DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-024-01414-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38753068

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-16

استشهد بـ

تاريخ الاستلام: 8 فبراير 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 16 مايو 2024

© المؤلفون 2024

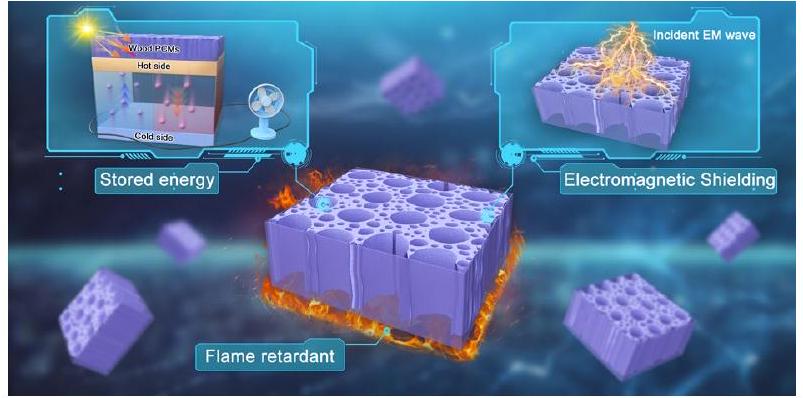

مواد مركبة ذات تغيير في الطور من الخشب ذات مورفولوجيا جينية مقاومة للتسرب، ومثبطة للاشتعال، ودرع كهرومغناطيسي لجمع الطاقة الشمسية الحرارية

النقاط البارزة

- تم استغلال فئة مبتكرة من مواد تغيير الطور المركبة المستقرة في الشكل (CPCMs) المتعددة الاستخدامات بنجاح، والتي تتميز بترسيب هجين من MXene وحمض الفيتيك على الخشب غير المحترق كدعم قوي.

- تظهر المواد المركبة القائمة على الخشب موصلية حرارية محسّنة لـ

(4.6 مرة من بولي إيثيلين جلايكول) بالإضافة إلى حرارة كامنة عالية لـ ( تغليف) مع متانة حرارية واستقرار على مدار 200 دورة تسخين وتبريد على الأقل. - تمتاز المواد القائمة على الخشب بخصائص جيدة في تحويل الطاقة الشمسية إلى حرارية وكهربائية، ومقاومة اللهب، وخصائص درع كهرومغناطيسي.

الملخص

توفر مواد تغيير الطور (PCMs) حلاً واعدًا لمواجهة التحديات التي تطرحها التقطع والتقلبات في استخدام الطاقة الشمسية الحرارية. ومع ذلك، فإن المواد العضوية الصلبة والسائلة (PCMs) تواجه مشكلات مثل التسرب، وانخفاض الموصلية الحرارية، ونقص الوسائط الشمسية الحرارية الفعالة، وقابلية الاشتعال، مما قيد تطبيقاتها الواسعة. هنا، نقدم فئة مبتكرة من مواد تغيير الطور المركبة المتعددة الاستخدامات (CPCMs) التي تم تطويرها من خلال نهج تخليق سهل وصديق للبيئة، مستفيدين من الأنيسوتروبي الطبيعي والتم porosity أحادي الاتجاه لهلام الخشب (نانوالخشب) لـ دعم بولي إيثيلين جلايكول (PEG). تتضمن عملية تعديل الخشب دمج حمض الفيتيك (PA) وهيكل MXene الهجين من خلال طريقة التجميع الناتجة عن التبخر، والتي يمكن أن تمنح تعبئة PEG غير المتسربة بينما تسهل في الوقت نفسه التوصيل الحراري، وامتصاص الضوء، ومقاومة اللهب. وبالتالي، فإن CPCMs المعتمدة على الخشب التي تم إعدادها تظهر موصلية حرارية محسنة.

دعم بولي إيثيلين جلايكول (PEG). تتضمن عملية تعديل الخشب دمج حمض الفيتيك (PA) وهيكل MXene الهجين من خلال طريقة التجميع الناتجة عن التبخر، والتي يمكن أن تمنح تعبئة PEG غير المتسربة بينما تسهل في الوقت نفسه التوصيل الحراري، وامتصاص الضوء، ومقاومة اللهب. وبالتالي، فإن CPCMs المعتمدة على الخشب التي تم إعدادها تظهر موصلية حرارية محسنة.

1 المقدمة

تحضير مواد تغيير الطور المركبة المستقرة شكلًا (CPCMs). ومع ذلك، أدت عملية التصنيع المعقدة إلى زيادة تكاليف الإنتاج بالإضافة إلى توليد العديد من المنتجات الثانوية السامة والملوثات، مما يشكل تحديًا كبيرًا لمبادئ التنمية المستدامة. لذلك، هناك حاجة ملحة لتطوير هياكل مسامية ثلاثية الأبعاد تكون فعالة ومستدامة، تتميز بسهولة التصنيع وضمان الصداقة البيئية. لحسن الحظ، ألهمت الهياكل الرائعة الموجودة في الكائنات البيولوجية تطوير مصفوفات تغليف اصطناعية بديلة. يمكن الحصول على المواد المستندة إلى الطبيعة من خلال “نهج من الأعلى إلى الأسفل” السهل، مما يلغي الحاجة إلى عمليات بناء معقدة. أما بالنسبة للخشب، فهو مثال رئيسي على تصميم الطبيعة المعقد، حيث يتميز بهياكله المرتبة بدقة مثل الأوعية المجوفة، وعناصر التراخيد، والأغشية مثل الحفر المصممة لنقل الماء والأيونات بكفاءة. إن المسامية الهرمية الموجودة في الخشب، التي تمتد من المقياس الكلي إلى المقياس النانوي، تجعله مادة وظيفية واعدة للغاية. بالإضافة إلى أدواره المعروفة في امتصاص السوائل وترشيح السوائل، يظهر الخشب كمرشح جذاب لتغليف مواد تغيير الطور. حقق ليو وآخرون كفاءات تغليف تصل إلى

تأثير القوى الجاذبية. يُذكر أن استخدام تقنيات هندسة السطح لتعزيز نمو المواد النانوية الوظيفية ثنائية الأبعاد (2D) على سطح الهيكل الخشبي المستمد من الخشب يمثل نهجًا قابلاً للتطبيق لمعالجة التحديات المذكورة أعلاه [36، 37]. على سبيل المثال، يتم الحصول على MXene، وهو مادة لاميلارية ثنائية الأبعاد جديدة تتكون من كربيدات وكربونات المعادن الانتقالية، من خلال النقش والتقشير لمراحل MAX [38]، مما يظهر قدرات استثنائية في تحويل الطاقة الضوئية إلى حرارية [39]، وموصلية حرارية [40]، وتطبيقات بصرية [41]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يتم إثراء سطح MXene بمجموعة وفيرة من المجموعات الوظيفية النشطة، مثل

أنها كانت حاسمة في منع التسرب أثناء عمليات التخزين الحراري. تم إجراء تقييم شامل، يشمل التركيب الكيميائي، والحالة البلورية، والميكروسكوبية، وقدرة الاحتواء، وأداء تغيير الطور، وإعادة التكرار الحراري، وسلوك مقاومة اللهب، وتحويل الطاقة الشمسية إلى حرارية وكهربائية، وفعالية الحماية من التداخل الكهرومغناطيسي، لتوفير فهم دقيق للخصائص العامة لـ CPCMs. كما هو متوقع، يعزز النهج متعدد الأوجه من خلال تعديل الخشب الهجين السهل MXene وPA من تعدد الوظائف لـ CPCMs المستقرة الشكل التي تم إعدادها، مما يجعلها مرشحة واعدة لتطبيقات متنوعة.

2 القسم التجريبي

2.1 تصنيع هيدروجيل الخشب وتعديل الهجين MXene/PA

في إطار هيدروجيل الخشب، أي

2.2 النقع بـ PEG لتحضير CPCMs

تحويل الطاقة الشمسية إلى كهرباء وأداء الحماية الكهرومغناطيسية، كلها موضحة في المعلومات الداعمة.

3 النتائج والمناقشة

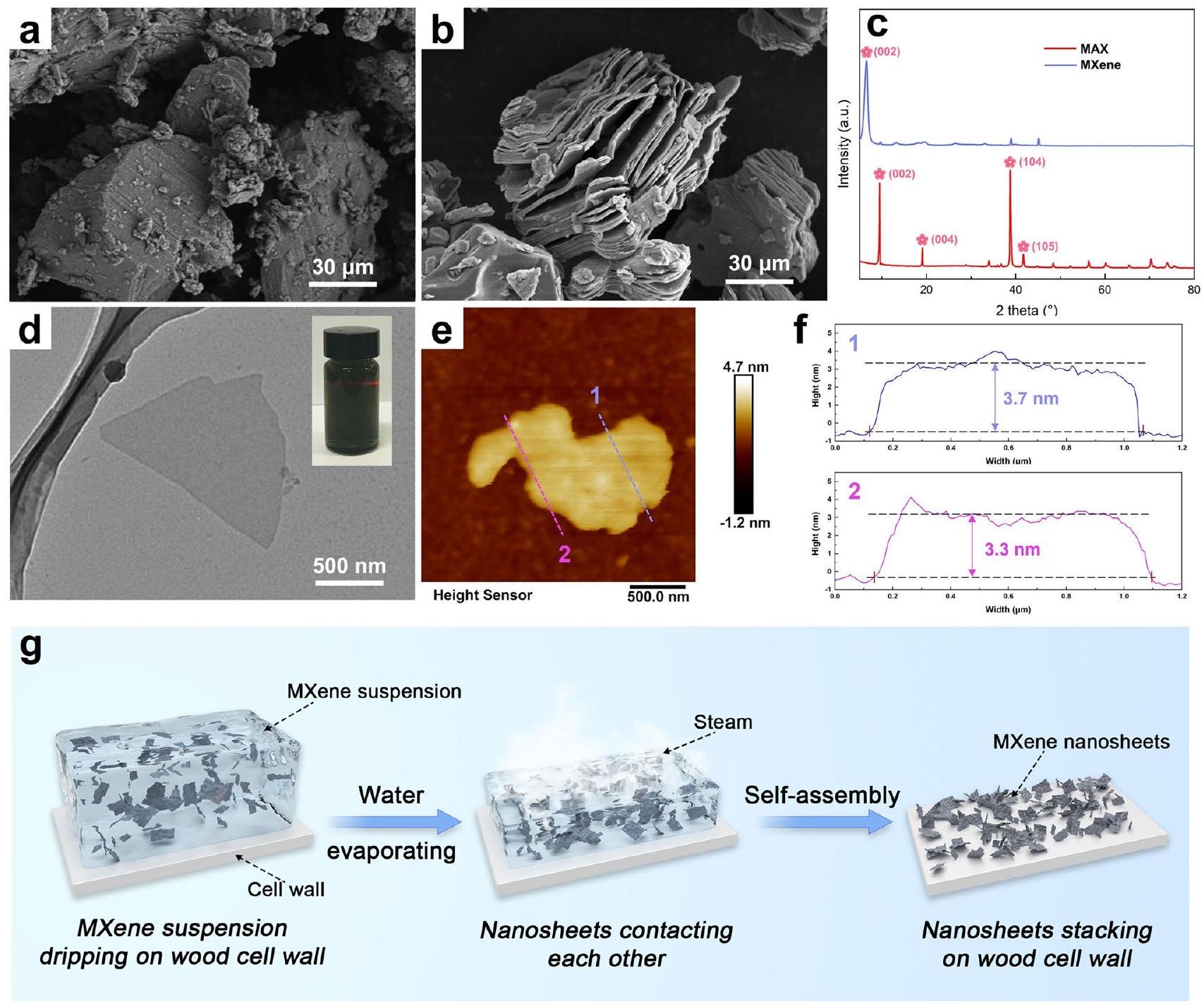

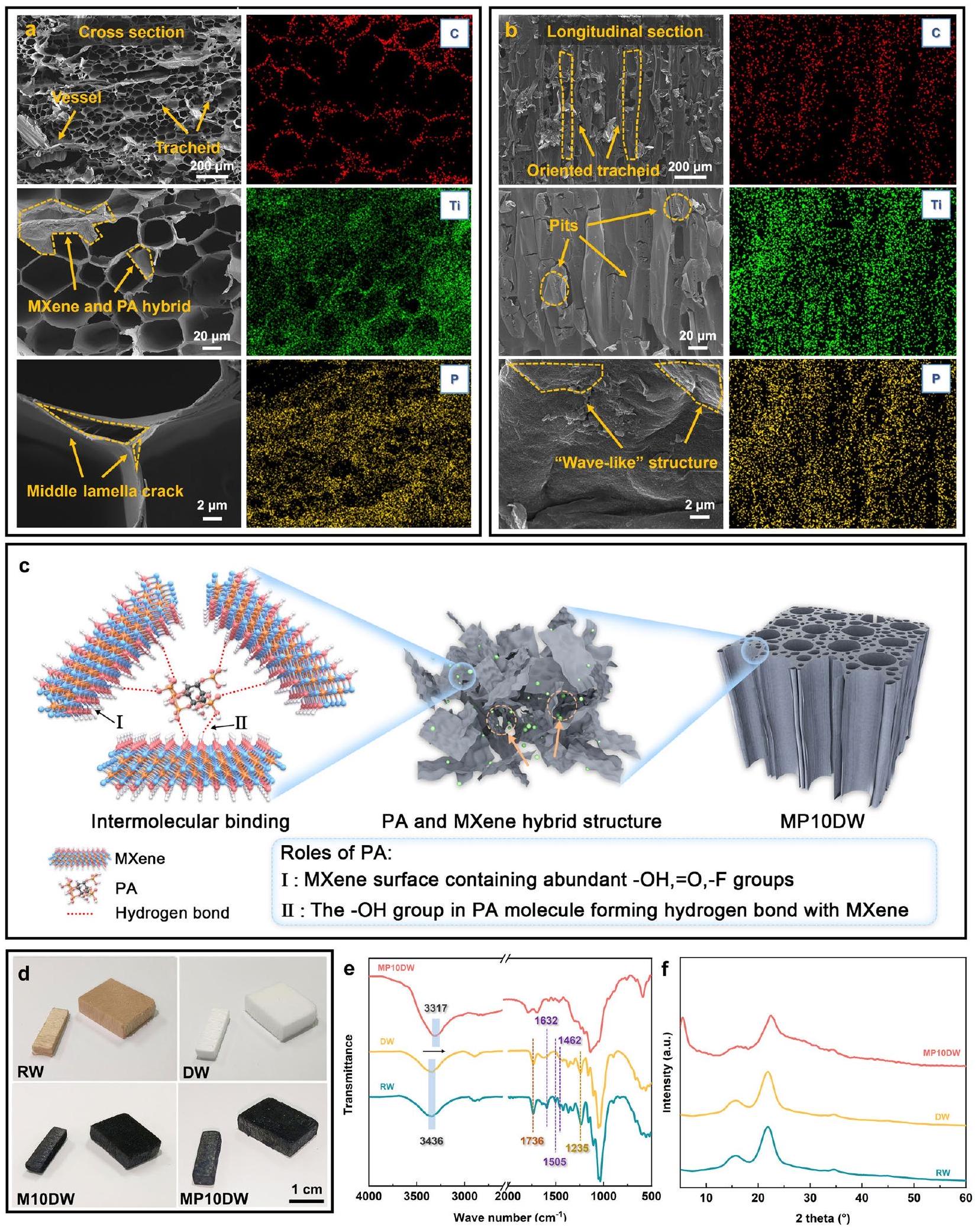

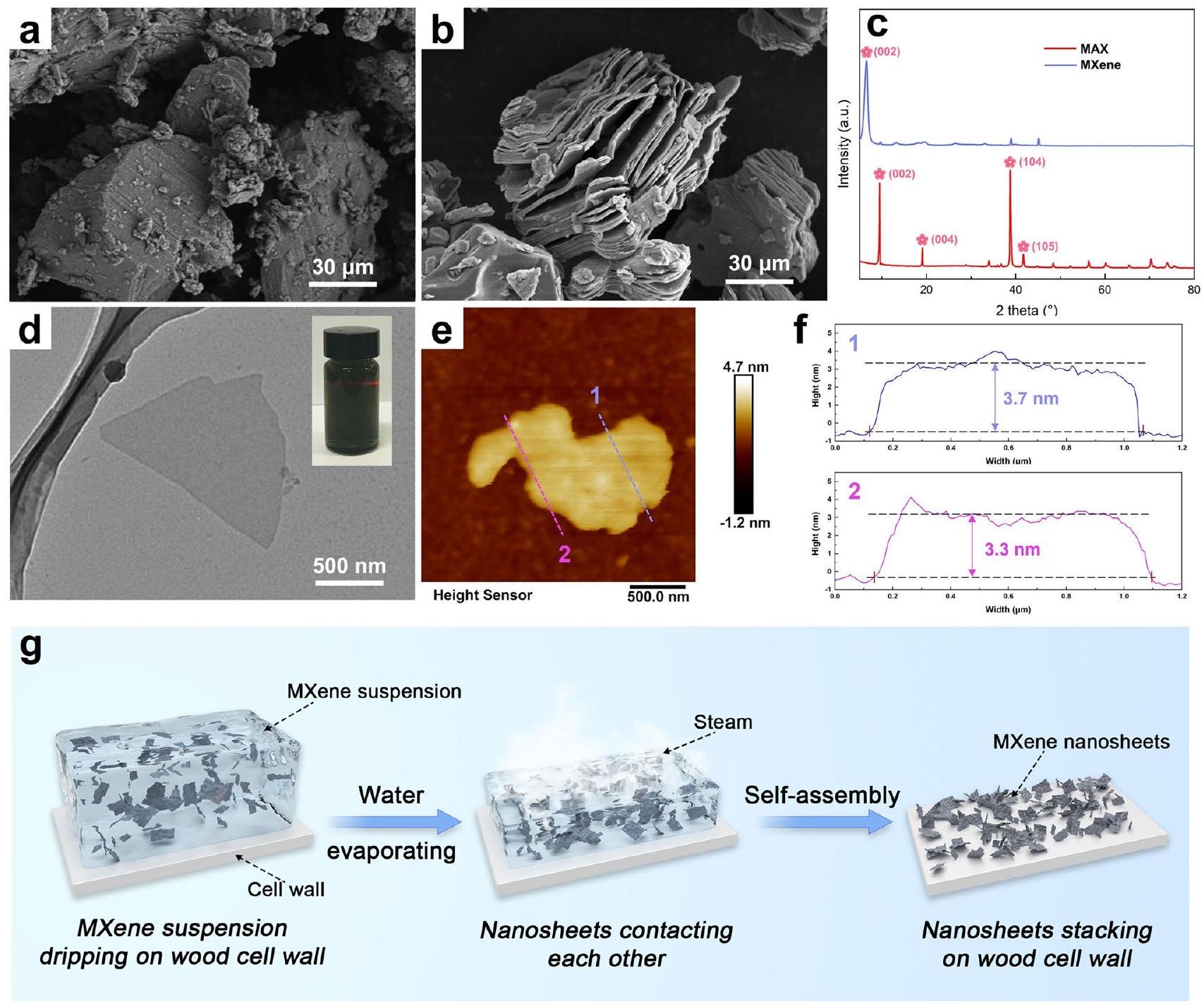

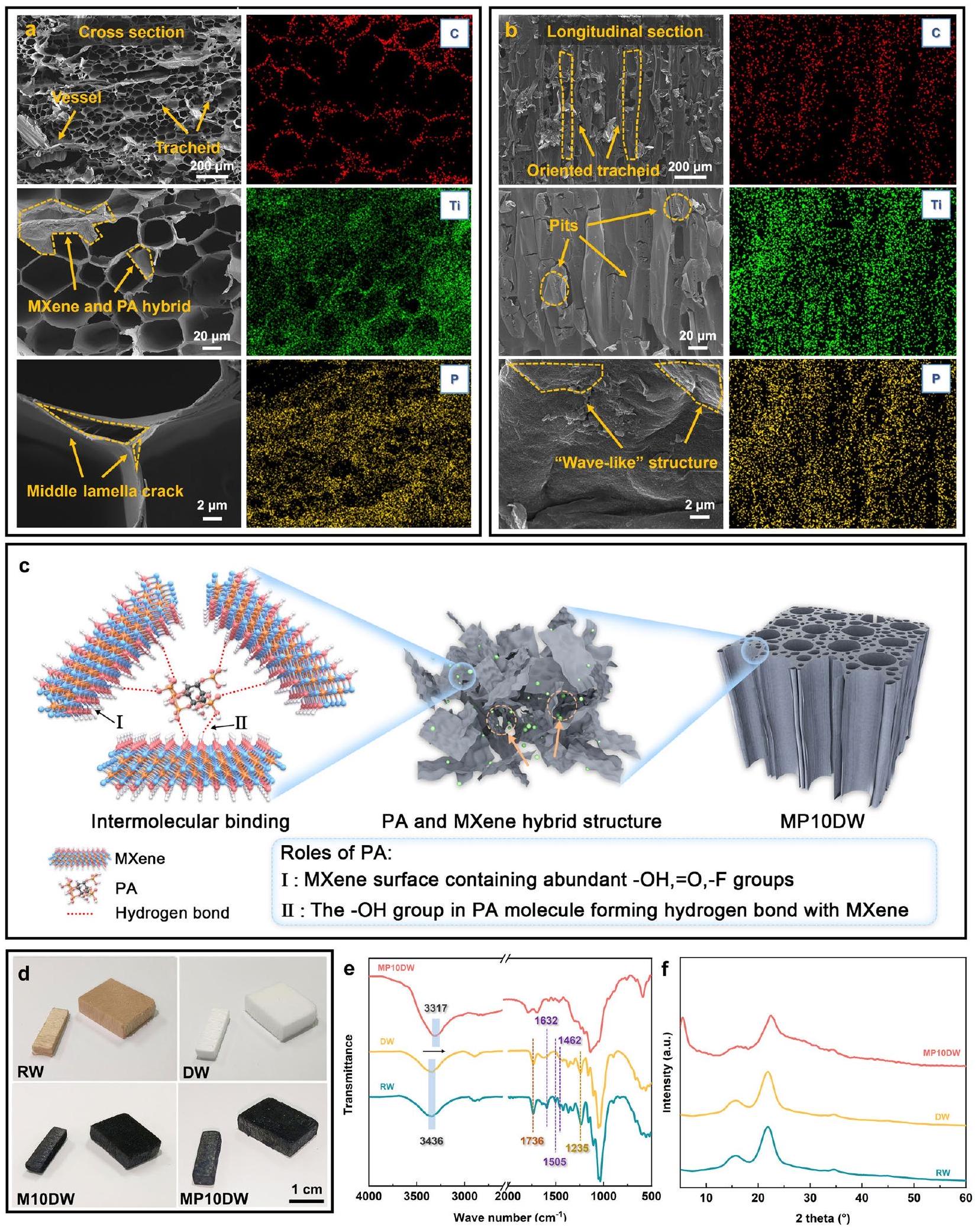

3.1 إطار العمل المستمد من البلسا وتعديل الهجين MXene/PA

لـ MXene أحادي الطبقة أو قليل الطبقات الذي يظهر تشتت تيندال الملحوظ (الشكل 2d). وهذا يشهد على قابلية MXene الممتازة للتشتت في الماء، بفضل مجموعاته الوظيفية المحبة للماء الوفيرة (على سبيل المثال،

على التوالي [57]. كلاهما يدل على الهيميسليلوز، وبشكل خاص على البوليمرات غير المتبلورة. كما تم الكشف عن قمم خفيفة عند 1590 و1505، و

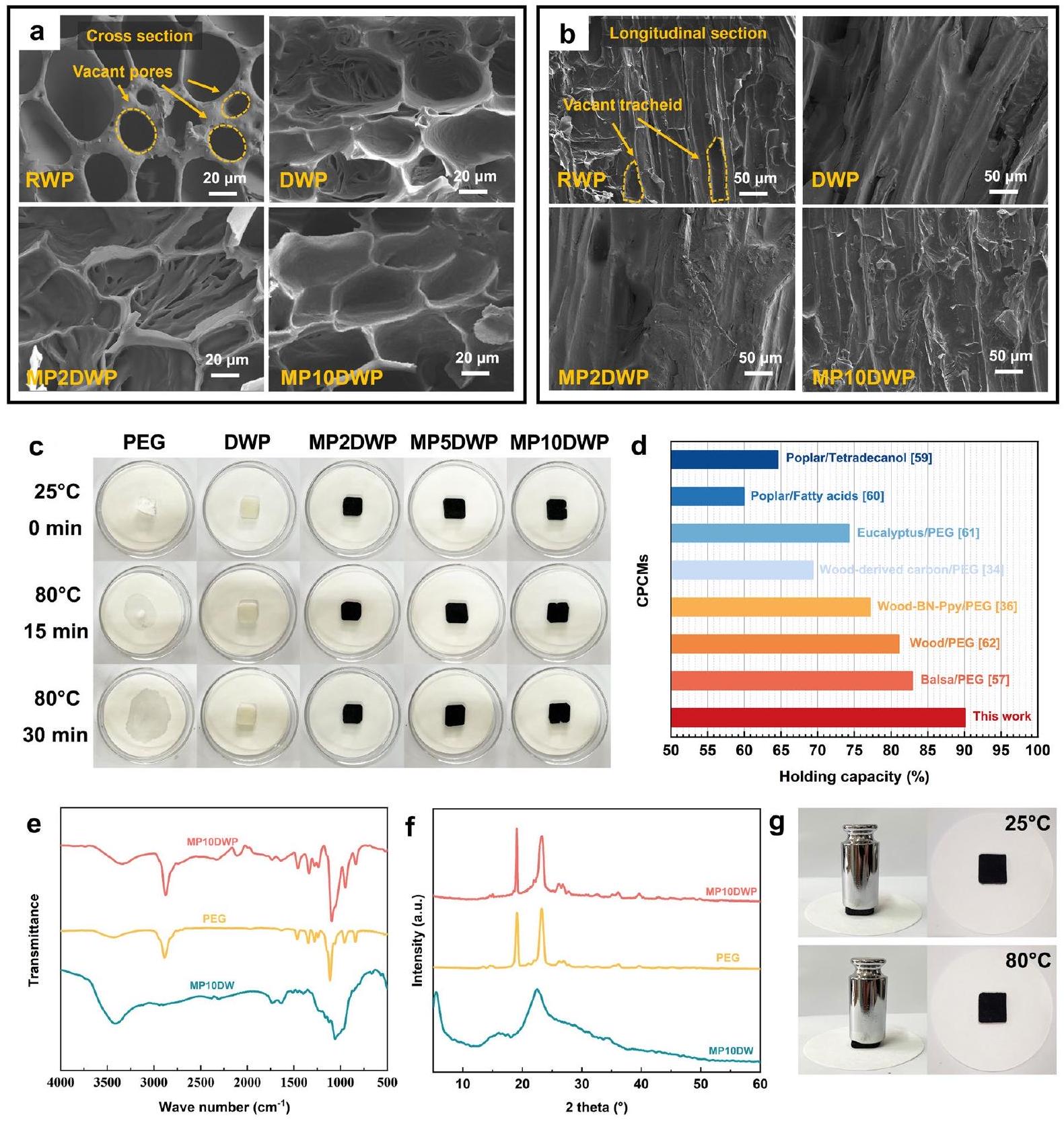

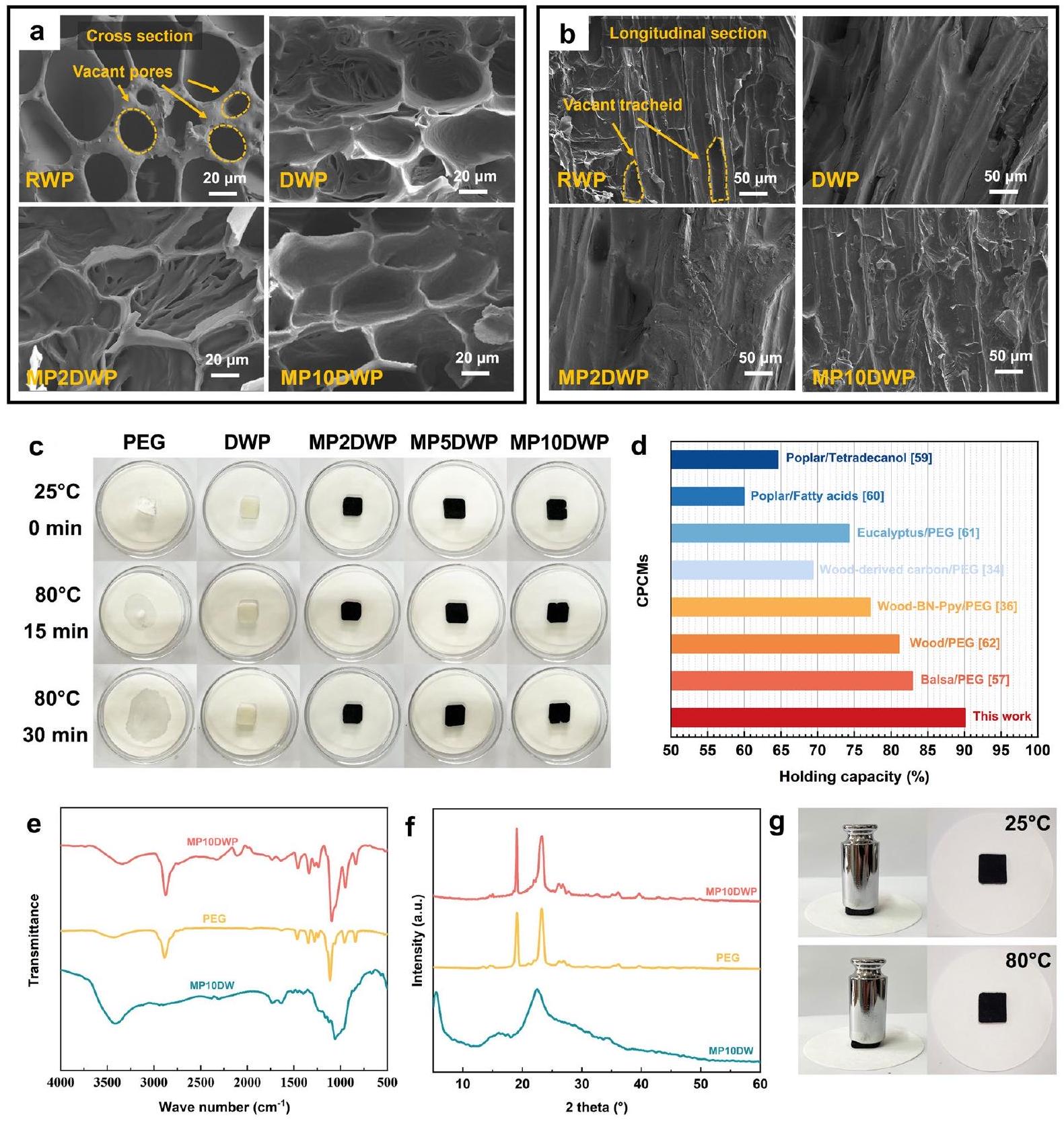

3.2 مورفولوجيا CPCMs وقدرتها على الت encapsulation

سقالة نانوود، بينما تعرض المزيد من المجموعات المحبة للماء (مثل،

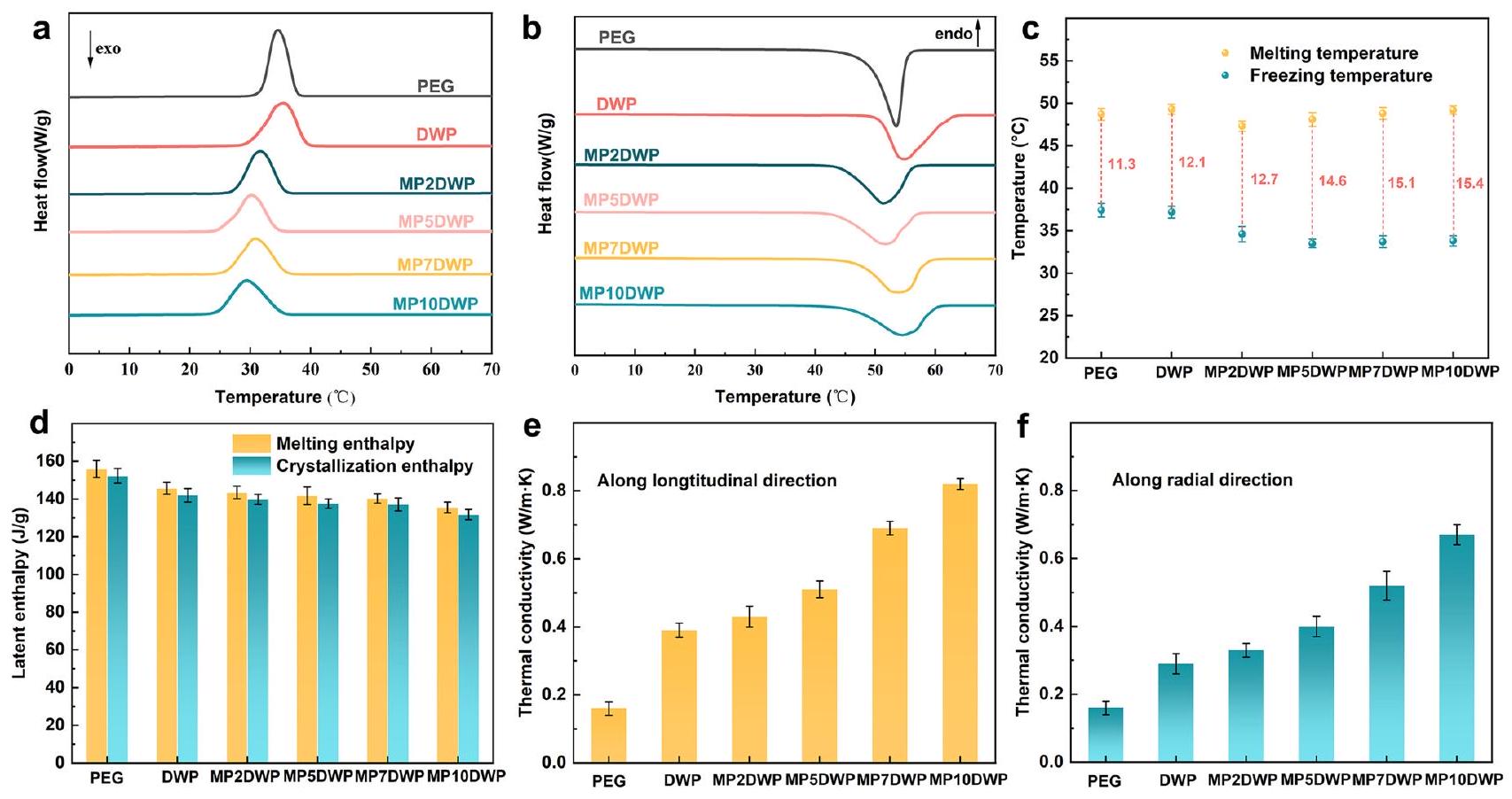

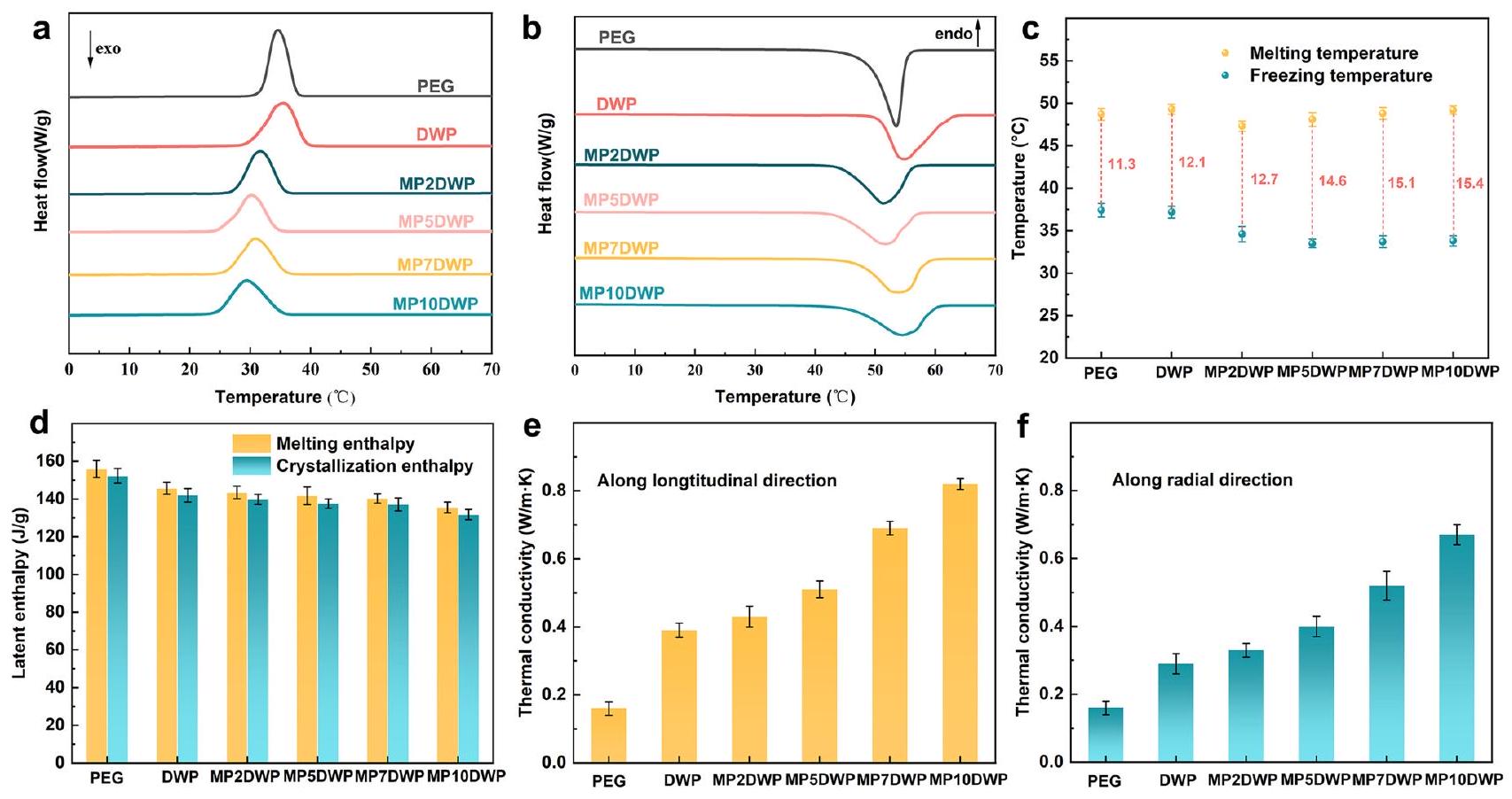

3.3 الخصائص الحرارية وسلوك تغيير الطور لمواد تغيير الطور المستمدة من البلسا

نقطة (

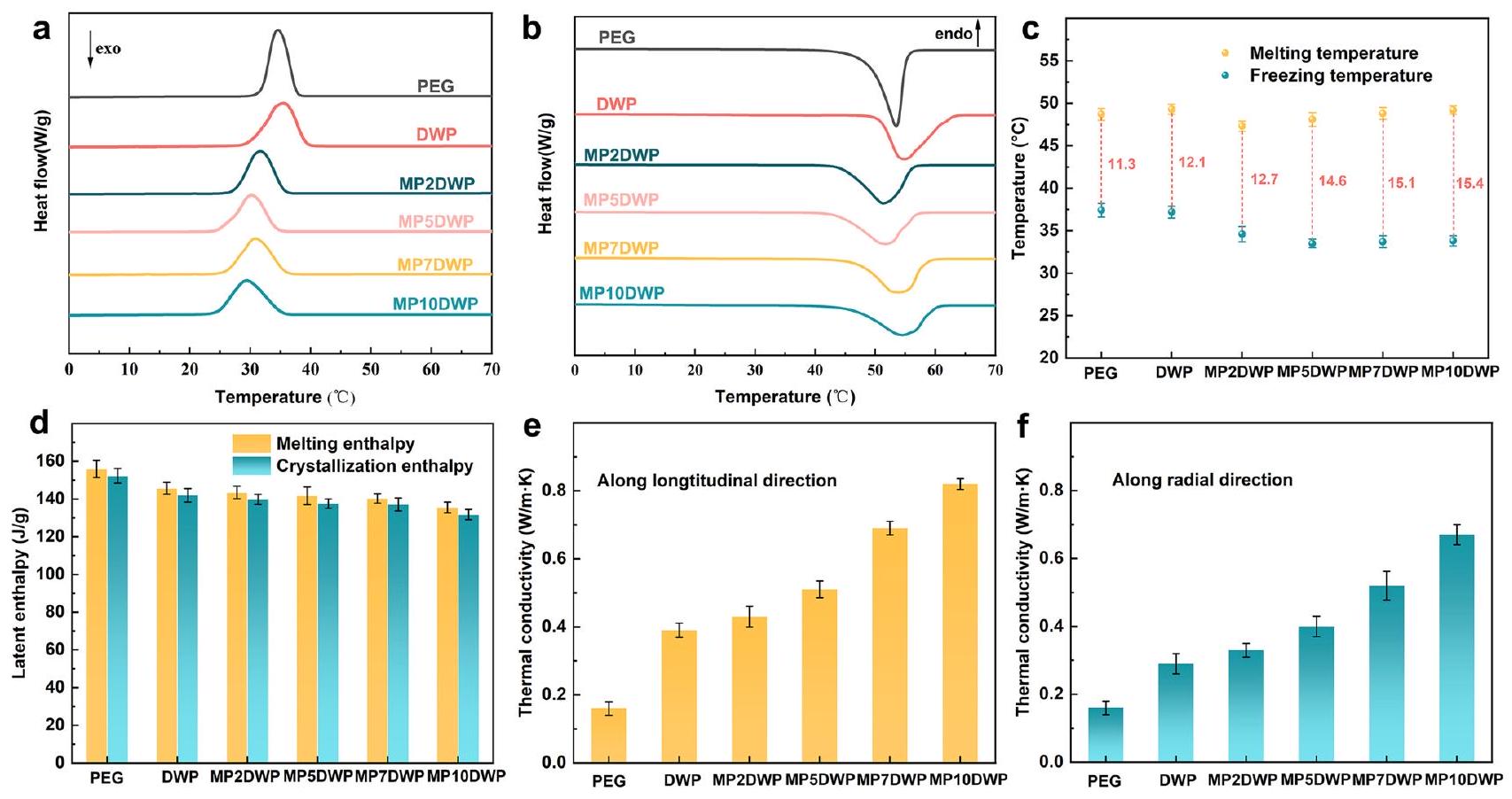

الحد المشترك لمواد تغيير الطور العضوية. عند احتوائها في الخشب النانوي، فإن الإطار الموجه يحفز التوصيل الحراري غير المتساوي. على طول الاتجاه الطولي، تخلق جدران خلايا التراخيد العمودية مسارات حرارية موجهة، مما يسهل توصيل الحرارة بسرعة (الشكل 5e). ومع ذلك، بالنسبة لـ DWP، بسبب التوصيل الحراري المنخفض بطبيعته للخشب النانوي، فإن الزيادة تكون فقط بمقدار 2.2 مرة. في الاتجاه الشعاعي (الشكل 5f)، يتضمن توصيل الحرارة تكرارات عبر جدران خلايا رقيقة إلى PEG والعودة، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة أقل أهمية، بمقدار 1.6 مرة فقط. تتماشى هذه النتائج مع دراسة يانغ وآخرون [33]. إن إدخال MXene كحشو موصل حراري يعزز بشكل كبير من التوصيل الحراري لمواد تغيير الطور المركبة.

التبريد الفائق أقل من

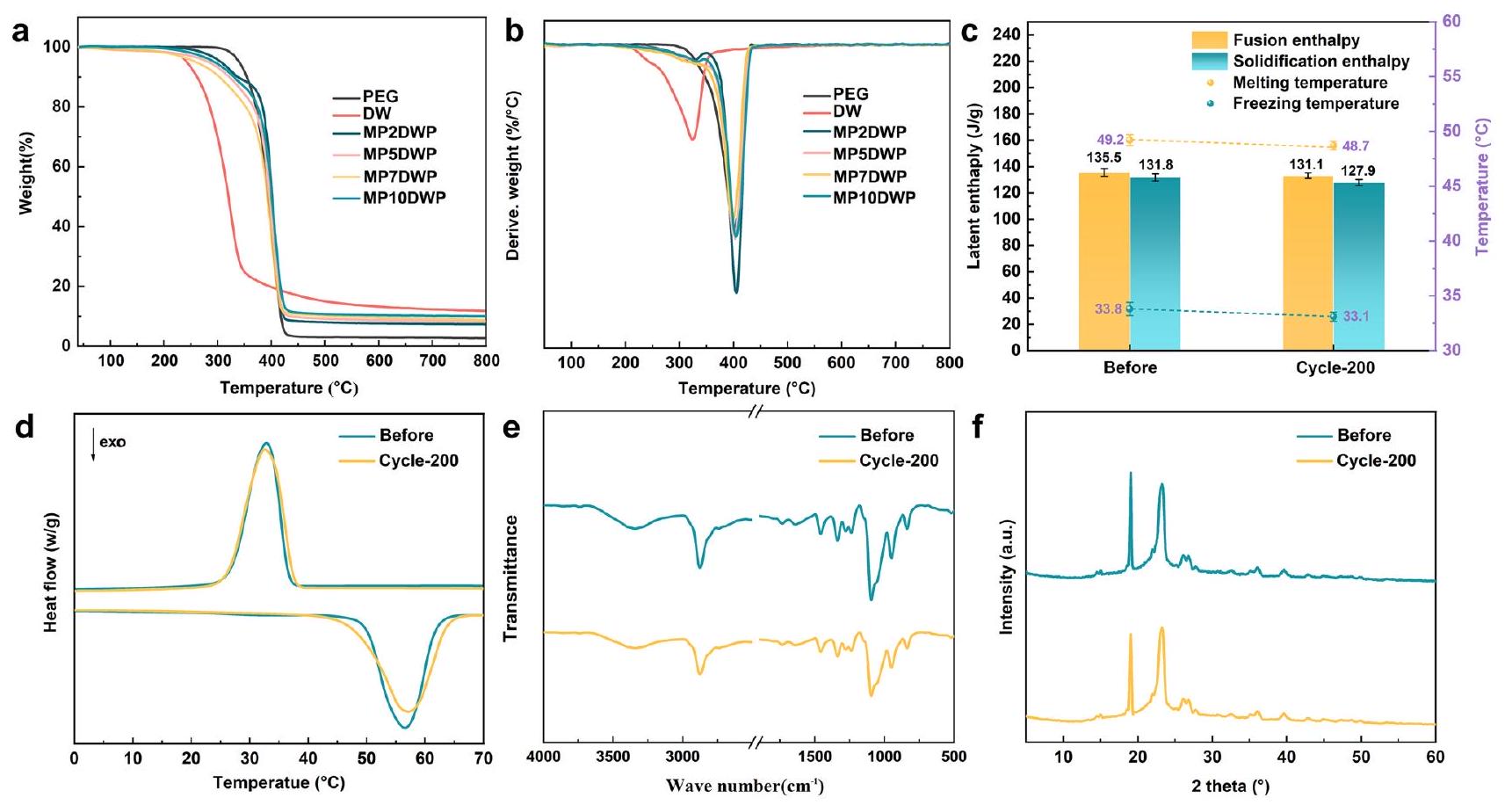

3.4 الموثوقية الحرارية وقابلية التكرار لمواد تغيير الطور المستمدة من البلسا

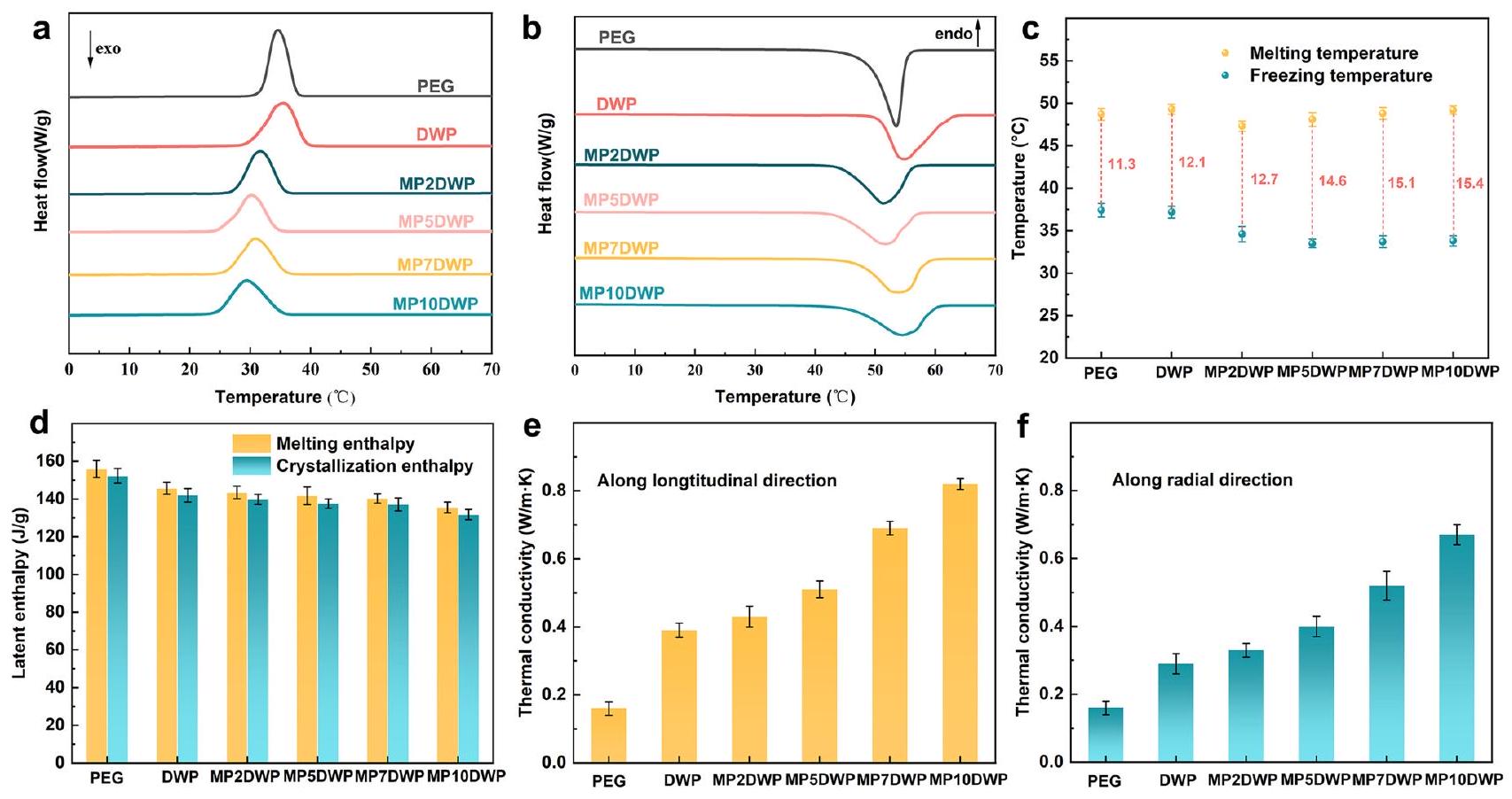

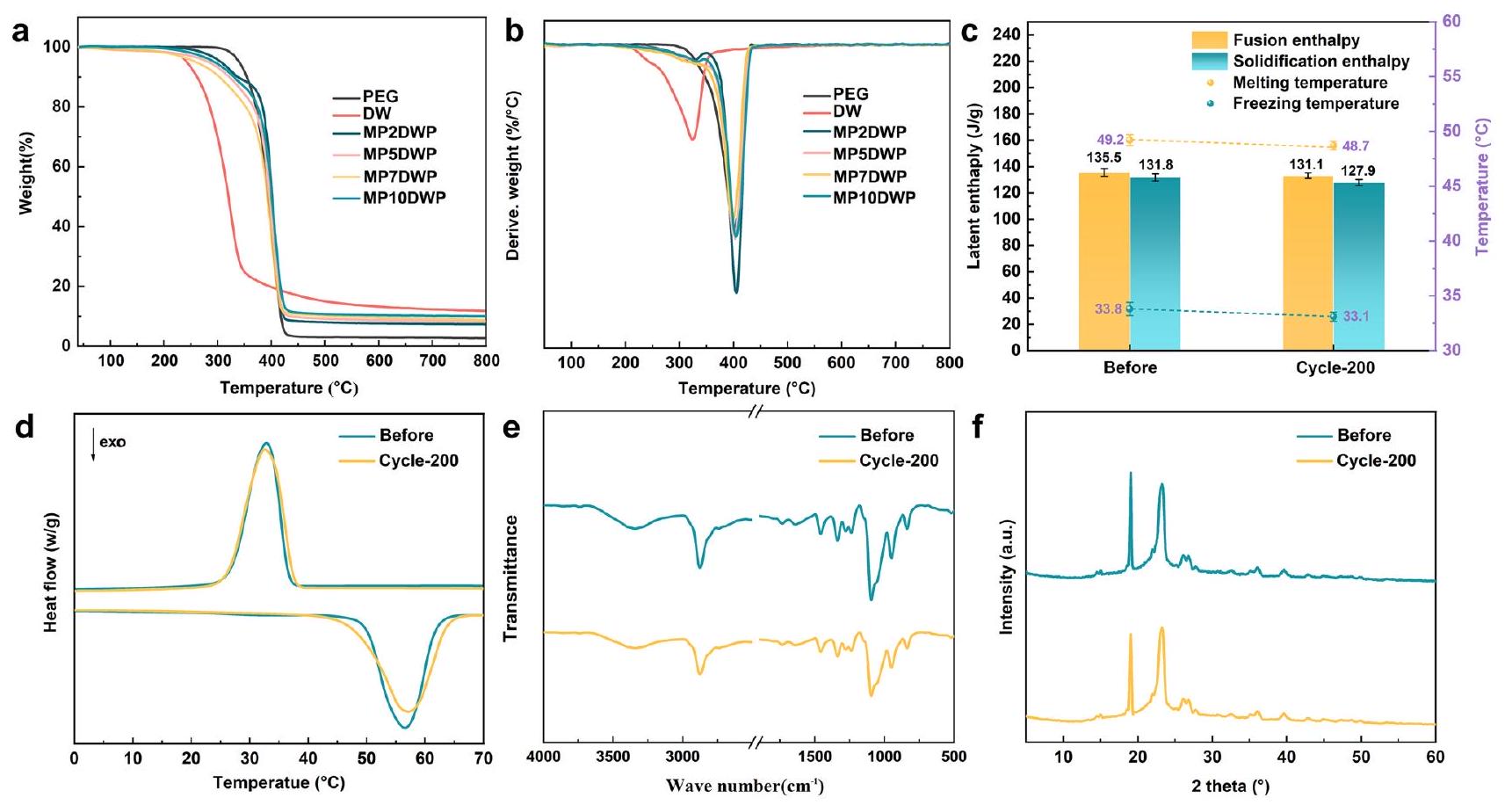

عملية الكربنة أثناء التحلل. كما هو متوقع، فإن الفرضيات المذكورة مدعومة بقيم الكربون المتبقية من MPDWPs. مع زيادة محتوى MXene، هناك اتجاه تصاعدي ملحوظ في قيم الكربون المتبقية، حيث تصل إلى 7.3% عند محتوى 10.1% من MXene. بالنظر إلى التطبيقات العملية لـ CPCMs، وخاصة في تحويل الطاقة الشمسية إلى حرارية وتخزينها، فإن جميع MPDWPs تظهر تدهورًا حراريًا بالكاد تحت

مناسب تمامًا للتطبيقات العملية في تخزين الطاقة الحرارية القابلة للعكس.

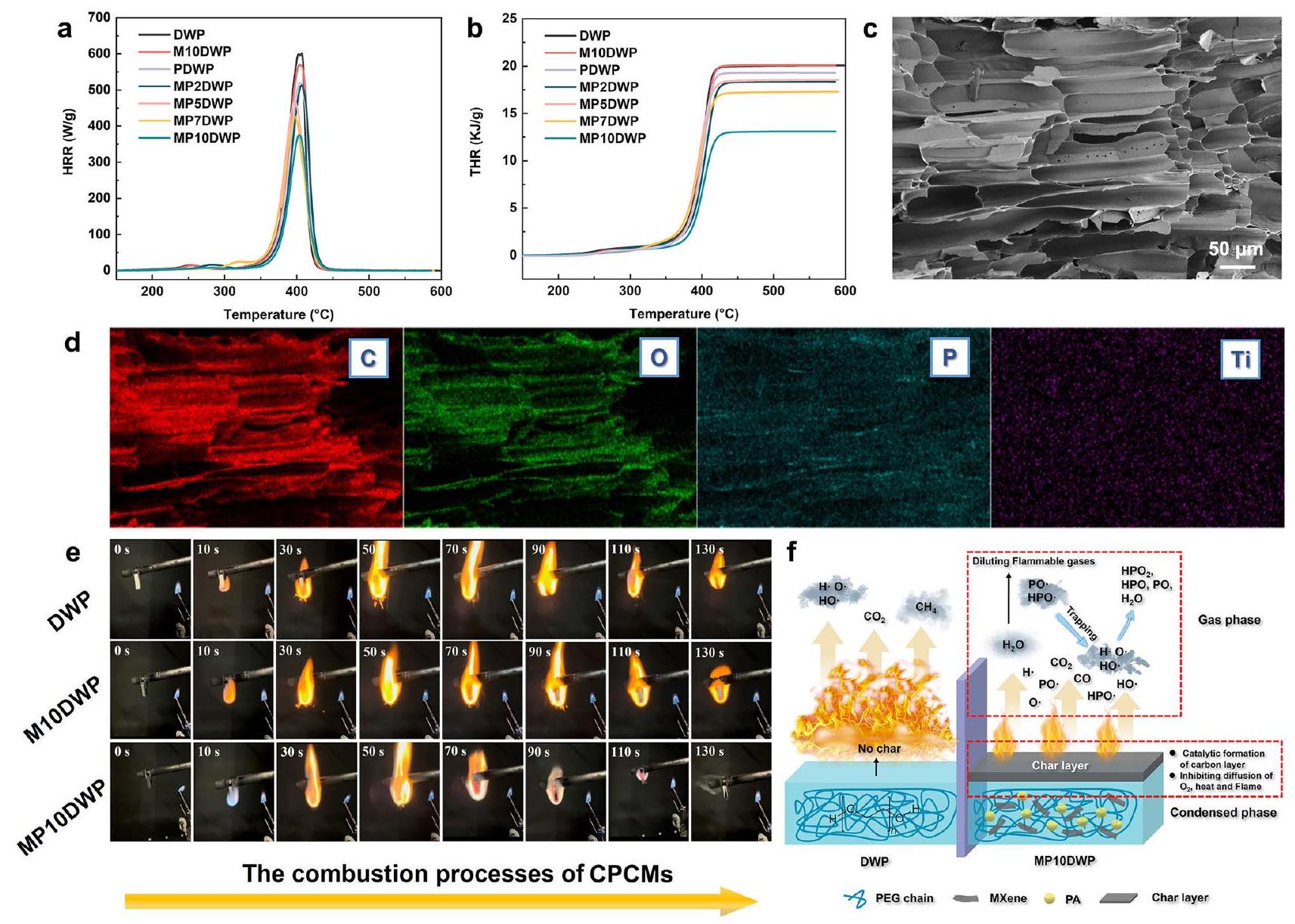

3.5 أداء مقاومة اللهب لمواد تغيير الطور المستندة إلى البلسا

الذي يمنع بشكل فعال كل من غاز الاحتراق وانتقال الحرارة.

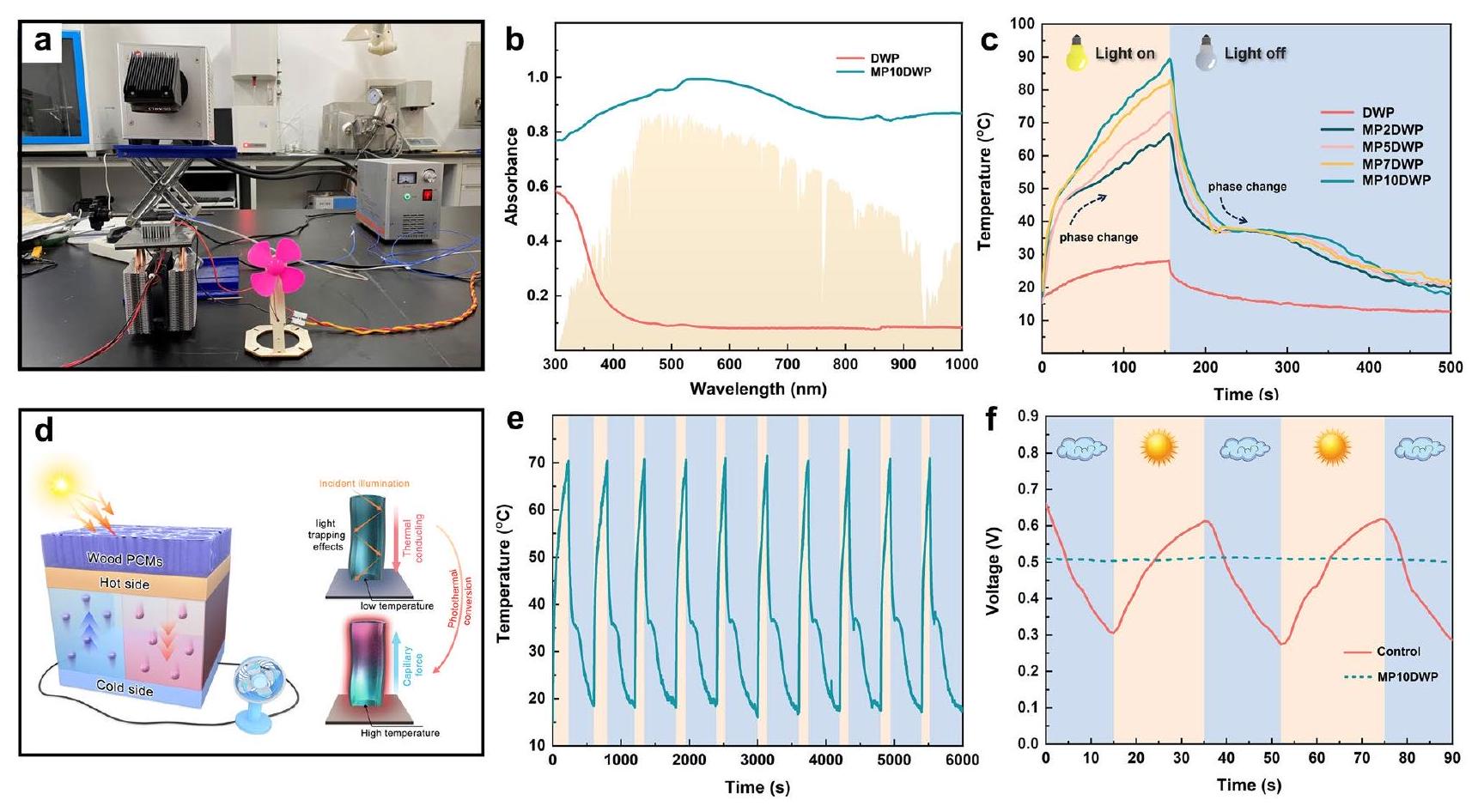

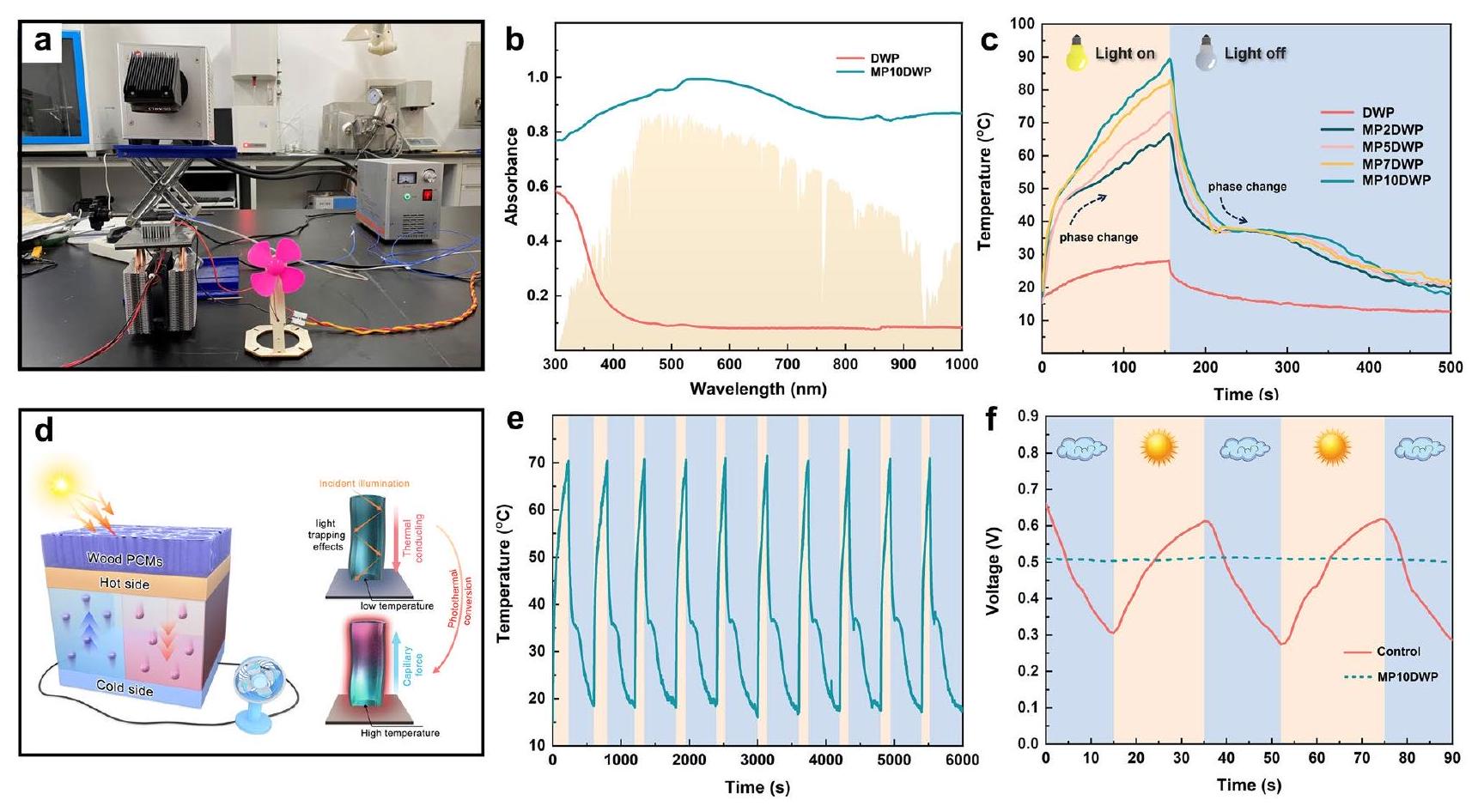

3.6 تحويل الطاقة الشمسية إلى كهرباء من مواد تغيير الطور المستمدة من البلسا

أين

يمثل مساحة سطح العينات. المعلمات

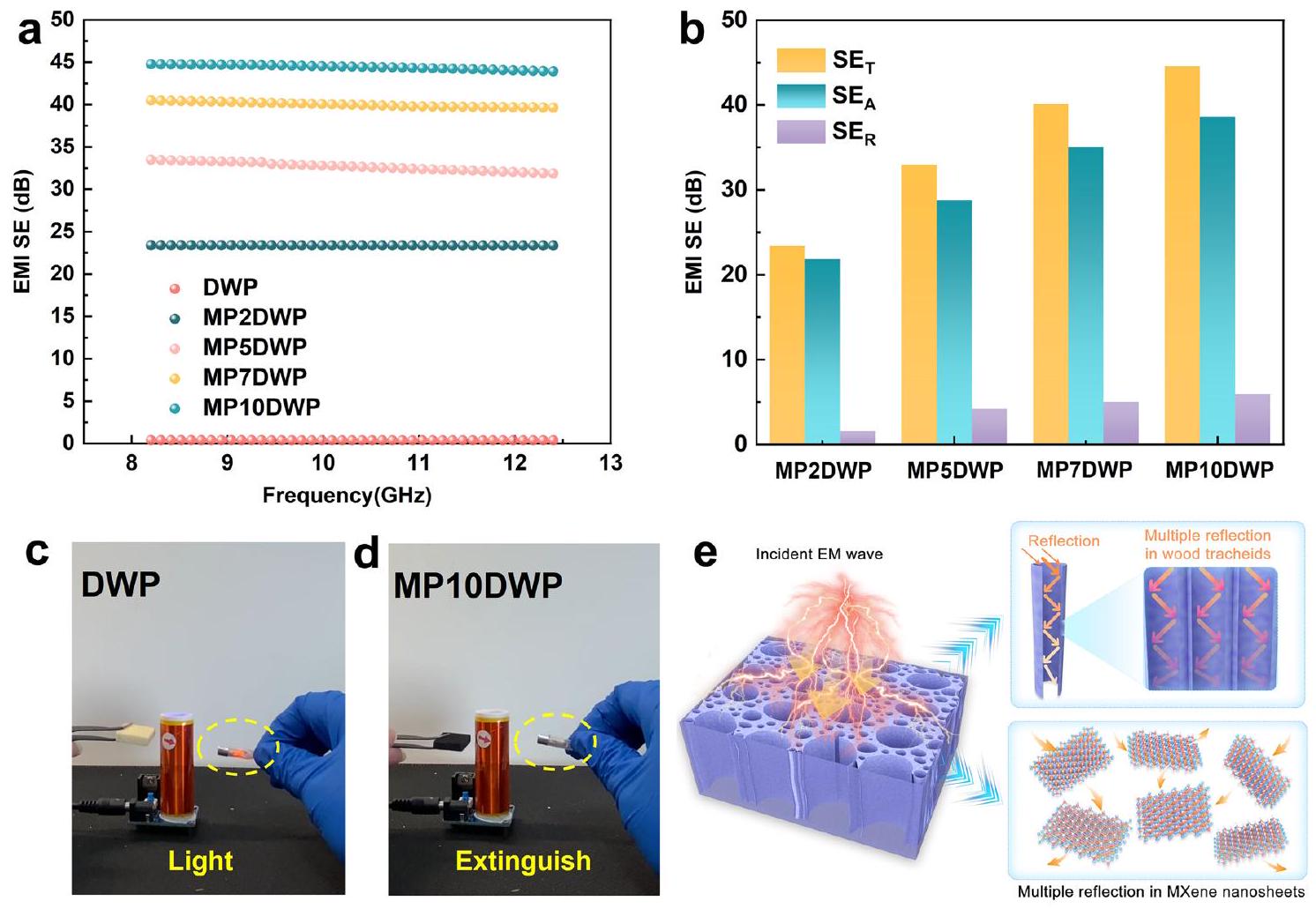

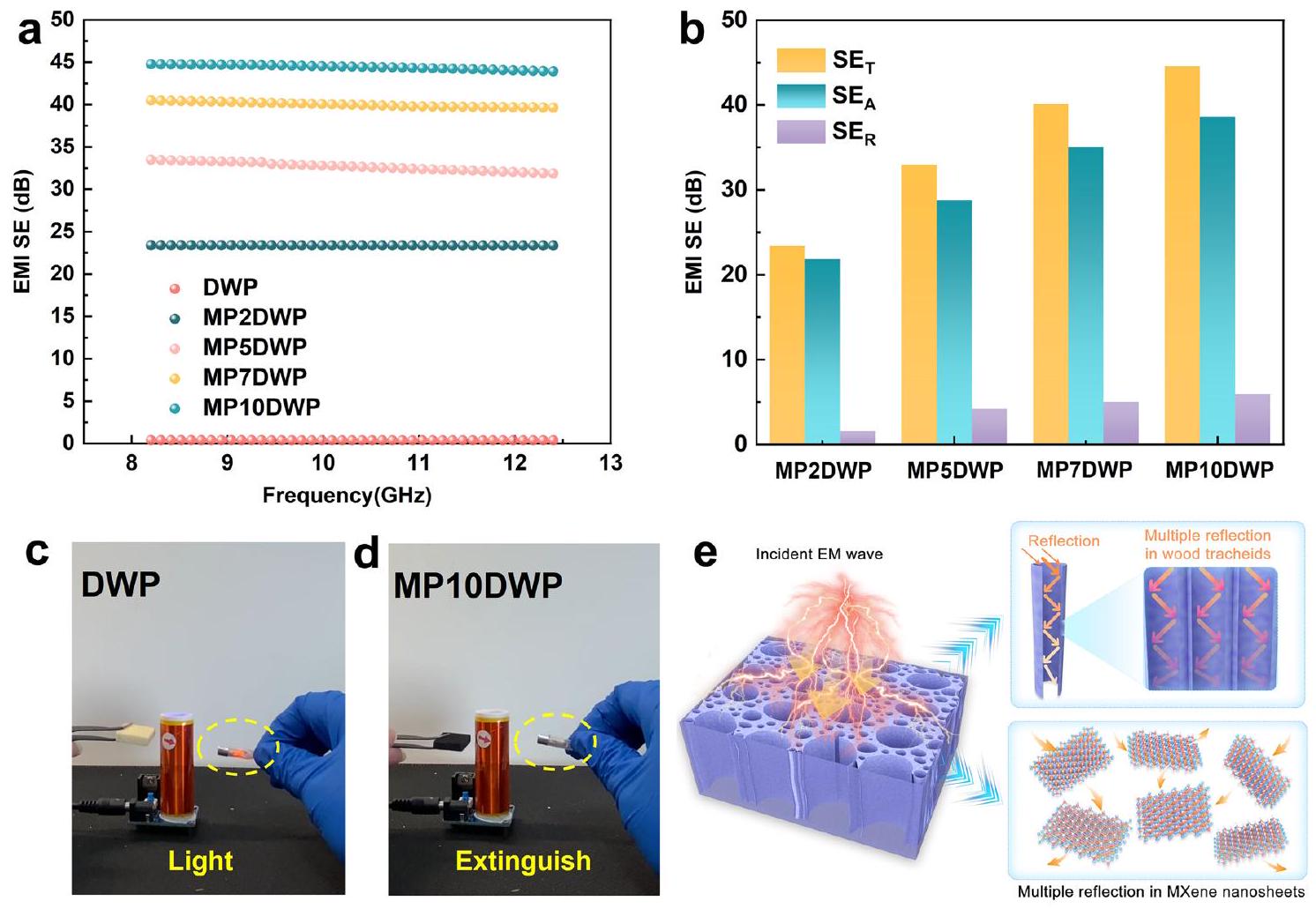

3.7 أداء درع الكهرومغناطيسية لمواد تغيير الطور المستندة إلى البلسا

فعالية الحماية، بما يتماشى مع النتائج في الشكل 9أ. كما هو متوقع، عندما اقترب MP10DWP من الملف، لوحظ أن المصباح انطفأ. حدث ذلك لأن تدخل MP10DWP عطل الانتشار الأصلي للموجات الكهرومغناطيسية، مما يبرز فعالية استراتيجية تعديل MXene المصممة.

4 الاستنتاجات

on MP10DWP، مع انخفاض معلمات مقاومة الحريق الحرجة مثل معدل إطلاق الحرارة الأقصى وإجمالي إطلاق الحرارة بنسبة

الإعلانات

References

- Y. Lin, Q. Kang, Y. Liu, Y. Zhu, P. Jiang et al., Flexible, highly thermally conductive and electrically insulating phase change materials for advanced thermal management of 5G base stations and thermoelectric generators. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 31 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-01003-3

- G. Simonsen, R. Ravotti, P. O’Neill, A. Stamatiou, Biobased phase change materials in energy storage and thermal management technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 184, 113546 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113546

- M. Shao, Z. Han, J. Sun, C. Xiao, S. Zhang et al., A review of multi-criteria decision making applications for renewable energy site selection. Renew. Energy 157, 377-403 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.04.137

- H. Sadeghi, R. Jalali, R.M. Singh, A review of borehole thermal energy storage and its integration into district heating systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 192, 114236 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.114236

- Y. Ma, J. Gong, P. Zeng, M. Liu, Recent progress in interfacial dipole engineering for perovskite solar cells. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 173 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01131-4

- G. Wang, Z. Tang, Y. Gao, P. Liu, Y. Li et al., Phase change thermal storage materials for interdisciplinary applications. Chem. Rev. 123, 6953-7024 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/ acs.chemrev.2c00572

- X. Li, X. Sheng, Y. Guo, X. Lu, H. Wu et al., Multifunctional HDPE/CNTs/PW composite phase change materials with excellent thermal and electrical conductivities. J. Mater. Sci. Techn. 37, 171-179 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2021.02.009

- J. Shen, Y. Ma, F. Zhou, X. Sheng, Y. Chen, Thermophysical properties investigation of phase change microcapsules with low supercooling and high energy storage capability: potential for efficient solar energy thermal management. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 191, 199-208 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst. 2024.01.014

- Y. Cao, P. Lian, Y. Chen, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Novel organically modified disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydratebased phase change composite for efficient solar energy storage and conversion. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 268, 112747 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2024.112747

- P. Lian, R. Yan, Z. Wu, Z. Wang, Y. Chen et al., Thermal performance of novel form-stable disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydrate-based composite phase change materials for building thermal energy storage. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 74 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00655-y

- Q. Xu, L. Zhu, Y. Pei, C. Yang, D. Yang et al., Heat transfer enhancement performance of microencapsulated phase change materials latent functional thermal fluid in solid/liquid phase transition regions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 214, 124461 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2023.124461

- D. Huang, Y. Chen, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Flexible thermoregulatory microcapsule/polyurethane-MXene composite films with multiple thermal management functionalities and excellent EMI shielding performance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 165, 27-38 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2023.05.013

- H. Liu, F. Zhou, X. Shi, K. Sun, Y. Kou et al., A thermoregulatory flexible phase change nonwoven for all-season highefficiency wearable thermal management. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 29 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-00991-6

- J. Wu, M. Wang, L. Dong, Y. Zhang, J. Shi et al., Highly integrated, breathable, metalized phase change fibrous membranes based on hierarchical coaxial fiber structure for multimodal personal thermal management. Chem. Eng. J. 465, 142835 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.142835

- D. Huang, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Y. Chen, Facile strategy for constructing highly thermally conductive PVDF-BN/PEG

phase change composites based on a salt template toward efficient thermal management of electronics. Appl. Therm. Eng. 232, 121041 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng. 2023.121041 - Y. Lin, Q. Kang, H. Wei, H. Bao, P. Jiang et al., Spider webinspired graphene skeleton-based high thermal conductivity phase change nanocomposites for battery thermal management. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 180 (2021). https://doi.org/10. 1007/s40820-021-00702-7

- H. He, M. Dong, Q. Wang, J. Zhang, Q. Feng et al., A multifunctional carbon-base phase change composite inspired by “fruit growth”. Carbon 205, 499-509 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.carbon.2023.01.038

- K. Chen, X. Yu, C. Tian, J. Wang, Preparation and characterization of form-stable paraffin/polyurethane composites as phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 77, 13-21 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. enconman.2013.09.015

- B. Liu, Y. Wang, T. Rabczuk, T. Olofsson, W. Lu, Multi-scale modeling in thermal conductivity of polyurethane incorporated with phase change materials using physics-informed neural networks. Renew. Energy 220, 119565 (2024). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2023.119565

- C. Zhu, Y. Hao, H. Wu, M. Chen, B. Quan et al., Self-assembly of binderless MXene aerogel for multiple-scenario and responsive phase change composites with ultrahigh thermal energy storage density and exceptional electromagnetic interference shielding. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 57 (2023). https://doi.org/10. 1007/s40820-023-01288-y

- M. Cheng, J. Hu, J. Xia, Q. Liu, T. Wei et al., One-step in situ green synthesis of cellulose nanocrystal aerogel based shape stable phase change material. Chem. Eng. J. 431, 133935 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.133935

- F. Pan, Z. Liu, B. Deng, Y. Dong, X. Zhu et al., Lotus leafderived gradient hierarchical porous

morphology genetic composites with wideband and tunable electromagnetic absorption performance. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 43 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00568-1 - L.A. Berglund, I. Burgert, Bioinspired wood nanotechnology for functional materials. Adv. Mater. 30, e1704285 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 201704285

- G. Yan, S. He, G. Chen, S. Ma, A. Zeng et al., Highly flexible and broad-range mechanically tunable all-wood hydrogels with nanoscale channels via the hofmeister effect for human motion monitoring. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 84 (2022). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-00827-3

- F. Qi, L. Wang, Y. Zhang, Z. Ma, H. Qiu et al., Robust

MXene/starch derived carbon foam composites for superior EMI shielding and thermal insulation. Mater. Today Phys. 21, 100512 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtphys.2021.100512 - T. Farid, M.I. Rafiq, A. Ali, W. Tang, Transforming wood as next-generation structural and functional materials for a sustainable future. EcoMat 4, e12154 (2022). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/eom2.12154

- J. Song, C. Chen, S. Zhu, M. Zhu, J. Dai et al., Processing bulk natural wood into a high-performance structural material.

28. S. Xiao, C. Chen, Q. Xia, Y. Liu, Y. Yao et al., Lightweight, strong, moldable wood via cell wall engineering as a sustainable structural material. Science 374, 465-471 (2021). https:// doi.org/10.1126/science.abg9556

29. B. Zhao, X. Shi, S. Khakalo, Y. Meng, A. Miettinen et al., Wood-based superblack. Nat. Commun. 14, 7875 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43594-4

30. K. Sheng, M. Tian, J. Zhu, Y. Zhang, B. Van der Bruggen, When coordination polymers meet wood: from molecular design toward sustainable solar desalination. ACS Nano 17, 15482-15491 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c014 21

31. S. Liu, H. Wu, Y. Du, X. Lu, J. Qu, Shape-stable composite phase change materials encapsulated by bio-based balsa wood for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 230, 111187 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2021.111187

32. H. Yang, S. Wang, X. Wang, W. Chao, N. Wang et al., Woodbased composite phase change materials with self-cleaning superhydrophobic surface for thermal energy storage. Appl. Energy 261, 114481 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apene rgy.2019.114481

33. H. Yang, W. Chao, X. Di, Z. Yang, T. Yang et al., Multifunctional wood based composite phase change materials for mag-netic-thermal and solar-thermal energy conversion and storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 200, 112029 (2019). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112029

34. L. Shu, H. Fang, S. Feng, J. Sun, F. Yang et al., Assembling all-wood-derived carbon/carbon dots-assisted phase change materials for high-efficiency thermal-energy harvesters. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 256, 128365 (2024). https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128365

35. Y. Liu, H. Yang, Y. Wang, C. Ma, S. Luo et al., Fluorescent thermochromic wood-based composite phase change materials based on aggregation-induced emission carbon dots for visual solar-thermal energy conversion and storage. Chem. Eng. J. 424, 130426 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.130426

36. X. Shi, Y. Meng, R. Bi, Z. Wan, Y. Zhu et al., Enabling unidirectional thermal conduction of wood-supported phase change material for photo-to-thermal energy conversion and heat regulation. Compos. Part B Eng. 245, 110231 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110231

37. W. Huang, H. Li, X. Lai, Z. Chen, L. Zheng et al., Graphene wrapped wood-based phase change composite for efficient electro-thermal energy conversion and storage. Cellulose 29, 223-232 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-021-04297-5

38. J. Wu, Y. Chen, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Electrostatic self-assembled MXene@PDDA-

39. Y. Cao, Z. Zeng, D. Huang, Y. Chen, L. Zhang et al., Multifunctional phase change composites based on biomass/ MXene-derived hybrid scaffolds for excellent electromagnetic interference shielding and superior solar/electro-thermal

energy storage. Nano Res. 15, 8524-8535 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1007/s12274-022-4626-6

40. L. Wang, Z. Ma, Y. Zhang, H. Qiu, K. Ruan et al., Mechanically strong and folding-endurance

41. Y. Zhang, K. Ruan, Y. Guo, J. Gu, Recent advances of MXenes-based optical functional materials. Adv. Photonics Res. 4, 2300224 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adpr. 20230 0224

42. Y. Zhang, K. Ruan, K. Zhou, J. Gu, Controlled distributed

43. X. Huang, Q. Weng, Y. Chen, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Accelerating phosphating process via hydrophobic MXene@SA nanocomposites for the significant improvement in anti-corrosion performance of plain carbon steel. Surf. Interfaces 45, 103911 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2024.103911

44. H. Jiang, Y. Xie, Y. Jiang, Y. Luo, X. Sheng et al., Rationally assembled sandwich structure of MXene-based phosphorous flame retardant at ultra-low loading nanosheets enabling fire-safe thermoplastic polyurethane. Appl. Surf. Sci. 649, 159111 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc. 2023.159111

45. C. Liang, H. Qiu, P. Song, X. Shi, J. Kong et al., Ultra-light MXene aerogel/wood-derived porous carbon composites with wall-like “mortar/brick” structures for electromagnetic interference shielding. Sci. Bull. 65, 616-622 (2020). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.scib.2020.02.009

46. Y. Jiang, X. Ru, W. Che, Z. Jiang, H. Chen et al., Flexible, mechanically robust and self-extinguishing MXene/wood composite for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. Part B Eng. 229, 109460 (2022). https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.compositesb.2021.109460

47. Y. Zhang, Y. Huang, M.-C. Li, S. Zhang, W. Zhou et al., Bioinspired, stable adhesive

48. H. Gao, N. Bing, Z. Bao, H. Xie, W. Yu, Sandwich-structured MXene/wood aerogel with waste heat utilization for continuous desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 454, 140362 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.140362

49. D. Zhang, K. Yang, X. Liu, M. Luo, Z. Li et al., Boosting the photothermal conversion efficiency of MXene film by porous wood for light-driven soft actuators. Chem. Eng. J. 450, 138013 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej. 2022.138013

50. M. Luo, D. Zhang, K. Yang, Z. Li, Z. Zhu et al., A flexible vertical-section wood/MXene electrode with excellent performance fabricated by building a highly accessible bonding interface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 40460-40468 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c12819

51. P.-L. Wang, C. Ma, Q. Yuan, T. Mai, M.-G. Ma, Novel

52. Y. Li, X. Li, D. Liu, X. Cheng, X. He et al., Fabrication and properties of polyethylene glycol-modified wood composite for energy storage and conversion. BioResources 11, 7790-7802 (2016). https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.11.3. 7790-7802

53. Y. Zhang, Y. Yan, H. Qiu, Z. Ma, K. Ruan et al., A mini-review of MXene porous films: preparation, mechanism and application. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 103, 42-49 (2022). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmst.2021.08.001

54. X. He, J. Wu, X. Huang, Y. Chen, L. Zhang et al., Three-inone polymer nanocomposite coating via constructing tannic acid functionalized MXene/BP hybrids with superior corrosion resistance, friction resistance, and flame-retardancy. Chem. Eng. Sci. 283, 119429 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ces.2023.119429

55. Y. Cao, M. Weng, M.H.H. Mahmoud, A.Y. Elnaggar, L. Zhang et al., Flame-retardant and leakage-proof phase change composites based on MXene/polyimide aerogels toward solar thermal energy harvesting. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 12531267 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00504-4

56. Y. Wei, C. Hu, Z. Dai, Y. Zhang, W. Zhang et al., Highly anisotropic MXene@Wood composites for tunable electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 168, 107476 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compo sitesa.2023.107476

57. Y. Meng, J. Majoinen, B. Zhao, O.J. Rojas, Form-stable phase change materials from mesoporous balsa after selective removal of lignin. Compos. Part B Eng. 199, 108296 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108296

58. Y. Yun, W. Chi, R. Liu, Y. Ning, W. Liu et al., Self-assembled polyacylated anthocyanins on anionic wood film as a multicolor sensor for tracking TVB-N of meat. Ind. Crops Prod. 208, 117834 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023. 117834

59. H. Yang, Y. Wang, Q. Yu, G. Cao, R. Yang et al., Composite phase change materials with good reversible thermochromic ability in delignified wood substrate for thermal energy storage. Appl. Energ. 212, 455-464 (2018). https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.apenergy.2017.12.006

60. L. Ma, C. Guo, R. Ou, L. Sun, Q. Wang et al., Preparation and characterization of modified porous wood flour/lauric-myristic acid eutectic mixture as a form-stable phase change material. Energy Fuels 32, 5453-5461 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/ acs.energyfuels.7b03933

61. B. Liang, X. Lu, R. Li, W. Tu, Z. Yang et al., Solvent-free preparation of bio-based polyethylene glycol/wood flour composites as novel shape-stabilized phase change materials for solar thermal energy storage. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. C 200, 110037 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2019.110037

62. R. Xia, W. Zhang, Y. Yang, J. Zhao, Y. Liu et al., Transparent wood with phase change heat storage as novel green energy

storage composites for building energy conservation. J. Clean. Prod. 296, 126598 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro. 2021.126598

63. M. He, J. Hu, H. Yan, X. Zhong, Y. Zhang et al., Shape anisotropic chain-like

64. X. Zhong, M. He, C. Zhang, Y. Guo, J. Hu et al., Heterostructured BN@Co-C@C endowing polyester composites excellent thermal conductivity and microwave absorption at C band. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2313544 (2024). https:// doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202313544

65. X. Chen, H. Gao, L. Xing, W. Dong, A. Li et al., Nanoconfinement effects of N -doped hierarchical carbon on thermal behaviors of organic phase change materials. Energy Storage Mater. 18, 280-288 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm. 2018.08.024

66. I. Shamseddine, F. Pennec, P. Biwole, F. Fardoun, Supercooling of phase change materials: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 158, 112172 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. rser.2022.112172

67. Z. Zeng, D. Huang, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Y. Chen, An innovative modified calcium chloride hexahydrate-based composite phase change material for thermal energy storage and indoor temperature regulation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 80 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00654-z

68. Y. Luo, Y. Xie, W. Geng, G. Dai, X. Sheng et al., Fabrication of thermoplastic polyurethane with functionalized MXene towards high mechanical strength, flame-retardant, and smoke suppression properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 606, 223-235 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2021.08. 025

69. J. Wang, H. Yue, Z. Du, X. Cheng, H. Wang et al., Flameretardant and form-stable delignified wood-based phase change composites with superior energy storage density and reversible thermochromic properties for visual thermoregulation. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 11, 3932-3943 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c07635

70. L. Tang, K. Ruan, X. Liu, Y. Tang, Y. Zhang et al., Flexible and robust functionalized boron nitride/poly( p -phenylene benzobisoxazole) nanocomposite paper with high thermal conductivity and outstanding electrical insulation. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 38 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01257-5

71. S. Yin, X. Ren, R. Zheng, Y. Li, J. Zhao et al., Improving fire safety and mechanical properties of waterborne polyurethane by montmorillonite-passivated black phosphorus. Chem. Eng. J. 464, 142683 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023. 142683

72. P. Lin, J. Xie, Y. He, X. Lu, W. Li et al., MXene aerogel-based phase change materials toward solar energy conversion. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 206, 110229 (2020). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.solmat.2019.110229

73. C. Liang, H. Qiu, Y. Zhang, Y. Liu, J. Gu, External fieldassisted techniques for polymer matrix composites with

electromagnetic interference shielding. Sci. Bull. 68, 19381953 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2023.07.046

74. S. Shi, Y. Jiang, H. Ren, S. Deng, J. Sun et al., 3D-printed carbon-based conformal electromagnetic interference shielding module for integrated electronics. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 85 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01317-w

75. C. Liang, Z. Gu, Y. Zhang, Z. Ma, H. Qiu et al., Structural design strategies of polymer matrix composites for electromagnetic interference shielding: a review. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 181 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-021-00707-2

76. J. Xiao, B. Zhan, M. He, X. Qi, X. Gong et al., Interfacial polarization loss improvement induced by the hollow engineering of necklace-like PAN/carbon nanofibers for boosted microwave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2316722 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202316722

77. J. Yang, H. Wang, Y. Zhang, H. Zhang, J. Gu, Layered structural PBAT composite foams for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 31 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01246-8

Yang Meng, mengyang@kust.edu.cn; Xinxin Sheng, xinxin.sheng@gdut.edu.cn; Delong Xie, cedlxie@kust.edu.cn

Yunnan Provincial Key Laboratory of Energy Saving in Phosphorus Chemical Engineering and New Phosphorus Materials, The International Joint Laboratory for Sustainable Polymers of Yunnan Province, The Higher Educational Key Laboratory for Phosphorus Chemical Engineering of Yunnan Province, Faculty of Chemical Engineering, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming 650500, People’s Republic of China

Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Functional Soft Condensed Matter, School of Materials and Energy, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou 510006, People’s Republic of China

Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Macromolecular Science and Technology, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710072, People’s Republic of China

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-024-01414-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38753068

Publication Date: 2024-05-16

Cite as

Received: 8 February 2024

Published online: 16 May 2024

© The Author(s) 2024

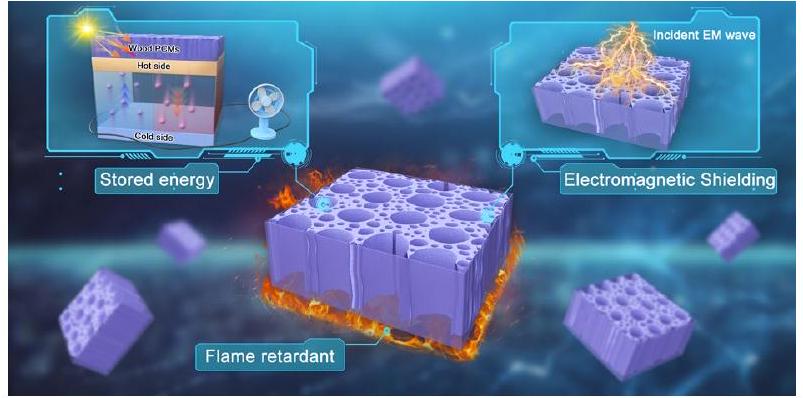

Leakage Proof, Flame-Retardant, and Electromagnetic Shield Wood Morphology Genetic Composite Phase Change Materials for Solar Thermal Energy Harvesting

HIGHLIGHTS

- An innovative class of versatile form-stable composite phase change materials (CPCMs) was fruitfully exploited, featuring MXene/ phytic acid hybrid depositing on non-carbonized wood as a robust support.

- The wood-based CPCMs showcase enhanced thermal conductivity of

( 4.6 times than polyethylene glycol) as well as high latent heat of ( encapsulation) with thermal durability and stability throughout at least 200 heating and cooling cycles. - The wood-based CPCMs have good solar-thermal-electricity conversion, flame-retardant, and electromagnetic shielding properties.

Abstract

Phase change materials (PCMs) offer a promising solution to address the challenges posed by intermittency and fluctuations in solar thermal utilization. However, for organic solid-liquid PCMs, issues such as leakage, low thermal conductivity, lack of efficient solar-thermal media, and flammability have constrained their broad applications. Herein, we present an innovative class of versatile composite phase change materials (CPCMs) developed through a facile and environmentally friendly synthesis approach, leveraging the inherent anisotropy and unidirectional porosity of wood aerogel (nanowood) to  support polyethylene glycol (PEG). The wood modification process involves the incorporation of phytic acid (PA) and MXene hybrid structure through an evaporation-induced assembly method, which could impart non-leaking PEG filling while concurrently facilitating thermal conduction, light absorption, and flame-retardant. Consequently, the as-prepared wood-based CPCMs showcase enhanced thermal conductivity (

support polyethylene glycol (PEG). The wood modification process involves the incorporation of phytic acid (PA) and MXene hybrid structure through an evaporation-induced assembly method, which could impart non-leaking PEG filling while concurrently facilitating thermal conduction, light absorption, and flame-retardant. Consequently, the as-prepared wood-based CPCMs showcase enhanced thermal conductivity (

1 Introduction

preparation of form-stable composite phase change materials (CPCMs). However, the intricate manufacturing process has resulted in increased production costs as well as the generation of numerous toxic by-products and pollutants, posing a significant challenge to the principles of sustainable development. Therefore, there is a compelling need for the development of 3D porous scaffolds that are both effective and sustainable, featuring ease of manufacturing and ensuring environmental friendliness. Fortunately, the exquisite structures found in biological organisms have inspired the development of alternative synthetic encapsulation matrices [22]. Derived from natural structures, biobased materials can be obtained through a facile “top-down approach”, eliminating the need for complex construction processes [23-25]. As for wood, a prime example of nature’s intricate design, featuring meticulously aligned structures like hollow vessels, tracheid elements, and membranes such as pits designed for efficient water and ion transport [26]. The hierarchical porosity inherent in wood, extending from the macroscale to the nanoscale, positions it as a highly promising functional material [27, 28]. Beyond its well-known roles in liquid absorption and fluid filtration [29,30], wood emerges as a compelling candidate for encapsulating PCMs. Liu et al. [31] achieved encapsulation efficiencies of

influence of gravitational forces. It is reported that utilizing surface engineering techniques to foster the growth of functional two-dimensional (2D) nanofillers on the surface of the wood-derived scaffold represents a viable approach to address the aforementioned challenges [36, 37]. For instance, MXene, a novel 2D stacked lamellar material constituting transition metal carbides and carbonitrides, is obtained through the etching and exfoliation of MAX phases [38], showcasing exceptional capabilities in photothermal conversion [39], thermal conductivity [40], and optical application [41]. In addition, the surface of MXene is enriched with plentiful active functional groups, such as

mechanism proved to be instrumental in preventing leakage during thermal storage processes. A comprehensive evaluation, encompassing chemical structure, crystalline state, microscopic morphology, encapsulation capability, phase change performance, thermal repeatability, fireretardant behavior, solar-thermal-electricity conversion, and electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness, was conducted to provide a nuanced understanding of the overall properties of the CPCMs. As anticipated, the multi-faceted approach via facile MXene and PA hybrid wood modification promotes the multifunctionalization of the as-prepared form-stable CPCMs, making them promising candidates for diverse applications.

2 Experimental Section

2.1 Fabrication of Wood Aerogel and MXene/PA Hybrid Modification

mass fractions in the wood aerogel framework of

2.2 Impregnation with PEG for the Preparation of CPCMs

of solar to electricity conversion and electromagnetic shielding performance, are all demonstrated in Supporting Information.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Balsa-Derived Framework and MXene/PA Hybrid Modification

of single-layer or few-layer MXene that exhibits pronounced Tyndall scattering (Fig. 2d). This attests to the superior dispersibility of MXene in water, owing to its abundant hydrophilic functional groups (e.g.,

respectively [57]. Both are indicative of hemicelluloses, specifically amorphous polysaccharides. Also, faint peaks detected at 1590,1505 , and

3.2 CPCMs Morphology and Encapsulation Capability

nanowood scaffold, while the exposure of more hydrophilic groups (e.g.,

3.3 Thermal Properties and Phase Change Behavior of the Balsa-Derived CPCMs

point (

common limitation of organic PCMs. When encapsulated in nanowood, the oriented framework induces anisotropic thermal conductivity. Along the longitudinal direction, upright axial tracheid cell walls create directed thermal pathways, facilitating rapid heat conduction (Fig. 5e). However, for DWP, due to the inherently low thermal conductivity of nanowood, the increase is only by a factor of 2.2 times. In the radial direction (Fig. 5f), heat conduction involves repetitions through thin cell walls to PEG and back, resulting in a less significant increase, merely by a factor of 1.6 times. These findings align with Yang et al. [33]’s study. The introduction of MXene as a thermal conductive filler substantially boosts the CPCMs’ thermal conductivity. Specifically, with

supercooling less than

3.4 Thermal Reliability and Repeatability of Balsa-Derived CPCMs

carbonization process during decomposition. As expected, the aforementioned hypotheses are substantiated by the residual carbon values of MPDWPs. With an increase in MXene content, there is an observable upward trend in residual carbon values, notably reaching 7.3% at 10.1% MXene content. Considering practical applications of CPCMs, particularly in solar-to-thermal conversion and storage, all MPDWPs exhibit barely thermal degradation below

well-suited for practical applications in reversible thermal energy storage.

3.5 Flame-Retardant Performance of Balsa-Derived CPCMs

of PA and MXene, which effectively inhibit both combustion gas and heat transmission.

3.6 Solar to Electricity Conversion of Balsa-Derived CPCMs

where

stands for the surface area of the samples. The parameters

3.7 Electromagnetic Shielding Performance of Balsa-Derived CPCMs

shielding effectiveness, consistent with the results in Fig. 9a. As anticipated, when MP10DWP approached the coil, the bulb was observed to extinguish. This occurred because the intervention of MP10DWP disrupted the original propagation of electromagnetic waves, emphasizing the effectiveness of the designed MXene modification strategy.

4 Conclusions

on MP10DWP, with critical fire-retardant parameters such as peak heat release rate and total heat release decreasing by

Declarations

References

- Y. Lin, Q. Kang, Y. Liu, Y. Zhu, P. Jiang et al., Flexible, highly thermally conductive and electrically insulating phase change materials for advanced thermal management of 5G base stations and thermoelectric generators. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 31 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-01003-3

- G. Simonsen, R. Ravotti, P. O’Neill, A. Stamatiou, Biobased phase change materials in energy storage and thermal management technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 184, 113546 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113546

- M. Shao, Z. Han, J. Sun, C. Xiao, S. Zhang et al., A review of multi-criteria decision making applications for renewable energy site selection. Renew. Energy 157, 377-403 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.04.137

- H. Sadeghi, R. Jalali, R.M. Singh, A review of borehole thermal energy storage and its integration into district heating systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 192, 114236 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.114236

- Y. Ma, J. Gong, P. Zeng, M. Liu, Recent progress in interfacial dipole engineering for perovskite solar cells. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 173 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01131-4

- G. Wang, Z. Tang, Y. Gao, P. Liu, Y. Li et al., Phase change thermal storage materials for interdisciplinary applications. Chem. Rev. 123, 6953-7024 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/ acs.chemrev.2c00572

- X. Li, X. Sheng, Y. Guo, X. Lu, H. Wu et al., Multifunctional HDPE/CNTs/PW composite phase change materials with excellent thermal and electrical conductivities. J. Mater. Sci. Techn. 37, 171-179 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2021.02.009

- J. Shen, Y. Ma, F. Zhou, X. Sheng, Y. Chen, Thermophysical properties investigation of phase change microcapsules with low supercooling and high energy storage capability: potential for efficient solar energy thermal management. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 191, 199-208 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst. 2024.01.014

- Y. Cao, P. Lian, Y. Chen, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Novel organically modified disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydratebased phase change composite for efficient solar energy storage and conversion. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 268, 112747 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2024.112747

- P. Lian, R. Yan, Z. Wu, Z. Wang, Y. Chen et al., Thermal performance of novel form-stable disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydrate-based composite phase change materials for building thermal energy storage. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 74 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00655-y

- Q. Xu, L. Zhu, Y. Pei, C. Yang, D. Yang et al., Heat transfer enhancement performance of microencapsulated phase change materials latent functional thermal fluid in solid/liquid phase transition regions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 214, 124461 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2023.124461

- D. Huang, Y. Chen, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Flexible thermoregulatory microcapsule/polyurethane-MXene composite films with multiple thermal management functionalities and excellent EMI shielding performance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 165, 27-38 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2023.05.013

- H. Liu, F. Zhou, X. Shi, K. Sun, Y. Kou et al., A thermoregulatory flexible phase change nonwoven for all-season highefficiency wearable thermal management. Nano-Micro Lett. 15, 29 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-00991-6

- J. Wu, M. Wang, L. Dong, Y. Zhang, J. Shi et al., Highly integrated, breathable, metalized phase change fibrous membranes based on hierarchical coaxial fiber structure for multimodal personal thermal management. Chem. Eng. J. 465, 142835 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.142835

- D. Huang, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Y. Chen, Facile strategy for constructing highly thermally conductive PVDF-BN/PEG

phase change composites based on a salt template toward efficient thermal management of electronics. Appl. Therm. Eng. 232, 121041 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng. 2023.121041 - Y. Lin, Q. Kang, H. Wei, H. Bao, P. Jiang et al., Spider webinspired graphene skeleton-based high thermal conductivity phase change nanocomposites for battery thermal management. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 180 (2021). https://doi.org/10. 1007/s40820-021-00702-7

- H. He, M. Dong, Q. Wang, J. Zhang, Q. Feng et al., A multifunctional carbon-base phase change composite inspired by “fruit growth”. Carbon 205, 499-509 (2023). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.carbon.2023.01.038

- K. Chen, X. Yu, C. Tian, J. Wang, Preparation and characterization of form-stable paraffin/polyurethane composites as phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 77, 13-21 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. enconman.2013.09.015

- B. Liu, Y. Wang, T. Rabczuk, T. Olofsson, W. Lu, Multi-scale modeling in thermal conductivity of polyurethane incorporated with phase change materials using physics-informed neural networks. Renew. Energy 220, 119565 (2024). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2023.119565

- C. Zhu, Y. Hao, H. Wu, M. Chen, B. Quan et al., Self-assembly of binderless MXene aerogel for multiple-scenario and responsive phase change composites with ultrahigh thermal energy storage density and exceptional electromagnetic interference shielding. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 57 (2023). https://doi.org/10. 1007/s40820-023-01288-y

- M. Cheng, J. Hu, J. Xia, Q. Liu, T. Wei et al., One-step in situ green synthesis of cellulose nanocrystal aerogel based shape stable phase change material. Chem. Eng. J. 431, 133935 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.133935

- F. Pan, Z. Liu, B. Deng, Y. Dong, X. Zhu et al., Lotus leafderived gradient hierarchical porous

morphology genetic composites with wideband and tunable electromagnetic absorption performance. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 43 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00568-1 - L.A. Berglund, I. Burgert, Bioinspired wood nanotechnology for functional materials. Adv. Mater. 30, e1704285 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma. 201704285

- G. Yan, S. He, G. Chen, S. Ma, A. Zeng et al., Highly flexible and broad-range mechanically tunable all-wood hydrogels with nanoscale channels via the hofmeister effect for human motion monitoring. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 84 (2022). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-00827-3

- F. Qi, L. Wang, Y. Zhang, Z. Ma, H. Qiu et al., Robust

MXene/starch derived carbon foam composites for superior EMI shielding and thermal insulation. Mater. Today Phys. 21, 100512 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtphys.2021.100512 - T. Farid, M.I. Rafiq, A. Ali, W. Tang, Transforming wood as next-generation structural and functional materials for a sustainable future. EcoMat 4, e12154 (2022). https://doi.org/ 10.1002/eom2.12154

- J. Song, C. Chen, S. Zhu, M. Zhu, J. Dai et al., Processing bulk natural wood into a high-performance structural material.

28. S. Xiao, C. Chen, Q. Xia, Y. Liu, Y. Yao et al., Lightweight, strong, moldable wood via cell wall engineering as a sustainable structural material. Science 374, 465-471 (2021). https:// doi.org/10.1126/science.abg9556

29. B. Zhao, X. Shi, S. Khakalo, Y. Meng, A. Miettinen et al., Wood-based superblack. Nat. Commun. 14, 7875 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43594-4

30. K. Sheng, M. Tian, J. Zhu, Y. Zhang, B. Van der Bruggen, When coordination polymers meet wood: from molecular design toward sustainable solar desalination. ACS Nano 17, 15482-15491 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c014 21

31. S. Liu, H. Wu, Y. Du, X. Lu, J. Qu, Shape-stable composite phase change materials encapsulated by bio-based balsa wood for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 230, 111187 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2021.111187

32. H. Yang, S. Wang, X. Wang, W. Chao, N. Wang et al., Woodbased composite phase change materials with self-cleaning superhydrophobic surface for thermal energy storage. Appl. Energy 261, 114481 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apene rgy.2019.114481

33. H. Yang, W. Chao, X. Di, Z. Yang, T. Yang et al., Multifunctional wood based composite phase change materials for mag-netic-thermal and solar-thermal energy conversion and storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 200, 112029 (2019). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112029

34. L. Shu, H. Fang, S. Feng, J. Sun, F. Yang et al., Assembling all-wood-derived carbon/carbon dots-assisted phase change materials for high-efficiency thermal-energy harvesters. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 256, 128365 (2024). https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128365

35. Y. Liu, H. Yang, Y. Wang, C. Ma, S. Luo et al., Fluorescent thermochromic wood-based composite phase change materials based on aggregation-induced emission carbon dots for visual solar-thermal energy conversion and storage. Chem. Eng. J. 424, 130426 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.130426

36. X. Shi, Y. Meng, R. Bi, Z. Wan, Y. Zhu et al., Enabling unidirectional thermal conduction of wood-supported phase change material for photo-to-thermal energy conversion and heat regulation. Compos. Part B Eng. 245, 110231 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110231

37. W. Huang, H. Li, X. Lai, Z. Chen, L. Zheng et al., Graphene wrapped wood-based phase change composite for efficient electro-thermal energy conversion and storage. Cellulose 29, 223-232 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10570-021-04297-5

38. J. Wu, Y. Chen, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Electrostatic self-assembled MXene@PDDA-

39. Y. Cao, Z. Zeng, D. Huang, Y. Chen, L. Zhang et al., Multifunctional phase change composites based on biomass/ MXene-derived hybrid scaffolds for excellent electromagnetic interference shielding and superior solar/electro-thermal

energy storage. Nano Res. 15, 8524-8535 (2022). https://doi. org/10.1007/s12274-022-4626-6

40. L. Wang, Z. Ma, Y. Zhang, H. Qiu, K. Ruan et al., Mechanically strong and folding-endurance

41. Y. Zhang, K. Ruan, Y. Guo, J. Gu, Recent advances of MXenes-based optical functional materials. Adv. Photonics Res. 4, 2300224 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/adpr. 20230 0224

42. Y. Zhang, K. Ruan, K. Zhou, J. Gu, Controlled distributed

43. X. Huang, Q. Weng, Y. Chen, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Accelerating phosphating process via hydrophobic MXene@SA nanocomposites for the significant improvement in anti-corrosion performance of plain carbon steel. Surf. Interfaces 45, 103911 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2024.103911

44. H. Jiang, Y. Xie, Y. Jiang, Y. Luo, X. Sheng et al., Rationally assembled sandwich structure of MXene-based phosphorous flame retardant at ultra-low loading nanosheets enabling fire-safe thermoplastic polyurethane. Appl. Surf. Sci. 649, 159111 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc. 2023.159111

45. C. Liang, H. Qiu, P. Song, X. Shi, J. Kong et al., Ultra-light MXene aerogel/wood-derived porous carbon composites with wall-like “mortar/brick” structures for electromagnetic interference shielding. Sci. Bull. 65, 616-622 (2020). https://doi. org/10.1016/j.scib.2020.02.009

46. Y. Jiang, X. Ru, W. Che, Z. Jiang, H. Chen et al., Flexible, mechanically robust and self-extinguishing MXene/wood composite for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. Part B Eng. 229, 109460 (2022). https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.compositesb.2021.109460

47. Y. Zhang, Y. Huang, M.-C. Li, S. Zhang, W. Zhou et al., Bioinspired, stable adhesive

48. H. Gao, N. Bing, Z. Bao, H. Xie, W. Yu, Sandwich-structured MXene/wood aerogel with waste heat utilization for continuous desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 454, 140362 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2022.140362

49. D. Zhang, K. Yang, X. Liu, M. Luo, Z. Li et al., Boosting the photothermal conversion efficiency of MXene film by porous wood for light-driven soft actuators. Chem. Eng. J. 450, 138013 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej. 2022.138013

50. M. Luo, D. Zhang, K. Yang, Z. Li, Z. Zhu et al., A flexible vertical-section wood/MXene electrode with excellent performance fabricated by building a highly accessible bonding interface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 40460-40468 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c12819

51. P.-L. Wang, C. Ma, Q. Yuan, T. Mai, M.-G. Ma, Novel

52. Y. Li, X. Li, D. Liu, X. Cheng, X. He et al., Fabrication and properties of polyethylene glycol-modified wood composite for energy storage and conversion. BioResources 11, 7790-7802 (2016). https://doi.org/10.15376/biores.11.3. 7790-7802

53. Y. Zhang, Y. Yan, H. Qiu, Z. Ma, K. Ruan et al., A mini-review of MXene porous films: preparation, mechanism and application. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 103, 42-49 (2022). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmst.2021.08.001

54. X. He, J. Wu, X. Huang, Y. Chen, L. Zhang et al., Three-inone polymer nanocomposite coating via constructing tannic acid functionalized MXene/BP hybrids with superior corrosion resistance, friction resistance, and flame-retardancy. Chem. Eng. Sci. 283, 119429 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ces.2023.119429

55. Y. Cao, M. Weng, M.H.H. Mahmoud, A.Y. Elnaggar, L. Zhang et al., Flame-retardant and leakage-proof phase change composites based on MXene/polyimide aerogels toward solar thermal energy harvesting. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 5, 12531267 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-022-00504-4

56. Y. Wei, C. Hu, Z. Dai, Y. Zhang, W. Zhang et al., Highly anisotropic MXene@Wood composites for tunable electromagnetic interference shielding. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 168, 107476 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compo sitesa.2023.107476

57. Y. Meng, J. Majoinen, B. Zhao, O.J. Rojas, Form-stable phase change materials from mesoporous balsa after selective removal of lignin. Compos. Part B Eng. 199, 108296 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108296

58. Y. Yun, W. Chi, R. Liu, Y. Ning, W. Liu et al., Self-assembled polyacylated anthocyanins on anionic wood film as a multicolor sensor for tracking TVB-N of meat. Ind. Crops Prod. 208, 117834 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023. 117834

59. H. Yang, Y. Wang, Q. Yu, G. Cao, R. Yang et al., Composite phase change materials with good reversible thermochromic ability in delignified wood substrate for thermal energy storage. Appl. Energ. 212, 455-464 (2018). https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.apenergy.2017.12.006

60. L. Ma, C. Guo, R. Ou, L. Sun, Q. Wang et al., Preparation and characterization of modified porous wood flour/lauric-myristic acid eutectic mixture as a form-stable phase change material. Energy Fuels 32, 5453-5461 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/ acs.energyfuels.7b03933

61. B. Liang, X. Lu, R. Li, W. Tu, Z. Yang et al., Solvent-free preparation of bio-based polyethylene glycol/wood flour composites as novel shape-stabilized phase change materials for solar thermal energy storage. Sol. Energ. Mat. Sol. C 200, 110037 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2019.110037

62. R. Xia, W. Zhang, Y. Yang, J. Zhao, Y. Liu et al., Transparent wood with phase change heat storage as novel green energy

storage composites for building energy conservation. J. Clean. Prod. 296, 126598 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro. 2021.126598

63. M. He, J. Hu, H. Yan, X. Zhong, Y. Zhang et al., Shape anisotropic chain-like

64. X. Zhong, M. He, C. Zhang, Y. Guo, J. Hu et al., Heterostructured BN@Co-C@C endowing polyester composites excellent thermal conductivity and microwave absorption at C band. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2313544 (2024). https:// doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202313544

65. X. Chen, H. Gao, L. Xing, W. Dong, A. Li et al., Nanoconfinement effects of N -doped hierarchical carbon on thermal behaviors of organic phase change materials. Energy Storage Mater. 18, 280-288 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm. 2018.08.024

66. I. Shamseddine, F. Pennec, P. Biwole, F. Fardoun, Supercooling of phase change materials: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 158, 112172 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. rser.2022.112172

67. Z. Zeng, D. Huang, L. Zhang, X. Sheng, Y. Chen, An innovative modified calcium chloride hexahydrate-based composite phase change material for thermal energy storage and indoor temperature regulation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 6, 80 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42114-023-00654-z

68. Y. Luo, Y. Xie, W. Geng, G. Dai, X. Sheng et al., Fabrication of thermoplastic polyurethane with functionalized MXene towards high mechanical strength, flame-retardant, and smoke suppression properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 606, 223-235 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2021.08. 025

69. J. Wang, H. Yue, Z. Du, X. Cheng, H. Wang et al., Flameretardant and form-stable delignified wood-based phase change composites with superior energy storage density and reversible thermochromic properties for visual thermoregulation. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 11, 3932-3943 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c07635

70. L. Tang, K. Ruan, X. Liu, Y. Tang, Y. Zhang et al., Flexible and robust functionalized boron nitride/poly( p -phenylene benzobisoxazole) nanocomposite paper with high thermal conductivity and outstanding electrical insulation. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 38 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01257-5

71. S. Yin, X. Ren, R. Zheng, Y. Li, J. Zhao et al., Improving fire safety and mechanical properties of waterborne polyurethane by montmorillonite-passivated black phosphorus. Chem. Eng. J. 464, 142683 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023. 142683

72. P. Lin, J. Xie, Y. He, X. Lu, W. Li et al., MXene aerogel-based phase change materials toward solar energy conversion. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 206, 110229 (2020). https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.solmat.2019.110229

73. C. Liang, H. Qiu, Y. Zhang, Y. Liu, J. Gu, External fieldassisted techniques for polymer matrix composites with

electromagnetic interference shielding. Sci. Bull. 68, 19381953 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2023.07.046

74. S. Shi, Y. Jiang, H. Ren, S. Deng, J. Sun et al., 3D-printed carbon-based conformal electromagnetic interference shielding module for integrated electronics. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 85 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01317-w

75. C. Liang, Z. Gu, Y. Zhang, Z. Ma, H. Qiu et al., Structural design strategies of polymer matrix composites for electromagnetic interference shielding: a review. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 181 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-021-00707-2

76. J. Xiao, B. Zhan, M. He, X. Qi, X. Gong et al., Interfacial polarization loss improvement induced by the hollow engineering of necklace-like PAN/carbon nanofibers for boosted microwave absorption. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2316722 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202316722

77. J. Yang, H. Wang, Y. Zhang, H. Zhang, J. Gu, Layered structural PBAT composite foams for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Nano-Micro Lett. 16, 31 (2023). https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40820-023-01246-8

Yang Meng, mengyang@kust.edu.cn; Xinxin Sheng, xinxin.sheng@gdut.edu.cn; Delong Xie, cedlxie@kust.edu.cn

Yunnan Provincial Key Laboratory of Energy Saving in Phosphorus Chemical Engineering and New Phosphorus Materials, The International Joint Laboratory for Sustainable Polymers of Yunnan Province, The Higher Educational Key Laboratory for Phosphorus Chemical Engineering of Yunnan Province, Faculty of Chemical Engineering, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming 650500, People’s Republic of China

Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Functional Soft Condensed Matter, School of Materials and Energy, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou 510006, People’s Republic of China

Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Macromolecular Science and Technology, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Northwestern Polytechnical University, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710072, People’s Republic of China