DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47872-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38778013

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-22

فقدان التنوع البيولوجي يقلل من تخزين الكربون الأرضي العالمي

تم القبول: 11 أبريل 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 22 مايو 2024

الملخص

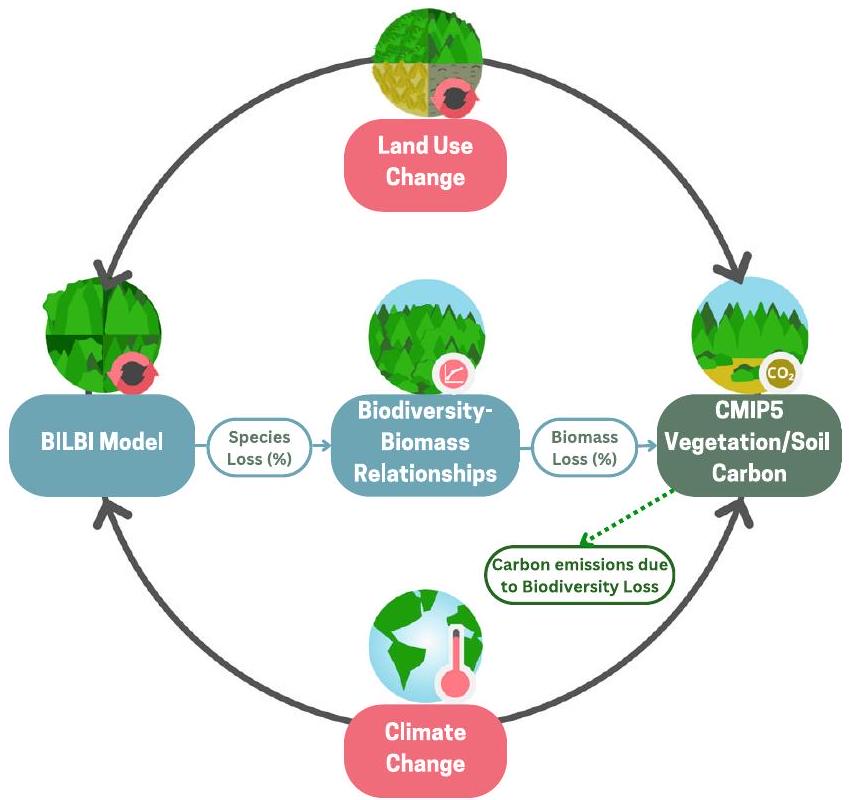

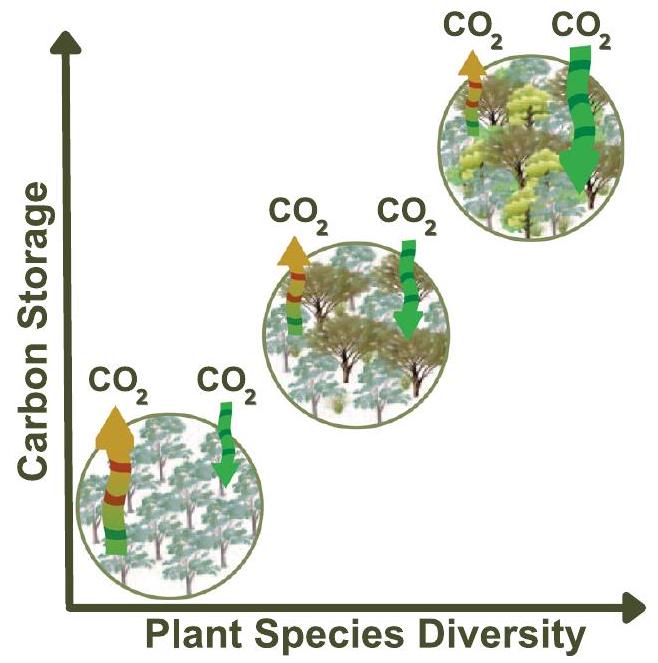

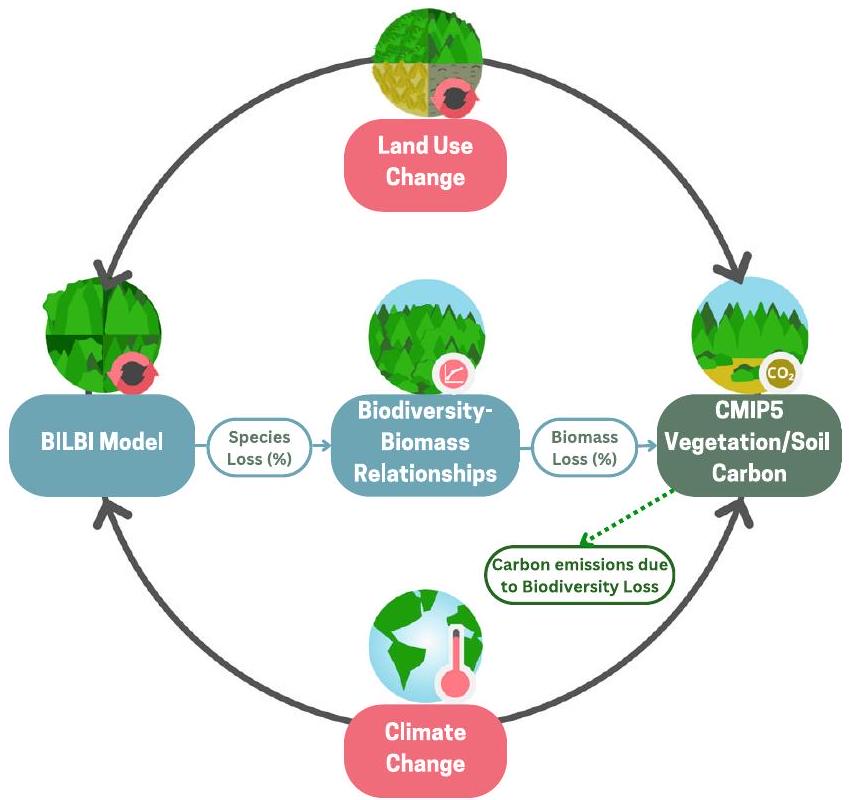

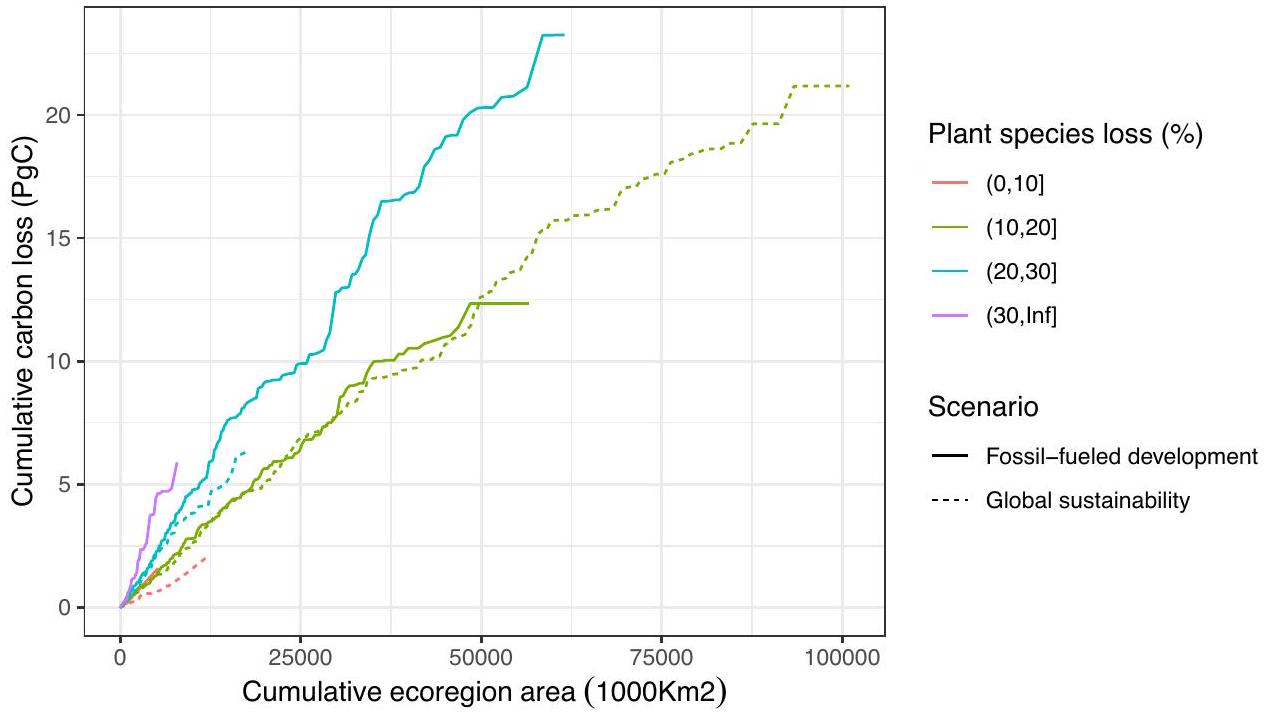

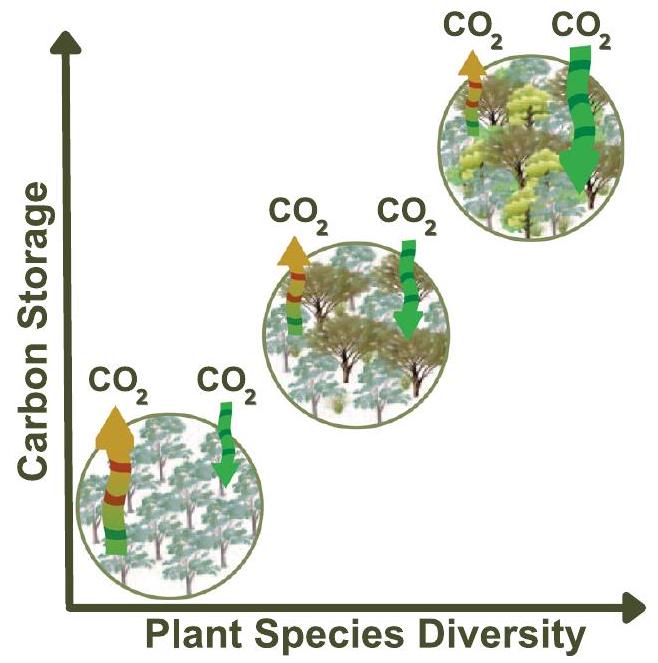

تخزن النظم البيئية الطبيعية كميات كبيرة من الكربون على مستوى العالم، حيث تمتص الكائنات الحية الكربون من الغلاف الجوي لبناء هياكل كبيرة وطويلة الأمد أو بطيئة التحلل مثل لحاء الأشجار أو أنظمة الجذور. يرتبط إمكان احتجاز الكربون في النظام البيئي ارتباطًا وثيقًا بتنوعه البيولوجي. ومع ذلك، عند النظر في التوقعات المستقبلية، تفشل العديد من نماذج احتجاز الكربون في أخذ دور التنوع البيولوجي في تخزين الكربون بعين الاعتبار. هنا، نقيم عواقب فقدان تنوع النباتات على تخزين الكربون تحت سيناريوهات متعددة من تغير المناخ واستخدام الأراضي. نربط نموذجًا ماكروإيكولوجيًا يتوقع تغييرات في غنى النباتات الوعائية تحت سيناريوهات مختلفة مع بيانات تجريبية حول العلاقات بين التنوع البيولوجي والكتلة الحيوية. نجد أن الانخفاض في التنوع البيولوجي نتيجة لتغير المناخ واستخدام الأراضي قد يؤدي إلى فقدان عالمي يتراوح بين 7.44-103.14 PgC (سيناريو الاستدامة العالمية) و10.87-145.95 PgC (سيناريو التنمية المعتمدة على الوقود الأحفوري). وهذا يشير إلى حلقة تغذية راجعة تعزز نفسها، حيث تؤدي مستويات أعلى من تغير المناخ إلى فقدان أكبر للتنوع البيولوجي، مما يؤدي بدوره إلى انبعاثات كربونية أكبر وفي النهاية إلى مزيد من تغير المناخ. على العكس من ذلك، يمكن أن يساعد الحفاظ على التنوع البيولوجي واستعادته في تحقيق أهداف التخفيف من تغير المناخ.

تقليل المنافسة، زيادة التسهيلات، أو كليهما، مما يؤدي إلى استخدام أكثر كفاءة للموارد بشكل عام

النتائج

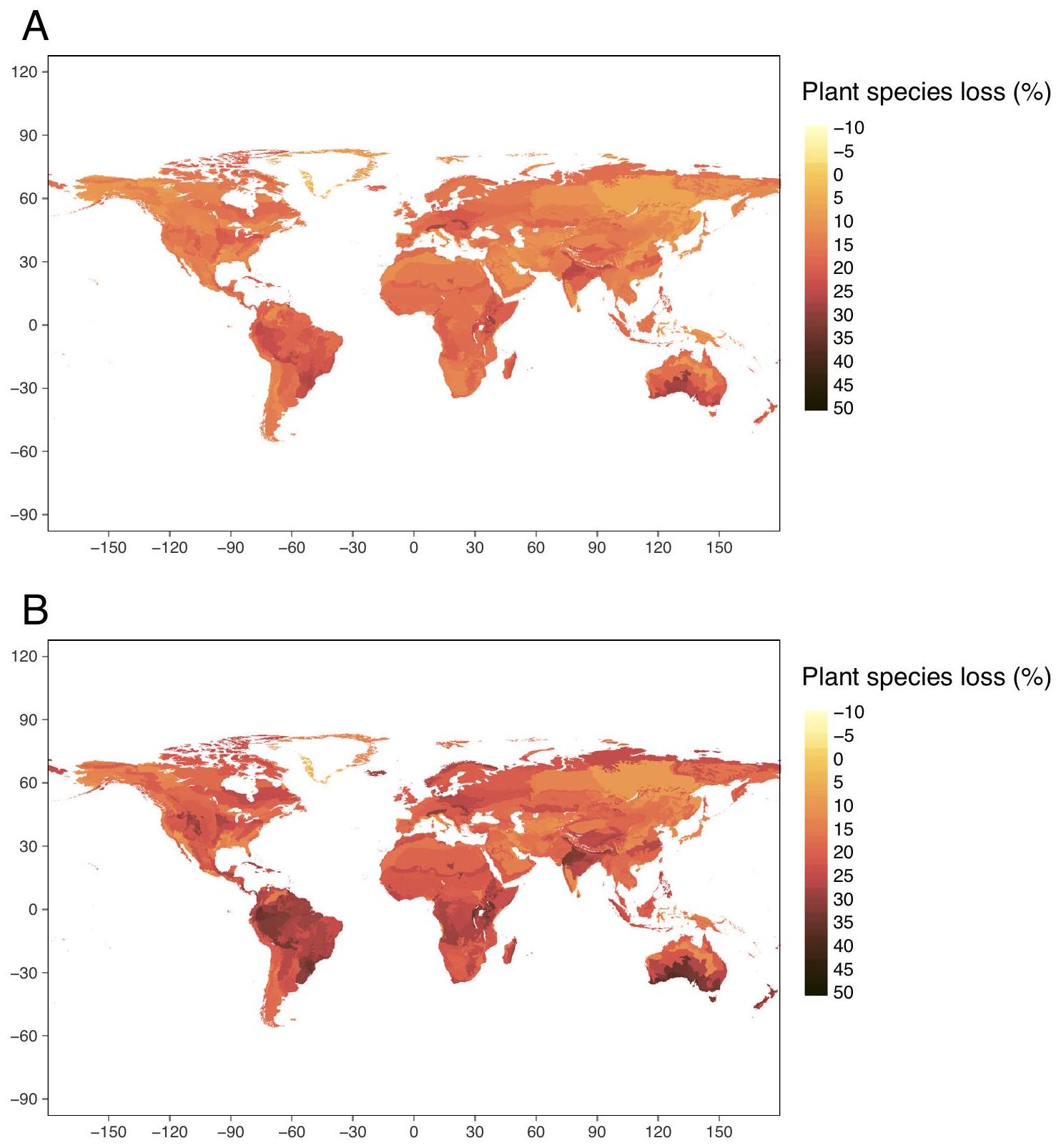

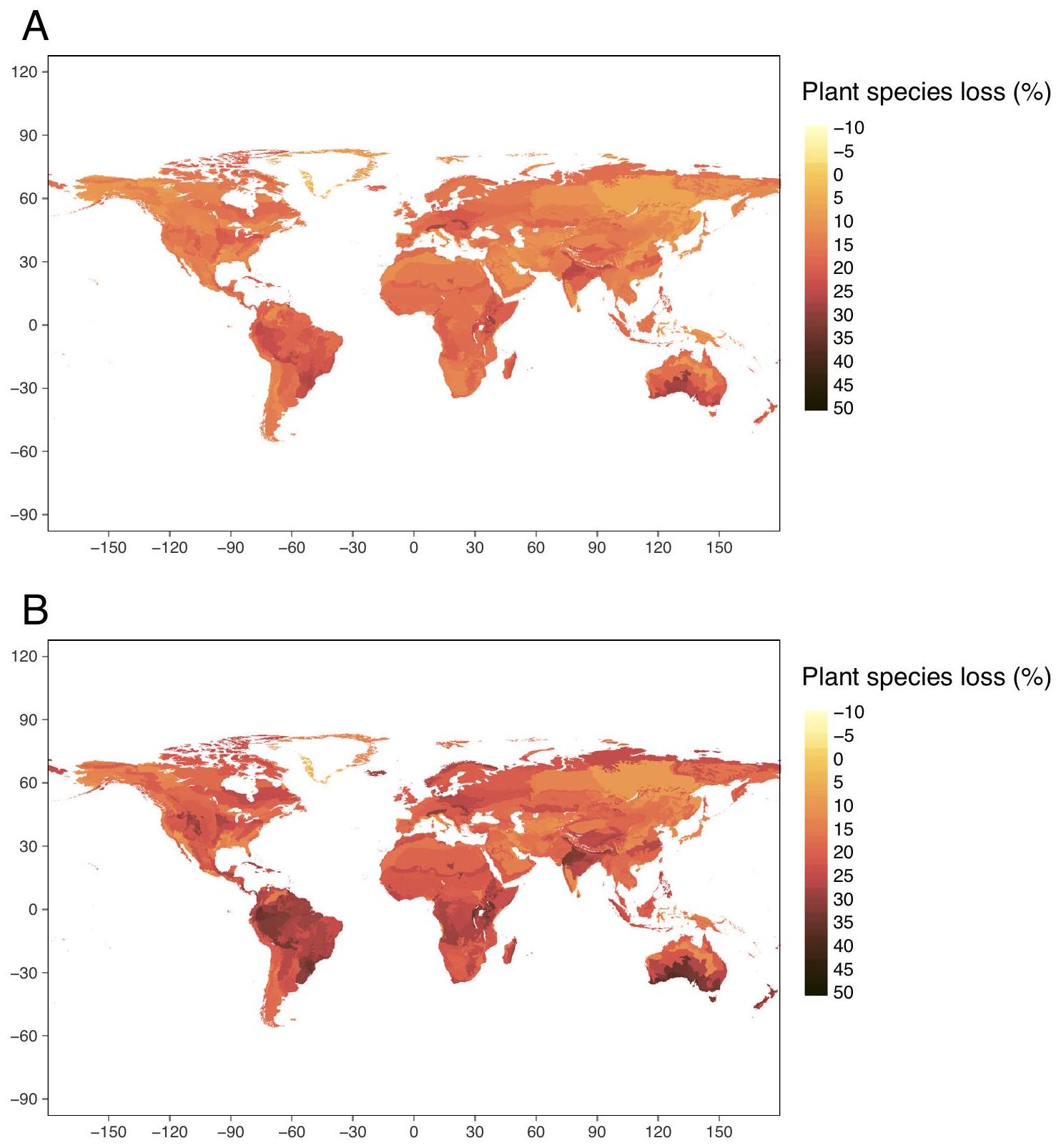

تشير إلى فقدان أكبر في أنواع النباتات. تقديرات فقدان الأنواع هي ما يُتوقع على المدى الطويل، عندما تقترب النظم البيئية من حالات التوازن الجديدة الخاصة بها، استنادًا إلى التغيرات المناخية واستخدام الأراضي المتوقعة لعام 2050.

العلاقة بين التغير في غنى الأنواع والكتلة الحيوية) 0.26 ، تتراوح من

شرق أوروبا، وبعض مناطق أمريكا الجنوبية أيضًا شهدت خسائر كبيرة.

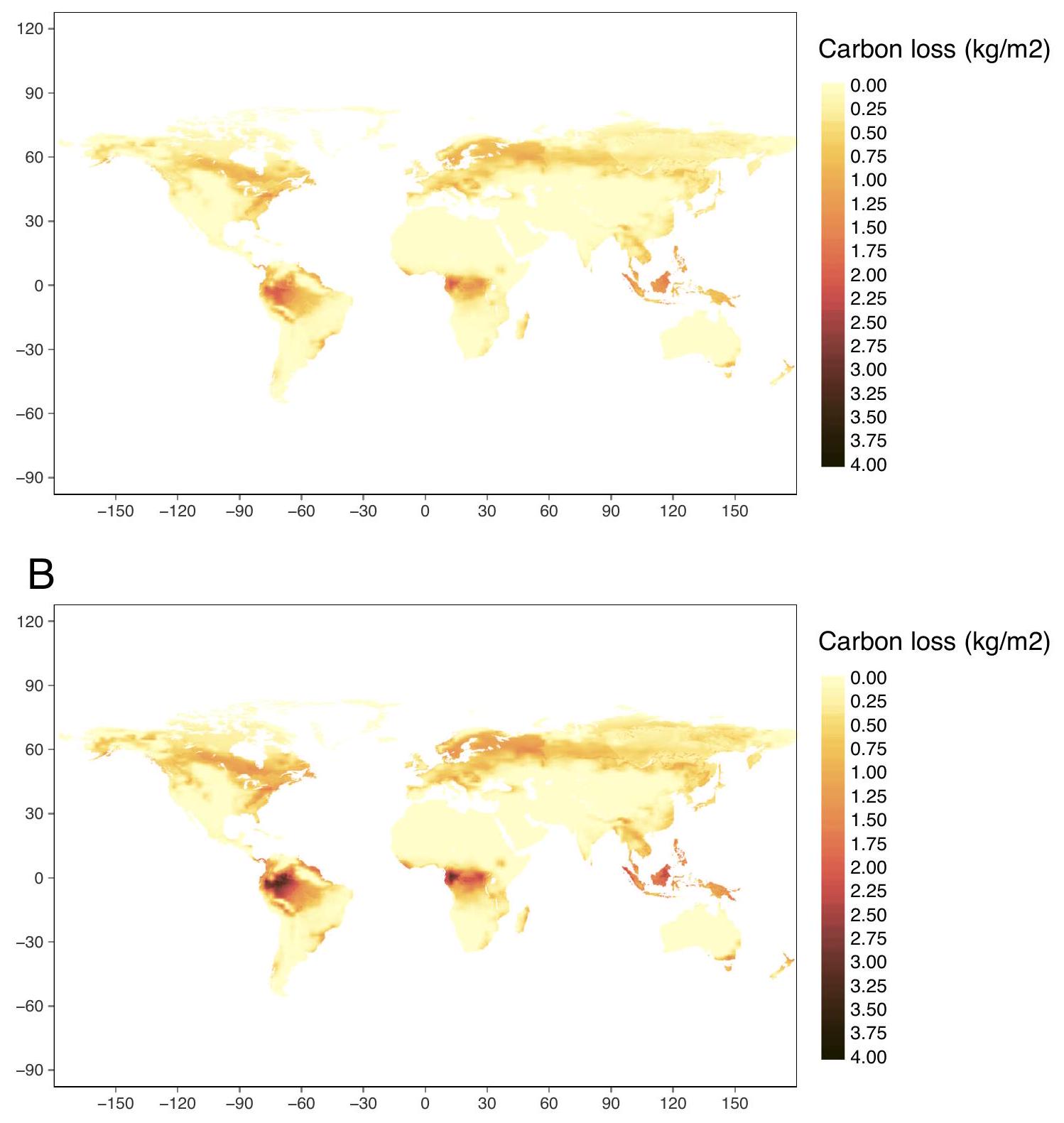

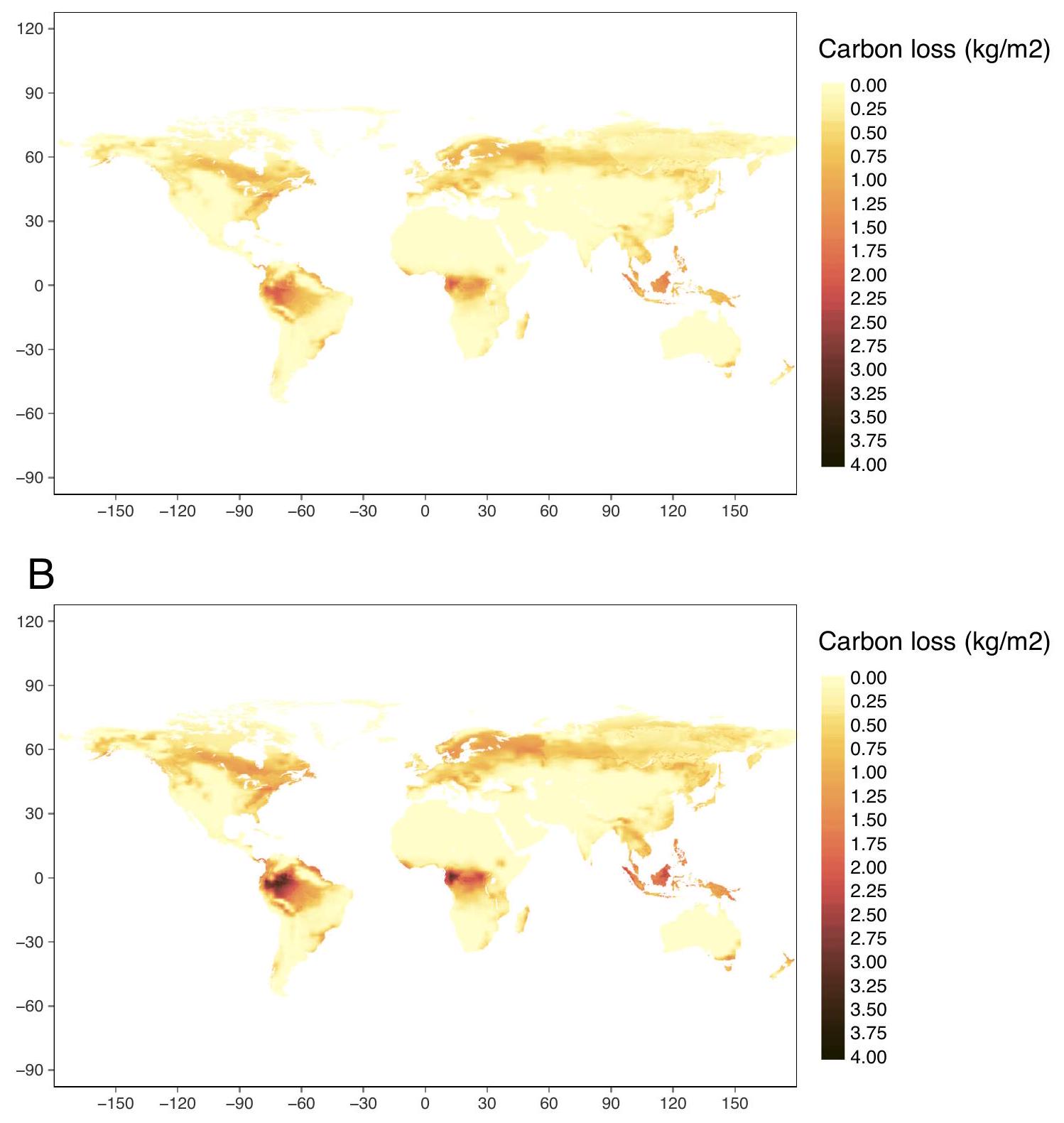

أ

النباتات نتيجة لفقدان التنوع البيولوجي، بالإضافة إلى أي فقدان للكربون ناتج عن التأثير المباشر لتغير استخدام الأراضي (مثل إزالة الغابات) تحت سيناريو معين. تقديرات فقدان الكربون هي ما يُتوقع على المدى الطويل، عندما تقترب النظم البيئية من حالات التوازن الجديدة الخاصة بها، استنادًا إلى التغيرات المناخية واستخدام الأراضي المتوقعة لعام 2050.

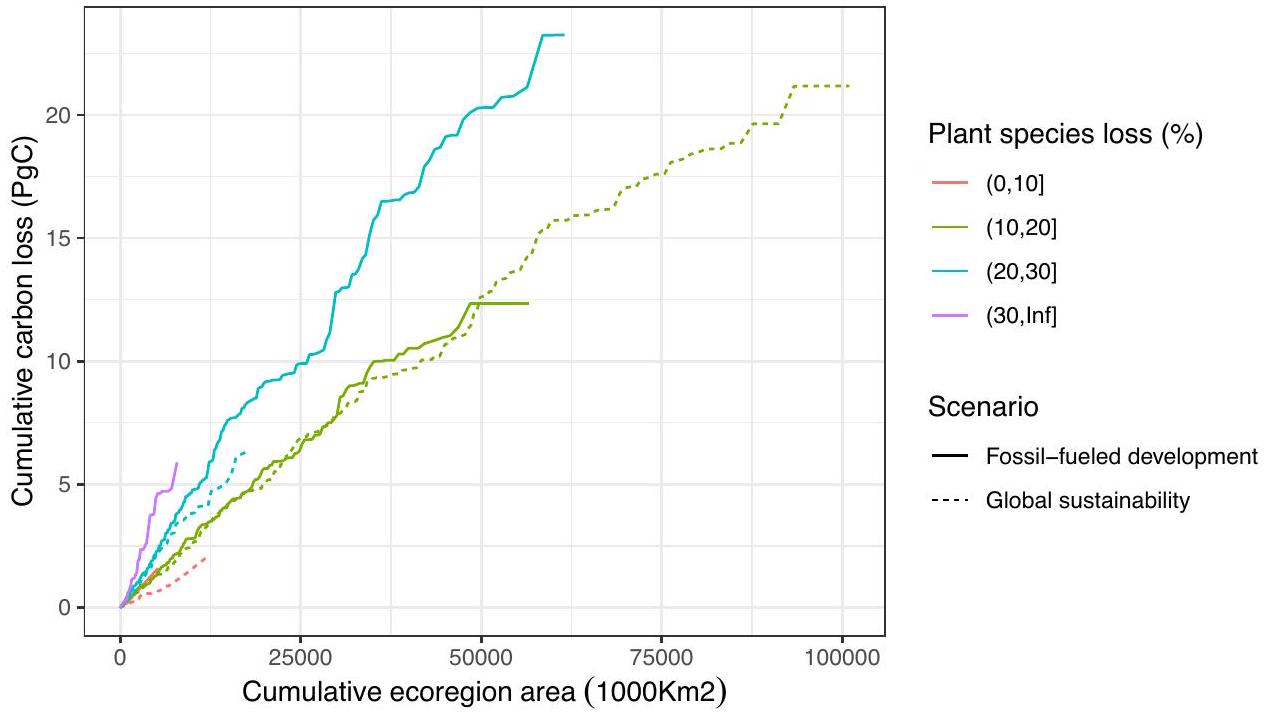

المناطق البيئية التي فقدت 10-20% من تنوع الأنواع النباتية مقارنة بالمناطق البيئية التي فقدت

يمكن أن تساهم بشكل جماعي في فقدان الكربون الإجمالي أكثر من المناطق التي تعاني من فقدان التنوع البيولوجي العالي. بالنسبة لسيناريو الاستدامة العالمية، فإن فقدان الكربون من المناطق الإيكولوجية التي فقدت أكثر من

حول

نقاش

نموذج الغطاء النباتي، وجد أنماطًا مشابهة لفقدان الكربون عبر أمريكا الجنوبية ووسط أفريقيا

المناطق القطبية

| مكون النموذج | اتجاهات البحث المستقبلية | ||||||

| نموذج التنوع البيولوجي |

|

||||||

| علاقة التنوع البيولوجي-إنتاج الكتلة الحيوية |

|

||||||

| تقديرات الكربون | – تحسين فهم كيفية تأثير الإنتاجية وتخزين الكربون على تغير المناخ |

طرق

الخطوة 1-استخدام نموذج BILBI لتقدير نسبة الأنواع النباتية المتوقع أن تستمر في كل منطقة بيئية تحت سيناريوهات مناخية واستخدام أراضٍ مختلفة

(1) حساب المساحة الإجمالية للبيئات البيئية المماثلة بالنسبة لخلية معينة، من خلال جمع التشابه التكويني المتوقع مع جميع الخلايا الأخرى تحت المناخ الحالي، وفرضياً افتراض أن موائل جميع الخلايا في حالة مثالية.

(2) حساب المساحة المحتملة للبيئات البيئية المماثلة تحت سيناريو مستقبلي معين، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار كل من التغير المتوقع في المناخ والحالة المتوقعة للموائل تحت ذلك السيناريو.

(3) التعبير عن المساحة الفعالة للموائل، عبر البيئات البيئية المماثلة، المتوقع تحت سيناريو معين (من الخطوة 2 أعلاه)، كنسبة من المساحة الإجمالية للبيئات المماثلة قبل تغير المناخ واستخدام الأراضي (من الخطوة 1 أعلاه، البيانات متاحة في

من

الخطوة 2: استخدم العلاقات التجريبية لربط التغيرات في غنى الأنواع بالتغيرات في الكتلة الحيوية

لدينا حاليًا تقديرات حول كيفية تغير العلاقات في المستقبل. تشير الأدلة التجريبية، مع ذلك، إلى أن العلاقات الإيجابية بين التنوع البيولوجي والإنتاجية قوية أمام الجفاف والتغيرات في توفر المغذيات.

الخطوة 3: تقدير التغيرات الإجمالية في تخزين الكربون ومقارنتها بمحركات التغير العالمي الأخرى

https://data.isric.org/geonetwork/srv/eng/catalog.search#/metadata/5c301e97-9662-4f77-aa2d-48facd3c9e14

قمنا بإجراء جميع التحليلات باستخدام R الإصدار 4.1.1

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Di Marco, M. et al. Synergies and trade-offs in achieving global biodiversity targets. Conserv. Biol. 30, 189-195 (2016).

- Soto-Navarro, C. et al. Mapping co-benefits for carbon storage and biodiversity to inform conservation policy and action. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 375, 20190128 (2020).

- Strassburg, B. B. N. et al. Global priority areas for ecosystem restoration. Nature 586, 724-729 (2020).

- Mori, A. S. et al. Biodiversity-productivity relationships are key to nature-based climate solutions. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 1-8 (2021).

- Pörtner, H. O. et al. IPBES-IPCC Co-Sponsored Workshop Report on Biodiversity and Climate Change. www.ipbes.net; https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo. 4782538 (2021).

- Cardinale, B. J. et al. The functional role of producer diversity in ecosystems. Am. J. Bot. 98, 572-592 (2011).

- Cardinale, B. J. et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 489, 326-326 (2012).

- Duffy, E. J., Godwin, C. M. & Cardinale, B. J. Biodiversity effects in the wild are common and as strong as key drivers of productivity. Nature 549, 261-264 (2017).

- O’Connor, M. I. et al. A general biodiversity-function relationship is mediated by trophic level. Oikos 126, 18-31 (2017).

- Hooper, D. U. et al. Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge. Ecol. Monogr. 75, 3-35 (2005).

- Loreau, M. & Hector, A. Partitioning selection and complementarity in biodiversity experiments. Nature 412, 72-76 (2001).

- Tilman, D., Lehman, C. L. & Thomson, K. T. Plant diversity and ecosystem productivity: theoretical considerations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 1857-1861 (1997).

- Aarssen, L. W. High productivity in grassland ecosystems: effected by species diversity or productive species? Oikos 80, 183 (1997).

- Hooper, D. U. The role of complementarity and competition in ecosystem responses to variation in plant diversity. Ecology 79, 704-719 (1998).

- Hooper, D. U. et al. A global synthesis reveals biodiversity loss as a major driver of ecosystem change. Nature 486, 105-108 (2012).

- Weiskopf, S. R. et al. Climate change effects on biodiversity, ecosystems, ecosystem services, and natural resource management in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 733, 137782 (2020).

- Seddon, N., Turner, B., Berry, P., Chausson, A. & Girardin, C. A. J. Grounding nature-based climate solutions in sound biodiversity science. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 84-87 (2019).

- Ferrier, S., Ninan, K. N., Leadley, P. & Alkemade, R. The Methodological Assessment Report on Scenarios and Models of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services 32 (IPBES, 2016).

- O’Connor, M. I. et al. Grand challenges in biodiversity-ecosystem functioning research in the era of science-policy platforms require explicit consideration of feedbacks. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 288, 20210783 (2021).

- Zhou, J. et al. A traceability analysis system for model evaluation on land carbon dynamics: design and applications. Ecol. Process. 10, 12 (2021).

- Wei, N. et al. Evolution of uncertainty in terrestrial carbon storage in Earth system models from CMIP5 to CMIP6. J. Clim. 35, 5483-5499 (2022).

- Isbell, F., Tilman, D., Polasky, S. & Loreau, M. The biodiversitydependent ecosystem service debt. Ecol. Lett. 18, 119-134 (2015).

- Reich, P. B. et al. Impacts of biodiversity loss escalate through time as redundancy fades. Science 336, 589-592 (2012).

- Fulton, E. A. & Gorton, R. Adaptive Futures for SE Australian Fisheries & Aquaculture: Climate Adaptation Simulations (CSIRO, 2014).

- Weiskopf, S. R. et al. A conceptual framework to integrate biodiversity, ecosystem function, and ecosystem service models. BioScience. 72, 1-12 (2022).

- O’Connor, M. I., Bernhardt, J. R., Stark, K., Usinowicz, J. & Whalen, M. A. In The Ecological and Societal Consequences of Biodiversity Loss (eds Loreau, M., Hector, A. & Isbell, F.) 97-118 (Wiley, 2022).

- Wang, S. & Loreau, M. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability across scales in metacommunities. Ecol. Lett. 19, 510-518 (2016).

- Isbell, F. et al. Linking the influence and dependence of people on biodiversity across scales. Nature 546, 65-72 (2017).

- Mori, A. S., Isbell, F. & Seidl, R.

-Diversity, community assembly, and ecosystem functioning. Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 549-564 (2018). - Hoskins, A. J. et al. BILBI: supporting global biodiversity assessment through high-resolution macroecological modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 132, 104806 (2020).

- Di Marco, M. et al. Projecting impacts of global climate and land-use scenarios on plant biodiversity using compositional-turnover modelling. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 2763-2778 (2019).

- Kim, H. et al. A protocol for an intercomparison of biodiversity and ecosystem services models using harmonized land-use and climate scenarios. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 4537-4562 (2018).

- Dufresne, J. L. et al. Climate change projections using the IPSL-CM5 Earth system model: from CMIP3 to CMIP5. Clim. Dyn. 40, 2123-2165 (2013).

- Asamoah, E. F. et al. Land-use and climate risk assessment for Earth’s remaining wilderness. Curr. Biol. 32, 4890-4899.e4 (2022).

- Mendez Angarita, V. Y., Maiorano, L., Dragonetti, C. & Di Marco, M. Implications of exceeding the Paris Agreement for mammalian biodiversity. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 5, e12889 (2023).

- Yang, Y. et al. Restoring abandoned farmland to mitigate climate change on a full Earth. One Earth 3, 176-186 (2020).

- Chen, X. et al. Effects of plant diversity on soil carbon in diverse ecosystems: a global meta-analysis. Biol. Rev. 95, 167-183 (2020).

- Chen, X. et al. Tree diversity increases decadal forest soil carbon and nitrogen accrual. Nature 618, 94-101 (2023).

- Yang, Y., Tilman, D., Furey, G. & Lehman, C. Soil carbon sequestration accelerated by restoration of grassland biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 10, 1-7 (2019).

- Cimatti, M., Chaplin-Kramer, R. & Marco, M. D. Regions of High Biodiversity Value Preserve Nature’s Contributions to People under Climate Change. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs2013582/v1; https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2013582/v1 (2022).

- Canadell, J. G. et al. Global carbon and other biogeochemical cycles and feedbacks. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 673-816 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

- Pereira, H. M. et al. Global trends in biodiversity and ecosystem services from 1900 to 2050. bioRxiv 1, 1-5 (2020).

- Mori, A. S. Advancing nature-based approaches to address the biodiversity and climate emergency. Ecol. Lett. 23, 1729-1732 (2020).

- Andres, S. E. et al. Defining biodiverse reforestation: why it matters for climate change mitigation and biodiversity. Plants People Planet

doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10329 (2022). - van der Plas, F., Hennecke, J., Chase, J. M., van Ruijven, J. & Barry, K. E. Universal beta-diversity-functioning relationships are neither observed nor expected. Trends Ecol. Evol. S0169534723000125 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2023.01.008 (2023).

- Hisano, M., Searle, E. B. & Chen, H. Y. H. Biodiversity as a solution to mitigate climate change impacts on the functioning of forest ecosystems. Biol. Rev. 93, 439-456 (2018).

- Winfree, R., Fox, J. W., Williams, N. M., Reilly, J. R. & Cariveau, D. P. Abundance of common species, not species richness, drives delivery of a real-world ecosystem service. Ecol. Lett. 18, 626-635 (2015).

- Gonzalez, A. et al. Scaling-up biodiversity-ecosystem functioning research. Ecol. Lett. 23, 757-776 (2020).

- Thompson, P. L. et al. Scaling up biodiversity-ecosystem functioning relationships: the role of environmental heterogeneity in space and time. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 288, 20202779 (2021).

- Benito Garzón, M., Robson, T. M. & Hampe, A.

TraitSDMs: species distribution models that account for local adaptation and phenotypic plasticity. N. Phytologist 222, 1757-1765 (2019). - Sinclair, S. J., White, M. D. & Newell, G. R. How useful are species distribution models for managing biodiversity under future climates? Ecol. Soc. 15, 8 (2010).

- Bush, A. et al. Incorporating evolutionary adaptation in species distribution modelling reduces projected vulnerability to climate change. Ecol. Lett. 19, 1468-1478 (2016).

- Wilsey, B. J., Teaschner, T. B., Daneshgar, P. P., Isbell, F. I. & Polley, H. W. Biodiversity maintenance mechanisms differ between native and novel exotic-dominated communities. Ecol. Lett. 12, 432-442 (2009).

- Dee, L. E. et al. Clarifying the effect of biodiversity on productivity in natural ecosystems with longitudinal data and methods for causal inference. Nat. Commun. 14, 2607 (2023).

- Isbell, F. I. & Wilsey, B. J. Increasing native, but not exotic, biodiversity increases aboveground productivity in ungrazed and intensely grazed grasslands. Oecologia 165, 771-781 (2011).

- Rosenzweig, M. L. Heeding the warning in biodiversity’s basic law. Science 284, 276-277 (1999).

- Thuiller, W., Guéguen, M., Renaud, J., Karger, D. N. & Zimmermann, N. E. Uncertainty in ensembles of global biodiversity scenarios. Nat. Commun. 10, 1446 (2019).

- Leclère, D. et al. Bending the curve of terrestrial biodiversity needs an integrated strategy. Nature 585, 551-556 (2020).

- Arora, V. K. et al. Carbon-concentration and carbon-climate feedbacks in CMIP6 models and their comparison to CMIP5 models. Biogeosciences 17, 4173-4222 (2020).

- Anav, A. et al. Evaluating the land and ocean components of the global carbon cycle in the CMIP5 Earth system models. J. Clim. 26, 6801-6843 (2013).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015).

- United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. KunmingMontreal Global Biodiversity Framework. (2022).

- Rosa, I. M. D. et al. Multiscale scenarios for nature futures. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1416-1419 (2017).

- Rosa, I. M. D. et al. Challenges in producing policy-relevant global scenarios of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 22, e00886 (2020).

- van der Plas, F. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in naturally assembled communities. Biol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv. 12499 (2019).

- Newbold, T. et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 520, 45-50 (2015).

- Brooks, T. M. et al. Habitat loss and extinction in the hotspots of biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. 16, 909-923 (2002).

- Elith, J. et al. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29, 129-151 (2006).

- Blois, J. L., Williams, J. W., Fitzpatrick, M. C., Jackson, S. T. & Ferrier, S. Space can substitute for time in predicting climate-change effects on biodiversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 9374-9379 (2013).

- Ware, C. et al. Improving biodiversity surrogates for conservation assessment: a test of methods and the value of targeted biological surveys. Divers. Distrib. 24, 1333-1346 (2018).

- Pimm, S. L., Jenkins, C. N. & Li, B. V. How to protect half of earth to ensure it protects sufficient biodiversity. Sci. Adv. 4, 1-9 (2018).

- Di Marco, M., Hoskins, A. J., Harwood, T. D., Ware, C. & Ferrier, S. BILBI model data for SSP1/RCP2.6 and SSP5/RCP8.5. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 25188650 (2024).

- Diamond, J. M. Biogeographic kinetics: estimation of relaxation times for Avifaunas of Southwest Pacific Islands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 69, 3199-3203 (1972).

- Gonzalez, A. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences https://doi.org/10. 1002/9780470015902.a0021230 (Wiley, 2009).

- Kriegler, E. et al. Fossil-fueled development (SSP5): an energy and resource intensive scenario for the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 297-315 (2017).

- van Vuuren, D. P. et al. Energy, land-use and greenhouse gas emissions trajectories under a green growth paradigm. Glob.

Environ. Change 42, 237-250 (2017). - Ciais, P. et al. Carbon and other biogeochemical cycles. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the iltergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 465-570 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Hurtt, G. C. et al. Harmonization of global land use change and management for the period 850-2100 (LUH2) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 5425-5464 (2020).

- Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G. & Jarvis, A. WorldClim Global Climate Data Version 1. http://worldclim.org/ version1 (2017).

- Liang, J. et al. Positive biodiversity-productivity relationship predominant in global forests. Science 354, aaf8957 (2016).

- Craven, D. et al. Plant diversity effects on grassland productivity are robust to both nutrient enrichment and drought. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150277 (2016).

- Hurtt, G. C. et al. Harmonization of land-use scenarios for the period 1500-2100: 600 years of global gridded annual land-use transitions, wood harvest, and resulting secondary lands. Clim. Change 109, 117 (2011).

- Hengl, T. et al. SoilGrids250m: global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 12, e0169748 (2017).

- Hijmans, R. J. terra: Spatial Data Analysis. R package version 1.739. (2023).

- Balvanera, P. et al. Quantifying the evidence for biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning and services. Ecol. Lett. 9, 1146-1156 (2006).

- Mori, A. S., Cornelissen, J. H. C., Fujii, S., Okada, K. & Isbell, F. A meta-analysis on decomposition quantifies afterlife effects of plant diversity as a global change driver. Nat. Commun. 11, 1-9 (2020).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (SpringerVerlag, 2016).

- Tennekes, M. tmap: Thematic Maps in R. J. Stat. Softw. 84, 1-39 (2018).

- Weiskopf, S. R. et al. Biodiversity Loss Reduces Global Terrestrial Carbon Storage-Data. U.S. Geological Survey data release (2024).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47872-7.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© إيزبيل، أرس-بلاتا، دي ماركو، هارفوت، جونسون، موري، وينغ، فيرير. أجزاء من هذا العمل كتبها مؤلفون من الحكومة الفيدرالية الأمريكية وليست محمية بحقوق الطبع والنشر في الولايات المتحدة؛ قد تنطبق حماية حقوق الطبع والنشر الأجنبية 2024

- (T) تحقق من التحديثات

مركز علوم التكيف المناخي الوطني التابع لهيئة المسح الجيولوجي الأمريكية، ريستون، فيرجينيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الحفاظ على البيئة، جامعة ماساتشوستس، أمهيرست، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم البيئة والتطور والسلوك، جامعة مينيسوتا، سانت بول، مينيسوتا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم العلوم البيولوجية، جامعة مونتريال، مونتريال، كيبك H3T 1J4، كندا. قسم البيولوجيا والتكنولوجيا الحيوية، جامعة سابينزا في روما، روما، إيطاليا. فيزوالتي، 123 شارع فونكارال، 28010 مدريد، إسبانيا. قسم الاقتصاد التطبيقي، جامعة مينيسوتا، 1994 بوفورد أفينيو، سانت بول، MN 55105، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. محطة الأبحاث الشمالية التابعة لخدمة الغابات الأمريكية، أمهرست، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز علوم التكيف المناخي في المسح الجيولوجي الأمريكي، شمال وسط، بولدر، كولورادو، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز علوم التكيف المناخي التابع لمسح جيولوجيا الولايات المتحدة، أمهرست، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز أبحاث العلوم والتكنولوجيا المتقدمة، جامعة طوكيو، 4-6-1 كوماتا، ميغورو، طوكيو 153-8904، اليابان. جامعة كولومبيا / معهد غودارد لدراسات الفضاء التابع لناسا، 2880 برودواي، نيويورك، NY 10025، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. CSIRO البيئة، كانبيرا، ACT 2601، أستراليا. البريد الإلكتروني: sweiskopf@usgs.gov

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47872-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38778013

Publication Date: 2024-05-22

Biodiversity loss reduces global terrestrial carbon storage

Accepted: 11 April 2024

Published online: 22 May 2024

Abstract

Natural ecosystems store large amounts of carbon globally, as organisms absorb carbon from the atmosphere to build large, long-lasting, or slowdecaying structures such as tree bark or root systems. An ecosystem’s carbon sequestration potential is tightly linked to its biological diversity. Yet when considering future projections, many carbon sequestration models fail to account for the role biodiversity plays in carbon storage. Here, we assess the consequences of plant biodiversity loss for carbon storage under multiple climate and land-use change scenarios. We link a macroecological model projecting changes in vascular plant richness under different scenarios with empirical data on relationships between biodiversity and biomass. We find that biodiversity declines from climate and land use change could lead to a global loss of between 7.44-103.14 PgC (global sustainability scenario) and 10.87145.95 PgC (fossil-fueled development scenario). This indicates a selfreinforcing feedback loop, where higher levels of climate change lead to greater biodiversity loss, which in turn leads to greater carbon emissions and ultimately more climate change. Conversely, biodiversity conservation and restoration can help achieve climate change mitigation goals.

reduced competition, increased facilitation, or both, which leads to overall more efficient resource use

Results

indicate greater plant species loss. Species-loss estimates are what is expected over the long term, when ecosystems approach their new equilibrium states, based on climate and land-use changes projected for 2050.

relationship between a change in species richness and biomass) of 0.26 , ranging from

eastern Europe, and some regions of South America also had high losses.

A

vegetation as a result of biodiversity loss, over and above any carbon loss resulting from the direct impact of land-use change (e.g., deforestation) under a given scenario. Carbon-loss estimates are what is expected over the long term, when ecosystems approach their new equilibrium states, based on climate and land-use changes projected for 2050.

ecoregions that have lost 10-20% of plant species diversity compared to ecoregions that lost

collectively, can contribute more to overall carbon loss than areas of high biodiversity loss. For the global sustainability scenario, carbon loss from ecoregions that lost more than

about

Discussion

vegetation models, found similar patterns of carbon loss across South America and central Africa

circumpolar regions

| Model component | Future research directions | ||||||

| Biodiversity model |

|

||||||

| Biodiversity-biomass production relationship |

|

||||||

| Carbon estimates | – Improve understanding of how productivity and carbon storage are affected by changing climates |

Methods

Step 1-Use BILBI model to estimate proportion of plant species expected to persist in each ecoregion under different climate and land-use scenarios

(1) Calculating the total area of similar ecological environments relative to a given cell, by summing the predicted compositional similarity with all other cells under the present climate, and hypothetically assuming the habitat of all cells is in perfect condition.

(2) Calculating the potential area of similar ecological environments under a given future scenario, accounting for both the projected change in climate and the expected condition of habitat under that scenario.

(3) Expressing the effective area of habitat, across similar ecological environments, expected under a given scenario (from step 2 above), as a proportion of the total area of similar environments prior to climate and land-use change (from step 1 above, data available at

from the

Step 2: Use empirical relationships to link changes in species richness to changes in biomass

currently have estimates of how relationships may change in the future. Experimental evidence suggests, however, that positive biodiversity-productivity relationships are robust to droughts and changes in nutrient availability

Step 3: Estimate total changes in carbon storage and compare to other global change drivers

https://data.isric.org/geonetwork/srv/eng/catalog.search#/metadata/ 5c301e97-9662-4f77-aa2d-48facd3c9e14

We conducted all analyses in R version 4.1.1

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Di Marco, M. et al. Synergies and trade-offs in achieving global biodiversity targets. Conserv. Biol. 30, 189-195 (2016).

- Soto-Navarro, C. et al. Mapping co-benefits for carbon storage and biodiversity to inform conservation policy and action. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 375, 20190128 (2020).

- Strassburg, B. B. N. et al. Global priority areas for ecosystem restoration. Nature 586, 724-729 (2020).

- Mori, A. S. et al. Biodiversity-productivity relationships are key to nature-based climate solutions. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 1-8 (2021).

- Pörtner, H. O. et al. IPBES-IPCC Co-Sponsored Workshop Report on Biodiversity and Climate Change. www.ipbes.net; https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo. 4782538 (2021).

- Cardinale, B. J. et al. The functional role of producer diversity in ecosystems. Am. J. Bot. 98, 572-592 (2011).

- Cardinale, B. J. et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 489, 326-326 (2012).

- Duffy, E. J., Godwin, C. M. & Cardinale, B. J. Biodiversity effects in the wild are common and as strong as key drivers of productivity. Nature 549, 261-264 (2017).

- O’Connor, M. I. et al. A general biodiversity-function relationship is mediated by trophic level. Oikos 126, 18-31 (2017).

- Hooper, D. U. et al. Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge. Ecol. Monogr. 75, 3-35 (2005).

- Loreau, M. & Hector, A. Partitioning selection and complementarity in biodiversity experiments. Nature 412, 72-76 (2001).

- Tilman, D., Lehman, C. L. & Thomson, K. T. Plant diversity and ecosystem productivity: theoretical considerations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 1857-1861 (1997).

- Aarssen, L. W. High productivity in grassland ecosystems: effected by species diversity or productive species? Oikos 80, 183 (1997).

- Hooper, D. U. The role of complementarity and competition in ecosystem responses to variation in plant diversity. Ecology 79, 704-719 (1998).

- Hooper, D. U. et al. A global synthesis reveals biodiversity loss as a major driver of ecosystem change. Nature 486, 105-108 (2012).

- Weiskopf, S. R. et al. Climate change effects on biodiversity, ecosystems, ecosystem services, and natural resource management in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 733, 137782 (2020).

- Seddon, N., Turner, B., Berry, P., Chausson, A. & Girardin, C. A. J. Grounding nature-based climate solutions in sound biodiversity science. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 84-87 (2019).

- Ferrier, S., Ninan, K. N., Leadley, P. & Alkemade, R. The Methodological Assessment Report on Scenarios and Models of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services 32 (IPBES, 2016).

- O’Connor, M. I. et al. Grand challenges in biodiversity-ecosystem functioning research in the era of science-policy platforms require explicit consideration of feedbacks. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 288, 20210783 (2021).

- Zhou, J. et al. A traceability analysis system for model evaluation on land carbon dynamics: design and applications. Ecol. Process. 10, 12 (2021).

- Wei, N. et al. Evolution of uncertainty in terrestrial carbon storage in Earth system models from CMIP5 to CMIP6. J. Clim. 35, 5483-5499 (2022).

- Isbell, F., Tilman, D., Polasky, S. & Loreau, M. The biodiversitydependent ecosystem service debt. Ecol. Lett. 18, 119-134 (2015).

- Reich, P. B. et al. Impacts of biodiversity loss escalate through time as redundancy fades. Science 336, 589-592 (2012).

- Fulton, E. A. & Gorton, R. Adaptive Futures for SE Australian Fisheries & Aquaculture: Climate Adaptation Simulations (CSIRO, 2014).

- Weiskopf, S. R. et al. A conceptual framework to integrate biodiversity, ecosystem function, and ecosystem service models. BioScience. 72, 1-12 (2022).

- O’Connor, M. I., Bernhardt, J. R., Stark, K., Usinowicz, J. & Whalen, M. A. In The Ecological and Societal Consequences of Biodiversity Loss (eds Loreau, M., Hector, A. & Isbell, F.) 97-118 (Wiley, 2022).

- Wang, S. & Loreau, M. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability across scales in metacommunities. Ecol. Lett. 19, 510-518 (2016).

- Isbell, F. et al. Linking the influence and dependence of people on biodiversity across scales. Nature 546, 65-72 (2017).

- Mori, A. S., Isbell, F. & Seidl, R.

-Diversity, community assembly, and ecosystem functioning. Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 549-564 (2018). - Hoskins, A. J. et al. BILBI: supporting global biodiversity assessment through high-resolution macroecological modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 132, 104806 (2020).

- Di Marco, M. et al. Projecting impacts of global climate and land-use scenarios on plant biodiversity using compositional-turnover modelling. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 2763-2778 (2019).

- Kim, H. et al. A protocol for an intercomparison of biodiversity and ecosystem services models using harmonized land-use and climate scenarios. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 4537-4562 (2018).

- Dufresne, J. L. et al. Climate change projections using the IPSL-CM5 Earth system model: from CMIP3 to CMIP5. Clim. Dyn. 40, 2123-2165 (2013).

- Asamoah, E. F. et al. Land-use and climate risk assessment for Earth’s remaining wilderness. Curr. Biol. 32, 4890-4899.e4 (2022).

- Mendez Angarita, V. Y., Maiorano, L., Dragonetti, C. & Di Marco, M. Implications of exceeding the Paris Agreement for mammalian biodiversity. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 5, e12889 (2023).

- Yang, Y. et al. Restoring abandoned farmland to mitigate climate change on a full Earth. One Earth 3, 176-186 (2020).

- Chen, X. et al. Effects of plant diversity on soil carbon in diverse ecosystems: a global meta-analysis. Biol. Rev. 95, 167-183 (2020).

- Chen, X. et al. Tree diversity increases decadal forest soil carbon and nitrogen accrual. Nature 618, 94-101 (2023).

- Yang, Y., Tilman, D., Furey, G. & Lehman, C. Soil carbon sequestration accelerated by restoration of grassland biodiversity. Nat. Commun. 10, 1-7 (2019).

- Cimatti, M., Chaplin-Kramer, R. & Marco, M. D. Regions of High Biodiversity Value Preserve Nature’s Contributions to People under Climate Change. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs2013582/v1; https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2013582/v1 (2022).

- Canadell, J. G. et al. Global carbon and other biogeochemical cycles and feedbacks. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) 673-816 (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

- Pereira, H. M. et al. Global trends in biodiversity and ecosystem services from 1900 to 2050. bioRxiv 1, 1-5 (2020).

- Mori, A. S. Advancing nature-based approaches to address the biodiversity and climate emergency. Ecol. Lett. 23, 1729-1732 (2020).

- Andres, S. E. et al. Defining biodiverse reforestation: why it matters for climate change mitigation and biodiversity. Plants People Planet

doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10329 (2022). - van der Plas, F., Hennecke, J., Chase, J. M., van Ruijven, J. & Barry, K. E. Universal beta-diversity-functioning relationships are neither observed nor expected. Trends Ecol. Evol. S0169534723000125 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2023.01.008 (2023).

- Hisano, M., Searle, E. B. & Chen, H. Y. H. Biodiversity as a solution to mitigate climate change impacts on the functioning of forest ecosystems. Biol. Rev. 93, 439-456 (2018).

- Winfree, R., Fox, J. W., Williams, N. M., Reilly, J. R. & Cariveau, D. P. Abundance of common species, not species richness, drives delivery of a real-world ecosystem service. Ecol. Lett. 18, 626-635 (2015).

- Gonzalez, A. et al. Scaling-up biodiversity-ecosystem functioning research. Ecol. Lett. 23, 757-776 (2020).

- Thompson, P. L. et al. Scaling up biodiversity-ecosystem functioning relationships: the role of environmental heterogeneity in space and time. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 288, 20202779 (2021).

- Benito Garzón, M., Robson, T. M. & Hampe, A.

TraitSDMs: species distribution models that account for local adaptation and phenotypic plasticity. N. Phytologist 222, 1757-1765 (2019). - Sinclair, S. J., White, M. D. & Newell, G. R. How useful are species distribution models for managing biodiversity under future climates? Ecol. Soc. 15, 8 (2010).

- Bush, A. et al. Incorporating evolutionary adaptation in species distribution modelling reduces projected vulnerability to climate change. Ecol. Lett. 19, 1468-1478 (2016).

- Wilsey, B. J., Teaschner, T. B., Daneshgar, P. P., Isbell, F. I. & Polley, H. W. Biodiversity maintenance mechanisms differ between native and novel exotic-dominated communities. Ecol. Lett. 12, 432-442 (2009).

- Dee, L. E. et al. Clarifying the effect of biodiversity on productivity in natural ecosystems with longitudinal data and methods for causal inference. Nat. Commun. 14, 2607 (2023).

- Isbell, F. I. & Wilsey, B. J. Increasing native, but not exotic, biodiversity increases aboveground productivity in ungrazed and intensely grazed grasslands. Oecologia 165, 771-781 (2011).

- Rosenzweig, M. L. Heeding the warning in biodiversity’s basic law. Science 284, 276-277 (1999).

- Thuiller, W., Guéguen, M., Renaud, J., Karger, D. N. & Zimmermann, N. E. Uncertainty in ensembles of global biodiversity scenarios. Nat. Commun. 10, 1446 (2019).

- Leclère, D. et al. Bending the curve of terrestrial biodiversity needs an integrated strategy. Nature 585, 551-556 (2020).

- Arora, V. K. et al. Carbon-concentration and carbon-climate feedbacks in CMIP6 models and their comparison to CMIP5 models. Biogeosciences 17, 4173-4222 (2020).

- Anav, A. et al. Evaluating the land and ocean components of the global carbon cycle in the CMIP5 Earth system models. J. Clim. 26, 6801-6843 (2013).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2015).

- United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. KunmingMontreal Global Biodiversity Framework. (2022).

- Rosa, I. M. D. et al. Multiscale scenarios for nature futures. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1416-1419 (2017).

- Rosa, I. M. D. et al. Challenges in producing policy-relevant global scenarios of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 22, e00886 (2020).

- van der Plas, F. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in naturally assembled communities. Biol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv. 12499 (2019).

- Newbold, T. et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 520, 45-50 (2015).

- Brooks, T. M. et al. Habitat loss and extinction in the hotspots of biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. 16, 909-923 (2002).

- Elith, J. et al. Novel methods improve prediction of species’ distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29, 129-151 (2006).

- Blois, J. L., Williams, J. W., Fitzpatrick, M. C., Jackson, S. T. & Ferrier, S. Space can substitute for time in predicting climate-change effects on biodiversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 9374-9379 (2013).

- Ware, C. et al. Improving biodiversity surrogates for conservation assessment: a test of methods and the value of targeted biological surveys. Divers. Distrib. 24, 1333-1346 (2018).

- Pimm, S. L., Jenkins, C. N. & Li, B. V. How to protect half of earth to ensure it protects sufficient biodiversity. Sci. Adv. 4, 1-9 (2018).

- Di Marco, M., Hoskins, A. J., Harwood, T. D., Ware, C. & Ferrier, S. BILBI model data for SSP1/RCP2.6 and SSP5/RCP8.5. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare. 25188650 (2024).

- Diamond, J. M. Biogeographic kinetics: estimation of relaxation times for Avifaunas of Southwest Pacific Islands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 69, 3199-3203 (1972).

- Gonzalez, A. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences https://doi.org/10. 1002/9780470015902.a0021230 (Wiley, 2009).

- Kriegler, E. et al. Fossil-fueled development (SSP5): an energy and resource intensive scenario for the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 297-315 (2017).

- van Vuuren, D. P. et al. Energy, land-use and greenhouse gas emissions trajectories under a green growth paradigm. Glob.

Environ. Change 42, 237-250 (2017). - Ciais, P. et al. Carbon and other biogeochemical cycles. In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the iltergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 465-570 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Hurtt, G. C. et al. Harmonization of global land use change and management for the period 850-2100 (LUH2) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 5425-5464 (2020).

- Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G. & Jarvis, A. WorldClim Global Climate Data Version 1. http://worldclim.org/ version1 (2017).

- Liang, J. et al. Positive biodiversity-productivity relationship predominant in global forests. Science 354, aaf8957 (2016).

- Craven, D. et al. Plant diversity effects on grassland productivity are robust to both nutrient enrichment and drought. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 371, 20150277 (2016).

- Hurtt, G. C. et al. Harmonization of land-use scenarios for the period 1500-2100: 600 years of global gridded annual land-use transitions, wood harvest, and resulting secondary lands. Clim. Change 109, 117 (2011).

- Hengl, T. et al. SoilGrids250m: global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 12, e0169748 (2017).

- Hijmans, R. J. terra: Spatial Data Analysis. R package version 1.739. (2023).

- Balvanera, P. et al. Quantifying the evidence for biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning and services. Ecol. Lett. 9, 1146-1156 (2006).

- Mori, A. S., Cornelissen, J. H. C., Fujii, S., Okada, K. & Isbell, F. A meta-analysis on decomposition quantifies afterlife effects of plant diversity as a global change driver. Nat. Commun. 11, 1-9 (2020).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (SpringerVerlag, 2016).

- Tennekes, M. tmap: Thematic Maps in R. J. Stat. Softw. 84, 1-39 (2018).

- Weiskopf, S. R. et al. Biodiversity Loss Reduces Global Terrestrial Carbon Storage-Data. U.S. Geological Survey data release (2024).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-47872-7.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© Isbell, Arce-Plata, Di Marco, Harfoot, Johnson, Mori, Weng, Ferrier. Parts of this work were authored by US Federal Government authors and are not under copyright protection in the US; foreign copyright protection may apply 2024

- (T) Check for updates

U.S. Geological Survey National Climate Adaptation Science Center, Reston, VA, USA. Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA. Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, University of Minnesota, Saint Paul, MN, USA. Département de Sciences Biologiques, Université de Montréal, Montréal, QC H3T 1J4, Canada. Department of Biology and Biotechnologies, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy. Vizzuality, 123 Calle de Fuencarral, 28010 Madrid, Spain. Department of Applied Economics, University of Minnesota, 1994 Buford Ave, Saint Paul, MN 55105, USA. USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station, Amherst, MA, USA. U.S. Geological Survey North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center, Boulder, CO, USA. U.S. Geological Survey Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center, Amherst, MA, USA. Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, the University of Tokyo, 4-6-1 Komaba, Meguro, Tokyo 153-8904, Japan. Columbia University/NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, 2880 Broadway, New York, NY 10025, USA. CSIRO Environment, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. e-mail: sweiskopf@usgs.gov