DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01039-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38459205

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-08

سد الفجوة في محو الأمية لموافقات الجراحة: نهج تعاوني بين الذكاء الاصطناعي والخبراء البشريين

الملخص

على الرغم من أهمية الموافقة المستنيرة في الرعاية الصحية، فإن قابلية قراءة ونوعية نماذج الموافقة غالبًا ما تعيق فهم المرضى. تبحث هذه الدراسة في استخدام GPT-4 لتبسيط نماذج الموافقة الجراحية وتقدم نهجًا تعاونيًا بين الذكاء الاصطناعي والخبراء البشريين للتحقق من ملاءمة المحتوى. تم تقييم نماذج الموافقة من مؤسسات متعددة من حيث قابلية القراءة وتم تبسيطها باستخدام GPT-4، مع مقارنة مقاييس قابلية القراءة قبل وبعد التبسيط باستخدام اختبارات غير معلمية. تم إجراء مراجعات مستقلة من قبل مؤلفين طبيين ومحامي دفاع عن الأخطاء الطبية. أخيرًا، تم تقييم إمكانية GPT-4 في إنشاء نماذج موافقة محددة للإجراءات الجديدة، مع تقييم النماذج باستخدام مقياس موثق من 8 عناصر ومراجعة من جراحين متخصصين. أظهرت تحليل نماذج الموافقة من 15 مركزًا طبيًا أكاديميًا انخفاضات كبيرة في متوسط وقت القراءة، ندره الكلمات، وتكرار الجمل المبنية للمجهول (جميع

النقاش الذي يحمي كل من المريض والطبيب. عندما يتم تصميمها بشكل جيد، توفر الموافقة الجراحية للمرضى معلومات واضحة وموجزة وقابلة للفهم بشأن المخاطر والفوائد والبدائل للإجراء الجراحي المقترح. ومع ذلك، فإن التحدي الكبير في تحقيق

النتائج

نماذج الموافقة الجراحية

بمراجعة الموافقات قبل وبعد التبسيط وقرر أن جميع أزواج الموافقة الـ 15 تلبي نفس الكفاية القانونية.

نماذج موافقة محددة للإجراءات

نقاش

في دمج الذكاء الاصطناعي في الطب، من الضروري أن يعمل الأطباء على ضمان أن استخدام هذه التقنيات يحسن، بدلاً من أن يعزز، الفجوات القائمة في رعاية المرضى.

أظهرت الدراسة أن GPT-4 حسّن بشكل كبير من قابلية قراءة نماذج الموافقة العامة المستخدمة حاليًا في المؤسسات، من خلال خفض مستوى القراءة المطلوب من مستوى طالب السنة الأولى في الكلية الأمريكية (الصف 13) إلى مستوى الصف الثامن، مما جعل النماذج أكثر وصولاً لفئة أوسع من المرضى. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهرت النماذج المبسطة انخفاضًا كبيرًا في نسبة الجمل المكتوبة بصيغة المبني للمجهول.

نسب المئوية (

تشير إلى لغة أكثر وضوحًا ووضوحًا. لأن مستوى قراءة فليتش-كينكايد ودرجة سهولة قراءة فليتش لا تلتقط عوامل مثل تكرار الكلمات أو التعقيد، والتي تعتبر أيضًا عوامل مهمة تؤثر على فهم القارئ.

التطبيقات في الطب السريري، تمهد الطريق من أجل تواصل رعاية صحية أكثر شمولاً وسهولة، مع الحفاظ على الصرامة المناسبة.

طرق

جمع البيانات وتحليلها

تبسيط

معيار لتقييم جودة نموذج الموافقة

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

نُشر على الإنترنت: 08 مارس 2024

References

- Paasche-Orlow, M. K., Taylor, H. A. & Brancati, F. L. Readability standards for informed-consent forms as compared with actual readability. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 721-726 (2003).

- Sand, K., Eik-Nes, N. L. & Loge, J. H. Readability of informed consent documents (1987-2007) for clinical trials: a linguistic analysis. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 7, 67-78 (2012).

- Bothun, L. S., Feeder, S. E. & Poland, G. A. Readability of participant informed consent forms and informational documents: from phase 3 COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials in the United States. Mayo Clin. Proc. 96, 2095-2101 (2021).

- Grundner, T. M. On the readability of surgical consent forms. N. Engl. J. Med. 302, 900-902 (1980).

- Amezcua, L., Rivera, V. M., Vazquez, T. C., Baezconde-Garbanati, L. & Langer-Gould, A. Health disparities, inequities, and social determinants of health in multiple sclerosis and related disorders in the US: a review. JAMA Neurol. 78, 1515-1524 (2021).

- Kessels, R. P. Patients’ memory for medical information. J. R. Soc. Med. 96, 219-222 (2003).

- Nutbeam, D. & Lloyd, J. E. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 42, 159-173 (2021).

- Yee, L. M. et al. Association of health literacy among nulliparous individuals and maternal and neonatal outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2122576 (2021).

- Adams, L. C. et al. Leveraging GPT-4 for Post hoc transformation of free-text radiology reports into structured reporting: a multilingual feasibility study. Radiology 230725. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol. 230725 (2023).

- Lee, P., Bubeck, S. & Petro, J. Benefits, limits, and risks of GPT-4 as an AI chatbot for medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1233-1239 (2023).

- Spatz, E. S. et al. An instrument for assessing the quality of informed consent documents for elective procedures: development and testing. BMJ Open 10, e033297 (2020).

- Eltorai, A. E. et al. Readability of invasive procedure consent forms. Clin. Transl. Sci. 8, 830-833 (2015).

- Gordon, E. J. et al. Are informed consent forms for organ transplantation and donation too difficult to read? Clin. Transplant. 26, 275-283 (2012).

- Hannabass, K. & Lee, J. Readability analysis of otolaryngology consent documents on the iMed consent platform. Mil. Med. 188, 780-785 (2023).

- Smith, B. & Magnani, J. W. New technologies, new disparities: the intersection of electronic health and digital health literacy. Int J Cardiol 292, 280-282 (2019).

- Yusefi, A. R. et al. Health literacy and health promoting behaviors among inpatient women during COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Womens Health 22, 77 (2022).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Use caution with readability formulas for quality reports, https://www.ahrq.gov/ talkingquality/resources/writing/tip6.html (2015).

- Glaser, J. et al. Interventions to improve patient comprehension in informed consent for medical and surgical procedures: an updated systematic review. Med. Decis. Making 40, 119-143 (2020).

- Rivera Perla, K. M. et al. Predicting access to postoperative treatment after glioblastoma resection: an analysis of neighborhood-level disadvantage using the Area Deprivation Index (ADI). J. Neurooncol. 158, 349-357 (2022).

- Ammanuel, S. G., Edwards, C. S., Alhadi, R. & Hervey-Jumper, S. L. Readability of online neuro-oncology-related patient education materials from tertiary-care academic centers. World Neurosurg. 134, e1108-e1114 (2020).

- Hansberry, D. R. et al. Analysis of the readability of patient education materials from surgical subspecialties. Laryngoscope 124, 405-412 (2014).

- Goss, R. M. Investigations of doctors by General Medical Council. The procedure for consent still leaves much to be desired. BMJ 321, 111 (2000).

- Ozhan, M. O. et al. Do the patients read the informed consent? Balkan Med. J. 31, 132-136 (2014).

- Ntonti, P. et al. A systematic review of reading tests. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 16, 121-127 (2023).

- Sarica, S. & Luo, J. Stopwords in technical language processing. PLoS One 16, e0254937 (2021).

- Michalke, M. koRpus: text analysis with emphasis on POS tagging, readability, and lexical diversity, https://cran.r-project.org/web/ packages/koRpus/citation.html (2021).

- Spatz, E. S. et al. Quality of informed consent documents among U.S. hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 10, e033299 (2020).

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلفون 2024، نشر مصحح 2024

قسم جراحة الأعصاب، مستشفى رود آيلاند ومدرسة وارن ألبيرت الطبية بجامعة براون، بروفيدنس، رود آيلاند، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. معهد نورمان برينس لعلوم الأعصاب، بروفيدنس، رود آيلاند، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم جراحة الأعصاب، مستشفى ماساتشوستس العام، بوسطن، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الأمراض الجلدية، كلية وارن ألبيرت الطبية بجامعة براون، بروفيدنس، رود آيلاند، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم جراحة الأعصاب، مستشفى بريغهام والنساء، بوسطن، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الجراحة وقسم جراحة القلب والصدر، مستشفى رود آيلاند ومدرسة وارن ألبيرت الطبية بجامعة براون، بروفيدنس، رود آيلاند، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. راتكليف هارتن غالاماغا LLP، بروفيدنس، رود آيلاند، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. أقسام الهندسة الكهربائية، وعلوم البيانات الطبية الحيوية، وعلوم الحاسوب، جامعة ستانفورد، ستانفورد، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز تشان زوكربيرغ للبيولوجيا، سان فرانسيسكو، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: روهيد علي، إيان د. كونولي، أوليفر ي. تانغ، هائل ف. عبد الرزاق. البريد الإلكتروني: ali.rohaid@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01039-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38459205

Publication Date: 2024-03-08

Bridging the literacy gap for surgical consents: an Al-human expert collaborative approach

Abstract

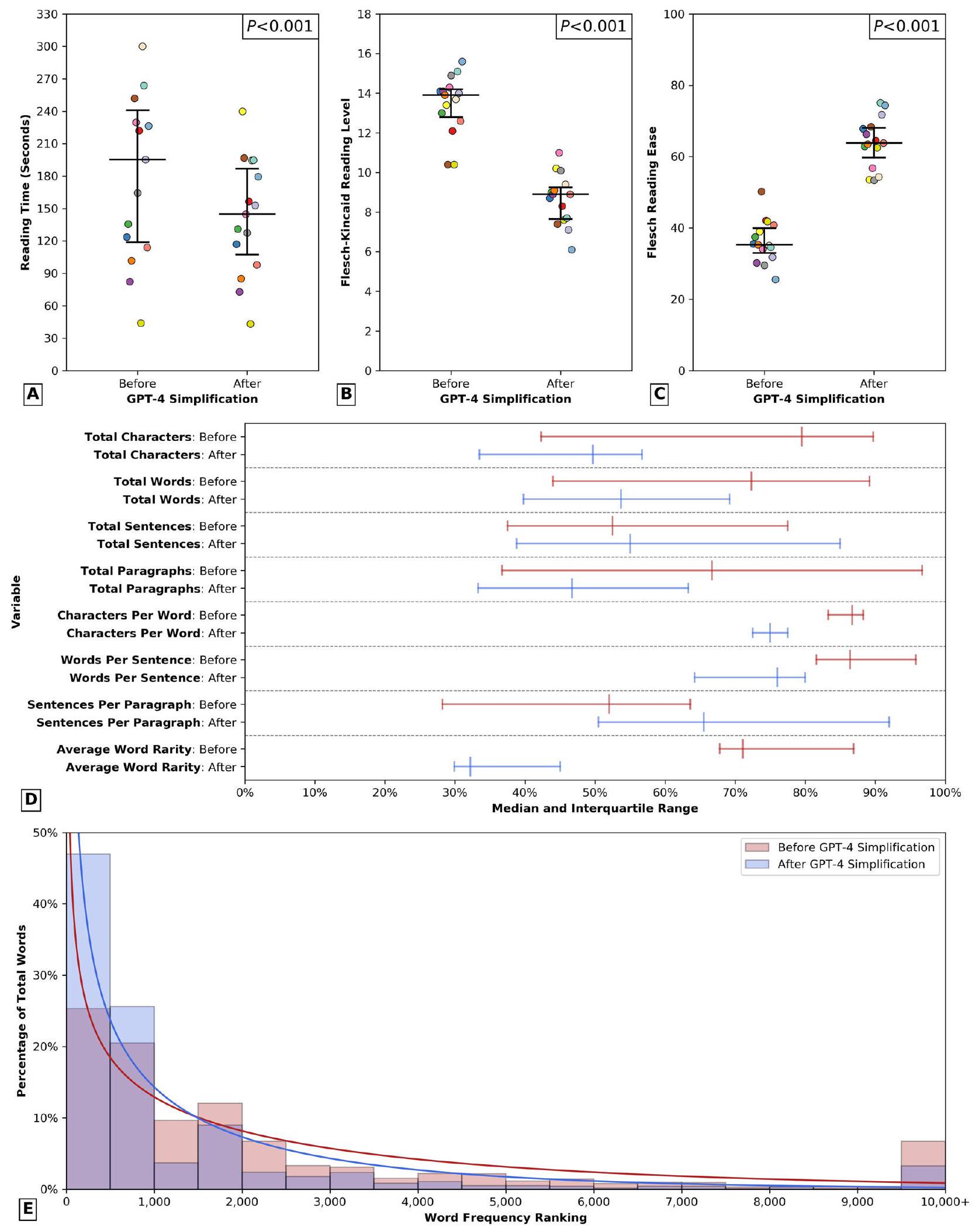

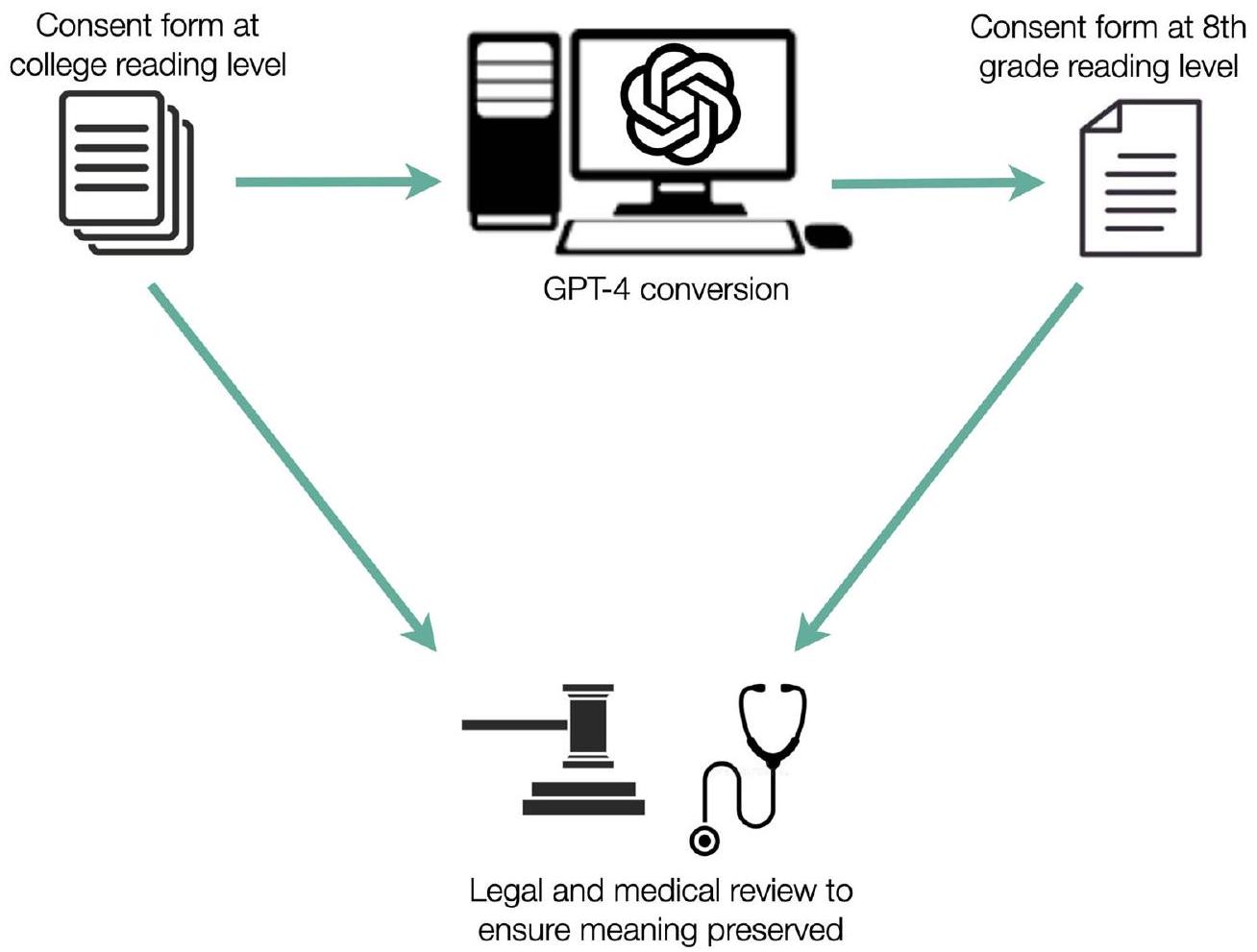

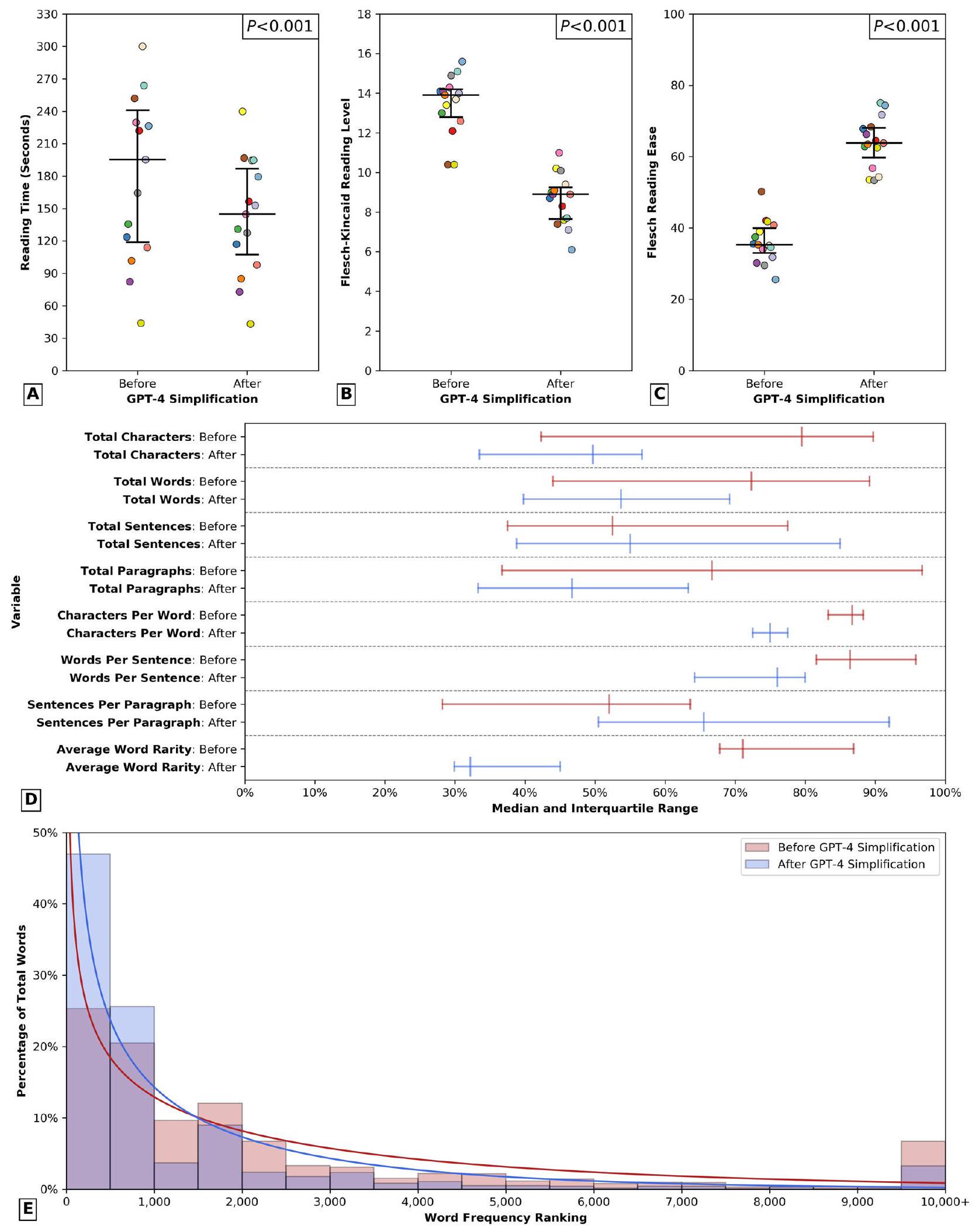

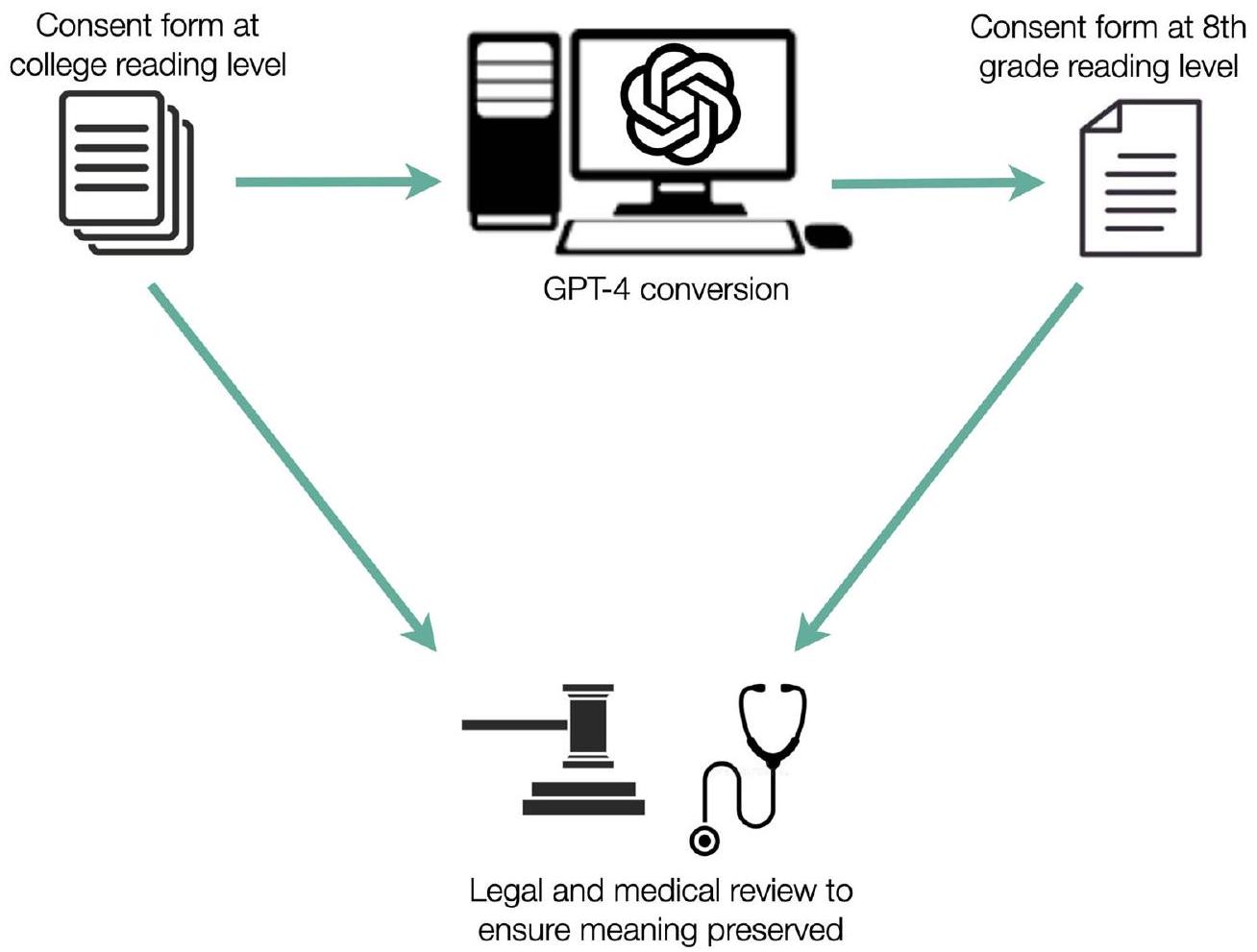

Despite the importance of informed consent in healthcare, the readability and specificity of consent forms often impede patients’ comprehension. This study investigates the use of GPT-4 to simplify surgical consent forms and introduces an AI-human expert collaborative approach to validate content appropriateness. Consent forms from multiple institutions were assessed for readability and simplified using GPT-4, with pre- and post-simplification readability metrics compared using nonparametric tests. Independent reviews by medical authors and a malpractice defense attorney were conducted. Finally, GPT-4’s potential for generating de novo procedure-specific consent forms was assessed, with forms evaluated using a validated 8 -item rubric and expert subspecialty surgeon review. Analysis of 15 academic medical centers’ consent forms revealed significant reductions in average reading time, word rarity, and passive sentence frequency (all

discussion that protects both patient and physician. When well-designed, the surgical consent provides patients with clear, concise, and comprehensible information regarding the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the proposed surgical procedure. However, a significant challenge in achieving

Results

Surgical consent forms

reviewed the consents before and after simplification and determined that all 15 consent pairs met the same legal sufficiency.

Procedure-sepcific consent forms

Discussion

integration of AI into medicine, it is imperative for clinicians to work to ensure that the utilization of these technologies ameliorates, rather than amplifies, existing disparities in patient care.

study, GPT-4 significantly enhanced the readability and reduced the reading time of generic consent forms currently in institutional use, by lowering the required reading level from that of an American college freshman (grade 13) to an 8th grade level, thereby making the forms more accessible to a broader patient population. Additionally, the simplified forms showed a significant reduction in the percentage of sentences written in the passive voice,

percentages (

indicating more clear, direct language. Because the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Level and Flesch Reading Ease score do not capture factors like word frequency or complexity, which are also important modulators of reader comprehension

applications within clinical medicine, paving the way for more inclusive and accessible healthcare communication that nonetheless maintains appropriate rigor.

Methods

Data collection and analysis

Al simplification

rubric for quantifying consent form quality

Data availability

Code availability

Published online: 08 March 2024

References

- Paasche-Orlow, M. K., Taylor, H. A. & Brancati, F. L. Readability standards for informed-consent forms as compared with actual readability. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 721-726 (2003).

- Sand, K., Eik-Nes, N. L. & Loge, J. H. Readability of informed consent documents (1987-2007) for clinical trials: a linguistic analysis. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 7, 67-78 (2012).

- Bothun, L. S., Feeder, S. E. & Poland, G. A. Readability of participant informed consent forms and informational documents: from phase 3 COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials in the United States. Mayo Clin. Proc. 96, 2095-2101 (2021).

- Grundner, T. M. On the readability of surgical consent forms. N. Engl. J. Med. 302, 900-902 (1980).

- Amezcua, L., Rivera, V. M., Vazquez, T. C., Baezconde-Garbanati, L. & Langer-Gould, A. Health disparities, inequities, and social determinants of health in multiple sclerosis and related disorders in the US: a review. JAMA Neurol. 78, 1515-1524 (2021).

- Kessels, R. P. Patients’ memory for medical information. J. R. Soc. Med. 96, 219-222 (2003).

- Nutbeam, D. & Lloyd, J. E. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 42, 159-173 (2021).

- Yee, L. M. et al. Association of health literacy among nulliparous individuals and maternal and neonatal outcomes. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2122576 (2021).

- Adams, L. C. et al. Leveraging GPT-4 for Post hoc transformation of free-text radiology reports into structured reporting: a multilingual feasibility study. Radiology 230725. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol. 230725 (2023).

- Lee, P., Bubeck, S. & Petro, J. Benefits, limits, and risks of GPT-4 as an AI chatbot for medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1233-1239 (2023).

- Spatz, E. S. et al. An instrument for assessing the quality of informed consent documents for elective procedures: development and testing. BMJ Open 10, e033297 (2020).

- Eltorai, A. E. et al. Readability of invasive procedure consent forms. Clin. Transl. Sci. 8, 830-833 (2015).

- Gordon, E. J. et al. Are informed consent forms for organ transplantation and donation too difficult to read? Clin. Transplant. 26, 275-283 (2012).

- Hannabass, K. & Lee, J. Readability analysis of otolaryngology consent documents on the iMed consent platform. Mil. Med. 188, 780-785 (2023).

- Smith, B. & Magnani, J. W. New technologies, new disparities: the intersection of electronic health and digital health literacy. Int J Cardiol 292, 280-282 (2019).

- Yusefi, A. R. et al. Health literacy and health promoting behaviors among inpatient women during COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Womens Health 22, 77 (2022).

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Use caution with readability formulas for quality reports, https://www.ahrq.gov/ talkingquality/resources/writing/tip6.html (2015).

- Glaser, J. et al. Interventions to improve patient comprehension in informed consent for medical and surgical procedures: an updated systematic review. Med. Decis. Making 40, 119-143 (2020).

- Rivera Perla, K. M. et al. Predicting access to postoperative treatment after glioblastoma resection: an analysis of neighborhood-level disadvantage using the Area Deprivation Index (ADI). J. Neurooncol. 158, 349-357 (2022).

- Ammanuel, S. G., Edwards, C. S., Alhadi, R. & Hervey-Jumper, S. L. Readability of online neuro-oncology-related patient education materials from tertiary-care academic centers. World Neurosurg. 134, e1108-e1114 (2020).

- Hansberry, D. R. et al. Analysis of the readability of patient education materials from surgical subspecialties. Laryngoscope 124, 405-412 (2014).

- Goss, R. M. Investigations of doctors by General Medical Council. The procedure for consent still leaves much to be desired. BMJ 321, 111 (2000).

- Ozhan, M. O. et al. Do the patients read the informed consent? Balkan Med. J. 31, 132-136 (2014).

- Ntonti, P. et al. A systematic review of reading tests. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 16, 121-127 (2023).

- Sarica, S. & Luo, J. Stopwords in technical language processing. PLoS One 16, e0254937 (2021).

- Michalke, M. koRpus: text analysis with emphasis on POS tagging, readability, and lexical diversity, https://cran.r-project.org/web/ packages/koRpus/citation.html (2021).

- Spatz, E. S. et al. Quality of informed consent documents among U.S. hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 10, e033299 (2020).

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2024, corrected publication 2024

Department of Neurosurgery, Rhode Island Hospital and The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, USA. Norman Prince Neurosciences Institute, Providence, RI, USA. Department of Neurosurgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA. Department of Dermatology, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, USA. Department of Neurosurgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA. Department of Surgery & Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Rhode Island Hospital and The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, USA. Ratcliffe Harten Galamaga LLP, Providence, RI, USA. Departments of Electrical Engineering, Biomedical Data Science, and Computer Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA. Chan Zuckerberg Biohub, San Francisco, CA, USA. These authors contributed equally: Rohaid Ali, lan D. Connolly, Oliver Y. Tang, Hael F. Abdulrazeq. e-mail: ali.rohaid@gmail.com