DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242×241237171

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38501268

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-19

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

نحو مؤشرات الاقتصاد الدائري: أدلة من الاتحاد الأوروبي

الملخص

الاتحاد الأوروبي (EU) يتحرك نحو التنمية المستدامة، وتلعب نماذج الاقتصاد الدائري (CE) دورًا رئيسيًا في تقليل الضغط على الموارد الطبيعية، وتوليد الوظائف وتعزيز الفرص الاقتصادية. المؤشرات قادرة على تجميع مجموعة متنوعة من المعلومات واستخدامها، من خلال استخدام تحليل القرار متعدد المعايير (MCDA)، يسمح بمراقبة أداء البدائل. يهدف هذا العمل إلى حساب أداء دول الاتحاد الأوروبي 27 في السنوات 2019 و2020 وفقًا لـ 15 مؤشرًا للاقتصاد الدائري متاحة على يوروستات. تظهر نتائج عملية التحليل الهرمي أن أكبر تأثير على الدائرية يتحدد من خلال فئة “التنافسية والابتكار”، التي تمثل مع فئة “الاستدامة العالمية والمرونة” ثلثي الوزن الإجمالي. تظهر نتائج MCDA أن بلجيكا تتفوق في كل من السيناريوهات الأساسية والبديلة، متقدمة على إيطاليا وهولندا على التوالي. بشكل عام، تتفوق السياسات الدائرية في دول غرب أوروبا، بينما أداء دول شرق أوروبا أضعف. تسلط تداعيات هذا العمل الضوء على الحواجز الرئيسية الثلاثة لتطوير نماذج الاقتصاد الدائري: (i) إدارة النفايات غير القانونية؛ (ii) نقص المعرفة وانخفاض مستوى الاستثمار في التقنيات الدائرية و (iii) انخفاض توزيع القيمة بين أصحاب المصلحة. بهذه الطريقة، ستمكن إدارة الموارد القائمة على الدائرية أوروبا من مواجهة تحديات الاستدامة مع تقليل الاعتماد على المواد الخام المستوردة.

الكلمات الرئيسية

مقدمة

نهج (لويزيا وآخرون، 2021) واندماجات في سياقات مختلفة (أربولينو وآخرون، 2021؛ فاكّي وآخرون، 2021).

من خلال خطط الأعمال، يمكن للشركات تحديد وتنفيذ المؤشر الأكثر ملاءمة للدائرية (باروس وآخرون، 2023). المقارنة بين الدول مثيرة للاهتمام حيث يمكن أن تسمح للدول الفاضلة بأن تُكافأ من خلال التعاون الدولي في تبادل المعلومات، والحوافز لتدريب العمال، ومشاركة المعرفة والتكنولوجيا في إعادة التدوير (دي ألميدا وبورساتو، 2019). يمكن الحصول على دائرية أداء الدول الأوروبية من خلال تحليل القرار متعدد المعايير (MCDA) استنادًا إلى بيانات يوروستات (كولاسانتي وآخرون، 2022)، وهناك ارتباط بين الدائرية وكفاءة الطاقة والملاءة في دول الاتحاد الأوروبي (زيزوبولوس وآخرون، 2022).

طرق

| فئة | الاختصارات | المعايير | الاختصارات |

| الإنتاج والاستهلاك | PC | إنتاجية الموارد | PC1 |

| توليد النفايات الصلبة الحضرية للفرد | PC2 | ||

| توليد نفايات التعبئة للفرد | PC3 | ||

| إدارة النفايات | WM | معدل إعادة تدوير النفايات البلدية | WM1 |

| معدل إعادة تدوير نفايات التعبئة حسب نوع التعبئة | WM2 | ||

| معدل إعادة تدوير نفايات المعدات الكهربائية والإلكترونية التي تم جمعها بشكل منفصل | WM3 | ||

| المواد الخام الثانوية | RM | معدل استخدام المواد الدائرية | RM1 |

| تجارة المواد الخام القابلة لإعادة التدوير (الواردات) | RM2 | ||

| تجارة المواد الخام القابلة لإعادة التدوير (الصادرات) | RM3 | ||

| التنافسية والابتكار | Cl | الاستثمار الخاص والقيمة المضافة الإجمالية المتعلقة بقطاعات الاقتصاد الدائري | Cl1 |

| الأشخاص العاملون في قطاعات الاقتصاد الدائري | Cl2 | ||

| براءات الاختراع المتعلقة بإعادة التدوير والمواد الخام الثانوية | Cl3 | ||

| الاستدامة العالمية والمرونة | SR | البصمة الاستهلاكية | SR1 |

| انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة من الأنشطة الإنتاجية | SR2 | ||

| اعتماد استيراد المواد | SR3 |

المعايير التي اعتبرناها باستبعاد مؤشرين كانا يميلان إلى أن يكونا متشابهين جدًا مع مؤشرات أخرى تم اعتبارها بالفعل: ‘توليد نفايات التعبئة البلاستيكية للفرد’ مقارنة بالمؤشر ‘توليد نفايات التعبئة للفرد’ الموجود في نفس فئة PC و’البصمة المادية’ مقارنة بالمؤشر ‘البصمة الاستهلاكية’ الموجود في فئة SR. يقترح الجدول 1 قائمة الـ 15 معيارًا مقسمة إلى 5 فئات. يمكن العثور على وصف كامل لهذه المؤشرات كما اقترحته يوروستات في الجدول التكميلي S1.

إلى عدد معقول من المرشحين المحتملين (Ladu وآخرون، 2020)، وحدد البريد الإلكتروني أنه سيتم اختيار أول 10 فقط. احتوى البريد الإلكتروني على هدف الدراسة والمنهجية المستخدمة. تألفت اللجنة المختارة من

النتائج

(القسم ‘مؤشر الاقتصاد الدائري – سيناريو الأساس’) والسيناريو البديل (القسم ‘مؤشر الاقتصاد الدائري – السيناريو البديل’).

تجميع الأوزان

| الفئات | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | E8 | E9 | E10 | متوسط |

| حاسوب شخصي | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| WM | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| RM | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| كلور | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.34 |

| ريال سعودي | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.33 |

| معايير | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | E8 | E9 | E10 | متوسط |

| الإنتاج والاستهلاك | |||||||||||

| بي سي 1 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.39 |

| بي سي 2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.40 |

| بي سي 3 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.21 |

| إدارة النفايات | |||||||||||

| WM1 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.42 |

| WM2 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| WM3 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.38 |

| المواد الخام الثانوية | |||||||||||

| RM1 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.43 |

| RM2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.30 |

| RM3 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.28 |

| التنافسية والابتكار | |||||||||||

| كل1 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.45 |

| Cl2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.34 |

| كلور ثلاثي | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| الاستدامة العالمية والمرونة | |||||||||||

| SR1 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.36 |

| SR2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.37 |

| SR3 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.27 |

جمع إعادة التدوير، مما يمنح فوائد للمستهلكين الذين يقومون بسلوكيات أكثر فضيلة.

فرق كبير عن معيار آخر. على وجه الخصوص، أولى الخبراء اهتمامًا للميزة التي تشير إلى أن المعايير الثلاثة مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بأنماط الاقتصاد الدائري. تم إعطاء اهتمام خاص للمعيار CI1، بمتوسط وزن قدره 0.45 اختاره ثمانية خبراء كالأكثر صلة. يشير هذا المعيار إلى ثلاثة قطاعات: (i) إعادة التدوير، (ii) الإصلاح وإعادة الاستخدام و(iii) الإيجار والتأجير. من ناحية أخرى، أعطى خبيران أهمية أكبر للمعيار CI2 (0.34) الذي يشير إلى عدد الأشخاص المتأثرين المرتبطين مرة أخرى بالقطاعات المذكورة أعلاه. أخيرًا، يُشير الخبراء إلى أن المعيار الآخر CI3، بمتوسط وزن قدره 0.21، يُعتبر أيضًا مهمًا، ولكن في مقارنة ثنائية، تظهر الأرقام المتعلقة ببراءات اختراع الحلول الدائرية في وضع غير موات.

| معايير | أولوية محلية | تصنيف | أولوية عالمية | تصنيف |

| الإنتاج والاستهلاك (الأولوية: 0.0847) | ||||

| بي سي 1 | 0.390 | 2 | 0.0330 | 12 |

| بي سي 2 | 0.401 | 1 | 0.0340 | 10 |

| بي سي 3 | 0.209 | ٣ | 0.0177 | 15 |

| إدارة النفايات (الأولوية: 0.1378) | ||||

| WM1 | 0.419 | 1 | 0.0577 | ٧ |

| WM2 | 0.198 | ٣ | 0.0272 | 14 |

| WM3 | 0.383 | 2 | 0.0528 | ٨ |

| المواد الخام الثانوية (الأولوية: 0.1127) | ||||

| RM1 | 0.425 | 1 | 0.0479 | 9 |

| RM2 | 0.295 | 2 | 0.0333 | 11 |

| RM3 | 0.279 | ٣ | 0.0314 | ١٣ |

| التنافسية والابتكار (الأولوية: 0.3363) | ||||

| كل1 | 0.455 | 1 | 0.1530 | 1 |

| Cl2 | 0.336 | 2 | 0.1131 | ٤ |

| كلوريد ثلاثي | 0.209 | ٣ | 0.0703 | ٦ |

| الاستدامة العالمية والمرونة (الأولوية: 0.3286) | ||||

| SR1 | 0.360 | 2 | 0.1184 | ٣ |

| SR2 | 0.372 | 1 | 0.1222 | ٢ |

| SR3 | 0.268 | ٣ | 0.0879 | ٥ |

تجميع القيم

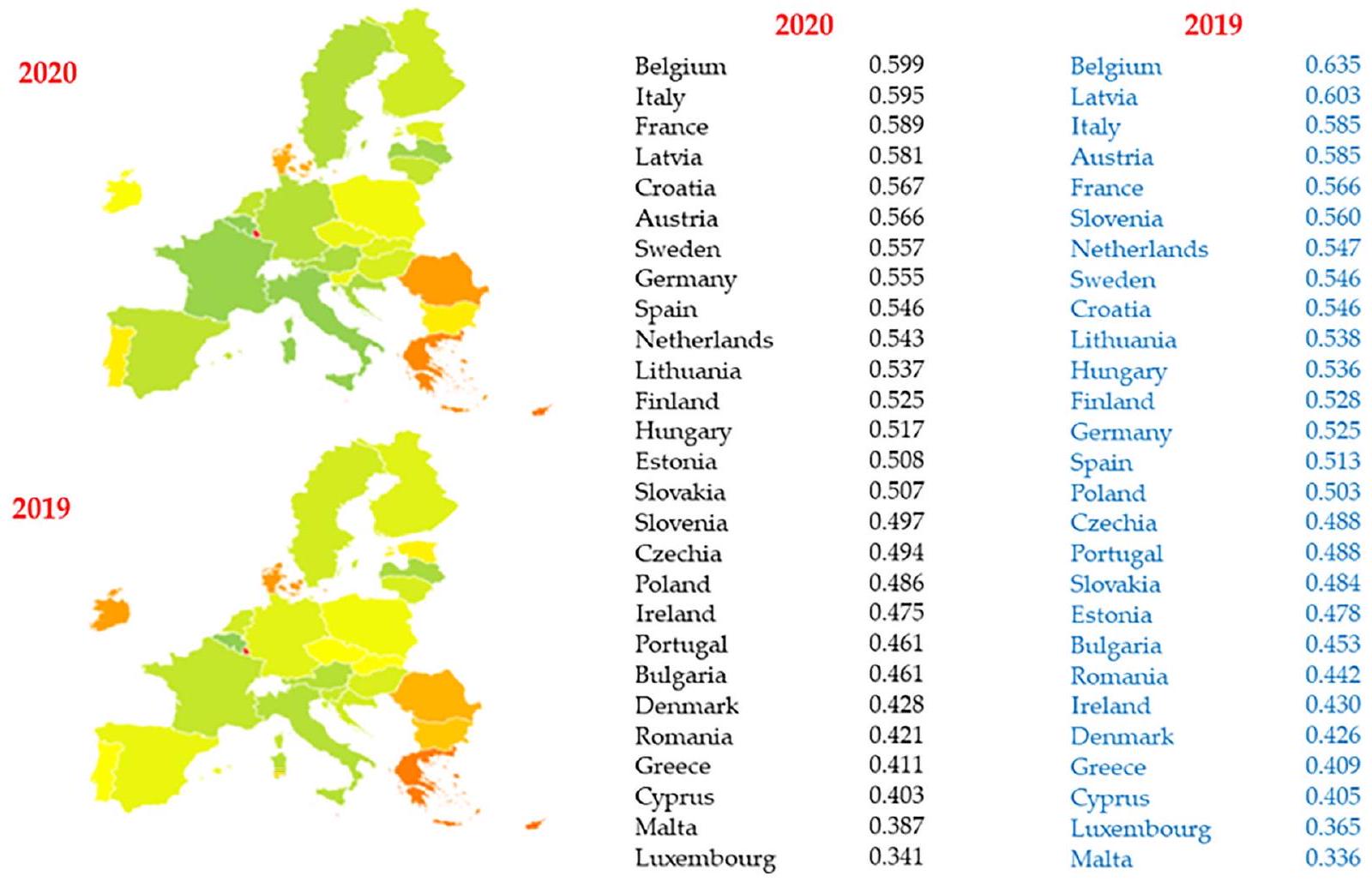

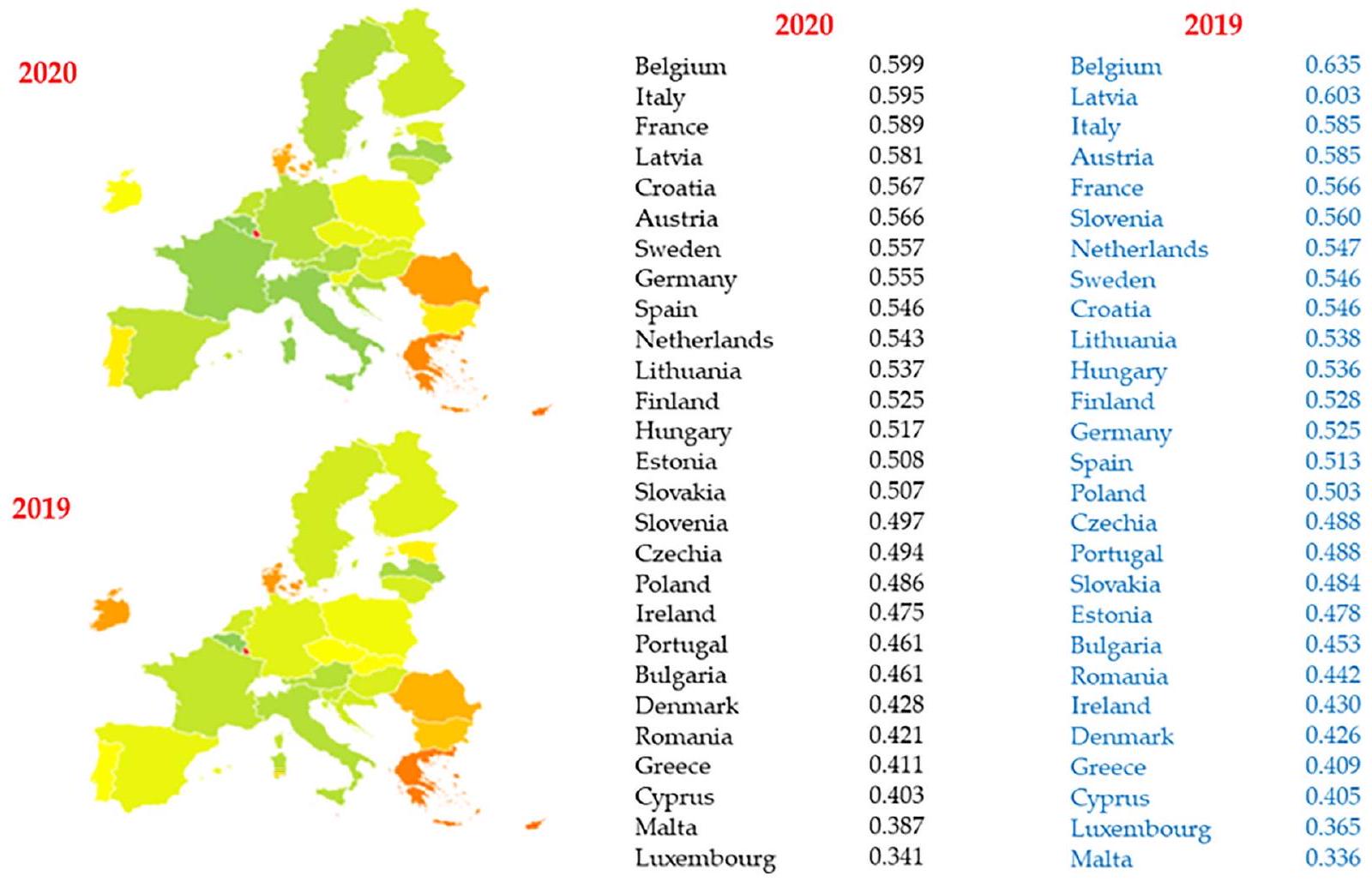

مؤشر CE: سيناريو الأساس

أكبر زيادة ملحوظة هي مالطا (+0.0509) تليها أيرلندا (+0.0445) وإسبانيا (+0.0326). الأداء الضعيف في عدة مؤشرات أدى إلى احتلال قبرص ومالطا ولوكسمبورغ المراتب الأخيرة في الترتيب الأوروبي.

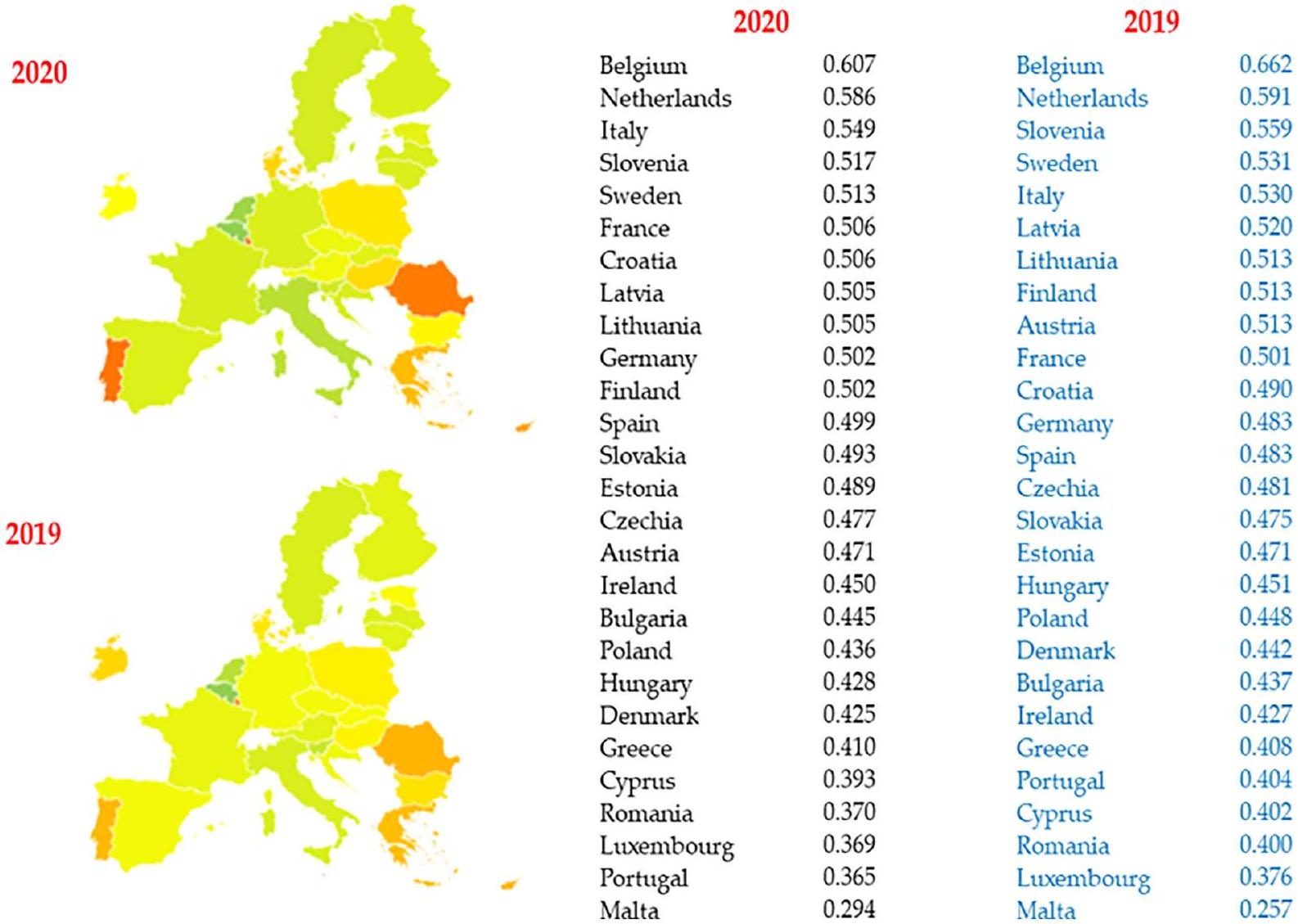

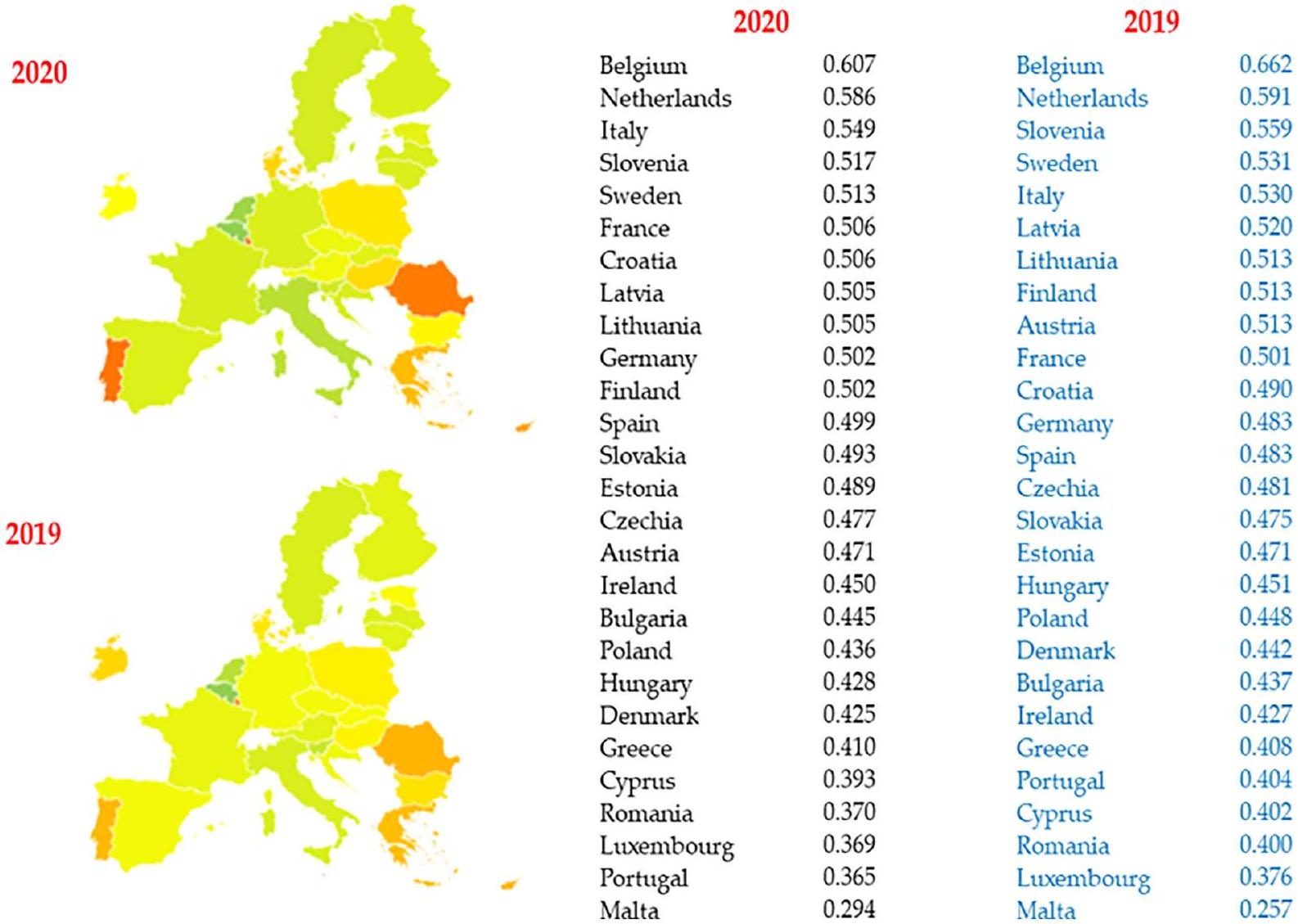

مؤشر CE: سيناريو بديل

| خط الأساس Rkg | بلد | قيمة الأساس | قيمة بديلة |

|

|

| 1 | بلجيكا | 0.599 | 0.607 | 0.008 | 0 |

| 2 | إيطاليا | 0.595 | 0.549 | -0.046 | -1 |

| ٣ | فرنسا | 0.589 | 0.506 | -0.083 | -3 |

| ٤ | لاتفيا | 0.581 | 0.505 | -0.075 | -٤ |

| ٥ | كرواتيا | 0.567 | 0.506 | -0.061 | -2 |

| ٦ | النمسا | 0.566 | 0.471 | -0.095 | -10 |

| ٧ | السويد | 0.557 | 0.513 | -0.044 | 2 |

| ٨ | ألمانيا | 0.555 | 0.502 | -0.052 | -2 |

| 9 | إسبانيا | 0.546 | 0.499 | -0.047 | -3 |

| 10 | هولندا | 0.543 | 0.586 | 0.044 | ٨ |

| 11 | ليتوانيا | 0.537 | 0.505 | -0.032 | 2 |

| 12 | فنلندا | 0.525 | 0.502 | -0.023 | 1 |

| ١٣ | المجر | 0.517 | 0.428 | -0.088 | -7 |

| 14 | إستونيا | 0.508 | 0.489 | -0.019 | 0 |

| 15 | سلوفاكيا | 0.507 | 0.493 | -0.014 | ٢ |

| 16 | سلوفينيا | 0.497 | 0.517 | 0.021 | 12 |

| 17 | التشيك | 0.494 | 0.477 | -0.017 | 2 |

| ١٨ | بولندا | 0.486 | 0.436 | -0.050 | -1 |

| 19 | أيرلندا | 0.475 | 0.450 | -0.025 | 2 |

| 20 | البرتغال | 0.461 | 0.365 | -0.096 | -6 |

| 21 | بلغاريا | 0.461 | 0.445 | -0.016 | ٣ |

| ٢٢ | الدنمارك | 0.428 | 0.425 | -0.003 | 1 |

| 23 | رومانيا | 0.421 | 0.370 | -0.051 | -1 |

| ٢٤ | اليونان | 0.411 | 0.410 | -0.001 | 2 |

| ٢٥ | قبرص | 0.403 | 0.393 | -0.011 | 2 |

| ٢٦ | مالطا | 0.387 | 0.294 | -0.093 | -1 |

| 27 | لوكسمبورغ | 0.341 | 0.369 | 0.028 | 2 |

نقاش

إن الطلب على التنمية المستدامة لا يتركز في أوروبا، يمكن أن يكون نموذج الاقتصاد الدائري استراتيجية لتقليل الاعتماد على الخارج. ومع ذلك، فإن هذا ممكن عندما يتم الحصول على المواد الخام التي لا تؤثر درجة نقائها على وظيفة المنتجات، وتصبح هذه المواد الخام بدائل لتلك التي تأتي من استخراج المواد الخام. إن خطر ارتداد الاقتصاد الدائري هو نهج غير مستدام حيث يتم تنفيذ النماذج الدائرية، ولكن لا يتبع ذلك أي تغيير في أنماط الاستهلاك (Caferra et al.، 2023؛ Kirchherr، 2022).

الاستنتاجات

- تقليل النفايات غير القانونية من أجل تطبيق المبادئ ليس فقط للوقاية ولكن أيضًا لمبادئ القرب.

- زيادة الاستثمار في التقنيات الدائرية من خلال الاستثمار في رأس المال البشري وتعزيز تطوير الشركات الناشئة والشركات الصغيرة والمتوسطة التي يقودها الشباب.

- توزيع أكثر استدامة للفوائد الناتجة عن النماذج الدائرية على فئات مختلفة من أصحاب المصلحة.

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

التمويل

معرفات ORCID

ماسيمو غاستالدي (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0867-3352

المواد التكميلية

References

Arbolino R, Boffardi R, De Simone L, et al. (2021) Multi-objective optimization technique: A novel approach in tourism sustainability planning. Journal of Environmental Management 285: 112016.

Awasthi A, Omrani H and Gerber P (2018) Investigating ideal-solution based multicriteria decision making techniques for sustainability evaluation of urban mobility projects. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 116: 247-259.

Bączkiewicz A and Kizielewicz B (2021) Towards sustainable energy consumption evaluation in europe for industrial sector based on MCDA methods. Procedia Computer Science 192: 1334-1346.

Barma M, Biniyamin HK, Modibbo UM, et al. (2022) Mathematical model for the optimization of municipal solid waste management. Frontiers in Sustainability 3: 880409.

Barma M and Modibbo UM (2022) Multiobjective mathematical optimization model for municipal solid waste management with economic analysis of reuse/recycling recovered waste materials. Journal of Computational and Cognitive Engineering 1: 122-137.

Barros MV, Salvador R, Gallego-Schmid A, et al. (2023) Circularity measurement of external resource flows in companies: The circular flow tool. Waste Management 158: 136-145.

Beekhuizen J, Heuvelink GBM, Huss A, et al. (2014) Impact of input data uncertainty on environmental exposure assessment models: A case study for electromagnetic field modelling from mobile phone base stations. Environmental Research 135: 148-155.

Bockreis A and Ragossnig AM (2023) Celebrating WM&R’s first 40 years. Waste Management & Research 41: 1-2.

Caferra R, Tsironis G, Morone A, et al. (2023) Is the circular economy proposed as sustainability in firm mission statements? A semantic analysis. Environmental Technology & Innovation 32: 103304.

Chen TL, Kim H, Pan SY, et al. (2020) Implementation of green chemistry principles in circular economy system towards sustainable development goals: Challenges and perspectives. Science of the Total Environment 716: 136998.

Chiappetta Jabbour CJ, Lopes de Sousa Jabbour AB, Sarkis J, et al. (2019) Unlocking the circular economy through new business models based on large-scale data: An integrative framework and research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 144: 546-552.

Colasante A, D’Adamo I, Morone P, et al. (2022) Assessing the circularity performance in a European cross-country comparison. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 93: 106730.

D’Adamo I, Desideri S, Gastaldi M, et al. (2023a) Sustainable food waste management in supermarkets. Sustainable Production and Consumption 43: 204-216.

D’Adamo I, Ferella F, Gastaldi M, et al. (2023b) Circular solar: evaluating the profitability of a photovoltaic panel recycling plant. Waste Management & Research 41: 1144-1154.

D’Adamo I, Mazzanti M, Morone P, et al. (2022) Assessing the relation between waste management policies and circular economy goals. Waste Managemen 154: 27-35.

D’Adamo I and Sassanelli C (2022) A mini-review of biomethane valorization: Managerial and policy implications for a circular resource. Waste Management & Research 40: 1745-1756.

D’Amato A, Mazzanti M, Nicolli F, et al. (2018) Illegal waste disposal: Enforcement actions and decentralized environmental policy. SocioEconomic Planning Sciences 64: 56-65.

De Almeida ST and Borsato M (2019) Assessing the efficiency of end of life technology in waste treatment – A bibliometric literature review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 140: 189-208.

De Pascale A, Arbolino R, Szopik-Depczyńska K, et al. (2021) A systematic review for measuring circular economy: The 61 indicators. Journal of Cleaner Production 281: 124942.

European Environment Agency (2016) Circular Economy in EuropeDeveloping the Knowledge Base. Copenhagen: Publications Office.

Fernández-Miguel A, Riccardi MP, Veglio V, et al. (2022) Disruption in resource-intensive supply chains: Reshoring and nearshoring as strategies to enable them to become more resilient and sustainable. Sustainability 14: 10909.

Hartley K, van Santen R and Kirchherr J (2020) Policies for transitioning towards a circular economy: Expectations from the European Union (EU). Resources, Conservation and Recycling 155: 104634.

Henry M, Bauwens T, Hekkert M, et al. (2020) A typology of circular startups: An analysis of 128 circular business models. Journal of Cleaner Production 245: 118528.

Ioppolo G, Saija G and Salomone R (2012) Developing a territory balanced scorecard approach to manage projects for local development: Two case studies. Land Use Policy 29: 629-640.

Islam A, Ahmed T, Awual MR, et al. (2020) Advances in sustainable approaches to recover metals from e-waste-A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 244: 118815.

Kirchherr J (2023) Bullshit in the sustainability and transitions literature: A provocation. Circular Economy and Sustainability 3: 167-172.

Kirchherr J (2022) Circular economy and growth: A critical review of ‘post-growth’ circularity and a plea for a circular economy that grows. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 179: 1-2.

Kirchherr J, Reike D and Hekkert M (2017) Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 127: 221-232.

Kirchherr J, Yang N-HN, Schulze-Spüntrup F, et al. (2023) Conceptualizing the circular economy (revisited): An analysis of 221 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 194: 107001.

Knäble D, de Quevedo Puente E, Pérez-Cornejo C, et al. (2022) The impact of the circular economy on sustainable development: A European panel data approach. Sustainable Production and Consumption 34: 233-243.

Ladu L, Imbert E, Quitzow R, et al. (2020) The role of the policy mix in the transition toward a circular forest bioeconomy. Forest Policy and Economics 110: 101937.

Laso J, Margallo M, García-Herrero I, et al. (2018) Combined application of Life Cycle Assessment and linear programming to evaluate food waste-to-food strategies: Seeking for answers in the nexus approach. Waste Management 80: 186-197.

Loizia P, Voukkali I, Chatziparaskeva G, et al. (2021) Measuring the level of environmental performance on coastal environment before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study from cyprus. Sustainability 13: 2485.

Lombardi GV, Gastaldi M, Rapposelli A, et al. (2021) Assessing efficiency of urban waste services and the role of tariff in a circular economy perspective: An empirical application for Italian municipalities. Journal of Cleaner Production 323: 129097.

Mazzanti M and Montini A (2014) Waste management beyond the NorthSouth divide: Spatial analyses of geographical, economic and institutional dimensions. In: Takeuchi K and Kinnaman TC (eds.) Handbook on Waste Management. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Pub. Ltd., pp. 1-22.

Moktadir MA, Kumar A, Ali SM, et al. (2020) Critical success factors for a circular economy: Implications for business strategy and the environment. Business Strategy and the Environment 29: 3611-3635.

Moraga G, Huysveld S, Mathieux F, et al. (2019) Circular economy indicators: What do they measure? Resources, Conservation and Recycling 146: 452-461.

Papamichael I and Zorpas AA (2022) End-of-waste criteria in the framework of end-of-life PV panels concerning circular economy strategy. Waste Management & Research 40: 1677-1679.

Pophali GR, Chelani AB and Dhodapkar RS (2011) Optimal selection of full scale tannery effluent treatment alternative using integrated AHP and GRA approach. Expert Systems with Applications 38: 10889-10895.

Quicker P, Consonni S and Grosso M (2020) The Zero Waste utopia and the role of waste-to-energy. Waste Management & Research 38: 481-484.

Ragossnig AM and Schneider DR (2019) Circular economy, recycling and end-of-waste. Waste Management & Research 37: 109-111.

Romano G, Lombardi GV, Rapposelli A, et al. (2022) The factors affecting Italian provinces’ separate waste-collection rates: An empirical investigation. Waste Management 139: 217-226.

Saaty TL (2008) Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. International Journal of Services Sciences 1: 83-98.

Saidani M, Yannou B, Leroy Y, et al. (2019) A taxonomy of circular economy indicators. Journal of Cleaner Production 207: 542-559.

Shooshtarian S, Maqsood T, Caldera S, et al. (2022) Transformation towards a circular economy in the Australian construction and demolition waste management system. Sustainable Production and Consumption 30: 89-106.

Tsui T, Peck D, Geldermans B, et al. (2021) The role of urban manufacturing for a circular economy in cities. Sustainability 13: 23.

Vacchi M, Siligardi C, Cedillo-González EI, et al. (2021) Industry 4.0 and smart data as enablers of the circular economy in manufacturing: Product re-engineering with circular eco-design. Sustainability 13: 10366.

Voukkali I, Papamichael I, Loizia P, et al. (2023) Waste metrics in the framework of circular economy. Waste Management & Research 41: 1741-1753.

Zink T and Geyer R (2017) Circular economy rebound. Journal of Industrial Ecology 21: 593-602.

Zisopoulos FK, Schraven DFJ and de Jong M (2022) How robust is the circular economy in Europe? An ascendency analysis with Eurostat data between 2010 and 2018. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 178: 106032.

Zorpas AA, Voukkali I and Navarro Pedreño J (2018) Tourist area metabolism and its potential to change through a proposed strategic plan in the framework of sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production 172: 3609-3620.

Department of Computer, Control and Management Engineering, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Department of Industrial and Information Engineering and Economics, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy

Department of Social Sciences and Business, Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark

Innovation Studies Group, Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands Cambridge Centre for Environment, Energy and Natural Resource Governance, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK المؤلف المراسل:

ماسيمو غاستالدي، قسم الهندسة الصناعية والمعلوماتية والاقتصاد، جامعة لاكويلا، عبر غرونشي 18، لاكويلا 67100، إيطاليا.

البريد الإلكتروني: massimo.gastaldidunivaq.it

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242×241237171

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38501268

Publication Date: 2024-03-19

© The Author(s) 2024

Towards circular economy indicators: Evidence from the European Union

Abstract

The European Union (EU) is moving towards sustainable development, and a key role is played by circular economy (CE) models geared towards reducing pressure on natural resources, generating jobs and fostering economic opportunities. Indicators are able to aggregate a variety of information and their use, through the use of multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), allows the performance of alternatives to be monitored. This work aims to calculate the performance of the EU27 in the years 2019 and 2020 according to 15 CE indicators available on Eurostat. The results of the Analytic Hierarchy process show that the greatest impact on circularity is determined by the category ‘competitiveness and innovation’, which together with the category ‘global sustainability and resilience’ accounts for two thirds of the overall weight. The MCDA results show that Belgium prevails in both the baseline and alternative scenarios, ahead of Italy and the Netherlands respectively. In general, circular policies see western European countries excel, while the performance of eastern European countries is weaker. The implications of this work highlight the three main barriers to the development of CE models: (i) illegal waste management; (ii) lack of knowledge and low level of investment in circular technologies and (iii) low distribution of value among stakeholders. In this way, resource management based on circularity will enable Europe to meet the challenges of sustainability with less dependence on imported raw materials.

Keywords

Introduction

approaches (Loizia et al., 2021) and integrations in different contexts (Arbolino et al., 2021; Vacchi et al., 2021).

business plans, firms can determine and implement the most appropriate circularity indicator (Barros et al., 2023). The comparison between countries is interesting as it can allow virtuous countries to be rewarded through international cooperation in the exchange of information, incentives for the training of workers and the sharing of knowledge and technology on recycling (De Almeida and Borsato, 2019). The circularity of European countries’ performance can be obtained through multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) based on Eurostat data (Colasante et al., 2022), and there is a link between circularity, energy efficiency and soundness in EU countries (Zisopoulos et al., 2022).

Methods

| Category | Acronyms | Criteria | Acronyms |

| Production and consumption | PC | Resource productivity | PC1 |

| Generation of MSW per capita | PC2 | ||

| Generation of packaging waste per capita | PC3 | ||

| Waste management | WM | Recycling rate of municipal waste | WM1 |

| Recycling rate of packaging waste by type of packaging | WM2 | ||

| Recycling rate of waste of electrical and electronic equipment separately collected | WM3 | ||

| Secondary raw materials | RM | Circular material use rate | RM1 |

| Trade in recyclable raw materials (imports) | RM2 | ||

| Trade in recyclable raw materials (exports) | RM3 | ||

| Competitiveness and innovation | Cl | Private investment and gross added value related to circular economy sectors | Cl1 |

| Persons employed in circular economy sectors | Cl2 | ||

| Patents related to recycling and secondary raw materials | Cl3 | ||

| Global sustainability and resilience | SR | Consumption footprint | SR1 |

| Greenhouse gases emissions from production activities | SR2 | ||

| Material import dependency | SR3 |

criteria we had considered excluding two indicators that tended to be very similar to other indicators already considered: ‘Generation of plastic packaging waste per capita’ compared to the indicator ‘Generation of packaging waste per capita’ found in the same PC category and ‘Material footprint’ compared to the indicator ‘Consumption footprint’ found in SR category. Table 1 proposes the list of the 15 criteria divided into the 5 categories. A complete description of these indicators as proposed by Eurostat can be found in Supplemental Table S1.

invitation was sent to a reasonable number of potential interviewees (Ladu et al., 2020), and the e-mail specified that only the first 10 would be selected. Contained within the email was the objective of the study and the methodology used. The selected panel consisted of

Results

(section ‘Circular economy indicator – Baseline scenario’) and the alternative scenario (section ‘Circular economy indicator Alternative scenario’).

Aggregation of weights

| Categories | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | E8 | E9 | E10 | Avg |

| PC | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| WM | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| RM | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Cl | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.28 | 0.34 |

| SR | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.33 |

| Criteria | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | E8 | E9 | E10 | Avg |

| Production and consumption | |||||||||||

| PC1 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.39 |

| PC2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.40 |

| PC3 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.21 |

| Waste management | |||||||||||

| WM1 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.42 |

| WM2 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| WM3 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.38 |

| Secondary raw materials | |||||||||||

| RM1 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.43 |

| RM2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.30 |

| RM3 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.28 |

| Competitiveness and innovation | |||||||||||

| Cl1 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.45 |

| Cl2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.34 |

| Cl3 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| Global sustainability and resilience | |||||||||||

| SR1 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.36 |

| SR2 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.37 |

| SR3 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.27 |

of recycling collection, giving benefits to consumers who perform even more virtuous behaviour.

significant difference from another criterion. In particular, experts paid attention to the feature that all three criteria are strongly correlated with CE patterns. Particular attention is given to criterion CI1, with an average weight of 0.45 chosen as most relevant by eight experts. This criterion refers to three sectors: (i) the recycling, (ii) repair and reuse and (iii) rental and leasing. Two experts, on the other hand, gave greater relevance to CI2 (0.34) referring to the number of people impregnated related again to the above-mentioned sectors. Finally, it is pointed out that according to the experts, the other criterion CI3, with an average weight of 0.21 , is also considered important, but in a pairwise comparison, the figure for patents of circular solutions comes out at a disadvantage.

| Criteria | Local priority | Ranking | Global priority | Ranking |

| Production and consumption (priority: 0.0847) | ||||

| PC1 | 0.390 | 2 | 0.0330 | 12 |

| PC2 | 0.401 | 1 | 0.0340 | 10 |

| PC3 | 0.209 | 3 | 0.0177 | 15 |

| Waste management (priority: 0.1378) | ||||

| WM1 | 0.419 | 1 | 0.0577 | 7 |

| WM2 | 0.198 | 3 | 0.0272 | 14 |

| WM3 | 0.383 | 2 | 0.0528 | 8 |

| Secondary raw materials (priority: 0.1127) | ||||

| RM1 | 0.425 | 1 | 0.0479 | 9 |

| RM2 | 0.295 | 2 | 0.0333 | 11 |

| RM3 | 0.279 | 3 | 0.0314 | 13 |

| Competitiveness and innovation (priority: 0.3363) | ||||

| Cl1 | 0.455 | 1 | 0.1530 | 1 |

| Cl2 | 0.336 | 2 | 0.1131 | 4 |

| Cl3 | 0.209 | 3 | 0.0703 | 6 |

| Global sustainability and resilience (priority: 0.3286) | ||||

| SR1 | 0.360 | 2 | 0.1184 | 3 |

| SR2 | 0.372 | 1 | 0.1222 | 2 |

| SR3 | 0.268 | 3 | 0.0879 | 5 |

Aggregation of values

CE indicator: Baseline scenario

the most significant increase is Malta ( +0.0509 ) followed by Ireland (+0.0445) and Spain (+0.0326). Weak performances in multiple indicators lead Cyprus, Malta and Luxembourg to close the European ranking.

CE indicator: Alternative scenario

| Baseline Rkg | Country | Baseline value | Alternative value |

|

|

| 1 | Belgium | 0.599 | 0.607 | 0.008 | 0 |

| 2 | Italy | 0.595 | 0.549 | -0.046 | -1 |

| 3 | France | 0.589 | 0.506 | -0.083 | -3 |

| 4 | Latvia | 0.581 | 0.505 | -0.075 | -4 |

| 5 | Croatia | 0.567 | 0.506 | -0.061 | -2 |

| 6 | Austria | 0.566 | 0.471 | -0.095 | -10 |

| 7 | Sweden | 0.557 | 0.513 | -0.044 | 2 |

| 8 | Germany | 0.555 | 0.502 | -0.052 | -2 |

| 9 | Spain | 0.546 | 0.499 | -0.047 | -3 |

| 10 | Netherlands | 0.543 | 0.586 | 0.044 | 8 |

| 11 | Lithuania | 0.537 | 0.505 | -0.032 | 2 |

| 12 | Finland | 0.525 | 0.502 | -0.023 | 1 |

| 13 | Hungary | 0.517 | 0.428 | -0.088 | -7 |

| 14 | Estonia | 0.508 | 0.489 | -0.019 | 0 |

| 15 | Slovakia | 0.507 | 0.493 | -0.014 | 2 |

| 16 | Slovenia | 0.497 | 0.517 | 0.021 | 12 |

| 17 | Czechia | 0.494 | 0.477 | -0.017 | 2 |

| 18 | Poland | 0.486 | 0.436 | -0.050 | -1 |

| 19 | Ireland | 0.475 | 0.450 | -0.025 | 2 |

| 20 | Portugal | 0.461 | 0.365 | -0.096 | -6 |

| 21 | Bulgaria | 0.461 | 0.445 | -0.016 | 3 |

| 22 | Denmark | 0.428 | 0.425 | -0.003 | 1 |

| 23 | Romania | 0.421 | 0.370 | -0.051 | -1 |

| 24 | Greece | 0.411 | 0.410 | -0.001 | 2 |

| 25 | Cyprus | 0.403 | 0.393 | -0.011 | 2 |

| 26 | Malta | 0.387 | 0.294 | -0.093 | -1 |

| 27 | Luxembourg | 0.341 | 0.369 | 0.028 | 2 |

Discussion

demand for sustainable development are not concentrated in Europe, the CE model could be a strategy to reduce foreign dependence. However, this is possible when RMs are obtained whose degree of purity does not compromise the functionality of products, and these RMs become substitutes for those that originate from the extraction of RMs. The risk of CE rebound is an incorrect sustainable approach in which circular models are implemented, but then no change in consumption patterns follows (Caferra et al., 2023; Kirchherr, 2022).

Conclusions

- The reduction of illegal waste in order to apply the principles not only of prevention but also those of proximity.

- Greater investment in circular technologies by investing in human capital and promoting the development of start-ups and youth-led small- and medium-sized enterprises.

- A more sustainable distribution of the benefits obtained from circular models to the different categories of stakeholders.

Declaration of conflicting interests

Funding

ORCID iDs

Massimo Gastaldi (D) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0867-3352

Supplemental material

References

Arbolino R, Boffardi R, De Simone L, et al. (2021) Multi-objective optimization technique: A novel approach in tourism sustainability planning. Journal of Environmental Management 285: 112016.

Awasthi A, Omrani H and Gerber P (2018) Investigating ideal-solution based multicriteria decision making techniques for sustainability evaluation of urban mobility projects. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 116: 247-259.

Bączkiewicz A and Kizielewicz B (2021) Towards sustainable energy consumption evaluation in europe for industrial sector based on MCDA methods. Procedia Computer Science 192: 1334-1346.

Barma M, Biniyamin HK, Modibbo UM, et al. (2022) Mathematical model for the optimization of municipal solid waste management. Frontiers in Sustainability 3: 880409.

Barma M and Modibbo UM (2022) Multiobjective mathematical optimization model for municipal solid waste management with economic analysis of reuse/recycling recovered waste materials. Journal of Computational and Cognitive Engineering 1: 122-137.

Barros MV, Salvador R, Gallego-Schmid A, et al. (2023) Circularity measurement of external resource flows in companies: The circular flow tool. Waste Management 158: 136-145.

Beekhuizen J, Heuvelink GBM, Huss A, et al. (2014) Impact of input data uncertainty on environmental exposure assessment models: A case study for electromagnetic field modelling from mobile phone base stations. Environmental Research 135: 148-155.

Bockreis A and Ragossnig AM (2023) Celebrating WM&R’s first 40 years. Waste Management & Research 41: 1-2.

Caferra R, Tsironis G, Morone A, et al. (2023) Is the circular economy proposed as sustainability in firm mission statements? A semantic analysis. Environmental Technology & Innovation 32: 103304.

Chen TL, Kim H, Pan SY, et al. (2020) Implementation of green chemistry principles in circular economy system towards sustainable development goals: Challenges and perspectives. Science of the Total Environment 716: 136998.

Chiappetta Jabbour CJ, Lopes de Sousa Jabbour AB, Sarkis J, et al. (2019) Unlocking the circular economy through new business models based on large-scale data: An integrative framework and research agenda. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 144: 546-552.

Colasante A, D’Adamo I, Morone P, et al. (2022) Assessing the circularity performance in a European cross-country comparison. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 93: 106730.

D’Adamo I, Desideri S, Gastaldi M, et al. (2023a) Sustainable food waste management in supermarkets. Sustainable Production and Consumption 43: 204-216.

D’Adamo I, Ferella F, Gastaldi M, et al. (2023b) Circular solar: evaluating the profitability of a photovoltaic panel recycling plant. Waste Management & Research 41: 1144-1154.

D’Adamo I, Mazzanti M, Morone P, et al. (2022) Assessing the relation between waste management policies and circular economy goals. Waste Managemen 154: 27-35.

D’Adamo I and Sassanelli C (2022) A mini-review of biomethane valorization: Managerial and policy implications for a circular resource. Waste Management & Research 40: 1745-1756.

D’Amato A, Mazzanti M, Nicolli F, et al. (2018) Illegal waste disposal: Enforcement actions and decentralized environmental policy. SocioEconomic Planning Sciences 64: 56-65.

De Almeida ST and Borsato M (2019) Assessing the efficiency of end of life technology in waste treatment – A bibliometric literature review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 140: 189-208.

De Pascale A, Arbolino R, Szopik-Depczyńska K, et al. (2021) A systematic review for measuring circular economy: The 61 indicators. Journal of Cleaner Production 281: 124942.

European Environment Agency (2016) Circular Economy in EuropeDeveloping the Knowledge Base. Copenhagen: Publications Office.

Fernández-Miguel A, Riccardi MP, Veglio V, et al. (2022) Disruption in resource-intensive supply chains: Reshoring and nearshoring as strategies to enable them to become more resilient and sustainable. Sustainability 14: 10909.

Hartley K, van Santen R and Kirchherr J (2020) Policies for transitioning towards a circular economy: Expectations from the European Union (EU). Resources, Conservation and Recycling 155: 104634.

Henry M, Bauwens T, Hekkert M, et al. (2020) A typology of circular startups: An analysis of 128 circular business models. Journal of Cleaner Production 245: 118528.

Ioppolo G, Saija G and Salomone R (2012) Developing a territory balanced scorecard approach to manage projects for local development: Two case studies. Land Use Policy 29: 629-640.

Islam A, Ahmed T, Awual MR, et al. (2020) Advances in sustainable approaches to recover metals from e-waste-A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 244: 118815.

Kirchherr J (2023) Bullshit in the sustainability and transitions literature: A provocation. Circular Economy and Sustainability 3: 167-172.

Kirchherr J (2022) Circular economy and growth: A critical review of ‘post-growth’ circularity and a plea for a circular economy that grows. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 179: 1-2.

Kirchherr J, Reike D and Hekkert M (2017) Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 127: 221-232.

Kirchherr J, Yang N-HN, Schulze-Spüntrup F, et al. (2023) Conceptualizing the circular economy (revisited): An analysis of 221 definitions. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 194: 107001.

Knäble D, de Quevedo Puente E, Pérez-Cornejo C, et al. (2022) The impact of the circular economy on sustainable development: A European panel data approach. Sustainable Production and Consumption 34: 233-243.

Ladu L, Imbert E, Quitzow R, et al. (2020) The role of the policy mix in the transition toward a circular forest bioeconomy. Forest Policy and Economics 110: 101937.

Laso J, Margallo M, García-Herrero I, et al. (2018) Combined application of Life Cycle Assessment and linear programming to evaluate food waste-to-food strategies: Seeking for answers in the nexus approach. Waste Management 80: 186-197.

Loizia P, Voukkali I, Chatziparaskeva G, et al. (2021) Measuring the level of environmental performance on coastal environment before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study from cyprus. Sustainability 13: 2485.

Lombardi GV, Gastaldi M, Rapposelli A, et al. (2021) Assessing efficiency of urban waste services and the role of tariff in a circular economy perspective: An empirical application for Italian municipalities. Journal of Cleaner Production 323: 129097.

Mazzanti M and Montini A (2014) Waste management beyond the NorthSouth divide: Spatial analyses of geographical, economic and institutional dimensions. In: Takeuchi K and Kinnaman TC (eds.) Handbook on Waste Management. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Pub. Ltd., pp. 1-22.

Moktadir MA, Kumar A, Ali SM, et al. (2020) Critical success factors for a circular economy: Implications for business strategy and the environment. Business Strategy and the Environment 29: 3611-3635.

Moraga G, Huysveld S, Mathieux F, et al. (2019) Circular economy indicators: What do they measure? Resources, Conservation and Recycling 146: 452-461.

Papamichael I and Zorpas AA (2022) End-of-waste criteria in the framework of end-of-life PV panels concerning circular economy strategy. Waste Management & Research 40: 1677-1679.

Pophali GR, Chelani AB and Dhodapkar RS (2011) Optimal selection of full scale tannery effluent treatment alternative using integrated AHP and GRA approach. Expert Systems with Applications 38: 10889-10895.

Quicker P, Consonni S and Grosso M (2020) The Zero Waste utopia and the role of waste-to-energy. Waste Management & Research 38: 481-484.

Ragossnig AM and Schneider DR (2019) Circular economy, recycling and end-of-waste. Waste Management & Research 37: 109-111.

Romano G, Lombardi GV, Rapposelli A, et al. (2022) The factors affecting Italian provinces’ separate waste-collection rates: An empirical investigation. Waste Management 139: 217-226.

Saaty TL (2008) Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. International Journal of Services Sciences 1: 83-98.

Saidani M, Yannou B, Leroy Y, et al. (2019) A taxonomy of circular economy indicators. Journal of Cleaner Production 207: 542-559.

Shooshtarian S, Maqsood T, Caldera S, et al. (2022) Transformation towards a circular economy in the Australian construction and demolition waste management system. Sustainable Production and Consumption 30: 89-106.

Tsui T, Peck D, Geldermans B, et al. (2021) The role of urban manufacturing for a circular economy in cities. Sustainability 13: 23.

Vacchi M, Siligardi C, Cedillo-González EI, et al. (2021) Industry 4.0 and smart data as enablers of the circular economy in manufacturing: Product re-engineering with circular eco-design. Sustainability 13: 10366.

Voukkali I, Papamichael I, Loizia P, et al. (2023) Waste metrics in the framework of circular economy. Waste Management & Research 41: 1741-1753.

Zink T and Geyer R (2017) Circular economy rebound. Journal of Industrial Ecology 21: 593-602.

Zisopoulos FK, Schraven DFJ and de Jong M (2022) How robust is the circular economy in Europe? An ascendency analysis with Eurostat data between 2010 and 2018. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 178: 106032.

Zorpas AA, Voukkali I and Navarro Pedreño J (2018) Tourist area metabolism and its potential to change through a proposed strategic plan in the framework of sustainable development. Journal of Cleaner Production 172: 3609-3620.

Department of Computer, Control and Management Engineering, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Department of Industrial and Information Engineering and Economics, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy

Department of Social Sciences and Business, Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark

Innovation Studies Group, Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands Cambridge Centre for Environment, Energy and Natural Resource Governance, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK Corresponding author:

Massimo Gastaldi, Department of Industrial and Information Engineering and Economics, University of L’Aquila, Via Gronchi 18, L’Aquila 67100, Italy.

Email: massimo.gastaldidunivaq.it