DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-2625-2024

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-04

مؤشرات التغير المناخي العالمي 2023: تحديث سنوي للمؤشرات الرئيسية لحالة نظام المناخ وتأثير الإنسان

قسم الجغرافيا، جامعة لودفيغ ماكسيميليان، ميونيخ، ألمانيا

تحليلات المناخ، برلين، ألمانيا

قسم الجغرافيا و IRI THESys، جامعة هومبولت في برلين، برلين، ألمانيا

معهد بيير سيمون لابلاس، مختبر علوم المناخ والبيئة، UMR8212 CNRS-CEA-UVSQ، جامعة باريس-ساكلاي، 91191، غيف-سور-إيفيت، فرنسا

مركز أبحاث المناخ ICARUS، جامعة مينوث، مينوث، أيرلندا

بيركلي إيرث، بيركلي، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

المراكز الوطنية لمعلومات البيئة التابعة للإدارة الوطنية للمحيطات والغلاف الجوي (NOAA)، آشفيل، نورث كارولينا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم الجغرافيا، جامعة سايمون فريزر، فانكوفر، كندا

الأكاديمية الصينية لعلوم الأرصاد الجوية، بكين، الصين

معهد ماكس بلانك للأرصاد الجوية، هامبورغ، ألمانيا

معهد CIRES، جامعة كولورادو بولدر، بولدر، كولورادو، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

جامعة واغنينغن للعلوم والبحوث، واغنينغن، هولندا

مختبر المحيط الهادئ الوطني، ريتشلاند، واشنطن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

لارك، ناسا، هامبتون، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

معهد الأرصاد الجوية الفنلندي، هلسنكي، فنلندا

دلترس، دلفت، هولندا

معهد الأنظمة العالمية، جامعة إكستر، إكستر، المملكة المتحدة

مؤسسة سكريبس لعلوم المحيطات، جامعة كاليفورنيا سان دييغو، لا جولا، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

متتبع تغير المناخ، مؤسسة البيانات من أجل العمل، أمستردام، هولندا

المراسلة: بيرس م. فورسترp.m.forster@leeds.ac.uk)

تمت المراجعة: 30 مايو 2024 – تم القبول: 31 مايو 2024 – تم النشر: 5 يونيو 2024

الملخص

تُعتبر تقييمات الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ (IPCC) المصدر الموثوق للأدلة العلمية في المفاوضات المناخية التي تجري تحت إطار اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة الإطارية بشأن تغير المناخ (UNFCCC). يجب أن تستند عملية اتخاذ القرار القائمة على الأدلة إلى معلومات محدثة وفي الوقت المناسب حول المؤشرات الرئيسية لحالة نظام المناخ وتأثير الإنسان على النظام المناخي العالمي. ومع ذلك، تُنشر تقارير IPCC المتعاقبة بفواصل زمنية تتراوح بين 5-10 سنوات، مما يخلق احتمال وجود فجوة معلوماتية بين دورات التقارير.

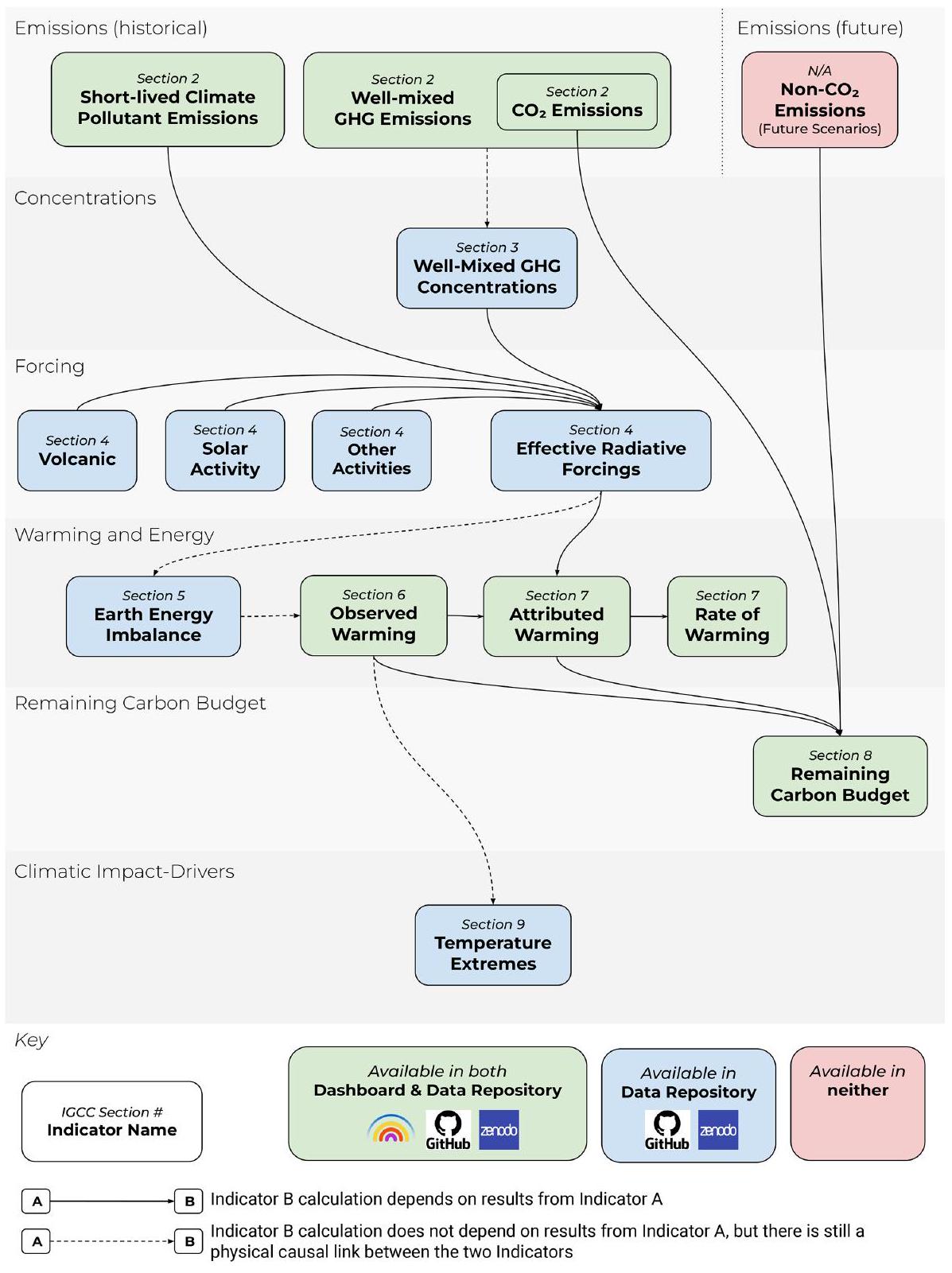

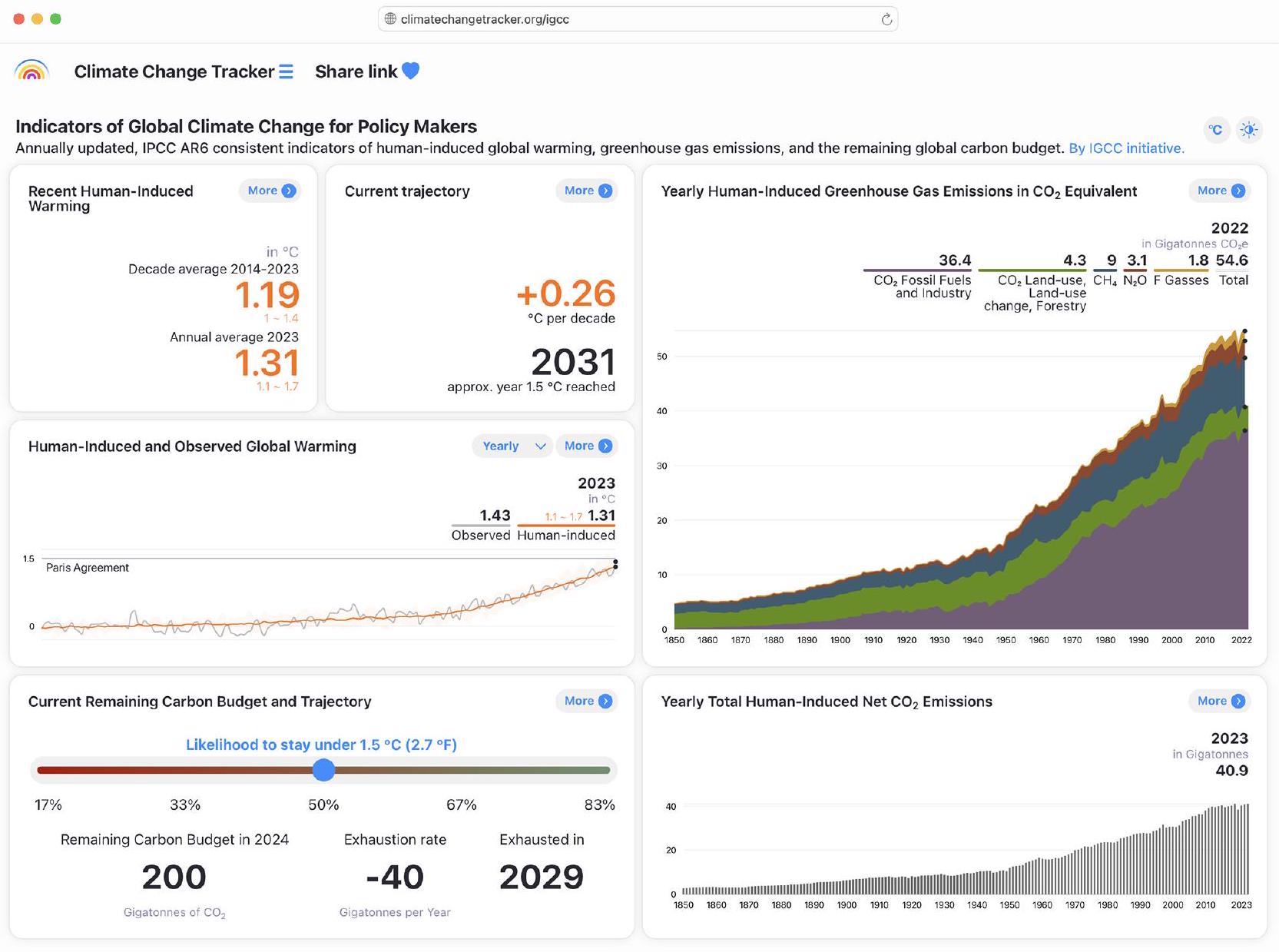

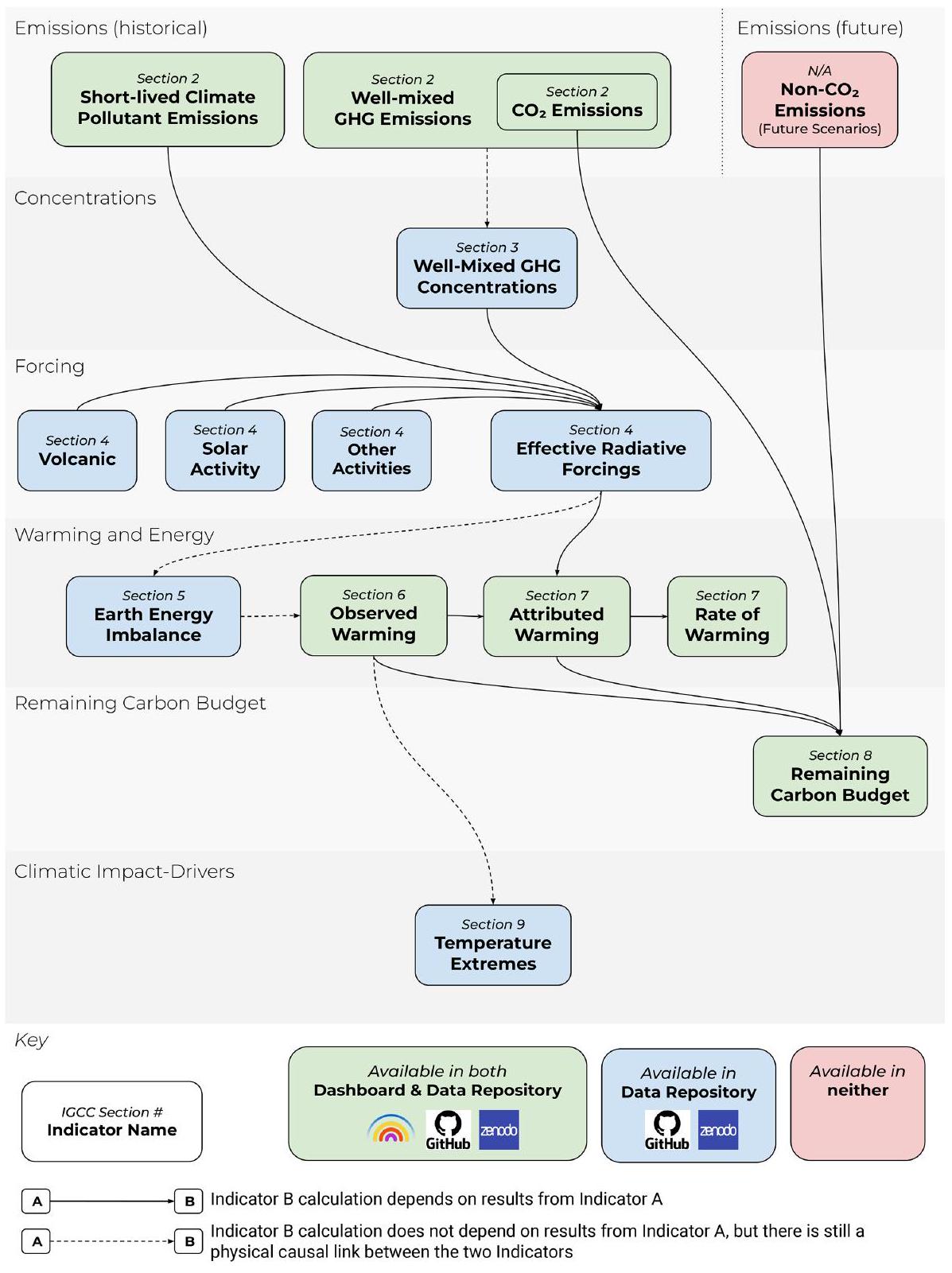

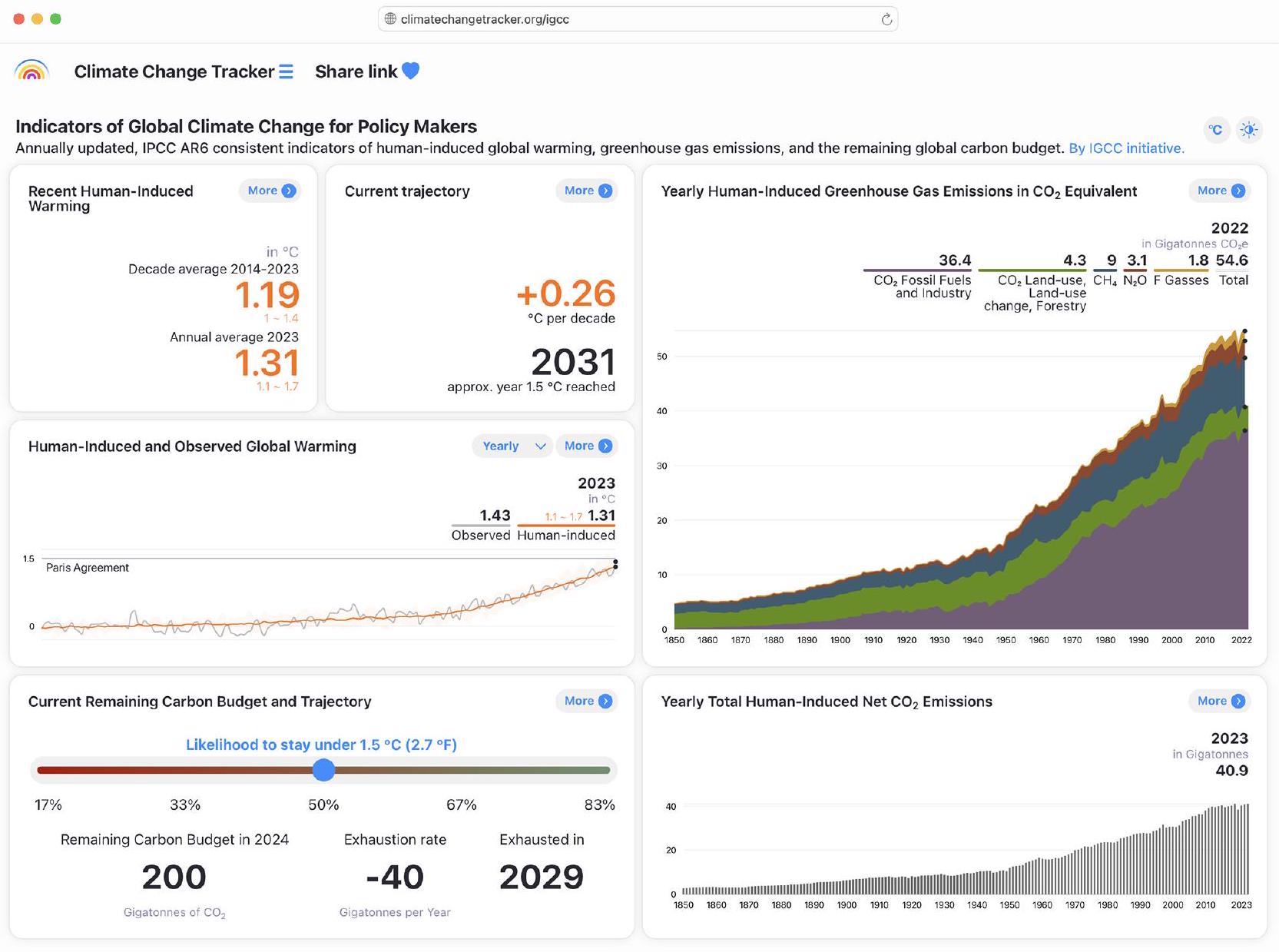

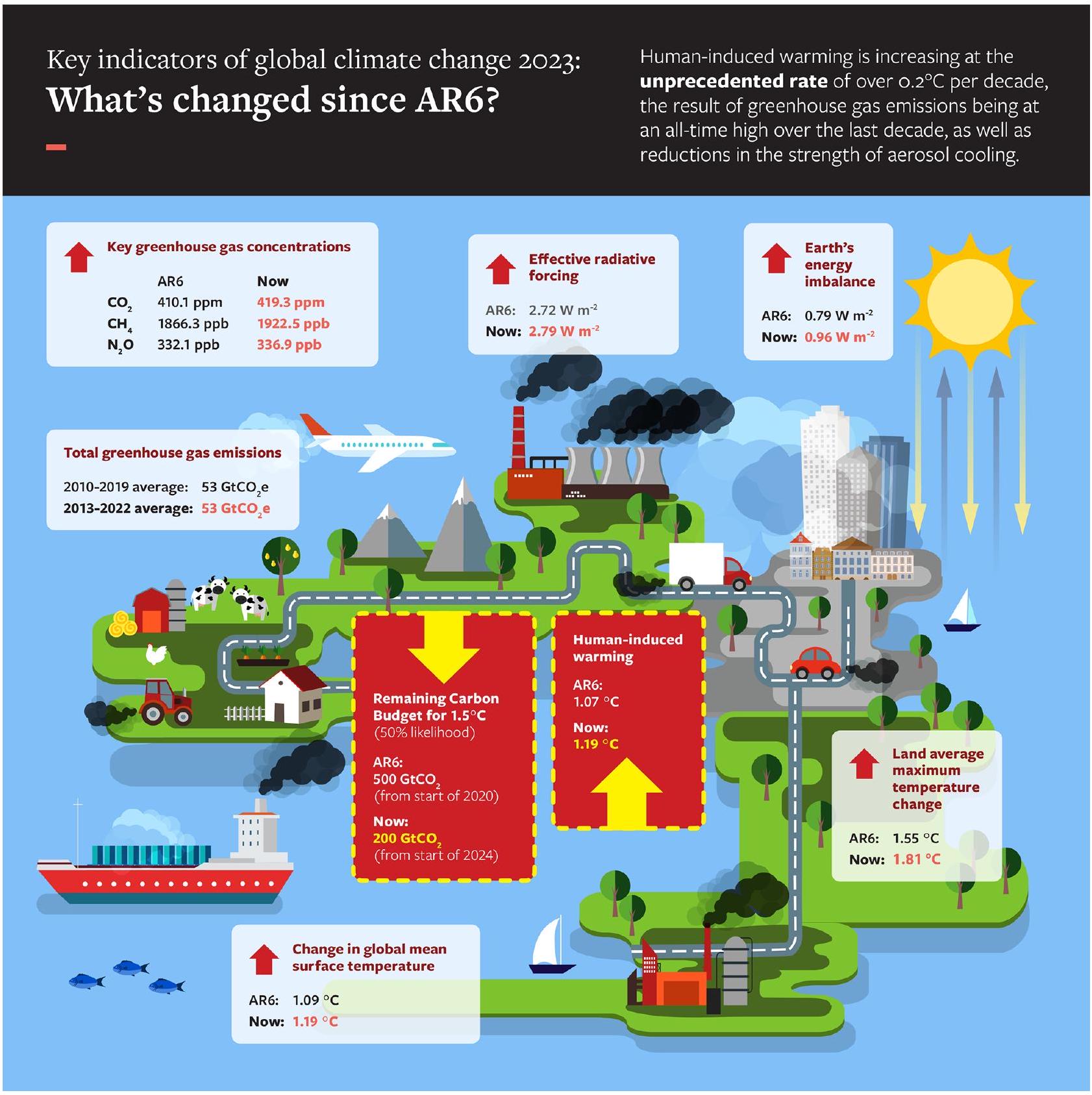

نتبع طرقًا قريبة قدر الإمكان من تلك المستخدمة في تقرير التقييم السادس (AR6) لفريق العمل الأول (WGI) التابع للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ (IPCC). نقوم بتجميع مجموعات بيانات المراقبة لإنتاج تقديرات لمؤشرات المناخ الرئيسية المتعلقة بضغط نظام المناخ: انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة والعوامل المناخية قصيرة الأجل، تركيزات غازات الدفيئة، الضغط الإشعاعي، عدم توازن الطاقة في الأرض، تغييرات درجة حرارة السطح، الاحترار المنسوب إلى الأنشطة البشرية، الميزانية الكربونية المتبقية، وتقديرات لدرجات الحرارة القصوى العالمية. الغرض من هذا الجهد، المستند إلى نهج البيانات المفتوحة والعلوم المفتوحة، هو جعل مؤشرات المناخ العالمية الموثوقة والمحدثة سنويًا متاحة في المجال العام.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11388387، سميث وآخرون، 2024أ). حيث يمكن تتبعها إلى طرق تقارير الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ، يمكن الوثوق بها من قبل جميع الأطراف المعنية في مفاوضات اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة الإطارية بشأن تغير المناخ وتساعد في نقل فهم أوسع لأحدث المعرفة حول نظام المناخ واتجاه تطوره.

تشير المؤشرات إلى أنه، بالنسبة لمتوسط عقد 2014-2023، كان الاحترار الملحوظ 1.19 [1.06 إلى

1 المقدمة

قابل فيhttps://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 11388387 (سميث وآخرون، 2024أ).

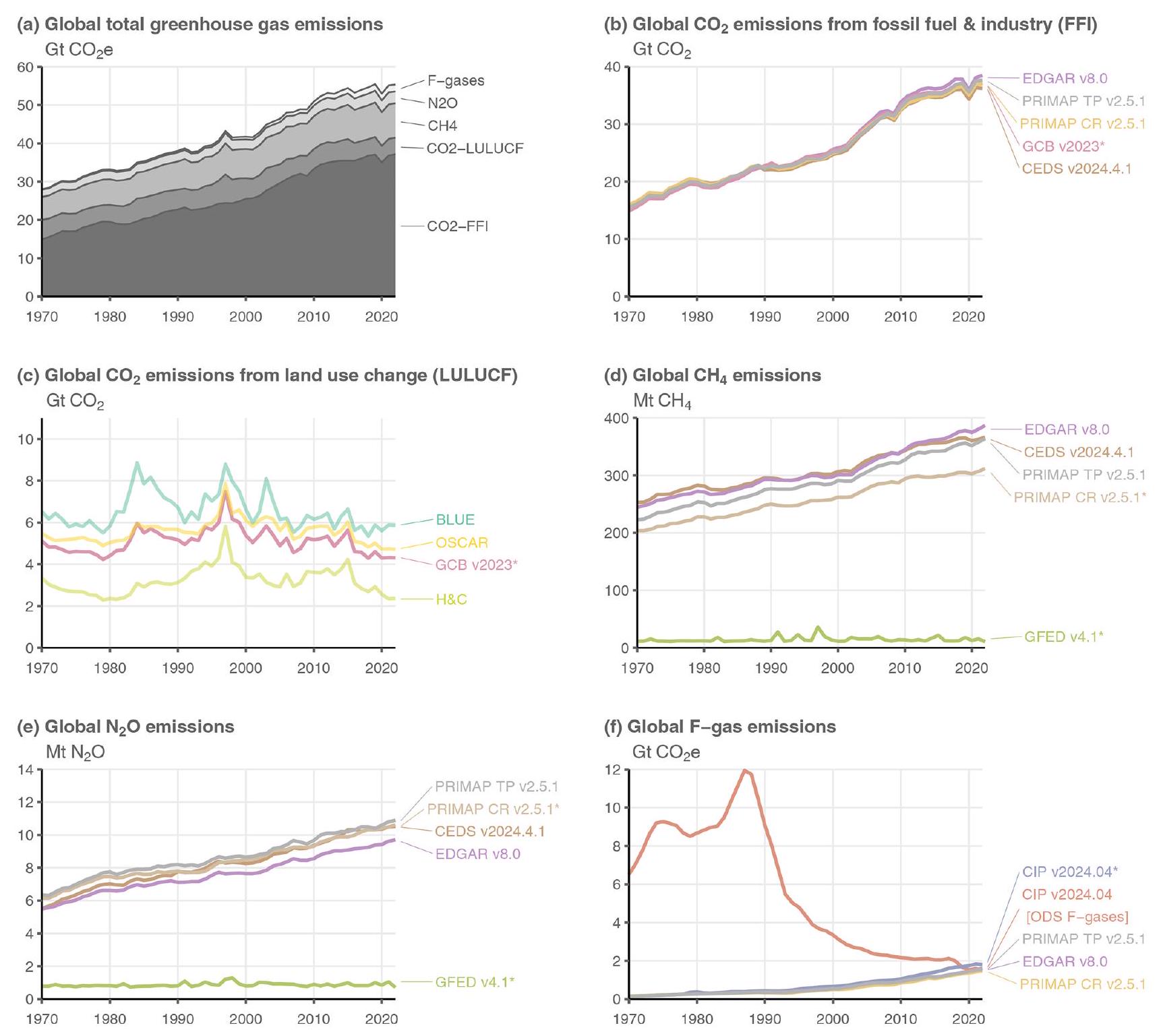

2 انبعاثات

2.1 طرق تقدير تغييرات انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة

عدم التناسق بين الأساليب المتنوعة (Friedlingstein et al., 2022; Grassi et al., 2023).

مسارات الانبعاثات (PRIMAP-hist؛ غوتشوف وآخرون، 2016، 2024) تغطي

و

2.2 انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة المحدثة

تشير إلى المجموع الكلي

التحول من EDGAR إلى GCB، حيث يتضمن الأخير مصيدة لثاني أكسيد الكربون الناتج عن الأسمنت لم يتم أخذها في الاعتبار في EDGAR. الفروقات في الغازات المتبقية لعام 2019 صغيرة نسبيًا من حيث الحجم (زيادة في

2.3 عوامل المناخ قصيرة الأمد غير الميثانية

| الوحدات:

|

1970-1979 | 1980-1989 | 1990-1999 | 2000-2009 | 2010-2019 | 2013-2022 | ٢٠٢٢ | 2023 (توقعات) |

| غازات الدفيئة |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| غازات F في اتفاقية الأمم المتحدة الإطارية بشأن تغير المناخ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

الاتجاهات على مدى السنوات الأخيرة غير مؤكدة، الانخفاض العام في بعض انبعاثات SLCF المستمدة من السجلات مدعوم بسنوات شاذة مؤقتة مع انبعاثات عالية من حرق الكتلة الحيوية بما في ذلك عام 2023، وذلك بدعم من قياسات عمق الضباب الهوائي بواسطة MODIS Terra وAqua (على سبيل المثال، كواس وآخرون، 2022؛ هودنبروغ وآخرون، 2024).

3 تركيزات غازات الدفيئة المختلطة جيدًا

| مركب | انبعاثات 1750

|

انبعاثات 2019 (

|

انبعاثات 2022 (

|

انبعاثات 2023 (

|

| ثاني أكسيد الكبريت (

|

2.8 | 84.2 | 75.3 | 79.1 |

| الكربون الأسود (BC) | 2.1 | ٧.٥ | 6.8 | 7.3 |

| الكربون العضوي (OC) | 15.5 | ٣٤.٢ | ٢٥.٨ | ٤٠.٧ |

| الأمونيا

|

6.6 | 67.6 | 67.3 | 71.1 |

| أكاسيد النيتروجين

|

19.4 | 141.7 | ١٣٠.٤ | ١٣٩.٤ |

| المركبات العضوية المتطايرة (VOCs) | 60.9 | ٢١٧.٣ | 183.9 | 228.1 |

| أول أكسيد الكربون (CO) | 348.4 | 853.8 | 686.4 | 917.5 |

4 التأثير الإشعاعي الفعال (ERF)

تقديرات ERF في الفصل 6 التي نسبت القوة إلى انبعاثات سابقة محددة (Szopa et al., 2021) وأيضًا أنشأت التاريخ الزمني لـ ERF الموضح في الشكل 2.10 من تقرير AR6 WGI والمناقش في الفصل 2 (Gulev et al., 2021). فقط التقديرات المعتمدة على التركيز تم تحديثها هنا.

| مجبِر |

|

|

|

سبب التغيير منذ العام الماضي | ||

|

|

2.16 [1.90 إلى 2.41] | 2.25 [1.98 إلى 2.52] | 2.28 [2.01 إلى 2.56] | زيادة تركيزات غازات الدفيئة الناتجة عن زيادة الانبعاثات | ||

|

|

0.54 [0.43 إلى 0.65] | 0.56 [0.45 إلى 0.67] | 0.56 [0.45 إلى 0.68] | |||

|

|

0.21 [0.18 إلى 0.24] | 0.22 [0.19 إلى 0.25] | 0.22 [0.19 إلى 0.26] | |||

| غازات الدفيئة الهالوجينية | 0.41 [0.33 إلى 0.49] | 0.41 [0.33 إلى 0.49] | 0.41 [0.33 إلى 0.49] | |||

| الأوزون | 0.47 [0.24 إلى 0.71] | 0.48 [0.24 إلى 0.72] | 0.51 [0.25 إلى 0.76] | زيادة في السلف

|

||

| بخار الماء في الستراتوسفير | 0.05 [0.00 إلى 0.10] | 0.05 [0.00 إلى 0.10] | 0.05 [0.00 إلى 0.10] | |||

| تفاعلات الهباء الجوي مع الإشعاع | -0.22 [-0.47 إلى +0.04] | -0.21 [-0.42 إلى 0.00] | -0.26 [-0.50 إلى -0.03] | زيادة كبيرة في جزيئات الهباء الجوي الناتجة عن حرق الكتلة الحيوية في عام 2023، استمرار التعافي من COVID-19، انخفاض في الكبريت الناتج عن الشحن | ||

| استخدام الأراضي (تغيرات البياض السطحي وتأثيرات الري) |

|

|

|

|||

| جزيئات تمتص الضوء على الثلج والجليد | 0.08 [0.00 إلى 0.18] | 0.06 [0.00 إلى 0.14] | 0.08 [0.00 إلى 0.17] | انتعاش انبعاثات كولومبيا البريطانية من حرق الكتلة الحيوية | ||

| الخطوط الجوية والسحب السيرية الناتجة عن الخطوط الجوية | 0.06 [0.02 إلى 0.10] | 0.05 [0.02 إلى 0.09] | 0.05 [0.02 إلى 0.09] | تقديرات نشاط الطيران قد بدأت في التعافي منذ الجائحة لكنها لا تزال دون مستويات عام 2019 في عام 2023. | ||

| الإجمالي البشري | 2.72 [1.96 إلى 3.48] | 2.91 [2.19 إلى 3.63] | 2.79 [1.78 إلى 3.61] | احتمال وجود تأثير قوي للجسيمات الهوائية في عام 2023 يعوض جزئيًا عن الزيادات في تأثيرات غازات الدفيئة والأوزون | ||

| شدة الإشعاع الشمسي | 0.01 [-0.06 إلى 0.08] | 0.01 [-0.06 إلى 0.08] | 0.01 [-0.06 إلى 0.08] |

(فورستر وآخرون، 2023) و

5 عدم توازن طاقة الأرض

تمت ملاحظته مع انخفاض الانعكاس بسبب السحب والجليد البحري وانخفاض الإشعاع الطويل الموجة الخارج (OLR) بسبب الزيادة في الغازات النادرة وبخار الماء (لوب وآخرون، 2021). درجة المساهمة من المحركات المختلفة غير مؤكدة ولا تزال قيد التحقيق النشط.

| فترة زمنية | عدم توازن طاقة الأرض

|

|

| التقرير السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ | هذه الدراسة | |

| 1971-2018 | 0.57 [0.43 إلى 0.72] | 0.57 [0.43 إلى 0.72] |

| 1971-2006 | 0.50 [0.32 إلى 0.69] | 0.50 [0.31 إلى 0.68] |

| 2006-2018 | 0.79 [0.52 إلى 1.06] | 0.79 [0.52 إلى 1.07] |

| 1976-2023 | – | 0.65 [0.48 إلى 0.82] |

| 2011-2023 | – | 0.96 [0.67 إلى 1.26] |

6 درجات حرارة السطح العالمية

| فترة زمنية | تغير درجة الحرارة من 1850 إلى 1900

|

|

| التقرير السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ | هذه الدراسة | |

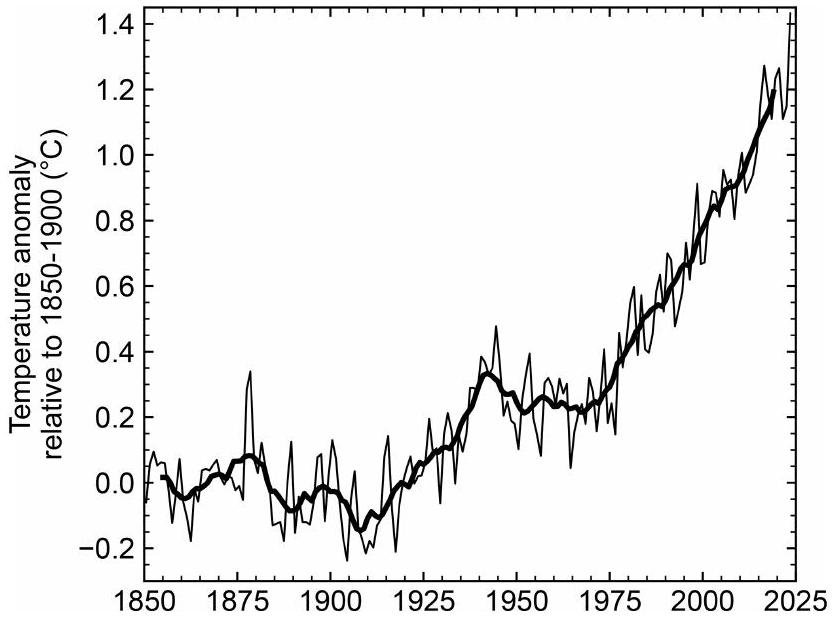

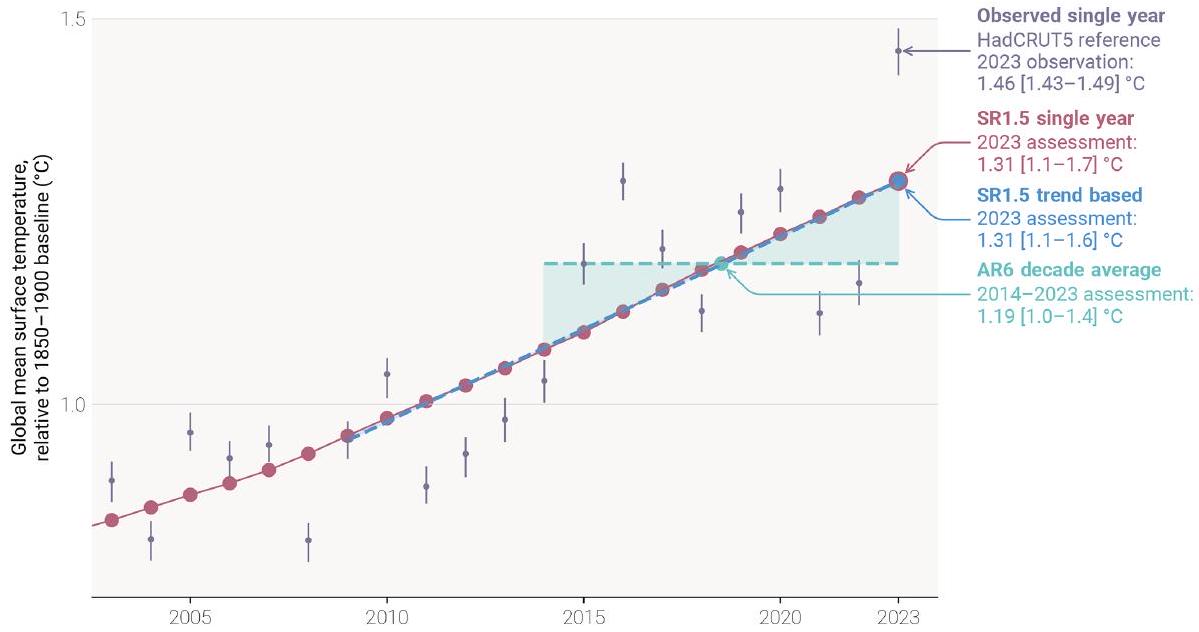

| عالمي، آخر 10 سنوات | 1.09 [0.95 إلى 1.20] (حتى 2011-2020) | 1.19 [1.06 إلى 1.30] (إلى 2014-2023) |

| عالمي، آخر 20 سنة | 0.99 [0.84 إلى 1.10] (حتى 2001-2020) | 1.05 [0.90 إلى 1.16] (من 2004 إلى 2023) |

| الأرض، آخر 10 سنوات | 1.59 [1.34 إلى 1.83] (حتى 2011-2020) | 1.71 [1.41 إلى 1.94] (إلى 2014-2023) |

| المحيط، آخر 10 سنوات | 0.88 [0.68 إلى 1.01] (حتى 2011-2020) | 0.97 [0.77 إلى 1.09] (إلى 2014-2023) |

7 الاحترار العالمي الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية

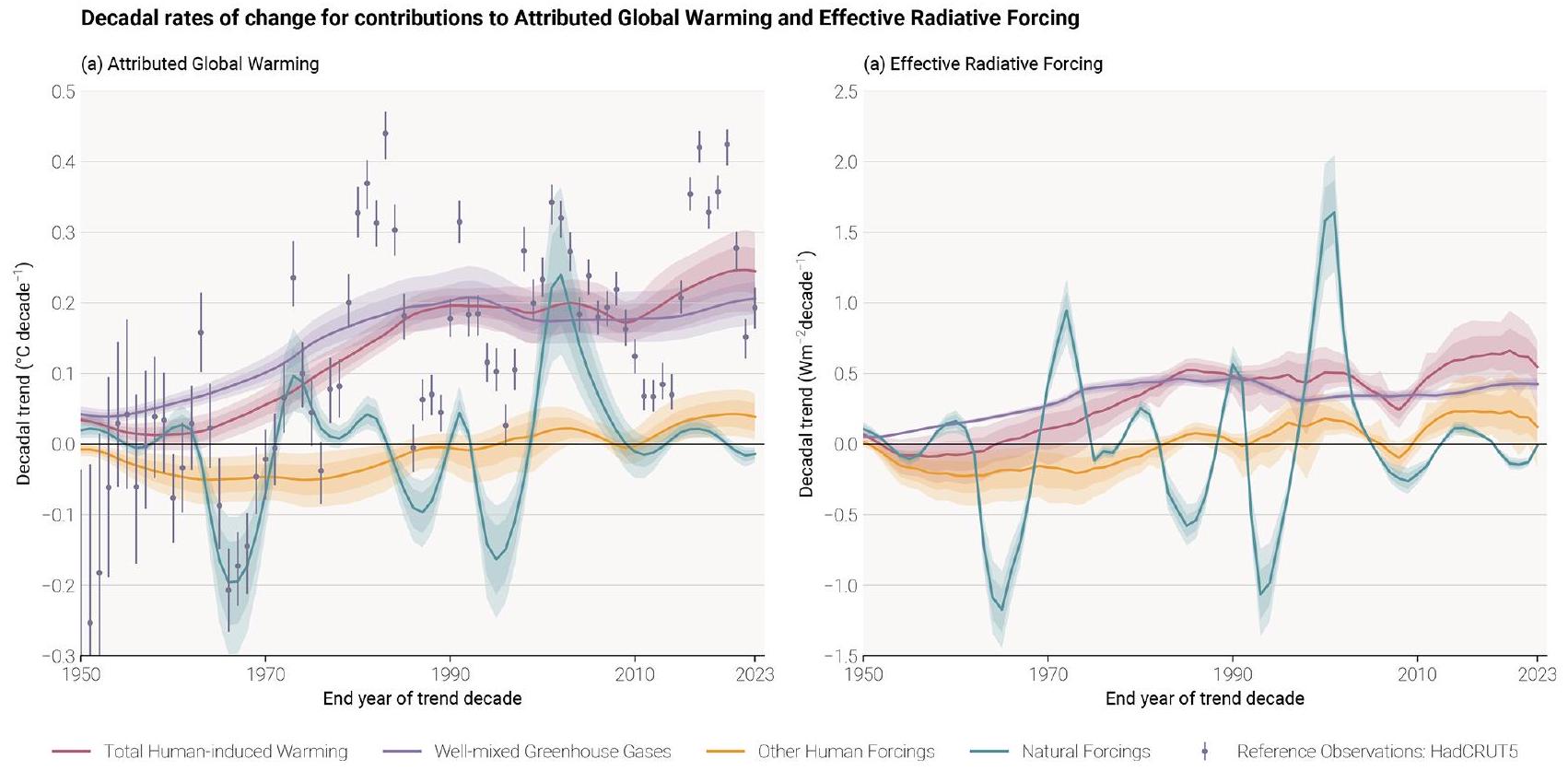

تغيرات نظام المناخ (مثل التغيرات المرتبطة بأحداث النينيو/النينيا).

7.1 تعريفات فترة الاحترار في دورة التقييم السادسة للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ

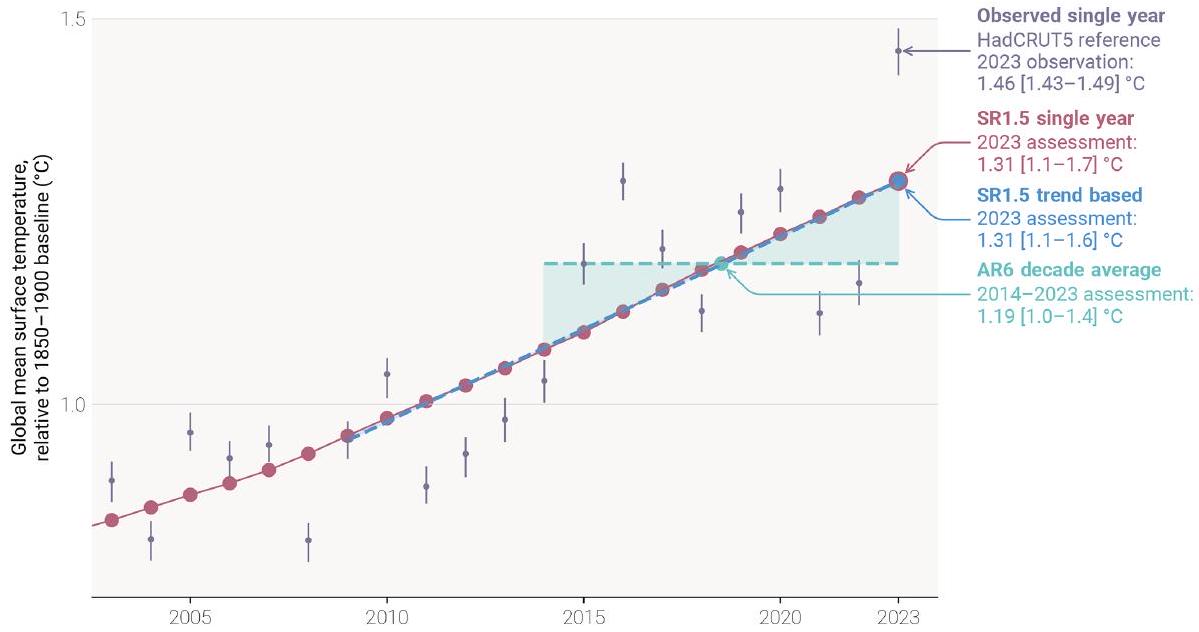

مستوى الاحترار الحالي كما عُرّف في SR1.5 هو متوسط الاحترار الناتج عن الإنسان، في متوسط درجة حرارة السطح العالمية (GMST)، لفترة 30 عامًا تتركز حول السنة الحالية، مع استقراء أي اتجاه متعدد العقود إلى المستقبل إذا لزم الأمر (انظر SR1.5 الفصل 1 القسم 1.2.1). إذا تم تفسير الاتجاه متعدد العقود على أنه خطي، فإن هذا التعريف للاحتباس الحراري الحالي يعادل نقطة النهاية لخط الاتجاه خلال السنوات الـ 15 الأخيرة من الاحترار الناتج عن الإنسان، وبالتالي يعتمد فقط على الاحترار التاريخي. تنتج هذه التفسير نتائج متطابقة تقريبًا مع القيمة السنوية الحالية للاحتباس الحراري الناتج عن الإنسان (انظر الشكل 6 والنتائج في الأقسام 7.3 و S7.3)، لذا في الممارسة العملية، كانت تقييمات النسبة في SR1.5 تعتمد على الاحترار المنسوب في سنة واحدة المحسوب باستخدام مؤشر الاحترار العالمي، وليس التعريف القائم على الاتجاه.

7.2 تحديث نهج التقييم للاحترار الناتج عن الإنسان حتى الآن

7.3 النتائج

7.4 معدل الاحترار العالمي الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية

7.4.1 تعريفات معدل الاحترار في SR1.5 و AR6

7.4.2 الطرق

| تعريف

|

(أ) تحديث متوسط الاحترار المنسوب إلى تقرير الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ AR6 لفترة السنوات العشر السابقة | (ب) تحديث قيمة الاحترار المنسوب إلى تقرير الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ SR1.5 لفترة سنة واحدة | ||||

| فترة

|

(ط) 2010-2019 مقتبس من التقرير السادس التقييمي الفصل 3 القسم 3.3.1.1.2 الجدول 3.1 | (ii) 2010-2019 إعادة حساب باستخدام الطرق والبيانات المحدثة | (iii) 2014— 2023 القيمة المحدثة باستخدام طرق ومجموعات بيانات محدثة | (ط) 2017 مقتبس من SR1.5 الفصل 1 القسم 1.2.1.3 | (ii) 2017 إعادة حساب باستخدام الطرق والمجموعات البيانية المحدثة | (iii) القيمة المحدثة لعام 2023 باستخدام طرق ومجموعات بيانات محدثة |

| مكون

|

||||||

| ملاحظ | 1.06 [0.88 إلى 1.21] | 1.07 [0.89 إلى 1.22]

|

1.19 [1.06 إلى 1.30]

|

– | – | 1.43 [1.32 إلى 1.53] |

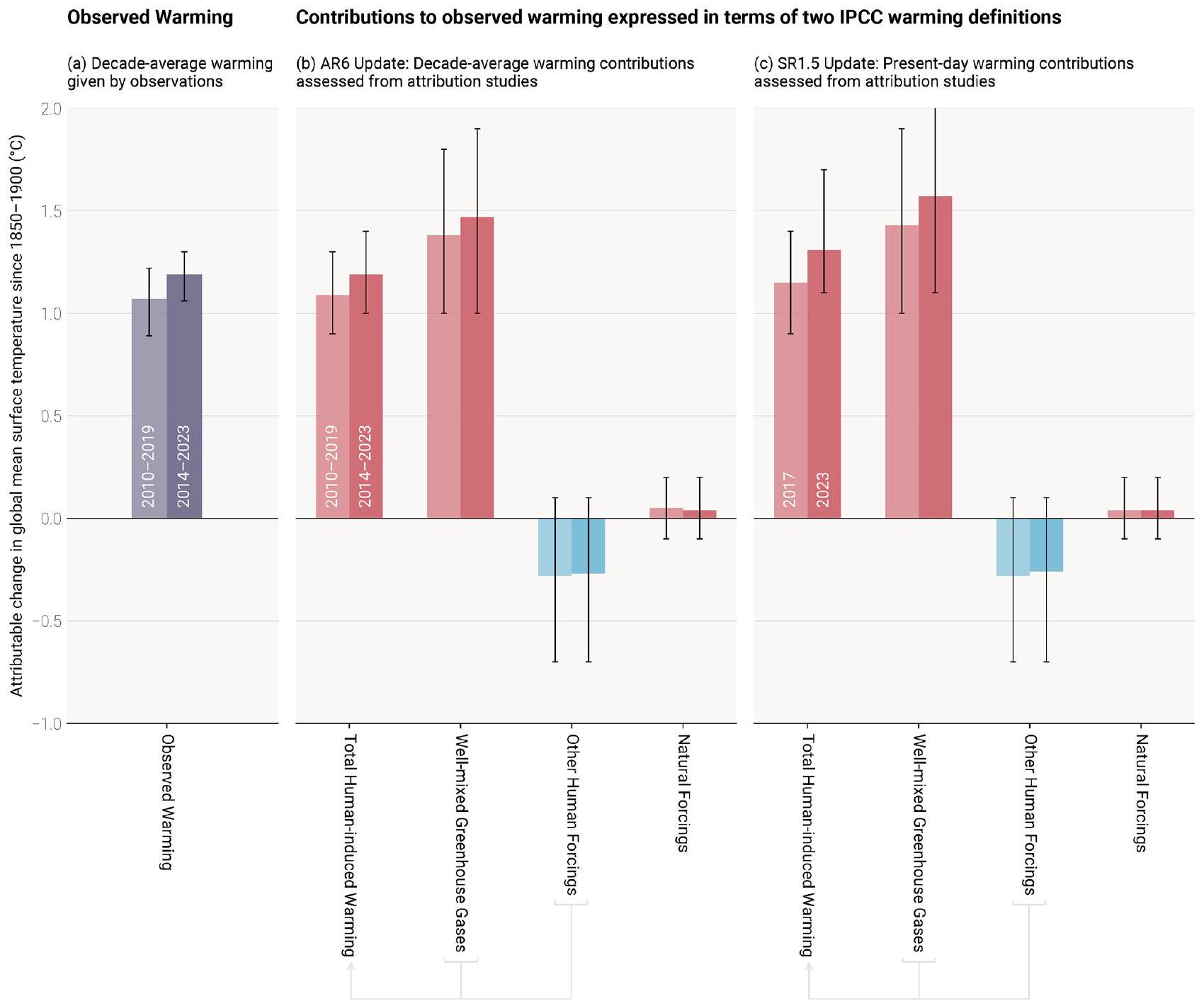

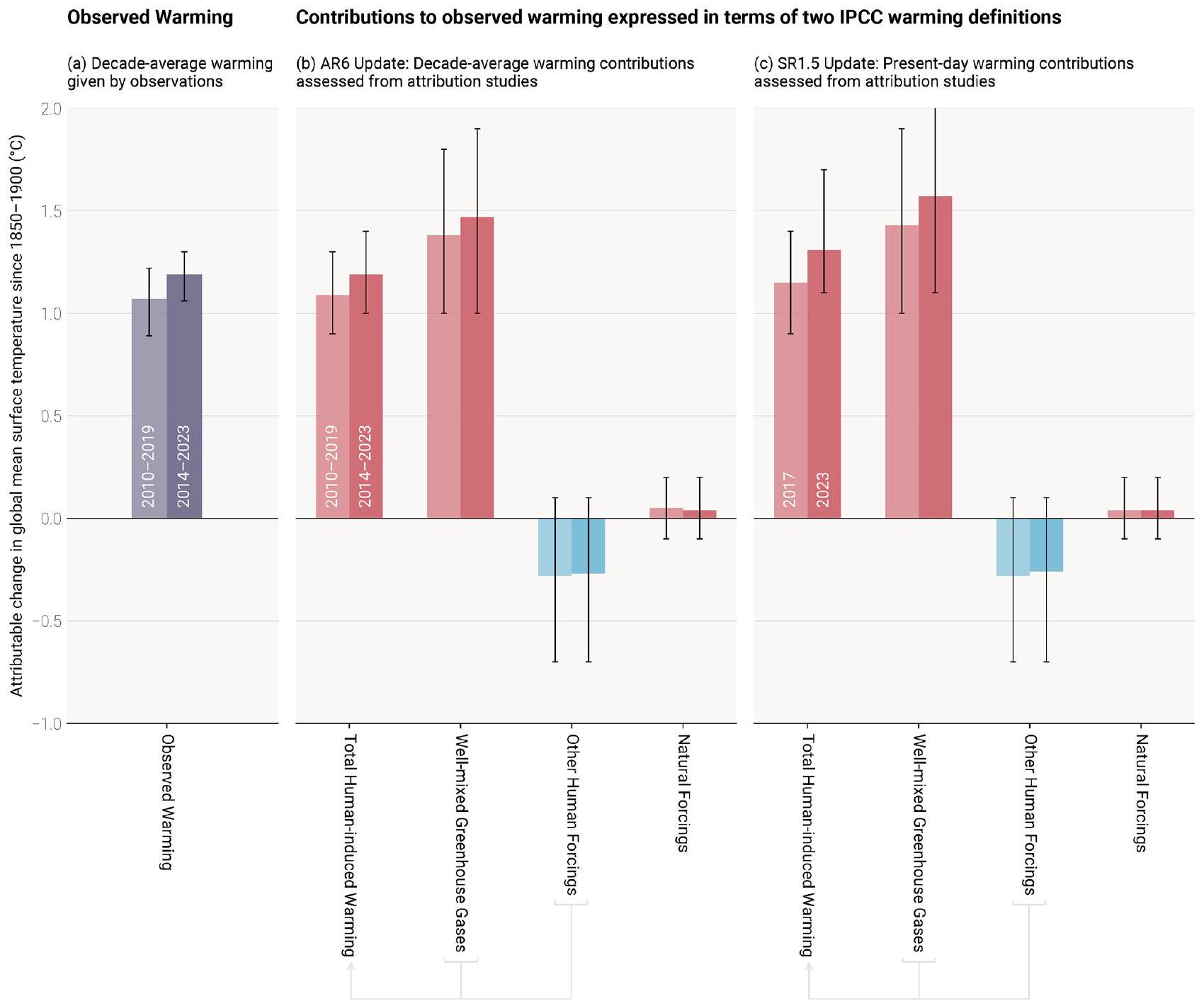

| أنثروبوجيني | 1.07 [0.8 إلى 1.3] | 1.09 [0.9 إلى 1.3] | 1.19 [1.0 إلى 1.4] | 1.0 [0.8 إلى 1.2]

|

1.15 [0.9 إلى 1.4] | 1.31 [1.1 إلى 1.7] |

| غازات الدفيئة المختلطة جيدًا |

|

1.38 [1.0 إلى 1.8] | 1.47 [1.0 إلى 1.9] | غير متوفر | 1.43 [1.0 إلى 1.9] | 1.57 [1.1 إلى 2.1] |

| قوى بشرية أخرى |

|

-0.28 [-0.7 إلى 0.1] | -0.27 [-0.7 إلى 0.1] | غير متوفر | -0.28 [-0.7 إلى 0.1] | -0.26 [-0.7 إلى 0.1] |

| القوى الطبيعية |

|

0.05 [-0.1 إلى 0.2] | 0.04 [-0.1 إلى 0.2] | غير متوفر | 0.04 [-0.1 إلى 0.2] | 0.04 [-0.1 إلى 0.2] |

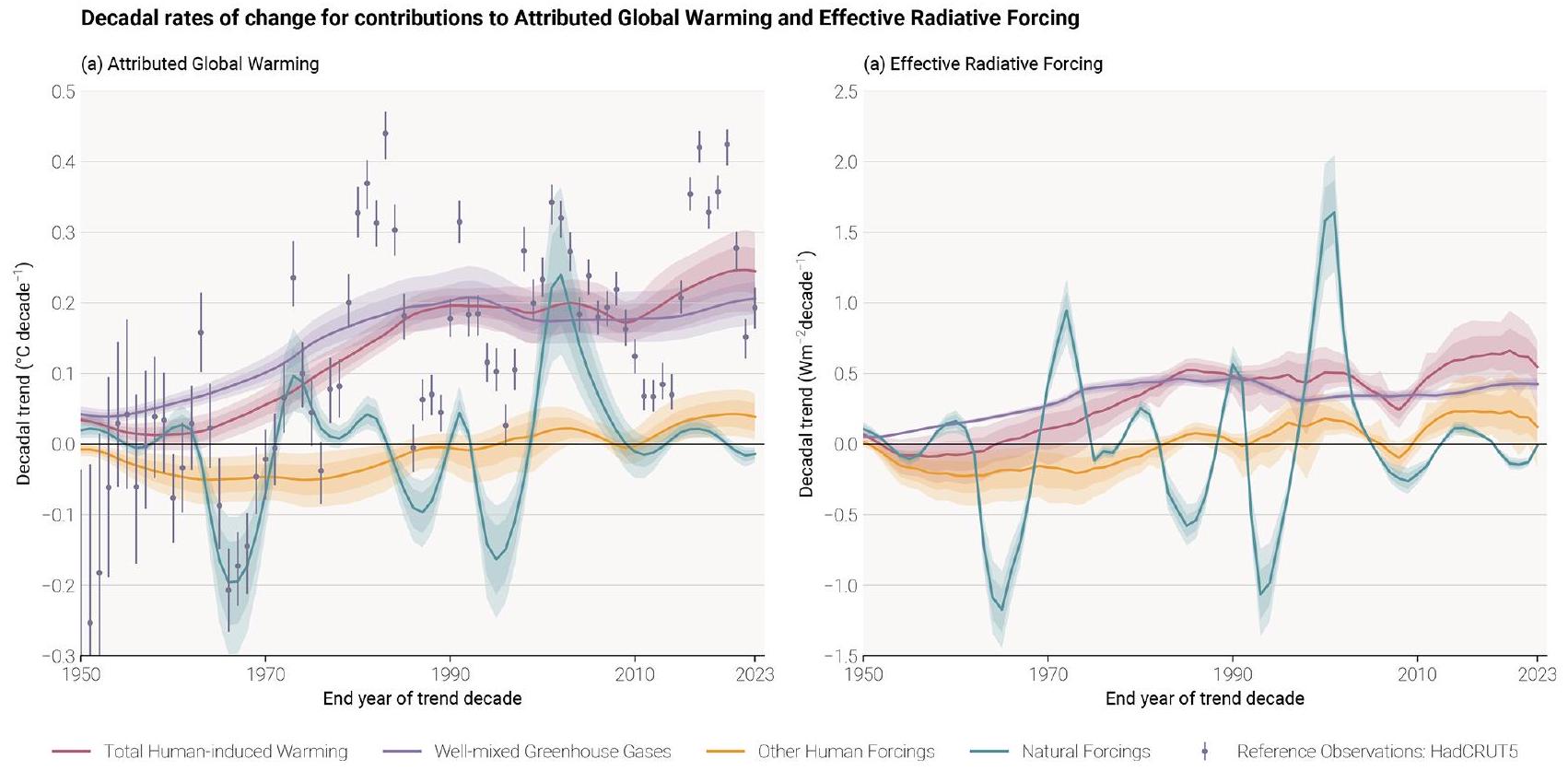

استخدمت مرة أخرى هنا لتقدير معدلات الاحترار البشرية المنفصلة.

7.4.3 النتائج

لـ GMST هنا وتتأثر بشكل أقوى بالتقلبات الداخلية المتبقية التي تبقى في إشارة الاحترار البشرية بسبب القيود في حجم مجموعة CMIP، كما يتضح من نطاقات عدم اليقين الأوسع. نظرًا لأن نتائج ROF تعتبر في هذا السياق شاذة، يتم اعتماد النهج القياسي لأخذ النتيجة المتوسطة للتقييم العام متعدد الطرق.

انخفاض تبريد الهباء الجوي (Forster et al., 2023; Quaas et al., 2022; Jenkins et al., 2022).

8 الميزانية المتبقية للكربون

| تعريف

|

تحديث معدل الاحترار الناتج عن الإنسان في IPCC AR6 الاتجاه الخطي في الاحترار الناتج عن الإنسان على مدى فترة 10 سنوات سابقة | ||||||

| الفترة

|

(i) 2010-2019 مقتبس من AR6 الفصل 3 القسم 3.3.1.1.2 الجدول 3.1 | (ii) 2010-2019 حساب متكرر باستخدام الطرق ومجموعات البيانات المحدثة | (iii) 2014-2023 قيمة محدثة باستخدام الطرق ومجموعات البيانات المحدثة | ||||

| الطريقة

|

|||||||

| تقييم معدل الاحترار الناتج عن الإنسان |

|

0.25 [0.2 إلى 0.4] | 0.26 [0.2 إلى 0.4] | ||||

| GWI | 0.23 [0.19 إلى 0.35] |

|

|

||||

| KCC | 0.23 [0.18 إلى 0.29] | 0.25 [0.20 إلى 0.30] | 0.26 [0.20 إلى 0.31] | ||||

| GSAT | GMST | GMST | |||||

| ROF | 0.35 [0.30 إلى 0.41] | 0.27 [0.17 إلى 0.38] | 0.38 [0.24 إلى 0.52] | ||||

| GSAT | GMST | GMST | |||||

- لاحظ أنه من أجل الوضوح وسهولة المقارنة مع تقييم هذا العام المحدث، فإن المعدل المقيَّم في العمود (i) يقتبس كل من التقييم من AR6 ويطبق بأثر رجعي النهج الوسيط المعتمد في هذه الورقة.

(iv) مساهمة درجة الحرارة من الانبعاثات غير-و (v) مصطلح تعديل لتغذية نظام الأرض التي لا يتم التقاطها بخلاف ذلك من خلال العوامل الأخرى. أعادت WGI AR6 تقييم جميع العوامل الخمسة (Canadell et al., 2021). تم النظر في دمج تغذية نظام الأرض بشكل أكبر من قبل Lamboll و Rogelj (2022). نظر Lamboll et al. (2023) بشكل أكبر في مساهمة درجة الحرارة من الانبعاثات غير- بينما أوضح Rogelj و Lamboll (2024) التخفيضات في غير- التي يُفترض أنها موجودة في تقدير RCB.

التي من المتوقع أن تنخفض مع مرور الوقت في مسارات الانبعاثات المنخفضة (روجيلج وآخرون، 2014؛ روجيلج ولامبول، 2024)، مما يسبب ارتفاع درجة الحرارة وتقليل ميزانية الكربون المتبقية (لامبول وآخرون، 2023). تعطي عدم اليقين الهيكلي حدودًا جوهرية لدقة قياس ميزانيات الكربون المتبقية. تؤثر هذه بشكل خاص على

| حالة/تحديث ميزانية الكربون المتبقية | سنة الأساس | الميزانيات الكربونية المتبقية المقدرة من بداية السنة الأساسية (

|

||||

| احتمالية الحد من ارتفاع درجة حرارة الأرض إلى حد درجة الحرارة | 17 % | ٣٣ ٪ | 50 % | 67 % | 83 % | |

|

|

٢٠٢٠ | ٩٠٠ | ٦٥٠ | ٥٠٠ | ٤٠٠ | ٣٠٠ |

| + نماذج AR6 والسيناريوهات | ٢٠٢٠ | 750 | ٥٠٠ | ٤٠٠ | ٣٠٠ | ٢٠٠ |

| + تقدير الاحترار المحدث | 2024 | ٤٥٠ | ٣٠٠ | ٢٠٠ | 150 | 100 |

|

|

٢٠٢٠ | 1450 | ١٠٥٠ | ٨٥٠ | ٧٠٠ | ٥٥٠ |

| + نماذج AR6 والسيناريوهات | ٢٠٢٠ | ١٣٠٠ | 950 | 750 | ٦٠٠ | ٥٠٠ |

| + تقدير الاحترار المحدث | ٢٠٢٤ | 1000 | ٧٠٠ | ٥٥٠ | ٤٥٠ | ٣٥٠ |

|

|

٢٠٢٠ | 2300 | ١٧٠٠ | 1350 | ١١٥٠ | ٩٠٠ |

| + نماذج AR6 والسيناريوهات | ٢٠٢٠ | ٢٢٠٠ | 1650 | ١٣٠٠ | ١١٠٠ | ٩٠٠ |

| + تقدير الاحترار المحدث | ٢٠٢٤ | 1900 | 1400 | ١١٠٠ | ٩٠٠ | 750 |

9 extremes المناخ والطقس

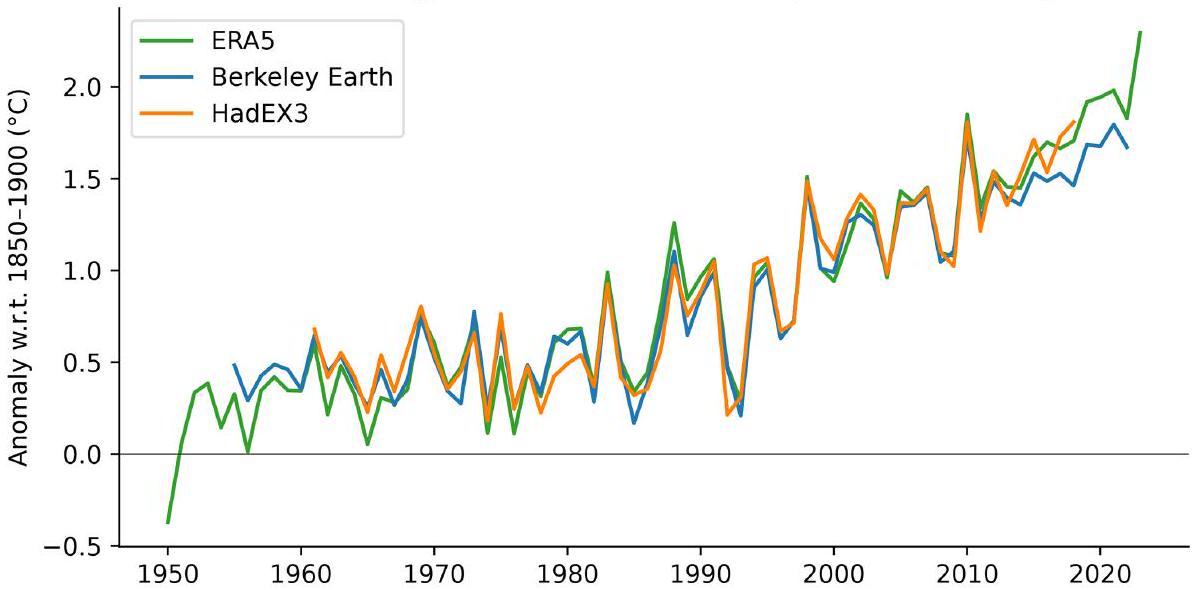

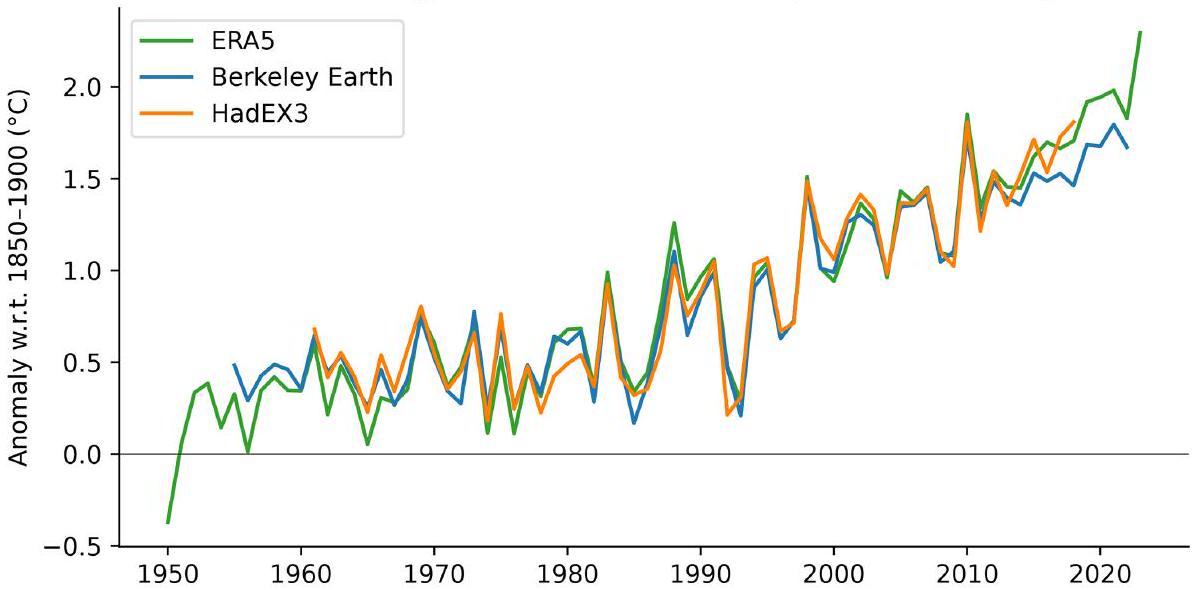

وشدة extremes المناخ والطقس. منذ حوالي عام 1980 فصاعدًا، تشير جميع مجموعات البيانات المستخدمة إلى زيادة قوية في TXx، والتي تتزامن مع الانتقال من التعتيم العالمي، المرتبط بزيادة الهباء الجوي، إلى الإضاءة، المرتبطة بانخفاض الهباء الجوي (Wild et al.، 2005، القسم 3). تقدير الاحترار القائم على ERA5 بالنسبة لـ 1850-1900 لعام 2023 هو عند

10 توفر الشيفرة والبيانات

| فترة | شذوذ بالنسبة لـ

|

شذوذ بالنسبة لـ

|

شذوذ بالنسبة لـ

|

| ERA5 | ERA5 | HadEX3 | |

| 2000-2009 | 1.21 | 0.69 | 0.72 |

| 2009-2018 | 1.54 | 1.02 | 1.01 |

| 2010-2019 | 1.62 | 1.11 | – |

| 2011-2020 | 1.63 | 1.12 | – |

| 2012-2021 | 1.70 | 1.18 | – |

| 2013-2022 | 1.73 | 1.21 | – |

| 2014-2023 | 1.81 | 1.29 | – |

11 المناقشة والاستنتاجات

لا تؤثر على معظم النتائج الأخرى. لاحظ أنها تزيد قليلاً من الميزانية الكربونية المتبقية، لكن هذا فقط بمقدار

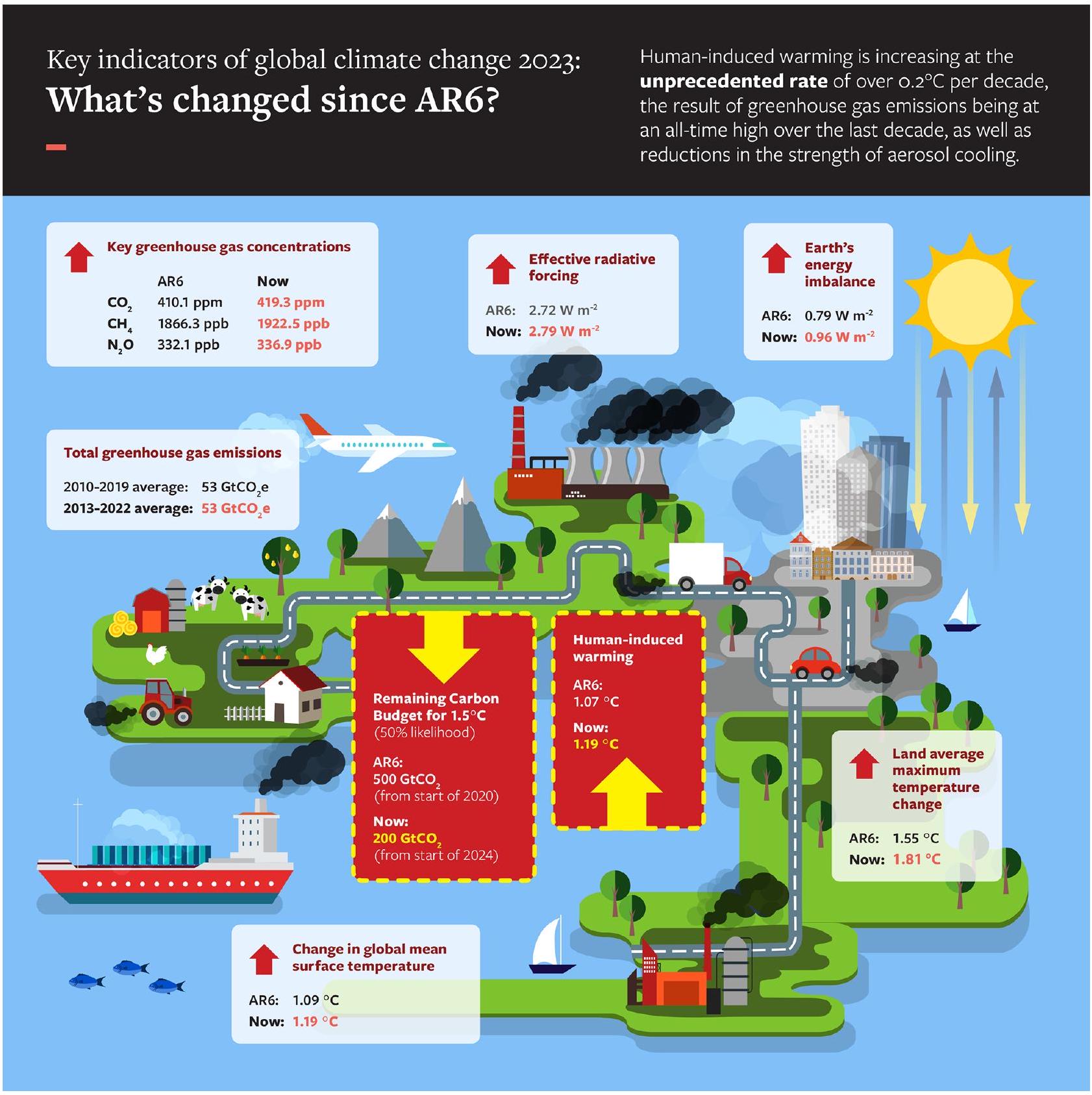

| مؤشر المناخ | تقييم AR6 2021 | هذا التقييم لعام 2023 | تفسير التغييرات | التحديثات المنهجية منذ التقرير السادس | ||

| انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة AR6 WGIII الفصل 2: ذكال وآخرون (2022)؛ انظر أيضًا مينكس وآخرون (2021) | متوسط 2010-2019:

|

متوسط 2010-2019:

|

نمت الانبعاثات المتوسطة في العقد الماضي بمعدل أبطأ من العقد السابق. التغيير من AR6 يرجع إلى مراجعة منهجية نحو الأسفل في

|

|

||

|

2019:

|

2023:

|

الزيادات الناتجة عن استمرار انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة الناتجة عن الأنشطة البشرية. | التحديثات استنادًا إلى بيانات NOAA وAGAGE (القسم 3). | ||

| تغيير القوة الإشعاعية الفعالة منذ عام 1750 تقرير التقييم السادس WGI الفصل 7: فورستر وآخرون (2021) | 2019: 2.72 [1.96 إلى 3.48]

|

2023: 2.79 [1.78 إلى 3.60]

|

الاتجاه منذ عام 2019 ناتج عن زيادة تركيزات غازات الدفيئة وتقليل المواد المسبقة للهباء الجوي. قد تكون تخفيضات انبعاثات الشحن قد أضافت حوالي

|

يتبع AR6 مع تحديث طفيف لعلاج سوائل الهباء الجوي وبيانات انبعاثات التي تنقح تقدير ERF لعام 2019 بالنسبة لعام 1750 نحو الأسفل (أكثر سلبية) بـ

|

||

| عدم توازن الطاقة في الأرض AR6 WGI الفصل 7: فورستر وآخرون (2021) | متوسط 2006-2018: 0.79 [ 0.52 إلى 1.06 ]

|

2010-2023. المتوسط: 0.96 [0.67 إلى 1.26]

|

زيادة كبيرة في عدم التوازن الطاقي مقدرة بناءً على زيادة معدل تسخين المحيطات. | تم تمديد سلسلة زمنية لمحتوى حرارة المحيط من 2018 إلى 2023 باستخدام أربعة من خمسة مجموعات بيانات AR6. تم تحديث مصطلحات جرد الحرارة الأخرى وفقًا لـ von Schuckmann et al. (2023a). يتم استخدام عدم اليقين في محتوى حرارة المحيط كبديل لعدم اليقين الكلي. مزيد من التفاصيل في القسم 5. | ||

| تغير متوسط درجة حرارة سطح الأرض العالمية منذ 1850-1900 تقرير التقييم السادس WGI الفصل 2: غوليف وآخرون (2021) | متوسط 2011-2020: 1.09 [0.95 إلى 1.20]

|

متوسط 2014-2023:

|

زيادة في

|

تتطابق الطرق مع أربعة مجموعات بيانات مستخدمة في AR6 (القسم 6). تحتوي مجموعات البيانات الفردية على بيانات تاريخية محدثة، لكن هذه التغييرات لا تؤثر بشكل جوهري على النتائج. | ||

|

متوسط 2010-2019: 1.07 [0.8 إلى 1.3]

|

متوسط 2010-2019: 1.09 [0.9 إلى 1.3]

|

زيادة في

|

تم الاحتفاظ بالطرق الثلاث كأساس لتقييم AR6، ولكن لكل منها بيانات مدخلة جديدة (القسم 7). | ||

| ميزانية الكربون المتبقية لـ

|

من بداية عام 2020:

|

من بداية عام 2024:

|

ال

|

لقد قللت محاكاة وتغيير السيناريو الميزانية منذ عام 2020 بمقدار

|

||

| تغير متوسط درجة حرارة الأرض القصوى مقارنةً بفترة ما قبل الصناعة. التقرير السادس لتقييم المناخ، الفصل 11: سيني فيراتني وآخرون، 2021 | متوسط 2009-2018:

|

متوسط 2014-2023:

|

يرتفع بمعدل أسرع بكثير مقارنة بمتوسط درجة حرارة سطح الأرض العالمية. | تم استبدال بيانات HadEX3 المستخدمة في AR6 ببيانات إعادة التحليل المستخدمة في هذا التقرير، والتي يمكن تحديثها بشكل أفضل في المستقبل. يضيف

|

يجب تطوير نهج لتوزيع الانبعاثات الجوية، وتغير التركيز، والقوة الإشعاعية. وبالمثل، نتبع الأدبيات الأساسية في معالجة الحرائق البرية المتعلقة بـ

تقدير دقيق للتغيرات قصيرة الأجل في تأثيرات الإشعاع. كما يبرز العمل أهمية البيانات الوصفية عالية الجودة لتوثيق التغيرات في المناهج المنهجية على مر الزمن. في السنوات القادمة، نأمل في تحسين متانة المؤشرات المقدمة هنا، ولكن أيضًا توسيع نطاق المؤشرات المبلغ عنها من خلال أنشطة بحث منسقة. على سبيل المثال، يمكننا البدء في استخدام بيانات جديدة من الأقمار الصناعية والبيانات الأرضية لتحسين مراقبة الغازات الدفيئة (على سبيل المثال، من خلال مبادرة مراقبة الغازات الدفيئة العالمية التابعة للمنظمة العالمية للأرصاد الجوية). يمكن أن تستكشف الجهود الموازية كيف يمكننا تحديث مؤشرات الظروف المناخية الإقليمية المتطرفة ونسبتها، والتي تعتبر ذات صلة خاصة لدعم الإجراءات المتعلقة بالتكيف والخسائر والأضرار.

تمت كتابة المخطوطة بدعم من الدكتور WFL الذي قاد القسم 2 بمساهمات من JCM و PF و GPP و JG و JP و RA. قاد CS القسم 3 بمساهمات من XL و JM و PK. قاد CS القسم 4 بمساهمات من BH و SS و VN و RMH و GM و AG و GW و MVMK و EM و JPK و MvM و XL. قاد BT القسم 5 بمساهمات من PT و CM و CK و JK و RR و RV. قاد KvS و MDP القسم 6 بمساهمات من LC و MI و TB و REK. قاد BT القسم 6 بمساهمات من PT و CM و CK و JK و RR و RV و LC. قاد TW القسم 7 بمساهمات وحسابات من AR و NG و SJ و MA. قاد RL القسم 8 بمساهمات من JR و KZ. قاد MH القسم 9 بمساهمات من SIS و XZ و DS. جميع المؤلفين إما قاموا بتحرير أو التعليق على المخطوطة. قام DR و AB و JAB بتنسيق جهود تصور البيانات.

References

Allison, L. C., Palmer, M. D., Allan, R. P., Hermanson, L., Liu, C., and Smith, D. M.: Observations of planetary heating since the 1980s from multiple independent datasets, Environ. Res. Commun., 2, 101001, https://doi.org/10.1088/25157620/abbb39, 2020.

Barnes, C., Boulanger, Y., Keeping, T., Gachon, P., Gillett, N., Haas, O., Wang, X., Roberge, F., Kew, S., Heinrich, D., Singh, R., Vahlberg, M., Van Aalst, M., Otto, F., Kimutai, J., Boucher, J., Kasoar, M., Zachariah, M., and Krikken, F.: Climate change more than doubled the likelihood of extreme fire weather conditions in Eastern Canada, Imperial College London, https://doi.org/10.25561/105981, 2023.

Basu, S., Lan, X., Dlugokencky, E., Michel, S., Schwietzke, S., Miller, J. B., Bruhwiler, L., Oh, Y., Tans, P. P., Apadula, F., Gatti, L. V., Jordan, A., Necki, J., Sasakawa, M., Morimoto, S., Di Iorio, T., Lee, H., Arduini, J., and Manca, G.: Estimating emissions of methane consistent with atmospheric measurements of methane and

Betts, R. A., Belcher, S. E., Hermanson, L., Klein Tank, A., Lowe, J. A., Jones, C. D., Morice, C. P., Rayner, N. A., Scaife, A. A., and Stott, P. A.: Approaching

Bond, T. C., Doherty, S. J., Fahey, D. W., Forster, P. M., Berntsen, T., DeAngelo, B. J., Flanner, M. G., Ghan, S., Kärcher, B., Koch, D., Kinne, S., Kondo, Y., Quinn, P. K., Sarofim, M. C., Schultz, M. G., Schulz, M., Venkataraman, C., Zhang, H., Zhang, S., Bellouin, N., Guttikunda, S. K., Hopke, P. K., Jacobson, M. Z., Kaiser, J. W., Klimont, Z., Lohmann, U., Schwarz, J. P., Shindell, D., Storelvmo, T., Warren, S. G., and Zender, C. S.: Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 118, 5380-5552, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrd.50171, 2013.

Bun, R., Marland, G., Oda, T., See, L., Puliafito, E., Nahorski, Z., Jonas, M., Kovalyshyn, V., Ialongo, I., Yashchun, O., and Romanchuk, Z.: Tracking unaccounted greenhouse gas emissions due to the war in Ukraine since 2022, Sci. Total Environ., 914, 169879, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.169879, 2024.

Canadell, J. G., Monteiro, P. M. S., Costa, M. H., Cotrim da Cunha, L., Cox, P. M., Eliseev, A. V., Henson, S., Ishii, M., Jaccard, S., Koven, C., Lohila, A., Patra, P. K., Piao, S., Rogelj, J., Syampungani, S., Zaehle, S., and Zickfeld, K.: Global Carbon and other Biogeochemical Cycles and Feedbacks. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud,

N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 673816, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.007, 2021.

Cheng, L., Abraham, J., Hausfather, Z., and Trenberth, K. E.: How fast are the oceans warming?, Science, 363, 128-129, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav7619, 2019.

Cheng, L., Von Schuckmann, K., Abraham, J. P., Trenberth, K. E., Mann, M. E., Zanna, L., England, M. H., Zika, J. D., Fasullo, J. T., Yu, Y., Pan, Y., Zhu, J., Newsom, E. R., Bronselaer, B., and Lin, X.: Past and future ocean warming, Nat. Rev. Earth. Environ., 3, 776-794, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-022-00345-1, 2022.

Collins, M., Knutti, R., Arblaster, J., Dufresne, J.-L., Fichefet, T., Friedlingstein, P., Gao, X., Gutowski, W.J., Johns, T., Krinner, G., Shongwe, M., Tebaldi, C., Weaver, A. J., and Wehner, M.: Long-term Climate Change: Projections, Commitments and Irreversibility, in: Stocker, V. B. T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G. K., Tignor, M., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., and Midgley, P. M., Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, Cambridge University Press, 1029-1136, 2013.

Crippa, M., Guizzardi, D., Schaaf, E., Monforti-Ferrario, F., Quadrelli, R., Risquez Martin, A., Rossi, S., Vignati, E., Muntean, M., Brandao De Melo, J., Oom, D., Pagani, F., Banja, M., Taghavi-Moharamli, P., Köykkä, J., Grassi, G., Branco, A., and San-Miguel, J.: GHG emissions of all world countries – 2023, Publications Office of the European Union, https://doi.org/10.2760/953322, 2023.

Cuesta-Valero, F. J., Beltrami, H., García-García, A., Krinner, G., Langer, M., MacDougall, A., Nitzbon, J., Peng, J., von Schuckmann, K., Seneviratne, S., Thiery, W., Vanderkelen, I., and Wu, T.: GCOS EHI 1960-2020 Continental Heat Content (Version 2), World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ, https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/GCOS_EHI_19602020_CoHC_v2, 2023.

Deng, Z., Ciais, P., Tzompa-Sosa, Z. A., Saunois, M., Qiu, C., Tan, C., Sun, T., Ke, P., Cui, Y., Tanaka, K., Lin, X., Thompson, R. L., Tian, H., Yao, Y., Huang, Y., Lauerwald, R., Jain, A. K., Xu, X., Bastos, A., Sitch, S., Palmer, P. I., Lauvaux, T., d’Aspremont, A., Giron, C., Benoit, A., Poulter, B., Chang, J., Petrescu, A. M. R., Davis, S. J., Liu, Z., Grassi, G., Albergel, C., Tubiello, F. N., Perugini, L., Peters, W., and Chevallier, F.: Comparing national greenhouse gas budgets reported in UNFCCC inventories against atmospheric inversions, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 14, 1639-1675, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-1639-2022, 2022.

Dhakal, S., Minx, J. C., Toth, F. L., Abdel-Aziz, A., Figueroa Meza, M. J., Hubacek, K., Jonckheere, I. G. C., Yong-Gun Kim, Nemet, G. F., Pachauri, S., Tan, X. C., and Wiedmann, T.: Emissions Trends and Drivers, in IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Shukla, P. R., Skea, J., Slade, R., Al Khourdajie, A., van Diemen, R., McCollum,

D., Pathak, M., Some, S., Vyas, P., Fradera, R., Belkacemi, M., Hasija, A., Lisboa, G., Luz, S., and Malley, J., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157926.004, 2022.

Douville, H., Raghavan, K., Renwick, J., Allan, R. P., Arias, P. A., Barlow, M., Cerezo-Mota, R., Cherchi, A., Gan, T. Y., Gergis, J., Jiang, D., Khan, A., Pokam Mba, W., Rosenfeld, D., Tierney, J., and Zolina, O.: Water Cycle Changes. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1055-1210, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.010, 2021.

Droste, E. S., Adcock, K. E., Ashfold, M. J., Chou, C., Fleming, Z., Fraser, P. J., Gooch, L. J., Hind, A. J., Langenfelds, R. L., Leedham Elvidge, E. C., Mohd Hanif, N., O’Doherty, S., Oram, D. E., Ou-Yang, C.-F., Panagi, M., Reeves, C. E., Sturges, W. T., and Laube, J. C.: Trends and emissions of six perfluorocarbons in the Northern Hemisphere and Southern Hemisphere, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 20, 4787-4807, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-20-4787-2020, 2020.

Dunn, R. J. H., Alexander, L. V., Donat, M. G., Zhang, X., Bador, M., Herold, N., Lippmann, T., Allan, R., Aguilar, E., Barry, A. A., Brunet, M., Caesar, J., Chagnaud, G., Cheng, V., Cinco, T., Durre, I., Guzman, R., Htay, T. M., Wan Ibadullah, W. M., Bin Ibrahim, M. K. I., Khoshkam, M., Kruger, A., Kubota, H., Leng, T. W., Lim, G., Li-Sha, L., Marengo, J., Mbatha, S., McGree, S., Menne, M., Milagros Skansi, M., Ngwenya, S., Nkrumah, F., Oonariya, C., Pabon-Caicedo, J. D., Panthou, G., Pham, C., Rahimzadeh, F., Ramos, A., Salgado, E., Salinger, J., Sané, Y., Sopaheluwakan, A., Srivastava, A., Sun, Y., Timbal, B., Trachow, N., Trewin, B., Schrier, G., VazquezAguirre, J., Vasquez, R., Villarroel, C., Vincent, L., Vischel, T., Vose, R., and Bin Hj Yussof, M. N.: Development of an updated global land in situ-based data set of temperature and precipitation extremes: HadEX3, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos., 125, e2019JD032263, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JD032263, 2020.

Dunn, R. J. H., Donat, M. G., and Alexander, L. V.: Comparing extremes indices in recent observational and reanalysis products, Front. Clim., 4, 98905, https://doi.org/10.3389/fclim.2022.989505, 2022.

Dunn, R. J. H., Alexander, L., Donat, M., Zhang, X., Bador, M., Herold, N., Lippmann, T., Allan, R. J., Aguilar, E., Aziz, A., Brunet, M., Caesar, J., Chagnaud, G., Cheng, V., Cinco, T., Durre, I., de Guzman, R., Htay, T.M., Wan Ibadullah, W. M., Bin Ibrahim, M. K. I., Khoshkam, M., Kruge, A., Kubota, H., Leng, T. W., Lim, G., Li-Sha, L., Marengo, J., Mbatha, S., McGree, S., Menne, M., de los Milagros Skansi, M., Ngwenya, S., Nkrumah, F., Oonariya, C., Pabon-Caicedo, J. D., Panthou, G., Pham, C., Rahimzadeh, F., Ramos, A., Salgado, E., Salinger, J., Sane, Y., Sopaheluwakan, A., Srivastava, A., Sun, Y., Trimbal, B., Trachow, N., Trewin, B., van der Schrier, G., VazquezAguirre, J., Vasquez, R., Villarroel, C., Vincent, L., Vischel, T., Vose, R., Bin Hj Yussof, and M. N. A.: HadEX3: Global land-surface climate extremes indices v3.0.4 (1901-2018),

Eyring, V., Gillett, N. P., Achuta Rao, K. M., Barimalala, R., Barreiro, M. Parrillo, Bellouin, N., Cassou, C., Durack, P. J., Kosaka, Y., McGregor, S., Min, S., Morgenstern, O., and Sun, Y.: Human Influence on the Climate System, in: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 423-552, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.005, 2021.

Feron, S., Malhotra, A., Bansal, S., Fluet-Chouinard, E., McNicol, G., Knox, S. H., Delwiche, K. B., Cordero, R. R., Ouyang, Z., Zhang, Z., Poulter, B., and Jackson, R. B.: Recent increases in annual, seasonal, and extreme methane fluxes driven by changes in climate and vegetation in boreal and temperate wetland ecosystems, Global Change Biol., 30, e17131, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.17131, 2024.

Forster, P. M., Forster, H. I., Evans, M. J., Gidden, M. J., Jones, C. D., Keller, C. A., Lamboll, R. D., Le Quéré, C., Rogelj, J., Rosen, D., Schleussner, C. F., Richardson, T. B., Smith, C. J., and Turnock, S. T.: Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19, Nature Clim. Chang, 10, 913-919, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0883-0, 2020.

Forster, P., Storelvmo, T., Armour, K., Collins, W., Dufresne, J.L., Frame, D., Lunt, D. J., Mauritsen, T., Palmer, M. D., Watanabe, M., Wild, M., and Zhang, H.: The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 9231054, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.009, 2021.

Forster, P. M., Smith, C. J., Walsh, T., Lamb, W. F., Lamboll, R., Hauser, M., Ribes, A., Rosen, D., Gillett, N., Palmer, M. D., Rogelj, J., von Schuckmann, K., Seneviratne, S. I., Trewin, B., Zhang, X., Allen, M., Andrew, R., Birt, A., Borger, A., Boyer, T., Broersma, J. A., Cheng, L., Dentener, F., Friedlingstein, P., Gutiérrez, J. M., Gütschow, J., Hall, B., Ishii, M., Jenkins, S., Lan, X., Lee, J.-Y., Morice, C., Kadow, C., Kennedy, J., Killick, R., Minx, J. C., Naik, V., Peters, G. P., Pirani, A., Pongratz, J., Schleussner, C.-F., Szopa, S., Thorne, P., Rohde, R., Rojas Corradi, M., Schumacher, D., Vose, R., Zickfeld, K., MassonDelmotte, V., and Zhai, P.: Indicators of Global Climate Change 2022: annual update of large-scale indicators of the state of the

climate system and human influence, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 2295-2327, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-2295-2023, 2023.

Fox-Kemper, B., Fox-Kemper, B., Hewitt, H. T., Xiao, C., Aðalgeirsdóttir, G., Drijfhout, S. S., Edwards, T. L., Golledge, N. R., Hemer, M., Kopp, R. E., Krinner, G., Mix, A., Notz, D., Nowicki, S., Nurhati, I. S., Ruiz, L., Sallée, J.-B., Slangen, A. B. A., and Yu, Y.: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1211-1362, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.011, 2021.

Francey, R. J., Steele, L. P., Langenfelds, R. L., and Pak, B. C.: High precision long-term monitoring of radiativelyactive trace gases at surface sites and from ships and aircraft in the Southern Hemisphere atmosphere, J. Atmos. Science, 56, 279-285 https://doi.org/10.1175/15200469(1999)056<0279:HPLTMO>2.0.CO;2, 1999.

Friedlingstein, P., O’Sullivan, M., Jones, M. W., Andrew, R. M., Hauck, J., Olsen, A., Peters, G. P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Sitch, S., Le Quéré, C., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Alin, S., Aragão, L. E. O. C., Arneth, A., Arora, V., Bates, N. R., Becker, M., Benoit-Cattin, A., Bittig, H. C., Bopp, L., Bultan, S., Chandra, N., Chevallier, F., Chini, L. P., Evans, W., Florentie, L., Forster, P. M., Gasser, T., Gehlen, M., Gilfillan, D., Gkritzalis, T., Gregor, L., Gruber, N., Harris, I., Hartung, K., Haverd, V., Houghton, R. A., Ilyina, T., Jain, A. K., Joetzjer, E., Kadono, K., Kato, E., Kitidis, V., Korsbakken, J. I., Landschützer, P., Lefèvre, N., Lenton, A., Lienert, S., Liu, Z., Lombardozzi, D., Marland, G., Metzl, N., Munro, D. R., Nabel, J. E. M. S., Nakaoka, S.-I., Niwa, Y., O’Brien, K., Ono, T., Palmer, P. I., Pierrot, D., Poulter, B., Resplandy, L., Robertson, E., Rödenbeck, C., Schwinger, J., Séférian, R., Skjelvan, I., Smith, A. J. P., Sutton, A. J., Tanhua, T., Tans, P. P., Tian, H., Tilbrook, B., van der Werf, G., Vuichard, N., Walker, A. P., Wanninkhof, R., Watson, A. J., Willis, D., Wiltshire, A. J., Yuan, W., Yue, X., and Zaehle, S.: Global Carbon Budget 2020, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 12, 32693340, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-3269-2020, 2020.

Friedlingstein, P., O’Sullivan, M., Jones, M. W., Andrew, R. M., Gregor, L., Hauck, J., Le Quéré, C., Luijkx, I. T., Olsen, A., Peters, G. P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Schwingshackl, C., Sitch, S., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Alin, S. R., Alkama, R., Arneth, A., Arora, V. K., Bates, N. R., Becker, M., Bellouin, N., Bittig, H. C., Bopp, L., Chevallier, F., Chini, L. P., Cronin, M., Evans, W., Falk, S., Feely, R. A., Gasser, T., Gehlen, M., Gkritzalis, T., Gloege, L., Grassi, G., Gruber, N., Gürses, Ö., Harris, I., Hefner, M., Houghton, R. A., Hurtt, G. C., Iida, Y., Ilyina, T., Jain, A. K., Jersild, A., Kadono, K., Kato, E., Kennedy, D., Klein Goldewijk, K., Knauer, J., Korsbakken, J. I., Landschützer, P., Lefèvre, N., Lindsay, K., Liu, J., Liu, Z., Marland, G., Mayot, N., McGrath, M. J., Metzl, N., Monacci, N. M., Munro, D. R., Nakaoka, S.-I., Niwa, Y., O’Brien, K., Ono, T., Palmer, P. I., Pan, N., Pierrot, D., Pocock, K., Poulter, B., Resplandy, L., Robertson, E., Rödenbeck, C., Rodriguez, C., Rosan, T. M., Schwinger,

J., Séférian, R., Shutler, J. D., Skjelvan, I., Steinhoff, T., Sun, Q., Sutton, A. J., Sweeney, C., Takao, S., Tanhua, T., Tans, P. P., Tian, X., Tian, H., Tilbrook, B., Tsujino, H., Tubiello, F., van der Werf, G. R., Walker, A. P., Wanninkhof, R., Whitehead, C., Willstrand Wranne, A., Wright, R., Yuan, W., Yue, C., Yue, X., Zaehle, S., Zeng, J., and Zheng, B.: Global Carbon Budget 2022, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 14, 4811-4900, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-48112022, 2022.

Friedlingstein, P., O’Sullivan, M., Jones, M. W., Andrew, R. M., Bakker, D. C. E., Hauck, J., Landschützer, P., Le Quéré, C., Luijkx, I. T., Peters, G. P., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Schwingshackl, C., Sitch, S., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Jackson, R. B., Alin, S. R., Anthoni, P., Barbero, L., Bates, N. R., Becker, M., Bellouin, N., Decharme, B., Bopp, L., Brasika, I. B. M., Cadule, P., Chamberlain, M. A., Chandra, N., Chau, T.-T.-T., Chevallier, F., Chini, L. P., Cronin, M., Dou, X., Enyo, K., Evans, W., Falk, S., Feely, R. A., Feng, L., Ford, D. J., Gasser, T., Ghattas, J., Gkritzalis, T., Grassi, G., Gregor, L., Gruber, N., Gürses, Ö., Harris, I., Hefner, M., Heinke, J., Houghton, R. A., Hurtt, G. C., Iida, Y., Ilyina, T., Jacobson, A. R., Jain, A., Jarníková, T., Jersild, A., Jiang, F., Jin, Z., Joos, F., Kato, E., Keeling, R. F., Kennedy, D., Klein Goldewijk, K., Knauer, J., Korsbakken, J. I., Körtzinger, A., Lan, X., Lefèvre, N., Li, H., Liu, J., Liu, Z., Ma, L., Marland, G., Mayot, N., McGuire, P. C., McKinley, G. A., Meyer, G., Morgan, E. J., Munro, D. R., Nakaoka, S.-I., Niwa, Y., O’Brien, K. M., Olsen, A., Omar, A. M., Ono, T., Paulsen, M., Pierrot, D., Pocock, K., Poulter, B., Powis, C. M., Rehder, G., Resplandy, L., Robertson, E., Rödenbeck, C., Rosan, T. M., Schwinger, J., Séférian, R., Smallman, T. L., Smith, S. M., Sospedra-Alfonso, R., Sun, Q., Sutton, A. J., Sweeney, C., Takao, S., Tans, P. P., Tian, H., Tilbrook, B., Tsujino, H., Tubiello, F., van der Werf, G. R., van Ooijen, E., Wanninkhof, R., Watanabe, M., WimartRousseau, C., Yang, D., Yang, X., Yuan, W., Yue, X., Zaehle, S., Zeng, J., and Zheng, B.: Global Carbon Budget 2023, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 5301-5369, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-53012023, 2023.

Gasser, T., Crepin, L., Quilcaille, Y., Houghton, R. A., Ciais, P., and Obersteiner, M.: Historical

Gettelman, A., Christensen, M. A., Diamond, M. S., Gryspeerdt, E., Manshausen, P., Sieir, P., Watson-Parris, D., Yang, M., Yoshioka, M., and Yuan, T.: Has Reducing Ship Emissions Brought Forward Global Warming?, Geophys. Res. Lett., submitted, 2024.

Gillett, N. P., Kirchmeier-Young, M., Ribes, A., Shiogama, H., Hegerl, G. C., Knutti, R., Gastineau, G., John, J. G., Li, L., Nazarenko, L., Rosenbloom, N., Seland, Ø., Wu, T., Yukimoto, S., and Ziehn, T.: Constraining human contributions to observed warming since the pre-industrial period, Nat. Clim. Chang., 11, 207-212, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00965-9, 2021.

Gleckler, P. J., Durack, P. J., Stouffer, R. J., Johnson, G. C., and Forest, C. E.: Industrial-era global ocean heat uptake doubles in recent decades, Nat. Clim. Chang., 6, 394-398, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2915, 2016.

Grassi, G., Schwingshackl, C., Gasser, T., Houghton, R. A., Sitch, S., Canadell, J. G., Cescatti, A., Ciais, P., Federici, S., Friedlingstein, P., Kurz, W. A., Sanz Sanchez, M. J., Abad Viñas, R., Alkama, R., Bultan, S., Ceccherini, G., Falk, S., Kato, E., Kennedy, D., Knauer, J., Korosuo, A., Melo, J., McGrath, M.

J., Nabel, J. E. M. S., Poulter, B., Romanovskaya, A. A., Rossi, S., Tian, H., Walker, A. P., Yuan, W., Yue, X., and Pongratz, J.: Harmonising the land-use flux estimates of global models and national inventories for 2000-2020, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 1093-1114, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-1093-2023, 2023.

Gulev, S. K., Thorne, P. W., Ahn, J., Dentener, F. J., Domingues, C. M., Gerland, S., Gong, D., Kaufman, D. S., Nnamchi, H. C., Quaas, J., Rivera, J. A., Sathyendranath, S., Smith, S. L., Trewin, B., von Schuckmann, K., and Vose, R. S.: Changing State of the Climate System, in: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 287-422, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.004, 2021.

Gütschow, J., Jeffery, M. L., Gieseke, R., Gebel, R., Stevens, D., Krapp, M., and Rocha, M.: The PRIMAP-hist national historical emissions time series, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 8, 571-603, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-8-571-2016, 2016.

Gütschow, J., Pflüger, M., and Busch, D.: The PRIMAP-hist national historical emissions time series v2.5.1 (1750-2022) (2.5.1), Zenodo [data set] https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10705513, 2024.

Hansen, J. E., Sato, M., Simons, L., Nazarenko, L. S., Sangha, I., Kharecha, P., Zachos, J. C., von Schuckmann, K., Loeb, N. G., Osman, M. B., Jin, Q., Tselioudis, G., Jeong, E., Lacis, A., Ruedy, R., Russell, G., Cao, J., and Li, J.: Global warming in the pipeline, Oxford Open Climate Change, 3, kgad008, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfclm/kgad008, 2023.

Hansis, E., Davis, S. J., and Pongratz, J.: Relevance of methodological choices for accounting of land use change carbon fluxes, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 29, 1230-1246, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GB004997, 2015.

Haustein, K., Allen, M. R., Forster, P. M., Otto, F. E. L., Mitchell, D. M., Matthews, H. D., and Frame, D. J.: A real-time Global Warming Index, Sci. Rep.-UK, 7, 15417, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14828-5, 2017.

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Hirahara, S., Horányi, A., Muñoz-Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Abdalla, S., Abellan, X., Balsamo, G., Bechtold, P., Biavati, G., Bidlot, J., Bonavita, M., De Chiara, G., Dahlgren, P., Dee, D., Diamantakis, M., Dragani, R., Flemming, J., Forbes, R., Fuentes, M., Geer, A., Haimberger, L., Healy, S., Hogan, R. J., Hólm, E., Janisková, M., Keeley, S., Laloyaux, P., Lopez, P., Lupu, C., Radnoti, G., de Rosnay, P., Rozum, I., Vamborg, F., Villaume, S., and Thépaut, J.-N.: The ERA5 global reanalysis, Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 146, 19992049, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803, 2020.

Hodnebrog, Ø., Aamaas, B., Fuglestvedt, J. S., Marston, G., Myhre, G., Nielsen, C. J., Sandstad, M., Shine, K. P., and Wallington, T. J.: Updated Global Warming Potentials and

Hodnebrog, Ø., Myhre, G., Jouan, C., Andrews, T., Forster, P. M., Jia, H., Loeb, N. G., Olivié, D. J. L., Paynter, D., Quaas, J., Raghuraman, S. P., and Schulz, M.: Recent reductions in aerosol emissions have increased Earth’s energy imbalance, Commun. Earth Environ., 5, 166, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01324-8, 2024.

Hoesly, R. and Smith, S.: CEDS v_2024_04_01 Release Emission Data (v_2024_04_01), Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10904361, 2024.

Hoesly, R. M., Smith, S. J., Feng, L., Klimont, Z., JanssensMaenhout, G., Pitkanen, T., Seibert, J. J., Vu, L., Andres, R. J., Bolt, R. M., Bond, T. C., Dawidowski, L., Kholod, N., Kurokawa, J.-I., Li, M., Liu, L., Lu, Z., Moura, M. C. P., O’Rourke, P. R., and Zhang, Q.: Historical (1750-2014) anthropogenic emissions of reactive gases and aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS), Geosci. Model Dev., 11, 369-408, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-369-2018, 2018.

Houghton, R. A. and Castanho, A.: Annual emissions of carbon from land use, land-use change, and forestry from 1850 to 2020, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 2025-2054, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-2025-2023, 2023.

Houghton, R. A. and Nassikas, A. A.: Global and regional fluxes of carbon from land use and land cover change 1850-2015, Global Biogeochem. Cy., 31, 456-472, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GB005546, 2017.

Hu, Y., Yue, X., Tian, C., Zhou, H., Fu, W., Zhao, X., Zhao, Y., and Chen, Y.: Identifying the main drivers of the spatiotemporal variations in wetland methane emissions during 2001-2020, Front. Environ. Sci., 11, 1275742, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1275742, 2023.

IATA: Air Passenger Monthly Analysis March 2024, https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/ economic-reports/air-passenger-market-analysis-march-2024/ (last access: 20 May 2024), 2024.

IEA:

IPCC: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Stocker, T. F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S. K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., and Midgley, P. M., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324, 2013.

IPCC: Summary for Policymakers, in: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 3-32, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.001, 2021b.

IPCC: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D. C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E. S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., Okem, A., and Rama, B., Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844, 2022.

IPCC: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Core Writing Team, Lee, H., and Romero, J., IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland., Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647, 2023a.

IPCC: Climate Change 2023: Summary for Policy Makers. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Core Writing Team, Lee, H., and Romero, J., IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland., Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR69789291691647, 2023b.

Iturbide, M., Fernández, J., Gutiérrez, J. M., Pirani, A., Huard, D., Al Khourdajie, A., Baño-Medina, J., Bedia, J., Casanueva, A., Cimadevilla, E., Cofiño, A. S., De Felice, M., Diez-Sierra, J., García-Díez, M., Goldie, J., Herrera, D. A., Herrera, S., Manzanas, R., Milovac, J., Radhakrishnan, A., San-Martín, D., Spinuso, A., Thyng, K. M., Trenham, C., and Yelekçi, Ö.: Implementation of FAIR principles in the IPCC: the WGI AR6 Atlas repository, Sci. Data, 9, 629, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01739-y, 2022.

Janardanan, R., Maksyutov, S., Wang, F., Nayagam, L., Sahu, S. K., Mangaraj, P., Saunois, M., Lan, X., and Matsunaga, T.: Country-level methane emissions and their sectoral trends during 2009-2020 estimated by high-resolution inversion of GOSAT and surface observations, Environ. Res. Lett., 19, 034007, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ad2436, 2024.

Jenkins, S., Povey, A., Gettelman, A., Grainger, R., Stier, P., and Allen, M.: Is Anthropogenic Global Warming Accelerating?, J. Climate, 35, 7873-7890, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-220081.1, 2022.

anomaly above

Kirchengast, G., Gorfer, M., Mayer, M., Steiner, A. K., and Haimberger, L.: GCOS EHI 1960-2020 Atmospheric Heat Content, https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/GCOS_EHI_1960-2020_AHC, 2022.

Krotkov, N. A., Lamsal, L. N., Marchenko, S. V., Celarier, E. A., Bucsela, E. J., Swartz, W. H., Joiner, J., and the OMI core team: OMI/Aura

Lamboll, R. D. and Rogelj, J.: Code for estimation of remaining carbon budget in IPCC AR6 WGI, Zenodo [code], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6373365, 2022.

Lamboll, R. D., Jones, C. D., Skeie, R. B., Fiedler, S., Samset, B. H., Gillett, N. P., Rogelj, J., and Forster, P. M.: Modifying emissions scenario projections to account for the effects of COVID19: protocol for CovidMIP, Geosci. Model Dev., 14, 3683-3695, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-14-3683-2021, 2021.

Lamboll, R. and Rogelj, J.: Carbon Budget Calculator, 2024, Github [code], https://github.com/Rlamboll/AR6CarbonBudgetCalc/ tree/v1.0.1, last access: 25 April 2024.

Lamboll, R. D., Nicholls, Z. R. J., Smith, C. J., Kikstra, J. S., Byers, E., and Rogelj, J.: Assessing the size and uncertainty of remaining carbon budgets, Nat. Climate Change, 13, 1360-1367, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01848-5, 2023.

Lan, X., Tans, P. and Thoning, K. W.: Trends in globallyaveraged

Lan, X., Thoning, K. W., and Dlugokencky, E.J.: Trends in globally-averaged

Laube, J., Newland, M., Hogan, C., Brenninkmeijer, A. M., Fraser, P. J., Martinerie, P., Oram, D. E., Reeves, C. E., Röckmann, T., Schwander, J., Witrant, E., Sturges, W. T.: Newly detected ozonedepleting substances in the atmosphere. Nature Geosci., 7, 266269, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2109, 2014.

Lee, J.-Y., Marotzke, J., Bala, G., Cao, L., Corti, S., Dunne, J. P., Engelbrecht, F., Fischer, E., Fyfe, J. C., Jones, C., Maycock, A., Mutemi, J., Ndiaye, O., Panickal, S., and Zhou, T.: Future Global Climate: Scenario-Based Projections and NearTerm Information, in: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 553672,https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.006, 2021.

Loeb, N. G., Johnson, G. C., Thorsen, T. J., Lyman, J. M., Rose, F. G., Kato, S.: Satellite and ocean data reveal marked increase in Earth’s heating rate. Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e2021GL093047, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GL093047, 2021.

McKenna, C. M., Maycock, A. C., Forster, P. M., Smith, C. J., and Tokarska, K. B.: Stringent mitigation substantially reduces risk of unprecedented near-term warming rates, Nat. Clim. Change, 11, 126-131, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00957-9, 2021.

Minière, A., von Schuckmann, K., Sallée, J.-B., and Vogt, L.: Robust acceleration of Earth system heating observed over the past six decades, Sci. Rep.-UK, 13, 22975, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49353-1, 2023.

Minx, J. C., Lamb, W. F., Andrew, R. M., Canadell, J. G., Crippa, M., Döbbeling, N., Forster, P. M., Guizzardi, D., Olivier, J., Peters, G. P., Pongratz, J., Reisinger, A., Rigby, M., Saunois, M., Smith, S. J., Solazzo, E., and Tian, H.: A comprehensive and synthetic dataset for global, regional, and national greenhouse gas emissions by sector 1970-2018 with an extension to 2019, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 13, 5213-5252, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-5213-2021, 2021.

Nisbet, E. G., Manning, M. R., Dlugokencky, E. J., Michel, S. E., Lan, X., Roeckmann, T., Gon, H. A. D. V. D., Palmer, P., Oh, Y., Fisher, R., Lowry, D., France, J. L., and White, J. W. C.: Atmospheric methane: Comparison between methane’s record in 2006-2022 and during glacial terminations, Preprints, https://doi.org/10.22541/essoar.167689502.25042797/v1, 2023.

Nitzbon, J., Krinner, G., and Langer, M.: GCOS EHI 1960-2020 Permafrost Heat Content, World Data Center for Climate (WDCC) at DKRZ, https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/GCOS_EHI_1960-2020_PHC, 2022.

ture, 612, 477-482, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05447w, 2022.

Pirani, A., Alegria, A., Khourdajie, A. A., Gunawan, W., Gutiérrez, J. M., Holsman, K., Huard, D., Juckes, M., Kawamiya, M., Klutse, N., Krey, V., Matthews, R., Milward, A., Pascoe, C., Van Der Shrier, G., Spinuso, A., Stockhause, M., and Xiaoshi Xing: The implementation of FAIR data principles in the IPCC AR6 assessment process, Zenodo [data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.6504469, 2022.

Pongratz, J., Schwingshackl, C., Bultan, S., Obermeier, W., Havermann, F., and Guo, S.: Land Use Effects on Climate: Current State, Recent Progress, and Emerging Topics, Curr. Clim. Change Rep., 7, 99-120, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-021-00178-y, 2021.

Prinn, R. G., Weiss, R. F., Arduini, J., Arnold, T., DeWitt, H. L., Fraser, P. J., Ganesan, A. L., Gasore, J., Harth, C. M., Hermansen, O., Kim, J., Krummel, P. B., Li, S., Loh, Z. M., Lunder, C. R., Maione, M., Manning, A. J., Miller, B. R., Mitrevski, B., Mühle, J., O’Doherty, S., Park, S., Reimann, S., Rigby, M., Saito, T., Salameh, P. K., Schmidt, R., Simmonds, P. G., Steele, L. P., Vollmer, M. K., Wang, R. H., Yao, B., Yokouchi, Y., Young, D., and Zhou, L.: History of chemically and radiatively important atmospheric gases from the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE), Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 10, 9851018, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-10-985-2018, 2018.

Quaas, J., Jia, H., Smith, C., Albright, A. L., Aas, W., Bellouin, N., Boucher, O., Doutriaux-Boucher, M., Forster, P. M., Grosvenor, D., Jenkins, S., Klimont, Z., Loeb, N. G., Ma, X., Naik, V., Paulot, F., Stier, P., Wild, M., Myhre, G., and Schulz, M.: Robust evidence for reversal of the trend in aerosol effective climate forcing, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 22, 12221-12239, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-22-12221-2022, 2022.

Raghuraman, S. P., Paynter, D., and Ramaswamy, V.: Anthropogenic forcing and response yield observed positive trend in Earth’s energy imbalance, Nat. Commun., 12, 4577, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24544-4, 2021.

Ribes, A., Qasmi, S., and Gillett, N. P.: Making climate projections conditional on historical observations, Sci. Adv., 7, eabc0671, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abc0671, 2021.

Rogelj, J. and Lamboll, R. D.: Substantial reductions in non-

Rogelj, J., Rao, S., McCollum, D. L., Pachauri, S., Klimont, Z., Krey, V., and Riahi, K: Air-pollution emission ranges consistent with the representative concentration pathways, Nature Clim. Chang., 4, 446-450, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2178, 2014.

Rogelj, J., Shindell, D., Jiang, K., Fifita, S., Forster, P., Ginzburg, V., Handa, C., Kheshgi, H., Kobayashi, S., Kriegler, E., Mundaca, L., Séférian, R., and Vilariño, M. V.: Mitigation Pathways Compatible with

B. R., Chen, Y., Zhou, X., Gomis, M. I., Lonnoy, E., Maycock, T., Tignor, M., and Waterfield, T., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 93-174, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157940.004, 2018.

Rogelj, J., Forster, P. M., Kriegler, E., Smith, C. J., and Séférian, R.: Estimating and tracking the remaining carbon budget for stringent climate targets, Nature, 571, 335-342, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1368-z, 2019.

Rohde, R., Muller, R., Jacobsen, R., Perlmutter, S., Rosenfeld, A., Wurtele, J., Curry, J., Wickham, C., and Mosher, S.: Berkeley Earth Temperature Averaging Process, Geoinfor. Geostat.: An Overview 1:2., https://doi.org/10.4172/2327-4581.1000103, 2013.

Schmidt, G.: Climate models can’t explain 2023’s huge heat anomaly – we could be in uncharted territory, Nature, 627, 467467, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00816-z, 2024.

Seneviratne, S. I., Zhang, X., Adnan, M., Badi, W., Dereczynski, C., Di Luca, A., Ghosh, S., Iskandar, I., Kossin, J., Lewis, S., Otto, F., Pinto, I., Satoh, M., Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Wehner, M., and Zhou, B.: Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 15131766, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.013, 2021.

Simmonds, P. G., Rigby, M., McCulloch, A., O’Doherty, S., Young, D., Mühle, J., Krummel, P. B., Steele, P., Fraser, P. J., Manning, A. J., Weiss, R. F., Salameh, P. K., Harth, C. M., Wang, R. H. J., and Prinn, R. G.: Changing trends and emissions of hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and their hydrofluorocarbon (HFCs) replacements, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 17, 4641-4655, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-17-4641-2017, 2017.

Sippel, S., Zscheischler, J., Heimann, M., Otto, F. E. L., Peters, J., and Mahecha, M. D.: Quantifying changes in climate variability and extremes: Pitfalls and their overcoming, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, 9990-9998, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GL066307, 2015.

Smith, C., Nicholls, Z. R. J., Armour, K., Collins, W., Forster, P., Meinshausen, M., Palmer, M. D., and Watanabe, M.: The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity Supplementary Material, in: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., 2021.

Smith, C., Walsh, T., Gillett, N., Hall, B., Hauser, M., Krummel, P., Lamb, W., Lamboll, R., Lan, X., Muhle, J., Palmer, M., Ribes, A., Schumacher, D., Seneviratne, S., Trewin, B., von Schuckmann, K., and Forster, P.: Indicators of Global Climate Change 2023, Github [code], https://github.com/ClimateIndicator/data/ tree/v2024.05.29b, last access: 25 April 2024b.

Smith, S. J., van Aardenne, J., Klimont, Z., Andres, R. J., Volke, A., and Delgado Arias, S.: Anthropogenic sulfur dioxide emissions: 1850-2005, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 1101-1116, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-11-1101-2011, 2011.

Storto, A. and Yang, C.: Acceleration of the ocean warming from 1961 to 2022 unveiled by large-ensemble reanalyses, Nat. Commun., 15, 545, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-447497, 2024.

Szopa, S., Naik, V., Adhikary, B., Artaxo, P., Berntsen, T., Collins, W. D., Fuzzi, S., Gallardo, L., Kiendler-Scharr, A., Klimont, Z., Liao, H., Unger, N., and Zanis, P.: Short-Lived Climate Forcers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by: Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S. L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M. I., Huang, M., Leitzell, K., Lonnoy, E., Matthews, J. B. R., Maycock, T. K., Waterfield, T., Yelekçi, O., Yu, R., and Zhou, B., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 817-922, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.008, 2021.

Tibrewal, K., Ciais, P., Saunois, M., Martinez, A., Lin, X., Thanwerdas, J., Deng, Z., Chevallier, F., Giron, C., Albergel, C., Tanaka, K., Patra, P., Tsuruta, A., Zheng, B., Belikov, D., Niwa, Y., Janardanan, R., Maksyutov, S., Segers, A., TzompaSosa, Z. A., Bousquet, P., and Sciare, J.: Assessment of methane emissions from oil, gas and coal sectors across inventories and atmospheric inversions, Commun. Earth Environ., 5, 26, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-01190-w, 2024.

Vanderkelen, I. and Thiery, W.: GCOS EHI 1960-2020 Inland Water Heat Content, https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/GCOS_EHI_19602020_IWHC, 2022.

van der Werf, G. R., Randerson, J. T., Giglio, L., van Leeuwen, T. T., Chen, Y., Rogers, B. M., Mu, M., van Marle, M. J. E., Morton, D. C., Collatz, G. J., Yokelson, R. J., and Kasibhatla, P. S.: Global fire emissions estimates during 1997-2016, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 9, 697-720, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-9-697-2017, 2017.

van Marle, M. J. E., Kloster, S., Magi, B. I., Marlon, J. R., Daniau, A.-L., Field, R. D., Arneth, A., Forrest, M., Hantson, S., Kehrwald, N. M., Knorr, W., Lasslop, G., Li, F., Mangeon, S., Yue, C., Kaiser, J. W., and van der Werf, G. R.: Historic global biomass burning emissions for CMIP6 (BB4CMIP) based on merging satellite observations with proxies and fire models (1750-2015), Geosci. Model Dev., 10, 3329-3357, https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-10-3329-2017, 2017.

Vollmer, M. K., Young, D., Trudinger, C. M., Mühle, J., Henne, S., Rigby, M., Park, S., Li, S., Guillevic, M., Mitrevski, B., Harth, C. M., Miller, B. R., Reimann, S., Yao, B., Steele, L. P., Wyss, S. A., Lunder, C. R., Arduini, J., McCulloch, A., Wu, S., Rhee, T. S., Wang, R. H. J., Salameh, P. K., Hermansen, O., Hill, M., Langenfelds, R. L., Ivy, D., O’Doherty, S., Krummel, P. B., Maione, M., Etheridge, D. M., Zhou, L., Fraser, P. J., Prinn, R. G., Weiss, R. F., and Simmonds, P. G.: Atmospheric histories and emissions of chlorofluorocarbons CFC-13 (CClF3),

von Schuckmann, K., Cheng, L., Palmer, M. D., Hansen, J., Tassone, C., Aich, V., Adusumilli, S., Beltrami, H., Boyer, T., Cuesta-Valero, F. J., Desbruyères, D., Domingues, C., García-García, A., Gentine, P., Gilson, J., Gorfer, M., Haimberger, L., Ishii, M., Johnson, G. C., Killick, R., King, B. A., Kirchengast, G., Kolodziejczyk, N., Lyman, J., Marzeion, B., Mayer, M., Monier, M., Monselesan, D. P., Purkey, S., Roemmich, D., Schweiger, A., Seneviratne, S. I., Shepherd, A., Slater, D. A., Steiner, A. K., Straneo, F., Timmermans, M.-L., and Wijffels, S. E.: Heat stored in the Earth system: where does the energy go?, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 12, 2013-2041, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-2013-2020, 2020.

von Schuckmann, K., Minière, A., Gues, F., Cuesta-Valero, F. J., Kirchengast, G., Adusumilli, S., Straneo, F., Ablain, M., Allan, R. P., Barker, P. M., Beltrami, H., Blazquez, A., Boyer, T., Cheng, L., Church, J., Desbruyeres, D., Dolman, H., Domingues, C. M., García-García, A., Giglio, D., Gilson, J. E., Gorfer, M., Haimberger, L., Hakuba, M. Z., Hendricks, S., Hosoda, S., Johnson, G. C., Killick, R., King, B., Kolodziejczyk, N., Korosov, A., Krinner, G., Kuusela, M., Landerer, F. W., Langer, M., Lavergne, T., Lawrence, I., Li, Y., Lyman, J., Marti, F., Marzeion, B., Mayer, M., MacDougall, A. H., McDougall, T., Monselesan, D. P., Nitzbon, J., Otosaka, I., Peng, J., Purkey, S., Roemmich, D., Sato, K., Sato, K., Savita, A., Schweiger, A., Shepherd, A., Seneviratne, S. I., Simons, L., Slater, D. A., Slater, T., Steiner, A. K., Suga, T., Szekely, T., Thiery, W., Timmermans, M.-L., Vanderkelen, I., Wjiffels, S. E., Wu, T., and Zemp, M.: Heat stored in the Earth system 1960-2020: where does the energy go?, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 15, 1675-1709, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-1675-2023, 2023a.

von Schuckmann, K., Minière, A., Gues, F., Cuesta-Valero, F. J., Kirchengast, G., Adusumilli, S., Straneo, F., Ablain, M., Allan, R. P., Barker, P. M., Beltrami, H., Blazquez, A., Boyer, T., Cheng, L., Church, J., Desbruyeres, D., Dolman, H., Domingues, C. M., García-García, A., Giglio, D., Gilson, J. E., Gorfer, M., Haimberger, L., Hakuba, M. Z., Hendricks, S., Hosoda, S., Johnson, G. C., Killick, R., King, B., Kolodziejczyk, N., Korosov, A., Krinner, G., Kuusela, M., Landerer, F. W., Langer, M., Lavergne, T., Lawrence, I., Li, Y., Lyman, J., Marti, F., Marzeion, B., Mayer, M., MacDougall, A. H., McDougall, T., Monselesan, D. P., Nitzbon, J., Otosaka, I., Peng, J., Purkey, S., Roemmich, D., Sato, K., Sato, K., Savita, A., Schweiger, A., Shepherd, A., Seneviratne, S. I., Simons, L., Slater, D. A., Slater, T., Steiner, A. K., Suga, T., Szekely, T., Thiery, W., Timmermans, M.-L., Vanderkelen, I., Wjiffels, S. E., Wu, T., and Zemp, M.: GCOS EHI 1960-2020 Earth Heat Inventory Ocean Heat Content (Version 2), https://doi.org/10.26050/WDCC/GCOS_EHI_19602020_OHC_v2, 2023b.

Western, L. M., Vollmer, M. K., Krummel, P. B., Adcock, K. E., Fraser, P. J., Harth, C. M., Langenfelds, R. L., Montzka, S. A., Mühle, J., O’Doherty, S., Oram, D. E., Reimann, S., Rigby, M., Vimont, I., Weiss, R. F., Young, D., and Laube, J. C.: Global increase of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons from 2010 to 2020, Nat. Geosci., 16, 309-313, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-023-01147-w, 2023.

Wild, M., Gilgen, H., Roesch, A., Ohmura, A., Long, C. N., Dutton, E. G., Forgan, B., Kallis, A., Russak, V., and Tsvetkov, A.: From Dimming to Brightening: Decadal Changes in Solar Radiation at Earth’s Surface, Science, 308, 847-850, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1103215, 2005.

Zhang, Z., Poulter, B., Feldman, A.F., Ying, Q., Ciais, P., Peng, S., and Xin, L.: Recent intensification of wetland methane feedback, Nat. Clim. Chang., 13, 430-433, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01629-0, 2023.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-2625-2024

Publication Date: 2024-06-04

Indicators of Global Climate Change 2023: annual update of key indicators of the state of the climate system and human influence

Department für Geographie, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Munich, Germany

Climate Analytics, Berlin, Germany

Geography Department and IRI THESys, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, Laboratoire des sciences du climat et de l’environnement, UMR8212 CNRS-CEA-UVSQ, Université Paris-Saclay, 91191, Gif-sur-Yvette, France

ICARUS Climate Research Centre, Maynooth University, Maynooth, Ireland

Berkeley Earth, Berkeley, CA, USA

NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), Asheville, NC, USA

Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada

Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing, China

Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Hamburg, Germany

CIRES, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO, USA

Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen, the Netherlands

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA, USA

LARC, NASA, Hampton, USA

Finnish Meteorological Institute, Helsinki, Finland

Delteras, Delft, the Netherlands

Global Systems Institute, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK

Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA

Climate Change Tracker, Data for Action Foundation, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Correspondence: Piers M. Forster (p.m.forster@leeds.ac.uk)

Revised: 30 May 2024 – Accepted: 31 May 2024 – Published: 5 June 2024

Abstract

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessments are the trusted source of scientific evidence for climate negotiations taking place under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Evidence-based decision-making needs to be informed by up-to-date and timely information on key indicators of the state of the climate system and of the human influence on the global climate system. However, successive IPCC reports are published at intervals of 5-10 years, creating potential for an information gap between report cycles.

We follow methods as close as possible to those used in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) Working Group One (WGI) report. We compile monitoring datasets to produce estimates for key climate indicators related to forcing of the climate system: emissions of greenhouse gases and short-lived climate forcers, greenhouse gas concentrations, radiative forcing, the Earth’s energy imbalance, surface temperature changes, warming attributed to human activities, the remaining carbon budget, and estimates of global temperature extremes. The purpose of this effort, grounded in an open-data, open-science approach, is to make annually updated reliable global climate indicators available in the public domain (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.11388387, Smith et al., 2024a). As they are traceable to IPCC report methods, they can be trusted by all parties involved in UNFCCC negotiations and help convey wider understanding of the latest knowledge of the climate system and its direction of travel.

The indicators show that, for the 2014-2023 decade average, observed warming was 1.19 [1.06 to

1 Introduction

able at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 11388387 (Smith et al., 2024a).

2 Emissions

2.1 Methods of estimating greenhouse gas emissions changes

of consistency between the varying approaches (Friedlingstein et al., 2022; Grassi et al., 2023).

emissions Paths (PRIMAP-hist; Gütschow et al., 2016, 2024) cover

and

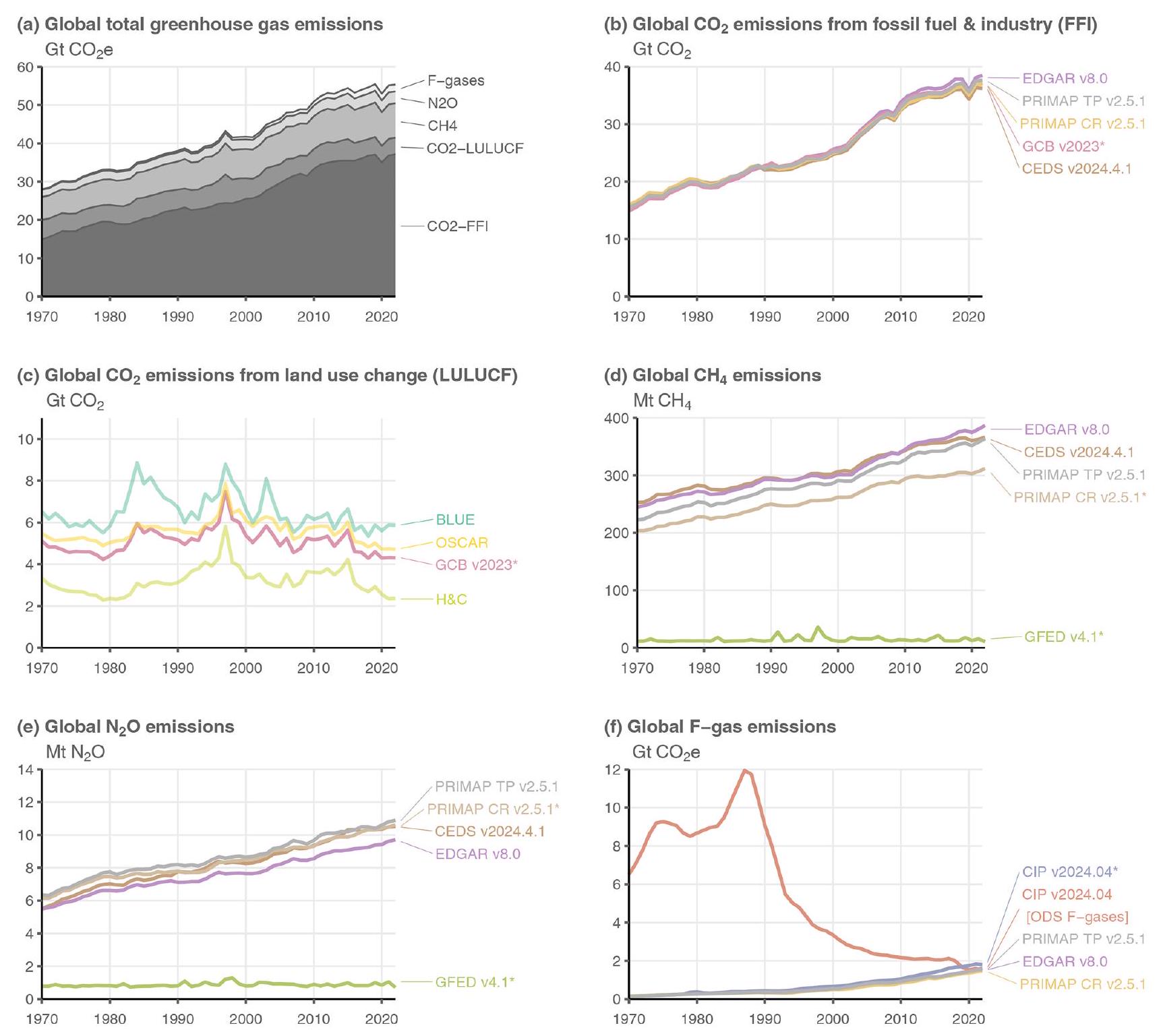

2.2 Updated greenhouse gas emissions

indicate that total

switch from EDGAR to GCB, as the latter includes a cement carbonation sink not considered in EDGAR. Differences in the remaining gases for 2019 are relatively small in magnitude (increases in

2.3 Non-methane short-lived climate forcers

| Units:

|

1970-1979 | 1980-1989 | 1990-1999 | 2000-2009 | 2010-2019 | 2013-2022 | 2022 | 2023 (projection) |

| GHG |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| UNFCCC F-gases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

trends over recent years are uncertain, the general decline in some SLCF emissions derived from inventories punctuated by temporary anomalous years with high biomass burning emissions including 2023 is supported by MODIS Terra and Aqua aerosol optical depth measurements (e.g. Quaas et al., 2022; Hodnebrog et al., 2024).

3 Well-mixed greenhouse gas concentrations

| Compound | 1750 emissions (

|

2019 emissions (

|

2022 emissions (

|

2023 emissions (

|

| Sulfur dioxide (

|

2.8 | 84.2 | 75.3 | 79.1 |

| Black carbon (BC) | 2.1 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 7.3 |

| Organic carbon (OC) | 15.5 | 34.2 | 25.8 | 40.7 |

| Ammonia (

|

6.6 | 67.6 | 67.3 | 71.1 |

| Oxides of nitrogen (

|

19.4 | 141.7 | 130.4 | 139.4 |

| Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) | 60.9 | 217.3 | 183.9 | 228.1 |

| Carbon monoxide (CO) | 348.4 | 853.8 | 686.4 | 917.5 |

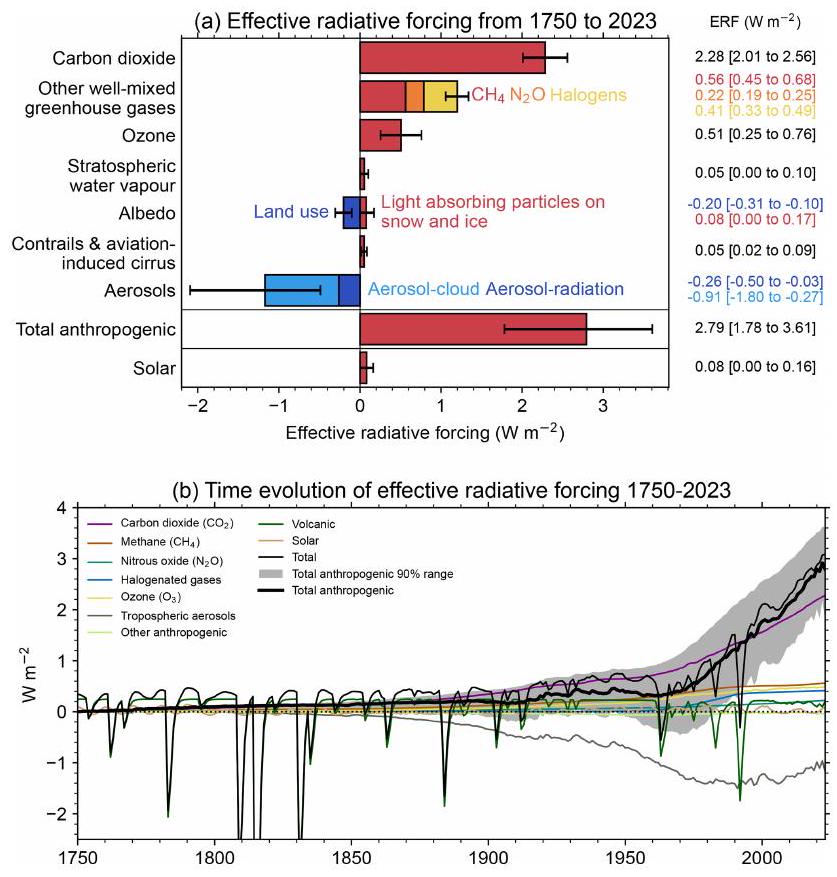

4 Effective radiative forcing (ERF)

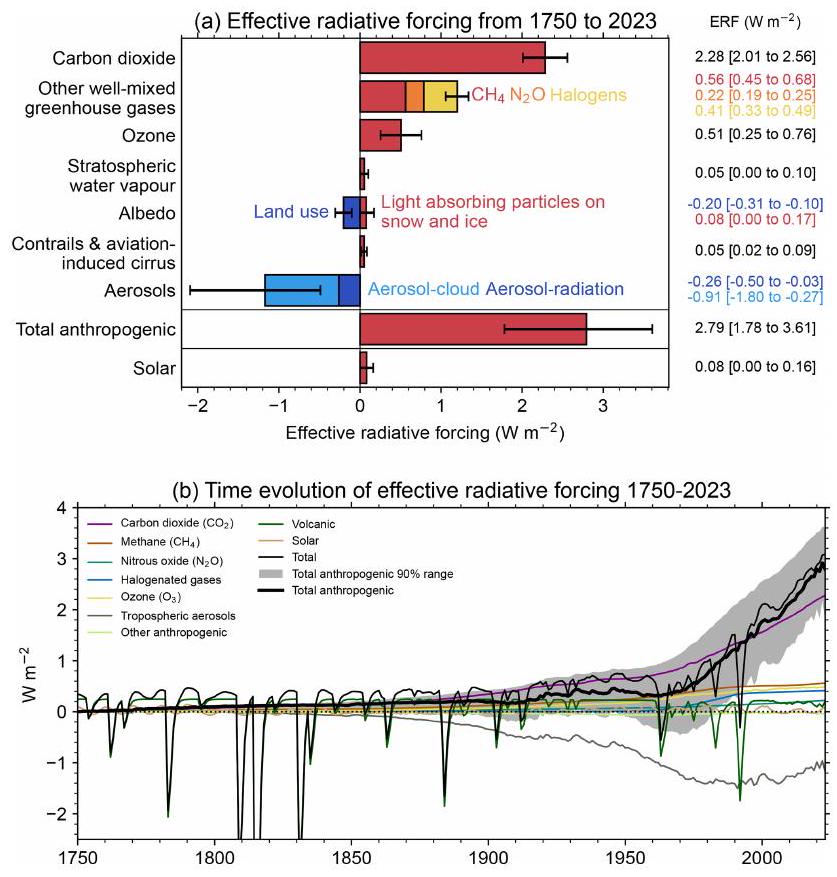

timates of ERF in Chap. 6 that attributed forcing to specific precursor emissions (Szopa et al., 2021) and also generated the time history of ERF shown in AR6 WGI Fig. 2.10 and discussed in Chap. 2 (Gulev et al., 2021). Only the concentration-based estimates are updated herein.

| Forcer |

|

|

|

Reason for change since last year | ||

|

|

2.16 [1.90 to 2.41] | 2.25 [1.98 to 2.52] | 2.28 [2.01 to 2.56] | Increases in GHG concentrations resulting from increases in emissions | ||

|

|

0.54 [0.43 to 0.65] | 0.56 [0.45 to 0.67] | 0.56 [0.45 to 0.68] | |||

|

|

0.21 [0.18 to 0.24] | 0.22 [0.19 to 0.25] | 0.22 [0.19 to 0.26] | |||

| Halogenated GHGs | 0.41 [0.33 to 0.49] | 0.41 [0.33 to 0.49] | 0.41 [0.33 to 0.49] | |||

| Ozone | 0.47 [0.24 to 0.71] | 0.48 [0.24 to 0.72] | 0.51 [0.25 to 0.76] | Increase in precursors (

|

||

| Stratospheric water vapour | 0.05 [0.00 to 0.10] | 0.05 [0.00 to 0.10] | 0.05 [0.00 to 0.10] | |||

| Aerosol-radiation interactions | -0.22 [-0.47 to +0.04] | -0.21 [-0.42 to 0.00] | -0.26 [-0.50 to -0.03] | Large increases in biomass burning aerosol in 2023, continued recovery from COVID-19, drop in sulfur from shipping | ||

| Land use (surface albedo changes and effects of irrigation) |

|

|

|

|||

| Light-absorbing particles on snow and ice | 0.08 [0.00 to 0.18] | 0.06 [0.00 to 0.14] | 0.08 [0.00 to 0.17] | Rebound in BC emissions from biomass burning | ||

| Contrails and contrailinduced cirrus | 0.06 [0.02 to 0.10] | 0.05 [0.02 to 0.09] | 0.05 [0.02 to 0.09] | Estimates of aviation activity have been rebounding since the pandemic but were still below 2019 levels in 2023 | ||

| Total anthropogenic | 2.72 [1.96 to 3.48] | 2.91 [2.19 to 3.63] | 2.79 [1.78 to 3.61] | Possible strong aerosol forcing in 2023 partly offset by increases in GHG and ozone forcing | ||

| Solar irradiance | 0.01 [-0.06 to 0.08] | 0.01 [-0.06 to 0.08] | 0.01 [-0.06 to 0.08] |

(Forster et al., 2023) and

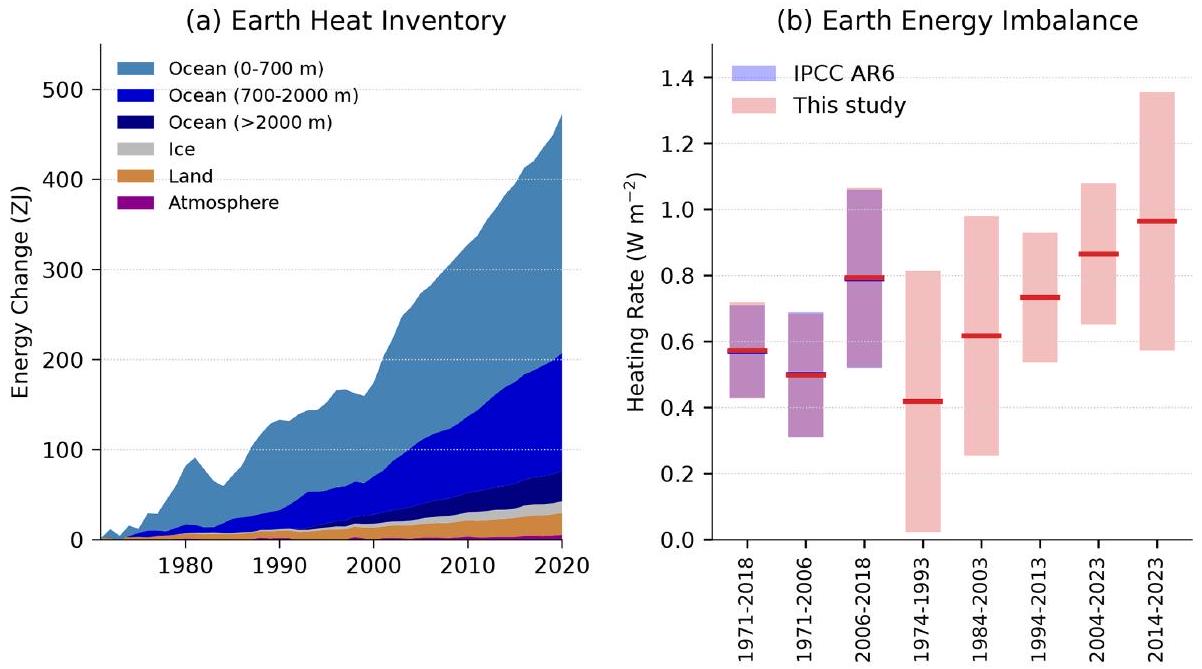

5 Earth energy imbalance

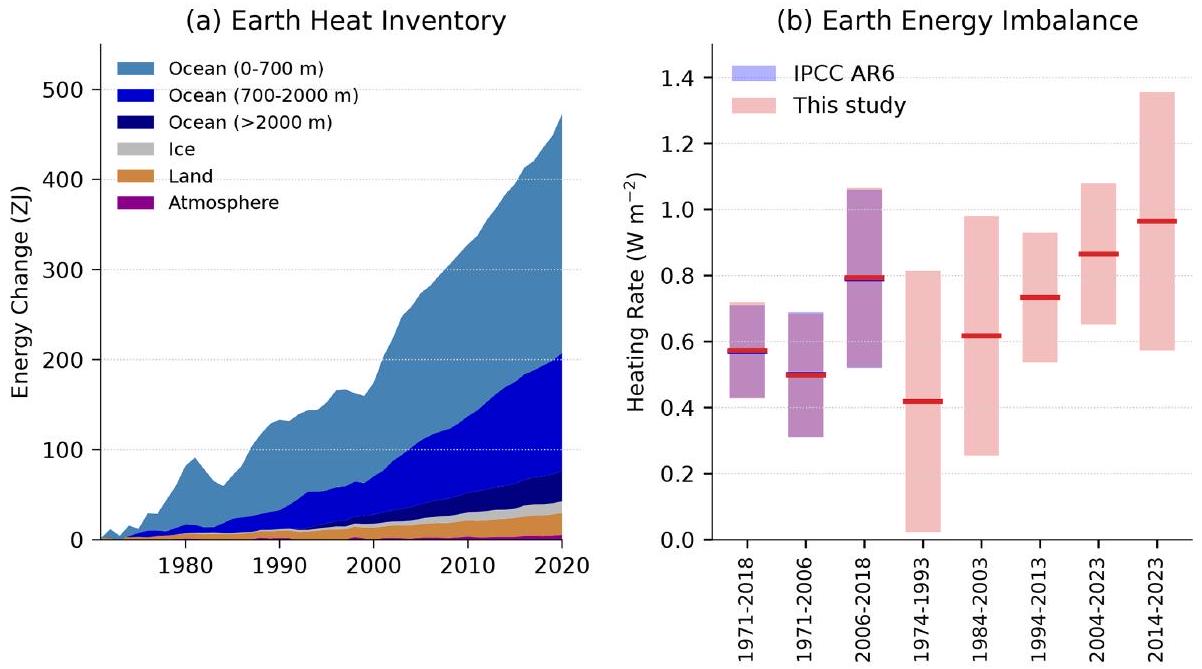

ated with decreased reflection by clouds and sea ice and a decrease in outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) due to increases in trace gases and water vapour (Loeb et al., 2021). The degree of contribution from the different drivers is uncertain and still under active investigation.

| Time period | Earth energy imbalance (

|

|

| IPCC AR6 | This study | |

| 1971-2018 | 0.57 [0.43 to 0.72] | 0.57 [0.43 to 0.72] |

| 1971-2006 | 0.50 [0.32 to 0.69] | 0.50 [0.31 to 0.68] |

| 2006-2018 | 0.79 [0.52 to 1.06] | 0.79 [0.52 to 1.07] |

| 1976-2023 | – | 0.65 [0.48 to 0.82] |

| 2011-2023 | – | 0.96 [0.67 to 1.26] |

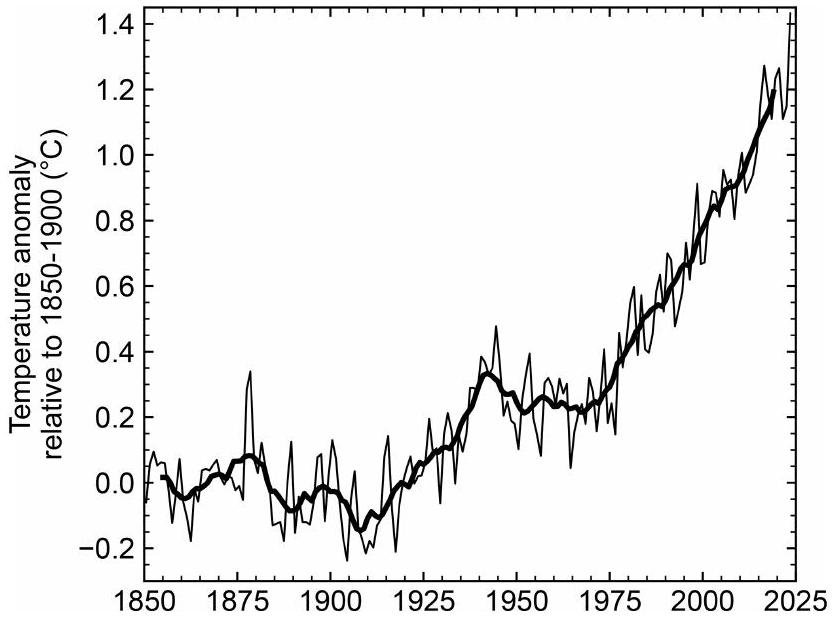

6 Global surface temperatures

| Time period | Temperature change from 1850-1900 (

|

|

| IPCC AR6 | This study | |

| Global, most recent 10 years | 1.09 [0.95 to 1.20] (to 2011-2020) | 1.19 [1.06 to 1.30] (to 2014-2023) |

| Global, most recent 20 years | 0.99 [0.84 to 1.10] (to 2001-2020) | 1.05 [0.90 to 1.16] (to 2004-2023) |

| Land, most recent 10 years | 1.59 [1.34 to 1.83] (to 2011-2020) | 1.71 [1.41 to 1.94] (to 2014-2023) |

| Ocean, most recent 10 years | 0.88 [0.68 to 1.01] (to 2011-2020) | 0.97 [0.77 to 1.09] (to 2014-2023) |

7 Human-induced global warming

variability of the climate system (such as variability related to El Niño/La Nina events).

7.1 Warming period definitions in the IPCC sixth assessment cycle

ing level with a crossing time 5 years in the past, so it would need to be combined with a projection of temperature change over the next decade to give a 20 -year mean with crossing time at the current year (Betts et al., 2023); we do not focus on this here due to the need for further examination of methods and implications. SR1.5 defined the current level of warming as the average human-induced warming, in global mean surface temperature (GMST), of a 30-year period centred on the current year, extrapolating any multidecadal trend into the future if necessary (see SR1.5 Chap. 1 Sect. 1.2.1). If the multidecadal trend is interpreted as being linear, this definition of current warming is equivalent to the end point of the trend line through the most recent 15 years of humaninduced warming and therefore depends only on historical warming. This interpretation produces results that are almost all identical to the present-day single-year value of humaninduced warming (see Fig. 6 and results in Sects. 7.3 and S7.3), so in practice the attribution assessment in SR1.5 was based on the single-year-attributed warming calculated using the Global Warming Index, not the trend-based definition.

7.2 Updated assessment approach of human-induced warming to date

7.3 Results

7.4 Rate of human-induced global warming

7.4.1 SR1.5 and AR6 definitions of warming rate

7.4.2 Methods

| Definition

|

(a) IPCC AR6-attributable warming update Average value for previous 10-year period | (b) IPCC SR1.5-attributable warming update Value for single-year period | ||||

| Period

|

(i) 2010-2019 Quoted from AR6 Chap. 3 Sect. 3.3.1.1.2 Table 3.1 | (ii) 2010-2019 Repeat calculation using the updated methods and datasets | (iii) 2014— 2023 Updated value using updated methods and datasets | (i) 2017 Quoted from SR1.5 Chap. 1 Sect. 1.2.1.3 | (ii) 2017 Repeat calculation using the updated methods and datasets | (iii) 2023 Updated value using updated methods and datasets |

| Component

|

||||||

| Observed | 1.06 [0.88 to 1.21] | 1.07 [0.89 to 1.22]

|

1.19 [1.06 to 1.30]

|

– | – | 1.43 [1.32 to 1.53] |

| Anthropogenic | 1.07 [0.8 to 1.3] | 1.09 [0.9 to 1.3] | 1.19 [1.0 to 1.4] | 1.0 [0.8 to 1.2]

|

1.15 [0.9 to 1.4] | 1.31 [1.1 to 1.7] |

| Well-mixed greenhouse gases |

|

1.38 [1.0 to 1.8] | 1.47 [1.0 to 1.9] | not available | 1.43 [1.0 to 1.9] | 1.57 [1.1 to 2.1] |

| Other human forcings |

|

-0.28 [-0.7 to 0.1] | -0.27 [-0.7 to 0.1] | not available | -0.28 [-0.7 to 0.1] | -0.26 [-0.7 to 0.1] |

| Natural forcings |

|

0.05 [-0.1 to 0.2] | 0.04 [-0.1 to 0.2] | not available | 0.04 [-0.1 to 0.2] | 0.04 [-0.1 to 0.2] |

used again here to estimate separate anthropogenic warming rates.

7.4.3 Results

for GMST here and are more strongly influenced by residual internal variability that remains in the anthropogenic warming signal due to the limitations in size of the CMIP ensemble, as reflected in their broader uncertainty ranges. Given that the ROF results are in this sense outlying, the standard approach of taking the median result for the overall multimethod assessment is adopted.

declining aerosol cooling (Forster et al., 2023; Quaas et al., 2022; Jenkins et al., 2022).

8 Remaining carbon budget

| Definition

|

IPCC AR6 anthropogenic warming rate update Linear trend in anthropogenic warming over the trailing 10-year period | ||||||

| Period

|

(i) 2010-2019 Quoted from AR6 Chap. 3 Sect. 3.3.1.1.2 Table 3.1 | (ii) 2010-2019 Repeat calculation using the updated methods and datasets | (iii) 2014-2023 Updated value using updated methods and datasets | ||||

| Method

|

|||||||

| Anthropogenic warming rate assessment |

|

0.25 [0.2 to 0.4] | 0.26 [0.2 to 0.4] | ||||

| GWI | 0.23 [0.19 to 0.35] |

|

|

||||

| KCC | 0.23 [0.18 to 0.29] | 0.25 [0.20 to 0.30] | 0.26 [0.20 to 0.31] | ||||

| GSAT | GMST | GMST | |||||

| ROF | 0.35 [0.30 to 0.41] | 0.27 [0.17 to 0.38] | 0.38 [0.24 to 0.52] | ||||

| GSAT | GMST | GMST | |||||