DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/gels10040284

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38667703

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-22

مركبات الليبوسوم-الهيدروجيل لتطبيقات توصيل الأدوية المتحكم بها

الملخص

تم تطوير أنظمة توصيل محكومة متنوعة (CDSs) للتغلب على عيوب تركيبات الأدوية التقليدية (الأقراص، الكبسولات، الشراب، المراهم، إلخ). من بين أنظمة CDSs المبتكرة، أظهرت الهيدروجيلات والليبوسومات وعدًا كبيرًا للتطبيقات السريرية بفضل فعاليتها من حيث التكلفة، وكيميائها المعروفة، وقابليتها للتصنيع، وقابليتها للتحلل البيولوجي، وتوافقها الحيوي، واستجابتها للمؤثرات الخارجية. حتى الآن، تم الموافقة على عدة منتجات قائمة على الليبوسومات والهيدروجيلات لعلاج السرطان، بالإضافة إلى العدوى الفطرية والفيروسية، وبالتالي فإن دمج الليبوسومات في الهيدروجيلات قد جذب اهتمامًا متزايدًا بسبب الفائدة من كليهما في منصة واحدة، مما يؤدي إلى تركيبة دوائية متعددة الوظائف، وهو أمر أساسي لتطوير أنظمة توصيل محكومة فعالة. تهدف هذه المراجعة القصيرة إلى تقديم تقرير محدث حول التقدم في أنظمة الليبوسوم-هيدروجيل لأغراض توصيل الأدوية.

تمت المراجعة: 17 أبريل 2024

تم القبول: 18 أبريل 2024

نُشر: 22 أبريل 2024

1. المقدمة

1.1. الحويصلات الدهنية

| تطبيق | اسم المنتج | واجهة برمجة التطبيقات | السنة/المنطقة المعتمدة | المؤشرات العلاجية |

| علاج السرطان | دوكسيل

|

دوكسوروبيسين هيدروكلوريد (DOXHCl) | 1995 (الولايات المتحدة) 1996 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | سرطان الثدي وسرطان المبيض، ساركوما كابوسي |

| داونوكسوم

|

داونوروبيسين | 1996 (الولايات المتحدة، الاتحاد الأوروبي) | ساركوما كابوسي | |

| أونيفيد

|

هيدروكلوريد إيرينوتيكان ثلاثي الماء | 1996 (الولايات المتحدة) 2016 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | سرطان الغدة البنكرياسية | |

| مايوست

|

دوكسوروبيسين | 2000 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | سرطان الثدي | |

| ميباكت

|

ميفامورتييد | 2009 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | الساركوما العظمية | |

| ماركيبو

|

فينيرستين | 2012 (الولايات المتحدة) | لوكيميا | |

| فيكزيوس

|

داوروبيسين + سيتارابين | 2017 (الولايات المتحدة) 2018 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | لوكيميا | |

| زولسكيتيلي

|

دوكسوروبيسين | 2022 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | سرطان الثدي وسرطان المبيض، المايلوما المتعددة، ساركوما كابوسي | |

| تطبيقات أخرى | أمبيسوم

|

أمفوتيريسين ب | 1997 (الولايات المتحدة، الاتحاد الأوروبي) | العدوى الفطرية |

| ديبو سيت

|

سايتارابين | 1999 (الولايات المتحدة) 2001 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | التهاب السحايا اللمفاوي | |

| فيسودين

|

فيرتيبروفين | 2000 (الولايات المتحدة، الاتحاد الأوروبي) | التنكس البقعي المرتبط بالعمر | |

| ديبودور

|

سلفات المورفين | 2004 (الولايات المتحدة، الاتحاد الأوروبي) | إدارة الألم |

| أريكايس

|

أميكاسين | 2018 (الولايات المتحدة، الاتحاد الأوروبي) | التهابات الرئة | |

| إكسباريل

|

بوبيفاكائين | 2020 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | تخدير | |

| اللقاحات | إيباكسال

|

فيروس التهاب الكبد A غير النشط (سلالة RG-SB) | 1994 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | التهاب الكبد A |

| إنفليكسال V

|

مستضدات سطح فيروس الإنفلونزا (الهيماغلوتينين والنيورامينيداز)، فيروسمال، 3 سلالات مختلفة | 1997 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | إنفلونزا | |

| موسكيركسTM | البروتينات الموجودة على سطح طفيليات البلازموديوم فالباريوم وفيروس التهاب الكبد الوبائي ب | 2015 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | الملاريا | |

| شينغريكس

|

بروتين الغلاف E لفيروس الحماق النطاقي المؤتلف | 2017 (الولايات المتحدة) 2018 (الاتحاد الأوروبي) | الهربس النطاقي والألم العصبي التالي للهربس | |

| كوميرناتي

|

mRNA | 2021 (الولايات المتحدة، الاتحاد الأوروبي) | كوفيد-19 | |

| سبايكفكس

|

mRNA | 2022 (الولايات المتحدة، الاتحاد الأوروبي) | كوفيد-19 |

الهلام التقليدي) المرتبط بعملية إنتاجه المكلفة. وهذا يبرز الحاجة إلى تصميم تركيبي دقيق لتطوير التصنيع الصناعي المستدام.

(1) ترطيب الفيلم الرقيق من الدهون هو المنهجية الأكثر شيوعًا، المستخدمة لتحضير هياكل مختلفة، بما في ذلك الحويصلات الصغيرة أحادية الطبقة (SUVs)، متعددة الطبقات (MLVs) أو الحويصلات العملاقة أحادية الطبقة (GUVs) [23-25]. تشمل قيود هذه الطريقة توزيع الحجم الواسع، ودرجة الحرارة العالية، واحتمالية تدهور الليبوسوم عند التعرض للموجات فوق الصوتية أو انخفاض عائد احتواء الدواء.

(2) التبخر العكسي [26] هو التقنية الثانية الأكثر استخدامًا للحصول على حويصلات أحادية الطبقة كبيرة الحجم باستخدام تكوين الماء في الزيت من خليط السطح/الدهون مع محلول مائي من الدواء. ثم يتم إزالة المذيب العضوي تحت ضغط منخفض؛ ومع ذلك، يمكن أن تؤثر كميات المذيب العضوي المتبقية في التركيبة النهائية على استقرار الحويصلات.

(3) تعتمد حقن المذيب على حقن محلول فوسفوليبيد عضوي في مرحلة مائية من الدواء المختار عند درجة حرارة أعلى من نقطة غليان المذيب العضوي. يمكن التحكم في حجم الحويصلات بهذه الطريقة؛ ومع ذلك، تعتبر وجود المذيب العضوي في المنتج النهائي عيبًا رئيسيًا لهذه الطريقة.

لمعالجة قيود هذه الطرق التقليدية، يتم تطوير أساليب جديدة أكثر كفاءة. في هذا الصدد، تطورت تقنية الميكروفلويديك على كل من النطاقات المخبرية والصناعية للحصول على ليبوزومات متجانسة الحجم من خلال التحكم في معايير مثل حجم القنوات الدقيقة ومعدلات التدفق. المزايا الرئيسية لهذه الطريقة هي العوائد العالية، توزيع ليبوزومي فعال وكفاءات عالية في احتجاز الأدوية. ومع ذلك، قد تكون عملية تصنيع الأجهزة وتحسين مراحل السوائل المختلفة ومدخلات السوائل المتعددة تحديًا عند التوسع، وبالتالي تعتبر هذه القيود الرئيسية لتقنيات الميكروفلويديك.

(مع

| طريقة التحضير | حجم الجسيمات (نانومتر) | المزايا | العيوب | مرجع |

| ترطيب فيلم رقيق من الدهون | 100-1000 | أكثر الطرق استخدامًا | كفاءات تغليف منخفضة، سونكيشن، تعرض لدرجات حرارة، توزيع حجم غير متجانس | [40] |

| تبخر الطور العكسي | 100-1000 | كفاءة عالية في التغطية | آثار المذيبات العضوية | [41] |

| حقن المذيب (إيثر أو إيثانول) | 70-200 | القدرة على التحكم في حجم الحويصلات | تخفيف الحويصلات الدهنية، تجمعات غير متجانسة، استخدام درجات حرارة عالية | [42] |

| تقنيات الميكروفلويديك | 100-300 | تركيب الحويصلات الدهنية أحادية التشتت، كفاءة عالية في الاحتواء | قد تكون التصنيع على نطاق واسع معقدة وتتطلب تحسينًا | [٤٣] |

| تبخر الطور العكسي فوق الحرج | 100-1200 | عملية صديقة للبيئة، كفاءة عالية في التغطية | ضغوط ودرجات حرارة عالية | [٤٤] |

| التجفيف بالرش | 100-1000 | التحكم في تشكيل الجسيمات، مما يسهل الترجمة إلى الإنتاج على نطاق واسع | مكلف ويستغرق وقتًا طويلاً | [٤٥] |

| تكنولوجيا ملامس الأغشية |

|

أحجام متجانسة وصغيرة، كفاءة عالية في الت encapsulation، بساطة في التوسع | تحتاج تغليف الأدوية المحبة للماء إلى تحسين | [46] |

| حقن التدفق المتقاطع |

|

ليبوبومات بحجم محدد | عدم استقرار الحويصلات بسبب المذيب المتبقي | [47] |

| المزايا | العيوب | ||

|

انخفاض الذوبانية | ||

| تعزيز استقرار الدواء | عمر نصف قصير |

| غير سامة، مرنة، متوافقة حيويًا، قابلة للتحلل البيولوجي وغير مناعية | احتمالية أكسدة الفوسفوليبيد وتفاعلات مشابهة للتحلل المائي |

| انخفاض السمية للدواء المغلف | تسرب واندماج الأدوية المغلفة |

| تقليل تعرض الأنسجة الحساسة للأدوية السامة | ارتفاع تكاليف الإنتاج |

| أثر تجنب الموقع | انخفاض الاستقرار |

| تحسين الديناميكا الدوائية |

1.2. الهيدروجيلات

1.3. دمج الهيدروجيلات والليبوزومات (ليبوزومات-هيدروجيلات)

ليبوزومات-هيدروجيلات (كلاهما هيدروجيلات صناعية وطبيعية) للحصول على مواد هجينة استجابة للمؤثرات.

2. الليبوزومات المغلفة في أنواع مختلفة من الهيدروجيلات

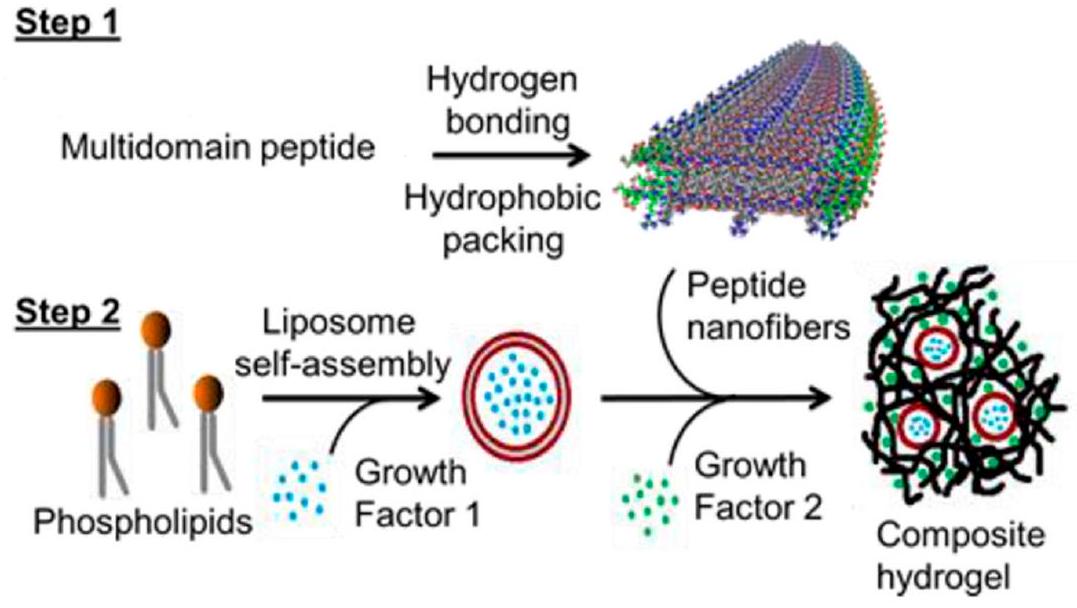

2.1. الليبوزومات المغلفة في هيدروجيلات ببتيد/أميلويد

أظهرت العوامل إطلاقًا مستدامًا بواسطة الحويصلات الدهنية في الهيدروجيل مقارنةً بإطلاق سريع من الهيدروجيل النقي. يمكن دراسة تركيبة هيدروجيل الحويصلات الدهنية-الببتيد بشكل أعمق في الأنظمة التي قد تكون فيها تسلسلات زمنية من الإشارات البيولوجية ذات قيمة، مثل تطبيقات تجديد الأنسجة.

2.2. الحويصلات الدهنية المحصورة في الهلاميات الحيوية البوليمرية

الهيدروجيل CF (الإفراج التراكمي عن

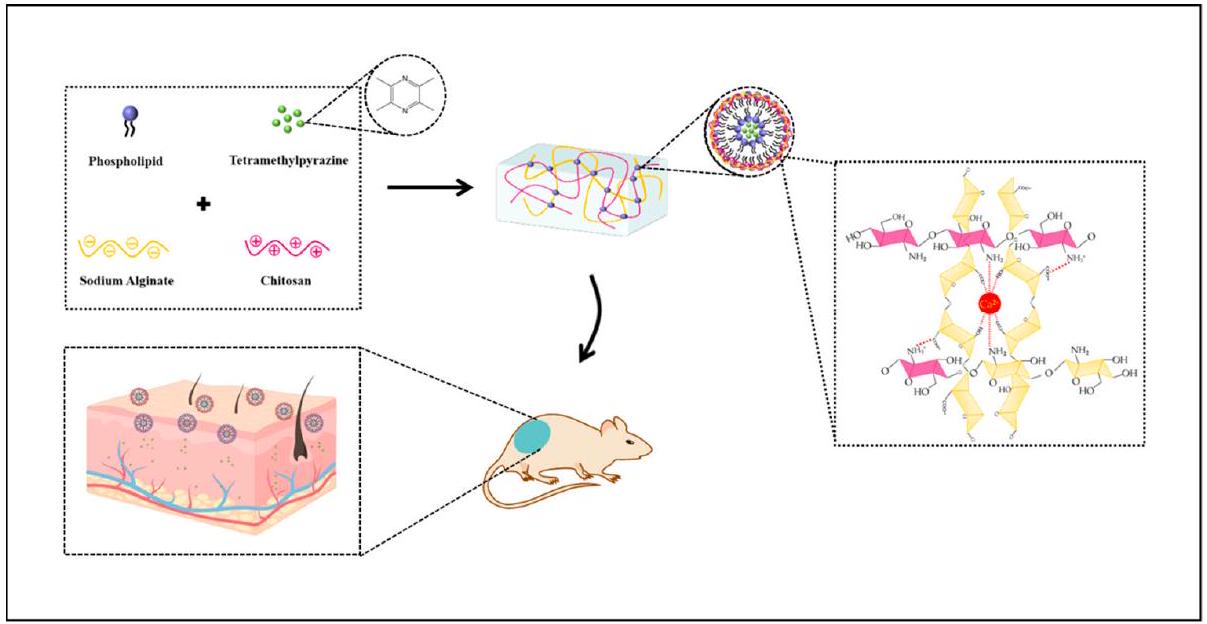

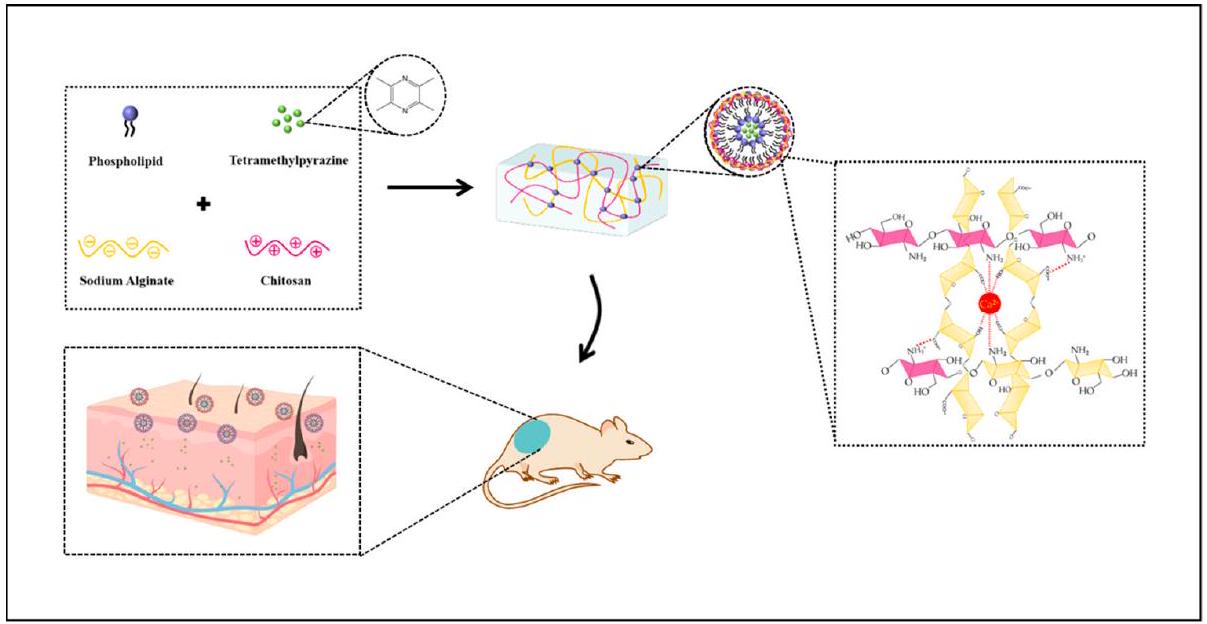

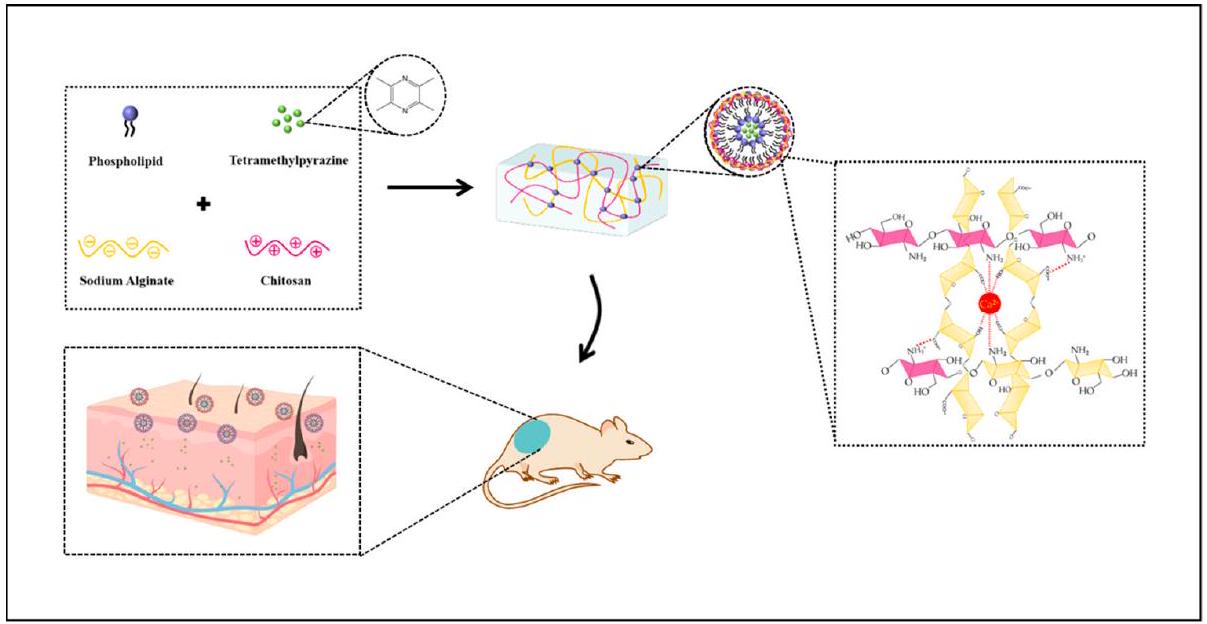

تأثيرات (بسبب وجود TMP). علاوة على ذلك، قدمت هيدروجيل TMP-liposome/ALG-CS نفاذية أفضل للجلد بسبب بيئة الشفاء الرطبة لجلد AD الجاف، مما حقق إطلاقًا محكومًا للدواء، وهو أمر ضروري لعلاج AD. تم استخدام 1-Chloro2,4dinitrobenzene لتحفيز الآفات في تجارب حية على الفئران. خففت هيدروجيل TMP-liposome/ALG-CS من الإجهاد التأكسدي وزادت من نشاط SOD في الفئران المعالجة.

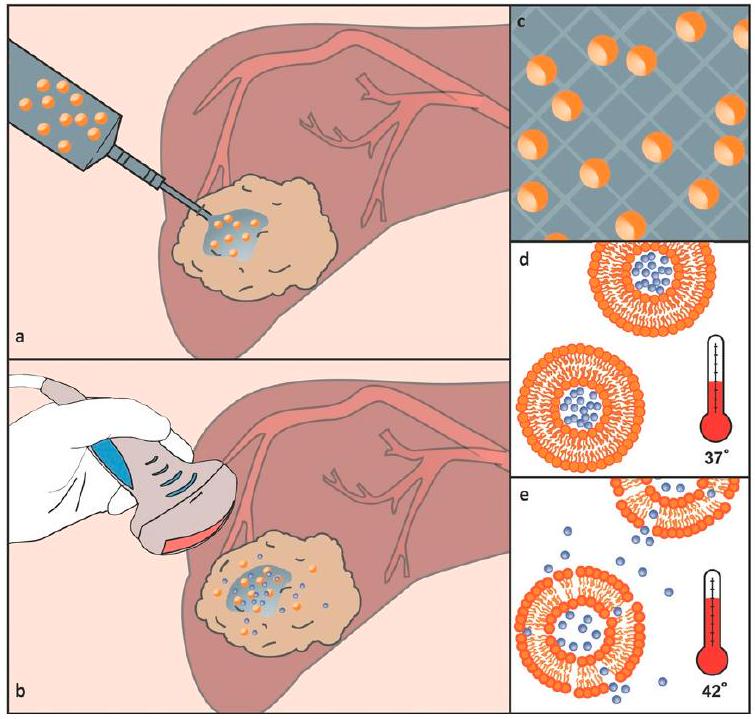

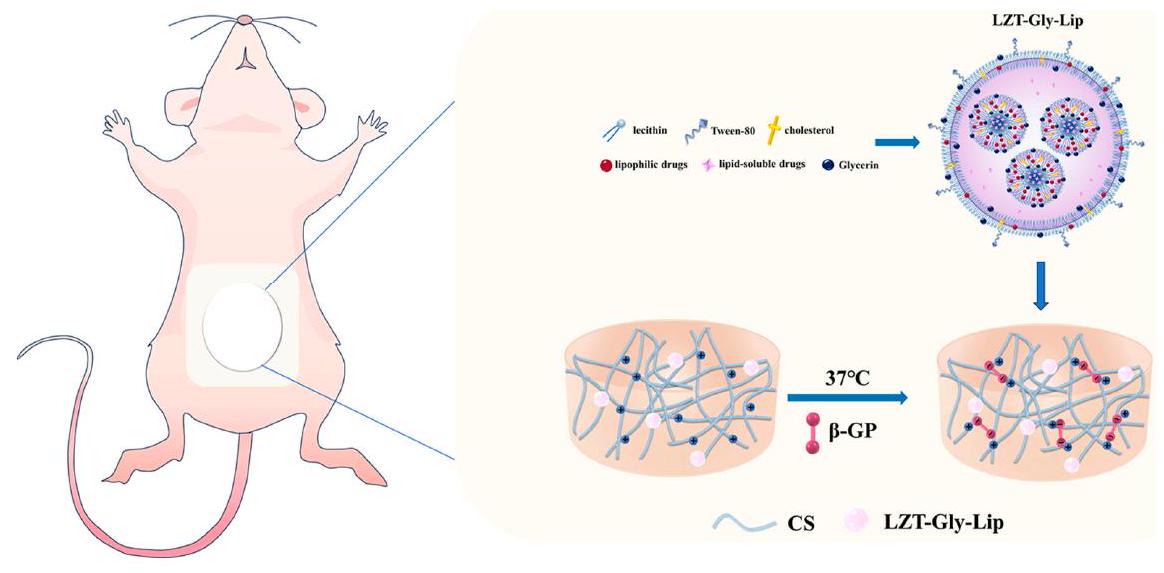

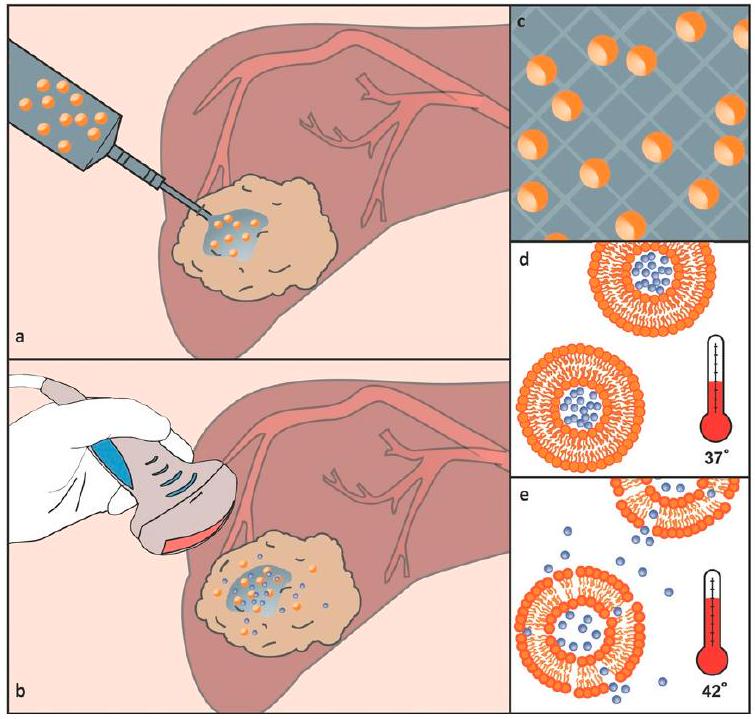

إطلاق الجزيء العلاجي في موقع الهدف [94-103]. من بين هذه المواد، تعزز تركيبات الهيدروجيل-دواء التي تتجلى في الموقع بشكل كبير من التأثيرات العلاجية وتتغلب على القيود الدوائية لحقن الوريد [104،105]. بناءً على هذا المفهوم، صمم لوبيز-نورياجا وآخرون مركبًا جديدًا من الهيدروجيل الحساس للحرارة مع الحويصلات الدهنية لتمكين الإطلاق الموضعي للدوكسوروبيسين من خلال دمج الحويصلات الدهنية الحساسة للحرارة (المحمّلة بالدوكسوروبيسين) في مادة استجابة حرارية.

أظهرت أن البروتينات والبروتينات المحاطة بالأغشية الدهنية لم تؤثر على الاستقرار الميكانيكي للهيدروجيل. كانت الأغشية الدهنية نظام حماية فعال لتوصيل FGF2-STAB. أيضًا، أظهرت هذه الأغشية الدهنية أنها تعزز بشكل كبير آلية إطلاق FGF2-STAB، مما يبرز إمكانياتها في الأساليب العلاجية المتقدمة. ومع ذلك، أظهرت هذه الدراسة أن مجموعات -COOH في الهيدروجيل تأثرت بالشحنة الموجبة للبروتين، مما يقلل من الاستقرار المائي للنظام؛ لذلك، يجب استبدال أو إخفاء المجموعات الكربوكسيلية للهيدروجيل لتقليل تفاعلات الشبكة-البروتين للتطبيقات المستقبلية.

| بوليمر حيوي | الحويصلات الدهنية | وكيل التسليم | المراجع |

| كيتوزان (CS) | ليبوبروتينات الفوسفاتيديل كولين بأحجام مختلفة | موبيروسين | [110-116] |

| جيلاتين | حويصلات مصنوعة من أوليات الصوديوم | كالسيين | [117-125] |

| ديكستران | Liposomes SOPC/DOTAP | غير متوفر | [126-128] |

| حمض الهيالورونيك | الحويصلات المستجيبة للحرارة (أي، ثنائي بالميتويل فوسفاتيديل كولين (DPPC) وثنائي ميريستويل فوسفاتيديل كولين (DMPC)) | إنزيم الفجل الحار | [117,129-135] |

| الألجينات | ليبوبلازات ديفالميتويلفوسفاتيديلكولين | سايتوكروم-ج | [136-148] |

| كاراجينان | النيوزومات المستندة إلى جزيء سطحي غير أيوني وكوليسترول | ميلوكسيكام | [132,149,150] |

| ميثيل السليلوز | النيوزومات المستندة إلى اثنين من المواد الخافضة للتوتر السطحي غير الأيونية (سبان 20 وسبان 60) والكوليسترول | أسيكلوفير | [151] |

| صمغ الزانثان | نيوزومات السطحي غير الأيوني المستندة إلى توين 20 والكوليسترول | الكافيين، الإيبوبروفين | [152,153] |

2.3. الحويصلات الدهنية المحصورة في الهلاميات البوليمرية الاصطناعية

hydrogels (ehydroxylethyl-cellulose (HEC)، كاربوبول 974 أو مزيج من الاثنين). تم مراقبة إطلاق GRF أو الكالسيفين بواسطة تقنيات الطيف الضوئي والفلووريسنس، على التوالي. أظهرت النتائج أن إطلاق الكالسيفين من هيدروجيل الحويصلات أبطأ، مقارنةً بالهلامات الضابطة، ويمكن التحكم فيه وتأخيره بشكل أكبر باستخدام حويصلات ذات غشاء صلب. علاوة على ذلك، لم يتأثر إطلاق الكالسيفين بكمية الدهون (في النطاق من 2 إلى

3. الاستنتاجات: التحديات الحالية والاتجاهات المستقبلية

مساهمات المؤلفين: كتابة – إعداد المسودة الأصلية، ف.هـ.هـ. و ر.ب.; الكتابة – المراجعة والتحرير، س.ب. و ل.ج.; التصور، ف.هـ.هـ. و ر.ب.; الإشراف، س.ب. و ل.ج. جميع المؤلفين قرأوا ووافقوا على النسخة المنشورة من المخطوطة.

بيان توفر البيانات: غير قابل للتطبيق.

تعارض المصالح: يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود أي تعارض في المصالح.

References

- Grijalvo, S.; Mayr, J.; Eritja, R.; Díaz, D.D. Biodegradable Liposome-Encapsulated Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications: A Marriage of Convenience. Biomater. Sci. 2016, 4, 555-574. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5BM00481K.

- Chronopoulou, L.; Falasca, F.; Di Fonzo, F.; Turriziani, O.; Palocci, C. siRNA Transfection Mediated by Chitosan Microparticles for the Treatment of HIV-1 Infection of Human Cell Lines. Materials 2022, 15, 5340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15155340.

- Liu, P.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J. A Review of Liposomes as a Drug Delivery System: Current Status of Approved Products, Regulatory Environments, and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27041372.

- Düzgüneş, N.; Gregoriadis, G. Introduction: The Origins of Liposomes: Alec Bangham at Babraham. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; Volume 391, pp. 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(05)91029-X.

- Bangham, A.D.; Horne, R.W. Negative staining of phospholipids and their structural modification by surface-active agents as observed in the electron microscope. J. Mol. Biol. 1964, 8, 660-668. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-2836(64)80115-7.

- Niu, M.; Lu, Y.; Hovgaard, L.; Guan, P.; Tan, Y.; Lian, R.; Qi, J.; Wu, W. Hypoglycemic activity and oral bioavailability of insulinloaded liposomes containing bile salts in rats: The effect of cholate type, particle size and administered dose. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 81, 265-272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.02.009.

- Wang, N.; Wang, T.; Li, T.; Deng, Y. Modulation of the physicochemical state of interior agents to prepare controlled release liposomes. Colloids Surf. B 2009, 69, 232-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.11.033.

- Zeng, H.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Peng, W.; Zhang, Y. Nanomaterials toward the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Recent advances and future trends. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 1857-1868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2021.01.014.

- Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, Y.; Wang, J.; Lin, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, P. STING-activating drug delivery systems: Design strategies and biomedical applications. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 1615-1625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2021.01.001.

- Giordani, S.; Marassi, V.; Zattoni, A.; Roda, B.; Reschiglian, P. Liposomes characterization for market approval as pharmaceutical products: Analytical methods, guidelines and standardized protocols. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 2023, 236, 115751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2023.115751.

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic: Nanoparticles in the Clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2016, 1, 10-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/btm2.10003.

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic: An update. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2019, 4, e10143. https://doi.org/10.1002/btm2.10143.

- Elkhoury, K.; Koçak, P.; Kang, A.; Arab-Tehrany, E.; Ward, J.E.; Shin, S.R. Engineering Smart Targeting Nanovesicles and Their Combination with Hydrogels for Controlled Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12090849.

- Ferraris, C.F.; Rimicci, C.; Garelli, S.; Ugazio, E.; Battaglia, L. Nanosystems in Cosmetic Products: A Brief Overview of functional, market, regulatory and safety concerns. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13091408.

- Yadwade, R.; Gharpure, S.; Ankamwar, B. Nanotechnology in cosmetics pros and cons. Nano Express 2021, 2, 022003. https://doi.org/10.1088/2632-959x/abf46b.

- Fernández-García, R.; Lalatsa, A.; Statts, L.; Bolás-Fernández, F.; Ballesteros, M.P.; Serrano, D.R. Transferosomes as nanocarriers for drugs across the skin: Quality by design from lab to industrial scale. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 573, 118817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.118817.

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Langer, R. Transdermal drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1261-1268. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1504.

- Malakar, J.; Sen, S.O.; Nayak, A.K.; Sen, K.K. Formulation, optimization and evaluation of transferosomal gel for transdermal insulin delivery. Saudi Pharm. J. 2012, 20, 355-363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2012.02.001.

- Karpiński, T.M. Selected medicines used in iontophoresis. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics10040204.

- Ita, K. Perspectives on transdermal electroporation. Pharmaceutics 2016, 8, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics8010009.

- Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Song, Y. Recent advances of microneedles for biomedical applications: Drug delivery and beyond. Acta Pharm. Sinic. B 2019, 9, 469-483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2019.03.007.

- Rother, M.; Seidel, E.; Clarkson, P.M.; Mazgareanu, S.; Vierl, U.; Rother, I. Efficacy of epicutaneous Diractin (ketoprofen in Transfersome gel) for the treatment of pain related to eccentric muscle contractions. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2009, 3, 143-149. https://doi.org/10.2147/dddt.s5501.

- Bangham, A.D.; De Gier, J.; Greville, G.D. Osmotic Properties and Water Permeability of Phospholipid Liquid Crystals. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1967, 1, 225-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-3084(67)90030-8.

- Saunders, L.; Perrin, J.; Gammack, D. Ultrasonic Irradiation of Some Phospholipid Sols. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1962, 14, 567-572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7158.1962.tb11141.x.

- Parente, R.A.; Lentz, B.R. Phase Behavior of Large Unilamellar Vesicles Composed of Synthetic Phospholipids. Biochemistry 1984, 23, 2353-2362. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00306a005.

- Szoka, F.; Papahadjopoulos, D. Procedure for Preparation of Liposomes with Large Internal Aqueous Space and High Capture by Reverse-Phase Evaporation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 4194-4198. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.75.9.4194.

- Jahn, A.; Vreeland, W.N.; Gaitan, M.; Locascio, L.E. Controlled Vesicle Self-Assembly in Microfluidic Channels with Hydrodynamic Focusing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2674-2675. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja0318030.

- van Swaay, D.; deMello, A. Microfluidic Methods for Forming Liposomes. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 752-767. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2LC41121K.

- Chronopoulou, L.; Donati, L.; Bramosanti, M.; Rosciani, R.; Palocci, C.; Pasqua, G.; Valletta, A. Microfluidic synthesis of methyl jasmonate-loaded PLGA nanocarriers as a new strategy to improve natural defenses in Vitis vinifera. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18322. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54852-1.

- Serrano, D.R.; Kara, A.; Yuste, I.; Luciano, F.C.; Ongoren, B.; Anaya, B.J.; Molina, G.; Díez, L.G.; Ramirez, B.I.; Ramirez, I.O.; et al. 3D printing technologies in personalized medicine, nanomedicines, and biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15020313.

- Garg, S.; Heuck, G.; Ip, S.; Ramsay, E. Microfluidics: A transformational tool for nanomedicine development and production. J. Drug Target. 2016, 24, 821-835. https://doi.org/10.1080/1061186X.2016.1198354.

- Colombo, S.; Beck-Broichsitter, M.; Bøtker, J.P.; Malmsten, M.; Rantanen, J.; Bohr, A. Transforming nanomedicine manufacturing toward Quality by Design and microfluidics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 128, 115-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2018.04.004.

- Gale, B.K.; Jafek, A.R.; Lambert, C.J.; Goenner, B.L.; Moghimifam, H.; Nze, U.C.; Kamarapu, S.K. A Review of Current Methods in Microfluidic Device Fabrication and Future Commercialization Prospects. Inventions 2018, 3, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions3030060.

- Tiboni, M.; Tiboni, M.; Pierro, A.; Del Papa, M.; Sparaventi, S.; Cespi, M.; Casettari, L. Microfluidics for nanomedicines manufacturing: An affordable and low-cost 3D printing approach. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 599, 120464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120464.

- Chen, Z.; Han, J.Y.; Shumate, L.; Fedak, R.; DeVoe, D.L. High Throughput Nanoliposome Formation Using 3D Printed Microfluidic Flow Focusing Chips. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1800511. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.201800511.

- Chiado, A.; Palmara, G.; Chiappone, A.; Tanzanu, C.; Pirri, C.F.; Roppolo, I.; Frascell, F. A modular 3D printed lab-on-a-chip for early cancer detection. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 665-674. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9LC01108K.

- Rolley, N.; Bonnin, M.; Lefebvre, G.; Verron, S.; Bargiel, S.; Robert, L.; Riou, J.; Simonsson, C.; Bizien, T.; Gimel, J.C.; et al. Galenic Lab-on-a-Chip concept for lipid nanocapsules production. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 11899-11912. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1NR00879J.

- Ballacchino, G.; Weaver, E.; Mathew, E.; Dorati, R.; Genta, I.; Conti, B.; Lamprou, D.A. Manufacturing of 3D-Printed Microfluidic Devices for the Synthesis of Drug-Loaded Liposomal Formulations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22158064.

- Tiboni, M.; Benedetti, S.; Skouras, A.; Curzi, G.; Perinelli, D.R.; Palmieri, G.F.; Casettari, L. 3D-printed microfluidic chip for the preparation of glycyrrhetinic acid-loaded ethanolic liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 584, 119436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119436.

- Jiang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J. Lipid-Based Nanotechnology: Liposome. Pharmaceutics 2024,

. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16010034. - Shi, N.-Q.; Qi, X.-R. Preparation of drug liposomes by Reverse-Phase evaporation. In Liposome-Based Drug Delivery Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017, pp. 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-49231-4_3-1.

- Šturm, L.; Poklar Ulrih, N. Basic Methods for Preparation of Liposomes and Studying Their Interactions with Different Compounds, with the Emphasis on Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126547.

- Mehraji, S.; DeVoe, D.L. Microfluidic synthesis of lipid-based nanoparticles for drug delivery: Recent advances and opportunities. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 1154-1174. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3lc00821e.

- Bigazzi, W.; Penoy, N.; Évrard, B.; Piel, G. Supercritical fluid methods: An alternative to conventional methods to prepare liposomes. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 383, 123106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.123106.

- Kasapoğlu, K.N.; Gültekin-Özgüven, M.; Kruger, J.; Frank, J.; Bayramoğlu, P.; Demirkoz, A.B.; Özçelik, B. Effect of Spray Drying on Physicochemical Stability and Antioxidant Capacity of Rosa pimpinellifolia Fruit Extract-Loaded Liposomes Conjugated with Chitosan or Whey Protein During In Vitro Digestion. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-024-03317-z.

- Nsairat, H.; Alshaer, W.; Odeh, F.; Essawi, E.; Khater, D.; Bawab, A.A.; El-Tanani, M.; Awidi, A.; Mubarak, M.S. Recent advances in using liposomes for delivery of nucleic acid-based therapeutics. OpenNano 2023, 11, 100132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onano.2023.100132.

- Wagner, A.; Vorauer-Uhl, K.; Katinger, H. Liposomes produced in a pilot scale: Production, purification and efficiency aspects. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2002, 54, 213-219. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0939-6411(02)00062-0.

- Otake, K.; Imura, T.; Sakai, H.; Abe, M. Development of a New Preparation Method of Liposomes Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Langmuir 2001, 17, 3898-3901. https://doi.org/10.1021/la010122k.

- Peschka, R.; Purmann, T.; Schubert, R. Cross-Flow Filtration-An Improved Detergent Removal Technique for the Preparation of Liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 1998, 162, 177-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-5173(97)00424-9.

- Jaafar-Maalej, C.; Charcosset, C.; Fessi, H. A New Method for Liposome Preparation Using a Membrane Contactor. J. Liposome Res. 2011, 21, 213-220. https://doi.org/10.3109/08982104.2010.517537.

- Skalko-Basnet, N.; Pavelic, Z.; Becirevic-Lacan, M. Liposomes Containing Drug and Cyclodextrin Prepared by the One-Step Spray-Drying Method. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2000, 26, 1279-1284. https://doi.org/10.1081/DDC-100102309.

- Leitgeb, M.; Knez, Ž.; Primožič, M. Sustainable technologies for liposome preparation. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2020, 165, 104984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2020.104984.

- Peppas, N.A.; Hilt, J.Z.; Khademhosseini, A.; Langer, R. Hydrogels in Biology and Medicine: From Molecular Principles to Bionanotechnology. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 1345-1360. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200501612.

- Hajareh Haghighi, F.; Binaymotlagh, R.; Fratoddi, I.; Chronopoulou, L.; Palocci, C. Peptide-Hydrogel Nanocomposites for AntiCancer Drug Delivery. Gels 2023, 9, 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels9120953.

- Binaymotlagh, R.; Hajareh Haghighi, F.; Di Domenico, E.G.; Sivori, F.; Truglio, M.; Del Giudice, A.; Fratoddi, I.; Chronopoulou, L.; Palocci, C. Biosynthesis of Peptide Hydrogel-Titania Nanoparticle Composites with Antibacterial Properties. Gels 2023, 9, 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels9120940.

- Peppas, N.A.; Bures, P.; Leobandung, W.S.; Ichikawa, H. Hydrogels in Pharmaceutical Formulations. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2000, 50, 27-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0939-6411(00)00090-4.

- Caló, E.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Biomedical Applications of Hydrogels: A Review of Patents and Commercial Products. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 65, 252-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2014.11.024.

- Binaymotlagh, R.; Chronopoulou, L.; Haghighi, F.H.; Fratoddi, I.; Palocci, C. Peptide-Based Hydrogels: New Materials for Biosensing and Biomedical Applications. Materials 2022, 15, 5871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15175871.

- Binaymotlagh, R.; Chronopoulou, L.; Palocci, C. Peptide-Based Hydrogels: Template Materials for Tissue Engineering. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 233. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb14040233.

- Hajareh Haghighi, F.; Binaymotlagh, R.; Chronopoulou, L.; Cerra, S.; Marrani, A.G.; Amato, F.; Palocci, C.; Fratoddi, I. SelfAssembling Peptide-Based Magnetogels for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Water. Gels 2023, 9, 621. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels9080621.

- Chronopoulou, L.; Binaymotlagh, R.; Cerra, S.; Haghighi, F.H.; Di Domenico, E.G.; Sivori, F.; Fratoddi, I.; Mignardi, S.; Palocci, C. Preparation of Hydrogel Composites Using a Sustainable Approach for In Situ Silver Nanoparticles Formation. Materials 2023, 16, 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16062134.

- Binaymotlagh, R.; Del Giudice, A.; Mignardi, S.; Amato, F.; Marrani, A.G.; Sivori, F.; Cavallo, I.; Di Domenico, E.G.; Palocci, C.; Chronopoulou, L. Green In Situ Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles-Peptide Hydrogel Composites: Investigation of Their Antibacterial Activities. Gels 2022, 8, 700. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels8110700.

- Ahmed, E.M. Hydrogel: Preparation, Characterization, and Applications: A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2015, 6,

. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2013.07.006. - Wichterle, O.; Lím, D. Hydrophilic Gels for Biological Use. Nature 1960, 185, 117-118. https://doi.org/10.1038/185117a0.

- Martinez, A.W.; Caves, J.M.; Ravi, S.; Li, W.; Chaikof, E.L. Effects of Crosslinking on the Mechanical Properties, Drug Release and Cytocompatibility of Protein Polymers. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 26-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2013.08.029.

- Sankaranarayanan, J.; Mahmoud, E.A.; Kim, G.; Morachis, J.M.; Almutairi, A. Multiresponse Strategies To Modulate Burst Degradation and Release from Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 5930-5936. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn100968e.

- Xiang, Z.; Sarazin, P.; Favis, B.D. Controlling Burst and Final Drug Release Times from Porous Polylactide Devices Derived from Co-Continuous Polymer Blends. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 2053-2066. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm8013632.

- Thirumaleshwar, S.; Kulkarni, K.P.; Gowda, V.D. Liposomal Hydrogels: A Novel Drug Delivery System for Wound Dressing. Curr. Drug Ther. 2012, 7, 212-218. https://doi.org/10.2174/157488512803988021.

- Ibrahim, M.; Nair, A.B.; Al-Dhubiab, B.E.; Shehata, T.M. Hydrogels and Their Combination with Liposomes, Niosomes, or Transfersomes for Dermal and Transdermal Drug Delivery. In Liposomes; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.68158.

- Kazakov, S.; Levon, K. Liposome-Nanogel Structures for Future Pharmaceutical Applications. Curr. Pharm. Design. 2006, 12, 4713-4728. https://doi.org/10.2174/138161206779026281.

- Weiner, A.L.; Carpenter-Green, S.S.; Soehngen, E.C.; Lenk, R.P.; Popescu, M.C. Liposome-Collagen Gel Matrix: A Novel Sustained Drug Delivery System. J. Pharm. Sci. 1985, 74, 922-925. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.2600740903.

- Zhang, Z.; Ai, S.; Yang, Z.; Li, X. Peptide-Based Supramolecular Hydrogels for Local Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 174, 482-503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2021.05.010.

- Gallo, E.; Diaferia, C.; Rosa, E.; Smaldone, G.; Morelli, G.; Accardo, A. Peptide-Based Hydrogels and Nanogels for Delivery of Doxorubicin. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 1617-1630. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S296272.

- Carvalho, C.; Santos, X.R.; Cardoso, S.; Correia, S.; Oliveira, J.P.; Santos, S.M.; Moreira, I.P. Doxorubicin: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Effect. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 3267-3285. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986709788803312.

- Yang, L.; Li, H.; Yao, L.; Yu, Y.; Ma, G. Amyloid-Based Injectable Hydrogel Derived from Hydrolyzed Hen Egg White Lysozyme. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 8071-8080. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.8b03492.

- Kumari, A.; Ahmad, B. The physical basis of amyloid-based hydrogels by lysozyme. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 37424-37435. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9RA07179B.

- Trusova, V.; Vus, K.; Tarabara, U.; Zhytniakivska, O.; Deligeorgiev, T.; Gorbenko, G. Liposomes Integrated with Amyloid Hydrogels: A Novel Composite Drug Delivery Platform. BioNanoScience 2020, 10, 446-454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-020-00729-x.

- Wickremasinghe, N.C.; Kumar, V.A.; Hartgerink, J.D. Two-Step Self-Assembly of Liposome-Multidomain Peptide Nanofiber Hydrogel for Time-Controlled Release. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 3587-3595. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm500856c.

- Mufamadi, M.S.; Pillay, V.; Choonara, Y.E.; Du Toit, L.C.; Modi, G.; Naidoo, D.; Ndesendo, V.M.K. A Review on Composite Liposomal Technologies for Specialized Drug Delivery. J. Drug Deliv. 2011, 2011, 939851. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/939851.

- Koo, O.M.; Rubinstein, I.; Onyuksel, H. Role of Nanotechnology in Targeted Drug Delivery and Imaging: A Concise Review. Nanomedicine 2005, 1, 193-212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2005.06.004.

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liang, D. Behaviors of Liposomes in a Thermo-Responsive Poly (N-Isopropylacrylamide) Hydrogel. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 4517-4523. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2SM25092F.

- Suri, A.; Campos, R.; Rackus, D.G.; Spiller, N.J.S.; Richardson, C.; Pålsson, L.-O.; Kataky, R. Liposome-Doped Hydrogel for Implantable Tissue. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 7071-7077. https://doi.org/10.1039/C1SM05530E.

- Hurler, J.; Berg, O.A.; Skar, M.; Conradi, A.H.; Johnsen, P.J.; Škalko-Basnet, N. Improved Burns Therapy: Liposomes-inHydrogel Delivery System for Mupirocin. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 101, 3906-3915. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps.23260.

- Ruel-Gariépy, È.; Leclair, G.; Hildgen, P.; Gupta, A.; Leroux, J. Thermosensitive chitosan-based hydrogel containing liposomes for the delivery of hydrophilic molecules. J. Control. Release 2002, 82, 373-383. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00146-3.

- Ciobanu, B.; Cadinoiu, A.N.; Popa, M.; Desbrières, J.; Peptu, C.A. Modulated release from liposomes entrapped in chitosan/gelatin hydrogels. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 43, 383-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2014.07.036.

- Billard, A.; Pourchet, L.; Malaise, S.; Alcouffe, P.; Montembault, A.; Ladavière, C. Liposome-loaded chitosan physical hydrogel: Toward a promising delayed-release biosystem. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 115, 651-657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.08.120.

- Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Tan, G.; Cao, Y.; Lao, Y.; Huang, Y. Research on liposomal hydrogels loaded with “Liu Zi Tang” compound Chinese medicine for the treatment of primary ovarian insufficiency. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med. 2023, 10, 100337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prmcm.2023.100337.

- Bieber, T. Atopic dermatitis. N. Eng. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1483-1494. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra074081.

- Avena-Woods, C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am. J. Manag. Care 2017, 23, S115-S123.

- Xia, Y.; Cao, K.; Jia, R.; Chen, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Xia, H.; Xu, Y.; Xie, Z. Tetramethylpyrazine-loaded liposomes surrounded by hydrogel based on sodium alginate and chitosan as a multifunctional drug delivery System for treatment of atopic dermatitis. Eur. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2024, 193, 106680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2023.106680.

- Madani, S.Z.M.; Safaee, M.M.; Gravely, M.; Silva, C.; Kennedy, S.; Bothun, G.D.; Roxbury, D. Carbon Nanotube-Liposome complexes in hydrogels for controlled drug delivery via Near-Infrared laser stimulation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 4, 331342. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.0c02700.

- Palmese, L.L.; Fan, M.; Scott, R.; Tan, H.; Kiick, K.L. Multi-stimuli-responsive, liposome-crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for drug delivery. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2020, 32, 635-656. https://doi.org/10.1080/09205063.2020.1855392.

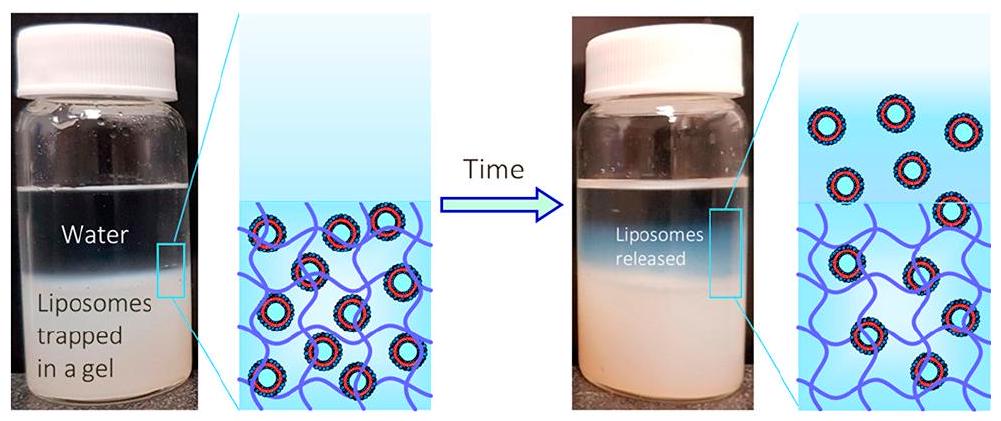

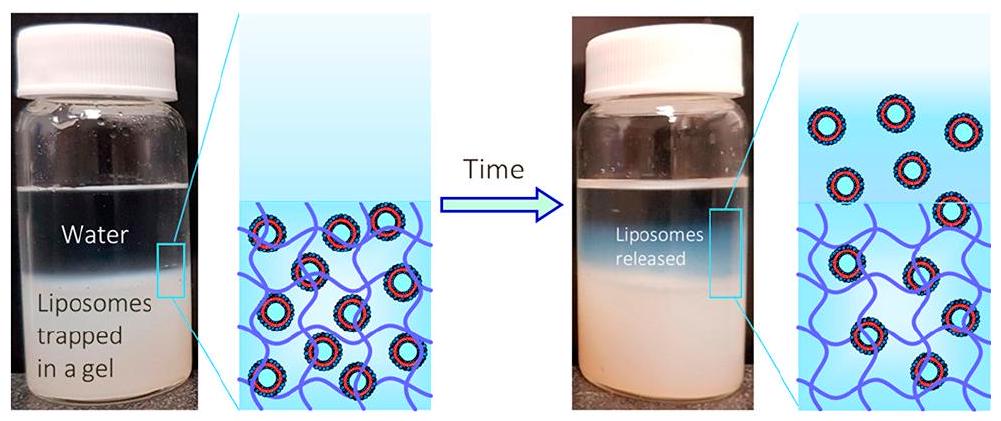

- Thompson, B.R.; Zarket, B.C.; Lauten, E.H.; Amin, S.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Raghavan, S.R. Liposomes Entrapped in Biopolymer Hydrogels Can Spontaneously Release into the External Solution. Langmuir 2020, 36, 7268-7276. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.0c00596.

- Lim, E.; Huh, Y.M.; Yang, J.; Lee, K.; Suh, J.S.; Haam, S. PH-Triggered Drug-Releasing magnetic nanoparticles for cancer therapy guided by molecular imaging by MRI. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 2436-2442. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201100351.

- Niu, C.; Wang, Z.; Lu, G.; Krupka, T.M.; Sun, Y.; You, Y.F.; Song, W.; Ran, H.; Li, P.; Zheng, Y. Doxorubicin loaded superparamagnetic PLGA-iron oxide multifunctional microbubbles for dual-mode US/MR imaging and therapy of metastasis in lymph nodes. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 2307-2317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.12.003.

- Ruiz, J.; Baeza, A.; Vallet-Regı, M. Smart Drug Delivery through DNA/Magnetic Nanoparticle Gates. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 12591266. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn1029229.

- Vallet-Regı, M.; Ruiz, J. Bioceramics: From bone regeneration to cancer nanomedicine. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 5177-5218. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201101586.

- Peng, J.; Qi, T.; Liao, J.; Chu, B.; Yang, Q.; Li, W.; Qu, Y.; Luo, F.; Zhang, Q. Controlled release of cisplatin from pH-thermal dual responsive nanogels. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 8726-8740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.092.

- Rauta, P.R.; Mackeyev, Y.; Sanders, K.L.; Kim, J.B.K.; Gonzalez, V.; Zahra, Y.; Shohayeb, M.A.; Abousaida, B.; Vijay, G.V.; Tezcan, O.; et al. Pancreatic tumor microenvironmental acidosis and hypoxia transform gold nanorods into cell-penetrant particles for potent radiosensitization. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm9729. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abm9729.

- Affram, K.; Udofot, O.; Singh, M.; Krishnan, S.; Reams, R.; Rosenberg, J.T.; Agyare, E. Smart thermosensitive liposomes for effective solid tumor therapy and in vivo imaging. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185116. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185116.

- Seneviratne, D.S.; Saifi, O.; Mackeyev, Y.; Malouff, T.D.; Krishnan, S. Next-Generation boron Drugs and rational translational studies driving the revival of BNCT. Cells 2023, 12, 1398. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12101398.

- Krishnan, S.; Reddy, C.M.; Reddy, C.B. Optimization of Site-Specific drug delivery system of tyrosine kinase inhibitor using response surface methodology. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021, 33, 273-286. https://doi.org/10.9734/jpri/2021/v33i46b32941.

- Quini, C.C.; Próspero, A.G.; De Freitas Calabresi, M.F.; Moretto, G.M.; Zufelato, N.; Krishnan, S.; De Pina, D.R.; De Oliveira, R.B.; Baffa, O.; Bakuzis, A.F.; et al. Real-time liver uptake and biodistribution of magnetic nanoparticles determined by AC biosusceptometry. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2017, 13, 1519-1529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2017.02.005.

- Kang, Y.S.; Kim, G.H.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, B.N.; Yoon, S.M.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.S. In vivo efficacy of an intratumorally injected in situ-forming doxorubicin/poly(ethylene glycol)-b-polycaprolactone diblock copolymer. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 45564564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.007.

- Van Tomme, S.R.; Van Nostrum, C.F.; Dijkstra, M.; De Smedt, S.C.; Hennink, W.E. Effect of particle size and charge on the network properties of microsphere-based hydrogels. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2008, 70, 522-530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.05.013.

- López-Noriega, A.; Hastings, C.L.; Ozbakir, B.; O’Donnell, K.; O’Brien, F.J.; Storm, G.; Hennink, W.E.; Duffy, G.P.; Ruiz, J. Hyperthermia-Induced Drug Delivery from Thermosensitive Liposomes Encapsulated in an Injectable Hydrogel for Local Chemotherapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 854-859. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm. 201300649.

- Kadlecová, Z.; Sevriugina, V.; Lysáková, K.; Rychetský, M.; Chamradová, I.; Vojtová, L. Liposomes affect protein release and stability of ITA-Modified PLGA-PEG-PLGA hydrogel carriers for controlled drug delivery. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 67-76. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.3c00736.

- Rowley, J.; Vander Hoorn, S.; Korenromp, E.; Low, N.; Unemo, M.; Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Chico, R.M.; Smolak, A.; Newman, L.; Gottlieb, S. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: Global prevalence and incidence estimates 2016. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 548-562. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.18.228486.

- Jøraholmen, M.W.; Johannessen, M.; Gravningen, K.; Puolakkainen, M.; Acharya, G.; Basnet, P.; Škalko-Basnet, N. Liposomes-In-Hydrogel delivery system enhances the potential of resveratrol in combating vaginal chlamydia infection. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12121203.

- Lee, J.-H.; Oh, H.; Baxa, U.; Raghavan, S.R.; Blumenthal, R. Biopolymer-Connected liposome networks as injectable biomaterials capable of sustained local drug delivery. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3388-3394. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm301143d.

- Hurler, J.; Žakelj, S.; Mravljak, J.; Pajk, S.; Kristl, A.; Schubert, R.; Škalko-Basnet, N. The effect of lipid composition and liposome size on the release properties of liposomes-in-hydrogel. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 456, 49-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.08.033.

- Alinaghi, A.; Rouini, M.-R.; Daha, F.J.; Moghimi, H. The influence of lipid composition and surface charge on biodistribution of intact liposomes releasing from hydrogel-embedded vesicles. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 459, 30-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.11.011.

- Hurler, J.; Sørensen, K.K.; Fallarero, A.; Vuorela, P.; Škalko-Basnet, N. Liposomes-in-Hydrogel Delivery System with Mupirocin:In VitroAntibiofilm Studies andIn VivoEvaluation in Mice Burn Model. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 498485. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/498485.

- Hosny, K.M. Preparation and evaluation of thermosensitive liposomal hydrogel for enhanced transcorneal permeation of ofloxacin. AAPS PharmSciTech 2009, 10, 1336-1342. https://doi.org/10.1208/s12249-009-9335-x.

- Mantha, S.; Pillai, S.; Khayambashi, P.; Upadhyay, A.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, O.; Pham, H.M.; Tran, S.D. Smart hydrogels in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Materials 2019, 12, 3323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12203323.

- Gordon, S.; Young, K.; Wilson, R.; Rizwan, S.B.; Kemp, R.A.; Rades, T.; Hook, S. Chitosan hydrogels containing liposomes and cubosomes as particulate sustained release vaccine delivery systems. J. Liposome Res. 2011, 22, 193-204. https://doi.org/10.3109/08982104.2011.637502.

- Song, J.; Leeuwenburgh, S.C.G. Sustained delivery of biomolecules from gelatin carriers for applications in bone regeneration. Ther. Deliv. 2014, 5, 943-958. https://doi.org/10.4155/tde.14.42.

- Santoro, M.; Tatara, A.M.; Mikos, A.G. Gelatin carriers for drug and cell delivery in tissue engineering. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 210-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.04.014.

- Elzoghby, A.O. Gelatin-based nanoparticles as drug and gene delivery systems: Reviewing three decades of research. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 1075-1091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.09.019.

- Wu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, W.; Xiang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, X.; Yu, X.; Lang, M. Controlled release of gentamicin from gelatin/genipin reinforced beta-tricalcium phosphate scaffold for the treatment of osteomyelitis. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 3304. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3tb20261e.

- Sung, B.; Kim, C.-J.; Kim, M. Biodegradable colloidal microgels with tunable thermosensitive volume phase transitions for controllable drug delivery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 450, 26-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2015.02.068.

- Narayanan, D.; Geena, M.G.; Lakshmi, H.D.S.G.; Koyakutty, M.; Nair, S.V.; Menon, D. Poly-(ethylene glycol) modified gelatin nanoparticles for sustained delivery of the anti-inflammatory drug Ibuprofen-Sodium: An in vitro and in vivo analysis. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2013, 9, 818-828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2013.02.001.

- Kasper, F.K.; Jerkins, E.; Tanahashi, K.; Barry, M.A.; Tabata, Y.; Mikos, A.G. Characterization of DNA release from composites of oligo(poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate) and cationized gelatin microspheres in vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 78, 823-835. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.30736.

- Dowling, M.B.; Lee, J.-H.; Raghavan, S.R. PH-Responsive Jello: Gelatin gels containing fatty acid vesicles. Langmuir 2009, 25, 8519-8525. https://doi.org/10.1021/la804159g.

- Cistola, D.P.; Hamilton, J.A.; Jackson, D.S.; Small, D. Ionization and phase behavior of fatty acids in water: Application of the Gibbs phase rule. Biochemistry 1988, 27, 1881-1888. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00406a013.

- Van Thienen, T.G.; Lucas, B.; Flesch, F.M.; Van Nostrum, C.F.; Demeester, J.; De Smedt, S.C. On the Synthesis and Characterization of Biodegradable Dextran Nanogels with Tunable Degradation Properties. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 8503-8511. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma050822m.

- De Geest, B.G.; Stubbe, B.G.; Jonas, A.M.; Van Thienen, T.; Hinrichs, W.L.J.; Demeester, J.; De Smedt, S.C. Self-Exploding LipidCoated microgels. Biomacromolecules 2005, 7, 373-379. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm0507296.

- Mora, N.L.; Hansen, J.S.; Gao, Y.; Ronald, A.A.; Kieltyka, R.E.; Malmstadt, N.; Kros, A. Preparation of size tunable giant vesicles from cross-linked dextran(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 1953-1955. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3cc49144g.

- Kechai, N.E.; Bochot, A.; Huang, N.; Nguyen, Y.; Ferrary, É.; Agnely, F. Effect of liposomes on rheological and syringeability properties of hyaluronic acid hydrogels intended for local injection of drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 487, 187-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.04.019.

- Lee, K.; Silva, E.A.; Mooney, D.J. Growth factor delivery-based tissue engineering: General approaches and a review of recent developments. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 8, 153-170. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2010.0223.

- Li, L.; Wei, Y.; Gong, C. Polymeric nanocarriers for Non-Viral Gene Delivery. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2015, 11, 739-770. https://doi.org/10.1166/jbn.2015.2069.

- Dong, J.; Jiang, D.; Wang, Z.; Wu, G.; Miao, L.; Huang, L. Intra-articular delivery of liposomal celecoxib-hyaluronate combination for the treatment of osteoarthritis in rabbit model. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 441, 285-290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.11.031.

- Lajavardi, L.; Camelo, S.; Agnely, F.; Luo, W.; Goldenberg, B.; Naud, M.; Behar-Cohen, F.; De Kozak, Y.; Bochot, A. New formulation of vasoactive intestinal peptide using liposomes in hyaluronic acid gel for uveitis. J. Control. Release 2009, 139, 2230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.033.

- Widjaja, L.K.; Bora, M.; Chan, P.N.P.H.; Lipik, V.; Wong, T.; Venkatraman, S.S. Hyaluronic acid-based nanocomposite hydrogels for ocular drug delivery applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 102, 3056-3065. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.34976.

- Ren, C.D.; Kurisawa, M.; Chung, J.E.; Ying, J.Y. Liposomal delivery of horseradish peroxidase for thermally triggered injectable hyaluronic acid-tyramine hydrogel scaffolds. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 4663-4670. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4tb01832j.

- Monshipouri, M.; Rudolph, A.S. Liposome-encapsulated alginate: Controlled hydrogel particle formation and release. J. Microencapsul. 1995, 12, 117-127. https://doi.org/10.3109/02652049509015282.

- Takagi, I.; Shimizu, H.; Yotsuyanagi, T. Application of alginate gel as a vehicle for liposomes. I. Factors affecting the loading of Drug-Containing liposomes and drug release. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996, 44, 1941-1947. https://doi.org/10.1248/cpb.44.1941.

- Takagi, I.; Nakashima, H.; Takagi, M.; Yotsuyanagi, T.; Ikeda, K. Application of alginate gel as a vehicle for liposomes. II. Erosion of alginate gel beads and the release of loaded liposomes. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1997, 45, 389-393. https://doi.org/10.1248/cpb.45.389.

- Liu, X.; Chen, D.; Xie, L.; Zhang, R. Oral colon-specific drug delivery for bee venom peptide: Development of a coated calcium alginate gel beads-entrapped liposome. J. Control. Release 2003, 93, 293-300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.08.019.

- Dai, C.; Wang, B.; Zhao, H.; Li, B.; Wang, J. Preparation and characterization of liposomes-in-alginate (LIA) for protein delivery system. Colloids Surf. B 2006, 47, 205-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2005.07.013.

- Smith, A.M.; Jaime-Fonseca, M.R.; Grover, L.M.; Bakalis, S. Alginate-Loaded liposomes can protect encapsulated alkaline phosphatase functionality when exposed to gastric

. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 4719-4724. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf904466p. - Ullrich, M.; Hanuš, J.; Dohnal, J.; Štěpánek, F. Encapsulation stability and temperature-dependent release kinetics from hydrogel-immobilised liposomes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 394, 380-385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2012.11.016.

- Cejková, J.; Haufová, P.; Gorný, D.; Hanuš, J.; Štěpánek, F. Biologically triggered liberation of sub-micron particles from alginate microcapsules. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 5456. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3tb20388c.

- Hanuš, J.; Ullrich, M.; Dohnal, J.; Singh, M.; Štěpánek, F. Remotely Controlled Diffusion from Magnetic Liposome Microgels. Langmuir 2013, 29, 4381-4387. https://doi.org/10.1021/la4000318.

- Kang, D.H.; Jung, H.; Ahn, N.; Yang, S.M.; Seo, S.; Suh, K.Y.; Chang, P.; Jeon, N.L.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, K. Janus-Compartmental alginate microbeads having polydiacetylene liposomes and magnetic nanoparticles for visual Lead(II) detection. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 10631-10637. https://doi.org/10.1021/am502319m.

- Machluf, M.; Apte, R.N.; Regev, O.; Cohen, S. Enhancing the Immunogenicity of Liposomal Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg) By Controlling Its Delivery From polymeric Microspheres. J. Pharm. Sci. 2000, 89, 1550-1557. https://doi.org/10.1002/15206017(200012)89:12.

- Aikawa, T.; Ito, S.; Shinohara, M.; Kaneko, M.; Kondo, T.; Yuasa, M. A drug formulation using an alginate hydrogel matrix for efficient oral delivery of the manganese porphyrin-based superoxide dismutase mimic. Biomater. Sci. 2015, 3, 861-869. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5bm00056d.

- Van Elk, M.; Ozbakir, B.; Barten-Rijbroek, A.D.; Storm, G.; Nijsen, J.F.W.; Hennink, W.E.; Vermonden, T.; Deckers, R. Alginate microspheres containing temperature sensitive liposomes (TSL) for MR-Guided embolization and triggered release of doxorubicin. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141626. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0141626.

- Kulkarni, C.V.; Moinuddin, Z.; Patil-Sen, Y.; Littlefield, R.; Hood, M. Lipid-hydrogel films for sustained drug release. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 479, 416-421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.01.013.

- El-Menshawe, S.F.; Hussein, A.K. Formulation and evaluation of meloxicam niosomes as vesicular carriers for enhanced skin delivery. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2011, 18, 779-786. https://doi.org/10.3109/10837450.2011.598166.

- Kapadia, R.; Khambete, H.; Katara, R.; Ramteke, S. A novel approach for ocular delivery of acyclovir via niosomes entrapped in situ hydrogel system. J. Pharm. Res. 2009, 2, 745-751.

- Prajapati, V.D.; Jani, G.K.; Moradiya, N.G.; Randeria, N.P.; Nagar, B.J. Locust bean gum: A versatile biopolymer. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 814-821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.086.

- Carafa, M.; Marianecci, C.; Di Marzio, L.; Rinaldi, F.; Di Meo, C.; Matricardi, P.; Alhaique, F.; Coviello, T. A new vesicle-loaded hydrogel system suitable for topical applications: Preparation and characterization. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 14, 336. https://doi.org/10.18433/j3160b.

- Vanić, Ž.; Hurler, J.; Ferderber, K.; Gašparović, P.G.; Škalko-Basnet, N.; Filipović-Grčić, J. Novel vaginal drug delivery system: Deformable propylene glycol liposomes-in-hydrogel. J. Liposome Res. 2013, 24, 27-36. https://doi.org/10.3109/08982104.2013.826242.

- Li, W.; Zhao, N.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Bao-Hua, H.; Kong, P.; Zhang, C. Post-expansile hydrogel foam aerosol of PGliposomes: A novel delivery system for vaginal drug delivery applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 47, 162-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2012.06.001.

- Chugh, R.; Sangwan, V.; Patil, S.; Dudeja, V.; Dawra, R.; Banerjee, S.; Schumacher, R.J.; Blazar, B.R.; Georg, G.I.; Vickers, S.M.; et al. A preclinical evaluation of minnelide as a therapeutic agent against pancreatic cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 156 ra139. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3004334.

- Alexander, A.; Khan, J.; Saraf, S.; Saraf, S. Poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) based thermosensitive injectable hydrogels for biomedical applications. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 715-729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.10.006.

- Supper, S.; Anton, N.; Seidel, N.; Riemenschnitter, M.; Curdy, C.; Vandamme, T.F. Thermosensitive chitosan/glycerophosphatebased hydrogel and its derivatives in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2013, 11, 249-267. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425247.2014.867326.

- Mao, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, G.; Wang, S. Thermosensitive hydrogel system with paclitaxel liposomes used in localized drug delivery system for in situ treatment of tumor: Better antitumor efficacy and lower toxicity. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 194-204. https://doi.org/10.1002/jps. 24693.

- Kakinoki, S.; Taguchi, T.; Saito, H.; Tanaka, J.; Tateishi, T. Injectable in situ forming drug delivery system for cancer chemotherapy using a novel tissue adhesive: Characterization and in vitro evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2007, 66, 383390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2006.11.022.

- Mourtas, S.; Fotopoulou, S.; Duraj, S.; Sfika, V.; Tsakiroglou, C.D.; Antimisiaris, S.G. Liposomal drugs dispersed in hydrogels. Colloids Surf. B 2007, 55, 212-221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.12.005.

- Zhang, Z.J.; Osmałek, T.; Michniak-Kohn, B. Deformable Liposomal Hydrogel for Dermal and Transdermal Delivery of Meloxicam. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 9319-9335. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s274954.

- Torchilin, V.P. Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 145-160. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1632.

- Zhang, L.; Pornpattananangkul, D.; Hu, C.; Huang, C.M. Development of nanoparticles for antimicrobial drug delivery. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 585-594. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986710790416290.

- Gao, W.; Hu, C.; Fang, R.H.; Zhang, L. Liposome-like nanostructures for drug delivery. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 6569. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3tb21238f.

- Marrink, S.J.; Mark, A.E. The mechanism of vesicle fusion as revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11144-11145. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja036138.

- Haluska, C.K.; Riske, K.A.; Marchi-Artzner, V.; Lehn, J.-M.; Lipowsky, R.; Dimova, R. Time scales of membrane fusion revealed by direct imaging of vesicle fusion with high temporal resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 15841-15846. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 0602766103.

- Gao, W.; Vecchio, D.; Li, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, V.; Li, J.; Thamphiwatana, S.; Lu, D.; Zhang, L. Hydrogel containing Nanoparticle-Stabilized liposomes for topical antimicrobial delivery. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2900-2907. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn500110a.

- Andresen, S.R.; Biering-Sørensen, F.; Hagen, E.M.; Nielsen, J.F.; Bach, F.W.; Finnerup, N.B. Pain, spasticity and quality of life in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury in Denmark. Spinal Cord 2016, 54, 973-979. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2016.46.

- Rivers, C.S.; Fallah, N.; Noonan, V.K.; Whitehurst, D.G.T.; Schwartz, C.E.; Finkelstein, J.; Craven, B.C.; Ethans, K.; ÓConnell, C.; Truchon, B.C.; et al. Health conditions: Effect on function, Health-Related Quality of life, and life satisfaction after traumatic spinal cord injury. A Prospective Observational Registry Cohort study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 443-451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.06.012.

- Hiremath, S.V.; Hogaboom, N.; Roscher, M.; Worobey, L.A.; Oyster, M.; Boninger, M.L. Longitudinal prediction of Quality-ofLife scores and locomotion in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 2385-2392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.05.020.

- Ahuja, C.S.; Martín, A.; Fehlings, M.G. Recent advances in managing a spinal cord injury secondary to trauma. F1000 Res. 2016, 5, 1017. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7586.1.

- Kwon, B.K. Pathophysiology and pharmacologic treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Spine J. 2004, 4, 451-464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2003.07.007.

- Tykocki, T.; Poniatowski, Ł.A.; Czyż, M.; Koziara, M.; Wynne-Jones, G. Intraspinal pressure monitoring and extensive duroplasty in the acute phase of traumatic spinal cord injury: A Systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2017, 105, 145-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.05.138.

- Nowrouzi, B.; Assan-Lebbe, A.; Sharma, B.; Casole, J.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B. Spinal cord injury: A review of the most-cited publications. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 26, 28-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4669-z.

- Widerström-Noga, E. Neuropathic pain and spinal cord injury: Phenotypes and pharmacological management. Drugs 2017, 77, 967-984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-017-0747-8.

- Wei, D.; Huang, Y.; Liang, M.; Ren, P.; Tao, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, T.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, Q. Polypropylene composite hernia mesh with anti-adhesion layer composed of PVA hydrogel and liposomes drug delivery system. Colloids Surf. B 2023, 223, 113159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2023.113159.

- Tse, C.M.; Chisholm, A.E.; Lam, T.; Eng, J.J. A systematic review of the effectiveness of task-specific rehabilitation interventions for improving independent sitting and standing function in spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2017, 41, 254-266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2017.1350340.

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; ZhuGe, D.; Guo, X.; Xu, H.; et al. Novel multi-drug delivery hydrogel using scar-homing liposomes improves spinal cord injury repair. Theranostics 2018, 8, 4429-4446. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno. 26717.

- Elango, S.; Perumalsamy, S.; Ramachandran, K.; Vadodaria, K. Mesh materials and hernia repair. Biomedicine 2017, 7, 16. https://doi.org/10.1051/bmdcn/2017070316.

- Papavramidou, N.; Christopoulou-Aletras, H. Treatment of “Hernia” in the writings of Celsus (First century AD). World J. Surg. 2005, 29, 1343-1347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-7808-y.

- Xie, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, H. Rapamycin loaded TPGS-Lecithins-Zein nanoparticles based on core-shell structure for oral drug administration. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 568, 118529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.118529.

- Patel, G.; Dalwadi, C. Recent Patents on Stimuli Responsive Hydrogel Drug Delivery System. Recent Pat. Drug Deliv. Formul. 2013, 7, 206-215. https://doi.org/10.2174/1872211307666131118141600.

- FDA. FDA Executive Summary: Classification of Wound Dressings Combined with Drugs. In Proceedings of the Meeting of the General and Plastic Surgery Devices-Advisory Panel, Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 20-21 September 2016.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/gels10040284

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38667703

Publication Date: 2024-04-22

Liposome-Hydrogel Composites for Controlled Drug Delivery Applications

Abstract

Various controlled delivery systems (CDSs) have been developed to overcome the shortcomings of traditional drug formulations (tablets, capsules, syrups, ointments, etc.). Among innovative CDSs, hydrogels and liposomes have shown great promise for clinical applications thanks to their cost-effectiveness, well-known chemistry and synthetic feasibility, biodegradability, biocompatibility and responsiveness to external stimuli. To date, several liposomal- and hydrogel-based products have been approved to treat cancer, as well as fungal and viral infections, hence the integration of liposomes into hydrogels has attracted increasing attention because of the benefit from both of them into a single platform, resulting in a multifunctional drug formulation, which is essential to develop efficient CDSs. This short review aims to present an updated report on the advancements of liposome-hydrogel systems for drug delivery purposes.

Revised: 17 April 2024

Accepted: 18 April 2024

Published: 22 April 2024

1. Introduction

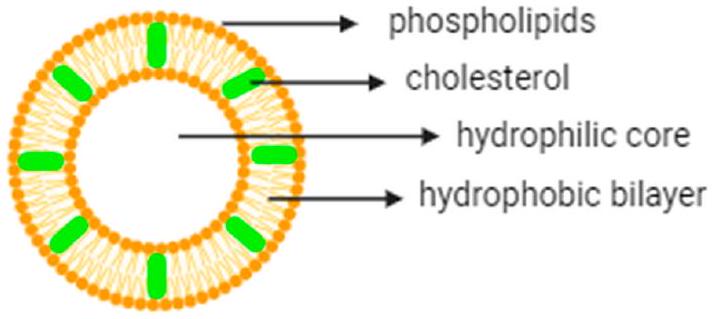

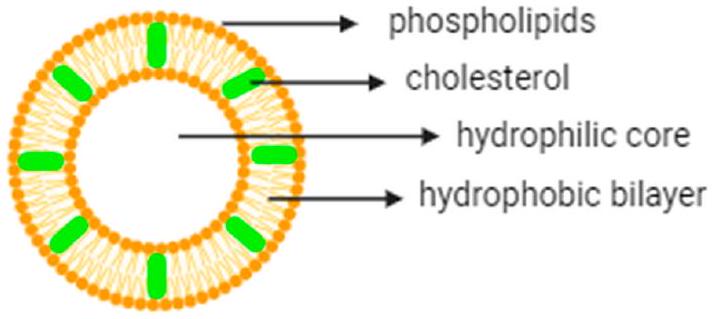

1.1. Liposomes

| Application | Product Name | API | Approved Year/Area | Therapeutic Indications |

| Cancer therapy | Doxil

|

Doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOXHCl) | 1995 (US) 1996 (EU) | Breast and ovarian cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| DaunoXome

|

Daunorubicin | 1996 (US,EU) | Kaposi’s sarcoma | |

| Onivyde

|

Irinotecan hydrochloride trihydrate | 1996 (US) 2016 (EU) | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | |

| Myocet

|

Doxorubicin | 2000 (EU) | Breast cancer | |

| Mepact

|

Mifamurtide | 2009 (EU) | Osteosarcoma | |

| Marqibo

|

Vineristine | 2012 (US) | Leukemia | |

| Vyxeos

|

Daunorubicin + cytrabine | 2017 (US) 2018 (EU) | Leukemia | |

| Zolsketil

|

Doxorubicin | 2022 (EU) | Breast and ovarian cancer, multiple myeloma, Kaposi’s sarcoma | |

| Other applications | AmBisome

|

Amphotericin B | 1997 (US, EU) | Fungal infections |

| DepoCyt

|

Cytarabine | 1999 (US) 2001 (EU) | Lymphomatous meningitis | |

| Visudyne

|

Verteporphin | 2000 (US, EU) | Age-related macular degeneration | |

| DepoDur

|

Morphine sulfate | 2004 (US, EU) | Pain management |

| Arikayce

|

Amikacin | 2018 (US, EU) | Lung infections | |

| Exparel

|

Bupivacaine | 2020 (EU) | Anesthesia | |

| Vaccines | Epaxal

|

Inactivated hepatitis A virus (RG-SB strain) | 1994 (EU) | Hepatitis A |

| Inflexal V

|

Influenza virus surface antigens (haemagglutinin and neuraminidase), Virosomal, 3 different strains | 1997 (EU) | Influenza | |

| MosquirixTM | Proteins found on the surface of the Plasmodium falciparum parasites and the hepatitis B virus | 2015 (EU) | Malaria | |

| Shingrix

|

Recombinant varicellazoster virus glycoprotein E | 2017 (US) 2018 (EU) | Shingles and post-herpetic neuralgia | |

| COMIRNATY

|

mRNA | 2021 (US, EU) | COVID-19 | |

| SPIKEVAX

|

mRNA | 2022 (US, EU) | COVID-19 |

conventional gels) linked to its expensive production process. This highlights the need for precise formulation design for the development of sustainable industrial manufacturing.

(1) Thin-lipid film hydration is the most common methodology, used to prepare different structures, including small unilamellar (SUVs), multilamellar (MLVs) or giant unilamellar (GUVs) vesicles [23-25]. The limitations of this method are broad size distribution, high temperature, possible liposome degradation upon sonication or low drug encapsulation yield.

(2) Reverse-phase evaporation [26] is the second most used technique to obtain large unilamellar vesicles using water-in-oil formation from a surfactant/lipid mixture with an aqueous solution of the drug. The organic solvent is then removed under reduced pressure; however, the trace amounts of organic solvent in the final formulation can influence vesicle stability.

(3) Solvent injection is based on the injection of an organic phospholipid solution into an aqueous phase of the selected drug at a temperature above the organic solvent boiling point. Vesicle size can be controlled with this method; however the presence of organic solvent in the final product is considered a major disadvantage for this approach.

To address the limitations of such traditional methods, more efficient novel approaches are being developed. In this regard, microfluidic technology has evolved at both lab and industrial scales to obtain monodisperse liposomes [27,28] by controlling parameters such as micro-channel size and flow rates. The main advantages of this method are high yields, efficient liposomal distribution and high drug encapsulation efficiencies. However, for scaling-up, the device fabrication and optimization of different fluid phases and multiple fluid inputs may be challenging and are, therefore, considered the main limitations of microfluidic technologies.

(with

| Preparation Method | Particle Size (nm) | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

| Thin-lipid film hydration | 100-1000 | Most widely used method | Low encapsulation efficiencies, sonication, temperature exposure, heterogeneous size distribution | [40] |

| Reverse-phase evaporation | 100-1000 | High encapsulation efficiency | Organic solvent traces | [41] |

| Solvent injection (ether or ethanol) | 70-200 | Ability to control vesicle size | Dilution of liposomes, heterogeneous populations, use of high temperatures | [42] |

| Microfluidic technologies | 100-300 | Synthesis of monodisperse liposomes, high encapsulation efficiency | Large-scale fabrication may be complex and requires optimization | [43] |

| Supercritical reverse-phase evaporation | 100-1200 | Environmentally friendly process, high encapsulation efficiency | High pressures and temperatures | [44] |

| Spray drying | 100-1000 | Control over particle formation, easily translated to large-scale production | Expensive and time-consuming | [45] |

| Membrane contactor technology |

|

Homogeneous and small sizes, high encapsulation efficiency, simplicity for scaling-up | Hydrophilic drug encapsulation needs optimization | [46] |

| Crossflow injection |

|

Liposomes of defined size | Vessicle instability due to residual solvent | [47] |

| Advantages | Disadvantages | ||

|

Low solubility | ||

| Enhanced drug stablility | Short half-life |

| Non-toxic, flexible, biocompatible, biodegradable and non-immunogenic | Possible phospholipid oxidation and hydrolysis-like reactions |

| Decreased toxicity to the encapsulated drug | Leakage and fusion of encapsulated drugs |

| Reduction in the exposure of sensitive tissues to toxic drugs | High production costs |

| Site avoidance effect | Low stability |

| Improved pharmacokinetics |

1.2. Hydrogels

1.3. Integration of Hydrogels and Liposomes (Liposomes-Hydrogels)

liposomes-hydrogels (both synthetic and natural hydrogels) to obtain stimuli-responsive hybrid materials.

2. Liposomes Encapsulated in Different Types of Hydrogels

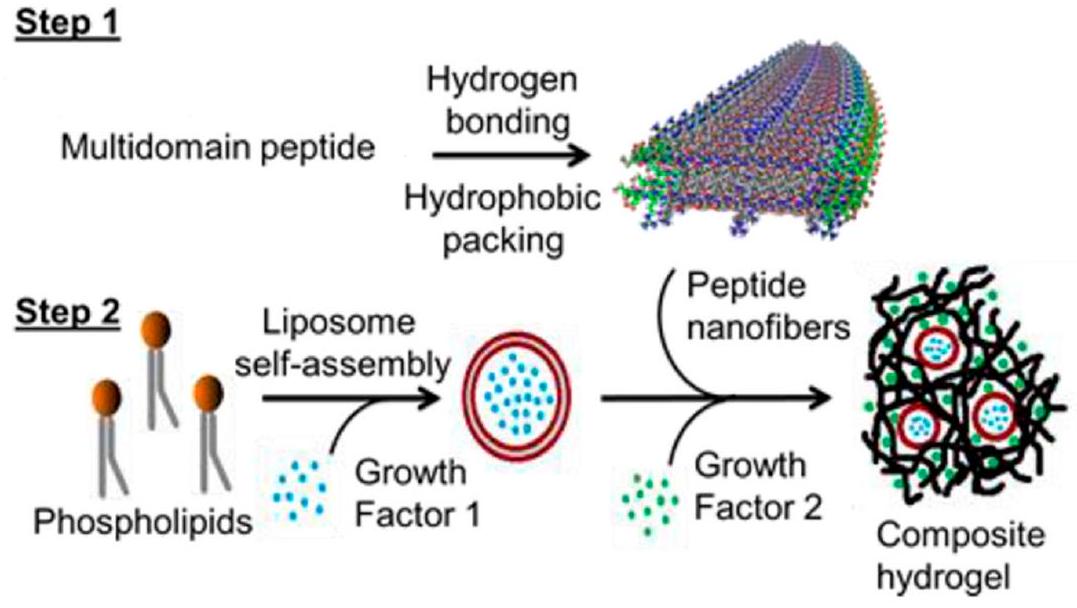

2.1. Liposomes Encapsulated in Peptide/Amyloid Hydrogels

factors showed a sustained release by liposomes in the hydrogel compared to a rapid release from the pristine hydrogel. This liposome-peptide hydrogel formulation can be further studied in systems where timed cascades of biological signals may be valuable, such as in tissue regeneration applications.

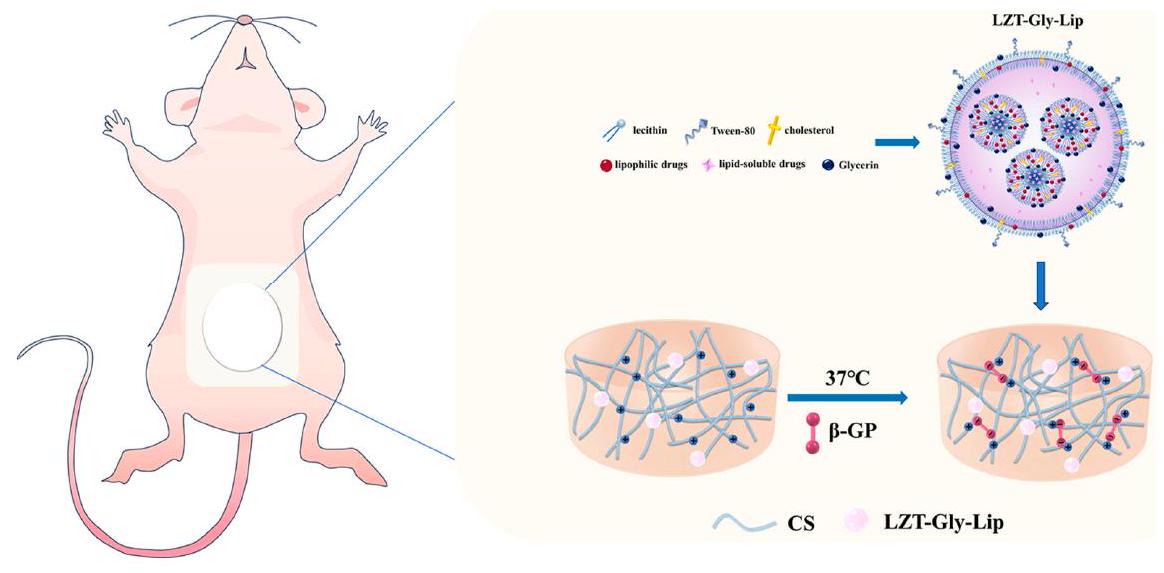

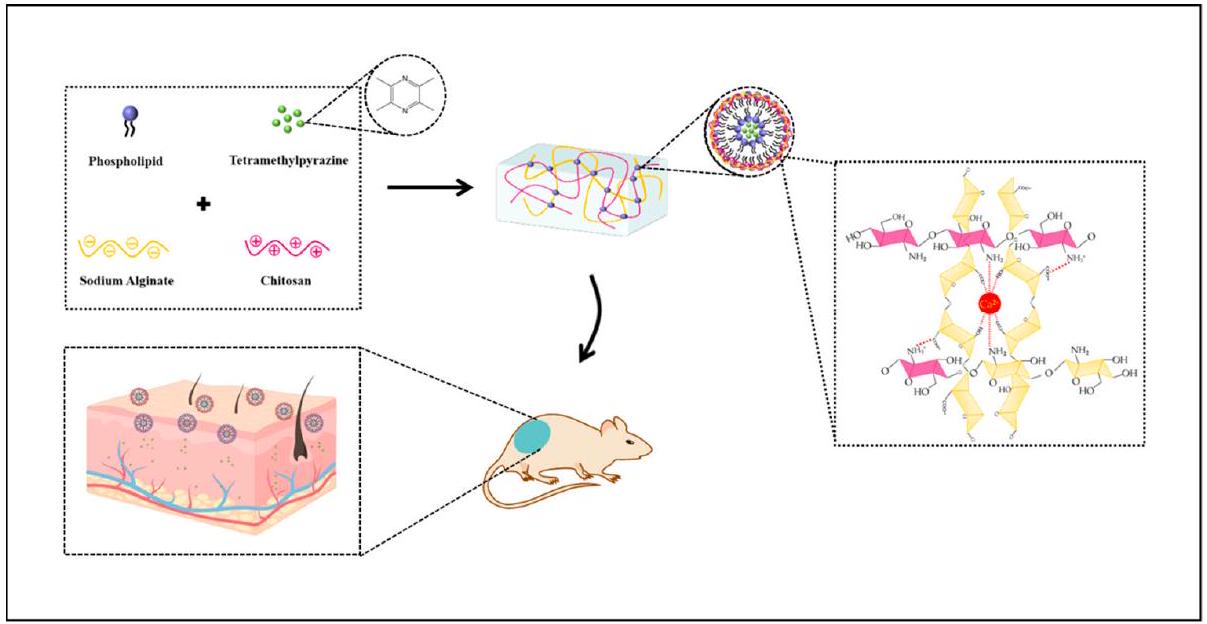

2.2. Liposomes Encapsulated in Biopolymeric Hydrogels

the CF hydrogel (cumulative release of

effects (due to the presence of TMP). Furthermore, TMP-liposome/ALG-CS hydrogels provided better skin permeability due to a moist healing environment for AD dry skin, achieving a controlled drug release, which is necessary for treating AD. The 1-Chloro2,4dinitrobenzene was used to induce the lesions for in vivo experiments in mice. TMP-lip-osome/ALG-CS hydrogels alleviated oxidative stress and increased SOD activity in treated mice.

release of the therapeutic molecule at the target site [94-103]. Among these materials, in situ gelling hydrogel-drug formulations significantly enhance therapeutic effects and overcome the pharmacokinetic limitations of intravenous injection [104,105]. Following this concept, López-Noriega et al. designed a novel thermo-sensitive liposome-hydrogel composite for enabling the localized release of Dox by the incorporation of thermo-sensitive liposomes (loaded with Dox) in a thermo-responsive CS/

showed that the proteins and liposome-encapsulated proteins did not impact the mechanical stability of the hydrogel. The liposomes were an effective protective system for the delivery of FGF2-STAB. Also, these liposomes demonstrated to significantly enhance the release mechanism of FGF2-STAB, underscoring their potential in advanced therapeutic approaches. However, this study showed that the -COOH groups of the hydrogel were affected by the positive charge of the protein, which lowers the hydrolytic stability of the system; therefore, the carboxylic groups of the hydrogel should be replaced or masked to reduce the network-protein interactions for future applications.

| Biopolymer | Liposomes | Delivered Agent | References |

| Chitosan (CS) | phosphatidylcholine liposomes of various sizes | Mupirocin | [110-116] |

| Gelatin | vesicles made of sodium oleate | Calcein | [117-125] |

| Dextran | SOPC/DOTAP liposomes | N/A | [126-128] |

| Hyaluronic acid | thermo-responsive liposomes (i.e., dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) and dimyristoylphosphatidyl choline (DMPC)) | horseradish peroxidase | [117,129-135] |

| Alginate | dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine liposomes | cytochrome-c | [136-148] |

| Carrageenan | niosomes based on a non-ionic surfactant molecule and cholesterol | meloxicam | [132,149,150] |

| Methylcellulose | niosomes based on two non-ionic surfactants (span 20 and span 60) and cholesterol | acyclovir | [151] |

| Xanthan gum | non-ionic surfactant niosomes based on Tween 20 and cholesterol | caffeine, ibuprofen | [152,153] |

2.3. Liposomes Encapsulated in Synthetic Polymeric Hydrogels

hydrogels (ehydroxylethyl-cellulose (HEC), carbopol 974 or a mixture of the two). GRF or calcein release was monitored by spectrophotometric and fluorescence techniques, respectively. The results showed that calcein release from liposome hydrogels is slower, compared to control gels, and can be further controlled and delayed by using rigid-membrane liposomes. Furthermore, calcein release was not influenced by the lipid amount (in the range from 2 to

3. Conclusions: Current Challenges and Future Trends

Author Contributions: Writing-original draft preparation, F.H.H. and R.B.; writing-review and editing, C.P. and L.C.; visualization, F.H.H. and R.B.; supervision, C.P. and L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grijalvo, S.; Mayr, J.; Eritja, R.; Díaz, D.D. Biodegradable Liposome-Encapsulated Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications: A Marriage of Convenience. Biomater. Sci. 2016, 4, 555-574. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5BM00481K.

- Chronopoulou, L.; Falasca, F.; Di Fonzo, F.; Turriziani, O.; Palocci, C. siRNA Transfection Mediated by Chitosan Microparticles for the Treatment of HIV-1 Infection of Human Cell Lines. Materials 2022, 15, 5340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15155340.

- Liu, P.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J. A Review of Liposomes as a Drug Delivery System: Current Status of Approved Products, Regulatory Environments, and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27041372.

- Düzgüneş, N.; Gregoriadis, G. Introduction: The Origins of Liposomes: Alec Bangham at Babraham. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; Volume 391, pp. 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(05)91029-X.

- Bangham, A.D.; Horne, R.W. Negative staining of phospholipids and their structural modification by surface-active agents as observed in the electron microscope. J. Mol. Biol. 1964, 8, 660-668. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-2836(64)80115-7.

- Niu, M.; Lu, Y.; Hovgaard, L.; Guan, P.; Tan, Y.; Lian, R.; Qi, J.; Wu, W. Hypoglycemic activity and oral bioavailability of insulinloaded liposomes containing bile salts in rats: The effect of cholate type, particle size and administered dose. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 81, 265-272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpb.2012.02.009.

- Wang, N.; Wang, T.; Li, T.; Deng, Y. Modulation of the physicochemical state of interior agents to prepare controlled release liposomes. Colloids Surf. B 2009, 69, 232-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2008.11.033.

- Zeng, H.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Peng, W.; Zhang, Y. Nanomaterials toward the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Recent advances and future trends. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 1857-1868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2021.01.014.

- Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, Y.; Wang, J.; Lin, J.; Li, Z.; Huang, P. STING-activating drug delivery systems: Design strategies and biomedical applications. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 1615-1625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2021.01.001.

- Giordani, S.; Marassi, V.; Zattoni, A.; Roda, B.; Reschiglian, P. Liposomes characterization for market approval as pharmaceutical products: Analytical methods, guidelines and standardized protocols. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 2023, 236, 115751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2023.115751.

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic: Nanoparticles in the Clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2016, 1, 10-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/btm2.10003.

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Nanoparticles in the clinic: An update. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2019, 4, e10143. https://doi.org/10.1002/btm2.10143.

- Elkhoury, K.; Koçak, P.; Kang, A.; Arab-Tehrany, E.; Ward, J.E.; Shin, S.R. Engineering Smart Targeting Nanovesicles and Their Combination with Hydrogels for Controlled Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics12090849.

- Ferraris, C.F.; Rimicci, C.; Garelli, S.; Ugazio, E.; Battaglia, L. Nanosystems in Cosmetic Products: A Brief Overview of functional, market, regulatory and safety concerns. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13091408.

- Yadwade, R.; Gharpure, S.; Ankamwar, B. Nanotechnology in cosmetics pros and cons. Nano Express 2021, 2, 022003. https://doi.org/10.1088/2632-959x/abf46b.

- Fernández-García, R.; Lalatsa, A.; Statts, L.; Bolás-Fernández, F.; Ballesteros, M.P.; Serrano, D.R. Transferosomes as nanocarriers for drugs across the skin: Quality by design from lab to industrial scale. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 573, 118817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.118817.

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Langer, R. Transdermal drug delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1261-1268. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1504.

- Malakar, J.; Sen, S.O.; Nayak, A.K.; Sen, K.K. Formulation, optimization and evaluation of transferosomal gel for transdermal insulin delivery. Saudi Pharm. J. 2012, 20, 355-363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2012.02.001.

- Karpiński, T.M. Selected medicines used in iontophoresis. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics10040204.

- Ita, K. Perspectives on transdermal electroporation. Pharmaceutics 2016, 8, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics8010009.

- Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Song, Y. Recent advances of microneedles for biomedical applications: Drug delivery and beyond. Acta Pharm. Sinic. B 2019, 9, 469-483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2019.03.007.

- Rother, M.; Seidel, E.; Clarkson, P.M.; Mazgareanu, S.; Vierl, U.; Rother, I. Efficacy of epicutaneous Diractin (ketoprofen in Transfersome gel) for the treatment of pain related to eccentric muscle contractions. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2009, 3, 143-149. https://doi.org/10.2147/dddt.s5501.

- Bangham, A.D.; De Gier, J.; Greville, G.D. Osmotic Properties and Water Permeability of Phospholipid Liquid Crystals. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1967, 1, 225-246. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-3084(67)90030-8.

- Saunders, L.; Perrin, J.; Gammack, D. Ultrasonic Irradiation of Some Phospholipid Sols. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1962, 14, 567-572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2042-7158.1962.tb11141.x.

- Parente, R.A.; Lentz, B.R. Phase Behavior of Large Unilamellar Vesicles Composed of Synthetic Phospholipids. Biochemistry 1984, 23, 2353-2362. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00306a005.

- Szoka, F.; Papahadjopoulos, D. Procedure for Preparation of Liposomes with Large Internal Aqueous Space and High Capture by Reverse-Phase Evaporation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 4194-4198. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.75.9.4194.

- Jahn, A.; Vreeland, W.N.; Gaitan, M.; Locascio, L.E. Controlled Vesicle Self-Assembly in Microfluidic Channels with Hydrodynamic Focusing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2674-2675. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja0318030.

- van Swaay, D.; deMello, A. Microfluidic Methods for Forming Liposomes. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 752-767. https://doi.org/10.1039/C2LC41121K.

- Chronopoulou, L.; Donati, L.; Bramosanti, M.; Rosciani, R.; Palocci, C.; Pasqua, G.; Valletta, A. Microfluidic synthesis of methyl jasmonate-loaded PLGA nanocarriers as a new strategy to improve natural defenses in Vitis vinifera. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18322. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54852-1.

- Serrano, D.R.; Kara, A.; Yuste, I.; Luciano, F.C.; Ongoren, B.; Anaya, B.J.; Molina, G.; Díez, L.G.; Ramirez, B.I.; Ramirez, I.O.; et al. 3D printing technologies in personalized medicine, nanomedicines, and biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 313. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15020313.

- Garg, S.; Heuck, G.; Ip, S.; Ramsay, E. Microfluidics: A transformational tool for nanomedicine development and production. J. Drug Target. 2016, 24, 821-835. https://doi.org/10.1080/1061186X.2016.1198354.

- Colombo, S.; Beck-Broichsitter, M.; Bøtker, J.P.; Malmsten, M.; Rantanen, J.; Bohr, A. Transforming nanomedicine manufacturing toward Quality by Design and microfluidics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 128, 115-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2018.04.004.

- Gale, B.K.; Jafek, A.R.; Lambert, C.J.; Goenner, B.L.; Moghimifam, H.; Nze, U.C.; Kamarapu, S.K. A Review of Current Methods in Microfluidic Device Fabrication and Future Commercialization Prospects. Inventions 2018, 3, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/inventions3030060.

- Tiboni, M.; Tiboni, M.; Pierro, A.; Del Papa, M.; Sparaventi, S.; Cespi, M.; Casettari, L. Microfluidics for nanomedicines manufacturing: An affordable and low-cost 3D printing approach. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 599, 120464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120464.

- Chen, Z.; Han, J.Y.; Shumate, L.; Fedak, R.; DeVoe, D.L. High Throughput Nanoliposome Formation Using 3D Printed Microfluidic Flow Focusing Chips. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1800511. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.201800511.

- Chiado, A.; Palmara, G.; Chiappone, A.; Tanzanu, C.; Pirri, C.F.; Roppolo, I.; Frascell, F. A modular 3D printed lab-on-a-chip for early cancer detection. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 665-674. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9LC01108K.

- Rolley, N.; Bonnin, M.; Lefebvre, G.; Verron, S.; Bargiel, S.; Robert, L.; Riou, J.; Simonsson, C.; Bizien, T.; Gimel, J.C.; et al. Galenic Lab-on-a-Chip concept for lipid nanocapsules production. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 11899-11912. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1NR00879J.

- Ballacchino, G.; Weaver, E.; Mathew, E.; Dorati, R.; Genta, I.; Conti, B.; Lamprou, D.A. Manufacturing of 3D-Printed Microfluidic Devices for the Synthesis of Drug-Loaded Liposomal Formulations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8064. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22158064.

- Tiboni, M.; Benedetti, S.; Skouras, A.; Curzi, G.; Perinelli, D.R.; Palmieri, G.F.; Casettari, L. 3D-printed microfluidic chip for the preparation of glycyrrhetinic acid-loaded ethanolic liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 584, 119436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119436.

- Jiang, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J. Lipid-Based Nanotechnology: Liposome. Pharmaceutics 2024,

. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16010034. - Shi, N.-Q.; Qi, X.-R. Preparation of drug liposomes by Reverse-Phase evaporation. In Liposome-Based Drug Delivery Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017, pp. 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-49231-4_3-1.

- Šturm, L.; Poklar Ulrih, N. Basic Methods for Preparation of Liposomes and Studying Their Interactions with Different Compounds, with the Emphasis on Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126547.

- Mehraji, S.; DeVoe, D.L. Microfluidic synthesis of lipid-based nanoparticles for drug delivery: Recent advances and opportunities. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 1154-1174. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3lc00821e.

- Bigazzi, W.; Penoy, N.; Évrard, B.; Piel, G. Supercritical fluid methods: An alternative to conventional methods to prepare liposomes. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 383, 123106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.123106.

- Kasapoğlu, K.N.; Gültekin-Özgüven, M.; Kruger, J.; Frank, J.; Bayramoğlu, P.; Demirkoz, A.B.; Özçelik, B. Effect of Spray Drying on Physicochemical Stability and Antioxidant Capacity of Rosa pimpinellifolia Fruit Extract-Loaded Liposomes Conjugated with Chitosan or Whey Protein During In Vitro Digestion. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11947-024-03317-z.

- Nsairat, H.; Alshaer, W.; Odeh, F.; Essawi, E.; Khater, D.; Bawab, A.A.; El-Tanani, M.; Awidi, A.; Mubarak, M.S. Recent advances in using liposomes for delivery of nucleic acid-based therapeutics. OpenNano 2023, 11, 100132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onano.2023.100132.

- Wagner, A.; Vorauer-Uhl, K.; Katinger, H. Liposomes produced in a pilot scale: Production, purification and efficiency aspects. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2002, 54, 213-219. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0939-6411(02)00062-0.

- Otake, K.; Imura, T.; Sakai, H.; Abe, M. Development of a New Preparation Method of Liposomes Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Langmuir 2001, 17, 3898-3901. https://doi.org/10.1021/la010122k.

- Peschka, R.; Purmann, T.; Schubert, R. Cross-Flow Filtration-An Improved Detergent Removal Technique for the Preparation of Liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 1998, 162, 177-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-5173(97)00424-9.

- Jaafar-Maalej, C.; Charcosset, C.; Fessi, H. A New Method for Liposome Preparation Using a Membrane Contactor. J. Liposome Res. 2011, 21, 213-220. https://doi.org/10.3109/08982104.2010.517537.

- Skalko-Basnet, N.; Pavelic, Z.; Becirevic-Lacan, M. Liposomes Containing Drug and Cyclodextrin Prepared by the One-Step Spray-Drying Method. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2000, 26, 1279-1284. https://doi.org/10.1081/DDC-100102309.

- Leitgeb, M.; Knez, Ž.; Primožič, M. Sustainable technologies for liposome preparation. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2020, 165, 104984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.supflu.2020.104984.

- Peppas, N.A.; Hilt, J.Z.; Khademhosseini, A.; Langer, R. Hydrogels in Biology and Medicine: From Molecular Principles to Bionanotechnology. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 1345-1360. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.200501612.

- Hajareh Haghighi, F.; Binaymotlagh, R.; Fratoddi, I.; Chronopoulou, L.; Palocci, C. Peptide-Hydrogel Nanocomposites for AntiCancer Drug Delivery. Gels 2023, 9, 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels9120953.