DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-00979-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38755344

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-16

يمكن أن يزيد إنتاج الأسمدة الأمونية اللامركزية القابلة للتنافس من حيث التكلفة من الأمن الغذائي

تاريخ القبول: 9 أبريل 2024

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 16 مايو 2024

(D) تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

تجعل التهيئة المركزية الحالية لصناعة الأمونيا إنتاج الأسمدة النيتروجينية عرضة لتقلبات أسعار الوقود الأحفوري وتنطوي على سلاسل إمداد معقدة بتكاليف نقل لمسافات طويلة. يتكون البديل من إنتاج الأمونيا اللامركزي في الموقع باستخدام تقنيات وحدات صغيرة، مثل هابر-بوش الكهربائية أو الاختزال الكهروكيميائي. هنا نقيم تنافسية تكلفة إنتاج الأمونيا منخفضة الكربون على نطاق المزرعة، من نظام زراعي شمسي، أو باستخدام الكهرباء من الشبكة، ضمن صناعة الأسمدة العالمية الجديدة. يتم مقارنة التكاليف المتوقعة لإنتاج الأمونيا اللامركزية بأسعار السوق التاريخية من الإنتاج المركزي. نجد أن تنافسية تكلفة الإنتاج اللامركزي تعتمد على تكاليف النقل واضطرابات سلسلة الإمداد. مع الأخذ في الاعتبار كلا العاملين، يمكن أن تحقق الإنتاجية اللامركزية تنافسية التكلفة لما يصل إلى

استخدام الأمونيا

أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء

النتائج

تكلفة تنافسية العرض والطلب على الأمونيا

يتم اعتبار نظامين: متصلان بالشبكة مع الكهرباء من مزيج من تقنيات التحويل ومزودان بالكهرباء من الألواح الشمسية الزراعية. تكاليف مرجعية لإنتاج الأمونيا من الإنتاج المركزي هي

تكنولوجيات وتكلفة المتغيرة المجمعة مع تكلفة الكهرباء المحلية المستوية، نقوم بتحديد تكلفة إنتاج الأمونيا المحلية بناءً على تقنيات هابر-بوش الكهربائية والكهروكيميائية لإنتاج الأمونيا. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، نقارن تكلفة إنتاج الأمونيا المحلية مع السعر التاريخي لسوق الأمونيا لتحديد النسبة والموقع للأمونيا التي يمكن توفيرها بشكل تنافسي من الإنتاج اللامركزي. تم أخذ البيانات التاريخية لأسعار سوق الأمونيا من قاعدة بيانات أسعار السلع التابعة للبنك الدولي للفترة من 2008 إلى 2022.

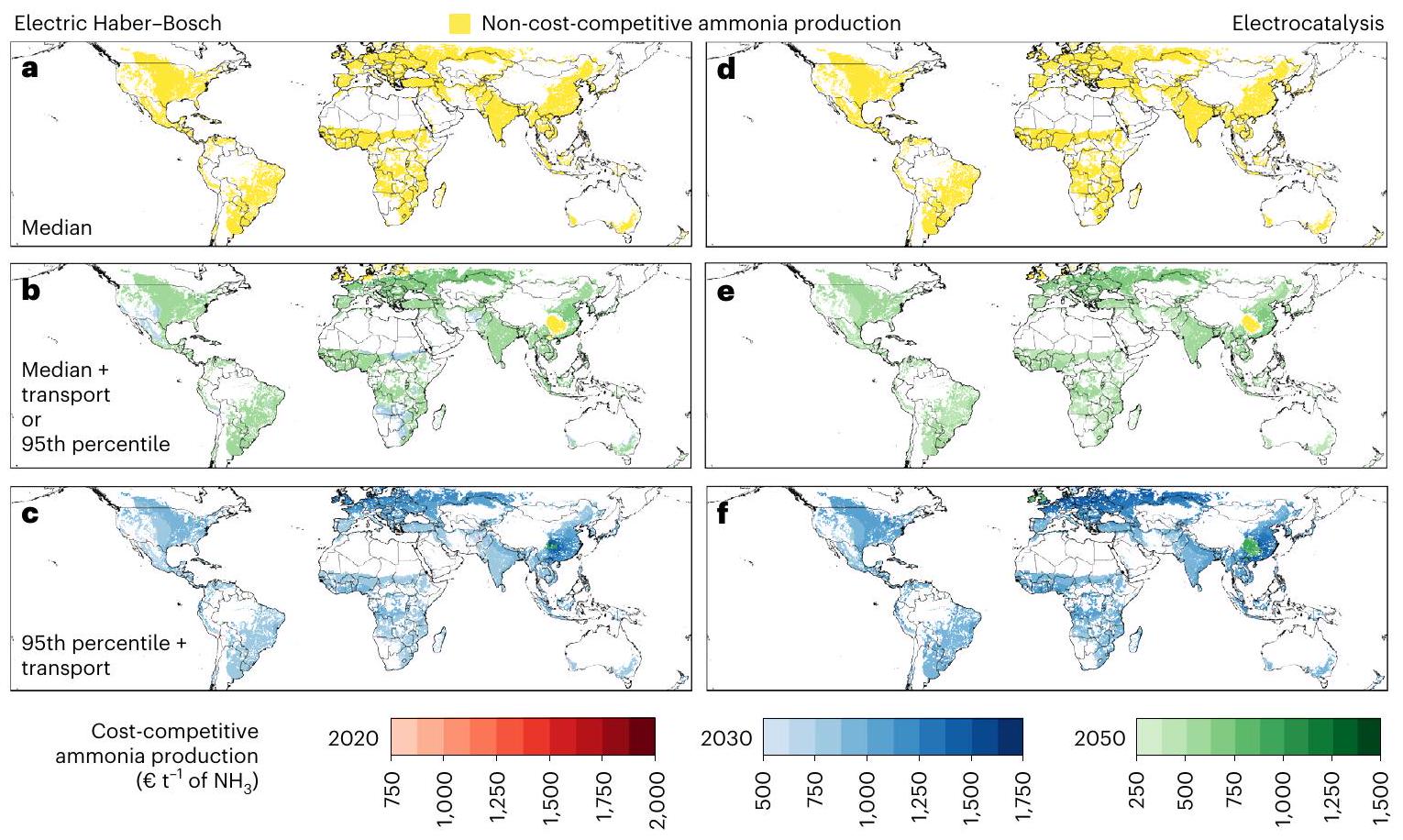

يساوي

الإنتاج القائم على الوقود الأحفوري تحت أسعار السوق المنخفضة من الإنتاج المركزي واستبعاد تكلفة نقل الأمونيا. ب، ج، يتم تحقيق القدرة التنافسية من حيث التكلفة بناءً على عملية هابر-بوش الكهربائية للتطور التكنولوجي المتوقع في عام 2030 و2050 ومقارنةً بالتكلفة المتوسطة للإنتاج المجمعة مع تكلفة النقل (ما يعادل التكلفة في النسبة المئوية 95 لإنتاج الأمونيا) (ب) وتكلفة الإنتاج في النسبة المئوية 95 مع تكلفة النقل الإضافية (ج). هـ، و، يتم تحقيق القدرة التنافسية من حيث التكلفة بناءً على التحفيز الكهربائي اللامركزي للتطور التكنولوجي المتوقع في عام 2030 و2050 ومقارنةً بالتكلفة المتوسطة للإنتاج المجمعة مع تكلفة النقل (ما يعادل التكلفة في النسبة المئوية 95 لإنتاج الأمونيا) (هـ) وتكلفة الإنتاج في النسبة المئوية 95 مع تكلفة النقل الإضافية (و). تمثل البكسلات الملونة باللون الأصفر المناطق التي لا يكون فيها الإنتاج اللامركزي تنافسيًا من حيث التكلفة. القيم بالنسبة لـ

غشاء تبادل البروتون الكهربائي و8-9 في حالة الإلكتروليز القلوي) في سيناريوهات نشر التكنولوجيا على المدى القصير إلى المتوسط

سعر المرجع للأمونيا) في حالة الأنظمة المتصلة بالشبكة والأنظمة الزراعية الشمسية، على التوالي، مع الباقي بحلول عام 2050 (الشكل 1d). في الحالة التي تتساوى فيها أسعار الأمونيا مع النسبة المئوية 95 وتكاليف النقل الإضافية،

تكلفة التوريد التنافسية اللامركزية المحددة مكانيًا

| الطلب الحالي (مليون طن سنويًا)

|

تكلفة مرجعية تقليدية هابر-بوش | الطلب الفعال من حيث التكلفة (% من الطلب الحالي) | ||

| ٢٠٢٠ | ٢٠٣٠ | ٢٠٥٠ | ||

| آسيا

|

الوسيط | – | – | – |

| الـ 95 بالمئة أو الوسيط + النقل | – | 1% | 93٪ | |

| النسبة المئوية 95+ النقل | – | 99% | 100% | |

| أوروبا

|

الوسيط | – | – | – |

| الـ 95 بالمئة أو الوسيط + النقل | – | – | 89% | |

| النسبة المئوية 95+ النقل | – | 100% | 100% | |

| أفريقيا

|

الوسيط | – | – | – |

| الـ 95 بالمئة أو الوسيط + النقل | – | 40٪ | 100% | |

| النسبة المئوية 95+النقل | – | 100% | 100% | |

| أمريكا الجنوبية

|

الوسيط | – | – | – |

| الـ 95 بالمئة أو الوسيط + النقل | – | – | 100% | |

| النسبة المئوية 95+النقل | – | 100% | 100% | |

| أوقيانوسيا

|

الوسيط | – | – | – |

| الـ 95 بالمئة أو الوسيط + النقل | – | 50٪ | 100% | |

| النسبة المئوية 95+النقل | – | 100% | 100% | |

| أمريكا الشمالية

|

الوسيط | – | – | – |

| الـ 95 بالمئة أو الوسيط + النقل | – | 11% | 100% | |

| النسبة المئوية 95+ النقل | – | 100% | 100% | |

| عالمي

|

الوسيط | – | – | – |

| الـ 95 بالمئة أو الوسيط + النقل | – | ٥٪ | 94% | |

| النسبة المئوية 95+النقل | – | 100% | 100% | |

نحدد المناطق في جميع أنحاء العالم حيث يمكن أن يكون إنتاج الأمونيا اللامركزي تنافسيًا من حيث التكلفة مقارنة بإنتاج الأمونيا التاريخي من المصانع الصناعية المركزية. توضح الشكل 2 التوزيع الجغرافي لنسبة الطلب على الأمونيا في أقرب عام تحقق فيه التنافسية من حيث التكلفة بسبب التطور التكنولوجي لتقنية هابر-بوش الكهربائية والكهروكيميائية. عند مقارنة تكلفة إنتاج الأمونيا مع الوسيط لسعر إنتاج الأمونيا المركزي التاريخي (

تكلفة النقل الإضافية (

إمدادات لامركزية محددة حسب القارة والدولة

نقاش

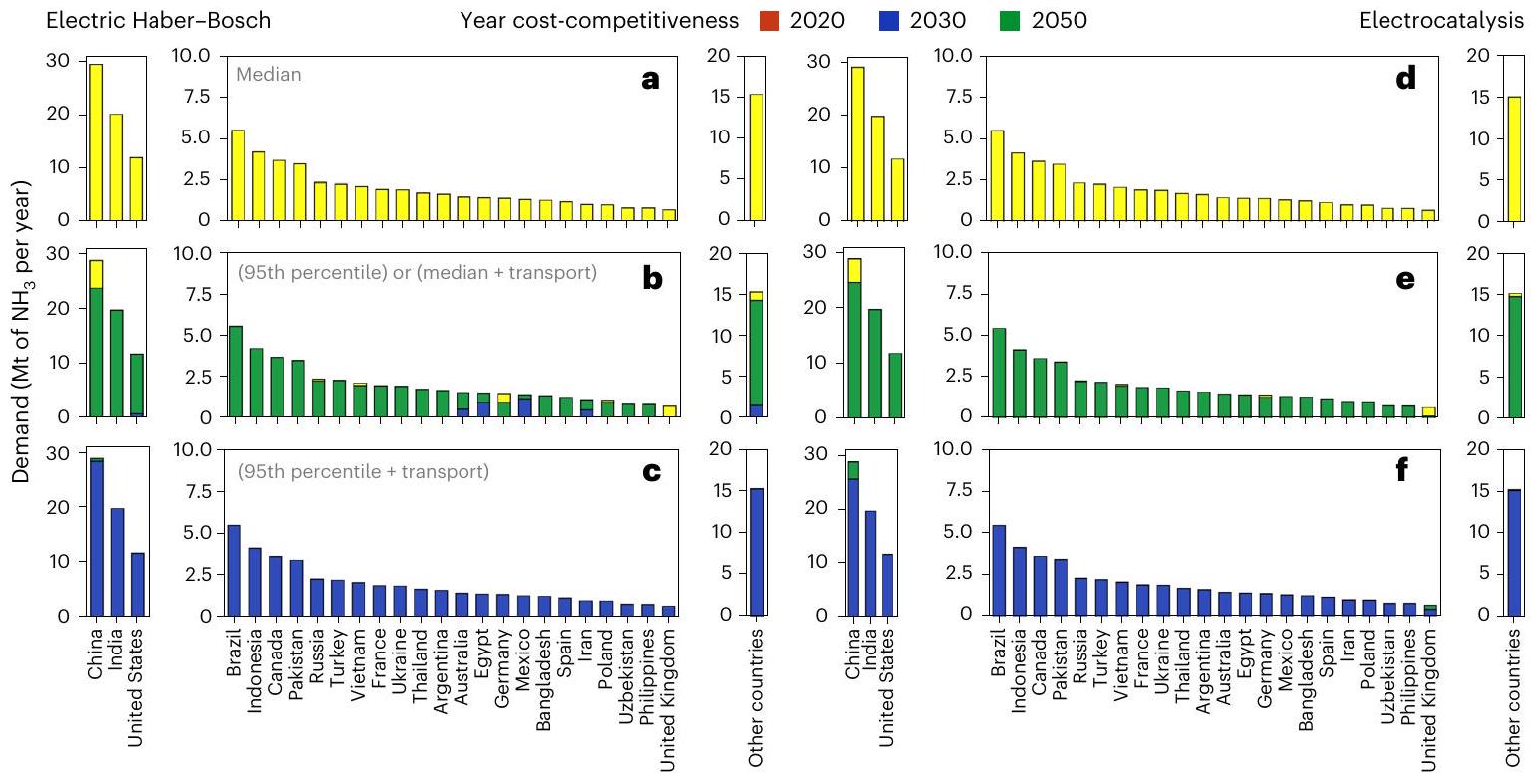

a-f، مقارنة إنتاج الأمونيا تعتمد على تكلفة التكنولوجيا في عام 2020 (باللون الأحمر) وافتراضات التطور التكنولوجي لعام 2030 (باللون الأزرق) و2050 (باللون الأخضر) لتقنية هابر-بوش الكهربائية (أ-ج) والكهروكيميائية (د-و). تكاليف مرجعية لإنتاج الأمونيا من المصانع المركزية هي

€1,560 للطن

اعتمادًا على إمدادات ثاني أكسيد الكربون للتخليق. بدلاً من اليوريا، التي يتم تسويقها في شكل كريات صلبة ومخففة للتوزيع على الأراضي الزراعية، يمكن إنتاج الأسمدة الأمونية في الموقع في شكل أمونيا أنhydrous أو مائية. تسمح الأمونيا أنhydrous بالوصول إلى تركيزات عالية من الأمونيا ولكنها تتطلب ضغوطًا عالية للحفاظ عليها في شكل غازي وآلات متطورة للحقن في التربة

في عامي 2030 و2050، استند تحليلنا إلى تكلفة الكهرباء المستوية المستمدة من الإشعاع الشمسي المحدد مكانيًا. ومن المزايا الإضافية الناتجة عن إنتاج الأسمدة اللامركزي هو الحد الأدنى من متطلبات التخزين للأسمدة. بينما في حالة الإنتاج المركزي، يتطلب توصيل الأمونيا بناءً على التجارة (عدة مرات في السنة) خزانات تخزين لتلبية أنماط استهلاك الزراعة، فإن الإنتاج اللامركزي يسمح بالإنتاج والتطبيق المستمر.

لإنتاج الهيدروجين من الكهرباء المتجددة والكربون من مصدر خارجي لإنتاج اليوريا. في الحالة الأولى، لا يزال تكلفة إنتاج الأمونيا تعتمد على تكلفة الغاز الطبيعي. في الحالة الثانية، التكلفة الرئيسية للمواد الخام هي التكلفة المحلية للكهرباء من الشبكة أو المنتجة بتقنيات متجددة مخصصة. إن التقاط انبعاثات الكربون من إنتاج الأمونيا المستند إلى الغاز الطبيعي يعني تكلفة إضافية من

طرق

طلب الأمونيا

الطلب على الأمونيا للاستخدام الزراعي مستمد من تقديرات منظمة الأغذية والزراعة

إنتاج الطاقة

تكلفة إنتاج الكهرباء والأمونيا

تم تحديد تكلفة إنتاج الأمونيا من الكهرباء الناتجة عن الألواح الشمسية التي تغذي عملية هابر-بوش الكهربائية والاختزال الكهروكيميائي المباشر في هذه الدراسة باستخدام منهجية مرجعية.

استهلاك لتشغيل وحدة فصل الهواء

تحذيرات

التكوينات المركزية واللامركزية. التجارة الدولية للأمونيا كسلعة، المطلوبة في حالة الإنتاج من تكوين مركزي، تعني أن أسعار الأمونيا المستقبلية ستحددها قوانين العرض والطلب. اعتمادًا على المسارات المستقبلية لإنتاج الأمونيا المركزي، ستعتمد أسعار الأمونيا إما على سعر الغاز الطبيعي لمسارات التقاط الكربون من سوق السلع أو على سعر الكهرباء لإنتاج الهيدروجين الكهربائي في مسار استخدام الكربون من سوق الطاقة. بينما

تحققت في المناطق التي تمثل فيها وسائل النقل من الإنتاج المركزي أكبر نسبة في توزيع سعر الأسمدة. يجب أن تركز الأبحاث المستقبلية على مقاييس جغرافية أصغر وإجراء مقارنة تكاليف بناءً على مصانع الإنتاج المركزي الحالية وتكلفة النقل لتوزيع الطلب على الأمونيا في الأراضي الزراعية. يجب إجراء تحليل شامل للتنافسية من حيث التكلفة مع الأخذ في الاعتبار المتطلبات البنية التحتية والتكنولوجية لحلول التحديث في مصانع إنتاج الأمونيا المركزية الحالية والحوافز السياسية الخاصة بكل دولة لتبني تقنيات منخفضة الكربون.

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Davis, S. J. et al. Net-zero emissions energy systems. Science 360, eaas9793 (2018).

- Rosa, L. & Gabrielli, P. Achieving net-zero emissions in agriculture: a review. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 063002 (2023).

- Bergero, C. et al. Pathways to net-zero emissions from aviation. Nat. Sustain. 6, 404-414 (2023).

- Gabrielli, P. et al. Net-zero emissions chemical industry in a world of limited resources. One Earth 6, 682-704 (2023).

- Gao, Y. & Cabrera Serrenho, A. Greenhouse gas emissions from nitrogen fertilizers could be reduced by up to one-fifth of current levels by 2050 with combined interventions. Nat. Food 4, 170-178 (2023).

- Rosa, L. & Gabrielli, P. Energy and food security implications of transitioning synthetic nitrogen fertilizers to net-zero emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 014008 (2022).

- Ouikhalfan, M., Lakbita, O., Delhali, A., Assen, A. H. & Belmabkhout, Y. Toward net-zero emission fertilizers industry: greenhouse gas emission analyses and decarbonization solutions. Energy Fuels 36, 4198-4223 (2022).

- Ammonia Technology Roadmap (International Energy Agency, 2021); https://www.iea.org/reports/ammonia-technology-roadmap

- FAOSTAT Fertilizers by Nutrient (FAO, 2022); http://www.fao.org/ faostat/en/#data/RFN

- FAOSTAT Climate Change: Agrifood Systems Emissions, Emissions from Crops, Element: Synthetic Ferilizers (Agricultural Use), Item: Nutrient Nitrogen N (Total) (FAO, 2023); http://www.fao.org/ faostat/en/#data/GCE

- Beltran-Peña, A., Rosa, L. & D’Odorico, P. Global food selfsufficiency in the 21st century under sustainable intensification of agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 095004 (2020).

- Van Dijk, M., Morley, T., Rau, M. L. & Saghai, Y. A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010-2050. Nat. Food 2, 494-501 (2021).

- McArthur, J. W. & McCord, G. C. Fertilizing growth: agricultural inputs and their effects in economic development. J. Dev. Econ. 127, 133-152 (2017).

- Innovation Outlook: Renewable Ammonia (International Renewable Energy Agency & Ammonia Energy Association, 2022); https:// www.irena.org/publications/2022/May/Innovation-Outlook-Renewable-Ammonia

- Lim, J., Fernández, C. A., Lee, S. W. & Hatzell, M. C. Ammonia and nitric acid demands for fertilizer use in 2050. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 3676-3685 (2021).

- MacFarlane, D. R. et al. A roadmap to the ammonia economy. Joule 4, 1186-1205 (2020).

- Fernandez, C. A. & Hatzell, M. C. Editors’ choice-economic considerations for low-temperature electrochemical ammonia production: achieving Haber-Bosch parity. J. Electrochem. Soc. 167, 143504 (2020).

- Alexander, P. et al. High energy and fertilizer prices are more damaging than food export curtailment from Ukraine and Russia for food prices, health and the environment. Nat. Food 4, 84-95 (2023).

- Srivastava, N. et al. Prospects of solar-powered nitrogenous fertilizers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 187, 113691 (2023).

- Bonilla Cedrez, C., Chamberlin, J., Guo, Z. & Hijmans, R. J. Spatial variation in fertilizer prices in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 15, e0227764 (2020).

- Gabrielli, P., Gazzani, M. & Mazzotti, M. The role of carbon capture and utilization, carbon capture and storage, and biomass to enable a net-zero-

emissions chemical industry. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 7033-7045 (2020). - Terlouw, T., Bauer, C., Rosa, L. & Mazzotti, M. Life cycle assessment of carbon dioxide removal technologies: a critical review. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 1701-1721 (2021).

- Antonini, C. et al. Hydrogen production from natural gas and biomethane with carbon capture and storage-a technoenvironmental analysis. Sustain. Energy Fuels 4, 2967-2986 (2020).

- Ammonia: Zero-Carbon Fertiliser, Fuel and Energy Store (The Royal Society, 2020); https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/ green-ammonia/green-ammonia-policy-briefing.pdf

- Rosa, L. & Mazzotti, M. Potential for hydrogen production from sustainable biomass with carbon capture and storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 157, 112123 (2022).

- Feng, Y. & Rosa, L. Global biomethane and carbon dioxide removal potential through anaerobic digestion of waste biomass. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 024024 (2024).

- Gabrielli, P., Charbonnier, F., Guidolin, A. & Mazzotti, M. Enabling low-carbon hydrogen supply chains through use of biomass and carbon capture and storage: a Swiss case study. Appl. Energy 275, 115245 (2020).

- Tonelli, D. et al. Global land and water limits to electrolytic hydrogen production using wind and solar resources. Nat. Commun. 14, 5532 (2023).

- Morris M., Kelly V. A., Kopicki R. J. & Byerlee D. Fertilizer Use in African Agriculture, Lessons Learned and Good Practice Guidelines (World Bank, 2007); https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/ en/498591468204546593/pdf/390370AFROFert101OFFICIALOUS EOONLY1.pdf

- D’Angelo, S. C. et al. Environmental and economic potential of decentralized electrocatalytic ammonia synthesis powered by solar energy. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 3314-3330 (2023).

- Comer, B. M. et al. Prospects and challenges for solar fertilizers. Joule 3, 1578-1605 (2019).

- Valera-Medina, A. et al. Review on ammonia as a potential fuel: from synthesis to economics. Energy Fuels 35, 6964-7029 (2021).

- Chen, S., Perathoner, S., Ampelli, C. & Centi, G. Electrochemical dinitrogen activation: to find a sustainable way to produce ammonia. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 178, 31-46 (2019).

- Smith, C., Hill, A. K. & Torrente-Murciano, L. Current and future role of Haber-Bosch ammonia in a carbon-free energy landscape. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 331-344 (2020).

- Winter, L. R. & Chen, J. G.

fixation by plasma-activated processes. Joule 5, 300-315 (2021). - Huang, P. W. & Hatzell, M. C. Prospects and good experimental practices for photocatalytic ammonia synthesis. Nat. Commun. 13, 7908 (2022).

- Martín, A. J., Shinagawa, T. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Electrocatalytic reduction of nitrogen: from Haber-Bosch to ammonia artificial leaf. Chem 5, 263-283 (2019).

- Giddey, S., Badwal, S. P. S. & Kulkarni, A. Review of electrochemical ammonia production technologies and materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 38, 14576-14594 (2013).

- Wang, M. et al. Can sustainable ammonia synthesis pathways compete with fossil-fuel based Haber-Bosch processes? Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 2535-2548 (2021).

- D’Angelo, S. C. et al. Planetary boundaries analysis of low-carbon ammonia production routes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 97409749 (2021).

- Mueller, N. D. et al. Closing yield gaps through nutrient and water management. Nature 490, 254-257 (2012).

- Adalibieke, W., Cui, X., Cai, H., You, L. & Zhou, F. Global crop-specific nitrogen fertilization dataset in 1961-2020. Sci. Data 10, 617 (2023).

- Adeh, E. H., Good, S. P., Calaf, M. & Higgins, C. W. Solar PV power potential is greatest over croplands. Sci. Rep. 9, 11442 (2019).

- Dinesh, H. & Pearce, J. M. The potential of agrivoltaic systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 54, 299-308 (2016).

- Amaducci, S., Yin, X. & Colauzzi, M. Agrivoltaic systems to optimise land use for electric energy production. Appl. Energy 220, 545-561 (2018).

- Barron-Gafford, G. A. et al. Agrivoltaics provide mutual benefits across the food-energy-water nexus in drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2, 848-855 (2019).

- Ha, J., Ayhan Kose M. & Ohnsorge, F. One-Stop Source: A Global Database of Inflation Policy Research Working Paper 9737 (World Bank, 2021).

- Stevens, C. J. Nitrogen in the environment. Science 363, 578-580 (2019).

- Menegat, S., Ledo, A. & Tirado, R. Greenhouse gas emissions from global production and use of nitrogen synthetic fertilisers in agriculture. Sci. Rep. 12, 14490 (2022).

- Bertagni, M. B. et al. Minimizing the impacts of the ammonia economy on the nitrogen cycle and climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2311728120 (2023).

- Rouwenhorst, K. H., Van der Ham, A. G., Mul, G. & Kersten, S. R. Islanded ammonia power systems: technology review and conceptual process design. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 114, 109339 (2019).

- Text – H.R.5376-117th Congress (2021-2022): Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (Library of Congress, 2022); https://www.congress. gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text

- Net Zero Industry Act. COM(2023) 161, SWD(2023) 68 (European Commission, Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, 2023); https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/publications/net-zero-industry-act_en

- Emissions Factor 2021 (International Energy Agency, 2021); https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/ emissions-factors-2021

- Direct Air Capture (International Energy Agency, 2021); https://www.iea.org/reports/direct-air-capture

- Electricity Information: Overview (International Energy Agency, 2021); https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-informationoverview

- Global Solar Atlas 2.0: Technical Report ESMAP Paper (World Bank, 2019); https://globalsolaratlas.info/map

- Cardoso, J. S. et al. Ammonia as an energy vector: current and future prospects for low-carbon fuel applications in internal combustion engines. J. Clean. Prod. 296, 126562 (2021).

- Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction: Scaling up Electrolysers to Meet the

Climate Goal (International Renewable Energy Agency, 2020). - Yates, J. et al. Techno-economic analysis of hydrogen electrolysis from off-grid stand-alone photovoltaics incorporating uncertainty analysis. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 1, 100209 (2020).

- Branker, K., Pathak, M. J. M. & Pearce, J. M. A review of solar photovoltaic levelized cost of electricity. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15, 4470-4482 (2011).

- Hochman, G. et al. Potential economic feasibility of direct electrochemical nitrogen reduction as a route to ammonia. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 8938-8948 (2020).

- Patonia, A. & Poudineh, R. Ammonia as a Storage Solution for Future Decarbonized Energy Systems OIES Paper EL 42 https:// www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/ammonia-as-a-storage-solution-for-future-decarbonized-energy-systems/(2020)

- Wolfram, P., Kyle, P., Zhang, X., Gkantonas, S. & Smith, S. Using ammonia as a shipping fuel could disturb the nitrogen cycle. Nat. Energy 7, 1112-1114 (2022).

- Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the

Goal in Reach (International Energy Agency, 2023); https://www.iea.org/ reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-Oc-goal-in-reach - Northrup, D. L., Basso, B., Wang, M. Q., Morgan, C. L. & Benfey, P. N. Novel technologies for emission reduction complement conservation agriculture to achieve negative emissions from row-crop production. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2022666118 (2021).

- Brill, W. J. Biological nitrogen fixation. Sci. Am. 236, 68-81 (1977).

- Mus, F. et al. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation and the challenges to its extension to nonlegumes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 36983710 (2016).

- Tonelli, D., Rosa, L., Gabrielli, P., Parente, A. & Contino, F. Costcompetitiveness of distributed ammonia production for the global fertilizer industry. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ zenodo. 8155141 (2024).

- Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90-95 (2007).

- Jordahl, K. et al. geopandas/geopandas: v0.8.1. Zenodo https:// doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 3946761 (2020).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

(ج) المؤلفون 2024

natureportfolio

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

تم التأكيد

اختبار(ات) الإحصائية المستخدمة وما إذا كانت أحادية أو ثنائية الجانب

يجب وصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ وصف تقنيات أكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

تحتوي مجموعتنا على الويب حول الإحصائيات لعلماء الأحياء على مقالات حول العديد من النقاط أعلاه.

البرمجيات والرموز

معلومات السياسة حول توفر كود الكمبيوتر

| جمع البيانات | البيانات الخام المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة هي من الأدبيات العلمية ذات الوصول المفتوح ولم يتم استخدام أي برنامج لجمع البيانات. |

| تحليل البيانات | تم استخدام رموز مصنوعة خصيصًا لتطوير البيانات، التحليل والتصور. جميع السكربتات مكتوبة بلغة بايثون 3.9.12. تم إنشاء الخرائط باستخدام حزم Matplotlib وGeopandas. جميع الرموز مخزنة في مستودع Zenodo ذو الوصول المفتوح http://doi.org/10.5281/ zenodo. 8155141 |

البيانات

معلومات السياسة حول توفر البيانات

- رموز الوصول، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا

المستخدمة في الدراسة تأتي من مجموعات بيانات مفتوحة المصدر:

- أسعار الأسمدة التاريخية: 47. ها، جونغريم، م. أيهان كوس، & فرانزيسكا أونزورغ. مصدر شامل: قاعدة بيانات عالمية لسياسة التضخم. ورقة عمل بحثية للبنك الدولي 9737 (2021).

- الطلب على النيتروجين المحدد مكانيًا في 2020: 42. أداليبيكي، و.، كوي، إكس.، كاي، إتش.، يو، ل. & زو، ف. مجموعة بيانات تخصيب النيتروجين الخاصة بالمحاصيل العالمية في 1961-2020. بيانات علمية 10(1)، 617 (2023).

- الإشعاع الشمسي المحدد مكانيًا: ESMAP. الأطلس الشمسي العالمي 2.0. تقرير فني، البنك الدولي. https://globalsolaratlas.info/map (2019).

البحث الذي يشمل المشاركين البشريين، بياناتهم، أو المواد البيولوجية

| التقرير عن الجنس والجندر | لم يشارك أي مشارك بشري في هذا العمل. |

| التقرير عن العرق، الإثنية، أو مجموعات اجتماعية أخرى ذات صلة | لم يشارك أي مشارك بشري في هذا العمل. |

| خصائص السكان | لم يشارك أي مشارك بشري في هذا العمل. |

| التوظيف | لم يشارك أي مشارك بشري في هذا العمل. |

| الإشراف الأخلاقي | لم يشارك أي مشارك بشري في هذا العمل. |

التقرير الخاص بالمجال

العلوم البيئية والتطورية والإيكولوجية

تصميم دراسة العلوم البيئية والتطورية والإيكولوجية

| وصف الدراسة | تعتمد الدراسة على بيانات مدخلة من منشورات علمية مفتوحة المصدر ولا تشمل أي قياسات مختبرية أو عمل ميداني. | |||||

| عينة البحث |

|

|||||

| استراتيجية أخذ العينات | تأتي البيانات المحددة مكانيًا من تقديرات حتمية، استنادًا إلى افتراضات محددة جيدًا. | |||||

| جمع البيانات | تأتي جميع البيانات من الأدبيات الموثقة ذات المصدر المفتوح. | |||||

| التوقيت والنطاق المكاني | لا ينطبق هذا النقطة حيث أن البيانات المستخدمة تأتي من حسابات عددية. | |||||

| استبعاد البيانات | لم يتم إدخال أي تصحيح للبيانات بخلاف الحسابات المذكورة في المقال. | |||||

| إمكانية التكرار | جميع الحسابات في المقال قابلة للتكرار بناءً على الأكواد في المجلد المفتوح الوصول. | |||||

| العشوائية | التخصيصات الوحيدة للبيانات ضمن هذه الدراسة هي تجميع البيانات على مستوى البكسل إلى دول وقارات. يعتمد تخصيص البيانات، القابل للتكرار مع الأكواد المشتركة، على مضلعات تصف شكل الدول الفردية والبكسلات الموجودة داخل المضلعات. | |||||

| التعمية | هذه النقطة لا تنطبق لأن البيانات المستخدمة تأتي من حسابات عددية. | |||||

| هل شملت الدراسة عملًا ميدانيًا؟ |

|

التقارير عن مواد وأنظمة وطرق محددة

| المواد والأنظمة التجريبية | الطرق | ||

| غير متاح | مشارك في الدراسة | غير متاح | مشارك في الدراسة |

| X |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

النباتات

| مخزونات البذور |

|

||

| أنماط نباتية جديدة |

|

||

| التحقق |

|

معهد الميكانيكا والمواد والهندسة المدنية، UCLouvain، أوتينيس-لوفان-لا-نيوف، بلجيكا. قسم الديناميكا الهوائية والحرارية، ULB، بروكسل، بلجيكا. قسم البيئة العالمية، مؤسسة كارنيجي للعلوم، ستانفورد، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. معهد الطاقة وهندسة العمليات، ETH زيورخ، زيورخ، سويسرا. البريد الإلكتروني:davidetonelli@outlook.com; Irosa@carnegiescience.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-00979-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38755344

Publication Date: 2024-05-16

Cost-competitive decentralized ammonia fertilizer production can increase food security

Accepted: 9 April 2024

Published online: 16 May 2024

(D) Check for updates

Abstract

The current centralized configuration of the ammonia industry makes the production of nitrogen fertilizers susceptible to the volatility of fossil fuel prices and involves complex supply chains with long-distance transport costs. An alternative consists of on-site decentralized ammonia production using small modular technologies, such as electric Haber-Bosch or electrocatalytic reduction. Here we evaluate the cost-competitiveness of producing low-carbon ammonia at the farm scale, from a solar agrivoltaic system, or using electricity from the grid, within a novel global fertilizer industry. Projected costs for decentralized ammonia production are compared with historical market prices from centralized production. We find that the cost-competitiveness of decentralized production relies on transport costs and supply chain disruptions. Taking both factors into account, decentralized production could achieve cost-competitiveness for up to

of ammonia usage

sub-Saharan Africa

Results

Ammonia supply-demand cost-competitiveness

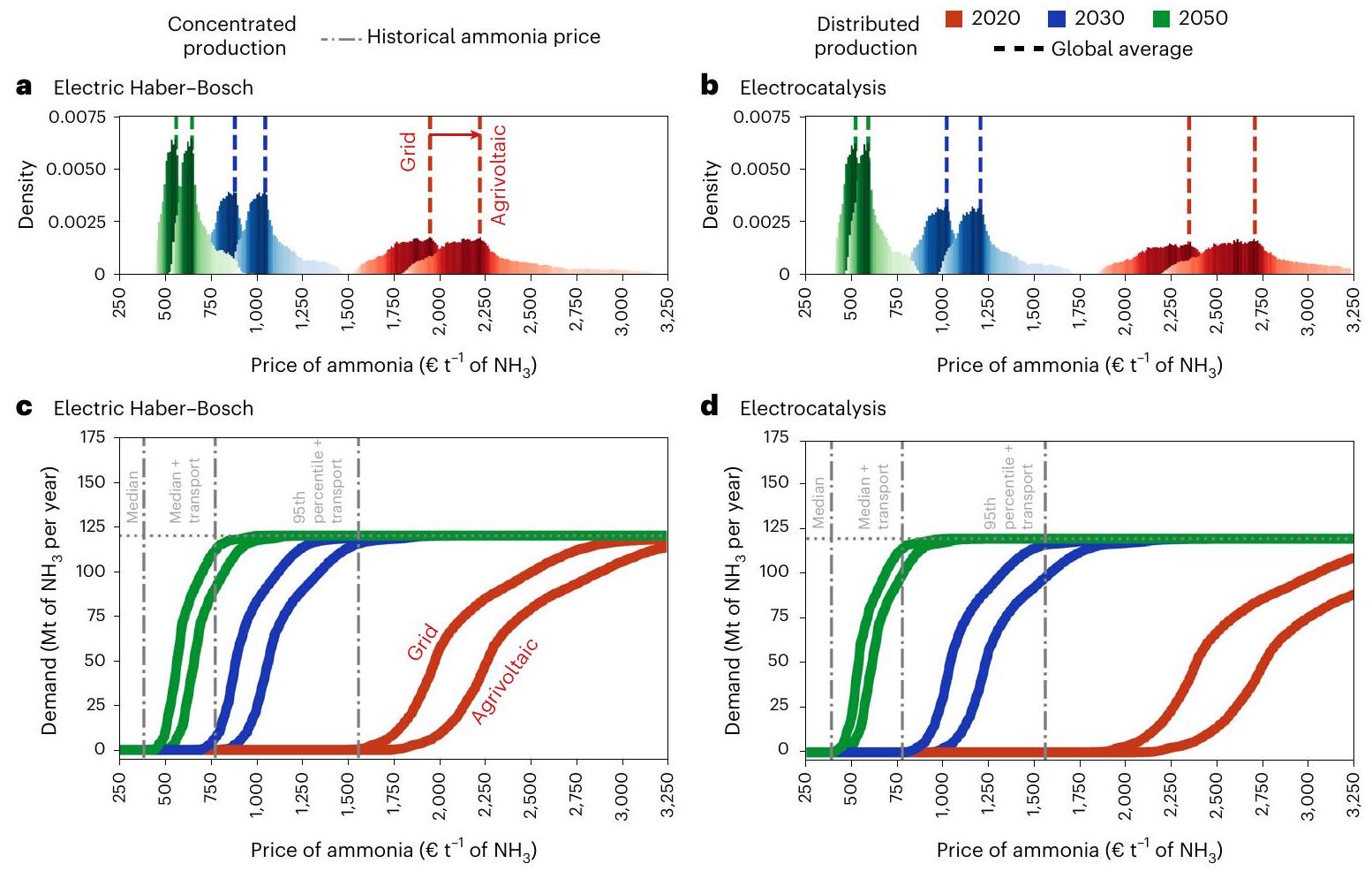

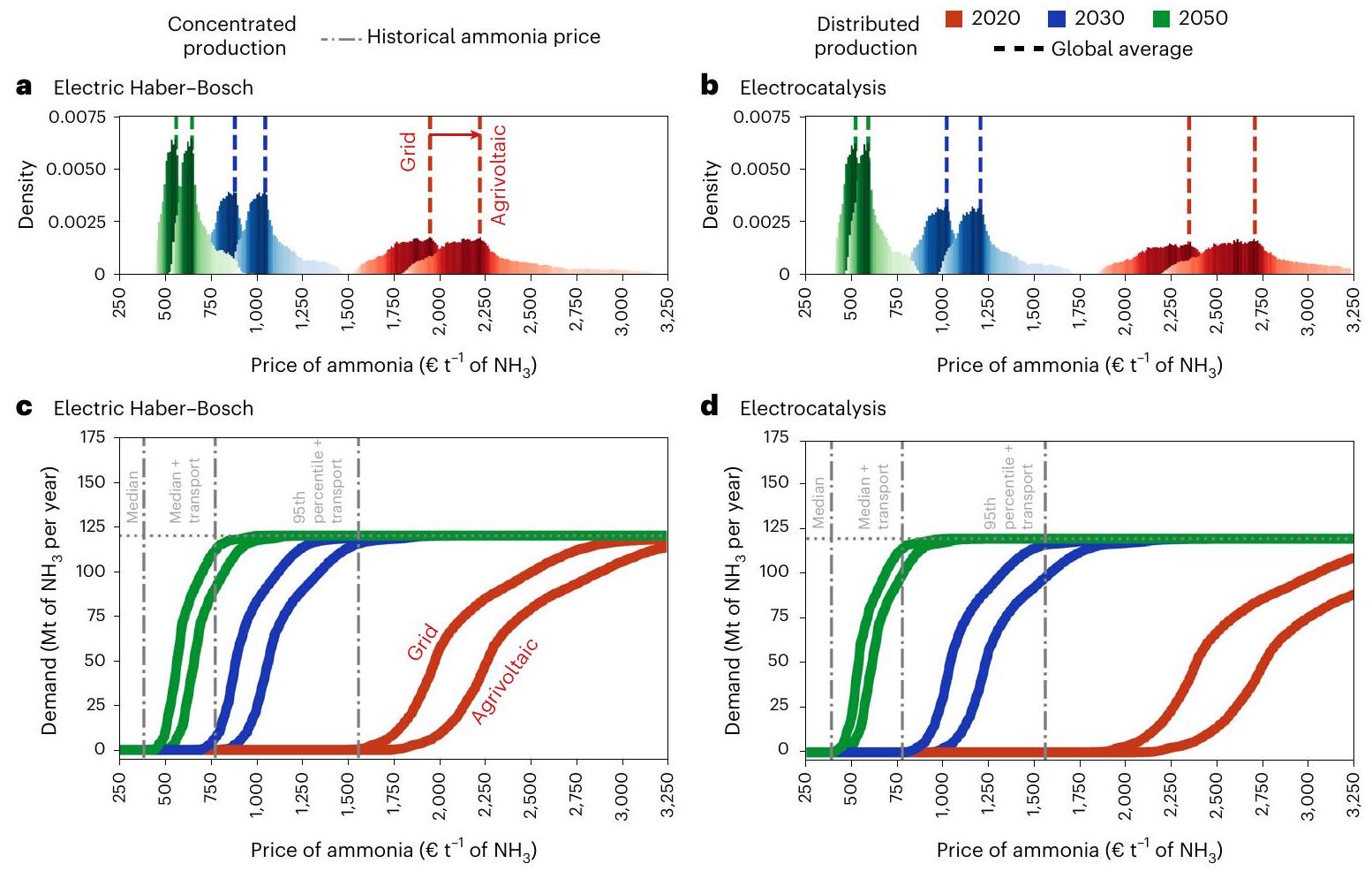

two systems are considered: connected to the grid with electricity from a mix of conversion technologies and fed with electricity from agrivoltaic solar panels. Reference costs of ammonia production from centralized production are

technologies and the variable cost combined with the local levelized cost of electricity, we quantify the local cost of ammonia production based on electric Haber-Bosch and electrocatalysis technologies for ammonia production. In addition, we compare the local cost of ammonia production with the historical ammonia market price to identify the fraction and location of ammonia that can be cost-competitively supplied from decentralized production. Historical data of ammonia market prices are taken from the World Bank commodity price database for 2008-2022

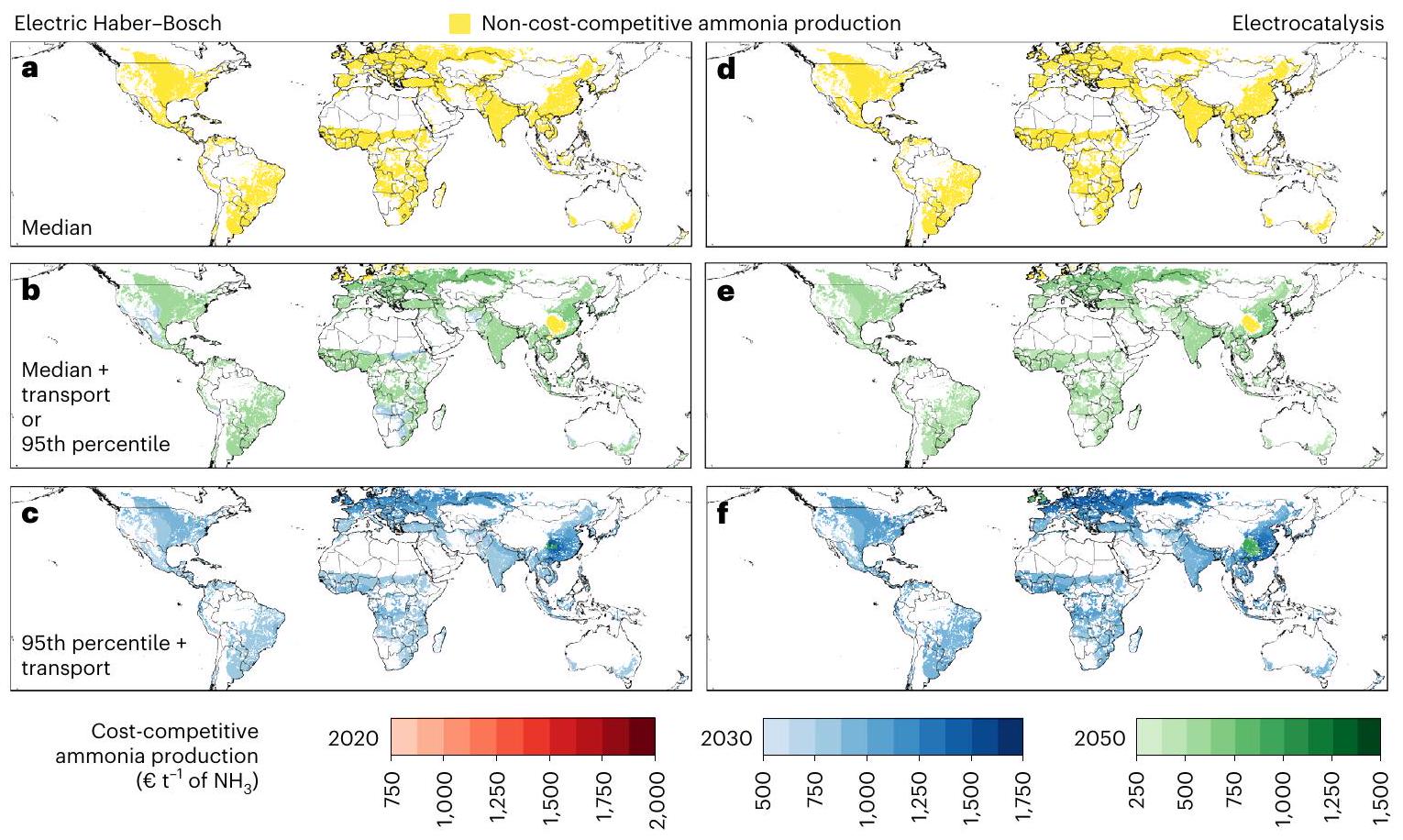

equalling

fossil-based production under low market prices from centralized production and excluding the cost of transport of ammonia. b,c, Cost-competitiveness based on electric Haber-Bosch is reached for the projected technological development in 2030 and 2050 and in comparison with the median cost of production combined with the cost of transport (equivalent to the 95th percentile cost of ammonia production) (b) and the 95th percentile cost of production with the additional cost of transport (c). e,f, Cost-competitiveness based on decentralized electrocatalysisis is reached for the projected technological development in 2030 and 2050 and in comparison with the median cost of production combined with the cost of transport (equivalent to the 95th percentile cost of ammonia production) (e) and the 95th percentile cost of production with the additional cost of transport (f). Yellow-coloured pixels represent regions where decentralized production is not cost-competitive. Values relative to

proton-exchange membrane electrolyser and 8-9 in the case of an alkaline electrolyser) in scenarios of short- to medium-term technology deployment

reference price of ammonia) in the case of grid-connected and agrivoltaic-based systems, respectively, with the remaining by 2050 (Fig. 1d). In the case where ammonia prices equal the 95th percentile and additional transport cost,

Spatially explicit decentralized supply cost-competitiveness

| Current demand (Mtyr

|

Reference cost traditional Haber-Bosch | Cost-effective demand (% of current demand) | ||

| 2020 | 2030 | 2050 | ||

| Asia

|

median | – | – | – |

| 95th percentile or median+transport | – | 1% | 93% | |

| 95th percentile+transport | – | 99% | 100% | |

| Europe

|

median | – | – | – |

| 95th percentile or median+transport | – | – | 89% | |

| 95th percentile+transport | – | 100% | 100% | |

| Africa

|

median | – | – | – |

| 95th percentile or median+transport | – | 40% | 100% | |

| 95th percentile+transport | – | 100% | 100% | |

| South America

|

median | – | – | – |

| 95th percentile or median+transport | – | – | 100% | |

| 95th percentile+transport | – | 100% | 100% | |

| Oceania

|

median | – | – | – |

| 95th percentile or median+transport | – | 50% | 100% | |

| 95th percentile+transport | – | 100% | 100% | |

| North America

|

median | – | – | – |

| 95th percentile or median+transport | – | 11% | 100% | |

| 95th percentile+transport | – | 100% | 100% | |

| Global

|

median | – | – | – |

| 95th percentile or median+transport | – | 5% | 94% | |

| 95th percentile+transport | – | 100% | 100% | |

we identify regions worldwide where decentralized ammonia production can be cost-competitive with historical ammonia production from centralized industrial plants. Figure 2 shows the geographical distribution of the fraction of ammonia demand in the earliest year that achieves cost-competitiveness due to technological development for electric Haber-Bosch and electrocatalysis. When the production cost of ammonia is compared with the median of the historical price of centralized ammonia production (

additional cost of transport (

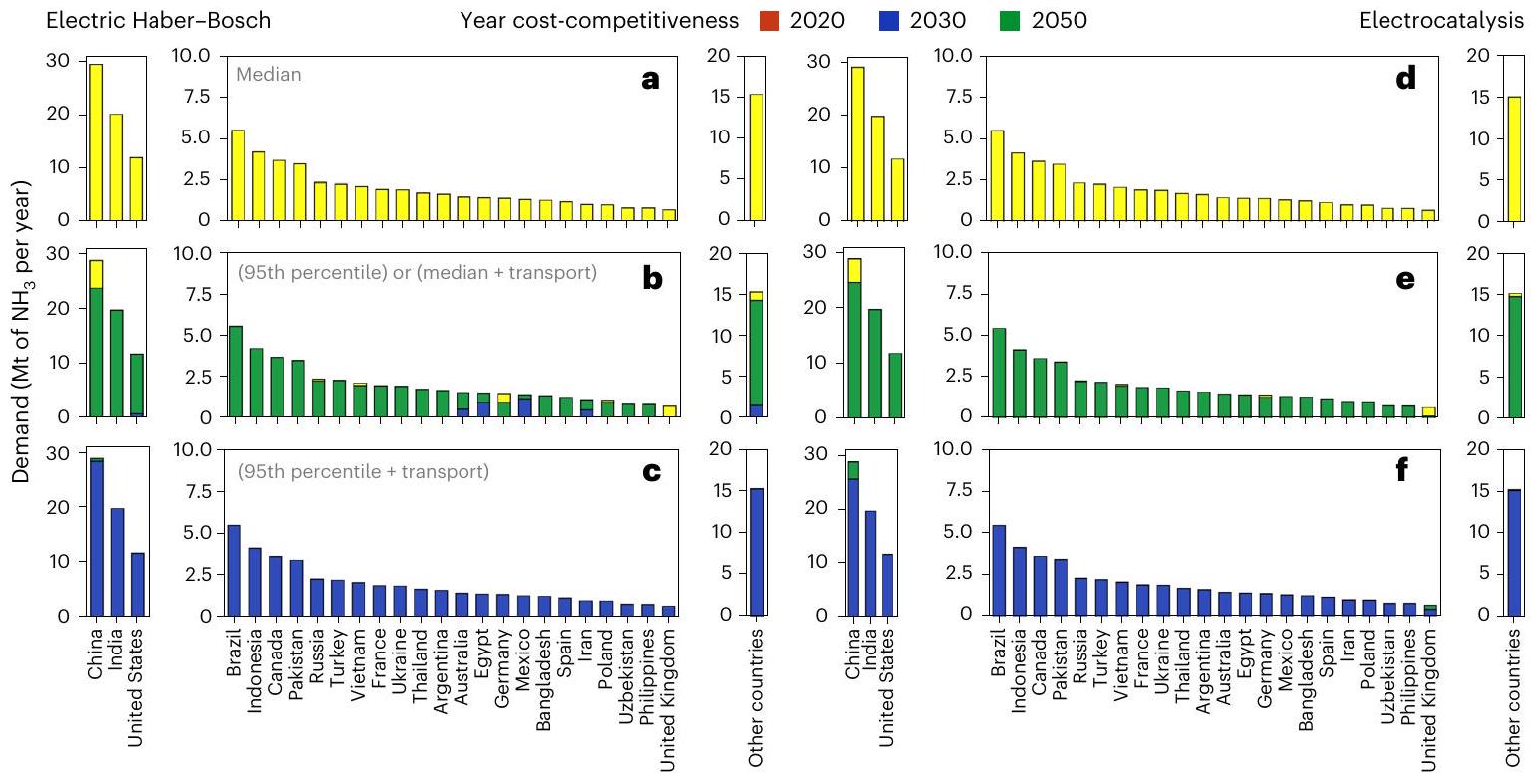

Continent- and country-specific decentralized supply

Discussion

a-f, Comparison of ammonia production is based on technology cost in 2020 (red) and assumptions of technological development for 2030 (blue) and 2050 (green) for electric Haber-Bosch (a-c) and electrocatalysis (d-f). Reference costs of ammonia production from centralized plants are

€1,560 t

relying on the supply of carbon dioxide for synthesis. Instead of urea, commercialized in the form of solid prills and diluted for distribution on croplands, ammonia fertilizers can be produced on-site in the form of anhydrous or aqueous ammonia. Anhydrous ammonia allows to reach high ammonia concentrations but requires high pressures for conservation in gaseous form and sophisticated machines for injection into the soil

electricity in 2030 and 2050, we based our analysis on the levelized cost of electricity derived from spatially explicit solar irradiation. An additional advantage derived from decentralized fertilizer production is the minimal requirement of storage for fertilizers. While in the case of centralized production the delivery of ammonia based on trade (a couple of times per year) requires storage vessels to accommodate agricultural consumption patterns, decentralized production allows continuous production and application

for hydrogen production from renewable electricity and carbon from an external source for urea production. In the former case, the cost of ammonia production is still dependent on the cost of natural gas. In the latter, the main cost of feedstocks is the local cost of electricity from the grid or produced with dedicated renewable technologies. Capturing carbon emissions from ammonia production based on natural gas implies an additional cost of

Methods

Ammonia demand

demand for ammonia for agricultural use derived from estimations by the Food and Agriculture Organization

Energy production

Electricity and ammonia production cost

The cost of producing ammonia from electricity from solar panels feeding the electric Haber-Bosch and the direct electrochemical reduction is determined in this study using a reference methodology

consumption for the operation of the ASU and

Caveats

centralized and decentralized configurations. The international trade of ammonia as a commodity, required in the case of production from a centralized configuration, implies that future ammonia prices will be determined by the law of supply and demand. Depending on the future routes of centralized ammonia production, ammonia price will depend on either the price of natural gas for carbon capture routes from the commodity market or the price of electricity for electrolytic hydrogen production in the carbon usage route from the power market. While

achieved in regions where transportation from centralized production represents the largest fraction in the breakdown of fertilizer price. Future research should concentrate on smaller geographical scales and conduct a cost comparison based on existing centralized production plants and the cost of transportation to distribute ammonia demand on croplands. An extensive cost-competitiveness analysis should be carried out considering infrastructural and technological requirements for retrofitting solutions in existing centralized ammonia production plants and country-specific political incentives for the adoption of low-carbon technologies.

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Davis, S. J. et al. Net-zero emissions energy systems. Science 360, eaas9793 (2018).

- Rosa, L. & Gabrielli, P. Achieving net-zero emissions in agriculture: a review. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 063002 (2023).

- Bergero, C. et al. Pathways to net-zero emissions from aviation. Nat. Sustain. 6, 404-414 (2023).

- Gabrielli, P. et al. Net-zero emissions chemical industry in a world of limited resources. One Earth 6, 682-704 (2023).

- Gao, Y. & Cabrera Serrenho, A. Greenhouse gas emissions from nitrogen fertilizers could be reduced by up to one-fifth of current levels by 2050 with combined interventions. Nat. Food 4, 170-178 (2023).

- Rosa, L. & Gabrielli, P. Energy and food security implications of transitioning synthetic nitrogen fertilizers to net-zero emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 014008 (2022).

- Ouikhalfan, M., Lakbita, O., Delhali, A., Assen, A. H. & Belmabkhout, Y. Toward net-zero emission fertilizers industry: greenhouse gas emission analyses and decarbonization solutions. Energy Fuels 36, 4198-4223 (2022).

- Ammonia Technology Roadmap (International Energy Agency, 2021); https://www.iea.org/reports/ammonia-technology-roadmap

- FAOSTAT Fertilizers by Nutrient (FAO, 2022); http://www.fao.org/ faostat/en/#data/RFN

- FAOSTAT Climate Change: Agrifood Systems Emissions, Emissions from Crops, Element: Synthetic Ferilizers (Agricultural Use), Item: Nutrient Nitrogen N (Total) (FAO, 2023); http://www.fao.org/ faostat/en/#data/GCE

- Beltran-Peña, A., Rosa, L. & D’Odorico, P. Global food selfsufficiency in the 21st century under sustainable intensification of agriculture. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 095004 (2020).

- Van Dijk, M., Morley, T., Rau, M. L. & Saghai, Y. A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010-2050. Nat. Food 2, 494-501 (2021).

- McArthur, J. W. & McCord, G. C. Fertilizing growth: agricultural inputs and their effects in economic development. J. Dev. Econ. 127, 133-152 (2017).

- Innovation Outlook: Renewable Ammonia (International Renewable Energy Agency & Ammonia Energy Association, 2022); https:// www.irena.org/publications/2022/May/Innovation-Outlook-Renewable-Ammonia

- Lim, J., Fernández, C. A., Lee, S. W. & Hatzell, M. C. Ammonia and nitric acid demands for fertilizer use in 2050. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 3676-3685 (2021).

- MacFarlane, D. R. et al. A roadmap to the ammonia economy. Joule 4, 1186-1205 (2020).

- Fernandez, C. A. & Hatzell, M. C. Editors’ choice-economic considerations for low-temperature electrochemical ammonia production: achieving Haber-Bosch parity. J. Electrochem. Soc. 167, 143504 (2020).

- Alexander, P. et al. High energy and fertilizer prices are more damaging than food export curtailment from Ukraine and Russia for food prices, health and the environment. Nat. Food 4, 84-95 (2023).

- Srivastava, N. et al. Prospects of solar-powered nitrogenous fertilizers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 187, 113691 (2023).

- Bonilla Cedrez, C., Chamberlin, J., Guo, Z. & Hijmans, R. J. Spatial variation in fertilizer prices in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 15, e0227764 (2020).

- Gabrielli, P., Gazzani, M. & Mazzotti, M. The role of carbon capture and utilization, carbon capture and storage, and biomass to enable a net-zero-

emissions chemical industry. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 7033-7045 (2020). - Terlouw, T., Bauer, C., Rosa, L. & Mazzotti, M. Life cycle assessment of carbon dioxide removal technologies: a critical review. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 1701-1721 (2021).

- Antonini, C. et al. Hydrogen production from natural gas and biomethane with carbon capture and storage-a technoenvironmental analysis. Sustain. Energy Fuels 4, 2967-2986 (2020).

- Ammonia: Zero-Carbon Fertiliser, Fuel and Energy Store (The Royal Society, 2020); https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/ green-ammonia/green-ammonia-policy-briefing.pdf

- Rosa, L. & Mazzotti, M. Potential for hydrogen production from sustainable biomass with carbon capture and storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 157, 112123 (2022).

- Feng, Y. & Rosa, L. Global biomethane and carbon dioxide removal potential through anaerobic digestion of waste biomass. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 024024 (2024).

- Gabrielli, P., Charbonnier, F., Guidolin, A. & Mazzotti, M. Enabling low-carbon hydrogen supply chains through use of biomass and carbon capture and storage: a Swiss case study. Appl. Energy 275, 115245 (2020).

- Tonelli, D. et al. Global land and water limits to electrolytic hydrogen production using wind and solar resources. Nat. Commun. 14, 5532 (2023).

- Morris M., Kelly V. A., Kopicki R. J. & Byerlee D. Fertilizer Use in African Agriculture, Lessons Learned and Good Practice Guidelines (World Bank, 2007); https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/ en/498591468204546593/pdf/390370AFROFert101OFFICIALOUS EOONLY1.pdf

- D’Angelo, S. C. et al. Environmental and economic potential of decentralized electrocatalytic ammonia synthesis powered by solar energy. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 3314-3330 (2023).

- Comer, B. M. et al. Prospects and challenges for solar fertilizers. Joule 3, 1578-1605 (2019).

- Valera-Medina, A. et al. Review on ammonia as a potential fuel: from synthesis to economics. Energy Fuels 35, 6964-7029 (2021).

- Chen, S., Perathoner, S., Ampelli, C. & Centi, G. Electrochemical dinitrogen activation: to find a sustainable way to produce ammonia. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 178, 31-46 (2019).

- Smith, C., Hill, A. K. & Torrente-Murciano, L. Current and future role of Haber-Bosch ammonia in a carbon-free energy landscape. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 331-344 (2020).

- Winter, L. R. & Chen, J. G.

fixation by plasma-activated processes. Joule 5, 300-315 (2021). - Huang, P. W. & Hatzell, M. C. Prospects and good experimental practices for photocatalytic ammonia synthesis. Nat. Commun. 13, 7908 (2022).

- Martín, A. J., Shinagawa, T. & Pérez-Ramírez, J. Electrocatalytic reduction of nitrogen: from Haber-Bosch to ammonia artificial leaf. Chem 5, 263-283 (2019).

- Giddey, S., Badwal, S. P. S. & Kulkarni, A. Review of electrochemical ammonia production technologies and materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 38, 14576-14594 (2013).

- Wang, M. et al. Can sustainable ammonia synthesis pathways compete with fossil-fuel based Haber-Bosch processes? Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 2535-2548 (2021).

- D’Angelo, S. C. et al. Planetary boundaries analysis of low-carbon ammonia production routes. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 97409749 (2021).

- Mueller, N. D. et al. Closing yield gaps through nutrient and water management. Nature 490, 254-257 (2012).

- Adalibieke, W., Cui, X., Cai, H., You, L. & Zhou, F. Global crop-specific nitrogen fertilization dataset in 1961-2020. Sci. Data 10, 617 (2023).

- Adeh, E. H., Good, S. P., Calaf, M. & Higgins, C. W. Solar PV power potential is greatest over croplands. Sci. Rep. 9, 11442 (2019).

- Dinesh, H. & Pearce, J. M. The potential of agrivoltaic systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 54, 299-308 (2016).

- Amaducci, S., Yin, X. & Colauzzi, M. Agrivoltaic systems to optimise land use for electric energy production. Appl. Energy 220, 545-561 (2018).

- Barron-Gafford, G. A. et al. Agrivoltaics provide mutual benefits across the food-energy-water nexus in drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2, 848-855 (2019).

- Ha, J., Ayhan Kose M. & Ohnsorge, F. One-Stop Source: A Global Database of Inflation Policy Research Working Paper 9737 (World Bank, 2021).

- Stevens, C. J. Nitrogen in the environment. Science 363, 578-580 (2019).

- Menegat, S., Ledo, A. & Tirado, R. Greenhouse gas emissions from global production and use of nitrogen synthetic fertilisers in agriculture. Sci. Rep. 12, 14490 (2022).

- Bertagni, M. B. et al. Minimizing the impacts of the ammonia economy on the nitrogen cycle and climate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2311728120 (2023).

- Rouwenhorst, K. H., Van der Ham, A. G., Mul, G. & Kersten, S. R. Islanded ammonia power systems: technology review and conceptual process design. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 114, 109339 (2019).

- Text – H.R.5376-117th Congress (2021-2022): Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (Library of Congress, 2022); https://www.congress. gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text

- Net Zero Industry Act. COM(2023) 161, SWD(2023) 68 (European Commission, Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, 2023); https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/publications/net-zero-industry-act_en

- Emissions Factor 2021 (International Energy Agency, 2021); https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-product/ emissions-factors-2021

- Direct Air Capture (International Energy Agency, 2021); https://www.iea.org/reports/direct-air-capture

- Electricity Information: Overview (International Energy Agency, 2021); https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-informationoverview

- Global Solar Atlas 2.0: Technical Report ESMAP Paper (World Bank, 2019); https://globalsolaratlas.info/map

- Cardoso, J. S. et al. Ammonia as an energy vector: current and future prospects for low-carbon fuel applications in internal combustion engines. J. Clean. Prod. 296, 126562 (2021).

- Green Hydrogen Cost Reduction: Scaling up Electrolysers to Meet the

Climate Goal (International Renewable Energy Agency, 2020). - Yates, J. et al. Techno-economic analysis of hydrogen electrolysis from off-grid stand-alone photovoltaics incorporating uncertainty analysis. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 1, 100209 (2020).

- Branker, K., Pathak, M. J. M. & Pearce, J. M. A review of solar photovoltaic levelized cost of electricity. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15, 4470-4482 (2011).

- Hochman, G. et al. Potential economic feasibility of direct electrochemical nitrogen reduction as a route to ammonia. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 8938-8948 (2020).

- Patonia, A. & Poudineh, R. Ammonia as a Storage Solution for Future Decarbonized Energy Systems OIES Paper EL 42 https:// www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/ammonia-as-a-storage-solution-for-future-decarbonized-energy-systems/(2020)

- Wolfram, P., Kyle, P., Zhang, X., Gkantonas, S. & Smith, S. Using ammonia as a shipping fuel could disturb the nitrogen cycle. Nat. Energy 7, 1112-1114 (2022).

- Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the

Goal in Reach (International Energy Agency, 2023); https://www.iea.org/ reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-Oc-goal-in-reach - Northrup, D. L., Basso, B., Wang, M. Q., Morgan, C. L. & Benfey, P. N. Novel technologies for emission reduction complement conservation agriculture to achieve negative emissions from row-crop production. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2022666118 (2021).

- Brill, W. J. Biological nitrogen fixation. Sci. Am. 236, 68-81 (1977).

- Mus, F. et al. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation and the challenges to its extension to nonlegumes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 36983710 (2016).

- Tonelli, D., Rosa, L., Gabrielli, P., Parente, A. & Contino, F. Costcompetitiveness of distributed ammonia production for the global fertilizer industry. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/ zenodo. 8155141 (2024).

- Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90-95 (2007).

- Jordahl, K. et al. geopandas/geopandas: v0.8.1. Zenodo https:// doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 3946761 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

(c) The Author(s) 2024

natureportfolio

Reporting Summary

Statistics

Confirmed

The statistical test(s) used AND whether they are one- or two-sided

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Software and code

Policy information about availability of computer code

| Data collection | The raw data used in this study are from open access scientific literature and no software was used for data collection. |

| Data analysis | Custom made codes were used for data elaboration, analysis and visualization. All the scripts are written in Python 3.9.12. Maps were created with Matplotlib and Geopandas packages. All the codes are stored in the open access Zenodo repository http://doi.org/10.5281/ zenodo. 8155141 |

Data

Policy information about availability of data

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

data used in the study come from open-source datasets:

- Historical fertilizer prices: 47. Ha, Jongrim, M. Ayhan Kose, & Franziska Ohnsorge. One-Stop Source: A Global Database of Inflation Policy. World Bank Research Working Paper 9737 (2021).

- Spatially-explicit nitrogen demand in 2020: 42. Adalibieke, W., Cui, X., Cai, H., You, L. & Zhou, F. Global crop-specific nitrogen fertilization dataset in 1961-2020. Scientific Data 10(1), 617 (2023).

- Spatially-explicit solar irradiation: ESMAP. Global Solar Atlas 2.0. Technical Report, World Bank. https://globalsolaratlas.info/map (2019).

Research involving human participants, their data, or biological material

| Reporting on sex and gender | No human research participant was involved in this work. |

| Reporting on race, ethnicity, or other socially relevant groupings | No human research participant was involved in this work. |

| Population characteristics | No human research participant was involved in this work. |

| Recruitment | No human research participant was involved in this work. |

| Ethics oversight | No human research participant was involved in this work. |

Field-specific reporting

Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences

Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences study design

| Study description | The study relies on input data from open source scientific publications and do not involve any laboratory measurements or field work. | |||||

| Research sample |

|

|||||

| Sampling strategy | The spatially-explicit data comes from deterministic estimations, based on well defined assumptions. | |||||

| Data collection | All the data comes from open-source documented literature. | |||||

| Timing and spatial scale | This point does not apply since the data used comes from numerical calculations. | |||||

| Data exclusions | No data correction was introduced beyond the calculations stated in the article. | |||||

| Reproducibility | All the calculations in the article are reproducible based on the codes in the folder open-access. | |||||

| Randomization | The only allocations of data within this study is the aggregation of data at pixel-level into countries and continents. Data allocation, reproducible with the shared codes, is based on polygons describing the shape of single countries and the pixels contained within the polygons. | |||||

| Blinding | This point does not apply since the data used comes from numerical calculations. | |||||

| Did the study involve field work? |

|

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

| Materials & experimental systems | Methods | ||

| n/a | Involved in the study | n/a | Involved in the study |

| X |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Plants

| Seed stocks |

|

||

| Novel plant genotypes |

|

||

| Authentication |

|

Institute of Mechanics, Materials and Civil Engineering, UCLouvain, Ottignies-Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. Aero-Thermo-Mechanics Department, ULB, Brussels, Belgium. Department of Global Ecology, Carnegie Institution for Science, Stanford, CA, USA. Institute of Energy and Process Engineering, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. e-mail: davidetonelli@outlook.com; Irosa@carnegiescience.edu