DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-025-02514-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40050729

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-06

طرق المشاركة المشتركة في أبحاث الصحة العامة – الخصائص والفوائد والتحديات: مراجعة شاملة لمشروع Health CASCADE

الملخص

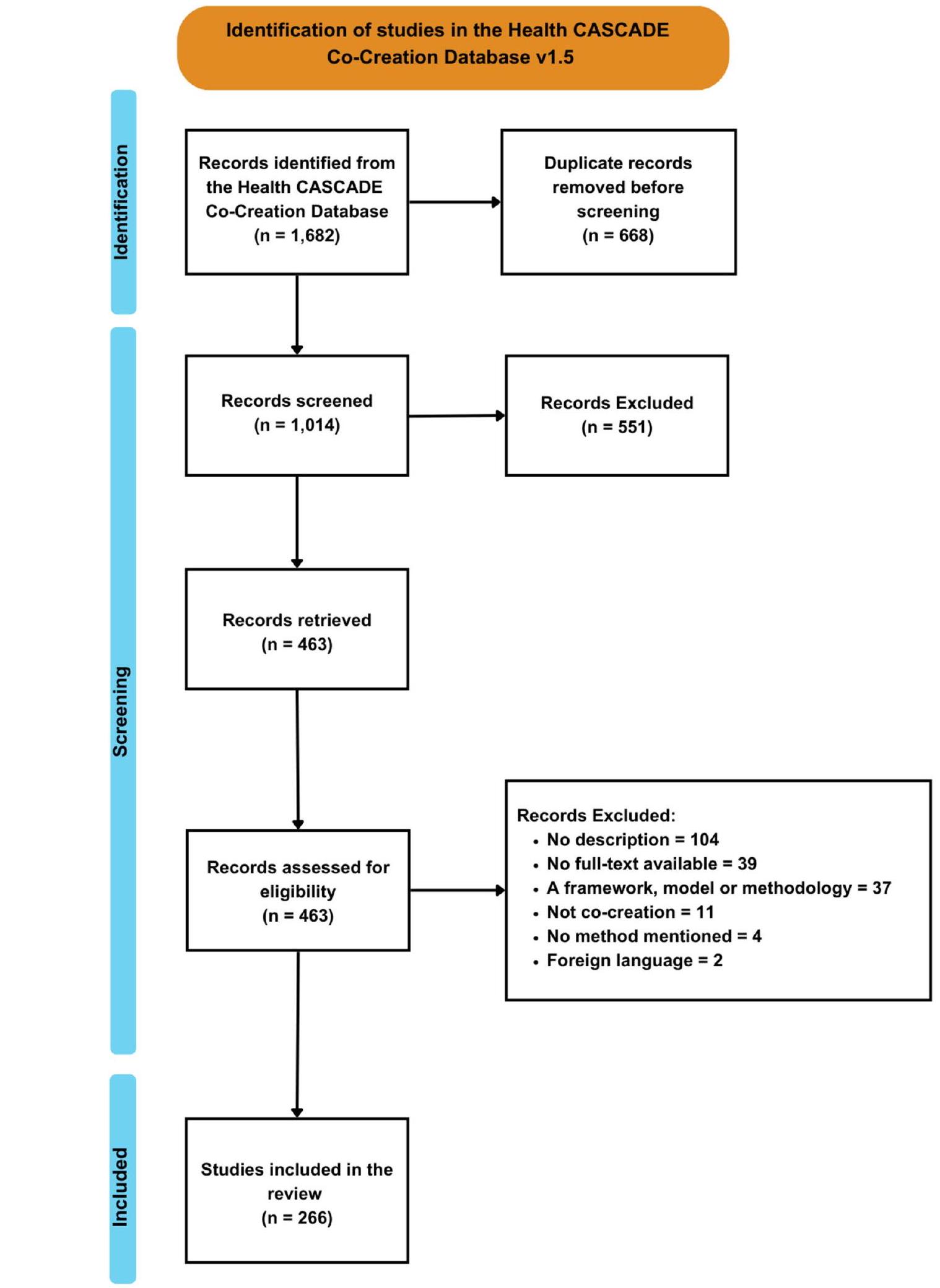

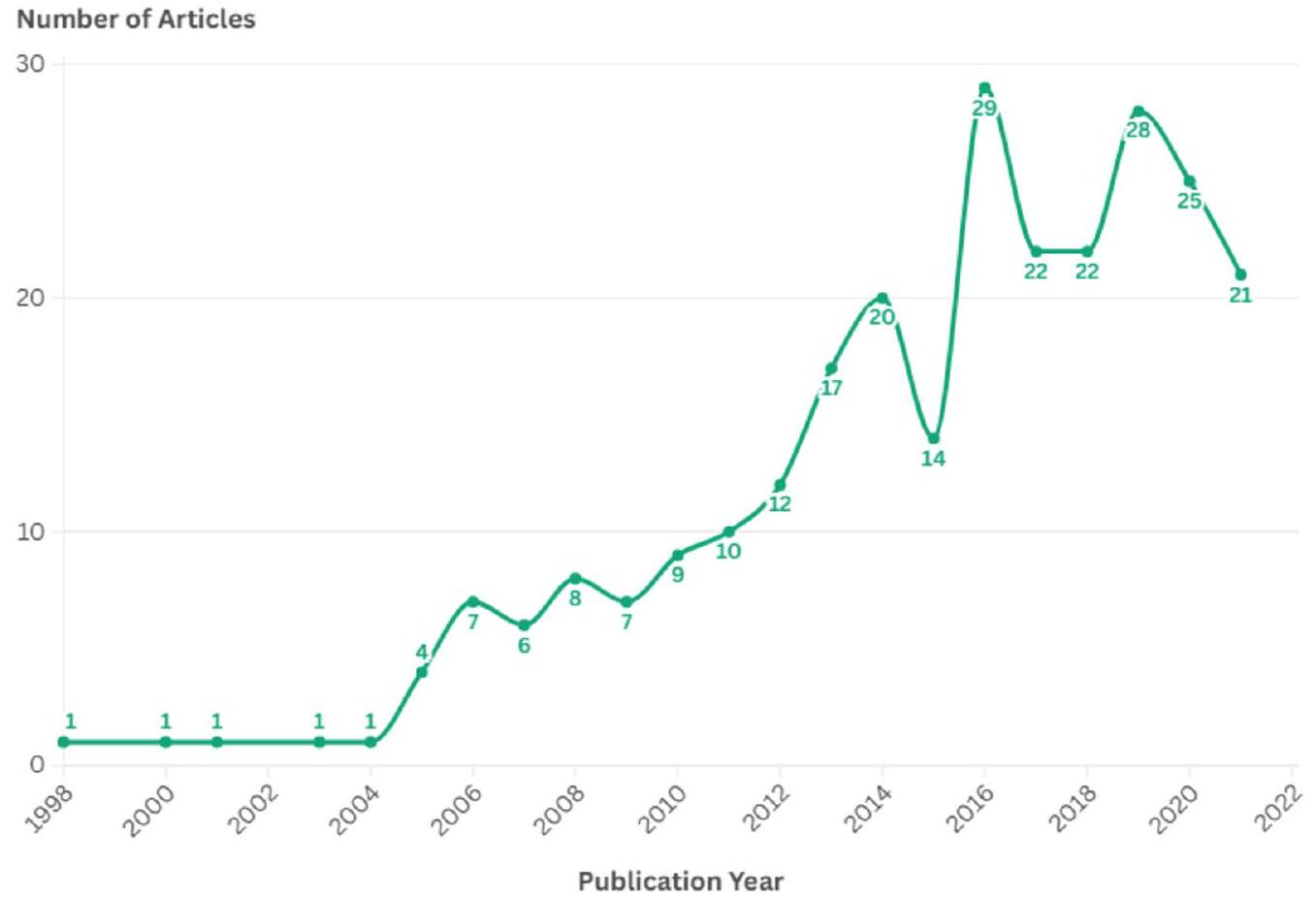

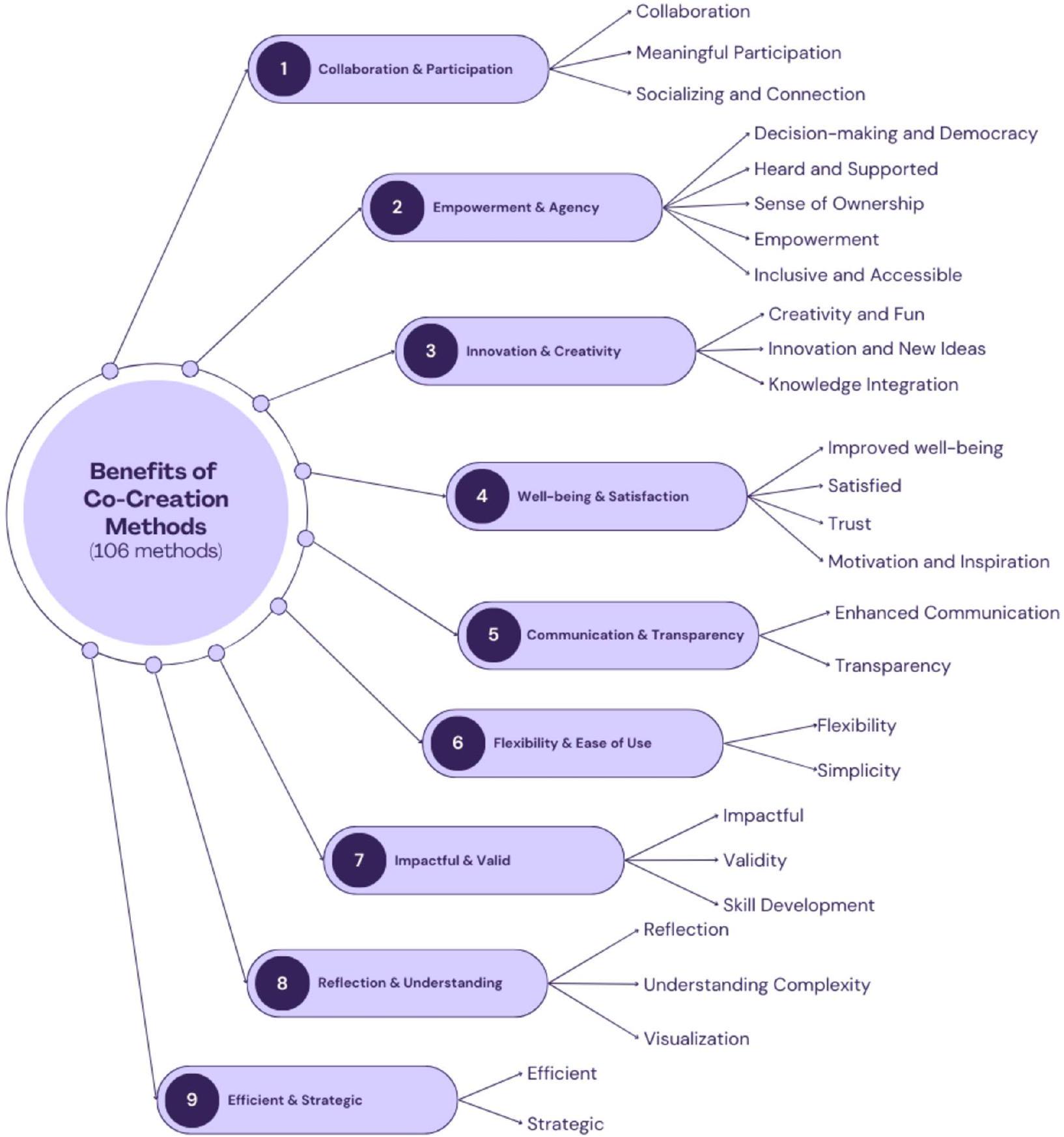

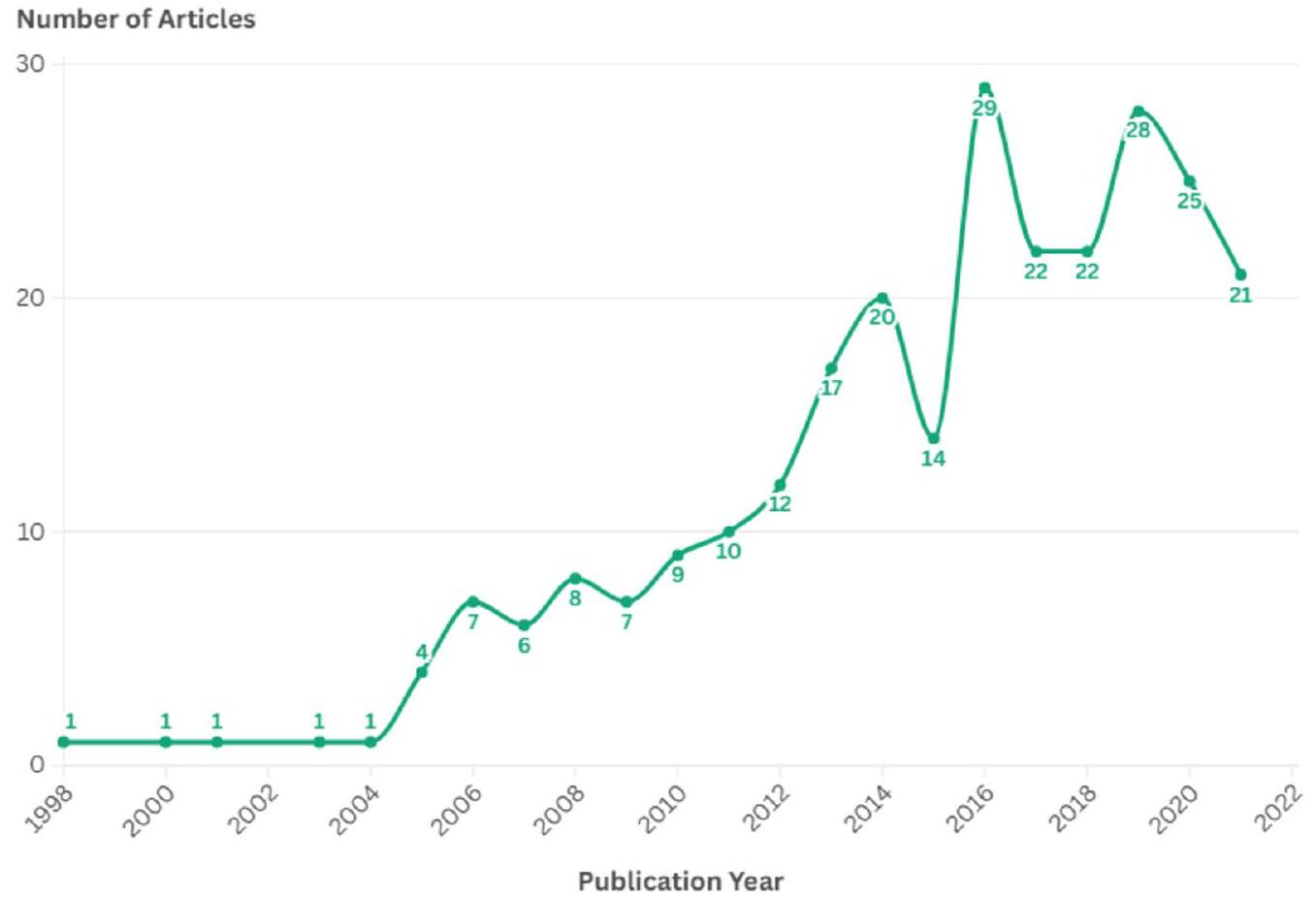

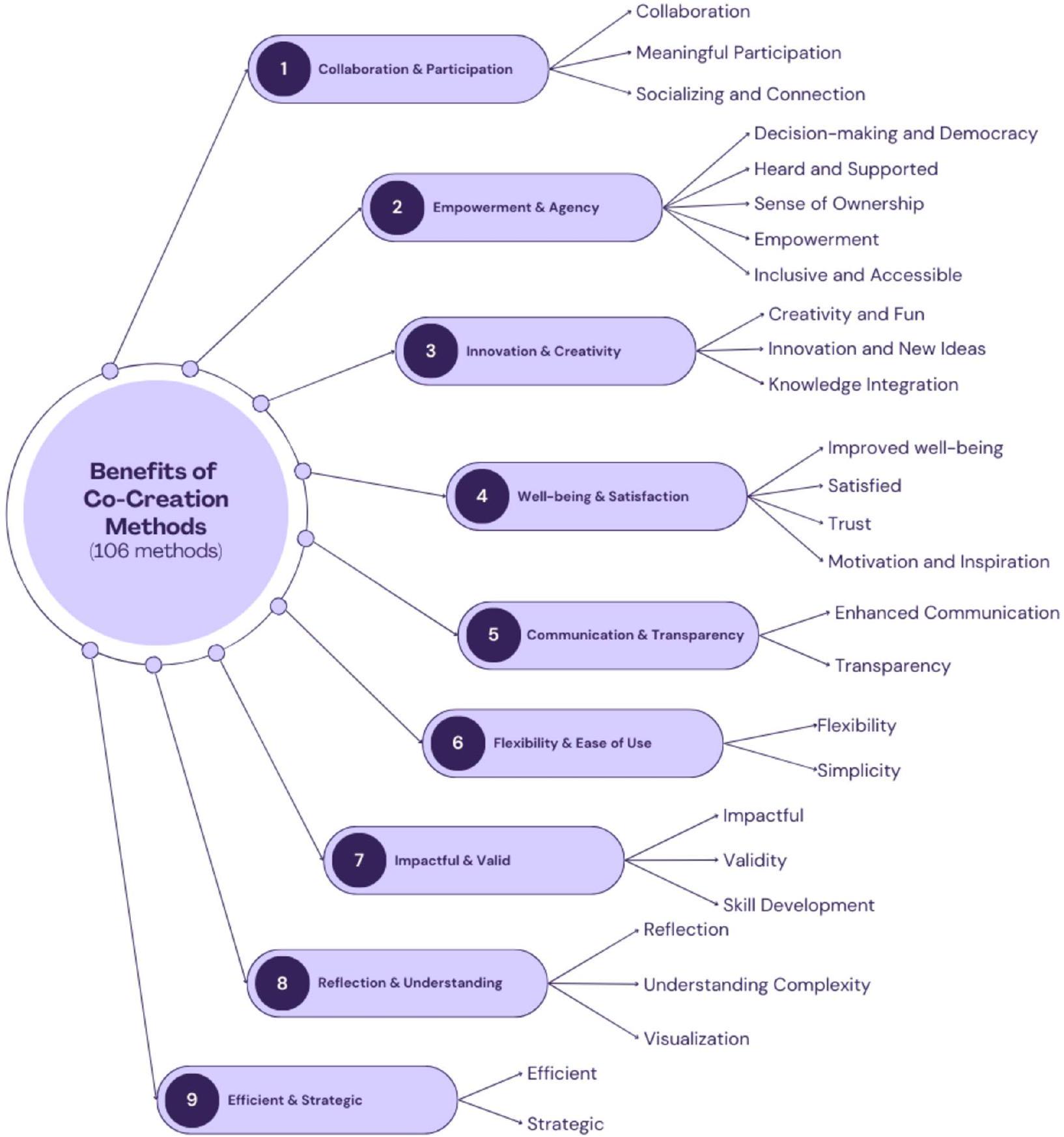

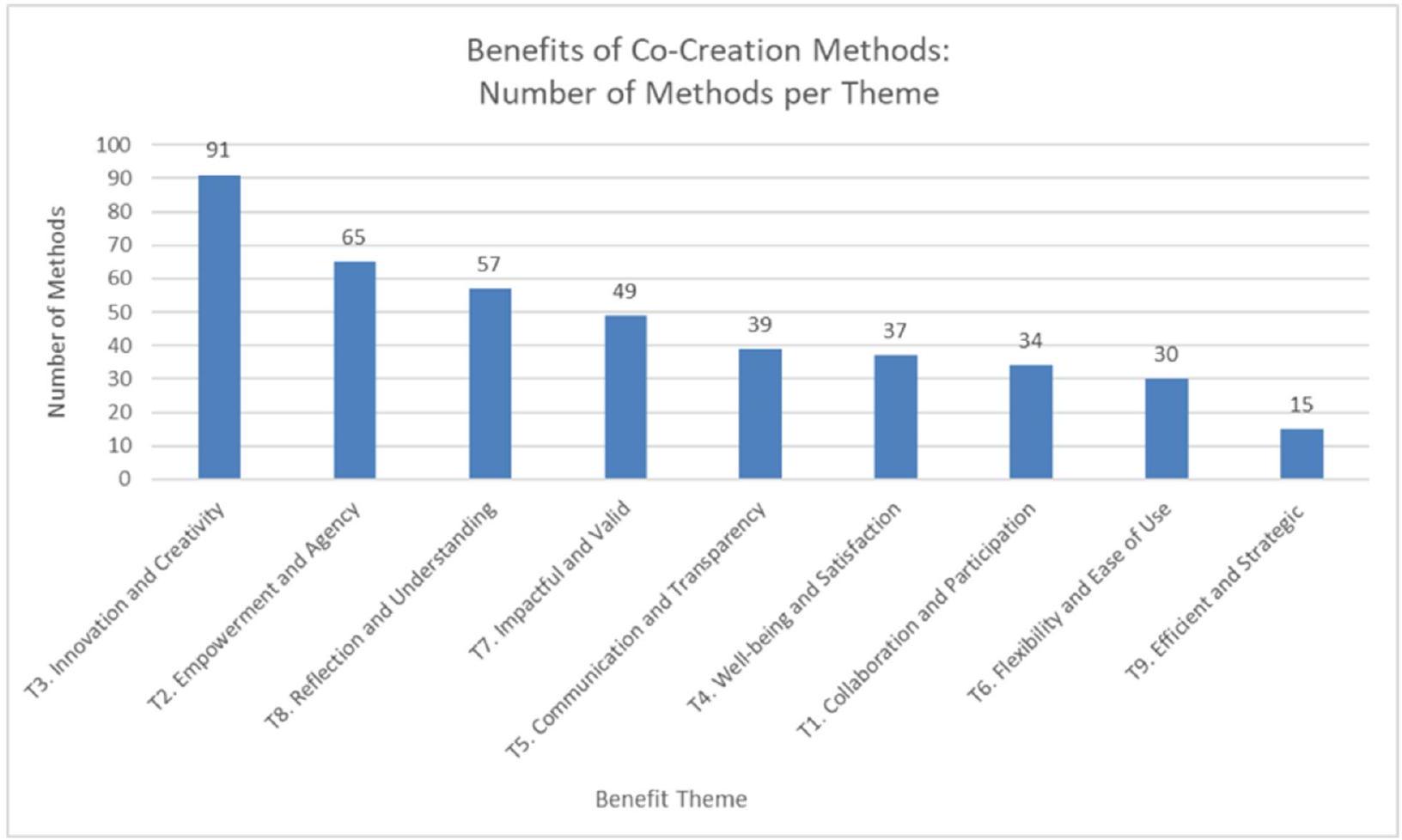

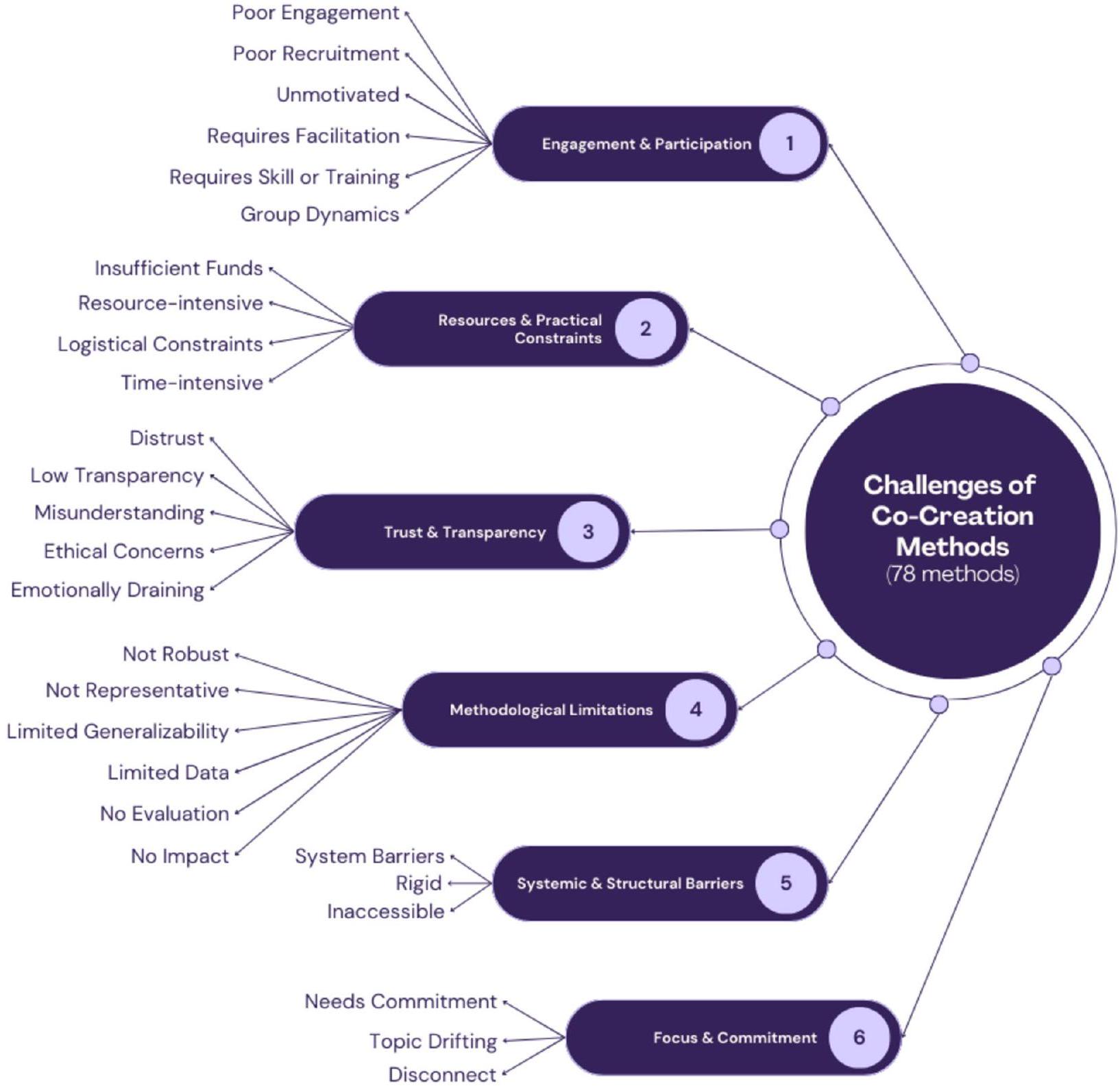

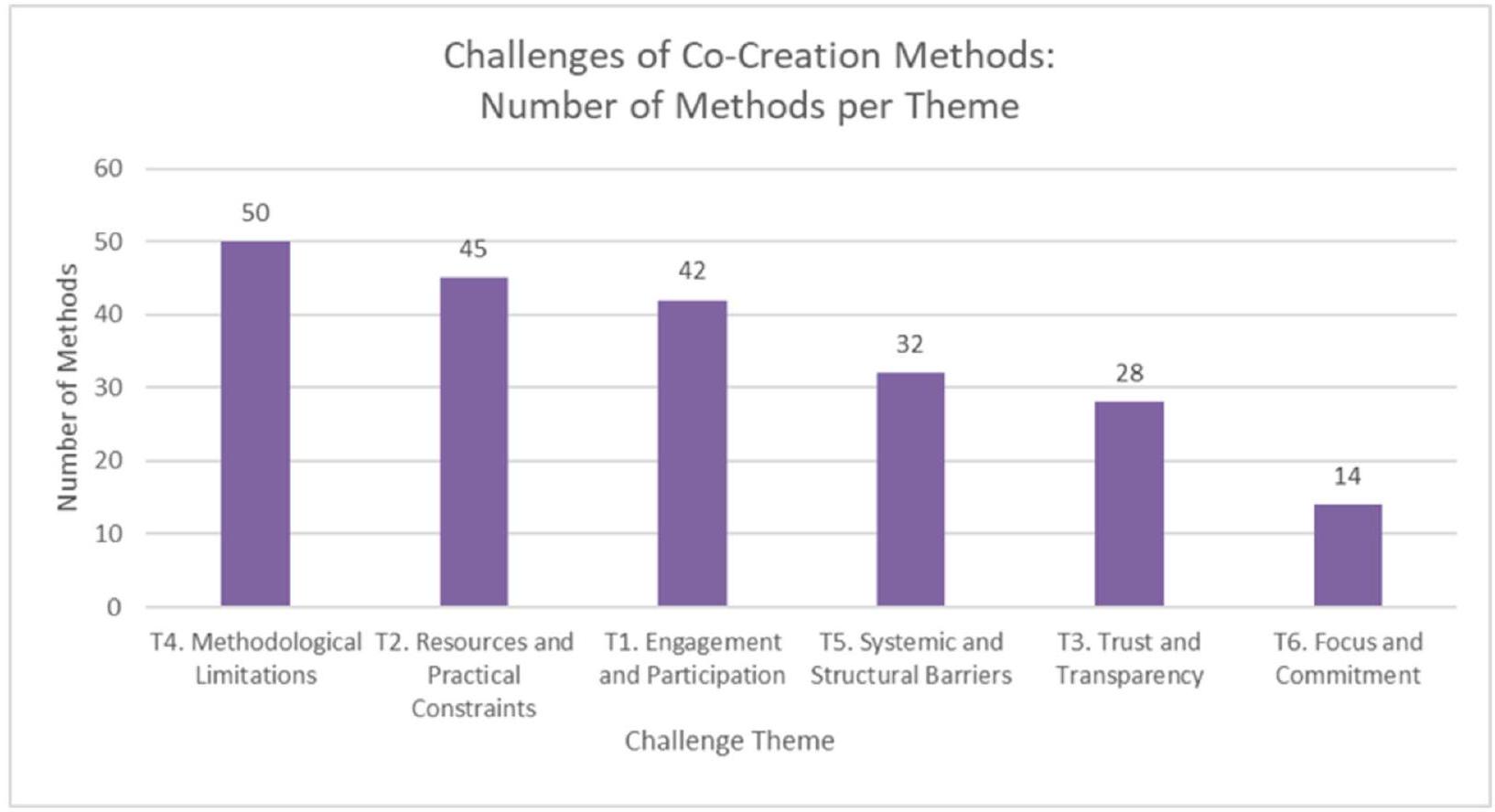

خلفية: يشارك التعاون أصحاب المصلحة المتنوعين، بما في ذلك الفئات المهمشة، في حل المشكلات بشكل تعاوني لتعزيز المشاركة وتطوير حلول مناسبة للسياق. يتم التعرف عليه بشكل متزايد كوسيلة لديمقراطية البحث وتحسين تأثير التدخلات والخدمات والسياسات. ومع ذلك، فإن نقص الأدلة المجمعة حول طرق التعاون يحد من الصرامة المنهجية وإقامة أفضل الممارسات. تهدف هذه المراجعة إلى تحديد طرق التعاون في الأدبيات الأكاديمية وتحليل خصائصها والمجموعات المستهدفة والفوائد والتحديات المرتبطة بها. الطرق: تتبع هذه المراجعة الشاملة العناصر المفضلة للإبلاغ عن المراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية. تم إجراء البحث في قاعدة بيانات صحة CASCADE الإصدار 1.5 (بما في ذلك CINAHL وPubMed و17 قاعدة بيانات إضافية عبر ProQuest) من يناير 1970 إلى مارس 2022. تم تجميع البيانات وتلخيصها، وتم تحليل البيانات النوعية باستخدام نهج التحليل الموضوعي ذو الست مراحل لبراون وكلارك. النتائج: شملت المراجعة 266 مقالة، وحددت 248 طريقة تعاون متميزة نشرت بين عامي 1998 و2022. كانت معظم الطرق متجذرة في نماذج المشاركة (147 طريقة)، مع 49 طريقة مستمدة من مقاربات مشتركة مثل التعاون والتصميم المشترك والإنتاج المشترك، و11 من تعزيز الصحة المجتمعية وأبحاث العمل. تم تطبيق الطرق عبر 40 مجموعة مستهدفة، بما في ذلك الأطفال والبالغين والفئات المهمشة. تم تقديم العديد من الطرق (62.3%) وجهًا لوجه، مع تضمين 40 مقالة أدوات رقمية. كشفت التحليلات الموضوعية عن تسع فوائد، مثل تعزيز الإبداع، وتمكين الأفراد، وتحسين التواصل، وستة تحديات، بما في ذلك قيود الموارد والحواجز النظامية والهيكلية. الخلاصة: تؤكد هذه المراجعة على أهمية التوثيق والتحليل القوي لطرق التعاون لإبلاغ تطبيقها في الصحة العامة. تدعم النتائج تطوير عمليات التعاون التعاوني التي تستجيب لاحتياجات الفئات المتنوعة، مما يعزز الفعالية العامة والحساسية الثقافية للنتائج. تسلط هذه المراجعة الضوء على إمكانيات طرق التعاون لتعزيز العدالة والشمولية مع التأكيد على أهمية تقييم واختيار الطرق المناسبة للأهداف المحددة، مما يوفر موردًا حيويًا للتخطيط والتنفيذ وتقييم مشاريع التعاون.

الخلفية

التعاون هو أي فعل من الإبداع الجماعي الذي يشمل مجموعة واسعة من الفاعلين المعنيين والمتأثرين في حل المشكلات الإبداعية التي تهدف إلى إنتاج نتيجة مرغوبة [8]. يحمل وعدًا لتعزيز مشاركة أصحاب المصلحة، وضمان أن تكون التدخلات مصممة لتلبية الاحتياجات والسياقات المحددة، مما يعزز من ملاءمتها وقبولها وفعاليتها [3، 9]. على عكس العمليات التقليدية من الأعلى إلى الأسفل أو من الأسفل إلى الأعلى، يتبنى التعاون نهجًا متعدد الاتجاهات لحل المشكلات [10] ويعزز العمليات الديمقراطية وإنتاج المعرفة [11-13]. يُنظر إلى التعاون بشكل متزايد على أنه منهجية لجعل البحث وتصميم الخدمات أكثر شمولية وديمقراطية وتنوعًا [8، 14]، ويطمح إلى خلق تعاون يعترف بالرؤى المشتركة، ويعمل بشكل عادل، ويشارك السلطة [15]. ومع ذلك، فإن هذا الوعد صحيح فقط إذا كانت الطرق المستخدمة ضمن عملية التعاون تدعم وتنفذ مبادئ التعاون، مثل تضمين جميع وجهات النظر والمهارات، واستخدام منظور نظامي، وتمكين نهج إبداعي للبحث، ومشاركة السلطة واتخاذ القرار [3، 9، 16، 17]. لتحسين العدالة الصحية، يحتاج التعاون إلى تمكين جميع أصحاب المصلحة المعنيين للمشاركة بطريقة عادلة [4]. هذا صحيح بشكل خاص بالنسبة للفئات المهمشة، حيث إنهم غالبًا ما يعانون من تفاوتات صحية بسبب الحواجز النظامية والاجتماعية والثقافية [6، 18] ويشاركون بشكل ضئيل في جهود البحث [4].

على الرغم من الاعتراف المتزايد بالتعاون، إلا أن هناك نقصًا في الأبحاث حول الطرق المستخدمة في التعاون [8، 9، 20]. علاوة على ذلك، فإن التقارير حول عملية التعاون (بما في ذلك الطرق) نادرة، حيث تأتي معظم الموارد من القطاع الخاص [21]. على سبيل المثال، حددت النتائج الأخيرة التي توصل إليها أجنيلو وآخرون فجوة كبيرة في الأدبيات الأكاديمية، مما يبرز نقص الإبلاغ عن الطرق المشاركة والإبداعية في أبحاث التعاون التجريبية، فضلاً عن وجود فرق مفاجئ بين الطرق المستخدمة في المصادر الأكاديمية وغير الأكاديمية، مما يحد من الصرامة المنهجية وإقامة أفضل الممارسات [9].

الهدف

أسئلة البحث

- ما هي طرق التعاون الموصوفة في الأدبيات الأكاديمية؟

- من أي منهجيات تستمد هذه الطرق؟

- ما هي الخصائص الرئيسية لهذه الطرق التي يمكن أن تمكن من تكرارها وتطبيقها في دراسات أخرى؟

- ما هي المجموعات المستهدفة التي تم تطبيق هذه الطرق عليها؟

- ما هي الفوائد والتحديات المرتبطة باستخدام هذه الطرق في التعاون؟

الطرق

استراتيجية البحث

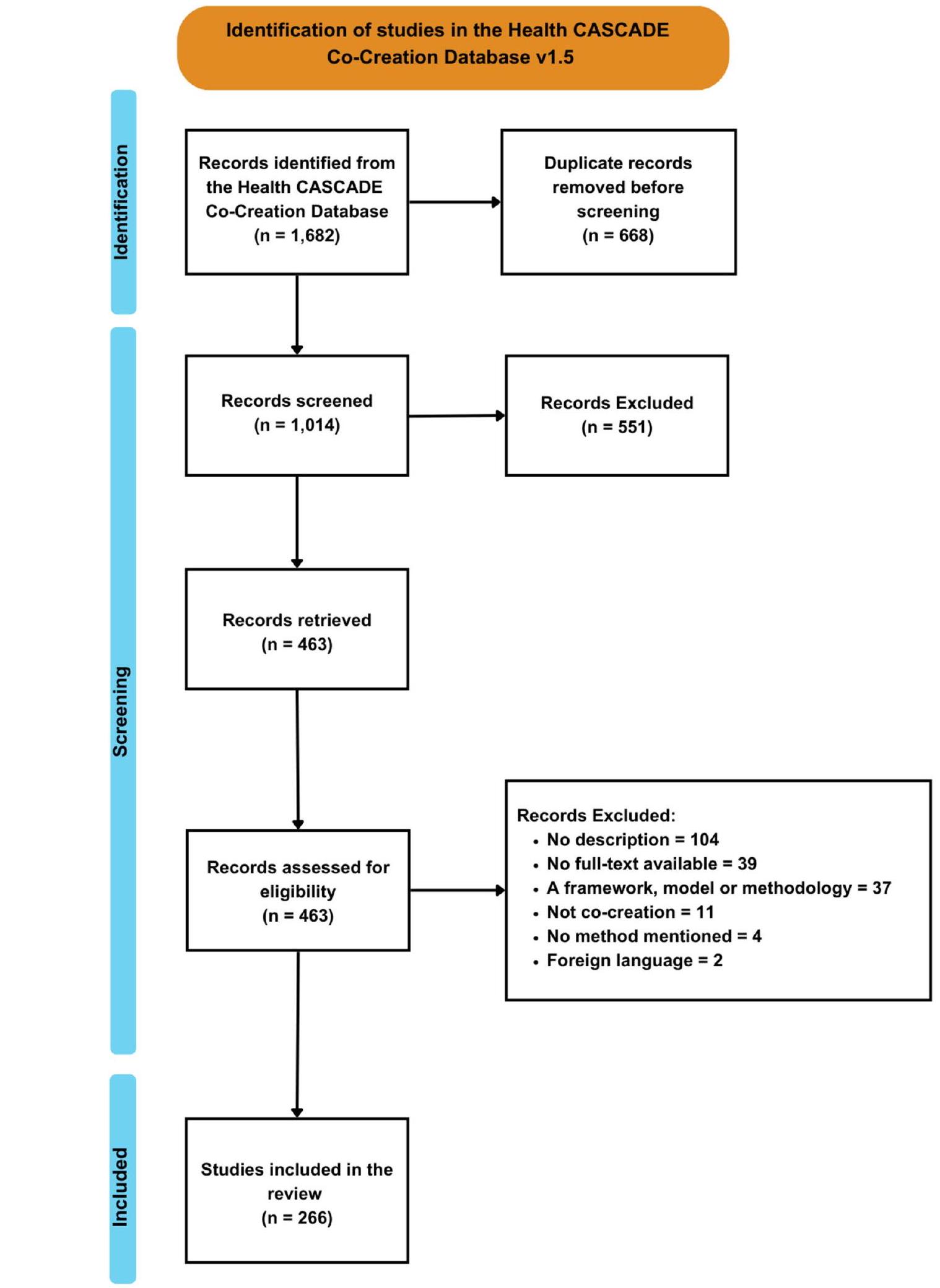

اتبعت المراجعة الشاملة العناصر المفضلة للإبلاغ عن المراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية (PRISMA-ScR) [22]. لمعالجة نقص الإجماع والاستخدام المتبادل لمختلف المقاربات المشتركة، فضلاً عن تداخلها مع منهجيات البحث المشاركة [8]، تم إجراء بحث شامل في قاعدة بيانات صحة CASCADE المنسقة والمراجعة من قبل الأقران الإصدار 1.5 من يناير 1970 إلى مارس 2022 [23]. تم تطوير هذه القاعدة من قبل شبكة صحة CASCADE، التي تشمل الأدبيات المتعلقة بالتعاون من CINAHL وPubMed و17 قاعدة بيانات إضافية متاحة عبر ProQuest [8].

قاعدة البيانات تستبعد جميع المواد التالية: المدونات، المواقع الإلكترونية، البودكاست، السير الذاتية، ملخصات المؤتمرات، الأوراق والمداولات، الرسائل الجامعية والأطروحات، الرسالة (الرسائل) إلى المحرر، الصحف، المجلات، الكتيبات أو المنشورات، الخطابات، المحاضرات، أو العروض التقديمية، الأوراق العملية، الأعمال الصوتية والمرئية، الأعمال الفنية والجمالية، الموسوعات وأعمال المراجع، أو المقالات والمقابلات. كانت استراتيجية البحث تشمل الكلمات الرئيسية التي تمثل طريقة في الجدول 1. تم إجراء البحث في العنوان فقط، حيث تحتوي جميع الملخصات على مصطلح ‘طريقة’. لم يكن البحث مقصورًا على مجال الصحة العامة، حيث كان الهدف هو الحصول على طرق التشارك في الإبداع بغض النظر عن المجال أو التخصص الأصلي. تم اختبار استراتيجية البحث من قبل المؤلف الرئيسي (DMA)، مع جولات من المدخلات والتقييم من الباحثة الكبيرة (SC)، للتحقق من ملاءمة الكلمات الرئيسية ولضمان تحديد الدراسات المطلوبة. تم إجراء البحث باللغة الإنجليزية فقط بسبب قيود اللغة لفريق الدراسة.

لم يكن من الضروري إضافة مصطلحات رئيسية محددة تمثل التشارك في الإبداع في هذه الدراسة، حيث أن قاعدة البيانات المستخدمة في هذه المراجعة مشتقة من مراجعة منهجية جمعت بشكل شامل جميع الأدبيات المتعلقة بالتشارك في الإبداع [8]. للتوضيح، يوفر الجدول 2 الكلمات الرئيسية المستخدمة لإنشاء قاعدة بيانات التشارك في الإبداع.

الفرز

بعد فرز العنوان والملخص، تم تصدير المقالات المضمنة كملف RIS وانتقلت إلى مرحلة فرز النص الكامل. تم إعادة تحميل ملف RIS إلى Rayyan، وتم تقسيم الاقتباسات المضمنة بين ستة باحثين (JB، LRD، LMcC، QA، QL، وVAK). نظرًا للحجم الكبير من المقالات، قام كل باحث بفرز حزمة المواد المخصصة له باستخدام معايير الاختيار في الجدول 4. لضمان القوة والاتساق، قام الباحث الرئيسي

| المصطلح المستهدف | الكلمات الرئيسية |

| طريقة | طريقة” أو “طرق” أو “منهجية” أو “منهجيات” أو “أداة” أو “أدوات” أو “تقنيات” أو “تقنية” أو “إجراء” أو “إجراءات |

| المصطلح المستهدف | الكلمات الرئيسية |

| التشارك في الإبداع | التشارك في الإبداع*” أو “التصميم المشترك” أو “الإنتاج المشترك” أو “مشاركة الجمهور والمرضى” أو “مشاركة الجمهور” أو “مشاركة” أو “تصميم قائم على التجربة” أو “التصميم المشترك” أو “مشاركة المستخدم” أو “التصميم التعاوني” أو “علم المواطن |

| يتم تضمين المادة إذا كانت تلبي جميع ما يلي: | يتم استبعاد المادة إذا كانت تلبي واحدًا أو أكثر من ما يلي: | ||

| تتضمن على الأقل واحدة من الكلمات الرئيسية المستخدمة في البحث (أعلاه) في العنوان أو الملخص | لا تتضمن على الأقل واحدة من الكلمات الرئيسية المستخدمة في البحث (أعلاه) في العنوان أو الملخص | ||

| تم ذكر طريقة (طرق) بالاسم في العنوان أو الملخص | لا يذكر العنوان أو الملخص/يصف على الأقل طريقة واحدة | ||

| يوفر الملخص وصفًا (موجزًا) للطريقة (الطرق) أو يشير إلى أن الدراسة تتعلق بتطوير أو تقييم أو تطبيق الطريقة أو الطرق | لا يحتوي الملخص على وصف للطريقة أو هو ورقة إرشادية أو إطار عمل | ||

|

تم كتابة العنوان أو الملخص بلغة غير الإنجليزية ليس هو التشارك في الإبداع |

استخراج البيانات

تم استخراج البيانات لكل طريقة، باستخدام نموذج الاستخراج في Google Forms (Google Workspace) [26]. على سبيل المثال، إذا كان لدى مقال طريقتان، فسيتم إكمال نموذجين لذلك المقال. دفع نموذج الاستخراج الباحث لاستخراج تفاصيل حول كل طريقة، بما في ذلك 1) وصف المقال (مثل اسم المقال، السنة، المؤلفون)؛ 2) تفاصيل حول الطريقة (مثل الاسم، الخطوات، النوع، تفاصيل التنفيذ)؛ و3) بيانات داعمة حول عملية التشارك في الإبداع (مثل النماذج أو الأطر المستخدمة، الأدوات الرقمية، المنهجية أو النظرية). من المهم ملاحظة أن جميع التصنيفات، مثل نوع الطريقة والنهج المنهجي، تم تحديدها بناءً على اللغة المستخدمة في المقال المصدر. يظهر ملف إضافي نموذج الاستخراج (انظر الملف الإضافي 1).

التحليل

تم تحليل البيانات النوعية المستخرجة من المقالات المضمنة، بهدف تحديد الفوائد (الإيجابيات) والتحديات (السلبيات) لكل طريقة، بطريقة تحترم ذاتية ووجهات نظر مؤلفي المقالات المضمنة، مع تقليل التفسير الإضافي من قبل الباحثين والتركيز على تجميع الرؤى المبلغ عنها [27]. تم تحليل البيانات باستخدام نهج تحليل موضوعي استقرائي في NVivo الإصدار 1.7.2 (لوميفيرو) [28] وفقًا للست مراحل الموضحة بواسطة براون وكلارك [29].

تماشيًا مع إرشادات براون وكلارك، لم يتم تطبيق إطار ترميز موجود مسبقًا، وظهرت الموضوعات المبلغ عنها من خلال الترميز المفتوح وتطوير الموضوعات التكرارية [29]. تم تنفيذ المرحلة 1 (التعرف)، المرحلة 2 (توليد الرموز الأولية)، والمرحلة 3 (توليد الموضوعات) بواسطة الباحث الرئيسي (DMA)، مع تنفيذ المراحل اللاحقة 4 (مراجعة الموضوعات المحتملة) بواسطة أربعة باحثين (DMA، GRL، LRD، وVAK) لضمان الدقة والتماسك. تم إكمال المرحلة 5 (تحديد وتسميه الموضوعات) والمرحلة 6 (إنتاج التقرير) بواسطة الباحث الرئيسي (DMA)، وتمت مراجعة الموضوعات وتعديلها والموافقة عليها من قبل ثمانية باحثين (DMA، GRL، JB، LMcC، LRD، QA، SC، وVAK). في حالات الاختلاف، تمت مناقشة القضايا بين المؤلفين المشاركين حتى تم التوصل إلى توافق.

| يتم تضمين المادة إذا كانت تلبي جميع ما يلي: | يتم استبعاد المادة إذا كانت تلبي واحدًا أو أكثر من ما يلي: |

| النص الكامل متاح | النص الكامل غير متاح |

| تم ذكر طريقة (طرق) بالاسم في النص الكامل | لا يذكر المقال أو يصف على الأقل طريقة واحدة |

| المقال يقدم وصفًا (موجزًا) للطريقة أو يشير إلى أن الدراسة تتعلق بتطوير أو تقييم أو تطبيق الطريقة أو الطرق. | المقال يذكر فقط اسم الطريقة ولكنه لا يصف الطريقة نفسها، ولا يقدم أي تفاصيل عن الطريقة، ولا يصف متى أو كيف تم استخدامها في الدراسة (على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن تكون هذه دراسة أولية). |

| المقال يتحدث عن طريقة واحدة، أو طرق، مستخدمة في عملية. | المقال يتناول منهجية (مثل: عملية كاملة، نموذج، أو إطار عمل) وليس عن طريقة واحدة، أو طرق، مستخدمة في عملية. |

| يعتبر ‘التعاون في الإبداع’، استنادًا إلى تعريف أغنيليو ولوازيل وآخرون للتعاون في الإبداع [8] | ليس التعاون في الإبداع |

| النص الكامل كُتب باللغة الإنجليزية | النص الكامل كُتب بلغة غير الإنجليزية |

النتائج

استراتيجية البحث والفحص

البيانات المستخرجة

من بين 404 استخراجًا،

تم استخدام طرق في المشاريع التي كانت لديها أوضاع تسليم مختلفة. على سبيل المثال،

الأسس المنهجية

علاوة على ذلك، كان عدد الطرق المستخرجة لكل منهجية يختلف مع مرور الوقت وفقًا لسنة النشر. كما ساهم كل نهج بعدد معين من الطرق. توضح الجدول 6 توزيع الطرق على مر الزمن وعبر المنهجيات. يحتوي الملف الإضافي على جدول الاستخراج، الذي يتضمن الطرق لكل منهجية (انظر الملف الإضافي 3).

أنواع الطرق

اعتمادًا على المقال الذي تم الاستناد إليه، تم الإبلاغ عن بعض الطرق كأنواع طرق مختلفة، لذا تم تصنيف تلك الطرق تحت كلا النوعين (مثل: المشاركة والنوعية، أو المشاركة والبصرية). على سبيل المثال، صنفت مصادر مختلفة تقنية فوتوفويس كنوع نوعي (

في 174 حالة، أبلغ المؤلفون عن طرق تم استخدامها معًا في عملية التعاون، مما يوفر رؤى حول كيفية دمج الطرق. تم تجميع التركيبات المستخرجة حسب نوع الطريقة. تحليل التكرارات المشتركة بين الطرق المصدر والهدف يوضح الأنماط الرئيسية، والتي تم عرضها في الجدول 8.

توضح هذه النتائج الطرق المتنوعة التي تتقاطع بها الأساليب، حيث تهيمن الأساليب التشاركية والنوعية على المشهد، بينما تظل التركيبات البصرية والكمية نادرة نسبيًا. يحتوي ملف إضافي على المجموعة الكاملة من الأساليب المدمجة ورؤية بصرية لتركيبات الأساليب (انظر الملف الإضافي 5).

السكان المستهدفون

تراوحت الفئات المشاركة بين الأكاديميين، والمهنيين في الرعاية الصحية، ومقدمي الرعاية، إلى مجموعات أكثر تهميشًا مثل الأطفال المصابين بالتوحد، والأفراد من مجتمع LGBTQAI +، واللاجئين، والأشخاص

| عدد المقالات | نوع النهج | المنهجيات |

| ١٤٤ | النهج التشاركي | البحث التشاركي، البحث التشاركي القائم على المجتمع، نهج البحث التشاركي القائم على العمل، البحث التشاركي القائم على الشباب، أو التصميم التشاركي |

| 30 | النهج المشترك | التشارك في الإبداع، التشارك في التصميم، والتشارك في الإنتاج |

| 20 | أنواع مختلفة | البحث العملي، التقييم التشاركي، النهج الإثنوغرافي، تصميم موجه نحو المستخدم، ومشاركة المجتمع |

| عدد الطرق | نهج | المنهجيات | سنوات |

| 147 | النهج التشاركي | البحث العملي التشاركي، البحث التشاركي، البحث القائم على المجتمع التشاركي، وتصميم تشاركي | 1998 إلى 2022 |

| ٤٩ | النهج المشترك | التعاون في الإبداع، التعاون في التصميم، التعاون في الإنتاج | 2008 إلى 2022 |

| 11 | متنوع | تعزيز الصحة القائم على المجتمع وبحث العمل | 2014 إلى 2022 |

استنباط

| نوع الطريقة | عدد الطرق |

| مشاركة | ١٣٧ |

| نوعي | 99 |

| الطرق المختلطة | ٣٥ |

| كمّي | 16 |

| بصري | ٤ |

| النمذجة شبه الكمية | ٤ |

| أخذ العينات | ٢ |

| رصدية | 1 |

| نوع طريقة المصدر | نوع طريقة الهدف | نسبة التكرار %

|

| مشاركة | مشاركة | ٢٦.٧٪

|

| نوعي | نوعي | 18.2% (

|

| مشاركة | نوعي | 17.9% (

|

| نوعي | مشاركة |

|

| مختلط | نوعي | 4.9% (

|

| كمّي | نوعي | 3.2% (

|

| مختلط | مشاركة | 2.5% (

|

| مختلط | مختلط | 2.5% (

|

| بصري | نوعي | 2.5% (

|

| كمّي | مشاركة | 2.1% (

|

| نوعي | مختلط | 1.8% (

|

| كمّي | مختلط | 1.8% (

|

| بصري | مشاركة |

|

| بصري | بصري | 1.4% (

|

| أخذ العينات | أخذ العينات | 1.4% (

|

| نوعي | كمّي | 0.7% (

|

| مختلط | كمّي | 0.7% (

|

| نوعي | أخذ العينات |

|

| كمّي | كمّي | 0.4% (

|

| مشاركة | بصري | 0.4% (

|

| بصري | كمّي | 0.4% (

|

| كمّي | بصري |

|

| بصري | رصدية | 0.4% (

|

| مشاركة | رصدية | 0.4% (

|

التحليل الموضوعي

فوائد الطريقة

يتضمن ملف إضافي أسماء الموضوعات الفرعية، والأوصاف، والأساليب المرتبطة بها ومراجعها (انظر الملف الإضافي 8).

الموضوع 1: التعاون والمشاركة

الانخراط المعنوي هو المفتاح، حيث أظهر أوريلي-دي برون وآخرون كيف أن الأساليب “لديها القدرة على تسهيل الانخراط المعنوي الذي يدمج تلقائيًا التوليد المشترك والتحليل المشترك للبيانات من قبل ومع أصحاب المصلحة” [54]. كما تعزز أساليب التشارك في الإبداع الاتصال وبناء العلاقات، مما يضمن شعور المشاركين بالاندماج. ويعكس هذا الجانب العلاقي في الدراسات التي تشير إلى كيف “يمكن إقامة الاتصال في المرحلة المبكرة جدًا من المشروع، كأساس لنتيجة مستدامة” [55] وكيف أن “الناس سيقومون أيضًا بإنشاء اتصالات مع رؤى أخرى وأشخاص آخرين” [56].

الموضوع 2: التمكين والوكالة

| السكان المستهدفون | الطريقة (المرجع) |

| 1. الأكاديميات | تقرير بيانات الشراكة للتفكير [22] ومقهى العالم [23] |

| 2. المراهقون | مقابلة سردية قائمة على الفن [24]؛ نهر الحياة [22]؛ صوت الصورة [25، 26]؛ فرز البطاقات [27]؛ ومختبر الواقع الافتراضي [28] |

| 3. البالغون | اختبار المقابلة ثلاثي الخطوات [29]؛ الملصقات [30]؛ أداة تحليل الوضع [31]؛ نهر الحياة [22]؛ المقابلة [32]؛ نماذج صفحات الويب [33]؛ الملاحظة المشاركة [34]؛ قصص المستخدمين [35]؛ عائلة الصراع (نشاط سرد قصصي ثقافي) [36]؛ نهر مشترك [37]؛ تحليل القرار متعدد المعايير [38]؛ صوت الصورة [39-41]؛ طريقة MUST [42]؛ استدلال الصورة [43]؛ التصميم المشترك من خلال استغلال الإمكانيات [44]؛ الرؤية [45]؛ رسم خرائط الأنظمة التشاركية [46]؛ أداة Geo-Wiki عبر الإنترنت [47]؛ مجموعة السرد القصصي [48]؛ فهم المعنى [35]؛ أداة التصور المستندة إلى الويب [49]؛ وتحليل الشبكات الاجتماعية [50] |

| 4. الأطفال المصابون بالتوحد | تفاعل كامل الجسم [51] |

| 5. الناجون من السرطان | صوت الصورة [52] |

| 6. مقدمو الرعاية | جمعية مقدمي الرعاية [53] وعينة هادفة [54] |

| 7. الأطفال (تحت 18 سنة) | عني [55]؛ صناعة الفن [56]؛ صناعة الكتب [56]؛ بناء نموذج [56]؛ قوائم التحديات وبطاقات الأصول [57]؛ تصنيف الماس [58]؛ السرد الرقمي [59، 60]؛ تقنية الرسم والكتابة [61-64]؛ الرسم [65]؛ خريطة الحقول الخمسة [66]؛ طريقة FUBI [67]؛ الرسوم البيانية على مر الزمن [68]؛ مسرح الصور [59]؛ المقابلات غير الرسمية [61]؛ لعب Lego الجاد [69]؛ النهج الموزائيكي [63، 70]؛ مقياس الجدة: برطمانات الحلوى [55]؛ مقاييس الجدة: الوجوه المبتسمة [55]؛ الملاحظة المشاركة [71]؛ تصوير المشاركين [72]؛ استنباط الموضوعات بالمشاركة [73]؛ الفيديو التشاركي [59]؛ استنباط الصور [55، 58]؛ صوت الصورة [26، 74، 75]؛ الدمى [63]؛ تمثيل الأدوار [56]؛ الملاحظات شبه المشاركة [61]؛ اختبار لصق النجوم [61]؛ لوحة القصة [76]؛ طريقة الخمسة لماذا [77]؛ يوميات الفيديو [78]؛ طريقة الأصوات البصرية [79]؛ ولعبة البحث عن الكلمات [76] |

| 8. الأطفال ذوو الاحتياجات الخاصة | تصنيف الماس [80]؛ بطاقات تفضيل المدرسة [80]؛ قوائم المراقبة SCERTS [80]؛ وجدار الجرافيتي [80] |

| 9. أعضاء المجتمع | رسم خرائط الأصول [81]؛ رسم خرائط المفاهيم (المعروف أيضًا برسم الخرائط المعرفية) [82]؛ مجموعات التركيز باستخدام خريطة النقاط [83]؛ تقرير بيانات الشراكة للتفكير [22]؛ المسارات [45]؛ صوت الصورة [84]؛ سجلات النشاط المدعومة بالصور الفضائية [83]؛ مقهى العالم [23]؛ وطريقة نظام يونمنكاigi [85] |

| 10. الأشخاص ذوو الإعاقة | تحليل الظواهر التفسيرية [86]؛ طريقة تقرير المخاوف [87]؛ وصوت الصورة [88] |

| 11. المزارعون | استطلاع مقطعي [89]؛ وصوت الصورة [90] |

| 12. المجتمعات الغابية | سيناريوهات بديلة [45] |

| 13. المتخصصون في الرعاية الصحية | رسم الخرائط المفهومية (المعروف أيضًا برسم الخرائط المعرفية) [91]؛ تقنية المجموعة الاسمية (لجنة الخبراء) [92]؛ المقابلة شبه المنظمة [78]؛ السوسيوقرام (الرسم البياني الموجه) [93]؛ مقهى العالم [23]؛ ومراجعة منهجية مدفوعة من قبل المستخدم [94] |

| 14. المشردون | صوت الصورة [95] |

| 15. المهاجرون | رسم الخرائط المفهومية (رسم الخرائط المعرفية) [96] |

| 16. الشعوب الأصلية | سرد القصص [97]؛ طريقة البحث البصري Gaataa’aabing [98]؛ مجموعات التركيز التفسيرية [99]؛ سرد القصص الرقمي [100]؛ ومقابلة جماعية [101] |

| 17. المجتمعات الإنويت التي تعيش مع مرض السكري | سرد القصص [102] |

| 18. LGBTQAI + | رسم الخرائط المجتمعية [103] وصوت الصورة [26] |

| 19. الأشخاص ذوو الدخل المنخفض | قياسات الجسم [104]؛ مخطط الحلقة السببية [68]؛ الرسوم البيانية على مر الزمن [68]؛ عينة كرة الثلج [54]؛ وطريقة تقرير المخاوف [87] |

| 20. الأشخاص المهمشون | سيناريوهات بديلة [45]؛ فيديو تشاركي [105]؛ رسم الماندالا [106]؛ كوميديا أنشأها المشاركون [45]؛ وصوت الصورة [107، 108] |

| 21. النساء المسلمات | طريقة قائمة على الفنون التوضيحية [109] |

| 22. الشباب غير الثنائي | رسم الجسم [110] |

| 23. الممرضات | تيسير الرسوم البيانية [93]؛ الاستدلال الفوتوغرافي [93]؛ ورسم العلاقات الاجتماعية (الرسم البياني الموجه) [93] |

| 24. كبار السن | صوت الصورة [111، 112]؛ المقابلة [32]؛ السيناريوهات البديلة [45]؛ المختبر الحي [113]؛ استثارة الصورة [43، 114]؛ لوحة القصة والرسوم المتحركة [113]؛ ومقهى الحياة [115] |

| 25. الآباء | مقابلة سردية [78] |

| 26. الأشخاص الذين يعيشون مع سرطان الثدي | تقنية الحوادث الحرجة [116] |

| 27. الأشخاص الذين يعانون من ألم مزمن غير سرطاني | العينة الغرضية [54] |

| 28. الأشخاص المصابون بالخرف | سرد القصص [117] ومقهى السياسات [53] |

| 29. الأشخاص المصابون بالسكري | تقنية المجموعة الاسمية (لجنة الخبراء) [92] |

| 30. الأشخاص ذوو مستوى منخفض من محو الأمية | سيناريوهات بديلة [45] واستدعاء الصور [118] |

| 31. الأشخاص الذين يواجهون تحديات في الصحة النفسية | التخطيط التشاركي [119] |

| 32. اللاجئون | مسرح المنتدى [120] ومسرح العرض [120] |

| 33. السكان الريفيون | صوت الصورة [95] |

| السكان المستهدفون | الطريقة (المرجع) |

| 34. الأمهات العازبات | صوت الصورة [121] |

| 35. الطلاب | نهر تم إنشاؤه بشكل مشترك [37]؛ مختصر تم إعادة تحريره مع عناصر الألعاب [122]؛ وصوت الصورة [41] |

| 36. المعلمون | المنهجية البصرية التشاركية [123] |

| 37. الأشخاص المعرضون للخطر الذين لا يحصلون على الخدمات الكافية | استدعاء الصور [43] |

| 38. الأشخاص المعرضون للخطر | نهج مختلط: صوت الصورة واستنباط الصورة [124]؛ يوميات سفر مساحة النشاط اليومي [125]؛ ألعاب الجيوكاشينغ [83]؛ الإدراج، التقييم، التصنيف [126]؛ تصوير المشاركين [72]؛ رسم الخرائط الجغرافية التشاركية [125]؛ إنتاج الصور مع المقابلات [117]؛ صوت الصورة [62، 108، 127-131]؛ عملية التحليل الهرمي [132]؛ والسيناريوهات البديلة [133] |

| 39. النساء اللاتي لديهن تاريخ من سكري الحمل | مجموعة فيسبوك [134] |

| 40. الشباب (15-24 سنة) | رسم الخرائط المجتمعية [83، 103]؛ سرد القصص الرقمية [59، 60]؛ مجموعات التركيز على خريطة النقاط [83]؛ ألعاب الجيوكاشينغ [83]؛ مسرح الصور [59]؛ لعب ليغو الجاد [69]؛ طريقة الفنون التوضيحية [109]؛ تصوير المشاركين [72]؛ استنباط الموضوعات التشاركية [73]؛ الفيديو التشاركي [59]؛ التصوير الفوتوغرافي التشاركي/الانعكاسي [135]؛ المقابلات بين الأقران [136]؛ صوت الصورة [39، 127، 128، 137]؛ سجلات الأنشطة المدعومة بالصور الفضائية [83]؛ أداة البحث عن العافية [138]؛ وطريقة تحليل بيانات شباب ReACT (البحث في تفعيل التفكير النقدي) [139] |

جانب رئيسي من التمكين هو ضمان شعور المشاركين بأنهم مسموعون ومدعومون. تقدم طرق مثل صوت الصورة للمشاركين “فرصة لمشاركة تجاربهم وآلامهم ومشاعرهم مع الآخرين” [88]، بينما يصف كيوغ وآخرون كيف سمحت جمعية مقدمي الرعاية للمشاركين بالشعور بأنهم “مسموعون وكثيرون أبلغوا، ولأول مرة كمقدمي رعاية عائلية، شعروا بأنهم ذوو قيمة ولديهم صوت” [35]. تبني هذه الطرق الثقة وتعزز الحوار الشامل، حتى في حالات النزاع.

الملكية هي عنصر حيوي آخر، مما يسمح للمشاركين بالتحكم في نتائج البحث والتأثير عليها. يشير أوريلي-دي برون إلى كيف أن الترتيب المباشر “يعطي [للمشاركين] القوة” [54] من خلال السماح لهم بتحديد أولوياتهم الخاصة، بينما يؤكد تاونلي وآخرون كيف يمكن أن يسمح رسم الخرائط التشاركي للأفراد “برسم خرائطهم الخاصة، بدلاً من الاعتماد على الخرائط المرسومة مسبقًا أو حدود التعداد” [108].

بعيدًا عن تمكين الأفراد، تتحدى العديد من الطرق بنشاط الهياكل السلطوية وتخلق شراكات متساوية. يشير تاونلي وآخرون إلى أن رسم الخرائط التشاركي مكن المشاركين من “شرح مجتمعاتهم من وجهات نظرهم الفريدة” [108]، ويضع الفيديو التشاركي المشاركين كـ”شركاء متساوين”

جنبًا إلى جنب مع السلطات الحكومية لتوفير نهج تعاوني لحل المشكلات” [109]. تعزز هذه إعادة توزيع السلطة المشاركة المجتمعية، وتعزز العدالة الاجتماعية وتضمن أن الأصوات التي تم استبعادها تقليديًا تلعب دورًا في اتخاذ القرار.

تعتبر الشمولية وإمكانية الوصول مكونات أساسية، تضمن أن الحواجز مثل محو الأمية، اللغة، أو المعرفة التقنية لا تستبعد المشاركين. يصف لورز كيف وجد المشاركون قوائم التحقق “أسهل في الارتباط” [110]، بينما يذكر ليناباري وآخرون كيف وجد المشاركون طريقة عائلة النزاع “مرنة وقابلة للوصول” [111]. يعلق أوريلي-دي برون وآخرون على كيف أن الترتيب المباشر “يمكن أن يجذب مجموعة واسعة من أصحاب المصلحة، بما في ذلك أولئك الذين يواجهون تحديات في محو الأمية و/أو الحساب” [54]، مما يساعد على خلق مساحات آمنة تشاركية للأطفال، والمجتمعات المهمشة، والمجموعات التي يصعب الوصول إليها.

من خلال إعادة توزيع السلطة، وتضخيم أصوات المشاركين، وتعزيز الشمولية، تعزز طرق التشارك في هذا الموضوع الملكية المشتركة، والتمكين، وعمليات اتخاذ القرار الديمقراطية.

الموضوع 3: الابتكار والإبداع

يساعدون “المشاركين على رؤية ما وراء التركيز السابق وبدلاً من ذلك أدى إلى [تحديد] مجموعة أوسع من خيارات التدخل” [66]. تقدم بعض الطرق تقنيات جمع البيانات وتحليلها غير التقليدية، مثل وصف فيلكر-كانتر وآخرون لـ”نهج مبتكر لجمع بيانات مساحة النشاط” [118]. هذه القدرة على توليد استراتيجيات جديدة تجعل هذه الطرق ذات قيمة خاصة في التشارك.

من خلال تعزيز اللعب، والابتكار، ودمج المعرفة المعنوية، تمكّن طرق التشارك المشاركين من التفكير خارج الحلول التقليدية والمساهمة في التغيير التحويلي.

الموضوع 4: الرفاهية والرضا

. يصف فير تشايلد وماكفيران كيف يمكن أن يقدم التشارك “آثارًا علاجية” [112]، بينما يذكر بلودجيتا وآخرون كيف يمكن لرسم الماندالا “تخفيف التوتر والقلق الذي قد يشعر به المشاركون في سياق البحث” [139]. يعزز هذا الدعم العاطفي المشاركة ويسمح بحوار أكثر انفتاحًا.

يعبر المشاركون بشكل متكرر عن رضاهم العالي، ويصفون التشارك بأنه تجربة مجزية وذات مغزى. يذكر تيموتييفيتش وراتس أن “الرضا الذاتي عن الأحداث كان مرتفعًا” [62]، وأشار دودز وآخرون إلى أن “المشاركين استمتعوا بمشاركتهم في مراحل البحث” [129]. يعزز هذا الشعور بالإنجاز المشاركة المستمرة ويزيد من احتمالية الاستمرار في الانخراط. إن خلق مساحات آمنة للحوار يعزز أيضًا رفاهية المشاركين، كما يتضح من عمل سومر وآخرين في تنزانيا، حيث مكنت الطرق التشاركية الشباب من مشاركة أوصاف صادقة لتجاربهم الحياتية في مساحات شعروا فيها بأنهم مسموعون [104].

الثقة هي نتيجة حاسمة أخرى، تعزز الانخراط الأعمق وتقوي العلاقات. يشير تيموتييفيتش وراتس إلى أن المشاركين “شعروا أن المنظم كان موثوقًا” [62]، بينما وصف فاليلي وآخرون كيف أن القوائم، والتسجيل، والترتيب تعزز “الثقة والفهم بين الباحثين، والمشاركين في الدراسة و

“تمثيل المجتمع” [140]. إن بناء الثقة هذا أمر حيوي عند العمل مع مواضيع حساسة أو مجتمعات مهمشة، حيث يضع الأساس للتعاون المفتوح.

أخيرًا، تحافظ طرق التعاون على المشاركة من خلال تعزيز الدافع والإلهام، مما يشجع المشاركين على تحمل المسؤولية والبحث عن الحلول. يشير باير وآخرون إلى أن المشاركين “يصبحون متحمسين للبحث عن الحلول” [117]، وأشار لاهتينن وآخرون إلى أن ورشة العمل المستقبلية كانت “تُعتبر ملهمة من قبل المشاركين” [116]. وغالبًا ما يغادر المشاركون عمليات التعاون بحماس ورغبة في الاستمرار في المشاركة في تحديد ومعالجة التحديات الرئيسية.

من خلال تعزيز الرفاهية العاطفية، وزيادة الرضا، وبناء الثقة، والحفاظ على الدافع، تمكّن طرق التعاون المشاركين من الانخراط بعمق والمساهمة بشكل ذي مغزى في حل المشكلات بشكل تعاوني.

الموضوع 5: التواصل والشفافية

من خلال تحفيز الحوار المركز وتمكين أشكال التعبير التشاركي، تضمن هذه الأساليب مشاركة وفهم وجهات نظر متنوعة. على سبيل المثال، يمكن استخدام Photovoice مع المشاركين الذين لديهم مجموعة متنوعة من احتياجات التواصل، بينما تلتقط Participatory/Reflective Photography نمطًا متزايد الهيمنة ثقافيًا من التواصل البشري والتعبير عن الذات. تساعد هذه الأساليب في التنقل عبر مواضيع معقدة أو مثيرة للجدل من خلال حوار طبيعي وثقافي ذي دلالة، مما يتماشى مع تجارب المشاركين الحياتية.

الشفافية مهمة بنفس القدر، حيث تضمن أن يشعر المشاركون بأنهم مطلعون ومشاركون في اتخاذ القرار. تعزز طرق التعاون العمليات المفتوحة، مما يوفر فرصًا منظمة للمشاركين للتعبير عن آرائهم. يشير إيفانز وآخرون إلى أن السيناريوهات البديلة تدعم الشفافية من خلال “فرص لجميع المشاركين”.

“للتعبير عن آرائهم بطريقة أكثر تنظيمًا” [46]، و”النمذجة التشاركية تزيد من الشفافية وتسمح بإعادة بناء وتحليل ما حدث” [45]. هذه الانفتاحية تعزز الثقة والمساءلة والشمولية.

من خلال تحسين التواصل، وزرع الثقة من خلال الشفافية، وتشجيع التعبير التشاركي، تعزز طرق التعاون العلاقات بين أصحاب المصلحة وتضمن أن تساهم جميع الأصوات بشكل ذي مغزى في العملية.

الموضوع 6: المرونة وسهولة الاستخدام

تضمن هذه القابلية للتكيف أن يتمكن الباحثون من الاستجابة للاحتياجات المتغيرة، مما يحسن فعالية البحث. على سبيل المثال، تم استخدام تقنية فوتوفويس مع مجموعة واسعة من الفئات السكانية، بما في ذلك الأطفال، والمراهقين، والأفراد من مجتمع LGBTQAI +، وناجي السرطان، والأمهات العازبات، والعاملين في مجال الجنس، والبالغين المصابين بالتوحد، والشباب المتورطين في الشارع.

بالإضافة إلى المرونة، تعطي هذه الأساليب الأولوية للبساطة، مما يضمن سهولة الوصول للمشاركين الذين لديهم تدريب أو خبرة تقنية محدودة. تصميمها سهل الاستخدام يسمح بالتنفيذ المباشر. يصف باركر وآخرون تقرير بيانات الشراكة للتفكير بأنه “ملموس، حيث يتم تقسيم القضايا إلى أجزاء قابلة للإدارة” [127]، ورؤية بأنه “سهل الاستخدام” [127]. من خلال تقليل التعقيد وتوفير حلول فورية، تضمن هذه الأساليب مشاركة واسعة وانخراطًا ذا مغزى.

تقدم طرق التعاون في هذا الموضوع أدوات عملية لمجموعة متنوعة من بيئات البحث والممارسة من خلال تحقيق التوازن بين القابلية للتكيف والبساطة.

الموضوع 7: مؤثر وصالح

من خلال إشراك مجموعة متنوعة من أصحاب المصلحة في اتخاذ القرار، تعزز هذه الأساليب صحة البحث، وتحسن دقة البيانات، وتلتقط نقاط القوة في المجتمع. يبرز لايتفوت وآخرون كيف أن رسم الأصول “يمكن أن يكون له صحة أعلى من البيانات المستمدة من الأساليب التقليدية، حيث يتم إشراك جميع أصحاب المصلحة في اختيار الأصول التي سيتم رسمها” [151]، بينما “قيم المشاركون في ورشة المواطنين فعالية العملية بشكل عالٍ” [62]. تساعد هذه الأساليب في ضمان أن التدخلات المشتركة المعلومات مدروسة جيدًا، وقابلة للتكيف، وتعكس الظروف الواقعية.

بالإضافة إلى التأثير والصلاحية، توفر طرق التشارك في الإبداع فرصًا قيمة لتطوير المهارات، مما يجهز المشاركين للمشاركة بشكل هادف في البحث واتخاذ القرار. إنها تعزز التعلم المتبادل بين الباحثين والمستخدمين النهائيين، مما يخلق فرصًا للتفكير النقدي، والعمل الجماعي، وتطوير القيادة. يصف أوريلي-دي برون وآخرون كيف أن مخططات التعليق “عززت التعلم” [54]، بينما “تساعد سرد القصص الرقمية [المشاركين] على تطوير مهارات التفكير النقدي” [68]. تعزز هذه المكونة لبناء القدرات قدرة المشاركين على المساهمة في جهود التشارك في الإبداع المستقبلية وقيادتها.

من خلال دمج التطبيقات الواقعية، وضمان صحة البحث، وبناء المهارات الأساسية، تساهم طرق التعاون في تحسينات فورية وطويلة الأمد في البحث والممارسة.

الموضوع 8: التأمل والفهم

من خلال تعزيز عمليات التفكير التكرارية والتحول الشخصي، تخلق طرق التعاون بيئات تأملية حيث يمكن للمشاركين الانخراط في التقييم الذاتي وتتبع التقدم. يصف ريفيز وآخرون كيف أن دلفي المعدلة تعزز “الانعكاسية كعملية تفكير نقدي تشمل الباحثين والمشاركين في استجواب نماذجهم الخاصة”، بينما تمتلك فوتوفويس “القدرة على تسهيل التأمل الذاتي وزيادة وعي المريض بنجاحاته وصعوباته”. تساعد هذه الممارسات التأملية المشاركين على استكشاف القضايا الشخصية والاجتماعية، مما يعمق الانخراط ويبني وعيًا أكبر.

التفاعلات، مما يوفر لصانعي القرار رؤى شاملة حول القضايا الاجتماعية والبيئية. يوضح فوينوف وآخرون كيف أن النماذج المعتمدة على الوكلاء “مناسبة تمامًا لتمثيل التفاعلات المكانية المعقدة في ظل ظروف غير متجانسة ولنمذجة اتخاذ القرار اللامركزي المستقل” [45]، بينما يصف ليتوفو وآخرون كيف أن مقابلة السرد “أسفرت عن بيانات أعمق وأوسع مقارنة حول التعقيد المكاني والطبيعة متعددة الأطراف لتجربة الخدمة” [156]. من خلال تجاوز القيود المعرفية، تضمن طرق التعاون طريقة أكثر دقة وغمرًا لفحص المواضيع متعددة الأوجه.

تلعب التصوير دورًا حاسمًا في هذا الموضوع، حيث تقدم طرقًا واضحة وجذابة لعرض البيانات المعقدة. تعزز هذه الطرق استكشاف وتمثيل بيانات الصحة، والأنماط المكانية، والاتجاهات الناشئة، مما يجعل المعلومات أكثر سهولة وقابلية للتنفيذ. يشرح باير وآخرون أن نظم المعلومات الجغرافية تعزز “الاستكشاف البصري وعرض بيانات الصحة” وتكون مفيدة لـ”إنشاء رسومات كبيرة وجذابة بصريًا” [117]. يرفع الاستدلال البصري من وضوح القضايا، ويحفز النقاش، ويولد رؤى غنية. على سبيل المثال، “استخدام الصور في عملية رسم الخرائط المفاهيمية مكن المشاركين من تحديد الروابط الطبيعية بين العوامل” [132].

من خلال تعزيز التفكير النقدي، وتحسين فهم التعقيد، وتعزيز تصور البيانات، تمكّن طرق التعاون المشاركين من الانخراط بعمق، والتواصل بفعالية، واتخاذ قرارات مستنيرة بناءً على تمثيلات دقيقة وجذابة بصريًا للمعلومات.

الموضوع 9: الكفاءة والتفكير الاستراتيجي

تحسن هذه الطرق من كفاءة الوقت وتسهّل المناقشات الجماعية الفعالة، مما يسمح بالتقييمات السريعة ودمج الرؤى المحلية مع الحد الأدنى من المساعدة من الموظفين. تقدم نهجًا منظمًا ولكنه مرن لمعالجة تحديات متعددة في وقت واحد، مما يضمن عمليات شاملة ولكن قابلة للإدارة. يصف فوينوف وآخرون رسم الخرائط المعرفية الضبابية بأنه “أداة مفيدة لتقييم هيكل ووظيفة مشكلة ديناميكية بسرعة وكفاءة” [45]. هذا التركيز على الكفاءة يجعل هذه الطرق ذات قيمة خاصة في البيئات المحدودة الموارد أو في بيئات اتخاذ القرار السريعة.

من خلال تحسين استخدام الموارد، وتشجيع الرؤى الاستراتيجية، وتعزيز اتخاذ القرارات المنظم، تدعم طرق التعاون في هذا الموضوع كل من الكفاءة وحل المشكلات على مستوى عالٍ، مما يجعلها أدوات قيمة لمعالجة التحديات المعقدة عبر سياقات متنوعة.

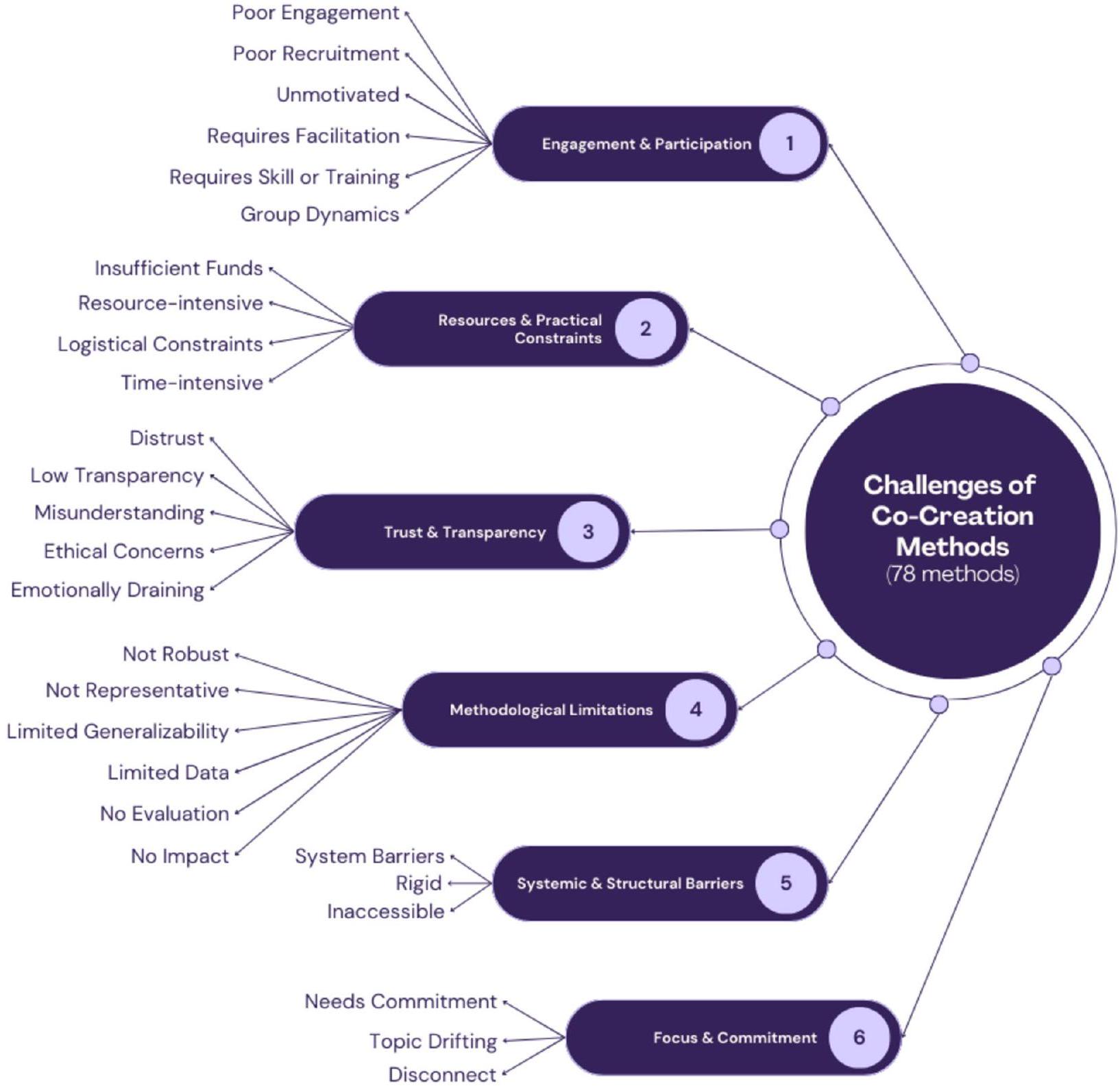

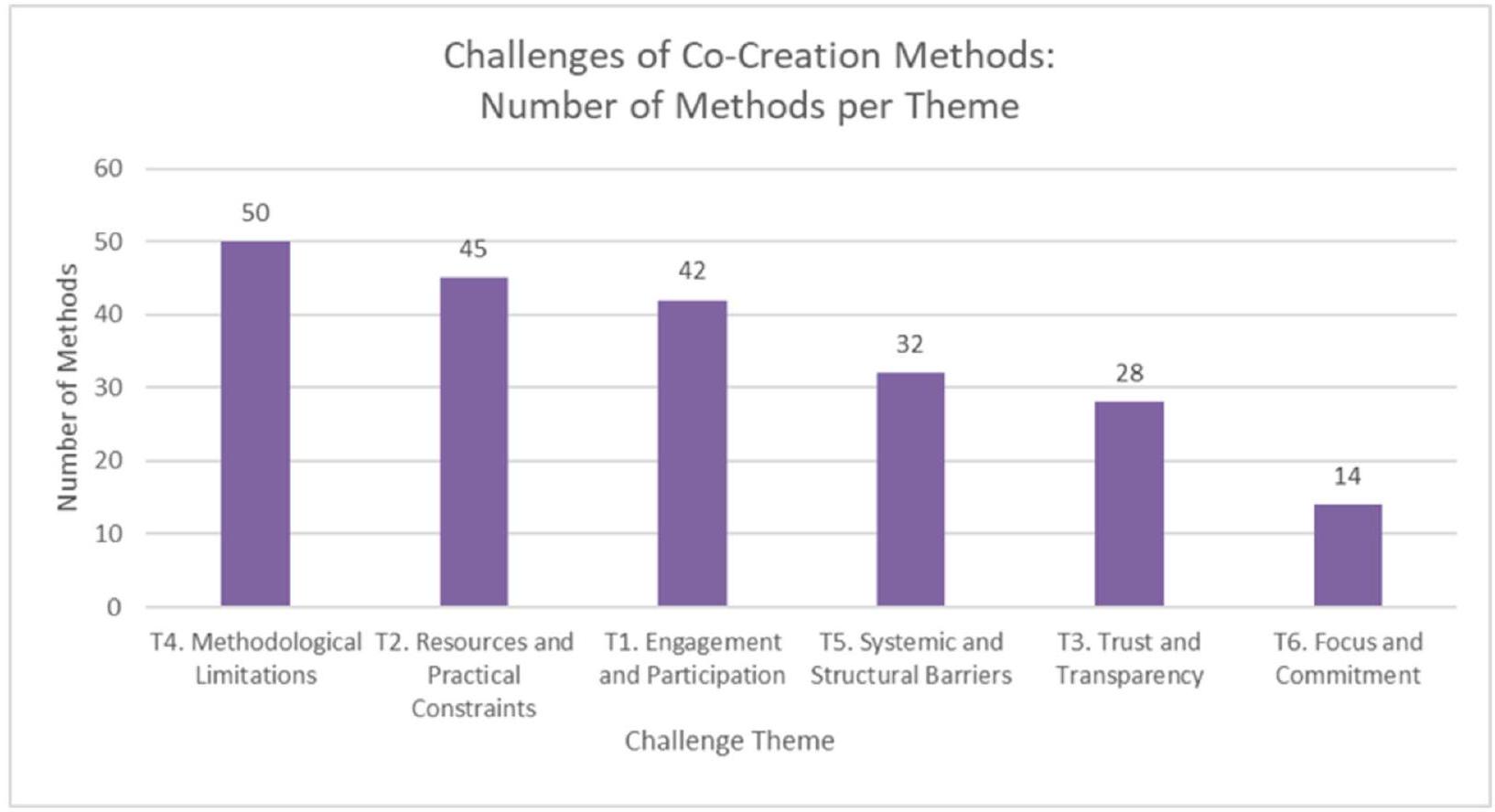

تحديات الطريقة

يحتوي ملف إضافي على أسماء الموضوعات الفرعية، والأوصاف، والطرق المرتبطة (انظر الملف الإضافي 8).

الموضوع 1: المشاركة والانخراط

يمثل الدافع حاجزًا آخر. يمكن أن تثني الطرق التي تتطلب وقتًا أو جهدًا كبيرًا المشاركين، خاصة عندما تكون الفوائد المتوقعة غير واضحة. يوضح لامبرت وآخرون أنه خلال المقابلات غير الرسمية، “قد يشعر الأطفال بالملل من التفاعل اللفظي، ويترددون في التحدث ويقدمون ردودًا محدودة وعميقة” [48]، بينما يحذر بيريرا وآخرون من أن العملية التي تستغرق وقتًا “يمكن أن تحد غالبًا من مشاركة بعض الأشخاص ما لم يروا فائدة مباشرة لعملهم” [114]. يتطلب الحفاظ على الانخراط أنشطة منظمة جيدًا تحافظ على اهتمام المشاركين واستثمارهم.

يلعب التيسير دورًا حاسمًا في العديد من طرق التعاون، حيث تعتمد النتائج غالبًا على خبرة الميسر. بدون توجيه ماهر، قد يكافح المشاركون للتنقل في المناقشات أو استخلاص رؤى ذات مغزى. تشير لورز إلى أن المشاركين اعتمدوا على “أعضاء فريق المشروع حول القضايا التي قد يرغبون في استكشافها أكثر” [110]. يؤكد سمادار وآخرون أن “الكثير من جوانب ورشة العمل تعتمد على مهارات تيسير الميسر” [162]. هذه الاعتمادية تقدم تباينًا وتجعل من الصعب توسيع نطاق هذه الطرق.

تشكل متطلبات التدريب والمهارات أيضًا تحديات كبيرة. يمكن أن يؤدي التدريب غير الكافي إلى أخطاء في تفسير البيانات والتنفيذ. يذكر بيليو وآخرون أخطاء في تمرين مخطط الحلقة السببية بسبب “التدريب غير الكافي لإجراء مثل هذا التمرين” [66]، بينما يبرز لايتفوت وآخرون أن “رسم الخرائط للأصول يستغرق وقتًا طويلاً ويتطلب قدرًا كبيرًا من التدريب والإشراف” [151]. تعتبر برامج التدريب المنظمة ضرورية لضمان تطبيق الطرق بشكل متسق ودقيق.

أخيرًا، يمكن أن تشكل ديناميات المجموعة نجاح عمليات التعاون. قد تؤثر الأصوات السائدة أو التأثيرات الاجتماعية على السرد وتخ suppress وجهات نظر متنوعة. يؤكد واجيمكرز وآخرون أن مجموعة التركيز “تحتاج إلى مهارات تيسير قوية لإدارة ديناميات المجموعة” [163]، بينما يشير كابتاني ويوفال-دافيس إلى أن السرد “يتأثر بسرد المشاركين الآخرين” [34]. إن الإدارة الفعالة لديناميات المجموعة أمر حاسم لإنشاء بيئة شاملة حيث تُسمع جميع الأصوات.

من خلال معالجة التحديات المتعلقة بالانخراط، والتوظيف، والدافع، والتيسير، والتدريب، وديناميات المجموعة

الموضوع 2: الموارد والقيود العملية

واستثمار الوقت الكبير. هذه التحديات واضحة بشكل خاص في المشاريع الكبيرة أو طويلة الأمد، حيث يمكن أن تصبح الطبيعة الكثيفة للموارد لطرق التعاون ساحقة [62،63،66،112،115،158].

يعد نقص التمويل عائقًا رئيسيًا، مما يحد من القدرة على تغطية التكاليف الأساسية مثل التدريب، ووقت الموظفين، وحوافز المشاركين. غالبًا ما تجعل القيود المالية من الصعب الحفاظ على المشاريع. يشير فان لون وآخرون إلى أنه في الممارسة الإبداعية، لم يكن هناك “تمويل كافٍ لتقييم الفعالية” [63]، بينما يبرز فورمان وآخرون كيف أن نقص “التمويل شكل تحديات مترابطة”

تضيف القيود اللوجستية تعقيدًا للتعاون، حيث يلزم التخطيط الدقيق لتنظيم الأنشطة، والوصول إلى البيانات السرية، وإدارة لوجستيات العمل الميداني. يؤكد غرين على الحاجة إلى “اعتبارات لوجستية عند تسهيل الأنشطة الفنية مع الأطفال، خاصة في الطبيعة، حيث يمكن أن يكون صنع الفن فوضويًا” [47]. وبالمثل، يتطلب جدولة المقابلات، وإنتاج المواد التعليمية، والتعامل مع كميات كبيرة من البيانات جهدًا كبيرًا، كما ورد في دراسة شافاريا وآخرون [158]. يمكن أن تؤخر هذه العقبات اللوجستية التقدم وتحد من قابلية توسيع جهود التعاون.

تتطلب الطرق الكثيفة للوقت التزامًا كبيرًا من كل من المشاركين والميسرين، مما يمكن أن يعيق المشاركة، خاصة لأولئك الذين لديهم مسؤوليات مت competing. يصف لايتفوت وآخرون “رسم الخرائط للأصول كثيف الوقت” [151]، بينما يشير زوريلا وآخرون إلى أن “التدريب الكثيف للوقت مطلوب لإتقان [الشبكات البايزية]” [143]. يمكن أن تقلل هذه المطالب من القيمة المدركة وتجعل من الصعب الحفاظ على المشاركة،

خاصة في البيئات السريعة أو المحدودة الموارد. يعد تحقيق توازن بين المشاركة المعنوية وقيود الوقت أمرًا ضروريًا للحفاظ على قيمة أساليب التعاون.

من خلال معالجة قيود التمويل، ومتطلبات الموارد، والحواجز اللوجستية، وقيود الوقت، يمكن تكييف طرق التعاون بشكل أفضل للتنفيذ العملي. يعد الإدارة الاستباقية للموارد، والتخطيط، والجدولة مفتاحًا لضمان استدامتها وتأثيرها على المدى الطويل.

الموضوع 3: الثقة والشفافية

تعيق انعدام الثقة ومخاوف الخصوصية المشاركة، خاصة بين المشاركين من سياقات الرعاية أو العلاج الذين قد يخشون العواقب غير المقصودة. يمكن أن يؤدي التردد في مشاركة المعلومات بسبب المخاوف بشأن السرية إلى مشاركة انتقائية وردود محجوبة. يشير فاليريو وآخرون إلى أن “المشاركين قد لا يشاركون المعلومات بحرية خوفًا من الخصوصية أو السرية” [148]، مما يجعل من الصعب

التقاط تجاربهم الحياتية. تعتبر الثقة والشفافية ضرورية لتشجيع المشاركة المعنوية، خاصة للأفراد من خلفيات ضعيفة قد يخشون الحكم أو الوصم [33، 46، 64].

يثير انخفاض الشفافية في طرق التعاون مخاوف بشأن دقة وفعالية ووضوح نتائج البحث. تعاني بعض الطرق من أهداف أو مخرجات غير واضحة، مما يجعل من الصعب على المشاركين فهم دورهم أو كيفية اشتقاق النتائج. كما تصف أوريلي-ديبرون أن التصنيف المباشر قد يواجه أيضًا تحديات تتعلق بالنتائج أو الأهداف غير الواضحة [54]، بينما يبرز فوينوف وآخرون أن النمذجة المعتمدة على الوكلاء (ABM) تعاني من “انخفاض الشفافية” [45]. قد تؤدي هذه المخاوف إلى الشك وانخفاض المشاركة.

تزيد سوء الفهم في التفسير من تعقيد الشفافية والثقة. يمكن أن تكون الطرق البصرية والفنية، على الرغم من قيمتها في المشاركة، صعبة التفسير بدقة، مما يعرضها لسوء التمثيل. يشرح لامبرت وآخرون أن تقنيات الرسم والكتابة تتضمن “تحديات تفسيرية” [48]، بينما يصف نورث وآخرون كيف أن “أول الرسوم الاجتماعية التي أنتجها [المشاركون] كانت كثيفة الرسم، مما جعل التفسير والتحليل صعبًا” [121]. التواصل الواضح والتمثيل ضروريان لضمان نتائج دقيقة وشاملة.

تضيف القضايا الأخلاقية المتعلقة بالموافقة، والملكية، وإدارة البيانات طبقة أخرى من التعقيد. تثير المحتويات التي ينتجها المشاركون، وخاصة الصور، والبيانات البصرية، تساؤلات حول من يتحكم في البيانات وكيف يتم مشاركتها. يبرز رونزي وآخرون المخاوف بشأن “ملكية الصور والأفراد الذين يظهرون في الصور” و”التحديات في تصوير المفاهيم الاجتماعية السلبية” [101]. يصف لامبرت وآخرون القضايا المتعلقة بـ”تحديات السرية وقضايا الملكية” [48]. تثير الصور الحساسة والبيانات الشخصية معضلات أخلاقية تتعلق بالموافقة، والسرية، والملكية [48، 49، 76، 95، 96، 100، 101، 145، 148]. بدون عمليات موافقة قوية، يمكن أن تؤدي هذه المخاوف إلى عدم الارتياح والتردد في المشاركة.

بعيدًا عن الثقة والشفافية، فإن بعض طرق التعاون مرهقة عاطفيًا، خاصة عندما تتعلق بمواضيع حساسة، أو تأمل شخصي، أو عمليات غير مألوفة. يصف نومخويزي مايابا وود كيف أن تقنية الرسم والكتابة “يمكن أن تسبب مشاعر سلبية” [106]، بينما يشير بلودجيتا وآخرون إلى “تجربة المشاركين للقلق لرسم شيء ما، [بسبب] خوفهم من الحكم السلبي” [139]. يعد إدارة الاستجابات العاطفية وضمان رفاهية المشاركين أمرًا حيويًا للحفاظ على المشاركة وحماية الصحة النفسية للمشاركين.

من خلال معالجة التحديات المتعلقة بالثقة، والشفافية، والاعتبارات الأخلاقية، يمكن أن تصبح طرق التعاون

أكثر دعمًا وشمولية. يضمن التواصل الواضح، وإدارة البيانات بعناية، والحساسية لتجارب المشاركين العاطفية بيئة يشعر فيها المشاركون بالأمان، والقيمة، والتمكين طوال العملية.

الموضوع 4: القيود المنهجية

تظهر المخاوف بشأن قوة المنهجية من ضعف الصرامة التحليلية، ونقص عمليات التحقق، والانحيازات المحتملة التي تدخلها عينات الراحة. تفتقر بعض الطرق إلى آليات لتأسيس التتبع والتحقق بشكل منهجي، مما يؤثر على موثوقيتها. يعلق دينرلين وآخرون أن التصميم المشترك من خلال الاستحواذ على الإمكانيات يواجه عدة تحديات، بما في ذلك نقص “طرق لتأسيس التتبع والتحقق بشكل منهجي” [165]. يمكن أن تقوض هذه الضعف مصداقية البحث ودقة البيانات.

تمثل التمثيلية قضية رئيسية أخرى، حيث تفشل العديد من الطرق في التقاط وجهات نظر متنوعة. تقلل أحجام العينات الصغيرة، والاختيار الذاتي، واستبعاد مجموعات معينة من الشمولية وتعيق التطبيق الأوسع للنتائج. يلاحظ تيموتييفيتش وراتس أن المشاركين “لم يعتقدوا أن الحدث قد التقط مجموعة تمثيلية من كبار السن” [62]، بينما يبرز أوريليدي برون كيف أن معايير الاستبعاد قد تقدم تمثيلية محدودة إذا تم استبعاد المشاركين المهاجرين [54]. يمكن أن تحرف هذه التحديات النتائج وتحد من أهميتها للمجتمعات الممثلة تمثيلاً ناقصًا.

تحد محدودية القابلية للتعميم من إمكانية نقل النتائج إلى سياقات أو سكان جدد. العديد من طرق التعاون تعتمد بشكل كبير على السياق، مما يجعل من الصعب تطبيق النتائج خارج إعداداتها الأصلية. كما يشير سكوت-بوتومز وروا، قد يحد الفن الحواري من قابلية تعميم النتائج لأنه “كان دراسة حالة أجريت في منطقة محددة واحدة، مع مشاركين يختارون أنفسهم” [160]. بدون تكرار أوسع، تظل هذه النتائج محلية وصعبة التوسع.

تضعف قيود البيانات عمق وجودة الرؤى. تركز بعض الطرق على العلاقات الخطية بدلاً من التقاط التفاعلات المعقدة النموذجية للتعاون. يوضح فوينوف وآخرون كيف أن رسم الخرائط المعرفية الضبابية “محدود إلى حد كبير في تعريف العلاقات الخطية بين المفاهيم” [45] بينما يشير لامبرت

وآخرون إلى أن المقابلات غير الرسمية “تقدم استجابات محدودة وعميقة” [48]. تتطلب هذه القيود استخدام طرق إضافية للحصول على فهم أكثر شمولاً.

كما أن نقص آليات التقييم يقلل من فعالية طرق التعاون. نادراً ما يتم اختبار بعض الأساليب خارج الإعدادات المعزولة، مما يحد من قاعدة الأدلة لتأثيرها. يصف كوهفيلدت ولانغوت كيف أن طريقة “الخمسة لماذا” مقيدة بمجموعة واحدة فقط لأن “البيانات [كانت] مستندة إلى مشروع واحد [بحث عمل شبابي تشاركي] داخل بيئة مدرسية” [126]، بينما يشير سزكبانسكا وآخرون إلى أنه في الميزانية المدنية “قد يكون تقييم المقترحات المقدمة مشكلة لأن طرق التصنيف لا تستخدم معايير تقييم كمية” [107].

يعد التأثير في العالم الحقيقي تحديًا آخر، حيث تكافح العديد من الطرق للتأثير على السياسات أو التغيير المؤسسي. حتى عند جمع مدخلات المجتمع، فإن نقص المتابعة أو مشاركة أصحاب المصلحة يقلل من فعالية العملية. يلاحظ إيفانز وآخرون أن “طرق المسارات لم تحقق أي استجابة من الحكومة المحلية” [46].

من خلال معالجة هذه المخاوف المتعلقة بالصرامة، والتمثيل، والقابلية للتعميم، وقيود البيانات، والتقييم، والتأثير في العالم الحقيقي، يمكن تحسين طرق التعاون لتعزيز مصداقيتها وتطبيقها الأوسع. سيساهم تعزيز هذه المجالات في ضمان أن ينتج البحث التعاوني رؤى قوية وقابلة للتنفيذ مع نتائج ملموسة.

الموضوع 5: الحواجز النظامية والهيكلية

تحد الحواجز النظامية غالبًا من قوة اتخاذ القرار على مستوى المجتمع من خلال فرض بروتوكولات صارمة وعمليات قطاعية مجزأة تعقد التعاون. يمكن أن تؤدي الأنظمة الرسمية المعقدة وتوافر البيانات غير المكتمل إلى تحيز النتائج وتثبيط المشاركة. كما يشير فيلكر-كانتر، “المشاركون الذين تتقاطع مسارات نشاطهم اليومي مع المساحات الجغرافية التي لا توجد بها بيانات، ستتأثر تقديرات التعرض” [118]، بينما يصف نورث وآخرون كيف أن “أنظمة الترميز المعقدة قد تكون صعبة التطبيق في التسجيل في الوقت الحقيقي” [121]. تجعل هذه الحواجز تنفيذ طرق التعاون تحديًا خاصًا في البيئات اللامركزية أو سريعة التطور.

تظل عدم القابلية للوصول حاجزًا حرجًا، خاصة بالنسبة للمجموعات المهمشة والأفراد ذوي الاحتياجات الخاصة. تعتمد بعض الطرق بشكل كبير على المعرفة التقنية، والنصوص الكثيفة، أو التنسيقات العامة التي تستبعد المشاركين عن غير قصد. يحذر إيفانز وآخرون من أن “الطبيعة العامة للأنشطة يمكن أن تستبعد المجموعات المهمشة” [46]، ويصف فيلكر-كانتر كيف أن “بعض المشاركين لم يكونوا معتادين على قراءة خريطة أو إعطاء اتجاهات” [118]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يناقش سويتزر وآخرون كيف أن النهج المدمج: التصوير الفوتوغرافي والتصوير الاستدلالي، قد يكون متقدمًا جدًا لبعض الأفراد ذوي الاحتياجات الصحية المعقدة، مما يطرح تحديات للمشاركة الفعالة [64]. إن ضمان أن تكون الطرق شاملة وقابلة للوصول أمر حاسم لالتقاط مجموعة واسعة من التجارب وتعزيز المشاركة المعنوية.

من خلال معالجة الحواجز المتعلقة بتعقيد النظام، والصرامة، والوصول، يمكن أن تصبح طرق التعاون أكثر قابلية للتكيف، وشمولية، وفعالية، مما يمكّن في النهاية من عمليات اتخاذ القرار الأكثر عدلاً وتمثيلاً.

الموضوع 6: التركيز والالتزام

الالتزام المستمر ضروري للتعاون ولكنه صعب الحفاظ عليه مع مرور الوقت، مما يطرح تحديات لوجستية وتحفيزية للمشاركين، والباحثين، والمؤسسات. يشير هاك وروساس إلى أن رسم الخرائط المفاهيمية “يتطلب التزامًا واستثمارًا كبيرين من المشاركين، والباحثين، والمؤسسة الداعمة” [132]. بدون مشاركة مستمرة، تخاطر المشاريع بفقدان الزخم والفشل في إنتاج نتائج ذات مغزى.

يمكن أن يعيق الانفصال بين جهود المشاركة المشتركة والأنظمة أو السياسات الأوسع التأثير طويل الأمد لهذه الأساليب. غالبًا ما يكون قياس آثار التدخلات وربطها بتغييرات سياسية محددة أمرًا صعبًا، مما يحد من الدعم المؤسسي والتبني. يشير غولدن إلى أن “قليلًا جدًا من دراسات التصوير الفوتوغرافي الإبداعي تشير إلى أنها أثرت فعليًا على السياسات أو صانعي السياسات، مع ملاحظة العديد من المؤلفين عدم قدرتهم على التواصل مع صانعي السياسات على الإطلاق”. وبالمثل، يصف فان لون وآخرون كيف كانت “تفاعلاتهم مع صانعي السياسات محدودة بعدد قليل من التبادلات في بداية ونهاية المشروع” وأنهم “لم يكونوا متواجدين في المجتمع كما كانوا يرغبون”. إن تعزيز الروابط بين نتائج المشاركة المشتركة وعمليات السياسة أمر حاسم لترجمة البحث إلى عمل ذي مغزى.

من خلال معالجة التحديات المتعلقة بالالتزام والتركيز والتكامل النظامي، يمكن أن تصبح طرق التعاون أكثر فعالية في جذب المشاركين، والحفاظ على صلة المشروع، والتأثير على التغيير الأوسع.

نقاش

يمكن أن تساعد نتائج هذا الاستعراض الباحثين في استغلال الإمكانات الكاملة للتعاون من أجل تطوير حلول مبتكرة وشاملة في أبحاث الصحة العامة. توضح الأدبيات حول أساليب التعاون التحديات التي قد تنشأ خلال العملية، مثل انعدام الثقة،

مشكلات التواصل والقيود اللوجستية. من خلال تحديد هذه العقبات المحتملة، يوفر هذا الاستعراض رؤى قيمة حول كيفية التغلب عليها، مما يعزز من احتمالية التنفيذ الناجح. كما يقدم هذا الاستعراض مجموعة من الفوائد الرئيسية، موضحًا كيف يمكن أن تزيد طرق التعاون من مشاركة الجمهور ورفاهيتهم ورضا المشاركين، وتساعد في تطوير حلول تلبي احتياجات المجتمع. على الرغم من أن التحديات مثل محدودية تعميم النتائج وسوء التقييم يمكن أن تعيق فعاليتها مقارنة بالأساليب التقليدية، إلا أن التعاون يعزز شعور الملكية والتمكين بين المشاركين، مما يؤدي إلى مستويات أعلى من المشاركة والالتزام.

مجموعات مستهدفة متنوعة

البحث التشاركي والتعاون في الإبداع

فوائد الطريقة

تُبرز المقارنة مع مراجعة حديثة قام بها لونغوورث وآخرون، والتي بحثت في facilitators of co-creation في البلدان ذات الدخل المنخفض والمتوسط، عدة مجالات تتماشى مع نتائج هذه المراجعة. يؤكد لونغوورث وآخرون على أهمية إنشاء مساحات آمنة، وبناء الثقة، وتعزيز الشعور بالملكية، واختيار الأساليب التي تناسب الفئة المستهدفة، وهو ما يتوازى مع الفوائد المحددة هنا، لا سيما في مواضيع ‘التمكين والوكالة’ و’الرفاهية والرضا’. ومع ذلك، حددت هذه المراجعة أيضًا فوائد إضافية لم يتم تناولها في عمل لونغوورث وآخرين، مما يوفر منظورًا أوسع حول كيفية دعم co-creation لأبحاث الصحة العامة.

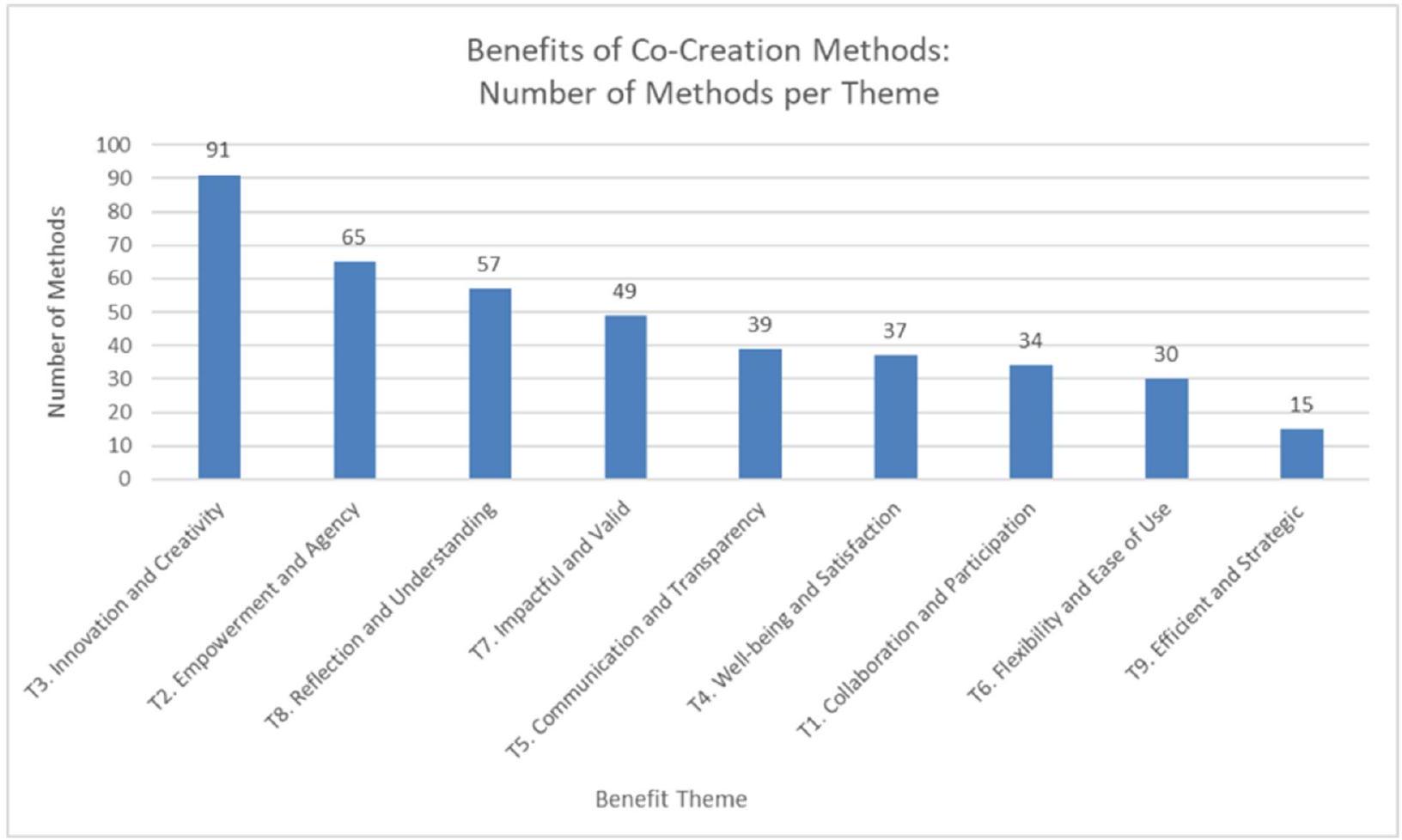

تتوافق العديد من الفوائد التي تم تحديدها في هذا الاستعراض مع عمل سميث وآخرين [20] وأجنيلو وآخرين [9]، الذين أكدوا على دور المشاركة المشتركة والإنتاج المشترك في تعزيز الابتكار والإبداع. في هذا الاستعراض، برزت ‘الابتكار والإبداع’ كأكثر الموضوعات بروزًا (91 طريقة)، مما يبرز قدرة المشاركة المشتركة على تحفيز الحلول الجديدة وتشجيع التفكير الإبداعي في إنشاء التدخلات الصحية. تعالج هذه النتائج الفجوات التي أبرزها آن وآخرون [5] وأجنيلو وآخرون [9]، الذين أشاروا إلى نقص في الإبلاغ عن الطرق الإبداعية. يوفر هذا الاستعراض ثروة من المعلومات حول الطرق التي يمكن أن تمكّن الإبداع في المشاركة المشتركة.

وبالمثل، فإن ‘التمكين والوكالة’ (65 طريقة) يبرز أهمية تمكين المشاركين كصانعي قرار نشطين، وهي نقطة دعا إليها أيضًا شتاينر وفارمر، اللذان أكدا على أهمية منح المشاركين في الإنتاج المشترك الفرصة للتأثير على القرارات التي تؤثر على حياتهم [173]. تُظهر هذه المراجعة أهمية تمكين المشاركين كمنشئين مشتركين مع الوكالة لاتخاذ القرارات ضمن عملية الإبداع المشترك. التمكين ضروري لضمان أن تكون التدخلات الصحية العامة ذات صلة بالسياق وحساسة ثقافيًا، حيث إنه يغير ديناميات القوة بعيدًا عن الممارسات البحثية التقليدية.

نحو أساليب أكثر شمولية ومشاركة [173، 174].

تشمل الموضوعات البارزة الأخرى ‘التفكير والفهم’ (57 طريقة) و’التأثير والموثوقية’ (49 طريقة)، والتي تساهم في تأسيس نتائج مستدامة وحلول موجهة نحو المجتمع. تحمل طرق التعاون المشترك وعدًا كبيرًا للتطبيقات العملية في الصحة العامة من خلال تقليل تحيز الباحثين والتحقق من معرفة المجتمع، مما يضمن أن النتائج تتماشى مع التجارب الحياتية للمشاركين. إن دمج التفكير الشخصي والاجتماعي لا يوضح فقط قيم أصحاب المصلحة، بل يعزز أيضًا صلة التدخل.

على النقيض، كانت ‘الطرق الفعالة والاستراتيجية’ (15 طريقة) هي الأقل تكرارًا في التقارير. وهذا يشير إلى وجود فجوة محتملة في الأدبيات وفرصة لمزيد من الاستكشاف حول كيفية تمكين التعاون المشترك من التقييمات السريعة، ودمج الرؤى المحلية بكفاءة، وتعزيز التخطيط الاستراتيجي للعمل.

تظهر نتائج هذا الاستعراض أن التعاون المشترك يمكّن أصحاب المصلحة المتنوعين من التعاون بطرق تعزز التعلم الجماعي وحل المشكلات، وهو أمر حاسم لمعالجة التحديات الصحية المعقدة. يجب أن تستكشف الأبحاث المستقبلية كيف يمكن أن تُفيد هذه الفوائد في اختيار الأساليب لمساعدة الباحثين على استغلال الإمكانات الكاملة للتعاون المشترك في تعزيز البحث الشامل والفعال.

تحديات المنهج

مقارنة مع مراجعة حديثة قام بها لونغوورث وآخرون، التي بحثت في الحواجز أمام التعاون في البلدان ذات الدخل المنخفض والمتوسط، تسلط الضوء على عدة مجالات تتماشى مع نتائج هذه المراجعة. حدد لونغوورث وآخرون الحواجز الرئيسية، وهي: نقص الاستثمار المالي، قيود التمويل، الظروف النظامية، مستوى التعليم، تأثير استراتيجية التوظيف على العملية، بناء الثقة يستغرق وقتًا، ونقص البيانات وأنظمة المراقبة، مما يتوازى مع التحديات المحددة هنا، لا سيما في المواضيع ‘الموارد والقيود العملية’، ‘الحواجز النظامية والهيكلية’، ‘المشاركة والانخراط’، ‘الثقة والشفافية’ و’القيود المنهجية.’ ومع ذلك، حددت هذه المراجعة أيضًا تحديات إضافية لم يتم تناولها في عمل لونغوورث وآخرين، مما يوفر منظورًا أوسع حول التحديات المحتملة التي تواجه عند إجراء التعاون.

وبالمثل، تؤكد ‘الموارد والقيود العملية’ على الطبيعة المستهلكة للموارد للتعاون المشترك، الذي غالبًا ما يتطلب تمويلًا كبيرًا، ووقتًا، وموارد بشرية، ودعمًا. تبرز الحواجز مثل نقص الأموال، والعمليات التي تتطلب وقتًا طويلاً وموارد كثيفة، قضية نظامية أوسع في أنظمتنا الحالية للبحث والتمويل، التي لم تُصمم لدعم الطبيعة المرنة والإبداعية للتعاون المشترك. غالبًا ما تفشل الجداول الزمنية والميزانيات المدفوعة من قبل المانحين في أخذ متطلبات الوقت والموارد للتعاون المشترك في الاعتبار. كما أن الأطر المؤسسية الصارمة تقيد المزيد من التكيف المطلوب لعمليات التعاون المشترك الديناميكية والتكرارية. علاوة على ذلك، تترك الأطر المؤسسية الصارمة وعمليات البحث مجالًا ضئيلًا للتكيف المطلوب لاستيعاب الطبيعة الديناميكية والتكرارية للتعاون المشترك، كما يتضح من تحدي ‘الحواجز النظامية والهيكلية’ (32 طريقة).

يكشف موضوع ‘المشاركة والانخراط’ (42 طريقة) عن الصعوبات في تحفيز واستدامة انخراط المشاركين، خاصة عندما تُستخدم طرق تعتمد فقط على الكلام مثل المقابلات. غالبًا ما تتطلب الطرق المعقدة تدريبًا ومهارات متخصصة للتنفيذ، مما يجعل الانخراط تحديًا، ويخلق اعتمادًا على التيسير والإرشاد المهاري. واحدة من العقبات الرئيسية هي انخراط ومشاركة أصحاب المصلحة، والتي يمكن أن تتأثر بعوامل مثل التردد في المشاركة. تتماشى هذه النتائج مع مناقشة أوسع من قبل كارجو وميرسر حول أهمية بناء القدرات في البحث التشاركي لدعم الانخراط المستدام على المدى الطويل.

في المقابل، يمثل ‘التركيز والالتزام’ (14 طريقة) أقل موضوع تم الإبلاغ عنه بشكل متكرر ولكنه لا يزال يبرز التحديات الحرجة. الطرق التي تتطلب تفانيًا كبيرًا من جميع المعنيين تحمل مستوى أعلى من

خطر الفشل، خاصة عندما يتم تمديد الفترات الزمنية أو عندما تؤدي الاختلافات الثقافية إلى تحويل الانتباه عن العملية الرئيسية. يمكن أن تؤدي التدخلات غير المتوافقة إلى نتائج غير مرغوب فيها عندما تعقد النطاقات الجغرافية الواسعة جمع البيانات وتحليلها، مما يحد من التأثير العام.

على الرغم من هذه التحديات، لا تزال طرق التعاون المشترك تحمل وعدًا كبيرًا في إثراء أبحاث الصحة العامة. يتطلب معالجة هذه الحواجز تخطيطًا استراتيجيًا، وتخصيص موارد فعّال، وتيسيرًا ماهرًا، وتواصلًا واضحًا لضمان مشاركة ذات مغزى وشاملة ونتائج ناجحة. والأهم من ذلك، أن التغييرات الهيكلية ومستوى النظام ضرورية لإنشاء بيئات يمكن أن تزدهر فيها المرونة والإبداع والشمولية. يجب أن تستكشف الأبحاث المستقبلية كيفية التغلب على هذه الحواجز من خلال تعزيز الأطر التكيفية، وتحسين جهود بناء القدرات، والدعوة إلى سياسات تدعم البحث التشاركي.

تطبيق أساليب المشاركة في الإبداع

العواقب والبحوث المستقبلية

مجموعة من طرق التعاون المشترك. سيسهل ذلك فهمًا أكثر تماسكًا، وتطبيقًا، وإبلاغًا عن هذه الطرق عبر سياقات مختلفة. يمكن أن تعمل مثل هذه التصنيفات على توحيد المصطلحات، وتقليل الغموض، وتعزيز التواصل بين الباحثين، والممارسين، وجميع المعنيين. علاوة على ذلك، فإن تنظيم طرق التعاون المشترك في تصنيف يدعم الباحثين في اختيار الطرق الأكثر ملاءمة بناءً على أسئلة البحث المحددة أو أهداف التدخل. هذا أمر حاسم في الصحة العامة وغيرها من المجالات، حيث يجب أن تكون التدخلات ذات صلة بالسياق وحساسة ثقافيًا. أخيرًا، يمكن أن يدعم هذا التصنيف تقييم ومقارنة طرق التعاون المشترك، على سبيل المثال من خلال تصنيف الطرق بناءً على الفوائد والتحديات المعروفة. يمكن أن تؤدي هذه التحليلات المقارنة إلى تحديد أفضل الممارسات وتحسين الطرق الحالية، مما يعزز في النهاية مجال التعاون المشترك.

يعد التحليل المفصل للطرق المستخدمة من قبل كل فئة مستهدفة مصدرًا قيمًا للباحثين الذين يسعون لتكرار الاستراتيجيات الناجحة في عملهم. عند معالجة التحديات التي تواجه طرق التعاون المشترك، يجب أن تركز الدراسات المستقبلية على تطوير أساليب مخصصة تعالج هذه العقبات بشكل خاص، مما يضمن سماع وتقدير جميع الأصوات خلال عملية التعاون المشترك. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن تحسين قدرة الباحثين على تطبيق الطرق المستمدة من هذه المراجعة، فضلاً عن استكشاف كيفية دمج هذه الطرق، أمر حاسم لتعزيز فعالية جهود التعاون المشترك والتقاط وجهات نظر متنوعة من أصحاب المصلحة. كما وصف فوينوف وآخرون، فإن الاختيار الدقيق والواعي للطرق، ودمج الطرق، مهم لعمليات النمذجة ونتائجها. من المثالي أن يكون الاختيار مصحوبًا بتقييمات لمراقبة تأثير الطرق الفردية على العملية [45]. وهذا يبرز الحاجة إلى اختيار طرق مستنير، بالإضافة إلى إرشادات حول كيفية تقييم الطرق لتمكين تقييم الفعالية والأثر.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تشير النتائج في هذه المراجعة إلى تفضيل واضح لأساليب التوصيل وجهًا لوجه، مما يبرز فجوة محتملة في الأدبيات بشأن طرق التعاون عبر الإنترنت أو الهجينة، التي أصبحت ذات صلة متزايدة في المشهد الرقمي اليوم. يمكن أن يوفر الاستكشاف الإضافي لكيفية تأثير أساليب التوصيل المختلفة على فعالية وملاءمة طرق التعاون رؤى مهمة للدراسات المستقبلية. تشير دمج الأدوات الرقمية، كما هو موضح في 40 مقالًا، إلى اتجاه متزايد في الاستفادة من التكنولوجيا لتعزيز عمليات التعاون. تشير مجموعة الأدوات المستخدمة، بدءًا من نظم المعلومات الجغرافية إلى البرمجيات الشائعة مثل Microsoft Excel، إلى تحول نحو

المزيد من الممارسات الرقمية. يمكن أن يؤثر ذلك على شمولية عمليات المشاركة المشتركة، حيث قد لا تتمتع بعض المجتمعات الضعيفة أو المهمشة بالوصول إلى الأدوات والمنصات الرقمية. يجب أن تبحث الأبحاث المستقبلية في كيفية تسهيل هذه الأدوات الرقمية أو عرقلتها لمشاركة أوسع وانخراط بين السكان المتنوعين.

القيود

الخاتمة

تظهر نتائجنا الطبيعة متعددة الأبعاد لأساليب المشاركة المشتركة وآثارها في تعزيز العدالة والشمولية في أبحاث الصحة العامة وزيادة كفاءة وقابلية تطبيق النتائج المشتركة.

النتائج. من خلال التركيز على هذه المجالات الحيوية، يمكننا تعميق فهمنا للتعاون المشترك وإمكاناته في تقليل الفجوات الصحية. إن إشراك الفئات المستهدفة المتنوعة في عمليات التعاون المشترك أمر حيوي لتطوير تدخلات صحية عادلة تستجيب لاحتياجات جميع أعضاء المجتمع. يمكن أن يكون التعاون المشترك شاملاً للفئات المهمشة من خلال تنفيذ استراتيجيات وأفضل الممارسات المدعومة بالأدبيات العلمية. تقدم هذه المراجعة تلك الأدبيات، بالإضافة إلى تأملات رئيسية بشأن المشاركة المتنوعة، وأهمية بناء الثقة والاحترام المتبادل، فضلاً عن القدرة على التكيف المستمر مع الظروف المتغيرة، والموارد، والسياقات الديناميكية.

من خلال تسليط الضوء على الأساليب المختلفة المستخدمة مع هذه الفئات، تساهم هذه المراجعة في التطوير المستمر لممارسات البحث الشاملة. تبرز الرؤى المستخلصة من هذه المراجعة المزايا المتنوعة لأساليب التعاون. من خلال التعرف على الاستفادة من كل من فوائد وتحديات أساليب التعاون، يمكن للباحثين تحسين جودة وملاءمة وشمولية أعمالهم، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى نتائج صحية أكثر عدلاً للفئات المتنوعة. تدعو هذه النتائج الباحثين والممارسين على حد سواء إلى تبني التعاون، وأساليبه المتنوعة، كنهج أساسي في أبحاث وممارسات الصحة العامة.

معلومات إضافية

ملف إضافي 2.

ملف إضافي 3.

ملف إضافي 4.

الملف الإضافي 5.

الملف الإضافي 6.

الملف الإضافي 7.

ملف إضافي 8.

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 06 مارس 2025

References

- Morgan J, Neufeld SD, Holroyd H, Ruiz J, Taylor T, Nolan S, et al. Commu-nity-Engaged Research Ethics Training (CERET): developing accessible and relevant research ethics training for community-based participatory research with people with lived and living experience using illicit drugs and harm reduction workers. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20:86.

- Loignon C, Dupéré S, Bush P, Truchon K, Boyer S, Hudon C. Using photovoice to reflect on poverty and address social inequalities among primary care teams. Action Res. 2023;21:211-29.

- Grindell C, Coates E, Croot L, O’Cathain A. The use of co-production, co-design and co-creation to mobilise knowledge in the management of health conditions: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:877.

- Loignon C, Dupéré S, Leblanc C, Truchon K, Bouchard A, Arsenault J, et al. Equity and inclusivity in research: co-creation of a digital platform with representatives of marginalized populations to enhance the involvement in research of people with limited literacy skills. Res Involv Engagem. 2021;7:70.

- An Q, Sandlund M, Agnello D, McCaffrey L, Chastin S, Helleday R, et al. A scoping review of co-creation practice in the development of nonpharmacological interventions for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a health CASCADE study. Respir Med. 2023;211:107193.

- Hubbard L, Hardman M, Race O, Palmai M, Vamosi G. Research with marginalized communities: reflections on engaging roma women in Northern England. Qual Inq. 2024;30:514-25.

- Vargas C, Whelan J, Brimblecombe J, Allender S. Co-creation, co-design, co-production for public health – a perspective on definition and distinctions. Public Health Res Pract. 2022;32. Available from: https://www. phrp.com.au/?p=41678. Cited 2023 May 18.

- Agnello DM, Loisel QEA, An Q, Balaskas G, Chrifou R, Dall P, et al. Establishing a health CASCADE-curated open-access database to consolidate knowledge about co-creation: novel artificial intelligenceassisted methodology based on systematic reviews. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e45059.

- Agnello DM, Balaskas G, Steiner A, Chastin S. Methods used in co-creation within the health CASCADE co-creation database and gray literature: systematic methods overview. Interact J Med Res. 2024;13:e59772.

- Leino H, Puumala E. What can co-creation do for the citizens? Applying co-creation for the promotion of participation in cities. Environ Plan C Polit Space. 2020; Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/ full/https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420957337. Cited 2024 Oct 21.

- Mallakin M, Dery C, Vaillancourt S, Gupta S, Sellen K. Web-based codesign in health care: considerations for renewed participation. Interact J Med Res. 2023;12:e36765.

- Wong C-C, Kumpulainen K, Kajamaa A. Collaborative creativity among education professionals in a co-design workshop: a multidimensional analysis. Think Ski Creat. 2021;42:100971.

- Wise S, Paton RA, Gegenhuber T. Value co-creation through collective intelligence in the public sector.

- Verloigne M, Altenburg T, Cardon G, Chinapaw M, Dall P, Deforche B, et al. Making co-creation a trustworthy methodology for closing the implementation gap between knowledge and action in health promotion: the Health CASCADE project. Perspect Public Health. 2023;143:196-8.

- Mulvale G, Moll S, Phoenix M, Buettgen A, Freeman B, Murray-Leung L, et al. Co-creating a new Charter for equitable and inclusive co-creation: insights from an international forum of academic and lived experience experts. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e078950.

- Agnello DM, An Q, de Boer J, Calo F, Delfmann L, Hutcheon D, et al. Developing and Validating the Co-Creation Rainbow Framework: Assessing Whether Methods Enact Co-Creation Characteristics in a Mixed-Methods Health CASCADE Study. Zenodo; 2023 [cited 2024 Nov 30]. Available from: https://zenodo.org/records/10391410.

- Greenhalgh T, Jackson C, Shaw S, Janamian T. Achieving research impact through co-creation in community-based health services: literature review and case study. Milbank Q. 2016;94:392-429.

- Cyril S, Smith BJ, Possamai-Inesedy A, Renzaho AMN. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: a systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:29842.

- Slattery P, Saeri AK, Bragge P. Research co-design in health: a rapid overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2020;18:17.

- Smith H, Budworth L, Grindey C, Hague I, Hamer N, Kislov R, et al. Coproduction practice and future research priorities in United Kingdomfunded applied health research: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20:36.

- Lazo-Porras M, Perez-Leon S, Cardenas MK, Pesantes MA, Miranda JJ, Suggs LS, et al. Lessons learned about co-creation: developing a complex intervention in rural Peru. Glob Health Action. 2020;13:1754016.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467-73.

- Loisel Q, Agnello D, Chastin S. Co-Creation Database. Zenodo; 2022 [cited 2024 Nov 30]. Available from: https://zenodo.org/records/67730 28.

- Zotero | Your personal research assistant. Available from: https://www. zotero.org/. Cited 2024 Nov 21.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210.

- Google Forms: Online Form Creator | Google Workspace. Available from: https://www.facebook.com/GoogleDocs/. Cited 2024 Nov 30.

- Byrne D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Quant. 2022;56:1391-412.

- NVivo Leading Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QDAS) by Lumivero. Lumivero. Available from: https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/. Cited 2024 Nov 21.

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol;18. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/https://doi.org/10.1080/14780 887.2020.1769238. Cited 2024 Sep 24.

- Malinverni L, Mora-Guiard J, Pares N. Towards methods for evaluating and communicating participatory design: A multimodal approach.

- Furman E, Singh AK, Miller Z. “A Space Where People Get It”: A Methodological Reflection of Arts-Informed Community-Based Participatory Research With Nonbinary Youth. Int J Qual Methods. 2019; Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1609406919858530.

- Amsden J, VanWynsberghe R. Community mapping as a research tool with youth. Action Res. 2005;3:357-81.

- Lal S, Jarus T, Suto MJ. A scoping review of the photovoice method: implications for occupational therapy research. Can J Occup Ther. 2012;79:181-90.

- Kaptani E, Yuval-Davis N. Participatory theatre as a research methodology: identity, performance and social action among refugees. Sociol Res Online. 2008;13:1-12.

- Keogh F, Carney P, O’Shea E. Innovative methods for involving people with dementia and carers in the policymaking process. Health Expect Int J Public Particip Health Care Health Policy. 2021;24:800-9.

- Kort HSM, Steunenberg B, van Hoof J. Methods for involving people living with dementia and their informal carers as co-developers of technological solutions. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2019;47:149-56.

- Valiquette-Tessier S-C, Vandette M-P, Gosselin J. In her own eyes: photovoice as an innovative methodology to reach disadvantaged single mothers. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2015;34:1-16.

- Fraser SL. What stories to tell? A trilogy of methods used for knowledge exchange in a community-based participatory research project. Action Res. 2018;16:207-22.

- Redman-MacLaren M, Mills J, Tommbe R. Interpretive focus groups: a participatory method for interpreting and extending secondary analysis of qualitative data. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:25214.

- Salmon A. Walking the talk: how participatory interview methods can democratize research. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(7):982-93.

- Bennett B, Maar M, Manitowabi D, Moeke-Pickering T, Trudeau-Peltier D, Trudeau S. The gaataa’aabing visual research method: a culturally safe anishinaabek transformation of photovoice. Int J Qual Methods. 2019;18:1609406919851635.

- Williams L, Gott M, Moeke-Maxwell T, Black S, Kothari S, Pearson S, et al. Can digital stories go where palliative care research has never gone before? A descriptive qualitative study exploring the application of an emerging public health research method in an indigenous palliative care context.

- Wood L, Olivier T. Video production as a tool for raising educator awareness about collaborative teacher-parent partnerships. Educ Res. 2011;53:399-414.

- Smetschka B, Gaube V. Co-creating formalized models: participatory modelling as method and process in transdisciplinary research and its impact potentials. Environ Sci Policy. 2020;103:41-9.

- Voinov A, Jenni K, Gray S, Kolagani N, Glynn PD, Bommel P, et al. Tools and methods in participatory modeling: Selecting the right tool for the job. Environ Model Softw. 2018;109:232-55.

- Evans K, de Jong W, Cronkleton P, Nghi TH. Participatory methods for planning the future in forest communities. Soc Nat Resour. 2010;23:604-19.

- Green C. Four methods for engaging young children as environmental education researchers. Int J Emerg Issues Early Child Educ. 2023;5:6.

- Lambert V, Glacken M, McCarron M. Using a range of methods to access children’s voices. J Res Nurs. 2013;18:601-16.

- Sewell K. Researching sensitive issues: a critical appraisal of ‘draw-andwrite’ as a data collection technique in eliciting children’s perceptions. Int J Res Method Educ. 2011;34:175-91.

- Haijes HA, van Thiel GJMW. Participatory methods in pediatric participatory research: a systematic review. Pediatr Res. 2016;79:676-83.

- Gerodimos R. Youth and the City: reflective photography as a tool of Urban voice. J Media Lit Educ. 2018;10:82-103.

- Barry J, Higgins A. Photovoice: an ideal methodology for use within recovery-oriented mental health research. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2021;42:676-81.

- Hartwig RT. Ethnographic facilitation as a complementary methodology for conducting applied communication scholarship. J Appl Commun Res. 2014;42:60-84.

- O’Reilly-de Brún M, de Brún T, O’Donnell CA, Papadakaki M, Saridaki A, Lionis C, et al. Material practices for meaningful engagement: an analysis of participatory learning and action research techniques for data generation and analysis in a health research partnership. Health Expect. 2018;21:159-70.

- Sandman H, Levänen J, Savela N. Using empathic design as a tool for urban sustainability in low-resource settings. Sustainability. 2018;10:2493.

- Doornbos A, Rooij M van, Smit M, Verdonschot S. From Fairytales to Spherecards: Towards a New Research Methodology for Improving Knowledge Productivity. Forum Qual Sozialforschung Forum Qual Soc Res. 2008;9. Available from: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index. php/fqs/article/view/386. Cited 2024 Sep 10.

- Nedelcu A. Analysing students’ drawings of their classroom: a childfriendly research method. Rev Cercet Si Interv Sociala. 2013;42:275-93.

- McCarthy L, Muthuri JN. Engaging fringe stakeholders in business and society research: applying visual participatory research methods. Bus Soc. 2018;57:131-73.

- Barker J, Weller S. “Is it fun?” developing children centred research methods. Int J Sociol Soc Policy. 2003;23:33-58.

- Woolner P, Clark J, Hall E, Tiplady L, Thomas U, Wall K. Pictures are necessary but not sufficient: using a range of visual methods to engage users about school design. Learn Environ Res. 2010;13:1-22.

- Hill V, Croydon A, Greathead S, Kenny L, Yates R, Pellicano E. Research methods for children with multiple needs: Developing techniques to facilitate all children and young people to have’a voice.’Educ Child Psychol. 2016;33:26-43.

- Timotijevic L, Raats MM. Evaluation of two methods of deliberative participation of older people in food-policy development. Health Policy Amst Neth. 2007;82:302-19.

- Van Loon AF, Lester-Moseley I, Rohse M, Jones P, Day R. Creative practice as a tool to build resilience to natural hazards in the Global South. Geosci Commun. 2020;3:453-74.

- Switzer S, Guta A, de Prinse K, Chan Carusone S, Strike C. Visualizing harm reduction: methodological and ethical considerations. Soc Sci Med. 1982;2015(133):77-84.

- Gerritsen S, Harré S, Rees D, Renker-Darby A, Bartos AE, Waterlander WE, et al. Community group model building as a method for engaging participants and mobilising action in public health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3457.

- BeLue R, Carmack C, Myers KR, Weinreb-Welch L, Lengerich EJ. Systems Thinking Tools as Applied to Community-Based Participatory Research: A Case Study. 2012;39. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/ doi/https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198111430708. Cited 2024 Sep 28.

- Wright PR, Wakholi PM. Festival as methodology: the African cultural youth arts festival. Mark Vicars and Dr Jon Austin D, editor. Qual Res J. 2015;15:213-27.

- D’Amico M, Denov M, Khan F, Linds W, Akesson B. Research as intervention? Exploring the health and well-being of children and youth facing global adversity through participatory visual methods. Glob Public Health. 2016;11:528-45.

- Lorenz LS, Kolb B. Involving the public through participatory visual research methods. Health Expect. 2009;12:262-74.

- Molloy JK. Photovoice as a tool for social justice workers. J Progress Hum Serv. 2007;18:39-55.

- Walker A, Oomen-Early J. Do you see what I see? Using photovoice to teach health education students the value of using community-based participatory methods. J Health Educ Teach Tech. 2014;1:41-52.

- Rania N, Coppola I, Pinna L. Adapting qualitative methods during the COVID-19 Era: factors to consider for successful use of online photovoice. Qual Rep. 2021;26:2711-29.

- Saunders G, Dillard L, Frederick M, Silverman S. Examining the utility of photovoice as an audiological counseling tool. J Am Acad Audiol. 2019;30:406-16.

- Sutton-Brown CA. Photovoice: a methodological guide.

- Drawson AS, Toombs E, Mushquash CJ. Indigenous research methods: a systematic review. Int Indig Policy J. 2017;8. Available from: https://ojs. lib.uwo.ca/index.php/iipj/article/view/7515. Cited 2024 Sep 10.

- Teti M, Murray C, Johnson L, Binson D. Photovoice as a communitybased participatory research method among women living with HIV/ AIDS: ethical opportunities and challenges. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2012;7:34-43.

- Campbell RB, Larsen M, DiGiandomenico A, Davidson MA, Booth GL, Hwang SW, et al. The challenges of managing diabetes while homeless: a qualitative study using photovoice methodology. CMAJ. 2021;193:E1034-41.

- Madrigal DS, Salvatore A, Casillas G, Casillas C, Vera I, Eskenazi B, et al. Health in my community: conducting and evaluating photovoice as a tool to promote environmental health and leadership among Latino/a Youth. Prog Community Health Partnersh Res Educ Action. 2014;8:317-29.

- MacFarlane EK, Shakya R, Berry HL, Kohrt BA. Implications of participatory methods to address mental health needs associated with climate change: ‘photovoice’ in Nepal. BJPsych Int. 2015;12:33-5.

- Houle J, Coulombe S, Radziszewski S, Leloup X, Saïas T, Torres J, et al. An intervention strategy for improving residential environment and positive mental health among public housing tenants: rationale, design and methods of Flash on my neighborhood! BMC Public Health. 2017;17:737.

- Aw S, Koh GC, Oh YJ, Wong ML, Vrijhoef HJ, Harding SC, et al. Interacting with place and mapping community needs to context: Comparing and triangulating multiple geospatial-qualitative methods using the focus-expand-compare approach. Methodol Innov. 2021;14:205979912098777.

- Nykiforuk CIJ, Vallianatos H, Nieuwendyk LM. Photovoice as a method for revealing community perceptions of the built and social environment. Int J Qual Methods. 2011;10:103-24.

- Kramer L, Schwartz P, Cheadle A, Rauzon S. Using photovoice as a participatory evaluation tool in kaiser permanente’s community health initiative. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14:686-94.

- Downey LH, Ireson CL, Scutchfield FD. The use of photovoice as a method of facilitating deliberation. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10:419-27.

- Pauwels L. ‘Participatory’ visual research revisited: A critical-constructive assessment of epistemological, methodological and social activist tenets. Ethnography. 2015;16:95-117.

- Livingood WC, Monticalvo D, Bernhardt JM, Wells KT, Harris T, Kee K, et al. Engaging Adolescents Through Participatory and Qualitative Research Methods to Develop a Digital Communication Intervention to Reduce Adolescent Obesity.

- Golden T. Reframing photovoice: building on the method to develop more equitable and responsive research practices. Qual Health Res. 2020;30:960-72.

- Baker TA, Wang CC. Photovoice: use of a participatory action research method to explore the chronic pain experience in older adults. Qual Health Res. 2006;16:1405-13.

- Johnson LR, Drescher CF, Assenga SH, Marsh RJ. Assessing assets among street-connected youth: new angles with participatory methods in Tanzania. J Adolesc Res. 2019;34:619-51.

- Bisung E, Elliott SJ, Abudho B, Karanja DM, Schuster-Wallace CJ. Using Photovoice as a Community Based Participatory Research Tool for Changing Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Behaviours in Usoma, Kenya.

- Marshalsey L, Sclater M. Arts-Based Educational Research: The Challenges of Social Media and Video-Based Research Methods in Communication Design Education.

- Maclean K, Woodward E. Photovoice evaluated: an appropriate visual methodology for aboriginal water resource research. Geogr Res. 2013;51:94-105.

- Witkowski K, Matiz Reyes A, Padilla M. Teaching diversity in public participation through participatory research: a case study of the photovoice methodology. J Public Aff Educ. 2021;27:218-37.

- Fay

. The impact of the school space on research methodology, child participation and safety: views from children in Zanzibar. Child Geogr. 2018;16:405-17. - Umurungi J-P, Mitchell C, Gervais M, Ubalijoro E, Kabarenzi V. Photovoice as a methodological tool to address HIV and AIDS and gender violence amongst girls on the Street in Rwanda. J Psychol Afr. 2008;18:413-9.

- Capous-Desyllas M, Forro VA. Tensions, challenges, and lessons learned: methodological reflections from two photovoice projects with sex workers. J Community Pract. 2014;22:150-75.

- Sitter KC. Taking a closer look at photovoice as a participatory action research method. J Progress Hum Serv. 2017;28:36-48.

- Peabody CG. Using photovoice as a tool to engage social work students in social justice. J Teach Soc Work. 2013;33:251-65.

- Russinova Z, Mizock L, Bloch P. Photovoice as a tool to understand the experience of stigma among individuals with serious mental illnesses. Stigma Health. 2018;3:171-85.

- Novek S, Morris-Oswald T, Menec V. Using photovoice with older adults: some methodological strengths and issues. Ageing Soc. 2012;32:451-70.

- Ronzi S, Pope D, Orton L, Bruce N. Using photovoice methods to explore older people’s perceptions of respect and social inclusion in

cities: opportunities, challenges and solutions. SSM – Popul Health. 2016;2:732-45. - Krutt H, Dyer L, Arora A, Rollman J, Jozkowski AC. PhotoVoice is a feasible method of program evaluation at a center serving adults with autism. Eval Program Plann. 2018;68:74-80.

- Doucet M, Pratt H, Dzhenganin M, Read J. Nothing about us without us: using Participatory Action Research (PAR) and arts-based methods as empowerment and social justice tools in doing research with youth “aging out” of care. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;130:105358.

- Sommer M, Ibitoye M, Likindikoki S, Parker R. Participatory Methodologies With Adolescents: A Research Approach Used to Explore Structural Factors Affecting Alcohol Use and Related Unsafe Sex in Tanzania. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2021;42:363-84.

- Foster-Fishman P, Nowell B, Deacon Z, Nievar MA, McCann P. Using methods that matter: the impact of reflection, dialogue, and voice. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;36:275-91.

- Nomakhwezi Mayaba N, Wood L. Using drawings and collages as data generation methods with children: definitely not child’s play. Int J Qual Methods. 2015;14:1609406915621407.

- Szczepańska A, Zagroba M, Pietrzyk K. Participatory budgeting as a method for improving public spaces in major polish cities. Soc Indic Res. 2022;162:231-52.

- Townley G, Kloos B, Wright PA. Understanding the experience of place: expanding methods to conceptualize and measure community integration of persons with serious mental illness. Health Place. 2009;15:520-31.

- Tremblay C. Towards inclusive waste management: participatory video as a communication tool. Proc Inst Civ Eng – Waste Resour Manag. 2013;166:177-86.

- Leurs R. The role of the state in enabling private sector development: an assessment methodology. Public Adm Dev. 2000; Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-162X(200002)20:1<43::AID-PAD110% 3E3.0.CO;2-R. Cited 2024 Sep 10.

- Linabary JR, Krishna A, Connaughton SL. The conflict family: storytelling as an activity and a method for locally led. Community-Based Peacebuilding. 2016;34:431-53.

- Fairchild R, McFerran KS. Understanding children’s resources in the context of family violence through a collaborative songwriting method. Child Aust. 2018;43:255-66.

- Green EP, Warren VR, Broverman S, Ogwang B, Puffer ES. Participatory mapping in low-resource settings: Three novel methods used to engage Kenyan youth and other community members in communitybased HIV prevention research. Glob Public Health. 2016;11:583-99.

- Pereira L, Hichert T, Hamann M, Preiser R, Biggs R. Using futures methods to create transformative spaces: visions of a good Anthropocene in southern Africa. Ecol Soc. 2018;23. Available from: https://www.ecolo gyandsociety.org/vol23/iss1/art19/. Cited 2024 Sep 28.

- O’Hara L, Higgins K. Participant photography as a research tool: ethical issues and practical implementation. Sociol Methods Res. 2019;48:369-99.

- Lahtinen M, Nenonen S, Rasila H, Lehtelä J, Ruohomäki V, Reijula K. Rehabilitation centers in change: participatory methods for managing redesign and renovation. HERD Health Environ Res Des J. 2014;7:57-75.

- Beyer KMM, Comstock S, Seagren R. Disease maps as context for community mapping: a methodological approach for linking confidential health information with local geographical knowledge for community health research. J Community Health. 2010;35:635-44.

- Felker-Kantor E, Polanco C, Perez M, Donastorg Y, Andrinopoulos K, Kendall C, et al. Participatory geographic mapping and activity space diaries: innovative data collection methods for understanding environmental risk exposures among female sex workers in a low-to middle-income country. Int J Health Geogr. 2021;20:25.

- Pedell S, Keirnan A, Priday G, Miller T, Mendoza A, Lopez-Lorca A, et al. Methods for supporting older users in communicating their emotions at different phases of a living lab project. Technol Innov Manag Rev. 2017;7:7-19.

- O’Brien N, Heaven B, Teal G, Evans EH, Cleland C, Moffatt S, et al. integrating evidence from systematic reviews, qualitative research, and expert knowledge using co-design techniques to develop a

web-based intervention for people in the retirement transition. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e5790. - North N, Sieberhagen S, Leonard A, Bonaconsa C, Coetzee M. Making children’s nursing practices visible: using visual and participatory techniques to describe family involvement in the care of hospitalized children in southern african settings. Int J Qual Methods. 2019;18:1609406919849324.

- Najib Balbale S, Schwingel A, Chodzko-Zajko W, Huhman M. Visual and participatory research methods for the development of health messages for underserved populations. Health Commun. 2014;29:728-40.

- Due C, Riggs DW, Augoustinos M. Research with children of migrant and refugee backgrounds: a review of child-centered research methods. Child Indic Res. 2014;7:209-27.

- Sebastião E, Gálvez PAE, Bobitt J, Adamson BC, Schwingel A. Visual and participatory research techniques: photo-elicitation and its potential to better inform public health about physical activity and eating behavior in underserved populations. J Public Health. 2016;24:3-7.

- Bird S, Wiles JL, Okalik L, Kilabuk J, Egeland GM. Methodological consideration of story telling in qualitative research involving Indigenous Peoples. Glob Health Promot. 2009;16:16-26.

- Kohfeldt D, Langhout R. The five whys method: a tool for developing problem definitions in collaboration with children. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2012;22:316-29.

- Parker M, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Magarati M, Burgess E, SanchezYoungman S, et al. Engage for Equity: Development of communitybased participatory research tools. 2020;47. Available from: https:// journals.sagepub.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198120921188.

- Wang Q. Art-based narrative interviewing as a dual methodological process: a participatory research method and an approach to coaching in secondary education. Int Coach Psychol Rev. 2016;11:39-56.