المجلة: International Journal of Nanomedicine

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s466042

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38887692

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-01

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s466042

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38887692

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-01

منصات نانوية تستهدف خلايا الورم وتستجيب للبيئة الدقيقة للورم للعلاج متعدد الأنماط الموجه بالتصوير الضوئي الديناميكي/الحراري الضوئي/الديناميكي الكيميائي لسرطان عنق الرحم

الغرض: العلاج الضوئي، المعروف بانتقائيته العالية، وقلة آثاره الجانبية، وقوة تحكمه، وتعزيز التآزر للعلاجات المجمعة، يُستخدم على نطاق واسع في علاج الأمراض مثل سرطان عنق الرحم.

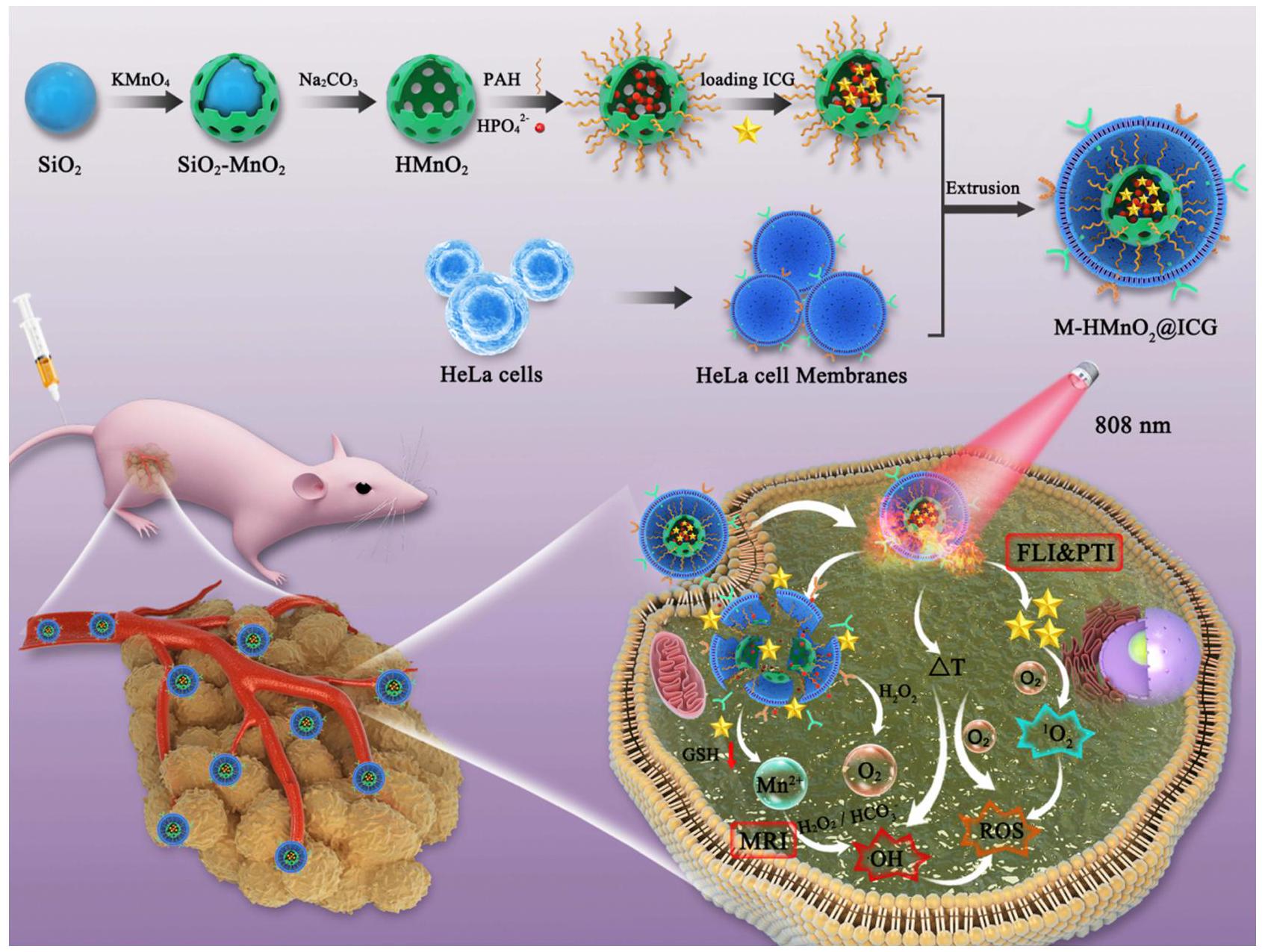

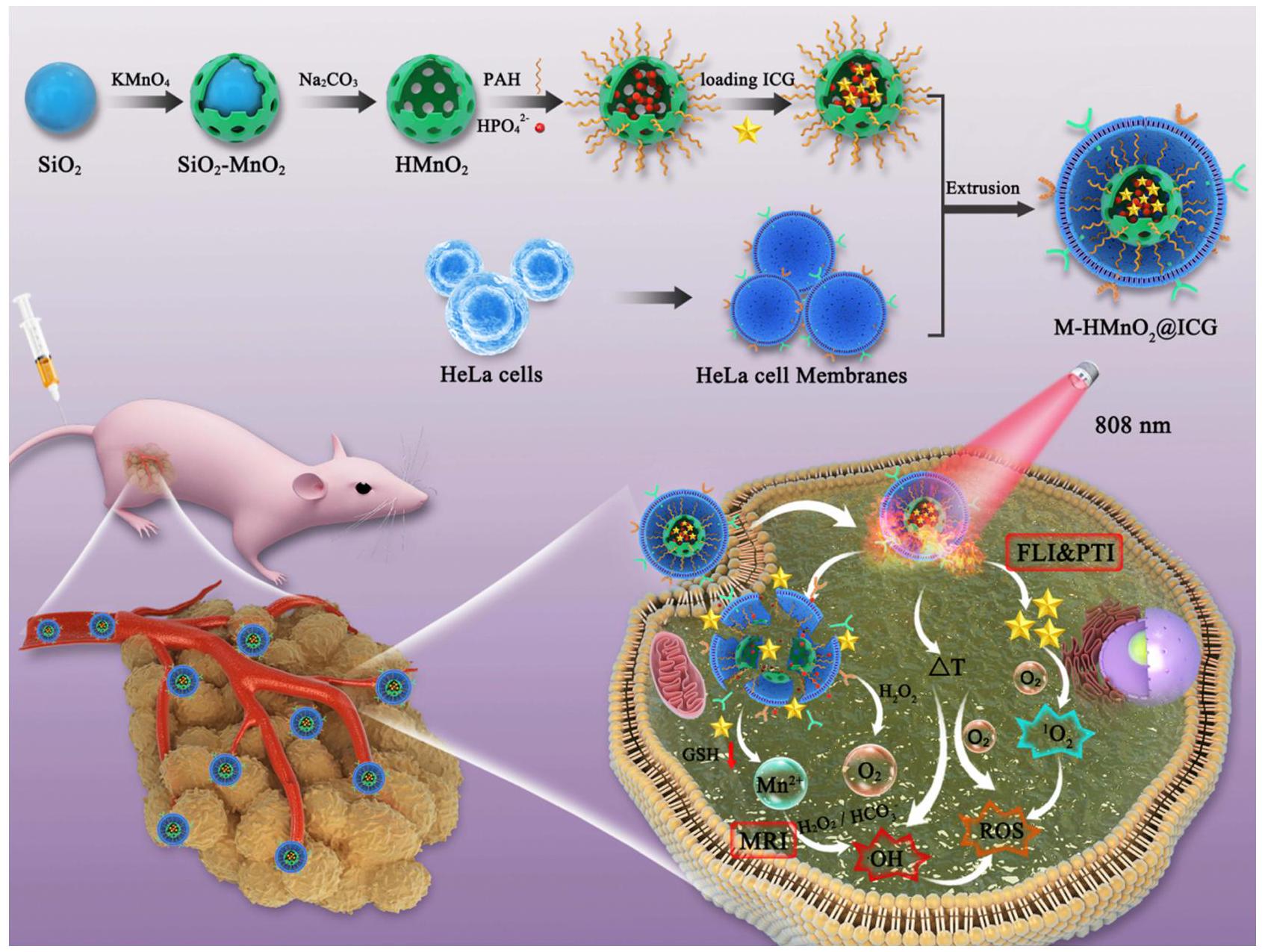

الطرق: في هذه الدراسة، تم استخدام ثاني أكسيد المنغنيز المسامي المجوف كحامل لبناء جزيئات نانوية مشحونة إيجابياً معدلة بواسطة بولي (هيدروكلوريد الأليل أمين). تم تحميل NP بكفاءة مع المحسس الضوئي إندوسيانين الأخضر (ICG) من خلال إضافة أيونات هيدروجين فوسفات لإنتاج تأثير تجميع الأيونات المضادة. تم تنفيذ تغليف غشاء خلايا هيلا لتحقيق M-HMnO النهائية

النتائج:

الاستنتاج: في هذه الدراسة، صممنا نظام توصيل نانوي حيوي يحسن نقص الأكسجين، ويستجيب للبيئة الدقيقة للورم، ويحمّل ICG بكفاءة. يوفر استراتيجية جديدة اقتصادية ومريحة للعلاج الضوئي التآزري وCDT لسرطان عنق الرحم.

الكلمات الرئيسية: العلاج الضوئي، أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية، تخفيف نقص الأكسجين، العلاج التعاوني

الطرق: في هذه الدراسة، تم استخدام ثاني أكسيد المنغنيز المسامي المجوف كحامل لبناء جزيئات نانوية مشحونة إيجابياً معدلة بواسطة بولي (هيدروكلوريد الأليل أمين). تم تحميل NP بكفاءة مع المحسس الضوئي إندوسيانين الأخضر (ICG) من خلال إضافة أيونات هيدروجين فوسفات لإنتاج تأثير تجميع الأيونات المضادة. تم تنفيذ تغليف غشاء خلايا هيلا لتحقيق M-HMnO النهائية

النتائج:

الاستنتاج: في هذه الدراسة، صممنا نظام توصيل نانوي حيوي يحسن نقص الأكسجين، ويستجيب للبيئة الدقيقة للورم، ويحمّل ICG بكفاءة. يوفر استراتيجية جديدة اقتصادية ومريحة للعلاج الضوئي التآزري وCDT لسرطان عنق الرحم.

الكلمات الرئيسية: العلاج الضوئي، أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية، تخفيف نقص الأكسجين، العلاج التعاوني

المقدمة

سرطان عنق الرحم هو رابع أكثر الأورام الخبيثة النسائية شيوعًا في العالم، مما يتسبب في أكثر من 300,000 حالة وفاة سنويًا.

نظرًا لأن التركيب التشريحي لعنق الرحم مرتبط بتركيب المهبل، فقد جذبت استخدام العلاجات الضوئية لسرطان عنق الرحم اهتمامًا بحثيًا واسعًا.

مع التقدم في مجال العلاج الضوئي، تم اعتماد عوامل مثل بروتوبورفيرين IX، وديهيدروكلورين e6، وميثيلين الأزرق (MB) للعلاج السريري للأورام الجلدية، والمريئية، والرئوية.

إندوسيانين الأخضر (ICG) لديه قمة امتصاص قوية بين 780 و800 نانومتر، وبالتالي قدرة امتصاص جيدة في NIR.

لقد جعلت التقدمات الحديثة في تكنولوجيا النانو الاستخدام المشترك للمواد النانوية وتقنيات العلاج الضوئي نهجًا قابلاً للتطبيق لعلاج الأورام. لتحسين المزايا العلاجية لـ ICG وتأثير العلاج الحراري الضوئي / العلاج الضوئي المشترك، قام الباحثون بإنشاء مواد مركبة جديدة. شيوه وآخرون

الهياكل المسامية عند التسخين والمعادن المختلطة، ذات القيم المختلطة

الهياكل المسامية عند التسخين والمعادن المختلطة، ذات القيم المختلطة

في هذه الدراسة، استخدمنا ثاني أكسيد المنغنيز المسامي المجوف

المخطط I الرسم التخطيطي لـ M-HMnO

أكد نموذج الفأر الحي أن

المواد والطرق

المواد

تيترايثيل أورثوسيليكات (TEOS)، PAH (الوزن الجزيئي

أولاً، صلب

تحضير M-HMnO2@ICG

للحصول على حويصلات غشاء خلايا هيلا، تم طرد خلايا سرطان عنق الرحم البشرية.

غشاء البولي كربونات خمس مرات على الأقل. ثم تم طرد الخليط مركزيًا (

غشاء البولي كربونات خمس مرات على الأقل. ثم تم طرد الخليط مركزيًا (

توصيف المواد

تمت ملاحظة مورفولوجيا الجسيمات النانوية (NP) وحجمها وتوزيع العناصر تحت مجهر إلكتروني نافذ (TEM؛ Tecnai G2 F20؛ FEI، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية). تم تحديد مساحة السطح وحجم المسام للمواد باستخدام جهاز ASAP2460 3.01 لقياس إيزوثرم امتصاص-إزالة النيتروجين (Micromeritics، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية). تم تحديد تشتت الضوء الديناميكي (DLS) والجهود الزاوية للجسيمات باستخدام جهاز Zetasizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern). تم استخدام طيف الأشعة السينية للالكترونات (XPS) الذي تم جمعه باستخدام مجهر ESCALAB 250Xi (Thermo Scientific) لتحليل التركيب العنصري للجسيمات النانوية وتوزيعات التكافؤ. تم استخدام مطيافية الانبعاث الضوئي بالبلازما المقترنة بالحث (ICP-OES) لتحديد محتوى المنغنيز. تم الحصول على أطياف الفلورية باستخدام مطياف F-2700 (Hitachi، اليابان). تم قياس أطياف الامتصاص UV/Vis-NIR باستخدام مطياف UV-2600 (Shimadzu، اليابان).

توصيف البروتينات الغشائية

أنواع ومحتويات بروتينات الغشاء في

تقييم الأداء الضوئي الحراري في المختبر

مائي م-

أين

تقييم M-HMnO2@ICG

لاختبار السائل خارج الخلية

تقييم الخصائص الضوئية الديناميكية في المختبر

لتحقيق الخصائص الضوئية الديناميكية لـ

خارجي

لتقييم الانحلال والاستجابة للتوليد

تجربة إطلاق ICG في المختبر

تشتت م-

زراعة الخلايا

تم شراء خلايا هيلا وخلايا اللوكيميا أحادية النواة الماوس (RAW264.7) من مركز شيانغيا للخلايا (تشانغشا، الصين). تم زراعة الخلايا في وسط إيجل المعدل (MEM) ووسط معهد روسويل بارك التذكاري 1640، على التوالي، مع إضافة

تقييم القدرة على الاستهداف في المختبر وهروب البلعميات من البلع

تم تلقيح خلايا HeLa أو RAW264.7 في

تجربة كشف السمية الخلوية وعوامل الالتهاب

تم اختبار السمية الخلوية والآثار العلاجية للمواد النانوية بواسطة اختبار CCK8. تم حضن خلايا هيلا في أطباق 96 بئرًا في

صبغة الخلايا الحية والميتة وتقييم الموت الخلوي

تم تقييم السمية الخلوية في المجموعة الضابطة، NIR،

كشف الأكسجين داخل الخلايا، الجلوتاثيون، وأنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية

للتحقق من داخل الخلايا

لتحديد تأثير المواد النانوية الناتجة

لتحديد محتوى GSH داخل الخلايا، تم تلقيح خلايا HeLa في أطباق 6 آبار بكثافة

لتحليل ROS، تم تلقيح خلايا هيلا في أطباق 24 بئرًا بكثافة

نماذج الحيوانات والأورام

تم الحصول على فئران BALB/c عارية (من 6 إلى 8 أسابيع، 18-20 جرام) من شركة هونان سيلالك لتجارب الحيوانات. تم الموافقة على جميع تجارب الحيوانات من قبل لجنة أخلاقيات الحيوانات المخبرية في جامعة جنوب الوسطى (رقم CSU-20230227) وتم تنفيذها وفقًا لقانون جمهورية الصين الشعبية بشأن استخدام الحيوانات المخبرية. تم جمع خلايا HeLa وتفريقها في PBS.

الإبطين للفئران لإنشاء نموذج يحمل ورمًا. عندما وصل حجم الورم إلى

الإبطين للفئران لإنشاء نموذج يحمل ورمًا. عندما وصل حجم الورم إلى

اختبار انحلال الدم

تم الحصول على عينات دم من فئران BALB/c العارية الطبيعية وتم طردها مركزيًا

تصوير الفلورسنت داخل الجسم وخارجه

تم حقن الفئران الحاملة للأورام في الوريد الذيل بـ

التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي داخل الجسم وخارجه

خصائص التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي T1 في المختبر لـ M-

قياسات توزيع الأحياء

تم تقسيم الفئران الحاملة للأورام إلى ثلاث مجموعات

التصوير الضوئي الحراري داخل الجسم

فحص تأثيرات العلاج المضاد للأورام في الجسم الحي

ورم هيلا

بعد 14 يومًا، تم euthanize الفئران وجمع عينات تمثيلية من أنسجة الورم، وتم تصويرها ووزنها. تم صبغ أنسجة الورم والأعضاء الرئيسية للفئران من مجموعات العلاج المختلفة بصبغة الهيماتوكسيلين والإيوزين (H&E)، وتم صبغ أنسجة ورم الفئران بواسطة نقل الديوكسي نيوكليوتيديل الطرفي dUTP لتحديد موت الخلايا المبرمج (TUNEL). للكشف عن نقص الأكسجة في خلايا HeLa، تم صبغ أنسجة الورم من كل مجموعة علاج بمضاد HIF-1.

بعد 14 يومًا، تم euthanize الفئران وجمع عينات تمثيلية من أنسجة الورم، وتم تصويرها ووزنها. تم صبغ أنسجة الورم والأعضاء الرئيسية للفئران من مجموعات العلاج المختلفة بصبغة الهيماتوكسيلين والإيوزين (H&E)، وتم صبغ أنسجة ورم الفئران بواسطة نقل الديوكسي نيوكليوتيديل الطرفي dUTP لتحديد موت الخلايا المبرمج (TUNEL). للكشف عن نقص الأكسجة في خلايا HeLa، تم صبغ أنسجة الورم من كل مجموعة علاج بمضاد HIF-1.

تحليل السلامة الحيوية

لفحص السلامة الحيوية لـ

التحليل الإحصائي

تُعبر البيانات عن المتوسطات

النتائج والمناقشة

تحضير وتوصيف جزيئات M-HMnO2@ICG

أولاً، يحدث تفاعل أكسدة-اختزال بين

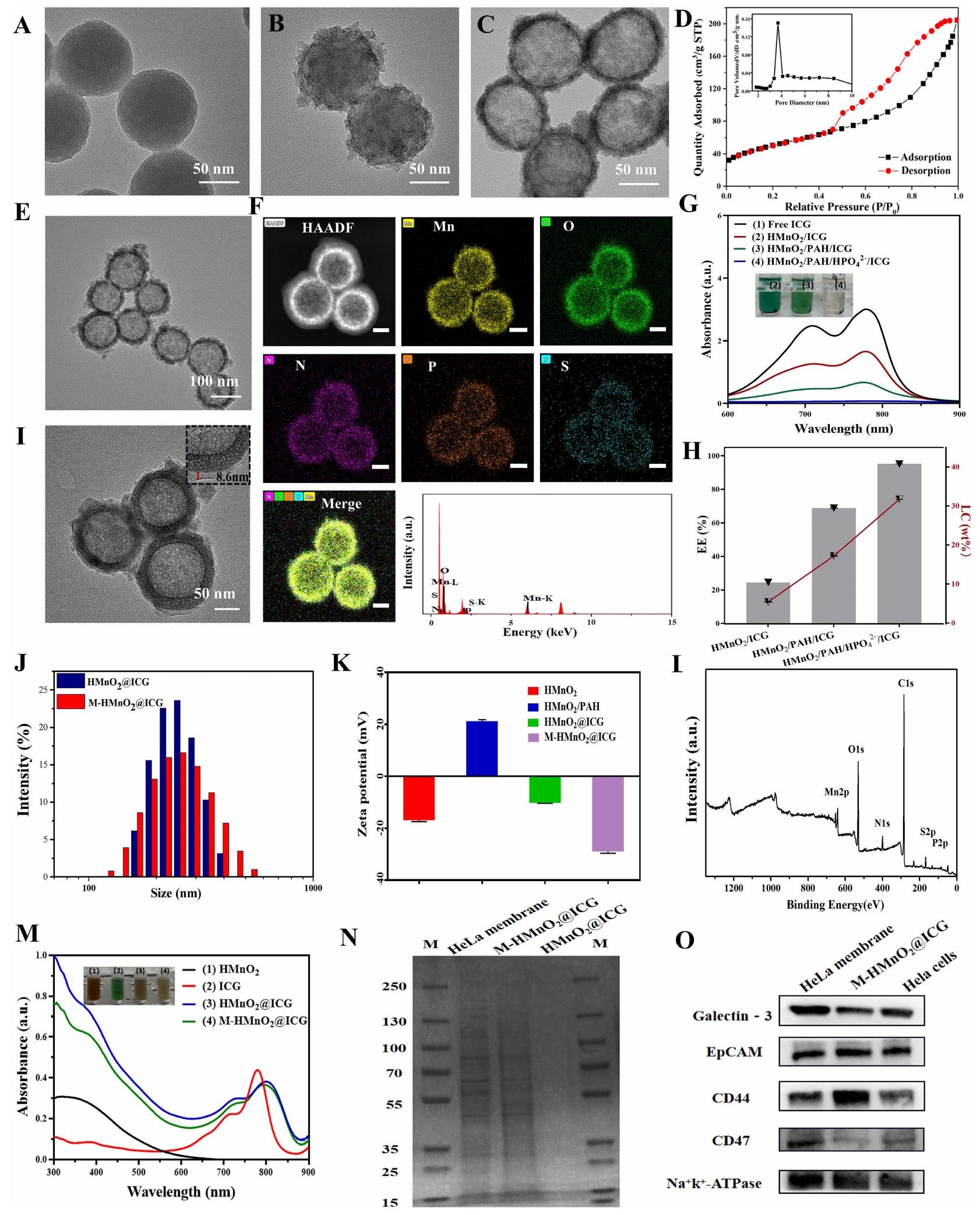

بعد

تحت ظروف تفاعل ثابتة، قمنا بدراسة تأثير التعديلات المختلفة على الحامل على سعة تحميل الدواء وكفاءة الت encapsulation لـ ICG. لاحظنا أنه، مقارنةً بالعناصر مع

أظهرت ملاحظات TEM أن المغلف

الشكل I (A-C) صور مجهر إلكتروني ناقل لـ

إمكانات

تم الكشف عن قمم الامتصاص بواسطة مطيافية الإلكترونات بالأشعة السينية (XPS) لـ

طيف XPS عالي الدقة لـ S2p أظهر

سلامة البروتينات السطحية بعد

خصائص M-HMnO2@ICG الضوئية الحرارية، الضوئية الديناميكية، والخصائص الحركية الكيميائية، وخصائص التحلل التي تعكس استجابة بيئة الورم الدقيقة

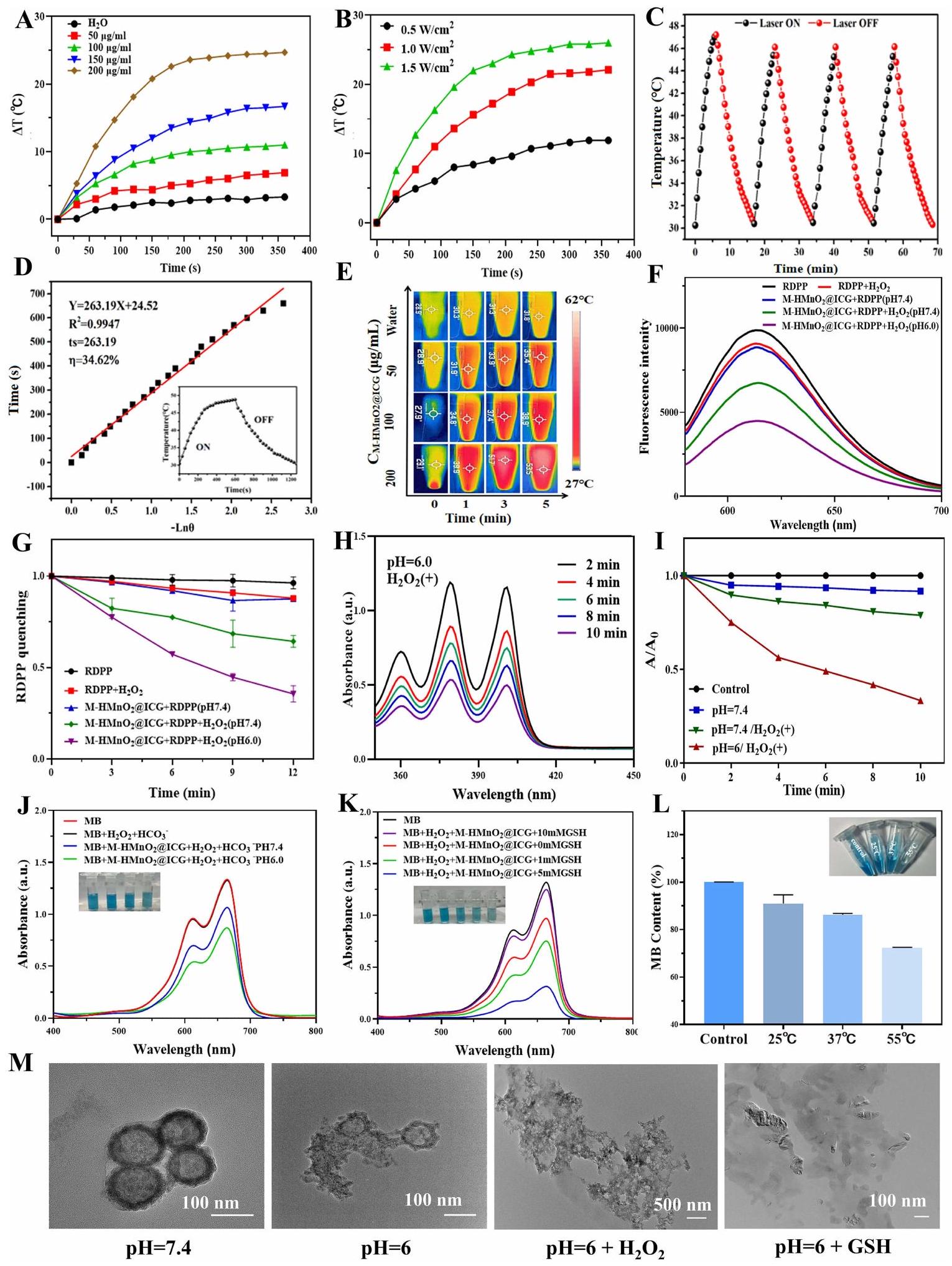

بينما أظهر ICG المحمّل على M-HMnO2 @ICG امتصاصًا كبيرًا في

الشكل 2 (أ) الخصائص الضوئية الحرارية في المختبر لـ M-HMnO

بعد ذلك، استخدمنا RDPP كأداة للتحقيق في

بالإضافة إلى زيادة التأثير الضوئي الديناميكي من خلال التحفيز

لتقييم بصري

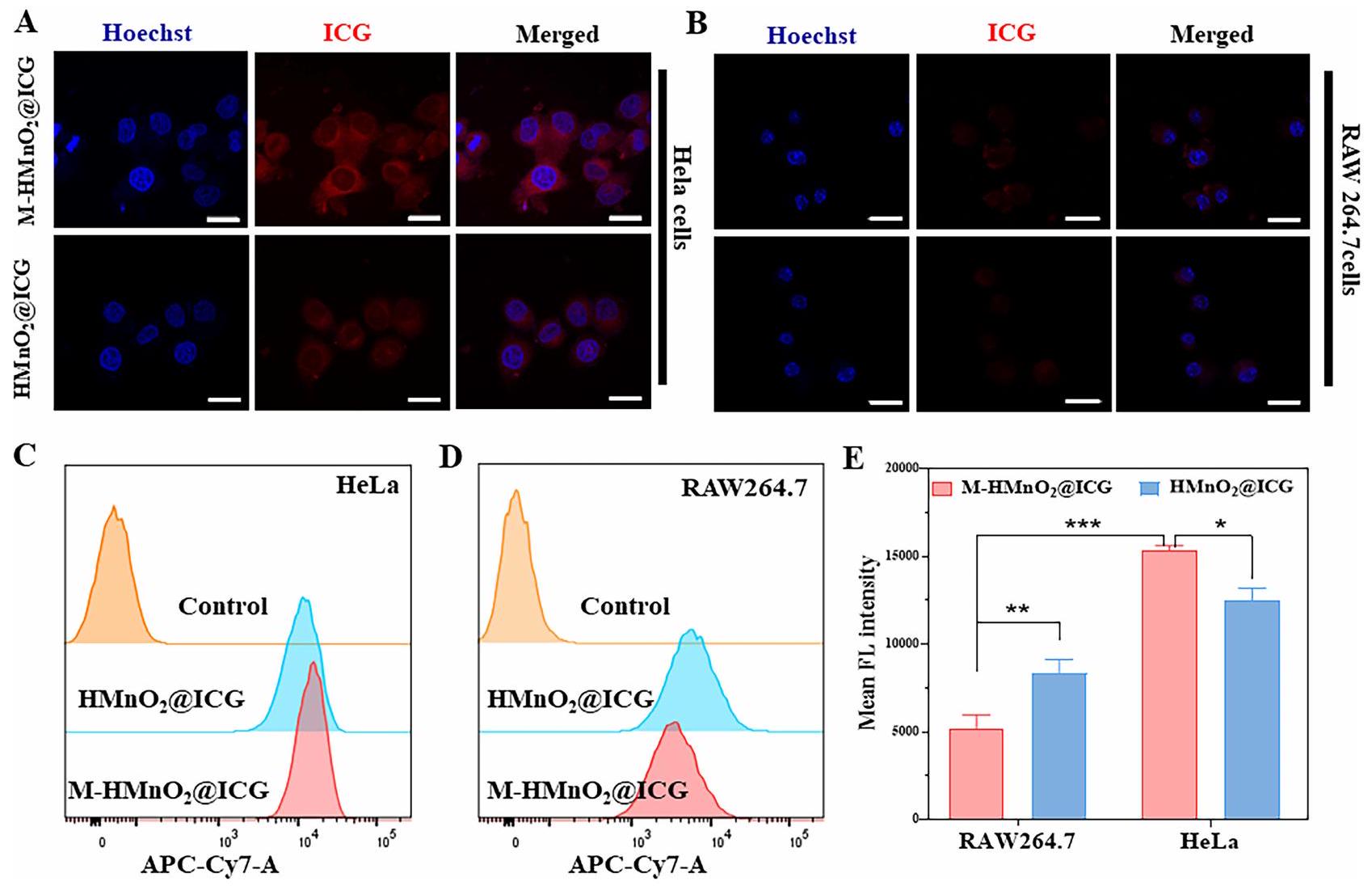

استهداف الورم في المختبر وخصائص الهروب المناعي لـ

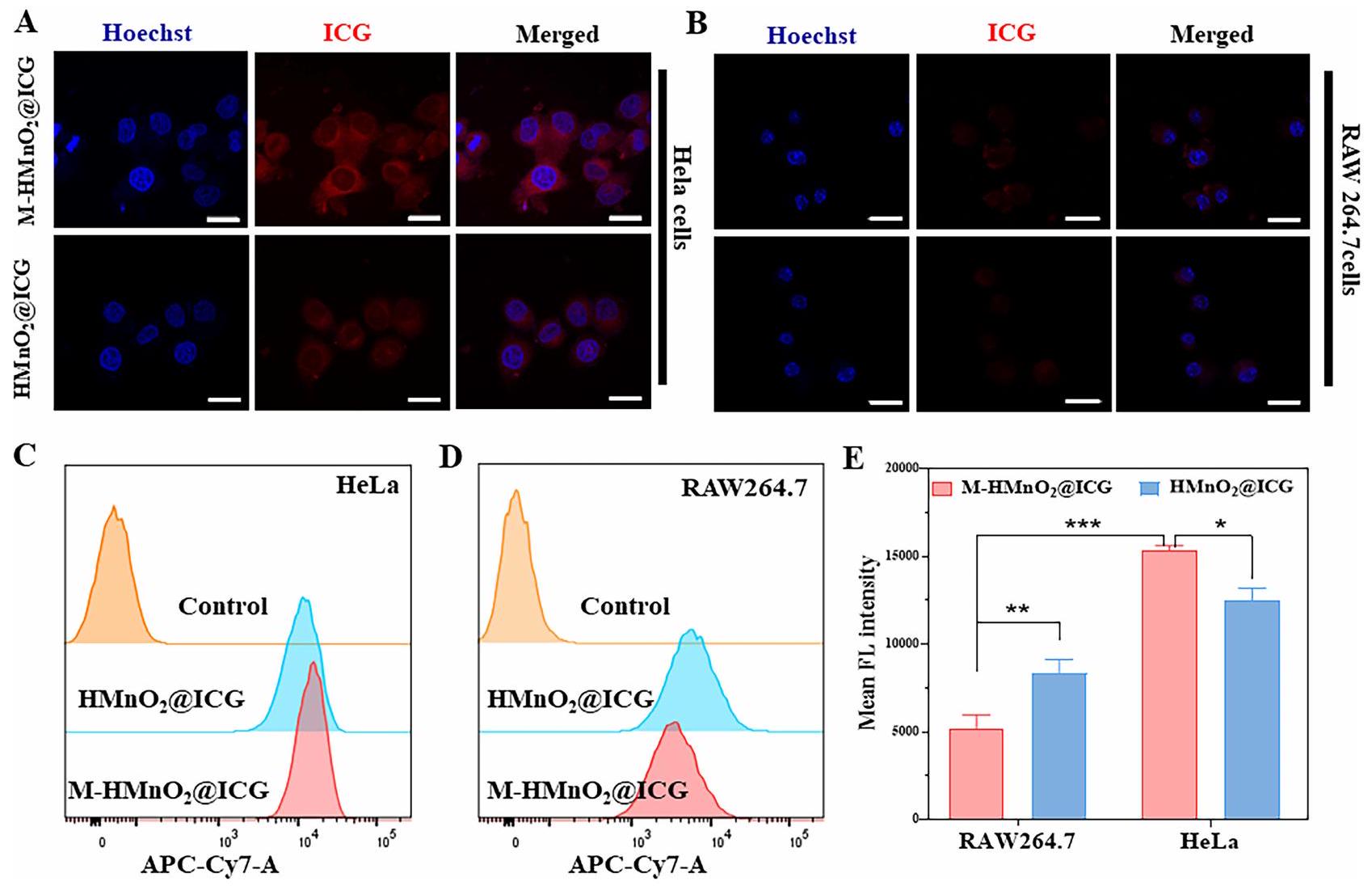

في هذه الدراسة، تم تغليف الجسيمات النانوية بأغشية خلايا الورم بهدف تمكينها من التهرب من الإزالة غير المحددة التي تقوم بها البلعميات، وإطالة مدة بقائها في مجرى الدم، وتعزيز التفاعل مع خلايا الورم، وتحقيق توصيل مستهدف متجانس إلى خلايا الورم. للتحقق من فعالية هذا النهج، استخدمنا خلايا RAW كبلعميات وخلايا HeLa كأهداف لدراسة الهروب البلعمي والامتصاص المتجانس لـ M-HMnO.

استخدمنا الفلورية العفوية لـ ICG لتتبع الجسيمات النانوية وصبغة 4’،6-diamidino-2-phenylindole لتحديد مواقع الخلايا. أظهرت خلايا HeLa المعالجة بـ M-HMnO2 @ICG فلورية حمراء أكثر بكثير من تلك التي تم تحضينها مع

خصائص مضادة للورم في المختبر

أظهرت التجارب على مستوى أنبوب الاختبار أن الجسيمات النانوية التي تم إعدادها في هذه الدراسة كانت لها خصائص تآزرية في العلاج الحراري الضوئي / العلاج الضوئي / العلاج الكيميائي. تم الكشف عن تأثير الجسيمات النانوية M-HMnO2 @ICG على بقاء خلايا هيلا من خلال اختبار CCK8 لتقييم النشاط المضاد للورم في المختبر للجسيمات النانوية. في غياب الضوء، M-

الشكل 3 (A و B) صور مجهرية بالليزر الماسح الضوئي التداخلي لخلايا HeLa و RAW264.7 المعالجة بجزيئات HMnO2@ICG و M-HMnO2@ICG لمدة 6 ساعات (مقياس الرسم =

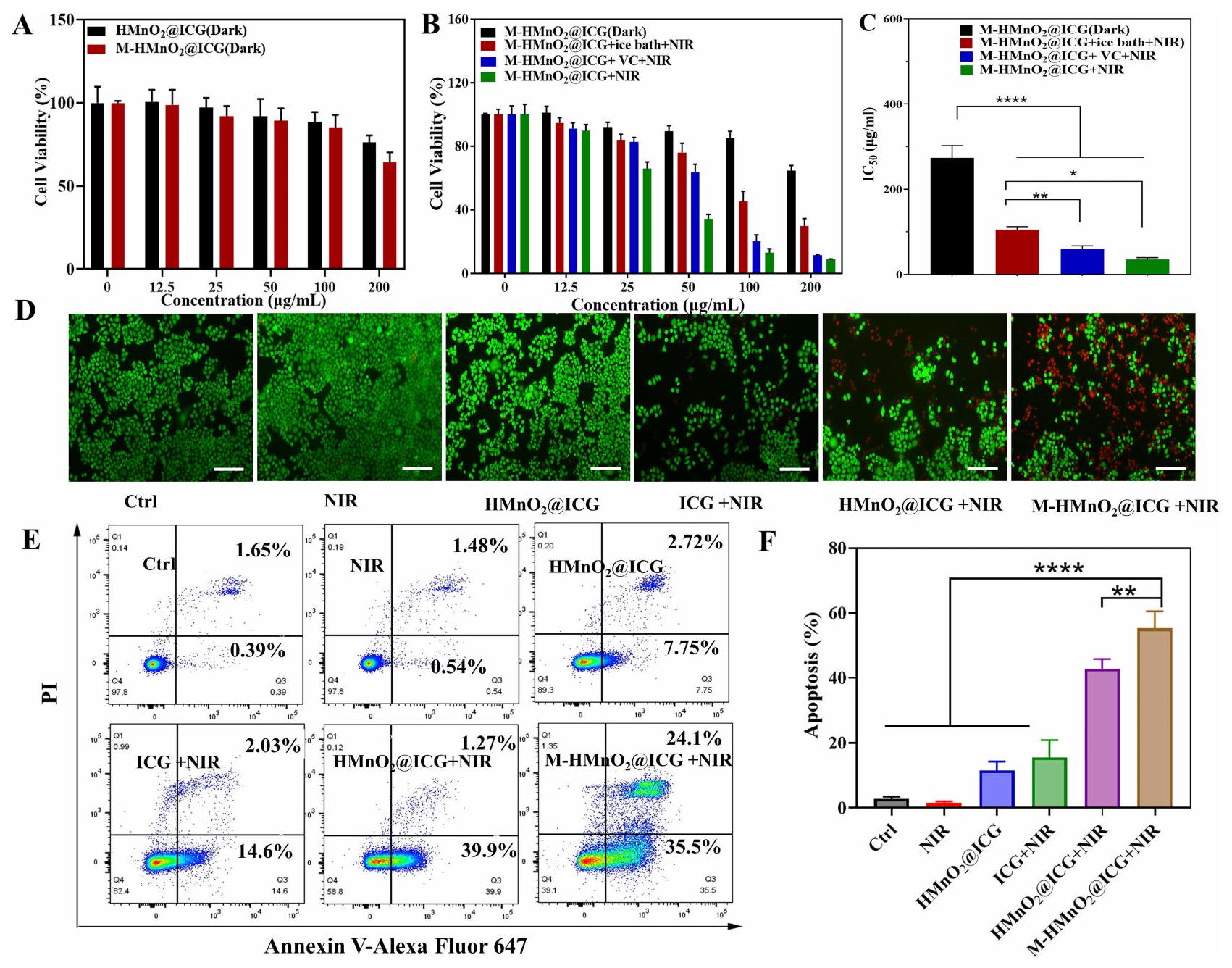

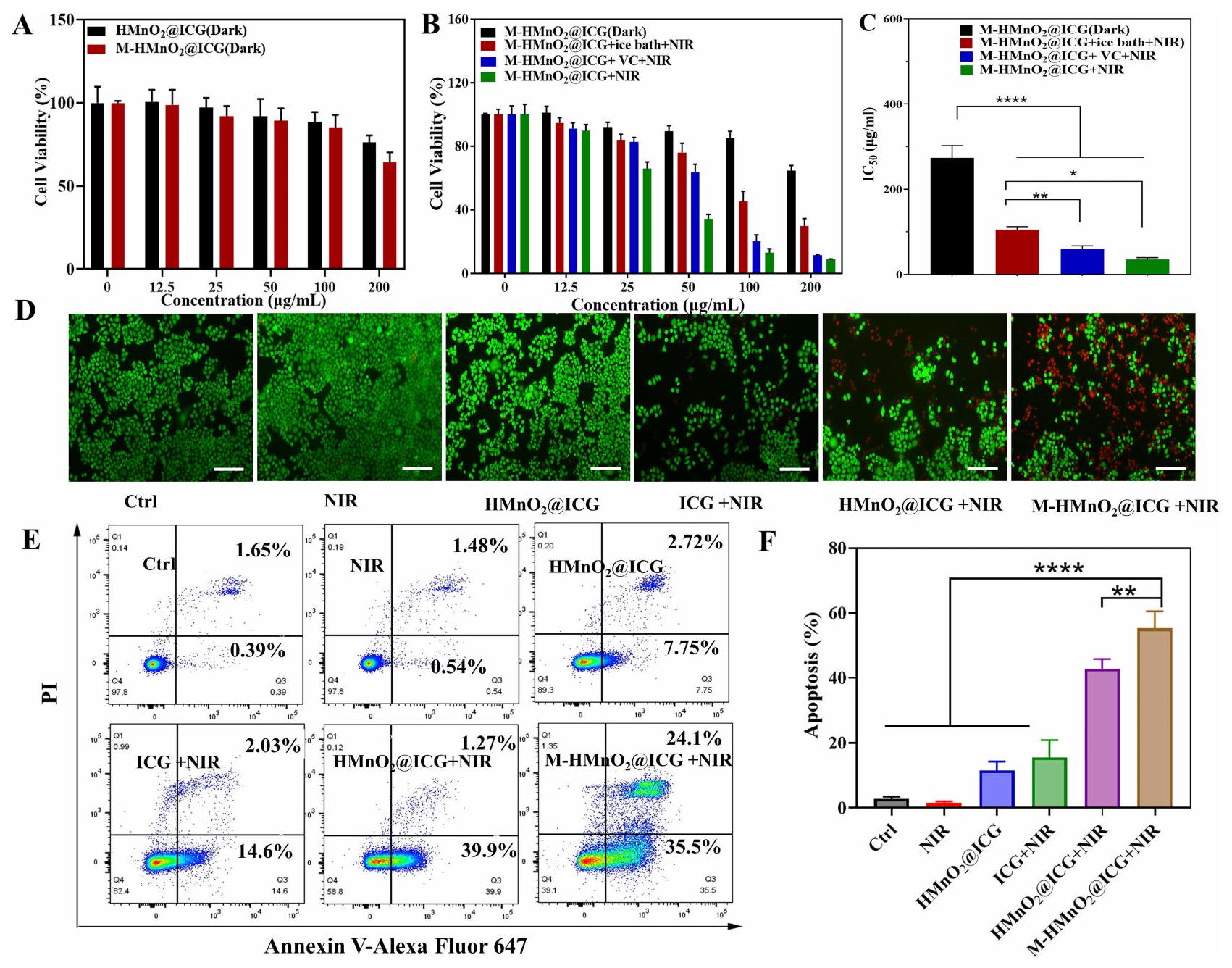

الشكل 4 (أ) تأثيرات تركيزات مختلفة من M-HMnO2@ICG و

المجموعة التي أظهرت زيادة في تعبير IL-1

تم تصور نشاط NPs المضاد للورم من خلال صبغ الخلايا الحية/الميتة. بعد إشعاع NIR، M-

التحقق على مستوى الخلايا لآلية تعزيز مضادات الأورام

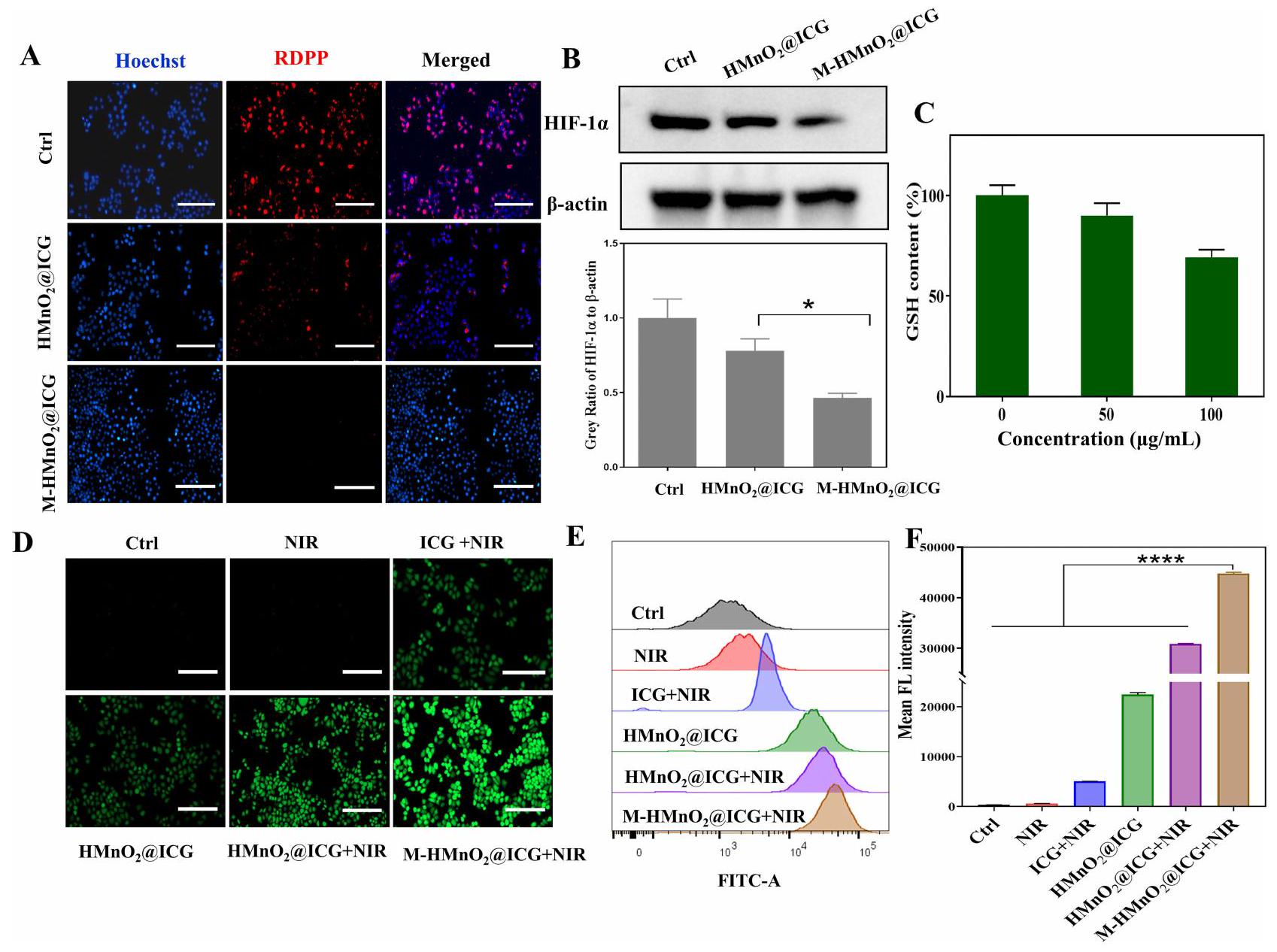

على مستوى أنبوب الاختبار، أظهرنا أن

الشكل 5 (أ) صور الفلورية لتلوين RDPP لخلايا هيلا تحت علاجات مختلفة (مقياس الرسم:

هيئة HIF-1 داخل الخلايا

تركيزات عالية من الجلوتاثيون (GSH) في خلايا الورم تحمي من أضرار الإجهاد التأكسدي، مما يقلل من تأثير قتل خلايا الورم الناتج عن الجذور الحرة للأكسجين (ROS).

استخدمنا مجس DCFHDA للكشف عن إنتاج ROS في خلايا HeLa بواسطة NPs المختلفة. كانت الفلورية الخضراء لـ DCFHDA في الخلايا ضعيفة جدًا تحت ظروف التحكم والإشعاع فقط (الشكل 5D). تحت إشعاع الليزر، أدى ICG الحر إلى إحداث إشارة فلورية ضعيفة في خلايا HeLa. من أجل

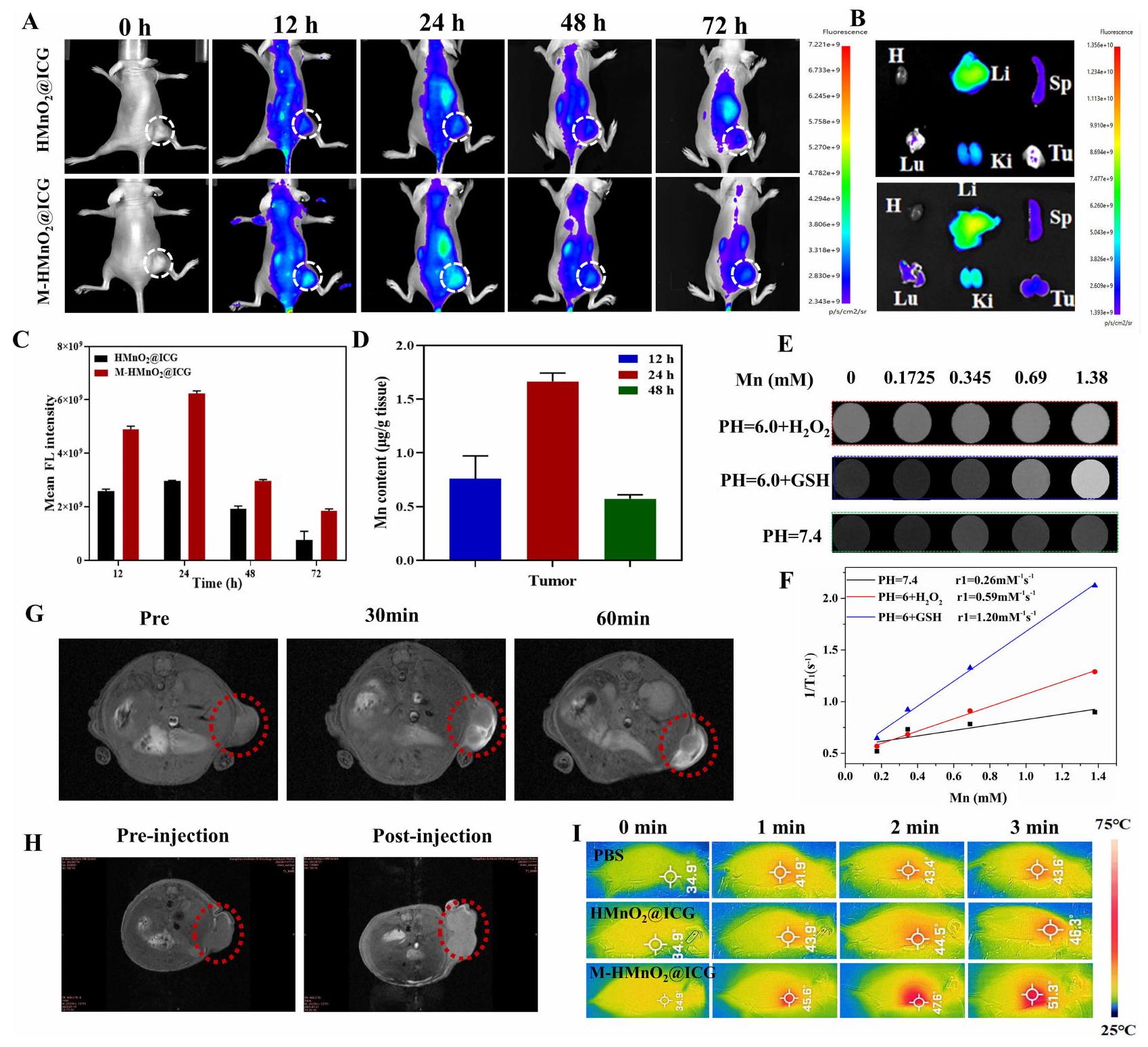

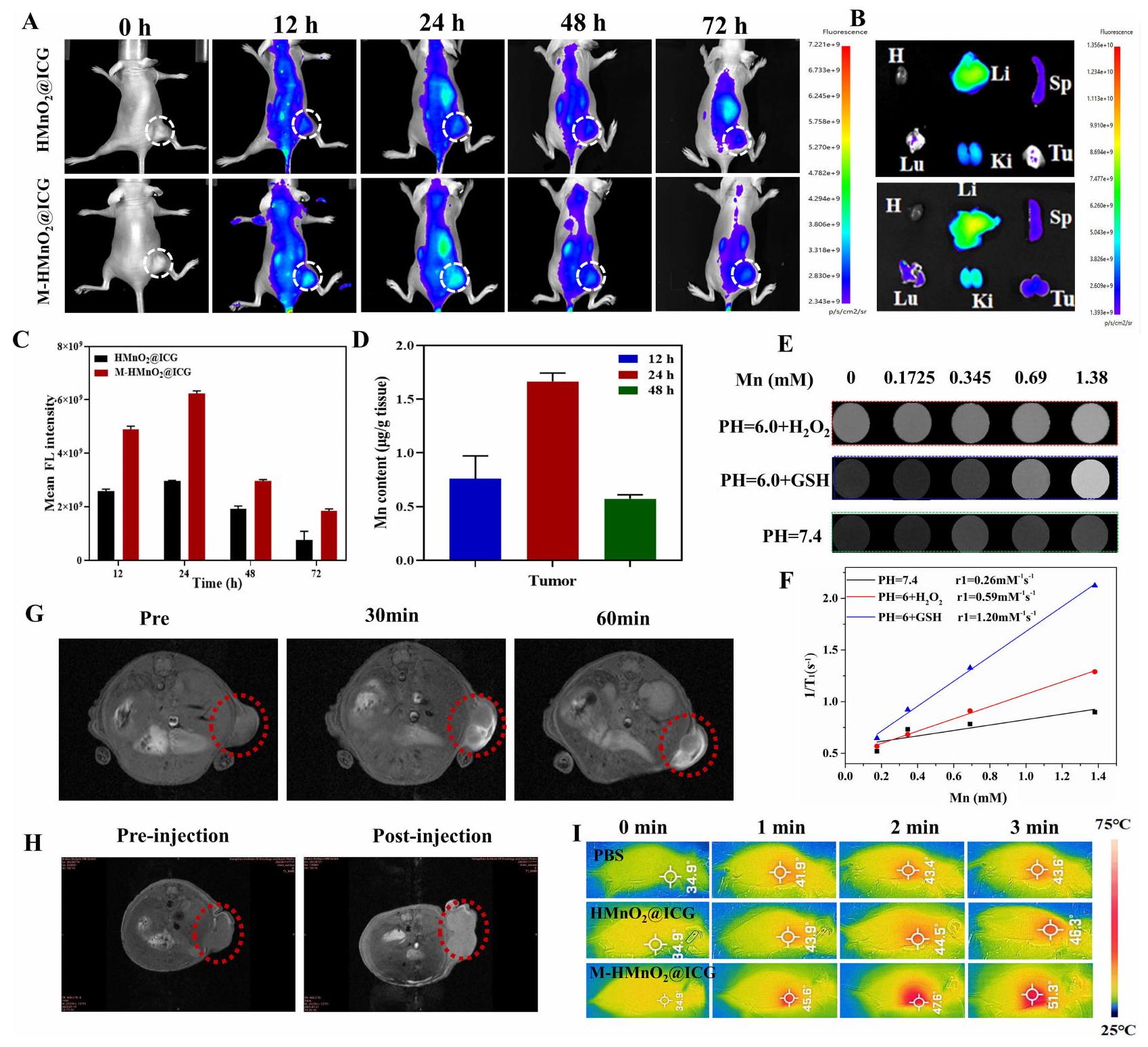

خصائص استهداف الورم في الجسم الحي لـ M-HMnO2@ICG

بعد توضيح النشاط المضاد للأورام لـ

ال

الشكل 6 (أ) تصوير الفلورية داخل الجسم لفئران تحمل ورم هيلا في نقاط زمنية مختلفة بعد الحقن الوريدي لـ

الملاحظة بين أنسجة الورم قبل M-

علاج الأورام في الجسم الحي والسلامة الحيوية

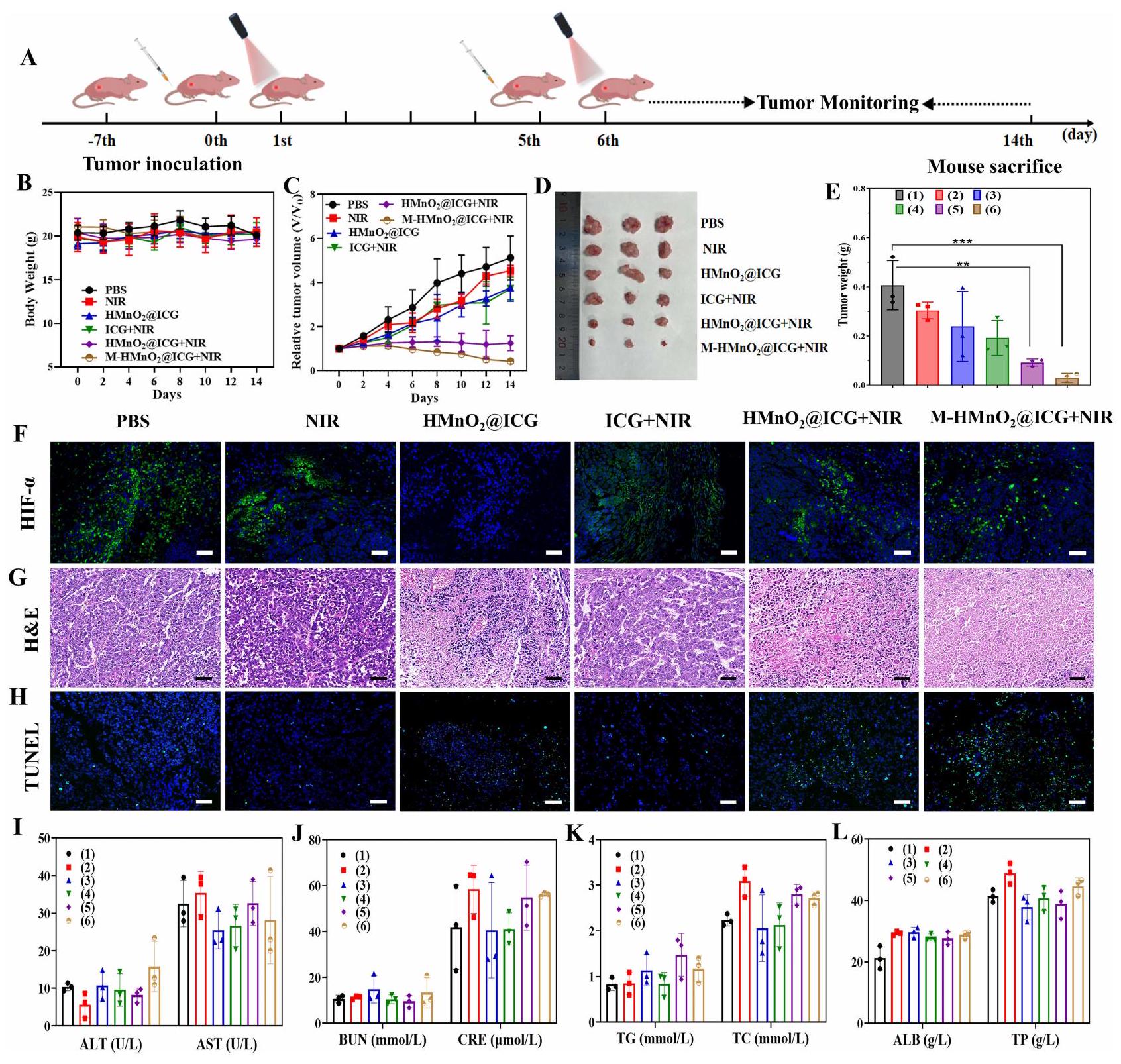

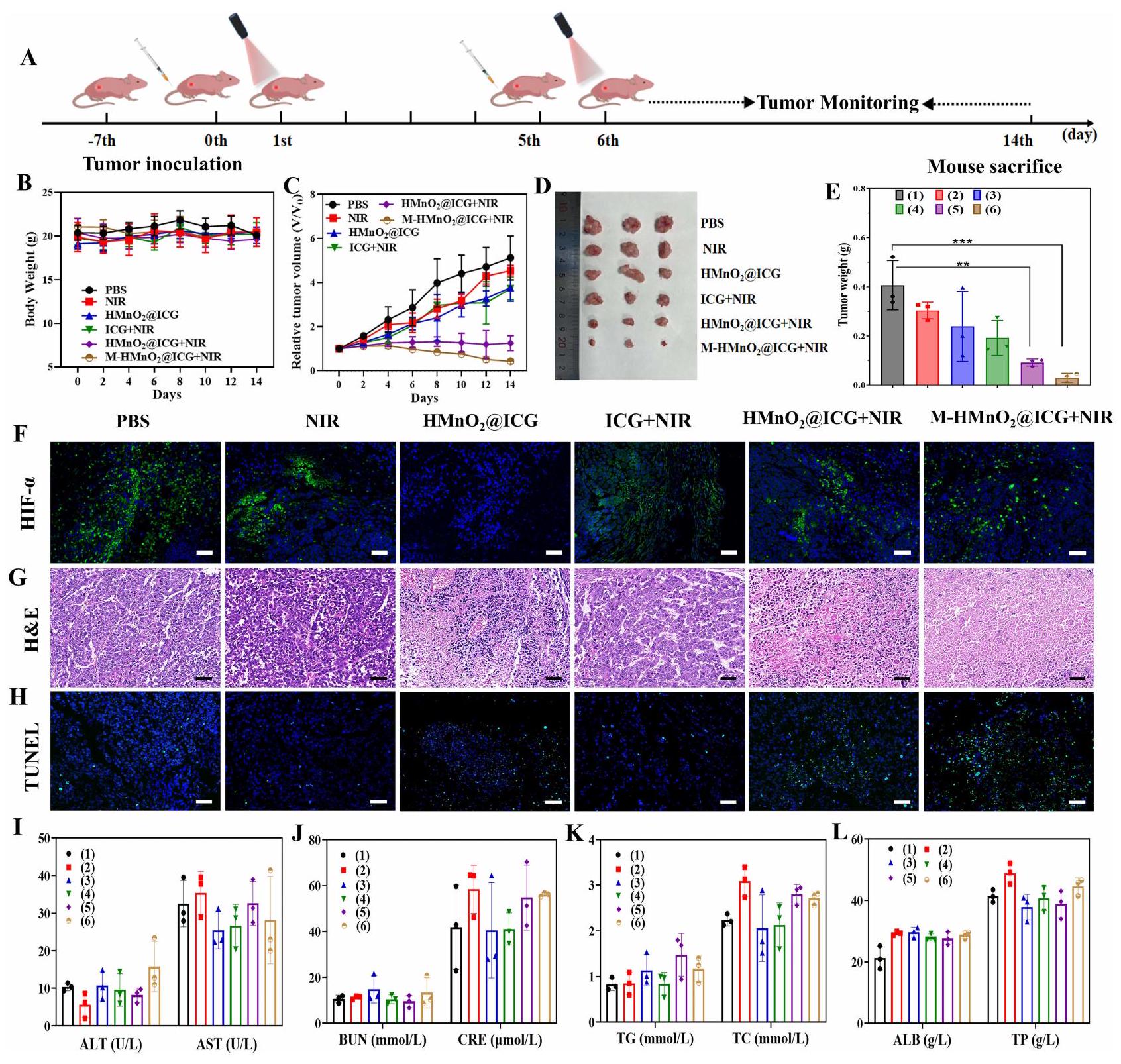

التأثيرات المضادة للورم لـ

الشكل 7 (أ) مخطط توضيحي لعلاج الفئران الحاملة للأورام. أوزان أجسام الفئران (ب) وأحجام الأورام النسبية (ج). (د) صور للأورام المجمعة من الفئران في اليوم 14 بعد الحقن الوريدي. (هـ) أوزان أنسجة الأورام. تُعبر البيانات عن المتوسط

أثره. كان التأثير العلاجي محدودًا في

لزيادة التحقق من الاستراتيجية التآزرية لتعزيز العلاج الضوئي، قمنا بفحص مستويات نقص الأكسجين في الجسم الحي من خلال صبغ الأنسجة الورمية للفئران باستخدام التألق المناعي لـ HIF-1.

لم تتغير مؤشرات السيروم البيوكيميائية في أي مجموعة علاج (الشكل 7I-L)، مما يشير إلى أن العلاجات كانت ذات أمان حيوي ممتاز. لم تكشف صبغة H&E للأعضاء الرئيسية عن أي تغيير مورفولوجي كبير أو تسلل التهابي (الشكل S13)، مما يؤكد الأمان الحيوي طويل الأمد للمواد النانوية. كانت تأثيرات العلاج المضاد للورم في الجسم الحي متسقة مع النتائج في المختبر.

الخاتمة

في هذه الدراسة، استخدمنا مساميات مجوفة

شكر وتقدير

تم دعم هذا العمل من خلال منح بحث علمي من المؤسسة الوطنية للعلوم الطبيعية في الصين (رقم U20A20339)، المؤسسة الوطنية للعلوم الطبيعية في الصين (رقم 82271880).

إفصاح

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود أي تضارب في المصالح في هذا العمل.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. 2021;71(3):209-249. doi:10.3322/caac. 21660

- Abu-Rustum NR, Yashar CM, Arend R, et al. NCCN Guidelines

insights: cervical cancer, version 1.2024. J National Compr Cancer Network. 2023;21(12):1224-1233. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2023.0062 - Iwata T, Machida H, Matsuo K, et al. The validity of the subsequent pregnancy index score for fertility-sparing trachelectomy in early-stage cervical cancer. Fertil Sterility. 2021;115(5):1250-1258. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.09.162

- Slama J, Runnebaum IB, Scambia G, et al. Analysis of risk factors for recurrence in cervical cancer patients after fertility-sparing treatment: the FERTIlity Sparing Surgery retrospective multicenter study. Am J Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228(4):443.e441-443.e410. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2022.11.1295

- Zeien J, Qiu W, Triay M, et al. Clinical implications of chemotherapeutic agent organ toxicity on perioperative care. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;146:112503. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112503

- Wang X, Liu S, Guan Y, Ding J, Ma C, Xie Z. Vaginal drug delivery approaches for localized management of cervical cancer. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2021;174:114-126. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2021.04.009

- Luo L, Zhou H, Wang S, et al. The application of nanoparticle-based imaging and phototherapy for female reproductive organs diseases. Small. 2023:e2207694. doi:10.1002/smll. 202207694

- He P, Yang G, Zhu D, et al. Biomolecule-mimetic nanomaterials for photothermal and photodynamic therapy of cancers: bridging nanobiotechnology and biomedicine. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):483. doi:10.1186/s12951-022-01691-4

- Li X, Lovell JF, Yoon J, Chen X. Clinical development and potential of photothermal and photodynamic therapies for cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(11):657-674. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-0410-2

- Jung HS, Verwilst P, Sharma A, Shin J, Sessler JL, Kim JS. Organic molecule-based photothermal agents: an expanding photothermal therapy universe. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47(7):2280-2297. doi:10.1039/c7cs00522a

- Seung Lee J, Kim J, Y-s Y, T-i K. Materials and device design for advanced phototherapy systems. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2022;186. doi:10.1016/j. addr.2022.114339

- Li S, Meng X, Peng B, et al. Cell membrane-based biomimetic technology for cancer phototherapy: mechanisms, recent advances and perspectives. Acta Biomater. 2024;174:26-48. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2023.11.029

- Zhong YT, Cen Y, Xu L, Li SY, Cheng H. Recent progress in carrier-free nanomedicine for tumor phototherapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12(4): e2202307. doi:10.1002/adhm. 202202307

- Liu Y, Bhattarai P, Dai Z, Chen X. Photothermal therapy and photoacoustic imaging via nanotheranostics in fighting cancer. Chem Soc Rev. 2019;48 (7):2053-2108. doi:10.1039/c8cs00618k

- Nasseri B, Turk M, Kosemehmetoglu K, et al. The pimpled gold nanosphere: a superior candidate for plasmonic photothermal therapy. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:2903-2920. doi:10.2147/ijn.S248327

- Meng Z, Xue H, Wang T, et al. Aggregation-induced emission photosensitizer-based photodynamic therapy in cancer: from chemical to clinical. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):344. doi:10.1186/s12951-022-01553-z

- Xu X, Huang B, Zeng Z, et al. Broaden sources and reduce expenditure: tumor-specific transformable oxidative stress nanoamplifier enabling economized photodynamic therapy for reinforced oxidation therapy. Theranostics. 2020;10(23):10513-10530. doi:10.7150/thno. 49731

- Wang R, Li X, Yoon J. Organelle-targeted photosensitizers for precision photodynamic therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13 (17):19543-19571. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c02019

- Overchuk M, Weersink RA, Wilson BC, Zheng G. Photodynamic and photothermal therapies: synergy opportunities for nanomedicine. ACS Nano. 2023;17(9):7979-8003. doi:10.1021/acsnano.3c00891

- Wang Y, Luo S, Wu Y, et al. Highly penetrable and on-demand oxygen release with tumor activity composite nanosystem for photothermal/ photodynamic synergetic therapy. ACS Nano. 2020;14(12):17046-17062. doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c06415

- Kong C, Chen X. Combined photodynamic and photothermal therapy and immunotherapy for cancer treatment: a review. Int

Nanomed. 2022;17:6427-6446. doi:10.2147/ijn.S388996 - Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA. 2011;61(4):250-281. doi:10.3322/caac.20114

- Cao W, Zhu Y, Wu F, et al. Three birds with one stone: acceptor engineering of hemicyanine dye with NIR-II emission for synergistic photodynamic and photothermal anticancer therapy. Small. 2022;18(49):e2204851. doi:10.1002/smll. 202204851

- Wu P, Zhu Y, Chen L, Tian Y, Xiong H. A fast-responsive OFF-ON Near-infrared-II fluorescent probe for in vivo detection of hypochlorous acid in rheumatoid arthritis. Anal Chem. 2021;93(38):13014-13021. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.1c02831

- Wu P, Zhu Y, Liu S, Xiong H. Modular design of high-brightness ph-activatable near-infrared bodipy probes for noninvasive fluorescence detection of deep-seated early breast cancer bone metastasis: remarkable axial substituent effect on performance. ACS Cent Sci. 2021;7(12):2039-2048. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.1c01066

- Porcu EP, Salis A, Gavini E, Rassu G, Maestri M, Giunchedi P. Indocyanine green delivery systems for tumour detection and treatments. Biotechnol Adv. 2016;34(5):768-789. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.04.001

- Sun X, He G, Xiong C, et al. One-pot fabrication of hollow porphyrinic mof nanoparticles with ultrahigh drug loading toward controlled delivery and synergistic cancer therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(3):3679-3693. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c20617

- Jaiswal S, Roy R, Dutta SB, et al. Role of doxorubicin on the loading efficiency of ICG within silk fibroin nanoparticles. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022;8(7):3054-3065. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c01616

- Chaudhary Z, Khan GM, Abeer MM, et al. Efficient photoacoustic imaging using indocyanine green (ICG) loaded functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Biomater Sci. 2019;7(12):5002-5015. doi:10.1039/c9bm00822e

- Ma Y, Chen L, Li X, et al. Rationally integrating peptide-induced targeting and multimodal therapies in a dual-shell theranostic platform for orthotopic metastatic spinal tumors. Biomaterials. 2021:275. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120917

- Sun Y, Wang Y, Liu Y, et al. Intelligent tumor microenvironment-activated multifunctional nanoplatform coupled with turn-on and always-on fluorescence probes for imaging-guided cancer treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(45):53646-53658. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c17642

- Fang C, Yan P, Ren Z, et al. Multifunctional MoO2-ICG nanoplatform for 808 nm -mediated synergetic photodynamic/photothermal therapy. Appl. Mater. Today. 2019;15:472-481. doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2019.03.008

- Deng K, Hou Z, Deng X, Yang P, Li C, and Lin J. Enhanced antitumor efficacy by 808 nm laser-induced synergistic photothermal and photodynamic therapy based on a indocyanine-green-attached W18O49 nanostructure. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25(47):7280-7290. doi:10.1002/ adfm. 201503046

- Xue P, Yang R, Sun L, et al. Indocyanine green-conjugated magnetic prussian blue nanoparticles for synchronous photothermal/photodynamic tumor therapy. Nano-Micro Lett. 2018;10(4):74. doi:10.1007/s40820-018-0227-z

- Fukasawa T, Hashimoto M, Nagamine S, et al. Fabrication of ICG dye-containing particles by growth of polymer/salt aggregates and measurement of photoacoustic signals. Chem Lett. 2014;43(4):495-497. doi:10.1246/cl.131088

- Yu J, Javier D, Yaseen MA, et al. Self-assembly synthesis, tumor cell targeting, and photothermal capabilities of antibody-coated indocyanine green nanocapsules. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(6):1929-1938. doi:10.1021/ja908139y

- Sun Q, Wang Z, Liu B, et al. Self-generation of oxygen and simultaneously enhancing photodynamic therapy and MRI effect: an intelligent nanoplatform to conquer tumor hypoxia for enhanced phototherapy. Chem Eng J. 2020:390. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.124624

- Huang P-Y, Zhu -Y-Y, Zhong H, et al. Autophagy-inhibiting biomimetic nanodrugs enhance photothermal therapy and boost antitumor immunity. Biomater Sci. 2022;10(5):1267-1280. doi:10.1039/d1bm01888d

- Chen X, Zhao C, Liu D, et al. Intelligent Pd1.7Bi@CeO2 nanosystem with dual-enzyme-mimetic activities for cancer hypoxia relief and synergistic photothermal/photodynamic/chemodynamic therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(18):21804-21818. doi:10.1021/acsami.3c00056

- Cheng Y, Wen C, Sun YQ, Yu H, Yin XB. Mixed-Metal MOF-derived hollow porous nanocomposite for trimodality imaging guided reactive oxygen species-augmented synergistic therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2021;31(37):2. doi:10.1002/adfm.202104378.

- Yu J, Yaseen MA, Anvari B, Wong MS. Synthesis of near-infrared-absorbing nanoparticle-assembled capsules. Chem Mater. 2007;19 (6):1277-1284. doi:10.1021/cm062080x

- Zeng W, Zhang H, Deng Y, et al. Dual-response oxygen-generating MnO2 nanoparticles with polydopamine modification for combined photothermal-photodynamic therapy. Chem Eng J. 2020:389. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.124494

- Liu X, Li R, Zhou Y, et al. An all-in-one nanoplatform with near-infrared light promoted on-demand oxygen release and deep intratumoral penetration for synergistic photothermal/photodynamic therapy. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;608:1543-1552. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2021.10.082

- Gao J, Qin H, Wang F, et al. Hyperthermia-triggered biomimetic bubble nanomachines. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):4867. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-40474-9

- Xi Y, Xie X, Peng Y, Liu P, Ding J, Zhou W. DNAzyme-adsorbed polydopamine@MnO2 core-shell nanocomposites for enhanced photothermal therapy via the self-activated suppression of heat shock protein 70. Nanoscale. 2021;13(9):5125-5135. doi:10.1039/d0nr08845e

- Sun W, Xu Y, Yao Y, et al. Self-oxygenation mesoporous MnO2 nanoparticles with ultra-high drug loading capacity for targeted arteriosclerosis therapy. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):88. doi:10.1186/s12951-022-01296-x

- Gostynski R, Conradie J, Erasmus E. Significance of the electron-density of molecular fragments on the properties of manganese(iii)

-diketonato complexes: an XPS and DFT study. RSC Adv. 2017;7(44):27718-27728. doi:10.1039/c7ra04921h - Quan B, S-H Y, Chung DY, et al. Single source precursor-based solvothermal synthesis of heteroatom-doped graphene and its energy storage and conversion applications. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5639. doi:10.1038/srep05639

- Liu J, Li RS, Zhang L, et al. Enzyme-activatable polypeptide for plasma membrane disruption and antitumor immunity elicitation. Small. 2023;19 (24):e2206912. doi:10.1002/smll. 202206912

- Xu B, Zeng F, Deng J, et al. A homologous and molecular dual-targeted biomimetic nanocarrier for EGFR-related non-small cell lung cancer therapy. Bioact Mater. 2023;27:337-347. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.04.005

- Fan Y, Cui Y, Hao W, et al. Carrier-free highly drug-loaded biomimetic nanosuspensions encapsulated by cancer cell membrane based on homology and active targeting for the treatment of glioma. Bioact Mater. 2021;6(12):4402-4414. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.04.027

- Du X, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Cancer cell membrane camouflaged biomimetic nanosheets for enhanced chemo-photothermal-starvation therapy and tumor microenvironment remodeling. Appl Mater Today. 2022;29. doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2022.101677

- Guan S, Liu X, Li C, et al. Intracellular mutual amplification of oxidative stress and inhibition multidrug resistance for enhanced sonodynamic/ chemodynamic/chemo therapy. Small. 2022;18(13):e2107160. doi:10.1002/smll. 202107160

International Journal of Nanomedicine

انشر عملك في هذه المجلة

المجلة الدولية للنانوميديسين هي مجلة دولية محكمة تركز على تطبيق تكنولوجيا النانو في التشخيص والعلاج وأنظمة توصيل الأدوية في جميع مجالات الطب الحيوي. هذه المجلة مفهرسة في PubMed Central وMedLine وCAS وSciSearch

قم بتقديم مخطوطتك هنا: https://www.dovepress.com/international-journal-of-nanomedicine-journal

Journal: International Journal of Nanomedicine

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s466042

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38887692

Publication Date: 2024-06-01

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/ijn.s466042

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38887692

Publication Date: 2024-06-01

Tumor Cell-Targeting and Tumor Microenvironment-Responsive Nanoplatforms for the Multimodal Imaging-Guided Photodynamic/Photothermal/Chemodynamic Treatment of Cervical Cancer

Purpose: Phototherapy, known for its high selectivity, few side effects, strong controllability, and synergistic enhancement of combined treatments, is widely used in treating diseases like cervical cancer.

Methods: In this study, hollow mesoporous manganese dioxide was used as a carrier to construct positively charged, poly(allylamine hydrochloride)-modified nanoparticles (NPs). The NP was efficiently loaded with the photosensitizer indocyanine green (ICG) via the addition of hydrogen phosphate ions to produce a counterion aggregation effect. HeLa cell membrane encapsulation was performed to achieve the final M-HMnO

Results:

Conclusion: In this study, we designed a nano-biomimetic delivery system that improves hypoxia, responds to the tumor microenvironment, and efficiently loads ICG. It provides a new economical and convenient strategy for synergistic phototherapy and CDT for cervical cancer.

Keywords: phototherapy, reactive oxygen species, hypoxia relief, collaborative therapy

Methods: In this study, hollow mesoporous manganese dioxide was used as a carrier to construct positively charged, poly(allylamine hydrochloride)-modified nanoparticles (NPs). The NP was efficiently loaded with the photosensitizer indocyanine green (ICG) via the addition of hydrogen phosphate ions to produce a counterion aggregation effect. HeLa cell membrane encapsulation was performed to achieve the final M-HMnO

Results:

Conclusion: In this study, we designed a nano-biomimetic delivery system that improves hypoxia, responds to the tumor microenvironment, and efficiently loads ICG. It provides a new economical and convenient strategy for synergistic phototherapy and CDT for cervical cancer.

Keywords: phototherapy, reactive oxygen species, hypoxia relief, collaborative therapy

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common gynecological malignancy in the world, causing more than 300,000 deaths annually.

Given that the cervical anatomical structure is connected to that of the vagina, the use of optical therapies for cervical cancer have attracted extensive research attention.

With advances in the field of phototherapy, agents such as protoporphyrin IX, dihydrochlorin e6, and methylene blue (MB) have been approved for the clinical treatment of skin, esophageal, and lung tumors.

Indocyanine green (ICG) has a strong absorption peak between 780 and 800 nm , and thus good absorption capacity in the NIR.

Recent advances in nanotechnology have made the combined use of nanomaterials and phototherapy techniques a viable approach for tumor treatment. To improve the therapeutic advantages of ICG and the effect of combined PTT/PDT, researchers have constructed novel composite materials. Xue et al

porous structures upon heating and mixed-metal, mixed-valence (

porous structures upon heating and mixed-metal, mixed-valence (

In this study, we used hollow mesoporous manganese dioxide (

Scheme I Schematic diagram of M-HMnO

An in-vivo mouse model confirmed that

Materials and Methods

Materials

Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), PAH (molecular weight

First, solid

M-HMnO2@ICG Preparation

To obtain HeLa cell membrane vesicles, human cervical cancer cells were centrifuged for

polycarbonate membrane at least 5 times. The mixture was then centrifuged (

polycarbonate membrane at least 5 times. The mixture was then centrifuged (

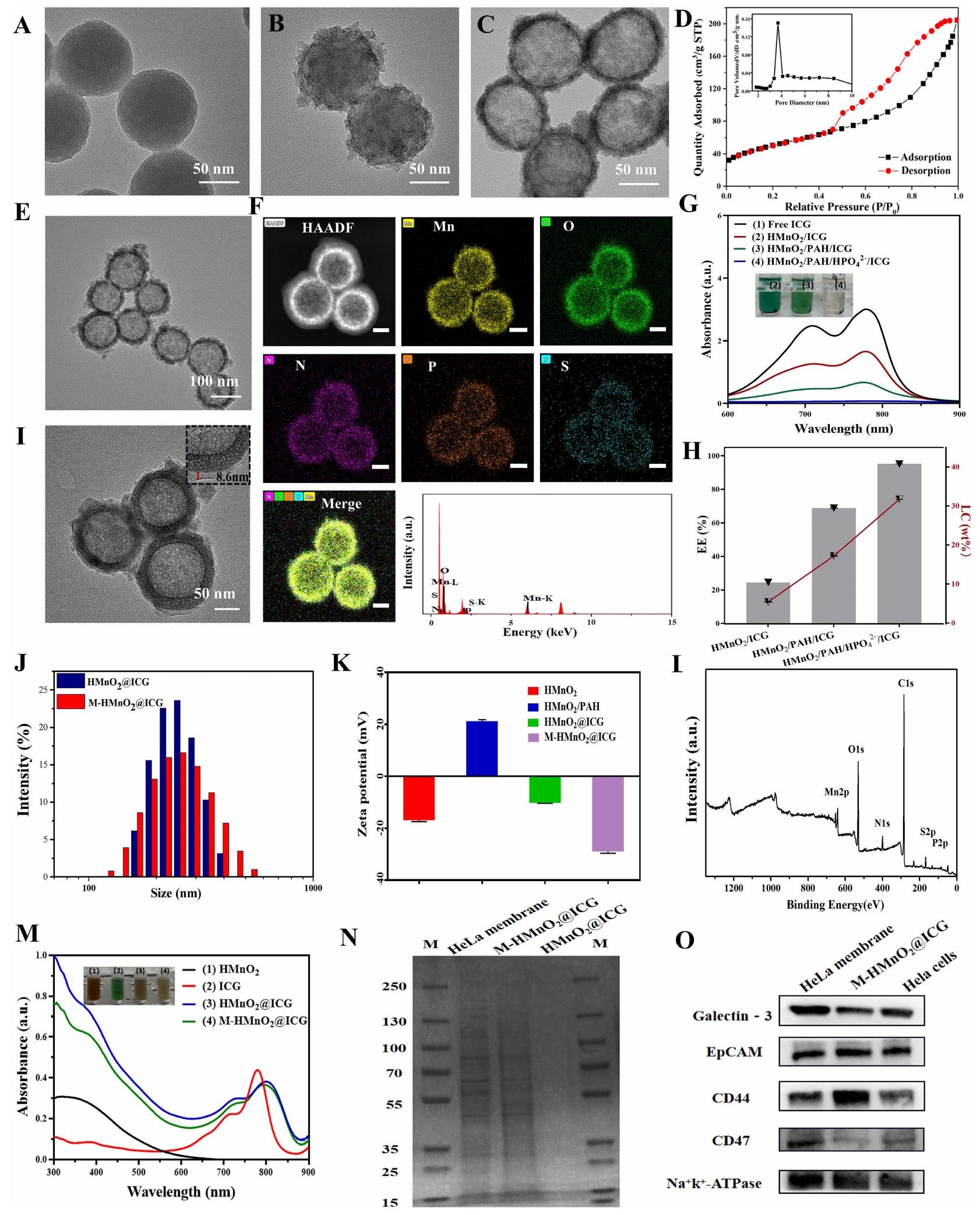

Material Characterization

The NP morphology, size, and elemental distribution were observed under a transmission electron microscope (TEM; Tecnai G2 F20; FEI, USA). The materials’ Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller (BET) surface area and pore volume were determined using an ASAP2460 3.01 nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm (Micromeritics, USA). The particles’ dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potentials were determined using a Zetasizer Nano ZS90 device (Malvern). X-ray photoelectron spectra collected using an ESCALAB 250Xi microprobe (Thermo Scientific) were used to analyze the NPs’ elemental composition and valence distributions. Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) was used to determine the Mn content. Fluorescence spectra were obtained using an F-2700 spectrometer (Hitachi, Japan). UV/Vis-NIR absorption spectra were measured using a UV-2600 spectrometer (Shimadzu, Japan).

Membrane Protein Characterization

The types and contents of membrane proteins in the

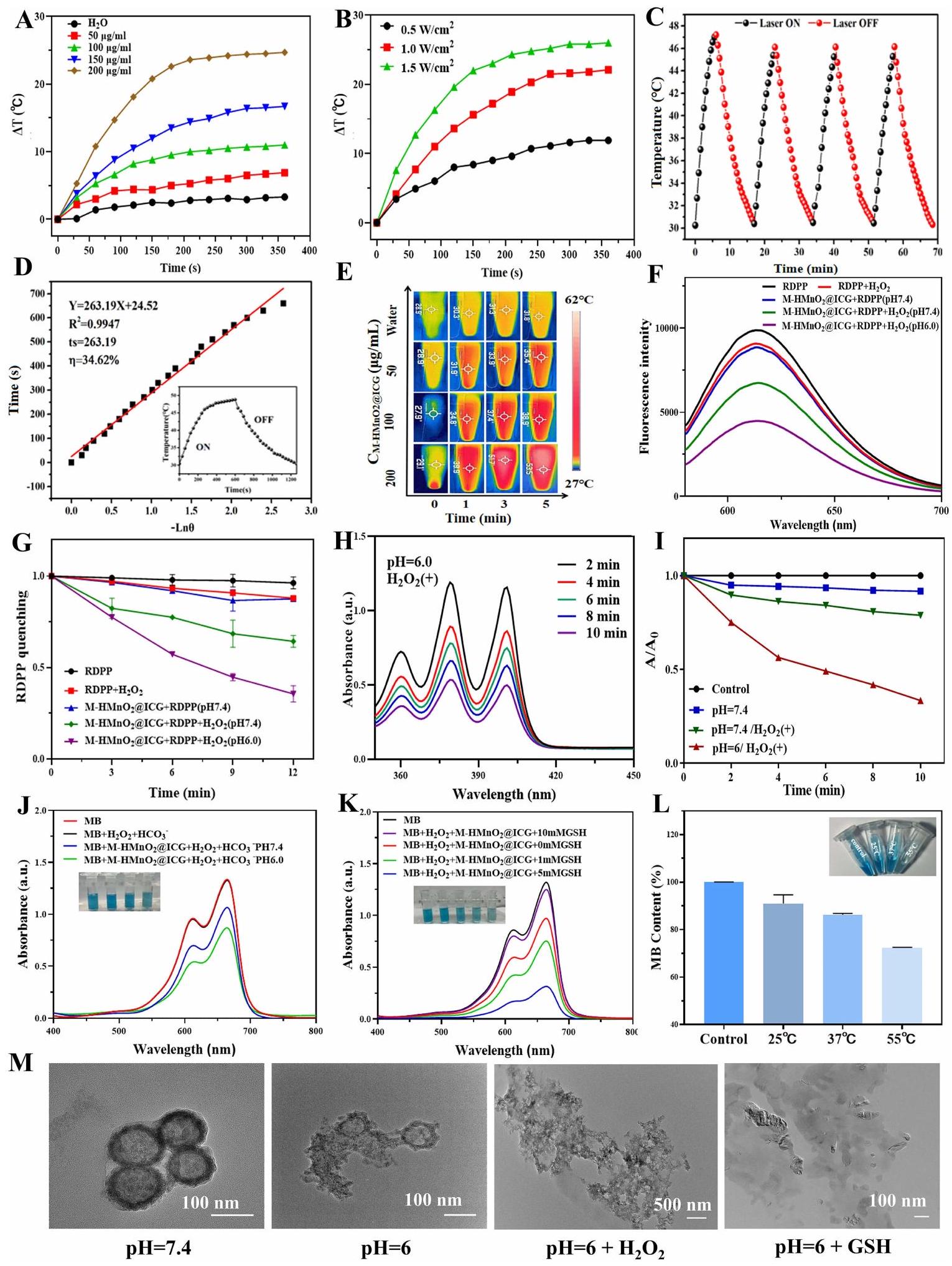

In-Vitro Photothermal Performance Assessment

Aqueous M-

where

Assessment of M-HMnO2@ICG’s

To test the extracellular

In-Vitro Photodynamic Property Assessment

To investigate the photodynamic properties of

Extracellular

To evaluate the responsive degradation and generation of

In vitro Release Experiment of ICG

Disperse M-

Cell Culture

HeLa cells and mouse monocyte macrophage leukemia (RAW264.7) cells were purchased from Xiangya Cell Center (Changsha, China). The cells were cultured in modified Eagle medium (MEM) and Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium, respectively, supplemented with

Assessment of in-vitro Targeting Capacity and Macrophage Phagocytic Escape

HeLa or RAW264.7 cells were inoculated in

Cytotoxicity and Inflammation Factor Detection Experiment

The cytotoxicity and therapeutic effects of the nanomaterials were tested by CCK8 assay. HeLa cells were incubated in 96-well plates at

Live-Dead Cell Staining and Assessment of Apoptosis

Cytotoxicity was evaluated in the control, NIR,

Intracellular Oxygen, Glutathione, and Reactive Oxygen Species Detection

To verify intracellular

To determine the effect of nanomaterial-generated

To determine the intracellular GSH content, HeLa cells were inoculated in 6-well plates at a density of

For the ROS assay, HeLa cells were inoculated in 24 -well plates at a density of

Animal and Tumor Models

Nude BALB/c mice (6-8 weeks old, 18-20 g) were obtained from Hunan Silaike Experimental Animal Co. All animal experiments were approved by the Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Central South University (no. CSU-20230227) and were conducted in accordance with the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Use of Laboratory Animals. HeLa cells were collected and dispersed in PBS (

axillae of the mice to establish a tumor-bearing model. When the tumor volume had reached

axillae of the mice to establish a tumor-bearing model. When the tumor volume had reached

Hemolysis Assay

Blood samples were obtained from normal nude BALB/c mice and centrifuged (

In-Vivo and Ex-Vivo Fluorescence Imaging

Tumor-bearing mice were injected in the tail vein with

In-Vivo and in-vitro Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The in-vitro T1-weighted imaging properties of M-

Biodistribution Measurements

Hela tumor-bearing mice were divided into three groups (

In-Vivo Photothermal Imaging

In-Vivo Examination of Antitumor Treatment Effects

HeLa tumor (

period. After 14 days, the mice were euthanized and representative tumor tissue samples were collected, photographed, and weighed. The tumor tissues and major organs of mice from the different treatment groups were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and mouse tumor tissues were stained by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) to detect apoptosis. To detect HeLa cell hypoxia, tumor tissues from each treatment group were stained with anti-HIF-1

period. After 14 days, the mice were euthanized and representative tumor tissue samples were collected, photographed, and weighed. The tumor tissues and major organs of mice from the different treatment groups were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and mouse tumor tissues were stained by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) to detect apoptosis. To detect HeLa cell hypoxia, tumor tissues from each treatment group were stained with anti-HIF-1

Biosafety Analysis

To examine the biosafety of

Statistical Analysis

The data are expressed as means

Results and Discussion

M-HMnO2@ICG NP Preparation and Characterization

Firstly, an oxidation-reduction reaction occurs between

After

Under consistent reaction conditions, we investigated the effect of different carrier modifications on the drug loading capacity and encapsulation efficiency of ICG. We observed that, compared to the samples with

TEM observation showed that the encapsulated

Figure I (A-C) Transmission electron microscopic images of

potential of

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) detected absorption peaks for

The high-resolution XPS spectrum of S2p showed

The integrity of surface proteins after

M-HMnO2@ICG Photothermal, Photodynamic, and Chemical Kinetic Properties, and Degradation Properties Reflecting Tumor Microenvironment Responsiveness

As the ICG loaded on M-HMnO2 @ICG showed significant absorption in the

Figure 2 (A) In-vitro photothermal properties of M-HMnO

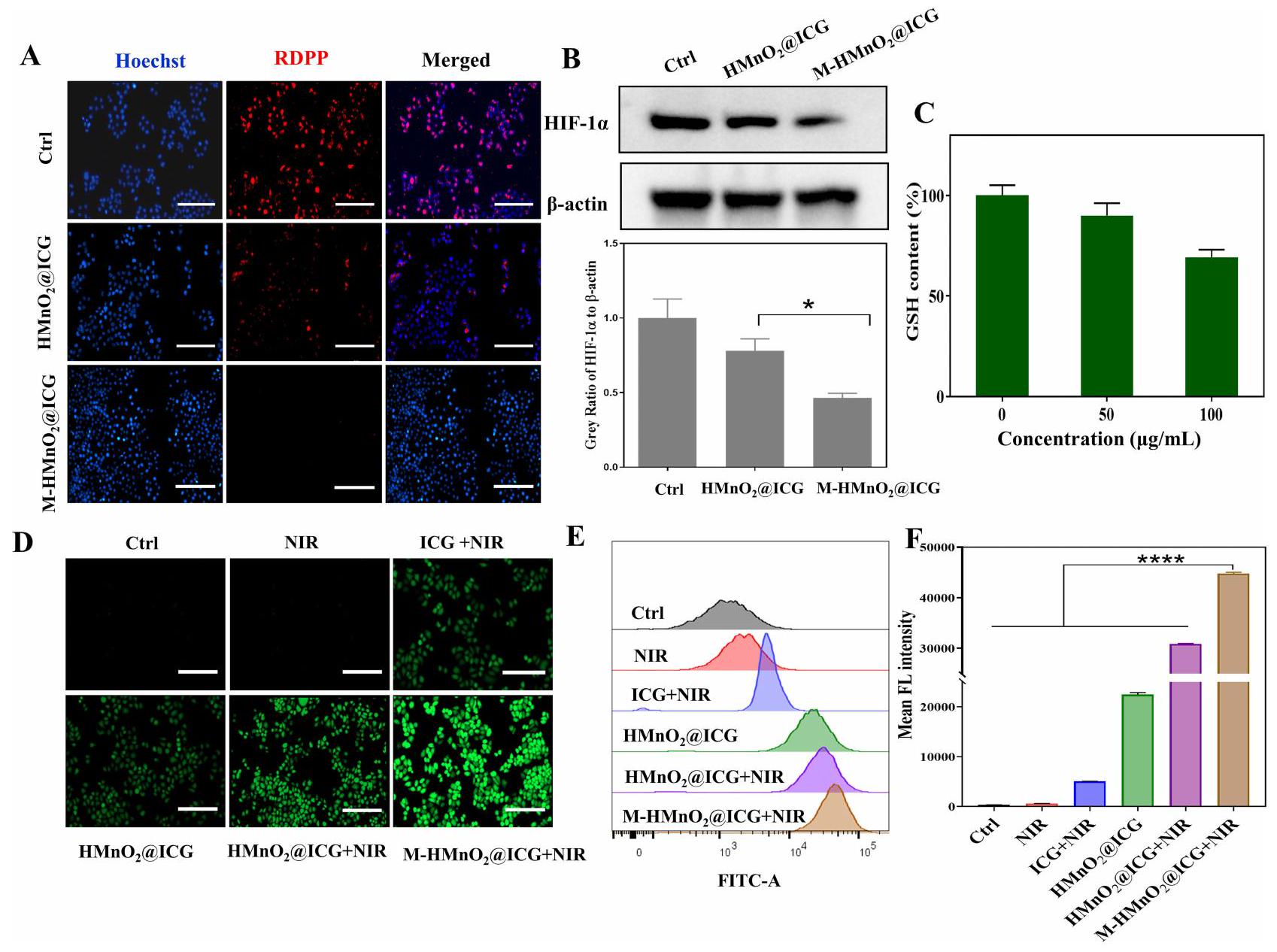

Next, We used RDPP as a probe to investigate the

In addition to increasing the photodynamic effect through catalytic

To visually assess

In-Vitro Tumor Targeting and Immune Escape Properties of

In this study, NPs were coated with tumor cell membranes with the aim of enabling them to evade macrophage-mediated nonspecific clearance, prolong the circulation time in the bloodstream, enhance interaction with tumor cells, and achieve homologous targeted delivery to tumor cells. To verify the effectiveness of this approach, we used RAW cells as phagocytes and HeLa cells as targets to study phagocytic escape and homologous uptake of M-HMnO

We used the spontaneous fluorescence of ICG to trace the NPs and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining of nuclei to localize cells. HeLa cells treated with M-HMnO2 @ICG showed significantly more red fluorescence than did those incubated with

In-Vitro Antitumor Properties

The test tube-level experiments showed that the NPs prepared in this study had synergistic PTT/PDT/CDT properties. The effect of M-HMnO2 @ICG NPs on HeLa cell viability was detected by CCK8 assay to evaluate the in-vitro antitumor activity of the NPs. In the absence of light, M-

Figure 3 (A and B) Confocal laser scanning microscopic images of HeLa and RAW264.7 cells treated with HMnO2@ICG and M-HMnO2@ICG nanoparticles for 6 h (scale bar =

Figure 4 (A) Effects of different concentrations of M-HMnO2@ICG and

group, which exhibited increased expression of IL-1

The NPs’ antitumor activity was visualized by live/dead cell staining. After NIR irradiation, M-

Cellular-Level Validation of the Antitumor Potentiation Mechanism of

At the test tube level, we demonstrated that

Figure 5 (A) Fluorescence images of RDPP staining of HeLa cells under different treatments (scale bar:

intracellular HIF-1

High GSH concentrations in tumor cells protect against oxidative stress damage, thereby reducing the tumor cell-killing effect of ROS.

We used a DCFHDA probe to detect the ROS production in HeLa cells by different NPs. The green DCFHDA fluorescence in the cells was very weak under the control and irradiation-only conditions (Figure 5D). Under laser irradiation, free ICG induced a weak fluorescent signal in HeLa cells. For

In-Vivo Tumor Targeting Properties of M-HMnO2@ICG

After clarifying the antitumor activity of

The

Figure 6 (A) In-vivo fluorescence imaging of HeLa tumor-bearing mice at different timepoints after the intravenous injection of

observed between the tumor tissues before M-

In-Vivo Antitumor Treatment and Biosafety

The antitumor effects of

Figure 7 (A) Schematic diagram of the treatment of tumor-bearing mice. Mouse body weights (B) and relative tumor volumes (C). (D) Photographs of tumors collected from the mice on day 14 after intravenous injection. (E) Tumor tissue weights. Data are expressed as mean

effect on it. The therapeutic effect was limited in the

To further validate the synergistic strategy for PDT enhancement, we examined in-vivo hypoxia levels via immunofluorescence staining of mouse tumor tissue sections for HIF-1

Serum biochemical indexes did not change in any treatment group (Figure 7I-L), indicating that the treatments had excellent biosafety. H&E staining of major organs revealed no significant morphological change or inflammatory infiltration (Figure S13), confirming the long-term biosafety of the nanomaterials. The in-vivo antitumor treatment effects were consistent with the in-vitro results.

Conclusion

In this study, we used hollow mesoporous

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (number U20A20339), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (number 82271880).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. 2021;71(3):209-249. doi:10.3322/caac. 21660

- Abu-Rustum NR, Yashar CM, Arend R, et al. NCCN Guidelines

insights: cervical cancer, version 1.2024. J National Compr Cancer Network. 2023;21(12):1224-1233. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2023.0062 - Iwata T, Machida H, Matsuo K, et al. The validity of the subsequent pregnancy index score for fertility-sparing trachelectomy in early-stage cervical cancer. Fertil Sterility. 2021;115(5):1250-1258. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.09.162

- Slama J, Runnebaum IB, Scambia G, et al. Analysis of risk factors for recurrence in cervical cancer patients after fertility-sparing treatment: the FERTIlity Sparing Surgery retrospective multicenter study. Am J Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228(4):443.e441-443.e410. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2022.11.1295

- Zeien J, Qiu W, Triay M, et al. Clinical implications of chemotherapeutic agent organ toxicity on perioperative care. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;146:112503. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112503

- Wang X, Liu S, Guan Y, Ding J, Ma C, Xie Z. Vaginal drug delivery approaches for localized management of cervical cancer. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2021;174:114-126. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2021.04.009

- Luo L, Zhou H, Wang S, et al. The application of nanoparticle-based imaging and phototherapy for female reproductive organs diseases. Small. 2023:e2207694. doi:10.1002/smll. 202207694

- He P, Yang G, Zhu D, et al. Biomolecule-mimetic nanomaterials for photothermal and photodynamic therapy of cancers: bridging nanobiotechnology and biomedicine. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):483. doi:10.1186/s12951-022-01691-4

- Li X, Lovell JF, Yoon J, Chen X. Clinical development and potential of photothermal and photodynamic therapies for cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(11):657-674. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-0410-2

- Jung HS, Verwilst P, Sharma A, Shin J, Sessler JL, Kim JS. Organic molecule-based photothermal agents: an expanding photothermal therapy universe. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47(7):2280-2297. doi:10.1039/c7cs00522a

- Seung Lee J, Kim J, Y-s Y, T-i K. Materials and device design for advanced phototherapy systems. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2022;186. doi:10.1016/j. addr.2022.114339

- Li S, Meng X, Peng B, et al. Cell membrane-based biomimetic technology for cancer phototherapy: mechanisms, recent advances and perspectives. Acta Biomater. 2024;174:26-48. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2023.11.029

- Zhong YT, Cen Y, Xu L, Li SY, Cheng H. Recent progress in carrier-free nanomedicine for tumor phototherapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12(4): e2202307. doi:10.1002/adhm. 202202307

- Liu Y, Bhattarai P, Dai Z, Chen X. Photothermal therapy and photoacoustic imaging via nanotheranostics in fighting cancer. Chem Soc Rev. 2019;48 (7):2053-2108. doi:10.1039/c8cs00618k

- Nasseri B, Turk M, Kosemehmetoglu K, et al. The pimpled gold nanosphere: a superior candidate for plasmonic photothermal therapy. Int J Nanomed. 2020;15:2903-2920. doi:10.2147/ijn.S248327

- Meng Z, Xue H, Wang T, et al. Aggregation-induced emission photosensitizer-based photodynamic therapy in cancer: from chemical to clinical. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):344. doi:10.1186/s12951-022-01553-z

- Xu X, Huang B, Zeng Z, et al. Broaden sources and reduce expenditure: tumor-specific transformable oxidative stress nanoamplifier enabling economized photodynamic therapy for reinforced oxidation therapy. Theranostics. 2020;10(23):10513-10530. doi:10.7150/thno. 49731

- Wang R, Li X, Yoon J. Organelle-targeted photosensitizers for precision photodynamic therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13 (17):19543-19571. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c02019

- Overchuk M, Weersink RA, Wilson BC, Zheng G. Photodynamic and photothermal therapies: synergy opportunities for nanomedicine. ACS Nano. 2023;17(9):7979-8003. doi:10.1021/acsnano.3c00891

- Wang Y, Luo S, Wu Y, et al. Highly penetrable and on-demand oxygen release with tumor activity composite nanosystem for photothermal/ photodynamic synergetic therapy. ACS Nano. 2020;14(12):17046-17062. doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c06415

- Kong C, Chen X. Combined photodynamic and photothermal therapy and immunotherapy for cancer treatment: a review. Int

Nanomed. 2022;17:6427-6446. doi:10.2147/ijn.S388996 - Agostinis P, Berg K, Cengel KA, et al. Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA. 2011;61(4):250-281. doi:10.3322/caac.20114

- Cao W, Zhu Y, Wu F, et al. Three birds with one stone: acceptor engineering of hemicyanine dye with NIR-II emission for synergistic photodynamic and photothermal anticancer therapy. Small. 2022;18(49):e2204851. doi:10.1002/smll. 202204851

- Wu P, Zhu Y, Chen L, Tian Y, Xiong H. A fast-responsive OFF-ON Near-infrared-II fluorescent probe for in vivo detection of hypochlorous acid in rheumatoid arthritis. Anal Chem. 2021;93(38):13014-13021. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.1c02831

- Wu P, Zhu Y, Liu S, Xiong H. Modular design of high-brightness ph-activatable near-infrared bodipy probes for noninvasive fluorescence detection of deep-seated early breast cancer bone metastasis: remarkable axial substituent effect on performance. ACS Cent Sci. 2021;7(12):2039-2048. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.1c01066

- Porcu EP, Salis A, Gavini E, Rassu G, Maestri M, Giunchedi P. Indocyanine green delivery systems for tumour detection and treatments. Biotechnol Adv. 2016;34(5):768-789. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.04.001

- Sun X, He G, Xiong C, et al. One-pot fabrication of hollow porphyrinic mof nanoparticles with ultrahigh drug loading toward controlled delivery and synergistic cancer therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(3):3679-3693. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c20617

- Jaiswal S, Roy R, Dutta SB, et al. Role of doxorubicin on the loading efficiency of ICG within silk fibroin nanoparticles. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022;8(7):3054-3065. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c01616

- Chaudhary Z, Khan GM, Abeer MM, et al. Efficient photoacoustic imaging using indocyanine green (ICG) loaded functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Biomater Sci. 2019;7(12):5002-5015. doi:10.1039/c9bm00822e

- Ma Y, Chen L, Li X, et al. Rationally integrating peptide-induced targeting and multimodal therapies in a dual-shell theranostic platform for orthotopic metastatic spinal tumors. Biomaterials. 2021:275. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120917

- Sun Y, Wang Y, Liu Y, et al. Intelligent tumor microenvironment-activated multifunctional nanoplatform coupled with turn-on and always-on fluorescence probes for imaging-guided cancer treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(45):53646-53658. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c17642

- Fang C, Yan P, Ren Z, et al. Multifunctional MoO2-ICG nanoplatform for 808 nm -mediated synergetic photodynamic/photothermal therapy. Appl. Mater. Today. 2019;15:472-481. doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2019.03.008

- Deng K, Hou Z, Deng X, Yang P, Li C, and Lin J. Enhanced antitumor efficacy by 808 nm laser-induced synergistic photothermal and photodynamic therapy based on a indocyanine-green-attached W18O49 nanostructure. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25(47):7280-7290. doi:10.1002/ adfm. 201503046

- Xue P, Yang R, Sun L, et al. Indocyanine green-conjugated magnetic prussian blue nanoparticles for synchronous photothermal/photodynamic tumor therapy. Nano-Micro Lett. 2018;10(4):74. doi:10.1007/s40820-018-0227-z

- Fukasawa T, Hashimoto M, Nagamine S, et al. Fabrication of ICG dye-containing particles by growth of polymer/salt aggregates and measurement of photoacoustic signals. Chem Lett. 2014;43(4):495-497. doi:10.1246/cl.131088

- Yu J, Javier D, Yaseen MA, et al. Self-assembly synthesis, tumor cell targeting, and photothermal capabilities of antibody-coated indocyanine green nanocapsules. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(6):1929-1938. doi:10.1021/ja908139y

- Sun Q, Wang Z, Liu B, et al. Self-generation of oxygen and simultaneously enhancing photodynamic therapy and MRI effect: an intelligent nanoplatform to conquer tumor hypoxia for enhanced phototherapy. Chem Eng J. 2020:390. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.124624

- Huang P-Y, Zhu -Y-Y, Zhong H, et al. Autophagy-inhibiting biomimetic nanodrugs enhance photothermal therapy and boost antitumor immunity. Biomater Sci. 2022;10(5):1267-1280. doi:10.1039/d1bm01888d

- Chen X, Zhao C, Liu D, et al. Intelligent Pd1.7Bi@CeO2 nanosystem with dual-enzyme-mimetic activities for cancer hypoxia relief and synergistic photothermal/photodynamic/chemodynamic therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(18):21804-21818. doi:10.1021/acsami.3c00056

- Cheng Y, Wen C, Sun YQ, Yu H, Yin XB. Mixed-Metal MOF-derived hollow porous nanocomposite for trimodality imaging guided reactive oxygen species-augmented synergistic therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2021;31(37):2. doi:10.1002/adfm.202104378.

- Yu J, Yaseen MA, Anvari B, Wong MS. Synthesis of near-infrared-absorbing nanoparticle-assembled capsules. Chem Mater. 2007;19 (6):1277-1284. doi:10.1021/cm062080x

- Zeng W, Zhang H, Deng Y, et al. Dual-response oxygen-generating MnO2 nanoparticles with polydopamine modification for combined photothermal-photodynamic therapy. Chem Eng J. 2020:389. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.124494

- Liu X, Li R, Zhou Y, et al. An all-in-one nanoplatform with near-infrared light promoted on-demand oxygen release and deep intratumoral penetration for synergistic photothermal/photodynamic therapy. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;608:1543-1552. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2021.10.082

- Gao J, Qin H, Wang F, et al. Hyperthermia-triggered biomimetic bubble nanomachines. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):4867. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-40474-9

- Xi Y, Xie X, Peng Y, Liu P, Ding J, Zhou W. DNAzyme-adsorbed polydopamine@MnO2 core-shell nanocomposites for enhanced photothermal therapy via the self-activated suppression of heat shock protein 70. Nanoscale. 2021;13(9):5125-5135. doi:10.1039/d0nr08845e

- Sun W, Xu Y, Yao Y, et al. Self-oxygenation mesoporous MnO2 nanoparticles with ultra-high drug loading capacity for targeted arteriosclerosis therapy. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):88. doi:10.1186/s12951-022-01296-x

- Gostynski R, Conradie J, Erasmus E. Significance of the electron-density of molecular fragments on the properties of manganese(iii)

-diketonato complexes: an XPS and DFT study. RSC Adv. 2017;7(44):27718-27728. doi:10.1039/c7ra04921h - Quan B, S-H Y, Chung DY, et al. Single source precursor-based solvothermal synthesis of heteroatom-doped graphene and its energy storage and conversion applications. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5639. doi:10.1038/srep05639

- Liu J, Li RS, Zhang L, et al. Enzyme-activatable polypeptide for plasma membrane disruption and antitumor immunity elicitation. Small. 2023;19 (24):e2206912. doi:10.1002/smll. 202206912

- Xu B, Zeng F, Deng J, et al. A homologous and molecular dual-targeted biomimetic nanocarrier for EGFR-related non-small cell lung cancer therapy. Bioact Mater. 2023;27:337-347. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.04.005

- Fan Y, Cui Y, Hao W, et al. Carrier-free highly drug-loaded biomimetic nanosuspensions encapsulated by cancer cell membrane based on homology and active targeting for the treatment of glioma. Bioact Mater. 2021;6(12):4402-4414. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.04.027

- Du X, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Cancer cell membrane camouflaged biomimetic nanosheets for enhanced chemo-photothermal-starvation therapy and tumor microenvironment remodeling. Appl Mater Today. 2022;29. doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2022.101677

- Guan S, Liu X, Li C, et al. Intracellular mutual amplification of oxidative stress and inhibition multidrug resistance for enhanced sonodynamic/ chemodynamic/chemo therapy. Small. 2022;18(13):e2107160. doi:10.1002/smll. 202107160

International Journal of Nanomedicine

Publish your work in this journal

The International Journal of Nanomedicine is an international, peer-reviewed journal focusing on the application of nanotechnology in diagnostics, therapeutics, and drug delivery systems throughout the biomedical field. This journal is indexed on PubMed Central, MedLine, CAS, SciSearch

Submit your manuscript here: https://www.dovepress.com/international-journal-of-nanomedicine-journal