DOI: https://doi.org/10.70176/3007-973x.1020

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-05

المجلد 2 | العدد 1

الماصّ الحيوي المركّب من الكيتوسان المطعَّم بالبنزالدهيد/بكتيريا Lactobacillus casei لإزالة صبغة الأحمر الحمضي 88: تحسين تصميم Box–Behnken ونهج دراسة الآلية

مواد ماصة حيوية مركبة من الكيتوزان-بنزالدهيد/بكتيريا لاكتوباسيلس كاسي لإزالة صبغة الأحمر الحمضي 88: تحسين تصميم بوكس-بينكن ونهج الآلية

الملخص

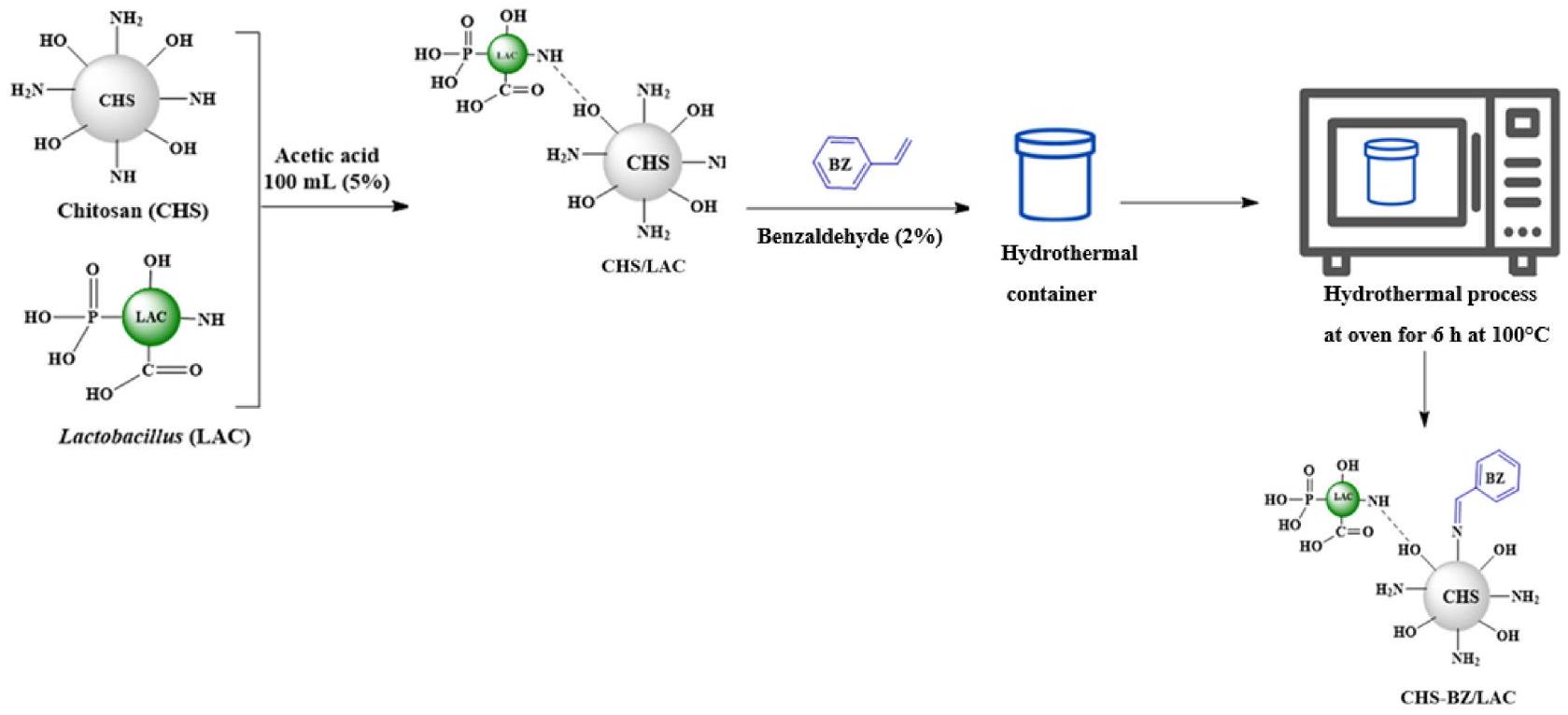

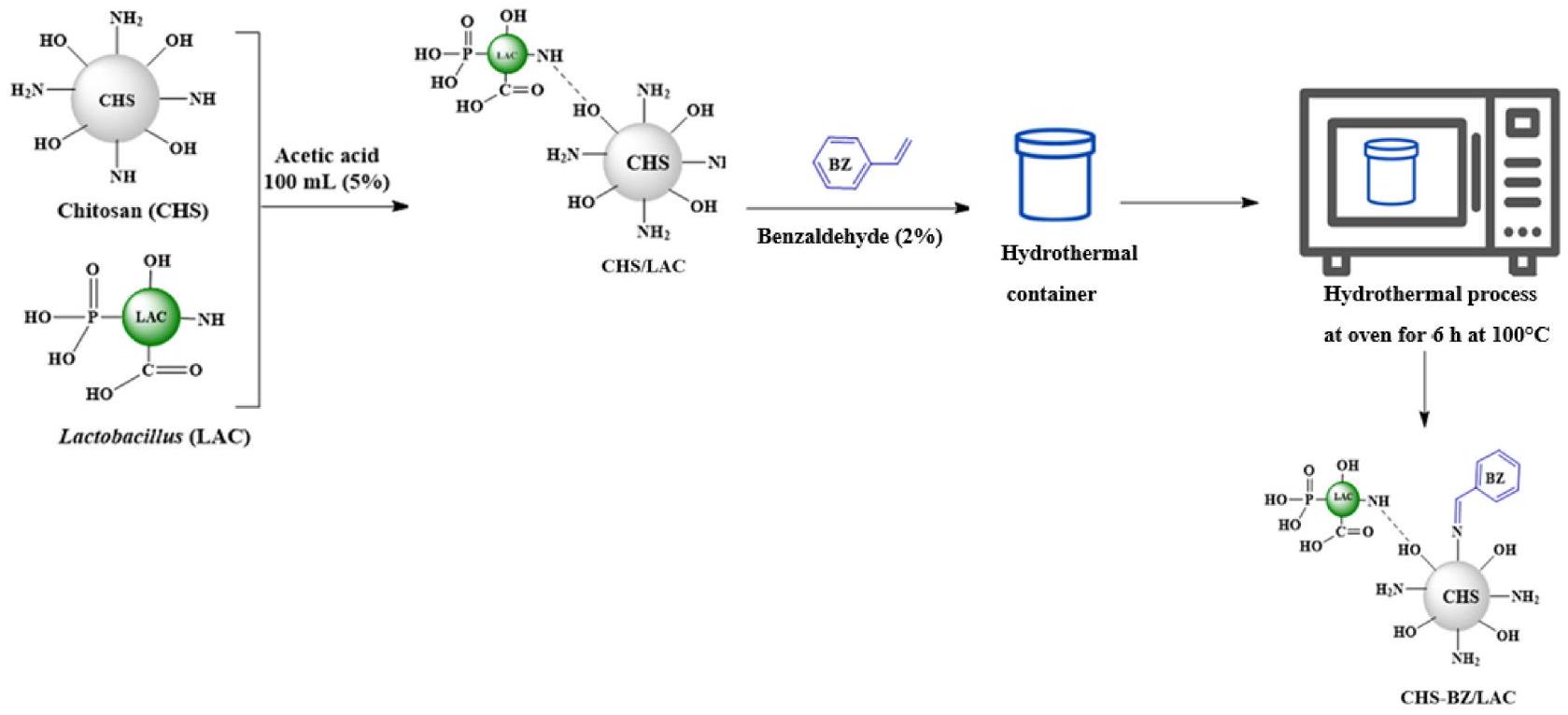

هنا، تم إنتاج مادة ماصة حيوية هجينة من زراعة الكيتوزان بنزالدهيد/لاكتوباسيلس كاسي (CHSBZ/LAC) لإزالة صبغة الأحمر الحمضي 88 (AR88). تم تصنيع CHS-BZ/LAC باستخدام عملية هيدروحرارية تحت ظروف

1. المقدمة

المعالجة، أصباغ عضوية (مثل الأحمر الحمضي 88؛ AR88) [1]. تؤدي غسيل المنتجات المنسوجة المطبوعة إلى كميات كبيرة من مياه الصرف تحتوي على أصباغ متنوعة، مما يؤدي إلى توليد نفايات

مسحوق casei (LAC)، وهو مادة حيوية محتملة تتميز بعدة مجموعات وظيفية. تؤدي هذه التركيبة إلى إنشاء مادة مركبة حيوية. تم تحسين الخصائص الفيزيائية والكيميائية لـ CHS/LAC بشكل أكبر من خلال تكوين نظام قاعدة شيف مع عامل التعديل بنزالدهيد (BZ) من خلال عملية هيدروحرارية. يسعى التجربة إلى تعزيز قدرة مادة CHS-BZ/LAC الحيوية على امتصاص صبغة AR88 من المحاليل المائية، مع تحسين توافقها البيئي في الوقت نفسه. تم استخدام تصميم Box-Behnken الإحصائي (BBD) لتحسين المتغيرات الرئيسية لعملية الامتصاص، بما في ذلك مدة الاتصال، وجرعة CHS-BZ/LAC، ودرجة الحموضة. يسهل تصميم Box-Behnken تحسين العديد من المعلمات في إزالة صبغة AR88 من مياه الصرف الصحي عبر CHS-BZ/LAC. تم توصيف الخصائص الفيزيائية والكيميائية لمادة CHS-BZ/LAC الحيوية بواسطة حيود الأشعة السينية (XRD)، وطيف تحويل فورييه للأشعة تحت الحمراء (FTIR)، والمجهر الإلكتروني الماسح (SEM) وتحليل الأشعة السينية المشتتة للطاقة (EDX). علاوة على ذلك، تبحث الدراسة في آلية الامتصاص الحيوي لصبغة AR88 على سطح مادة CHS-BZ/LAC الحيوية.

2. المواد والأساليب

2.1. المواد

2.2. زراعة وتجفيف Lactobacillus casei

عند

2.3. إجراء تخليق CHS-BZ/LAC

2.4. إجراء توصيف CHS-BZ/LAC

| رموز | المتغيرات | المستوى 1 (-1) | المستوى 2 (0) | المستوى 3 (+1) |

|

|

CHS-BZ/LAC | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.1 |

|

|

||||

|

|

درجة الحموضة | ٤ | ٧ | 10 |

|

|

الوقت (دقيقة) | 10 | ٢٥ | 40 |

2.5. تصميم التجربة

| ركض | أ: الجرعة (غ) | ب: الرقم الهيدروجيني | ج: الوقت (دقيقة) | نسبة إزالة AR88 (%) |

| 1 | 0.02 | ٤ | ٢٥ | 61.0 |

| ٢ | 0.1 | ٤ | ٢٥ | 94.5 |

| ٣ | 0.02 | 10 | 25 | ٢٣.٦ |

| ٤ | 0.1 | 10 | ٢٥ | ٣٥.٥ |

| ٥ | 0.02 | ٧ | 10 | ٤٦.٨ |

| ٦ | 0.1 | ٧ | 10 | ٥٥.٤ |

| ٧ | 0.02 | ٧ | 40 | ٥٥.٠ |

| ٨ | 0.1 | ٧ | 40 | 81.8 |

| ٩ | 0.06 | ٤ | 10 | 79.8 |

| 10 | 0.06 | 10 | 10 | 21.4 |

| 11 | 0.06 | ٤ | 40 | 86.3 |

| 12 | 0.06 | 10 | 40 | 53.7 |

| ١٣ | 0.06 | ٧ | 25 | ٥٢.١ |

| 14 | 0.06 | ٧ | ٢٥ | 54.7 |

| 15 | 0.06 | ٧ | 25 | 53.7 |

| 16 | 0.06 | ٧ | ٢٥ | ٥٦.٠ |

| 17 | 0.06 | ٧ | ٢٥ | ٤٩.٤ |

3. النتائج والمناقشة

3.1. توصيف CHS-BZ/LAC

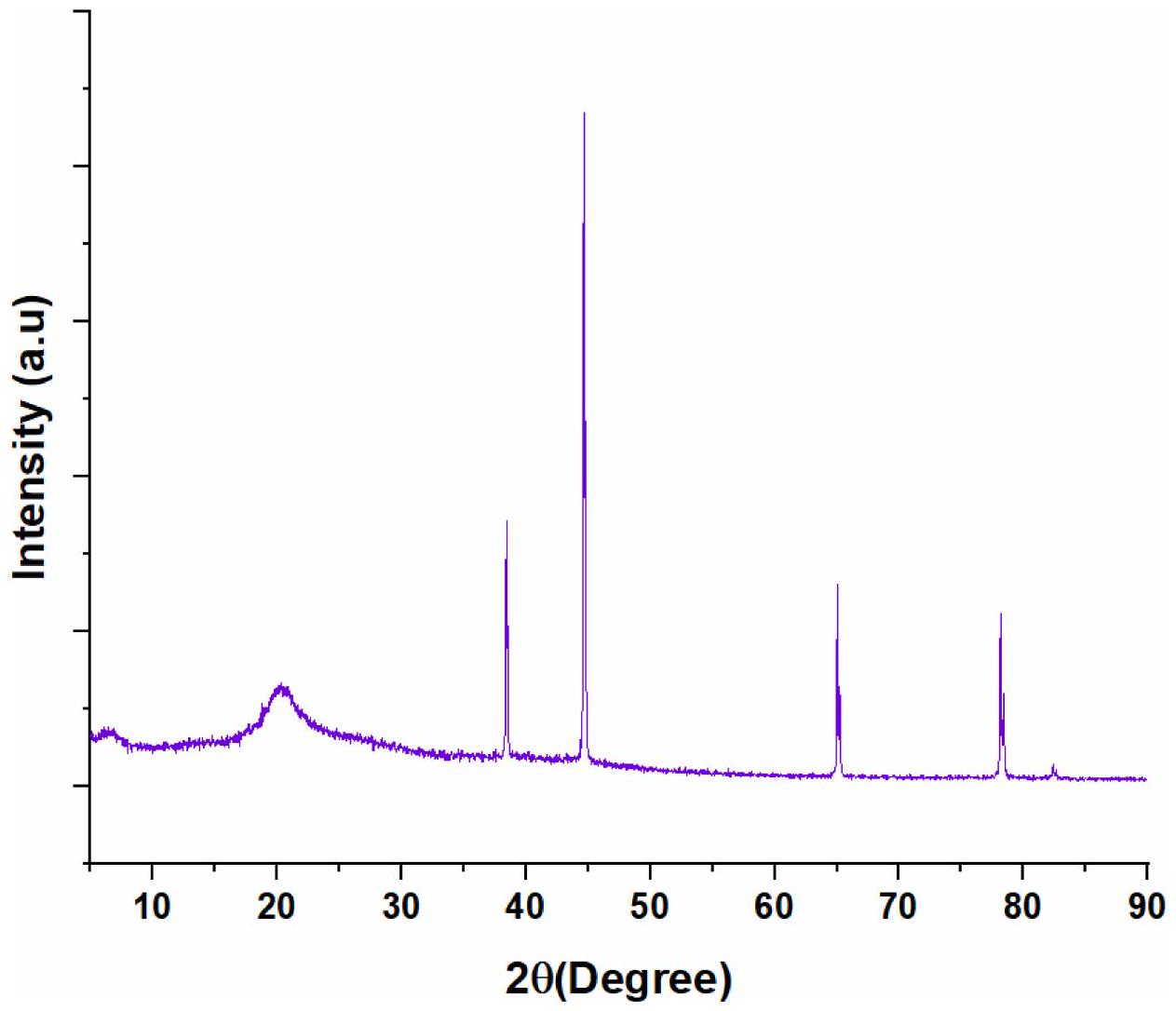

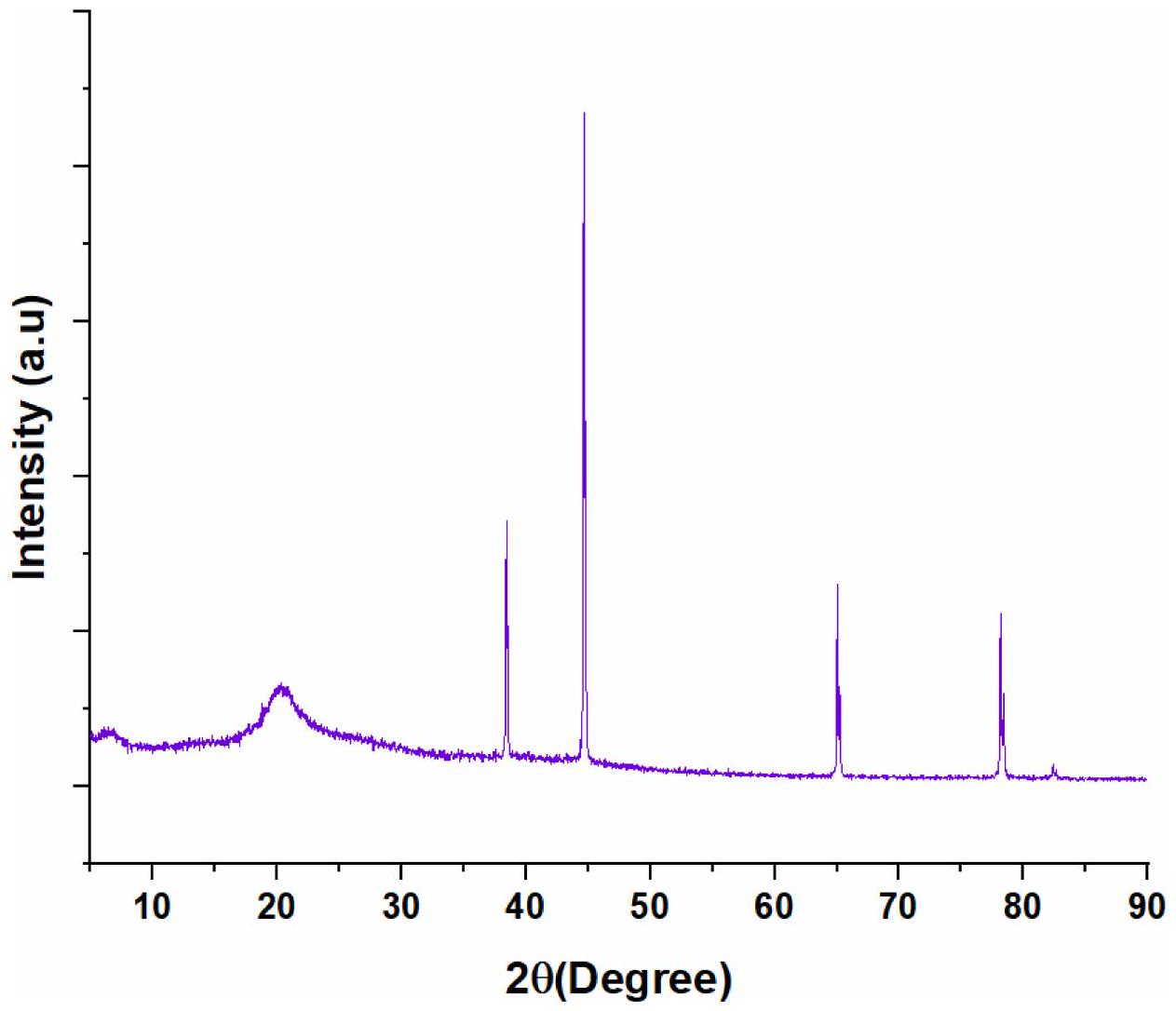

قد يؤدي تدخل LAC في التخليق إلى إدخال مراحل معدنية، مثل مركبات الكالسيوم، مما يساهم في القمم الانكسارية الملحوظة، مما يتماشى مع الدراسات حول التمعدن الحيوي في المركبات الميكروبية.

| مصدر | مجموع المربعات | df | المتوسط التربيعي | قيمة F | قيمة p | ملاحظة |

| نموذج | 6432.84 | 9 | 714.76 | ١١٢.٨٤ | <0.0001 | مهم |

| جرعة | 816.08 | 1 | 816.08 | 128.84 | <0.0001 | مهم |

| ب-درجة الحموضة | ٤٣٨٩.٨٤ | 1 | ٤٣٨٩.٨٤ | 693.06 | <0.0001 | مهم |

| وقت-سي | ٦٧٣.٤٥ | 1 | ٦٧٣.٤٥ | ١٠٦.٣٢ | <0.0001 | مهم |

| أب | ١١٦.٦٤ | 1 | ١١٦.٦٤ | 18.41 | 0.0036 | مهم |

| مكيف الهواء | 82.81 | 1 | 82.81 | 13.07 | 0.0086 | مهم |

| قبل الميلاد | ١٦٦.٤١ | 1 | ١٦٦.٤١ | ٢٦.٢٧ | 0.0014 | مهم |

| أ

|

0.0067 | 1 | 0.0067 | 0.0011 | 0.9749 | غير مهم |

|

|

1.10 | 1 | 1.10 | 0.1729 | 0.6900 | غير مهم |

|

|

183.97 | 1 | 183.97 | ٢٩.٠٤ | 0.0010 | مهم |

| متبقي | 44.34 | ٧ | 6.33 | |||

| نقص التوافق | ١٨.٣٥ | ٣ | 6.12 | 0.9415 | 0.4997 | غير مهم |

| خطأ نقي | 25.99 | ٤ | ٦.٥٠ | |||

| كور توتال | ٦٤٧٧.١٨ | 16 | ||||

|

|

0.9932 | معدل

|

0.9844 | متوقع

|

0.9484 |

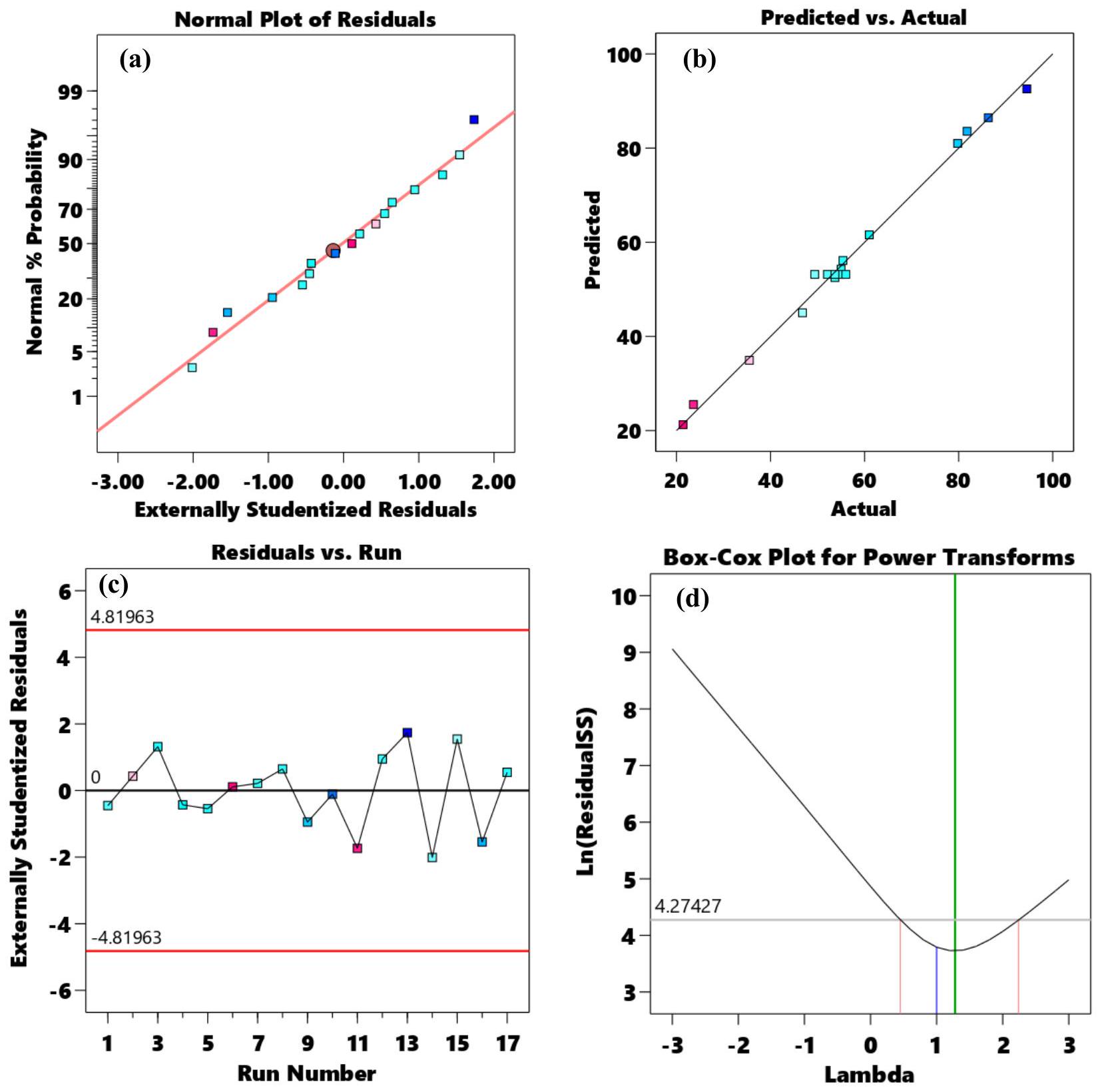

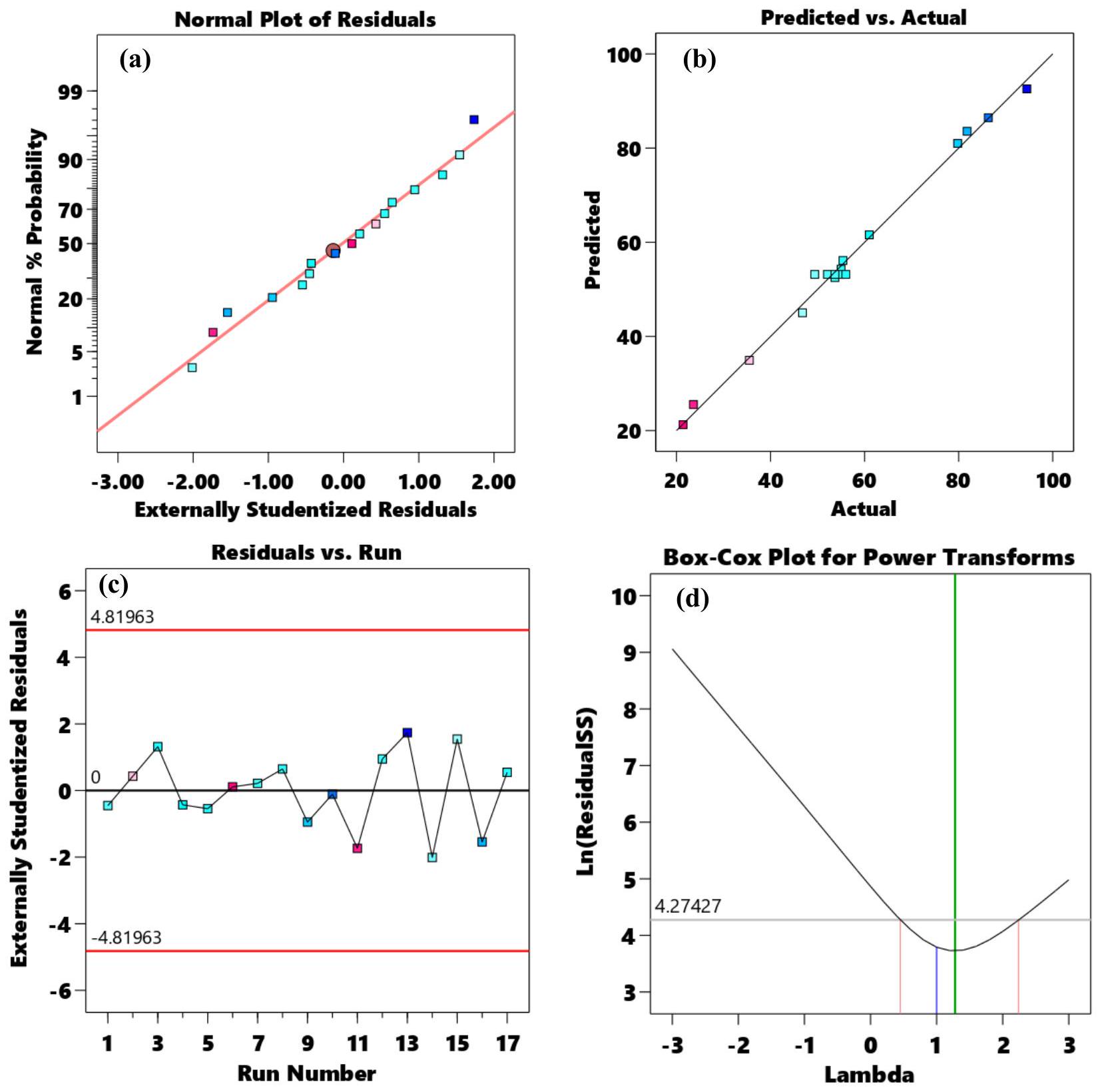

3.2. التحسين الإحصائي

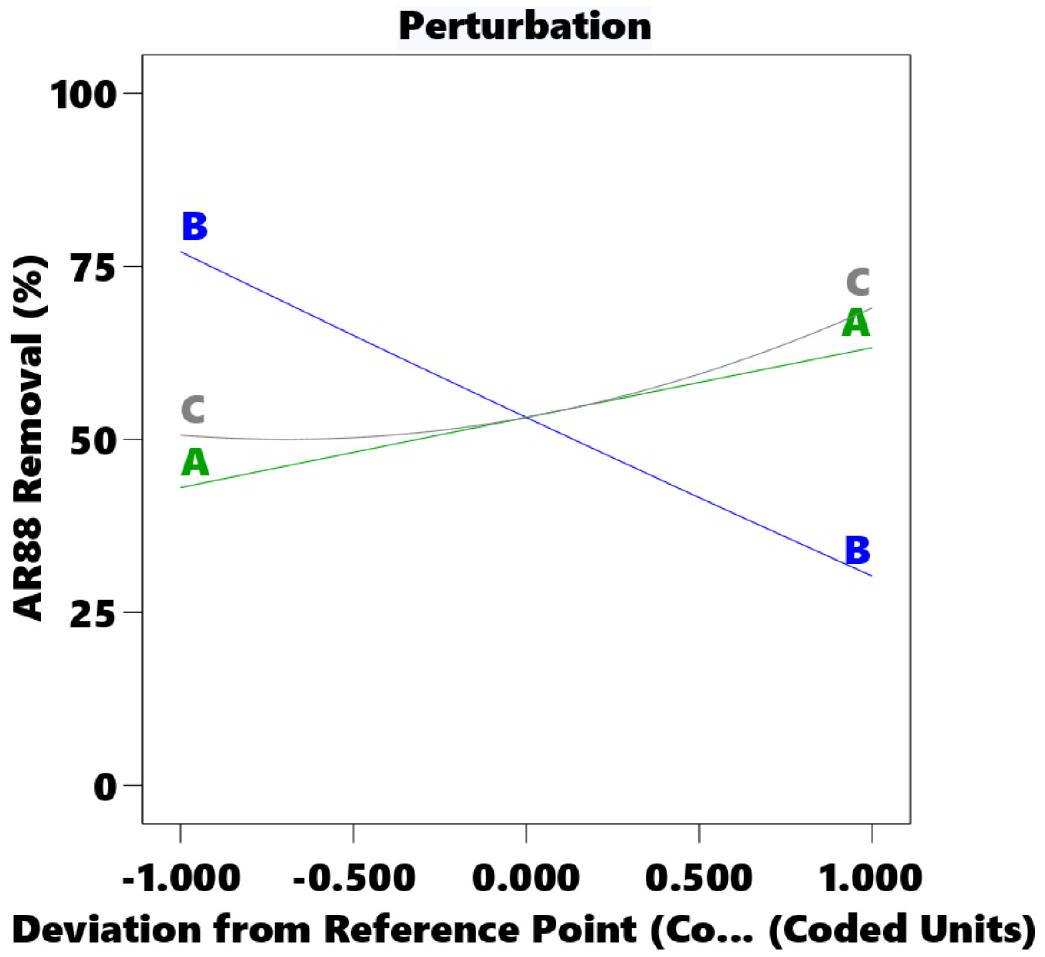

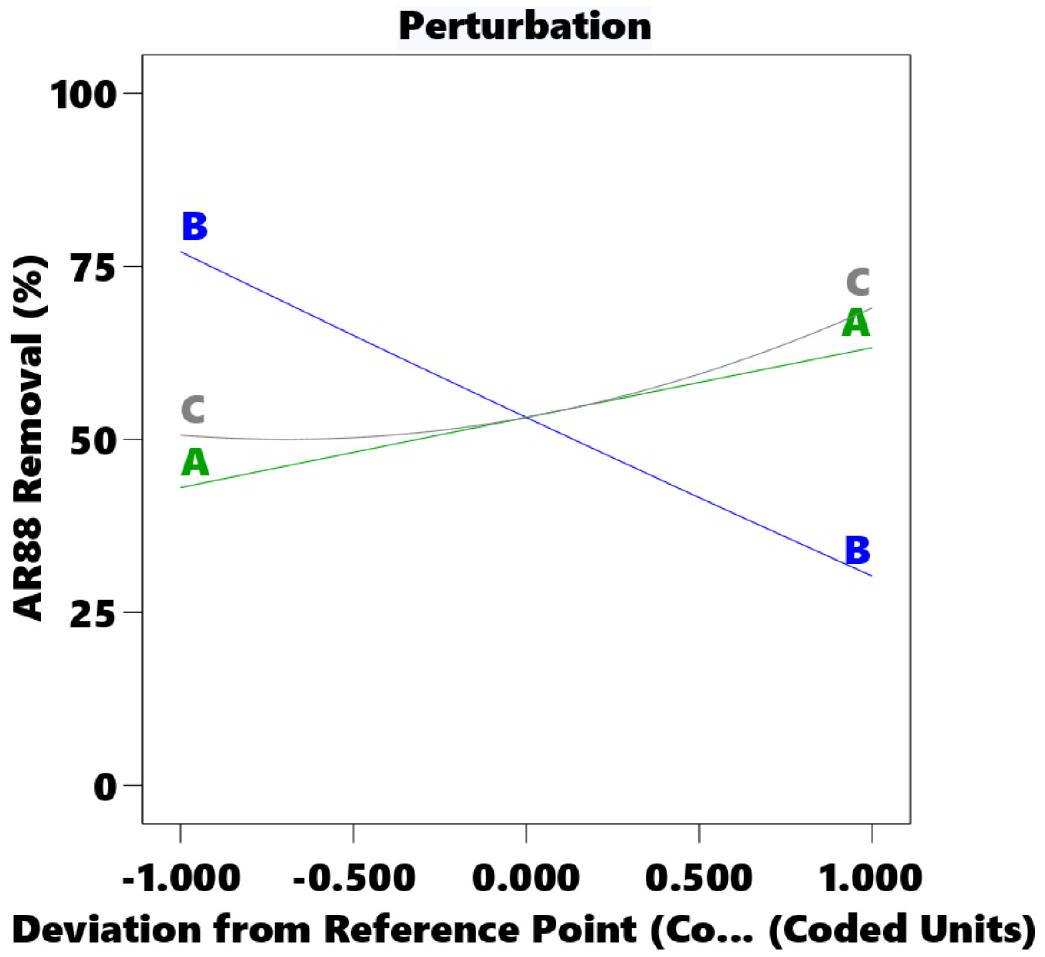

3.3. اضطراب إزالة صبغة AR88

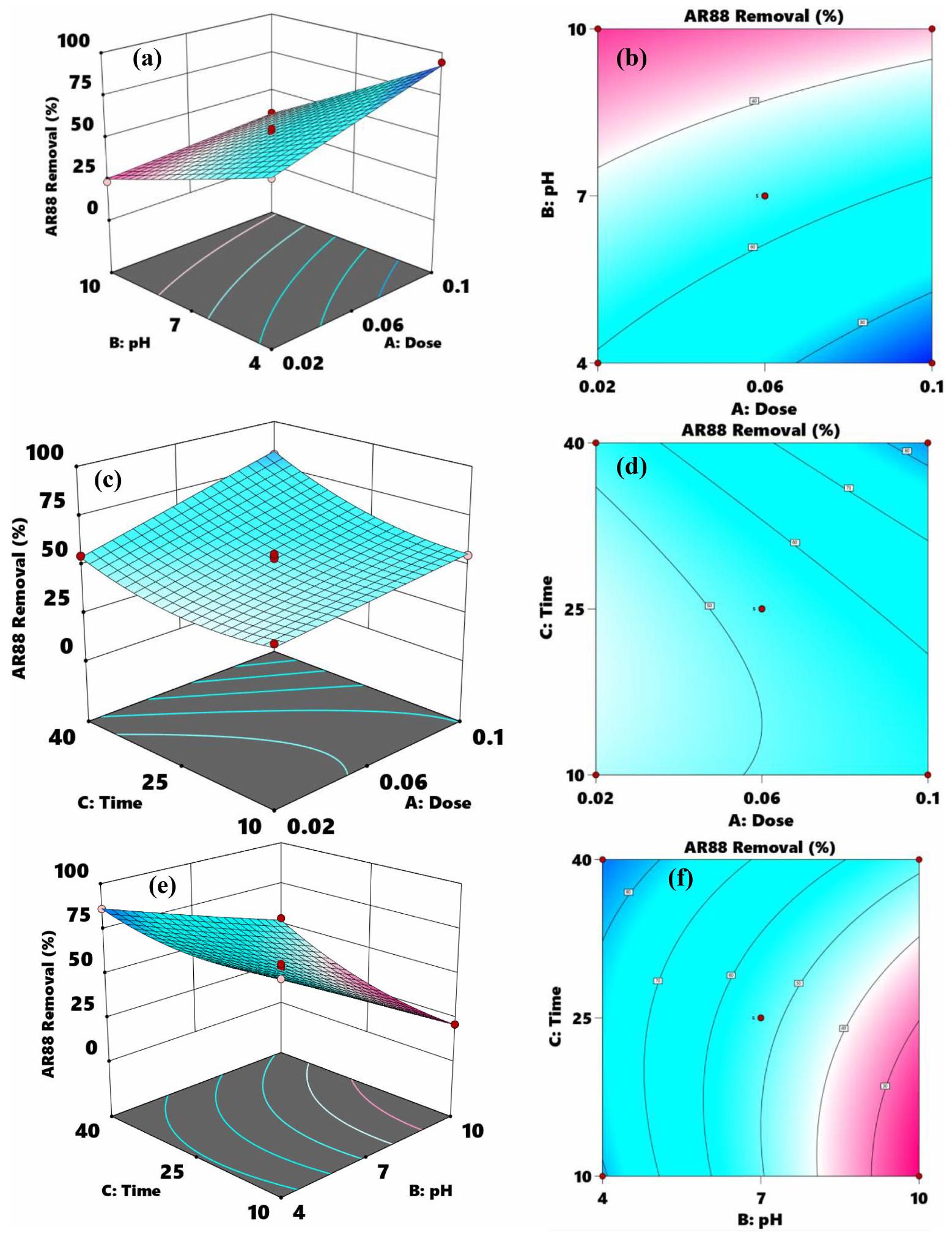

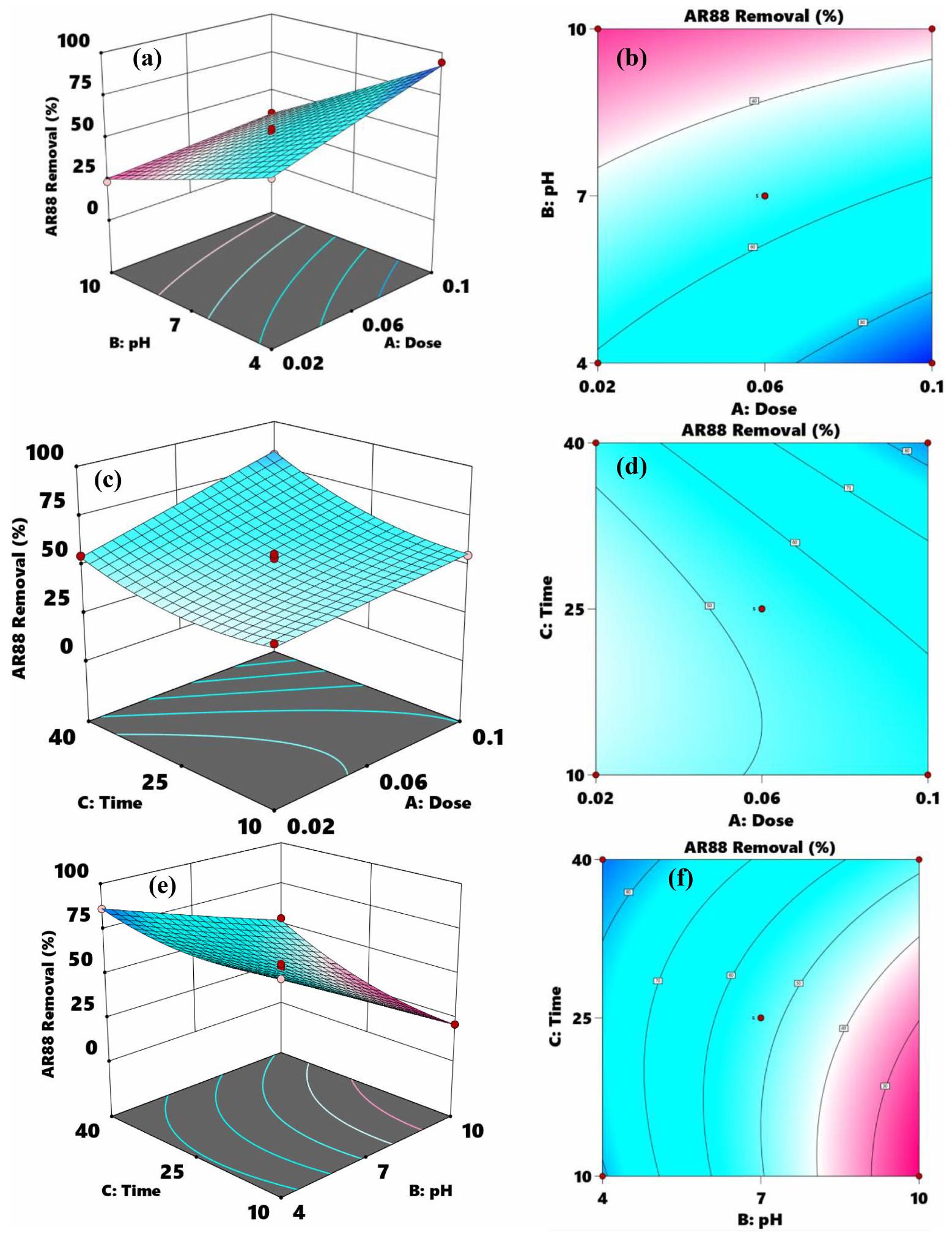

3.4. التأثير المزدوج ثلاثي الأبعاد وثنائي الأبعاد للمعلمات في إزالة AR88

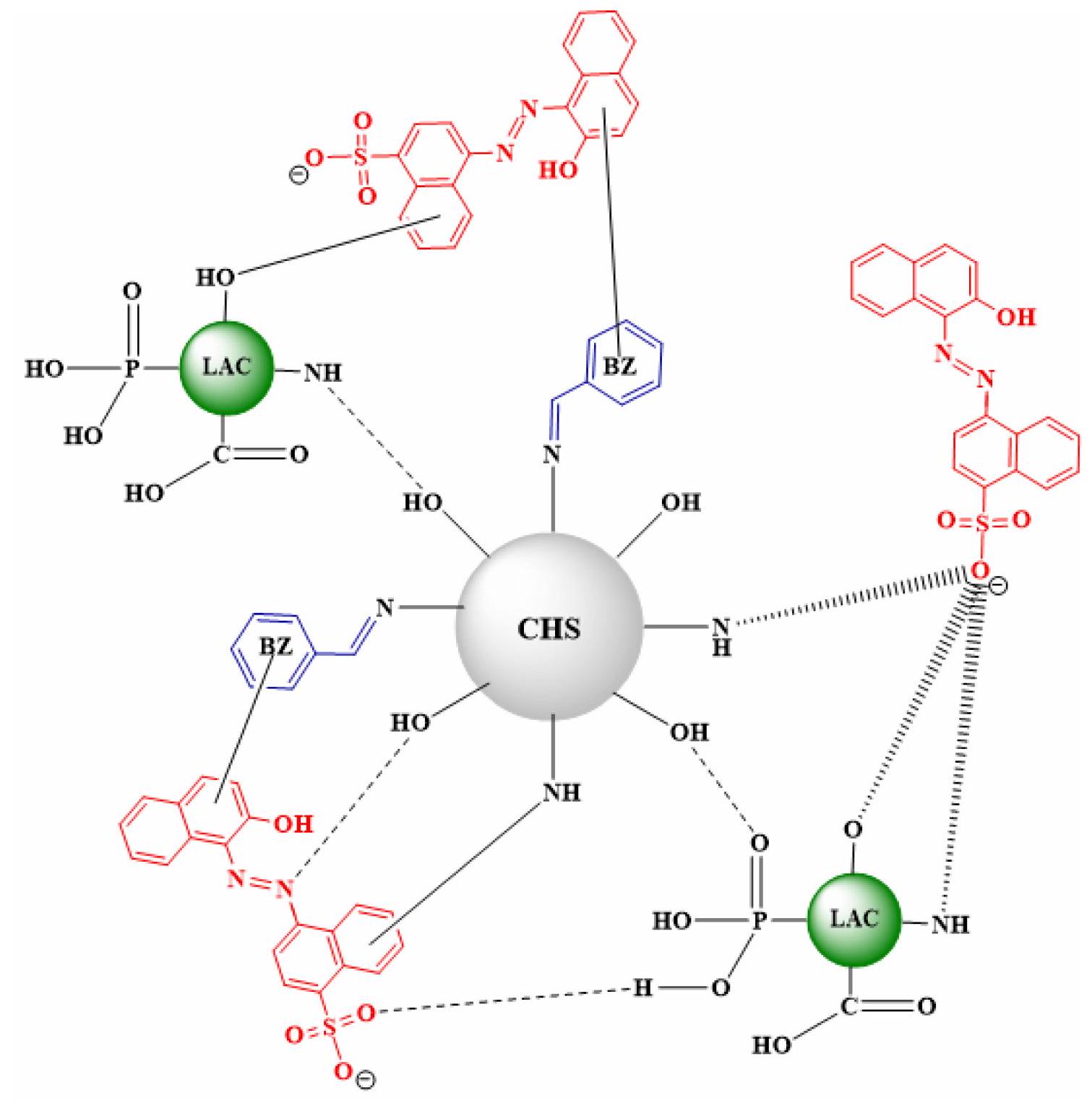

3.5. آلية الامتزاز الحيوي

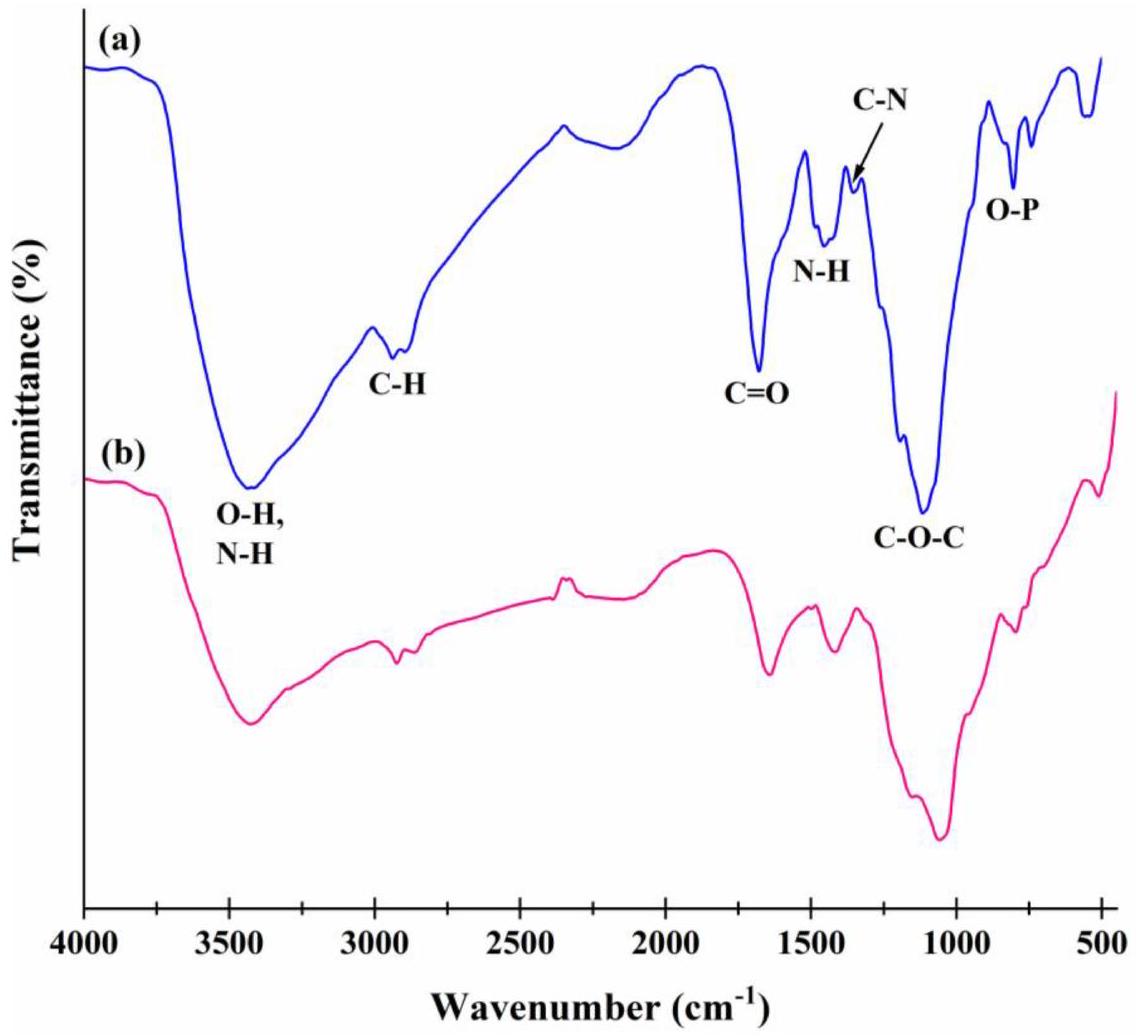

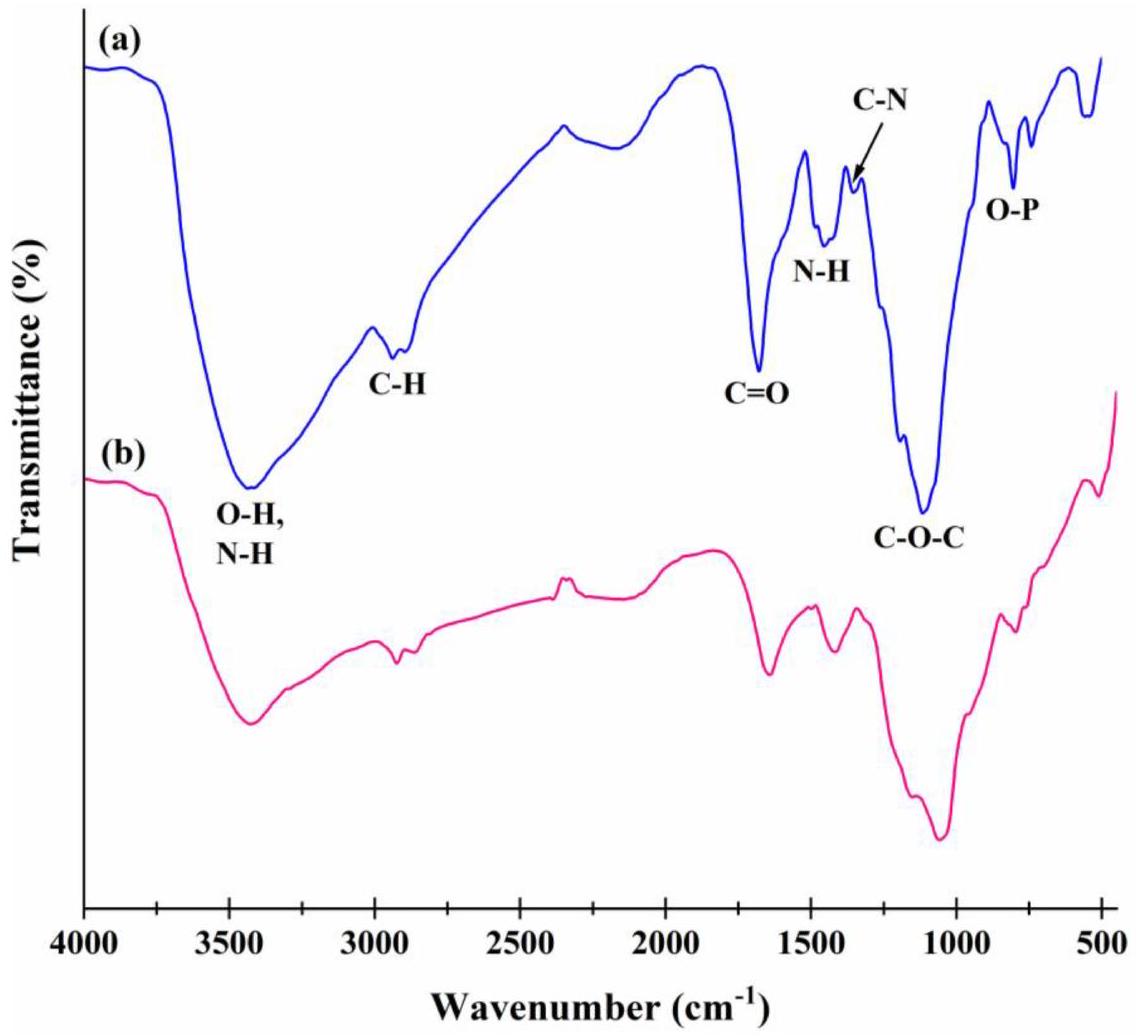

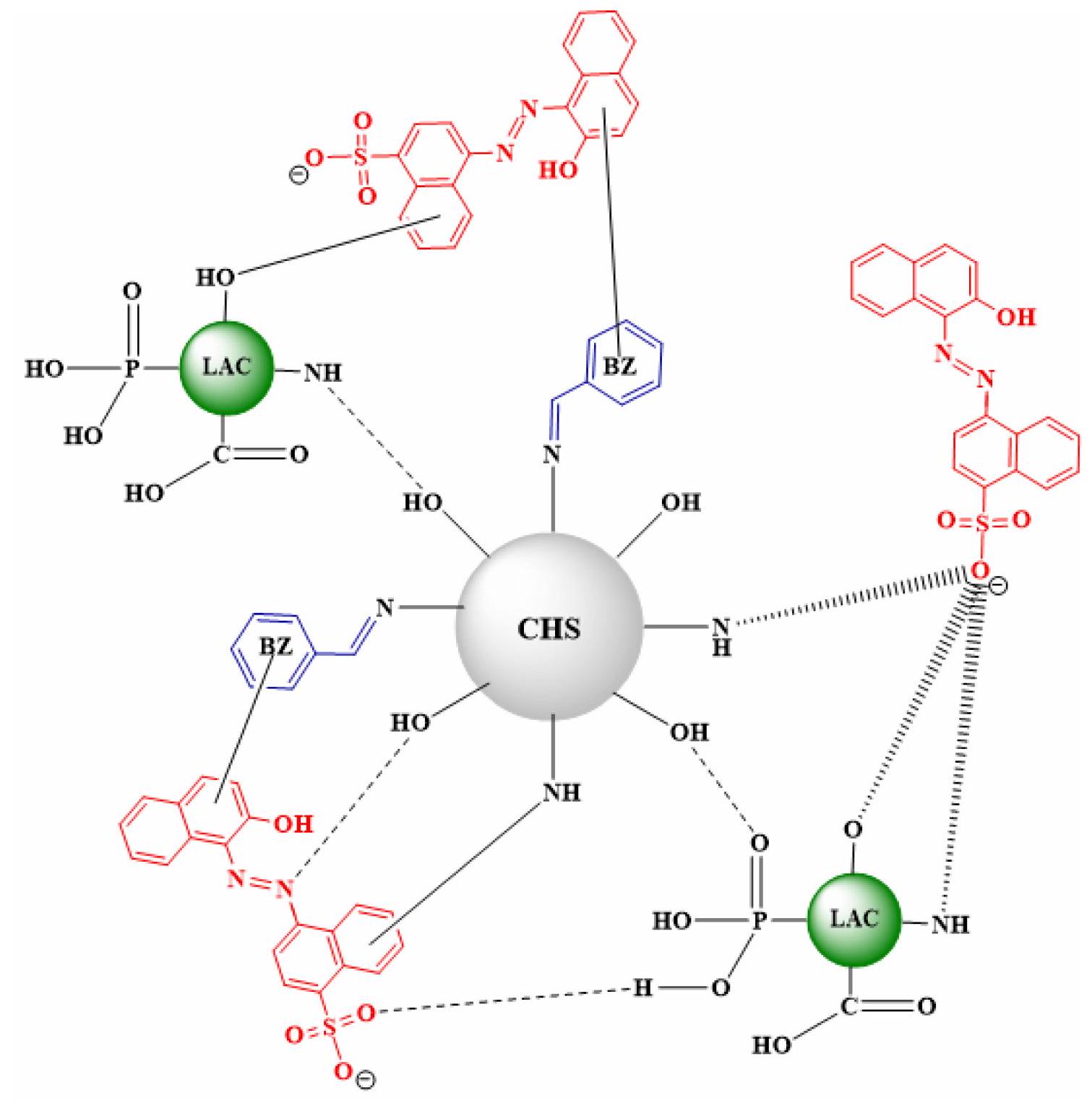

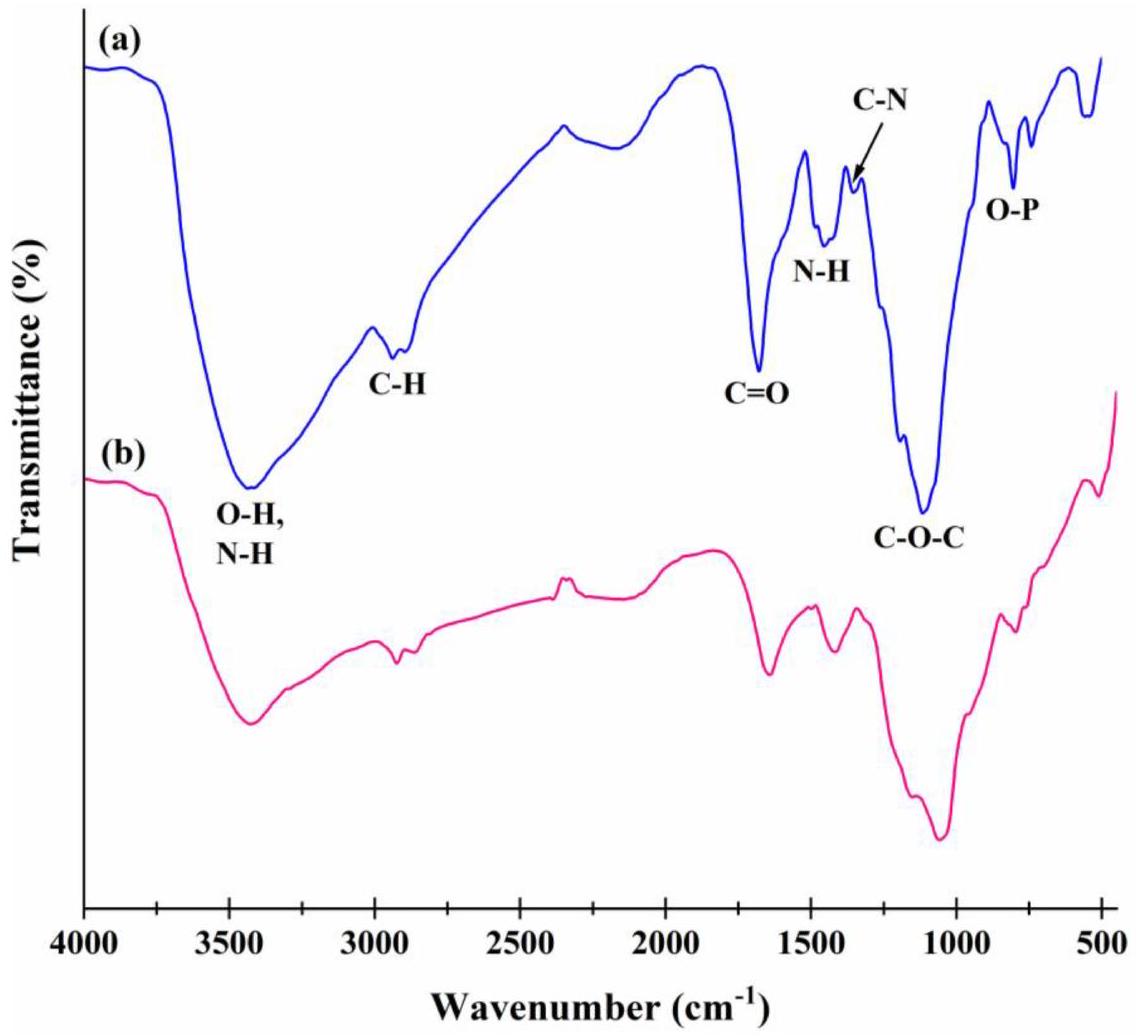

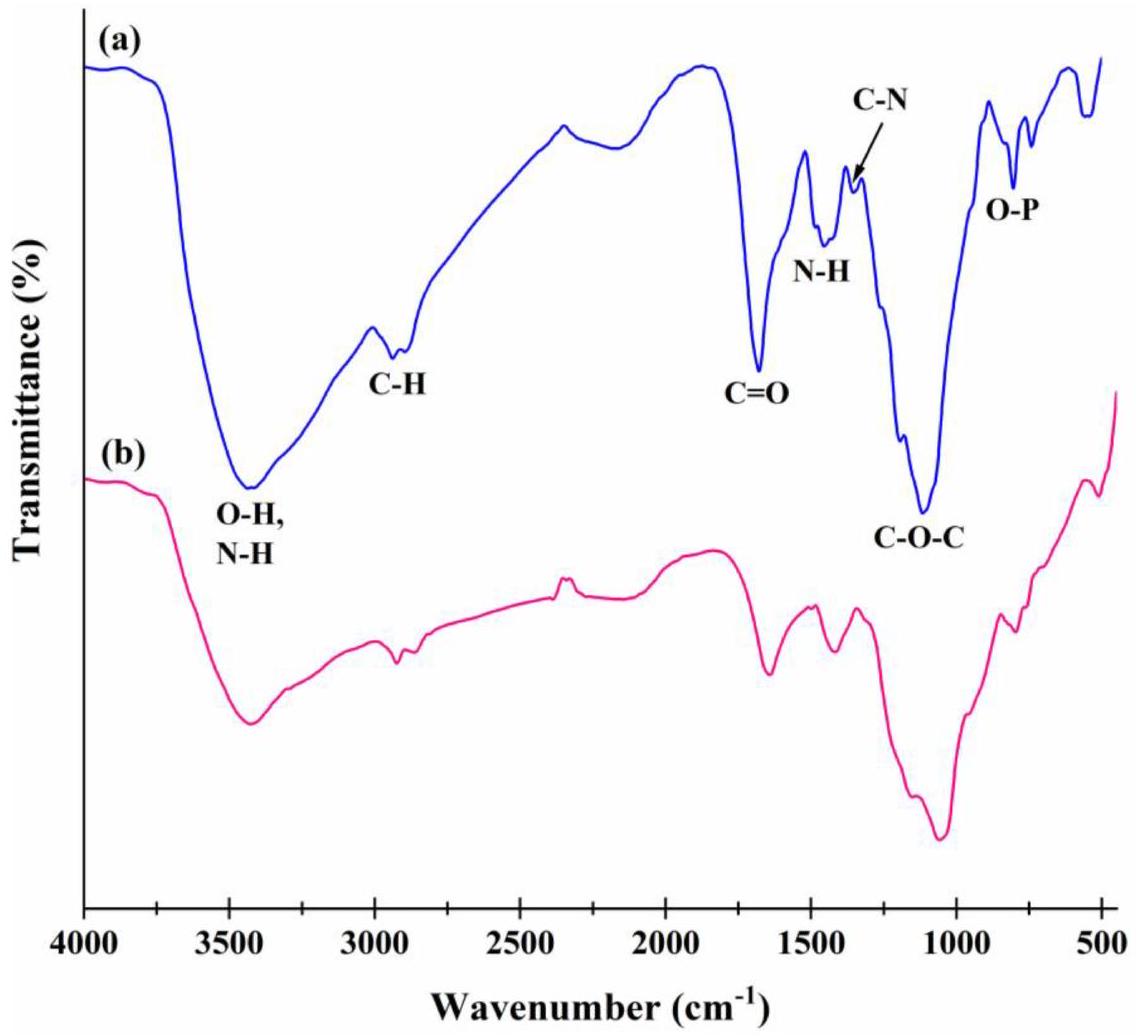

تدعم نتائج دراسة توصيف CHS-BZ/LAC مثل FTIR تعزيز الآلية المحتملة للامتزاز التي تؤثر على امتزاز صبغة AR88 بواسطة CHS-BZ/LAC. يتم تقديم التفاعل المحتمل لـ AR88 مع CHS-BZ/LAC في الشكل 8. تظهر نتائج FTIR أن الممتز الحيوي CHS-BZ/LAC يحتوي على مجموعات وظيفية متنوعة تؤثر على عملية ارتباط AR88. تتكون المجموعة الوظيفية من الكربوكسيل (-COOH) والأمين (

التفاعل و

) من صبغة AR88 أنتجت الجذب الكهروستاتيكي. تلعب تفاعلات الهيدروجين دورًا حاسمًا في آلية الامتزاز لصبغة AR88. تحدث التفاعلات بين ذرات الهيدروجين على الهيكل السطحي لـ CHS-BZ/LAC وذرات الأكسجين والنيتروجين في هيكل صبغة AR88 [61، 62].

التي تشمل

4. الاستنتاج

بيان أخلاقي

بيان تضارب المصالح

بيان توفر البيانات

التمويل

مساهمات المؤلفين

References

- Jorge N, Teixeira AR, Gomes A, Lucas MS, Peres JA. Removal of azo dye acid red 88 by Fenton-based processes optimized by response surface methodology box-Behnken design. The 4th International Electronic Conference on Applied Sciences. 2023;56:164. Basel Switzerland: MDPI. doi: 10. 3390/ASEC2023-15501.

- Berradi M, Hsissou R, Khudhair M, Assouag M, Cherkaoui O , El harfi A . Textile finishing dyes and their impact on aquatic environs. Heliyon 2019;5:e02711. doi: 10.1016/j. heliyon.2019.e02711.

- Yaseen DA, Scholz M. Textile dye wastewater characteristics and constituents of synthetic effluents: A critical review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;16:1193-1226. doi: 10.1007/ s13762-018-2130-z.

- Tejashwini DM, Harini HV, Nagaswarupa HP, Naik R, Chidananda B. A comparative study of green and chemical approaches for photocatalytic activity of novel hybrid bismuth magnesium ferrites (

) nanoparticles for Acid Red-88 dye degradation. Results Chem. 2024;7:101267. doi: 10.1016/j.rechem.2023.101267. - Dong G, Chen B, Liu B, Hounjet LJ, Cao Y, Stoyanov SR, Yang M, Zhang B. Advanced oxidation processes in microreactors for water and wastewater treatment: Development, challenges, and opportunities. Water Res. 2022;211:118047. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118047.

- Swanckaert B, Geltmeyer J, Rabaey K, De Buysser K, Bonin L, De Clerck K. A review on ion-exchange nanofiber membranes: Properties, structure and application in electrochemical (waste) water treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022;287:120529. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120529.

- Hu P, Ren J, Hu X, Yang H. Comparison of two starchbased flocculants with polyacrylamide for the simultaneous removal of phosphorus and turbidity from simulated and actual wastewater samples in combination with

. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;167:223-232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac. 2020.11.176. - Santoso SP, Angkawijaya AE, Bundjaja V, Hsieh CW, Go AW, Yuliana M, Hsu HY, Tran-Nguyen PL, Soetaredjo FE, Ismadji S.

/guar gum hydrogel composite for adsorption and photodegradation of methylene blue. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;193:721-733. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.10.044. - Li Z, Xie W, Zhang Z, Wei S, Chen J, Li Z. Multifunctional sodium alginate/chitosan-modified graphene oxide reinforced membrane for simultaneous removal of nanoplastics, emulsified oil, and dyes in water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;245:125524.

- Mushahary N, Sarkar A, Das B, Rokhum SL, Basumatary S. A facile and green synthesis of corn cob-based graphene oxide and its modification with corn cob-

for efficient removal of methylene blue dye: Adsorption mechanism, isotherm, and kinetic studies. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2024;101(11):01409. - Agha HM, Abdulhameed AS, Jawad AH, ALOthman ZA, Wilson LD, Algburi S. Fabrication of glutaraldehyde crosslinked chitosan/algae biomaterial via hydrothermal process: Statistical optimization and adsorption mechanism for MV 2B dye removal. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2025;15:1105-1119. doi: 10. 1007/s13399-023-05143-3.

- Brazesh B, Mousavi SM, Zarei M, Ghaedi M, Bahrani S, Hashemi SA. Biosorption. In M. N. V. Prasad & A. Vithanage (Eds.), Handbook of Metal-Microbe Interactions and Bioremediation 2021;33:587-628. Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-818805-7.00003-5.

- Ravindran B, Karmegam N, Yuvaraj A, Thangaraj R, Chang SW, Zhang Z, Awasthi MK. Cleaner production of agriculturally valuable benignant materials from industry generated bio-wastes: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021;320:124281. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.124281

- Nawaz S, Tabassum A, Muslim S, Nasreen T, Baradoke A, Kim TH, Boczkaj G, Jesionowski T, Bilal M. Effective assessment of biopolymer-based multifunctional sorbents for the remediation of environmentally hazardous contaminants from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere, 2023;329:138552.

- Pham VHT, Kim J, Chang S, Chung W. Bacterial biosorbents, an efficient heavy metals green clean-up strategy: Prospects, challenges, and opportunities. Microorganisms 2022;10(3):610.

- Radzun KA, Agha HM, Abdullah NFF, Ahmad MI, Ivanovski I, Mohammed AA, Alkamil A A. Media optimization techniques for microalgae through technological advancements: A mini review AUIQ. Complem. Biol. Syst. 2024;1(1):60-69.

- Taketa TB, Mahl CR, Calais GB, Beppu MM. Amino acidfunctionalized chitosan beads for in vitro copper ions uptake in the presence of histidine. Int. J. Boil. Macromol. 2021;188:421-431.

- Bekheit MM, Nawar N, Addison AW, Abdel-Latif DA, and Monier M. Preparation and characterization of chitosan-grafted-poly(2-amino-4,5-pentamethylene-thiophene-3 carboxylic acid N’-acryloyl-hydrazide) chelating resin for removal of Cu (II), Co (II) and Ni (II) metal ions from aqueous solutions. Int. J. Boil. Macromol. 2011;48(4):558-565.

- Sahib SAA, Awad SH. Synthesis, Characterization of chitosan para- hydroxyl benzaldehyde schiff base linked maleic anhydride and the evaluation of its antimicrobial activities. Baghdad Sci. J. 2022;19(6):1265.

- Khan A, Alamry KA. Recent advances of emerging green chitosan-based biomaterials with potential biomedical applications: A review. Carbohydr. Res. 2021;506:108368.

- Jawad AH, Hameed BH, Abdulhameed AS. Synthesis of biohybrid magnetic chitosan-polyvinyl alcohol/ MgO nanocomposite blend for remazol brilliant blue R dye adsorption: Solo and collective parametric optimization. Polym. Bull. 2023;80(5):4927-4947.

- Agha HM, Jawad AH, ALOthman Z A, Wilson LD. Design of chitosan and watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) seed shell composite adsorbent for reactive orange 16 dye removal: Multivariable optimization and dye adsorption mechanism study. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024. doi: 10.1007/s13399-024-06362y.

- Tahira I, Aslam Z, Abbas A, Monim-ul-Mehboob M, Ali S, Asghar A. Adsorptive removal of acidic dye onto grafted chitosan: A plausible grafting and adsorption mechanism. Int. J. Boil. Macromol. 2019;136:1209-1218.

- Hermosillo-Ochoa E, Picos-Corrales LA, Licea-Claverie A. Ecofriendly flocculants from chitosan grafted with PNVCL and PAAc: Hybrid materials with enhanced removal properties for water remediation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021;258:118052.

- Huang C, Liao H, Ma X, Xiao M, Liu X, Gong S, Zhou X. Adsorption performance of chitosan Schiff base towards anionic dyes: Electrostatic interaction effects. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021;780:138958.

- Arni LA, Hapiz A, Abdulhameed AS, Khadiran T, ALOthman ZA, Wilson LD, Jawad AH. Design of separable magnetic chitosan grafted-benzaldehyde for azo dye removal via a response surface methodology: Characterization and adsorption mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;242:125086. doi: 10.1016/j.jjbiomac.2023.125086.

- Sun Y, Kang Y, Zhong W, Liu Y, Dai Y. A simple phosphorylation modification of hydrothermally cross-linked chitosan for selective and efficient removal of U (VI). J. Solid State Chem. 2020;292:121731.

- Sayilgan E, Cakmakci O. Treatment of textile dyeing wastewater by biomass of Lactobacillus: Lactobacillus 12 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2012;20(3):1556-1564. doi: 10.1007/s11356-012-1009-7.

- Seesuriyachan P, Kuntiya A, Sasaki K, Techapun C. Comparative study on methyl orange removal by growing cells and washed cell suspensions of Lactobacillus casei TISTR 1500. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;25:973-979.

- Capozzi V, Tufariello M, De Simone N, Fragasso M, Grieco F. Biodiversity of oenological lactic acid bacteria: Species- and strain-dependent plus/minus effects on wine quality and safety. Fermentation 2021;7:24. doi: 10.3390/ fermentation7010024.

- Mora-Villalobos JA, Montero-Zamora J, Barboza N, RojasGarbanzo C, Usaga J, Redondo-Solano M, Schroedter L, Olszewska-Widdrat A, López-Gómez JP. Multi-product lactic acid bacteria fermentations: A review. Fermentation 2020;6:23. doi: 10.3390/fermentation6010023.

- Aazmi S, Teh LK, Ramasamy K, Rahman T, Salleh MZ. Comparison of the anti-obesity and hypocholesterolaemic effects of single Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota and probiotic cocktail. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015;50(7):1589-1597.

- Şuteu D, Zaharia C, Blaga AC, Peptu AC. Biosorbents based on residual biomass of Lactobacillus sp. bacteria consortium immobilized in sodium alginate for Orange 16 dye retention from aqueous solutions. Desalination Water Treat. 2022;246:315324. doi: 10.5004/dwt.2022.28018.

- Begum S, Yuhana NY, Saleh NM, Kamarudin NN, Sulong AB. Review of chitosan composite as a heavy metal adsorbent: Material preparation and properties. Carbohydr. Poly. 2021;259:117613.

- Mehrotra T, Dev S, Banerjee A, Chatterjee A, Singh R, Aggarwal S. Use of immobilized bacteria for environmental bioremediation: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021;9(5):105920.

- Agha HM, Jawad AH, Wilson LD, ALOthman ZA. Preparation and characterisation of chitosan/bacterial Escherichia coli biocomposite for malachite green dye removal: Modeling and optimisation of the adsorption process. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2024;1-23. doi: 10.1080/03067319.2024.2426730.

- Tertsegha S, Akubor PI, Iordekighir AA, Christopher K, Okike OO. Extraction and characterization of chitosan from snail shells (Achatina fulica). J. Food Qual. Hazards Control. 2024;11(3):186-196.

- Jayakumar R, Prabaharan M, Nair SV, Tamura H. Novel chitin and chitosan nanofibers in biomedical applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010;28(1):142-150.

- Okunzuwa GI, Enaroseha OO, Okunzuwa SI. Synthesis and characterization of Fe (III) chitosan nanoparticles n-benzaldehyde Schiff base for biomedical application. Chem. Pap. 2024;78(5):3253-3260. doi: 10.1007/s11696-024-03309-5.

- Singh S, Singh G, Kang TS. Biomineralization and its application in bioinspired green composites: Emerging research and opportunities. In handbook of research on green engineering techniques for modern manufacturing. IGI Global. 2020;1-25.

- Wang W, Hu J, Zhang R, Yan C, Cui L, Zhu J. A pHresponsive carboxymethyl cellulose/chitosan hydrogel for adsorption and desorption of anionic and cationic dyes. Cellulose 2021;28:897-909. doi: 10.1007/s10570-020-03561-4.

- Abdulqader MA, Suliman MA, Ahmed TA, Wu R, Bobaker A, Tiyasha T, Al-Areeq N. Conversion of chicken rice waste into char via hydrothermal, pyrolysis, and microwave carbonization processes: A comparative study. AUIQ Complem. Biol. Syst. 2024;1(1):1-9.

- Kekes T, Tzia C. Adsorption of indigo carmine on functional chitosan and

-cyclodextrin/chitosan beads: Equilibrium, kinetics and mechanism studies. J. Environ. Manage. 2024;262:110372. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110372. - Pérez-Calderón J, Santos MV, Zaritzky N. Synthesis, characterization and application of cross-linked chitosan/oxalic acid hydrogels to improve azo dye (Reactive Red 195) adsorption. React. Funct. Polym. 2020;155:104699. doi: 10.1016/j. reactfunctpolym.2020.104699.

- Fatoni A, Hariani PL, Hermansyah H, Lesbani A. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan linked by methylene bridge and schiff base of 4, 4-diaminodiphenyl ether-vanillin. Indones. J. Chem. 2018;18(1):92-101. doi: 10.22146/ijc. 25866.

- El-Sakhawy M, Kamel S, Salama A, Tohamy HAS. Preparation and infrared study of cellulose based amphiphilic materials. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2018;52(3-4):193-200.

- Zhao W, Liu S, Yin M, He Z, Bi D. Co-pyrolysis of cellulose with urea and chitosan to produce nitrogen-containing compounds and nitrogen-doped biochar: Product distribution characteristics and reaction path analysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2023;169:105795. doi: 10.1016/j.jaap.2022.105795.

- Amrutha SR, Suja NR, Menon S. Morphological analysis of Biomass. In Thomas, S., Hosur, M., Pasquini, D., Jose Chirayil, C. (Eds.). Handbook of Biomass. Springer, Singapore. 2023. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-6772-6_15-1.

- Kutluay S, Temel T. Silica gel based new adsorbent having enhanced VOC dynamic adsorption/desorption performance. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022;609:125848.

- Es-Haghi A, Taghavizadeh Yazdi ME, Sharifalhoseini M, Baghani M, Yousefi E, Rahdar A, Baino F. Application of response surface methodology for optimizing the therapeutic activity of ZnO nanoparticles biosynthesized from Aspergillus niger. Biomimetics 2021;6(2):34. doi: 10.3390/ biomimetics6020034.

- Onu CE, Nwabanne JT, Ohale PE, Asadu CO. Comparative analysis of RSM, ANN and ANFIS and the mechanistic modeling in eriochrome black-T dye adsorption using modified clay. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2021;36:24-42. doi: 10.1016/j. sajce.2020.12.003.

- Gonbadi M, Sabbaghi S, Rasouli J, Rasouli K, Saboori R, Narimani M. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles for spent caustic recovery: Adsorbent characterization and process optimization using I-optimal method. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023;158:111460. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2023.111460.

- Nayak AK, Pal A. Statistical modeling and performance evaluation of biosorptive removal of Nile blue A by lignocellulosic

agricultural waste under the application of high-strength dye concentrations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020;8(2):103677. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.103677. - Foroutan R, Peighambardoust SJ, Mohammadi R, Peighambardoust SH, Ramavandi B. Development of new magnetic adsorbent of walnut shell ash/starch/

for effective copper ions removal: Treatment of groundwater samples. Chemosphere 2022;296:133978. - Al-dhawi BNS, Kutty SRM, Alawag AM, Almahbashi NMY, Al-Towayti FAH, Algamili A, Jagaba AH. Optimal parameters for boron recovery in a batch adsorption study: Synthesis, characterization, regeneration, kinetics, and isotherm studies. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2023;8:100508. doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2023.100508.

- Abdulhameed AS, Mohammad A-T, Jawad AH. Modeling and mechanism of reactive orange 16 dye adsorption by chitosanglyoxal/

nanocomposite: Application of response surface methodology. Desalination Water Treat. 2019;164:346-360. - Aragaw TA, Alene AN. A comparative study of acidic, basic, and reactive dyes adsorption from aqueous solution onto kaolin adsorbent: Effect of operating parameters, isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamics. Emerg. Contam. 2022;8:59-74. doi: 10.1016/j.emcon.2022.01.002.

- Agha HM, Allaq A, Jawad AH, Aazmi S, ALOthman ZA, Wilson LD. Immobilization of Bacillus subtilis bacteria into biohybrid crosslinked chitosan-glutaraldehyde for acid red 88 dye removal: Box-Behnken design optimization and mechanism study. J Inorg Organomet Polym. 2024. doi: 10.1007/s10904-024-03264-4.

- Al-Hazmi GA, Alayyafi AA, El-Desouky MG, El-Bindary AA. Chitosan-nano CuO composite for removal of mercury (II): Box-Behnken design optimization and adsorption mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;261:129769.

- Mary Ealias A, Saravanakumar MP. A critical review on ultrasonic-assisted dye adsorption: Mass transfer, half-life and half-capacity concentration approach with future industrial perspectives. Crit. Rev. Env. Sci. Tec. 2019;49(21):1959-2015. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2019.1601488.

- Reghioua A, Barkat D, Jawad AH, Abdulhameed AS, Rangabhashiyam S, Khan MR, ALOthman ZA. Magnetic chitosanglutaraldehyde/zinc oxide/

nanocomposite: Optimization and adsorptive mechanism of Remazol Brilliant Blue R dye removal. J. Polym. Environ. 2021;29:3932-3947. doi: 10.1007/s10924-021-02133-8. - Blachnio M, Zienkiewicz-Strzalka M, Derylo-Marczewska A. Synthesis of composite sorbents with chitosan and varied silica phases for the adsorption of Anionic Dyes. Molecules 2024;29(9):2087. doi: 10.3390/molecules29092087.

- Singh SK, Das A. The

interaction: A rapidly emerging non-covalent interaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17(15):9596-9612. doi: 10.1039/C4CP05665A.

- Recommended Citation

Aghaa, Hasan M.; Musa, Salis A.; Hapiz, Ahmad; Wu, Ruihong; Al-Essa, Khansaa; Saleh, Ali Mohammed; and Reghioua, Abdallah (2025), Biocomposite Adsorbent of Grafted Chitosan-benzaldehyde/Lactobacillus Casei Bacteria for Removal of Acid Red 88 Dye: Box-Benken Design Optimization and Mechanism Approach, AUIQ Complementary Biological System: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, 1-14.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.70176/3007-973X. 1020

Available at: https://acbs.alayen.edu.iq/journal/vol2/iss1/1 - Received 10 January 2025; revised 13 January 2025; accepted 19 January 2025.

Available online 5 March 2025- Corresponding authors.

E-mail addresses: hasanagha586@gmail.com (H. M. Agha), ahmad.hapiz01@gmail.com (A. Hapiz).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.70176/3007-973x.1020

Publication Date: 2025-03-05

Volume 2 | Issue 1

Biocomposite Adsorbent of Grafted Chitosan-benzaldehyde/Lactobacillus Casei Bacteria for Removal of Acid Red 88 Dye: Box-Benken Design Optimization and Mechanism Approach

Biocomposite Adsorbent of Grafted Chitosan-benzaldehyde/Lactobacillus Casei Bacteria for Removal of Acid Red 88 Dye: Box-Benken Design Optimization and Mechanism Approach

Abstract

Herein, biohybrid biosorbent material was produced from grafting chitosan benzaldehyde/Lactobacillus casei (CHSBZ/LAC) for the removal of anionic dye acid red 88 (AR88). CHS-BZ/LAC was fabricated using a hydrothermal process under the condition of

1. Introduction

treatment, utilized organic dyes (e.g. Acid Red 88; AR88) [1]. The washing of printed textile products results in significant volumes of wastewater containing various dyes, leading to waste generation

casei (LAC) powder, a potential biosorbent characterized by several functional groups. This amalgamation results in the creation of a biocomposite substance. The physicochemical property of CHS/LAC was further improved by the formation of Schiff base system with grafting agent benzaldehyde (BZ) through a hydrothermal process. The experiment seeks to enhance the capacity of a CHS-BZ/LAC biosorbent to adsorb AR88 dye from aqueous solutions, while simultaneously improving its environmental compatibility. The statistical Box-Behnken design (BBD) were employed to optimize key adsorption variables, including contact duration, CHS-BZ/LAC dose, and pH . The Box-Behnken design facilitates the simultaneous optimization of many parameters in the removal of AR88 dye from wastewater via CHS-BZ/LAC. The physicochemical properties of the CHS-BZ/LAC biosorbent were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energydispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis. Furthermore, the study investigates the biosorption mechanism of AR88 onto the CHS-BZ/LAC biosorbent surface.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cultivation and lyophilization of Lactobacillus casei

at

2.3. Synthesis procedure of CHS-BZ/LAC

2.4. Characterization procedure of CHS-BZ/LAC

| Codes | Variables | Level 1 (-1) | Level 2 (0) | Level 3 (+1) |

|

|

CHS-BZ/LAC | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.1 |

|

|

||||

|

|

pH | 4 | 7 | 10 |

|

|

Time (min) | 10 | 25 | 40 |

2.5. Experimental design

| Run | A: Dose (g) | B: pH | C: Time (min) | AR88 removal (%) |

| 1 | 0.02 | 4 | 25 | 61.0 |

| 2 | 0.1 | 4 | 25 | 94.5 |

| 3 | 0.02 | 10 | 25 | 23.6 |

| 4 | 0.1 | 10 | 25 | 35.5 |

| 5 | 0.02 | 7 | 10 | 46.8 |

| 6 | 0.1 | 7 | 10 | 55.4 |

| 7 | 0.02 | 7 | 40 | 55.0 |

| 8 | 0.1 | 7 | 40 | 81.8 |

| 9 | 0.06 | 4 | 10 | 79.8 |

| 10 | 0.06 | 10 | 10 | 21.4 |

| 11 | 0.06 | 4 | 40 | 86.3 |

| 12 | 0.06 | 10 | 40 | 53.7 |

| 13 | 0.06 | 7 | 25 | 52.1 |

| 14 | 0.06 | 7 | 25 | 54.7 |

| 15 | 0.06 | 7 | 25 | 53.7 |

| 16 | 0.06 | 7 | 25 | 56.0 |

| 17 | 0.06 | 7 | 25 | 49.4 |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of CHS-BZ/LAC

crystallinity [38, 39]. The involvement of LAC in the synthesis may introduce mineral phases, such as calcium compounds, contributing to the observed diffraction peaks, aligning with studies on biomineralization in microbial composites [40].

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F-value | p-value | Remark |

| Model | 6432.84 | 9 | 714.76 | 112.84 | <0.0001 | significant |

| A-Dose | 816.08 | 1 | 816.08 | 128.84 | <0.0001 | significant |

| B-pH | 4389.84 | 1 | 4389.84 | 693.06 | <0.0001 | significant |

| C-Time | 673.45 | 1 | 673.45 | 106.32 | <0.0001 | significant |

| AB | 116.64 | 1 | 116.64 | 18.41 | 0.0036 | significant |

| AC | 82.81 | 1 | 82.81 | 13.07 | 0.0086 | significant |

| BC | 166.41 | 1 | 166.41 | 26.27 | 0.0014 | significant |

| A

|

0.0067 | 1 | 0.0067 | 0.0011 | 0.9749 | not significant |

|

|

1.10 | 1 | 1.10 | 0.1729 | 0.6900 | not significant |

|

|

183.97 | 1 | 183.97 | 29.04 | 0.0010 | significant |

| Residual | 44.34 | 7 | 6.33 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 18.35 | 3 | 6.12 | 0.9415 | 0.4997 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 25.99 | 4 | 6.50 | |||

| Cor Total | 6477.18 | 16 | ||||

|

|

0.9932 | Adjusted

|

0.9844 | Predicted

|

0.9484 |

3.2. Statistical optimization

3.3. Perturbation of AR88 dye removal

3.4. 3D and 2D dual impact of parameters in AR88 removal

doses [59]. Additionally, Fig. 7e and 7f illustrate the combined effects of pH and time on the rate of AR88 removal, with a constant CHS-BZ/LAC dose of 0.1 g . Fig. 7e and 7f demonstrate that the adsorption efficiency of the AR88 dye improved with an increase in contact time from 10 to 25 min . The AR88 dye necessitates an optimal duration for effective penetration into the internal structure of CHS-BZ/LAC [60]. The optimal removal of AR88 dye is achieved at pH 4 . This discovery indicates that optimal conditions for AR88 adsorption are found in an acidic environment.

3.5. Biosorption mechanism

Electrostatic force

biosorbent with a group (

involving

4. Conclusion

Ethical statement

Conflict of interest statement

Data availability statement

Funding

Author contributions

References

- Jorge N, Teixeira AR, Gomes A, Lucas MS, Peres JA. Removal of azo dye acid red 88 by Fenton-based processes optimized by response surface methodology box-Behnken design. The 4th International Electronic Conference on Applied Sciences. 2023;56:164. Basel Switzerland: MDPI. doi: 10. 3390/ASEC2023-15501.

- Berradi M, Hsissou R, Khudhair M, Assouag M, Cherkaoui O , El harfi A . Textile finishing dyes and their impact on aquatic environs. Heliyon 2019;5:e02711. doi: 10.1016/j. heliyon.2019.e02711.

- Yaseen DA, Scholz M. Textile dye wastewater characteristics and constituents of synthetic effluents: A critical review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;16:1193-1226. doi: 10.1007/ s13762-018-2130-z.

- Tejashwini DM, Harini HV, Nagaswarupa HP, Naik R, Chidananda B. A comparative study of green and chemical approaches for photocatalytic activity of novel hybrid bismuth magnesium ferrites (

) nanoparticles for Acid Red-88 dye degradation. Results Chem. 2024;7:101267. doi: 10.1016/j.rechem.2023.101267. - Dong G, Chen B, Liu B, Hounjet LJ, Cao Y, Stoyanov SR, Yang M, Zhang B. Advanced oxidation processes in microreactors for water and wastewater treatment: Development, challenges, and opportunities. Water Res. 2022;211:118047. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118047.

- Swanckaert B, Geltmeyer J, Rabaey K, De Buysser K, Bonin L, De Clerck K. A review on ion-exchange nanofiber membranes: Properties, structure and application in electrochemical (waste) water treatment. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022;287:120529. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120529.

- Hu P, Ren J, Hu X, Yang H. Comparison of two starchbased flocculants with polyacrylamide for the simultaneous removal of phosphorus and turbidity from simulated and actual wastewater samples in combination with

. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;167:223-232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac. 2020.11.176. - Santoso SP, Angkawijaya AE, Bundjaja V, Hsieh CW, Go AW, Yuliana M, Hsu HY, Tran-Nguyen PL, Soetaredjo FE, Ismadji S.

/guar gum hydrogel composite for adsorption and photodegradation of methylene blue. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;193:721-733. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.10.044. - Li Z, Xie W, Zhang Z, Wei S, Chen J, Li Z. Multifunctional sodium alginate/chitosan-modified graphene oxide reinforced membrane for simultaneous removal of nanoplastics, emulsified oil, and dyes in water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;245:125524.

- Mushahary N, Sarkar A, Das B, Rokhum SL, Basumatary S. A facile and green synthesis of corn cob-based graphene oxide and its modification with corn cob-

for efficient removal of methylene blue dye: Adsorption mechanism, isotherm, and kinetic studies. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2024;101(11):01409. - Agha HM, Abdulhameed AS, Jawad AH, ALOthman ZA, Wilson LD, Algburi S. Fabrication of glutaraldehyde crosslinked chitosan/algae biomaterial via hydrothermal process: Statistical optimization and adsorption mechanism for MV 2B dye removal. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2025;15:1105-1119. doi: 10. 1007/s13399-023-05143-3.

- Brazesh B, Mousavi SM, Zarei M, Ghaedi M, Bahrani S, Hashemi SA. Biosorption. In M. N. V. Prasad & A. Vithanage (Eds.), Handbook of Metal-Microbe Interactions and Bioremediation 2021;33:587-628. Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-818805-7.00003-5.

- Ravindran B, Karmegam N, Yuvaraj A, Thangaraj R, Chang SW, Zhang Z, Awasthi MK. Cleaner production of agriculturally valuable benignant materials from industry generated bio-wastes: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021;320:124281. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.124281

- Nawaz S, Tabassum A, Muslim S, Nasreen T, Baradoke A, Kim TH, Boczkaj G, Jesionowski T, Bilal M. Effective assessment of biopolymer-based multifunctional sorbents for the remediation of environmentally hazardous contaminants from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere, 2023;329:138552.

- Pham VHT, Kim J, Chang S, Chung W. Bacterial biosorbents, an efficient heavy metals green clean-up strategy: Prospects, challenges, and opportunities. Microorganisms 2022;10(3):610.

- Radzun KA, Agha HM, Abdullah NFF, Ahmad MI, Ivanovski I, Mohammed AA, Alkamil A A. Media optimization techniques for microalgae through technological advancements: A mini review AUIQ. Complem. Biol. Syst. 2024;1(1):60-69.

- Taketa TB, Mahl CR, Calais GB, Beppu MM. Amino acidfunctionalized chitosan beads for in vitro copper ions uptake in the presence of histidine. Int. J. Boil. Macromol. 2021;188:421-431.

- Bekheit MM, Nawar N, Addison AW, Abdel-Latif DA, and Monier M. Preparation and characterization of chitosan-grafted-poly(2-amino-4,5-pentamethylene-thiophene-3 carboxylic acid N’-acryloyl-hydrazide) chelating resin for removal of Cu (II), Co (II) and Ni (II) metal ions from aqueous solutions. Int. J. Boil. Macromol. 2011;48(4):558-565.

- Sahib SAA, Awad SH. Synthesis, Characterization of chitosan para- hydroxyl benzaldehyde schiff base linked maleic anhydride and the evaluation of its antimicrobial activities. Baghdad Sci. J. 2022;19(6):1265.

- Khan A, Alamry KA. Recent advances of emerging green chitosan-based biomaterials with potential biomedical applications: A review. Carbohydr. Res. 2021;506:108368.

- Jawad AH, Hameed BH, Abdulhameed AS. Synthesis of biohybrid magnetic chitosan-polyvinyl alcohol/ MgO nanocomposite blend for remazol brilliant blue R dye adsorption: Solo and collective parametric optimization. Polym. Bull. 2023;80(5):4927-4947.

- Agha HM, Jawad AH, ALOthman Z A, Wilson LD. Design of chitosan and watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) seed shell composite adsorbent for reactive orange 16 dye removal: Multivariable optimization and dye adsorption mechanism study. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2024. doi: 10.1007/s13399-024-06362y.

- Tahira I, Aslam Z, Abbas A, Monim-ul-Mehboob M, Ali S, Asghar A. Adsorptive removal of acidic dye onto grafted chitosan: A plausible grafting and adsorption mechanism. Int. J. Boil. Macromol. 2019;136:1209-1218.

- Hermosillo-Ochoa E, Picos-Corrales LA, Licea-Claverie A. Ecofriendly flocculants from chitosan grafted with PNVCL and PAAc: Hybrid materials with enhanced removal properties for water remediation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021;258:118052.

- Huang C, Liao H, Ma X, Xiao M, Liu X, Gong S, Zhou X. Adsorption performance of chitosan Schiff base towards anionic dyes: Electrostatic interaction effects. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021;780:138958.

- Arni LA, Hapiz A, Abdulhameed AS, Khadiran T, ALOthman ZA, Wilson LD, Jawad AH. Design of separable magnetic chitosan grafted-benzaldehyde for azo dye removal via a response surface methodology: Characterization and adsorption mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;242:125086. doi: 10.1016/j.jjbiomac.2023.125086.

- Sun Y, Kang Y, Zhong W, Liu Y, Dai Y. A simple phosphorylation modification of hydrothermally cross-linked chitosan for selective and efficient removal of U (VI). J. Solid State Chem. 2020;292:121731.

- Sayilgan E, Cakmakci O. Treatment of textile dyeing wastewater by biomass of Lactobacillus: Lactobacillus 12 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2012;20(3):1556-1564. doi: 10.1007/s11356-012-1009-7.

- Seesuriyachan P, Kuntiya A, Sasaki K, Techapun C. Comparative study on methyl orange removal by growing cells and washed cell suspensions of Lactobacillus casei TISTR 1500. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009;25:973-979.

- Capozzi V, Tufariello M, De Simone N, Fragasso M, Grieco F. Biodiversity of oenological lactic acid bacteria: Species- and strain-dependent plus/minus effects on wine quality and safety. Fermentation 2021;7:24. doi: 10.3390/ fermentation7010024.

- Mora-Villalobos JA, Montero-Zamora J, Barboza N, RojasGarbanzo C, Usaga J, Redondo-Solano M, Schroedter L, Olszewska-Widdrat A, López-Gómez JP. Multi-product lactic acid bacteria fermentations: A review. Fermentation 2020;6:23. doi: 10.3390/fermentation6010023.

- Aazmi S, Teh LK, Ramasamy K, Rahman T, Salleh MZ. Comparison of the anti-obesity and hypocholesterolaemic effects of single Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota and probiotic cocktail. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015;50(7):1589-1597.

- Şuteu D, Zaharia C, Blaga AC, Peptu AC. Biosorbents based on residual biomass of Lactobacillus sp. bacteria consortium immobilized in sodium alginate for Orange 16 dye retention from aqueous solutions. Desalination Water Treat. 2022;246:315324. doi: 10.5004/dwt.2022.28018.

- Begum S, Yuhana NY, Saleh NM, Kamarudin NN, Sulong AB. Review of chitosan composite as a heavy metal adsorbent: Material preparation and properties. Carbohydr. Poly. 2021;259:117613.

- Mehrotra T, Dev S, Banerjee A, Chatterjee A, Singh R, Aggarwal S. Use of immobilized bacteria for environmental bioremediation: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021;9(5):105920.

- Agha HM, Jawad AH, Wilson LD, ALOthman ZA. Preparation and characterisation of chitosan/bacterial Escherichia coli biocomposite for malachite green dye removal: Modeling and optimisation of the adsorption process. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2024;1-23. doi: 10.1080/03067319.2024.2426730.

- Tertsegha S, Akubor PI, Iordekighir AA, Christopher K, Okike OO. Extraction and characterization of chitosan from snail shells (Achatina fulica). J. Food Qual. Hazards Control. 2024;11(3):186-196.

- Jayakumar R, Prabaharan M, Nair SV, Tamura H. Novel chitin and chitosan nanofibers in biomedical applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010;28(1):142-150.

- Okunzuwa GI, Enaroseha OO, Okunzuwa SI. Synthesis and characterization of Fe (III) chitosan nanoparticles n-benzaldehyde Schiff base for biomedical application. Chem. Pap. 2024;78(5):3253-3260. doi: 10.1007/s11696-024-03309-5.

- Singh S, Singh G, Kang TS. Biomineralization and its application in bioinspired green composites: Emerging research and opportunities. In handbook of research on green engineering techniques for modern manufacturing. IGI Global. 2020;1-25.

- Wang W, Hu J, Zhang R, Yan C, Cui L, Zhu J. A pHresponsive carboxymethyl cellulose/chitosan hydrogel for adsorption and desorption of anionic and cationic dyes. Cellulose 2021;28:897-909. doi: 10.1007/s10570-020-03561-4.

- Abdulqader MA, Suliman MA, Ahmed TA, Wu R, Bobaker A, Tiyasha T, Al-Areeq N. Conversion of chicken rice waste into char via hydrothermal, pyrolysis, and microwave carbonization processes: A comparative study. AUIQ Complem. Biol. Syst. 2024;1(1):1-9.

- Kekes T, Tzia C. Adsorption of indigo carmine on functional chitosan and

-cyclodextrin/chitosan beads: Equilibrium, kinetics and mechanism studies. J. Environ. Manage. 2024;262:110372. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110372. - Pérez-Calderón J, Santos MV, Zaritzky N. Synthesis, characterization and application of cross-linked chitosan/oxalic acid hydrogels to improve azo dye (Reactive Red 195) adsorption. React. Funct. Polym. 2020;155:104699. doi: 10.1016/j. reactfunctpolym.2020.104699.

- Fatoni A, Hariani PL, Hermansyah H, Lesbani A. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan linked by methylene bridge and schiff base of 4, 4-diaminodiphenyl ether-vanillin. Indones. J. Chem. 2018;18(1):92-101. doi: 10.22146/ijc. 25866.

- El-Sakhawy M, Kamel S, Salama A, Tohamy HAS. Preparation and infrared study of cellulose based amphiphilic materials. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2018;52(3-4):193-200.

- Zhao W, Liu S, Yin M, He Z, Bi D. Co-pyrolysis of cellulose with urea and chitosan to produce nitrogen-containing compounds and nitrogen-doped biochar: Product distribution characteristics and reaction path analysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2023;169:105795. doi: 10.1016/j.jaap.2022.105795.

- Amrutha SR, Suja NR, Menon S. Morphological analysis of Biomass. In Thomas, S., Hosur, M., Pasquini, D., Jose Chirayil, C. (Eds.). Handbook of Biomass. Springer, Singapore. 2023. doi: 10.1007/978-981-19-6772-6_15-1.

- Kutluay S, Temel T. Silica gel based new adsorbent having enhanced VOC dynamic adsorption/desorption performance. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022;609:125848.

- Es-Haghi A, Taghavizadeh Yazdi ME, Sharifalhoseini M, Baghani M, Yousefi E, Rahdar A, Baino F. Application of response surface methodology for optimizing the therapeutic activity of ZnO nanoparticles biosynthesized from Aspergillus niger. Biomimetics 2021;6(2):34. doi: 10.3390/ biomimetics6020034.

- Onu CE, Nwabanne JT, Ohale PE, Asadu CO. Comparative analysis of RSM, ANN and ANFIS and the mechanistic modeling in eriochrome black-T dye adsorption using modified clay. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2021;36:24-42. doi: 10.1016/j. sajce.2020.12.003.

- Gonbadi M, Sabbaghi S, Rasouli J, Rasouli K, Saboori R, Narimani M. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles for spent caustic recovery: Adsorbent characterization and process optimization using I-optimal method. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023;158:111460. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2023.111460.

- Nayak AK, Pal A. Statistical modeling and performance evaluation of biosorptive removal of Nile blue A by lignocellulosic

agricultural waste under the application of high-strength dye concentrations. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020;8(2):103677. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.103677. - Foroutan R, Peighambardoust SJ, Mohammadi R, Peighambardoust SH, Ramavandi B. Development of new magnetic adsorbent of walnut shell ash/starch/

for effective copper ions removal: Treatment of groundwater samples. Chemosphere 2022;296:133978. - Al-dhawi BNS, Kutty SRM, Alawag AM, Almahbashi NMY, Al-Towayti FAH, Algamili A, Jagaba AH. Optimal parameters for boron recovery in a batch adsorption study: Synthesis, characterization, regeneration, kinetics, and isotherm studies. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2023;8:100508. doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2023.100508.

- Abdulhameed AS, Mohammad A-T, Jawad AH. Modeling and mechanism of reactive orange 16 dye adsorption by chitosanglyoxal/

nanocomposite: Application of response surface methodology. Desalination Water Treat. 2019;164:346-360. - Aragaw TA, Alene AN. A comparative study of acidic, basic, and reactive dyes adsorption from aqueous solution onto kaolin adsorbent: Effect of operating parameters, isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamics. Emerg. Contam. 2022;8:59-74. doi: 10.1016/j.emcon.2022.01.002.

- Agha HM, Allaq A, Jawad AH, Aazmi S, ALOthman ZA, Wilson LD. Immobilization of Bacillus subtilis bacteria into biohybrid crosslinked chitosan-glutaraldehyde for acid red 88 dye removal: Box-Behnken design optimization and mechanism study. J Inorg Organomet Polym. 2024. doi: 10.1007/s10904-024-03264-4.

- Al-Hazmi GA, Alayyafi AA, El-Desouky MG, El-Bindary AA. Chitosan-nano CuO composite for removal of mercury (II): Box-Behnken design optimization and adsorption mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024;261:129769.

- Mary Ealias A, Saravanakumar MP. A critical review on ultrasonic-assisted dye adsorption: Mass transfer, half-life and half-capacity concentration approach with future industrial perspectives. Crit. Rev. Env. Sci. Tec. 2019;49(21):1959-2015. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2019.1601488.

- Reghioua A, Barkat D, Jawad AH, Abdulhameed AS, Rangabhashiyam S, Khan MR, ALOthman ZA. Magnetic chitosanglutaraldehyde/zinc oxide/

nanocomposite: Optimization and adsorptive mechanism of Remazol Brilliant Blue R dye removal. J. Polym. Environ. 2021;29:3932-3947. doi: 10.1007/s10924-021-02133-8. - Blachnio M, Zienkiewicz-Strzalka M, Derylo-Marczewska A. Synthesis of composite sorbents with chitosan and varied silica phases for the adsorption of Anionic Dyes. Molecules 2024;29(9):2087. doi: 10.3390/molecules29092087.

- Singh SK, Das A. The

interaction: A rapidly emerging non-covalent interaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17(15):9596-9612. doi: 10.1039/C4CP05665A.

- Recommended Citation

Aghaa, Hasan M.; Musa, Salis A.; Hapiz, Ahmad; Wu, Ruihong; Al-Essa, Khansaa; Saleh, Ali Mohammed; and Reghioua, Abdallah (2025), Biocomposite Adsorbent of Grafted Chitosan-benzaldehyde/Lactobacillus Casei Bacteria for Removal of Acid Red 88 Dye: Box-Benken Design Optimization and Mechanism Approach, AUIQ Complementary Biological System: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, 1-14.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.70176/3007-973X. 1020

Available at: https://acbs.alayen.edu.iq/journal/vol2/iss1/1 - Received 10 January 2025; revised 13 January 2025; accepted 19 January 2025.

Available online 5 March 2025- Corresponding authors.

E-mail addresses: hasanagha586@gmail.com (H. M. Agha), ahmad.hapiz01@gmail.com (A. Hapiz).