DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.13875

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-08

مرض ذبول الصنوبر: تهديد عالمي للغابات

وايلي

مرض ذبول الصنوبر: تهديد عالمي للغابات

المراسلات

البريد الإلكتروني: mback@harper-adams.ac.uk

معلومات التمويل

الملخص

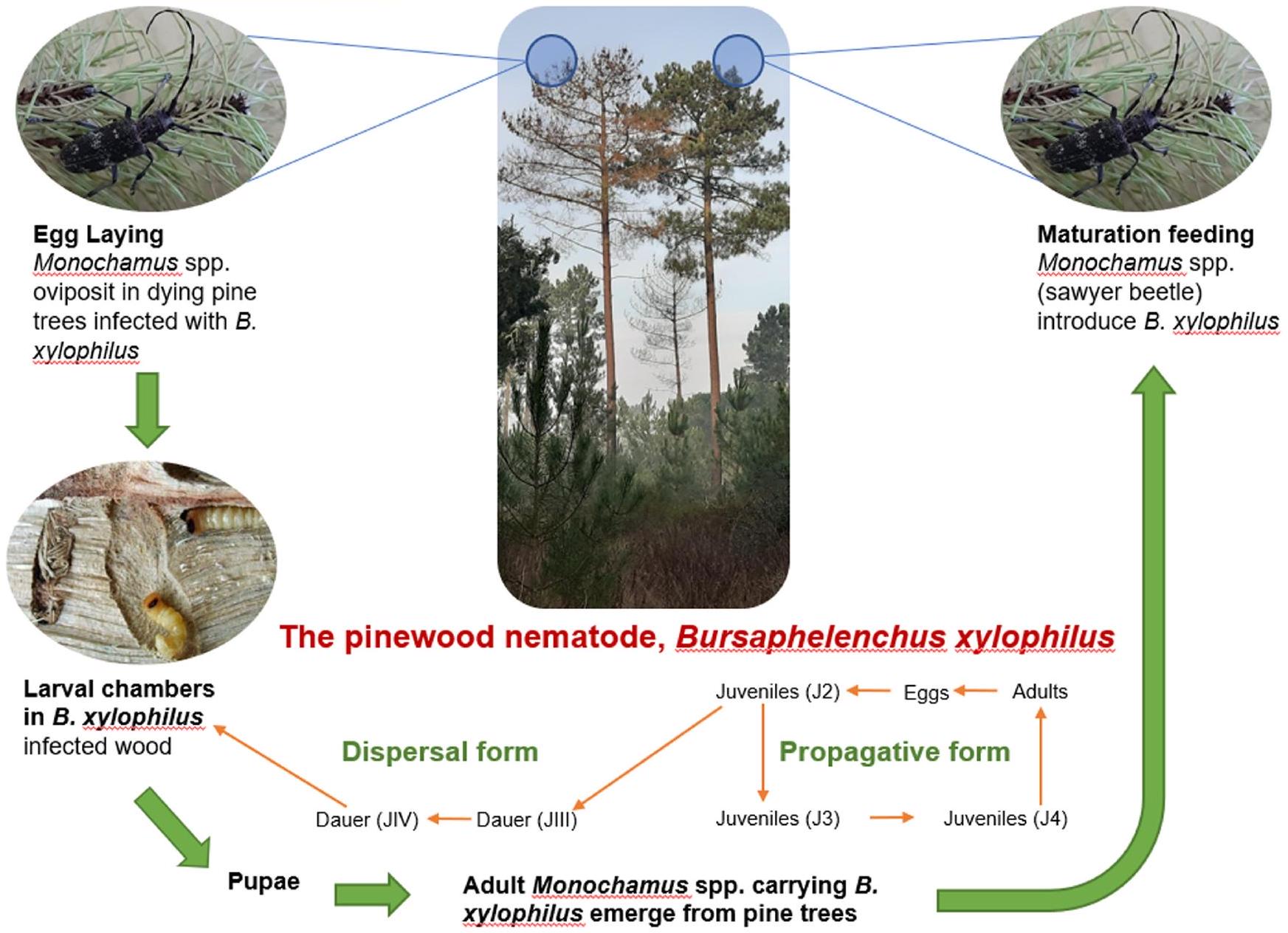

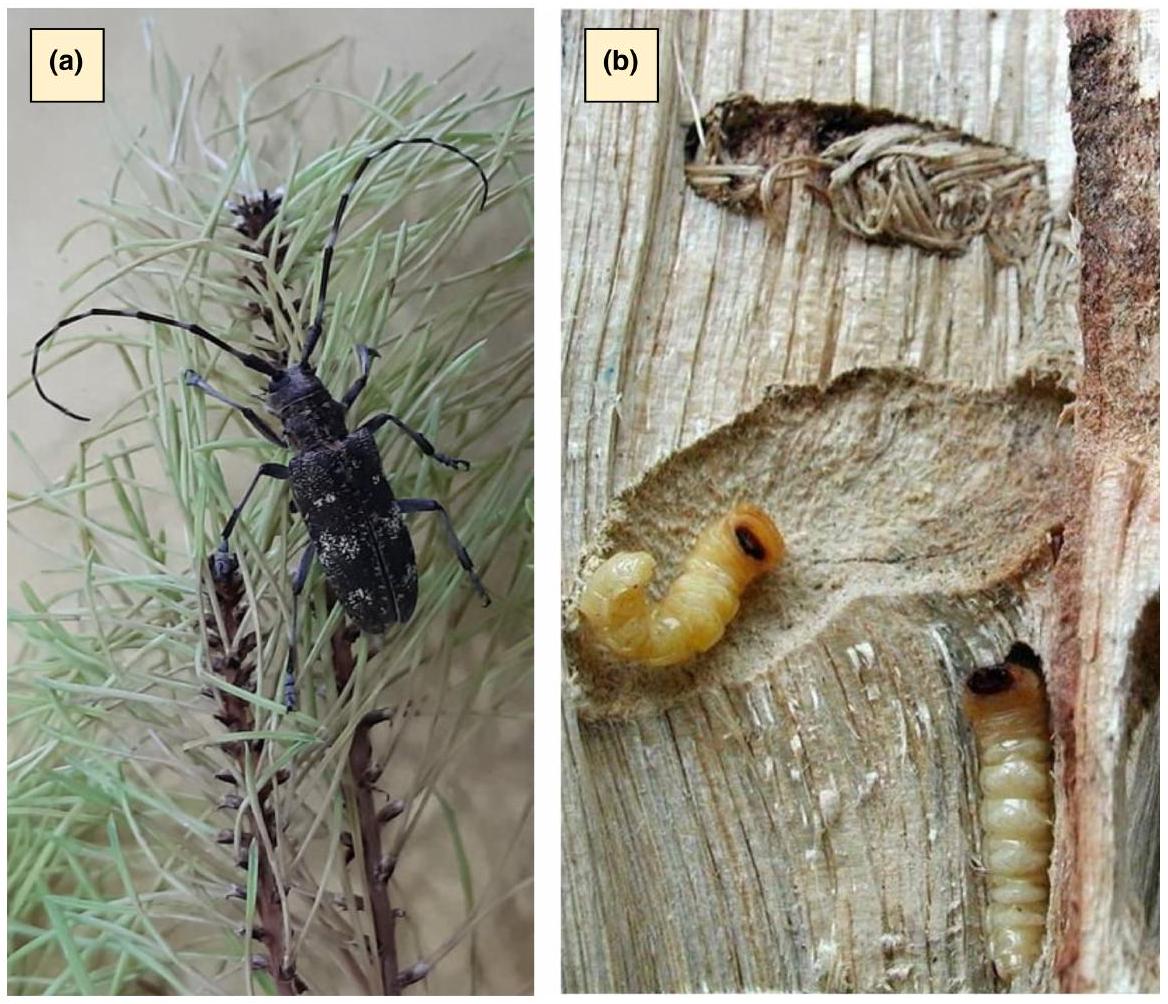

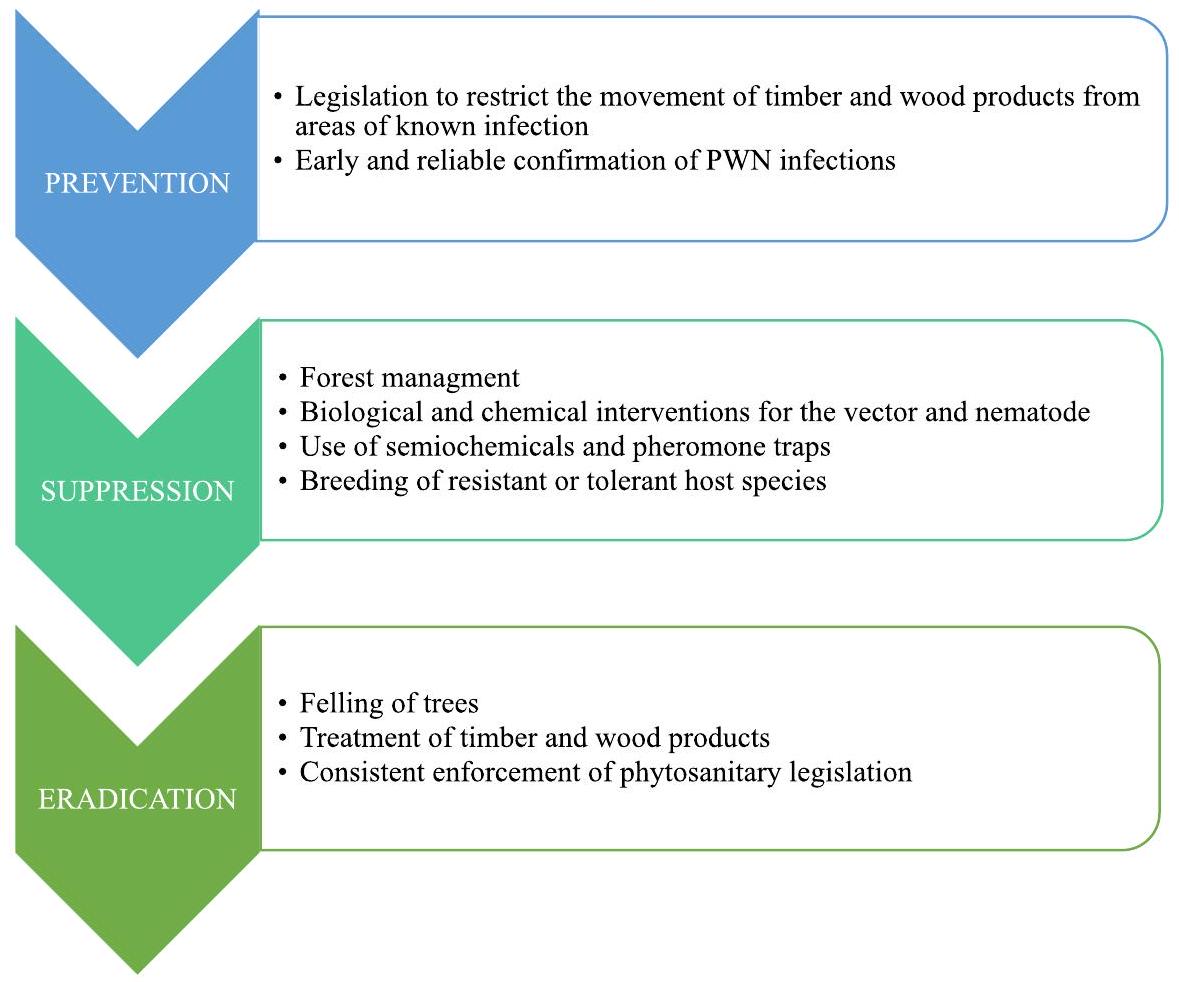

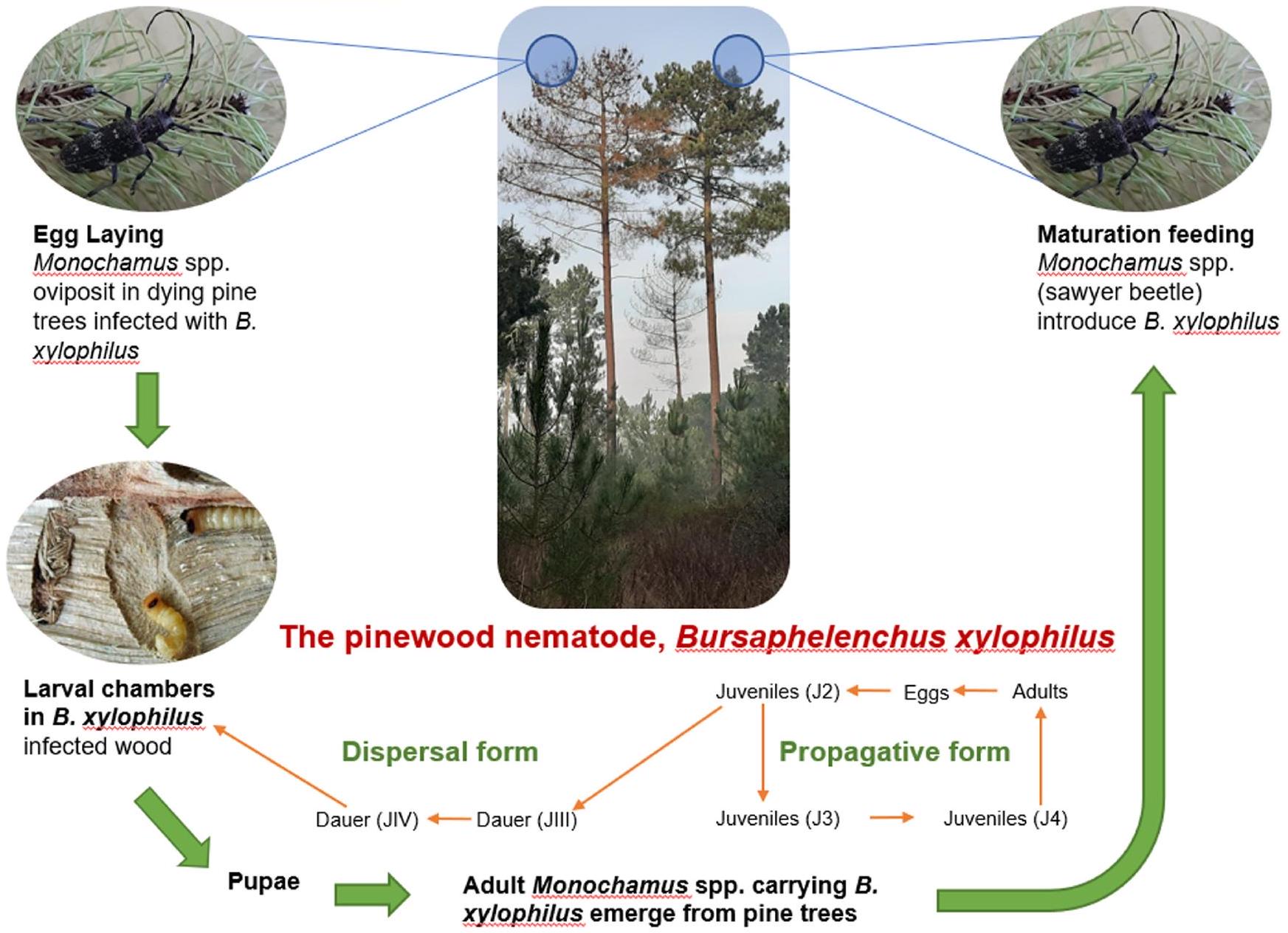

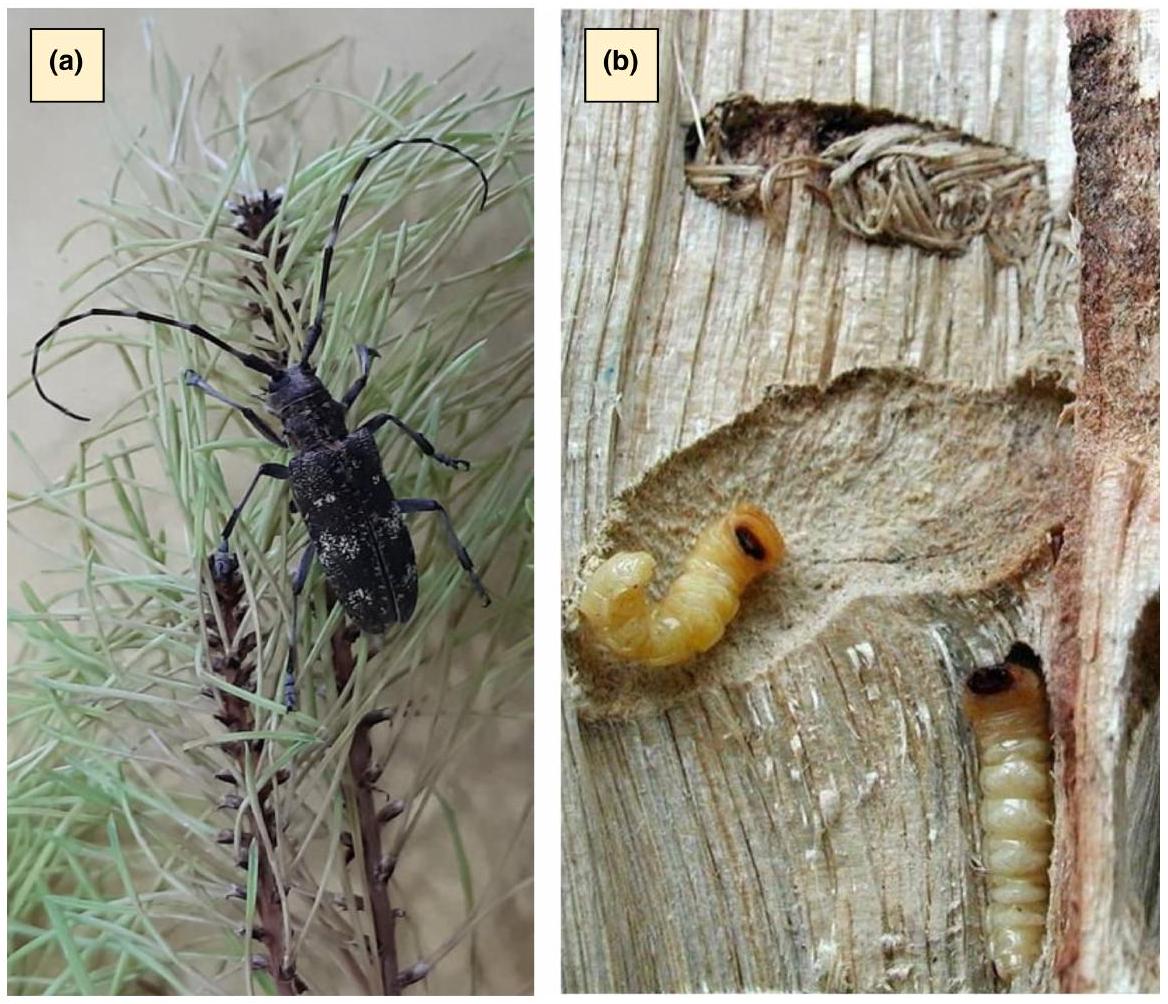

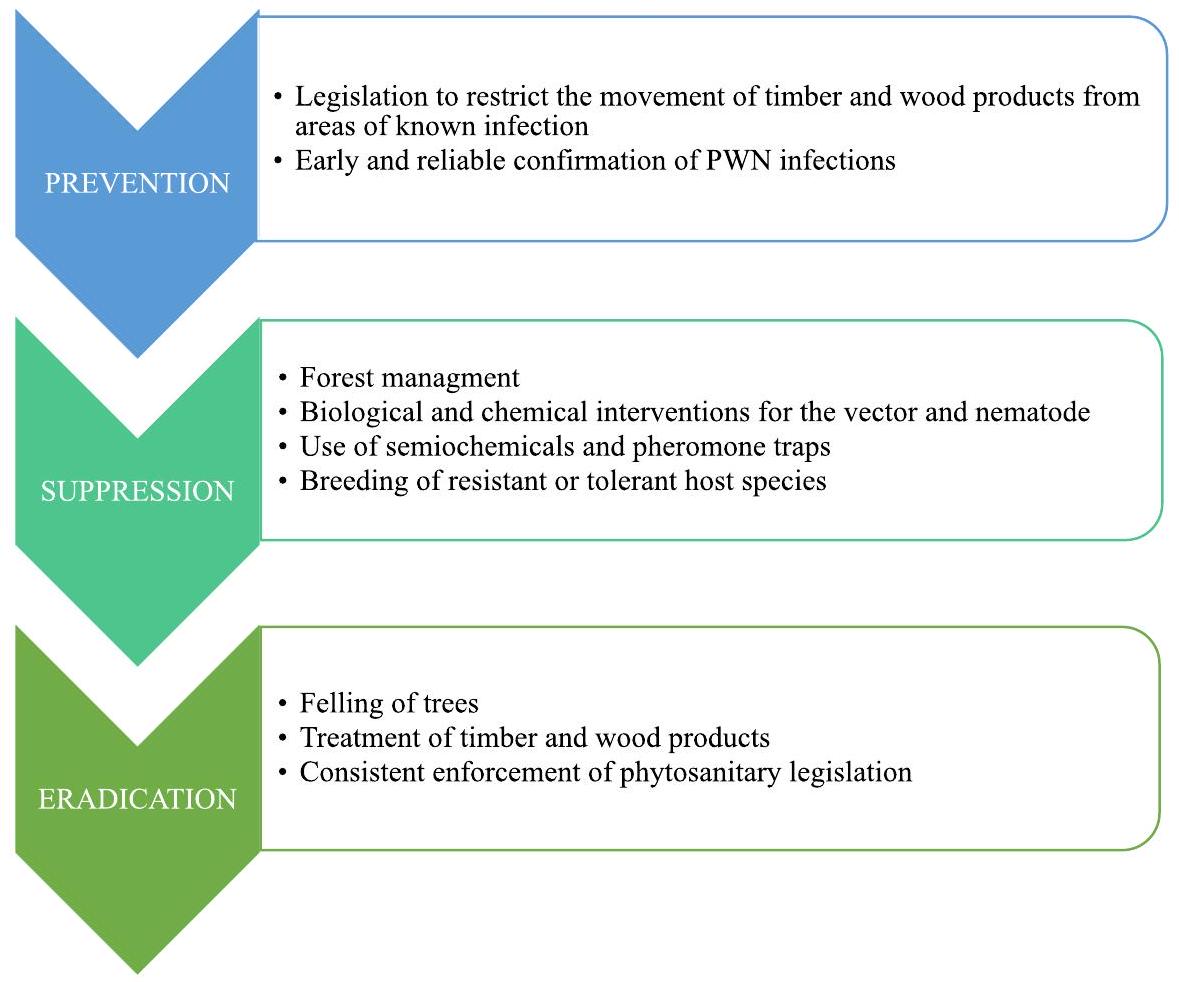

تعتبر أشجار الصنوبر الأكثر أهمية اقتصادية في العالم، ومعها أشجار الأوكاليبتوس، تهيمن على الغابات التجارية. لكن نجاح عدد قليل نسبيًا من الأنواع المزروعة على نطاق واسع، مثل صنوبر البحر (Pinus pinaster)، يأتي بتكلفة. تعتبر أشجار الصنوبر جذابة للآفات الضارة والجراثيم، بما في ذلك دودة الخشب الصنوبري (PWN)، Bursaphelenchus xylophilus، المسبب لمرض ذبول الصنوبر (PWD). تم وصف PWD في الأصل في اليابان، وقد تسبب في دمار واسع النطاق للغابات في دول مثل الصين وتايوان والبرتغال وإسبانيا والولايات المتحدة. تتسبب PWN في أضرار لا يمكن إصلاحها لنظام الأوعية الدموية في أشجار الصنوبر المضيفة، مما يؤدي إلى الوفاة في غضون 3 أشهر. تعتبر خنافس المنشار الصنوبرية (Monochamus spp.) ناقلات رئيسية لـ PWD، حيث تقوم بإدخال PWN إلى الأشجار السليمة أثناء التغذية. تساهم كائنات أخرى في انتشار وتطور PWD، بما في ذلك البكتيريا والفطريات وخنافس اللحاء. تشمل تدابير السيطرة قطع الأشجار لمنع انتقال الناقلات لـ PWN، وعلاجات المبيدات الحشرية، وفخاخ Monochamus spp. وتربية الأشجار من أجل مقاومة النباتات. تعتبر PWN مسببًا للحجر الصحي وتخضع للتشريعات المنتظمة والتدابير الصحية النباتية التي تهدف إلى تقييد الحركة ومنع إدخالها إلى مناطق جديدة. تبحث الأبحاث الحالية في استخدام المبيدات الحيوية ضد PWN وMonochamus spp. تستعرض هذه المراجعة علم الأحياء، وعلم الأوبئة، والأثر، وإدارة PWD من خلال الأبحاث المنشورة، والأدبيات الرمادية، والمقابلات مع الأشخاص المعنيين مباشرة بإدارة المرض في البرتغال.

الكلمات الرئيسية

1 | الديدان الخيطية وناقلاتها

العلاقة بين دودة الخشب الصنوبرية (PWN) وخنافس المنشار الصنوبرية (Monochamus spp.) الناقلة لها.

القنوات، حيث تتغذى على خلايا الظهارة والبارينشيم. تم تقديم وصف مفصل لآلية مرض الديدان الخيطية المسببة للأمراض بواسطة مايرز (1988) وكورودا (1989) وكورودا (2012). يبدو أن الديدان الخيطية المسببة للأمراض تمر بحدثين هجرين بمجرد دخولها الشجرة. أولاً، تهاجر عدد محدود من الديدان الخيطية (تلك التي تنجو من الراتنج اللزج المودع في قنوات الراتنج) إلى اللحاء، الخشب والكامبيوم. ثانياً، يبدأ التكاثر مع اتساع آفات التغذية وتوقف إنتاج الراتنج، وتهاجر العديد من الديدان الخيطية إلى الأنسجة الوعائية.

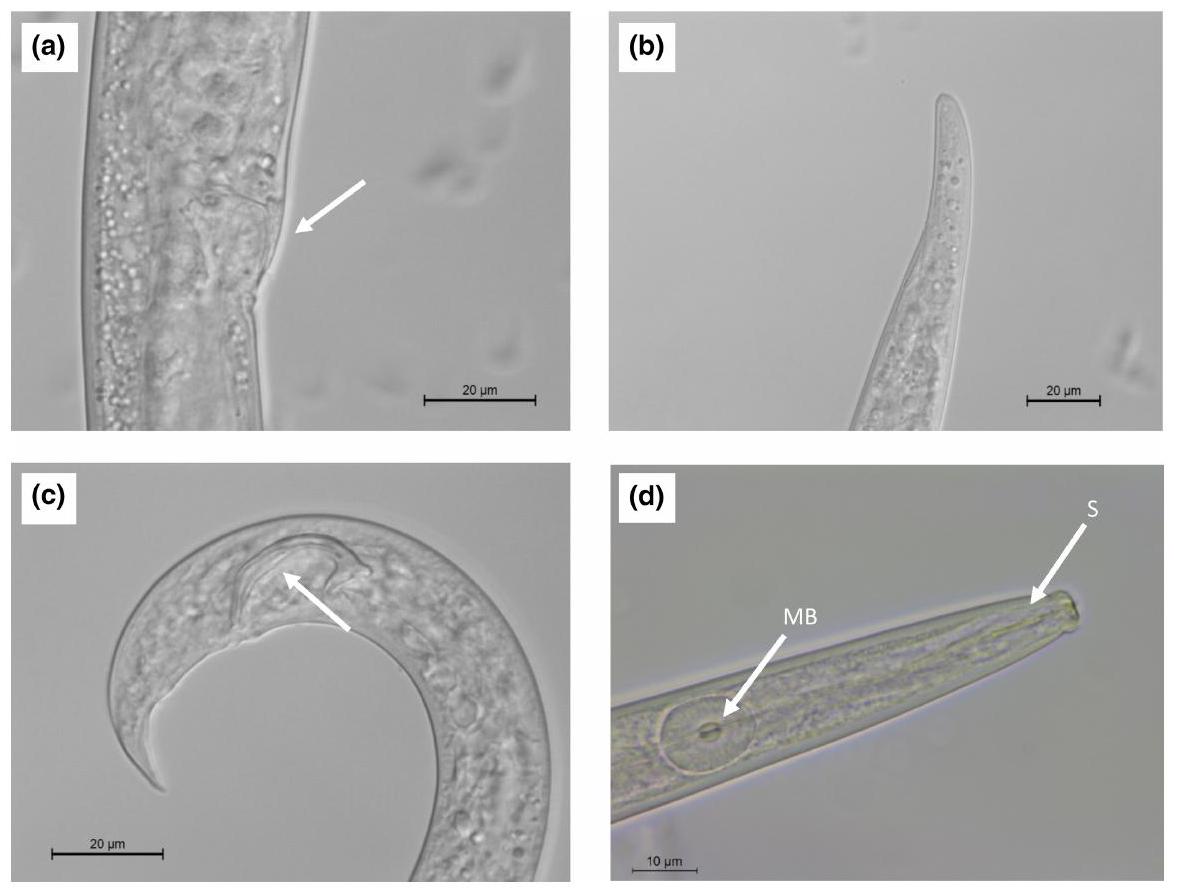

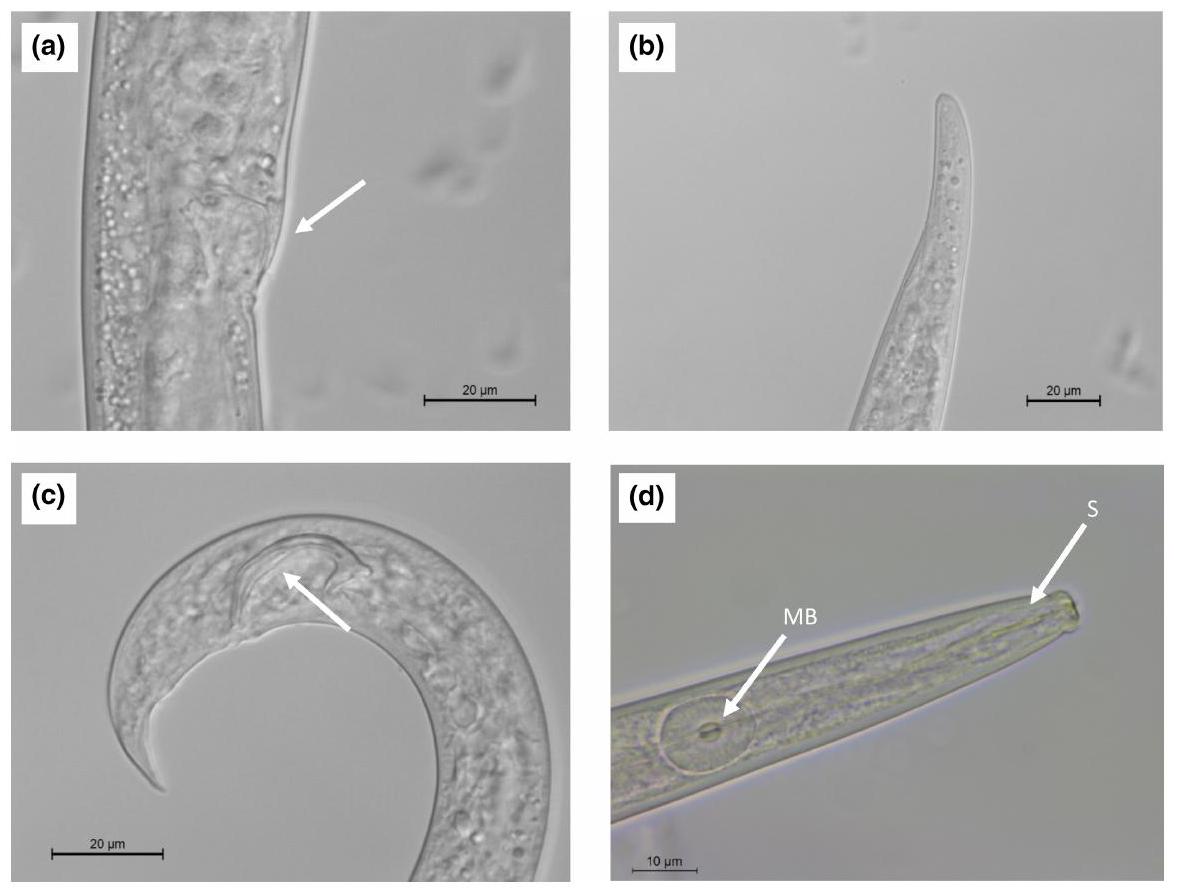

2 | تحديد الديدان الخيطية

3 | توزيع B. xylophilus

ويعتقد أن B. xylophilus قد نشأ في الولايات الشرقية من الولايات المتحدة، حيث تم تسجيله في 36 ولاية. كما أن الدودة الخيطية منتشرة أيضًا في كندا، حيث توجد في جميع الأقاليم والمقاطعات، باستثناء جزيرة الأمير إدوارد.

4 | الناقلات، مونوشاموس spp.

| نوع | موجود في الاتحاد الأوروبي | حدوث |

| م. ألتيرناتوس | لا | الصين، اليابان، كوريا، تايوان |

| م. كارولينينسيس | لا | كندا، الولايات المتحدة |

| م. كلوماتور | لا | كندا، الولايات المتحدة |

| م. غالوبروفينسياليس | نعم | آسيا، أوروبا، شمال أفريقيا |

| م. مارموراتور | لا | كندا، الولايات المتحدة |

| M. mutator | لا | كندا، الولايات المتحدة |

| م. نيتنس | لا | اليابان |

| م. نوتاتوس | لا | كندا، الولايات المتحدة |

| م. أوبتوس | لا | كندا، الولايات المتحدة |

| م. روزنميلري (أوروسوفي) | نعم | الصين، اليابان، شمال أوروبا، روسيا |

| م. سالتواريوس | نعم | الصين، اليابان، كوريا، تايوان |

| م. سوتيلاتوس | لا | كندا، الولايات المتحدة |

| م. تيتيلاتور | لا | كندا، الولايات المتحدة |

خلال فترة حياتهم، يمكنهم السفر لمسافة تصل إلى 10 كيلومترات (ماس وآخرون، 2013؛ توغاشي وشيديسادا، 2006). يمثل هذا تحديًا كبيرًا في محاولة احتواء المناطق المصابة، وسيتم مناقشته لاحقًا. يمكن أيضًا نقل الخنافس الحاملة لبكتيريا ب. زيلوفيلاس في الخشب المقطوع والخشب المدور، وهو خطر محتمل وكبير على المناطق التي لم يحدث فيها مرض موت الصنوبر بعد.

5 | المتجهات وموائلها الرئيسية

يمتلك P. pinaster ثلاثة أنواع كيميائية مختلفة تتعلق بنسبة ووجود المركبات العضوية المتطايرة المختلفة. وجد غونكالفيس وآخرون (2020)، الذين عملوا أيضًا في البرتغال، أن انبعاثات المركبات العضوية المتطايرة زادت عندما كانت M. galloprovincialis تتغذى على P. pinaster وأن كثافة السكان للناقل قد تكون عاملًا حاسمًا في كيفية انتشار مرض PWD وتطوره. لقد فتحت الأبحاث حول المركبات العضوية المتطايرة إمكانية استخدام محاصيل فخ لجذب الناقلات بعيدًا عن الصنوبر، وسيتم مناقشتها لاحقًا في المراجعة.

6 | التفاعلات الميكروبية وB. xylophilus

6.1 | بكتيريا مرتبطة بالديدان الخيطية

نباتات أخرى ذات قيمة عالية. يعود نجاحها جزئيًا إلى البكتيريا التي تحملها، مثل Photorhabdus spp. وXenorhabdus spp.، وهي بكتيريا سالبة الجرام مرتبطة بـ Heterorhabditis وSteinernema، وهما نوعان شائعان من EPNs. بمجرد دخولها إلى عوائلها الحشرية، تطلق EPNs (تسترجع) بكتيرياها المرتبطة، التي تفرز سمومًا تقمع جهاز المناعة لدى الحشرة، وتكسر أنسجة الحشرة وتحث على تكاثر EPNs (دزيديخ وآخرون، 2020).

6.2 | البكتيريا الداخلية ومرض ذبول الصنوبر

في سلسلة من المسارات الخلوية، التي تحفز جزيئات دفاع النبات مثل البروتينات المرتبطة بالمسببات (PR)، وأنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) والفيتو أليكسينات. يُشار إلى المحفز لهذا النوع من تنشيط الدفاع عادةً باسم أنماط جزيئية مرتبطة بالضرر (DAMPs). قد يكون لبعض الأنواع البكتيرية الداخلية أيضًا تأثير سلبي على صحة شجرة الصنوبر من خلال المساهمة في PWD. قارن ألفيس وآخرون (2016) الميكروبيومات لـ M. galloprovincialis وB. xylophilus مع تلك الخاصة بـ P. pinaster، أحد أنواع الصنوبر التي تهاجمها PWD. كانت المجتمعات البكتيرية المرتبطة بالناقل والديدان الخيطية و

6.3 | دور الفطريات في مرض ذبول الصنوبر

(تشاو وآخرون، 2014). الأسيكاروسيدات هي جزيئات منخفضة الوزن توجد في الفيرومونات التي تفرزها الديدان الخيطية الحرة والديدان الطفيلية للنباتات لتسهيل سلوكيات مثل التشتت، والتجمع، وبدء الدوامة، والجذب الجنسي (تشاو وآخرون، 2016). بشكل غير متوقع، زادت الأسيكاروسيدات asc-C5 وasc-

7 | الأعراض

8 | الخسائر والأثر الاقتصادي

8.1 | آسيا

8.2 | أوروبا

8.3 | أمريكا الشمالية

9 | الحفاظ على المرض بعيدًا

9.1 | التدابير الصحية النباتية، التشريعات والاستجابات الوطنية

التحكم من خلال التطبيق الجوي للمبيدات الحشرية، وهي ممارسة بدأت في السبعينيات. يتم استخدام استراتيجية مماثلة في الصين، التي تقوم أيضًا بإجراء تفتيشات صارمة على الأخشاب المستوردة وغيرها من منتجات الصنوبر في الموانئ (تشاو وآخرون، 2020، 2021).

9.2 | إدارة المرض: الأساليب الحالية

9.3 | إدارة المرض: أساليب جديدة

9.4 | استهداف دودة الخشب الصنوبري

تم العثور على تباين في المقاومة لـ (P. pinaster) مقارنةً بما تم الإبلاغ عنه في الأصل (Carrasquinho et al., 2018). تم اختيار السلالات المقاومة عشوائيًا من برنامج فحص ظاهري، مما يبرز المشكلات المحتملة مع هذا النهج. يشير استخدام العلامات الجزيئية (مواقع الصفات الكمية) المرتبطة بالمقاومة إلى طريقة أكثر موثوقية لتحديد خطوط الأشجار المناسبة، على الرغم من الحاجة إلى مزيد من البحث.

10 | دراسة حالة البرتغال: تأملات شخصية

تم السيطرة على تفشي المرض. تم إجراء مقابلات مع عدة علماء لمعرفة المزيد عن تجاربهم والرؤى التي اكتسبوها من المشاركة الطويلة مع المرض. تم تقديم نتائج المقابلات مع خبيرين رئيسيين في مرض PWD أدناه. تم إعداد قائمة قصيرة من الأسئلة مسبقًا، ولكن تم تشجيع المشاركين في المقابلات أيضًا على مشاركة المعلومات حول مواضيع أخرى.

10.1 | الأستاذ مانويل غالفاو دي ميلو إي موتا

نيمالاب-ميد وقسم البيولوجيا، جامعة إيفورا

10.2 | الدكتور لويس بونيفاسيو

المعهد الوطني للبحث الزراعي والبيطري (INIAV)

بتنسيق مع الدكتور هيو إيفانز من لجنة الغابات. في الآونة الأخيرة، عمل على دراسة حالة في شبه جزيرة ترويا، وهي منتجع سياحي يقع على الضفة الجنوبية لنهر سادو، بالقرب من مدينة سيتوبال (منطقة سيتوبال). وقال إن هذا كان مثالًا رائعًا على كيفية تقليل نهج الإدارة المتكاملة لحدوث مرض PWD إلى ما دون

| أنواع الأشجار | مساحة 1995 (هكتار) | مساحة 2010 (هكتار) |

| الصنوبر البحري |

|

715,000 |

| البلوط الفليني | ٦٦٠,٠٠٠ | 735,000 |

| الأوكاليبتوس غلوبولوس | ٥٠٠,٠٠٠ | ٨١٠,٠٠٠ |

ضغط الاختيار على متغيرات B. xylophilus وغيرها من الآفات والأمراض المحلية للصنوبر.

11 | الاستنتاجات

لكن هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من التطوير التجاري. إن النجاح في تسويق B. bassiana لمكافحة خنفساء الصنوبر السوداء في اليابان هو خطوة واعدة إلى الأمام.

الشكر والتقدير

بيان توفر البيانات

ORCID

ماريا ل. إيناسيو ® https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6883-5288

REFERENCES

Afzal, I., Shinwari, Z.K., Sikandar, S. & Shahzad, S. (2019) Plant beneficial endophytic bacteria: mechanisms, diversity, host range and genetic determinants. Microbiological Research, 221, 36-49.

Álvarez, G., Etxebeste, I., Gallego, D., David, G., Bonifacio, L., Jactel, H. et al. (2015) Optimization of traps for live trapping of pine wood nematode vector Monochamus galloprovincialis. Journal of Applied Entomology, 139, 618-626.

Alves, M., Pereira, A., Matos, P., Henriques, J., Vicente, C., Aikawa, T. et al. (2016) Bacterial community associated to the pine wilt disease insect vectors Monochamus galloprovincialis and Monochamus alternatus. Scientific Reports, 6, 23908.

Anonymous. (2020) Nagano communities plagued by pine parasite at odds over pesticide. The Japan Times. Available at: https://www. japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/05/22/national/nagano-tree-paras ites-chemicals/#:~:text=Nagano%20communities%20plagued% 20by%20pine,over%20pesticide%20%2D%20The%20Japan% 20Times [Accessed 14th September 2023].

Bi, Z., Gong, Y., Huang, X., Yu, H., Bai, L. & Hu, J. (2015) Efficacy of four nematicides against the reproduction and development of pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Journal of Nematology, 47, 126-132.

Bonifácio, L., Naves, P. & Sousa, E. (2015) Vector-Plant. In: Sousa, E., Vale, F. & Abrantes, I. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease in Europe – biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon: FNAPF-Federação Nacional das Associações de Proprietários Florestais, pp. 125-158.

Braasch, H. (2001) Bursaphelenchus species in conifers in Europe: distribution and morphological relationships. EPPO Bulletin, 31, 127-142.

Braasch, H. & Schönfeld, U. (2015) Improved morphological key to the species of the Xylophilus group of the genus Bursaphelenchus Fuchs, 1937. EPPO Bulletin, 45, 73-80.

Carrasquinho, I., Lisboa, A., Inácio, M.L. & Gonçalves, E. (2018) Genetic variation in susceptibility to pine wilt disease of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Aiton) half-sib families. Annals of Forest Science, 75, 85.

Cheng, X.-Y., Tian, X.-L., Wang, Y.-S., Lin, R.-M., Mao, Z.-C., Chen, N. et al. (2013) Metagenomic analysis of the pinewood nematode microbiome reveals a symbiotic relationship critical for xenobiotics degradation. Scientific Reports, 3, 1869.

de la Fuente, B. & Saura, S. (2021) Long-term projections of the natural expansion of the pine wood nematode in the Iberian Peninsula. Forests, 12, 849.

Donald, P.A., Stamps, W.T., Linit, M.J. & Todd, T.C. (2016) Pine wilt disease. The Plant Health Instructor. Available at: https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/disandpath/nematode/pdlessons/Pages/Pine Wilt.aspx [Accessed 14th September 2023].

Dziedziech, A., Shivankar, S. & Theopold, U. (2020) High-resolution infection kinetics of entomopathogenic nematodes entering Drosophila melanogaster. Insects, 11, 60.

EPPO. (2013) EPPO standards PM 7/4 (3) Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. EPPO Bulletin, 43, 105-118.

EPPO. (2023) EPPO standards PM 7/4 (4) Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. EPPO Bulletin, 53, 156-183.

EUSTAFOR. (2013) NATURA 2000 Management in European state forests. Brussels: European State Forest Association. Available at: https:// eustafor.eu/uploads/EUSTAFOR_Natura_2000_Booklet_20191 218-compressed_compressed.pdf [Accessed 14th September 2023].

FAO. (2018) ISPM 15 Regulation of wood packaging material in international trade. Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/mb160e/ mb160e.pdf [Accessed 13th September 2023].

Faria, J.M., Barbosa, P., Bennett, R.N., Mota, M. & Figueiredo, A.C. (2013) Bioactivity against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus: nematotoxics from essential oils, essential oils fractions and decoction waters. Phytochemistry, 94, 220-228.

Fonseca, L., Cardoso, J. & Abrantes, I. (2015) Plant-nematode. In: Sousa, E., Vale, F. & Abrantes, I. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease in Europe – biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon: FNAPF-Federação Nacional das Associações de Proprietários Florestais, pp. 34-78.

Fonseca, L., Cardoso, J., Lopes, A., Pestana, M., Abreu, F., Nunes, N. et al. (2012) The pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, in Madeira Island. Helminthologia, 49, 96-103.

Forest Research. (2020) Pine wood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Available at: https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools -and-resources/pest-and-disease-resources/pinewood-nematode-embursaphelenchus-xylophilus [Accessed 30th January 2023].

Forestry Commission. (2017) Contingency plan for the pine wood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus) and its longhorn beetle (Monochamus spp.) vectors. Available at: https://cdn.forestrese arch.gov.uk/2022/02/pwncontingencyplan21november2017.pdf [Accessed 7th June 2023].

Futai, K. (2013) Pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 51, 61-83.

Gonçalves, E., Figueiredo, A.C., Barroso, J.G., Henriques, J., Sousa, E. & Bonifácio, L. (2020) Effect of Monochamus galloprovincialis feeding on Pinus pinaster and Pinus pinea, oleoresin and insect volatiles. Phytochemistry, 169, 112-159.

Gonçalves, E., Figueiredo, A.C., Barroso, J.G., Millar, J.G., Henriques, J., Sousa, E. et al. (2021) Characterization of cuticular compounds of the cerambycid beetles Monochamus galloprovincialis, Arhopalus syriacus, and Pogonocherus perroudi, potential vectors of pinewood nematode. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 169, 183-194.

Gruffudd, H.R., Schröder, T., Jenkins, T.A.R. & Evans, H.F. (2019) Modeling pine wilt disease (PWD) for current and future climate scenarios as part of a pest risk analysis for pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner and Buhrer) Nickle in Germany. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 126, 129-144.

Hirata, A., Nakamura, K., Nakao, K., Kominami, Y., Tanaka, N., Ohashi, H. et al. (2017) Potential distribution of pine wilt disease under future climate change scenarios. PLoS One, 12, e0182837.

Ibeas, F., Gallego, D., Díez, J.J. & Pajares, J.A. (2007) An operative kairomonal lure for managing pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis (Coleoptera: Cerymbycidae). Journal of Applied Entomology, 131, 13-20.

ICNF. (2015) 6th Inventário Florestal Nacional. Relatório Final. Available at: https://www.icnf.pt/api/file/doc/c8cc40b3b7ec8541 [Accessed 18th September 2023].

ICNF. (2023) Limpeza de terrenos junto a habitações. Available at: https:// www.icnf.pt/florestas/gfr/gfrfaq [Accessed 18th September 2023].

Jactel, H., Bonifacio, L., Van Halder, I., Vétillard, F., Robinet, C. & David, G. (2019) A novel, easy method for estimating pheromone trap attraction range: application to the pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis. Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 21, 8-14.

Kamata, N. (2008) Integrated pest management of pine wilt disease in Japan: tactics and strategies. In: Zhao, B.G., Futai, K., Sutherland,

J.R. & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 304-322.

Kanzaki, N. & Giblin-Davis, R.M. (2018) Diversity and plant pathogenicity of Bursaphelenchus and related nematodes in relation to their vector bionomics. Current Forestry Reports, 4, 85-100.

Kawazu, K. (1998) Pathogenic toxins of pine wilt disease. Kagaku to Seibutsu, 36, 120-124.

Kiyohara, T. & Bolla, R.I. (1990) Pathogenic variability among populations of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Forest Science, 36, 1061-1076.

Kobayashi, T., Sasaki, K. & Mamiya, Y. (1974) Fungi associated with Bursaphelenchus lignicolus, the pine wood nematode (I). Journal of the Japanese Forestry Society, 56, 136-145.

Kosaka, H., Aikawa, T., Ogura, N., Tabata, K. & Kiyohara, T. (2001) Pine wilt disease caused by the pine wood nematode: the induced resistance of pine trees by the avirulent isolates of nematode. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 107, 667-675.

Kuroda, K. (1989) Terpenoids causing tracheid-cavitation in Pinus thunbergii infected by the pine wood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Japanese Journal of Phytopathology, 55, 170-178.

Kuroda, K. (2012) Monitoring of xylem embolism and dysfunction by the acoustic emission technique in Pinus thunbergii inoculated with the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Journal of Forest Research, 17, 58-64.

Lee, H.-J. & Park, O.K. (2019) Lipases associated with plant defense against pathogens. Plant Science, 279, 51-58.

Liu, G., Lin, X., Xu, S., Liu, G., Liu, Z., Liu, F. et al. (2020) Efficacy of fluopyram as a candidate trunk-injection agent against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 157, 403-411.

Maehara, N. & Futai, K. (1996) Factors affecting both the numbers of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae), carried by the Japanese pine sawyer, Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), and the nematode’s life history. Applied Entomology and Zoology, 31, 443-452.

Maehara, N. & Futai, K. (2000) Population changes of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae), on fungi growing in pine-branch segments. Applied Entomology and Zoology, 35, 413-417.

Maehara, N., Hata, K. & Futai, K. (2005) Effect of blue-stain fungi on the number of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae) carried by Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). Nematology, 7, 161-167.

Mamiya, Y. (1983) Pathology of the pine wilt disease caused by Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 21, 201-220.

Mamiya, Y. & Kiyohara, T. (1972) Description of Bursaphelenehus lignicolus n. sp. (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae) from pine wood and histopathology of nematode-infested trees. Nematologica, 18, 120-124.

Mas, H., Hernández, R., Villaroya, M., Sánchez, G., Pérez-Laorga, E., González, E. et al. (2013) Comportamiento de dispersión y capacidad de vuelo a larga distancia de Monochamus galloprovincialis (Olivier 1795). 6th Congreso forestal español. 6CFE01-393. Available from: http://secforestales.org/publicaciones/index.php/ congresos_forestales/article/view/14702 [Accessed 30th January 2024].

Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. (2023) Nematodo de la madera del pino (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Available from: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/agricultura/temas/sanidad-vegetal/ organismos-nocivos/nematodo-de-la-madera-del-pino/ [Accessed 13th September 2023].

Morais, P.V., Proença, D.N., Francisco, R. & Paiva, G. (2015) Bacteria-nematode-plant. In: Sousa, E., Vale, F. & Abrantes, I. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease in Europe – biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon: FNAPF-Federação Nacional das Associações de Proprietários Florestais, pp. 161-192.

Mota, M., Futai, K. & Vieira, P. (2009) Pine wilt disease and the pinewood nematode. In: Ciancio, A. & Mukerji, K.G. (Eds.) Integrated management of fruit crops and forest nematodes, Vol. IV. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 253-274.

Mota, M.M., Braasch, H., Bravo, M.A., Penas, A.C., Burgermeister, W., Metge, K. et al. (1999) First report of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in Portugal and in Europe. Nematology, 1, 727-734.

Myers, R.F. (1988) Pathogenesis in pine wilt caused by pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Journal of Nematology, 20, 236-244.

Nakamura-Matori, K. (2008) Vector-host tree relationships and the abiotic environment. In: Zhao, B.G., Fautai, K., Sutherlans, J.R. & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease. New York: Springer, pp. 144-161.

Nascimento, F.X., Hasegawa, K., Mota, M. & Vicente, C.S.L. (2015) Bacterial role in pine wilt disease development. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 7, 51-63.

Naves, P., Bonifácio, L., Inácio, M. & Sousa, E. (2018) Integrated management of pine wilt disease in Troia. Review de Ciências Agrárias, 41, 12-19.

Naves, P., Bonifácio, L. & Sousa, E. (2016) The pine wood nematode and its local vectors in the Mediterranean basin. In: Paine, T.D. & Lieutier, F. (Eds.) Insects and diseases of mediterranean forest systems. New York: Springer, pp. 329-378.

Naves, P., Camacho, S., De Sousa, E. & Quartau, J. (2006) Entrance and distribution of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus on the body of its vector Monochamus galloprovincialis. Entomologia Generalis, 29, 71-80.

Naves, P., Kenis, M. & Sousa, E. (2005) Parasitoids associated with Monochamus galloprovincialis (Oliv.) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) within the pine wilt nematode-affected zone in Portugal. Journal of Pest Science, 78, 57-62.

Nickle, W.A.R., Golden, A.M., Mamiya, Y. & Wergin, W.P. (1981) On the taxonomy and morphology of the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner & Buhrer 1934) Nickle 1970. Journal of Nematology, 13, 385-392.

Nose, M. & Shiraishi, S. (2008) Breeding for resistance to pine wilt disease. In: Zhao, B.G., Futai, K., Sutherland, J.R. & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 334-350.

Oku, H., Shiraishi, T., Ouchi, S., Kurozumi, S. & Ohta, H. (1980) Pine wilt toxin, the metabolite of a bacterium associated with a nematode. Naturwissenschaften, 67, 198-199.

Pajares, J.A., Alvarez, G., Ibeas, F., Gallego, D., Hall, D.R. & Farman, D.I. (2010) Identification and field activity of a male-produced aggregation pheromone in the pine sawyer beetle, Monochamus galloprovincialis. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 36, 570-583.

Pan, C.-S. (2011) Sōng cái xiànchóng bìng yánjiū jìnzhǎn [Development of studies on pinewood nematodes disease]. Journal of Xiamen University (Natural Science), 50, 476-483.

Pires, D., Vicente, C.S.L., Inácio, M.L. & Mota, M. (2022) The potential of Esteya spp. for the biocontrol of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Microorganisms, 10, 168.

Plantard, O., Picard, D., Valette, S., Scurrah, M., Grenier, E. & Mugiéry, D. (2008) Origin and genetic diversity of Western European populations of the potato cyst nematode (Globodera pallida) inferred from mitochondrial sequences and microsatellite loci. Molecular Ecology, 17, 2208-2218.

Proença, D.N., Francisco, R., Kublik, S., Schöler, A., Vestergaard, G., Schloter, M. et al. (2017) The microbiome of endophytic, wood colonizing bacteria from pine trees as affected by pine wilt disease. Scientific Reports, 7, 4205.

Proença, D.N., Francisco, R., Santos, C.V., Lopes, A., Fonseca, L., Abrantes, I.M. et al. (2010) Diversity of bacteria associated with

Rajasekharan, S.K., Raorane, C.J. & Lee, J. (2020) Nematicidal effects of piperine on the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology, 23, 863-868.

Rodrigues, A.M., Mendes, M.D., Lima, A.S., Barbosa, P.M., Ascensão, L., Barroso, J.G. et al. (2017) Pinus halepensis, Pinus pinaster, Pinus pinea, and Pinus sylvestris essential oil chemotypes and monoterpene hydrocarbon enantiomers, before and after inoculation with the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Chemical Biodiversity, 14, e1600153.

Schenk, M., Loomans, A., den Nijs, L., Hoppe, B., Kinkar, M. & Vos, S. (2020) Pest survey card on Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. EFSA Supporting Publications, 17, EN-1782. Available from: https://doi. org/10.2903/sp.efsa.2020.EN-1782

Shimazu, M. (2009) Use of microbes for control of Monochamus alternatus, vector of the invasive pinewood nematode. In: Hajek, A.E., Glare, T.R. & O’Callaghan, M. (Eds.) Use of microbes for control and eradication of invasive arthropods. Progress in biological control, Vol. 6. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 141-157.

Shin, S.C. (2008) Pine wilt disease in Korea. In: Zhao, B.G., Futai, K., Sutherland, J.R. & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 26-32.

Soliman, T., Mourits, M.C.M., van der Werf, W., Hengeveld, G.M., Robinet, C. & Oude Lansink, A.G.J.M. (2012) Framework for modelling economic impacts of invasive species, applied to pine wood nematode in Europe. PLoS One, 7, e45505.

Sousa, E., Bonifácio, L., Naves, P. & Viera, M. (2015) Pine wilt disease management. In: Sousa, E., Vale, F. & Abrantes, I. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease in Europe – biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon: FNAPF-Federação Nacional das Associações de Proprietários Florestais, pp. 125-158.

Sousa, E., Naves, P. & Vieira, M. (2013) Prevention of pine wilt disease induced by Bursaphelenchus xylophilus and Monochamus galloprovincialis by trunk injection of emamectin benzoate. Phytoparasitica, 41, 143-148.

Sousa, E., Rodrigues, J.M., Bonifácio, L.F., Naves, P.M. & Rodrigues, A. (2011) Management and control of the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, in Portugal. In: Boeri, F. & Chung, J.A. (Eds.) Nematodes: morphology, functions and management strategies. New York: Nova Publishers, pp. 157-178.

Steiner, G. & Buhrer, E.M. (1934) Aphelenchoides xylophilus n. sp., a nematode associated with blue-stain and other fungi in timber. Journal of Agricultural Research, 48, 949-951.

Takai, K., Soejima, T., Suzuki, T. & Kawazu, K. (2000) Emamectin benzoate as a candidate for a trunk-injection agent against the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Pest Management Science, 56, 937-941.

Togashi, K. (1990) Change in the activity of adult Monochamus alternatus Hope (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in relation to age. Applied Entomology and Zoology, 25, 153-159.

Togashi, K. & Shigesada, N. (2006) Spread of the pinewood nematode vectored by the Japanese pine sawyer: modelling and analytical approaches. Population Ecology, 48, 271-283.

Vasconcelos, T. & Duarte, I. (2015) Biotic/abiotic factors-plant. In: Sousa, E., Vale, F. & Abrantes, I. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease in Europe – biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon: FNAPF-Federação Nacional das Associações de Proprietários Florestais, pp. 195-220.

Vicente, C.S., Ikuyo, Y., Shinya, R., Mota, M. & Hasegawa, K. (2015) Catalases induction in high virulence pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus under hydrogen peroxide-induced stress. PLoS One, 10, e0123839.

Vieira, P., Burgermeister, W., Mota, M., Metge, K. & Silva, G. (2007) Lack of genetic variation of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in Portugal revealed by RAPD-PCR analyses. Journal of Nematology, 39, 118-126.

Yano, S. (1913) Investigation on pine death in Nagasaki prefecture. Sanrin-Kouhou, 4, 1-14.

Yi, C.K., Byun, B.H., Park, J.D., Yang, S.I. & Chang, K.H. (1989) First finding of the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner et Buhrer) Nickle and its insect vector in Korea. Research Reports of the Forest Research Institute, 3, 141-149.

Yu, H.B., Jung, Y.H., Lee, S.M., Choo, H.Y. & Lee, D.W. (2016) Biological control of Japanese pine sawyer, Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) using Korean entomopathogenic nematode isolates. The Korean Journal of Pesticide Science, 20, 361-368.

Zhao, B.G. (2008) Pine wilt disease in China. In: Zhao, B.G., Futai, K., Sutherland, J.R. & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 18-25.

Zhao, J., Hu, K., Chen, K. & Shi, J. (2021) Quarantine supervision of wood packaging materials (WPM) at Chinese ports of entry from 2003 to 2016. PLoS One, 16, e0255762.

Zhao, L., Mota, M., Vieira, P., Butcher, R.A. & Sun, J. (2014) Interspecific communication between pinewood nematode, its insect vector, and associated microbes. Trends in Parasitology, 30, 299-308.

Zhao, L., Zhang, X., Wei, Y., Zhou, J., Zhang, W., Qin, P. et al. (2016) Ascarosides coordinate the dispersal of a plant-parasitic nematode with the metamorphosis of its vector beetle. Nature Communications, 7, e12341.

Zhao, L.L., Zhang, S., Wei, W., Hao, H.J., Zhang, B., Butcher, R.A. et al. (2013) Chemical signals synchronize the life cycles of a plantparasitic nematode and its vector beetle. Current Biology, 23, 2038-2043.

- This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and is not used for commercial purposes.

© 2024 The Authors. Plant Pathology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of British Society for Plant Pathology.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/ppa.13875

Publication Date: 2024-02-08

Pine wilt disease: a global threat to forestry

Wiley

Pine wilt disease: A global threat to forestry

Correspondence

Email: mback@harper-adams.ac.uk

Funding information

Abstract

Pines are the most economically important trees in the world and, together with eucalyptus, they dominate commercial forests. But the success of a relatively small number of widely planted species, such as Pinus pinaster, the maritime pine, comes at a price. Pines are attractive to damaging pathogens and insect pests, including the pinewood nematode (PWN), Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, the causal agent of pine wilt disease (PWD). Originally described in Japan, PWD has caused widespread destruction to forests in countries such as China, Taiwan, Portugal, Spain and the United States. PWN causes irreparable damage to the vascular system of its pine hosts, leading to mortality within 3 months. Pine sawyer beetles (Monochamus spp.) are key vectors of PWD, introducing the PWN to healthy trees during feeding. Other organisms contribute to PWD spread and development, including bacteria, fungi and bark beetles. Control measures include tree felling to prevent vector transmission of PWN, insecticide treatments, trapping of Monochamus spp. and tree breeding for plant resistance. The PWN is a quarantine pathogen and subject to regular legislation and phytosanitary measures aimed at restricting movement and preventing introduction to new areas. Current research is investigating the use of biopesticides against PWN and Monochamus spp. This review examines the biology, epidemiology, impact and management of PWD through published research, grey literature and interviews with people directly involved in the management of the disease in Portugal.

KEYWORDS

1 | THE NEMATODE AND ITS VECTORS

relationship between the pinewood nematode (PWN) and its pine sawyer beetle (Monochamus spp.) vectors.

canals, where they feed on the epithelial and parenchyma cells. A detailed description of the pathogenesis of PWNs is given by Myers (1988), Kuroda (1989) and Kuroda (2012). PWNs appear to have two migration events once they enter the tree. First, a limited number of nematodes (those that escape the sticky oleoresin deposited in resin canals) migrate to the phloem, xylem and cambium. Second, reproduction begins as the feeding lesions enlarge and oleoresin production ceases, and many more nematodes migrate to the vascular tissues.

2 | NEMATODE IDENTIFICATION

3 | DISTRIBUTION OF B. xylophilus

and North America (United States, Canada and Mexico). B. xylophilus is thought to have originated in the eastern states of the United States, where it has been recorded from 36 states. The nematode is also widespread in Canada, where it occurs in all territories and provinces, with the exception of Prince Edward Island.

4 | THE VECTORS, MONOCHAMUS SPP.

| Species | Present in the EU | Occurrence |

| M. alternatus | No | China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan |

| M. carolinensis | No | Canada, USA |

| M. clamator | No | Canada, USA |

| M. galloprovincialis | Yes | Asia, Europe, northern Africa |

| M. marmorator | No | Canada, USA |

| M. mutator | No | Canada, USA |

| M. nitens | No | Japan |

| M. notatus | No | Canada, USA |

| M. obtusus | No | Canada, USA |

| M. rosenmelleri (urussovi) | Yes | China, Japan, northern Europe, Russia |

| M. saltuarius | Yes | China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan |

| M. scutellatus | No | Canada, USA |

| M. titillator | No | Canada, USA |

their life span they can travel as much as 10 km (Mas et al., 2013; Togashi & Shigesada, 2006). This represents a major challenge in trying to contain infested areas and is discussed later. Beetles carrying B. xylophilus can also be transported in sawn and round wood, another potential and substantial risk to regions where PWD has yet to occur.

5 | VECTORS AND THEIR PINE HOSTS

P. pinaster has three different chemotypes related to the ratio and occurrence of different VOCs. Gonçalves et al. (2020), also working in Portugal, found that VOC emissions increased when M. galloprovincialis was feeding on P. pinaster and that the population density of the vector may be a critical factor on how PWD is spread and develops. Research on VOCs has opened the possibility of using trap crops to lure the vectors away from pines and is discussed later in the review.

6 | MICROBIAL INTERACTIONS AND B. xylophilus

6.1 | Nematode-related bacteria

other high-value plants. Their success is partly due to the bacteria they harbour, such as Photorhabdus spp. and Xenorhabdus spp., gramnegative bacteria associated with Heterorhabditis and Steinernema, two popular types of EPNs. Once inside their insect hosts, EPNs release (regurgitate) their associated bacteria, which secrete toxins that suppress the insect’s immune system, breakdown insect tissues and induce reproduction of the EPNs (Dziedziech et al., 2020).

6.2 | Endophytic bacteria and pine wilt disease

molecules in a cascade of cellular pathways, that trigger plant defence molecules such as pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and phytoalexins. The trigger for this type of defence activation is commonly referred to as damageassociated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Certain endophytic bacteria species may also have a negative effect on pine tree health by contributing to PWD. Alves et al. (2016) compared the microbiomes of M. galloprovincialis and B. xylophilus with that of P. pinaster, one of the pine species attacked by PWD. The insect vector, nematode and

6.3 | The role of fungi in pine wilt disease

(Zhao et al., 2014). Ascarosides are low-weight molecules found in pheromones secreted by free-living and plant-parasitic nematodes to mediate behaviours such as dispersal, aggregation, dauer initiation and sexual attraction (Zhao et al., 2016). Unexpectedly, the ascarosides asc-C5 and asc-

7 | SYMPTOMS

8 | LOSSES AND ECONOMIC IMPACT

8.1 | Asia

8.2 | Europe

8.3 | North America

9 | KEEPING THE DISEASE AT BAY

9.1 | Phytosanitary measures, legislation and national responses

control through aerial application of insecticides, a practice that began in the 1970s. A similar strategy is used in China, which also carries out rigorous inspections of imported timber and other pine products at ports (Zhao et al., 2020, 2021).

9.2 | Managing the disease: Current approaches

9.3 | Managing the disease: New approaches

9.4 | Targeting the pinewood nematode

(P. pinaster) found variation in resistance to that originally reported (Carrasquinho et al., 2018). The resistant lines were randomly selected from a phenotypic screening programme, highlighting potential problems with this approach. The use of molecular markers (quantitative trait loci) associated with resistance suggests a more reliable way of identifying suitable tree lines, although further research is needed.

10 | PORTUGAL CASE STUDY: PERSONAL REFLECTIONS

the outbreak under control. Several scientists were interviewed to learn more about their experiences and insights gained from a long involvement with the disease. The results of interviews with two key experts on PWD are presented below. A short list of questions was prepared in advance but interviewees were also encouraged to share information on other topics.

10.1 | Professor Manuel Galvão de Melo e Mota

NemaLab-MED & Department of Biology, Universidade de Évora

10.2 | Dr Luís Bonifácio

Instituto Nacional de Investigação Agraria e Veterinaria (INIAV)

coordinated by Dr Hugh Evans of the Forest Commission. More recently, he has worked on a case study in Troia peninsula, a tourist resort based on the south bank of the Sado River, near the city of Setúbal (Setúbal District). He said this was a great example of how integrated management approaches can reduce PWD incidence below

| Tree species | 1995 area (ha) | 2010 area (ha) |

| Pinus pinaster |

|

715,000 |

| Quercus suber | 660,000 | 735,000 |

| Eucalyptus globulus | 500,000 | 810,000 |

selection pressure for variants of B. xylophilus and other native pine pests and diseases”.

11 | CONCLUSIONS

but more commercial development is needed. The successful commercialization of B. bassiana against black pine sawyer suppression in Japan is a promising step forward.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

ORCID

Maria L. Inácio ® https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6883-5288

REFERENCES

Afzal, I., Shinwari, Z.K., Sikandar, S. & Shahzad, S. (2019) Plant beneficial endophytic bacteria: mechanisms, diversity, host range and genetic determinants. Microbiological Research, 221, 36-49.

Álvarez, G., Etxebeste, I., Gallego, D., David, G., Bonifacio, L., Jactel, H. et al. (2015) Optimization of traps for live trapping of pine wood nematode vector Monochamus galloprovincialis. Journal of Applied Entomology, 139, 618-626.

Alves, M., Pereira, A., Matos, P., Henriques, J., Vicente, C., Aikawa, T. et al. (2016) Bacterial community associated to the pine wilt disease insect vectors Monochamus galloprovincialis and Monochamus alternatus. Scientific Reports, 6, 23908.

Anonymous. (2020) Nagano communities plagued by pine parasite at odds over pesticide. The Japan Times. Available at: https://www. japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/05/22/national/nagano-tree-paras ites-chemicals/#:~:text=Nagano%20communities%20plagued% 20by%20pine,over%20pesticide%20%2D%20The%20Japan% 20Times [Accessed 14th September 2023].

Bi, Z., Gong, Y., Huang, X., Yu, H., Bai, L. & Hu, J. (2015) Efficacy of four nematicides against the reproduction and development of pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Journal of Nematology, 47, 126-132.

Bonifácio, L., Naves, P. & Sousa, E. (2015) Vector-Plant. In: Sousa, E., Vale, F. & Abrantes, I. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease in Europe – biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon: FNAPF-Federação Nacional das Associações de Proprietários Florestais, pp. 125-158.

Braasch, H. (2001) Bursaphelenchus species in conifers in Europe: distribution and morphological relationships. EPPO Bulletin, 31, 127-142.

Braasch, H. & Schönfeld, U. (2015) Improved morphological key to the species of the Xylophilus group of the genus Bursaphelenchus Fuchs, 1937. EPPO Bulletin, 45, 73-80.

Carrasquinho, I., Lisboa, A., Inácio, M.L. & Gonçalves, E. (2018) Genetic variation in susceptibility to pine wilt disease of maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Aiton) half-sib families. Annals of Forest Science, 75, 85.

Cheng, X.-Y., Tian, X.-L., Wang, Y.-S., Lin, R.-M., Mao, Z.-C., Chen, N. et al. (2013) Metagenomic analysis of the pinewood nematode microbiome reveals a symbiotic relationship critical for xenobiotics degradation. Scientific Reports, 3, 1869.

de la Fuente, B. & Saura, S. (2021) Long-term projections of the natural expansion of the pine wood nematode in the Iberian Peninsula. Forests, 12, 849.

Donald, P.A., Stamps, W.T., Linit, M.J. & Todd, T.C. (2016) Pine wilt disease. The Plant Health Instructor. Available at: https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/disandpath/nematode/pdlessons/Pages/Pine Wilt.aspx [Accessed 14th September 2023].

Dziedziech, A., Shivankar, S. & Theopold, U. (2020) High-resolution infection kinetics of entomopathogenic nematodes entering Drosophila melanogaster. Insects, 11, 60.

EPPO. (2013) EPPO standards PM 7/4 (3) Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. EPPO Bulletin, 43, 105-118.

EPPO. (2023) EPPO standards PM 7/4 (4) Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. EPPO Bulletin, 53, 156-183.

EUSTAFOR. (2013) NATURA 2000 Management in European state forests. Brussels: European State Forest Association. Available at: https:// eustafor.eu/uploads/EUSTAFOR_Natura_2000_Booklet_20191 218-compressed_compressed.pdf [Accessed 14th September 2023].

FAO. (2018) ISPM 15 Regulation of wood packaging material in international trade. Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/mb160e/ mb160e.pdf [Accessed 13th September 2023].

Faria, J.M., Barbosa, P., Bennett, R.N., Mota, M. & Figueiredo, A.C. (2013) Bioactivity against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus: nematotoxics from essential oils, essential oils fractions and decoction waters. Phytochemistry, 94, 220-228.

Fonseca, L., Cardoso, J. & Abrantes, I. (2015) Plant-nematode. In: Sousa, E., Vale, F. & Abrantes, I. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease in Europe – biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon: FNAPF-Federação Nacional das Associações de Proprietários Florestais, pp. 34-78.

Fonseca, L., Cardoso, J., Lopes, A., Pestana, M., Abreu, F., Nunes, N. et al. (2012) The pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, in Madeira Island. Helminthologia, 49, 96-103.

Forest Research. (2020) Pine wood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Available at: https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools -and-resources/pest-and-disease-resources/pinewood-nematode-embursaphelenchus-xylophilus [Accessed 30th January 2023].

Forestry Commission. (2017) Contingency plan for the pine wood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus) and its longhorn beetle (Monochamus spp.) vectors. Available at: https://cdn.forestrese arch.gov.uk/2022/02/pwncontingencyplan21november2017.pdf [Accessed 7th June 2023].

Futai, K. (2013) Pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 51, 61-83.

Gonçalves, E., Figueiredo, A.C., Barroso, J.G., Henriques, J., Sousa, E. & Bonifácio, L. (2020) Effect of Monochamus galloprovincialis feeding on Pinus pinaster and Pinus pinea, oleoresin and insect volatiles. Phytochemistry, 169, 112-159.

Gonçalves, E., Figueiredo, A.C., Barroso, J.G., Millar, J.G., Henriques, J., Sousa, E. et al. (2021) Characterization of cuticular compounds of the cerambycid beetles Monochamus galloprovincialis, Arhopalus syriacus, and Pogonocherus perroudi, potential vectors of pinewood nematode. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 169, 183-194.

Gruffudd, H.R., Schröder, T., Jenkins, T.A.R. & Evans, H.F. (2019) Modeling pine wilt disease (PWD) for current and future climate scenarios as part of a pest risk analysis for pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner and Buhrer) Nickle in Germany. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection, 126, 129-144.

Hirata, A., Nakamura, K., Nakao, K., Kominami, Y., Tanaka, N., Ohashi, H. et al. (2017) Potential distribution of pine wilt disease under future climate change scenarios. PLoS One, 12, e0182837.

Ibeas, F., Gallego, D., Díez, J.J. & Pajares, J.A. (2007) An operative kairomonal lure for managing pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis (Coleoptera: Cerymbycidae). Journal of Applied Entomology, 131, 13-20.

ICNF. (2015) 6th Inventário Florestal Nacional. Relatório Final. Available at: https://www.icnf.pt/api/file/doc/c8cc40b3b7ec8541 [Accessed 18th September 2023].

ICNF. (2023) Limpeza de terrenos junto a habitações. Available at: https:// www.icnf.pt/florestas/gfr/gfrfaq [Accessed 18th September 2023].

Jactel, H., Bonifacio, L., Van Halder, I., Vétillard, F., Robinet, C. & David, G. (2019) A novel, easy method for estimating pheromone trap attraction range: application to the pine sawyer beetle Monochamus galloprovincialis. Agricultural and Forest Entomology, 21, 8-14.

Kamata, N. (2008) Integrated pest management of pine wilt disease in Japan: tactics and strategies. In: Zhao, B.G., Futai, K., Sutherland,

J.R. & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 304-322.

Kanzaki, N. & Giblin-Davis, R.M. (2018) Diversity and plant pathogenicity of Bursaphelenchus and related nematodes in relation to their vector bionomics. Current Forestry Reports, 4, 85-100.

Kawazu, K. (1998) Pathogenic toxins of pine wilt disease. Kagaku to Seibutsu, 36, 120-124.

Kiyohara, T. & Bolla, R.I. (1990) Pathogenic variability among populations of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Forest Science, 36, 1061-1076.

Kobayashi, T., Sasaki, K. & Mamiya, Y. (1974) Fungi associated with Bursaphelenchus lignicolus, the pine wood nematode (I). Journal of the Japanese Forestry Society, 56, 136-145.

Kosaka, H., Aikawa, T., Ogura, N., Tabata, K. & Kiyohara, T. (2001) Pine wilt disease caused by the pine wood nematode: the induced resistance of pine trees by the avirulent isolates of nematode. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 107, 667-675.

Kuroda, K. (1989) Terpenoids causing tracheid-cavitation in Pinus thunbergii infected by the pine wood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Japanese Journal of Phytopathology, 55, 170-178.

Kuroda, K. (2012) Monitoring of xylem embolism and dysfunction by the acoustic emission technique in Pinus thunbergii inoculated with the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Journal of Forest Research, 17, 58-64.

Lee, H.-J. & Park, O.K. (2019) Lipases associated with plant defense against pathogens. Plant Science, 279, 51-58.

Liu, G., Lin, X., Xu, S., Liu, G., Liu, Z., Liu, F. et al. (2020) Efficacy of fluopyram as a candidate trunk-injection agent against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 157, 403-411.

Maehara, N. & Futai, K. (1996) Factors affecting both the numbers of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae), carried by the Japanese pine sawyer, Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae), and the nematode’s life history. Applied Entomology and Zoology, 31, 443-452.

Maehara, N. & Futai, K. (2000) Population changes of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae), on fungi growing in pine-branch segments. Applied Entomology and Zoology, 35, 413-417.

Maehara, N., Hata, K. & Futai, K. (2005) Effect of blue-stain fungi on the number of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae) carried by Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). Nematology, 7, 161-167.

Mamiya, Y. (1983) Pathology of the pine wilt disease caused by Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 21, 201-220.

Mamiya, Y. & Kiyohara, T. (1972) Description of Bursaphelenehus lignicolus n. sp. (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae) from pine wood and histopathology of nematode-infested trees. Nematologica, 18, 120-124.

Mas, H., Hernández, R., Villaroya, M., Sánchez, G., Pérez-Laorga, E., González, E. et al. (2013) Comportamiento de dispersión y capacidad de vuelo a larga distancia de Monochamus galloprovincialis (Olivier 1795). 6th Congreso forestal español. 6CFE01-393. Available from: http://secforestales.org/publicaciones/index.php/ congresos_forestales/article/view/14702 [Accessed 30th January 2024].

Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. (2023) Nematodo de la madera del pino (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Available from: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/agricultura/temas/sanidad-vegetal/ organismos-nocivos/nematodo-de-la-madera-del-pino/ [Accessed 13th September 2023].

Morais, P.V., Proença, D.N., Francisco, R. & Paiva, G. (2015) Bacteria-nematode-plant. In: Sousa, E., Vale, F. & Abrantes, I. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease in Europe – biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon: FNAPF-Federação Nacional das Associações de Proprietários Florestais, pp. 161-192.

Mota, M., Futai, K. & Vieira, P. (2009) Pine wilt disease and the pinewood nematode. In: Ciancio, A. & Mukerji, K.G. (Eds.) Integrated management of fruit crops and forest nematodes, Vol. IV. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 253-274.

Mota, M.M., Braasch, H., Bravo, M.A., Penas, A.C., Burgermeister, W., Metge, K. et al. (1999) First report of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in Portugal and in Europe. Nematology, 1, 727-734.

Myers, R.F. (1988) Pathogenesis in pine wilt caused by pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Journal of Nematology, 20, 236-244.

Nakamura-Matori, K. (2008) Vector-host tree relationships and the abiotic environment. In: Zhao, B.G., Fautai, K., Sutherlans, J.R. & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease. New York: Springer, pp. 144-161.

Nascimento, F.X., Hasegawa, K., Mota, M. & Vicente, C.S.L. (2015) Bacterial role in pine wilt disease development. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 7, 51-63.

Naves, P., Bonifácio, L., Inácio, M. & Sousa, E. (2018) Integrated management of pine wilt disease in Troia. Review de Ciências Agrárias, 41, 12-19.

Naves, P., Bonifácio, L. & Sousa, E. (2016) The pine wood nematode and its local vectors in the Mediterranean basin. In: Paine, T.D. & Lieutier, F. (Eds.) Insects and diseases of mediterranean forest systems. New York: Springer, pp. 329-378.

Naves, P., Camacho, S., De Sousa, E. & Quartau, J. (2006) Entrance and distribution of the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus on the body of its vector Monochamus galloprovincialis. Entomologia Generalis, 29, 71-80.

Naves, P., Kenis, M. & Sousa, E. (2005) Parasitoids associated with Monochamus galloprovincialis (Oliv.) (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) within the pine wilt nematode-affected zone in Portugal. Journal of Pest Science, 78, 57-62.

Nickle, W.A.R., Golden, A.M., Mamiya, Y. & Wergin, W.P. (1981) On the taxonomy and morphology of the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner & Buhrer 1934) Nickle 1970. Journal of Nematology, 13, 385-392.

Nose, M. & Shiraishi, S. (2008) Breeding for resistance to pine wilt disease. In: Zhao, B.G., Futai, K., Sutherland, J.R. & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 334-350.

Oku, H., Shiraishi, T., Ouchi, S., Kurozumi, S. & Ohta, H. (1980) Pine wilt toxin, the metabolite of a bacterium associated with a nematode. Naturwissenschaften, 67, 198-199.

Pajares, J.A., Alvarez, G., Ibeas, F., Gallego, D., Hall, D.R. & Farman, D.I. (2010) Identification and field activity of a male-produced aggregation pheromone in the pine sawyer beetle, Monochamus galloprovincialis. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 36, 570-583.

Pan, C.-S. (2011) Sōng cái xiànchóng bìng yánjiū jìnzhǎn [Development of studies on pinewood nematodes disease]. Journal of Xiamen University (Natural Science), 50, 476-483.

Pires, D., Vicente, C.S.L., Inácio, M.L. & Mota, M. (2022) The potential of Esteya spp. for the biocontrol of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Microorganisms, 10, 168.

Plantard, O., Picard, D., Valette, S., Scurrah, M., Grenier, E. & Mugiéry, D. (2008) Origin and genetic diversity of Western European populations of the potato cyst nematode (Globodera pallida) inferred from mitochondrial sequences and microsatellite loci. Molecular Ecology, 17, 2208-2218.

Proença, D.N., Francisco, R., Kublik, S., Schöler, A., Vestergaard, G., Schloter, M. et al. (2017) The microbiome of endophytic, wood colonizing bacteria from pine trees as affected by pine wilt disease. Scientific Reports, 7, 4205.

Proença, D.N., Francisco, R., Santos, C.V., Lopes, A., Fonseca, L., Abrantes, I.M. et al. (2010) Diversity of bacteria associated with

Rajasekharan, S.K., Raorane, C.J. & Lee, J. (2020) Nematicidal effects of piperine on the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology, 23, 863-868.

Rodrigues, A.M., Mendes, M.D., Lima, A.S., Barbosa, P.M., Ascensão, L., Barroso, J.G. et al. (2017) Pinus halepensis, Pinus pinaster, Pinus pinea, and Pinus sylvestris essential oil chemotypes and monoterpene hydrocarbon enantiomers, before and after inoculation with the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Chemical Biodiversity, 14, e1600153.

Schenk, M., Loomans, A., den Nijs, L., Hoppe, B., Kinkar, M. & Vos, S. (2020) Pest survey card on Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. EFSA Supporting Publications, 17, EN-1782. Available from: https://doi. org/10.2903/sp.efsa.2020.EN-1782

Shimazu, M. (2009) Use of microbes for control of Monochamus alternatus, vector of the invasive pinewood nematode. In: Hajek, A.E., Glare, T.R. & O’Callaghan, M. (Eds.) Use of microbes for control and eradication of invasive arthropods. Progress in biological control, Vol. 6. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 141-157.

Shin, S.C. (2008) Pine wilt disease in Korea. In: Zhao, B.G., Futai, K., Sutherland, J.R. & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 26-32.

Soliman, T., Mourits, M.C.M., van der Werf, W., Hengeveld, G.M., Robinet, C. & Oude Lansink, A.G.J.M. (2012) Framework for modelling economic impacts of invasive species, applied to pine wood nematode in Europe. PLoS One, 7, e45505.

Sousa, E., Bonifácio, L., Naves, P. & Viera, M. (2015) Pine wilt disease management. In: Sousa, E., Vale, F. & Abrantes, I. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease in Europe – biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon: FNAPF-Federação Nacional das Associações de Proprietários Florestais, pp. 125-158.

Sousa, E., Naves, P. & Vieira, M. (2013) Prevention of pine wilt disease induced by Bursaphelenchus xylophilus and Monochamus galloprovincialis by trunk injection of emamectin benzoate. Phytoparasitica, 41, 143-148.

Sousa, E., Rodrigues, J.M., Bonifácio, L.F., Naves, P.M. & Rodrigues, A. (2011) Management and control of the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, in Portugal. In: Boeri, F. & Chung, J.A. (Eds.) Nematodes: morphology, functions and management strategies. New York: Nova Publishers, pp. 157-178.

Steiner, G. & Buhrer, E.M. (1934) Aphelenchoides xylophilus n. sp., a nematode associated with blue-stain and other fungi in timber. Journal of Agricultural Research, 48, 949-951.

Takai, K., Soejima, T., Suzuki, T. & Kawazu, K. (2000) Emamectin benzoate as a candidate for a trunk-injection agent against the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Pest Management Science, 56, 937-941.

Togashi, K. (1990) Change in the activity of adult Monochamus alternatus Hope (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) in relation to age. Applied Entomology and Zoology, 25, 153-159.

Togashi, K. & Shigesada, N. (2006) Spread of the pinewood nematode vectored by the Japanese pine sawyer: modelling and analytical approaches. Population Ecology, 48, 271-283.

Vasconcelos, T. & Duarte, I. (2015) Biotic/abiotic factors-plant. In: Sousa, E., Vale, F. & Abrantes, I. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease in Europe – biological interactions and integrated management. Lisbon: FNAPF-Federação Nacional das Associações de Proprietários Florestais, pp. 195-220.

Vicente, C.S., Ikuyo, Y., Shinya, R., Mota, M. & Hasegawa, K. (2015) Catalases induction in high virulence pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus under hydrogen peroxide-induced stress. PLoS One, 10, e0123839.

Vieira, P., Burgermeister, W., Mota, M., Metge, K. & Silva, G. (2007) Lack of genetic variation of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus in Portugal revealed by RAPD-PCR analyses. Journal of Nematology, 39, 118-126.

Yano, S. (1913) Investigation on pine death in Nagasaki prefecture. Sanrin-Kouhou, 4, 1-14.

Yi, C.K., Byun, B.H., Park, J.D., Yang, S.I. & Chang, K.H. (1989) First finding of the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner et Buhrer) Nickle and its insect vector in Korea. Research Reports of the Forest Research Institute, 3, 141-149.

Yu, H.B., Jung, Y.H., Lee, S.M., Choo, H.Y. & Lee, D.W. (2016) Biological control of Japanese pine sawyer, Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) using Korean entomopathogenic nematode isolates. The Korean Journal of Pesticide Science, 20, 361-368.

Zhao, B.G. (2008) Pine wilt disease in China. In: Zhao, B.G., Futai, K., Sutherland, J.R. & Takeuchi, Y. (Eds.) Pine wilt disease. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 18-25.

Zhao, J., Hu, K., Chen, K. & Shi, J. (2021) Quarantine supervision of wood packaging materials (WPM) at Chinese ports of entry from 2003 to 2016. PLoS One, 16, e0255762.

Zhao, L., Mota, M., Vieira, P., Butcher, R.A. & Sun, J. (2014) Interspecific communication between pinewood nematode, its insect vector, and associated microbes. Trends in Parasitology, 30, 299-308.

Zhao, L., Zhang, X., Wei, Y., Zhou, J., Zhang, W., Qin, P. et al. (2016) Ascarosides coordinate the dispersal of a plant-parasitic nematode with the metamorphosis of its vector beetle. Nature Communications, 7, e12341.

Zhao, L.L., Zhang, S., Wei, W., Hao, H.J., Zhang, B., Butcher, R.A. et al. (2013) Chemical signals synchronize the life cycles of a plantparasitic nematode and its vector beetle. Current Biology, 23, 2038-2043.

- This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and is not used for commercial purposes.

© 2024 The Authors. Plant Pathology published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of British Society for Plant Pathology.