DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06862-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38200294

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-10

100 جينوم قديم يظهر تغييرات متكررة في السكان في الدنمارك النيوثية

تاريخ الاستلام: 6 أبريل 2023

تم القبول: 13 نوفمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 10 يناير 2024

الوصول المفتوح

تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

تمت مضاهاة الأحداث الكبرى للهجرة في العصر الهولوسيني في أوراسيا جينياً على نطاقات إقليمية واسعة.

يتضمن عنصرًا أقوى من انتشار الثقافة

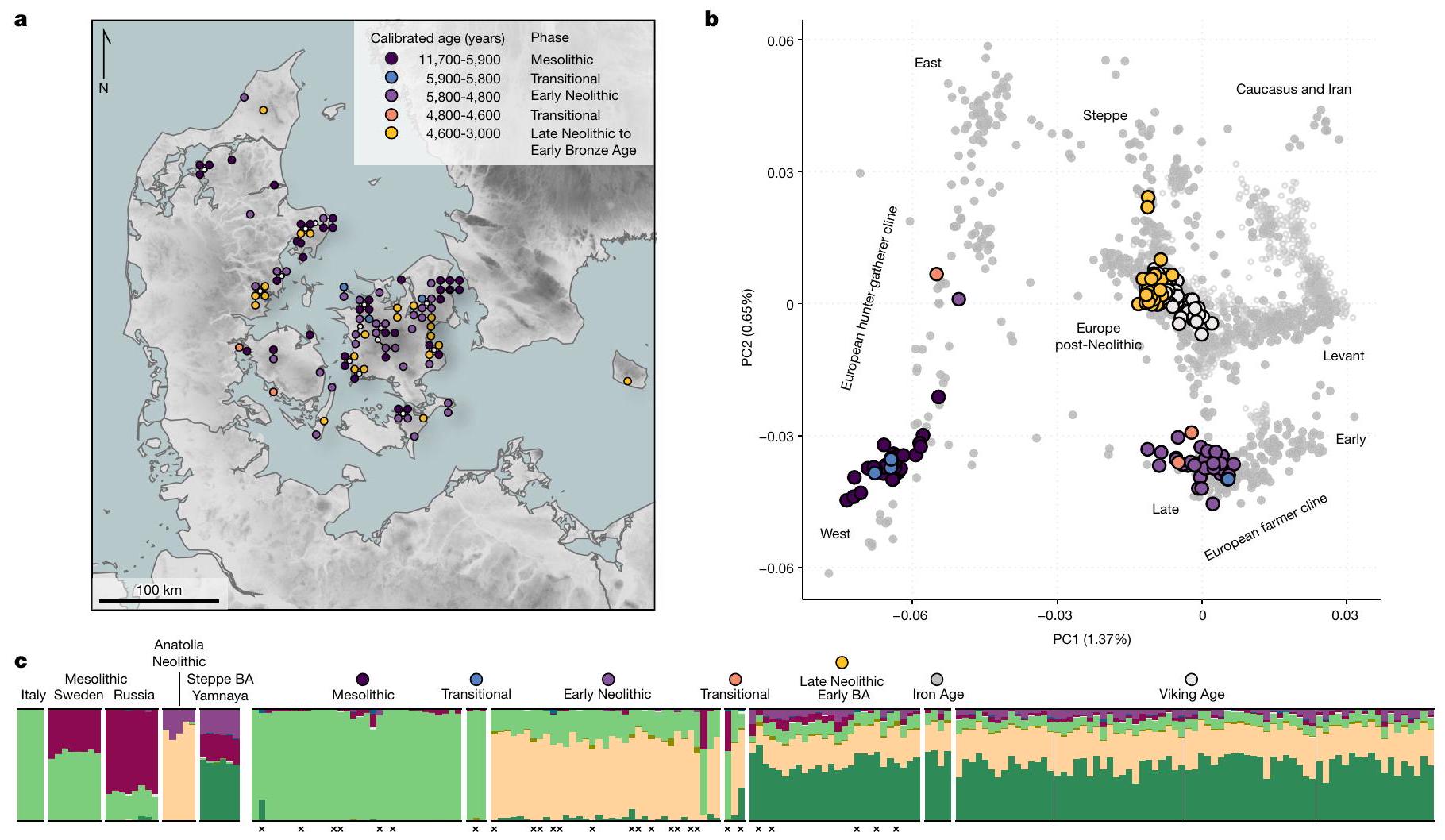

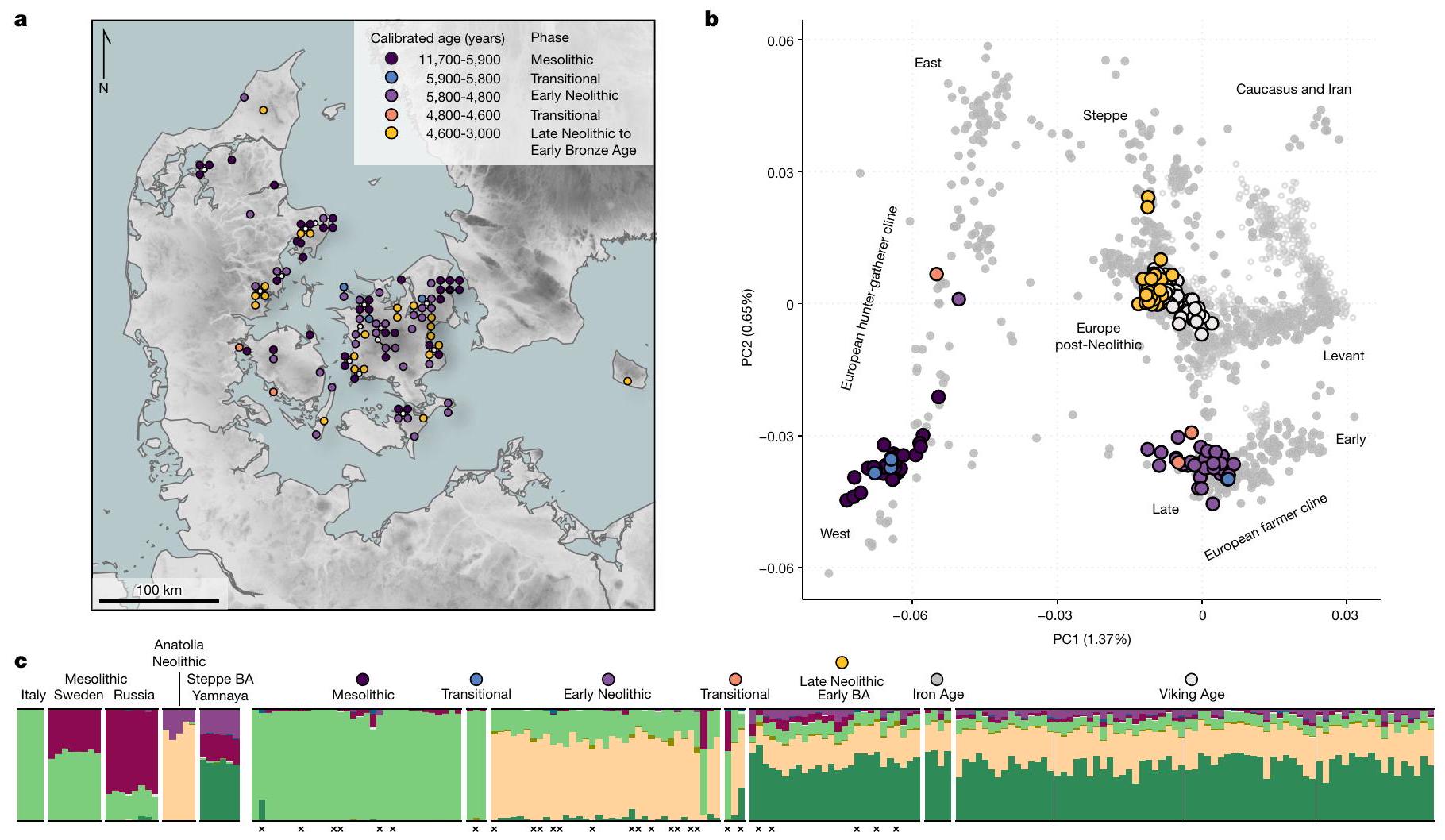

دوائر). الأفراد القدماء من الدنمارك ملونون وفقًا للفترة كما هو محدد في أ و ج. ج، التجميع القائم على النموذج غير المراقب (ADMIXTURE) لـ

الجينومات المدخلة

فترة الميزوليت

وقد قدمت رؤى مهمة حول الأنثروبولوجيا الفيزيائية والثقافة الروحية في تلك الفترة.

تم الادعاء بأن لها أصل شرقي

أغراض تدل على تاريخ مبكر من العصر النيوزيلندي

تظهر احتمالات ألوان الشعر (الأشقر، البني، الأسود والأحمر) وألوان العيون (الزرقاء والبنية)، مع الرمادي يدل على احتمال لون العين المتوسطة (بما في ذلك الرمادي، الأخضر والبني). تُظهر اللوحة السفلية التغيرات الكمية في تغطية الغطاء النباتي، استنادًا إلى تحليلات حبوب اللقاح في بحيرة هويبي في زيلاند. لاحظ أن لوحة الغطاء النباتي تغطي فترة زمنية أقصر من اللوحات الأخرى. تحدد الخطوط الرأسية السوداء أول ظهور لأصل المزارعين النيوزيلنديين الأناضوليين وأصل مرتبط بالسافانا، على التوالي. يتم الإشارة إلى الأفراد ذوي التغطية الجينومية المنخفضة، وعلامات التلوث المحتمل و/أو درجات توقع النمط الجيني المنخفضة (GP) (الطرق).

وابنته. تظهر بياناتنا أيضًا أن الرجل في القبر المجاور (‘رجل دراجشولم’، NEO962) لم يكن مرتبطًا بالامرأتين. تظهر هذه الحالات أن القرابة البيولوجية الوثيقة كانت ذات أهمية اجتماعية لمجموعات العصر الحجري الحديث المتأخر في شمال أوروبا وأثرت على معاملة الموتى من أعضاء مجتمعهم.

الانتقال النيوليتي المبكر

(أوروباW_13500BP_8000BP). يتم العثور على سلالة مرتبطة بصيادي وجامعي الثمار من العصر الحجري الوسيط الدنماركي (الدنمارك_10500BP_6000BP) بنسب أصغر (أقل من حوالي

نشأت ثقافة الفخار المثقوب (PWC) في شبه الجزيرة الاسكندنافية وجزر البلطيق شرق البر الرئيسي السويدي ولكنها ظهرت حوالي

العصر الحجري الحديث المتأخر وعصر البرونز

للمجمع CWC. تم تمييز الانتقال إلى القبور الفردية في التلال الدائرية أثريًا من خلال مرحلتين من التوسع: احتلال أولي وسريع لمركز وغرب وشمال يولاند (غرب الدنمارك) بدءًا من حوالي

من قبر Gjerrild

التأثير البيئي

دوافع التغيير

على الإقليم. مع هذا الوصول، تم تعديل المناظر الطبيعية المحلية لتناسب نمط حياة وثقافة المهاجرين. هذه هي علامة العصر الأنثروبوسي، التي لوحظت هنا بدقة عالية في الدنمارك ما قبل التاريخ.

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- Allentoft، M. E. وآخرون. علم الجينوم السكاني في العصر البرونزي في أوراسيا. Nature 522، 167-172 (2015).

- Haak، W. وآخرون. كانت الهجرة الضخمة من السافانا مصدرًا للغات الهندو-أوروبية في أوروبا. Nature 522، 207-211 (2015).

- Allentoft، M. E. وآخرون. علم الجينوم السكاني لأوراسيا الغربية بعد العصر الجليدي. Nature https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06865-0 (2024).

- Posth، C. وآخرون. علم الجينوم القديم للصيادين وجامعي الثمار من العصر الحجري العلوي إلى النيوليتي. Nature 615، 117-126 (2023).

- Johannsen، N. N.، Larson، G.، Meltzer، D. J. & Vander Linden، M. نافذة مركبة في تاريخ البشرية. Science 356، 1118-1120 (2017).

- Furholt، M. التنقل والتغيير الاجتماعي: فهم الفترة النيوليتية الأوروبية بعد ثورة علم الجينوم الأثري. J. Archaeol. Res. 29، 481-535 (2021).

- Kristiansen، K. علم الآثار والثورة الجينية في ما قبل التاريخ الأوروبي (عناصر في علم آثار أوروبا) (Cambridge Univ. Press، 2022).

- Fischer، A. & Kristiansen، K. النيوليتية في الدنمارك. 150 عامًا من النقاش (J. R. Collis، 2002).

- Günther، T. وآخرون. علم الجينوم السكاني في الميزوليت الإسكندنافي: التحقيق في طرق الهجرة المبكرة بعد العصر الجليدي والتكيف مع العروض العالية. PLoS Biol. 16، e2003703 (2018).

- Kashuba، N. وآخرون. الحمض النووي القديم من الماستيكس يثبت العلاقة بين الثقافة المادية وجينات الصيادين وجامعي الثمار في الميزوليت في الإسكندنافيا. Commun. Biol. 2، 185 (2019).

- Fischer، A. في النيوليتية في الدنمارك-150 عامًا من النقاش (محررون Fischer، A. & Kristiansen، K.) 343-393 (J. R. Collis، 2002).

- Price، T. D. أول مزارعي أوروبا (Cambridge Univ. Press، 2000).

- Lipson، M. وآخرون. تكشف المقاطع الأثرية الموازية عن تاريخ جيني معقد للمزارعين الأوروبيين الأوائل. Nature 551، 368-372 (2017).

- Mathieson، I. وآخرون. التاريخ الجيني لجنوب شرق أوروبا. Nature 555، 197-203 (2018).

- براس، س. وآخرون. الجينومات القديمة تشير إلى استبدال السكان في بريطانيا في العصر الحجري الحديث المبكر. نات. إيكول. إيفول. 3، 765-771 (2019).

- ميدجلي، م. ثقافة TRB: أول مزارعين في السهول الأوروبية الشمالية (دار نشر جامعة إدنبرة، 1992).

- إيفرسن، ر. في تتبع الهندو-أوروبيين: أدلة جديدة من علم الآثار واللغويات التاريخية (تحرير أولسن، ب. أ.، أولاندر، ت. وكريستيانسن، ك.) 73-95 (أوكس بو، 2019).

- نيلسن، س. ك. وجوهانسن، ن. ن. حواجز الموتى، القبور الفردية، والامتزاج الثقافي: تأسيس ثقافة الأواني الملتفة في شبه جزيرة يوتلاند. المجلة ما قبل التاريخhttps://doi.org/10.1515/pz-2023-2022 (2023).

- كريستيانسن، ك. الهجرات ما قبل التاريخ – حالة ثقافات القبر الفردي وثقافات الأواني الملتفة. مجلة الآثار الدنماركية 8، 211-225 (1991).

- لويس، ج. ب. وآخرون. وفرة الموارد البحرية دفعت زيادة السكان قبل الزراعة في عصر الحجر في اسكندنافيا. نات. كوميونيك. 11، 2006 (2020).

- سوزا دا موتا، ب. وآخرون. استكمال الجينومات البشرية القديمة. نات. كوميونيك. 14، 3660 (2023).

- شيلينغ، هـ. في العصر الحجري الأوسط في الحركة (تحرير لارسون، ل. وآخرون) 351-358 (2003).

- بيترسن، ب. ف. التغير الزمني والإقليمي في العصر الميزوليتي المتأخر في شرق الدنمارك. مجلة الآثار الدنماركية 3، 7-18 (1984).

- فيشر، أ. في جسر الدانمارك ستوربيلت منذ العصر الجليدي (تحرير: بيدرسن، ل.، فيشر، أ. وأابي، ب.) 63-77 (البحر والغابة، 1997).

- سورنسن، س. أ. ثقافة كونغيموس (دار نشر جامعة جنوب الدنمارك، 2017).

- دولبونوفا، إ. وآخرون. نقل تقنية الفخار بين الصيادين وجامعي الثمار في أوروبا ما قبل التاريخ. سلوك الإنسان الطبيعي 7، 171-183 (2023).

- كلاسن، ل. جاد وكوبر: دراسات حول عملية النيوليثية في منطقة بحر البلطيق الغربية مع مراعاة خاصة لتطور الثقافة في أوروبا 5500-3500 قبل الميلاد المجلد 47 (دار نشر جامعة آرهوس، 2004).

- برايس، ت. د. البحث عن أول المزارعين في غرب شيلاند، الدنمارك: علم الآثار لانتقال الزراعة في شمال أوروبا (أوكس بوكس، 2022).

- هانسن، ج. وآخرون. هيكل مغلموسيان من كويلبيرغ: إعادة النظر في تحديد الجنس والأصل. المجلة الدنماركية للآثار 6، 55-66 (2017).

- سورنسن، م. في بيئة الاستيطان المبكر في شمال أوروبا: شروط البقاء والعيش. الاستيطان المبكر في شمال أوروبا المجلد 1 (تحرير: بيرسون، ب.، ريده، ف. وسكار، ب.) 277-301 (إكوينكس، 2018).

- بيزونكا، هـ. وآخرون. تسلسل الفخار في العصر الحجري القديم في منطقة الغابات شمال شرق أوروبا: نتائج جديدة من قياسات الكربون المشع وقياسات نظائر الأكسجين على قشور الطعام. راديكاربون 58، 267-289 (2016).

- ماثيسون، I. وآخرون. أنماط الانتقاء على مستوى الجينوم في 230 من الأوراسيين القدماء. الطبيعة 528، 499-503 (2015).

- إيرفينغ-بيز، إ. ك. وآخرون. مشهد الاختيار والإرث الجيني للإنسان القديم في أوراسيا. الطبيعةhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06705-1 (2024).

- فيشر، أ. وآخرون. التنقل بين الساحل والداخل والنظام الغذائي في العصر الميزوليتي والنيولتي في الدنمارك: أدلة من قيم النظائر المستقرة للبشر والكلاب. مجلة علوم الآثار 34، 2125-2150 (2007).

- فيشر، أ. وآخرون. تركيبة غذاء العصر الميزوليتي – أدلة من مستوطنة غارقة على بنك أرجوس، الدنمارك. أكتا أرشيو. 78، 163-178 (2007).

- برينش بيترسن، إي. القبور في دراجشولم. من الصيادين إلى المزارعين قبل 6000 عام. أعمال المتحف الوطني 1974، 112-120 (1974).

- برايس، ت. د. وآخرون. معلومات جديدة عن قبور العصر الحجري في دراجشولم، الدنمارك. أكتا أرشيو. 78، 193-219 (2007).

- سورنسن، ل. من صياد إلى مزارع في شمال أوروبا. الهجرة والتكيف خلال العصر الحجري الحديث وعصر البرونز. أكتا أرخيولوجيكا المجلد 85 (وايلي-بلاكويل، 2014).

- نيلسن، ب. أ. ونيلسن، ف. أ. س. أول المزارعين في جزيرة بورنهولم (الجمعية الملكية للآثار الشمالية ودار نشر جامعة جنوب الدنمارك، 2020).

- سجورن، ك.-ج. وفيشر، أ. تسلسل الدفنات الدنماركية. نتائج من

تواريخ على العظام البشرية. ج. نييوليت. آثار. 25،https://doi.org/10.12766/jna.2023.1 (2023). - ديهن، ت. & هانسن، س. آي. لحاء البتولا في قبور الممرات الدنماركية. مجلة الآثار الدنماركية 14، 23-44 (2006).

- إيبيسن، ك. قبور بسيطة، تاريخية. كتب سنوية للآثار والتاريخ الإسكندنافي 1992، 47-102 (1994).

- جرون، ك. ج. وسورنسن، ل. التفاوض الثقافي والاقتصادي: منظور جديد حول الانتقال النيوليثي في جنوب اسكندنافيا. الأنتيكويتي 92، 958-974 (2018).

- شينتالاباتي، م.، باترسون، ن. ومورجاني، ب. الأنماط الزمانية والمكانية للأحداث الكبرى للاختلاط البشري خلال الهولوسين الأوروبي. eLife 11، e77625 (2022).

- غونزاليس-فورتس، ج. وآخرون. أدلة بالجينوم القديم على الاختلاط عبر أجيال متعددة بين المزارعين النيوليثيين وجامعي الصيد في حوض الدانوب السفلي. بيولوجيا حالية 27، 1801-1810.e10 (2017).

- فيلاالبا-موكو، ف. وآخرون. بقاء سلالة الصيادين وجامعي الثمار من أواخر العصر الجليدي في شبه الجزيرة الإيبيرية. البيولوجيا الحالية 29، 1169-1177.e7 (2019).

- جينسن، ت. ز. ت. وآخرون. جينوم بشري عمره 5700 عام وميكروبيوم فموي من قلف البتولا الممضوغ. نات. كوميونيك. 10، 5520 (2019).

- أولادي، إ. وآخرون. الأليلات المناعية والأليلات الصبغية السلفية المستمدة في إنسان أوروبي من العصر الميزوليتي عمره 7000 عام. ناتشر 507، 225-228 (2014).

- كوك، س. ل.، راف، س. ب.، ماير، ر. م. وماثيسون، آي. المساهمات الجينية في التباين في طول القامة البشرية في أوروبا ما قبل التاريخ. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 116، 21484-21492 (2019).

- كلسن، ل. (محرر) ثقافة الفخار المنقوش على جزيرة ديورسلاند: الأهمية فوق الإقليمية والاتصالات في العصر النيوليثي الأوسط في جنوب اسكندنافيا (دار نشر جامعة آرهوس، 2020).

- إيفرسن، ر.، فيليبسن، ب. & بيرسون، ب. إعادة النظر في تسلسل زمن الفخار المنقوش. مجلة ما قبل التاريخ 96، 44-88 (2021).

- كوتينيو، أ. وآخرون. لم يتأثر جامعو ثقافة الفخار المنقوش من العصر الحجري الحديث ثقافيًا ولكن ليس وراثيًا برعاة ثقافة الفأس القتالي. المجلة الأمريكية لعلم الإنسان الفيزيائي 172، 638-649 (2020).

- جلوب، ب. ف. دراسات حول ثقافة القبور الفردية في جوتلاند (غيلدنال، 1945).

- مولر، ج. وفاندكيلد، هـ. في تباينات العصر البرونزي الإسكندنافي. مقالات تكريماً لكريستوفر بريسكوت (محررون: أوستفول، ك.إ.، هيم إريكسن، م.، فريدريكسن، ب.د.، ميلهايم، أ.ل.، بروش-دانييلسن، ل.، سكوغستران، ل.) 29-48 (بريبولس، 2020).

- إيفرسن، ر. تحول المجتمعات النيوزيلندية. منظور دنماركي شرقي عن الألفية الثالثة قبل الميلاد المجلد 88 (جمعية جوتلاند الأثرية، 2015).

- دام، سي. ثقافة القبر الفردي الدنماركية – هجرة عرقية أم بناء اجتماعي؟ مجلة الآثار الدنماركية 10، 199-204 (1991).

- إيجفجورد، أ. ف.-هـ. وآخرون. الأنساب الجينية للسهوب في الهياكل العظمية من ثقافة القبر الفردي في العصر الحجري الحديث في الدنمارك. PLoS ONE 16، e0244872 (2021).

- غراسغروبر، ب.، سيبيرة، م.، هرازدييرا، إ.، تشاتشيك، ج. وكالينا، ت. العوامل الرئيسية المرتبطة بطول الذكور: دراسة لـ 105 دول. الاقتصاد. البيولوجيا البشرية 21، 172-195 (2016).

- باباك، ل. وآخرون. التغيرات الديناميكية في الهياكل الجينومية والاجتماعية في وسط أوروبا في الألفية الثالثة قبل الميلاد. ساينس. أدف. 7، eabi6941 (2021).

- بلانك، م. التنقل، وسبل العيش، وممارسات الدفن. دراسة متعددة التخصصات عن السكان الميغاليثيين في العصر الحجري الحديث والعصر البرونزي المبكر في جنوب غرب السويد. أطروحة دكتوراه، جامعة غوتنبرغ (2021).

- وينثر يوهانسن، ج. التوسع في العصر النيوليثي المتأخر. مجلة الآثار الدنماركية 12،https://doi.org/10.7146/dja.v12i1.132093 (2023).

- بادرسن، سي. بي. وآخرون. عينة الحالة-المنطقة iPSYCH2O12: اتجاهات جديدة لفك شفرة الهياكل الوراثية والبيئية للاضطرابات النفسية الشديدة. علم النفس الجزيئي 23، 6-14 (2017).

- أودغارد، ب. ف. تاريخ الغطاء النباتي في الهولوسين في شمال غرب يولاند، الدنمارك. مجلة النباتات الشمالية 14، 546-546 (1994).

- هاك، و. وآخرون في اللغز الهندو-أوروبي المعاد زيارته: دمج علم الآثار، وعلم الوراثة، واللغويات (تحرير كريستيانسن، ك.، كرونن، ج. وويليرسليف، إ.) 63-80 (2023).

- فيشر، أ.، غوتفريدسن، أ. ب.، ميدوز، ج.، بيدرسن، ل. وستافورد، م. التكيفات البحرية في مكب مطبخ رودهالس في نهاية العالم الميزوليتي. مجلة علوم الآثار 39، 103102 (2021).

- بينيك، ب. في جسر الدانمارك ستوربيلت منذ العصر الجليدي (تحرير: بيدرسن، ل.، فيشر، أ. وأابي، ب.) 99-105 (A/S ستوربيلت فيكسد لينك، 1997).

- واردن، ل. وآخرون. التغيرات الديموغرافية والثقافية البشرية الناتجة عن المناخ في شمال أوروبا خلال منتصف الهولوسين. تقارير العلوم. 7، 15251 (2017).

- كروسّا، ف. ر. وآخرون. التغير المناخي الإقليمي وبداية الزراعة في شمال ألمانيا وجنوب اسكندنافيا. هولوسين 27، 1589-1599 (2017).

- إيفرسن، ر. رؤوس السهام كمؤشرات على العنف بين الأفراد وهُوية المجموعة بين صيادي الفخار المنقوش من العصر الحجري الحديث في جنوب غرب اسكندنافيا. مجلة الأنثروبولوجيا والآثار 44، 69-86 (2016).

- ليدكي، ج. العنف في ثقافة القبر الفردي في شمال ألمانيا؟ في العصي، الحجارة، والعظام المكسورة: العنف النيوليثي في منظور أوروبي (تحرير شولتنج، ر. ج. وفايبيجر، ل.) 139-150https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199573066.003.0008 (أوكسفورد، 2012).

- شرويدر، هـ. وآخرون. فك شيفرة النسب، القرابة، والعنف في قبر جماعي من العصر الحجري الحديث المتأخر. وقائع الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية 116، 10705-10710 (2019).

- راسموسن، س. وآخرون. سلالات مبكرة متباينة من يرسينيا بيستيس في أوراسيا قبل 5000 عام. خلية 163، 571-582 (2015).

- راسكووان، ن. وآخرون. ظهور وانتشار السلالات الأساسية من يرسينيا بيستيس خلال الانحدار النيوليثي. خلية 176، 295-305.e10 (2019).

- هينز، م. وآخرون. في تنوعات العصر الحجري الحديث: وجهات نظر من مؤتمر في لوند، السويد 43-51 (جامعة لوند، 2015).

- فيزر، إ.، دورفلر، و.، كنيزل، ج.، هينز، م. ودرايبروت، س. التأثير البشري وديناميات السكان في العصر الحجري الحديث وعصر البرونز: أدلة متعددة المصادر من شمال غرب وسط أوروبا. هولوسين 29، 1596-1606 (2019).

- مارغاريان، أ. وآخرون. علم الجينوم السكاني لعالم الفايكنج. ناتشر 585، 390-396 (2020).

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

طرق

تحليلات الجينوم القديمة

- مجموعة بيانات ‘1000 G’: بيانات تسلسل الجينوم الكامل لـ 2504 فردًا من 26 مجموعة سكانية حول العالم من مشروع الجينومات الألف، مع الأنماط الجينية في

SNPs جسيمية. - ‘مجموعة بيانات ‘HO’: بيانات مصفوفة SNP لـ 2,180 فردًا حديثًا من 213 مجموعة سكانية حول العالم، مع أنماط وراثية عند 535,880 SNPs جسمية.

تواريخ الكربون المشع ونمذجة بايزيان لجدول النسب

عمر الكربون المشع (البيانات التكميلية 1؛ مزيد من

نظائر مستقرة ك proxies للنظام الغذائي والتنقل

نمذجة الغطاء النباتي

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

77. دامغارد، ب. ب. وآخرون. تحسين الوصول إلى الحمض النووي الداخلي في العظام والأسنان القديمة. ساينتيفيك ريبورتس 5، 11184 (2015).

78. مجموعة مشروع الجينوم البشري. مرجع عالمي للتنوع الجيني البشري. ناتشر 526، 68-74 (2015).

79. ماير، ر.، فليغونتوف، ب.، فليغونتوفا، أ.، إيشيلداك، أ.، تشانغماي، ب. ورايش، د. حول حدود ملاءمة نماذج معقدة لتاريخ السكان مع إحصائيات f. إيلف 12، e85492 (2023).

80. براونينغ، ب. ل. وبراونينغ، س. ر. الكشف عن الهوية من خلال النسب وتقدير معدلات خطأ الجينوتيب في بيانات التسلسل. المجلة الأمريكية لعلم الوراثة البشرية 93، 840-851 (2013).

81. أبادرائي، ف. وآخرون. دقة تقدير الهبلايوت ونمذجة الجينوم الكامل تؤثر على تحليلات الصفات المعقدة في البنوك الحيوية المعقدة. اتصالات. بيولوجيا. 6، 101 (2023).

82. بيرسيل، س. وآخرون. PLINK: مجموعة أدوات لتحليل الارتباط على مستوى الجينوم الكامل وتحليل الروابط القائم على السكان. المجلة الأمريكية لعلم الوراثة البشرية 81، 559-575 (2007).

83. والش، س. وآخرون. نظام HIrisPlex للتنبؤ المتزامن بلون الشعر والعين من الحمض النووي. علوم الطب الشرعي. دولي. علم الوراثة 7، 98-115 (2013).

84. بايكروفت، سي. وآخرون. مورد بنك المملكة المتحدة مع تصنيف عميق وبيانات جينومية. ناتشر 562، 203-209 (2018).

85. برونك رامزي، سي. تطوير برنامج المعايرة بالكربون المشع أوكسكال. راديكربون 43، 355-363 (2001).

86. برونك رامزي، سي. نماذج الإيداع للسجلات الزمنية. مراجعة العلوم الكمية 27، 42-60 (2008).

87. برونك رامزي، سي. تحليل بايزي لتواريخ الكربون المشع. راديكربون 51، 337-360 (2009).

88. برونك رامزي، سي. التعامل مع القيم الشاذة والانحرافات. الكربون المشع 51، 1023-1045 (2009).

89. رايمر، ب.، أوستن، و. & بارد، إ. منحنى معايرة عمر الكربون المشع لنصف الكرة الشمالي IntCal20 (0-55 كالف BP). الكربون المشع 62، 725-757 (2020).

90. كارلسبرغ، أ. ج. طرق بايزي المرنة لتأريخ الآثار. رسالة دكتوراه، جامعة شيفيلد (2006).

91. لي، س. ورامسي، ج. تطوير وتطبيق نموذج شبه المنحرف للتسلسلات الزمنية الأثرية. الكربون المشع 54، 107-122 (2012).

92. ميدوز، ج. وآخرون. تأثيرات خزانات المياه العذبة الغذائية وأعمار الكربون المشع لعظام البشر ما قبل التاريخ من زفيجنكي، لاتفيا. مجلة علوم الآثار 6، 678-689 (2016).

93. روز، هـ. أ.، ميدوز، ج. وبييريجارد، م. تأريخ عالي الدقة لقبر جماعي من العصور الوسطى. الكربون المشع 60، 1547-1559 (2018).

94. هيدجز، ر. إ. م.، كليمنت، ج. ج.، ديفيد، ج.، توماس، ل. وأوكونيل، ت. س. دوران الكولاجين في منتصف عظمة الفخذ لدى البالغين: تم نمذجته من قياسات مؤشرات الكربون المشع الناتجة عن الأنشطة البشرية. المجلة الأمريكية للأنثروبولوجيا الفيزيائية 133، 808-816 (2007).

95. يوركوف، م. ل. س.، هاينماير، ج. ولينيروب، ن. عظمة الصدغ – موقع جديد لأخذ العينات لتحديد أنماط النظام الغذائي المبكر في الدراسات المستقرة لل isotopes. المجلة الأمريكية للأنثروبولوجيا الفيزيائية 138، 199-209 (2009).

96. شونيغر، م. ج. ومور، ك. دراسات نظائر العظام المستقرة في علم الآثار. مجلة ما قبل التاريخ العالمي 6، 247-296 (1992).

97. هيدجز، ر. إ. م. & رينارد، ل. م. نظائر النيتروجين ومستوى التغذية للبشر في علم الآثار. مجلة علوم الآثار 34، 1240-1251 (2007).

98. رايمر، ب. وآخرون. بروتوكولات المختبر المستخدمة في تأريخ الكربون المشع بواسطة AMS في مركز 14 كرونو. سلسلة تقارير أبحاث التراث الإنجليزي 5-2015https://historicengland.org.uk/البحث/النتائج/التقارير/6272/بروتوكولات المختبر المستخدمة في تأريخ الكربون المشع في مركز 14CHRONO بجامعة الملكة بلفاست (2015).

99. لونجين، ر. طريقة جديدة لاستخراج الكولاجين لتأريخ الكربون المشع. ناتشر 230، 241-242 (1971).

مقالة

- أمبروز، س. هـ. ودي نيرو، م. ج. البيئة النظيرية لثدييات شرق إفريقيا. أوكولوجيا 69، 395-406 (1986).

- فان كلينكن، ج. مؤشرات جودة الكولاجين العظمي لقياسات النظام الغذائي القديم والكربون المشع. مجلة علوم الآثار 26، 687-695 (1999).

- ألكسندر بينتلي، R. نظائر السترانشيوم من الأرض إلى الهيكل العظمي الأثري: مراجعة. مجلة طرق ونظرية الآثار 13، 135-187 (2006).

- فراي، ك. م. و برايس، ت. د. نظائر السترانشيوم والتنقل البشري في الدنمارك ما قبل التاريخ. علوم الآثار والأنثروبولوجيا 4، 103-114 (2012).

- هولت، إ.، إيفانز، ج. أ. ومادجويك، ر. سترونتيوم (

المسح: مراجعة نقدية للطرق والأساليب. مراجعات علوم الأرض 216، 103593 (2021). - برايس، ت. د.، بورتون، ج. هـ. وبنتلي، ر. أ. توصيف نسب نظائر السترونتيوم المتاحة بيولوجيًا لدراسة الهجرة ما قبل التاريخ. الأركيومترية 44، 117-135 (2002).

- ثومسن، إ.، أندرياسن، ر. وراسموسن، ت. ل. يمكن أن تحتوي المناظر الطبيعية الجليدية المتجانسة على تباين محلي عالٍ في توقيعات نظائر السترونتيوم: تداعيات لدراسات الهجرة ما قبل التاريخ. فرونت. إيكول. إيفول. 8، 588318 (2021).

- برايس، ت. د.، كلاسن، ل. و سيوغرين، ك. ج. ثقافة الفخار المثقوب: دليل نظائري على الاتصال بين السويد والدنمارك عبر كاتيغات في العصر النيوليثي الأوسط، حوالي 3000 قبل الميلاد. ج. أنثروبول. أرشيو. 61، 101254 (2021).

- هدى، م. يو. التغيرات المناخية والبيئية في الهولوسين المسجلة في رواسب البحيرات عالية الدقة من بحيرة هوجبي، الدنمارك. رسالة دكتوراه، جامعة كوبنهاغن (2008).

- سوجيتا، س. نظرية إعادة بناء الغطاء النباتي الكمي I: حبوب اللقاح من المواقع الكبيرة تكشف عن تركيبة الغطاء النباتي الإقليمي. هولوسين 17، 229-241 (2007).

- سوجيتا، س. نظرية إعادة بناء الغطاء النباتي الكمي II: كل ما تحتاجه هو الحب. هولوسين 17، 243-257 (2007).

- نيلسن، أ. ب. وآخرون. إعادة بناء كمية للتغيرات في الانفتاح الإقليمي في شمال وسط أوروبا تكشف عن رؤى جديدة حول أسئلة قديمة. مراجعة العلوم الكمية 47، 131-147 (2012).

- غيذومبي، إ. وآخرون. خرائط قائمة على حبوب اللقاح لتغطية الغطاء النباتي الإقليمي في أوروبا على مدى اثني عشر ألف عام – تقييم وإمكانات. أمام. علم البيئة. التطور.https://doi.org/10.3389/فيڤو.2022.795794 (2022).

- نيلسن، أ. ب. وأودغارد، ب. ف. الديناميات الكمية للمناظر الطبيعية في الدنمارك على مدى الألفية الماضية استنادًا إلى نهج خوارزمية إعادة بناء المناظر الطبيعية. تاريخ النباتات وعلم الآثار النباتية 19، 375-387 (2010).

- سوي، ن. إ.، أودغارد، ب. ف.، نيلسن، أ. ب.، أولسن، ج. وكريستيانسن، س. م. تطور المناظر الطبيعية في أواخر الهولوسين حول قبر جماعي من عصر الحديد الروماني، ألكن إنجي، الدنمارك. تاريخ النباتات وعلم الآثار النباتية 26، 277-292 (2017).

- مازيير، ف. وآخرون. اختبار تأثير اختيار الموقع وإعداد المعلمات على تقديرات نموذج REVEALS لوفرة النباتات باستخدام قاعدة بيانات بالينولوجيا الرباعية التشيكية. مراجعة. باليوبيولوجيا. بالينولوجيا. 187، 38-49 (2012).

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى مورتن إي. ألينتوف، مارتن سيكورا أو إيسكي ويليرسليف.

تُعرب مجلة Nature عن شكرها لباتريشيا فال، بيرغيت سكار والمراجعين الآخرين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة هذا العمل.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/reprints.

الجينومات التسعة والتسعين المقدمة هنا (التلوث

مقالة

الشكل 2 من البيانات الموسعة | مشاركة الأليل للأفراد الدنماركيين من العصر الميزوليتي.

EO932 / تودسي هاج / 7398 –

سواء كانت الأفراد الدنماركيون من العصر الحجري الأوسط يشكلون مجموعة مع مجموعة جينية من الأفراد الصيادين الجامعين في غرب أوروبا (EuropeW_13500BP_8000BP) باستثناء مجموعة جينية من الأفراد الصيادين الجامعين في شرق أوروبا (RussiaNW_11000BP_8000BP). تشير أشرطة الخطأ إلى ثلاثة أخطاء معيارية.

خريطة حرارية تظهر الكمية الزوجية من الطول الإجمالي للـ IBD المشترك بين 72 فردًا دنماركيًا قديمًا يعود تاريخهم إلى أكثر من 3000 سنة قبل الحاضر. الألوان في الحدود

تشير النصوص إلى عضوية الكتلة الجينية، وتظهر الشجرات النسبية تسلسل التجميع.

مقالة

نسب الأنساب لـ 72 فردًا قديمًا من الدنمارك يعود تاريخهم إلى العصور القديمة

من

مجموعات مختلفة من مجموعات مصادر الأنساب (عميق، fEur، ما بعد النيوليت، إضافي)

تتميز بيانات IV) في صفوف الوجوه. عضوية التجمع الجيني للدنماركيين

يتم الإشارة إلى الأفراد المستهدفين بواسطة أعمدة الجوانب. ب، التوزيع المكاني لـ

نسب الأنساب المقدرة لثلاثة مصادر مختلفة من الصيادين الجامعين للعصر الحجري الحديث

أفراد المزارعين من الدول الاسكندنافية وبولندا. ج، التوزيع المكاني لـ

نسب الأنساب المقدرة لمصدرين مختلفين من المزارعين لـ LNBA

الأفراد من الدول الاسكندنافية وبولندا. د، نسب الأنساب لـ

أفراد عصر الحديد الإسكندنافي وعصر الفايكنج (مجموعة مرجعية بعد العصر البرونزي).

نسب الأنساب للأفراد الأوروبيين القدماء المختارين مع الأنساب

مرتبط بأفراد LNBA الإسكندنافيين (المصدر Scandinavia_4000BP_3000BP،

مجموعة مرجع postBA، البيانات التكميلية IV).

مقالة

محفظة الطبيعة

المؤلف (المؤلفون) المراسلون: ويليرسليف

آخر تحديث من المؤلف(ين): 18 أكتوبر 2023

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

حجم العينة بالضبط

بيان حول ما إذا كانت القياسات قد أُخذت من عينات متميزة أو ما إذا كانت نفس العينة قد تم قياسها عدة مرات

يجب أن تُوصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ واصفًا التقنيات الأكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

وصف لجميع المتغيرات المشتركة التي تم اختبارها

وصف لأي افتراضات أو تصحيحات، مثل اختبارات الطبيعية والتعديل للمقارنات المتعددة

لاختبار الفرضية الصفرية، إحصائية الاختبار (على سبيل المثال،

لتحليل بايزي، معلومات حول اختيار القيم الأولية وإعدادات سلسلة ماركوف مونت كارلو

للتصاميم الهرمية والمعقدة، تحديد المستوى المناسب للاختبارات والتقارير الكاملة عن النتائج

تقديرات أحجام التأثير (مثل حجم تأثير كوهين)

تحتوي مجموعتنا على الإنترنت حول الإحصائيات لعلماء الأحياء على مقالات تتناول العديد من النقاط المذكورة أعلاه.

البرمجيات والشيفرة

جمع البيانات

تُدار بيانات التسلسل والبيانات الوصفية المتعلقة بتسلسل الجينومات القديمة على خوادم آمنة في معهد غلوب، جامعة كوبنهاغن، ومن خلال منصة Illumina Inc. BaseSpace. تُدار بيانات مطيافية الكتلة المعجلة والبيانات الوصفية المرتبطة بها في قسم الدراسات التاريخية، جامعة غوتنبرغ.

البرامج النصية المخصصة المستخدمة لتطبيق كروموباينتر من بيانات المرحلة الكبيرة متاحة علىhttps://github.com/will-camb/Nero/tree/master/scripts/cp_panel_scripts. اعتمدت جميع التحليلات الأخرى على البرمجيات المتاحة التي تم الإشارة إليها بالكامل في المخطوطة ومفصلة في الملاحظات التكميلية ذات الصلة. وتشمل هذه:

كاسافا (الإصدار 1.8.2)

إزالة المحول (الإصدار 2.1.3)

بيكارد (الإصدار 1.127)

جاتك (الإصدار 3.3.0)

سام تولز (1.9)

سام تولز كالم د (الإصدار 1.10)

بايسام (https://github.com/pysam-developers/pysam)

أدوات BED (الإصدار 2.23.0)

نظام mapDamage2.0 (الإصدار 2.2.1)

BWA (0.7-17)

شمتزي (الإصدار؟)

كونتام ميكس (الإصدار؟)

ANGSD (0.938)

لمحة (الإصدار 1.0.1)

BCFtools 1.10

مافت (الإصدار 7.490)

RAxML-ng (الإصدار 1.1.0)

ري_كومبيوت (v0.4)

EPA-ng (0.3.8)

نغس ريلات (الإصدار 2)

الخلط (1.3.0)

سمارت بي سي إيه

جي سي تي إيه

إصدار R 4.0

ADMIXTOOLS2

gstat (2.0-9)

IBDseq (الإصدار r1206)

جينوميك رينجز (3.15)

لايدن ألغ (الإصدار 1.01،https://github.com/kharchenkolab/leidenAlg)

إيجرَاف (0.9.9)

limSolve (1.5.6)

سكيت-ليرن (0.21.2)

كروموبينتر (0.0.4)

البنية الدقيقة (0.0.5)

QCTOOL v2 (https://www.well.ox.ac.uk/~gav/qctool_v2/)

آرك جي آي إس أونلاين (www.arcgis.com)

أوكسكال v4.4

LRA v0.1.0 (https://github.com/petrkunes/LRA)

بالنسبة للمخطوطات التي تستخدم خوارزميات أو برامج مخصصة تكون مركزية في البحث ولكن لم يتم وصفها بعد في الأدبيات المنشورة، يجب أن تكون البرمجيات متاحة للمحررين والمراجعين. نحن نشجع بشدة على إيداع الشيفرة في مستودع مجتمعي (مثل GitHub). راجع إرشادات مجموعة Nature لتقديم الشيفرة والبرمجيات لمزيد من المعلومات.

بيانات

يجب أن تتضمن جميع المخطوطات بيانًا عن توفر البيانات. يجب أن يوفر هذا البيان المعلومات التالية، حيثما ينطبق:

- رموز الانضمام، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا

مشاركون في الأبحاث البشرية

| التقارير عن الجنس والنوع الاجتماعي | لم يتأثر أي من المشاركين في البحث من البشر الأحياء أو المتوفين حديثًا بهذه الدراسة. |

| خصائص السكان | وصف الخصائص السكانية ذات الصلة بالمتغيرات للباحثين المشاركين في الدراسة (مثل العمر، المعلومات الجينية، التشخيصات والعلاجات السابقة والحالية). إذا كنت قد قمت بملء أسئلة تصميم الدراسة في العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية وليس لديك ما تضيفه هنا، اكتب “انظر أعلاه.” |

| التوظيف | وصف كيفية تجنيد المشاركين. تحديد أي انحياز محتمل للاختيار الذاتي أو أي انحيازات أخرى قد تكون موجودة وكيف من المحتمل أن تؤثر هذه على النتائج. |

| رقابة الأخلاقيات | حدد المنظمة (المنظمات) التي وافقت على بروتوكول الدراسة. |

التقارير المتخصصة في المجال

علوم الحياة العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية

العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

لنسخة مرجعية من الوثيقة بجميع الأقسام، انظرnature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

تصميم دراسة العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

| وصف الدراسة | أجرت الدراسة تحليل الجينوم السكاني لأفراد قدامى من الدنمارك، استنادًا إلى البيانات من المنشور المرافق ‘الجينوم السكاني لعصر الحجر في أوراسيا’، بالإضافة إلى تحليل بيانات النظائر المستقرة (13C، 15N، 87Sr) وبيانات الكربون المشع. |

| عينة البحث | 100 فرد من البشر (Homo sapiens) من مواقع أثرية في جميع أنحاء الدنمارك، جميعها تزيد عن 1000 عام. |

| استراتيجية أخذ العينات | قمنا بأخذ عينات بشكل أساسي من الأفراد من الفترات الميزوليتية والنيوليتية من المواقع الأثرية الدنماركية؛ كانت العينات مقيدة بتلك التي تتوفر فيها كمية كافية من الحفاظ على الحمض النووي لتحليل على مستوى الجينوم. |

| جمع البيانات | تم جمع بيانات الجينوم القديمة وفقًا لبروتوكولات المختبر المعتمدة، المصممة لتقليل تدمير العينات وتجنب التلوث. يتم تفصيل هذه البروتوكولات بشكل أكثر ملاءمة في المنشور المرافق الذي يصف إنشاء مجموعة البيانات هذه. |

| توقيت ومقياس مكاني | أقدم عينة لها عمر كربوني مصحح يبلغ 10,465 سنة؛ وأحدث عينة لها عمر كربوني مصحح يبلغ 3,297 سنة. جميع العينات تأتي من الدولة الحالية الدنمارك. |

| استبعاد البيانات | تم اختيار بيانات من المنشور المرافق ‘الجينوم السكاني لعصر الحجر في أوراسيا’ لتشمل فقط عينات من الدنمارك. |

| إمكانية التكرار | تعتبر البقايا الأثرية المحفوظة فريدة ونادرة، لذلك لم يتم عادةً إجراء التكرار. تم أخذ جودة البيانات وعدم اليقين (مثل التلوث) في الاعتبار في التحليلات الحسابية لتقييم قوة الاستنتاجات، وجميع الطرق والبيانات متاحة للتكرار في المستقبل. |

| العشوائية | لا تنطبق العشوائية في أخذ عينات البقايا الأثرية في هذه الحالة. |

| التعمية | لم تكن التعمية قابلة للتطبيق على هذه الدراسة. |

| هل شملت الدراسة العمل الميداني؟ |

|

التقارير عن مواد وأنظمة وطرق محددة

| المواد والأنظمة التجريبية | الطرق | ||

| غير متاح | مشارك في الدراسة | غير متاح | مشارك في الدراسة |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

تدفق الخلايا |

|

علم الحفريات وعلم الآثار |  |

|

|

الحيوانات وغيرها من الكائنات الحية | ||

|

|

||

|

البحث ذو الاستخدام المزدوج المثير للقلق | ||

علم الحفريات وعلم الآثار

| أصل العينة | تفاصيل أصل العينة متاحة في المنشور المرافق ‘الجينوم السكاني لعصر الحجر في أوراسيا’، حيث يتم تقديم مجموعة البيانات الكاملة للعينة. |

| إيداع العينة | انظر أعلاه؛ جميع العينات المدروسة متاحة عند الاتصال المباشر/الطلب من علماء الآثار أو القيمين أو المسؤولين عن إدارتها في المؤسسة التي تحتفظ بها. |

الإشراف الأخلاقي

تم أخذ العينات بموافقة أخلاقية من المتاحف والمؤسسات التي تقدم عينات أو مرافق.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06862-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38200294

Publication Date: 2024-01-10

100 ancient genomes show repeated population turnovers in Neolithic Denmark

Received: 6 April 2023

Accepted: 13 November 2023

Published online: 10 January 2024

Open access

Check for updates

Abstract

Major migration events in Holocene Eurasia have been characterized genetically at broad regional scales

involving a stronger element of cultural diffusion

circles). Ancient individuals from Denmark are coloured according to the period as defined in a and c. c, Unsupervised model-based clustering (ADMIXTURE) for

imputed genomes

The Mesolithic period

and they have provided important insights into the physical anthropology and spiritual culture of the period.

argued to have an eastern origin

goods suggesting an Early Neolithic date for the latter

probabilities for the hair colours (blond, brown, black and red) and eye colours (blue and brown) are shown, with grey denoting probability of intermediate eye colour (including grey, green and hazel). Lower panel shows the quantitative changes in vegetation cover, based on pollen analyses at Lake Højby in Zealand. Note that the vegetation panel covers a shorter time interval than the other panels. Black vertical lines mark the first presence of Anatolian Neolithic farmer ancestry and Steppe-related ancestry, respectively. Individuals with low genomic coverage, signs of possible contamination and/or low genotype prediction score (GP) are indicated (Methods).

and daughter. Our data also show that the male in the adjacent burial (‘Dragsholm Man’, NEO962) was not related to the two women. These cases show that close biological kinship was socially relevant to Late Mesolithic groups in Northern Europe and affected the mortuary treatment of dead members of their society.

Early Neolithic transition

(EuropeW_13500BP_8000BP). Ancestry related to Danish Mesolithic hunter-gatherers (Denmark_10500BP_6000BP) is found in smaller proportions (less than around

Pitted Ware culture (PWC) originated on the Scandinavian peninsula and the Baltic islands east of the Swedish mainland but emerged around

Later Neolithic and Bronze Age

manifestation of the CWC complex. The transition to single graves in round tumuli has been characterized archaeologically by two expansion phases: a primary and rapid occupation of central, western and northern Jutland (west Denmark) starting around

from the Gjerrild grave

Environmental impact

Drivers of change

the territory. With this arrival, the local landscape was modified to fit the lifestyle and culture of the immigrants. This is the hallmark of the Anthropocene, observed here in high resolution in prehistoric Denmark.

Online content

- Allentoft, M. E. et al. Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature 522, 167-172 (2015).

- Haak, W. et al. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522, 207-211 (2015).

- Allentoft, M. E. et al. Population genomics of post-glacial western Eurasia. Nature https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06865-0 (2024).

- Posth, C. et al. Palaeogenomics of Upper Palaeolithic to Neolithic European hunter-gatherers. Nature 615, 117-126 (2023).

- Johannsen, N. N., Larson, G., Meltzer, D. J. & Vander Linden, M. A composite window into human history. Science 356, 1118-1120 (2017).

- Furholt, M. Mobility and social change: understanding the European Neolithic period after the archaeogenetic revolution. J. Archaeol. Res. 29, 481-535 (2021).

- Kristiansen, K. Archaeology and the Genetic Revolution in European Prehistory (Elements in the Archaeology of Europe) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

- Fischer, A. & Kristiansen, K. The Neolithisation of Denmark. 150 Years of Debate (J. R. Collis, 2002).

- Günther, T. et al. Population genomics of Mesolithic Scandinavia: investigating early postglacial migration routes and high-latitude adaptation. PLoS Biol. 16, e2003703 (2018).

- Kashuba, N. et al. Ancient DNA from mastics solidifies connection between material culture and genetics of mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Scandinavia. Commun. Biol. 2, 185 (2019).

- Fischer, A. in The Neolithisation of Denmark-150 years of debate (eds Fischer, A. & Kristiansen, K.) 343-393 (J. R. Collis, 2002).

- Price, T. D. Europe’s First Farmers (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000).

- Lipson, M. et al. Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers. Nature 551, 368-372 (2017).

- Mathieson, I. et al. The genomic history of southeastern Europe. Nature 555, 197-203(2018).

- Brace, S. et al. Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 765-771 (2019).

- Midgley, M. TRB Culture: The First Farmers of the North European Plain (Edinburgh Univ. Press, 1992).

- Iversen, R. in Tracing the Indo-Europeans: New evidence from Archaeology and Historical Linguistics (eds Olsen, B. A., Olander, T. & Kristiansen, K.) 73-95 (Oxbow, 2019).

- Nielsen, S. K. & Johannsen, N. N. Mortuary palisades, single graves, and cultural admixture: the establishment of Corded Ware culture on the Jutland Peninsula. Praehistorische Zeitschrift https://doi.org/10.1515/pz-2023-2022 (2023).

- Kristiansen, K. Prehistoric migrations-the case of the Single Grave and Corded Ware Cultures. J. Dan. Archaeol. 8, 211-225 (1991).

- Lewis, J. P. et al. Marine resource abundance drove pre-agricultural population increase in Stone Age Scandinavia. Nat. Commun. 11, 2006 (2020).

- Sousa da Mota, B. et al. Imputation of ancient human genomes. Nat. Commun. 14, 3660 (2023).

- Schilling, H. in Mesolithic on the Move (eds Larsson, L. et al.) 351-358 (2003).

- Petersen, P. V. Chronological and regional variation in the Late Mesolithic of Eastern Denmark. J. Dan. Archaeol. 3, 7-18 (1984).

- Fischer, A. in The Danish Storebælt Since the Ice Age (eds Pedersen, L., Fischer, A. & Aaby, B.) 63-77 (Sea and Forest, 1997).

- Sørensen, S. A. The Kongemose Culture (Univ. Press of Southern Denmark, 2017).

- Dolbunova, E. et al. The transmission of pottery technology among prehistoric European hunter-gatherers. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 171-183 (2023).

- Klassen, L. Jade und Kupfer: Untersuchungen zum Neolithisierungsprozess im westlichen Ostseeraum unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Kulturentwicklung Europas 5500-3500 bc vol. 47 (Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2004).

- Price, T. D. Seeking the First Farmers in Western Sjælland, Denmark: The Archaeology of the Transition to Agriculture in Northern Europe (Oxbow Books, 2022).

- Hansen, J. et al. The Maglemosian skeleton from Koelbjerg revisited: Identifying sex and provenance. Dan. J. Archaeol. 6, 55-66 (2017).

- Sørensen, M. in Ecology of Early Settlement in Northern Europe: Conditions for Subsistence and Survival. The Early Settlement of Northern Europe Vol. 1 (eds. Persson, P., Riede, F. & Skar, B.) 277-301 (Equinox, 2018).

- Piezonka, H. et al. Stone Age pottery chronology in the Northeast European Forest Zone: new AMS and EA-IRMS results on foodcrusts. Radiocarbon 58, 267-289 (2016).

- Mathieson, I. et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature 528, 499-503 (2015).

- Irving-Pease, E. K. et al. The selection landscape and genetic legacy of ancient Eurasians. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06705-1 (2024).

- Fischer, A. et al. Coast-inland mobility and diet in the Danish Mesolithic and Neolithic: evidence from stable isotope values of humans and dogs. J. Archaeol. Sci. 34, 2125-2150 (2007).

- Fischer, A. et al. The composition of Mesolithic food-evidence from a submerged settlement on the Argus Bank, Denmark. Acta Archaeol. 78, 163-178 (2007).

- Brinch Petersen, E. Gravene ved Dragsholm. Fra jægere til bønder for 6000 år siden. Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark 1974, 112-120 (1974).

- Price, T. D. et al. New information on the Stone Age graves at Dragsholm, Denmark. Acta Archaeol. 78, 193-219 (2007).

- Sørensen, L. From Hunter to Farmer in Northern Europe. Migration and adaptation during the Neolithic and Bronze Age. Acta Archaeologica Vol. 85 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2014).

- Nielsen, P. O. & Nielsen, F. O. S. First Farmers on the Island of Bornholm (The Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries and Univ. Press of Southern Denmark, 2020).

- Sjögren, K.-G. & Fischer, A. The chronology of Danish dolmens. Results from

dates on human bones. J. Neolit. Archaeol. 25, https://doi.org/10.12766/jna.2023.1 (2023). - Dehn, T. & Hansen, S. I. Birch bark in Danish passage graves. J. Dan. Archaeol. 14, 23-44 (2006).

- Ebbesen, K. Simple, tidligneolitiske grave. Aarbøger for nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie 1992, 47-102 (1994).

- Gron, K. J. & Sørensen, L. Cultural and economic negotiation: a new perspective on the Neolithic Transition of Southern Scandinavia. Antiquity 92, 958-974 (2018).

- Chintalapati, M., Patterson, N. & Moorjani, P. The spatiotemporal patterns of major human admixture events during the European Holocene. eLife 11, e77625 (2022).

- González-Fortes, G. et al. Paleogenomic evidence for multi-generational mixing between Neolithic farmers and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in the Lower Danube Basin. Curr. Biol. 27, 1801-1810.e10 (2017).

- Villalba-Mouco, V. et al. Survival of Late Pleistocene hunter-gatherer ancestry in the Iberian Peninsula. Curr. Biol. 29, 1169-1177.e7 (2019).

- Jensen, T. Z. T. et al. A 5700 year-old human genome and oral microbiome from chewed birch pitch. Nat. Commun. 10, 5520 (2019).

- Olalde, I. et al. Derived immune and ancestral pigmentation alleles in a 7,000-year-old Mesolithic European. Nature 507, 225-228 (2014).

- Cox, S. L., Ruff, C. B., Maier, R. M. & Mathieson, I. Genetic contributions to variation in human stature in prehistoric Europe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 21484-21492 (2019).

- Klassen, L. (ed.) The Pitted Ware Culture on Djursland: Supra-regional Significance and Contacts in the Middle Neolithic of Southern Scandinavia (Aarhus Univ. Press, 2020).

- Iversen, R., Philippsen, B. & Persson, P. Reconsidering the Pitted Ware chronology. Praehistorische Zeitschrift 96, 44-88 (2021).

- Coutinho, A. et al. The Neolithic Pitted Ware culture foragers were culturally but not genetically influenced by the Battle Axe culture herders. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 172, 638-649 (2020).

- Glob, P. V. Studier over den Jyske Enkeltgravskultur (Gyldendal, 1945).

- Müller, J. & Vandkilde, H. in Contrasts of the Nordic Bronze Age. Essays in Honour of Christopher Prescott (eds. Austvoll, K.I., Hem Eriksen, M., Fredriksen, P.D., Melheim, A.L., Prøsch-Danielsen, L., Skogstrand, L.) 29-48 (Brepols, 2020).

- Iversen, R. The Transformation of Neolithic Societies. An Eastern Danish Perspective on the 3rd Millennium BC Vol. 88 (Jutland Archaeological Society, 2015).

- Damm, C. The Danish Single Grave Culture-ethnic migration or social construction? J. Dan. Archaeol. 10, 199-204 (1991).

- Egfjord, A. F.-H. et al. Genomic steppe ancestry in skeletons from the Neolithic Single Grave Culture in Denmark. PLoS ONE 16, e0244872 (2021).

- Grasgruber, P., Sebera, M., Hrazdíra, E., Cacek, J. & Kalina, T. Major correlates of male height: a study of 105 countries. Econ. Hum. Biol. 21, 172-195 (2016).

- Papac, L. et al. Dynamic changes in genomic and social structures in third millennium BCE central Europe. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi6941 (2021).

- Blank, M. Mobility, Subsistence and Mortuary practices. An Interdisciplinary Study of Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Megalithic Populations of Southwestern Sweden. PhD thesis, Univ. of Gothenburg (2021).

- Winther Johannsen, J. Late Neolithic expansion. Dan. J. Archaeol. 12, https://doi.org/ 10.7146/dja.v12i1.132093 (2023).

- Pedersen, C. B. et al. The iPSYCH2O12 case-cohort sample: new directions for unravelling genetic and environmental architectures of severe mental disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 6-14 (2017).

- Odgaard, B. V. The Holocene vegetation history of northern West Jutland, Denmark. Nord. J. Bot. 14, 546-546 (1994).

- Haak, W. et al. in The Indo-European Puzzle Revisited: Integrating Archaeology, Genetics, and Linguistics (eds Kristiansen, K., Kroonen, G. & Willerslev, E.) 63-80 (2023).

- Fischer, A., Gotfredsen, A. B., Meadows, J., Pedersen, L. & Stafford, M. The Rødhals kitchen midden-marine adaptations at the end of the Mesolithic world. J. Archaeol. Sci. 39, 103102 (2021).

- Bennike, P. in The Danish Storebælt Since the Ice Age (eds Pedersen, L., Fischer, A. & Aaby, B.) 99-105 (A/S Storebælt Fixed Link, 1997).

- Warden, L. et al. Climate induced human demographic and cultural change in northern Europe during the mid-Holocene. Sci Rep. 7, 15251 (2017).

- Krossa, V. R. et al. Regional climate change and the onset of farming in northern Germany and southern Scandinavia. Holocene 27, 1589-1599 (2017).

- Iversen, R. Arrowheads as indicators of interpersonal violence and group identity among the Neolithic Pitted Ware hunters of southwestern Scandinavia. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 44, 69-86 (2016).

- Lidke, G. Violence in the Single Grave Culture of northern Germany? in Sticks, Stones, and Broken Bones: Neolithic Violence in a European Perspective (eds Schulting, R. J. & Fibiger, L.) 139-150 https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199573066.003.0008 (Oxford, 2012).

- Schroeder, H. et al. Unraveling ancestry, kinship, and violence in a Late Neolithic mass grave. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 10705-10710 (2019).

- Rasmussen, S. et al. Early divergent strains of Yersinia pestis in Eurasia 5,000 years ago. Cell 163, 571-582 (2015).

- Rascovan, N. et al. Emergence and spread of basal lineages of Yersinia pestis during the Neolithic decline. Cell 176, 295-305.e10 (2019).

- Hinz, M. et al. in Neolithic Diversities: Perspectives from a Conference in Lund, Sweden 43-51 (Lund Univ., 2015).

- Feeser, I., Dörfler, W., Kneisel, J., Hinz, M. & Dreibrodt, S. Human impact and population dynamics in the Neolithic and Bronze Age: multi-proxy evidence from north-western Central Europe. Holocene 29, 1596-1606 (2019).

- Margaryan, A. et al. Population genomics of the Viking world. Nature 585, 390-396 (2020).

© The Author(s) 2024

Methods

Ancient genomic analyses

- ‘1000 G’ dataset: whole-genome sequencing data of 2,504 individuals from 26 world-wide populations from the 1000 Genomes project, with genotypes at

autosomal SNPs. - ‘HO’ dataset: SNP array data of 2,180 modern individuals from 213 world-wide populations, with genotypes at 535,880 autosomal SNPs.

Radiocarbon dates and Bayesian modelling of ancestry chronology

radiocarbon age (Supplementary Data 1; further

Stable isotope proxies for diet and mobility

Vegetation modelling

Reporting summary

Data availability

77. Damgaard, P. B. et al. Improving access to endogenous DNA in ancient bones and teeth. Sci. Rep. 5, 11184 (2015).

78. 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68-74 (2015).

79. Maier, R., Flegontov, P., Flegontova, O., Işıldak, U., Changmai, P. & Reich, D. On the limits of fitting complex models of population history to f-statistics. Elife 12, e85492 (2023).

80. Browning, B. L. & Browning, S. R. Detecting identity by descent and estimating genotype error rates in sequence data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93, 840-851 (2013).

81. Appadurai, V. et al. Accuracy of haplotype estimation and whole genome imputation affects complex trait analyses in complex biobanks. Commun. Biol. 6, 101 (2023).

82. Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559-575 (2007).

83. Walsh, S. et al. The HIrisPlex system for simultaneous prediction of hair and eye colour from DNA. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 7, 98-115 (2013).

84. Bycroft, C. et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 562, 203-209 (2018).

85. Bronk Ramsey, C. Development of the radiocarbon calibration program OxCal. Radiocarbon 43, 355-363 (2001).

86. Bronk Ramsey, C. Deposition models for chronological records. Q. Sci. Rev. 27, 42-60 (2008).

87. Bronk Ramsey, C. Bayesian analysis of radiocarbon dates. Radiocarbon 51, 337-360 (2009).

88. Bronk Ramsey, C. Dealing with outliers and offsets. Radiocarbon 51, 1023-1045 (2009).

89. Reimer, P., Austin, W. & Bard, E. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0-55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 62, 725-757 (2020).

90. Karlsberg, A. J. Flexible Bayesian Methods for Archaeological Dating. PhD thesis, Univ. Sheffield (2006).

91. Lee, S. & Ramsey, C. Development and application of the trapezoidal model for archaeological chronologies. Radiocarbon 54, 107-122 (2012).

92. Meadows, J. et al. Dietary freshwater reservoir effects and the radiocarbon ages of prehistoric human bones from Zvejnieki, Latvia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 6, 678-689 (2016).

93. Rose, H. A., Meadows, J. & Bjerregaard, M. High-resolution dating of a medieval multiple grave. Radiocarbon 60, 1547-1559 (2018).

94. Hedges, R. E. M., Clement, J. G., David, C., Thomas, L. & O’Connell, T. C. Collagen turnover in the adult femoral mid-shaft: modeled from anthropogenic radiocarbon tracer measurements. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 133, 808-816 (2007).

95. Jørkov, M. L. S., Heinemeier, J. & Lynnerup, N. The petrous bone-a new sampling site for identifying early dietary patterns in stable isotopic studies. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 138, 199-209 (2009).

96. Schoeninger, M. J. & Moore, K. Bone stable isotope studies in archaeology. J. World Prehist. 6, 247-296 (1992).

97. Hedges, R. E. M. & Reynard, L. M. Nitrogen isotopes and the trophic level of humans in archaeology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 34, 1240-1251 (2007).

98. Reimer, P. et al. Laboratory protocols used for AMS radiocarbon dating at the 14 Chrono Centre. English Heritage Research Report Series 5-2015 https://historicengland.org.uk/ research/results/reports/6272/TheQueen%E2%80%99sUniversityBelfast_ LaboratoryprotocolsusedforAMSradiocarbondatingatthe14CHRONOCentre (2015).

99. Longin, R. New method of collagen extraction for radiocarbon dating. Nature 230, 241-242 (1971).

Article

- Ambrose, S. H. & DeNiro, M. J. The isotopic ecology of East African mammals. Oecologia 69, 395-406 (1986).

- van Klinken, G. J. Bone collagen quality indicators for palaeodietary and radiocarbon measurements. J. Archaeol. Sci. 26, 687-695 (1999).

- Alexander Bentley, R. Strontium isotopes from the earth to the archaeological skeleton: A review. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 13, 135-187 (2006).

- Frei, K. M. & Price, T. D. Strontium isotopes and human mobility in prehistoric Denmark. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 4, 103-114 (2012).

- Holt, E., Evans, J. A. & Madgwick, R. Strontium (

) mapping: a critical review of methods and approaches. Earth Sci. Rev. 216, 103593 (2021). - Price, T. D., Burton, J. H. & Bentley, R. A. Characterization of biologically available strontium isotope ratios for the study of prehistoric migration. Archaeometry 44, 117-135 (2002).

- Thomsen, E., Andreasen, R. & Rasmussen, T. L. Homogeneous glacial landscapes can have high local variability of strontium isotope signatures: implications for prehistoric migration studies. Front. Ecol. Evol. 8, 588318 (2021).

- Price, T. D., Klassen, L. & Sjögren, K. G. Pitted ware culture: isotopic evidence for contact between Sweden and Denmark across the Kattegat in the Middle Neolithic, ca. 3000 BC. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 61, 101254 (2021).

- Hede, M. U. Holocene Climate and Environmental Changes Recorded in High-resolution Lake Sediments from Højby Sø, Denmark. PhD thesis, Univ. Copenhagen (2008).

- Sugita, S. Theory of quantitative reconstruction of vegetation I: pollen from large sites REVEALS regional vegetation composition. Holocene 17, 229-241 (2007).

- Sugita, S. Theory of quantitative reconstruction of vegetation II: all you need is LOVE. Holocene 17, 243-257 (2007).

- Nielsen, A. B. et al. Quantitative reconstructions of changes in regional openness in north-central Europe reveal new insights into old questions. Q. Sci. Rev. 47, 131-147 (2012).

- Githumbi, E. et al. Pollen-based maps of past regional vegetation cover in Europe over twelve millennia-evaluation and potential. Front. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fevo.2022.795794 (2022).

- Nielsen, A. B. & Odgaard, B. V. Quantitative landscape dynamics in Denmark through the last three millennia based on the landscape reconstruction algorithm approach. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 19, 375-387 (2010).

- Søe, N. E., Odgaard, B. V., Nielsen, A. B., Olsen, J. & Kristiansen, S. M. Late Holocene landscape development around a Roman Iron Age mass grave, Alken Enge, Denmark. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 26, 277-292 (2017).

- Mazier, F. et al. Testing the effect of site selection and parameter setting on REVEALS-model estimates of plant abundance using the Czech Quaternary Palynological Database. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 187, 38-49 (2012).

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Morten E. Allentoft, Martin Sikora or Eske Willerslev.

Peer review information Nature thanks Patricia Fall, Birgitte Skar and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

the herein presented 93 genomes (contamination

Article

Extended Data Fig. 2 | Allele sharing of Danish Mesolithic individuals.

EO932 / Tudse Hage / 7398 –

whether Danish Mesolithic individuals form a clade with a genetic cluster of Western European HG individuals (EuropeW_13500BP_8000BP) to the exclusion of a genetic cluster of Eastern European HG individuals (RussiaNW_11000BP_8000BP). Error bars indicate three standard errors.

Heatmap showing pairwise amount of total length of IBD shared between 72 ancient Danish individuals dated to older than 3,000 cal. BP. Colours in border

and text indicate genetic cluster membership, and dendrograms show clustering hierarchy.

Article

of ancestry proportions for 72 ancient individuals from Denmark dated to older

than

different sets of ancestry source groups (deep, fEur, postNeol, Supplementary

Data IV) are distinguished in facet rows. Genetic cluster membership for Danish

target individuals is indicated by column facets. b, Spatial distribution of

estimated ancestry proportions of three different HG sources for Neolithic

farmer individuals from Scandinavia and Poland. c, Spatial distribution of

estimated ancestry proportions of two different farmer sources for LNBA

individuals from Scandinavia and Poland. d, Ancestry proportions for

Scandinavian Iron Age and Viking Age individuals (postBA reference set).

e, Ancestry proportions for selected ancient European individuals with ancestry

related to Scandinavian LNBA individuals (source Scandinavia_4000BP_3000BP,

postBA reference set, Supplementary Data IV).

Article

natureportfolio

Corresponding author(s): Willerslev

Last updated by author(s): Oct 18, 2023

Reporting Summary

Statistics

The exact sample size

A statement on whether measurements were taken from distinct samples or whether the same sample was measured repeatedly

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

A description of all covariates tested

A description of any assumptions or corrections, such as tests of normality and adjustment for multiple comparisons

For null hypothesis testing, the test statistic (e.g.

For Bayesian analysis, information on the choice of priors and Markov chain Monte Carlo settings

For hierarchical and complex designs, identification of the appropriate level for tests and full reporting of outcomes

Estimates of effect sizes (e.g. Cohen’s

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Software and code

Data collection

Sequencing data and metadata pertaining to the sequencing of ancient genomes is managed on secure servers at the Globe Institute, University of Copenhagen, and via the Illumina Inc. BaseSpace platform. Accelerator Mass Spectrometry data and associated metadata is managed at the Department of Historical Studies, University of Gothenberg.

Custom scripts used to apply chromopainter from large-scale phased data are available at https://github.com/will-camb/Nero/tree/master/ scripts/cp_panel_scripts. All other analyses relied upon available software which has been fully referenced in the manuscript and detailed in the relevant supplementary notes. These comprise:

CASAVA (v.1.8.2)

AdapterRemoval (v.2.1.3)

Picard (v.1.127)

GATK (v.3.3.0)

Samtools (1.9)

Samtools calmd (v.1.10)

pysam (https://github.com/pysam-developers/pysam)

BEDtools (v.2.23.0)

mapDamage2.0 (v2.2.1)

BWA (0.7-17)

Schmutzi (VERSION?)

ContamMix (VERSION?)

ANGSD (0.938)

GLIMPSE (v1.0.1)

BCFtools 1.10

MAFFT (v7.490)

RAxML-ng (v1.1.0)

ry_compute (v0.4)

EPA-ng (0.3.8)

NgsRelate (v2)

ADMIXTURE (1.3.0)

smartpca

GCTA

R version 4.0

ADMIXTOOLS2

gstat (2.0-9)

IBDseq (version r1206)

GenomicRanges (3.15)

leidenAlg (v1.01, https://github.com/kharchenkolab/leidenAlg)

igraph (0.9.9)

limSolve (1.5.6)

Scikit-learn (0.21.2)

Chromopainter (0.0.4)

fineSTRUCTURE (0.0.5)

QCTOOL v2 (https://www.well.ox.ac.uk/~gav/qctool_v2/)

ArcGIS Online (www.arcgis.com)

OxCal v4.4

LRA v0.1.0 (https://github.com/petrkunes/LRA)

For manuscripts utilizing custom algorithms or software that are central to the research but not yet described in published literature, software must be made available to editors and reviewers. We strongly encourage code deposition in a community repository (e.g. GitHub). See the Nature Portfolio guidelines for submitting code & software for further information.

Data

All manuscripts must include a data availability statement. This statement should provide the following information, where applicable:

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

Human research participants

| Reporting on sex and gender | No living or recently deceased human research participants were affected by this study |

| Population characteristics | Describe the covariate-relevant population characteristics of the human research participants (e.g. age, genotypic information, past and current diagnosis and treatment categories). If you filled out the behavioural & social sciences study design questions and have nothing to add here, write “See above.” |

| Recruitment | Describe how participants were recruited. Outline any potential self-selection bias or other biases that may be present and how these are likely to impact results. |

| Ethics oversight | Identify the organization(s) that approved the study protocol. |

Field-specific reporting

Life sciences Behavioural & social sciences

Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences

For a reference copy of the document with all sections, see nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences study design

| Study description | The study undertook population genomics analysis of ancient individuals from Denmark, on data from the accompanying publication ‘Population Genomics of Stone Age Eurasia’, in addition to stable isotope (13C, 15N, 87Sr) and radiocarbon data analysis. |

| Research sample | 100 human (Homo_sapiens) individuals from archaeological sites across Denmark, all >1000 years old. |

| Sampling strategy | We sampled primarily individuals from the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods from Danish archaeological sites; sampling was restricted to samples where sufficient DNA preservation was available for genome-scale analysis. |

| Data collection | Ancient genomic data was collected following established laboratory protocols, designed to minimise sample destruction and avoid contamination. These are more appropriately detailed in the accompanying publication describing the generation of this dataset. |

| Timing and spatial scale | The oldest sample has a corrected radiocarbon age of 10,465years; the most recent has a corrected radiocarbon age of 3297years. All samples originate from the present-day country of Denmark. |

| Data exclusions | Data from the accompanying publication ‘Population Genomics of Stone Age Eurasia’ was subset to only include samples from Denmark. |

| Reproducibility | Preserved archaeological remains are unique and rare, therefore replication was generally not undertaken. Data quality and uncertainty (e.g. contamination) was accounted for in computational analyses to assess robustness of inferences, and all methods and data are made available for future replication. |

| Randomization | Randomization of sampling of archaeological remains is not applicable in this case. |

| Blinding | Blinding was not applicable to this study. |

| Did the study involve field work? |

|

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

| Materials & experimental systems | Methods | ||

| n/a | Involved in the study | n/a | Involved in the study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Flow cytometry |

|

Palaeontology and archaeology |  |

|

|

Animals and other organisms | ||

|

|

||

|

Dual use research of concern | ||

Palaeontology and Archaeology

| Specimen provenance | Details of specimen provenance are provided in the accompanying publication ‘Population Genomics of Stone Age Eurasia’, where the full sample dataset is presented. |

| Specimen deposition | See above; all specimens studied are available upon direct contact/request to the archaeologists, curators or officials responsible for their curation at the organisation where they are held. |

Ethics oversight

Sampling was undertaken with the ethical approval of museums and institutions providing samples or facilities.