DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01049-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38413767

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-27

فهم العوامل المؤثرة الكامنة في اعتماد الصحة الرقمية في الممارسات العامة من خلال تحليل مختلط الأساليب

الملخص

ليزا ويك ©

أظهرت الأبحاث المكثفة القيمة المحتملة لحلول الصحة الرقمية وأبرزت أهمية اعتماد الأطباء. نظرًا لأن الأطباء العامين هم نقطة الاتصال الأولى للمرضى، فإن فهم العوامل المؤثرة على اعتمادهم للصحة الرقمية يعد أمرًا مهمًا بشكل خاص لاشتقاق توصيات عملية مخصصة. باستخدام نهج مختلط، تحدد هذه الدراسة بشكل عام حواجز الاعتماد واستراتيجيات التحسين المحتملة في الممارسات العامة، بما في ذلك تأثير الخصائص الجوهرية للأطباء العامين – وخاصة شخصياتهم – على اعتماد الصحة الرقمية. تكشف نتائج استطلاعنا عبر الإنترنت مع 216 طبيبًا عامًا عن حواجز متوسطة بشكل عام على مقياس ليكرت من 5 نقاط، مع التعديلات المطلوبة في سير العمل (

حواجز متنوعة

النتائج

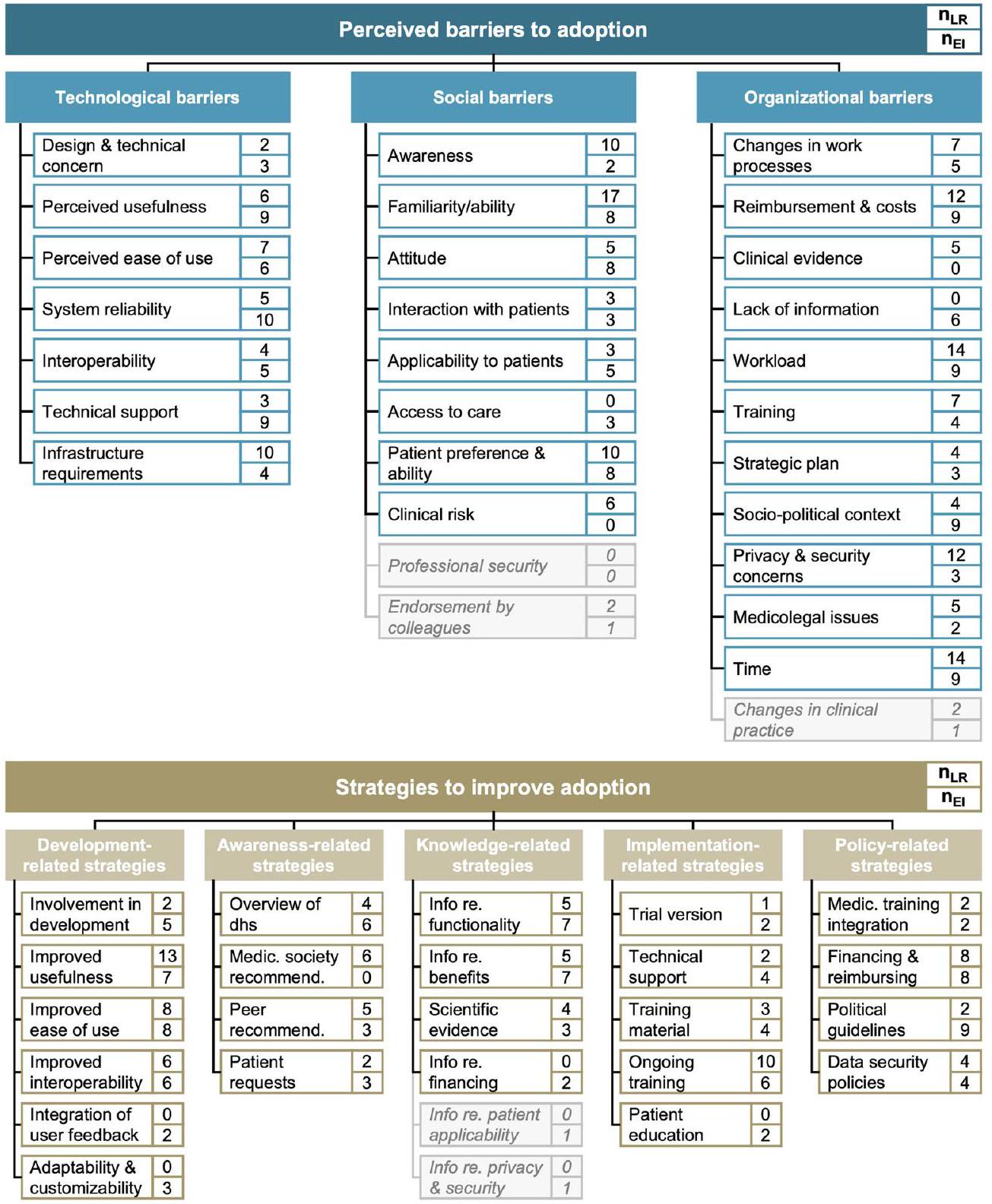

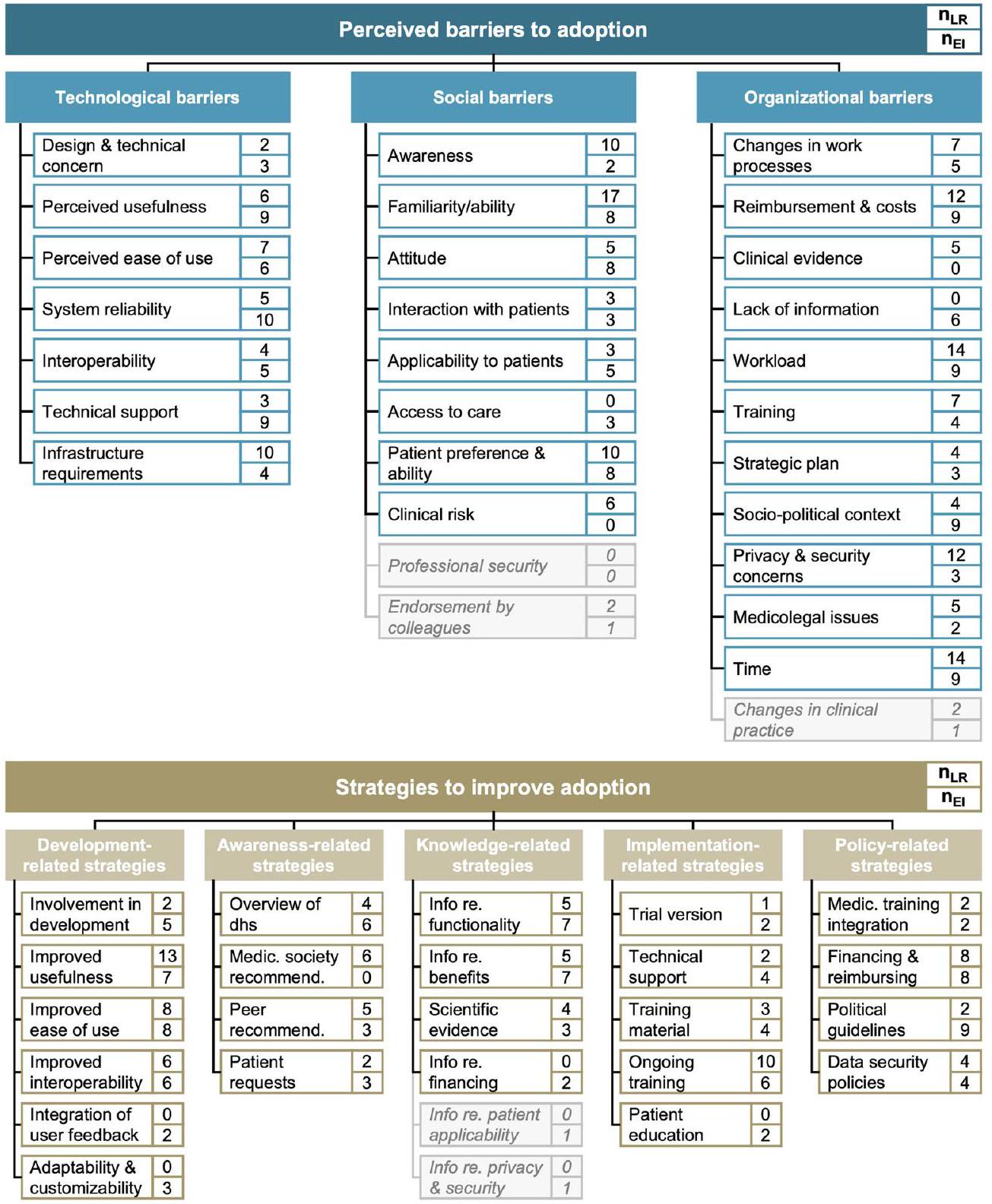

حواجز التبني واستراتيجيات التحسين في الممارسات العامة (مراجعة الأدبيات ونتائج مقابلات الخبراء)

تعويض

عوامل تؤثر على حواجز التبني واستراتيجيات التحسين (نتائج الاستطلاع عبر الإنترنت)

تم تحديده في مراجعة الأدبيات التي تقترح الحاجز (الاستراتيجية)؛

واستراتيجيات متعلقة بالمعرفة (

اختبار)، كانوا جداً (

| خصائص | % | |||

| جنس | ذكر | 97 | ٤٤.٩ | |

| أنثى | ١١٩ | ٥٥.١ | ||

| غواصون | 0 | |||

| لا إجابة | 0 | – | ||

| عمر | < ٢٦ | 0 | – | |

| ٢٦-٣٥ | ٢٢ | 10.2 | ||

| ٣٦-٤٥ | ٥٦ | ٢٥.٩ | ||

| ٤٦-٥٥ | ٥٥ | ٢٥.٥ | ||

| ٥٦-٦٥ | 74 | ٣٤.٣ | ||

| > 65 | 9 | ٤.٢ | ||

| حجم موقع الممارسة (# من السكان) | < 5,000 | 42 | 19.4 | |

| 5,000-20,000 | 72 | ٣٣.٣ | ||

| 20,001-100,000 | 41 | 19.0 | ||

| 100,001-500,000 | 26 | 12.0 | ||

| > 500,000 | ٣٥ | 16.2 | ||

| الخبرة المهنية (عدد السنوات) | <1 | 0 | ||

| 1-5 | 23 | 10.6 | ||

| ٦-١٠ | 31 | 14.4 | ||

| 11-20 | ٥٨ | ٢٦.٩ | ||

| 21-30 | ٥٩ | ٢٧.٣ | ||

| >30 | ٤٥ | ٢٠.٨ | ||

| فئة المرضى | فقط المؤمن عليهم صحياً بشكل خاص | 0 | – | |

| فقط المؤمن عليهم صحياً بموجب القانون | 0 | – | ||

| كلاهما | 100.0 | |||

| نوع الممارسة | ممارسة فردية | ١٠٢ | ٤٧.٢ | |

| ممارسة المشاركة | 10 | ٤.٦ | ||

| ممارسة جماعية | 93 | ٤٣.١ | ||

| عيادة التدريب | 0 | – | ||

| شبكة الممارسة | 0 | – | ||

| مركز الرعاية الطبية | 11 | 5.1 | ||

| مختبر تعاوني | 0 | |||

| الاستخدام الحالي للحلول الصحية الرقمية | أبداً | 20 | 9.3 | |

| أقل من مرة في الشهر | ٤٧ | 21.8 | ||

| شهري | ٢٤ | 11.1 | ||

| أسبوعي | 32 | 14.8 | ||

| يومي | 93 | ٤٣.١ | ||

| الاستخدام المتوقع المستقبلي لحلول الصحة الرقمية | (1) غير محتمل جداً | 11 | 5.1 | |

| (2) غير محتمل إلى حد كبير | ٢٩ | 13.4 | ||

| (3) لا / ولا | 15 | 6.9 | ||

| (4) من المحتمل جداً | 50 | ٢٣.١ | ||

| (5) من المحتمل جداً | 111 | ٥١.٤ | ||

| الانجذاب الرقمي المدرك لمساعدي الأطباء | (1) ليس له أي علاقة رقمية على الإطلاق | ٤ | 1.9 | |

| (2) بالأحرى ليس بشكل رقمي متجانس | 40 | 18.5 | ||

| (3) لا / ولا متوافق رقميًا | ٥٥ | ٢٥.٥ | ||

| (4) بدلاً من ذلك، متجه رقميًا | 91 | 42.1 | ||

| (5) متجانس رقمي بالكامل | 26 | 12.0 | ||

الاستخدام الحالي والاستخدام المتوقع المستقبلي للصحة الرقمية، مستوى العصابية، ومستوى النضج الرقمي (انظر الشكل 5). أظهرت اختبارات ما بعد التحليل أن المستجيبين الذين كانوا إناثاً (

| عنصر | ن | يعني | SD | % أ | (1) | (5) | |||

| السل | أنا متشكك بشأن التصميم والقدرات التقنية لـ DHS. | 216 | 2.89 | 1.12 | 31٪ |  |

|||

| استخدام نظام الـ DHS لا يقدم قيمة إضافية مقارنة بعمليات ممارستي الحالية. | 216 | ٢.٧٥ | 1.19 | ٢٩٪ | *

|

||||

| استخدام نظام الـ DHS يعتبر مرهقًا نسبيًا ويستغرق وقتًا طويلاً. | 215 | ٣.٤٠ | 1.10 | ٤٧٪ |  |

||||

| أنا متشكك بشأن الموثوقية التقنية لـ DHS. | 216 | 3.03 | 1.22 | ٣٨٪ |  |

||||

| تتكامل أنظمة Dhs بشكل سيء مع برامج وأدوات الممارسة الحالية. | 216 | ٣.١٤ | 1.10 | ٣٦٪ |  |

||||

| لا يوجد دعم فني كافٍ من المزود عندما تظهر مشاكل فنية. | ٢١٤ | 3.35 | 1.18 | ٤٩٪ | * ** | ||||

| المعدات التقنية في عيادتي غير كافية لتنفيذ نظام DHS. | 216 | 1.97 | 1.07 | 11% | * |  |

|||

| SB | لا أعرف أي من خدمات الدعم الاجتماعي متاحة حاليًا وما هي أهدافها وغاياتها. | 216 | 2.81 | 1.23 | 31٪ |  |

|||

| أنا لست على دراية بـ dhs ولا أستطيع استخدامها. | 216 | ٢.٤٧ | 1.18 | 20٪ |

|

||||

| أنا متشكك ومعارض لتنفيذ نظام الدهس. | 216 | 2.61 | 1.24 | 25% | *

|

||||

| أخشى أن تعيق إدارة خدمات الصحة التواصل مع المرضى. | 216 | 2.38 | 1.23 | 21% | * * | ||||

| أنا قلق من أن نظام الرعاية الصحية لن يكون قابلاً للتطبيق أو مناسباً إلا لبعض المرضى. | 216 | 3.47 | 1.14 | ٥٦٪ |  |

||||

| لا أعتقد أن وزارة الأمن الداخلي ستُحسن وصول مرضاي إلى الرعاية. | 216 | 2.88 | 1.17 | 32% |  |

|

|||

| مرضاي غير مهتمين أو غير قادرين على استخدام نظام الرعاية الصحية. | 215 | 3.04 | 1.03 | ٣٤٪ | |||||

| أنا قلق من أن DHS قد يكون له عواقب طبية سلبية. | 216 | 2.40 | 1.08 | 17% | * * | ||||

| OB | يتطلب اعتماد نظام إدارة البيانات (DHS) تعديلات على العمليات والممارسات الحالية. | 216 | ٤.١٣ | 0.93 | 87% | ||||

| تنفيذ نظام الرعاية الصحية الرقمية مكلف والاستخدام اللاحق لا يتم تعويضه بشكل كاف. | 216 | ٤.٠٢ | 1.02 | 71٪ | |||||

| لا توجد أدلة تجريبية كافية حول فوائد نظام الرعاية الصحية للمرضى. | 216 | 3.22 | 1.12 | 40٪ |  |

||||

| ليس لدي معلومات كافية عن أنظمة الـ DHS الحالية وكيفية عملها. | 216 | 3.06 | 1.27 | 42% |

|

||||

| سيؤدي تنفيذ نظام إدارة البيانات إلى زيادة عبء العمل. | 216 | ٣.٤٥ | 1.14 | ٤٨٪ |  |

||||

| ستتطلب تنفيذ نظام إدارة البيانات (DHS) جهدًا كبيرًا في التدريب والتأقلم. | 216 | 3.87 | 1.01 | 67% |  |

||||

| ليس لدي خطة استراتيجية لتقديم الدهس. | 215 | ٣.٤٩ | 1.29 | ٥٦٪ |

|

||||

| لا توجد لوائح وإرشادات وسياسات صحية واضحة وكافية حول الدهس. | 216 | 3.74 | 1.08 | 68% |  |

||||

| أنا متشكك بشأن سرية وأمان المعلومات الشخصية المتعلقة بـ DHS. | 216 | 3.37 | 1.29 | ٥٢٪ | *

|

||||

| أنا قلق بشأن المخاطر الطبية القانونية المتعلقة بـ DHS، مثل مخاطر المسؤولية. | 216 | ٣.٢٥ | 1.24 | ٤٩٪ |  |

||||

| ليس لدي وقت كافٍ لتنفيذ واستخدام نظام إدارة البيانات. | 216 | 3.58 | 1.17 | ٥٦٪ | |||||

|

|

|||||||||

التشغيل البيني، وتحسين التعويض كأهم استراتيجيات التحسين. بالمقابل، بالنسبة للمشاركين الذكور، كانت هناك تحسينات في التشغيل البيني، وزيادة الفائدة، وتحسين قابلية الاستخدام (انظر الشكل 4). بشكل عام، وجدنا نتائج مشابهة لعدد استراتيجيات التحسين، باستثناء وجود فرق كبير إضافي بناءً على مستوى الوعي لدى المستجيبين (ويلش)

من التباين في قوة الحواجز، وصولاً إلى الدلالة الإحصائية للنموذج،

| عنصر | ن | يعني | SD | % أ | (1) | (5) | |

| دي إس | …إذا كنت مشاركًا في تصميم وتخطيط وتنفيذ الـ DHS. | 216 | 3.26 | 1.12 | ٤٧٪ |  |

|

| …إذا قام مقدمو الخدمة بتحسين الفوائد لممارستي ومرضاي. | 216 | ٤.١٥ | 0.80 | 87% |  |

||

| …إذا قام المزودون بتحسين سهولة الاستخدام وملاءمة المستخدم. | 216 | ٤.٢٠ | 0.88 | 83% |  |

||

| …إذا قام المزودون بتحسين قابلية التكامل مع البرمجيات والأدوات الحالية. | 215 | ٤.٣٨ | 0.81 | 90٪ | ** * | ||

| …إذا تم دمج ملاحظات المستخدمين في تطوير وتحسين نظام إدارة البيانات. | 216 | ٤.٠٦ | 0.99 | 78% |  |

||

| …إذا كانت هناك إمكانية لتخصيص وتفريد نظام الرعاية الصحية لعملي. | 216 | 3.84 | 0.99 | 66% |  |

||

| كما | …إذا كان لدي نظرة عامة على خدمات DHS المقدمة، وأهدافها، والاستخدام المقصود لها. | 216 | 3.96 | 0.99 | 74% |  |

|

| …إذا كانت هناك توصيات من الجمعيات الطبية أو المجتمعات العلمية. | 216 | 3.86 | 1.07 | 68% |  |

||

| …إذا كان الزملاء أو القادة المؤثرون المهمون سيبلغون عن تجارب إيجابية. | 216 | ٣.٦٥ | 1.04 | 60٪ |

|

||

| …إذا كان المرضى يرغبون في رؤية استخدام أو إدخال نظام الرعاية الصحية. | 216 | 3.34 | 1.01 | 44% |

|

||

| كيه إس | …إذا كان لدي المزيد من المعلومات حول الوظائف والتكامل في سير العمل. | 216 | 3.75 | 0.94 | 69% |  |

|

| …إذا كان لدي المزيد من المعلومات حول الفوائد المحتملة للأطباء والمرضى. | 216 | 3.96 | 0.91 | 78% |  |

||

| …إذا كان هناك أبحاث ومعلومات إضافية حول الفوائد والمخاطر المحتملة. | 216 | 3.77 | 1.06 | 69% |  |

||

| …إذا كان لدي المزيد من المعلومات حول نماذج السداد والتمويل المتاحة. | 216 | 3.91 | 1.03 | 75% | |||

| الدولة الإسلامية | …إذا أتيحت لي الفرصة لاختبار نظام إدارة البيانات قبل التنفيذ كجزء من نسخة تجريبية. | 216 | 3.84 | 1.08 | 70٪ |  |

|

| …إذا تلقيت دعمًا فنيًا مستمرًا من المزود قبل وبعد التنفيذ. | 216 | ٤.٣٣ | 0.91 | ٨٨٪ |  |

||

| …إذا كان المزود سيقدم مواد تدريبية موثوقة حول استخدام نظام إدارة البيانات. | 216 | ٤.١٤ | 0.97 | 80٪ |  |

||

| …إذا تلقيت تدريبًا منتظمًا على نظام إدارة البيانات كجزء من تعليمي المهني المستمر. | 216 | ٣.٥٥ | 1.08 | 57% |

|

||

| …إذا كانت هناك فرص تعليمية للمرضى حول خدمات الرعاية الصحية والفوائد المرتبطة بها. | 216 | 3.65 | 1.09 | 63% |

|

||

| ملاحظة | …إذا تم تضمين الكفاءات في استخدام نظم المعلومات الصحية في تدريب المهنيين الطبيين. | 216 | 3.62 | 1.12 | 63% |  |

|

| …إذا كانت هناك حوافز مالية أو تم تحسين التعويض. | 216 | ٤.١٥ | 1.01 | 77% |  |

||

| …إذا تم تبسيط السياسات واللوائح وكان هناك إرشادات حول المخاطر الطبية القانونية. | 216 | ٤.٠٧ | 1.04 | 78% |  |

||

| …إذا كانت هناك لوائح قانونية تبسط حماية البيانات والتعامل مع البيانات الشخصية. | 216 | ٤.١٤ | 1.05 | 76% |  |

||

|

|

|||||||

الإطار الأحمر يظهر اختلافات كبيرة بين المجموعات. %A نسبة المستجيبين الذين يوافقون على البيان وبالتالي يصنفون الاستراتيجية المعنية على أنها مهمة بتقييم (4) أو (5)؛ استراتيجيات متعلقة بتطوير نظم المعلومات؛ استراتيجيات متعلقة بالوعي؛ استراتيجيات متعلقة بالمعرفة؛ استراتيجيات متعلقة بالتنفيذ؛ استراتيجيات متعلقة بالسياسة؛ حلول الصحة الرقمية.

| تحليل التباين الأحادي، قوة الحواجز | اختبارات ما بعد hoc لتحليل التباين ذو الدلالة الإحصائية | ||||||||

| متغير | “ف” ويلش |

|

|

|

فئات | ن | يعني | SD | |

| جنس | -1.908 | ٢١٤ | – | . 029 | ذكر | ١١٩ | ٢.٩٩ | 0.71 | 0.64 |

| عمر | 1.109 | ٤ | 44.74 | . 364 | أبداً | 20 | 3.42 | 0.64 | |

| ٤ | أقل من

|

٤٧ | 3.26 | 0.74 | |||||

| حجم موقع الممارسة | 0.915 | ٨٨.٤٩ | . ٤٥٩ | شهري | ٢٤ | 3.23 | 0.41 | لو. | |

| خبرة | 0.903 | ٤ | ٨٨.٩٣ | . ٤٦٦ | أسبوعي | 32 | 2.97 | 0.60 | |

| يومي | 93 | 2.93 | 0.68 | ||||||

| نوع الممارسة | 1.976 | ٣ | 25.13 | . 143 | غير محتمل جداً | 11 | 3.48 | 0.77 | |

| الاستخدام الحالي | ٤.٠٨٠ | ٤ | 72.01 | . 005 | غير محتمل إلى حد كبير | ٢٩ | 3.61 | 0.59 | |

| الاستخدام المستقبلي | 8.606 | ٤ | ٤٠.٩٦ | . 000 | من المحتمل جداً | 50 | 3.09 | 0.53 | |

| الملاءمة الرقمية للماجستير | ٢.٤٨٠ | ٤ | 21.01 | . 075 | من المحتمل جداً | 111 | 2.89 | 0.66 | |

| أقل من ATI | ٣٩ | 3.53 | 0.71 | ||||||

| مستوى ATI | 14.929 | 2 | 91.15 | . 000 | ATI معتدل | ١١٥ | 3.10 | 0.61 | 0.62 |

| مستوى الانفتاح | 5.439 | 2 | ٥٦.٧٠ | . 007 | إي لو | 21 | 3.43 | 0.64 | |

| مستوى التوافق | 0.298 | 2 | ٤٣.٠٣ | . 744 | إ م معتدل | ١١٧ | 3.17 | 0.61 | هو |

| مستوى الضمير | 1.411 | 2 | 2.65 | . ٣٨٣ | ن منخفض | ١١٢ | 2.92 | 0.69 | |

| مستوى العصابية | 10.527 | 2 | ٣٤.٢٨ | . 000 | N معتدل | 91 | 3.21 | 0.61 | |

| مستوى الانفتاح | 0.064 | 2 | ١٣.٢٦ | . 938 | دي إم منخفض | 14 | 3.43 | 0.56 |  |

| مستوى النضج الرقمي | 10.718 | 2 | ٣٤.٧٣ | . 000 | إدارة متوسطة | ١٣٧ | ٣.٢١ | 0.56 | |

| تحليل التباين الأحادي، أهمية الاستراتيجيات | اختبارات ما بعد hoc لتحليل التباين ذو الدلالة الإحصائية | ||||||||

| متغير | “ف” ويلش |

|

|

|

فئات | ن | يعني | SD | |

| جنس | -2.125 | 184.09 | – | . 017 | ذكر | ١١٩ | 3.79 | 0.68 | ]

|

| عمر | ٢.٢٩٢ | ٤ | ٤٦.٤١ | . 074 | 1-5 سنوات | 23 | ٤.١٢ | 0.48 | |

| حجم موقع الممارسة | 0.377 | ٤ | ٨٨.٨٧ | . 824 | 6-10 سنوات | 31 | ٣.٩٩ | 0.51 | |

| خبرة | ٣.٤٣٢ | ٤ | ٨٩.٣٤ | . 012 | 21-30 سنة | ٥٩ | 3.72 | 0.65 | |

| نوع الممارسة | 0.822 | ٣ | ٢٦.٨٠ | . 493 | >30 سنة | ٤٥ | 3.77 | 0.61 | |

| الاستخدام الحالي | 3.117 | ٤ | 68.62 | . 020 | أبداً | 20 | ٣.٤٠ | 0.70 | |

| الاستخدام المستقبلي | 3.338 | ٤ | ٤٠.٢٦ | . 019 | شهري | ٢٤ | ٤.٠٠ | 0.54 | ọc |

| الملاءمة الرقمية للماجستير | 1.177 | ٤ | ٢٠.٦٧ | . ٣٥٠ | يومي | 93 | 3.95 | 0.62 | |

| مستوى ATI | 1.471 | 2 | ٨٦.١٠ | . 235 | غير محتمل جداً | 11 | 3.21 | 0.68 | |

| غير محتمل إلى حد كبير | ٢٩ | 3.78 | 0.75 | ||||||

| مستوى الانفتاح | 0.627 | 2 | 53.87 | . 538 | لا / ولا | 15 | 3.81 | 0.66 | |

| مستوى التوافق | 0.557 | 2 | 42.64 | . 577 | من المحتمل جداً | 111 | 3.95 | 0.45 | |

| مستوى الضمير | 7.480 | ٢ | ٢.٩٠ | . 072 | ن منخفض | ١١٢ | 3.84 | 0.61 | |

| N معتدل | 91 | 3.90 | 0.63 | ||||||

| مستوى العصابية | ٤.٩٦٠ | ٢ | ٣٩.٠٧ | . 012 | N عالي | ١٣ | ٤.٢٢ | 0.39 | |

| مستوى الانفتاح | 0.524 | 2 | 14.39 | . 603 | دي إم منخفض | 14 | ٤.١٥ | 0.46 | |

| إدارة متوسطة | ١٣٧ | 3.82 | 0.58 | ||||||

| مستوى النضج الرقمي | ٣.٥٨٨ | 2 | ٣٧.٢٨ | . 038 | دي إم عالي | 65 | 3.97 | 0.70 | |

هي متغير ثنائي، قمنا بإجراء اختبار ذو طرفين

الارتباط بعمر المستجيبين: أن يكون العمر بين 46 و 55

نقاش

| رقم الطراز | المتغيرات المضمنة | ف |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1 | الخصائص السكانية وخصائص الممارسة | 1.198 | 16 | 199 | 0.272 | 0.088 | 0.088 | 0.272 | |||||

| 2 |

|

٢.٥٧٣ | 21 | 194 | <0.001 | 0.218 | 0.130 | <0.001 | |||||

| ٣ |

|

3.684 | 23 | 192 | <0.001 | 0.306 | 0.088 | <0.001 | |||||

| ٤ |

|

٤.٦٢٠ | ٢٨ | 187 | <0.001 | 0.٤٠٩ | 0.١٠٣ | <0.001 | |||||

| ٥ |

|

٥.١٣٩ | ٢٩ | 186 | <0.001 | 0.445 | 0.036 | <0.001 |

الود، الضمير الحي، العصابية، الانفتاح؛ النموذج 5 (متغيرات النموذج 4، النضج الرقمي).

الود، الضمير الحي، العصابية، الانفتاح؛ النموذج 5 (متغيرات النموذج 4، النضج الرقمي).| رقم الطراز | المتغيرات المضمنة | ف |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1 | الخصائص السكانية وخصائص الممارسة | 1.407 | ١٨ | 199 | 0.141 | 0.102 | 0.102 | 0.141 | |||||

| 2 |

|

2.305 | 21 | 194 | 0.002 | 0.200 | 0.098 | <0.001 | |||||

| ٣ |

|

2.109 | 23 | 192 | 0.003 | 0.202 | 0.002 | 0.788 | |||||

| ٤ |

|

1.829 | ٢٨ | 187 | 0.010 | 0.215 | 0.013 | 0.675 | |||||

| ٥ |

|

1.757 | ٢٩ | 186 | 0.014 | 0.215 | 0.000 | 0.874 |

الود، الضمير الحي، العصابية، الانفتاح؛ النموذج 5 (متغيرات النموذج 4، النضج الرقمي).

الود، الضمير الحي، العصابية، الانفتاح؛ النموذج 5 (متغيرات النموذج 4، النضج الرقمي).كانت الألفة الرقمية، والعديد من سمات الشخصية، والنضج الرقمي من المتنبئين المهمين لقوة الحواجز المدركة. أما بالنسبة لأهمية استراتيجيات التحسين المدركة، فقد كانت المتغيرات الديموغرافية والمتعلقة باستخدام الصحة الرقمية مرة أخرى من المتنبئين المهمين.

أنفسهم، متناقضين مع مراجعة سابقة أخرى

القدرة على دمج حلول الصحة الرقمية بسلاسة في سير العمل الحالي وتبادل المعلومات مع مقدمي الرعاية الصحية الآخرين كحاجز قوي.

تفاوتت قوة الحواجز وأهمية الاستراتيجيات بين الأطباء العامين بناءً على الجنس، حيث كانت المشاركات الإناث يرون الحواجز أعلى والاستراتيجيات أكثر أهمية من زملائهن الذكور. يتماشى هذا مع الدراسات التي أفادت بأن كون الشخص ذكراً كان مرتبطاً باستخدام تكنولوجيا الصحة الرقمية.

الممارسين الصحيين

استخدام الصحة الرقمية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، من خلال التعرف على تأثير سمات الشخصية على الحواجز المدركة، يمكن لصانعي السياسات النظر في تخصيص برامج التدريب لتلبية الخصائص المتنوعة للأطباء العامين لتعزيز فعالية مبادرات التدريب بشكل أكبر.

طرق

تصميم الدراسة

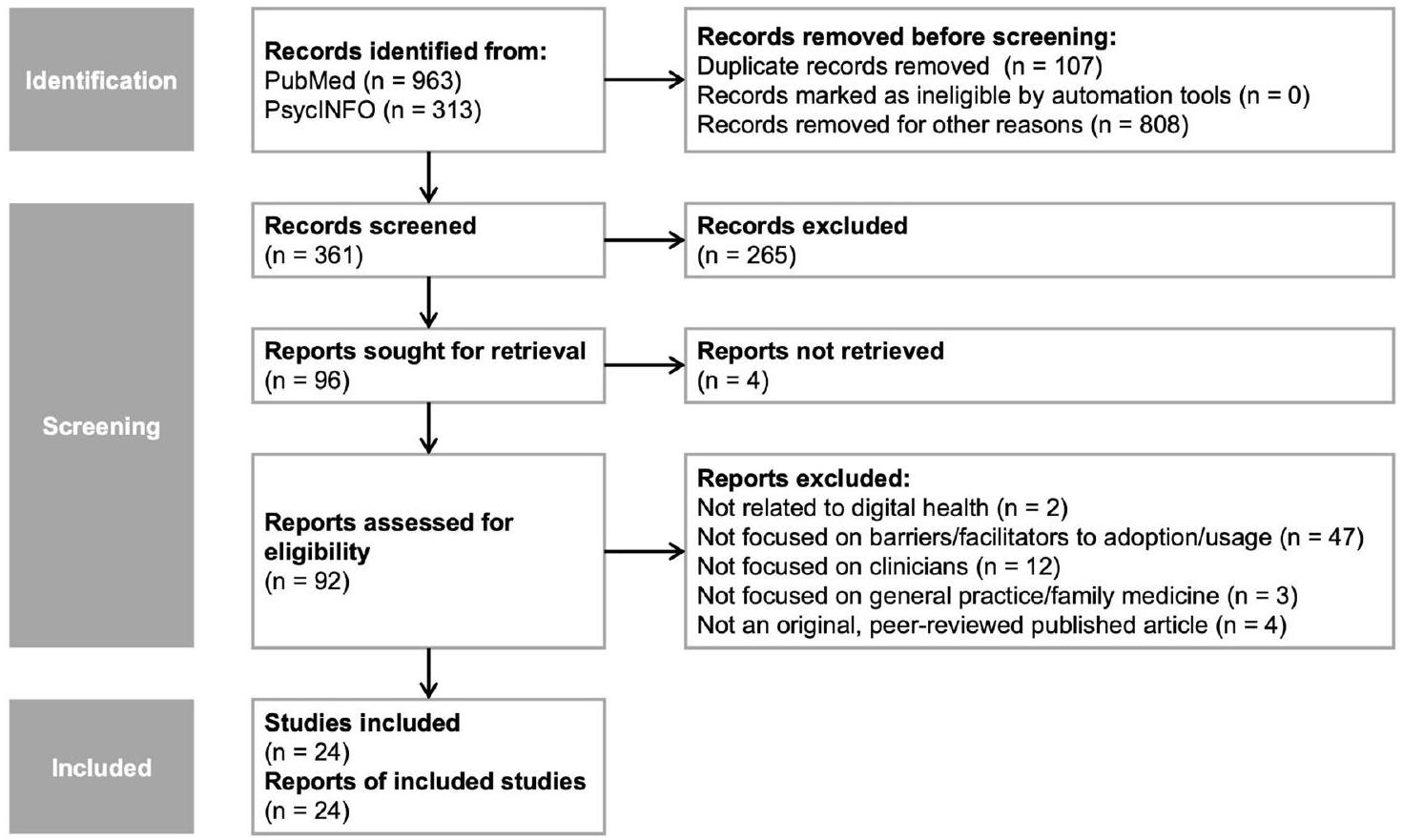

مراجعة الأدبيات

المقابلات مع الخبراء

النضج، (3) الحواجز أمام تبني الصحة الرقمية، و(4) الاستراتيجيات ذات الصلة لتحسين تبني الصحة الرقمية. تركز هذه الدراسة بشكل خاص على الموضوعين الأخيرين، بينما سيكون الأول جزءًا من تحليل منفصل.

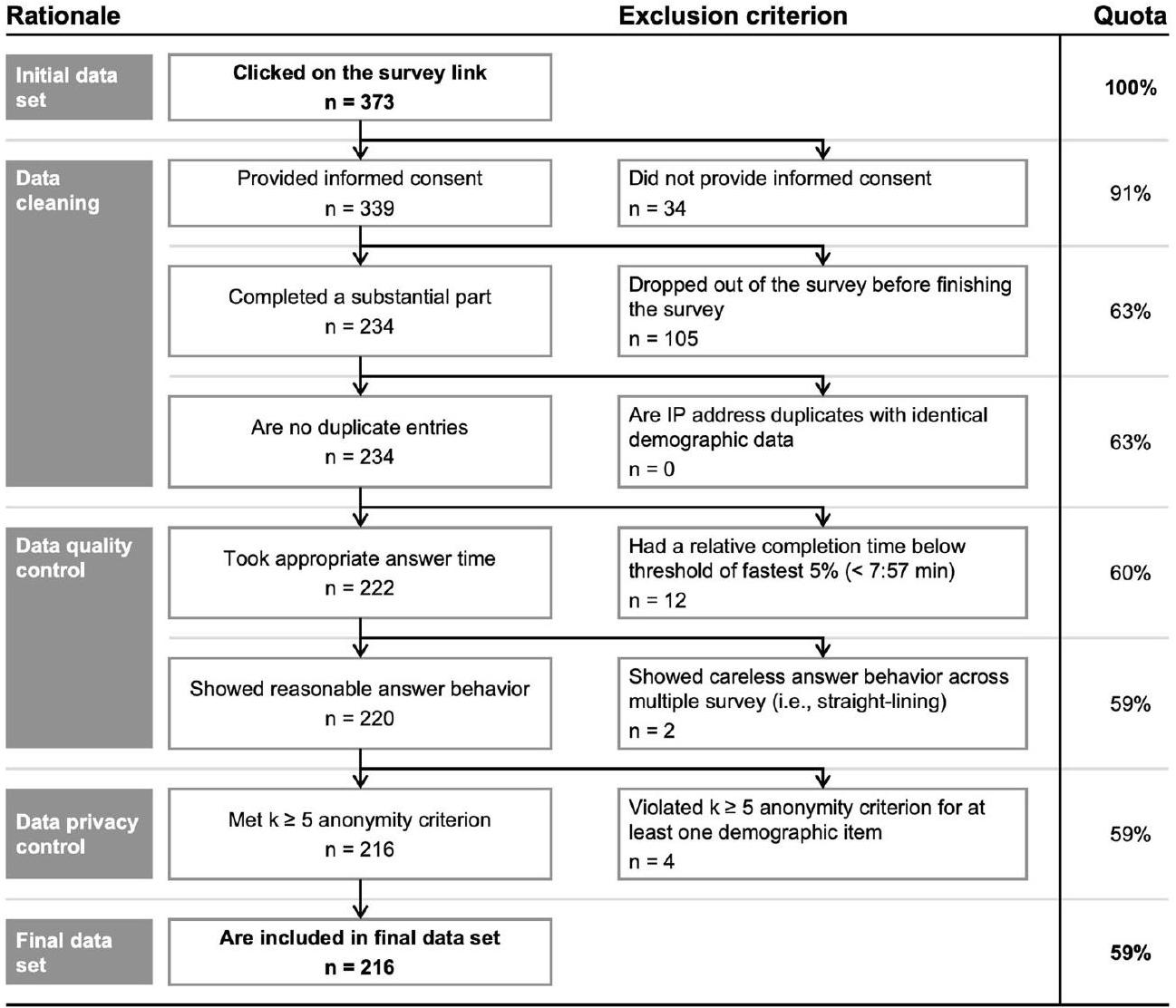

استبيان عبر الإنترنت

استراتيجيات متعلقة بالوعي، ومتعلقة بالمعرفة، ومتعلقة بالتنفيذ، ومتعلقة بالسياسات.

استراتيجيات، قمنا أيضًا بحساب مقياسين عامين للنتائج لكلا المتغيرين: يمثل أحد مقاييس النتائج عدد الحواجز (الاستراتيجيات) وتم حسابه كمجموع الحواجز (الاستراتيجيات) التي حصلت على درجة 4 أو أعلى على مقياس ليكرت من 5 نقاط وبالتالي تم إدراكها على هذا النحو. تم حساب مقياس النتيجة الثاني كمتوسط عبر الحواجز (الاستراتيجيات) ويمثل القوة المدركة للحواجز (الأهمية المدركة للاستراتيجيات). SPSS الإصدار 29.0 لنظام ماكنتوش

| مقياس | بعد |

|

يعني | SD | # عناصر |

|

|

| الانجذاب لتفاعل التكنولوجيا (ATI) | الانجذاب لتفاعل التكنولوجيا | 216 | 3.66 | 1.08 | 9 | 0.89 | 0.92 |

| الشخصية الخمسة الكبرى (BFI-K) | الانفتاح | 216 | ٣.٦٤ | 0.80 | ٤ | 0.86 | 0.83 |

| الشخصية الخمسة الكبرى (BFI-K) | الود | 216 | 3.53 | 0.75 | ٤ | 0.64 | 0.68 |

| الشخصية الخمسة الكبرى (BFI-K) | الضمير الحي | 216 | ٤.١٠ | 0.59 | ٤ | 0.70 | 0.61 |

| الشخصية الخمسة الكبرى (BFI-K) | العصابية | 216 | 2.42 | 0.71 | ٤ | 0.74 | 0.72 |

| الشخصية الخمسة الكبرى (BFI-K) | الانفتاح | 216 | 3.85 | 0.68 | ٥ | 0.66 | 0.73 |

| الحواجز المدركة | تكنولوجي | 213 | 2.93 | 0.76 | ٧ | – | 0.76 |

| الحواجز المدركة | اجتماعي | 215 | 2.76 | 0.79 | ٨ | – | 0.84 |

| الحواجز المدركة | تنظيمي | 215 | ٣.٥٦ | 0.71 | 11 | – | 0.84 |

| استراتيجيات التحسين | مرتبط بالتنمية | 215 | 3.98 | 0.67 | ٦ | – | 0.79 |

| استراتيجيات التحسين | مرتبط بالوعي | 216 | ٣.٧٠ | 0.74 | ٤ | – | 0.72 |

| استراتيجيات التحسين | متعلق بالمعرفة | 216 | 3.85 | 0.81 | ٤ | – | 0.84 |

| استراتيجيات التحسين | متعلق بالتنفيذ | 216 | 3.90 | 0.78 | ٥ | – | 0.77 |

| استراتيجيات التحسين | متعلق بالسياسة | 216 | ٤.٠٠ | 0.81 | ٤ | – | 0.74 |

تم تطوير استراتيجيات التحسين بناءً على مراجعة الأدبيات ونتائج مقابلات الخبراء. وبالتالي، لا يمكن عرض ألفا كرونباخ للدراسات الأصلية.

تم تطوير استراتيجيات التحسين بناءً على مراجعة الأدبيات ونتائج مقابلات الخبراء. وبالتالي، لا يمكن عرض ألفا كرونباخ للدراسات الأصلية.تم استخدامه فقط في تحليلات ANOVA الخاصة بنا كمؤشر أولي للاختلافات في هذه المتغيرات بين الأطباء العامين. ثم تم تحليل هذه الاختلافات بشكل أكثر تفصيلاً في نموذج الانحدار الخاص بنا باستخدام المتغيرات المستمرة دون تصنيف.

توفر البيانات

نُشر على الإنترنت: 27 فبراير 2024

References

- Amarasingham, R., Plantinga, L., Diener-West, M., Gaskin, D. J. & Powe, N. R. Clinical information technologies and inpatient outcomes. Arch. Intern. Med. 169, 108 (2009).

- Martin, G. et al. Evaluating the impact of organisational digital maturity on clinical outcomes in secondary care in England. NPJ Digit. Med. 2, 41 (2019).

- Chaudhry, B. et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann. Intern. Med. 144, 742 (2006).

- Buntin, M. B., Burke, M. F., Hoaglin, M. C. & Blumenthal, D. The benefits of health information technology: a review of the recent literature shows predominantly positive results. Health Aff. 30, 464-471 (2011).

- Campanella, P. et al. The impact of electronic health records on healthcare quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European J. Public Health 26, 60-64 (2016).

- Lingg, M. & Lütschg, V. Health system stakeholders’ perspective on the role of mobile health and its adoption in the swiss health system: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8, e17315 (2020).

- Poissant, L., Pereira, J., Tamblyn, R. & Kawasumi, Y. The impact of electronic health records on time efficiency of physicians and nurses: a systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 12, 505-516 (2005).

- Golinelli, D. et al. Adoption of digital technologies in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review of early scientific literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e22280 (2020).

- Choi, W. S., Park, J., Choi, J. Y. B. & Yang, J.-S. Stakeholders’ resistance to telemedicine with focus on physicians: utilizing the Delphi technique. J Telemed Telecare 25, 378-385 (2019).

- Greenhalgh, T. et al. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e367 (2017).

- Jacob, C., Sanchez-Vazquez, A. & Ivory, C. Social, organizational, and technological factors impacting clinicians’ adoption of mobile health tools: systematic literature review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8, e15935 (2020).

- Gagnon, M. P. et al. Systematic review of factors influencing the adoption of information and communication technologies by healthcare professionals. J. Med. Syst. 36, 241-277 (2012).

- Jetty, A., Moore, M. A., Coffman, M., Petterson, S. & Bazemore, A. Rural family physicians are twice as likely to use telehealth as urban family physicians. Telemed. e-Health 24, 268-276 (2018).

- Wanderås, M. R., Abildsnes, E., Thygesen, E. & Martinez, S. G. Video consultation in general practice: a scoping review on use, experiences, and clinical decisions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 316 (2023).

- Byambasuren, O., Beller, E. & Glasziou, P. Current knowledge and adoption of mobile health apps among Australian general practitioners: survey study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7, e13199 (2019).

- Gagnon, M. P., Ngangue, P., Payne-Gagnon, J. & Desmartis, M. M-Health adoption by healthcare professionals: a systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 23, 212-220 (2016).

- O’Donnell, A., Kaner, E., Shaw, C. & Haighton, C. Primary care physicians’ attitudes to the adoption of electronic medical records: a systematic review and evidence synthesis using the clinical adoption framework. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 18, 101 (2018).

- Rahal, R. M., Mercer, J., Kuziemsky, C. & Yaya, S. Factors affecting the mature use of electronic medical records by primary care physicians: a systematic review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 21, 67 (2021).

- Iversen, T. & Ma, C. A. Technology adoption by primary care physicians. Health Econ 31, 443-465 (2022).

- Leppert, F. et al. Economic aspects as influencing factors for acceptance of remote monitoring by healthcare professionals in Germany. J. Int. Soc. Telemed. eHealth. 3, e12 (2015).

- Hammerton, M., Benson, T. & Sibley, A. Readiness for five digital technologies in general practice: perceptions of staff in one part of southern England. BMJ Open Qual 11, e001865 (2022).

- Dahlhausen, F. et al. Physicians’ attitudes toward prescribable mhealth apps and implications for adoption in Germany: mixed methods study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9, e33012 (2021).

- Byambasuren, O., Beller, E., Hoffmann, T. & Glasziou, P. Barriers to and facilitators of the prescription of mHealth apps in Australian general practice: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8, e17447 (2020).

- Scott, A., Bai, T. & Zhang, Y. Association between telehealth use and general practitioner characteristics during COVID-19: findings from a nationally representative survey of Australian doctors. BMJ Open 11, e046857 (2021).

- EURACT & WONCA Europe. The European Definition of General Practice / Family Medicine – Short Version.

https://www.woncaeurope.org/file/61a77842-76c2-45dd-a435e0a8b875f30a/Definition EURACTshort version revised %202011.pdf (2011). - Kringos, D. S., Boerma, W., van der Zee, J. & Groenewegen, P. Europe’s strong primary care systems are linked to better population health but also to higher health spending. Health Aff. 32, 686-694 (2013).

- Zaresani, A. & Scott, A. Does digital health technology improve physicians’ job satisfaction and work-life balance? A cross-sectional national survey and regression analysis using an instrumental variable. BMJ Open 10, e041690 (2020).

- Krog, M. D. et al. Barriers and facilitators to using a web-based tool for diagnosis and monitoring of patients with depression: a qualitative study among Danish general practitioners. BMC Health Serv Res 18, 503 (2018).

- Poppe, L. et al. Process evaluation of an eHealth intervention implemented into general practice: general practitioners’ and patients’ views. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 1475 (2018).

- Breedvelt, J. J. et al. GPs’ attitudes towards digital technologies for depression: an online survey in primary care. Br. J. General Pract. 69, e164-e170 (2019).

- Lin, D., Papi, E. & McGregor, A. H. Exploring the clinical context of adopting an instrumented insole: a qualitative study of clinicians’ preferences in England. BMJ Open 9, e023656 (2019).

- Buhtz, C. et al. Receptiveness of GPs in the South Of Saxony-Anhalt, Germany to obtaining training on technical assistance systems for caregiving: a cross-sectional study. Clin. Interv. Aging 14, 1649-1656 (2019).

- Lim, H. M. et al. mHealth adoption among primary care physicians in Malaysia and its associated factors: a cross-sectional study. Fam Pract. 38, 210-217 (2021).

- Girdhari, R. et al. Electronic communication between family physicians and patients. Can. Family Phys. 67, 39-46 (2021).

- Muehlensiepen, F. et al. Acceptance of telerheumatology by rheumatologists and general practitioners in Germany: nationwide cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e23742 (2021).

- Jakobsen, P. R. et al. Identification of important factors affecting use of digital individualised coaching and treatment of Type 2 diabetes in general practice: a qualitative feasibility study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 3924 (2021).

- Volpato, L., del Río Carral, M., Senn, N. & Santiago Delefosse, M. General practitioners’ perceptions of the use of wearable electronic health monitoring devices: qualitative analysis of risks and benefits. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9, e23896 (2021).

- Della Vecchia, C. et al. Willingness of French general practitioners to prescribe mHealth apps and devices: quantitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 10, e28372 (2022).

- Meurs, M., Keuper, J., Sankatsing, V., Batenburg, R. & van Tuyl, L. “Get used to the fact that some of the care is really going to take place in a different way”: general practitioners’ experiences with E-Health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 5120 (2022).

- Löbner, M. et al. What comes after the trial? An observational study of the real-world uptake of an E-mental health intervention by general practitioners to reduce depressive symptoms in their patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 6203 (2022).

- Fischer, S. et al. Einschätzung deutscher Hausärztinnen und Hausärzte zur integrierten Versorgung mittels Kommunikationstechnologien. MMW Fortschr Med 164, 16-22 (2022).

- Poon, Z. & Tan, N. C. A qualitative research study of primary care physicians’ views of telehealth in delivering postnatal care to women. BMC Primary Care 23, 206 (2022).

- Wangler, J. & Jansky, M. Welche Potenziale und Mehrwerte bieten DiGA für die hausärztliche Versorgung? – Ergebnisse einer Befragung von Hausärzt*innen in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 65, 1334-1343 (2022).

- Job, J., Nicholson, C., Calleja, Z., Jackson, C. & Donald, M. Implementing a general practitioner-to-general physician eConsult service (eConsultant) in Australia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 1278 (2022).

- Franke, T., Attig, C. & Wessel, D. A personal resource for technology interaction: development and validation of the affinity for technology interaction (ATI) scale. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact 35, 456-467 (2019).

- Rammstedt, B. & John, O. P. Kurzversion des Big Five Inventory (BFIK): Entwicklung und Validierung eines ökonomischen Inventars zur Erfassung der fünf Faktoren der Persönlichkeit. Diagnostica 51, 195-206 (2005).

- Sclafani, J., Tirrell, T. F. & Franko, O. I. Mobile tablet use among academic physicians and trainees. J. Med. Syst. 37, 9903 (2013).

- Bundesanzeiger Verlag. Gesetz Für Sichere Digitale Kommunikation Und Anwendungen Im Gesundheitswesen. Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2015 Teil I Nr. 54 (https://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/text. xav?SID=&tf=xaver.component.Text_0&tocf=&qmf=&hlf=xaver. component.Hitlist_0&bk=bgbl&start=%2F%2F*%5B%40node_id% 3D%27944185%27%5D&skin=pdf&tlevel=-2&nohist=1&sinst= 3A147306 2015).

- Poba-Nzaou, P., Uwizeyemungu, S. & Liu, X. Adoption and performance of complementary clinical information technologies:

analysis of a survey of general practitioners. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e16300 (2020). - Djalali, S., Ursprung, N., Rosemann, T., Senn, O. & Tandjung, R. Undirected health IT implementation in ambulatory care favors paperbased workarounds and limits health data exchange. Int. J. Med. Inform. 84, 920-932 (2015).

- Holanda, A. A., do Carmo e Sá, H. L., Vieira, A. P. G. F. & Catrib, A. M. F. Use and satisfaction with electronic health record by primary care physicians in a health district in Brazil. J. Med. Syst. 36, 3141-3149 (2012).

- Goujon, A., Jacobs-Crisioni, C., Natale, F. & Lavalle, C. The Demographic Landscape of EU Territories – Challenges and Opportunities in Diversely Ageing Regions. https://doi.org/10.2760/658945 (2021).

- Slevin, P. et al. Exploring the barriers and facilitators for the use of digital health technologies for the management of COPD: a qualitative study of clinician perceptions. QJM: Int. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcz241 (2019).

- Devaraj, S., Easley, R. F. & Crant, J. M. How does personality matter? Relating the five-factor model to technology acceptance and use. Inform. Syst. Res. 19, 93-105 (2008).

- Su, J., Dugas, M., Guo, X. & Gao, G. Influence of personality on mHealth use in patients with diabetes: prospective pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8, e17709 (2020).

- McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. J. Pers Soc. Psychol. 52, 81-90 (1987).

- Duncan, R., Eden, R., Woods, L., Wong, I. & Sullivan, C. Synthesizing dimensions of digital maturity in hospitals: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 24, e32994 (2022).

- Kelders, S. M., Kok, R. N., Ossebaard, H. C. & Van Gemert-Pijnen, J. E. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 14, e152 (2012).

- Schrimpf, A., Bleckwenn, M. & Braesigk, A. COVID-19 Continues to Burden General Practitioners: Impact on Workload, Provision of Care, and Intention to Leave. Healthcare 11, 320 (2023).

- Hanna, L., May, C. & Fairhurst, K. Non-face-to-face consultations and communications in primary care: the role and perspective of general practice managers in Scotland. J. Innov. Health Inform. 19, 17-24 (2011).

- KVWL. Digi-Managerin: Neue Fortbildung für nicht-ärztliches Praxispersonal. https://www.kvwl.de/themen-a-z/digi-managerin (2023).

- Eden, R., Burton-Jones, A., Scott, I., Staib, A. & Sullivan, C. Effects of eHealth on hospital practice: synthesis of the current literature. Aust. Health Rev. 42, 568-578 (2018).

- Lezhnina, O. & Kismihók, G. A multi-method psychometric assessment of the affinity for technology interaction (ATI) scale. Comp. Hum. Behav. Rep. 1, 100004 (2020).

- Tricco, A. C. et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467-473 (2018).

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P. & Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Quality Health Care 19, 349-357 (2007).

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 6, e34 (2004).

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2022. (2021).

- Kuckartz, U. & Rädiker, S. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. (Beltz Juventa, Weinheim, Basel, 2022).

- Weik, L., Fehring, L., Mortsiefer, A. & Meister, S. Big 5 personality traits and individual- and practice-related characteristics as influencing

factors of digital maturity in general practices: quantitative web-based survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e52085 (2024). - Leiner, D. J. Too fast, too straight, too weird: non-reactive indicators for meaningless data in internet surveys. Surv. Res. Methods 13, 229-248 (2019).

- Bais, F., Schouten, B. & Toepoel, V. Investigating response patterns across surveys: do respondents show consistency in undesirable answer behaviour over multiple surveys? Bull. Sociol. Methodol. 147-148, 150-168 (2020).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 29.0. (2022).

- Tavakol, M. & Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2, 53-55 (2011).

- Welch, B. L. On the comparison of several mean values: an alternative approach. Biometrika 38, 330 (1951).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. (Sage Publications, London, 2018).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. (Routledge, New York, 2013).

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01049-0.

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

معلومات الرعاية الصحية، كلية الصحة، مدرسة الطب، جامعة ويتن/هيرديك، ويتن، ألمانيا. مستشفى هليوس الجامعي في ووبيرتال، قسم أمراض الجهاز الهضمي، جامعة ويتن/هيرديك، ووبيرتال، ألمانيا. كلية الصحة، مدرسة الطب، جامعة ويتن/هيرديك، ويتن، ألمانيا. الممارسة العامة II وتركيز المريض في الرعاية الأولية، معهد الممارسة العامة والرعاية الأولية، كلية الصحة، مدرسة الطب، جامعة ويتن/هيرديك، ويتن، ألمانيا. قسم الرعاية الصحية، معهد فراونهوفر لهندسة البرمجيات وأنظمة الهندسة ISST، دورتموند، ألمانيا. – البريد الإلكتروني:سفن.مايستر@uni-wh.de

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01049-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38413767

Publication Date: 2024-02-27

Understanding inherent influencing factors to digital health adoption in general practices through a mixedmethods analysis

Abstract

Lisa Weik ©

Extensive research has shown the potential value of digital health solutions and highlighted the importance of clinicians’ adoption. As general practitioners (GPs) are patients’ first point of contact, understanding influencing factors to their digital health adoption is especially important to derive personalized practical recommendations. Using a mixed-methods approach, this study broadly identifies adoption barriers and potential improvement strategies in general practices, including the impact of GPs’ inherent characteristics – especially their personality – on digital health adoption. Results of our online survey with 216 GPs reveal moderate overall barriers on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with required workflow adjustments (

various barriers

Results

Adoption barriers and improvement strategies in general practices (literature review and expert interview results)

reimbursement (

Factors influencing adoption barriers and improvement strategies (online survey results)

identified in the literature review proposing the barrier (strategy);

and knowledge-related strategies (

test), were very (

| Characteristics | % | |||

| Gender | Male | 97 | 44.9 | |

| Female | 119 | 55.1 | ||

| Divers | 0 | |||

| No Answer | 0 | – | ||

| Age | < 26 | 0 | – | |

| 26-35 | 22 | 10.2 | ||

| 36-45 | 56 | 25.9 | ||

| 46-55 | 55 | 25.5 | ||

| 56-65 | 74 | 34.3 | ||

| > 65 | 9 | 4.2 | ||

| Practice location size (# inhabitants) | < 5,000 | 42 | 19.4 | |

| 5,000-20,000 | 72 | 33.3 | ||

| 20,001-100,000 | 41 | 19.0 | ||

| 100,001-500,000 | 26 | 12.0 | ||

| > 500,000 | 35 | 16.2 | ||

| Professional experience (# years) | <1 | 0 | ||

| 1-5 | 23 | 10.6 | ||

| 6-10 | 31 | 14.4 | ||

| 11-20 | 58 | 26.9 | ||

| 21-30 | 59 | 27.3 | ||

| >30 | 45 | 20.8 | ||

| Patient population | Only privately health-insured | 0 | – | |

| Only statutory health-insured | 0 | – | ||

| Both | 100.0 | |||

| Practice type | Single practice | 102 | 47.2 | |

| Practice sharing | 10 | 4.6 | ||

| Group practice | 93 | 43.1 | ||

| Practice clinic | 0 | – | ||

| Practice network | 0 | – | ||

| Medical care center | 11 | 5.1 | ||

| Collaborative laboratory | 0 | |||

| Current usage of digital health solutions | Never | 20 | 9.3 | |

| Less than once per month | 47 | 21.8 | ||

| Monthly | 24 | 11.1 | ||

| Weekly | 32 | 14.8 | ||

| Daily | 93 | 43.1 | ||

| Expected future usage of digital health solutions | (1) Very unlikely | 11 | 5.1 | |

| (2) Rather unlikely | 29 | 13.4 | ||

| (3) Neither / nor | 15 | 6.9 | ||

| (4) Rather likely | 50 | 23.1 | ||

| (5) Very likely | 111 | 51.4 | ||

| Perceived digital affinity of medical assistants | (1) Not at all digitally affine | 4 | 1.9 | |

| (2) Rather not digitally affine | 40 | 18.5 | ||

| (3) Neither / nor digitally affine | 55 | 25.5 | ||

| (4) Rather digitally affine | 91 | 42.1 | ||

| (5) Fully digitally affine | 26 | 12.0 | ||

current usage and expected future digital health usage, the level of neuroticism, and the level of digital maturity (see Fig. 5). Post hoc tests revealed that respondents who were female (

| Item | n | mean | SD | % A | (1) | (5) | |||

| TB | I am skeptical about the design and technical capabilities of dhs. | 216 | 2.89 | 1.12 | 31% |  |

|||

| The use of dhs offers no additional value compared to my current practice processes. | 216 | 2.75 | 1.19 | 29% | *

|

||||

| The use of dhs is relatively cumbersome and time-consuming. | 215 | 3.40 | 1.10 | 47% |  |

||||

| I am skeptical about the technical reliability of dhs. | 216 | 3.03 | 1.22 | 38% |  |

||||

| Dhs integrate rather poorly with existing practice software and tools. | 216 | 3.14 | 1.10 | 36% |  |

||||

| There is insufficient technical support from the provider when technical problems arise. | 214 | 3.35 | 1.18 | 49% | * ** | ||||

| The technical equipment in my practice is not sufficient for the implementation of dhs. | 216 | 1.97 | 1.07 | 11% | * |  |

|||

| SB | I do not know which dhs are currently offered and what their goals and purposes are. | 216 | 2.81 | 1.23 | 31% |  |

|||

| I am not familiar with dhs and am unable to use them. | 216 | 2.47 | 1.18 | 20% |

|

||||

| I am skeptical and averse to the implementation of dhs. | 216 | 2.61 | 1.24 | 25% | *

|

||||

| I am afraid that dhs will hinder my communication with patients. | 216 | 2.38 | 1.23 | 21% | * * | ||||

| I am concerned that dhs will only be applicable or appropriate for some patients. | 216 | 3.47 | 1.14 | 56% |  |

||||

| I do not believe that dhs will improve my patients’ access to care. | 216 | 2.88 | 1.17 | 32% |  |

|

|||

| My patients are not interested in or able to use dhs. | 215 | 3.04 | 1.03 | 34% | |||||

| I am concerned that dhs may have negative medical consequences. | 216 | 2.40 | 1.08 | 17% | * * | ||||

| OB | The adoption of dhs requires adjustments to existing practice processes and workflows. | 216 | 4.13 | 0.93 | 87% | ||||

| The implementation of dhs is costly and subsequent use is not adequately reimbursed. | 216 | 4.02 | 1.02 | 71% | |||||

| There is insufficient empirical evidence about the benefits of dhs for patients. | 216 | 3.22 | 1.12 | 40% |  |

||||

| I do not have sufficient information on existing dhs and how they work. | 216 | 3.06 | 1.27 | 42% |

|

||||

| The implementation of dhs will lead to an increased workload. | 216 | 3.45 | 1.14 | 48% |  |

||||

| The implementation of dhs will require a high training and familiarization effort. | 216 | 3.87 | 1.01 | 67% |  |

||||

| I do not have a strategic plan for the introduction of dhs. | 215 | 3.49 | 1.29 | 56% |

|

||||

| There are no clear and adequate regulations, guidelines, and health policies around dhs. | 216 | 3.74 | 1.08 | 68% |  |

||||

| I am skeptical about the confidentiality and security of personal information related to dhs. | 216 | 3.37 | 1.29 | 52% | *

|

||||

| I am concerned about medicolegal risks related to dhs, e.g., liability risks. | 216 | 3.25 | 1.24 | 49% |  |

||||

| I have insufficient time to implement and use dhs. | 216 | 3.58 | 1.17 | 56% | |||||

|

|

|||||||||

interoperability, and improved reimbursement as the most vital improvement strategies. In contrast, for male participants, it was an enhanced interoperability, improved usefulness, and improved usability (see Fig. 4). Overall, we found similar results for the number of improvement strategies, except that there was an additional significant difference based on respondents’ level of conscientiousness (Welch’s

of the variance in the strength of barriers, reaching statistical significance of the model,

| Item | n | mean | SD | % A | (1) | (5) | |

| DS | …if I were involved in the design, planning and realization of dhs. | 216 | 3.26 | 1.12 | 47% |  |

|

| …if providers improved the benefits for my practice and my patients. | 216 | 4.15 | 0.80 | 87% |  |

||

| …if providers optimized user-friendliness and ease of use. | 216 | 4.20 | 0.88 | 83% |  |

||

| …if providers improved integrability with existing software and tools. | 215 | 4.38 | 0.81 | 90% | ** * | ||

| …if user feedback were incorporated into the development and improvement of dhs. | 216 | 4.06 | 0.99 | 78% |  |

||

| …if there was the possibility to customize and individualize dhs for my practice. | 216 | 3.84 | 0.99 | 66% |  |

||

| AS | …if I had an overview of dhs offered, their goals, and their intended use. | 216 | 3.96 | 0.99 | 74% |  |

|

| …if there were recommendations from medical associations or scientific societies. | 216 | 3.86 | 1.07 | 68% |  |

||

| …if colleagues or important opinion leaders would report about positive experiences. | 216 | 3.65 | 1.04 | 60% |

|

||

| …if patients would like to see the use or introduction of dhs. | 216 | 3.34 | 1.01 | 44% |

|

||

| KS | …if I had more information about the functionalities and integration into workflows. | 216 | 3.75 | 0.94 | 69% |  |

|

| …if I had more information about the potential benefits for physicians and for patients. | 216 | 3.96 | 0.91 | 78% |  |

||

| …if there was additional research and information about benefits and potential risks. | 216 | 3.77 | 1.06 | 69% |  |

||

| …if I had more information about available reimbursement and financing models. | 216 | 3.91 | 1.03 | 75% | |||

| IS | …if I had the opportunity to test dhs before implementation as part of a trial version. | 216 | 3.84 | 1.08 | 70% |  |

|

| …if I received continuous technical support from the provider before and after rollout. | 216 | 4.33 | 0.91 | 88% |  |

||

| …if the provider would offer reliable training material on the use of the dhs. | 216 | 4.14 | 0.97 | 80% |  |

||

| …if I received regular training on dhs as part of my continuing professional education. | 216 | 3.55 | 1.08 | 57% |

|

||

| …if there were educational opportunities for patients about dhs and associated benefits. | 216 | 3.65 | 1.09 | 63% |

|

||

| PS | …if competencies in the use of dhs were included in medical professional training. | 216 | 3.62 | 1.12 | 63% |  |

|

| …if there were financial incentives or the reimbursement were improved. | 216 | 4.15 | 1.01 | 77% |  |

||

| …if policies and regulations were simplified and there were guidelines on medico-legal risks. | 216 | 4.07 | 1.04 | 78% |  |

||

| …if there were legal regulations that simplified data protection and handling of personal data. | 216 | 4.14 | 1.05 | 76% |  |

||

|

|

|||||||

with red framing show substantial differences between groups. %A Percentage of respondents agreeing to the statement and thus rating the respective strategy as important rating of (4) or (5); DS development-related strategies; AS awarenessrelated strategies; KS knowledge-related strategies; IS implementation-related strategies; PS policy-related strategies; dhs digital health solutions.

| Univariate ANOVA, strength of barriers | Post hoc tests for significant ANOVAs | ||||||||

| Variable | Welch’s F |

|

|

|

Categories | n | mean | SD | |

| Gender | -1.908 | 214 | – | . 029 | Male | 119 | 2.99 | 0.71 | 0.64 |

| Age | 1.109 | 4 | 44.74 | . 364 | Never | 20 | 3.42 | 0.64 | |

| 4 | Less than

|

47 | 3.26 | 0.74 | |||||

| Practice location size | 0.915 | 88.49 | . 459 | Monthly | 24 | 3.23 | 0.41 | ลู. | |

| Experience | 0.903 | 4 | 88.93 | . 466 | Weekly | 32 | 2.97 | 0.60 | |

| Daily | 93 | 2.93 | 0.68 | ||||||

| Practice type | 1.976 | 3 | 25.13 | . 143 | Very unlikely | 11 | 3.48 | 0.77 | |

| Current usage | 4.080 | 4 | 72.01 | . 005 | Rather unlikely | 29 | 3.61 | 0.59 | |

| Future usage | 8.606 | 4 | 40.96 | . 000 | Rather likely | 50 | 3.09 | 0.53 | |

| MA digital affinity | 2.480 | 4 | 21.01 | . 075 | Very likely | 111 | 2.89 | 0.66 | |

| ATI low | 39 | 3.53 | 0.71 | ||||||

| Level of ATI | 14.929 | 2 | 91.15 | . 000 | ATI moderate | 115 | 3.10 | 0.61 | 0.62 |

| Level of extraversion | 5.439 | 2 | 56.70 | . 007 | E low | 21 | 3.43 | 0.64 | |

| Level of agreeableness | 0.298 | 2 | 43.03 | . 744 | E moderate | 117 | 3.17 | 0.61 | है |

| Level of conscientiousness | 1.411 | 2 | 2.65 | . 383 | N low | 112 | 2.92 | 0.69 | |

| Level of neuroticism | 10.527 | 2 | 34.28 | . 000 | N moderate | 91 | 3.21 | 0.61 | |

| Level of openness | 0.064 | 2 | 13.26 | . 938 | DM low | 14 | 3.43 | 0.56 |  |

| Level of digital maturity | 10.718 | 2 | 34.73 | . 000 | DM moderate | 137 | 3.21 | 0.56 | |

| Univariate ANOVA, importance of strategies | Post hoc tests for significant ANOVAs | ||||||||

| Variable | Welch’s F |

|

|

|

Categories | n | mean | SD | |

| Gender | -2.125 | 184.09 | – | . 017 | Male | 119 | 3.79 | 0.68 | ]

|

| Age | 2.292 | 4 | 46.41 | . 074 | 1-5 years | 23 | 4.12 | 0.48 | |

| Practice location size | 0.377 | 4 | 88.87 | . 824 | 6-10 years | 31 | 3.99 | 0.51 | |

| Experience | 3.432 | 4 | 89.34 | . 012 | 21-30 years | 59 | 3.72 | 0.65 | |

| Practice type | 0.822 | 3 | 26.80 | . 493 | >30 years | 45 | 3.77 | 0.61 | |

| Current usage | 3.117 | 4 | 68.62 | . 020 | Never | 20 | 3.40 | 0.70 | |

| Future usage | 3.338 | 4 | 40.26 | . 019 | Monthly | 24 | 4.00 | 0.54 | ọc |

| MA digital affinity | 1.177 | 4 | 20.67 | . 350 | Daily | 93 | 3.95 | 0.62 | |

| Level of ATI | 1.471 | 2 | 86.10 | . 235 | Very unlikely | 11 | 3.21 | 0.68 | |

| Rather unlikely | 29 | 3.78 | 0.75 | ||||||

| Level of extraversion | 0.627 | 2 | 53.87 | . 538 | Neither / nor | 15 | 3.81 | 0.66 | |

| Level of agreeableness | 0.557 | 2 | 42.64 | . 577 | Very likely | 111 | 3.95 | 0.45 | |

| Level of conscientiousness | 7.480 | 2 | 2.90 | . 072 | N low | 112 | 3.84 | 0.61 | |

| N moderate | 91 | 3.90 | 0.63 | ||||||

| Level of neuroticism | 4.960 | 2 | 39.07 | . 012 | N high | 13 | 4.22 | 0.39 | |

| Level of openness | 0.524 | 2 | 14.39 | . 603 | DM low | 14 | 4.15 | 0.46 | |

| DM moderate | 137 | 3.82 | 0.58 | ||||||

| Level of digital maturity | 3.588 | 2 | 37.28 | . 038 | DM high | 65 | 3.97 | 0.70 | |

is a dichotomous variable, we conducted a two-tailed

association with respondents’ age: Being aged between 46 and 55 (

Discussion

| Model # | Included variables | F |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1 | Demographics & practice-related characteristics | 1.198 | 16 | 199 | 0.272 | 0.088 | 0.088 | 0.272 | |||||

| 2 |

|

2.573 | 21 | 194 | <0.001 | 0.218 | 0.130 | <0.001 | |||||

| 3 |

|

3.684 | 23 | 192 | <0.001 | 0.306 | 0.088 | <0.001 | |||||

| 4 |

|

4.620 | 28 | 187 | <0.001 | 0.409 | 0.103 | <0.001 | |||||

| 5 |

|

5.139 | 29 | 186 | <0.001 | 0.445 | 0.036 | <0.001 |

agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness); Model 5 (model 4 variables, digital maturity).

agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness); Model 5 (model 4 variables, digital maturity).| Model # | Included variables | F |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1 | Demographics & practice-related characteristics | 1.407 | 18 | 199 | 0.141 | 0.102 | 0.102 | 0.141 | |||||

| 2 |

|

2.305 | 21 | 194 | 0.002 | 0.200 | 0.098 | <0.001 | |||||

| 3 |

|

2.109 | 23 | 192 | 0.003 | 0.202 | 0.002 | 0.788 | |||||

| 4 |

|

1.829 | 28 | 187 | 0.010 | 0.215 | 0.013 | 0.675 | |||||

| 5 |

|

1.757 | 29 | 186 | 0.014 | 0.215 | 0.000 | 0.874 |

agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness); Model 5 (model 4 variables, digital maturity).

agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness); Model 5 (model 4 variables, digital maturity).digital affinity, several personality traits, and digital maturity were significant predictors of the perceived strength of barriers. For the perceived importance of improvement strategies, demographics, and digital health usage-related variables were again significant predictors.

themselves, contrasting with another previous review

ability to integrate digital health solutions flawlessly into existing workflows and exchange information with other healthcare providers as a strong barrier.

strength of barriers and the importance of strategies differed between GPs based on gender, with female participants perceiving barriers as higher and strategies as more important than their male colleagues. This is in line with studies reporting that being male was associated with using digital health technology

clinicians

of digital health usage. In addition, recognizing the influence of personality traits on perceived barriers, policymakers could consider personalizing training programs to cater to the diverse characteristics of GPs to further enhance the effectiveness of training initiatives.

Methods

Study design

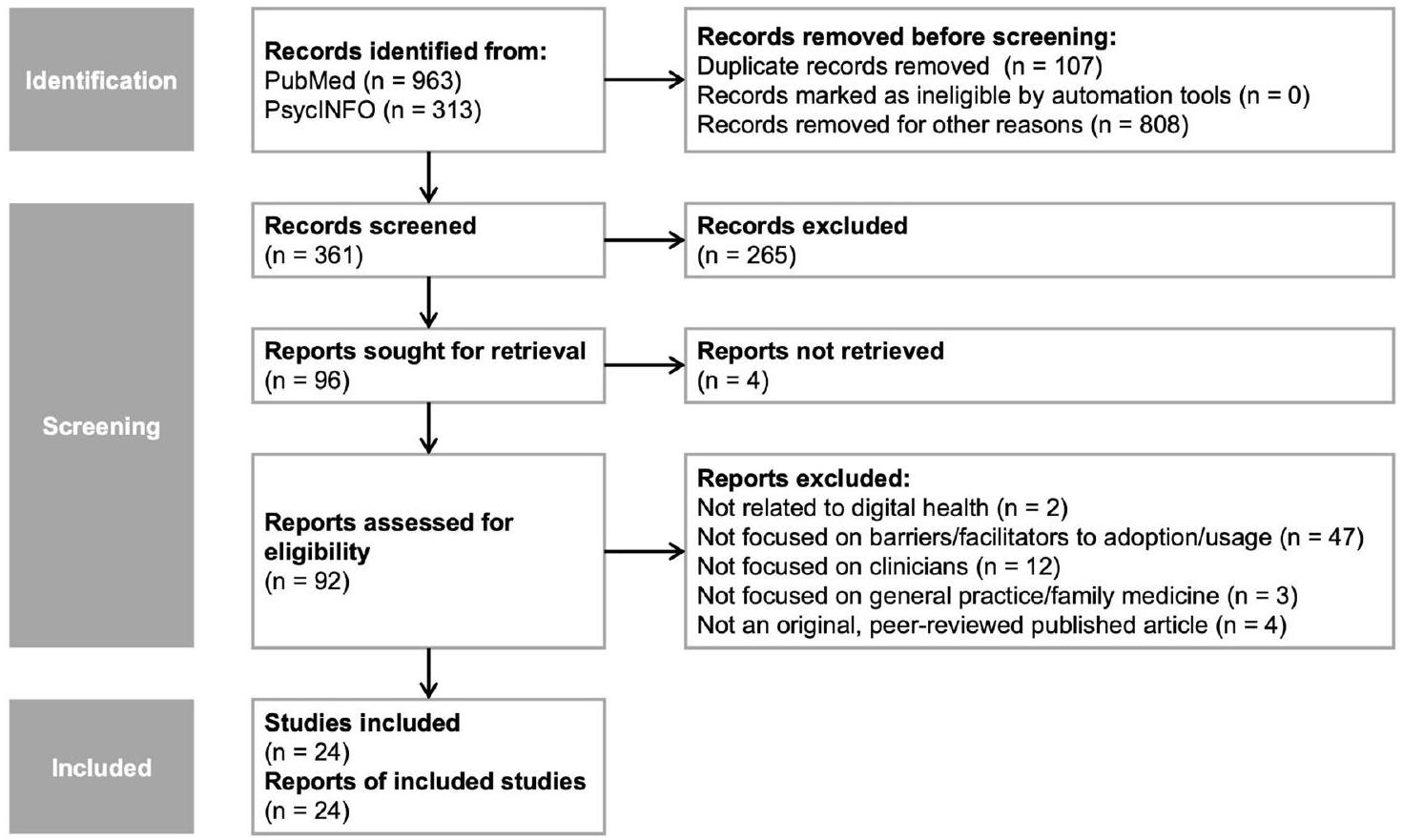

Literature review

Expert interviews

maturity, (3) barriers to digital health adoption, and (4) relevant strategies to improve digital health adoption. This study specifically focuses on the latter two topics, while the first will be part of a separate analysis.

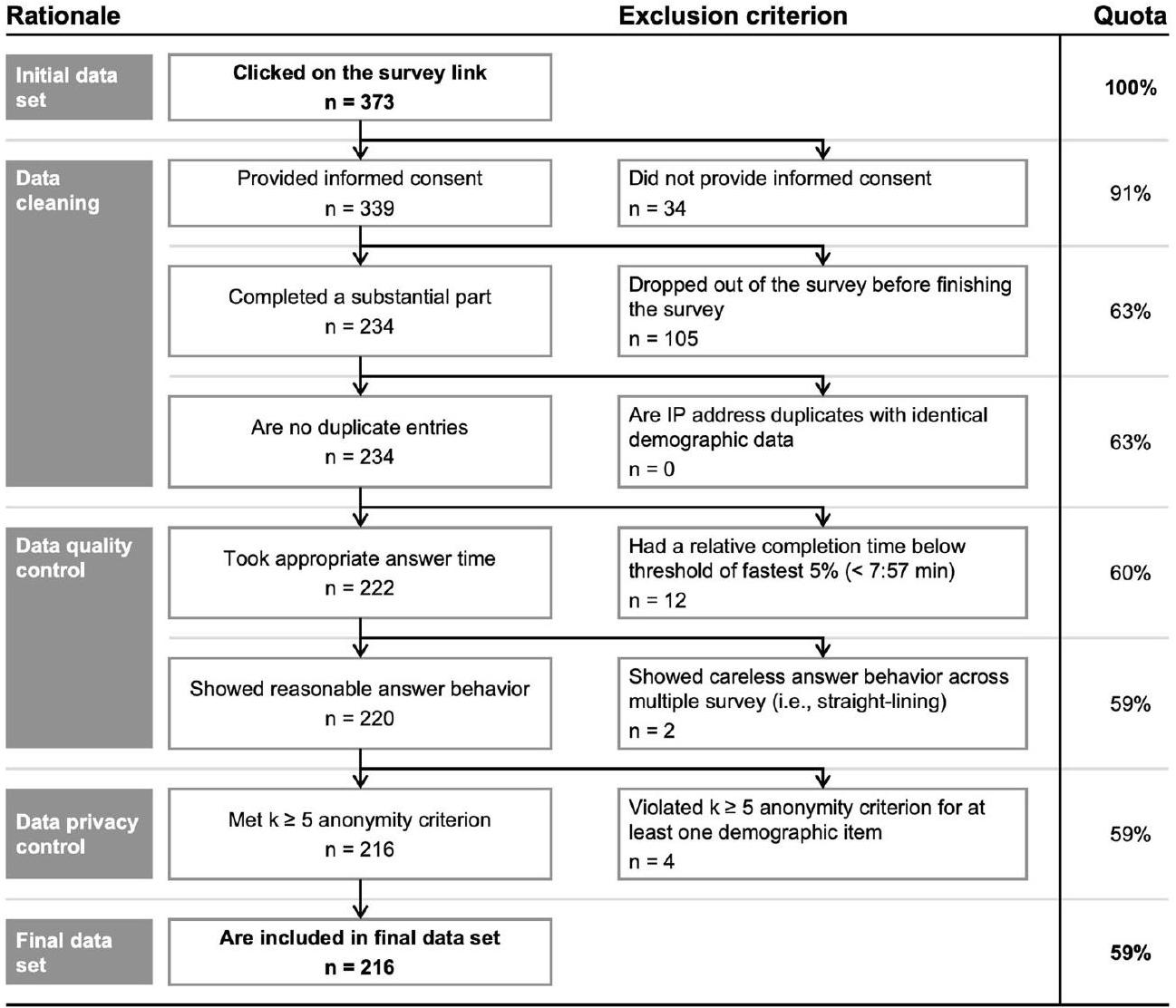

Online survey

awareness-related, knowledge-related, implementation-related, and policyrelated strategies.

strategies, we further computed two overall outcome measures for both variables: One outcome measure represents the number of barriers (strategies) and was calculated as the sum of barriers (strategies) that received a score of 4 or higher on our 5-point Likert-type scale and were thus perceived as such. The second outcome measure was calculated as the average across barriers (strategies) and represents the perceived strength of barriers (the perceived importance of strategies). SPSS version 29.0 for Macintosh

| Scale | Dimension |

|

mean | SD | # items |

|

|

| Affinity for technology interaction (ATI) | Affinity for technology interaction | 216 | 3.66 | 1.08 | 9 | 0.89 | 0.92 |

| Big five personality (BFI-K) | Extraversion | 216 | 3.64 | 0.80 | 4 | 0.86 | 0.83 |

| Big five personality (BFI-K) | Agreeableness | 216 | 3.53 | 0.75 | 4 | 0.64 | 0.68 |

| Big five personality (BFI-K) | Conscientiousness | 216 | 4.10 | 0.59 | 4 | 0.70 | 0.61 |

| Big five personality (BFI-K) | Neuroticism | 216 | 2.42 | 0.71 | 4 | 0.74 | 0.72 |

| Big five personality (BFI-K) | Openness | 216 | 3.85 | 0.68 | 5 | 0.66 | 0.73 |

| Perceived barriers | Technological | 213 | 2.93 | 0.76 | 7 | – | 0.76 |

| Perceived barriers | Social | 215 | 2.76 | 0.79 | 8 | – | 0.84 |

| Perceived barriers | Organizational | 215 | 3.56 | 0.71 | 11 | – | 0.84 |

| Improvement strategies | Development-related | 215 | 3.98 | 0.67 | 6 | – | 0.79 |

| Improvement strategies | Awareness-related | 216 | 3.70 | 0.74 | 4 | – | 0.72 |

| Improvement strategies | Knowledge-related | 216 | 3.85 | 0.81 | 4 | – | 0.84 |

| Improvement strategies | Implementation-related | 216 | 3.90 | 0.78 | 5 | – | 0.77 |

| Improvement strategies | Policy-related | 216 | 4.00 | 0.81 | 4 | – | 0.74 |

improvement strategies were developed based on the literature review and expert interview results. Thus, Cronbach’s Alpha for the original studies cannot be shown.

improvement strategies were developed based on the literature review and expert interview results. Thus, Cronbach’s Alpha for the original studies cannot be shown.was only used in our ANOVAs as an initial indicator for differences in these variables between GPs. These differences were then analyzed more granularly in our regression model utilizing the continuous variables without categorization.

Data availability

Published online: 27 February 2024

References

- Amarasingham, R., Plantinga, L., Diener-West, M., Gaskin, D. J. & Powe, N. R. Clinical information technologies and inpatient outcomes. Arch. Intern. Med. 169, 108 (2009).

- Martin, G. et al. Evaluating the impact of organisational digital maturity on clinical outcomes in secondary care in England. NPJ Digit. Med. 2, 41 (2019).

- Chaudhry, B. et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann. Intern. Med. 144, 742 (2006).

- Buntin, M. B., Burke, M. F., Hoaglin, M. C. & Blumenthal, D. The benefits of health information technology: a review of the recent literature shows predominantly positive results. Health Aff. 30, 464-471 (2011).

- Campanella, P. et al. The impact of electronic health records on healthcare quality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European J. Public Health 26, 60-64 (2016).

- Lingg, M. & Lütschg, V. Health system stakeholders’ perspective on the role of mobile health and its adoption in the swiss health system: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8, e17315 (2020).

- Poissant, L., Pereira, J., Tamblyn, R. & Kawasumi, Y. The impact of electronic health records on time efficiency of physicians and nurses: a systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 12, 505-516 (2005).

- Golinelli, D. et al. Adoption of digital technologies in health care during the COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review of early scientific literature. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e22280 (2020).

- Choi, W. S., Park, J., Choi, J. Y. B. & Yang, J.-S. Stakeholders’ resistance to telemedicine with focus on physicians: utilizing the Delphi technique. J Telemed Telecare 25, 378-385 (2019).

- Greenhalgh, T. et al. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 19, e367 (2017).

- Jacob, C., Sanchez-Vazquez, A. & Ivory, C. Social, organizational, and technological factors impacting clinicians’ adoption of mobile health tools: systematic literature review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8, e15935 (2020).

- Gagnon, M. P. et al. Systematic review of factors influencing the adoption of information and communication technologies by healthcare professionals. J. Med. Syst. 36, 241-277 (2012).

- Jetty, A., Moore, M. A., Coffman, M., Petterson, S. & Bazemore, A. Rural family physicians are twice as likely to use telehealth as urban family physicians. Telemed. e-Health 24, 268-276 (2018).

- Wanderås, M. R., Abildsnes, E., Thygesen, E. & Martinez, S. G. Video consultation in general practice: a scoping review on use, experiences, and clinical decisions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 23, 316 (2023).

- Byambasuren, O., Beller, E. & Glasziou, P. Current knowledge and adoption of mobile health apps among Australian general practitioners: survey study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7, e13199 (2019).

- Gagnon, M. P., Ngangue, P., Payne-Gagnon, J. & Desmartis, M. M-Health adoption by healthcare professionals: a systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 23, 212-220 (2016).

- O’Donnell, A., Kaner, E., Shaw, C. & Haighton, C. Primary care physicians’ attitudes to the adoption of electronic medical records: a systematic review and evidence synthesis using the clinical adoption framework. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 18, 101 (2018).

- Rahal, R. M., Mercer, J., Kuziemsky, C. & Yaya, S. Factors affecting the mature use of electronic medical records by primary care physicians: a systematic review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 21, 67 (2021).

- Iversen, T. & Ma, C. A. Technology adoption by primary care physicians. Health Econ 31, 443-465 (2022).

- Leppert, F. et al. Economic aspects as influencing factors for acceptance of remote monitoring by healthcare professionals in Germany. J. Int. Soc. Telemed. eHealth. 3, e12 (2015).

- Hammerton, M., Benson, T. & Sibley, A. Readiness for five digital technologies in general practice: perceptions of staff in one part of southern England. BMJ Open Qual 11, e001865 (2022).

- Dahlhausen, F. et al. Physicians’ attitudes toward prescribable mhealth apps and implications for adoption in Germany: mixed methods study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9, e33012 (2021).

- Byambasuren, O., Beller, E., Hoffmann, T. & Glasziou, P. Barriers to and facilitators of the prescription of mHealth apps in Australian general practice: qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8, e17447 (2020).

- Scott, A., Bai, T. & Zhang, Y. Association between telehealth use and general practitioner characteristics during COVID-19: findings from a nationally representative survey of Australian doctors. BMJ Open 11, e046857 (2021).

- EURACT & WONCA Europe. The European Definition of General Practice / Family Medicine – Short Version.

https://www.woncaeurope.org/file/61a77842-76c2-45dd-a435e0a8b875f30a/Definition EURACTshort version revised %202011.pdf (2011). - Kringos, D. S., Boerma, W., van der Zee, J. & Groenewegen, P. Europe’s strong primary care systems are linked to better population health but also to higher health spending. Health Aff. 32, 686-694 (2013).

- Zaresani, A. & Scott, A. Does digital health technology improve physicians’ job satisfaction and work-life balance? A cross-sectional national survey and regression analysis using an instrumental variable. BMJ Open 10, e041690 (2020).

- Krog, M. D. et al. Barriers and facilitators to using a web-based tool for diagnosis and monitoring of patients with depression: a qualitative study among Danish general practitioners. BMC Health Serv Res 18, 503 (2018).

- Poppe, L. et al. Process evaluation of an eHealth intervention implemented into general practice: general practitioners’ and patients’ views. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 1475 (2018).

- Breedvelt, J. J. et al. GPs’ attitudes towards digital technologies for depression: an online survey in primary care. Br. J. General Pract. 69, e164-e170 (2019).

- Lin, D., Papi, E. & McGregor, A. H. Exploring the clinical context of adopting an instrumented insole: a qualitative study of clinicians’ preferences in England. BMJ Open 9, e023656 (2019).

- Buhtz, C. et al. Receptiveness of GPs in the South Of Saxony-Anhalt, Germany to obtaining training on technical assistance systems for caregiving: a cross-sectional study. Clin. Interv. Aging 14, 1649-1656 (2019).

- Lim, H. M. et al. mHealth adoption among primary care physicians in Malaysia and its associated factors: a cross-sectional study. Fam Pract. 38, 210-217 (2021).

- Girdhari, R. et al. Electronic communication between family physicians and patients. Can. Family Phys. 67, 39-46 (2021).

- Muehlensiepen, F. et al. Acceptance of telerheumatology by rheumatologists and general practitioners in Germany: nationwide cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e23742 (2021).

- Jakobsen, P. R. et al. Identification of important factors affecting use of digital individualised coaching and treatment of Type 2 diabetes in general practice: a qualitative feasibility study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 3924 (2021).

- Volpato, L., del Río Carral, M., Senn, N. & Santiago Delefosse, M. General practitioners’ perceptions of the use of wearable electronic health monitoring devices: qualitative analysis of risks and benefits. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9, e23896 (2021).

- Della Vecchia, C. et al. Willingness of French general practitioners to prescribe mHealth apps and devices: quantitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 10, e28372 (2022).

- Meurs, M., Keuper, J., Sankatsing, V., Batenburg, R. & van Tuyl, L. “Get used to the fact that some of the care is really going to take place in a different way”: general practitioners’ experiences with E-Health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 5120 (2022).

- Löbner, M. et al. What comes after the trial? An observational study of the real-world uptake of an E-mental health intervention by general practitioners to reduce depressive symptoms in their patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 6203 (2022).

- Fischer, S. et al. Einschätzung deutscher Hausärztinnen und Hausärzte zur integrierten Versorgung mittels Kommunikationstechnologien. MMW Fortschr Med 164, 16-22 (2022).

- Poon, Z. & Tan, N. C. A qualitative research study of primary care physicians’ views of telehealth in delivering postnatal care to women. BMC Primary Care 23, 206 (2022).

- Wangler, J. & Jansky, M. Welche Potenziale und Mehrwerte bieten DiGA für die hausärztliche Versorgung? – Ergebnisse einer Befragung von Hausärzt*innen in Deutschland. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 65, 1334-1343 (2022).

- Job, J., Nicholson, C., Calleja, Z., Jackson, C. & Donald, M. Implementing a general practitioner-to-general physician eConsult service (eConsultant) in Australia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22, 1278 (2022).

- Franke, T., Attig, C. & Wessel, D. A personal resource for technology interaction: development and validation of the affinity for technology interaction (ATI) scale. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact 35, 456-467 (2019).

- Rammstedt, B. & John, O. P. Kurzversion des Big Five Inventory (BFIK): Entwicklung und Validierung eines ökonomischen Inventars zur Erfassung der fünf Faktoren der Persönlichkeit. Diagnostica 51, 195-206 (2005).

- Sclafani, J., Tirrell, T. F. & Franko, O. I. Mobile tablet use among academic physicians and trainees. J. Med. Syst. 37, 9903 (2013).

- Bundesanzeiger Verlag. Gesetz Für Sichere Digitale Kommunikation Und Anwendungen Im Gesundheitswesen. Bundesgesetzblatt Jahrgang 2015 Teil I Nr. 54 (https://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/text. xav?SID=&tf=xaver.component.Text_0&tocf=&qmf=&hlf=xaver. component.Hitlist_0&bk=bgbl&start=%2F%2F*%5B%40node_id% 3D%27944185%27%5D&skin=pdf&tlevel=-2&nohist=1&sinst= 3A147306 2015).

- Poba-Nzaou, P., Uwizeyemungu, S. & Liu, X. Adoption and performance of complementary clinical information technologies:

analysis of a survey of general practitioners. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e16300 (2020). - Djalali, S., Ursprung, N., Rosemann, T., Senn, O. & Tandjung, R. Undirected health IT implementation in ambulatory care favors paperbased workarounds and limits health data exchange. Int. J. Med. Inform. 84, 920-932 (2015).

- Holanda, A. A., do Carmo e Sá, H. L., Vieira, A. P. G. F. & Catrib, A. M. F. Use and satisfaction with electronic health record by primary care physicians in a health district in Brazil. J. Med. Syst. 36, 3141-3149 (2012).

- Goujon, A., Jacobs-Crisioni, C., Natale, F. & Lavalle, C. The Demographic Landscape of EU Territories – Challenges and Opportunities in Diversely Ageing Regions. https://doi.org/10.2760/658945 (2021).

- Slevin, P. et al. Exploring the barriers and facilitators for the use of digital health technologies for the management of COPD: a qualitative study of clinician perceptions. QJM: Int. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcz241 (2019).

- Devaraj, S., Easley, R. F. & Crant, J. M. How does personality matter? Relating the five-factor model to technology acceptance and use. Inform. Syst. Res. 19, 93-105 (2008).

- Su, J., Dugas, M., Guo, X. & Gao, G. Influence of personality on mHealth use in patients with diabetes: prospective pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8, e17709 (2020).

- McCrae, R. R. & Costa, P. T. Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. J. Pers Soc. Psychol. 52, 81-90 (1987).

- Duncan, R., Eden, R., Woods, L., Wong, I. & Sullivan, C. Synthesizing dimensions of digital maturity in hospitals: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 24, e32994 (2022).

- Kelders, S. M., Kok, R. N., Ossebaard, H. C. & Van Gemert-Pijnen, J. E. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 14, e152 (2012).

- Schrimpf, A., Bleckwenn, M. & Braesigk, A. COVID-19 Continues to Burden General Practitioners: Impact on Workload, Provision of Care, and Intention to Leave. Healthcare 11, 320 (2023).

- Hanna, L., May, C. & Fairhurst, K. Non-face-to-face consultations and communications in primary care: the role and perspective of general practice managers in Scotland. J. Innov. Health Inform. 19, 17-24 (2011).

- KVWL. Digi-Managerin: Neue Fortbildung für nicht-ärztliches Praxispersonal. https://www.kvwl.de/themen-a-z/digi-managerin (2023).

- Eden, R., Burton-Jones, A., Scott, I., Staib, A. & Sullivan, C. Effects of eHealth on hospital practice: synthesis of the current literature. Aust. Health Rev. 42, 568-578 (2018).

- Lezhnina, O. & Kismihók, G. A multi-method psychometric assessment of the affinity for technology interaction (ATI) scale. Comp. Hum. Behav. Rep. 1, 100004 (2020).

- Tricco, A. C. et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467-473 (2018).

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P. & Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Quality Health Care 19, 349-357 (2007).

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 6, e34 (2004).

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2022. (2021).

- Kuckartz, U. & Rädiker, S. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. (Beltz Juventa, Weinheim, Basel, 2022).

- Weik, L., Fehring, L., Mortsiefer, A. & Meister, S. Big 5 personality traits and individual- and practice-related characteristics as influencing

factors of digital maturity in general practices: quantitative web-based survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e52085 (2024). - Leiner, D. J. Too fast, too straight, too weird: non-reactive indicators for meaningless data in internet surveys. Surv. Res. Methods 13, 229-248 (2019).

- Bais, F., Schouten, B. & Toepoel, V. Investigating response patterns across surveys: do respondents show consistency in undesirable answer behaviour over multiple surveys? Bull. Sociol. Methodol. 147-148, 150-168 (2020).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 29.0. (2022).

- Tavakol, M. & Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2, 53-55 (2011).

- Welch, B. L. On the comparison of several mean values: an alternative approach. Biometrika 38, 330 (1951).

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. (Sage Publications, London, 2018).

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. (Routledge, New York, 2013).

Author contributions

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

Supplementary Material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01049-0.

© The Author(s) 2024

Health Care Informatics, Faculty of Health, School of Medicine, Witten/Herdecke University, Witten, Germany. Helios University Hospital Wuppertal, Department of Gastroenterology, Witten/Herdecke University, Wuppertal, Germany. Faculty of Health, School of Medicine, Witten/Herdecke University, Witten, Germany. General Practice II and Patient-Centredness in Primary Care, Institute of General Practice and Primary Care, Faculty of Health, School of Medicine, Witten/ Herdecke University, Witten, Germany. Department Healthcare, Fraunhofer Institute for Software and Systems Engineering ISST, Dortmund, Germany. – e-mail: sven.meister@uni-wh.de