DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00532-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38697170

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-29

لصقة ميكرونيدل لقاح الحصبة والحصبة الألمانية في غامبيا: تجربة عشوائية مزدوجة التعمية، مزدوجة الدواء الوهمي، من المرحلة 1/2، مضبوطة نشطة، بتخفيض العمر

الملخص

ملخص الخلفية تم تصنيف لصقات الإبر الدقيقة (MNPs) كأعلى أولوية عالمية للابتكار في التغلب على حواجز التطعيم في البلدان ذات الدخل المنخفض والمتوسط. كان الهدف من هذه التجربة هو تقديم البيانات الأولى حول تحمل وسلامة واستجابة المناعة للقاح الحصبة والحصبة الألمانية (MRV)-MNP لدى الأطفال.

الطرق: هذه دراسة مركزية واحدة، المرحلة

مشروع قانون تمويل مؤسسة بيل وميليندا غيتس.

حقوق الطبع والنشر © 2024 المؤلفون. نُشر بواسطة إلسفير المحدودة. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب ترخيص CC BY 4.0.

مقدمة

تم تجنب الوفيات في هذه الفترة.

لقد التزمت جميع المناطق الست التابعة لمنظمة الصحة العالمية بالقضاء على الحصبة.

البحث في السياق

الأدلة قبل هذه الدراسة

القيمة المضافة لهذه الدراسة

لقاحات الحصبة والحصبة الألمانية. في البالغين، كانت لقاحات الحصبة والحصبة الألمانية التي تم إعطاؤها للأطفال الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 15-18 شهرًا، والرضع الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 9-10 أشهر، مقبولة جيدًا وآمنة. كانت التورمات في موقع التطبيق شائعة، حيث حدثت في ما يقرب من نصف جميع الأطفال والرضع، لكنها كانت خفيفة في جميع الحالات وحلّت دون علاج. لم تكن أي من ردود الفعل المحلية مصدر قلق من الناحية الأمنية. كما كانت تغيرات اللون في موقع التطبيق، التي كانت تقريبًا حصريًا فرط تصبغ، شائعة أيضًا، حيث حدثت في ما يقرب من 50% من الأطفال.

تداعيات جميع الأدلة المتاحة

تغطية لقاح الحصبة عبر جميع المناطق.

كانت

الأطفال الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 9 أشهر إلى

تقدم لصقات الإبر الدقيقة (MNPs) عددًا من المزايا البرمجية مقارنةً بإعطاء MRV بواسطة الإبرة والمحاقن.

تحتوي MRV-MNP المستخدمة في هذه التجربة على MRV حي مُضعف مدرج في مجموعة من الإبر الدقيقة. عند تطبيق MNP على الجلد، تخترق الإبر الدقيقة البشرة والطبقة العليا من الأدمة، وتذوب، وتحرر اللقاح. تم تصميم التطبيق للسماح بالإعطاء من قبل أشخاص ليسوا من المتخصصين في الرعاية الصحية، وهو غير مؤلم إلى حد كبير.

تم إجراء هذه التجربة السريرية استنادًا إلى بيانات ما قبل السريرية الداعمة لـ MRV-MNP، وبيانات عن استخدام نفس تقنية MNP القابلة للذوبان لتوصيل لقاحات الإنفلونزا للبالغين.

طرق

تصميم الدراسة والمشاركين

كان يجب أن يكون المشاركون أصحاء وفقًا لمعايير الإدراج والاستبعاد المحددة للتجربة (الملحق الصفحات 3-5). قدم جميع المشاركين أو الآباء أو الأوصياء على المشاركين موافقة خطية مستنيرة. تمت الموافقة على الدراسة من قبل لجنة الأخلاقيات المشتركة بين حكومة غامبيا/MRC (LEO 22420)، ولجنة الأخلاقيات البحثية بمدرسة لندن للصحة العامة والطب الاستوائي، ووكالة مراقبة الأدوية الغامبية.

العشوائية والتعمية

الإجراءات

مقالات

تم تأكيد انحلال الإبر الدقيقة بعد التطبيق بواسطة المجهر. كانت الإبر الدقيقة الوهمية تحتوي على نفس المواد المساعدة الموجودة في الإبر الدقيقة الخاصة باللقاح، ولكن بدون الفيروسات اللقاحية. تم استخدام ممارسات التصنيع الجيدة طوال الوقت. كانت المادة الوهمية للحقن تحت الجلد تتكون من 0.5 مل من

تم تطبيق MNP على الجانب الظهري من المعصم لمدة 5 دقائق ثم تمت إزالته. تم مراقبة المشاركين عن كثب طوال هذه الفترة لمنع إزعاج MNP. تم إعطاء الحقن تحت الجلد فوق منطقة منتصف العضلة الدالية في الذراع المقابلة لدى البالغين وفي الفخذ لدى الأطفال الصغار.

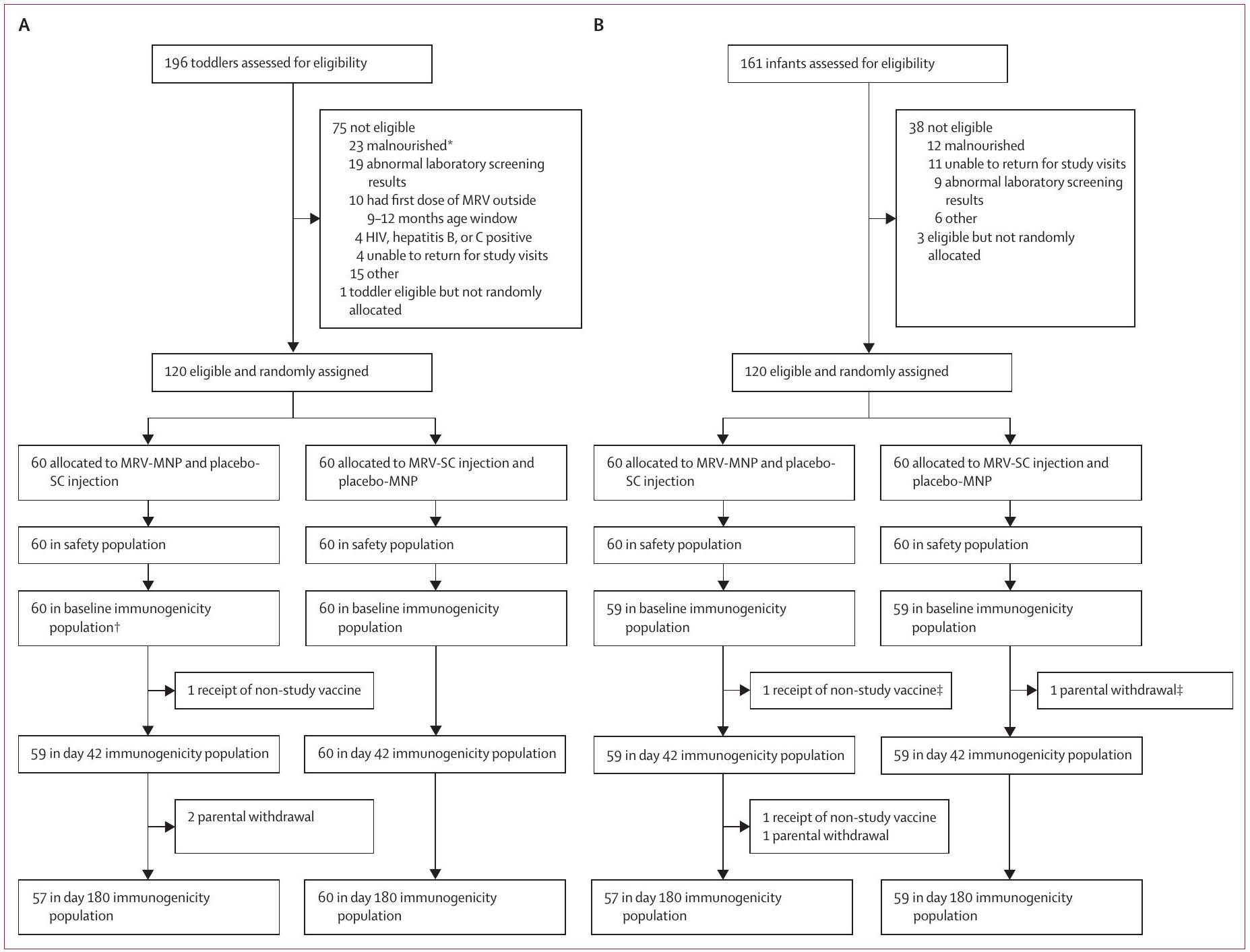

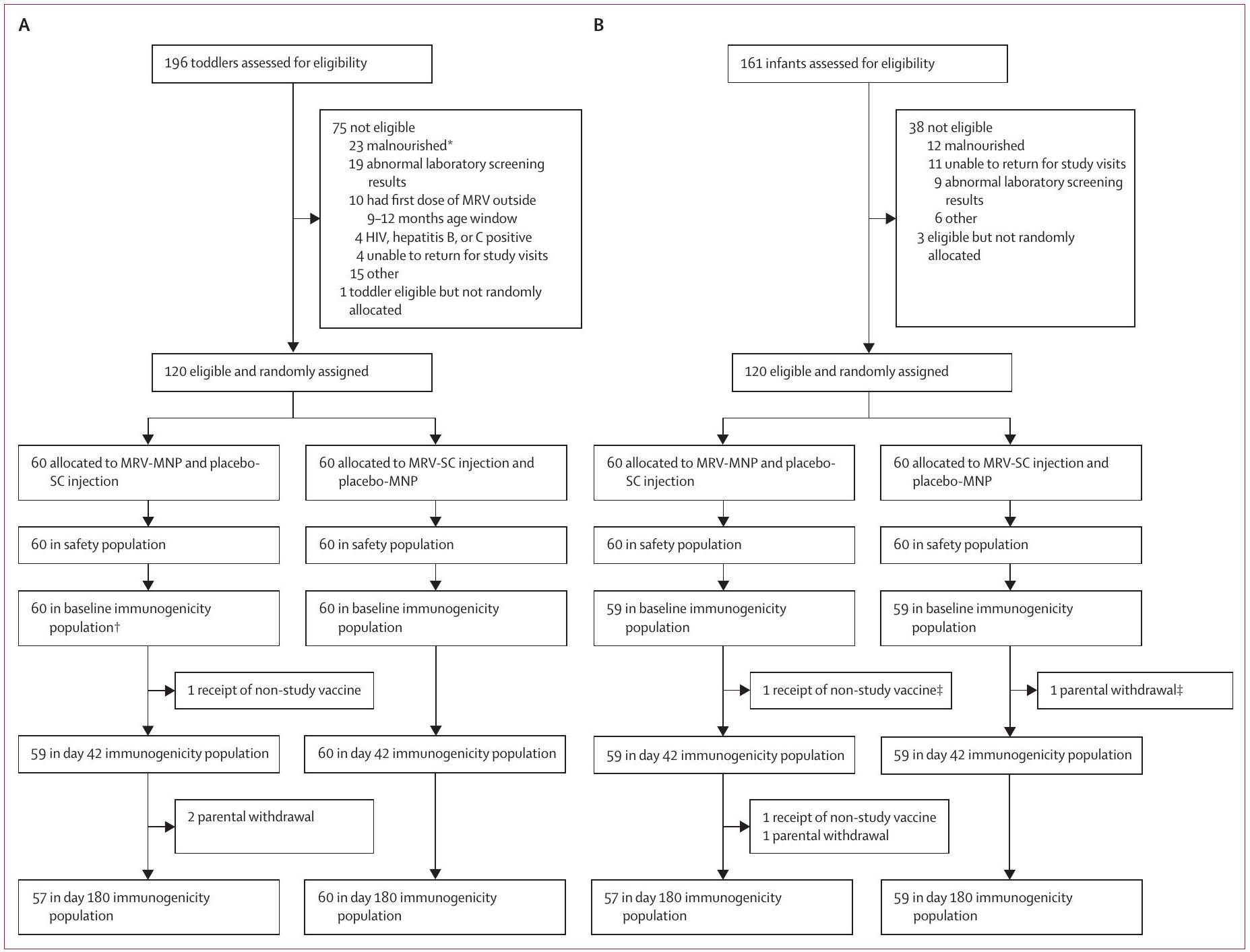

(أ) مجموعة الأطفال الصغار (ب) مجموعة الرضع. MNP=لصقة الإبر الدقيقة. MRV=لقاح الحصبة والحصبة الألمانية. SC=تحت الجلد. *يُعرف بأنه درجة Z للوزن بالنسبة للطول أقل من 2 انحراف معياري تحت المتوسط. †في مجموعة لقاح الحصبة والحصبة الألمانية للأطفال الصغار، تم تحليل عينة المناعة الأساسية للطفل الذي تلقى لقاحًا غير تابع للدراسة بين الأساس واليوم 42، وبالتالي كانت هناك 60 نتيجة عينة أساسية متاحة.

تم جمع الأحداث السلبية النظامية والأحداث السلبية المحلية في موقع تطبيق MNP وموقع الحقن تحت الجلد وتصنيفها حسب الشدة (الملحق الصفحات 11-16) في يوم إدارة منتج الدراسة (اليوم 0) ولمدة 13 يومًا إضافيًا، من خلال زيارات منزلية قام بها عمال ميدانيون مدربون. تم جمع الأحداث السلبية غير المطلوبة من يوم الإدارة حتى اليوم 180، وتصنيفها حسب المصطلح المفضل وفقًا لقاموس المصطلحات الطبية للشؤون التنظيمية وتصنيفها حسب الشدة (الملحق الصفحة 17).

تم إجراء اختبارات السلامة في علم الدم والكيمياء الحيوية في مختبرات MRCG السريرية المعتمدة باستخدام اختبارات موثوقة. تم فصل المصل عن عينات الدم، التي تم جمعها في البداية، في اليوم 42، وفي اليوم 180، وتم تجميدها عند درجات حرارة أقل من

كان تخفيض العمر بين المجموعات قائمًا على مراجعة غير مُعَمّاة لجميع بيانات السلامة حتى اليوم الرابع عشر بعد إدارة منتج الدراسة في المجموعة السابقة من قبل لجنة مستقلة لمراقبة البيانات.

النتائج

تم تقييم نتائج المناعية باستخدام كل من الأجسام المضادة SNA والأجسام المضادة IgG للحصبة والحصبة الألمانية، وكانت معدلات التحول المصلية (نسبة المشاركين الذين كانوا سلبية المصل في البداية وأصبحوا إيجابيين في اليوم 42)؛ ومعدلات الزيادة الرباعية في الأجسام المضادة (نسبة المشاركين الذين كانوا إيجابيين في المصل في…

خط الأساس ومن كان لديه زيادة أربعة أضعاف في تركيزات الأجسام المضادة بحلول اليوم 42)؛ معدلات الاستجابة المناعية (بدمج عدد المشاركين الذين خضعوا لتحول مصلّي وتجربة زيادة أربعة أضعاف في الأجسام المضادة)؛ النسبة المئوية للمشاركين الذين كانوا إيجابيين للمصل؛ متوسط تركيزات الأجسام المضادة الهندسية (GMCs) في اليوم 42 واليوم 180؛ ومتوسط الزيادة الهندسية (GMFR) في تركيزات الأجسام المضادة بين خط الأساس واليوم 42. تم تعريف الإيجابية للمصل على أنها تركيزات الأجسام المضادة بوحدات دولية (IUs) من

التحليل الإحصائي

| الأطفال الصغار | الرضع | |||

| MRV-MNP ودواء وهمي تحت الجلد (

|

MRV-SC ودواء وهمي MNP

|

MRV-MNP ودواء وهمي تحت الجلد (

|

MRV-SC ودواء وهمي MNP

|

|

| العمر، بالأشهر* | ||||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | 15 (15 إلى 16) | 15 (15 إلى 16) | 9 (9 إلى 9) | 9 (9 إلى 9) |

| جنس | ||||

| ذكر | 30 (50%) | 30 (50%) | ٢٦ (٤٣٪) | 25 (42%) |

| أنثى | 30 (50%) | 30 (50%) | 34 (57%) | ٣٥ (٥٨٪) |

| العرق | ||||

| أفريقي | 60 (100%) | 60 (100%) | 60 (100%) | 60 (100%) |

| قبيلة

|

||||

| ماندينكا | 39 (65%) | 27 (45%) | ٣٥ (٥٨٪) | 28 (47%) |

| ولوف | 6 (10%) | 7 (12%) | 4 (7%) | 7 (12%) |

| فولا | 4 (7%) | 9 (15%) | 6 (10%) | 3 (5%) |

| جولا | 4 (7%) | 12 (20%) | 10 (17%) | 7 (12%) |

| آخر | 7 (12%) | 5 (8%) | 5 (8%) | 15 (25%) |

| الوزن

|

||||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | 8.9 (8.4 إلى 9.7) | 9.0 (8.7 إلى 9.8) |

|

8.0 (7.3 إلى 8.8) |

| الطول، سم

|

||||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) |

|

|

|

70.0 (68.7 إلى 72.0) |

| درجة ز الوزن للطول

|

||||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | -0.9 (-1.6 إلى -0.5) |

|

-0.3 (-0.8 إلى 0.5) |

|

| البيانات هي

|

||||

مقالات

| الأطفال الصغار | الرضع | |||

| MRV-MNP ودواء وهمي-SC،

|

MRV-SC ودواء وهمي-MNP،

|

MRV-MNP ودواء وهمي-SC،

|

MRV-SC ودواء وهمي-MNP،

|

|

| رد فعل تحسسي حاد | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| الأحداث السلبية المحلية المطلوبة | ||||

| موقع تقديم طلب نقل الرقم | ||||

| أي حدث محلي مطلوب* | ||||

| إجمالي | 50 (83%) | 18 (30%) | 46 (77%) | 18 (30%) |

| خفيف (الدرجة 1) | 50 (83%) | 18 (30%) | ٤٦ (٧٧٪) | 18 (30%) |

| عطف | ||||

| إجمالي | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| خفيف (الدرجة 1) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| حمامي | ||||

| إجمالي | 10 (17%) | 9 (15%) | 18 (30%) | 14 (23%) |

| خفيف (الدرجة 1) | 10 (17%) | 9 (15%) | 18 (30%) | 14 (23%) |

| تصلب | ||||

| إجمالي | 46 (77%) | 9 (15%) | 39 (65%) | 6 (10%) |

| خفيف (الدرجة 1) | 46 (77%) | 9 (15%) | 39 (65%) | 6 (10%) |

| موقع حقن تحت الجلد | ||||

| أي حدث محلي مطلوب* | ||||

| أي رد فعل | 8 (13%) | 5 (8%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (7%) |

| خفيف (الدرجة 1) | 6 (10%) | 5 (8%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (7%) |

| معتدل (الدرجة 2) | 2 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| الأحداث السلبية المطلوبة النظامية | ||||

| حمى | ||||

| إجمالي | 5 (8%) | 11 (18%) | 8 (13%) | 4 (7%) |

| خفيف (الدرجة 1) | 1 (2%) | 9 (15%) | 5 (8%) | 4 (7%) |

| معتدل (الدرجة 2) | 4 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (5%) | 0 |

| شديد (الدرجة 3) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| أي حدث منهجي مطلوب

|

||||

| إجمالي | 27 (45%) | 30 (50%) | 31 (52%) | 24 (40%) |

| خفيف (الدرجة 1) | 24 (40%) | 23 (38%) | 28 (47%) | 23 (38%) |

| معتدل (الدرجة 2) | 3 (5%) | 7 (12%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) |

دور مصدر التمويل

النتائج

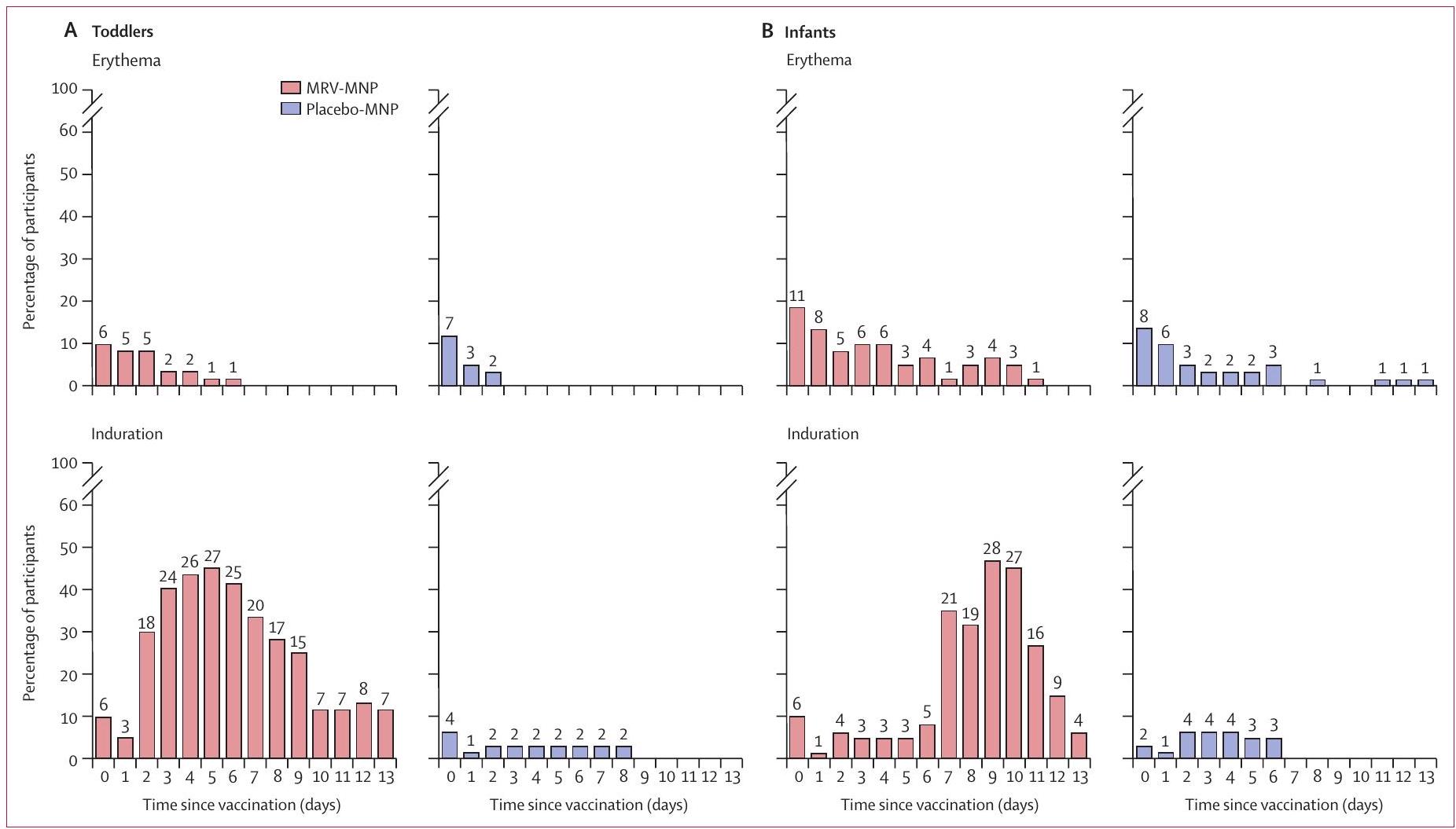

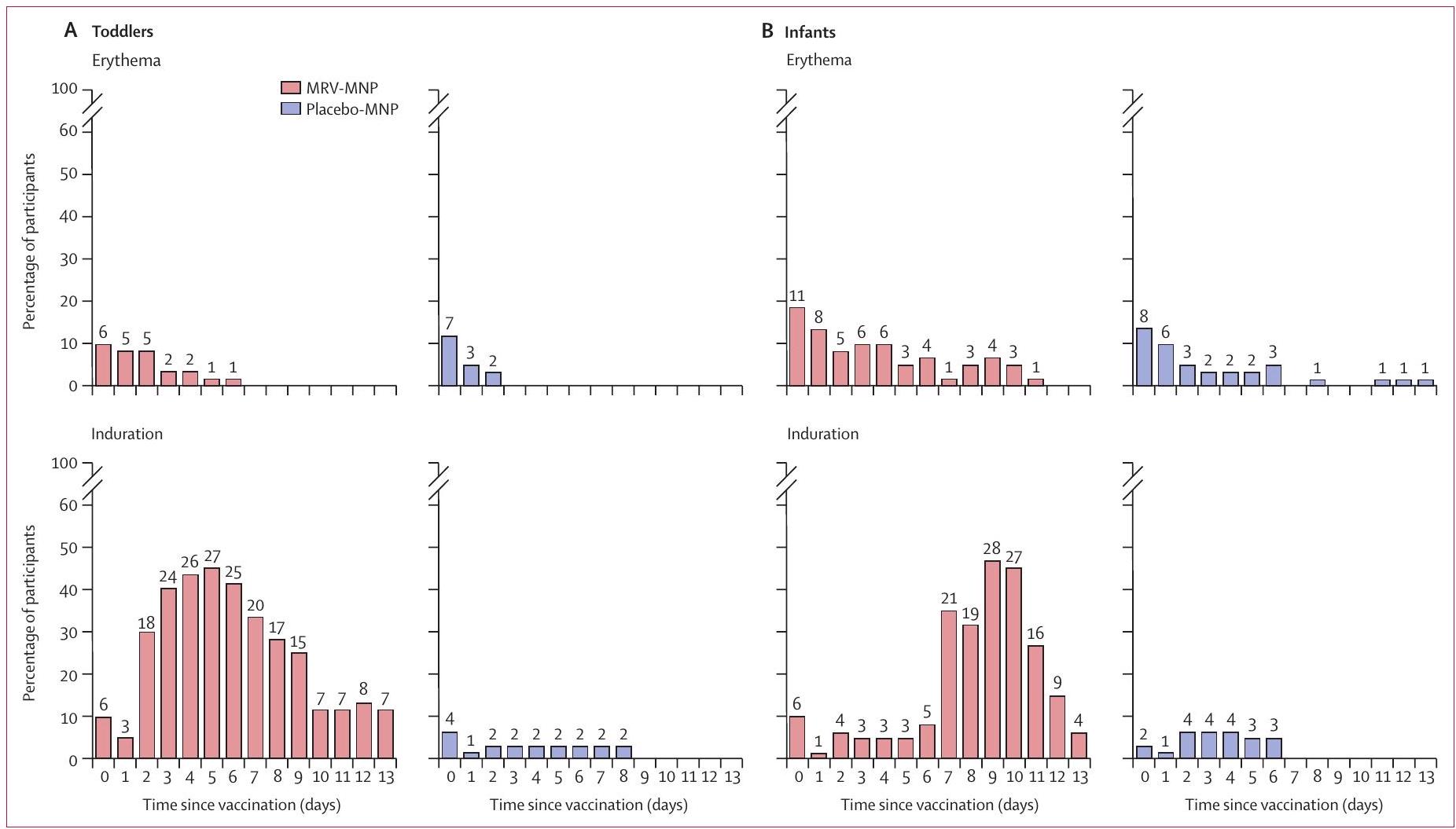

(أ) مجموعة الأطفال الصغار (ب) مجموعة الرضع. الأرقام تمثل العدد المطلق للمشاركين، من بين 60 في كل مجموعة عشوائية ومجموعة، المتأثرين في كل يوم. كانت جميع التفاعلات المحلية خفيفة في الشدة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كان لدى طفل صغير شعور خفيف بالألم في اليوم الثامن بعد MRV-MNP وكان لدى طفل صغير آخر شعور خفيف بالألم في اليوم الأول بعد placebo-MNP (البيانات غير معروضة بشكل رسومي).

استنادًا إلى SNA، انخفضت GMC الحصبة في مجموعة MRV-MNP من

في البالغين، انتقل متوسط تركيز الأجسام المضادة ضد الحصبة الألمانية في مجموعة MRV-MNP من

كان متوسط عمر الأطفال الصغار 15 شهرًا، وكان هناك توزيع متساوٍ بين الذكور والإناث في

كل من مجموعة MRV-MNP ومجموعة الدواء الوهمي-MNP (الجدول 1). كان جميع الأطفال من أصول أفريقية.

لم تكن هناك ردود فعل تحسسية حادة لدى الأطفال الصغار (الجدول 2). 50 طفلاً صغيراً (

مقالات

| الأطفال الصغار | الرضع | |||||||

| MRV-MNP ودواء وهمي-SC، ن=60 | MRV-SC ودواء وهمي-MNP،

|

MRV-MNP ودواء وهمي-SC،

|

MRV-SC ودواء وهمي-MNP،

|

|||||

| ن (%) | E | ن (%) | E | ن (%) | E | ن (%) | E | |

| الأحداث السلبية | ||||||||

| إجمالي | ٥٩ (٩٨٪) | ٢٠٣ | 56 (93%) | 187 | 60 (100%) | ٣٤٧ | ٥٩ (٩٨٪) | ٢٨٥ |

| خفيف (الدرجة 1) | 47 (78%) | 190 | ٣٨ (٦٣٪) | 162 | 39 (65%) | ٣١٥ | 44 (73%) | 267 |

| معتدل (الدرجة 2) | 11 (18%) | 12 | 13 (22%) | 20 | 21 (35%) | 32 | 14 (23%) | 17 |

| شديد (الدرجة 3) | 1 (2%) | 1 | 5 (8%) | ٥ | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 1 |

| أحداث سلبية خطيرة | 1 (2%) | 1 | 7 (12%) | ٨ | 1 (2%) | 1 | 1 (2%) | 1 |

| الأحداث السلبية التي أدت إلى الانقطاع عن الدراسة | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| الأحداث السلبية المرتبطة | ||||||||

| إجمالي | ٣٥ (٥٨٪) | 43 | 16 (27%) | 16 | 57 (95%) | 75 | ٣٨ (٦٣٪) | 41 |

| خفيف (الدرجة 1) | 35 (58%) | 42 | 16 (27%) | 16 | 57 (95%) | 75 | ٣٨ (٦٣٪) | 41 |

| تغير لون موقع MNP | ٢٩ (٤٨٪) | ٢٩ | 12 (20%) | 12 | 50 (83%) | 50 | 32 (53%) | ٣٢ |

| تقشير موقع MNP | 5 (8%) | ٥ | 1 (2%) | 1 | 14 (23%) | 14 | 6 (10%) | ٦ |

| تصلب موقع MNP | 3 (5%) | ٣ | 0 | 0 | 7 (12%) | ٧ | 1 (2%) | 1 |

| آخر | 5 (8%) | 5 نجوم | 3 (5%) |

|

4 (7%) |

|

2 (3%) | 2§ |

| معتدل (الدرجة 2) | 1 (2%) | 1ศ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| الأحداث السلبية الجادة المرتبطة | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

حدث سلبي خطير غير مرتبط واحد (2%) في الأطفال الصغار الذين تلقوا لقاح MRV-MNP مقارنةً بثمانية أحداث غير مرتبطة في سبعة أطفال صغار.

لم تكن هناك اختلافات ملحوظة في حالة الأجسام المضادة للحصبة بين الأطفال الصغار في مجموعة MRV-MNP والأطفال الصغار في مجموعة MRV-SC في البداية بناءً على SNA (الجدول 4؛ الشكل 4A). على مدار

(GMFR

كان جميع الأطفال الصغار محميين من الحصبة الألمانية في البداية بناءً على تركيزات SNA (الجدول 4؛ الشكل 4A). انخفض متوسط تركيز الأجسام المضادة للحصبة الألمانية من

كان متوسط عمر الرضع 9 أشهر، وكانت نسبة الجنس

لم تكن هناك ردود فعل تحسسية حادة لدى الرضع (الجدول 2). 46 رضيعاً (

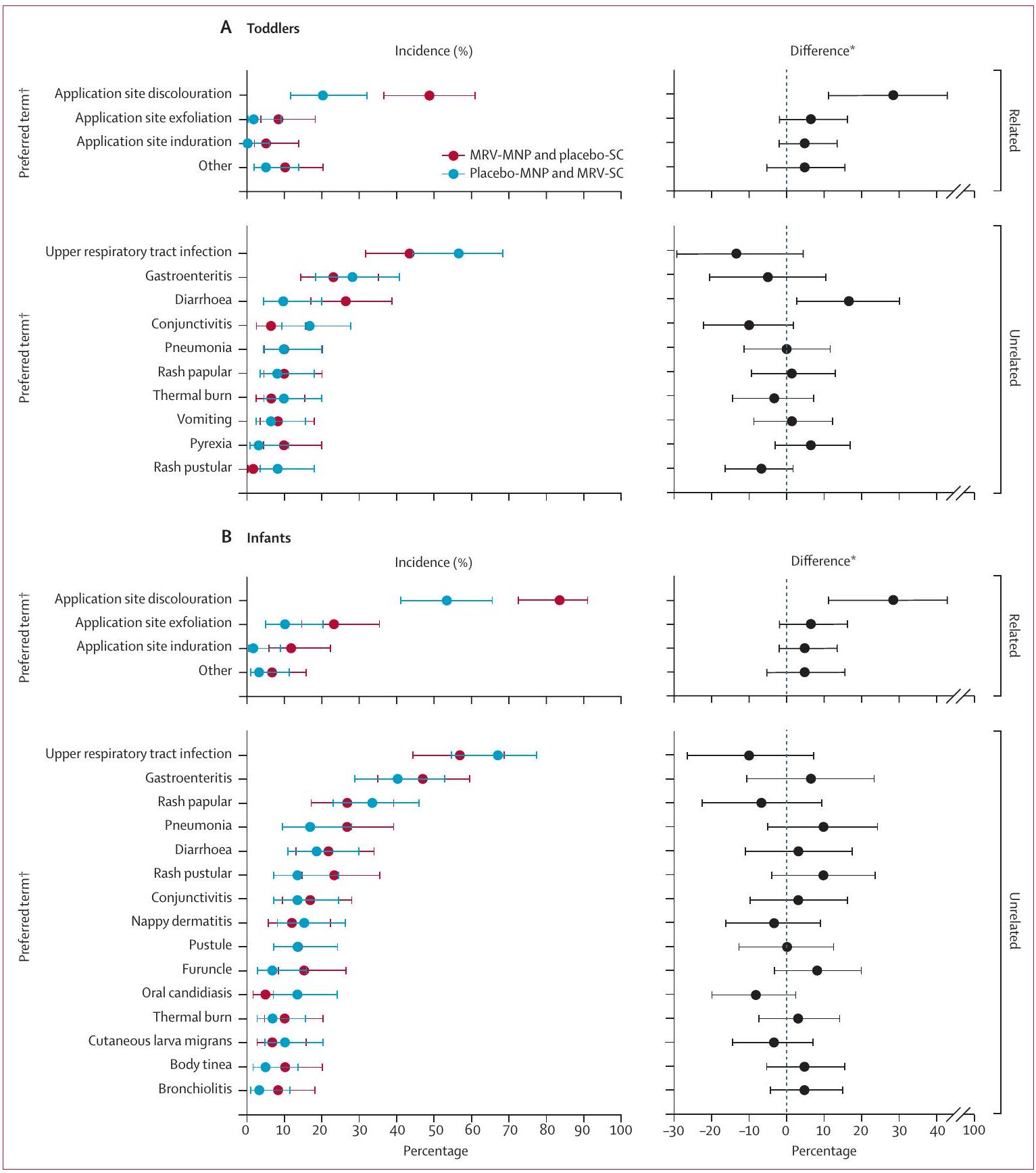

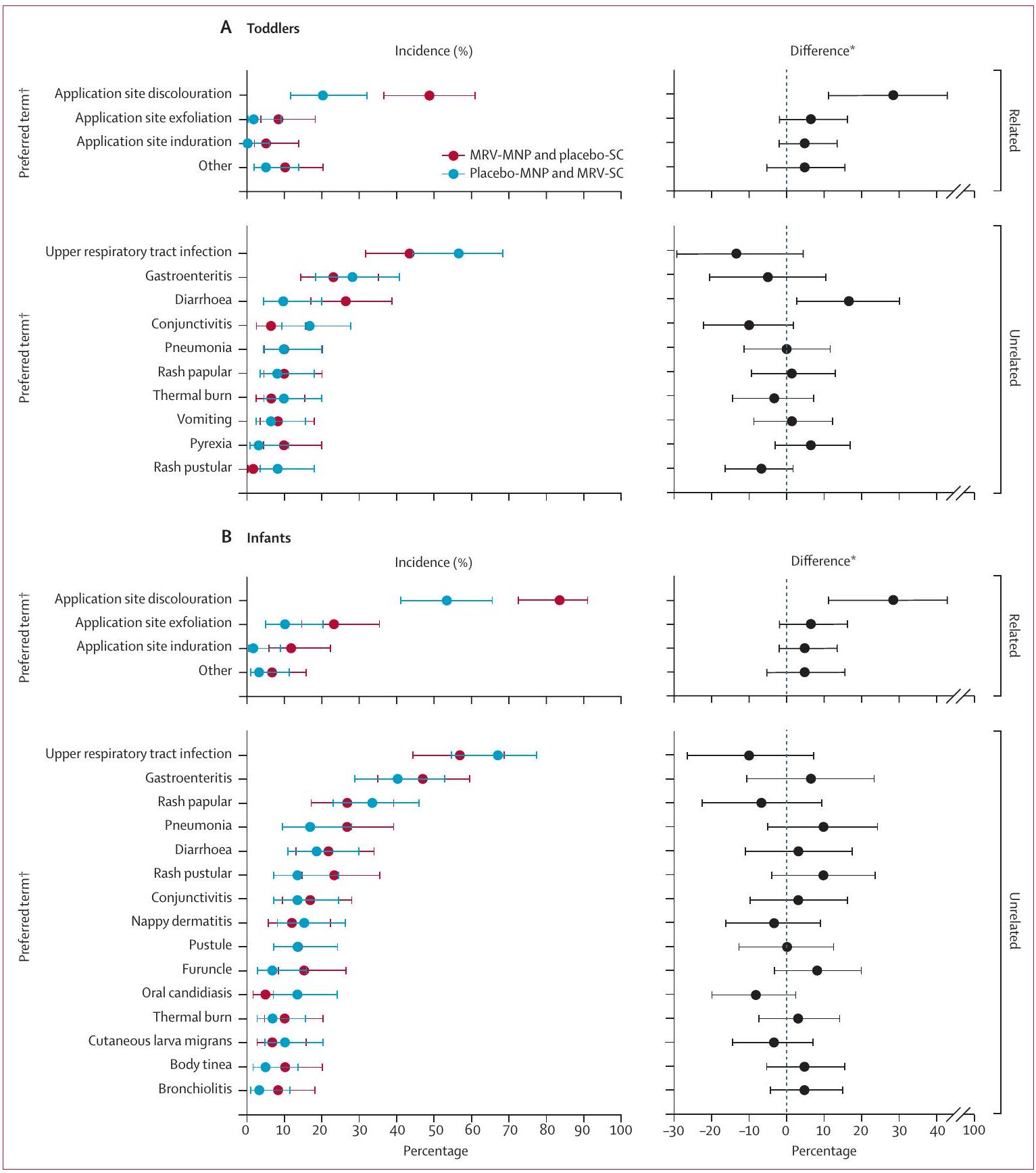

(أ) مجموعة الأطفال الصغار (ب) مجموعة الرضع. الحدوث أو فرق الحدوث و

مقالات

واحد من 59 رضيعاً (

| الحصبة | الحصبة الألمانية | |||||

| MRV-MNP ودواء وهمي-SC | MRV-SC ودواء وهمي-MNP | نسبة* أو فرق

|

MRV-MNP ودواء وهمي-SC | MRV-SC ودواء وهمي-MNP | نسبة* أو فرق

|

|

| الأطفال الصغار | ||||||

| خط الأساس | ||||||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | 489 (279 إلى 1159) | ٥٩١ (٣١٩ إلى ٩٦١) | غير متوفر | 152 (85 إلى 275) | 151 (73 إلى 241) | غير متوفر |

| جي إم سي (95% فترة الثقة) |

|

566.9 (

|

1•01* (0.73 إلى 1.41) | 151.6 (

|

126.4 (101.2 إلى 157.9) | 1•20* (0.90 إلى 1.59) |

| الحماية المناعية، ن/ن (%؛ 95% فاصل الثقة) | 54/59 (92%; 81.7 إلى 96.3) | 55/60 (92%; 81.9 إلى 96.4) |

|

59/59 (100%; 93.9 إلى 100.0) | 60/60 (100%;

|

|

| الزيارة 4 (اليوم 42) | ||||||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | 2222 (1678 إلى 3447) | 1791 (1284 إلى 2807) | غير متوفر | 278 (182 إلى 406) | 247 (174 إلى 338) | غير متوفر |

| جي إم سي (95% فترة الثقة) |

|

|

1•21* (0.95 إلى 1.53) | 268.2 (228.3 إلى 315.0) |

|

1•14* (0.91 إلى 1.43) |

| GMFR (فترة الثقة 95%) | 3.8 ( 3.0 إلى 4.9 ) | 3.2 (

|

1.19* (0.85 إلى 1.68) | 1.8 ( 1.4 إلى 2.2 ) | 1.9 ( 1.5 إلى 2.9 ) | 0.96* (0.71 إلى 1.28) |

| الحماية المصلية، ن (%؛ 95% فترة الثقة) | 59/59 (100%;

|

59/60 (98%; 91.1 إلى 99.7) |

|

59/59 (100%; 93.9 إلى 100) | 60/60 (100%; 94.0 إلى 100) |

|

| سلبية الأجسام المضادة الأساسية، ن | ٥ | ٥ | غير متوفر | 0 | 0 | غير متوفر |

| تحول المصل، ن/ن (%؛ 95% فاصل الثقة) | 5/5 (100%; 56.6 إلى 100.0) | 4/5 (80%; 37.6 إلى 96.4) |

|

غير متوفر | غير متوفر | غير متوفر |

| إيجابي المصل في الخط الأساسي، ن | ٥٤ | ٥٥ | غير متوفر | ٥٩ | 60 | غير متوفر |

| زيادة أربعة أضعاف، ن/ن (%؛ 95% CI) | 23/54 (43%; 30.3 إلى 55.8) | 21/55 (38%; 26.5 إلى 51.4) |

|

5/59 (8%; 3.7 إلى 18.4) | 8/60 (13%; 6.9 إلى 24.2) |

|

| استجابة مناعية

|

28/59 (47%; 35.3 إلى 60.0) | 25/60 (42%;

|

|

5/59 (8%; 3.7 إلى 18.4) | 8/60 (13%; 6.9 إلى 24.2) |

|

| الزيارة 5 (اليوم 180) | ||||||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | 1311 (654 إلى 2048) | 1203 (844 إلى 1961) | غير متوفر | 181 (110 إلى 261) | 141 (98 إلى 224) | غير متوفر |

| جي إم سي (95% فترة الثقة) | 1195.2 (958.7 إلى 1489.9) | 1290.8 (

|

0.93* (0.70 إلى 1.22) |

|

|

1.29* (1.03 إلى 1.62 ) |

| الحماية المصلية n/N (%; 95% CI) | 56/57 (98%; 90.7 إلى 99.7) | 60/60 (100%; 94.0 إلى 100.0) |

|

57/57 (100%; 93.7 إلى 100.0) | 60/60 (100%; 94.0 إلى 100.0) |

|

| (الجدول 4 يستمر في الصفحة التالية) | ||||||

| الحصبة | الحصبة الألمانية | |||||

| MRV-MNP ودواء وهمي-SC | MRV-SC ودواء وهمي-MNP | نسبة أو فرق

|

MRV-MNP ودواء وهمي-SC | MRV-SC ودواء وهمي-MNP | نسبة أو فرق

|

|

| (مستمر من الصفحة السابقة) | ||||||

| الرضع | ||||||

| خط الأساس | ||||||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | 8 (7 إلى 12) | 7 (6 إلى 9) | غير متوفر | 6 (5 إلى 6) | 5 (5 إلى 6) | غير متوفر |

| جي إم سي (95% فترة الثقة) |

|

11.3 ( 8.5 إلى 15.1 ) | 1.13* (0.75 إلى 1.70) | 6.9 (6.4 إلى 7.4) |

|

1.05* (0.96 إلى 1.15) |

| الحماية المصلية (%)؛ (95% فترة الثقة) | 3/59 (5%; 1.7 إلى 13.9) | 1/59 (2%; 0.3 إلى 9.0) |

|

1/59 (2%; 0.3 إلى 9.0) | 0/59 ( 0.0 إلى 6.1 ) |

|

| الزيارة 4 (اليوم 42) | ||||||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | 505 (309 إلى 716) | 494 (311 إلى 671) | غير متوفر | 123 (74 إلى 176) | 156 (113 إلى 201) | غير متوفر |

| جي إم سي (95% فترة الثقة) |

|

495.2 (402.5 إلى 609.3) | 1.05* (0.78 إلى 1.41) |

|

|

0.86* (0.68 إلى 1.09) |

| GMFR (فترة الثقة 95%) |

|

٤٣.٧ ( ٣٤.٨ إلى ٥٤.٨ ) | 0.93* (0.68 إلى 1.29) |

|

21.4 ( 18.5 إلى 24.9 ) | 0.82* (0.63 إلى 1.05) |

| الحماية المصلية ن/ن (%؛ 95% فاصل الثقة) | 55/59 (93%; 83.8 إلى 97.3) | 53/59 (90%; 79.5 إلى 95.3) |

|

59/59 (100%; 93.9 إلى 100.0) | 59/59 (100%; 93.9 إلى 100.0) |

|

| سلبية الأجسام المضادة الأساسية، ن | ٥٦ | ٥٨ | غير متوفر | ٥٦ | ٥٩ | غير متوفر |

| تحول المصل n (%؛ 95% CI) | 52/56 (93%; 83.0 إلى 97.2) | 52/58 (90%;

|

|

58/58 (100%; 93.8 إلى 100.0) | 59/59 (100%; 93.9 إلى 100.0) |

|

| إيجابي المصل الأساسي، ن | ٣ | 1 | غير متوفر | 1 | 0 | غير متوفر |

| زيادة أربعة أضعاف ن/ن (%؛ 95% CI) | 1/3 (33%; 6.2 إلى 79.2) | 0/1 (0.0 إلى 79.4) |

|

0/1 (0.0 إلى 79.4) | غير متوفر | غير متوفر |

| الزيارة 5 (اليوم 180) | ||||||

| الوسيط (المدى interquartile) | 654 (347 إلى 1100) | 706 (329 إلى 985) | غير متوفر | 125 (89 إلى 178) | 139 (94 إلى 216) | غير متوفر |

| جي إم سي (95% فترة الثقة) | 661.2 (501.5 إلى 871.9) | 629.0 (498.7 إلى

|

1.05* (0.74 إلى 1.50) |

|

140.7 (

|

0.89* (0.73 إلى 1.08) |

| الحماية المناعية n/N (%; 95% CI) | 52/57 (91%;

|

55/59 (93%; 83.8 إلى 97.3) |

|

57/57 (100%; 93.7 إلى 100.0) | 59/59 (100%; 93.9 إلى 100.0) |

|

(120.9-162.7) في مجموعة MRV-SC، وكانت مشابهة في اليوم 180.

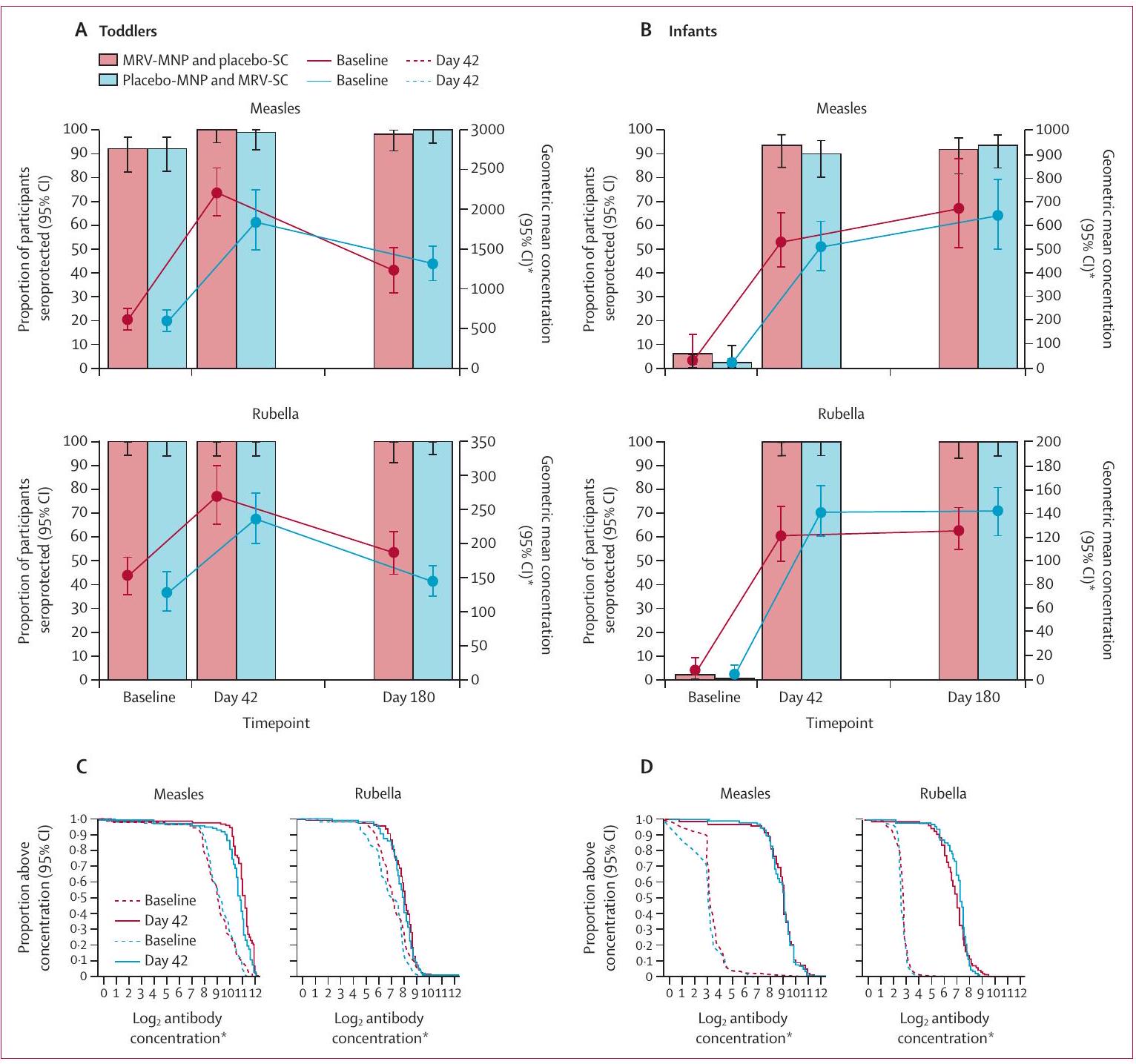

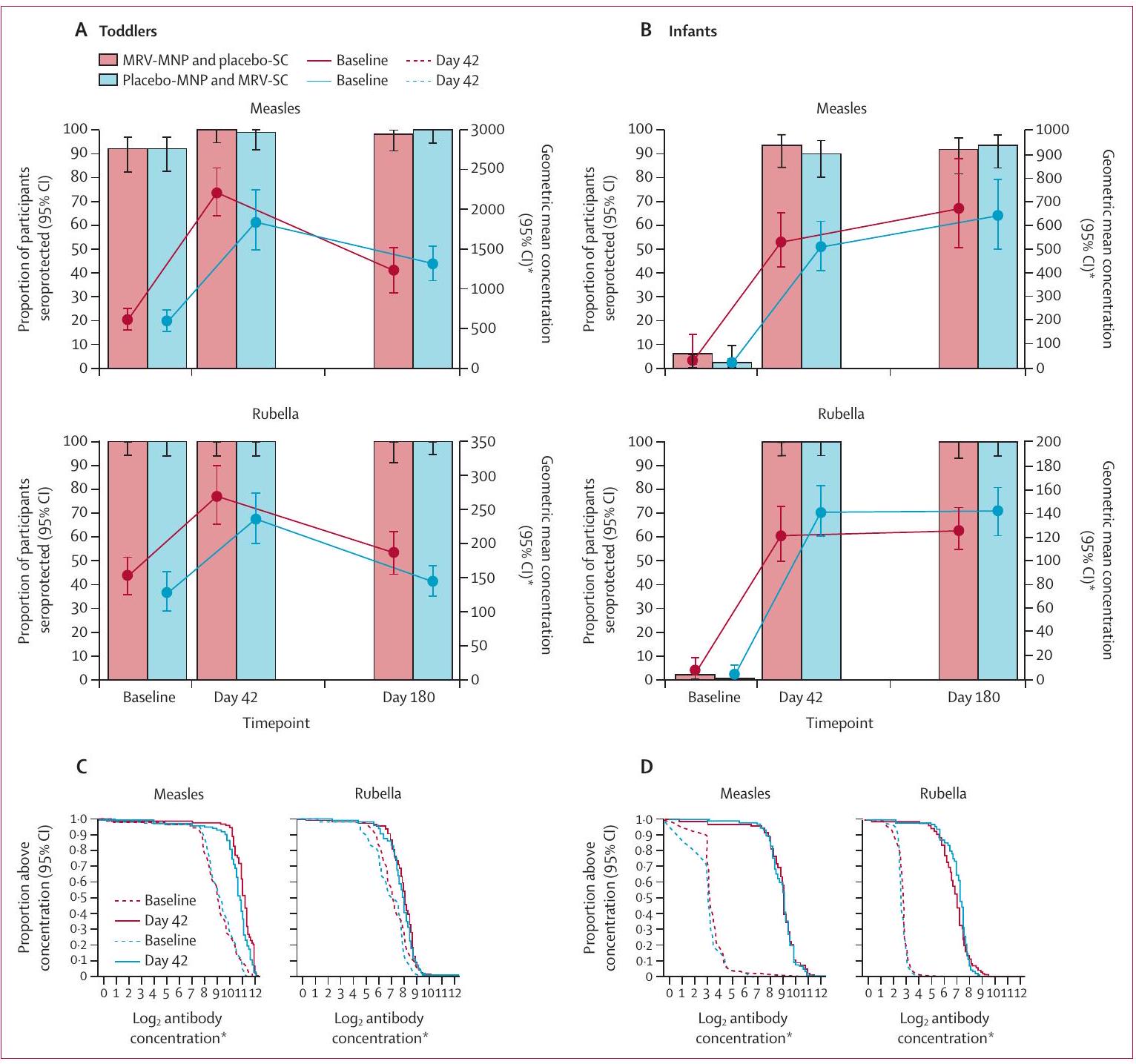

توضح منحنيات التوزيع التراكمي العكسي محاذاة توزيع الأجسام المضادة بين مجموعتي MRV-MNP و MRV-SC قبل وبعد إعطاء اللقاح (الشكل 4C، D؛ الملحق ص 58). تتوفر بيانات عن استجابات الأجسام المضادة IgG للحصبة والحصبة الألمانية (الملحق ص 58-63) وتقدم صورة مشابهة لاستجابات SNA.

نقاش

وكانت المناعية المناعية للقاح MRV عند إعطائه بواسطة MNP مشابهة للمناعة المناعية للقاح عند إعطائه تحت الجلد بواسطة الإبرة والمحاقن. تتماشى النتائج مع الدراسات ما قبل السريرية التي أظهرت أن MRV-MNP يولد استجابات SNA وقائية في الرئيسيات غير البشرية.

نظرًا لتوصيل فيروسات اللقاح مباشرة إلى الجلد، كانت ردود الفعل المحلية الخفيفة في موقع تطبيق MRV-MNP أكثر شيوعًا من موقع الحقن تحت الجلد. كانت التصلب هو الحدث المحلي الأكثر شيوعًا المطلوب في الأطفال الصغار والرضع. تشير الذروة المبكرة في الحدوث في الأطفال الصغار (اليوم 5) مقارنة بالرضع (اليوم 9) إلى استجابة مناعية.

مقالات

معدلات حماية الأجسام المضادة المصلية ضد الحصبة والحصبة الألمانية لمجموعة الأطفال الصغار (A) ومجموعة الرضع (B) (الأعمدة الصلبة) وفواصل الثقة 95%. تُعرف معدلات الحماية بأنها النسبة المئوية للمشاركين القابلين للتقييم الذين لديهم تركيز أجسام مضادة أعلى من

حدثت فرط تصبغ موقع التطبيق بشكل متكرر بعد MRV-MNP، على الرغم من أنها حدثت أيضًا بعد placebo-MNP، لذا لم تكن مدفوعة فقط بالاستجابة لفيروسات اللقاح. لقد أظهرت وسائط التهابية متنوعة وأخرى قابلة للذوبان أنها تزيد من إنتاج الميلانين، بينما

فرط التصبغ ما بعد الالتهاب يحدث بشكل أكثر تكرارًا في البشرة الداكنة.

كانت جرعات الفيروسات المخففة التي تم توصيلها بواسطة MNP والحقن تحت الجلد متشابهة، على الرغم من أن الإمكانية لتوفير جرعة من المستضد، من خلال توصيل اللقاح عن طريق الطريق الجلدي، مباشرة إلى شبكة من خلايا تقديم المستضد بدلاً من الطريق تحت الجلد، تستدعي النظر في المستقبل.

معدل التحول المناعي لـ

يتماشى وقت ارتداء اللصقة لمدة 5 دقائق مع الحد الأدنى من المتطلبات المحددة في ملف المنتج المستهدف لـ MRV-MNP.

كان للدراسة عدة نقاط قوة. استخدام تصميم الدوبل دمي (الذي سمح للموظفين الذين يطبقون MNP ويعطون الحقن تحت الجلد، والمشاركين والآباء، وجميع الموظفين الذين يجمعون نقاط نهاية الدراسة أن يكونوا غير مدركين لمجموعة التخصيص) يقلل من مخاطر التحيز في الأداء أثناء تطبيق MNP ومن التحيز الملاحظ المتعلق بجمع نقاط نهاية السلامة. كما يقلل التصميم من خطر التحيز الناتج عن الجدة، حيث توجد ميول للإبلاغ عن العلاجات على أنها أفضل بناءً على كونها جديدة، وهو ما كان يمكن أن يؤثر في هذه الحالة على بيانات نقاط نهاية السلامة.

كان للتجربة عدة قيود تعكس بشكل أساسي تصميمها في المرحلة المبكرة. على الرغم من أنها أكبر تجربة لمادة MNP أجريت حتى الآن والوحيدة في الأطفال، إلا أن حجم العينة كان صغيرًا نسبيًا. التحليل وصفي ولا يستبعد الفروق ذات الدلالة الإحصائية أو السريرية في نقاط نهاية السلامة والمناعة التي قد تظهر في تجارب أكبر. كانت معايير الأهلية مقيدة عمدًا في جميع الفئات العمرية. تم تجنيد الأصحاء

كان المشاركون يهدفون إلى تقليل حدوث الأحداث غير المتعلقة بالسلامة، مما يزيد من فرص اكتشاف إشارات السلامة منخفضة المستوى. ومع ذلك، يجب أن تكون التجارب المستقبلية ممثلة قدر الإمكان، وخاصةً من خلال تضمين الأطفال الذين يعانون من سوء التغذية ومجموعات أخرى ضعيفة. سيكون من المهم أيضًا جمع البيانات عن الأطفال الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 6 أشهر في الوقت المناسب، نظرًا للاستخدام الموصى به للقاح MRV من هذا العمر في حالات التفشي.

باختصار، يقدم هذا التجربة البيانات الأولى حول استخدام MNP لتوصيل اللقاحات للأطفال والرضع. تم تصنيف تقنية MNP مؤخرًا كأعلى أولوية ابتكار عالمية لتحقيق العدالة في تغطية التطعيم في البلدان ذات الدخل المنخفض والمتوسط، بينما يُعتبر MRV-MNPs على نطاق واسع أنها قد تكون أداة حيوية للقضاء على الحصبة والحصبة الألمانية. تدعم بيانات التحمل والسلامة والاستجابة المناعية المتولدة تسريع تطوير هذه التقنية الأساسية.

المساهمون

إعلان المصالح

مشاركة البيانات

شكر وتقدير

References

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71: 1489-95.

3 WHO. Measles and rubella strategic framework: 2021-2030. Feb 23, 2021. https://measlesrubellainitiative.org/measles-rubella-strategic-framework-2021-2030/ (accessed March 13, 2022).

4 WHO. Measles vaccines: WHO position paper – April 2017. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2017; 17: 205-28.

5 Winter AK, Moss WJ. Rubella. Lancet 2022; 399: 1336-46.

6 Wariri O, Nkereuwem E, Erondu NA, et al. A scorecard of progress towards measles elimination in 15 west African countries, 2001-19: a retrospective, multicountry analysis of national immunisation coverage and surveillance data. Lancet Glob Health 2021; 9: e280-90.

7 Utazi CE, Wagai J, Pannell O, et al. Geospatial variation in measles vaccine coverage through routine and campaign strategies in Nigeria: analysis of recent household surveys. Vaccine 2020; 38: 3062-71.

8 Orenstein WA, Hinman A, Nkowane B, Olive JM, Reingold A. Measles and rubella global strategic plan 2012-2020 midterm review. Vaccine 2018; 36 (suppl 1): A1-34.

9 Verguet S, Johri M, Morris SK, Gauvreau CL, Jha P, Jit M. Controlling measles using supplemental immunization activities: a mathematical model to inform optimal policy. Vaccine 2015; 33: 1291-96.

10 Chopra M, Bhutta Z, Chang Blanc D, et al. Addressing the persistent inequities in immunization coverage. Bull World Health Organ 2020; 98: 146-48.

11 Portnoy A, Jit M, Helleringer S, Verguet S. Comparative distributional impact of routine immunization and supplementary immunization activities in delivery of measles vaccine in low- and middle-income countries. Value Health 2020; 23: 891-97.

12 Postolovska I, Helleringer S, Kruk ME, Verguet S. Impact of measles supplementary immunisation activities on utilisation of maternal and child health services in low-income and middleincome countries. BMJ Glob Health 2018; 3: e000466.

13 Hasso-Agopsowicz M, Crowcroft N, Biellik R, et al. Accelerating the development of measles and rubella microarray patches to eliminate measles and rubella: recent progress, remaining challenges. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 809675.

14 Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Vaccine Innovation Prioritisation Strategy (VIPS). Feb 9, 2024. https://www.gavi.org/our-alliance/ market-shaping/vaccine-innovation-prioritisation-strategy (accessed March 1, 2024).

15 UNICEF. Measles-rubella microarray patch (MR-MAP) target product profile. June, 2019. https://www.unicef.org/supply/target-product-profile-measles-rubella-microarray-patch (accessed May 27, 2023).

16 Arya J, Henry S, Kalluri H, McAllister DV, Pewin WP, Prausnitz MR. Tolerability, usability and acceptability of dissolving microneedle patch administration in human subjects. Biomaterials 2017; 128: 1-7.

18 Joyce JC, Carroll TD, Collins ML, et al. A microneedle patch for measles and rubella vaccination is immunogenic and protective in infant rhesus macaques. J Infect Dis 2018; 218: 124-32.

19 Rouphael NG, Paine M, Mosley R, et al. The safety, immunogenicity, and acceptability of inactivated influenza vaccine delivered by microneedle patch (TIV-MNP 2015): a randomised, partly blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet 2017; 390: 649-58.

20 Cohen BJ, Audet S, Andrews N, Beeler J. Plaque reduction neutralization test for measles antibodies: description of a standardised laboratory method for use in immunogenicity studies of aerosol vaccination. Vaccine 2007; 26: 59-66.

21 Lambert ND, Haralambieva IH, Kennedy RB, Ovsyannikova IG, Pankratz VS, Poland GA. Polymorphisms in HLA-DPB1 are associated with differences in rubella virus-specific humoral immunity after vaccination. J Infect Dis 2015; 211: 898-905.

22 Coughlin MM, Matson Z, Sowers SB, et al. Development of a measles and rubella multiplex bead serological assay for assessing population immunity. J Clin Microbiol 2021; 59: e02716-20.

23 Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med 1998; 17: 857-72.

24 Newcombe RG. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions: comparison of eleven methods. Stat Med 1998; 17: 873-90.

25 WHO. The immunological basis for immunization series: module 7: measles: update 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/ handle/10665/331533 (accessed Dec 3, 2023).

26 WHO. The immunological basis for immunization series: module 11: rubella: update 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/ 10665/43922 (accessed Dec 3, 2023).

27 Fu C, Chen J, Lu J, et al. Roles of inflammation factors in melanogenesis. Mol Med Rep 2020; 21: 1421-30.

28 Beals CR, Railkar RA, Schaeffer AK, et al. Immune response and reactogenicity of intradermal administration versus subcutaneous administration of varicella-zoster virus vaccine: an exploratory, randomised, partly blinded trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16: 915-22.

29 Teunissen MB, Haniffa M, Collin MP. Insight into the immunobiology of human skin and functional specialization of skin dendritic cell subsets to innovate intradermal vaccination design. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2012; 351: 25-76.

30 van den Boogaard J, de Gier B, de Oliveira Bressane Lima P, et al. Immunogenicity, duration of protection, effectiveness and safety of rubella containing vaccines: a systematic literature review and metaanalysis. Vaccine 2021; 39: 889-900.

31 Persaud N, Heneghan C. Novelty bias. Catalogue Of Bias. https:// catalogofbias.org/biases/novelty-bias/ (accessed May 27, 2023).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)00532-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38697170

Publication Date: 2024-04-29

A measles and rubella vaccine microneedle patch in The Gambia: a phase 1/2, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, active-controlled, age de-escalation trial

Abstract

Summary Background Microneedle patches (MNPs) have been ranked as the highest global priority innovation for overcoming immunisation barriers in low-income and middle-income countries. This trial aimed to provide the first data on the tolerability, safety, and immunogenicity of a measles and rubella vaccine (MRV)-MNP in children.

Methods This single-centre, phase

Funding Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license.

Introduction

deaths have been averted in this period.

All six WHO regions have committed to measles elimination.

Research in context

Evidence before this study

Added value of this study

measles and rubella MNPs. In adults, MRV-primed toddlers aged 15-18 months, and MRV-naive infants aged 9-10 months, the MRV-MNPs were well tolerated and safe. Induration at the application site was common, occurring in nearly half of all toddlers and infants but was mild in all cases and resolved without treatment. None of the local reactions were of any safety concern. Discolouration at the application site, almost exclusively hyperpigmentation, was also common, occurring in nearly 50% of toddlers and over

Implications of all the available evidence

measles vaccine coverage across all districts.

was

children aged 9 months to

Microneedle patches (MNPs) offer a number of programmatic advantages over needle and syringe-based MRV administration.

The MRV-MNP used in this trial contains liveattenuated MRV embedded in an array of microneedles. On application of the MNP to the skin, the microneedles penetrate the epidermis and upper dermis, dissolve, and release the vaccine. Application is designed to allow for administration by people who are not health-care professionals, and is largely painless.

This clinical trial was undertaken based on supportive preclinical data for MRV-MNP, and data on the use of the same dissolving MNP technology to deliver influenza vaccines to adults.

Methods

Study design and participants

participants had to be healthy according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria defined for the trial (appendix pp 3-5). All participants or parents or guardians of participants provided written informed consent. The study was approved by The Gambia Government/MRC Joint Ethics Committee (LEO 22420), the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Research Ethics Committee, and the Gambian Medicines Control Agency.

Randomisation and masking

Procedures

Articles

dissolution of the microneedles following application was confirmed by microscopy. The placebo-MNPs contained the same excipients as those contained in the MRV-MNP, but without the vaccine viruses. Good manufacturing practice was used throughout. The placebo for subcutaneous injection consisted of 0.5 mL of

The MNP was applied to the dorsal aspect of the wrist for 5 min then removed. Participants were observed closely throughout this time to prevent the MNP from being disturbed. The subcutaneous injection was administered over the mid-deltoid region of the contralateral arm in adults and into the thigh in toddlers

(A) Toddler cohort (B) Infant cohort. MNP=microneedle patch. MRV=measles and rubella vaccine. SC=subcutaneous. *Defined as weight-for-length Z score of <2 SDs below the mean. †In the toddler MRV-MNP group the baseline immunogenicity sample was analysed for the toddler who received a non-study vaccine between baseline and day 42 , thus 60 baseline sample results were available.

Solicited systemic adverse events and local adverse events at the MNP application site and subcutaneous injection site were collected and graded for severity (appendix pp 11-16) on the day of study product administration (day 0 ) and for a further 13 days, through home visits conducted by trained field workers. Unsolicited adverse events were collected from the day of administration until day 180, categorised by preferred term according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Affairs and graded for severity (appendix p 17 ).

Safety haematology and biochemistry testing was done in the accredited MRCG clinical laboratories using validated assays. Serum was separated from blood samples, collected at baseline, day 42 , and day 180 , and frozen at below

Age de-escalation between cohorts was based on an unmasked review of all safety data to day 14 following study product administration in the preceding cohort by an independent data monitoring committee.

Outcomes

The immunogenicity outcomes were assessed using both SNA and IgG binding antibodies to measles and rubella, and were seroconversion rates (the percentage of participants who were seronegative at baseline and seropositive at day 42); rates of four-fold antibody rise (the percentage of participants who were seropositive at

baseline and who had a four-fold increase in antibody concentrations by day 42); immune response rates (combining the number of participants undergoing seroconversion and experiencing a four-fold rise in antibodies); the percentage of participants who were seropositive; the geometric mean antibody concentrations (GMCs) at day 42 and day 180; and the geometric mean fold rise (GMFR) in antibody concentrations between baseline and day 42. Seropositivity was defined as antibody concentrations in international units (IUs) of

Statistical analysis

| Toddlers | Infants | |||

| MRV-MNP and placebo SC (

|

MRV-SC and placebo MNP (

|

MRV-MNP and placebo SC (

|

MRV-SC and placebo MNP (

|

|

| Age, months* | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 15 (15 to 16) | 15 (15 to 16) | 9 (9 to 9) | 9 (9 to 9) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 30 (50%) | 30 (50%) | 26 (43%) | 25 (42%) |

| Female | 30 (50%) | 30 (50%) | 34 (57%) | 35 (58%) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| African | 60 (100%) | 60 (100%) | 60 (100%) | 60 (100%) |

| Tribe

|

||||

| Mandinka | 39 (65%) | 27 (45%) | 35 (58%) | 28 (47%) |

| Wolof | 6 (10%) | 7 (12%) | 4 (7%) | 7 (12%) |

| Fula | 4 (7%) | 9 (15%) | 6 (10%) | 3 (5%) |

| Jola | 4 (7%) | 12 (20%) | 10 (17%) | 7 (12%) |

| Other | 7 (12%) | 5 (8%) | 5 (8%) | 15 (25%) |

| Weight,

|

||||

| Median (IQR) | 8.9 (8.4 to 9.7) | 9.0 (8.7 to 9.8) |

|

8.0 (7.3 to 8.8) |

| Length, cm

|

||||

| Median (IQR) |

|

|

|

70.0 (68.7 to 72.0 ) |

| Weight-for-length Z score

|

||||

| Median (IQR) | -0.9 (-1.6 to -0.5) |

|

-0.3 (-0.8 to 0.5) |

|

| Data are

|

||||

Articles

| Toddlers | Infants | |||

| MRV-MNP and placebo-SC,

|

MRV-SC and placebo-MNP,

|

MRV-MNP and placebo-SC,

|

MRV-SC and placebo-MNP,

|

|

| Acute allergic reaction | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Local solicited adverse events | ||||

| MNP application site | ||||

| Any local solicited event* | ||||

| Total | 50 (83%) | 18 (30%) | 46 (77%) | 18 (30%) |

| Mild (grade 1) | 50 (83%) | 18 (30%) | 46 (77%) | 18 (30%) |

| Tenderness | ||||

| Total | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Mild (grade 1) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Erythema | ||||

| Total | 10 (17%) | 9 (15%) | 18 (30%) | 14 (23%) |

| Mild (grade 1) | 10 (17%) | 9 (15%) | 18 (30%) | 14 (23%) |

| Induration | ||||

| Total | 46 (77%) | 9 (15%) | 39 (65%) | 6 (10%) |

| Mild (grade 1) | 46 (77%) | 9 (15%) | 39 (65%) | 6 (10%) |

| SC injection site | ||||

| Any local solicited event* | ||||

| Any reaction | 8 (13%) | 5 (8%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (7%) |

| Mild (grade 1) | 6 (10%) | 5 (8%) | 2 (3%) | 4 (7%) |

| Moderate (grade 2) | 2 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Systemic solicited adverse events | ||||

| Fever | ||||

| Total | 5 (8%) | 11 (18%) | 8 (13%) | 4 (7%) |

| Mild (grade 1) | 1 (2%) | 9 (15%) | 5 (8%) | 4 (7%) |

| Moderate (grade 2) | 4 (7%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (5%) | 0 |

| Severe (grade 3) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Any systemic solicited event

|

||||

| Total | 27 (45%) | 30 (50%) | 31 (52%) | 24 (40%) |

| Mild (grade 1) | 24 (40%) | 23 (38%) | 28 (47%) | 23 (38%) |

| Moderate (grade 2) | 3 (5%) | 7 (12%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) |

Role of the funding source

Results

(A) Toddler cohort (B) Infant cohort. Numbers represent the absolute number of participants, from among the 60 in each randomisation group and cohort, affected on each day. All local reactions were mild in severity. In addition, one toddler had mild tenderness on day 8 following MRV-MNP and one toddler had mild tenderness on day 1 following placebo-MNP (data not shown graphically).

Based on SNA, measles GMC in the MRV-MNP group went from

In adults, rubella SNA GMC in the MRV-MNP group went from

The median age of the toddlers was 15 months, and there was an equal split between males and females in

both the MRV-MNP group and the placebo-MNP group (table 1). All the toddlers were African.

There were no acute allergic reactions in toddlers (table 2). 50 toddlers (

Articles

| Toddlers | Infants | |||||||

| MRV-MNP and placebo-SC, n=60 | MRV-SC and placebo-MNP,

|

MRV-MNP and placebo-SC,

|

MRV-SC and placebo-MNP,

|

|||||

| n (%) | E | n (%) | E | n (%) | E | n (%) | E | |

| Adverse events | ||||||||

| Total | 59 (98%) | 203 | 56 (93%) | 187 | 60 (100%) | 347 | 59 (98%) | 285 |

| Mild (grade 1) | 47 (78%) | 190 | 38 (63%) | 162 | 39 (65%) | 315 | 44 (73%) | 267 |

| Moderate (grade 2) | 11 (18%) | 12 | 13 (22%) | 20 | 21 (35%) | 32 | 14 (23%) | 17 |

| Severe (grade 3) | 1 (2%) | 1 | 5 (8%) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 1 |

| Serious adverse events | 1 (2%) | 1 | 7 (12%) | 8 | 1 (2%) | 1 | 1 (2%) | 1 |

| Adverse events resulting in discontinuation from the study | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Related adverse events | ||||||||

| Total | 35 (58%) | 43 | 16 (27%) | 16 | 57 (95%) | 75 | 38 (63%) | 41 |

| Mild (grade 1) | 35 (58%) | 42 | 16 (27%) | 16 | 57 (95%) | 75 | 38 (63%) | 41 |

| MNP site discolouration | 29 (48%) | 29 | 12 (20%) | 12 | 50 (83%) | 50 | 32 (53%) | 32 |

| MNP site exfoliation | 5 (8%) | 5 | 1 (2%) | 1 | 14 (23%) | 14 | 6 (10%) | 6 |

| MNP site induration | 3 (5%) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7 (12%) | 7 | 1 (2%) | 1 |

| Other | 5 (8%) | 5* | 3 (5%) |

|

4 (7%) |

|

2 (3%) | 2§ |

| Moderate (grade 2) | 1 (2%) | 1ศ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Related serious adverse events | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

one (2%) unrelated serious adverse event in toddlers who received the MRV-MNP compared with eight unrelated events in seven toddlers (

There were no notable differences in measles serological status between toddlers in the MRV-MNP group and toddlers in the MRV-SC group at baseline based on SNA (table 4; figure 4A). Over

(GMFR

All the toddlers were rubella seroprotected at baseline based on SNA concentrations (table 4; figure 4A). Rubella GMC went from

The median age of the infants was 9 months, and the sex ratio was

There were no acute allergic reactions in infants (table 2). 46 infants (

(A) Toddler cohort (B) Infant cohort. Incidence or incidence difference and

Articles

One of 59 infants (

| Measles | Rubella | |||||

| MRV-MNP and placebo-SC | MRV-SC and placebo-MNP | Ratio* or difference

|

MRV-MNP and placebo-SC | MRV-SC and placebo-MNP | Ratio* or difference

|

|

| Toddlers | ||||||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 489 (279 to 1159) | 591 (319 to 961) | NA | 152 (85 to 275) | 151 (73 to 241) | NA |

| GMC (95% CI) |

|

566.9 (

|

1•01* (0.73 to 1.41) | 151.6 (

|

126.4 (101.2 to 157.9) | 1•20* (0.90 to 1.59) |

| Seroprotection, n/N (%; 95% CI) | 54/59 (92%; 81.7 to 96.3 ) | 55/60 (92%; 81.9 to 96.4 ) |

|

59/59 (100%; 93.9 to 100.0 ) | 60/60 (100%;

|

|

| Visit 4 (day 42) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 2222 (1678 to 3447) | 1791 (1284 to 2807) | NA | 278 (182 to 406) | 247 (174 to 338) | NA |

| GMC (95% CI) |

|

|

1•21* (0.95 to 1.53) | 268.2 (228.3 to 315.0) |

|

1•14* (0.91 to 1.43) |

| GMFR (95% CI) | 3.8 ( 3.0 to 4.9 ) | 3.2 (

|

1.19* (0.85 to 1.68) | 1.8 ( 1.4 to 2.2 ) | 1.9 ( 1.5 to 2.9 ) | 0.96* (0.71 to 1.28) |

| Seroprotection, n (%; 95% CI) | 59/59 (100%;

|

59/60 (98%; 91.1 to 99.7 ) |

|

59/59 (100%; 93.9 to 100 ) | 60/60 (100%; 94.0 to 100 ) |

|

| Baseline seronegative, n | 5 | 5 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Seroconversion, n/N (%; 95% CI) | 5/5 (100%; 56.6 to 100.0 ) | 4/5 (80%; 37.6 to 96.4 ) |

|

NA | NA | NA |

| Baseline seropositive, n | 54 | 55 | NA | 59 | 60 | NA |

| Four-fold rise, n/N (%; 95% CI) | 23/54 (43%; 30.3 to 55.8 ) | 21/55 (38%; 26.5 to 51.4 ) |

|

5/59 (8%; 3.7 to 18.4 ) | 8/60 (13%; 6.9 to 24.2 ) |

|

| Immune response

|

28/59 (47%; 35.3 to 60.0 ) | 25/60 (42%;

|

|

5/59 (8%; 3.7 to 18.4 ) | 8/60 (13%; 6.9 to 24.2 ) |

|

| Visit 5 (day 180) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 1311 (654 to 2048) | 1203 (844 to 1961) | NA | 181 (110 to 261) | 141 (98 to 224) | NA |

| GMC (95% CI) | 1195.2 (958.7 to 1489.9) | 1290.8 (

|

0.93* (0.70 to 1.22) |

|

|

1.29* (1.03 to 1.62 ) |

| Seroprotection n/N (%; 95% CI) | 56/57 (98%; 90.7 to 99.7 ) | 60/60 (100%; 94.0 to 100.0 ) |

|

57/57 (100%; 93.7 to 100.0 ) | 60/60 (100%; 94.0 to 100.0 ) |

|

| (Table 4 continues on next page) | ||||||

| Measles | Rubella | |||||

| MRV-MNP and placebo-SC | MRV-SC and placebo-MNP | Ratio*or difference

|

MRV-MNP and placebo-SC | MRV-SC and placebo-MNP | Ratio*or difference

|

|

| (Continued from previous page) | ||||||

| Infants | ||||||

| Baseline | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 8 (7 to 12) | 7 (6 to 9) | NA | 6 (5 to 6) | 5 (5 to 6) | NA |

| GMC (95% CI) |

|

11.3 ( 8.5 to 15.1 ) | 1.13* (0.75 to 1.70) | 6.9 (6.4 to 7.4 ) |

|

1.05* (0.96 to 1.15) |

| Seroprotection n (%; 95% CI) | 3/59 (5%; 1.7 to 13.9 ) | 1/59 (2%; 0.3 to 9.0 ) |

|

1/59 (2%; 0.3 to 9.0 ) | 0/59 ( 0.0 to 6.1 ) |

|

| Visit 4 (day 42) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 505 (309 to 716) | 494 (311 to 671) | NA | 123 (74 to 176) | 156 (113 to 201) | NA |

| GMC (95% CI) |

|

495.2 (402•5 to 609•3) | 1.05* (0.78 to 1.41) |

|

|

0.86* (0.68 to 1.09) |

| GMFR (95% CI) |

|

43.7 ( 34.8 to 54.8 ) | 0.93* (0.68 to 1.29) |

|

21.4 ( 18.5 to 24.9 ) | 0.82* (0.63 to 1.05) |

| Seroprotection n/N (%; 95% CI) | 55/59 (93%; 83.8 to 97.3 ) | 53/59 (90%; 79.5 to 95.3 ) |

|

59/59 (100%; 93.9 to 100.0 ) | 59/59 (100%; 93.9 to 100.0 ) |

|

| Baseline seronegative, n | 56 | 58 | NA | 56 | 59 | NA |

| Seroconversion n (%; 95% CI) | 52/56 (93%; 83.0 to 97.2 ) | 52/58 (90%;

|

|

58/58 (100%; 93.8 to 100.0 ) | 59/59 (100%; 93.9 to 100.0 ) |

|

| Baseline seropositive, n | 3 | 1 | NA | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Four-fold rise n/N (%; 95% CI) | 1/3 (33%; 6.2 to 79.2 ) | 0/1 ( 0.0 to 79.4 ) |

|

0/1 ( 0.0 to 79.4 ) | NA | NA |

| Visit 5 (day 180) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 654 (347 to 1100) | 706 (329 to 985) | NA | 125 (89 to 178) | 139 (94 to 216) | NA |

| GMC (95% CI) | 661.2 (501.5 to 871.9) | 629.0 (498.7 to

|

1.05* (0.74 to 1.50) |

|

140.7 (

|

0.89* (0.73 to 1.08) |

| Seroprotection n/N (%; 95% CI) | 52/57 (91%;

|

55/59 (93%; 83.8 to 97.3 ) |

|

57/57 (100%; 93.7 to 100.0 ) | 59/59 (100%; 93.9 to 100.0 ) |

|

(120.9-162.7) in the MRV-SC group, and were similar at day 180 .

Reverse cumulative distribution curves illustrate the alignment of the antibody distribution between MRV-MNP and MRV-SC groups before and after vaccine administration (figure 4C, D; appendix p 58). Data on measles and rubella IgG antibody responses are provided (appendix pp 58-63) and provide a similar picture to the SNA responses.

Discussion

and safe. The immunogenicity of the MRV when administered by MNP was similar to the immunogenicity of the vaccine when administered subcutaneously by needle and syringe. The results are consistent with preclinical studies which showed the MRV-MNP generates protective SNA responses in non-human primates.

Given the delivery of the vaccine viruses directly into the skin, mild local reactions at the MRV-MNP application site were more frequent than at the subcutaneous injection site. Induration was the most common local solicited event in toddlers and infants. The earlier peak in incidence in the toddlers (day 5) compared with the infants (day 9 ) suggests an anamnestic

Articles

Toddler cohort (A) and infant cohort (B) measles and rubella serum neutralising antibody seroprotection rates (solid bars) and 95% Cls. Seroprotection rates are defined as the percentage of evaluable participants with an antibody concentration higher than

Application site hyperpigmentation occurred most frequently following the MRV-MNP, although it also occurred following placebo-MNP, so was not solely driven by responses to the vaccine viruses. Diverse inflammatory and other soluble mediators have been shown to increase melanin production, while

post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation is also more frequent in dark skin.

The doses of the attenuated viruses delivered by MNP and subcutaneous injection were similar, although the potential for antigen dose-sparing, through the delivery of vaccine by the intradermal route, directly to a network of antigen-presenting cells rather than by the subcutaneous route, warrants future consideration.

seroconversion rate of

The 5 min wear time for the patch aligns with the minimum requirements set out in the target product profile for MRV-MNP.

The trial had several strengths. The use of the doubledummy design (which allowed the staff applying the MNP and administering the subcutaneous injection, participants and parents, and all staff collecting study endpoints to be masked to allocation group) minimises the risks of performance bias during MNP application and of observer bias related to the collection of safety endpoints. The design also reduces the risk of novelty bias, where there is a tendency to report treatments as being better based on the fact they are new, which in this case could have affected safety endpoint data.

The trial had several limitations which predominantly reflect its early phase design. Although it is the largest trial of MNP conducted to date and the only trial in children, the samples size was relatively small. The analysis is descriptive and does not exclude statistically or clinically significant differences in safety and immunogenicity endpoints becoming apparent in larger trials. The eligibility criteria were deliberately restrictive in all age groups. The recruitment of healthy

participants aimed to minimise the occurrence of unrelated safety events, thus increasing the chances of detecting low-level safety signals. Nonetheless, future trials should be as representative as possible, in particular including malnourished children and other vulnerable groups. Generating data in children aged 6 months will also be important in due course, considering the recommended use of MRV from this age in outbreaks.

In summary, this trial reports the first data on the use of MNP to deliver vaccines to children and infants. The MNP technology has recently been ranked as being the highest global innovation priority for achieving equity in vaccination coverage in low-income and middle-income countries, while MRV-MNPs are widely considered to be potentially instrumental for measles and rubella elimination. The tolerability, safety and immunogenicity data generated support accelerating the development of this key technology.

Contributors

Declaration of interests

Data sharing

Acknowledgments

References

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71: 1489-95.

3 WHO. Measles and rubella strategic framework: 2021-2030. Feb 23, 2021. https://measlesrubellainitiative.org/measles-rubella-strategic-framework-2021-2030/ (accessed March 13, 2022).

4 WHO. Measles vaccines: WHO position paper – April 2017. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2017; 17: 205-28.

5 Winter AK, Moss WJ. Rubella. Lancet 2022; 399: 1336-46.

6 Wariri O, Nkereuwem E, Erondu NA, et al. A scorecard of progress towards measles elimination in 15 west African countries, 2001-19: a retrospective, multicountry analysis of national immunisation coverage and surveillance data. Lancet Glob Health 2021; 9: e280-90.

7 Utazi CE, Wagai J, Pannell O, et al. Geospatial variation in measles vaccine coverage through routine and campaign strategies in Nigeria: analysis of recent household surveys. Vaccine 2020; 38: 3062-71.

8 Orenstein WA, Hinman A, Nkowane B, Olive JM, Reingold A. Measles and rubella global strategic plan 2012-2020 midterm review. Vaccine 2018; 36 (suppl 1): A1-34.

9 Verguet S, Johri M, Morris SK, Gauvreau CL, Jha P, Jit M. Controlling measles using supplemental immunization activities: a mathematical model to inform optimal policy. Vaccine 2015; 33: 1291-96.

10 Chopra M, Bhutta Z, Chang Blanc D, et al. Addressing the persistent inequities in immunization coverage. Bull World Health Organ 2020; 98: 146-48.

11 Portnoy A, Jit M, Helleringer S, Verguet S. Comparative distributional impact of routine immunization and supplementary immunization activities in delivery of measles vaccine in low- and middle-income countries. Value Health 2020; 23: 891-97.

12 Postolovska I, Helleringer S, Kruk ME, Verguet S. Impact of measles supplementary immunisation activities on utilisation of maternal and child health services in low-income and middleincome countries. BMJ Glob Health 2018; 3: e000466.

13 Hasso-Agopsowicz M, Crowcroft N, Biellik R, et al. Accelerating the development of measles and rubella microarray patches to eliminate measles and rubella: recent progress, remaining challenges. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 809675.

14 Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Vaccine Innovation Prioritisation Strategy (VIPS). Feb 9, 2024. https://www.gavi.org/our-alliance/ market-shaping/vaccine-innovation-prioritisation-strategy (accessed March 1, 2024).

15 UNICEF. Measles-rubella microarray patch (MR-MAP) target product profile. June, 2019. https://www.unicef.org/supply/target-product-profile-measles-rubella-microarray-patch (accessed May 27, 2023).

16 Arya J, Henry S, Kalluri H, McAllister DV, Pewin WP, Prausnitz MR. Tolerability, usability and acceptability of dissolving microneedle patch administration in human subjects. Biomaterials 2017; 128: 1-7.

18 Joyce JC, Carroll TD, Collins ML, et al. A microneedle patch for measles and rubella vaccination is immunogenic and protective in infant rhesus macaques. J Infect Dis 2018; 218: 124-32.

19 Rouphael NG, Paine M, Mosley R, et al. The safety, immunogenicity, and acceptability of inactivated influenza vaccine delivered by microneedle patch (TIV-MNP 2015): a randomised, partly blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet 2017; 390: 649-58.

20 Cohen BJ, Audet S, Andrews N, Beeler J. Plaque reduction neutralization test for measles antibodies: description of a standardised laboratory method for use in immunogenicity studies of aerosol vaccination. Vaccine 2007; 26: 59-66.

21 Lambert ND, Haralambieva IH, Kennedy RB, Ovsyannikova IG, Pankratz VS, Poland GA. Polymorphisms in HLA-DPB1 are associated with differences in rubella virus-specific humoral immunity after vaccination. J Infect Dis 2015; 211: 898-905.

22 Coughlin MM, Matson Z, Sowers SB, et al. Development of a measles and rubella multiplex bead serological assay for assessing population immunity. J Clin Microbiol 2021; 59: e02716-20.

23 Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med 1998; 17: 857-72.

24 Newcombe RG. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions: comparison of eleven methods. Stat Med 1998; 17: 873-90.

25 WHO. The immunological basis for immunization series: module 7: measles: update 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/ handle/10665/331533 (accessed Dec 3, 2023).

26 WHO. The immunological basis for immunization series: module 11: rubella: update 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/ 10665/43922 (accessed Dec 3, 2023).

27 Fu C, Chen J, Lu J, et al. Roles of inflammation factors in melanogenesis. Mol Med Rep 2020; 21: 1421-30.

28 Beals CR, Railkar RA, Schaeffer AK, et al. Immune response and reactogenicity of intradermal administration versus subcutaneous administration of varicella-zoster virus vaccine: an exploratory, randomised, partly blinded trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16: 915-22.

29 Teunissen MB, Haniffa M, Collin MP. Insight into the immunobiology of human skin and functional specialization of skin dendritic cell subsets to innovate intradermal vaccination design. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2012; 351: 25-76.

30 van den Boogaard J, de Gier B, de Oliveira Bressane Lima P, et al. Immunogenicity, duration of protection, effectiveness and safety of rubella containing vaccines: a systematic literature review and metaanalysis. Vaccine 2021; 39: 889-900.

31 Persaud N, Heneghan C. Novelty bias. Catalogue Of Bias. https:// catalogofbias.org/biases/novelty-bias/ (accessed May 27, 2023).