DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49004-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38839799

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-05

نقل الإلكترونات فائق السرعة عند واجهة مخطط S لـ In2O3/Nb2O5 لتقليل CO2 بالضوء

تم القبول: 21 مايو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 05 يونيو 2024

(T) تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

شيانيو دينغ

الملخص

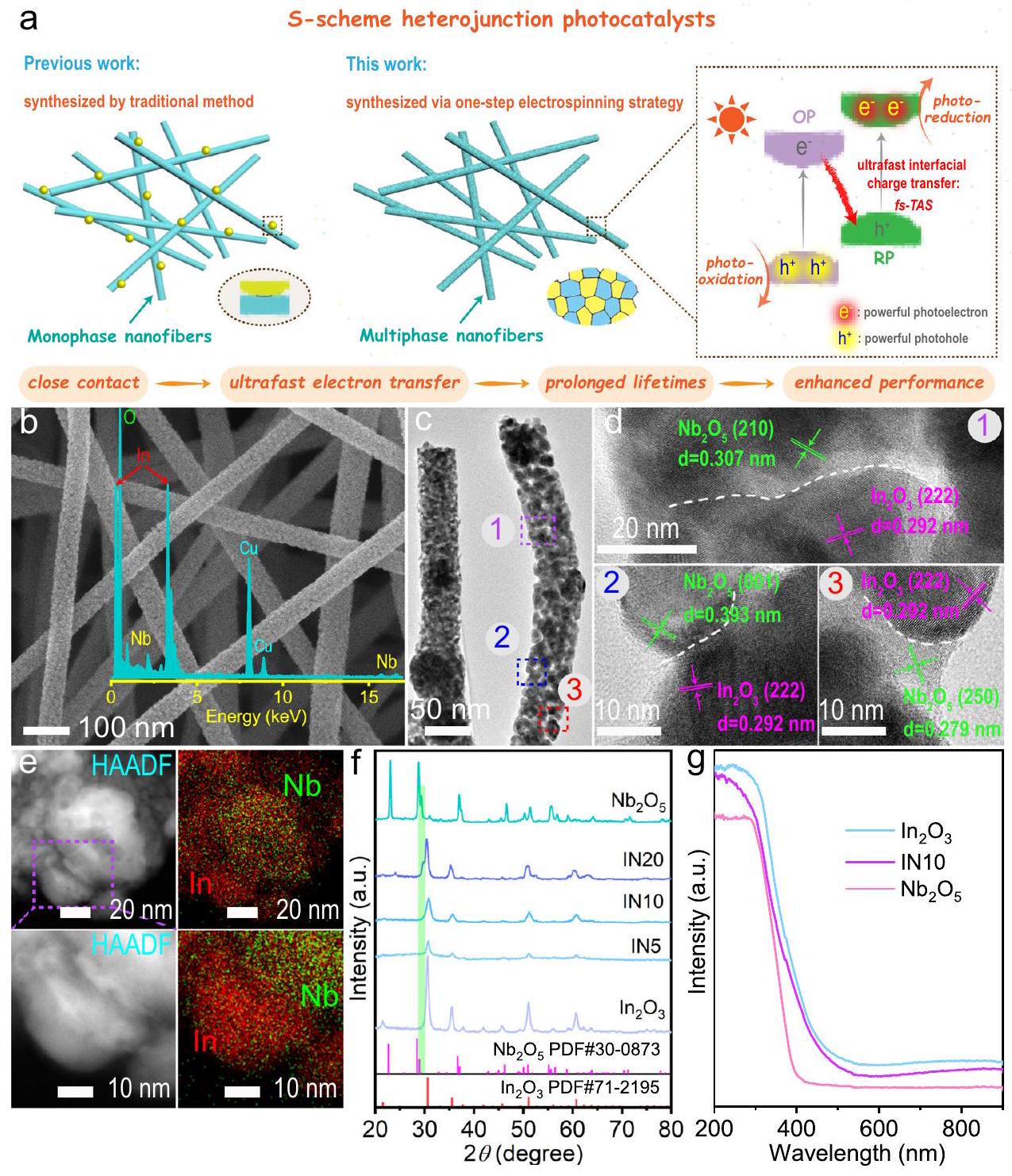

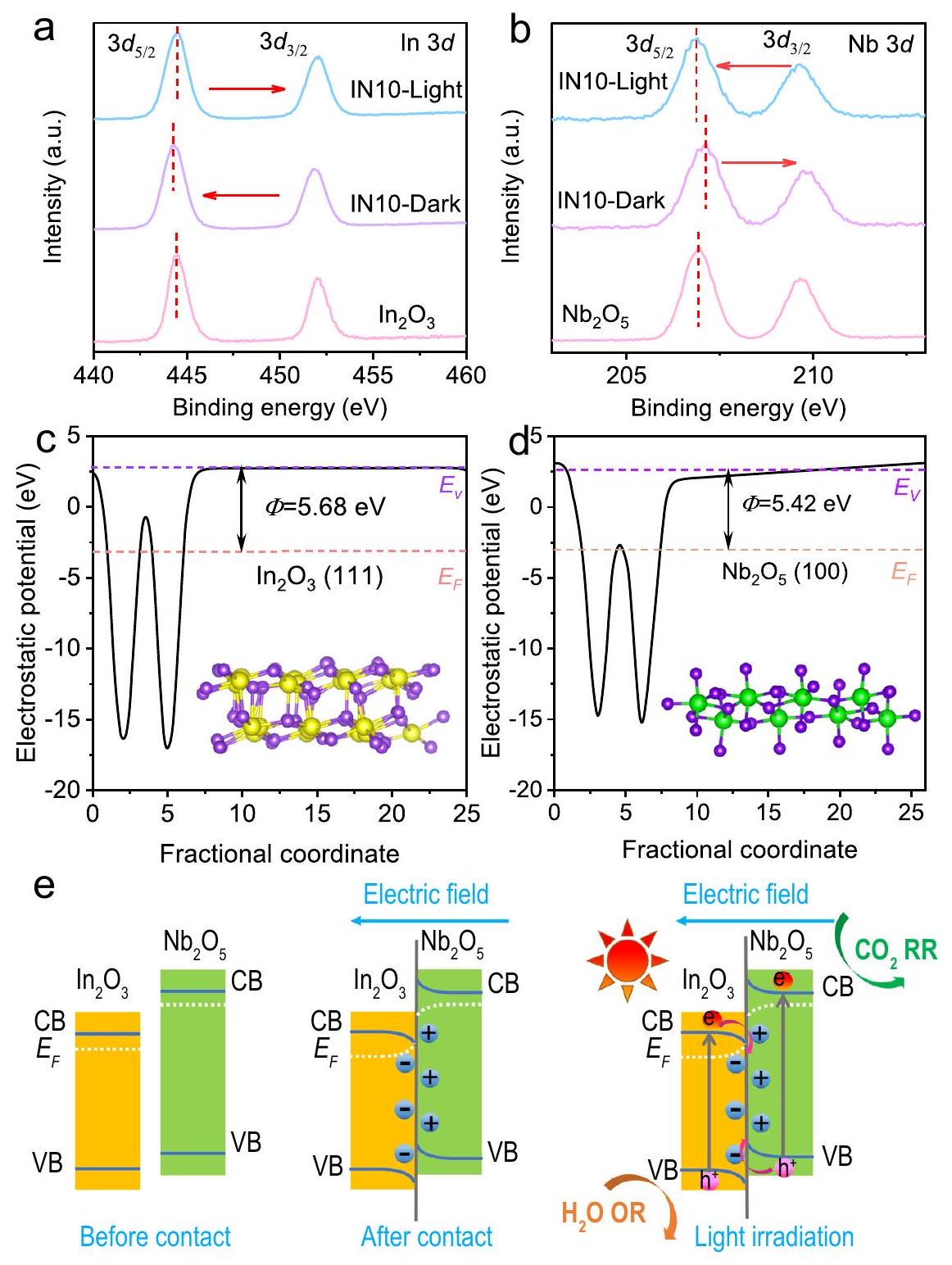

يثبت بناء الوصلات غير المتجانسة من نوع S كفاءته في تحقيق الفصل المكاني لحاملات الشحنة الناتجة عن الضوء للمشاركة في التفاعلات الضوئية. ومع ذلك، فإن المناطق المحدودة للتلامس بين المرحلتين داخل الهياكل غير المتجانسة من نوع S تؤدي إلى نقل غير فعال للشحنة عند الواجهة، مما ينتج عنه كفاءة ضوئية منخفضة من منظور حركي. هنا،

النتائج والمناقشة

خصائص وآلية فصل الشحنات لـ

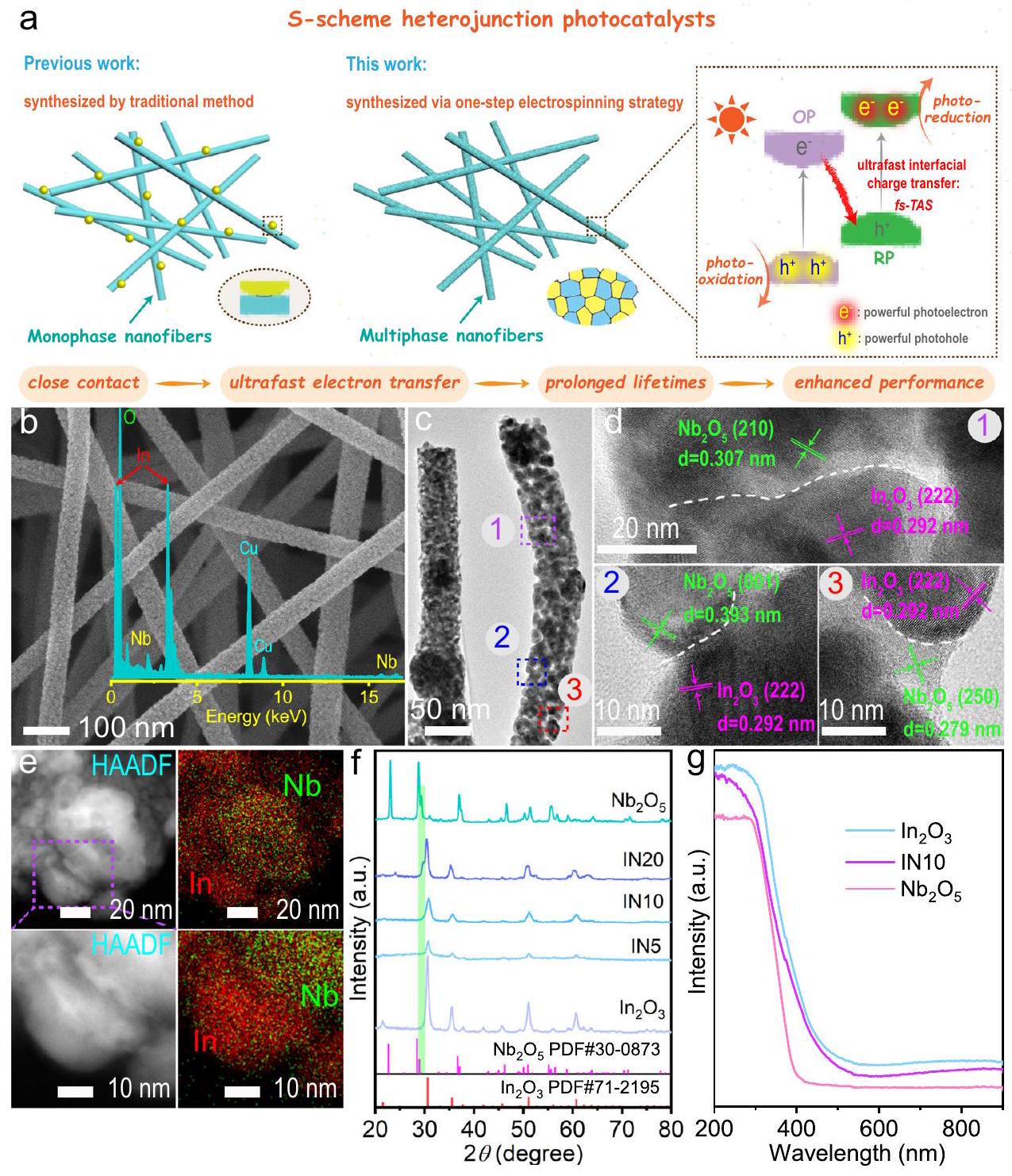

صورة الحقل المظلم الحلقي بزاوية عالية (HAADF) ورسم خرائط العناصر EDX لعناصر الإنديوم (In) والنيوبيوم (Nb) في IN10 بتكبيرات مختلفة.

تشكيل

شكل ليفي موحد مع سطح خشن وأقطار أقل من 100 نانومتر، كما لوحظ عبر كل من المجهر الإلكتروني الماسح (FESEM) والمجهر الإلكتروني الناقل (TEM) (الشكل 1ب، ج). تكشف صور TEM عالية الدقة (HRTEM) لـ IN10 عن حدود حبيبية ثنائية المرحلة واضحة مع خطوط شبكية تتوافق مع

الاندماج في الداخل

نصف قطر القوس الأصغر في مخطط نايكويست مقارنةً بالعارية

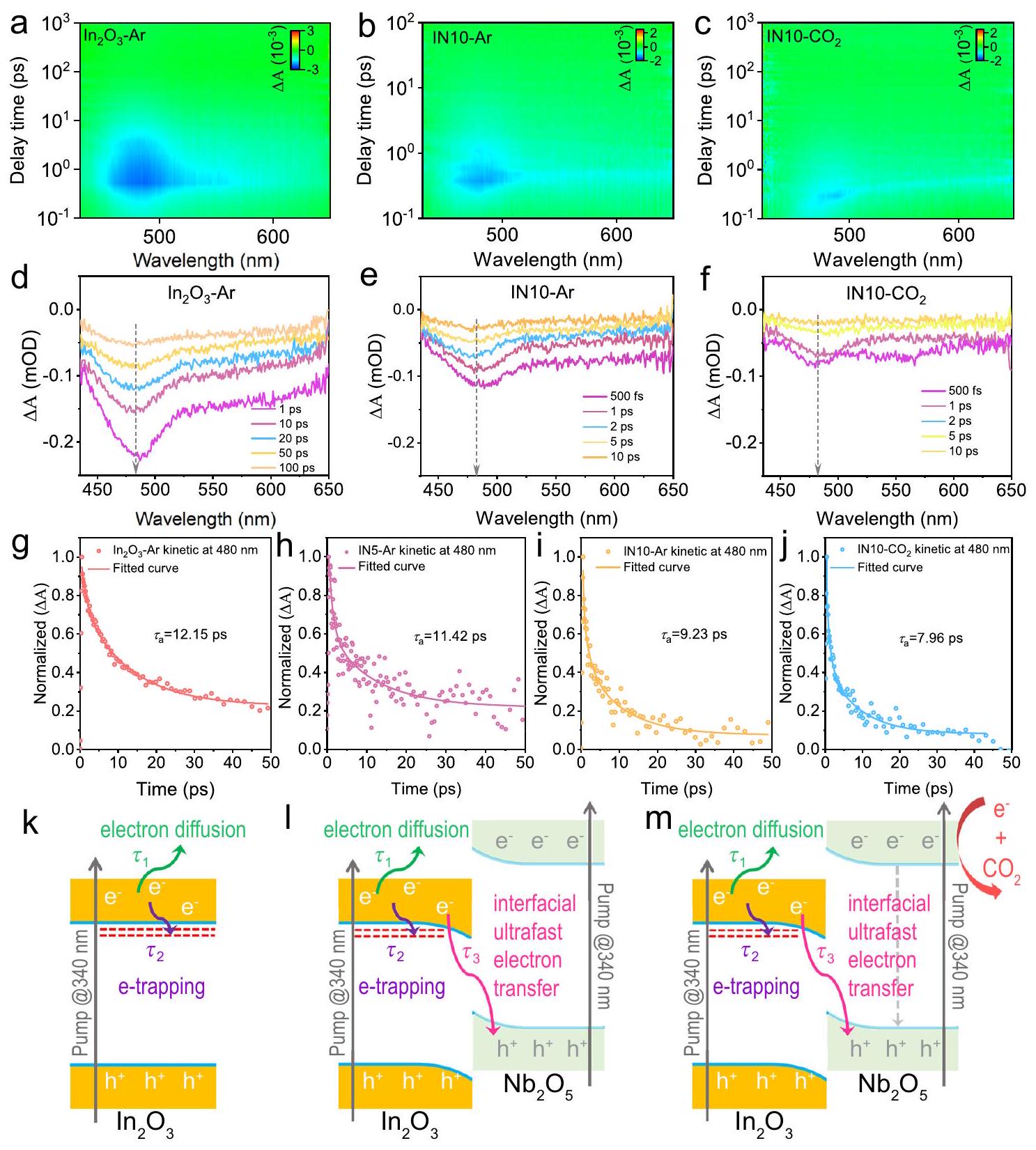

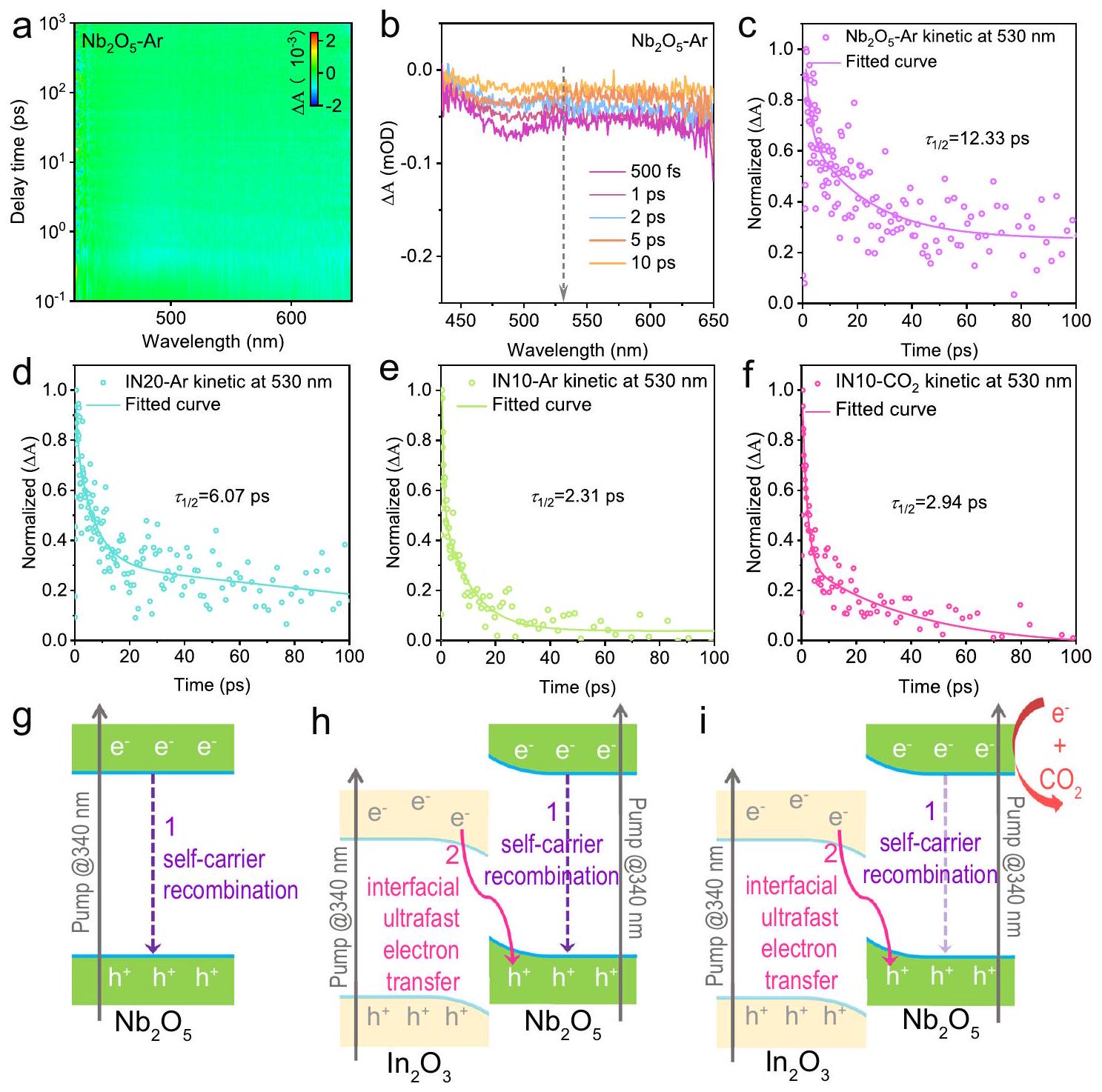

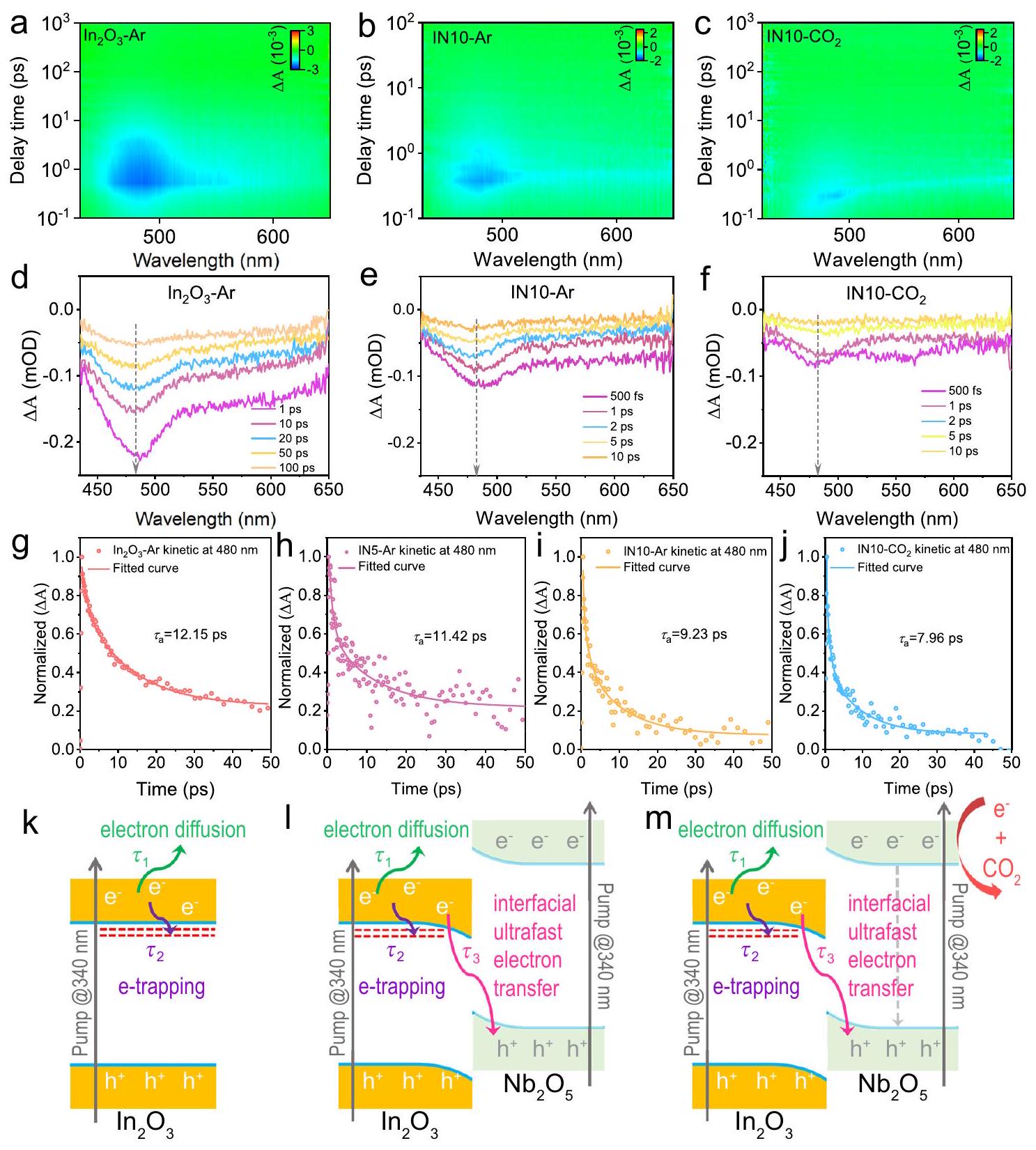

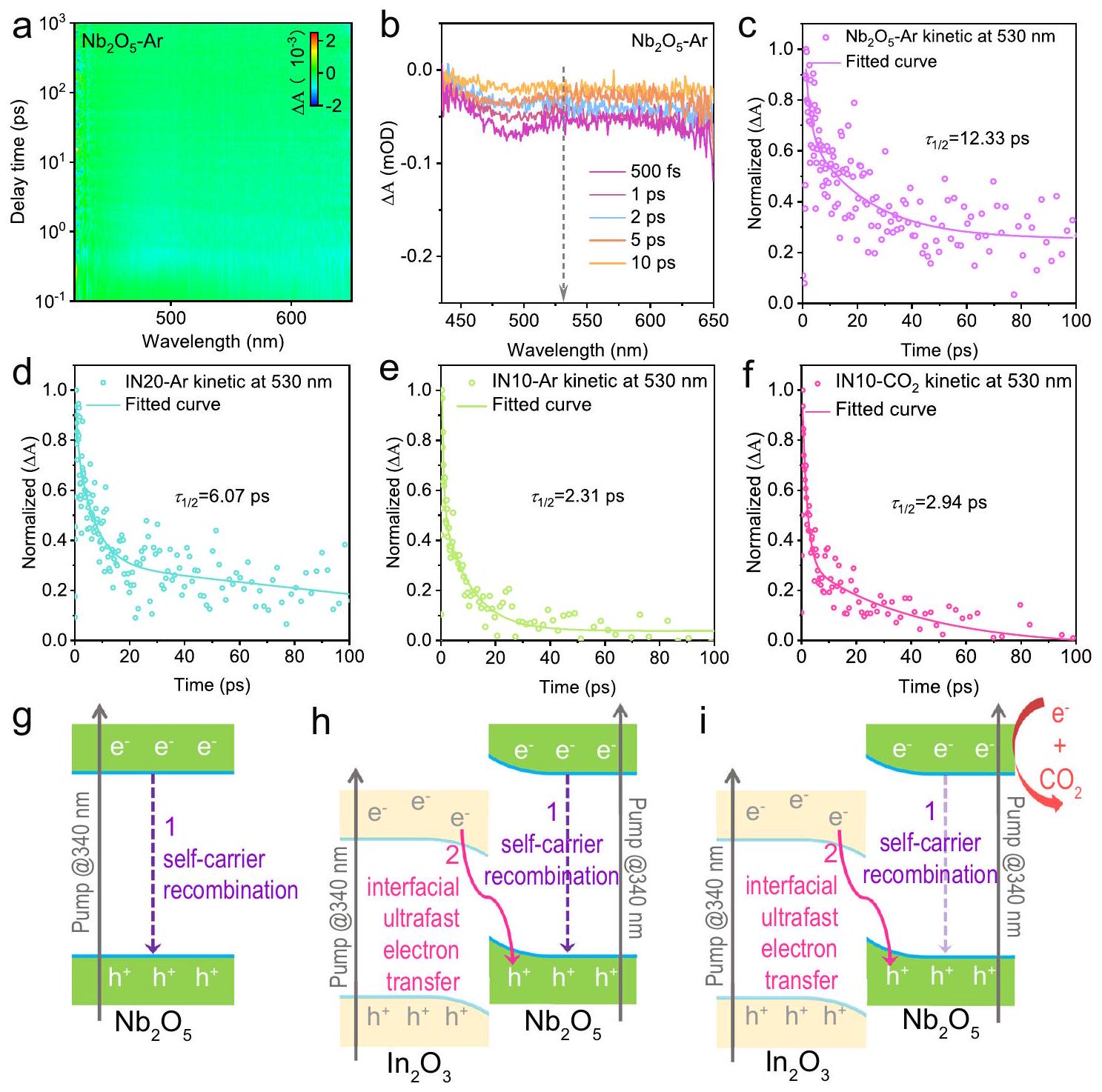

نقل الإلكترونات فائق السرعة في

منحنيات التحلل عند 480 نانومتر خلال 50 بيكوثانية:

تشير إلى هجرة الفوتوالكترونات من

إلى

منع إعادة تركيب الحاملات الذاتية، وفصل الفوتونات القوية والفجوات الضوئية، وتمديد أعمارها الطويلة.

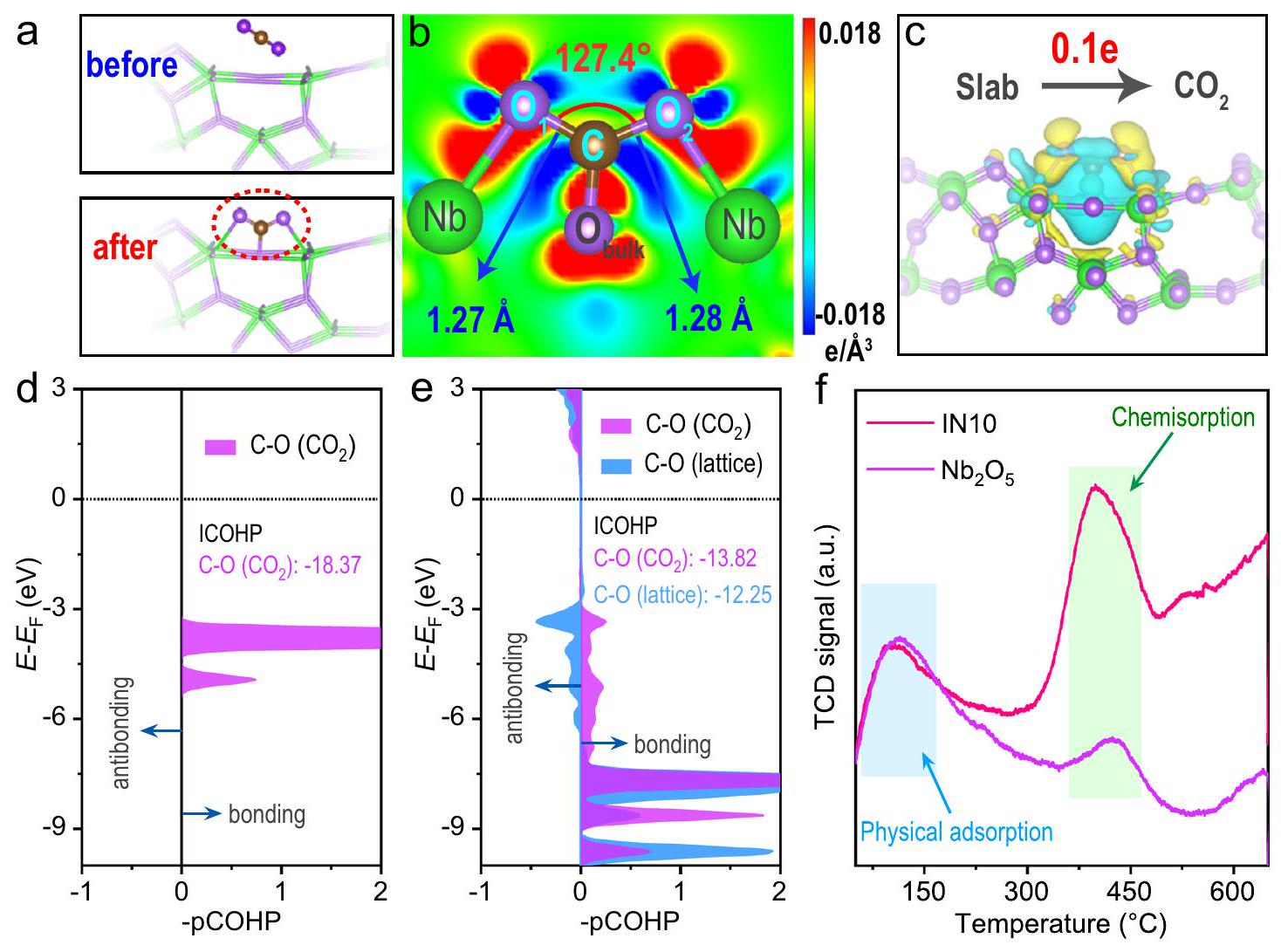

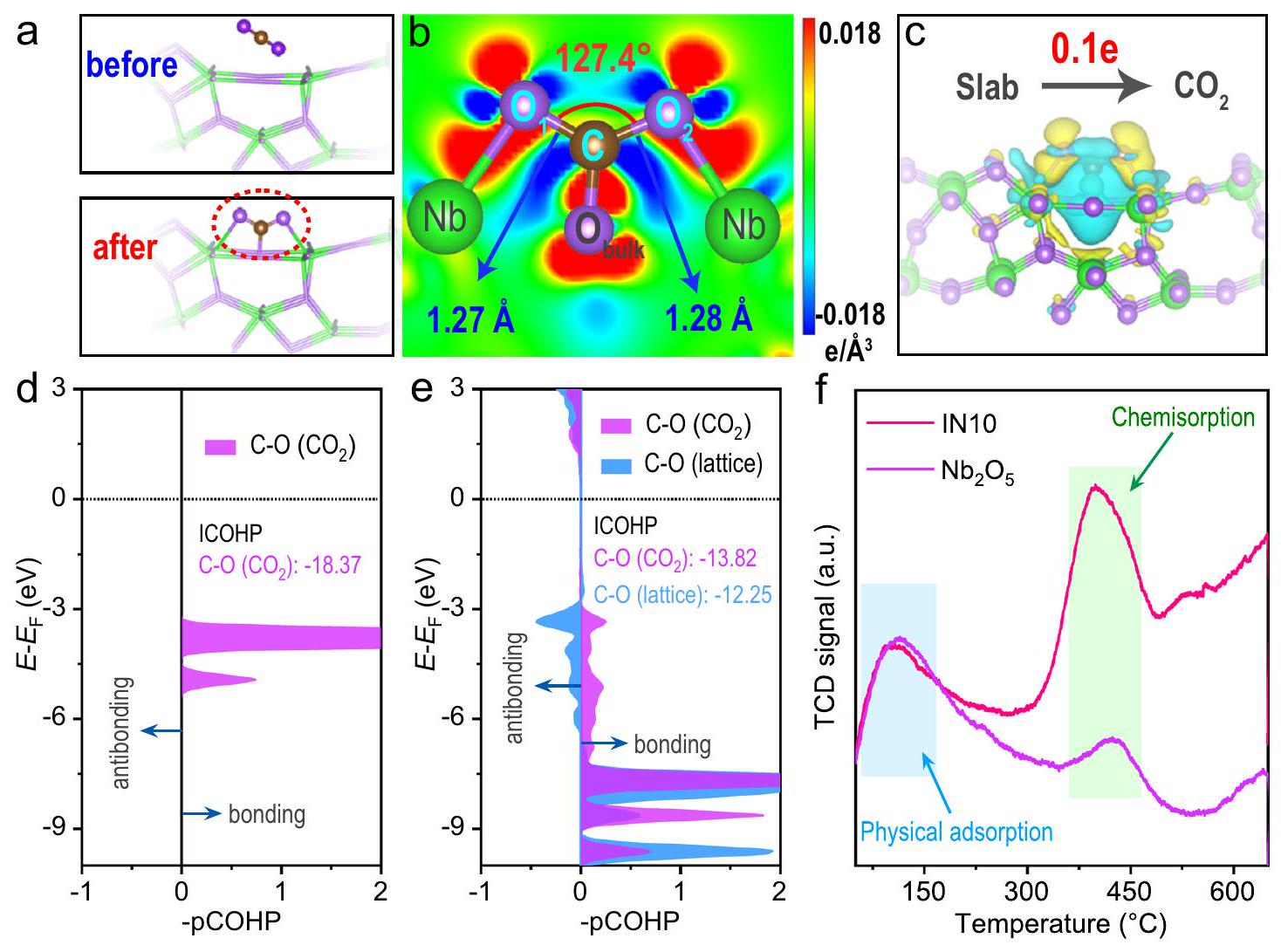

الامتصاص الكيميائي، التنشيط والاختزال الضوئي لـ

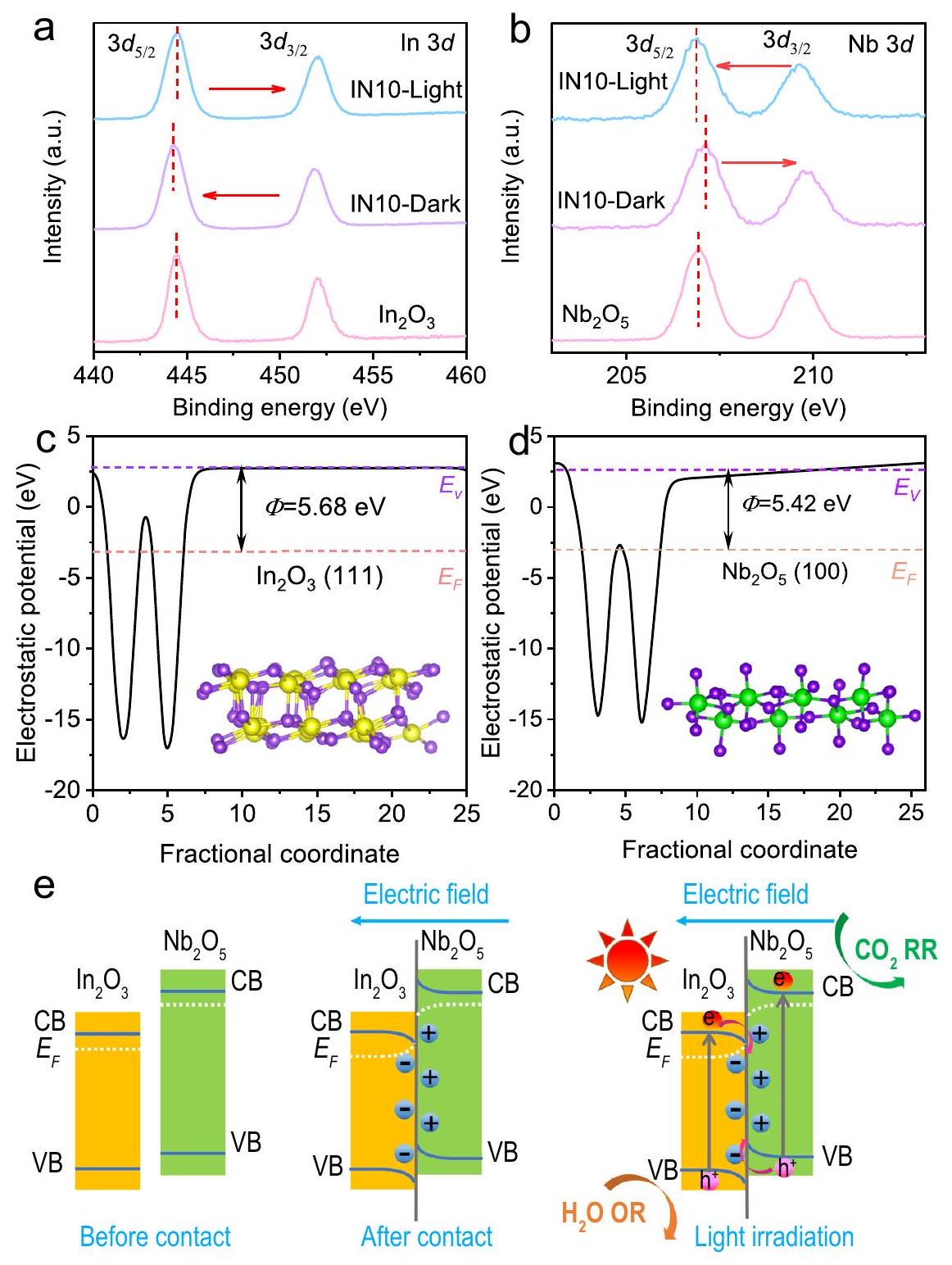

نقص الإلكترونات وتراكمها، على التوالي. تم تعيين مستوى السطح المتساوي إلى

-12.25 eV يوفر دليلاً إضافياً مقنعاً على القوة

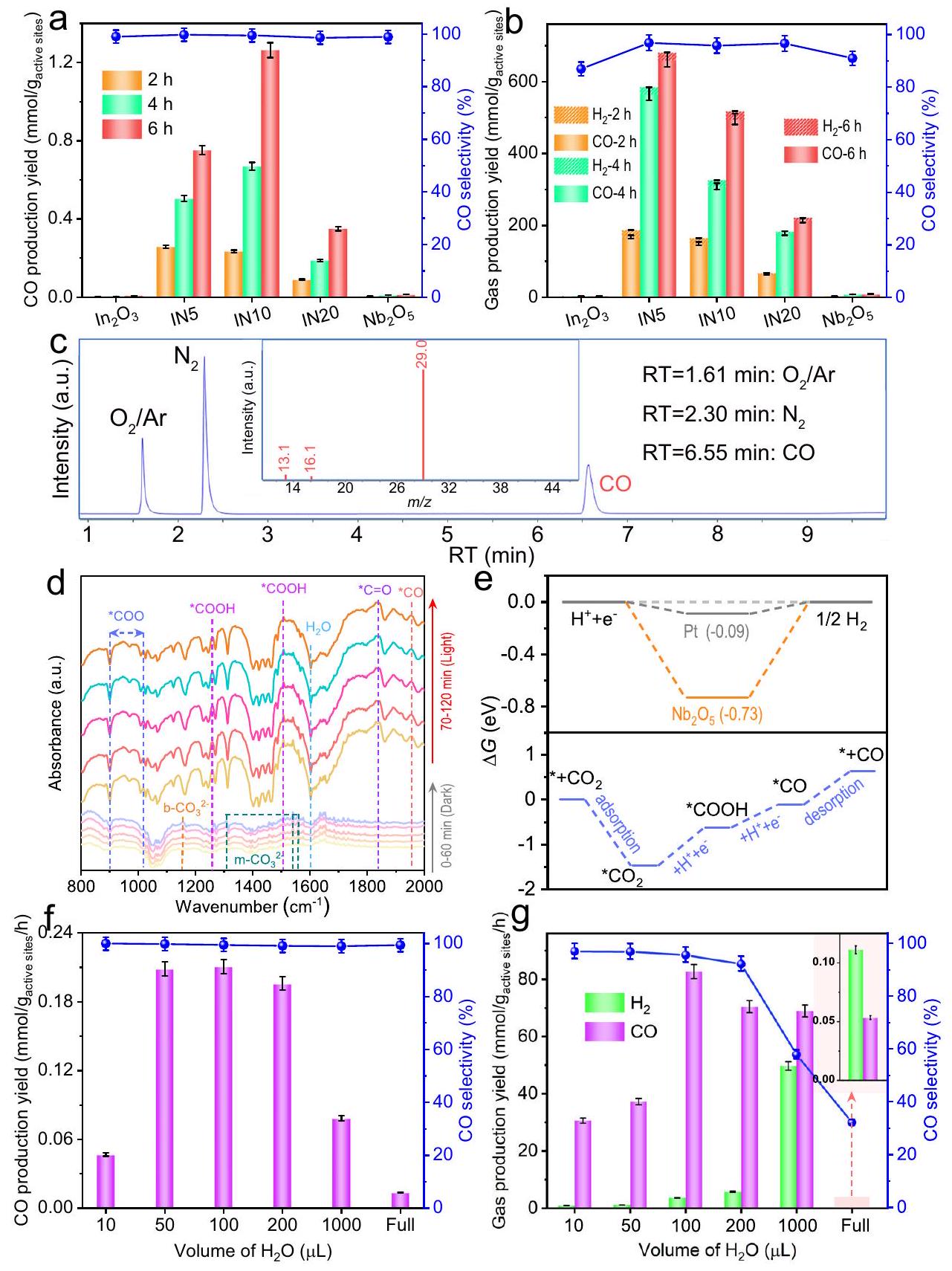

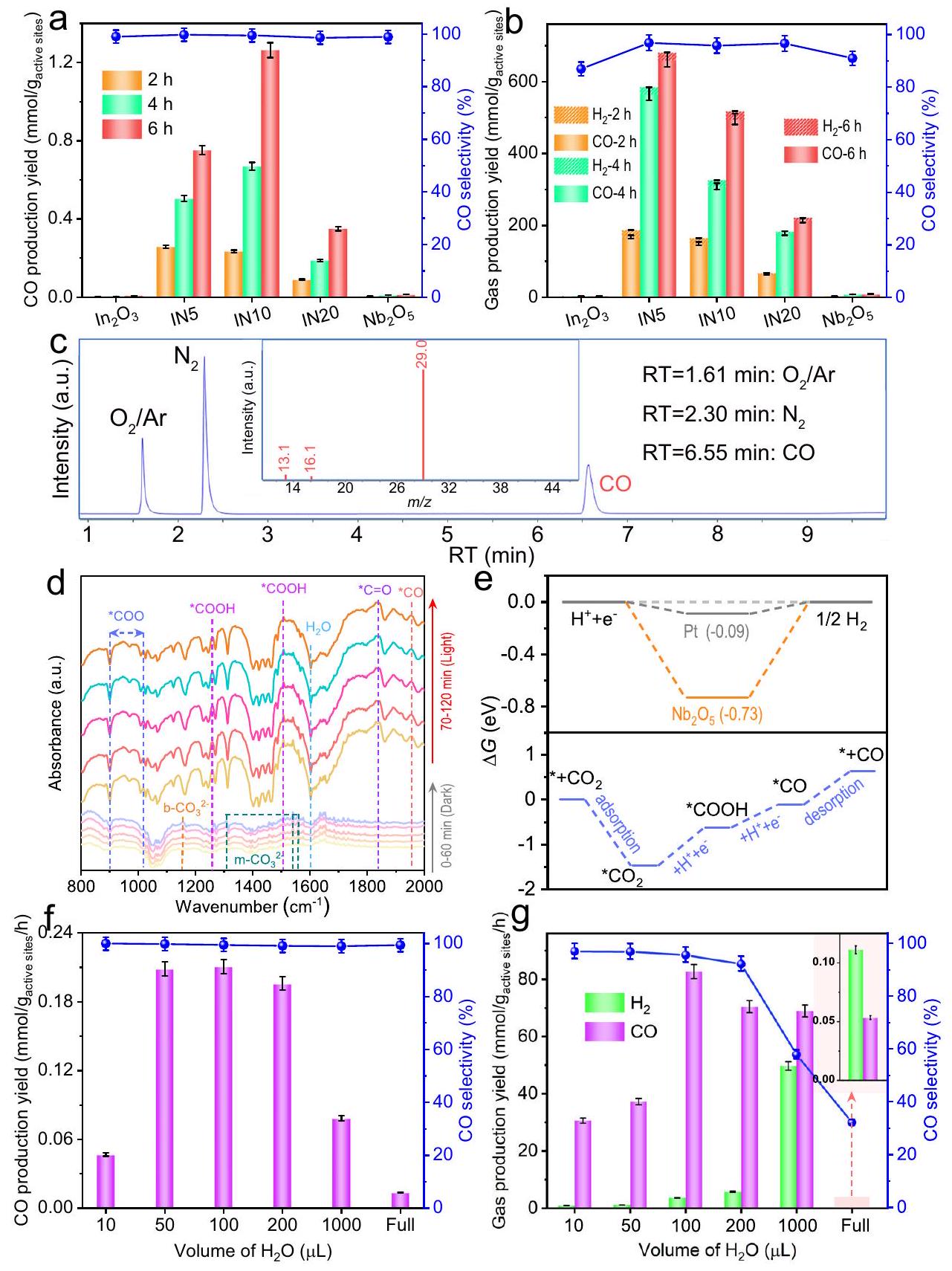

تحفيز ضوئي

مقترح كما يلي، حيث * يدل على موقع التفاعل النشط

طرق

المواد الكيميائية

تركيب

تركيب نقي

تركيب نقي

تحفيز ضوئي

الإحصائيات وإمكانية التكرار

توفر البيانات

References

- Bai, S. et al. On factors of ions in seawater for

reduction. Appl. Catal. B 323, 122166 (2023). - Chang, X., Wang, T. & Gong, J.

photo-reduction: insights into activation and reaction on surfaces of photocatalysts. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 2177-2196 (2016). - Chang, X. et al. The development of cocatalysts for photoelectrochemical

reduction. Adv. Mater. 31, 18404710 (2019). - Liu, Z. et al. Photocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide on triethanolamine: unheeded catalytic performance of sacrificial agent. Appl. Catal. B 326, 122338 (2023).

- Lu, M. et al. Covalent organic framework based functional materials: important catalysts for efficient

utilization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200003 (2022). - Vu, N. N., Kaliaguine, S. & Do, T. O. Critical aspects and recent advances in structural engineering of photocatalysts for sunlightdriven photocatalytic reduction of

into fuels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1901825 (2019). -

. et al. Highly selective photoconversion of to over heterojunctions assisted by S-Scheme Charge separation. ACS Catal. 13, 12623-12633 (2023). - Li, Y. et al. Plasmonic hot electrons from oxygen vacancies for infrared light-driven catalytic

reduction on . Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 910-916 (2021). - de Vrijer, T. & Smets, A. H. M. Infrared analysis of catalytic

reduction in hydrogenated germanium. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 10241-10248 (2022). - Jiao, X. et al. Partially oxidized

atomic layers achieving efficient visible-light-driven reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18044-18051 (2017). - Sayed, M. et al. EPR investigation on electron transfer of

S-Scheme heterojunction for enhanced photoreduction. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 6, 2100264 (2022). - Hu, C. et al. Near-infrared-featured broadband

reduction with water to hydrocarbons by surface plasmon. Nat. Commun. 14, 221 (2023). - Wang, Z. et al. S-Scheme 2D/2D Bi

van der Waals heterojunction for photoreduction. Chin. J. Catal. 43, 1657-1666 (2022). - Wageh, S. et al. Ionized cocatalyst to promote

photoreduction activity over core-triple-shell ZnO hollow spheres. Rare Met. 41, 1077-1079 (2022). - Wang, J. et al. Nanostructured metal sulfides: classification, modification strategy, and solar-driven

reduction application. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2008008 (2021). - Shen, G. et al. Growth of directly transferable

nanowire mats for transparent thin-film transistor applications. Adv. Mater. 23, 771-775 (2011). - Yin, J. et al. The built-in electric field across

interface for efficient electrochemical reduction of to CO . Nat. Commun. 14, 1724 (2023). - Zhang, Z. et al. Internal electric field engineering step-schemebased heterojunction using lead-free

perovskite-modified for selective photocatalytic reduction to CO. Appl. Catal. B 313, 121426 (2022). - He, Y. et al. Selective conversion of

to enhanced by -scheme heterojunction photocatalysts with efficient activation. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 14860-14869 (2023). - Tébar-Soler, C. et al. Low-oxidation-state Ru sites stabilized in carbon-doped

with low-temperature activation to yield methane. Nat. Mater. 22, 762-768 (2023). - Cao, S. et al.

-production and electron-transfer mechanism of a noble-metal-free S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 17174-17184 (2022). - Han, G. et al. Artificial photosynthesis over tubular

heterojunctions assisted by efficient activation and S -Scheme charge separation. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 7, 2200381 (2022). - Deng,

. et al. Enhanced solar fuel production over hierarchical nanofibers with S-Scheme charge separation mechanism. Small 19, 2305410 (2023). - Li, K. et al. Synergistic effect of cyano defects and

in graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets for efficient visible-light-driven photocatalytic NO removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 442, 130040 (2023). - Xia, Y.-S. et al. Tandem utilization of

photoreduction products for the carbonylation of aryl iodides. Nat. Commun. 13, 2964 (2022). - He, Y. et al. Boosting artificial photosynthesis:

chemisorption and S-Scheme charge separation via anchoring inorganic QDs on COFs. ACS Catal. 14, 1951-1961 (2024). - Tao, Y. et al. Kinetically-enhanced polysulfide redox reactions by

nanocrystals for high-rate lithium-sulfur battery. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 3230-3239 (2016). - Su, K. et al.

-based photocatalysts. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003156 (2021). - Lin, X. et al. Fabrication of flexible mesoporous black

nanofiber films for visible-light-driven photocatalytic reduction into . Adv. Mater. 34, 2200756 (2022). - Jeon, T. H. et al. Dual modification of hematite photoanode by Sndoping and

layer for water oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 201, 591-599 (2017). - Sayed, M. et al. Sustained

-photoreduction activity and high selectivity over Mn, C-codoped ZnO core-triple shell hollow spheres. Nat. Commun. 12, 4936 (2021). - Han, J. et al. Ambient

fixation to at ambient conditions: using nanofiber as a high-performance electrocatalyst. Nano Energy 52, 264-270 (2018). - Pei, C. et al. Structural properties and electrochemical performance of different polymorphs of

in magnesium-based batteries. J. Energy Chem. 58, 586-592 (2021). - Xu, F. et al. Unique S-scheme heterojunctions in self-assembled

hybrids for photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 11, 4613 (2020). - Jiang, Z. et al. A review on ZnO -based S -scheme heterojunction photocatalysts. Chin. J. Catal. 52, 32-49 (2023).

- Zhao, X. et al. 3D Fe-MOF embedded into 2D thin layer carbon nitride to construct 3D/2D S-scheme heterojunction for enhanced photoreduction of

. Chin. J. Catal. 43, 2625-2636 (2022). - Zhu, B. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic

reduction over 2D/1D -scheme heterostructure. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 38, 2111008 (2021). -

. et al. Step-by-step mechanism insights into the S-Scheme photocatalyst for enhanced aniline production with water as a proton source. ACS Catal. 12, 164-172 (2022). - Zhang, J. et al. Molecular-level engineering of S -scheme heterojunction: the site-specific role for directional charge transfer. Chin. J. Struc. Chem. 41, 2206003-2206005 (2022).

- Feng, C. et al. Effectively enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production performance of one-pot synthesized

clusters/CdS nanorod heterojunction material under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 345, 404-413 (2018). - Xu, J. et al. In situ cascade growth-induced strong coupling effect toward efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of

. Appl. Catal. B 328, 122493 (2023). - Yang, H. et al. Constructing electrostatic self-assembled 2D/2D ultra-thin

protonated heterojunctions for excellent photocatalytic performance under visible light. Appl. Catal. B 256, 117862 (2019). - Hu, X. et al. In situ fabrication of superfine perovskite composite nanofibers with ultrahigh stability by one-step electrospinning toward white light-emitting diode. Adv. Fiber Mater. 5, 183-197 (2023).

- Yan, Z. et al. Interpreting the enhanced photoactivities of OD/1D heterojunctions of CdS quantum dots

nanotube arrays using femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. Appl. Catal. B 275, 119151 (2020). - Zhang, Y. et al. Fabricating Ag/CN/ZnIn

-Scheme heterojunctions with plasmonic effect for enhanced light-driven photocatalytic reduction. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 39, 2211051 (2023). - Peng, J. et al. Uncovering the mechanism for urea electrochemical synthesis by coupling

and on -MXene. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 41, 2209094-2209104 (2022). - Gao, R. et al. Pyrene-benzothiadiazole-based Polymer/CdS 2D/2D Organic/Inorganic Hybrid S-scheme Heterojunction for Efficient Photocatalytic

Evolution. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 41, 2206031-2206038 (2022). - Wang, Y. et al. Selective electrocatalytic reduction of

to formate via carbon-shell-encapsulated nanoparticles/graphene nanohybrids. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 121, 220-226 (2022). - Xu, K. et al. Efficient interfacial charge transfer of BiOCl-

stepscheme heterojunction for boosted photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 121, 236-244 (2022). - Li, S. et al. Constructing

-scheme heterojunction for boosted photocatalytic antibiotic oxidation and reduction. Adv. Powder Mater. 2, 100073 (2023). - Wang, L. et al. S-scheme heterojunction photocatalysts for

reduction. Matter 5, 4187-4211 (2022). - Li, H., Gong, H. & Jin, Z. In

-modified three-dimensional nanoflower form S -scheme heterojunction for efficient hydrogen production. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 38, 2201037 (2022). - Zhao, X. et al. UV light-induced oxygen doping in graphitic carbon nitride with suppressed deep trapping for enhancement in

photoreduction activity. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 133, 135-144 (2023). - Wang, L. et al. Dual transfer channels of photo-carriers in 2D/2D/2D sandwich-like

MXene S-scheme/Schottky heterojunction for boosting photocatalytic evolution. Chin. J. Catal. 43, 2720-2731 (2022). - Yang, T. et al. Simultaneous photocatalytic oxygen production and hexavalent chromium reduction in

S-scheme heterojunction. Chin. J. Struc. Chem. 41, 2206023-2206030 (2022). - Huang, B. et al. Chemically bonded

heterojunction with fast hole extraction dynamics for continuous photoreduction. Adv. Powder Mater. 3, 100140 (2024). - Zhang, J. et al. Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy investigation into the electron transfer mechanism in photocatalysis. Chem. Commun. 59, 688-699 (2023).

- Cheng, C. et al. Verifying the charge-transfer mechanism in S-Scheme heterojunctions using femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218688 (2023).

- Wang, S. et al. Designing reliable and accurate isotope-tracer experiments for

photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 14, 2534 (2023). - Su, B. et al. Hydroxyl-Bonded Ru on metallic TiN surface catalyzing

reduction with by Infrared Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27415-27423 (2023). - Zou, W. et al. Metal-free photocatalytic

reduction to and under non-sacrificial ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313392 (2023). - Li, F. et al. Balancing hydrogen adsorption/desorption by orbital modulation for efficient hydrogen evolution catalysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 4060 (2019).

- Kang, J., Sahin, H. & Peeters, F. M. Tuning carrier confinement in the

lateral heterostructure. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 9580-9586 (2015).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

مختبر الوقود الشمسي، كلية علوم المواد والكيمياء، جامعة علوم الأرض الصينية، ووهان 430078، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. كلية الصيدلة، جامعة دالي، دالي 671003، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. مختبر هوباي الرئيسي للمواد والأجهزة البصرية منخفضة الأبعاد، جامعة هوباي للفنون والعلوم، شيانغيانغ 441053، جمهورية الصين الشعبية. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: شيانيو دينغ، جيانجون زانغ. البريد الإلكتروني: xufeiyan@cug.edu.cn; yujiaguo93@cug.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49004-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38839799

Publication Date: 2024-06-05

Ultrafast electron transfer at the

Accepted: 21 May 2024

Published online: 05 June 2024

(T) Check for updates

Abstract

Xianyu Deng

Abstract

Constructing S-scheme heterojunctions proves proficient in achieving the spatial separation of potent photogenerated charge carriers for their participation in photoreactions. Nonetheless, the restricted contact areas between two phases within S-scheme heterostructures lead to inefficient interfacial charge transport, resulting in low photocatalytic efficiency from a kinetic perspective. Here,

Results and discussion

Characterizations and charge separation mechanism of

e High-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) image and EDX elemental mappings of In and Nb elements in IN10 at different magnifications.

e The formation of

uniform fibrous morphology with a rough surface and diameters below 100 nm , as observed via both FESEM and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 1b, c). High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images of IN10 reveal discernible two-phase grain boundaries with lattice fringes corresponding to

emerge in the IN

smaller arc radius in the Nyquist plot compared to bare

Ultrafast electron transfer at the

decay curves at 480 nm within 50 ps :

signifying the migration of photoelectrons from the

to the

preventing the recombination of self-carriers, separating powerful photoelectrons and photoholes, and extending their long lifetimes.

Chemisorption, activation and photoreduction of

electron depletion and accumulation, respectively. The isosurface level is set to

-12.25 eV provides additional compelling evidence of the robust

photocatalytic

proposed as follows, where * denotes the reaction active site

Methods

Chemicals

Synthesis of

Synthesis of pure

Synthesis of pure

Photocatalytic

Statistics and reproducibility

Data availability

References

- Bai, S. et al. On factors of ions in seawater for

reduction. Appl. Catal. B 323, 122166 (2023). - Chang, X., Wang, T. & Gong, J.

photo-reduction: insights into activation and reaction on surfaces of photocatalysts. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 2177-2196 (2016). - Chang, X. et al. The development of cocatalysts for photoelectrochemical

reduction. Adv. Mater. 31, 18404710 (2019). - Liu, Z. et al. Photocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide on triethanolamine: unheeded catalytic performance of sacrificial agent. Appl. Catal. B 326, 122338 (2023).

- Lu, M. et al. Covalent organic framework based functional materials: important catalysts for efficient

utilization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200003 (2022). - Vu, N. N., Kaliaguine, S. & Do, T. O. Critical aspects and recent advances in structural engineering of photocatalysts for sunlightdriven photocatalytic reduction of

into fuels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1901825 (2019). -

. et al. Highly selective photoconversion of to over heterojunctions assisted by S-Scheme Charge separation. ACS Catal. 13, 12623-12633 (2023). - Li, Y. et al. Plasmonic hot electrons from oxygen vacancies for infrared light-driven catalytic

reduction on . Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 910-916 (2021). - de Vrijer, T. & Smets, A. H. M. Infrared analysis of catalytic

reduction in hydrogenated germanium. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 10241-10248 (2022). - Jiao, X. et al. Partially oxidized

atomic layers achieving efficient visible-light-driven reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18044-18051 (2017). - Sayed, M. et al. EPR investigation on electron transfer of

S-Scheme heterojunction for enhanced photoreduction. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 6, 2100264 (2022). - Hu, C. et al. Near-infrared-featured broadband

reduction with water to hydrocarbons by surface plasmon. Nat. Commun. 14, 221 (2023). - Wang, Z. et al. S-Scheme 2D/2D Bi

van der Waals heterojunction for photoreduction. Chin. J. Catal. 43, 1657-1666 (2022). - Wageh, S. et al. Ionized cocatalyst to promote

photoreduction activity over core-triple-shell ZnO hollow spheres. Rare Met. 41, 1077-1079 (2022). - Wang, J. et al. Nanostructured metal sulfides: classification, modification strategy, and solar-driven

reduction application. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2008008 (2021). - Shen, G. et al. Growth of directly transferable

nanowire mats for transparent thin-film transistor applications. Adv. Mater. 23, 771-775 (2011). - Yin, J. et al. The built-in electric field across

interface for efficient electrochemical reduction of to CO . Nat. Commun. 14, 1724 (2023). - Zhang, Z. et al. Internal electric field engineering step-schemebased heterojunction using lead-free

perovskite-modified for selective photocatalytic reduction to CO. Appl. Catal. B 313, 121426 (2022). - He, Y. et al. Selective conversion of

to enhanced by -scheme heterojunction photocatalysts with efficient activation. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 14860-14869 (2023). - Tébar-Soler, C. et al. Low-oxidation-state Ru sites stabilized in carbon-doped

with low-temperature activation to yield methane. Nat. Mater. 22, 762-768 (2023). - Cao, S. et al.

-production and electron-transfer mechanism of a noble-metal-free S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 17174-17184 (2022). - Han, G. et al. Artificial photosynthesis over tubular

heterojunctions assisted by efficient activation and S -Scheme charge separation. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 7, 2200381 (2022). - Deng,

. et al. Enhanced solar fuel production over hierarchical nanofibers with S-Scheme charge separation mechanism. Small 19, 2305410 (2023). - Li, K. et al. Synergistic effect of cyano defects and

in graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets for efficient visible-light-driven photocatalytic NO removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 442, 130040 (2023). - Xia, Y.-S. et al. Tandem utilization of

photoreduction products for the carbonylation of aryl iodides. Nat. Commun. 13, 2964 (2022). - He, Y. et al. Boosting artificial photosynthesis:

chemisorption and S-Scheme charge separation via anchoring inorganic QDs on COFs. ACS Catal. 14, 1951-1961 (2024). - Tao, Y. et al. Kinetically-enhanced polysulfide redox reactions by

nanocrystals for high-rate lithium-sulfur battery. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 3230-3239 (2016). - Su, K. et al.

-based photocatalysts. Adv. Sci. 8, 2003156 (2021). - Lin, X. et al. Fabrication of flexible mesoporous black

nanofiber films for visible-light-driven photocatalytic reduction into . Adv. Mater. 34, 2200756 (2022). - Jeon, T. H. et al. Dual modification of hematite photoanode by Sndoping and

layer for water oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 201, 591-599 (2017). - Sayed, M. et al. Sustained

-photoreduction activity and high selectivity over Mn, C-codoped ZnO core-triple shell hollow spheres. Nat. Commun. 12, 4936 (2021). - Han, J. et al. Ambient

fixation to at ambient conditions: using nanofiber as a high-performance electrocatalyst. Nano Energy 52, 264-270 (2018). - Pei, C. et al. Structural properties and electrochemical performance of different polymorphs of

in magnesium-based batteries. J. Energy Chem. 58, 586-592 (2021). - Xu, F. et al. Unique S-scheme heterojunctions in self-assembled

hybrids for photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 11, 4613 (2020). - Jiang, Z. et al. A review on ZnO -based S -scheme heterojunction photocatalysts. Chin. J. Catal. 52, 32-49 (2023).

- Zhao, X. et al. 3D Fe-MOF embedded into 2D thin layer carbon nitride to construct 3D/2D S-scheme heterojunction for enhanced photoreduction of

. Chin. J. Catal. 43, 2625-2636 (2022). - Zhu, B. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic

reduction over 2D/1D -scheme heterostructure. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 38, 2111008 (2021). -

. et al. Step-by-step mechanism insights into the S-Scheme photocatalyst for enhanced aniline production with water as a proton source. ACS Catal. 12, 164-172 (2022). - Zhang, J. et al. Molecular-level engineering of S -scheme heterojunction: the site-specific role for directional charge transfer. Chin. J. Struc. Chem. 41, 2206003-2206005 (2022).

- Feng, C. et al. Effectively enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production performance of one-pot synthesized

clusters/CdS nanorod heterojunction material under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 345, 404-413 (2018). - Xu, J. et al. In situ cascade growth-induced strong coupling effect toward efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of

. Appl. Catal. B 328, 122493 (2023). - Yang, H. et al. Constructing electrostatic self-assembled 2D/2D ultra-thin

protonated heterojunctions for excellent photocatalytic performance under visible light. Appl. Catal. B 256, 117862 (2019). - Hu, X. et al. In situ fabrication of superfine perovskite composite nanofibers with ultrahigh stability by one-step electrospinning toward white light-emitting diode. Adv. Fiber Mater. 5, 183-197 (2023).

- Yan, Z. et al. Interpreting the enhanced photoactivities of OD/1D heterojunctions of CdS quantum dots

nanotube arrays using femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. Appl. Catal. B 275, 119151 (2020). - Zhang, Y. et al. Fabricating Ag/CN/ZnIn

-Scheme heterojunctions with plasmonic effect for enhanced light-driven photocatalytic reduction. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 39, 2211051 (2023). - Peng, J. et al. Uncovering the mechanism for urea electrochemical synthesis by coupling

and on -MXene. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 41, 2209094-2209104 (2022). - Gao, R. et al. Pyrene-benzothiadiazole-based Polymer/CdS 2D/2D Organic/Inorganic Hybrid S-scheme Heterojunction for Efficient Photocatalytic

Evolution. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 41, 2206031-2206038 (2022). - Wang, Y. et al. Selective electrocatalytic reduction of

to formate via carbon-shell-encapsulated nanoparticles/graphene nanohybrids. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 121, 220-226 (2022). - Xu, K. et al. Efficient interfacial charge transfer of BiOCl-

stepscheme heterojunction for boosted photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 121, 236-244 (2022). - Li, S. et al. Constructing

-scheme heterojunction for boosted photocatalytic antibiotic oxidation and reduction. Adv. Powder Mater. 2, 100073 (2023). - Wang, L. et al. S-scheme heterojunction photocatalysts for

reduction. Matter 5, 4187-4211 (2022). - Li, H., Gong, H. & Jin, Z. In

-modified three-dimensional nanoflower form S -scheme heterojunction for efficient hydrogen production. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 38, 2201037 (2022). - Zhao, X. et al. UV light-induced oxygen doping in graphitic carbon nitride with suppressed deep trapping for enhancement in

photoreduction activity. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 133, 135-144 (2023). - Wang, L. et al. Dual transfer channels of photo-carriers in 2D/2D/2D sandwich-like

MXene S-scheme/Schottky heterojunction for boosting photocatalytic evolution. Chin. J. Catal. 43, 2720-2731 (2022). - Yang, T. et al. Simultaneous photocatalytic oxygen production and hexavalent chromium reduction in

S-scheme heterojunction. Chin. J. Struc. Chem. 41, 2206023-2206030 (2022). - Huang, B. et al. Chemically bonded

heterojunction with fast hole extraction dynamics for continuous photoreduction. Adv. Powder Mater. 3, 100140 (2024). - Zhang, J. et al. Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy investigation into the electron transfer mechanism in photocatalysis. Chem. Commun. 59, 688-699 (2023).

- Cheng, C. et al. Verifying the charge-transfer mechanism in S-Scheme heterojunctions using femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218688 (2023).

- Wang, S. et al. Designing reliable and accurate isotope-tracer experiments for

photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 14, 2534 (2023). - Su, B. et al. Hydroxyl-Bonded Ru on metallic TiN surface catalyzing

reduction with by Infrared Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27415-27423 (2023). - Zou, W. et al. Metal-free photocatalytic

reduction to and under non-sacrificial ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313392 (2023). - Li, F. et al. Balancing hydrogen adsorption/desorption by orbital modulation for efficient hydrogen evolution catalysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 4060 (2019).

- Kang, J., Sahin, H. & Peeters, F. M. Tuning carrier confinement in the

lateral heterostructure. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 9580-9586 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© The Author(s) 2024

Laboratory of Solar Fuel, Faculty of Materials Science and Chemistry, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan 430078, PR China. College of Pharmacy, Dali University, Dali 671003, PR China. Hubei Key Laboratory of Low Dimensional Optoelectronic Materials and Devices, Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang 441053, PR China. These authors contributed equally: Xianyu Deng, Jianjun Zhang. e-mail: xufeiyan@cug.edu.cn; yujiaguo93@cug.edu.cn