DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(24)00034-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38402895

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-22

مقارنة مصنفة حسب العلامات البيولوجية لاستراتيجيات العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل مقابل استراتيجيات العلاج المتسارعة للمرضى الذين تم تشخيصهم حديثًا بمرض كرون (PROFILE): تجربة عشوائية محكومة مفتوحة متعددة المراكز

الملخص

ملخص الخلفية تختلف استراتيجيات الإدارة والنتائج السريرية بشكل كبير في المرضى الذين تم تشخيصهم حديثًا بمرض كرون. قمنا بتقييم استخدام علامة حيوية محتملة للتنبؤ لتوجيه العلاج من خلال تقييم النتائج في المرضى الذين تم توزيعهم عشوائيًا إما إلى استراتيجية العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل (أي، تثبيط المناعة المبكر المشترك مع إنفليكسيماب وعوامل تعديل المناعة) أو استراتيجية العلاج المتسارعة التقليدية.

طرق PROFILE (توقع النتائج لمرض كرون باستخدام علامة حيوية جزيئية) كانت تجربة عشوائية محكومة متعددة المراكز، مفتوحة، مصنفة حسب العلامات الحيوية، شملت البالغين الذين تم تشخيصهم حديثًا بمرض كرون النشط (مؤشر هارفي-برادشو

حقوق الطبع والنشر © 2024 المؤلفون. نُشر بواسطة إلسفير المحدودة. هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول بموجب رخصة CC BY 4.0.

*المؤلفون الرئيسيون المشتركين

مقالات

كارشالتون، المملكة المتحدة (د. ب. باتيل)؛ قسم من

أمراض الجهاز الهضمي، مستشفيات جامعة ليفربول NHS، ليفربول، المملكة المتحدة (البروفيسور سي إس بروبرت MD);

البحث في السياق

الأدلة قبل هذه الدراسة

القيمة المضافة لهذه الدراسة

تداعيات جميع الأدلة المتاحة

مقدمة

لا يزال مطلوبًا في

مقالات

طرق

تصميم الدراسة

المشاركون

مرض عرضي (يتوافق مع مؤشر هارفي-برادشو

العشوائية والتعتيم

الإجراءات

المراسلة إلى: البروفيسور مايلز باركس، قسم الطب، جامعة كامبريدج، كلية الطب السريري ومستشفيات جامعة كامبريدج NHS، كامبريدج، CB2 0QQ، المملكة المتحدة mp372@cam.ac.uk

المقالات

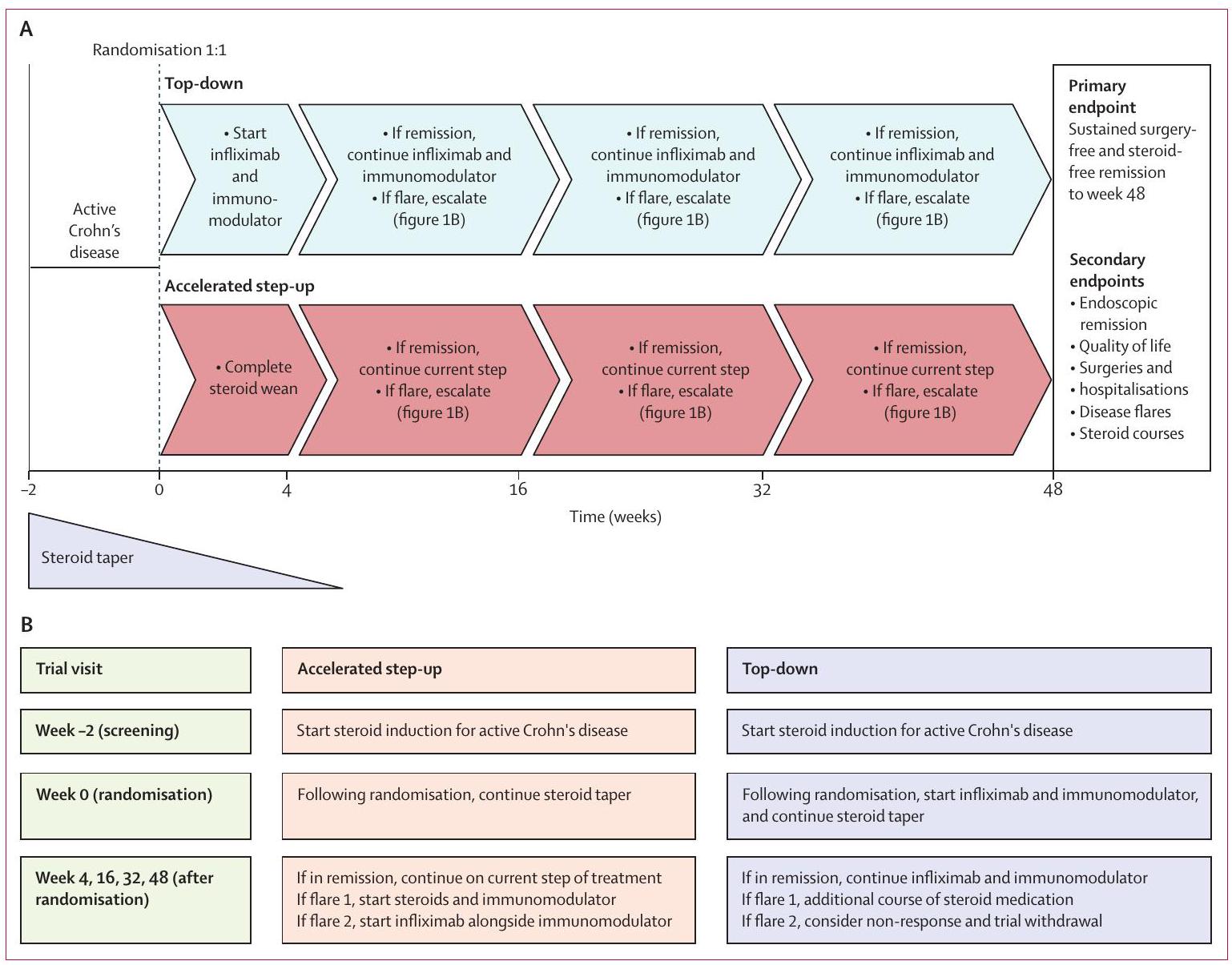

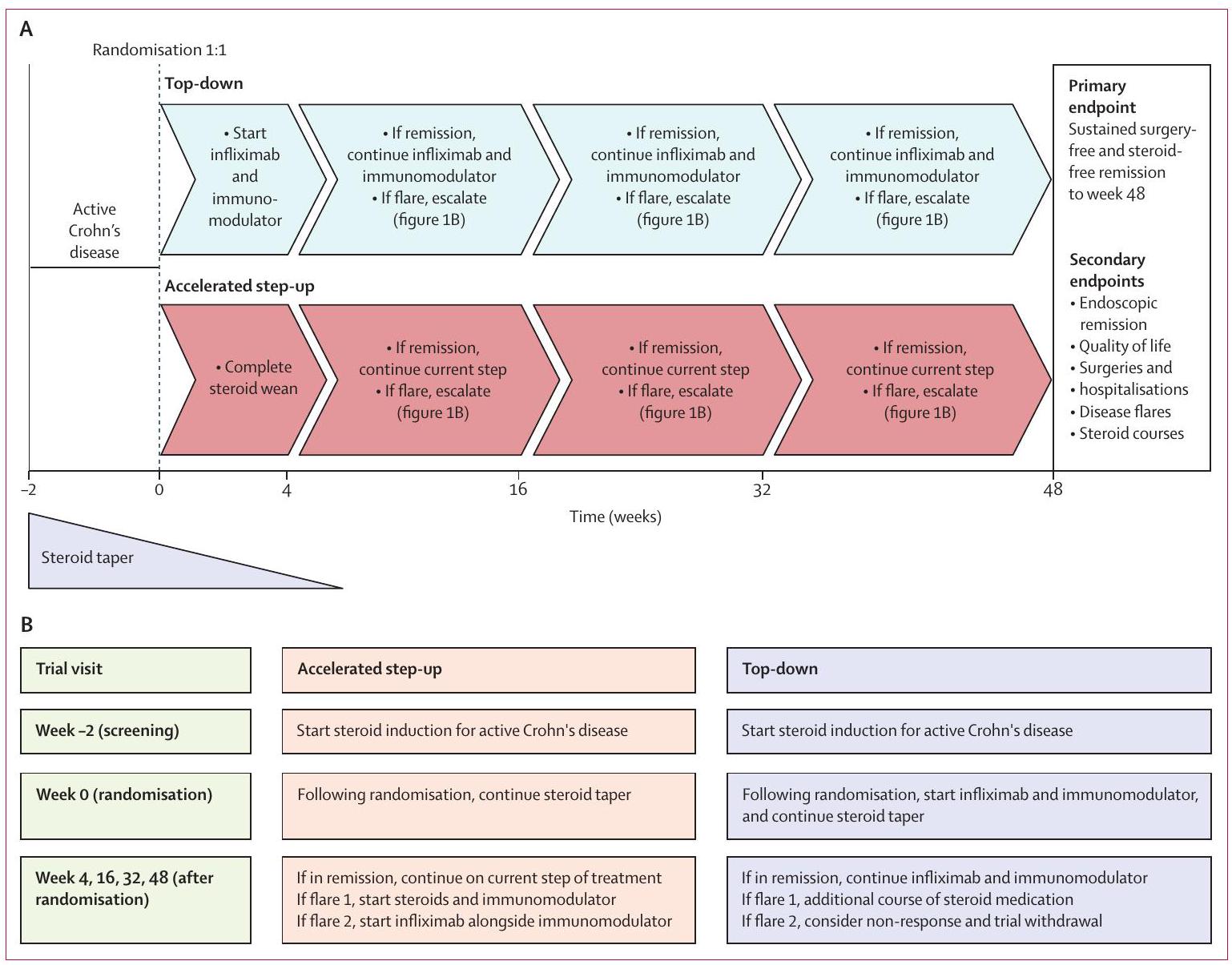

(أ) تصميم التجربة. (ب) ملخص الزيارات والتصعيد.

بالنسبة للمشاركين الذين بدأوا على إنفليكسيماب، تم استخدام جرعة

تم مراجعة المشاركين في الأسابيع

النتائج

إغلاق قاعدة البيانات وقبل إجراء أي تحليل (الملحق 2).

كانت النقاط النهائية الثانوية الهرمية هي: (1) الشفاء التنظيري في الأسبوع 48 المحدد بعدم وجود تقرحات (بما في ذلك التقرحات القلاعية) – أي، درجة التقرح SES-CD من 0 – بناءً على الدرجات التنظيرية المقروءة مركزيًا،

كانت النقاط النهائية الثانوية غير مرتبة وشملت تقييمات الوقت حتى الحدث من خط الأساس إلى أول وثاني تفجر أو جراحة؛ استجابة CRP في الأسابيع 4 و16 و32 و48 (مقارنة الوسيط CRP في كل مجموعة)؛ استجابة الكالبركتين في الأسابيع 16 و32 و48 (مقارنة الوسيط الكالبركتين في كل مجموعة)؛ وشفاء حيوي في الأسبوع 48 (CRP

التحليل الإحصائي

ركز التحليل الأساسي لدراسة PROFILE على تفاعل العلامات الحيوية مع العلاج. كانت التحليلات الرئيسية والتكميلية المحددة مسبقًا في خطة التحليل الإحصائي تهدف إلى مقارنة تأثيرات العلاج والسلامة بين مجموعتي العلاج بالتسريع والتدرج العلاجي. استخدمت جميع تحليلات النقاط النهائية الأساسية والثانوية والثالثية مجموعة التحليل الكاملة المحددة على أنها جميع المشاركين الذين استوفوا معايير الأهلية لدراسة PROFILE وتم توزيعهم عشوائيًا (ما يعادل تحليل النية للعلاج). تم تضمين المرضى الذين يتلقون إنفليكسيماب بجرعات مكثفة أو الذين اضطروا إلى التوقف عن إنفليكسيماب أو المناعية بسبب عدم التحمل في التحليل الأساسي للسكان الكليين للدراسة، ولكن تم استبعادهم من التحليل وفقًا للبروتوكول.

تطلبت مجموعة السلامة أيضًا تلقي بعض العلاجات التجريبية؛ وفي الواقع، كان هذا يتطابق مع مجموعة التحليل الكاملة. تم إجراء تحليلات إضافية محددة مسبقًا باستخدام مجموعة علاج معدلة وفقًا للبروتوكول، والتي تم تعريفها على أنها جميع المشاركين الذين لم ينحرفوا بشكل كبير عن بروتوكول العلاج. وقد تم تحديد ذلك من قبل لجنة تحكيم خبراء قامت أيضًا بتقييم العدد الإجمالي لدورات الستيرويد و

تصعيد العلاجات لكل مشارك. تم احتساب الوقت باستخدام كثيرات الحدود التربيعية العمودية في نموذج الانحدار الطولي، ونقدم مقارنات التأثير الرئيسي للعلاج والبيومارك.

تم افتراض أن القيم المفقودة مفقودة بشكل عشوائي. تم إجراء تحليلات الانحدار التي تم تعديلها لتناسب المتغيرات المشتركة أو

مقالات

| مجموعة الارتقاء

|

مجموعة من الأعلى إلى الأسفل

|

|

| الخصائص الأساسية | ||

| العمر (بالسنوات) |

|

|

| جنس | ||

| أنثى | 88/193 (46%) | 91/193 (47%) |

| ذكر | 105/193 (54%) | 102/193 (52%) |

| العرق | ||

| أبيض | 168/193 (87%) | 171/192 (89%) |

| آخر | 25/193 (13%) | 21/192 (11%) |

| مدخن حالي | 42/193 (22%) | 49/191 (26%) |

| الوزن (كجم) | ٧٤.٩ (١٧.٥) | ٧٤.٧ (١٩.٣) |

| موقع المرض | ||

| إيليال | 63/193 (33%) | 65/192 (34%) |

| قولوني | 50/193 (26%) | 53/192 (28%) |

| إيليوكولوني | 80/193 (41%) | 74/192 (39%) |

| سلوك المرض | ||

| التهابي (B1) | 161/190 (85%) | 169/192 (88%) |

| التشديد (B2) | 27/190 (14%) | 22/192 (11%) |

| اختراق (B3) | 2/190 (1%) | 1/192 (1%) |

| متوسط درجة HBI | 9.8 (2.9) | 10.0 (2.9) |

| متوسط CRP (ملغ/لتر) | ٢١ (٢٦) | 19 (27) |

| متوسط CRP (ملغ/لتر) | 12 (5-24.2) | 11 (5-20) |

| متوسط الكالبركتين

|

993 (797) | ١٠٣٥ (٩٩١) |

| الوسيط الكالبيكتين

|

835 (322->1800) | 747 (381->1800) |

| متوسط SES-CD |

|

|

| الوسيط SES-CD | 9 (7-13) | 9 (7-14) |

| دورة الستيرويدات قبل التسجيل | 40/192 (21%) | 30/193 (16%) |

| متوسط الوقت من التشخيص إلى التسجيل (أيام) |

|

|

| الوقت الوسيط من التشخيص إلى التسجيل (أيام؛ الحد الأدنى – الحد الأقصى) | 14 (0-191) | 9 (0-168) |

| عوامل تصنيف العشوائية | ||

| حالة العلامة الحيوية | ||

| IBDhi | 97/193 (50%) | 94/193 (49%) |

| IBDlo | 96/193 (50%) | 99/193 (51%) |

| موقع المرض | ||

| قولوني | 51/193 (26%) | 50/193 (26%) |

| آخر | 142/193 (74%) | 143/193 (74%) |

| التهاب بالمنظار | ||

| خفيف | 14/193 (7%) | 13/193 (7%) |

| معتدل | 136/193 (70%) | 136/193 (70%) |

| شديد | 43/193 (22%) | 44/193 (23%) |

| البيانات هي

|

||

| الجدول 1: الخصائص الأساسية | ||

دور مصدر التمويل

النتائج

كان متوسط مدة العلاج بالإنفليكسيماب في مجموعة العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل 15 يومًا (IQR 13-20). 161 (

كان الاستمرار في الشفاء بدون استخدام الستيرويدات وبدون جراحة حتى الأسبوع 48 أكثر شيوعًا في مجموعة العلاج العلوي (149 [79%] من 189 مريضًا) مقارنةً بمجموعة العلاج المتسارع (29 [15%] من 190 مريضًا)، مع فرق مطلق قدره 64 نقطة مئوية.

كانت جميع النتائج الثانوية أفضل بشكل ملحوظ في مجموعة العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل مقارنة بمجموعة العلاج المتسارع، ولكن لم يكن هناك دليل على تفاعل المؤشر الحيوي مع العلاج لأي منها (الجدول 2). كانت حالة الشفاء بالمنظار (درجة قرحة SES-CD تساوي 0) أكثر شيوعًا في مجموعة العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل (90 [67%] من 134 مريضًا) مقارنة بمجموعة العلاج المتسارع (52 [44%] من 119 مريضًا) (الجدول 2، الشكل 3). ضمن مجموعة العلاج المتسارع، كانت حالة الشفاء بالمنظار عند

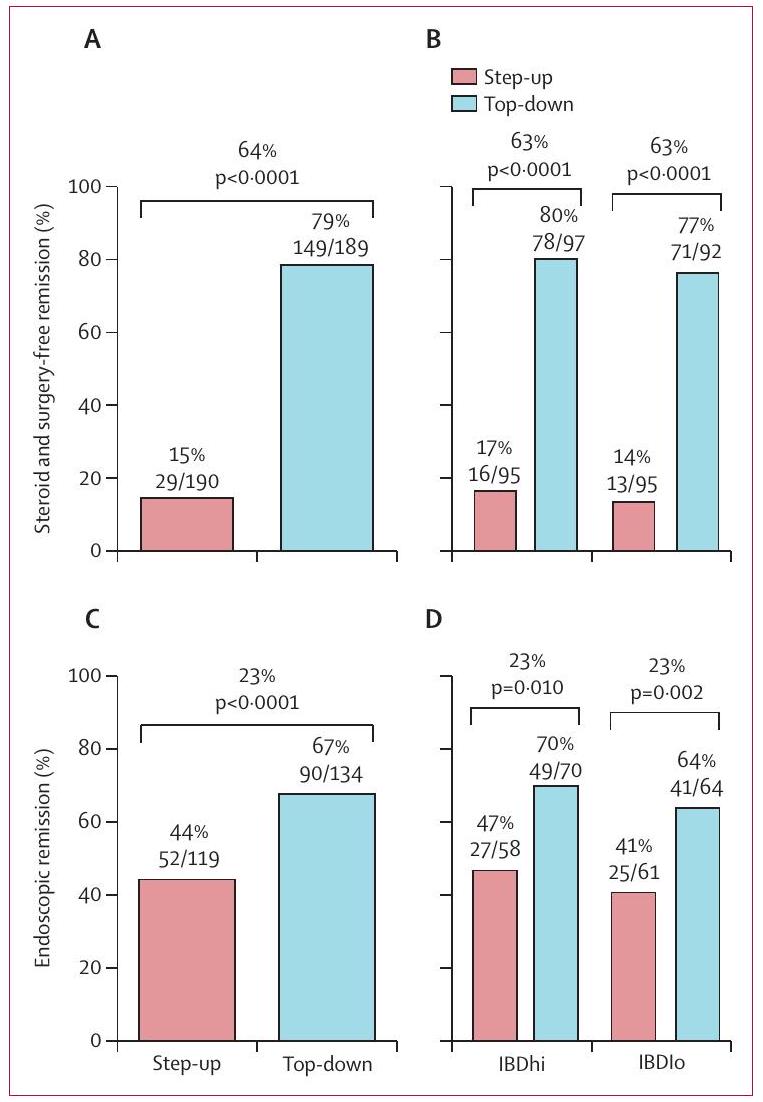

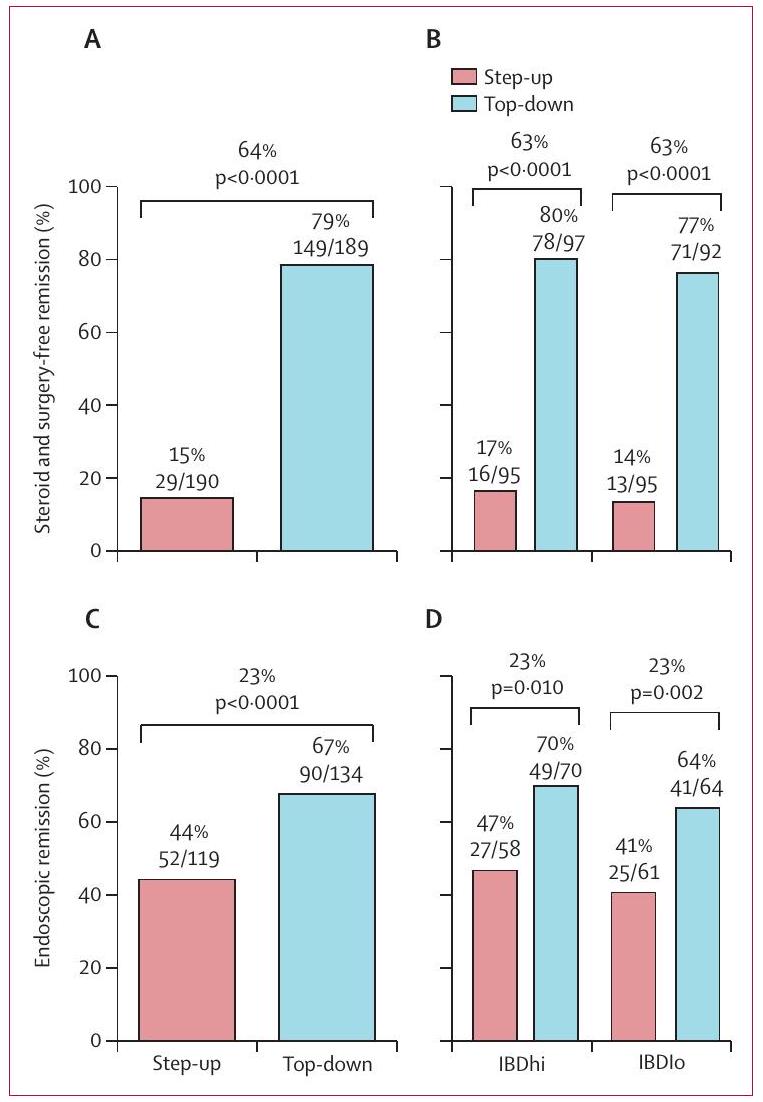

(أ) استمرارية الشفاء بدون ستيرويدات وبدون جراحة حتى الأسبوع 48 لمجموعات العلاج. (ب) استمرارية الشفاء بدون ستيرويدات وبدون جراحة حتى الأسبوع 48 لمجموعات العلاج حسب العلامات البيولوجية. (ج) الشفاء بالمنظار (غياب القرحة) في الأسبوع 48 لمجموعات العلاج. (د) الشفاء بالمنظار (غياب القرحة) في الأسبوع 48 لمجموعات العلاج حسب العلامات البيولوجية.

| أثر العلاج (الفرق بين المجموعات؛ 95% فترة الثقة) | قيمة p | |

| أثر العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل مقابل تأثير العلاج المتسارع | ||

| مقياس النتيجة الأساسي | ||

| تحسن مستمر بدون استخدام الستيرويدات وبدون جراحة | 64 نقطة مئوية (57 إلى 72) | <0.0001 |

| مقياس النتيجة الثانوية | ||

| الشفاء بالمنظار | 23 نقطة مئوية (11 إلى 36) | <0.0001 |

| درجة جودة الحياة (IBD-Q) العددية | 8.54 ( 3.51 إلى 13.60 ) | <0.0001 |

| عدد الفليرات | -1.29 (-1.42 إلى -1.16) | <0.0001 |

| عدد دورات الستيرويد | -0.87 (-0.97 إلى -0.76) | <0.0001 |

| عدد حالات دخول المستشفى والعمليات الجراحية | -0.12 (-0.23 إلى -0.02) | 0.023 |

| أثر تفاعل العلامات الحيوية مع العلاج | ||

| مقياس النتيجة الأساسي | ||

| تحسن مستمر بدون استخدام الستيرويدات وبدون جراحة | نقطة مئوية واحدة (-15 إلى 15) | 0.944 |

| مقياس النتيجة الثانوية | ||

| الشفاء بالمنظار | نقطتان مئويتان (-24 إلى 25) | 0.902 |

| درجة جودة الحياة (IBD-Q) العددية | 1.42 (-8.76 إلى 11.60) | 0.784 |

| عدد الفليرات | 0.06 (-0.33 إلى 0.20) | 0.640 |

| عدد دورات الستيرويد | 0.05 (-0.16 إلى 0.26) | 0.638 |

| عدد حالات دخول المستشفى والعمليات الجراحية | -0.11 (-0.32 إلى 0.11) | 0.332 |

اختلاف في خطر الإصابة بعدوى خطيرة بين استراتيجيات العلاج وعدم الإبلاغ عن أي أورام خبيثة أو وفيات خلال التجربة (الجدول 3).

اعتبرت تحليلات الوقت حتى الحدث الأحداث كمركب من تفجر المرض، تصعيد العلاج، أو الجراحة. كان الوقت حتى الحدث الأول والثاني أطول للمشاركين في مجموعة التوجه من الأعلى إلى الأسفل مقارنة بمجموعة التصعيد المتسارع، دون وجود فرق بين مجموعات العلامات البيولوجية (الشكل 4).

في الأسبوع 48، استجابة بالمنظار (تحسن SES-CD

| مجموعة الارتقاء

|

مجموعة من الأعلى إلى الأسفل

|

|

| أي حدث سلبي | ||

| نوبة من مرض كرون | 225، 132 (68%) | 30، 26 (13%) |

| عدوى | 20، 12 (6%) | 23، 16 (8%) |

| عدم تحمل الثيوبرين | ٥٩، ٤٨ (٢٥٪) | 87، 62 (32%) |

| عدم تحمل الميثوتريكسات | 9، 4 (2%) | 8، 6 (3%) |

| عدم تحمل إنفليكسيماب | 0 | 8، 8 (4%) |

| ورم خبيث | 0 | 0 |

| آخر | 2، 2 (1%) | 12، 8 (4%) |

| أحداث سلبية خطيرة | ||

| الاستشفاء بسبب تفجر مرض كرون | 15، 12 (6%) | 3، 3 (2%) |

| جراحة لمضاعفات المرض | 11، 10 (5%) | 2، 2 (1%) |

| جراحة البطن | 10، 9 (5%) | 1، 1 (1%) |

| جراحة حول الشرج | 1، 1 (1%) | 1، 1 (1%) |

| متعلق بالأدوية | 1، 1 (1%) | 1، 1 (1%) |

| عدوى خطيرة | 8، 4 (2%) | 3,3 (2%) |

| ورم خبيث | 0 | 0 |

| الموت | 0 | 0 |

| آخر | 7، 6 (3%) | 6، 4 (2%) |

مجموعة التسريع التدريجي (الملحق 1 ص 22). كانت هناك اختلافات ملحوظة بين مجموعات العلاج في استجابات CRP والكالبروتكتين طوال فترة الدراسة، مع تطبيع كامل ومستدام أسرع (حتى في الأسبوع الرابع) في مجموعة من الأعلى إلى الأسفل مقارنةً بمجموعة التسريع التدريجي، ومعدلات أعلى من الشفاء البيوكيميائي في الأسبوع 48 (الملحق 1 ص 23-25).

كان التعديل لعوامل الخط الأساس في التحليل الأساسي يقدر نسبة الأرجحية الشرطية لتأثيرها على النقطة النهائية الأساسية. بدا أن احتمال البقاء في حالة مغفرة خالية من الستيرويدات والجراحة كان أقل للمرضى الذين تلقوا الستيرويدات قبل التسجيل وأعلى لأولئك الذين لديهم مشاركة قولونية مقارنة بالمرض المعوي النقي ومدة أطول من الإيليو-كولونوسكوبي إلى التسجيل في التجربة (الملحق 1 ص 26). بدا أن الالتهاب المعتدل أو الشديد في الإيليو-كولونوسكوبي مرتبطًا بزيادة احتمال المغفرة (الملحق 1 ص 26). لم تكن أي من عوامل الخط الأساس الأخرى مرتبطة بالنتيجة، بما في ذلك CRP، الكالبركتين البرازي، حالة التدخين، أو مؤشر كتلة الجسم (الملحق 1 ص 26)؛ ولم يكن هناك أي عوامل مرتبطة بتفاعل مع استجابة العلاج أو تفاعل العلامة الحيوية مع العلاج.

كانت استنتاجات تحليل البروتوكول المعدل متسقة مع التحليل الكامل عبر جميع النقاط النهائية (البيانات غير معروضة). 351 (91%) من 386 مشاركًا (164 [85%] من المرضى في مجموعة الزيادة المتسارعة و187 [97%] في مجموعة الترتيب العلوي) التزموا ببروتوكول علاج PROFILE. أظهر تحليل الحساسية لتقييم تأثير COVID-19 عدم وجود فرق ذي دلالة إحصائية لأي مقياس نتيجة بين الفترة السابقة للجائحة (

المناقشة

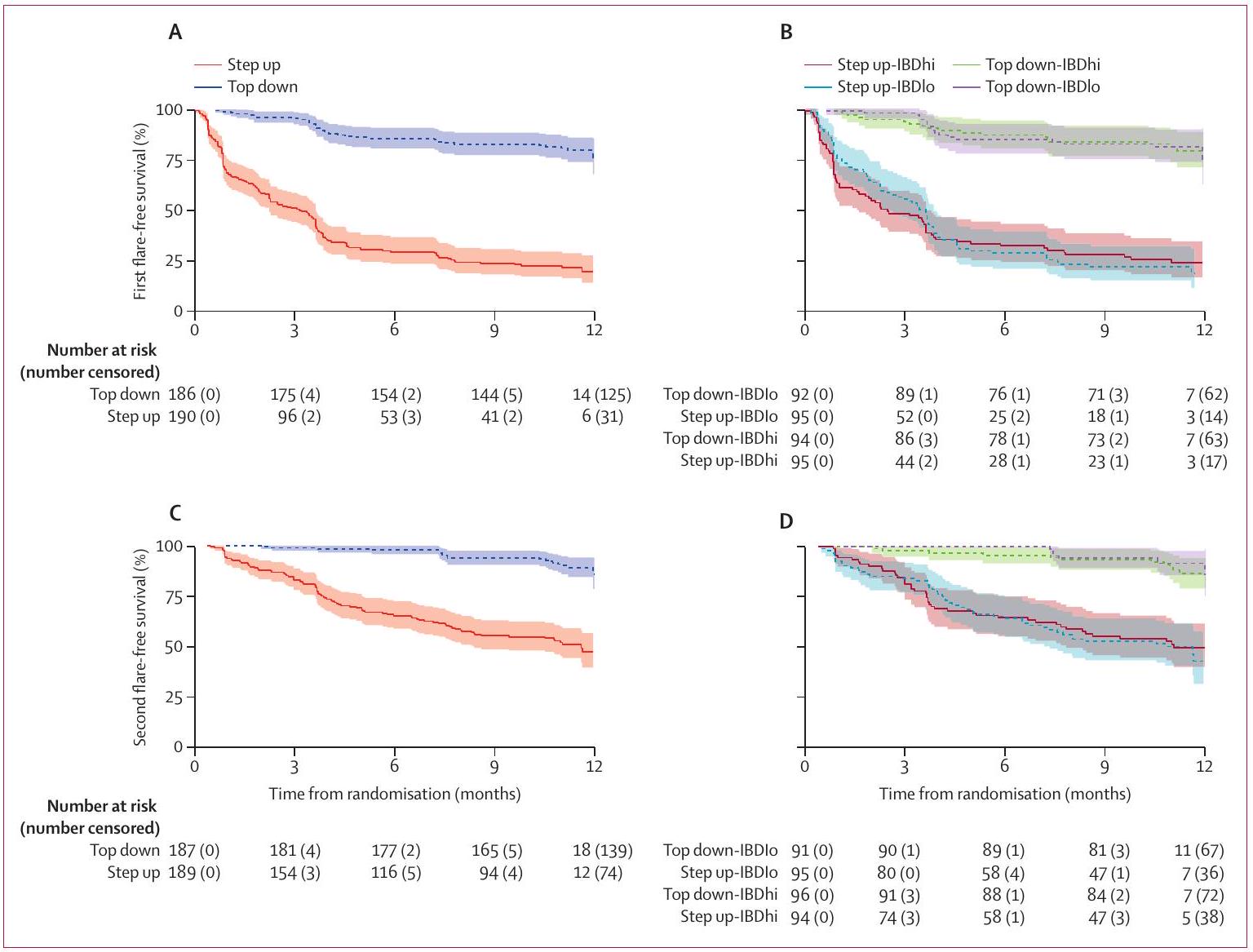

(أ) الوقت حتى الحدث الأول حسب مجموعة العلاج مع بيانات مقيدة عند 12 شهرًا. (ب) الوقت حتى الحدث الأول حسب مجموعة المؤشر الحيوي-العلاج مع بيانات مقيدة عند 12 شهرًا.

(ج) الوقت حتى الحدث الثاني حسب مجموعة العلاج مع بيانات مقيدة عند 12 شهرًا. (د) الوقت حتى الحدث الثاني حسب مجموعة المؤشر الحيوي-العلاج مع بيانات مقيدة

عند 12 شهرًا. قد لا تتطابق أعداد المرضى المعرضين للخطر عند 0 شهر مع العدد الإجمالي للمرضى الذين تم توزيعهم عشوائيًا على كل مجموعة بسبب البيانات المفقودة.

هذه النتائج قد تكون تحويلية لإدارة مرض كرون. كانت الحاجة إلى مؤشر تنبؤي تعتمد على عدم وجود استراتيجية علاجية فعالة وآمنة وميسورة التكلفة للمرضى الذين تم تشخيصهم حديثًا. بينما لم تحدد PROFILE مؤشرًا حيويًا مفيدًا سريريًا، فقد قدمت أدلة واضحة فيما يتعلق باستراتيجية العلاج المثلى من وقت التشخيص. في الواقع، فإن حجم الفائدة من الإدارة من الأعلى إلى الأسفل كما تم قياسه في PROFILE، إذا استمر، سيضعف بشكل كبير الحاجة إلى مؤشر تنبؤي.

مع توزيع المرضى بين مجموعات من الأعلى إلى الأسفل ومجموعات التسريع التدريجي، تبني نتائج العلاج من PROFILE على الأدلة من التجارب السابقة بشأن فوائد العلاج المبكر المضاد لـ TNF.

يعكس عدم اليقين بشأن توقيت العلاج والقلق بشأن التكلفة والسلامة.

في PROFILE، تم تسليط الضوء على التكرار والوتيرة الأعلى بشكل ملحوظ التي عاد فيها المرضى إلى الانتكاس واحتاجوا إلى تصعيد العلاج في ذراع التسريع التدريجي في تحليل الوقت حتى الحدث (الشكل 4). كما لوحظت اختلافات كبيرة لجميع النقاط الثانوية. كانت نسبة المغفرة التنظيرية

من المعروف أن المغفرة التنظيرية ترتبط بنتائج أفضل على المدى الطويل، بما في ذلك تقليل الحاجة إلى الجراحة.

كانت مطلوبة في مريض واحد فقط في مجموعة من الأعلى إلى الأسفل، بسبب انسداد المرارة، بينما احتاج تسعة مرضى في مجموعة التسريع التدريجي إلى استئصال الأمعاء بسبب مضاعفات تضيق أو ناسور. هذه النتائج التنظيرية والجراحية مهمة بشكل خاص لأنها أقل تأثراً بتصميم الدراسة وتخصيص العلاج المفتوح مقارنة بالنقطة الأساسية، وبالتالي توفر سياقًا مهمًا لتحليل النقطة الأساسية. يعرف الأطباء أن البيولوجيات تحافظ بفعالية على المغفرة، ومن ثم قد يكون الفرق بين ذراعي العلاج بالنسبة للنقطة الأساسية متوقعًا. قد تكون فائدة العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل في تقليل الحاجة إلى الجراحة بعامل يقارب 10 حتى في السنة الأولى على الرغم من تصعيد العلاج المبكر على نطاق واسع في مجموعة التسريع التدريجي أكثر إثارة للدهشة. هذا يبرز أهمية بدء علاج فعال للغاية للسيطرة على الالتهاب في أقرب وقت ممكن بعد التشخيص. تدعم بيانات مستوى السكان هذا: حتى في الفترات الأكثر حداثة، يحتاج أكثر من

dليلًا على الارتباط بنتائج المرض (الملحق 1 ص 25). 70 (18%) من المشاركين كانوا قد أكملوا دورة ستيرويد في الأشهر الستة التي سبقت التسجيل في التجربة؛ بدا أن هؤلاء المرضى (ربما بشكل متوقع) لديهم احتمال أقل للحفاظ على المغفرة خلال التجربة، كما فعل أولئك الذين كانت لديهم مشاركة حصرية في الإيليوم. بشكل غير بديهي، كان لدى المرضى الذين يعانون من التهاب مخاطي معتدل أو شديد عند تنظير القولون الإيليو في البداية احتمال أعلى للمغفرة مقارنة بأولئك الذين يعانون من التهاب خفيف، على الرغم من أن فقط

تنظير القولون الإيلي في البداية. ما إذا كان مثل هؤلاء المرضى سيستفيدون أيضًا من العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل غير معروف. ثالثًا، لم يتم تضمين مراقبة الأدوية العلاجية وتحسين الجرعة، والتي قد تكون قد عززت فعالية infliximab، في بروتوكول التجربة. رابعًا، خلال جائحة COVID-19، أثر استخدام الاستشارات عن بُعد سلبًا على أخذ عينات الدم والبراز، على الرغم من أن المستويات العالية لا تزال محفوظة (الملحق 1 ص 4). خامسًا، لم يكن ثلث المرضى لديهم تنظير القولون الإيلي في نهاية التجربة، ويرجع ذلك إلى حد كبير إلى إغلاق الخدمات المرتبط بالجائحة،

كان لدى PROFILE أيضًا عدة نقاط قوة رئيسية. لقد اختبرت العلامة الحيوية بشكل قوي وهي أول تجربة عشوائية في مرض كرون تقارن بين استراتيجيات العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل والتسريع من التشخيص. تطلبت مشاركة المشاركين وجود أعراض نشطة بالإضافة إلى دليل كيميائي حيوي وموضوعي على الالتهاب النشط، وتم تمثيل طيف واسع من شدة المرض. تطلب تحقيق الهدف الأساسي من المشاركين البقاء في حالة شفاء طوال فترة الدراسة، بدلاً من نقطة أو نقطتين زمنيتين. تدعم فائدة العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل عبر جميع النقاط الثانوية الثقة في النتيجة. كانت ميزة فريدة من نوعها في PROFILE هي الوقت القصير (المتوسط 12 يومًا) من التشخيص إلى التسجيل وبدء العلاج. وهذا يوفر رؤى لم يتم تقديرها سابقًا حول الفعالية الحقيقية للعلاج المبكر من الأعلى إلى الأسفل.

يثير PROFILE أسئلة مهمة للبحث المستقبلي. يمكن أن تُعلم المتابعة طويلة الأجل الحاجة إلى استمرار العلاج المناعي بجانب infliximab. نظرًا للوجستيات وتكاليف توصيل الأدوية عن طريق الوريد، فإن الأسئلة ذات الصلة هي ما إذا كان infliximab تحت الجلد أو تركيبات بديلة أرخص من مضادات TNF ستظهر نفس الفوائد. قد يحسن ذلك الوصول عالميًا. سؤال آخر هو ما إذا كانت الفائدة التي لوحظت في مجموعة العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل المعتمدة على مضادات TNF ستظهر أيضًا مع علاجات متقدمة أخرى أو تركيبات.

يوفر PROFILE دليلًا قاطعًا على فائدة العلاج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل مقارنة بالعلاج المتسارع، على الأقل للمرضى الذين يستوفون معايير إدخال التجربة من الأعراض النشطة،

ارتفاع CRP أو الكالبركتين من

المساهمون

إعلان المصالح

مشاركة البيانات

شكر وتقدير

References

2 Wintjens D, Bergey F, Saccenti E, et al. Disease activity patterns of Crohn’s disease in the first ten years after diagnosis in the populationbased IBD South Limburg Cohort. J Crohns Colitis 2021; 15: 391-400.

4 Eberhardson M, Söderling JK, Neovius M, et al. Anti-TNF treatment in Crohn’s disease and risk of bowel resection-a population based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 46: 589-98.

5 Panés J, López-Sanromán A, Bermejo F, et al. Early azathioprine therapy is no more effective than placebo for newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 766-64.

6 Cosnes J, Bourrier A, Laharie D, et al. Early administration of azathioprine vs conventional management of Crohn’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 758-65.

7 Kayal M, Ungaro RC, Bader G, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Stalgis C. Net remission rates with biologic treatment in Crohn’s disease: a reappraisal of the clinical trial data. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023; 21: 1348-50.

8 Ben-Horin S, Novack L, Mao R, et al. Efficacy of biologic drugs in short-duration versus long-duration inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and an individual-patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterology 2022; 162: 482-94.

9 Safroneeva E, Vavricka SR, Fournier N, et al. Impact of the early use of immunomodulators or TNF antagonists on bowel damage and surgery in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 977-89.

10 D’Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, et al. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet 2008; 371: 660-67.

11 Khanna R, Bressler B, Levesque BG, et al. Early combined immunosuppression for the management of Crohn’s disease (REACT): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 1825-34.

12 Colombel JF, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn’s disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 390: 2779-89.

13 Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019; 68: S1-106.

14 Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis 2020; 14: 4-22.

15 Feuerstein JD, Ho EY, Shmidt E, et al. AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2021; 160: 2496-508.

16 Noor NM, Verstockt B, Parkes M, Lee JC. Personalised medicine in Crohn’s disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5: 80-92.

17 Biasci D, Lee JC, Noor NM, et al. A blood-based prognostic biomarker in IBD. Gut 2019; 68: 1386-95.

18 Parkes M, Noor NM, Dowling F, et al. PRedicting Outcomes for Crohn’s disease using a moLecular biomarkEr (PROFILE): protocol for a multicentre, randomised, biomarker-stratified trial. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e026767.

19 Raine T, Pavey H, Qian W, et al. Establishment of a validated central reading system for ileocolonoscopy in an academic setting. Gut 2022; 71: 661-64.

20 Iacucci M, Cannatelli R, Labarile N, et al. Endoscopy in inflammatory bowel diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic period. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5: 598-606.

21 Siegel CA, Yang F, Eslava S, Cai Z. Treatment pathways leading to biologic therapies for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in the United States. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2020; 11: e00128.

22 Narula N, Wong ECL, Dulai PS, Marshall JK, Jairath V, Reinisch W. Comparative effectiveness of biologics for endoscopic healing of the ileum and colon in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2022; 117: 1106-17.

23 Shah SC, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Narula N. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Mucosal healing is associated with improved longterm outcomes in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43: 317-33.

24 Burr NE, Lord R, Hull MA, Subramanian V. Decreasing risk of first and subsequent surgeries in patients with Crohn’s disease in England from 1994 through 2013. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17: 2042-49.

26 Kugathasan S, Saubermann LJ, Smith L, et al. Mucosal T-cell immunoregulation varies in early and late inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2007; 56: 1696-705.

27 Lee JC, Lyons PA, McKinney EF, et al. Gene expression profiling of CD8+ T cells predicts prognosis in patients with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 4170-79.

29 Kakarmath S, Esteva A, Arnaout R, et al. Best practices for authors of healthcare-related artificial intelligence manuscripts. NPJ Digit Med 2020; 3: 134.

30 Jayasooriya N, Baillie S, Blackwell J, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: time to diagnosis and the impact of delayed diagnosis on clinical outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2023; 57: 635-52.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(24)00034-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38402895

Publication Date: 2024-02-22

A biomarker-stratified comparison of top-down versus accelerated step-up treatment strategies for patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease (PROFILE): a multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial

Abstract

Summary Background Management strategies and clinical outcomes vary substantially in patients newly diagnosed with Crohn’s disease. We evaluated the use of a putative prognostic biomarker to guide therapy by assessing outcomes in patients randomised to either top-down (ie, early combined immunosuppression with infliximab and immunomodulator) or accelerated step-up (conventional) treatment strategies.

Methods PROFILE (PRedicting Outcomes For Crohn’s disease using a moLecular biomarker) was a multicentre, open-label, biomarker-stratified, randomised controlled trial that enrolled adults with newly diagnosed active Crohn’s disease (Harvey-Bradshaw Index

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license.

*Joint first authors

Articles

Carshalton, UK (P Patel MD); Department of

Gastroenterology, Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, UK (Prof C S Probert MD);

Research in context

Evidence before this study

Added value of this study

Implications of all the available evidence

Introduction

is still required in

Articles

Methods

Study design

Participants

symptomatic disease (corresponding to Harvey-Bradshaw Index

Randomisation and masking

Procedures

Correspondence to: Prof Miles Parkes, Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, CB2 0QQ, UK mp372@cam.ac.uk

Articles

(A) Trial design. (B) Trial visits and escalation summary.

For participants starting on infliximab, a

Participants were reviewed at weeks

Outcomes

database lock and before any analysis being undertaken (appendix 2).

The hierarchical secondary endpoints were: (1) endoscopic remission at week 48 defined by absence of ulceration (including aphthous ulceration)-ie, SES-CD ulcer subscore of 0-based on centrally read endoscopic scores,

Tertiary endpoints were unranked and included assessments of time to event from baseline to first and to second flare or surgery; CRP response at weeks 4, 16, 32, and 48 (comparison of median CRP in each group); calprotectin response at weeks 16,32 , and 48 (comparison of median calprotectin in each group); and week 48 biochemical remission (CRP

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis of PROFILE focused on the biomarker-treatment interaction. Key and complementary analyses prespecified in the statistical analysis plan were to compare treatment and safety effects between the accelerated step-up and top-down therapy groups. All primary, secondary, and tertiary endpoint analyses used the full analysis population defined as all participants who met PROFILE eligibility criteria and were randomised (equivalent to an intention-to-treat analysis). Patients receiving dose-intensified infliximab or who had to stop infliximab or immunomodulators due to intolerance were included in the full trial population primary analysis but excluded from the per-protocol analysis.

The safety population additionally required receipt of some trial treatment; in reality this matched the full analysis population. Additional prespecified analyses were performed using a modified per-protocol treatment population, defined as all participants not substantially deviating from the treatment protocol. This was determined by an expert adjudication committee who also assessed the total number of steroid courses and

treatment escalations for each participant. Time was accounted for using orthogonal quadratic polynomials in the longitudinal regression model, and we report the main effect comparisons of treatment and biomarker.

Missing values were assumed missing at random. Regression analyses that adjusted for covariates or

Articles

| Step-up group (

|

Top-down group (

|

|

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Age (years) |

|

|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 88/193 (46%) | 91/193 (47%) |

| Male | 105/193 (54%) | 102/193 (52%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 168/193 (87%) | 171/192 (89%) |

| Other | 25/193 (13%) | 21/192 (11%) |

| Current smoker | 42/193 (22%) | 49/191 (26%) |

| Weight (kg) | 74.9 (17.5) | 74.7 (19.3) |

| Disease location | ||

| Ileal | 63/193 (33%) | 65/192 (34%) |

| Colonic | 50/193 (26%) | 53/192 (28%) |

| Ileocolonic | 80/193 (41%) | 74/192 (39%) |

| Disease behaviour | ||

| Inflammatory (B1) | 161/190 (85%) | 169/192 (88%) |

| Stricturing (B2) | 27/190 (14%) | 22/192 (11%) |

| Penetrating (B3) | 2/190 (1%) | 1/192 (1%) |

| Mean HBI score | 9.8 (2.9) | 10.0 (2.9) |

| Mean CRP (mg/L) | 21 (26) | 19 (27) |

| Median CRP (mg/L) | 12 (5-24.2) | 11 (5-20) |

| Mean calprotectin (

|

993 (797) | 1035 (991) |

| Median calprotectin (

|

835 (322->1800) | 747 (381->1800) |

| Mean SES-CD |

|

|

| Median SES-CD | 9 (7-13) | 9 (7-14) |

| Steroid course prior to enrolment | 40/192 (21%) | 30/193 (16%) |

| Mean time from diagnosis to enrolment (days) |

|

|

| Median time from diagnosis to enrolment (days; min-max) | 14 (0-191) | 9 (0-168) |

| Randomisation stratification factors | ||

| Biomarker status | ||

| IBDhi | 97/193 (50%) | 94/193 (49%) |

| IBDlo | 96/193 (50%) | 99/193 (51%) |

| Disease location | ||

| Colonic | 51/193 (26%) | 50/193 (26%) |

| Other | 142/193 (74%) | 143/193 (74%) |

| Endoscopic inflammation | ||

| Mild | 14/193 (7%) | 13/193 (7%) |

| Moderate | 136/193 (70%) | 136/193 (70%) |

| Severe | 43/193 (22%) | 44/193 (23%) |

| Data are

|

||

| Table 1: Baseline characteristics | ||

Role of funding source

Results

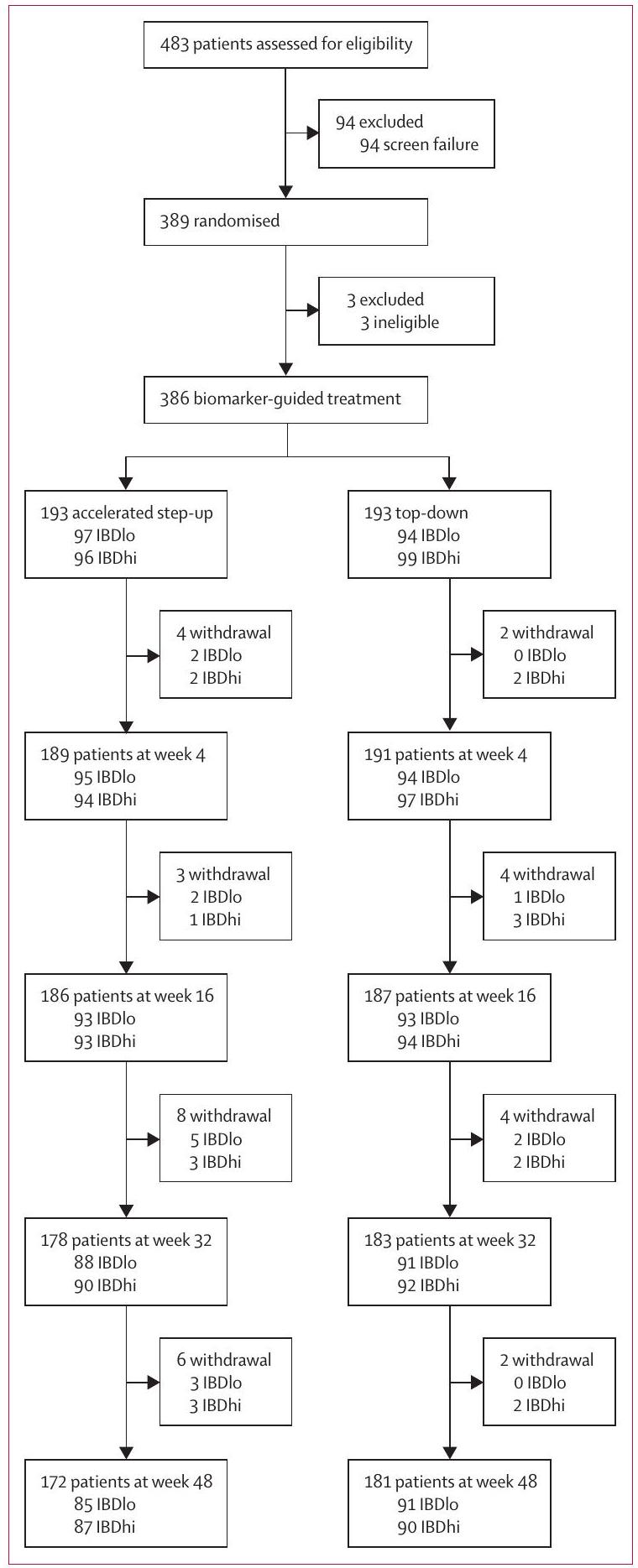

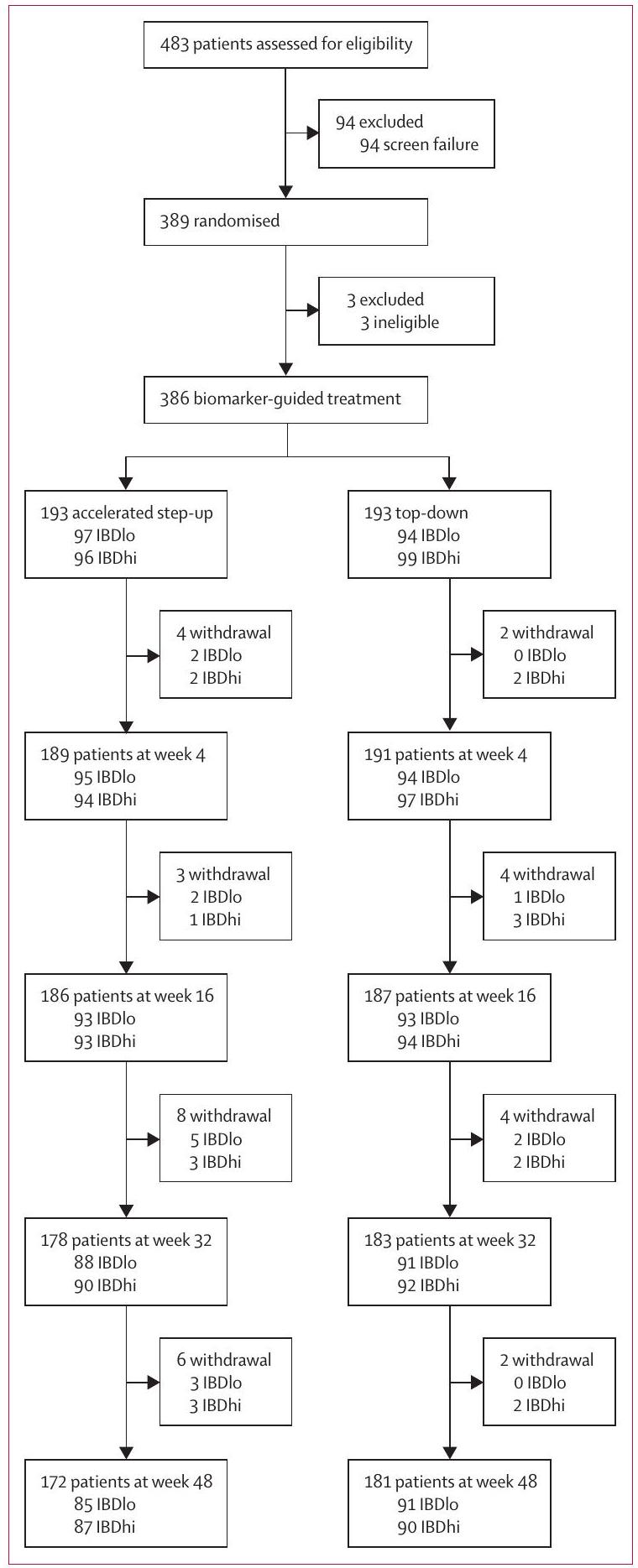

infliximab in the top-down group was 15 days (IQR 13-20). 161 (

Sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission to week 48 was more frequent in the top-down group (149 [79%] of 189 patients) than in the accelerated step-up group ( 29 [15%] of 190 patients), with an absolute difference of 64 percentage points (

All secondary outcomes were significantly better in the top-down versus the accelerated step-up, group but there was no evidence of biomarker-treatment interaction for any of them (table 2). Endoscopic remission (SES-CD ulcer subscore of 0 ) was more frequent in the top-down group ( 90 [67%] of 134 patients) than in the accelerated step-up group (52 [44%] of 119 patients (table 2, figure 3). Within the accelerated step-up group, endoscopic remission at

(A) Sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission until week 48 for treatment groups. (B) Sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission until week 48 for biomarker-treatment subgroups. (C) Endoscopic remission (absence of ulceration) at week 48 for treatment groups. (D) Endoscopic remission (absence of ulceration) at week 48 for biomarker-treatment subgroups.

| Treatment effect (difference between groups; 95% CI) | p value | |

| Top-down vs accelerated step-up treatment effect | ||

| Primary outcome measure | ||

| Sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission | 64 percentage points (57 to 72) | <0.0001 |

| Secondary outcome measure | ||

| Endoscopic remission | 23 percentage points (11 to 36) | <0.0001 |

| Quality of life (IBD-Q) numerical score | 8.54 ( 3.51 to 13.60 ) | <0.0001 |

| Number of flares | -1.29 (-1.42 to -1.16) | <0.0001 |

| Number of steroid courses | -0.87 (-0.97 to -0.76) | <0.0001 |

| Number of hospital admissions and surgeries | -0.12 (-0.23 to -0.02) | 0.023 |

| Biomarker-treatment interaction effect | ||

| Primary outcome measure | ||

| Sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission | 1 percentage point (-15 to 15) | 0.944 |

| Secondary outcome measure | ||

| Endoscopic remission | 2 percentage points (-24 to 25) | 0.902 |

| Quality of life (IBD-Q) numerical score | 1.42 (-8.76 to 11.60) | 0.784 |

| Number of flares | 0.06 (-0.33 to 0.20) | 0.640 |

| Number of steroid courses | 0.05 (-0.16 to 0.26) | 0.638 |

| Number of hospital admissions and surgeries | -0.11 (-0.32 to 0.11) | 0.332 |

difference in risk of serious infection between treatment strategies and no reported malignancies or deaths during the trial (table 3 ).

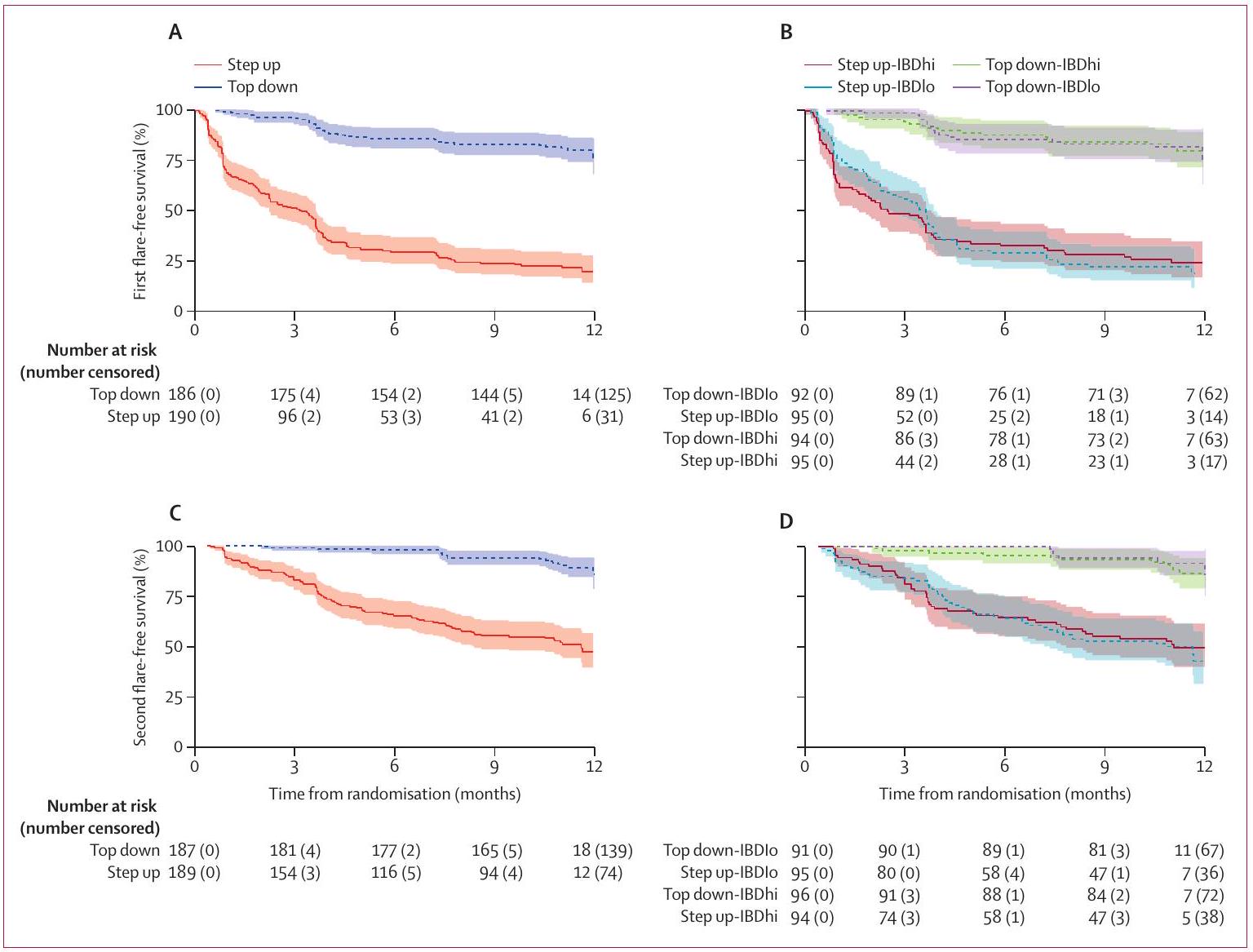

The time-to-event analyses considered events as a composite of disease flare, treatment escalation, or surgery. Time to both first and second event were longer for participants in the top-down group than in the accelerated step-up group, with no difference between biomarker subgroups (figure 4).

At week 48, endoscopic response (SES-CD improvement

| Step-up group (

|

Top-down group (

|

|

| Any adverse event | ||

| Flare of Crohn’s disease | 225, 132 (68%) | 30, 26 (13%) |

| Infection | 20, 12 (6%) | 23, 16 (8%) |

| Thiopurine intolerance | 59, 48 (25%) | 87, 62 (32%) |

| Methotrexate intolerance | 9, 4 (2%) | 8, 6 (3%) |

| Infliximab intolerance | 0 | 8, 8 (4%) |

| Malignancy | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 2, 2 (1%) | 12, 8 (4%) |

| Serious adverse events | ||

| Hospitalisation for flare of Crohn’s disease | 15, 12 (6%) | 3, 3 (2%) |

| Surgery for disease complication | 11, 10 (5%) | 2, 2 (1%) |

| Abdominal surgery | 10, 9 (5%) | 1, 1 (1%) |

| Perianal surgery | 1, 1 (1%) | 1, 1 (1%) |

| Medication related | 1, 1 (1%) | 1, 1 (1%) |

| Serious infection | 8, 4 (2%) | 3,3 (2%) |

| Malignancy | 0 | 0 |

| Death | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 7, 6 (3%) | 6, 4 (2%) |

the accelerated step-up group (appendix 1 p 22). There were notable differences between the treatment groups in the CRP and calprotectin responses throughout the study period, with more rapid (even by week 4) complete and sustained normalisation in the top-down group than in the accelerated step-up group and higher rates of biochemical remission at week 48 (appendix 1 pp 23-25).

The adjustment for baseline covariates in the primary analysis estimated a conditional odds ratio for their influence on the primary endpoint. The likelihood of being in sustained steroid-free and surgery-free remission appeared lower for patients who received steroids before enrolment and higher for those with colonic involvement versus pure ileal disease and longer time from ileo-colonoscopy to trial enrolment (appendix 1 p 26). Moderate or severe inflammation at ileo-colonoscopy appeared to be associated with a higher likelihood of remission (appendix 1 p 26). None of the other baseline covariates were associated with outcome, including CRP, faecal calprotectin, smoking status, or BMI (appendix 1 p 26); and no covariates had an interaction with treatment response or biomarker-treatment interaction.

The conclusions of the modified per-protocol analysis were consistent with the full analysis across all endpoints (data not shown). 351 (91%) of 386 participants ( 164 [85%] patients in the accelerated step-up group and 187 [97%] in the top-down group) adhered to the PROFILE treatment protocol. A sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of COVID-19 showed no significant difference for any outcome measure between prepandemic (

Discussion

(A) Time to first event by treatment group with data censored at 12 months. (B) Time to first event by biomarker-treatment group with data censored at 12 months.

(C) Time to second event by treatment group with data censored at 12 months. (D) Time to second event by biomarker-treatment group with data censored

at 12 months. Numbers of patients at risk at 0 months may not match the total number of patients randomised to each group due to missing data.

These findings are potentially transformative for the management of Crohn’s disease. The need for a prognostic biomarker was predicated on the lack of an effective, safe, and affordable treatment strategy for newly diagnosed patients. While PROFILE did not identify a clinically useful biomarker, it has provided clear evidence with regards to the optimal treatment strategy from diagnosis. Indeed, the scale of the benefit with top-down management quantified in PROFILE would, if sustained, substantially weaken the case-of-need for a prognostic biomarker.

With patients randomised between top-down and accelerated step-up groups, the treatment outcomes from PROFILE build on evidence from previous trials regarding the benefits of early anti-TNF therapy.

reflecting uncertainty regarding treatment timing and concerns regarding cost and safety.

In PROFILE, the markedly higher frequency and rate at which patients relapsed and required treatment escalation in the accelerated step-up arm was highlighted in the time-to-event analysis (figure 4). Substantial differences were also observed for all secondary endpoints. The endoscopic remission rate of

Endoscopic remission is well recognised to correlate with better long-term outcomes, including reduced need for surgery.

was required in just one patient in the top-down group, for gallstone ileus, whereas nine patients in the accelerated step-up group required intestinal resection for stricturing or fistulating complications. These endoscopic and surgical outcomes are particularly important in being less influenced by the study design and open treatment allocation than the primary outcome, and thus provide important context for the primary endpoint analysis. Clinicians know that biologics effectively maintain remission, and hence the difference between treatment arms for the primary outcome might have been expected. The benefit of top-down treatment in reducing need for surgery by a factor of approximately 10 even within the first year and despite widespread early therapy escalation in the accelerated step-up group may be more surprising. This further underlines the importance of initiating highly effective treatment to control inflammation as soon as possible after diagnosis. Population-level data corroborate this: even in the most recent eras more than

evidence of association with disease outcomes (appendix 1 p 25). 70 (18%) of participants had completed a steroid course in the 6 months before trial enrolment; these patients appeared (perhaps expectedly) to have a lower likelihood of maintaining remission during the trial, as did those with exclusively ileal involvement. Counterintuitively, patients with moderate or severe mucosal inflammation at baseline ileo-colonoscopy had a higher likelihood of remission compared to those with mild inflammation, although only

baseline ileo-colonoscopy were excluded. Whether such patients would also benefit from top-down therapy is unknown. Third, therapeutic drug monitoring and dose optimisation, which might have further enhanced the efficacy of infliximab, were not included in the trial protocol. Fourth, during the COVID-19 pandemic use of remote consultations adversely affected blood and stool sampling, although high levels were still maintained (appendix 1 p 4). Fifth, a third of patients did not have an end-of-trial ileo-colonoscopy, largely due to pandemicrelated service shutdowns,

PROFILE also had several key strengths. It robustly tested the biomarker and is the first randomised trial in Crohn’s disease to have compared top-down and accelerated step-up treatment strategies from diagnosis. Participant inclusion required active symptoms plus objective biochemical and endoscopic evidence of active inflammation, and a wide spectrum of disease severity was represented. Meeting the primary endpoint required participants to remain in remission throughout the study period, rather than at one or two timepoints. The benefit of top-down treatment across all secondary endpoints underpins confidence in the result. A unique feature of PROFILE was the short time (median 12 days) from diagnosis to enrolment and treatment initiation. This provides previously unappreciated insights into the true efficacy of early top-down therapy.

PROFILE raises important questions for future research. Longer term follow-up could inform the need for continued immunomodulator therapy alongside infliximab. Given the logistics and costs of intravenous drug delivery, relevant questions are whether subcutaneous infliximab or alternative, cheaper formulations of anti-TNF would show the same benefits. This would potentially improve access globally. Another question is whether the benefit seen in the anti-TNF-based top-down group would also be seen with other advanced therapies or combinations.

PROFILE provides definitive evidence for the benefit of top-down over accelerated step-up treatment, at least for patients meeting the trial inclusion criteria of active

symptoms, raised CRP or calprotectin of

Contributors

Declaration of interests

Data sharing

Acknowledgments

References

2 Wintjens D, Bergey F, Saccenti E, et al. Disease activity patterns of Crohn’s disease in the first ten years after diagnosis in the populationbased IBD South Limburg Cohort. J Crohns Colitis 2021; 15: 391-400.

4 Eberhardson M, Söderling JK, Neovius M, et al. Anti-TNF treatment in Crohn’s disease and risk of bowel resection-a population based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 46: 589-98.

5 Panés J, López-Sanromán A, Bermejo F, et al. Early azathioprine therapy is no more effective than placebo for newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 766-64.

6 Cosnes J, Bourrier A, Laharie D, et al. Early administration of azathioprine vs conventional management of Crohn’s disease: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 758-65.

7 Kayal M, Ungaro RC, Bader G, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Stalgis C. Net remission rates with biologic treatment in Crohn’s disease: a reappraisal of the clinical trial data. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023; 21: 1348-50.

8 Ben-Horin S, Novack L, Mao R, et al. Efficacy of biologic drugs in short-duration versus long-duration inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and an individual-patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterology 2022; 162: 482-94.

9 Safroneeva E, Vavricka SR, Fournier N, et al. Impact of the early use of immunomodulators or TNF antagonists on bowel damage and surgery in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 977-89.

10 D’Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, et al. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet 2008; 371: 660-67.

11 Khanna R, Bressler B, Levesque BG, et al. Early combined immunosuppression for the management of Crohn’s disease (REACT): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 1825-34.

12 Colombel JF, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn’s disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 390: 2779-89.

13 Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019; 68: S1-106.

14 Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis 2020; 14: 4-22.

15 Feuerstein JD, Ho EY, Shmidt E, et al. AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2021; 160: 2496-508.

16 Noor NM, Verstockt B, Parkes M, Lee JC. Personalised medicine in Crohn’s disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5: 80-92.

17 Biasci D, Lee JC, Noor NM, et al. A blood-based prognostic biomarker in IBD. Gut 2019; 68: 1386-95.

18 Parkes M, Noor NM, Dowling F, et al. PRedicting Outcomes for Crohn’s disease using a moLecular biomarkEr (PROFILE): protocol for a multicentre, randomised, biomarker-stratified trial. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e026767.

19 Raine T, Pavey H, Qian W, et al. Establishment of a validated central reading system for ileocolonoscopy in an academic setting. Gut 2022; 71: 661-64.

20 Iacucci M, Cannatelli R, Labarile N, et al. Endoscopy in inflammatory bowel diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic period. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5: 598-606.

21 Siegel CA, Yang F, Eslava S, Cai Z. Treatment pathways leading to biologic therapies for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in the United States. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2020; 11: e00128.

22 Narula N, Wong ECL, Dulai PS, Marshall JK, Jairath V, Reinisch W. Comparative effectiveness of biologics for endoscopic healing of the ileum and colon in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2022; 117: 1106-17.

23 Shah SC, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Narula N. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Mucosal healing is associated with improved longterm outcomes in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43: 317-33.

24 Burr NE, Lord R, Hull MA, Subramanian V. Decreasing risk of first and subsequent surgeries in patients with Crohn’s disease in England from 1994 through 2013. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17: 2042-49.

26 Kugathasan S, Saubermann LJ, Smith L, et al. Mucosal T-cell immunoregulation varies in early and late inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2007; 56: 1696-705.

27 Lee JC, Lyons PA, McKinney EF, et al. Gene expression profiling of CD8+ T cells predicts prognosis in patients with Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 4170-79.

29 Kakarmath S, Esteva A, Arnaout R, et al. Best practices for authors of healthcare-related artificial intelligence manuscripts. NPJ Digit Med 2020; 3: 134.

30 Jayasooriya N, Baillie S, Blackwell J, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: time to diagnosis and the impact of delayed diagnosis on clinical outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2023; 57: 635-52.