DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-024-3378-5

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-11

– ورقة أصلية –

درجات حرارة المحيطات القياسية الجديدة ومؤشرات المناخ ذات الصلة في عام 2023

الملخص

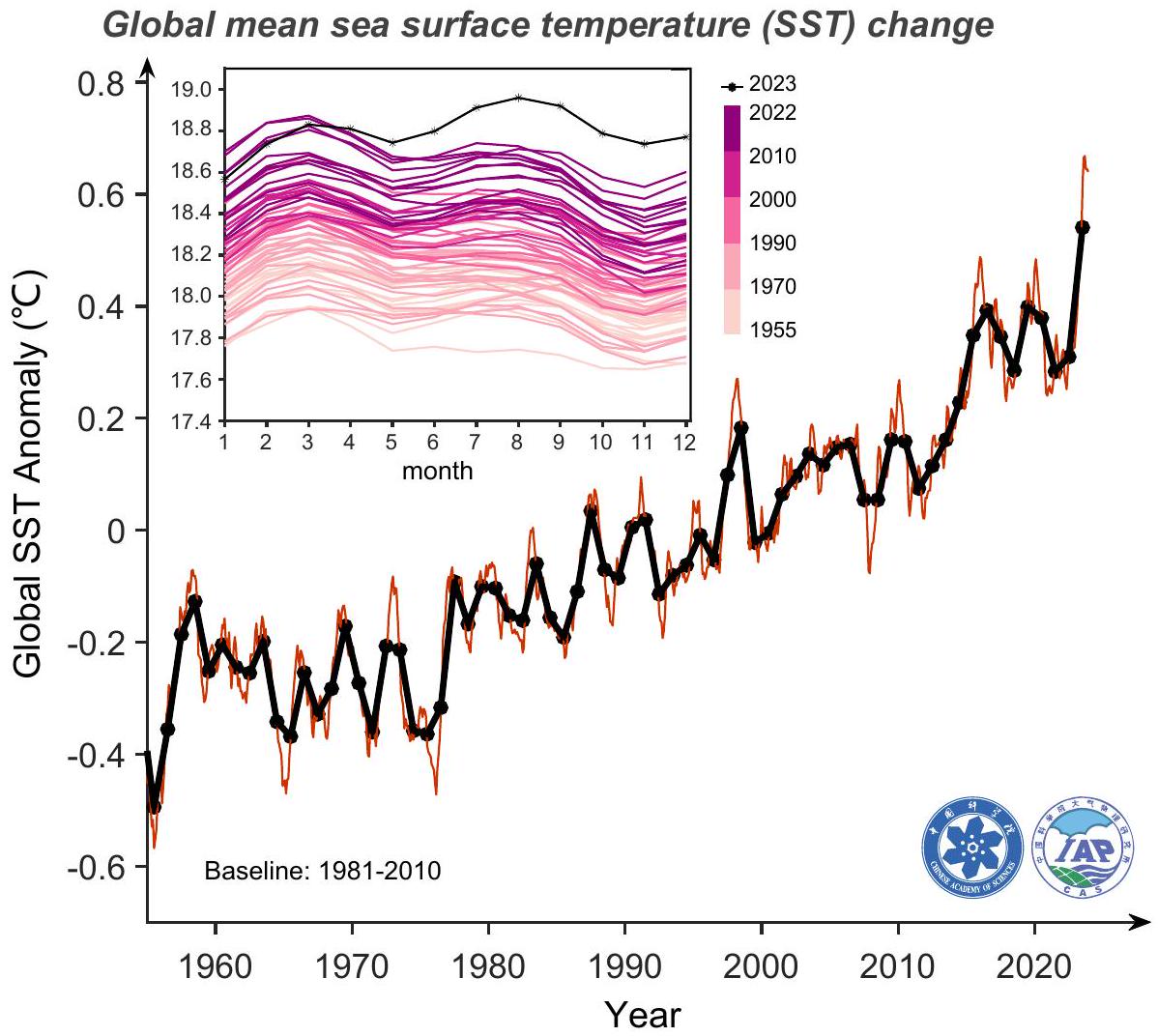

لقد تم تغيير البيئة الفيزيائية والبيوجيوكيميائية العالمية بشكل كبير استجابةً لزيادة غازات الدفيئة في الغلاف الجوي الناتجة عن الأنشطة البشرية. في عام 2023، وصلت درجة حرارة سطح البحر (SST) ومحتوى حرارة المحيط في عمق 2000 متر (OHC) إلى مستويات قياسية.

الاقتباس: تشينغ، ل. ج.، والمؤلفون المشاركون، 2024: سجلات جديدة لدرجات حرارة المحيطات ومؤشرات المناخ ذات الصلة في 2023. علوم الغلاف الجوي المتقدمة، 41(6)، 1068-1082،https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-024-3378-5.

نقاط بارزة في المقال:

- في عام 2023، كانت متوسط درجة حرارة سطح البحر السنوي العالمي ومحتوى حرارة المحيط في أعلى 2000 متر هما الأعلى على الإطلاق المسجل بواسطة الأدوات الحديثة.

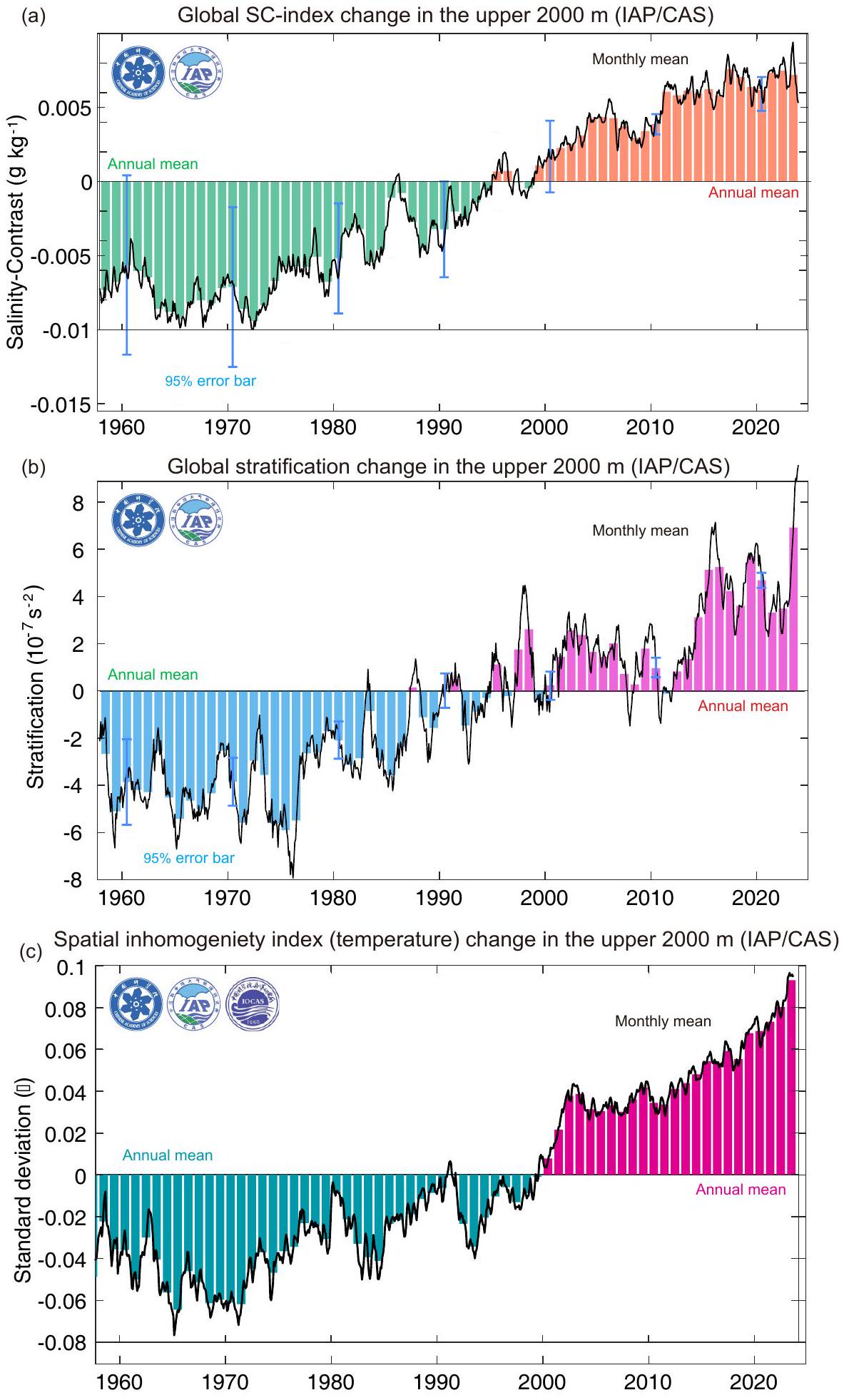

- حققت مؤشرات محيطية أخرى، بما في ذلك تدرج الكثافة وعدم تجانس درجة الحرارة المكاني، مستويات قياسية.

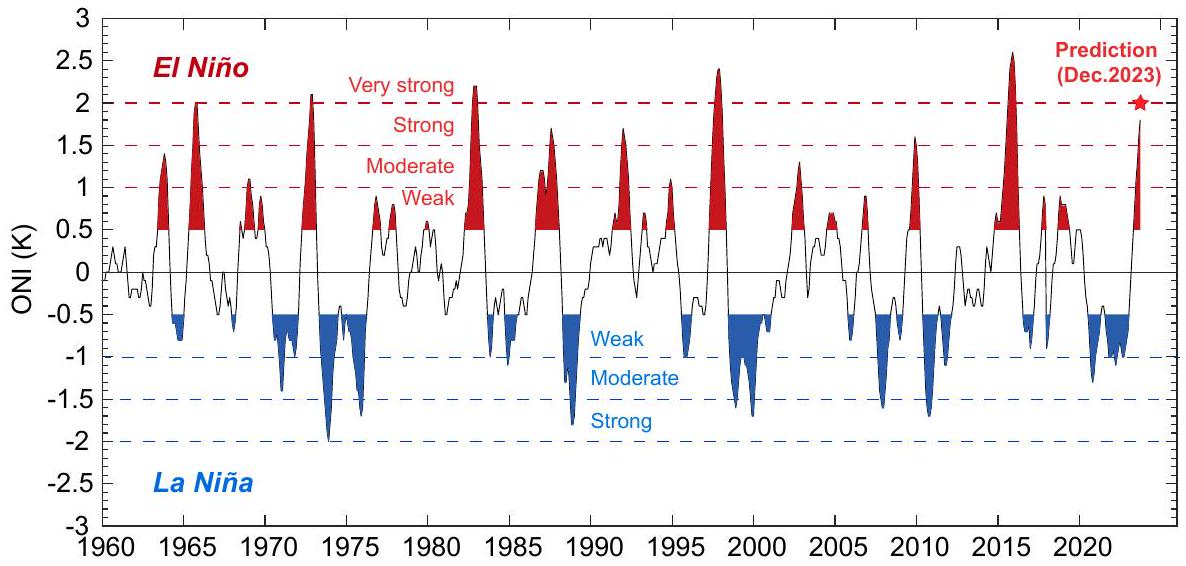

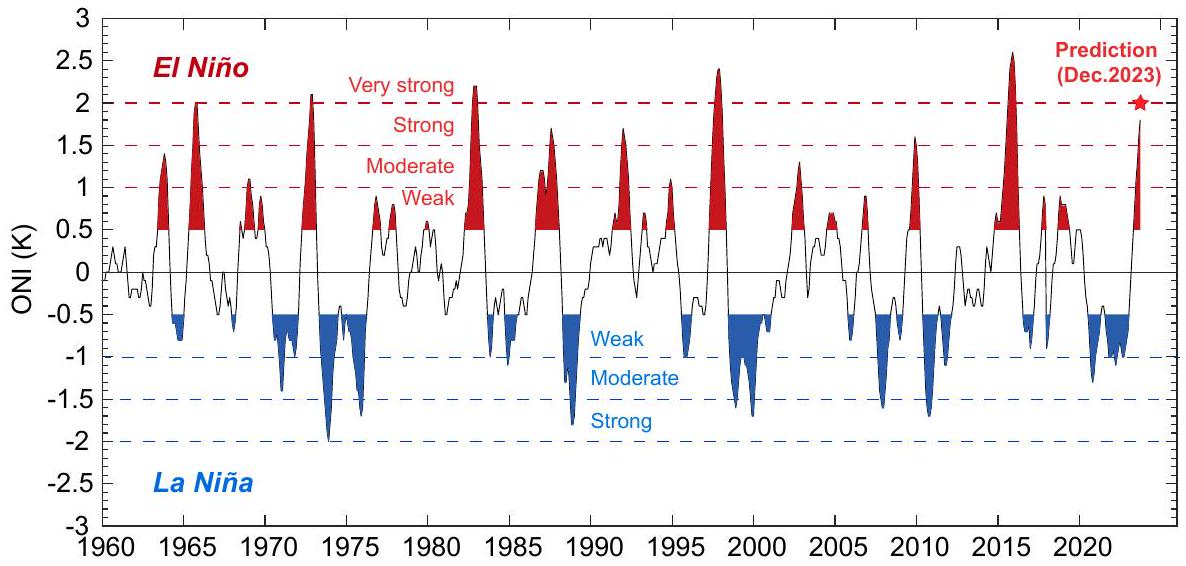

- تطور ظاهرة النينيو القوية خلال عام 2023 وأثرت على أنماط الاحترار والشذوذ في الملوحة.

1. المقدمة

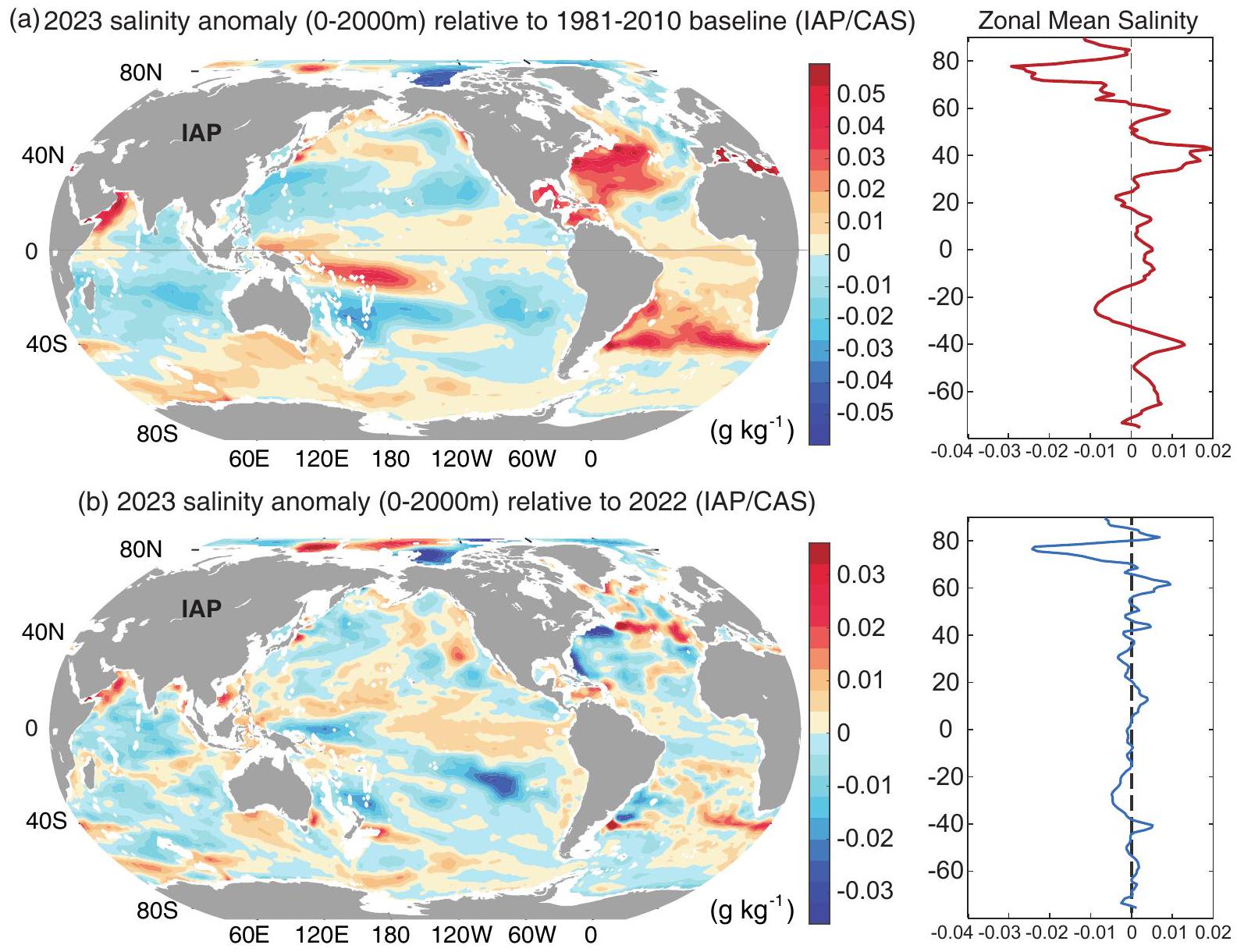

مع تغيرات درجة الحرارة، تنظم تيارات المحيطات وتؤثر على الاستقرار العمودي للمحيط. تُميز اتجاهات ملوحة المحيطات عمومًا بنمط تغيير “المالح يصبح أكثر ملوحة، والعذب يصبح أكثر عذوبة”، مما يعني أن المناطق التي هي حاليًا عذبة تصبح أكثر عذوبة، والمناطق التي هي حاليًا مالحة تصبح أكثر ملوحة (دوراك وويفيلز، 2010). يمكن قياس هذه العملية بواسطة مؤشر “تباين الملوحة” (SC) الذي يحسب الفرق في الملوحة بين المناطق ذات الملوحة العالية والمنخفضة مقارنةً بمتوسط عالمي (تشنغ وآخرون، 2020).

2. البيانات والأساليب

تساهم السفن البحثية، والحيوانات المجهزة بالأدوات، والطائرات الانزلاقية، والعوامات المربوطة، والمقاييس المرتبطة بالجليد، في تعزيز الملاحظات على مستوى العالم وتعتبر مصادر رئيسية في البحار الضحلة/رفوف القارات، والمناطق المغطاة بالجليد الموسمي في العروض العليا. تنشأ الفروقات بين منتجات البيانات من الملاحظات الإضافية في الموقع التي تمتلكها مركز البيانات، ومراقبة جودة البيانات (QC)، وعلم المناخ، والتداخل العمودي، وسد الفجوات، وتقنيات معالجة البيانات الأخرى (أبراهام وآخرون، 2013؛ بوير وآخرون، 2016؛ تشينغ وآخرون، 2022أ). تُستخدم جميع البيانات instrumentية لمنتجات IAP/CAS وNCEI/NOAA. يقدم هذا البحث أحدث المعلومات من IAP/CAS وNCEI/NOAA لعام 2023، مع دمج أحدث تقنيات معالجة جودة البيانات ورسم الخرائط. كل من مجموعات بيانات IAP/CAS وNCEI/NAA هي منتجات مصفوفة شهرية، ولديها

3. التغيرات العالمية في المحيطات من حيث محتوى الحرارة المحيطية، والملوحة، والتصنيف الطبقي

3.1. درجة حرارة OHC والسطح

في العقود الأخيرة. ارتفعت درجة حرارة الجزء العلوي من المحيطات العالمية بمتوسط قدره 2000 متر

| رتبة | سنة | OHC (IAP/CAS) (الوحدات: ZJ) | OHC (NCEI/NOAA) (الوحدات: زJ) | شذوذ درجة حرارة سطح البحر (IAP/CAS) (الوحدات:

|

| 1 | ٢٠٢٣ | 286 | 247 | 0.54 |

| 2 | ٢٠٢٢ | ٢٧١ | 238 | 0.31 |

| ٣ | ٢٠٢١ | 254 | 229 | 0.28 |

| ٤ | ٢٠٢٠ | 237 | 211 | 0.38 |

| ٥ | 2019 | 228 | ٢١٠ | 0.40 |

سجل. انحراف درجة حرارة سطح البحر الشهري في عام 2023 مقارنةً بالفترة من 1981 إلى 2010 زاد من

3.2. مؤشرات المناخ المحيطي الأخرى

مؤشر OHC و SC لأنه يكشف عن تغييرات أكبر في المحيط العلوي، مما يظهر شذوذات أقوى من المحيط الأعمق. في عام 2023، زادت طبقية الـ 2000 متر العليا إلى

4. الأنماط الإقليمية لارتفاع درجة حرارة المحيطات والملوحة

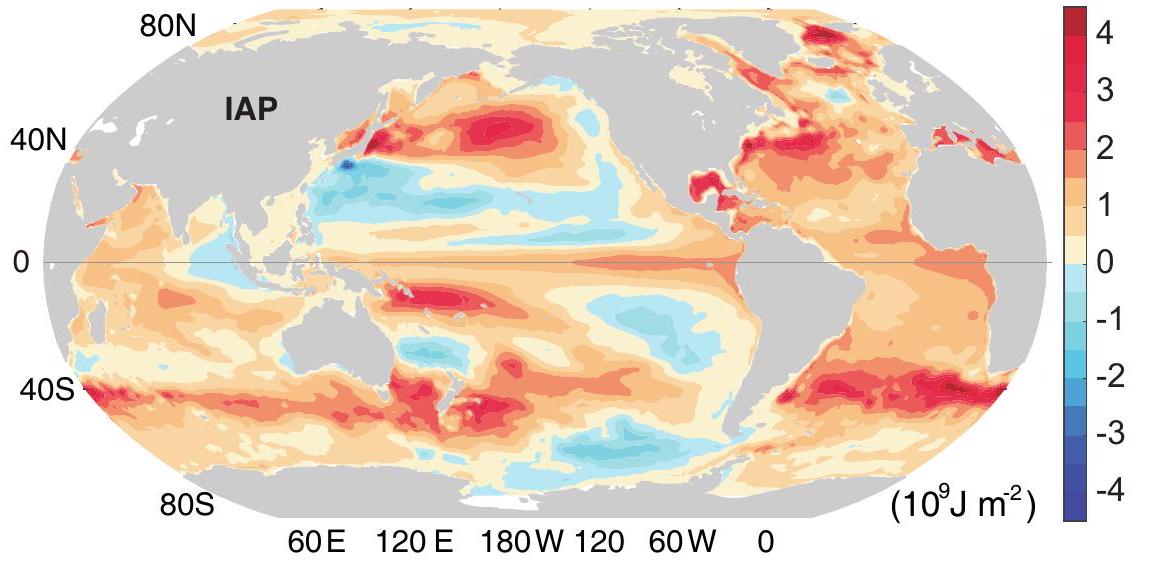

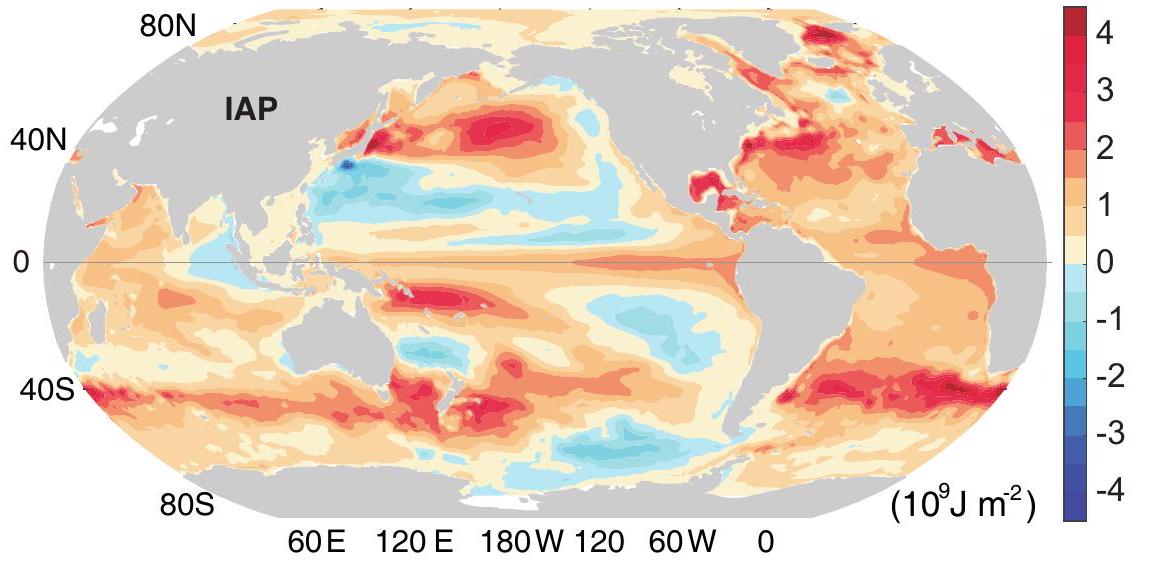

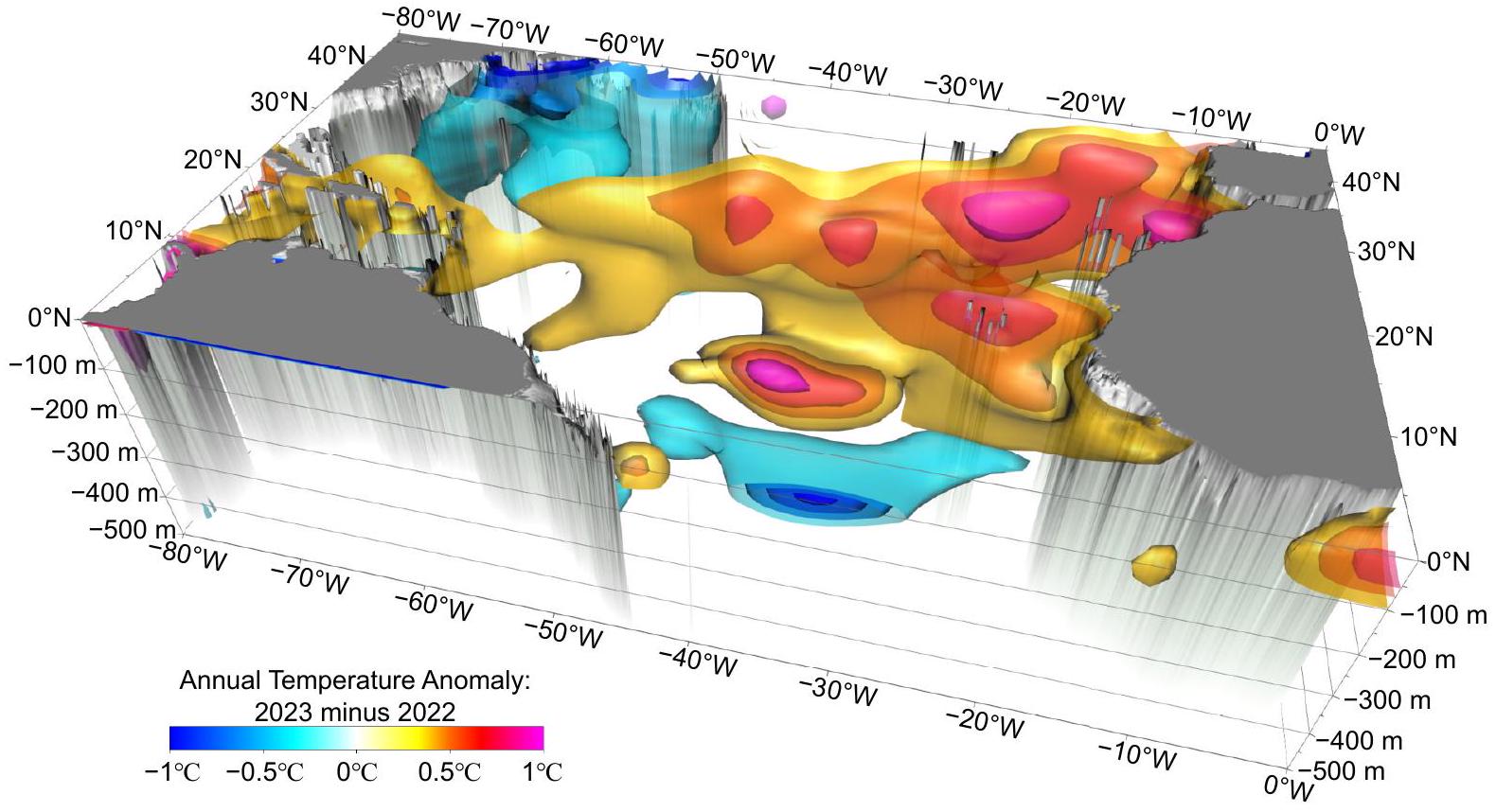

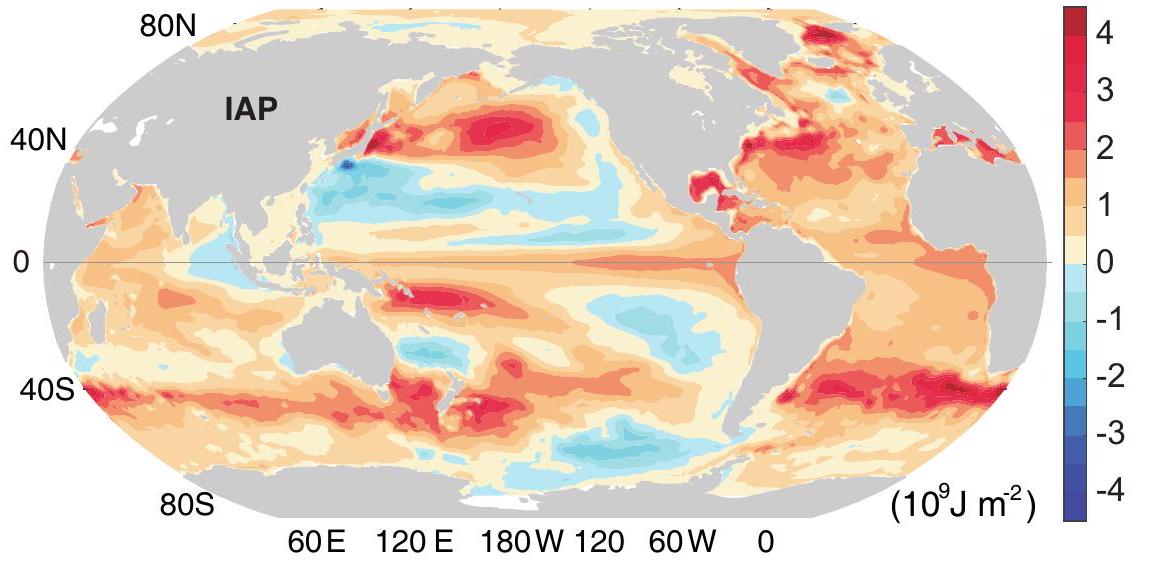

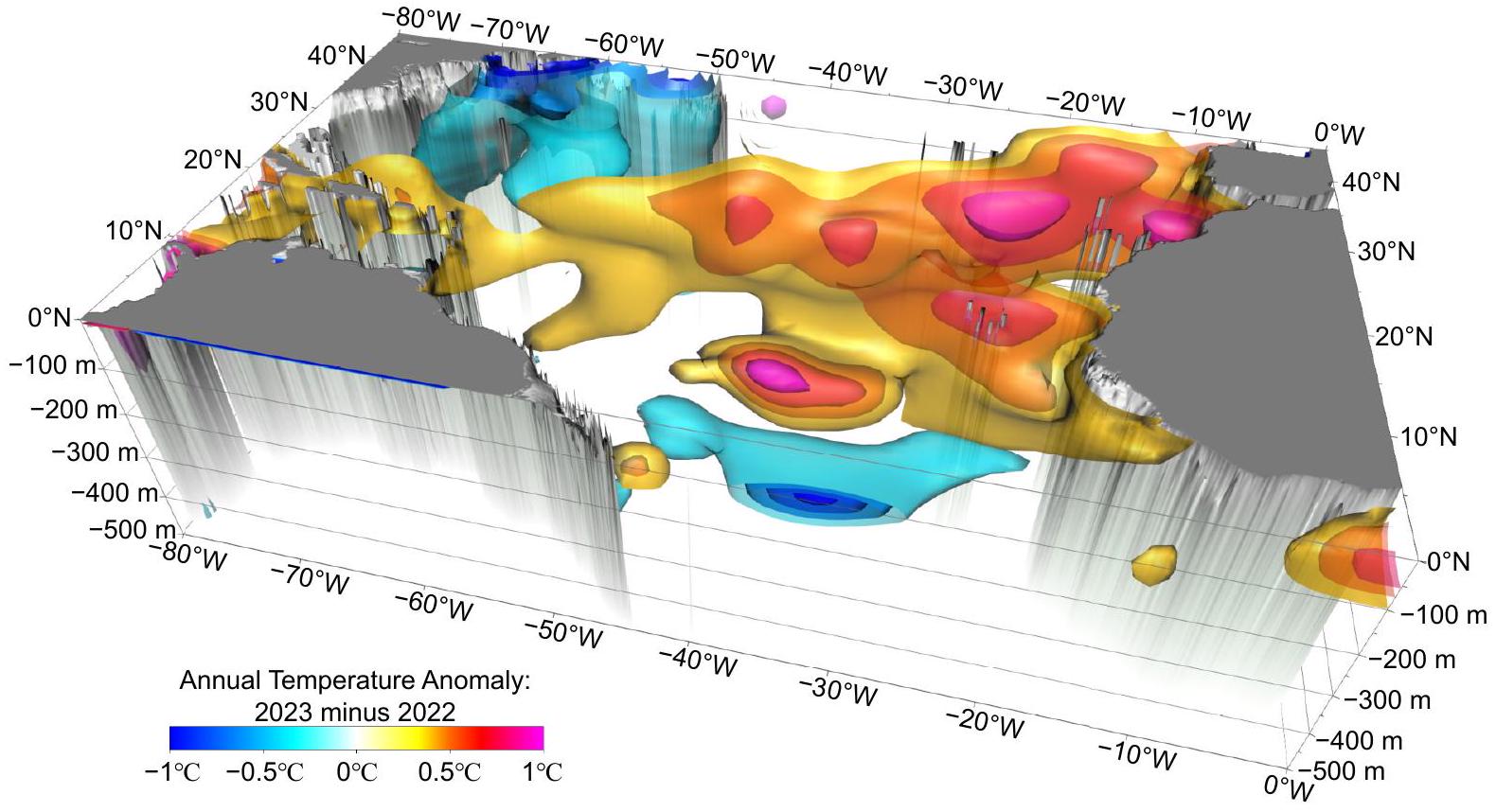

يتم تقديم الفرق السنوي المتوسط لـ OHC بين عامي 2023 و2022 في الشكل 6. في المحيط الهادئ الاستوائي، توجد انحرافات حرارية قوية في المحيط الهادئ الشرقي وانحرافات تبريد…

تقع في غرب المحيط الهادئ في عام 2023 (الشكل 6) تشير إلى ارتفاع مستوى الطبقة الحرارية الاستوائية المرتبطة بظاهرة النينيو. يظهر محتوى الحرارة المحيطية الأفقي تسخينًا استوائيًا قويًا ضمن

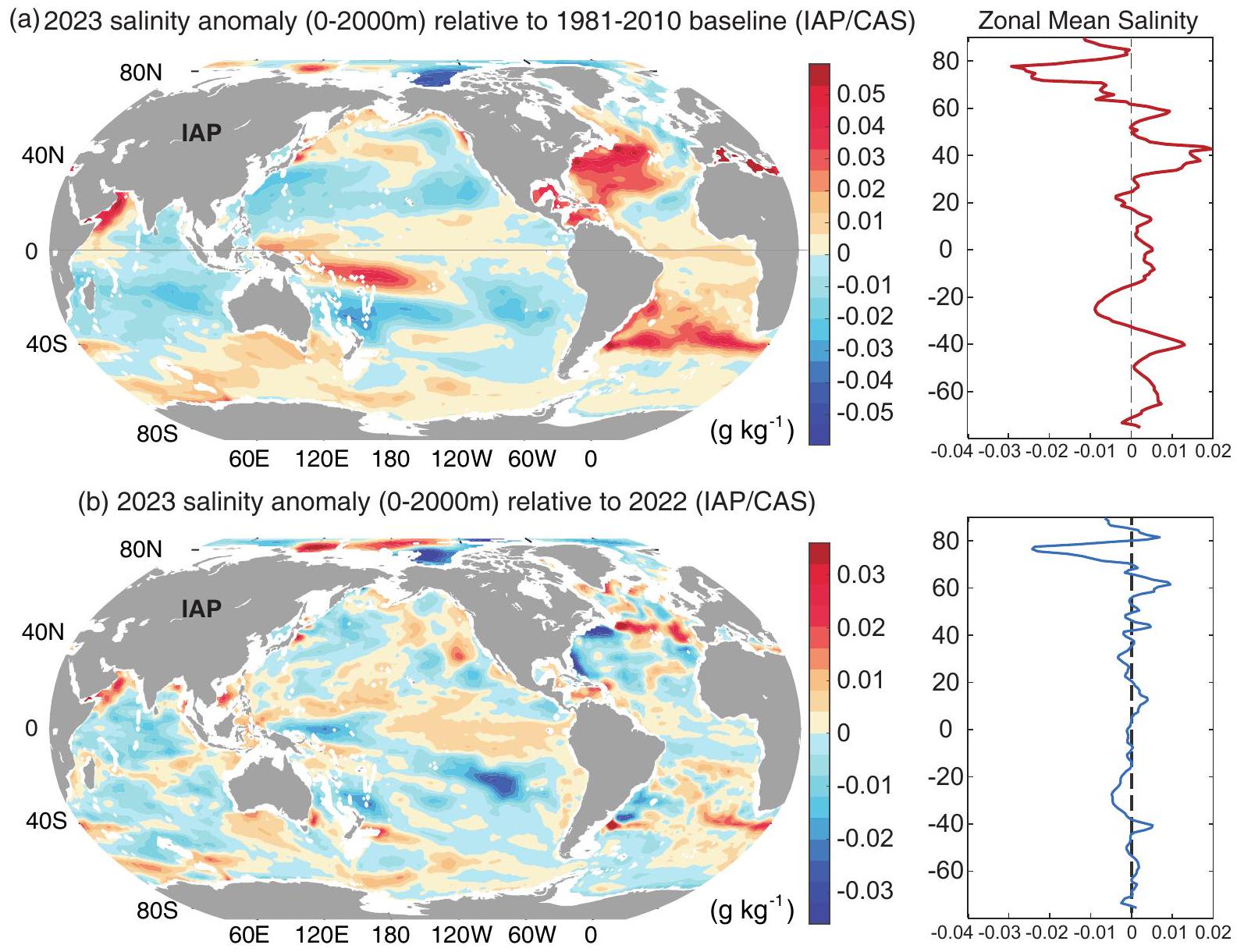

تزداد ملوحة المحيط الأطلسي في المناطق المتوسطة، والبحر الأبيض المتوسط، والمحيط الهندي الغربي. هذه ظاهرة نموذجية تُظهر أن “الماء العذب يصبح أكثر عذوبة، والماء المالح يصبح أكثر ملوحة”، وهي تغيير مدفوع بتعزيز دورة المياه الجوية. تكشف التغيرات في ملوحة المناطق الاستوائية عن المزيد من تأثير ظاهرة النينيو، خاصة في المحيط الهادئ الغربي وحول المنطقة الاستوائية.

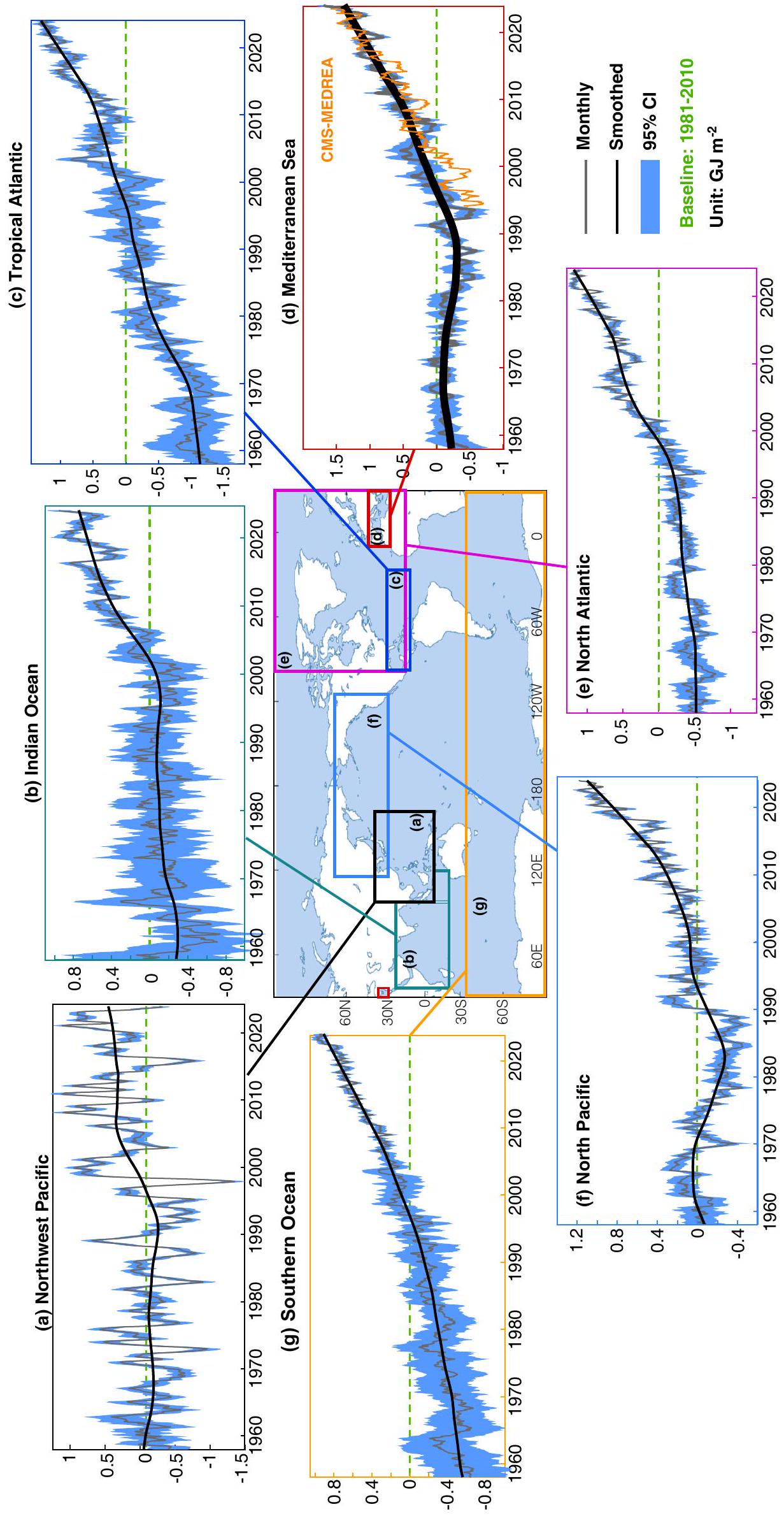

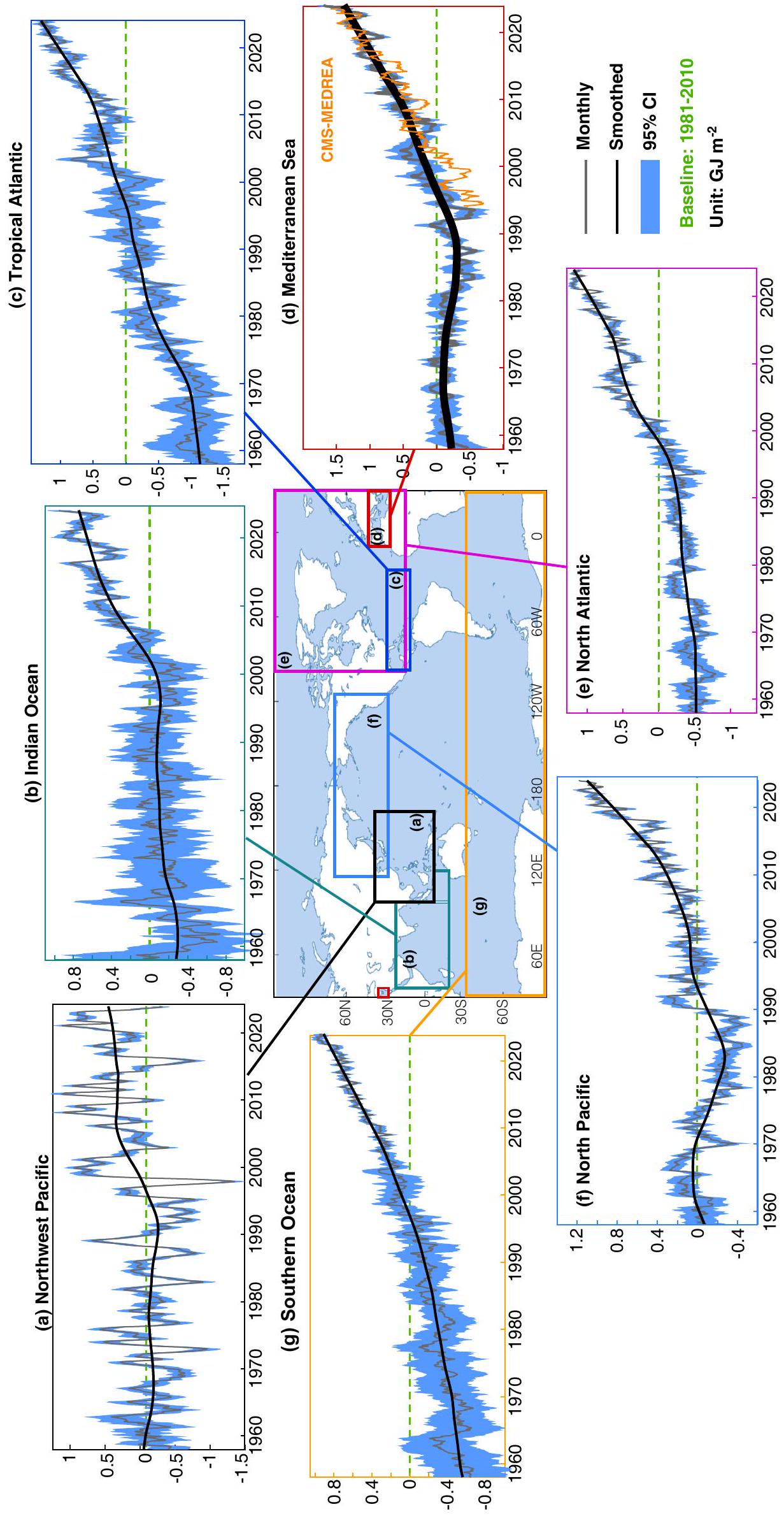

5. تغييرات حرارة المحيطات على مستوى الحوض والنقاط الساخنة الإقليمية

مع الميل السلبي لحرارة المحيط الهندي خلال ظاهرة لانيينا (تشنغ وآخرون، 2019)، المدفوع أساسًا بتقليل نقل الحرارة عبر ممرات تدفق إندونيسيا خلال مرحلة تلاشي لانيينا (ترينبرث وزانغ، 2019؛ لي وآخرون، 2020ب؛ فولكوف وآخرون، 2020). ومع ذلك، فقد أظهرت حرارة المحيط الهندي زيادة مستمرة منذ يناير 2023، المرتبطة بإنهاء لانيينا وتطور النينيو.

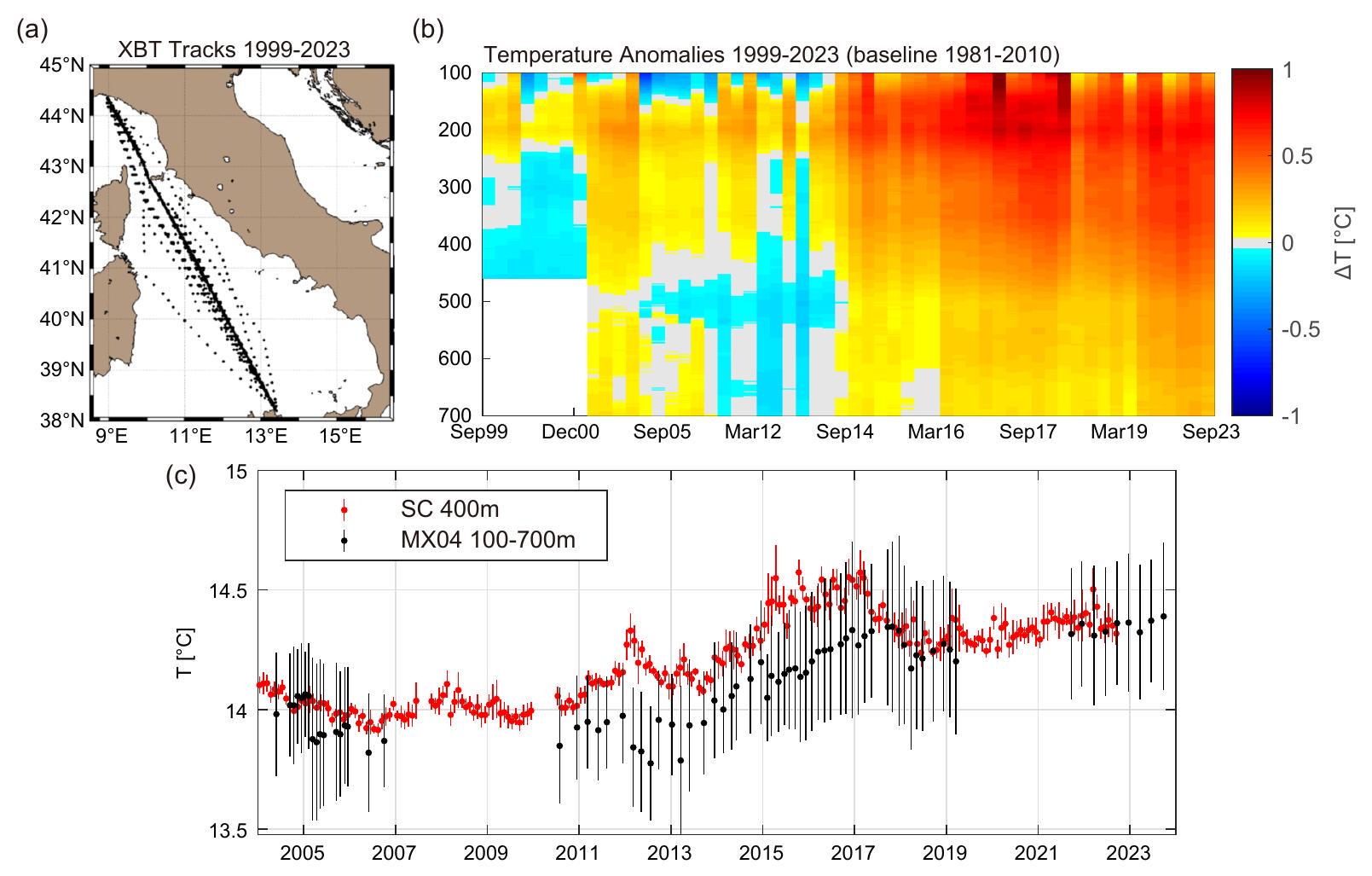

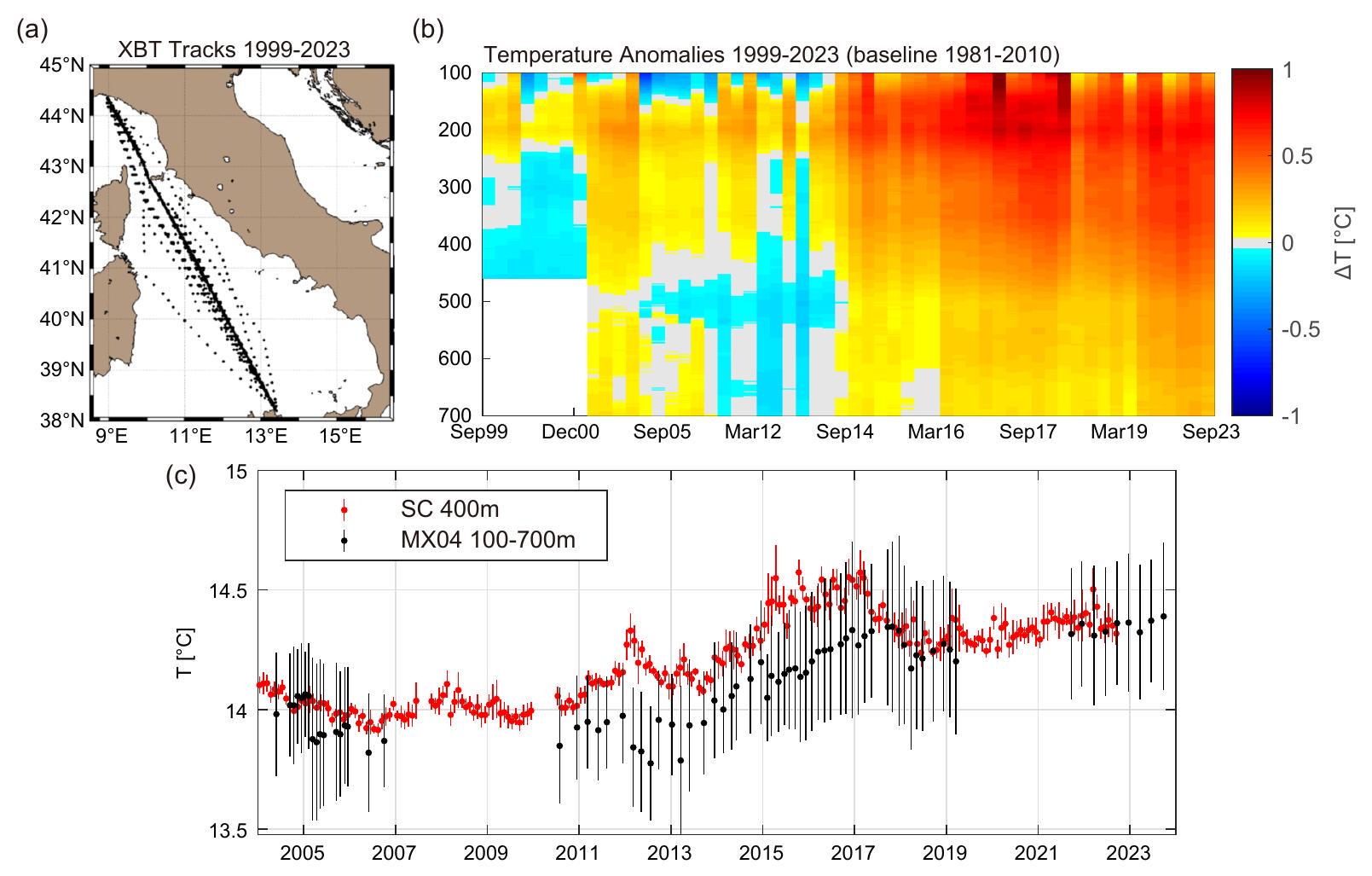

سيللي وآخرون، 2023) (الشكل 10أ)، أشاروا إلى ارتفاع واضح في درجة الحرارة في

6. ملاحظات ختامية

مؤسسة العلوم الطبيعية الوطنية في الصين (أرقام المنح 42076202، 42122046، 42206208 و42261134536)، مؤسسة العلوم الأساسية الجديدة من خلال جائزة XPLORER، زميل أكاديمية DAMO الشاب، جمعية تعزيز الابتكار الشبابي، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم؛ مشروع البنية التحتية العلمية والتكنولوجية الوطنية الرئيسية “منشأة محاكاة النظام الأرضي” (EarthLab). تم إجراء الحسابات في هذه الدراسة على الحاسوب الفائق ORISE. يتم رعاية NCAR من قبل مؤسسة العلوم الوطنية الأمريكية. استخدمنا بعض البيانات التي تم جمعها على متن السفينة R/V Shiyan 6 التي تنفذ الرحلة البحثية المفتوحة NORC2022-10+NORC2022-303 المدعومة من مشاريع مشاركة وقت السفن NSFC 42149910. تم دعم جهود الدكتور فاسولو في هذا العمل من خلال جوائز ناسا 80NSSC17K0565، 80NSSC21K1191، و80NSSC22K0046 ومن خلال مكون تحليل النماذج الإقليمية والعالمية (RGMA) من برنامج نمذجة النظام الأرضي والبيئي التابع لمكتب أبحاث البيولوجيا والبيئة (BER) في وزارة الطاقة الأمريكية عبر مؤسسة العلوم الوطنية IA 1947282. تم دعم جهود الدكتور ميشونوف من قبل NOAA (رقم المنحة NA19NES4320002 إلى CISESS-MD في جامعة ماريلاند). بيانات IAP/CAS متاحة فيhttp://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/ و https://msdc.qdio.ac.cn/تتوفر بيانات NCEI/NOAA على https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/climate-data-records/global-

محتوى حرارة المحيط. تم إجراء هذه الدراسة باستخدام أيضًا معلومات خدمة كوبرنيكوس البحرية التابعة للاتحاد الأوروبيhttps://marine.copernicus.eu/) لتقديرات OHC في البحر الأبيض المتوسط. يتم دعم G. LI من قبل مشروع دعم المواهب الشابة لجمعية قوانغتشو للعلوم والتكنولوجيا.

REFERENCES

Abraham, J., L. J. Cheng, M. E. Mann, K. Trenberth, and K. Von Schuckmann, 2022: The ocean response to climate change guides both adaptation and mitigation efforts. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett., 15, 100221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aosl.2022. 100221.

Argo, 2023: Argo Float Data and Metadata from Global Data Assembly Centre (Argo GDAC). SEANOE. Available from https://doi.org/10.17882/42182.

Ben Ismail S., K. Schroeder, J. Chiggiato, S. Sparnocchia, and M. Borghini, 2021: Long term changes monitored in two Mediterranean Channels. Copernicus Marine Service Ocean State Report, Issue 5, K. Von Schuckmann et al., Eds., 48-52, https://doi.org/10.1080/1755876X.2021.1946240.

Boyer, T., and Coauthors, 2016: Sensitivity of global upperocean heat content estimates to mapping methods, XBT bias corrections, and baseline climatologies. J. Climate, 29, 4817-4842, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0801.1.

Boyer, T. P., and Coauthors, 2018: World ocean database 2018. NOAA Atlas NESDIS 87.

Cheng, L. J., J. Zhu, R. Cowley, T. Boyer, and S. Wijffels, 2014: Time, probe type, and temperature variable bias corrections

to historical expendable bathythermograph observations.

Cheng, L. J., K. Trenberth, J. Fasullo, J. Abraham, T. Boyer, K. Von Schuckmann, and J. Zhu, 2018: Taking the pulse of the planet. Eos, 99, 14-16, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO 081839.

Cheng, L. J., and Coauthors, 2022a: Past and future ocean warming. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 3, 776-794, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00345-1.

Cheng, L. J., G. Foster, Z. Hausfather, K. E. Trenberth, and J. Abraham, 2022b: Improved quantification of the rate of ocean warming. J. Climate, 35, 4827-4840, https://doi.org/10. 1175/JCLI-D-21-0895.1.

Cheng, L. J, and Coauthors, 2022c: Another record: Ocean warming continues through 2021 despite La Niña conditions. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 39(3), 373-385, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-1461-3.

Cheng, L. J., and Coauthors, 2023: Another year of record heat for the oceans. Adv. Atmos. Sci, 40, 963-974, https://doi.org/

Durack, P. J., and S. E. Wijffels, 2010: Fifty-year trends in global ocean salinities and their relationship to broad-scale warming. J. Climate, 23, 4342-4362, https://doi.org/10.1175/ 2010JCLI3377.1.

Escudier, R., and Coauthors, 2021: A high resolution reanalysis for the mediterranean sea. Front. Earth Sci., 9, 702285, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.702285.

Fischer, E. M., S. Sippel, and R. Knutti, 2021: Increasing probability of record-shattering climate extremes. Nature Climate Change, 11, 689-695, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01092-9.

Fasullo, J. T., Gent, P. R., and Nerem, R. S. 2020: Forced patterns of sea level rise in the community earth system model large ensemble from 1920 to 2100. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 125, e2019JC016030. https://doi.org/10. 1029/2019JC016030

Gouretski, V., and L. J. Cheng, 2020: Correction for systematic errors in the global dataset of temperature profiles from mechanical bathythermographs. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol., 37(5), 841-855, https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH-D-190205.1.

Gouretski, V., F. Roquet, and L. J. Cheng, 2023: Measurement biases in ocean temperature profiles from marine mammal data loggers. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol., submitted.

Gulev, S., and Coauthors, 2021: Changing state of the climate sys-

tem. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, V. Mas-son-Delmotte et al., Eds., Cambridge University Press.

Huang, B. Y., and Coauthors, 2017: Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): Upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Climate, 30, 8179-8205, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0836.1.

Johnson, G., and Coauthors, 2018: Ocean heat content [in State of the Climate in 2017]. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 99, S72-S77.

Levitus, S., J. I. Antonov, T. P. Boyer, R. A. Locarnini, H. E. Garcia, and A. V. Mishonov, 2009: Global ocean heat content 1955-2008 in light of recently revealed instrumentation problems. Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L07608, https://doi.org/10. 1029/2008GL037155.

Levitus, S., and Coauthors, 2012: World ocean heat content and thermosteric sea level change (

Li, G. C., L. J. Cheng, J. Zhu, K. E. Trenberth, M. E. Mann, and J. P. Abraham, 2020a: Increasing ocean stratification over the past half-century. Nature Climate Change, 10, 1116-1123, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00918-2.

Li, K. X., F. Zheng, L. J. Cheng, T. Y. Zhang, and J. Zhu, 2023: Record-breaking global temperature and crises with strong El Niño in 2023-2024. The Innovation Geoscience, 1(2), 100030. https://doi.org/10.59717/j.xinn-geo.2023.100030.

Li, Y. L., W. Q. Han, F. Wang, L. Zhang, and J. Duan, 2020b: Vertical structure of the upper-Indian Ocean thermal variability. J. Climate, 33, 7233-7253, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0851.1.

Loeb, N. G., G. C. Johnson, T. J. Thorsen, J. M. Lyman, F. G. Rose, and S. Kato, 2021: Satellite and ocean data reveal marked increase in Earth’s heating rate. Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2021GL093047, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL09 3047.

Pinardi, N., and Coauthors, 2015: Mediterranean Sea large-scale low-frequency ocean variability and water mass formation rates from 1987 to 2007: A retrospective analysis. Progress in Oceanography, 132, 318-332, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. pocean.2013.11.003.

Purkey, S., and G. C. Johnson, 2010: Warming of global abyssal and deep Southern Ocean waters between the 1990s and 2000s: Contributions to global heat and sea level rise budgets. J. Climate, 23, 6336-6351, https://doi.org/10.1175/ 2010JCLI3682.1.

Ren, Q. P., Y.-O. Kwon, J. Y. Yang, R.-X. Huang, Y. L. Li, and F. Wang, 2022: Increasing inhomogeneity of the global

oceans. Geophys. Res. Lett., 49, e2021GL097598, https://doi. org/10.1029/2021GL097598.

Reseghetti, F., C. Fratianni, and S. Simoncelli, 2023: Reprocessed of XBT dataset in the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian seas (1999-2019). Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV). [Available online from https://doi.org/10.13127/ rep_xbt_1999_2019].

Rhein, M., and Coauthors, 2013: Observations: Ocean pages. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, T. F. Stocker et al., Eds., Cambridge University Press.

Scannell, H. A., G. C. Johnson, L. Thompson, J. M. Lyman, and S. C. Riser, 2020: Subsurface evolution and persistence of marine heatwaves in the Northeast Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2020GL090548, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020 GL090548.

Schroeder, K., J. Chiggiato, S. A. Josey, M. Borghini, S. Aracri, and S. Sparnocchia, 2017: Rapid response to climate change in a marginal sea. Scientific Reports, 7, 4065, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-017-04455-5.

Simoncelli, S., N. Pinardi, C. Fratianni, C. Dubois, and G. Notarstefano, 2018: Water mass formation processes in the Mediterranean Sea over the past 30 years. In: Copernicus Marine Service Ocean State Report, Issue 2, Journal of Operational Oceanography, 11:sup1, s13-s16, https://doi.org/10.1080/ 1755876X.2018.1489208.

Simoncelli, S., Reseghetti, F., Fratianni, C., Cheng, L., and Raiteri, G., 2023: Reprocessing of XBT profiles from the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian seas over the time period 1999-2019 with full metadata upgrade, Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2023-525, in review.

Tan, Z. T., L. J. Cheng, V. Gouretski, B. Zhang, Y. J. Wang, F. C. Li, Z. H. Liu, and J. Zhu, 2023: A new automatic quality control system for ocean profile observations and impact on ocean warming estimate. Deep-Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap., 194, 103961, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2022. 103961.

Trenberth, K. E., J. M. Caron, D. P. Stepaniak, and S. Worley, 2002: Evolution of El Niño-Southern Oscillation and global atmospheric surface temperatures. J. Geophys. Res., 107, AAC 5-1-AAC 5-17, doi: 10.1029/2000JD000298.

Trenberth, K. E., L. J. Cheng, P. Jacobs, Y. X. Zhang, and J. Fasullo, 2018: Hurricane Harvey links to ocean heat content and climate change adaptation. Earth’s Future, 6, 730-744, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EF000825.

Trenberth, K. E., and Y. X. Zhang, 2019: Observed interhemispheric meridional heat transports and the role of the Indonesian Throughflow in the Pacific Ocean. J. Climate, 32, 8523-8536, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0465.1.

Volkov, D. L., S.-K. Lee, A. L. Gordon, and M. Rudko, 2020: Unprecedented reduction and quick recovery of the South Indian Ocean heat content and sea level in 2014-2018. Science Advances, 6, eabc1151, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv. abc1151.

Von Schuckmann, K., and Coauthors, 2020: Heat stored in the Earth system: Where does the energy go? Earth System Sci-

ence Data, 12, 2013-2041, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-2013-2020.

Zheng, F., and J. Zhu, 2016: Improved ensemble-mean forecasting of ENSO events by a zero-mean stochastic error model of an intermediate coupled model. Climate Dyn., 47, 3901-3915, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-016-3048-0.

- Corresponding author: Lijing CHENG

Email: chenglij@mail.iap.ac.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-024-3378-5

Publication Date: 2024-01-11

– Original Paper –

New Record Ocean Temperatures and Related Climate Indicators in 2023

Abstract

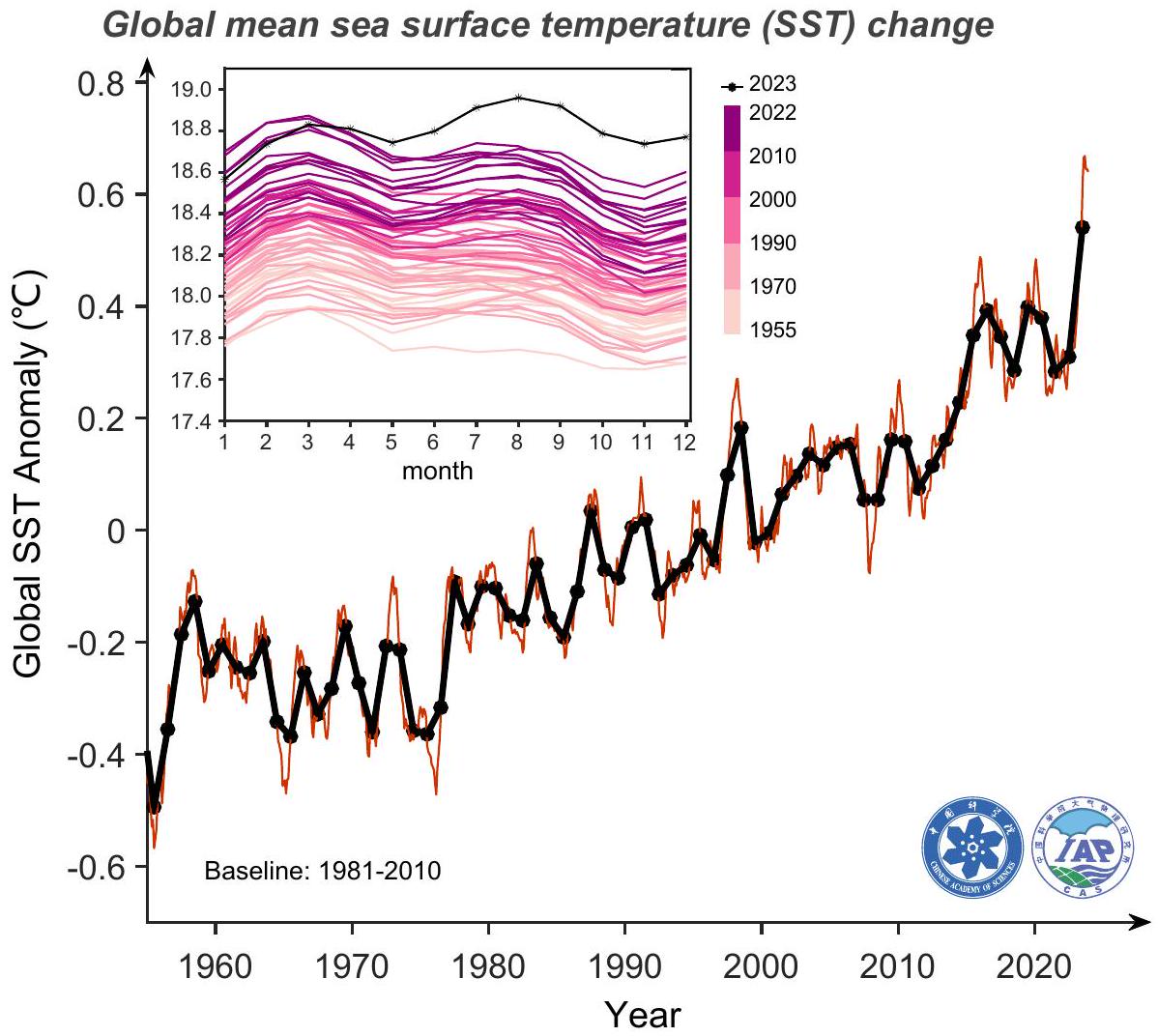

The global physical and biogeochemical environment has been substantially altered in response to increased atmospheric greenhouse gases from human activities. In 2023, the sea surface temperature (SST) and upper 2000 m ocean heat content (OHC) reached record highs. The

Citation: Cheng, L. J., and Coauthors, 2024: New record ocean temperatures and related climate indicators in 2023. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 41(6), 1068-1082, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-024-3378-5.

Article Highlights:

- In 2023, the global annual mean SST and upper 2000 m ocean heat content were the highest ever recorded by modern instruments.

- Other oceanic indices, including density stratification and spatial temperature inhomogeneity, attained record highs.

- A strong El Niño developed during 2023 and influenced warming and salinity anomaly patterns.

1. Introduction

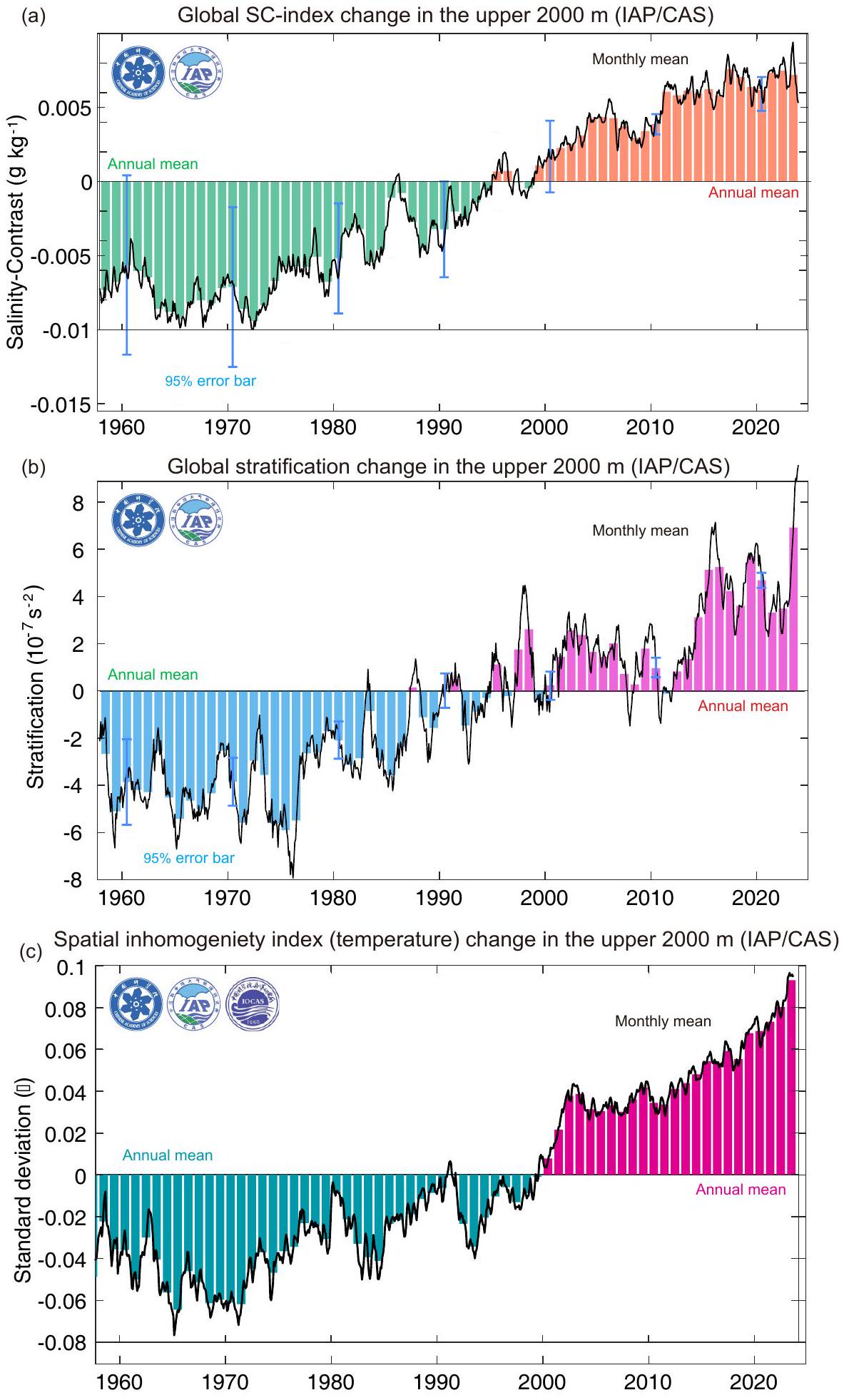

with temperature changes, regulate the ocean currents and impact the vertical stability of the ocean. Ocean salinity trends are generally characterized by a “fresh gets fresher, salty gets saltier” change pattern, meaning areas that are currently fresh are becoming fresher, and areas that are currently salty are becoming more saline (Durack and Wijffels, 2010). This process can be quantified by a “salinity-contrast” (SC) index that calculates the salinity difference between the higher and lower salinity regions compared to a global average (Cheng et al., 2020).

2. Data and methods

from research ships, instrumented animals, gliders, moored buoys, and ice-tethered profilers, augment observations globally and are primary sources in shallow seas/continental shelves, and high-latitude seasonal ice covered areas. The differences between the data products arise from additional in situ observations owned by the data center, data quality control (QC), climatology, vertical interpolation, gap-filling, and other data processing techniques (Abraham et al., 2013; Boyer et al., 2016; Cheng et al., 2022a). All instrumental data are used for the IAP/CAS and NCEI/NOAA products. This paper presents the most up-to-date information from IAP/CAS and NCEI/NOAA for 2023, incorporating the latest data quality processing and mapping techniques. Both the IAP/CAS and NCEI/NAA datasets are monthly gridded products, have

3. Global ocean changes of OHC, salinity, and stratification

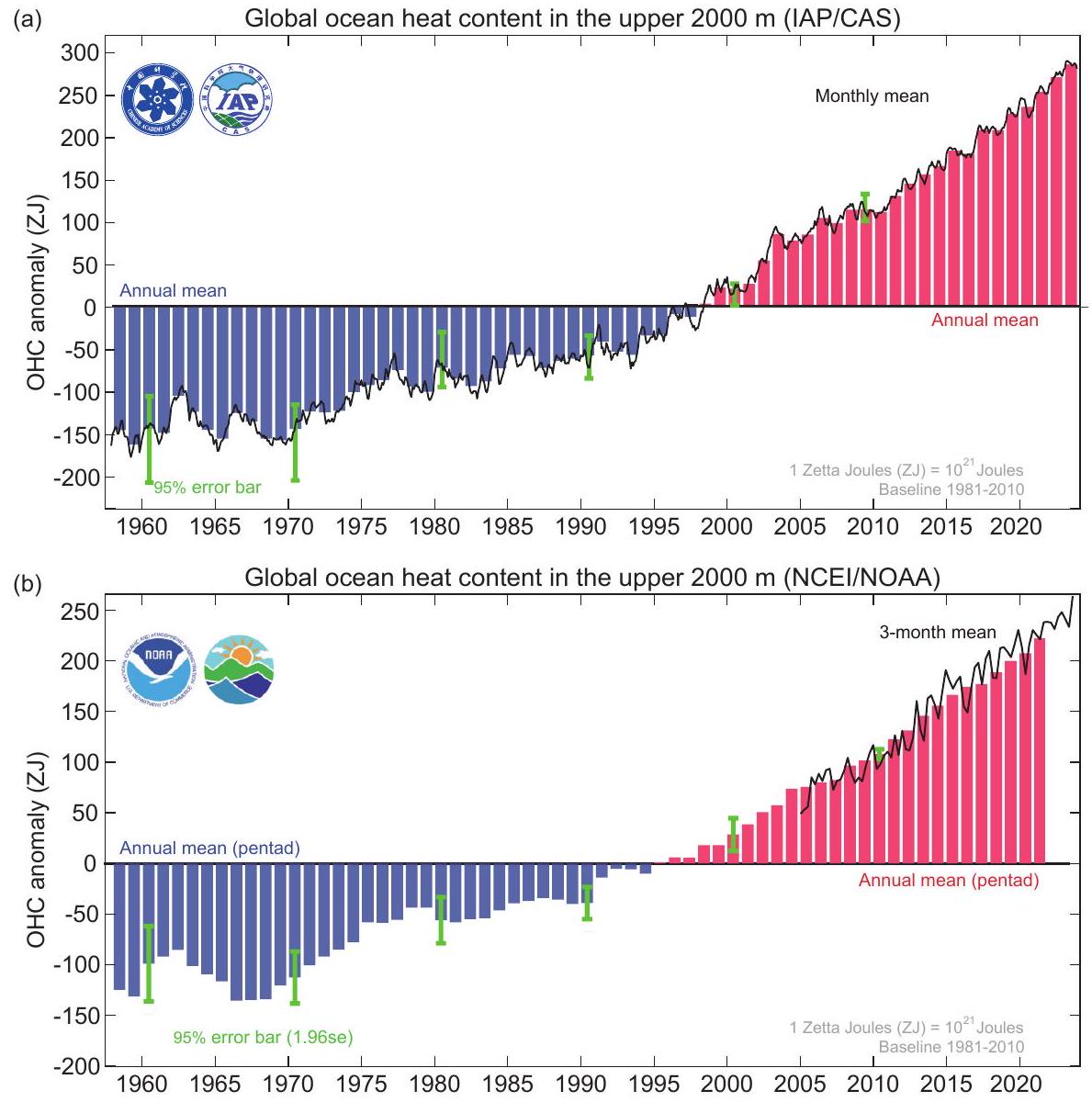

3.1. OHC and surface temperatures

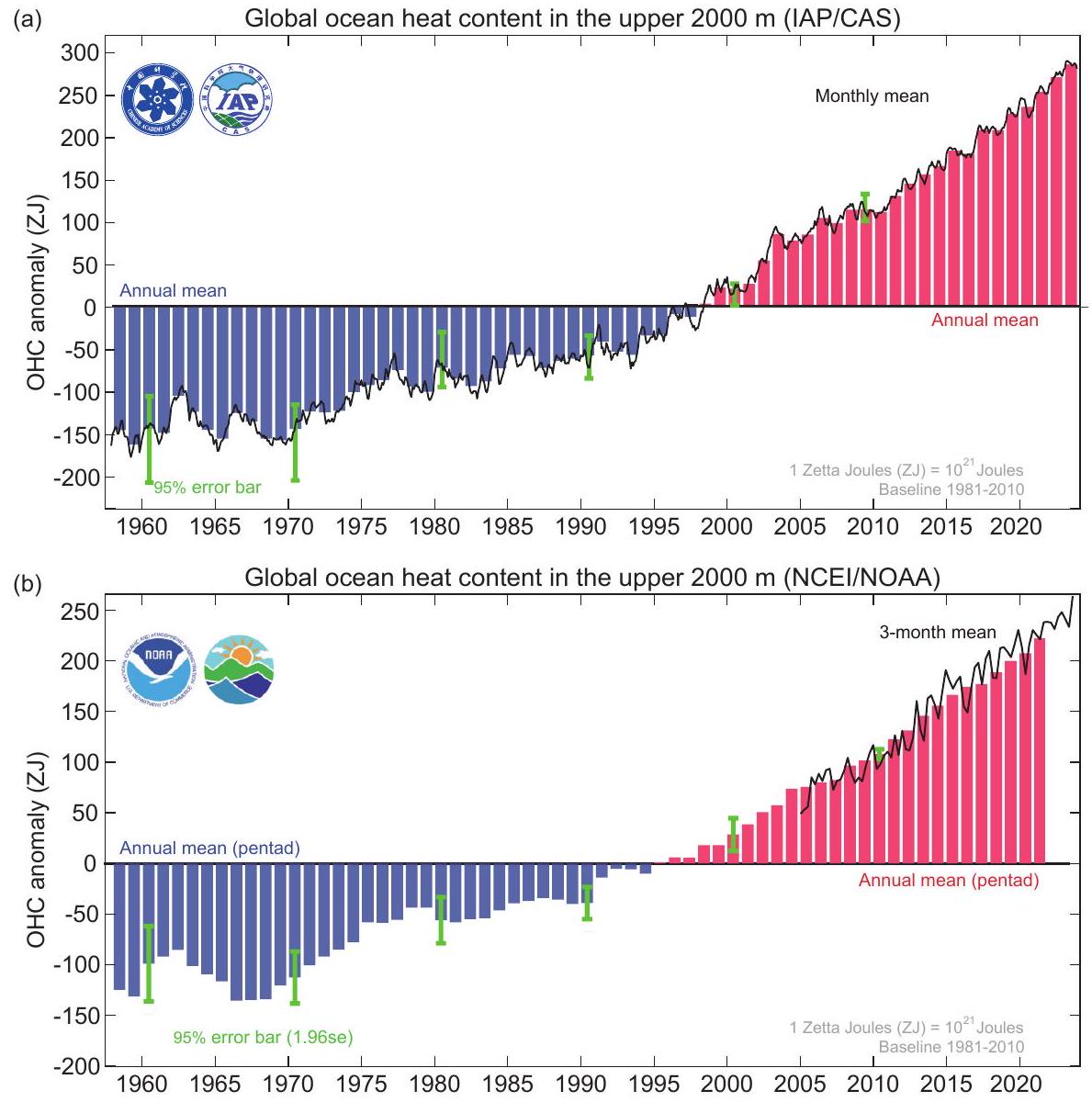

recent decades. The upper 2000 m of the world’s ocean has warmed on average by

| Rank | Year | OHC (IAP/CAS) (units: ZJ) | OHC (NCEI/NOAA) (units: ZJ) | SST anomaly (IAP/CAS) (units:

|

| 1 | 2023 | 286 | 247 | 0.54 |

| 2 | 2022 | 271 | 238 | 0.31 |

| 3 | 2021 | 254 | 229 | 0.28 |

| 4 | 2020 | 237 | 211 | 0.38 |

| 5 | 2019 | 228 | 210 | 0.40 |

record. The monthly SST anomaly in 2023 relative to 1981-2010 grew from

3.2. Other oceanic climate indicators

the OHC and SC-index because it reveals more upper-ocean changes, which shows stronger anomalies than the deeper ocean. In 2023, the upper 2000 m stratification increased to

4. Regional patterns of ocean warming and salinity

The OHC annual mean difference between 2023 and 2022 is presented in Fig. 6. In the tropical Pacific, strong warming anomalies in the eastern Pacific and cooling anoma-

lies in the western Pacific in 2023 (Fig. 6) indicate the shoaling of the equatorial thermocline associated with El Niño. The zonal OHC shows strong tropical warming within

as the midlatitude Atlantic, the Mediterranean Sea, and the West Indian Ocean becoming more saline. This is a typical “fresh gets fresher, salty gets saltier” pattern change driven by atmospheric hydrological cycle amplification. The tropical salinity changes reveal more of the impact of El Niño, especially in the western Pacific and around the Intertropical Con-

5. Basin-wide OHC changes and regional hotspots

with the negative Indian OHC tendency during La Niña (Cheng et al., 2019), driven mainly by decreasing the heat transport through the Indonesian Throughflow passages during the decaying stage of La Niña (Trenberth and Zhang, 2019; Li et al., 2020b; Volkov et al., 2020). However, the Indian OHC has shown a continuous increase since January 2023, associated with the cessation of La Nina and the development of El Niño.

celli et al., 2023) (Fig. 10a), indicated clear warming in the

6. Concluding remarks

the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42076202, 42122046, 42206208 and 42261134536), the new Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE, DAMO Academy Young Fellow, Youth Innovation Promotion Association, Chinese Academy of Sciences; National Key Scientific and Technological Infrastructure project “Earth System Science Numerical Simulator Facility” (EarthLab). The calculations in this study were carried out on the ORISE Supercomputer. NCAR is sponsored by the US National Science Foundation. We used some data collected onboard R/V Shiyan 6 implementing the Open Research Cruise NORC2022-10+NORC2022-303 supported by NSFC shiptime Sharing Projects 42149910. The efforts of Dr. Fasullo in this work were supported by NASA Awards 80NSSC17K0565, 80NSSC21K1191, and 80NSSC22K0046 and by the Regional and Global Model Analysis (RGMA) component of the Earth and Environmental System Modeling Program of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Biological & Environmental Research (BER) via National Science Foundation IA 1947282. The efforts of Dr. MISHONOV were supported by NOAA (Grant No. NA19NES4320002 to CISESS-MD at the University of Maryland). The IAP/CAS data are available at http://www.ocean.iap.ac.cn/ and https://msdc.qdio.ac.cn/. The NCEI/NOAA data are available athttps://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/climate-data-records/global-

ocean-heat-content. This study has been conducted using also E.U. Copernicus Marine Service Information (https://marine.copernicus.eu/) for the Mediterranean OHC estimates. G. LI is supported by the Young Talent Support Project of Guangzhou Association for Science and Technology. The

REFERENCES

Abraham, J., L. J. Cheng, M. E. Mann, K. Trenberth, and K. Von Schuckmann, 2022: The ocean response to climate change guides both adaptation and mitigation efforts. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett., 15, 100221, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aosl.2022. 100221.

Argo, 2023: Argo Float Data and Metadata from Global Data Assembly Centre (Argo GDAC). SEANOE. Available from https://doi.org/10.17882/42182.

Ben Ismail S., K. Schroeder, J. Chiggiato, S. Sparnocchia, and M. Borghini, 2021: Long term changes monitored in two Mediterranean Channels. Copernicus Marine Service Ocean State Report, Issue 5, K. Von Schuckmann et al., Eds., 48-52, https://doi.org/10.1080/1755876X.2021.1946240.

Boyer, T., and Coauthors, 2016: Sensitivity of global upperocean heat content estimates to mapping methods, XBT bias corrections, and baseline climatologies. J. Climate, 29, 4817-4842, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0801.1.

Boyer, T. P., and Coauthors, 2018: World ocean database 2018. NOAA Atlas NESDIS 87.

Cheng, L. J., J. Zhu, R. Cowley, T. Boyer, and S. Wijffels, 2014: Time, probe type, and temperature variable bias corrections

to historical expendable bathythermograph observations.

Cheng, L. J., K. Trenberth, J. Fasullo, J. Abraham, T. Boyer, K. Von Schuckmann, and J. Zhu, 2018: Taking the pulse of the planet. Eos, 99, 14-16, https://doi.org/10.1029/2017EO 081839.

Cheng, L. J., and Coauthors, 2022a: Past and future ocean warming. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 3, 776-794, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00345-1.

Cheng, L. J., G. Foster, Z. Hausfather, K. E. Trenberth, and J. Abraham, 2022b: Improved quantification of the rate of ocean warming. J. Climate, 35, 4827-4840, https://doi.org/10. 1175/JCLI-D-21-0895.1.

Cheng, L. J, and Coauthors, 2022c: Another record: Ocean warming continues through 2021 despite La Niña conditions. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 39(3), 373-385, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-022-1461-3.

Cheng, L. J., and Coauthors, 2023: Another year of record heat for the oceans. Adv. Atmos. Sci, 40, 963-974, https://doi.org/

Durack, P. J., and S. E. Wijffels, 2010: Fifty-year trends in global ocean salinities and their relationship to broad-scale warming. J. Climate, 23, 4342-4362, https://doi.org/10.1175/ 2010JCLI3377.1.

Escudier, R., and Coauthors, 2021: A high resolution reanalysis for the mediterranean sea. Front. Earth Sci., 9, 702285, https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.702285.

Fischer, E. M., S. Sippel, and R. Knutti, 2021: Increasing probability of record-shattering climate extremes. Nature Climate Change, 11, 689-695, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01092-9.

Fasullo, J. T., Gent, P. R., and Nerem, R. S. 2020: Forced patterns of sea level rise in the community earth system model large ensemble from 1920 to 2100. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 125, e2019JC016030. https://doi.org/10. 1029/2019JC016030

Gouretski, V., and L. J. Cheng, 2020: Correction for systematic errors in the global dataset of temperature profiles from mechanical bathythermographs. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol., 37(5), 841-855, https://doi.org/10.1175/JTECH-D-190205.1.

Gouretski, V., F. Roquet, and L. J. Cheng, 2023: Measurement biases in ocean temperature profiles from marine mammal data loggers. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol., submitted.

Gulev, S., and Coauthors, 2021: Changing state of the climate sys-

tem. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, V. Mas-son-Delmotte et al., Eds., Cambridge University Press.

Huang, B. Y., and Coauthors, 2017: Extended reconstructed sea surface temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): Upgrades, validations, and intercomparisons. J. Climate, 30, 8179-8205, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0836.1.

Johnson, G., and Coauthors, 2018: Ocean heat content [in State of the Climate in 2017]. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 99, S72-S77.

Levitus, S., J. I. Antonov, T. P. Boyer, R. A. Locarnini, H. E. Garcia, and A. V. Mishonov, 2009: Global ocean heat content 1955-2008 in light of recently revealed instrumentation problems. Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L07608, https://doi.org/10. 1029/2008GL037155.

Levitus, S., and Coauthors, 2012: World ocean heat content and thermosteric sea level change (

Li, G. C., L. J. Cheng, J. Zhu, K. E. Trenberth, M. E. Mann, and J. P. Abraham, 2020a: Increasing ocean stratification over the past half-century. Nature Climate Change, 10, 1116-1123, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00918-2.

Li, K. X., F. Zheng, L. J. Cheng, T. Y. Zhang, and J. Zhu, 2023: Record-breaking global temperature and crises with strong El Niño in 2023-2024. The Innovation Geoscience, 1(2), 100030. https://doi.org/10.59717/j.xinn-geo.2023.100030.

Li, Y. L., W. Q. Han, F. Wang, L. Zhang, and J. Duan, 2020b: Vertical structure of the upper-Indian Ocean thermal variability. J. Climate, 33, 7233-7253, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0851.1.

Loeb, N. G., G. C. Johnson, T. J. Thorsen, J. M. Lyman, F. G. Rose, and S. Kato, 2021: Satellite and ocean data reveal marked increase in Earth’s heating rate. Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2021GL093047, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL09 3047.

Pinardi, N., and Coauthors, 2015: Mediterranean Sea large-scale low-frequency ocean variability and water mass formation rates from 1987 to 2007: A retrospective analysis. Progress in Oceanography, 132, 318-332, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. pocean.2013.11.003.

Purkey, S., and G. C. Johnson, 2010: Warming of global abyssal and deep Southern Ocean waters between the 1990s and 2000s: Contributions to global heat and sea level rise budgets. J. Climate, 23, 6336-6351, https://doi.org/10.1175/ 2010JCLI3682.1.

Ren, Q. P., Y.-O. Kwon, J. Y. Yang, R.-X. Huang, Y. L. Li, and F. Wang, 2022: Increasing inhomogeneity of the global

oceans. Geophys. Res. Lett., 49, e2021GL097598, https://doi. org/10.1029/2021GL097598.

Reseghetti, F., C. Fratianni, and S. Simoncelli, 2023: Reprocessed of XBT dataset in the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian seas (1999-2019). Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV). [Available online from https://doi.org/10.13127/ rep_xbt_1999_2019].

Rhein, M., and Coauthors, 2013: Observations: Ocean pages. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, T. F. Stocker et al., Eds., Cambridge University Press.

Scannell, H. A., G. C. Johnson, L. Thompson, J. M. Lyman, and S. C. Riser, 2020: Subsurface evolution and persistence of marine heatwaves in the Northeast Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett., 47, e2020GL090548, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020 GL090548.

Schroeder, K., J. Chiggiato, S. A. Josey, M. Borghini, S. Aracri, and S. Sparnocchia, 2017: Rapid response to climate change in a marginal sea. Scientific Reports, 7, 4065, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-017-04455-5.

Simoncelli, S., N. Pinardi, C. Fratianni, C. Dubois, and G. Notarstefano, 2018: Water mass formation processes in the Mediterranean Sea over the past 30 years. In: Copernicus Marine Service Ocean State Report, Issue 2, Journal of Operational Oceanography, 11:sup1, s13-s16, https://doi.org/10.1080/ 1755876X.2018.1489208.

Simoncelli, S., Reseghetti, F., Fratianni, C., Cheng, L., and Raiteri, G., 2023: Reprocessing of XBT profiles from the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian seas over the time period 1999-2019 with full metadata upgrade, Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. [preprint], https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2023-525, in review.

Tan, Z. T., L. J. Cheng, V. Gouretski, B. Zhang, Y. J. Wang, F. C. Li, Z. H. Liu, and J. Zhu, 2023: A new automatic quality control system for ocean profile observations and impact on ocean warming estimate. Deep-Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap., 194, 103961, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2022. 103961.

Trenberth, K. E., J. M. Caron, D. P. Stepaniak, and S. Worley, 2002: Evolution of El Niño-Southern Oscillation and global atmospheric surface temperatures. J. Geophys. Res., 107, AAC 5-1-AAC 5-17, doi: 10.1029/2000JD000298.

Trenberth, K. E., L. J. Cheng, P. Jacobs, Y. X. Zhang, and J. Fasullo, 2018: Hurricane Harvey links to ocean heat content and climate change adaptation. Earth’s Future, 6, 730-744, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EF000825.

Trenberth, K. E., and Y. X. Zhang, 2019: Observed interhemispheric meridional heat transports and the role of the Indonesian Throughflow in the Pacific Ocean. J. Climate, 32, 8523-8536, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-19-0465.1.

Volkov, D. L., S.-K. Lee, A. L. Gordon, and M. Rudko, 2020: Unprecedented reduction and quick recovery of the South Indian Ocean heat content and sea level in 2014-2018. Science Advances, 6, eabc1151, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv. abc1151.

Von Schuckmann, K., and Coauthors, 2020: Heat stored in the Earth system: Where does the energy go? Earth System Sci-

ence Data, 12, 2013-2041, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-2013-2020.

Zheng, F., and J. Zhu, 2016: Improved ensemble-mean forecasting of ENSO events by a zero-mean stochastic error model of an intermediate coupled model. Climate Dyn., 47, 3901-3915, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-016-3048-0.

- Corresponding author: Lijing CHENG

Email: chenglij@mail.iap.ac.cn