DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-024-00994-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38221607

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-14

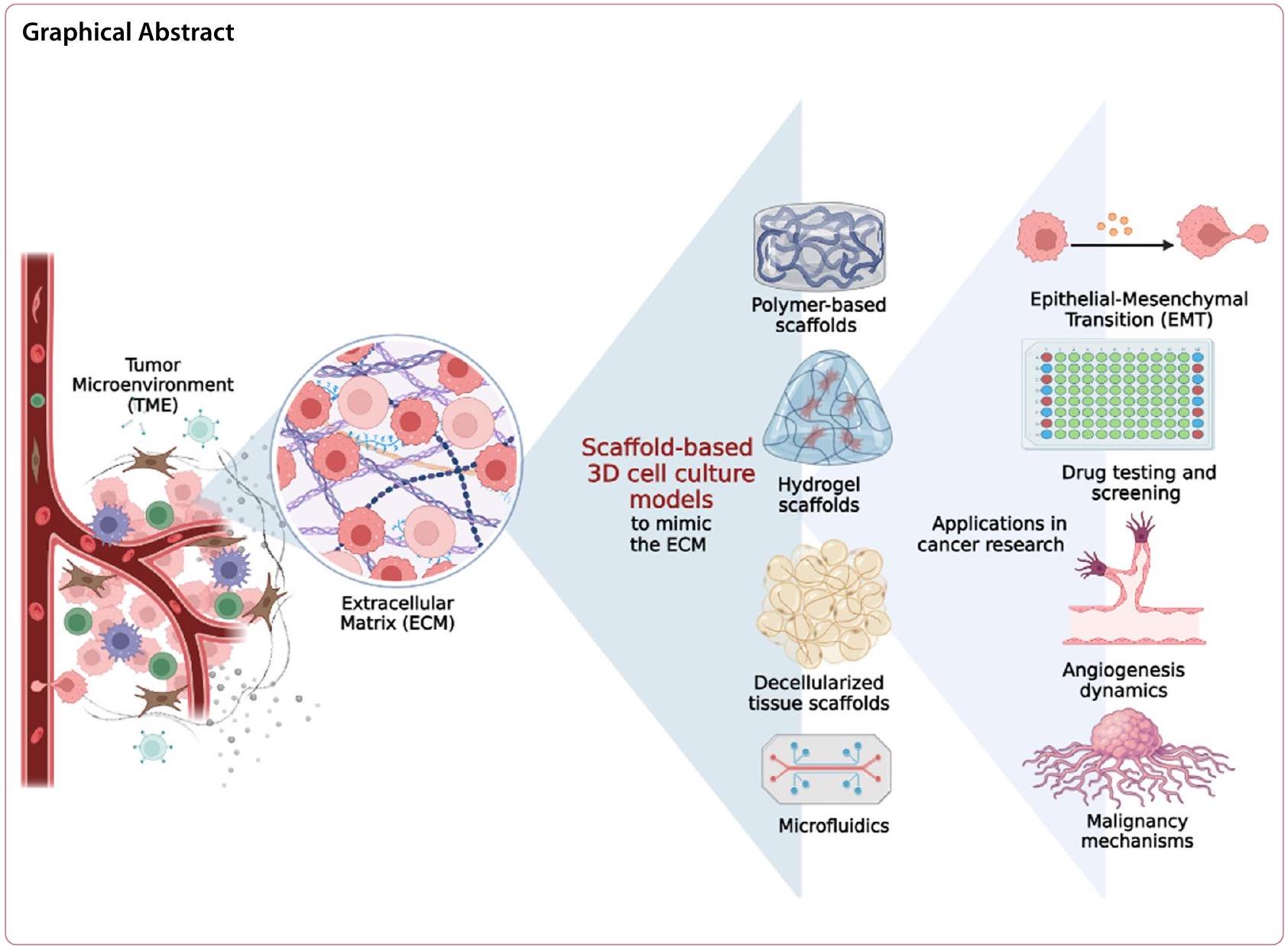

نماذج زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد المعتمدة على الهياكل في أبحاث السرطان

الملخص

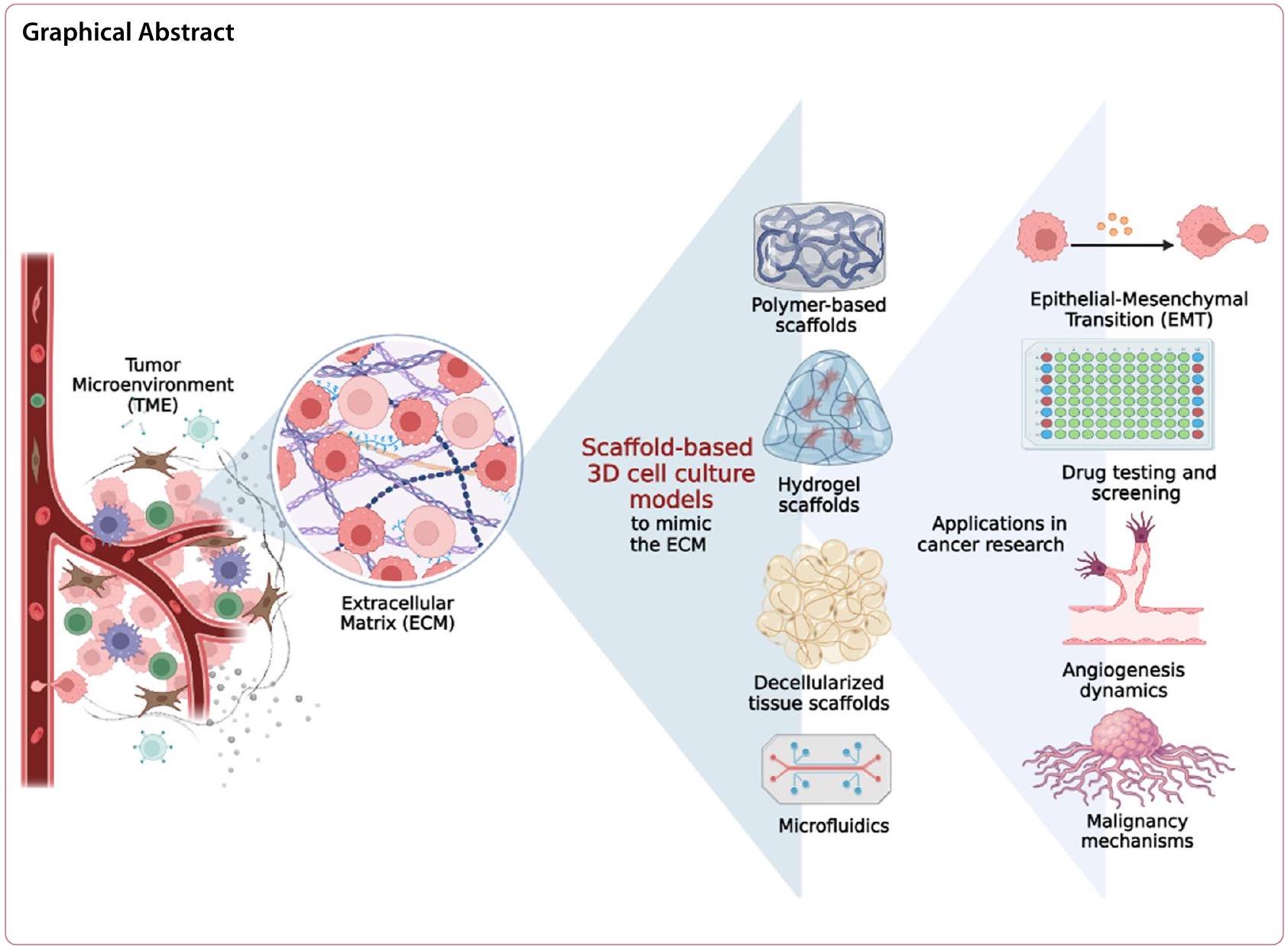

ظهرت زراعات الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد (3D) كأدوات قيمة في أبحاث السرطان، حيث تقدم مزايا كبيرة مقارنة بأنظمة زراعة الخلايا ثنائية الأبعاد التقليدية (2D). في زراعات الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد، تنمو خلايا السرطان في بيئة تحاكي بشكل أقرب العمارة ثلاثية الأبعاد وتعقيد الأورام في الجسم. لقد أحدث هذا النهج ثورة في أبحاث السرطان من خلال توفير تمثيل أكثر دقة للبيئة الدقيقة للورم (TME) وتمكين دراسة سلوك الورم واستجابته للعلاجات في سياق أكثر ملاءمة فسيولوجيًا. واحدة من الفوائد الرئيسية لزراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد في أبحاث السرطان هي القدرة على إعادة إنتاج التفاعلات المعقدة بين خلايا السرطان والستروما المحيطة بها. تتكون الأورام ليس فقط من خلايا السرطان ولكن أيضًا من أنواع خلايا أخرى متنوعة، بما في ذلك خلايا الستروما، وخلايا المناعة، والأوعية الدموية. هذه النماذج تربط بين زراعات الخلايا ثنائية الأبعاد التقليدية ونماذج الحيوانات، مما يوفر بديلاً فعالاً من حيث التكلفة، وقابل للتوسع، وأخلاقي للبحث قبل السريري. مع تقدم هذا المجال، من المتوقع أن تلعب زراعات الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد دورًا محوريًا في فهم بيولوجيا السرطان وتسريع تطوير علاجات فعالة لمكافحة السرطان. يسلط هذا المقال الاستعراضي الضوء على المزايا الرئيسية لزراعات الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد، والتقدم في تقنيات الزراعة الأكثر شيوعًا القائمة على السقالات، والأدبيات ذات الصلة حول تطبيقاتها في أبحاث السرطان، والتحديات المستمرة.

المقدمة

طرق العلاج، وتطوير أدوات تشخيصية أكثر تطورًا، وفهم الآليات الجينية والجزيئية المعنية في تطوره وتقدمه [3].

الأهمية الفسيولوجية لزراعات الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد بالنسبة للمصفوفة خارج الخلية

الحالة الأيضية الخلوية. من الجدير بالذكر أن الخلايا المزروعة في المصفوفة خارج الخلية للورم أظهرت مستويات مرتفعة من NADH الحرة، مما يشير إلى زيادة في معدل التحلل الجليكولي مقارنة بتلك المزروعة في المصفوفة خارج الخلية الطبيعية. تؤكد هذه النتائج التأثير الكبير للمصفوفة خارج الخلية على نمو خلايا السرطان والأوعية الدموية المصاحبة (مثل زيادة طول الأوعية، وزيادة تغايرية الأوعية). يمكن أن تُعزى التغيرات في تركيبة المصفوفة خارج الخلية للورم، مثل زيادة ترسيب وتداخل ألياف الكولاجين، إلى التواصل بين خلايا الورم وخلايا الستروما المرتبطة بالورم.

| نوع السرطان | نموذج الثقافة ثلاثي الأبعاد (نوع الخلية) | |||

| سرطان الرئة |

|

|||

| ورم دبقي متعدد الأشكال |

|

|||

| سرطان الثدي |

|

|||

| سرطان البنكرياس |

|

|||

| سرطان المبيض |

|

|||

| سرطان القولون |

|

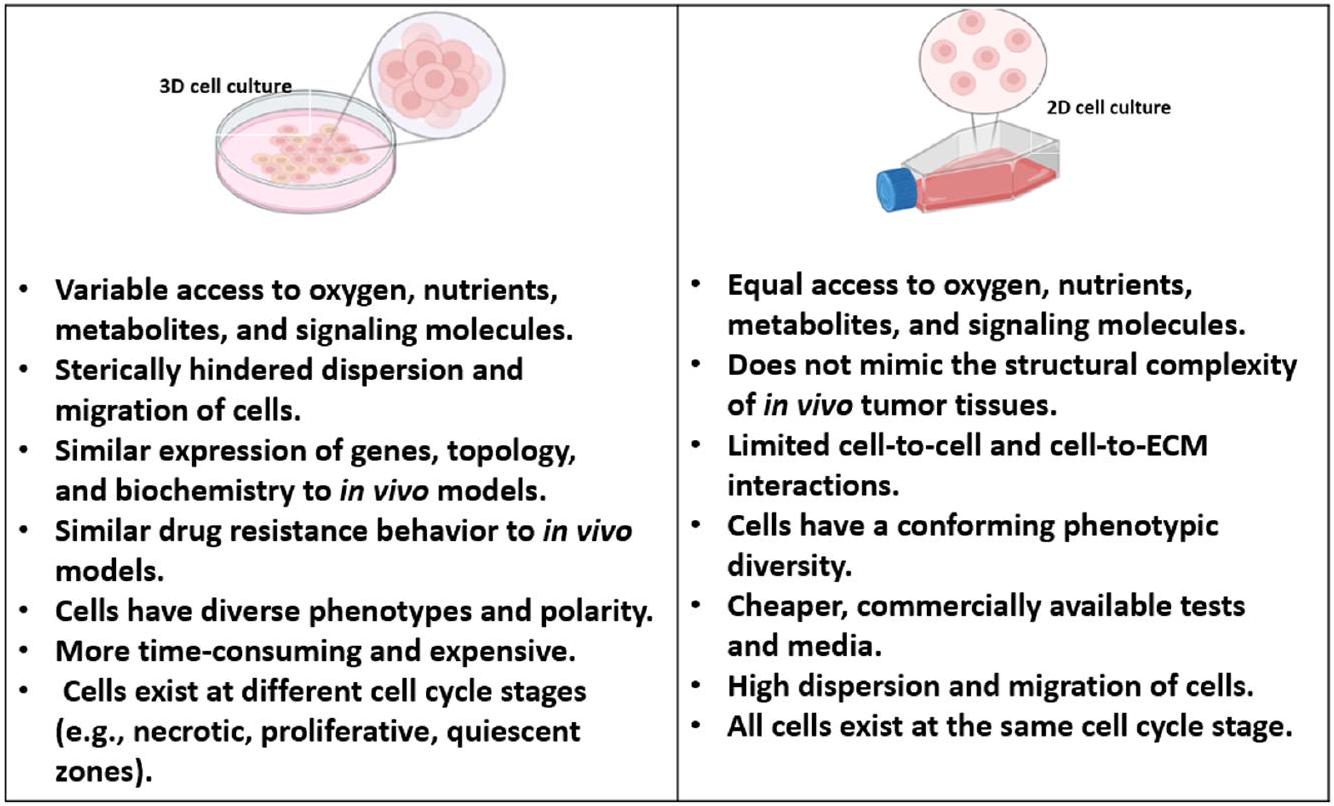

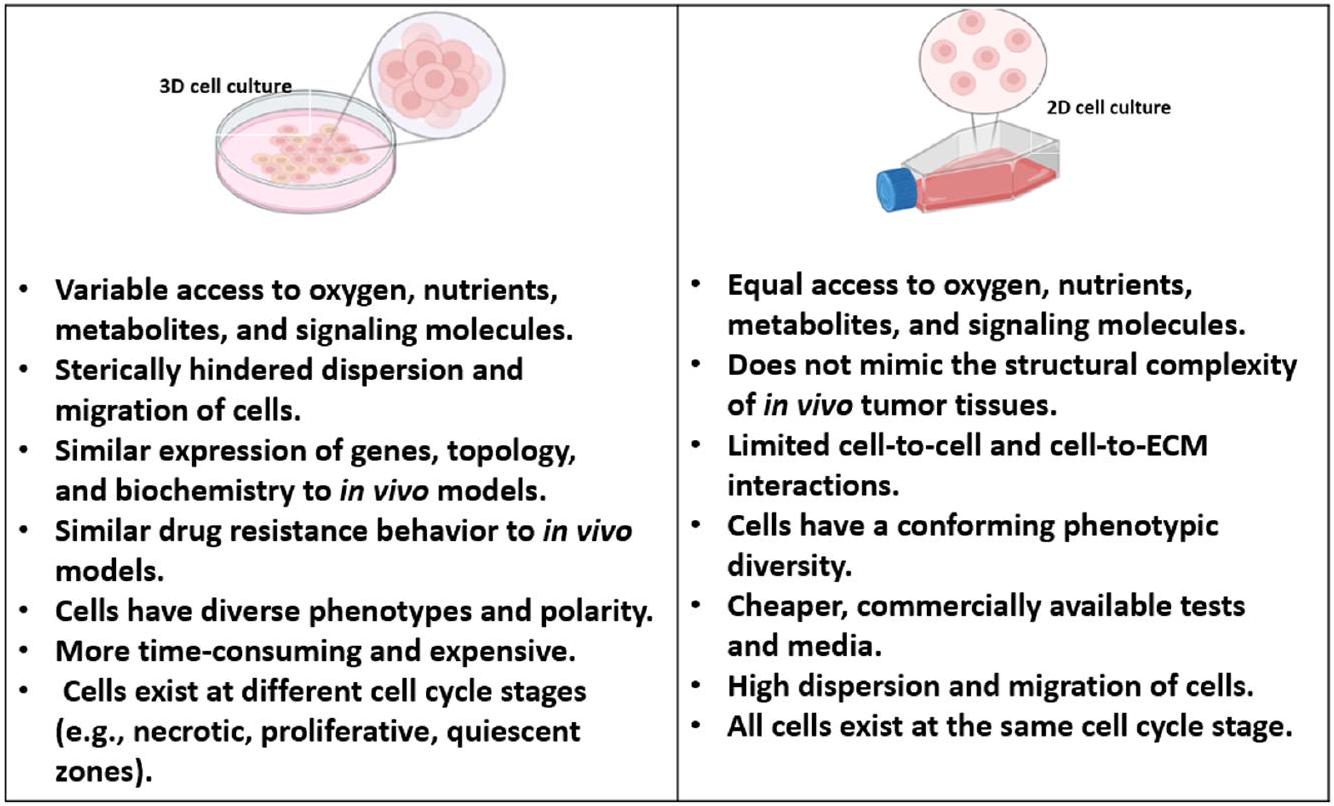

تُلخص الشكل 1 الخصائص الرئيسية لزراعة الخلايا ثنائية وثلاثية الأبعاد. إن الانتقال إلى زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد هو تقدم كبير في البحث المختبري، حيث يوفر نموذجًا أكثر ملاءمة من الناحية الفسيولوجية لدراسة الخلايا.

العمليات والأمراض. بينما لا تزال بعض التحديات بحاجة إلى معالجة، فإن مزايا الثقافة ثلاثية الأبعاد تفوق قيود الثقافة ثنائية الأبعاد. مع استمرار تطور التكنولوجيا، من المحتمل أن تصبح الثقافة ثلاثية الأبعاد أداة حاسمة بشكل متزايد في أبحاث السرطان وحقول العلوم الطبية الحيوية الأخرى.

مصادر الخلايا وتنوع الثقافة ثلاثية الأبعاد

خزان من خلايا الإنسان، قادر على التطور إلى أي نوع من الخلايا المطلوبة للتطبيقات العلاجية. خلايا الجذع المستحثة متعددة القدرات (HiPSCs) ذات صلة خاصة في أبحاث السرطان (الجدول 3) [47]. وبالتالي، فإن عملية إعادة البرمجة التي روج لها شينيا ياماناكا قد فتحت آفاقًا جديدة لتقدم علم السرطان، واكتشاف الأدوية، والطب التجديدي في علاج السرطان. أخيرًا، خلايا الجذع البالغة أو الجسدية هي خلايا محددة الأنسجة، تعكس خصائص أصلها، وتثير مخاوف أخلاقية أقل لأنها مشتقة من أنسجة بالغة. ومع ذلك، فإن لديها قدرة محدودة على التمايز وعمرًا محدودًا في الثقافة. يؤثر اختيار مصدر الخلايا بشكل كبير على التركيب والسلوك في الثقافة ثلاثية الأبعاد. خلايا الجذع و iPSCs، المعروفة بتعدد قدراتها، تقدم تباينًا متأصلًا بسبب قدرتها على التمايز إلى أنواع مختلفة من الخلايا [45، 46].

| نوع النموذج | ميزات | المزايا | العيوب | |||||||

| زراعة الخلايا ثنائية الأبعاد | تشمل الخلايا المزروعة في طبقة مسطحة ثنائية الأبعاد، عادةً على أطباق الزرع. | بروتوكولات راسخة. نمو الخلايا وانقسامها بسرعة. بسيطة وفعالة من حيث التكلفة. سهلة التلاعب والتحليل. مناسبة للفحص عالي الإنتاجية. | تمثيل مبسط للغاية لظروف داخل الجسم. يفتقر إلى تفاعلات الخلايا مع بعضها البعض وتفاعلات الخلايا مع المصفوفة. شكل مسطح، مما قد يغير الاستجابات الخلوية. | |||||||

| زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد | تمثيل ترتيب ثلاثي الأبعاد للخلايا يحاكي التعقيد المكاني للبيئات الحية. يمكن أن تكون هذه الأنظمة خالية من الدعائم أو قائمة على الدعائم، حيث يتم زراعة الخلايا في الدعائم أو المصفوفات، مما يسمح بالتفاعلات التي تعيد تمثيل الظروف الفسيولوجية بشكل أفضل. | تحسين توقع استجابة الأدوية. يسمح بدراسة البيئة المجهرية للورم ويسهل التحقيق في تباين الأورام. | تباين في البروتوكولات والمنهجيات. قابلية محدودة للتوسع في الاختبارات عالية الإنتاجية. | |||||||

| الأنسجة والأعضاء | يتضمن زراعة الخلايا في تكوينات تحاكي بنية ووظيفة أعضاء أو أجزاء تشريحية محددة. توفر هذه الأنظمة بيئة أكثر تعقيدًا وشمولية من الخلايا الفردية، مما يسمح بتمثيل أقرب للظروف داخل الجسم. من خلال تنظيم الخلايا في هياكل تشبه الأعضاء أو الأنسجة، يمكن للباحثين دراسة التفاعلات بين أنواع الخلايا المختلفة واكتساب رؤى حول الاستجابات الخاصة بالأعضاء تجاه السرطان وعلاجاته. |

|

|

|||||||

| الحيوانات | نماذج الحيوانات، مثل الفئران أو الجرذان، هي كائنات حية تُستخدم لدراسة السرطان. |

|

|

|||||||

| المرضى | تشمل أنظمة نماذج المرضى في أبحاث السرطان استخدام عينات مستمدة مباشرة من المرضى. يمكن أن تشمل هذه النماذج زراعة الأورام المستمدة من المرضى (PDX) أو الأعضاء المصغرة أو نماذج مخصصة أخرى. تهدف هذه الأنظمة إلى التقاط الخصائص الفريدة لأورام المرضى الأفراد، مما يسمح بإجراء دراسات أكثر تخصيصًا وملاءمة لكل مريض. |

|

|

إن الاستجابات المحددة الغامضة، في حين أن التماثل المفرط قد يبسط بشكل مفرط تمثيل بيئة الأنسجة الدقيقة. لذلك، فإن فهمًا دقيقًا لمصدر الخلايا أمر ضروري لتكييف نماذج زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد لتعكس بدقة تعقيدات الأنسجة والأعضاء الفعلية.

تقنيات قائمة على السقالات لزراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد

| الخلايا المستخدمة في زراعة الخلايا في المختبر | فضائل | عيوب | الدراسات ذات الصلة | |||||

| الخلايا الجذعية |

|

تتمتع خلايا الجذع البالغة أو الجسدية بإمكانات تمايز أكثر تقييدًا من خلايا الجذع متعددة القدرات، مما يحد من مرونتها في نمذجة الأنسجة المتنوعة. | خلايا جذعية من المايلوما [48]. خلايا جذعية من الميلانوما [49]. خلايا جذعية من سرطان الثدي [50]. | |||||

| خلايا جذعية متعددة القدرات المستحثة (iPSCs) | تسمح الطبيعة متعددة القدرات لخلايا HiPSCs بإنشاء نماذج في المختبر تعكس خصائص خلايا السرطان بشكل وثيق، مما يوفر رؤى قيمة حول تطور السرطان وتقدمه. |

|

|

|||||

| خلايا أولية |

|

|

خلايا سرطان الثدي الأولية [56]. خلايا سرطان البروستاتا الأولية [57]. خلايا الورم الدبقي الأولية [58]. |

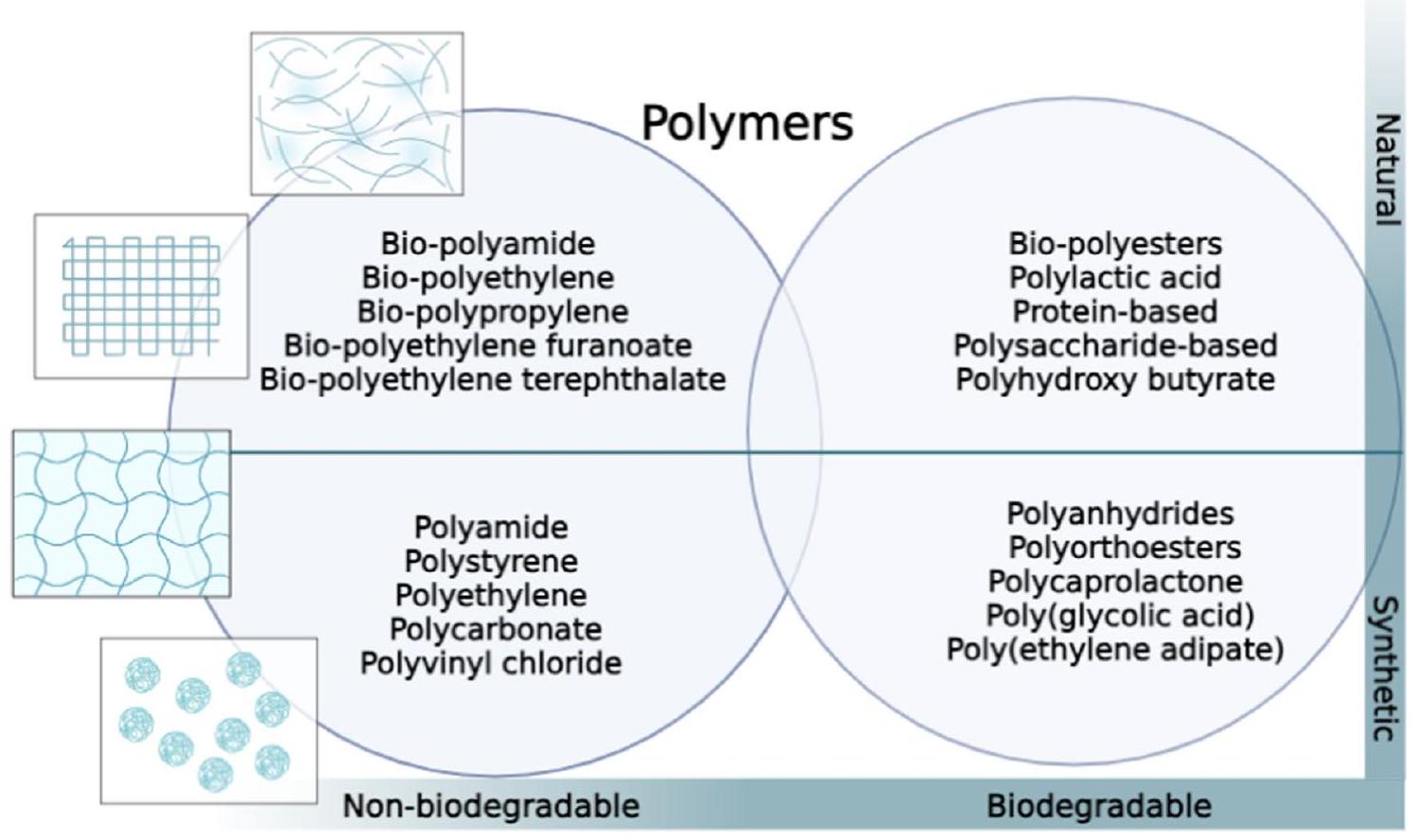

إلى فحص النماذج القائمة على الدعائم لزراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد. تعتبر الدعائم مكونات أساسية في أنظمة زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد، حيث توفر بيئة ثلاثية الأبعاد لنمو الخلايا وتفاعلها مع بعضها البعض ومع محيطها [61، 62]. يمكن تصنيف المواد الحيوية المستخدمة في مثل هذه النماذج إلى المجموعات الرئيسية التالية: دعائم بوليمرية، هيدروجيل، دعائم أنسجة غير خلوية، ودعائم هجينة (مثل دمج أجهزة ميكروفلويديك). تلخص الجداول 4 و 5 مزايا وقيود تقنيات زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد الخالية من الدعائم والقائمة على الدعائم على التوالي.

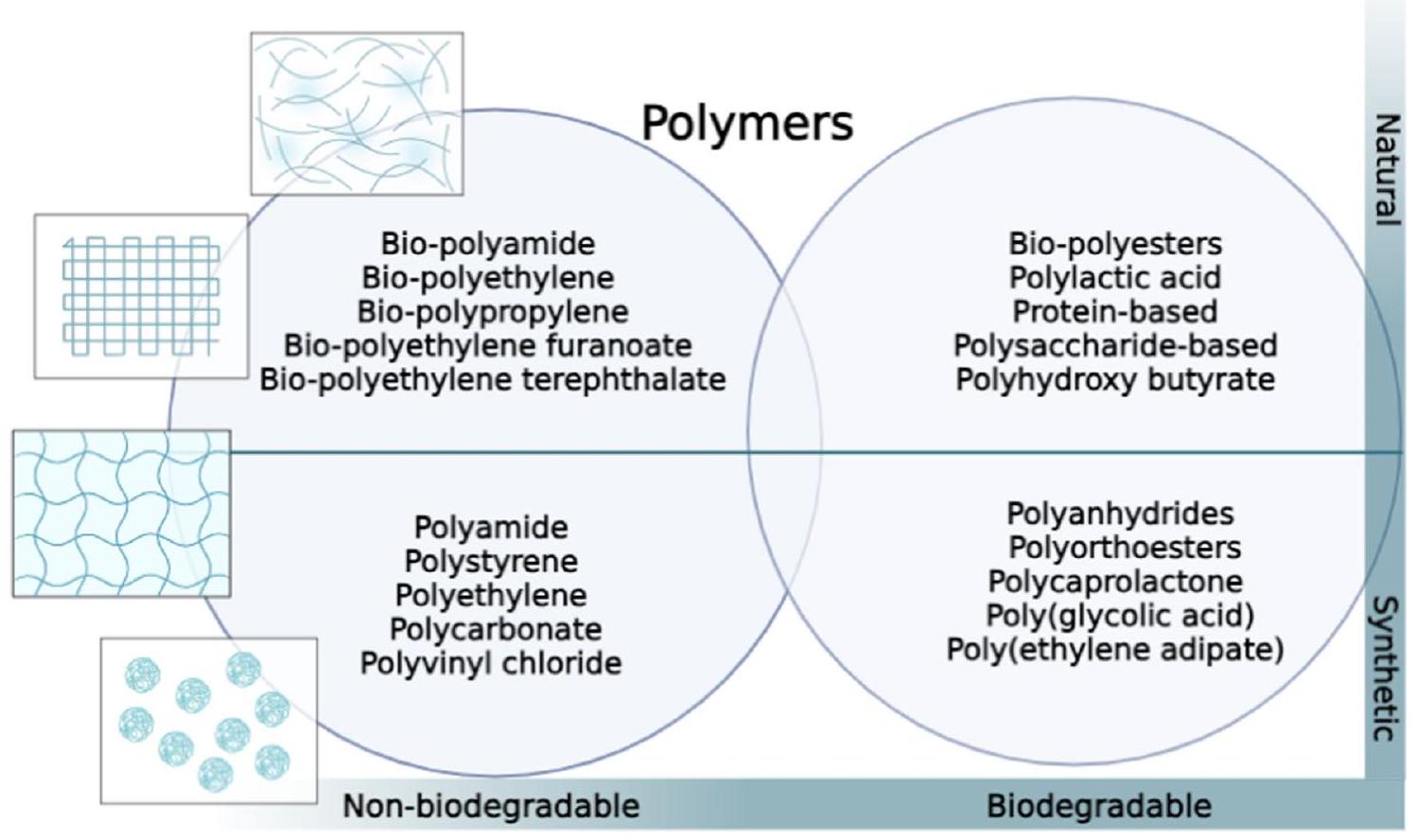

دعائم قائمة على البوليمر

| تقنية خالية من الدعائم | الوصف | المزايا | القيود | المراجع | |||||||||||||

| الأشكال المعلقة أو الأشكال المعلقة المربوطة | تُعرف أيضًا بالأشكال المعلقة المربوطة. يتم تعليق الخلايا في قطرة من الوسط التي تُعلق من سطح. توفر القطرة بيئة ثلاثية الأبعاد لنمو الخلايا وتشكيل الأشكال. لا تتطلب الأشكال المربوطة دعامة أو مصفوفة لدعم الخلايا. عادةً، يمكن الحفاظ عليها لمدة 10 إلى 14 يومًا. |

|

|

[63-67] | |||||||||||||

| الأشكال غير الملتصقة أو الأشكال ذات الالتصاق المنخفض جدًا | تُعرف أيضًا باختبار تشكيل كرات الورم متعددة الخلايا. تشكل الخلايا كرات ورمية من خلال آليات نمو مستقلة عن التثبيت. عادةً، يمكن الحفاظ على هذه الكرات لمدة تصل إلى 7 أيام. |

|

|

[68-71] | |||||||||||||

| الطباعة الحيوية الخالية من الدعائم | تشمل الطباعة المباشرة لتجمعات الخلايا أو الخلايا الفردية دون استخدام دعامة خارجية. في هذه الطريقة، يتم طباعة الخلايا بطريقة تسمح لها بالتجمع الذاتي والتفاعل مع الخلايا المجاورة، مما يشكل هياكل تشبه الأنسجة ثلاثية الأبعاد دون الحاجة إلى دعامة داعمة. عادةً، يمكن الحفاظ عليها لمدة 2 إلى 4 أيام. |

|

|

[72-77] | |||||||||||||

| الرفع المغناطيسي | إنها طريقة جديدة نسبيًا خالية من الدعائم لزراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد. في هذه الطريقة، يتم خلط الخلايا مع جزيئات نانوية مغناطيسية ويتم رفعها باستخدام مجال مغناطيسي. بينما تطفو الخلايا، تتجمع وتشكل هياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد. يسمح الرفع المغناطيسي بإنشاء هياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد معقدة. عادةً، يمكن الحفاظ على زراعة الخلايا لأكثر من 7 أيام. |

|

|

[78-83] | |||||||||||||

| الميكروفلويديات الخالية من الدعائم | تعزز بيئات زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد دون مصفوفات داعمة، مثل الهيدروجيل أو الدعائم. تخلق هذه الأجهزة بيئات ميكروية محكومة داخل قنوات ميكروفلويدية لتسهيل تجمع وتنظيم الخلايا السرطانية ذاتيًا، مما يعزز تشكيل هياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد، بما في ذلك الأشكال أو الأعضاء. |

|

|

[٨٤، ٨٥] |

من ناحية أخرى، تتكون الدعائم المعتمدة على البوليسكاريد من سلاسل طويلة من جزيئات السكر (مثل الكيتوزان وحمض الهيالورونيك). إنها متوافقة حيوياً وقابلة للتحلل البيولوجي، وغالباً ما يمكن تعديلها لضبط خصائصها الفيزيائية والبيولوجية. طور آريا وآخرون [97] نموذج زراعة خلايا ثلاثي الأبعاد باستخدام دعامة من الكيتوزان، وهو بوليمر طبيعي مشتق من الكيتين، لدراسة سلوك سرطان الثدي. تم ربط الدعامة مع الجينيبين، وهو رابط طبيعي، لتعزيز استقرارها. وجدت الدراسة أن دعامة الكيتوزان-جيلاتين (GC) وفرت بيئة مناسبة لنمو خلايا سرطان الثدي MCF-7، حيث أظهرت الخلايا التصاقاً جيداً وتكاثراً. كما دعمت الدعامة تشكيل تجمعات خلوية، والتي تمثل ظروف الورم في الجسم الحي بشكل أفضل مقارنة بالزراعات ثنائية الأبعاد. الدراسة

خلصت الدراسة إلى أن الهيكل الداعم من الكيتوزان/الجيلاتين يمكن أن يكون مفيدًا لدراسة سرطان الثدي في المختبر، حيث يوفر نموذجًا أكثر ملاءمة من الناحية الفسيولوجية مقارنة بالثقافات التقليدية ثنائية الأبعاد. لقد أظهرت هياكل GC أنها تدعم تشكيل الأورام الصغيرة التي تحاكي الأورام التي تنمو في الجسم، مما يجعلها نموذجًا محسنًا للأورام في المختبر. تم استخدام هذه الهياكل بنجاح لدراسة سرطان الرئة، بالإضافة إلى أنواع أخرى من السرطان، مثل سرطان الثدي، وسرطان عنق الرحم، وسرطان العظام. لقد أظهرت هذه الهياكل ملفات تعبير جيني مشابهة لتلك الموجودة في الأورام التي تنمو في الجسم، مما يشير إلى إمكانياتها لدراسة تقدم السرطان واختبار الأدوية للأورام الصلبة. كما أظهرت هياكل GC أنها تحسن من القدرة التنبؤية للدراسات قبل السريرية وتعزز من الترجمة السريرية للعلاجات. بشكل عام، توفر هياكل GC أداة قيمة لدراسة تطور الأورام وتقييم فعالية الأدوية المضادة للسرطان في بيئة المختبر.

| نوع السقالة | وصف | المزايا | القيود | المراجع | ||||||

| بوليمرات طبيعية | إنها مشتقة من مصادر طبيعية مثل الكولاجين، الفيبرين، أو الألجينات. هذه الهياكل تحاكي المصفوفة خارج الخلوية الأصلية وتوفر بيئة ميكروية ملائمة لنمو الخلايا. |

|

|

[٨٦، ٨٧] | ||||||

| بوليمرات قابلة للتحلل الاصطناعي | تم تصنيعها باستخدام مواد قابلة للتحلل الحيوي صناعية مثل بولي كابرو لاكتون (PCL) أو بولي (حمض اللاكتيك-حمض الجليكوليك) (PLGA). توفر هذه الهياكل تحكمًا دقيقًا في خصائصها ويمكن تخصيصها لتلبية متطلبات محددة. |

|

|

[88] | ||||||

| الهلاميات المائية | يتكون من شبكة ثلاثية الأبعاد من سلاسل البوليمر المحبة للماء القادرة على الاحتفاظ بكميات كبيرة من الماء. توفر بيئة رطبة وناعمة لنمو الخلايا. |

|

|

[89] | ||||||

| أنسجة خالية من الخلايا | يتضمن ذلك إزالة المكونات الخلوية من الأنسجة الأصلية، مما يترك وراءه هيكل ECM والجزيئات النشطة حيوياً. توفر هذه الهياكل بيئة تشبه إلى حد كبير البيئة الميكروية للأنسجة الأصلية. |

|

|

[90] |

| نوع السقالة | وصف | المزايا | القيود | المراجع | |||

| الميكروفلويديات المعتمدة على السقالات | تُزرع الخلايا داخل قنوات ميكروسكوبية توفر بيئة ميكروية محكومة لنمو الخلايا في هيكل محمل بالخلايا. | – يمكن إنشاء تحكم دقيق في الزمان والمكان على ظروف زراعة الخلايا (مثل تدفق السوائل، التدرجات الكيميائية، وتوصيل الأكسجين والمواد الغذائية). – يمكن أن تحاكي واجهات الأنسجة. |

|

[91,92] |

زراعة الدعامات. في الوقت نفسه، كانت تعبيره مرتفعًا بشكل ملحوظ داخل الأورام المستمدة من دعامات PLGA المحملة بخلايا MDA-MB-231. تشير هذه النتيجة إلى أن مجموعة خلايا السرطان داخل الدعامات أظهرت تكاثرًا سريعًا عند تضمينها في الأنسجة الثديية الأصلية.

دعائم الهيدروجيل

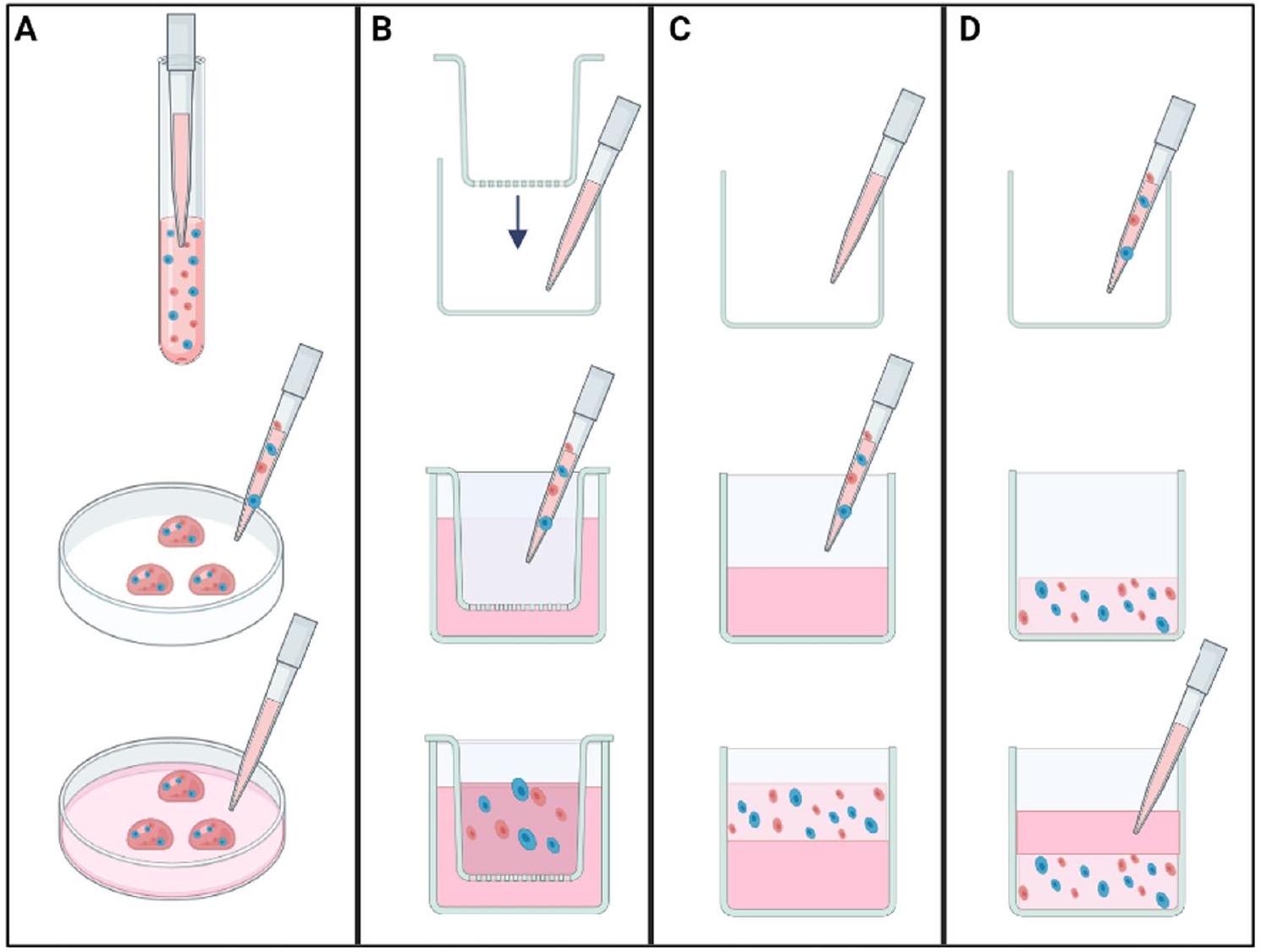

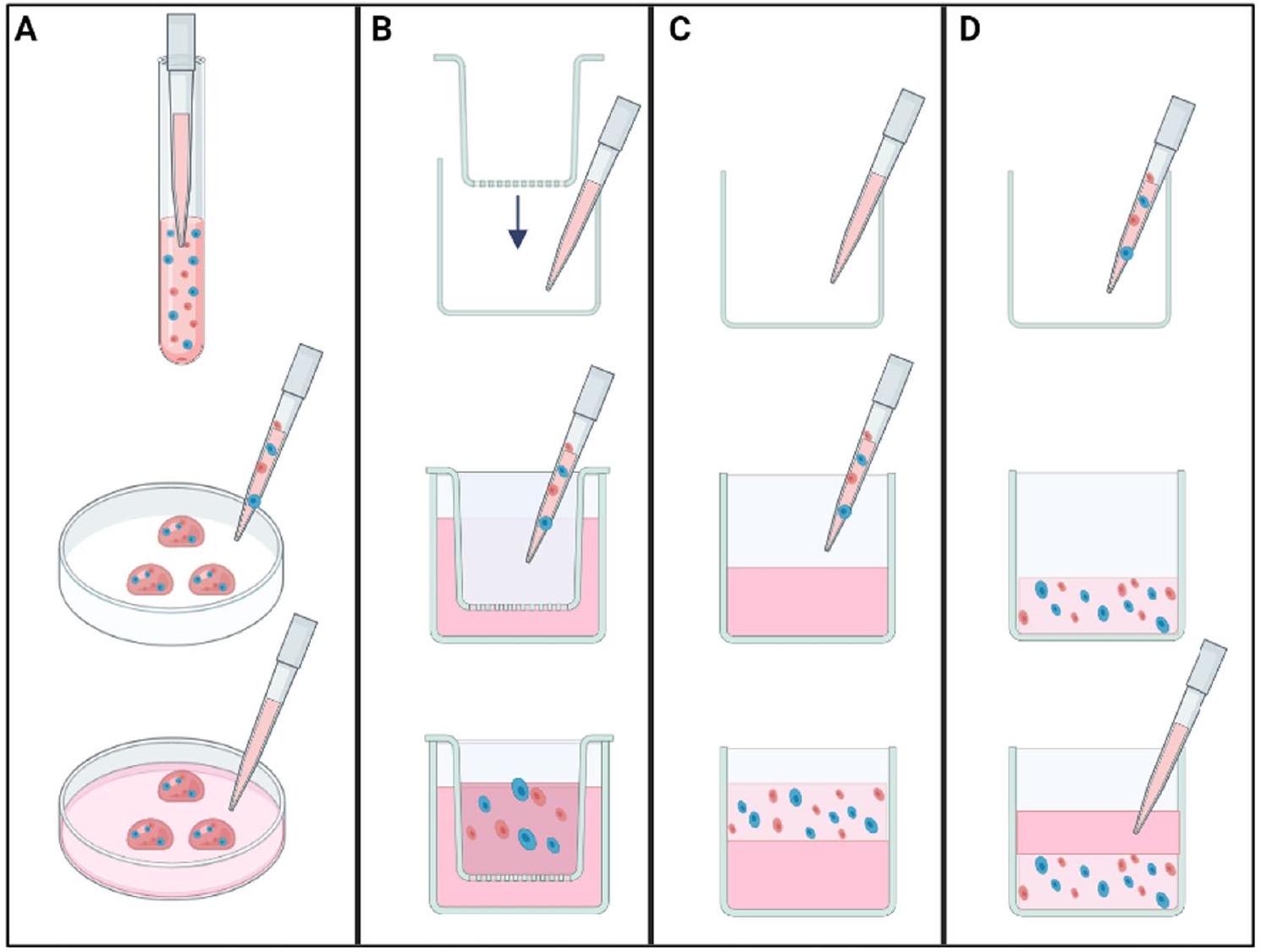

هيكل ثلاثي الأبعاد بسيط ومعزول. توضح الشكل 3B تقنية الآبار المضافة، التي تتكون من إضافات مسامية لحمل خليط الخلايا والهيدروجيل بينما يتم إضافة وسط زراعة الخلايا إلى البئر المحيط بالإضافة. تخلق هذه الفجوة بيئة تفاضلية، مما يسمح بتبادل المغذيات مع الحفاظ على ثقافة ثلاثية الأبعاد متميزة داخل الإضافة. ستتشكل كريات غير متجانسة في النهاية في قاع الإضافة بسبب الجاذبية وتفاعلات الخلايا. يمكن استخدام مثل هذا النموذج لدراسة غزو الخلايا أو هجراتها عن طريق وضع خليط الخلايا والهيدروجيل على جانب واحد من غشاء قابل للاختراق والمواد الكيميائية الجاذبة على الجانب الآخر. تتضمن طريقة دعم قاع الهلام (انظر الشكل 3C) إنشاء طبقة سميكة من الهيدروجيل في قاع بئر الزراعة، يتم وضع تعليق الخلايا فوقها. على سبيل المثال، يمكن استخدام هذه الطريقة لتضمين الخلايا داخل هياكل هيدروجيل ذات مسام كبيرة، مثل AlgiMatrix.

نظرًا لخصائصها القابلة للتعديل، تقدم الهيدروجيل الاصطناعية فوائد ملحوظة في ثقافة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد. ببتيد RADA16-I هو ببتيد يتجمع ذاتيًا مستمد من جزء من زيوت، وهو بروتين يرتبط بـ Z-DNA بيد اليسار تم اكتشافه في الأصل في الخميرة. لقد ظهر هذا الببتيد كمادة نانوية جديدة بسبب قدرته على تشكيل هياكل نانوية. وبالتالي، توفر هذه الهياكل إطارًا داعمًا يعزز نمو الخلايا ويعزز بيئة ثلاثية الأبعاد ملائمة لثقافة الخلايا.

يمكن تعديل تسلسل الببتيد لدمج مجموعات وظيفية محددة، مما يتيح ضبط الخصائص الميكانيكية والكيميائية والبيولوجية للهيكل الناتج. هذه المرونة الرائعة تمكن من التخصيص لتتناسب بدقة مع المتطلبات الفريدة للخلايا المزروعة أو الأهداف التجريبية المقصودة. هذه الهياكل، التي يبلغ قطرها حوالي 10 نانومتر، مدفوعة بمتبقيات مشحونة إيجابيًا وسلبيًا من خلال تفاعلات أيونية مكملة. عند إذابتها في الماء، يشكل ببتيد RADA16-I هيدروجيل مستقر (شبكات ألياف نانوية بحجم مسام حوالي

هيالورونيداز. يسمح الاستجابة للجلوتاثيون بالتحلل استجابةً للبيئة المؤكسدة، والتي غالبًا ما تتعطل في خلايا السرطان. في الوقت نفسه، تجعل استجابة الهيالورونيداز الهيدروجيل حساسًا لإنزيم يتم تنظيمه عادةً في خلايا السرطان الغازية. بشكل ملحوظ، أظهرت خلايا MCF-7 المزروعة في هيدروجيل HA زيادة في التعبير عن عامل نمو بطانة الأوعية الدموية (VEGF)، والإنترلوكين-8 (IL-8)، وعامل نمو الألياف الأساسية (bFGF) مقارنةً بنظيراتها المزروعة ثنائية الأبعاد. هذه الجزيئات هي وسطاء رئيسيون في تكوين الأوعية الدموية والالتهاب في السرطان، مما يشير إلى أن بيئة هيدروجيل HA تحاكي بشكل أفضل الظروف التي تعزز هذه العمليات في الأورام. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهرت الخلايا المزروعة في الهيدروجيل قدرات معززة على الهجرة والغزو، وهي سمات رئيسية لخلايا السرطان العدوانية. دعمت الدراسات في الجسم هذه النتائج وأكدت القدرة الورمية المتفوقة لخلايا MCF-7 المزروعة في هيدروجيل HA مقارنةً بتلك المزروعة في 2D. من المتوقع أن تكون نتائج هذا البحث

لها آثار بعيدة المدى على كل من دراسة سرطان الثدي في المختبر وتطوير استراتيجيات علاجية فعالة.

أيدت دراسة أخرى أجراها وانغ وزملاؤه [108] أن مستوى الميثاكريليشن أثر بشكل كبير على الميكروستركشر للهيدروجيل، والخصائص الميكانيكية، وقدرته على امتصاص السوائل والتحلل. عرض الهيدروجيل المكرر، الذي تم تصنيعه من خلال الربط الضوئي لحمض الهيالورونيك الميثاكريل، هيكلًا مساميًا عاليًا، ونسبة انتفاخ متوازنة عالية، وخصائص ميكانيكية مناسبة، وعملية تحلل تستجيب للهيالورونيداز. وُجد أن هيدروجيل حمض الهيالورونيك يعزز نمو وتكاثر خلايا MCF-7، التي شكلت تجمعات داخل الهيدروجيل. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهرت خلايا MCF-7 المزروعة في بيئة ثلاثية الأبعاد زيادة في تعبير VEGF وbFGF وinterleukin-8، وقدرات متزايدة على الغزو وتكوين الأورام مقارنة بنظيراتها المزروعة في بيئة ثنائية الأبعاد. وبالتالي، أثبت هيدروجيل حمض الهيالورونيك أنه بديل موثوق لبناء نماذج الأورام. الجيلاتين الميثاكريلي (GelMA) هو مادة حيوية طبيعية أخرى تُستخدم بشكل شائع في هياكل الهيدروجيل ثلاثية الأبعاد في أبحاث السرطان. يتم اشتقاق GelMA من الجيلاتين، وهو بروتين طبيعي يتم الحصول عليه من مصادر غنية بالكولاجين. يتم تعديله عن طريق إضافة مجموعات ميثاكريلويل التي تمكنه من الخضوع للربط الضوئي عند تعرضه للأشعة فوق البنفسجية (UV). تتيح هذه الخاصية لـ GelMA تشكيل شبكات هيدروجيل مستقرة، مما يجعله مناسبًا لإنشاء هياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد تحاكي بيئة الورم الدقيقة (TME). تجعل الخصائص الميكانيكية والبيوكيميائية القابلة للتعديل لهيدروجيل GelMA، والتوافق الحيوي، والقدرة على دعم نمو الخلايا منها أدوات قيمة لدراسة سلوك خلايا السرطان، وغزو الورم، واختبار الأدوية، وغيرها من جوانب أبحاث السرطان. طور كيم وزملاؤه [109] نموذج زراعة خلايا ثلاثي الأبعاد للمثانة من خلال استخدام مصفوفة خلوية جديدة ومفاعل حيوي. تم استخدام GelMA كهيكل ثلاثي الأبعاد لزراعة خلايا سرطان المثانة، مع ارتفاع هيكل مثالي يبلغ 0.08 مم ووقت ربط يبلغ 120 ثانية [110]. بعد ذلك، تم زراعة خلايا 5637 وT24 في بيئات ثنائية وثلاثية الأبعاد وتعرضت لعلاجات دوائية باستخدام الراباميسين وبكتيريا كالميت-غرين (BCG). وُجد أن نموذج زراعة خلايا سرطان المثانة ثلاثي الأبعاد أظهر عملية إنشاء أسرع وثباتًا أكبر مقارنة بالنموذج ثنائي الأبعاد. علاوة على ذلك، أظهرت خلايا السرطان المزروعة في بيئة ثلاثية الأبعاد مقاومة متزايدة للأدوية وحساسية منخفضة مقارنة بالخلايا المزروعة في بيئة ثنائية الأبعاد. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، لاحظ الباحثون تفاعل الخلايا مع بعضها البعض ونشاطًا قاعديًا في النموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد، مما يشبه البيئة داخل الجسم.

على نفس المنوال، قام آريا وآخرون [111] بالتحقيق في ملاءمة هلاميات GelMA كنظم زراعة ثلاثية الأبعاد في المختبر لنمذجة الخصائص الرئيسية للانتقال.

تقدم سرطان الثدي، تحديدًا الغزارة والاستجابة للعلاج الكيميائي. تم ضبط الخصائص الميكانيكية والشكلية للهيدروجيل من خلال تغيير نسبة GelMA المستخدمة. أظهرت اختبارات الضغط أن صلابة

or الضغط. في الجيلاتين الأكثر صلابة، أدت الهياكل المضغوطة إلى تكوين كريات أصغر مقارنة بالتروية وحدها، بينما لم يكن للضغط تأثير كبير في الجيلاتين الأكثر ليونة. أظهر التلوين المناعي تعبير البروتينات المرتبطة بالانتقال العظمي داخل الكريات، بما في ذلك الأوستيوپونتين، وبروتين هرمون الغدة الجار درقية، والفبرونكتين. كان علامة التكاثر Ki67 موجودة في جميع الكريات في اليوم الرابع. اختلفت شدة تلوين Ki67 اعتمادًا على ظروف الثقافة وصلابة الجيلاتين. وأبرزت الحساسية الميكانيكية لخلايا سرطان الثدي 4T1 وأظهرت كيف يمكن أن تؤثر المحفزات الميكانيكية على تكاثرها وتعبير البروتينات داخل المواد اللينة التي تحاكي الخصائص الميكانيكية لنخاع العظام. وأكدت النتائج على دور البيئة الميكانيكية في العظام لكل من نماذج السرطان في الجسم الحي وفي المختبر.

من خلال صلابة الركيزة وسلوك الخلايا، يمكن للباحثين تطوير نماذج في المختبر أكثر واقعية تعكس بشكل أفضل البيئة الدقيقة للأورام الصلبة. يمكن أن تعزز هذه النماذج فهمنا لتطور السرطان وتساعد في تطوير العلاجات المستهدفة من خلال السماح بالتحقيق في تفاعلات الخلايا مع بعضها البعض وتفاعلات الخلايا مع المصفوفة في بيئة أكثر دقة.

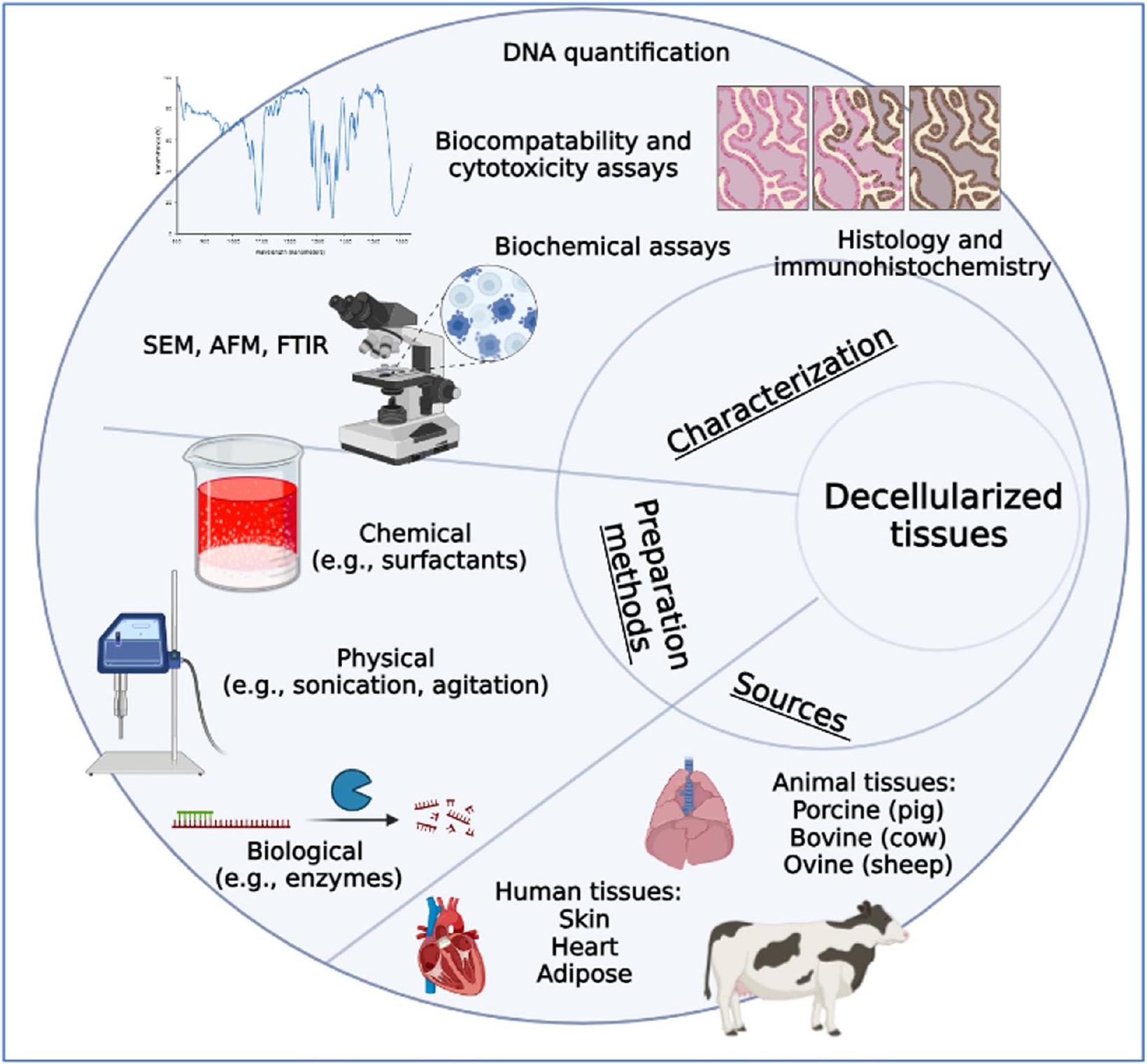

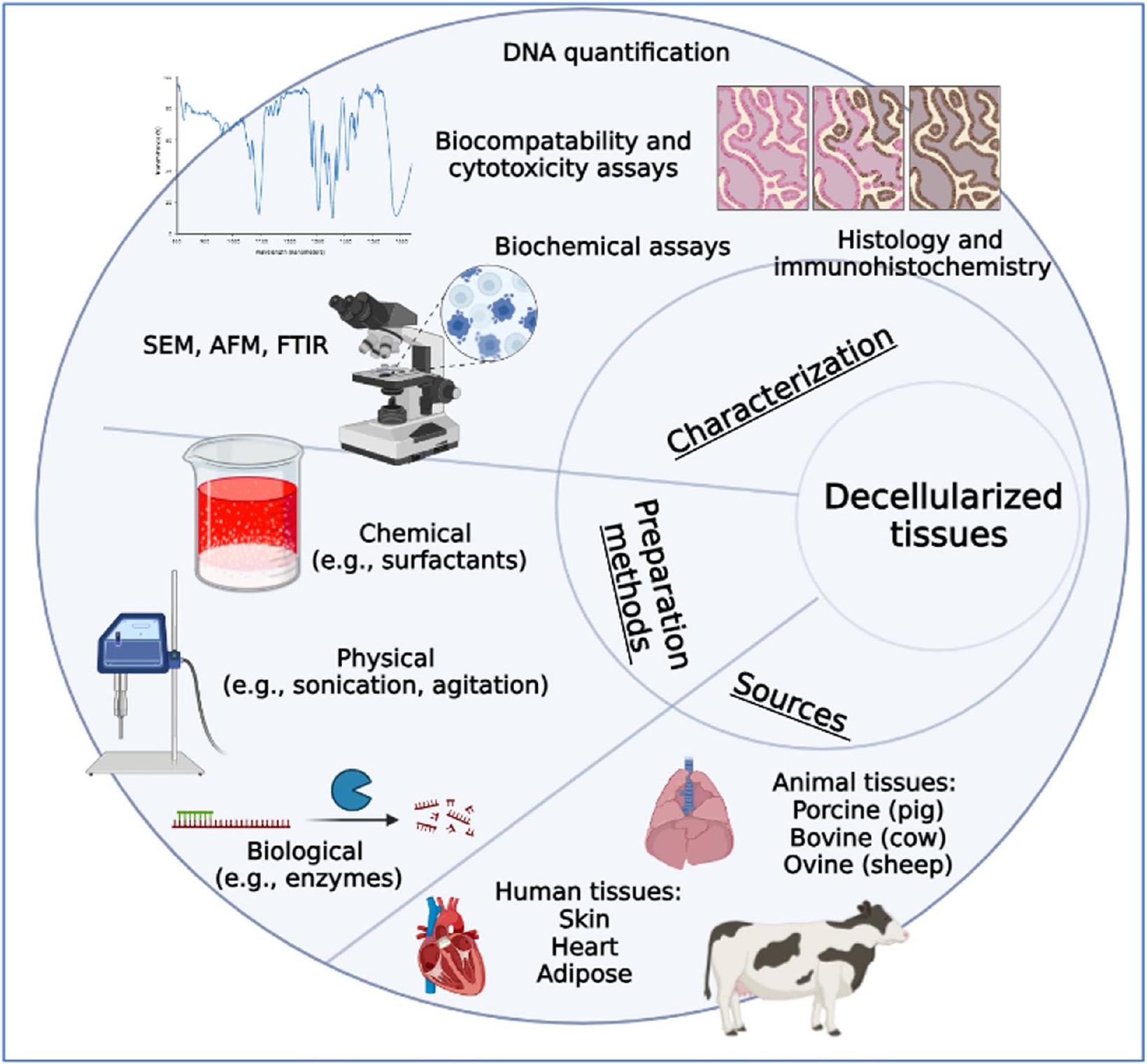

هياكل الأنسجة الخالية من الخلايا

يمكن أن تعزز تقنيات مثل الميكروفلويديات أو أنظمة الأعضاء على شريحة الوظائف والأهمية لنماذج الأنسجة الخالية من الخلايا.

تساهم في فهمنا لسرطان القولون والمستقيم وبيولوجيا النقائل. توفر هذه النماذج، إلى جانب نماذج أخرى، رؤى قيمة حول التفاعل المعقد بين خلايا الورم والمصفوفة خارج الخلوية، مما يمهد الطريق لاكتشاف أهداف علاجية جديدة وتطوير استراتيجيات علاج شخصية للنقائل البريتونية.

مسارات. درس الباحثون الفروق في التنظيم فوق المجهري وتكوين ECM المشتق من الخلايا الميلانية (NGM-ECM) و ECM المشتق من الميلانوما (MV3-ECM). تم الكشف عن مستويات أعلى من التيناسين-C واللامينين وتعبير أقل عن الفيبرو نكتين في MV3-ECM. علاوة على ذلك، خضعت الخلايا البطانية المزروعة في MV3-ECM لتحولات شكلية وأظهرت زيادة في الالتصاق والحركة والنمو وتكوين الأنابيب. أدت التفاعلات بين الخلايا البطانية والمصفوفة الخلوية المنزوعة إلى تنشيط إشارة الإنتغرين، مما أدى إلى فسفرة كيناز الالتصاق البؤري (FAK) وارتباطه بـ Src (وهو بروتين غير مستقبل).

| طريقة | وكلاء أو تقنيات | وصف | المزايا | العيوب |

| طرق كيميائية | سلفات الدوديلي الصوديوم (SDS)، تريتون X-100، ديوكسيكولات الصوديوم. | يتضمن استخدام مجموعة متنوعة من العوامل الكيميائية التي تعطل أغشية الخلايا وتذيب البروتينات الخلوية، مما يسهل إطلاق المكونات الخلوية من الأنسجة مع الحفاظ على المصفوفة خارج الخلوية. | نسبيًا بسيط إزالة المواد الخلوية بكفاءة. | يجب تحسين اختيار العوامل الكيميائية وتركيزها بعناية لتجنب إتلاف المصفوفة خارج الخلوية والتأثير على سلامتها الهيكلية والوظيفية. |

| طرق فيزيائية | دورات التجمد والذوبان، الاهتزاز، الصوتنة، القوى الهيدروديناميكية. | تشمل القوى الميكانيكية أو العلاجات الفيزيائية لإزالة المكونات الخلوية. على سبيل المثال، تتسبب دورات التجميد والذوبان في تمزق أغشية الخلايا وإطلاق المحتويات الخلوية، بينما تستخدم طرق التحريك التحريك الميكانيكي أو الاهتزاز لإزاحة الخلايا من سطح الأنسجة. | لا تتطلب عوامل كيميائية قد تؤثر على تركيبة ECM. | قد يكون من الصعب إزالة جميع بقايا الخلايا تمامًا، بما في ذلك البروتينات داخل الخلايا والأحماض النووية. |

| طرق بيولوجية | نوكلياز (DNase، RNase) لتحطيم الأحماض النووية، بروتياز (مثل التربسين أو الكولاجيناز) لتفكيك البروتينات، وجليكوزيداز لإزالة الجليكوزامينوجليكان. | استخدم الإنزيمات لتفكيك المكونات الخلوية بشكل انتقائي، مما يسهل إزالة الخلايا. | تقدم انتقائية في إزالة المكونات الخلوية ويمكن تخصيصها لتناسب أنسجة معينة أو تركيبات المصفوفة خارج الخلوية. | يتطلب تحسين دقيق لتركيزات الإنزيمات، وأوقات الحضانة، ودرجة الحرارة لضمان إزالة الخلايا بكفاءة مع الحفاظ على سلامة مصفوفة extracellular. |

الهياكل الهجينة

أداء خطوط خلايا الساركوما العظمية البشرية (MG63 و SAOS-2) وخلايا السركومة الجذعية الغنية ضمن هذه النماذج المعقدة لزراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد. تم استخدام تقنية التألق المناعي وتقنيات توصيف أخرى لتقييم استجابة خطوط خلايا الساركوما العظمية وخلايا السركومة الجذعية للهياكل البيولوجية المقلدة. أظهرت النتائج التكوين الناجح للكرات السركومية، وهي كريات مستقرة غنية بخلايا السركومة الجذعية، بحد أدنى من القطر

بيئة العظام الدقيقة. هذه النتائج أساسية لتطوير استراتيجيات علاجية مستهدفة ضد نقائل سرطان البروستاتا في العظام. أجرى باي وزملاؤه [142] دراسة قاموا فيها بإدماج أكسيد الجرافين (GO) في بوليمر مشترك من حمض الأكريليك-ج-حمض البولي لاكتيك (PAA-g-PLLA) لإنشاء هيكل استجابة للتحفيز. هذا الهيكل، المدمج مع PCL وحمض الجامبوغ (GA)، أظهر استجابة انتقائية تجاه الأورام وأظهر تراكمًا كبيرًا لـ GO/GA في خلايا سرطان الثدي (خلايا MCF-7) في ظروف حمضية (pH 6.8)، بينما أظهر تأثيرًا ضئيلًا على الخلايا الطبيعية (خلايا MCF-10A) عند pH الفسيولوجي (pH 7.4). كشفت الدراسة أيضًا أن الاستخدام التآزري للتحويل الضوئي الحراري المستجيب لـ pH كان أكثر فعالية في تثبيط نمو الورم مقارنة بالعلاجات المستقلة. أظهرت التجارب الحية تثبيطًا ملحوظًا للورم (تخفيض بنسبة 99% خلال 21 يومًا) من خلال تفتت أنسجة الورم، والتنكس، والتثبيط العام للورم عند العلاج بهياكل GO-GA المدمجة مع العلاج الضوئي الحراري، مقارنة بالمجموعات الضابطة أو تلك المعالجة إما بهياكل GO-GA أو الإشعاع تحت الأحمر القريب (NIR) بمفرده.

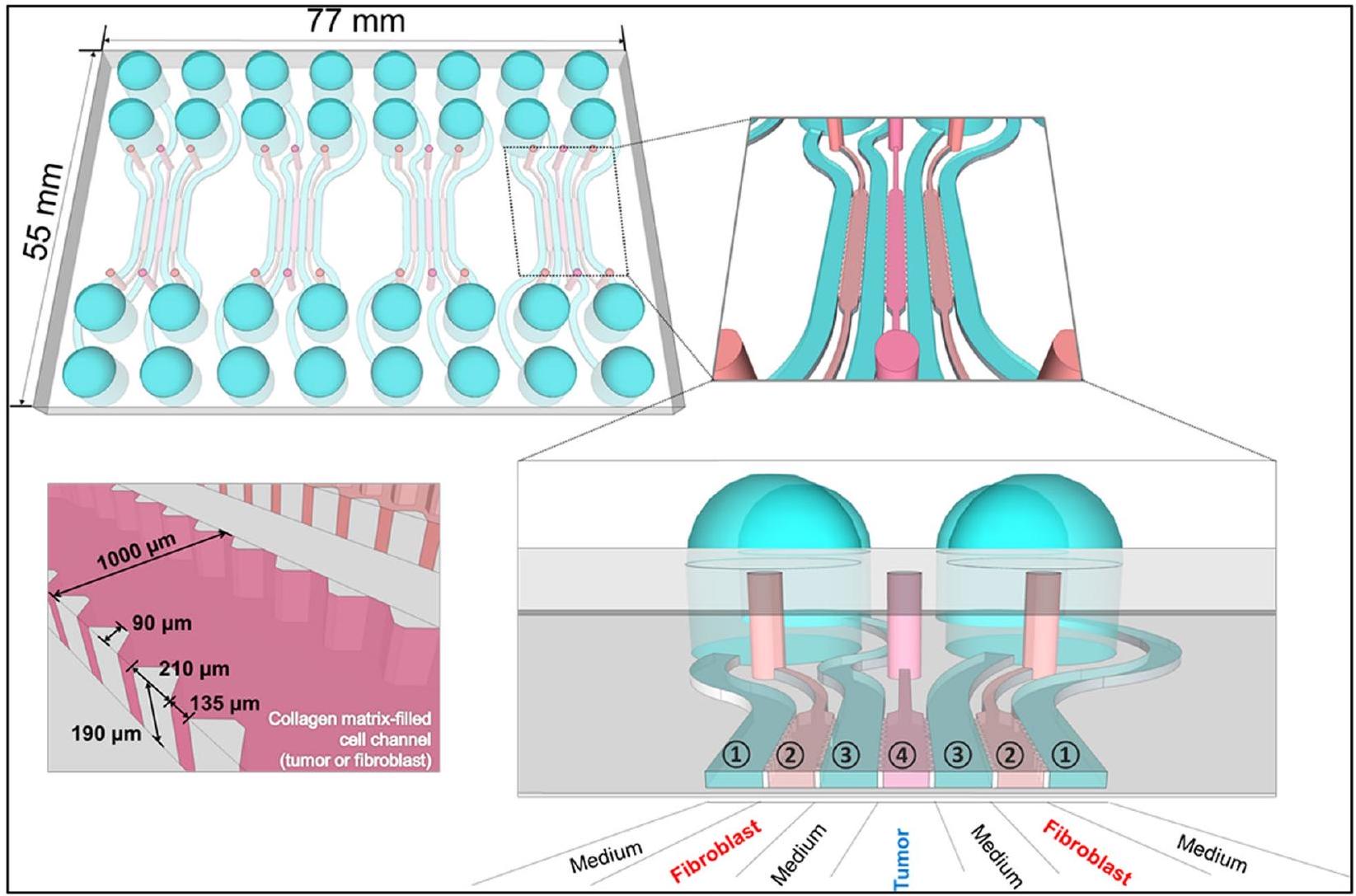

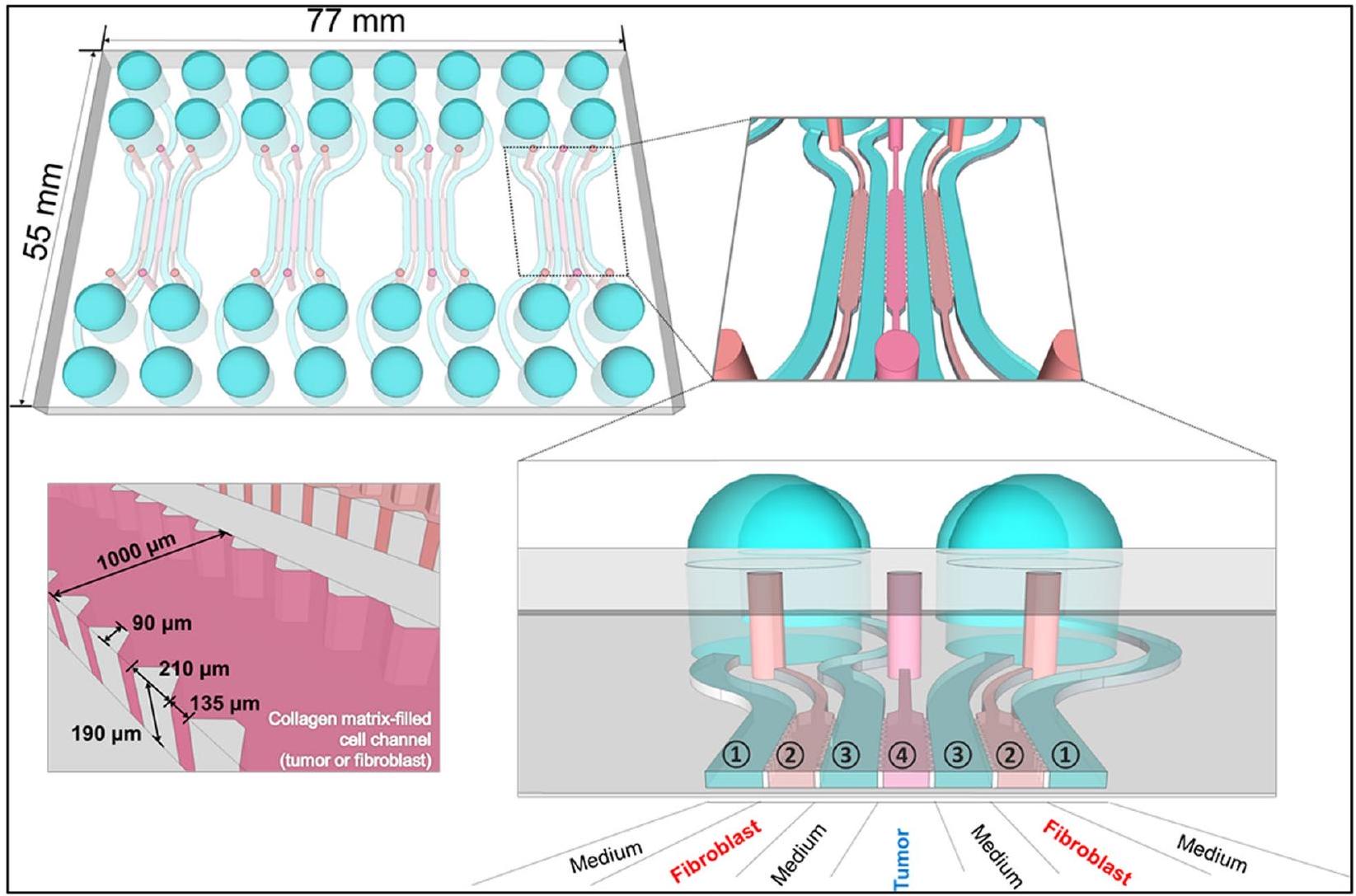

توفر الميكروفلويديات منصة متعددة الاستخدامات لزراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد، حيث تقدم كل من الأساليب المعتمدة على الدعائم والأساليب الخالية من الدعائم. يمكن للباحثين تخصيص المنصة لتناسب المتطلبات المحددة لتجاربهم، سواء كانت تتضمن دعائم محملة بالخلايا أو تجمع الخلايا لتشكيل كتل كروية أو عضيات. يسمح الإعداد الميكروفلويدي بالتحكم الدقيق في البيئة الدقيقة، بما في ذلك تدفق المغذيات والأكسجين، فضلاً عن القدرة على إدخال تدرجات من جزيئات محددة. استخدم لي وآخرون [143] الطباعة اللينة لتصنيع لوحة قنوات ميكروفلويدية مكونة من 7 قنوات باستخدام بولي ديميثيل سيليكون (PDMS). داخل قنوات منفصلة، تم زراعة خلايا سرطان البنكرياس PANC-1 وخلايا النجمية البنكرياسية (PSCs) داخل مصفوفة الكولاجين I. لاحظت الدراسة تشكيل كتل كروية ثلاثية الأبعاد بواسطة خلايا PANC-1 خلال خمسة أيام. ومن المثير للاهتمام، أن وجود PSCs المزروعة معًا أدى إلى زيادة عدد الكتل الكروية، مما يشير إلى تأثير محتمل لـ PSCs على نمو الورم. في إعداد الزراعة المشتركة، أظهرت PSCs تعبيرًا مرتفعًا عن

كشفت عن تفاعل معقد بين خلايا PANC-1 وخلايا PSCs داخل البيئة المجهرية للورم. ومع ذلك، أظهر الجمع بين الجيمسيتابين والباكليتاكسيل وعدًا في التغلب على المقاومة وكبح نمو الورم. إن تداعيات هذه النتائج مهمة لفهم التفاعل المعقد بين خلايا الورم والخلايا الداعمة المحيطة بها داخل البيئة المجهرية للورم. تلعب تفاعلات الورم والدعامة دورًا حاسمًا في تقدم السرطان واستجابة العلاج. يسمح استخدام نماذج الزراعة المشتركة ثلاثية الأبعاد المعتمدة على الميكروفلويديك للباحثين بإعادة تمثيل الظروف داخل الجسم بشكل أفضل، مما يوفر تمثيلًا أكثر دقة لسلوك الورم واستجابات العلاج.

| الهيدروجيل (الأصل) | نوع السرطان/خط الخلايا | الهدف (الأهداف) | النتائج | المراجع | |||

| هلام الأجاروز (طبيعي) | سرطان البروستاتا/ PC3، DU145 | لمقارنة تعبير العلامات الرئيسية لعملية التحول الظهاري (أي، E-cadherin، N-cadherin، الأكتين العضلي الأملس (a-SMA)، الفيمنتين، Snail، Slug، Twist، و Zeb1) في زراعة الخلايا ثنائية الأبعاد مقابل ثلاثية الأبعاد. | – لوحظت اختلافات كبيرة في الشكل والظواهر بين الخلايا المزروعة في طبقات ثنائية الأبعاد مقابل الكريات ثلاثية الأبعاد. – انخفاض تعبير علامات النمط الظاهري الميزانشيمي في الثقافة ثلاثية الأبعاد. | [125] | |||

| الكولاجين الأول (طبيعي) | ورم الأرومة العصبية / SH-SY5Y | لمقارنة آليات النمو وتعبير الجينات لخلايا الورم العصبي البشري SHSY5Y في الثقافات ثنائية الأبعاد مقابل الثقافات ثلاثية الأبعاد. |

|

[126] | |||

| الكولاجين الأول (طبيعي) | سرطان المبيض/ OV-2008 | لإعادة تلخيص بنية المصفوفة خارج الخلوية في ورم صلب والتحقيق في حركة الخلايا وقدرتها على الغزو واستجابتها للعلاج الكيميائي. |

|

[127] | |||

| ماتريجيل (طبيعي) | سرطان البنكرياس/ MCW670 | لإنشاء منصة ثلاثية الأبعاد لزراعة الأعضاء المستمدة من مرضى سرطان البنكرياس. | – سمح النموذج بالتحقيق الدقيق في تفاعلات الورم-الستروما وتفاعلات الورم-المناعة في نظام الأورغانويد. – لوحظ تنشيط يعتمد على الوقت للألياف السرطانية. | [128] | |||

| ماتريجيل (طبيعي) | سرطان المعدة / BGC-823 | لتقييم التأثيرات العلاجية للبروتينات المؤتلفة (مثل، مضاد EGFR ومضاد EGFR-iRGD) بالاشتراك مع العلاج الكيميائي (مثل، دوكسوروبيسين) على امتصاص الدواء وفعاليته في كريات الورم متعددة الخلايا. |

|

[129] | |||

| ماتريجيل (طبيعي) | أوستيوساكروما / MG-63 | للتحقيق في تأثيرات ترتيب الخلايا المتنوع في نموذج زراعة الخلايا ثلاثي الأبعاد. |

|

[130] |

| الهيدروجيل (الأصل) | نوع السرطان/خط الخلايا | الهدف (الأهداف) | النتائج | المراجع | |||

| ألياف الحرير تسار (طبيعي) | سرطان الكبد/ HEPG2 و HepR21 | لتقييم فعالية مصفوفة الفيبروين من حرير التيسار كشبكة ثقافة ثلاثية الأبعاد لخلايا سرطان الكبد. |

|

[131] | |||

| الخلايا في الجل في الورق (CiGiP) (اصطناعي) | سرطان الرئة/ A549 | لدراسة حساسية الأيض للخلايا تجاه الإشعاع المؤين باستخدام نموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد جديد قائم على الورق. أنشأ النموذج تدرجًا متناقصًا من الأكسجين والمواد المغذية عبر أكوام الورق، حيث كانت الخلايا العليا معرضة لبيئة غنية بالأكسجين. في المقابل، كانت الخلايا السفلية معرضة لظروف نقص الأكسجين. |

|

[132] | |||

| motifs ربط الإنتغرين الخلوية (ببتيدات RGD (اصطناعية) | سرطان المبيض / KLK4-7 | لتطوير نموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد يحاكي تكاثر الخلايا، استجابات البقاء، والتفاعلات مع الإنتغرينات في البيئة المجاورة للورم. | – أظهرت النتائج أن العلاج المشترك بين باكليتاكسيل وKLK/MAPK أظهر تأثيرات أكثر وضوحًا من العلاج الكيميائي بمفرده. | [١٣٣] | |||

| ببتيد RADA16-I (اصطناعي) | سرطان المبيض الظهاري / A2780، A2780/DDP، و SK-OV-3 | لتقييم فعالية سقالة الألياف النانوية كمضيف لزراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد وتأثير المادة على التصاق الخلايا، الشكل، الهجرة، والحساسية للأدوية. |

|

[105] | |||

| مصفوفة الأنسجة الخالية من الخلايا | نوع السرطان/ خط الخلايا | الهدف (الأهداف) | الحكام | ||||

| الغشاء المخاطي والطبقة تحت المخاطية للأمعاء الدقيقة | سرطان الرئة / HCC827 و A549 | لإنشاء نموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد يتيح خيارات قراءة متعددة، لمراقبة التغيرات في إشارات الخلايا، والتكاثر، والموت الخلوي استجابةً للأدوية. |

|

| الجدول 7 (مستمر) | |||||||

| مصفوفة الأنسجة غير الخلوية | نوع السرطان/ خط الخلايا | الهدف (الأهداف) | النتائج | الحكام | |||

| الأنسجة الدهنية | سرطان الثدي / MCF-7، SKBR3، BT474 | لإنشاء هيكل ثلاثي الأبعاد يشبه بيئة سرطان الثدي. |

|

[135] | |||

| نسيج الدهون في الجرذ | غليوبلاستوما/T98G؛ هيرباتوما بشري/Hep3B؛ أدينوكارسينوما القولون/WiDr | لتحقيق سلوك الخلايا في خطوط خلايا السرطان المختلفة في المختبر باستخدام منصة مستمدة من الأنسجة الدهنية غير الخلوية. |

|

[136] | |||

| نسيج سرطان القولون والمستقيم وطبقة المخاط الصحية للقولون | سرطان القولون والمستقيم / خلايا HT29 و HCT116 | لإنشاء نموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد مشتق من المرضى يمكن استخدامه لتقييم الأدوية في سرطان القولون. |

|

[137] | |||

| الجدول 7 (مستمر) | ||||||||||

| مصفوفة الأنسجة المنزوعة الخلايا | نوع السرطان/ خط الخلايا | الهدف (الأهداف) | النتائج | الحكام | ||||||

| أنسجة الكبد السليمة والمصابة بالتشمع | سرطان الخلايا الكبدية / خلايا HCC | لفحص وتحديد الخصائص المميزة لبيئة المصفوفة خارج الخلوية للكبد البشري المصاب بالتشمع، والتي تعزز تطور سرطان الكبد الخلوي. |

|

[138] | ||||||

| نسيج لسان الحيوان | سرطان الخلايا الحرشفية في اللسان / CAL27 | لتقييم جدوى استخدام مصفوفة الأنسجة الخلوية المنزوعة من اللسان في أبحاث سرطان الخلايا الحرشفية في اللسان وتجديد اللسان. | – لوحظ غنى كبير في إشارات الإنتجرين في مصفوفة extracellular للسان. بالإضافة إلى تأثيره على بقاء الخلايا وتكاثرها، كانت لمصفوفة extracellular للسان أيضًا تأثيرات منسقة على التفاعلات بين الخلايا والمصفوفة extracellular والخلايا المجاورة، مما يؤثر على نمط ومدى حركة الخلايا. | [139] | ||||||

| مصفوفة الأنسجة الخالية من الخلايا | نوع السرطان/ خط الخلايا | الهدف (الأهداف) | النتائج | الحكام | ||||

| نسيج صدر الخنزير | سرطان الثدي / MCF-7 و hAMSCs | لإنشاء هياكل ثدي خالية من الخلايا غنية بالجليكوزامينوجليكان (GAGs) والكولاجين. |

|

[140] | ||||

| مصفوفة الأنسجة الخالية من الخلايا | نوع السرطان/خط الخلايا | الهدف (الأهداف) | النتائج | المراجع | ||||

| الغشاء المخاطي والطبقة تحت المخاطية للأمعاء الدقيقة | سرطان الرئة / HCC827 و A549 | لإنشاء نموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد يتيح خيارات قراءة متعددة، لمراقبة التغيرات في إشارات الخلايا، والتكاثر، والموت الخلوي استجابةً للأدوية. |

|

[134] | ||||

| الأنسجة الدهنية | سرطان الثدي / MCF-7، SKBR3، BT474 | لإنشاء هيكل ثلاثي الأبعاد يشبه بيئة سرطان الثدي. |

|

[135] | ||||

| نسيج الدهون في الجرذ | غليوبلاستوما/T98G؛ ورم الكبد البشري/ Hep3B؛ أدينوكارسينوما القولون/ WiDr | لتحقيق سلوك الخلايا في خطوط خلايا السرطان المختلفة في المختبر باستخدام منصة مستمدة من الأنسجة الدهنية غير الخلوية. |

|

[136] |

| مصفوفة الأنسجة المنزوعة الخلايا | نوع السرطان/خط الخلايا | الهدف (الأهداف) | النتائج | المراجع | ||||||

| نسيج سرطان القولون والمستقيم وطبقة المخاط الصحية للقولون | سرطان القولون والمستقيم / خلايا HT29 و HCT116 | لإنشاء نموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد مشتق من المرضى يمكن استخدامه لتقييم الأدوية في سرطان القولون. |

|

[137] | ||||||

| أنسجة الكبد السليمة والمصابة بالتشمع | سرطان الخلايا الكبدية / خلايا HCC | لفحص وتحديد الخصائص المميزة لبيئة المصفوفة خارج الخلوية للكبد البشري المصاب بالتشمع، والتي تعزز تطور سرطان الكبد الخلوي. |

|

[138] |

| مصفوفة الأنسجة غير الخلوية | نوع السرطان/خط الخلايا | الهدف (الأهداف) | النتائج | ||

| نسيج لسان الحيوان | سرطان الخلايا الحرشفية في اللسان / CAL27 | لتقييم جدوى استخدام مصفوفة الأنسجة الخلوية المنزوعة من اللسان في أبحاث سرطان الخلايا الحرشفية في اللسان وتجديد اللسان. | – لوحظ إثراء كبير في إشارات الإنتجرين [139] في مصفوفة extracellular للسان. بالإضافة إلى تأثيره على بقاء الخلايا وتكاثرها، فإن مصفوفة extracellular للسان أثرت أيضًا بشكل منسق على التفاعلات بين الخلايا والمصفوفة extracellular والخلايا المجاورة، مما يؤثر على نمط ومدى حركة الخلايا. | ||

| نسيج صدر الخنزير | سرطان الثدي / MCF-7 و hAMSCs | لإنشاء هياكل ثدي خالية من الخلايا غنية بالجليكوزامينوجليكان (GAGs) والكولاجين. |

|

التحديات وآفاق المستقبل

| طريقة تصنيع الأجهزة الميكروفلويدية | نوع السرطان/خط الخلايا | الهدف (الأهداف) | النتائج | المراجع | ||

| الطباعة الضوئية القياسية | سرطان الثدي / MDA-MB-231 | لإنشاء مصفوفة تحفز البيئة المجهرية للورم. |

|

[84] | ||

| الطباعة الضوئية القياسية | سرطان الرئة / SPCA-1 و HFL1 | لتطوير زراعة خلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد في جهاز ميكروفلويديك يسمح بالاختبار المتوازي لمختلف العلاجات الكيميائية. |

|

[85] | ||

| الطباعة الضوئية الناعمة | سرطان الثدي / MCF-7 | لإنشاء نموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد باستخدام هياكل الهيدروجيل في آبار دقيقة، ولتقييم الفعالية العلاجية، والتوزيع، واختراق دوكسوروبيسين في زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد. |

|

[146] | ||

| أكسدة البلازما ذات الضغط المنخفض | سرطان الرئة/ H292 | لتقييم المؤشر العلاجي للأجسام المضادة المضادة لمستقبلات EGFR سيتوكسيماب باستخدام اختبار زراعة الأنسجة البشرية. | -إن دمج نموذج ورمي مع نموذج مصغر من جلد الإنسان الوظيفي أنشأ منصة اختبار مثالية لتقييم فعالية مثبطات EGFR وعلاجات واعدة أخرى في مجال الأورام. | [147] | ||

| الطباعة الضوئية متعددة الطبقات | سرطان المبيض عالي الدرجة / OVCAR-8، FTSEC | لإنتاج جهاز ميكروفلويدي مصمم خصيصًا لعزل الإكسوزومات من عينات مصل المرضى والخلايا المزروعة. | -يمكن أن يسهل المقياس المجهري تحديد وعزل العلامات الحيوية المستمدة من الإكسوزومات، والتي يمكن استخدامها في اختبارات الكشف المبكر عن سرطان المبيض الحليمي عالي الدرجة. | [148] |

علاوة على ذلك، تعتبر إمكانية الوصول إلى الأكسجين اعتبارًا حاسمًا في طرق زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد، وتنوعه داخل هذه البيئات يمثل تحديًا كبيرًا في تكرار الظروف الفسيولوجية والحصول على نتائج تجريبية دقيقة. غالبًا ما تواجه الخلايا الموجودة في داخل الهياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد، مثل الكريات، توفرًا محدودًا من الأكسجين بسبب عوامل البيئة الدقيقة (أي، تتطور الكريات الورمية بشكل طبيعي إلى مناطق ناقصة الأكسجين بسبب التوعية غير المنتظمة في الأورام) وحواجز الانتشار (مثل، الخلايا المعبأة بكثافة، المصفوفات خارج الخلية، هياكل الدعم) [153]. مع تكاثر الخلايا وتشكيلها لهياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد، تزداد الحاجة إلى الأكسجين بسبب الحجم الأكبر الذي يجب أن يقطعه الأكسجين. يصبح انتشار الأكسجين من وسط الزراعة المحيط معوقًا بشكل متزايد مع زيادة المسافة من سطح الزراعة إلى داخل الهيكل ثلاثي الأبعاد. وهذا يؤدي إلى تدرج في الأكسجين، حيث تمتلك الخلايا القريبة من المحيط كمية كافية من الأكسجين، ولكن تلك الموجودة في القلب تواجه نقصًا في الأكسجين، مما يؤدي إلى نقص الأكسجين. غالبًا ما تظهر خلايا القلب الناقصة الأكسجين تعبيرًا جينيًا متغيرًا، وتكاثرًا منخفضًا، وتغيرات في المسارات الأيضية عندما تدخل في حالة سكون وتتوقف عن الدورة عندما تُحرم من الأكسجين والمواد الغذائية. تجعل هذه النشاطات المنخفضة منها مقاومة نسبيًا للأدوية الساكنة التي تستهدف بشكل أساسي الخلايا التي تنقسم بنشاط، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة مقاومة الأدوية، كما هو الحال غالبًا في الأورام الصلبة [154، 155]. يمكن استخدام المجهر الضوئي المجهري لرؤية الخلايا الساكنة عن طريق وسمها بنظير نوكليوزيد، مما يسمح بتحديد كميتها وتمييزها عن الخلايا التي تنقسم بنشاط

الخلايا. يتم تخفيف هذا النظير في الخلايا التي تنقسم بنشاط. ومع ذلك، فإنه يبقى محتفظًا به في خلايا السرطان الساكنة وغير المنقسمة، مما يوفر أداة قيمة لتمييزها عن الخلايا المحيطة التي تنقسم بنشاط [156]. من خلال الاستفادة من هذه الخاصية للكريات ثلاثية الأبعاد، فإنها تقدم طرقًا محتملة لتطوير علاجات جديدة تستهدف خلايا السرطان المقاومة للأدوية الساكنة المضادة للسرطان. قام وينزل وآخرون [157] بزراعة خلايا سرطان الثدي T47D في زراعات ثلاثية الأبعاد واستخدموا التصوير المجهري التداخلي لتمييز الخلايا داخل القلب الداخلي عن تلك الموجودة في القلب الخارجي المحيط. أظهرت الخلايا في القلب الداخلي، التي تعاني من وصول محدود إلى الأكسجين والمواد الغذائية، نشاطًا أيضيًا منخفضًا مقارنة بنظيراتها في القلب الخارجي. من خلال فحص مكتبات الجزيئات الصغيرة ضد هذه الزراعات ثلاثية الأبعاد، حدد المؤلفون تسعة مركبات تستهدف وتقتل خلايا سرطان القلب الداخلي بشكل انتقائي بينما تترك الخلايا الخارجية الأكثر انقسامًا. أثرت الأدوية المحددة بشكل أساسي على مسار سلسلة التنفس، مما يتماشى مع النشاط الأيضي المتغير للخلايا التي تعاني من نقص الأكسجين والتي تنتقل من الأيض الهوائي إلى الأيض اللاهوائي. وبالتالي، فإن المركبات التي تستهدف خلايا السرطان الساكنة بشكل انتقائي حسنت بشكل كبير من فعالية الأدوية الساكنة المضادة للسرطان المستخدمة عادة. بدلاً من ذلك، يمكن استخدام أجهزة ميكروفلويديك التي تمكن من إنشاء تدرجات أكسجين محكومة داخل الزراعات، ودمج مواد قابلة لاختراق الأكسجين، وإضافة مركبات تطلق الأكسجين لتوفير توزيع أكثر تجانسًا للأكسجين في المختبر. ومع ذلك، من المهم الاعتراف بأن هذه الاستراتيجيات قد لا تعيد إنتاج تعقيد تدرجات الأكسجين في الأنسجة الحقيقية بالكامل [158]. قدم بويز وآخرون [159] تصميمًا وتوصيفًا لجهاز معياري استغل خصائص نفاذية الغاز من السيليكون لإنشاء تدرجات أكسجين داخل المناطق المحتوية على خلايا. تم بناء الجهاز المجهري عن طريق تكديس صفائح الأكريليك المطبوعة بالليزر وصفائح مطاط السيليكون، حيث لم يسهل السيليكون فقط تشكيل تدرجات الأكسجين ولكن أيضًا عمل كحاجز، يفصل الغازات المتدفقة عن وسط زراعة الخلايا لمنع التبخر أو تكوين الفقاعات خلال فترات الحضانة الممتدة. قدمت مكونات الأكريليك استقرارًا هيكليًا، مما يضمن بيئة زراعة معقمة. باستخدام أفلام استشعار الأكسجين، يمكن تحقيق تدرجات ذات نطاقات وزوايا مختلفة في الجهاز المجهري عن طريق ضبط تركيبة الغازات المتدفقة عبر عناصر السيليكون. علاوة على ذلك، أظهرت تجربة قائمة على الخلايا أن الاستجابات الخلوية لنقص الأكسجين كانت متناسبة مباشرة مع توتر الأكسجين الذي تم إنشاؤه داخل النظام، مما يثبت الفعالية.

دعائم الهيدروجيل القابلة للتحلل دمج روابط قابلة للكسر و/أو مكونات قابلة للتفكيك في الهيكل البوليمري أو دمج مكونات ECM القابلة للتحلل بشكل طبيعي مثل حمض الهيالورونيك، واللامينين، والفبرونيكتين، والكولاجين [160]. ومع ذلك، فإن تقنيات التفكيك التقليدية تثبت أنها غير فعالة بشكل ملحوظ وتتأثر بالتعقيدات الهيكلية الفطرية لنظام الزراعة. يعتبر التحلل الإنزيمي، على سبيل المثال بواسطة الكولاجيناز، طريقة مستخدمة على نطاق واسع لاسترجاع الخلايا من دعائم زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد المعتمدة على الكولاجين. يتم اختيار الإنزيم ليتناسب مع نوع الكولاجين المحدد في الدعامة. خلال الحضانة، يقوم الكولاجيناز بتفكيك ألياف الكولاجين إنزيميًا، مما يحرر الخلايا التي كانت مدمجة أو ملتصقة بهذه الألياف. بمجرد أن يتم تفكيك الكولاجين، يتم جمع الخلايا كتعليق في وسط الزراعة [161]. عادةً ما يتم إجراء تقييمات لسلامة الخلايا ووظيفتها للحفاظ على صحة الخلايا ووظيفتها. بينما يعتبر استخدام التحلل الإنزيمي لدعائم زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد شائعًا، إلا أنه يظل نهجًا معقدًا مرتبطًا بعدة قيود. من المهم عدم التقليل من تأثير الكولاجيناز أو الإنزيمات الأخرى على سلامة الخلايا ووظيفتها. إن تحسين وقت الهضم وتركيز الإنزيم بعناية أمر ضروري لتحقيق توازن بين تفكيك الدعامة بكفاءة والحفاظ على جودة الخلايا [162]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن التغيرات المحتملة في نمط الخلايا أثناء الهضم تمثل مصدر قلق كبير، مما يتطلب مراقبة دقيقة لمعايير الهضم. في الدعائم ثلاثية الأبعاد المعقدة، وخاصة تلك ذات الهياكل المعقدة، قد يكون التحلل الإنزيمي أقل فعالية، مما يدفع الباحثين لاستكشاف طرق استرجاع بديلة أو تعديل عملية الهضم. كما تلعب الاعتبارات الأخلاقية دورًا، خاصة عند العمل مع خلايا مشتقة من البشر أو الحيوانات، مما يثير القلق بشأن استخدام إنزيمات مثل الكولاجيناز. الالتزام بالإرشادات الأخلاقية واللوائح المؤسسية أمر حاسم للحفاظ على ممارسات البحث المسؤولة والأخلاقية.

تظهر الطريقة المعتمدة على NFC إنتاجًا مشابهًا للـ EV لكل خلية، مما يوفر قابلية التوسع، ويحافظ على نمط الخلية وسلامتها، ويزيد من بساطة التشغيل، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى زيادة إنتاجية الـ EV. تعتمد طريقة أخرى على التحلل الذي تسببه الخلايا للهياكل الهلامية، حيث تقوم الخلايا الحية بتفكيك الهيكل الهلامي بنشاط. تعتبر هذه الآلية التحليلية ذات صلة خاصة في هندسة الأنسجة والطب التجديدي. عندما يتم احتواء الخلايا داخل هيكل هلامي، يمكنها إفراز إنزيمات وجزيئات أخرى تتفاعل مع مكوناته، مما يؤدي إلى تحلله التدريجي. مع تكاثر الخلايا وإعادة تشكيل بيئتها الدقيقة، قد تقوم بتغيير خصائص الهيكل وفي النهاية تسهل تحلله. تسمح هذه العملية الديناميكية بالإفراج المنظم عن الخلايا وعوامل النمو وغيرها من المواد الحيوية النشطة داخل الهلام، مما يجعلها تقنية قيمة لتطبيقات توصيل الأدوية.

بعض الفحوصات البيوكيميائية المتطورة جيدًا لأنظمة ثلاثية الأبعاد. تميل الخلايا إلى التجمع في كتل كثيفة و/أو كبيرة مع مرور الوقت، حتى في الدعائم المسامية الكبيرة، مما يسبب قيودًا في الانتشار عند إجراء فحوصات التوصيف في الموقع. تنشأ القيود بسبب عرقلة الانتشار وحصر الغازات والمواد المغذية والنفايات والمواد الكيميائية داخل النظام، بالإضافة إلى التحديات عند قياس وتطبيع البيانات بين الثقافات البيولوجية المقلدة المختلفة. على سبيل المثال، أظهر توتي وآخرون أن تقييم ثقافة خلايا سرطان البنكرياس في دعائم من رغوة البولي يوريثان المسامية الكبيرة باستخدام اختبار 3-(4،5-ثنائي ميثيل ثيازول-2-يل)-5-(3-كربوكسي ميثوكسي فينيل)-2-(4-سلفوفينيل)-2H-تيترازوليوم (MTS) أظهر اختلافات طفيفة بين ظروف الدعائم المختلفة (مثل طلاءات ECM على الدعائم). ومع ذلك، كشفت عملية القطع، والتلوين المناعي، والتصوير عن تمايز أوضح في تكاثر الخلايا، والشكل، والنمو بين الظروف. وبالمثل، فشل اختبار 3-(4،5-ثنائي ميثيل ثيازول-2-يل)-2،5-ثنائي فينيل-2H-تيترازوليوم بروميد (MTT) في التقاط الاختلافات في حيوية خلايا البنكرياس المزروعة في دعائم البولي يوريثان بعد فحص الأدوية والإشعاع، والتي تم إدراكها باستخدام المجهر المتقدم والتصوير. لذلك، من الضروري أن يأخذ الباحثون في الاعتبار بعناية النهج التحليلي المناسب الذي يتماشى مع أهداف دراستهم قبل البدء في تحليل أي ثقافات ثلاثية الأبعاد. كما يجب أن يكونوا على دراية بأن بعض الأساليب الكلاسيكية المعتمدة المستخدمة في الثقافات ثنائية الأبعاد قد لا تكون قابلة للتطبيق مباشرة في البيئات ثلاثية الأبعاد، كما أظهر حمدي وآخرون أنه من غير الممكن استخراج الخلايا من الكتل الكروية لاختبارات تشكيل المستعمرات، والتي تستخدم لتطوير منحنيات البقاء بعد العلاج. وبالتالي، اقترح الباحثون قراءات التوصيف في الموقع، والتي هي جديدة و/أو مختلفة عن بروتوكولات الثقافة ثنائية الأبعاد الحالية.

مكانيًا وزمانيًا داخل الكُرَيَّات، مما يجعل من الصعب تتبع وتفسير التغيرات في تعبير العلامات على مر الزمن. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، في الكُرَيَّات الأكبر، قد لا تخترق علامات الخلايا الجذعية بشكل فعال قلب الكُرَيَّة، مما يحد من القدرة على تقييم مجموعة الخلايا الجذعية في المناطق الداخلية. يمكن للباحثين استخدام عدة استراتيجيات للتغلب على هذه التحديات واستخدام علامات الخلايا الجذعية بفعالية في ثقافات الكُرَيَّات ثلاثية الأبعاد. تتضمن طريقة بديلة دمج الخلايا الجذعية وعلامات خلوية أخرى لفهم أفضل للتكوين الخلوي داخل الكُرَيَّة. يمكن أن تساعد هذه الطريقة متعددة العلامات في التخفيف من المشكلات المتعلقة بتنوع العلامات. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن توفر تقنيات التصوير الحي، مثل المجهر الضوئي المجهري، رؤى في الوقت الحقيقي حول ديناميات تعبير العلامات داخل الكُرَيَّات. يعد التحكم في حجم الكُرَيَّات استراتيجية أخرى لتعزيز اختراق العلامات والوصول إلى الخلايا الداخلية. يسمح استخدام تقنيات الميكروفلويديك بتنظيم دقيق لحجم الكُرَيَّات، مما يضمن اختراقًا فعالًا للعلامات في جميع مناطق الكُرَيَّة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تمكّن طرق تحليل الخلايا الفردية، مثل تسلسل RNA للخلايا الفردية والتحليل البروتيني، من توصيف الخلايا الفردية داخل الكُرَيَّات. يمكن أن تحدد هذه الطريقة أنماط التعبير الجيني أو البروتيني الفريدة وتسلط الضوء على سلوك مجموعات الخلايا الجذعية. استراتيجية قيمة أخرى هي إنشاء كُرَيَّات مع مراسلين جينيين للخلايا الجذعية، والتي تنتج إشارات فلورية أو مضيئة في الخلايا الجذعية، مما يجعلها أكثر وضوحًا وقابلية للتتبع. أخيرًا، يمكن أن يساعد تقليد مكان الخلايا الجذعية أو البيئة الدقيقة ضمن ظروف الثقافة ثلاثية الأبعاد في الحفاظ على خصائص الخلايا الجذعية وتعبير العلامات في الكُرَيَّات.

لقد تم إحراز تقدم كبير في إنشاء هياكل ديناميكية يمكن أن تستجيب أو توجه الخلايا المقيمة. على سبيل المثال، أثبتت الهلاميات الحرارية مثل بولي-نيسوبروبيل أكريلاميد (pNIPAm) فعاليتها في جمع تجمعات الخلايا. علاوة على ذلك، ساهم دمج تقنيات المقياس المجهري لزراعة الخلايا مع تصاميم الهلاميات القابلة للتكيف في تسهيل العديد من التحقيقات. تشمل هذه التحقيقات دراسة هجرة الخلايا داخل الهلاميات الميكروفلويدية وإقامة منصات فحص عالية الإنتاجية لاستكشاف التفاعلات بين الخلايا والمواد. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن مجال الميكانيوبولوجيا مهتم بمجموعة متنوعة من الهلاميات الديناميكية ميكانيكياً التي يمكن أن تتصلب أو تطرى أو تنتقل بشكل عكسي بين هذه الحالات لدراسة استجابات الخلايا. توفر هذه الركائز الديناميكية وسيلة لفحص كيفية تأثير الإشارات الميكانيكية على سلوك الخلايا، مشابهة لدراسة العوامل القابلة للذوبان على مدى عقود. كما تتقدم التقنيات لإدخال التباين وأنواع الخلايا المتعددة داخل الهياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد. يشمل ذلك طرقاً مبتكرة حيث تعمل الهلاميات كحبر حيوي لطباعة الخلايا، إما طبقة تلو الأخرى من قاعدة ثنائية الأبعاد أو مباشرة داخل فضاء ثلاثي الأبعاد محاط بهلام آخر. مع تقدم هذه المنصات، من المتوقع أن تصبح أكثر سهولة في الوصول. في هذه الأثناء، يبقى من الضروري الحفاظ على حوار مفتوح وتعاوني بين علماء الخلايا وعلماء المواد والمهندسين. ستضمن هذه الجهود التعاونية أن تكون الجيل القادم من أنظمة زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد المعتمدة على الهياكل مجهزة جيدًا لمواجهة التحديات الكبيرة التي تطرحها التعقيدات البيولوجية والتقنية المتزايدة.

الخاتمة

يمكن أن تمكّن الإفراج المنظم عن الأدوية وعوامل النمو، مما يسهل فحص الأدوية وتطوير العلاجات المستهدفة. علاوة على ذلك، توفر الهيدروجيل توافقًا حيويًا عاليًا ويمكن تفعيله بإشارات حيوية لتوجيه سلوك الخلايا وتكوين الأنسجة. في أبحاث السرطان، توفر الهيدروجيل منصة للتحقيق في تأثير الإشارات الميكانيكية على نمو الورم، وتسلل خلايا المناعة، وتكوين الأوعية الدموية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن سهولة دمج أنواع خلايا متعددة داخل الهيدروجيل يمكّن من دراسة تفاعلات الورم مع النسيج المحيط. وبالمثل، تحتفظ الدعائم النسيجية غير الخلوية بتكوين ECM الأصلي، والتضاريس، والخصائص الميكانيكية، مما يحاكي عن كثب البيئة الدقيقة الطبيعية للورم. نتيجة لذلك، يمكن أن تظهر خلايا السرطان المزروعة في الدعائم النسيجية غير الخلوية سلوكيات ورمية أكثر دقة، بما في ذلك الغزو وتكوين الأوعية. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تُشتق هذه الدعائم من أنسجة محددة للمرضى، مما يمكّن من اتباع نهج الطب الشخصي ويحسن من قابلية التنبؤ باستجابة الأدوية. أخيرًا، توفر الدعائم الهجينة التي تدمج قنوات ميكروفلويديك مزايا فريدة لأبحاث السرطان. من خلال دمج زراعة الخلايا ثلاثية الأبعاد مع الميكروفلويديك، يمكن للباحثين دراسة تكوين الأوعية الدموية في الورم، والانتقال، واختراق الأدوية بطريقة أكثر ملاءمة فسيولوجيًا. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تسهل الميكروفلويديك الفحص عالي الإنتاجية للأدوية المضادة للسرطان، مما يمكّن من اختبار سريع وفعال من حيث التكلفة للعلاجات المحتملة.

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نُشر على الإنترنت: 14 يناير 2024

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7-33.

- Grønning T. History of cancer. In: Colditz GA, editor. The sage encyclopedia of cancer and society. 2nd ed. CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2015. p. 549-54.

- Guimarães* I dos S, Daltoé* RD, Herlinger AL, Madeira KP, LadislauT, Valadão IC, Junior PCML, Fernandes Teixeira S, Amorim GM, Santos DZ dos, Demuth KR, Rangel LBA. Conventional Cancer Treatment. Cancer Treatment-Conventional and Innovative Approaches. 2013; Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/42057.

- De Vita VT. The evolution of therapeutic research in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;298(16):907-10.

- Loessner D, Holzapfel BM, Clements JA. Engineered microenvironments provide new insights into ovarian and prostate cancer progression and drug responses. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;15(79):193-213.

- Xu X, Farach-Carson MC, Jia X. Three-dimensional in vitro tumor models for cancer research and drug evaluation. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32(7):1256-68.

- Pickup MW, Mouw JK, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014;15(12):1243-53.

- Brassart-Pasco S, Brézillon S, Brassart B, Ramont L, Oudart JB, Monboisse JC. Tumor microenvironment: extracellular matrix alterations influence tumor progression. Front Oncol. 2020;10:397.

- Nazemi M, Rainero E. Cross-talk between the tumor microenvironment, extracellular matrix, and cell metabolism in cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10.

- Jackson HW, Defamie V, Waterhouse P, Khokha R. TIMPs: versatile extracellular regulators in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(1):38-53.

- Li J, Xu R. Obesity-associated ECM remodeling in cancer progression. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(22):5684.

- Popovic A, Tartare-Deckert S. Role of extracellular matrix architecture and signaling in melanoma therapeutic resistance. Front Oncol. 2022;12.

- Gordon-Weeks A, Yuzhalin AE. Cancer extracellular matrix proteins regulate tumour immunity. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(11):1-25.

- Romero-López M, Trinh AL, Sobrino A, Hatch MMS, Keating MT, Fimbres C, Lewis DE, Gershon PD, Botvinick EL, Digman M, Lowengrub JS, Hughes CCW. Recapitulating the human tumor microenvironment: colon tumor-derived extracellular matrix promotes angiogenesis and tumor cell growth. Biomaterials. 2017;116:118-29.

- Brown Y, Hua S, Tanwar PS. Extracellular matrix in high-grade serous ovarian cancer: advances in understanding of carcinogenesis and cancer biology. Matrix Biol. 2023;118:16-46.

- Frantz C, Stewart KM, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 24):4195-200.

- Langhans SA. Three-dimensional in vitro cell culture models in drug discovery and drug repositioning. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9(JAN):6.

- Rozario T, DeSimone DW. The extracellular matrix in development and morphogenesis: a dynamic view. Dev Biol. 2010;341(1):126-40.

- Luca AC, Mersch S, Deenen R, Schmidt S, Messner I, Schäfer KL, Baldus SE, Huckenbeck W, Piekorz RP, Knoefel WT, Krieg A, Stoecklein NH. Impact of the 3D microenvironment on phenotype, gene expression, and EGFR inhibition of colorectal cancer cell lines. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e59689.

- Li L, Zhao Q, Kong W. Extracellular matrix remodeling and cardiac fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2018;1(68-69):490-506.

- Kiss DL, Windus LCE, Avery VM. Chemokine receptor expression on integrin-mediated stellate projections of prostate cancer cells in 3D culture. Cytokine. 2013;64(1):122-30.

- Urbanczyk M, Layland SL, Schenke-Layland K. The role of extracellular matrix in biomechanics and its impact on bioengineering of cells and 3D tissues. Matrix Biol. 2020;1(85-86):1-14.

- Harunaga JS, Yamada KM. Cell-matrix adhesions in 3D. Matrix Biol. 2011;30(7-8):363-8.

- Schmitz A, Fischer SC, Mattheyer C, Pampaloni F, Stelzer EHK. Multiscale image analysis reveals structural heterogeneity of the cell microenvironment in homotypic spheroids. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1-13.

- Imamura Y, Mukohara T, Shimono Y, Funakoshi Y, Chayahara N, Toyoda M, Kiyota N, Takao S, Kono S, Nakatsura T, Minami H. Comparison of

26. Loessner D, Stok KS, Lutolf MP, Hutmacher DW, Clements JA, Rizzi SC. Bioengineered 3D platform to explore cell-ECM interactions and drug resistance of epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Biomaterials. 2010;31(32):8494-506.

27. Zhou CH, Yang SF, Li PQ. Human lung cancer cell line SPC-A1 contains cells with characteristics of cancer stem cells. Neoplasma. 2012;59(6):685-92.

28. Gamerith G, Rainer J, Huber JM, Hackl H, Trajanoski Z, Koeck S, Lorenz E, Kern J, Kofler R, Kelm JM, Zwierzina H, Amann A, Gamerith G, Rainer J, Huber JM, HackI H, Trajanoski Z, Koeck S, Lorenz E, Kern J, Kofler R, Kelm JM, Zwierzina H, Amann A. 3D-cultivation of NSCLC cell lines induce gene expression alterations of key cancer-associated pathways and mimic in-vivo conditions. Oncotarget. 2017;8(68):112647-61.

29. Jiang R, Huang J, Sun X, Chu X, Wang F, Zhou J, Fan Q, Pang L. Construction of in vitro 3-D model for lung cancer-cell metastasis study. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09546-9.

30. Chong YK, Toh TB, Zaiden N, Poonepalli A, Leong SH, Ong CEL, Yu Y, Tan PB, See SJ, Ng WH, Ng I, Hande MP, Kon OL, Ang BT, Tang C. Cryopreservation of neurospheres derived from human glioblastoma multiforme. Stem Cells. 2009;27(1):29.

31. Panchalingam K, Paramchuk W, Hothi P, Shah N, Hood L, Foltz G, Behie LA, Panchalingam K, Paramchuk W, Hothi P, Shah N, Hood L, Foltz G, Behie LA. Large-scale production of human glioblastoma-derived cancer stem cell tissue in suspension bioreactors to facilitate the development of novel oncolytic therapeutics. Cancer Stem Cells-The Cutting Edge. 2011;475-502.

32. Sutherland RM, Inch WR, McCredie JA, Kruuv J. A multi-component radiation survival curve using an in vitro tumour model. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1970;18(5):491-5.

33. Youn BS, Sen A, Behie LA, Girgis-Gabardo A, Hassell JA. Scale-up of breast cancer stem cell aggregate cultures to suspension bioreactors. Biotechnol Prog. 2006;22(3):801-10. https://doi.org/10.1021/bp050 430z.

34. Kuo CT, Chiang CL, Chang CH, Liu HK, Huang GS, Huang RYJ, Lee H, Huang CS, Wo AM. Modeling of cancer metastasis and drug resistance via biomimetic nano-cilia and microfluidics. Biomaterials. 2014;35(5):1562-71.

35. Ware MJ, Keshishian V, Law JJ, Ho JC, Favela CA, Rees P, Smith B, Mohammad S, Hwang RF, Rajapakshe K, Coarfa C, Huang S, Edwards DP, Corr SJ, Godin B, Curley SA. Generation of an in vitro 3D PDAC stroma rich spheroid model. Biomaterials. 2016;108:129-42.

36. Rice AJ, Cortes E, Lachowski D, Cheung BCH, Karim SA, Morton JP, Del Río Hernández A. Matrix stiffness induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promotes chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogenesis. 2017;6(7):e352.

37. Kuo CT, Chiang CL, Huang RYJ, Lee H, Wo AM. Configurable 2D and 3D spheroid tissue cultures on bioengineered surfaces with acquisition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition characteristics. NPG Asia Mater. 2012;4(9):e27.

38. Michy T, Massias T, Bernard C, Vanwonterghem L, Henry M, Guidetti M, Royal G, Coll JL, Texier I, Josserand V, Hurbin A. Verteporfin-loaded lipid nanoparticles improve ovarian cancer photodynamic therapy in vitro and in vivo. Cancers. 2019;11(11):1760.

39. Hirst J, Pathak HB, Hyter S, Pessetto ZY, Ly T, Graw S, Koestler DC, Krieg AJ, Roby KF, Godwin AK. Licofelone enhances the efficacy of paclitaxel in ovarian cancer by reversing drug resistance and tumor stem-like properties. Cancer Res. 2018;78(15):4370-85. https://doi.org/10.1158/ 0008-5472.CAN-17-3993.

40. Goodwin TJ, Milburn Jessup J, Wolf DA. Morphologic differentiation of colon carcinoma cell lines HT-29 and HT-29KM in rotating-wall vessels. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1992;28A(1):47-60.

41. Dainiak MB, Savina IN, Musolino I, Kumar A, Mattiasson B, Galaev IY. Biomimetic macroporous hydrogel scaffolds in a high-throughput screening format for cell-based assays. Biotechnol Prog. 2008;24(6):1373-83.

42. Chandrasekaran S, Deng H, Fang Y. PTEN deletion potentiates invasion of colorectal cancer spheroidal cells through 3D Matrigel. Integr Biol (Camb). 2015;7(3):324-34.

43. Poornima K, Francis AP, Hoda M, Eladl MA, Subramanian S, Veeraraghavan VP, El-Sherbiny M, Asseri SM, Hussamuldin ABA, Surapaneni KM, Mony U, Rajagopalan R. Implications of three-dimensional cell culture in cancer therapeutic research. Front Oncol. 2022;12.

44. Gunti S, Hoke ATK, Vu KP, London NR. Organoid and spheroid tumor models: techniques and applications. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(4):1-18.

45. Lovitt CJ, Shelper TB, Avery VM. Advanced cell culture techniques for cancer drug discovery. Biology. 2014;3(2):345-67.

46. Zeilinger K, Freyer N, Damm G, Seehofer D, Knöspel F. Cell sources for in vitro human liver cell culture models. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2016;241(15):1684-98.

47. Eglen RM, Reisine T. Human iPS cell-derived patient tissues and 3D cell culture part 2: spheroids, organoids, and disease modeling. SLAS Technol. 2019;24(1):18-27.

48. Su J, Zhang L, Zhang W, Choi DS, Wen J, Jiang B, Chang CC, Zhou X. Targeting the biophysical properties of the myeloma initiating cell niches: a pharmaceutical synergism analysis using multi-scale agent-based modeling. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e85059.

49. Valyi-Nagy K, Kormos B, Ali M, Shukla D, Valyi-Nagy T. Stem cell marker CD271 is expressed by vasculogenic mimicry-forming uveal melanoma cells in three-dimensional cultures. Mol Vis. 2012;18:588.

50. Lombardo Y, Filipovicá A, Molyneux G, Periyasamy M, Giamas G, Hu Y, Trivedi PS, Wang J, Yaguë E, Michel L, Coombes RC. Nicastrin regulates breast cancer stem cell properties and tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(41):16558-63.

51. Sgodda M, Dai Z, Zweigerdt R, Sharma AD, Ott M, Cantz T. A scalable approach for the generation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatic organoids with sensitive hepatotoxicity features. Stem Cells Dev. 2017;26(20):1490-504.

52. Meier F, Freyer N, Brzeszczynska J, Knöspel F, Armstrong L, Lako M, Greuel S, Damm G, Ludwig-Schwellinger E, Deschl U, Ross JA, Beilmann M, Zeilinger K. Hepatic differentiation of human iPSCs in different 3D models: a comparative study. Int J Mol Med. 2017;40(6):1759.

53. Weng KC, Kurokawa YK, Hajek BS, Paladin JA, Shirure VS, George SC. Human induced pluripotent stem-cardiac-endothelial-tumor-on-achip to assess anticancer efficacy and cardiotoxicity. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2020;26(1):44-55. https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.tec.2019.0248.

54. Liu S, Fang C, Zhong C, Li J, Xiao Q. Recent advances in pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiac organoids and heart-on-chip applications for studying anti-cancer drug-induced cardiotoxicity. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2023;39:2527.

55. Han R, Sun Q, Wu J, Zheng P, Zhao G. Sodium butyrate upregulates miR203 expression to exert anti-proliferation effect on colorectal cancer cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;39(5):1919-29.

56. Fontoura JC, Viezzer C, dos Santos FG, Ligabue RA, Weinlich R, Puga RD, Antonow D, Severino P, Bonorino C. Comparison of 2D and 3D cell culture models for cell growth, gene expression and drug resistance. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2020;1(107): 110264.

57. Ingram M, Techy GB, Saroufeem R, Yazan O, Narayan KS, Goodwin TJ, Spaulding GF. Three-dimensional growth patterns of various human tumor cell lines in simulated microgravity of a NASA bioreactor. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1997;33(6):459-66.

58. Lv D, Yu SC, Ping YF, Wu H, Zhao X, Zhang H, Cui Y, Chen B, Zhang X, Dai J, Bian XW, Yao XH. A three-dimensional collagen scaffold cell culture system for screening anti-glioma therapeutics. Oncotarget. 2016;7(35):56904.

59. Spill F, Reynolds DS, Kamm RD, Zaman MH. Impact of the physical microenvironment on tumor progression and metastasis. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2016;40:41-8.

60. Ravi M, Paramesh V, Kaviya SR, Anuradha E, Paul Solomon FD. 3D cell culture systems: advantages and applications. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(1):16-26. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.24683.

61. Campuzano S, Pelling AE. Scaffolds for 3D cell culture and cellular agriculture applications derived from non-animal sources. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2019;17(3):38.

62. Hippler M, Lemma ED, Bertels S, Blasco E, Barner-Kowollik C, Wegener M, Bastmeyer M. 3D scaffolds to study basic cell biology. Adv Mater. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201808110.

63. Cavo M, Delle Cave D, D’Amone E, Gigli G, Lonardo E, del Mercato LL. A synergic approach to enhance long-term culture and manipulation of MiaPaCa-2 pancreatic cancer spheroids. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1).

64. Ware MJ, Colbert K, Keshishian V, Ho J, Corr SJ, Curley SA, Godin B. Generation of homogenous three-dimensional pancreatic cancer cell spheroids using an improved hanging drop technique. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2016;22(4):312-21.

65. Foty R. A simple hanging drop cell culture protocol for generation of

66. Timmins NE, Nielsen LK. Generation of multicellular tumor spheroids by the hanging-drop method. Methods Mol Med. 2007;140:141-51.

67. Zhao L, Xiu J, Liu Y, Zhang T, Pan W, Zheng X, Zhang X. A 3D printed hanging drop dripper for tumor spheroids analysis without recovery. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1-14.

68. Gao W, Wu D, Wang Y, Wang Z, Zou C, Dai Y, Ng CF, Teoh JYC, Chan FL. Development of a novel and economical agar-based non-adherent three-dimensional culture method for enrichment of cancer stemlike cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9(1):243. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13287-018-0987-x.

69. Madoux F, Tanner A, Vessels M, Willetts L, Hou S, Scampavia L, Spicer TP. A 1536-well 3D viability assay to assess the cytotoxic effect of drugs on spheroids. SLAS Discov. 2017;22(5):516-24.

70. Khawar IA, Park JK, Jung ES, Lee MA, Chang S, Kuh HJ. Three dimensional mixed-cell spheroids mimic stroma-mediated chemoresistance and invasive migration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2018;20(8):800-12.

71. Song Y, Kim JS, Choi EK, Kim J, Kim KM, Seo HR, Song Y, Kim JS, Kyung Choi E, Kim J, Mo Kim K, Ran Seo H. TGF-

72. Ma L, Li Y, Wu Y, Aazmi A, Zhang B, Zhou H, Yang H. The construction of in vitro tumor models based on 3D bioprinting. Biodes Manuf. 2020;3(3):227-36.

73. Xie M, Gao Q, Fu J, Chen Z, He Y. Bioprinting of novel 3D tumor array chip for drug screening. Biodes Manuf. 2020;3(3):175-88.

74. Datta P, Dey M, Ataie Z, Unutmaz D, Ozbolat IT. 3D bioprinting for reconstituting the cancer microenvironment. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2020;4(1).

75. LaBarge W, Morales A, Pretorius D, Kahn-Krell AM, Kannappan R, Zhang J. Scaffold-free bioprinter utilizing layer-by-layer printing of cellular spheroids. Micromachines (Basel). 2019;10(9):570.

76. Khoshnood N, Zamanian A. A comprehensive review on scaffold-free bioinks for bioprinting. Bioprinting. 2020;1(19): e00088.

77. Norotte C, Marga FS, Niklason LE, Forgacs G. Scaffold-free vascular tissue engineering using bioprinting. Biomaterials. 2009;30(30):5910-7.

78. Anil-Inevi M, Delikoyun K, Mese G, Tekin HC, Ozcivici E. Magnetic levitation assisted biofabrication, culture, and manipulation of 3D cellular structures using a ring magnet based setup. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2021;118(12):4771-85.

79. Anil-Inevi M, Yaman S, Yildiz AA, Mese G, Yalcin-Ozuysal O, Tekin HC, Ozcivici E. Biofabrication of in situ self assembled 3D cell cultures in a weightlessness environment generated using magnetic levitation. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1).

80. Türker E, Demirçak N, Arslan-Yildiz A. Correction: scaffold-free threedimensional cell culturing using magnetic levitation. Biomater Sci. 2018;6(7):1996.

81. Haisler WL, Timm DM, Gage JA, Tseng H, Killian TC, Souza GR. Three-dimensional cell culturing by magnetic levitation. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(10):1940-9.

82. Jaganathan H, Gage J, Leonard F, Srinivasan S, Souza GR, Dave B, Godin B. Three-dimensional in vitro co-culture model of breast tumor using magnetic levitation. Sci Rep. 2014;4.

83. Caleffi JT, Aal MCE, de Gallindo H, Caxali GH, Crulhas BP, Ribeiro AO, Souza GR, Delella FK. Magnetic 3D cell culture: state of the art and current advances. Life Sci. 2021;286:120028.

84. Rogers M, Sobolik T, Schaffer DK, Samson PC, Johnson AC, Owens P, Codreanu SG, Sherrod SD, McLean JA, Wikswo JP, Richmond A. Engineered microfluidic bioreactor for examining the three-dimensional breast tumor microenvironment. Biomicrofluidics. 2018;12(3):34102.

85. Xu Z, Gao Y, Hao Y, Li E, Wang Y, Zhang J, Wang W, Gao Z, Wang Q. Application of a microfluidic chip-based 3D co-culture to test drug sensitivity for individualized treatment of lung cancer. Biomaterials. 2013;34(16):4109-17.

86. Ruedinger F, Lavrentieva A, Blume C, Pepelanova I, Scheper T. Hydrogels for 3D mammalian cell culture: a starting guide for laboratory practice. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99(2):623-36.

87. Zhang N, Milleret V, Thompson-Steckel G, Huang NP, Vörös J, Simona

88. Rijal G, Bathula C, Li W. Application of synthetic polymeric scaffolds in breast cancer 3D tissue cultures and animal tumor models. Int J Biomater. 2017;2017:9.

89. Unnikrishnan K, Thomas LV, Ram Kumar RM. Advancement of scaffoldbased 3D cellular models in cancer tissue engineering: an update. Front Oncol. 2021;11.

90. van Tienderen GS, Conboy J, Muntz I, Willemse J, Tieleman J, Monfils K, Schurink IJ, Demmers JAA, Doukas M, Koenderink GH, van der Laan LJW, Verstegen MMA. Tumor decellularization reveals proteomic and mechanical characteristics of the extracellular matrix of primary liver cancer. Biomater Adv. 2023;1(146): 213289.

91. Li X, Valadez AV, Zuo P, Nie Z. Microfluidic 3D cell culture: potential application for tissue-based bioassays. Bioanalysis. 2012;4(12):1509.

92. Zhong Q, Ding H, Gao B, He Z, Gu Z. Advances of microfluidics in biomedical engineering. Adv Mater Technol. 2019;4(6).

93. Santos SC, Custódio CA, Mano JF. Human protein-based porous scaffolds as platforms for xeno-free 3D cell culture. Adv Healthc Mater. 2022;11(12).

94. Afewerki S, Sheikhi A, Kannan S, Ahadian S, Khademhosseini A. Gelatin-polysaccharide composite scaffolds for 3D cell culture and tissue engineering: Towards natural therapeutics. Bioeng Transl Med. 2018;4(1):96-115.

95. Chen L, Xiao Z, Meng Y, Zhao Y, Han J, Su G, Chen B, Dai J. The enhancement of cancer stem cell properties of MCF-7 cells in 3D collagen scaffolds for modeling of cancer and anti-cancer drugs. Biomaterials. 2012;33(5):1437-44.

96. McGrath J, Panzica L, Ransom R, Withers HG, Gelman IH. Identification of genes regulating breast cancer dormancy in 3D bone endosteal niche cultures. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17(4):860-9.

97. Arya N, Sardana V, Saxena M, Rangarajan A, Katti DS. Recapitulating tumour microenvironment in chitosan-gelatin three-dimensional scaffolds: an improved in vitro tumour model. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9(77):3288-302.

98. Bassi G, Panseri S, Dozio SM, Sandri M, Campodoni E, Dapporto M, Sprio S, Tampieri A, Montesi M. Scaffold-based 3D cellular models mimicking the heterogeneity of osteosarcoma stem cell niche. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):22294.

99. Kievit FM, Wang K, Erickson AE, Lan Levengood SK, Ellenbogen RG, Zhang M. Modeling the tumor microenvironment using chitosanalginate scaffolds to control the stem-like state of glioblastoma cells. Biomater Sci. 2016;4(4):610.

100. Li W, Hu X, Wang S, Xing Y, Wang H, Nie Y, Liu T, Song K. Multiple comparisons of three different sources of biomaterials in the application of tumor tissue engineering in vitro and in vivo. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;130:166-76.

101. Palomeras S, Rabionet M, Ferrer I, Sarrats A, Garcia-Romeu ML, Puig T, Ciurana J. Breast cancer stem cell culture and enrichment using Poly(

102. Pradhan S, Clary JM, Seliktar D, Lipke EA. A three-dimensional spheroidal cancer model based on PEG-fibrinogen hydrogel microspheres. Biomaterials. 2017;1(115):141-54.

103. Godugu C, Patel AR, Desai U, Andey T, Sams A, Singh M. AlgiMatrix

104. Andersen T, Auk-Emblem P, Dornish M. 3D cell culture in alginate hydrogels. Microarrays. 2015;4(2):133-61.

105. Yang Z, Zhao X. A 3D model of ovarian cancer cell lines on peptide nanofiber scaffold to explore the cell-scaffold interaction and chemotherapeutic resistance of anticancer drugs. Int J Nanomed. 2011;6:310.

106. Song H, Cai GH, Liang J, Ao DS, Wang H, Yang ZH. Three-dimensional culture and clinical drug responses of a highly metastatic human ovarian cancer HO-8910PM cells in nanofibrous microenvironments of three hydrogel biomaterials. J Nanobiotechnol. 2020;18(1):90.

107. Suo A, Xu W, Wang Y, Sun T, Ji L, Qian J. Dual-degradable and injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogel mimicking extracellular matrix for 3D culture of breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;211:336-48.

108. Wang J, Xu W, Qian J, Wang Y, Hou G, Suo A. Photo-crosslinked hyaluronic acid hydrogel as a biomimic extracellular matrix to recapitulate in vivo features of breast cancer cells. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2022;209:112159.

109. Kim MJ, Chi BH, Yoo JJ, Ju YM, Whang YM, Chang IH. Structure establishment of three-dimensional (3D) cell culture printing model for bladder cancer. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(10):e0223689.

110. Loessner D, Meinert C, Kaemmerer E, Martine LC, Yue K, Levett PA, Klein TJ, Melchels FPW, Khademhosseini A, Hutmacher DW. Functionalization, preparation and use of cell-laden gelatin methacryloyl-based hydrogels as modular tissue culture platforms. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(4):727-46.

111. Arya AD, Hallur PM, Karkisaval AG, Gudipati A, Rajendiran S, Dhavale V, Ramachandran B, Jayaprakash A, Gundiah N, Chaubey A. Gelatin methacrylate hydrogels as biomimetic three-dimensional matrixes for modeling breast cancer invasion and chemoresponse in vitro. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(34):22005-17.

112. Curtis KJ, Schiavi J, Mc Garrigle MJ, Kumar V, McNamara LM, Niebur GL. Mechanical stimuli and matrix properties modulate cancer spheroid growth in three-dimensional gelatin culture. J R Soc Interface. 2020;17(173):20200568.

113. Cavo M, Fato M, Peñuela L, Beltrame F, Raiteri R, Scaglione S. Microenvironment complexity and matrix stiffness regulate breast cancer cell activity in a 3D in vitro model. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):1-13.

114. VandenHeuvel SN, Farris HA, Noltensmeyer DA, Roy S, Donehoo DA, Kopetz S, Haricharan S, Walsh AJ, Raghavan S. Decellularized organ biomatrices facilitate quantifiable in vitro 3D cancer metastasis models. Soft Matter. 2022;18(31):5791-806.

115. Landberg G, Fitzpatrick P, Isakson P, Jonasson E, Karlsson J, Larsson E, Svanström A, Rafnsdottir S, Persson E, Gustafsson A, Andersson D, Rosendahl J, Petronis S, Ranji P, Gregersson P, Magnusson Y, Håkansson J, Ståhlberg A. Patient-derived scaffolds uncover breast cancer promoting properties of the microenvironment. Biomaterials. 2020;1(235): 119705.

116. Zhang

117. D’angelo E, Natarajan D, Sensi F, Ajayi O, Fassan M, Mammano E, Pilati P, Pavan P, Bresolin S, Preziosi M, Miquel R, Zen Y, Chokshi S, Menon K, Heaton N, Spolverato G, Piccoli M, Williams R, Urbani L, Agostini M. Patientderived scaffolds of colorectal cancer metastases as an organotypic 3D model of the liver metastatic microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(2):364.

118. Varinelli L, Guaglio M, Brich S, Zanutto S, Belfiore A, Zanardi F, lannelli F, Oldani A, Costa E, Chighizola M, Lorenc E, Minardi SP, Fortuzzi S, Filugelli M, Garzone G, Pisati F, Vecchi M, Pruneri G, Kusamura S, Baratti D, Cattaneo L, Parazzoli D, Podestà A, Milione M, Deraco M, Pierotti MA, Gariboldi M. Decellularized extracellular matrix as scaffold for cancer organoid cultures of colorectal peritoneal metastases. J Mol Cell Biol. 2023;14(11).

119. Tian X, Werner ME, Roche KC, Hanson AD, Foote HP, Yu SK, Warner SB, Copp JA, Lara H, Wauthier EL, Caster JM, Herring LE, Zhang L, Tepper JE, Hsu DS, Zhang T, Reid LM, Wang AZ. Organ-specific metastases obtained by culturing colorectal cancer cells on tissue-specific decellularized scaffolds. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2(6):443-52.

120. Li H, Dai W, Xia X, Wang R, Zhao J, Han L, Mo S, Xiang W, Du L, Zhu G, Xie J, Yu J, Liu N, Huang M, Zhu J, Cai G. Modeling tumor development and metastasis using paired organoids derived from patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):1-6. https://doi. org/10.1186/s13045-020-00957-4.

121. Parkinson GT, Salerno S, Ranji P, Håkansson J, Bogestål Y, Wettergren Y, Ståhlberg A, Bexe Lindskog E, Landberg G. Patient-derived scaffolds as a model of colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2021;10(3):867-82.

122. Jian M, Ren L, Ren L, He G, He G, Lin Q, Lin Q, Tang W, Tang W, Chen Y, Chen J, Chen J, Liu T, Ji M, Ji M, Wei Y, Wei Y, Chang W, Chang W, Xu J, Xu J. A novel patient-derived organoids-based xenografts model for preclinical drug response testing in patients with colorectal liver metastases. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):1-17. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12967-020-02407-8.

123. Pinto

124. Helal-Neto E, Brandão-Costa RM, Saldanha-Gama R, Ribeiro-Pereira C, Midlej V, Benchimol M, Morandi V, Barja-Fidalgo C. Priming endothelial cells with a melanoma-derived extracellular matrix triggers the activation of avß3/VEGFR2 axis. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231(11):2464-73.

125. Fontana F, Raimondi M, Marzagalli M, Sommariva M, Limonta P, Gagliano N. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition markers and CD44 isoforms are differently expressed in 2D and 3D cell cultures of prostate cancer cells. Cells. 2019;8(2):143.

126. Li GN, Livi LL, Gourd CM, Deweerd ES, Hoffman-Kim D. Genomic and morphological changes of neuroblastoma cells in response to threedimensional matrices. Tissue Eng. 2007;13(5):1035-47.

127. Sarwar M, Sykes PH, Chitcholtan K, Evans JJ. Collagen I dysregulation is pivotal for ovarian cancer progression. Tissue Cell. 2022;74.

128. Tsai S, McOlash L, Palen K, Johnson B, Duris C, Yang Q, Dwinell MB, Hunt

129. Sha H, Zou Z, Xin K, Bian X, Cai X, Lu W, Chen J, Chen G, Huang L, Blair AM, Cao P, Liu B. Tumor-penetrating peptide fused EGFR single-domain antibody enhances cancer drug penetration into 3D multicellular spheroids and facilitates effective gastric cancer therapy. J Control Release. 2015;28(200):188-200.

130. Monteiro MV, Gaspar VM, Ferreira LP, Mano JF. Hydrogel 3D in vitro tumor models for screening cell aggregation mediated drug response. Biomater Sci. 2020;8(7):1855-64.

131. Kundu B, Saha P, Datta K, Kundu SC. A silk fibroin based hepatocarcinoma model and the assessment of the drug response in hyaluronan-binding protein 1 overexpressed HepG2 cells. Biomaterials. 2013;34(37):9462-74.

132. Simon KA, Mosadegh B, Minn KT, Lockett MR, Mohammady MR, Boucher DM, Hall AB, Hillier SM, Udagawa T, Eustace BK, Whitesides GM. Metabolic response of lung cancer cells to radiation in a paper-based 3D cell culture system. Biomaterials. 2016;1(95):47-59.

133. Loessner D, Rizzi SC, Stok KS, Fuehrmann T, Hollier B, Magdolen V, Hutmacher DW, Clements JA. A bioengineered 3D ovarian cancer model for the assessment of peptidase-mediated enhancement of spheroid growth and intraperitoneal spread. Biomaterials. 2013;34(30):7389-400.

134. Stratmann AT, Fecher D, Wangorsch G, Göttlich C, Walles T, Walles H, Dandekar T, Dandekar G, Nietzer SL. Establishment of a human 3D lung cancer model based on a biological tissue matrix combined with a Boolean in silico model. Mol Oncol. 2014;8(2):351-65. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.11.009.

135. Dunne LW, Huang Z, Meng W, Fan X, Zhang N, Zhang Q, An Z. Human decellularized adipose tissue scaffold as a model for breast cancer cell growth and drug treatments. Biomaterials. 2014;35(18):4940-9.

136. Çetin EA. Investigation of the viability of different cancer cells on decelIularized adipose tissue. Celal Bayar Univ J Sci. 2023;19(2):113-9.

137. Sensi F, D’angelo E, Piccoli M, Pavan P, Mastrotto F, Caliceti P, Biccari A, Corallo D, Urbani L, Fassan M, Spolverato G, Riello P, Pucciarelli S, Agostini M. Recellularized colorectal cancer patient-derived scaffolds as in vitro pre-clinical 3D model for drug screening. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(3).

138. Mazza G, Telese A, Al-Akkad W, Frenguelli L, Levi A, Marrali M, Longato L, Thanapirom K, Vilia MG, Lombardi B, Crowley C, Crawford M, Karsdal MA, Leeming DJ, Marrone G, Bottcher K, Robinson B, Del Rio HA, Tamburrino D, Spoletini G, Malago M, Hall AR, Godovac-Zimmermann J, Luong TV, De Coppi P, Pinzani M, Rombouts K. Cirrhotic human liver extracellular matrix 3D scaffolds promote smad-dependent TGF-

139. Zhao L, Huang L, Yu S, Zheng J, Wang H, Zhang Y. Decellularized tongue tissue as an in vitro model for studying tongue cancer and tongue regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2017;58:122-35.

140. Blanco-Fernandez B, Rey-Vinolas S, Bağcl G, Rubi-Sans G, Otero J, Navajas D, Perez-Amodio S, Engel E. Bioprinting decellularized breast tissue

for the development of three-dimensional breast cancer models. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(26):29467-82. https://doi.org/10.1021/ acsami.2c00920.

141. Molla MDS, Katti DR, Katti KS. An in vitro model of prostate cancer bone metastasis for highly metastatic and non-metastatic prostate cancer using nanoclay bone-mimetic scaffolds. Springer Link. 2019;4(21):120713. https://doi.org/10.1557/adv.2018.682.

142. Bai G, Yuan P, Cai B, Qiu X, Jin R, Liu S, Li Y, Chen X. Stimuli-responsive scaffold for breast cancer treatment combining accurate photothermal therapy and adipose tissue regeneration. Adv Funct Mater. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201904401.

143. Lee JH, Kim SK, Khawar IA, Jeong SY, Chung S, Kuh HJ. Microfluidic co-culture of pancreatic tumor spheroids with stellate cells as a novel 3D model for investigation of stroma-mediated cell motility and drug resistance. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37(1):1-12. https://doi.org/10. 1186/s13046-017-0654-6.

144. Chen Y, Sun W, Kang L, Wang Y, Zhang M, Zhang H, Hu P. Microfluidic co-culture of liver tumor spheroids with stellate cells for the investigation of drug resistance and intercellular interactions. Analyst. 2019;144(14):4233-40.

145. Jeong SY, Lee JH, Shin Y, Chung S, Kuh HJ. Co-culture of tumor spheroids and fibroblasts in a collagen matrix-incorporated microfluidic chip mimics reciprocal activation in solid tumor microenvironment. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159013.

146. Shin CS, Kwak B, Han B, Park K. Development of an in vitro 3D tumor model to study therapeutic efficiency of an anticancer drug. Mol Pharm. 2013;10(6):2167-75. https://doi.org/10.1021/mp300595a.

147. Hübner J, Raschke M, Rütschle I, Gräßle S, Hasenberg T, Schirrmann K, Lorenz A, Schnurre S, Lauster R, Maschmeyer I, Steger-Hartmann T, Marx U. Simultaneous evaluation of anti-EGFR-induced tumour and adverse skin effects in a microfluidic human 3D co-culture model. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1-12.

148. Dorayappan KDP, Gardner ML, Hisey CL, Zingarelli RA, Smith BQ, Lightfoot MDS, Gogna R, Flannery MM, Hays J, Hansford DJ, Freitas MA, Yu L, Cohn DE, Selvendiran K. A microfluidic chip enables isolation of exosomes and establishment of their protein profiles and associated signaling pathways in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79(13):3503-13.

149. Booij TH, Price LS, Danen EHJ. 3D cell-based assays for drug screens: challenges in imaging, image analysis, and high-content analysis. SLAS Discovery. 2019;24(6):615-27.

150. Eskes C, Boström AC, Bowe G, Coecke S, Hartung T, Hendriks G, Pamies D, Piton A, Rovida C. Good cell culture practices & in vitro toxicology. Toxicol In Vitro. 2017;1(45):272-7.

151. Coecke S, Balls M, Bowe G, Davis J, Gstraunthaler G, Hartung T, Hay R, Merten OW, Price A, Schechtman L, Stacey G, Stokes W. Guidance on good cell culture practice: a report of the Second ECVAM Task Force on good cell culture practice. Altern Lab Anim. 2005;33(3):261-87.

152. Kasendra M, Troutt M, Broda T, Bacon WC, Wang TC, Niland JC, Helmrath MA. The engineered gut: use of stem cells and tissue engineering to study physiological mechanisms and disease processes: intestinal organoids: roadmap to the clinic. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2021;321(1):G1.

153. Al-Ani A, Toms D, Kondro D, Thundathil J, Yu Y, Ungrin M. Oxygenation in cell culture: critical parameters for reproducibility are routinely not reported. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0204269.

154. Blatchley MR, Hall F, Ntekoumes D, Cho H, Kailash V, Vazquez-Duhalt R, Gerecht S. Discretizing three-dimensional oxygen gradients to modulate and investigate cellular processes. Adv Sci. 2021;8(14):2100190. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs. 202100190.

155. Martinez NJ, Titus SA, Wagner AK, Simeonov A. High-throughput fluorescence imaging approaches for drug discovery using in vitro and in vivo three-dimensional models. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2015;10(12):1347-61.

156. Robertson FM, Ogasawara MA, Ye Z, Chu K, Pickei R, Debeb BG, Woodward WA, Hittelman WN, Cristofanilli M, Barsky SH. Imaging and analysis of 3D tumor spheroids enriched for a cancer stem cell phenotype. J Biomol Screen. 2010;15(7):820-9.

157. Wenzel C, Riefke B, Gründemann S, Krebs A, Christian S, Prinz F, Osterland M, Golfier S, Räse S, Ansari N, Esner M, Bickle M, Pampaloni F, Mattheyer C, Stelzer EH, Parczyk K, Prechtl S, Steigemann P. 3D high-content

screening for the identification of compounds that target cells in dormant tumor spheroid regions. Exp Cell Res. 2014;323(1):131-43.

158. Palacio-Castañeda V, Velthuijs N, Le Gac S, Verdurmen WPR. Oxygen control: the often overlooked but essential piece to create better in vitro systems. Lab Chip. 2022;22(6):1068-92.

159. Boyce MW, Simke WC, Kenney RM, Lockett MR. Generating linear oxygen gradients across 3D cell cultures with block-layered oxygen controlled chips (BLOCCs). Anal Methods. 2020;12(1):18.

160. Li Y, Yang HY, Lee DS. Biodegradable and injectable hydrogels in biomedical applications. Biomacromol. 2022;23(3):609-18. https://doi.org/ 10.1021/acs.biomac.1c01552.

161. Osaki T, Sivathanu V, Kamm RD. Engineered 3D vascular and neuronal networks in a microfluidic platform. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1-13.