DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44663-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38212316

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-11

فصل اليورانيوم الفائق الانتقائية من خلال التكوين في الموقع لـ

تم القبول: 19 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 11 يناير 2024

(أ) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

مع التطور السريع للطاقة النووية، أدت المشاكل المتعلقة بسلسلة إمداد اليورانيوم وتراكم النفايات النووية إلى تحفيز الباحثين على تحسين طرق فصل اليورانيوم. هنا نعرض نموذجًا لتحقيق هذا الهدف يعتمد على التكوين في الموقع لـ

مشابهة جسديًا وكيميائيًا

النتائج

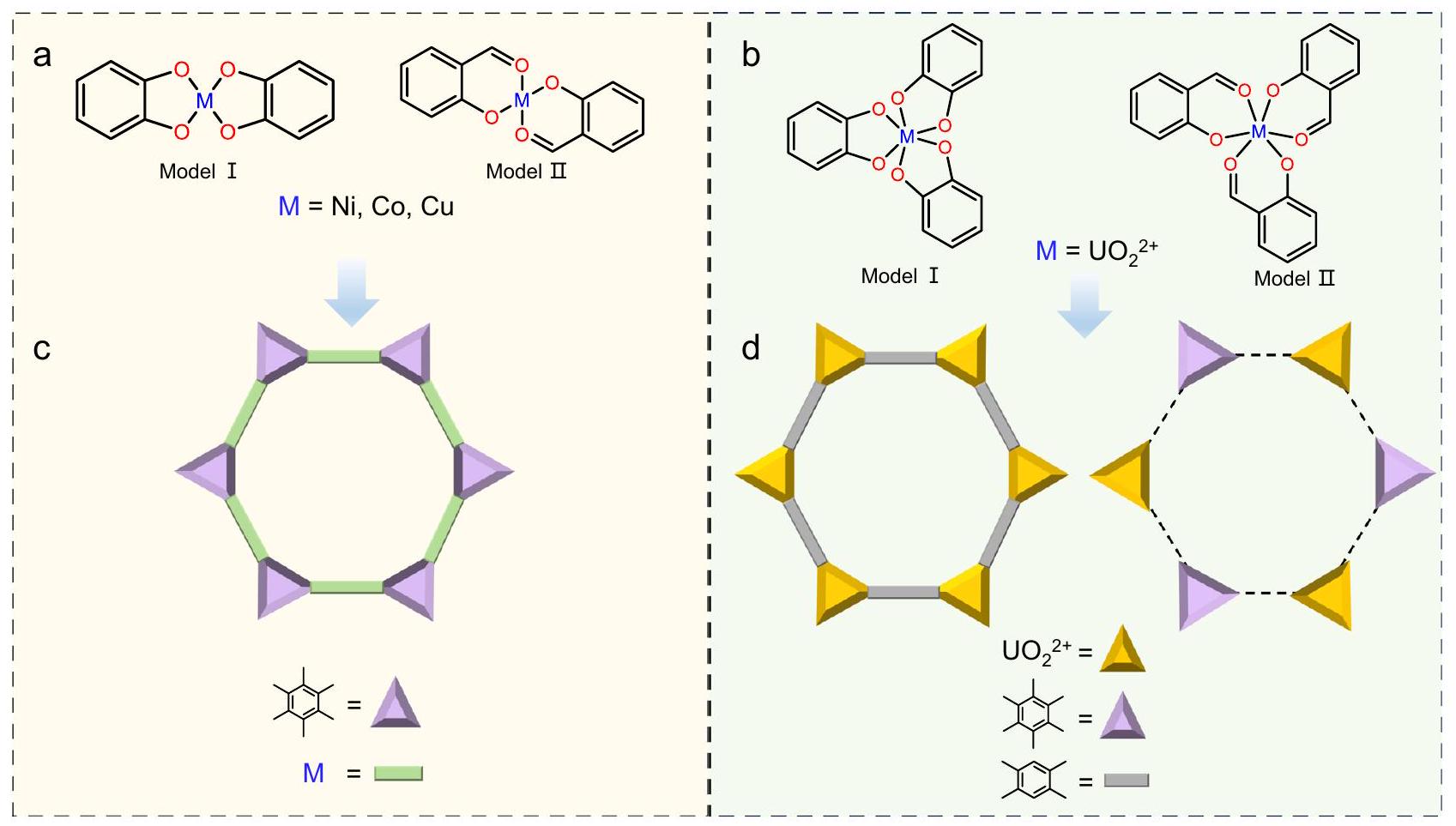

تصميم MOF ثنائي الأبعاد والليغاند

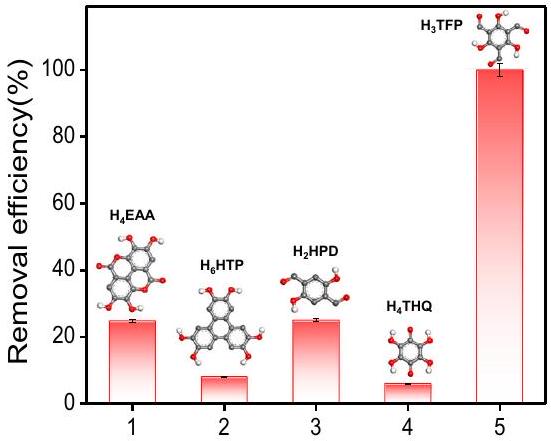

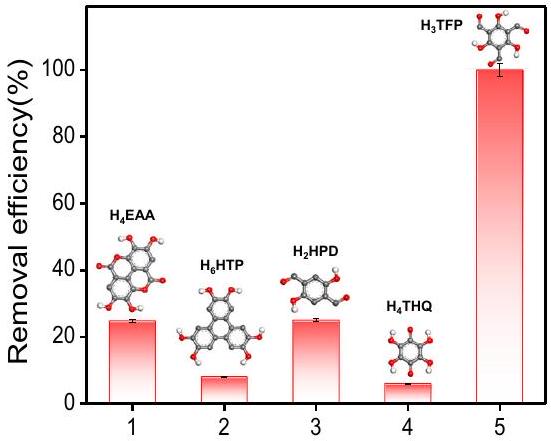

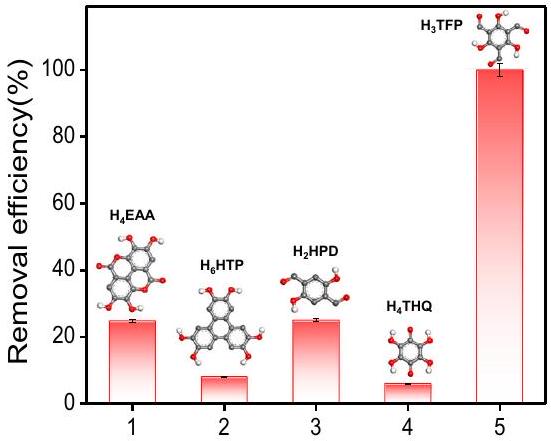

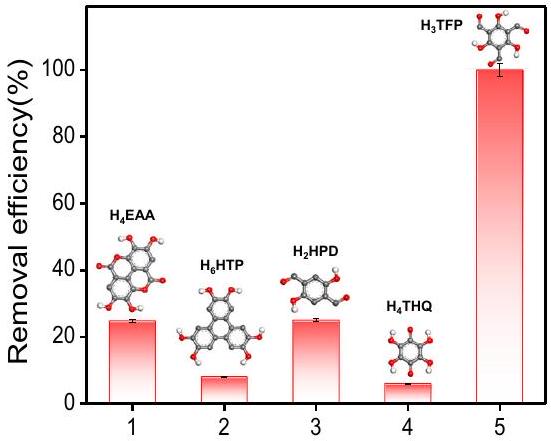

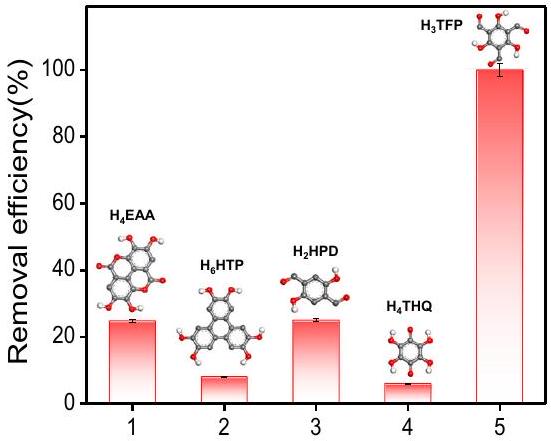

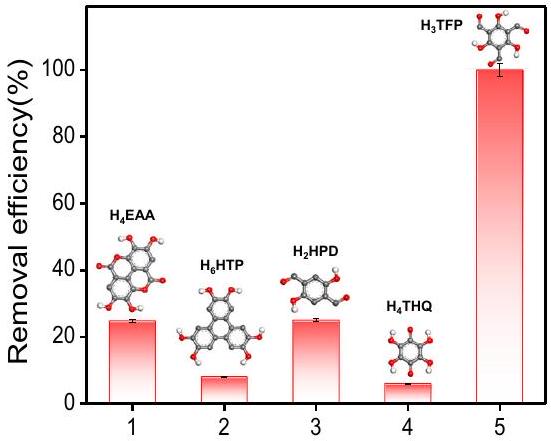

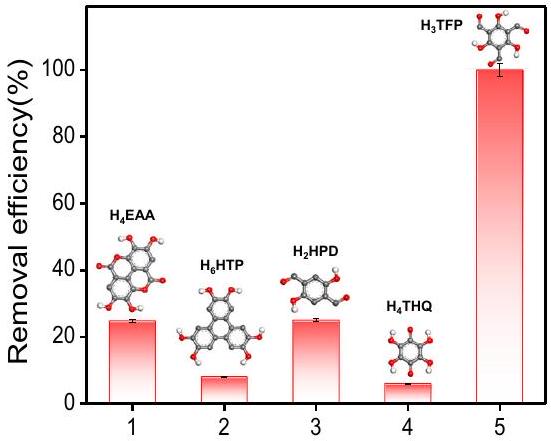

على التوالي. في هذا الصدد، قمنا بفحص خمسة من الروابط المتقاربة والمسطحة، المكونة من مركبات مكونة من ستة استبدالات

تعزيز تنسيق U-O وتكوين التنسيق المسطح على حساب التنسيق الخلاب من اثنين من الأكسجين الهيدروكسي (مثل

ديناميكا الامتزاز

السعة بين المبلغ عنها

سعة الامتزاز

تأثير الرقم الهيدروجيني

الانتقائية تجاه

لإحداث تأثير كبير على

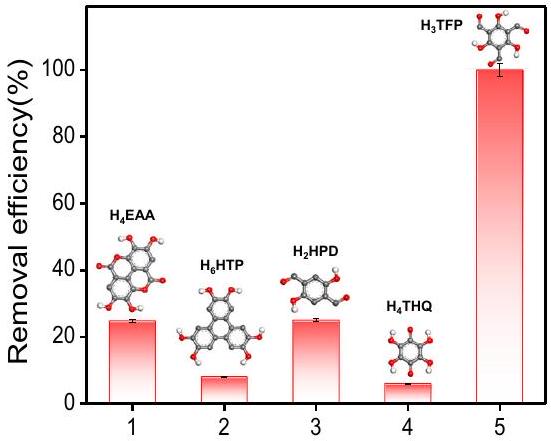

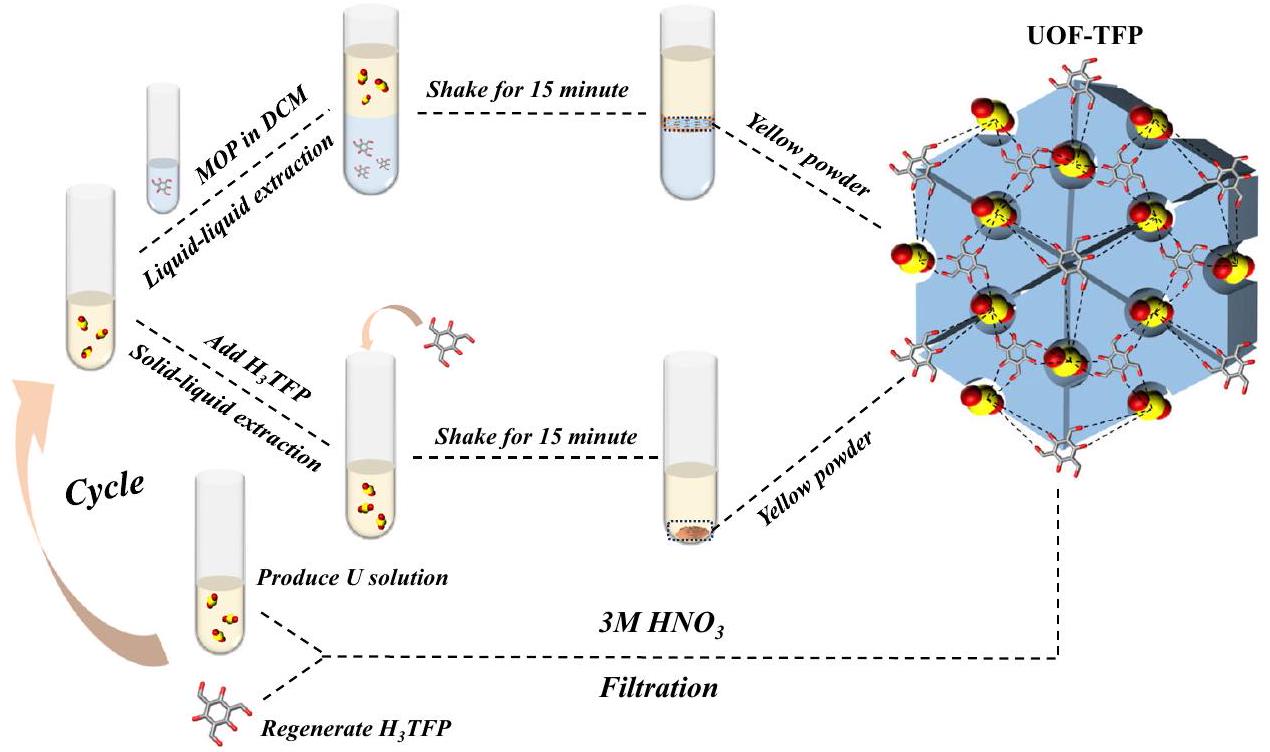

إعادة التدوير والاستخراج السائل-السائل

دورات الامتزاز-التحرر المتكررة (الشكل 4) 11 مرة (الشكل التكميلية 4).

استخراج اليورانيوم من مياه البحر

نقاش

آلية التقاط اليورانيوم

تجميع، في حين أن الآخرين

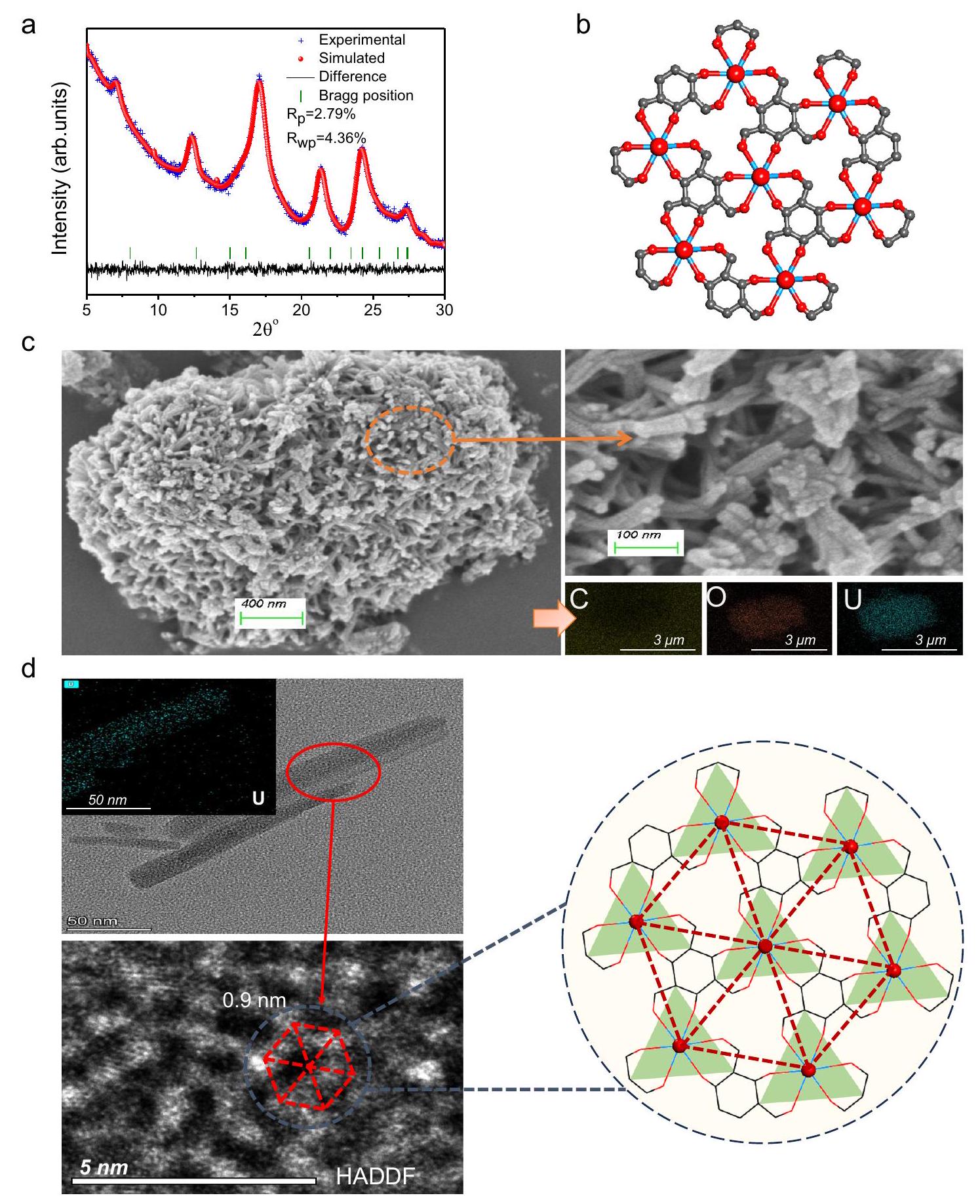

تخطيط UOF-TFP. صور STEM-HADDF و

مسافة حوالي 0.9 نانومتر بين اثنين متجاورين

و

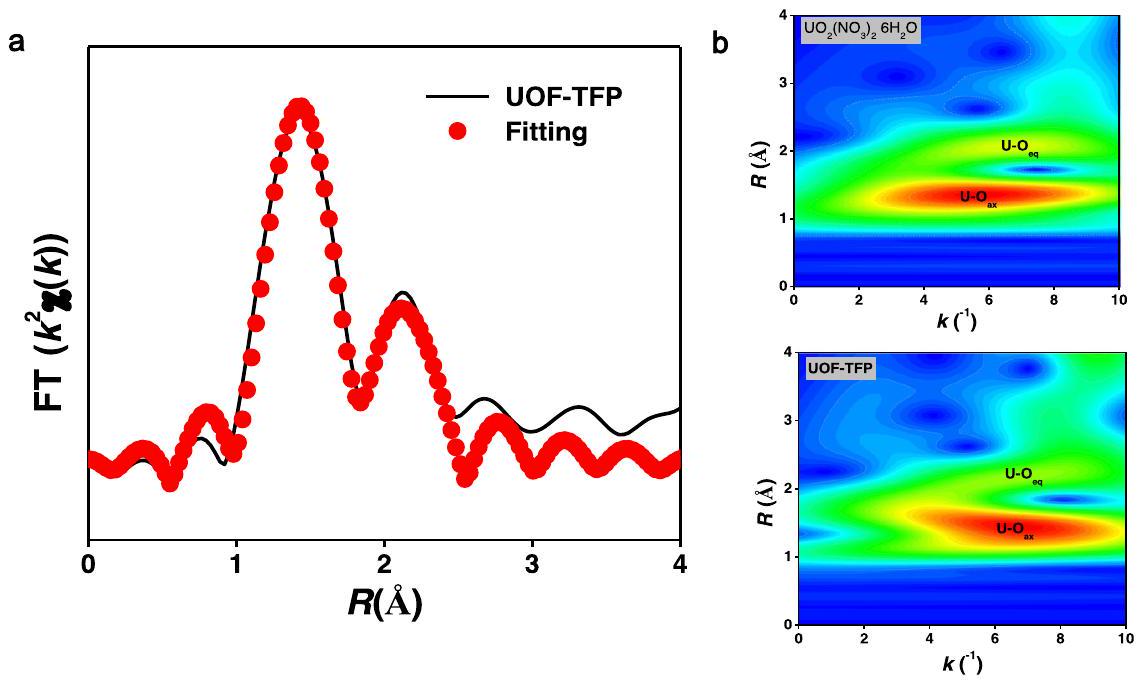

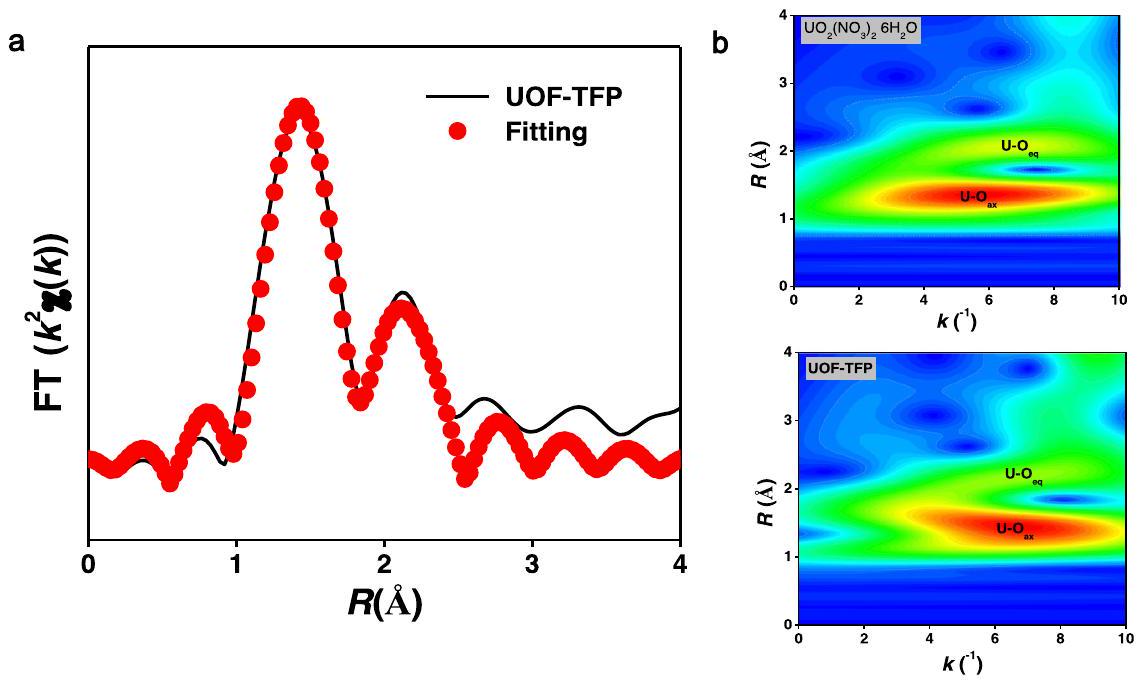

نتائج من بيانات EXAFS مع نتائج المحاكاة الهيكلية، ووجدت أن

طرق

المواد والقياسات

توفر البيانات

References

- Hoffert, M. I. et al. Energy implications of future stabilization of atmospheric

content. Nature 395, 881-884 (1998). - DeCanio, S. J. & Fremstad, A. Economic feasibility of the path to zero net carbon emissions. Energy Policy 39, 1144-1153 (2011).

- Nuclear key to a clean energy future: IEA World Energy Outlook (2016). https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2016.

- Nifenecker, H. Future electricity production methods. Part 1: Nuclear energy. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 022801 (2011).

- Sovacool, B. K. Valuing the greenhouse gas emissions from nuclear power: a critical survey. Energy Policy 36, 2940-2953 (2008).

- Craft, E. et al. Depleted and natural uranium: chemistry and toxicological effects. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 7, 297-317 (2004).

- Wang, D. et al. Significantly enhanced uranium extraction from seawater with mass produced fully amidoximated nanofiber adsorbent. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1802607 (2018).

- Sun, Q. et al. Covalent organic frameworks as a decorating platform for utilization and affinity enhancement of chelating sites for radionuclide sequestration. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705479 (2018).

- Sun, Q. et al. Bio-inspired nano-traps for uranium extraction from seawater and recovery from nuclear waste. Nat. Commun. 9, 1644 (2018).

- Wang, X. X. et al. Synthesis of novel nanomaterials and their application in efficient removal of radionuclides. Sci. China Chem. 62, 933-967 (2019).

- Yuan, Y. et al. Molecularly imprinted porous aromatic frameworks and their composite components for selective extraction of uranium ions. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706507 (2018).

- Li, J. et al. Metal-organic framework-based materials: superior adsorbents for the capture of toxic and radioactive metal ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 2322-2356 (2018).

- Zheng, T. et al. Overcoming the crystallization and designability issues in the ultrastable zirconium phosphonate framework system. Nat. Commun. 8, 15369 (2017).

- Yang, H. et al. Tuning local charge distribution in multicomponent covalent organic frameworks for dramatically enhanced photocatalytic uranium extraction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303129 (2023).

- Chen, Z. S. et al. Tuning excited state electronic structure and charge transport in covalent organic frameworks for enhanced photocatalytic performance. Nat. Commun. 14, 1106 (2023).

- Zhang, H. L. et al. Three mechanisms in one material: uranium capture by a polyoxometalate-organic framework through combined complexation, chemical reduction, and photocatalytic reduction. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 58, 16110-16114 (2019).

- Wang, Z. Y. et al. Constructing an ion pathway for uranium extraction from seawater. Chem 6, 1683-1691 (2020).

- Feng, L. J. et al. In situ synthesis of uranyl-imprinted nanocage for selective uranium recovery from seawater. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, 82-86 (2022).

- Cui, W. R. et al. Regenerable covalent organic frameworks for photo-enhanced uranium adsorption from seawater. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 17684-17690 (2020).

- Yuan, Y. et al. A molecular coordination template strategy for designing selective porous aromatic framework materials for uranyl capture. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 1432-1439 (2019).

- Yuan, Y. & Zhu, G. S. Porous aromatic frameworks as a platform for multifunctional applications. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 409-418 (2019).

- Kalaj, M. et al. MOF-polymer hybrid materials: from simple composites to tailored architectures. Chem. Rev. 120, 8267-8302 (2020).

- Yuan, Y. H. et al. A Bio-inspired nano-pocket spatial structure for targeting uranyl capture. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 4262-4268 (2020).

- Chen, Z. et al. N, P, and S codoped graphene-like carbon nanosheets for ultrafast uranium (VI) capture with high capacity. Adv. Sci. 5, 1800235 (2018).

- Yu, Q. H. et al. A universally applicable strategy for construction of anti-biofouling adsorbents for enhanced uranium recovery from seawater. Adv. Sci. 6, 1900002 (2019).

- Skorupskii, G. et al. Efficient and tunable one-dimensional charge transport in layered lanthanide metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 12, 131-136 (2020).

- Sheberla, D. et al. Conductive MOF electrodes for stable supercapacitors with high areal capacitance. Nat. Mater. 16, 220-224 (2016).

- Feng, D. W. et al. Robust and conductive two-dimensional metalorganic frameworks with exceptionally high volumetric and areal capacitance. Nat. Energy 3, 30-36 (2018).

- Dou, J. H. et al. Signature of metallic behavior in the metal-organic frameworks

(hexaiminobenzene) . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13608-13611 (2017). - Sheng, S. C. et al. A one-dimensional conductive metal-organic framework with extended

conjugated nanoribbon layers. Nat. Commun. 13, 7599 (2022). - Xing, G. L. et al. Conjugated nonplanar copper-catecholate conductive metal-organic frameworks via contorted hexabenzocoronene ligands for electrical conduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8979-8987 (2023).

- Lv, K., Fichter, S., Gu, M., März, J. & Schmidt, M. An updated status and trends in actinide metal-organic frameworks (An-MOFs): From synthesis to application. Coor. Chem. Rev. 446, 214011 (2021).

- Mei, S. et al. Assembling a heterobimetallic actinide metal-organic framework by a reaction-induced preorganization strategy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306360 (2023).

- Hanna, S. L. et al. Discovery of spontaneous de-interpenetration through charged point-point repulsions. Chem 8, 225-242 (2022).

- Zhang, Z. et al. Ultrafast interfacial self-assembly toward supramolecular metal-organic films for water desalination. Adv. Sci. 9, 2201624 (2022).

- Xie, L. S., Skorupskii, G. & Dincă, M. Electrically conductive metalorganic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 120, 8536-8580 (2020).

- Song, Y. P. et al. Nanospace decoration with uranyl-specific “hooks” for selective uranium extraction from seawater with ultrahigh enrichment index. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 1650 (2021).

- Wang, Z. Y. et al. Constructing uranyl-specific nanofluidic channels for unipolar ionic transport to realize ultrafast uranium extraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 14523-14529 (2021).

- Yuan, Y. H. et al. Charge balanced anti-adhesive polyacrylamidoxime hydrogel membrane for enhancing uranium extraction from seawater. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1805380 (2019).

- Mei, D. C., Liu, L. J. & Yan, B. Adsorption of uranium (VI) by metalorganic frameworks and covalent-organic frameworks from water. Coor. Chem. Rev. 475, 214917 (2023).

- Zhang, J. C. et al. Diaminomaleonitrile functionalized doubleshelled hollow MIL-101 (Cr) for selective removal of uranium from simulated seawater. Chem. Eng. J. 368, 951-958 (2019).

- Liu, R., Zhang, W., Chen, Y. T. & Wang, Y. S. Uranium (VI) adsorption by copper and copper/iron bimetallic central MOFs. Colloid Surf. A. 587, 124334 (2020).

- Niu, C. P. et al. A conveniently synthesized redox-active fluorescent covalent organic framework for selective detection and adsorption of uranium. J. Hazard. Mater. 425, 127951 (2022).

- Xiong, X. H. et al. Ammoniating covalent organic framework (COF) for high-performance and selective extraction of toxic and radioactive uranium ions. Adv. Sci. 6, 1900547 (2019).

- Xu, Y., Yu, Z. W., Zhang, Q. Y. & Luo, F. Sulfonic-pendent vinylenelinked covalent organic frameworks enabling benchmark potential in advanced energy. Adv. Sci. 10, 2300408 (2023).

- Yuan, Y. H. et al. Selective extraction of uranium from seawater with biofouling-resistant polymeric peptide. Nat. Sustain. 4, 708-714 (2021).

- Yang, L. S. et al. Bioinspired hierarchical porous membrane for efficient uranium extraction from seawater. Nat. Sustain. 5, 71-80 (2022).

- Wang, Y. L. et al. Umbellate distortions of the uranyl coordination environment result in a stable and porous polycatenated framework that can effectively remove cesium from aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6144-6147 (2015).

- Zhang, H. L. et al. Ultrafiltration separation of Am(VI)-polyoxometalate from lanthanides. Nature 616, 482-487 (2023).

- Wang, Y. X. et al. Emergence of uranium as a distinct metal center for building intrinsic X-ray scintillators. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 7883-7887 (2018).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44663-4.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© المؤلفون 2024

مدرسة الكيمياء وعلوم المواد، جامعة شرق الصين للتكنولوجيا، نانتشانغ 330013، الصين. المختبر الرئيسي لفيزياء وتكنولوجيا الواجهات، معهد شنغهاي للفيزياء التطبيقية، الأكاديمية الصينية للعلوم، شنغهاي 201800، الصين. المختبر الوطني الرئيسي لحماية NBC للمدنيين، بكين 100191، الصين. المركز الوطني للبحوث الهندسية لتخليق الكربوهيدرات، جامعة جيانغشي العادية، نانتشانغ 330027، الصين. – البريد الإلكتروني:ecitluofeng@163.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44663-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38212316

Publication Date: 2024-01-11

Ultra-selective uranium separation by in-situ formation of

Accepted: 19 December 2023

Published online: 11 January 2024

(A) Check for updates

Abstract

With the rapid development of nuclear energy, problems with uranium supply chain and nuclear waste accumulation have motivated researchers to improve uranium separation methods. Here we show a paradigm for such goal based on the in-situ formation of

physically and chemically similar

Results

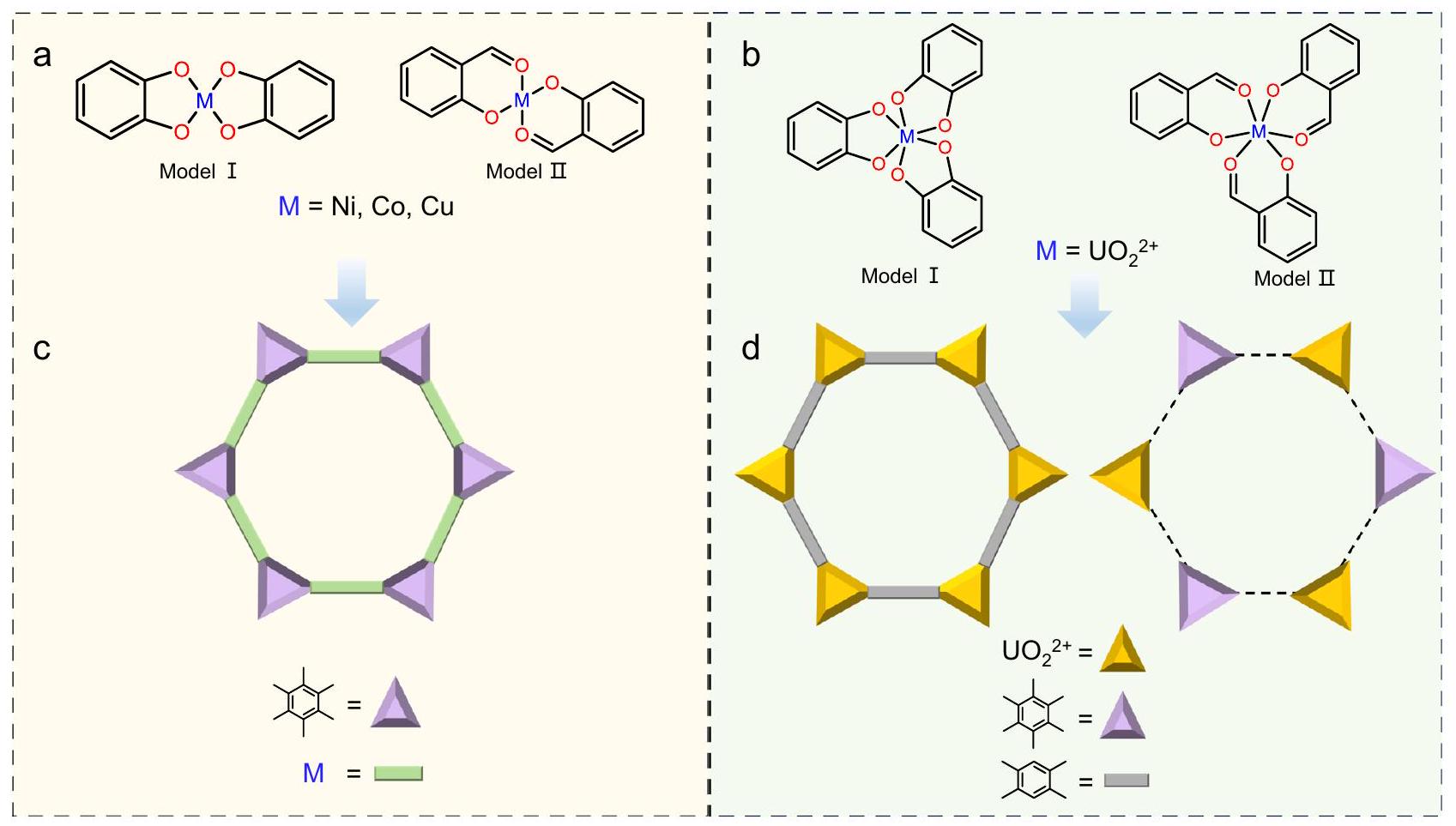

2D MOF and ligand design

respectively. In this regard, we screened five comparable, planar conjugated ligands, composed of hexa-substituted

strengthening U-O coordination and planar coordination configuration over the chelate coordination from two hydroxyl oxygens (such as

Adsorption kinetics

capacity between reported

Adsorption capacity

pH effect

Selectivity towards

to give significant effect on

Recycle use and liquid-liquid extraction

repeating adsorption-desorption cycles (Fig. 4) for 11 times (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Extraction of uranium from seawater

Discussion

Uranium capture mechanism

assembly, whereas other

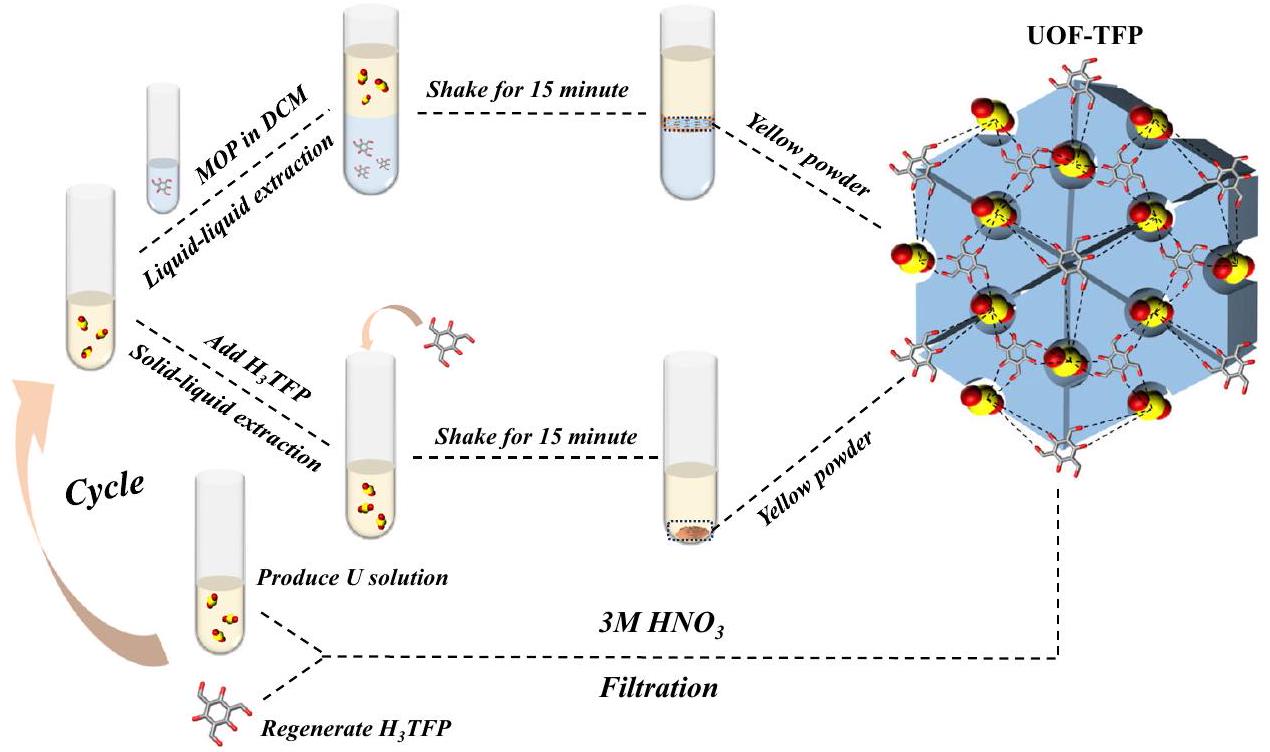

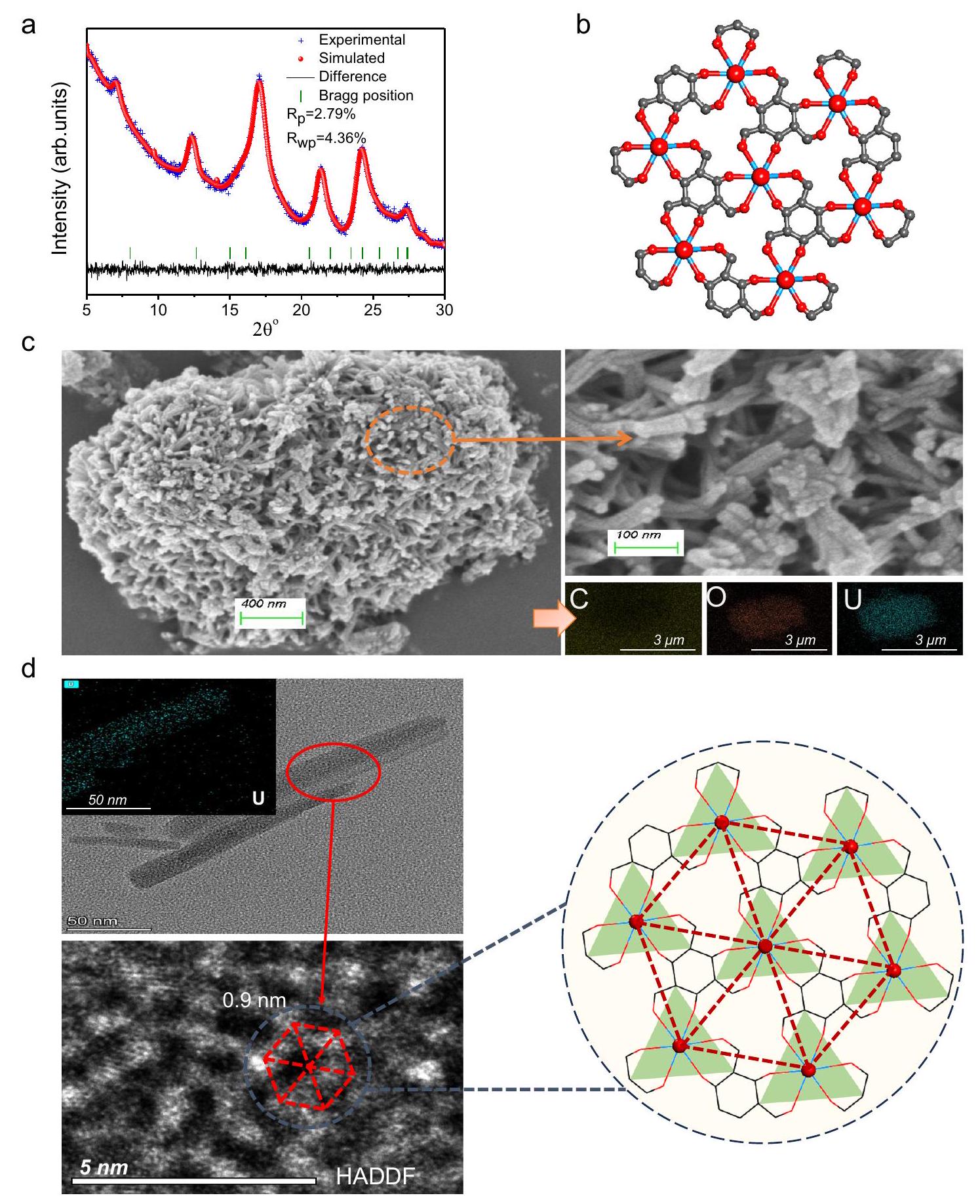

mapping of UOF-TFP. d STEM-HADDF images and

a distance of ca. 0.9 nm between two adjacent

and

results from EXAFS data with the results from structural simulation, and found that the

Methods

Materials and measurements

Data availability

References

- Hoffert, M. I. et al. Energy implications of future stabilization of atmospheric

content. Nature 395, 881-884 (1998). - DeCanio, S. J. & Fremstad, A. Economic feasibility of the path to zero net carbon emissions. Energy Policy 39, 1144-1153 (2011).

- Nuclear key to a clean energy future: IEA World Energy Outlook (2016). https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2016.

- Nifenecker, H. Future electricity production methods. Part 1: Nuclear energy. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 022801 (2011).

- Sovacool, B. K. Valuing the greenhouse gas emissions from nuclear power: a critical survey. Energy Policy 36, 2940-2953 (2008).

- Craft, E. et al. Depleted and natural uranium: chemistry and toxicological effects. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 7, 297-317 (2004).

- Wang, D. et al. Significantly enhanced uranium extraction from seawater with mass produced fully amidoximated nanofiber adsorbent. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1802607 (2018).

- Sun, Q. et al. Covalent organic frameworks as a decorating platform for utilization and affinity enhancement of chelating sites for radionuclide sequestration. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705479 (2018).

- Sun, Q. et al. Bio-inspired nano-traps for uranium extraction from seawater and recovery from nuclear waste. Nat. Commun. 9, 1644 (2018).

- Wang, X. X. et al. Synthesis of novel nanomaterials and their application in efficient removal of radionuclides. Sci. China Chem. 62, 933-967 (2019).

- Yuan, Y. et al. Molecularly imprinted porous aromatic frameworks and their composite components for selective extraction of uranium ions. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706507 (2018).

- Li, J. et al. Metal-organic framework-based materials: superior adsorbents for the capture of toxic and radioactive metal ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 2322-2356 (2018).

- Zheng, T. et al. Overcoming the crystallization and designability issues in the ultrastable zirconium phosphonate framework system. Nat. Commun. 8, 15369 (2017).

- Yang, H. et al. Tuning local charge distribution in multicomponent covalent organic frameworks for dramatically enhanced photocatalytic uranium extraction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303129 (2023).

- Chen, Z. S. et al. Tuning excited state electronic structure and charge transport in covalent organic frameworks for enhanced photocatalytic performance. Nat. Commun. 14, 1106 (2023).

- Zhang, H. L. et al. Three mechanisms in one material: uranium capture by a polyoxometalate-organic framework through combined complexation, chemical reduction, and photocatalytic reduction. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 58, 16110-16114 (2019).

- Wang, Z. Y. et al. Constructing an ion pathway for uranium extraction from seawater. Chem 6, 1683-1691 (2020).

- Feng, L. J. et al. In situ synthesis of uranyl-imprinted nanocage for selective uranium recovery from seawater. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, 82-86 (2022).

- Cui, W. R. et al. Regenerable covalent organic frameworks for photo-enhanced uranium adsorption from seawater. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 17684-17690 (2020).

- Yuan, Y. et al. A molecular coordination template strategy for designing selective porous aromatic framework materials for uranyl capture. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 1432-1439 (2019).

- Yuan, Y. & Zhu, G. S. Porous aromatic frameworks as a platform for multifunctional applications. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 409-418 (2019).

- Kalaj, M. et al. MOF-polymer hybrid materials: from simple composites to tailored architectures. Chem. Rev. 120, 8267-8302 (2020).

- Yuan, Y. H. et al. A Bio-inspired nano-pocket spatial structure for targeting uranyl capture. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 4262-4268 (2020).

- Chen, Z. et al. N, P, and S codoped graphene-like carbon nanosheets for ultrafast uranium (VI) capture with high capacity. Adv. Sci. 5, 1800235 (2018).

- Yu, Q. H. et al. A universally applicable strategy for construction of anti-biofouling adsorbents for enhanced uranium recovery from seawater. Adv. Sci. 6, 1900002 (2019).

- Skorupskii, G. et al. Efficient and tunable one-dimensional charge transport in layered lanthanide metal-organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 12, 131-136 (2020).

- Sheberla, D. et al. Conductive MOF electrodes for stable supercapacitors with high areal capacitance. Nat. Mater. 16, 220-224 (2016).

- Feng, D. W. et al. Robust and conductive two-dimensional metalorganic frameworks with exceptionally high volumetric and areal capacitance. Nat. Energy 3, 30-36 (2018).

- Dou, J. H. et al. Signature of metallic behavior in the metal-organic frameworks

(hexaiminobenzene) . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13608-13611 (2017). - Sheng, S. C. et al. A one-dimensional conductive metal-organic framework with extended

conjugated nanoribbon layers. Nat. Commun. 13, 7599 (2022). - Xing, G. L. et al. Conjugated nonplanar copper-catecholate conductive metal-organic frameworks via contorted hexabenzocoronene ligands for electrical conduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8979-8987 (2023).

- Lv, K., Fichter, S., Gu, M., März, J. & Schmidt, M. An updated status and trends in actinide metal-organic frameworks (An-MOFs): From synthesis to application. Coor. Chem. Rev. 446, 214011 (2021).

- Mei, S. et al. Assembling a heterobimetallic actinide metal-organic framework by a reaction-induced preorganization strategy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306360 (2023).

- Hanna, S. L. et al. Discovery of spontaneous de-interpenetration through charged point-point repulsions. Chem 8, 225-242 (2022).

- Zhang, Z. et al. Ultrafast interfacial self-assembly toward supramolecular metal-organic films for water desalination. Adv. Sci. 9, 2201624 (2022).

- Xie, L. S., Skorupskii, G. & Dincă, M. Electrically conductive metalorganic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 120, 8536-8580 (2020).

- Song, Y. P. et al. Nanospace decoration with uranyl-specific “hooks” for selective uranium extraction from seawater with ultrahigh enrichment index. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 1650 (2021).

- Wang, Z. Y. et al. Constructing uranyl-specific nanofluidic channels for unipolar ionic transport to realize ultrafast uranium extraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 14523-14529 (2021).

- Yuan, Y. H. et al. Charge balanced anti-adhesive polyacrylamidoxime hydrogel membrane for enhancing uranium extraction from seawater. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1805380 (2019).

- Mei, D. C., Liu, L. J. & Yan, B. Adsorption of uranium (VI) by metalorganic frameworks and covalent-organic frameworks from water. Coor. Chem. Rev. 475, 214917 (2023).

- Zhang, J. C. et al. Diaminomaleonitrile functionalized doubleshelled hollow MIL-101 (Cr) for selective removal of uranium from simulated seawater. Chem. Eng. J. 368, 951-958 (2019).

- Liu, R., Zhang, W., Chen, Y. T. & Wang, Y. S. Uranium (VI) adsorption by copper and copper/iron bimetallic central MOFs. Colloid Surf. A. 587, 124334 (2020).

- Niu, C. P. et al. A conveniently synthesized redox-active fluorescent covalent organic framework for selective detection and adsorption of uranium. J. Hazard. Mater. 425, 127951 (2022).

- Xiong, X. H. et al. Ammoniating covalent organic framework (COF) for high-performance and selective extraction of toxic and radioactive uranium ions. Adv. Sci. 6, 1900547 (2019).

- Xu, Y., Yu, Z. W., Zhang, Q. Y. & Luo, F. Sulfonic-pendent vinylenelinked covalent organic frameworks enabling benchmark potential in advanced energy. Adv. Sci. 10, 2300408 (2023).

- Yuan, Y. H. et al. Selective extraction of uranium from seawater with biofouling-resistant polymeric peptide. Nat. Sustain. 4, 708-714 (2021).

- Yang, L. S. et al. Bioinspired hierarchical porous membrane for efficient uranium extraction from seawater. Nat. Sustain. 5, 71-80 (2022).

- Wang, Y. L. et al. Umbellate distortions of the uranyl coordination environment result in a stable and porous polycatenated framework that can effectively remove cesium from aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6144-6147 (2015).

- Zhang, H. L. et al. Ultrafiltration separation of Am(VI)-polyoxometalate from lanthanides. Nature 616, 482-487 (2023).

- Wang, Y. X. et al. Emergence of uranium as a distinct metal center for building intrinsic X-ray scintillators. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 7883-7887 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44663-4.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© The Author(s) 2024

School of Chemistry and Materials Science, East China University of Technology, Nanchang 330013, China. Key Laboratory of Interfacial Physics and Technology, Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 201800, China. State Key Laboratory of NBC Protection for Civilian, Beijing 100191, China. National Engineering Research Center for Carbonhydrate Synthesis, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang 330027, China. – e-mail: ecitluofeng@163.com