DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02619-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39095913

تاريخ النشر: 2024-08-02

أتمتة اكتشاف السجلات المكررة للمراجعات النظامية: أداة إزالة التكرار

الملخص

الخلفية لوصف الخوارزمية والتحقيق في فعالية أداة جديدة لأتمتة المراجعات المنهجية “المزيل المكرر” لإزالة السجلات المكررة من بحث مراجعة منهجية متعددة القواعد. الطرق قمنا ببناء واختبار فعالية أداة المزيل المكرر من خلال استخدام 10 نتائج سابقة لمراجعات كوكراين المنهجية لمقارنة خوارزمية المزيل المكرر ‘المتوازنة’ بطريقة EndNote شبه اليدوية. قام باحثان كل منهما بإجراء إزالة التكرار على 10 مكتبات من نتائج البحث. بالنسبة لخمس من تلك المكتبات، استخدم باحث واحد المزيل المكرر، بينما قام الآخر بإجراء إزالة التكرار شبه اليدوية باستخدام EndNote. ثم قاما بتبديل الطرق لبقية المكتبات الخمس. بالإضافة إلى هذا التحليل، تم إجراء مقارنة بين الخوارزميات الثلاثة المختلفة للمزيل المكرر (‘المتوازنة’، ‘المركزة’ و’المريحة’) على مجموعتين من بيانات نتائج البحث التي تم إزالة التكرار منها سابقًا.

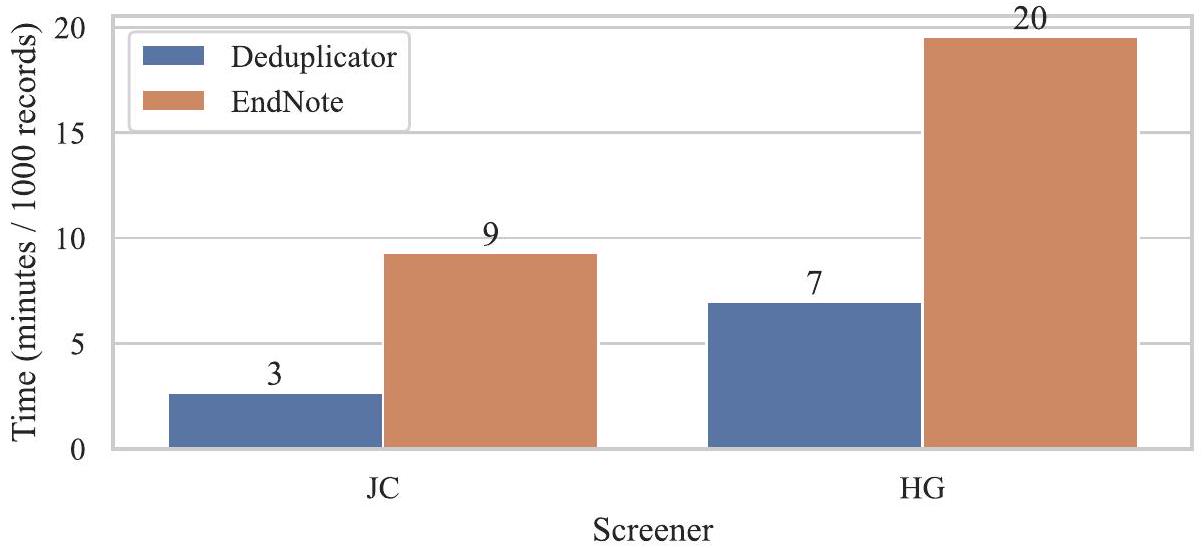

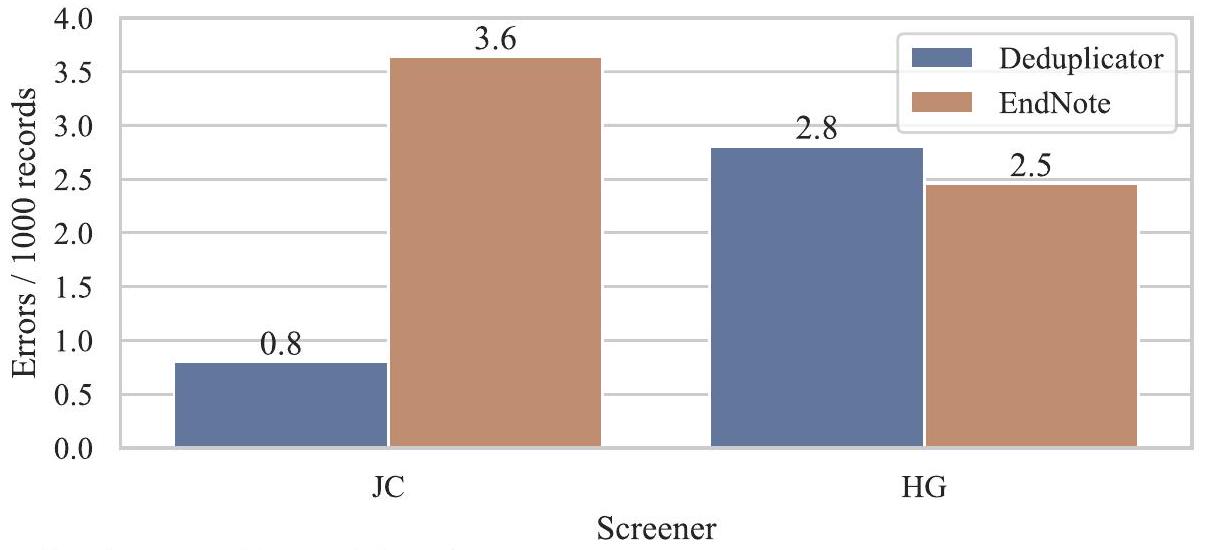

النتائج قبل إزالة التكرار، كان متوسط حجم المكتبة للمراجعات النظامية العشر 1962 سجلًا. عند استخدام أداة إزالة التكرار، كان متوسط الوقت لإزالة التكرار 5 دقائق لكل 1000 سجل مقارنة بـ 15 دقيقة مع EndNote. كان متوسط معدل الخطأ مع أداة إزالة التكرار 1.8 خطأ لكل 1000 سجل مقارنة بـ 3.1 مع EndNote. أظهرت تقييمات خوارزميات أداة إزالة التكرار المختلفة أن الخوارزمية ‘المتوازنة’ كانت لديها أعلى متوسط درجة F1 بلغ 0.9647. كانت الخوارزمية ‘المركزة’ لديها أعلى دقة متوسطة بلغت 0.9798 وأعلى استرجاع بلغ 0.9757. كانت الخوارزمية ‘المريحة’ لديها أعلى دقة متوسطة بلغت 0.9896. الاستنتاجات هذا يوضح أن استخدام أداة إزالة التكرار لاكتشاف السجلات المكررة يقلل من الوقت المستغرق لإزالة التكرار، مع الحفاظ على الدقة أو تحسينها مقارنة باستخدام طريقة EndNote شبه اليدوية. ومع ذلك، يجب إجراء مزيد من الأبحاث لمقارنة المزيد من طرق إزالة التكرار لتحديد الأداء النسبي لأداة إزالة التكرار مقابل طرق إزالة التكرار الأخرى.

الخلفية

يجب إزالة السجلات المكررة في عملية تُسمى الفحص. تُعرف هذه العملية باسم إزالة التكرار.

هناك طرق متعددة لإزالة التكرار من السجلات المستخرجة من البحث عن المراجعات المنهجية. إحدى طرق إزالة التكرار التي يستخدمها الباحثون هي استخدام طريقة شبه يدوية، تجمع بين برامج مثل EndNote والتحقق البشري، على الرغم من أن هذه الطريقة لا تزال عرضة للأخطاء. على الرغم من أن إزالة التكرار هي مهمة روتينية في المراجعات المنهجية، إلا أنه لا يوجد توافق كبير حول أفضل طريقة لإزالة التكرار. على الرغم من وجود محاولات لتوحيد طرق إزالة التكرار شبه اليدوية، إلا أنها تعتمد على تطبيق الخطوات بشكل متسق ومحدودة على بعض برامج إدارة المراجع (مثل EndNote). كما شهدت أيضًا زيادة في عدد الأدوات الآلية بالكامل التي يمكنها إزالة التكرار دون أي تدخل بشري. إحدى قيود هذه الأدوات هي أنها غالبًا ما تكون مرتبطة ببرامج ملكية وغالبًا ما تكون مغلقة المصدر، مما يعني أن طريقة عمل هذه الخوارزميات غير معروفة إلى حد كبير.

طرق

تطوير أداة إزالة التكرار

تطوير خوارزمية إزالة التكرار

2 سلبية صحيحة

3 إيجابية خاطئة

4 نتيجة سلبية خاطئة

2 الدقة: توفر عدد الدراسات الفريدة التي تمت إزالتها بشكل غير صحيح في عملية إزالة التكرار (المعادلة 2)

3 الاسترجاع: يوفر عدد النسخ المكررة التي تم تفويتها في عملية إزالة التكرار (المعادلة 3)

درجة F1: تجمع بين مقاييس الاسترجاع والدقة وتمثل الأداء العام للنموذج (المعادلة 4)

بالإضافة إلى كل خوارزم، يتم تحديد مجموعة من المحولات في أعلى ملف التكوين. تلعب هذه دورًا رئيسيًا حيث تهدف إلى توحيد الاختلافات بين الحقول في كل قاعدة بيانات. على سبيل المثال، سيقوم محول إعادة كتابة المؤلف بتوحيد الطرق المختلفة لكتابة أسماء المؤلفين (مثل ‘جون سميث’ مقابل ‘سميث، ج’ مقابل ‘ج. سميث’). سيحاول محول الألفا رقمي حل الاختلافات في أحرف Unicode بين المقالات، وسيقوم محول رقم الصفحة بتوحيد الاختلافات بين أنظمة ترقيم الصفحات (مثل ‘356-357’ مقابل ‘356-7’). يمكن أن تختلف أحرف Unicode عبر اللغات، لذلك هناك حاجة إلى المحول لتوحيدها، مثل تغيير أسماء المؤلفين Rolečková أو Hammarström إلى Roleckova أو Hammarstrom. يمكن العثور على جدول كامل من المحولات وما تقوم به في المواد التكميلية (المُلحق 2). يتم تطبيق هذه المحولات قبل إزالة التكرار، وبالتالي ستُشار إلى عملية تطبيق جميع المحولات على أنها المعالجة المسبقة.

كيف تحدد خوارزم إزالة التكرار السجلات المكررة

قيمة بين صفر وواحد بناءً على مدى قرب تطابق السلاسل. تعمل الخوارزم كما يلي:

2 لكل ‘خطوة’ محددة في الخوارزم (المُلحق 3):

(أ) ترتيب قائمة السجلات بناءً على حقل ‘الترتيب’ المحدد (مثل “العنوان”)

(ب) تقسيم السجلات إلى مجموعات فرعية منفصلة بناءً على الإدخالات المطابقة لحقل ‘الترتيب’ المحدد (مثل إذا كان “العنوان”، سيتم تجميع جميع السجلات التي تحمل عنوان “أتمتة اكتشاف السجلات المكررة للمراجعات المنهجية” معًا)

(ج) حساب درجة التشابه لكل مجموعة من السجلات داخل المجموعة الفرعية

4 إذا كانت درجتا تشابه سجلين أكبر من عتبة (مثل 0.01)، يتم وضع علامة على السجلين على أنهما مكرران

أكبر من 0.01، فيُفترض أن السجلين مكرران.

تُستخدم درجة التشابه المتوسطة أيضًا لتصنيف مدى احتمال أن يكون سجلا مكرران. ستضع درجة أكبر من أو تساوي 0.9 السجلات المكررة في مجموعة “مكررات محتملة للغاية”. ستضع درجة أكبر من أو تساوي 0.7 السجلات المكررة في مجموعة “مكررات محتملة بشدة”. أي درجة أقل من 0.7 ولكن أكبر من 0.01 ستضع المكررات في مجموعة “مكررات محتملة”. تم اختيار هذه العتبات بشكل تعسفي بعد الاختبار ضد سيناريوهات تكرار مختلفة. وُجد أن هذه الدرجات مثالية لمجموعاتها النسبية، بحيث أن مجموعتي “مكررات محتملة للغاية” و”مكررات محتملة بشدة” من غير المحتمل أن تحتوي على أي سجلات فريدة (إيجابيات كاذبة).

معلومات إضافية والكود الخاص بالخوارزم متاحة عبر مستودع GitHub IEBH/dedupe-sweep [12].

تقييم خوارزم إزالة التكرار

تعريف السجل المكرر

- عناصر التقرير المفضلة للمراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية: بيان PRISMA. موهر د، ليبراتي أ، تيتزلاف ج، ألتمان د. مجموعة PRISMA. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 أكتوبر؛62(10):1006-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi. 2009 . 06.005

- عناصر التقرير المفضلة للمراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية: بيان PRISMA. موهر، د.، ليبراتي، أ.، تيتزلاف، ج.، ألتمان، د. ج. (2009). مجلة علم الأوبئة السريرية، 62(10)، 1006-1012.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

- موهر د، ليبراتي أ، تيتزلاف ج، ألتمان د. عناصر التقرير المفضلة للمراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية: بيان PRISMA. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009؛62(10):1006-1012. doi:10.1016/j. jclinepi.2009.06.005

- عناصر التقرير المفضلة للمراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية: بيان PRISMA. موهر د، ليبراتي أ، تيتزلاف ج، ألتمن د. ج؛ مجموعة PRISMA. المجلة الدولية للجراحة. 2010؛8(5):336-41. doi: 10.1016/j. ijsu.2010.02.007

- عناصر التقرير المفضلة للمراجعات النظامية والتحليلات التلوية: بيان PRISMA. موهر د، ليبراتي أ، تيتزلاف ج، ألتمن د. ج؛ مجموعة PRISMA. ج Clin Epidemiol. أكتوبر 2009؛62(10):1006-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

- عناصر التقرير المفضلة للمراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية: بيان PRISMA. موهر د، ليبراتي أ، تيتزلاف ج، ألتمن دي جي؛ مجموعة PRISMA. BMJ. 21 يوليو 2009؛339: b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

اختيار المراجعات المنهجية لإزالة التكرار

معايير الشمول في المراجعات المنهجية

- يجب الإبلاغ عن جميع سلاسل البحث لجميع قواعد البيانات في المراجعة

- كان يجب أن يكون عدد قواعد البيانات التي تم البحث فيها في المراجعة اثنتين أو أكثر

- كان يجب أن يكون العدد الإجمالي لنتائج البحث التي تم العثور عليها من خلال مجموعة جميع عبارات البحث بين 500 و 10,000 سجل.

الحصول على العينة التي سيتم إزالة التكرار منها

إزالة التكرار من نتائج البحث

تحقق من إزالة التكرار

تم إزالة التكرار. تم التحقق يدويًا من أي تناقضات وتم التحقق منها بالتوافق بين مؤلفين (HG و CF). أدى ذلك إلى إنتاج مكتبة EndNote النهائية “المزالة بشكل صحيح” لكل مجموعة عينات. وهذا مكن من تحديد الأخطاء من مكتبة كل مراجع، حيث تم تصنيف المقالة الفريدة التي تمت إزالتها بشكل غير صحيح على أنها “إيجابية خاطئة”، بينما تم تصنيف التكرار الذي تم تفويته بشكل غير صحيح على أنه “سلبية خاطئة”.

النتائج

2 دراسات فريدة تمت إزالتها/إيجابيات زائفة: عدد السجلات في المكتبة التي صنفها المراجع على أنها مكررة بينما كانت سجلاً فريداً

3 تكرارات مفقودة/سلبيات كاذبة: عدد السجلات في المكتبة التي صنفها المراجع كسجل فريد عندما كانت سجلًا مكررًا

4 إجمالي الأخطاء: (إيجابيات خاطئة + سلبيات خاطئة)

مقارنة بين خوارزميات إزالة التكرار

| رقم المجموعة | مراجعة منهجية (المؤلف السنة) | عدد السجلات | هانا غرينوود | جاستن كلارك |

| 1 | لورنتزن 2020 [14] | 813 | إنهاء الملاحظة | إزالة التكرار |

| 2 | أليبد 2020 [15] | 1479 | إزالة التكرار | إنهاء الملاحظة |

| ٣ | داوسون 2021 [16] | ٣٩١٢ | إنهاء الملاحظة | إزالة التكرار |

| ٤ | ويفن 2017 [17] | ١٠٢٨ | إزالة التكرار | إنهاء الملاحظة |

| ٥ | كاماث 2020 [18] | 1785 | إنهاء الملاحظة | إزالة التكرار |

| ٦ | غبارا 2017 [19] | 1807 | إزالة التكرار | إنهاء الملاحظة |

| ٧ | بنيت 2018 [20] | 2111 | إنهاء الملاحظة | إزالة التكرار |

| ٨ | هانون 2021 [21] | 1061 | إزالة التكرار | إنهاء الملاحظة |

| 9 | روبرتس 2020 [22] | 3181 | إنهاء الملاحظة | إزالة التكرار |

| 10 | ياسشينسكي 2018 [23] | 2447 | إزالة التكرار | إنهاء الملاحظة |

كما هو الحال مع مكتبات التطوير، كانت الدقة والدقة والاسترجاع ودرجة F1 هي المقاييس الأربعة المستخدمة للمقارنة بين خوارزميات إزالة التكرار. تشير درجة الدقة العالية إلى أنه تم تحديد عدد قليل من الدراسات الفريدة على أنها مكررة. تشير درجة الاسترجاع العالية إلى أنه تم تصنيف عدد قليل جدًا من الدراسات المكررة بشكل غير صحيح على أنها دراسات فريدة. درجة F1 هي درجة مركبة تجمع بين الدقة والاسترجاع. يتم تقديم صيغة هذه المقاييس في المعادلات 2 و 3 و 4.

النتائج

الوقت المستغرق لإزالة التكرار

| دراسة | عدد السجلات | عدد النسخ المكررة | عدد الدراسات الفريدة |

| فحص الخلايا | 1856 | ١٤٠٤ | ٤٥٢ |

| أمراض الدم | 1415 | 246 | 1169 |

| تنفسي | 1988 | ٧٩٩ | 1189 |

| جلطة | 1292 | ٥٠٧ | 785 |

عدد الأخطاء

معدلات الوقت والخطأ المعيارية

تحليل بين الفلاتر

| مراجعة منهجية | إجمالي السجلات | إزالة التكرار | إنهاء الملاحظة | ||||

| تمت إزالة الدراسات الفريدة | تكرارات مفقودة | إجمالي الأخطاء | تم إزالة الدراسات الفريدة | تكرارات مفقودة | إجمالي الأخطاء | ||

| لورنتزن 2020 | 813 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ٢ |

| أليبد 2020 | 1479 | 1 | ٥ | ٦ | ٥ | ٣ | ٨ |

| داوسون 2021 | ٣٩١٢ | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | ٥ | ٧ |

| ويفن 2017 | ١٠٢٨ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| كاماث 2020 | 1785 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| غبارا 2017 | 1807 | 2 | ٤ | ٦ | ٣ | 2 | ٥ |

| بنيت 2018 | 2111 | 1 | 2 | ٣ | 2 | 2 | ٤ |

| هانون 2021 | 1061 | ٣ | 0 | ٣ | 2 | ٣ | ٥ |

| روبرتس 2020 | 3181 | ٣ | 0 | ٣ | 12 | ٤ | 16 |

| ياسشينسكي 2018 | 2447 | 2 | ٥ | ٧ | ٥ | ٨ | ١٣ |

| معنى | 1962.4 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 6.2 |

| مراجعة منهجية | الوقت لكل 1000 سجل (دقائق) | إجمالي الأخطاء لكل 1000 سجل | ||

| إزالة التكرار | إنهاء الملاحظة | إزالة التكرار | إنهاء الملاحظة | |

| لورنتزن 2020 | ٥ | 37 | 0.0 | 2.5 |

| أليبد 2020 | 10 | 10 | ٤.١ | ٥.٤ |

| داوسون 2021 | 2 | 19 | 0.5 | 1.8 |

| ويفن 2017 | 9 | ٧ | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| كاماث 2020 | 2 | 20 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| غبارا 2017 | ٤ | ١٣ | 3.3 | 2.8 |

| بنيت 2018 | 2 | 17 | 1.4 | 1.9 |

| هانون 2021 | ٥ | ٦ | 2.8 | ٤.٧ |

| روبرتس 2020 | ٣ | ٥ | 0.9 | 5.0 |

| ياسشينسكي 2018 | ٨ | 11 | 2.9 | ٥.٣ |

| معنى | ٥ | 15 | 1.8 | 3.1 |

مقارنة بين خوارزميات إزالة التكرار

نقاش

| خوارزمية | دراسة | دقة | دقة | استدعاء | درجة F1 |

| متوازن | الضوء الأزرق | 0.9989 | 1.0000 | 0.9979 | 0.9990 |

| متوازن | نحاس | 0.9822 | 0.9892 | 0.9786 | 0.9839 |

| متوازن | السكري | 0.9909 | 0.9890 | 0.9919 | 0.9904 |

| متوازن | تافينوكوين | 0.9888 | 1.0000 | 0.9825 | 0.9912 |

| متوازن | التهاب المسالك البولية | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| مركّز | الضوء الأزرق | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| مركّز | نحاس | 0.9941 | 0.9894 | 1.0000 | 0.9947 |

| مركّز | السكري | 0.9913 | 0.9823 | 0.9997 | 0.9909 |

| مركّز | تافينوكوين | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| مركّز | التهاب المسالك البولية | 0.9981 | 0.9950 | 1.0000 | 0.9975 |

| مسترخي | الضوء الأزرق | 0.9977 | 1.0000 | 0.9958 | 0.9979 |

| مسترخي | نحاس | 0.9921 | 1.0000 | 0.9858 | 0.9928 |

| مسترخي | السكري | 0.9934 | 0.9982 | 0.9878 | 0.9930 |

| مسترخي | تافينوكوين | 0.9944 | 1.0000 | 0.9912 | 0.9956 |

| مسترخي | التهاب المسالك البولية | 0.9799 | 1.0000 | 0.9475 | 0.9730 |

| متوازن | معنى | 0.9921 | 0.9956 | 0.9902 | 0.9929 |

| مركّز | معنى | 0.9967 | 0.9934 | 0.9999 | 0.9966 |

| مسترخي | معنى | 0.9915 | 0.9996 | 0.9816 | 0.9905 |

سجلات بدون أي فحص يدوي وأولئك الذين أرادوا أن يكونوا قادرين على فحص كل قرار اتخذته أداة إزالة التكرار. أدى ذلك إلى تطوير خوارزميتين، ‘مسترخية’ و’مركزة’، اللتين استبدلتا الخوارزمية ‘المتوازنة’. عند مقارنة الخوارزميات، كانت خوارزمية ‘المركزة’ لديها أعلى درجة استرجاع، مما يدل على أنها الأفضل في العثور على جميع التكرارات؛ ومع ذلك، لديها أدنى درجة دقة مما يعني أن النتائج تحتاج إلى فحص. كانت خوارزمية ‘المسترخية’ لديها أعلى دقة، مما يعني أنه من غير المحتمل أن تزيل أي دراسات فريدة؛ ومع ذلك، لديها أدنى درجة استرجاع مما يعني أن بعض الدراسات المكررة ستبقى بعد إزالة التكرار (الجدولان 5 و6). لذلك، نوصي باستخدام خوارزمية ‘المسترخية’ للمكتبات الكبيرة من السجلات (> 2000 سجل)، حيث لا يرغب الناس في فحص النتائج، وخوارزمية ‘المركزة’ للمكتبات الصغيرة من السجلات (< 2000 سجل) حيث أن هذا عدد قابل للفحص يدويًا. قد تتغير هذه الأرقام اعتمادًا على قيود الوقت للدراسة الفردية.

| خوارزمية | دراسة | دقة | دقة | استدعاء | درجة F1 |

| متوازن | فحص الخلايا | 0.9758 | 0.9836 | 0.9843 | 0.9840 |

| متوازن | أمراض الدم | 0.9696 | 0.9177 | 0.9065 | 0.9121 |

| متوازن | تنفسي | 0.9819 | 0.9823 | 0.9725 | 0.9774 |

| متوازن | سكتة دماغية | 0.9884 | 0.9824 | 0.9882 | 0.9853 |

| مركّز | فحص الخلايا | 0.9790 | 0.9789 | 0.9936 | 0.9862 |

| مركّز | أمراض الدم | 0.9654 | 0.8774 | 0.9309 | 0.9034 |

| مركّز | تنفسي | 0.9864 | 0.9801 | 0.9862 | 0.9832 |

| مركّز | سكتة دماغية | 0.9884 | 0.9786 | 0.9921 | 0.9853 |

| مسترخي | فحص الخلايا | 0.9763 | 0.9885 | 0.9801 | 0.9843 |

| مسترخي | أمراض الدم | 0.9710 | 0.9812 | 0.8496 | 0.9107 |

| مسترخي | تنفسي | 0.9779 | 0.9948 | 0.9499 | 0.9718 |

| مسترخي | سكتة دماغية | 0.9853 | 0.9939 | 0.9684 | 0.9810 |

| متوازن | معنى | 0.9789 | 0.9665 | 0.9629 | 0.9647 |

| مركّز | معنى | 0.9798 | 0.9538 | 0.9757 | 0.9645 |

| مسترخي | معنى | 0.9776 | 0.9896 | 0.9370 | 0.9619 |

برامج أو منصات قواعد البيانات. ومع ذلك، على عكس بعض الأدوات مثل كوفيدنس، يتطلب ديدوبليكاتور تصدير المكتبة من مدير المراجع ثم استيراد النتيجة مرة أخرى إلى مدير المراجع أو أداة الفحص للاستمرار في الفحص. بينما يتم العمل على هذا، قد يجد بعض المستخدمين أنه غير مرغوب فيه نقل سجلاتهم بين أدوات مختلفة.

القيود

في المراجعة المنهجية “Wiffen، 2017″، كان برنامج Deduplicator أبطأ قليلاً في إزالة التكرارات [HG] مقارنةً بطريقة EndNote شبه اليدوية [JC]. من المحتمل أن تكون الخبرة الإضافية لـ JC قد سهلت إزالة التكرارات شبه اليدوية بسرعة ودقة من مكتبة Wiffen الصغيرة أسرع مما استطاع HG تحقيقه باستخدام Deduplicator. يتم التخفيف جزئيًا من هذا الاختلاف في سرعة/دقة إزالة التكرارات بين المؤلفين من خلال التقسيم المتساوي للطرق المستخدمة من قبل كل مؤلف، لكن هذا لا يلغي هذا التحيز تمامًا. على الرغم من هذه الفجوة، فإن استخدام Deduplicator زاد من السرعة التي يمكن بها لكل من المراجعين إزالة التكرارات من مجموعات نتائج البحث (الشكل 2). يمكن أيضًا أن يُقال إن Deduplicator من المحتمل أن يُستخدم من قبل الباحثين ذوي مجموعة واسعة من الخبرات، وبالتالي فإن وجود نوعين من مستويات خبرة المراجعين في هذه الدراسة يجعلها أكثر تمثيلاً للظروف الواقعية.

القيود الثانية هي إمكانية أن يكون كلا المؤلفين قد ارتكب نفس الخطأ، على سبيل المثال، كلاهما فاتته نفس السجل المكرر. هذا الخطأ لن يظهر في النتائج، حيث تم تحديد الأخطاء من خلال مقارنة نتائج كلا المراجعين. ولكن، نظرًا لأن عملية إزالة التكرار تمت بشكل منفصل من قبل شخصين بمساعدة خوارزمية حاسوبية، يمكننا أن نكون واثقين إلى حد كبير من أن هذا الرقم منخفض. أيضًا، بما أن هذه مقارنة لتحديد أي طريقة لإزالة التكرار كانت أفضل، إذا لم يكن لدى أي منهما الخطأ المسجل ضده، فلن يؤثر ذلك على المقارنة في الأخطاء التي ارتكبت بين الطريقتين.

ثالثًا، تم تقييم الخوارزمية ‘المتوازنة’ فقط في المقارنة المباشرة مع EndNote. منذ إكمال الدراسة، تم استبدال الخوارزمية ‘المتوازنة’ بخوارزميتين جديدتين: ‘المريحة’ و ‘المركزة’. على الرغم من أنه لم يتم مقارنتهما مباشرة مع EndNote، إلا أنهما تم مقارنتهما مع الخوارزمية ‘المتوازنة’. تم تقديم نتائج هذه التحليل في الجدول 6.

البحث المستقبلي

الخاتمة

الاختصارات

مسرع المراجعة المنهجية SRA

معلومات إضافية

الملف الإضافي 3. ملف PDF يمثل كود JSON المستخدم لخوارزمية مقارنة إزالة التكرار.

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 أغسطس 2024

References

- Borah R, Brown AW, Capers PL, Kaiser KA. Analysis of the time and workers needed to conduct systematic reviews of medical interventions using data from the PROSPERO registry. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012545. https:// doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012545.

- Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. BMJ Evid-Based Med. 2016;21(4):125-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/ ebmed-2016-110401.

- Michelson M, Reuter K. The significant cost of systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a call for greater involvement of machine learning to assess the promise of clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;16:100443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100443.

- Scott AM, Glasziou P, Clark J. We extended the 2-week systematic review (2weekSR) methodology to larger, more complex systematic reviews: a case series. J Clin Epidemiol. 2023;157:112-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jclinepi.2023.03.007.

- Tufanaru C, Surian D, Scott AM, Glasziou P, Coiera E. The 2-week systematic review (2weekSR) method was successfully blind-replicated by another team: a case study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2024;165. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.jclinepi.2023.10.013.

- Beller E, Clark J, Tsafnat G, Adams C, Diehl H, Lund H, et al. Making progress with the automation of systematic reviews: principles of the International Collaboration for the Automation of Systematic Reviews (ICASR). Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0740-7.

- Tsafnat G, Glasziou P, Choong MK, Dunn A, Galgani F, Coiera E. Systematic review automation technologies Syst Rev. 2014;3:74. https://doi.org/10. 1186/2046-4053-3-74.

- Qi X, Yang M, Ren W, Jia J, Wang J, Han G, et al. Find duplicates among the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library Databases in systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 00718 38.

- Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(3):240-3. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014.

- McKeown S, Mir ZM. Considerations for conducting systematic reviews: evaluating the performance of different methods for deduplicating references. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13643-021-01583-y.

- IEBH. The Systematic Review Accelerator. 2018. https://sr-accelerator.com. Accessed 11 Nov 2022.

- IEBH. Deduplicator GitHub Repository. 2020. https://github.com/IEBH/ dedupe-sweep. Accessed 11 Nov 2022.

- Winkler W. String comparator metrics and enhanced decision rules in the Fellegi-Sunter model of record linkage. Proceedings of the Section on Survey Research Methods. American Statistical Association. Alexandri: American Statistical Association; 1990. Avaliable at: https://eric.ed.gov/? id=ED325505.

- Lorentzen

, Davis , Penninga . Interventions for frostbite injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;12(12):CD012980. https://doi.org/10. 1002/14651858.CD012980.pub2. - Alabed

, Sabouni A, Al Dakhoul S, Bdaiwi Y. Beta-blockers for congestive heart failure in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7(7):CD007037. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007037.pub4. - Dawson JA, Summan R, Badawi N, Foster JP. Push versus gravity for intermittent bolus gavage tube feeding of preterm and low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;8(8):CD005249. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/14651858.CD005249.pub3.

- Wiffen PJ, Cooper TE, Anderson AK, Gray AL, Grégoire MC, Ljungman G, et al. Opioids for cancer-related pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7(7):CD012564. https://doi.org/10. 1002/14651858.CD012564.pub2.

- Kamath MS, Mascarenhas M, Kirubakaran R, Bhattacharya S. Number of embryos for transfer following in vitro fertilisation or intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8(8):CD003416. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003416.pub5.

- Ghobara T, Gelbaya TA, Ayeleke RO. Cycle regimens for frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7(7):CD003414. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003414.pub3.

- Bennett MH, Feldmeier J, Smee R, Milross C. Hyperbaric oxygenation for tumour sensitisation to radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4(4):CD005007. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005007.pub4.

- Hannon CW, McCourt C, Lima HC, Chen S, Bennett C. Interventions for cutaneous disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;3(3):CD007478. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007 478.pub2.

- Roberts KE, Rickett K, Feng S, Vagenas D, Woodward NE. Exercise therapies for preventing or treating aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal symptoms in early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1(1):CD012988. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012988.pub2.

- Jaschinski T, Mosch CG, Eikermann M, Neugebauer EA, Sauerland S. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11(11):CD001546. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651 858.CD001546.pub4.

- Rathbone J, Carter M, Hoffmann T, Glasziou P. Better duplicate detection for systematic reviewers: evaluation of Systematic Review AssistantDeduplication Module. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/ 2046-4053-4-6.

- Guimarães NS, Ferreira AJF, Ribeiro Silva RdC, de Paula AA, Lisboa CS, Magno L, et al. Deduplicating records in systematic reviews: there are free, accurate automated ways to do so. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;152:110115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.10.009.

- Borissov N, Haas Q, Minder B, Kopp-Heim D, von Gernler M, Janka H, et al. Reducing systematic review burden using Deduklick: a novel, automated, reliable, and explainable deduplication algorithm to foster medical research. Syst Rev. 2022;11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02045-9.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

كونور فوربس

cforbes@bond.edu.au

معهد الرعاية الصحية المستندة إلى الأدلة، جامعة بوند، جولد كوست، أستراليا

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02619-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39095913

Publication Date: 2024-08-02

Automation of duplicate record detection for systematic reviews: Deduplicator

Abstract

Background To describe the algorithm and investigate the efficacy of a novel systematic review automation tool “the Deduplicator” to remove duplicate records from a multi-database systematic review search. Methods We constructed and tested the efficacy of the Deduplicator tool by using 10 previous Cochrane systematic review search results to compare the Deduplicator’s ‘balanced’ algorithm to a semi-manual EndNote method. Two researchers each performed deduplication on the 10 libraries of search results. For five of those libraries, one researcher used the Deduplicator, while the other performed semi-manual deduplication with EndNote. They then switched methods for the remaining five libraries. In addition to this analysis, comparison between the three different Deduplicator algorithms (‘balanced’, ‘focused’ and ‘relaxed’) was performed on two datasets of previously deduplicated search results.

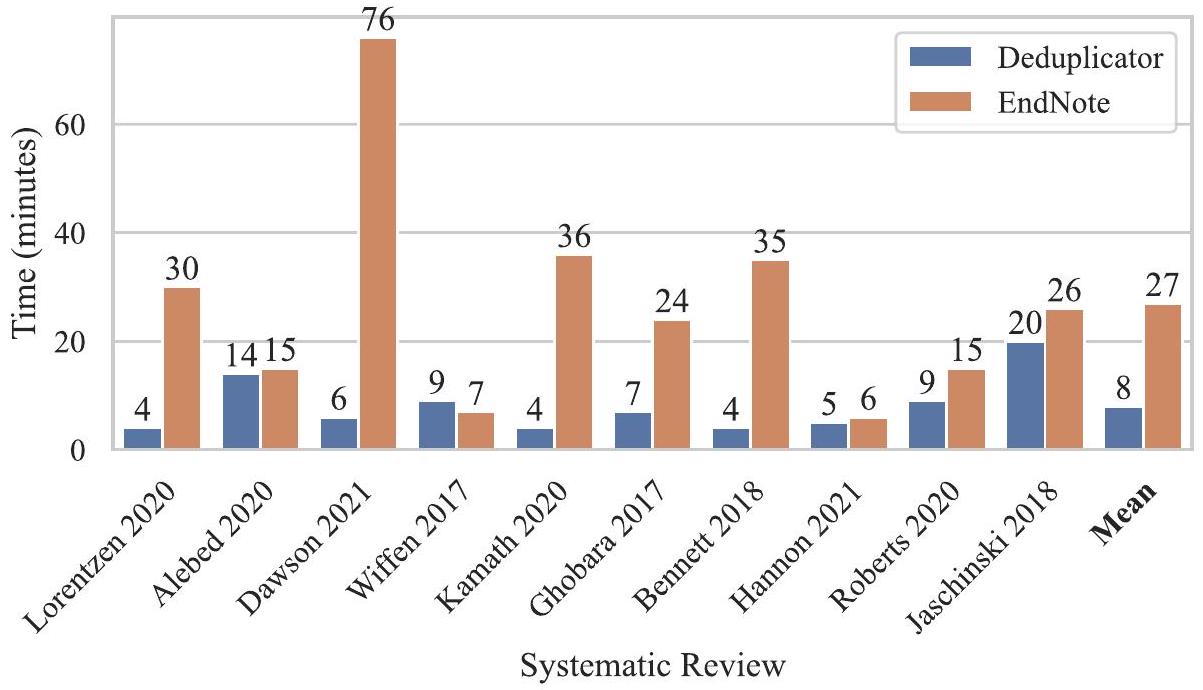

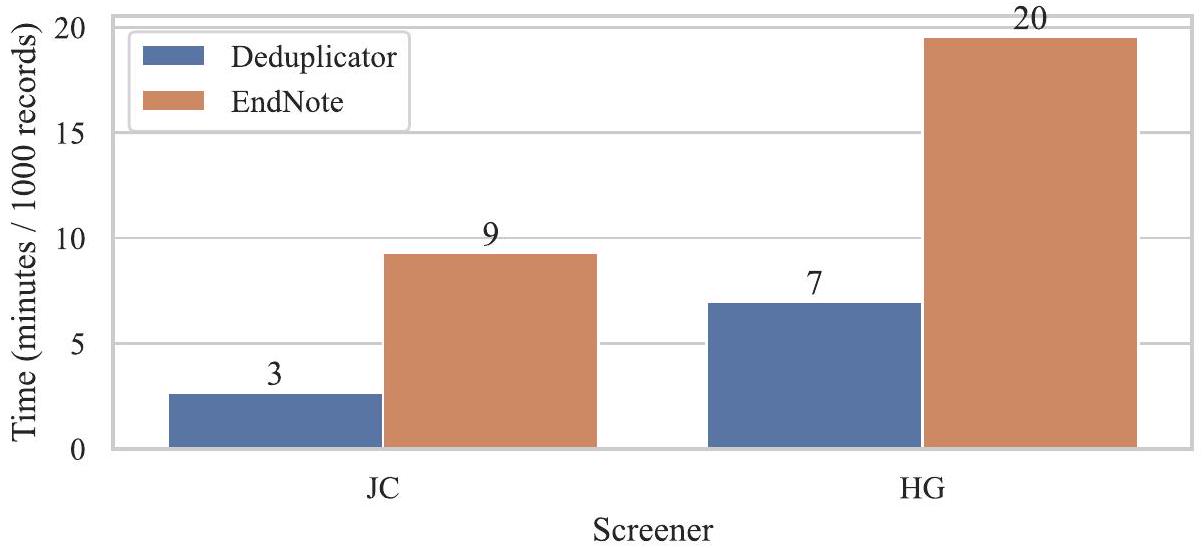

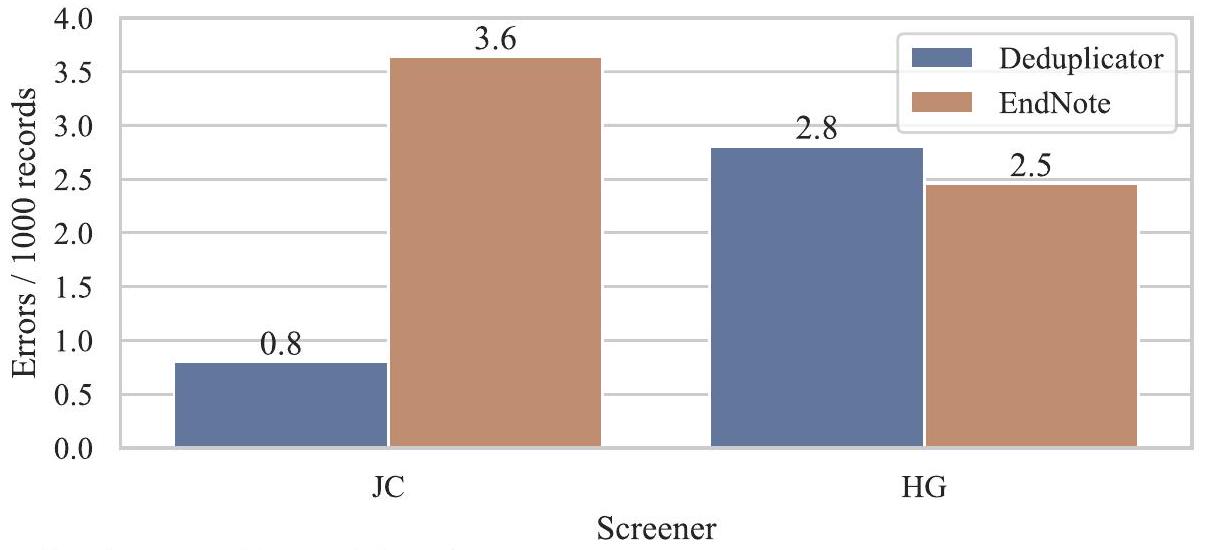

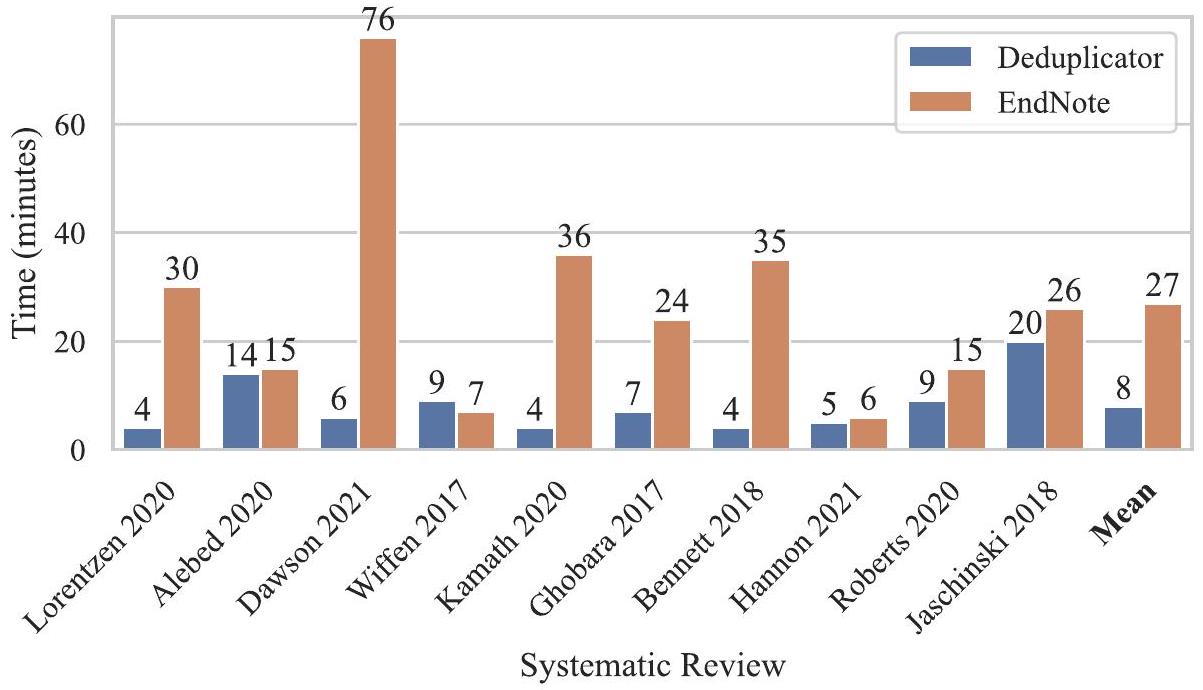

Results Before deduplication, the mean library size for the 10 systematic reviews was 1962 records. When using the Deduplicator, the mean time to deduplicate was 5 min per 1000 records compared to 15 min with EndNote. The mean error rate with Deduplicator was 1.8 errors per 1000 records in comparison to 3.1 with EndNote. Evaluation of the different Deduplicator algorithms found that the ‘balanced’ algorithm had the highest mean F1 score of 0.9647. The ‘focused’ algorithm had the highest mean accuracy of 0.9798 and the highest recall of 0.9757 . The ‘relaxed’ algorithm had the highest mean precision of 0.9896 . Conclusions This demonstrates that using the Deduplicator for duplicate record detection reduces the time taken to deduplicate, while maintaining or improving accuracy compared to using a semi-manual EndNote method. However, further research should be performed comparing more deduplication methods to establish relative performance of the Deduplicator against other deduplication methods.

Background

process called screening), the duplicate records must be removed. This process is referred to as deduplication.

There are multiple methods to deduplicate records retrieved from searching for systematic reviews. One method of deduplication utilised by researchers is to use a semi-manual method, combining software such as EndNote with human checking, although this method is still prone to errors [8]. Despite deduplication being a routine task in systematic reviews, there is little consensus about the best method of deduplication [8]. Although there have been attempts to standardise semi-manual deduplication methods, they rely on the steps being applied consistently and are limited to certain reference management software (e.g. EndNote) [9]. There has also been a growth in the number of fully automated tools that can deduplicate without any human involvement [10]. One limitation of these tools is that they are often tied to proprietary software and are often closed-source, meaning that the internal workings of these algorithms are largely unknown.

Methods

Development of the Deduplicator

Development of the deduplication algorithm

2 True negative

3 False positive

4 False negative

2 Precision: provides the number of unique studies incorrectly removed in the deduplication process (Eq. 2)

3 Recall: provides the number of duplicates missed in the deduplication process (Eq. 3)

4 F1 score: combines recall and precision metrics and represents the overall performance of the model (Eq. 4)

Along with each algorithm, a set of mutators are specified at the top of the configuration file. These play a key role as they aim to unify differences between fields in each database. For instance, an author rewrite mutator will unify the different ways of writing author names (e.g. ‘John Smith’ vs ‘Smith, J’ vs ‘J. Smith’). An alphanumeric mutator will attempt to resolve differences in Unicode characters between articles and a page number mutator will unify differences between the page numbering systems (e.g. ‘356-357’ vs ‘356-7’). Unicode characters can differ across languages therefore the mutator is needed to standardise them, e.g. changing the author names Rolečková or Hammarström to Roleckova or Hammarstrom. A full table of mutators and what they do can be found in the supplementary materials (Supplement 2). These mutators are applied before deduplication and hence the process of applying all mutators will be referred to as pre-processing.

How the Deduplicator algorithm identifies duplicate records

a value between zero and one based on how closely the strings match. The algorithm works as below:

2 For each ‘step’ specified in the algorithm (Supplement 3):

(a) Sort the list of records based on the specified ‘sort’ field (e.g. “title”)

(b) Split the records into separate sub-groups based on matching entries for the specified ‘sort’ field (e.g. If “title”, all records with a title of “Automation of Duplicate Record Detection for Systematic Reviews” will be grouped together)

(c) Calculate the similarity score for every combination of records inside the sub-group

4 If two records have an average similarity score greater than a threshold (e.g. 0.01), the two records are marked as duplicates

greater than 0.01 , then the two records are presumed to be duplicates.

The mean similarity score is also used to classify how likely it is that two records are duplicates. A score greater than or equal to 0.9 will put duplicate records in the “Extremely Likely Duplicates” group. A score greater than or equal to 0.7 will put duplicate records in the “Highly Likely Duplicates” group. Any score less than 0.7 but greater than 0.01 will put the duplicates in the “Likely Duplicates” group. These score thresholds are arbitrarily chosen after testing against various duplication scenarios. These scores were found to be ideal for their relative groups, such that the “Extremely Likely Duplicates” and “Highly Likely Duplicates” groups are very unlikely to contain any unique records (false positives).

Further information and the code for the algorithm is available via the IEBH/dedupe-sweep GitHub repository [12].

Evaluation of the Deduplicator

Definition of a duplicate record

- Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 Oct;62(10):1006-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi. 2009 . 06.005

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G. (2009). Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1006-1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006-1012. doi:10.1016/j. jclinepi.2009.06.005

- Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group.Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336-41. doi: 10.1016/j. ijsu.2010.02.007

- Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group.J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 Oct;62(10):1006-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi. 2009 . 06.005

- Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. BMJ. 2009 Jul 21;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535

Selection of systematic reviews to be deduplicated

Inclusion criteria of the systematic reviews

- All search strings for all databases needed to be reported in the review

- The number of databases searched in the review had to be two or more

- The total number of search results found by the combination of all search strings had to be between 500 and 10,000 records

Obtaining the sample to be deduplicated

Deduplication of search results

Validation of deduplication

had been deduplicated. Any discrepancies were manually checked and verified by consensus between two authors (HG and CF). This produced a final “correctly deduplicated” EndNote library for each sample set. This enabled the identification of errors from each screeners’ library, with an incorrectly removed unique article labelled a “false positive”, while a duplicate which was incorrectly missed was labelled as a “false negative”.

Outcomes

2 Unique studies removed/False positives: the number of records in the library the screener classified as a duplicate when they were a unique record

3 Duplicates missed/False negatives: the number of records in the library the screener classified as a unique record when it was a duplicate record

4 Total errors: (false positives + false negatives)

Comparison between Deduplicator algorithms

| Set no. | Systematic review (author year) | Number of records | Hannah Greenwood | Justin Clark |

| 1 | Lorentzen 2020 [14] | 813 | EndNote | Deduplicator |

| 2 | Alebed 2020 [15] | 1479 | Deduplicator | EndNote |

| 3 | Dawson 2021 [16] | 3912 | EndNote | Deduplicator |

| 4 | Wiffen 2017 [17] | 1028 | Deduplicator | EndNote |

| 5 | Kamath 2020 [18] | 1785 | EndNote | Deduplicator |

| 6 | Ghobara 2017 [19] | 1807 | Deduplicator | EndNote |

| 7 | Bennett 2018 [20] | 2111 | EndNote | Deduplicator |

| 8 | Hannon 2021 [21] | 1061 | Deduplicator | EndNote |

| 9 | Roberts 2020 [22] | 3181 | EndNote | Deduplicator |

| 10 | Jaschinski 2018 [23] | 2447 | Deduplicator | EndNote |

Like with the development libraries, accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score were the four measures used for comparison between the Deduplicator algorithms. A high precision score indicates that few unique studies were identified as duplicates. A high recall score indicates that very few duplicate studies were incorrectly classified as unique studies. F1 score is a combination score of both precision and recall. The formula for these measures are presented in Eqs. 2, 3 and 4.

Results

Time taken to deduplicate

| Study | Number of records | Number of duplicates | Number of unique studies |

| Cytology screening | 1856 | 1404 | 452 |

| Haematology | 1415 | 246 | 1169 |

| Respiratory | 1988 | 799 | 1189 |

| Stroke | 1292 | 507 | 785 |

Number of errors

Normalised time and error rates

Analysis between screeners

| Systematic review | Total records | Deduplicator | EndNote | ||||

| Unique studies removed | Duplicates missed | Total errors | Unique studies removed | Duplicates missed | Total errors | ||

| Lorentzen 2020 | 813 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Alebed 2020 | 1479 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Dawson 2021 | 3912 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Wiffen 2017 | 1028 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kamath 2020 | 1785 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ghobara 2017 | 1807 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Bennett 2018 | 2111 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Hannon 2021 | 1061 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Roberts 2020 | 3181 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 4 | 16 |

| Jaschinski 2018 | 2447 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Mean | 1962.4 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 6.2 |

| Systematic review | Time per 1000 records (minutes) | Total errors per 1000 records | ||

| Deduplicator | EndNote | Deduplicator | EndNote | |

| Lorentzen 2020 | 5 | 37 | 0.0 | 2.5 |

| Alebed 2020 | 10 | 10 | 4.1 | 5.4 |

| Dawson 2021 | 2 | 19 | 0.5 | 1.8 |

| Wiffen 2017 | 9 | 7 | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| Kamath 2020 | 2 | 20 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Ghobara 2017 | 4 | 13 | 3.3 | 2.8 |

| Bennett 2018 | 2 | 17 | 1.4 | 1.9 |

| Hannon 2021 | 5 | 6 | 2.8 | 4.7 |

| Roberts 2020 | 3 | 5 | 0.9 | 5.0 |

| Jaschinski 2018 | 8 | 11 | 2.9 | 5.3 |

| Mean | 5 | 15 | 1.8 | 3.1 |

Comparison between Deduplicator algorithms

Discussion

| Algorithm | Study | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 score |

| Balanced | Blue light | 0.9989 | 1.0000 | 0.9979 | 0.9990 |

| Balanced | Copper | 0.9822 | 0.9892 | 0.9786 | 0.9839 |

| Balanced | Diabetes | 0.9909 | 0.9890 | 0.9919 | 0.9904 |

| Balanced | Tafenoquine | 0.9888 | 1.0000 | 0.9825 | 0.9912 |

| Balanced | UTI | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Focused | Blue light | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Focused | Copper | 0.9941 | 0.9894 | 1.0000 | 0.9947 |

| Focused | Diabetes | 0.9913 | 0.9823 | 0.9997 | 0.9909 |

| Focused | Tafenoquine | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Focused | UTI | 0.9981 | 0.9950 | 1.0000 | 0.9975 |

| Relaxed | Blue light | 0.9977 | 1.0000 | 0.9958 | 0.9979 |

| Relaxed | Copper | 0.9921 | 1.0000 | 0.9858 | 0.9928 |

| Relaxed | Diabetes | 0.9934 | 0.9982 | 0.9878 | 0.9930 |

| Relaxed | Tafenoquine | 0.9944 | 1.0000 | 0.9912 | 0.9956 |

| Relaxed | UTI | 0.9799 | 1.0000 | 0.9475 | 0.9730 |

| Balanced | Mean | 0.9921 | 0.9956 | 0.9902 | 0.9929 |

| Focused | Mean | 0.9967 | 0.9934 | 0.9999 | 0.9966 |

| Relaxed | Mean | 0.9915 | 0.9996 | 0.9816 | 0.9905 |

records without any manual check and those who wanted to be able to check each decision made by the Deduplicator. This led to the development of two algorithms, ‘relaxed’ and ‘focused’ which replaced the ‘balanced’ algorithm. When comparing algorithms, the ‘focused’ algorithm had the highest recall score, indicating it was the best at finding all duplicates; however, it has the lowest precision score which means that the results need to be checked. The ‘relaxed’ algorithm had the highest precision, meaning it is unlikely to remove any unique studies; however, it has the lowest recall meaning that some duplicate studies will remain after deduplication (Tables 5 and 6). Therefore, we recommend the ‘relaxed’ algorithm for large libraries of records (> 2000 records), where people do not wish to check the results and the ‘focused’ algorithm for small libraries of records (< 2000 records) as this is a feasible number to check manually. These numbers may change depending on the time constraints of the individual study.

| Algorithm | Study | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 score |

| Balanced | Cytologyscreening | 0.9758 | 0.9836 | 0.9843 | 0.9840 |

| Balanced | Haematology | 0.9696 | 0.9177 | 0.9065 | 0.9121 |

| Balanced | Respiratory | 0.9819 | 0.9823 | 0.9725 | 0.9774 |

| Balanced | Stroke | 0.9884 | 0.9824 | 0.9882 | 0.9853 |

| Focused | Cytologyscreening | 0.9790 | 0.9789 | 0.9936 | 0.9862 |

| Focused | Haematology | 0.9654 | 0.8774 | 0.9309 | 0.9034 |

| Focused | Respiratory | 0.9864 | 0.9801 | 0.9862 | 0.9832 |

| Focused | Stroke | 0.9884 | 0.9786 | 0.9921 | 0.9853 |

| Relaxed | Cytologyscreening | 0.9763 | 0.9885 | 0.9801 | 0.9843 |

| Relaxed | Haematology | 0.9710 | 0.9812 | 0.8496 | 0.9107 |

| Relaxed | Respiratory | 0.9779 | 0.9948 | 0.9499 | 0.9718 |

| Relaxed | Stroke | 0.9853 | 0.9939 | 0.9684 | 0.9810 |

| Balanced | Mean | 0.9789 | 0.9665 | 0.9629 | 0.9647 |

| Focused | Mean | 0.9798 | 0.9538 | 0.9757 | 0.9645 |

| Relaxed | Mean | 0.9776 | 0.9896 | 0.9370 | 0.9619 |

software or database platforms. However, unlike some tools such as Covidence, Deduplicator requires exporting the library from a reference manager and then importing the result back into the reference manager or screening tool to continue with screening. While this is something that is being worked on, some users may find it undesirable to move their records between different tools.

Limitations

the “Wiffen, 2017” systematic review, the Deduplicator was slightly slower to deduplicate [HG] compared to the semi-manual EndNote method [JC]. JC’s extra experience probably facilitated quick, accurate semi-manual deduplication of the small Wiffen library faster than HG could achieve using the Deduplicator. This difference in deduplication speed/accuracy between authors is partially mitigated by the equal split of methods used by each author, but this does not eliminate this bias entirely. Despite this disparity, using the Deduplicator increased the speed with which both screeners could deduplicate sets of search results (Fig. 2). It could also be argued that Deduplicator will likely be used by researchers with a broad range of experience, and therefore having two types of screener experience level in this study makes it more representative of real world conditions.

A second limitation is the possibility that both authors made the same mistake, e.g. both missed the same duplicate record. This error would not show up in the results, as the errors were determined by comparing both screeners’ results. But, since deduplication was done separately by two people with the aid of a computer algorithm, we can be fairly confident this number is low. Also, as this is a comparison to determine which deduplication method was better, if neither had the error marked against them, this would not affect the comparison in errors made between the two methods.

Third, only the Beta, or ‘balanced’ algorithm was assessed in the direct comparison to EndNote. Since the completion of the study, the ‘balanced’ algorithm has been replaced by two new algorithms: the ‘relaxed’ and ‘focused’ algorithms. While these were not compared directly against EndNote, they were compared against the ‘balanced’ algorithm. The results for this analysis is presented in Table 6.

Future research

Conclusion

Abbreviations

SRA Systematic Review Accelerator

Supplementary Information

Additional file 3. A PDF file representing the JSON code that is used for the deduplication comparison algorithm.

Acknowledgements

Authors’ contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 02 August 2024

References

- Borah R, Brown AW, Capers PL, Kaiser KA. Analysis of the time and workers needed to conduct systematic reviews of medical interventions using data from the PROSPERO registry. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):e012545. https:// doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012545.

- Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. BMJ Evid-Based Med. 2016;21(4):125-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/ ebmed-2016-110401.

- Michelson M, Reuter K. The significant cost of systematic reviews and meta-analyses: a call for greater involvement of machine learning to assess the promise of clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;16:100443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100443.

- Scott AM, Glasziou P, Clark J. We extended the 2-week systematic review (2weekSR) methodology to larger, more complex systematic reviews: a case series. J Clin Epidemiol. 2023;157:112-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jclinepi.2023.03.007.

- Tufanaru C, Surian D, Scott AM, Glasziou P, Coiera E. The 2-week systematic review (2weekSR) method was successfully blind-replicated by another team: a case study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2024;165. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.jclinepi.2023.10.013.

- Beller E, Clark J, Tsafnat G, Adams C, Diehl H, Lund H, et al. Making progress with the automation of systematic reviews: principles of the International Collaboration for the Automation of Systematic Reviews (ICASR). Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0740-7.

- Tsafnat G, Glasziou P, Choong MK, Dunn A, Galgani F, Coiera E. Systematic review automation technologies Syst Rev. 2014;3:74. https://doi.org/10. 1186/2046-4053-3-74.

- Qi X, Yang M, Ren W, Jia J, Wang J, Han G, et al. Find duplicates among the PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library Databases in systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71838. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 00718 38.

- Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(3):240-3. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014.

- McKeown S, Mir ZM. Considerations for conducting systematic reviews: evaluating the performance of different methods for deduplicating references. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13643-021-01583-y.

- IEBH. The Systematic Review Accelerator. 2018. https://sr-accelerator.com. Accessed 11 Nov 2022.

- IEBH. Deduplicator GitHub Repository. 2020. https://github.com/IEBH/ dedupe-sweep. Accessed 11 Nov 2022.

- Winkler W. String comparator metrics and enhanced decision rules in the Fellegi-Sunter model of record linkage. Proceedings of the Section on Survey Research Methods. American Statistical Association. Alexandri: American Statistical Association; 1990. Avaliable at: https://eric.ed.gov/? id=ED325505.

- Lorentzen

, Davis , Penninga . Interventions for frostbite injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;12(12):CD012980. https://doi.org/10. 1002/14651858.CD012980.pub2. - Alabed

, Sabouni A, Al Dakhoul S, Bdaiwi Y. Beta-blockers for congestive heart failure in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7(7):CD007037. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007037.pub4. - Dawson JA, Summan R, Badawi N, Foster JP. Push versus gravity for intermittent bolus gavage tube feeding of preterm and low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;8(8):CD005249. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/14651858.CD005249.pub3.

- Wiffen PJ, Cooper TE, Anderson AK, Gray AL, Grégoire MC, Ljungman G, et al. Opioids for cancer-related pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7(7):CD012564. https://doi.org/10. 1002/14651858.CD012564.pub2.

- Kamath MS, Mascarenhas M, Kirubakaran R, Bhattacharya S. Number of embryos for transfer following in vitro fertilisation or intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8(8):CD003416. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003416.pub5.

- Ghobara T, Gelbaya TA, Ayeleke RO. Cycle regimens for frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7(7):CD003414. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003414.pub3.

- Bennett MH, Feldmeier J, Smee R, Milross C. Hyperbaric oxygenation for tumour sensitisation to radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;4(4):CD005007. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005007.pub4.

- Hannon CW, McCourt C, Lima HC, Chen S, Bennett C. Interventions for cutaneous disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;3(3):CD007478. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007 478.pub2.

- Roberts KE, Rickett K, Feng S, Vagenas D, Woodward NE. Exercise therapies for preventing or treating aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal symptoms in early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1(1):CD012988. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012988.pub2.

- Jaschinski T, Mosch CG, Eikermann M, Neugebauer EA, Sauerland S. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11(11):CD001546. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651 858.CD001546.pub4.

- Rathbone J, Carter M, Hoffmann T, Glasziou P. Better duplicate detection for systematic reviewers: evaluation of Systematic Review AssistantDeduplication Module. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/ 2046-4053-4-6.

- Guimarães NS, Ferreira AJF, Ribeiro Silva RdC, de Paula AA, Lisboa CS, Magno L, et al. Deduplicating records in systematic reviews: there are free, accurate automated ways to do so. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;152:110115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.10.009.

- Borissov N, Haas Q, Minder B, Kopp-Heim D, von Gernler M, Janka H, et al. Reducing systematic review burden using Deduklick: a novel, automated, reliable, and explainable deduplication algorithm to foster medical research. Syst Rev. 2022;11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02045-9.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Connor Forbes

cforbes@bond.edu.au

Institute for Evidence-Based Healthcare, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia