DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-024-00956-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39877429

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-15

فضاء التصميم للجهود بين الذرات المركزية حول الذرات المتساوية E(3)

نُشر على الإنترنت: 15 يناير 2025

تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

محاكاة الديناميكا الجزيئية هي أداة مهمة في علوم المواد الحاسوبية والكيمياء، وفي العقد الماضي تم إحداث ثورة فيها بواسطة التعلم الآلي. لقد أنتج هذا التقدم السريع في إمكانيات التفاعل بين الذرات عددًا من الهياكل الجديدة في السنوات القليلة الماضية. ومن بين هذه الهياكل، يُعتبر توسيع الكتل الذرية بارزًا، حيث وحد العديد من الأفكار السابقة حول الوصف القائم على كثافة الذرات، وPotentials Interatomic Equivariant Neural (NequIP)، وهو شبكة عصبية تمرير الرسائل مع ميزات متساوية أظهرت دقة متقدمة في ذلك الوقت. هنا نقوم ببناء إطار رياضي يوحد هذه النماذج: يتم توسيع توسيع الكتل الذرية وإعادة صياغته كطبقة واحدة من هيكل متعدد الطبقات، بينما يُفهم النسخة الخطية من NequIP كنوع معين من التبسيط لنموذج متعدد الحدود أكبر بكثير. يوفر إطارنا أيضًا أداة عملية لاستكشاف خيارات مختلفة بشكل منهجي في هذه المساحة التصميمية الموحدة. دراسة إلغاء NequIP، من خلال مجموعة من التجارب التي تبحث في دقة النطاقين الداخلي والخارجي والتقدير السلس بعيدًا جدًا عن بيانات التدريب، تسلط بعض الضوء على الخيارات التصميمية الحرجة لتحقيق دقة عالية. نسخة مبسطة جدًا من NequIP، التي نسميها BOTnet (شبكة موتر مرتبة حسب الجسم)، لها هيكل قابل للتفسير وتحافظ على دقتها في مجموعات البيانات المرجعية.

تباديل الذرات من نفس العنصر في البيئة

متعدد-ACE

ترابط القنوات

|

|

تحديث

|

|

|

ترتيب الارتباط الكلي |

|

التزاوج (ف) | |

| صابون

|

|

0 | ٢ | 1 |

|

|

|

| ACE الخطي

|

|

0 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

| تتبع

|

|

0 |

|

1 |

|

|

لم |

| شنت

|

0 | 0 | 1 |

|

|

|

|

| دايم نت

|

0 | 0 | ٢ |

|

2T |

|

|

| الغطاس

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

| نيكولب

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

| جيم نت

|

|

|

٣ |

|

|

|

|

| مايس

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| نيوتن نت

|

1 | 1 | 1 |

|

|

المتجهات الكارتيزية | – |

| EGNN

|

1 | 1 | 1 |

|

|

المتجهات الكارتيزية | – |

| باين

|

1 | 1 | 1 |

|

|

المتجهات الكارتيزية | – |

| تورش إم دي-نت

|

1 | 1 | 1 |

|

|

المتجهات الكارتيزية | – |

تفسير النماذج كـ Multi-ACE

تمرير الرسائل كطريقة مستوحاة كيميائيًا للتقليل من الكثافة

|

|

16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | |

| عدد المعلمات | ٤٣٧,٣٣٦ | 1,130,648 | 3,415,832 | 11,580,440 | |

| 300 ألف |

|

3.7 | 3.1 | 3.0 (0.2) | 2.9 |

|

|

12.9 | 11.9 | 11.6 (0.2) | 10.6 | |

| 600 ألف |

|

12.9 | 12.7 | 11.9 (1.1) | 10.7 |

|

|

٣٢.١ | 30.3 | ٢٩.٤ (٠.٨) | ٢٦.٩ | |

| 1,200,000 |

|

٤٨.٦ | ٤٩.٥ | ٤٩.٨ (٤.٠) | ٤٦.٠ |

|

|

١٠٤.٢ | 101.6 | 97.1 (5.6) | 86.6 | |

الخيارات في فضاء تصميم الإمكانات بين الذرات المتكافئة

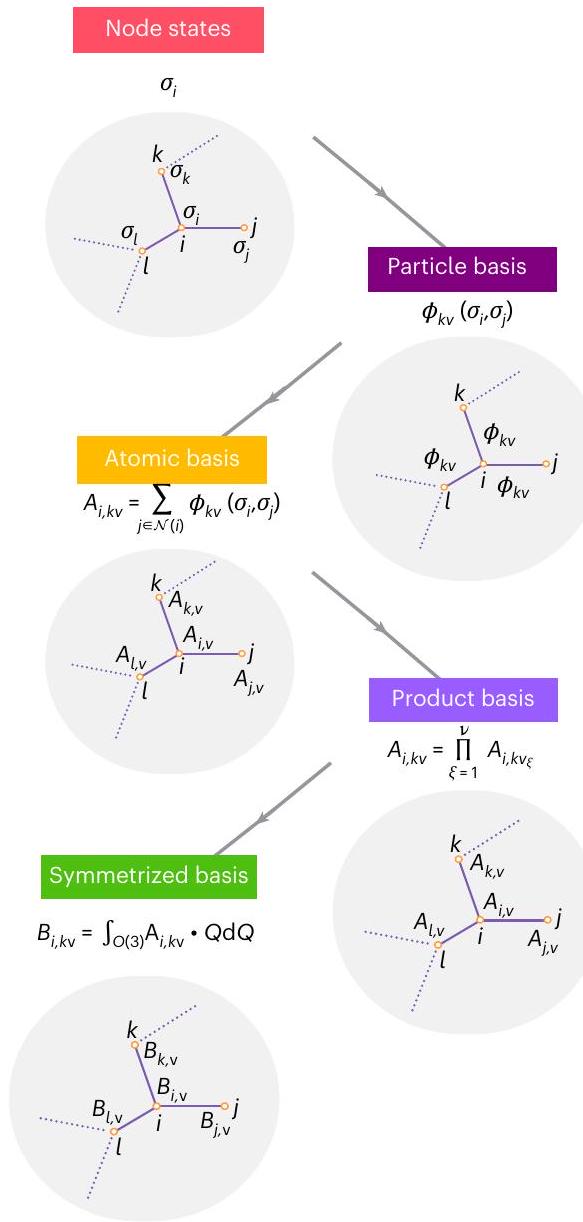

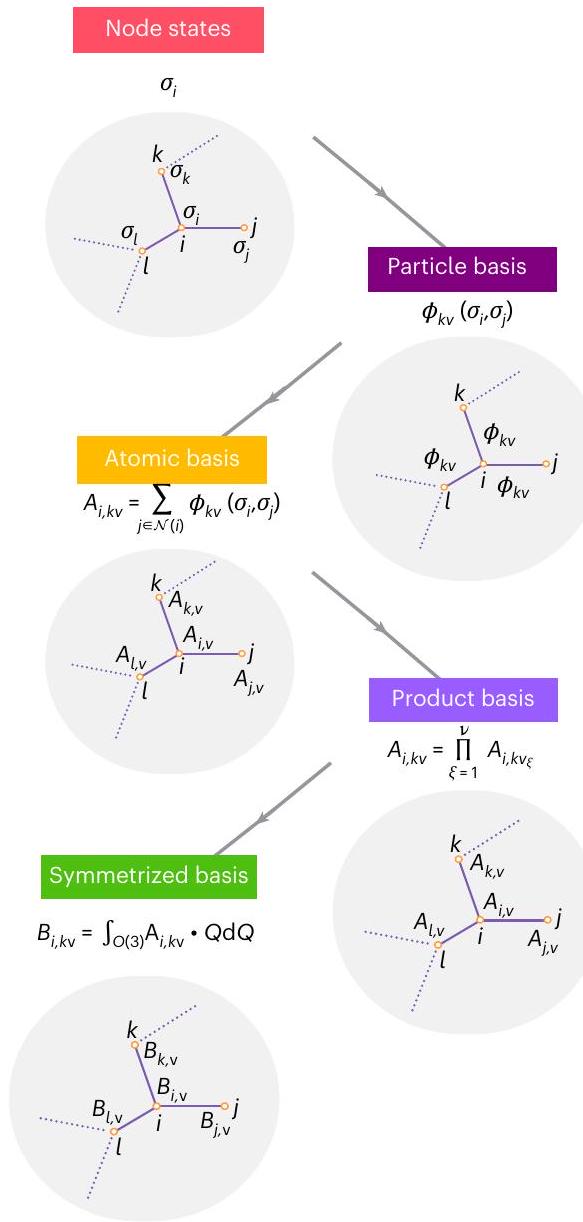

أساس الجسيم الواحد

| نموذج | نيكويب تان | نيكويب سيلو | نيكويب الخطي | شبكة بوت خطية | شبكة الروبوتات | |

| رمز | شبكة الروبوتات | نيكويب | شبكة الروبوتات | شبكة الروبوتات | شبكة الروبوتات | |

| 300 ألف |

|

٤.٨ | 3.0 (0.2) | 3.7 | ٣.٣ | 3.1 (0.13) |

|

|

18.5 | 11.6 (0.2) | 13.9 | 12.0 | 11.0 (0.14) | |

| 600 ك |

|

٢٠.١ | 11.9 (1.1) | 15.4 | 11.8 | 11.5 (0.6) |

|

|

42.5 | ٢٩.٤ (٠.٨) | ٣٤.١ | 30.0 | ٢٦.٧ (٠.٢٩) | |

| 1,200 ألف |

|

75.7 | ٤٩.٨ (٤.٠) | 61.92 | 53.7 | ٣٩.١ (١.١) |

|

|

156.1 | ٩٧.١ (٥.٦) | ١٠٩.٥ | 97.8 | 81.1 (1.5) | |

تعتمد على العناصر الكيميائية للذرتين، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار الفروق في أنصاف الأقطار الذرية.

تنشيطات غير خطية

لتكون مفيدة لأنها تعزز تعلم التمثيلات ذات الأبعاد المنخفضة للبيانات، وهو انحياز استقرائي ممتاز لتحسين الاستقراء. في ما يلي، نقوم بتحليل تفعيلات غير الخطية المختلفة وتأثيراتها على ترتيب الجسم.

من المحتمل أن يكون ذلك لأن دالة التانجنت المائل (tanh) لديها تدرج يساوي 0 للإدخالات الكبيرة الموجبة والسالبة، مما يجعل عملية التحسين صعبة بسبب تلاشي التدرجات.

نقاش

طرق

ACE المتساوي مع تضمين مستمر وقنوات غير مرتبطة

الأساس الناتج هو أساس كامل من الدوال الثابتة تحت التبديل لبيئة الذرات.

إمكانات MPNN

الدول شبه المحلية

صيغة تمرير الرسائل

رسائل متكافئة

الإحداثيات الكروية. هذا يتماشى مع العديد من النماذج المتكافئة مثل SOAP-GAP

رسائل مرتبة حسب الجسم

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Musil, F. et al. Physics-inspired structural representations for molecules and materials. Chem. Rev. 121, 9759-9815 (2021).

- Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

- Bartók, A. P., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. On representing chemical environments. Phys. Rev. B 87, 184115 (2013).

- Behler, J. Four generations of high-dimensional neural network potentials. Chem. Rev. 121, 10037-10072 (2021).

- Deringer, V. L. et al. Gaussian process regression for materials and molecules. Chem. Rev. 121, 10073-10141 (2021).

- Cheng, B. et al. Mapping materials and molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1981-1991 (2020).

- Drautz, R. Atomic cluster expansion for accurate and transferable interatomic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 99, 014104 (2019).

- Dusson, G. et al. Atomic cluster expansion: completeness, efficiency and stability. J. Comput. Phys. 454, 110946 (2022).

- Bartók, A. P., Payne, M. C., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. Gaussian approximation potentials: the accuracy of quantum mechanics, without the electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 136403 (2010).

- Shapeev, A. V. Moment tensor potentials: a class of systematically improvable interatomic potentials. Multisc. Model. Sim. 14, 1153-1173 (2016).

- Drautz, R. Atomic cluster expansion of scalar, vectorial, and tensorial properties including magnetism and charge transfer. Phys. Rev. B 102, 024104 (2020).

- Kovács, D. P. et al. Linear atomic cluster expansion force fields for organic molecules: beyond RMSE. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 17, 7696-7711 (2021).

- Keith, J. A. et al. Combining machine learning and computational chemistry for predictive insights into chemical systems. Chem. Rev. 121, 9816-9872 (2021).

- Faber, F. A., Christensen, A. S., Huang, B. & von Lilienfeld, O. A. Alchemical and structural distribution based representation for universal quantum machine learning. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 241717 (2018).

- Zhu, L. et al. A fingerprint based metric for measuring similarities of crystalline structures. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 034203 (2016).

- Schütt, K. et al. SchNet: a continuous-filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 30 (eds Guyon, I. et al.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017); https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/ file/303ed4c69846ab36c2904d3ba8573050-Paper.pdf

- Gilmer, J., Schoenholz, S. S., Riley, P. F., Vinyals, O. & Dahl, G. E. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. In Proc. 34th International Conference on Machine Learning Vol. 70 (eds Precup, D. & Teh, Y. W.) 1263-1272 (PMLR, 2017); https://proceedings.mlr. press/v70/gilmer17a.html

- Unke, O. T. & Meuwly, M. PhysNet: a neural network for predicting energies, forces, dipole moments, and partial charges. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 15, 3678-3693 (2019).

- Gasteiger, J., Groß, J. & Günnemann, S. Directional message passing for molecular graphs. In Proc. International Conference on Leaning Representations (2020); https://iclr.cc/virtual_2020/ poster_B1eWbxStPH.html

- Anderson, B., Hy, T. S. & Kondor, R. Cormorant: covariant molecular neural networks. In Proc. 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Larochelle, H. et al.) (Curran Associates, 2019); https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2019/file/ 03573b32b2746e6e8ca98b9123f2249b-Paper.pdf

- Thomas, N. et al. Tensor field networks: rotation- and translationequivariant neural networks for 3d point clouds. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1802.08219 (2018).

- Weiler, M., Geiger, M., Welling, M., Boomsma, W. & Cohen, T. 3D steerable CNNs: learning rotationally equivariant features in volumetric data. In Proc. 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Bengio, S. et al.) (Curran Associates, 2018).

- Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

- Satorras, V. G., Hoogeboom, E. & Welling, M. E(n) equivariant graph neural networks. In Proc. 38th International Conference on Machine Learning Vol. 139 (eds Meila, M. & Zhang, T.) 9323-9332 (PMLR, 2021).

- Schütt, K. T., Unke, O. T. & Gastegger, M. Equivariant message passing for the prediction of tensorial properties and molecular spectra. In Proc. 38th International Conference on Machine Learning Vol. 139 (eds Meila, M. & Zhang, T.) 9377-9388 (PMLR, 2021).

- Haghighatlari, M. et al. NewtonNet: a Newtonian message passing network for deep learning of interatomic potentials and forces. Digit. Discov. 1, 333-343 (2022).

- Klicpera, J., Becker, F. & Günnemann, S. Gemnet: universal directional graph neural networks for molecules. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (NeurIPS 2021) (eds Ranzato, M. et al.) 6790-6802 (Curran Associates, 2021).

- Thölke, P. & Fabritiis, G. D. Equivariant transformers for neural network based molecular potentials. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2022); https://openreview.net/ forum?id=zNHzqZ9wrRB

- Brandstetter, J., Hesselink, R., van der Pol, E., Bekkers, E. J. & Welling, M. Geometric and physical quantities improve

- Musaelian, A. et al. Learning local equivariant representations for large-scale atomistic dynamics. Nat. Commun. 14, 579 (2023).

- Kondor, R. N-body networks: a covariant hierarchical neural network architecture for learning atomic potentials. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.01588 (2018).

- Batatia, I. et al. The design space of E(3)-equivariant atom-centered interatomic potentials. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/abs/2205.06643 (2022).

- Nigam, J., Pozdnyakov, S., Fraux, G. & Ceriotti, M. Unified theory of atom-centered representations and message-passing machine-learning schemes. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 204115 (2022).

- Bochkarev, A., Lysogorskiy, Y., Ortner, C., Csányi, G. & Drautz, R. Multilayer atomic cluster expansion for semilocal interactions. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, LO42O19 (2022).

- Batatia, I., Kovacs, D. P., Simm, G. N. C., Ortner, C. & Csanyi, G. MACE: Higher order equivariant message passing neural networks for fast and accurate force fields. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS2O22) (eds Koyejo,S. et al.) Curran Associates, 2022); https://proceedings.neurips.cc/ paper_files/paper/2022/hash/4a36c3c51af11ed9f34615b81ed b5bbc-Abstract-Conference.html

- Batatia, I. et al. Code for the paper titled “The Design Space of E(3)-Equivariant Atom-Centered Interatomic Potentials”. Github https://github.com/gncs/botnet/tree/v1.0.1 (2024).

- Darby, J. P. et al. Tensor-reduced atomic density representations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 028001 (2023).

- Allen-Zhu, Z., Li, Y. & Liang, Y. Learning and generalization in overparameterized neural networks, going beyond two layers. In Neural Information Processing Systems (2018).

- Lopanitsyna, N., Fraux, G., Springer, M. A., De, S. & Ceriotti, M. Modeling high-entropy transition metal alloys with alchemical compression. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 045802 (2023).

- Thompson, A., Swiler, L., Trott, C., Foiles, S. & Tucker, G. Spectral neighbor analysis method for automated generation of quantumaccurate interatomic potentials. J. Comput. Phys. 285, 316-330 (2015).

- Caro, M. A. Optimizing many-body atomic descriptors for enhanced computational performance of machine learning based interatomic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 100, 024112 (2019).

- Musil, F. et al. Efficient implementation of atom-density representations. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 114109 (2021).

- Himanen, L. et al. DScribe: library of descriptors for machine learning in materials science. Comp. Phys. Commun. 247, 106949 (2020).

- Goscinski, A., Musil, F., Pozdnyakov, S., Nigam, J. & Ceriotti, M. Optimal radial basis for density-based atomic representations. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 104106 (2021).

- Bigi, F., Huguenin-Dumittan, K. K., Ceriotti, M. & Manolopoulos, D. E. A smooth basis for atomistic machine learning. J. Chem. Phys. 157, 243101 (2022).

- Witt, W. C. et al. ACEpotentials.jl: a Julia implementation of the atomic cluster expansion. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 164101 (2023); https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jcp/article/159/16/164101/2918010/ ACEpotentials-jl-A-Julia-implementation-of-the

- Goscinski, A., Musil, F., Pozdnyakov, S., Nigam, J. & Ceriotti, M. Optimal radial basis for density-based atomic representations. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 104106 (2021).

- Bochkarev, A. et al. Efficient parametrization of the atomic cluster expansion. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 013804 (2022).

- Elfwing, S., Uchibe, E. & Doya, K. Sigmoid-weighted linear units for neural network function approximation in reinforcement learning. Neural Networks 107, 3-11 (2018); https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.neunet.2017.12.012

- Lysogorskiy, Y. et al. Performant implementation of the atomic cluster expansion (PACE) and application to copper and silicon. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 97 (2021).

- Kaliuzhnyi, I. & Ortner, C. Optimal evaluation of symmetry-adapted

- Zhang, L. et al. Equivariant analytical mapping of first principles Hamiltonians to accurate and transferable materials models. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 158 (2022); https://www.nature.com/articles/ s41524-022-00843-2

- Nigam, J., Pozdnyakov, S. & Ceriotti, M. Recursive evaluation and iterative contraction of

- Battaglia, P. W. et al. Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.01261 (2018).

- Bronstein, M. M., Bruna, J., Cohen, T. & Velićković, P. Geometric deep learning: grids, groups, graphs, geodesics, and gauges. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.13478 (2021).

- Weyl, H. The Classical Groups: Their Invariants and Representations (Princeton Univ. Press, 1939).

- Thomas, J., Chen, H. & Ortner, C. Body-ordered approximations of atomic properties. Arch. Rational Mech. Anal. 246, 1-60 (2022); https://doi.org/10.1007/s00205-022-01809-w

- Drautz, R. & Pettifor, D. G. Valence-dependent analytic bond-order potential for transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 74, 174117 (2006).

- van der Oord, C., Dusson, G., Csányi, G. & Ortner, C. Regularised atomic body-ordered permutation-invariant polynomials for the construction of interatomic potentials. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 1, 015004 (2020).

- Drautz, R., Fähnle, M. & Sanchez, J. M. General relations between many-body potentials and cluster expansions in multicomponent systems. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 16, 3843 (2004).

- Kovács, D. P. et al. BOTNet datasets: v0.1.O. Zenodo https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo. 14013500 (2024).

- Musaelian, M. et al. NEquIP: v0.5.4. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ zenodo. 14013469 (2024).

- Geiger, M. et al. E3NN v0.5.4. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ zenodo. 5292912 (2020).

- Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: an imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 32 (eds Wallach, H. et al.) 8026-8037 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2019).

- Sim, G. & Batatia, I. Body-ordered Tensor Network (BOTNet). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14052468 (2024).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

وحدد ما إذا تم إجراء تغييرات. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، فسيتعين عليك الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذا الترخيص، قم بزيارةhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/بواسطة/4.0/.

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2025

| شنت | نيكويب | ACE الخطي | |

| وظيفة الرسالة

|

|

|

|

| تجميع متماثل

|

|

|

|

| وظيفة التحديث

|

|

|

– |

- ¹مختبر الهندسة، جامعة كامبريدج، كامبريدج، المملكة المتحدة. ²قسم الكيمياء، ENS باريس-ساكلاي، جامعة باريس-ساكلاي، غيف-سور-إيفيت، فرنسا.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-024-00956-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39877429

Publication Date: 2025-01-15

The design space of E(3)-equivariant atom-centred interatomic potentials

Published online: 15 January 2025

Check for updates

Abstract

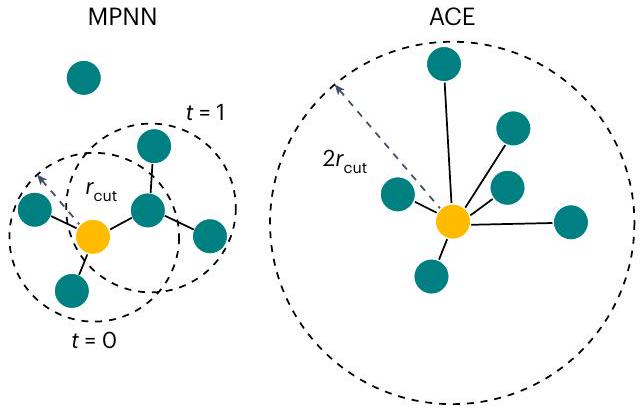

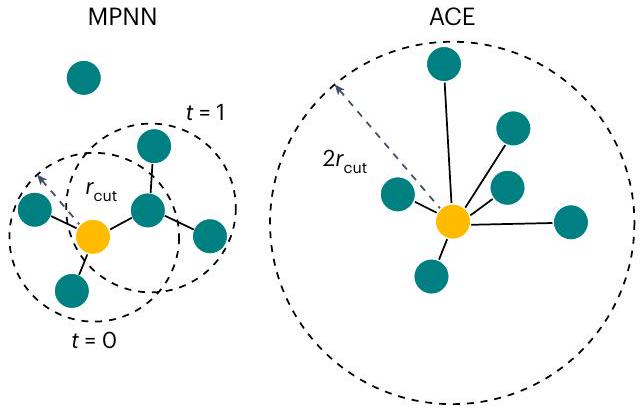

Molecular dynamics simulation is an important tool in computational materials science and chemistry, and in the past decade it has been revolutionized by machine learning. This rapid progress in machine learning interatomic potentials has produced a number of new architectures in just the past few years. Particularly notable among these are the atomic cluster expansion, which unified many of the earlier ideas around atom-density-based descriptors, and Neural Equivariant Interatomic Potentials (NequIP), a message-passing neural network with equivariant features that exhibited state-of-the-art accuracy at the time. Here we construct a mathematical framework that unifies these models: atomic cluster expansion is extended and recast as one layer of a multi-layer architecture, while the linearized version of NequIP is understood as a particular sparsification of a much larger polynomial model. Our framework also provides a practical tool for systematically probing different choices in this unified design space. An ablation study of NequIP, via a set of experiments looking at in- and out-of-domain accuracy and smooth extrapolation very far from the training data, sheds some light on which design choices are critical to achieving high accuracy. A much-simplified version of NequIP, which we call BOTnet (for body-ordered tensor network), has an interpretable architecture and maintains its accuracy on benchmark datasets.

permutations of atoms of the same element in the environment

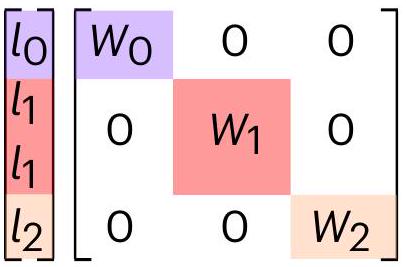

Multi-ACE

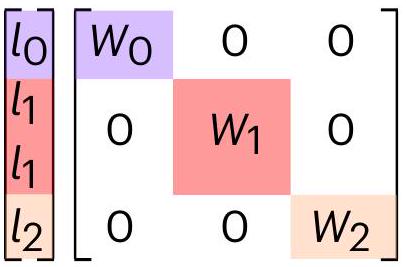

Coupling of channels

|

|

Update

|

|

|

Total correlation order |

|

Coupling (v) | |

| SOAP

|

|

0 | 2 | 1 |

|

|

|

| Linear ACE

|

|

0 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

| TrACE

|

|

0 |

|

1 |

|

|

lm |

| SchNet

|

0 | 0 | 1 |

|

|

|

|

| DimeNet

|

0 | 0 | 2 |

|

2T |

|

|

| Cormorant

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

| NequlP

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

| GemNet

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

| MACE

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NewtonNet

|

1 | 1 | 1 |

|

|

Cartesian vectors | – |

| EGNN

|

1 | 1 | 1 |

|

|

Cartesian vectors | – |

| PaINN

|

1 | 1 | 1 |

|

|

Cartesian vectors | – |

| TorchMD-Net

|

1 | 1 | 1 |

|

|

Cartesian vectors | – |

Interpreting models as Multi-ACE

Message passing as a chemically inspired sparsification

|

|

16 | 32 | 64 | 128 | |

| Number of parameters | 437,336 | 1,130,648 | 3,415,832 | 11,580,440 | |

| 300K |

|

3.7 | 3.1 | 3.0 (0.2) | 2.9 |

|

|

12.9 | 11.9 | 11.6 (0.2) | 10.6 | |

| 600K |

|

12.9 | 12.7 | 11.9 (1.1) | 10.7 |

|

|

32.1 | 30.3 | 29.4 (0.8) | 26.9 | |

| 1,200K |

|

48.6 | 49.5 | 49.8 (4.0) | 46.0 |

|

|

104.2 | 101.6 | 97.1 (5.6) | 86.6 | |

Choices in the equivariant interatomic potential design space

One-particle basis

| Model | NequIP tanh | NequIP Silu | NequIP linear | BOTNet linear | BOTNet | |

| Code | botnet | nequip | botnet | botnet | botnet | |

| 300K |

|

4.8 | 3.0 (0.2) | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.1 (0.13) |

|

|

18.5 | 11.6 (0.2) | 13.9 | 12.0 | 11.0 (0.14) | |

| 600 K |

|

20.1 | 11.9 (1.1) | 15.4 | 11.8 | 11.5 (0.6) |

|

|

42.5 | 29.4 (0.8) | 34.1 | 30.0 | 26.7 (0.29) | |

| 1,200K |

|

75.7 | 49.8 (4.0) | 61.92 | 53.7 | 39.1 (1.1) |

|

|

156.1 | 97.1 (5.6) | 109.5 | 97.8 | 81.1 (1.5) | |

dependent on the chemical elements of the two atoms, accounting for the differences in atomic radii.

Nonlinear activations

to be beneficial because it enforces the learning of low-dimensional representations of the data, which is an excellent inductive bias for better extrapolation. In the following, we analyse different nonlinear activations and their effects on body ordering.

is probably because the tanh function has 0 gradient for large positive and negative inputs, which makes the optimization difficult due to vanishing gradients

Discussion

Methods

Equivariant ACE with continuous embedding and uncoupled channels

tuple. The product basis is a complete basis of permutation-invariant functions of the atomic environment.

MPNN potentials

Semi-local states

Message-passing formalism

Equivariant messages

spherical coordinates. This is in line with many equivariant models such as SOAP-GAP

Body-ordered messages

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Musil, F. et al. Physics-inspired structural representations for molecules and materials. Chem. Rev. 121, 9759-9815 (2021).

- Behler, J. & Parrinello, M. Generalized neural-network representation of high-dimensional potential-energy surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 146401 (2007).

- Bartók, A. P., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. On representing chemical environments. Phys. Rev. B 87, 184115 (2013).

- Behler, J. Four generations of high-dimensional neural network potentials. Chem. Rev. 121, 10037-10072 (2021).

- Deringer, V. L. et al. Gaussian process regression for materials and molecules. Chem. Rev. 121, 10073-10141 (2021).

- Cheng, B. et al. Mapping materials and molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 1981-1991 (2020).

- Drautz, R. Atomic cluster expansion for accurate and transferable interatomic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 99, 014104 (2019).

- Dusson, G. et al. Atomic cluster expansion: completeness, efficiency and stability. J. Comput. Phys. 454, 110946 (2022).

- Bartók, A. P., Payne, M. C., Kondor, R. & Csányi, G. Gaussian approximation potentials: the accuracy of quantum mechanics, without the electrons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 136403 (2010).

- Shapeev, A. V. Moment tensor potentials: a class of systematically improvable interatomic potentials. Multisc. Model. Sim. 14, 1153-1173 (2016).

- Drautz, R. Atomic cluster expansion of scalar, vectorial, and tensorial properties including magnetism and charge transfer. Phys. Rev. B 102, 024104 (2020).

- Kovács, D. P. et al. Linear atomic cluster expansion force fields for organic molecules: beyond RMSE. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 17, 7696-7711 (2021).

- Keith, J. A. et al. Combining machine learning and computational chemistry for predictive insights into chemical systems. Chem. Rev. 121, 9816-9872 (2021).

- Faber, F. A., Christensen, A. S., Huang, B. & von Lilienfeld, O. A. Alchemical and structural distribution based representation for universal quantum machine learning. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 241717 (2018).

- Zhu, L. et al. A fingerprint based metric for measuring similarities of crystalline structures. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 034203 (2016).

- Schütt, K. et al. SchNet: a continuous-filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 30 (eds Guyon, I. et al.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017); https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/ file/303ed4c69846ab36c2904d3ba8573050-Paper.pdf

- Gilmer, J., Schoenholz, S. S., Riley, P. F., Vinyals, O. & Dahl, G. E. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. In Proc. 34th International Conference on Machine Learning Vol. 70 (eds Precup, D. & Teh, Y. W.) 1263-1272 (PMLR, 2017); https://proceedings.mlr. press/v70/gilmer17a.html

- Unke, O. T. & Meuwly, M. PhysNet: a neural network for predicting energies, forces, dipole moments, and partial charges. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 15, 3678-3693 (2019).

- Gasteiger, J., Groß, J. & Günnemann, S. Directional message passing for molecular graphs. In Proc. International Conference on Leaning Representations (2020); https://iclr.cc/virtual_2020/ poster_B1eWbxStPH.html

- Anderson, B., Hy, T. S. & Kondor, R. Cormorant: covariant molecular neural networks. In Proc. 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Larochelle, H. et al.) (Curran Associates, 2019); https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2019/file/ 03573b32b2746e6e8ca98b9123f2249b-Paper.pdf

- Thomas, N. et al. Tensor field networks: rotation- and translationequivariant neural networks for 3d point clouds. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1802.08219 (2018).

- Weiler, M., Geiger, M., Welling, M., Boomsma, W. & Cohen, T. 3D steerable CNNs: learning rotationally equivariant features in volumetric data. In Proc. 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Bengio, S. et al.) (Curran Associates, 2018).

- Batzner, S. et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2453 (2022).

- Satorras, V. G., Hoogeboom, E. & Welling, M. E(n) equivariant graph neural networks. In Proc. 38th International Conference on Machine Learning Vol. 139 (eds Meila, M. & Zhang, T.) 9323-9332 (PMLR, 2021).

- Schütt, K. T., Unke, O. T. & Gastegger, M. Equivariant message passing for the prediction of tensorial properties and molecular spectra. In Proc. 38th International Conference on Machine Learning Vol. 139 (eds Meila, M. & Zhang, T.) 9377-9388 (PMLR, 2021).

- Haghighatlari, M. et al. NewtonNet: a Newtonian message passing network for deep learning of interatomic potentials and forces. Digit. Discov. 1, 333-343 (2022).

- Klicpera, J., Becker, F. & Günnemann, S. Gemnet: universal directional graph neural networks for molecules. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (NeurIPS 2021) (eds Ranzato, M. et al.) 6790-6802 (Curran Associates, 2021).

- Thölke, P. & Fabritiis, G. D. Equivariant transformers for neural network based molecular potentials. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2022); https://openreview.net/ forum?id=zNHzqZ9wrRB

- Brandstetter, J., Hesselink, R., van der Pol, E., Bekkers, E. J. & Welling, M. Geometric and physical quantities improve

- Musaelian, A. et al. Learning local equivariant representations for large-scale atomistic dynamics. Nat. Commun. 14, 579 (2023).

- Kondor, R. N-body networks: a covariant hierarchical neural network architecture for learning atomic potentials. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.01588 (2018).

- Batatia, I. et al. The design space of E(3)-equivariant atom-centered interatomic potentials. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/abs/2205.06643 (2022).

- Nigam, J., Pozdnyakov, S., Fraux, G. & Ceriotti, M. Unified theory of atom-centered representations and message-passing machine-learning schemes. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 204115 (2022).

- Bochkarev, A., Lysogorskiy, Y., Ortner, C., Csányi, G. & Drautz, R. Multilayer atomic cluster expansion for semilocal interactions. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, LO42O19 (2022).

- Batatia, I., Kovacs, D. P., Simm, G. N. C., Ortner, C. & Csanyi, G. MACE: Higher order equivariant message passing neural networks for fast and accurate force fields. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS2O22) (eds Koyejo,S. et al.) Curran Associates, 2022); https://proceedings.neurips.cc/ paper_files/paper/2022/hash/4a36c3c51af11ed9f34615b81ed b5bbc-Abstract-Conference.html

- Batatia, I. et al. Code for the paper titled “The Design Space of E(3)-Equivariant Atom-Centered Interatomic Potentials”. Github https://github.com/gncs/botnet/tree/v1.0.1 (2024).

- Darby, J. P. et al. Tensor-reduced atomic density representations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 028001 (2023).

- Allen-Zhu, Z., Li, Y. & Liang, Y. Learning and generalization in overparameterized neural networks, going beyond two layers. In Neural Information Processing Systems (2018).

- Lopanitsyna, N., Fraux, G., Springer, M. A., De, S. & Ceriotti, M. Modeling high-entropy transition metal alloys with alchemical compression. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 045802 (2023).

- Thompson, A., Swiler, L., Trott, C., Foiles, S. & Tucker, G. Spectral neighbor analysis method for automated generation of quantumaccurate interatomic potentials. J. Comput. Phys. 285, 316-330 (2015).

- Caro, M. A. Optimizing many-body atomic descriptors for enhanced computational performance of machine learning based interatomic potentials. Phys. Rev. B 100, 024112 (2019).

- Musil, F. et al. Efficient implementation of atom-density representations. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 114109 (2021).

- Himanen, L. et al. DScribe: library of descriptors for machine learning in materials science. Comp. Phys. Commun. 247, 106949 (2020).

- Goscinski, A., Musil, F., Pozdnyakov, S., Nigam, J. & Ceriotti, M. Optimal radial basis for density-based atomic representations. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 104106 (2021).

- Bigi, F., Huguenin-Dumittan, K. K., Ceriotti, M. & Manolopoulos, D. E. A smooth basis for atomistic machine learning. J. Chem. Phys. 157, 243101 (2022).

- Witt, W. C. et al. ACEpotentials.jl: a Julia implementation of the atomic cluster expansion. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 164101 (2023); https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jcp/article/159/16/164101/2918010/ ACEpotentials-jl-A-Julia-implementation-of-the

- Goscinski, A., Musil, F., Pozdnyakov, S., Nigam, J. & Ceriotti, M. Optimal radial basis for density-based atomic representations. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 104106 (2021).

- Bochkarev, A. et al. Efficient parametrization of the atomic cluster expansion. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 013804 (2022).

- Elfwing, S., Uchibe, E. & Doya, K. Sigmoid-weighted linear units for neural network function approximation in reinforcement learning. Neural Networks 107, 3-11 (2018); https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.neunet.2017.12.012

- Lysogorskiy, Y. et al. Performant implementation of the atomic cluster expansion (PACE) and application to copper and silicon. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 97 (2021).

- Kaliuzhnyi, I. & Ortner, C. Optimal evaluation of symmetry-adapted

- Zhang, L. et al. Equivariant analytical mapping of first principles Hamiltonians to accurate and transferable materials models. npj Comput. Mater. 8, 158 (2022); https://www.nature.com/articles/ s41524-022-00843-2

- Nigam, J., Pozdnyakov, S. & Ceriotti, M. Recursive evaluation and iterative contraction of

- Battaglia, P. W. et al. Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.01261 (2018).

- Bronstein, M. M., Bruna, J., Cohen, T. & Velićković, P. Geometric deep learning: grids, groups, graphs, geodesics, and gauges. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.13478 (2021).

- Weyl, H. The Classical Groups: Their Invariants and Representations (Princeton Univ. Press, 1939).

- Thomas, J., Chen, H. & Ortner, C. Body-ordered approximations of atomic properties. Arch. Rational Mech. Anal. 246, 1-60 (2022); https://doi.org/10.1007/s00205-022-01809-w

- Drautz, R. & Pettifor, D. G. Valence-dependent analytic bond-order potential for transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 74, 174117 (2006).

- van der Oord, C., Dusson, G., Csányi, G. & Ortner, C. Regularised atomic body-ordered permutation-invariant polynomials for the construction of interatomic potentials. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 1, 015004 (2020).

- Drautz, R., Fähnle, M. & Sanchez, J. M. General relations between many-body potentials and cluster expansions in multicomponent systems. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 16, 3843 (2004).

- Kovács, D. P. et al. BOTNet datasets: v0.1.O. Zenodo https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo. 14013500 (2024).

- Musaelian, M. et al. NEquIP: v0.5.4. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ zenodo. 14013469 (2024).

- Geiger, M. et al. E3NN v0.5.4. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ zenodo. 5292912 (2020).

- Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: an imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 32 (eds Wallach, H. et al.) 8026-8037 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2019).

- Sim, G. & Batatia, I. Body-ordered Tensor Network (BOTNet). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14052468 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/.

(c) The Author(s) 2025

| SchNet | NequIP | Linear ACE | |

| Message function

|

|

|

|

| Symmetric pooling

|

|

|

|

| Update function

|

|

|

– |

- ¹Engineering Laboratory, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. ²Department of Chemistry, ENS Paris-Saclay, Université Paris-Saclay, Gif-sur-Yvette, France.