المجلة: Kidney International، المجلد: 106، العدد: 3

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2024.05.015

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38844295

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-05

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2024.05.015

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38844295

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-05

دور المكمل في أمراض الكلى: استنتاجات من مؤتمر جدل حول أمراض الكلى: تحسين النتائج العالمية (KDIGO)

يمكن أن يسبب أو يساهم تنشيط المكمل غير المنضبط في إصابة الكبيبات في العديد من أمراض الكلى. على الرغم من أن تنشيط المكمل يلعب دورًا سببيًا في متلازمة الانحلال الدموي اليوريمي غير النمطية واعتلال الكبيبات C3، فقد أظهرت مجموعة متزايدة من الأدلة على مدى العقد الماضي دورًا لتنشيط المكمل في العديد من أمراض الكلى الأخرى، بما في ذلك اعتلال الكلى السكري والعديد من التهاب الكبيبات. كما زاد عدد العلاجات المثبطة للمكمل المتاحة خلال نفس الفترة. في عام 2022، نظمت أمراض الكلى: تحسين النتائج العالمية (KDIGO) مؤتمرًا للجدل، “دور المكمل في أمراض الكلى”، لمعالجة الدور المتزايد لخلل تنظيم المكمل في الفيزيولوجيا المرضية، والتشخيص، وإدارة مختلف أمراض الكبيبات، السكري.

استلم في 22 ديسمبر 2023؛ تم تنقيحه في 25 أبريل 2024؛ تم قبوله في 22 مايو 2024؛ نُشر على الإنترنت في 4 يونيو 2024

اعتلال الكلى، وأشكال أخرى من متلازمة الانحلال الدموي اليوريمي. استعرض المشاركون في المؤتمر الأدلة على دور المكملات في كونها سببًا رئيسيًا أو ثانويًا في تقدم عدة حالات مرضية واعتبروا كيف يمكن أن تُفيد الأدلة المتعلقة بمشاركة المكملات في إدارة هذه الحالات. وصف المرضى المشاركون الذين يعانون من أمراض متعددة مرتبطة بالمكملات ومقدمو الرعاية مخاوف تتعلق بالتخطيط للحياة، والآثار المحيطة بالاختبارات الجينية، والحاجة إلى تنفيذ شامل للعلاجات الجديدة الفعالة في الممارسة السريرية. تم فحص قيمة المؤشرات الحيوية في مراقبة مسار المرض ودور البيئة الدقيقة الكبيبية في استجابة المكملات، وتم تحديد الفجوات الرئيسية في المعرفة وأولويات البحث.

المجلة الدولية للكلى (2024) 106، 369-391؛https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2024.05.015

اعتلال الكلى، وأشكال أخرى من متلازمة الانحلال الدموي اليوريمي. استعرض المشاركون في المؤتمر الأدلة على دور المكملات في كونها سببًا رئيسيًا أو ثانويًا في تقدم عدة حالات مرضية واعتبروا كيف يمكن أن تُفيد الأدلة المتعلقة بمشاركة المكملات في إدارة هذه الحالات. وصف المرضى المشاركون الذين يعانون من أمراض متعددة مرتبطة بالمكملات ومقدمو الرعاية مخاوف تتعلق بالتخطيط للحياة، والآثار المحيطة بالاختبارات الجينية، والحاجة إلى تنفيذ شامل للعلاجات الجديدة الفعالة في الممارسة السريرية. تم فحص قيمة المؤشرات الحيوية في مراقبة مسار المرض ودور البيئة الدقيقة الكبيبية في استجابة المكملات، وتم تحديد الفجوات الرئيسية في المعرفة وأولويات البحث.

المجلة الدولية للكلى (2024) 106، 369-391؛https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2024.05.015

الكلمات الرئيسية: مثبط المكمل؛ إصابة ناتجة عن المكمل؛ إصابة كبيبية

© 2024 مرض الكلى: تحسين النتائج العالمية (KDIGO). نُشر بواسطة إلسفير إنك نيابة عن الجمعية الدولية لأمراض الكلى. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب ترخيص CC BY-NC-ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

© 2024 مرض الكلى: تحسين النتائج العالمية (KDIGO). نُشر بواسطة إلسفير إنك نيابة عن الجمعية الدولية لأمراض الكلى. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب ترخيص CC BY-NC-ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

في عام 2015، نظمت جمعية تحسين نتائج أمراض الكلى العالمية (KDIGO) مؤتمرًا حول الجدل بشأن مرضين نموذجيين من أمراض الكلى المرتبطة بالتكامل: متلازمة الانحلال الدموي اليوريمي غير النمطية (aHUS) واعتلال الكلية C3.

(C3G).

(C3G).

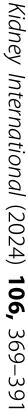

في عام 2022، عقدت KDIGO مؤتمرها الثاني حول القضايا لمناقشة الدور المتنوع والمتزايد لخلل تنظيم المكملات في أمراض الكلى. كان هذا التوقيت مناسبًا، حيث توسعت العلاجات المثبطة للمكملات لأمراض الكلى من الإكوليزوماب ومشتقه طويل المفعول الرابوليزوماب (مثبطات C5 المستخدمة في aHUS) إلى الأفاكوبان (مثبط مستقبلات C5a المستخدم في التهاب الأوعية الدموية المرتبط بالأجسام المضادة للخلايا المتعادلة [ANCA]) وعدد من العوامل العلاجية الجديدة، بعضها في الاستخدام السريري لمؤشرات أخرى (الجدول 1، الشكل 3، والجدول التكميلي S1).

في المؤتمر، قام المشاركون بمراجعة الأدلة المتعلقة بكل مرض تم النظر فيه، لتحديد ما إذا كان المكمل يلعب دورًا أساسيًا أو ثانويًا في المرض وتطوره. كما قام المشاركون بفحص نقدي لقيمة المؤشرات الحيوية لنشاط المكمل في مراقبة مسار المرض، وما إذا كانت المحركات المحددة (أي، الوراثية أو المكتسبة) تعطل نشاط المكمل، والأثر المحتمل/دور البيئة المجهرية الكبيبية في المساهمة في استجابة المكمل. تم وصف كيف أن الأدلة الحالية تؤثر على الإدارة من حيث التقييمات المصلية أو الوراثية أو الأساليب المتعلقة بتثبيط المكمل. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، وصف المرضى ومقدمو الرعاية تجاربهم واهتماماتهم المتعلقة بالتشخيص والتنبؤ والإدارة (الجدول 2).

قدمت المؤتمر فرصة لإعادة النظر في الأدبيات الحالية حول aHUS وC3G لتقييم ما إذا كانت الإرشادات الموضحة في تقرير المؤتمر لعام 2015 تتطلب تحديثًا. بالنسبة للأمراض الأولية (C3G، التهاب كبيبات الكلى الغشائي التكاثري المعتمد على الأجسام المضادة [IC-MPGN]، والأشكال المعتمدة على المكملات من HUS)، كان التركيز على المعلومات الجديدة التي تؤثر على الإدارة منذ اجتماع 2015. بالنسبة لجميع الأمراض، تم تحديد مجالات التوافق (الجدول التكميلي S2) وأهم الفجوات المعرفية ذات الصلة سريريًا والأولويات الرئيسية للبحث (الجدول 3).

العروض التقديمية العامة للمؤتمر متاحة على موقع KDIGO،https://kdigo.org/conferences/controversies-conference-on-complement-in-ckd/.

اعتلال الكلى السكري والتصلب الكبيبي البؤري المتقطع (FSGS)

مرض الكلى السكري

على الرغم من أن البيانات التجريبية الحالية لا تدعم تنشيط المكمل كسبب رئيسي في مرض الكلى السكري (المعروف أيضًا باعتلال الكلى السكري)، تشير عدة أدلة إلى أنه يلعب دورًا مساهمًا في تقدم المرض.

FSGS

في نماذج الحيوانات، هناك أدلة على أن المكمل يتم تفعيله ويلعب دورًا في تقدم FSGS.

الآثار السريرية لإدارة مرض الكلى السكري وFSGS

تدعم الأدلة تنشيط المكملات في مرض الكلى السكري استنادًا إلى دراسات تحليل البول والبلازما والكلى.

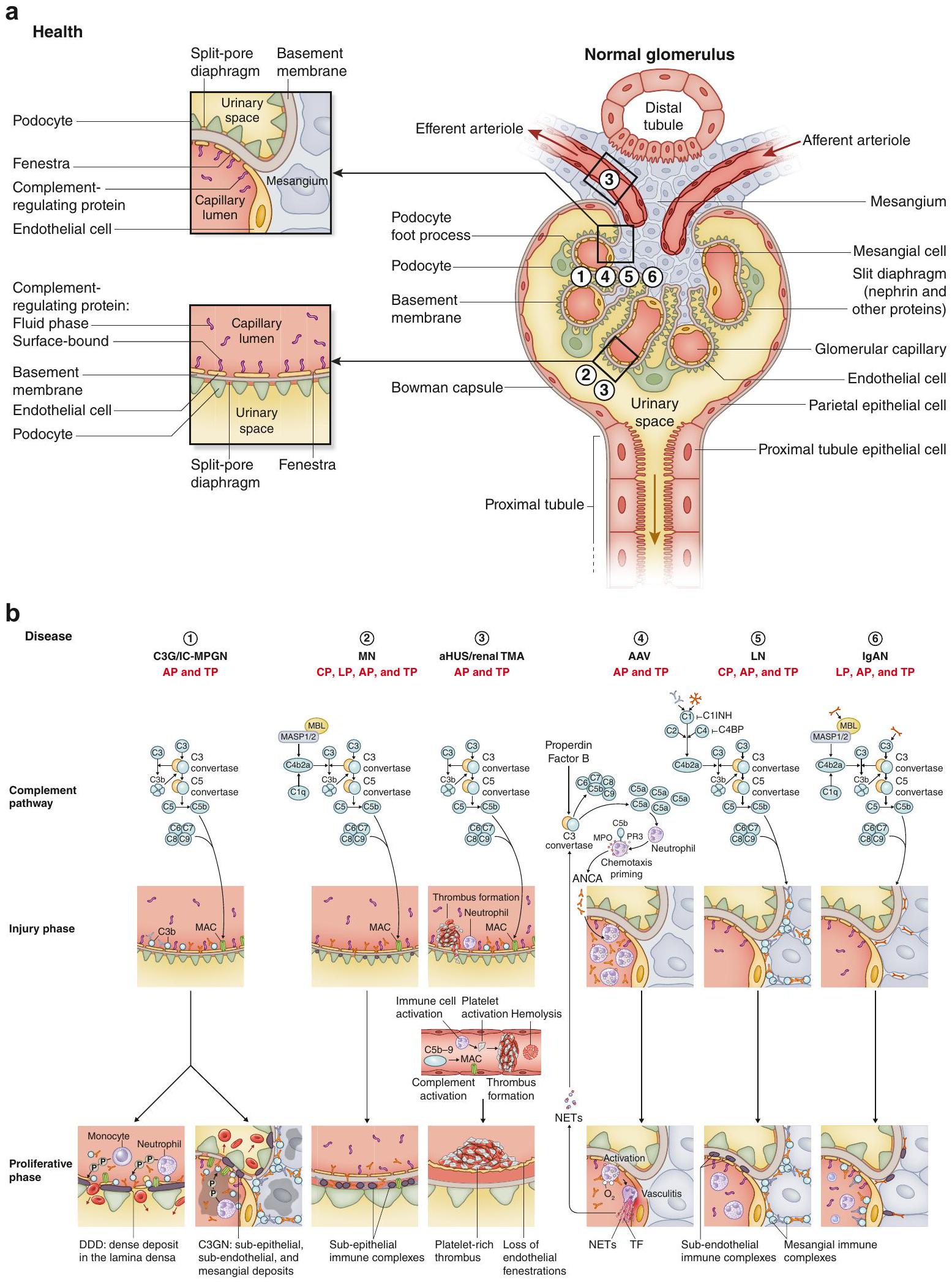

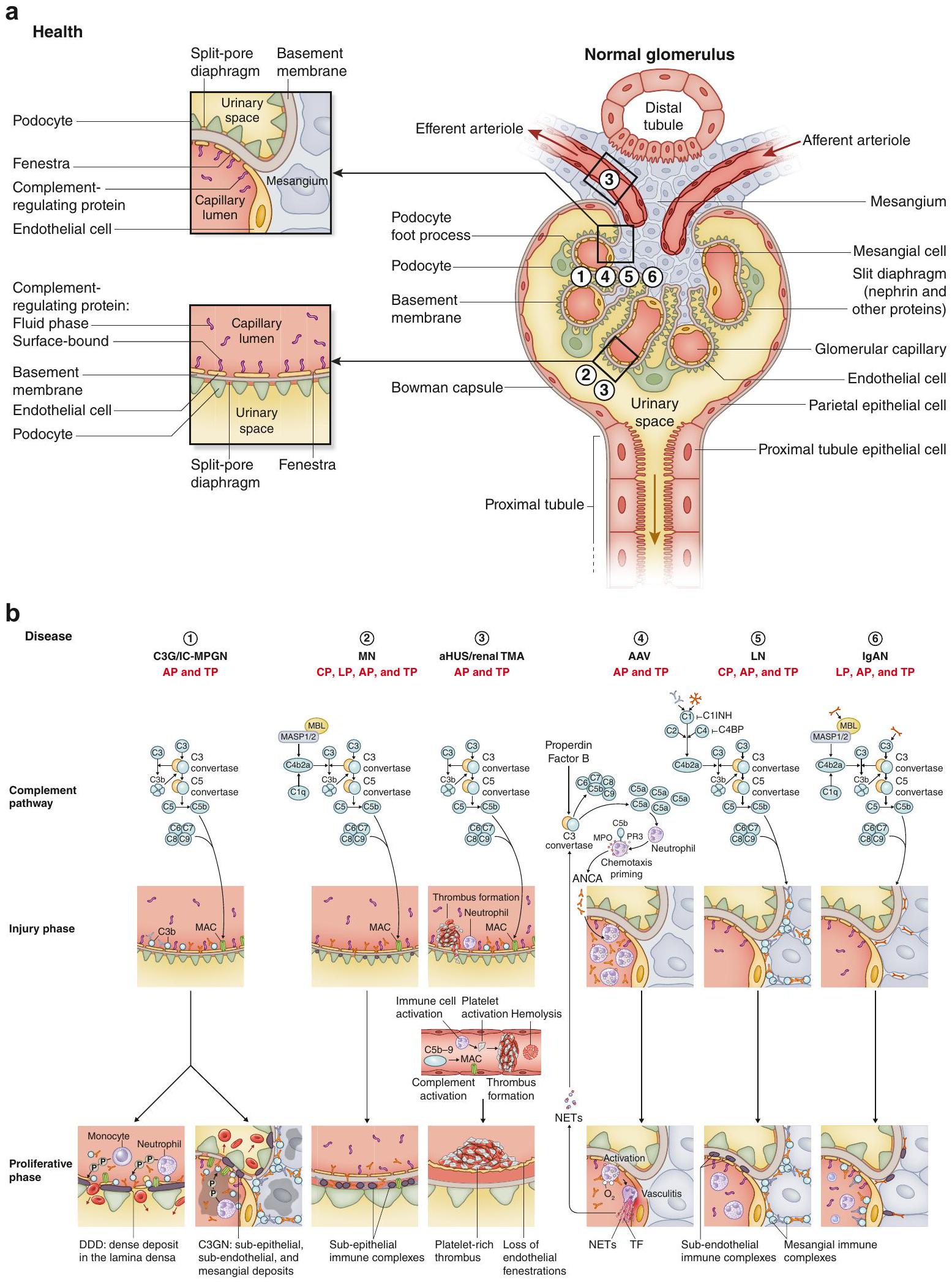

الشكل 1 | دور المكمل في أمراض الكلى المختلفة. يمكن أن يؤدي تنشيط المكمل غير المنضبط إلى التسبب أو المساهمة في إصابة الكبيبات في العديد من أمراض الكلى. (أ) الكبيبة الكلوية هي شبكة شعرية فريدة. تختلف خلايا بطانة الكبيبة الوعائية (GECs) عن معظم خلايا البطانة في أنها مسطحة بشكل استثنائي ومثقبّة بكثافة بواسطة فتحات عبر الخلايا، والتي تشكل

| الأمراض النادرة النموذجية | ||||||||||

| وظيفة المكمل لها دور أساسي | خلل المكمل هو المحرك الثانوي للإصابة | |||||||||

| الأمراض متعددة العوامل الشائعة | ||||||||||

|

|

التهاب كبيبات الكلى الثانوي MPGN الثانوي |

|

|||||||

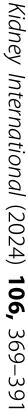

الشكل 2| الأمراض الكلوية الناتجة عن خلل تنظيم المكملات. وجهة نظر متفق عليها تقارن بين الأمراض النادرة ولكن النموذجية التي تتوسطها المكملات مثل متلازمة انحلال الدم اليوريمي غير النمطية (aHUS) واعتلال الكلية الناتج عن مكون المكمل 3 (C3G) مع الأمراض الأكثر تعقيدًا متعددة العوامل التي قد تلعب فيها تنشيط المكملات دورًا ثانويًا في المساهمة في عبء المرض. يتطلب دور المكملات في الأمراض متعددة العوامل التحقق من خلال التجارب السريرية ودراسات مؤشرات المكملات. AAV، التهاب الأوعية الدموية المرتبط بالأجسام المضادة للخلايا المتعادلة (ANCA)؛ APS، متلازمة الأجسام المضادة للفوسفوليبيد؛ FSGS، تصلب الكبيبات البؤري القطاعي؛ IC-MPGN، التهاب كبيبات الكلى الغشائي التكاثري المعتمد على المعقد المناعي؛ IgAN، اعتلال الكلية IgA؛ IgAVN، التهاب الأوعية الدموية المرتبط بـ IgA مع التهاب الكلى؛ MN، اعتلال الكلية الغشائي؛ MPGN، التهاب كبيبات الكلى التكاثري؛ SLE، الذئبة الحمامية الجهازية؛ TMA، الميكروأوعية الدموية التخثرية.

التأثير المحتمل لتثبيط المكمل

الخزعات في كل من المرضى ونماذج الحيوانات.

الخزعات في كل من المرضى ونماذج الحيوانات.

ليس من المعروف ما إذا كان تثبيط المكملات يوفر حماية في اعتلال الكلى السكري.

في كلا الحالتين، قد تكون التصاميم التجريبية المبتكرة (مثل التجارب السلة وتجارب المنصة) مفيدة لتقييم الفوائد المحتملة لدى المرضى الذين يظهرون تنشيطًا للمكمل.

التهاب كبيبات الكلى IgA والتهاب الأوعية المرتبط بـ IgA مع التهاب الكلى

تشير البيانات الحالية إلى أن تنشيط المكملات مهم بنفس القدر في مسببات مرض الكلى الناتج عن IgA (IgAN) والتهاب الأوعية المرتبط بـ IgA مع التهاب الكلى (IgAVN).

الشكل 1 | (مستمر) الضرر والإصابة. (ب) يتم تنشيط سلسلة المتممات بشكل مستمر بسبب تفاعل C3. لا تستطيع مكونات المتممات النشطة التمييز بين الذات وغير الذات، حيث يعتمد الصحة على منظمات تنشيط المتممات (RCA) لمنع حدوث الضرر الناتج عن المتممات. تعبر خلايا الكبيبات عن عامل تسريع الانحلال، وبروتين المساعد الغشائي، ومجموعة التمايز 59 (CD59)؛ ومع ذلك، فإن تنظيم المتممات فوق الفتحات يعتمد على بروتينات RCA في الطور السائل مثل العامل H، والعامل I، وبروتين ربط C4b (C4BP)، ومثبط C1. لكل من 6 أمراض كبيبية (اعتلال الكبيبات الناتج عن المكون 3 [C3G]/التهاب كبيبات الكلى الغشائي المرتبط بالمعقد المناعي [IC-MPGN]، التهاب الكلى الغشائي [MN]، متلازمة انحلال الدم اليوريمي غير النمطية [aHUS]، التهاب الأوعية الدموية المرتبط بالأجسام المضادة للخلايا المتعادلة [ANCA] [AAV]، التهاب الكلى الذئبي [LN]، واعتلال الكلى IgA [IgAN])، يتم عرض المسار الرئيسي للمتممات، حيث يؤدي تنشيطه إلى الإصابة، مما ينتقل إلى مرحلة تكاثرية من الضرر الكبيبي. إذا لم يحدث تندب، فمن المتوقع أن تكون العديد من هذه التغيرات الكبيبية قابلة للعكس. مع تزايد عدد العوامل العلاجية التي تستهدف أجزاء مختلفة من سلسلة المتممات، سيكون من الضروري فهم كيف يساهم تنشيط المتممات في هذه الأمراض إذا كنا نرغب في استخدام هذه الأدوية الجديدة بحكمة لتحسين نتائج المرضى. AP، المسار البديل؛ C1INH، مثبط استراز C1؛ CP، المسار الكلاسيكي؛ DDD، مرض الترسب الكثيف؛ IgAVN، التهاب الأوعية المرتبط بـ IgA مع التهاب الكلى؛ LP، المسار المحفز؛ MAC، معقد الهجوم الغشائي؛ MASP، بروتين السيرين المرتبط بالليكتين (MBL)؛ MPO، ميويلوبيروكسيداز؛ NET، مصائد الخلايا المتعادلة خارج الخلوية؛ PR3، بروتيناز 3؛ TF، عامل الأنسجة؛ TMA، الميكروأوعية التخثرية؛ TP، المسار النهائي.

الجدول 1 | مثبطات المكملات في التطوير السريري

| هدف التثبيط | دواء | نوع المثبط | آلية | مسار | التجارب السريرية | ||||||

| C1 | ANX009 | أجسام مضادة | يعيق تفاعلات ركيزة C1q | SC | NCT05780515 (التهاب الكلى الذئبي، المرحلة 1، قيد التجنيد) | ||||||

| C3، C3b | بيغسيتاكوبلان | الببتيدات المرتبطة بالبولي إيثيلين جلايكول | يرتبط بـ C3 و C3b ويمنع التفاعل والنشاط لمحوّلات C3 و C5 في المسارات الكلاسيكية والليكتين والبديلة | SC مرتين في الأسبوع |

|

||||||

| C3 | AMY101 | ببتيد صغير | يرتبط بـ C3 ويمنع ارتباطه وتقطيعه بواسطة محولات C3 إلى C3a و C3b | الرابع | NCT03316521 (المرحلة 1 متطوعين أصحاء من الذكور، مكتمل) | ||||||

| C3 | ARO-C3 | RNA صغيرة متداخلة | يعيق تخليق C3 في الكبد | SC | NCT05083364 (المرحلة 1/2a تصعيد الجرعة: متطوعون أصحاء، مرضى بالغون يعانون من C3G وIgAN، قيد التجنيد) | ||||||

| C3b، C5 | كي بي 104 | الأجسام المضادة بالإضافة إلى مجال تنظيم العامل H | يعيق المسارات البديلة والنهائية | الرابع |

|

||||||

| C5 | سيمديسيران | RNA صغيرة متداخلة | يمنع تخليق C5 في الكبد | SC | NCT03841448 (IgAN، المرحلة 2، مكتمل)

|

||||||

| C5 | كروفاليماب | أجسام مضادة | يمنع انقسام C5 بواسطة المحول C5 | وريدياً، ثم تحت الجلد |

|

||||||

| C5 | إيكوليزوماب | أجسام مضادة | يمنع انقسام C5 بواسطة المحول C5 | الرابع |

|

||||||

| C5 | جيفوروليماب (ALXN1720) | جسم مصغر ثنائي التخصص | يرتبط بـ C5، مما يمنع انقسامه إلى C5a و C5b. كما أنه يرتبط بالألبومين، مما يزيد من نصف عمره. | SC | NCT05314231 (بروتينوريا، المرحلة 1B، مكتمل) | ||||||

| C5 | رافوليزوماب | أجسام مضادة | يمنع انقسام C5 بواسطة المحول C5 | الرابع، تحت الجلد |

|

الجدول 1 | (مستمر) مثبطات المكملات في التطوير السريري

| هدف التثبيط | دواء | نوع المثبط | آلية | مسار | التجارب السريرية | ||||||||

| C5 | نوماكوبان أو كوفرسين (rVA576) | بروتين صغير | يمنع تنشيط المكمل النهائي من خلال الارتباط بإحكام بـ C5 ومنع إفراز C5a وتكوين C5b-9، ويمنع الليوكوترين B4 عن طريق التقاط الأحماض الدهنية داخل جسم بروتين النوموكوبان. | SC | NCT04784455 (متلازمة انحلال الدم اليوريمي بعد زراعة النخاع العظمي للأطفال، المرحلة 3، قيد التجنيد) | ||||||||

| C5a | فيلوبليماب (IFX-1) | أجسام مضادة | يمنع نشاط C5a بشكل انتقائي مع ترك MAC intact | الرابع |

|

||||||||

| C5aR1 | أفاكوبان | جزيء صغير | يمنع ارتباط الأنفيلاكتوكين C5a بمستقبل C5aR1 | عن طريق الفم مرتين يومياً |

|

||||||||

| العامل ب | أيونيس-إف بي-أل آر إكس | أوليغونوكليوتيد مضاد | يعيق تخليق العامل ب في الكبد | SC |

|

||||||||

| العامل ب | إبتاكوبان (LNP023) | جزيء صغير | يمنع نشاط إنزيمات التحويل C3 و C5 في المسار البديل | عن طريق الفم مرتين يومياً |

|

||||||||

| عامل Bb | NM8074 | الأجسام المضادة وحيدة النسيلة | من خلال ربط Bb، فإنه قادر على تثبيط كل من المحولات C3 وC5 وتكوين MAC. | الرابع |

|

||||||||

| العامل D | BCX10013 | جزيء صغير | يمنع تكوين المحولات C3 و C5 في المسار البديل بشكل أكثر كفاءة من BCX9930 | عن طريق الفم مرة واحدة يومياً | NCT06100900 (PNH، المرحلة 1، زيادة الجرعة) |

| العامل D | دانيكوبان (ALXN2040، ACH-4471) | جزيء صغير | يمنع تكوين المحولات C3 و C5 في المسار البديل | عن طريق الفم مرتين يومياً |

|

|||||

|

العامل D | فيميركوبان (ALXN2050، ACH0145228) | جزيء صغير | يمنع تكوين المحولات C3 و C5 في المسار البديل | شفوي | NCT05097989 (IgAN أو LN، المرحلة 2، قيد التجنيد) | ||||

| ماسپ-2 | CM338 | الأجسام المضادة وحيدة النسيلة | يعيق بدء مسار الليكتين | SC | NCT05775042 (IgAN، المرحلة 2، قيد التجنيد) | |||||

| ماسپ-2 | نارسوبليما (OMS721) | أجسام مضادة | يعيق بدء مسار الليكتين | الرابع |

|

|||||

| ماسپ-3 | OMS906 | أجسام مضادة | يعيق بدء مسار الليكتين | الرابع | NCT06209736 (C3G، IC-MPGN، المرحلة 2، لم يبدأ التسجيل بعد) | |||||

| رينين

|

أليسكيرين | جزيء صغير | يمنع انقسام C3 الذي يتم بوساطة الرينين | فموي | NCT04183101 (C3G، المرحلة 2، قيد التجنيد) | |||||

|

| العامل D | دانيكوبان (ALXN2040، ACH-4471) | جزيء صغير | يمنع تكوين المحولات C3 و C5 في المسار البديل | عن طريق الفم مرتين يومياً |

|

||||

| العامل D | فيميركوبان (ALXN2050، ACH0145228) | جزيء صغير | يمنع تكوين C3 و C5 المحولات في المسار البديل | عن طريق الفم | NCT05097989 (IgAN أو LN، المرحلة 2، قيد التجنيد) | ||||

| MASP-2 | CM338 | أجسام مضادة وحيدة النسيلة | يعيق بدء مسار اللكتين | SC | NCT05775042 (IgAN، المرحلة 2، قيد التجنيد) | ||||

| MASP-2 | نارسوبليماب (OMS721) | أجسام مضادة | يعيق بدء مسار اللكتين | IV |

|

||||

| MASP-3 | OMS906 | أجسام مضادة | يعيق بدء مسار اللكتين | IV | NCT06209736 (C3G، IC-MPGN، المرحلة 2، لم يتم التجنيد بعد) | ||||

| رينين

|

أليسكيرين | جزيء صغير | يعيق انقسام C3 بواسطة الرينين | عن طريق الفم | NCT04183101 (C3G، المرحلة 2، قيد التجنيد) |

متلازمة؛ GPA، التهاب الأوعية الدموية الحبيبي؛ HUS، متلازمة انحلال الدم اليوريمي؛ IC-MPGN، التهاب كبيبات الكلى المناعي؛ IgAN، اعتلال الكلى IgA؛ IV، عن طريق الوريد؛ LN، التهاب الكلى الذئبي؛ MAC،

مركب الهجوم الغشائي (C5b-9)؛ MASP، إنزيم سيرين المرتبط باللكتين المرتبط بالمانان؛ MN، اعتلال الكلى الغشائي؛ MPA، التهاب الأوعية الدقيقة؛ PNH، بيلة دموية ليلية متقطعة؛ SC، تحت الجلد؛ STEC، الإشريكية القولونية المنتجة للسموم شيجا؛ TMA، ميكروأوعية دموية خثارية.

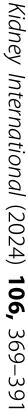

الشكل 3| مثبطات علاجية لنشاط المكمل. في المستقبل القريب، ستتوفر أدوية متعددة تستهدف نظام المكمل. من المحتمل جدًا أن يختلف تأثير الدواء اعتمادًا على عملية المرض الأساسية وعوامل محددة للمريض مثل وجود متغيرات جينية في جينات المكمل أو الأجسام المضادة الذاتية لمكونات المكمل المختلفة، مما سيجعل الطب الدقيق ممكنًا. العوامل المكتوبة بخط عريض وصلت إلى المرحلة 3 أو لاحقًا في التطوير. CD59، دفاع المكمل 59؛ DAF، عامل تسريع الانحلال؛ FB، العامل B؛ FH، العامل H؛ FI، العامل I؛ MAC، مركب الهجوم الغشائي؛ MASP، إنزيم سيرين المرتبط باللكتين المرتبط بالمانان؛ MBL، اللكتين المرتبط بالمانان؛ MCP، بروتين المساعد الغشائي؛ TAFla، مثبط انحلال الفيبرين النشط؛ THBD، جين الثrombomodulin.

تلعب دورًا، حيث أظهرت ترسبات Clq الميسانجية أنها تتنبأ بأسوأ النتائج لـ IgAN فقط في السكان الآسيويين.

تشير الدراسات غير المعتمدة في مركز واحد إلى وجود ارتباط في IgAN بين تفاقم النتائج وزيادة علامات تنشيط المكمل في الكلى والبول والدم. تحتاج هذه الدراسات إلى التحقق المستقل، ويجب تقييم العلامات الحيوية لتحديد ما إذا كانت يمكن أن تحسن الدقة التنبؤية لأداة توقع مخاطر IgAN الدولية.

الآثار السريرية

في IgAN وIgAVN، لا توجد حاليًا علامات حيوية مرتبطة بالمكمل معتمدة (صبغات خزعة الكلى، علامات حيوية في البلازما أو البول، وأنماط وراثية) التي تُعلم

التنبؤ، اختيار العلاج، أو مراقبة استجابة العلاج.

التنبؤ، اختيار العلاج، أو مراقبة استجابة العلاج.

هناك حاجة ملحة لتقييم دور العلاجات المكملية في IgAVN،

الجدول 2| مخاوف المرضى ومقدمي الرعاية، الاحتياجات غير الملباة، ووجهات النظر حول الاختبارات الجينية والخزعات المتكررة

المخاوف

- الأمراض الكلوية التي يكون فيها دور اختلال المكمل محوريًا غالبًا ما لا تتوفر لها خيارات علاج فعالة معروفة، مما يؤدي إلى فشل كلوي وخطر التكرار بعد زراعة الكلى

- يمكن أن تؤثر الأمراض الكلوية التي تتضمن فرط تنشيط المكمل بشكل عميق على الحياة اليومية للمرضى ومقدمي الرعاية، مما يحد من المشاركة في الأنشطة المهمة أو ذات المعنى

- بالنسبة للمرضى الشباب، يؤدي نقص بيانات التاريخ الطبيعي إلى عدم اليقين بشأن مسار المرض وتأثيره، مما يمكن أن يؤثر على القرارات المتعلقة بالوظيفة وتخطيط الأسرة

- الأدلة حول الإدارة الصحيحة للعديد من اعتلالات الكلى المرتبطة بالمكمل محدودة من حيث الكمية والجودة، وغالبًا ما تكون الوعي بالعلاجات المبتكرة (سواء في التجارب السريرية أو في السوق) غير كافٍ

- العوامل المعتمدة ليست متاحة عالميًا بسبب محدودية القدرة على تحمل التكاليف

- يؤخر نقص الوعي بالأمراض المرتبطة بالمكمل بين المهنيين الصحيين التشخيص ويعيق الإدارة المثلى

- نظرًا لأن العلاجات المثبطة للمكمل تزيد من خطر العدوى، فإن استخدامها على المدى الطويل قد يكون مقلقًا

الاحتياجات غير الملباة

- فهم أكثر انتشارًا وخبرة في علاج الأمراض الكلوية المرتبطة بالمكمل بين أطباء الكلى في جميع أنحاء العالم

- دراسات التاريخ الطبيعي والعلامات الحيوية في الحالات النادرة

- الوعي بالدراسات الحالية وإمكانية التسجيل بين المرضى ومقدمي الرعاية الصحية

- تصميمات التجارب التي تزيد من احتمال تلقي العلاج النشط إما من خلال نسب غير 1:1 نشط:دواء وهمي أو من خلال تمديد مفتوح

- برامج مع وصول مبكر للعلاج في الفئة العمرية المراهقة/الأطفال بمجرد إثبات السلامة

- توفر علاجات مبتكرة يُعتقد أنها أكثر فعالية من الخيارات الحالية كعلاج خط أول في أشكال المرض العدوانية

- النظر في اعتماد استراتيجيات علاج متسلسلة نظرًا لتنوع مسار المرض واستجابة العلاج داخل بعض الأمراض المرتبطة بالمكمل

الاختبارات الجينية والفحص

- الآراء والتفضيلات بشأن الفحص والاختبار الجيني متغيرة للغاية بين المرضى

- يريد بعض الأفراد معرفة أكبر قدر ممكن عن مرضهم، خاصة إذا كان التشخيص المبكر يمكن أن يؤدي إلى نتائج أفضل

- البعض الآخر لا يريد، خاصة إذا كانت المعرفة غير قابلة للتنفيذ

- ما إذا كانت وكيف يمكن أن تؤثر النتائج الجينية على التأمين أو أهلية الزرع

- المعلومات الدقيقة حول وفهم المخاطر المرتبطة بالمتغيرات الجينية للمرض أمر بالغ الأهمية

- من غير المرغوب فيه استبعاد زراعة الأعضاء من الأقارب الأحياء أو الخضوع لاختيار الأجنة بسبب أليل من غير المحتمل أن يسبب المرض

- يعد الاستشارة الجينية المناسبة والمبنية على معلومات جيدة أمرًا حيويًا، حيث يمكن أن يعاني الآباء من عبء نفسي كبير إذا قيل لهم إنهم نقلوا متغيرًا جينيًا ضارًا إلى طفلهم

خزعة متكررة في سياق تجربة سريرية

- بشكل عام، يتردد المرضى في الخضوع لخزعات متكررة، خاصة في سياق متلازمة انحلال الدم اليوريمي غير النمطية، حيث قد يكون ذلك أكثر خطورة وحيث يتم تأسيس معايير موثوقة أخرى لاستجابة العلاج (مثل عدد الصفائح الدموية، إنزيم اللاكتات ديهيدروجيناز، ومستوى الكرياتينين في المصل)

- ومع ذلك، خاصة في الأمراض الكبيبية ذات نقاط النهاية الفعالية الأقل وضوحًا وتقدم المرض بشكل أكثر تدريجي، يدرك المرضى ومقدمو الرعاية الحاجة إلى إثبات نسيجي لوكيل علاجي يؤثر على تقدم المرض وقد يكونون متحمسين للتعاون في تطوير، من خلال بيانات من خزعات متكررة، طرق تشخيص غير جراحية (مثل تقنيات التصوير الجديدة، علامات حيوية تشخيصية محسنة، وطرق خزعة سائلة)

على وجه الخصوص، العدوى بالبكتيريا المغلفة (حيث قد يتم النظر في التطعيم و/أو المضادات الحيوية الوقائية لمثبطات المسار البديل والنهائي).

اعتلال الكلى الغشائي

التهاب الكلى الغشائي الأولي (MN) مدفوع بإنتاج الأجسام المضادة الذاتية وتكوين معقدات مناعية في الموقع، يتبعه تنشيط المكمل.

وجود العامل C 3

وجود العامل C 3

تظهر معظم خزعات الغدد اللمفاوية الأولية تلوينًا قويًا لـ IgG4 و C3 بواسطة التألق المناعي، مع وجود حد أدنى من C1q.

الجدول 3 | الأسئلة الرئيسية واحتياجات البحث المتعلقة بمشاركة المكملات في أمراض الكلى (الأولويات القصوى مميزة بالخط العريض)

| شرط | فجوات معرفية هامة وأسئلة رئيسية | استراتيجيات البحث والترجمة المحتملة | |||||||||||||

| اعتلال الكلى السكري |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| التصلب الجلدي البؤري |

|

– استخراج الدراسات الشاملة الحالية لعينات الأنسجة، النسخ الجيني، الإيبيجينوم، البروتيوم، الميتابولوم، “كومبليمنتوم” (علم الأوميات المتعلق بالمكملات) | |||||||||||||

| ذئبة | – سواء كان قياس منتجات تنشيط المكملات في البلازما والأنسجة والبول يمكن أن يساهم في توجيه العلاج |

|

|||||||||||||

| APS | – أدوات سريرية لتقييم تنشيط المكمل |

|

|||||||||||||

| AAV |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| إيجان، إيجافن |

|

||||||||||||||

| MN |

|

|

الجدول 3| (مستمر)

| شرط | فجوات معرفية هامة وأسئلة رئيسية | استراتيجيات البحث والترجمة المحتملة | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| أشكال متلازمة انحلال الدم اليوريمي المرتبطة بالملحق |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| IC-MPGN و C3G |

|

|

AAV، التهاب الأوعية الدموية المرتبط بالأجسام المضادة السيتوبلازمية المضادة للعدلات (ANCA)؛ aPL، مضاد الفوسفوليبيد؛ APS، متلازمة الأجسام المضادة المضادة للفوسفوليبيد؛ C3G، اعتلال الكبيبات الناتج عن مكون التكمل 3؛ C5aR، مستقبل C5a؛ C5b-9، مركب الهجوم الغشائي؛ eGFR، معدل الترشيح الكبيبي المقدر؛ FB، العامل B؛ FH، العامل H؛ FSGS، تصلب الكبيبات البؤري القطاعي؛ HUS، متلازمة انحلال الدم اليوريمي؛ IC-MPGN، التهاب الكبيبات المناعي المعتمد على المجمعات؛ IgAN، اعتلال الكلى IgA؛ IgAVN، التهاب الأوعية الدموية المرتبط بـ IgA مع التهاب الكلى؛ LN، التهاب الكلى الذئبي؛ MN، اعتلال الكلى الغشائي؛ NeF، عامل التهاب الكلى؛ RCT، تجربة سريرية عشوائية محكومة؛ STEC، الإشريكية القولونية المنتجة للسموم شيجا؛ TMA، الميكروأوعية الدموية التخثرية.

مقترحًا مسارات مشابهة لتنشيط التكمل في الأنماط الفرعية المختلفة للمرض (على الرغم من أن نمطًا فرعيًا واحدًا من MN الأولي المرتبط بالأجسام المضادة للبروتوكاديرين-7 يبدو أنه يظهر تلوينًا ضئيلًا لـ C3

مقترحًا مسارات مشابهة لتنشيط التكمل في الأنماط الفرعية المختلفة للمرض (على الرغم من أن نمطًا فرعيًا واحدًا من MN الأولي المرتبط بالأجسام المضادة للبروتوكاديرين-7 يبدو أنه يظهر تلوينًا ضئيلًا لـ C3

الآثار السريرية

تشير الأدلة الحالية بوضوح إلى أن المسارات البديلة، والليكتين، وربما أيضًا المسارات الكلاسيكية للتكمل تلعب دورًا في دفع MN الأولي، ولكن لم يتم التحقق من أي مؤشرات حيوية للتكمل. تجري التجارب السريرية من المرحلة الثانية تقييم تثبيط التكمل

C3، المسار البديل، وتثبيط مسار الليكتين في MN (انظر الجدول 1). في MN الأولي، قد يكون استهداف مسارات الليكتين والبديل مناسبًا، بينما قد يكون تثبيط المسار الكلاسيكي مفيدًا في إدارة الأشكال الثانوية من MN. تشير ملاحظة حديثة لحدوث MN أولي متكرر في مريض يتلقى الإكوليزوماب لعلاج نقص عامل التكمل Ideficient aHUS إلى أن استهداف المسار النهائي قد لا يكون له فعالية كبيرة.

الذئبة الحمراء الجهازية (SLE)

في SLE، تسبب آليات فعالة متعددة التهاب الكبيبات. استنادًا إلى بيانات نماذج حيوانية، تقوم المجمعات المناعية بتحفيز التهاب الكبيبات من خلال ارتباط مستقبل Fc وتنشيط المسارات الكلاسيكية والنهائية، على الرغم من أن المسار البديل هو الذي يدفع الكثير من تلف الكلى.

لـ SLE. ومع ذلك، يقوم Clq بتعديل الأيض الميتوكوندري لـ CD8+ T cells، مما يخفف من الاستجابة للمستضدات الذاتية. قد يفسر هذا الرابط بين Clq و

لـ SLE. ومع ذلك، يقوم Clq بتعديل الأيض الميتوكوندري لـ CD8+ T cells، مما يخفف من الاستجابة للمستضدات الذاتية. قد يفسر هذا الرابط بين Clq و

الآثار السريرية

تتنبأ مستويات C3 وC4 الدائرية المنخفضة بالاستجابة للبليموماب،

هناك العديد من التقارير التي تقيم شظايا تنشيط التكمل كعلامات حيوية سريرية في SLE.

متلازمة الأجسام المضادة المضادة للفوسفوليبيد (APS)

يُعتبر التكمل متورطًا في مسببات 3 أشكال من APS الأولي (الأوعية، والتوليد، والكوارث).

الآثار السريرية

في APS الكارثية، قد يكون استخدام مثبطات التكمل خيارًا علاجيًا مناسبًا، وتم إدراج الإكوليزوماب كخيار علاج في توصيات إرشادات التحالف الأوروبي لجمعيات الروماتيزم.

التهاب الأوعية الدموية المرتبط بـ ANCA

تشير الأدلة السابقة الموصوفة في المختبر، وفي الجسم الحي، والسريرية إلى أن تنشيط المكملات يلعب دورًا في تطور التهاب الأوعية الدموية المرتبط بالتهاب الكلى.

التفاعل مع مستقبل C5a وليس مع معقد الهجوم الغشائي هو الذي يقود التهاب الكبيبات. أظهرت الدراسات في المختبر أن تنشيط الخلايا المهيأة (أي، عامل نخر الورم-

التفاعل مع مستقبل C5a وليس مع معقد الهجوم الغشائي هو الذي يقود التهاب الكبيبات. أظهرت الدراسات في المختبر أن تنشيط الخلايا المهيأة (أي، عامل نخر الورم-

الآثار السريرية

تدعم بيانات التجارب السريرية استخدام الأفاكوبان (حجب C5aR1) كعلاج يقلل من استخدام الستيرويدات في التهاب الأوعية الدموية المرتبط بالتهاب الكبيبات (التهاب الأوعية الدموية مع التهاب حبيبي والتهاب الأوعية الدموية المجهرية؛ الجدول التكميلي S1).

TMAs، أشكال HUS المدعومة بالمكملات – المصطلحات

تحتاج المصطلحات الحالية للـ HUS غير النمطية، الأولية، والثانوية إلى تحديث لأنها مربكة ولا تعكس الآلية المرضية. قامت مؤسسة الكلى الوطنية مؤخرًا بمراجعة طيف الحالات المرتبطة بالـ TMA واقترحت نهجًا تشخيصيًا يجب أن يعكس في المثالي الآليات المرضية الأساسية، ودور المكملات والعوامل المحفزة الأخرى، والاستجابة لحجب المكملات.

مشاركة المكملات والمرضية المرتبطة بها

تشير الأدلة الحالية بقوة إلى أن اختلال تنظيم المسارات البديلة والنهائية يقود معظم أشكال متلازمة الانحلال الدموي اليوريمي. بالإضافة إلى اختلال تنظيم المكمل، هناك العديد من الأسباب الأخرى.

بما في ذلك نقص كيناز الدياسيلغليسيرول-ɛ (DGKe)، نقص الكوبالامين-C، الإنترفيرون

بما في ذلك نقص كيناز الدياسيلغليسيرول-ɛ (DGKe)، نقص الكوبالامين-C، الإنترفيرون

يمكن أن تساعد المؤشرات الحيوية (مستويات المكملات والاختبارات الوظيفية؛ الجدول التكميلي S3)، واكتشاف الأجسام المضادة الذاتية ضد العامل H (FH)، وعلم وراثة المكملات في تمييز تنشيط/خلل المكملات المؤقت مقابل الدائم في سياقات محددة. قد يكون تنشيط المكملات ذاتيًا. عدم تنظيم AP الدائم لا يعني بالضرورة تنشيطًا دائمًا يتطلب علاجًا مستمرًا. قد يكون تنشيط المكملات حدثًا يسبب TMA، أو عاملًا معززًا، أو منتجًا ثانويًا. من غير الواضح ما إذا كان هذا التمييز سيكون مفيدًا لإعادة تصنيف TMA/HUS. ومع ذلك، قد يكون مفيدًا للإدارة طويلة الأمد للمرضى، لا سيما في تحديد مدة تثبيط المكملات.

المؤشرات الحيوية

أبرز التقرير من مؤتمر الجدل لعام 2015 الحاجة إلى مؤشرات حيوية محددة يمكن أن تساعد في تشخيص ومراقبة أشكال HUS (TMA) التي تتوسطها المكملات.

حتى الآن، لم يتم التحقق من أي علامة حيوية قادرة على تحديد اختلال تنظيم مكمل AP في سياق HUS للاستخدام السريري في إدارة المرضى واختيار المرشحين لكتلة C5 عند بداية المرض. لا يستبعد ملف مكمل الدم الطبيعي وجود HUS mediated by complement. ومع ذلك، فإن العلامات الحيوية/الاختبارات مفيدة لمراقبة تثبيط المكمل وخطر الانتكاس (مثل اختبار مكمل الدم الكلي [CH50]، C5 الحر، sC5b-9، الأجسام المضادة الذاتية antiFH). في الممارسة الروتينية، يتم استخدام CH50 ومستويات الإكوليزوماب في القاع فقط لتقييم درجة كتلة المكمل النهائية. تم اقتراح اختبارات جديدة تم تطويرها، مثل الاختبارات المعتمدة على الخلايا ex vivo (اختبار خلايا الأوعية الدقيقة الجلدية البشرية-1 واختبار هام المعدل)، لتشخيص ومراقبة أشكال TMA المعتمدة على المكمل.

علم الوراثة

تُدرج الفحوصات الجينية وفحص الأجسام المضادة الذاتية في المرضى الذين يُشتبه في إصابتهم بمتلازمة انحلال الدم اليوريمي المرتبطة بالتكامل في الجدول التكميلي S4. يجب تفسير النتائج الجينية المتعلقة بالتكامل (الطفرات الشائعة والنادرة، تغييرات عدد النسخ، إلخ) من قبل مختبر لديه خبرة في الأمراض المرتبطة بالتكامل. يجب استخدام مصطلح “طفرات” بدلاً من “تحورات”، مع تصنيف الطفرات المحددة على أنها مسببة للأمراض/محتملة التسبب في الأمراض، أو ذات دلالة غير مؤكدة، أو حميدة/محتملة أن تكون حميدة (الجدول التكميلي S5). تمتلك متلازمة انحلال الدم اليوريمي غير النمطية نفاذية متغيرة (منخفضة)، وتعتبر الطفرات النادرة في جينات التكامل عوامل مسببة فقط للمرض.

يمكن أن تحلل الجينات تصنيف خطر تكرار/عودة aHUS بعد توقف العلاج وزراعة الكلى (الشكل التوضيحي التكميلي S1).

قد تفسر تعدد أشكال C5 المقاومة للتثبيط باستخدام الإكوليزوماب والرافوليزوماب، ولكن هذه الحالات نادرة جدًا ومقيدة بشكل رئيسي بالسكان الآسيويين.

العلاج

متاح حاليًا. يعتبر تثبيط C5، عند توفره، هو العلاج القياسي الذهبي للأشكال المعتمدة على المكمل من aHUS.

أو زراعة كبد وكلى مشتركة. من الجدير بالذكر أن الحمل/ما بعد الولادة-HUS، والذي يُعتبر تشخيصًا استبعاديًا، يُعتبر ضمن طيف TMA المعتمد على المكمل في الكلى، وبالتالي يجب علاجه باستخدام تثبيط C5.

أو زراعة كبد وكلى مشتركة. من الجدير بالذكر أن الحمل/ما بعد الولادة-HUS، والذي يُعتبر تشخيصًا استبعاديًا، يُعتبر ضمن طيف TMA المعتمد على المكمل في الكلى، وبالتالي يجب علاجه باستخدام تثبيط C5.

الناشئة. بالنسبة للمرحلة الحادة و/أو مرحلة الشفاء، تتوفر أو قيد التطوير مجموعة متنوعة من مثبطات C5، بما في ذلك الأجسام المضادة، والـ RNA الصغيرة المتداخلة، والأدوية قصيرة وطويلة المفعول مع طرق متعددة للإدارة. استهداف المسار البديل عند مستوى تنشيط C3/FB/تثبيط العامل D هو بديل محتمل (الجدول 1؛ الشكل 3). بشكل عام، نظرًا لشدة المرض، يجب أن يقتصر استخدام أي عوامل ناشئة بشكل أساسي على الحفاظ على الشفاء حتى يتم إثبات عدم تفوقها على الإكوليزوماب بوضوح في المرحلة الحادة. تظهر البيانات الحالية (الجدول التكميلي S1) فعالية الرافوليزوماب عند البداية وفي مرحلة الصيانة، خاصة في الأطفال.

وقف العلاج. بمجرد تحسن وظيفة الكلى واستقرارها، يجب النظر في التوقف عن العلاج لدى المرضى الذين لا يحملون طفرات مسببة للأمراض في جينات المكمل. خطر الانتكاس بعد التوقف في هؤلاء المرضى منخفض جدًا.

تثبيط C5 غير فعال في المرضى الذين لديهم طفرات DGKe أو نقص سيانوكوبالامين C في غياب طفرات المكمل. لا يوجد أيضًا دليل على أن تثبيط المكمل مفيد في الأشكال المتوسطة أو الشديدة من HUS المرتبطة بإنتاج سموم شيغا من الإشريكية القولونية (STEC)،

(الإكوليزوماب في STEC؛ EudraCT 2016-000997-39) العشوائية متوقعة.

(الإكوليزوماب في STEC؛ EudraCT 2016-000997-39) العشوائية متوقعة.

تثبيط المكمل في أشكال أخرى من HUS. لم يتم إثبات زيادة الطفرات المسببة للأمراض في المكمل في أشكال أخرى من TMA. أسفرت البيانات الاستعادية عن نتائج متناقضة بشأن الفائدة من تثبيط C5 على المدى القصير.

مرض الكلى الغشائي المناعي ومرض الكلى الغشائي التكاثري C3

C3G. يظهر C3G عادةً كنمط تكاثري غشائي، على الرغم من أن الأنماط المسننة، والتكاثر داخل الشعيرات الدموية، والنمط الهلالي، والأنماط المتصلبة قد تكون موجودة مع المجهر الضوئي. مع المجهر المناعي الفلوري، يكون C3 هو السائد و Clq عادةً سلبيًا.

IC-MPGN. يتميز IC-MPGN بترسب معقدات مناعية تحتوي على كل من الأجسام المضادة متعددة النسائل والمكمل. هذه الإصابة تنجم تقليديًا عن وجود مستضد مزمن مع أو بدون معقدات مناعية دائرية وعادة ما تكون بسبب العدوى أو المناعة الذاتية.

حقيقة أن MPGN المرتبطة بالأجسام المضادة الأولية نادرة في البالغين. إنها أكثر شيوعًا في الأطفال وغالبًا ما تكون مرتبطة بأدلة جينية و/أو مصلية على عدم تنظيم المسار البديل.

الاختبارات الجينية

جينات C3G و IC-MPGN معقدة، وفي رأي معظم المشاركين، يجب تقييمها في جميع المرضى الذين لديهم C3G سلبية للبارا بروتين و ICMPGN الأولية. تشير الدراسات إلى أن الطفرات النادرة (تكرار الأليل الصغير

.

.

C3G العائلية نادرة وقد ارتبطت بـ (i) إعادة ترتيب جينومي وراثي سائد يؤدي إلى توليد جينات اندماج مرتبطة بـ CFH (CFHR) مع تكرار مجالات التثني المبدئية مثل اعتلال الكلى CFHR5 الكلاسيكي (المتوطنة في قبرص؛ CFHR5/5)، على الرغم من أن أمثلة أخرى تشمل

تحديد عوامل الخطر الجينية غير الأحادية الجين لمرض C3G و IC-MPGN. تؤثر المتغيرات الشائعة في HLA (مستضد الكريات البيضاء البشرية) و C3 و CFH و CD46 (MCP) على خطر الإصابة بمرض C3G و ICMPGN ولكن لها تأثيرات متواضعة فقط (نسبة الأرجحية:

اختبار السيرولوجيا

العوامل الكلوية (NeFs) موجودة في

عادة ما يرتبط وجود NeFs بانخفاض في C3 المتداول وزيادة في منتجات تنشيط المكملات. مرتفع

مع مستويات منخفضة من C 3 (C 3 NeF و C 5 NeF) ومستويات عالية من sC5b-9 (C 5 NeF). C 3 NeF أكثر شيوعًا في مرض الترسبات الكثيفة، وC 5 NeF أكثر شيوعًا في التهاب كبيبات الكلى من النوع C 3 وIC-MPGN.

مع مستويات منخفضة من C 3 (C 3 NeF و C 5 NeF) ومستويات عالية من sC5b-9 (C 5 NeF). C 3 NeF أكثر شيوعًا في مرض الترسبات الكثيفة، وC 5 NeF أكثر شيوعًا في التهاب كبيبات الكلى من النوع C 3 وIC-MPGN.

يجب أن يرافق فحص NeF تحليل علامات البيولوجية التكميلية لتحديد درجة اختلال التنظيم المرافق للمكمل (الجدول التكميلي S6). دور تحليل التجمع في كشف تأثير C 3 NeFs و C5NeFs على التشخيص وتوضيح مسببات المرض واعد ولكنه يحتاج إلى التحقق.

لا توجد اختبارات تجارية لمؤشرات NeF متاحة، ويتم إجراء الاختبارات في مختبرات متخصصة. تعمل العديد من هذه المختبرات بنشاط مع لجنة الاتحاد الدولي لجمعيات المناعة من أجل توحيد وتقييم جودة قياسات المكملات للتحقق المتبادل من اختبارات المكملات وضمان الدقة وإمكانية التكرار في نتائج الاختبارات. يجب التحقق من صحة بروتوكولات مختبرات المرجع الشائعة ونشرها لاختبار الأجسام المضادة الذاتية لـ FH و NeFs ومكونات المكمل الفردية ومنتجات تحللها. إن ارتباط قياسات المكملات بالنتائج السريرية مهم للسماح بتقييم فعالية الأدوية في المستقبل.

الأجسام المضادة الأحادية النسيلة

يجب فحص جميع البالغين الذين تزيد أعمارهم عن 50 عامًا والذين يعانون من C3G/IC-MPGN للكشف عن الغاموباثي الأحادية.

العلاج

التاريخ الطبيعي لـ C3G و IC-MPGN غير مفهوم بشكل كامل، مما يجعل من الصعب تحديد القيمة التنبؤية للمعايير المبكرة للمرض. ومع ذلك، هناك أدلة على أن ميزات الخزعة، والبروتين في البول، ووظيفة الكلى هي علامات تنبؤية مهمة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد تكون مؤشرات المكملات الدائرية في البلازما ذات قيمة تنبؤية.

الأهمية لأن معظم الحالات تظهر تنشيط المكمل في المرحلة السائلة.

الأهمية لأن معظم الحالات تظهر تنشيط المكمل في المرحلة السائلة.

في C3G، تشير تكرارية وتأثير NeFs الوظيفي بالإضافة إلى وجود متغيرات في جينات المكمل المرتبطة بترسب C3 في الكبيبة بقوة إلى أن تنشيط المسار البديل للمكمل يلعب دورًا مركزيًا ومبكرًا في علم الأمراض للمرض. بالنسبة لـ C3G المدفوع بـ (C3NeF) المناعي الذاتي، لم تثبت العلاجات المستهدفة للأجسام المضادة الذاتية فعاليتها، مما يشير إلى أن كميات صغيرة من NeF قد تكون كافية لدفع المرض وأن الإزالة الكاملة غير قابلة للتحقيق مع الاستراتيجيات المثبطة للمناعة المتاحة حاليًا. تعتبر العلاجات المستهدفة للمسار البديل نهجًا جذابًا في هذا المرض وقد تلبي حاجة طبية كبيرة غير ملباة.

العلاجات الداعمة المحددة مفيدة. في الحالات الخفيفة (مثل، البروتين في البول)

للمرضى الذين يعانون من البروتين في البول

مثبطات التكامل الطرفي / علاج البلازما. تشير تقارير الحالات والسلاسل الحالة إلى أن المرض المتقدم بسرعة على شكل هلال أو وجود آفات TMA (أحيانًا ولكن ليس دائمًا مع مستويات مرتفعة من sC5b-9 في الدورة الدموية) من المرجح أن تستجيب للإكوليزوماب.

مع الإيكوليزوماب في بعض المرضى الذين يعانون من هذه العروض الشديدة؛ ومع ذلك، فإن الوصول إلى الإيكوليزوماب محدود جدًا في معظم البلدان. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن ندرة وسرعة فقدان وظيفة الكلى في هؤلاء المرضى تعني أنهم ممثلون بشكل ضعيف في التجارب السريرية، لذا فإن بيانات سلسلة الحالات من غير المرجح أن تكون متاحة قريبًا. يبدو أن فعالية الإيكوليزوماب في الأشكال التقدمية البطيئة من C3G محدودة.

مع الإيكوليزوماب في بعض المرضى الذين يعانون من هذه العروض الشديدة؛ ومع ذلك، فإن الوصول إلى الإيكوليزوماب محدود جدًا في معظم البلدان. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن ندرة وسرعة فقدان وظيفة الكلى في هؤلاء المرضى تعني أنهم ممثلون بشكل ضعيف في التجارب السريرية، لذا فإن بيانات سلسلة الحالات من غير المرجح أن تكون متاحة قريبًا. يبدو أن فعالية الإيكوليزوماب في الأشكال التقدمية البطيئة من C3G محدودة.

قد يقدم تثبيط مسار البديل للمكملات فائدة للمرضى الذين تشير الميزات السريرية أو الكيميائية الحيوية أو النسيجية إلى خطر مرتفع من النتائج السيئة، مثل أولئك الذين لديهم درجة نشاط عالية، ومؤشر مزمن منخفض، وبروتينوريا، ومتلازمة كلوية، أو انخفاض في eGFR. تشير نتائج المرحلة 2 ونتائج المرحلة 3 الأولية مع الأفاكوبان (مضاد C5aR)،

الأدلة التي تدعم تثبيط المكملات أكثر محدودية في IC-MPGN.

نقاط النهاية. النقاط المقترحة لتقييم فعالية العلاج هي انخفاض في البروتينوريا واستقرار أو تحسين في eGFR.

الخزعات ليس بالضرورة غير مقبول للمشاركة في التجارب.

الخزعات ليس بالضرورة غير مقبول للمشاركة في التجارب.

باستثناء البيانات التي تشير إلى فائدة حجب المسار النهائي في حالات مختارة،

الاستنتاجات والاتجاهات المستقبلية

تظهر العديد من خطوط الأدلة أن تنشيط أو اختلال تنظيم المكمل يلعب دورًا ما في مسببات مجموعة متزايدة من أمراض الكلى. على الرغم من أن اختلال تنظيم المسار البديل في aHUS و C3G/ IC-MPGN يبدو أنه المحرك الرئيسي للمرض، في حالات أخرى، قد يلعب المكمل دورًا أكثر دقة، على سبيل المثال، perpetuating إصابة الكبيبات بعد ترسب المعقد المناعي، كما في MN، أو المساهمة في الضرر المزمن، كما في مرض الكلى السكري أو FSGS. مع توفر عدد متزايد من العوامل العلاجية التي تستهدف أجزاء مختلفة من سلسلة المكملات، يتطلب فهم كيفية ومتى استخدامها تحسينًا كبيرًا في قدرتنا على تحديد المسار أو البروتين المعني في كل مريض وتوصيف دوره (مركزي أو هامشي) ومرحلة (حاد أو مزمن). يسلط الجدول 2 الضوء على المخاوف والاحتياجات لدى السكان المرضى التي يجب تكريمها ومعالجتها. يلخص الجدول التكميلي S2 توافق المجموعة حول مكاننا بالنسبة لجميع أمراض الكلى الموصوفة بناءً على الأبحاث المتاحة حاليًا، بينما يحدد الجدول 3 أولويات البحث التي من المحتمل أن تحسن فهمنا لاختلال تنظيم المكمل في أمراض الكلى وتحسين رعاية المرضى. من الضروري أن تكون هناك دراسات علامات حيوية لتحديد لوحات علامات حيوية محددة للمرض يمكن أن تسهل التشخيص، ومراقبة العلاج، و/أو تقييم أمراض الكبيبات المختلفة.

نظرًا لأن هذه الأمراض الكلوية نادرة ومتنوعة في الغالب، يمكن تحقيق تقدم كبير فقط من خلال جهود منسقة ومتعددة الجنسيات لتحديد علامات تنشيط/اختلال تنظيم المكمل، وتوحيد قياسها، وتعزيز تنفيذها العالمي. تحتاج التجارب السريرية التي تهدف إلى تقييم مثبطات المكملات في أمراض الكلى إلى جمع بيانات مصلية، دم كامل، بول، وأنسجة خزعة كلوية بشكل استباقي للتحقق من الأدوات التشخيصية والتنبؤية الحالية والمستقبلية. يجب أن يكون نشر البيانات حول علامات المكمل في الأنسجة والبلازما والبول مطلوبًا في هذه الدراسات. البيانات المحدودة المتاحة بالفعل عن العلامات الحيوية مدرجة في الجدول التكميلي S3. يحتاج جميع أصحاب المصلحة المعنيين (جمعيات المرضى ومقدمي الرعاية، الجمعيات الطبية، السلطات الصحية الوطنية والدولية، والشركات الدوائية) إلى التآزر لتعزيز السجلات، البنوك الحيوية، تبادل البيانات، والوصول المفتوح إلى نتائج التجارب للسماح لفهمنا ومواردنا بالتطور إلى النقطة التي يمكننا فيها بصمة المرضى الأفراد وتقديم تشخيص مبكر ودقيق وعلاج آمن وفعال وميسور التكلفة.

الملحق

المشاركون الإضافيون في المؤتمر

فيديريكو ألبيري، إيطاليا؛ لوكا أنتونوتشي، إيطاليا؛ تاديج أفشين، سلوفينيا؛ أرفيند باجا، الهند؛ إنغيبورغ م. بايما، هولندا؛ ميكيل بلاسكو، إسبانيا؛ صوفي شوفية، فرنسا؛ إتش. تيرينس كوك، المملكة المتحدة؛ باولو كرافيدي، الولايات المتحدة؛ ماري-أجنيس دراجون-دوري، فرنسا؛ لورين فيشر، الولايات المتحدة؛ أغنيس ب. فوكو، الولايات المتحدة؛ أشلي فريزر-أبل، الولايات المتحدة؛ فيرونيك فريمو-باكي، فرنسا؛ نينا غورليتش، ألمانيا؛ مارك هاوس، الولايات المتحدة؛ أليستر همفريز، المملكة المتحدة؛ فيفيكاناند جها، الهند؛ أرين جاوهال، كندا؛ ديفيد كافانا، المملكة المتحدة؛ أندرياس كرونبيكلر، المملكة المتحدة؛ ريتشارد أ. لافاييت، الولايات المتحدة؛ لين د. لانيغ، الولايات المتحدة؛ ماثيو ليمير، كندا؛ موغلي لو كوانتريك، فرنسا؛ كريستوف ليشت، كندا؛ أدريان ليو، سنغافورة؛ ستيفن ب. مكادو، المملكة المتحدة؛ نيكولاس ر. ميدجرال-توماس، المملكة المتحدة؛ بيير لويجي ميروني، إيطاليا؛ يوهان موريلي، بلجيكا؛ كارلا م. نيستر، الولايات المتحدة؛ مانويل براغا، إسبانيا؛ راجا راماشاندران، الهند؛ هيذر ن. رايش، كندا؛ جوزيبي ريموزي، إيطاليا؛ سانتياغو رودريغيز دي قرطبة، إسبانيا؛ غاري روبنسون، المملكة المتحدة؛ بيير رونكو، فرنسا؛ بيتر روسينغ، الدنمارك؛ ديفيد ج. سالانت، الولايات المتحدة؛ سانجيف سيثي، الولايات المتحدة؛ ماريان سيلكجار نيلسن، الدنمارك؛ وين-تشاو سونغ، الولايات المتحدة؛ فابريزيو سبولتي، إيطاليا؛ رونالد ب. تايلور، الولايات المتحدة؛ نيكول ك. أ. ج. فان دي كار، هولندا؛ سيس فان كوتن، هولندا؛ لين وودوارد، المملكة المتحدة؛ يوزهو زانغ، الولايات المتحدة؛ بيتر ف. زيبفل، ألمانيا؛ وماركو زوكاتو، الإمارات العربية المتحدة

الإفصاحات

قدمت KDIGO دعمًا للسفر والكتابة الطبية لجميع المشاركين في المؤتمر. يكشف MV عن مشاركته في التجارب السريرية المدعومة وتلقيه لرسوم استشارية من Alexion وApellis وBayer وBioCryst وChemoCentryx وChinook Therapeutics وNovartis وPurespring Therapeutics وRoche وTravere Therapeutics. يكشف JB عن تلقيه تمويلًا بحثيًا من Alexion وArgenx وNovartis وOmeros؛ ورسوم استشارية من Alexion وAlnylam Pharmaceuticals وArgenx وBioCryst وKira Pharmaceuticals وNovartis وOmeros وQ32 Bio وRoche. يكشف LHB عن تلقيه رسوم استشارية من CANbridge Pharmaceuticals وCerium Pharmaceuticals وNovartis وTravere Therapeutics. يتم دعم LHB جزئيًا من قبل المعهد الوطني للسكري وأمراض الجهاز الهضمي وأمراض الكلى (NIDDK) R01 DK 126978. يكشف FF عن تلقيه رسوم استشارية مدفوعة لمؤسسته من Alexion وApellis وNovartis وRoche وSobi، ومشاركته في اللجان الاستشارية لـ Alexion وApellis وNovartis وRoche وSobi. يكشف DPG عن تلقيه رسوم استشارية من Alexion وAlnylam وNovartis ويعمل كرئيس للجنة الأمراض النادرة في جمعية الكلى البريطانية. يكشف EGdJ عن تلقيه منح أو عقود من الاتحاد الأوروبي وMinisterio de Ciencia e Innovación؛ ورسوم استشارية مدفوعة لمؤسستها من Q32 Bio؛ وأتعاب المتحدثين من Alexion وSobi؛ وعمله كأمين لشبكة التكامل الأوروبية وعضو في مجلس إدارة شبكة التكامل الأوروبية. يكشف MN عن تلقيه منح أو رسوم استشارية من Alexion وBioCryst وChemoCentryx وGemini وNovartis وSobi. تم دعم MN من قبل Fondazione Regionale per la Ricerca Biomedica (Regione Lombardia)، المشروع ERAPERMED2020-151، GA 779282. يكشف MCP عن تلقيه منح مؤسسية من زمالة Wellcome Senior وOmeros؛ ورسوم استشارية من Alexion وAnnexon Biosciences وCatalyst Biosciences وComplement Therapeutics وGemini Therapeutics وGyroscope Therapeutics وPurespring Therapeutics وSobi؛ ومدفوعات لشهادة الخبراء من Osborne Clarke؛ ومدفوعات لعمله كعضو في لجنة مراجعة المنح لـ Barts Charity. MCP هو زميل كبير في Wellcome في العلوم السريرية (212252/Z/18/Z). يعترف بالدعم من المعهد الوطني للبحوث الصحية (NIHR) مركز البحوث البيولوجية القائم في Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service Trust وImperial College London ومن شبكة البحوث السريرية NIHR. الآراء المعبر عنها هي آراء المؤلف وليست بالضرورة آراء خدمة الصحة الوطنية أو NIHR أو وزارة الصحة.

يكشف KS عن تلقيه أتعاب المتحدثين من GSK وNovo Nordisk وPfizer، ومنح مؤسسية من AstraZeneca وBoehringer Ingelheim وGenentech وGilead Sciences وGSK وKKC Corporation وNovartis وRegeneron Pharmaceuticals. يكشف JMT عن تلقيه منح من وزارة الدفاع الأمريكية للمعاهد الوطنية للصحة؛ ورسوم استشارية من وامتلاكه أسهم في Q32 Bio وإمكانية تلقيه دخل من حقوق الملكية منها؛ وأتعاب المتحدثين من مؤسسة الكلى الوطنية الأمريكية؛ ومشاركته في اللجان الاستشارية لـ BioMarin وRocket Pharmaceuticals. يكشف MJ عن المدفوعات التالية لمؤسسته: منح من AstraZeneca؛ ورسوم استشارية من Astellas وAstraZeneca وBayer وBoehringer Ingelheim وCardioRenal وCSL Vifor وGSK وSTADA Eurogenerics وVertex Pharmaceuticals؛ وأتعاب المتحدثين من AstraZeneca وBayer وBoehringer Ingelheim؛ ومدفوعات لشهادة الخبراء من Astellas وSTADA Eurogenerics؛ وتلقيه دعمًا للسفر من AstraZeneca وBoehringer Ingelheim. يكشف MJ أيضًا عن عمله كرئيس مشارك تطوعي لـ KDIGO. يكشف WCW عن تلقيه منح أو عقود من المعاهد الوطنية للصحة؛ ورسوم استشارية من Akebia وArdelyx وAstraZeneca وBayer وBoehringer Ingelheim وGSK وMerck Sharp & Dohme وNatera وPharmacosmos وReata Pharmaceuticals وUnicycive وVera Therapeutics وZydus Lifesciences؛ وأتعاب المتحدثين من GSK وPharmacosmos؛ ودعم السفر من KDIGO؛ ومشاركته في مراقبة سلامة البيانات أو اللجان الاستشارية لـ Akebia/Otsuka وAstraZeneca وBayer وBoehringer Ingelheim/Lilly وGSK وMerck Sharp & Dohme وNatera وPharmacosmos وReata Pharmaceuticals وVera Therapeutics وZydus Lifesciences؛ وعمله كرئيس مشارك لـ KDIGO. يكشف RJHS عن توجيهه لمختبرات الأبحاث الجزيئية للأنف والأذن والحنجرة والكلى. جميع المؤلفين الآخرين أعلنوا عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

يكشف KS عن تلقيه أتعاب المتحدثين من GSK وNovo Nordisk وPfizer، ومنح مؤسسية من AstraZeneca وBoehringer Ingelheim وGenentech وGilead Sciences وGSK وKKC Corporation وNovartis وRegeneron Pharmaceuticals. يكشف JMT عن تلقيه منح من وزارة الدفاع الأمريكية للمعاهد الوطنية للصحة؛ ورسوم استشارية من وامتلاكه أسهم في Q32 Bio وإمكانية تلقيه دخل من حقوق الملكية منها؛ وأتعاب المتحدثين من مؤسسة الكلى الوطنية الأمريكية؛ ومشاركته في اللجان الاستشارية لـ BioMarin وRocket Pharmaceuticals. يكشف MJ عن المدفوعات التالية لمؤسسته: منح من AstraZeneca؛ ورسوم استشارية من Astellas وAstraZeneca وBayer وBoehringer Ingelheim وCardioRenal وCSL Vifor وGSK وSTADA Eurogenerics وVertex Pharmaceuticals؛ وأتعاب المتحدثين من AstraZeneca وBayer وBoehringer Ingelheim؛ ومدفوعات لشهادة الخبراء من Astellas وSTADA Eurogenerics؛ وتلقيه دعمًا للسفر من AstraZeneca وBoehringer Ingelheim. يكشف MJ أيضًا عن عمله كرئيس مشارك تطوعي لـ KDIGO. يكشف WCW عن تلقيه منح أو عقود من المعاهد الوطنية للصحة؛ ورسوم استشارية من Akebia وArdelyx وAstraZeneca وBayer وBoehringer Ingelheim وGSK وMerck Sharp & Dohme وNatera وPharmacosmos وReata Pharmaceuticals وUnicycive وVera Therapeutics وZydus Lifesciences؛ وأتعاب المتحدثين من GSK وPharmacosmos؛ ودعم السفر من KDIGO؛ ومشاركته في مراقبة سلامة البيانات أو اللجان الاستشارية لـ Akebia/Otsuka وAstraZeneca وBayer وBoehringer Ingelheim/Lilly وGSK وMerck Sharp & Dohme وNatera وPharmacosmos وReata Pharmaceuticals وVera Therapeutics وZydus Lifesciences؛ وعمله كرئيس مشارك لـ KDIGO. يكشف RJHS عن توجيهه لمختبرات الأبحاث الجزيئية للأنف والأذن والحنجرة والكلى. جميع المؤلفين الآخرين أعلنوا عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

الشكر والتقدير

كان المؤتمر برعاية مرض الكلى: تحسين النتائج العالمية (KDIGO) وتم دعمه جزئيًا من خلال منح تعليمية غير مقيدة من Alexion وAlnylam Pharmaceuticals وApellis وBioCryst وCalliditas Therapeutics وChemoCentryx وChinook Therapeutics وCSL Vifor وNovartis وOmeros وOtsuka وRoche وSanofi وVisterra.

يشكر المؤلفون ديبي ميزيلز على مساعدتها في الرسوم التوضيحية.

المواد التكميلية متاحة عبر الإنترنت على www.kidneyinternational.org.

المواد التكميلية متاحة عبر الإنترنت على www.kidneyinternational.org.

REFERENCES

- Goodship TH, Cook HT, Fakhouri F, et al. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and C3 glomerulopathy: conclusions from a “Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes” (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2017;91:539-551.

- Thurman JM. Complement and the kidney: an overview. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27:86-94.

- Zipfel PF, Wiech T, Rudnick R, et al. Complement inhibitors in clinical trials for glomerular diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2166.

- Dixon BP, Greenbaum LA, Huang L, et al. Clinical safety and efficacy of pegcetacoplan in a Phase 2 study of patients with C3 glomerulopathy and other complement-mediated glomerular diseases. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8:2284-2293.

- Barratt J, Liew A, Yeo SC, et al. Phase 2 trial of cemdisiran in adult patients with IgA nephropathy: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2024;19:452-462.

- Garnier A, Brochard K, Kwon T, et al. Efficacy and safety of eculizumab in pediatric patients affected by Shiga toxin-related hemolytic and uremic syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;34:1561-1573.

- Bruchfeld A, Magin H, Nachman P, et al. C5a receptor inhibitor avacopan in immunoglobulin A nephropathy-an open-label pilot study. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15:922-928.

- Jayne DRW, Merkel PA, Schall TJ, et al. Avacopan for the treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:599-609.

8a. Barbour S, Makris A, Hladunewich MA, et al. An exploratory trial of an investigational RNA therapeutic, IONIS FB-LRx, for treatment of IgA nephropathy: new interim results [ASN Kidney Week 2023 abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;34:988. - Wong E, Nester C, Cavero T, et al. Efficacy and safety of iptacopan in patients with C3 glomerulopathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8:2754-2764.

- Zhang H, Rizk DV, Perkovic V, et al. Results of a randomized doubleblind placebo-controlled Phase 2 study propose iptacopan as an alternative complement pathway inhibitor for IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2024;105:189-199.

- Nester C, Appel GB, Bomback AS, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with C3G or IC-MPGN treated with the Factor D inhibitor danicopan: final results from two Phase 2 studies. Am J Nephrol. 2022;53:687700.

- Podos SD, Trachtman H, Appel GB, et al. Baseline clinical characteristics and complement biomarkers of patients with C 3 glomerulopathy enrolled in two Phase 2 studies investigating the Factor D inhibitor danicopan. Am J Nephrol. 2022;53:675-686.

- Zhang Y, Martin B, Spies MA, et al. Renin and renin blockade have no role in complement activity. Kidney Int. 2024;105:328-337.

- Dick J, Gan PY, Ford SL, et al. C5a receptor 1 promotes autoimmunity, neutrophil dysfunction and injury in experimental antimyeloperoxidase glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2018;93:615-625.

- Xiao H, Dairaghi DJ, Powers JP, et al. C5a receptor (CD88) blockade protects against MPO-ANCA GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:225231.

- Thomas MC, Brownlee M, Susztak K, et al. Diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15018.

- Reidy K, Kang HM, Hostetter T, et al. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2333-2340.

- Lu Q, Hou Q, Cao K, et al. Complement factor B in high glucose-induced podocyte injury and diabetic kidney disease. JCI Insight. 2021;6: e147716.

- Li L, Wei T, Liu S, et al. Complement C5 activation promotes type 2 diabetic kidney disease via activating STAT3 pathway and disrupting the gut-kidney axis. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:960-974.

- Tan SM, Ziemann M, Thallas-Bonke V, et al. Complement C5a induces renal injury in diabetic kidney disease by disrupting mitochondrial metabolic agility. Diabetes. 2020;69:83-98.

- Morigi M, Perico L, Corna D, et al. C3a receptor blockade protects podocytes from injury in diabetic nephropathy. JCI Insight. 2020;5: e131849.

- Hansen TK, Tarnow L, Thiel S, et al. Association between mannosebinding lectin and vascular complications in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53:1570-1576.

- Saraheimo M, Forsblom C, Hansen TK, et al. Increased levels of mannanbinding lectin in type 1 diabetic patients with incipient and overt nephropathy. Diabetologia. 2005;48:198-202.

- Sheng X, Qiu C, Liu H, et al. Systematic integrated analysis of genetic and epigenetic variation in diabetic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:29013-29024.

- Acosta J, Hettinga J, Flückiger R, et al. Molecular basis for a link between complement and the vascular complications of diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5450-5455.

- Woroniecka KI, Park AS, Mohtat D, et al. Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes. 2011;60:2354-2369.

- Angeletti A, Cantarelli C, Petrosyan A, et al. Loss of decay-accelerating factor triggers podocyte injury and glomerulosclerosis. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20191699.

- Han R, Hu S, Qin W, et al. C3a and suPAR drive versican V1 expression in tubular cells of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. JCI Insight. 2019;4: e122912.

- van de Lest NA, Zandbergen M, Wolterbeek R, et al. Glomerular C4d deposition can precede the development of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2019;96:738-749.

- Thurman JM, Wong M, Renner B, et al. Complement activation in patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. PLoS One. 2015;10: e0136558.

- Trachtman H, Laskowski J, Lee C, et al. Natural antibody and complement activation characterize patients with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2021;321:F505-F516.

- Jiang S, Di D, Jiao Y, et al. Complement deposition predicts worsening kidney function and underlines the clinical significance of the 2010 Renal Pathology Society Classification of Diabetic Nephropathy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:868127.

- Ajjan RA, Schroeder V. Role of complement in diabetes. Mol Immunol. 2019;114:270-277.

- Rauterberg EW, Lieberknecht HM, Wingen AM, et al. Complement membrane attack (MAC) in idiopathic IgA-glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1987;31:820-829.

- Janssen U, Bahlmann F, Kohl J, et al. Activation of the acute phase response and complement C 3 in patients with IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:21-28.

- Nakagawa H, Suzuki S, Haneda M, et al. Significance of glomerular deposition of C3c and C3d in IgA nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 2000;20: 122-128.

- Garcia-Fuentes M, Martin A, Chantler C, et al. Serum complement components in Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Arch Dis Child. 1978;53:417419.

- Dumont C, Merouani A, Ducruet T, et al. Clinical relevance of membrane attack complex deposition in children with IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020;35:843-850.

- Touchard G, Maire P, Beauchant M, et al. Vascular IgA and C3 deposition in gastrointestinal tract of patients with Henoch-Schoenlein purpura. Lancet. 1983;1:771-772.

- Morichau-Beauchant

, Touchard , Maire , et al. Jejunal IgA and C3 deposition in adult Henoch-Schonlein purpura with severe intestinal manifestations. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:1438-1442. - Roos A, Bouwman LH, van Gijlswijk-Janssen DJ, et al. Human IgA activates the complement system via the mannan-binding lectin pathway. J Immunol. 2001;167:2861-2868.

- Roos A, Rastaldi MP, Calvaresi N, et al. Glomerular activation of the lectin pathway of complement in IgA nephropathy is associated with more severe renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1724-1734.

- Segarra A, Romero K, Agraz I, et al. Mesangial C4d deposits in early IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:258-264.

- Guo WY, Zhu L, Meng SJ, et al. Mannose-binding lectin levels could predict prognosis in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:31753181.

- Hisano S, Matsushita M, Fujita T, et al. Activation of the lectin complement pathway in Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:295-302.

- Damman J, Mooyaart AL, Bosch T, et al. Lectin and alternative complement pathway activation in cutaneous manifestations of IgAvasculitis: a new target for therapy? Mol Immunol. 2022;143:114-121.

- Zhu L, Zhai YL, Wang FM, et al. Variants in complement factor H and complement factor H-related protein genes, CFHR3 and CFHR1, affect complement activation in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26: 1195-1204.

- Zhu L, Guo WY, Shi SF, et al. Circulating complement factor H-related protein 5 levels contribute to development and progression of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2018;94:150-158.

- Medjeral-Thomas NR, Lomax-Browne HJ, Beckwith H, et al. Circulating complement factor H-related proteins 1 and 5 correlate with disease activity in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2017;92:942-952.

- Medjeral-Thomas NR, Troldborg A, Constantinou N, et al. Progressive IgA nephropathy is associated with low circulating mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease-3 (MASP-3) and increased glomerular factor H-related protein-5 (FHR5) deposition. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3: 426-438.

- Tan L, Tang Y, Pei G, et al. A multicenter, prospective, observational study to determine association of mesangial C1q deposition with renal outcomes in IgA nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5467.

- Lee HJ, Choi SY, Jeong KH, et al. Association of C1q deposition with renal outcomes in IgA nephropathy. Clin Nephrol. 2013;80:98-104.

- Barbour SJ, Coppo R, Zhang H, et al. Application of the International IgA Nephropathy Prediction Tool one or two years post-biopsy. Kidney Int. 2022;102:160-172.

- Barbour SJ, Canney M, Coppo R, et al. Improving treatment decisions using personalized risk assessment from the International

Nephropathy Prediction Tool. Kidney Int. 2020;98:1009-1019. - Selvaskandan H, Shi S, Twaij S, et al. Monitoring immune responses in IgA nephropathy: biomarkers to guide management. Front Immunol. 2020;11:572754.

- Patel DM, Cantley L, Moeckel G, et al. IgA vasculitis complicated by acute kidney failure with thrombotic microangiopathy: successful use of eculizumab. J Nephrol. 2021;34:2141-2145.

- Selvaskandan H, Kay Cheung C, Dormer J, et al. Inhibition of the lectin pathway of the complement system as a novel approach in the management of IgA vasculitis-associated nephritis. Nephron. 2020;144: 453-458.

- Herzog AL, Wanner C, Amann K, et al. First treatment of relapsing rapidly progressive IgA nephropathy with eculizumab after living kidney donation: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2017;49:1574-1577.

- Nakamura H, Anayama M, Makino M, et al. Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with complement factor H mutation and IgA nephropathy: a case report successfully treated with eculizumab. Nephron. 2018;138:324-327.

- Matsumura D, Tanaka A, Nakamura T, et al. Coexistence of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and crescentic IgA nephropathy treated with eculizumab: a case report. Clin Nephrol Case Stud. 2016;4:24-28.

- Rosenblad T, Rebetz J, Johansson M, et al. Eculizumab treatment for rescue of renal function in IgA nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29: 2225-2228.

- Ring T, Pedersen BB, Salkus G, et al. Use of eculizumab in crescentic IgA nephropathy: proof of principle and conundrum? Clin Kidney J. 2015;8: 489-491.

- Lafayette RA, Rovin BH, Reich HN, et al. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of narsoplimab, a novel MASP-2 inhibitor for the treatment of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:2032-2041.

- Barratt J, Rovin B, Zhang H, et al. POS-546 Efficacy and safety of iptacopan in IgA nephropathy: results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase 2 study at 6 months. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7: S236.

- Kistler AD, Salant DJ. Complement activation and effector pathways in membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2024;105:473-483.

- Salant DJ, Belok S, Madaio MP, et al. A new role for complement in experimental membranous nephropathy in rats. J Clin Invest. 1980;66: 1339-1350.

- Groggel GC, Adler S, Rennke HG, et al. Role of the terminal complement pathway in experimental membranous nephropathy in the rabbit. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1948-1957.

- Cybulsky AV, Quigg RJ, Salant DJ. The membrane attack complex in complement-mediated glomerular epithelial cell injury: formation and stability of C5b-9 and C5b-7 in rat membranous nephropathy. J Immunol. 1986;137:1511-1516.

- Saran AM, Yuan H, Takeuchi E, et al. Complement mediates nephrin redistribution and actin dissociation in experimental membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64:2072-2078.

- Huang CC, Lehman A, Albawardi A, et al. IgG subclass staining in renal biopsies with membranous glomerulonephritis indicates subclass switch during disease progression. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:799805.

- Bally S, Debiec H, Ponard D, et al. Phospholipase A2 receptor-related membranous nephropathy and mannan-binding lectin deficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:3539-3544.

- Espinosa-Hernandez M, Ortega-Salas R, Lopez-Andreu M, et al. C4d as a diagnostic tool in membranous nephropathy. Nefrologia. 2012;32:295299.

- Val-Bernal JF, Garijo MF, Val D, et al. C4d immunohistochemical staining is a sensitive method to confirm immunoreactant deposition in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue in membranous glomerulonephritis. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26:1391-1397.

- Haddad G, Lorenzen JM, Ma H, et al. Altered glycosylation of IgG4 promotes lectin complement pathway activation in anti-PLA2R1associated membranous nephropathy. J Clin Invest. 2021;131: e140453.

- Gao S, Cui Z, Zhao MH. Complement C3a and C3a receptor activation mediates podocyte injuries in the mechanism of primary membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33:1742-1756.

- Hayashi N, Okada K, Matsui Y, et al. Glomerular mannose-binding lectin deposition in intrinsic antigen-related membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33:832-840.

- Sethi S, Madden B, Debiec H, et al. Protocadherin 7-associated membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:1249-1261.

- Hanset N, Aydin S, Demoulin N, et al. Podocyte antigen staining to identify distinct phenotypes and outcomes in membranous nephropathy: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:624-635.

- Sethi S. Membranous nephropathy: a single disease or a pattern of injury resulting from different diseases. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14:2166-2169.

- Seifert L, Zahner G, Meyer-Schwesinger C, et al. The classical pathway triggers pathogenic complement activation in membranous nephropathy. Nat Commun. 2023;14:473.

- Saleem M, Shaikh S, Hu Z, et al. Post-transplant thrombotic microangiopathy due to a pathogenic mutation in complement Factor I in a patient with membranous nephropathy: case report and review of literature. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:909503.

- Birmingham DJ, Irshaid F, Nagaraja HN, et al. The complex nature of serum C3 and C4 as biomarkers of lupus renal flare. Lupus. 2010;19: 1272-1280.

- Kostopoulou M, Ugarte-Gil MF, Pons-Estel B, et al. The association between lupus serology and disease outcomes: a systematic literature review to inform the treat-to-target approach in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2022;31:307-318.

- Macedo AC, Isaac L. Systemic lupus erythematosus and deficiencies of early components of the complement classical pathway. Front Immunol. 2016;7:55.

- Ling GS, Crawford G, Buang N, et al. C1q restrains autoimmunity and viral infection by regulating CD8(+) T cell metabolism. Science. 2018;360:558-563.

- Castrejón I, Tani C, Jolly M, et al. Indices to assess patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in clinical trials, long-term observational studies, and clinical care. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32. S-85-95.

- Weinstein A, Alexander RV, Zack DJ. A review of complement activation in SLE. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2021;23:16.

- Maslen T, Bruce IN, D’Cruz D, et al. Efficacy of belimumab in two serologically distinct high disease activity subgroups of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: post-hoc analysis of data from the phase III programme. Lupus Sci Med. 2021;8:e00045.

- van Vollenhoven RF, Petri MA, Cervera R, et al. Belimumab in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus: high disease activity predictors of response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1343-1349.

- Dall’Era M, Stone D, Levesque V, et al. Identification of biomarkers that predict response to treatment of lupus nephritis with mycophenolate mofetil or pulse cyclophosphamide. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:351357.

- Wisnieski JJ, Baer AN, Christensen J, et al. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. Clinical and serologic findings in 18 patients. Medicine. 1995;74:24-41.

- Pickering MC, Ismajli M, Condon MB, et al. Eculizumab as rescue therapy in severe resistant lupus nephritis. Rheumatology. 2015;54: 2286-2288.

- Coppo R, Peruzzi L, Amore A, et al. Dramatic effects of eculizumab in a child with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis resistant to conventional therapy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:167-172.

- Giles JL, Choy E, van den Berg C, et al. Functional analysis of a complement polymorphism (rs17611) associated with rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol. 2015;194:3029-3034.

- Toy CR, Song H, Nagaraja HN, et al. The influence of an elastasesensitive complement C5 variant on lupus nephritis and its flare. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:2105-2113.

- Pickering MC, Walport MJ. Links between complement abnormalities and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39:133-141.

- Manzi S, Navratil JS, Ruffing MJ, et al. Measurement of erythrocyte C4d and complement receptor 1 in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3596-3604.

- Tedesco F, Borghi MO, Gerosa M, et al. Pathogenic role of complement in antiphospholipid syndrome and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1388.

- Chaturvedi S, Brodsky RA, McCrae KR. Complement in the pathophysiology of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:449.

- Meroni PL, Macor P, Durigutto P, et al. Complement activation in antiphospholipid syndrome and its inhibition to prevent rethrombosis after arterial surgery. Blood. 2016;127:365-367.

- Ruffatti A, Tarzia V, Fedrigo M, et al. Evidence of complement activation in the thrombotic small vessels of a patient with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome treated with eculizumab. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18:561-563.

- Breen KA, Seed P, Parmar K, et al. Complement activation in patients with isolated antiphospholipid antibodies or primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:423-429.

- Oku K, Atsumi T, Bohgaki M, et al. Complement activation in patients with primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68: 1030-1035.

- Lonati PA, Scavone M, Gerosa M, et al. Blood cell-bound C4d as a marker of complement activation in patients with the antiphospholipid syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:773.

- Ruffatti A, Tonello M, Calligaro A, et al. High plasma C5a and C5b-9 levels during quiescent phases are associated to severe antiphospholipid syndrome subsets. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022;40:20882096.

- Nalli C, Lini D, Andreoli L, et al. Low preconception complement levels are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes in a multicenter study of 260 pregnancies in 197 women with antiphospholipid syndrome or carriers of antiphospholipid antibodies. Biomedicines. 2021;9:671.

- Kim MY, Guerra MM, Kaplowitz E, et al. Complement activation predicts adverse pregnancy outcome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and/or antiphospholipid antibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:549-555.

- López-Benjume B, Rodríguez-Pintó I, Amigo MC, et al. Eculizumab use in catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS): descriptive analysis from the “CAPS Registry.”. Autoimmun Rev. 2022;21:103055.

- Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:1296-1304.

- Meroni PL, Borghi MO, Raschi E, et al. Pathogenesis of antiphospholipid syndrome: understanding the antibodies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7: 330-339.

- Chen M, Jayne DRW, Zhao MH. Complement in ANCA-associated vasculitis: mechanisms and implications for management. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:359-367.

- Xing GQ, Chen M, Liu G, et al. Complement activation is involved in renal damage in human antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody associated pauci-immune vasculitis. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29:282-291.

- Gou SJ, Yuan J, Chen M, et al. Circulating complement activation in patients with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Kidney Int. 2013;83:129-137.

- Xiao H, Schreiber A, Heeringa P, et al. Alternative complement pathway in the pathogenesis of disease mediated by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:52-64.

- Schreiber A, Xiao H, Jennette JC, et al. C5a receptor mediates neutrophil activation and ANCA-induced glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:289-298.

- Merkel PA, Niles J, Jimenez R, et al. Adjunctive treatment with avacopan, an oral C5a receptor inhibitor, in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2:662-671.

- Jayne DRW, Bruchfeld AN, Harper L, et al. Randomized trial of C5a receptor inhibitor avacopan in ANCA-associated vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:2756-2767.

117a. Genest DS, Patriquin CJ, Licht C, et al. Renal thrombotic microangiopathy: a review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;81:591-605. - Brocklebank V, Kumar G, Howie AJ, et al. Long-term outcomes and response to treatment in diacylglycerol kinase epsilon nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2020;97:1260-1274.

- Blanc C, Roumenina LT, Ashraf Y, et al. Overall neutralization of complement factor H by autoantibodies in the acute phase of the autoimmune form of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Immunol. 2012;189:3528-3537.

- Noris M, Galbusera M, Gastoldi S, et al. Dynamics of complement activation in aHUS and how to monitor eculizumab therapy. Blood. 2014;124:1715-1726.

- Galbusera M, Noris M, Gastoldi S, et al. An ex vivo test of complement activation on endothelium for individualized eculizumab therapy in hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74:56-72.

- Gavriilaki E, Yuan X, Ye Z, et al. Modified Ham test for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood. 2015;125:3637-3646.

- Caprioli J, Noris M, Brioschi S, et al. Genetics of HUS: The impact of MCP, CFH, and IF mutations on clinical presentation, response to treatment, and outcome. Blood. 2006;108:1267-1279.

- Esparza-Gordillo J, Goicoechea de Jorge E, Buil A, et al. Predisposition to atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome involves the concurrence of different susceptibility alleles in the regulators of complement activation gene cluster in 1q32. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:703-712.

- Arjona E, Huerta A, Goicoechea de Jorge E, et al. Familial risk of developing atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Blood. 2020;136: 1558-1561.

- Zuber J, Frimat M, Caillard S, et al. Use of highly individualized complement blockade has revolutionized clinical outcomes after kidney transplantation and renal epidemiology of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:2449-2463.

- Ariceta G, Fakhouri F, Sartz L, et al. Eculizumab discontinuation in atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome: TMA recurrence risk and renal outcomes. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14:2075-2084.

- Sullivan M, Rybicki LA, Winter A, et al. Age-related penetrance of hereditary atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Ann Hum Genet. 2011;75:639-647.

- Fakhouri F, Fila M, Provôt F, et al. Pathogenic variants in complement genes and risk of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome relapse after eculizumab discontinuation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:50-59.

- Donne RL, Abbs I, Barany P, et al. Recurrence of hemolytic uremic syndrome after live related renal transplantation associated with subsequent de novo disease in the donor. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:E22.

- Nishimura J, Yamamoto M, Hayashi S, et al. Genetic variants in C5 and poor response to eculizumab. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:632-639.

- Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2169-2181.

- Duineveld C , Verhave JC, Berger SP, et al. Living donor kidney transplantation in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70:770-777.

- Ariceta G , Dixon BP , Kim SH , et al. The long-acting C 5 inhibitor, ravulizumab, is effective and safe in pediatric patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome naïve to complement inhibitor treatment. Kidney Int. 2021;100:225-237.

- Rondeau E, Scully M, Ariceta G, et al. The long-acting C5 inhibitor, Ravulizumab, is effective and safe in adult patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome naïve to complement inhibitor treatment. Kidney Int. 2020;97:1287-1296.

- Fakhouri F, Fila M, Hummel A, et al. Eculizumab discontinuation in children and adults with atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome: a prospective multicenter study. Blood. 2021;137:2438-2449.

- Chaturvedi S, Dhaliwal N, Hussain S, et al. Outcomes of a cliniciandirected protocol for discontinuation of complement inhibition therapy in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood Adv. 2021;5:1504-1512.

- Gutstein NL, Wofsy D. Administration of F(ab’)2 fragments of monoclonal antibody to L3T4 inhibits humoral immunity in mice without depleting L3T4+ cells. J Immunol. 1986;137:3414-3419.

- Kielstein JT, Beutel G, Fleig S, et al. Best supportive care and therapeutic plasma exchange with or without eculizumab in Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli O104:H4 induced haemolytic-uraemic syndrome: an analysis of the German STEC-HUS registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:38073815.

- Yesilbas O, Yozgat CY , Akinci N , et al. Acute myocarditis and eculizumab caused severe cholestasis in a 17-month-old child who has hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2021;10:216-220.

- Mauras M, Bacchetta J, Duncan A, et al. Escherichia coli-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome and severe chronic hepatocellular cholestasis: complication or side effect of eculizumab? Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:1289-1293.

- Le Clech A, Simon-Tillaux N, Provôt F, et al. Atypical and secondary hemolytic uremic syndromes have a distinct presentation and no common genetic risk factors. Kidney Int. 2019;95:1443-1452.

- Cavero T, Rabasco C, López A, et al. Eculizumab in secondary atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:466474.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Glomerular Diseases Work Group. KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Glomerular Diseases. Kidney Int. 2021;100(4S):S1S276.

- Zand L, Fervenza FC, Nasr SH, et al. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with autoimmune diseases. J Nephrol. 2014;27:165-171.

- Nasr SH, Radhakrishnan J, D’Agati VD. Bacterial infection-related glomerulonephritis in adults. Kidney Int. 2013;83:792-803.

- Nasr SH, Satoskar A, Markowitz GS, et al. Proliferative glomerulonephritis with monoclonal IgG deposits. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2055-2064.

- Meuleman MS, Vieira-Martins P, El Sissy C, et al. Rare variants in complement gene in C3 glomerulopathy and immunoglobulinmediated membranoproliferative GN. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;18: 1435-1445.

- latropoulos P, Noris M, Mele C, et al. Complement gene variants determine the risk of immunoglobulin-associated MPGN and C3 glomerulopathy and predict long-term renal outcome. Mol Immunol. 2016;71:131-142.

- Bu F, Borsa NG, Jones MB, et al. High-throughput genetic testing for thrombotic microangiopathies and C3 glomerulopathies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:1245-1253.

- Gale DP, Goicoechea de Jorge E, Cook HT, et al. Identification of a mutation in complement factor H-related protein 5 in patients of Cypriot origin with glomerulonephritis. Lancet. 2010;376:794-801.

- Malik TH, Lavin PJ, Goicoechea de Jorge E, et al. A hybrid CFHR3-1 gene causes familial C3 glomerulopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:11551160.

- Tortajada A , Yébenes H, Abarrategui-Garrido C , et al. C 3 glomerulopathy-associated CFHR1 mutation alters FHR oligomerization and complement regulation. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2434-2446.

- Chen Q, Wiesener M, Eberhardt HU , et al. Complement factor H-related hybrid protein deregulates complement in dense deposit disease. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:145-155.

- Togarsimalemath SK, Sethi SK, Duggal R, et al. A novel CFHR1-CFHR5 hybrid leads to a familial dominant C3 glomerulopathy. Kidney Int. 2017;92:876-887.

- Martínez-Barricarte R, Heurich M, Valdes-Cañedo F, et al. Human C3 mutation reveals a mechanism of dense deposit disease pathogenesis and provides insights into complement activation and regulation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3702-3712.

- Chauvet S , Roumenina LT, Bruneau S , et al. A familial C3GN secondary to defective C3 regulation by complement receptor 1 and complement Factor H. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:1665-1677.

- Levy M, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L, Gubler MC, et al. H deficiency in two brothers with atypical dense intramembranous deposit disease. Kidney Int. 1986;30:949-956.

- Ault BH, Schmidt BZ, Fowler NL, et al. Human factor H deficiency. Mutations in framework cysteine residues and block in H protein secretion and intracellular catabolism. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2516825175.

- Zhang Y , Kremsdorf RA, Sperati CJ, et al. Mutation of complement factor B causing massive fluid-phase dysregulation of the alternative complement pathway can result in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int. 2020;98:1265-1274.

- Levine AP, Chan MMY, Sadeghi-Alavijeh O, et al. Large-scale wholegenome sequencing reveals the genetic architecture of primary membranoproliferative GN and C3 glomerulopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:365-373.

- Finn JE, Mathieson PW. Molecular analysis of C3 allotypes in patients with nephritic factor. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;91:410-414.

- Hocking HG, Herbert AP, Kavanagh D, et al. Structure of the N -terminal region of complement factor H and conformational implications of disease-linked sequence variations. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9475-9487.

- Heurich M, Martínez-Barricarte R, Francis NJ, et al. Common polymorphisms in C3, factor B, and factor H collaborate to determine systemic complement activity and disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8761-8766.

- Ding Y, Zhao W, Zhang T, et al. A haplotype in CFH family genes confers high risk of rare glomerular nephropathies. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6004.

- Marinozzi MC, Chauvet S, Le Quintrec M, et al. C5 nephritic factors drive the biological phenotype of C3 glomerulopathies. Kidney Int. 2017;92: 1232-1241.

166a. Hauer JJ, Zhang Y, Goodfellow R, et al. Defining nephritic factors as diverse drivers of systemic complement dysregulation in C3 glomerulopathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;9:464-477. - Donadelli R, Pulieri P, Piras R, et al. Unraveling the molecular mechanisms underlying complement dysregulation by nephritic factors in C3G and IC-MPGN. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2329.

- Chauvet S, Hauer JJ, Petitprez F, et al. Results from a nationwide retrospective cohort measure the impact of C3 and soluble C5b-9 levels on kidney outcomes in C3 glomerulopathy. Kidney Int. 2022;102:904-916.

- Garam N, Prohászka Z, Szilágyi Á, et al. Validation of distinct pathogenic patterns in a cohort of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis patients by cluster analysis. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13:225-234.

- Iatropoulos P, Daina E, Curreri M, et al. Cluster analysis identifies distinct pathogenetic patterns in C3 glomerulopathies/immune complexmediated membranoproliferative GN. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:283-294.

- Chauvet

, Berthaud , Devriese , et al. Anti-factor B antibodies and acute postinfectious GN in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:829-840.

171a. Chauvet, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Petitprez F, et al. Treatment of B-cell disorder improves renal outcome of patients with monoclonal gammopathy-associated C3 glomerulopathy. Blood. 2017;129:14371447. - Caravaca-Fontán F, Lucientes L, Serra N, et al. C3 glomerulopathy associated with monoclonal gammopathy: impact of chronic histologic lesions and beneficial effects of clone-targeted therapies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;37:2128-2137.

- Smith RJH, Appel GB, Blom AM, et al. C3 glomerulopathyunderstanding a rare complement-driven renal disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15:129-143.

- Servais A, Noël LH, Roumenina LT, et al. Acquired and genetic complement abnormalities play a critical role in dense deposit disease and other C3 glomerulopathies. Kidney Int. 2012;82:454-464.

- Békássy ZD, Kristoffersson AC, Rebetz J, et al. Aliskiren inhibits reninmediated complement activation. Kidney Int. 2018;94:689-700.

- Bomback AS, Santoriello D, Avasare RS, et al. C3 glomerulonephritis and dense deposit disease share a similar disease course in a large United States cohort of patients with C3 glomerulopathy. Kidney Int. 2018;93: 977-985.

- Caravaca-Fontán F, Trujillo H, Alonso M, et al. Validation of a histologic scoring index for C3 glomerulopathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77:684-695. e681.

- Rabasco C, Cavero T, Román E, et al. Effectiveness of mycophenolate mofetil in C3 glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2015;88:1153-1160.

- Avasare RS, Canetta PA, Bomback AS, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in combination with steroids for treatment of C3 glomerulopathy: a case series. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:406-413.

- Caravaca-Fontán F, Díaz-Encarnación MM, Lucientes L , et al. Mycophenolate mofetil in C3 glomerulopathy and pathogenic drivers of the disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15:1287-1298.

- Bharati J, Tiewsoh K, Kumar A, et al. Usefulness of mycophenolate mofetil in Indian patients with C3 glomerulopathy. Clin Kidney J. 2019;12:483-487.

- Caliskan Y, Torun ES, Tiryaki TO, et al. Immunosuppressive treatment in C3 glomerulopathy: is it really effective? Am J Nephrol. 2017;46:96-107.

- Khandelwal P, Bhardwaj S, Singh G, et al. Therapy and outcomes of C3 glomerulopathy and immune-complex membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36:591-600.

- Ravindran A, Fervenza FC, Smith RJH, et al. C3 glomerulopathy: ten years’ experience at Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:991-1008.

- Le Quintrec