة في تكرار نجاح علاج CAR-T في الأورام الصلبة.

البيانات التي تدعم نتائج هذه المراجعة متاحة بالكامل لأولئك الذين يرغبون في استشارة المصادر الأصلية.

الإعلانات

References

Amer HT, Stein U, El Tayebi HM (2022) The monocyte, a maestro in the Tumor Microenvironment (TME) of breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215460

Arlauckas SP, Garren SB, Garris CS, Kohler RH, Oh J, Pittet MJ, Weissleder R (2018) Arg1 expression defines immunosuppressive subsets of tumor-associated macrophages. Theranostics 8(21):5842-5854. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno. 26888

Becker JC, Andersen MH, Schrama D, Thor Straten P (2013) Immunesuppressive properties of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Immunother 62(7):1137-1148. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00262-013-1434-6

Beury DW, Parker KH, Nyandjo M, Sinha P, Carter KA, OstrandRosenberg S (2014) Cross-talk among myeloid-derived suppressor cells, macrophages, and tumor cells impacts the inflammatory milieu of solid tumors. J Leukoc Biol 96(6):1109-1118. https:// doi.org/10.1189/jlb.3A0414-210R

Bhattacharya S, Aggarwal A (2019) M2 macrophages and their role in rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol Int 39(5):769-780. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00296-018-4120-3

Bied M, Ho WW, Ginhoux F, Bleriot C (2023) Roles of macrophages in tumor development: a spatiotemporal perspective. Cell Mol Immunol 20(9):983-992. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41423-023-01061-6

Binnewies M, Pollack JL, Rudolph J, Dash S, Abushawish M, Lee T, Sriram V (2021) Targeting TREM2 on

tumor-associated macrophages enhances immunotherapy. Cell Rep 37(3):109844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021. 109844

Biswas SK, Mantovani A (2010) Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol 11(10):889-896. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni. 1937

Boutilier AJ, Elsawa SF (2021) Macrophage polarization states in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijms22136995

Briana GN, Fengshen K, Ming L, Kristelle C, Mytrang D, Ruth AF, Ming OL (2020) IRF8 governs tumor-associated macrophage control of T cell exhaustion. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/ 2020.03.12.989731

Cao X, Geng Q, Fan D, Wang Q, Wang X, Zhang M, Xiao C (2023) m (6)A methylation: a process reshaping the tumour immune microenvironment and regulating immune evasion. Mol Cancer 22(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-022-01704-8

Cassetta L, Pollard JW (2023) A timeline of tumour-associated macrophage biology. Nat Rev Cancer 23(4):238-257. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41568-022-00547-1

Cendrowicz E, Sas Z, Bremer E, Rygiel TP (2021) The role of macrophages in cancer development and therapy. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13081946

Chanmee T, Ontong P, Konno K, Itano N (2014) Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel) 6(3):1670-1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/cance rs6031670

Chen Y, Zhang X (2017) Pivotal regulators of tissue homeostasis and cancer: macrophages. Exp Hematol Oncol 6:23. https://doi.org/

Chen Y, Song Y, Du W, Gong L, Chang H, Zou Z (2019) Tumor-associated macrophages: an accomplice in solid tumor progression. J Biomed Sci 26(1):78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-019-0568-z

Chen S, Saeed A, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Xu H, Xiao GG, Duo Y (2023) Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8(1):207. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41392-023-01452-1

Cheng C, Huang C, Ma TT, Bian EB, He Y, Zhang L, Li J (2014) SOCS1 hypermethylation mediated by DNMT1 is associated with lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory cytokines in macrophages. Toxicol Lett 225(3):488-497. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.toxlet.2013.12.023

Cheng N, Bai X, Shu Y, Ahmad O, Shen P (2021) Targeting tumorassociated macrophages as an antitumor strategy. Biochem Pharmacol 183:114354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114354

Cheng K, Cai N, Zhu J, Yang X, Liang H, Zhang W (2022) Tumorassociated macrophages in liver cancer: from mechanisms to therapy. Cancer Commun (lond) 42(11):1112-1140. https://doi. org/10.1002/cac2.12345

Christofides A, Strauss L, Yeo A, Cao C, Charest A, Boussiotis VA (2022) The complex role of tumor-infiltrating macrophages. Nat Immunol 23(8):1148-1156. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41590-022-01267-2

Colegio OR, Chu NQ, Szabo AL, Chu T, Rhebergen AM, Jairam V, Medzhitov R (2014) Functional polarization of tumourassociated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature 513(7519):559-563. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13490

Corzo CA, Condamine T, Lu L, Cotter MJ, Youn JI, Cheng P, Gabrilovich DI (2010) HIF-1alpha regulates function and differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. J Exp Med 207(11):2439-2453. https://doi. org/10.1084/jem. 20100587

Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM (2008) IL-10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol 180(9):5771-5777. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5771

Dallavalasa S, Beeraka NM, Basavaraju CG, Tulimilli SV, Sadhu SP, Rajesh K, Madhunapantula SV (2021) The role of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) in cancer progression, chemoresistance, angiogenesis and metastasis – current status. Curr Med Chem 28(39):8203-8236. https://doi.org/10.2174/09298 67328666210720143721

DeNardo DG, Ruffell B (2019) Macrophages as regulators of tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 19(6):369382. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0127-6

Deng R, Lu J, Liu X, Peng XH, Wang J, Li XP (2020) PD-L1 expression is highly associated with tumor-associated macrophage infiltration in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res 12:11585-11596. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S274913

Depil S, Duchateau P, Grupp SA, Mufti G, Poirot L (2020) ‘Off-theshelf’ allogeneic CAR T cells: development and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov 19(3):185-199. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41573-019-0051-2

Doedens AL, Stockmann C, Rubinstein MP, Liao D, Zhang N, DeNardo DG, Johnson RS (2010) Macrophage expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha suppresses T-cell function and promotes tumor progression. Cancer Res 70(19):74657475. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1439

Du J, Liao W, Liu W, Deb DK, He L, Hsu PJ, Li YC (2020) N(6)adenosine methylation of Socs 1 mRNA is required to sustain the negative feedback control of macrophage activation. Dev Cell 55(6):737-753 e737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel. 2020.10.023

macrophages. Eur J Immunol 44(10):2903-2917. https://doi. org/10.1002/eji. 201444612

Dwyer AR, Greenland EL, Pixley FJ (2017) Promotion of Tumor Invasion by Tumor-Associated Macrophages: The Role of CSF-1-Activated Phosphatidylinositol 3 Kinase and Src Family Kinase Motility Signaling. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10. 3390/cancers9060068

Ebeling S, Kowalczyk A, Perez-Vazquez D, Mattiola I (2023) Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by the crosstalk between innate immunity and endothelial cells. Front Oncol 13:1171794. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1171794

Edin S, Wikberg ML, Dahlin AM, Rutegard J, Oberg A, Oldenborg PA, Palmqvist R (2012) The distribution of macrophages with a M1 or M2 phenotype in relation to prognosis and the molecular characteristics of colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 7(10):e47045. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0047045

Egawa M, Mukai K, Yoshikawa S, Iki M, Mukaida N, Kawano Y, Karasuyama H (2013) Inflammatory monocytes recruited to allergic skin acquire an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype via basophilderived interleukin-4. Immunity 38(3):570-580. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.014

Fernandes TJ, Hodge JM, Singh PP, Eeles DG, Collier FM, Holten I, Quinn JM (2013) Cord blood-derived macrophage-lineage cells rapidly stimulate osteoblastic maturation in mesenchymal stem cells in a glycoprotein-130 dependent manner. PLoS One 8(9):e73266. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0073266

Flavahan WA, Gaskell E, Bernstein BE (2017) Epigenetic plasticity and the hallmarks of cancer. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/ science.aal2380

Fu LQ, Du WL, Cai MH, Yao JY, Zhao YY, Mou XZ (2020) The roles of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Cell Immunol 353:104119. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.cellimm.2020.104119

Gao J, Liang Y, Wang L (2022a) Shaping polarization of tumor-associated macrophages in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 13:888713. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.888713

Gao R, Shi GP, Wang J (2022b) Functional diversities of regulatory T cells in the context of cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 13:833667. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.833667

Geiger R, Rieckmann JC, Wolf T, Basso C, Feng Y, Fuhrer T, Lanzavecchia A (2016) L-arginine modulates T cell metabolism and enhances survival and anti-tumor activity. Cell 167(3):829-842 e813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.031

Genin M, Clement F, Fattaccioli A, Raes M, Michiels C (2015) M1 and M2 macrophages derived from THP-1 cells differentially modulate the response of cancer cells to etoposide. BMC Cancer 15:577. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-015-1546-9

Giussani M, Triulzi T, Sozzi G, Tagliabue E (2019) Tumor extracellular matrix remodeling: new perspectives as a circulating tool in the diagnosis and prognosis of solid tumors. Cells. https://doi. org/10.3390/cells8020081

Gonda TA, Fang J, Salas M, Do C, Hsu E, Zhukovskaya A, Tycko B (2020) A DNA hypomethylating drug alters the tumor microenvironment and improves the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 80(21):4754-4767. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472. CAN-20-0285

Gordon S, Pluddemann A (2017) Tissue macrophages: heterogeneity and functions. BMC Biol 15(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12915-017-0392-4

Goswami KK, Ghosh T, Ghosh S, Sarkar M, Bose A, Baral R (2017) Tumor promoting role of anti-tumor macrophages in tumor

microenvironment. Cell Immunol 316:1-10. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.cellimm.2017.04.005

Grivennikov SI, Wang K, Mucida D, Stewart CA, Schnabl B, Jauch D, Karin M (2012) Adenoma-linked barrier defects and microbial products drive IL-23/IL-17-mediated tumour growth. Nature 491(7423):254-258. https://doi.org/10.1038/natur e11465

Gunaydin G (2021) CAFs interacting with TAMs in tumor microenvironment to enhance tumorigenesis and immune evasion. Front Oncol 11:668349. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.668349

Haist M, Stege H, Grabbe S, Bros M (2021) The functional crosstalk between myeloid-derived suppressor cells and regulatory T cells within the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13020210

Hamilton JA, Cook AD, Tak PP (2016) Anti-colony-stimulating factor therapies for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16(1):53-70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2016.231

Han S, Bao X, Zou Y, Wang L, Li Y, Yang L, Guo J (2023) d-lactate modulates M2 tumor-associated macrophages and remodels immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adg2697

Hao NB, Lu MH, Fan YH, Cao YL, Zhang ZR, Yang SM (2012) Macrophages in tumor microenvironments and the progression of tumors. Clin Dev Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/948098

Hao S, Meng J, Zhang Y, Liu J, Nie X, Wu F, Xu H (2017) Macrophage phenotypic mechanomodulation of enhancing bone regeneration by superparamagnetic scaffold upon magnetization. Biomaterials 140:16-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.013

Hatziioannou A, Alissafi T, Verginis P (2017) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells and T regulatory cells in tumors: unraveling the dark side of the force. J Leukoc Biol 102(2):407-421. https://doi.org/ 10.1189/jlb.5VMR1116-493R

Hiam-Galvez KJ, Allen BM, Spitzer MH (2021) Systemic immunity in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 21(6):345-359. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41568-021-00347-z

Hibbs JB Jr, Taintor RR, Vavrin Z, Rachlin EM (1988) Nitric oxide: a cytotoxic activated macrophage effector molecule. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 157(1):87-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0006-291x (88)80015-9

Huang B, Pan PY, Li Q, Sato AI, Levy DE, Bromberg J, Chen SH (2006) Gr-1+CD115+ immature myeloid suppressor cells mediate the development of tumor-induced T regulatory cells and T-cell anergy in tumor-bearing host. Cancer Res 66(2):11231131. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1299

Ingersoll MA, Spanbroek R, Lottaz C, Gautier EL, Frankenberger M, Hoffmann R, Randolph GJ (2010) Comparison of gene expression profiles between human and mouse monocyte subsets. Blood 115(3):e10-19. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-07-235028

Jayaraman P, Parikh F, Lopez-Rivera E, Hailemichael Y, Clark A, Ma G, Sikora AG (2012) Tumor-expressed inducible nitric oxide synthase controls induction of functional myeloid-derived suppressor cells through modulation of vascular endothelial growth factor release. J Immunol 188(11):5365-5376. https://doi.org/10. 4049/jimmunol. 1103553

Jayasingam SD, Citartan M, Thang TH, Mat Zin AA, Ang KC, Ch’ng ES (2019) Evaluating the polarization of tumor-associated macrophages into M1 and M2 phenotypes in human cancer tissue:

technicalities and challenges in routine clinical practice. Front Oncol 9:1512. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.01512

Jeannin P, Paolini L, Adam C, Delneste Y (2018) The roles of CSFs on the functional polarization of tumor-associated macrophages. Febs j 285(4):680-699. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs. 14343

Jha AK, Huang SC, Sergushichev A, Lampropoulou V, Ivanova Y, Loginicheva E, Artyomov MN (2015) Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity 42(3):419-430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.005

Kalluri R, LeBleu VS (2020) The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/scien ce.aau6977

Kang SU, Cho SY, Jeong H, Han J, Chae HY, Yang H, Kwon MJ (2022) Matrix metalloproteinase 11 (MMP11) in macrophages promotes the migration of HER2-positive breast cancer cells and monocyte recruitment through CCL2-CCR2 signaling. Lab Invest 102(4):376-390. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-021-00699-y

Kelly B, O’Neill LA (2015) Metabolic reprogramming in macrophages and dendritic cells in innate immunity. Cell Res 25(7):771-784. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr. 2015.68

Kennel KB, Greten FR (2021) Immune cell – produced ROS and their impact on tumor growth and metastasis. Redox Biol 42:101891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2021.101891

Kersten K, Hu KH, Combes AJ, Samad B, Harwin T, Ray A, Krummel MF (2022) Spatiotemporal co-dependency between macrophages and exhausted CD8(+) T cells in cancer. Cancer Cell 40(6):624638 e629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2022.05.004

Kim H, Wang SY, Kwak G, Yang Y, Kwon IC, Kim SH (2019) Exo-some-guided phenotypic switch of M1 to M2 macrophages for cutaneous wound healing. Adv Sci (weinh) 6(20):1900513. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs. 201900513

Klichinsky M, Ruella M, Shestova O, Lu XM, Best A, Zeeman M, Gill S (2020) Human chimeric antigen receptor macrophages for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Biotechnol 38(8):947-953. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-0462-y

Koppenol WH, Bounds PL, Dang CV (2011) Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer 11(5):325-337. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3038

Koru-Sengul T, Santander AM, Miao F, Sanchez LG, Jorda M, Gluck S, Torroella-Kouri M (2016) Breast cancers from black women exhibit higher numbers of immunosuppressive macrophages with proliferative activity and of crown-like structures associated with lower survival compared to non-black Latinas and Caucasians. Breast Cancer Res Treat 158(1):113-126. https://doi.org/10. 1007/s10549-016-3847-3

Ku AW, Muhitch JB, Powers CA, Diehl M, Kim M, Fisher DT, Evans SS (2016) Tumor-induced MDSC act via remote control to inhibit L-selectin-dependent adaptive immunity in lymph nodes. Elife. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife. 17375

Kumar S, Ramesh A, Kulkarni A (2020) Targeting macrophages: a novel avenue for cancer drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov 15(5):561-574. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460441.2020. 1733525

Kumari N, Choi SH (2022) Tumor-associated macrophages in cancer: recent advancements in cancer nanoimmunotherapies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 41(1):68. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13046-022-02272-x

Kusmartsev S, Eruslanov E, Kubler H, Tseng T, Sakai Y, Su Z, Vieweg J (2008) Oxidative stress regulates expression of VEGFR1 in myeloid cells: link to tumor-induced immune suppression in renal cell carcinoma. J Immunol 181(1):346-353. https://doi. org/10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.346

La Fleur L, Boura VF, Alexeyenko A, Berglund A, Ponten V, Mattsson JSM, Botling J (2018) Expression of scavenger receptor MARCO defines a targetable tumor-associated macrophage

subset in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer 143(7):17411752. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc. 31545

Lai Q, Wang H, Li A, Xu Y, Tang L, Chen Q, Du Z (2018) Decitibine improve the efficiency of anti-PD-1 therapy via activating the response to IFN/PD-L1 signal of lung cancer cells. Oncogene 37(17):2302-2312. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-018-0125-3

Lan C, Huang X, Lin S, Huang H, Cai Q, Wan T, Liu J (2013) Expression of M2-polarized macrophages is associated with poor prognosis for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat 12(3):259-267. https://doi.org/10.7785/tcrt. 2012.500312

Larionova I, Kazakova E, Gerashchenko T, Kzhyshkowska J (2021) New angiogenic regulators produced by TAMs: perspective for targeting tumor angiogenesis. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/ 10.3390/cancers13133253

Lei A, Yu H, Lu S, Lu H, Ding X, Tan T, Zhang J (2024) A secondgeneration M1-polarized CAR macrophage with antitumor efficacy. Nat Immunol 25(1):102-116. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41590-023-01687-8

Li L, Tian Y (2023) The role of metabolic reprogramming of tumorassociated macrophages in shaping the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Biomed Pharmacother 161:114504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114504

Li YL, Zhao H, Ren XB (2016) Relationship of VEGF/VEGFR with immune and cancer cells: staggering or forward? Cancer Biol Med 13(2):206-214. https://doi.org/10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941. 2015.0070

Li Z, Maeda D, Yoshida M, Umakoshi M, Nanjo H, Shiraishi K, Goto A (2018) The intratumoral distribution influences the prognostic impact of CD68- and CD204-positive macrophages in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 123:127-135. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.lungcan.2018.07.015

Li M, He L, Zhu J, Zhang P, Liang S (2022) Targeting tumor-associated macrophages for cancer treatment. Cell Biosci 12(1):85. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s13578-022-00823-5

Lifsted T, Le Voyer T, Williams M, Muller W, Klein-Szanto A, Buetow KH, Hunter KW (1998) Identification of inbred mouse strains harboring genetic modifiers of mammary tumor age of onset and metastatic progression. Int J Cancer 77(4):640-644. https://doi. org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980812)77:4%3c640::aid-ijc26% 3e3.0.co;2-8

Liguori M, Solinas G, Germano G, Mantovani A, Allavena P (2011) Tumor-associated macrophages as incessant builders and destroyers of the cancer stroma. Cancers (basel) 3(4):3740-3761. https:// doi.org/10.3390/cancers3043740

Lin Y, Xu J, Lan H (2019) Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor metastasis: biological roles and clinical therapeutic

applications. J Hematol Oncol 12(1):76. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13045-019-0760-3

Lin P, Ji HH, Li YJ, Guo SD (2021) Macrophage Plasticity and Atherosclerosis Therapy. Front Mol Biosci 8:679797. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fmolb.2021.679797

Lischer C, Bruns H (2023) Breaking barriers: NEK2 inhibition shines in multiple myeloma treatment. Cell Reports Medicine 4(10):101237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.101237

Liu PS, Wang H, Li X, Chao T, Teav T, Christen S, Ho PC (2017) alpha-ketoglutarate orchestrates macrophage activation through metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming. Nat Immunol 18(9):985-994. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni. 3796

Liu J, Geng X, Hou J, Wu G (2021) New insights into M1/M2 macrophages: key modulators in cancer progression. Cancer Cell Int 21(1):389. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-021-02089-2

Liu M, Liu L, Song Y, Li W, Xu L (2022) Targeting macrophages: a novel treatment strategy in solid tumors. J Transl Med 20(1):586. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03813-w

Long Y, Niu Y, Liang K, Du Y (2022) Mechanical communication in fibrosis progression. Trends Cell Biol 32(1):70-90. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.tcb.2021.10.002

Lopez-Yrigoyen M, Cassetta L, Pollard JW (2021) Macrophage targeting in cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1499(1):18-41. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/nyas. 14377

Lu G, Zhang R, Geng S, Peng L, Jayaraman P, Chen C, Xiong H (2015) Myeloid cell-derived inducible nitric oxide synthase suppresses M1 macrophage polarization. Nat Commun 6:6676. https://doi. org/10.1038/ncomms7676

Lubitz GS, Brody JD (2022) Not just neighbours: positive feedback between tumour-associated macrophages and exhausted T cells. Nat Rev Immunol 22(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41577-021-00660-6

Luen SJ, Savas P, Fox SB, Salgado R, Loi S (2017) Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and the emerging role of immunotherapy in breast cancer. Pathology 49(2):141-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. pathol.2016.10.010

Lundholm M, Hagglof C, Wikberg ML, Stattin P, Egevad L, Bergh A, Edin S (2015) Secreted factors from colorectal and prostate cancer cells skew the immune response in opposite directions. Sci Rep 5:15651. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep15651

Lv B, Wang Y, Ma D, Cheng W, Liu J, Yong T, Wang C (2022) Immunotherapy: reshape the tumor immune microenvironment. Front Immunol 13:844142. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022. 844142

Malfitano AM, Pisanti S, Napolitano F, Di Somma S, Martinelli R, Portella G (2020) Tumor-associated macrophage status in cancer treatment. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers120 71987

Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P (2017) Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 14(7):399-416. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nrclinonc.2016.217

Martinez FO, Helming L, Milde R, Varin A, Melgert BN, Draijer C, Gordon S (2013) Genetic programs expressed in resting and IL-4 alternatively activated mouse and human macrophages: similarities and differences. Blood 121(9):e57-69. https://doi.org/10. 1182/blood-2012-06-436212

Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM (2000) M-1/ M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol 164(12):6166-6173. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.164. 12.6166

Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, Baeten M, Stange G, Van den Bossche J, Van Ginderachter JA (2010) Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Res 70(14):5728-5739. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472. CAN-09-4672

Murray PJ, Wynn TA (2011) Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol 11(11):723-737. https:// doi.org/10.1038/nri3073

Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, Wynn TA (2014) Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity 41(1):1420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008

Niu Z, Shi Q, Zhang W, Shu Y, Yang N, Chen B, Shen P (2017) Cas-pase-1 cleaves PPARgamma for potentiating the pro-tumor action of TAMs. Nat Commun 8(1):766. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41467-017-00523-6

Nixon BG, Kuo F, Ji L, Liu M, Capistrano K, Do M, Li MO (2022) Tumor-associated macrophages expressing the transcription factor IRF8 promote T cell exhaustion in cancer. Immunity 55(11):2044-2058 e2045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni. 2022.10.002

Noman MZ, Janji B, Berchem G, Mami-Chouaib F, Chouaib S (2012) Hypoxia-induced autophagy: a new player in cancer immunotherapy? Autophagy 8(4):704-706. https://doi.org/10.4161/auto. 19572

Nosho K, Shima K, Irahara N, Kure S, Baba Y, Kirkner GJ, Ogino S (2009) DNMT3B expression might contribute to CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 15(11):3663-3671. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432. CCR-08-2383

Obermajer N, Kalinski P (2012) Generation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells using prostaglandin E2. Transplant Res 1(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-1440-1-15

O’Neill LA, Kishton RJ, Rathmell J (2016) A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat Rev Immunol 16(9):553-565. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2016.70

Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P (2009) Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol 182(8):44994506. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol. 0802740

an M1-like phenotype and inhibits tumor metastasis. Cell Rep 20(7):1654-1666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.054

Pan W, Zhu S, Qu K, Meeth K, Cheng J, He K, Lu J (2017) The DNA methylcytosine dioxygenase Tet2 sustains immunosuppressive function of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells to promote melanoma progression. Immunity 47(2):284-297 e285. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.immuni.2017.07.020

Pan Y, Yu Y, Wang X, Zhang T (2020) Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor immunity. Front Immunol 11:583084. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fimmu.2020.583084

Pavlova NN, Zhu J, Thompson CB (2022) The hallmarks of cancer metabolism: Still emerging. Cell Metab 34(3):355-377. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2022.01.007

Penny HL, Sieow JL, Adriani G, Yeap WH, See Chi Ee P, San Luis B, Wong SC (2016) Warburg metabolism in tumor-conditioned macrophages promotes metastasis in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncoimmunology 5(8):e1191731. https://doi. org/10.1080/2162402X.2016.1191731

Perez S, Rius-Perez S (2022) Macrophage polarization and reprogramming in acute inflammation: a redox perspective. Antioxidants (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11071394

Petty AJ, Owen DH, Yang Y, Huang X (2021) Targeting tumor-associated macrophages in cancer immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13215318

Pittet MJ, Michielin O, Migliorini D (2022) Clinical relevance of tumour-associated macrophages. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 19(6):402421. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-022-00620-6

Raber PL, Thevenot P, Sierra R, Wyczechowska D, Halle D, Ramirez ME, Rodriguez PC (2014) Subpopulations of myeloid-derived suppressor cells impair T cell responses through independent nitric oxide-related pathways. Int J Cancer 134(12):2853-2864. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc. 28622

Raes G, Van den Bergh R, De Baetselier P, Ghassabeh GH, Scotton C, Locati M, Sozzani S (2005) Arginase-1 and Ym1 are markers for murine, but not human, alternatively activated myeloid cells. J Immunol 174(11):6561-6562. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmu nol.174.11.6561

Raggi F, Pelassa S, Pierobon D, Penco F, Gattorno M, Novelli F, Bosco MC (2017) Regulation of human macrophage M1-M2 polarization balance by hypoxia and the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-1. Front Immunol 8:1097. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fimmu.2017.01097

Rakaee M, Busund LR, Jamaly S, Paulsen EE, Richardsen E, Andersen S, Kilvaer TK (2019) Prognostic value of macrophage phenotypes in resectable non-small cell lung cancer assessed by multiplex immunohistochemistry. Neoplasia 21(3):282-293. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2019.01.005

Rath M, Muller I, Kropf P, Closs EI, Munder M (2014) Metabolism via arginase or nitric oxide synthase: two competing arginine pathways in macrophages. Front Immunol 5:532. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00532

and supports tumor growth in mammary adenocarcinoma mouse model. Oncotarget 7(21):31097-31110. https://doi.org/10.18632/ oncotarget. 8857

Rodriguez PC, Quiceno DG, Ochoa AC (2007) L-arginine availability regulates T-lymphocyte cell-cycle progression. Blood 109(4):1568-1573. https://doi.org/10.1182/ blood-2006-06-031856

Ruffell B, Chang-Strachan D, Chan V, Rosenbusch A, Ho CM, Pryer N, Coussens LM (2014) Macrophage IL-10 blocks CD8+ T cell-dependent responses to chemotherapy by suppressing IL-12 expression in intratumoral dendritic cells. Cancer Cell 26(5):623-637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.006

Sadhukhan P, Seiwert TY (2023) The role of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment and tumor metabolism. Semin Immunopathol 45(2):187-201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-023-00988-2

Saeidi V, Doudican N, Carucci JA (2023) Understanding the squamous cell carcinoma immune microenvironment. Front Immunol 14:1084873. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1084873

Sangaletti S, Chiodoni C, Tripodo C, Colombo MP (2017) The good and bad of targeting cancer-associated extracellular matrix. Curr Opin Pharmacol 35:75-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2017. 06.003

Semenza GL (2003) Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 3(10):721-732. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1187

Shabo I, Olsson H, Sun XF, Svanvik J (2009) Expression of the macrophage antigen CD163 in rectal cancer cells is associated with early local recurrence and reduced survival time. Int J Cancer 125(8):1826-1831. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc. 24506

Shi R, Zhao K, Wang T, Yuan J, Zhang D, Xiang W, Miao H (2022) 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine potentiates anti-tumor immunity in colorectal peritoneal metastasis by modulating ABC A9-mediated cholesterol accumulation in macrophages. Theranostics 12(2):875-890. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno. 66420

Shibutani M, Nakao S, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Kashiwagi S, Hirakawa K, Ohira M (2021) The impact of tumor-associated macrophages on chemoresistance via angiogenesis in colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res 41(9):4447-4453. https://doi.org/10.21873/antic anres. 15253

Shikanai S, Yamada N, Yanagawa N, Sugai M, Osakabe M, Saito H, Sugai T (2023) Prognostic impact of tumor-associated macrophage-related markers in patients with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Ann Surg Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1245/ s10434-023-13384-9

Sica A, Mantovani A (2012) Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest 122(3):787-795. https://doi.org/10. 1172/JCI59643

Sickert D, Aust DE, Langer S, Haupt I, Baretton GB, Dieter P (2005) Characterization of macrophage subpopulations in colon cancer using tissue microarrays. Histopathology 46(5):515-521. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02129.x

Soliman H, Theret M, Scott W, Hill L, Underhill TM, Hinz B, Rossi FMV (2021) Multipotent stromal cells: One name, multiple identities. Cell Stem Cell 28(10):1690-1707. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.stem.2021.09.001

Sousa S, Brion R, Lintunen M, Kronqvist P, Sandholm J, Monkkonen J, Maatta JA (2015) Human breast cancer cells educate macrophages toward the M2 activation status. Breast Cancer Res 17(1):101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-015-0621-0

Spiller KL, Koh TJ (2017) Macrophage-based therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 122:74-83. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2017.05.010

Swierczynski J, Hebanowska A, Sledzinski T (2014) Role of abnormal lipid metabolism in development, progression, diagnosis and therapy of pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 20(9):2279-2303. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i9.2279

Swoboda DM, Sallman DA (2020) The promise of macrophage directed checkpoint inhibitors in myeloid malignancies. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 33(4):101221. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.beha.2020.101221

Takayama H, Nonomura N, Nishimura K, Oka D, Shiba M, Nakai Y, Okuyama A (2009) Decreased immunostaining for macrophage scavenger receptor is associated with poor prognosis of prostate cancer. BJU Int 103(4):470-474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1464-410X.2008.08013.x

Tang K, Ma J, Huang B (2022) Macrophages’ M1 or M2 by tumor microparticles: lysosome makes decision. Cell Mol Immunol 19(10):1196-1197. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41423-022-00892-z

Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, O’Neill LA (2013) Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF1alpha. Nature 496(7444):238-242. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nature 11986

Tao H, Zhong X, Zeng A, Song L (2023) Unveiling the veil of lactate in tumor-associated macrophages: a successful strategy for immunometabolic therapy. Front Immunol 14:1208870. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1208870

Tiainen S, Tumelius R, Rilla K, Hamalainen K, Tammi M, Tammi R, Auvinen P (2015) High numbers of macrophages, especially M2-like (CD163-positive), correlate with hyaluronan accumulation and poor outcome in breast cancer. Histopathology 66(6):873-883. https://doi.org/10.1111/his. 12607

Tie Y, Tang F, Wei YQ, Wei XW (2022) Immunosuppressive cells in cancer: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. J Hematol Oncol 15(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-022-01282-8

Tien FM, Lu HH, Lin SY, Tsai HC (2023) Epigenetic remodeling of the immune landscape in cancer: therapeutic hurdles and opportunities. J Biomed Sci 30(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12929-022-00893-0

T’Jonck W, Guilliams M, Bonnardel J (2018) Niche signals and transcription factors involved in tissue-resident macrophage development. Cell Immunol 330:43-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celli mm.2018.02.005

Travers M, Brown SM, Dunworth M, Holbert CE, Wiehagen KR, Bachman KE, Zahnow CA (2019) DFMO and 5-azacytidine increase M1 macrophages in the tumor microenvironment of murine ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 79(13):3445-3454. https:// doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-4018

Tsai TL, Zhou TA, Hsieh YT, Wang JC, Cheng HK, Huang CH, Hsu CL (2022) Multiomics reveal the central role of pentose phosphate pathway in resident thymic macrophages to cope with efferocytosis-associated stress. Cell Rep 40(2):111065. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111065

Vinay DS, Ryan EP, Pawelec G, Talib WH, Stagg J, Elkord E, Kwon BS (2015) Immune evasion in cancer: mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin Cancer Biol 35(Suppl):S185-S198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.004

Vitale I, Manic G, Coussens LM, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L (2019) Macrophages and metabolism in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Metab 30(1):36-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.001

Wang H, Yung MMH, Ngan HYS, Chan KKL, Chan DW (2021) The impact of the tumor microenvironment on macrophage polarization in cancer metastatic progression. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijms22126560

Wang Y, Lin Q, Zhang H, Wang S, Cui J, Hu Y, Su J (2023) M2 macrophage-derived exosomes promote diabetic fracture healing by acting as an immunomodulator. Bioact Mater 28:273-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.05.018

Wang H, Wang X, Zhang X, Xu W (2024) The promising role of tumorassociated macrophages in the treatment of cancer. Drug Resist Updat 73:101041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drup.2023.101041

Wei Q, Qian Y, Yu J, Wong CC (2020) Metabolic rewiring in the promotion of cancer metastasis: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Oncogene 39(39):6139-6156. https://doi.org/10. 1038/s41388-020-01432-7

Weiss JM, Subleski JJ, Back T, Chen X, Watkins SK, Yagita H, Wiltrout RH (2014) Regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment undergo Fasdependent cell death during IL-2/alphaCD40 therapy. J Immunol 192(12):5821-5829. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol. 1400404

Wen Y, Zhu Y, Zhang C, Yang X, Gao Y, Li M, Tang H (2022) Chronic inflammation, cancer development and immunotherapy. Front Pharmacol 13:1040163. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022. 1040163

Wu G, Zhang J, Zhao Q, Zhuang W, Ding J, Zhang C, Xie HY (2020) Molecularly engineered macrophage-derived exosomes with inflammation tropism and intrinsic heme biosynthesis for atherosclerosis treatment. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 59(10):40684074. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie. 201913700

Xia T, Fu S, Yang R, Yang K, Lei W, Yang Y, Zhang T (2023) Advances in the study of macrophage polarization in inflammatory immune skin diseases. J Inflamm (lond) 20(1):33. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12950-023-00360-z

Xiao L, Wang Q, Peng H (2023) Tumor-associated macrophages: new insights on their metabolic regulation and their influence in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 14:1157291. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1157291

Xu Y, Wang X, Liu L, Wang J, Wu J, Sun C (2022b) Role of macrophages in tumor progression and therapy (Review). Int J Oncol. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2022.5347

Xu Y, Zeng H, Jin K, Liu Z, Zhu Y, Xu L, Xu J (2022c) Immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages expressing interlukin-10 conferred poor prognosis and therapeutic vulnerability in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer. J Immunother Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2021-003416

Xue VW, Chung JY, Cordoba CAG, Cheung AH, Kang W, Lam EW, Tang PM (2020) Transforming growth factor-beta: a multifunctional regulator of cancer immunity. Cancers (Basel). https://doi. org/10.3390/cancers12113099

Yan WL, Shen KY, Tien CY, Chen YA, Liu SJ (2017) Recent progress in GM-CSF-based cancer immunotherapy. Immunotherapy 9(4):347-360. https://doi.org/10.2217/imt-2016-0141

Yang X, Wang X, Liu D, Yu L, Xue B, Shi H (2014) Epigenetic regulation of macrophage polarization by DNA methyltransferase 3b. Mol Endocrinol 28(4):565-574. https://doi.org/10.1210/me. 2013-1293

Yang L, Wang F, Wang L, Huang L, Wang J, Zhang B, Zhang Y (2015) CD163+ tumor-associated macrophage is a prognostic biomarker and is associated with therapeutic effect on malignant pleural effusion of lung cancer patients. Oncotarget 6(12): 10592-10603. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget. 3547

Yang Q, Guo N, Zhou Y, Chen J, Wei Q, Han M (2020a) The role of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in tumor progression and relevant advance in targeted therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B 10(11):2156-2170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.04.004

Yang Y, Guo J, Huang L (2020b) Tackling TAMs for cancer immunotherapy: it’s nano time. Trends Pharmacol Sci 41(10):701-714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2020.08.003

Yang B, Meng F, Zhang J, Chen K, Meng S, Cai K, Zhao Y, Dai L (2023a) Engineered drug delivery nanosystems for tumor microenvironment normalization therapy. Nano Today. 49:101766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nantod.2023.101766

Yang YL, Yang F, Huang ZQ, Li YY, Shi HY, Sun Q, Xu FH (2023b) T cells, NK cells, and tumor-associated macrophages in cancer immunotherapy and the current state of the art of drug delivery systems. Front Immunol 14:1199173. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fimmu.2023.1199173

Yin M, Li X, Tan S, Zhou HJ, Ji W, Bellone S, Min W (2016) Tumorassociated macrophages drive spheroid formation during early transcoelomic metastasis of ovarian cancer. J Clin Invest 126(11):4157-4173. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI87252

Yoshimura A (2024) Fibrosis: from mechanisms to novel treatments. Inflamm Regen 44(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s41232-023-00314-1

Yu J, Xu Z, Guo J, Yang K, Zheng J, Sun X (2021) Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) depend on MMP1 for their cancer-promoting role. Cell Death Discov 7(1):343. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41420-021-00730-7

Yu H, Huang Y, Yang L (2022) Research progress in the use of mesenchymal stem cells and their derived exosomes in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Ageing Res Rev 80:101684. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.arr.2022.101684

Zeng J, Sun Z, Zeng F, Gu C, Chen X (2023a) M2 macrophage-derived exosome-encapsulated microneedles with mild photothermal therapy for accelerated diabetic wound healing. Mater Today Bio 20:100649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100649

Zeng W, Li F, Jin S, Ho PC, Liu PS, Xie X (2023b) Functional polarization of tumor-associated macrophages dictated by metabolic reprogramming. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 42(1):245. https://doi. org/10.1186/s13046-023-02832-9

Zhang BC, Gao J, Wang J, Rao ZG, Wang BC, Gao JF (2011) Tumorassociated macrophages infiltration is associated with peritumoral lymphangiogenesis and poor prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Med Oncol 28(4):1447-1452. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12032-010-9638-5

Zhang QW, Liu L, Gong CY, Shi HS, Zeng YH, Wang XZ, Wei YQ (2012) Prognostic significance of tumor-associated macrophages in solid tumor: a meta-analysis of the literature. PLoS ONE 7(12):e50946. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0050946

Zhang M, He Y, Sun X, Li Q, Wang W, Zhao A, Di W (2014) A high M1/M2 ratio of tumor-associated macrophages is associated with extended survival in ovarian cancer patients. J Ovarian Res 7:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1757-2215-7-19

Zhang X, Huang S, Guo J, Zhou L, You L, Zhang T, Zhao Y (2016) Insights into the distinct roles of MMP-11 in tumor biology and

future therapeutics (Review). Int J Oncol 48(5):1783-1793. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2016.3400

Zhang SY, Song XY, Li Y, Ye LL, Zhou Q, Yang WB (2020) Tumorassociated macrophages: A promising target for a cancer immunotherapeutic strategy. Pharmacol Res 161:105111. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105111

Zhang M, Pan X, Fujiwara K, Jurcak N, Muth S, Zhou J, Zheng L (2021) Pancreatic cancer cells render tumor-associated macrophages metabolically reprogrammed by a GARP and DNA methylation-mediated mechanism. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6(1):366. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00769-z

Zhang J, Wang S, Guo X, Lu Y, Liu X, Jiang M, You J (2022) Arginine supplementation targeting tumor-killing immune cells reconstructs the tumor microenvironment and enhances the antitumor immune response. ACS Nano 16(8):12964-12978. https://doi. org/10.1021/acsnano.2c05408

Zhao X, Chen J, Sun H, Zhang Y, Zou D (2022) New insights into fibrosis from the ECM degradation perspective: the macrophage-MMP-ECM interaction. Cell Biosci 12(1):117. https://doi.org/10. 1186/s13578-022-00856-w

Zhao Y, Du J, Shen X (2023) Targeting myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor immunotherapy: Current, future and beyond. Front Immunol 14:1157537. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu. 2023.1157537

Zhou J, Tang Z, Gao S, Li C, Feng Y, Zhou X (2020a) Tumor-associated macrophages: recent insights and therapies. Front Oncol 10:188. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00188

Zhou K, Cheng T, Zhan J, Peng X, Zhang Y, Wen J, Ying M (2020b) Targeting tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Oncol Lett 20(5):234. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol. 2020.12097

Zhou H, Yin K, Zhang Y, Tian J, Wang S (2021) The RNA m6A writer METTL14 in cancers: Roles, structures, and applications. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 1876(2):188609. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188609

Zhu S, Yi M, Wu Y, Dong B, Wu K (2021) Roles of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor progression: implications on therapeutic strategies. Exp Hematol Oncol 10(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s40164-021-00252-z

Zhu S, Yi M, Wu Y, Dong B, Wu K (2022) Correction to: Roles of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor progression: implications on therapeutic strategies. Exp Hematol Oncol 11(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40164-022-00258-1

Chang CI, Liao JC, Kuo L (2001) Macrophage arginase promotes tumor cell growth and suppresses nitric oxide-mediated tumor cytotoxicity. Cancer Res 61(3):1100-1106. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11221839

Girault I, Tozlu S, Lidereau R, Bieche I (2003). Expression analysis of DNA methyltransferases 1, 3A, and 3B in sporadic breast carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res, 9(12):4415-4422. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14555514

Gong L, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Ruan Z (2016) The macrophage polarization regulates msc osteoblast differentiation in vitro. Ann Clin Lab Sci 46(1):65-71. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pubmed/26927345

Hibbs JB, Vavrin Z, Taintor RR (1987) L-arginine is required for expression of the activated macrophage effector mechanism causing selective metabolic inhibition in target cells. J Immunol 138(2):550-565. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmed/2432129

Hoskin DW, Mader JS, Furlong SJ, Conrad DM, Blay J (2008) Inhibition of T cell and natural killer cell function by adenosine and its contribution to immune evasion by tumor cells (Review). Int J Oncol 32(3): 527-535. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pubmed/18292929

Laviron M, Boissonnas A (2019) Ontogeny of tumor-associated macrophages. Front Immunol 10: 1799.:https://doi.org/10.3389/ fimmu.2019.01799

Mills CD, Shearer J, Evans R, Caldwell MD (1992). Macrophage arginine metabolism and the inhibition or stimulation of cancer. J Immunol 149(8), 2709-2714. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1401910

Mills CD (1991) Molecular basis of “suppressor” macrophages. Arginine metabolism via the nitric oxide synthetase pathway. J Immunol 146(8):2719-2723. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pubmed/1707918

Nakayama Y, Nagashima N, Minagawa N, Inoue Y, Katsuki T, Onitsuka K, Itoh H (2002) Relationships between tumor-associated macrophages and clinicopathological factors in patients with colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res 22(6C):4291-4296. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12553072

Yusen W, Xia W, Shengjun Y, Shaohui Z, Hongzhen Z (2018) The expression and significance of tumor associated macrophages and CXCR4 in non-small cell lung cancer. J BUON 23(2):398-402. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29745083

- Siyu Chen

siyu.chen@shsmu.edu.cn

Department of Oncology, Xin Hua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200092, China

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-024-05777-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38713256

Publication Date: 2024-05-07

REVIEW

The role of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor immune evasion

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

Background Tumor growth is closely linked to the activities of various cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME), particularly immune cells. During tumor progression, circulating monocytes and macrophages are recruited, altering the TME and accelerating growth. These macrophages adjust their functions in response to signals from tumor and stromal cells. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), similar to M2 macrophages, are key regulators in the TME. Methods We review the origins, characteristics, and functions of TAMs within the TME. This analysis includes the mechanisms through which TAMs facilitate immune evasion and promote tumor metastasis. Additionally, we explore potential therapeutic strategies that target TAMs. Results TAMs are instrumental in mediating tumor immune evasion and malignant behaviors. They release cytokines that inhibit effector immune cells and attract additional immunosuppressive cells to the TME. TAMs primarily target effector T cells, inducing exhaustion directly, influencing activity indirectly through cellular interactions, or suppressing through immune checkpoints. Additionally, TAMs are directly involved in tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. Summary Developing innovative tumor-targeted therapies and immunotherapeutic strategies is currently a promising focus in oncology. Given the pivotal role of TAMs in immune evasion, several therapeutic approaches have been devised to target them. These include leveraging epigenetics, metabolic reprogramming, and cellular engineering to repolarize TAMs, inhibiting their recruitment and activity, and using TAMs as drug delivery vehicles. Although some of these strategies remain distant from clinical application, we believe that future therapies targeting TAMs will offer significant benefits to cancer patients.

Introduction

Overview of the TME

substances encourage tumor expansion and alter the surrounding extracellular matrix, thus aiding the invasion and spread of tumor cells.

Concept and significance of immune evasion in cancer

Overview of TAMs

in clinicopathology have implied that an accumulation of TAMs within tumors is linked with unfavorable clinical outcomes. Consistent with these findings, a range of experimental and animal model studies have supported the notion that TAMs may contribute to creating a favorable environment for both the emergence and progression of tumors. This concept is reinforced by observations across different types of research, highlighting TAMs potential impact on tumor dynamics (Chanmee et al. 2014).

Origin of TAMs

Proportion and significance of TAMs in the TME

differentiate into two phenotypes, M1 and M2, stimulated by more cytokines in the TME, and ultimately exert specific effects on tumor cells and other immune cells within the TME. The image was created using https://www.biorender.com/

treatment regimens (Zhou et al. 2020a, b, c). Furthermore, TAMs have been associated with drug resistance, a trait that further delineates their role in therapy evasion and underscores the challenges in cancer treatment (Pan et al. 2020). TAMs exhibit a remarkable degree of functional plasticity, manifested through their polarization into M1-like and M2-like TAMs. This functional diversity plays a critical role in dictating the immunological landscape of the TME. The ability to alter their functional phenotype also presents a potential avenue for therapeutic interventions targeting TAMs repolarization. For instance, reversing the tumor hypoxia microenvironment has aided TAMs repolarization, suggesting the prospect of developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting TAMs (Yang et al. 2020a, b). The extensive understanding of the roles and significance of TAMs within the TME has spurred the exploration of TAM-targeted cancer immunotherapies. Despite the promising strides, challenges remain in optimizing such strategies for enhanced clinical efficacy. Moreover, the expression of various molecular mediators by TAMs, including cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, further elucidates their integral roles in tumor progression and immune modulation (Zhu et al. 2022).

Epigenetic modifications of TAMs

activation. METTL3-driven methylation positively regulates macrophage activation by accelerating the decay of IRKAM transcripts that inhibit TLR signaling (Tong et al. 2021). Furthermore, METTL3 promotes M1 macrophage polarization through m6A-mediated enhancement of STAT1 expression. METTL14 maintains negative feedback control of TLR4/NF-

Subtypes of TAMs and their biological characteristics

disease. Generally speaking, M1 macrophages are essential in driving inflammatory responses and fighting against tumors, whereas M2 macrophages promote anti-inflammatory effects and support tumor growth (Chanmee et al. 2014). However, the role of TAMs in different tumor tissues is complex, with TAMs characterized by different markers influencing various aspects such as cancer typing, clinical staging, prognosis, etc. Here, we summarize the phenotype and function of TAMs in some common tumor types (Table 1).

Characteristics and functions of M1 macrophages

Characteristics and functions of M2 macrophages

Expression of Anti-inflammatory Molecules and Immune Regulation

Tissue repair and healing

| Types of cancer | TAMs markers | TAMs Function | References | |||||||||||

| Breast cancer |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Colorectal cancer |

|

|

(Edin et al. 2012; Nakayama et al. 2002; Sickert et al. 2005; Cavnar et al. 2017; Shabo et al. 2009) | |||||||||||

| Non-small cell lung cancer |

|

|

(Almatroodi et al. 2016; Rakaee et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2011; Yusen et al. 2018; Li et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2015; La Fleur et al. 2018) | |||||||||||

| Ovarian cancer |

|

|

(Lan et al. 2013; No et al. 2013; Yin et al. 2016) | |||||||||||

| Prostate cancer |

|

|

(Lundholm et al. 2015; Takayama et al. 2009) |

Extracellular matrix remodeling

directional movement of cancer cells (Liguori et al. 2011). They actively remodel the ECM through extensive matrix breakdown and production of ECM proteins. The lack of TAMs notably reduces the density and cross-linking of collagen, particularly diminishing the expression of collagen types I and XIV in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (Afik et al. 2016). The assembly of the ECM is a crucial and highly controlled step in the process of tissue repair. When the group of ECM is impaired, it often results in fibrosis, a significant health concern that contributes to a high morbidity and mortality rate (Yoshimura 2024; Zhao et al. 2022). Fibrosis can affect many tissues, including the liver, kidney, lungs, heart, and skin. According to prevailing research, M1 macrophages are generally recognized as initiators of the healing process, whereas M2 macrophages are considered to facilitate the resolution of healing (Spiller and Koh 2017). In cases where the wound healing process is prolonged or does not correctly conclude, a pathological form of fibrosis, driven by Th2 responses and mediated by M2 macrophages, is commonly believed to occur (Wynn and Barron 2010).M2 macrophages promote tissue remodeling and angiogenesis within the TME, contributing to tumor progression ( Liu et al. 2022). They can remodel the TME through interactions with other cells, impacting their number, activity, and phenotype associated with drug resistance (Wang, et al. 2021). M2 macrophages express MARCO, which triggers a sequential remodeling of the endothelium-interstitial matrix, forming a pre-metastatic niche in the microfluidic TME (Cendrowicz et al. 2021). M2 macrophages also express enzymes such as MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-9, MMP-11, MMP-12, and cyclooxygenase-2, which are involved in matrix remodeling and regulation of angiogenesis (Egawa et al. 2013; Hao et al. 2017; Lin et al. 2021). The secretion of MMPs from M2 macrophages, particularly the high expression of MMP-11, plays a crucial role in facilitating cancer cell metastasis, with an overexpression of MMP-11 in M2 macrophages (Saeidi et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2016). This overexpression increases monocyte recruitment and promotes the migration of HER2 + breast cancer cells through the CCL2/CCR2/ MAPK pathway, underscoring the significant impact of TAM-derived MMP-11 on the progression and metastatic potential of breast cancer (Kang et al. 2022).

Metabolic reprogramming of TAMs

Glucose Metabolism Features of TAMs

cellular responses to low oxygen levels, actively promoting the shift towards glycolytic energy production pathways (Semenza 2003). Moreover, HIF-1

Amino Acid and Lipid Metabolism Features of TAMs

fueling the TCA cycle and supporting OXPHOS, thereby generating more energy for TAMs (Huang et al. 2014). Following M2 polarization, genes involved in FA uptake, lipolysis, and FA synthesis are subsequently upregulated. FAO supports the pro-tumor potential of TAMs, as inhibiting FAO may inhibit tumorigenesis by promoting the antitumor properties of TAMs (Niu et al. 2017).

The balance between M1 and M2 and its impact on tumors

demonstrated to induce a tumor-suppressive effect, highlighting the therapeutic potential of modulating macrophage polarization in cancer treatment (Duan and Luo 2021; Zhou et al. 2020a, b, c). This transition can lead to more favorable clinical outcomes, and specific genes are closely associated with M1 macrophages, demonstrating a potential molecular basis for macrophage-related antitumor immunity (Xu et al. 2022a, b, c).

Distinctions between human and murine TAMs

differences (Ingersoll et al. 2010; Martinez et al. 2013). The typical markers for mouse M1 and M2 cells are inducible nitric oxide synthase and Arg1 expression, respectively, neither is expressed in human macrophages (Raes et al. 2005). Moreover, most genes that characterize mouse M1 and M2 cells have unknown functions, complicating the extrapolation of their roles in tumors. Supporting these findings, Zilionis et al. effectively showed that TAMs in lung tumors display distinct profiles based on their species, highlighting the critical need to study human macrophages directly rather than making assumptions based on mouse data (Zilionis et al. 2019).

Role of TAMs in immune evasion

how they interact with other immunosuppressive cell types and their relationship with tumor immune checkpoints to mediate immune evasion.

Immunosuppressive factors released and their implications

provides a protective shield for tumor cells against immune attacks.

Inhibition and exhaustion of T cell functions

promise on the therapeutic frontier. For instance, targeting TREM2 on TAMs or inhibiting NEK2 has been observed to reduce TAMs and alleviate T cell exhaustion, favoring the immune system’s anticancer response (Binnewies et al. 2021; Lischer & Bruns 2023). Moreover, the spatiotemporal dynamics between TAMs and T cells reveal a complex interplay in the TME. A comprehensive understanding of these dynamics is imperative to develop effective therapeutic strategies. The variability in patient responses to treatments can be attributed, at least partially, to the influence of TAMs. This underscores the importance of a more in-depth investigation into the interactions between TAMs and T cells within tumor immunology (Lubitz & Brody 2022).

Promotion of other immunosuppressive cell roles

the intertwined roles of these immunosuppressive cell populations within the TME (Haist et al. 2021).

Relationship between TAMs and tumor immune checkpoints

and the production of oxygen radicals (Molon et al. 2011; Movahedi et al. 2010). Additionally, TAMs contribute to T cell suppression by increasing programmed deathligand 1 (PD-L1) levels and presenting various co-regulatory molecules on their surface (Noman et al. 2012). These molecules include PD-L1, PD-L2, the ligands for CTLA-4 (B7-1 and B7-2), T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (Tim-3), CD47, the V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA), and B7-H4 (Calabrese et al. 2020; Mantovani et al. 2017; Swoboda and Sallman 2020). This array of molecules is linked to T cell exhaustion, a suppressive TME, and unfavorable outcomes in clinical settings.

Association of TAMs with tumor progression

Proliferation

Invasion

Metastasis

Angiogenesis

(Fu et al. 2020). The nexus between TAMs and angiogenesis has a profound impact on tumor growth and extends to the metastatic propensity of tumors as well (Cassetta and Pollard 2023).

Potential therapeutic strategies targeting TAMs

immunosuppression, devising strategies to modulate TAM activity or exploit their functionalities could substantially augment the efficacy of cancer therapies.

Repolarizing TAMs phenotypes

TAMs repolarization by epigenetic intervention

TAMs repolarization by metabolic reprogramming

differentiation by increasing glutamine levels. Ablation of GS promotes M1-like reprogramming in TAMs and leads to CTL accumulation (Palmieri et al. 2017). Studies show that GS inhibition by methionine sulfoximine (MSO) biases M2 macrophages toward an M1-like phenotype in IL10-treated macrophages (Palmieri et al. 2017). GS inhibition induces metabolic rewiring involving glucose shunting into the TCA cycle and succinate accumulation. A low

Reprogramming TAMs by using CAR-M

Inhibiting recruitment and activation of TAMs

inhibiting TAMs recruitment and inducing TAMs exhaustion, including inhibiting CSF-1R, blocking CCL2/CCR2, and targeting CD40, among others (Zhu et al. 2021). Targeting TAMs for cancer treatment includes promoting phagocytosis of TAMs to tumor cells. Although CSF-1R inhibitor PLX3397 exerts anticancer effects by inhibiting the recruitment of TAMs, signaling also regulates macrophage proliferation and activation (Li et al. 2022). Other strategies in this realm include limiting monocyte recruitment, targeting TAMs activation, reprogramming TAMs into antitumor activity, and targeting TAMs-specific markers (Pan et al. 2020). Current methods are mainly divided into two types: inhibiting pro-tumor TAMs, including inhibiting TAM recruitment and depleting TAMs, and activating antitumor TAMs, which refers to reprogramming pro-tumorigenic macrophages into anti-tumorigenic macrophages (Zhang et al. 2020). Although TAMs targeting strategies focused on macrophage depletion and inhibition of their recruitment have shown limited therapeutic efficacy, trials are still underway with combination therapies (Lopez-Yrigoyen et al. 2021).

Utilizing TAMs as vehicles for drug delivery

Conclusion and outlook

play a significant role in promoting tumor immune escape. Cancer cells, TAMs, and T cells form an interactive triangle. On one hand, TAMs indirectly suppress immune cells or activate immunoregulatory cells, thereby inhibiting the function of cytotoxic T cells in killing cancer cells. On the other hand, after receiving signals from tumor cells, TAMs further turn off T cells by inhibiting their immune checkpoints. TAMs also promote various biological processes in tumor development. Targeting TAMs has been a focal point of research in tumor immunotherapy. Specifically, the re-polarization of TAMs is seen as a promising approach, where from both an epigenetic and metabolic perspective, there is potential to shift TAMs towards an M1 phenotype or reverse the M2 phenotype, ultimately improving the immunosuppressive TME. In recent years, new therapies have emerged, such as the CAR-M therapy using cell engineering to modify macrophages, considered promising in replicating the success of CAR-T therapy in solid tumors.

data supporting the findings of this review are fully accessible to those wishing to consult the original sources.

Declarations

References

Amer HT, Stein U, El Tayebi HM (2022) The monocyte, a maestro in the Tumor Microenvironment (TME) of breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215460

Arlauckas SP, Garren SB, Garris CS, Kohler RH, Oh J, Pittet MJ, Weissleder R (2018) Arg1 expression defines immunosuppressive subsets of tumor-associated macrophages. Theranostics 8(21):5842-5854. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno. 26888

Becker JC, Andersen MH, Schrama D, Thor Straten P (2013) Immunesuppressive properties of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Immunother 62(7):1137-1148. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00262-013-1434-6

Beury DW, Parker KH, Nyandjo M, Sinha P, Carter KA, OstrandRosenberg S (2014) Cross-talk among myeloid-derived suppressor cells, macrophages, and tumor cells impacts the inflammatory milieu of solid tumors. J Leukoc Biol 96(6):1109-1118. https:// doi.org/10.1189/jlb.3A0414-210R

Bhattacharya S, Aggarwal A (2019) M2 macrophages and their role in rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol Int 39(5):769-780. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00296-018-4120-3

Bied M, Ho WW, Ginhoux F, Bleriot C (2023) Roles of macrophages in tumor development: a spatiotemporal perspective. Cell Mol Immunol 20(9):983-992. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41423-023-01061-6

Binnewies M, Pollack JL, Rudolph J, Dash S, Abushawish M, Lee T, Sriram V (2021) Targeting TREM2 on

tumor-associated macrophages enhances immunotherapy. Cell Rep 37(3):109844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021. 109844

Biswas SK, Mantovani A (2010) Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol 11(10):889-896. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni. 1937

Boutilier AJ, Elsawa SF (2021) Macrophage polarization states in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijms22136995

Briana GN, Fengshen K, Ming L, Kristelle C, Mytrang D, Ruth AF, Ming OL (2020) IRF8 governs tumor-associated macrophage control of T cell exhaustion. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/ 2020.03.12.989731

Cao X, Geng Q, Fan D, Wang Q, Wang X, Zhang M, Xiao C (2023) m (6)A methylation: a process reshaping the tumour immune microenvironment and regulating immune evasion. Mol Cancer 22(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-022-01704-8

Cassetta L, Pollard JW (2023) A timeline of tumour-associated macrophage biology. Nat Rev Cancer 23(4):238-257. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41568-022-00547-1

Cendrowicz E, Sas Z, Bremer E, Rygiel TP (2021) The role of macrophages in cancer development and therapy. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13081946

Chanmee T, Ontong P, Konno K, Itano N (2014) Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel) 6(3):1670-1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/cance rs6031670

Chen Y, Zhang X (2017) Pivotal regulators of tissue homeostasis and cancer: macrophages. Exp Hematol Oncol 6:23. https://doi.org/

Chen Y, Song Y, Du W, Gong L, Chang H, Zou Z (2019) Tumor-associated macrophages: an accomplice in solid tumor progression. J Biomed Sci 26(1):78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-019-0568-z

Chen S, Saeed A, Liu Q, Jiang Q, Xu H, Xiao GG, Duo Y (2023) Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8(1):207. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41392-023-01452-1

Cheng C, Huang C, Ma TT, Bian EB, He Y, Zhang L, Li J (2014) SOCS1 hypermethylation mediated by DNMT1 is associated with lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory cytokines in macrophages. Toxicol Lett 225(3):488-497. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.toxlet.2013.12.023