DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43860-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38191521

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-08

يمكن أن يحسن التعلم الآلي الموجه بالمعرفة من تقدير دورة الكربون في النظم الزراعية

تاريخ القبول: 22 نوفمبر 2023

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 08 يناير 2024

(A) تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

ليتشينغ ليو (1)

الملخص

يعد التقدير الدقيق والفعال من حيث التكلفة لدورة الكربون في النظم الزراعية على مقاييس ذات صلة بالقرار أمرًا حاسمًا للتخفيف من تغير المناخ وضمان إنتاج غذائي مستدام. ومع ذلك، فإن الأساليب التقليدية القائمة على العمليات أو المدفوعة بالبيانات وحدها تحمل عدم يقين كبير في التنبؤ بسبب العمليات البيوجيوكيميائية المعقدة التي يجب نمذجتها ونقص الملاحظات لتقييد العديد من المتغيرات الرئيسية للحالة والتدفق. هنا نقترح إطار عمل للتعلم الآلي الموجه بالمعرفة (KGML) الذي يعالج التحديات المذكورة أعلاه من خلال دمج المعرفة المضمنة في نموذج قائم على العمليات، وملاحظات الاستشعار عن بعد عالية الدقة، وتقنيات التعلم الآلي (ML). باستخدام حزام الذرة الأمريكي كحقل اختبار، نوضح أن KGML يمكن أن يتفوق على النماذج التقليدية القائمة على العمليات ونماذج ML السوداء في تقدير ديناميات دورة الكربون. يكشف نهجنا عالي الدقة بشكل كمي عن

من قبل المحاصيل يزيل أيضًا كميات كبيرة من ثاني أكسيد الكربون (

تعديل KGML-ag-Carbon باستخدام بيانات عوائد المحاصيل منخفضة الدقة وبيانات تدفقات الكربون من مواقع تباين موزعة بشكل نادر. تم تصميم الخسائر الموجهة بالمعرفة بناءً على النموذج القائم على العمليات لتقييد استجابة المتغيرات المستهدفة للمتغيرات المدخلة خلال كل من عمليات التدريب المسبق للنموذج وعملية التعديل.

النتائج

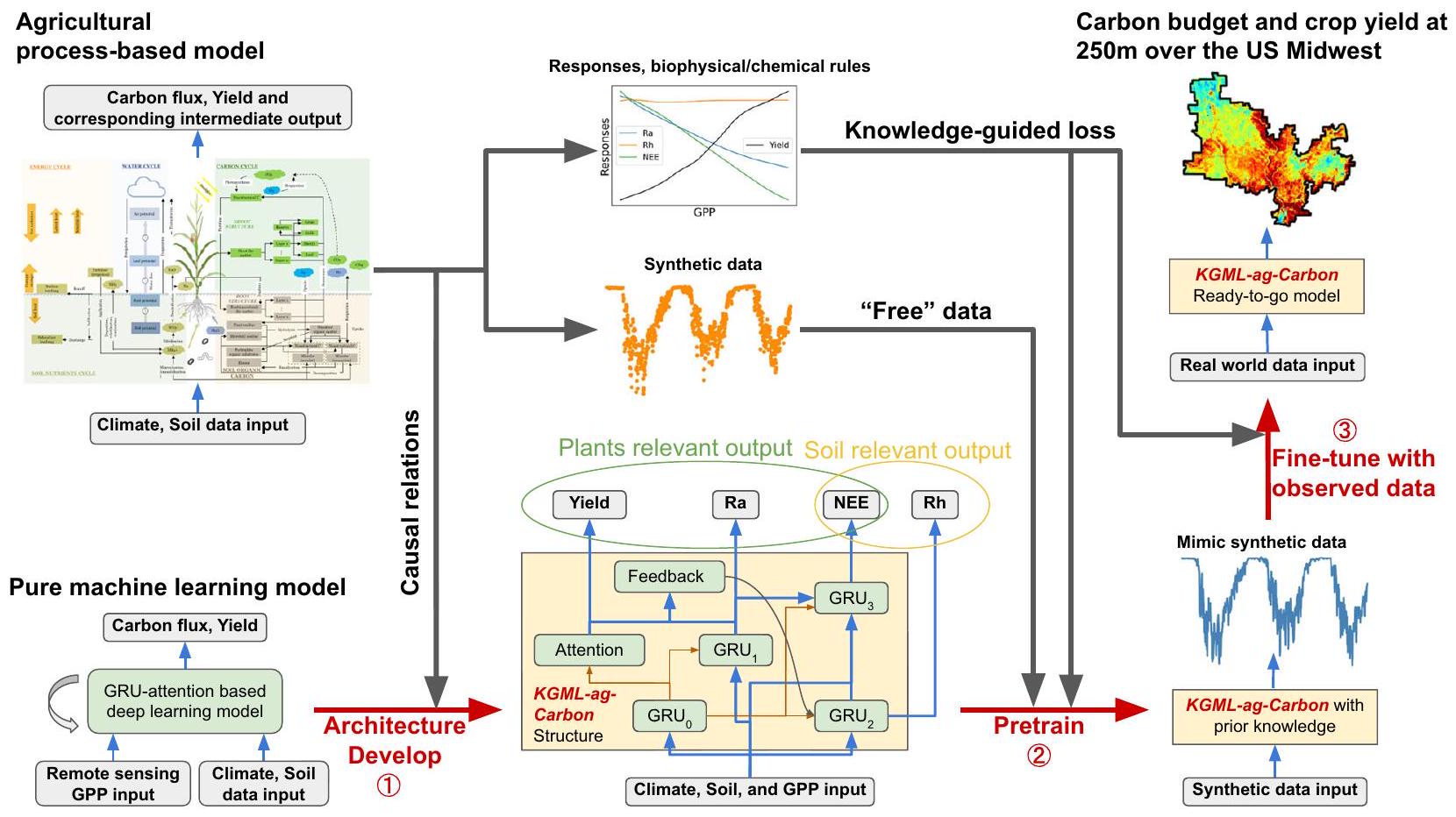

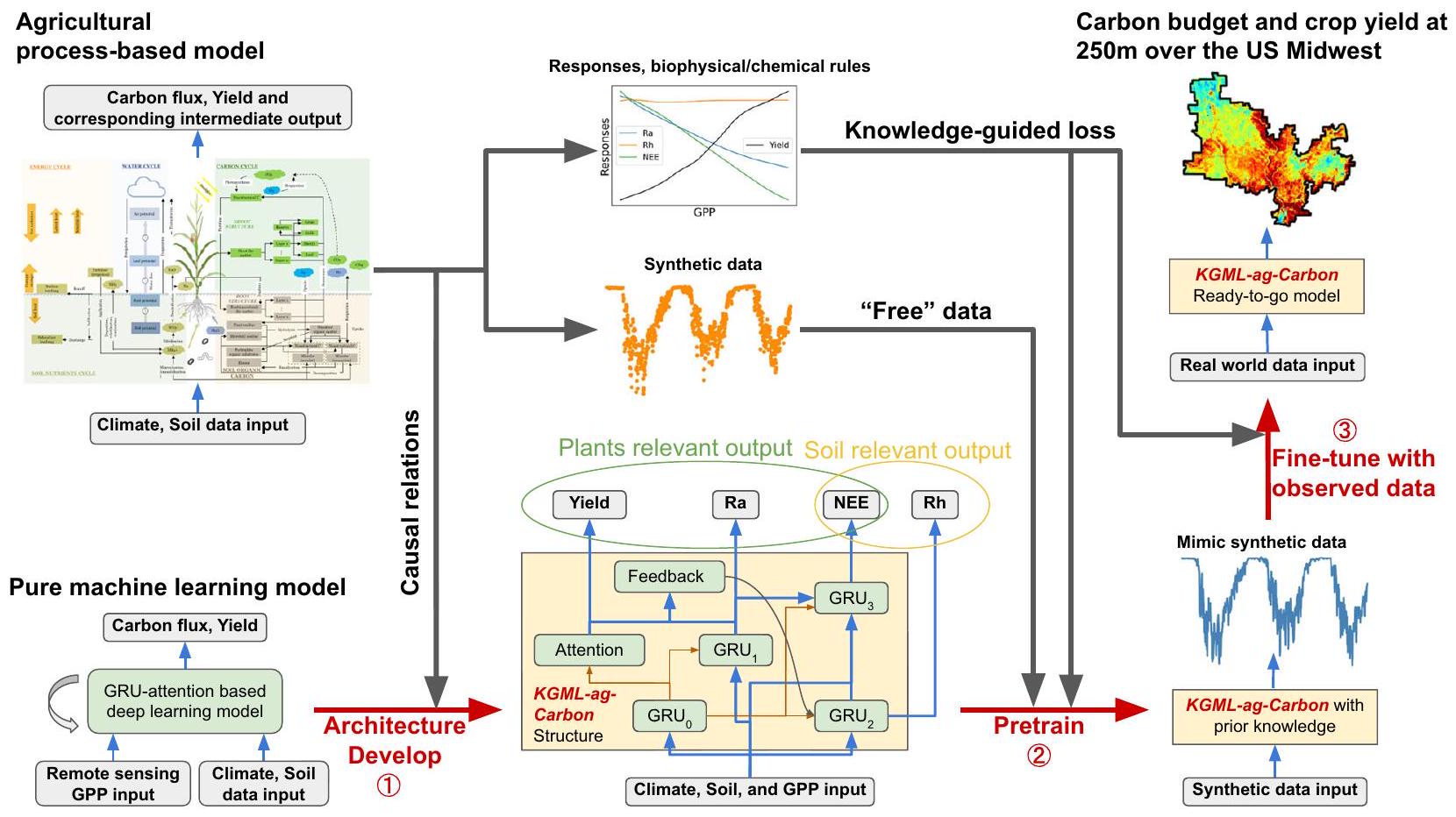

نظرة عامة على إطار KGML-ag-Carbon

استراتيجيات التدريب لنموذج KGML-ag-Carbon موضحة في قسم الطرق.

أداء النموذج في توقعات إنتاج المحاصيل وتدفقات الكربون

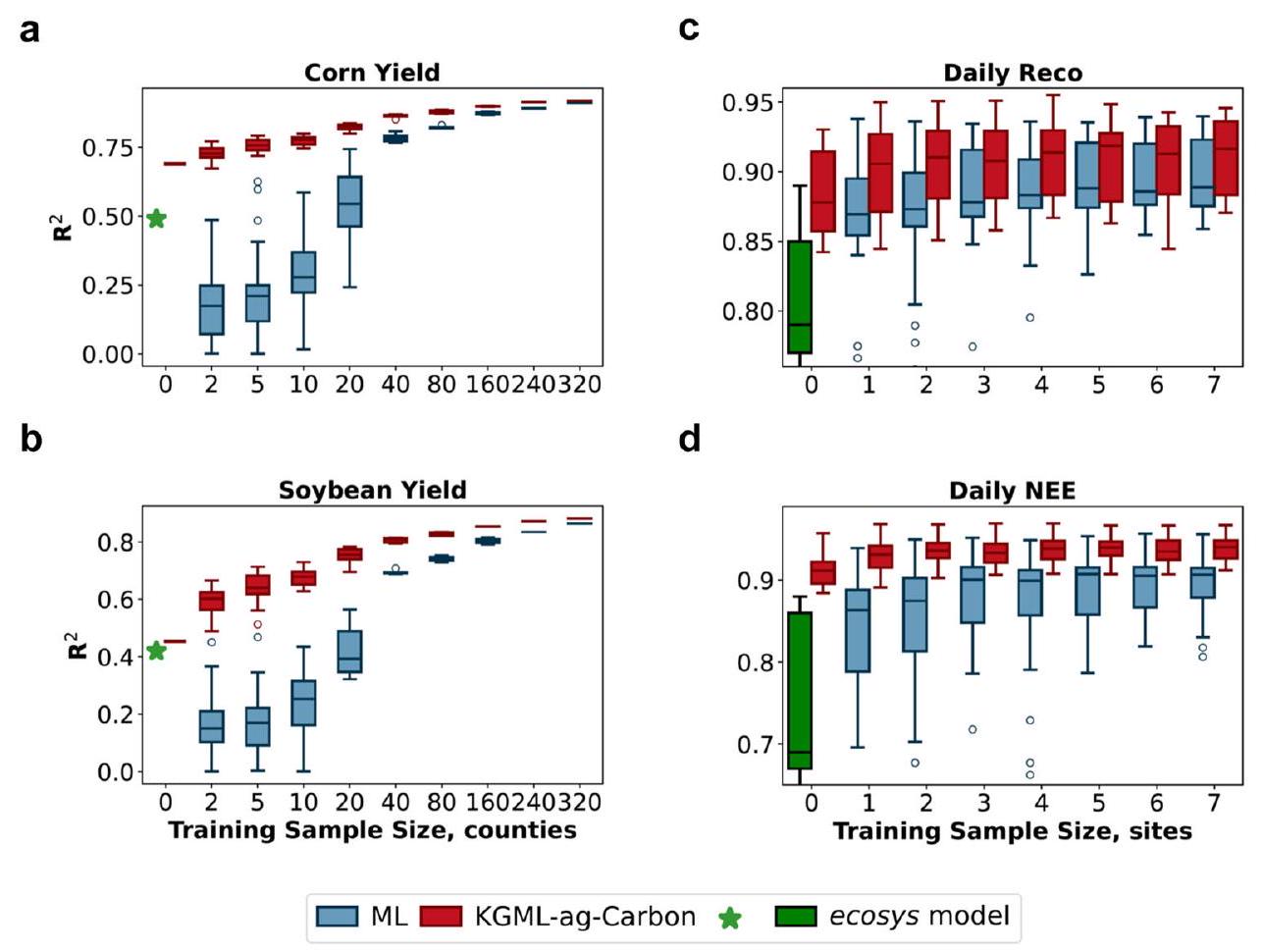

عينات البيانات لتدريب النموذج. أ، ب أداء توقع العائد عبر 210 مقاطعة.

حسب الموقع، تتراوح من 5 إلى 19 عامًا). توضح كل مخطط صندوقي الربع الأول والثالث (حواف الصندوق السفلية والعلوية)، الوسيط (الخط المركزي)، والحد الأدنى والحد الأقصى (الشعيرات السفلية والعلوية)، مع القيم الشاذة كدوائر مستديرة. تمثل النجوم الخضراء أداء ecosys في محاكاة عائد المحاصيل عبر الولايات الأمريكية إلينوي وآيوا وإنديانا المقيدة بـ GPP المستشعر عن بُعد والعائد المرصود، وتمثل الصناديق الخضراء أداء ecosys في محاكاة تدفقات الكربون في 7 مواقع برج تدفق EC عبر الغرب الأوسط الأمريكي من Zhou et al.

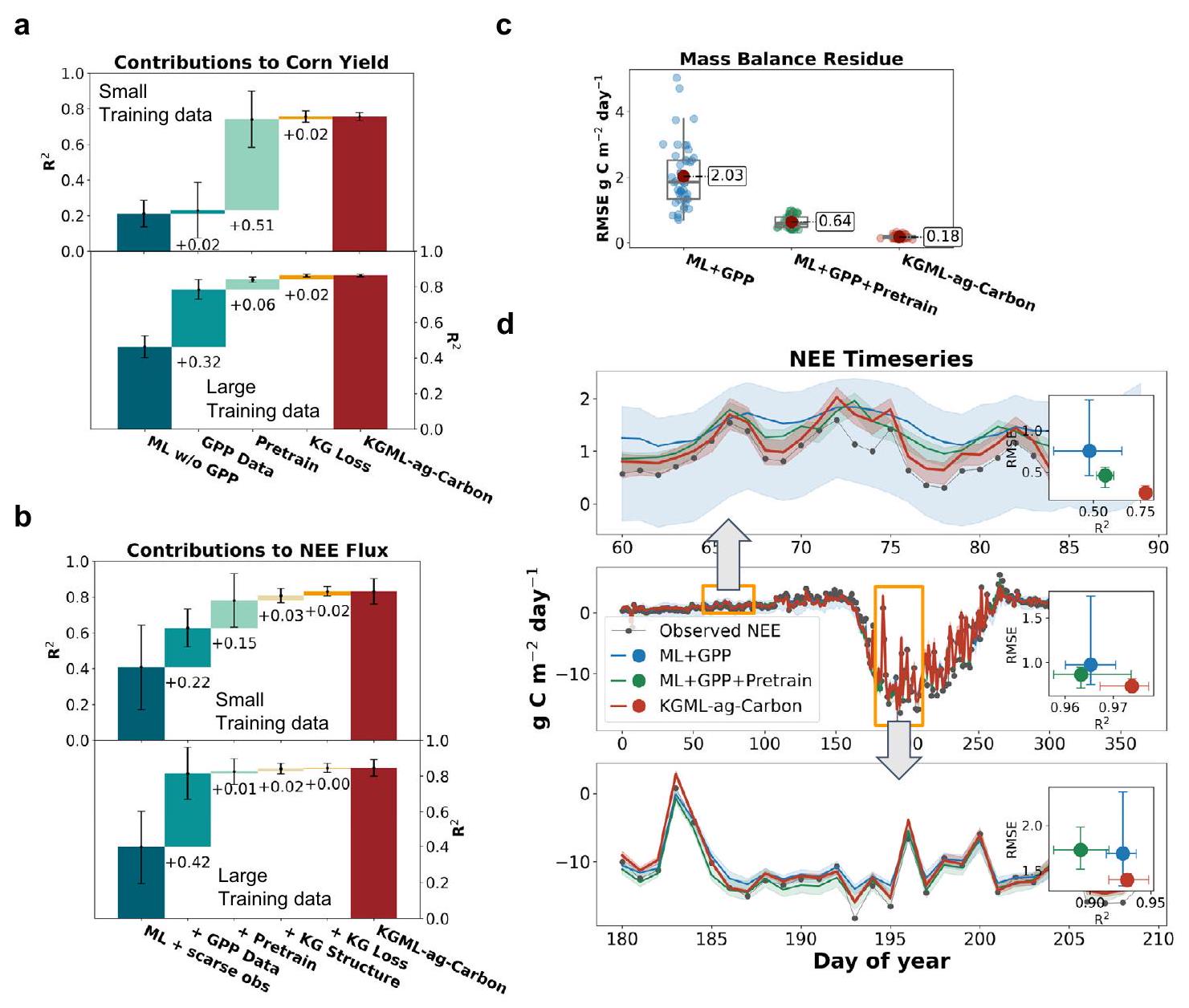

طرق لتقليل عدم اليقين في KGML-ag-Carbon

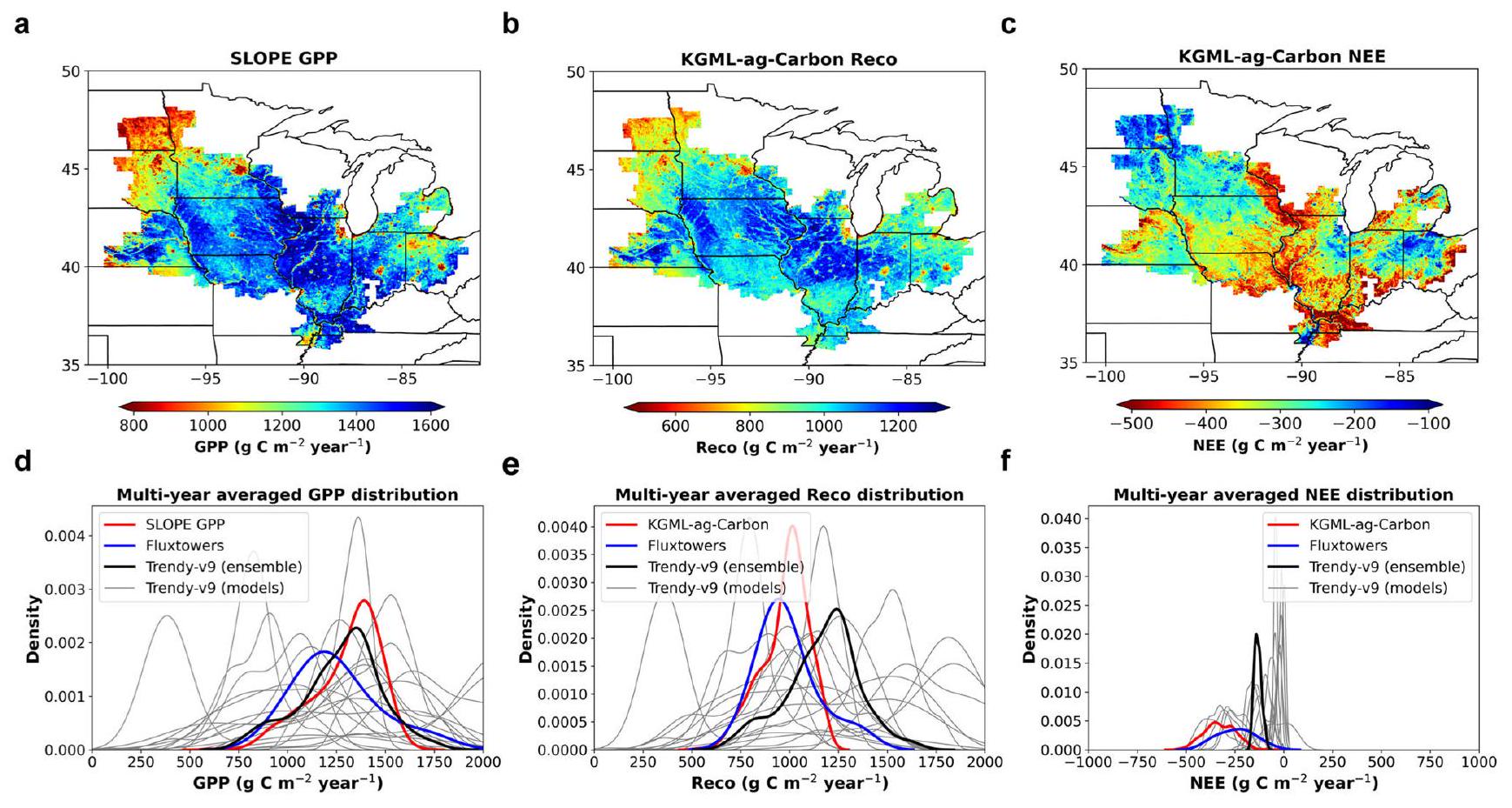

تقديرات تدفق الكربون عالية الدقة عبر الغرب الأوسط الأمريكي

معلومات، خرائط دوران المحاصيل، ومنتج GPP. تأتي الدقة الزمنية العالية من بيانات المناخ وبيانات منتج GPP، التي توفر معلومات يومية عن الظروف البيئية ومدخلات كربون النظام البيئي. يتم تقديم الإجراءات اللازمة لتوليد توقعات عالية الدقة عبر الغرب الأوسط الأمريكي في قسم “الطرق”.

الملخص

Reco و NEE، على التوالي، من توقعات KGML-ag-Carbon وTrendy-v9 خلال الفترة من 2000 إلى 2019 ومواقع قياس تدفق الإيدى في الأراضي الزراعية المختارة في وسط غرب الولايات المتحدة. المنتج Trendy المستخدم في هذه المقارنة هو منتج جماعي من نماذج متعددة قائمة على العمليات تحاكي ميزانية الكربون (خط رمادي واحد في

نقاش

فوائد ميزانيات الكربون عالية الدقة

قيود البيانات الملاحظة المباشرة. ومع ذلك، فإن هذه المتغيرات أساسية لفهم الآليات الأساسية. لذلك، تبرز هذه الدراسة أيضًا الحاجة إلى دقة البيانات على مستوى الميدان.

الرؤى المستفادة من تطوير KGML-ag-Carbon

لإعادة تدريب نموذج KGML وتصميم دوال خسارة KGML. تشير نتائجنا إلى أن المعرفة السابقة المستفادة من البيانات الاصطناعية تساهم بشكل كبير في تحسين أداء KGML-agCarbon، خاصة في الحالات التي تفتقر إلى البيانات (الأشكال 2 و 4). (2) قد تتضمن الملاحظات في الموقع (مثل أبراج تدفق EC، والغرف) بعض المتغيرات الوسيطة المهمة ويمكن أن تكون كثيفة زمنياً (ملاحظات طويلة الأمد، متكررة)، لكنها غالباً ما تكون متفرقة مكانياً بسبب تكاليف التركيب والعمالة. يمكن استخدامها لضبط نموذج KGML لالتقاط الديناميات الزمنية والعمليات الوسيطة، ولكن من الضروري التحكم في الاستجابات لعوامل معينة ثابتة زمنياً ولكنها متنوعة مكانياً (مثل خصائص التربة) التي تم تعلمها من نموذج PB (الشكل S7). (3) قد تحتوي الملاحظات على نطاق إقليمي بدقة خشن (مثل بيانات مسح إنتاج المحاصيل على مستوى المقاطعة) على عدم تطابق في المقياس مع متغيرات الإدخال/الإخراج لنموذج KGML. إن استخدام تلك البيانات ببساطة لتدريب KGML عن طريق تكبير (أو متوسط) مخرجات النموذج إلى مقياس خشن لحساب الخسارة قد يجبر توقعات النموذج الدقيق على الوضع المتوسط للملاحظات ذات المقياس الخشن. للتغلب على هذه العيوب، يجب أن تكون استجابات المتغيرات المستهدفة لعوامل مكانية وزمنية متنوعة موجهة بواسطة المعرفة الميدانية أثناء استخدام الملاحظات بدقة خشن لتقييد النموذج (الشكل S5).

طرق محتملة لتحسين تقديرات غازات الدفيئة الزراعية بواسطة KGML

الارتباطات الزمنية للحالات، والشبكات العصبية التلافيفية (CNN)، التي تتضمن الارتباطات المكانية للحالات. يمكن تعزيز إطار التعلم المتعدد المهام لـ KGML-ag-Carbon، جنبًا إلى جنب مع الهيكل الهرمي، من خلال دمج عمليات أكثر تمثيلاً ومحاكاة المتغيرات الوسيطة الرئيسية.

قابلية نقل KGML-ag-Carbon إلى تطبيقات أخرى

مسارات من المتغيرات المدخلة إلى المتغيرات المستهدفة. ثانياً، يمكن أن يؤدي دمج البيانات من مصادر متعددة إلى توسيع الإطار ليشمل مناطق أكبر وأنواع أكثر من النظم البيئية.

طرق

بيانات التدريب الاصطناعي المسبق لنموذج KGML

مجموعة البيانات للتخصيص، والتحقق، والاستنتاجات

هيكل KGML-ag-Carbon

استراتيجيات التدريب لـ KGML-ag-carbon

| خطوات التدريب | الأغراض ومجموعات البيانات | الوحدات الفرعية | دوال الخسارة | التكوينات |

| الخطوة 1 | العائد المسبق ورا مع بيانات اصطناعية | GRU_الأساس؛ وحدة الانتباه؛ GRU_را | برنامج MSE الذاتي (التفاصيل في الملاحظة التكميلية S1) | محسن آدم؛ معدل التعلم = 0.001؛ تراجع بمقدار 0.5 مرة كل 100 دورة؛ الحد الأقصى 1000 دورة؛ حجم الدفعة = 500 عينة؛ خلط عشوائي؛ إيقاف مبكر بعد 100 دورة |

| الخطوة 2 | تدريب Ra و Rh و NEE مسبقًا باستخدام بيانات اصطناعية | GRU_Ra; GRU_Rh; GRU_NEE | تحكم في MSE + توازن الكتلة + تحكم في الاستجابة (التفاصيل في الملاحظة التكميلية S2) | محسن آدم؛ معدل التعلم = 0.001؛ تراجع بمقدار 0.5 مرة كل 20 دورة؛ الحد الأقصى 80 دورة؛ حجم الدفعة = 500 عينة؛ خلط عشوائي؛ إيقاف مبكر لمدة 10 دورات |

| الخطوة 3 | تحسين العائد باستخدام بيانات العائد من وزارة الزراعة الأمريكية (USDA NASS) والبيانات الاصطناعية | GRU_الأساس؛ وحدة الانتباه | تحكم في MSE + التحكم في العتبة + التحكم في الاستجابة (التفاصيل في الملاحظة التكميلية S3) | محسن آدم؛ معدل التعلم

|

| الخطوة 4 | الحفاظ على النموذج المدرب مسبقًا

|

GRU_Ra; GRU_Rh; GRU_NEE | تحكم في MSE + توازن الكتلة + تحكم في الاستجابة (مشابه للخطوة 2) | محسن آدم؛ معدل التعلم = 0.001؛ تراجع بمقدار 0.5 مرة كل 10 عصور؛ الحد الأقصى 40 عصرًا؛ حجم الدفعة = 500 عينة؛ خلط عشوائي؛ إيقاف مبكر لمدة 5 عصور |

| الخطوة 5 | تحسين Ra و Rh و NEE باستخدام بيانات برج تدفق EC وبيانات تركيبية | GRU_Ra; GRU_Rh; GRU_NEE | تحكم في MSE + توازن الكتلة + تحكم في الاستجابة (التفاصيل في الملاحظة التكميلية S4) | محسن آدم؛ معدل التعلم

|

اختبار القوة لأداء KGML-ag-Carbon

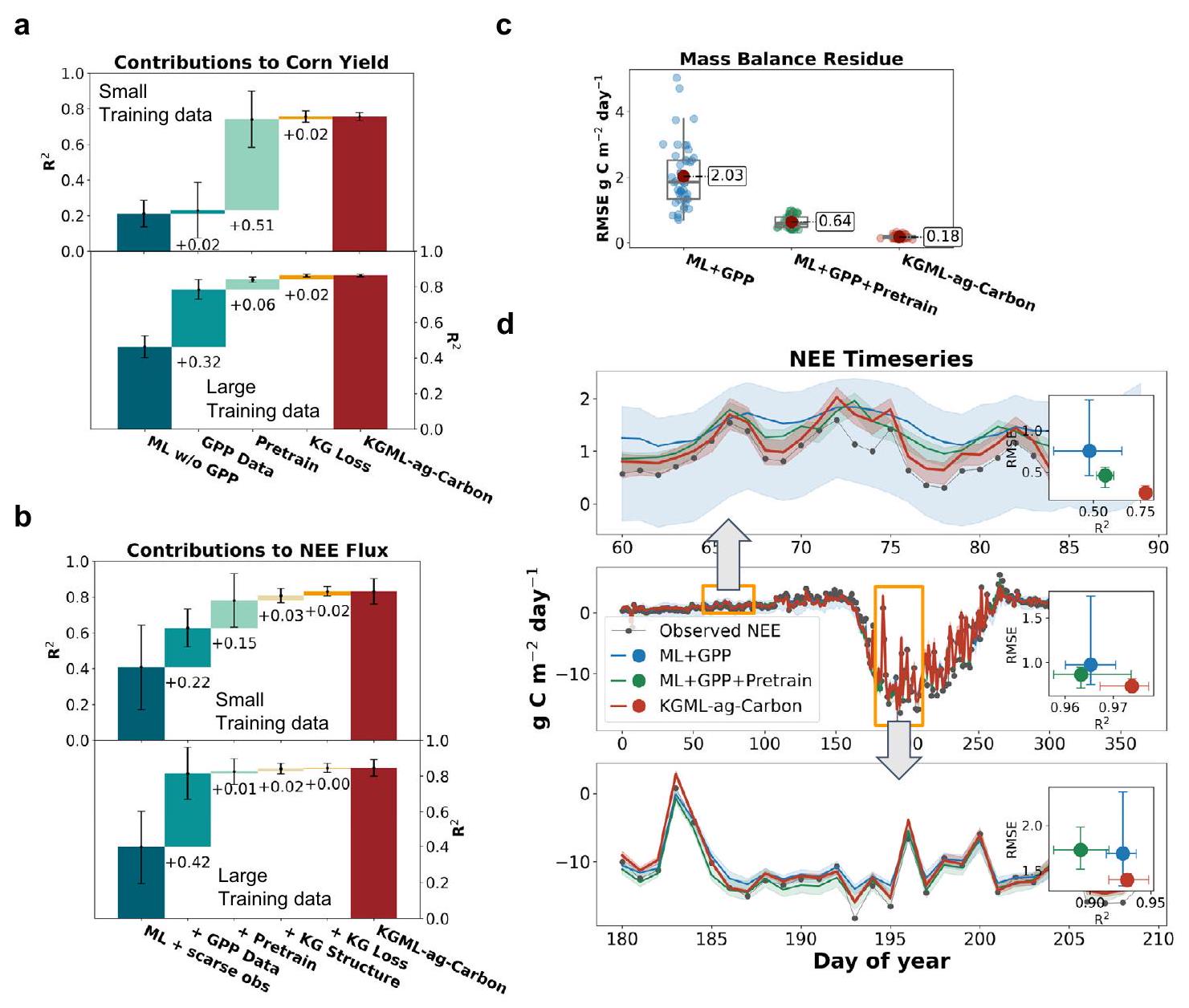

كشف مساهمات مكونات KGML-ag-Carbon

(1 و 7 مواقع) لتدريب النماذج، المشار إليها على أنها مجموعات عينات تدريب صغيرة وكبيرة، على التوالي. تم اختبار النماذج المحسّنة على مجموعات بيانات خارج العينة، والتي تشمل غلات NASS من 210 مقاطعات مختارة عشوائيًا وReco وNEE من 6 مجموعات من مواقع أبراج تدفق EC (تم تدريب النماذج التي تم اختبارها على مجموعة واحدة والتحقق من صحتها باستخدام بيانات من مواقع مختارة من مجموعات أخرى). قمنا بحساب المتوسط والانحراف المعياري لدقة التنبؤ لجميع النماذج من تجارب التجميع واكتشفنا تغييرات الأداء من خلال مقارنة النماذج مع وبدون كل مكون من مكونات KGML-ag-Carbon (الشكل S11). لتوضيح العوامل التي تساهم في أداء نموذج KGML-ag-Carbon، اخترنا خمسة نماذج تمثيلية من بين 16 نموذجًا تم تدريبها لعرض اتجاه تحسين الأداء. تشمل هذه النماذج (1) ML، (2) ML + GPP، (3) ML + GPP + التدريب المسبق، (4)

تنبؤات عالية الدقة عبر منطقة الغرب الأوسط الأمريكي

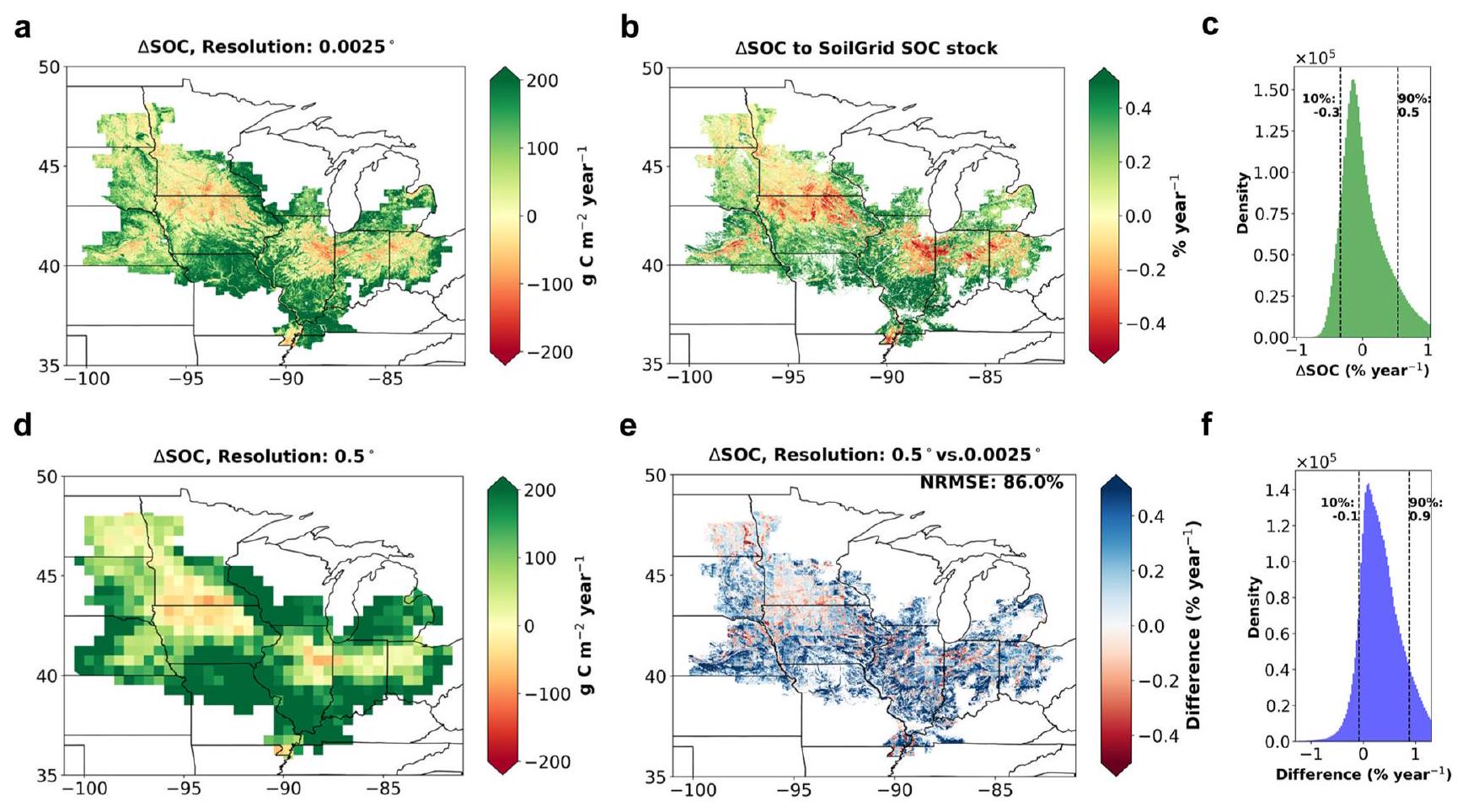

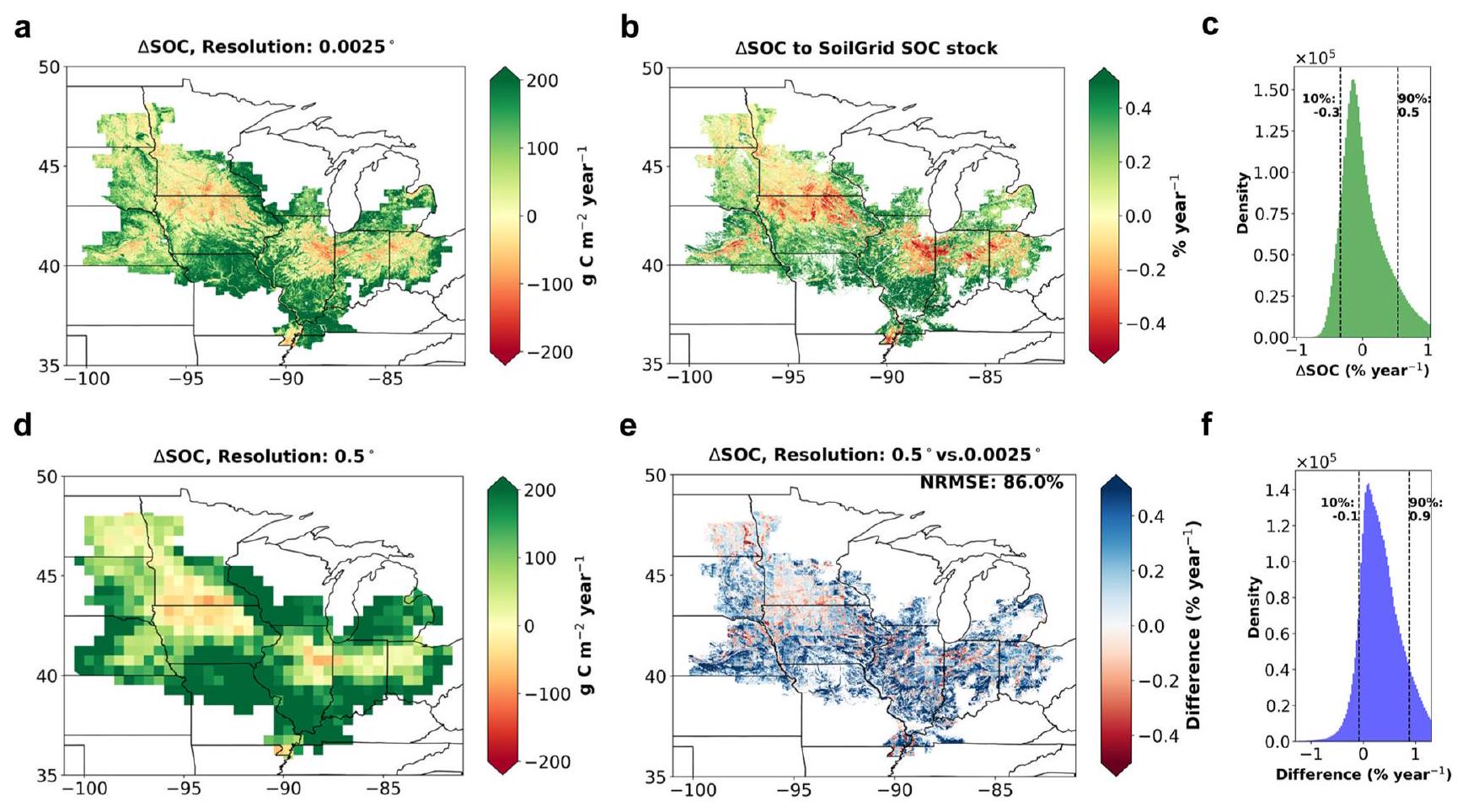

التحقيق في فوائد القياس عالي الدقة

نسبة الكتلة من الكربون العضوي في التربة عند أعماق مختلفة إلى إجمالي المخزون (يفترض أن يكون الكربون العضوي في التربة في

وصف بيئة التطوير

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

لإجراء معالجة البيانات ومكتبة بايثون قابلة للتنفيذ لنماذج KGML-agCarbon لتشغيل بيانات العرض متاحة من خلال Zenodo تحت رمز الوصولhttps://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10155516.

References

- Forster, P. et al. Chapter 7: The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity. https://doi.org/10.25455/ WGTN.16869671.V1 (2021).

- Skea, J. et al. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/ (2022).

- Clark, M. A. et al. Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the

and climate change targets. Science 370, 705-708 (2020). - Bossio, D. A. et al. The role of soil carbon in natural climate solutions. Nat. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0491-z (2020).

- Fargione, J. E. et al. Natural climate solutions for the United States. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat1869 (2018).

- Wollenberg, E. et al. Reducing emissions from agriculture to meet the

target. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 3859-3864 (2016). - Oldfield, E. E. et al. Crediting agricultural soil carbon sequestration. Science 375, 1222-1225 (2022).

- Novick, K. A. et al. Informing nature-based climate solutions for the United States with the best-available science. Glob. Chang. Biol. 28, 3778-3794 (2022).

- Bradford, M. A. et al. Soil carbon science for policy and practice. Nat. Sustain. 2, 1070-1072 (2019).

- Ranganathan, J., Waite, R., Searchinger, T. & Zionts, J. Regenerative Agriculture: Good for Soil Health, but Limited Potential to Mitigate Climate Change. https://www.wri.org/insights/regenerative-agriculture-good-soil-health-limited-potential-mitigate-climatechange (2020).

- Smith, P. et al. How to measure, report and verify soil carbon change to realize the potential of soil carbon sequestration for atmospheric greenhouse gas removal. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 219-241 (2020).

- Guan, K. et al. A scalable framework for quantifying field-level agricultural carbon outcomes. Earth-Science Reviews 243, 104462 (2023).

- Zhou, W. et al. Quantifying carbon budget, crop yields and their responses to environmental variability using the ecosys model for U.S. Midwestern agroecosystems. Agric. Meteorol. 307, 108521 (2021).

- Irrgang, C. et al. Towards neural Earth system modelling by integrating artificial intelligence in Earth system science. Nat. Mach. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-021-00374-3 (2021).

- Jung, M. et al. Scaling carbon fluxes from eddy covariance sites to globe: synthesis and evaluation of the FLUXCOM approach. Biogeosciences 17, 1343-1365 (2020).

- Rasp, S., Pritchard, M. S. & Gentine, P. Deep learning to represent subgrid processes in climate models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9684-9689 (2018).

- Zhan, W. et al. Two for one: partitioning CO2 fluxes and understanding the relationship between solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence and gross primary productivity using machine learning. Agric. Meteorol. 321, 108980 (2022).

- Hutson, M. TAUGHT TO THE TEST: AI software clears high hurdles on IQ tests but still makes dumb mistakes. Can better benchmarks help?. Science 376, 570-573 (2022).

- Karpatne, A. et al. Theory-guided data science: a new paradigm for scientific discovery from data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 29, 2318-2331 (2017).

- Grosz, B. et al. The implication of input data aggregation on upscaling soil organic carbon changes. Environ. Model. Softw. 96, 361-377 (2017).

- Karpatne, A., Kannan, R. & Kumar, V. Knowledge Guided Machine Learning: Accelerating Discovery using Scientific Knowledge and Data. (CRC Press, 2022).

- Willard, J., Jia, X., Xu, S., Steinbach, M. & Kumar, V. Integrating scientific knowledge with machine learning for engineering and environmental systems. ACM Comput. Surv. https://doi.org/10. 1145/3514228 (2022).

- Kraft, B., Jung, M., Körner, M., Koirala, S. & Reichstein, M. Towards hybrid modeling of the global hydrological cycle. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-26-1579-2022 (2022).

- ElGhawi, R. et al. Hybrid Modeling of evapotranspiration: inferring stomatal and aerodynamic resistances using combined physicsbased and machine learning. ESSOAr https://doi.org/10.1002/ essoar. 10512258.1 (2022).

- He, X. et al. Improving predictions of evapotranspiration by integrating multi-source observations and land surface model. Agric. Water Manag. 272, 107827 (2022).

- Beucler, T. et al. Enforcing analytic constraints in neural networks emulating physical systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 098302 (2021).

- Reichstein, M. et al. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 566, 195-204 (2019).

- Liu, L. et al. KGML-ag: a modeling framework of knowledge-guided machine learning to simulate agroecosystems: a case study of estimating N2O emission using data from mesocosm experiments. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 2839-2858 (2022).

- Grant, R. A Review of the Canadian Ecosystem Model-ecosys. in Modeling Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics for Soil Management (CRC Press, 2001).

- Cho, K., van Merrienboer, B., Bahdanau, D. & Bengio, Y. On the Properties of Neural Machine Translation: Encoder-Decoder Approaches. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1409.1259 (2014).

- Stuart Chapin, F., III, Matson, P. A. & Mooney, H. A. Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

- Reichle, D. E. The Global Carbon Cycle and Climate Change. (Elsevier Science Publishing, 2019).

- Baker, J. M. & Griffis, T. J. Examining strategies to improve the carbon balance of corn/soybean agriculture using eddy covariance and mass balance techniques. Agric. Meteorol. 128, 163-177 (2005).

- Jiang, C., Guan, K., Wu, G., Peng, B. & Wang, S. A daily, 250 m and real-time gross primary productivity product (2000-present) covering the contiguous United States. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 281-298 (2021).

- Sitch, S. et al. Recent trends and drivers of regional sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Biogeosciences 12, 653-679 (2015).

- Al-Kaisi, M. M. & Kwaw-Mensah, D. Quantifying soil carbon change in a long-term tillage and crop rotation study across lowa landscapes. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 84, 182-202 (2020).

- Ibrahim, M. A., Chua-Ona, T., Liebman, M. & Thompson, M. L. Soil organic carbon storage under biofuel cropping systems in a humid, continental climate. Agron. J. 110, 1748-1753 (2018).

- Poffenbarger, H. J. et al. Maximum soil organic carbon storage in Midwest U.S. cropping systems when crops are optimally nitrogenfertilized. PLoS ONE 12, e0172293 (2017).

- Olson, K., Ebelhar, S. A. & Lang, J. M. Long-term effects of cover crops on crop yields, soil organic carbon stocks and sequestration. Open J. Soil Sci. 04, 284-292 (2014).

- Jin, V. L. et al. Twelve years of Stover removal increases soil erosion potential without impacting yield. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 79, 1169-1178 (2015).

- Schmer, M. R., Jin, V. L., Wienhold, B. J., Varvel, G. E. & Follett, R. F. Tillage and residue management effects on soil carbon and nitrogen under irrigated continuous corn. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 78, 1987-1996 (2014).

- Stanley, P., Spertus, J., Chiartas, J., Stark, P. B. & Bowles, T. Valid inferences about soil carbon in heterogeneous landscapes. Geoderma 430, 116323 (2023).

- Goidts, E., Van Wesemael, B. & Crucifix, M. Magnitude and sources of uncertainties in soil organic carbon (SOC) stock assessments at various scales. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 60, 723-739 (2009).

- Asseng, S., Ewert, F. & Rosenzweig, C. Uncertainty in simulating wheat yields under climate change. Nature Clim Change. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 827-832 (2013).

- Mezbahuddin, S. et al. Assessing effects of agronomic nitrogen management on crop nitrogen use and nitrogen losses in the western Canadian prairies. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4, 512292 (2020).

- Grant, R. F. et al. Net biome productivity of irrigated and rainfed maize-soybean rotations: Modeling vs. Measurements. Agron. J. 99, 1404-1423 (2007).

- Grant, R. F. et al. Controlled Warming Effects on Wheat Growth and Yield: Field Measurements and Modeling. Crop Ecol. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2011.0158 (2011).

- Zhou, Q. et al. Recent rapid increase of cover crop adoption across the U.S. midwest detected by fusing multi-source satellite data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100249 (2022).

- Wang, S. et al. Cross-scale sensing of field-level crop residue cover: Integrating field photos, airborne hyperspectral imaging, and satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 285, 113366 (2023).

- Zhang, J. et al. Combining remotely sensed evapotranspiration and an agroecosystem model to estimate center-pivot irrigation water use at high spatio-temporal resolution. Water Resour. Res. 59, e2022WR032967 (2023).

- Ghosh, R. et al. Robust Inverse Framework using knowledge-guided self-supervised learning. in Proc 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. https://doi.org/10.1145/ 3534678.3539448 (ACM, 2022).

- Ding, F. & Xue, Y. X-MEN: guaranteed XOR-maximum entropy constrained inverse reinforcement learning. in Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence 589-598 (PMLR, 2022).

- Jia, X. et al. Graph-based reinforcement learning for active learning in real time: an application in modeling river networks. Proc 2021 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (SDM). 621-629 https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611976700.70 (2021).

- Mekonnen, Z. A., Riley, W. J., Randerson, J. T., Grant, R. F. & Rogers, B. M. Expansion of high-latitude deciduous forests driven by interactions between climate warming and fire. Nat. Plants 5, 952-958 (2019).

- Grant, R. F., Lin, S. & Hernandez-Ramirez, G. Modelling nitrification inhibitor effects on N 2 O emissions after fall- and spring-applied slurry by reducing nitrifier NH4 oxidation rate. Biogeosciences https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-2021-2020 (2020).

- Qin, Z. et al. Assessing the impacts of cover crops on maize and soybean yield in the U.S. Midwestern agroecosystems. Field Crops Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108264 (2021).

- Li, Z. et al. Assessing the impacts of pre-growing-season weather conditions on soil nitrogen dynamics and corn productivity in the U.S. Midwest. Field Crops Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2022. 108563 (2022).

- Ma, Z. et al. Interaction of hydrological and anthropogenic processes controls the relationship between streamflow discharge and nitrogen concentration in the U.S. Midwestern watersheds. B45L-1769 (2021).

- Yang, Y. et al. Distinct driving mechanisms of non-growing season N2O emissions call for spatial-specific mitigation strategies in the US Midwest. Agricult. Forest Meteorol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. agrformet.2022.109108 (2022).

- Walther, S. et al. Technical note: a view from space on global flux towers by MODIS and Landsat: the FluxnetEO data set. Biogeosciences https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-2805-2022 (2022).

- Pastorello, G. et al. The FLUXNET2O15 dataset and the ONEFlux processing pipeline for eddy covariance data. Sci. Data 7, 225 (2020).

- Bauer, P. et al. The digital revolution of Earth-system science. Nat. Comput. Sci. 1, 104-113 (2021).

- Wang, S., Di Tommaso, S., Deines, J. M. & Lobell, D. B. Mapping twenty years of corn and soybean across the US Midwest using the Landsat archive. Sci. Data 7, 307 (2020).

- Khandelwal, A. et al. Physics Guided Machine Learning Methods for Hydrology. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2012.02854 (2020).

- Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735-1780 (1997).

- Chung, J., Gulcehre, C., Cho, K. & Bengio, Y. Empirical Evaluation of Gated Recurrent Neural Networks on Sequence Modeling. https:// doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1412.3555 (2014).

- Bahdanau, D., Cho, K. & Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.1409.0473 (2014).

- Xu, S. et al. Mini-Batch Learning Strategies for modeling long term temporal dependencies: a study in environmental applications. in Proc 2023 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (SDM) 649-657 (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2023).

- Kumar, M. P., Packer, B. & Koller, D. Self-paced learning for latent variable models. in Proc 24th Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 1189-1197 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2010).

- Bengio, Y., Louradour, J., Collobert, R. & Weston, J. Curriculum learning. in Proc 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning. https://doi.org/10.1145/1553374.1553380 (ACM, 2009).

- Poggio, L. et al. SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. SOIL 7, 217-240 (2021).

- Cao, Q. et al. On the spatial variability and influencing factors of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen stocks in a desert oasis ecotone of northwestern China. Catena 206, 105533 (2021).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43860-5.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

قسم المنتجات الحيوية وهندسة الأنظمة الحيوية، جامعة مينيسوتا، سانت بول، MN 55108، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز استدامة النظم الزراعية، معهد الاستدامة والطاقة والبيئة، جامعة إلينوي في أوربانا-شامبين، أوربانا، إلينوي 61801، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الموارد الطبيعية وعلوم البيئة، كلية الزراعة والمستهلك والعلوم البيئية، جامعة إلينوي في أوربانا-شامبين، أوربانا، إلينوي 61801، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علوم الحاسوب، جامعة إلينوي في أوربانا-شامبين، أوربانا، إلينوي 61801، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. المركز الوطني لتطبيقات الحوسبة الفائقة، جامعة إلينوي في أوربانا-شامبين، أوربانا، إلينوي 61801، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علوم الحاسوب والهندسة، جامعة مينيسوتا، مينيابوليس، MN 55455، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. علوم الأرض والبيئة، مختبر لورانس بيركلي الوطني، بيركلي، كاليفورنيا 94720، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علوم الحاسوب، جامعة بيتسبرغ، بيتسبرغ، بنسلفانيا 15260، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الزراعة البيئية، جامعة آرهوس، 4200 سلاجلز، الدنمارك. مدرسة همفري للشؤون العامة، جامعة مينيسوتا، مدن التوأم، مينيسوتا 55455، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الموارد المتجددة، جامعة ألبرتا، إدمونتون، ألبرتا T6G2E3، كندا. فرع المعرفة البيئية والتنبؤ، وزارة البيئة والمناطق المحمية في ألبرتا، إدمونتون، ألبرتا T5K 2J6، كندا. هؤلاء المؤلفون ساهموا بالتساوي: ليشينغ ليو، وانغ زو. البريد الإلكتروني:kaiyug@illinois.edu; jinzn@umn.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43860-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38191521

Publication Date: 2024-01-08

Knowledge-guided machine learning can improve carbon cycle quantification in agroecosystems

Accepted: 22 November 2023

Published online: 08 January 2024

(A) Check for updates

Abstract

Licheng Liu (1)

Abstract

Accurate and cost-effective quantification of the carbon cycle for agroecosystems at decision-relevant scales is critical to mitigating climate change and ensuring sustainable food production. However, conventional process-based or data-driven modeling approaches alone have large prediction uncertainties due to the complex biogeochemical processes to model and the lack of observations to constrain many key state and flux variables. Here we propose a Knowledge-Guided Machine Learning (KGML) framework that addresses the above challenges by integrating knowledge embedded in a process-based model, high-resolution remote sensing observations, and machine learning (ML) techniques. Using the U.S. Corn Belt as a testbed, we demonstrate that KGML can outperform conventional process-based and black-box ML models in quantifying carbon cycle dynamics. Our high-resolution approach quantitatively reveals

uptake by crops also removes large amounts of carbon dioxide (

fine-tuning KGML-ag-Carbon using observed low-resolution crop yield data and carbon fluxes from sparsely distributed eddy-covariance sites. The knowledgeguided losses were designed based on the process-based model to further constrain the response of target variables to input variables during both model pretraining and fine-tuning processes.

Results

Overview of the KGML-ag-Carbon framework

training strategies for the KGML-ag-Carbon model are provided in the Methods section.

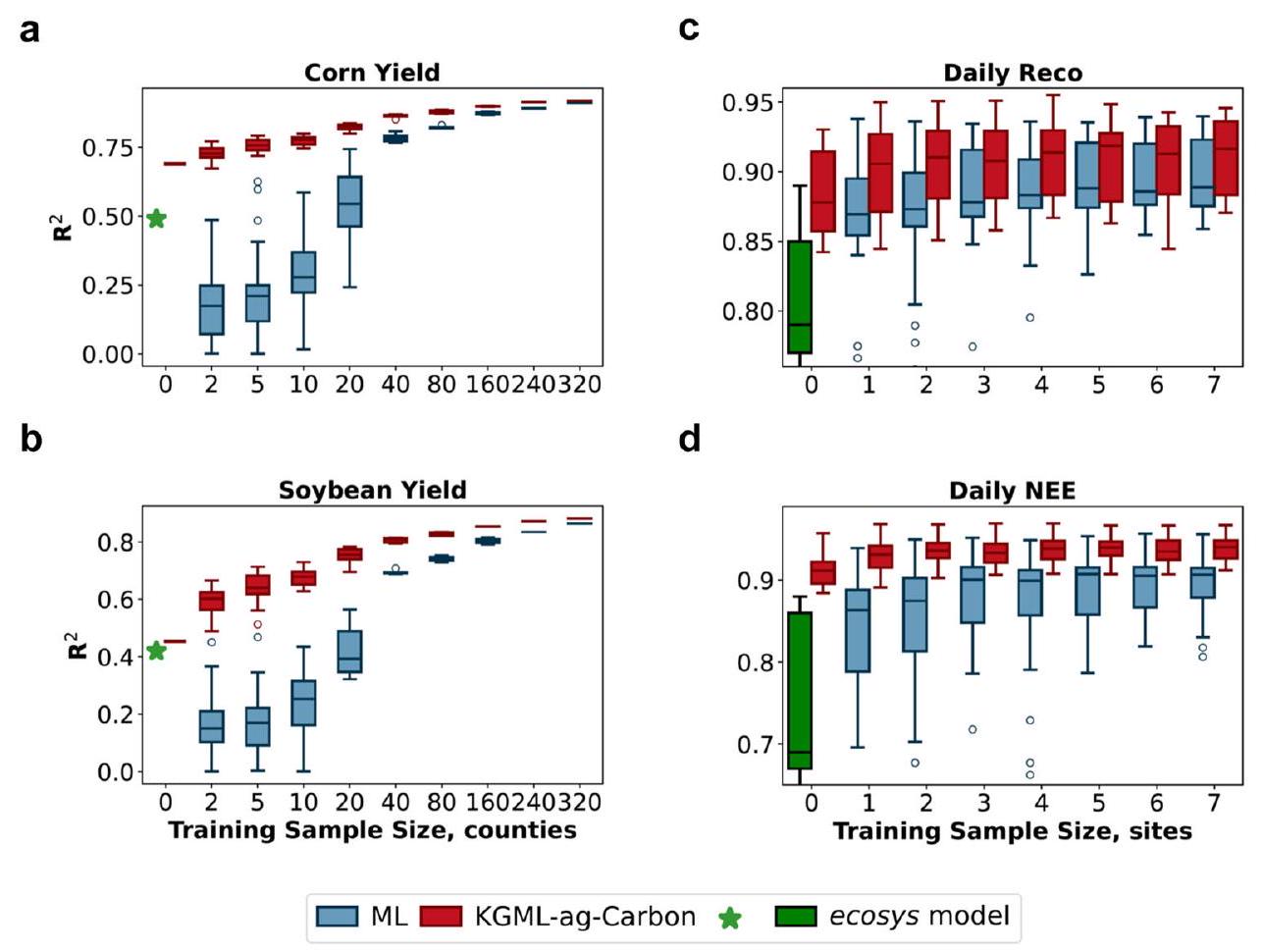

Model performance in crop yield and carbon flux predictions

data samples for model training. a, b The yield prediction performance over 210 counties.

by site, ranging from 5 to 19 years). Each box plot illustrates the first and third quartiles (lower and upper box edges), median (central line), and minimum and maximum (lower and upper whiskers), with outliers as round circles. The green stars represent the performance of ecosys in crop yield simulations across the U.S. states of Illinois, Iowa, and Indiana constrained with remotely sensed GPP and observed yield, and the green boxes represent the performance of ecosys in carbon flux simulations at 7 EC flux tower sites across the U.S. Midwest from Zhou et al.

Pathways to reduce KGML-ag-Carbon uncertainty

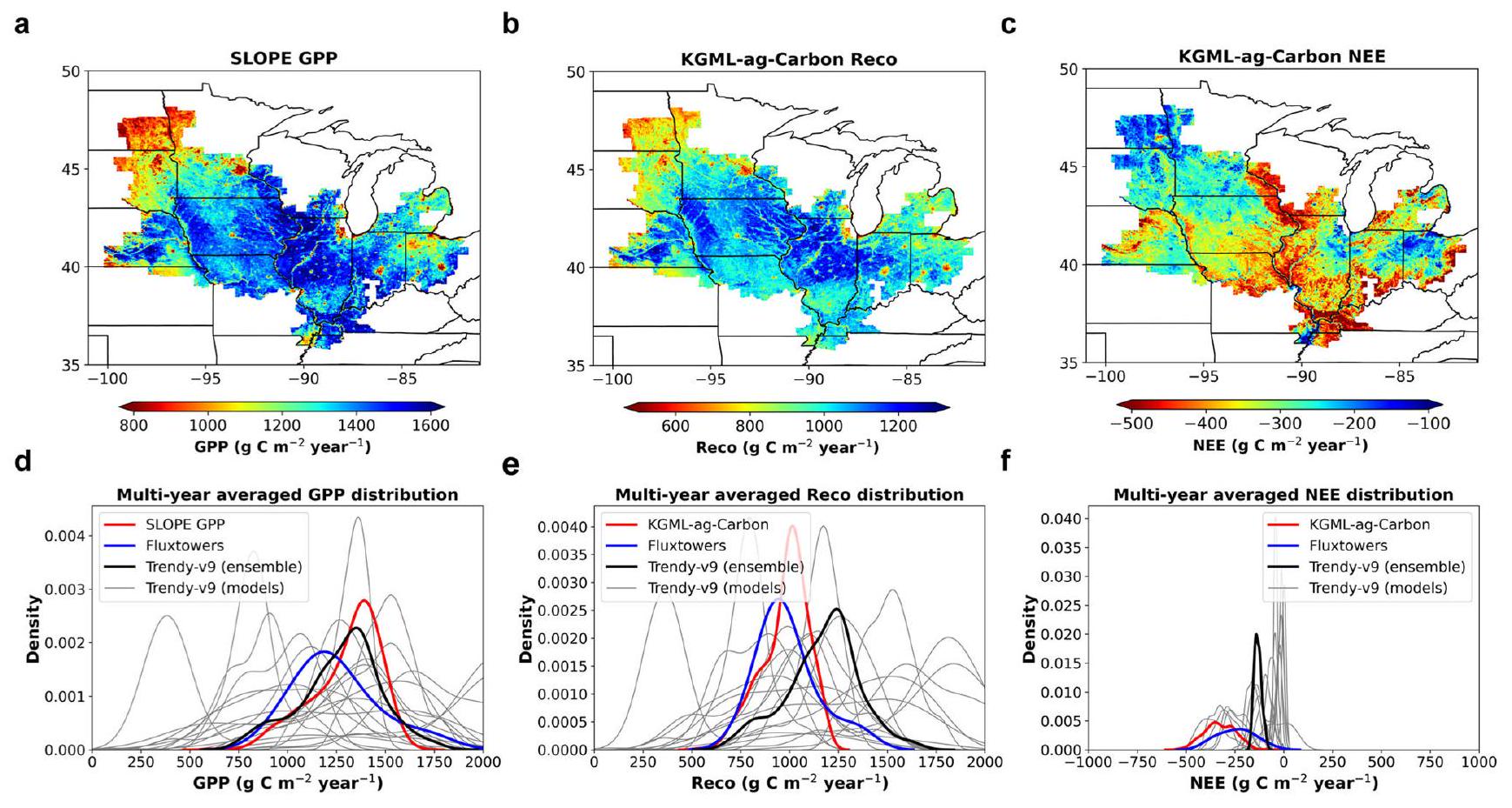

High-resolution carbon flux estimates across the U.S. Midwest

information, crop rotation maps, and the GPP product. The high temporal resolution comes from the climate and GPP product data, which provide daily information on environmental conditions and ecosystem carbon inputs. The procedures for generating highresolution predictions across the U.S. Midwest are given in the “Methods” section.

Abstract

Reco, and NEE, respectively, from KGML-ag-Carbon predictions and Trendy-v9 during 2000-2019 and selected cropland eddy-covariance sites in the U.S. Midwest. The Trendy product used in this comparison is an ensemble product from multiple process-based models simulated carbon budget (a single gray line in

Discussion

The benefits of high-resolution carbon budgets

direct observational data constraints. These variables, however, are fundamental to understanding the underlying mechanisms. Therefore, this study also highlights the need for accurate field-level

Insights gained from the development of KGML-ag-Carbon

for KGML model pre-training and designing KGML loss functions. Our results indicate that the prior knowledge learned from the synthetic data strongly contributes to improving the performance of KGML-agCarbon, especially in data-sparse situations (Figs. 2 and 4). (2) In-situ observations (e.g., EC flux towers, chambers) may include some important intermediate variables and can be temporally dense (longterm, frequent observations), but are often spatially sparse due to installation and labor expenses. They can be used to fine-tune the KGML model to capture temporal dynamics and intermediate processes, but it is necessary to control the responses to certain temporally static but spatially diverse factors (such as soil properties) learned from the PB model (Fig. S7). (3) Regional-scale observations at coarse resolution (e.g., county-level crop yield survey data) may have scale mismatches with the KGML input/output variables. Simply using those data to train the KGML by upscaling (or averaging) the model outputs to a coarse scale to calculate loss may force predictions of the finescale model to the average status of the coarse-scale observations. To overcome these shortcomings, the responses of target variables to diverse spatial and temporal factors must be guided by domain knowledge while using observations at coarse resolution to constrain the model (Fig. S5).

Potential paths to improve agricultural GHG estimations by KGML

temporal correlations of states, and convolutional neural networks (CNN), which incorporate the spatial correlations of states. The multitask learning framework of KGML-ag-Carbon, along with the hierarchical structure, can be further enhanced by incorporating more representative processes and simulating key intermediate variables

Transferability of the KGML-ag-Carbon to other applications

pathways from input variables to target variables. Second, assimilating multi-source data can extend the framework to larger regions and more ecosystem types

Methods

Synthetic pre-training data for the KGML model

Datasets for fine-tuning, validation, and extrapolations

The structure of KGML-ag-Carbon

Training strategies for KGML-ag-carbon

| Training steps | Purposes and datasets | Submodules | Loss functions | Configurations |

| Step 1 | Pretrain yield and Ra with synthetic data | GRU_Basis; Attention module; GRU_Ra | Self-paced MSE (details in supplementary Note S1) | Adam optimizer; Learning rate = 0.001; Decay by 0.5 times per 100 epochs; Maximum 1000 epochs; Batch size = 500 samples; Random shuffle; 100-epoch early stop |

| Step 2 | Pretrain Ra, Rh, and NEE with synthetic data | GRU_Ra; GRU_Rh; GRU_NEE | MSE + Mass balance control + Response control (details in supplementary Note S2) | Adam optimizer; Learning rate = 0.001; Decay by 0.5 times per 20 epochs; Maximum 80 epochs; Batch size = 500 samples; Random shuffle; 10-epoch early stop lasting |

| Step 3 | Fine-tune yield with USDA NASS yield and synthetic data | GRU_Basis; Attention module | MSE + threshold control + response control (details in supplementary Note S3) | Adam optimizer; Learning rate

|

| Step 4 | Maintain pretrained

|

GRU_Ra; GRU_Rh; GRU_NEE | MSE + Mass balance control + Response control (similar as Step 2) | Adam optimizer; Learning rate = 0.001; Decay by 0.5 times per 10 epochs; Maximum 40 epochs; Batch size = 500 samples; Random shuffle; 5-epoch early stop lasting |

| Step 5 | Finetune Ra, Rh, and NEE with EC flux tower data and synthetic data | GRU_Ra; GRU_Rh; GRU_NEE | MSE + Mass balance control + Response control (details in supplementary Note S4) | Adam optimizer; Learning rate

|

Robustness test for the performance of KGML-ag-Carbon

Detecting the contributions of KGML-ag-Carbon components

(1 and 7 sites) to train the models, referred to as small and large training sample sets, respectively. The optimized models were tested on out-ofsample data sets, which are NASS yields from 210 randomly selected counties and Reco and NEE from 6 groups of EC flux tower sites (the models tested on one group were trained and validated with data from sites chosen from other groups). We calculated the mean and STD of the prediction accuracy for all the models from ensemble experiments and detected the performance changes by comparing the models with and without each KGML-ag-Carbon component (Fig. S11). To illustrate the factors that contribute to the KGML-ag-Carbon model performance, we selected five representative models from the 16 trained models to showcase the direction of performance improvement. These models include (1) ML, (2) ML + GPP, (3) ML + GPP + pre-training, (4)

High-resolution predictions across the U.S. Midwest

Investigating the benefits of high-resolution quantification

the percentage fraction of SOC at different depths to total stock (assumed to be SOC in

Development environment description

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

for data processing and an executable Python library of KGML-agCarbon models for running demo data are accessible through Zenodo under accession code https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10155516.

References

- Forster, P. et al. Chapter 7: The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks, and Climate Sensitivity. https://doi.org/10.25455/ WGTN.16869671.V1 (2021).

- Skea, J. et al. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/ (2022).

- Clark, M. A. et al. Global food system emissions could preclude achieving the

and climate change targets. Science 370, 705-708 (2020). - Bossio, D. A. et al. The role of soil carbon in natural climate solutions. Nat. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0491-z (2020).

- Fargione, J. E. et al. Natural climate solutions for the United States. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat1869 (2018).

- Wollenberg, E. et al. Reducing emissions from agriculture to meet the

target. Glob. Chang. Biol. 22, 3859-3864 (2016). - Oldfield, E. E. et al. Crediting agricultural soil carbon sequestration. Science 375, 1222-1225 (2022).

- Novick, K. A. et al. Informing nature-based climate solutions for the United States with the best-available science. Glob. Chang. Biol. 28, 3778-3794 (2022).

- Bradford, M. A. et al. Soil carbon science for policy and practice. Nat. Sustain. 2, 1070-1072 (2019).

- Ranganathan, J., Waite, R., Searchinger, T. & Zionts, J. Regenerative Agriculture: Good for Soil Health, but Limited Potential to Mitigate Climate Change. https://www.wri.org/insights/regenerative-agriculture-good-soil-health-limited-potential-mitigate-climatechange (2020).

- Smith, P. et al. How to measure, report and verify soil carbon change to realize the potential of soil carbon sequestration for atmospheric greenhouse gas removal. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 219-241 (2020).

- Guan, K. et al. A scalable framework for quantifying field-level agricultural carbon outcomes. Earth-Science Reviews 243, 104462 (2023).

- Zhou, W. et al. Quantifying carbon budget, crop yields and their responses to environmental variability using the ecosys model for U.S. Midwestern agroecosystems. Agric. Meteorol. 307, 108521 (2021).

- Irrgang, C. et al. Towards neural Earth system modelling by integrating artificial intelligence in Earth system science. Nat. Mach. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-021-00374-3 (2021).

- Jung, M. et al. Scaling carbon fluxes from eddy covariance sites to globe: synthesis and evaluation of the FLUXCOM approach. Biogeosciences 17, 1343-1365 (2020).

- Rasp, S., Pritchard, M. S. & Gentine, P. Deep learning to represent subgrid processes in climate models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9684-9689 (2018).

- Zhan, W. et al. Two for one: partitioning CO2 fluxes and understanding the relationship between solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence and gross primary productivity using machine learning. Agric. Meteorol. 321, 108980 (2022).

- Hutson, M. TAUGHT TO THE TEST: AI software clears high hurdles on IQ tests but still makes dumb mistakes. Can better benchmarks help?. Science 376, 570-573 (2022).

- Karpatne, A. et al. Theory-guided data science: a new paradigm for scientific discovery from data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 29, 2318-2331 (2017).

- Grosz, B. et al. The implication of input data aggregation on upscaling soil organic carbon changes. Environ. Model. Softw. 96, 361-377 (2017).

- Karpatne, A., Kannan, R. & Kumar, V. Knowledge Guided Machine Learning: Accelerating Discovery using Scientific Knowledge and Data. (CRC Press, 2022).

- Willard, J., Jia, X., Xu, S., Steinbach, M. & Kumar, V. Integrating scientific knowledge with machine learning for engineering and environmental systems. ACM Comput. Surv. https://doi.org/10. 1145/3514228 (2022).

- Kraft, B., Jung, M., Körner, M., Koirala, S. & Reichstein, M. Towards hybrid modeling of the global hydrological cycle. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-26-1579-2022 (2022).

- ElGhawi, R. et al. Hybrid Modeling of evapotranspiration: inferring stomatal and aerodynamic resistances using combined physicsbased and machine learning. ESSOAr https://doi.org/10.1002/ essoar. 10512258.1 (2022).

- He, X. et al. Improving predictions of evapotranspiration by integrating multi-source observations and land surface model. Agric. Water Manag. 272, 107827 (2022).

- Beucler, T. et al. Enforcing analytic constraints in neural networks emulating physical systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 098302 (2021).

- Reichstein, M. et al. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 566, 195-204 (2019).

- Liu, L. et al. KGML-ag: a modeling framework of knowledge-guided machine learning to simulate agroecosystems: a case study of estimating N2O emission using data from mesocosm experiments. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 2839-2858 (2022).

- Grant, R. A Review of the Canadian Ecosystem Model-ecosys. in Modeling Carbon and Nitrogen Dynamics for Soil Management (CRC Press, 2001).

- Cho, K., van Merrienboer, B., Bahdanau, D. & Bengio, Y. On the Properties of Neural Machine Translation: Encoder-Decoder Approaches. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1409.1259 (2014).

- Stuart Chapin, F., III, Matson, P. A. & Mooney, H. A. Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Ecology. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2011).

- Reichle, D. E. The Global Carbon Cycle and Climate Change. (Elsevier Science Publishing, 2019).

- Baker, J. M. & Griffis, T. J. Examining strategies to improve the carbon balance of corn/soybean agriculture using eddy covariance and mass balance techniques. Agric. Meteorol. 128, 163-177 (2005).

- Jiang, C., Guan, K., Wu, G., Peng, B. & Wang, S. A daily, 250 m and real-time gross primary productivity product (2000-present) covering the contiguous United States. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 281-298 (2021).

- Sitch, S. et al. Recent trends and drivers of regional sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Biogeosciences 12, 653-679 (2015).

- Al-Kaisi, M. M. & Kwaw-Mensah, D. Quantifying soil carbon change in a long-term tillage and crop rotation study across lowa landscapes. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 84, 182-202 (2020).

- Ibrahim, M. A., Chua-Ona, T., Liebman, M. & Thompson, M. L. Soil organic carbon storage under biofuel cropping systems in a humid, continental climate. Agron. J. 110, 1748-1753 (2018).

- Poffenbarger, H. J. et al. Maximum soil organic carbon storage in Midwest U.S. cropping systems when crops are optimally nitrogenfertilized. PLoS ONE 12, e0172293 (2017).

- Olson, K., Ebelhar, S. A. & Lang, J. M. Long-term effects of cover crops on crop yields, soil organic carbon stocks and sequestration. Open J. Soil Sci. 04, 284-292 (2014).

- Jin, V. L. et al. Twelve years of Stover removal increases soil erosion potential without impacting yield. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 79, 1169-1178 (2015).

- Schmer, M. R., Jin, V. L., Wienhold, B. J., Varvel, G. E. & Follett, R. F. Tillage and residue management effects on soil carbon and nitrogen under irrigated continuous corn. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 78, 1987-1996 (2014).

- Stanley, P., Spertus, J., Chiartas, J., Stark, P. B. & Bowles, T. Valid inferences about soil carbon in heterogeneous landscapes. Geoderma 430, 116323 (2023).

- Goidts, E., Van Wesemael, B. & Crucifix, M. Magnitude and sources of uncertainties in soil organic carbon (SOC) stock assessments at various scales. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 60, 723-739 (2009).

- Asseng, S., Ewert, F. & Rosenzweig, C. Uncertainty in simulating wheat yields under climate change. Nature Clim Change. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 827-832 (2013).

- Mezbahuddin, S. et al. Assessing effects of agronomic nitrogen management on crop nitrogen use and nitrogen losses in the western Canadian prairies. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4, 512292 (2020).

- Grant, R. F. et al. Net biome productivity of irrigated and rainfed maize-soybean rotations: Modeling vs. Measurements. Agron. J. 99, 1404-1423 (2007).

- Grant, R. F. et al. Controlled Warming Effects on Wheat Growth and Yield: Field Measurements and Modeling. Crop Ecol. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2011.0158 (2011).

- Zhou, Q. et al. Recent rapid increase of cover crop adoption across the U.S. midwest detected by fusing multi-source satellite data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100249 (2022).

- Wang, S. et al. Cross-scale sensing of field-level crop residue cover: Integrating field photos, airborne hyperspectral imaging, and satellite data. Remote Sens. Environ. 285, 113366 (2023).

- Zhang, J. et al. Combining remotely sensed evapotranspiration and an agroecosystem model to estimate center-pivot irrigation water use at high spatio-temporal resolution. Water Resour. Res. 59, e2022WR032967 (2023).

- Ghosh, R. et al. Robust Inverse Framework using knowledge-guided self-supervised learning. in Proc 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. https://doi.org/10.1145/ 3534678.3539448 (ACM, 2022).

- Ding, F. & Xue, Y. X-MEN: guaranteed XOR-maximum entropy constrained inverse reinforcement learning. in Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence 589-598 (PMLR, 2022).

- Jia, X. et al. Graph-based reinforcement learning for active learning in real time: an application in modeling river networks. Proc 2021 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (SDM). 621-629 https://doi.org/10.1137/1.9781611976700.70 (2021).

- Mekonnen, Z. A., Riley, W. J., Randerson, J. T., Grant, R. F. & Rogers, B. M. Expansion of high-latitude deciduous forests driven by interactions between climate warming and fire. Nat. Plants 5, 952-958 (2019).

- Grant, R. F., Lin, S. & Hernandez-Ramirez, G. Modelling nitrification inhibitor effects on N 2 O emissions after fall- and spring-applied slurry by reducing nitrifier NH4 oxidation rate. Biogeosciences https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-2021-2020 (2020).

- Qin, Z. et al. Assessing the impacts of cover crops on maize and soybean yield in the U.S. Midwestern agroecosystems. Field Crops Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2021.108264 (2021).

- Li, Z. et al. Assessing the impacts of pre-growing-season weather conditions on soil nitrogen dynamics and corn productivity in the U.S. Midwest. Field Crops Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2022. 108563 (2022).

- Ma, Z. et al. Interaction of hydrological and anthropogenic processes controls the relationship between streamflow discharge and nitrogen concentration in the U.S. Midwestern watersheds. B45L-1769 (2021).

- Yang, Y. et al. Distinct driving mechanisms of non-growing season N2O emissions call for spatial-specific mitigation strategies in the US Midwest. Agricult. Forest Meteorol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. agrformet.2022.109108 (2022).

- Walther, S. et al. Technical note: a view from space on global flux towers by MODIS and Landsat: the FluxnetEO data set. Biogeosciences https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-2805-2022 (2022).

- Pastorello, G. et al. The FLUXNET2O15 dataset and the ONEFlux processing pipeline for eddy covariance data. Sci. Data 7, 225 (2020).

- Bauer, P. et al. The digital revolution of Earth-system science. Nat. Comput. Sci. 1, 104-113 (2021).

- Wang, S., Di Tommaso, S., Deines, J. M. & Lobell, D. B. Mapping twenty years of corn and soybean across the US Midwest using the Landsat archive. Sci. Data 7, 307 (2020).

- Khandelwal, A. et al. Physics Guided Machine Learning Methods for Hydrology. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2012.02854 (2020).

- Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735-1780 (1997).

- Chung, J., Gulcehre, C., Cho, K. & Bengio, Y. Empirical Evaluation of Gated Recurrent Neural Networks on Sequence Modeling. https:// doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1412.3555 (2014).

- Bahdanau, D., Cho, K. & Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.1409.0473 (2014).

- Xu, S. et al. Mini-Batch Learning Strategies for modeling long term temporal dependencies: a study in environmental applications. in Proc 2023 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (SDM) 649-657 (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 2023).

- Kumar, M. P., Packer, B. & Koller, D. Self-paced learning for latent variable models. in Proc 24th Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 1189-1197 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2010).

- Bengio, Y., Louradour, J., Collobert, R. & Weston, J. Curriculum learning. in Proc 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning. https://doi.org/10.1145/1553374.1553380 (ACM, 2009).

- Poggio, L. et al. SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. SOIL 7, 217-240 (2021).

- Cao, Q. et al. On the spatial variability and influencing factors of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen stocks in a desert oasis ecotone of northwestern China. Catena 206, 105533 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43860-5.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© The Author(s) 2024

Department of Bioproducts and Biosystems Engineering, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA. Agroecosystem Sustainability Center, Institute for Sustainability, Energy, and Environment, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. Department of Computer Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. National Center for Supercomputing Applications, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA. Earth and Environmental Sciences Area, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Department of Computer Science, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA. Department of Agroecology, Aarhus University, 4200 Slagelse, Denmark. Humphrey School of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, MN 55455, USA. Department of Renewable Resources, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G2E3, Canada. Environmental Knowledge and Prediction Branch, Alberta Environment and Protected Areas, Edmonton, AB T5K 2J6, Canada. These authors contributed equally: Licheng Liu, Wang Zhou. e-mail: kaiyug@illinois.edu; jinzn@umn.edu