DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00467-0

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-16

هل لديك اعتماد على الذكاء الاصطناعي؟ أدوار الكفاءة الذاتية الأكاديمية، والضغط الأكاديمي، وتوقعات الأداء في سلوك استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي الإشكالي

جانغ هيون كيم

alohakim@skku.edu

الملخص

على الرغم من أن الدراسات السابقة قد سلطت الضوء على سلوكيات استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) الإشكالية في السياقات التعليمية، مثل الاعتماد المفرط على الذكاء الاصطناعي، لم تستكشف أي دراسة العوامل المسببة والعواقب المحتملة التي تسهم في هذه المشكلة. لذلك، تبحث هذه الدراسة في أسباب ونتائج الاعتماد على الذكاء الاصطناعي باستخدام ChatGPT كمثال. باستخدام نموذج تفاعل الشخص-العاطفة-الإدراك-التنفيذ (I-PACE)، تستكشف هذه الدراسة الروابط الداخلية بين الكفاءة الذاتية الأكاديمية، والضغط الأكاديمي، وتوقعات الأداء، والاعتماد على الذكاء الاصطناعي. كما تحدد العواقب السلبية للاعتماد على الذكاء الاصطناعي. أظهرت تحليل البيانات من 300 طالب جامعي أن العلاقة بين الكفاءة الذاتية الأكاديمية والاعتماد على الذكاء الاصطناعي كانت متوسطة بواسطة الضغط الأكاديمي وتوقعات الأداء. تشمل أعلى خمسة آثار سلبية للاعتماد على الذكاء الاصطناعي زيادة الكسل، انتشار المعلومات المضللة، انخفاض مستوى الإبداع، وتقليل التفكير النقدي والمستقل. توفر النتائج تفسيرات وحلول للتخفيف من الآثار السلبية للاعتماد على الذكاء الاصطناعي.

المقدمة

مراجعة الأدبيات

نموذج I-PACE

الكفاءة الذاتية الأكاديمية والاعتماد على الذكاء الاصطناعي

الدور الوسيط للضغط الأكاديمي

الكفاءة الذاتية تؤدي إلى زيادة في الضغط الأكاديمي (نيلسن وآخرون، 2018؛ فانتجيهم وفان هوت، 2015).

الدور الوسيط لتوقعات الأداء

الأدوار الوسيطة المتسلسلة للضغط الأكاديمي وتوقعات الأداء

الآثار السلبية للاستخدام المتكرر لتكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي

المواد والطرق

المشاركون

| تردد | نسبة مئوية | ||

| جنس | ذكر | 150 | 50٪ |

| أنثى | 150 | 50٪ | |

| عمر | <= 18 | ٣٩ | 13% |

| 19-29 | 255 | 85٪ | |

| >= 30 | ٦ | 2% | |

| مستوى التعليم | طالب جامعي | ٢٦٩ | 90٪ |

| خريج | 31 | 10٪ | |

| تكرار الاستخدام | تقريبًا يوميًا | 30 | 10٪ |

| عدة مرات في الأسبوع | ١٣٤ | ٤٥٪ | |

| عدة مرات في الشهر | ١٣٦ | ٤٥٪ | |

| غرض الاستخدام | البحث عن مساعدة أكاديمية (مثل: دروس خصوصية في الواجبات المنزلية، فهم المفاهيم، إرشادات البحث) | ٢٥١ | 83% |

| دعم الكتابة (مثل الترجمة، التدقيق اللغوي، إلخ) | 148 | ٤٩٪ | |

| استكشاف وتعلم معلومات جديدة أو مواضيع تهمك | 121 | 40٪ | |

| إرضاء الفضول أو استكشاف قدرات ChatGPT | 97 | 32% | |

| البحث عن المساعدة في أمور الحياة | 73 | ٢٤٪ | |

| تمضية الوقت أو للترفيه | 64 | 21% | |

| البحث عن الدعم العاطفي أو النصيحة | 27 | 9% | |

| أخرى (يرجى التحديد) | 2 | 1% | |

القياسات

الكفاءة الذاتية الأكاديمية (ألفا كرونباخ

الضغط الأكاديمي (كرونباخ

توقعات الأداء (كرونباخ)

اعتماد (كرونباخ)

عواقب الاعتماد على الذكاء الاصطناعي

تحليل البيانات

| ASF | مساعدة | كما | التربية البدنية | |

| ASF | 1 | |||

| مساعدة | -0.116* | 1 | ||

| كما | -0.217** | 0.242** | 1 | |

| التربية البدنية | -0.081 | 0.575** | 0.164** | 1 |

| معنى | 3.796 | ٢.٨٠٦ | ٣.٥٦٨ | ٣.٧٨٢ |

| SD | 0.862 | 0.788 | 0.587 | 0.732 |

| المتغير التابع | المتغير المستقل | ب | SE | ت | فترة الثقة 95% | |

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| كما | ASF | -0.217 | 0.039 | -3.834*** | -0.224 | -0.072 |

| التربية البدنية | ASF | -0.048 | 0.050 | -0.820 | -0.139 | 0.057 |

| كما | 0.154 | 0.073 | 2.627** | 0.048 | 0.335 | |

| مساعدة | ASF | -0.040 | 0.044 | -0.841 | -0.123 | 0.049 |

| كما | 0.143 | 0.065 | 2.954** | 0.064 | 0.320 | |

| التربية البدنية | 0.548 | 0.051 | 11.568*** | 0.490 | 0.691 | |

| أثر | SE | ت | LLCI | ULCI | |

| التأثير الكلي لـ ASF على AID | -0.106 | 0.053 | -2.014* | -0.209 | -0.002 |

| التأثير المباشر للـ ASF على AID | -0.037 | 0.044 | -0.841 | -0.123 | 0.049 |

| التأثيرات غير المباشرة لفيروس ASF على المساعدات الإنسانية | |||||

| التأثير غير المباشر الإجمالي لـ ASF على AID | -0.069 | 0.035 | -0.142 | -0.005 | |

| التأثير غير المباشر 1: ASF

|

-0.028 | 0.015 | -0.062 | -0.006 | |

| التأثير غير المباشر 2: ASF

|

-0.024 | 0.032 | -0.088 | 0.034 | |

| التأثير غير المباشر 3: ASF

|

-0.017 | 0.009 | -0.037 | -0.002 | |

النتائج

تحليل البيانات الوصفية والارتباطية

تحليل الوساطة

لم يتم العثور على علاقة ذات دلالة إحصائية بين الكفاءة الذاتية الأكاديمية والاعتماد على الذكاء الاصطناعي.

| عاقبة | تردد |

| زيادة الكسل | 113 |

| إبداع مقيد | ١١٢ |

| زيادة المعلومات غير الصحيحة | 67 |

| تفكير نقدي مقيد | ٥٦ |

| تفكير مستقل مقيد | ٤٧ |

| قدرة محدودة على البحث عن المعلومات | 17 |

| زيادة معدل الانتحال | ١٣ |

| زيادة انتهاك حقوق الطبع والنشر | 12 |

| قدرة محدودة على حل المشكلات | 14 |

| معلومات مقيدة – القدرة على الحكم | ٦ |

تحليل سحابة الكلمات

حرج (

نقاش

تحليل إضافي

القدرة على التوجيه الذاتي انتهاك حقوق الطبع والنشر التفكير المستقل الإبداع الانتحال القدرة على البحث عن المعلومات

قدرة الحكم على المعلومات قدرة الاستكشاف

المساهمات النظرية والعملية

القيود والدراسات المستقبلية

الاستنتاجات

الشكر

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

تاريخ الاستلام: 15 يناير 2024 / تاريخ القبول: 19 أبريل 2024

References

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501-517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517.

Aronson, E., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1962). Performance expectancy as a determinant of actual performance. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 65(3), 178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0042291.

Babadi-Akashe, Z., Zamani, B. E., Abedini, Y., Akbari, H., & Hedayati, N. (2014). The relationship between mental health and addiction to mobile phones among university students of Shahrekord, Iran. Addiction & Health, 6(3-4), 93. https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4354213/.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs NJ, 1986, 23-28. https://goo.su/iEzU.

Bedewy, D., & Gabriel, A. (2015). Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: The perception of academic stress scale. Health Psychology Open, 2(2), 2055102915596714. https://doi. org/10.1177/2055102915596714.

Beranuy, M., Oberst, U., Carbonell, X., & Chamarro, A. (2009). Problematic internet and mobile phone use and clinical symptoms in college students: The role of emotional intelligence. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(5), 1182-1187. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.03.001.

Bergdahl, J., & Bergdahl, M. (2002). Perceived stress in adults: Prevalence and association of depression, anxiety and medication in a Swedish population. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 18(5), 235-241. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.946.

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: An Interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. neubiorev.2016.08.033.

Chuah, S. H. W., Rauschnabel, P. A., Krey, N., Nguyen, B., Ramayah, T., & Lade, S. (2016). Wearable technologies: The role of usefulness and visibility in smartwatch adoption. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 276-284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. chb.2016.07.047.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87. https://doi. org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. Mis Quarterly, 319-340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008.

Davis, R. A. (2001). A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 17(2), 187-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8.

De Wit, H. (2009). Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: A review of underlying processes. Addiction Biology, 14(1), 22-31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Jeyaraj, A., Clement, M., & Williams, M. D. (2019). Re-examining the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): Towards a revised theoretical model. Information Systems Frontiers, 21, 719-734. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10796-017-9774-y.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., Baabdullah, A. M., Koohang, A., Raghavan, V., & Ahuja, M. (2023). So what if ChatGPT wrote it? Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinfomgt.2023.102642.

Elhai, J. D., Tiamiyu, M., & Weeks, J. (2018). Depression and social anxiety in relation to problematic smartphone use: The prominent role of rumination. Internet Research, 28(2), 315-332. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-01-2017-0019.

Elkaseh, A. M., Wong, K. W., & Fung, C. C. (2016). Perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness of social media for e-learning in Libyan higher education: A structural equation modeling analysis. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 6(3), 192. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJIET.2016.V6.683.

Fitria, T. N. (2023). Artificial intelligence (AI) technology in OpenAI ChatGPT application: A review of ChatGPT in writing English essay. ELT Forum: Journal of English Language Teaching, 12(1), 44-58. https://doi.org/10.15294/elt.v12i1.64069.

Han, S., Kim, K. J., & Kim, J. H. (2017). Understanding nomophobia: Structural equation modeling and semantic network analysis of smartphone separation anxiety. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 20(7), 419-427. https://doi. org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0113.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. In: University of Kansas, KS. http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

Hitches, E., Woodcock, S., & Ehrich, J. (2022). Building self-efficacy without letting stress knock it down: Stress and academic self-efficacy of university students. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 100124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijedro.2022.100124.

Honicke, T., & Broadbent, J. (2016). The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 17, 63-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.11.002.

Hu, B., Mao, Y., & Kim, K. J. (2023). How social anxiety leads to problematic use of conversational AI: The roles of loneliness, rumination, and mind perception. Computers in Human Behavior, 145, 107760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107760.

Jackson, A., Mentzer, N., & Kramer-Bottiglio, R. (2019). Pilot analysis of the impacts of soft robotics design on high-school student engineering perceptions. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 29(5), 1083-1104. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10798-018-9478-8.

Jarvis, J. A., Corbett, A. W., Thorpe, J. D., & Dufur, M. J. (2020). Too much of a good thing: Social capital and academic stress in South Korea. Social Sciences, 9(11), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9110187.

Jun, S., & Choi, E. (2015). Academic stress and internet addiction from general strain theory framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 282-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.001.

Kasneci, E., Seßler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., & Hüllermeier, E. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274.

Khan, M. (2013). Academic self-efficacy, coping, and academic performance in college. International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities, 5(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.7710/2168-0620.1006.

King, M. R., & ChatGPT. (2023). A conversation on artificial intelligence, chatbots, and plagiarism in higher education. Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering, 16(1), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12195-022-00754-8.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company. https://goo.su/8sRkSa.

Lee-Won, R. J., Herzog, L., & Park, S. G. (2015). Hooked on Facebook: The role of social anxiety and need for social assurance in problematic use of Facebook. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 18(10), 567-574. https://doi.org/10.1089/ cyber.2015.0002.

Li, L., Gao, H., & Xu, Y. (2020). The mediating and buffering effect of academic self-efficacy on the relationship between smartphone addiction and academic procrastination. Computers & Education, 159, 104001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2020.104001.

Li, Y., Li, G. X., Yu, M. L., Liu, C. L., Qu, Y. T., & Wu, H. (2021). Association between anxiety symptoms and problematic smartphone use among Chinese university students: The mediating/moderating role of self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 581367. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.581367.

Liebrenz, M., Schleifer, R., Buadze, A., Bhugra, D., & Smith, A. (2023). Generating scholarly content with ChatGPT: Ethical challenges for medical publishing. The Lancet Digital Health, 5(3), e105-e106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(23)00019-5.

Lin, C. W., Lin, Y. S., Liao, C. C., & Chen, C. C. (2021). Utilizing technology acceptance model for influences of smartphone addiction on behavioural intention. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2021, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5592187.

Lund, B. D., & Wang, T. (2023). Chatting about ChatGPT: How may AI and GPT impact academia and libraries? Library Hi Tech News, 40(3), 26-29. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-01-2023-0009.

Manoharan, S., Speidel, U., Ward, A. E., & Ye, X. (2023, June). Contract Cheating-Dead or Reborn? In 2023 32nd Annual Conference of the European Association for Education in Electrical and Information Engineering (EAEEIE) (pp. 1-5). IEEE. https://doi. org/10.23919/EAEEIE55804.2023.10182073.

Meng, J., & Dai, Y. (2021). Emotional support from Al chatbots: Should a supportive partner self-disclose or not? Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 26(4), 207-222. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmab005.

Metzger, I. W., Blevins, C., Calhoun, C. D., Ritchwood, T. D., Gilmore, A. K., Stewart, R., & Bountress, K. E. (2017). An examination of the impact of maladaptive coping on the association between stressor type and alcohol use in college. Journal of American College Health, 65(8), 534-541. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2017.1351445.

Mhlanga, D. (2023). Open AI in education, the responsible and ethical use of ChatGPT towards lifelong learning. Education, the Responsible and Ethical Use of ChatGPT Towards Lifelong Learning (February 11, 2023). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4354422.

Mun, I. B. (2023). Academic stress and first-/third-person shooter game addiction in a large adolescent sample: A serial mediation model with depression and impulsivity. Computers in Human Behavior, 145, 107767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. chb.2023.107767.

Nan, D., Lee, H., Kim, Y., & Kim, J. H. (2022). My video game console is so cool! A coolness theory-based model for intention to use video game consoles. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 176, 121451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. techfore.2021.121451.

Nayak, J. K. (2018). Relationship among smartphone usage, addiction, academic performance and the moderating role of gender: A study of higher education students in India. Computers & Education, 123, 164-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2018.05.007.

Ng, D. T. K., Leung, J. K. L., Chu, S. K. W., & Qiao, M. S. (2021). Conceptualizing AI literacy: An exploratory review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100041. 2.

Nielsen, T., Dammeyer, J., Vang, M. L., & Makransky, G. (2018). Gender fairness in self-efficacy? A rasch-based validity study of the General Academic self-efficacy scale (GASE). Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(5), 664-681. https://doi.org/1 0.1080/00313831.2017.1306796.

Noreen, A. (2013). Relationship between internet addiction and academic performance among university undergraduates. Educational Research and Reviews, 8(19), 1793-1796. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2013.1539.

Odaci, H. (2011). Academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination as predictors of problematic internet use in university students. Computers & Education, 57(1), 1109-1113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.01.005.

Odacı, H. (2013). Risk-taking behavior and academic self-efficacy as variables accounting for problematic internet use in adolescent university students. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(1), 183-187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. childyouth.2012.09.011.

Pajares, F. (2002). Gender and perceived self-efficacy in self-regulated learning. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 116-125. https://doi. org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_8.

Parmaksız, İ. (2022). The mediating role of personality traits on the relationship between academic self-efficacy and digital addiction. Education and Information Technologies, 27(6), 8883-8902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10996-8.

Paul, J., Ueno, A., & Dennis, C. (2023). ChatGPT and consumers: Benefits, pitfalls and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(4), 1213-1225. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs. 12928.

Pitafi, A. H., Kanwal, S., & Khan, A. N. (2020). Effects of perceived ease of use on SNSs-addiction through psychological dependence, habit: The moderating role of perceived usefulness. International Journal of Business Information Systems, 33(3), 383-407. https://doi.org/10.1504/JBIS.2020.105831.

Quintans-Júnior, L. J., Gurgel, R. Q., Araújo, A. A. D. S., Correia, D., & Martins-Filho, P. R. (2023). ChatGPT: The new panacea of the academic world. Revista Da Sociedade Brasileira De Medicina Tropical, 56, e0060-2023. https://doi. org/10.1590/0037-8682-0060-2023.

Rahman, M. M., & Watanobe, Y. (2023). ChatGPT for education and research: Opportunities, threats, and strategies. Applied Sciences, 13(9), 5783. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13095783.

Rani, P. S., Rani, K. R., Daram, S. B., & Angadi, R. V. (2023). Is it feasible to reduce academic stress in Net-Zero Energy buildings? Reaction from ChatGPT. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-023-03286-y.

Ray, P. P. (2023). ChatGPT: A comprehensive review on background, applications, key challenges, bias, ethics, limitations and future scope. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iotcps.2023.04.003.

Reddy, K. J., Menon, K. R., & Thattil, A. (2018). Academic stress and its sources among university students. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal, 11(1), 531-537. https://doi.org/10.13005/bpj/1404.

Rothen, S., Briefer, J. F., Deleuze, J., Karila, L., Andreassen, C. S., Achab, S., Thorens, G., Khazaal, Y., Zullino, D., & Billieux, J. (2018). Disentangling the role of users’ preferences and impulsivity traits in problematic Facebook use. PloS One, 13(9), e0201971. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201971.

Salah, M., Alhalbusi, H., Abdelfattah, F., & Ismail, M. M. (2023). Chatting with ChatGPT: Investigating the impact on Psychological Well-being and self-esteem with a focus on harmful stereotypes and job Anxiety as Moderator. https://doi.org/10.21203/ rs.3.rs-2610655/v2.

Shen, Y., Heacock, L., Elias, J., Hentel, K. D., Reig, B., Shih, G., & Moy, L. (2023). ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology, 307(2), e230163. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.230163.

Sriwilai, K., & Charoensukmongkol, P. (2016). Face it, don’t Facebook it: Impacts of social media addiction on mindfulness, coping strategies and the consequence on emotional exhaustion. Stress and Health, 32(4), 427-434. https://doi.org/10.1002/ smi. 2637.

Struthers, C. W., Perry, R. P., & Menec, V. H. (2000). An examination of the relationship among academic stress, coping, motivation, and performance in college. Research in Higher Education, 41, 581-592. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007094931292.

Sujarwoto, Saputri, R. A. M., & Yumarni, T. (2023). Social media addiction and mental health among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(1), 96-110. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11469-021-00582-3.

Vantieghem, W., & Van Houtte, M. (2015). Are girls more resilient to gender-conformity pressure? The association between gender-conformity pressure and academic self-efficacy. Sex Roles, 73, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0509-6.

Wilks, S. E. (2008). Resilience amid academic stress: The moderating impact of social support among social work students. Advances in Social Work, 9(2), 106-125. https://doi.org/10.18060/51.

You, J. W. (2018). Testing the three-way interaction effect of academic stress, academic self-efficacy, and task value on persistence in learning among Korean college students. Higher Education, 76(5), 921-935. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10734-018-0255-0.

Zeljko, B. (2022). Internet addiction disorder (IAD) as a consequence of the expansion of Information technologies. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science Engineering and Education, 10(3), 155-165. https://doi. org/10.23947/2334-8496-2022-10-3-155-165.

Zhang, S., Che, S., Nan, D., & Kim, J. H. (2023a). How does online social interaction promote students’ continuous learning intentions? Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1098110.

Zhang, S., Shan, C., Lee, J. S. Y., Che, S., & Kim, J. H. (2023b). Effect of chatbot-assisted language learning: A meta-analysis. Education and Information Technologies, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11805-6.

Zhu, Y. Q., Chen, L. Y., Chen, H. G., & Chern, C. C. (2011). How does internet information seeking help academic performance? The moderating and mediating roles of academic self-efficacy. Computers & Education, 57(4), 2476-2484. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.07.006.

Zhu, Z., Qin, S., Yang, L., Dodd, A., & Conti, M. (2023). Emotion regulation tool design principles for arts and design university students. Procedia CIRP, 119, 115-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2023.03.085.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- © The Author(s) 2024. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-024-00467-0

Publication Date: 2024-05-16

Do you have AI dependency? The roles of academic self-efficacy, academic stress, and performance expectations on problematic Al usage behavior

Jang Hyun Kim

alohakim@skku.edu

Abstract

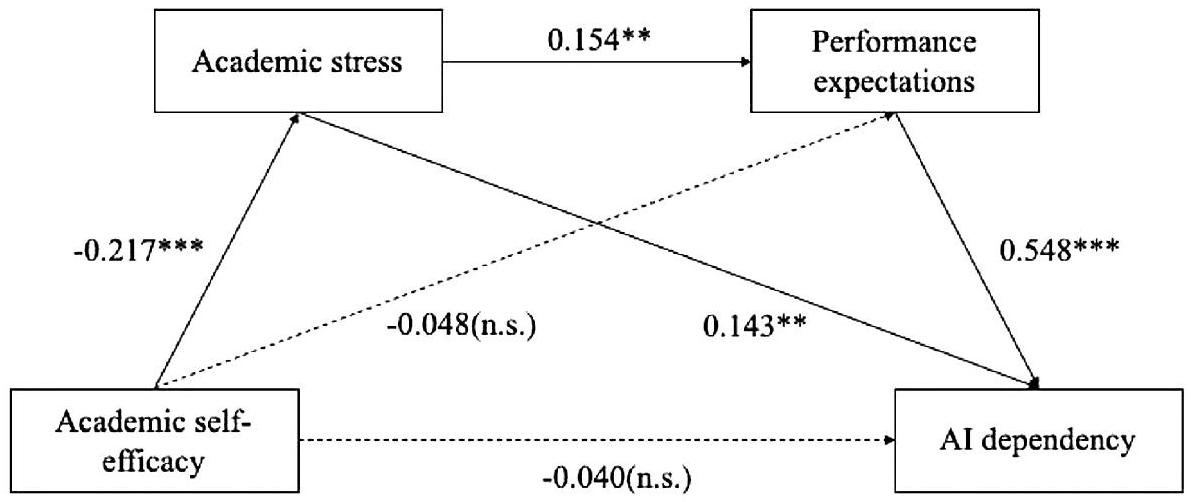

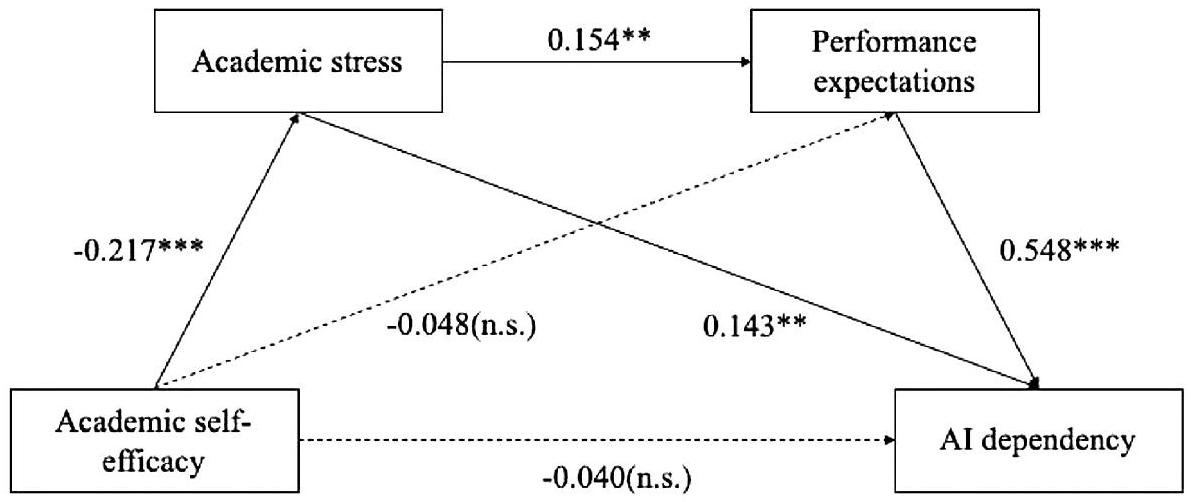

Although previous studies have highlighted the problematic artificial intelligence (AI) usage behaviors in educational contexts, such as overreliance on AI, no study has explored the antecedents and potential consequences that contribute to this problem. Therefore, this study investigates the causes and consequences of AI dependency using ChatGPT as an example. Using the Interaction of the Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model, this study explores the internal associations between academic self-efficacy, academic stress, performance expectations, and AI dependency. It also identifies the negative consequences of AI dependency. Analysis of data from 300 university students revealed that the relationship between academic self-efficacy and AI dependency was mediated by academic stress and performance expectations. The top five negative effects of Al dependency include increased laziness, the spread of misinformation, a lower level of creativity, and reduced critical and independent thinking. The findings provide explanations and solutions to mitigate the negative effects of AI dependency.

Introduction

Literature review

IPACE model

Academic self-efficacy and AI dependency

Mediating role of academic stress

self-efficacy leads to an increase in academic stress (Nielsen et al., 2018; Vantieghem & Van Houtte, 2015).

Mediating role of performance expectations

Serial mediating roles of academic stress and performance expectations

Negative effects of frequent use of AI technology

Materials and methods

Participants

| Frequency | Percent | ||

| Gender | Male | 150 | 50% |

| Female | 150 | 50% | |

| Age | <= 18 | 39 | 13% |

| 19-29 | 255 | 85% | |

| >= 30 | 6 | 2% | |

| Education level | Undergraduate | 269 | 90% |

| Graduate | 31 | 10% | |

| Usage frequency | Almost daily | 30 | 10% |

| Several times a week | 134 | 45% | |

| Several times a month | 136 | 45% | |

| Usage purpose | Seeking academic assistance (e.g., homework tutoring, concept understanding, research guidance) | 251 | 83% |

| Writing support (e.g., translation, proofreading, etc.) | 148 | 49% | |

| Exploring and learning about new information or topics of interest | 121 | 40% | |

| Satisfying curiosity or exploring ChatGPT’s capabilities | 97 | 32% | |

| Seeking help with life matters | 73 | 24% | |

| Passing time or for entertainment | 64 | 21% | |

| Seeking emotional support or advice | 27 | 9% | |

| Other (please specify) | 2 | 1% | |

Measurements

Academic self-efficacy (Cronbach’s

Academic stress (Cronbach’s

Performance expectations (Cronbach’s

Al dependency (Cronbach’s

Consequences of AI dependency

Data analysis

| ASF | AID | AS | PE | |

| ASF | 1 | |||

| AID | -0.116* | 1 | ||

| AS | -0.217** | 0.242** | 1 | |

| PE | -0.081 | 0.575** | 0.164** | 1 |

| Mean | 3.796 | 2.806 | 3.568 | 3.782 |

| SD | 0.862 | 0.788 | 0.587 | 0.732 |

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | b | SE | t | 95% CI | |

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| AS | ASF | -0.217 | 0.039 | -3.834*** | -0.224 | -0.072 |

| PE | ASF | -0.048 | 0.050 | -0.820 | -0.139 | 0.057 |

| AS | 0.154 | 0.073 | 2.627** | 0.048 | 0.335 | |

| AID | ASF | -0.040 | 0.044 | -0.841 | -0.123 | 0.049 |

| AS | 0.143 | 0.065 | 2.954** | 0.064 | 0.320 | |

| PE | 0.548 | 0.051 | 11.568*** | 0.490 | 0.691 | |

| EFFECT | SE | T | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Total effect of ASF on AID | -0.106 | 0.053 | -2.014* | -0.209 | -0.002 |

| Direct effect of ASF on AID | -0.037 | 0.044 | -0.841 | -0.123 | 0.049 |

| Indirect effects of ASF on AID | |||||

| Total indirect effect of ASF on AID | -0.069 | 0.035 | -0.142 | -0.005 | |

| Indirect effect 1: ASF

|

-0.028 | 0.015 | -0.062 | -0.006 | |

| Indirect effect 2: ASF

|

-0.024 | 0.032 | -0.088 | 0.034 | |

| Indirect effect 3: ASF

|

-0.017 | 0.009 | -0.037 | -0.002 | |

Results

Analysis of descriptive and correlative data

Mediation analysis

No statistically significant relationship was found between academic self-efficacy and AI dependency (

| Consequence | Frequency |

| Increased laziness | 113 |

| Restricted creativity | 112 |

| Increased incorrect information | 67 |

| Restricted critical thinking | 56 |

| Restricted independent thinking | 47 |

| Restricted information-seeking ability | 17 |

| Increased plagiarism rate | 13 |

| Increased copyright infringement | 12 |

| Restricted problem-solving ability | 14 |

| Restricted information-judgment ability | 6 |

Word Cloud analysis

critical (

Discussion

Further analysis

self -directed ability copyright infringement independent thinking creativity plagiarism information seeking ability

information judgment ability exploration ability

Theoretical and practical contributions

Limitations and future studies

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Competing interests

Received: 15 January 2024 / Accepted: 19 April 2024

References

Andreassen, C. S., Torsheim, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501-517. https://doi.org/10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517.

Aronson, E., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1962). Performance expectancy as a determinant of actual performance. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 65(3), 178. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0042291.

Babadi-Akashe, Z., Zamani, B. E., Abedini, Y., Akbari, H., & Hedayati, N. (2014). The relationship between mental health and addiction to mobile phones among university students of Shahrekord, Iran. Addiction & Health, 6(3-4), 93. https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4354213/.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs NJ, 1986, 23-28. https://goo.su/iEzU.

Bedewy, D., & Gabriel, A. (2015). Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: The perception of academic stress scale. Health Psychology Open, 2(2), 2055102915596714. https://doi. org/10.1177/2055102915596714.

Beranuy, M., Oberst, U., Carbonell, X., & Chamarro, A. (2009). Problematic internet and mobile phone use and clinical symptoms in college students: The role of emotional intelligence. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(5), 1182-1187. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.03.001.

Bergdahl, J., & Bergdahl, M. (2002). Perceived stress in adults: Prevalence and association of depression, anxiety and medication in a Swedish population. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 18(5), 235-241. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.946.

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: An Interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252-266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. neubiorev.2016.08.033.

Chuah, S. H. W., Rauschnabel, P. A., Krey, N., Nguyen, B., Ramayah, T., & Lade, S. (2016). Wearable technologies: The role of usefulness and visibility in smartwatch adoption. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 276-284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. chb.2016.07.047.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87. https://doi. org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. Mis Quarterly, 319-340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008.

Davis, R. A. (2001). A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 17(2), 187-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8.

De Wit, H. (2009). Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: A review of underlying processes. Addiction Biology, 14(1), 22-31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Rana, N. P., Jeyaraj, A., Clement, M., & Williams, M. D. (2019). Re-examining the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): Towards a revised theoretical model. Information Systems Frontiers, 21, 719-734. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10796-017-9774-y.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., Baabdullah, A. M., Koohang, A., Raghavan, V., & Ahuja, M. (2023). So what if ChatGPT wrote it? Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management, 71, 102642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinfomgt.2023.102642.

Elhai, J. D., Tiamiyu, M., & Weeks, J. (2018). Depression and social anxiety in relation to problematic smartphone use: The prominent role of rumination. Internet Research, 28(2), 315-332. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-01-2017-0019.

Elkaseh, A. M., Wong, K. W., & Fung, C. C. (2016). Perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness of social media for e-learning in Libyan higher education: A structural equation modeling analysis. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 6(3), 192. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJIET.2016.V6.683.

Fitria, T. N. (2023). Artificial intelligence (AI) technology in OpenAI ChatGPT application: A review of ChatGPT in writing English essay. ELT Forum: Journal of English Language Teaching, 12(1), 44-58. https://doi.org/10.15294/elt.v12i1.64069.

Han, S., Kim, K. J., & Kim, J. H. (2017). Understanding nomophobia: Structural equation modeling and semantic network analysis of smartphone separation anxiety. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 20(7), 419-427. https://doi. org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0113.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. In: University of Kansas, KS. http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

Hitches, E., Woodcock, S., & Ehrich, J. (2022). Building self-efficacy without letting stress knock it down: Stress and academic self-efficacy of university students. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 100124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijedro.2022.100124.

Honicke, T., & Broadbent, J. (2016). The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 17, 63-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.11.002.

Hu, B., Mao, Y., & Kim, K. J. (2023). How social anxiety leads to problematic use of conversational AI: The roles of loneliness, rumination, and mind perception. Computers in Human Behavior, 145, 107760. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107760.

Jackson, A., Mentzer, N., & Kramer-Bottiglio, R. (2019). Pilot analysis of the impacts of soft robotics design on high-school student engineering perceptions. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 29(5), 1083-1104. https://doi. org/10.1007/s10798-018-9478-8.

Jarvis, J. A., Corbett, A. W., Thorpe, J. D., & Dufur, M. J. (2020). Too much of a good thing: Social capital and academic stress in South Korea. Social Sciences, 9(11), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9110187.

Jun, S., & Choi, E. (2015). Academic stress and internet addiction from general strain theory framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 282-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.001.

Kasneci, E., Seßler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., & Hüllermeier, E. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2023.102274.

Khan, M. (2013). Academic self-efficacy, coping, and academic performance in college. International Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities, 5(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.7710/2168-0620.1006.

King, M. R., & ChatGPT. (2023). A conversation on artificial intelligence, chatbots, and plagiarism in higher education. Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering, 16(1), 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12195-022-00754-8.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company. https://goo.su/8sRkSa.

Lee-Won, R. J., Herzog, L., & Park, S. G. (2015). Hooked on Facebook: The role of social anxiety and need for social assurance in problematic use of Facebook. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 18(10), 567-574. https://doi.org/10.1089/ cyber.2015.0002.

Li, L., Gao, H., & Xu, Y. (2020). The mediating and buffering effect of academic self-efficacy on the relationship between smartphone addiction and academic procrastination. Computers & Education, 159, 104001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2020.104001.

Li, Y., Li, G. X., Yu, M. L., Liu, C. L., Qu, Y. T., & Wu, H. (2021). Association between anxiety symptoms and problematic smartphone use among Chinese university students: The mediating/moderating role of self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 581367. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.581367.

Liebrenz, M., Schleifer, R., Buadze, A., Bhugra, D., & Smith, A. (2023). Generating scholarly content with ChatGPT: Ethical challenges for medical publishing. The Lancet Digital Health, 5(3), e105-e106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(23)00019-5.

Lin, C. W., Lin, Y. S., Liao, C. C., & Chen, C. C. (2021). Utilizing technology acceptance model for influences of smartphone addiction on behavioural intention. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2021, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5592187.

Lund, B. D., & Wang, T. (2023). Chatting about ChatGPT: How may AI and GPT impact academia and libraries? Library Hi Tech News, 40(3), 26-29. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHTN-01-2023-0009.

Manoharan, S., Speidel, U., Ward, A. E., & Ye, X. (2023, June). Contract Cheating-Dead or Reborn? In 2023 32nd Annual Conference of the European Association for Education in Electrical and Information Engineering (EAEEIE) (pp. 1-5). IEEE. https://doi. org/10.23919/EAEEIE55804.2023.10182073.

Meng, J., & Dai, Y. (2021). Emotional support from Al chatbots: Should a supportive partner self-disclose or not? Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 26(4), 207-222. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmab005.

Metzger, I. W., Blevins, C., Calhoun, C. D., Ritchwood, T. D., Gilmore, A. K., Stewart, R., & Bountress, K. E. (2017). An examination of the impact of maladaptive coping on the association between stressor type and alcohol use in college. Journal of American College Health, 65(8), 534-541. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2017.1351445.

Mhlanga, D. (2023). Open AI in education, the responsible and ethical use of ChatGPT towards lifelong learning. Education, the Responsible and Ethical Use of ChatGPT Towards Lifelong Learning (February 11, 2023). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn. 4354422.

Mun, I. B. (2023). Academic stress and first-/third-person shooter game addiction in a large adolescent sample: A serial mediation model with depression and impulsivity. Computers in Human Behavior, 145, 107767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. chb.2023.107767.

Nan, D., Lee, H., Kim, Y., & Kim, J. H. (2022). My video game console is so cool! A coolness theory-based model for intention to use video game consoles. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 176, 121451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. techfore.2021.121451.

Nayak, J. K. (2018). Relationship among smartphone usage, addiction, academic performance and the moderating role of gender: A study of higher education students in India. Computers & Education, 123, 164-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. compedu.2018.05.007.

Ng, D. T. K., Leung, J. K. L., Chu, S. K. W., & Qiao, M. S. (2021). Conceptualizing AI literacy: An exploratory review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100041. 2.

Nielsen, T., Dammeyer, J., Vang, M. L., & Makransky, G. (2018). Gender fairness in self-efficacy? A rasch-based validity study of the General Academic self-efficacy scale (GASE). Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(5), 664-681. https://doi.org/1 0.1080/00313831.2017.1306796.

Noreen, A. (2013). Relationship between internet addiction and academic performance among university undergraduates. Educational Research and Reviews, 8(19), 1793-1796. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2013.1539.

Odaci, H. (2011). Academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination as predictors of problematic internet use in university students. Computers & Education, 57(1), 1109-1113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.01.005.

Odacı, H. (2013). Risk-taking behavior and academic self-efficacy as variables accounting for problematic internet use in adolescent university students. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(1), 183-187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. childyouth.2012.09.011.

Pajares, F. (2002). Gender and perceived self-efficacy in self-regulated learning. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 116-125. https://doi. org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_8.

Parmaksız, İ. (2022). The mediating role of personality traits on the relationship between academic self-efficacy and digital addiction. Education and Information Technologies, 27(6), 8883-8902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10996-8.

Paul, J., Ueno, A., & Dennis, C. (2023). ChatGPT and consumers: Benefits, pitfalls and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(4), 1213-1225. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs. 12928.

Pitafi, A. H., Kanwal, S., & Khan, A. N. (2020). Effects of perceived ease of use on SNSs-addiction through psychological dependence, habit: The moderating role of perceived usefulness. International Journal of Business Information Systems, 33(3), 383-407. https://doi.org/10.1504/JBIS.2020.105831.

Quintans-Júnior, L. J., Gurgel, R. Q., Araújo, A. A. D. S., Correia, D., & Martins-Filho, P. R. (2023). ChatGPT: The new panacea of the academic world. Revista Da Sociedade Brasileira De Medicina Tropical, 56, e0060-2023. https://doi. org/10.1590/0037-8682-0060-2023.

Rahman, M. M., & Watanobe, Y. (2023). ChatGPT for education and research: Opportunities, threats, and strategies. Applied Sciences, 13(9), 5783. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13095783.

Rani, P. S., Rani, K. R., Daram, S. B., & Angadi, R. V. (2023). Is it feasible to reduce academic stress in Net-Zero Energy buildings? Reaction from ChatGPT. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-023-03286-y.

Ray, P. P. (2023). ChatGPT: A comprehensive review on background, applications, key challenges, bias, ethics, limitations and future scope. Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iotcps.2023.04.003.

Reddy, K. J., Menon, K. R., & Thattil, A. (2018). Academic stress and its sources among university students. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal, 11(1), 531-537. https://doi.org/10.13005/bpj/1404.

Rothen, S., Briefer, J. F., Deleuze, J., Karila, L., Andreassen, C. S., Achab, S., Thorens, G., Khazaal, Y., Zullino, D., & Billieux, J. (2018). Disentangling the role of users’ preferences and impulsivity traits in problematic Facebook use. PloS One, 13(9), e0201971. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201971.

Salah, M., Alhalbusi, H., Abdelfattah, F., & Ismail, M. M. (2023). Chatting with ChatGPT: Investigating the impact on Psychological Well-being and self-esteem with a focus on harmful stereotypes and job Anxiety as Moderator. https://doi.org/10.21203/ rs.3.rs-2610655/v2.

Shen, Y., Heacock, L., Elias, J., Hentel, K. D., Reig, B., Shih, G., & Moy, L. (2023). ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology, 307(2), e230163. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.230163.

Sriwilai, K., & Charoensukmongkol, P. (2016). Face it, don’t Facebook it: Impacts of social media addiction on mindfulness, coping strategies and the consequence on emotional exhaustion. Stress and Health, 32(4), 427-434. https://doi.org/10.1002/ smi. 2637.

Struthers, C. W., Perry, R. P., & Menec, V. H. (2000). An examination of the relationship among academic stress, coping, motivation, and performance in college. Research in Higher Education, 41, 581-592. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007094931292.

Sujarwoto, Saputri, R. A. M., & Yumarni, T. (2023). Social media addiction and mental health among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(1), 96-110. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11469-021-00582-3.

Vantieghem, W., & Van Houtte, M. (2015). Are girls more resilient to gender-conformity pressure? The association between gender-conformity pressure and academic self-efficacy. Sex Roles, 73, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0509-6.

Wilks, S. E. (2008). Resilience amid academic stress: The moderating impact of social support among social work students. Advances in Social Work, 9(2), 106-125. https://doi.org/10.18060/51.

You, J. W. (2018). Testing the three-way interaction effect of academic stress, academic self-efficacy, and task value on persistence in learning among Korean college students. Higher Education, 76(5), 921-935. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10734-018-0255-0.

Zeljko, B. (2022). Internet addiction disorder (IAD) as a consequence of the expansion of Information technologies. International Journal of Cognitive Research in Science Engineering and Education, 10(3), 155-165. https://doi. org/10.23947/2334-8496-2022-10-3-155-165.

Zhang, S., Che, S., Nan, D., & Kim, J. H. (2023a). How does online social interaction promote students’ continuous learning intentions? Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1098110.

Zhang, S., Shan, C., Lee, J. S. Y., Che, S., & Kim, J. H. (2023b). Effect of chatbot-assisted language learning: A meta-analysis. Education and Information Technologies, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11805-6.

Zhu, Y. Q., Chen, L. Y., Chen, H. G., & Chern, C. C. (2011). How does internet information seeking help academic performance? The moderating and mediating roles of academic self-efficacy. Computers & Education, 57(4), 2476-2484. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.07.006.

Zhu, Z., Qin, S., Yang, L., Dodd, A., & Conti, M. (2023). Emotion regulation tool design principles for arts and design university students. Procedia CIRP, 119, 115-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2023.03.085.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- © The Author(s) 2024. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.