DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08628-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39821164

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-16

معاينة المقال المعجلة

نموذج توليدي لتصميم المواد غير العضوية

تاريخ القبول: 10 يناير 2025

معاينة المقال المعجلة

نموذج توليدي لتصميم المواد غير العضوية

الملخص

تصميم المواد الوظيفية ذات الخصائص المرغوبة أمر أساسي في دفع التقدم التكنولوجي في مجالات مثل تخزين الطاقة، التحفيز، والتقاط الكربون [1-3]. توفر النماذج التوليدية نموذجًا جديدًا لتصميم المواد من خلال توليد مواد جديدة مباشرةً وفقًا لقيود الخصائص المرغوبة، ولكن الطرق الحالية لديها معدل نجاح منخفض في اقتراح بلورات مستقرة أو يمكنها فقط تلبية مجموعة محدودة من قيود الخصائص [4-11]. هنا، نقدم MatterGen، نموذجًا يولد مواد غير عضوية مستقرة ومتنوعة عبر الجدول الدوري ويمكن ضبطه بشكل أكبر لتوجيه التوليد نحو مجموعة واسعة من قيود الخصائص. مقارنةً بالنماذج التوليدية السابقة [4، 12]، فإن الهياكل التي تنتجها

الملخص

MatterGen أكثر من ضعف احتمالية أن تكون جديدة ومستقرة، وأكثر من 10 مرات أقرب إلى الحد الأدنى للطاقة المحلية. بعد الضبط الدقيق، يقوم MatterGen بنجاح بتوليد مواد مستقرة وجديدة ذات كيمياء مرغوبة، تماثل، بالإضافة إلى خصائص ميكانيكية وإلكترونية ومغناطيسية. كدليل على المفهوم، نقوم بتخليق أحد الهياكل المولدة ونقيس قيمة خاصيته لتكون ضمن

1 المقدمة

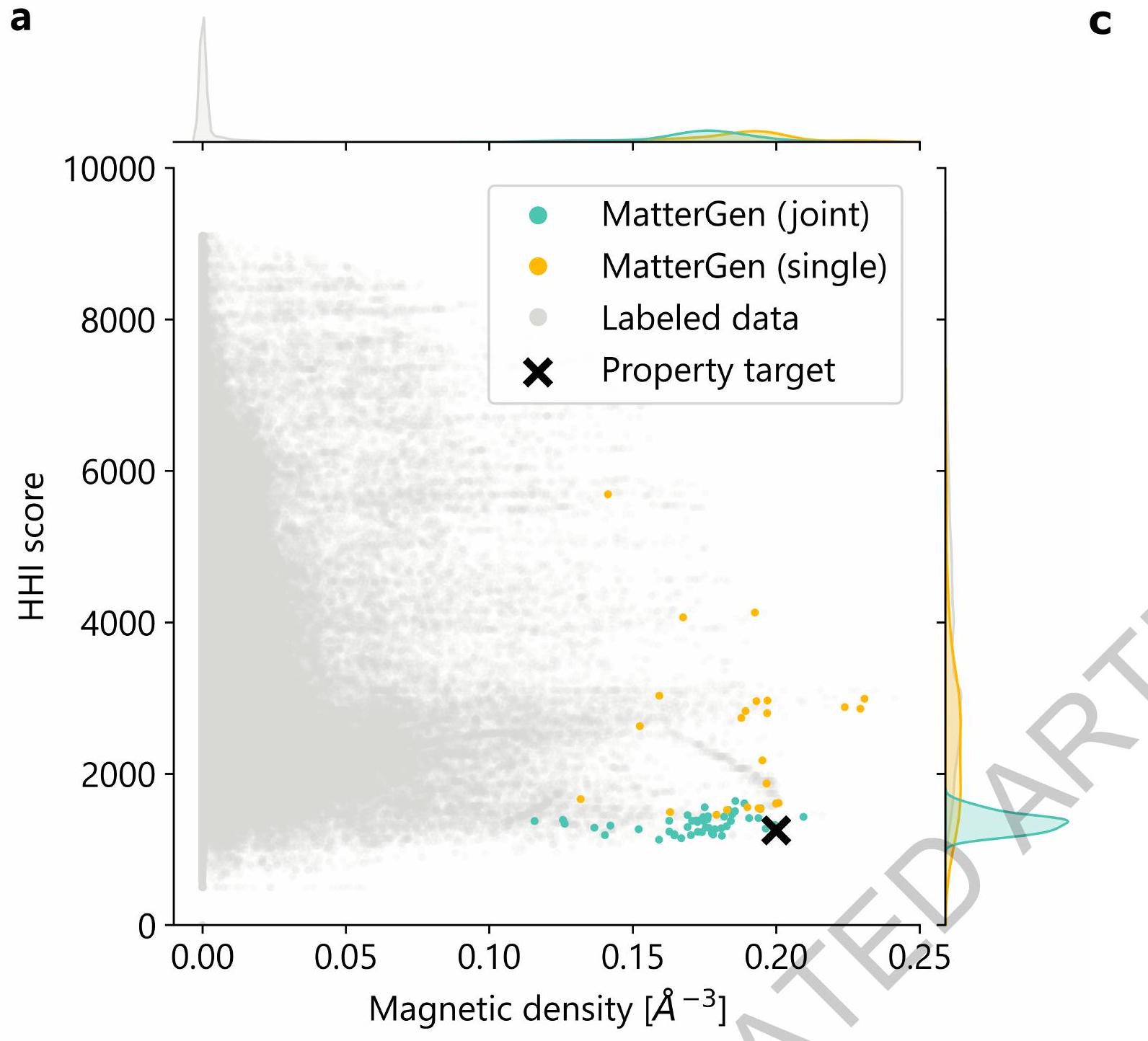

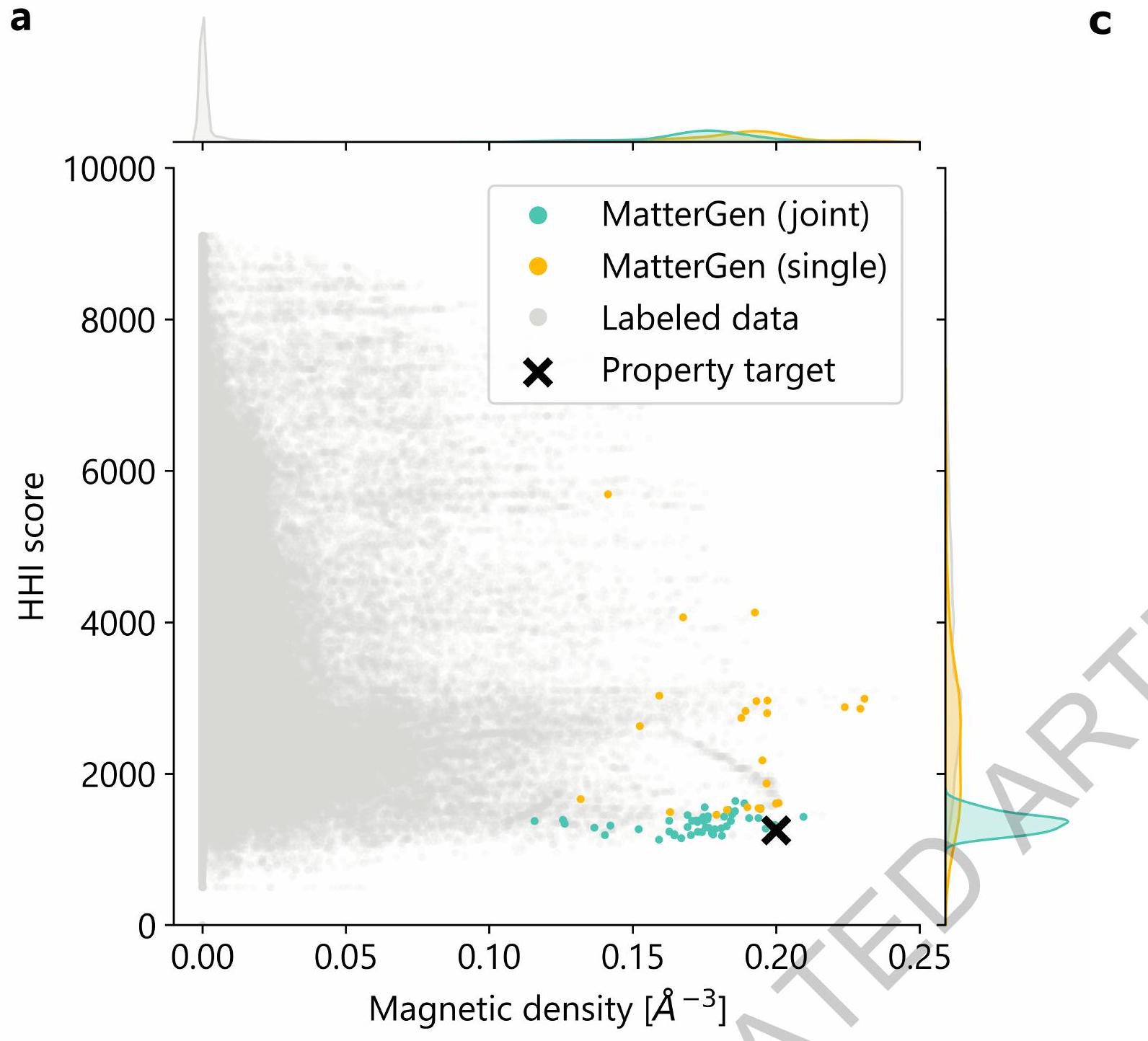

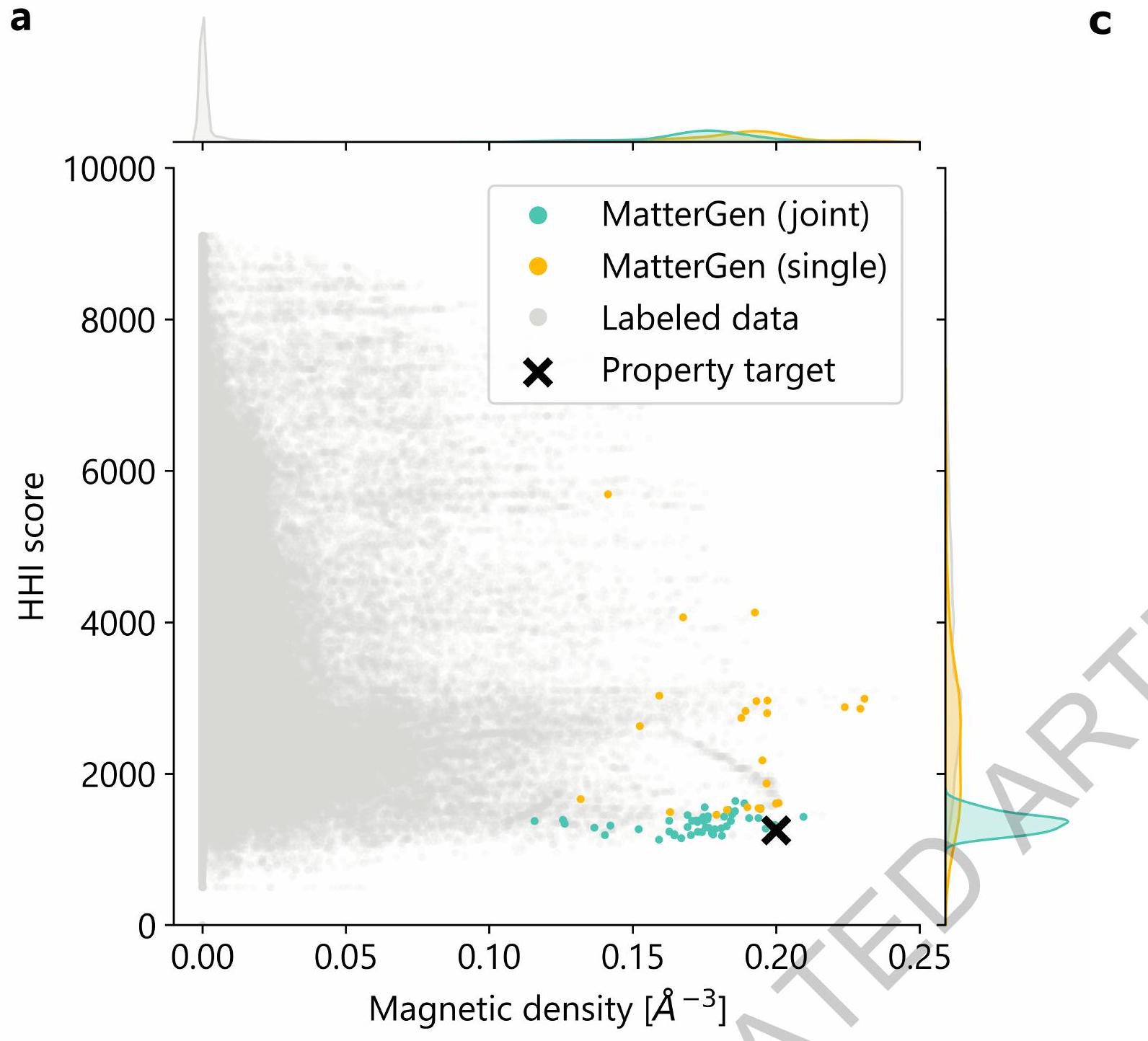

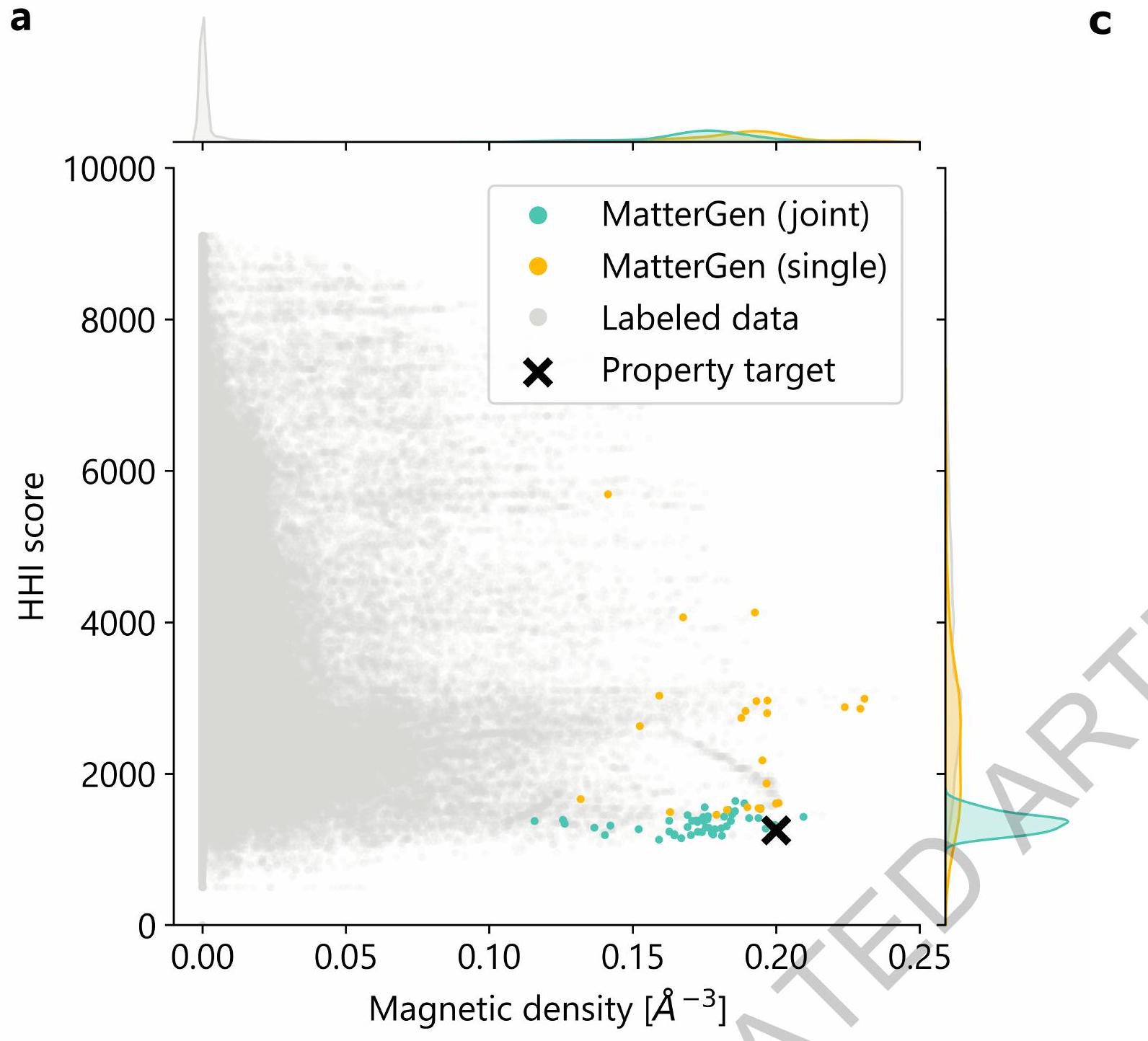

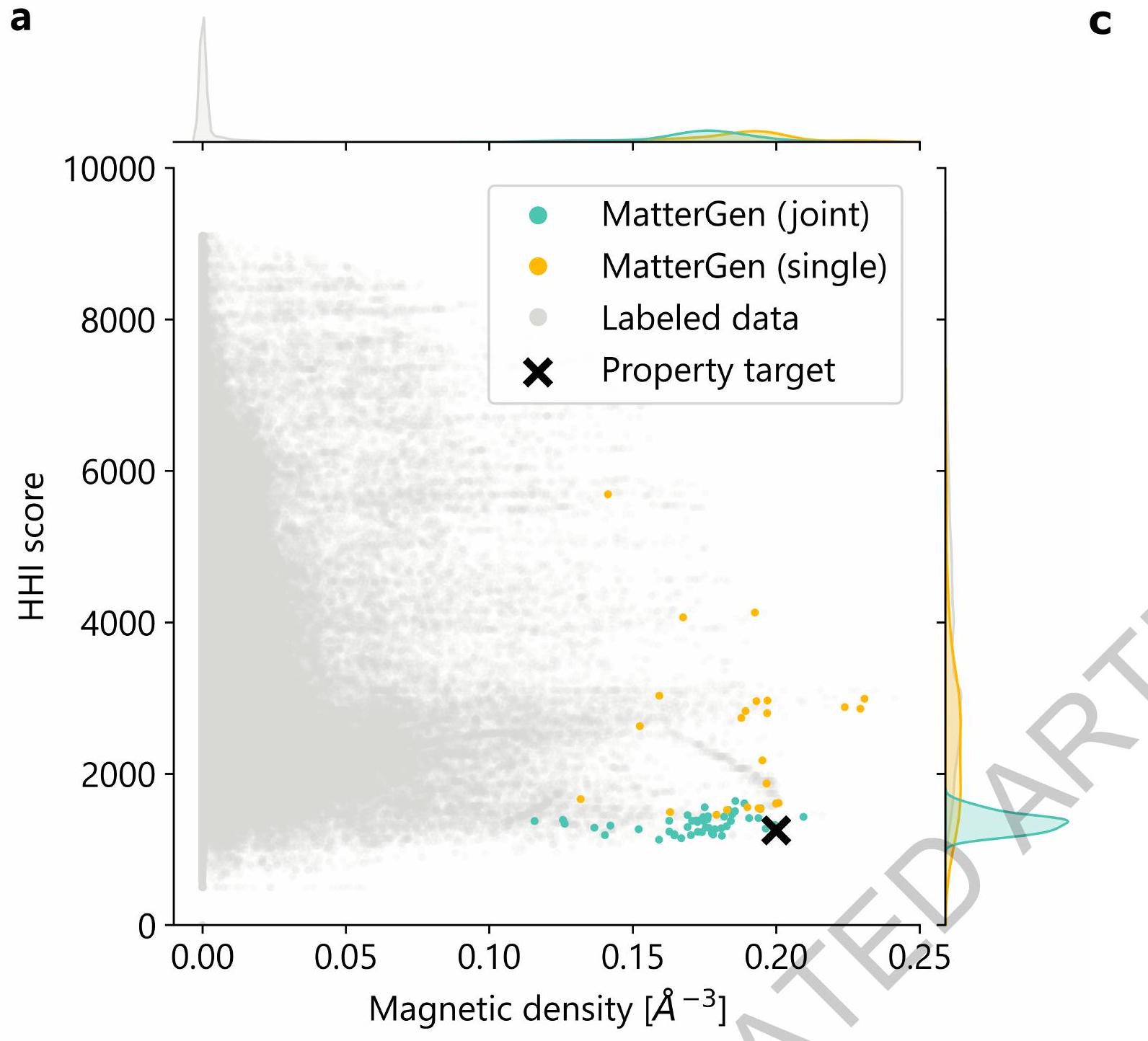

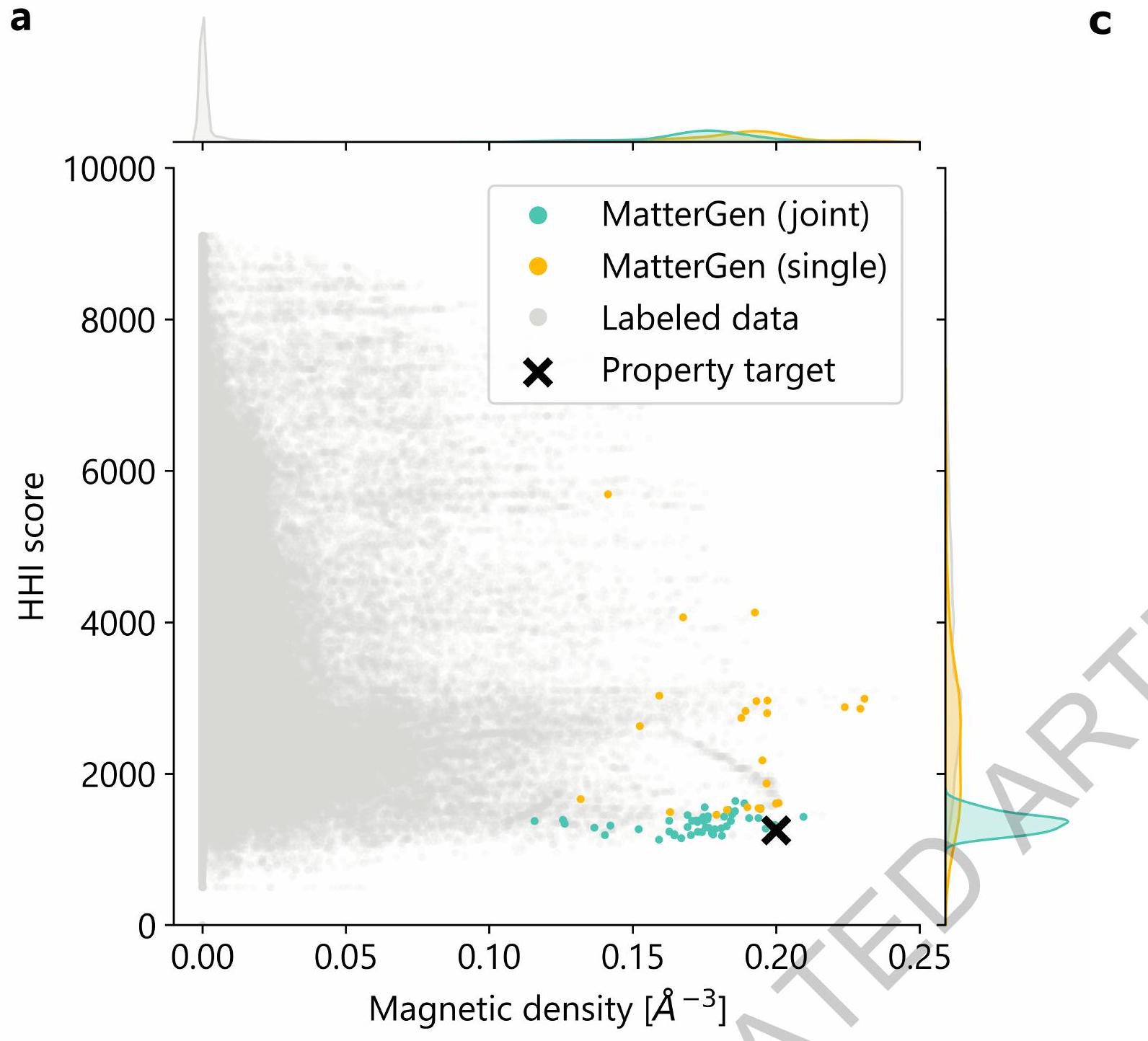

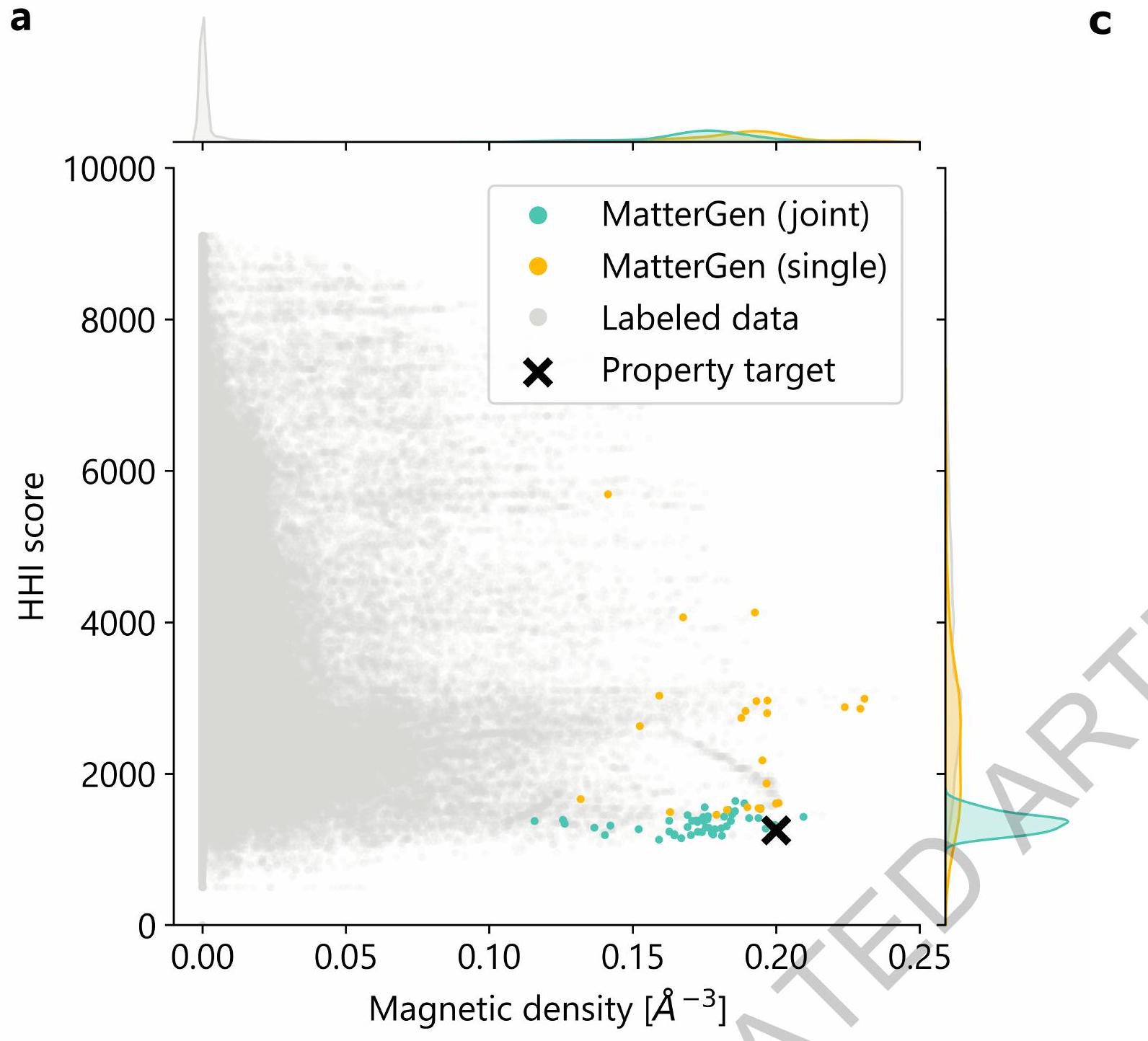

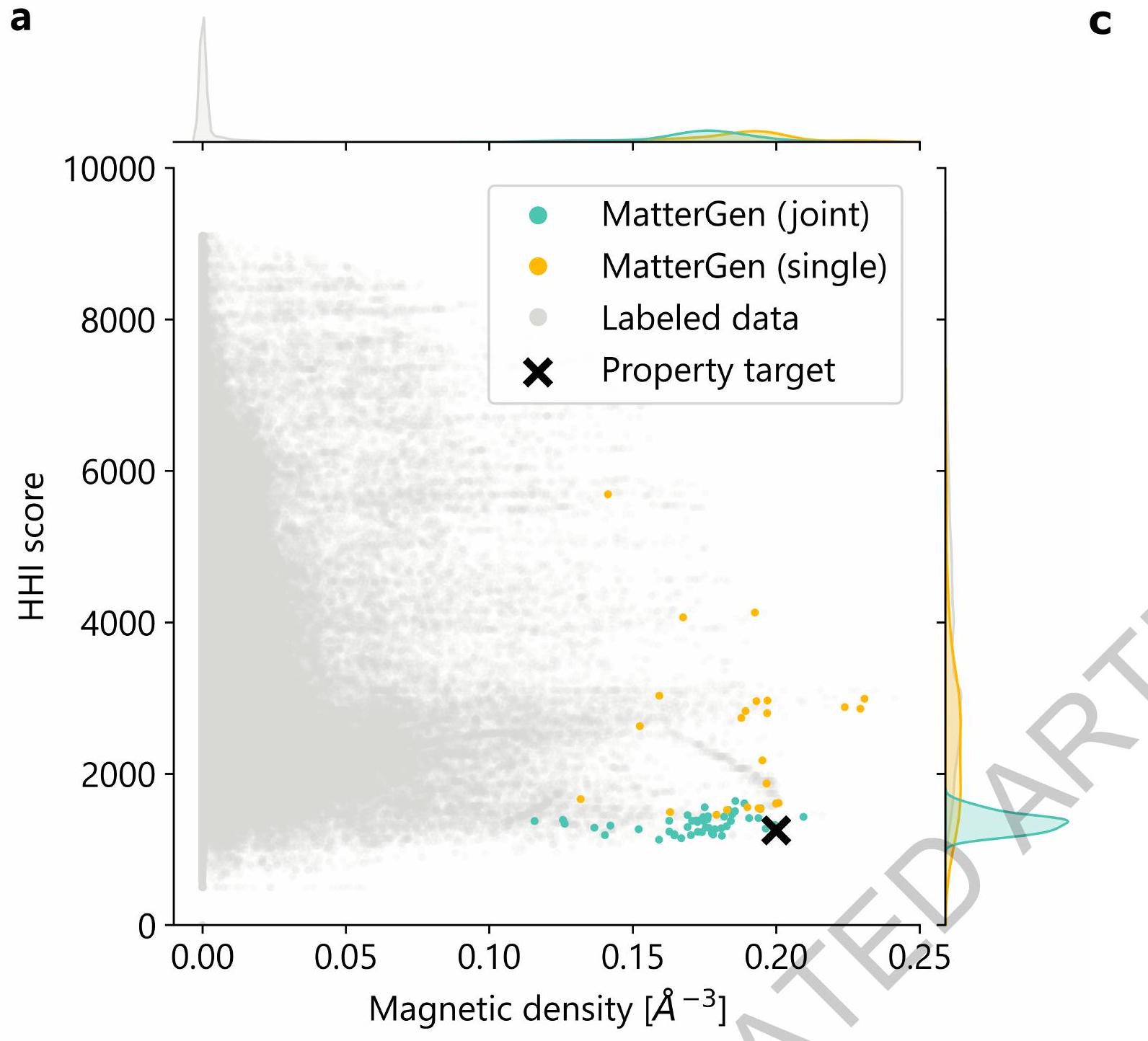

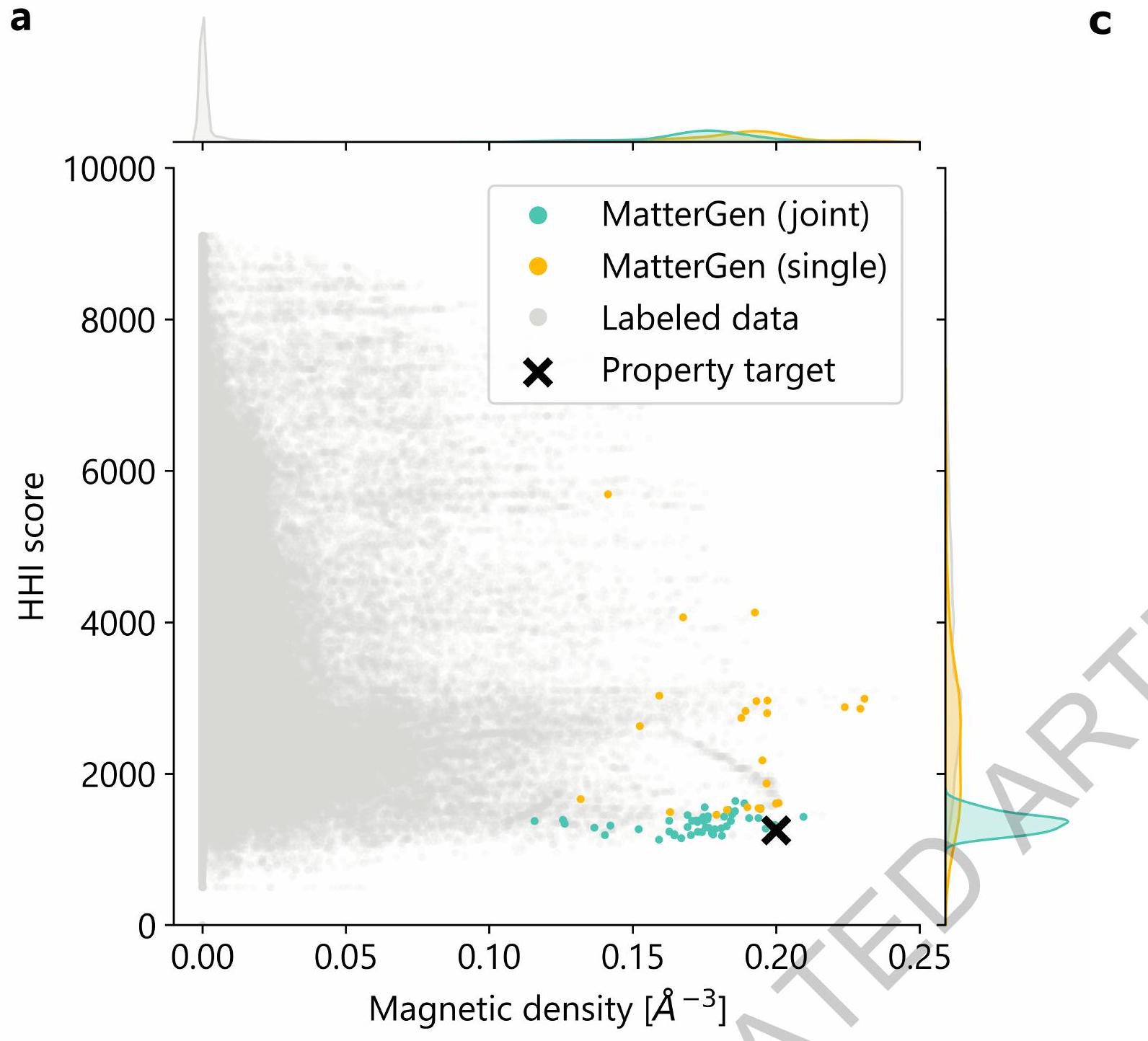

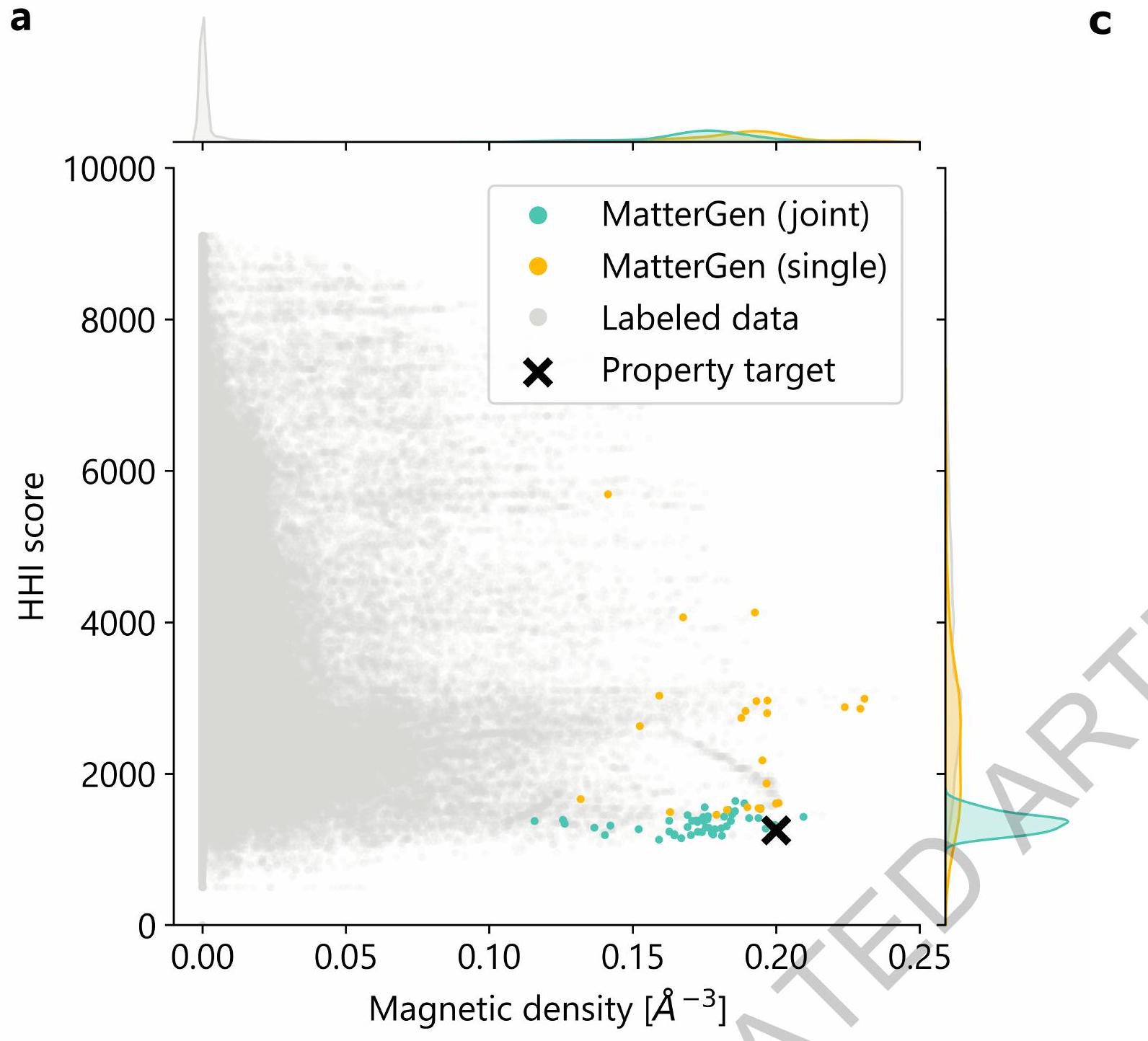

mمكن تصميم المواد العكسية لمجموعة أوسع بكثير من المشكلات مقارنة بالنماذج التوليدية السابقة. عند الضبط الدقيق، غالبًا ما ينتج MatterGen المزيد من المواد S.U.N. في الأنظمة الكيميائية المستهدفة مقارنةً بالطرق المعروفة مثل الاستبدال والبحث عن الهياكل العشوائية (RSS) (الشكل 3)، وهو قادر على توليد هياكل متجانسة للغاية نظرًا لمجموعات الفضاء المرغوبة (الشكل D8)، وينتج مباشرةً مواد S.U.N. تلبي قيود الخصائص الميكانيكية والإلكترونية والمغناطيسية المستهدفة (الشكل 4). كما أن MatterGen قادر على تصميم مواد وفقًا لعدة قيود خصائص، على سبيل المثال، كثافة مغناطيسية عالية وتركيب كيميائي مع مخاطر منخفضة في سلسلة التوريد (الشكل 5). كدليل على المفهوم، نتحقق من قدرات تصميم MatterGen من خلال تخليق مادة مولدة وقياس خاصيتها لتكون ضمن

2 النتائج

2.1 عملية الانتشار للمواد

2.2 توليد مواد مستقرة ومتنوعة

في القسم 2.6. النتائج الخاصة بضبط التوافق مع قيود التناظر موجودة في المكمل D.7.

2.3 التصميم الموجه بالكيمياء

يمكن تحقيقها مع النماذج التوليدية من خلال اقتراح مرشحين أوليين أفضل. أخيرًا، نوضح أن MatterGen يجد ثلاث هياكل جديدة (أربعة بشكل عام) على القبة المجمعة لـ V-Sr-O – مثال على نظام ثلاثي تم استكشافه جيدًا – بينما يجد الاستبدال ثلاث (خمسة بشكل عام)، وRSS واحدة فقط (اثنان بشكل عام) (الشكل 3 (هـ)). الهياكل التي اكتشفها MatterGen موضحة في الشكل 3 (و-ي)، وتم تحليلها في المكمل D.6.2.

2.4 التصميم الموجه بالخصائص

مع أفضل قيم الخصائص المتوقعة التي تم توليدها بواسطة MatterGen لكل مهمة، مع تحليل إضافي في المكمل D.8.2.

2.5 تصميم مغناطيسات ذات مخاطر سلسلة إمداد منخفضة

2.6 التحقق التجريبي

3 المناقشة

مثل تثبيت النيتروجين [50] والتقاط الكربون [3]. يمكن توسيع قيود الخصائص لتشمل كميات غير عددية مثل هيكل النطاق أو طيف XRD، مما سيمكن التطبيقات من هندسة النطاق إلى التنبؤ بالهياكل الذرية لطيف XRD المقاس تجريبيًا لعينات غير معروفة.

References

[2] Zhao, Z.-J., Liu, S., Zha, S., Cheng, D., Studt, F., Henkelman, G., Gong, J.: Theory-guided design of catalytic materials using scaling relationships and reactivity descriptors. Nature Reviews Materials 4(12), 792-804 (2019)

[3] Sumida, K., Rogow, D.L., Mason, J.A., McDonald, T.M., Bloch, E.D., Herm, Z.R., Bae, T.-H., Long, J.R.: Carbon dioxide capture in metal-organic frameworks. Chemical reviews 112(2), 724-781 (2012)

[4] Xie, T., Fu, X., Ganea, O.-E., Barzilay, R., Jaakkola, T.S.: Crystal diffusion variational autoencoder for periodic material generation. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2022)

[5] Zhao, Y., Siriwardane, E.M.D., Wu, Z., Fu, N., Al-Fahdi, M., Hu, M., Hu, J.: Physics guided deep learning for generative design of crystal materials with symmetry constraints. npj Computational Materials 9(1), 38 (2023)

[6] Kim, S., Noh, J., Gu, G.H., Aspuru-Guzik, A., Jung, Y.: Generative adversarial networks for crystal structure prediction. ACS central science 6(8), 1412-1420 (2020)

[7] Zheng, S., He, J., Liu, C., Shi, Y., Lu, Z., Feng, W., Ju, F., Wang, J., Zhu, J., Min, Y., et al.: Towards predicting equilibrium distributions for molecular systems with deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05445 (2023)

[8] Yang, M., Cho, K., Merchant, A., Abbeel, P., Schuurmans, D., Mordatch, I., Cubuk, E.D.: Scalable diffusion for materials generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.09235 (2023)

[9] Noh, J., Kim, J., Stein, H.S., Sanchez-Lengeling, B., Gregoire, J.M., AspuruGuzik, A., Jung, Y.: Inverse design of solid-state materials via a continuous representation. Matter 1(5), 1370-1384 (2019)

[10] Antunes, L.M., Butler, K.T., Grau-Crespo, R.: Crystal structure generation with autoregressive large language modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.04340 (2023)

[11] Mila AI4Science, Hernandez-Garcia, A., Duval, A., Volokhova, A., Bengio, Y., Sharma, D., Carrier, P.L., Koziarski, M., Schmidt, V.: Crystal-GFN:

sampling crystals with desirable properties and constraints. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.04925 (2023)

[12] Jiao, R., Huang, W., Lin, P., Han, J., Chen, P., Lu, Y., Liu, Y.: Crystal structure prediction by joint equivariant diffusion. In: Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (2023). https://openreview.net/forum? id=DNdN26m2Jk

[13] Curtarolo, S., Hart, G.L., Nardelli, M.B., Mingo, N., Sanvito, S., Levy, O.: The high-throughput highway to computational materials design. Nature materials 12(3), 191-201 (2013)

[14] Jain, A., Ong, S.P., Hautier, G., Chen, W., Richards, W.D., Dacek, S., Cholia, S., Gunter, D., Skinner, D., Ceder, G., Persson, K.A.: Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL materials 1(1), 011002 (2013)

[15] Curtarolo, S., Setyawan, W., Hart, G.L., Jahnatek, M., Chepulskii, R.V., Taylor, R.H., Wang, S., Xue, J., Yang, K., Levy, O., et al.: AFLOW: An automatic framework for high-throughput materials discovery. Computational Materials Science 58, 218-226 (2012)

[16] Kirklin, S., Saal, J.E., Meredig, B., Thompson, A., Doak, J.W., Aykol, M., Rühl, S., Wolverton, C.: The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD): assessing the accuracy of DFT formation energies. npj Computational Materials 1(1), 1-15 (2015)

[17] Talirz, L., Kumbhar, S., Passaro, E., Yakutovich, A.V., Granata, V., Gargiulo, F., Borelli, M., Uhrin, M., Huber, S.P., Zoupanos, S., et al.: Materials Cloud, a platform for open computational science. Scientific data 7(1), 299 (2020)

[18] Xie, T., Grossman, J.C.: Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Physical review letters 120(14), 145301 (2018)

[19] Chen, C., Ye, W., Zuo, Y., Zheng, C., Ong, S.P.: Graph networks as a universal machine learning framework for molecules and crystals. Chemistry of Materials 31(9), 3564-3572 (2019)

[20] Unke, O.T., Chmiela, S., Sauceda, H.E., Gastegger, M., Poltavsky, I., Schütt, K.T., Tkatchenko, A., Müller, K.-R.: Machine learning force fields. Chemical Reviews 121(16), 10142-10186 (2021)

[21] Chen, C., Ong, S.P.: A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nature Computational Science 2(11), 718-728 (2022)

[22] Zhong, M., Tran, K., Min, Y., Wang, C., Wang, Z., Dinh, C.-T., De Luna,

P., Yu, Z., Rasouli, A.S., Brodersen, P., et al.: Accelerated discovery of CO2 electrocatalysts using active machine learning. Nature 581(7807), 178-183 (2020)

[23] Merchant, A., Batzner, S., Schoenholz, S.S., Aykol, M., Cheon, G., Cubuk, E.D.: Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature (2023)

[24] Shen, J., Griesemer, S.D., Gopakumar, A., Baldassarri, B., Saal, J.E., Aykol, M., Hegde, V.I., Wolverton, C.: Reflections on one million compounds in the open quantum materials database (OQMD). Journal of Physics: Materials 5(3), 031001 (2022)

[25] Schmidt, J., Hoffmann, N., Wang, H.-C., Borlido, P., Carriço, P.J., Cerqueira, T.F., Botti, S., Marques, M.A.: Large-scale machine-learning-assisted exploration of the whole materials space. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.00579 (2022)

[26] Davies, D.W., Butler, K.T., Jackson, A.J., Morris, A., Frost, J.M., Skelton, J.M., Walsh, A.: Computational screening of all stoichiometric inorganic materials. Chem 1(4), 617-627 (2016)

[27] Sanchez-Lengeling, B., Aspuru-Guzik, A.: Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science 361(6400), 360-365 (2018)

[28] Schmidt, J., Marques, M.R., Botti, S., Marques, M.A.: Recent advances and applications of machine learning in solid-state materials science. npj Computational Materials 5(1), 83 (2019)

[29] Allahyari, Z., Oganov, A.R.: Coevolutionary search for optimal materials in the space of all possible compounds. npj Computational Materials 6(1), 55 (2020)

[30] Law, J.N., Pandey, S., Gorai, P., St. John, P.C.: Upper-bound energy minimization to search for stable functional materials with graph neural networks. JACS Au 3(1), 113-123 (2022)

[31] Ren, Z., Tian, S.I.P., Noh, J., Oviedo, F., Xing, G., Li, J., Liang, Q., Zhu, R., Aberle, A.G., Sun, S., et al.: An invertible crystallographic representation for general inverse design of inorganic crystals with targeted properties. Matter 5(1), 314-335 (2022)

[32] Sultanov, A., Crivello, J.-C., Rebafka, T., Sokolovska, N.: Data-driven score-based models for generating stable structures with adaptive crystal cells. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 63(22), 6986-6997 (2023)

[33] Song, Y., Ermon, S.: Generative modeling by estimating gradients of the data distribution. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (2019)

[34] Ho, J., Jain, A., Abbeel, P.: Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances

in Neural Information Processing Systems 33, 6840-6851 (2020)

[35] Song, Y., Sohl-Dickstein, J., Kingma, D.P., Kumar, A., Ermon, S., Poole, B.: Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2021)

[36] Zhang, L., Rao, A., Agrawala, M.: Adding conditional control to text-to-image diffusion models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 3836-3847 (2023)

[37] Ho, J., Salimans, T.: Classifier-free diffusion guidance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.12598 (2022)

[38] Schmidt, J., Wang, H.-C., Cerqueira, T.F., Botti, S., Marques, M.A.: A dataset of 175 k stable and metastable materials calculated with the PBEsol and SCAN functionals. Scientific Data 9(1), 64 (2022)

[39] Zagorac, D., Müller, H., Ruehl, S., Zagorac, J., Rehme, S.: Recent developments in the inorganic crystal structure database: theoretical crystal structure data and related features. Journal of Applied Crystallography 52(5), 918-925 (2019)

[40] Leeman, J., Liu, Y., Stiles, J., Lee, S.B., Bhatt, P., Schoop, L.M., Palgrave, R.G.: Challenges in high-throughput inorganic materials prediction and autonomous synthesis. PRX Energy 3(1), 011002 (2024)

[41] Gebauer, N., Gastegger, M., Schütt, K.: Symmetry-adapted generation of 3D point sets for the targeted discovery of molecules. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (2019)

[42] Oganov, A.R., Pickard, C.J., Zhu, Q., Needs, R.J.: Structure prediction drives materials discovery. Nature Reviews Materials 4(5), 331-348 (2019)

[43] Pickard, C.J., Needs, R.J.: Ab initio random structure searching. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 23(5), 053201 (2011)

[44] Ferreira, P.P., Conway, L.J., Cucciari, A., Di Cataldo, S., Giannessi, F., Kogler, E., Eleno, L.T., Pickard, C.J., Heil, C., Boeri, L.: Search for ambient superconductivity in the Lu-NH system. Nature Communications 14(1), 5367 (2023)

[45] Yang, H., Hu, C., Zhou, Y., Liu, X., Shi, Y., Li, J., Li, G., Chen, Z., Chen, S., Zeni, C., et al.: MatterSim: A deep learning atomistic model across elements, temperatures and pressures. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04967 (2024)

[46] Cui, J., Kramer, M., Zhou, L., Liu, F., Gabay, A., Hadjipanayis, G., Balasubramanian, B., Sellmyer, D.: Current progress and future challenges in rare-earth-free permanent magnets. Acta Materialia 158, 118-137 (2018)

[47] Gaultois, M.W., Sparks, T.D., Borg, C.K., Seshadri, R., Bonificio, W.D., Clarke,

D.R.: Data-driven review of thermoelectric materials: performance and resource considerations. Chemistry of Materials 25(15), 2911-2920 (2013)

[48] Ramesh, A., Dhariwal, P., Nichol, A., Chu, C., Chen, M.: Hierarchical textconditional image generation with CLIP latents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125 1(2), 3 (2022)

[49] Watson, J.L., Juergens, D., Bennett, N.R., Trippe, B.L., Yim, J., Eisenach, H.E., Ahern, W., Borst, A.J., Ragotte, R.J., Milles, L.F., et al.: De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature

[50] Guo, W., Zhang, K., Liang, Z., Zou, R., Xu, Q.: Electrochemical nitrogen fixation and utilization: theories, advanced catalyst materials and system design. Chemical Society Reviews 48(24), 5658-5716 (2019)

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى تيان شيا أو ريوتا توميوكا.

معلومات مراجعة الأقران

(C2/m)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08628-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39821164

Publication Date: 2025-01-16

Accelerated Article Preview

A generative model for inorganic materials design

Accepted: 10 January 2025

Accelerated Article Preview

A generative model for inorganic materials design

Abstract

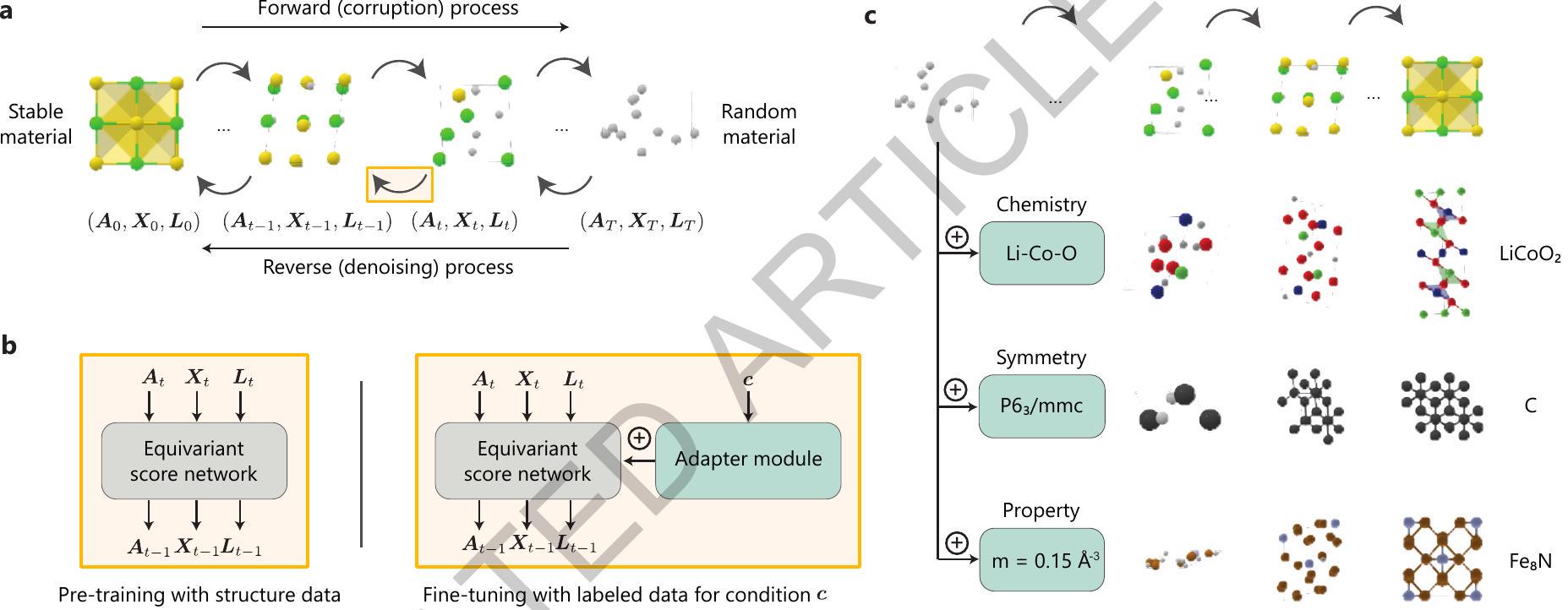

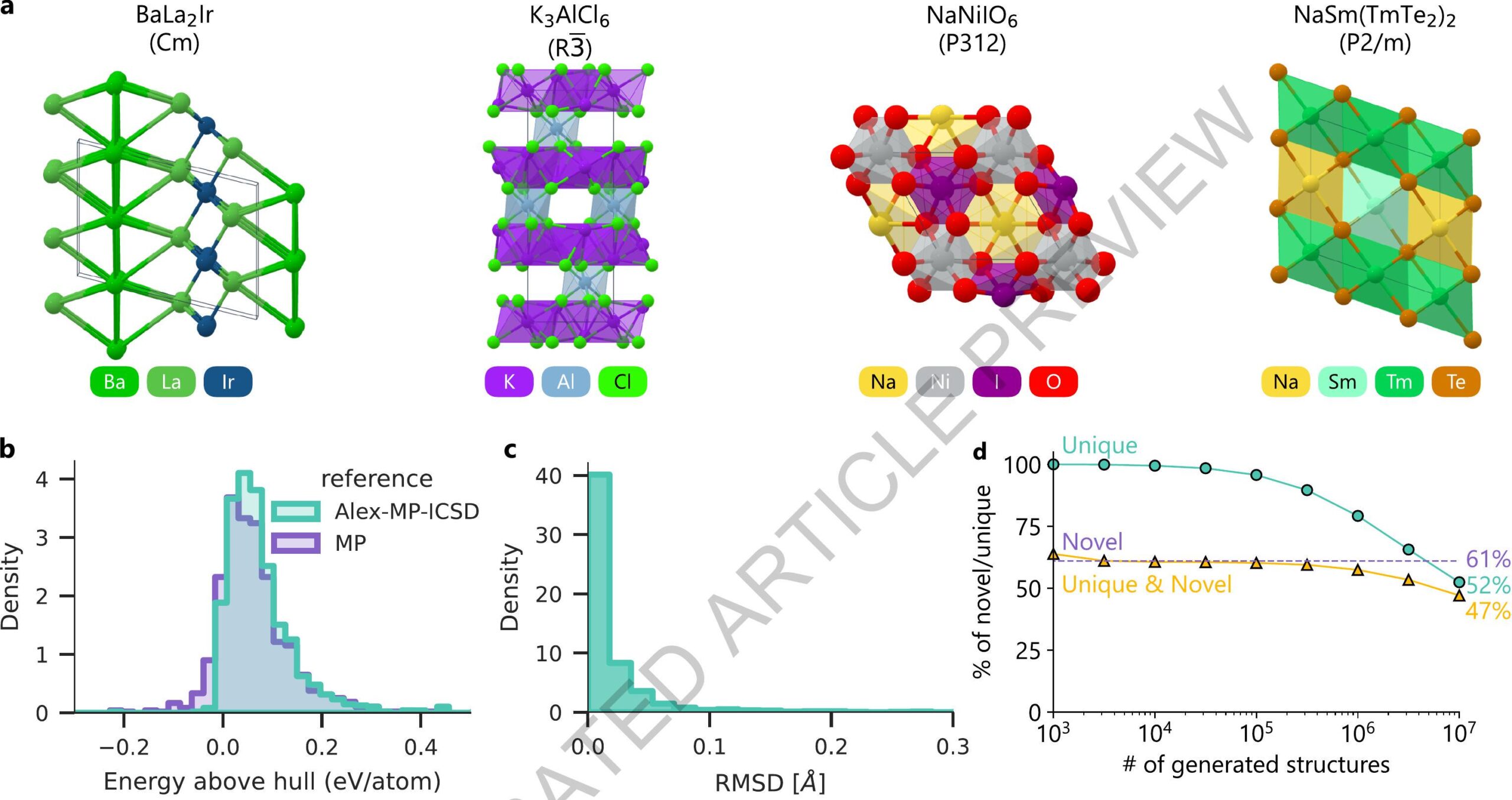

The design of functional materials with desired properties is essential in driving technological advances in areas like energy storage, catalysis, and carbon capture [1-3]. Generative models provide a new paradigm for materials design by directly generating novel materials given desired property constraints, but current methods have low success rate in proposing stable crystals or can only satisfy a limited set of property constraints [4-11]. Here, we present MatterGen, a model that generates stable, diverse inorganic materials across the periodic table and can further be fine-tuned to steer the generation towards a broad range of property constraints. Compared to prior generative models [4, 12], structures produced by

Abstract

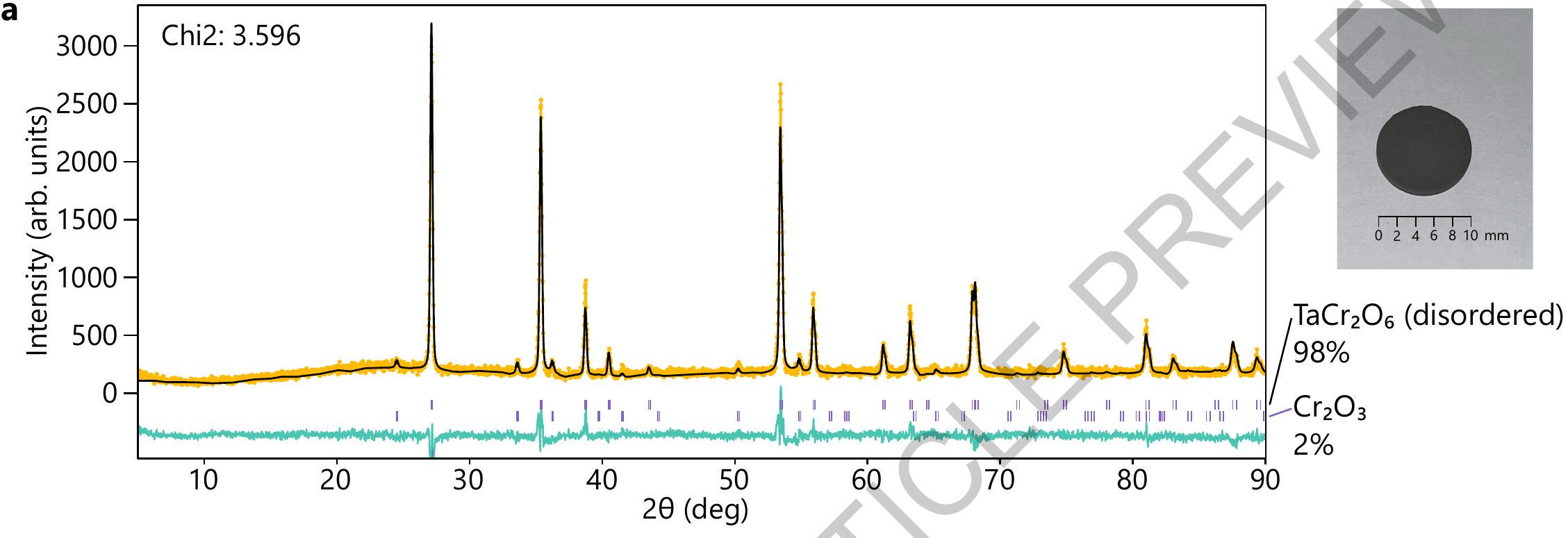

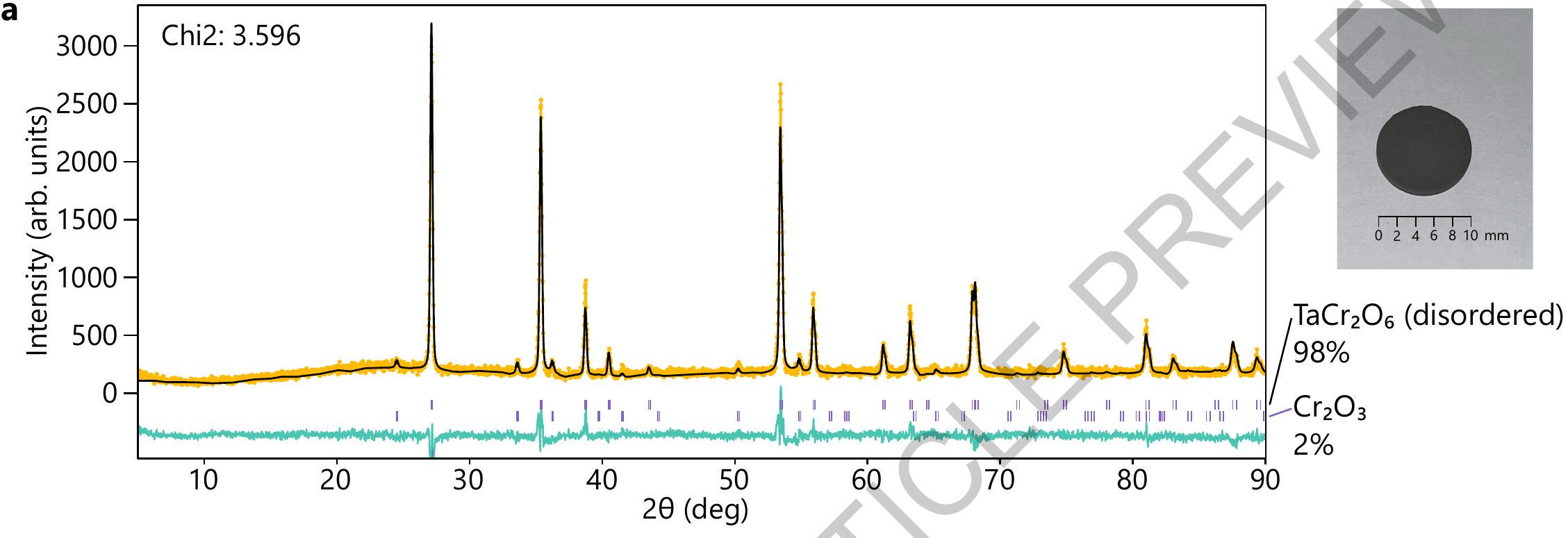

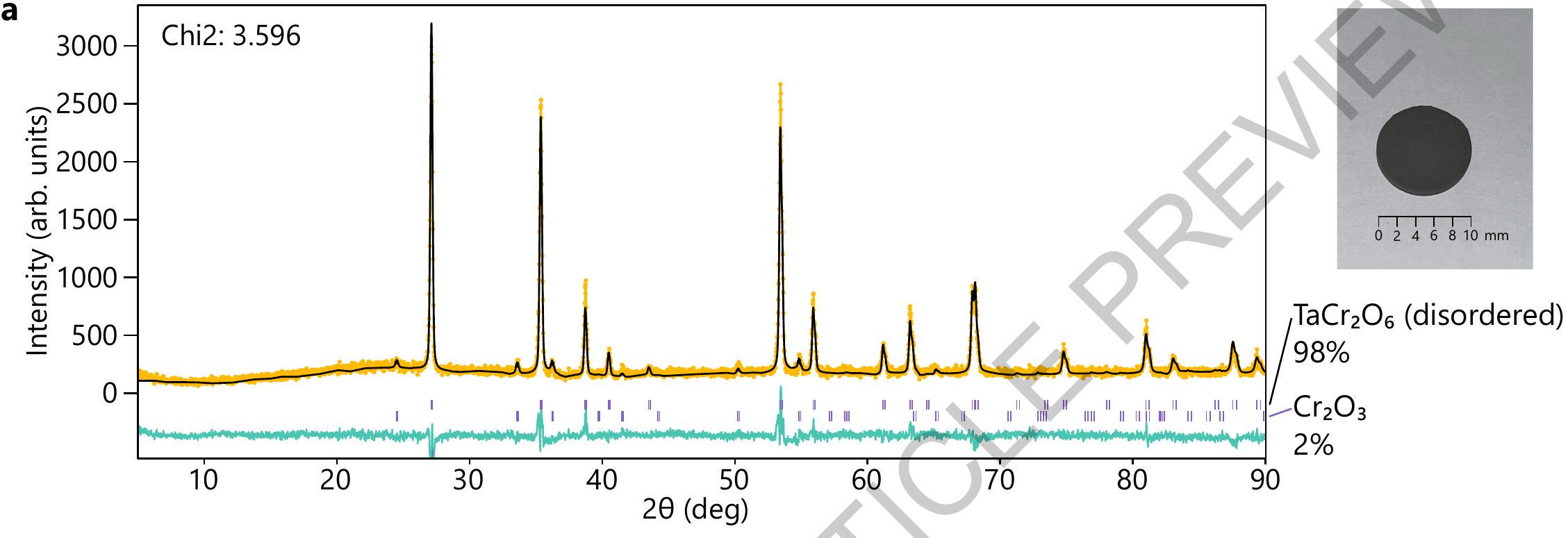

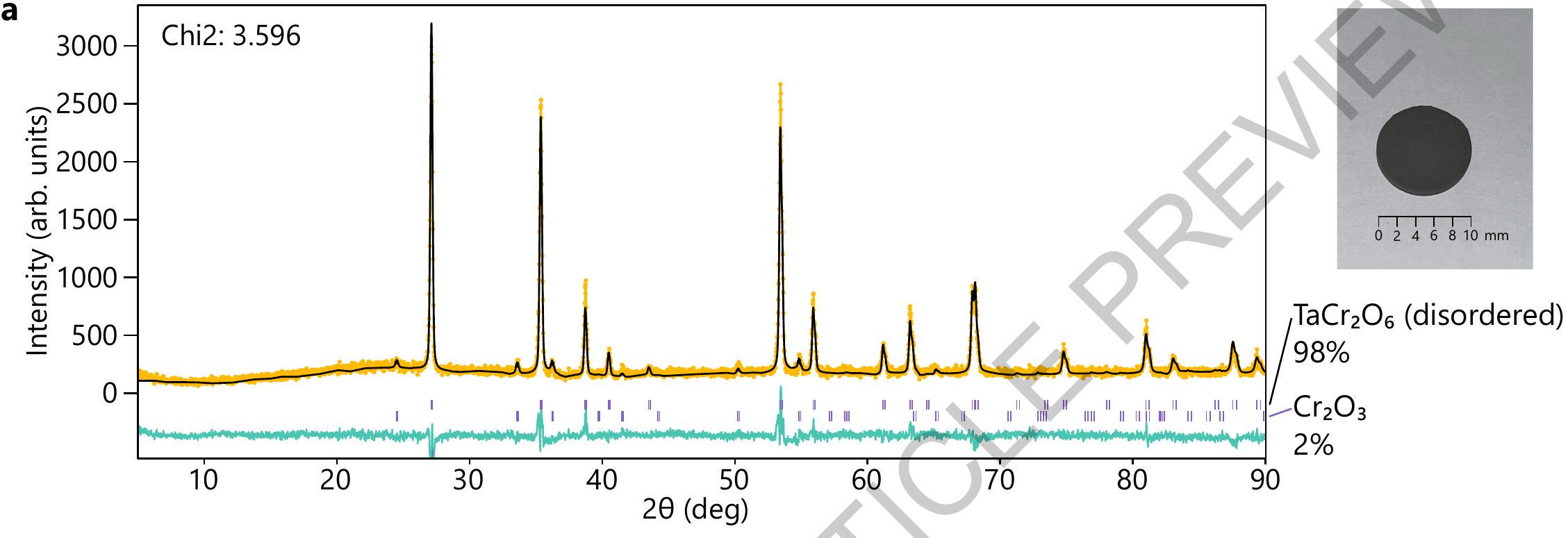

MatterGen are more than twice as likely to be novel and stable, and more than 10 times closer to the local energy minimum. After fine-tuning, MatterGen successfully generates stable, novel materials with desired chemistry, symmetry, as well as mechanical, electronic and magnetic properties. As a proof of concept, we synthesize one of the generated structures and measure its property value to be within

1 Introduction

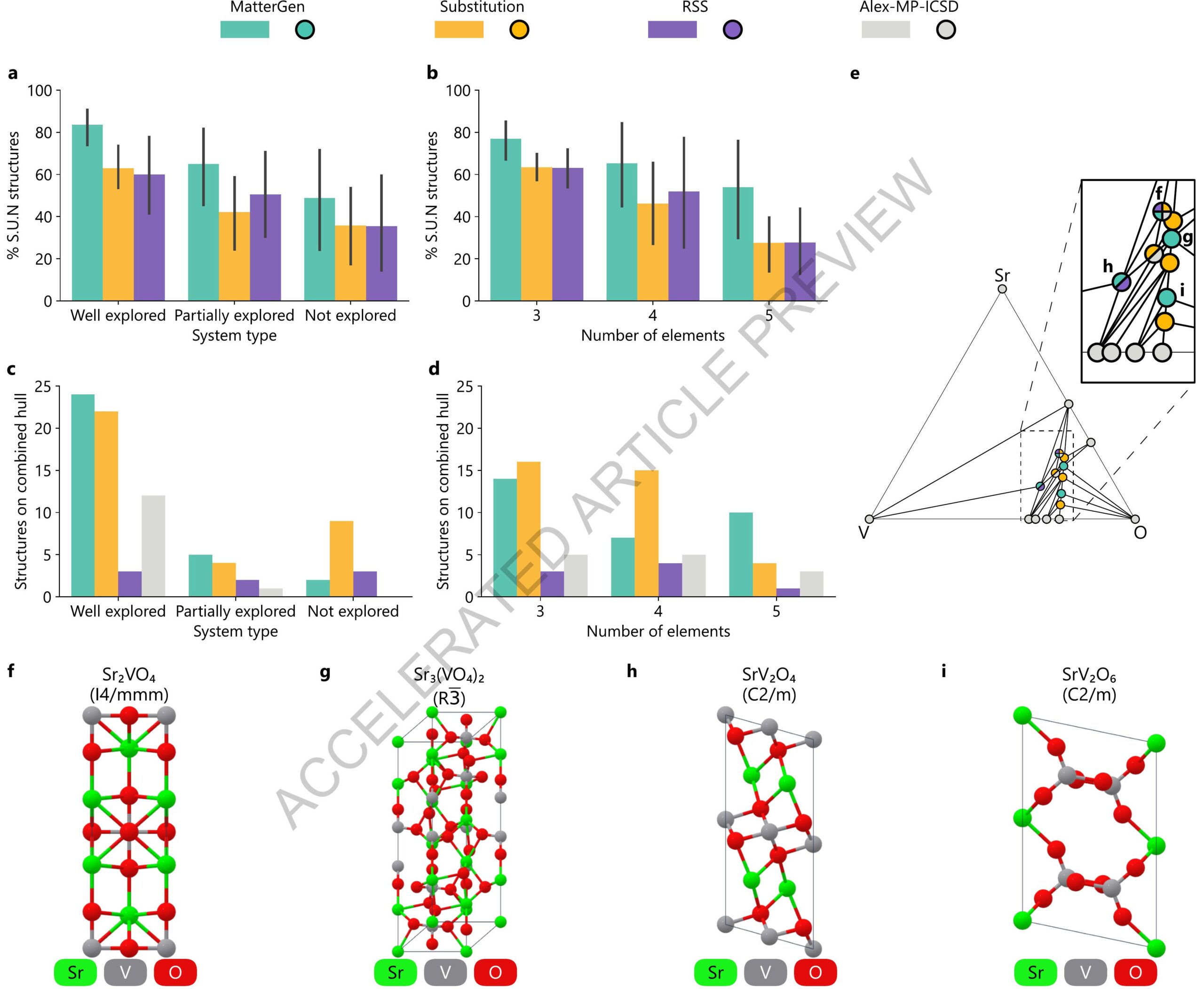

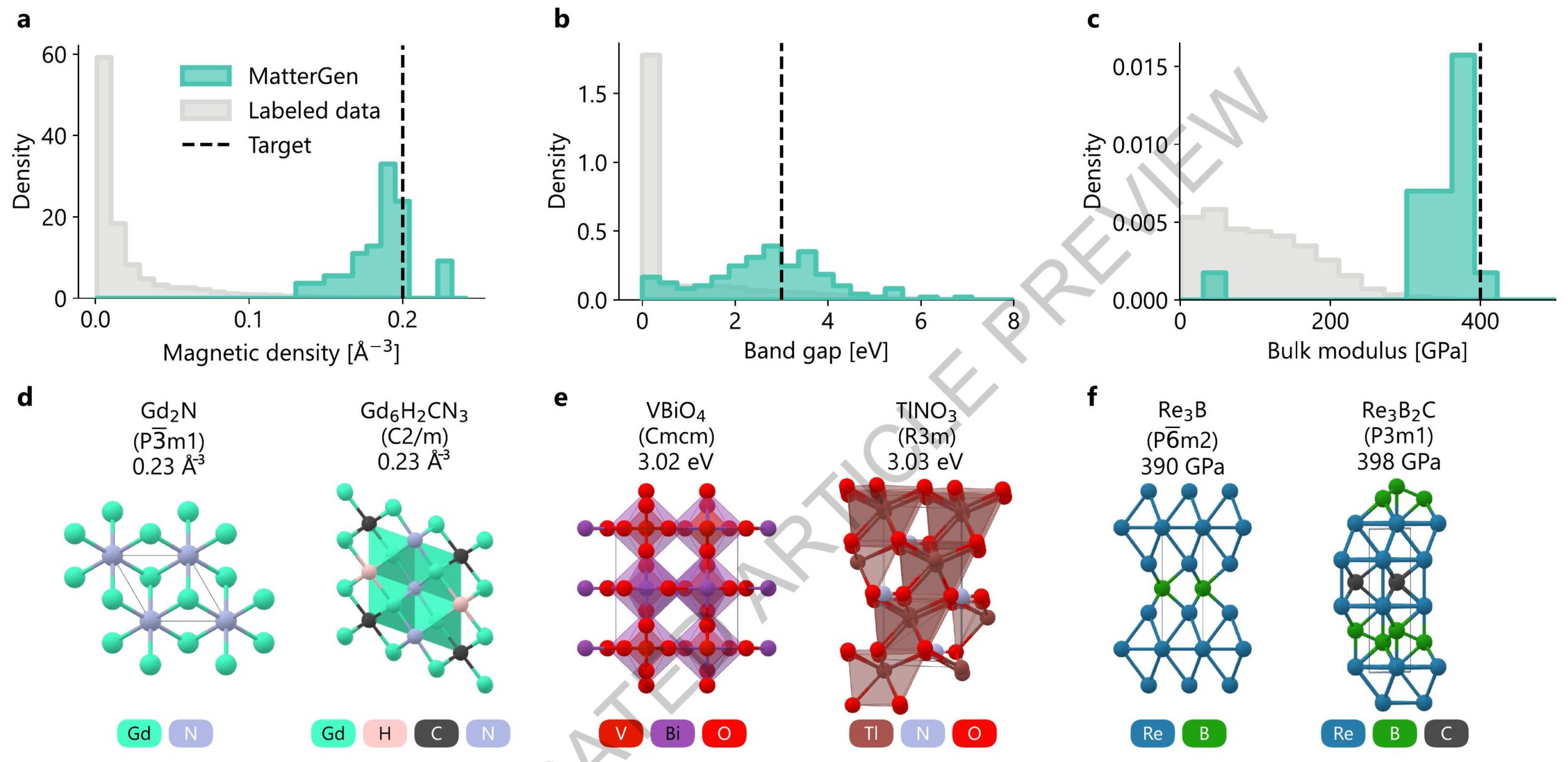

enable inverse materials design for a much wider range of problems than prior generative models. When fine-tuned, MatterGen often generates more S.U.N. materials in target chemical systems than well-established methods like substitution and random structure search (RSS) (Fig. 3), is capable of generating highly symmetric structures given desired space groups (Fig. D8), and directly generates S.U.N. materials that satisfy target mechanical, electronic, and magnetic property constraints (Fig. 4). MatterGen is also able to design materials given multiple property constraints, e.g., high magnetic density and a chemical composition with low supply-chain risk (Fig. 5). As a proof of concept, we validate MatterGen’s design capabilities by synthesizing a generated material and measuring its property to be within

2 Results

2.1 Diffusion process for materials

2.2 Generating stable, diverse materials

in Section 2.6. Results for fine-tuning on symmetry constraints are in Supplementary D.7.

2.3 Chemistry-guided design

be realized with generative models by proposing better initial candidates. Finally, we show that MatterGen finds three novel (four overall) structures on the combined hull for V-Sr-O-an example of a well-explored ternary system-while substitution finds three (five overall), and RSS only one (two overall) (Fig. 3(e)). Structures discovered by MatterGen are shown in Fig. 3(f-i), and are analyzed in Supplementary D.6.2.

2.4 Property-guided design

structures with the best predicted property values generated by MatterGen for each task, with additional analysis in Supplementary D.8.2.

2.5 Designing low-supply-chain-risk magnets

2.6 Experimental validation

3 Discussion

like nitrogen fixation [50] and carbon capture [3]. The property constraints can be extended to non-scalar quantities like the band structure or XRD spectrum, which would enable applications ranging from band engineering to the prediction of atomic structures of experimentally-measured XRD spectra of unknown samples.

References

[2] Zhao, Z.-J., Liu, S., Zha, S., Cheng, D., Studt, F., Henkelman, G., Gong, J.: Theory-guided design of catalytic materials using scaling relationships and reactivity descriptors. Nature Reviews Materials 4(12), 792-804 (2019)

[3] Sumida, K., Rogow, D.L., Mason, J.A., McDonald, T.M., Bloch, E.D., Herm, Z.R., Bae, T.-H., Long, J.R.: Carbon dioxide capture in metal-organic frameworks. Chemical reviews 112(2), 724-781 (2012)

[4] Xie, T., Fu, X., Ganea, O.-E., Barzilay, R., Jaakkola, T.S.: Crystal diffusion variational autoencoder for periodic material generation. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2022)

[5] Zhao, Y., Siriwardane, E.M.D., Wu, Z., Fu, N., Al-Fahdi, M., Hu, M., Hu, J.: Physics guided deep learning for generative design of crystal materials with symmetry constraints. npj Computational Materials 9(1), 38 (2023)

[6] Kim, S., Noh, J., Gu, G.H., Aspuru-Guzik, A., Jung, Y.: Generative adversarial networks for crystal structure prediction. ACS central science 6(8), 1412-1420 (2020)

[7] Zheng, S., He, J., Liu, C., Shi, Y., Lu, Z., Feng, W., Ju, F., Wang, J., Zhu, J., Min, Y., et al.: Towards predicting equilibrium distributions for molecular systems with deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05445 (2023)

[8] Yang, M., Cho, K., Merchant, A., Abbeel, P., Schuurmans, D., Mordatch, I., Cubuk, E.D.: Scalable diffusion for materials generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.09235 (2023)

[9] Noh, J., Kim, J., Stein, H.S., Sanchez-Lengeling, B., Gregoire, J.M., AspuruGuzik, A., Jung, Y.: Inverse design of solid-state materials via a continuous representation. Matter 1(5), 1370-1384 (2019)

[10] Antunes, L.M., Butler, K.T., Grau-Crespo, R.: Crystal structure generation with autoregressive large language modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.04340 (2023)

[11] Mila AI4Science, Hernandez-Garcia, A., Duval, A., Volokhova, A., Bengio, Y., Sharma, D., Carrier, P.L., Koziarski, M., Schmidt, V.: Crystal-GFN:

sampling crystals with desirable properties and constraints. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.04925 (2023)

[12] Jiao, R., Huang, W., Lin, P., Han, J., Chen, P., Lu, Y., Liu, Y.: Crystal structure prediction by joint equivariant diffusion. In: Thirty-seventh Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (2023). https://openreview.net/forum? id=DNdN26m2Jk

[13] Curtarolo, S., Hart, G.L., Nardelli, M.B., Mingo, N., Sanvito, S., Levy, O.: The high-throughput highway to computational materials design. Nature materials 12(3), 191-201 (2013)

[14] Jain, A., Ong, S.P., Hautier, G., Chen, W., Richards, W.D., Dacek, S., Cholia, S., Gunter, D., Skinner, D., Ceder, G., Persson, K.A.: Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL materials 1(1), 011002 (2013)

[15] Curtarolo, S., Setyawan, W., Hart, G.L., Jahnatek, M., Chepulskii, R.V., Taylor, R.H., Wang, S., Xue, J., Yang, K., Levy, O., et al.: AFLOW: An automatic framework for high-throughput materials discovery. Computational Materials Science 58, 218-226 (2012)

[16] Kirklin, S., Saal, J.E., Meredig, B., Thompson, A., Doak, J.W., Aykol, M., Rühl, S., Wolverton, C.: The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD): assessing the accuracy of DFT formation energies. npj Computational Materials 1(1), 1-15 (2015)

[17] Talirz, L., Kumbhar, S., Passaro, E., Yakutovich, A.V., Granata, V., Gargiulo, F., Borelli, M., Uhrin, M., Huber, S.P., Zoupanos, S., et al.: Materials Cloud, a platform for open computational science. Scientific data 7(1), 299 (2020)

[18] Xie, T., Grossman, J.C.: Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Physical review letters 120(14), 145301 (2018)

[19] Chen, C., Ye, W., Zuo, Y., Zheng, C., Ong, S.P.: Graph networks as a universal machine learning framework for molecules and crystals. Chemistry of Materials 31(9), 3564-3572 (2019)

[20] Unke, O.T., Chmiela, S., Sauceda, H.E., Gastegger, M., Poltavsky, I., Schütt, K.T., Tkatchenko, A., Müller, K.-R.: Machine learning force fields. Chemical Reviews 121(16), 10142-10186 (2021)

[21] Chen, C., Ong, S.P.: A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nature Computational Science 2(11), 718-728 (2022)

[22] Zhong, M., Tran, K., Min, Y., Wang, C., Wang, Z., Dinh, C.-T., De Luna,

P., Yu, Z., Rasouli, A.S., Brodersen, P., et al.: Accelerated discovery of CO2 electrocatalysts using active machine learning. Nature 581(7807), 178-183 (2020)

[23] Merchant, A., Batzner, S., Schoenholz, S.S., Aykol, M., Cheon, G., Cubuk, E.D.: Scaling deep learning for materials discovery. Nature (2023)

[24] Shen, J., Griesemer, S.D., Gopakumar, A., Baldassarri, B., Saal, J.E., Aykol, M., Hegde, V.I., Wolverton, C.: Reflections on one million compounds in the open quantum materials database (OQMD). Journal of Physics: Materials 5(3), 031001 (2022)

[25] Schmidt, J., Hoffmann, N., Wang, H.-C., Borlido, P., Carriço, P.J., Cerqueira, T.F., Botti, S., Marques, M.A.: Large-scale machine-learning-assisted exploration of the whole materials space. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.00579 (2022)

[26] Davies, D.W., Butler, K.T., Jackson, A.J., Morris, A., Frost, J.M., Skelton, J.M., Walsh, A.: Computational screening of all stoichiometric inorganic materials. Chem 1(4), 617-627 (2016)

[27] Sanchez-Lengeling, B., Aspuru-Guzik, A.: Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science 361(6400), 360-365 (2018)

[28] Schmidt, J., Marques, M.R., Botti, S., Marques, M.A.: Recent advances and applications of machine learning in solid-state materials science. npj Computational Materials 5(1), 83 (2019)

[29] Allahyari, Z., Oganov, A.R.: Coevolutionary search for optimal materials in the space of all possible compounds. npj Computational Materials 6(1), 55 (2020)

[30] Law, J.N., Pandey, S., Gorai, P., St. John, P.C.: Upper-bound energy minimization to search for stable functional materials with graph neural networks. JACS Au 3(1), 113-123 (2022)

[31] Ren, Z., Tian, S.I.P., Noh, J., Oviedo, F., Xing, G., Li, J., Liang, Q., Zhu, R., Aberle, A.G., Sun, S., et al.: An invertible crystallographic representation for general inverse design of inorganic crystals with targeted properties. Matter 5(1), 314-335 (2022)

[32] Sultanov, A., Crivello, J.-C., Rebafka, T., Sokolovska, N.: Data-driven score-based models for generating stable structures with adaptive crystal cells. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 63(22), 6986-6997 (2023)

[33] Song, Y., Ermon, S.: Generative modeling by estimating gradients of the data distribution. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (2019)

[34] Ho, J., Jain, A., Abbeel, P.: Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances

in Neural Information Processing Systems 33, 6840-6851 (2020)

[35] Song, Y., Sohl-Dickstein, J., Kingma, D.P., Kumar, A., Ermon, S., Poole, B.: Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations. In: International Conference on Learning Representations (2021)

[36] Zhang, L., Rao, A., Agrawala, M.: Adding conditional control to text-to-image diffusion models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 3836-3847 (2023)

[37] Ho, J., Salimans, T.: Classifier-free diffusion guidance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.12598 (2022)

[38] Schmidt, J., Wang, H.-C., Cerqueira, T.F., Botti, S., Marques, M.A.: A dataset of 175 k stable and metastable materials calculated with the PBEsol and SCAN functionals. Scientific Data 9(1), 64 (2022)

[39] Zagorac, D., Müller, H., Ruehl, S., Zagorac, J., Rehme, S.: Recent developments in the inorganic crystal structure database: theoretical crystal structure data and related features. Journal of Applied Crystallography 52(5), 918-925 (2019)

[40] Leeman, J., Liu, Y., Stiles, J., Lee, S.B., Bhatt, P., Schoop, L.M., Palgrave, R.G.: Challenges in high-throughput inorganic materials prediction and autonomous synthesis. PRX Energy 3(1), 011002 (2024)

[41] Gebauer, N., Gastegger, M., Schütt, K.: Symmetry-adapted generation of 3D point sets for the targeted discovery of molecules. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (2019)

[42] Oganov, A.R., Pickard, C.J., Zhu, Q., Needs, R.J.: Structure prediction drives materials discovery. Nature Reviews Materials 4(5), 331-348 (2019)

[43] Pickard, C.J., Needs, R.J.: Ab initio random structure searching. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 23(5), 053201 (2011)

[44] Ferreira, P.P., Conway, L.J., Cucciari, A., Di Cataldo, S., Giannessi, F., Kogler, E., Eleno, L.T., Pickard, C.J., Heil, C., Boeri, L.: Search for ambient superconductivity in the Lu-NH system. Nature Communications 14(1), 5367 (2023)

[45] Yang, H., Hu, C., Zhou, Y., Liu, X., Shi, Y., Li, J., Li, G., Chen, Z., Chen, S., Zeni, C., et al.: MatterSim: A deep learning atomistic model across elements, temperatures and pressures. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04967 (2024)

[46] Cui, J., Kramer, M., Zhou, L., Liu, F., Gabay, A., Hadjipanayis, G., Balasubramanian, B., Sellmyer, D.: Current progress and future challenges in rare-earth-free permanent magnets. Acta Materialia 158, 118-137 (2018)

[47] Gaultois, M.W., Sparks, T.D., Borg, C.K., Seshadri, R., Bonificio, W.D., Clarke,

D.R.: Data-driven review of thermoelectric materials: performance and resource considerations. Chemistry of Materials 25(15), 2911-2920 (2013)

[48] Ramesh, A., Dhariwal, P., Nichol, A., Chu, C., Chen, M.: Hierarchical textconditional image generation with CLIP latents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125 1(2), 3 (2022)

[49] Watson, J.L., Juergens, D., Bennett, N.R., Trippe, B.L., Yim, J., Eisenach, H.E., Ahern, W., Borst, A.J., Ragotte, R.J., Milles, L.F., et al.: De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature

[50] Guo, W., Zhang, K., Liang, Z., Zou, R., Xu, Q.: Electrochemical nitrogen fixation and utilization: theories, advanced catalyst materials and system design. Chemical Society Reviews 48(24), 5658-5716 (2019)

Data availability

Code availability

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Tian Xie or Ryota Tomioka.

Peer review information

(C2/m)