DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09047-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40468063

تاريخ النشر: 2025-06-04

يؤدي الاحترار إلى تسريع شدة الجفاف العالمي

تاريخ القبول: 18 أبريل 2025

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 4 يونيو 2025

الوصول المفتوح

تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

يعتبر الجفاف من أكثر المخاطر الطبيعية شيوعًا وتعقيدًا التي تؤثر على البيئة والاقتصادات والسكان على مستوى العالم

شدة الجفاف

اتجاهات الجفاف العالمية

حوالي 50 كم)، تغطي الفترة من 1950 إلى 2022 ومن 1901 إلى 2022، على التوالي. من خلال دمج مجموعات بيانات متعددة وفترات زمنية مختلفة، نهدف إلى التقاط نطاق أوسع من عدم اليقين المحتمل في بيانات القوة وتقديم تقييم أكثر شمولاً لأنماط الجفاف. من خلال استخدام AED المناخي وهطول الأمطار، قمنا بتطوير مجموعات بيانات مكافئة تمكننا من قياس مساهمات تغييرات AED وهطول الأمطار في اتجاه SPEI، فضلاً عن تكرار ومدة وشدة أحداث الجفاف. هنا نركز على SPEI لمدة 6 أشهر، حيث إنه يلتقط ظروف الجفاف السائدة على المدى القصير إلى المتوسط.

محركات التغيرات في الجفاف

الاتجاه في المناطق المتأثرة بالجفاف بناءً على هطول الأمطار الملحوظ و AEDclm هو

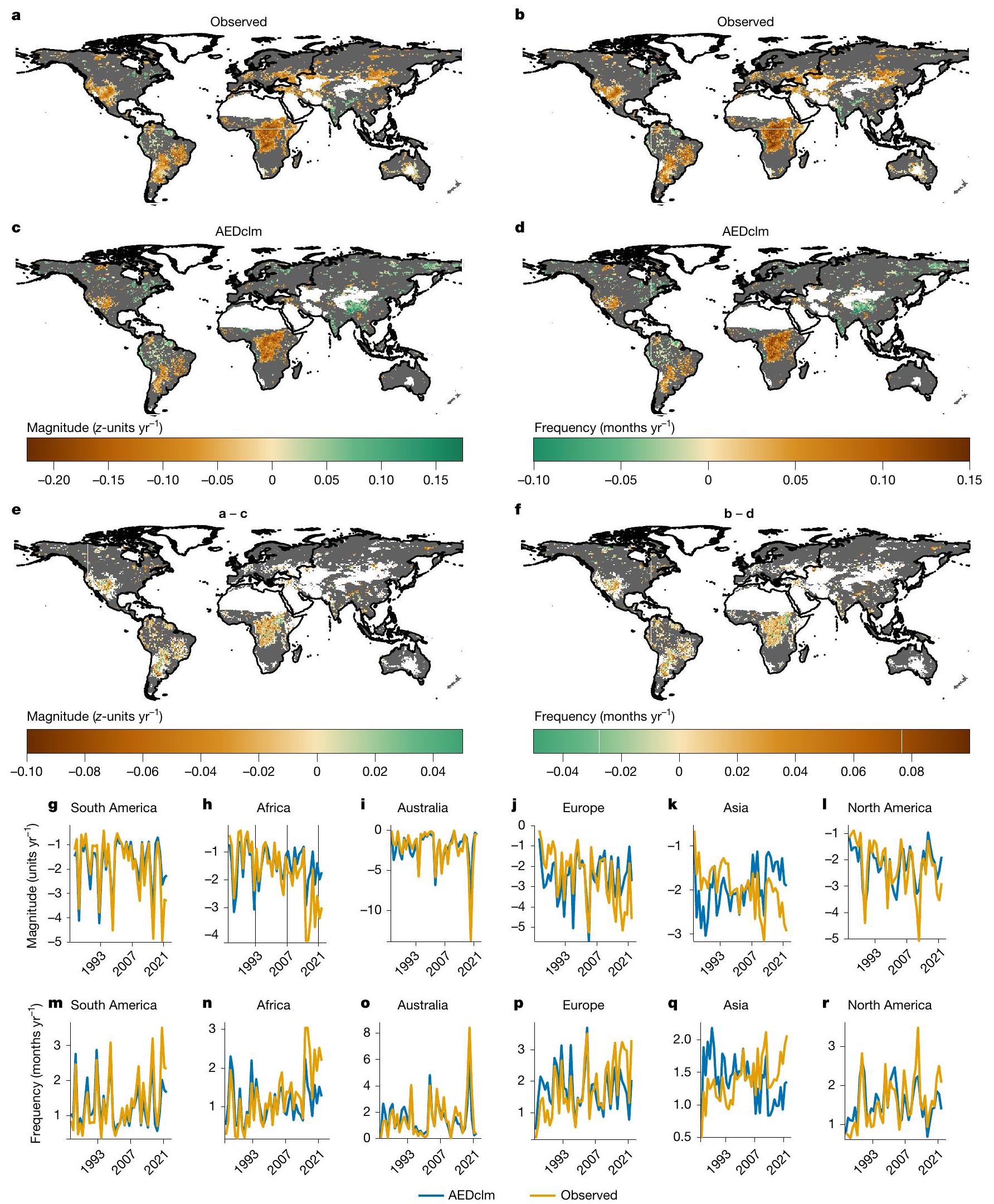

لقد زادت التغيرات الملحوظة في AED أيضًا من شدة وتكرار الجفاف على مستوى العالم (الشكل 2). مقارنةً بـ AEDcIm، تُظهر الاتجاهات الملحوظة شدة جفاف أكثر سلبية (حتى

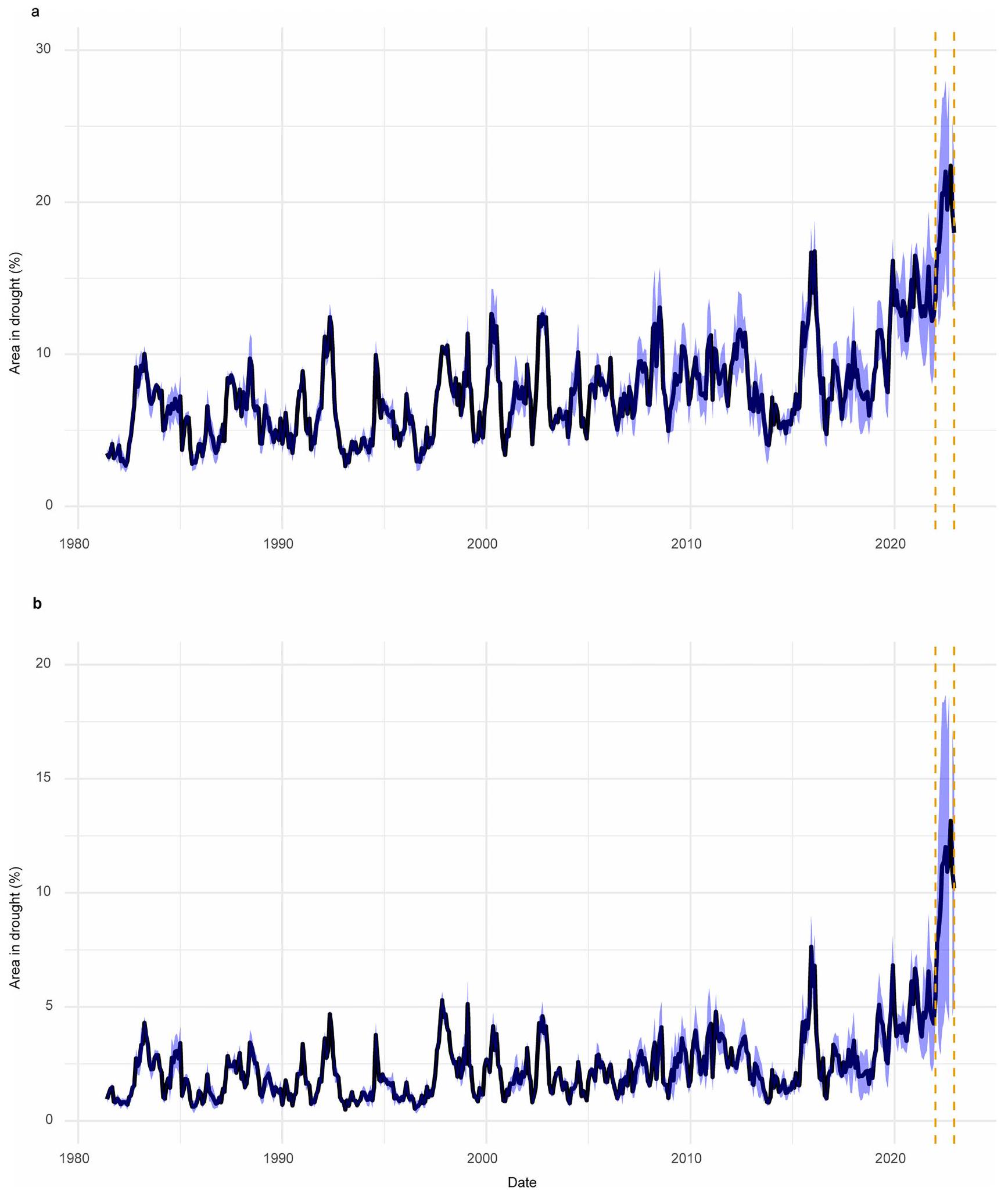

1981-2022. أ، المتوسط شبه العالمي (

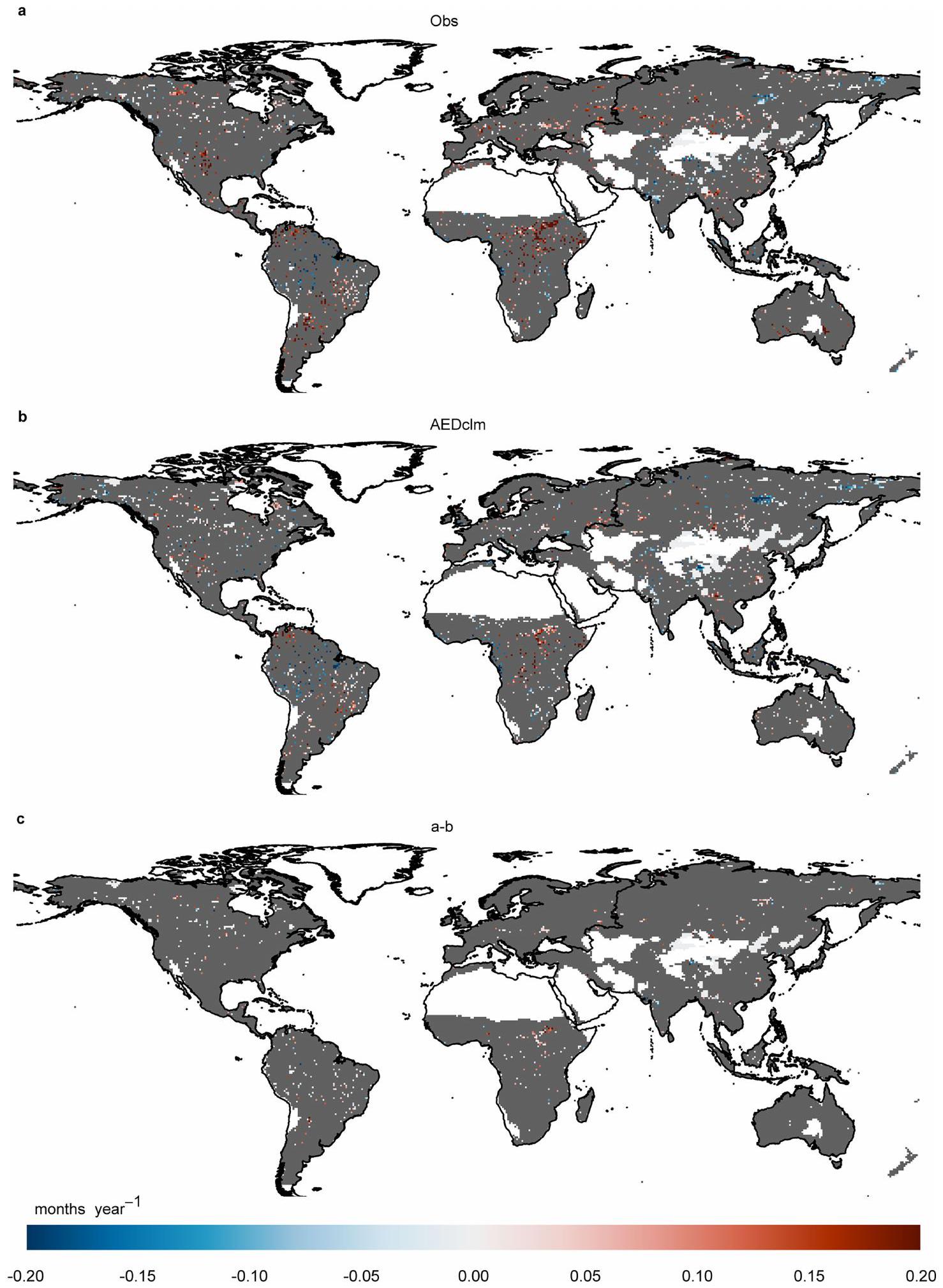

الملاحظات (هطول الأمطار الملاحظ و AED) و SPEI بناءً على هطول الأمطار الملاحظ والمناخ لـ AED (AEDclm). ج، الفرق في الاتجاه بين SPEI بناءً على الملاحظات و SPEI بناءً على AED الملاحظ والمناخ لهطول الأمطار (Prclm). الاتجاهات غير المهمة (

التردد ( -0.02 شهر

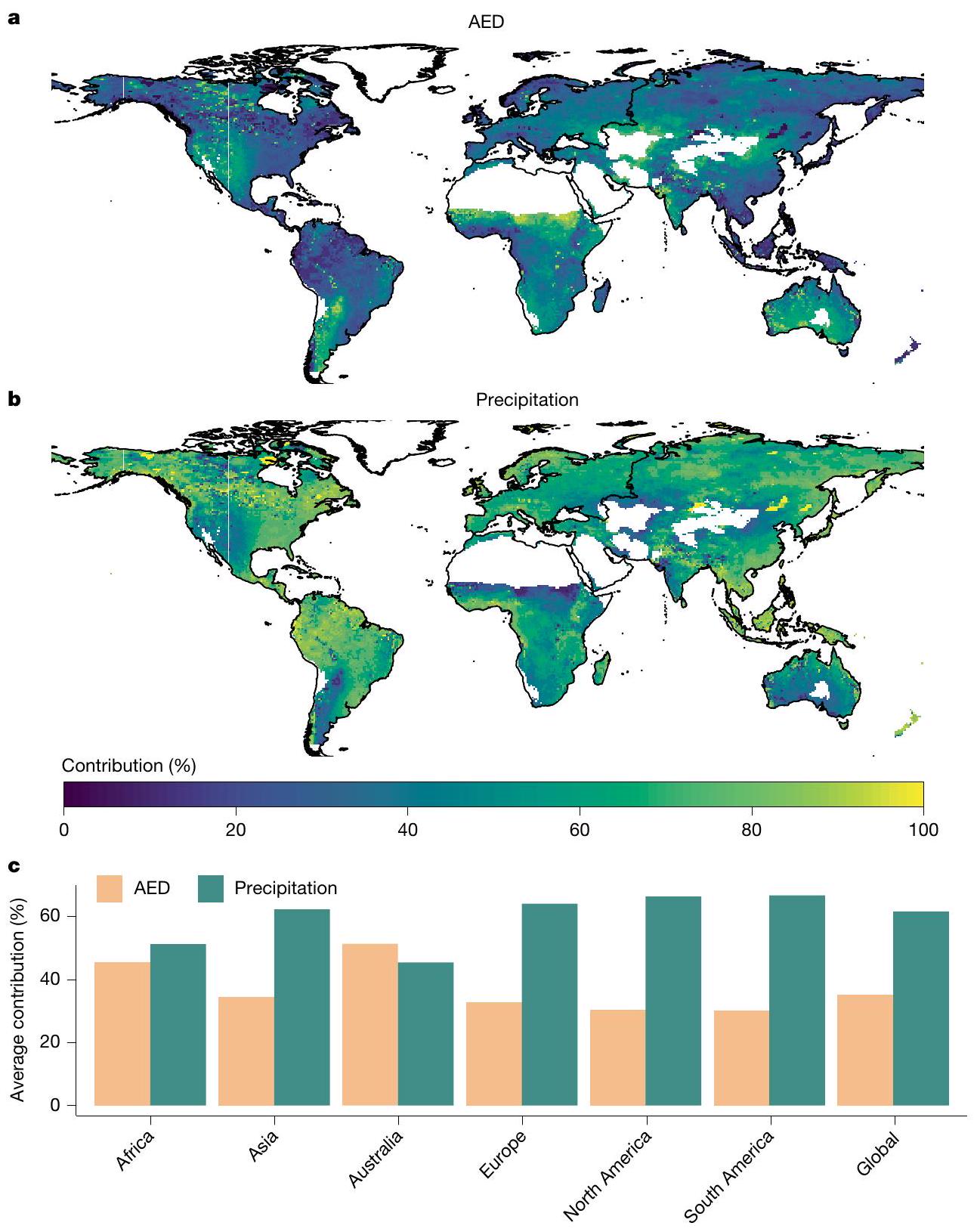

مساهمة AED في اتجاهات الجفاف في أمريكا الشمالية والجنوبية، وأوروبا، وآسيا حوالي

تسارع الجفاف

أكبر من AEDcIm. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كان متوسط SPEI -0.85 وحدة

نقاش

تعويض الزيادة الكبيرة في درجة الحرارة. وقد اقترحت بعض الدراسات الحديثة أيضًا زيادة في شدة أحداث الجفاف على مساحات شاسعة من الأراضي استنادًا إلى مقاييس مثل رطوبة التربة المحاكاة.

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

9. غريف، ب.، غودموندسون، ل. وسينيفيراتني، س. آي. القياس الإقليمي لمتوسط هطول الأمطار السنوي وتوافر المياه مع تغير درجة الحرارة العالمية. ديناميات نظام الأرض 9، 227-240 (2018).

10. غريف، ب.، رودريك، م. ل. وسينيفيراتني، س. أ. التغيرات المحاكاة في الجفاف من الحد الأقصى الجليدي الأخير إلى 4xCO2. رسائل البحث البيئي 12، 114021 (2017).

11. بادرو، ر. س. وآخرون. التغيرات الملحوظة في توفر المياه خلال موسم الجفاف المنسوبة إلى التغير المناخي الناتج عن الأنشطة البشرية. نات. جيوسي. 13، 477-481 (2020).

12. ماهيتشا، م. د. وآخرون. فقدان التنوع البيولوجي والظواهر المناخية المتطرفة – دراسة التفاعلات. ناتشر 612، 30-32 (2022).

13. سيني فيراتني، س.إ. وآخرون. أحداث الطقس والمناخ المتطرفة في مناخ متغير. في تغير المناخ 2021: الأساس العلمي الفيزيائي. مساهمة مجموعة العمل الأولى في التقرير التقييمي السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ (تحرير ماسون-ديلموتي، ف. وآخرون) الفصل 11، 1513-1766 (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، كامبريدج، 2021)؛https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.013.

14. زو، ب. وآخرون. الاحترار يقلل من الإنتاج الزراعي العالمي من خلال تقليل تكرار الزراعة والمحاصيل. نات. مناخ. تغيير 12، 1016-1023 (2022).

15. باومان، د. وآخرون. زادت وفيات الأشجار الاستوائية مع ارتفاع ضغط المياه في الغلاف الجوي. ناتشر 608، 528-533 (2022).

16. كيكسترا، ج. وآخرون. تقرير التقييم السادس للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ WGIII تقييم المناخ لمسارات التخفيف: من الانبعاثات إلى درجات الحرارة العالمية. EGUspherehttps://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2022-471 (2022).

17. فيسنتي-سيرانو، س. م. وآخرون. الاتجاهات العالمية للجفاف والتوقعات المستقبلية. فيل. ترانس. ر. سوس. رياضيات. فيزيائية. هندسية. علوم. 380، 20210285 (2022).

18. دوفيلي، هـ. وويليت، ك. م. مستقبل أكثر جفافًا مما كان متوقعًا، مدعومًا بملاحظات الرطوبة النسبية القريبة من السطح. ساينس أدفانس 9، eade6253 (2023).

19. داي، أ. زيادة الجفاف تحت الاحترار العالمي في الملاحظات والنماذج. نات. مناخ. تغيير 3، 52-58 (2013).

20. تقرير التقييم الشامل لتغير المناخ 2014 (تحرير فريق الكتابة الأساسي، باتشوري، ر. ك. وماير، ل. أ.) (الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ، 2014).

21. ألين، سي. دي.، بريشيرز، دي. دي. ومكدوال، إن. جي. حول التقليل من تقدير الضعف العالمي تجاه موت الأشجار وموت الغابات بسبب الجفاف الأكثر حرارة في الأنثروبوسين. إيكوسفير 6، 129 (2015).

22. بيرغ، أ. وشيفيلد، ج. تغير المناخ والجفاف: منظور رطوبة التربة. تقارير تغير المناخ الحالية 4، 180-191 (2018).

23. كوك، ب. آي. وآخرون. توقعات الجفاف في القرن الحادي والعشرين في سيناريوهات الضغط CMIP6. مستقبل الأرض 8، e2019EF001461 (2020).

24. غاريدو-بيريز، ج. م. وآخرون. دراسة الجفاف البارز في منطقة اليورو-المتوسط لعام 2021-2022 وسياقه التاريخي. مجلة الهيدرولوجيا 630، 130653 (2024).

25. بيفاكوا، إ. وآخرون. أثرت تأثيرات تغير المناخ المباشرة والمتأخرة على جفاف أوروبا في عام 2022. نات. جيوساي. 17، 1100-1107 (2024).

26. تقرير الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بتغير المناخ 2022: الآثار، التكيف، والضعف (تحرير بورتنر هـ.-أو. وآخرون) (مطبعة جامعة كامبريدج، 2022).

27. كينغستون، د. ج.، تود، م. س.، تايلور، ر. ج.، طومسون، ج. ر. وأرنيل، ن. و. عدم اليقين في تقدير التبخر المحتمل تحت تغير المناخ. رسائل أبحاث الجيوفيزياء 36، L20403 (2009).

28. فان دير شراير، ج.، باريتشيفيتش، ج.، بريفا، ك. ر. وجونز، ب. د. مجموعة بيانات عالمية قائمة على scPDSI لفترات الجفاف والرطوبة من 1901 إلى 2009. مجلة أبحاث الجيوفيزياء. أتموس. 118، 4025-4048 (2013).

29. بيك، هـ. إ. وآخرون. تقييم عالمي لـ 22 مجموعة بيانات هطول الأمطار باستخدام ملاحظات القياس والنمذجة الهيدرولوجية. علوم الأرض والهيدرولوجيا 21، 6201-6217 (2017).

30. Gebrechorkos، S. H. وآخرون. تقييم عالمي لمجموعات بيانات الهطول لنمذجة الهيدرولوجيا. علوم الأرض والهيدرولوجيا 28، 3099-3118 (2024).

31. فيسنتي-سيرانو، س. م.، بيغويريا، س. و لوبيز-مورينو، ج. I. مؤشر جفاف متعدد المقاييس حساس للاحتباس الحراري: مؤشر التبخر والنتح المطري الموحد. مجلة المناخ 23، 1696-1718 (2010).

32. توماس-بورغويرا، م. وآخرون. التوصيف العالمي للاستجابات المتنوعة لمؤشر التبخر-النتح القياسي للطلب التبخيري الجوي. مجلة أبحاث الغلاف الجوي، 125، e2020JD033017 (2020).

33. هايل، ج. ج. وآخرون. التغير الزمني والمكاني طويل الأمد لأنماط الجفاف في منطقة القرن الأفريقي الكبرى. العلوم. البيئة الكلية 704، 135299 (2020).

34. كامروززمان، م. وآخرون. تحليل الجفاف الزماني والمكاني في بنغلاديش باستخدام مؤشر هطول الأمطار المعياري (SPI) ومؤشر تبخر هطول الأمطار المعياري (SPEI). تقارير علمية 12، 20694 (2022).

35. سبينوني، ج. وآخرون. النقاط الساخنة المستقبلية للجفاف الميتورولوجي العالمي: دراسة مستندة إلى بيانات CORDEX. مجلة المناخ 33، 3635-3661 (2020).

36. وانغ، تي، تو، إكس، سينغ، في. بي، تشين، إكس. ولين، ك. تقييم وتحليل البيانات العالمية لخصائص الجفاف استنادًا إلى CMIP6. مجلة الهيدرولوجيا 596، 126091 (2021).

37. سبينوني، ج. وآخرون. قاعدة بيانات عالمية جديدة لأحداث الجفاف المناخي من 1951 إلى 2016. مجلة الدراسات الإقليمية للهيدرولوجيا 22، 100593 (2019).

38. بيغويريا، س.، فيسنتي-سيرانو، س. م.، ريج، ف. ولاتور، ب. إعادة النظر في مؤشر تبخر-تعرق الأمطار الموحد (SPEI): ملاءمة المعلمات، نماذج التبخر-تعرق، الأدوات، مجموعات البيانات ومراقبة الجفاف. المجلة الدولية لعلم المناخ 34، 3001-3023 (2014).

39. وانغ، ق. وآخرون. الخصائص الزمنية والمكانية لأحداث الجفاف الشديدة وتأثيرها على الزراعة على نطاق عالمي. كوات. إنترن. 349، 10-21 (2014).

40. فنك، سي. وآخرون. سجلات المناخ للأمطار بالأشعة تحت الحمراء مع المحطات – سجل بيئي جديد لرصد الظروف المتطرفة. بيانات العلوم 2، 150066 (2015).

41. بيك، هـ. إ. وآخرون. MSWEP V2 العالمية كل 3 ساعات

42. ميرانيس، د. ج. وآخرون. GLEAM4: مجموعة بيانات تبخر المياه من اليابسة ورطوبة التربة على مستوى

43. سينجر، م. ب. وآخرون. التبخر المحتمل الساعي عند

44. داي، أ. وزهاو، ت. عدم اليقين في التغيرات التاريخية والتوقعات المستقبلية للجفاف. الجزء الأول: تقديرات التغيرات التاريخية للجفاف. تغير المناخ 144، 519-533 (2017).

45. سونغ، إكس، سونغ، واي وتشين، واي. الاتجاه العلماني للجفاف العالمي منذ 1950. رسائل البحث البيئي 15، 094073 (2020).

46. علي زاده، م. ر. وآخرون. الاحترار مكن التقدم في حرائق الغابات في غرب الولايات المتحدة. إجراءات الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة 118، e2009717118 (2021).

47. باخماير، س.، تانغوي، م.، هانا فورد، ج. وستال، ك. إلى أي مدى تمثل المؤشرات الجوية الجفاف الزراعي والغابات عبر أوروبا؟ رسائل البحث البيئي 13، 034042 (2018).

48. ناومان، ج. وآخرون. التغيرات العالمية في ظروف الجفاف تحت مستويات مختلفة من الاحترار. رسائل البحث الجيوفيزيائي 45، 3285-3296 (2018).

ترخيص دولي 4.0، الذي يسمح بالاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو تنسيق، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد تم إجراؤها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في خط ائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، فستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

ترخيص دولي 4.0، الذي يسمح بالاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو تنسيق، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد تم إجراؤها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في خط ائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، فستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.© المؤلفون 2025

طرق

مؤشر الجفاف

مجموعات بيانات المناخ العالمية و AED

حتى الآن

تعتبر hPET مجموعة بيانات عالمية للطلب على التبخر المحتمل AED تم تطويرها باستخدام مجموعات بيانات المناخ ERA5 ومعادلة بنمان-مونتيث التابعة لمنظمة الأغذية والزراعة (FAO) (المعادلة (1)). hPET متاحة لسطح الأرض العالمي بدقة

سطح الأرض العالمي (الشكل التمديدي 9b)، ومتوسط الفرق الشهري بينهما يصل إلى

الطلب على التبخر الجوي

تحليل الاتجاه

توفر البيانات

من خلال مركز تحليل بيانات البيئة (CEDA) على https:// doi.org/10.5285/ac43da11867243a1bb414e1637802dec وعلى JASMIN على/badc/hydro-jules/data/Global_drought_indices. يمكن الوصول إلى بيانات CHIRPS عبر مجموعة مخاطر المناخ (CHG) على https://www. chc.ucsb.edu/data/chirps/ (المرجع 40). مجموعة بيانات هطول الأمطار MSWEP متاحة من موقع GloH2O على https://www.gloh2o.org/ mswep/ (المرجع 41). مجموعة بيانات hPET مستضافة من قبل جامعة بريستول على https://data.bris.ac.uk/data/dataset/qb8ujazzda0s2aykkv0oq0ctp (المرجع 43). يمكن الوصول إلى بيانات AED من GLEAM على https://www. gleam.eu/ (المرجع 42). تتوفر مجموعات بيانات هطول الأمطار و AED من CRU-TS من خلال CEDA على https://data.ceda.ac.uk/badc/cru/data/ cru_ts/cru_ts_4.08/(المرجع 50). مجموعة بيانات ERA5 متاحة للتنزيل من متجر بيانات المناخ لخدمة تغير المناخ كوبيرنيكوس على https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets (المرجع 51).

توفر الكود

49. أغنيو، سي. تي. استخدام SPI لتحديد الجفاف. أخبار شبكة الجفاف 1994-2001 (مركز معلومات الجفاف الدولي ومركز التخفيف من آثار الجفاف، كلية الموارد الطبيعية، جامعة نبراسكا – لينكولن، 2000).

50. هاريس، آي.، أوزبورن، تي. جي.، جونز، بي. وليستر، دي. الإصدار 4 من مجموعة بيانات المناخ الشهرية عالية الدقة CRU TS. بيانات Sci. 7، 109 (2020).

51. هيرسباخ، إتش. وآخرون. إعادة التحليل العالمية ERA5. كوارتر. ج. ر. جمعية الأرصاد الجوية 146، 1999-2049 (2020).

52. جيبريتشوركوس، إس. إتش. وآخرون. مؤشرات الجفاف العالمية عالية الدقة للفترة من 1981 إلى 2022. بيانات علوم الأرض 15، 5449-5466 (2023).

53. جيبريتشوركوس، إس. إتش. solomonsg/Globdrought: حساب مؤشرات الجفاف والاتجاهات. زينودو https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 15073433 (2025).

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى سليمان هـ. جبرخوركوس. معلومات مراجعة الأقران تشكر Nature المراجعين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة الأقران لهذا العمل. تقارير مراجعي الأقران متاحة.

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints.

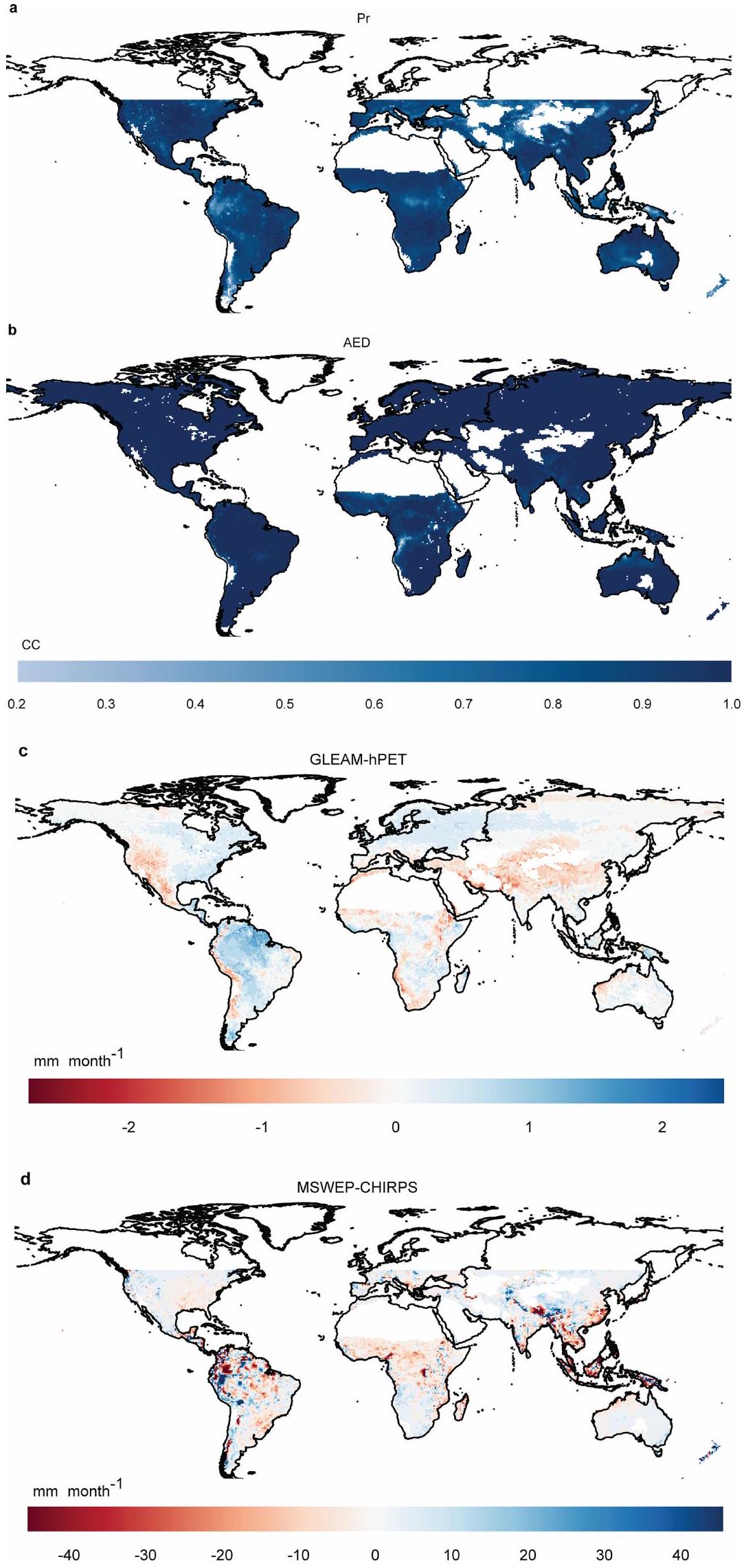

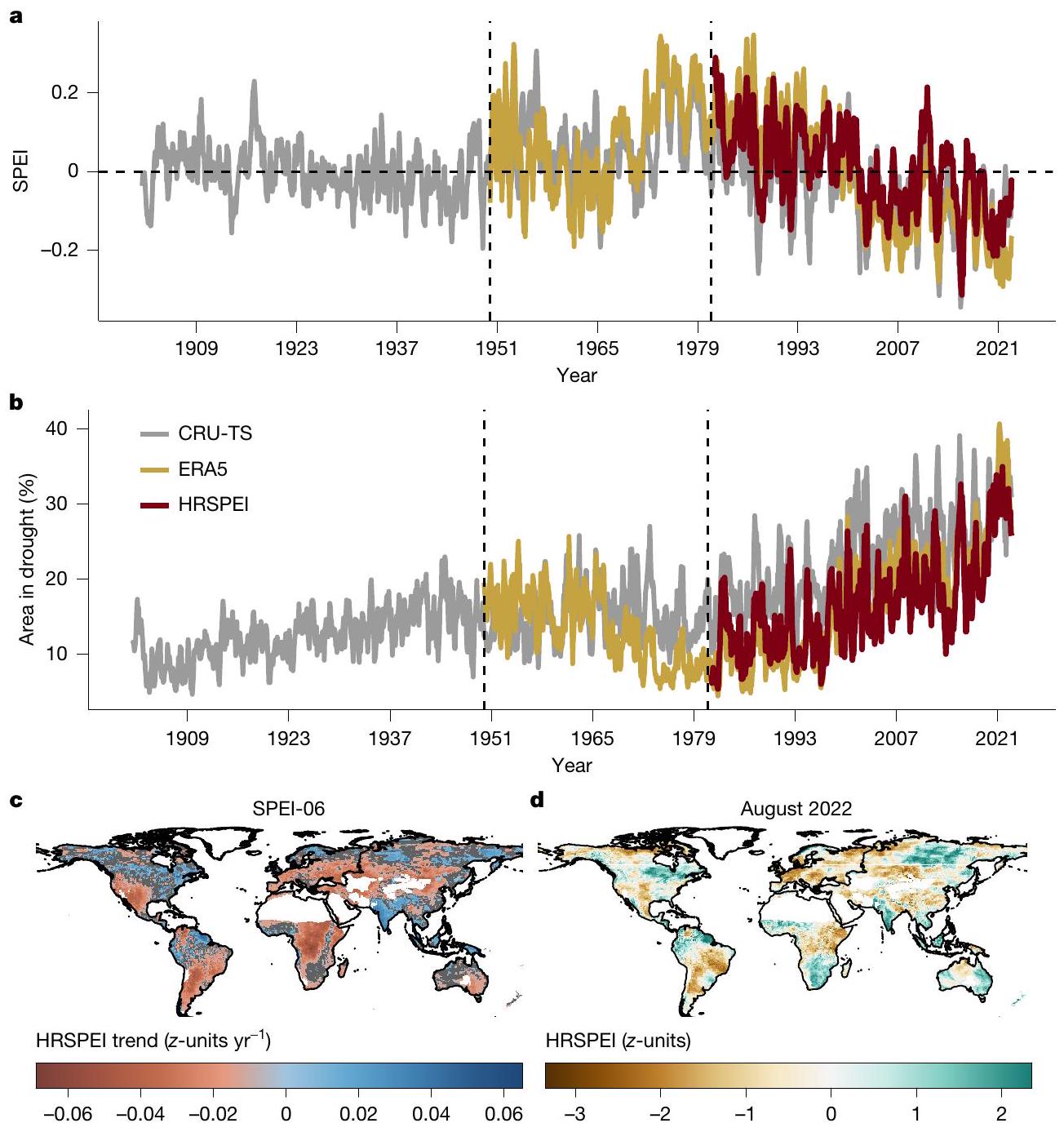

ومناطق الجفاف بناءً على HRSPEI وCRU-TS وERA5. الاتجاه المستمد من HRSPEI يمثل الاتجاه العام، بينما الانحراف (±) يعكس انتشار الاتجاهات لمجموعات البيانات الفردية (MSWEP_hPET وMSWEP_GLEAM وCHIRPS_hPET وCHIRPS_GLEAM) حول الاتجاه المتوسط لـ HRSPEI. يتم حساب الانحراف كمعيار الانحراف للاتجاهات عبر هذه المجموعات الأربعة، مما يبرز التباين في الاتجاهات بالنسبة لاتجاه HRSPEI.

يستند إلى MSWEP_hPET، مع حساب مدة الجفاف لكل عام حيث تكون قيم SPEI أقل من -1. الاتجاهات غير المهمة (قيمة P

تشير القيم السلبية إلى الانخفاضات، بينما تشير القيم الإيجابية إلى الزيادات مقارنةً بالمتوسط طويل الأجل. يتم احتساب هطول الأمطار بناءً على MSWEP، و AED يعتمد على hPET.

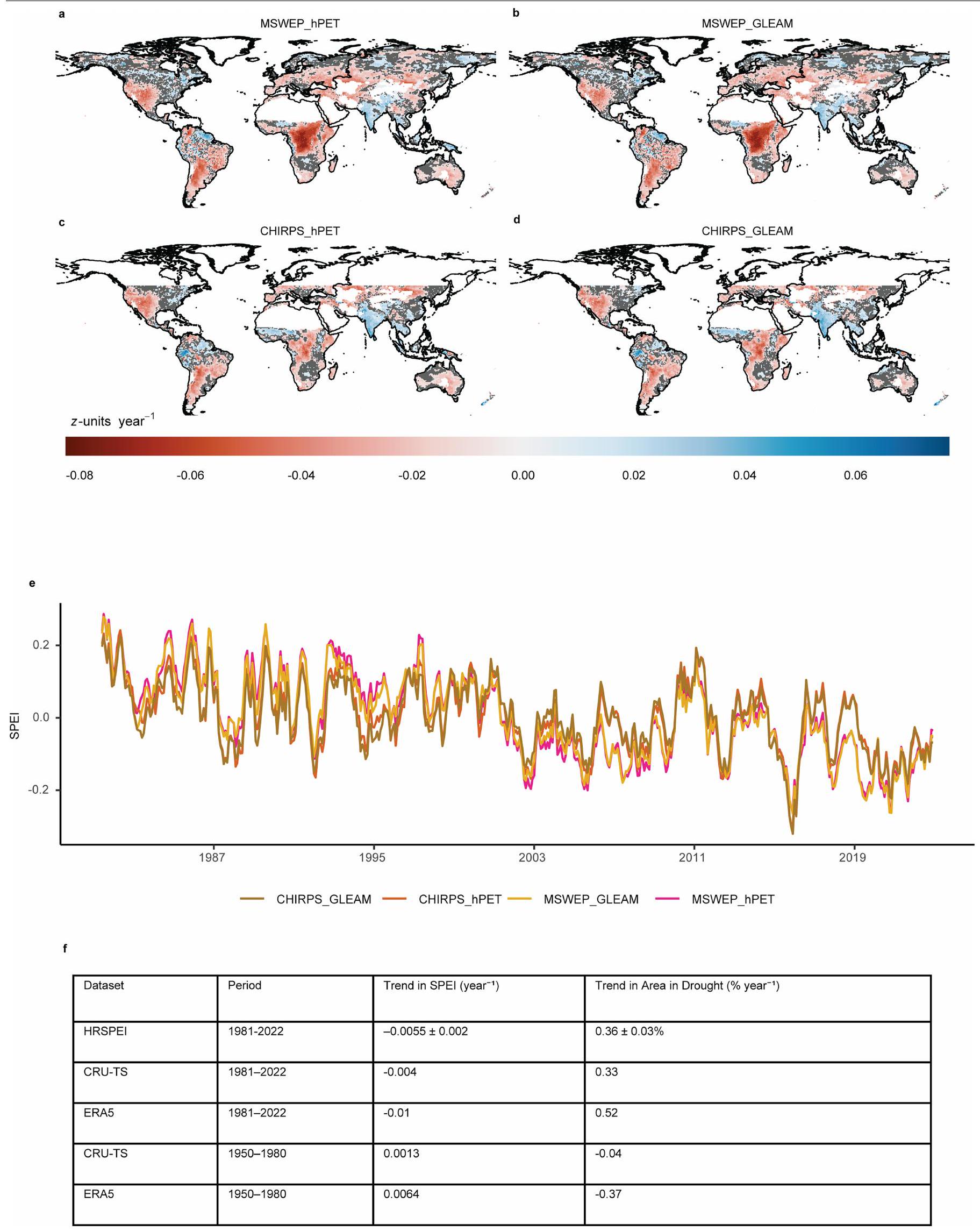

1981-2022. تم حساب قيم SPEI لمدة 6 أشهر باستخدام مجموعة بيانات ERA5 المناخية مع تركيبات من AED المرصود، وهطول الأمطار المرصود، وAED المناخي (AEDclm)، وهطول الأمطار المناخي (Prclm). توضح اللوحة (أ) الاتجاه بناءً على هطول الأمطار المرصود وAED (Obs). تقدم اللوحة (ب) الاتجاه بناءً على AEDclm وهطول الأمطار المرصود.

(AEDclm)، بينما توضح اللوحة ج) الاتجاه بناءً على Prclm و AED الملحوظ (Prclm). الاتجاهات غير المهمة (قيمة P

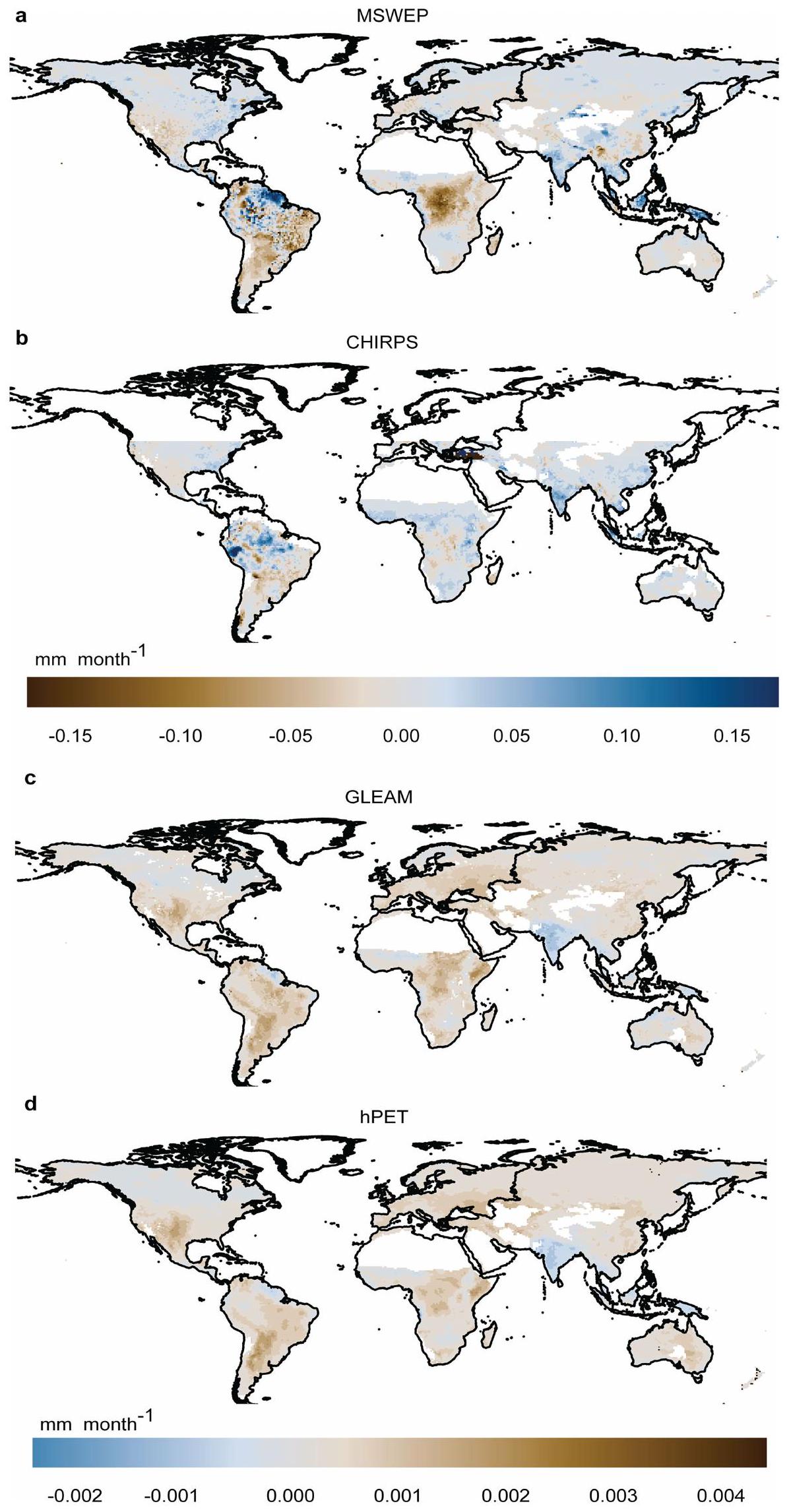

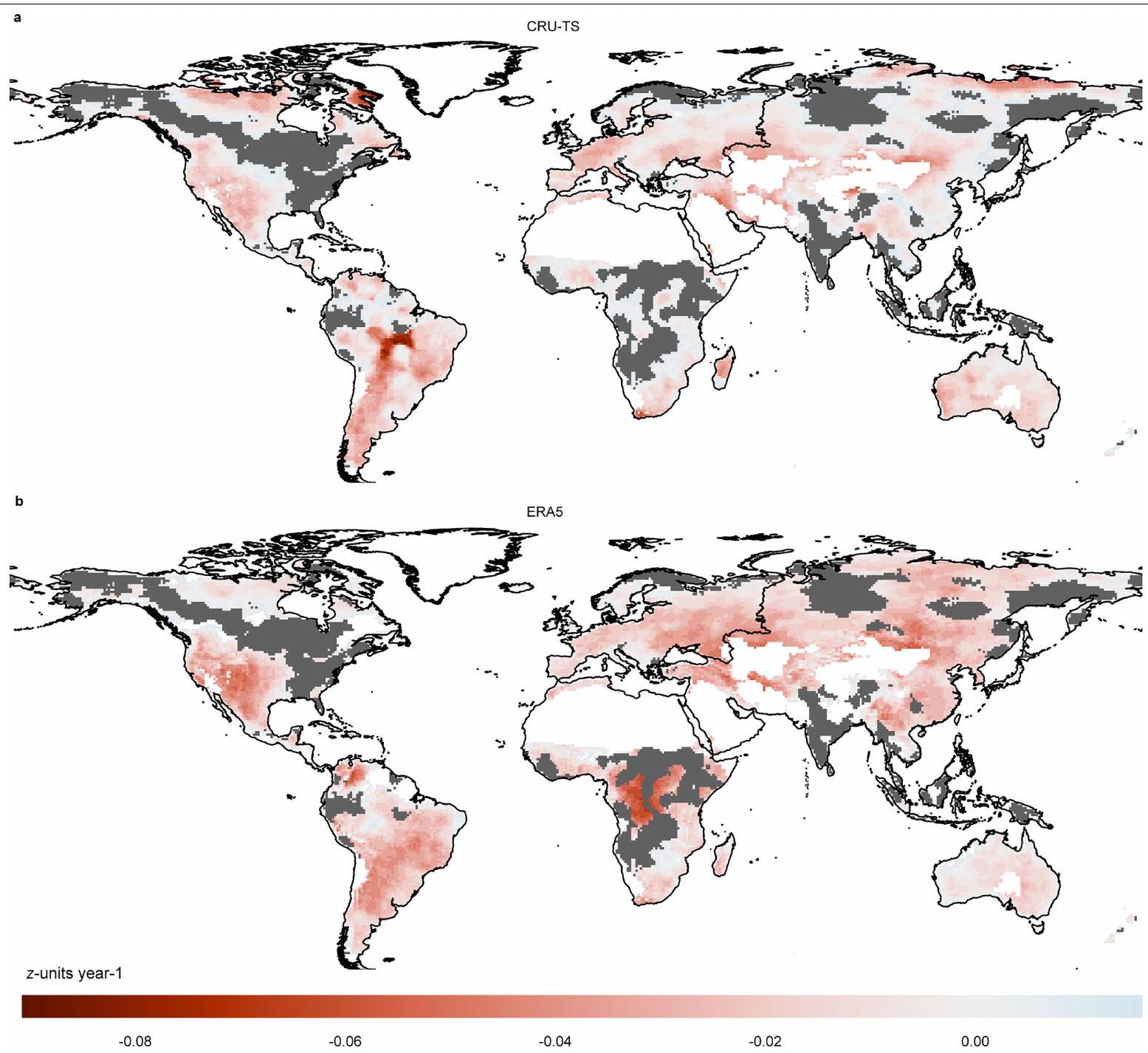

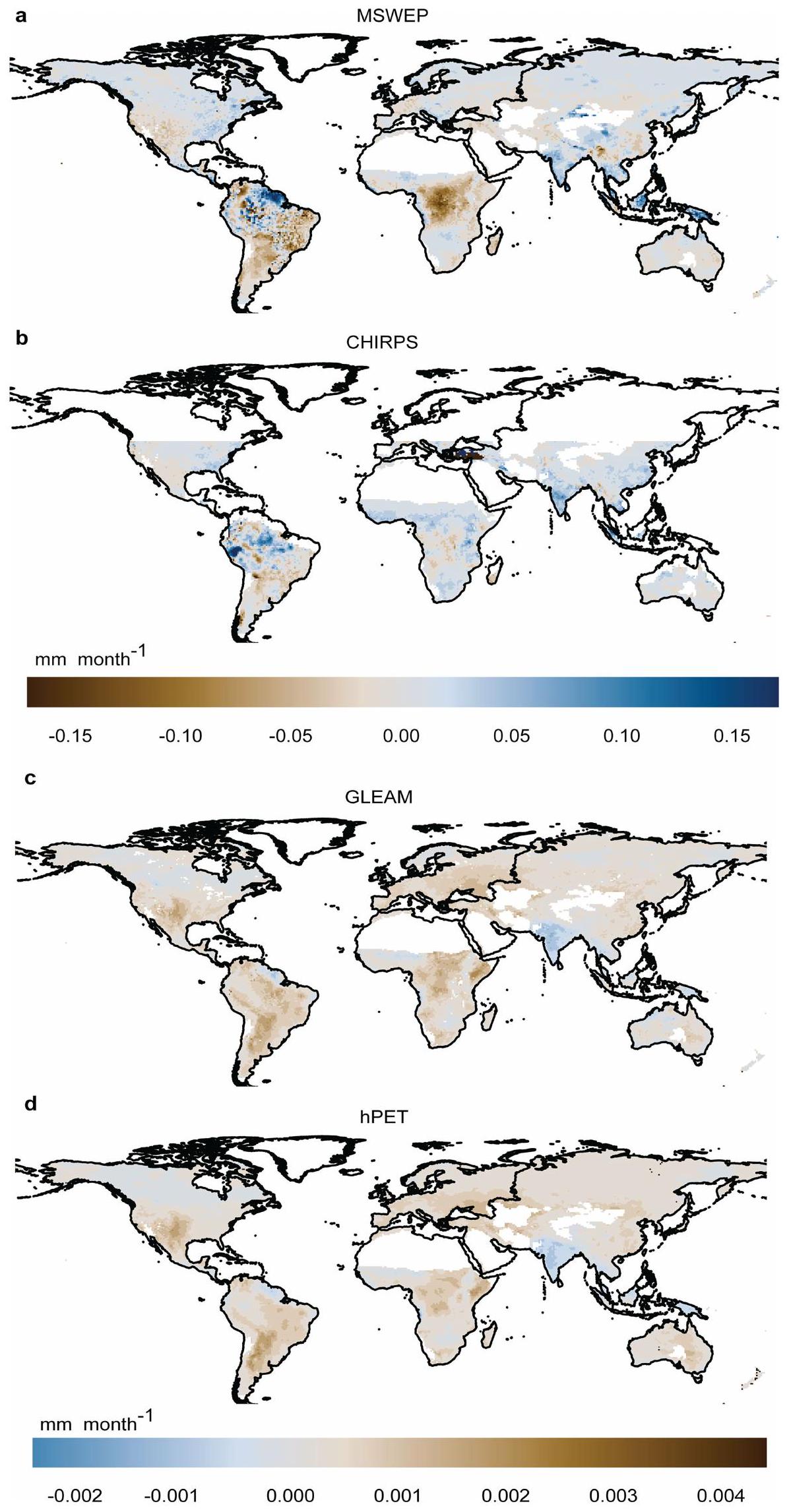

تقديم الاتجاهات في AED الشهري، المستمدة من مجموعات بيانات GLEAM و hPET، على التوالي. لاحظ أن مجموعة بيانات CHIRPS تغطي خطوط العرض حتى

نسبة المناطق المتأثرة بالجفاف استنادًا إلى مؤشر SPEI المحسوب باستخدام هطول الأمطار المرصود و AED المناخي (AEDclm). تبرز الخطوط العمودية السوداء المتقطعة الفترة من 2018 إلى 2022. تلخص اللوحة h) نسبة المناطق المتأثرة بالجفاف خلال 2018-2022، مقارنة بالفترة 1981-2017، استنادًا إلى كل من البيانات المرصودة و AEDclm.

مقالة

| فئات SPEI | قيم SPEI

|

| رطب للغاية | >1.83 |

| رطب جداً | 1.43 إلى 1.82 |

| معتدل رطب | 1.0 إلى 1.42 |

| قريب من الطبيعي | -0.99 إلى 0.99 |

| جاف بشكل معتدل | -1.0 إلى -1.42 |

| جاف بشكل شديد | -1.43 إلى -1.82 |

| جاف للغاية | <-1.83 |

مدرسة الجغرافيا والبيئة، جامعة أكسفورد، أكسفورد، المملكة المتحدة. مدرسة الجغرافيا وعلوم البيئة، جامعة ساوثهامبتون، ساوثهامبتون، المملكة المتحدة. المعهد البيريني للإيكولوجيا، المجلس الأعلى للبحوث العلمية (IPE-CSIC)، سرقسطة، إسبانيا. مركز مخاطر المناخ في سانتا باربرا، جامعة كاليفورنيا، سانتا باربرا، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مختبر extremes المناخية المائية (H-CEL)، جامعة غنت، غنت، بلجيكا. قسم الاستشعار عن بُعد، مركز هيلمهولتز للبحوث البيئية – UFZ، لايبزيغ، ألمانيا. معهد علوم نظام الأرض والاستشعار عن بُعد، جامعة لايبزيغ، لايبزيغ، ألمانيا. المركز البريطاني لعلم البيئة والهيدرولوجيا، والينغفورد، المملكة المتحدة. مبادرة المناخ وقابلية العيش، جامعة الملك عبدالله للعلوم والتقنية، ثول، المملكة العربية السعودية. مدرسة علوم الأرض والبيئة، جامعة كارديف، كارديف، المملكة المتحدة. معهد أبحاث الأرض، جامعة كاليفورنيا، سانتا باربرا، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. معهد أبحاث المياه، جامعة كارديف، كارديف، المملكة المتحدة. البريد الإلكتروني: solomon.gebrechorkos@ouce.ox.ac.uk - بوخرل، ي. وآخرون. التخزين العالمي للمياه الأرضية وشدة الجفاف تحت تغير المناخ. نات. مناخ. تغيير 11، 226-233 (2021).

- تشيانغ، ف.، مزدياسني، أ. وأغا كوشاك، أ. دليل على التأثيرات البشرية على تكرار الجفاف العالمي، ومدته، وشدته. نات. كوم. 12، 2754 (2021).

- شيفيلد، ج.، وود، إ. ف. & رودريك، م. ل. تغير طفيف في الجفاف العالمي على مدى الستين عامًا الماضية. ناتشر 491، 435-438 (2012).

- ترينبيرث، ك. إ. وآخرون. الاحترار العالمي والتغيرات في الجفاف. نات. مناخ. تغيير 4، 17-22 (2014).

- سيني فيراتني، س. آي. إعادة النظر في اتجاهات الجفاف التاريخية. ناتشر 491، 338-339 (2012).

- لو، ج.، كاربون، ج. ج. & جريغو، ج. م. عدم اليقين والنقاط الساخنة في توقعات الجفاف الزراعي في القرن الحادي والعشرين من نماذج CMIP5. ساينس. ريب. 9، 4922 (2019).

- تاروجا، ب.، تشيانغ، ف.، أغا كوشاك، أ. وسامويلسن، س. تقييم قيود موارد المياه المستقبلية على موارد الطاقة المتجددة المعتمدة على الحرارة في كاليفورنيا. الطاقة التطبيقية 226، 49-60 (2018).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09047-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40468063

Publication Date: 2025-06-04

Warming accelerates global drought severity

Accepted: 18 April 2025

Published online: 4 June 2025

Open access

Check for updates

Abstract

Drought is one of the most common and complex natural hazards affecting the environment, economies and populations globally

drought severity

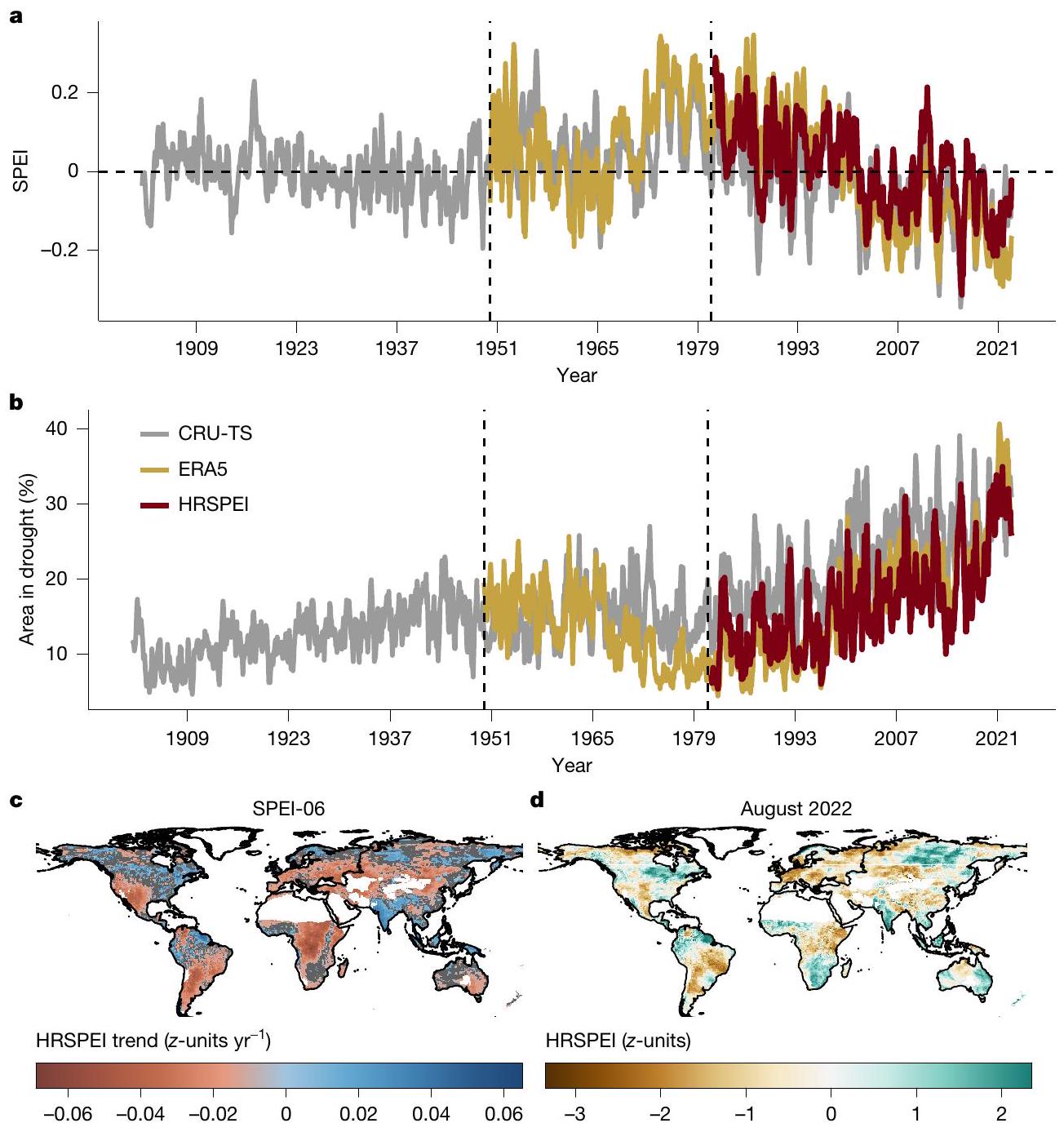

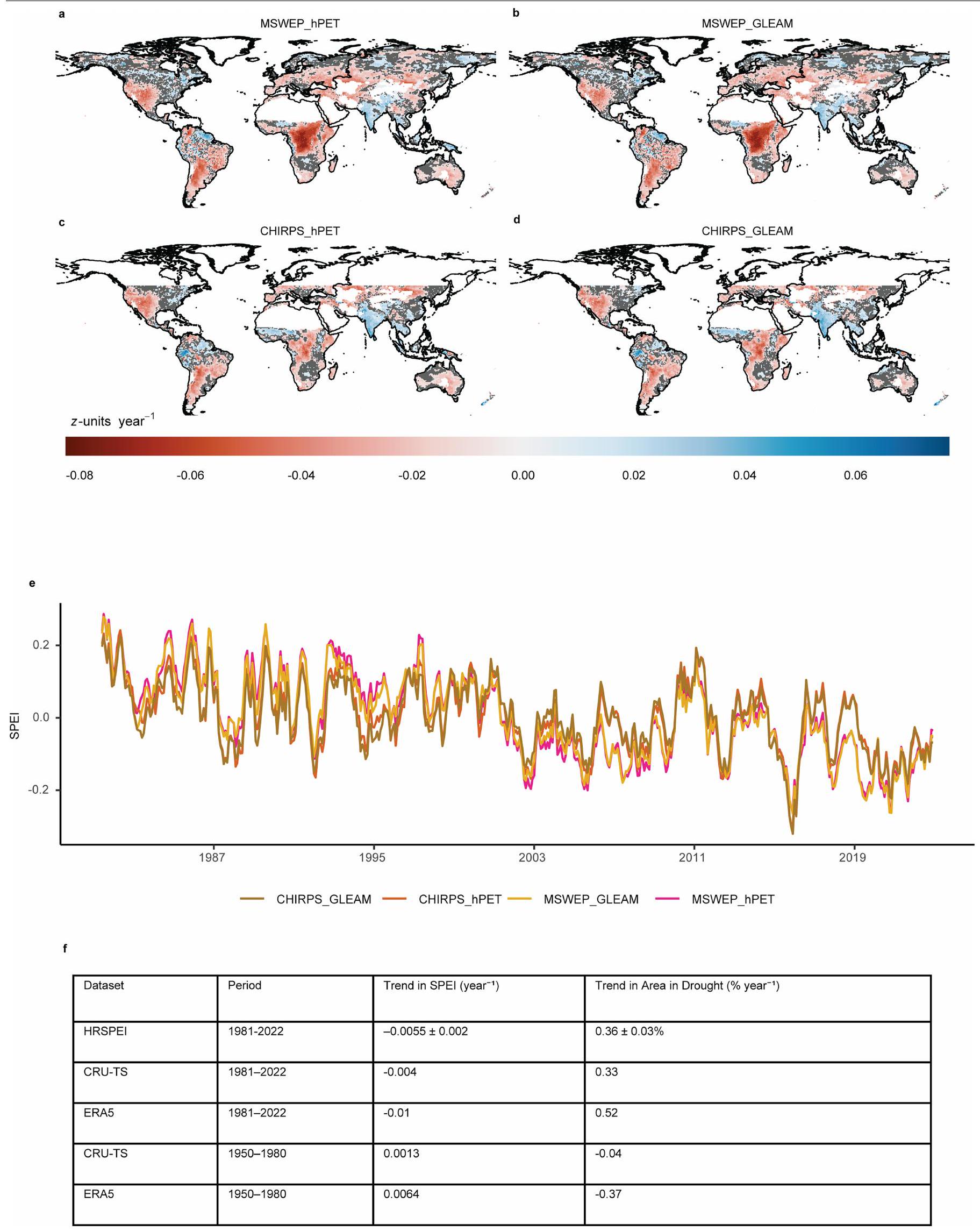

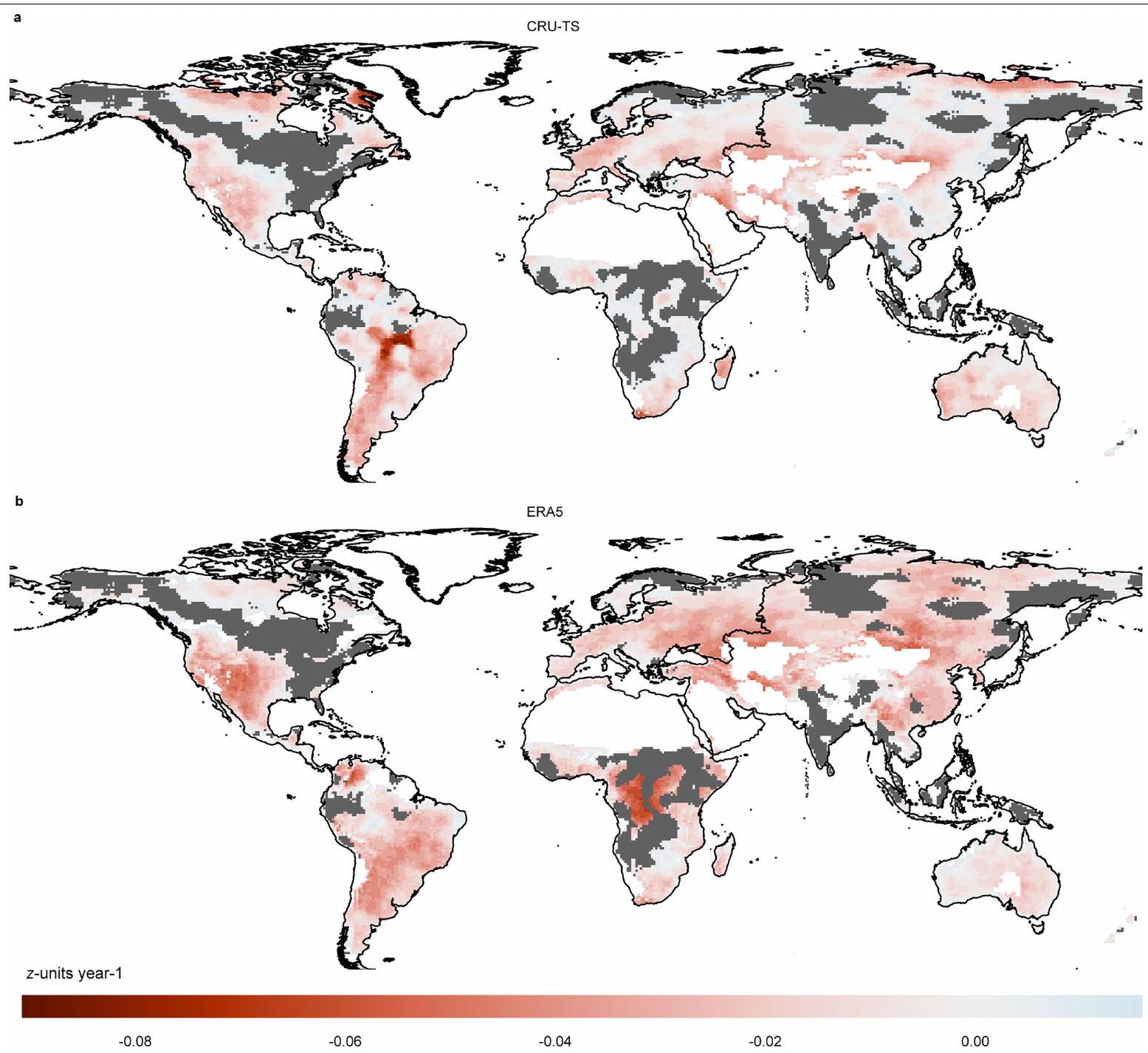

Global drought trends

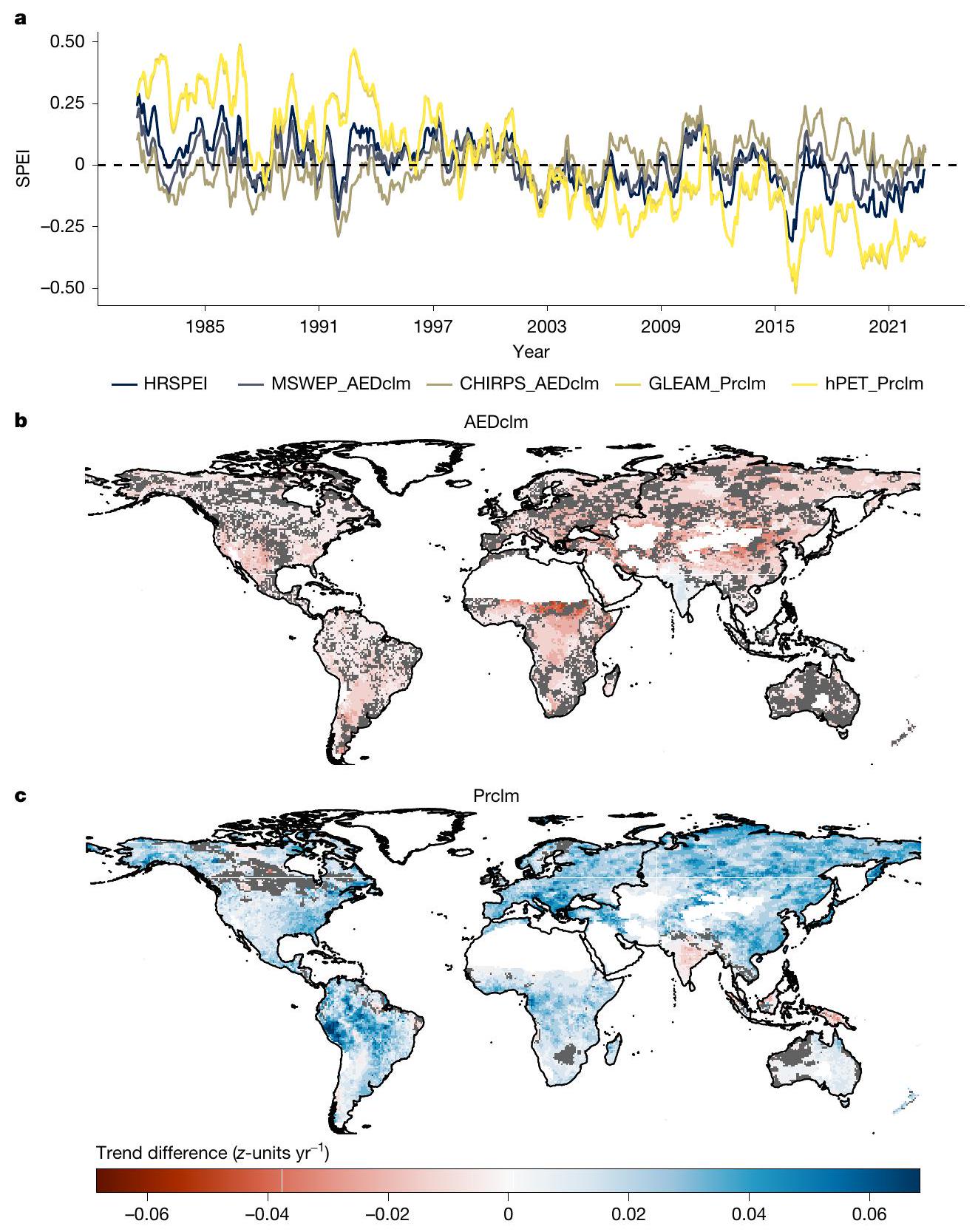

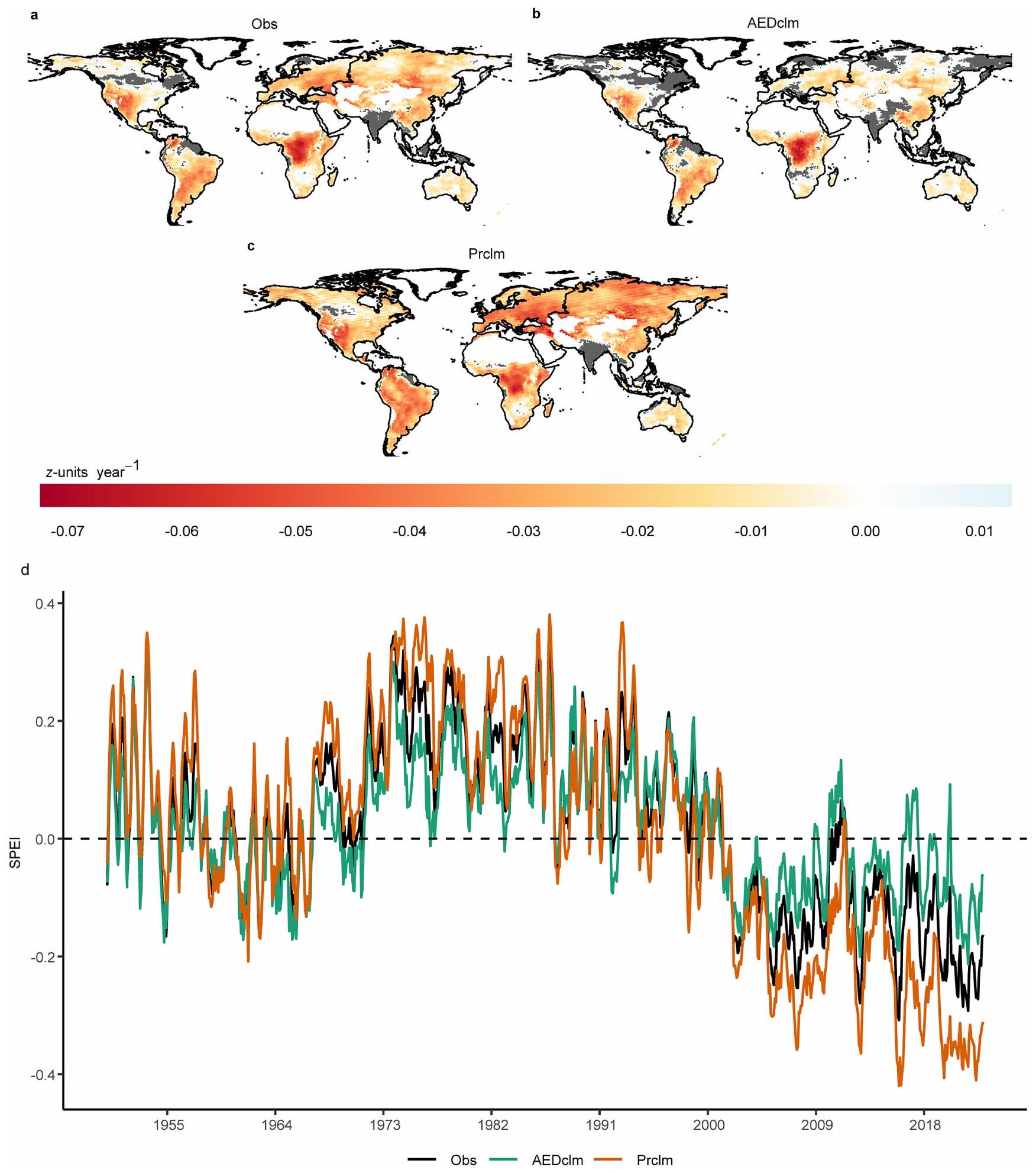

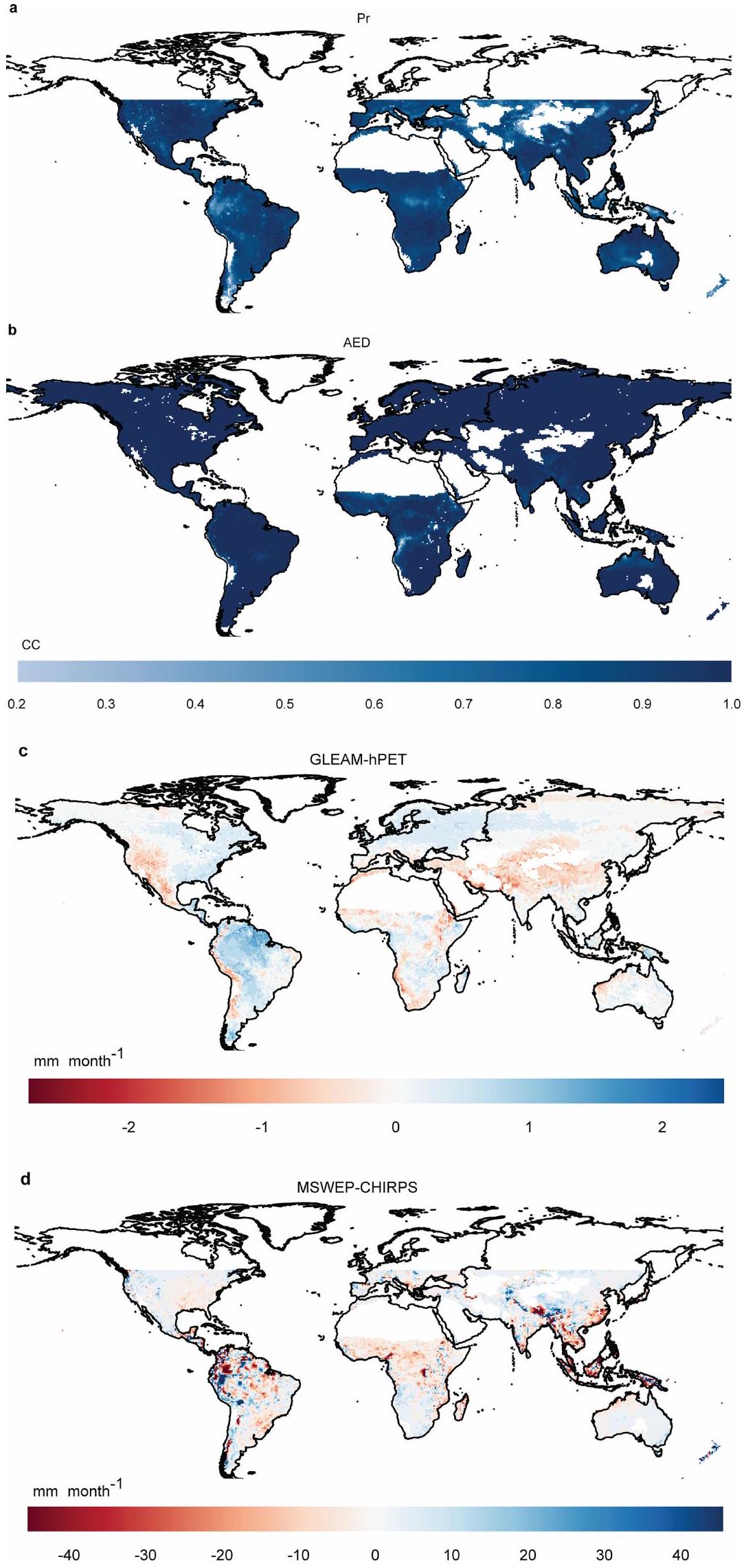

about 50 km ), covering 1950-2022 and 1901-2022, respectively. By incorporating multiple datasets and different periods, we aim to capture a broader range of potential uncertainties in the forcing data and provide a more comprehensive assessment of drought patterns. Through using climatological AED and precipitation, we developed equivalent datasets that enable us to quantify the contributions of AED and precipitation changes to the SPEI trend, as well as to the frequency, duration and magnitude of drought events. Here we focus on the 6-month SPEI, as it captures prevalent short-to medium-term drought conditions.

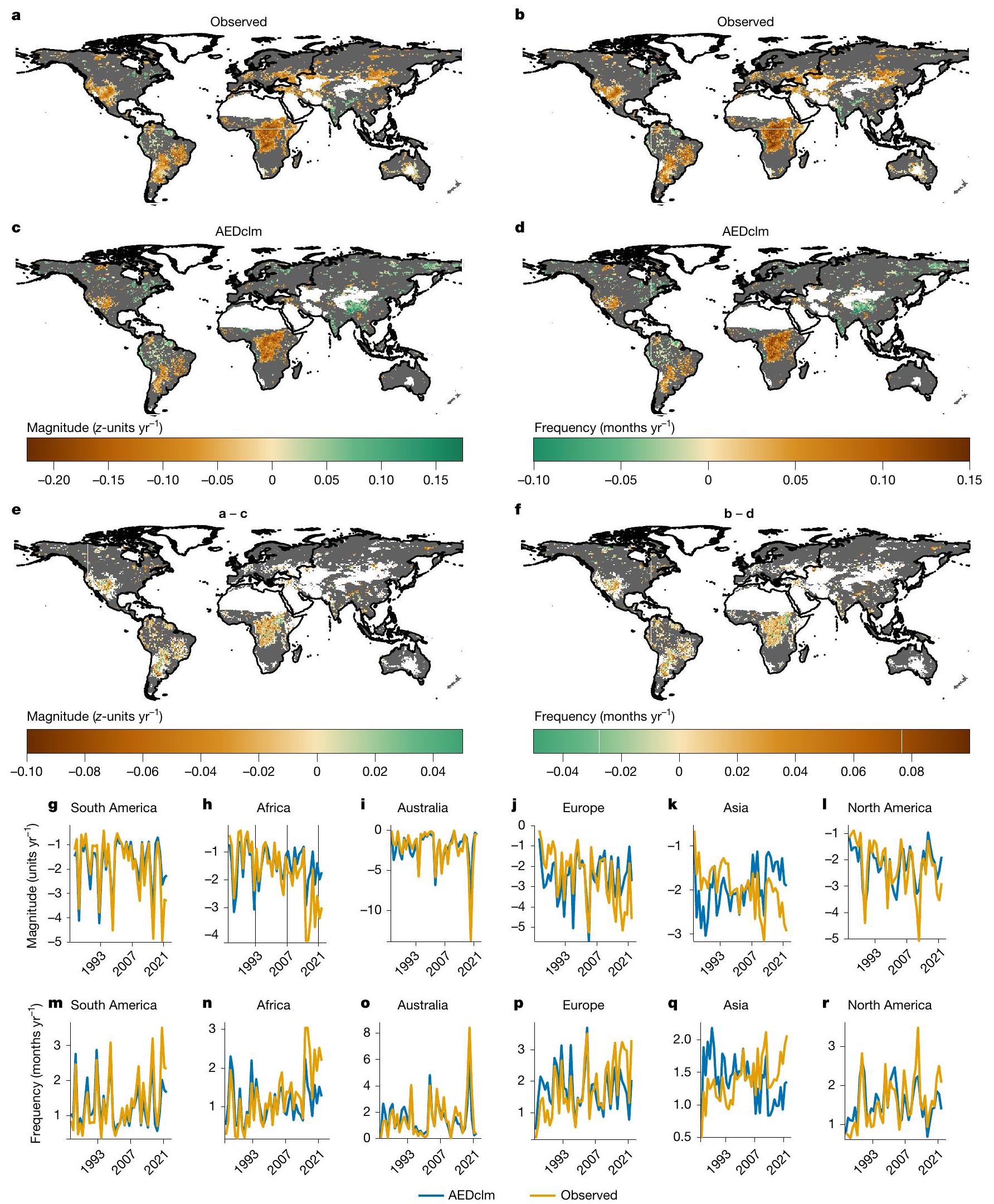

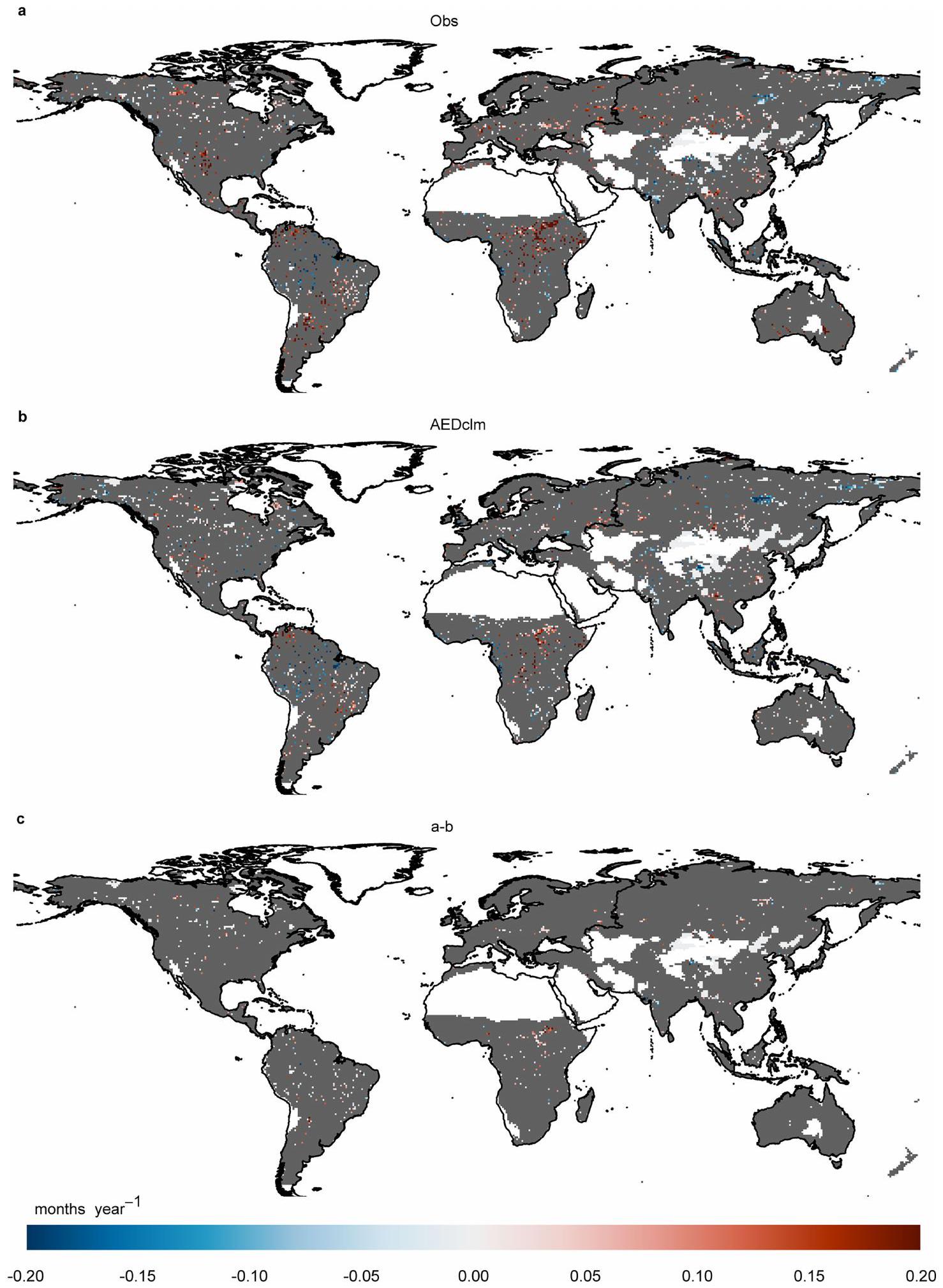

Drivers of changes in drought

trend in areas in drought based on the observed precipitation and AEDclm is

Observed changes in AED have also intensified the magnitude and frequency of droughts globally (Fig. 2). Compared with AEDcIm, observed trends show a more negative drought magnitude (up to

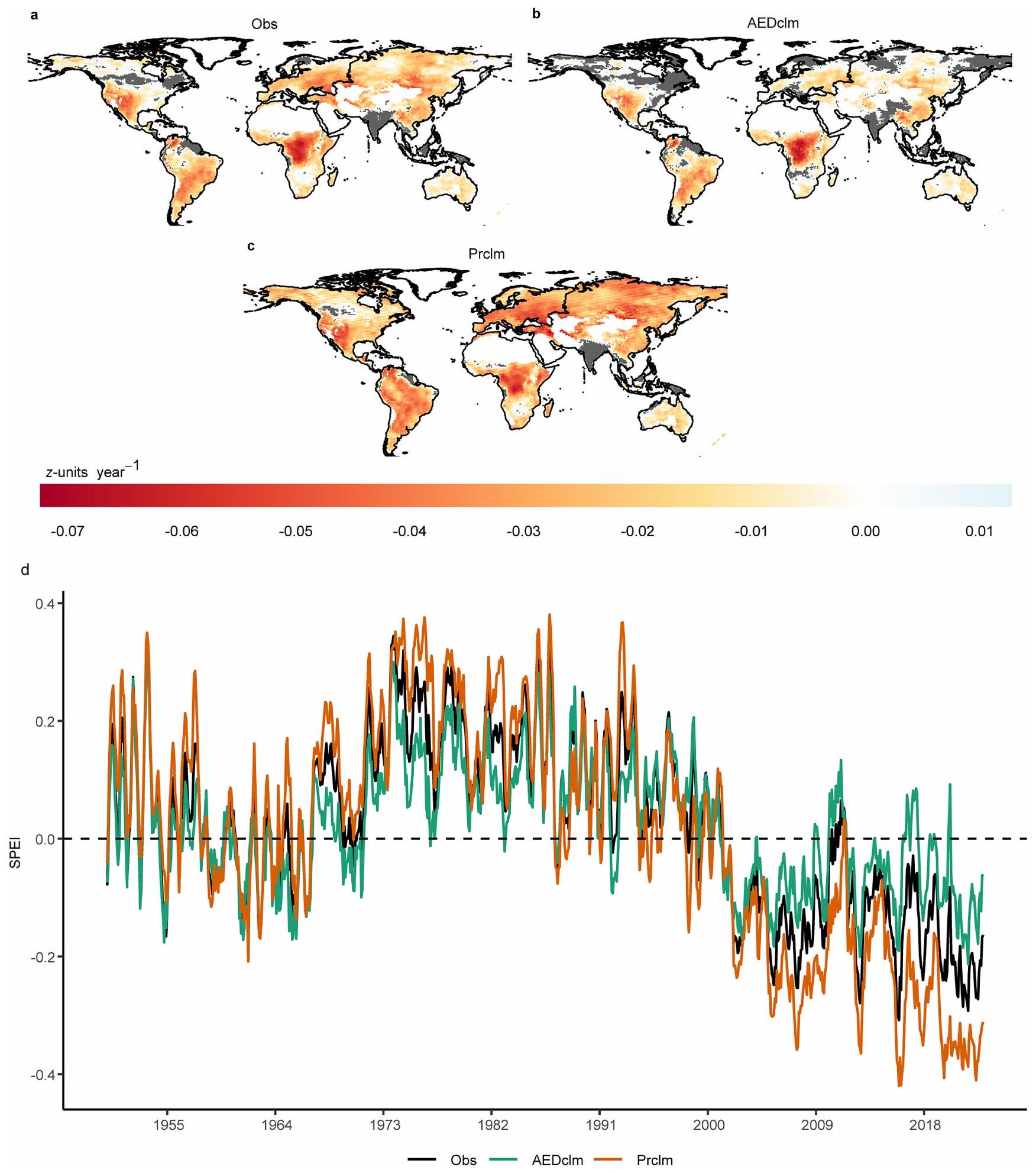

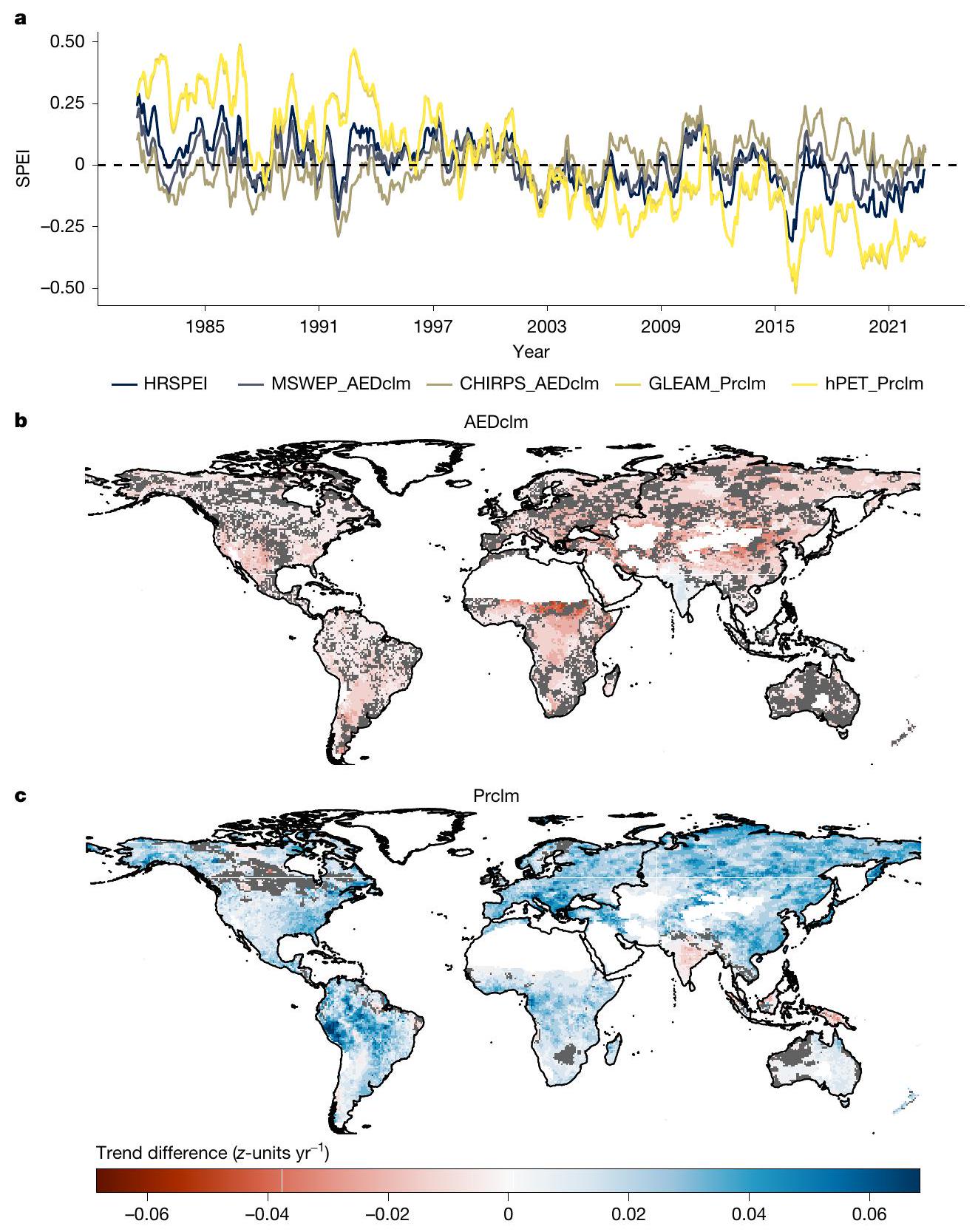

1981-2022. a, The quasi-global average (

observations (observed precipitation and AED) and SPEI based on observed precipitation and climatology of AED (AEDclm). c, The trend difference between SPEI based on observations and SPEI based on observed AED and climatology of precipitation (Prclm). Non-significant trends (

frequency ( -0.02 months

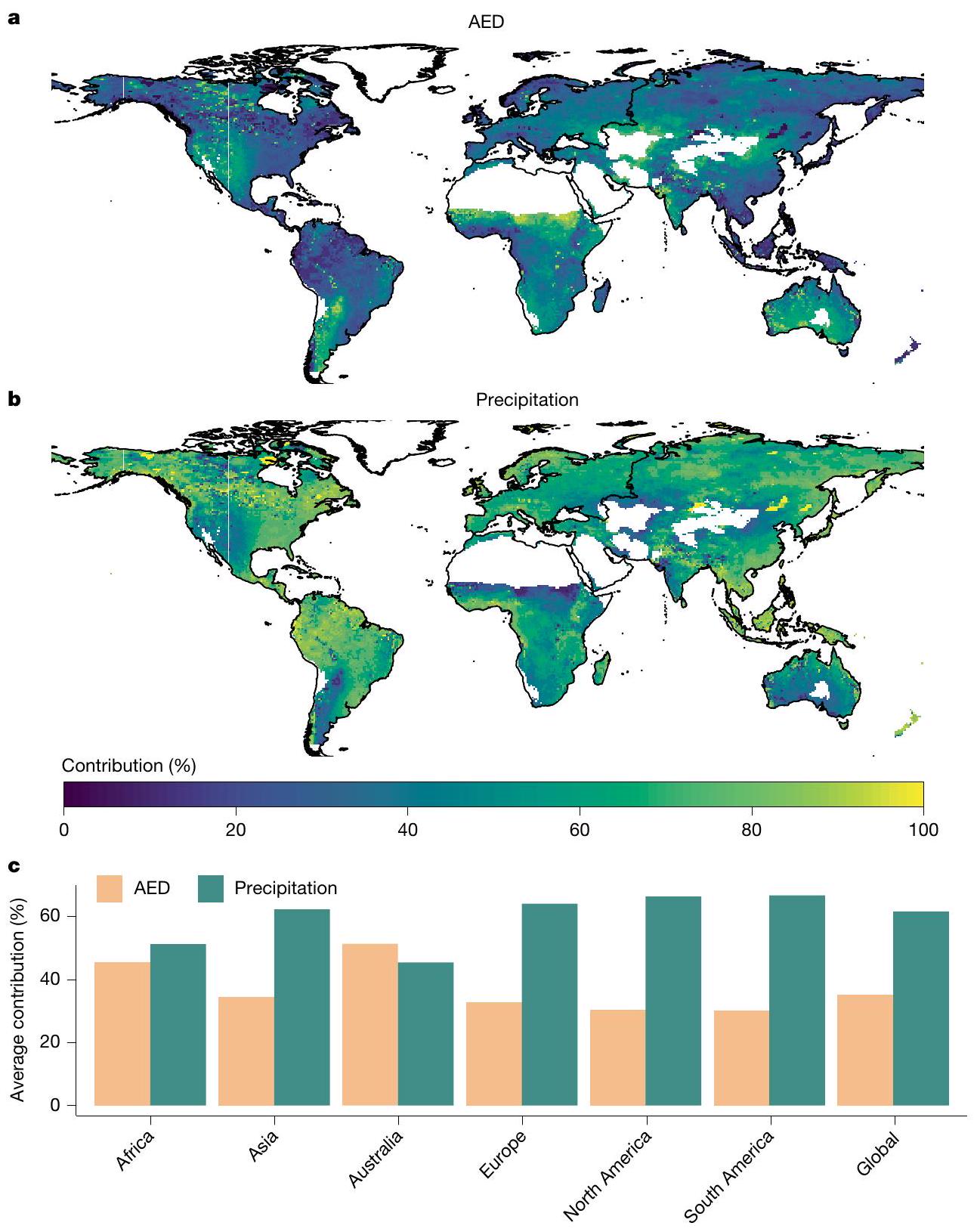

contribution of AED to drought trends in North and South America, Europe, and Asia is around

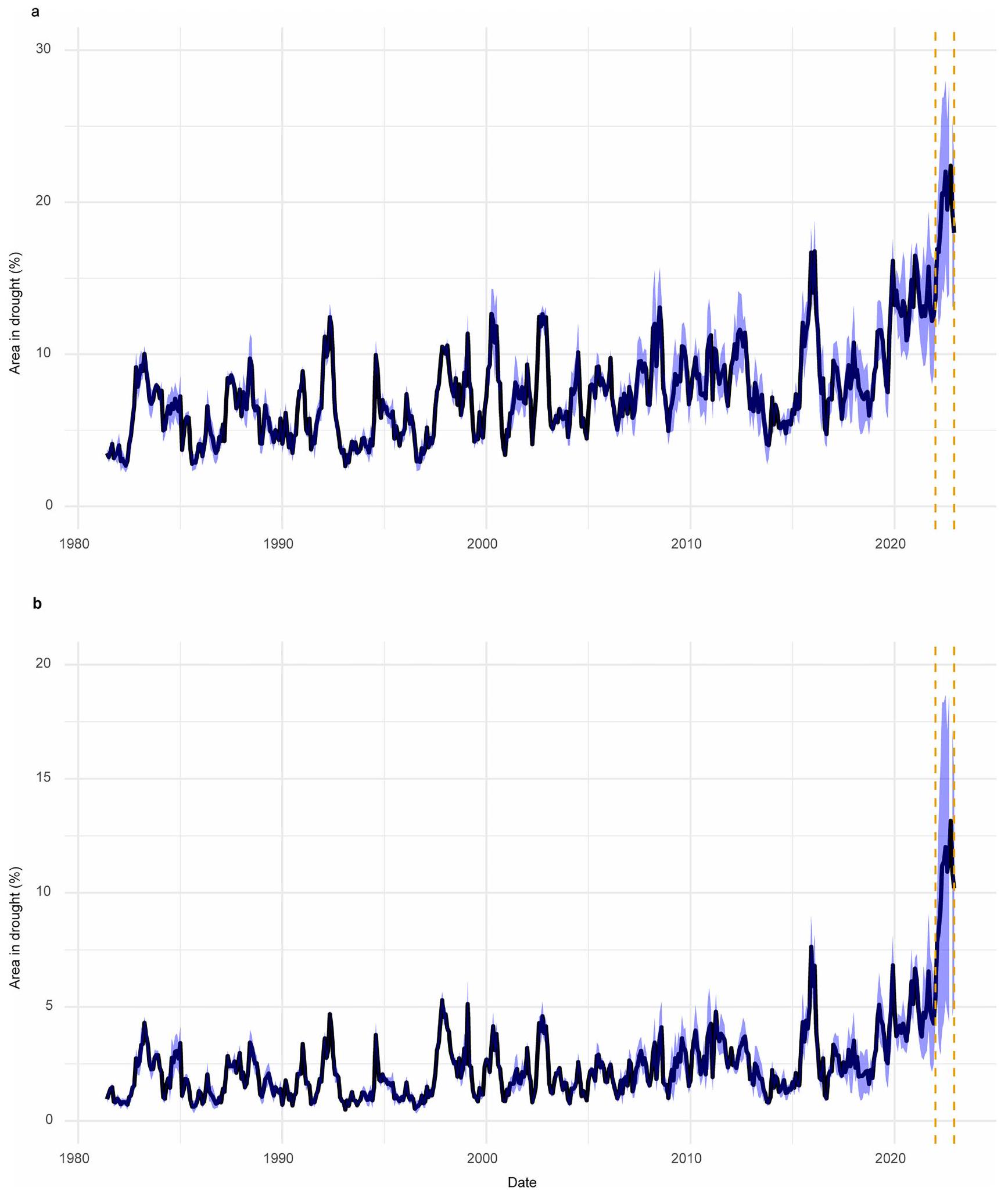

Acceleration of droughts

greater than AEDcIm. In addition, the average SPEI was -0.85 units

Discussion

compensate for the large temperature increase. Some recent studies have also suggested an increase in the severity of drought events over large land areas based on metrics such as modelled soil moisture

Online content

9. Greve, P., Gudmundsson, L. & Seneviratne, S. I. Regional scaling of annual mean precipitation and water availability with global temperature change. Earth Syst. Dyn. 9, 227-240 (2018).

10. Greve, P., Roderick, M. L. & Seneviratne, S. I. Simulated changes in aridity from the last glacial maximum to 4xCO2. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 114021 (2017).

11. Padrón, R. S. et al. Observed changes in dry-season water availability attributed to human-induced climate change. Nat. Geosci. 13, 477-481(2020).

12. Mahecha, M. D. et al. Biodiversity loss and climate extremes-study the feedbacks. Nature 612, 30-32 (2022).

13. Seneviratne, S.I. et al. Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) Ch. 11, 1513-1766 (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2021); https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.013.

14. Zhu, P. et al. Warming reduces global agricultural production by decreasing cropping frequency and yields. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 1016-1023 (2022).

15. Bauman, D. et al. Tropical tree mortality has increased with rising atmospheric water stress. Nature 608, 528-533 (2022).

16. Kikstra, J. et al. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report WGIII climate assessment of mitigation pathways: from emissions to global temperatures. EGUsphere https://doi.org/10.5194/ egusphere-2022-471 (2022).

17. Vicente-Serrano, S. M. et al. Global drought trends and future projections. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 380, 20210285 (2022).

18. Douville, H. & Willett, K. M. A drier than expected future, supported by near-surface relative humidity observations. Sci. Adv. 9, eade6253 (2023).

19. Dai, A. Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 52-58 (2013).

20. IPCC Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report (eds Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R. K. & Meyer L. A.) (IPCC, 2014).

21. Allen, C. D., Breshears, D. D. & McDowell, N. G. On underestimation of global vulnerability to tree mortality and forest die-off from hotter drought in the Anthropocene. Ecosphere 6, 129 (2015).

22. Berg, A. & Sheffield, J. Climate change and drought: the soil moisture perspective. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4, 180-191 (2018).

23. Cook, B. I. et al. Twenty-first century drought projections in the CMIP6 forcing scenarios. Earths Future 8, e2019EF001461 (2020).

24. Garrido-Perez, J. M. et al. Examining the outstanding Euro-Mediterranean drought of 2021-2022 and its historical context. J. Hydrol. 630, 130653 (2024).

25. Bevacqua, E. et al. Direct and lagged climate change effects intensified the 2022 European drought. Nat. Geosci. 17, 1100-1107(2024).

26. IPCC Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability (eds Pörtner H.-O. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

27. Kingston, D. G., Todd, M. C., Taylor, R. G., Thompson, J. R. & Arnell, N. W. Uncertainty in the estimation of potential evapotranspiration under climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L20403 (2009).

28. van der Schrier, G., Barichivich, J., Briffa, K. R. & Jones, P. D. A scPDSI-based global data set of dry and wet spells for 1901-2009. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 4025-4048 (2013).

29. Beck, H. E. et al. Global-scale evaluation of 22 precipitation datasets using gauge observations and hydrological modeling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 6201-6217 (2017).

30. Gebrechorkos, S. H. et al. Global-scale evaluation of precipitation datasets for hydrological modelling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 3099-3118 (2024).

31. Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Beguería, S. & López-Moreno, J. I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 23, 1696-1718 (2010).

32. Tomas-Burguera, M. et al. Global characterization of the varying responses of the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index to atmospheric evaporative demand. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2020JD033017 (2020).

33. Haile, G. G. et al. Long-term spatiotemporal variation of drought patterns over the Greater Horn of Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 704, 135299 (2020).

34. Kamruzzaman, M. et al. Spatiotemporal drought analysis in Bangladesh using the Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) and Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI). Sci. Rep. 12, 20694 (2022).

35. Spinoni, J. et al. Future global meteorological drought hot spots: a study based on CORDEX data. J. Clim. 33, 3635-3661(2020).

36. Wang, T., Tu, X., Singh, V. P., Chen, X. & Lin, K. Global data assessment and analysis of drought characteristics based on CMIP6. J. Hydrol. 596, 126091 (2021).

37. Spinoni, J. et al. A new global database of meteorological drought events from 1951 to 2016. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 22, 100593 (2019).

38. Beguería, S., Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Reig, F. & Latorre, B. Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) revisited: parameter fitting, evapotranspiration models, tools, datasets and drought monitoring. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 3001-3023 (2014).

39. Wang, Q. et al. Temporal-spatial characteristics of severe drought events and their impact on agriculture on a global scale. Quat. Int. 349, 10-21 (2014).

40. Funk, C. et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations-a new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Sci. Data 2, 150066 (2015).

41. Beck, H. E. et al. MSWEP V2 global 3-hourly

42. Miralles, D. G. et al. GLEAM4: Global Land Evaporation and Soil Moisture dataset at

43. Singer, M. B. et al. Hourly potential evapotranspiration at

44. Dai, A. & Zhao, T. Uncertainties in historical changes and future projections of drought. Part I: estimates of historical drought changes. Clim. Change 144, 519-533 (2017).

45. Song, X., Song, Y. & Chen, Y. Secular trend of global drought since 1950. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094073 (2020).

46. Alizadeh, M. R. et al. Warming enabled upslope advance in western US forest fires. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2009717118 (2021).

47. Bachmair, S., Tanguy, M., Hannaford, J. & Stahl, K. How well do meteorological indicators represent agricultural and forest drought across Europe? Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 034042 (2018).

48. Naumann, G. et al. Global changes in drought conditions under different levels of warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 3285-3296 (2018).

4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.© The Author(s) 2025

Methods

Drought index

Global climate and AED datasets

to present

The hPET is a global hourly AED dataset developed using ERA5 climate datasets and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)’s PenmanMonteith equation (equation (1)). hPET is available for the global land surface at

global land surface (Extended Data Fig. 9b), and the monthly average difference between them is up to

Atmospheric evaporative demand

Trend analysis

Data availability

through the Centre for Environmental Data Analysis (CEDA) at https:// doi.org/10.5285/ac43da11867243a1bb414e1637802dec and onJASMIN at/badc/hydro-jules/data/Global_drought_indices. The CHIRPS data can be accessed via the Climate Hazards Group (CHG) at https://www. chc.ucsb.edu/data/chirps/ (ref. 40). The MSWEP precipitation dataset is available from the GloH2O website at https://www.gloh2o.org/ mswep/ (ref. 41). The hPET dataset is hosted by the University of Bristol at https://data.bris.ac.uk/data/dataset/qb8ujazzda0s2aykkv0oq0ctp (ref. 43). The AED data from GLEAM can be accessed at https://www. gleam.eu/ (ref. 42). The CRU-TS precipitation and AED datasets are available through CEDA at https://data.ceda.ac.uk/badc/cru/data/ cru_ts/cru_ts_4.08/(ref.50). The ERA5 dataset is available for download from the Copernicus Climate Change Service’s Climate Data Store at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets (ref. 51).

Code availability

49. Agnew, C. T. Using the SPI to identify drought. Drought Network News 1994-2001 (International Drought Information Center and National Drought Mitigation Center, School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska – Lincoln, 2000).

50. Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. Data 7, 109 (2020).

51. Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999-2049 (2020).

52. Gebrechorkos, S. H. et al. Global high-resolution drought indices for 1981-2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 15, 5449-5466 (2023).

53. Gebrechorkos, S. H. solomonsg/Globdrought: drought indices and trends calculation. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 15073433 (2025).

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Solomon H. Gebrechorkos. Peer review information Nature thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

and areas in drought based on HRSPEI, CRU-TS, and ERA5. The trend derived from HRSPEI represents the overall trend, while the deviation ( ± ) reflects the spread in trends of the individual datasets (MSWEP_hPET, MSWEP_GLEAM, CHIRPS_hPET, and CHIRPS_GLEAM) around the HRSPEI mean trend. The deviation is calculated as the standard deviation of trends across these four datasets, highlighting the variability in the trends relative to the HRSPEI trend.

is based on MSWEP_hPET, with drought duration calculated for each year where SPEI values fall below -1 . Non-significant trends ( P -value

reductions, while positive values indicate increases compared to the long-term average. Precipitation is based on MSWEP, and AED is based on hPET.

1981-2022. The 6-month SPEI values were computed using the ERA5 meteorological dataset with combinations of observed AED, observed precipitation, climatological AED (AEDclm), and climatological precipitation (Prclm). Panel a) shows the trend based on observed precipitation and AED (Obs). Panel b) presents the trend based on AEDclm and observed precipitation

(AEDclm), while panel c) illustrates the trend based on Prclm and observed AED (Prclm). Non-significant trends (P-value

present the trends in monthly AED, derived from GLEAM and hPET datasets, respectively. Note that the CHIRPS dataset covers latitudes up to

percentage of areas in drought based on the SPEI computed using observed precipitation and climatological AED (AEDclm). The dashed black vertical lines highlight the period from 2018 to 2022. Panel h) summarizes the percentage of areas affected by drought during 2018-2022, compared to the period 1981-2017, based on both Obs and AEDclm.

Article

| SPEI categories | SPEI values

|

| Extremelywet | >1.83 |

| Very wet | 1.43 to 1.82 |

| Moderatewet | 1.0 to 1.42 |

| Near Normal | -0.99 to 0.99 |

| Moderately dry | -1.0 to -1.42 |

| Severely dry | -1.43 to -1.82 |

| Extremelydry | <-1.83 |

School of Geography and the Environment, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. School of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK. Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (IPE-CSIC), Zaragoza, Spain. Santa Barbara Climate Hazards Center, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA. Hydro-Climatic Extremes Lab (H-CEL), Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. Department of Remote Sensing, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research – UFZ, Leipzig, Germany. Institute for Earth System Science and Remote Sensing, Leipzig University, Leipzig, Germany. UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, Wallingford, UK. Climate and Livability Initiative, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Thuwal, Saudi Arabia. School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. Earth Research Institute, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA. Water Research Institute, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK. e-mail: solomon.gebrechorkos@ouce.ox.ac.uk - Pokhrel, Y. et al. Global terrestrial water storage and drought severity under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 226-233 (2021).

- Chiang, F., Mazdiyasni, O. & AghaKouchak, A. Evidence of anthropogenic impacts on global drought frequency, duration, and intensity. Nat. Commun. 12, 2754 (2021).

- Sheffield, J., Wood, E. F. & Roderick, M. L. Little change in global drought over the past 60 years. Nature 491, 435-438 (2012).

- Trenberth, K. E. et al. Global warming and changes in drought. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 17-22 (2014).

- Seneviratne, S. I. Historical drought trends revisited. Nature 491, 338-339 (2012).

- Lu, J., Carbone, G. J. & Grego, J. M. Uncertainty and hotspots in 21st century projections of agricultural drought from CMIP5 models. Sci. Rep. 9, 4922 (2019).

- Tarroja, B., Chiang, F., AghaKouchak, A. & Samuelsen, S. Assessing future water resource constraints on thermally based renewable energy resources in California. Appl. Energy 226, 49-60 (2018).