DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-024-09743-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39822851

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-14

هل هو بخيل في الأيض أم مسرف؟ رؤى حول جلد الكسلان الأرضي وعلم وظائف الحرارة الذي كشفت عنه النمذجة الفيزيائية الحيوية وقياسات درجة الحرارة القديمة باستخدام نظائر الكتلة.

© المؤلفون 2024، نشر مصحح 2025

الملخص

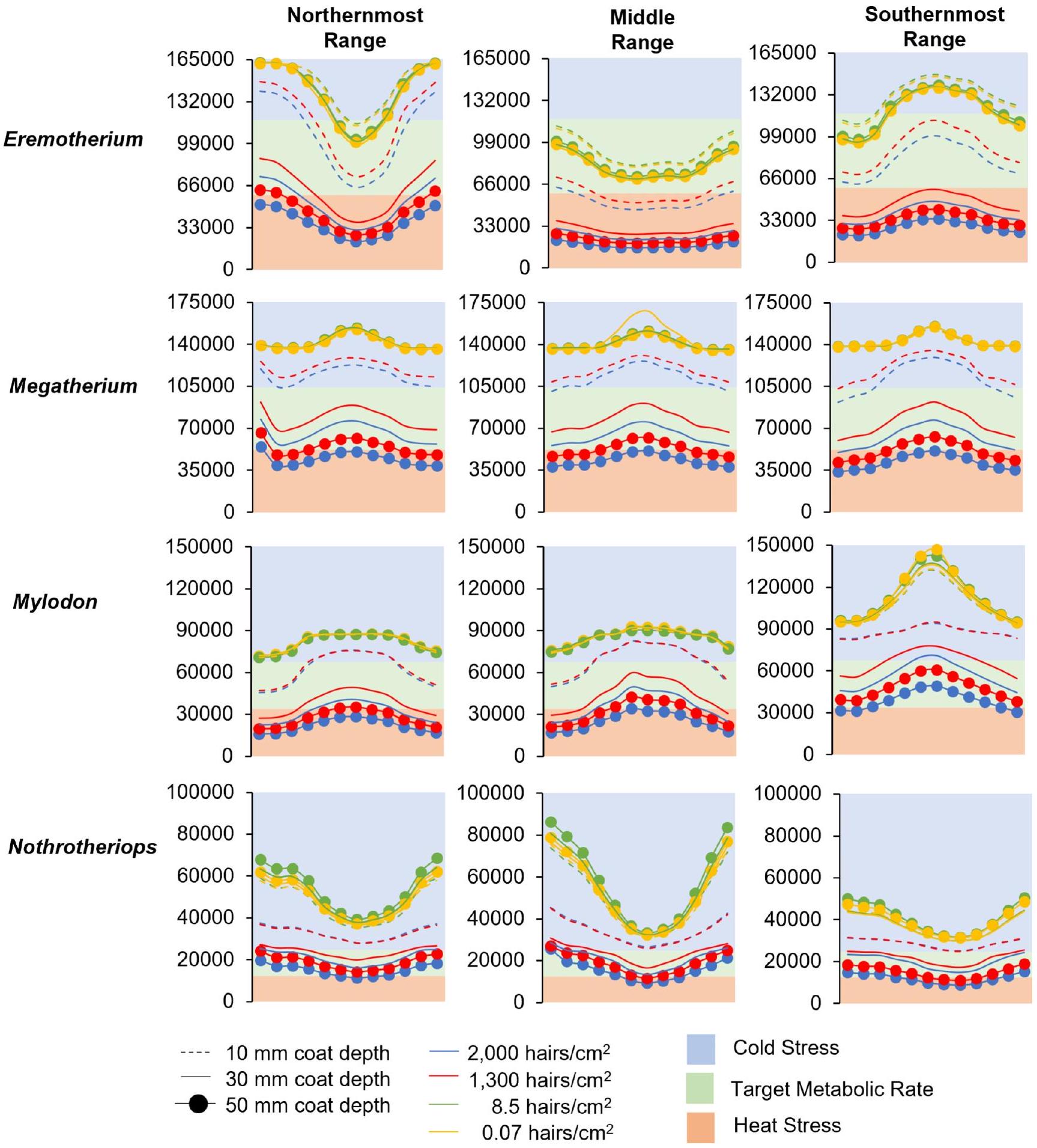

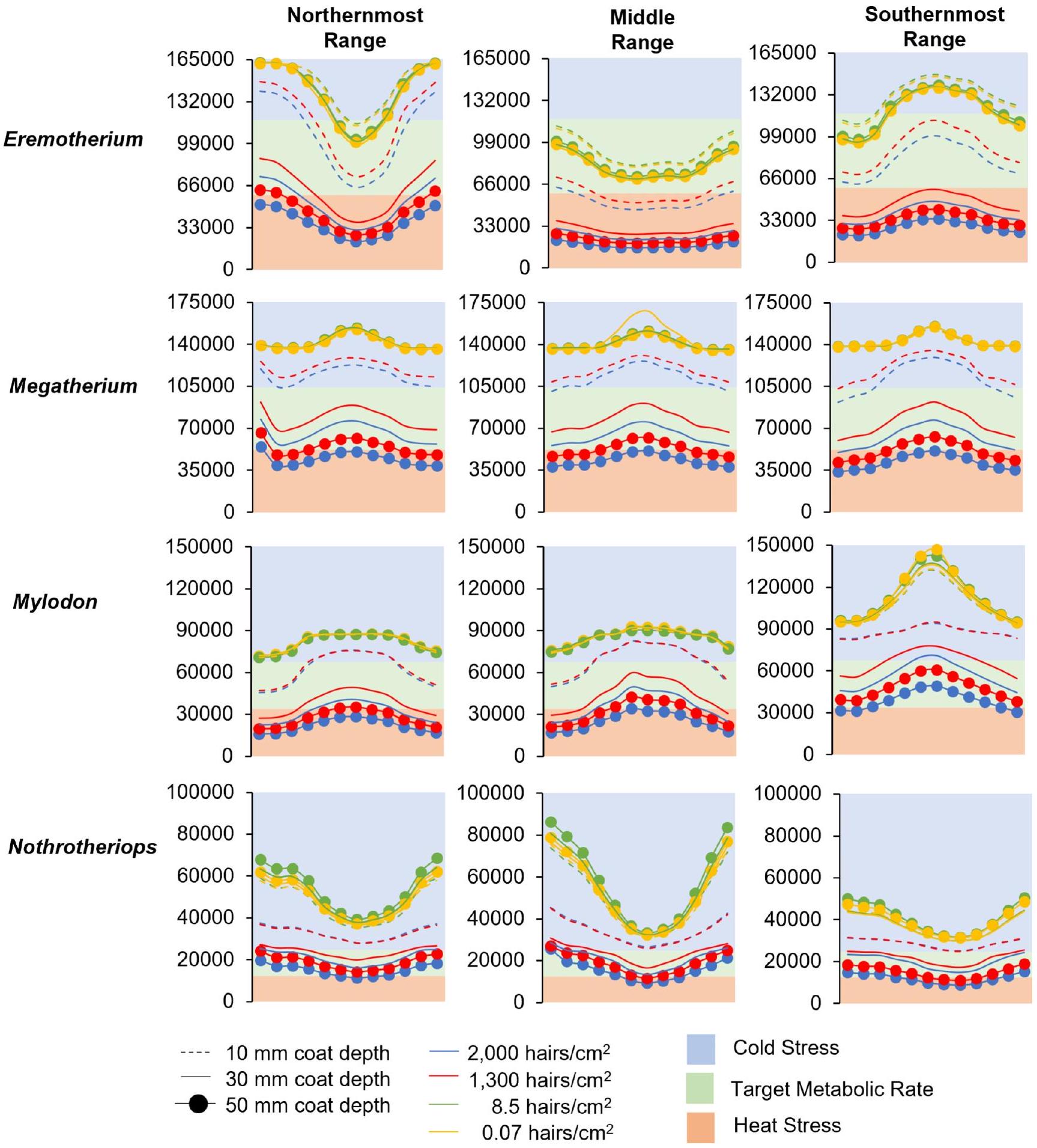

تم التعرف على بقايا الميجاثير منذ القرن الثامن عشر وكانت من بين أول الفقاريات الضخمة التي تم دراستها. بينما تظهر عدة أمثلة من الأنسجة المحفوظة تغطية كثيفة من الفراء للكسالى الأرضية الأصغر التي تعيش في المناخات الباردة مثل الميلودون والنوتروثيريوبس، فإن القليل جداً معروف عن جلد الميجاثير. بافتراض أن الميجاثير كان لديه أيض مشابه لأثداء الثدييات المشيمية، تم الافتراض سابقاً أنه سيكون لديه القليل من الفراء أو لا يوجد على الإطلاق لأنه حقق أحجاماً جسمية عملاقة. هنا يتم اختبار “نموذج الجلد الخالي من الشعر” باستخدام التحليلات الجيوكيميائية لتقدير درجة حرارة الجسم لإنشاء نماذج جديدة لأيض الكسالى الأرضية، وتغطية الفراء، والمناخ القديم باستخدام برنامج Niche Mapper. تشير المحاكاة التي تفترض نشاطاً أيضياً مشابهاً لتلك الموجودة في الزنارثرا الحديثة إلى أن تغطية الفراء القليلة ستؤدي إلى إجهاد بارد عبر معظم النطاقات العرضية التي كانت تسكنها الكسالى الأرضية المنقرضة. على وجه التحديد، كان الإريموتيريوم يحتاج بشكل أساسي إلى فراء كثيف بعمق 10 مم مع تداعيات لتغيرات موسمية في عمق الفراء في أقصى خطوط العرض الشمالية وفراء قليل في المناطق الاستوائية؛ بينما كان الميجاثير يحتاج إلى فراء كثيف بعمق 30 مم على مدار السنة في نطاقه الحصري من المناخات الأكثر برودة وجفافاً؛ وكان الميلودون والنوتروثيريوبس يحتاجان إلى فراء كثيف.

mtbutcher@ysu.edu

1 قسم العلوم الكيميائية والبيولوجية، جامعة يونغستاون ستيت، يونغستاون، أوهايو، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

2 قسم البيولوجيا التكاملي، جامعة ويسكونسن ماديسون، ماديسون، ويسكونسن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

3 قسم علوم الأرض، جامعة ويسكونسن ماديسون، ماديسون، ويسكونسن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

4 قسم علوم الأرض والفضاء، جامعة كاليفورنيا – لوس أنجلوس، لوس أنجلوس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

5 قسم العلوم الجوية والمحيطية، معهد البيئة والاستدامة، مركز القيادة المتنوعة في العلوم، جامعة كاليفورنيا – لوس أنجلوس، لوس أنجلوس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

مقدمة

أصبحت أنواع الكسلان مثل إيريموثيريوم وميغاثيريوم أكبر الكائنات ذات المفاصل الغريبة التي عاشت على الإطلاق، حيث وصلت إلى أحجام تعادل أو تتجاوز أحجام الفيلة الأفريقية الحديثة في السافانا.

عاشت، كانت هناك افتراضات حاسمة مطبقة على المنهجيات السابقة التي قد لا تكون قابلة للتطبيق. أولاً، معادلة الموصلية الحرارية المستخدمة من قبل فاريña (2002) تأخذ في الاعتبار فقط درجات حرارة الجسم الأساسية وتأثيرات درجات الحرارة المحيطة وحدها على التوازن الحراري دون الأخذ في الاعتبار عوامل بيئية أخرى. بينما تعتبر هذه الحسابات مفيدة في تحديد تدفق التوصيل الحراري، كان ينبغي أن تؤخذ في الاعتبار عوامل بيئية أخرى قد تؤثر على التوازن الحراري مثل الرطوبة النسبية وسرعة الرياح، بالإضافة إلى التغيرات في درجة الحرارة المحيطة عبر التوزيع الجغرافي الواسع لأجناس الكسلان الأرضي. ثانياً، لم يكن النموذج السابق (فاريña 2002) دقيقًا في حساب معدل الأيض الأساسي للزواحف الحالية في حسابات تدفق الحرارة، أو جلد الكسلان الحي السميك الذي سيؤثر على فقدان الحرارة. بدلاً من ذلك، تم تكبير معدل الأيض الأساسي لإنسان عارٍ بشكل متساوي إلى حجم ميغاثيريوم مع افتراض درجة حرارة الجسم الأساسية وسمك الجلد مشابهين لتلك الخاصة بالبشر (فاريña 2002). ثالثاً، تم تحديد معدل الأيض الأساسي لميغاثيريوم الأمريكي عن طريق تقليل معدل الأيض المقدر إلى النصف، مما أدى إلى الاستنتاجات بأنه لا يزال يمكن أن يكون بلا شعر وأن درجات الحرارة المنخفضة تصل إلى

يحدث إجهاد حراري، ودرجات الحرارة التي يحدث فيها الموت بسبب الإجهاد الحراري، على التوالي.

فروع النشوء والتطور للـ Folivora هي نتيجة متوقعة لهذه الدراسة.

المواد والأساليب

عينات الحفريات وتحضير العينات

| النوع/ معرف العينة | محلية | بيئة الترسيب |

|

REE

|

|

|

|

|

|

| إيريموثيريوم UF 95869 | إنغليس 1 أ، مقاطعة سيتروس، فلوريدا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | حفرة انهيارية | ٥ | 0.42 |

|

|

|

|

|

| نوتروثيريوبس UF 87131 | ليسي 1 أ، مقاطعة هيلزبورو، فلوريدا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | مصب | ٤ | 0.86 |

|

|

|

|

|

| ميغاثيريوم FMNH P13725 | وادي تارِيخا، الأرجنتين | نهري | ٤ | 0.12 |

|

|

|

|

|

| إيريموثيريوم UF 312730 | هالي 7G، مقاطعة ألاچوا، فلوريدا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | بحيري/ كارس | ٤ | 0.02 |

|

|

|

|

|

| بروماجاثيريوم FMNH 14404 | بوابة كورال كيمادو، الأرجنتين | أرضي غير محدد | ٣ | ٣٦.٦ |

|

|

|

|

|

تجفيفه طوال الليل في فرن عند

تحليل التغيرات الجيوكيميائية

تتكون من 25 تمريرة على

بيانات عظام الثدييات والمينا من Eagle وآخرون (2011). ج. مخطط تشتت للعلاقات بين

عينات ونسب

مع العينة الأولى. تم ترسيب الفوسفات العيني كفوسفات فضي

جنبًا إلى جنب مع عينات غير معروفة كمعيار تحضير وأسفر عن

كيمياء النظائر المستقرة للبيوآباتيت وتقديرات درجة حرارة الجسم

غير معروفة. تم بعد ذلك إسقاط هذه القيم المصححة غير الخطية في إطار مرجعي I-CDES (Bernasconi et al. 2021) باستخدام ETH-1-2 و ETH-3 جنبًا إلى جنب مع ثلاثة معايير داخلية. لم يتم تضمين ETH-4 في التصحيحات، بل تم استخدامه كتحقق من جودة البيانات. تم تطبيق التصحيحات على عينات الأسنان وبيانات المعايير على متوسط متحرك من 10 معايير على كل جانب من العينة المعطاة وتم حسابها باستخدام برنامج Easotope (جون وبوين 2016). تم اشتقاق درجات الحرارة المعاد بناؤها من

نمذجة الحيوانات والمناخ القديم

تم تحديد مناطق الحرارة المحايدة الناتجة ضمن نطاق مستهدف من

(أي، معدل الأيض الأساسي مضروبًا في عامل 2 محول إلى

تحليل إحصائي

نتائج

تحليل نظائر الكتلة المتجمعة وREER

تقديرات المناخ القديم ومعلمات الفسيولوجيا

محاكاة غرف الأيض ونطاقات المنطقة الحرارية المحايدة

تقديرات تتراوح من

محاكاة المناخ الصغير وتحمل درجات الحرارة للجلد

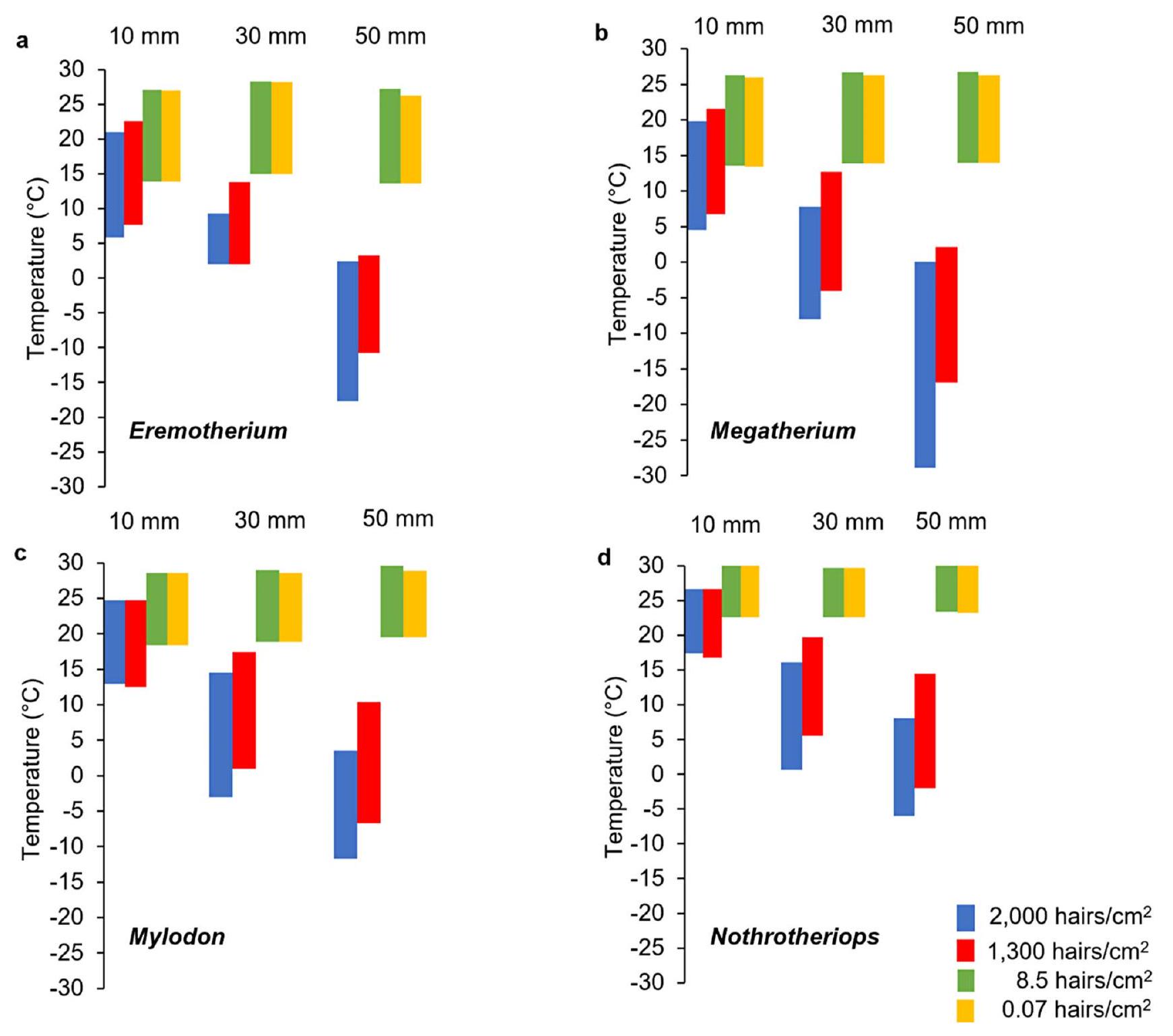

تم تصميمه ليكون بلا إجهاد حراري مع فرو بسمك 10 مم خلال أشهر السنة الأكثر حرارة، وأيضًا مع فرو بسمك 30 مم خلال أشهر السنة الأكثر برودة في المناطق الشمالية والمتوسطة (الشكل 6). تم تحديد أن كل من الميلودون في أقصى جنوب نطاقه ونوثروثيريوبس عبر نطاقه الجغرافي بالكامل لا يعانيان من إجهاد حراري مع فرو كثيف بسمك 50 مم.

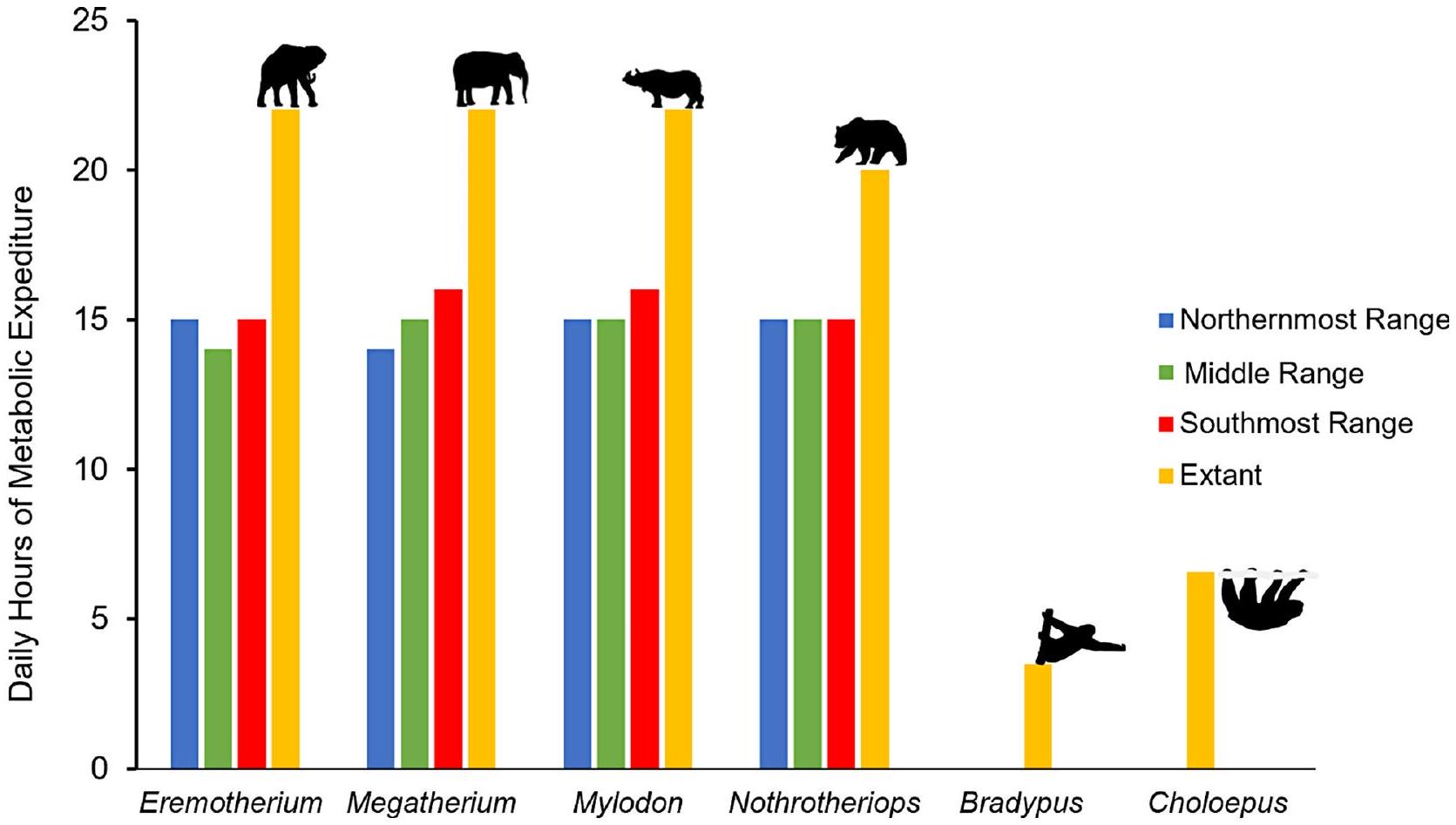

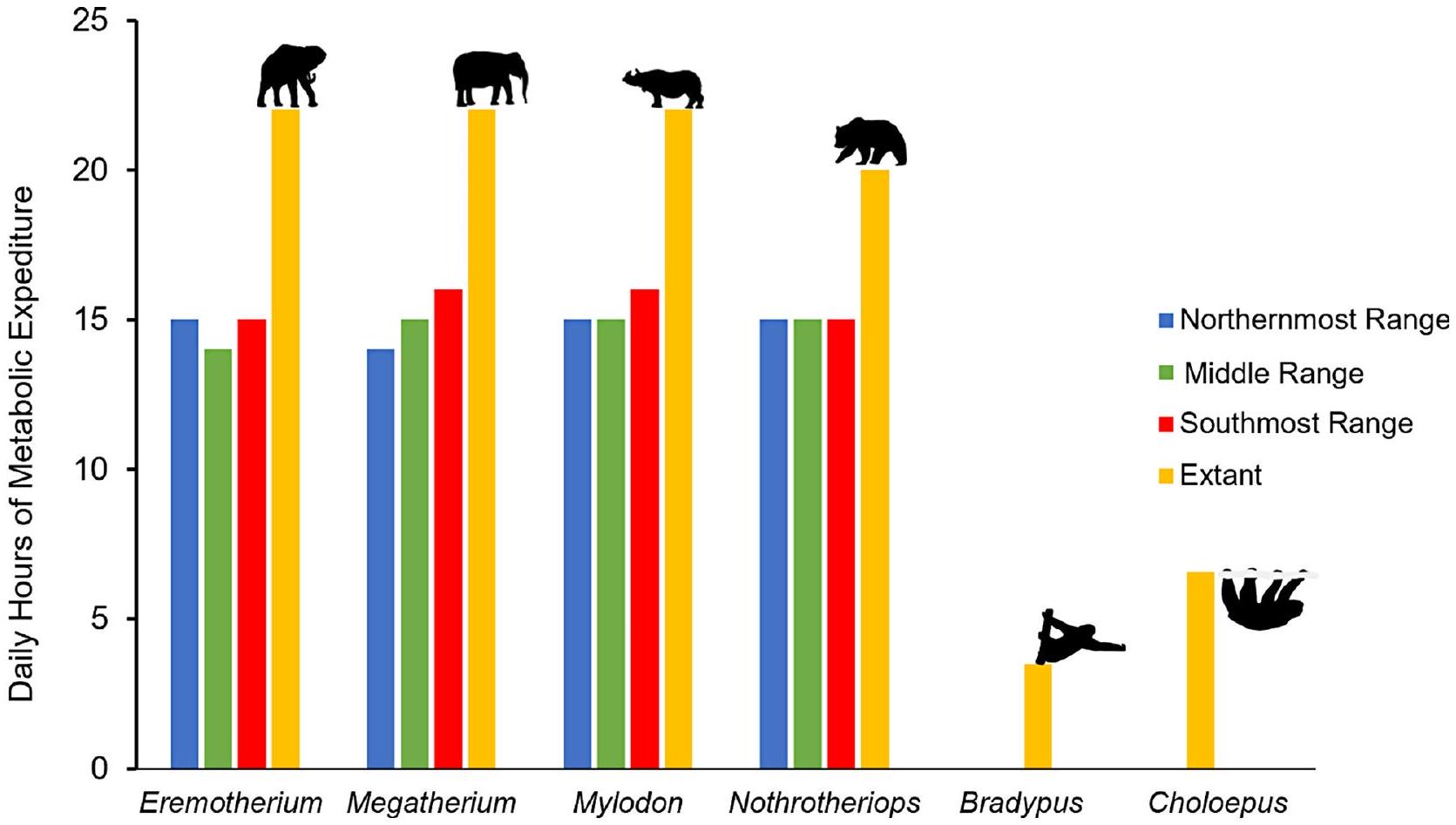

ساعات النشاط الأيضي النشطة اليومية

نطاقات جغرافية متوسطة العرض وجنوبية لميجاثيريوم)، أكبر عدد من ساعات النشاط الأيضي المستهلكة يوميًا (

(وحيد القرن الهندي؛ بالنسبة لـ Mylodon)، الدب البني (Ursus arctos؛ بالنسبة لـ Nothrotheriops)، Bradypus و Choloepus. تم الحصول على الظلال من PhyloPic.org (Michaud M، Taylor J، Keesey M، Morrow C، Jenkins X) وهي تحت الملكية العامة (ساعات النشاط الإجمالية للأنماط الحالية كانت مستندة إلى ساعات النوم اليومية المبلغ عنها في الأدبيات (Stelmock و Dean 1986؛ Deka و Sarma 2015؛ Gravett et al. 2017؛ Cliffe et al. 2023)

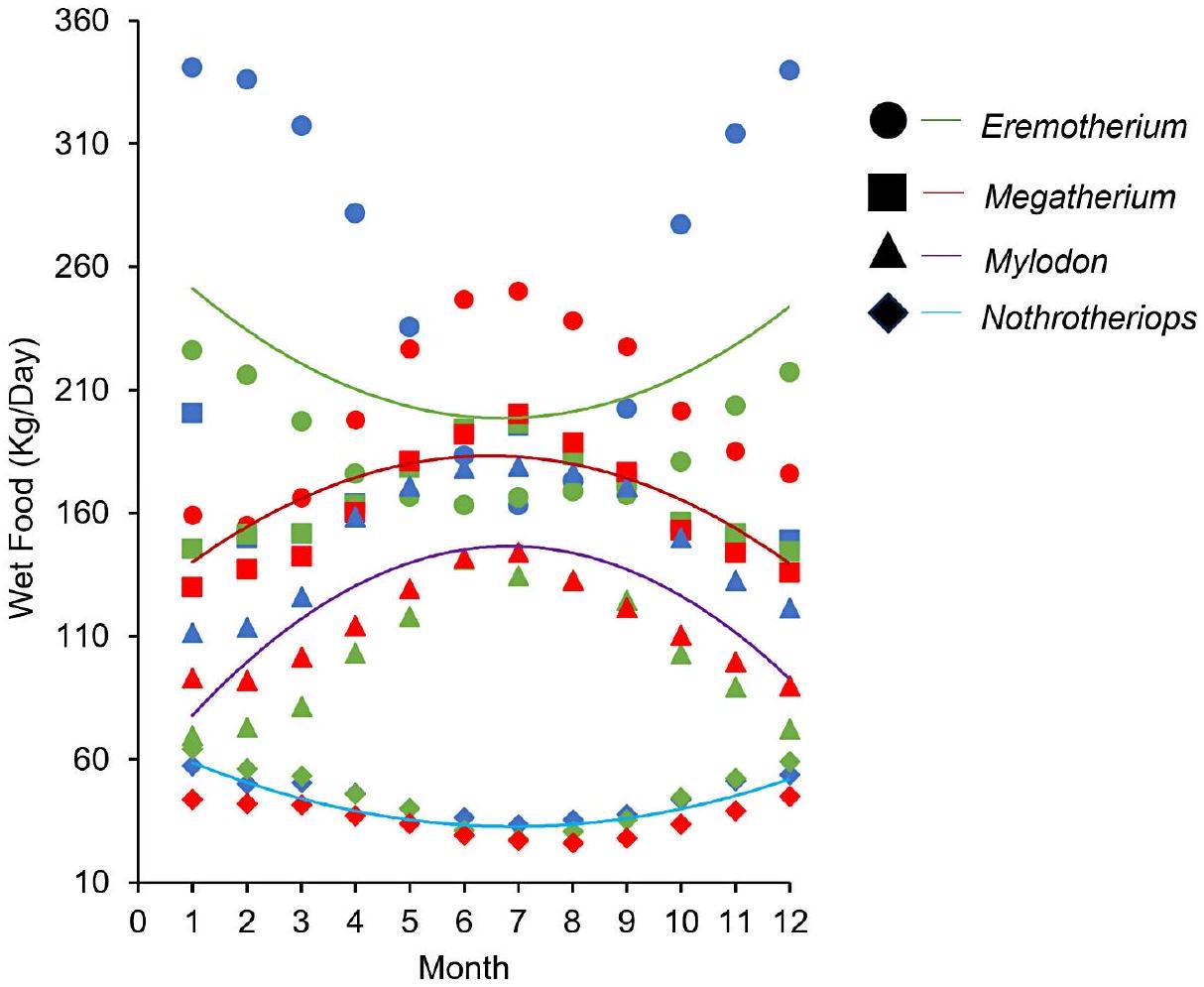

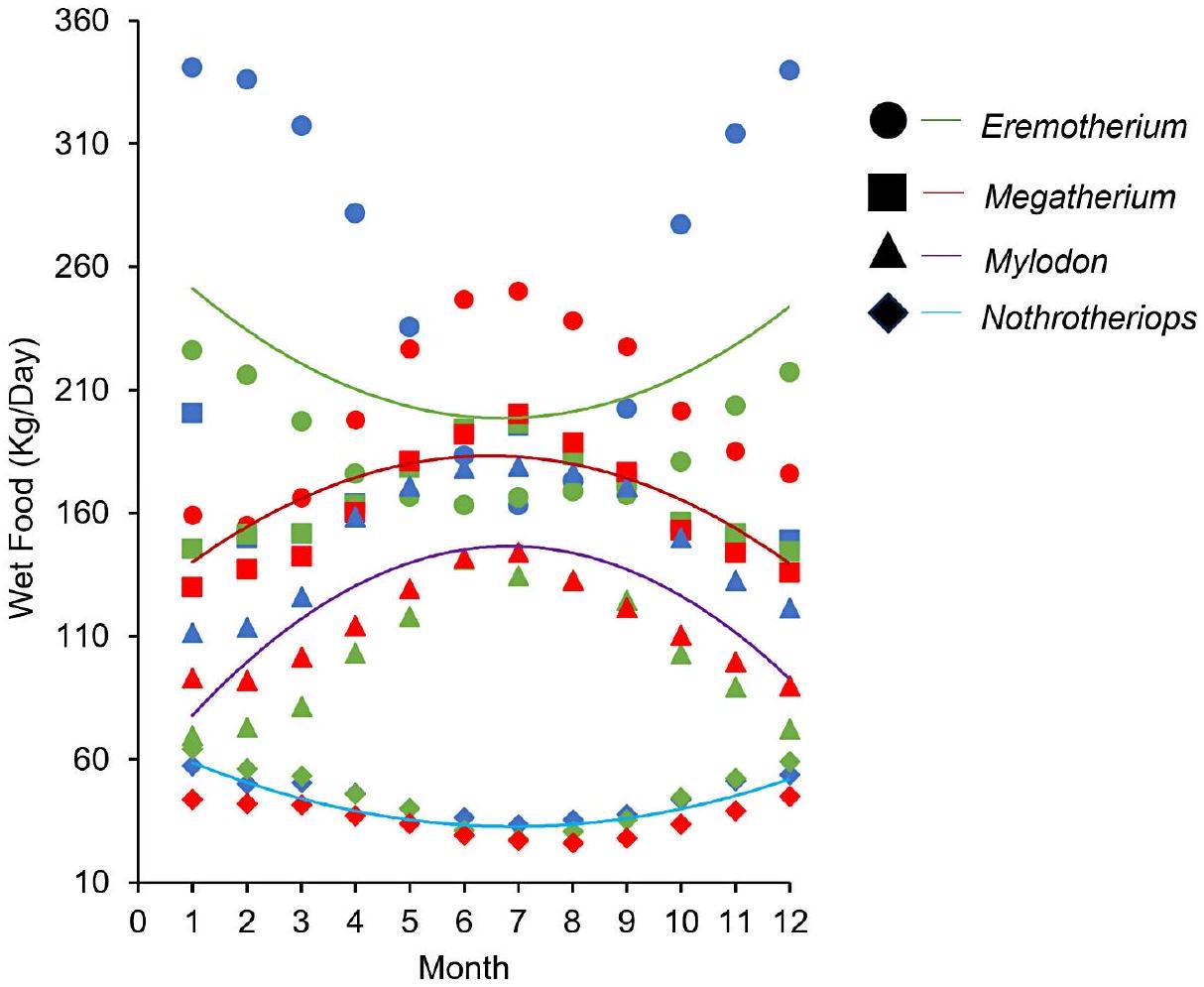

الاستهلاك الغذائي الشهري

استهلاك الطعام (

نقاش

الكيمياء الجيولوجية للأسنان الأحفورية وتفسيرات الفسيولوجيا

مقارنات مع التحليلات السابقة

الحياد الحراري للميغاثير والتوزيع الجغرافي

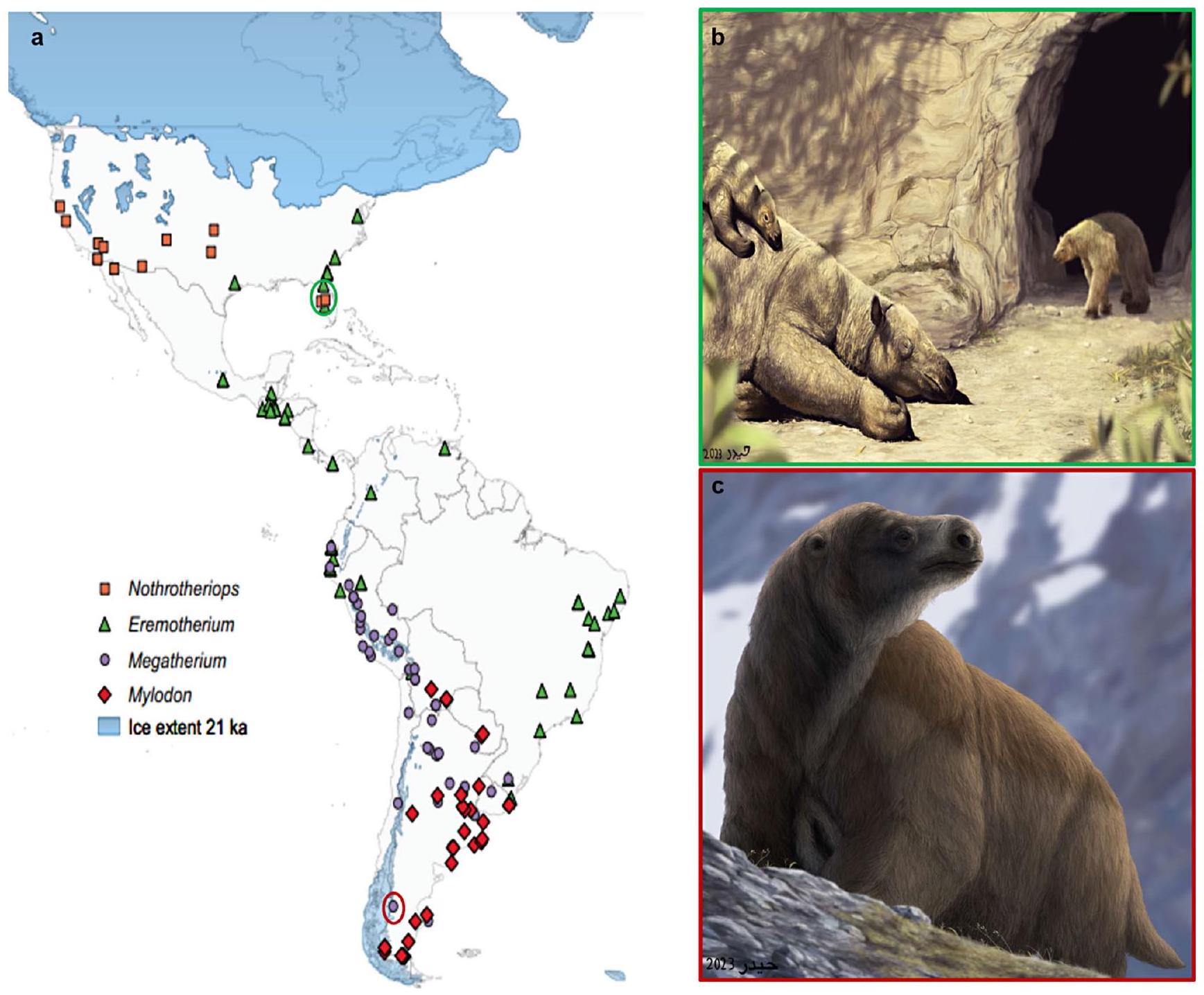

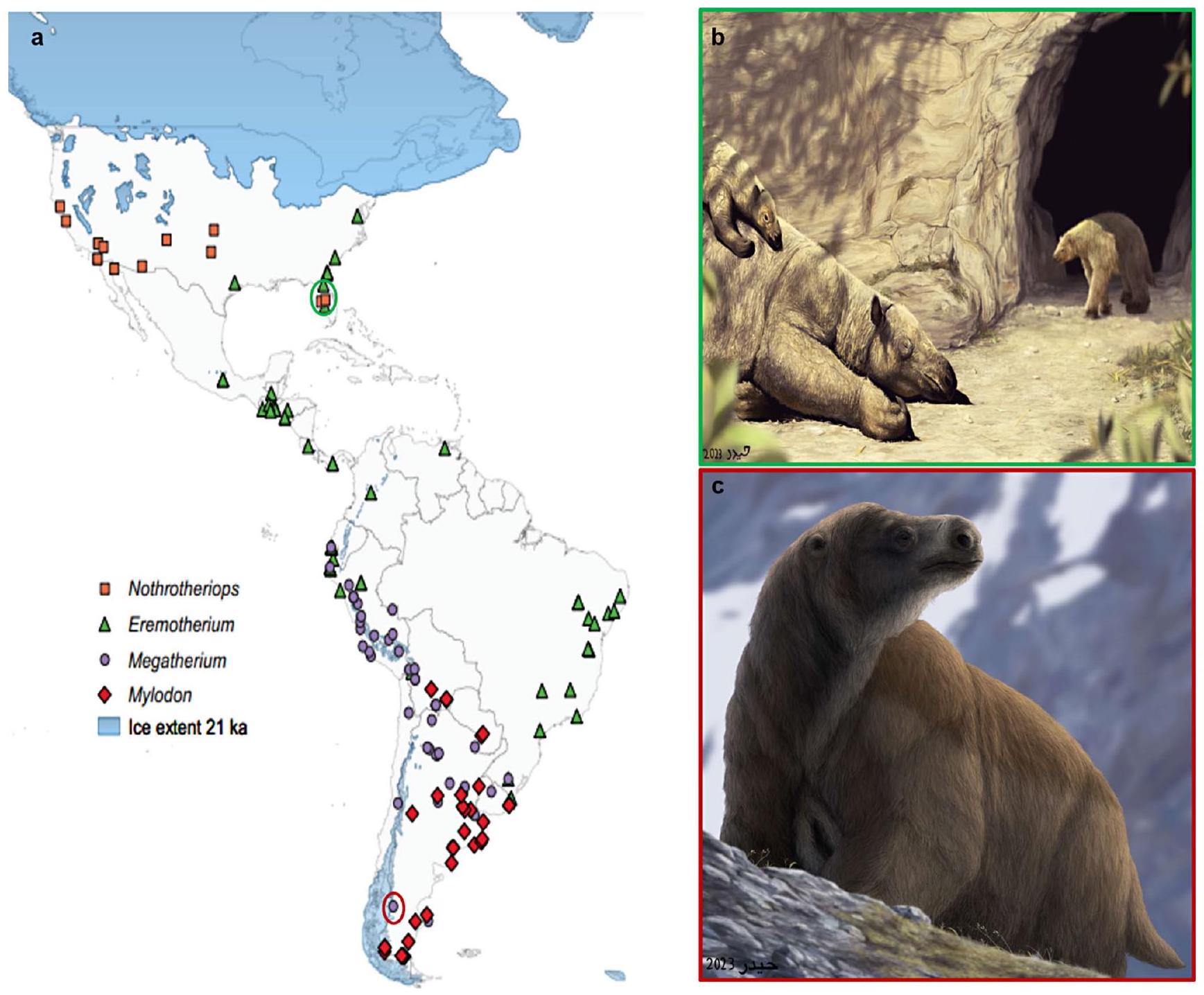

قاعدة بيانات علم الأحياء القديمة (paleobiodb.org). ب. إعادة بناء بالغ ورضيع من إيريموثيريوم أثناء تبديل الفراء الموسمي وهما يتدحرجان في بركة طينية خارج عرين كائن نوتروثيريوبس الناشئ في أوائل الربيع في فلوريدا خلال العصر الجليدي (الموقع موضح بالدائرة الخضراء في اللوحة 9a). ج. إعادة بناء ميغاثيريوم وهو يتحمل برودة ورياح بامباس الأرجنتين مع فرو سميك (الموقع موضح بالدائرة الحمراء في اللوحة 9a). فن باليو من هايدر سيد جعفري

أقصى مدى جنوبي لنطاقه (الشكل 9أ). تتفق هذه الفرضية بشكل ملحوظ مع غياب إيريموثيريوم في أمريكا الشمالية خلال أقصى حد جليدي.

كانت قيم درجة الحرارة وسرعة الرياح هما العاملان المناخيان اللذان يؤثران بشكل كبير على القيم المتوقعة لمعدل الأيض الميداني، في حين أن متغيرات الرطوبة النسبية وتغطية السحب كان لها تأثير ضئيل على الأيض المحاكى. وبالتالي، قد تكون الفراء الكثيف لميجاثيريوم ضرورية لمواجهة التعرض الأكبر للعوامل الجوية (مثل الرياح أو الأمطار أو الثلوج) في البيئات الأكثر انفتاحًا. تعكس حالة الجلد هذه نتائج محاكاة المناخ الحالية التي تشير إلى أنه مع تغطية كاملة للجسم بالفراء بعمق 10 مم، كان ميجاثيريوم سيعاني من إجهاد برودة مستمر بغض النظر عن كثافة الفراء، لكنه كان سيحقق حيادية حرارية كاملة في جميع التوزيعات العرضية مع الفراء الكثيف.

تنظيم الحرارة في الميلودون والنوتروثيريوبس

فترات من السكون و/أو السبات كوسيلة سلوكية لتحمل البرد.

لعظام ميلودون بواسطة توليدو وآخرون (2021) لا تظهر أي ميزات تشير إلى تخزين الأنسجة الدهنية على غرار تلك الموجودة في الأرماديلوس الحالية (كرمبوتش وآخرون 2009). بينما لم يتم إجراء قياسات التوصيل الحراري بعد، فقد أشار توليدو وآخرون (2021) إلى أن فرو الميلودونتيدات مثل ميلودون كان سيوفر كمية أكبر من العزل مقارنة بالعظام الوعائية.

العوامل الجلدية والسلوكية

مثل البيسون الأمريكي (Bison bison) تتخلص من فروها الشتوي الكثيف إلى فرو أخف ومتقطع يتزامن مع سلوك الاستحمام (مكميلان وآخرون 2000). كما كان من الممكن أن تشارك ميغاثيريوم الكبيرة في سلوك الاستحمام ولكنها لم تكن بحاجة إلى التخلص من الفرو بسبب حيادها الحراري على مدار السنة عندما يكون لديها فرو كثيف وعميق بسمك 30 مم (الأشكال 5 و6).

الميغاثيرينات مثل إيريموثيريوم وميغاثيريوم (كروفت وآخرون 2020). كانت أكبر الأنواع من النوتونغولات أعضاء في عائلات توكودونتيداي، ليونتينيداي، وهومالودوثيريداي. بينما عاشت التوكودونتيدات والماكراتشينييدات جنبًا إلى جنب مع الميغاثيرينات خلال أواخر العصر الجليدي (ووصلت إلى كتل جسمية من

القيود

القيم المقبولة لمؤشر REE

خلال عملية التحجر. بينما تم أخذ عينات من أقسام أخرى من الأسنان الأحفورية المستخدمة في التحليلات الجيوكيميائية، لم يتم استخدامها بسبب قيود الوقت والتمويل لهذه الدراسة. يمكن أن تشير التحليلات الإضافية لهذه العينات بشكل أفضل إلى دليل على حالة غير متجانسة سابقة حيث يمكن أن تكون الطبقة الداخلية من الأورثودنتين قد سجلت إشارات نظيرية مختلفة، وبالتالي تقديرات مختلفة لدرجة حرارة الجسم.

الاستنتاجات

كانت تحتاج إلى فراء كثيف وسميك مدعوم بتنظيم حراري سلوكي لتحمل المناخات الباردة على مدار العام. تشير بيانات النمذجة أيضًا إلى قابلية التكيف المدهشة لفيزيولوجيا الزنارثرا في كل من أكبر وأصغر الكسلان الأرضي. علاوة على ذلك، يُعتقد أن نماذج الجلد المتوقعة لأكبر الأنواع موثوقة ما لم يتم دحضها بواسطة عينة مستقبلية تحتوي على جلد محفوظ بشكل واسع. يجب أن تفحص النماذج المستقبلية المحتملة أنواعًا أخرى (مثل Megalonyx وThalassocnus وLestodon، إلخ) وتضم دراسات نسيجية للمساعدة في تحديد مدى انخفاض معدلات الأيض الأساسية للكسلان الأرضي التي قد تكون مفيدة، وبالتالي توفير مزيد من الرؤية حول فيزيولوجيا هذه الأنواع وغيرها من الزنارثرا الأحفورية وكيف أثرت معدلات الأيض على مظهر جلدها ومعدلات نموها وبيئتها وسلوكها.

الإعلانات

References

Anderson NT, Kelson JR, Kele S, Daëron M, Bonifacie M, Horita J, et al (2021) A unified clumped isotope thermometer calibration (

Barbosa FHDS, Alves-Silva L, Liparini A, Porpino KDO (2023) Reviewing the body size of some extinct Brazilian Quaternary xenarthrans. J Quat Sci https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs. 3560

Bargo MS, Vizcaíno SF, Archuby FM, Blanco RE (2000) Limb bone proportions, strength and digging in some Lujanian (Late Pleis-tocene-Early Holocene) mylodontid ground sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra). J Vertebr Paleontol 20(3):601-610. https://doi.org/10 .1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0601:LBPSAD]2.0.CO;2

Bargo MS, De Iuliis G, Vizcaíno SF (2006) Hypsodonty in Pleistocene ground sloths. Acta Paleontol Pol 51(1):53-61.

Bernasconi SM, Daëron M, Bergmann KD, Bonifacie M, Meckler AN, Affek HP et al (2021) InterCarb: A community effort to improve interlaboratory standardization of the carbonate clumped isotope thermometer using carbonate standards. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 22(5):e2020GC009588 https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GC009 588.

Blanco RE, Czerwonogora A (2003) The gait of Megatherium Cuvier 1796. Senckenb Biol 83: 61-68.

Boeskorov GG, Mashchenko EN, Plotnikov VV, Shchelchkova MV, Protopopov AV, Solomonov NG (2016). Adaptation of the woolly mammoth Mammuthus primigenius (Blumenbach, 1799) to habitat conditions in the glacial period. Contemp Probl Ecol 9:54453. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1995425516050024

Brassey CA, Gardiner JD (2015) An advanced shape-fitting algorithm applied to quadrupedal mammals: improving volumetric mass estimates. R Soc Open Sci 2(8):150302. https://doi.org/10.1098 /rsos. 150302

Chavagnac V, Milton JA, Green DRH, Breuer J, Bruguier O, Jacob DE, et al. (2007). Towards the development of a fossil bone geochemical standard: An inter-laboratory study. Anal Chim Acta 599(2):177-190

Christiansen P, Fariña RA (2003) Mass estimation of two fossil ground sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Mylodontidae). Senckenberg Biol 83(1):95-101

Clarke A, Rothery P (2008) Scaling of body temperature in mammals and birds. Funct Ecol 22(1):58-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 136 5-2435.2007.01341.x

Cliffe RN, Haupt RJ, Avey-Arroyo JA, Wilson RP (2015) Sloths like it hot: ambient temperature modulates food intake in the brownthroated sloth (Bradypus variegatus). PeerJ 3:e875. https://doi.o rg/10.7717/peerj. 875

Cliffe RN, Scantlebury DM, Kennedy SJ, Avey-Arroyo J, Mindich D, Wilson RP (2018) The metabolic response of the Bradypus sloth to temperature. PeerJ 6:e5600. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj. 5600

Cliffe RN, Haupt RJ, Kennedy S, Felton C, Williams HJ, Avey-Arroyo J, Wilson R (2023) The behaviour and activity budgets of two sympatric sloths; Bradypus variegatus and Choloepus hoffmanni. PeerJ 11:e15430. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj. 15430

Collins RL (1933) Mylodont (ground sloth) dermal ossicles from Colombia, South America. J Wash Acad Sci 23(9):426-429.

Conte GL, Lopes Le, Mine AH, Trayler RB, Kim SL (2024) SPORA, a new silver phosphate precipitation protocol for oxygen isotope analysis of small, organic-rich bioappatite samples. Chem Geol 65:122000. https://doi.org/10.1016/.chemgeo.2024. 122000

Copploe JV II, Blob RW, Parrish JHA, Butcher MT (2015) In vivo strains in the femur of the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). J Morphol 276:889-899. https://doi.org/10.1002 /jmor. 20387

Croft DA, Gelfo JN, López GM (2020) Splendid innovation: the extinct South American native ungulates. Ann Rev Earth Planet Sci 48:259-290.

Dantas, MAT, Omena ÉC, da Silva JLL, Sial A (2021) Could Eremotherium laurillardi (Lund, 1842) (Megatheriidae, Xenarthra) be an omnivore species? Anu Inst Geocienc 44:1-5. https://doi.org/10. 11137/1982-3908_2021_44_36492

Dantas MAT, Cherkinsky A, Bocherens H, Drefahl M, Bernardes C, de Melo França L (2017) Isotopic paleoecology of the Pleistocene megamammals from the Brazilian Intertropical Region: Feeding ecology (

Deka RJ, Sarma NK (2015) Studies on feeding behaviour and daily activities of Rhinoceros unicornis in natural and captive condition of Assam. Indiana J Anim Res 49(4):542-545.

Delsuc, F, Kuch M, Gibb GC, Karpinski, E, Hackenberger D, Szpak P, Billet G (2019) Ancient mitogenomes reveal the evolutionary history and biogeography of sloths. Curr Biol 29(12):2031-2042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043

Eagle RA, Schauble EA, Tripati AK, Tütken T, Hulbert RC, Eiler JM (2010) Body temperatures of modern and extinct vertebrates from

Eagle RA, Tütken T, Martin TS, Tripati AK, Fricke HC, Connely M, et al (2011) Dinosaur body temperatures determined from isotopic (

Fariña RA (2002) Megatherium, the hairless: appearance of the great Quaternary sloths (Mammalia; Xenarthra). Ameghiniana 39:241-244.

Fariña RA, Blanco RE (1996) Megatherium, the stabber. Proc R Soc B263(1377):1725-1729.

Fariña RA, Vizcaíno SF, Bargo MS (1998) Body mass estimations in Lujanian (late Pleistocene-early Holocene of South America) mammal megafauna. Mastozool Neotrop 5(2):87-108.

Feldhamer GA, Drickamer LC, Vessey SH, Merritt JF, Krajewski C (2007) Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, and Ecology. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Fricke HC, Rogers R (2000) Multiple taxa and multiple locality approach to providing oxygen isotope evidence for endothermic homeothermy in theropod dinosaurs. Geology 28(9):799-802.

Ghosh P, Adkins J, Affek H, Balta B, Guo W, Schauble EA, et al (2006)

González-Bernardo E, Russo LF, Valderrábano E, Fernández Á, Penteriani V (2020) Denning in brown bears. Ecol Evol 10(13):68446862. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6372

Gravett N, Bhagwandin A, Sutcliffe R, Landen K, Chase MJ, Lyamin OI, et al (2017) Inactivity/sleep in two wild free-roaming African elephant matriarchs-Does large body size make elephants the shortest mammalian sleepers? PL oS ONE 12(3):e0171903. https ://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0171903

Green, JL, Kalthoff, DC (2015) Xenarthran dental microstructure and dental microwear analyses, with new data for Megatherium americanum (Megatheriidae). J Mammal 96(4):645-657. https://doi.o rg/10.1093/mammal/gyv045

Griffiths ML, Eagle RA, Kim SL, Flores R, Becker MA, Maisch IV HM, et al (2023) Thermal physiology of extinct megatooth sharks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 120(27):e2218153120. https://d oi.org/10.1073/pnas. 2218153120

Hausman LA (1929) The ovate bodies of the hair of Nothrotherium shastense. Am J Sci 106:331-333.

Hayssen V (2011) Choloepus hoffmanni (Pilosa: Megalonychidae). Mammal Species 43(873):37-55. https://doi.org/10.1644/873.1

Ho TY (1967) Relationship between amino acid contents of mammalian bone collagen and body temperature as a basis for estimation of body temperature of prehistoric mammals. Comp Biochem Physiol 22:113-119.

Holden PB, Edwards NR, Rangel TF, Pereira EB, Tran GT, Wilkinson RD (2019) PALEO-PGEM v1. 0: a statistical emulator of Plio-cene-Pleistocene climate. Geosci Model Dev 12(12):5137-5155. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-5137-2019

Hutchinson JR, Schwerda D, Famini DJ, Dale RH, Fischer MS, Kram R (2006) The locomotor kinematics of Asian and African elephants:

changes with speed and size. J Exp Biol 209(19):3812-3827. http s://doi.org/10.1242/jeb. 02443

Idso SB, Jackson RD (1969) Thermal radiation from the atmosphere. J Geophys Res 74(23):5397-5403.

Jochum KP, Weis U, Schwager B, Stoll B, Wilson SA, Haug GH, et al. (2016). Reference values following ISO guidelines for frequently requested rock reference materials. Geostands Geoanal Res 40(3):333-350.

John CM, Bowen D (2016) Community software for challenging isotope analysis: First applications of ‘Easotope’ to clumped isotopes. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 30:2285-2300. https://doi .org/10.1002/rcm. 7720

Kleiber M (1932) Body size and metabolism. Hilgardia 6(11):315-353.

Knight F, Connor C, Venkataramanan R, Asher R (2020) Body temperatures, life history, and skeletal morphology in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). PCI Ecol. https://doi.org/10 .17863/CAM. 50971

Kohn MJ, Schoeninger MJ, Barker WW (1999) Altered states: effects of diagenesis on fossil tooth chemistry. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 63(18):2737-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(99)0 0208-2

Krmpotic CM, Carlini AA, Galliari FC, Favaron P, Miglino MA, Scarano AC, Barbeito CG (2014). Ontogenetic variation in the stratum granulosum of the epidermis of Chaetophractus vellerosus (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae) in relation to the development of cornified scales. Zoology 117(6):392-397 https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.zool.2014.06.003.

Larmon JT, McDonald HG, Ambrose S, DeSantis LR, Lucero LJ (2019) A year in the life of a giant ground sloth during the Last Glacial Maximum in Belize. Sci Adv 5(2): 1-9. https://doi.org/1 0.1126/sciadv.aau1200

Levesque DL, Marshall KE (2021) Do endotherms have thermal performance curves? J Exp Biol 224(3):jeb141309. https://doi.org/1 0.1242/jeb. 141309

Lovelace DM, Hartman SA, Mathewson PD, Linzmeier BJ, Porter WP (2020) Modeling Dragons: Using linked mechanistic physiological and microclimate models to explore environmental, physiological, and morphological constraints on the early evolution of dinosaurs. PLS ONE 15(5):e0223872. https://doi.org/10.17026/d ans-238-9pjs

MacFadden BJ, DeSantis LR, Hochstein JL Kamenov GD (2010) Physical properties, geochemistry, and diagenesis of xenarthran teeth: prospects for interpreting the paleoecology of extinct species. Paleogeogr Paleoclimatol Paleoecol 291(3-4):180-189. http s://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.02.021

Martin FM (2018) Cueva del Milodón. The hunting grounds of the Patagonian panther. Quat Int 466:212-222. https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.quaint.2016.05.005

McBee K, Baker RJ (1982) Dasypus novemcinctus. Mammal Species 162:1-9.

McCullough EC, Porter WP (1971) Computing clear day solar radiation spectra for the terrestrial ecological environment. Ecology 52:1008-1015.

McDonald HG (2022) Paleoecology of the Eextinct Shasta Ground Sloth, Nothrotheriops shastensis (Xenarthra, Nothrotheridae): The Physical environment. N M Mus Nat Sci Bull 88:33-43

McDonald HG, Lundelius Jr EL (2009) The giant ground sloth Eremotherium laurillardi (Xenarthra. Megatheriidae) in Texas. Bull Mus North Ariz 65:407-421.

McKamy AJ, Young MW, Mossor AM, Young, JW, Avey-Arroyo JA, Granatosky MC, Butcher MT (2023) Pump the Brakes! The hindlimbs of three-toed sloths control suspensory locomotion. J Exp Biol 226(8):jeb245622. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb. 245622

McMillan BR, Cottam MR, Kaufman DW (2000) Wallowing behavior of American bison (Bison bison) in tallgrass prairie: an examination of alternate explanations. Am Mid Nat 144(1):159-167.

McNab, BK (1985) Energetics, population biology, and distribution of xenarthrans, living and extinct. In: Montgomery GG (ed) The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. pp 219-232.

Mine AH, Waldeck A, Olack G, Hoerner ME, Alex S, Colman AS (2017) Microprecipitation and

Mitchell D, Snelling EP, Hetem RS, Maloney SK, Strauss WM, Fuller A (2018) Revisiting concepts of thermal physiology: predicting responses of mammals to climate change. J Anim Ecol 87(4):956-973. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12818

Myhrvold CL, Stone HA, Bou-Zeid E (2012) What is the use of elephant hair? PL oS ONE 7:e47018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journa 1.pone. 0047018

Naples VL (1990) Morphological changes in the facial region and a model of dental growth and wear pattern development in Nothrotheriops shastensis. J Vert Paleontol 10(3):372-389.

Nehme C, Todisco D, Breitenbach SF, Couchoud I, Marchegiano M, Peral M, et al (2022) Holocene hydroclimate variability along the Southern Patagonian margin (Chile) reconstructed from Cueva Chica speleothems. Glob Planet Change 222:104050. https://do i.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2023.104050

Pant SRA, Goswami A, Finarelli JA (2014) Complex body size trends in the evolution of sloths (Xenarthra: Pilosa). BMC Evol Biol 14:184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-014-0184-1

Pauli JN, Peery MZ, Fountain ED, Karasov WH (2016) Arboreal folivores limit their energetic output, all the way to slothfulness. Am Nat 188(2):196-204.

Poinar HN, Hofreiter M, Spaulding WG, Martin PS, Stankiewicz BA, Bland H, Evershed RP, Possnert G, Paabo S (1998) Molecular coproscopy: dung and diet of the extinct ground sloth Nothrotheriops shastensis. Science 128(5375):402-406.

Presslee S, Slater GJ, Pujos F, Forasiepi AM, Fischer R, Molloy K, et al. (2019). Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships. Nat Ecol Evol 3(7):1121-1130. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0 909-z

Prevosti FJ, Martin FM (2013) Paleoecology of the mammalian predator guild of Southern Patagonia during the latest Pleistocene: ecomorphology, stable isotopes, and taphonomy. Quat Int 305:74-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.12.039

Ridewood WG (1901). On the structure of the hairs of Mylodon listai and other South American Edentata. J Cell Sci 2(175):393-411. h ttps://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.s2-44.175.393

Santos LE, Ajala-Batista L, Carlini AA, de Araujo Monteiro-Filho EL (2024) Mylodon darwinii (Owen, 1840): hair morphology of an extinct sloth. Zoomorphology 2024:1-9.

Seitz VP, Puig S (2018) Aboveground activity, reproduction, body temperature and weight of armadillos (Xenarthra, Chlamyphoridae) according to atmospheric conditions in the central Monte (Argentina). Mammal Biol 88:43-51.

Seymour R S, Hu Q, Snelling E P, White C R (2019). Interspecific scaling of blood flow rates and arterial sizes in mammals. J Exp Biol 222(7):jeb199554. https://doi.org/10.1242/Jen. 199554

Stears K, McCauley DJ, Finlay JC, Mpemba J, Warrington IT, Mutayoba BM, et al (2018) Effects of the hippopotamus on the chemistry and ecology of a changing watershed. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 115(22):E5028-E5037. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 1800407115

Stelmock J, Dean FC (1986) Brown bear activity and habitat use, Denali National Park-1980. Int Conf Bear Res Manag 6:155-167.

Suárez MB, Passey BH (2014) Assessment of the clumped isotope composition of fossil bone carbonate as a recorder of subsurface temperatures. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 140:142-159. https:/ dol.org/10.1016|)- gca.2014.05.026

Sunquist ME, Montgomery GG (1973) Activity patterns and rates of movement of two-toed and three-toed sloths (Choloepus hoffmanni and Bradypus infuscatus). J Mammal 54(4):946-954.

Superina M, Abba AM (2014) Zaedyus pichiy (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mammal Species 46(905):1-10. https://doi.org/10.1644/90 5.1

Tagliavento M, Davies AJ, Bernecker M, Staudigel PT, Dawson RR, Dietzel M, et al (2023) Evidence for heterothermic endothermy and reptile-like eggshell mineralization in Troodon, a non-avian maniraptoran theropod. Proc Natl Acad Sci 120(15):e2213987120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 2213987120

Taube E, Vié JC, Fournier P, Genty C, Duplantier JM (1999) Distribution of two sympatric species of sloths (Choloepus didactylus and Bradypus tridactylus) along the Sinnamary River, French Guiana 1. Biotropica 31(4):686-691.

Tejada JV, Antoine PO, Münch P, Billet G, Hautier L, Delsuc F, Condamine FL (2024) Bayesian total-evidence dating revisits sloth phylogeny and biogeography: a cautionary tale on morphological clock analyses. Syst Biol 73(1):125-139. https://doi.org/10.1093 /sysbio/syad069

Toledo N, Boscaini A, Pérez LM (2021) The dermal armor of mylodontid sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from Cueva del Milodon (Ultima Esperanza, Chile). J Morphol 282(4):612-627. https://do i.org/10.1002/jmor. 21333

Tregear RT (1965) Hair density, wind speed, and heat loss in mammals. J Appl Physiol 20(4):796-801.

Varela L, Clavijo L, Tambusso PS, Fariña RA (2023). A window into a late Pleistocene megafauna community: Stable isotopes show niche partitioning among herbivorous taxa at the Arroyo del Vizcaíno site (Uruguay). Quat Sci Rev 317:108286. https://doi.org/1 0.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108286

Wang Y, Porter WP, Mathewson PD, Miller PA, Graham RW, Williams JW (2018) Mechanistic modeling of environmental drivers of

woolly mammoth carrying capacity declines on St. Paul Island. Ecology 99(12):2721-2730. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy. 2524

Wang Y, Widga C, Graham RW, McGuire JL, Porter WP, D. Wårlind, D, Williams JW (2020) Caught in a bottleneck: Habitat loss for woolly mammoths in central North America and the ice-free corridor during the last deglaciation. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 30(2):527542. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb. 13238

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-024-09743-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39822851

Publication Date: 2025-01-14

Metabolic skinflint or spendthrift? Insights into ground sloth integument and thermophysiology revealed by biophysical modeling and clumped isotope paleothermometry

© The Author(s) 2024, corrected publication 2025

Abstract

Remains of megatheres have been known since the 18th -century and were among the first megafaunal vertebrates to be studied. While several examples of preserved integument show a thick coverage of fur for smaller ground sloths living in cold climates such as Mylodon and Nothrotheriops, comparatively very little is known about megathere skin. Assuming a typical placental mammal metabolism, it was previously hypothesized that megatheres would have had little-to-no fur as they achieved giant body sizes. Here the “hairless model of integument” is tested using geochemical analyses to estimate body temperature to generate novel models of ground sloth metabolism, fur coverage, and paleoclimate with Niche Mapper software. The simulations assuming metabolic activity akin to those of modern xenarthrans suggest that sparse fur coverage would have resulted in cold stress across most latitudinal ranges inhabited by extinct ground sloths. Specifically, Eremotherium predominantly required dense 10 mm fur with implications for seasonal changes of coat depth in northernmost latitudes and sparse fur in the tropics; Megatherium required dense 30 mm fur year-round in its exclusive range of cooler, drier climates; Mylodon and Nothrotheriops required dense

mtbutcher@ysu.edu

1 Department of Chemical and Biological Sciences, Youngstown State University, Youngstown, OH, USA

2 Department of Integrative Biology, University of Wisconsin Madison, Madison, WI, USA

3 Department of Geosciences, University of Wisconsin Madison, Madison, WI, USA

4 Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of California – Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

5 Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, Center for Diverse Leadership in Science, University of California – Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Introduction

sloth taxa such as Eremotherium and Megatherium became the largest xenarthrans ever in existence, reaching sizes comparable to or exceeding that of modern African savanna elephants.

lived, there were critical assumptions applied to the previous methodologies that may not be tenable. First, the thermal conductivity equation used by Fariña (2002) only accounts for core body temperatures and the effects of ambient temperatures alone on thermoneutrality without accounting for other environmental factors. While this calculation is useful in determining heat conduction flux, other environmental factors that could impact thermoneutrality such as relative humidity and wind speed, in addition to variations in ambient temperature across the broad geographic distribution of the ground sloth genera should have been considered. Second, the previous model (Fariña 2002) did not accurately account for the basal metabolism of extant xenarthrans for calculations of heat flux, or the thick skin of living sloths that would affect heat loss. Instead, the basal metabolic rate of a naked human was isometrically scaled up to the size of Megatherium assuming similar core body temperature and skin thickness to that of hominids (Fariña 2002). Third, determinations of the basal metabolic rate of Megatherium americanum were made by halving the estimated metabolic rate, thus leading to the conclusions that it could still be furless and that temperatures as low as

thermal stress occurs, and temperatures where death by thermal stress occurs, respectively.

phylogenetic branches of the Folivora is an expected outcome of this study.

Materials and methods

Fossil specimens and sample preparation

| Genus/ Sample ID | Locality | Depositional environment |

|

REE

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Eremotherium UF 95869 | Inglis 1 A, Citrus County, Florida, USA | Sinkhole | 5 | 0.42 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Nothrotheriops UF 87131 | Leisey 1 A, Hillsborough County, Florida, USA | Estuary | 4 | 0.86 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Megatherium FMNH P13725 | Tarija Valley, Argentina | Fluvial | 4 | 0.12 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Eremotherium UF 312730 | Halie 7G, Alachua County, Florida, USA | Lacustrine/ karst | 4 | 0.02 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Promegatherium FMNH 14404 | Puerta de Corral Quemado, Argentina | Terrestrial indet. | 3 | 36.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

drying overnight in an oven at

Geochemical alteration analysis

consist of 25 sweeps on

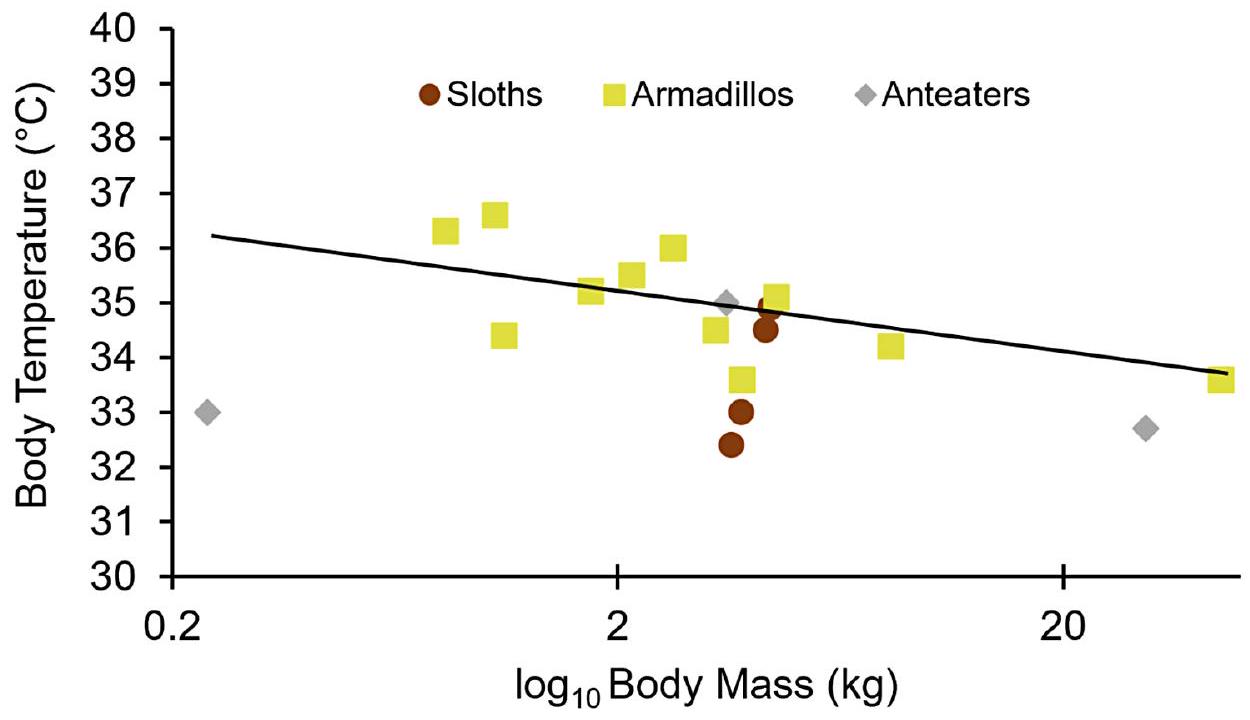

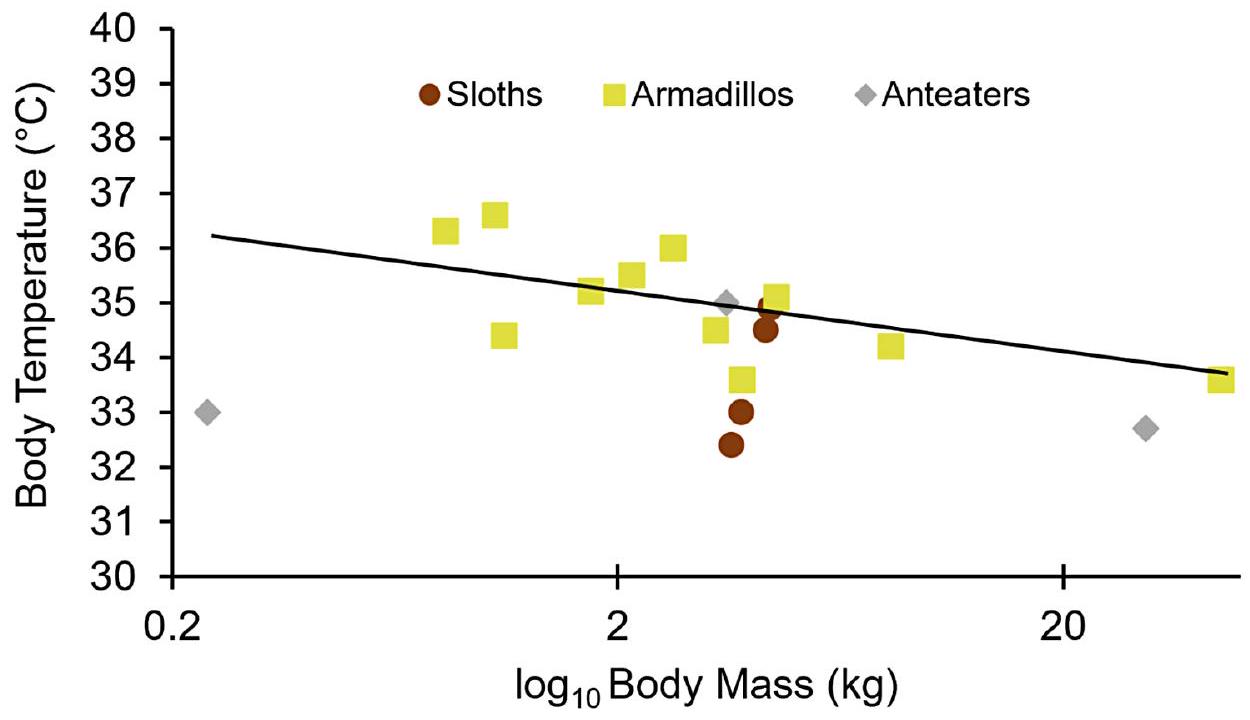

mammal bone and enamel data from Eagle et al. (2011). c. Scatter plot of the relationships between

samples, and ratios

with the first aliquot. Sample phosphate was precipitated as silver phosphate

alongside sample unknowns as a preparation standard and yielded a

Bioapatite stable isotope geochemistry and body temperature estimates

unknowns. These nonlinearity corrected values were then projected into an I-CDES reference frame (Bernasconi et al. 2021) using ETH-1-2, and ETH-3 along with three in-house standards. ETH-4 was not included in the corrections and was instead used as a check for data quality. Corrections were applied to tooth samples and standard data over a moving average of 10 standards on either side of a given sample and were calculated using Easotope software (John and Bowen 2016). Reconstructed temperatures were derived from a

Modeling of animals and paleoclimate

et al. 2018; Seitz and Puig 2018). Output thermoneutral zones were determined within a target range of

(i.e., basal metabolic rate multiplied by a factor of 2 converted to

Statistical analysis

Results

Clumped isotope paleothermometry and REE ratios

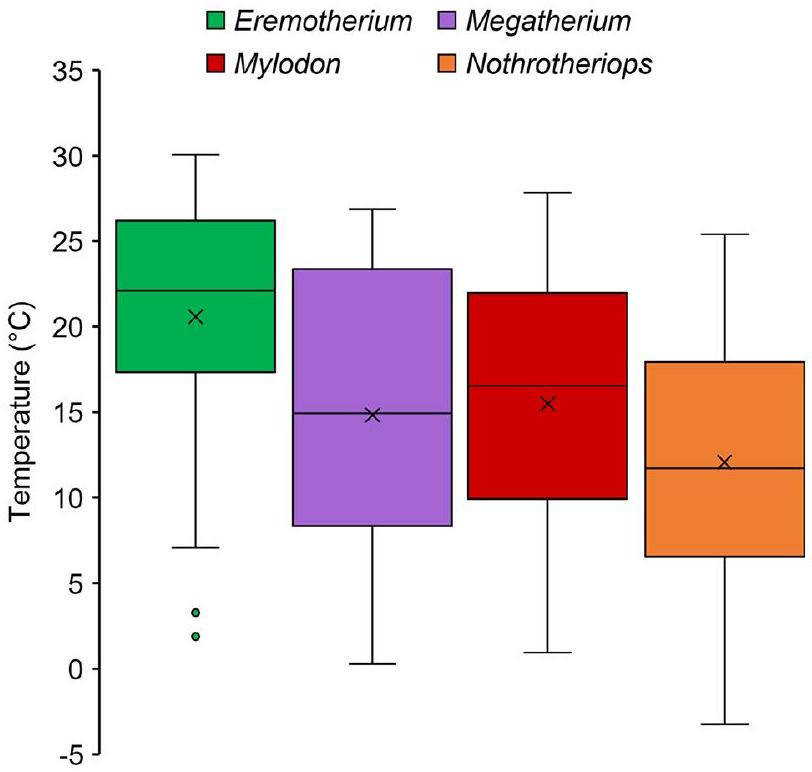

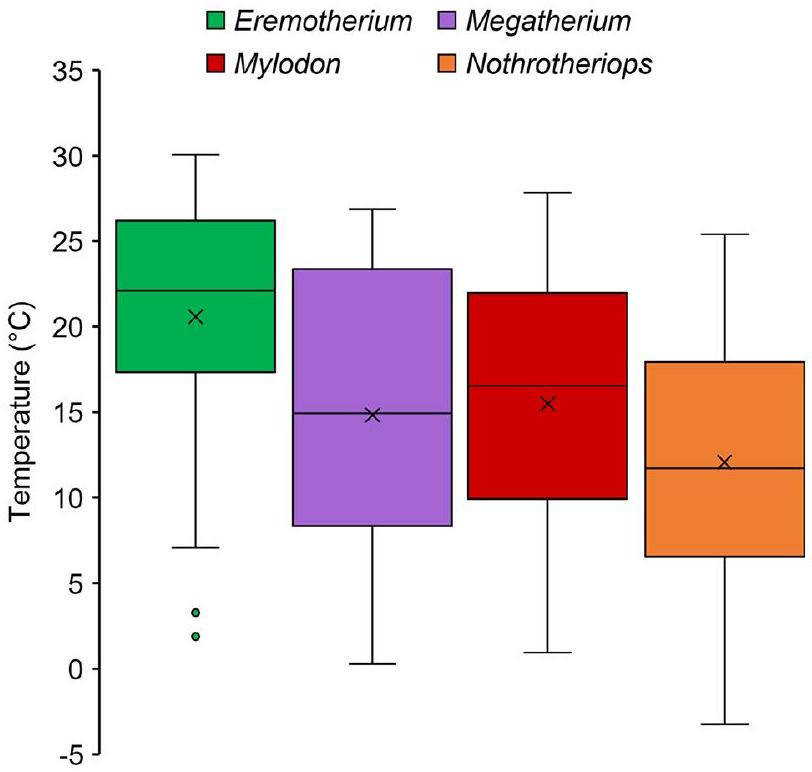

Estimates of paleoclimate and physiological parameters

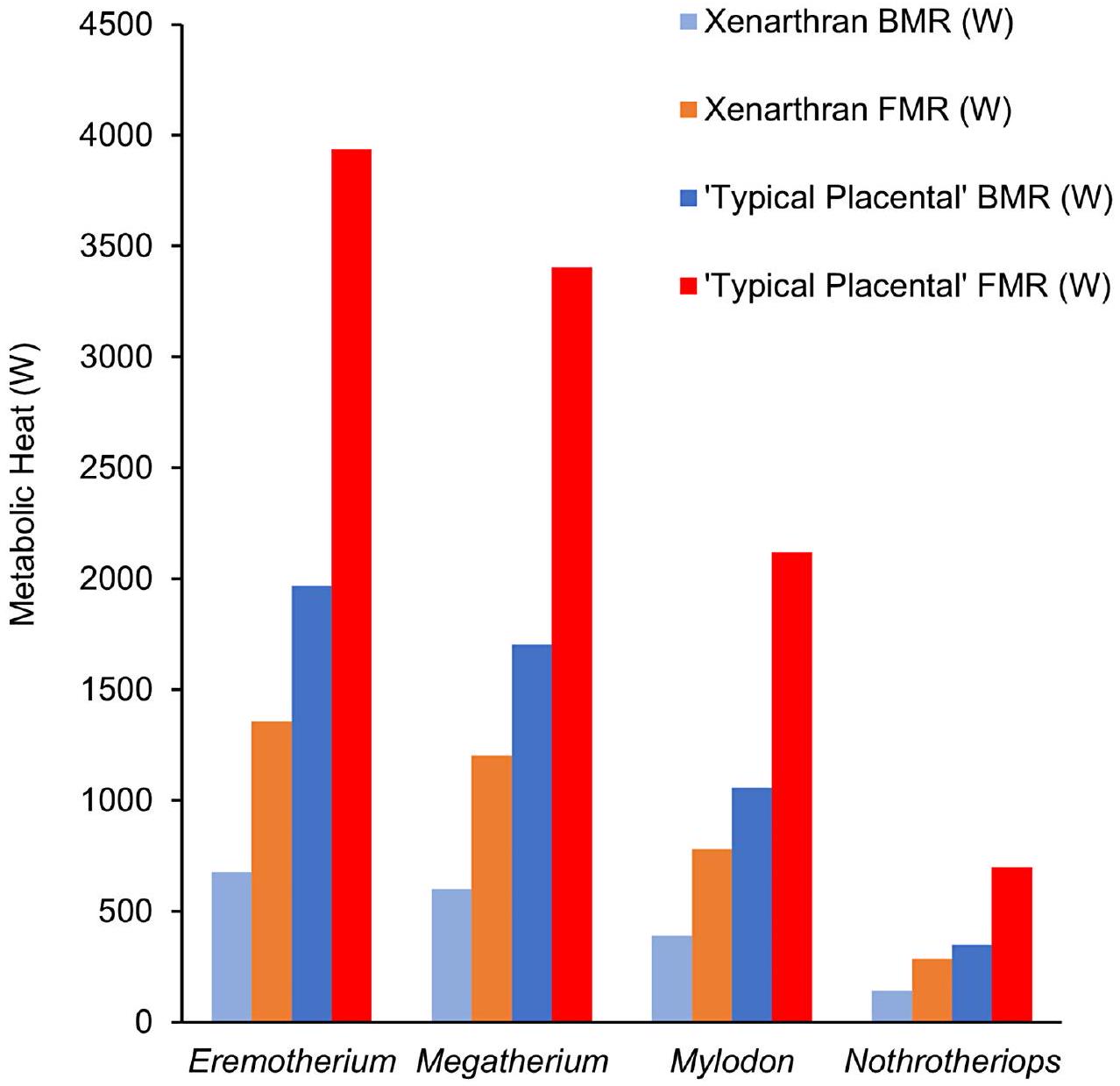

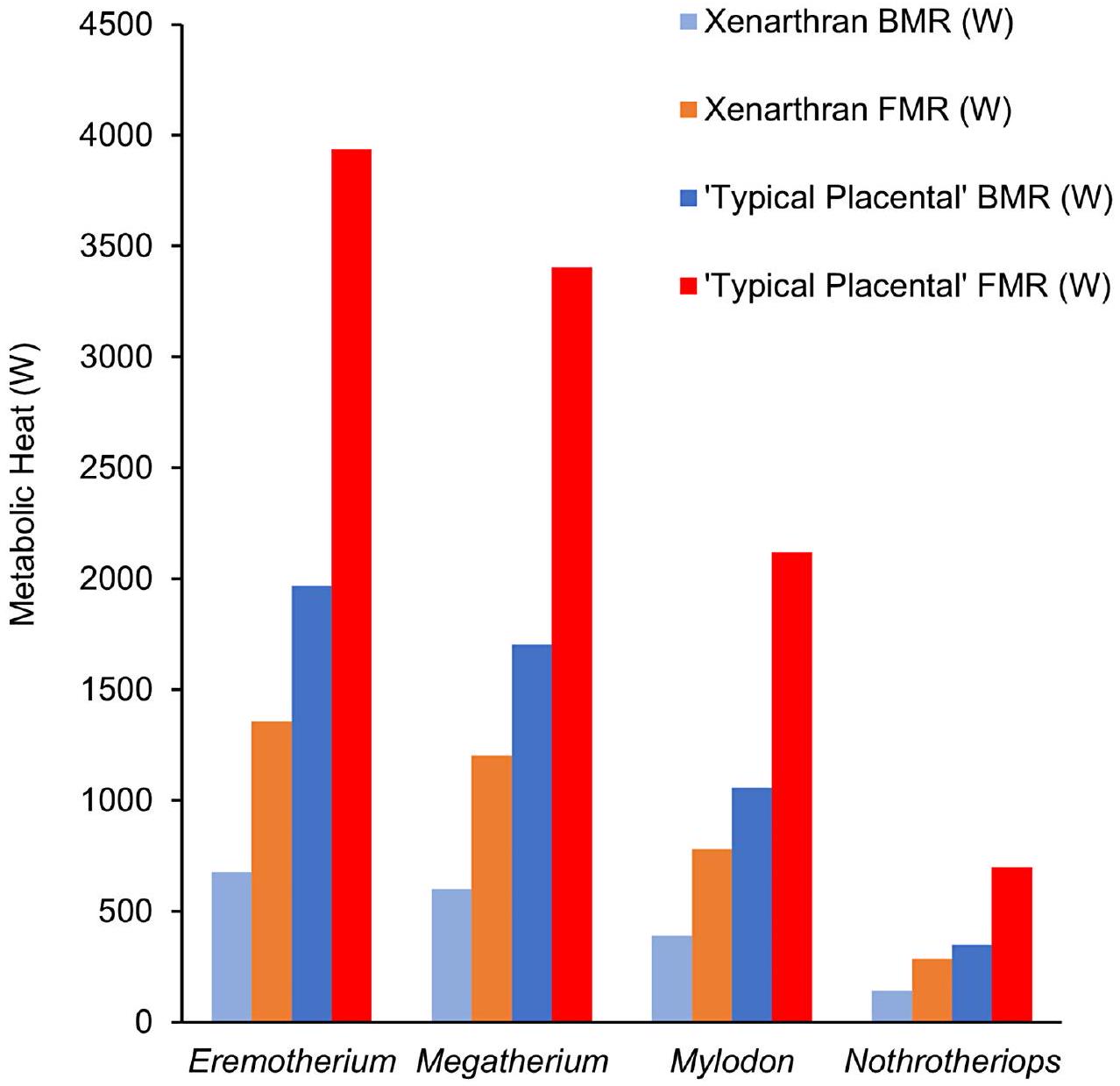

Metabolic chamber simulations and thermoneutral zone ranges

estimates ranging from

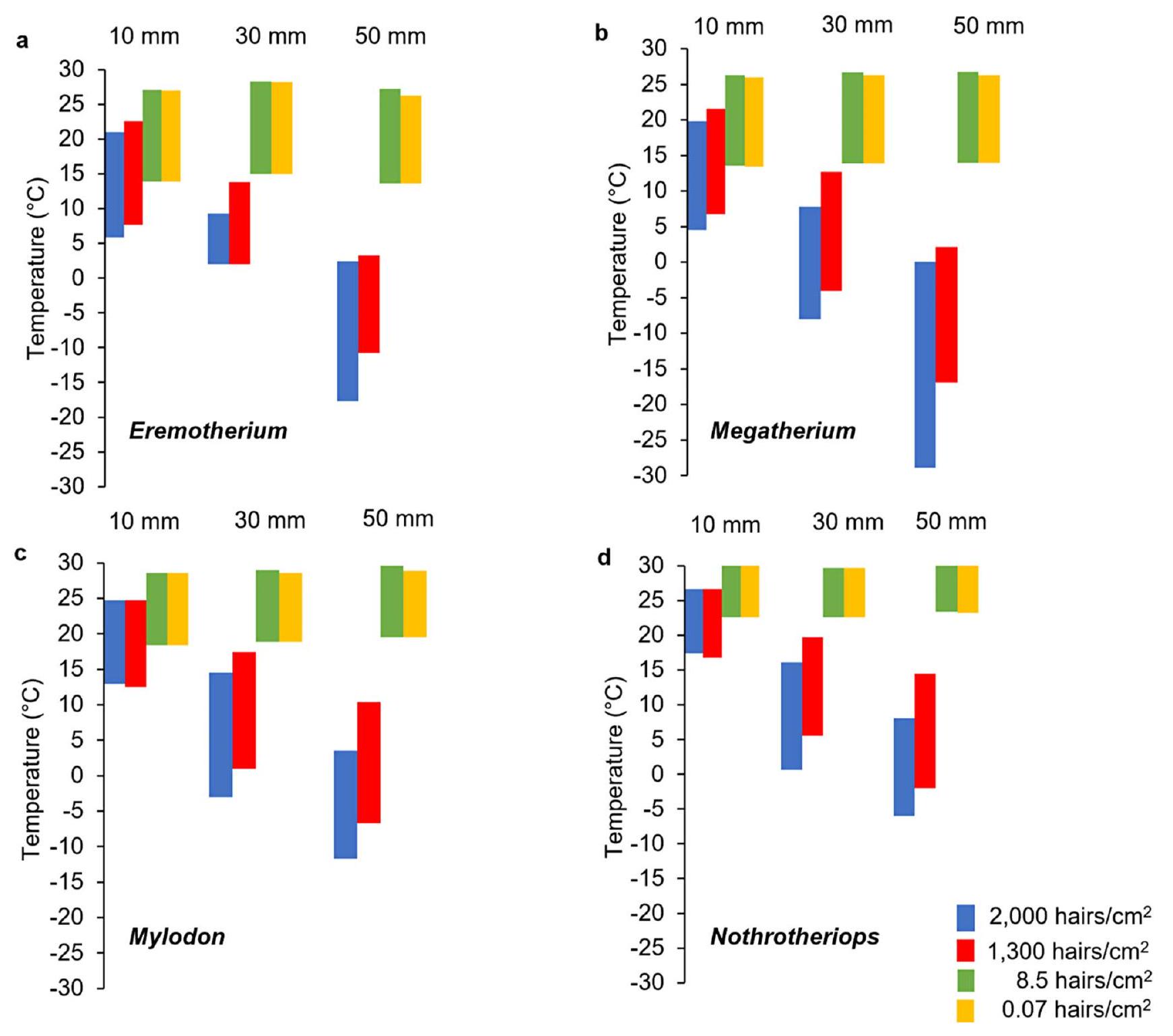

Microclimate simulations and integument thermal tolerances

was modeled to have no thermal stress with 10 mm fur during the warmest months of the year and also with 30 mm fur during the coldest months at northern and mid latitudes (Fig. 6). Both Mylodon at the southernmost extent of its range and Nothrotheriops across its entire geographic range were determined to have no heat stress with dense fur with a coat thickness of 50 mm .

Daily hours of active metabolic expenditure

mid-latitudinal and southern geographic ranges of Megatherium), the greatest number of hours of metabolic activity expended per day (

(Rhinoceros unicornis; for Mylodon), brown bear (Ursus arctos; for Nothrotheriops), Bradypus and Choloepus. Silhouettes were obtained from PhyloPic.org (Michaud M, Taylor J, Keesey M, Morrow C, Jenkins X) and are under public domain (Total hours of activity for extant analogues were based on daily hours of sleep reported in the literature (Stelmock and Dean 1986; Deka and Sarma 2015; Gravett et al. 2017; Cliffe et al. 2023)

Monthly dietary intake

food consumption (

Discussion

Geochemistry of fossil teeth and interpretations of physiology

Comparisons with previous analyses

Megathere thermal neutrality and geographic distribution

the Paleobiology Database (paleobiodb.org). b. Reconstruction of an adult and infant Eremotherium going through seasonal fur shedding while wallowing in a mudhole outside the cave den of an emerging Nothrotheriops in the early spring of Florida during the Pleistocene (location indicated by green circle in panel 9a). c. Reconstruction of Megatherium enduring the cool, windy Pampas of Argentina with a thick fur coat (location indicated by red circle in panel 9a). Paleoart by Haider Syed Jaffri

southernmost extent of its range (Fig. 9a). This hypothesis notably agrees with the absence of Eremotherium in North America during the last glacial maximum.

temperature and wind speed values were the two climatic factors that most strongly influence predicted values of field metabolic rate, whereas the variables of relative humidity and cloud coverage had little effect on simulated metabolism. Thus, dense fur for Megatherium might have been needed to counteract greater exposure to the elements (e.g., wind, rain, or snow) in more open environments (Fig. 9c). This integument condition is reflected in the present climate simulation results which indicate that with a full body coverage of fur at depths of 10 mm , Megatherium would have been constantly cold-stressed regardless of fur density, but it would have complete thermal neutrality in all latitudinal distributions with dense (

Thermoregulation in Mylodon and Nothrotheriops

periods of torpor and/or hibernation as a behavioral means of cold tolerance.

of Mylodon ossicles by Toledo et al. (2021) show no features indicating the storage of adipose tissue akin to those in extant armadillos (Krmpotic et al. 2009). While measurements of the thermal conductance have yet to be performed, Toledo et al. (2021) implied that the fur of mylodontids such as Mylodon would have provided a greater amount of insulation compared to vascularized osteoderms.

Integument and behavioral factors

ungulates such as the American bison (Bison bison) shed their dense winter coat to a lighter, patchy coat that coincides with wallowing behavior (McMillan et al. 2000). Large Megatherium also could have engaged in wallowing but would not have required shedding due to its year-round thermal neutrality when having a dense, deep 30 mm fur coat (Figs. 5 and 6).

megatherines such as Eremotherium and Megatherium (Croft et al. 2020). The largest of the notoungulates were members of the families Toxodontidae, Leontiniidae, and Homalodotheriidae. While toxodontids and macraucheniids lived alongside megatherines through the late Pleistocene (and reached body masses of

Limitations

al. (2010) of acceptable REE index values

during fossilization. While samples were taken from other sections of the fossil teeth used for the geochemical analyses, these were not used due to restrictions of time and funding for this study. Further analyses of these samples could better indicate evidence of a past heterothermic condition as the inner orthodentine could have recorded different isotopic signals, and thus different body temperature estimates.

Conclusions

have needed dense, thick fur supplemented with behavioral thermoregulation to endure cold climates throughout the year. The modeling data also point to surprising adaptability of xenarthran physiology in both the largest and smaller ground sloths. Moreover, the predicted integument models for the largest taxa are believed to be reliable unless refuted by a future specimen with extensive preserved integument. Prospective future models must examine other taxa (e.g., Megalonyx, Thalassocnus, Lestodon, etc.) and include histological studies to help determine how low the basal metabolic rates of ground sloths could have been beneficial, therefore providing further insight into the physiology of these and other fossil xenarthrans and how their metabolic rates impacted their integument appearance, growth rates, ecology, and behavior.

Declarations

References

Anderson NT, Kelson JR, Kele S, Daëron M, Bonifacie M, Horita J, et al (2021) A unified clumped isotope thermometer calibration (

Barbosa FHDS, Alves-Silva L, Liparini A, Porpino KDO (2023) Reviewing the body size of some extinct Brazilian Quaternary xenarthrans. J Quat Sci https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs. 3560

Bargo MS, Vizcaíno SF, Archuby FM, Blanco RE (2000) Limb bone proportions, strength and digging in some Lujanian (Late Pleis-tocene-Early Holocene) mylodontid ground sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra). J Vertebr Paleontol 20(3):601-610. https://doi.org/10 .1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0601:LBPSAD]2.0.CO;2

Bargo MS, De Iuliis G, Vizcaíno SF (2006) Hypsodonty in Pleistocene ground sloths. Acta Paleontol Pol 51(1):53-61.

Bernasconi SM, Daëron M, Bergmann KD, Bonifacie M, Meckler AN, Affek HP et al (2021) InterCarb: A community effort to improve interlaboratory standardization of the carbonate clumped isotope thermometer using carbonate standards. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 22(5):e2020GC009588 https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GC009 588.

Blanco RE, Czerwonogora A (2003) The gait of Megatherium Cuvier 1796. Senckenb Biol 83: 61-68.

Boeskorov GG, Mashchenko EN, Plotnikov VV, Shchelchkova MV, Protopopov AV, Solomonov NG (2016). Adaptation of the woolly mammoth Mammuthus primigenius (Blumenbach, 1799) to habitat conditions in the glacial period. Contemp Probl Ecol 9:54453. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1995425516050024

Brassey CA, Gardiner JD (2015) An advanced shape-fitting algorithm applied to quadrupedal mammals: improving volumetric mass estimates. R Soc Open Sci 2(8):150302. https://doi.org/10.1098 /rsos. 150302

Chavagnac V, Milton JA, Green DRH, Breuer J, Bruguier O, Jacob DE, et al. (2007). Towards the development of a fossil bone geochemical standard: An inter-laboratory study. Anal Chim Acta 599(2):177-190

Christiansen P, Fariña RA (2003) Mass estimation of two fossil ground sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Mylodontidae). Senckenberg Biol 83(1):95-101

Clarke A, Rothery P (2008) Scaling of body temperature in mammals and birds. Funct Ecol 22(1):58-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 136 5-2435.2007.01341.x

Cliffe RN, Haupt RJ, Avey-Arroyo JA, Wilson RP (2015) Sloths like it hot: ambient temperature modulates food intake in the brownthroated sloth (Bradypus variegatus). PeerJ 3:e875. https://doi.o rg/10.7717/peerj. 875

Cliffe RN, Scantlebury DM, Kennedy SJ, Avey-Arroyo J, Mindich D, Wilson RP (2018) The metabolic response of the Bradypus sloth to temperature. PeerJ 6:e5600. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj. 5600

Cliffe RN, Haupt RJ, Kennedy S, Felton C, Williams HJ, Avey-Arroyo J, Wilson R (2023) The behaviour and activity budgets of two sympatric sloths; Bradypus variegatus and Choloepus hoffmanni. PeerJ 11:e15430. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj. 15430

Collins RL (1933) Mylodont (ground sloth) dermal ossicles from Colombia, South America. J Wash Acad Sci 23(9):426-429.

Conte GL, Lopes Le, Mine AH, Trayler RB, Kim SL (2024) SPORA, a new silver phosphate precipitation protocol for oxygen isotope analysis of small, organic-rich bioappatite samples. Chem Geol 65:122000. https://doi.org/10.1016/.chemgeo.2024. 122000

Copploe JV II, Blob RW, Parrish JHA, Butcher MT (2015) In vivo strains in the femur of the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). J Morphol 276:889-899. https://doi.org/10.1002 /jmor. 20387

Croft DA, Gelfo JN, López GM (2020) Splendid innovation: the extinct South American native ungulates. Ann Rev Earth Planet Sci 48:259-290.

Dantas, MAT, Omena ÉC, da Silva JLL, Sial A (2021) Could Eremotherium laurillardi (Lund, 1842) (Megatheriidae, Xenarthra) be an omnivore species? Anu Inst Geocienc 44:1-5. https://doi.org/10. 11137/1982-3908_2021_44_36492

Dantas MAT, Cherkinsky A, Bocherens H, Drefahl M, Bernardes C, de Melo França L (2017) Isotopic paleoecology of the Pleistocene megamammals from the Brazilian Intertropical Region: Feeding ecology (

Deka RJ, Sarma NK (2015) Studies on feeding behaviour and daily activities of Rhinoceros unicornis in natural and captive condition of Assam. Indiana J Anim Res 49(4):542-545.

Delsuc, F, Kuch M, Gibb GC, Karpinski, E, Hackenberger D, Szpak P, Billet G (2019) Ancient mitogenomes reveal the evolutionary history and biogeography of sloths. Curr Biol 29(12):2031-2042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043

Eagle RA, Schauble EA, Tripati AK, Tütken T, Hulbert RC, Eiler JM (2010) Body temperatures of modern and extinct vertebrates from

Eagle RA, Tütken T, Martin TS, Tripati AK, Fricke HC, Connely M, et al (2011) Dinosaur body temperatures determined from isotopic (

Fariña RA (2002) Megatherium, the hairless: appearance of the great Quaternary sloths (Mammalia; Xenarthra). Ameghiniana 39:241-244.

Fariña RA, Blanco RE (1996) Megatherium, the stabber. Proc R Soc B263(1377):1725-1729.

Fariña RA, Vizcaíno SF, Bargo MS (1998) Body mass estimations in Lujanian (late Pleistocene-early Holocene of South America) mammal megafauna. Mastozool Neotrop 5(2):87-108.

Feldhamer GA, Drickamer LC, Vessey SH, Merritt JF, Krajewski C (2007) Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, and Ecology. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Fricke HC, Rogers R (2000) Multiple taxa and multiple locality approach to providing oxygen isotope evidence for endothermic homeothermy in theropod dinosaurs. Geology 28(9):799-802.

Ghosh P, Adkins J, Affek H, Balta B, Guo W, Schauble EA, et al (2006)

González-Bernardo E, Russo LF, Valderrábano E, Fernández Á, Penteriani V (2020) Denning in brown bears. Ecol Evol 10(13):68446862. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6372

Gravett N, Bhagwandin A, Sutcliffe R, Landen K, Chase MJ, Lyamin OI, et al (2017) Inactivity/sleep in two wild free-roaming African elephant matriarchs-Does large body size make elephants the shortest mammalian sleepers? PL oS ONE 12(3):e0171903. https ://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0171903

Green, JL, Kalthoff, DC (2015) Xenarthran dental microstructure and dental microwear analyses, with new data for Megatherium americanum (Megatheriidae). J Mammal 96(4):645-657. https://doi.o rg/10.1093/mammal/gyv045

Griffiths ML, Eagle RA, Kim SL, Flores R, Becker MA, Maisch IV HM, et al (2023) Thermal physiology of extinct megatooth sharks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 120(27):e2218153120. https://d oi.org/10.1073/pnas. 2218153120

Hausman LA (1929) The ovate bodies of the hair of Nothrotherium shastense. Am J Sci 106:331-333.

Hayssen V (2011) Choloepus hoffmanni (Pilosa: Megalonychidae). Mammal Species 43(873):37-55. https://doi.org/10.1644/873.1

Ho TY (1967) Relationship between amino acid contents of mammalian bone collagen and body temperature as a basis for estimation of body temperature of prehistoric mammals. Comp Biochem Physiol 22:113-119.

Holden PB, Edwards NR, Rangel TF, Pereira EB, Tran GT, Wilkinson RD (2019) PALEO-PGEM v1. 0: a statistical emulator of Plio-cene-Pleistocene climate. Geosci Model Dev 12(12):5137-5155. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-5137-2019

Hutchinson JR, Schwerda D, Famini DJ, Dale RH, Fischer MS, Kram R (2006) The locomotor kinematics of Asian and African elephants:

changes with speed and size. J Exp Biol 209(19):3812-3827. http s://doi.org/10.1242/jeb. 02443

Idso SB, Jackson RD (1969) Thermal radiation from the atmosphere. J Geophys Res 74(23):5397-5403.

Jochum KP, Weis U, Schwager B, Stoll B, Wilson SA, Haug GH, et al. (2016). Reference values following ISO guidelines for frequently requested rock reference materials. Geostands Geoanal Res 40(3):333-350.

John CM, Bowen D (2016) Community software for challenging isotope analysis: First applications of ‘Easotope’ to clumped isotopes. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 30:2285-2300. https://doi .org/10.1002/rcm. 7720

Kleiber M (1932) Body size and metabolism. Hilgardia 6(11):315-353.

Knight F, Connor C, Venkataramanan R, Asher R (2020) Body temperatures, life history, and skeletal morphology in the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). PCI Ecol. https://doi.org/10 .17863/CAM. 50971

Kohn MJ, Schoeninger MJ, Barker WW (1999) Altered states: effects of diagenesis on fossil tooth chemistry. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 63(18):2737-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7037(99)0 0208-2

Krmpotic CM, Carlini AA, Galliari FC, Favaron P, Miglino MA, Scarano AC, Barbeito CG (2014). Ontogenetic variation in the stratum granulosum of the epidermis of Chaetophractus vellerosus (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae) in relation to the development of cornified scales. Zoology 117(6):392-397 https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.zool.2014.06.003.

Larmon JT, McDonald HG, Ambrose S, DeSantis LR, Lucero LJ (2019) A year in the life of a giant ground sloth during the Last Glacial Maximum in Belize. Sci Adv 5(2): 1-9. https://doi.org/1 0.1126/sciadv.aau1200

Levesque DL, Marshall KE (2021) Do endotherms have thermal performance curves? J Exp Biol 224(3):jeb141309. https://doi.org/1 0.1242/jeb. 141309

Lovelace DM, Hartman SA, Mathewson PD, Linzmeier BJ, Porter WP (2020) Modeling Dragons: Using linked mechanistic physiological and microclimate models to explore environmental, physiological, and morphological constraints on the early evolution of dinosaurs. PLS ONE 15(5):e0223872. https://doi.org/10.17026/d ans-238-9pjs

MacFadden BJ, DeSantis LR, Hochstein JL Kamenov GD (2010) Physical properties, geochemistry, and diagenesis of xenarthran teeth: prospects for interpreting the paleoecology of extinct species. Paleogeogr Paleoclimatol Paleoecol 291(3-4):180-189. http s://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.02.021

Martin FM (2018) Cueva del Milodón. The hunting grounds of the Patagonian panther. Quat Int 466:212-222. https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.quaint.2016.05.005

McBee K, Baker RJ (1982) Dasypus novemcinctus. Mammal Species 162:1-9.

McCullough EC, Porter WP (1971) Computing clear day solar radiation spectra for the terrestrial ecological environment. Ecology 52:1008-1015.

McDonald HG (2022) Paleoecology of the Eextinct Shasta Ground Sloth, Nothrotheriops shastensis (Xenarthra, Nothrotheridae): The Physical environment. N M Mus Nat Sci Bull 88:33-43

McDonald HG, Lundelius Jr EL (2009) The giant ground sloth Eremotherium laurillardi (Xenarthra. Megatheriidae) in Texas. Bull Mus North Ariz 65:407-421.

McKamy AJ, Young MW, Mossor AM, Young, JW, Avey-Arroyo JA, Granatosky MC, Butcher MT (2023) Pump the Brakes! The hindlimbs of three-toed sloths control suspensory locomotion. J Exp Biol 226(8):jeb245622. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb. 245622

McMillan BR, Cottam MR, Kaufman DW (2000) Wallowing behavior of American bison (Bison bison) in tallgrass prairie: an examination of alternate explanations. Am Mid Nat 144(1):159-167.

McNab, BK (1985) Energetics, population biology, and distribution of xenarthrans, living and extinct. In: Montgomery GG (ed) The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. pp 219-232.

Mine AH, Waldeck A, Olack G, Hoerner ME, Alex S, Colman AS (2017) Microprecipitation and

Mitchell D, Snelling EP, Hetem RS, Maloney SK, Strauss WM, Fuller A (2018) Revisiting concepts of thermal physiology: predicting responses of mammals to climate change. J Anim Ecol 87(4):956-973. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12818

Myhrvold CL, Stone HA, Bou-Zeid E (2012) What is the use of elephant hair? PL oS ONE 7:e47018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journa 1.pone. 0047018

Naples VL (1990) Morphological changes in the facial region and a model of dental growth and wear pattern development in Nothrotheriops shastensis. J Vert Paleontol 10(3):372-389.

Nehme C, Todisco D, Breitenbach SF, Couchoud I, Marchegiano M, Peral M, et al (2022) Holocene hydroclimate variability along the Southern Patagonian margin (Chile) reconstructed from Cueva Chica speleothems. Glob Planet Change 222:104050. https://do i.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2023.104050

Pant SRA, Goswami A, Finarelli JA (2014) Complex body size trends in the evolution of sloths (Xenarthra: Pilosa). BMC Evol Biol 14:184. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-014-0184-1

Pauli JN, Peery MZ, Fountain ED, Karasov WH (2016) Arboreal folivores limit their energetic output, all the way to slothfulness. Am Nat 188(2):196-204.

Poinar HN, Hofreiter M, Spaulding WG, Martin PS, Stankiewicz BA, Bland H, Evershed RP, Possnert G, Paabo S (1998) Molecular coproscopy: dung and diet of the extinct ground sloth Nothrotheriops shastensis. Science 128(5375):402-406.

Presslee S, Slater GJ, Pujos F, Forasiepi AM, Fischer R, Molloy K, et al. (2019). Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships. Nat Ecol Evol 3(7):1121-1130. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-019-0 909-z

Prevosti FJ, Martin FM (2013) Paleoecology of the mammalian predator guild of Southern Patagonia during the latest Pleistocene: ecomorphology, stable isotopes, and taphonomy. Quat Int 305:74-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2012.12.039

Ridewood WG (1901). On the structure of the hairs of Mylodon listai and other South American Edentata. J Cell Sci 2(175):393-411. h ttps://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.s2-44.175.393

Santos LE, Ajala-Batista L, Carlini AA, de Araujo Monteiro-Filho EL (2024) Mylodon darwinii (Owen, 1840): hair morphology of an extinct sloth. Zoomorphology 2024:1-9.

Seitz VP, Puig S (2018) Aboveground activity, reproduction, body temperature and weight of armadillos (Xenarthra, Chlamyphoridae) according to atmospheric conditions in the central Monte (Argentina). Mammal Biol 88:43-51.

Seymour R S, Hu Q, Snelling E P, White C R (2019). Interspecific scaling of blood flow rates and arterial sizes in mammals. J Exp Biol 222(7):jeb199554. https://doi.org/10.1242/Jen. 199554

Stears K, McCauley DJ, Finlay JC, Mpemba J, Warrington IT, Mutayoba BM, et al (2018) Effects of the hippopotamus on the chemistry and ecology of a changing watershed. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 115(22):E5028-E5037. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 1800407115

Stelmock J, Dean FC (1986) Brown bear activity and habitat use, Denali National Park-1980. Int Conf Bear Res Manag 6:155-167.

Suárez MB, Passey BH (2014) Assessment of the clumped isotope composition of fossil bone carbonate as a recorder of subsurface temperatures. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 140:142-159. https:/ dol.org/10.1016|)- gca.2014.05.026

Sunquist ME, Montgomery GG (1973) Activity patterns and rates of movement of two-toed and three-toed sloths (Choloepus hoffmanni and Bradypus infuscatus). J Mammal 54(4):946-954.

Superina M, Abba AM (2014) Zaedyus pichiy (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mammal Species 46(905):1-10. https://doi.org/10.1644/90 5.1

Tagliavento M, Davies AJ, Bernecker M, Staudigel PT, Dawson RR, Dietzel M, et al (2023) Evidence for heterothermic endothermy and reptile-like eggshell mineralization in Troodon, a non-avian maniraptoran theropod. Proc Natl Acad Sci 120(15):e2213987120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas. 2213987120

Taube E, Vié JC, Fournier P, Genty C, Duplantier JM (1999) Distribution of two sympatric species of sloths (Choloepus didactylus and Bradypus tridactylus) along the Sinnamary River, French Guiana 1. Biotropica 31(4):686-691.

Tejada JV, Antoine PO, Münch P, Billet G, Hautier L, Delsuc F, Condamine FL (2024) Bayesian total-evidence dating revisits sloth phylogeny and biogeography: a cautionary tale on morphological clock analyses. Syst Biol 73(1):125-139. https://doi.org/10.1093 /sysbio/syad069

Toledo N, Boscaini A, Pérez LM (2021) The dermal armor of mylodontid sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from Cueva del Milodon (Ultima Esperanza, Chile). J Morphol 282(4):612-627. https://do i.org/10.1002/jmor. 21333

Tregear RT (1965) Hair density, wind speed, and heat loss in mammals. J Appl Physiol 20(4):796-801.

Varela L, Clavijo L, Tambusso PS, Fariña RA (2023). A window into a late Pleistocene megafauna community: Stable isotopes show niche partitioning among herbivorous taxa at the Arroyo del Vizcaíno site (Uruguay). Quat Sci Rev 317:108286. https://doi.org/1 0.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108286

Wang Y, Porter WP, Mathewson PD, Miller PA, Graham RW, Williams JW (2018) Mechanistic modeling of environmental drivers of

woolly mammoth carrying capacity declines on St. Paul Island. Ecology 99(12):2721-2730. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy. 2524

Wang Y, Widga C, Graham RW, McGuire JL, Porter WP, D. Wårlind, D, Williams JW (2020) Caught in a bottleneck: Habitat loss for woolly mammoths in central North America and the ice-free corridor during the last deglaciation. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 30(2):527542. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb. 13238