DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57796-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40148292

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-27

أصول مستقلة وتوقيعات اختيار غير متوازية لمقاومة التريكلا بندازول في فاسيولا هيباتيكا

تم القبول: 4 مارس 2025

الملخص

تريكلابندازول (TCBZ) هو العلاج الرئيسي للفاسيولاز، وهو مرض حيواني غذائي عالمي تسببه فاسيولا هيباتيكا. المقاومة الواسعة لـ TCBZ (TCBZ-R) في الماشية والزيادة السريعة في الإصابات البشرية المقاومة تمثل مخاوف كبيرة. لفهم الأساس الجيني لـ TCBZ-R، قمنا بتسلسل جينومات 99 دودة فلوكية حساسة لـ TCBZ (TCBZ-S) و210 دودة فلوكية مقاومة لـ TCBZ من 146 كبد بقر في كوسكو، بيرو. نحن نحدد مناطق جينومية ذات تمايز عالٍ (

والصوف، وانخفاض الخصوبة، وإدانة الكبد

النتائج

تسلسل جينوم سكان الكبد البالغ لفاسيولا هيفاتيكا مع اختلاف في قابلية التريكلابندازول

من العزلات إلى تراكلابندازول سلفوكسيد في المختبر، الأكثر نشاطًا من ناتج التحلل لتراكلابندازول

لا تظهر تجمعات الفاسيولا في منطقة كوسكو في بيرو هيكلًا جينيًا كبيرًا فيما يتعلق بظاهرة حساسية TCBZ الخاصة بها.

F. hepatica هو خنثى بنظام تزاوج مختلط يتضمن كل من التزاوج الداخلي والتزاوج الخارجي. في الأنواع التي تتزاوج داخليًا، غالبًا ما تظهر المواقع المرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا هيكلًا من الأنماط الوراثية يمكن اكتشافه كاختلال ارتباط مرتفع. في مجموعة الدراسة لدينا، تدهور الاختلال إلى قيمة

في بيرو، السكان بناءً على متوسط LD المحسوب في أطول 10 سقالات (النطاق:

تردد إعادة التركيب في جميع أنحاء الجينوم

تشمل المواقع المرشحة تحت اختيار TCBZ EGFR/PI3K-mTOR-

تحليل ملفات النسخ حدد اختلاف التعبير في الجينات المرتبطة بالميكروتوبولات في الديدان TCBZ-S و -R

عشوائيًا لحساب LD الثنائي لكل مقابل لكل

| معرّف الجين | رمز الجين | وصف |

|

ترتيب

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_1006_عمود-أغسطس-جين-0.3 | S6K | كيناز بروتين الريبوسوم S6 | ١١٢.٥ |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_790_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.11 | EGFR | بروتين كيناز التيروزين المستقبل | ١١٠.٨ |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_1058_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.8 | غالنت | بوليببتيد N-أسيتيلغالكتوزامينيلترانسفيراز | 96.5 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_259_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.103 | MPDZ | بروتين متعدد نطاقات PDZ | 94.1 |

|

| سناب_ماسكد-سقالة10x_1433_بيلون-معالج-جين-0.1 | كاسك | كالسيكويستين | 91.5 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_293_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.143 | سيبا | إيزوميراز البيبتيديل-بروتين من نوع سيكلوفيلي | 89.5 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_922_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.56 | KTNA1 | الوحدة A1 المحتوية على ATPase كاتانين p60 | ٨٧.٧ |

|

| سناب_ماسكد-سكافولد10x_1189_بيلون-معالج-جين-0.81 | SIK3 | كيناز البروتين سيرين/ثريونين SIK3 | 87.3 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_82_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.73 | دي إن إيه | سلسلة ثقيلة من الداينين الأكسونيمال | 85.2 |

|

تركيزات العلاج (انظر الطرق للحصول على تفاصيل حول النهج التجريبي، بما في ذلك إصابات الحلزونات والأرانب). تم حساب الأهمية الإحصائية للتعبيرات التفاضلية الزوجية بواسطة خوارزمية تعتمد على اختبار التوزيع الثنائي السالب.

تعديل ديناميات الأنابيب الدقيقة

يُعتبر أنه قد زاد (بالأحمر) أو انخفض (بالأزرق) التعبير بشكل كبير وتم تجميعه بناءً على أنماط التعبير (المجموعة 1 إلى 6، مع عدد الجينات بين قوسين). د توزيع الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف عبر المجموعات 1 إلى 4. هـ مصطلحات عملية بيولوجية مفرطة التمثيل من علم الأحياء الجيني (GO) للجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف. مصطلحات GO مع تعديل FDR

تم إثراء الجينات المنخفضة التنظيم بشكل كبير لعمليات قائمة على الأنابيب الدقيقة (GO: 0007017،

يمكن تمييز طفيليات TCBZ-S و -R باستخدام عدد محدود من SNPs المعلوماتية

آخر (

| الجدول 2 | الجينات ذات الاهتمام التي تعبر بشكل مختلف بين فاسيولا هيباتيكا الحساسة والمقاومة للتريكلابندازول دون استجابة وعند الاستجابة لعلاج التريكلابندازول | |||||||||

| معرّف الجين | وصف | غير معالج | لوغاريتم 2 للفرق | تم تعديل FDR

|

TCBZ-S |

|

تم تعديل FDR

|

||

| أعلى في TCBZ-R | أقل في TCBZ-R | أعلى مع علاج TCBZ | خفض مع علاج TCBZ | ||||||

| صانع-سقالة10x_1074_بيلون-سناب-جين-0.107 | ألفا-توبولين | ي | – | ٢.٣٠ |

|

– | – | -1.11 | 0.049 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_13_عمود-سناب-جين-2.125 | ألفا-توبولين | ي | – | 2.14 |

|

– | ي | -2.47 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_13_عمود-لقطة-جين-2.129 | ألفا-توبولين | ي | – | 1.94 |

|

– | ي | -2.08 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_1444_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.40 | ألفا-توبولين | ي | – | 1.17 |

|

– | – | -1.42 | 0.017 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_45_عمود-انقر-جين-0.45 | ألفا-توبولين | ي | – | 1.74 |

|

– | ي | -2.31 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_592_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.21 | ألفا-توبولين | ي | – | 1.87 |

|

– | – | -1.51 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_680_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.21 | ألفا-توبولين | ي | – | 1.30 |

|

– | – | -0.99 | 0.12 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_809_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.10 | ألفا-توبولين | ي | – | 1.69 |

|

– | – | -1.78 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_944_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.44 | ألفا-توبولين | ي | – | 2.40 |

|

– | – | -1.28 | 0.036 |

| سناب_ماسكد-سكافولد10x_1189_بيلون-معالج-جين-0.77 | ألفا-توبولين | ي | – | 2.36 |

|

– | – | -3.25 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_1708_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.5 | بروتين 5 الشبيه بكاربوكسي ببتيداز × 10 في السيتوسول | ي | – | 1.26 |

|

– | – | -0.86 | 0.13 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_1084_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.149 | دلتا-توبولين | – | – | 0.24 | 0.79 | – | ي | -2.90 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_486_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.86 | بروتين يحتوي على مجال C-terminal من EB1 | ي | – | 2.77 |

|

– | ي | -1.94 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_44_عمود-انقر-جين-0.4 | بروتين يحتوي على مجال مشابه لـ EGF | ي | – | 2.77 |

|

– | – | -1.53 | 0.16 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_157_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.185 | بروتين يحتوي على مجال مشابه لـ EGF | ي | – | 2.37 |

|

– | – | -1.74 | 0.046 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_157_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.196 | بروتين يحتوي على مجال مشابه لـ EGF | ي | – | 1.94 |

|

– | – | -2.04 | 0.035 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_206_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.64 | نمط IQ، موقع ارتباط EF-hand | ي | – | ٣.٥٠ |

|

– | – | -0.99 | 0.13 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_1309_بيلون-سناب-جين-0.85 | كيناز البروتين المنشط بواسطة الميتوجين | – | – | 0.51 | 0.24 | ي | – | 1.20 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_559_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.27 | مونوجلايسيل التوبولين | ي | – | 1.63 |

|

– | – | 0.16 | 0.87 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_61_عمود-انقر-جين-0.52 | بوليجليتاميلاز التوبولين | ي | – | 1.76 |

|

– | – | -1.30 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_234_عمود-أغسطس-جين-0.64 | بوليجليتاميلاز التوبولين | ي | – | 1.22 |

|

– | – | 0.37 | 0.57 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_242_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.27 | بوليجليتاميلاز التوبولين | ي | – | 1.44 |

|

– | – | -0.86 | 0.23 |

| ماكر-سقالة10x_383_بيلون-سناب-جين-1.0 | بوليجليتاميلاز التوبولين | ي | – | 1.65 |

|

– | – | -0.92 | 0.19 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_483_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.117 | بوليجليتاميلاز التوبولين | ي | – | 1.51 |

|

– | – | -0.22 | 0.69 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_908_بيلون-سناب-جين-1.169 | بوليجليتاميلاز التوبولين | ي | – | 1.60 |

|

– | – | -0.87 | 0.18 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_1306_بيلون-سناب-جين-0.14 | بوليجليتاميلاز التوبولين | ي | – | 1.74 |

|

– | – | -2.06 | 0.065 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_2067_عمود-أغسطس-جين-0.6 | بوليجليتاميلاز التوبولين | ي | – | 1.57 |

|

– | – | -1.11 | 0.032 |

| صانع-سقالة10x_66_عمود-لقطة-جين-0.15 | هيدروكسيلاز كربوكسيلي نهائي يوبكويتين | ي | – | 1.07 |

|

ي | – | 1.56 |

|

| صانع-سقالة10x_73_عمود-انقر-جين-0.14 | بروتين شبيه بالفازوهبين | ي | – | 2.07 |

|

– | ي | -2.70 |

|

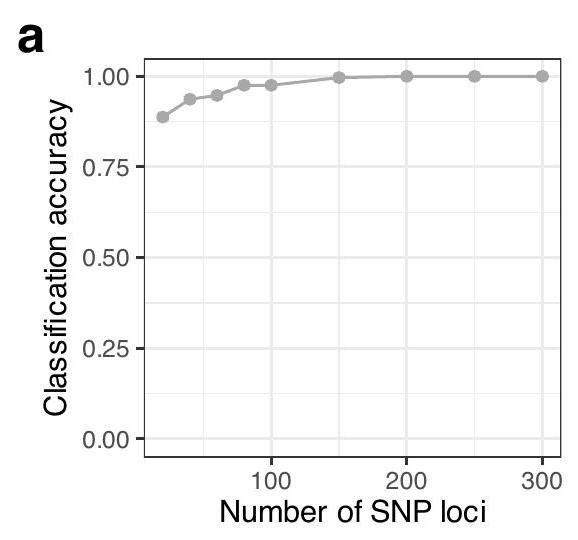

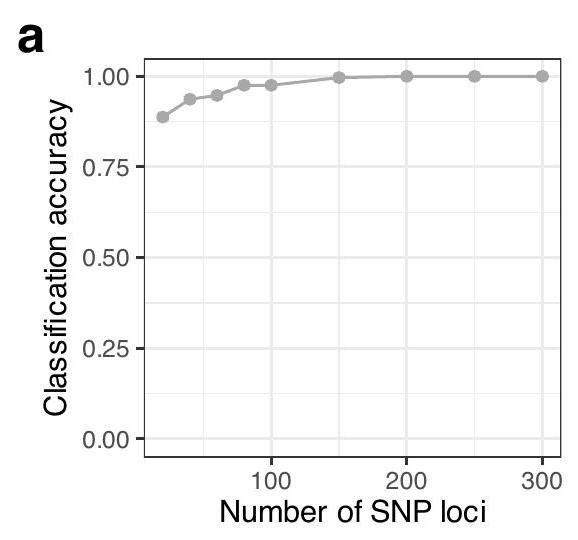

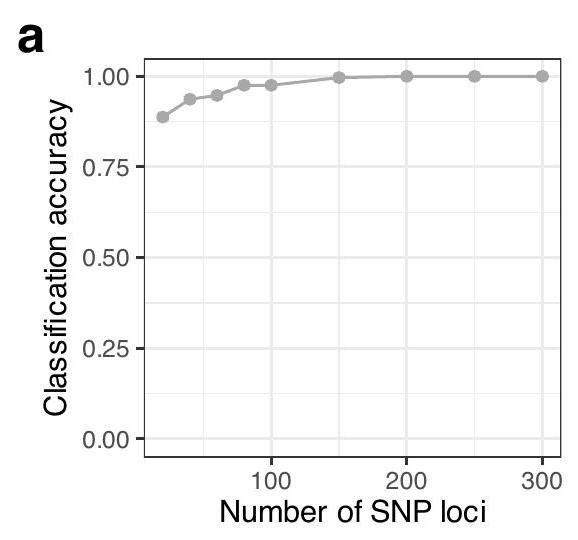

مستندة إلى ملفات SNP. تصنيف المجموعات بواسطة تحليل التمييز للمكونات الرئيسية (DAPC). تم استخدام أفضل 300 SNP، التي تظهر اختلافات ملحوظة في تردد الأليلات بين المجموعات وليست في توازن ربط قوي مع بعضها البعض، لتصنيف 91 عينة WGS من TCBZ-S و194 عينة من TCBZ-R.

b

معدل (1-الخصوصية) عند عتبات تصنيف مختلفة (الشكل 4ب). كانت المساحة تحت منحنى ROC (AUC)، التي توفر مقياسًا مجمعًا للأداء عبر جميع عتبات التصنيف الممكنة، 0.86 (إعادة أخذ عينات غير معلمية مقسمة).

نقاش

التعرض لتركيزات عالية من TCBZ (

تشير إلى الفروق في تطور الأعضاء أو الوظائف بين الديدان TCBZ-S و -R. يمكن أن توفر الدراسات النسيجية الإضافية أو تحليل تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية معلومات إضافية لدعم هذا التفسير. اعتبار آخر حاسم عند مقارنة النسخ الجينية للديدان TCBZ-S و TCBZ-R غير المعالجة هو التأثير المحتمل لتنوع الخلفية الجينية. يمكن أن تؤدي الفروق في الخلفية الجينية، غير المرتبطة بظاهرة المقاومة، إلى تشويش الفروق النسخية الملحوظة بين الديدان TCBZ-S و TCBZ-R. لمعالجة ذلك، سيكون من الضروري إجراء تجارب مع ديدان إضافية من مجموعة من الخلفيات الجينية لتحديد الفروق النسخية المرتبطة بشكل خاص بظاهرة المقاومة.

تم تحديده بسبب LD الممتد بين الجينات الموجودة على الموقع. لقد أظهر ARF4 أنه يتفاعل مع EGFR، مما يؤدي إلى تنشيط الفوسفوليباز D2.

طرق

الحصول على الطفيليات وتسلسل الجينوم الكامل

تحليلات مسح المتغيرات والاختيار على مستوى الجينوم

تم استدعاء المتغيرات (SNPs) باستخدام GATK v4.2.2

توليد TCBZ-S و -R ميتا سيركاريا

داخل الكيس البلاستيكي من نفس مجموعة الحلزونات المعروفة بحساسيتها لـ TCBZ وتم الاحتفاظ بها في الماء عند

توليد طفيليات TCBZ-S و -R البالغة

تجارب التعرض لـ Triclabendazole وتحليل التعبير الجيني باستخدام RNA-seq

تصميم لوحة الأمبليكون والتسلسل المستهدف (amplicon-seq)

استبعاد الأفراد المتشابهين في النسخ والأفراد المرتبطين ارتباطًا وثيقًا من عينات تسلسل الأمبليكون، PLINK v1.9

تمييز نمط حساسية TCBZ باستخدام مجموعة من علامات SNP

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Furst, T., Duthaler, U., Sripa, B., Utzinger, J. & Keiser, J. Trematode infections: liver and lung flukes. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 26, 399-419 (2012).

- Caravedo, M. A. & Cabada, M. M. Human fascioliasis: current epidemiological status and strategies for diagnosis, treatment, and control. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 11, 149-158 (2020).

- Charlier, J. et al. Initial assessment of the economic burden of major parasitic helminth infections to the ruminant livestock industry in Europe. Prev. Vet. Med. 182, 105103 (2020).

- Mehmood, K. et al. A review on epidemiology, global prevalence and economical losses of fasciolosis in ruminants. Micro. Pathog. 109, 253-262 (2017).

- Sanchez-Vazquez, M. J. & Lewis, F. I. Investigating the impact of fasciolosis on cattle carcase performance. Vet. Parasitol. 193, 307-311 (2013).

- Arenal, A. et al. Risk factors for the presence of Fasciola hepatica antibodies in bulk-milk samples and their association with milk production decreases, in Cuban dairy cattle. BMC Vet. Res. 14, 336 (2018).

- Schweizer, G., Braun, U., Deplazes, P. & Torgerson, P. R. Estimating the financial losses due to bovine fasciolosis in Switzerland. Vet. Rec. 157, 188-193 (2005).

- Lopez, M., White, A. C. Jr. & Cabada, M. M. Burden of Fasciola hepatica Infection among children from Paucartambo in Cusco, Peru. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 86, 481-485 (2012).

- Marcos, L. A. et al. Report of cases of human fascioliosis in the Specialized Children’s Health Institute, Lima, Peru (1988′-2003). Rev. Gastroenterol. Peru. 25, 198-205 (2005).

- Yentur Doni, N., Yildiz Zeyrek, F., Simsek, Z., Gurses, G. & Sahin, I. Risk factors and relationship between intestinal parasites and the growth retardation and psychomotor development delays of children in Sanliurfa, Turkey. Turkiye Parazitol. Derg. 39, 270-276 (2015).

- Chang Wong, M. R., Pinto Elera, J. O., Guzman Rojas, P., Terashima Iwashita, A. & Samalvides Cuba, F. Demographic and clinical aspects of hepatic fascioliasis between 2013-2010 in National Hospital Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru. Rev. Gastroenterol. Peru. 36, 23-28 (2016).

- Machicado, C., Machicado, J. D., Maco, V., Terashima, A. & Marcos, L. A. Association of fasciola hepatica infection with liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and cancer: a systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 10, e0004962 (2016).

- Castro-Hermida, J. A., Gonzalez-Warleta, M., Martinez-Sernandez, V., Ubeira, F. M. & Mezo, M. Current challenges for fasciolicide treatment in ruminant livestock. Trends Parasitol. 37, 430-444 (2021).

- Kelley, J. M. et al. Current threat of triclabendazole resistance in Fasciola hepatica. Trends Parasitol. 32, 458-469 (2016).

- Gandhi, P. et al. Triclabendazole in the treatment of human fascioliasis: a review. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 113, 797-804 (2019).

- Kamaludeen, J. et al. Lack of efficacy of triclabendazole against Fasciola hepatica is present on sheep farms in three regions of England, and Wales. Vet. Rec. 184, 502 (2019).

- Rose Vineer, H. et al. Increasing importance of anthelmintic resistance in European livestock: creation and meta-analysis of an open database. Parasite 27, 69 (2020).

- Olaechea, F., Lovera, V., Larroza, M., Raffo, F. & Cabrera, R. Resistance of Fasciola hepatica against triclabendazole in cattle in Patagonia (Argentina). Vet. Parasitol. 178, 364-366 (2011).

- Winkelhagen, A. J., Mank, T., de Vries, P. J. & Soetekouw, R. Apparent triclabendazole-resistant human Fasciola hepatica infection, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18, 1028-1029 (2012).

- Gil, L. C. et al. Resistant human fasciolasis: report of four patients. Rev. Med. Chil. 142, 1330-1333 (2014).

- Belgin, G. et al. Partial Hepatectomy for the Resistant Fasciola hepatica Infection in a Child. APSP J. Case Rep. 6, 27 (2015).

- Cabada, M. M. et al. Treatment failure after multiple courses of triclabendazole among patients with fascioliasis in cusco, peru: a case series. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0004361 (2016).

- Branco, E. A., Ruas, R., Nuak, J. & Sarmento, A. Treatment failure after multiple courses of triclabendazole in a Portuguese patient

with fascioliasis. BMJ Case Rep. 13, https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2019-232299 (2020). - Morales, M. L. et al. Triclabendazole treatment failure for Fasciola hepatica Infection among preschool and school-age children, cusco, peru(1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 1850-1857 (2021).

- Maco, V. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of two single-day regimens of triclabendazole for fascioliasis in Peruvian children. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 48, 445-453 (2015).

- Meaney, M. et al. Increased susceptibility of a triclabendazole (TCBZ)-resistant isolate of Fasciola hepatica to TCBZ following coincubation in vitro with the P-glycoprotein inhibitor, R(+)-verapamil. Parasitology 140, 1287-1303 (2013).

- Robinson, M. W., Lawson, J., Trudgett, A., Hoey, E. M. & Fairweather, I. The comparative metabolism of triclabendazole sulphoxide by triclabendazole-susceptible and triclabendazoleresistant Fasciola hepatica. Parasitol. Res. 92, 205-210 (2004).

- Alvarez, L. I. et al. Altered drug influx/efflux and enhanced metabolic activity in triclabendazole-resistant liver flukes. Parasitology 131, 501-510 (2005).

- Scarcella, S., Lamenza, P., Virkel, G. & Solana, H. Expression differential of microsomal and cytosolic glutathione-S-transferases in Fasciola hepatica resistant at triclabendazole. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 181, 37-39 (2012).

- Wilkinson, R. et al. An amino acid substitution in Fasciola hepatica P-glycoprotein from triclabendazole-resistant and triclabendazole-susceptible populations. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 186, 69-72 (2012).

- Elliott, T. P. & Spithill, T. W. The T687G SNP in a P-glycoprotein gene of Fasciola hepatica is not associated with resistance to triclabendazole in two resistant Australian populations. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 198, 45-47 (2014).

- Solana, M. V. et al. Different SNPs in Fasciola hepatica P-glycoprotein from diverse Latin American populations are not associated with Triclabendazole resistance. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 224, 57-60 (2018).

- Radio, S. et al. Pleiotropic alterations in gene expression in Latin American Fasciola hepatica isolates with different susceptibility to drugs. Parasit. Vectors 11, 56 (2018).

- Beesley, N. J. et al. A major locus confers triclabendazole resistance in Fasciola hepatica and shows dominant inheritance. PLoS Pathog. 19, e1011081 (2023).

- Fernandez-Baca, M. V. et al. The differences in the susceptibility patterns to triclabendazole sulfoxide in field isolates of Fasciola hepatica are associated with geographic, seasonal, and morphometric variations. Pathogens 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/ pathogens11060625 (2022).

- Choi, Y. J. et al. Adaptive radiation of the flukes of the family fasciolidae inferred from genome-wide comparisons of key species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 84-99 (2020).

- Cwiklinski, K. et al. The Fasciola hepatica genome: gene duplication and polymorphism reveals adaptation to the host environment and the capacity for rapid evolution. Genome Biol. 16, 71 (2015).

- McNulty, S. N. et al. Genomes of Fasciola hepatica from the Americas reveal colonization with neorickettsia endobacteria related to the agents of Potomac horse and human sennetsu fevers. PLoS Genet 13, e1006537 (2017).

- Morris, G. P. et al. Population genomic and genome-wide association studies of agroclimatic traits in sorghum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 453-458 (2013).

- Mather, K. A. et al. The extent of linkage disequilibrium in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genetics 177, 2223-2232 (2007).

- Charlesworth, D. Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 358, 1051-1070 (2003).

- Beissinger, T. M., Rosa, G. J., Kaeppler, S. M., Gianola, D. & de Leon, N. Defining window-boundaries for genomic analyses using smoothing spline techniques. Genet Sel. Evol. 47, 30 (2015).

- Fernandez, V. et al. A single amino acid substitution in isozyme GST mu in Triclabendazole resistant Fasciola hepatica (Sligo strain) can substantially influence the manifestation of anthelmintic resistance. Exp. Parasitol. 159, 274-279 (2015).

- Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106 (2010).

- Falcon, S. & Gentleman, R. Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics 23, 257-258 (2007).

- Nieuwenhuis, J. et al. Vasohibins encode tubulin detyrosinating activity. Science 358, 1453-1456 (2017).

- Vitre, B. et al. EB1 regulates microtubule dynamics and tubulin sheet closure in vitro. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 415-421 (2008).

- Redeker, V. et al. Polyglycylation of tubulin: a posttranslational modification in axonemal microtubules. Science 266, 1688-1691 (1994).

- Thines, L., Roushar, F. J., Hedman, A. C. & Sacks, D. B. The IQGAP scaffolds: critical nodes bridging receptor activation to cellular signaling. J. Cell Biol. 222, https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb. 202205062 (2023).

- Canovas, B. & Nebreda, A. R. Diversity and versatility of p38 kinase signalling in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 346-366 (2021).

- Gasic, I., Boswell, S. A. & Mitchison, T. J. Tubulin mRNA stability is sensitive to change in microtubule dynamics caused by multiple physiological and toxic cues. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000225 (2019).

- Wendt, G. et al. A single-cell RNA-seq atlas of Schistosoma mansoni identifies a key regulator of blood feeding. Science 369, 1644-1649 (2020).

- Ndiaye, P. I., Miquel, J., Fons, R. A. & Marchand, B. Spermiogenesis and sperm ultrastructure of the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica L., 1758 (Digenea, Fasciolidae): transmission and scanning electron microscopy, and tubulin immunocytochemistry. Acta Parasitol. 48, 182-194 (2003).

- Pantelouris, E. M. & Threadgold, L. T. The excretory system of the adult Fasciola hepatica L. Cellule 64, 61-67 (1963).

- Jombart, T., Devillard, S. & Balloux, F. Discriminant analysis of principal components: a new method for the analysis of genetically structured populations. BMC Genet. 11, 94 (2010).

- Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R. N. 2, 18-22 (2002).

- Fairweather, I., Brennan, G. P., Hanna, R. E. B., Robinson, M. W. & Skuce, P. J. Drug resistance in liver flukes. Int J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist 12, 39-59 (2020).

- Hac, A., Pierzynowska, K. & Herman-Antosiewicz, A. S6K1 is indispensible for stress-induced microtubule acetylation and autophagic flux. Cells 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/ cells10040929 (2021).

- Eshun-Wilson, L. et al. Effects of alpha-tubulin acetylation on microtubule structure and stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 10366-10371 (2019).

- LeDizet, M. & Piperno, G. Cytoplasmic microtubules containing acetylated alpha-tubulin in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: spatial arrangement and properties. J. Cell Biol. 103, 13-22 (1986).

- Wattanathamsan, O. et al. Tubulin acetylation enhances lung cancer resistance to paclitaxel-induced cell death through Mcl-1 stabilization. Cell Death Discov. 7, 67 (2021).

- Sfakianos, A. P. et al. The mTOR-S6 kinase pathway promotes stress granule assembly. Cell Death Differ. 25, 1766-1780 (2018).

- Csukasi, F. et al. The PTH/PTHrP-SIK3 pathway affects skeletogenesis through altered mTOR signaling. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aat9356 (2018).

- Beaman, E. M., Carter, D. R. F. & Brooks, S. A. GALNTs: master regulators of metastasis-associated epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)? Glycobiology 32, 556-579 (2022).

- Han, J. M. & Jung, H. J. Cyclophilin A/CD147 interaction: a promising target for anticancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, https:// doi.org/10.3390/ijms23169341 (2022).

- Ma, Z. et al. Cyclophilin A inhibits A549 cell oxidative stress and apoptosis by modulating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Biosci. Rep. 41, https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20203219 (2021).

- Franke, T. F., Hornik, C. P., Segev, L., Shostak, G. A. & Sugimoto, C. PI3K/Akt and apoptosis: size matters. Oncogene 22, 8983-8998 (2003).

- Chemale, G. et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of triclabendazole response in the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica. J. Proteome Res. 9, 4940-4951 (2010).

- Lemmon, M. A. & Schlessinger, J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 141, 1117-1134 (2010).

- Cwiklinski, K., Robinson, M. W., Donnelly, S. & Dalton, J. P. Complementary transcriptomic and proteomic analyses reveal the cellular and molecular processes that drive growth and development of Fasciola hepatica in the host liver. BMC Genomics 22, 46 (2021).

- Walker, S. M. et al. Stage-specific differences in fecundity over the life-cycle of two characterized isolates of the liver fluke, Fasciola hepatica. Parasitology 133, 209-216 (2006).

- Brennan, G. P. et al. Understanding triclabendazole resistance. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 82, 104-109 (2007).

- Kuo, Y. W. & Howard, J. Cutting, amplifying, and aligning microtubules with severing enzymes. Trends Cell Biol. 31, 50-61 (2021).

- Olivares-Ferretti, P., Beltran, J. F., Salazar, L. A. & Fonseca-Salamanca, F. Protein modelling and molecular docking analysis of Fasciola hepatica beta-tubulin’s interaction sites, with triclabendazole, triclabendazole sulphoxide and triclabendazole sulphone. Acta Parasitol. 68, 535-547 (2023).

- Robinson, M. W., McFerran, N., Trudgett, A., Hoey, L. & Fairweather, I. A possible model of benzimidazole binding to betatubulin disclosed by invoking an inter-domain movement. J. Mol. Graph Model 23, 275-284 (2004).

- Bennett, J. L. & Kohler, P. Fasciola hepatica: action in vitro of triclabendazole on immature and adult stages. Exp. Parasitol. 63, 49-57 (1987).

- Hanna, R. Fasciola hepatica: histology of the reproductive organs and differential effects of triclabendazole on drug-sensitive and drug-resistant fluke isolates and on flukes from selected field cases. Pathogens 4, 431-456 (2015).

- Akhmanova, A. et al. Clasps are CLIP-115 and -170 associating proteins involved in the regional regulation of microtubule dynamics in motile fibroblasts. Cell 104, 923-935 (2001).

- Isakoff, S. J. et al. Breast cancer-associated PIK3CA mutations are oncogenic in mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 65, 10992-11000 (2005).

- Ralph, P. & Coop, G. Parallel adaptation: one or many waves of advance of an advantageous allele? Genetics 186, 647-668 (2010).

- Overend, D. J. & Bowen, F. L. Resistance of Fasciola hepatica to triclabendazole. Aust. Vet. J. 72, 275-276 (1995).

- Redman, E. et al. The emergence of resistance to the benzimidazole anthlemintics in parasitic nematodes of livestock is characterised by multiple independent hard and soft selective sweeps. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0003494 (2015).

- Kim, S. W. et al. ADP-ribosylation factor 4 small GTPase mediates epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent phospholipase D2 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2661-2668 (2003).

- Wesolowski, J. et al. Chlamydia Hijacks ARF GTPases to coordinate microtubule posttranslational modifications and golgi complex positioning. mBio 8, e02280-16 (2017).

- Woo, I. S. et al. Identification of ADP-ribosylation factor 4 as a suppressor of N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide-induced cell death. Cancer Lett. 276, 53-60 (2009).

- Khanna, A. et al. The small GTPases Ras and Rap1 bind to and control TORC2 activity. Sci. Rep. 6, 25823 (2016).

- Kortholt, A. et al. A Rap/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway controls pseudopod formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 936-945 (2010).

- Cahill, M. E. et al. Bidirectional synaptic structural plasticity after chronic cocaine administration occurs through Rap1 Small GTPase signaling. Neuron 89, 566-582 (2016).

- Brecht, K. et al. Exogenous iron increases fasciocidal activity and hepatocellular toxicity of the synthetic endoperoxides OZ78 and MT04. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijms20194880 (2019).

- Duthaler, U., Smith, T. A. & Keiser, J. In vivo and in vitro sensitivity of Fasciola hepatica to triclabendazole combined with artesunate, artemether, or OZ78. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4596-4604 (2010).

- Sambrook, J. & Russell, D. W. Purification of nucleic acids by extraction with phenol:chloroform. CSH Protoc. 2006, pdb.prot4455 (2006).

- Tran, L., Toet, H. & Beddoe, T. Environmental detection of Fasciola hepatica by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. PeerJ 10, e13778 (2022).

- Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114-2120 (2014).

- Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754-1760 (2009).

- McKenna, A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297-1303 (2010).

- Van der Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 43, 11.10.1-11.10.33 (2013).

- Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6, 80-92 (2012).

- Wang, X. et al. CNVcaller: highly efficient and widely applicable software for detecting copy number variations in large populations. Gigascience 6, 1-12 (2017).

- Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet 81, 559-575 (2007).

- Manichaikul, A. et al. Robust relationship inference in genomewide association studies. Bioinformatics 26, 2867-2873 (2010).

- Arthur, R., Schulz-Trieglaff, O., Cox, A. J. & O’Connell, J. AKT: ancestry and kinship toolkit. Bioinformatics 33, 142-144 (2017).

- Zhang, C., Dong, S. S., Xu, J. Y., He, W. M. & Yang, T. L. PopLDdecay: a fast and effective tool for linkage disequilibrium decay analysis based on variant call format files. Bioinformatics 35, 1786-1788 (2019).

- Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236-1240 (2014).

- Gene Ontology, C. The gene ontology resource: enriching a GOId mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D325-D334 (2021).

- Blum, M. et al. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D344-D354 (2021).

- Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 726-731 (2016).

- Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG: integrating viruses and cellular organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D545-D551 (2021).

- Toronen, P. & Holm, L. PANNZER-A practical tool for protein function prediction. Protein Sci. 31, 118-128 (2022).

- Casimiro-Soriguer, C. S., Munoz-Merida, A. & Perez-Pulido, A. J. Sma3s: A universal tool for easy functional annotation of proteomes and transcriptomes. Proteomics 17, https://doi.org/10. 1002/pmic. 201700071 (2017).

- Hernandez-Plaza, A. et al. eggNOG 6.0: enabling comparative genomics across 12535 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D389-D394 (2023).

- Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D638-D646 (2023).

- Fairweather, I. et al. Development of an egg hatch assay for the diagnosis of triclabendazole resistance in Fasciola hepatica: proof of concept. Vet. Parasitol. 183, 249-259 (2012).

- Robles-Perez, D., Martinez-Perez, J. M., Rojo-Vazquez, F. A. & Martinez-Valladares, M. Screening anthelmintic resistance to triclabendazole in Fasciola hepatica isolated from sheep by means of an egg hatch assay. BMC Vet. Res. 11, 226 (2015).

- Jarujareet, W., Taira, K. & Ooi, H. K. Dynamics of liver enzymes in rabbits experimentally infected with Fasciola sp. (Intermediate form from Japan). J. Vet. Med. Sci. 80, 36-40 (2018).

- Kandil, O. M. et al. Anthelmintic efficacy of Moringa oleifera seed methanolic extract against Fasciola hepatica. J. Parasit. Dis. 42, 391-401 (2018).

- Maggioli, G. et al. A recombinant thioredoxin-glutathione reductase from Fasciola hepatica induces a protective response in rabbits. Exp. Parasitol. 129, 323-330 (2011).

- Mooney, L., Good, B., Hanrahan, J. P., Mulcahy, G. & de Waal, T. The comparative efficacy of four anthelmintics against a natural acquired Fasciola hepatica infection in hill sheep flock in the west of Ireland. Vet. Parasitol. 164, 201-205 (2009).

- White, P. RNA extraction from mammalian tissues. Methods Mol. Biol. 362, 315-327 (2007).

- Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graphbased genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907-915 (2019).

- Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. FeatureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923-930 (2014).

- Liao, Y., Wang, J., Jaehnig, E. J., Shi, Z. & Zhang, B. WebGestalt 2019: gene set analysis toolkit with revamped UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W199-W205 (2019).

- Supek, F., Bosnjak, M., Skunca, N. & Smuc, T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS ONE 6, e21800 (2011).

- Smith, G. C., Seaman, S. R., Wood, A. M., Royston, P. & White, I. R. Correcting for optimistic prediction in small data sets. Am. J. Epidemiol. 180, 318-324 (2014).

- Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1-26 (2008).

- Stevenson, M. et al. EpiR: an R package for the analysis of epidemiological data. 1, 9-43 (2013).

- Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinforma. 12, 77 (2011).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إضافية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57796-5.

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2025

- ¹قسم الأمراض المعدية، كلية الطب، جامعة واشنطن، سانت لويس، ميزوري، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ²مقر كوسكو، معهد الطب الاستوائي “ألكسندر فون هومبولت”، جامعة بيرو كايتانو هيريديا، كوسكو، بيرو.

مختبر المناعة، كلية العلوم البيطرية، الجامعة الوطنية في كاخاماركا، كاخاماركا، بيرو. قسم الأمراض المعدية، قسم الطب الباطني، فرع جامعة تكساس الطبية، غالفستون، تكساس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني: ميكابادا@يوتي.إم.بي.إي.دي.يو; mmitreva@wustl.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57796-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40148292

Publication Date: 2025-03-27

Independent origins and non-parallel selection signatures of triclabendazole resistance in Fasciola hepatica

Accepted: 4 March 2025

Abstract

Triclabendazole (TCBZ) is the primary treatment for fascioliasis, a global foodborne zoonosis caused by Fasciola hepatica. Widespread resistance to TCBZ (TCBZ-R) in livestock and a rapid rise in resistant human infections are significant concerns. To understand the genetic basis of TCBZ-R, we sequenced the genomes of 99 TCBZ-sensitive (TCBZ-S) and 210 TCBZ-R adult flukes from 146 bovine livers in Cusco, Peru. We identify genomic regions of high differentiation (

and wool, decreased fertility, and liver condemnation

Results

Population sequencing of adult Fasciola hepatica with divergent triclabendazole susceptibility

of the isolates to triclabendazole sulfoxide in vitro, the most active metabolite of TCBZ

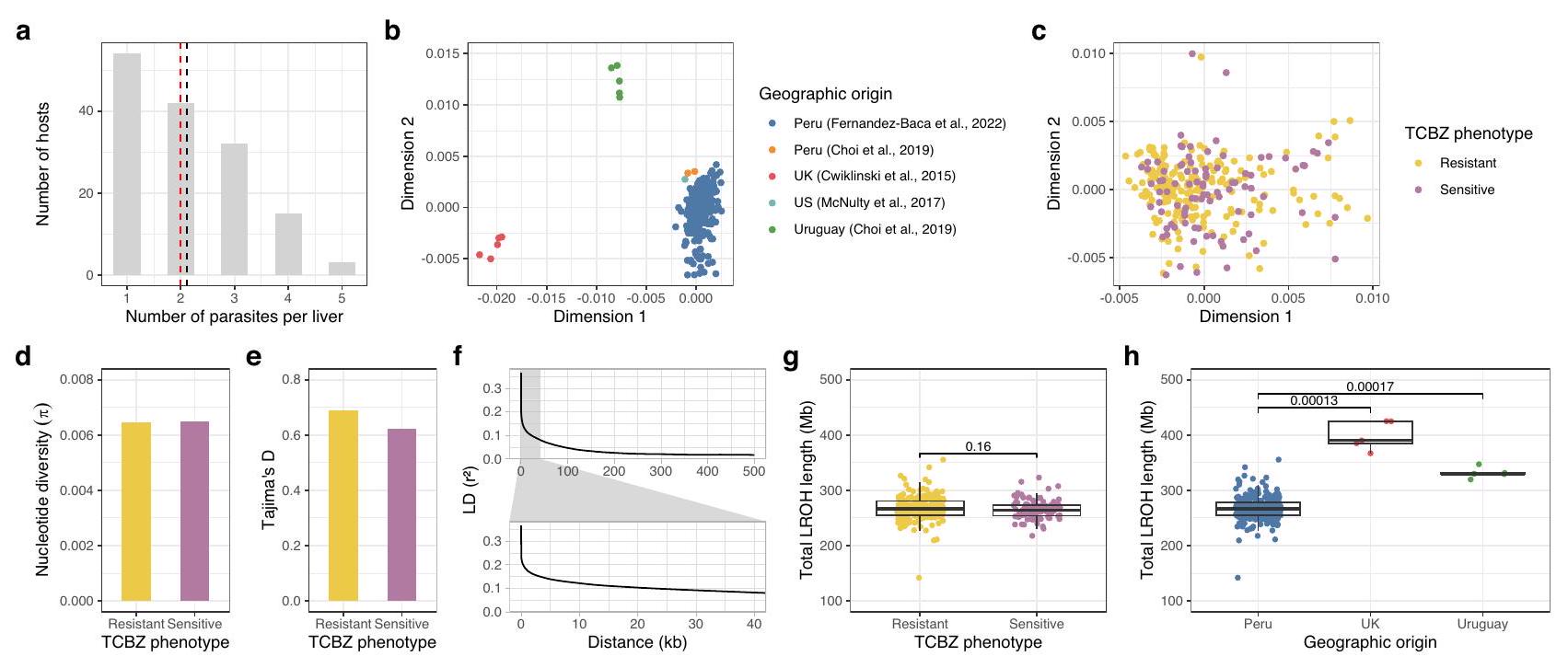

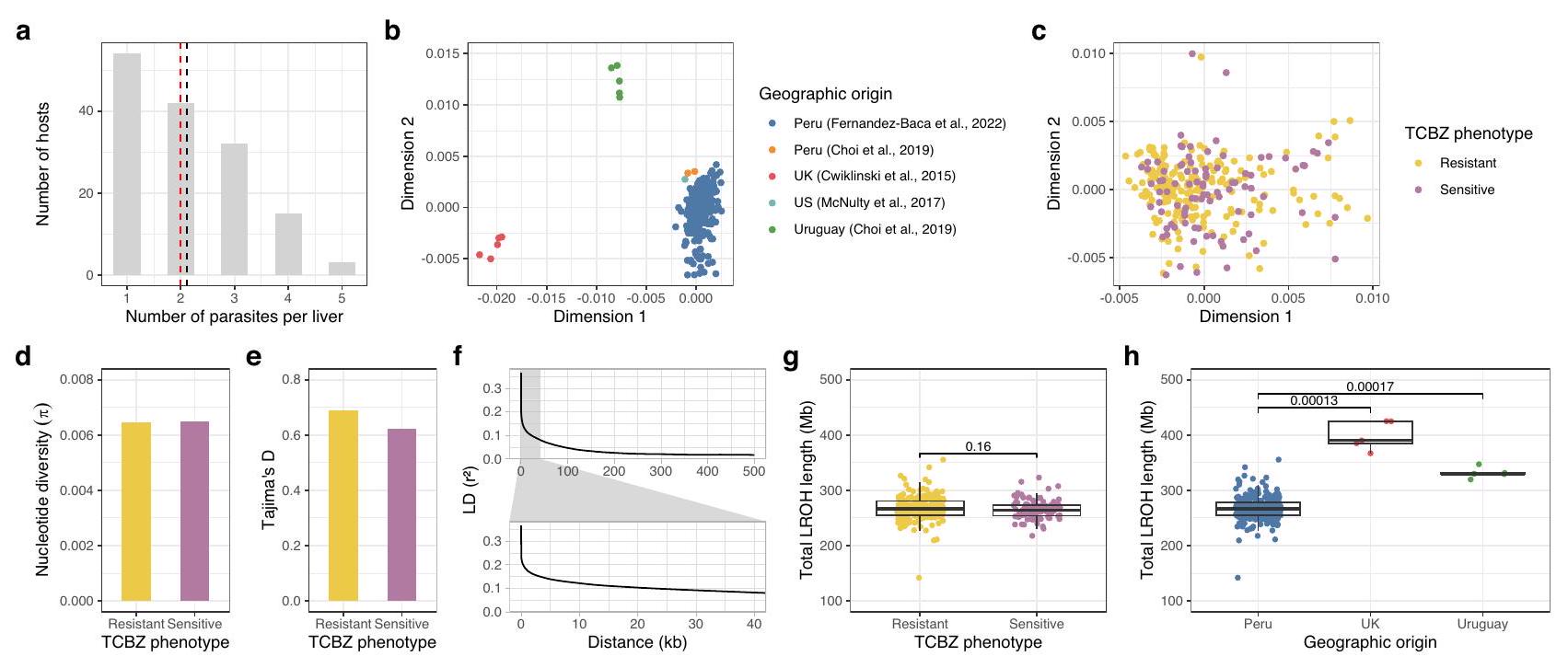

Fasciola populations in the Cusco region of Peru do not exhibit significant genetic structuring with respect to their TCBZ sensitivity phenotype

F. hepatica is a hermaphrodite with a mixed mating system involving both inbreeding and outcrossing. In inbreeders, closely linked sites often show haplotype structure detectable as high linkage disequilibrium (LD). In our study population, LD decayed to a value of

in Peru population based on mean LD calculated in 10 longest scaffolds (range:

recombination frequency throughout the genome

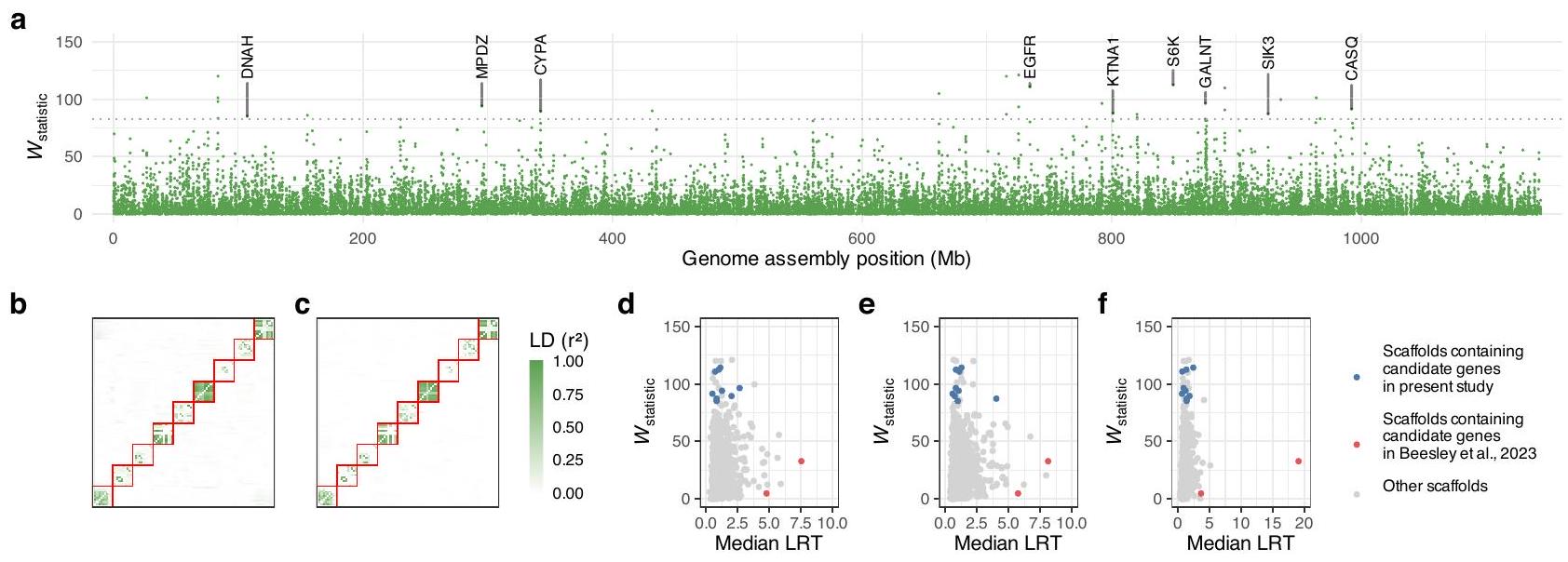

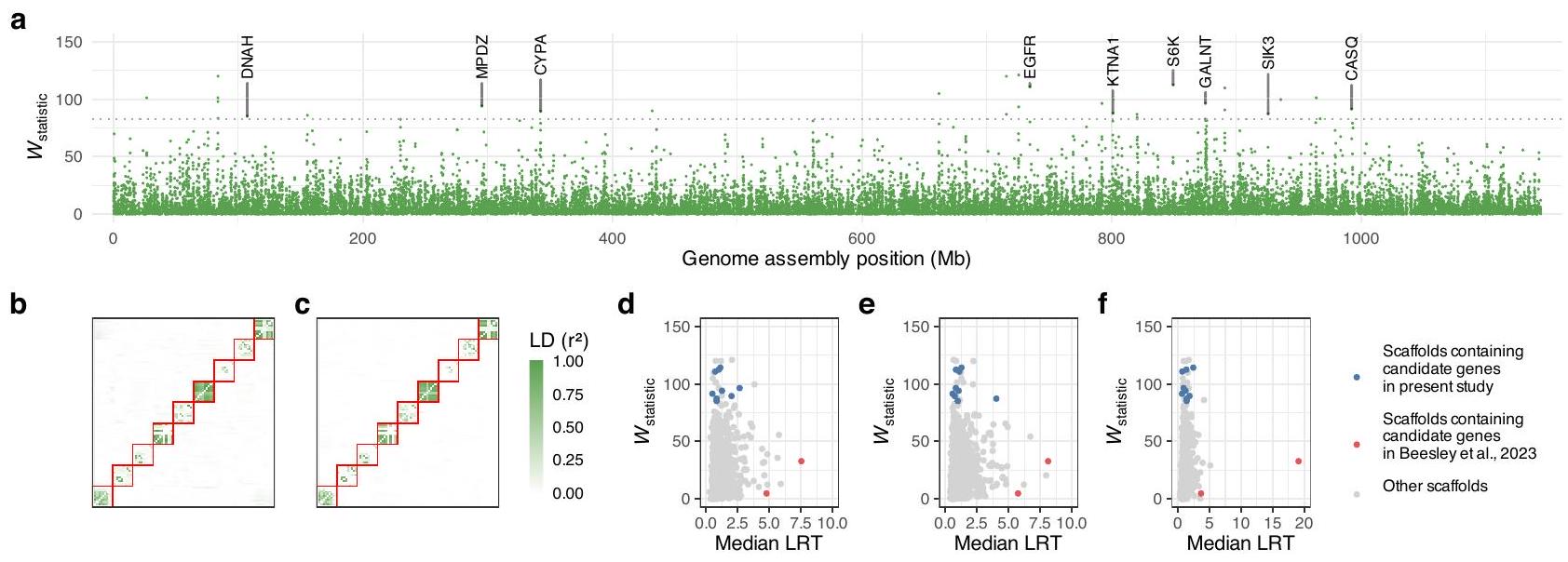

Candidate loci under TCBZ selection include EGFR/PI3K-mTOR-

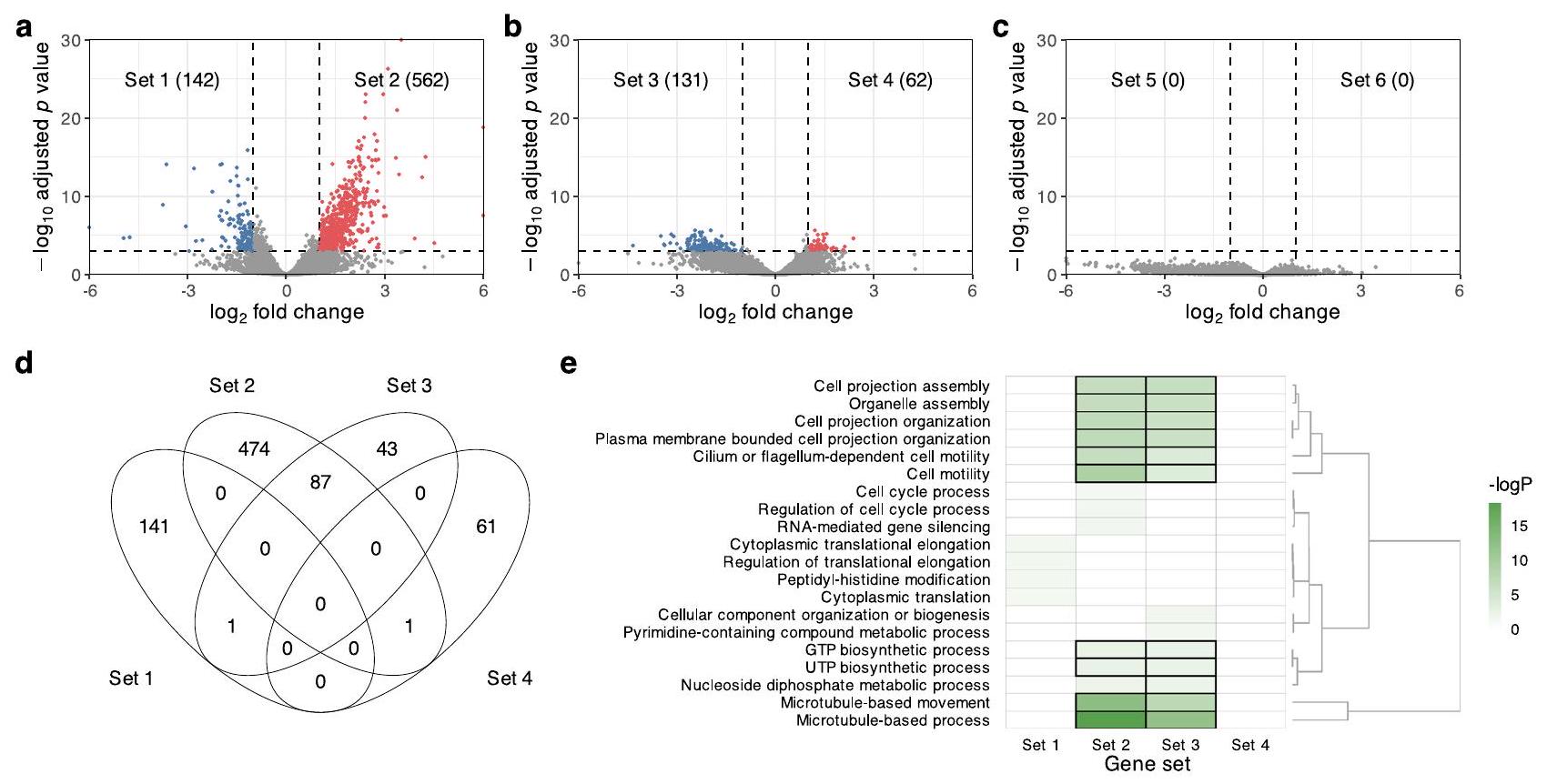

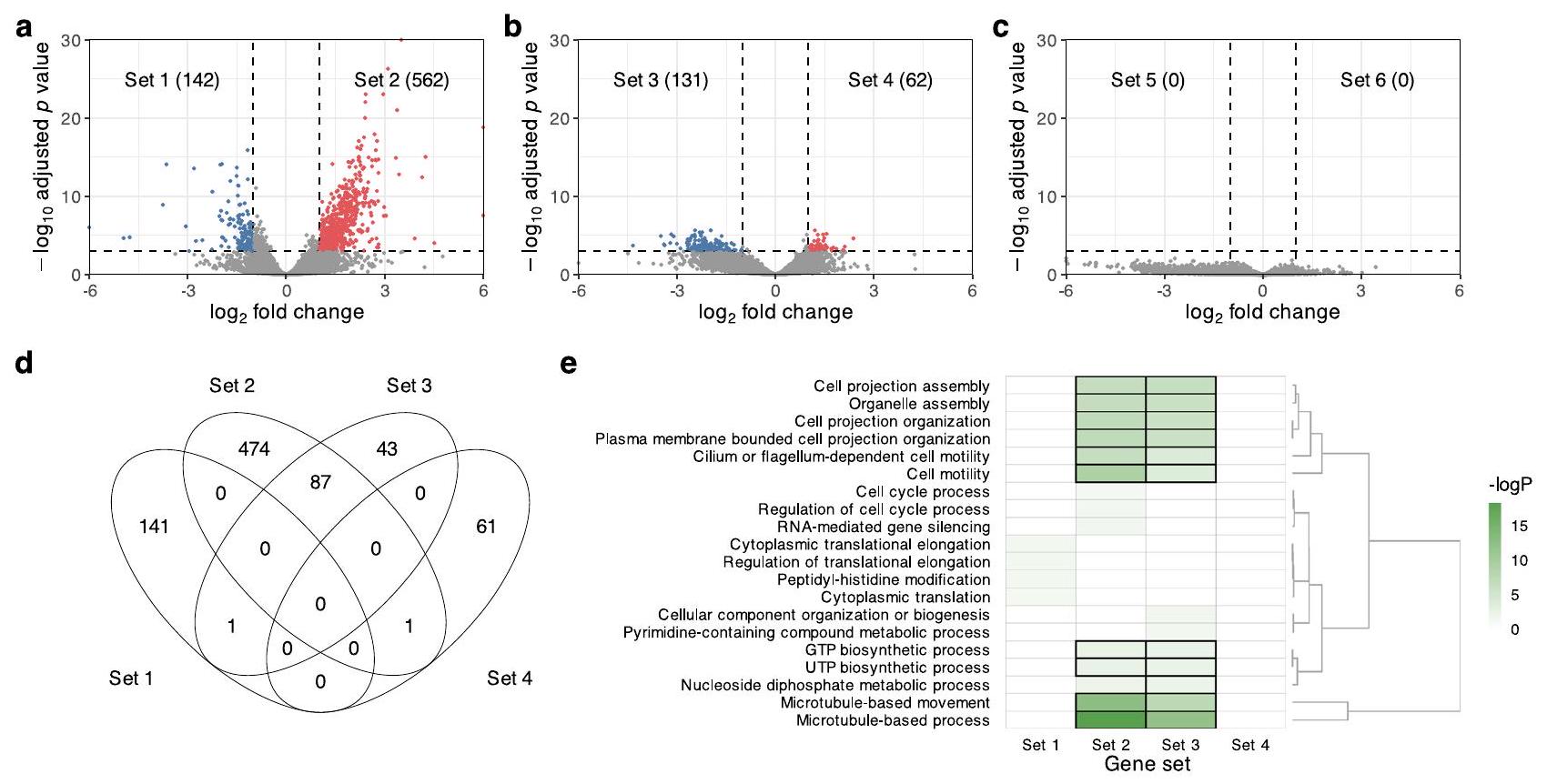

Analysis of transcriptional profiles identified expression difference in microtubule-related genes in TCBZ-S and -R flukes

randomly for all-vs-all pairwise LD calculation (

| Gene ID | Gene symbol | Description |

|

Permutation

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_1006_pilon-augustus-gene-0.3 | S6K | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase | 112.5 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_790_pilon-snap-gene-0.11 | EGFR | Receptor protein-tyrosine kinase | 110.8 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_1058_pilon-snap-gene-0.8 | GALNT | Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase | 96.5 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_259_pilon-snap-gene-0.103 | MPDZ | Multiple PDZ domain protein | 94.1 |

|

| Snap_masked-scaffold10x_1433_pilon-processed-gene-0.1 | CASQ | Calsequestrin | 91.5 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_293_pilon-snap-gene-0.143 | CYPA | Cyclophilin type peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase | 89.5 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_922_pilon-snap-gene-0.56 | KTNA1 | Katanin p60 ATPase-containing subunit A1 | 87.7 |

|

| Snap_masked-scaffold10x_1189_pilon-processed-gene-0.81 | SIK3 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase SIK3 | 87.3 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_82_pilon-snap-gene-0.73 | DNAH | Dynein axonemal heavy chain | 85.2 |

|

treatment concentrations (see Methods for details on the experimental approach, including snail and rabbit infections). The statistical significance of the pairwise differential expressions was calculated by the negative binomial test-based algorithm

modulating microtubule dynamics

deemed to have significantly increased (red) or decreased (blue) expression and were grouped based on expression patterns (Set 1 through 6, with gene counts in parentheses). d Distribution of differentially expressed genes across Sets 1 through 4. e Overrepresented biological process Gene Ontology (GO) terms of the differentially expressed genes. GO terms with an FDR-adjusted

downregulated genes were significantly enriched for microtubulebased processes (GO: 0007017,

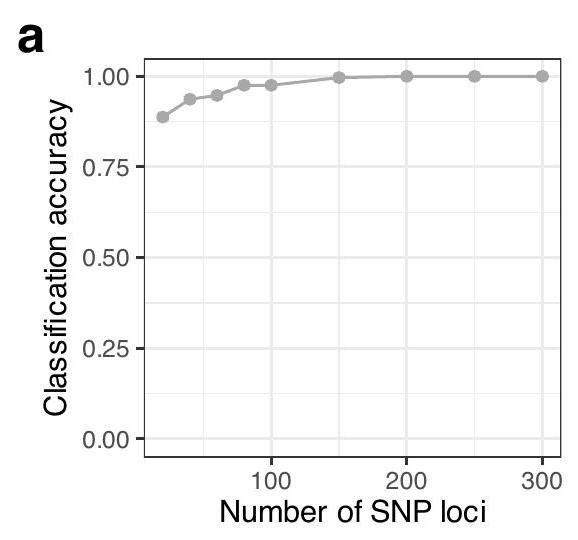

Differentiating TCBZ-S and -R parasites is possible using a limited number of informative SNPs

other (

| Table 2 | Genes of interest that are differentially expressed between triclabendazole-sensitive and -resistant Fasciola hepatica without and in response to triclabendazole treatment | |||||||||

| Gene ID | Description | Untreated | Log2 FC | FDRadjusted

|

TCBZ-S |

|

FDRadjusted

|

||

| Higher in TCBZ-R | Lower in TCBZ-R | Higher with TCBZ treatment | Lower with TCBZ treatment | ||||||

| Maker-scaffold10x_1074_pilon-snap-gene-0.107 | Alpha-tubulin | Y | – | 2.30 |

|

– | – | -1.11 | 0.049 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_13_pilon-snap-gene-2.125 | Alpha-tubulin | Y | – | 2.14 |

|

– | Y | -2.47 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_13_pilon-snap-gene-2.129 | Alpha-tubulin | Y | – | 1.94 |

|

– | Y | -2.08 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_1444_pilon-snap-gene-0.40 | Alpha-tubulin | Y | – | 1.17 |

|

– | – | -1.42 | 0.017 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_45_pilon-snap-gene-0.45 | Alpha-tubulin | Y | – | 1.74 |

|

– | Y | -2.31 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_592_pilon-snap-gene-0.21 | Alpha-tubulin | Y | – | 1.87 |

|

– | – | -1.51 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_680_pilon-snap-gene-0.21 | Alpha-tubulin | Y | – | 1.30 |

|

– | – | -0.99 | 0.12 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_809_pilon-snap-gene-0.10 | Alpha-tubulin | Y | – | 1.69 |

|

– | – | -1.78 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_944_pilon-snap-gene-0.44 | Alpha-tubulin | Y | – | 2.40 |

|

– | – | -1.28 | 0.036 |

| Snap_masked-scaffold10x_1189_pilon-processed-gene-0.77 | Alpha-tubulin | Y | – | 2.36 |

|

– | – | -3.25 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_1708_pilon-snap-gene-0.5 | Cytosolic carboxypeptidas × 10-like protein 5 | Y | – | 1.26 |

|

– | – | -0.86 | 0.13 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_1084_pilon-snap-gene-0.149 | Delta-tubulin | – | – | 0.24 | 0.79 | – | Y | -2.90 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_486_pilon-snap-gene-0.86 | EB1 C-terminal domain-containing protein | Y | – | 2.77 |

|

– | Y | -1.94 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_44_pilon-snap-gene-0.4 | EGF-like domain-containing protein | Y | – | 2.77 |

|

– | – | -1.53 | 0.16 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_157_pilon-snap-gene-0.185 | EGF-like domain-containing protein | Y | – | 2.37 |

|

– | – | -1.74 | 0.046 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_157_pilon-snap-gene-0.196 | EGF-like domain-containing protein | Y | – | 1.94 |

|

– | – | -2.04 | 0.035 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_206_pilon-snap-gene-0.64 | IQ motif, EF-hand binding site | Y | – | 3.50 |

|

– | – | -0.99 | 0.13 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_1309_pilon-snap-gene-0.85 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase | – | – | 0.51 | 0.24 | Y | – | 1.20 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_559_pilon-snap-gene-0.27 | Tubulin monoglycylase | Y | – | 1.63 |

|

– | – | 0.16 | 0.87 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_61_pilon-snap-gene-0.52 | Tubulin polyglutamylase | Y | – | 1.76 |

|

– | – | -1.30 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_234_pilon-augustus-gene-0.64 | Tubulin polyglutamylase | Y | – | 1.22 |

|

– | – | 0.37 | 0.57 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_242_pilon-snap-gene-0.27 | Tubulin polyglutamylase | Y | – | 1.44 |

|

– | – | -0.86 | 0.23 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_383_pilon-snap-gene-1.0 | Tubulin polyglutamylase | Y | – | 1.65 |

|

– | – | -0.92 | 0.19 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_483_pilon-snap-gene-0.117 | Tubulin polyglutamylase | Y | – | 1.51 |

|

– | – | -0.22 | 0.69 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_908_pilon-snap-gene-1.169 | Tubulin polyglutamylase | Y | – | 1.60 |

|

– | – | -0.87 | 0.18 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_1306_pilon-snap-gene-0.14 | Tubulin polyglutamylase | Y | – | 1.74 |

|

– | – | -2.06 | 0.065 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_2067_pilon-augustus-gene-0.6 | Tubulin polyglutamylase | Y | – | 1.57 |

|

– | – | -1.11 | 0.032 |

| Maker-scaffold10x_66_pilon-snap-gene-0.15 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase | Y | – | 1.07 |

|

Y | – | 1.56 |

|

| Maker-scaffold10x_73_pilon-snap-gene-0.14 | Vasohibin-like protein | Y | – | 2.07 |

|

– | Y | -2.70 |

|

hepatica based on SNP profiles. Group classification by Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components (DAPC). a The top 300 SNPs, exhibiting significant betweengroup allele frequency differences and not in strong linkage disequilibrium with each other, were used to classify 91 TCBZ-S and 194 TCBZ-R WGS samples.

b

rate (1-specificity) at different classification thresholds (Fig. 4b). The area under the ROC curve (AUC), which provides an aggregate measure of performance across all possible classification thresholds, was 0.86 (non-parametric stratified bootstrapping

Discussion

exposure to high-concentration TCBZ (

indicative of differences in organ development or function between TCBZ-S and -R flukes. Further histological studies or single-cell RNA sequencing analysis could provide additional information to support this interpretation. Another critical consideration when comparing the transcriptomes of untreated TCBZ-S and TCBZ-R flukes is the potential influence of genetic background variation. Differences in genetic background, unrelated to the resistance phenotype, could confound the transcriptional differences observed between TCBZ-S and TCBZ-R flukes. To address this, conducting experiments with additional flukes from a range of genetic backgrounds will be essential for pinpointing transcriptional differences that are specifically associated with the resistance phenotype.

determined due to an extended LD among the genes located on the locus. ARF4 has been shown to interact with EGFR, mediating the activation of phospholipase D2

Methods

Parasite procurement and whole-genome sequencing

Genome-wide variant and selection scan analyses

variants (SNPs) were called using GATK v4.2.2

Generation of TCBZ-S and -R metacercariae

the inside of the plastic bag from the same snail cohort and known TCBZ susceptibility were collected and kept in water at

Generation of TCBZ-S and -R adult

Triclabendazole exposure experiments and RNA-seq transcriptional profiling

Amplicon panel design and targeted sequencing (amplicon-seq)

exclude clonemates and closely related individuals among the amplicon-seq samples, PLINK v1.9

Discriminating TCBZ sensitivity phenotype using a panel of SNP markers

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Furst, T., Duthaler, U., Sripa, B., Utzinger, J. & Keiser, J. Trematode infections: liver and lung flukes. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 26, 399-419 (2012).

- Caravedo, M. A. & Cabada, M. M. Human fascioliasis: current epidemiological status and strategies for diagnosis, treatment, and control. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 11, 149-158 (2020).

- Charlier, J. et al. Initial assessment of the economic burden of major parasitic helminth infections to the ruminant livestock industry in Europe. Prev. Vet. Med. 182, 105103 (2020).

- Mehmood, K. et al. A review on epidemiology, global prevalence and economical losses of fasciolosis in ruminants. Micro. Pathog. 109, 253-262 (2017).

- Sanchez-Vazquez, M. J. & Lewis, F. I. Investigating the impact of fasciolosis on cattle carcase performance. Vet. Parasitol. 193, 307-311 (2013).

- Arenal, A. et al. Risk factors for the presence of Fasciola hepatica antibodies in bulk-milk samples and their association with milk production decreases, in Cuban dairy cattle. BMC Vet. Res. 14, 336 (2018).

- Schweizer, G., Braun, U., Deplazes, P. & Torgerson, P. R. Estimating the financial losses due to bovine fasciolosis in Switzerland. Vet. Rec. 157, 188-193 (2005).

- Lopez, M., White, A. C. Jr. & Cabada, M. M. Burden of Fasciola hepatica Infection among children from Paucartambo in Cusco, Peru. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 86, 481-485 (2012).

- Marcos, L. A. et al. Report of cases of human fascioliosis in the Specialized Children’s Health Institute, Lima, Peru (1988′-2003). Rev. Gastroenterol. Peru. 25, 198-205 (2005).

- Yentur Doni, N., Yildiz Zeyrek, F., Simsek, Z., Gurses, G. & Sahin, I. Risk factors and relationship between intestinal parasites and the growth retardation and psychomotor development delays of children in Sanliurfa, Turkey. Turkiye Parazitol. Derg. 39, 270-276 (2015).

- Chang Wong, M. R., Pinto Elera, J. O., Guzman Rojas, P., Terashima Iwashita, A. & Samalvides Cuba, F. Demographic and clinical aspects of hepatic fascioliasis between 2013-2010 in National Hospital Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru. Rev. Gastroenterol. Peru. 36, 23-28 (2016).

- Machicado, C., Machicado, J. D., Maco, V., Terashima, A. & Marcos, L. A. Association of fasciola hepatica infection with liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and cancer: a systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 10, e0004962 (2016).

- Castro-Hermida, J. A., Gonzalez-Warleta, M., Martinez-Sernandez, V., Ubeira, F. M. & Mezo, M. Current challenges for fasciolicide treatment in ruminant livestock. Trends Parasitol. 37, 430-444 (2021).

- Kelley, J. M. et al. Current threat of triclabendazole resistance in Fasciola hepatica. Trends Parasitol. 32, 458-469 (2016).

- Gandhi, P. et al. Triclabendazole in the treatment of human fascioliasis: a review. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 113, 797-804 (2019).

- Kamaludeen, J. et al. Lack of efficacy of triclabendazole against Fasciola hepatica is present on sheep farms in three regions of England, and Wales. Vet. Rec. 184, 502 (2019).

- Rose Vineer, H. et al. Increasing importance of anthelmintic resistance in European livestock: creation and meta-analysis of an open database. Parasite 27, 69 (2020).

- Olaechea, F., Lovera, V., Larroza, M., Raffo, F. & Cabrera, R. Resistance of Fasciola hepatica against triclabendazole in cattle in Patagonia (Argentina). Vet. Parasitol. 178, 364-366 (2011).

- Winkelhagen, A. J., Mank, T., de Vries, P. J. & Soetekouw, R. Apparent triclabendazole-resistant human Fasciola hepatica infection, the Netherlands. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18, 1028-1029 (2012).

- Gil, L. C. et al. Resistant human fasciolasis: report of four patients. Rev. Med. Chil. 142, 1330-1333 (2014).

- Belgin, G. et al. Partial Hepatectomy for the Resistant Fasciola hepatica Infection in a Child. APSP J. Case Rep. 6, 27 (2015).

- Cabada, M. M. et al. Treatment failure after multiple courses of triclabendazole among patients with fascioliasis in cusco, peru: a case series. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0004361 (2016).

- Branco, E. A., Ruas, R., Nuak, J. & Sarmento, A. Treatment failure after multiple courses of triclabendazole in a Portuguese patient

with fascioliasis. BMJ Case Rep. 13, https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2019-232299 (2020). - Morales, M. L. et al. Triclabendazole treatment failure for Fasciola hepatica Infection among preschool and school-age children, cusco, peru(1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 1850-1857 (2021).

- Maco, V. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of two single-day regimens of triclabendazole for fascioliasis in Peruvian children. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 48, 445-453 (2015).

- Meaney, M. et al. Increased susceptibility of a triclabendazole (TCBZ)-resistant isolate of Fasciola hepatica to TCBZ following coincubation in vitro with the P-glycoprotein inhibitor, R(+)-verapamil. Parasitology 140, 1287-1303 (2013).

- Robinson, M. W., Lawson, J., Trudgett, A., Hoey, E. M. & Fairweather, I. The comparative metabolism of triclabendazole sulphoxide by triclabendazole-susceptible and triclabendazoleresistant Fasciola hepatica. Parasitol. Res. 92, 205-210 (2004).

- Alvarez, L. I. et al. Altered drug influx/efflux and enhanced metabolic activity in triclabendazole-resistant liver flukes. Parasitology 131, 501-510 (2005).

- Scarcella, S., Lamenza, P., Virkel, G. & Solana, H. Expression differential of microsomal and cytosolic glutathione-S-transferases in Fasciola hepatica resistant at triclabendazole. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 181, 37-39 (2012).

- Wilkinson, R. et al. An amino acid substitution in Fasciola hepatica P-glycoprotein from triclabendazole-resistant and triclabendazole-susceptible populations. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 186, 69-72 (2012).

- Elliott, T. P. & Spithill, T. W. The T687G SNP in a P-glycoprotein gene of Fasciola hepatica is not associated with resistance to triclabendazole in two resistant Australian populations. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 198, 45-47 (2014).

- Solana, M. V. et al. Different SNPs in Fasciola hepatica P-glycoprotein from diverse Latin American populations are not associated with Triclabendazole resistance. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 224, 57-60 (2018).

- Radio, S. et al. Pleiotropic alterations in gene expression in Latin American Fasciola hepatica isolates with different susceptibility to drugs. Parasit. Vectors 11, 56 (2018).

- Beesley, N. J. et al. A major locus confers triclabendazole resistance in Fasciola hepatica and shows dominant inheritance. PLoS Pathog. 19, e1011081 (2023).

- Fernandez-Baca, M. V. et al. The differences in the susceptibility patterns to triclabendazole sulfoxide in field isolates of Fasciola hepatica are associated with geographic, seasonal, and morphometric variations. Pathogens 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/ pathogens11060625 (2022).

- Choi, Y. J. et al. Adaptive radiation of the flukes of the family fasciolidae inferred from genome-wide comparisons of key species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 84-99 (2020).

- Cwiklinski, K. et al. The Fasciola hepatica genome: gene duplication and polymorphism reveals adaptation to the host environment and the capacity for rapid evolution. Genome Biol. 16, 71 (2015).

- McNulty, S. N. et al. Genomes of Fasciola hepatica from the Americas reveal colonization with neorickettsia endobacteria related to the agents of Potomac horse and human sennetsu fevers. PLoS Genet 13, e1006537 (2017).

- Morris, G. P. et al. Population genomic and genome-wide association studies of agroclimatic traits in sorghum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 453-458 (2013).

- Mather, K. A. et al. The extent of linkage disequilibrium in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genetics 177, 2223-2232 (2007).

- Charlesworth, D. Effects of inbreeding on the genetic diversity of populations. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 358, 1051-1070 (2003).

- Beissinger, T. M., Rosa, G. J., Kaeppler, S. M., Gianola, D. & de Leon, N. Defining window-boundaries for genomic analyses using smoothing spline techniques. Genet Sel. Evol. 47, 30 (2015).

- Fernandez, V. et al. A single amino acid substitution in isozyme GST mu in Triclabendazole resistant Fasciola hepatica (Sligo strain) can substantially influence the manifestation of anthelmintic resistance. Exp. Parasitol. 159, 274-279 (2015).

- Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106 (2010).

- Falcon, S. & Gentleman, R. Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics 23, 257-258 (2007).

- Nieuwenhuis, J. et al. Vasohibins encode tubulin detyrosinating activity. Science 358, 1453-1456 (2017).

- Vitre, B. et al. EB1 regulates microtubule dynamics and tubulin sheet closure in vitro. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 415-421 (2008).

- Redeker, V. et al. Polyglycylation of tubulin: a posttranslational modification in axonemal microtubules. Science 266, 1688-1691 (1994).

- Thines, L., Roushar, F. J., Hedman, A. C. & Sacks, D. B. The IQGAP scaffolds: critical nodes bridging receptor activation to cellular signaling. J. Cell Biol. 222, https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb. 202205062 (2023).

- Canovas, B. & Nebreda, A. R. Diversity and versatility of p38 kinase signalling in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 346-366 (2021).

- Gasic, I., Boswell, S. A. & Mitchison, T. J. Tubulin mRNA stability is sensitive to change in microtubule dynamics caused by multiple physiological and toxic cues. PLoS Biol. 17, e3000225 (2019).

- Wendt, G. et al. A single-cell RNA-seq atlas of Schistosoma mansoni identifies a key regulator of blood feeding. Science 369, 1644-1649 (2020).

- Ndiaye, P. I., Miquel, J., Fons, R. A. & Marchand, B. Spermiogenesis and sperm ultrastructure of the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica L., 1758 (Digenea, Fasciolidae): transmission and scanning electron microscopy, and tubulin immunocytochemistry. Acta Parasitol. 48, 182-194 (2003).

- Pantelouris, E. M. & Threadgold, L. T. The excretory system of the adult Fasciola hepatica L. Cellule 64, 61-67 (1963).

- Jombart, T., Devillard, S. & Balloux, F. Discriminant analysis of principal components: a new method for the analysis of genetically structured populations. BMC Genet. 11, 94 (2010).

- Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R. N. 2, 18-22 (2002).

- Fairweather, I., Brennan, G. P., Hanna, R. E. B., Robinson, M. W. & Skuce, P. J. Drug resistance in liver flukes. Int J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist 12, 39-59 (2020).

- Hac, A., Pierzynowska, K. & Herman-Antosiewicz, A. S6K1 is indispensible for stress-induced microtubule acetylation and autophagic flux. Cells 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/ cells10040929 (2021).

- Eshun-Wilson, L. et al. Effects of alpha-tubulin acetylation on microtubule structure and stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 10366-10371 (2019).

- LeDizet, M. & Piperno, G. Cytoplasmic microtubules containing acetylated alpha-tubulin in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: spatial arrangement and properties. J. Cell Biol. 103, 13-22 (1986).

- Wattanathamsan, O. et al. Tubulin acetylation enhances lung cancer resistance to paclitaxel-induced cell death through Mcl-1 stabilization. Cell Death Discov. 7, 67 (2021).

- Sfakianos, A. P. et al. The mTOR-S6 kinase pathway promotes stress granule assembly. Cell Death Differ. 25, 1766-1780 (2018).

- Csukasi, F. et al. The PTH/PTHrP-SIK3 pathway affects skeletogenesis through altered mTOR signaling. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aat9356 (2018).

- Beaman, E. M., Carter, D. R. F. & Brooks, S. A. GALNTs: master regulators of metastasis-associated epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)? Glycobiology 32, 556-579 (2022).

- Han, J. M. & Jung, H. J. Cyclophilin A/CD147 interaction: a promising target for anticancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, https:// doi.org/10.3390/ijms23169341 (2022).

- Ma, Z. et al. Cyclophilin A inhibits A549 cell oxidative stress and apoptosis by modulating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Biosci. Rep. 41, https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20203219 (2021).

- Franke, T. F., Hornik, C. P., Segev, L., Shostak, G. A. & Sugimoto, C. PI3K/Akt and apoptosis: size matters. Oncogene 22, 8983-8998 (2003).

- Chemale, G. et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of triclabendazole response in the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica. J. Proteome Res. 9, 4940-4951 (2010).

- Lemmon, M. A. & Schlessinger, J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 141, 1117-1134 (2010).

- Cwiklinski, K., Robinson, M. W., Donnelly, S. & Dalton, J. P. Complementary transcriptomic and proteomic analyses reveal the cellular and molecular processes that drive growth and development of Fasciola hepatica in the host liver. BMC Genomics 22, 46 (2021).

- Walker, S. M. et al. Stage-specific differences in fecundity over the life-cycle of two characterized isolates of the liver fluke, Fasciola hepatica. Parasitology 133, 209-216 (2006).

- Brennan, G. P. et al. Understanding triclabendazole resistance. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 82, 104-109 (2007).

- Kuo, Y. W. & Howard, J. Cutting, amplifying, and aligning microtubules with severing enzymes. Trends Cell Biol. 31, 50-61 (2021).

- Olivares-Ferretti, P., Beltran, J. F., Salazar, L. A. & Fonseca-Salamanca, F. Protein modelling and molecular docking analysis of Fasciola hepatica beta-tubulin’s interaction sites, with triclabendazole, triclabendazole sulphoxide and triclabendazole sulphone. Acta Parasitol. 68, 535-547 (2023).

- Robinson, M. W., McFerran, N., Trudgett, A., Hoey, L. & Fairweather, I. A possible model of benzimidazole binding to betatubulin disclosed by invoking an inter-domain movement. J. Mol. Graph Model 23, 275-284 (2004).

- Bennett, J. L. & Kohler, P. Fasciola hepatica: action in vitro of triclabendazole on immature and adult stages. Exp. Parasitol. 63, 49-57 (1987).

- Hanna, R. Fasciola hepatica: histology of the reproductive organs and differential effects of triclabendazole on drug-sensitive and drug-resistant fluke isolates and on flukes from selected field cases. Pathogens 4, 431-456 (2015).

- Akhmanova, A. et al. Clasps are CLIP-115 and -170 associating proteins involved in the regional regulation of microtubule dynamics in motile fibroblasts. Cell 104, 923-935 (2001).

- Isakoff, S. J. et al. Breast cancer-associated PIK3CA mutations are oncogenic in mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 65, 10992-11000 (2005).

- Ralph, P. & Coop, G. Parallel adaptation: one or many waves of advance of an advantageous allele? Genetics 186, 647-668 (2010).

- Overend, D. J. & Bowen, F. L. Resistance of Fasciola hepatica to triclabendazole. Aust. Vet. J. 72, 275-276 (1995).

- Redman, E. et al. The emergence of resistance to the benzimidazole anthlemintics in parasitic nematodes of livestock is characterised by multiple independent hard and soft selective sweeps. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 9, e0003494 (2015).

- Kim, S. W. et al. ADP-ribosylation factor 4 small GTPase mediates epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent phospholipase D2 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2661-2668 (2003).

- Wesolowski, J. et al. Chlamydia Hijacks ARF GTPases to coordinate microtubule posttranslational modifications and golgi complex positioning. mBio 8, e02280-16 (2017).

- Woo, I. S. et al. Identification of ADP-ribosylation factor 4 as a suppressor of N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide-induced cell death. Cancer Lett. 276, 53-60 (2009).

- Khanna, A. et al. The small GTPases Ras and Rap1 bind to and control TORC2 activity. Sci. Rep. 6, 25823 (2016).

- Kortholt, A. et al. A Rap/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway controls pseudopod formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 936-945 (2010).

- Cahill, M. E. et al. Bidirectional synaptic structural plasticity after chronic cocaine administration occurs through Rap1 Small GTPase signaling. Neuron 89, 566-582 (2016).

- Brecht, K. et al. Exogenous iron increases fasciocidal activity and hepatocellular toxicity of the synthetic endoperoxides OZ78 and MT04. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijms20194880 (2019).

- Duthaler, U., Smith, T. A. & Keiser, J. In vivo and in vitro sensitivity of Fasciola hepatica to triclabendazole combined with artesunate, artemether, or OZ78. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4596-4604 (2010).

- Sambrook, J. & Russell, D. W. Purification of nucleic acids by extraction with phenol:chloroform. CSH Protoc. 2006, pdb.prot4455 (2006).

- Tran, L., Toet, H. & Beddoe, T. Environmental detection of Fasciola hepatica by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. PeerJ 10, e13778 (2022).

- Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114-2120 (2014).

- Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754-1760 (2009).

- McKenna, A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297-1303 (2010).

- Van der Auwera, G. A. et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma. 43, 11.10.1-11.10.33 (2013).

- Cingolani, P. et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 6, 80-92 (2012).

- Wang, X. et al. CNVcaller: highly efficient and widely applicable software for detecting copy number variations in large populations. Gigascience 6, 1-12 (2017).

- Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet 81, 559-575 (2007).

- Manichaikul, A. et al. Robust relationship inference in genomewide association studies. Bioinformatics 26, 2867-2873 (2010).

- Arthur, R., Schulz-Trieglaff, O., Cox, A. J. & O’Connell, J. AKT: ancestry and kinship toolkit. Bioinformatics 33, 142-144 (2017).

- Zhang, C., Dong, S. S., Xu, J. Y., He, W. M. & Yang, T. L. PopLDdecay: a fast and effective tool for linkage disequilibrium decay analysis based on variant call format files. Bioinformatics 35, 1786-1788 (2019).

- Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236-1240 (2014).

- Gene Ontology, C. The gene ontology resource: enriching a GOId mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D325-D334 (2021).

- Blum, M. et al. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D344-D354 (2021).

- Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 726-731 (2016).

- Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG: integrating viruses and cellular organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D545-D551 (2021).

- Toronen, P. & Holm, L. PANNZER-A practical tool for protein function prediction. Protein Sci. 31, 118-128 (2022).

- Casimiro-Soriguer, C. S., Munoz-Merida, A. & Perez-Pulido, A. J. Sma3s: A universal tool for easy functional annotation of proteomes and transcriptomes. Proteomics 17, https://doi.org/10. 1002/pmic. 201700071 (2017).

- Hernandez-Plaza, A. et al. eggNOG 6.0: enabling comparative genomics across 12535 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D389-D394 (2023).

- Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D638-D646 (2023).

- Fairweather, I. et al. Development of an egg hatch assay for the diagnosis of triclabendazole resistance in Fasciola hepatica: proof of concept. Vet. Parasitol. 183, 249-259 (2012).

- Robles-Perez, D., Martinez-Perez, J. M., Rojo-Vazquez, F. A. & Martinez-Valladares, M. Screening anthelmintic resistance to triclabendazole in Fasciola hepatica isolated from sheep by means of an egg hatch assay. BMC Vet. Res. 11, 226 (2015).

- Jarujareet, W., Taira, K. & Ooi, H. K. Dynamics of liver enzymes in rabbits experimentally infected with Fasciola sp. (Intermediate form from Japan). J. Vet. Med. Sci. 80, 36-40 (2018).

- Kandil, O. M. et al. Anthelmintic efficacy of Moringa oleifera seed methanolic extract against Fasciola hepatica. J. Parasit. Dis. 42, 391-401 (2018).

- Maggioli, G. et al. A recombinant thioredoxin-glutathione reductase from Fasciola hepatica induces a protective response in rabbits. Exp. Parasitol. 129, 323-330 (2011).

- Mooney, L., Good, B., Hanrahan, J. P., Mulcahy, G. & de Waal, T. The comparative efficacy of four anthelmintics against a natural acquired Fasciola hepatica infection in hill sheep flock in the west of Ireland. Vet. Parasitol. 164, 201-205 (2009).

- White, P. RNA extraction from mammalian tissues. Methods Mol. Biol. 362, 315-327 (2007).

- Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graphbased genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907-915 (2019).

- Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. FeatureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923-930 (2014).

- Liao, Y., Wang, J., Jaehnig, E. J., Shi, Z. & Zhang, B. WebGestalt 2019: gene set analysis toolkit with revamped UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W199-W205 (2019).

- Supek, F., Bosnjak, M., Skunca, N. & Smuc, T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS ONE 6, e21800 (2011).

- Smith, G. C., Seaman, S. R., Wood, A. M., Royston, P. & White, I. R. Correcting for optimistic prediction in small data sets. Am. J. Epidemiol. 180, 318-324 (2014).

- Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1-26 (2008).

- Stevenson, M. et al. EpiR: an R package for the analysis of epidemiological data. 1, 9-43 (2013).

- Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinforma. 12, 77 (2011).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

Supplementary information The online version contains

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57796-5.

(c) The Author(s) 2025

- ¹Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA. ²Sede Cusco, Instituto de Medicina Tropical “Alexander von Humboldt”, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Cusco, Peru.

Laboratorio de Inmunología, Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, Cajamarca, Peru. Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, USA. e-mail: micabada@utmb.edu; mmitreva@wustl.edu