DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0885715624000150

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-15

PDF-5+: ملف شامل لتشتت المسحوق™ لتوصيف المواد

الملخص

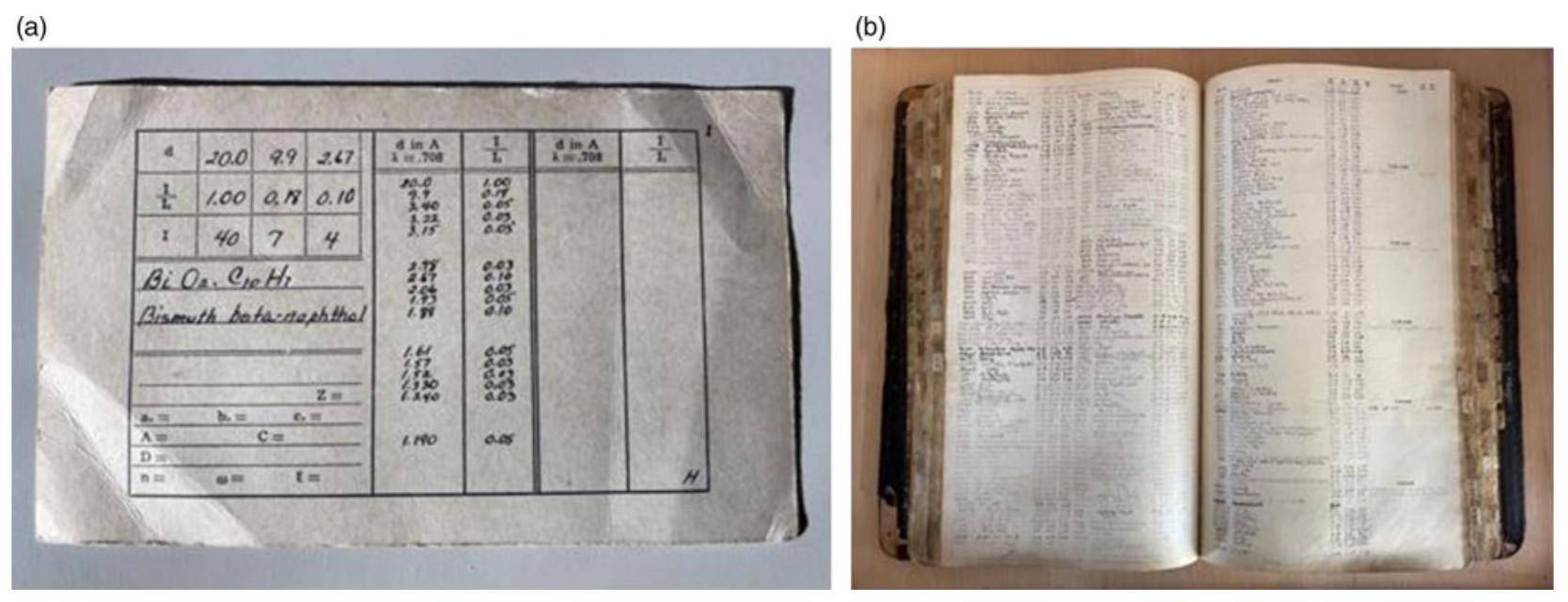

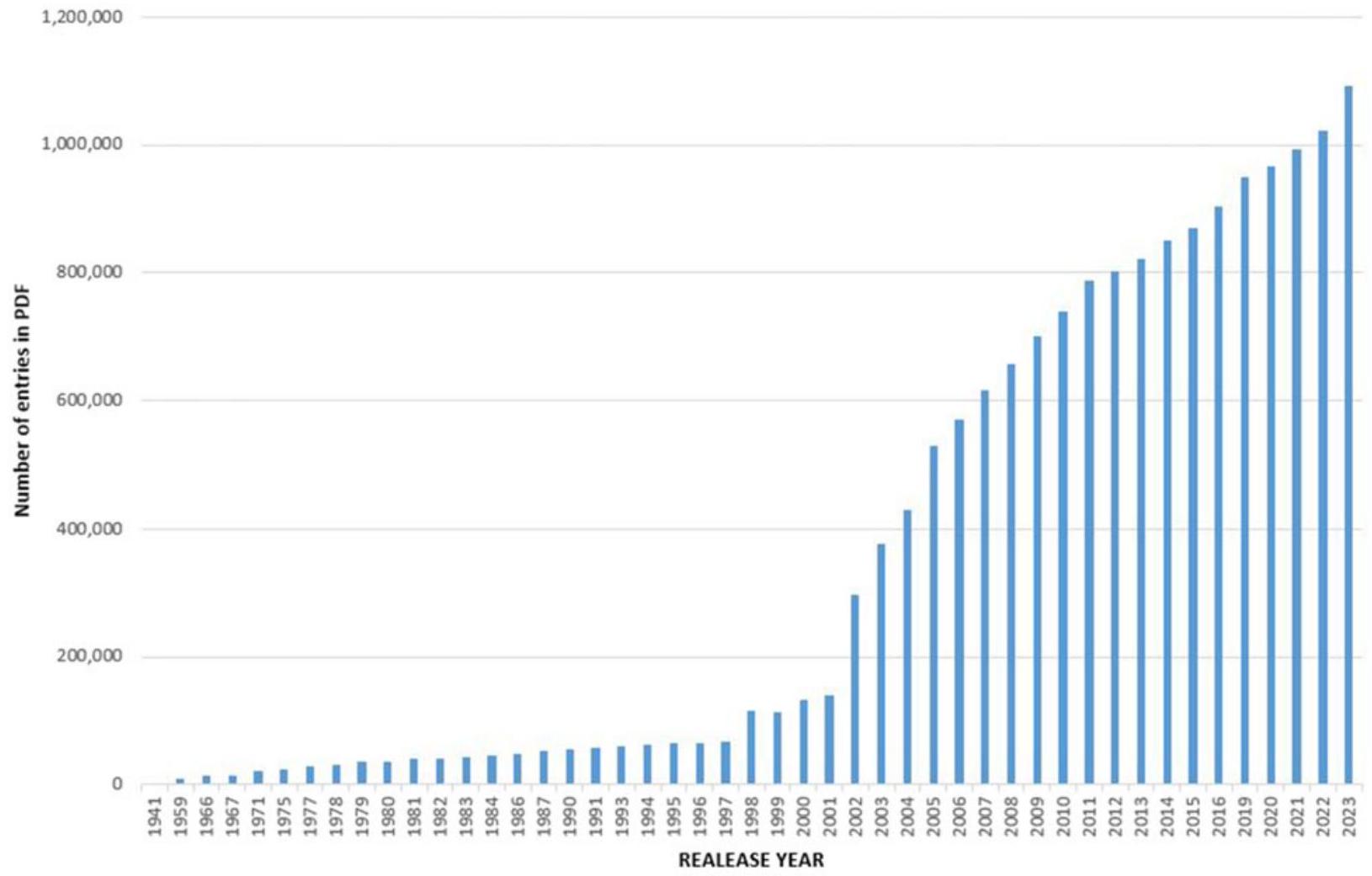

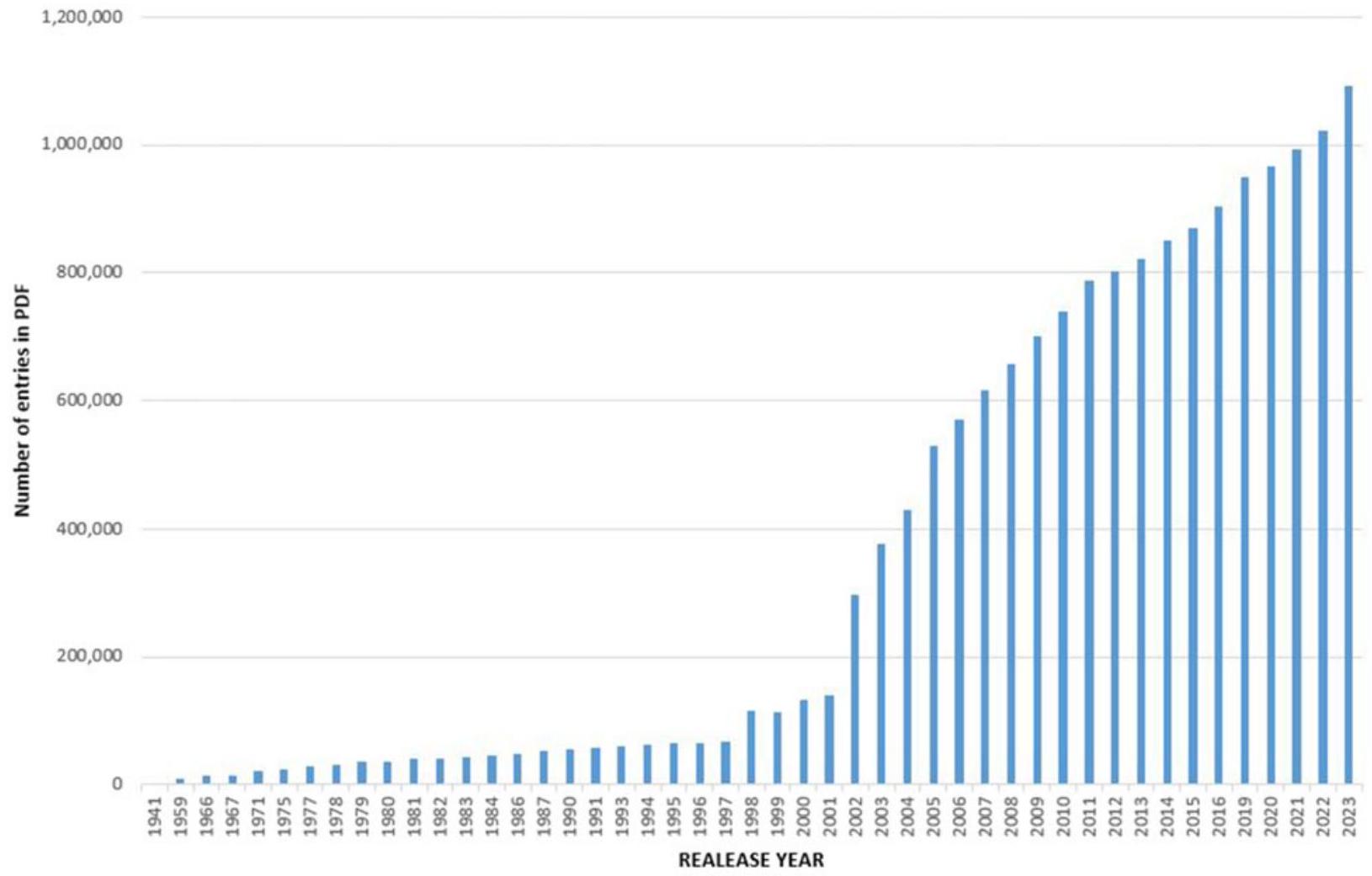

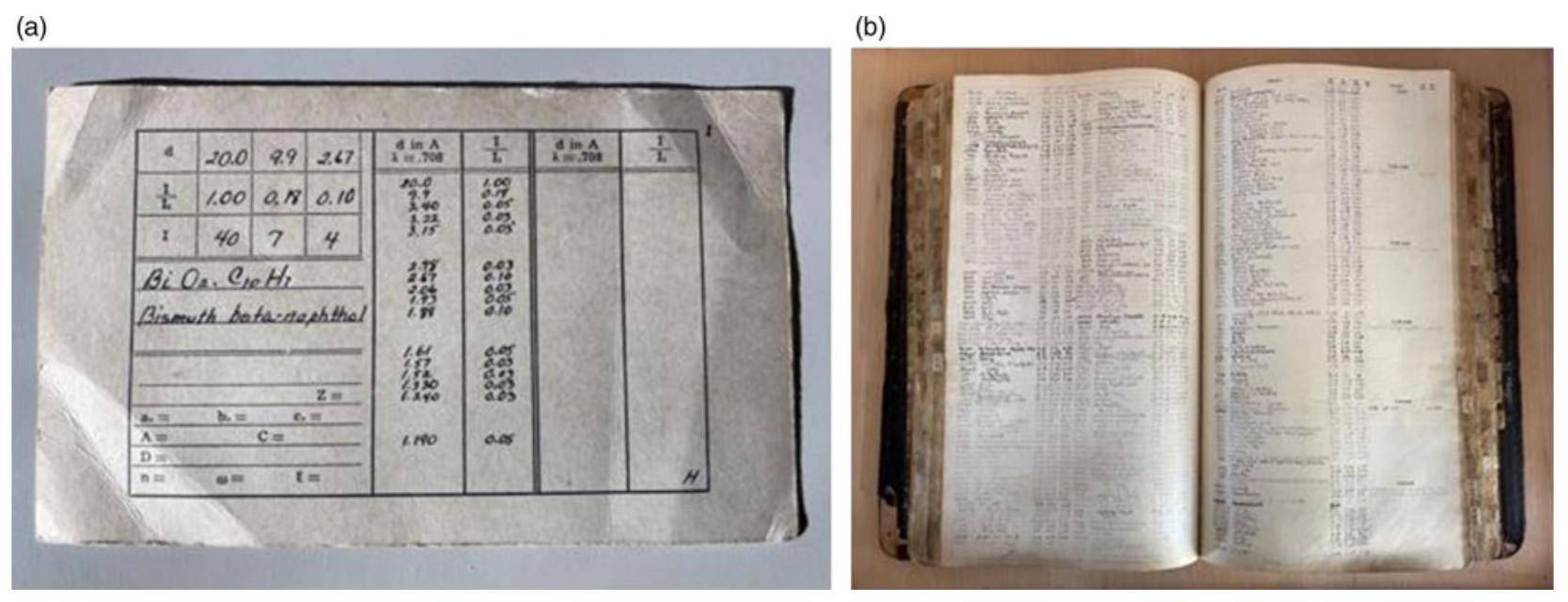

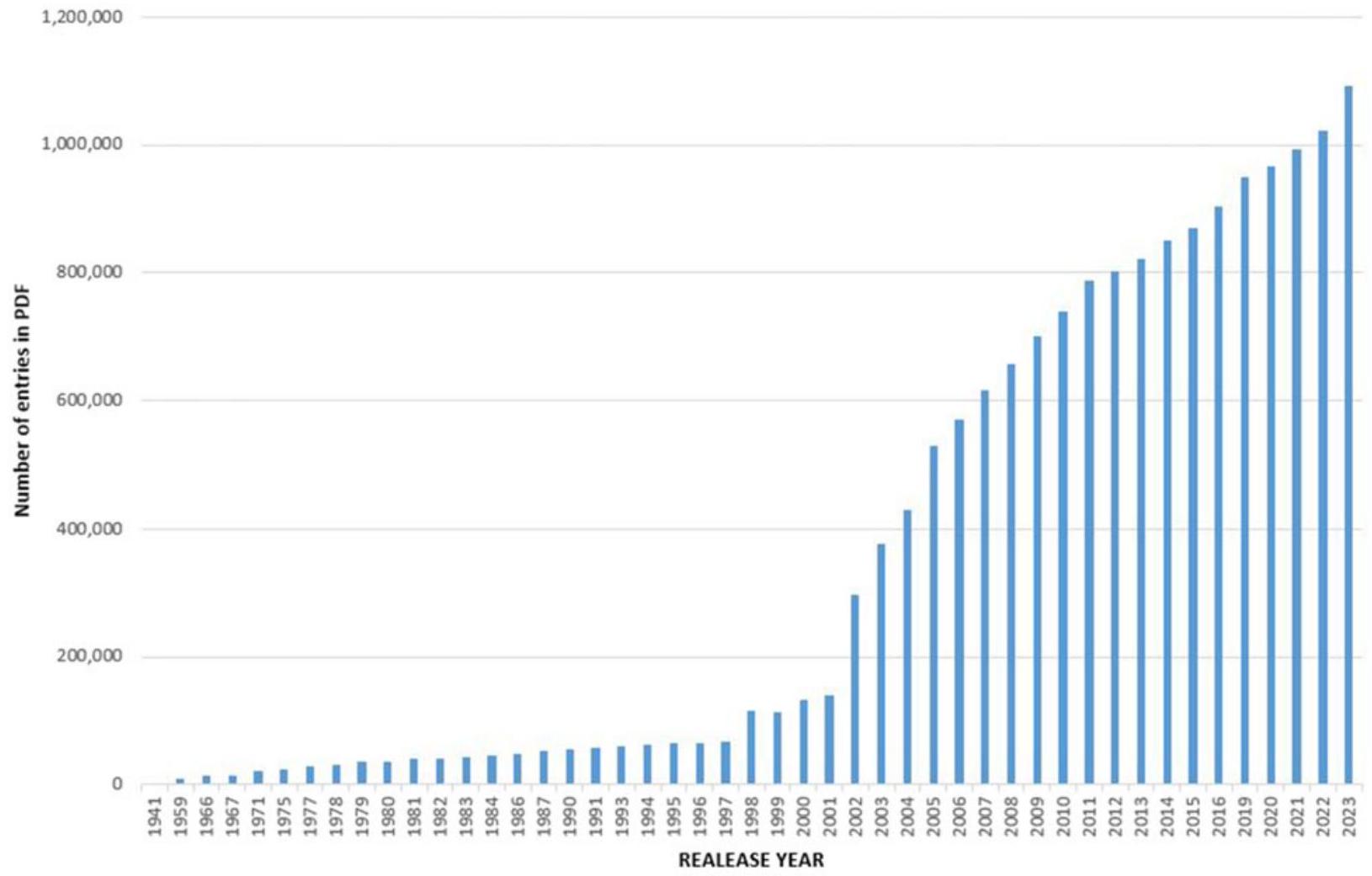

على مدى أكثر من 80 عامًا، استخدمت المجتمع العلمي بشكل واسع ملف حيود المسحوق (PDF®) من المركز الدولي لبيانات الحيود (ICDD®) لتوصيف المواد، بما في ذلك تحليل حيود الأشعة السينية للمسحوق. تاريخيًا، تم توفير PDF لنوعين رئيسيين من المواد: واحد للتحليل غير العضوي والآخر للتحليل العضوي. في السنوات الأولى من PDF، تم تنفيذ هذا النهج المكون من مادتين بسبب القدرات المحدودة للحواسيب. مع الإصدار 2024، يقدم ICDD قاعدة بيانات شاملة تتكون من كامل PDF في قاعدة بيانات واحدة تُسمى PDF-5+، وتتكون من أكثر من مليون إدخال.

[doi:10.1017/S0885715624000150]

الكلمات المفتاحية: حيود الأشعة السينية بالمسحوق، قاعدة بيانات XRD، علامة الجودة، الملفات الفرعية، بطاقة PDF

المقدمة

بيانات الحيود لتحديد المواد. تتكون عضوية ICDD من تمثيل عالمي من الأكاديميا والحكومة والصناعة. هذه الورقة هي تحديث لورقة سابقة تم نشرها (Gates-Rector و Blanton، 2019) حول PDF®. في هذه الورقة، نحاول التركيز على التغييرات الأخيرة في قاعدة بيانات PDF وبرامج قواعد البيانات العلائقية وتقليل تكرار الميزات التي تم تقديمها في ورقة Gates-Rector و Blanton لعام 2019.

II. تطوير قاعدة البيانات: PDF

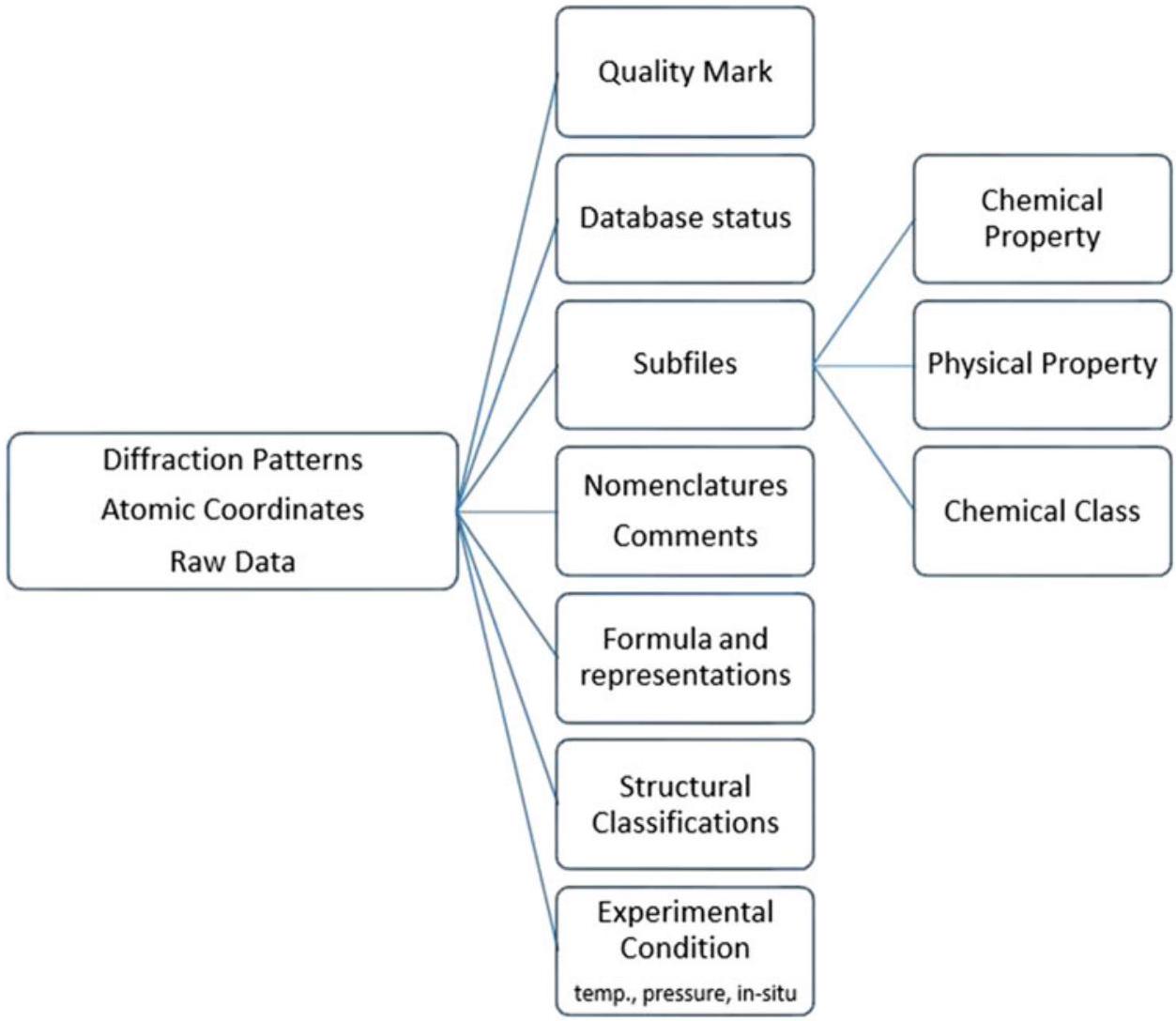

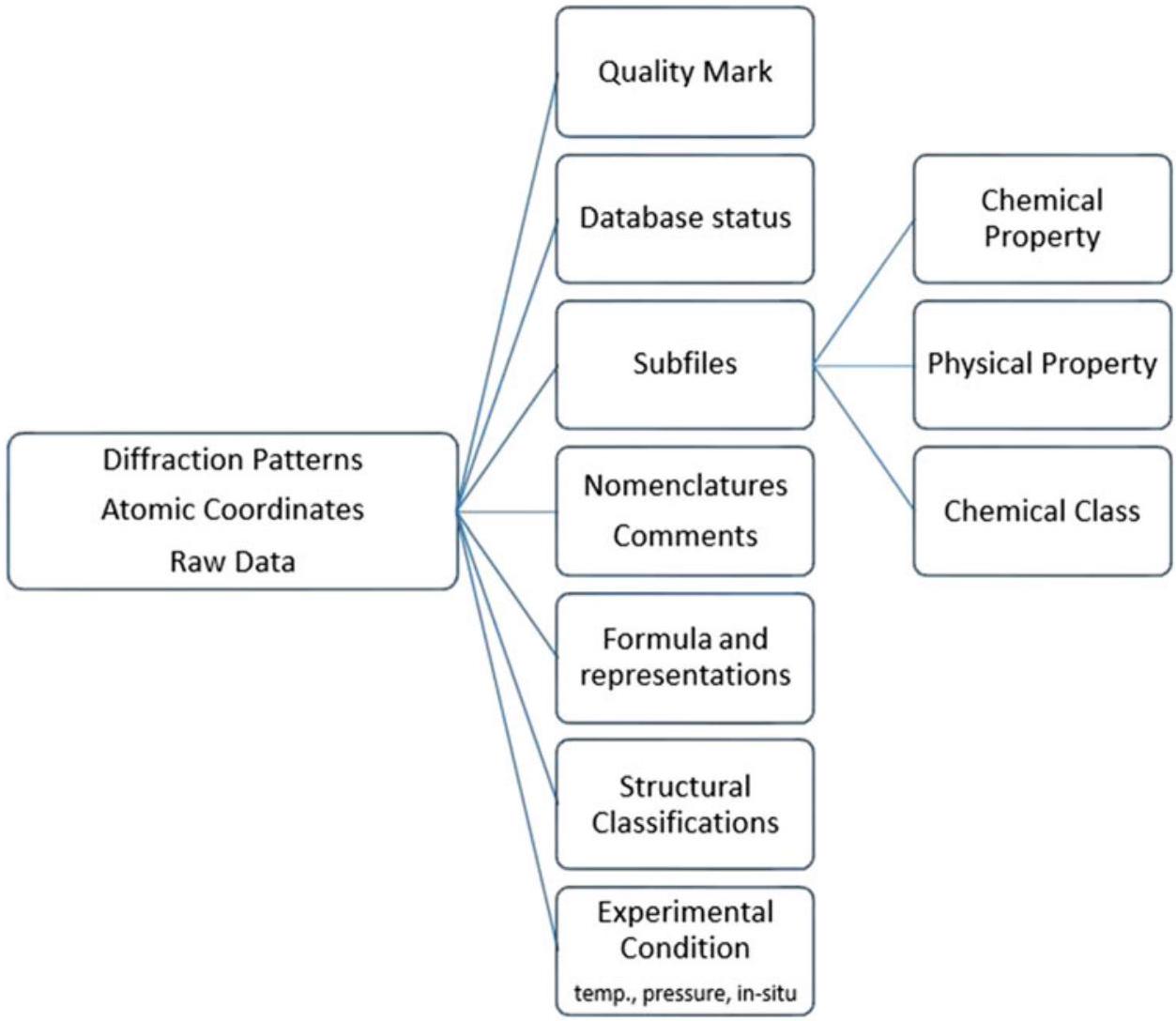

نظام إدارة قواعد البيانات العلائقية (RDBMS). يحتوي ملف PDF بتنسيق قاعدة البيانات العلائقية (RDB) على بيانات كيميائية وفيزيائية وببليوغرافية وكريستالوجرافية شاملة، بما في ذلك الإحداثيات الذرية التي تمكن من التوصيف والتحليل الحسابي. يوفر بناء RDB وصولاً مرنًا إلى قاعدة البيانات لدراسات استخراج البيانات ويعزز قدرات توصيف مواد PDF (Faber و Fawcett، 2002؛ Kabekkodu وآخرون، 2002). واحدة من الفوائد العميقة لـ RDB هي التنفيذ الأكثر بساطة لمبادئ FAIR (قابلية الاكتشاف، الوصول، التشغيل البيني، وإعادة الاستخدام) (Wilkinson وآخرون، 2016) وتحسين التشغيل البيني للبيانات. هذا النوع من البناء حيوي من منظور التشغيل البيني، نظرًا لوجود العديد من الروتينات البرمجية الآلية (من قبل مختلف مصنعي أجهزة قياس الحيود أو مطوري البرمجيات) المستخدمة لتحديد الكتلة وكمية الطور.

III. تنسيق البيانات

A. علامة الجودة وحالة قاعدة البيانات

وتقدم باستخدام تسمية علامة الجودة (QM) (Hubbard وآخرون، 1980؛ Jenkins و Smith، 1987؛ Bruno وآخرون، 2017؛ Gates-Rector و Blanton، 2019؛ Kaduk، 2019) التي توفر للمستخدم عملية منهجية لفهم جودة إدخال البيانات ونهج متسق في تقييم جودة المطابقة (GOM) لتحديد الطور. لقد مرت جميع البيانات في PDF بعملية تحرير متعددة المستويات.

| التسمية | الوصف |

| 1 | جميع البيانات: تستخدم قاعدة البيانات بالكامل |

| 2 | التركيز على غير العضوي: بشكل رئيسي للأطوار غير العضوية مع بعض المواد العضوية الشائعة (رمز DB 02- ومعظم 05- غير مدرجة) |

| 3 | التركيز على العضوي: بشكل رئيسي للأطوار العضوية مع بعض المواد غير العضوية الشائعة (مثل المواد المساعدة، والأصباغ، إلخ.) |

| A | بطاقات PDF: تفتح بطاقة PDF (إدخال) بالرقم PDF المعطى. كما تحتوي على ميزة لفتح إدخالات PDF المقابلة لمعرف قاعدة البيانات المتعاون (CSD، ICSD، NIST، LPF) |

| B | التفضيلات: يمكن تخصيص تفضيلات العرض مثل الحقول المرغوبة ومعلمات محاكاة الأنماط. |

| C | البحث: يفتح نافذة البحث الرئيسية. يمكن استخدام زر القائمة المنسدلة لاختيار عمليات البحث الأخيرة. |

| D | التاريخ: يحتوي على معايير البحث السابقة. يمكن دمج هذه العمليات باستخدام عوامل التشغيل البوليانية “و”، “أو” |

| E | النتائج: باستخدام زر القائمة المنسدلة، يمكن إعادة ملء نتائج البحث السابقة |

| F | رسم بياني للتكوين: يمكن رسم أي مجموعة من عنصرين أو ثلاثة كدالة لنسبة الذرات أو الوزن%. على سبيل المثال،

|

| G | SIeve+: يطلق برنامج البحث/المطابقة SIeve+ |

| H | التحليل الدقيق: التركيب العنصري من تحليل micro-XRF، تحليل المجهر، أو تحليل عنصر آخر |

عامل الإشغال، أو معلمات إزاحة مشكوك فيها بشكل كبير على تحديد الطور وبالتالي سيكون لها QM أقل. تتطلب أنماط PXRD التجريبية نوعًا مختلفًا من المعالجة من خلال مراعاة نقاء الطور، وجودة نمط الحيود، والفهرسة. تنطبق QMs G و M فقط على الأنماط ذات البلورات الضعيفة، والمواد النانوية، والأنماط غير المتبلورة. في هذه الحالة، تؤكد معايير QM على الجودة الكيميائية، وجودة البيانات، وتوصيفات أخرى (الطيفية، دالة توزيع الزوج، والميكروسكوبية). يصف الجدول II QMs المستخدمة في PDF.

| علامة |

|

معلومات كريستالوجرافية | تحذيرات | أخرى | ||||||||

| S أو (*) | متوسط

|

|

– لا شيء |

|

||||||||

| G |

|

|

|

(أي الطيفية، دوال توزيع الزوج، مصدر تجاري، إلخ). | ||||||||

| I |

|

|

|

يكون اكتمال النمط معقولًا. الانعكاسات التي تحتوي على

|

||||||||

| C |

|

– إذا كان النمط المحسوب لا يفي بمعايير علامة الجودة “S”، يتم تعيين QM = B | هذا QM يشير إلى الأنماط المحسوبة المنشورة من قبل المؤلف. يجب عدم الخلط بين تلك التي تحمل “C” والأنماط المحسوبة من قبل ICDD بناءً على الهياكل البلورية من قواعد البيانات المتعاونة. سيكون للنمط المحسوب من قبل ICDD QM غير C/G/M. | |||||||||

| M |

|

لا توجد بيانات تحليل كيميائي لدعم تركيبة المواد المقدمة (عادةً عينات تجارية). | ||||||||||

| B |

|

– بالنسبة للأنماط المحسوبة من قبل ICDD، تحتوي هذه على تحذيرات كبيرة بشأن الهيكل غير المكتمل، تحذيرات التناظر، معلمات الإزاحة غير الإيجابية، إلخ. | قد يحتوي النمط التجريبي على خطوط غير مفهرسة | |||||||||

| P | – ينطبق فقط على الأنماط المحسوبة | – بالنسبة للأنماط المحسوبة من قبل ICDD بناءً على نموذج الهيكل. هذه هي الحالات التي عيّن فيها المؤلف أو المحرر نوع الهيكل | ||||||||||

| 0 |

|

– عادةً، قام المحرر بإدراج تعليق لشرح سبب تعيين “O”. | تعني علامة الجودة ذات الدقة المنخفضة أن بيانات الانكسار قد تم أخذها على عينة مشكوك فيها أو واحدة تحتوي على شوائب كبيرة. | |||||||||

| H | – ينطبق فقط على الأنماط المحسوبة | بالنسبة للأنماط المحسوبة من قبل ICDD بناءً على الهياكل النظرية [مثل حسابات نظرية الكثافة الوظيفية (DFT)] |

| حالة قاعدة البيانات | الوصف |

| أساسي (P) | تم اختياره تحريرياً كمدخل تمثيلي لمرحلة معينة |

| بديل (A) | خيارات بديلة لمرحلة معينة. هذا لا يعني بالضرورة جودة أقل من الأساسي |

| محذوف (D) | عادةً ما تكون إدخالات مكررة، أخطاء غير محلولة، تم استبدالها بإدخالات تحتوي على بيانات أفضل. |

B. أرشفة البيانات الخام

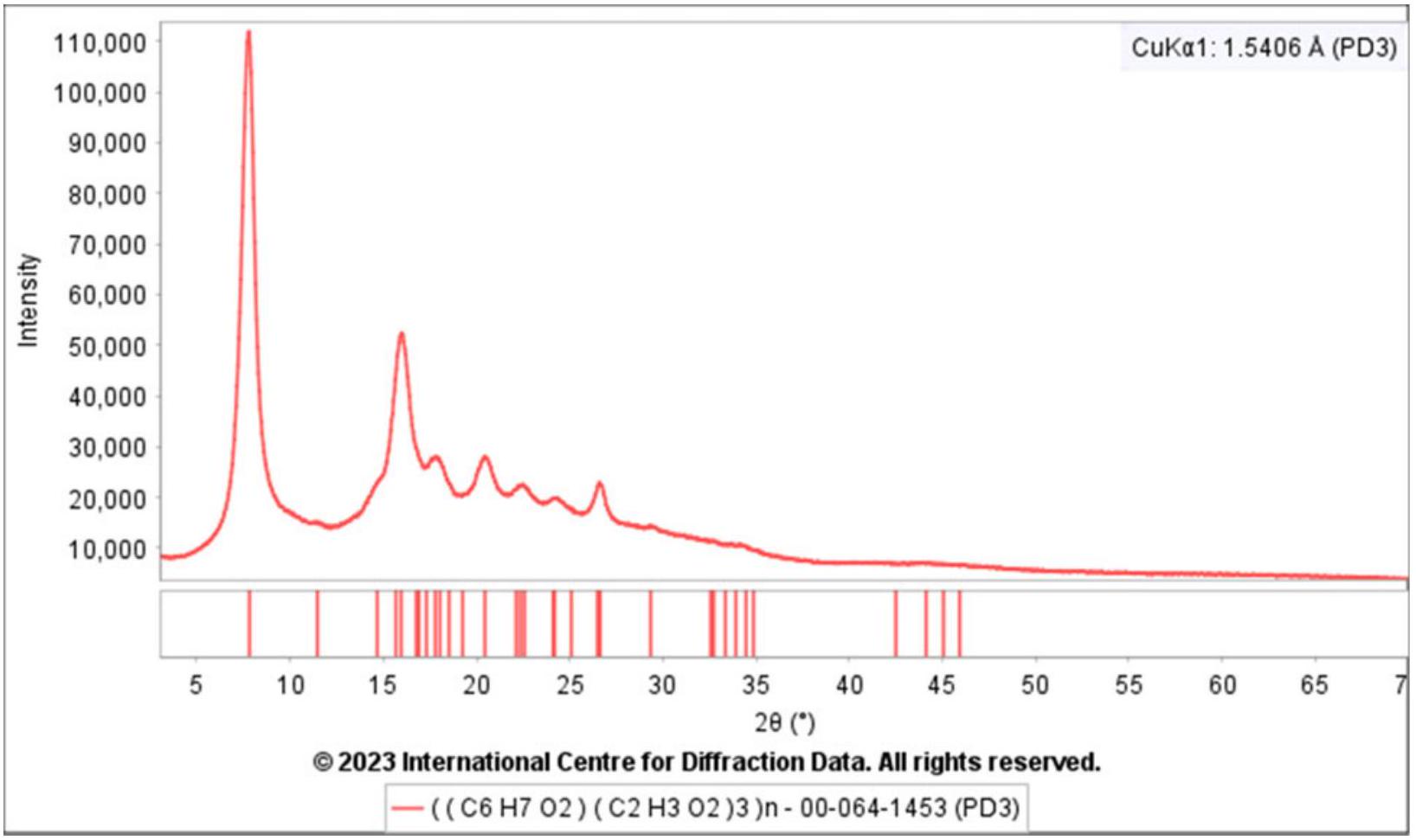

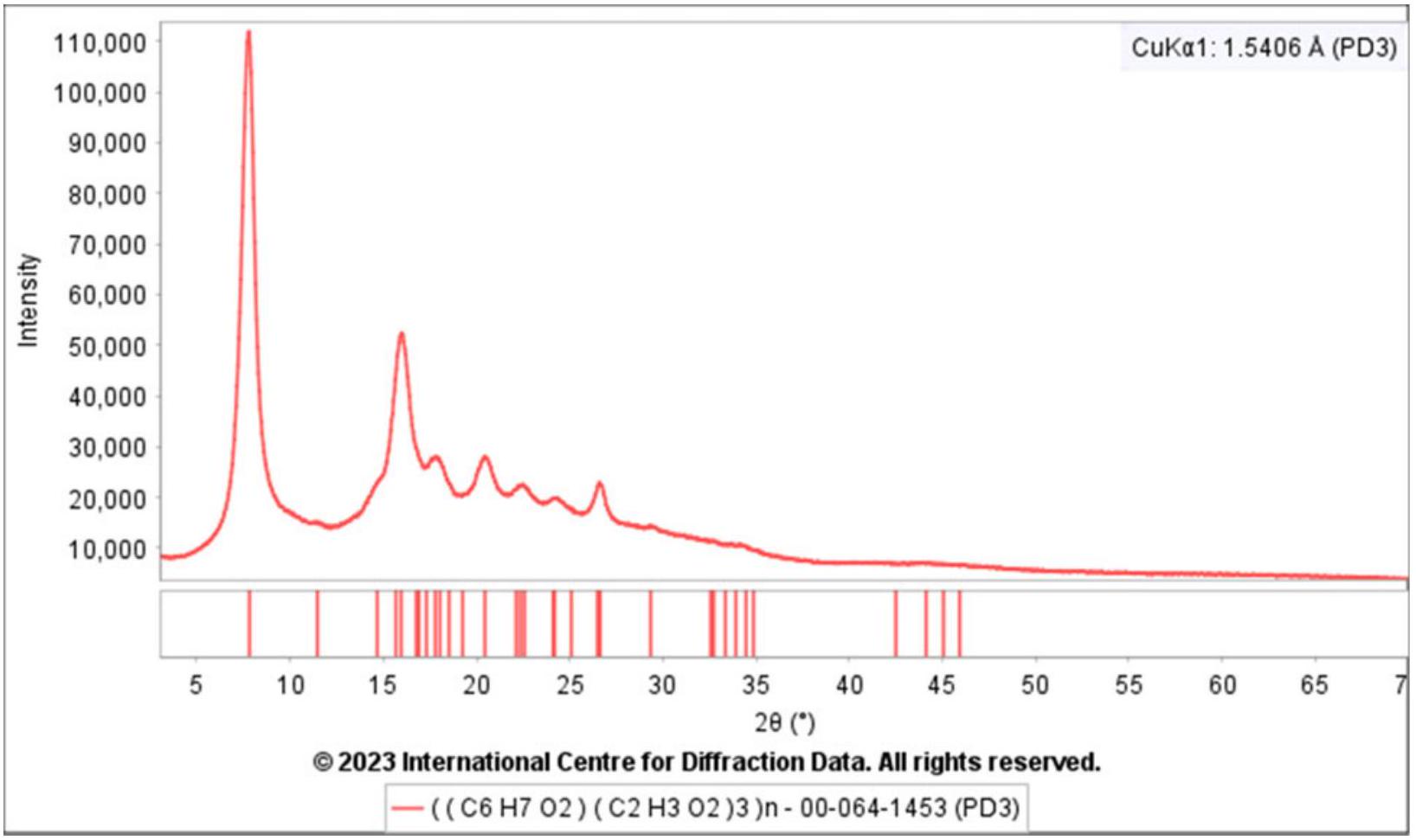

قاعدة البيانات (Fawcett et al., 2017, 2020)، والتي تعمل بشكل جيد للمرحلة البلورية بسبب قممها الحادة (الضيقة). من الواضح من الشكل 6 أن وجود البيانات الخام أمر ضروري لإجراء تحديد المرحلة في حالة الأنماط البلورية الضعيفة أو غير المتبلورة حيث لا يمكن تمثيلها بشكل مرضٍ كقائمة من المسافات بين المستويات (

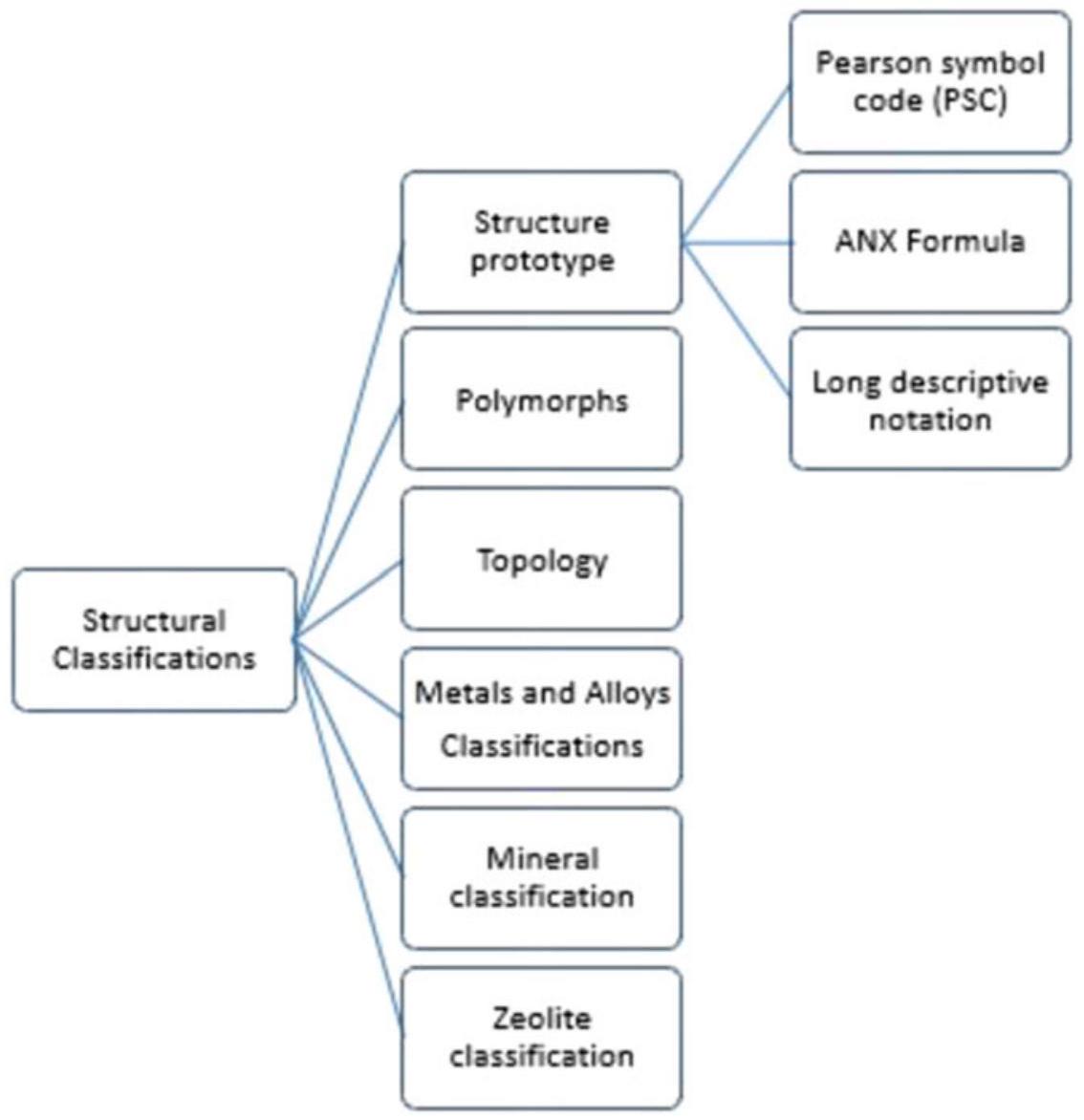

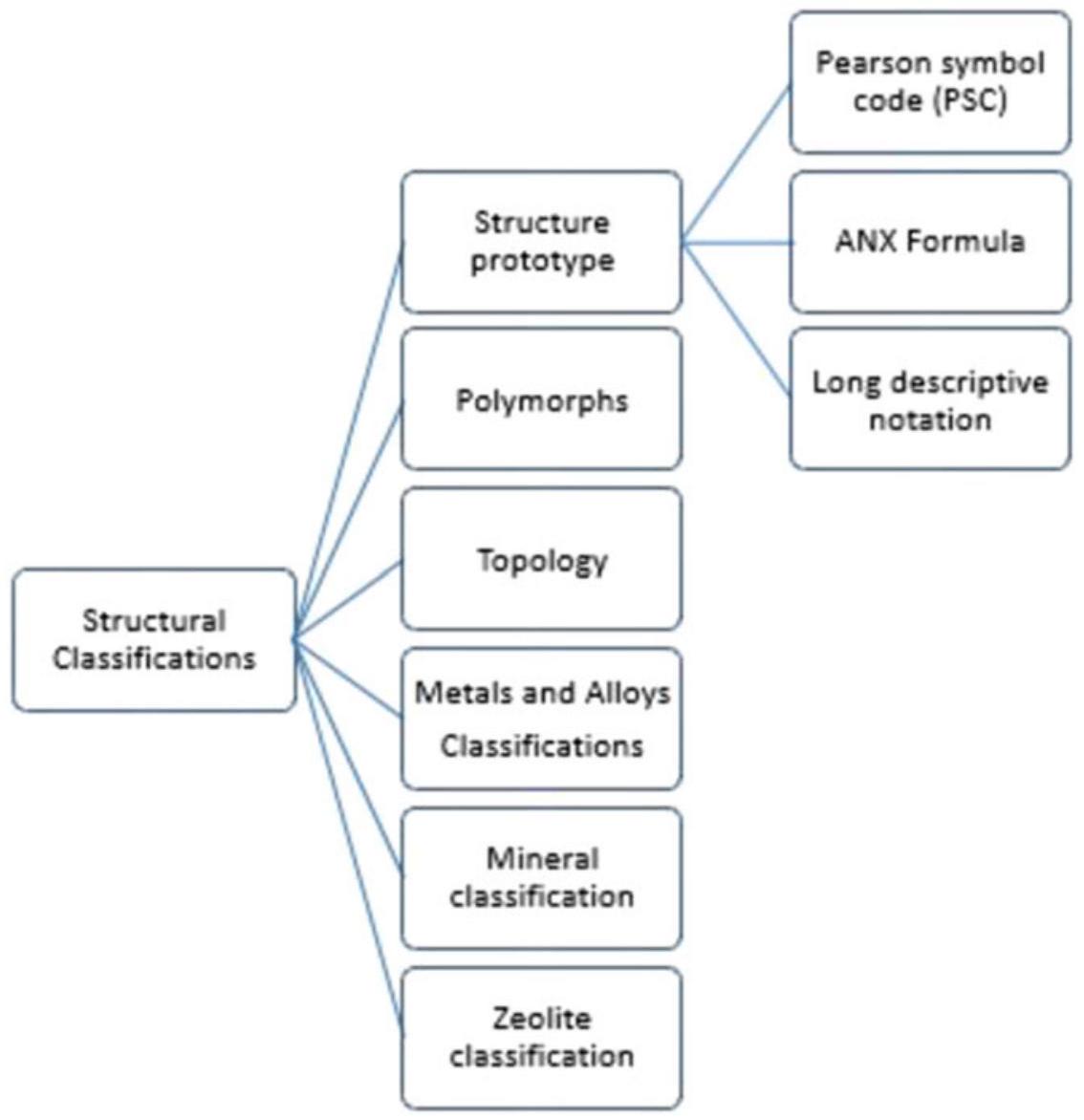

C. التصنيفات الهيكلية

a. يعتمد تدوين نوع الهيكل التقليدي على وحدة خلوية موحدة، ونسب محورية، ومجموعة فضاء، ورمز رمز بيرسون (Pearson، 1967)، وكيمياء (Wallace et al., 1994). عادةً ما يتم تعيين هذه الأوصاف يدويًا، على سبيل المثال، هيكل من نوع

b. يعتمد نوع ANX على نوع الأيون واحتلال الموقع. على سبيل المثال،

c. يعتمد نموذج الهيكل على طريقة التوحيد القياسي الموضحة بواسطة Gelato و Parthé، 1987، تليها تحليل بلوري مفصل للبيئة الذرية (Villars et al., 1998؛ Allmann و Hinek، 2007). على سبيل المثال،

d. يعتمد تصنيف الزيوليت على نوع الإطار (Baerlocher et al., 2007). عادةً ما يتم ملاحظتها بواسطة رمز مكون من ثلاثة أحرف كبيرة يصف شبكة من ذرات الإطار المنسقة رباعيًا.

تشارك ذرات الإطار. تنشر الجمعية الدولية للزيوليت (IZA) هذه الرموز ويتم إدراج الرموز على موقعها الإلكتروني (https:// america.iza-structure.org/IZA-SC/ftc_table.php)

e. يعتمد تصنيف المعادن على الخصائص الكيميائية البلورية (Smith et al., 1997). يهدف التصنيف إلى استغلال الخصائص الكيميائية البلورية والتشابه في نمط انكسار المسحوق بين أعضاء المجموعة المتشابهة لتعزيز جودة مراحل المعادن في PDF.

f. الطوبولوجيا: على عكس التحليل الهندسي، يوفر التحليل الطوبولوجي أداة لاستخدام البيانات البلورية واستكشاف الهيكل الطوبولوجي والتشابهات في الفضاء البلوري (Blatov et al., 2014). من وجهة نظر قاعدة البيانات، من المفيد البحث عن سلاسل متشابهة أو متشابهة. يمكن أيضًا استخدام التحليلات الطوبولوجية لتحسين جودة قاعدة البيانات.

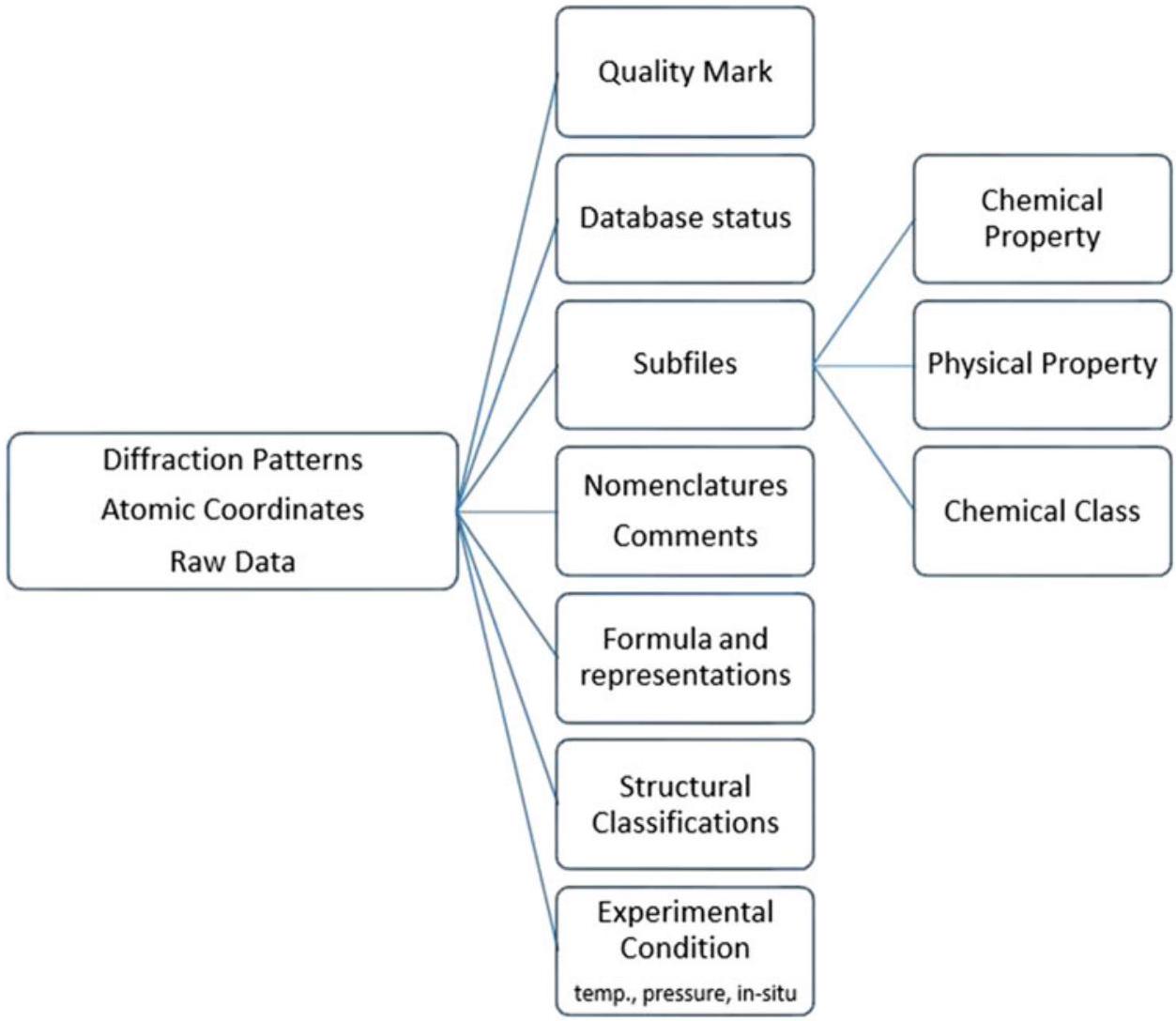

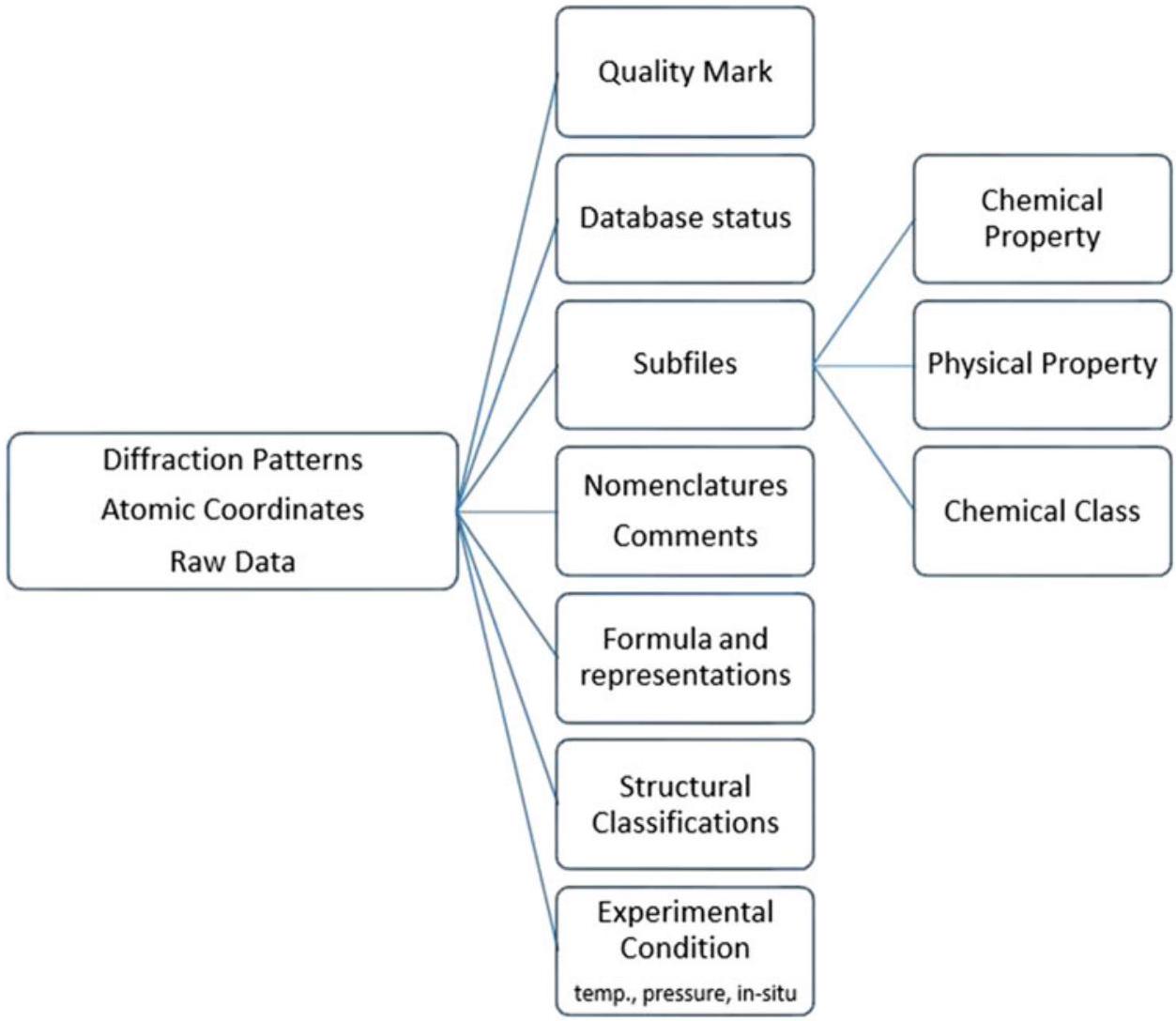

D. الملفات الفرعية

عادةً ما يكون أعضاء لجنة فرعية معينة من ICDD (https://www.icdd.com/technical-subcommittees/).

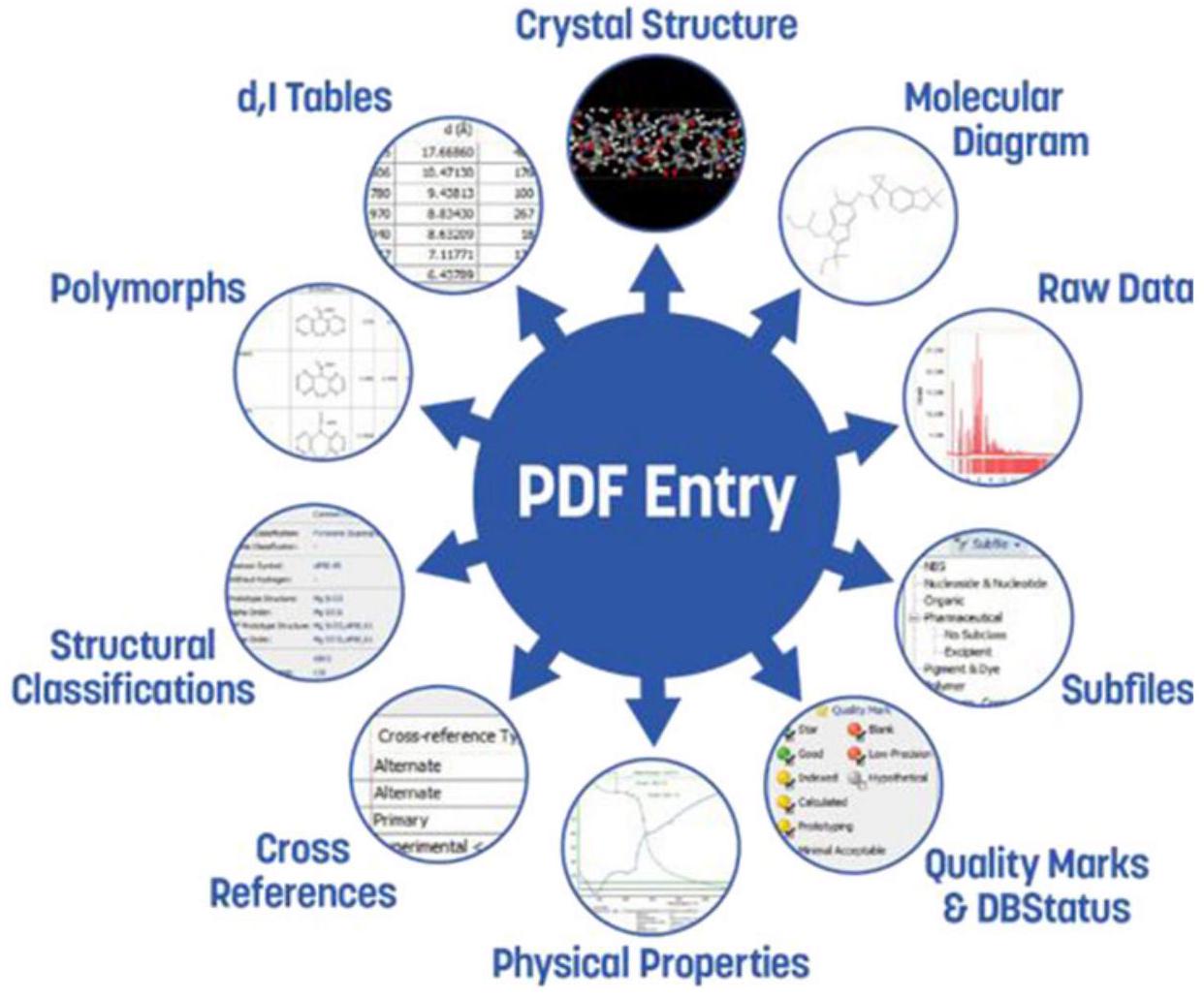

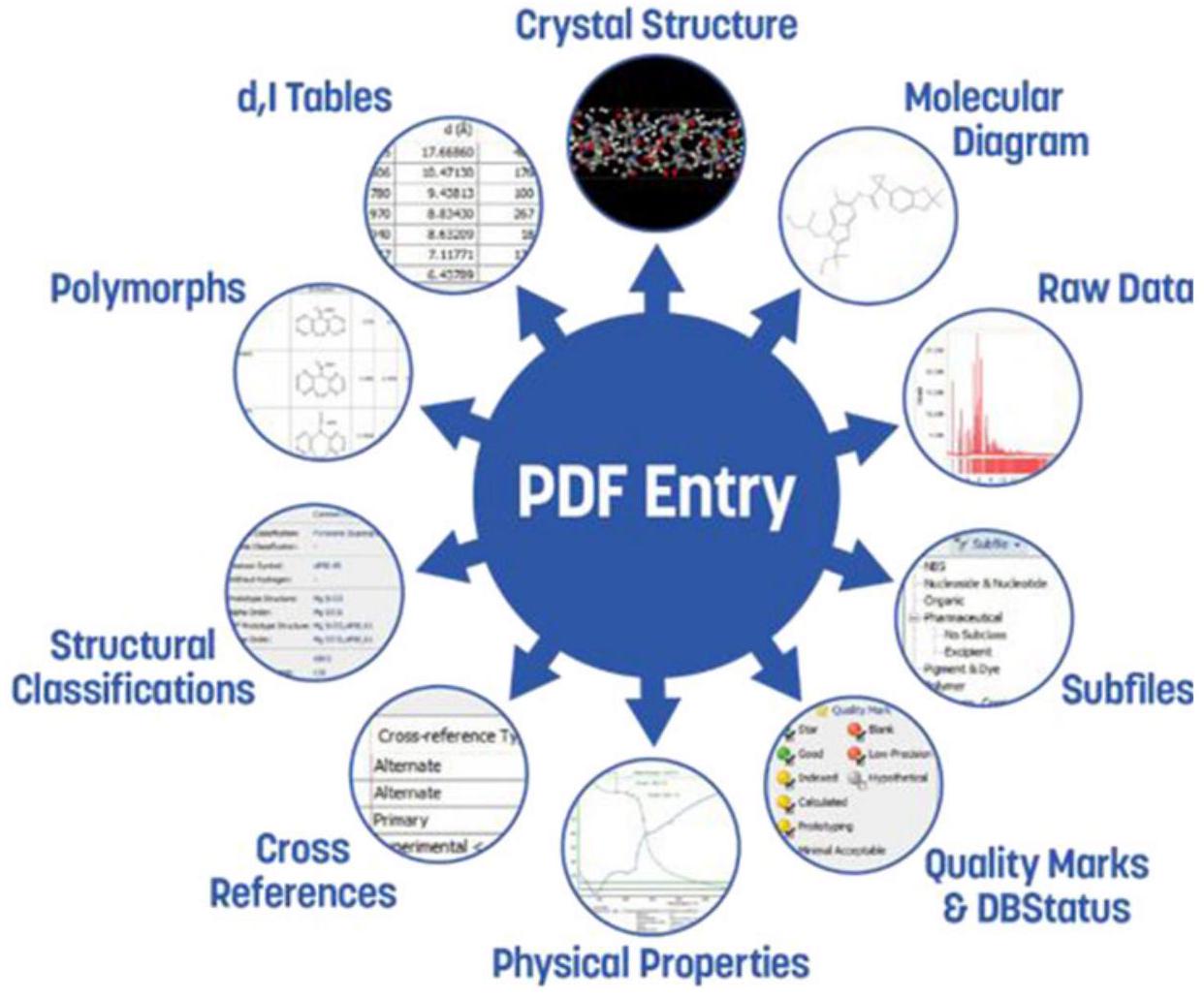

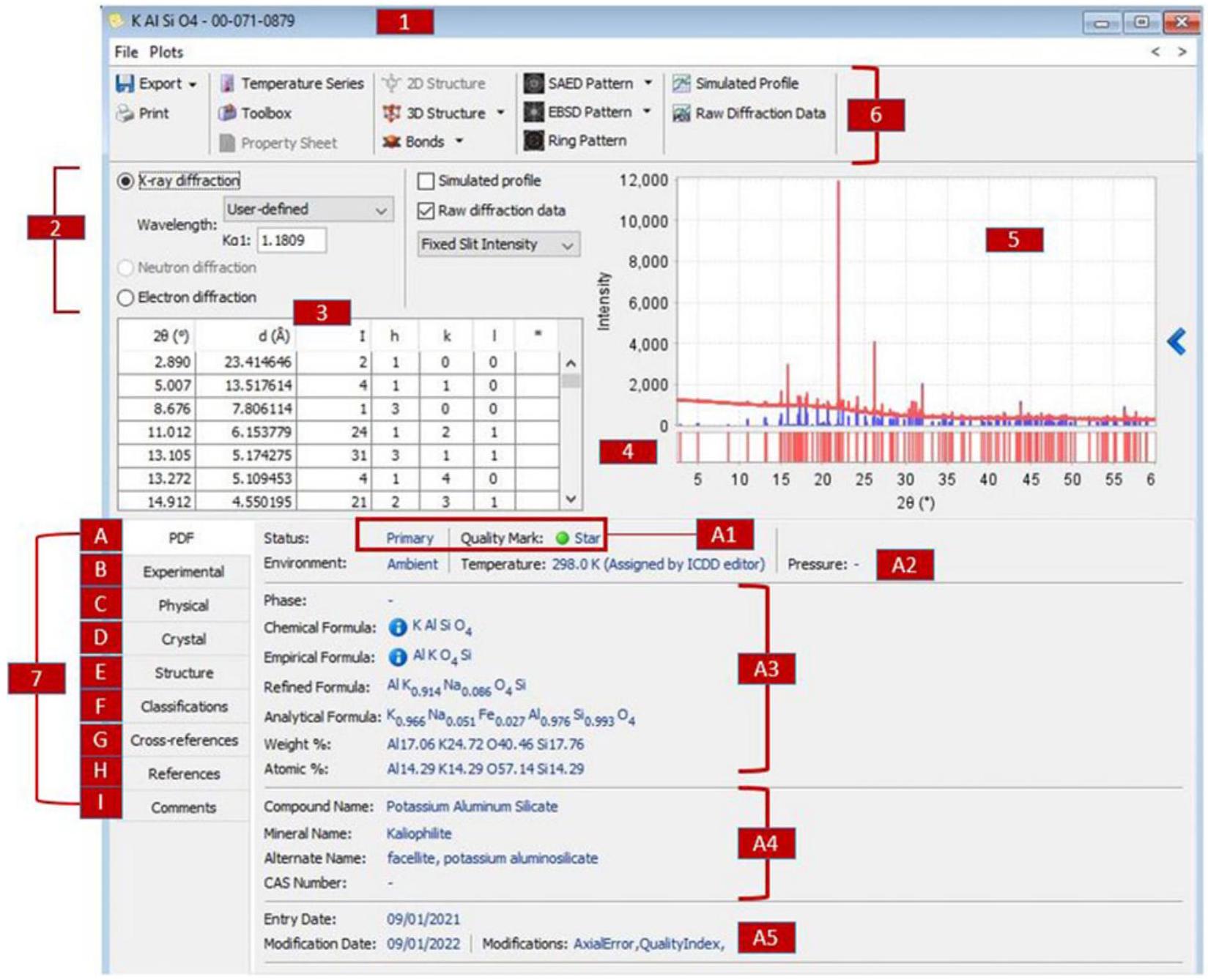

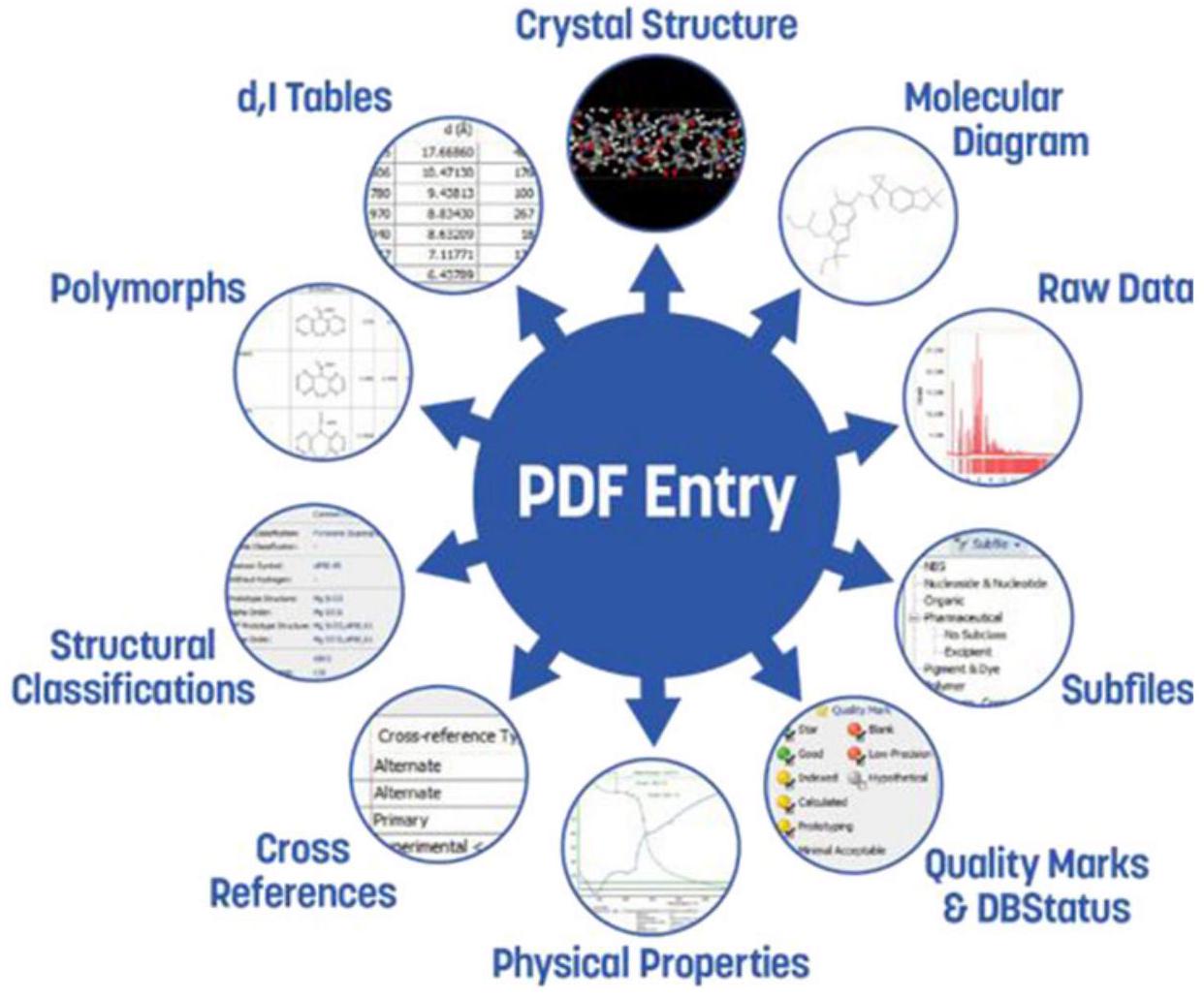

الرابع. إدخال PDF

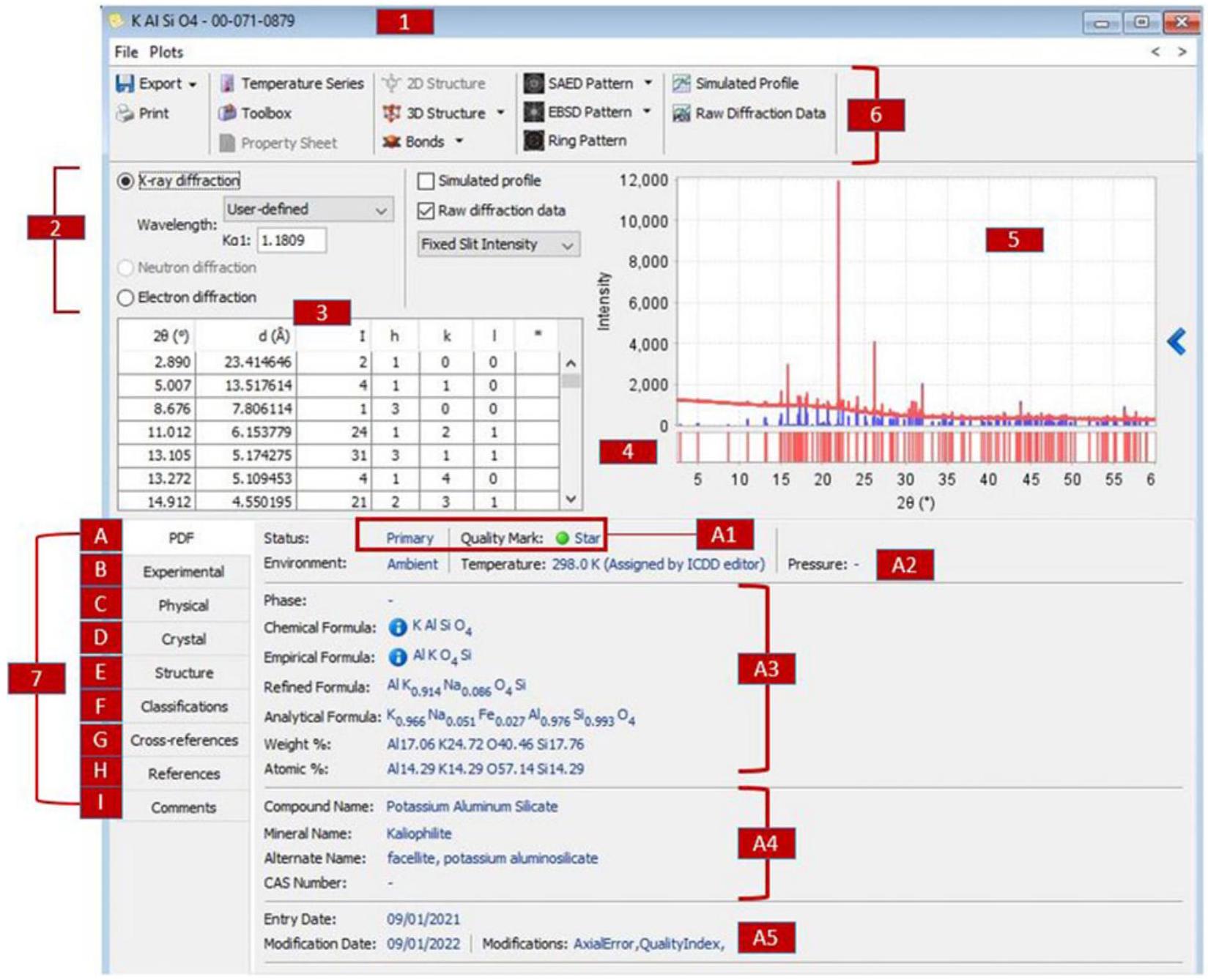

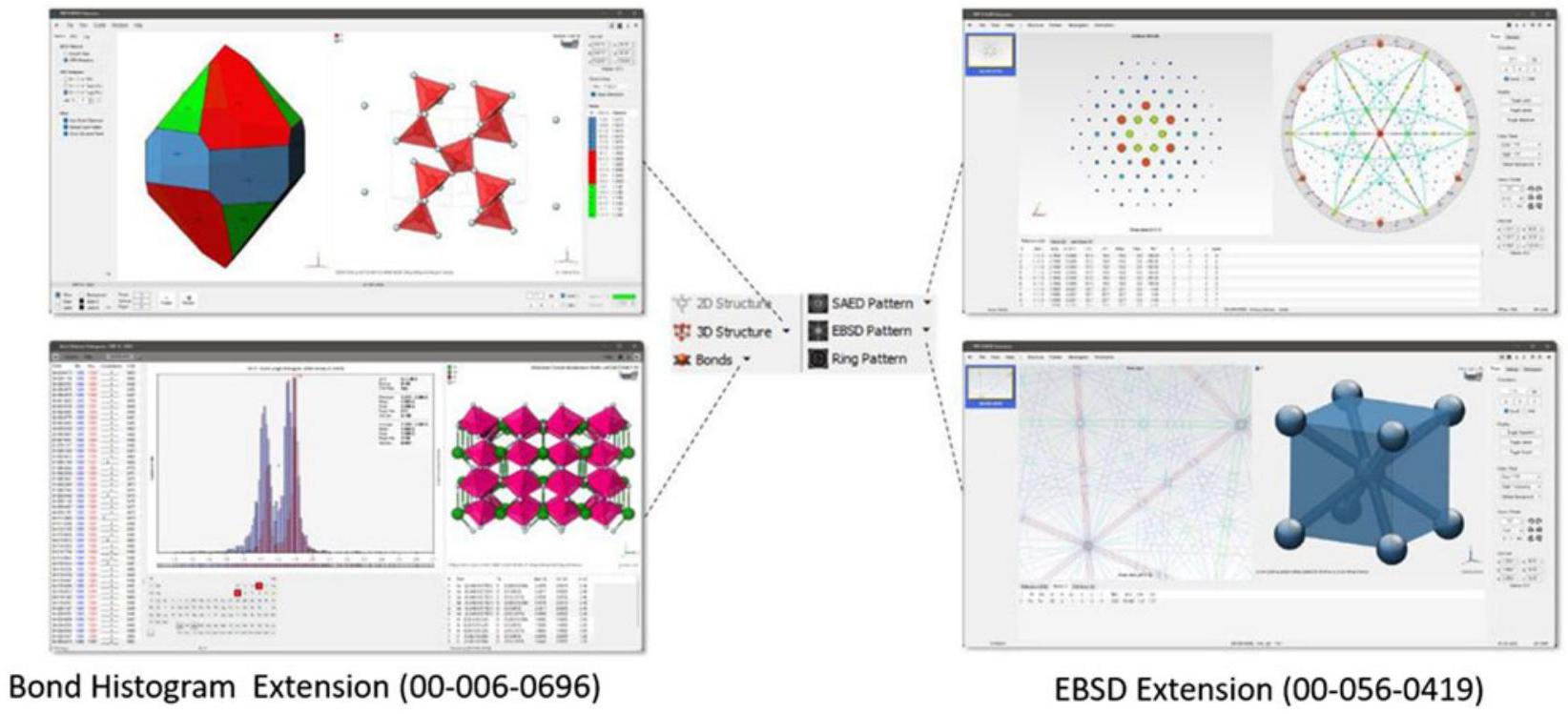

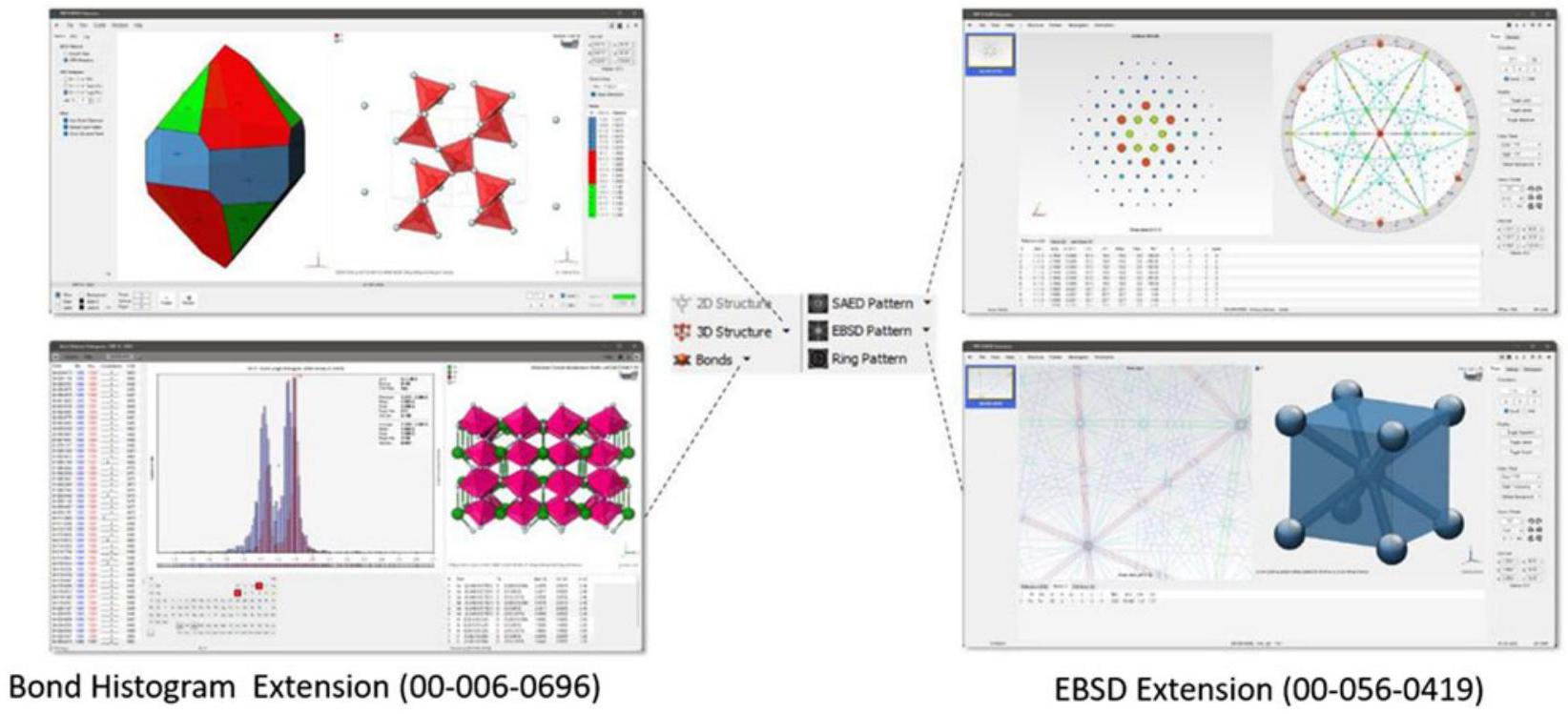

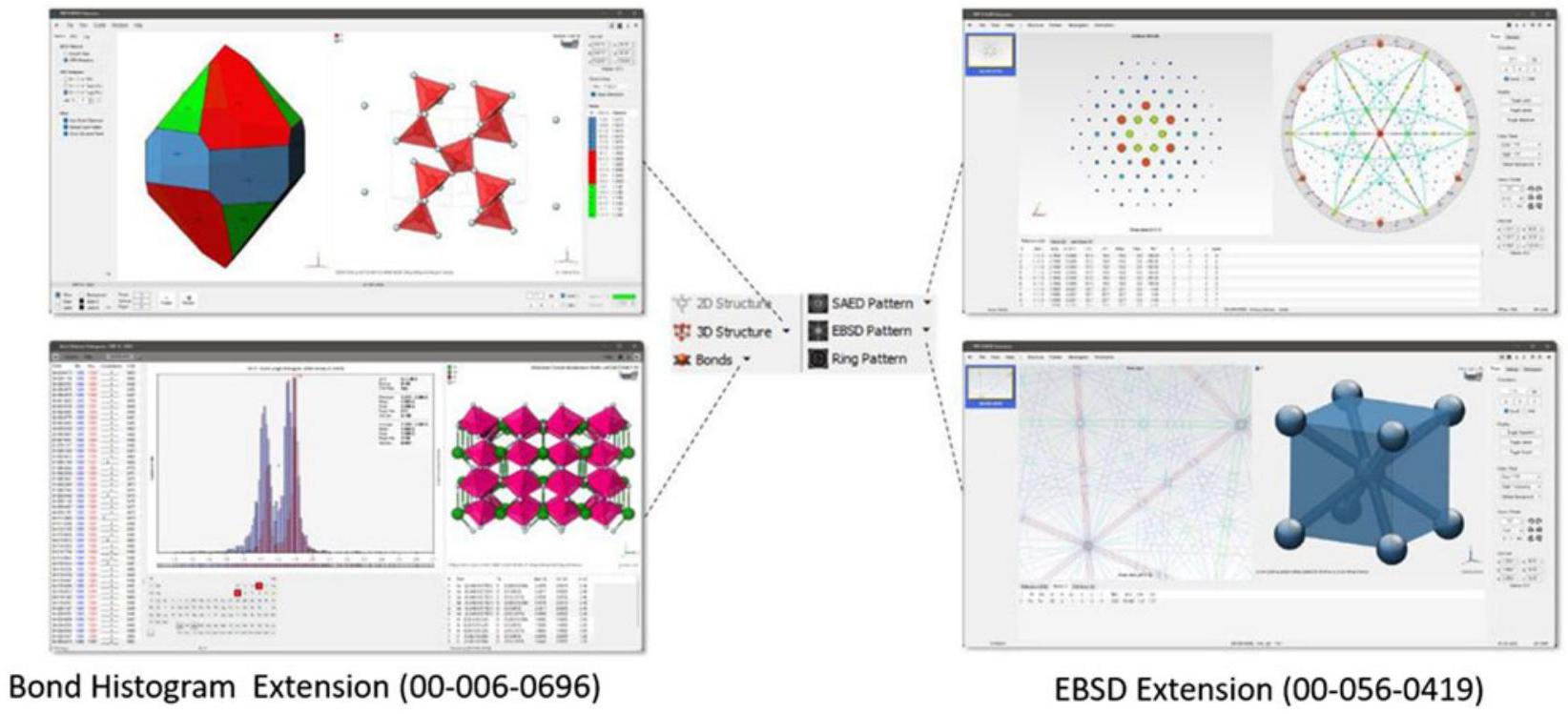

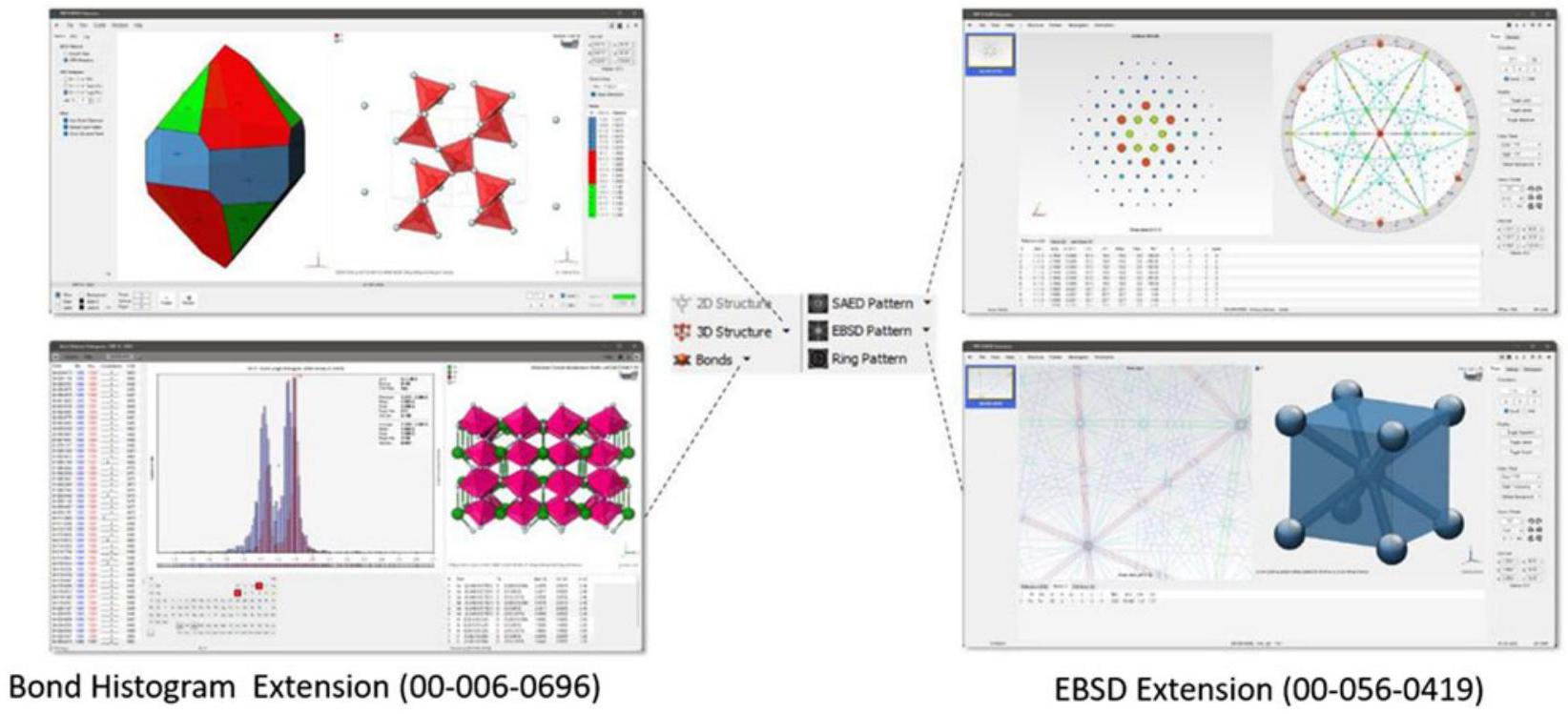

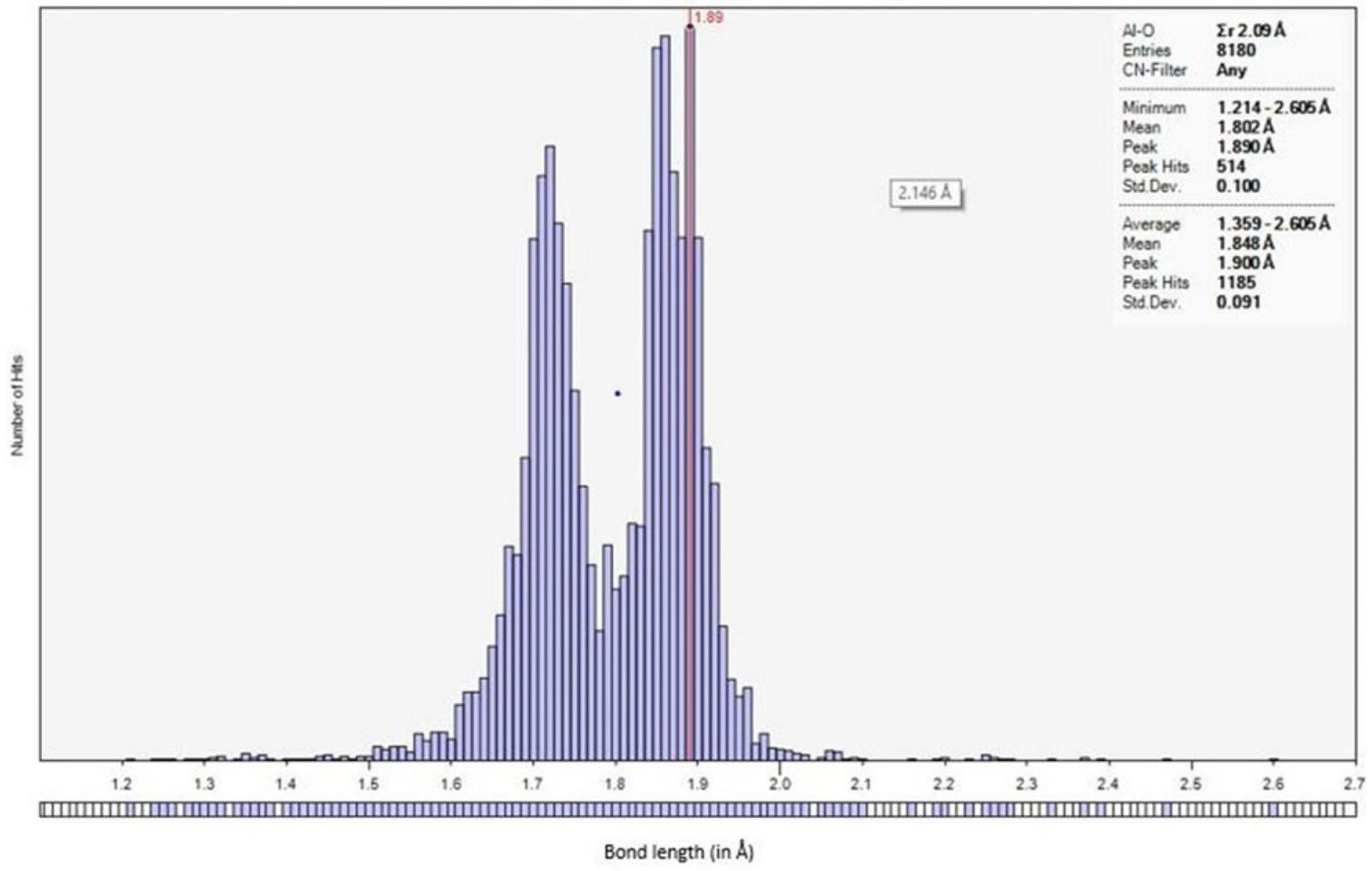

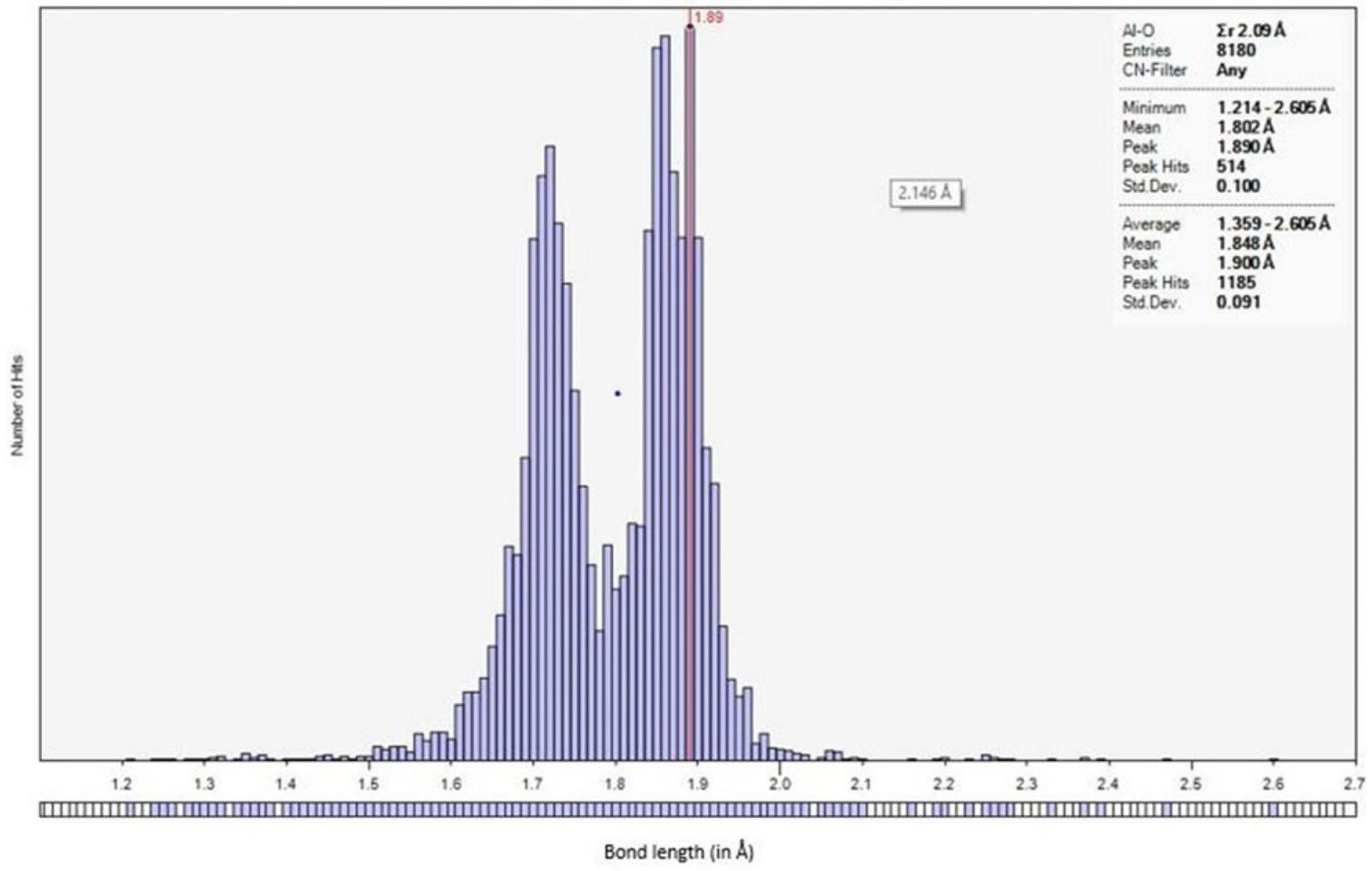

ملخص في الشكلين 9 و 10. بالإضافة إلى هذه الميزات، يقدم PDF-5+ امتدادات مجموعة أدوات JADE ويمكن تشغيلها من إدخال PDF كما هو موضح في الشكل 11.

أ. برافيس-فريدل-دوناي-هاركر (BFDH)

ب. حيّز الانكسار الإلكتروني المختار (SAED)

ج. حيود الإلكترونات المرتدة

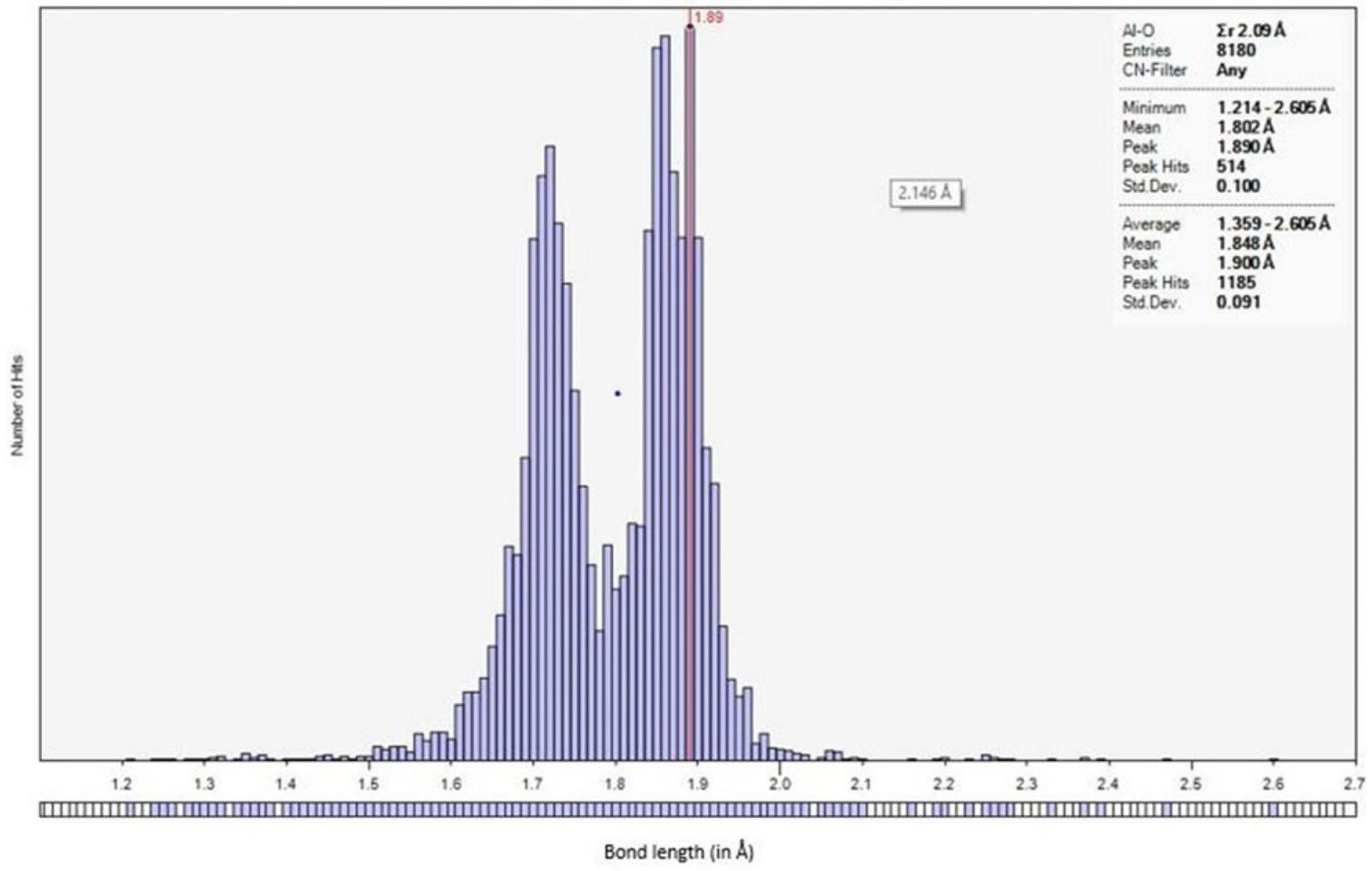

مخطط توزيع الروابط

| 1 | PDFID | رقم الدخول | ||||||

| 2 | نوع الإشعاع | الأشعة السينية، الإلكترون، النيوترون؛ الطول الموجي، وتباعد الشعاع، فتحات الأجهزة، إلخ. | ||||||

| ٣ |

|

فواصل الطبقات بين المستويات (d) والشدة (I). يتم سرد مؤشرات ميلر عند توفرها | ||||||

| ٤ | علامات التحقق | تمثيل بياني لموقع الذروة | ||||||

| ٥ | مخطط التشتت | الملف التجريبي (بيانات الانكسار الخام) أو ملف الانكسار المحاكى | ||||||

| ٦ | مفاتيح الوظائف | الأدوات والمحاكيات المرتبطة بإدخال PDF. تشير الرموز الرمادية إلى أن الأداة أو المحاكاة غير متاحة لهذا الإدخال. | ||||||

| ٧ | علامات المعلومات التكميلية |

|

| أ1 | تعيينات تحريرية | الحالة – أساسية، بديلة، أو محذوفة |

| علامة الجودة – انظر الجدول II: المعايير الرئيسية لتعيين علامة جودة PDF | ||

| A2 | شروط العينة | يحدد البيئة ودرجة الحرارة والضغط لجمع البيانات. |

| A3 | كيمياء | تشير إلى التسمية المتعددة الأشكال لمرحلة معينة، بالإضافة إلى الصيغة (الصيغ)، ونسبة الوزن، ونسبة الذرات المرتبطة بالدخول؛ حسب المتاح. |

| A4 | معرف المركب (المعرفات) | الأسماء وأرقام التسجيل المستخدمة لتحديد المركب |

| A5 | تاريخ | التفاصيل المتعلقة بالنشر الأولي للإدخالات، وإذا كان ذلك مناسبًا، التعديلات الأخيرة |

V. التوفر

المصنعون والمطورون المستقلون، ويعملون بجد على تطوير برامج تحليل البيانات التجارية التي تعمل بشكل مثالي مع قواعد بياناتنا.

VI. الخاتمة

شكر وتقدير

REFERENCES

Blatov, V. A., A. P. Shevchenko, and D. M. Proserpio. 2014. “Applied Topological Analysis of Crystal Structures with the Program Package ToposPro.” Crystal Growth & Design 14 (7): 3576-86. doi:10.1021/ cg500498k.

Bruno, I., S. Gražulis, J. R. Helliwell, S. N. Kabekkodu, B. McMahon, and J. Westbrook. 2017. “Crystallography and Databases.” Data Science Journal 16: 38. doi:10.5334/dsj-2017-038.

Donnay, J. D. H., and D. Harker. 1937. “A New Law of Crystal Morphology Extending the Law of Bravais” American Mineralogist 22: 446-67.

Dowty, E. 1976. “Crystal Structure and Crystal Growth: I. The Influence of Internal Structure on Morphology.” American Mineralogist 61: 448-59.

Faber, J., and T. Fawcett. 2002. “The Powder Diffraction File: Present and Future.” Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Science 58 (3): 325-32. doi:10.1107/S0108768102003312.

Fawcett, T. G., S. N. Kabekkodu, J. R. Blanton, and T. N. Blanton. 2017. “Chemical Analysis by Diffraction: The Powder Diffraction File

Fawcett, T. G., S. Gates-Rector, A. M. Gindhart, M. Rost, S. N. Kabekkodu, J. R. Blanton, and T. N. Blanton. 2019. “A Practical Guide to Pharmaceutical Analyses Using X-Ray Powder Diffraction.” Powder Diffraction 34 (2): 164-83. doi:10.1017/S088571561900023X.

Fawcett, T. G., S. Gates-Rector, A. M. Gindhart, M. Rost, S. N. Kabekkodu, J. R. Blanton, and T. N. Blanton. 2020. “Total Pattern Analyses for Non-Crystalline Materials.” Powder Diffraction 35 (2): 82-8. doi:10.1017/S0885715620000263.

Gates, S. D., T. N. Blanton, and T. G. Fawcett. 2014. “A New ‘Chain’ of Events: Polymers in the Powder Diffraction File

Gates-Rector, S., and T. Blanton. 2019. “The Powder Diffraction File: A Quality Materials Characterization Database.” Powder Diffraction 34 (4): 352-60. doi:10.1017/S0885715619000812.

Goehner, R. P., and J. R. Michael. 1996. “Phase Identification in a Scanning Electron Microscope Using Backscattered Electron Kikuchi Patterns.” Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology 101 (3): 301. doi:10.6028/jres.101.031.

Groom, C. R., I. J. Bruno, M. P. Lightfoot, and S. C. Ward. 2016. “The Cambridge Structural Database.” Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Science, Crystal Engineering and Materials 72 (2): 171-79. doi:10.1107/S2052520616003954.

Hanawalt, J. D. 1986. “Manual Search/Match Methods for Powder Diffraction in 1986.” Powder Diffraction 1 (1): 7-13.

Hanawalt, J. D., H. W. Rinn, and L. K. Frevel. 1938. “Chemical Analysis by X-ray Diffraction.” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Analytical Edition 10 (9): 457-512.

Helliwell, J. R., B. McMahon, J. Mitchell Guss, and L. M. J. KroonBatenburg. 2017. “The Science Is in the Data.” IUCrJ 4 (6): 714-22. doi:10.1107/S2052252517013690.

Hofmann, D. W. M., and L. Kuleshova. 2005. “New Similarity Index for Crystal Structure Determination from X-Ray Powder Diagrams.” Journal of Applied Crystallography 38 (6): 861-66. doi:10.1107/S0021889805023484.

Hubbard, C. R., J. K. Stalick, and A. D. Mighell. 1980. “NBS* AIDS80: A Fortran Program to Evaluate Crystallographic Data.” Advances in X-Ray Analysis 24: 99-109.

Jenkins, R. & Smith, D. (1987). Powder Diffraction File in F. H. Allen, G. Bergerhoff, and R. Sievers (Eds.) Crystallographic Databases (pp. 159-74). Data Commission of the International Union of Crystallography.

Jenkins, R., M. Holomany, and W. Wong-Ng. 1987. “On the Need for Users of the Powder Diffraction File to Update Regularly.” Powder Diffraction 2 (2): 84-87. doi:10.1017/S0885715600012434.

Johnson, G., and V. Vand. 1967. “A Computerized Powder Diffraction Identification System.” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry 59 (8): 19-31.

Kabekkodu, S. N., J. Faber, and T. Fawcett. 2002. “New Powder Diffraction File (PDF-4) in Relational Database Format: Advantages and Data-Mining Capabilities.” Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Science 58 (3): 333-37. doi:10.1107/S0108768102002458.

Kaduk, J. A. (2019). Crystallographic Databases and Powder Diffraction in J. A. K. C. Gilmore and H. Schenk (Eds.) International Tables for Crystallography Volume H: Powder Diffraction. 1st ed. (Chap. 3.7, pp. 304-24). New York, Wiley.

Messick, J. 2012. “The History of the International Centre for Diffraction Data.” Powder Diffraction 27 (1): 36-44. doi:10.1017/ S0885715612000085.

Pearson, W. B. 1967. Handbook of Lattice Spacings and Structures of Metals. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Reid, J. W., J. A. Kaduk, and M. Vickers. 2016. “The Crystal Structure of Trandolapril,

Smith, D. K., P. Bayliss, and A. C. Roberts. 1997. “Mineral Classification in the Mineral Powder Diffraction File.” Advances in X-Ray Analysis 41: 606-13.

Villars, P., & K. Cenzual. 2018. Pearson’s Crystal Data: Crystal Structure Database for Inorganic Compounds. Materials Park, OH, USA: ASM International.

Villars, P., N. Onodera, and S. Iwata. 1998. “The Linus Pauling File (LPF) and Its Application to Materials Design.” Journal of Alloys and Compounds 279 (1): 1-7. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(98)00605-7.

Wallace, P. L., S. Weissmanna, M. H. Mueller, L. D. Calveit, and R. Jenkins. 1994. “The New ICDD Metals and Alloys Indexes: Usefulness and Potentialities.” Powder Diffraction 9 (4): 239-45. doi:10.1017/ S0885715600018947.

Wilkinson, M. D., M. Dumontier, I. J. Aalbersberg, G. Appleton, M. Axton, A. Baak, N. Blomberg, et al. 2016. “The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship.” Scientific Data 3 (1): 160018. doi:10.1038/sdata.2016.18.

Zagorac, D., H. Müller, S. Ruehl, J. Zagorac, and S. Rehme. 2019. “Recent Developments in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database: Theoretical Crystal Structure Data and Related Features.” Journal of Applied Crystallography 52 (5): 918-25. doi:10.1107/S160057671900997X.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. Electronic mail: kabekkodu@icdd.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0885715624000150

Publication Date: 2024-04-15

PDF-5+: a comprehensive Powder Diffraction File

Abstract

For more than 80 years, the scientific community has extensively used International Centre for Diffraction Data’s (ICDD®) Powder Diffraction File (PDF®) for material characterization, including powder X-ray diffraction analysis. Historically, PDF was made available for two major material types: one for inorganic analysis and the other for organic analysis. In the early years of the PDF, this twomaterial approach was implemented due to limited computer capabilities. With Release 2024, ICDD provides a comprehensive database consisting of the entire PDF in one database called PDF-5+, comprised of more than one million entries (

[doi:10.1017/S0885715624000150]

Keywords: Powder X-ray diffraction, XRD database, quality mark, subfiles, PDF card

I. INTRODUCTION

diffraction data to identify materials. The membership of the ICDD consists of worldwide representation from academe, government, and industry. This paper is an update of a previously published paper (Gates-Rector and Blanton, 2019) on the PDF®. In this paper, we attempt to focus on the recent changes to the PDF database and relational database software and to minimize the duplication of features that were presented in the Gates-Rector and Blanton paper of 2019.

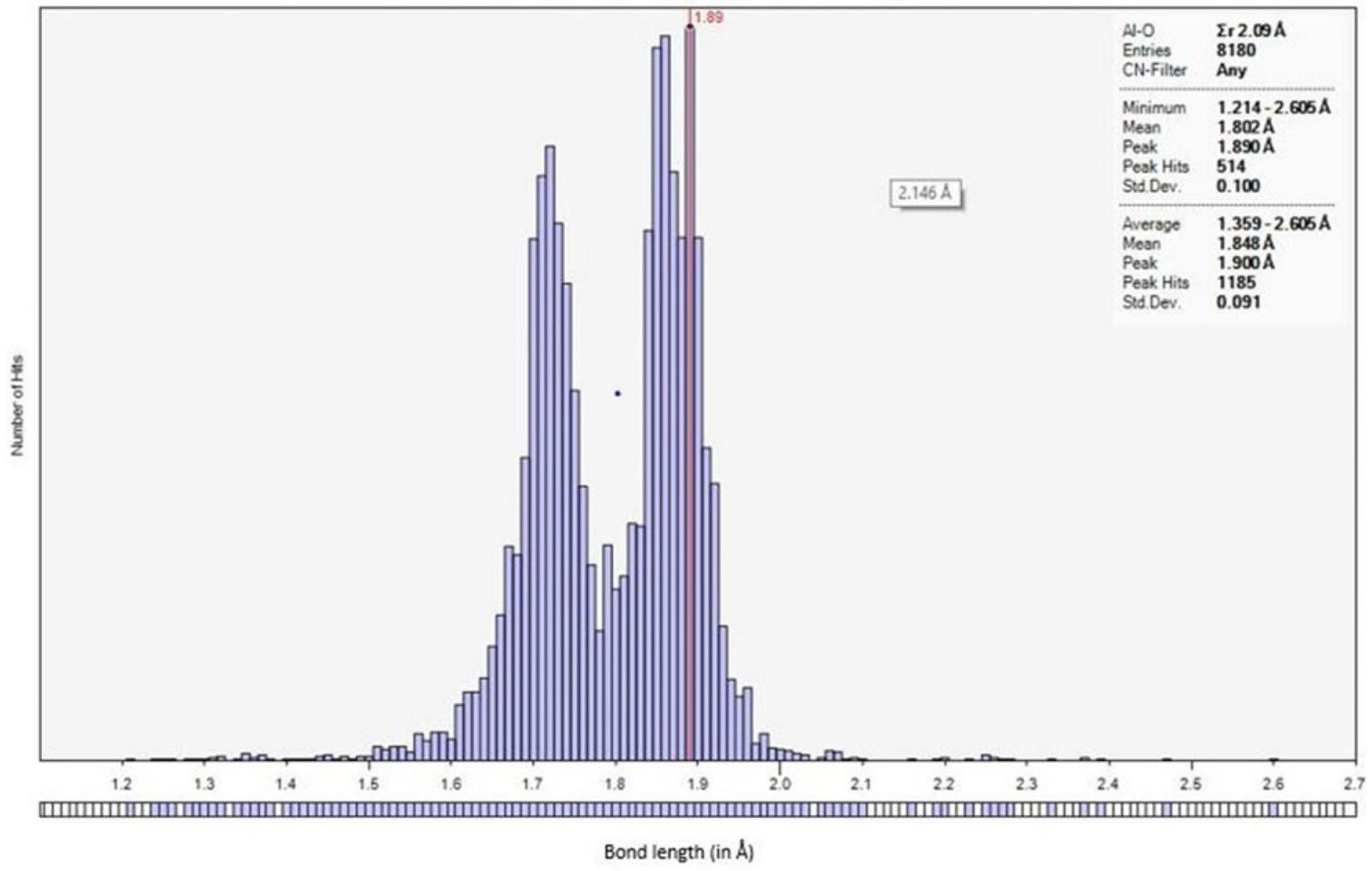

II. DATABASE DEVELOPMENT: PDF

management system (RDBMS). The PDF in relational database format (RDB) contains extensive chemical, physical, bibliographic, and crystallographic data, including atomic coordinates enabling characterization and computational analysis. The RDB construct provides pliable access to the database for data mining studies and enhances the PDF materials characterization capabilities (Faber and Fawcett, 2002; Kabekkodu et al., 2002). One of the profound benefits of RDB is the more straightforward implementation of FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) principles (Wilkinson et al., 2016) and better data interoperability. This type of construct is vital from an interoperability perspective, given the existence of multiple automated software routines (by various diffractometer manufacturers or software developers) used for phase identification and quantification.

III. DATA CURATION

A. Quality mark and database status

review and presented using a quality mark (QM) nomenclature (Hubbard et al., 1980; Jenkins and Smith, 1987; Bruno et al., 2017; Gates-Rector and Blanton, 2019; Kaduk, 2019) that provides the user with a systematic process for understanding data entry quality and a consistent approach in assessing the goodness-of-match (GOM) for phase identification. All of the data in the PDF has gone through a multi-tier editorial

| Label | Description |

| 1 | All Data: Uses the entire database |

| 2 | Inorganic Emphasized: Mainly for inorganic phases with some common organics (DB code 02- and most of 05- are not included) |

| 3 | Organic Emphasized: Mainly Organic phases with some common inorganics (like excipients, pigments, etc.) |

| A | PDF Cards: Opens a PDF card (entry) by the given PDF number. Also has a feature to open PDF entries corresponding to the collaborating database (CSD, ICSD, NIST, LPF) identifier |

| B | Preferences: Display preferences such as desired fields and pattern simulation parameters can be customized. |

| C | Search: Brings up the main search window. The dropdown button can be used to select recent searches. |

| D | History: Contains previous search criteria. These searches can be combined using Boolean “and”, “or” operators |

| E | Results: Using the dropdown button, previous search results can be repopulated |

| F | Composition Graph: Any 2 or 3 elements combination can be graphed as a function of atomic% or weight%. For example,

|

| G | SIeve+: Launches the search/match program SIeve+ |

| H | Microanalysis: Elemental composition from a micro-XRF analysis, microprobe analysis, or other elemental analysis |

occupation factor, or questionable displacement parameters can have a significant impact on phase identification and thus would have a lower QM. Experimental PXRD patterns require a different type of treatment by considering phase purity, quality of the diffraction pattern, and indexing. QMs G and M are applicable only for poorly crystalline, nano material, and amorphous patterns. In this case, QM criteria emphasizes the chemical, data quality, and other characterizations (spectroscopy, pair distribution function, and microscopy). Table II describes the QMs used in the PDF.

| Mark |

|

Crystallographic Information | Warnings | Other | ||||||||

| S or (*) | Average

|

|

– None |

|

||||||||

| G |

|

|

|

(I.e. spectroscopy, pair distribution functions, commercial source, etc.). | ||||||||

| I |

|

|

|

Completeness of the pattern is sensible. Reflections with

|

||||||||

| C |

|

– If calculated pattern does not meet the ” S ” quality mark parameters, it is assigned QM = B | This QM refers to author’s published calculated patterns. Those with “C” should not be confused with ICDD-calculated patterns based on crystal structures from the collaborating databases. ICDD-calculated pattern will have a QM other than C/G/M. | |||||||||

| M |

|

No chemical analysis data to support the materials composition provided (usually commercial samples). | ||||||||||

| B |

|

– For ICDD-calculated patterns, these have significant warnings on incomplete structure, symmetry warnings, nonpositive definite displacement parameters, etc. | Experimental pattern may have unindexed lines | |||||||||

| P | – Applicable only for calculated patterns | – For ICDD-calculated patterns based on structure prototype. These are the cases in which author or editor assigned the structure type | ||||||||||

| 0 |

|

– Usually, the editor has inserted a comment to explain why the “O” was assigned. | A low-precision quality mark means that the diffraction data have been taken on questionable sample or one that contains significant impurities. | |||||||||

| H | – Applicable only for calculated patterns | For ICDD-calculated patterns based on theoretical structures [e.g. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations] |

| Database status | Description |

| Primary (P) | Editorially chosen as a representative entry for a given phase |

| Alternate (A) | Alternate choices for a given phase. This does not necessarily mean lower quality than primary |

| Deleted (D) | Usually duplicate entries, unresolved errors, replaced by entries with better data. |

B. Raw data archival

the database (Fawcett et al., 2017, 2020), which works well for crystalline phases due to their sharp (narrow) peaks. It is evident from Figure 6 that having raw data is essential to carry out phase identification in the case of poorly crystalline or amorphous patterns as they cannot be represented satisfactorily as a list of interplanar spacing (

C. Structural classifications

a. Traditional structure type notation is based on standardized unit cell, axial ratios, space group, Pearson symbol code (Pearson, 1967), and chemistry (Wallace et al., 1994). These descriptors are usually assigned manually, for example, the

b. ANX type is based on the type of ion and site occupancy. For example,

c. Structure prototyping is based on the standardization method described by Gelato and Parthé, 1987, followed by a detailed crystallographic analysis of the atomic environment (Villars et al., 1998; Allmann and Hinek, 2007). For example,

d. Zeolite classification is based on framework type (Baerlocher et al., 2007). These are usually noted by a three-capital letter code describing a network of corner-

sharing tetrahedrally coordinated framework atoms. The International Zeolite Association (IZA) publishes these codes and the codes are listed on their website (https:// america.iza-structure.org/IZA-SC/ftc_table.php)

e. Mineral classification is based on the crystal chemistry characteristics (Smith et al., 1997). The classification aims to exploit the crystal chemistry characteristics and similarity of the powder diffraction pattern among isostructural group members to enhance the quality of the mineral phases in the PDF.

f. Topology: Unlike geometrical analysis, topological analysis provides a tool to use crystallographic data and explore the topological structure and the similarities in the crystal space (Blatov et al., 2014). From the database point of view, it is advantageous to look for isostructural or isoreticular series. Topological analyses can also be used to improve the quality of the database.

D. Subfiles

usually members of a designated ICDD Subcommittee (https://www.icdd.com/technical-subcommittees/).

IV. THE PDF ENTRY

summarized in Figures 9 and 10. In addition to these features, PDF-5+ offers JADE toolkit extensions and these can be launched from a PDF entry as shown in Figure 11.

A. Bravais-Friedel-Donnay-Harker (BFDH)

B. Selected aerea electron diffraction (SAED)

C. Electron back scattering diffraction

D. Bond histogram

| 1 | PDFID | Entry number | ||||||

| 2 | Radiation type | X-ray, electron, neutron; wavelength, and divergence of the beam, instrument apertures, etc. | ||||||

| 3 |

|

Interplanar spacings (d) & intensities (I). Miller indices are listed when available | ||||||

| 4 | Tick marks | Graphical representation of peak position | ||||||

| 5 | Diffractogram(s) | Experimental profile (raw diffraction data) or simulated profile diffractogram | ||||||

| 6 | Function keys | Tools & simulations associated with the PDF entry. Gray icons indicate the tool or simulation is not available for this entry | ||||||

| 7 | Supplemental Information tabs |

|

| A1 | Editorial designations | Status – primary, alternate, or deleted |

| Quality mark – see TABLE II: major criteria for PDF quality mark assignment | ||

| A2 | Sample Conditions | Specifies the environment, temperature, and pressure of data collection. |

| A3 | Chemistry | Indicates the polymorphic designation of a given phase, as well as the formula(e), weight percent, and atomic percent associate with entry; as available. |

| A4 | Compound Identifier(s) | Names and registry numbers used to identify the compound |

| A5 | History | Specifics pertaining to the entries initial publication, and if applicable, recent modifications |

V. AVAILABILITY

manufacturers and independent developers, and works diligently to cultivate commercial data analysis programs that work impeccably with our databases.

VI. CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

REFERENCES

Blatov, V. A., A. P. Shevchenko, and D. M. Proserpio. 2014. “Applied Topological Analysis of Crystal Structures with the Program Package ToposPro.” Crystal Growth & Design 14 (7): 3576-86. doi:10.1021/ cg500498k.

Bruno, I., S. Gražulis, J. R. Helliwell, S. N. Kabekkodu, B. McMahon, and J. Westbrook. 2017. “Crystallography and Databases.” Data Science Journal 16: 38. doi:10.5334/dsj-2017-038.

Donnay, J. D. H., and D. Harker. 1937. “A New Law of Crystal Morphology Extending the Law of Bravais” American Mineralogist 22: 446-67.

Dowty, E. 1976. “Crystal Structure and Crystal Growth: I. The Influence of Internal Structure on Morphology.” American Mineralogist 61: 448-59.

Faber, J., and T. Fawcett. 2002. “The Powder Diffraction File: Present and Future.” Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Science 58 (3): 325-32. doi:10.1107/S0108768102003312.

Fawcett, T. G., S. N. Kabekkodu, J. R. Blanton, and T. N. Blanton. 2017. “Chemical Analysis by Diffraction: The Powder Diffraction File

Fawcett, T. G., S. Gates-Rector, A. M. Gindhart, M. Rost, S. N. Kabekkodu, J. R. Blanton, and T. N. Blanton. 2019. “A Practical Guide to Pharmaceutical Analyses Using X-Ray Powder Diffraction.” Powder Diffraction 34 (2): 164-83. doi:10.1017/S088571561900023X.

Fawcett, T. G., S. Gates-Rector, A. M. Gindhart, M. Rost, S. N. Kabekkodu, J. R. Blanton, and T. N. Blanton. 2020. “Total Pattern Analyses for Non-Crystalline Materials.” Powder Diffraction 35 (2): 82-8. doi:10.1017/S0885715620000263.

Gates, S. D., T. N. Blanton, and T. G. Fawcett. 2014. “A New ‘Chain’ of Events: Polymers in the Powder Diffraction File

Gates-Rector, S., and T. Blanton. 2019. “The Powder Diffraction File: A Quality Materials Characterization Database.” Powder Diffraction 34 (4): 352-60. doi:10.1017/S0885715619000812.

Goehner, R. P., and J. R. Michael. 1996. “Phase Identification in a Scanning Electron Microscope Using Backscattered Electron Kikuchi Patterns.” Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology 101 (3): 301. doi:10.6028/jres.101.031.

Groom, C. R., I. J. Bruno, M. P. Lightfoot, and S. C. Ward. 2016. “The Cambridge Structural Database.” Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Science, Crystal Engineering and Materials 72 (2): 171-79. doi:10.1107/S2052520616003954.

Hanawalt, J. D. 1986. “Manual Search/Match Methods for Powder Diffraction in 1986.” Powder Diffraction 1 (1): 7-13.

Hanawalt, J. D., H. W. Rinn, and L. K. Frevel. 1938. “Chemical Analysis by X-ray Diffraction.” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Analytical Edition 10 (9): 457-512.

Helliwell, J. R., B. McMahon, J. Mitchell Guss, and L. M. J. KroonBatenburg. 2017. “The Science Is in the Data.” IUCrJ 4 (6): 714-22. doi:10.1107/S2052252517013690.

Hofmann, D. W. M., and L. Kuleshova. 2005. “New Similarity Index for Crystal Structure Determination from X-Ray Powder Diagrams.” Journal of Applied Crystallography 38 (6): 861-66. doi:10.1107/S0021889805023484.

Hubbard, C. R., J. K. Stalick, and A. D. Mighell. 1980. “NBS* AIDS80: A Fortran Program to Evaluate Crystallographic Data.” Advances in X-Ray Analysis 24: 99-109.

Jenkins, R. & Smith, D. (1987). Powder Diffraction File in F. H. Allen, G. Bergerhoff, and R. Sievers (Eds.) Crystallographic Databases (pp. 159-74). Data Commission of the International Union of Crystallography.

Jenkins, R., M. Holomany, and W. Wong-Ng. 1987. “On the Need for Users of the Powder Diffraction File to Update Regularly.” Powder Diffraction 2 (2): 84-87. doi:10.1017/S0885715600012434.

Johnson, G., and V. Vand. 1967. “A Computerized Powder Diffraction Identification System.” Industrial & Engineering Chemistry 59 (8): 19-31.

Kabekkodu, S. N., J. Faber, and T. Fawcett. 2002. “New Powder Diffraction File (PDF-4) in Relational Database Format: Advantages and Data-Mining Capabilities.” Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Science 58 (3): 333-37. doi:10.1107/S0108768102002458.

Kaduk, J. A. (2019). Crystallographic Databases and Powder Diffraction in J. A. K. C. Gilmore and H. Schenk (Eds.) International Tables for Crystallography Volume H: Powder Diffraction. 1st ed. (Chap. 3.7, pp. 304-24). New York, Wiley.

Messick, J. 2012. “The History of the International Centre for Diffraction Data.” Powder Diffraction 27 (1): 36-44. doi:10.1017/ S0885715612000085.

Pearson, W. B. 1967. Handbook of Lattice Spacings and Structures of Metals. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Reid, J. W., J. A. Kaduk, and M. Vickers. 2016. “The Crystal Structure of Trandolapril,

Smith, D. K., P. Bayliss, and A. C. Roberts. 1997. “Mineral Classification in the Mineral Powder Diffraction File.” Advances in X-Ray Analysis 41: 606-13.

Villars, P., & K. Cenzual. 2018. Pearson’s Crystal Data: Crystal Structure Database for Inorganic Compounds. Materials Park, OH, USA: ASM International.

Villars, P., N. Onodera, and S. Iwata. 1998. “The Linus Pauling File (LPF) and Its Application to Materials Design.” Journal of Alloys and Compounds 279 (1): 1-7. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(98)00605-7.

Wallace, P. L., S. Weissmanna, M. H. Mueller, L. D. Calveit, and R. Jenkins. 1994. “The New ICDD Metals and Alloys Indexes: Usefulness and Potentialities.” Powder Diffraction 9 (4): 239-45. doi:10.1017/ S0885715600018947.

Wilkinson, M. D., M. Dumontier, I. J. Aalbersberg, G. Appleton, M. Axton, A. Baak, N. Blomberg, et al. 2016. “The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship.” Scientific Data 3 (1): 160018. doi:10.1038/sdata.2016.18.

Zagorac, D., H. Müller, S. Ruehl, J. Zagorac, and S. Rehme. 2019. “Recent Developments in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database: Theoretical Crystal Structure Data and Related Features.” Journal of Applied Crystallography 52 (5): 918-25. doi:10.1107/S160057671900997X.

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. Electronic mail: kabekkodu@icdd.com