المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 15، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84936-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39747330

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-02

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84936-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39747330

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-02

تقارير علمية

افتح

فوسفوليباز A2 السيتوزولي في البلعميات المشتقة من وحيدات النوى المتسللة لا يؤثر على التعافي بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي في إناث الفئران

إصابة الحبل الشوكي (SCI) تؤدي إلى فقدان دائم في الحركة والإحساس، وهو ما يتفاقم بسبب الالتهاب داخل الحبل الشوكي ويستمر لعدة أشهر إلى سنوات بعد الإصابة. بعد الإصابة، تتسلل البلعميات المشتقة من وحيدات النواة (MDMs) إلى المنطقة المصابة للمساعدة في إزالة الحطام الغني بالميالين. خلال عملية إزالة الحطام، تتبنى MDMs نمطًا ظاهريًا مؤيدًا للالتهاب مما يزيد من التنكس العصبي ويعيق التعافي. السبب الأساسي لتحول نمط MDM المؤيد للالتهاب المرتبط بالدهون غير واضح. تشير أعمالنا السابقة إلى أن الفوسفوليباز A2 السيتوزولي (cPLA2) يلعب دورًا في تأثير تعزيز الالتهاب للميالين على البلعميات في المختبر. يقوم الفوسفوليباز A2 السيتوزولي (cPLA2) بتحرير حمض الأراكيدونيك من الفوسفوليبيدات، مما ينتج عنه الإيكوسانويدات التي تلعب دورًا مهمًا في الالتهاب والمناعة والدفاع عن المضيف. يتم التعبير عن cPLA2 في البلعميات إلى جانب أنواع خلايا متعددة أخرى بعد الإصابة، وقد تم الإبلاغ عن أن تثبيط cPLA2 يقلل من استعادة علم الأمراض الناتجة عن الإصابة الثانوية ويزيدها. دور cPLA2 في MDMs بعد الإصابة غير مفهوم تمامًا. نفترض أن تنشيط cPLA2 في MDMs بعد الإصابة يساهم في الإصابة الثانوية. هنا، نبلغ أن cPLA2 يلعب دورًا مهمًا في نمط البلعميات الالتهابية المستحثة بالميالين في المختبر باستخدام البلعميات المشتقة من نخاع العظام الذي تم حذف cPLA2 منه. علاوة على ذلك، للتحقيق في دور cPLA2 في MDMs بعد الإصابة، قمنا بإنشاء شيميرات من نخاع العظام الأنثوي باستخدام متبرعين محذوفين من cPLA2 وقمنا بتقييم استعادة الحركة باستخدام مقياس باسو للفئران (BMS)، ونظام تحليل المشي كات ووك، ومهمة السلم الأفقي على مدى ستة أسابيع. كما قمنا بتقييم الحفاظ على الأنسجة وكثافة المحاور داخل الإصابة بعد ستة أسابيع من الإصابة. لم تظهر الشيميرات المحذوفة من cPLA2 أي تغيير في استعادة الحركة أو علم الأمراض النسيجية بعد الإصابة مقارنةً بشيميرات التحكم WT. تشير هذه البيانات إلى أنه على الرغم من أن cPLA2 يلعب دورًا حاسمًا في تعزيز تنشيط البلعميات المؤيدة للالتهاب المستحث بالميالين في المختبر، إلا أنه قد لا يساهم في علم الأمراض الناتج عن الإصابة الثانوية في الجسم الحي بعد الإصابة.

الكلمات الرئيسية: إصابة الحبل الشوكي، فوسفوليباز A2 السيتوزولي، البلعميات، المايلين، الالتهاب

الاختصارات

| AACOCF3 | كيتون أراشيدونيل ثلاثي الفلورو ميثيل |

| تحليل التباين | تحليل التباين |

| CM-H2DCFDA | ديأسيتات كلوروميثيل 2′,7′-ثنائي كلوريد ثنائي هيدروفلوريسئين |

| cPLA2 | فوسفوليباز A2 السيتوزولي |

| نظام إدارة المباني | مقياس باسو للفأر |

| الجهاز العصبي المركزي | الجهاز العصبي المركزي |

| داب | 3,3′-ديامينوبنزيدين |

| DPI | أيام بعد الإصابة |

| جيس | رماديون |

| EDTA | حمض الإيثيلين diamine tetraacetic |

| الشهادة الثانوية العليا | خلايا جذعية دموية |

| HSTC | زراعة خلايا جذعية دموية |

| إدارة البيانات الرئيسية | البلاعم المشتقة من وحيدات النواة |

| MTT | بروميد ثيازوليل أزرق تترازوليوم |

| PACOCF3 | كيتون بالميتويل ثلاثي فلوروميثيل |

| PB | محلول فوسفات |

| PBS | محلول ملحي معزز بالفوسفات |

| SCI | إصابة الحبل الشوكي |

| WPI | أسابيع بعد الإصابة |

| WT | النوع البري |

إصابة الحبل الشوكي (SCI) هي حالة مدمرة تؤدي إلى عجز وظيفي كبير وتقلل بشكل كبير من جودة حياة الأفراد المصابين. تتبع الصدمة الميكانيكية الأولية على نسيج الحبل الشوكي، المعروفة بالإصابة الأولية، أحداث بيولوجية تفاقم من تلف الأنسجة. تشمل هذه الإصابة الثانوية سلسلة بيولوجية معقدة تتضمن، ولكن لا تقتصر على، الالتهاب، وتنشيط الخلايا العصبية المقيمة، وتسلل الكريات البيضاء المحيطية، والإجهاد التأكسدي. تفاقم الإصابة الثانوية تلف الأنسجة وتعيق التعافي، مما يحد من الإصلاح الذاتي.

في الحبل الشوكي المصاب، تلعب البلعميات المنشطة، المكونة من الخلايا الدبقية المقيمة والبلعميات المشتقة من وحيدات النوى المتسللة، دورًا كبيرًا في استجابة الإصابة الثانوية وتساهم في كل من الإصابة والإصلاح.

لقد أبلغنا سابقًا أن تنشيط الفوسفوليباز A2 السيتوزولي (cPLA2) قد يربط المايلين بالتفعيل المؤيد للالتهابات.

لقد كانت cPLA2 محورًا لعقود من البحث لأنها تستهدف بشكل محدد الفوسفوليبيدات التي تحتوي على مجموعة أراشيدونيك. حمض الأراشيدونيك هو حمض دهني غير مشبع متعدد الذي يعد سلفًا لإنتاج الإيكوسانويدات مثل البروستاجلاندينات، والبروستاسيكلينات، والثromboxanes، والليوكوترينات. تتمتع الإيكوسانويدات بأفعال فسيولوجية واسعة ومتنوعة تشمل نفاذية الأوعية الدموية، وتجنيد خلايا المناعة، والحمى، والألم، وتجمع الصفائح الدموية.

لقد كانت cPLA2 محورًا لعقود من البحث لأنها تستهدف بشكل محدد الفوسفوليبيدات التي تحتوي على مجموعة أراشيدونيك. حمض الأراشيدونيك هو حمض دهني غير مشبع متعدد الذي يعد سلفًا لإنتاج الإيكوسانويدات مثل البروستاجلاندينات، والبروستاسيكلينات، والثromboxanes، والليوكوترينات. تتمتع الإيكوسانويدات بأفعال فسيولوجية واسعة ومتنوعة تشمل نفاذية الأوعية الدموية، وتجنيد خلايا المناعة، والحمى، والألم، وتجمع الصفائح الدموية.

من هذه المعلومات، ليس من المستغرب أن تثبيط cPLA2 مفيد في العديد من عمليات المرض.

المواد والأساليب

الحيوانات

في هذه التجارب، إناث cPLA2 التي تتراوح أعمارها بين 2 إلى 4 أشهر

زراعة الخلايا

تم استخراج البلعميات المشتقة من نخاع العظم (BMDMs) من عظمة الفخذ وعظمة الساق من الفئران المعدلة وراثيًا cPLA2 KO والمجموعة الضابطة WT كما هو موصوف سابقًا.

عزل المايلين

ميالين نقاء معتدل

اختبار السمية العصبية

لتقييم السمية العصبية لبروتينات BMDMs المنشطة، تم الحفاظ على خط خلايا الورم العصبي الفأري (Neuro-2a أو N2A، هدية من كريس ريتشاردز، جامعة كنتاكي) في وسط نمو N2A الذي يتكون من 45% DMEM، 45% وسط OPTI-MEM منخفض المصل، 10% مصل بقري جنيني (FBS)، و1% بنسلين/ستربتوميسين. تم زرع خلايا N2A بكثافة

امتصاص الخلفية. يتم تطبيع هذه البيانات إلى قيم CTL غير السامة لتوليد انخفاض نسبي في قيم البقاء.

امتصاص الخلفية. يتم تطبيع هذه البيانات إلى قيم CTL غير السامة لتوليد انخفاض نسبي في قيم البقاء.

اختبار أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية

تم قياس إنتاج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) في البلعميات باستخدام الكلوروميثيل

اختبار نشاط الأرجيناز

تم قياس نشاط الأرجيناز في البلعميات الكبيرة باستخدام مجموعة اختبار نشاط الأرجيناز (ab180877). باختصار، تم زراعة بلعميات العظام المستمدة من نخاع العظام وتحفيزها كما هو موضح أعلاه. بعد إزالة السائل الفائق، تم غسل الخلايا مرتين في PBS بارد، وتم تجانسها في

فحص أكسيد النيتريك

تم قياس إنتاج أكسيد النيتريك من البلعميات باستخدام مجموعة كاشف غريس (G-7921). باختصار، تم زراعة BMDMs وتحفيزها كما هو موضح أعلاه باستثناء استبدال باستخدام RPMI خالي من الفينول الأحمر، وتم تقليل التحفيزات إلى تنسيق 96 بئرًا (

زراعة خلايا جذعية دموية

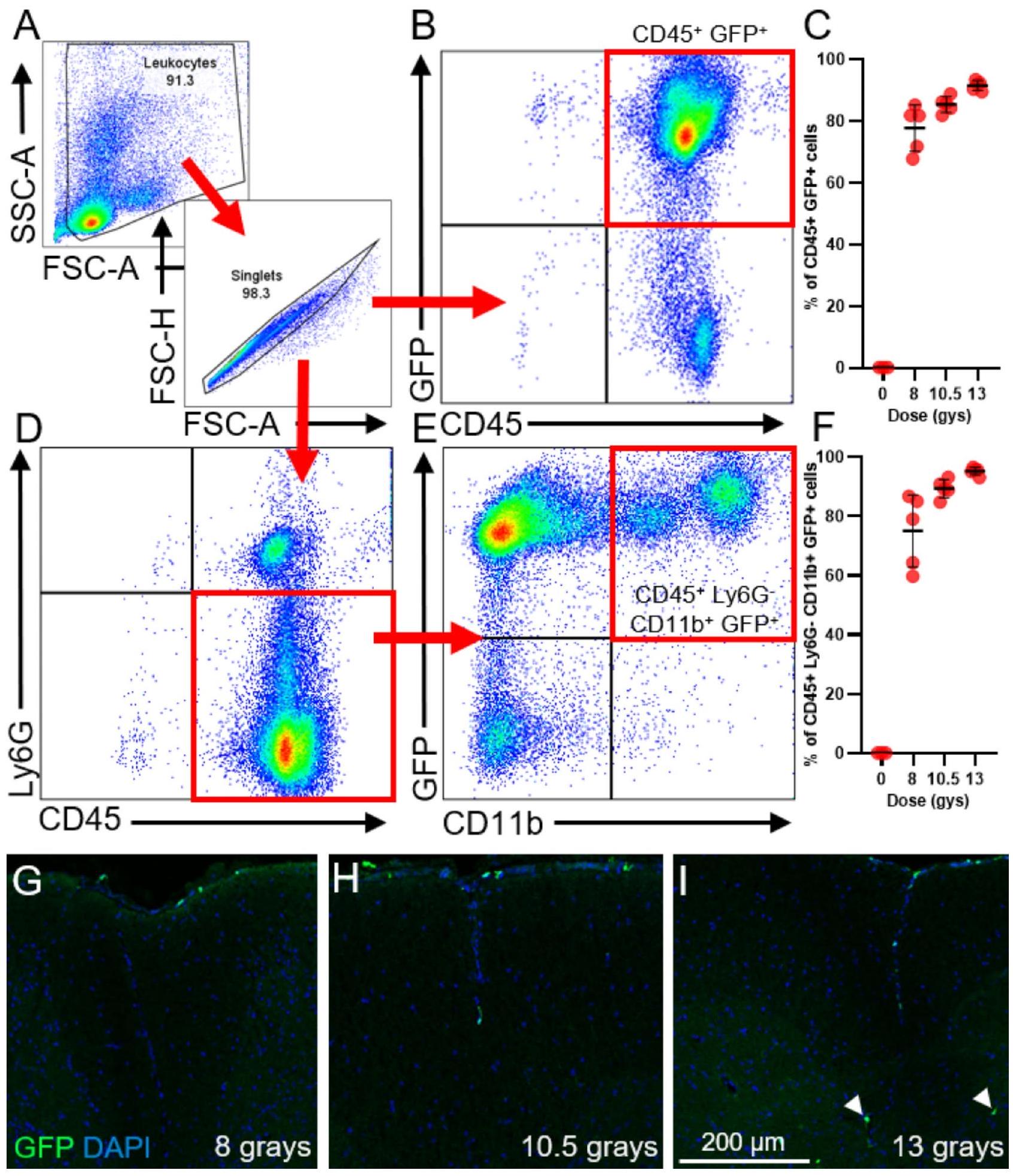

لتقليل التأثيرات غير المحددة للإشعاع على الحبل الشوكي، تم إجراء دراسة جرعات أولية. تم تعريض فئران C57BL6 من النوع البري لجرعة مقسمة من 8، 10.5، أو 13 غراي من الإشعاع من نواة سيزيوم-137 المشعة. تم فصل الجرعتين النصفيتين بفترة 3 ساعات. تم عزل خلايا الجذعية الدموية (HSCs) من المتبرعين Actin-GFP، و

إصابة الحبل الشوكي

كما هو موضح سابقًا

تقييم سلوكي لاستعادة الحركة

تم تقييم استعادة الحركة بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي باستخدام مقياس باسو للفئران (BMS) واختبار الحقل المفتوح، ونظام تحليل المشي CatWalk XT، واختبار السلم الأفقي. يستخدم BMS مقياس تقييم من 9 نقاط لوصف الوظائف الحركية العامة التي تتراوح من الشلل التام (الدرجة 0) إلى الوظائف الطبيعية (الدرجة 9) بينما تستكشف الفئران حقلًا مفتوحًا لمدة

| مجموعة |

|

الجنس | النتائج | نقطة زمنية | الاستبعاد | ||||||||

| A |

|

F | كفاءة التهجين في نخاع العظام ونفاذية الكريات البيضاء في الجهاز العصبي المركزي | 8 أسابيع بعد HSCT | لا شيء | ||||||||

| B |

|

F |

|

6 أسابيع | تم استبعاد فأرين من مجموعة WT وفأر واحد من مجموعة cPLA2 KO لتلبية معايير الاستبعاد المسبقة (درجة BMS

|

||||||||

| C |

|

F | تعبير الجينات من مستحلب الحبل الشوكي بواسطة nCounter (تقنيات نانوسترينغ) مصفوفة الجينات | 7 أيام | لا شيء |

الجدول 1. التصميم التجريبي للثلاث مجموعات بما في ذلك: حجم المجموعة قبل وبعد الاستبعاد، الجنس، النتائج، نقطة النهاية، ومعايير الاستبعاد لجميع المجموعات.

تستند الدرجات الفرعية لـ BMS إلى ميزات الحركة، مثل استقرار الجذع، والتنسيق، ووضع الكف، التي يمكن ملاحظتها في الفئران ذات الوظائف الأعلى. سمحت الدرجات الفرعية لـ BMS بدقة أفضل للتفريق بين الفئران ذات الدرجات الأعلى في BMS.

استخدمنا أيضًا نظام تحليل المشية CatWalk XT (نولدوس، فاجينينغن، هولندا) لتتبع معلمات معينة للمشية. بالنسبة لتحليل CatWalk، خضعت الفئران لثلاث جلسات اختبار: أسبوع واحد قبل الإصابة و4 و6 أسابيع بعد الإصابة. يتميز CatWalk بضوء أحمر فوق الرأس وممر مضاء باللون الأخضر، والذي يعكس الضوء استجابةً لملامسة كف الفأر الذي يتم التقاطه بعد ذلك عبر تسجيلات فيديو معايرة. تم إجراء تحليل المشية بواسطة نفس الباحث في غرفة مظلمة. باستخدام بروتوكولات التكييف والتحليل التي تم تطويرها سابقًا

تم استخدام اختبار السلم الأفقي لتقييم الخطوات والتنسيق في مراحل لاحقة من الاستعادة وفقًا للدراسات السابقة

التلوين المناعي

عند نهاية الدراسة، تم إعطاء الفئران جرعة قاتلة من الكيتامين والزلازين. ثم تم جمع الدم عن طريق ثقب القلب بإبرة وسرنجية مملوءة بالهيبارين ونقلها إلى أنبوب مغطى بـ EDTA (VWR، 101094-004) لعزل الكريات البيضاء (انظر أدناه). تم ضخ الفئران عبر القلب بمحلول PBS تلاه

لتقييم حجم الإصابة، تم صبغ جميع الأنسجة بصبغة إريوكروم سيانين والنيوروفيلامين الثقيل، والتي تصبغ المايلين والأكسونات السليمة، على التوالي. تم استخدام هذه العلامات لتمييز الأنسجة المصابة عن الأنسجة السليمة. لصبغ النيوروفيلامين، خضعت المقاطع لاسترجاع المستضد في محلول سترات (pH 6.0) عند

التخفيفات، وتم تنظيفها باستخدام Histoclear (101412-878؛ VWR Scientific)، وتم تغطيتها باستخدام Permount (SP15500؛ Fisher Scientific). تم تصوير الشرائح باستخدام Axioscan (نموذج Z1، Carl Zeiss AG.، Oberkochen، GE) بتكبير 20x وتم تصورها وقياسها باستخدام برنامج Halo (Indica Labs، Albuquerque، NM).

التخفيفات، وتم تنظيفها باستخدام Histoclear (101412-878؛ VWR Scientific)، وتم تغطيتها باستخدام Permount (SP15500؛ Fisher Scientific). تم تصوير الشرائح باستخدام Axioscan (نموذج Z1، Carl Zeiss AG.، Oberkochen، GE) بتكبير 20x وتم تصورها وقياسها باستخدام برنامج Halo (Indica Labs، Albuquerque، NM).

تحليل التعبير الجيني

عند نهاية الدراسة، تم جمع الدم المحيطي من جميع الفئران عبر ثقب القلب. تم إزالة كريات الدم الحمراء باستخدام محلول تحلل كريات الدم الحمراء (RBC) (BioLegend، 420301). تم خلط الدم الم collected مع محلول تحلل كريات الدم الحمراء وتركه في درجة حرارة الغرفة لمدة 5 دقائق. تم ترسيب الكريات البيضاء بواسطة الطرد المركزي عند 350 جرام لمدة 5 دقائق، وتم تكرار عملية التحلل مرتين. تم تجميد كريات الدم البيضاء على الثلج الجاف. تم عزل RNA من كريات الدم البيضاء باستخدام مجموعة RNeasy mini (Qiagen، 74104). تم تحديد تركيز RNA باستخدام جهاز Nanodrop (Nanodrop Lite؛ Thermo Fisher Waltham، MA). تم إعداد مكتبات cDNA باستخدام مجموعة النسخ العكسية عالية السعة (Applied Biosystems، 4368814). تم إجراء qRT-PCR باستخدام مزيج SYBR الأخضر الرئيسي والمجموعة التالية من البادئات الأمامية والعكسية: (pla2g4a الأمامية= “GATTCTGGAAATGTCTCTG GAAG”، العكسية=”GGCTGACATTTTTCATTAGCTC”؛ GAPDH، الأمامية=”CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGA CTG “، العكسية=”ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG “).

تم إجراء تحليل التعبير الجيني NanoString على مستحلب الحبل الشوكي بالكامل. بعد سبعة أيام من إصابة الحبل الشوكي، تم ضخ الفئران عبر القلب بمحلول PBS، وتم إزالة 6 مم من الحبل الشوكي وتجميده بسرعة في النيتروجين السائل. تم عزل RNA من الحبال الشوكية باستخدام مجموعة RNeasy mini (Qiagen، 74104). تم تحديد تركيز RNA باستخدام جهاز NanoDrop Lite (Thermo Fisher Waltham، MA)، وتم تخفيف العينات إلى

الإحصائيات

تم إجراء جميع الاختبارات الإحصائية باستخدام برنامج GraphPad Prism (v9.4.1، بوسطن، MA). تم تحليل جميع البيانات في المختبر باستخدام ANOVA العادية ذات الاتجاه الواحد تلاها اختبار المقارنات المتعددة Tukey. تم استخدام اختبار t لطلاب غير المقترنين لمقارنة تعبير cPLA2 بين cPLA2 KO و WT chimeras. بالنسبة لبيانات السلوك والتحليل النسيجي، تم استخدام ANOVA ذات الاتجاهين المتكررة. تمت مقارنة بيانات السلوك على مر الزمن، وتمت مقارنة البيانات النسيجية على مسافة من المركز.

النتائج

cPLA2 مطلوب لتقوية المايلين لتحفيز مثير التهابي في البلعميات المشتقة من نخاع العظام

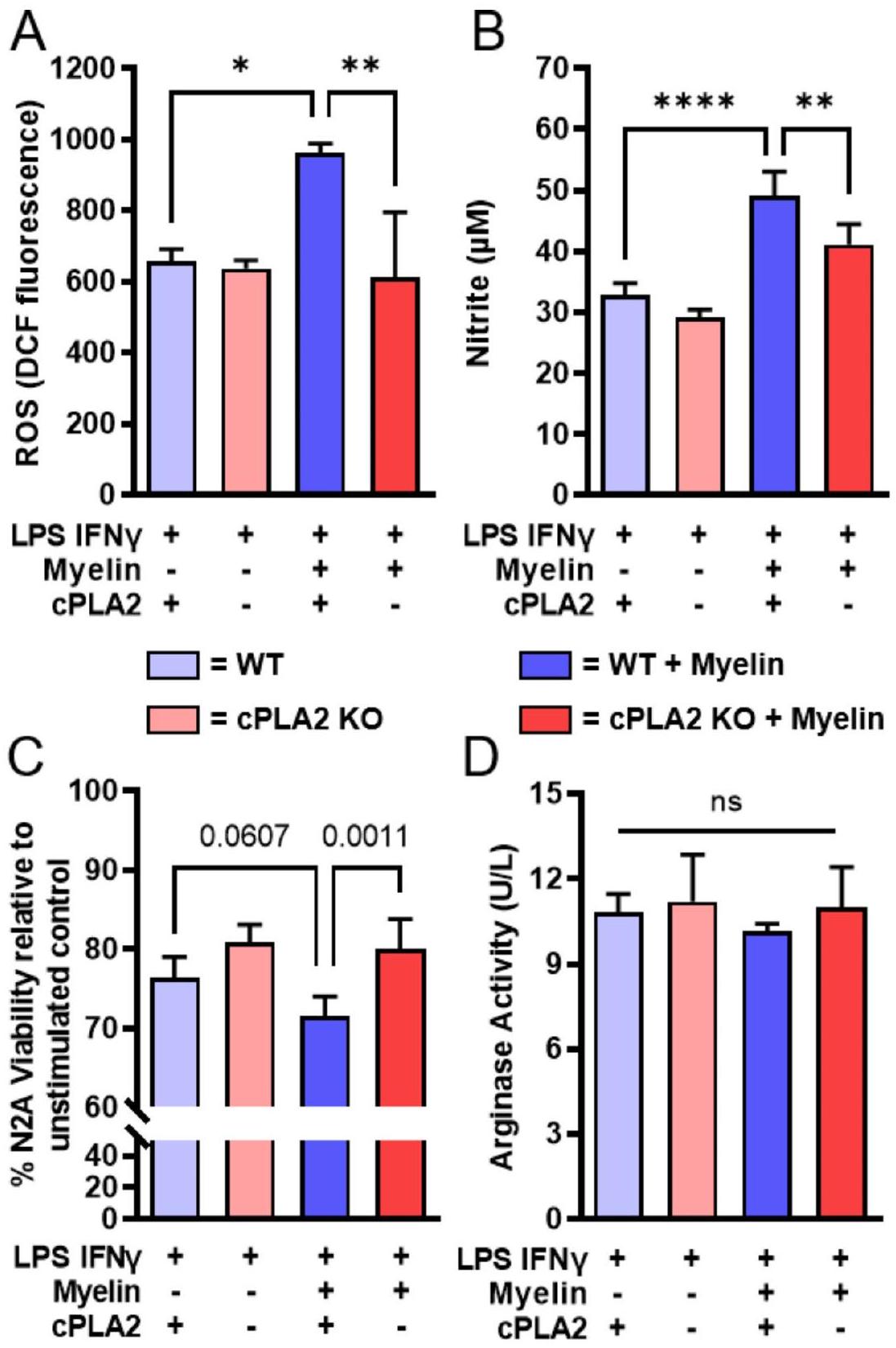

في سياق إصابة الحبل الشوكي، تتعرض البلعميات المشتقة من نخاع العظام (BMDMs) لمجموعة من المحفزات التي تعزز نمطًا التهابيًا

تحسين جرعة الإشعاع لتوليد الفئران الهجينة

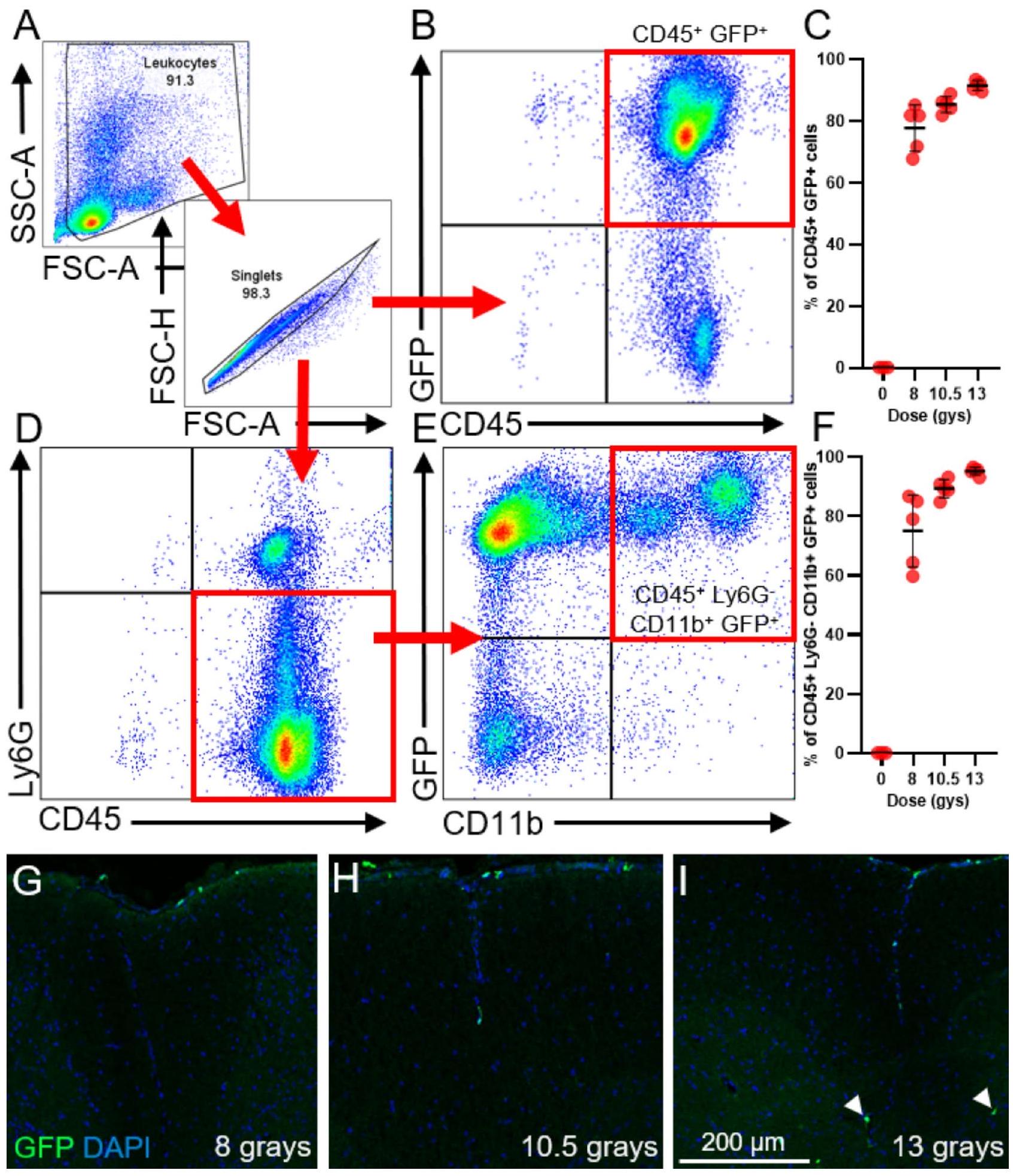

لاختبار ما إذا كان cPLA2 يعزز تنشيط البلعميات الالتهابية في الجسم الحي، استخدمنا نموذج الفأر الهجين. قمنا أولاً بإجراء تجربة تجريبية لتحسين جرعة الإشعاع في بروتوكول HSCT الخاص بنا. كان هدفنا هو تحقيق تشبع قوي لنخاع العظام مع تقليل تسلل خلايا المناعة إلى الجهاز العصبي المركزي السليم. تم حقن خلايا جذعية دموية (HSCs) معزولة من فئران Actin-GFP عن طريق الحقن خلف العين في فئران C57BL/6J بعد ثلاث جرعات مختلفة من الإشعاع (

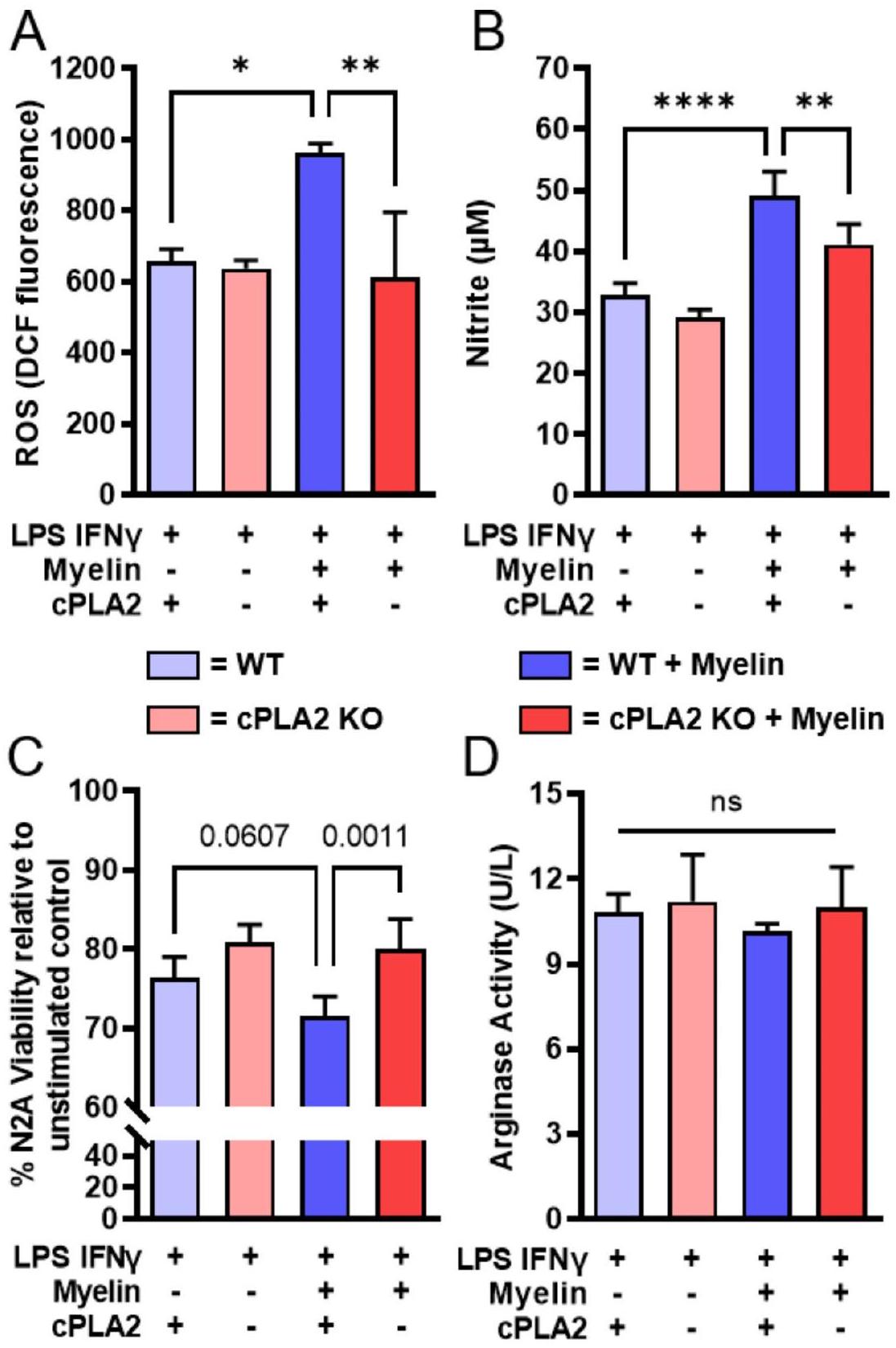

الشكل 1. ماكروفاجات مشتقة من نخاع العظم من الفئران المعدلة وراثياً cPLA2 KO تظهر استجابات طبيعية للمؤثرات المؤيدة للالتهاب ولكنها مقاومة لتأثير تعزيز المايلين. تم جمع نخاع العظم من فئران cPLA2 KO وأقرانها من النوع البري (WT) وتم تمايزها إلى ماكروفاجات مشتقة من نخاع العظم (BMDMs) وعولجت بمؤثر M1 (LPS و IFN-

لا تتغير استعادة الحركة ومرض الأنسجة في نماذج الكيميرا التي تفتقر إلى cPLA2

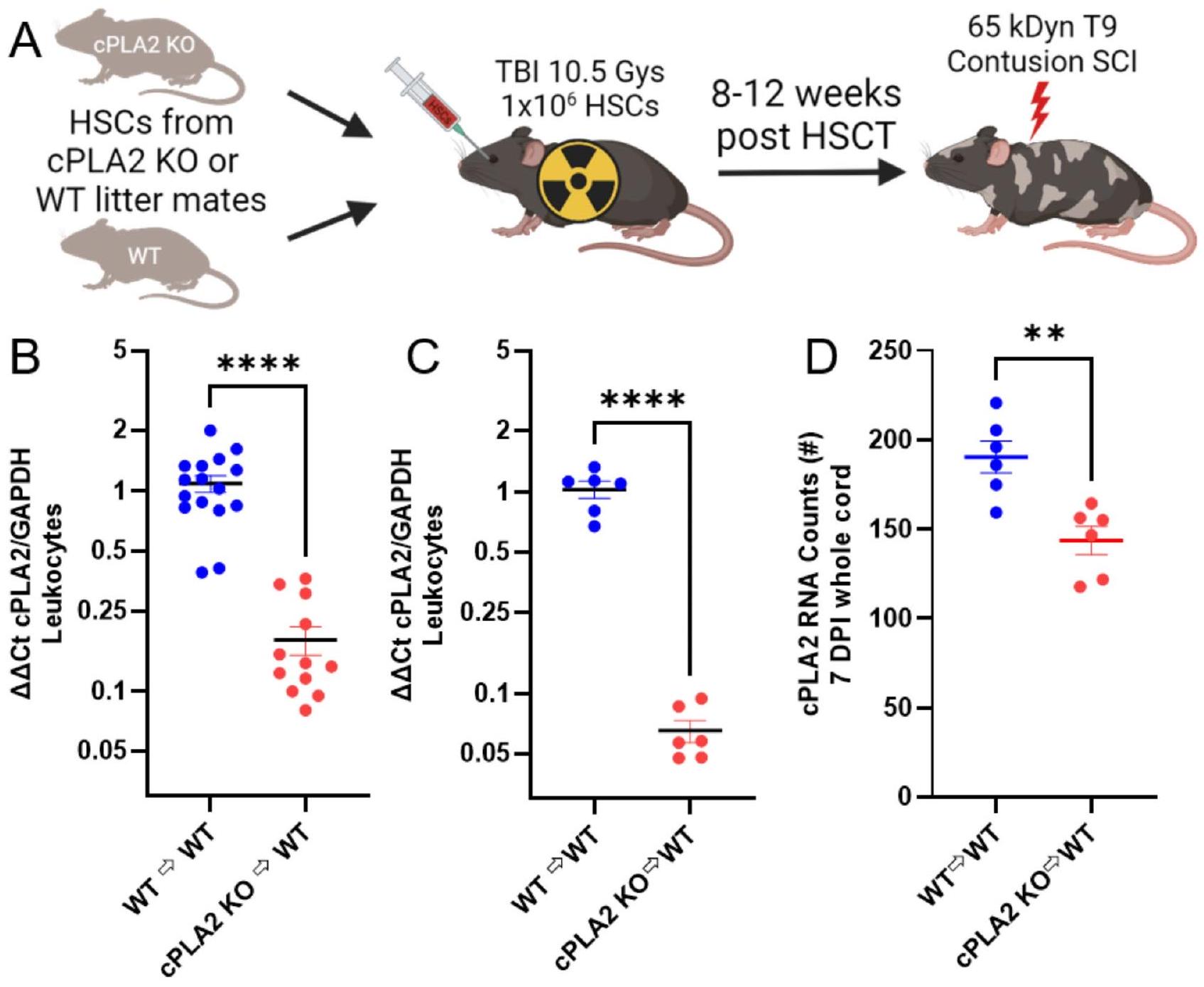

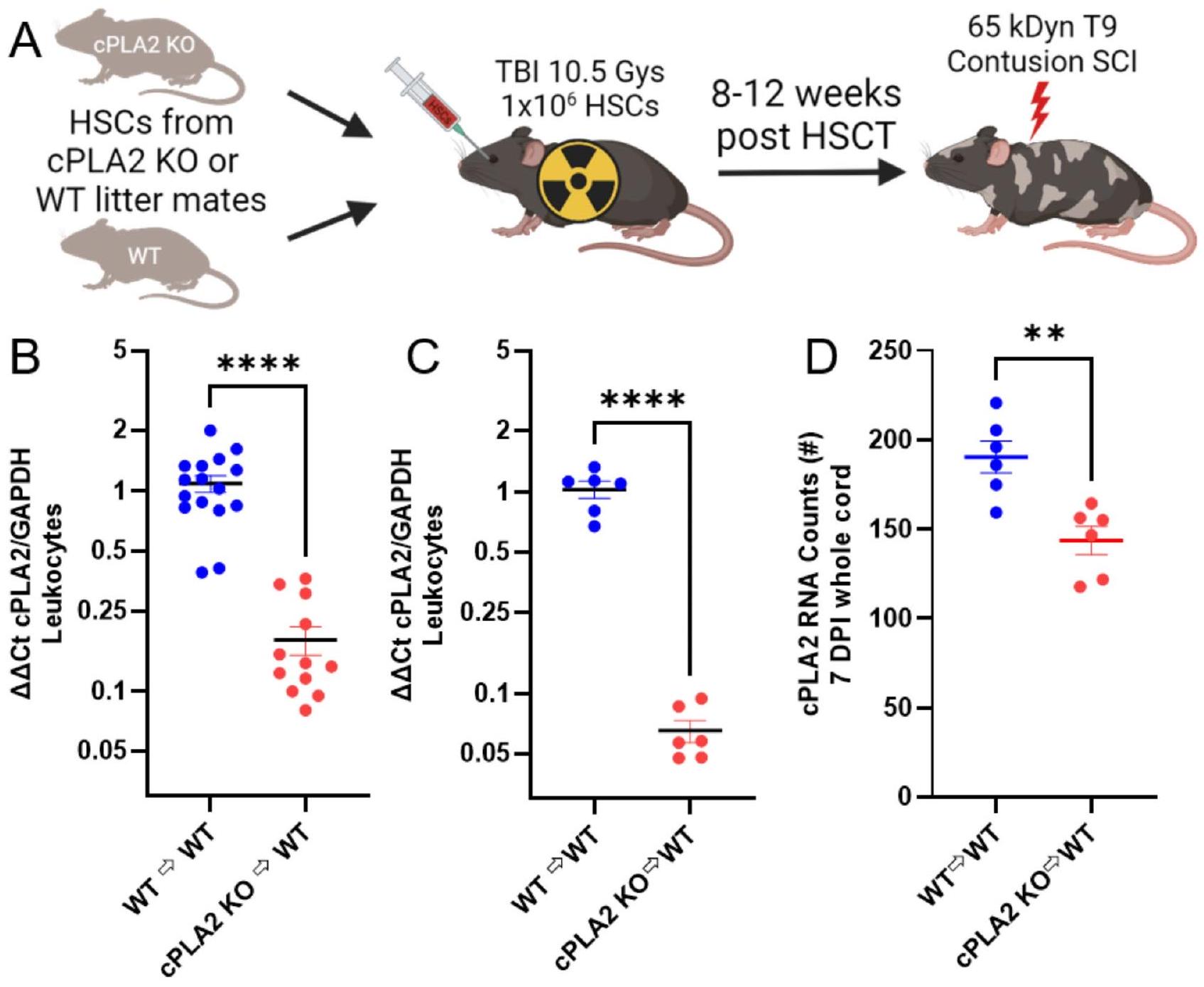

مكن بروتوكول زراعة الخلايا الجذعية المحسّن لدينا من استجواب دور cPLA2 في الخلايا الضامة بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي. تلقت فئران C57BL6/J البرية خلايا جذعية من متبرعين من نوع cPLA2 KO و WT بعد 10.5 جراي. بعد 8 إلى 12 أسبوعًا من زراعة الخلايا الجذعية، تلقت الفئران إصابة حبل شوكي من نوع T9 بضغط 65 كدين، وتم جمع الأنسجة بعد 7 أيام أو 6 أسابيع من الإصابة (الشكل 3A-B). تم جمع الدم الكامل في نقاط نهاية الدراسة، وتم قياس تعبير cPLA2 في الكريات البيضاء المعزولة. في جميع المجموعات الثلاث، كان تعبير cPLA2 منخفضًا تقريبًا بمقدار عشرة أضعاف في الحيوانات التي تلقت خلايا جذعية KO مقارنةً بتلك التي تلقت خلايا جذعية WT (الشكل 3B-C) (B،

الشكل 2. زراعة خلايا جذعية دموية (HSCT) عند جرعات إشعاع محددة تنتج تشيمرية قوية من الكريات البيضاء مع تقليل تسرب الكريات البيضاء إلى الحبل الشوكي. تلقت الفئران السليمة 8 و 10.5 و 13 غيغا من الإشعاع على جرعتين بعد حقن وريدية لخلايا جذعية دموية من متبرعين يحملون جين Actin-GFP. تم تحديد كفاءة التشيمرية وتسرب الكريات البيضاء إلى الحبل الشوكي بعد 9 أسابيع من زراعة خلايا الجذع. (أ) استراتيجية التصفية المستخدمة لتحديد كفاءة التشيمرية للكريات البيضاء CD45 المتداولة.

الشكل 3. زراعة الخلايا الجذعية المكونة للدم (HSCT) مع متبرعين يعانون من نقص إنزيم cPLA2 تقلل من تعبير cPLA2 في الكريات البيضاء الدائرة وفي الحبل الشوكي المصاب. (A) مخطط لبروتوكول HSCT. تم حقن الخلايا الجذعية المكونة للدم المعزولة من متبرعين يعانون من نقص إنزيم cPLA2 ومن متبرعين عاديين (WT) في فئران WT (C57BL/6J) بعد جرعة مقسمة قدرها 10.5 جراي (تم إنشاؤه في BioRender). في

كان كافياً لتقليل تعبير cPLA2 بشكل كبير في الحبل الشوكي بعد 7 أيام، مما يؤكد فعالية نهج KO الخاص بنا (الشكل 3D) (

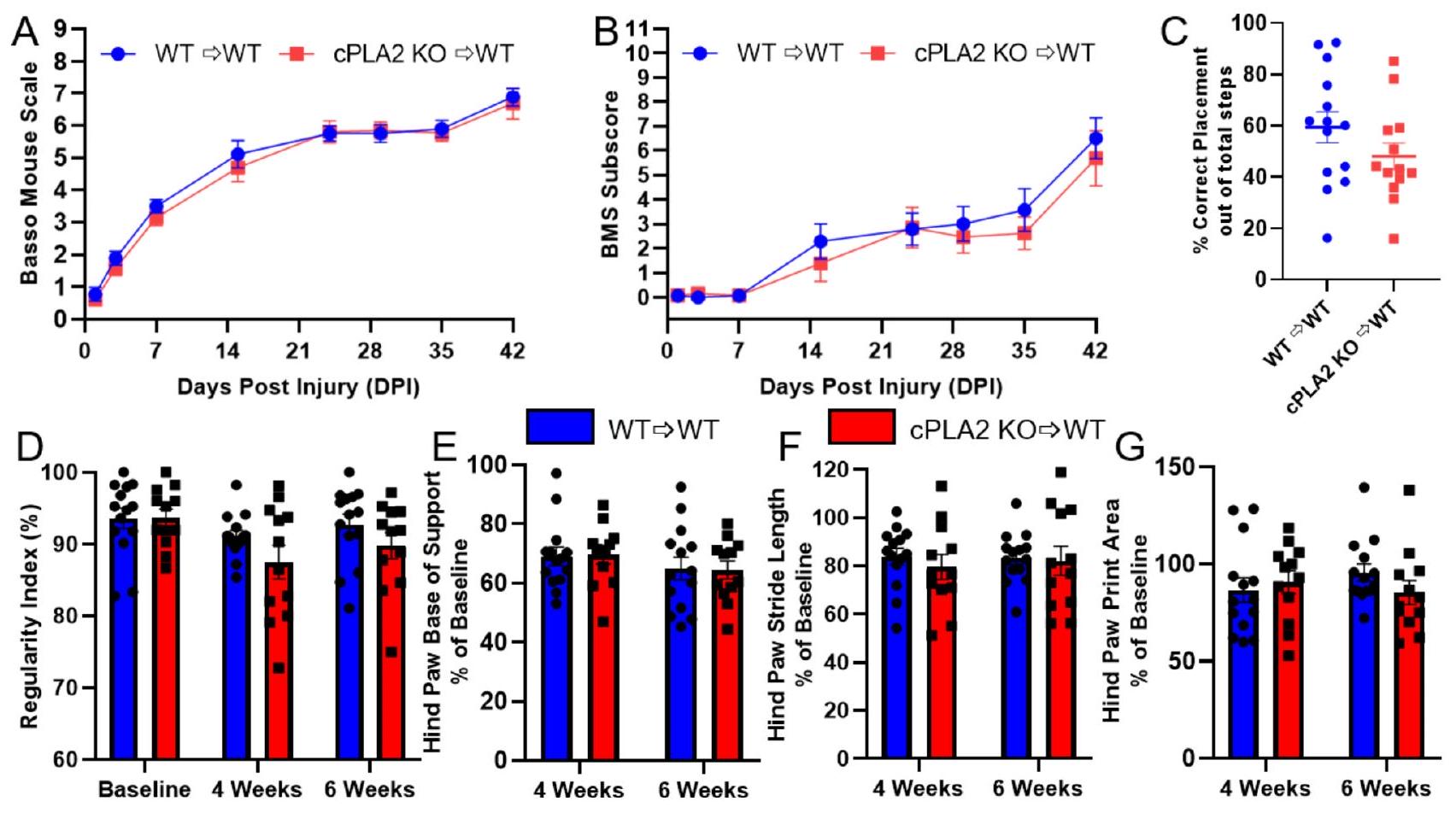

لاختبار الفرضية القائلة بأن MDM cPLA2 يحد من التعافي الحركي بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي، قمنا بتقييم التعافي الحركي لخلائط cPLA2 KO وخلائط WT كضوابط باستخدام درجة BMS، ودرجة BMS الفرعية، وسلّم السلم الأفقي، ونظام تحليل المشي CatWalkXT. أشارت درجات BMS والدرجات الفرعية إلى التعافي من الشلل الكامل مع بعض حركة الكاحل فقط (درجة 1 و 2) بعد يوم واحد من الإصابة (DPI) إلى خطوات plantar المتكررة والمتسقة مع خطوات منسقة بعد 6 أسابيع من الإصابة (WPI) (درجة

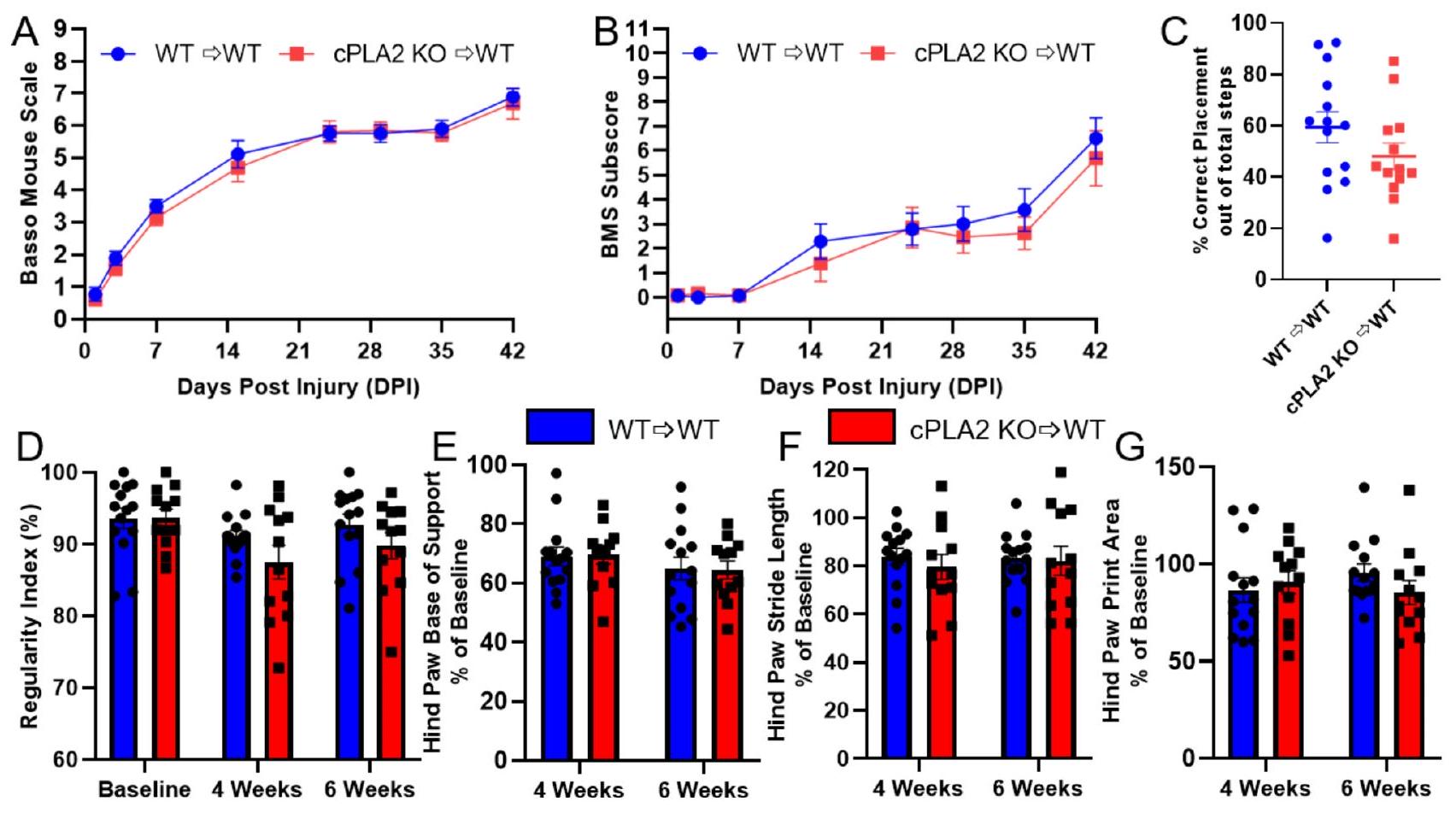

الشكل 4. لم يؤثر زراعة الخلايا الجذعية المكونة للدم (HSCT) مع متبرعين يعانون من نقص إنزيم cPLA2 على استعادة الحركة بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي (SCI) مقارنةً بالتحكمات من النوع البري (WT). تم إصابة الفئران بعد 10 أسابيع من زراعة الخلايا الجذعية، وتم تقييم الاستعادة لمدة 6 أسابيع بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي. (A-B) لم تكن درجات الحركة وفق مقياس باسو للفئران والدرجات الفرعية مختلفة بشكل كبير بين متلقي الخلايا الجذعية من النوع البري (WT) وذوي نقص إنزيم cPLA2. (C) تم تقييم استعادة الحركة والإحساس بالموضع بعد 6 أسابيع باستخدام اختبار السلم الأفقي، ولم يكن هناك فرق كبير بين متلقي الخلايا الجذعية من النوع البري وذوي نقص إنزيم cPLA2. (D-G) أظهر تحليل مشية CatWalk عدم وجود اختلافات بين المجموعات. (D) مؤشر الانتظام، (E) عرض قاعدة دعم القدم الخلفية، (F) طول خطوة القدم الخلفية، و

تم إجراء تحليل مشية CatWalk قبل الإصابة وبعد 4 و 6 أسابيع من الإصابة. باستخدام CatWalk XT، قمنا بتقييم مؤشر الانتظام، وقاعدة الدعم، وطول الخطوة، ومساحة الطباعة كقياسات مستمرة حساسة لإصابات الحبل الشوكي المتوسطة والشديدة. كان مؤشر الانتظام، وهو مقياس للتنسيق، قد انخفض بشكل ملحوظ بعد 4 أسابيع.

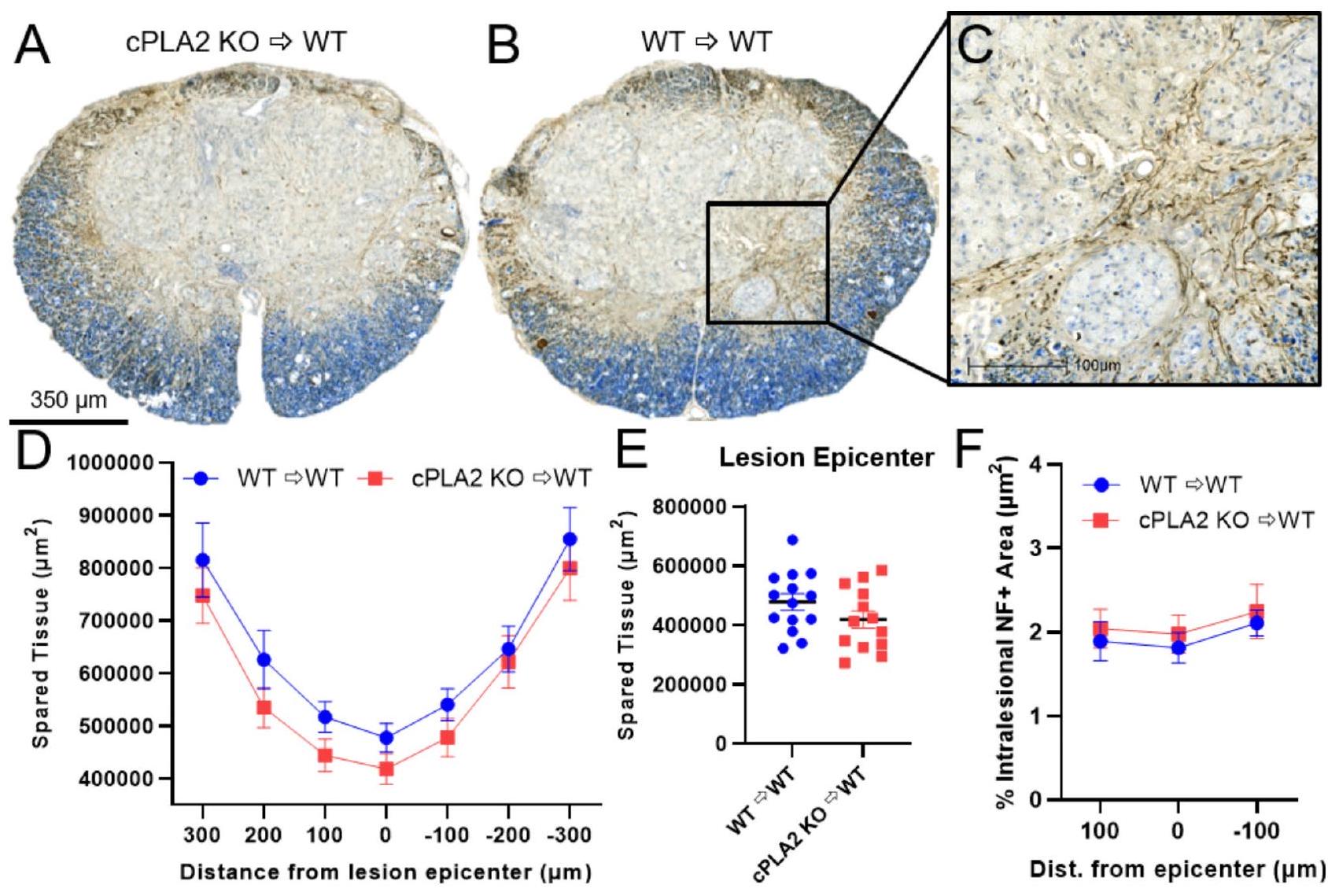

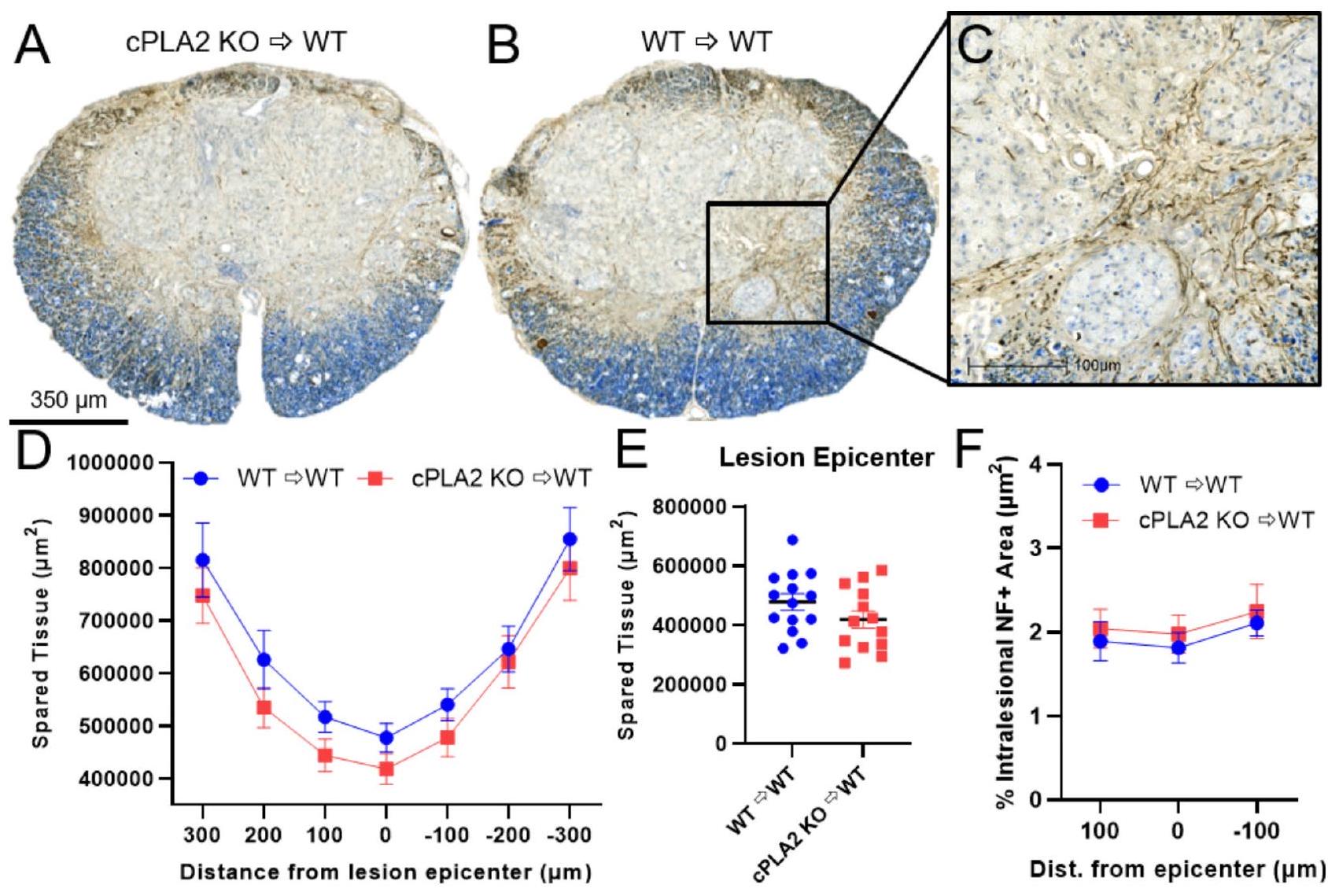

في نهاية الأسابيع الستة، تم جمع الأنسجة لتقييم تأثير تشكل الكيميرا cPLA2 KO على علم الأمراض النسيجية بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي. باستخدام صبغة إريوكروم سيانين (EC) وصبغة الألياف العصبية الثقيلة (NF)، تم تحديد الأنسجة المحفوظة على أنها محاور م myelinated مزدوجة الإيجابية (EC+، NF+). توضح صور مركز الإصابة التمثيلية تباينًا واضحًا بين مناطق الأنسجة المحفوظة ومناطق الإصابة الواضحة في نسيج الحبل الشوكي (الشكل 5A-B). لم يكن هناك اختلاف كبير في حفظ الأنسجة عند مركز الإصابة أو أمامه وخلفه بين الكيميرات cPLA2 KO و WT (الشكل 5D-E) (5E،

نقاش

البيئة الميكروبية الالتهابية التي تستمر بشكل مزمن في الحبل الشوكي المصاب تحد من التعافي. الآليات الأساسية التي تحرك الالتهاب بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي غير مفهومة جيدًا. قد تكون البلعميات المحملة بالحطام الدهني التي تبقى بشكل مزمن في موقع الإصابة هي المسؤولة.

الشكل 5. إزالة cPLA2 في الكريات البيضاء المتسللة لا تؤثر على الحفاظ على الأنسجة أو المحاور داخل الآفة بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي. (A،B) مقاطع تمثيلية لمركز الآفة ملونة بالألياف العصبية (المحاور – بني) مع صبغة إريوكروم سيانين (الأزرق – المايلين) كصبغة مضادة بعد 6 أسابيع من إصابة الحبل الشوكي. (C) صورة عالية القوة لـ B تشير إلى وسم المحاور النموذجي (بني) داخل مركز الآفة وتم قياسها في (F). كان لدى المتلقين من نوع cPLA2 KO و WT الحفاظ على الأنسجة بشكل مشابه في جميع أنحاء الآفة (D) وفي مركز الآفة (E). (F) تقييم كمي للحفاظ على المحاور/التفرع في مركز الآفة و

أظهر أن المايلين يمكن أن يحفز نمط ظاهري للبلاعم المؤيدة للالتهابات

cPLA2 يتم دراسته على نطاق واسع في العديد من الأمراض وهو إنزيم رئيسي في إنتاج حمض الأراكيدونيك

cPLA2 يتم دراسته على نطاق واسع في العديد من الأمراض وهو إنزيم رئيسي في إنتاج حمض الأراكيدونيك

بعد ذلك، أبلغت دراسة شاملة لجميع إنزيمات PLA2 التي تم تنظيمها بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي بواسطة لوبيز-فاليس وآخرين عن انخفاض في التعافي السلوكي وتفاقم في علم الأمراض النسيجي بعد تثبيط cPLA2 باستخدام مثبط انتقائي وقوي قائم على 2-أوكزاميد وفأر knockout عالمي لـ cPLA2.

في إصابة الحبل الشوكي، قد لا يساهم cPLA2 من نوع MDM في الإصابة الثانوية لأن معظم cPLA2 النشط يوجد في الخلايا العصبية، والأستروسيت، والميكروغليا. الدراسات المبكرة حددت الخلايا العصبية الإيجابية لـ cPLA2 في مناطق معينة من الدماغ والحبل الشوكي.

عصبونات الحبل الشوكي في الجهاز العصبي المركزي للجرذان غير المصابة مع إشارات خافتة فقط في الخلايا الدبقية

عصبونات الحبل الشوكي في الجهاز العصبي المركزي للجرذان غير المصابة مع إشارات خافتة فقط في الخلايا الدبقية

بدلاً من ذلك، قد يكون MDM cPLA2 ضارًا للتعافي، لكن التأثير المفيد لحذف MDM cPLA2 قد يت overshadowed بحذف cPLA2 في خلايا أخرى مشتقة من HSC، وهي الصفائح الدموية. تثبيط cPLA2 في الصفائح الدموية مع

تظهر نتائجنا أن cPLA2 في MDMs من المحتمل ألا تساهم بشكل كبير في الأمراض التي تسببها البلعميات بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي. لقد أظهرنا أولاً أن البلعميات التي تعاني من نقص cPLA2 محمية من التأثير المعزز للالتهابات الناتج عن المايلين. باستخدام شجرات نخاع العظام، قمنا بعد ذلك بالتحقيق في دور cPLA2 في MDMs بعد إصابة الحبل الشوكي. لم نجد أي تأثير لنقص cPLA2 في زراعة خلايا الدم الجذعية على التعافي الحركي أو علم الأمراض النسيجية. تكشف هذه الاكتشافات عن سلسلة من الملاحظات غير المتجانسة باستخدام نقص عالمي أو قمع cPLA2 في إصابة الحبل الشوكي.

توفر البيانات

جميع البيانات الخام المقدمة في الأشكال والجداول هنا متاحة للجمهور من خلال بيانات مفتوحة لمؤسسة إصابة الحبل الشوكي (ODC-SCI). ODC-SCI هو بوابة ومخزن مخصص لمشاركة البيانات في مجال إصابة الحبل الشوكي يتيح مشاركة البيانات مع الجمهور باستخدام DOI. DOI المرتبط بهذا العمل هو كما يلي: http://dx.doi.org/10.34945/F52307. ODC-SCI يتوافق مع مبادئ بيانات FAIR لضمان أن بيانات إصابة الحبل الشوكي قابلة للاكتشاف، والوصول، والتشغيل البيني، وإعادة الاستخدام.

تاريخ الاستلام: 6 سبتمبر 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 30 ديسمبر 2024

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2025

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2025

References

- Orr, M. B. & Gensel, J. C. Spinal cord Injury scarring and inflammation: therapies targeting glial and inflammatory responses. Neurotherapeutics 15(3), 541-553 (2018).

- Gensel, J. C. & Zhang, B. Macrophage activation and its role in repair and pathology after spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 1619, 1-11 (2015).

- Kigerl, K. A. et al. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 29(43), 13435-13444 (2009).

- Greenhalgh, A. D. & David, S. Differences in the phagocytic response of microglia and peripheral macrophages after spinal cord injury and its effects on cell death. J. Neurosci. 34(18), 6316-6322 (2014).

- Wang, X. et al. Macrophages in spinal cord injury: phenotypic and functional change from exposure to myelin debris. Glia 63(4), 635-651 (2015).

- Zhu, Y. et al. Macrophage Transcriptional Profile identifies lipid catabolic pathways that can be therapeutically targeted after spinal cord Injury. J. Neurosci. 37(9), 2362-2376 (2017).

- Ryan, C. B. et al. Myelin and non-myelin debris contribute to foamy macrophage formation after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 163, 105608 (2022).

- Kopper, T. J. et al. The effects of myelin on macrophage activation are phenotypic specific via cPLA2 in the context of spinal cord injury inflammation. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 6341 (2021).

- Khan, S. A. & Ilies, M. A. The phospholipase A2 superfamily: structure, isozymes, catalysis, physiologic and pathologic roles. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 24(2). (2023).

- Sun, G. Y. et al. Dynamic role of Phospholipases A2 in Health and diseases in the Central Nervous System. Cells, 10(11). (2021).

- Wang, B. et al. Metabolism pathways of arachidonic acids: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 6(1), 94 (2021).

- Clark, J. D. et al. A novel arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic PLA2 contains a ca(

)-dependent translocation domain with homology to PKC and GAP. Cell 65(6), 1043-1051 (1991). - Kramer, R. M. et al. 38 mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylates cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) in thrombinstimulated platelets. Evidence that proline-directed phosphorylation is not required for mobilization of arachidonic acid by cPLA2. J. Biol. Chem. 271(44), 27723-27729(1996).

- Linkous, A. & Yazlovitskaya, E. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 as a mediator of disease pathogenesis. Cell. Microbiol. 12(10), 13691377 (2010).

- Sarkar, C. et al. PLA2G4A/cPLA2-mediated lysosomal membrane damage leads to inhibition of autophagy and neurodegeneration after brain trauma. Autophagy 16(3), 466-485 (2020).

- Gijon, M. A. & Leslie, C. C. Regulation of arachidonic acid release and cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 65(3), 330-336 (1999).

- Liu, N. K. et al. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 protein as a novel therapeutic target for spinal cord injury. Ann. Neurol. 75(5), 644-658 (2014).

- Bonventre, J. V. et al. Reduced fertility and postischaemic brain injury in mice deficient in cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nature 390(6660), 622-625 (1997).

- Li, Y. et al. cPLA2 activation contributes to lysosomal defects leading to impairment of autophagy after spinal cord injury. Cell. Death Dis. 10(7), 531 (2019).

- Nagase, T. et al. Acute lung injury by sepsis and acid aspiration: a key role for cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nat. Immunol. 1(1), 42-46 (2000).

- Wang, S. et al. Calcium-dependent cytosolic phospholipase

activation is implicated in neuroinflammation and oxidative stress associated with ApoE4. Mol. Neurodegener. 17(1), 42 (2022). - Marusic, S. et al. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha-deficient mice are resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 202(6), 841-851 (2005).

- Ong, W. Y., Horrocks, L. A. & Farooqui, A. A. Immunocytochemical localization of cPLA2 in rat and monkey spinal cord. J. Mol. Neurosci. 12(2), 123-130 (1999).

- Liu, N. K. et al. A novel role of phospholipase A2 in mediating spinal cord secondary injury. Ann. Neurol. 59(4), 606-619 (2006).

- Huang, W. et al. Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone is neuroprotective after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 26(8), 1429-1434 (2009).

- Lopez-Vales, R. et al. Phospholipase A2 superfamily members play divergent roles after spinal cord injury. FASEB J. 25(12), 42404252 (2011).

- Street, I. P. et al. Slow- and tight-binding inhibitors of the

human phospholipase A2. Biochemistry 32(23), 5935-5940 (1993). - Stewart, A. N. et al. Acute inflammatory profiles differ with sex and age after spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflammation. 18(1), 113 (2021).

- Kilkenny, C. et al. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 8(6), e1000412 (2010).

- Burgess, A. W. et al. Purification of two forms of colony-stimulating factor from mouse L-cell-conditioned medium. J. Biol. Chem. 260(29), 16004-16011 (1984).

- Zhang, B. et al. Azithromycin drives alternative macrophage activation and improves recovery and tissue sparing in contusion spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflammation. 12, 218 (2015).

- Scheff, S. W. et al. Experimental modeling of spinal cord injury: characterization of a force-defined injury device. J. Neurotrauma. 20(2), 179-193 (2003).

- Basso, D. M. et al. Basso Mouse Scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J. Neurotrauma. 23(5), 635-659 (2006).

- Glaser, E. P. et al. Effects of Acute ethanol intoxication on spinal cord Injury outcomes in female mice. J. Neurotrauma, (2023).

- Cummings, B. J. et al. Adaptation of a ladder beam walking task to assess locomotor recovery in mice following spinal cord injury. Behav. Brain Res. 177(2), 232-241 (2007).

- Stewart, A. N. et al. Advanced Age and Neurotrauma Diminish glutathione and impair antioxidant defense after spinal cord Injury. J. Neurotrauma. 39(15-16), 1075-1089 (2022).

- Gensel, J. C. et al. Macrophages promote axon regeneration with concurrent neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 29(12), 3956-3968 (2009).

- Popovich, P. G. et al. Depletion of hematogenous macrophages promotes partial hindlimb recovery and neuroanatomical repair after experimental spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 158(2), 351-365 (1999).

- Zrzavy, T. et al. Acute and non-resolving inflammation associate with oxidative injury after human spinal cord injury. Brain 144(1), 144-161 (2021).

- Williams, K. et al. Activation of adult human derived microglia by myelin phagocytosis in vitro. J. Neurosci. Res. 38(4), 433-443 (1994).

- Leslie, C. C. Cytosolic phospholipase A(2): physiological function and role in disease. J. Lipid Res. 56(8), 1386-1402 (2015).

- Wu, X. et al. RhoA/Rho kinase mediates neuronal death through regulating cPLA(2) activation. Mol. Neurobiol. 54(9), 6885-6895 (2017).

- Wu, X. & Xu, X. M. RhoA/Rho kinase in spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 11(1), 23-27 (2016).

- Liu, N. K. et al. Inhibition of cytosolic phospholipase A(2) has neuroprotective effects on Motoneuron and muscle atrophy after spinal cord Injury. J. Neurotrauma. 38(9), 1327-1337 (2021).

- Kishimoto, K. et al. Localization of cytosolic phospholipase A2 messenger RNA mainly in neurons in the rat brain. Neuroscience 92(3), 1061-1077 (1999).

- Shibata, N. et al. Increased expression and activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in the spinal cord of patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 119(3), 345-354 (2010).

- Kishimoto, K. et al. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha amplifies early cyclooxygenase-2 expression, oxidative stress and MAP kinase phosphorylation after cerebral ischemia in mice. J. Neuroinflammation. 7, 42 (2010).

- Stephenson, D. et al. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is induced in reactive glia following different forms of neurodegeneration. Glia 27(2), 110-128 (1999).

- Milich, L. M. et al. Single-cell analysis of the cellular heterogeneity and interactions in the injured mouse spinal cord. J. Exp. Med., 218(8). (2021).

- Bartoli, F. et al. Tight binding inhibitors of

phospholipase A2 but not phospholipase A2 inhibit release of free arachidonate in thrombin-stimulated human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 269(22), 15625-15630 (1994). - Riendeau, D. et al. Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone, a potent inhibitor of

phospholipase A2, blocks production of arachidonate and 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid by calcium ionophore-challenged platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 269(22), 1561915624 (1994). - Wong, D. A. et al. Discrete role for cytosolic phospholipase

alpha in platelets: studies using single and double mutant mice of cytosolic and group IIA secretory phospholipase A(2). J. Exp. Med. 196(3), 349-357 (2002). - Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M. et al. Raplb is required for normal platelet function and hemostasis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 115(3), 680-687 (2005).

- Yoshizaki, S. et al. Tranexamic acid reduces heme cytotoxicity via the TLR4/TNF axis and ameliorates functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflammation. 16(1), 160 (2019).

- Kroner, A. et al. TNF and increased intracellular iron alter macrophage polarization to a detrimental M1 phenotype in the injured spinal cord. Neuron 83(5), 1098-1116 (2014).

- Aarabi, B. et al. Intramedullary Lesion Length on Postoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging is a strong predictor of ASIA Impairment Scale Grade Conversion following decompressive surgery in cervical spinal cord Injury. Neurosurgery 80(4), 610-620 (2017).

- Rutges, J. et al. A prospective serial MRI study following acute traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. Eur. Spine J. 26(9), 2324-2332 (2017).

الشكر والتقدير

نود أن نشكر الدكتور شياو-مينغ شو على تبرعه السخي بفئران cPLA2 KO. كما نود أن نشكر الدكتور سينثيلناثان بالانياندي والدكتور جوش مورغانتي على مساعدتهما التقنية.

مساهمات المؤلفين

التصور: E.G.، T.K.، J.G. المنهجية: E.G.، T.K.، J.G. التحقق: E.G. التحليلات الرسمية: E.G.، T.K. التحقيق: E.G.، T.K.، W.B.، R.K.، A.S.، H.K. تنسيق البيانات: E.G. الكتابة: E.G. المراجعة والتحرير: E.G.، J.G.، T.K. إدارة المشروع: E.G.، J.G. الحصول على التمويل: E.G.، T.K.، و J.G. الإشراف: J.G.

التمويل

تم تقديم دعم التمويل من قبل: مؤسسة كريغ إتش نيلسن بموجب الجائزة #651996، والمعهد الوطني للاضطرابات العصبية والسكتة الدماغية (NINDS) التابع للمعاهد الوطنية للصحة (NIH) بموجب الجوائز: F31NS105443، F30NS129251 و R01NS116068.

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات وطلبات المواد إلى J.C.G.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام غير التجاري، والتي تسمح بأي استخدام غير تجاري، ومشاركة، وتوزيع، وإعادة إنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح إذا قمت بتعديل المادة المرخصة. ليس لديك إذن بموجب هذه الرخصة لمشاركة المواد المعدلة المشتقة من هذه المقالة أو أجزاء منها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommo ns.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

© المؤلفون 2025

© المؤلفون 2025

قسم الفسيولوجيا، مركز أبحاث إصابة الحبل الشوكي والدماغ، كلية الطب بجامعة كنتاكي، ليكسينغتون، KY 40536، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم المناعة والميكروبيولوجيا، حرم جامعة كولورادو أنشوتز الطبي، 12800 E 19th Ave، أورورا، CO 80045، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علوم الأعصاب، مركز أبحاث إصابة الحبل الشوكي والدماغ، كلية الطب بجامعة كنتاكي، ليكسينغتون، KY 40536، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني: gensel.1@uky.edu

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 15, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84936-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39747330

Publication Date: 2025-01-02

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84936-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39747330

Publication Date: 2025-01-02

scientific reports

OPEN

Cytosolic phospholipase A2 in infiltrating monocyte derived macrophages does not impair recovery after spinal cord injury in female mice

Spinal cord injury (SCI) leads to permanent motor and sensory loss that is exacerbated by intraspinal inflammation and persists months to years after injury. After SCI, monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) infiltrate the lesion to aid in myelin-rich debris clearance. During debris clearance, MDMs adopt a proinflammatory phenotype that exacerbates neurodegeneration and hinders recovery. The underlying cause of the lipid-mediated MDM phenotype shift is unclear. Our previous work suggests that cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) plays a role in the proinflammatory potentiating effect of myelin on macrophages in vitro. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) frees arachidonic acid from phospholipids, generating eicosanoids that play an important role in inflammation, immunity, and host defense. cPLA2 is expressed in macrophages along with multiple other cell types after SCI, and cPLA2 inhibition has been reported to both reduce and exacerbate secondary injury pathology recovery. The role of cPLA2 in MDMs after SCI is not fully understood. We hypothesize that cPLA2 activation in MDMs after SCI contributes to secondary injury. Here, we report that cPLA2 plays an important role in the myelin-induced inflammatory macrophage phenotype in vitro using macrophages derived from cPLA2 knockout bone marrow. Furthermore, to investigate the role of cPLA2 in MDMs after SCI, we generated female bone marrow chimeras using cPLA2 knock-out donors and assessed locomotor recovery using the Basso Mouse Scale (BMS), CatWalk gait analysis system, and horizontal ladder task over six weeks. We also evaluated tissue sparing and intralesional axon density six weeks after injury. cPLA2 KO chimeras did not display altered locomotor recovery or tissue pathology after SCI compared to WT chimera controls. These data suggest that although cPLA2 plays a critical role in myelin-mediated potentiation of proinflammatory macrophage activation in vitro, it may not contribute to secondary injury pathology in vivo after SCI.

Keywords Spinal cord injury, Cytosolic phospholipase A2, Macrophage, Myelin, Inflammation

Abbreviations

| AACOCF3 | Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CM-H2DCFDA | chloromethyl 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| cPLA2 | cytosolic phospholipase A2 |

| BMS | Basso Mouse Scale |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| DAB | 3,3′-diaminobenzidine |

| DPI | days post injury |

| Gys | Grays |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| HSC | hematopoietic stem cell |

| HSTC | hematopoietic stem cell transplant |

| MDM | Monocyte-derived macrophage |

| MTT | thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide |

| PACOCF3 | Palmitoyl trifluoromethyl ketone |

| PB | Phosphate Buffer |

| PBS | Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| SCI | Spinal Cord Injury |

| WPI | weeks post injury |

| WT | Wild Type |

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating condition that results in significant functional deficits and dramatically decreases the quality of life of injured individuals. The initial mechanical trauma to the spinal cord tissue, known as primary injury, is followed by biological events that exacerbate tissue damage. This secondary injury involves a complex biological cascade that includes but is not limited to inflammation, activation of resident neuroglia, peripheral leukocyte infiltration, and oxidative stress. Secondary injury exacerbates tissue damage and hinders recovery thereby limiting endogenous repair

In the injured spinal cord, activated macrophages, made up of resident microglia and infiltrating monocytederived macrophages (MDMs), play a large role in the secondary injury response and contribute to both injury and repair

We previously reported that activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) may link myelin with proinflammatory activation

cPLA2 has been the focus of decades of research because it specifically targets phospholipids containing an arachidonic acid acyl moiety. Arachidonic acid is a polyunsaturated fatty acid that is the precursor for the production of eicosanoids such as prostaglandins, prostacyclins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes. Eicosanoids have widespread and diverse physiological actions that include vascular permeability, immune cell recruitment, fever, pain, and platelet aggregation

cPLA2 has been the focus of decades of research because it specifically targets phospholipids containing an arachidonic acid acyl moiety. Arachidonic acid is a polyunsaturated fatty acid that is the precursor for the production of eicosanoids such as prostaglandins, prostacyclins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes. Eicosanoids have widespread and diverse physiological actions that include vascular permeability, immune cell recruitment, fever, pain, and platelet aggregation

From this information, it is not surprising that cPLA2 inhibition is beneficial in numerous disease processes

Materials and methods

Animals

In these experiments, 2 – to 4 -month-old female cPLA2

Cell culture

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were extracted from the femur and tibia of cPLA2 KO and WT littermate controls as described previously

Myelin isolation

Moderate purity myelin (

Neurotoxicity assay

To assess the neurotoxicity of stimulated BMDMs, a mouse neuroblastoma cell line (Neuro-2a or N2A, a gift from Chris Richards, University of Kentucky) was maintained in N2A growth medium consisting of 45% DMEM, 45% OPTI-MEM reduced-serum medium, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin/ streptomycin. N2A cells were plated at a density of

the background absorbance. These data are normalized to the nontoxic CTL values to generate a proportional decrease in viability values.

the background absorbance. These data are normalized to the nontoxic CTL values to generate a proportional decrease in viability values.

Reactive oxygen species assay

Macrophage reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was measured using chloromethyl

Arginase activity assay

Macrophage arginase activity was measured using the Arginase Activity Assay Kit (ab180877). In short, BMDMs were cultured and stimulated as described above. Following the removal of the supernatant cells were washed 2 x in cold PBS, and homogenized in

Nitric oxide assay

Macrophage nitric oxide production was measured using the Griess Reagent Kit (G-7921). In short, BMDMs were cultured and stimulated as described above except for a substitution using phenol red-free RPMI, and the stimulations were scaled down to a 96-well plate format (

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

To reduce the nonspecific effects of irradiation on the spinal cord, a preliminary dosing study was performed. Wild-type C57BL6 mice were exposed to a split dose of 8, 10.5, or 13 Gy of radiation from a Cesium-137 radioactive core. The two half doses were separated by 3 h . Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) were isolated from Actin-GFP donors, and

Spinal cord Injury

As described previously

Behavioral assessment of locomotor recovery

Locomotor recovery was assessed after SCI with the Basso Mouse Scale (BMS) open field test, CatWalk XT gait analysis system, and the horizontal ladder test. The BMS utilizes a 9-point rating scale to characterize gross locomotor functions ranging from complete paralysis (score 0 ) to normal functions (score 9 ) as mice explore an open field for

| Cohort |

|

Sex | Outcomes | Timepoint | Exclusion | ||||||||

| A |

|

F | Bone marrow chimerization efficiency and CNS leukocyte permeability | 8 weeks post HSCT | None | ||||||||

| B |

|

F |

|

6 weeks | 2 mice from WT group and 1 mouse excluded from cPLA2 KO group for meeting a priori exclusion criteria (BMS score

|

||||||||

| C |

|

F | Gene expression of spinal cord homogenate by nCounter (NanoString Technologies) gene array | 7 days | None |

Table 1. Experimental design of the three cohorts including: group size pre and post exclusion, sex, outcomes, endpoint, and exclusion criteria for all groups.

BMS subscores are based on features of locomotion, such as trunk stability, coordination, and paw placement, that are observable in higher-functioning mice. BMS subscores permitted a better resolution to differentiate between mice with higher BMS scores.

We also used the CatWalk XT gait analysis system (Noldus, Wageningen, the Netherlands) to track specific parameters of gait. For CatWalk analysis, mice underwent three testing sessions: one week before injury and 4 – and 6 -weeks post-injury. The CatWalk features a red overhead light and green illuminated walkway, which reflects light in response to the contact of the mouse’s paw that is then captured via calibrated video recordings. Gait analysis was performed by the same researcher in a dark room. Using conditioning and analysis protocols developed previously

The horizontal ladder test was used to assess stepping and coordination at later stages of recovery according to previous studies

Immunohistochemistry

At the study endpoint, mice were given a lethal dose of ketamine and xylazine. Blood was then collected by cardiac puncture in a heparinized needle and syringe and transferred to an EDTA-coated tube (VWR, 101094-004) for leukocyte isolation (see below). Mice were transcardially perfused with PBS followed by

To assess lesion volume, all tissue was stained with eriochrome cyanine and neurofilament heavy, which stain intact myelin and axons, respectively. These markers were used to distinguish lesioned from intact tissue. To stain for neurofilament, sections underwent antigen retrieval in citrate buffer ( pH 6.0 ) at

dilutions, cleared using Histoclear (101412-878; VWR Scientific), and coverslipped using Permount (SP15500; Fisher Scientific). Slides were imaged using Axioscan (model Z1, Carl Zeiss AG., Oberkochen, GE) at 20x magnification and visualized and quantified using Halo software (Indica Labs, Albuquerque, NM).

dilutions, cleared using Histoclear (101412-878; VWR Scientific), and coverslipped using Permount (SP15500; Fisher Scientific). Slides were imaged using Axioscan (model Z1, Carl Zeiss AG., Oberkochen, GE) at 20x magnification and visualized and quantified using Halo software (Indica Labs, Albuquerque, NM).

Gene expression analysis

At the study endpoint, peripheral blood was collected from all mice via cardiac puncture. Erythrocytes were removed using red blood cell (RBC) lysis buffer (BioLegend, 420301). Collected blood was mixed with RBC lysis buffer and left at room temperature for 5 min . Leukocytes were pelleted by centrifugation at 350 g for 5 min , and the lysis process was repeated twice. Leukocyte pellets were frozen on dry ice. RNA was isolated from leukocyte pellets using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, 74104). RNA concentration was determined using a Nanodrop (Nanodrop Lite; Thermo Fisher Waltham, MA). cDNA libraries were made using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, 4368814). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR green master mix and the following forward and reverse primers: (pla2g4a forward= “GATTCTGGAAATGTCTCTG GAAG”, reverse=”GGCTGACATTTTTCATTAGCTC”; GAPDH, forward=”CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGA CTG “, reverse=”ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG “).

NanoString gene expression analysis was performed on whole spinal cord homogenate. Seven days after SCI, mice were transcardially perfused with PBS, and 6 mm of the spinal cord was removed and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was isolated from spinal cords using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, 74104). RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop Lite (Thermo Fisher Waltham, MA), and samples were diluted to

Statistics

All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism software (v9.4.1, Boston, MA). All in vitro data were analyzed using an ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. An unpaired Student’s t test was used to compare cPLA2 expression between cPLA2 KO and WT chimeras. For behavioral data and histological analysis, a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used. Behavioral data were compared over time, and histological data were compared over distance from the epicenter.

Results

cPLA2 is required for myelin to potentiate an inflammatory stimulus in bone marrow-derived macrophages

In the context of SCI, bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) are bombarded by an array of stimuli that potentiate a proinflammatory phenotype

Optimization of radiation dose for the generation of chimeric mice

To test whether cPLA2 potentiated proinflammatory macrophage activation in vivo, we utilized a chimeric mouse model. We first performed a pilot experiment to optimize the radiation dose in our HSCT protocol. Our goal was to achieve robust bone marrow chimerization while minimizing immune cell infiltration into the intact CNS. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) isolated from Actin-GFP mice were retro-orbitally injected into C57BL/6J mice after three different radiation doses (

Fig. 1. cPLA2 KO bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) have normal responses to proinflammatory stimuli but are resistant to the potentiating effect of myelin. Bone marrow harvested from cPLA2 KO mice and WT littermates was differentiated into BMDMs and treated with an M1 stimulus (LPS and IFN-

Locomotor recovery and tissue pathology are not altered in cPLA2 KO chimeras

Our optimized HSCT protocol enabled the interrogation of the role of cPLA2 in MDMs after SCI. WT C57BL6/J mice received HSCs from cPLA2 KO and WT littermate donors after 10.5 Gys. Eight to 12 weeks after HSCT, mice received a 65 kDyn T9 contusion SCI, and tissue was collected 7 days or 6 weeks after SCI (Fig. 3A-B). Whole blood was collected at the study endpoints, and cPLA2 expression was measured in isolated leukocytes. In all three cohorts, cPLA2 expression was decreased approximately tenfold in animals receiving KO vs. WT HSCs (Fig. 3B-C) (B,

Fig. 2. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) at specific radiation doses produces robust leukocyte chimerism while minimizing leukocyte spinal cord infiltration. Uninjured mice received 8, 10.5, and 13 Gy of radiation in two doses following intravenous injection of HSCs from Actin-GFP donors. Chimerization efficiency and spinal cord leukocyte infiltration were determined 9 weeks post-HSCT. (A) Gating strategy used to determine the chimerization efficiency of circulating CD45

Fig. 3. HSCT with cPLA2 KO donors reduces cPLA2 expression in circulating leukocytes and in the injured spinal cord. (A) Schematic for the HSCT protocol. HSCs isolated from cPLA2 KO and WT donors were injected into WT (C57BL/6J) mice after a split dose of 10.5 Gys (Created in BioRender). At

was sufficient to significantly reduce overall cPLA2 expression in the spinal cord at 7 days, further confirming the effectiveness of our KO approach (Fig. 3D) (

To test the hypothesis that MDM cPLA2 limits locomotor recovery after SCI, we assessed locomotor recovery of cPLA2 KO chimeras and WT chimera controls using the BMS score, BMS subscore, horizontal ladder, and CatWalkXT gait analysis system. BMS scoring and subscoring indicated recovery from complete paralysis with only some ankle movement (a score of 1 and 2 ) at 1 day postinjury (DPI) to frequent and consistent plantar stepping with coordinated stepping by 6 weeks postinjury (WPI) (a score of

Fig. 4. HSCT with cPLA2 KO donors did not alter locomotor recovery following SCI relative to WT controls. Mice were injured 10 weeks after HSCT, and recovery was assessed for 6 weeks after SCI. (A-B) Basso mouse scale locomotor scores and subscores were not significantly different between WT and cPLA2 KO HSC recipients. (C) Locomotor recovery and proprioception were assessed at 6 weeks using the horizontal ladder test, and there was no significant difference between WT and cPLA2 KO recipients. (D-G) CatWalk gait analysis revealed no differences between groups. (D) Regularity index, (E) hind paw base of support width, (F) hind paw stride length, and

CatWalk gait analysis was performed before injury and 4 – and 6 -weeks post-injury. Using the CatWalk XT, we specifically assessed the regularity index, base of support, stride length, and print area as continuous measures sensitive to moderate and severe SCI. The regularity index, a measure of coordination, was significantly decreased after 4 weeks

At the end of the 6 weeks, tissue was collected to assess the effect of cPLA2 KO chimerism on tissue pathology after SCI. Using eriochrome cyanine (EC) and neurofilament heavy (NF) staining, spared tissue was identified as double-positive (EC+, NF+) myelinated axons. Representative lesion epicenter images illustrate a clear contrast between areas of spared tissue and frank lesion areas in spinal cord tissue (Fig. 5A-B). Tissue sparing was not significantly different at the lesion epicenter or rostral and caudal to the epicenter between cPLA2 KO and WT chimeras (Fig. 5D-E) (5E,

Discussion

The inflammatory microenvironment that persists chronically in the injured spinal cord limits recovery. The underlying mechanisms driving inflammation after SCI are poorly understood. Lipid-debris-laden macrophages that chronically linger in the injury site may be the culprit

Fig. 5. cPLA2 ablation in infiltrating leukocytes does not alter tissue sparing or intralesional axons after SCI. (A,B) Representative sections of the lesion epicenter stained for neurofilament (axons-brown) with an eriochrome cyanine (blue-myelin) counterstain 6 weeks after SCI. (C) High-powered image of B indicative of typical axonal labeling (brown) within the lesion epicenter and quantified in (F). cPLA2 KO and WT recipients had similar tissue sparing throughout the lesion (D) and at the lesion epicenter (E). (F) A quantitative assessment of axon sparing/sprouting at the lesion epicenter and

shown that myelin can induce a proinflammatory macrophage phenotype

cPLA2 is widely studied in multiple diseases and is a key enzyme in arachidonic acid production

cPLA2 is widely studied in multiple diseases and is a key enzyme in arachidonic acid production

Next, a comprehensive study of all PLA2s upregulated after SCI by Lòpez-Vales et al. reported reduced behavioral recovery and exacerbated tissue pathology after cPLA2 inhibition using a selective and potent 2 -oxoamide-based inhibitor and a cPLA2 global knockout mouse

In SCI, MDM cPLA2 may not contribute to secondary injury because most of the active cPLA2 is in neurons, astrocytes, and microglia. Early studies identified cPLA2-positive neurons in specific brain regions and spinal

cord motor neurons in uninjured rodent CNS with only faint signals in glia

cord motor neurons in uninjured rodent CNS with only faint signals in glia

Alternatively, MDM cPLA2 may be detrimental to recovery, but the beneficial effect of MDM cPLA2 deletion could be overshadowed by deletion of cPLA2 in other HSC-derived cells, namely, platelets. cPLA2 inhibition in platelets with

Our results demonstrate that cPLA2 in MDMs likely does not contribute significantly to macrophage-mediated pathology after SCI. We first showed that cPLA2 KO macrophages are protected from the proinflammatory potentiating effect of myelin. Using bone marrow chimeras, we then investigated the role of cPLA2 in MDMs after SCI. We found no effect of cPLA2 KO HSCT on locomotor recovery or tissue pathology. This discovery sheds light on a series of heterogeneous observations using global KO or suppression of cPLA2 in SCI.

Data availability

All raw data presented in figures and tables herein is available to the public through the Open Data Commons for Spinal Cord Injury (ODC-SCI). The ODC-SCI is a dedicated data sharing portal and repository for the field of SCI that enables the sharing of data with the public using a DOI. The DOI associated with this work is as follows: http://dx.doi.org/10.34945/F52307. The ODC-SCI complies with the FAIR data principles to ensure that SCI data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable.

Received: 6 September 2024; Accepted: 30 December 2024

Published online: 02 January 2025

Published online: 02 January 2025

References

- Orr, M. B. & Gensel, J. C. Spinal cord Injury scarring and inflammation: therapies targeting glial and inflammatory responses. Neurotherapeutics 15(3), 541-553 (2018).

- Gensel, J. C. & Zhang, B. Macrophage activation and its role in repair and pathology after spinal cord injury. Brain Res. 1619, 1-11 (2015).

- Kigerl, K. A. et al. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 29(43), 13435-13444 (2009).

- Greenhalgh, A. D. & David, S. Differences in the phagocytic response of microglia and peripheral macrophages after spinal cord injury and its effects on cell death. J. Neurosci. 34(18), 6316-6322 (2014).

- Wang, X. et al. Macrophages in spinal cord injury: phenotypic and functional change from exposure to myelin debris. Glia 63(4), 635-651 (2015).

- Zhu, Y. et al. Macrophage Transcriptional Profile identifies lipid catabolic pathways that can be therapeutically targeted after spinal cord Injury. J. Neurosci. 37(9), 2362-2376 (2017).

- Ryan, C. B. et al. Myelin and non-myelin debris contribute to foamy macrophage formation after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 163, 105608 (2022).

- Kopper, T. J. et al. The effects of myelin on macrophage activation are phenotypic specific via cPLA2 in the context of spinal cord injury inflammation. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 6341 (2021).

- Khan, S. A. & Ilies, M. A. The phospholipase A2 superfamily: structure, isozymes, catalysis, physiologic and pathologic roles. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 24(2). (2023).

- Sun, G. Y. et al. Dynamic role of Phospholipases A2 in Health and diseases in the Central Nervous System. Cells, 10(11). (2021).

- Wang, B. et al. Metabolism pathways of arachidonic acids: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 6(1), 94 (2021).

- Clark, J. D. et al. A novel arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic PLA2 contains a ca(

)-dependent translocation domain with homology to PKC and GAP. Cell 65(6), 1043-1051 (1991). - Kramer, R. M. et al. 38 mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylates cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) in thrombinstimulated platelets. Evidence that proline-directed phosphorylation is not required for mobilization of arachidonic acid by cPLA2. J. Biol. Chem. 271(44), 27723-27729(1996).

- Linkous, A. & Yazlovitskaya, E. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 as a mediator of disease pathogenesis. Cell. Microbiol. 12(10), 13691377 (2010).

- Sarkar, C. et al. PLA2G4A/cPLA2-mediated lysosomal membrane damage leads to inhibition of autophagy and neurodegeneration after brain trauma. Autophagy 16(3), 466-485 (2020).

- Gijon, M. A. & Leslie, C. C. Regulation of arachidonic acid release and cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 65(3), 330-336 (1999).

- Liu, N. K. et al. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 protein as a novel therapeutic target for spinal cord injury. Ann. Neurol. 75(5), 644-658 (2014).

- Bonventre, J. V. et al. Reduced fertility and postischaemic brain injury in mice deficient in cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nature 390(6660), 622-625 (1997).

- Li, Y. et al. cPLA2 activation contributes to lysosomal defects leading to impairment of autophagy after spinal cord injury. Cell. Death Dis. 10(7), 531 (2019).

- Nagase, T. et al. Acute lung injury by sepsis and acid aspiration: a key role for cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nat. Immunol. 1(1), 42-46 (2000).

- Wang, S. et al. Calcium-dependent cytosolic phospholipase

activation is implicated in neuroinflammation and oxidative stress associated with ApoE4. Mol. Neurodegener. 17(1), 42 (2022). - Marusic, S. et al. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha-deficient mice are resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 202(6), 841-851 (2005).

- Ong, W. Y., Horrocks, L. A. & Farooqui, A. A. Immunocytochemical localization of cPLA2 in rat and monkey spinal cord. J. Mol. Neurosci. 12(2), 123-130 (1999).

- Liu, N. K. et al. A novel role of phospholipase A2 in mediating spinal cord secondary injury. Ann. Neurol. 59(4), 606-619 (2006).

- Huang, W. et al. Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone is neuroprotective after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 26(8), 1429-1434 (2009).

- Lopez-Vales, R. et al. Phospholipase A2 superfamily members play divergent roles after spinal cord injury. FASEB J. 25(12), 42404252 (2011).

- Street, I. P. et al. Slow- and tight-binding inhibitors of the

human phospholipase A2. Biochemistry 32(23), 5935-5940 (1993). - Stewart, A. N. et al. Acute inflammatory profiles differ with sex and age after spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflammation. 18(1), 113 (2021).

- Kilkenny, C. et al. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 8(6), e1000412 (2010).

- Burgess, A. W. et al. Purification of two forms of colony-stimulating factor from mouse L-cell-conditioned medium. J. Biol. Chem. 260(29), 16004-16011 (1984).

- Zhang, B. et al. Azithromycin drives alternative macrophage activation and improves recovery and tissue sparing in contusion spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflammation. 12, 218 (2015).

- Scheff, S. W. et al. Experimental modeling of spinal cord injury: characterization of a force-defined injury device. J. Neurotrauma. 20(2), 179-193 (2003).

- Basso, D. M. et al. Basso Mouse Scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J. Neurotrauma. 23(5), 635-659 (2006).

- Glaser, E. P. et al. Effects of Acute ethanol intoxication on spinal cord Injury outcomes in female mice. J. Neurotrauma, (2023).

- Cummings, B. J. et al. Adaptation of a ladder beam walking task to assess locomotor recovery in mice following spinal cord injury. Behav. Brain Res. 177(2), 232-241 (2007).

- Stewart, A. N. et al. Advanced Age and Neurotrauma Diminish glutathione and impair antioxidant defense after spinal cord Injury. J. Neurotrauma. 39(15-16), 1075-1089 (2022).

- Gensel, J. C. et al. Macrophages promote axon regeneration with concurrent neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 29(12), 3956-3968 (2009).

- Popovich, P. G. et al. Depletion of hematogenous macrophages promotes partial hindlimb recovery and neuroanatomical repair after experimental spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 158(2), 351-365 (1999).

- Zrzavy, T. et al. Acute and non-resolving inflammation associate with oxidative injury after human spinal cord injury. Brain 144(1), 144-161 (2021).

- Williams, K. et al. Activation of adult human derived microglia by myelin phagocytosis in vitro. J. Neurosci. Res. 38(4), 433-443 (1994).

- Leslie, C. C. Cytosolic phospholipase A(2): physiological function and role in disease. J. Lipid Res. 56(8), 1386-1402 (2015).

- Wu, X. et al. RhoA/Rho kinase mediates neuronal death through regulating cPLA(2) activation. Mol. Neurobiol. 54(9), 6885-6895 (2017).

- Wu, X. & Xu, X. M. RhoA/Rho kinase in spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 11(1), 23-27 (2016).

- Liu, N. K. et al. Inhibition of cytosolic phospholipase A(2) has neuroprotective effects on Motoneuron and muscle atrophy after spinal cord Injury. J. Neurotrauma. 38(9), 1327-1337 (2021).

- Kishimoto, K. et al. Localization of cytosolic phospholipase A2 messenger RNA mainly in neurons in the rat brain. Neuroscience 92(3), 1061-1077 (1999).

- Shibata, N. et al. Increased expression and activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in the spinal cord of patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 119(3), 345-354 (2010).

- Kishimoto, K. et al. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 alpha amplifies early cyclooxygenase-2 expression, oxidative stress and MAP kinase phosphorylation after cerebral ischemia in mice. J. Neuroinflammation. 7, 42 (2010).

- Stephenson, D. et al. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 is induced in reactive glia following different forms of neurodegeneration. Glia 27(2), 110-128 (1999).

- Milich, L. M. et al. Single-cell analysis of the cellular heterogeneity and interactions in the injured mouse spinal cord. J. Exp. Med., 218(8). (2021).

- Bartoli, F. et al. Tight binding inhibitors of

phospholipase A2 but not phospholipase A2 inhibit release of free arachidonate in thrombin-stimulated human platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 269(22), 15625-15630 (1994). - Riendeau, D. et al. Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl ketone, a potent inhibitor of

phospholipase A2, blocks production of arachidonate and 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid by calcium ionophore-challenged platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 269(22), 1561915624 (1994). - Wong, D. A. et al. Discrete role for cytosolic phospholipase

alpha in platelets: studies using single and double mutant mice of cytosolic and group IIA secretory phospholipase A(2). J. Exp. Med. 196(3), 349-357 (2002). - Chrzanowska-Wodnicka, M. et al. Raplb is required for normal platelet function and hemostasis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 115(3), 680-687 (2005).

- Yoshizaki, S. et al. Tranexamic acid reduces heme cytotoxicity via the TLR4/TNF axis and ameliorates functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflammation. 16(1), 160 (2019).

- Kroner, A. et al. TNF and increased intracellular iron alter macrophage polarization to a detrimental M1 phenotype in the injured spinal cord. Neuron 83(5), 1098-1116 (2014).

- Aarabi, B. et al. Intramedullary Lesion Length on Postoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging is a strong predictor of ASIA Impairment Scale Grade Conversion following decompressive surgery in cervical spinal cord Injury. Neurosurgery 80(4), 610-620 (2017).

- Rutges, J. et al. A prospective serial MRI study following acute traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. Eur. Spine J. 26(9), 2324-2332 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Xiao-Ming Xu for generously donating the cPLA2 KO mice. We would also like to thank Dr. Senthilnathan Palaniyandi and Dr. Josh Morganti for their technical assistance.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: E.G., T.K., J.G. Methodology: E.G., T.K., J.G. Validation: E.G. Formal Analyses: E.G.,T.K. Investigation: E.G., T.K., W.B., R.K., A.S., H.K. Data Curation: E.G. Writing: E.G. Reviewing and Editing: E.G., J.G., T.K. Project Administration: E.G., J.G. Funding Acquisition: E.G., T.K., & J.G. Supervision: J.G.

Funding

Funding support provided by: The Craig H. Neilsen Foundation under award #651996, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Awards: F31NS105443, F30NS129251 & R01NS116068.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.C.G.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommo ns.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2025

© The Author(s) 2025

Department of Physiology, Spinal Cord and Brain Injury Research Center, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, KY 40536, USA. Department of Immunology and Microbiology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, 12800 E 19th Ave, Aurora, CO 80045, USA. Department of Neuroscience, Spinal Cord and Brain Injury Research Center, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, KY 40536, USA. email: gensel.1@uky.edu