DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-03904-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38317209

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-05

أثر الواقع الافتراضي على تقليل قلق المرضى وألمهم أثناء جراحة زراعة الأسنان

الملخص

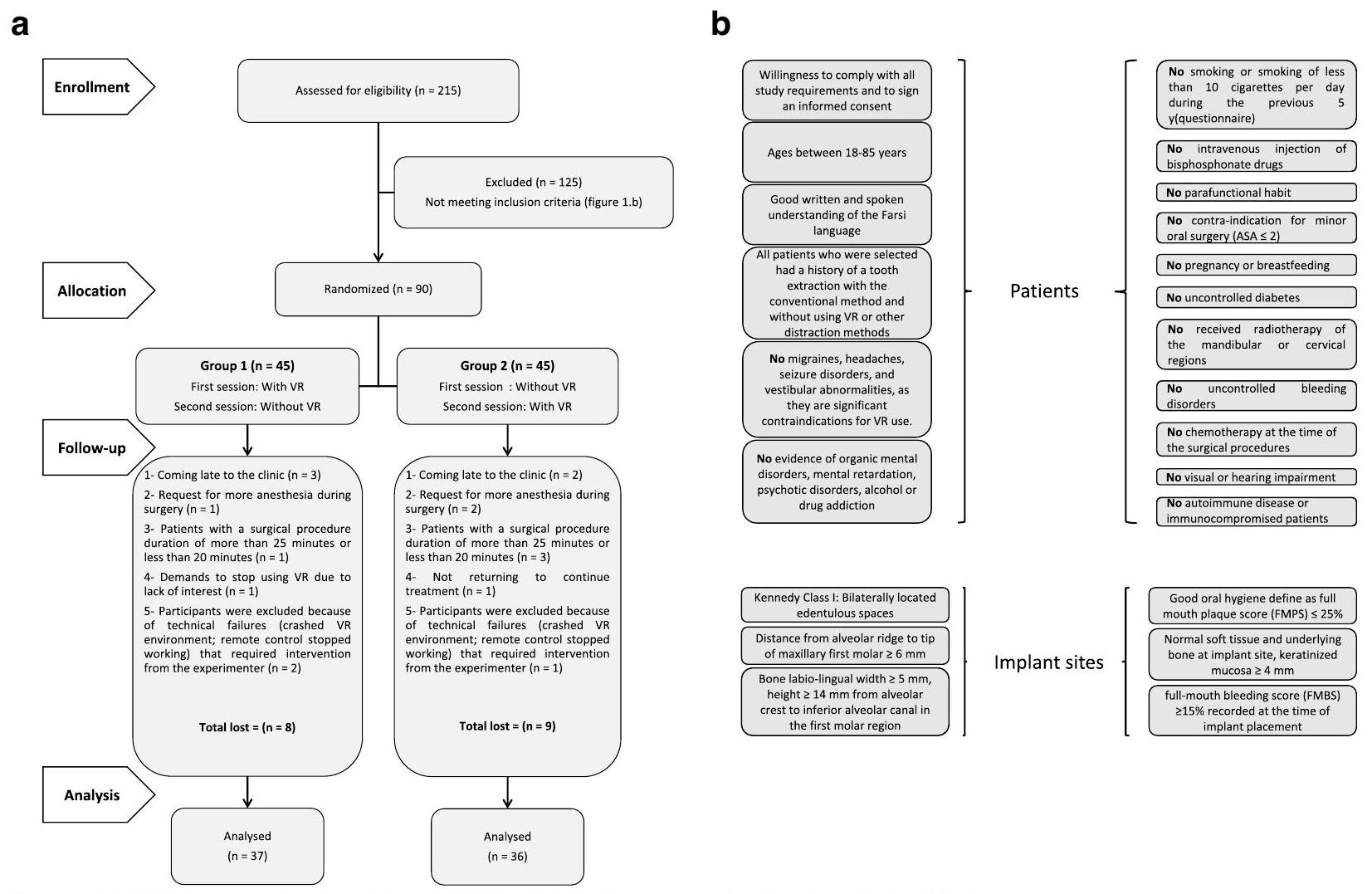

خلفية: يمثل قلق الأسنان والألم مشاكل خطيرة لكل من المرضى وأطباء الأسنان. واحدة من أكثر الإجراءات السنية إجهاداً ورعباً للمرضى هي جراحة زراعة الأسنان؛ حتى أن مجرد سماع اسمها يسبب لهم التوتر. يعتبر تشتيت الواقع الافتراضي (VR) تدخلاً فعالاً يستخدمه المتخصصون في الرعاية الصحية لمساعدة المرضى على التعامل مع الإجراءات غير السارة. هدفنا هو تقييم استخدام الواقع الافتراضي عالي الجودة والبيئات الطبيعية على مرضى زراعة الأسنان لتحديد تأثيره على تقليل الألم والقلق. الطرق: شارك ثلاثة وسبعون مريضاً خضعوا لجراحتين لزراعة الأسنان في تجربة عشوائية محكومة. كانت إحدى الجراحات باستخدام الواقع الافتراضي، والأخرى بدون. تم قياس القلق باستخدام مقياس القلق للحالة والسمات واختبارات مقياس قلق الأسنان المعدل. تم قياس الألم باستخدام مقاييس التقييم العددي. تم تقييم رضا المرضى، وضغط الجراح، ووضوح الذاكرة، وإدراك الوقت. تم جمع البيانات الفسيولوجية باستخدام جهاز التغذية الراجعة البيولوجية والتغذية الراجعة العصبية.

النتائج: قلل الواقع الافتراضي بشكل فعال من القلق والألم مقارنة بعدم استخدام الواقع الافتراضي. أكدت البيانات الفسيولوجية نتائج الاستبيانات. زاد رضا المرضى، مع

الاستنتاج: أظهرت التقييمات النفسية والنفسية الفسيولوجية أن الواقع الافتراضي قلل بنجاح من ألم المرضى وقلقهم. يجب على المزيد من أطباء الأسنان استخدام تقنية الواقع الافتراضي لإدارة قلق المرضى وألمهم.

*المراسلة:

هداية مرادبور

hedaiat.moradpoor@gmail.com

مقدمة

القلق هو استجابة شائعة للجراحة [40]، خاصةً لأن البقاء مستيقظاً أثناء الجراحة بمساعدة التخدير الموضعي يمكن أن يكون مليئاً بمخاوف وقلق محدد [16، 34، 51]. ليس فقط أن القلق غير مريح، ولكن تم ملاحظة علاقة متسقة بين القلق الجراحي،

الألم بعد الجراحة [4، 18]، وزيادة الحاجة إلى المسكنات [41]، وتأخر الشفاء [35]. أظهرت نتائج مسح كبير لصحة الأسنان للبالغين من قبل الخدمة الصحية الوطنية (NHS) أن أكثر من ثلث البالغين (36%) يعانون من قلق أسنان معتدل، و12% آخرين يعانون من قلق أسنان شديد. هؤلاء المرضى يذهبون إلى طبيب الأسنان فقط عند الشعور بالألم، مما يزيد من قلقهم أيضاً [3]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن المرضى القلقين أقل اهتماماً بالحفاظ على مواعيدهم الروتينية [24]، وتأخذ علاجاتهم وقتاً أطول، ويشعرون برضا أقل بعد العلاج [28]، ويعاني أطباء الأسنان أنفسهم من مزيد من الضغط عند علاج المرضى القلقين [12].

الألم هو تجربة ذاتية معقدة ومتعددة الأبعاد تشمل العمليات الحسية والعاطفية والمعرفية. يتأثر إدراك الألم بطيف واسع من الأبعاد والتفاعلات بين هذه العمليات، حيث تلعب الأبعاد المعرفية-التقييمية، والدافعية-العاطفية، والتمييزية دوراً في إدراك الألم [36، 37]. يتم الإبلاغ عن عدم الراحة من الألم بشكل متكرر من قبل المرضى الذين يخضعون للعلاج السني، حتى أثناء الإجراءات الترميمية الروتينية [26، 27]. في دراسة قائمة على السكان،

للتنويع عن الألم، حيث يتطلب بعض مستوى من الانتباه لتجربة الألم [25، 44].

المواد والأساليب

الموافقات التنظيمية

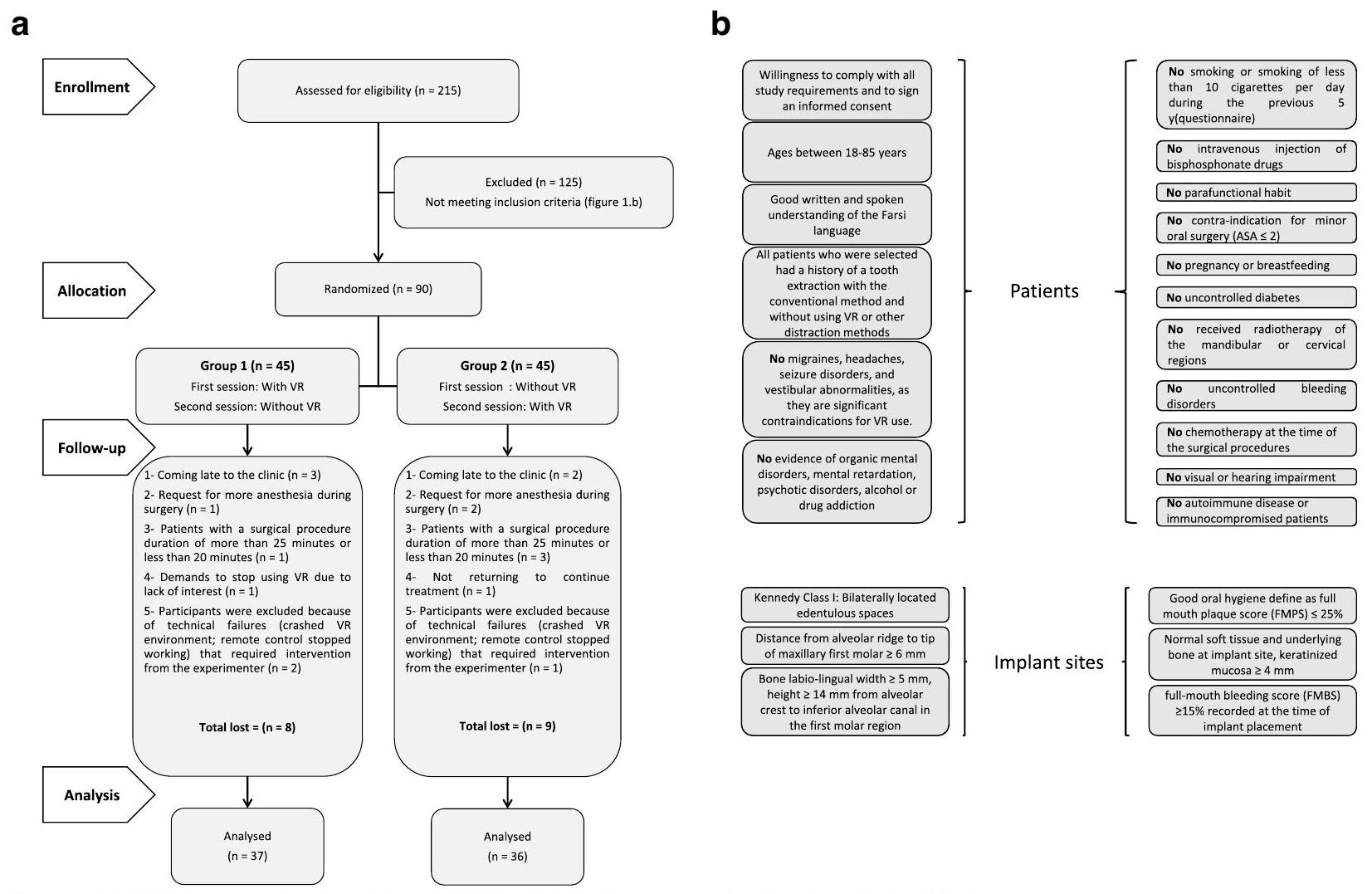

تصميم الدراسة

قبل الدراسة، أظهرت الفحوصات الأولية للمؤلفين على 10 مرضى أن متوسط طول

إجراء جراحة الزرع من قبل الجراح في هذه الدراسة كان 23 دقيقة (دون احتساب وقت تحضير المريض وحقن المخدر). لتعظيم توحيد الظروف لجميع المرضى، تم استبعاد أولئك الذين كانت مدة جراحتهم أكثر من 25 دقيقة أو أقل من 20 دقيقة من الدراسة. بالنسبة لأولئك المرضى الذين كانت عملية جراحتهم بين 20 إلى 25 دقيقة، استخدم الجراح أدوات أسنان أخرى وتظاهر بالعمل، محاولًا زيادة مدة العلاج إلى 25 دقيقة بحيث كانت المدة الفعلية المستغرقة هي نفسها لجميع المرضى. لهذا الغرض، تم تثبيت ساعة كبيرة أمام الجراح لمتابعة الوقت (الشكل 2). لتعظيم توحيد الظروف، طُلب من جميع المرضى الحضور إلى المكتب بمفردهم. عندما كانوا في غرفة الانتظار، لم يكن هناك مرضى آخرون موجودون، وساد الصمت (الشكل 3). كانت الأقلام المستخدمة جديدة جميعها ومن نفس العلامة التجارية لتقليل تأثير التدخلات التجريبية الأخرى.

المشاركون

من

الأجهزة

سماعة الواقع الافتراضي

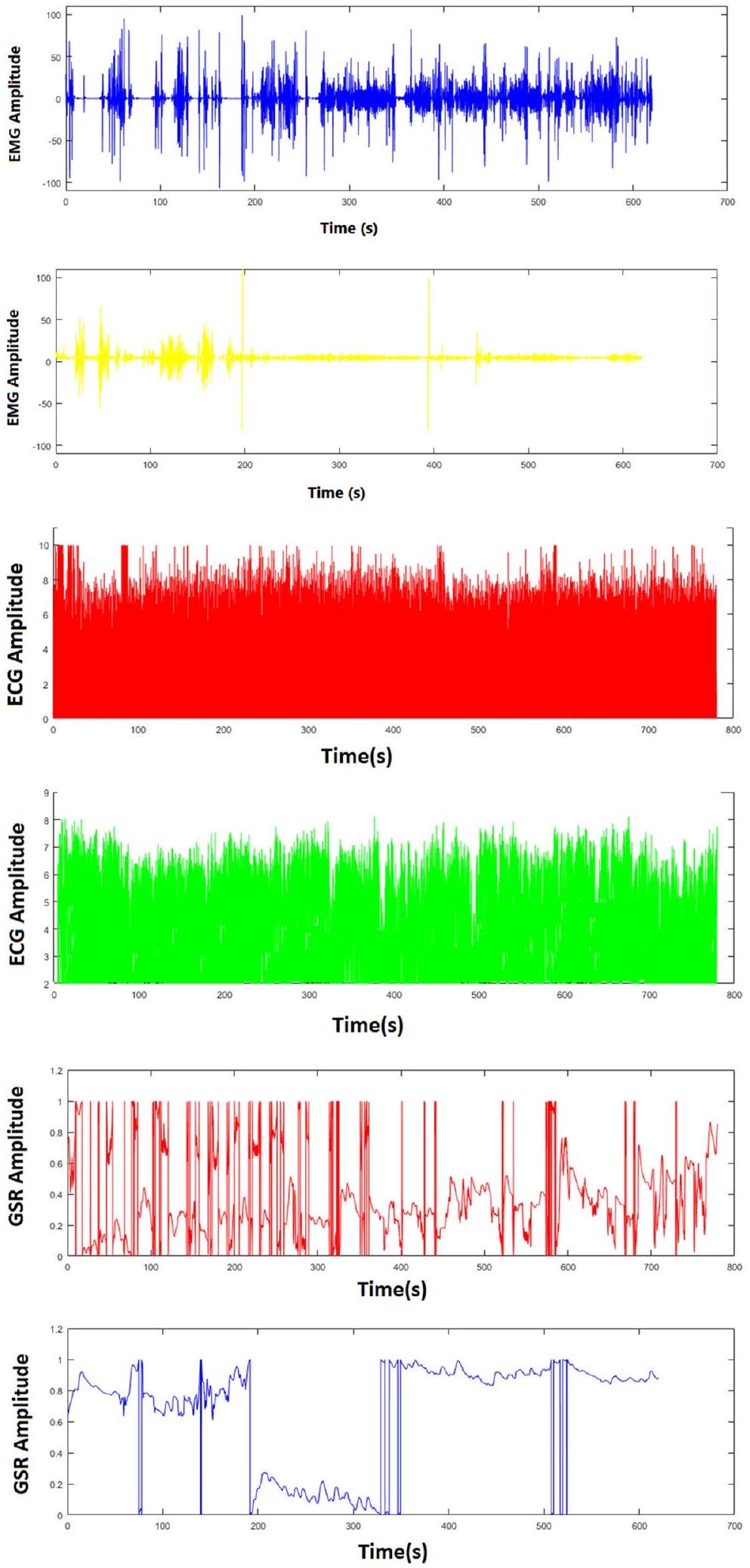

نظام التغذية الراجعة الحيوية والتغذية الراجعة العصبية

الإجراء

| الوقت | الاختبار | المعلمة | |||

| قبل الجراحة | القلق | STAI-T | |||

| الألم (المتوقع) | NRS 0-10 | ||||

| أثناء الجراحة |

|

||||

| EMG | |||||

| EKG |

|

||||

| SCR | متوسط الجذر التربيعي (RMS) | ||||

| بعد الجراحة | القلق | STAI-S | |||

| MDAS | |||||

| الألم (المعاناة) | NRS 0-10 | ||||

| NRS 0-10 | |||||

| الرضا | TDR | ||||

| استخدام الواقع الافتراضي مرة أخرى في المستقبل | |||||

| مدة العلاج | إدراك الوقت | ||||

| بعد أسبوع (عبر الهاتف) | وضوح الذكريات | NRS 0-10 |

التقييم النفسي

الألم

القلق

- استبيان STAI (استبيان القلق الحاد والمزمن). يتم استخدام هذا الاستبيان على نطاق واسع في الأبحاث والأنشطة السريرية ويشمل مقاييس تقرير ذاتي منفصلة لقياس القلق الحاد والمزمن [46]. يتكون كل مقياس من 20 عنصرًا يمكن تسجيلها من 1 (ليس على الإطلاق) إلى 4 (كثيرًا جدًا). يتراوح مجموع الدرجات لـ STAI-S أو STAI-T من 20 إلى 80. يمكن اعتبار الأسئلة العشرين الأولى، القلق الحاد (S)، كعرض مقطعي لحياة الشخص، مما يعني أن حدوثها هو ظرفي ومحدد لمواقف الضغط (المشاجرات، فقدان الوضع الاجتماعي، التهديدات للأمن والصحة البشرية) ويظهر مشاعر الشخص في تلك اللحظة. لكن الأسئلة العشرين التالية، القلق المزمن (T)، تشير إلى الفروق الفردية في الاستجابة لمواقف الضغط بدرجات متفاوتة من القلق الحاد. طُلب من المرضى اختيار خيار استجابة واحد فقط لكل سؤال وعدم ترك أي سؤال بدون إجابة.

- مقياس MDAS (مقياس القلق السني المعدل). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم تقييم مستوى قلق كل مريض باستخدام استبيان مقياس القلق السني المعدل (MDAS). يُعتبر MDAS هو الاستبيان الأكثر استخدامًا لقياس القلق السني في المملكة المتحدة وهو نسخة معدلة من استبيان DAS، وهو القياس الأكثر شيوعًا في الدراسات المتعلقة بالقلق السني [17]. يتكون هذا الاستبيان من خمسة عناصر لتقييم مستوى القلق في مواقف سنية مختلفة. يحتوي كل سؤال على استجابة مكونة من 5 نقاط على مقياس ليكرت تتراوح من “غير قلق” إلى “قلق للغاية”. يتم تسجيل كل استجابة، ويتم تسجيل مجموع جميع الاستجابات. يتراوح مجموع الدرجات على هذا المقياس من 5 إلى 25. من المهم ملاحظة أن همفريس وهال وجدا أن استخدام هذا الاستبيان لم يزيد من القلق [2].

الرضا

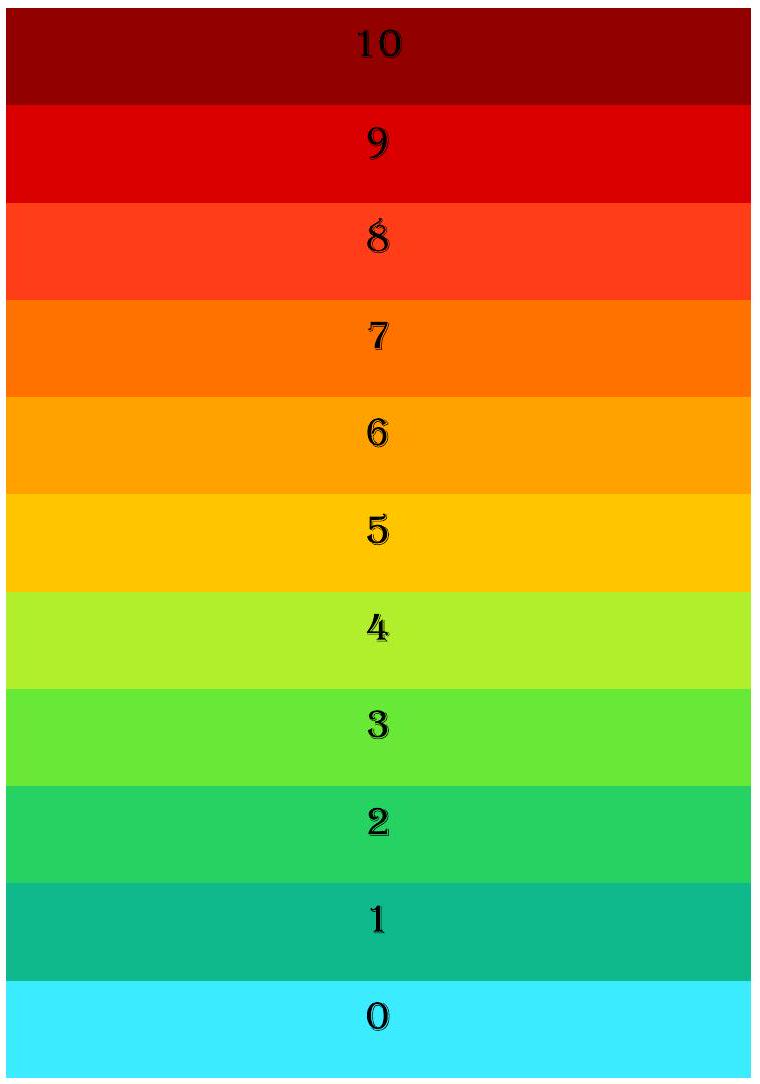

- بعد الجراحة، تم تطبيق استبيان NRS المكون من 11 نقطة على المشاركين لتقييم رضاهم عن علاجهم على مقياس من 0 (غير راضٍ تمامًا) إلى 10 (راضٍ تمامًا).

- طُلب من المرضى أيضًا إذا، في حال كان لديهم الخيار في المرة القادمة، كانوا يرغبون في أن يستخدم طبيب الأسنان نظارات الواقع الافتراضي مرة أخرى أم لا. كانت الخيارات هي نعم، لا، ولست متأكدًا. كان لدى المرضى خيار ترك تعليقاتهم في قسم ملاحظات الاستبيان.

- تم تقييم تصنيف ضغوط العلاج (TDR) بعد الانتهاء من العلاج لتقييم ضغوط طبيب الأسنان الناتجة عن الإجراء السني للمريض. بهذه الطريقة، طُلب من طبيب الأسنان تحديد مقدار الضغوط الناتجة عن الواقع الافتراضي أثناء العلاج وتداخلها مع حرية تصرف الجراح مقارنةً بمجموعة التحكم، أي عندما تم إجراء العلاج الروتيني (بدون واقع افتراضي) لهم. كان تنسيق الاستجابة مشابهًا لمقياس التقييم العددي المكون من 11 نقطة (NRS) للألم، حيث تم تعريف 0 على أنه “لا ضغوط على الإطلاق” و10 على أنه “أسوأ ضغوط ممكنة.”

وضوح الذكريات

نسبة إدراك الوقت

التقييم النفسفيزيولوجي

جمع البيانات

التحليل الإحصائي

تم إجراء الدراسة في قسمين: الإحصاءات الوصفية والإحصاءات الاستنتاجية. قدم قسم الإحصاءات الوصفية مقاييس النزعة المركزية والتشتت، بالإضافة إلى الجداول والرسوم البيانية. في قسم الإحصاءات الاستنتاجية، تم فحص طبيعة البيانات باستخدام اختبار كولموغوروف-سميرنوف. تم استخدام اختبار T لعينة مستقلة لمقارنة متغير العمر بين المجموعتين، واستخدم اختبار كاي-تربيع لمقارنة توزيع الجنس بين المجموعتين. تم استخدام نموذج المعادلات التقديرية العامة (GEE) للتحقيق في تأثير نوع التدخل، والجنس، ومتغيرات العمر. تم التحقق من افتراضات النموذج من خلال تحليل المتبقيات. تم استخدام برنامج SPSS Inc. لتحليل البيانات) صدر عام 2009. PASW Statistics لنظام ويندوز، الإصدار 18.0. شيكاغو: SPSS Inc. (تم اعتبار مستوى الدلالة في هذه الدراسة 0.05.)

النتائج

| المجموعة 1 (N: 37) | المجموعة 2 ( ن : 36 ) | إجمالي |

|

||||

| جنس | ذكر | ١٨ | ١٨ | ٣٦ |

|

||

| أنثى | 19 | 18 | 37 | ||||

|

سنة |

|

|

|

|

||

| المدرسة الابتدائية | ٤ | ٤ | ٨ | 0.942* | |||

| المدرسة الثانوية | 16 | 14 | 30 | ||||

| جامعة | 17 | ١٨ | ٣٥ | ||||

| تدخل | ||||

| بدون واقع افتراضي | مع الواقع الافتراضي | |||

| معنى | SD | معنى | SD | |

| الألم المتوقع | 5.85 | . 92 | 5.93 | . 89 |

| ألم مُعانَاة | ٤.٣٠ | 1.32 | ٢.٥٩ | 1.09 |

| MDAS | 17.42 | 3.76 | 12.88 | 2.64 |

| STAI-S | 41.07 | 6.04 | ٣٧.٦٢ | ٥.٦٨ |

| STAI-T | ٤١.٠٥ | ٤.٢٦ | ٤١.٢٣ | ٤.٢١ |

| الرضا | 7.64 | 1.19 | 8.78 | 1.20 |

| نسبة إدراك الوقت | 1.20 | . 20 | 1.08 | . 20 |

| حيوية الذكريات | ٤.٩٨ | . 87 | ٤.٢٩ | . 80 |

| تصنيف ضغوط العلاج | 3.49 | 1.20 | 6.95 | 1.70 |

| الجذر التربيعي لمتوسط المربعات (RMS) لسعة EMG | 62.22 | ٤.٠٣ | ٤٨.٠٦ | ٤.٧٢ |

| التردد الوسيط (MF) | ٧١.٢٢ | 3.65 | ٨٣.٩٩ | ٥.٤٢ |

| قوة نطاق التردد (أعلى من 100 هرتز) | 70.62 | ٤.١٤ | ٥١.٩٧ | 2.38 |

| تغير معدل ضربات القلب (HRV)(مللي ثانية) | ٥٨.٢٧ | 1.08 | ٥٤.٥٢ | . 56 |

| معدل ضربات القلب | 81.10 | 3.11 | 70.80 | ٢.٢٣ |

| الجذر التربيعي لمتوسط المربعات (RMS) لقياس استجابة الجلد (SCR) | 21.35 | 2.00 | 15.96 | 2.08 |

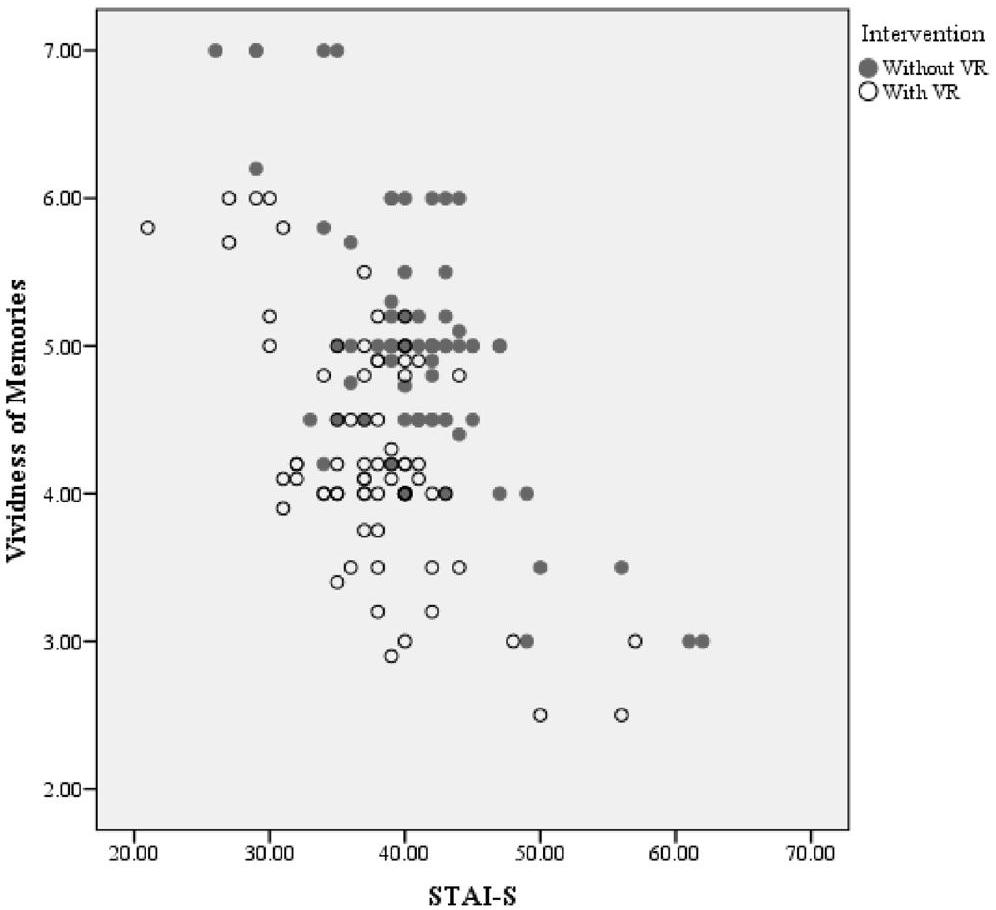

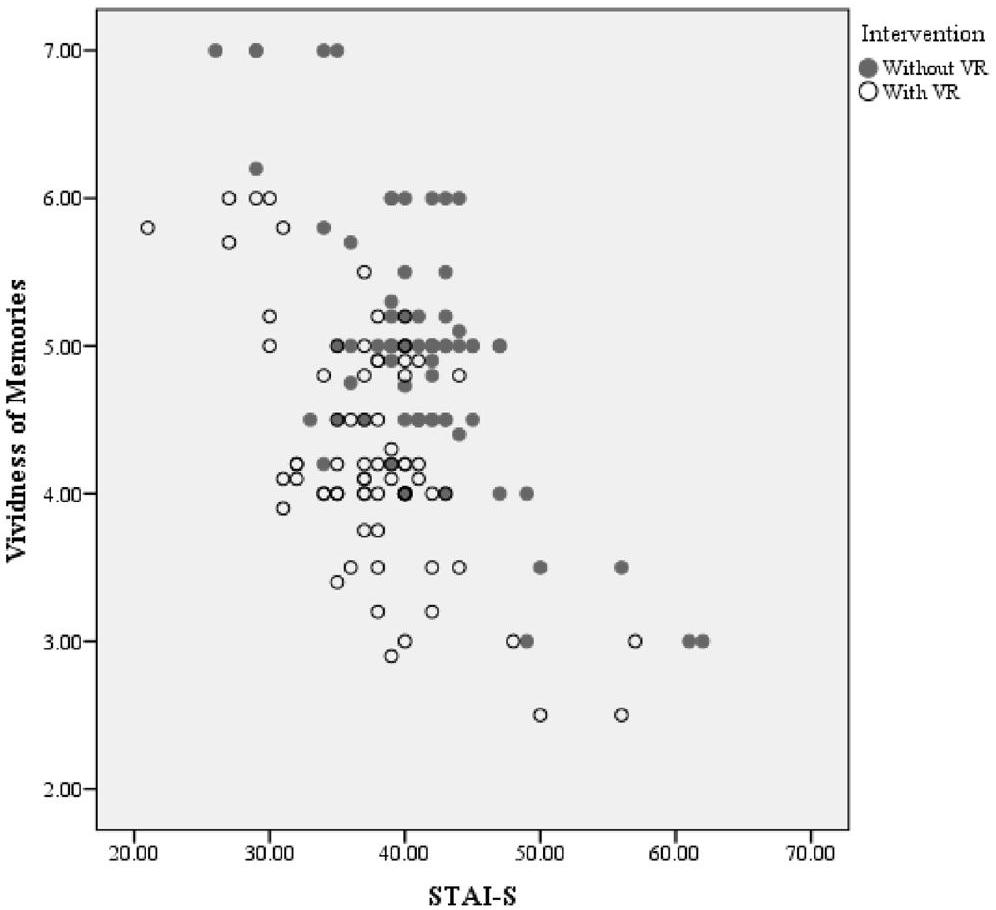

كان لنوع التدخل تأثير كبير على STAI-S (

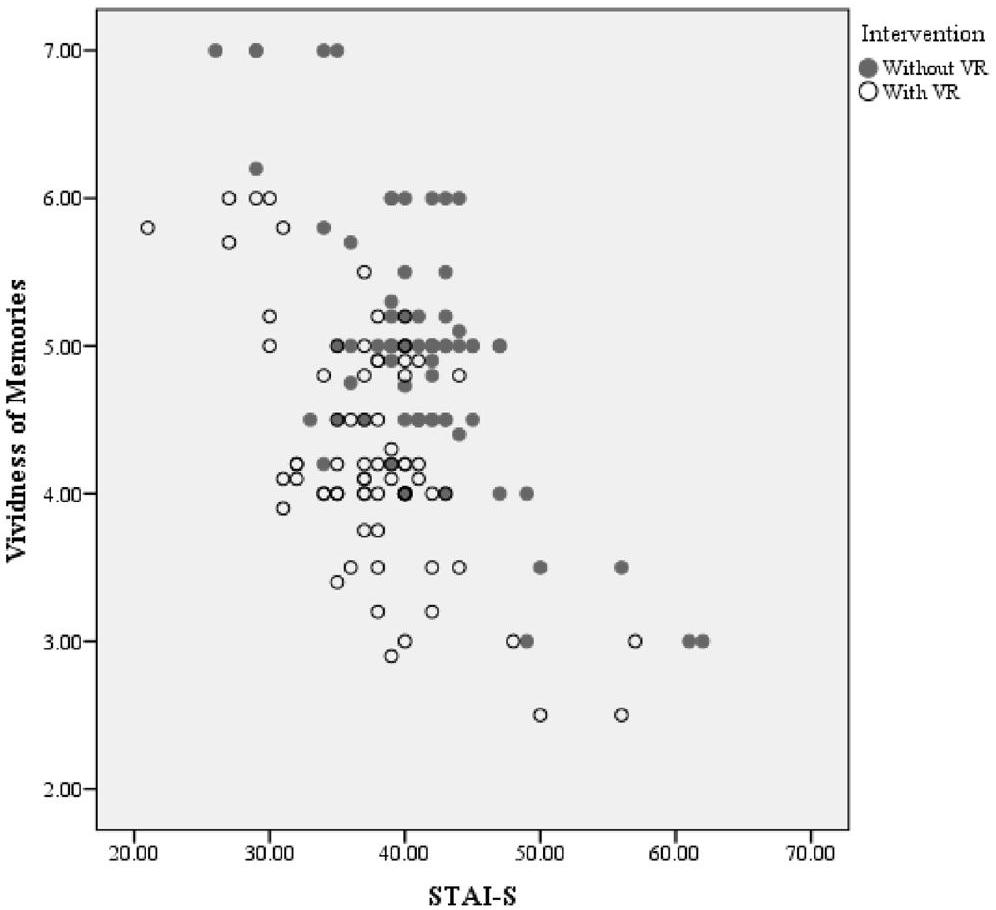

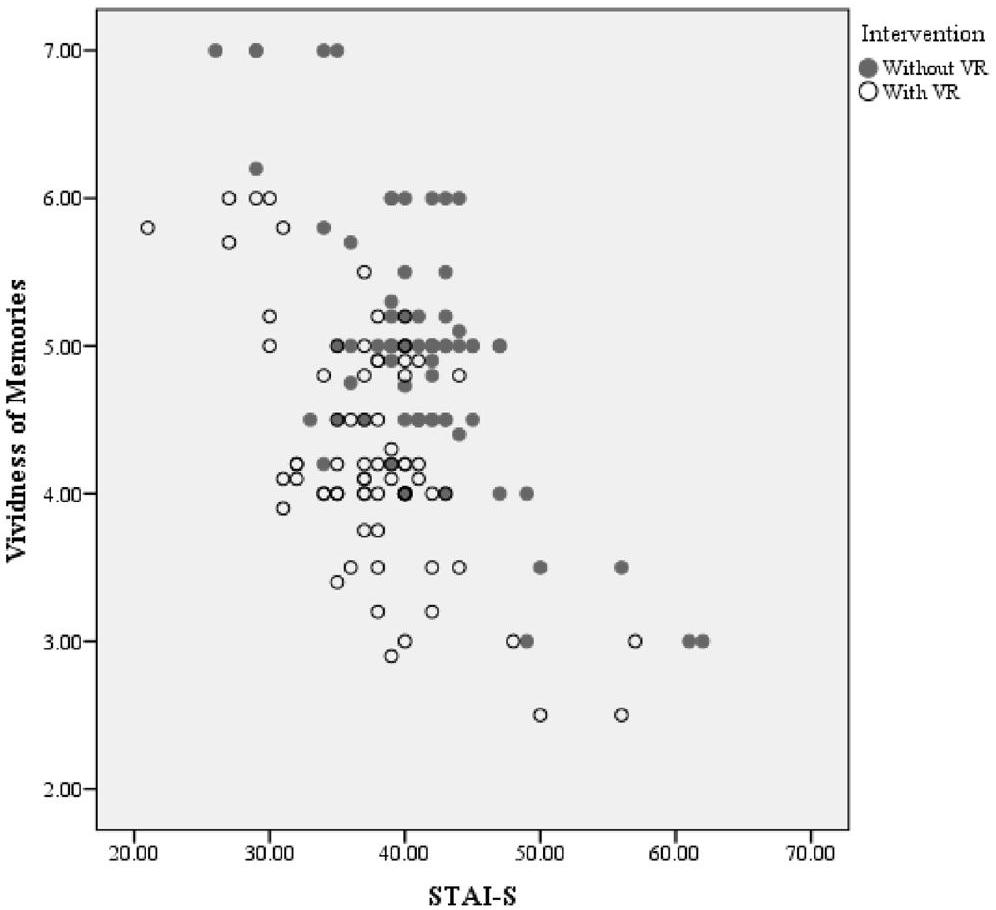

كان لنوع التدخل تأثير كبير على حيوية الذكريات

| المتغير التابع | معامل | ب | خطأ قياسي | فترة الثقة وولد بنسبة 95% | اختبار الفرضية | ||||

| أخفض | علوي | مربع كاي والد | df |

|

|||||

| الألم المتوقع | (الاعتراض) | ٥.٤٨١ | . 2789 | ٤.٩٣٥ | 6.028 | ٣٨٦٫٢٧٨ | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| جنس | أنثى | . 125 | . 1639 | -. 196 | . 446 | . 580 | 1 | . 446 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | . 007 | . 0057 | -. 004 | . 018 | 1.429 | 1 | . 232 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | . ٠٨٢ | . ١٢٩٦ | -. 172 | . 336 | . 402 | 1 | . 526 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | . 818 | ||||||||

| ألم مُعانَاة | (الاعتراض) | ٤.٣٩٦ | . 3560 | 3.699 | 5.094 | ١٥٢.٤٧٧ | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| جنس | أنثى | . 231 | . 1842 | -. 130 | . ٥٩٢ | 1.577 | 1 | . ٢٠٩ | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | -. 005 | . 0069 | -. 018 | . 009 | . 464 | 1 | . 496 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | -1.712 | . 2109 | -2.126 | -1.299 | 65.940 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | 1.470 | ||||||||

| MDAS | (الاعتراض) | 15.258 | 1.2519 | 12.804 | 17.711 | 148.545 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| جنس | أنثى | 1.150 | . 6847 | -. 192 | ٢.٤٩٢ | 2.820 | 1 | . 093 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | . 035 | . 0254 | -. 015 | . 085 | 1.925 | 1 | . 165 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | -4.548 | . 2642 | -5.066 | -4.030 | ٢٩٦٫٢٣٦ | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | 10.089 | ||||||||

| STAI-S | (الاعتراض) | ٣٨.٩٢٧ | ٢.٢٣٤٤ | ٣٤.٥٤٧ | ٤٣.٣٠٦ | ٣٠٣.٤٩٤ | 1 | <0.001 | |

| جنس | أنثى | 2.158 | 1.3535 | -. 495 | ٤.٨١٠ | ٢.٥٤٢ | 1 | . 111 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | . 023 | . 0535 | -. 082 | . 128 | . 190 | 1 | . 663 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | -3.452 | . 2131 | -3.870 | -3.034 | ٢٦٢.٣٢٤ | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | ٣٣.٥٣٩ | ||||||||

| STAI-T | (الاعتراض) | ٣٩.٧٩٣ | ٢.٠٥٥٣ | ٣٥.٧٦٥ | ٤٣.٨٢٢ | ٣٧٤.٨٥٤ | 1 | <0.001 | |

| جنس | أنثى | 1.463 | . 9331 | -. 365 | ٣.٢٩٢ | ٢.٤٦٠ | 1 | . ١١٧ | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | . 012 | . 0464 | -. 079 | . ١٠٣ | . 062 | 1 | . ٨٠٣ | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | . 178 | 2035 | -. 221 | . 577 | . 766 | 1 | . ٣٨٢ | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | 17.610 | ||||||||

| الرضا | (الاعتراض) | 9.140 | . 7308 | 7.708 | 10.572 | 156.438 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| جنس | أنثى | . ٠١٩ | . 1780 | -. 330 | . 368 | . 012 | 1 | . 914 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | -. 037 | . 0094 | -. 056 | -. 019 | 15.505 | 1 | < 0.001 | ||

| التعليم | المدرسة الابتدائية | . ٠٨٢ | . 4121 | -. 726 | . 889 | . 039 | 1 | . 843 | |

| المدرسة الثانوية | . 301 | . 4391 | -. 560 | 1.162 | . 469 | 1 | . 493 | ||

| الجامعة (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | 1.137 | . 1703 | . 803 | 1.471 | 44.551 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | 1.194 | ||||||||

| المتغير التابع | معامل | ب | خطأ قياسي | فترة الثقة وولد بنسبة 95% | اختبار الفرضية | ||||

| أخفض | علوي | مربع كاي والد | df |

|

|||||

| نسبة إدراك الوقت | (الاعتراض) | ١.٢٠٠ | . 0767 | 1.050 | 1.351 | ٢٤٥٫٠٠١ | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| جنس | أنثى | . 028 | . 0427 | -. 056 | . 112 | . 428 | 1 | . ٥١٣ | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | . 000 | . 0017 | -. 004 | . 003 | . 018 | 1 | . 893 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | -. 128 | . 0172 | -. 161 | -. 094 | ٥٥.٢٠٣ | 1 | <0.001 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | . 040 | ||||||||

| حيوية الذكريات | (الاعتراض) | ٥.٠١٨ | . 3549 | ٤.٣٢٢ | 5.713 | 199.881 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| جنس | أنثى | -. 096 | . 1881 | -. 465 | . 273 | . 261 | 1 | . 609 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | . 000 | . 0083 | -. 016 | . 016 | . 000 | 1 | . 984 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | -. 689 | . 0620 | -. 810 | -. 567 | 123.507 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | . 706 | ||||||||

| تصنيف ضغوط العلاج | (الاعتراض) | ٤.٠٧٤ | . 4374 | ٣.٢١٦ | ٤.٩٣١ | ٨٦.٧٤٦ | 1 | <0.001 | |

| جنس | أنثى | -. 314 | . ٢٥١٦ | -. 807 | . 179 | 1.555 | 1 | . 212 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | -. 009 | . 0090 | -. 027 | . 008 | 1.094 | 1 | . 296 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | ٣.٤٥٢ | . 2293 | ٣.٠٠٣ | ٣.٩٠١ | 226.733 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | ٢.١٥٤ | ||||||||

| الجذر التربيعي لمتوسط المربعات (RMS) لسعة EMG | (الاعتراض) | 60.283 | ٢.٤١٣٨ | ٥٥.٥٥٢ | 65.014 | 623.704 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| جنس | أنثى | -. 037 | 1.2182 | -2.424 | 2.351 | . 001 | 1 | . 976 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | . 049 | . 0596 | -. 067 | . 166 | . 686 | 1 | . ٤٠٨ | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | -14.158 | . 9975 | -16.113 | -12.203 | ٢٠١.٤٦٨ | 1 | <0.001 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | 19.742 | ||||||||

| التردد الوسيط (MF) | (الاعتراض) | 69.647 | ٢.٥٢٩٦ | 64.689 | ٧٤.٦٠٥ | 758.043 | 1 | . 000 | |

| جنس | أنثى | -. 534 | . 9449 | -2.386 | 1.318 | . 320 | 1 | . 572 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | . 048 | . 0616 | -. 073 | . 169 | . 611 | 1 | . 434 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | 12.766 | 1.3545 | 10.111 | 15.420 | ٨٨.٨٢٤ | 1 | . 000 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | 21.891 | ||||||||

| طاقة نطاق التردد (أعلى من 100 هرتز) | (الاعتراض) | 70.433 | 1.9098 | 66.690 | ٧٤.١٧٦ | ١٣٦٠.١٨٣ | 1 | . 000 | |

| جنس | أنثى | . 205 | . 9265 | -1.611 | 2.021 | . 049 | 1 | . 825 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | . 001 | . 0468 | -. 090 | . 093 | . 001 | 1 | . 974 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | -18.648 | . 8082 | -20.232 | -17.064 | 532.402 | 1 | . 000 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | ١١.٨٠٣ | ||||||||

| المتغير التابع | معامل | ب | خطأ قياسي | فترة الثقة وولد بنسبة 95% | اختبار الفرضية | ||||

| أخفض | علوي | مربع كاي والد | df |

|

|||||

| تغير معدل ضربات القلب (HRV)(مللي ثانية) | (الاعتراض) | ٥٨.٣٢٧ | . 4180 | ٥٧.٥٠٨ | ٥٩.١٤٦ | 19,471.727 | 1 | . 000 | |

| جنس | أنثى | -. 360 | . 2252 | -. 801 | . 081 | ٢.٥٥٦ | 1 | . ١١٠ | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | . 004 | . 0115 | -. 018 | . 027 | . 142 | 1 | . 707 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | -3.752 | . 2120 | -4.168 | -3.337 | ٣١٣.٣٨٨ | 1 | . 000 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | . 736 | ||||||||

| معدل ضربات القلب | (الاعتراض) | 80.965 | 1.1371 | 78.736 | ٨٣٫١٩٤ | 5069.845 | 1 | . 000 | |

| جنس | أنثى | . 505 | . 5823 | -. 636 | 1.647 | . 753 | 1 | . 386 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | -. 005 | . ٠٢٦٠ | -. 056 | . 046 | . 032 | 1 | . 858 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | -10.300 | . 7848 | -11.838 | -8.762 | 172.255 | 1 | . 000 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | 7.535 | ||||||||

| الجذر التربيعي لمتوسط المربعات (RMS) لقياس التوصيل الجلدي (GSR) | (الاعتراض) | 20.984 | 1.1730 | 18.685 | ٢٣٫٢٨٣ | ٣١٩.٩٩٦ | 1 | . 000 | |

| جنس | أنثى | . ٧٩٩ | . 5287 | -. 237 | 1.835 | ٢.٢٨٣ | 1 | . 131 | |

| ذكر (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| عمر | -. 003 | . 0279 | -. 058 | . 051 | . 015 | 1 | . 902 | ||

| تدخل | مع الواقع الافتراضي | -5.389 | . 5116 | -6.392 | -4.386 | ١١٠.٩٢٨ | 1 | . 000 | |

| بدون الواقع الافتراضي (مرجع) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (مقياس) | ٤.١٤٩ | ||||||||

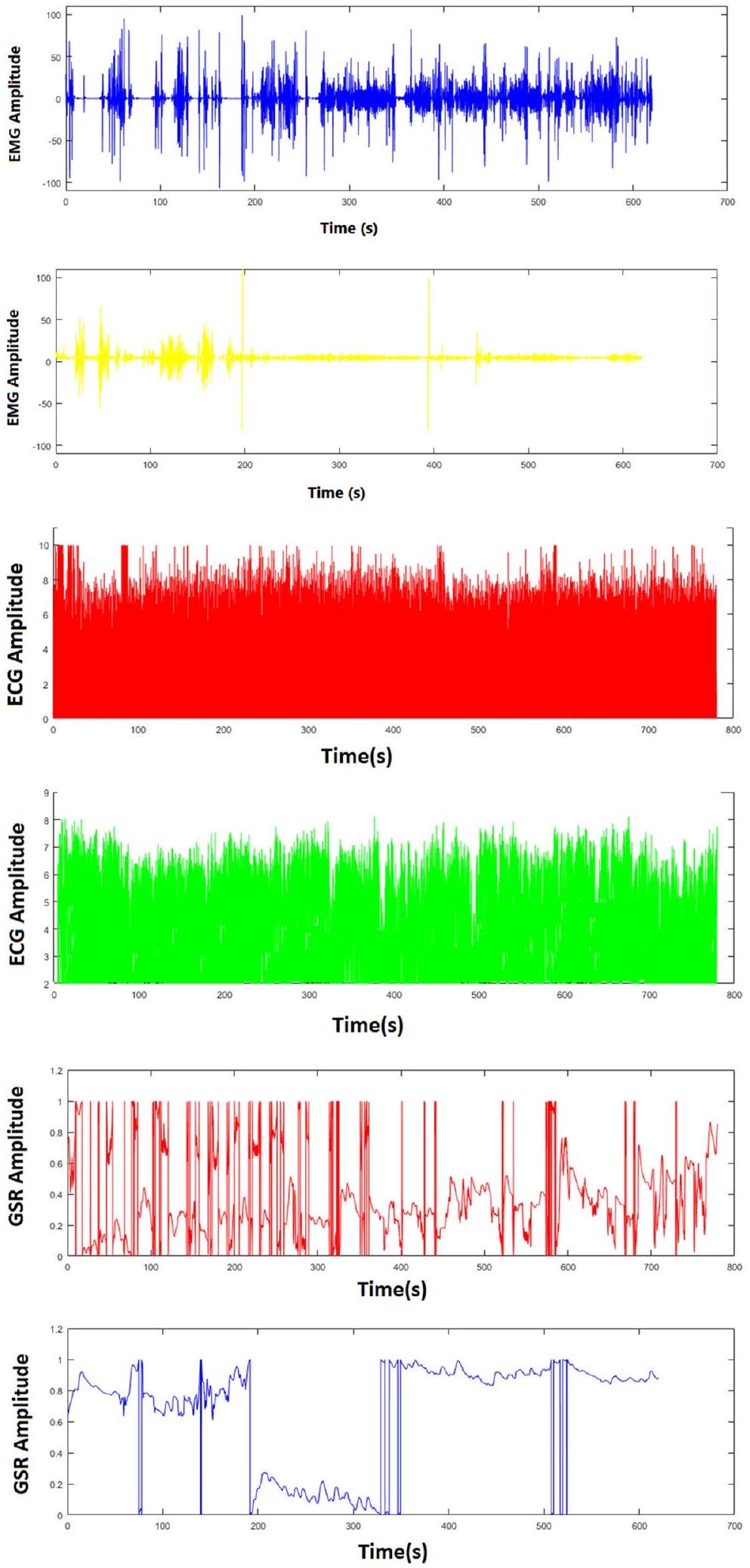

| EMG | الجذر التربيعي لمتوسط المربعات (RMS) لسعة EMG | يقيس هذا المعامل متوسط سعة إشارة EMG على مدى فترة زمنية معينة. وقد ارتبطت زيادة سعة RMS بزيادة توتر العضلات والألم. |

| التردد الوسيط (MF) | التردد الوسيط (MF): يقيس هذا المعامل التردد الذي يحتوي فيه نصف الطاقة في إشارة EMG. وقد ارتبط انخفاض MF بزيادة تعب العضلات والألم. | |

| طاقة نطاق التردد | قوة نطاق التردد: هذا المعامل يقيس قوة إشارة EMG في نطاقات تردد مختلفة. وقد ارتبطت زيادة القوة في نطاق التردد العالي (أعلى من 100 هرتز) بزيادة توتر العضلات والألم. | |

| تخطيط القلب الكهربائي (ECG) | معدل ضربات القلب | معدل ضربات القلب هو التردد بين بداية نبضة واحدة وبداية النبضة التالية ويُعبر عنه في فترة زمنية محددة (عادةً دقيقة واحدة). |

| تغير معدل ضربات القلب (HRV) | يصف التغيرات الطبيعية في معدل ضربات القلب من نبضة إلى أخرى. يرتبط تباين معدل ضربات القلب ارتباطًا وثيقًا بالاستثارة العاطفية: لقد وُجد أن تباين معدل ضربات القلب ينخفض في الحالات الحرجة والضغط العاطفي (مما يعني أن معدل ضربات القلب يصبح أكثر اتساقًا). كما لوحظ أن الأشخاص الذين يعانون من مزيد من الضغوط اليومية والقلق لديهم تباين أقل في معدل ضربات القلب. | |

| SCR (GSR) | الجذر التربيعي لمتوسط المربعات (RMS) لقياس التوصيل الكهربائي للجلد (GSR) | يقيس هذا المعامل التغير في توصيلية الجلد استجابةً لمحفز، مثل حدث مؤلم أو مثير للقلق. وقد ارتبطت زيادة توصيلية الجلد بزيادة نشاط الجهاز العصبي السمبثاوي والألم أو القلق. |

يوضح الرسم البياني في الشكل 8 أنه مع مرور الوقت، سيعتاد الجراح على استخدام الجهاز، حيث ينخفض معدل عدم الرضا من 9.2 للخمسة مرضى الأوائل إلى 5.4 للخمسة مرضى الأخيرين.

| الردود | تردد | نسبة النساء |

| نعم |

|

|

| لا |

|

|

| غير متأكد |

|

|

يدعم قوة النتائج؛ وبالتالي، فإن البيانات التي تم الحصول عليها تعود حقًا إلى التدخل.

من بين المعايير الستة التي قيمها جهاز التغذية الراجعة الحيوية والتغذية الراجعة العصبية (الجدول 4)، أشارت معظم النتائج إلى نجاح الواقع الافتراضي في تقليل الألم والقلق لدى المرضى أثناء الجراحة. أجرى هوفمان وزملاؤه دراسة تضمنت تصوير الرنين المغناطيسي الوظيفي للدماغ، وأظهرت نتائجها أن تأثير الواقع الافتراضي في تقليل الألم كان مرتبطًا بانخفاض كبير في الأنشطة الدماغية المتعلقة بالألم. يبدو أن مسكنات الألم بالواقع الافتراضي تغير كيفية معالجة الإشارات المستقبلة في الدماغ. خلال استخدام الواقع الافتراضي، قامت جميع المناطق الخمس المعنية في الدماغ (الجزء الجبهي، والمهاد، والقشرة الحزامية الأمامية، والقشرة الحسية الأولية والثانوية) بمعالجة عدد أقل من إشارات الألم. توفر هذه النتائج دليلًا إضافيًا على فعالية مسكنات الألم بالواقع الافتراضي.

بعد الانتهاء من جلسة العلاج والاستبيانات، تم إجراء مقابلة قصيرة مع هؤلاء المشاركين. كانت إحدى الفرضيات لهذه الفروق هي أنه في الأشخاص الثمانية الذين كانوا راضين جداً عن الواقع الافتراضي، كانت جذور قلقهم تتعلق بشيء محدد قبل بدء الجراحة، مثل حقنة التخدير (خمسة أشخاص) الذين ذكروا بعد الحقنة أنهم لم يعودوا يشعرون بالقلق، أو الجو العام في الغرفة (شخصان)، أو كلمة جراحة (شخص واحد)، ولكن في الأربعة الآخرين الذين كانوا أقل رضا، كان قلقهم وخوفهم الرئيسي هو الشعور بالضعف في عملية جراحة الزرع. وقد ذكروا أنهم لم يكونوا على دراية بما كان يفعله الجراح وشعروا بمزيد من القلق مع نظارات الواقع الافتراضي. لذلك، بقدر ما يمكننا تخيله، يمكن أن يكون استخدام الواقع الافتراضي لدى الأفراد ذوي الضغط العالي مفيدًا جدًا [10،47] أو غير مفيد [39]، وهذا يعتمد تمامًا على المريض نفسه وجذور مخاوفه. كانت إحدى فرضيات المؤلفين هي أن الأفراد ذوي القلق المنخفض سيكون لديهم رضا أقل مقارنةً بأولئك ذوي القلق المعتدل لأن مستوى قلقهم لم يكن مرتفعًا بما يكفي ليتم تقليله بشكل كبير بواسطة تأثيرات الواقع الافتراضي، ولكن في الممارسة العملية، كان الأفراد ذوو القلق المعتدل (متوسط الرضا

يبدو أن السكان هم خيار أفضل لاستخدام الواقع الافتراضي. ومع ذلك، على الرغم من عدد كبار السن الحالي، فإن عدد كبار السن في المستقبل سيكون أكبر بكثير من عدد كبار السن الحاليين، وسيكونون أيضًا أكثر تعرضًا للتقنيات المتقدمة. وهذا يبشر باستخدام أكبر للواقع الافتراضي في المستقبل.

بشكل عام، كانت وجهات نظر المشاركين إيجابية. أعرب معظم المشاركين عن رضاهم عن كيفية قدرة نظام الواقع الافتراضي على تشتيت انتباههم بطريقة قللت من مستويات القلق والألم التي يشعرون بها. وصف العديد من المرضى تجربة الواقع الافتراضي باستخدام مصطلحات مثل “الجنة”، “المتعة”، “تجربة خارج الجسم”، و”مذهل”.

بين جميع المشاركين، لم يعبر أي مريض عن عدم الراحة في نهاية علاج الواقع الافتراضي، مما يشير إلى أن الواقع الافتراضي على الأقل ذو قيمة كأداة لتشتيت الانتباه ولتقليل القلق في جراحات الزرع. ومع ذلك، لاحظ عدد قليل من المشاركين (خمسة أشخاص) أن عدم قدرتهم على رؤية ما يحدث من حولهم جعلهم يشعرون بعدم الراحة. ومن المدهش أن بعض الجراحين أعربوا عن مخاوف مماثلة، مما منعهم من المشاركة في الدراسة كجراحين، حيث كانوا يفضلون رؤية وجوه المرضى لتقييم استجابتهم للعلاج.

ربما تكون أكبر مشكلة مع هذا الجهاز في الوقت الحالي هي حجمه الكبير، مما يجعل من الصعب على أطباء الأسنان إجراء العلاج. الحفاظ على العزلة أيضًا صعب مع هذا الجهاز. تعيق الأجهزة الكبيرة عمل طبيب الأسنان وتحد من حريته في التصرف، مما يحد من رؤية الوصول إلى الموقع الجراحي.

لهذا السبب أعطى جراح دراستنا في البداية مريضه الأول درجة عدم الرضا 10. ولكن من الجدير بالذكر أن هذا الجراح قد أجرى جراحة الزرع لأكثر من 15 عامًا، لذا فإن مثل هذا التغيير الجذري في عمليته التي استمرت 15 عامًا سيقابل بطبيعة الحال بعدم الرضا. من المثير للاهتمام أن ميل الرسم البياني (الشكل 8) يظهر أنه مع مرور الوقت، سيعتاد الجراح على استخدام الجهاز، مع انخفاض درجة عدم الرضا من 9.2 للخمسة مرضى الأوائل إلى 5.4 للخمسة مرضى الأخيرين. مخاطر الأذى الناتجة عن استخدام الواقع الافتراضي منخفضة جدًا. الخطر الوحيد الذي قد ينشأ من استخدام الواقع الافتراضي هو مرض الفضاء الإلكتروني، الذي يظهر بأعراض مشابهة لمرض الحركة الكلاسيكي أثناء وبعد استخدام الواقع الافتراضي. مرض الفضاء الإلكتروني نادر وأحيانًا يزول بعد بضع دقائق من الراحة. يجب إجراء دراسات مستقبلية باستخدام سماعات واقع افتراضي ذات جودة أعلى وأصغر من أجل فحص مستوى رضا المعالجين والمرضى بشكل أفضل من خلال إزالة العوامل المزعجة مثل الوزن الكبير والسماعات الضخمة. يبدو أن مناقشة استخدام سماعات الواقع الافتراضي في العلاج مشابهة لاستخدام أجهزة التلفاز القديمة في المنزل، والسبب الرئيسي لاستخدامها المحدود حاليًا هو حجمها الكبير وسعرها المرتفع وجودتها المنخفضة نسبيًا، والتي تم حلها مع تقدم التكنولوجيا. سيكون مستقبل صناعة العلاج مرتبطًا بهذه الأداة.

الاستنتاجات

الاختصارات

| VR | الواقع الافتراضي |

| STAI | مقياس القلق للحالة والصفة |

| MDAS | مقياس القلق السني المعدل |

| NRS | مقاييس التقييم الرقمي |

| TDR | تقييم ضغوط العلاج |

| EMG | تخطيط كهربائية العضلات |

| EKG (ECG) | تخطيط القلب الكهربائي |

| SCR | استجابة توصيل الجلد |

| GEE | المعادلات التقديرية العامة |

| El | التدخلات المفصلة |

الشكر والتقدير

تعارض المصالح

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

تعارض المصالح

تاريخ الاستلام: 27 أكتوبر 2023 تاريخ القبول: 16 يناير 2024

References

- Ahmadpour N, Keep M, Janssen A, Rouf AS, Marthick M. Design strategies for virtual reality interventions for managing pain and anxiety in children and adolescents: scoping review. JMIR Serious Games. 2020;8:e14565.

- Appukuttan DP. Strategies to manage patients with dental anxiety and dental phobia: literature review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2016;8:35-50.

- Armfield JM, Stewart JF, John A, Spencer. The vicious cycle of dental fear: exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC oral health. 2007;7:1-15.

- Carr ECJ, Thomas VN, Wilson-Barnet J. Patient experiences of anxiety, depression and acute pain after surgery: a longitudinal perspective. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:521-30.

- Cohen LA, Harris SL, Bonito AJ, Manski RJ, Macek MD, Edwards RR, Cornelius LJ. Coping with toothache pain: a qualitative study of low-income persons and minorities. J Public Health Dent. 2007;67:28-35.

- Doerr PA, Paul Lang W, Nyquist LV, Ronis DL. Factors associated with dental anxiety. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1111-9.

- Economou GC. Dental anxiety and personality: investigating the relationship between dental anxiety and self-consciousness. J Dent Educ. 2003;67:970-80.

- Eijlers R, Utens EMWJ, Staals LM, de Nijs PFA, Berghmans JM, Wijnen RMH, Hillegers MHJ, Dierckx B, Legerstee JS. Systematic review and Metaanalysis of virtual reality in pediatrics: effects on pain and anxiety. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:1344-53.

- Eli I, Schwartz-Arad D, Baht R, Ben-Tuvim H. Effect of anxiety on the experience of pain in implant insertion. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:115-8.

- Gershon J, Zimand E, Pickering M, Rothbaum BO, Hodges L. A pilot and feasibility study of virtual reality as a distraction for children with cancer. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1243-9.

- Hartig T, Mitchell R, De Vries S, Frumkin H. Nature and health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:207-28.

- Hill KB, Hainsworth JM, Burke FJT, Fairbrother KJ. Evaluation of dentists’ perceived needs regarding treatment of the anxious patient. Br Dent J. 2008;204:E13-3.

- Hoffman HG, Richards TL, Coda B, Bills AR, Blough D, Richards AL, Sharar SR. Modulation of thermal pain-related brain activity with virtual reality: evidence from fMRI. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1245-8.

- Hoffman HG, Seibel EJ, Richards TL, Furness TA, Patterson DR, Sharar SR. Virtual reality helmet display quality influences the magnitude of virtual reality analgesia. J Pain. 2006;7:843-50.

- Huang T-K, Yang C-H, Hsieh Y-H, Wang J-C, Hung C-C. Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) applied in dentistry. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2018;34:243-8.

- Hudson BF, Ogden J, Whiteley MS. A thematic analysis of experiences of varicose veins and minimally invasive surgery under local anaesthesia. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:1502-12.

- Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The modified dental anxiety scale: validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. 1995;12:143-50.

- Ip HY, Vivian AA, Peng PWH, Wong J, Chung F. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. J Am Soc Anesthesiologists. 2009;111:657-77.

- Jerdan SW, Grindle M, Van Woerden HC, Kamel MN, Boulos. Headmounted virtual reality and mental health: critical review of current research. JMIR serious games. 2018;6:e9226.

- Kazancioglu H-O, Dahhan A-S, Acar A-H. How could multimedia information about dental implant surgery effects patients’ anxiety level? Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;22:e102.

- Kent G. Memory of dental pain. Pain. 1985;21:187-94.

- Kipping B, Rodger S, Miller K, Kimble RM. Virtual reality for acute pain reduction in adolescents undergoing burn wound care: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Burns. 2012;38:650-7.

- Klages U, Kianifard S, Ulusoy Ö, Wehrbein H. Anxiety sensitivity as predictor of pain in patients undergoing restorative dental procedures. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:139-45.

- Kleinknecht RA, Bernstein DA. The assessment of dental fear. Behav Ther. 1978;9:626-34.

- Legrain V, Crombez G, Verhoeven K, Mouraux A. The role of working memory in the attentional control of pain. Pain. 2011;152:453-9.

- Lindsay SJE, Wege P, Yates J. Expectations of sensations, discomfort and fear in dental treatment. Behav Res Ther. 1984;22:99-108.

- Litt MD. A model of pain and anxiety associated with acute stressors: distress in dental procedures. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:459-76.

- Locker D, Liddell AM. Correlates of dental anxiety among older adults. J Dent Res. 1991;70:198-203.

- Locker D. Psychosocial consequences of dental fear and anxiety. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:144-51.

- Locker D, Shapiro D, Liddell A. Negative dental experiences and their relationship to dental anxiety. Community Dent Health. 1996;13:86-92.

- López-Valverde N, Muriel-Fernández J, López-Valverde A, Valero-Juan LF, Ramírez JM, Flores-Fraile J, Herrero-Payo J, Blanco-Antona LA, Macedo-de-Sousa

. Use of virtual reality for the management of anxiety and pain in dental treatments: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1025. - Maggirias J, Locker D. Psychological factors and perceptions of pain associated with dental treatment. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:151-9.

- Malenbaum S, Keefe FJ, de Williams AC, Ulrich R, Somers TJ. Pain in its environmental context: implications for designing environments to enhance pain control. Pain. 2008;134:241-4.

- Mark M. Patient anxiety and modern elective surgery: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:806-15.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, Polyzos KA, Peppas G, Falagas ME. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:e20306.

- Melzack R. From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain. 1999;82:S121-6.

- Melzack R, Katz J. The gate control theory: reaching for the brain. Pain: Psych Pers; 2004. p.13-34.

- Moore R, Birn H, Kirkegaard E, Brødsgaard I, Scheutz F. Prevalence and characteristics of dental anxiety in Danish adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:292-6.

- Ougradar A, Ahmed B. Patients’ perceptions of the benefits of virtual reality during dental extractions. Br Dent J. 2019;227:813-6.

- Pierantognetti P, Covelli G, Vario M. Anxiety, stress and preoperative surgical nursing. Prof Inferm. 2002;55:180-91.

- Powell R, Marie Johnston W, Smith C, King PM, Alastair Chambers W, Krukowski Z, McKee L, Bruce J. Psychological risk factors for chronic postsurgical pain after inguinal hernia repair surgery: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:600-10.

- Schneider A, Andrade J, Tanja-Dijkstra K, White M, Moles DR. The psychological cycle behind dental appointment attendance: a cross-sectional study of experiences, anticipations, and behavioral intentions. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44:364-70.

- Schneider SM, Hood LE. Virtual reality: a distraction intervention for chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:39-46.

- Shahrbanian S, Ma X, Aghaei N, Korner-Bitensky N, Moshiri K, Simmonds MJ. Use of virtual reality (immersive vs. non immersive) for pain management in children and adults: a systematic review of evidence from randomized controlled trials. Eur J Exp Biol. 2012;2:1408-22.

- Skaret E, Raadal M, Berg E, Kvale G. Dental anxiety and dental avoidance among 12 to 18 year olds in Norway. Eur J Oral Sci. 1999;107:422-8.

- Spielberger CD. State-trait anxiety inventory for adults; 1983. https://doi. org/10.1037/t06496-000.

- Tanja-Dijkstra K, Pahl S, White MP, Andrade J, Qian C, Bruce M, May J, Moles DR. Improving dental experiences by using virtual reality distraction: a simulation study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91276.

- Tanja-Dijkstra K, Pahl S, White MP, Auvray M, Stone RJ, Andrade J, May J, Mills I, Moles DR. The soothing sea: a virtual coastal walk can reduce experienced and recollected pain. Environ Behav. 2018;50:599-625.

- Thomson WM, Locker D, Poulton R. Incidence of dental anxiety in young adults in relation to dental treatment experience. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:289-94.

- Vassend O. Anxiety, pain and discomfort associated with dental treatment. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31:659-66.

- Wetsch WA, Pircher I, Lederer W, Kinzl JF, Traweger C, Heinz-Erian P, Benzer A. Preoperative stress and anxiety in day-care patients and inpatients undergoing fast-track surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:199-205.

ملاحظة الناشر

- المتوسط

الانحراف المعياري والعدد (النسبة المئوية %) مقدمة للبيانات المستمرة والفئوية، على التوالي

اختبار T لعينة مستقلة

اختبار كاي-تربيع - كاي-تربيع مونت كارلو

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-03904-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38317209

Publication Date: 2024-02-05

The effect of virtual reality on reducing

Check for updates patients’ anxiety and pain during dental implant surgery

Abstract

Background Dental anxiety and pain pose serious problems for both patients and dentists. One of the most stressful and frightening dental procedures for patients is dental implant surgery; that even hearing its name causes them stress. Virtual reality (VR) distraction is an effective intervention used by healthcare professionals to help patients cope with unpleasant procedures. Our aim is to evaluate the use of high-quality VR and natural environments on dental implant patients to determine the effect on reducing pain and anxiety. Methods Seventy-three patients having two dental implant surgeries participated in a randomized controlled trial. One surgery was with VR, and one was without. Anxiety was measured with the the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale tests. The pain was measured with the Numerical Rating Scales. Patient satisfaction, surgeon distress, memory vividness, and time perception were evaluated. Physiological data were collected with biofeedback and neurofeedback device.

Results VR effectively reduced anxiety and pain compared to no VR. Physiological data validated the questionnaire results. Patient satisfaction increased, with

Conclusion Psychometric and psychophysiological assessments showed that VR successfully reduced patient pain and anxiety. More dental clinicians should use VR technology to manage patient anxiety and pain.

*Correspondence:

Hedaiat Moradpoor

hedaiat.moradpoor@gmail.com

Introduction

Anxiety is a common response to surgery [40], especially since being awake during surgery with the help of local anesthetics can be full of specific fears and anxieties [16, 34, 51]. Not only is anxiety unpleasant, but a consistent relationship has been observed between surgical

anxiety, postoperative pain [4, 18], an increased need for analgesics [41], and delayed recovery [35]. Results from a large adult dental health survey by the National Health Service (NHS) showed that over one-third of adults (36%) suffer from moderate dental anxiety, and a further 12% suffer from extreme dental anxiety. These patients only go to the dentist when experiencing pain, thus exacerbating their anxiety too [3]. In addition, anxious patients are less interested in keeping their routine appointments [24], their treatment takes longer, they feel less satisfied after treatment [28], and the dentists themselves experience more distress when treating anxious patients [12].

Pain is a complex, multidimensional subjective experience involving sensory, emotional, and cognitive processes. Pain perception is influenced by a wide spectrum of dimensions and interactions between these processes, with the cognitive-evaluative, motivational-affective, and discriminative dimensions all playing a role in pain perception [36, 37]. Discomfort from Pain is frequently reported by patients undergoing dental treatment, even during routine restorative procedures [26, 27]. In one population-based study,

for diversion from pain, as some level of attention is required to experience pain [25, 44].

Material & methods

Regulatory approvals

Study design

Prior to the study, the authors’ preliminary examinations of 10 patients showed that the average length of the

implant surgery procedure by the surgeon in this study was 23 minutes (without considering patient preparation time and anesthetic injection). To maximize the standardization of conditions for all patients, those whose surgery length was over 25 minutes or less than 20 minutes were excluded from the study. For those patients whose surgical process was between 20 to 25 minutes, the surgeon used other dental tools and pretended to work, trying to increase the treatment duration to 25 minutes so that the actual time spent was the same for all patients. For this purpose, a large clock was installed in front of the surgeon to keep track of time (Fig. 2). To maximize standardization of conditions, all patients were asked to attend the office alone. When in the waiting room, no other patients were present, and silence prevailed (Fig. 3). The pens used were all new and of the same brand to minimize the effect of other experimental interventions.

Participants

of

Hardware

VR headset

Biofeedback & neurofeedback system

Procedure

| Time | Test | Parameter | |||

| Before Surgery | Anxiety | STAI-T | |||

| Pain (Expected) | NRS 0-10 | ||||

| During Surgery |

|

||||

| EMG | |||||

| EKG |

|

||||

| SCR | Root mean square (RMS) | ||||

| After Surgery | Anxiety | STAI-S | |||

| MDAS | |||||

| Pain (Experienced) | NRS 0-10 | ||||

| NRS 0-10 | |||||

| Satisfaction | TDR | ||||

| Using VR again in the future | |||||

| Duration of Treatment | Time perception | ||||

| 1 week later (Telephone based) | Vividness of Memories | NRS 0-10 |

Psychometric assessment

Pain

Anxiety

- STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory). This questionnaire is extensively used in research and clinical activities and includes separate self-report scales for measuring state and trait anxiety [46]. Each scale consists of 20 items that can be scored from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). The total score for STAI-S or STAI-T ranges from 20 to 80 . The first 20 questions, state anxiety (S), can be considered as a cross-section of a person’s life, meaning its occurrence is situational and specific to stressful situations (arguments, loss of social status, threats to human security and health) and shows the person’s feelings at that moment. But the next 20 questions, trait anxiety ( T ), refer to individual differences in response to stressful situations with varying degrees of state anxiety. Patients were told to choose only one response option for each question and leave none unanswered.

- MDAS (modified dental anxiety scale). In addition, each patient’s anxiety level was assessed using the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS) questionnaire. The MDAS is the most commonly used dental anxiety questionnaire in the United Kingdom and is a modified version of the DAS questionnaire, the most prevalent measurement in studies related to dental anxiety [17]. This questionnaire consists of five items to assess the anxiety level in different dental situations. Each question has a 5-point Likert scale response ranging from “not anxious” to “extremely anxious”. Each response is scored, and the sum of all responses is recorded. The total score on this scale ranges from 5 to 25 . It is important to note that Humphris and Hall found that using this questionnaire did not increase anxiety [2].

Satisfaction

- After the surgery, an 11-point NRS questionnaire was administered to participants to rate their satisfaction with their treatment on a scale of 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied).

- Patients were also asked if, given the choice next time, they would want the dentist to use the virtual reality headset again or not. Options were yes, no, and not sure. Patients had the option to leave their comments in the questionnaire feedback section.

- Treatment Distress Rating (TDR) was evaluated after completion of treatment to assess the dentist’s distress resulting from the dental procedure for the patient. In this way, the dentist was asked to determine the amount of distress caused by VR during treatment and its interference with the surgeon’s freedom of action compared to the control group, i.e., when routine treatment (without VR) was performed for them. The response format was similar to the 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS) for pain, with 0 defined as “no distress at all” and 10 as the “worst possible distress.”

Vividness of memories

Time perception ratio

Psychophysiological assessment

Data collection

Statistical analysis

conducted in two sections: Descriptive Statistics and Inferential Statistics. The descriptive statistics section reported measures of central tendency and dispersion, along with tables and charts. In the inferential statistics section, the normality of the data was examined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The independent Samples T-test was used to compare the age variable between the two groups, and the Chi-Square test was used to compare the gender distribution between the two groups. The Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) model was used to investigate the effect of intervention type, gender, and age variables. Model assumptions were checked by residual analysis. SPSS Inc. software was used for data analysis) Released 2009. PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc. (The significance level in this study was considered 0.05.)

Results

| Group 1 ( N : 37) | Group 2 ( N : 36 ) | Total |

|

||||

| Gender | Male | 18 | 18 | 36 |

|

||

| Female | 19 | 18 | 37 | ||||

|

Year |

|

|

|

|

||

| Primary school | 4 | 4 | 8 | 0.942* | |||

| High school | 16 | 14 | 30 | ||||

| University | 17 | 18 | 35 | ||||

| Intervention | ||||

| Without VR | With VR | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Expected Pain | 5.85 | . 92 | 5.93 | . 89 |

| Experienced Pain | 4.30 | 1.32 | 2.59 | 1.09 |

| MDAS | 17.42 | 3.76 | 12.88 | 2.64 |

| STAI-S | 41.07 | 6.04 | 37.62 | 5.68 |

| STAI-T | 41.05 | 4.26 | 41.23 | 4.21 |

| Satisfaction | 7.64 | 1.19 | 8.78 | 1.20 |

| Time Perception Ratio | 1.20 | . 20 | 1.08 | . 20 |

| Vividness of Memories | 4.98 | . 87 | 4.29 | . 80 |

| Treatment Distress Rating | 3.49 | 1.20 | 6.95 | 1.70 |

| Root mean square (RMS) amplitude of EMG | 62.22 | 4.03 | 48.06 | 4.72 |

| Median frequency (MF) | 71.22 | 3.65 | 83.99 | 5.42 |

| Frequency band power(above 100 Hz ) | 70.62 | 4.14 | 51.97 | 2.38 |

| Heart rate variability (HRV)(ms) | 58.27 | 1.08 | 54.52 | . 56 |

| Heart rate | 81.10 | 3.11 | 70.80 | 2.23 |

| Root mean square (RMS) of GSR (SCR) | 21.35 | 2.00 | 15.96 | 2.08 |

The type of intervention had a significant effect on STAI-S (

The type of intervention had a significant effect on the vividness of memories (

| Dependent Variable | Parameter | B | Std. Error | 95% Wald Confidence Interval | Hypothesis Test | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Wald Chi-Square | df |

|

|||||

| Expected Pain | (Intercept) | 5.481 | . 2789 | 4.935 | 6.028 | 386.278 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | Female | . 125 | . 1639 | -. 196 | . 446 | . 580 | 1 | . 446 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | . 007 | . 0057 | -. 004 | . 018 | 1.429 | 1 | . 232 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | . 082 | . 1296 | -. 172 | . 336 | . 402 | 1 | . 526 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | . 818 | ||||||||

| Experienced Pain | (Intercept) | 4.396 | . 3560 | 3.699 | 5.094 | 152.477 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | Female | . 231 | . 1842 | -. 130 | . 592 | 1.577 | 1 | . 209 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | -. 005 | . 0069 | -. 018 | . 009 | . 464 | 1 | . 496 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | -1.712 | . 2109 | -2.126 | -1.299 | 65.940 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 1.470 | ||||||||

| MDAS | (Intercept) | 15.258 | 1.2519 | 12.804 | 17.711 | 148.545 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Female | 1.150 | . 6847 | -. 192 | 2.492 | 2.820 | 1 | . 093 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | . 035 | . 0254 | -. 015 | . 085 | 1.925 | 1 | . 165 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | -4.548 | . 2642 | -5.066 | -4.030 | 296.236 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 10.089 | ||||||||

| STAI-S | (Intercept) | 38.927 | 2.2344 | 34.547 | 43.306 | 303.494 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Female | 2.158 | 1.3535 | -. 495 | 4.810 | 2.542 | 1 | . 111 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | . 023 | . 0535 | -. 082 | . 128 | . 190 | 1 | . 663 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | -3.452 | . 2131 | -3.870 | -3.034 | 262.324 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 33.539 | ||||||||

| STAI-T | (Intercept) | 39.793 | 2.0553 | 35.765 | 43.822 | 374.854 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Female | 1.463 | . 9331 | -. 365 | 3.292 | 2.460 | 1 | . 117 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | . 012 | . 0464 | -. 079 | . 103 | . 062 | 1 | . 803 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | . 178 | . 2035 | -. 221 | . 577 | . 766 | 1 | . 382 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 17.610 | ||||||||

| Satisfaction | (Intercept) | 9.140 | . 7308 | 7.708 | 10.572 | 156.438 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | Female | . 019 | . 1780 | -. 330 | . 368 | . 012 | 1 | . 914 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | -. 037 | . 0094 | -. 056 | -. 019 | 15.505 | 1 | < 0.001 | ||

| Education | Primary School | . 082 | . 4121 | -. 726 | . 889 | . 039 | 1 | . 843 | |

| High School | . 301 | . 4391 | -. 560 | 1.162 | . 469 | 1 | . 493 | ||

| University (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Intervention | With VR | 1.137 | . 1703 | . 803 | 1.471 | 44.551 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 1.194 | ||||||||

| Dependent Variable | Parameter | B | Std. Error | 95% Wald Confidence Interval | Hypothesis Test | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Wald Chi-Square | df |

|

|||||

| Time Perception Ratio | (Intercept) | 1.200 | . 0767 | 1.050 | 1.351 | 245.001 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | Female | . 028 | . 0427 | -. 056 | . 112 | . 428 | 1 | . 513 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | . 000 | . 0017 | -. 004 | . 003 | . 018 | 1 | . 893 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | -. 128 | . 0172 | -. 161 | -. 094 | 55.203 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | . 040 | ||||||||

| Vividness of Memories | (Intercept) | 5.018 | . 3549 | 4.322 | 5.713 | 199.881 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Female | -. 096 | . 1881 | -. 465 | . 273 | . 261 | 1 | . 609 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | . 000 | . 0083 | -. 016 | . 016 | . 000 | 1 | . 984 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | -. 689 | . 0620 | -. 810 | -. 567 | 123.507 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | . 706 | ||||||||

| Treatment Distress Rating | (Intercept) | 4.074 | . 4374 | 3.216 | 4.931 | 86.746 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Female | -. 314 | . 2516 | -. 807 | . 179 | 1.555 | 1 | . 212 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | -. 009 | . 0090 | -. 027 | . 008 | 1.094 | 1 | . 296 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | 3.452 | . 2293 | 3.003 | 3.901 | 226.733 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 2.154 | ||||||||

| Root mean square (RMS) amplitude of EMG | (Intercept) | 60.283 | 2.4138 | 55.552 | 65.014 | 623.704 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | Female | -. 037 | 1.2182 | -2.424 | 2.351 | . 001 | 1 | . 976 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | . 049 | . 0596 | -. 067 | . 166 | . 686 | 1 | . 408 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | -14.158 | . 9975 | -16.113 | -12.203 | 201.468 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 19.742 | ||||||||

| Median frequency (MF) | (Intercept) | 69.647 | 2.5296 | 64.689 | 74.605 | 758.043 | 1 | . 000 | |

| Sex | Female | -. 534 | . 9449 | -2.386 | 1.318 | . 320 | 1 | . 572 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | . 048 | . 0616 | -. 073 | . 169 | . 611 | 1 | . 434 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | 12.766 | 1.3545 | 10.111 | 15.420 | 88.824 | 1 | . 000 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 21.891 | ||||||||

| Frequency band power (above 100 Hz ) | (Intercept) | 70.433 | 1.9098 | 66.690 | 74.176 | 1360.183 | 1 | . 000 | |

| Sex | Female | . 205 | . 9265 | -1.611 | 2.021 | . 049 | 1 | . 825 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | . 001 | . 0468 | -. 090 | . 093 | . 001 | 1 | . 974 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | -18.648 | . 8082 | -20.232 | -17.064 | 532.402 | 1 | . 000 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 11.803 | ||||||||

| Dependent Variable | Parameter | B | Std. Error | 95% Wald Confidence Interval | Hypothesis Test | ||||

| Lower | Upper | Wald Chi-Square | df |

|

|||||

| Heart rate variability (HRV)(ms) | (Intercept) | 58.327 | . 4180 | 57.508 | 59.146 | 19,471.727 | 1 | . 000 | |

| Sex | Female | -. 360 | . 2252 | -. 801 | . 081 | 2.556 | 1 | . 110 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | . 004 | . 0115 | -. 018 | . 027 | . 142 | 1 | . 707 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | -3.752 | . 2120 | -4.168 | -3.337 | 313.388 | 1 | . 000 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | . 736 | ||||||||

| Heart rate | (Intercept) | 80.965 | 1.1371 | 78.736 | 83.194 | 5069.845 | 1 | . 000 | |

| Sex | Female | . 505 | . 5823 | -. 636 | 1.647 | . 753 | 1 | . 386 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | -. 005 | . 0260 | -. 056 | . 046 | . 032 | 1 | . 858 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | -10.300 | . 7848 | -11.838 | -8.762 | 172.255 | 1 | . 000 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 7.535 | ||||||||

| Root mean square (RMS)of GSR | (Intercept) | 20.984 | 1.1730 | 18.685 | 23.283 | 319.996 | 1 | . 000 | |

| Sex | Female | . 799 | . 5287 | -. 237 | 1.835 | 2.283 | 1 | . 131 | |

| Male (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| Age | -. 003 | . 0279 | -. 058 | . 051 | . 015 | 1 | . 902 | ||

| Intervention | With VR | -5.389 | . 5116 | -6.392 | -4.386 | 110.928 | 1 | . 000 | |

| Without VR (ref) | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| (Scale) | 4.149 | ||||||||

| EMG | Root mean square (RMS) amplitude of EMG | This parameter measures the average amplitude of the EMG signal over a given time period. Increased RMS amplitude has been associated with increased muscle tension and pain. |

| Median frequency (MF) | Median frequency (MF): This parameter measures the frequency at which half of the power in the EMG signal is contained. Decreased MF has been associated with increased muscle fatigue and pain. | |

| Frequency band power | Frequency band power: This parameter measures the power of the EMG signal in different frequency bands. Increased power in the high frequency band (above 100 Hz ) has been associated with increased muscle tension and pain. | |

| EKG (ECG) | Heart rate | Heart rate is the frequency between the beginning of one pulse to the beginning of the next and is expressed in a specific time window (usually one minute). |

| Heart rate variability (HRV) | It describes the normal changes in heart rate from one beat to the next. HRV is closely related to emotional arousal: HRV has been found to decrease in critical situations and emotional stress (meaning the heart rate is more consistent). It has also been observed that people with more daily stress and worries have lower HRV. | |

| SCR (GSR) | Root mean square (RMS) of GSR | This parameter measures the change in skin conductance in response to a stimulus, such as a painful or anxiety-provoking event. Increased SCR has been associated with increased sympathetic nervous system activity and pain or anxiety. |

graph in the Fig. 8. shows that over time, the surgeon will become accustomed to using the device, with the dissatisfaction score decreasing from 9.2 for the first five patients to 5.4 for the last five patients.

| Responses | Frequency | Women’s percentage |

| Yes |

|

|

| No |

|

|

| Unsure |

|

|

supports the robustness of the findings; and therefore, the obtained data are truly attributable to the intervention.

Among the six parameters that the Biofeedback & Neurofeedback device assessed (table 4), most of the results indicated the success of VR in reducing pain and anxiety in patients during surgery. Hoffman et al. conducted a study involving functional magnetic resonance imaging brain scans, the results of which showed that the effect of VR on reducing pain was associated with a significant decrease in brain activities related to pain. VR analgesia appears to alter how signals received are processed in the brain. During the use of VR, all five regions of interest in the brain (the insula, thalamus, anterior cingulate cortex, and primary and secondary somatosensory cortex) processed fewer pain signals. These results provide additional evidence for the analgesic effectiveness of VR [13].

completing the treatment session and questionnaires, a brief interview was conducted with these participants. One hypothesis for this difference was that in the eight people who were very satisfied with VR, the root of their anxiety was a specific object before surgery started, such as an anesthesia injection (five people) who stated after the injection they no longer had anxiety, or the overall atmosphere of the room (two people), or the word surgery (one person), but in the other four with less satisfaction, their main anxiety and fear was being vulnerable in the implant surgery process. They stated that they were unaware of what the surgeon was doing and felt more anxious with the VR headset. Therefore, as far as we can imagine, the use of VR in individuals with high stress can be very helpful [10,47] or unhelpful [39], and this entirely depends on the patient themselves and the root of their fears. One hypothesis of the authors was that individuals with low anxiety would have less satisfaction compared to those with moderate anxiety because their anxiety level was not high enough to be greatly reduced by the effects of VR, but in practice, individuals with moderate anxiety (mean satisfaction

populations seem like a better choice for VR use. However, despite the current elderly population, the elderly in the future will be far greater than the current elderly population and also much more exposed to advanced technologies. This bodes well for greater VR use in the future.

Overall, participants perspectives were positive. Most participants expressed satisfaction with how the VR system could distract them in a way that reduced their perceived anxiety and pain levels. Several patients described VR using terms like “heaven”, “fun”, “out of body experience”, and “amazing”.

Among all participants, no patient expressed discomfort at the end of VR treatment, indicating VR is at least valuable as a distraction tool and for reducing anxiety in implant surgeries. However, a small number of participants (five people) noticed that their inability to see what was happening around them made them uncomfortable. Surprisingly, some surgeons expressed similar concerns, which deterred them from participating in the study as surgeons, as they preferred to see the patients’ faces to assess their response to treatment.

Perhaps the biggest problem with this device at present is its bulkiness, which makes it challenging for dentists to perform treatment. Maintaining isolation is also difficult with this device. Large devices hinder the dentist’s work and restrict their freedom of action, limiting visibility of and access to the surgical

site. This is why our study’s surgeon initially gave his first patient a dissatisfaction score of 10. But notably, this surgeon has been performing implant surgery for over 15 years, so such a drastic change in his 15-year process would naturally be met with dissatisfaction. Interestingly, the slope of the graph (Fig. 8) shows that over time, the surgeon will become accustomed to using the device, with the dissatisfaction score decreasing from 9.2 for the first five patients to 5.4 for the last five patients. The risks of harm from VR use are very low. The only risk that may arise from VR use is cybersickness, which manifests with symptoms similar to classical motion sickness during and after VR use. Cybersickness is rare and sometimes resolves after a few minutes of rest. Future studies should be conducted with higher quality and smaller virtual reality headsets in order to better examine the level of satisfaction of therapists and patients by removing disturbing factors such as high mass and bulky headsets. It seems that the discussion of using virtual reality headsets in treatment is similar to using old televisions at home, and the main reason for their current limited use is their bulkiness, high price, and relatively low quality, which have been solved with the advancement of technology. The future of the treatment industry will be tied to this tool.

Conclusions

Abbreviations

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| STAI | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| MDAS | Modified Dental Anxiety Scale |

| NRS | Numeric Rating Scales |

| TDR | Treatment Distress Rating |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| EKG (ECG) | Electrocardiogram |

| SCR | Skin Conductance Response |

| GEE | Generalized Estimating Eqs |

| El | Elaborated Intrusions |

Acknowledgements

Conflict of interest

Authors’ contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Received: 27 October 2023 Accepted: 16 January 2024

References

- Ahmadpour N, Keep M, Janssen A, Rouf AS, Marthick M. Design strategies for virtual reality interventions for managing pain and anxiety in children and adolescents: scoping review. JMIR Serious Games. 2020;8:e14565.

- Appukuttan DP. Strategies to manage patients with dental anxiety and dental phobia: literature review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2016;8:35-50.

- Armfield JM, Stewart JF, John A, Spencer. The vicious cycle of dental fear: exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC oral health. 2007;7:1-15.

- Carr ECJ, Thomas VN, Wilson-Barnet J. Patient experiences of anxiety, depression and acute pain after surgery: a longitudinal perspective. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005;42:521-30.

- Cohen LA, Harris SL, Bonito AJ, Manski RJ, Macek MD, Edwards RR, Cornelius LJ. Coping with toothache pain: a qualitative study of low-income persons and minorities. J Public Health Dent. 2007;67:28-35.

- Doerr PA, Paul Lang W, Nyquist LV, Ronis DL. Factors associated with dental anxiety. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1111-9.

- Economou GC. Dental anxiety and personality: investigating the relationship between dental anxiety and self-consciousness. J Dent Educ. 2003;67:970-80.

- Eijlers R, Utens EMWJ, Staals LM, de Nijs PFA, Berghmans JM, Wijnen RMH, Hillegers MHJ, Dierckx B, Legerstee JS. Systematic review and Metaanalysis of virtual reality in pediatrics: effects on pain and anxiety. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:1344-53.

- Eli I, Schwartz-Arad D, Baht R, Ben-Tuvim H. Effect of anxiety on the experience of pain in implant insertion. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:115-8.

- Gershon J, Zimand E, Pickering M, Rothbaum BO, Hodges L. A pilot and feasibility study of virtual reality as a distraction for children with cancer. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1243-9.

- Hartig T, Mitchell R, De Vries S, Frumkin H. Nature and health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:207-28.

- Hill KB, Hainsworth JM, Burke FJT, Fairbrother KJ. Evaluation of dentists’ perceived needs regarding treatment of the anxious patient. Br Dent J. 2008;204:E13-3.

- Hoffman HG, Richards TL, Coda B, Bills AR, Blough D, Richards AL, Sharar SR. Modulation of thermal pain-related brain activity with virtual reality: evidence from fMRI. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1245-8.

- Hoffman HG, Seibel EJ, Richards TL, Furness TA, Patterson DR, Sharar SR. Virtual reality helmet display quality influences the magnitude of virtual reality analgesia. J Pain. 2006;7:843-50.

- Huang T-K, Yang C-H, Hsieh Y-H, Wang J-C, Hung C-C. Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) applied in dentistry. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2018;34:243-8.

- Hudson BF, Ogden J, Whiteley MS. A thematic analysis of experiences of varicose veins and minimally invasive surgery under local anaesthesia. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:1502-12.

- Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The modified dental anxiety scale: validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. 1995;12:143-50.

- Ip HY, Vivian AA, Peng PWH, Wong J, Chung F. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. J Am Soc Anesthesiologists. 2009;111:657-77.

- Jerdan SW, Grindle M, Van Woerden HC, Kamel MN, Boulos. Headmounted virtual reality and mental health: critical review of current research. JMIR serious games. 2018;6:e9226.

- Kazancioglu H-O, Dahhan A-S, Acar A-H. How could multimedia information about dental implant surgery effects patients’ anxiety level? Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2017;22:e102.

- Kent G. Memory of dental pain. Pain. 1985;21:187-94.

- Kipping B, Rodger S, Miller K, Kimble RM. Virtual reality for acute pain reduction in adolescents undergoing burn wound care: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Burns. 2012;38:650-7.

- Klages U, Kianifard S, Ulusoy Ö, Wehrbein H. Anxiety sensitivity as predictor of pain in patients undergoing restorative dental procedures. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34:139-45.

- Kleinknecht RA, Bernstein DA. The assessment of dental fear. Behav Ther. 1978;9:626-34.

- Legrain V, Crombez G, Verhoeven K, Mouraux A. The role of working memory in the attentional control of pain. Pain. 2011;152:453-9.

- Lindsay SJE, Wege P, Yates J. Expectations of sensations, discomfort and fear in dental treatment. Behav Res Ther. 1984;22:99-108.

- Litt MD. A model of pain and anxiety associated with acute stressors: distress in dental procedures. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:459-76.

- Locker D, Liddell AM. Correlates of dental anxiety among older adults. J Dent Res. 1991;70:198-203.

- Locker D. Psychosocial consequences of dental fear and anxiety. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:144-51.

- Locker D, Shapiro D, Liddell A. Negative dental experiences and their relationship to dental anxiety. Community Dent Health. 1996;13:86-92.

- López-Valverde N, Muriel-Fernández J, López-Valverde A, Valero-Juan LF, Ramírez JM, Flores-Fraile J, Herrero-Payo J, Blanco-Antona LA, Macedo-de-Sousa

. Use of virtual reality for the management of anxiety and pain in dental treatments: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1025. - Maggirias J, Locker D. Psychological factors and perceptions of pain associated with dental treatment. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:151-9.

- Malenbaum S, Keefe FJ, de Williams AC, Ulrich R, Somers TJ. Pain in its environmental context: implications for designing environments to enhance pain control. Pain. 2008;134:241-4.

- Mark M. Patient anxiety and modern elective surgery: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:806-15.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, Polyzos KA, Peppas G, Falagas ME. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:e20306.

- Melzack R. From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain. 1999;82:S121-6.

- Melzack R, Katz J. The gate control theory: reaching for the brain. Pain: Psych Pers; 2004. p.13-34.

- Moore R, Birn H, Kirkegaard E, Brødsgaard I, Scheutz F. Prevalence and characteristics of dental anxiety in Danish adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:292-6.

- Ougradar A, Ahmed B. Patients’ perceptions of the benefits of virtual reality during dental extractions. Br Dent J. 2019;227:813-6.

- Pierantognetti P, Covelli G, Vario M. Anxiety, stress and preoperative surgical nursing. Prof Inferm. 2002;55:180-91.

- Powell R, Marie Johnston W, Smith C, King PM, Alastair Chambers W, Krukowski Z, McKee L, Bruce J. Psychological risk factors for chronic postsurgical pain after inguinal hernia repair surgery: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:600-10.

- Schneider A, Andrade J, Tanja-Dijkstra K, White M, Moles DR. The psychological cycle behind dental appointment attendance: a cross-sectional study of experiences, anticipations, and behavioral intentions. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016;44:364-70.

- Schneider SM, Hood LE. Virtual reality: a distraction intervention for chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:39-46.

- Shahrbanian S, Ma X, Aghaei N, Korner-Bitensky N, Moshiri K, Simmonds MJ. Use of virtual reality (immersive vs. non immersive) for pain management in children and adults: a systematic review of evidence from randomized controlled trials. Eur J Exp Biol. 2012;2:1408-22.

- Skaret E, Raadal M, Berg E, Kvale G. Dental anxiety and dental avoidance among 12 to 18 year olds in Norway. Eur J Oral Sci. 1999;107:422-8.

- Spielberger CD. State-trait anxiety inventory for adults; 1983. https://doi. org/10.1037/t06496-000.

- Tanja-Dijkstra K, Pahl S, White MP, Andrade J, Qian C, Bruce M, May J, Moles DR. Improving dental experiences by using virtual reality distraction: a simulation study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91276.

- Tanja-Dijkstra K, Pahl S, White MP, Auvray M, Stone RJ, Andrade J, May J, Mills I, Moles DR. The soothing sea: a virtual coastal walk can reduce experienced and recollected pain. Environ Behav. 2018;50:599-625.

- Thomson WM, Locker D, Poulton R. Incidence of dental anxiety in young adults in relation to dental treatment experience. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:289-94.

- Vassend O. Anxiety, pain and discomfort associated with dental treatment. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31:659-66.

- Wetsch WA, Pircher I, Lederer W, Kinzl JF, Traweger C, Heinz-Erian P, Benzer A. Preoperative stress and anxiety in day-care patients and inpatients undergoing fast-track surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:199-205.

Publisher’s Note

- Mean

standard deviation and count (percentage %) are presented for continuous and categorical data, respectively

Independent-Samples T-Test

Chi-Square Test - Chi-Square Monte Carlo