DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-023-01421-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38419691

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-04

علاج متعدد الوظائف قائم على السلفونيوم لألواح الطاقة الشمسية البيروفيسكايت مع فقدان كفاءة أقل من 1% خلال اختبارات استقرار تشغيلية لمدة 4500 ساعة

تم القبول: 21 نوفمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 4 يناير 2024

(ط) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

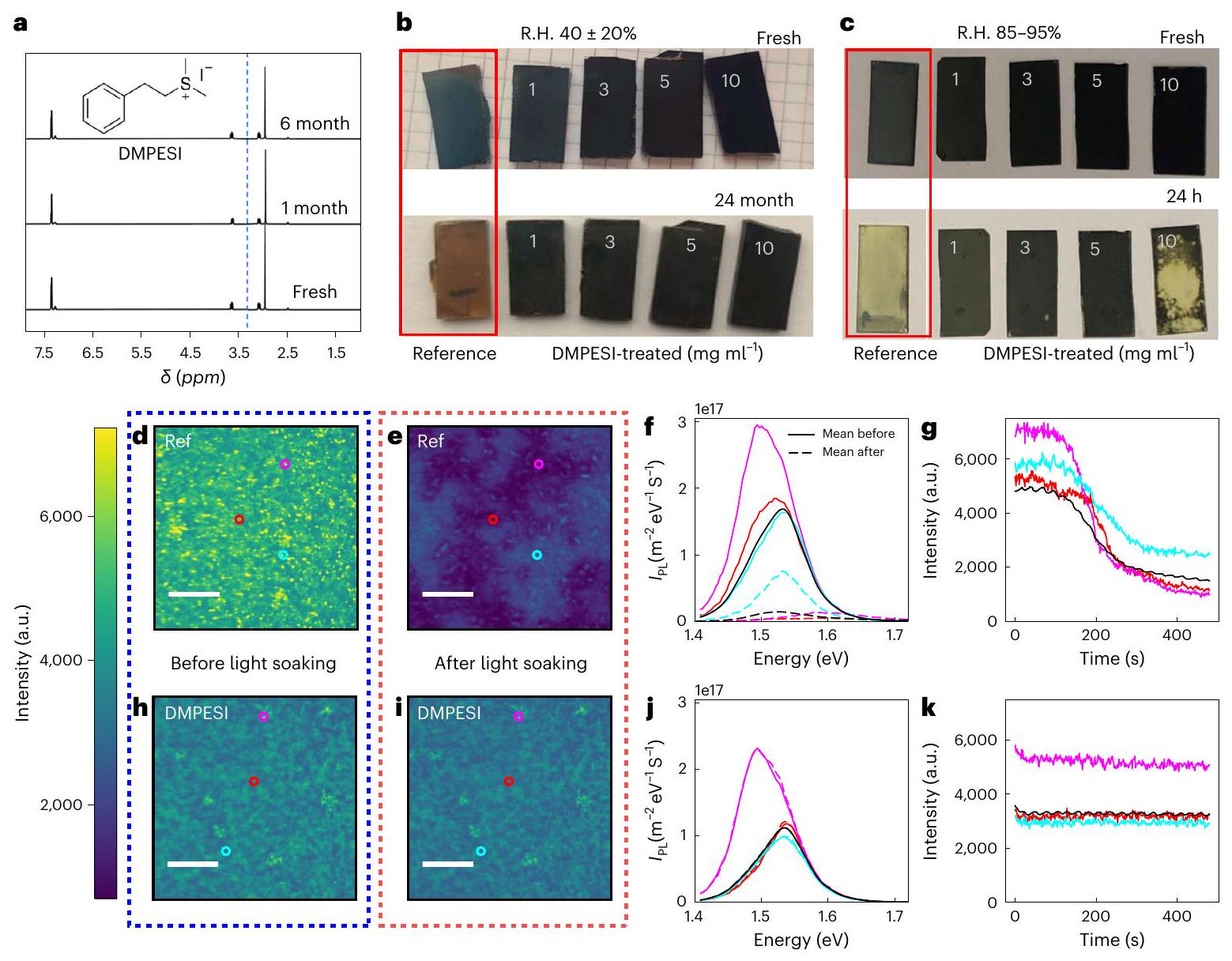

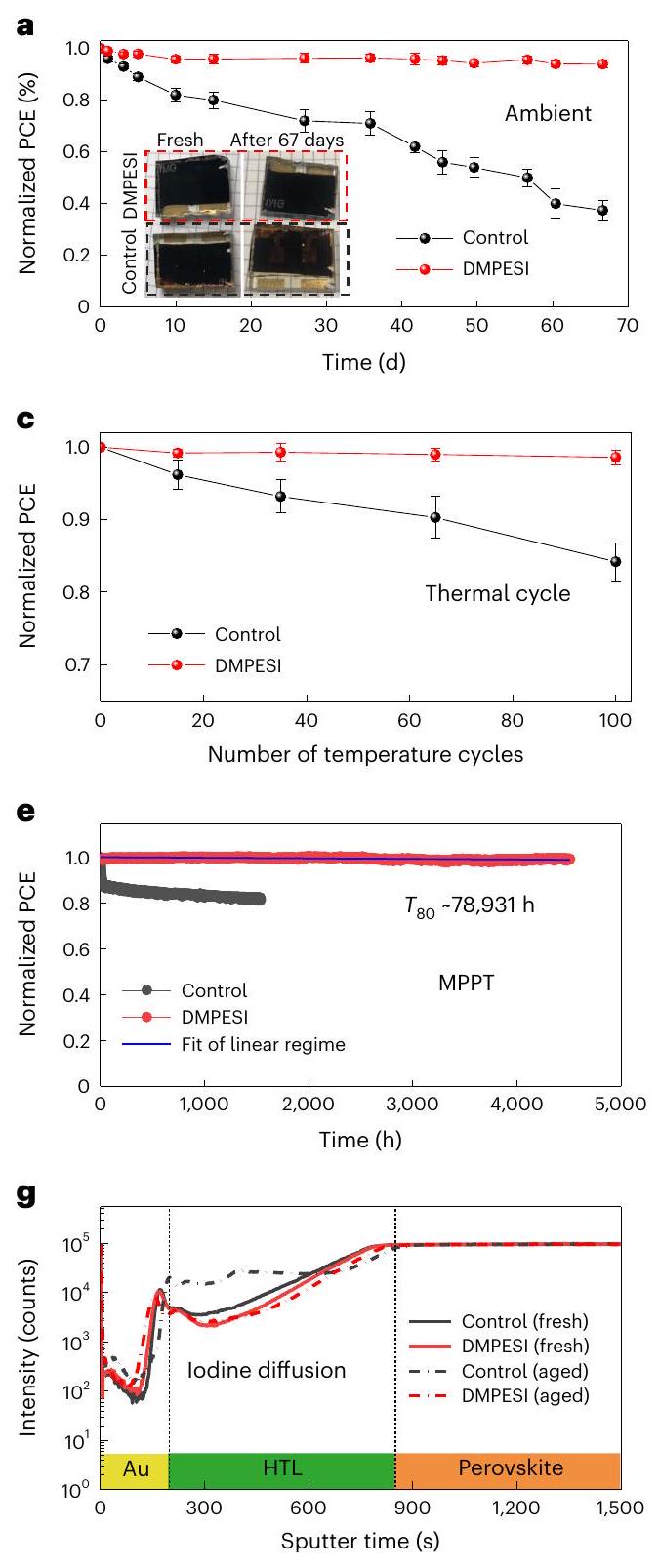

تثبيت حدود الحبوب والأسطح في طبقة البيروفسكيت أمر حاسم لتمديد متانة خلايا الشمس البيروفسكيتية. هنا قدمنا جزيء قائم على السلفونيوم، يوديد ديميثيلفينيثيلسلفونيوم (DMPESI)، للمعالجة بعد الترسيب لأفلام بيروفسكيت يوديد الرصاص الفورماميدينيوم. تظهر الأفلام المعالجة استقرارًا محسنًا عند التعرض للضوء وتظل باللون الأسود

للتراكم تحت الضغط الخارجي، مثل الإضاءة المستمرة، والبيئة الرطبة، وارتفاع درجة الحرارة

المجهرية لـ

تم تحضير كاتيون التريميثيلسلفونيوم، الذي يظهر استقرارًا كيميائيًا مرتفعًا

من سطح البيروفيسكايت، مما يعيق هجرة الأيونات ويعيق آليات التدهور الناجمة عن البيئة المحيطة. وبالتالي، فإن المعالجة بـ DMPESI

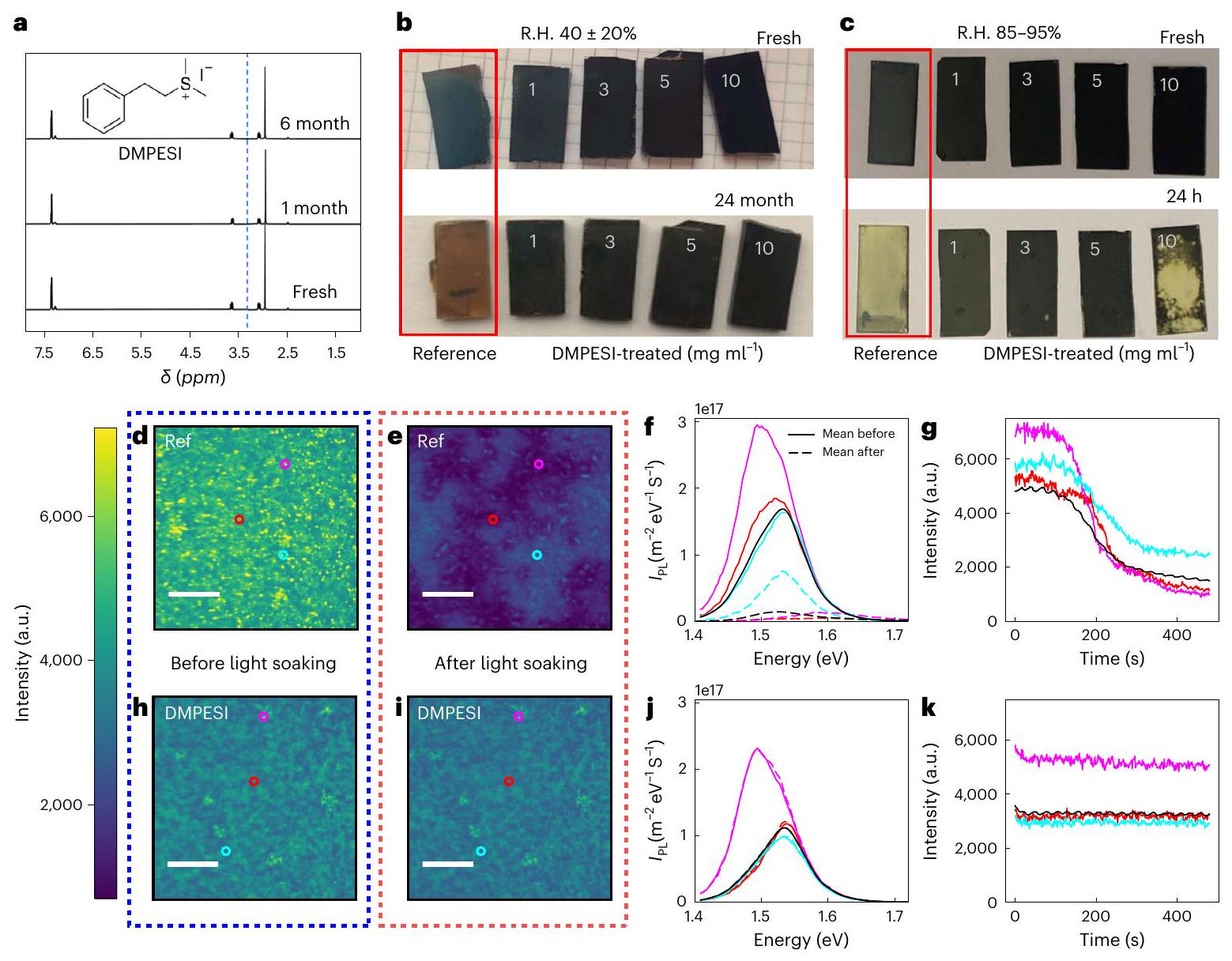

ثبات فيلم البيروفسكيت تحت الرطوبة والتعرض للضوء

تم نقعها لمدة 10 دقائق تحت شدة إضاءة تعادل شمس واحدة في ظروف محيطة. تُظهر الخرائط المقابلة لنفس مناطق العينات المرجعية والمعالجة في الشكل 1e و1i على التوالي. من الجدير بالذكر أن شدة العينة المرجعية تنخفض بشكل كبير أثناء الإضاءة وتظهر مناطق مميزة بحجم عشرات الميكرونات ذات انبعاث ضوئي أعلى أو أقل (الفيديو التكميلي 1). كما هو موضح في الشكل 1f والشكل التكميلي 9، فإن المناطق التي تفقد أكبر قدر من الشدة تظهر أيضًا تحولًا أزرقًا دراماتيكيًا في الانبعاث الضوئي.

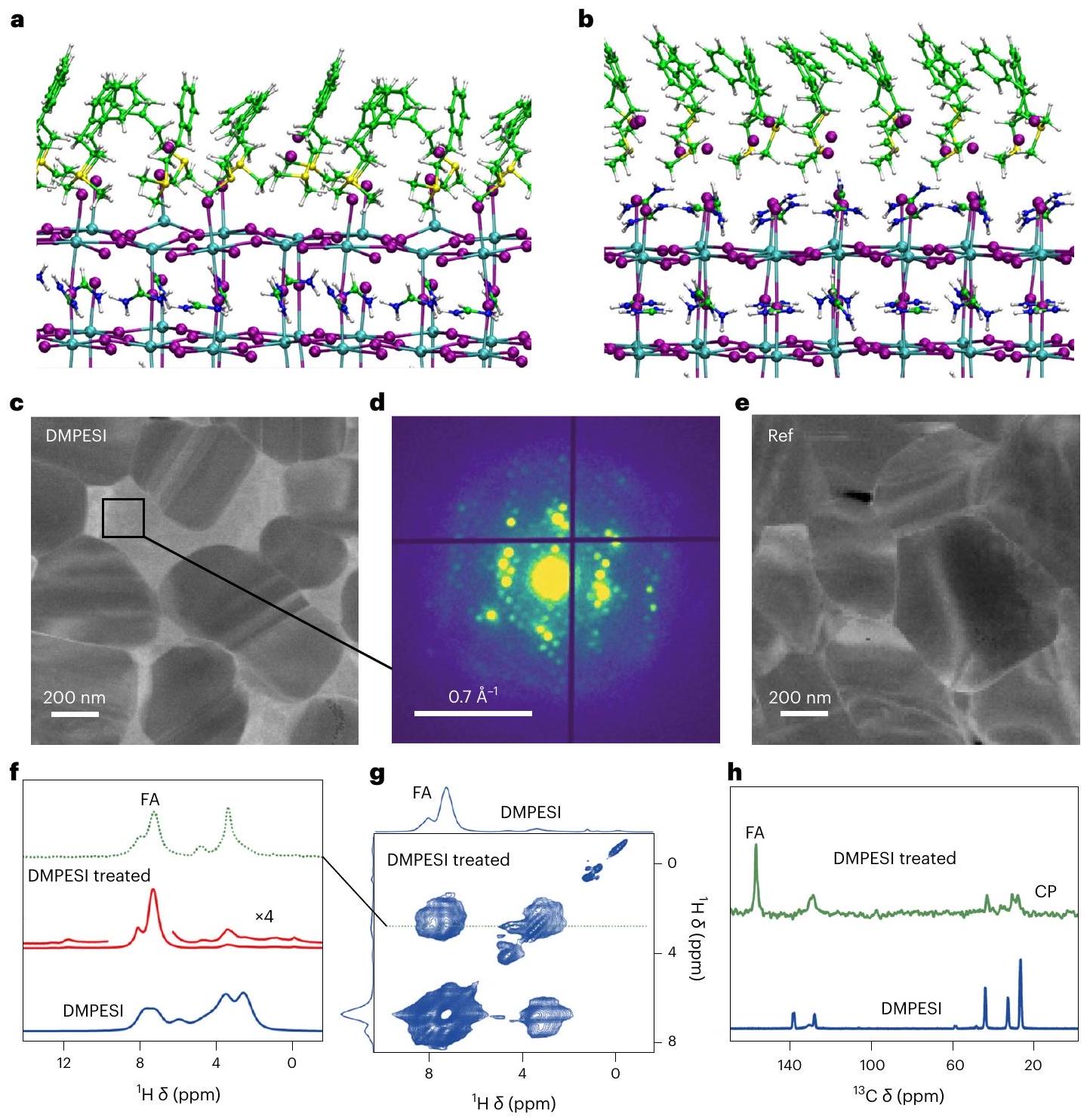

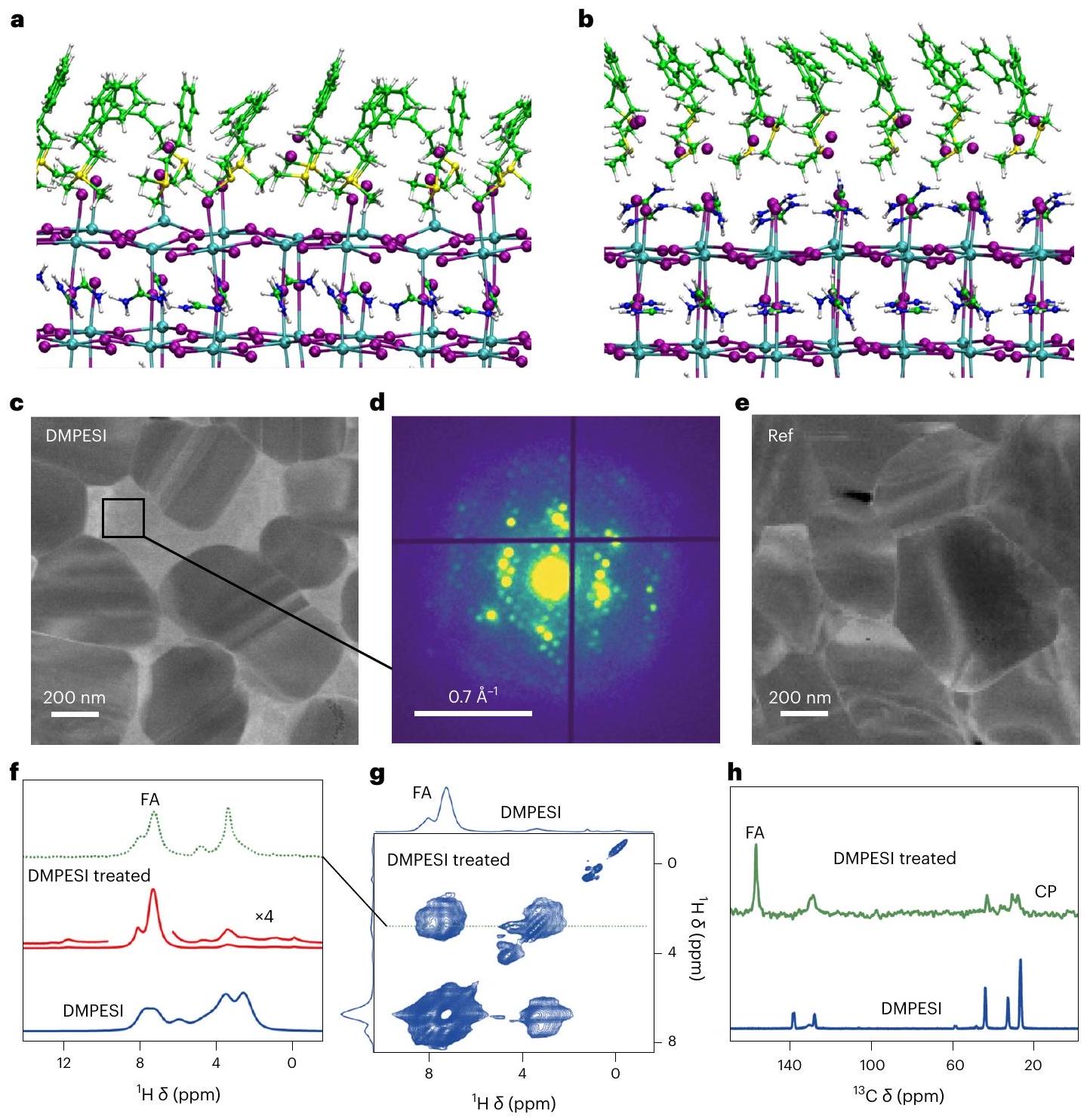

الآلية الذرية مع البيروفسكايت

الظهور في طور البيروفيسكا المكعب (الأسهم البيضاء في الشكل التكميلي 12ب)، يشير إلى وجود إمالة ثمانية السطوح، والتي ثبت أنها تعيق الانتقال الطوري من البيروفيسكا الغنية بـ FA النشطة ضوئيًا إلى البيروفيسكا غير النشطة ضوئيًا

موقع مع

فقط ارتباط ثنائي القطب داخل الجزيء مع بروتونات العطرية لـ DMPESI. يتضح هذا بناءً على شكل ذروة التقاطع، التي تحتوي على مكونين يتطابق موقعهما ونسبة شدتهما تمامًا مع إشارة FA (الشكل 2ج، المسار الأخضر). لتعزيز التحقق من تفاعل DMPESI مع

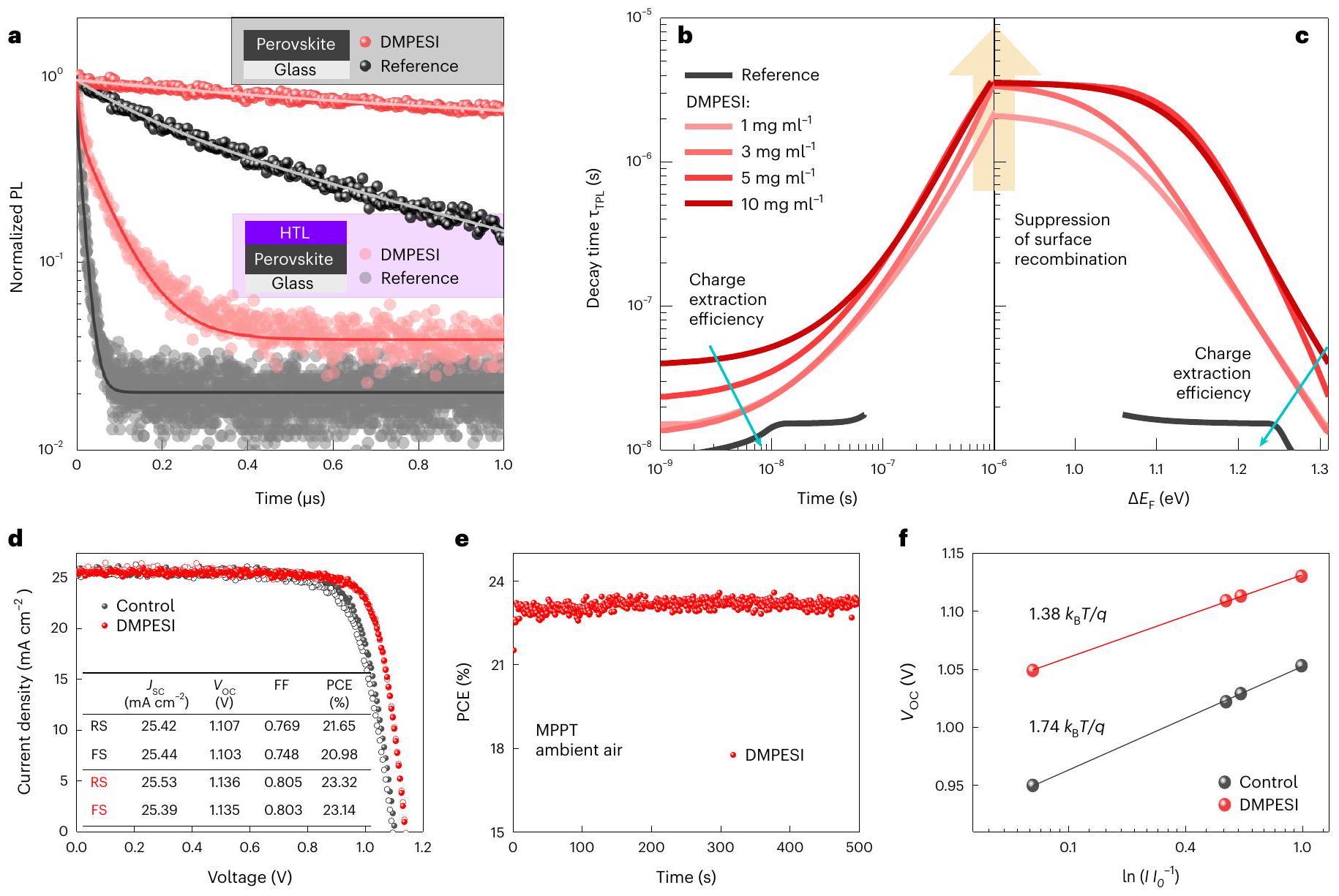

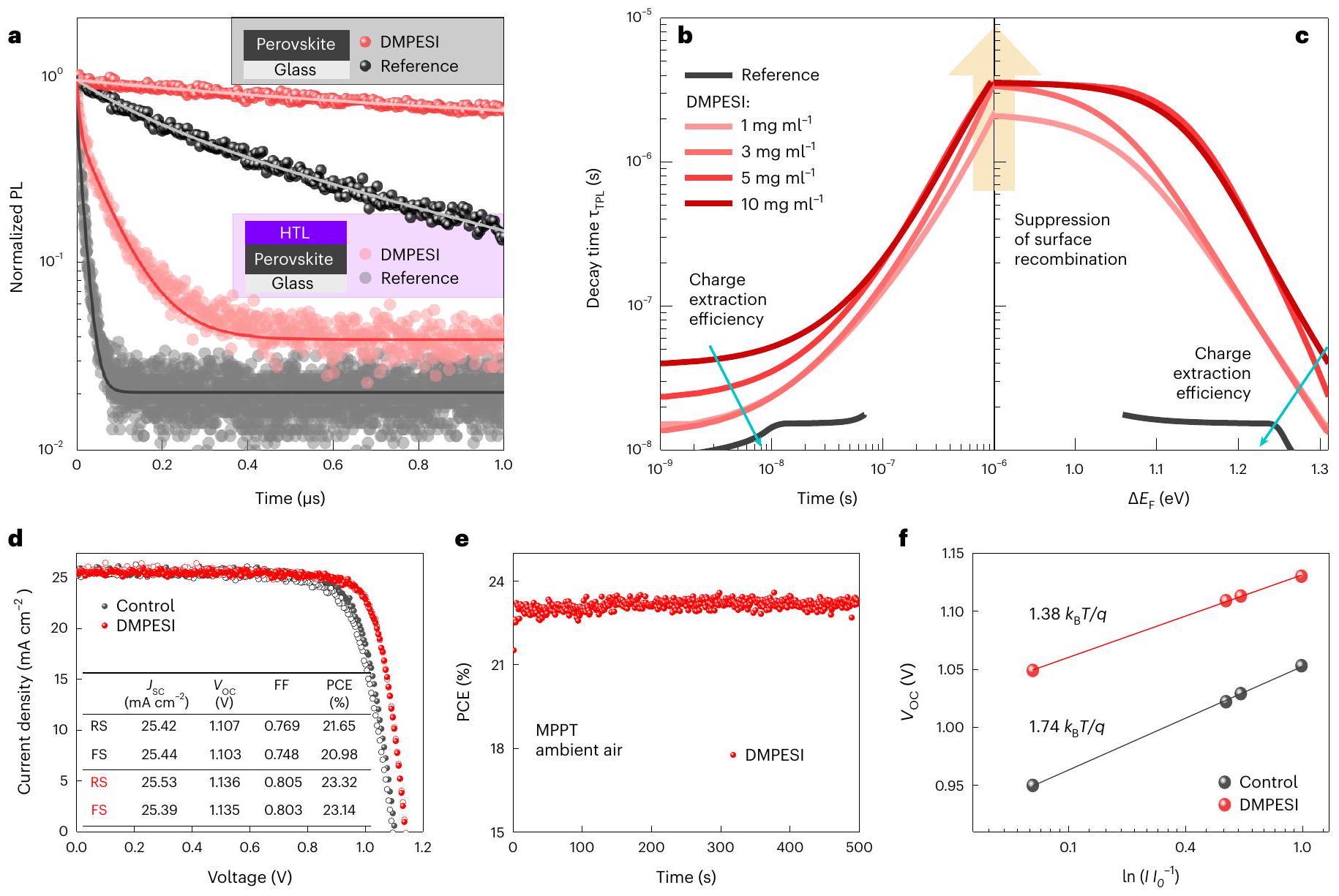

الخصائص البصرية الكهربائية لأفلام وأجهزة البيروفيسكايت

نقص حاملات الشحنة الزائدة، استخدمنا عمرًا تفاضليًا (

يقوم بتمرير الحالات غير المنظمة عند الواجهات وبالتالي يقلل بشكل كبير من إعادة التركيب غير الإشعاعية لتحسين الجهاز

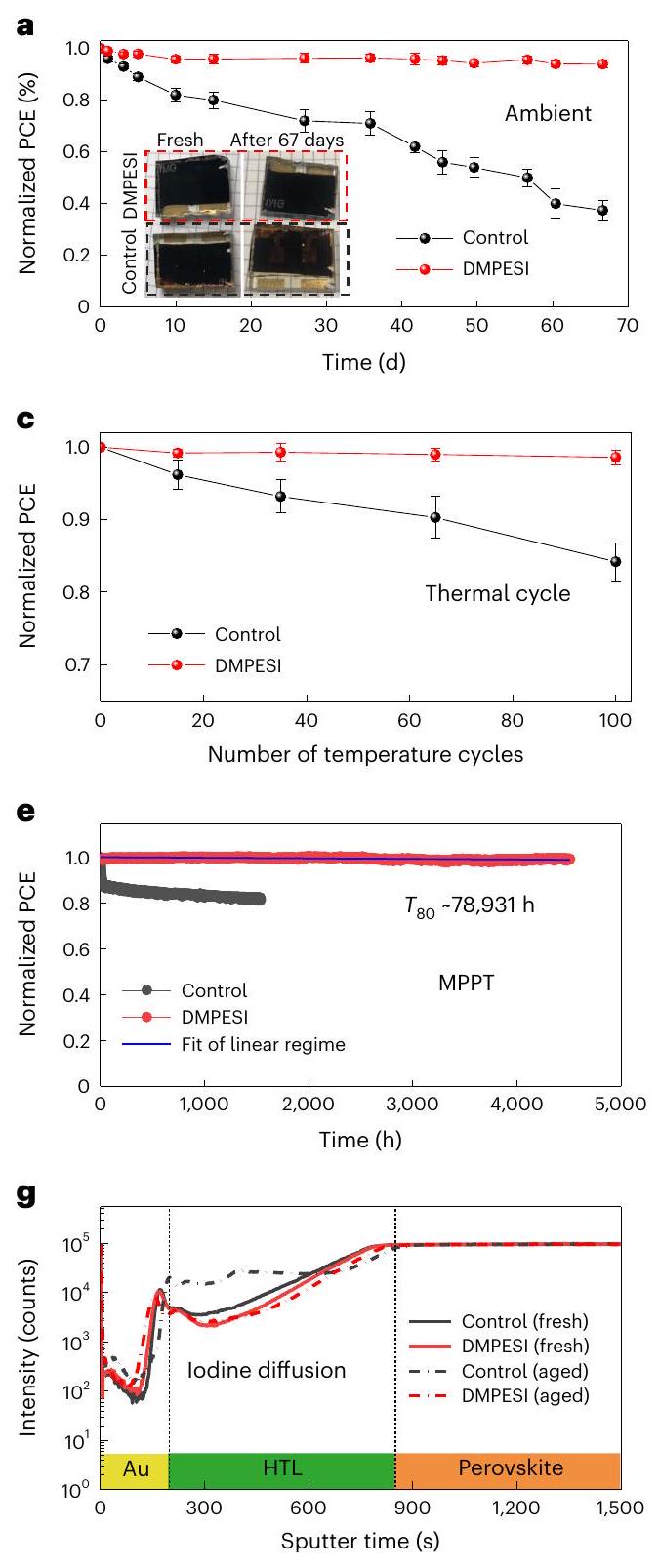

متانة خلايا الطاقة الشمسية ذات التوصيل المباشر

البيروفيسكايت، التي تظل ثابتة أيضًا حتى بعد فترة زمنية طويلة (الشكل 1ك)، مما يؤدي إلى أداء مستقر لخلايا PSC بدون تأثير الاحتراق الأولي (الشكل 4هـ).

الاستنتاجات

الطرق

تخليق DMPESI

(م، 2ه)، 3.10 (مزدوج مزدوج،

توليف

رَكيزة

طبقة البيروفسكايت

طبقة نقل الفجوات والاتصال العلوي من الذهب

توصيف PSC

وشركة Optik GmbH). تم معايرة شدة الضوء باستخدام فوتوديود سيليكون مع فلتر قطع الأشعة تحت الحمراء (KG2، Schott). تم تطبيق خصائص التيار-الجهد بواسطة جهد خارجي مع قياس التيار المقابل باستخدام Keithley 2400 تحت ظروف الهواء المحيط. كانت سرعة مسح الجهد

قياس حيود الأشعة السينية (XRD) وقياس حيود الأشعة السينية بزاوية دخول منخفضة (GIWAXS)

قياس SED

خريطة الفوتولومينيسنس الطيفية الفائقة

تم إجراء مسح طيفي فائق لعينة، ثم تم إضاءة العينة بشكل مستمر لفترة من الوقت وتم التقاط صور توهج عريض النطاق بشكل متقطع كل 1.5 ثانية. بمجرد انتهاء فترة التعرض للضوء هذه، تم إجراء مسح طيفي فائق نهائي مرة أخرى.

مطيافية الرنين المغناطيسي النووي في الحالة الصلبة

اختبار الاستقرار

قياسات أخرى

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

References

- Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart (NREL, 2022); www.nrel.gov/ pv/cell-efficiency.html

- Su, H. et al. Stable perovskite solar cells with

efficiency and area over by an all-in-one strategy. Sci. China Chem. 65, 1321-1329 (2022). - Ding, Y. et al. Single-crystalline

nanoparticles for stable and efficient perovskite modules. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 598-605 (2022). - Kim, M. et al. Conformal quantum dot-

layers as electron transporters for efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 375, 302-306 (2022). - Walker, E. and Thoubboron, K. Solar Panel Warranties: What to Know (Energysage, 2022); https://news.energysage.com/ shopping-solar-panels-pay-attention-to-solar-panels-warranty/

- Peters, I. M. et al. The value of stability in photovoltaics. Joule 5, 3137-3153 (2021).

- Khenkin, M. V. et al. Consensus statement for stability assessment and reporting for perovskite photovoltaics based on ISOS procedures. Nat. Energy 5, 35-49 (2020).

- Chen, S. et al. Stabilizing perovskite-substrate interfaces for high-performance perovskite modules. Science 373, 902-907 (2021).

- Meggiolaro, D., Mosconi, E. & De Angelis, F. Formation of surface defects dominates ion migration in lead-halide perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 779-785 (2019).

- Tan, S. et al. Stability-limiting heterointerfaces of perovskite photovoltaics. Nature 605, 268-273 (2022).

- Yang, S. et al. Stabilizing halide perovskite surfaces for solar cell operation with wide-bandgap lead oxysalts. Science 365, 473-478 (2019).

- Dunfield, S. P. et al. From defects to degradation: a mechanistic understanding of degradation in perovskite solar cell devices and modules. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1904054 (2020).

- Yusoff, A. R. M. et al. Passivation and process engineering approaches of halide perovskite films for high efficiency and stability perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 2906-2953 (2021).

- Jiang, Q. et al. Surface passivation of perovskite film for efficient solar cells. Nat. Photonics 13, 460-466 (2019).

- Suo, J. et al. Interfacial engineering from material to solvent: a mechanistic understanding on stabilizing

-formamidinium lead triiodide perovskite photovoltaics. Nano Energy 94, 106924 (2022). - Bi, D. et al. Polymer-templated nucleation and crystal growth of perovskite films for solar cells with effciency greater than

. Nat. Energy 1, 16142 (2016). - Kim, B. & Soek, S. I. Molecular aspects of organic cations affecting the humidity stability of perovskites. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 805-820 (2022).

- Kaltzoglou, A. et al. Trimethylsulfonium lead triiodide: an airstable hybrid halide perovskite. Inorg. Chem. 56, 6302-6309 (2017).

- Kim, B. et al. Enhanced moisture stability by butyldimethylsulfonium cation in perovskite solar cells. Adv. Sci. 7, 1901840 (2020).

- Cai, Y. et al. Organic sulfonium-stabilized high efficiency cesiumor methylammonium lead bromide perovskite nanocrystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202209 (2022).

- Zuo, X. et al. Passivating buried interface via self-assembled novel sulfonium salt toward stable and efficient perovskite solar cells. Chem. Eng. J. 431, 133209 (2022).

- Kim, M. et al. Methylammonium chloride induces intermediate phase stabilization for efficient perovskite solar cells. Joule 3, 2179-2192 (2019).

- Min, H. et al. Efficient, stable solar cells by using inherent bandgap of

-phase formamidinium lead iodide. Science 366, 749-753 (2019). - Wozny, S. et al. Controlled humidity study on the formation of higher efficiency formamidinium lead triiodide-based solar cells. Chem. Mater. 27, 4814-4820 (2015).

- Yang, B. et al. Outstanding passivation effect by a mixed-salt interlayer with internal interactions in perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 3159-3167 (2020).

- Suo, J. et al. Surface reconstruction engineering with synergistic effect of mixed-salt passivation treatment toward efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2102902 (2021).

- Ambrosio, F. et al. Charge localization and trapping at surfaces in lead-iodide perovskites: the role of polarons and defects. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 6882-6892 (2020).

- Meggiolaro, D. et al. Energy level tuning at the

perovskite/ contact interface using chemical treatment. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 2181-2184 (2019). - Orri, J. F. et al. Unveiling the interaction mechanisms of electron and X-ray radiation with halide perovskite semiconductors using scanning nanoprobe diffraction. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200383 (2022).

- Doherty, T. S. et al. Stabilized tilted-octahedra halide perovskites inhibit local formation of performance-limiting phases. Scinece 374, 1598-1605 (2021).

- Kubicki, D. J. et al. NMR spectroscopy probes microstructure, dynamics and doping of metal halide perovskites. Nat. Rev. Chem. 5, 624-645 (2021).

- Krückemeier, L. et al. Understanding transient photoluminescence in halide perovskite layer stacks and solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003489 (2021).

- Krogmeier, B. et al. Quantitative analysis of the transient photoluminescence of

heterojunctions by numerical simulations. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2, 1027-1034 (2018). - Al-Ashouri, A. et al. Monolithic perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell with >29% efficiency by enhanced hole extraction. Science 370, 1300-1309 (2020).

- Yang, B. et al. Interfacial passivation engineering of perovskite solar cells with fill factor over 82% and outstanding operational stability on n-i-p architecture. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 3916-3923 (2021).

- Tress, W. et al. Interpretation and evolution of open-circuit voltage, recombination, ideality factor and subgap defect states during reversible light-soaking and irreversible degradation of perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 151-165 (2018).

- Park, B. et al. Stabilization of formamidinium lead triiodide a-phase with isopropylammonium chloride for perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 6, 419-428 (2021).

- Domanski, K. et al. Systematic investigation of the impact of operation conditions on the degradation behaviour of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 3, 61-67 (2018).

- Ni, Z. et al. Evolution of defects during the degradation of metal halide perovskite solar cells under reverse bias and illumination. Nat. Energy 7, 65-73 (2022).

- Motti, S. G. et al. Controlling competing photochemical reactions stabilizes perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photonics 15, 532-539 (2019).

- Tan, S. et al. Shallow iodine defects accelerate the degradation of a-phase formamidinium perovskite. Joule 4, 2426-2442 (2020).

- Meggiolaro, D. et al. Formation of surface defects dominates ion migration in lead-halide perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 779-785 (2019).

- Wang, Y. et al. Stabilizing heterostructures of soft perovskite semiconductors. Science 365, 687-691 (2019).

- Zai, H. et al. Sandwiched electrode buffer for efficient and stable perovskite solar cells with dual back surface fields. Joule 5, 2148-2163 (2021).

- Hui, W. et al. Stabilizing black-phase formamidinium perovskite formation at room temperature and high humidity. Science 371, 1359-1364 (2021).

- Kim, G. et al. Impact of strain relaxation on performance of a-formamidinium lead iodide perovskite solar cells. Science 370, 108-112 (2020).

- Jeong, J. et al. Pseudo-halide anion engineering for

perovskite solar cells. Nature 592, 381-385 (2021). - Lu, H. et al. Vapor-assisted deposition of highly efficient, stable black-phase

perovskite solar cells. Science 370, eabb8985 (2020). - Yoo, J. J. et al. Efficient perovskite solar cells via improved carrier management. Nature 590, 587-593 (2021).

- Guo, P. et al. Interfacial embedding of laser-manufactured fluorinated gold clusters enabling stable perovskite solar cells with efficiency over 24%. Adv. Mater. 33, 2101590 (2021).

- Min, H. et al. Perovskite solar cells with atomically coherent interlayers on

electrodes. Nature 598, 444-450 (2021). - Yun, H.-S. et al. Ethanol-based green-solution processing of a-formamidinium lead triiodide perovskite layers. Nat. Energy 7, 828-834 (2022).

- Yoo, J. J. et al. An interface stabilized perovskite solar cell with high stabilized efficiency and low voltage loss. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 2192-2199 (2019).

- Zhu, H. et al. Tailored amphiphilic molecular mitigators for stable perovskite solar cells with 23.5% efficiency. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907757 (2020).

- Jang, Y.-W. et al. Intact 2D/3D halide junction perovskite solar cells via solid-phase in-plane growth. Nat. Energy 6, 63-71 (2021).

- Zhang, H. et al. Multimodal host-guest complexation for efficient and stable perovskite photovoltaics. Nat. Commun. 12, 3383 (2021).

- Pei, F. et al. Thermal management enables more efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 3029-3036 (2021).

- Xue, J. et al. Reconfiguring the band-edge states of photovoltaic perovskites by conjugated organic cations. Science 371, 636-640 (2021).

- Li, N. et al. Liquid medium annealing for fabricating durable perovskite solar cells with improved reproducibility. Science 373, 561-567 (2021).

- Jung, E. H. et al. Efficient, stable and scalable perovskite solar cells using poly(3-hexylthiophene). Nature 567, 511-515 (2019).

- Yang, Y. et al. Modulation of perovskite crystallization processes towards highly efficient and stable perovskite solar cells with MXene quantum dot-modified

. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3447-3454 (2021). - Zhu, H. et al. Synergistic effect of fluorinated passivator and hole transport dopant enables stable perovskite solar cells with an efficiency near

. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 3231-3237 (2021). - Su, T.-S. et al. Crown ether modulation enables over

efficient formamidinium-based perovskite solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19980-19991 (2020). - Wang, R. et al. Constructive molecular configurations for surface-defect passivation of perovskite photovoltaics. Science 366, 1509-1513 (2019).

- Wang, H. et al. Water stable haloplumbate modulation for efficient and stable hybrid perovskite photovoltaics. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2101082 (2021).

- Wang, P. et al. Cobalt chloride hexahydrate assisted in reducing energy loss in perovskite solar cells with record open-circuit voltage of 1.20 V. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2121-2128 (2021).

- Wang, P. et al. Gradient energy alignment engineering for planar perovskite solar cells with efficiency over 23%. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905766 (2020).

- Krishna, A. et al. Nanoscale interfacial engineering enables highly stable and efficient perovskite photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5552-5562 (2021).

- Zhang, F. et al. Metastable Dion-Jacobson 2D structure enables efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Science 375, 71-76 (2022).

- Peng, J. et al. Centimetre-scale perovskite solar cells with fill factors of more than 86 per cent. Nature 601, 573-578 (2022).

- Zhao, L. et al. Enabling full-scale grain boundary mitigation in polycrystalline perovskite solids. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo3733 (2022).

- Wang, T. et al. Transporting holes stably under iodide invasion in efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 377, 1227 (2022).

- Sidhik, S. et al. Deterministic fabrication of 3D/2D perovskite bilayer stacks for durable and efficient solar cells. Science 377, 1425-1430 (2022).

- Liu, C. et al. Tuning structural isomers of phenylenediammonium to afford efficient and stable perovskite solar cells and modules. Nat. Commun. 12, 6394 (2021).

- Cao, Q. et al. Star-polymer multidentate-cross-linking strategy for superior operational stability of inverted perovskite solar cells at high efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5406-5415 (2021).

- Li, X. et al. Constructing heterojunctions by surface sulfidation for efficient inverted perovskite solar cells. Science 375, 434-437 (2022).

- Li, Z. et al. Organometallic-functionalized interfaces for highly efficient inverted perovskite solar cells. Science 376, 416-420 (2022).

- Jiang, Q. et al. Surface reaction for efficient and stable inverted perovskite solar cells. Nature 611, 278-283 (2022).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

واجهة البيروفسكايت/طبقة النقل الثقيل. قام ت.أ.س.د. بإجراء قياسات SED وتحليل البيانات. قام ك.ف. وس.د.س. بإجراء قياسات خرائط PL الطيفية الفائقة وتحليل البيانات. قام د.ج.ك. بإجراء قياسات NMR في الحالة الصلبة وتحليل البيانات. قام ف.ف. بإجراء قياسات ToF-SIMS. قام ي.ك. بقياس زاوية التماس وساعد في استقرار فيلم البيروفسكايت تحت الرطوبة العالية. قام ت.ز. وف.ج. بإجراء قياسات AFM. شارك ج.س.، ب.ي.، إ.م.، د.ب.، ل.و. وأ. هاجفيلدت في تحرير المخطوطة. أ. هاجفيلدت أدار البحث بشكل عام. قرأ جميع المؤلفين المخطوطة وعلقوا عليها.

التمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

- البريد الإلكتروني:bowen.yang@kemi.uu.se; edoardo@thch.unipg.it; anders.hagfeldt@uu.se

بحوث الطبيعة

ملخص تقارير الخلايا الشمسية

لمزيد من المعلومات حول سياسات Nature Research، بما في ذلك سياسة توفر البيانات لدينا، راجع المؤلفون والمحكمون.

التصميم التجريبي

يرجى التحقق: هل تم الإبلاغ عن التفاصيل التالية في المخطوطة؟

1. الأبعاد

| مساحة الخلايا الشمسية المختبرة |

|

|

|

|

| الطريقة المستخدمة لتحديد مساحة الجهاز | |

|

|

2. توصيف التيار-الجهد

مخططات كثافة التيار-الجهد (J-V) في كلا الاتجاهين الأمامي نعم

والاتجاه العكسي لا

على سبيل المثال: اتجاه المسح، السرعة، أوقات التوقف لا

بيئة الاختبار نعم

على سبيل المثال: درجة حرارة التوصيف، في الهواء أو في صندوق القفازات لا

بروتوكول تهيئة الجهاز قبل تشغيله نعم

رقم التوصيف

استقرار خاصية التيار-الجهد نعم

تم التحقق من خلال تطور الزمن لنقطة القدرة القصوى أو بدون

التيار الضوئي عند نقطة القدرة القصوى؛ انظر المرجع 7 للتفاصيل.

S

الشكل 3هـ، الشكل 4أ، 4ج-4هـ

3. التباطؤ أو أي سلوك غير عادي آخر

الرقم التعريفي

نعم

لا

4. الكفاءة

كفاءة تحويل الفوتونات إلى تيار (IPCE) لا

مقارنة بين الاستجابة المتكاملة تحت نعم

طيف المرجع القياسي والاستجابة لا يوجد قياس تحت المحاكي

الجهد المستخدم لكل خلية فرعية رقم

5. المعايرة

رقم التوصيف

6. القناع/الفتحة

7. شهادة الأداء

توفير في المعلومات التكميلية

8. الإحصائيات

9. تحليل الاستقرار طويل الأمد

على سبيل المثال: نوع الإضاءة، درجة الحرارة، رطوبة الجو، طريقة التغليف، درجة حرارة التهيئة المسبقة

نعم

لا

لا

لا

نعم

لا

نعم

لا

نعم

لا

نعم

لا

- تظهر قائمة كاملة بالانتماءات في نهاية الورقة.

البريد الإلكتروني:bowen.yang@kemi.uu.se; edoardo@thch.unipg.it; anders.hagfeldt@uu.se

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-023-01421-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38419691

Publication Date: 2024-01-04

Multifunctional sulfonium-based treatment for perovskite solar cells with less than 1% efficiency loss over 4,500-h operational stability tests

Accepted: 21 November 2023

Published online: 4 January 2024

(i) Check for updates

Abstract

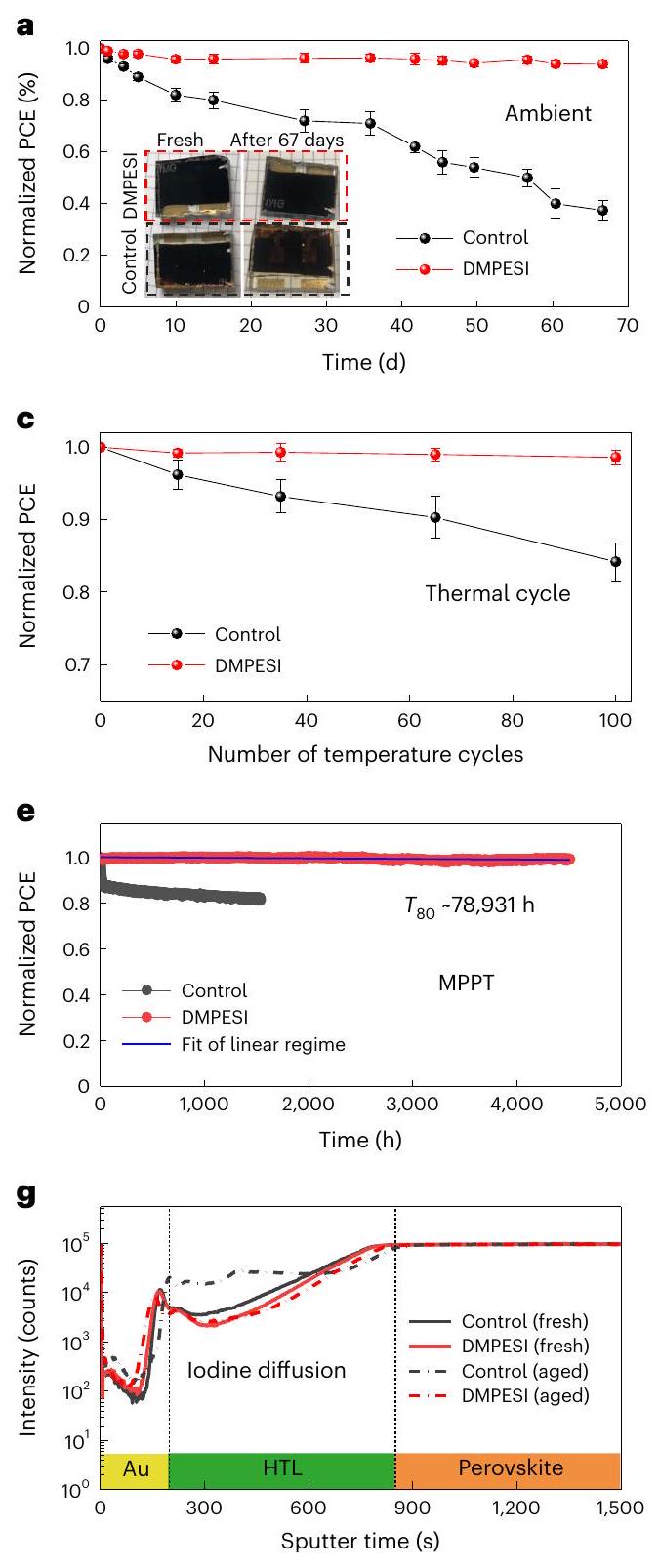

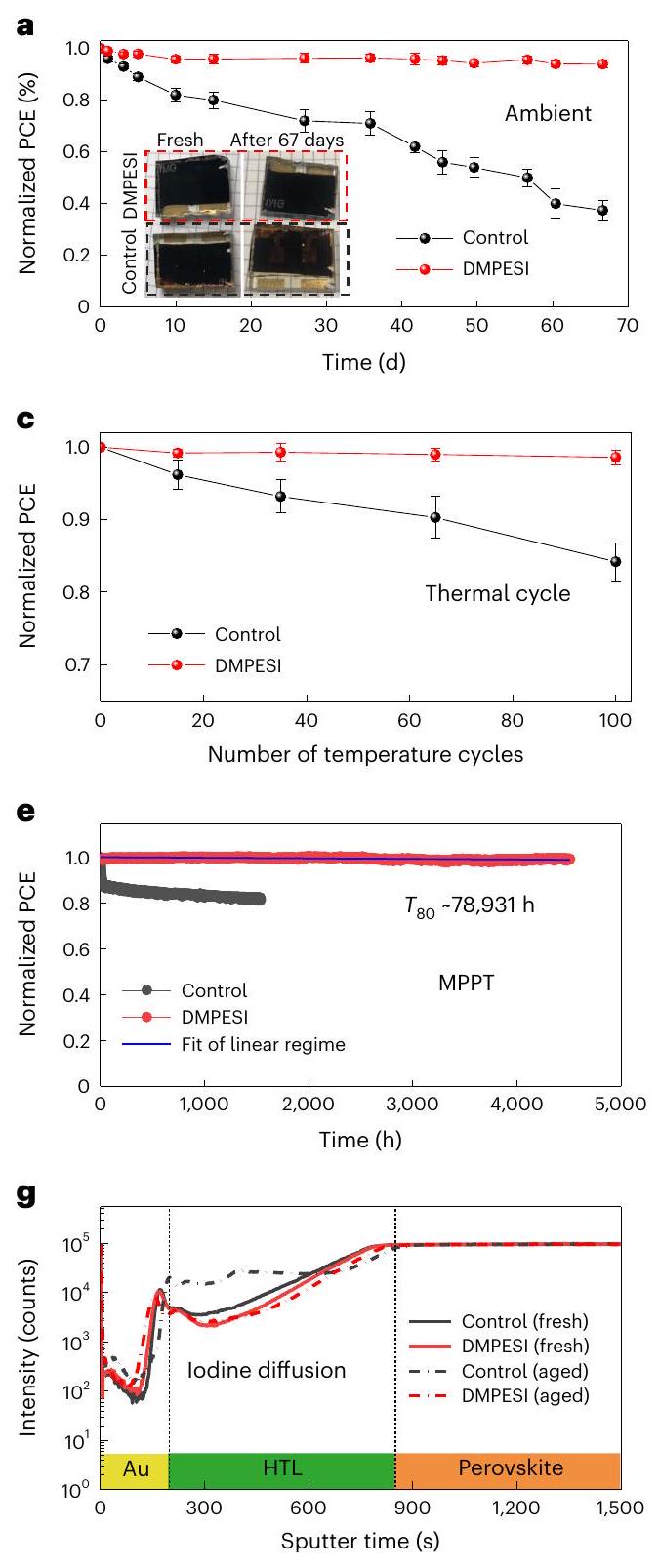

The stabilization of grain boundaries and surfaces of the perovskite layer is critical to extend the durability of perovskite solar cells. Here we introduced a sulfonium-based molecule, dimethylphenethylsulfonium iodide (DMPESI), for the post-deposition treatment of formamidinium lead iodide perovskite films. The treated films show improved stability upon light soaking and remains in the black

to accumulate under external stress, such as continuous illumination, humid environment and elevated temperature

microscopy of

based on the trimethylsulfonium cation has been synthesized, which exhibits elevated chemical stability

of the perovskite surface, which inhibits ion migration and impedes ambient-induced degradation mechanisms. Consequently, the DMPESI-treated

Perovskite film stability under moisture and light soaking

soaked for 10 minutes with 1-sun illumination intensity under ambient conditions. The corresponding maps of the same areas of the reference and treated samples are shown in Fig. 1e, i, respectively. Notably, the intensity of the reference sample drops dramatically during illumination and distinct regions tens of microns in size with higher or lower PL emerge (Supplementary Video 1). As shown in Fig. 1 f and Supplementary Fig. 9, the regions that lose the most intensity also display a dramatic PL blue shift of

Atomistic mechanism with perovskite

appearing in the cubic perovskite phase (white arrows in Supplementary Fig. 12b), indicates the presence of octahedral tilting, which has been shown to frustrate the phase transition from photoactive FA-rich perovskites to the photoinactive

site with

only an intramolecular dipolar coupling to the aromatic protons of DMPESI. This is evident based on the shape of the cross-peak, which has two components whose position and intensity ratio matches exactly those of the FA signal (Fig. 2g, green trace). To further corroborate the interaction of DMPESI with

Optoelectronic properties of perovskite films and devices

excess charge-carrier depopulation, we utilized a differential lifetime (

passivates the disordered states at the interfaces and thus strongly reduces non-radiative recombination to improve device

Durability of the PSCs

perovskite, which also remain constant even after long time duration (Fig. 1k), resulting in a stable PSC performance without the burn-in effect (Fig. 4e).

Conclusions

Methods

Synthesis of DMPESI

(m, 2H), 3.10 (dd,

Synthesis of

Substrate

Perovskite layer

Hole-transporting layer and Au top contact

PSC characterization

and Optik GmbH). The light intensity was calibrated with a silicon photodiode with an infrared-cut-off filter (KG2, Schott). Currentvoltage characteristics were applied by an external voltage bias while measuring the corresponding current with Keithley 2400 under ambient air condition. The voltage scan rate was

XRD and GIWAXS measurement

SED measurement

Hyperspectral photoluminescence map

a hyperspectral scan of a sample was performed, then the sample was continuously illuminated for a period of time and broadband luminescence images were intermittently captured every 1.5 seconds. Once this light-soaking period was complete, a final hyperspectral scan was once again performed.

Solid-state NMR

Stability test

Other measurements

Reporting summary

Data availability

References

- Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart (NREL, 2022); www.nrel.gov/ pv/cell-efficiency.html

- Su, H. et al. Stable perovskite solar cells with

efficiency and area over by an all-in-one strategy. Sci. China Chem. 65, 1321-1329 (2022). - Ding, Y. et al. Single-crystalline

nanoparticles for stable and efficient perovskite modules. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 598-605 (2022). - Kim, M. et al. Conformal quantum dot-

layers as electron transporters for efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 375, 302-306 (2022). - Walker, E. and Thoubboron, K. Solar Panel Warranties: What to Know (Energysage, 2022); https://news.energysage.com/ shopping-solar-panels-pay-attention-to-solar-panels-warranty/

- Peters, I. M. et al. The value of stability in photovoltaics. Joule 5, 3137-3153 (2021).

- Khenkin, M. V. et al. Consensus statement for stability assessment and reporting for perovskite photovoltaics based on ISOS procedures. Nat. Energy 5, 35-49 (2020).

- Chen, S. et al. Stabilizing perovskite-substrate interfaces for high-performance perovskite modules. Science 373, 902-907 (2021).

- Meggiolaro, D., Mosconi, E. & De Angelis, F. Formation of surface defects dominates ion migration in lead-halide perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 779-785 (2019).

- Tan, S. et al. Stability-limiting heterointerfaces of perovskite photovoltaics. Nature 605, 268-273 (2022).

- Yang, S. et al. Stabilizing halide perovskite surfaces for solar cell operation with wide-bandgap lead oxysalts. Science 365, 473-478 (2019).

- Dunfield, S. P. et al. From defects to degradation: a mechanistic understanding of degradation in perovskite solar cell devices and modules. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1904054 (2020).

- Yusoff, A. R. M. et al. Passivation and process engineering approaches of halide perovskite films for high efficiency and stability perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 2906-2953 (2021).

- Jiang, Q. et al. Surface passivation of perovskite film for efficient solar cells. Nat. Photonics 13, 460-466 (2019).

- Suo, J. et al. Interfacial engineering from material to solvent: a mechanistic understanding on stabilizing

-formamidinium lead triiodide perovskite photovoltaics. Nano Energy 94, 106924 (2022). - Bi, D. et al. Polymer-templated nucleation and crystal growth of perovskite films for solar cells with effciency greater than

. Nat. Energy 1, 16142 (2016). - Kim, B. & Soek, S. I. Molecular aspects of organic cations affecting the humidity stability of perovskites. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 805-820 (2022).

- Kaltzoglou, A. et al. Trimethylsulfonium lead triiodide: an airstable hybrid halide perovskite. Inorg. Chem. 56, 6302-6309 (2017).

- Kim, B. et al. Enhanced moisture stability by butyldimethylsulfonium cation in perovskite solar cells. Adv. Sci. 7, 1901840 (2020).

- Cai, Y. et al. Organic sulfonium-stabilized high efficiency cesiumor methylammonium lead bromide perovskite nanocrystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202209 (2022).

- Zuo, X. et al. Passivating buried interface via self-assembled novel sulfonium salt toward stable and efficient perovskite solar cells. Chem. Eng. J. 431, 133209 (2022).

- Kim, M. et al. Methylammonium chloride induces intermediate phase stabilization for efficient perovskite solar cells. Joule 3, 2179-2192 (2019).

- Min, H. et al. Efficient, stable solar cells by using inherent bandgap of

-phase formamidinium lead iodide. Science 366, 749-753 (2019). - Wozny, S. et al. Controlled humidity study on the formation of higher efficiency formamidinium lead triiodide-based solar cells. Chem. Mater. 27, 4814-4820 (2015).

- Yang, B. et al. Outstanding passivation effect by a mixed-salt interlayer with internal interactions in perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 5, 3159-3167 (2020).

- Suo, J. et al. Surface reconstruction engineering with synergistic effect of mixed-salt passivation treatment toward efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2102902 (2021).

- Ambrosio, F. et al. Charge localization and trapping at surfaces in lead-iodide perovskites: the role of polarons and defects. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 6882-6892 (2020).

- Meggiolaro, D. et al. Energy level tuning at the

perovskite/ contact interface using chemical treatment. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 2181-2184 (2019). - Orri, J. F. et al. Unveiling the interaction mechanisms of electron and X-ray radiation with halide perovskite semiconductors using scanning nanoprobe diffraction. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200383 (2022).

- Doherty, T. S. et al. Stabilized tilted-octahedra halide perovskites inhibit local formation of performance-limiting phases. Scinece 374, 1598-1605 (2021).

- Kubicki, D. J. et al. NMR spectroscopy probes microstructure, dynamics and doping of metal halide perovskites. Nat. Rev. Chem. 5, 624-645 (2021).

- Krückemeier, L. et al. Understanding transient photoluminescence in halide perovskite layer stacks and solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2003489 (2021).

- Krogmeier, B. et al. Quantitative analysis of the transient photoluminescence of

heterojunctions by numerical simulations. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2, 1027-1034 (2018). - Al-Ashouri, A. et al. Monolithic perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell with >29% efficiency by enhanced hole extraction. Science 370, 1300-1309 (2020).

- Yang, B. et al. Interfacial passivation engineering of perovskite solar cells with fill factor over 82% and outstanding operational stability on n-i-p architecture. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 3916-3923 (2021).

- Tress, W. et al. Interpretation and evolution of open-circuit voltage, recombination, ideality factor and subgap defect states during reversible light-soaking and irreversible degradation of perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 151-165 (2018).

- Park, B. et al. Stabilization of formamidinium lead triiodide a-phase with isopropylammonium chloride for perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 6, 419-428 (2021).

- Domanski, K. et al. Systematic investigation of the impact of operation conditions on the degradation behaviour of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 3, 61-67 (2018).

- Ni, Z. et al. Evolution of defects during the degradation of metal halide perovskite solar cells under reverse bias and illumination. Nat. Energy 7, 65-73 (2022).

- Motti, S. G. et al. Controlling competing photochemical reactions stabilizes perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photonics 15, 532-539 (2019).

- Tan, S. et al. Shallow iodine defects accelerate the degradation of a-phase formamidinium perovskite. Joule 4, 2426-2442 (2020).

- Meggiolaro, D. et al. Formation of surface defects dominates ion migration in lead-halide perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 779-785 (2019).

- Wang, Y. et al. Stabilizing heterostructures of soft perovskite semiconductors. Science 365, 687-691 (2019).

- Zai, H. et al. Sandwiched electrode buffer for efficient and stable perovskite solar cells with dual back surface fields. Joule 5, 2148-2163 (2021).

- Hui, W. et al. Stabilizing black-phase formamidinium perovskite formation at room temperature and high humidity. Science 371, 1359-1364 (2021).

- Kim, G. et al. Impact of strain relaxation on performance of a-formamidinium lead iodide perovskite solar cells. Science 370, 108-112 (2020).

- Jeong, J. et al. Pseudo-halide anion engineering for

perovskite solar cells. Nature 592, 381-385 (2021). - Lu, H. et al. Vapor-assisted deposition of highly efficient, stable black-phase

perovskite solar cells. Science 370, eabb8985 (2020). - Yoo, J. J. et al. Efficient perovskite solar cells via improved carrier management. Nature 590, 587-593 (2021).

- Guo, P. et al. Interfacial embedding of laser-manufactured fluorinated gold clusters enabling stable perovskite solar cells with efficiency over 24%. Adv. Mater. 33, 2101590 (2021).

- Min, H. et al. Perovskite solar cells with atomically coherent interlayers on

electrodes. Nature 598, 444-450 (2021). - Yun, H.-S. et al. Ethanol-based green-solution processing of a-formamidinium lead triiodide perovskite layers. Nat. Energy 7, 828-834 (2022).

- Yoo, J. J. et al. An interface stabilized perovskite solar cell with high stabilized efficiency and low voltage loss. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 2192-2199 (2019).

- Zhu, H. et al. Tailored amphiphilic molecular mitigators for stable perovskite solar cells with 23.5% efficiency. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907757 (2020).

- Jang, Y.-W. et al. Intact 2D/3D halide junction perovskite solar cells via solid-phase in-plane growth. Nat. Energy 6, 63-71 (2021).

- Zhang, H. et al. Multimodal host-guest complexation for efficient and stable perovskite photovoltaics. Nat. Commun. 12, 3383 (2021).

- Pei, F. et al. Thermal management enables more efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 3029-3036 (2021).

- Xue, J. et al. Reconfiguring the band-edge states of photovoltaic perovskites by conjugated organic cations. Science 371, 636-640 (2021).

- Li, N. et al. Liquid medium annealing for fabricating durable perovskite solar cells with improved reproducibility. Science 373, 561-567 (2021).

- Jung, E. H. et al. Efficient, stable and scalable perovskite solar cells using poly(3-hexylthiophene). Nature 567, 511-515 (2019).

- Yang, Y. et al. Modulation of perovskite crystallization processes towards highly efficient and stable perovskite solar cells with MXene quantum dot-modified

. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3447-3454 (2021). - Zhu, H. et al. Synergistic effect of fluorinated passivator and hole transport dopant enables stable perovskite solar cells with an efficiency near

. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 3231-3237 (2021). - Su, T.-S. et al. Crown ether modulation enables over

efficient formamidinium-based perovskite solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 19980-19991 (2020). - Wang, R. et al. Constructive molecular configurations for surface-defect passivation of perovskite photovoltaics. Science 366, 1509-1513 (2019).

- Wang, H. et al. Water stable haloplumbate modulation for efficient and stable hybrid perovskite photovoltaics. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2101082 (2021).

- Wang, P. et al. Cobalt chloride hexahydrate assisted in reducing energy loss in perovskite solar cells with record open-circuit voltage of 1.20 V. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 2121-2128 (2021).

- Wang, P. et al. Gradient energy alignment engineering for planar perovskite solar cells with efficiency over 23%. Adv. Mater. 32, 1905766 (2020).

- Krishna, A. et al. Nanoscale interfacial engineering enables highly stable and efficient perovskite photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5552-5562 (2021).

- Zhang, F. et al. Metastable Dion-Jacobson 2D structure enables efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Science 375, 71-76 (2022).

- Peng, J. et al. Centimetre-scale perovskite solar cells with fill factors of more than 86 per cent. Nature 601, 573-578 (2022).

- Zhao, L. et al. Enabling full-scale grain boundary mitigation in polycrystalline perovskite solids. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo3733 (2022).

- Wang, T. et al. Transporting holes stably under iodide invasion in efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 377, 1227 (2022).

- Sidhik, S. et al. Deterministic fabrication of 3D/2D perovskite bilayer stacks for durable and efficient solar cells. Science 377, 1425-1430 (2022).

- Liu, C. et al. Tuning structural isomers of phenylenediammonium to afford efficient and stable perovskite solar cells and modules. Nat. Commun. 12, 6394 (2021).

- Cao, Q. et al. Star-polymer multidentate-cross-linking strategy for superior operational stability of inverted perovskite solar cells at high efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5406-5415 (2021).

- Li, X. et al. Constructing heterojunctions by surface sulfidation for efficient inverted perovskite solar cells. Science 375, 434-437 (2022).

- Li, Z. et al. Organometallic-functionalized interfaces for highly efficient inverted perovskite solar cells. Science 376, 416-420 (2022).

- Jiang, Q. et al. Surface reaction for efficient and stable inverted perovskite solar cells. Nature 611, 278-283 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

perovskite/HTL interface. T.A.S.D. performed SED measurements and analysed the data. K.F. and S.D.S. performed the hyperspectral PL maps measurement and analysed the data. D.J.K carried out the solid-state NMR measurements and analysed the data. F.F. performed the ToF-SIMS measurements. Y.K. performed the contact angle measurement and assisted perovskite film stability under high humidity. T.Z. and F.G. performed the AFM measurement. J.S., B.Y., E.M., D.B., L.W. and A. Hagfeldt participated in editing the manuscript. A. Hagfeldt directed the overall research. All authors read and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2024

natureresearch

Solar Cells Reporting Summary

For further information on Nature Research policies, including our data availability policy, see Authors & Referees.

Experimental design

Please check: are the following details reported in the manuscript?

1. Dimensions

| Area of the tested solar cells |

|

|

|

|

| Method used to determine the device area | |

|

|

2. Current-voltage characterization

Current density-voltage (J-V) plots in both forward Yes

and backward direction No

For instance: scan direction, speed, dwell times No

Test environment Yes

For instance: characterization temperature, in air or in glove box No

Protocol for preconditioning of the device before its Yes

characterization No

Stability of the J-V characteristic Yes

Verified with time evolution of the maximum power point or with No

the photocurrent at maximum power point; see ref. 7 for details.

S

Figure 3e, Figure 4a, 4c-4e

3. Hysteresis or any other unusual behaviour

the characterization No

Yes

No

4. Efficiency

photons to current efficiency (IPCE) No

A comparison between the integrated response under Yes

the standard reference spectrum and the response No measure under the simulator

voltage used for each subcell No

5. Calibration

characterization No

6. Mask/aperture

7. Performance certification

Provide in Supplementary Information

8. Statistics

9. Long-term stability analysis

For instance: illumination type, temperature, atmosphere humidity, encapsulation method, preconditioning temperature

Yes

No

No

No

Yes

No

Yes

No

Yes

No

Yes

No

- A full list of affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

e-mail: bowen.yang@kemi.uu.se; edoardo@thch.unipg.it; anders.hagfeldt@uu.se