DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae043

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38321820

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-07

SDUه-

جامعة جنوب الدنمارك

زراعة صمام الأبهري عن طريق القسطرة أو الجراحة

نتائج دراسة NOTION بعد 10 سنوات

شتاينبروخيل، دانيال أندرياس؛ نيسن، هنريك؛ كيلدسن، بو جول؛ بيترسون، بيتر؛ دي باكر، أولي؛ أولسن، بيتر سكوف؛ سوندرغارد، لارس

مجلة القلب الأوروبية

10.1093/eurheartj/ehae043

2024

النسخة النهائية المنشورة

CC BY

هورستيد ثيريجود، إتش. جي.، يورغنسن، تي. إتش.، إيلهيمان، ن.، شتاينبروكل، د. أ.، نيسن، هـ.، كيلدسن، ب. ج.، بيترسون، ب.، دي باكر، أو.، أولسن، ب. س.، وسوندرغارد، ل. (2024). زراعة صمام الأبهري عبر القسطرة أو الجراحة: نتائج 10 سنوات من تجربة NOTION. مجلة القلب الأوروبية، 45(13)، 1116-1124.https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae043

شروط الاستخدام

ما لم يُذكر خلاف ذلك، فقد تم مشاركته وفقًا للشروط الخاصة بالأرشفة الذاتية.

إذا لم يتم ذكر ترخيص آخر، تنطبق هذه الشروط:

- يمكنك تنزيل هذا العمل للاستخدام الشخصي فقط.

- لا يجوز لك توزيع المادة بشكل إضافي أو استخدامها لأي نشاط يهدف إلى الربح أو لتحقيق مكاسب تجارية.

- يمكنك توزيع عنوان URL الذي يحدد هذه النسخة المفتوحة الوصول بحرية

زراعة صمام الأبهري عبر القسطرة أو الجراحة: نتائج 10 سنوات من تجربة NOTION

الملخص

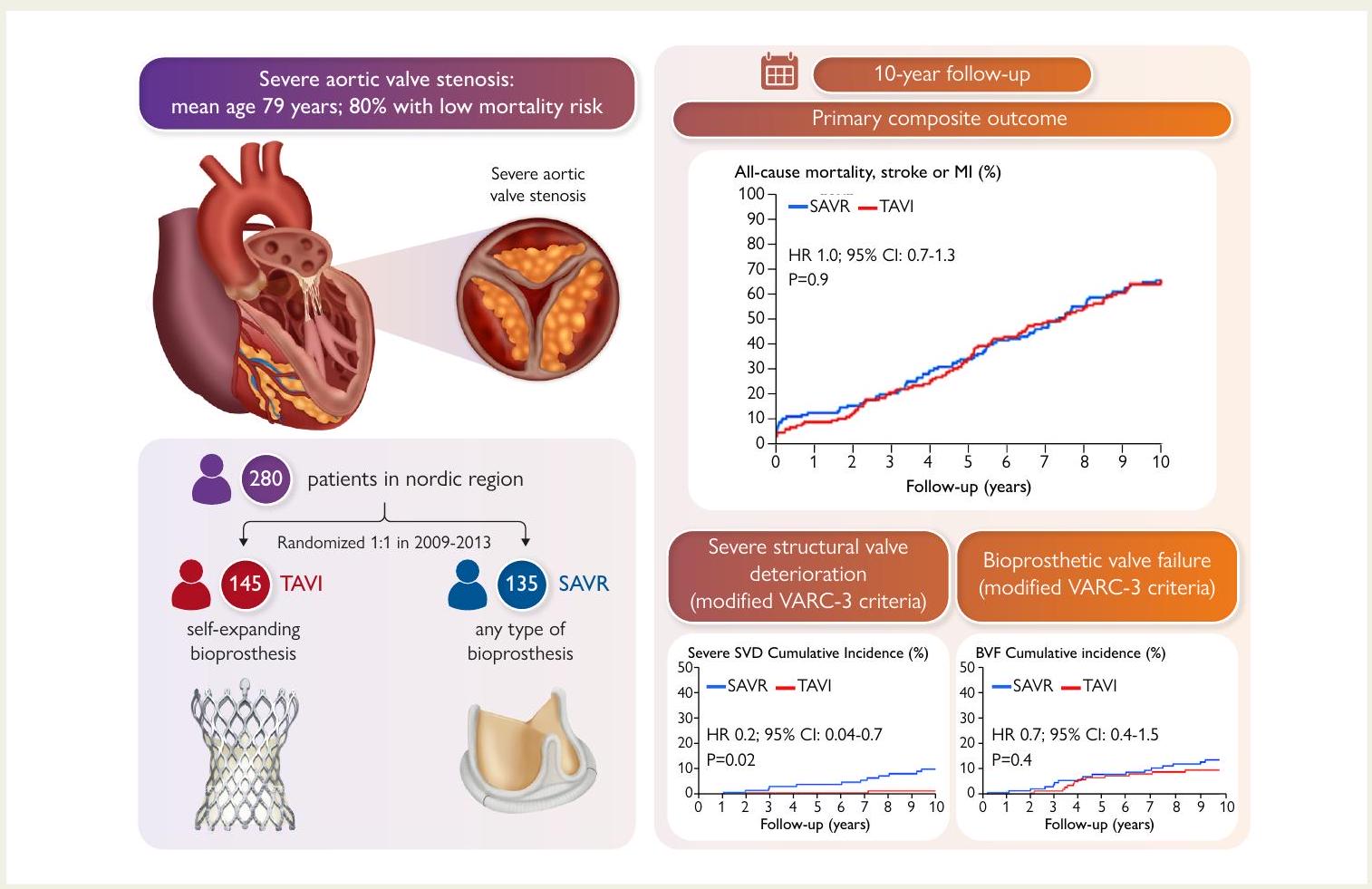

الخلفية وزرع الصمام الأبهري عبر القسطرة (TAVI) أصبح خيار علاج قابلاً للتطبيق للمرضى الذين يعانون من تضيق شديد في الصمام الأبهري عبر مجموعة واسعة من مخاطر الجراحة. كانت تجربة التدخل في الصمام الأبهري الشمالي (NOTION) الأولى التي عشوائية المرضى ذوي المخاطر الجراحية المنخفضة إلى TAVI أو استبدال الصمام الأبهري الجراحي (SAVR). كان الهدف من الدراسة الحالية هو الإبلاغ عن النتائج السريرية ونتائج البيوبروستhesis بعد 10 سنوات.

طرق التجربة تم توزيع 280 مريضًا عشوائيًا على عملية استبدال الصمام الأبهري عبر القسطرة باستخدام جهاز CoreValve (Medtronic Inc.) القابل للتوسع الذاتي.

كانت الخصائص الأساسية متشابهة بين TAVI و SAVR: العمر

الاستنتاجات

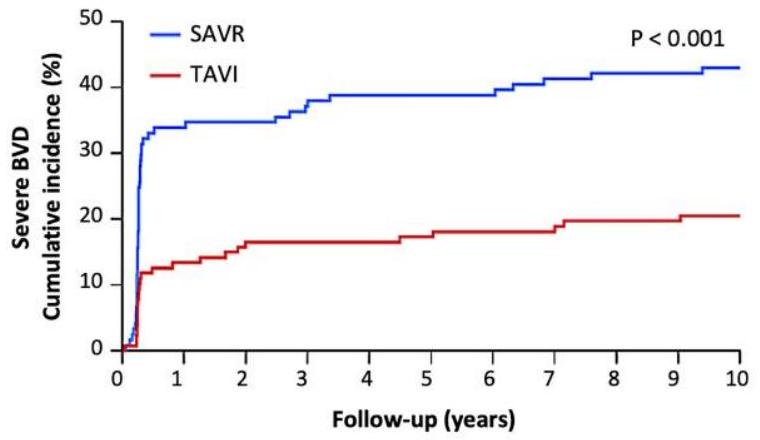

ملخص رسومي منظم

السؤال الرئيسي

النتيجة الرئيسية

تُظهر البيانات طويلة الأمد لصمامات الأبهري الذاتية التمدد من الجيل الأول نتائج مشابهة لصمامات الأبهري البيولوجية الجراحية. ومع ذلك، هناك حاجة إلى دراسات أكبر تشمل أنواعًا مختلفة من صمامات الأبهري البيولوجية لتعميم هذه النتائج.

الكلمات المفتاحية

مقدمة

لا يزال يُوصى به للمرضى الأصغر سناً وذوي المخاطر المنخفضة، principalmente لأن متانة صمامات القلب عبر القسطرة (THV) غير معروفة. التوصية العامة لاستخدام صمامات الشريان الأورطي البيولوجية الجراحية بدلاً من الصمامات الميكانيكية هي للمرضى الذين تزيد أعمارهم عن 65 عاماً، ولكن مع تقديم TAVI لعلاج أقل توغلاً، يتم الآن علاج عدد متزايد من المرضى الأصغر سناً باستخدام THV. في الولايات المتحدة، يخضع حوالي نصف المرضى الذين تقل أعمارهم عن 65 عاماً والذين تم علاجهم من تضيق الشريان الأورطي المعزول لـ TAVI.

طرق

المرضى

تعريفات النتائج

تدرج ما بعد الأطراف الاصطناعية

الإحصائيات

النتائج

| المرضى المعرضون للخطر | ||||||||||

| تافي | 145 | ١٣٦ | 132 | ١٢٢ | ١١٥ | ١٠١ | 86 | 78 | 69 | 61 |

| SAVR | 135 | 123 | ١٢٠ | ١١٢ | ١٠٢ | 95 | 83 | 75 | 64 | ٥٦ |

| تافي | 145 | ١٣٣ | 128 | 116 | ١١٠ | 93 | 81 | 73 | 65 | ٥٦ | ٤٩ |

| SAVR | 135 | ١٢٢ | ١١٨ | ١١٠ | 99 | 92 | ٨٠ | 71 | 60 | 52 | ٤٦ |

يمكن متابعة المرضى (فقدنا 2 من مرضى TAVI و1 من مرضى SAVR) ومن بين هؤلاء، كان 101 (36.1%) من المرضى على قيد الحياة. كانت البيانات الإيكو قلبية متاحة لـ 82 (81.2%) من المرضى الذين وصلوا إلى 10 سنوات. البيانات الإيكو المفقودة لمدة 10 سنوات لـ 12 من 52 (23.1%) من مرضى TAVI و7 من 49 (14.2%) من مرضى SAVR. لمزيد من التفاصيل الإجرائية، انظر البيانات التكميلية على الإنترنت، الجداول S1 وS2 وS4.

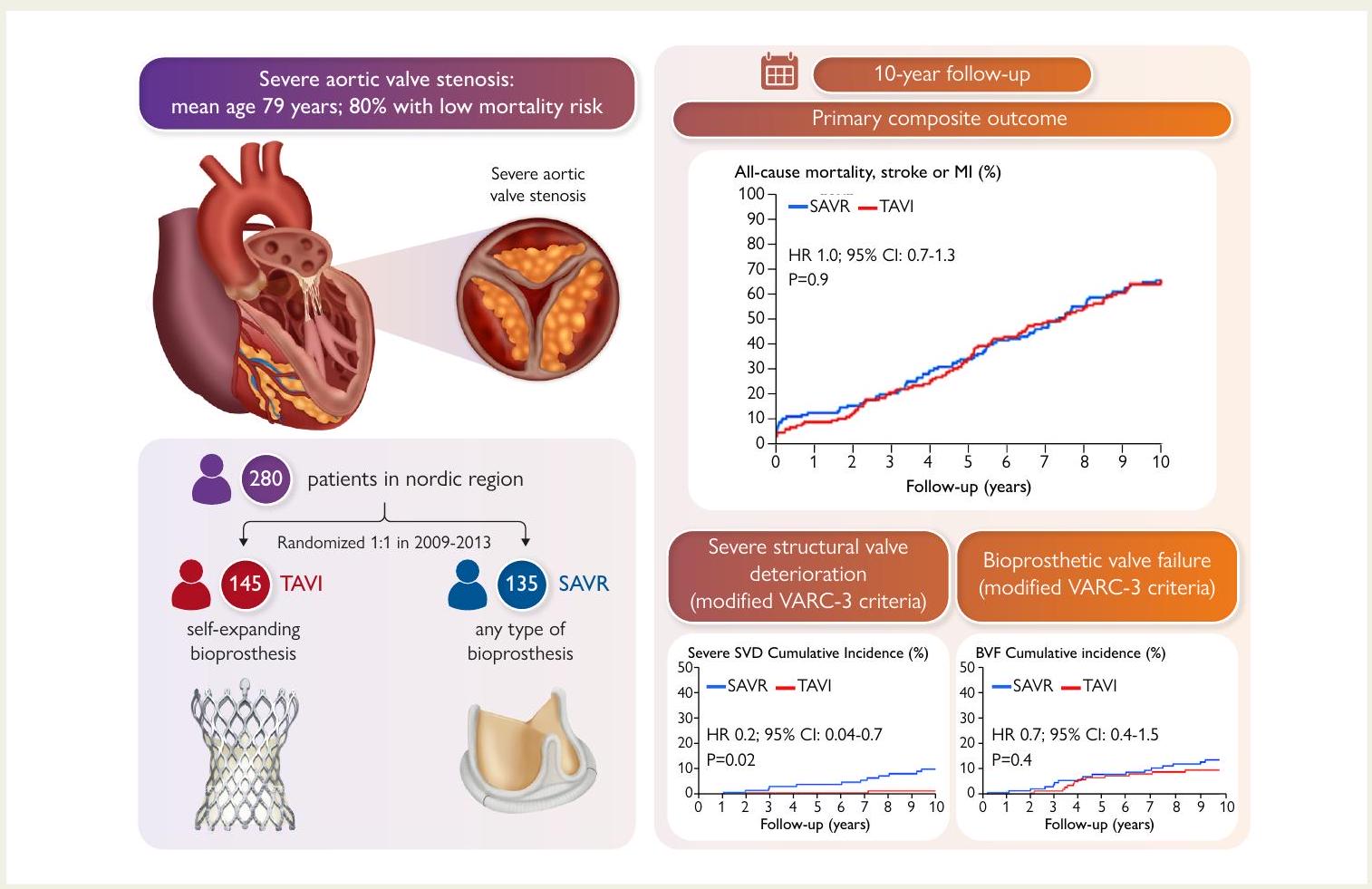

النتائج السريرية

| تافي

|

SAVR (

|

قيمة P | |

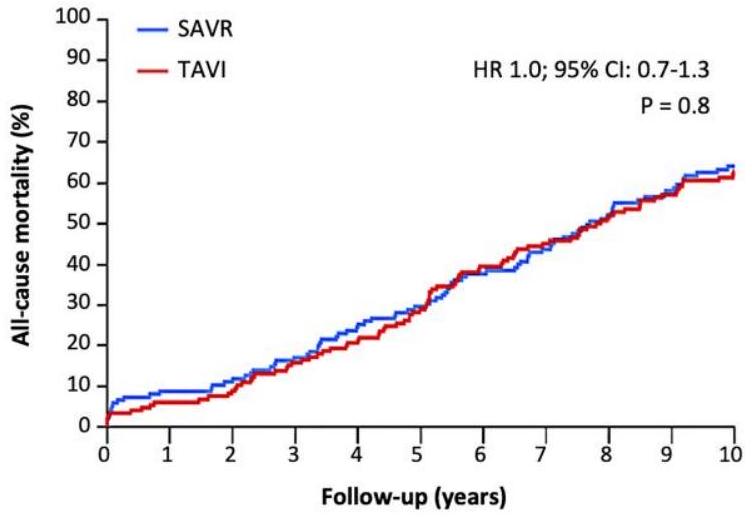

| الوفيات لجميع الأسباب | 62.7 | 64.0 | . 8 |

| وفاة قلبية وعائية | ٤٩.٥ | 51.2 | . 7 |

| سكتة دماغية

|

9.7 | 16.4 | . 1 |

| سكتة دماغية مع مضاعفات | 6.9 | 10.4 | . 3 |

| نوبة إقفارية عابرة | 9.7 | ٦.٧ | . 3 |

| احتشاء عضلة القلب | 11.0 | 8.2 | . ٤ |

| الرجفان الأذيني الجديد | ٥٢.٠ | 74.1 | <. 01 |

| جهاز تنظيم ضربات القلب الدائم الجديد | ٤٤.٧ | 14.0 | <. 01 |

تافي، زراعة صمام أبهري عبر القسطرة؛ سافير، استبدال صمام أبهري جراحي.

متشابه بين المجموعات (فئات NYHA I و II، TAVI 83.7% و SAVR

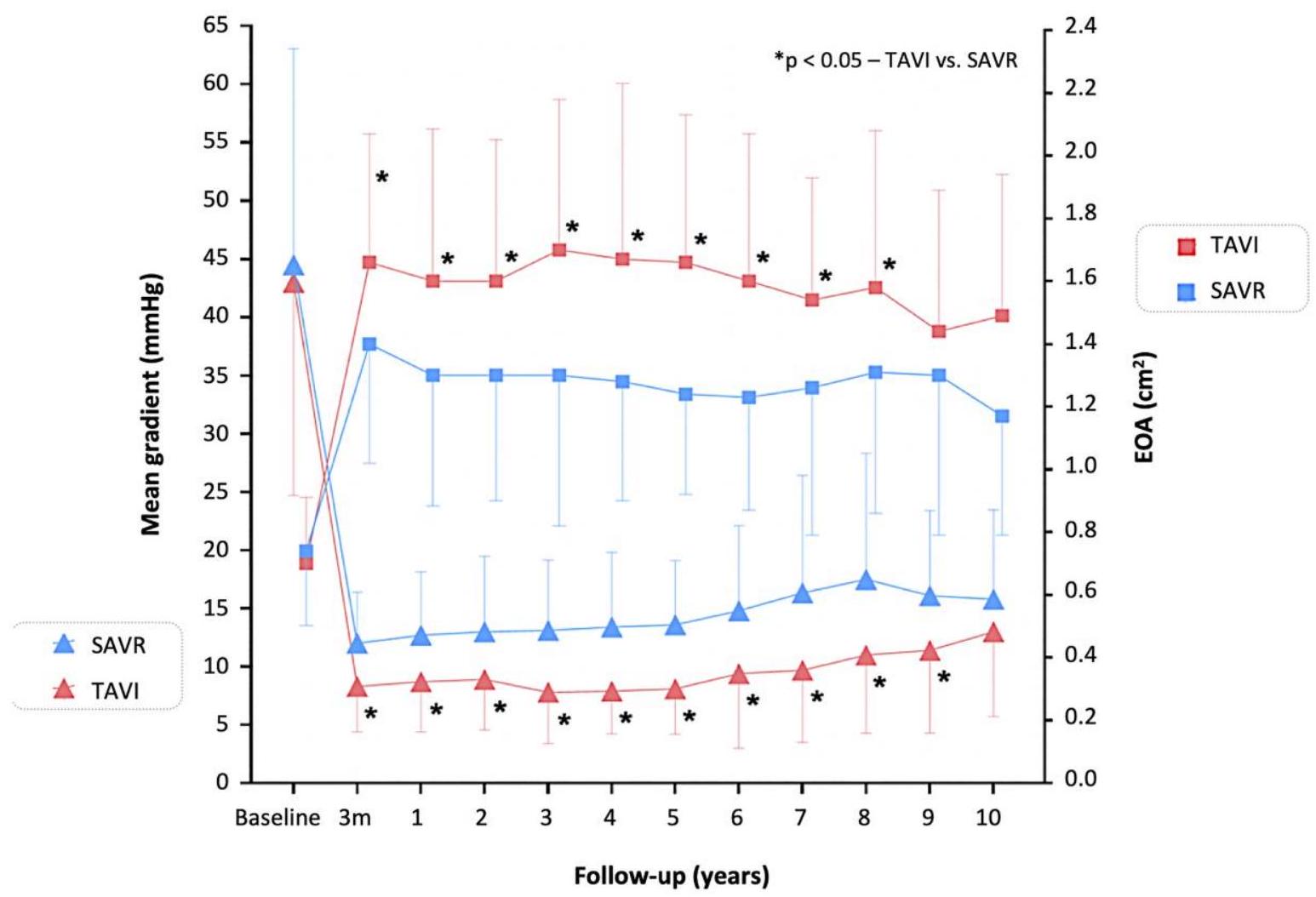

نتائج تخطيط صدى القلب

| المرضى المعرضون للخطر | ||||||||||||

| تافي-جرادينت | ١٢٤ | ١٢٦ | ١٢٢ | ١٠٥ | ١٠٧ | 96 | 79 | 67 | ٥٨ | ٤٤ | ٣٦ | ٣٦ |

| SAVR-gradient | ١١٧ | ١١٧ | ١١٦ | ١٠٩ | ١٠٦ | 96 | 84 | 70 | ٥٦ | ٤٦ | ٣٨ | ٣٨ |

| تافي-إيو إيه | ١٢٥ | ١٢٦ | ١١٨ | ١١٨ | 87 | 82 | 76 | ٥٦ | ٤٧ | ٤٤ | 32 | ٣٦ |

| SAVR-EOA | ١١٨ | ١١٦ | 116 | 111 | 95 | 77 | 83 | 61 | 51 | 42 | 37 | ٣٥ |

معدل الوفيات لمرضى PVL المعتدل/الشديد 62.0% وللذين لديهم PVL غير موجود/خفيف 55.0%،

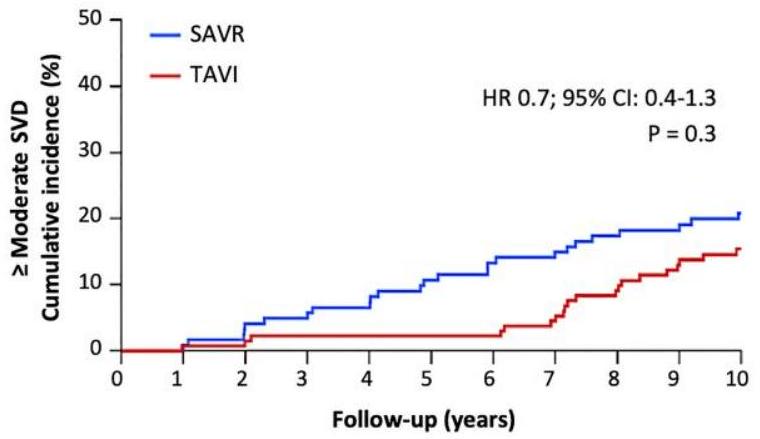

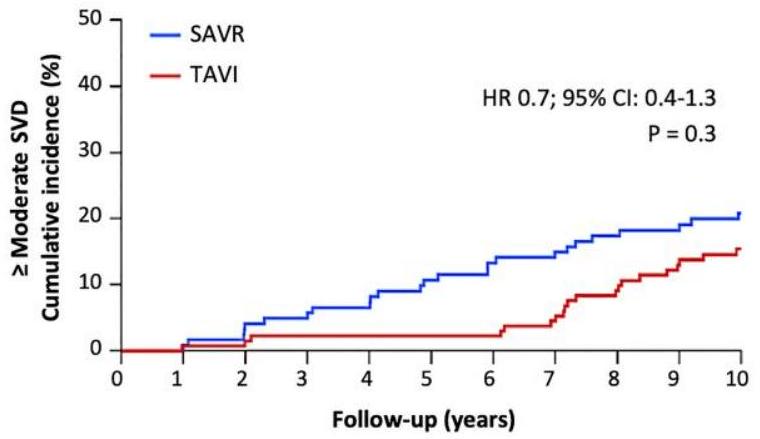

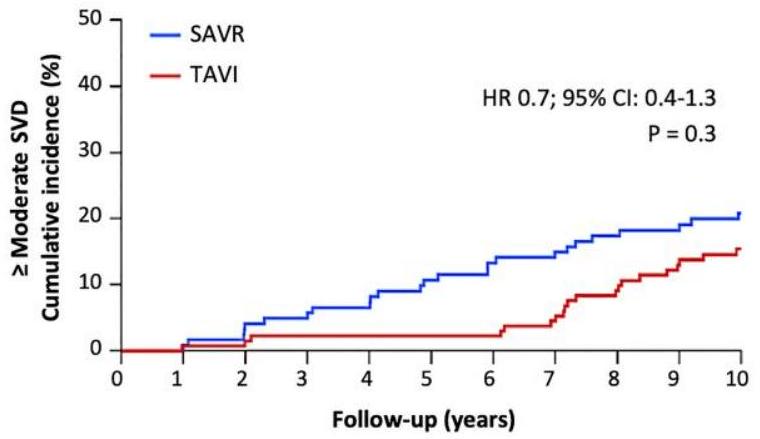

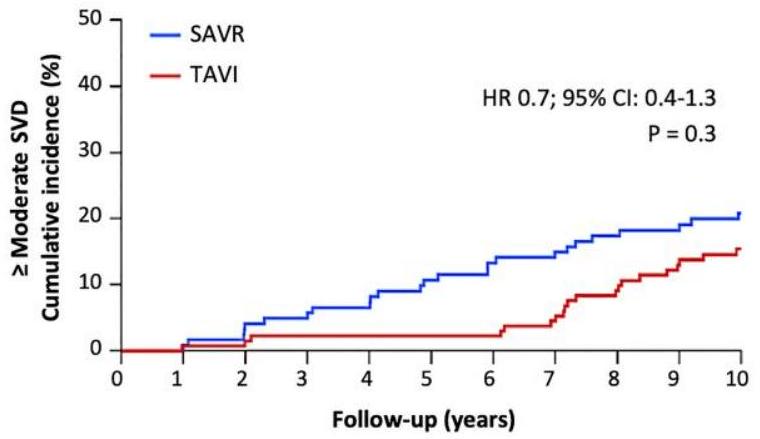

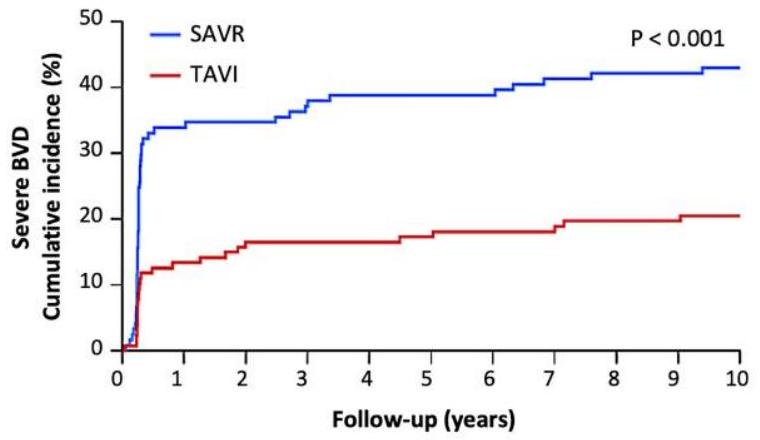

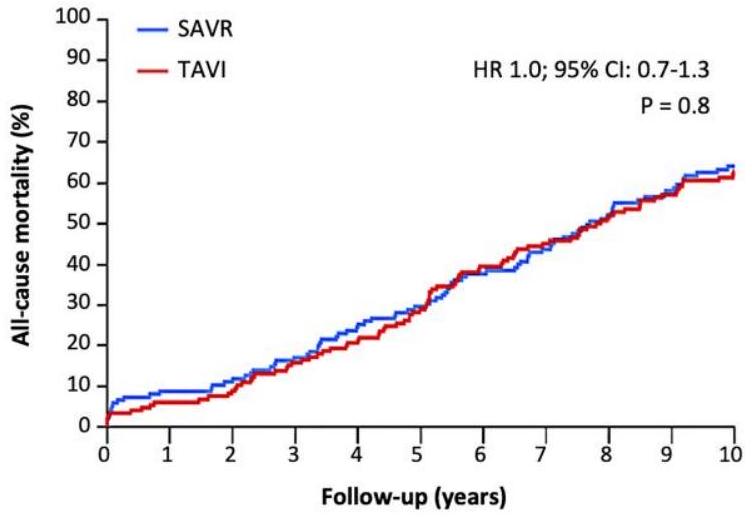

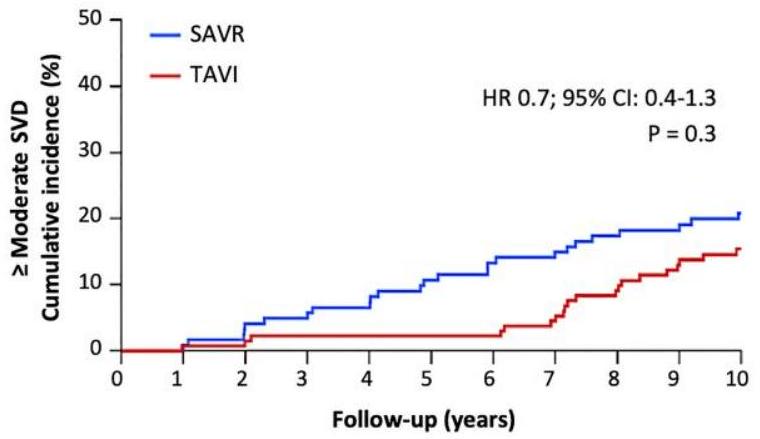

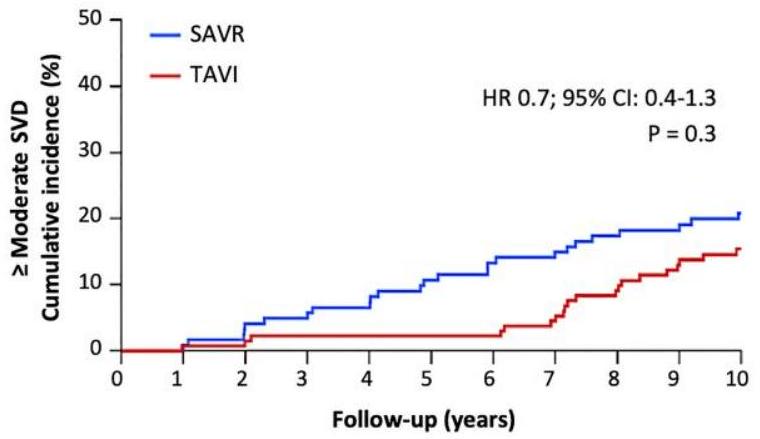

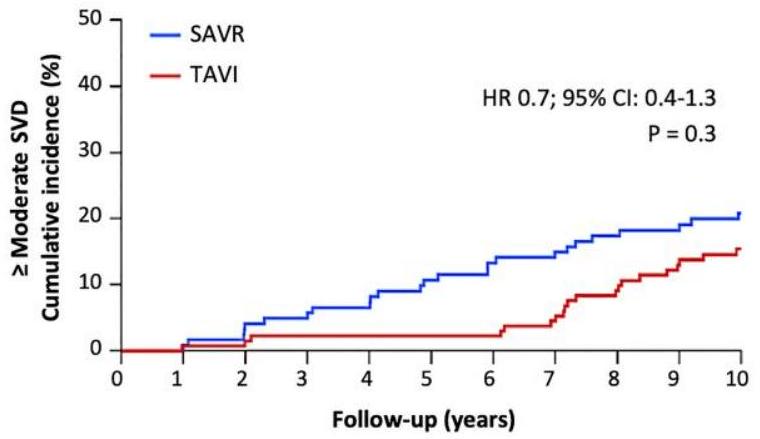

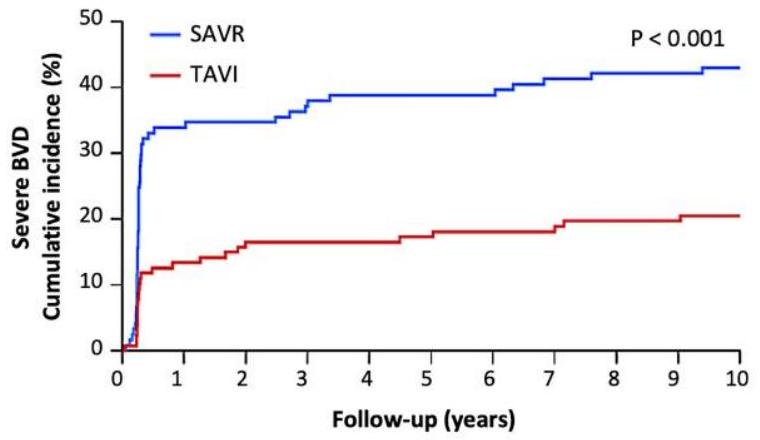

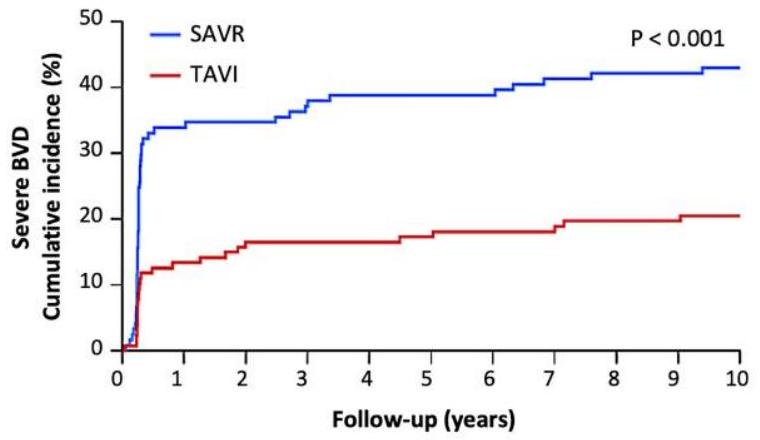

متانة البيوبروستhesis

نقاش

| تافي | SAVR | قيمة p | |

|

|

15.4% | ٢٠.٨٪ | 0.2 |

| الميل المتوسط

|

12.3% | ٢٠.٨٪ | 0.05 |

| قصور صمامي داخلي معتدل/شديد | ٤.٦٪ | 0 | 0.02 |

| تافي | SAVR | قيمة p | |

| قصور شديد في الصمامات | 1.5% | 10.0% | 0.004 |

| الميل المتوسط

|

1.5% | 10.0% | 0.004 |

| قصور شديد داخل البروستات | 0 | 0 | – |

النتائج السريرية

ديناميكا الدم ودوام البيوبروستhesis

| المرضى المعرضون للخطر | ||||||||||

| تافي | 127 | ١٠٨ | ١٠٢ | 95 | 91 | 79 | 69 | 62 | 53 | ٤٦ |

| SAVR | 121 | ٨٠ | 79 | 74 | 68 | 65 | ٥٨ | 50 | 42 | 37 |

| تافي | SAVR | قيمة p | ||||||||

| فيروس التهاب الأمعاء البقري الشديد | ٢٠.٥٪ | ٤٣٫٠٪ | <0.001 | |||||||

| قصور شديد في الصمامات | 1.5% | 10.0% | 0.004 | |||||||

| غير شديد غير SVD | 12.6% | 31.9% | <0.001 | |||||||

| تسرب شديد حول الصمام | 2.6% | 0 | 0.08 | |||||||

| عدم توافق شديد بين المريض والبدلة | 10.2% | 31.9% | <0.001 | |||||||

| جلطة صمامية سريرية | 0 | 0 | – | |||||||

| التهاب الشغاف | ٧.٢٪ | ٧.٤٪ | 0.95 | |||||||

| المرضى المعرضون للخطر | |||||||||

| تافي 134 | 132 | 128 | ١١٨ | ١٠٩ | 96 | 82 | 73 | 63 | ٥٤ |

|

|

١٢٠ | 111 | ١٠٢ | 93 | 81 | 72 | 60 | 52 | |

| تافي | SAVR | قيمة p | |||||||

| بي في إف | 9.7% | 13.8% | 0.3 | ||||||

| وفاة مرتبطة بالصمام | ٥٫٠٪ | 3.7% | 0.6 | ||||||

| قصور شديد في الصمامات | 1.5% | 10.0% | 0.004 | ||||||

| إعادة تدخل صمام الشريان الأورطي | ٤.٣٪ | 2.2% | 0.3 | ||||||

يعد جزءًا من تعريف NSVD. لم نلاحظ أي NSVD أخرى مثل احتباس القمة بواسطة البانوس، أو تمدد جذر الشريان الأورطي، أو تآكل البروستhesis، أو الانصمام. كانت نسبة SVD الشديدة أعلى بعد SAVR (على سبيل المثال، تغيير كبير في هيكل قمة البروستhesis مما أدى إلى زيادة في التدرج عبر البروستhesis). لم يكن لدى أي من المرضى ارتجاع شديد داخل البروستhesis. تعريف VARC-3 ‘الهيموديناميكي’ لـ SVD المستخدم في التقرير الحالي شمل فقط التدرج عبر البروستhesis وقد أظهر أنه أكثر تنبؤًا بالنتائج السريرية السلبية من التعريف الكامل لـ VARC-3.

كانت معايير VARC-3 ‘الديناميكية الدموية’ أقل بعد عملية استبدال الصمام الأبهري عبر القسطرة (TAVR) مقارنةً بعملية استبدال الصمام الأبهري الجراحية (SAVR) بعد 5 سنوات.

قيود التجربة

الاستنتاجات

البيانات التكميلية

الإعلانات

إفصاح عن المصلحة

توفر البيانات

التمويل

الموافقة الأخلاقية

رقم التجربة السريرية المسجل مسبقًا

References

- Kapadia SR, Leon MB, Makkar RR, Tuzcu EM, Svensson LG, Kodali S, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement compared with standard treatment for patients with inoperable aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl 2015;385:2485-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60290-2

- Arnold SV, Petrossian G, Reardon MJ, Kleiman NS, Yakubov SJ, Wang K, et al. Five-year clinical and quality of life outcomes from the CoreValve US Pivotal Extreme Risk Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14:e010258. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120. 010258

- Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, Miller DC, Moses JW, Tuzcu EM, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl 2015;385:2477-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60308-7

- Gleason TG, Reardon MJ, Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Lee JS, et al. 5-year outcomes of self-expanding transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:2687-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2146

- Makkar RR, Thourani VH, Mack MJ, Kodali SK, Kapadia S, Webb JG, et al. Five-year outcomes of transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med 2020;382: 799-809. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1910555

- Van Mieghem NM, Deeb GM, Søndergaard L, Grube E, Windecker S, Gada H, et al. Self-expanding transcatheter vs surgical aortic valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients: 5-year outcomes of the SURTAVI randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2022;7:1000-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2695

- Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, et al. 2021 ESC/ EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2022;43: 561-632. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

- Sharma T, Krishnan AM, Lahoud R, Polomsky M, Dauerman HL. National trends in TAVR and SAVR for patients with severe isolated aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80:2054-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.787

- Thyregod HGH, Steinbrüchel DA, Ihlemann N, Nissen H, Kjeldsen BJ, Petursson P, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis: 1-year results from the all-comers NOTION randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2184-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.014

- Jørgensen TH, Thyregod HGH, Ihlemann N, Nissen H, Petursson P, Kjeldsen BJ, et al. Eight-year outcomes for patients with aortic valve stenosis at low surgical risk randomized to transcatheter vs. surgical aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J 2021;42: 2912-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab375

- Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, Pibarot P, Hahn RT, Genereux P, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in low-risk patients at five years. N Engl J Med 2023;389: 1949-60. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2307447

- Forrest JK, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Gada H, Mumtaz MA, Ramlawi B, et al. 4-year outcomes of patients with aortic stenosis in the Evolut Low Risk Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;82:2163-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.09.813

- Thyregod HG, Søndergaard L, Ihlemann N, Franzen O, Andersen LW, Hansen PB, et al. The Nordic aortic valve intervention (NOTION) trial comparing transcatheter versus surgical valve implantation: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2013; 14:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-11

- Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document (VARC-2). Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg 2012;42:S45-60. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezs533

- VARC-3 WRITING COMMITTEE; Généreux P, Piazza N, Alu MC, Nazif T, Hahn RT, et al. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3: updated endpoint definitions for aortic valve clinical research. Eur Heart J 2021;42:1825-57. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ ehaa799

- Thourani VH, Habib R, Szeto WY, Sabik JF, Romano JC, MacGillivray TE, et al. Survival following surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients: a contemporary trial benchmark. Ann Thorac Surg 2024;117:106-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur. 2023.10.006

- Thyregod HGH, Ihlemann N, Jørgensen TH, Nissen H, Kjeldsen BJ, Petursson P, et al. Five-year clinical and echocardiographic outcomes from the NOTION randomized clinical trial in patients at lower surgical risk. Circulation 2019;139:2714-23. https://doi.org/ 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036606

- Jørgensen TH, De Backer O, Gerds TA, Bieliauskas G, Svendsen JH, Søndergaard L. Mortality and heart failure hospitalization in patients with conduction abnormalities after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019;12:52-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2018.10.053

- Gilard M, Eltchaninoff H, Donzeau-Gouge P, Chevreul K, Fajadet J, Leprince P, et al. Late outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients: the FRANCE-2 registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1637-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc. 2016.07.747

- Rodriguez-Gabella T, Voisine P, Puri R, Pibarot P, Rodés-Cabau J. Aortic bioprosthetic valve durability: incidence, mechanisms, predictors, and management of surgical and transcatheter valve degeneration. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1013-28. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.715

- Head SJ, Mokhles MM, Osnabrugge RLJ, Pibarot P, Mack MJ, Takkenberg JJM, et al. The impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch on long-term survival after aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 34 observational studies comprising 27186 patients with 133141 patient-years. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1518-29. https://doi. org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs003

- Ochi A, Cheng K, Zhao B, Hardikar AA, Negishi K. Patient risk factors for bioprosthetic aortic valve degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung Circ 2020; 29:668-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2019.09.013

- Thyregod HGH, Steinbrüchel DA, Ihlemann N, Ngo TA, Nissen H, Kjeldsen BJ, et al. No clinical effect of prosthesis-patient mismatch after transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in intermediate- and low-risk patients with severe aortic valve stenosis at mid-term follow-up: an analysis from the NOTION trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:721-8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezw095

- Ngo A, Hassager C, Thyregod HGH, Søndergaard L, Olsen PS, Steinbrüchel D, et al. Differences in left ventricular remodelling in patients with aortic stenosis treated with transcatheter aortic valve replacement with corevalve prostheses compared to surgery with porcine or bovine biological prostheses. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;19:39-46. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jew321

- O’Hair D, Yakubov SJ, Grubb KJ, Oh JK, Ito S, Deeb GM, et al. Structural valve deterioration after self-expanding transcatheter or surgical aortic valve implantation in patients at intermediate or high risk. JAMA Cardiol 2023;8:111-9. https://doi.org/10. 1001/jamacardio.2022.4627

- Roslan AB, Naser JA, Nkomo VT, Padang R, Lin G, Pislaru C, et al. Performance of echocardiographic algorithms for assessment of high aortic bioprosthetic valve gradients. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2022;35:682-91. e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2022.01.019

- Ueyama H, Kuno T, Takagi H, Kobayashi A, Misumida N, Pinto DS, et al. Meta-analysis comparing valve durability among different transcatheter and surgical aortic valve bioprosthesis. Am J Cardiol 2021;158:104-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.07. 046

- Pibarot P, Ternacle J, Jaber WA, Salaun E, Dahou A, Asch FM, et al. Structural deterioration of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve bioprostheses in the PARTNER-2 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:1830-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.049

- Strange JE, Østergaard L, Køber L, Bundgaard H, Iversen K, Voldstedlund M, et al. Patient characteristics, microbiology, and mortality of infective endocarditis after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Clin Infect Dis 2023;77:1617-25. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ ciad431

- Makkar RR, Fontana G, Jilaihawi H, Chakravarty T, Kofoed KF, De Backer O, et al. Possible subclinical leaflet thrombosis in bioprosthetic aortic valves.

Engl Med 2015;373:2015-24. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1509233 - Yerasi C, Rogers T, Forrestal BJ, Case BC, Khan JM, Ben-Dor I, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in young, low-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14:1169-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2021.03.058

- Barbanti M, Costa G, Picci A, Criscione E, Reddavid C, Valvo R, et al. Coronary cannulation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the RE-ACCESS study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2020;13:2542-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2020.07.006

- Buzzatti N, Romano V, De Backer O, Soendergaard L, Rosseel L, Maurovich-Horvat P, et al. Coronary access after repeated transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a glimpse into the future. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13:508-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg. 2019.06.025

- Park SJ, Ok YJ, Kim HJ, Kim YJ, Kim S, Ahn JM, et al. Evaluating reference ages for selecting prosthesis types for heart valve replacement in Korea. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6: e2314671. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.14671

- Mauri V, Abdel-Wahab M, Bleiziffer S, Veulemans V, Sedaghat A, Adam M, et al. Temporal trends of TAVI treatment characteristics in high volume centers in Germany 2013-2020. Clin Res Cardiol 2022;111:881-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00392-021-01963-3

- Writing Committee Members; Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021; 77:e25-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018

- Leon MB, Mack MJ, Hahn RT, Thourani VH, Makkar R, Kodali SK, et al. Outcomes 2 years after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients at low surgical risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:1149-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.052

- Forrest JK, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Gada H, Mumtaz MA, Ramlawi B, et al. 3-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;81:1663-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc. 2023.02.017

- Kalra A, Rehman H, Ramchandani M, Barker CM, Lawrie GM, Reul RM, et al. Early trifecta valve failure: report of a cluster of cases from a tertiary care referral center. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;154:1235-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.05.044

- Sénage T, Le Tourneau T, Foucher Y, Pattier S, Cueff C, Michel M, et al. Early structural valve deterioration of Mitroflow aortic bioprosthesis: mode, incidence, and impact on outcome in a large cohort of patients. Circulation 2014;130:2012-20. https://doi.org/ 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010400

- Grunkemeier GL, Furnary AP, Wu Y, Wang L, Starr A. Durability of pericardial versus porcine bioprosthetic heart valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:1381-6. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.08.060

- Corresponding author. Tel: +45 3545 1080, Email: hans.gustav.thyregod@regionh.dk

The first two authors shared first authorship.

Retired researcher.

© The Author(s) 2024. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Corresponding author. Tel: +45 3545 1080, Email: hans.gustav.thyregod@regionh.dk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae043

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38321820

Publication Date: 2024-02-07

SDUه-

University of Southern Denmark

Transcatheter or surgical aortic valve implantation

10-year outcomes of the NOTION trial

Steinbrüchel, Daniel Andreas; Nissen, Henrik; Kjeldsen, Bo Juel; Petursson, Petur; De Backer, Ole; Olsen, Peter Skov; Søndergaard, Lars

European Heart Journal

10.1093/eurheartj/ehae043

2024

Final published version

CC BY

Hørsted Thyregod, H. G., Jørgensen, T. H., Ihlemann, N., Steinbrüchel, D. A., Nissen, H., Kjeldsen, B. J., Petursson, P., De Backer, O., Olsen, P. S., & Søndergaard, L. (2024). Transcatheter or surgical aortic valve implantation: 10-year outcomes of the NOTION trial. European Heart Journal, 45(13), 1116-1124. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae043

Terms of use

Unless otherwise specified it has been shared according to the terms for self-archiving.

If no other license is stated, these terms apply:

- You may download this work for personal use only.

- You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain

- You may freely distribute the URL identifying this open access version

Transcatheter or surgical aortic valve implantation: 10-year outcomes of the NOTION trial

Abstract

Background and Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has become a viable treatment option for patients with severe aortic valve Aims stenosis across a broad range of surgical risk. The Nordic Aortic Valve Intervention (NOTION) trial was the first to randomize patients at lower surgical risk to TAVI or surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The aim of the present study was to report clinical and bioprosthesis outcomes after 10 years.

Methods The NOTION trial randomized 280 patients to TAVI with the self-expanding CoreValve (Medtronic Inc.) bioprosthesis (

Results Baseline characteristics were similar between TAVI and SAVR: age

Conclusions

Structured Graphical Abstract

Key Question

Key Finding

Long-term data for a first generation self-expanding transcatheter aortic valve are comparable to surgical bioprosthetic aortic valves. However, larger studies, including different types of bioprosthetic aortic valves, are warranted to generalize these findings.

Keywords

Introduction

is still recommended for younger and low-risk patients, mainly because the durability of transcatheter heart valves (THV) is unknown. The general recommendation for the use of surgical bioprosthetic aortic valves as opposed to mechanical valves is age older than 65 years, but as TAVI offers a less invasive treatment, an increasing number of younger patients are now treated with THV. In the United States, about half of the patients younger than 65 years treated for isolated AS undergoes TAVI.

Methods

Patients

Outcome definitions

transprosthetic gradient

Statistics

Results

| Patients at risk | ||||||||||

| TAVI | 145 | 136 | 132 | 122 | 115 | 101 | 86 | 78 | 69 | 61 |

| SAVR | 135 | 123 | 120 | 112 | 102 | 95 | 83 | 75 | 64 | 56 |

| TAVI | 145 | 133 | 128 | 116 | 110 | 93 | 81 | 73 | 65 | 56 | 49 |

| SAVR | 135 | 122 | 118 | 110 | 99 | 92 | 80 | 71 | 60 | 52 | 46 |

patients could be followed up (2 TAVI and 1 SAVR patients were lost) and of these 101 (36.1%) patients were alive. Echocardiographic data were available for 82 (81.2%) patients reaching 10 years. Missing 10-year echo data for 12 of 52 (23.1%) TAVI and 7 of 49 (14.2%) SAVR patients. For procedural details, see Supplementary data online, Tables S1, S2, and S4.

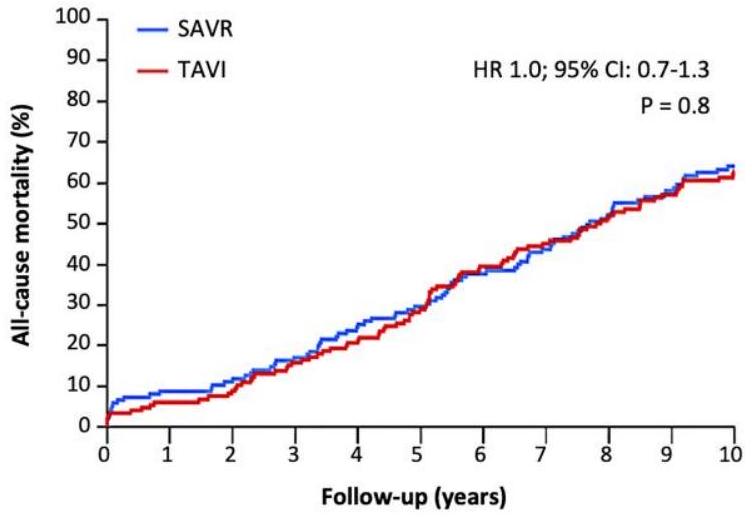

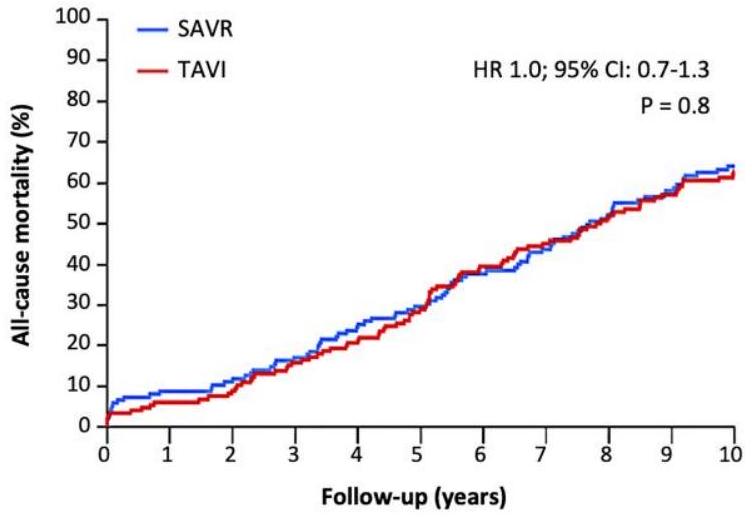

Clinical outcomes

| TAVI (

|

SAVR (

|

P-value | |

| All-cause mortality | 62.7 | 64.0 | . 8 |

| Cardiovascular death | 49.5 | 51.2 | . 7 |

| Stroke

|

9.7 | 16.4 | . 1 |

| Stroke with sequelae | 6.9 | 10.4 | . 3 |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 9.7 | 6.7 | . 3 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 11.0 | 8.2 | . 4 |

| New-onset atrial fibrillation | 52.0 | 74.1 | <. 01 |

| New permanent pacemaker | 44.7 | 14.0 | <. 01 |

TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement.

similar between groups (NYHA classes I and II, TAVI 83.7% and SAVR

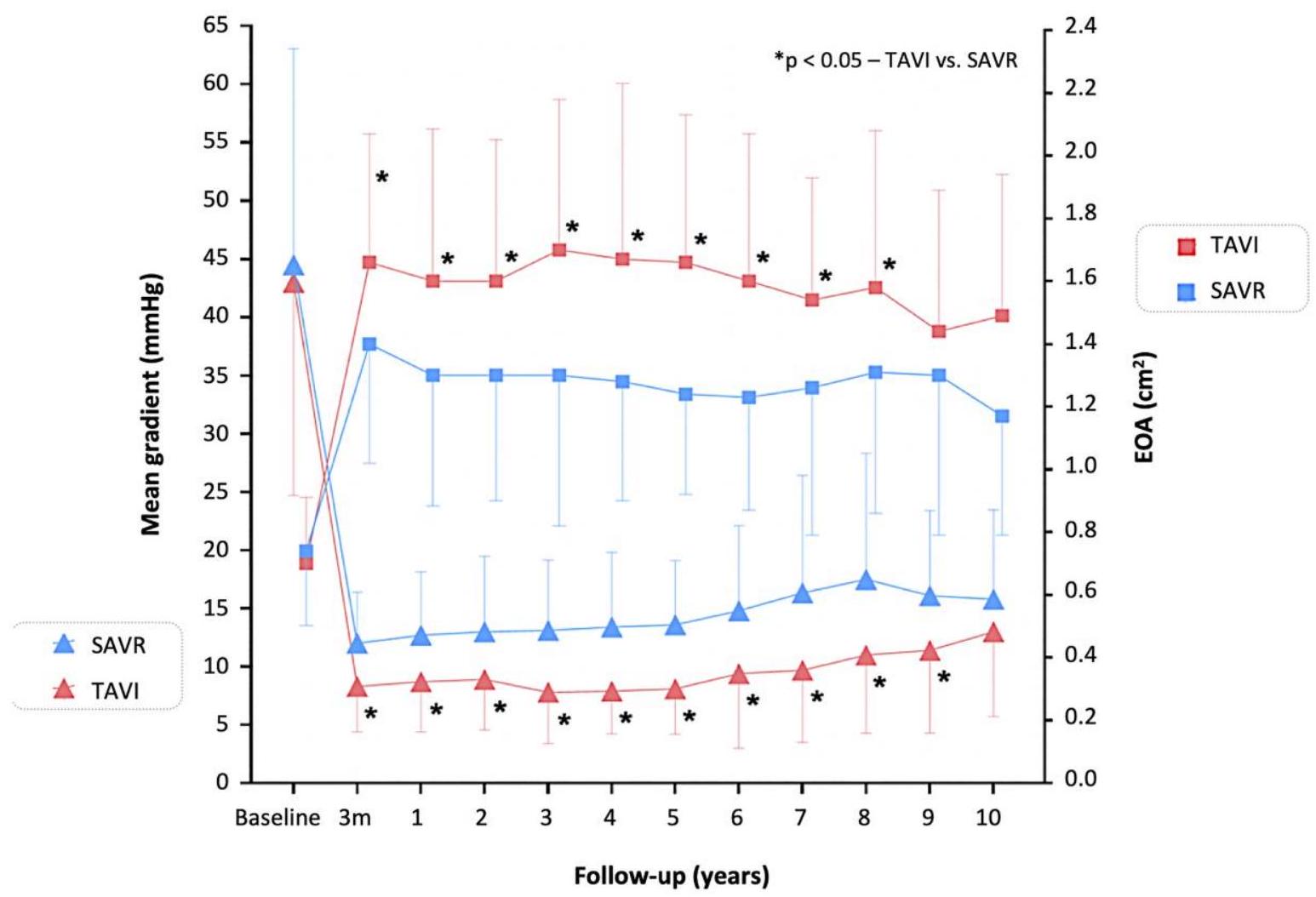

Echocardiographic outcomes

| Patients at risk | ||||||||||||

| TAVI-gradient | 124 | 126 | 122 | 105 | 107 | 96 | 79 | 67 | 58 | 44 | 36 | 36 |

| SAVR-gradient | 117 | 117 | 116 | 109 | 106 | 96 | 84 | 70 | 56 | 46 | 38 | 38 |

| TAVI-EOA | 125 | 126 | 118 | 118 | 87 | 82 | 76 | 56 | 47 | 44 | 32 | 36 |

| SAVR-EOA | 118 | 116 | 116 | 111 | 95 | 77 | 83 | 61 | 51 | 42 | 37 | 35 |

mortality for moderate/severe PVL 62.0% and no/mild PVL 55.0%,

Bioprosthesis durability

Discussion

| TAVI | SAVR | p value | |

|

|

15.4% | 20.8% | 0.2 |

| Mean gradient

|

12.3% | 20.8% | 0.05 |

| Moderate/severe intraprosthetic AR | 4.6% | 0 | 0.02 |

| TAVI | SAVR | p value | |

| Severe SVD | 1.5% | 10.0% | 0.004 |

| Mean gradient

|

1.5% | 10.0% | 0.004 |

| Severe intraprosthetic AR | 0 | 0 | – |

Clinical outcomes

Bioprosthesis haemodynamics and durability

| Patients at risk | ||||||||||

| TAVI | 127 | 108 | 102 | 95 | 91 | 79 | 69 | 62 | 53 | 46 |

| SAVR | 121 | 80 | 79 | 74 | 68 | 65 | 58 | 50 | 42 | 37 |

| TAVI | SAVR | p value | ||||||||

| Severe BVD | 20.5% | 43.0% | <0.001 | |||||||

| Severe SVD | 1.5% | 10.0% | 0.004 | |||||||

| Severe non-SVD | 12.6% | 31.9% | <0.001 | |||||||

| Severe paravalvular leak | 2.6% | 0 | 0.08 | |||||||

| Severe patient-prosthesis mismatch | 10.2% | 31.9% | <0.001 | |||||||

| Clinical valve thrombosis | 0 | 0 | – | |||||||

| Endocarditis | 7.2% | 7.4% | 0.95 | |||||||

| Patients at risk | |||||||||

| TAVI 134 | 132 | 128 | 118 | 109 | 96 | 82 | 73 | 63 | 54 |

|

|

120 | 111 | 102 | 93 | 81 | 72 | 60 | 52 | |

| TAVI | SAVR | p value | |||||||

| BVF | 9.7% | 13.8% | 0.3 | ||||||

| Valve-related death | 5.0% | 3.7% | 0.6 | ||||||

| Severe SVD | 1.5% | 10.0% | 0.004 | ||||||

| Aortic valve re-intervention | 4.3% | 2.2% | 0.3 | ||||||

is part of the NSVD definition. We did not observe any other NSVD such as cusp entrapment by pannus, dilatation of the aortic root, prosthesis erosion, or embolization. The rate of severe SVD was higher after SAVR (e.g. a significant change in prosthetic cusp structure leading to an increase in transprosthetic gradient). No patients had severe intraprosthetic regurgitation. The ‘haemodynamic’ VARC-3 definition of SVD used in the current report included only the transprosthetic gradient and has been shown to be more predictive of adverse clinical outcomes than the complete VARC-3 definition.

‘haemodynamic’ VARC-3 criteria was lower after TAVR compared with SAVR after 5 years (

Trial limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary data

Declarations

Disclosure of Interest

Data Availability

Funding

Ethical Approval

Pre-registered Clinical Trial Number

References

- Kapadia SR, Leon MB, Makkar RR, Tuzcu EM, Svensson LG, Kodali S, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement compared with standard treatment for patients with inoperable aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl 2015;385:2485-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60290-2

- Arnold SV, Petrossian G, Reardon MJ, Kleiman NS, Yakubov SJ, Wang K, et al. Five-year clinical and quality of life outcomes from the CoreValve US Pivotal Extreme Risk Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14:e010258. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.120. 010258

- Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, Miller DC, Moses JW, Tuzcu EM, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl 2015;385:2477-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60308-7

- Gleason TG, Reardon MJ, Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Lee JS, et al. 5-year outcomes of self-expanding transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:2687-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2146

- Makkar RR, Thourani VH, Mack MJ, Kodali SK, Kapadia S, Webb JG, et al. Five-year outcomes of transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med 2020;382: 799-809. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1910555

- Van Mieghem NM, Deeb GM, Søndergaard L, Grube E, Windecker S, Gada H, et al. Self-expanding transcatheter vs surgical aortic valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients: 5-year outcomes of the SURTAVI randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol 2022;7:1000-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2695

- Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, Milojevic M, Baldus S, Bauersachs J, et al. 2021 ESC/ EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2022;43: 561-632. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab395

- Sharma T, Krishnan AM, Lahoud R, Polomsky M, Dauerman HL. National trends in TAVR and SAVR for patients with severe isolated aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80:2054-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.787

- Thyregod HGH, Steinbrüchel DA, Ihlemann N, Nissen H, Kjeldsen BJ, Petursson P, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis: 1-year results from the all-comers NOTION randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2184-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.014

- Jørgensen TH, Thyregod HGH, Ihlemann N, Nissen H, Petursson P, Kjeldsen BJ, et al. Eight-year outcomes for patients with aortic valve stenosis at low surgical risk randomized to transcatheter vs. surgical aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J 2021;42: 2912-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab375

- Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, Pibarot P, Hahn RT, Genereux P, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in low-risk patients at five years. N Engl J Med 2023;389: 1949-60. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2307447

- Forrest JK, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Gada H, Mumtaz MA, Ramlawi B, et al. 4-year outcomes of patients with aortic stenosis in the Evolut Low Risk Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;82:2163-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.09.813

- Thyregod HG, Søndergaard L, Ihlemann N, Franzen O, Andersen LW, Hansen PB, et al. The Nordic aortic valve intervention (NOTION) trial comparing transcatheter versus surgical valve implantation: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2013; 14:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-11

- Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document (VARC-2). Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg 2012;42:S45-60. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezs533

- VARC-3 WRITING COMMITTEE; Généreux P, Piazza N, Alu MC, Nazif T, Hahn RT, et al. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3: updated endpoint definitions for aortic valve clinical research. Eur Heart J 2021;42:1825-57. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ ehaa799

- Thourani VH, Habib R, Szeto WY, Sabik JF, Romano JC, MacGillivray TE, et al. Survival following surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients: a contemporary trial benchmark. Ann Thorac Surg 2024;117:106-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur. 2023.10.006

- Thyregod HGH, Ihlemann N, Jørgensen TH, Nissen H, Kjeldsen BJ, Petursson P, et al. Five-year clinical and echocardiographic outcomes from the NOTION randomized clinical trial in patients at lower surgical risk. Circulation 2019;139:2714-23. https://doi.org/ 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036606

- Jørgensen TH, De Backer O, Gerds TA, Bieliauskas G, Svendsen JH, Søndergaard L. Mortality and heart failure hospitalization in patients with conduction abnormalities after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2019;12:52-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2018.10.053

- Gilard M, Eltchaninoff H, Donzeau-Gouge P, Chevreul K, Fajadet J, Leprince P, et al. Late outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients: the FRANCE-2 registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1637-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc. 2016.07.747

- Rodriguez-Gabella T, Voisine P, Puri R, Pibarot P, Rodés-Cabau J. Aortic bioprosthetic valve durability: incidence, mechanisms, predictors, and management of surgical and transcatheter valve degeneration. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1013-28. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.07.715

- Head SJ, Mokhles MM, Osnabrugge RLJ, Pibarot P, Mack MJ, Takkenberg JJM, et al. The impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch on long-term survival after aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 34 observational studies comprising 27186 patients with 133141 patient-years. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1518-29. https://doi. org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs003

- Ochi A, Cheng K, Zhao B, Hardikar AA, Negishi K. Patient risk factors for bioprosthetic aortic valve degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung Circ 2020; 29:668-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2019.09.013

- Thyregod HGH, Steinbrüchel DA, Ihlemann N, Ngo TA, Nissen H, Kjeldsen BJ, et al. No clinical effect of prosthesis-patient mismatch after transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in intermediate- and low-risk patients with severe aortic valve stenosis at mid-term follow-up: an analysis from the NOTION trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:721-8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezw095

- Ngo A, Hassager C, Thyregod HGH, Søndergaard L, Olsen PS, Steinbrüchel D, et al. Differences in left ventricular remodelling in patients with aortic stenosis treated with transcatheter aortic valve replacement with corevalve prostheses compared to surgery with porcine or bovine biological prostheses. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2018;19:39-46. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jew321

- O’Hair D, Yakubov SJ, Grubb KJ, Oh JK, Ito S, Deeb GM, et al. Structural valve deterioration after self-expanding transcatheter or surgical aortic valve implantation in patients at intermediate or high risk. JAMA Cardiol 2023;8:111-9. https://doi.org/10. 1001/jamacardio.2022.4627

- Roslan AB, Naser JA, Nkomo VT, Padang R, Lin G, Pislaru C, et al. Performance of echocardiographic algorithms for assessment of high aortic bioprosthetic valve gradients. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2022;35:682-91. e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2022.01.019

- Ueyama H, Kuno T, Takagi H, Kobayashi A, Misumida N, Pinto DS, et al. Meta-analysis comparing valve durability among different transcatheter and surgical aortic valve bioprosthesis. Am J Cardiol 2021;158:104-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.07. 046

- Pibarot P, Ternacle J, Jaber WA, Salaun E, Dahou A, Asch FM, et al. Structural deterioration of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve bioprostheses in the PARTNER-2 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:1830-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.049

- Strange JE, Østergaard L, Køber L, Bundgaard H, Iversen K, Voldstedlund M, et al. Patient characteristics, microbiology, and mortality of infective endocarditis after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Clin Infect Dis 2023;77:1617-25. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ ciad431

- Makkar RR, Fontana G, Jilaihawi H, Chakravarty T, Kofoed KF, De Backer O, et al. Possible subclinical leaflet thrombosis in bioprosthetic aortic valves.

Engl Med 2015;373:2015-24. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1509233 - Yerasi C, Rogers T, Forrestal BJ, Case BC, Khan JM, Ben-Dor I, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in young, low-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2021;14:1169-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2021.03.058

- Barbanti M, Costa G, Picci A, Criscione E, Reddavid C, Valvo R, et al. Coronary cannulation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the RE-ACCESS study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2020;13:2542-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2020.07.006

- Buzzatti N, Romano V, De Backer O, Soendergaard L, Rosseel L, Maurovich-Horvat P, et al. Coronary access after repeated transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a glimpse into the future. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020;13:508-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg. 2019.06.025

- Park SJ, Ok YJ, Kim HJ, Kim YJ, Kim S, Ahn JM, et al. Evaluating reference ages for selecting prosthesis types for heart valve replacement in Korea. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6: e2314671. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.14671

- Mauri V, Abdel-Wahab M, Bleiziffer S, Veulemans V, Sedaghat A, Adam M, et al. Temporal trends of TAVI treatment characteristics in high volume centers in Germany 2013-2020. Clin Res Cardiol 2022;111:881-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00392-021-01963-3

- Writing Committee Members; Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021; 77:e25-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018

- Leon MB, Mack MJ, Hahn RT, Thourani VH, Makkar R, Kodali SK, et al. Outcomes 2 years after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients at low surgical risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:1149-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.052

- Forrest JK, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, Gada H, Mumtaz MA, Ramlawi B, et al. 3-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;81:1663-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc. 2023.02.017

- Kalra A, Rehman H, Ramchandani M, Barker CM, Lawrie GM, Reul RM, et al. Early trifecta valve failure: report of a cluster of cases from a tertiary care referral center. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;154:1235-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.05.044

- Sénage T, Le Tourneau T, Foucher Y, Pattier S, Cueff C, Michel M, et al. Early structural valve deterioration of Mitroflow aortic bioprosthesis: mode, incidence, and impact on outcome in a large cohort of patients. Circulation 2014;130:2012-20. https://doi.org/ 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.010400

- Grunkemeier GL, Furnary AP, Wu Y, Wang L, Starr A. Durability of pericardial versus porcine bioprosthetic heart valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:1381-6. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.08.060

- Corresponding author. Tel: +45 3545 1080, Email: hans.gustav.thyregod@regionh.dk

The first two authors shared first authorship.

Retired researcher.

© The Author(s) 2024. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- Corresponding author. Tel: +45 3545 1080, Email: hans.gustav.thyregod@regionh.dk