DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-025-03476-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39838450

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-21

MaveDB 2024: قاعدة بيانات مجتمعية مُنسقة تحتوي على أكثر من سبعة ملايين تأثير متغير من اختبارات وظيفية متعددة.

قائمة كاملة بمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقال

الملخص

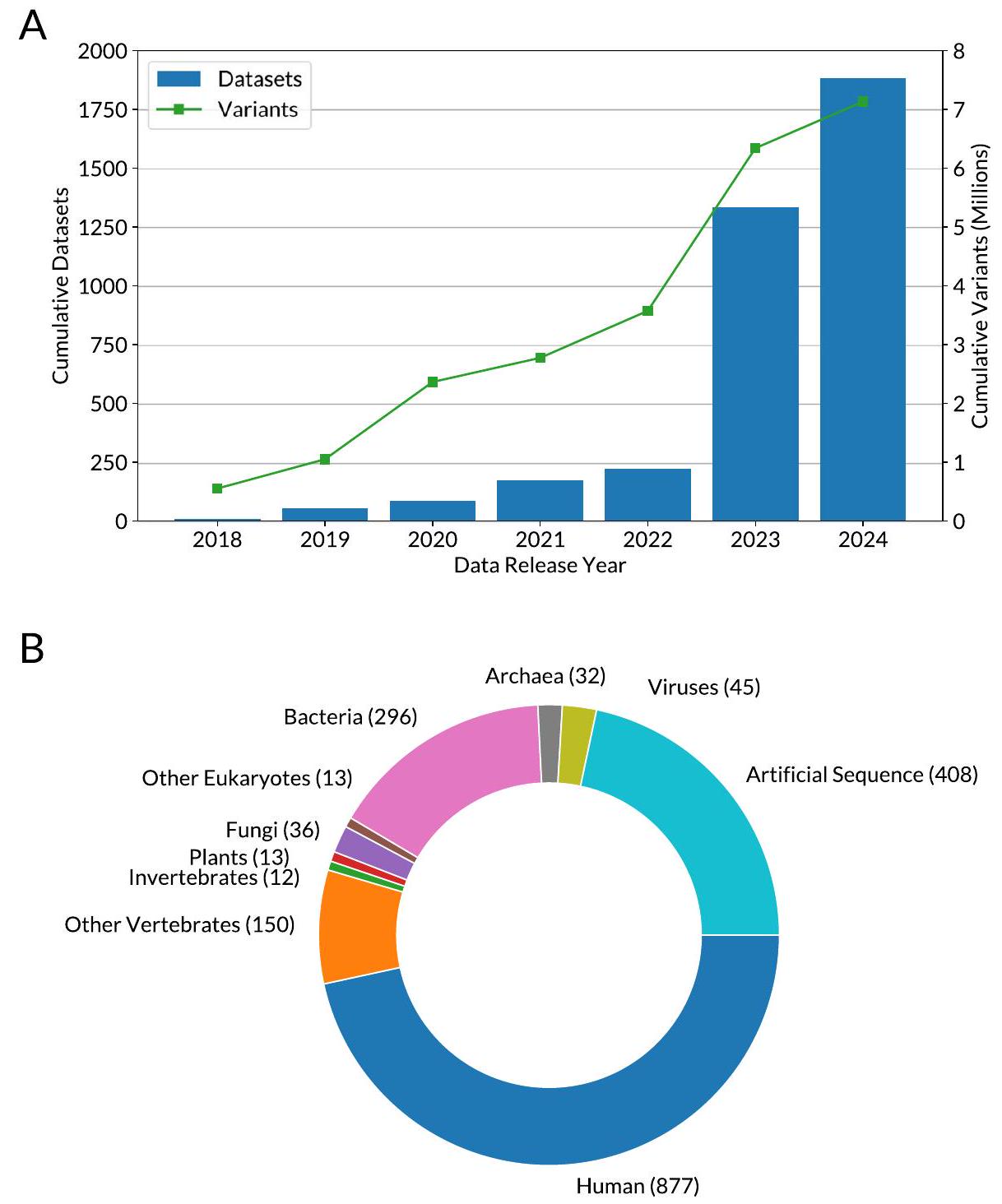

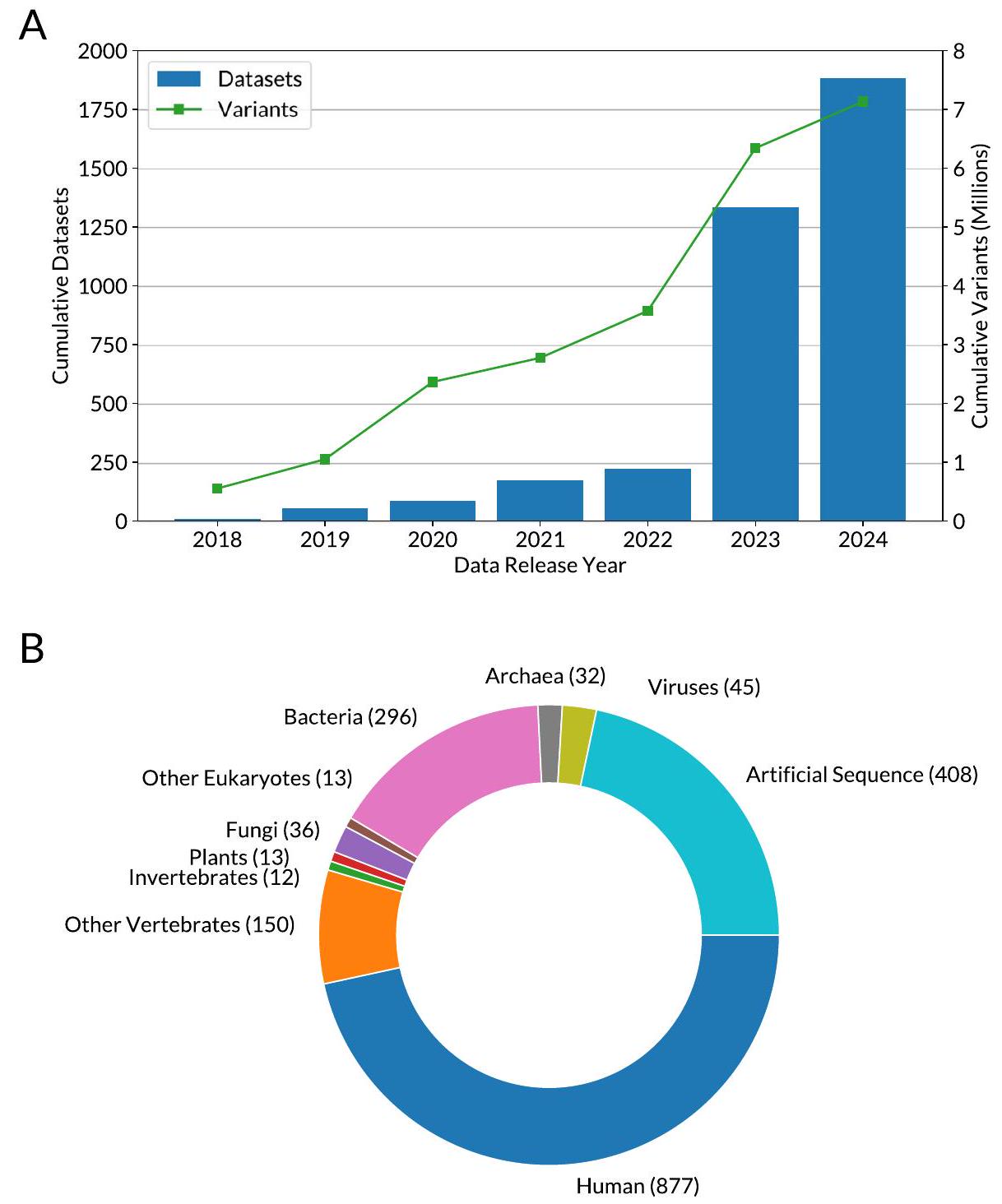

تعد الاختبارات المتعددة لآثار المتغيرات (MAVEs) أداة حيوية للباحثين والأطباء لفهم المتغيرات الجينية. هنا نصف تحديث 2024 لقاعدة بيانات MaveDB.https://www.mavedb.org/) مع أربعة تحسينات رئيسية لقاعدة بيانات مجتمع MAVE: المزيد من البيانات المتاحة بما في ذلك أكثر من 7 ملايين قياس لتأثير المتغيرات، نموذج بيانات محسّن يدعم الاختبارات مثل تحرير الجينوم بالتشبع، أدوات استكشاف وتصوير مدمجة جديدة، وواجهات برمجة تطبيقات قوية لتجميع البيانات وتبسيط عملية الإرسال والوصول. تدعم هذه التغييرات معًا دور MaveDB كمركز لتحليل ونشر MAVEs الآن وفي المستقبل.

الخلفية

كما أن الآخرين الذين سنواجههم مع تسلسل المزيد من الأفراد، فإن تأثير الأنماط الظاهرية الجزيئية والخلوية والعضوية يمثل تحديًا مركزيًا لعلم الجينوم.

تجربة من خلال إضافة تحميلات المستخدمين المعتمدة على واجهة برمجة التطبيقات (API) الموجهة للباحثين الذين يقدمون مجموعات بيانات كبيرة أو معقدة، أو الذين يشاركون في إنتاج بيانات MAVE على نطاق واسع.

البناء والمحتوى

الأداة والنقاش

واجهة الويب

يوفر تجربة مستخدم أكثر استجابة وتفاعلية مقارنةً بالإصدار السابق من MaveDB، الذي كان يعتمد على قوالب HTML الخاصة بـ Django.

تحسين دعم واجهة برمجة التطبيقات

إصدارات البيانات الضخمة

توصيات لرفع المستخدمين

الاستنتاجات

الشكر والتقدير

معلومات مراجعة الأقران

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإقرارات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم النشر على الإنترنت: 21 يناير 2025

References

- Chen S, Francioli LC, Goodrich JK, Collins RL, Kanai M, Wang Q, et al. A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature. 2024;625:92-100

- Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, Brown GR, Chao C, Chitipiralla S, et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1062-7.

- Fowler DM, Rehm HL. Will variants of uncertain significance still exist in 2030? Am J Hum Genet. 2024;111:5-10.

- Starita LM, Ahituv N, Dunham MJ, Kitzman JO, Roth FP, Seelig G, et al. Variant interpretation: functional assays to the rescue. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101:315-25.

- Tabet D, Parikh V, Mali P, Roth FP, Claussnitzer M. Scalable functional assays for the interpretation of human genetic variation. Annu Rev Genet. 2022;56:441-65.

- Fowler DM, Fields S. Deep mutational scanning: a new style of protein science. Nat Methods. 2014;11:801-7.

- Kinney JB, McCandlish DM. Massively parallel assays and quantitative sequence-function relationships. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2019;20:99-127.

- Weile J, Roth FP. Multiplexed assays of variant effects contribute to a growing genotype-phenotype atlas. Hum Genet. 2018;137:665-78.

- Fayer S, Horton C, Dines JN, Rubin AF, Richardson ME, McGoldrick K, et al. Closing the gap: systematic integration of multiplexed functional data resolves variants of uncertain significance in BRCA1, TP53, and PTEN. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:2248-58.

- Scott A, Hernandez F, Chamberlin A, Smith C, Karam R, Kitzman JO. Saturation-scale functional evidence supports clinical variant interpretation in Lynch syndrome. Genome Biol. 2022;23:266.

- Fowler DM, Araya CL, Fleishman SJ, Kellogg EH, Stephany JJ, Baker D, et al. High-resolution mapping of protein sequence-function relationships. Nat Methods. 2010;7:741-6.

- McLaughlin RN Jr, Poelwijk FJ, Raman A, Gosal WS, Ranganathan R. The spatial architecture of protein function and adaptation. Nature. 2012;491:138-42.

- Firnberg E, Labonte JW, Gray JJ, Ostermeier M. A comprehensive, high-resolution map of a gene’s fitness landscape. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:1581-92.

- Melnikov A, Rogov P, Wang L, Gnirke A, Mikkelsen TS. Comprehensive mutational scanning of a kinase in vivo reveals substrate-dependent fitness landscapes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e112-e112.

- Mishra P, Flynn JM, Starr TN, Bolon DNA. Systematic mutant analyses elucidate general and client-specific aspects of Hsp90 function. Cell Rep. 2016;15:588-98.

- Majithia AR, Tsuda B, Agostini M, Gnanapradeepan K, Rice R, Peloso G, et al. Prospective functional classification of all possible missense variants in PPARG. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1570-5.

- Weile J, Sun S, Cote AG, Knapp J, Verby M, Mellor JC, et al. A framework for exhaustively mapping functional missense variants. Mol Syst Biol. 2017;13:957.

- Matreyek KA, Starita LM, Stephany JJ, Martin B, Chiasson MA, Gray VE, et al. Multiplex assessment of protein variant abundance by massively parallel sequencing. Nat Genet. 2018;50:874-82.

- Findlay GM, Daza RM, Martin B, Zhang MD, Leith AP, Gasperini M, et al. Accurate classification of BRCA1 variants with saturation genome editing. Nature. 2018;562:217-22.

- Tsuboyama K, Dauparas J, Chen J, Laine E, Mohseni Behbahani Y, Weinstein JJ, et al. Mega-scale experimental analysis of protein folding stability in biology and design. Nature. 2023;620:434-44.

- Beltran A, Jiang X, Shen Y, Lehner B. Site-saturation mutagenesis of 500 human protein domains. Nature. 2025.

- Tinberg CE, Khare SD, Dou J, Doyle L, Nelson JW, Schena A, et al. Computational design of ligand-binding proteins with high affinity and selectivity. Nature. 2013;501:212-6.

- Rollins NJ, Brock KP, Poelwijk FJ, Stiffler MA, Gauthier NP, Sander C, et al. Inferring protein 3D structure from deep mutation scans. Nat Genet. 2019;51:1170-6.

- Schmiedel JM, Lehner B. Determining protein structures using deep mutagenesis. Nat Genet. 2019;51:1177-86.

- Ke S, Anquetil V, Zamalloa JR, Maity A, Yang A, Arias MA, et al. Saturation mutagenesis reveals manifold determinants of exon definition. Genome Res. 2018;28:11-24.

- Kircher M, Xiong C, Martin B, Schubach M, Inoue F, Bell RJA, et al. Saturation mutagenesis of twenty disease-associated regulatory elements at single base-pair resolution. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3583.

- Melnikov A, Murugan A, Zhang X, Tesileanu T, Wang L, Rogov P, et al. Systematic dissection and optimization of inducible enhancers in human cells using a massively parallel reporter assay. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:271-7.

- Patwardhan RP, Hiatt JB, Witten DM, Kim MJ, Smith RP, May D, et al. Massively parallel functional dissection of mammalian enhancers in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:265-70.

- Frazer J, Notin P, Dias M, Gomez A, Min JK, Brock K, et al. Disease variant prediction with deep generative models of evolutionary data. Nature. 2021;599:91-5.

- Gray VE, Hause RJ, Luebeck J, Shendure J, Fowler DM. Quantitative missense variant effect prediction using largescale mutagenesis data. Cell Syst. 2018;6:116-24.e3.

- Wu Y, Li R, Sun S, Weile J, Roth FP. Improved pathogenicity prediction for rare human missense variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:1891-906.

- Notin P, Dias M, Frazer J, Hurtado JM, Gomez AN, Marks D, et al. Tranception: protein fitness prediction with autoregressive transformers and inference-time retrieval. Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning in Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. 2022;162:16990-7017.

- IGVF Consortium. Deciphering the impact of genomic variation on function. Nature. 2024;633:47-57.

- Fowler DM, Adams DJ, Gloyn AL, Hahn WC, Marks DS, Muffley LA, et al. An Atlas of Variant Effects to understand the genome at nucleotide resolution. Genome Biol. 2023;24:147.

- Esposito D, Weile J, Shendure J, Starita LM, Papenfuss AT, Roth FP, et al. MaveDB: an open-source platform to distribute and interpret data from multiplexed assays of variant effect. Genome Biol. 2019;20:223.

- Findlay GM, Boyle EA, Hause RJ, Klein JC, Shendure J. Saturation editing of genomic regions by multiplex homologydirected repair. Nature. 2014;513:120-3.

- Radford EJ, Tan H-K, Andersson MHL, Stephenson JD, Gardner EJ, Ironfield H, et al. Saturation genome editing of DDX3X clarifies pathogenicity of germline and somatic variation. Nat Commun. 2023;14:7702.

- den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, Hart RK, Greenblatt MS, McGowan-Jordan J, et al. HGVS recommendations for the description of sequence variants: 2016 update. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:564-9.

- Wagner AH, Babb L, Alterovitz G, Baudis M, Brush M, Cameron DL, et al. The GA4GH Variation Representation Specification: a computational framework for variation representation and federated identification. Cell Genom. 2021;1: 100027.

- Suiter CC, Moriyama T, Matreyek KA, Yang W, Scaletti ER, Nishii R, et al. Massively parallel variant characterization identifies NUDT15 alleles associated with thiopurine toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:5394-401.

- Rubin AF, Gelman H, Lucas N, Bajjalieh SM, Papenfuss AT, Speed TP, et al. A statistical framework for analyzing deep mutational scanning data. Genome Biol. 2017;18:150.

- Hart RK, Rico R, Hare E, Garcia J, Westbrook J, Fusaro VA. A Python package for parsing, validating, mapping and formatting sequence variants using HGVS nomenclature. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:268-70.

- Wang M, Callenberg KM, Dalgleish R, Fedtsov A, Fox NK, Freeman PJ, et al. hgvs: a Python package for manipulating sequence variants using HGVS nomenclature: 2018 Update. Hum Mutat. 2018;39:1803-13.

- Hart RK, Prlić A. SeqRepo: a system for managing local collections of biological sequences. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0239883.

- Creative Commons – CC0 1.0 Universal. Available from: https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

- Creative Commons – Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International – CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Available from: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

- Arbesfeld JA, Da EY, Kuzma K, Paul A, Farris T, Riehle K, et al. Mapping MAVE data for use in human genomics applications. bioRxiv. 2023;2023.06.20.545702.

- Claussnitzer M, Parikh VN, Wagner AH, Arbesfeld JA, Bult CJ, Firth HV, et al. Minimum information and guidelines for reporting a multiplexed assay of variant effect. Genome Biol. 2024;25:100.

- Capodanno BJ, Stone J, Da EY, Grindstaff SB, Harrington MR, Moore N, Syder AE, Rubin AF. mavedb-api. GitHub. https://github.com/VariantEffect/MaveDB-API (2024).

- Capodanno BJ, Stone J, Da EY, Grindstaff SB, Harrington MR, Polunina PV, Syder AE, Rubin AF. mavedb-ui. GitHub. https://github.com/VariantEffect/MaveDB-UI (2024).

- Capodanno BJ, Stone J, Da EY, Grindstaff SB, Harrington MR, Moore N, Syder AE, Rubin AF. VariantEffect/mavedb-api: v2024.4.2. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14201451 (2024).

- Capodanno BJ, Stone J, Da EY, Grindstaff SB, Harrington MR, Polunina PV, Syder AE, Rubin AF. VariantEffect/mavedbui: v2024.4.3. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14207533 (2024).

- Rubin AF. mavehgvs. GitHub. https://github.com/VariantEffect/mavehgvs (2023).

- Rubin AF. mavehgvs. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 8281119 (2023).

- Rubin AF. MaveDB Analytics. GitHub. https://github.com/afrubin/mavedb-analytics (2024).

- Rubin AF. afrubin/mavedb-analytics: 0.1.0. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14172359 (2024).

- MaveDB contributors. MaveDB. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14172004 (2024).

ملاحظة الناشر

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-025-03476-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39838450

Publication Date: 2025-01-21

MaveDB 2024: a curated community database with over seven million variant effects from multiplexed functional assays

Check for updates

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Abstract

Multiplexed assays of variant effect (MAVEs) are a critical tool for researchers and clinicians to understand genetic variants. Here we describe the 2024 update to MaveDB (https://www.mavedb.org/) with four key improvements to the MAVE community’s database of record: more available data including over 7 million variant effect measurements, an improved data model supporting assays such as saturation genome editing, new built-in exploration and visualization tools, and powerful APIs for data federation and streamlined submission and access. Together these changes support MaveDB’s role as a hub for the analysis and dissemination of MAVEs now and into the future.

Background

well as others we will encounter as more individuals are sequenced, impact molecular, cellular, and organismal phenotypes represents a central challenge for genomics [3].

experience by adding API-based user uploads aimed at researchers who are submitting large or complex datasets, or engaging in MAVE data production at scale.

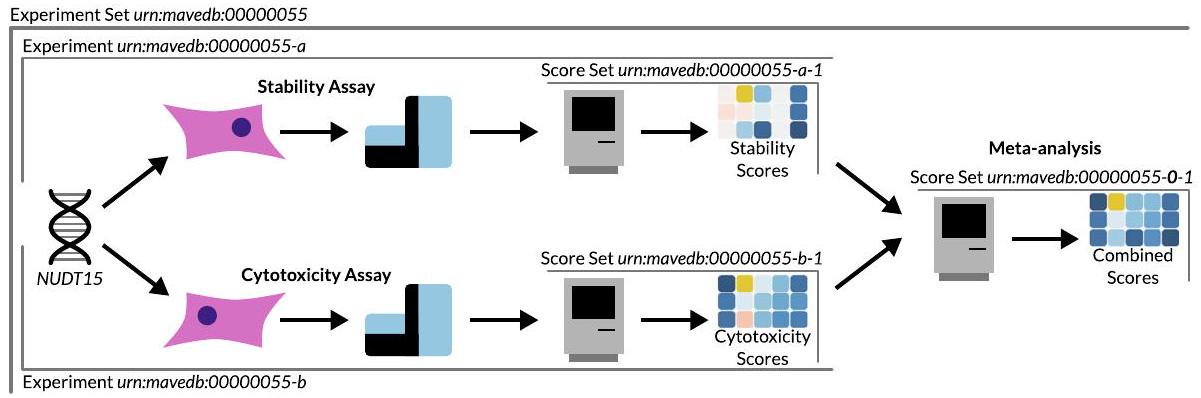

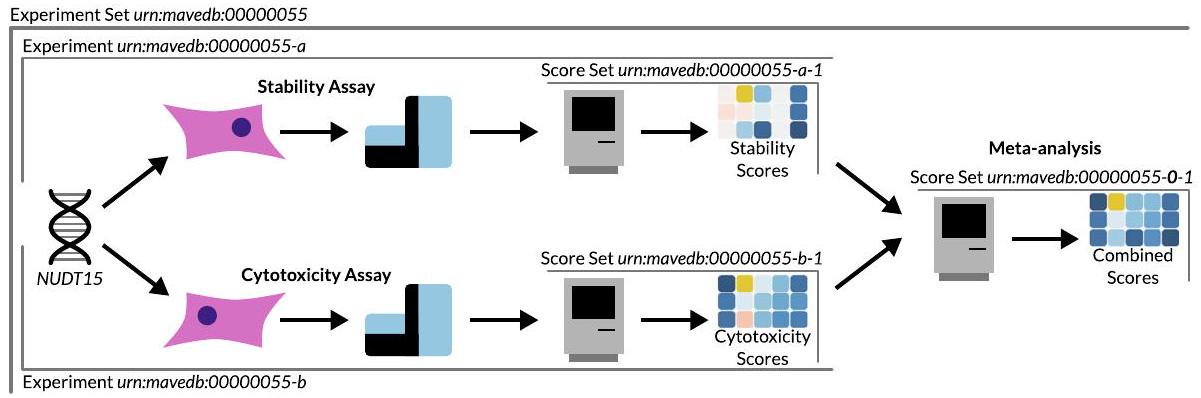

Construction and content

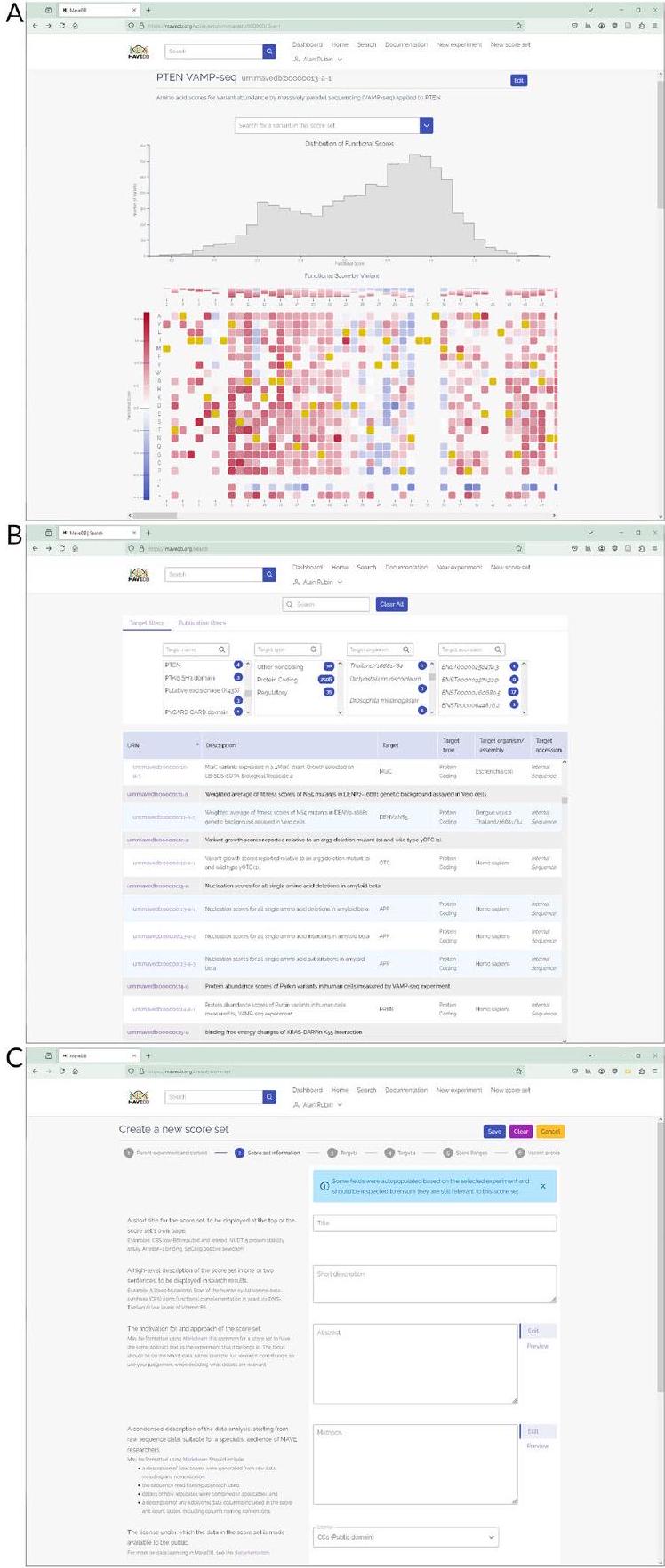

Utility and discussion

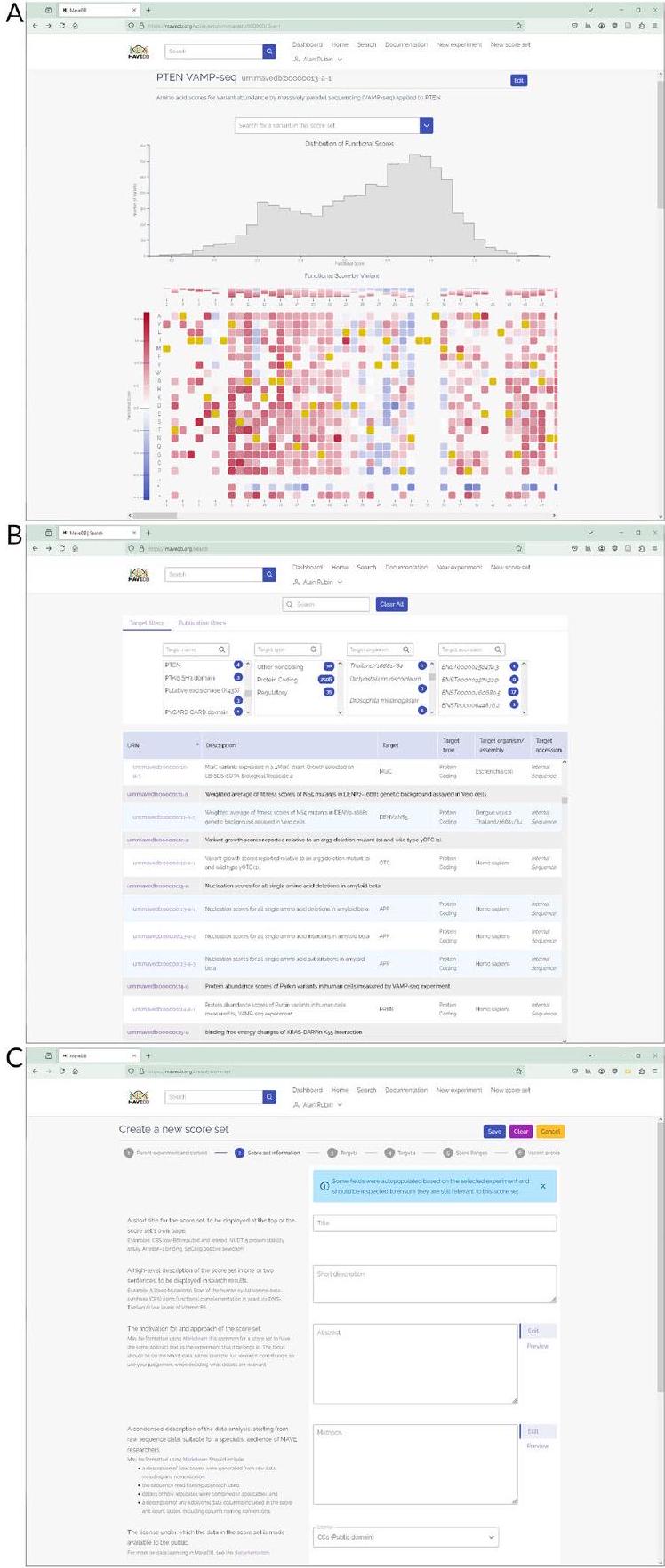

Web interface

delivers a more responsive and reactive user experience compared to the previous version of MaveDB, which was based on Django’s HTML templates.

Improved API support

Bulk data releases

Recommendations for user uploads

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Peer review information

Authors’ contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 21 January 2025

References

- Chen S, Francioli LC, Goodrich JK, Collins RL, Kanai M, Wang Q, et al. A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature. 2024;625:92-100

- Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, Brown GR, Chao C, Chitipiralla S, et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1062-7.

- Fowler DM, Rehm HL. Will variants of uncertain significance still exist in 2030? Am J Hum Genet. 2024;111:5-10.

- Starita LM, Ahituv N, Dunham MJ, Kitzman JO, Roth FP, Seelig G, et al. Variant interpretation: functional assays to the rescue. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101:315-25.

- Tabet D, Parikh V, Mali P, Roth FP, Claussnitzer M. Scalable functional assays for the interpretation of human genetic variation. Annu Rev Genet. 2022;56:441-65.

- Fowler DM, Fields S. Deep mutational scanning: a new style of protein science. Nat Methods. 2014;11:801-7.

- Kinney JB, McCandlish DM. Massively parallel assays and quantitative sequence-function relationships. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2019;20:99-127.

- Weile J, Roth FP. Multiplexed assays of variant effects contribute to a growing genotype-phenotype atlas. Hum Genet. 2018;137:665-78.

- Fayer S, Horton C, Dines JN, Rubin AF, Richardson ME, McGoldrick K, et al. Closing the gap: systematic integration of multiplexed functional data resolves variants of uncertain significance in BRCA1, TP53, and PTEN. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:2248-58.

- Scott A, Hernandez F, Chamberlin A, Smith C, Karam R, Kitzman JO. Saturation-scale functional evidence supports clinical variant interpretation in Lynch syndrome. Genome Biol. 2022;23:266.

- Fowler DM, Araya CL, Fleishman SJ, Kellogg EH, Stephany JJ, Baker D, et al. High-resolution mapping of protein sequence-function relationships. Nat Methods. 2010;7:741-6.

- McLaughlin RN Jr, Poelwijk FJ, Raman A, Gosal WS, Ranganathan R. The spatial architecture of protein function and adaptation. Nature. 2012;491:138-42.

- Firnberg E, Labonte JW, Gray JJ, Ostermeier M. A comprehensive, high-resolution map of a gene’s fitness landscape. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:1581-92.

- Melnikov A, Rogov P, Wang L, Gnirke A, Mikkelsen TS. Comprehensive mutational scanning of a kinase in vivo reveals substrate-dependent fitness landscapes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e112-e112.

- Mishra P, Flynn JM, Starr TN, Bolon DNA. Systematic mutant analyses elucidate general and client-specific aspects of Hsp90 function. Cell Rep. 2016;15:588-98.

- Majithia AR, Tsuda B, Agostini M, Gnanapradeepan K, Rice R, Peloso G, et al. Prospective functional classification of all possible missense variants in PPARG. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1570-5.

- Weile J, Sun S, Cote AG, Knapp J, Verby M, Mellor JC, et al. A framework for exhaustively mapping functional missense variants. Mol Syst Biol. 2017;13:957.

- Matreyek KA, Starita LM, Stephany JJ, Martin B, Chiasson MA, Gray VE, et al. Multiplex assessment of protein variant abundance by massively parallel sequencing. Nat Genet. 2018;50:874-82.

- Findlay GM, Daza RM, Martin B, Zhang MD, Leith AP, Gasperini M, et al. Accurate classification of BRCA1 variants with saturation genome editing. Nature. 2018;562:217-22.

- Tsuboyama K, Dauparas J, Chen J, Laine E, Mohseni Behbahani Y, Weinstein JJ, et al. Mega-scale experimental analysis of protein folding stability in biology and design. Nature. 2023;620:434-44.

- Beltran A, Jiang X, Shen Y, Lehner B. Site-saturation mutagenesis of 500 human protein domains. Nature. 2025.

- Tinberg CE, Khare SD, Dou J, Doyle L, Nelson JW, Schena A, et al. Computational design of ligand-binding proteins with high affinity and selectivity. Nature. 2013;501:212-6.

- Rollins NJ, Brock KP, Poelwijk FJ, Stiffler MA, Gauthier NP, Sander C, et al. Inferring protein 3D structure from deep mutation scans. Nat Genet. 2019;51:1170-6.

- Schmiedel JM, Lehner B. Determining protein structures using deep mutagenesis. Nat Genet. 2019;51:1177-86.

- Ke S, Anquetil V, Zamalloa JR, Maity A, Yang A, Arias MA, et al. Saturation mutagenesis reveals manifold determinants of exon definition. Genome Res. 2018;28:11-24.

- Kircher M, Xiong C, Martin B, Schubach M, Inoue F, Bell RJA, et al. Saturation mutagenesis of twenty disease-associated regulatory elements at single base-pair resolution. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3583.

- Melnikov A, Murugan A, Zhang X, Tesileanu T, Wang L, Rogov P, et al. Systematic dissection and optimization of inducible enhancers in human cells using a massively parallel reporter assay. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:271-7.

- Patwardhan RP, Hiatt JB, Witten DM, Kim MJ, Smith RP, May D, et al. Massively parallel functional dissection of mammalian enhancers in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:265-70.

- Frazer J, Notin P, Dias M, Gomez A, Min JK, Brock K, et al. Disease variant prediction with deep generative models of evolutionary data. Nature. 2021;599:91-5.

- Gray VE, Hause RJ, Luebeck J, Shendure J, Fowler DM. Quantitative missense variant effect prediction using largescale mutagenesis data. Cell Syst. 2018;6:116-24.e3.

- Wu Y, Li R, Sun S, Weile J, Roth FP. Improved pathogenicity prediction for rare human missense variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108:1891-906.

- Notin P, Dias M, Frazer J, Hurtado JM, Gomez AN, Marks D, et al. Tranception: protein fitness prediction with autoregressive transformers and inference-time retrieval. Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning in Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. 2022;162:16990-7017.

- IGVF Consortium. Deciphering the impact of genomic variation on function. Nature. 2024;633:47-57.

- Fowler DM, Adams DJ, Gloyn AL, Hahn WC, Marks DS, Muffley LA, et al. An Atlas of Variant Effects to understand the genome at nucleotide resolution. Genome Biol. 2023;24:147.

- Esposito D, Weile J, Shendure J, Starita LM, Papenfuss AT, Roth FP, et al. MaveDB: an open-source platform to distribute and interpret data from multiplexed assays of variant effect. Genome Biol. 2019;20:223.

- Findlay GM, Boyle EA, Hause RJ, Klein JC, Shendure J. Saturation editing of genomic regions by multiplex homologydirected repair. Nature. 2014;513:120-3.

- Radford EJ, Tan H-K, Andersson MHL, Stephenson JD, Gardner EJ, Ironfield H, et al. Saturation genome editing of DDX3X clarifies pathogenicity of germline and somatic variation. Nat Commun. 2023;14:7702.

- den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, Hart RK, Greenblatt MS, McGowan-Jordan J, et al. HGVS recommendations for the description of sequence variants: 2016 update. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:564-9.

- Wagner AH, Babb L, Alterovitz G, Baudis M, Brush M, Cameron DL, et al. The GA4GH Variation Representation Specification: a computational framework for variation representation and federated identification. Cell Genom. 2021;1: 100027.

- Suiter CC, Moriyama T, Matreyek KA, Yang W, Scaletti ER, Nishii R, et al. Massively parallel variant characterization identifies NUDT15 alleles associated with thiopurine toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:5394-401.

- Rubin AF, Gelman H, Lucas N, Bajjalieh SM, Papenfuss AT, Speed TP, et al. A statistical framework for analyzing deep mutational scanning data. Genome Biol. 2017;18:150.

- Hart RK, Rico R, Hare E, Garcia J, Westbrook J, Fusaro VA. A Python package for parsing, validating, mapping and formatting sequence variants using HGVS nomenclature. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:268-70.

- Wang M, Callenberg KM, Dalgleish R, Fedtsov A, Fox NK, Freeman PJ, et al. hgvs: a Python package for manipulating sequence variants using HGVS nomenclature: 2018 Update. Hum Mutat. 2018;39:1803-13.

- Hart RK, Prlić A. SeqRepo: a system for managing local collections of biological sequences. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0239883.

- Creative Commons – CC0 1.0 Universal. Available from: https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

- Creative Commons – Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International – CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Available from: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

- Arbesfeld JA, Da EY, Kuzma K, Paul A, Farris T, Riehle K, et al. Mapping MAVE data for use in human genomics applications. bioRxiv. 2023;2023.06.20.545702.

- Claussnitzer M, Parikh VN, Wagner AH, Arbesfeld JA, Bult CJ, Firth HV, et al. Minimum information and guidelines for reporting a multiplexed assay of variant effect. Genome Biol. 2024;25:100.

- Capodanno BJ, Stone J, Da EY, Grindstaff SB, Harrington MR, Moore N, Syder AE, Rubin AF. mavedb-api. GitHub. https://github.com/VariantEffect/MaveDB-API (2024).

- Capodanno BJ, Stone J, Da EY, Grindstaff SB, Harrington MR, Polunina PV, Syder AE, Rubin AF. mavedb-ui. GitHub. https://github.com/VariantEffect/MaveDB-UI (2024).

- Capodanno BJ, Stone J, Da EY, Grindstaff SB, Harrington MR, Moore N, Syder AE, Rubin AF. VariantEffect/mavedb-api: v2024.4.2. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14201451 (2024).

- Capodanno BJ, Stone J, Da EY, Grindstaff SB, Harrington MR, Polunina PV, Syder AE, Rubin AF. VariantEffect/mavedbui: v2024.4.3. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14207533 (2024).

- Rubin AF. mavehgvs. GitHub. https://github.com/VariantEffect/mavehgvs (2023).

- Rubin AF. mavehgvs. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 8281119 (2023).

- Rubin AF. MaveDB Analytics. GitHub. https://github.com/afrubin/mavedb-analytics (2024).

- Rubin AF. afrubin/mavedb-analytics: 0.1.0. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14172359 (2024).

- MaveDB contributors. MaveDB. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14172004 (2024).