DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-024-03739-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39810148

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-14

أطلس التنوع الجيني لسلالات بروسيلة ميلتينسيس من مقاطعة سيتشوان، الصين

الملخص

حمى البروسيلات البشرية هي مرض متجدد في مقاطعة سيتشوان، الصين. في هذه الدراسة، تم تطبيق علم الجراثيم، والتصنيف الحيوي التقليدي، وتحليل تسلسل المواقع المتعددة (MLST)، وتحليل تكرار المواقع المتعددة المتغيرة العدد (MLVA) لتوصيف السلالات بشكل أولي من حيث التنوع الجيني والروابط الوبائية. تم عزل ما مجموعه 101 سلالة من بروسيلة من 16 مدينة (دوائر ذاتية الحكم) من عام 2014 إلى 2021، وتم تحديد جميع السلالات على أنها بروسيلة ميلتينسيس bv. 3، مما يشير إلى أن المراقبة يجب أن تركز على المجترات. حدد تحليل MLST أربعة أنماط (STs)، وهي ST8 (

*المراسلة:

تشيغو ليو

liuzhiguo@icdc.cn

زهنجون لي

lizhenjun@icdc.cn

مقدمة

في الصين، تعتبر الحمى المالطية مرضًا متجددًا انتشر من مناطق المراعي الشمالية إلى المناطق المجاورة من المراعي والزراعة، ثم إلى المناطق الساحلية الجنوبية والجنوبية الغربية. في الوقت الحالي، تم الإبلاغ عن حالات الحمى المالطية البشرية من جميع المقاطعات الـ 31 أو المناطق ذاتية الحكم في البر الرئيسي للصين. بكتيريا ب. ميلتينسيس هي البكتيريا المسببة الرئيسية لتفشي الحمى المالطية في الصين. تقع مقاطعة سيتشوان في داخل جنوب غرب الصين، وتحدها مقاطعات قويتشو، تشينغهاي، قانسو، وشانشي، وتعتبر الحمى المالطية متوطنة في المنطقة. كانت مقاطعة سيتشوان منطقة متوطنة للحمى المالطية من الخمسينيات إلى الثمانينيات؛ وتم السيطرة على المرض في التسعينيات وعاد للظهور في عام 2008. منذ عام 2008، زاد عدد الحالات المبلغ عنها تدريجياً. تم الإبلاغ عن 417 حالة جديدة في عام 2023، وكانت موزعة بين عدة مدن. ومع ذلك، يجب توضيح مستوى التنوع الجيني والروابط الوبائية لبكتيريا البروسيلة المعزولة من مناطق مختلفة وفي أوقات مختلفة. لذلك، تم استخدام تصنيف الأنواع لتحديد الأنواع/الأنماط البيولوجية لسلالات البروسيلة المتداولة، وتم تطبيق طرق تحديد النمط الجيني لتحليل تسلسل المواقع المتعددة (MLST) وتحليل تكرار العدد المتغير لمواقع متعددة (MLVA) للتحقيق في التنوع الجيني والروابط الجزيئية بين السلالات. توفر النتائج قيمة للتخطيط لاستراتيجية السيطرة على الحمى المالطية في مقاطعة سيتشوان.

المواد والأساليب

العزل البكتيري والتصنيف الحيوي

استخراج الحمض النووي وتحديد النمط الجيني لسلالات البروسيلة

التنوع الجيني. تم اختيار تسعة مواقع جينومية لتحديد النمط الجيني باستخدام تقنية MLST بناءً على دراسة سابقة [9]، وهي: gap، aroA، glk، dnaK، gyrB، trpE، cobQ، omp25، وinthyp. تم إجراء تضخيم PCR للمواقع التسعة كما هو موصوف سابقًا [15]. تم تقييم منتجات PCR الإيجابية بواسطة

النتائج

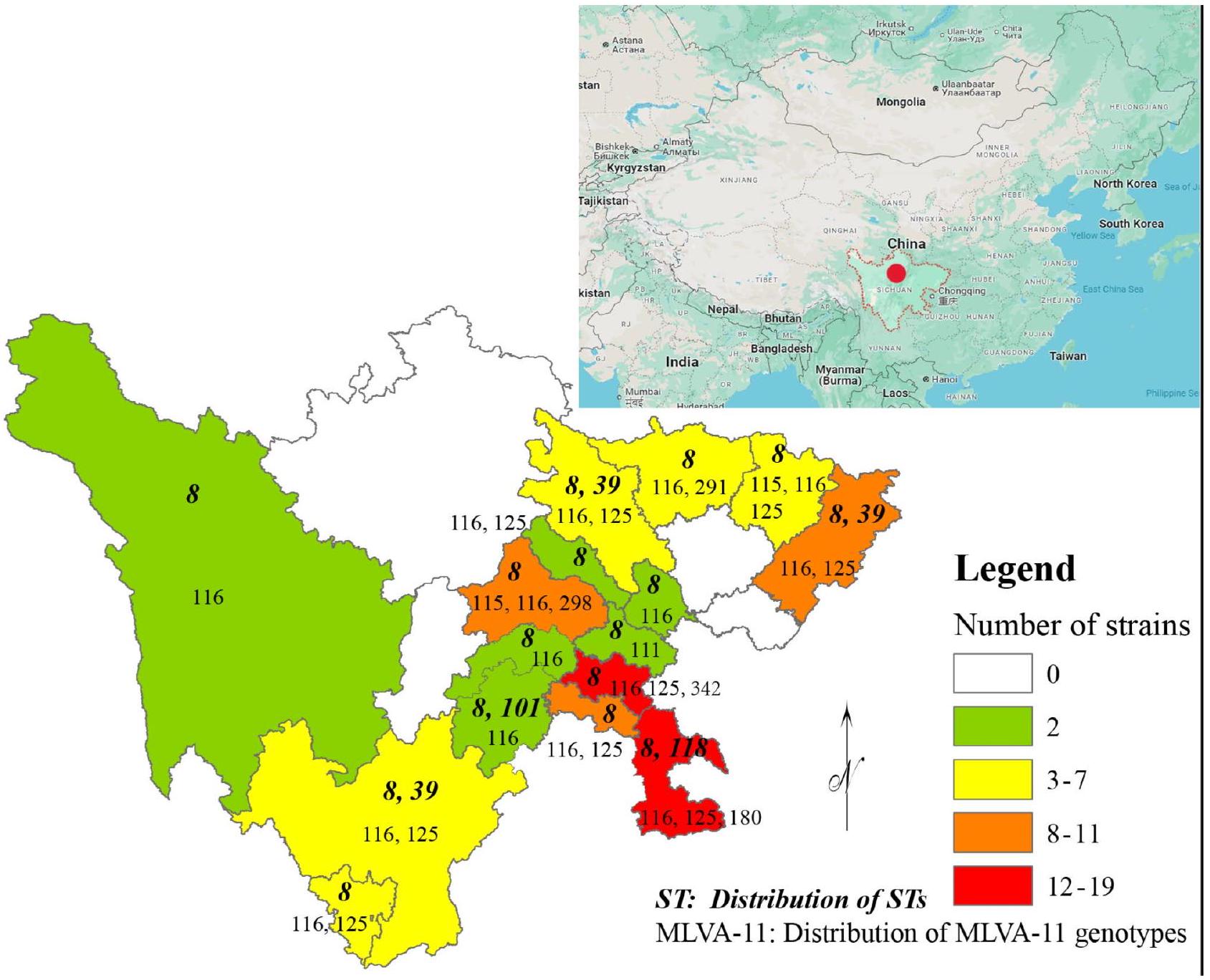

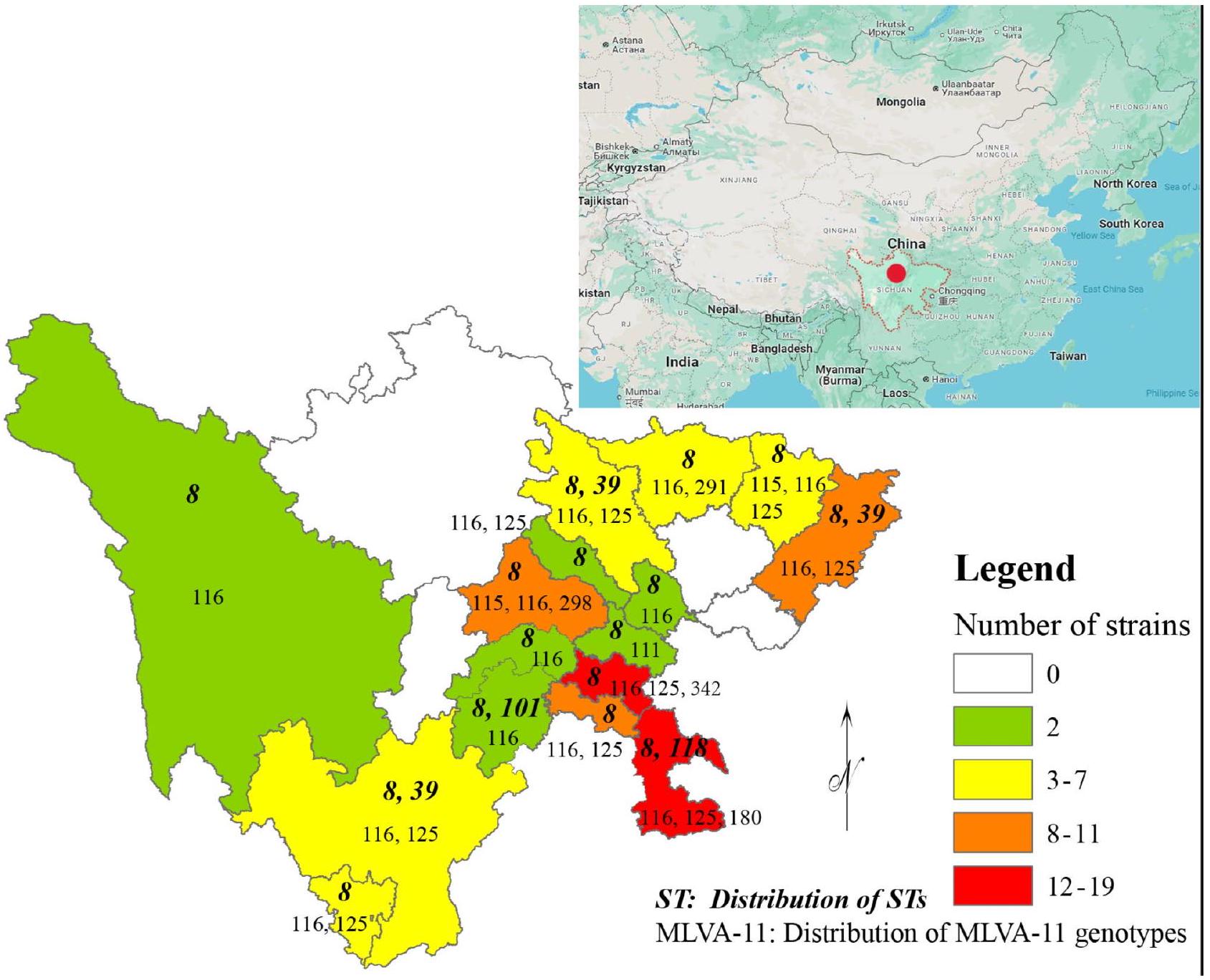

التوزيع الجغرافي والأنواع/الأنماط الحيوية لسلالات بروسيلة

| مدن/منطقة ذاتية الحكم | عدد السلالات | STs | MLVA-8 | MLVA-11 |

| بازهونغ | ٤ | ٨ | ٤٢، ٤٣، ٤٥ | ١١٥، ١١٦، ١٢٥ |

| تشينغدو | 10 | ٨ | 42، 43، 83 | ١١٥، ١١٦، ٢٩٨ |

| دازهو | 9 | 8، 39 | 42,43 | ١١٦، ١٢٥ |

| ديانغ | 2 | ٨ | 42,43 | ١١٦، ١٢٥ |

| غانزي | 1 | ٨ | 42 | 116 |

| قوانغيوان | ٥ | ٨ | 42,114 | ١١٦، ٢٩١ |

| ميانيانغ | ٥ | 8، 39 | 42,43 | ١١٦، ١٢٥ |

| ليشان | ٢ | 8,101 | 42 | ١١٦ |

| ليانغشان | ٧ | 8، 39 | 42,43 | ١١٦، ١٢٥ |

| لوزهو | 19 | ٨,١١٨ | 42,43 | ١١٦، ١٢٥، ١٨٠ |

| ميشان | 2 | ٨ | 42 | 116 |

| نيجيانغ | 17 | ٨ | ٤٢،٤٣ | ١١٦، ١٢٥، ٣٤٢ |

| بانزهيوا | ٤ | ٨ | ٤٢،٤٣ | ١١٦، ١٢٥ |

| سوينينغ | 2 | ٨ | 42 | 116 |

| زيغونغ | 11 | ٨ | ٤٢،٤٣ | ١١٦، ١٢٥ |

| زيانغ | 1 | ٨ | 63 | 111 |

ملفات تنوع VNTR والأليلات

وأن ظهور أنواع جديدة من الفيروسات يوضح الحاجة إلى المراقبة النشطة.

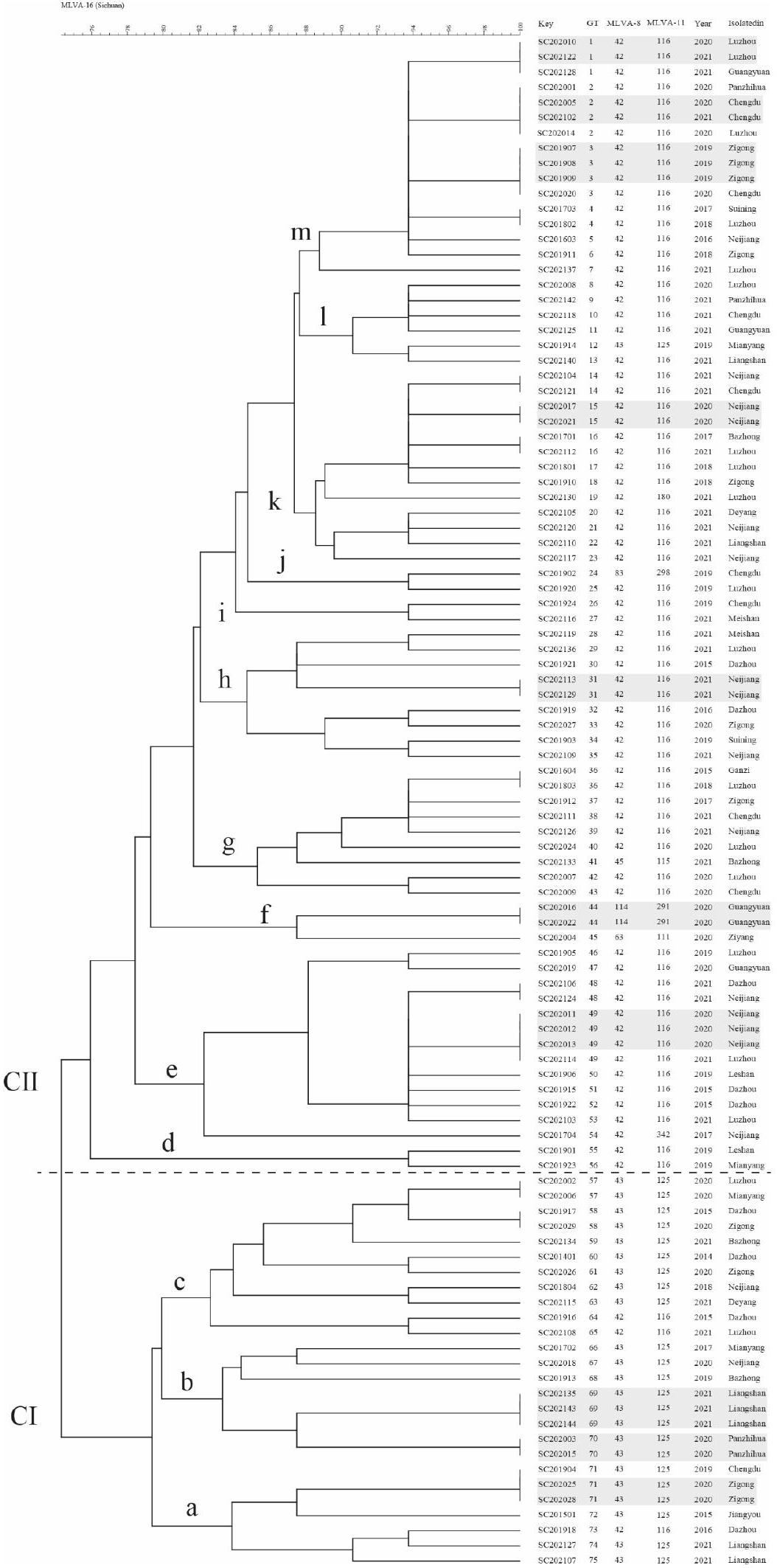

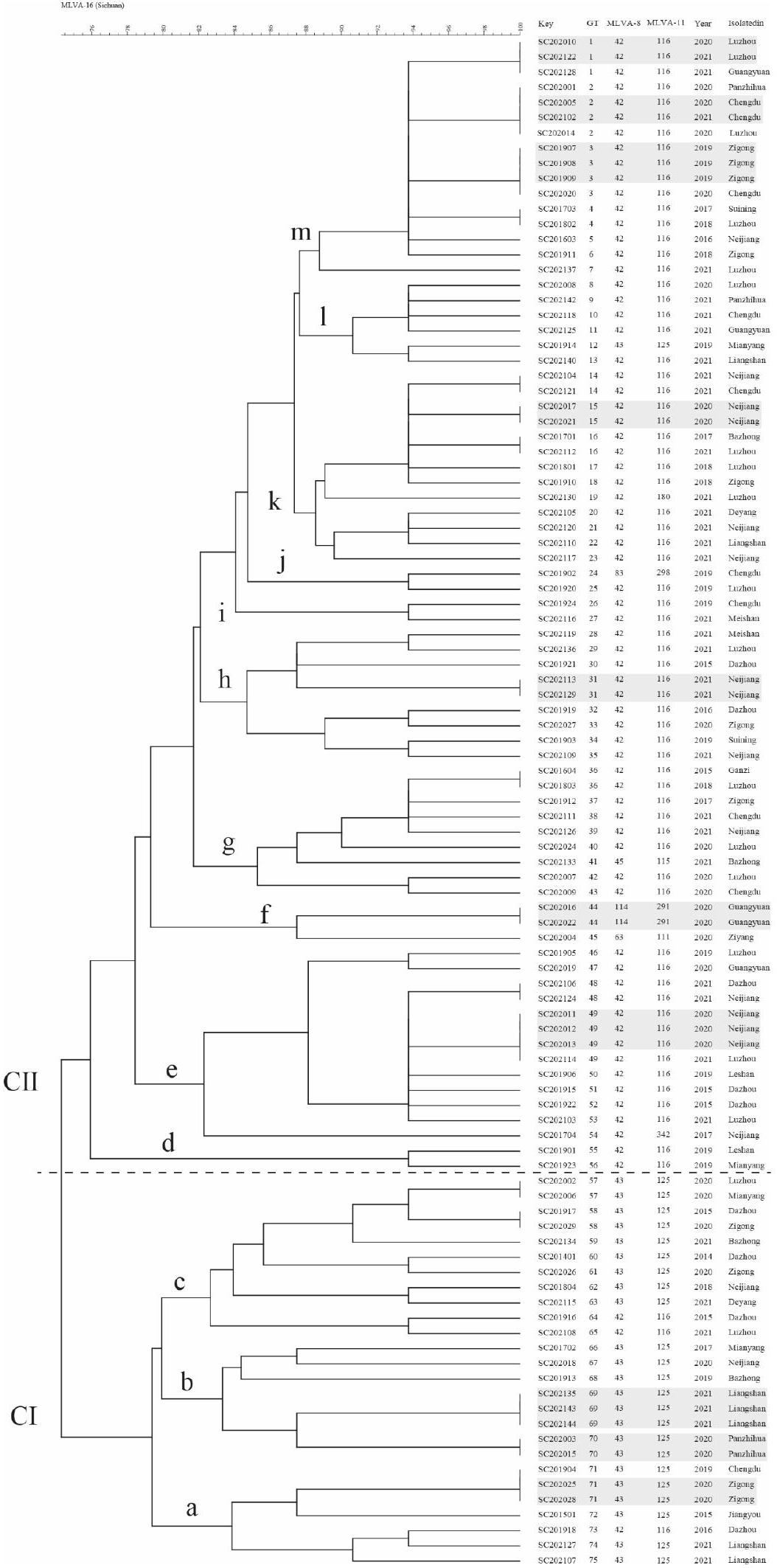

خصائص تحديد النمط الجيني MLVA لـ 101 سلالة من ب. ميلتينسيس

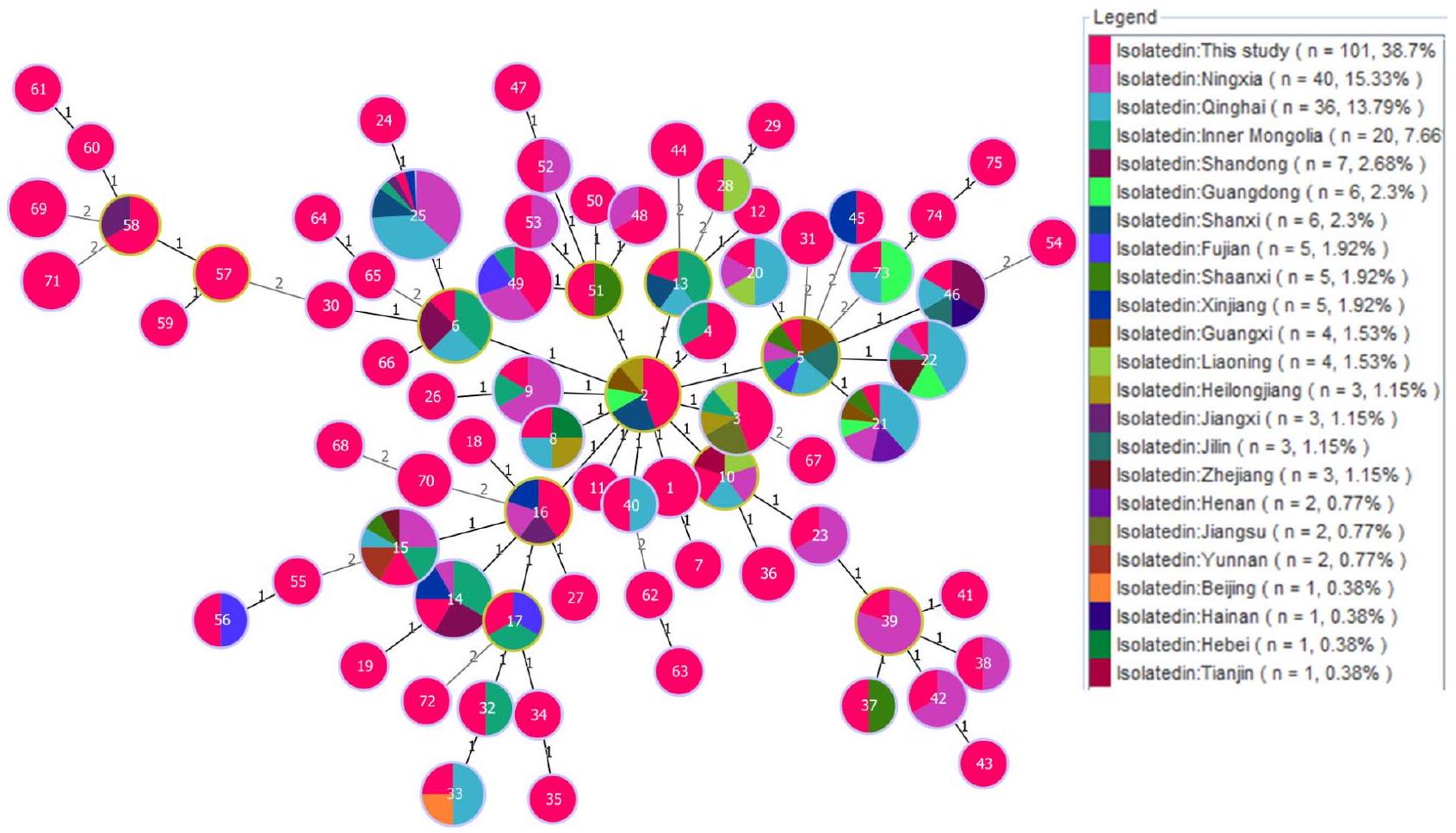

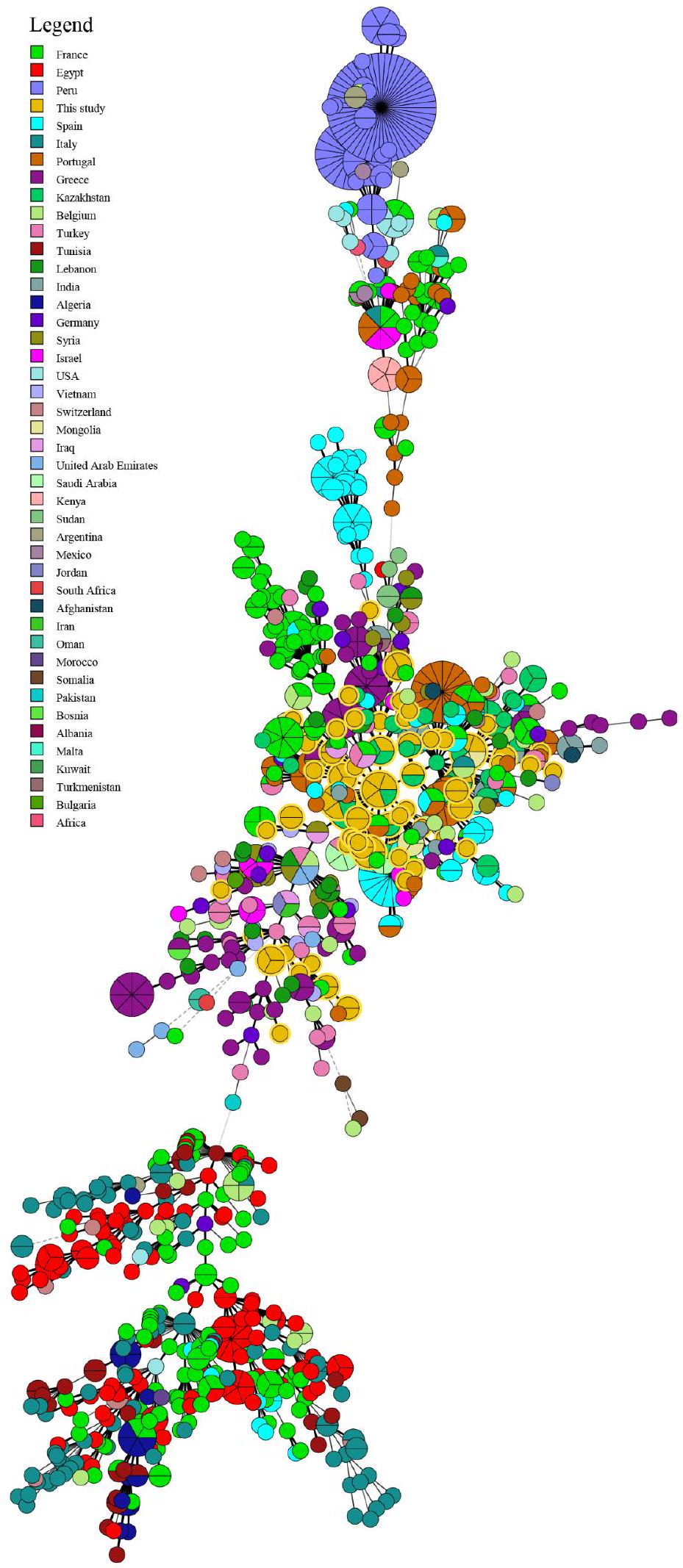

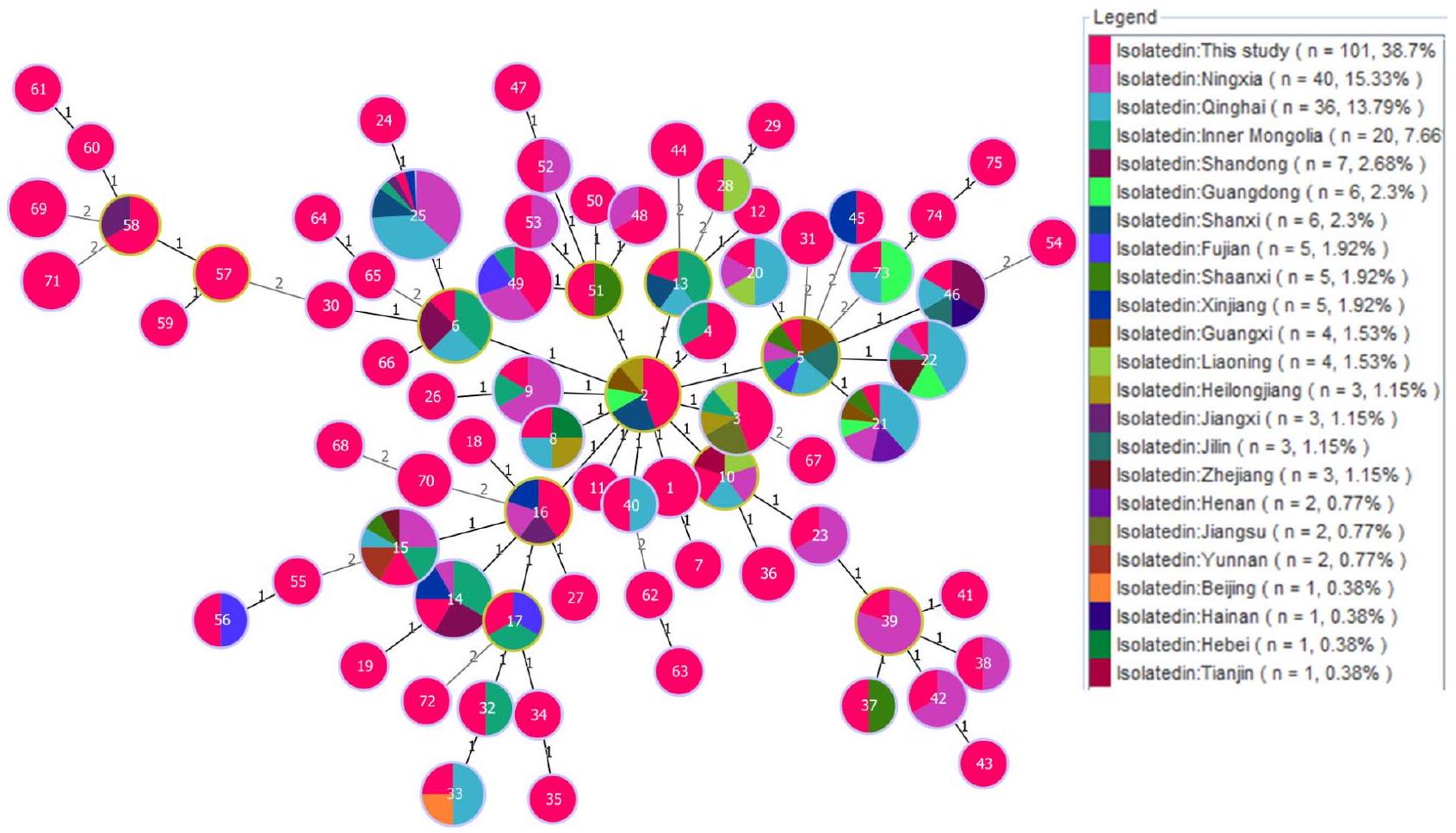

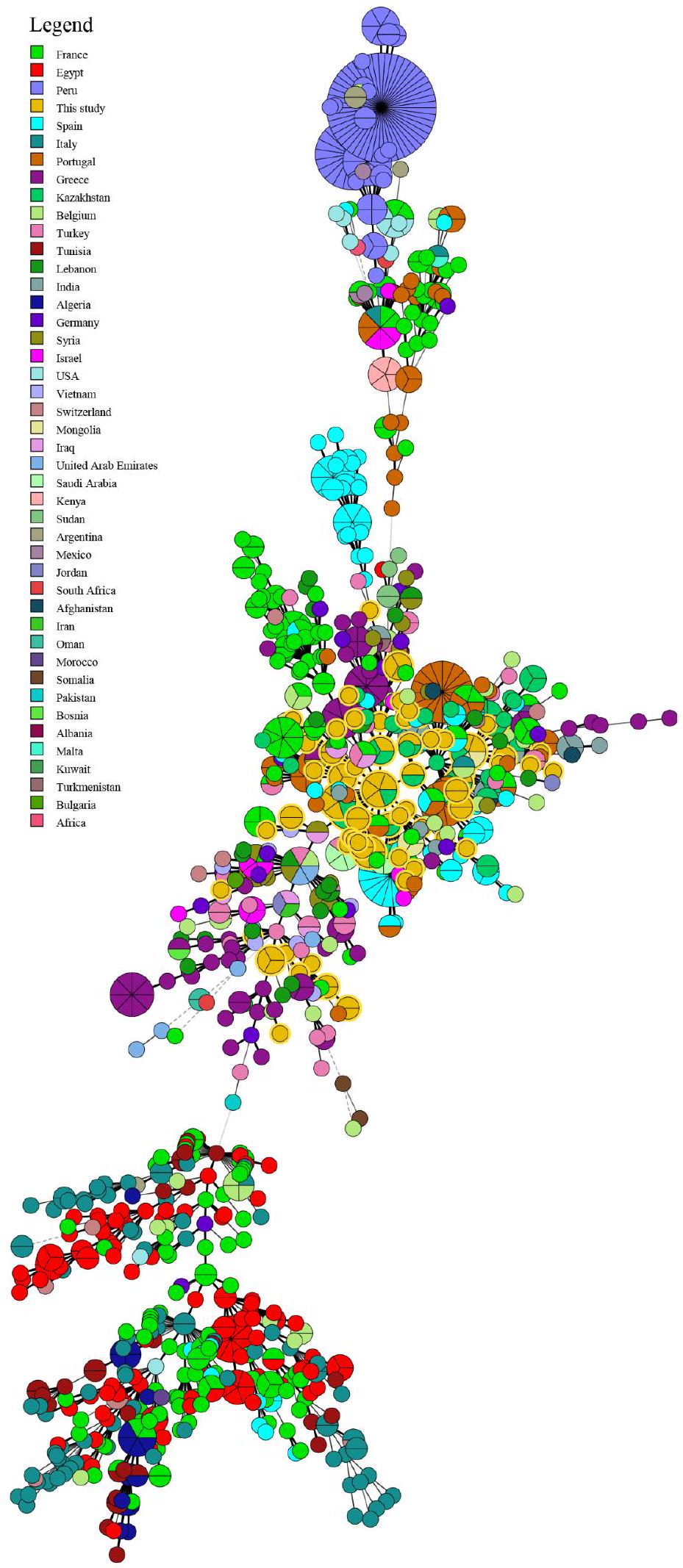

المقارنة الجينية لسلالات بروسيلة من الصين وعلى المستوى العالمي

ملاحظة: النقطة الحمراء (في الزاوية العليا اليمنى) تشير إلى موقع سيتشوان في الصين

نقاش

مرض يتجدد ظهوره. لقد حدثت حالات متفرقة منذ عام 2014، مع زيادة عدد الحالات المبلغ عنها من 25 في عام 2014 إلى 417 في عام 2023. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن مقاطعة سيتشوان تحدها العديد من المقاطعات من الغرب، بما في ذلك مقاطعات شانشي، تشينغهاي، قانسو، ويوننان، حيث إن داء البروسيلات البشري له انتشار مرتفع [18]. أيضًا، فإن أعداد تربية الأغنام والماعز مرتفعة في سيتشوان بسبب تطوير تربية الحيوانات لزيادة دخل المزارعين والرعاة المحليين.

زاد عدد الأغنام من 1689.19 (عشرات الآلاف) في عام 2013 إلى 1761.13 (عشرات الآلاف) في عام 2016، ثم انخفض إلى 1529.9 (عشرات الآلاف) في عام 2022. زادت إنتاجية لحم الضأن والأغنام من 22.45 (عشرة آلاف طن) في عام 2013 إلى 27.10 (عشرة آلاف طن) في عام 2023 (بيانات من مكتب الإحصاء، الصين). بسبب تطوير صناعة التربية، شهدت السكان المحليون تواصلًا غير مباشر ومباشر مع

| تحليل | موضع | معرف سيمبسون | أقسام | ماكس (باي)

|

فترة الثقة (95%) |

| MLST | أروأ | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) |

| cobQ | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| دي إن إيه كيه | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| فجوة | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| جلک | 0.131 | ٣ | 0.931 | (0.043-0.220) | |

| جير ب | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| int_hyp | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| omp25 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| trpE | 0.02 | 2 | 0.990 | (1.000-0.058) | |

| MLVA | بروس06 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) |

| بروس08 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| بروس11 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| بروس12 | 0.039 | ٣ | 0.980 | (1.000-0.093) | |

| بروس42 | 0.366 | ٢ | 0.762 | (0.277-0.455) | |

| بروس43 | 0.059 | ٣ | 0.970 | (1.000-0.123) | |

| بروس45 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| بروس55 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| بروس18 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.990 | (1.000-0.058) | |

| بروس19 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.990 | (1.000-0.058) | |

| بروس21 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| بروس04 | 0.808 | ٨ | 0.307 | (0.774-0.843) | |

| بروس07 | 0.039 | 2 | 0.980 | (1.000-0.092) | |

| بروس09 | 0.545 | 10 | 0.653 | (0.438-0.652) | |

| بروس16 | 0.741 | ٨ | 0.426 | (0.682-0.800) | |

| بروس30 | 0.671 | ٥ | 0.495 | (0.607-0.736) |

الحيوانات المجترة المصابة، وقد أدى ذلك إلى إعادة ظهور داء البروسيلات وظهور وباءات محلية.

توزعت السلالات التي تنتمي إلى ST8 في شمال وشمال شرق الصين، بما في ذلك منغوليا الداخلية، شينجيانغ، قانسو، تشينغهاي، شنشي، ومقاطعة هيلونغجيانغ [19]. تظهر التقارير الأخيرة أن ب. ميلتينسيس ST39 تم عزلها لأول مرة في مدينة زون يي، مقاطعة قويتشو في عام 2013، وقد تم عزل العديد من السلالات التي تنتمي إلى مجموعة ST في هذه المقاطعة [20]. تشير السلالات المعزولة من ب. ميلتينسيس ST8 و ST39 في سيتشوان إلى أن مصدر العدوى كان من خارج المقاطعة؛ ومع ذلك، تحتاج التفاصيل المتعلقة بالروابط الوبائية بين هذه السلالات إلى مزيد من التمييز بواسطة WGS-SNP [21]. علاوة على ذلك، تم اكتشاف نوعين جديدين من ST في هذه الدراسة، وكل منهما يمثل سلالة واحدة فقط. أظهر مقارنة التسلسل بين ST8 و ST101 أنهما يختلفان في

إن هيمنة الأنماط الجينية 116 و125 من MLVA-11 لبكتيريا البروسيلا في مقاطعة سيتشوان كانت متوافقة مع النمط في معظم مقاطعات الصين. النمط الجيني 116 هو النمط السائد لبكتيريا B. melitensis الذي يستمر في التوسع من شمال إلى جنوب الصين. كشفت تحليل مجموعة MLVA-16 عن نمط انتقال متزامن يهيمن عليه حالات متفرقة وأحداث تفشي متعددة ناجمة عن مصدر مشترك. كانت هذه النتيجة متوافقة مع الحالة الوبائية لحمى البروسيلا البشرية في هذه المقاطعة، حيث كانت نسبة الحدوث

أبرزت العديد من الدراسات ضرورة تسلسل الجينوم الكامل (WGS) لجمع مزيد من المعلومات لتحسين التحقيقات الوبائية [26، 27]. تعدد أشكال النوكليوتيدات المفردة في الجينوم الأساسي (cgSNP)

| STs | أروأ | cobQ | دي إن إيه كيه | فجوة | جل ك | جير ب | int_hyp | omp25 | trpE | عدد السلالات | توزيع المدن |

| ٨ | ٢ | ٣ | 2 | ٣ | ٣ | 1 | 2 | ٨ | ٥ | 93 | 17 |

| ٣٩ | 2 | ٣ | 2 | ٣ | ٢٤ | 1 | 2 | ٨ | ٥ | ٦ | ٦ |

| ١٠١ | 2 | ٣ | ٢ | ٣ | ٤٩ | 1 | 2 | ٨ | ٥ | 1 | 1 |

| ١١٨ | 2 | ٣ | 2 | ٣ | ٣ | 1 | 2 | ٨ | 31 | 1 | 1 |

القطاعات، والمزارعين؛ والتخلص غير المناسب من المواد المجهضة، وتعويض الحكومة غير الكافي للحيوانات المصابة، وتردد الجمهور في التطعيم، والحدود المفتوحة وحركة الحيوانات غير المنضبطة، ونقص التشخيص المناسب وطرق وأدوات التصنيف البيولوجي. لذلك، من الضروري تنفيذ سياسة صارمة للاختبار والذبح للقضاء على المجترات المصابة وتقليل حدوث داء البروسيلات لدى البشر. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يجب التحكم في حركة الحيوانات المصابة، حيث يجب أن تساعد الاستثمارات المالية والمادية من قبل الإدارات الحكومية في مشاركة المزارعين في برامج السيطرة.

الخاتمة

الاختصارات

| حمض نووي ريبوزي منقوص الأكسجين | حمض الديوكسي ريبونوكلييك |

| تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل | تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل |

| AMOS-PCR | تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل لفيروس الإجهاض – المليتنس – الأوي – السويس |

| HGDI | مؤشر تنوع هانتر-غاستون |

| UPGMA | طريقة المجموعة غير الموزونة مع المتوسط الحسابي |

| MLST | تحديد تسلسل متعدد المواقع |

| MLVA | تحليل تكرار عدد المواقع المتغيرة المتعددة |

| MST | شجرة التمدد الدنيا |

معلومات إضافية

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 14 يناير 2025

References

- Byndloss MX, Tsolis RM. Brucella spp. Virulence factors and immunity. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2016;4:111-27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-021 815-111326.

- Ahmed W, Zheng K, Liu ZF. Establishment of chronic infection: Brucella’s Stealth Strategy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016;6:30. https://doi.org/10.3389 /fcimb.2016.00030.

- Godfroid J, Cloeckaert A, Liautard JP, Kohler S, Fretin D, Walravens K, et al. From the discovery of the Malta fever’s agent to the discovery of a marine mammal reservoir, brucellosis has continuously been a re-emerging zoonosis. Vet Res. 2005;36(3):313-26. https://doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2005003.

- Liu Z, Gao L, Wang M, Yuan M, Li Z. Long ignored but making a comeback: a worldwide epidemiological evolution of human brucellosis. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024;13(1):2290839. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2023.2290839.

- Lai S, Zhou H, Xiong W, Gilbert M, Huang Z, Yu J, et al. Changing epidemiology of human brucellosis, China, 1955-2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(2):184-94. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2302.151710.

- Zhu X, Zhao Z, Ma S, Guo Z, Wang M, Li Z, et al. Brucella melitensis, a latent travel bacterium, continual spread and expansion from Northern to Southern China and its relationship to worldwide lineages. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1618-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1788995.

- Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Wang A, Yan Y, Chen Y, et al. An epidemiological study of brucellosis on mainland China during 2004-2018. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021;68(4):2353-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.13896.

- Deqiu S, Donglou X, Jiming Y. Epidemiology and control of brucellosis in China. Vet Microbiol. 2002;90(1-4):165-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-113 5(02)00252-3.

- Whatmore AM, Perrett LL, MacMillan AP. Characterisation of the genetic diversity of Brucella by multilocus sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-7-34.

- Al Dahouk S, Flèche PL, Nöckler K, Jacques I, Grayon M, Scholz HC, et al. Evaluation of Brucella MLVA typing for human brucellosis. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;69(1):137-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2006.12.015.

- Yagupsky P, Morata P, Colmenero JD. Laboratory diagnosis of human brucellosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33(1). https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00073-19.

- Al Dahouk S, Tomaso H, Nöckler K, Neubauer H, Frangoulidis D. Laboratorybased diagnosis of brucellosis-a review of the literature. Part II: serological tests for brucellosis. Clin Lab. 2003;49(11-12):577-89.

- Liu G, Ma X, Zhang R, Lü J, Zhou P, Liu B, et al. Epidemiological changes and molecular characteristics of Brucella strains in Ningxia, China. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1320845. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1320845.

- Bricker BJ, Halling SM. Differentiation of Brucella abortus Bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis Bv. 1 by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32(11):2660-6. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.32.11.2660-2666.1994.

- Liu ZG, Wang M, Zhao HY, Piao DR, Jiang H, Li ZJ. Investigation of the molecular characteristics of Brucella isolates from Guangxi Province, China. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19(1):292. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1665-6.

- Hunter PR, Gaston MA. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson’s index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26(11):2465-6. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.26.11.2465-2466.1988.

- Nascimento M, Sousa A, Ramirez M, Francisco AP, Carriço JA, Vaz C. PHYLOViZ 2.0: providing scalable data integration and visualization for multiple phylogenetic inference methods. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(1):128-9. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw582.

- Yang H, Chen Q, Li Y, Mu D, Zhang Y, Yin W, Epidemic Characteristics. High-risk areas and space-time clusters of human brucellosis – China, 2020-2021. China CDC Wkly. 2023;5(1):17-22. https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2023.004.

- An CH, Liu ZG, Nie SM, Sun YX, Fan SP, Luo BY, et al. Changes in the epidemiological characteristics of human brucellosis in Shaanxi Province from 2008 to 2020. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17367. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96774-x.

- Tan Q, Wang Y, Liu Y, Tao Z, Yu C, Huang Y, et al. Molecular epidemiological characteristics of Brucella in Guizhou Province, China, from 2009 to 2021. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1188469. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.118846 9.

- Xue H, Zhao Z, Wang J, Ma L, Li J, Yang X, et al. Native circulating Brucella melitensis lineages causing a brucellosis epidemic in Qinghai, China. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1233686. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1233686.

- Liu ZG, Di DD, Wang M, Liu RH, Zhao HY, Piao DR, et al. MLVA Genotyping Characteristics of Human Brucella melitensis isolated from Ulanqab of Inner Mongolia, China. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb. 201 7.00006.

- Liu Z, Wang C, Wei K, Zhao Z, Wang M, Li D, et al. Investigation of genetic relatedness of Brucella Strains in Countries along the Silk Road. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:539444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.539444.

- Ali S, Mushtaq A, Hassan L, Syed MA, Foster JT, Dadar M. Molecular epidemiology of brucellosis in Asia: insights from genotyping analyses. Vet Res Commun. 2024;48(6):3533-50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11259-024-10519-5.

- Refai M. Incidence and control of brucellosis in the Near East region. Vet Microbiol. 2002;90(1-4):81-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1135(02)0024 8-1.

- Ötkün S, Erdenliğ Gürbi Lek S. Whole-genome sequencing-based analysis of Brucella species isolated from ruminants in various regions of Türkiye. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):1220. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09921-w.

- Kydyshov K, Usenbaev N, Berdiev S, Dzhaparova A, Abidova A, Kebekbaeva N, et al. First record of the human infection of Brucella melitensis in Kyrgyzstan: evidence from whole-genome sequencing-based analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2022;11(1):120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-022-01044-1.

- Akar K, Holzer K, Hoelzle LE, YIldız Öz G, Abdelmegid S, Baklan EA, et al. An evaluation of the lineage of Brucella isolates in Turkey by a whole-genome

single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Vet Sci. 2024;11(7). https://doi.org/ 10.3390/vetsci11070316. - Kang SI, Her M, Erdenebaataar J, Vanaabaatar B, Cho H, Sung SR, et al. Molecular epidemiological investigation of Brucella melitensis circulating in Mongolia by MLVA16. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;50:16-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2016.11.003.

- Sami Ullah TJ, Muhammad, Asif. Waqas Ahmad and Heinrich Neubauer. Brucellosis remains a neglected disease in District Muzaffargarh of Pakistani Punjab: a call for multidisciplinary collaboration. German J Veterinary Res. 2022;2(1):36-9. https://doi.org/10.51585/gjvr.2022.1.0039.

- Liu ZG, Wang M, Ta N, Fang MG, Mi JC, Yu RP, et al. Seroprevalence of human brucellosis and molecular characteristics of Brucella strains in Inner Mongolia Autonomous region of China, from 2012 to 2016. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):263-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1720528.

- Leylabadlo HE, Bialvaei AZ, Samadi Kafil H. Brucellosis in Iran: why not eradicated? Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1629-30. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ64 6.

- Ahmed F. Hikal GWaAK. Brucellosis: why is it eradicated from domestic livestock in the United States but not in the Nile River Basin countries? German J Microbiol. 2023;3(2):19-25.

- Zamri-Saad M, Kamarudin MI. Control of animal brucellosis: the Malaysian experience. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;9(12):1136-40. https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.apjtm.2016.11.007.

ملاحظة الناشر

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-024-03739-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39810148

Publication Date: 2025-01-14

Genetic diversity atlas of Brucella melitensis strains from Sichuan Province, China

Abstract

Human brucellosis is a re-emerging disease in Sichuan Province, China. In this study, bacteriology, conventional bio-typing, multi-locus sequence typing (MLST), and multiple locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) were applied to preliminarily characterize the strains in terms of genetic diversity and epidemiological links. A total of 101 Brucella strains were isolated from 16 cities (autonomous prefectures) from 2014 to 2021, and all of the strains were identified as Brucella melitensis bv. 3, suggesting that surveillance should focus on ruminants. MLST analysis identified four STs, namely, ST8 (

*Correspondence:

Zhiguo Liu

liuzhiguo@icdc.cn

Zhenjun Li

lizhenjun@icdc.cn

Introduction

In China, brucellosis is a re-emerging disease that expanded from northern pastureland provinces to the adjacent grassland and agricultural areas, then to the southern coastal and southwestern regions [5]. At present, human brucellosis has been reported from all 31 provinces or autonomous regions in mainland China. B. melitensis is the main pathogenic bacteria causing brucellosis epidemics in China [6]. Sichuan Province is located in the interior of Southwest China, bordering on Guizhou, Qinghai, Gansu, and Shaanxi provinces, and brucellosis is endemic in the region [7]. Sichuan Province was an endemic area of brucellosis from the 1950s to 1980s; the disease was brought under control in the 1990s and re-emerged in 2008 [8]. Since 2008, the reported number of cases has gradually increased. A total of 417 new cases were reported in 2023, and these were distributed among multiple cities. However, the level of genetic diversity and the epidemiological links of Brucella isolated from different regions and at different times need to be clarified. Therefore, bio-typing was used to determine the species/biovars of circulating Brucella strains, and the genotyping methods of multi-locus sequence typing analysis (MLST) [9] and multi-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) [10] were applied to investigate the genetic diversity and molecular links among the strains. The results provide valuable for the planning of a control strategy for brucellosis in Sichuan Province.

Materials and methods

Bacteriological isolation and bio-typing

DNA extraction and genotyping of Brucella strains

genetic diversity. Nine genomic loci were selected for MLST genotyping based on a previous study [9], namely, gap, aroA, glk, dnaK, gyrB, trpE, cobQ, omp25, and inthyp. PCR amplification of the nine loci was performed as described previously [15]. Positive PCR products were evaluated by

Results

Geographic and species/biovars distribution of Brucella strains

| Cities/Autonomous prefecture | Number of strains | STs | MLVA-8 | MLVA-11 |

| Bazhong | 4 | 8 | 42,43,45 | 115, 116, 125 |

| Chengdu | 10 | 8 | 42, 43, 83 | 115, 116, 298 |

| Dazhou | 9 | 8, 39 | 42,43 | 116, 125 |

| Deyang | 2 | 8 | 42,43 | 116, 125 |

| Ganzi | 1 | 8 | 42 | 116 |

| Guangyuan | 5 | 8 | 42,114 | 116, 291 |

| Mianyang | 5 | 8, 39 | 42,43 | 116, 125 |

| Leshan | 2 | 8,101 | 42 | 116 |

| Liangshan | 7 | 8, 39 | 42,43 | 116, 125 |

| Luzhou | 19 | 8,118 | 42,43 | 116, 125, 180 |

| Meishan | 2 | 8 | 42 | 116 |

| Neijiang | 17 | 8 | 42,43 | 116, 125, 342 |

| Panzhihua | 4 | 8 | 42,43 | 116, 125 |

| Suining | 2 | 8 | 42 | 116 |

| Zigong | 11 | 8 | 42,43 | 116, 125 |

| Ziyang | 1 | 8 | 63 | 111 |

VNTR and allele diversity profiles

and that the rise of new STs illustrates the need for active surveillance.

MLVA genotyping characteristics of 101 B. melitensis strains

Genetic comparison of Brucella strains from China and the global scale

Note: The red dot (upper right figure) indicates the location of Sichuan in China

Discussion

re-emerging disease. Sporadic cases have occurred since 2014, with reported cases increasing from 25 in 2014 to 417 in 2023. In addition, Sichuan Province borders many provinces from the west, including Shaanxi, Qinghai, Gansu, and Yunnan provinces, where human brucellosis has a high prevalence [18]. Also, the breeding numbers of sheep and goats are high in Sichuan owing to the development of animal husbandry to increase the incomes of local farmers and herdsmen.

The sheep stock increased from 1689.19 (tens of thousands) in 2013 to 1761.13 (tens of thousands) in 2016, and then declined to 1529.9 (tens of thousands) in 2022. Mutton and lamb production increased from 22.45 (ten thousand tons) in 2013 to 27.10 (ten thousand tons) in 2023 (data from the Bureau of Statistics, China). Due to the development of the breeding industry, the local population experienced indirect and direct contact with

| Assay | Locus | Simpson’s ID | Partitions | Max (pi)

|

CI (95%) |

| MLST | aroA | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) |

| cobQ | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| dnaK | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| gap | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| glk | 0.131 | 3 | 0.931 | (0.043-0.220) | |

| gyrB | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| int_hyp | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| omp25 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| trpE | 0.02 | 2 | 0.990 | (1.000-0.058) | |

| MLVA | Bruce06 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) |

| Bruce08 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| Bruce11 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| Bruce12 | 0.039 | 3 | 0.980 | (1.000-0.093) | |

| Bruce42 | 0.366 | 2 | 0.762 | (0.277-0.455) | |

| Bruce43 | 0.059 | 3 | 0.970 | (1.000-0.123) | |

| Bruce45 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| Bruce55 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| Bruce18 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.990 | (1.000-0.058) | |

| Bruce19 | 0.02 | 2 | 0.990 | (1.000-0.058) | |

| Bruce21 | 0 | 1 | 1 | (0.000-0.000) | |

| Bruce04 | 0.808 | 8 | 0.307 | (0.774-0.843) | |

| Bruce07 | 0.039 | 2 | 0.980 | (1.000-0.092) | |

| Bruce09 | 0.545 | 10 | 0.653 | (0.438-0.652) | |

| Bruce16 | 0.741 | 8 | 0.426 | (0.682-0.800) | |

| Bruce30 | 0.671 | 5 | 0.495 | (0.607-0.736) |

infected ruminants, and this has driven the re-emergence of brucellosis and local epidemics.

Strains belonging to ST8 are distributed in northern and northeast China, including Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Gansu, Qinghai, Shaanxi, and Heilongjiang provinces [19]. The latest reports show that B. melitensis ST39 was first isolated in Zunyi City, Guizhou Province in 2013, and many strains belonging to the ST group have been isolated in this province [20]. The isolated B. melitensis ST8 and ST39 in Sichuan imply that the source of infection was from outside the province; however, the details concerning the epidemiological links among these strains need further discrimination by WGS-SNP [21]. Moreover, two new STs were detected in this study, and each represented only one strain. Sequence comparison between ST8 and ST101 showed that they differed at the

The predominance of the 116 and 125 of MLVA-11 genotypes of Brucella in Sichuan Province was consistent with the pattern in most provinces of China. Genotype 116 is the predominant genotype of B. melitensis that continues to expand from northern to southern China [6]. MLVA-16 cluster analysis revealed a co-existing transmission pattern dominated by sporadic cases and multiple outbreak events caused by a common source. This result was consistent with the epidemic status of human brucellosis in this province, where the incidence rate was

Many studied underscored that necessity of whole genome sequencing (WGS) to gather more information for improved epidemiological investigations [26, 27]. A core-genome single-nucleotide polymorphism (cgSNP)

| STs | aroA | cobQ | dnaK | gap | glk | gyrB | int_hyp | omp25 | trpE | Number of strains | Distribution of cities |

| 8 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 93 | 17 |

| 39 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 24 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| 101 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 49 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 118 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 31 | 1 | 1 |

sectors, and farmers; and inappropriate disposal of aborted materials, insufficient government compensation for infected animals, and public vaccination reluctance, open borders and uncontrolled animal movements, lack of proper diagnostics and bio-typing methods and tools [33]. Therefore, implementing a strict testing and slaughter policy is needed to eliminate the infected ruminants and reduce the incidence of human brucellosis [34]. In addition, the movement of infected animals should be controlled, where financial and material investment by government departments should aid farmers’ participation in control programs.

Conclusion

Abbreviations

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| AMOS-PCR | Abortus-melitensis-ovis-suis PCR |

| HGDI | Hunter-Gaston diversity index |

| UPGMA | Unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean |

| MLST | Multi-locus sequence typing |

| MLVA | Multiple locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis |

| MST | Minimum spanning tree |

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 14 January 2025

References

- Byndloss MX, Tsolis RM. Brucella spp. Virulence factors and immunity. Annu Rev Anim Biosci. 2016;4:111-27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-animal-021 815-111326.

- Ahmed W, Zheng K, Liu ZF. Establishment of chronic infection: Brucella’s Stealth Strategy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2016;6:30. https://doi.org/10.3389 /fcimb.2016.00030.

- Godfroid J, Cloeckaert A, Liautard JP, Kohler S, Fretin D, Walravens K, et al. From the discovery of the Malta fever’s agent to the discovery of a marine mammal reservoir, brucellosis has continuously been a re-emerging zoonosis. Vet Res. 2005;36(3):313-26. https://doi.org/10.1051/vetres:2005003.

- Liu Z, Gao L, Wang M, Yuan M, Li Z. Long ignored but making a comeback: a worldwide epidemiological evolution of human brucellosis. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024;13(1):2290839. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2023.2290839.

- Lai S, Zhou H, Xiong W, Gilbert M, Huang Z, Yu J, et al. Changing epidemiology of human brucellosis, China, 1955-2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(2):184-94. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2302.151710.

- Zhu X, Zhao Z, Ma S, Guo Z, Wang M, Li Z, et al. Brucella melitensis, a latent travel bacterium, continual spread and expansion from Northern to Southern China and its relationship to worldwide lineages. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):1618-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1788995.

- Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Wang A, Yan Y, Chen Y, et al. An epidemiological study of brucellosis on mainland China during 2004-2018. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021;68(4):2353-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.13896.

- Deqiu S, Donglou X, Jiming Y. Epidemiology and control of brucellosis in China. Vet Microbiol. 2002;90(1-4):165-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-113 5(02)00252-3.

- Whatmore AM, Perrett LL, MacMillan AP. Characterisation of the genetic diversity of Brucella by multilocus sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-7-34.

- Al Dahouk S, Flèche PL, Nöckler K, Jacques I, Grayon M, Scholz HC, et al. Evaluation of Brucella MLVA typing for human brucellosis. J Microbiol Methods. 2007;69(1):137-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2006.12.015.

- Yagupsky P, Morata P, Colmenero JD. Laboratory diagnosis of human brucellosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33(1). https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00073-19.

- Al Dahouk S, Tomaso H, Nöckler K, Neubauer H, Frangoulidis D. Laboratorybased diagnosis of brucellosis-a review of the literature. Part II: serological tests for brucellosis. Clin Lab. 2003;49(11-12):577-89.

- Liu G, Ma X, Zhang R, Lü J, Zhou P, Liu B, et al. Epidemiological changes and molecular characteristics of Brucella strains in Ningxia, China. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1320845. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1320845.

- Bricker BJ, Halling SM. Differentiation of Brucella abortus Bv. 1, 2, and 4, Brucella melitensis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella suis Bv. 1 by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32(11):2660-6. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.32.11.2660-2666.1994.

- Liu ZG, Wang M, Zhao HY, Piao DR, Jiang H, Li ZJ. Investigation of the molecular characteristics of Brucella isolates from Guangxi Province, China. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19(1):292. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1665-6.

- Hunter PR, Gaston MA. Numerical index of the discriminatory ability of typing systems: an application of Simpson’s index of diversity. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26(11):2465-6. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.26.11.2465-2466.1988.

- Nascimento M, Sousa A, Ramirez M, Francisco AP, Carriço JA, Vaz C. PHYLOViZ 2.0: providing scalable data integration and visualization for multiple phylogenetic inference methods. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(1):128-9. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw582.

- Yang H, Chen Q, Li Y, Mu D, Zhang Y, Yin W, Epidemic Characteristics. High-risk areas and space-time clusters of human brucellosis – China, 2020-2021. China CDC Wkly. 2023;5(1):17-22. https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2023.004.

- An CH, Liu ZG, Nie SM, Sun YX, Fan SP, Luo BY, et al. Changes in the epidemiological characteristics of human brucellosis in Shaanxi Province from 2008 to 2020. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17367. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96774-x.

- Tan Q, Wang Y, Liu Y, Tao Z, Yu C, Huang Y, et al. Molecular epidemiological characteristics of Brucella in Guizhou Province, China, from 2009 to 2021. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1188469. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.118846 9.

- Xue H, Zhao Z, Wang J, Ma L, Li J, Yang X, et al. Native circulating Brucella melitensis lineages causing a brucellosis epidemic in Qinghai, China. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1233686. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1233686.

- Liu ZG, Di DD, Wang M, Liu RH, Zhao HY, Piao DR, et al. MLVA Genotyping Characteristics of Human Brucella melitensis isolated from Ulanqab of Inner Mongolia, China. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb. 201 7.00006.

- Liu Z, Wang C, Wei K, Zhao Z, Wang M, Li D, et al. Investigation of genetic relatedness of Brucella Strains in Countries along the Silk Road. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:539444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.539444.

- Ali S, Mushtaq A, Hassan L, Syed MA, Foster JT, Dadar M. Molecular epidemiology of brucellosis in Asia: insights from genotyping analyses. Vet Res Commun. 2024;48(6):3533-50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11259-024-10519-5.

- Refai M. Incidence and control of brucellosis in the Near East region. Vet Microbiol. 2002;90(1-4):81-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1135(02)0024 8-1.

- Ötkün S, Erdenliğ Gürbi Lek S. Whole-genome sequencing-based analysis of Brucella species isolated from ruminants in various regions of Türkiye. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24(1):1220. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09921-w.

- Kydyshov K, Usenbaev N, Berdiev S, Dzhaparova A, Abidova A, Kebekbaeva N, et al. First record of the human infection of Brucella melitensis in Kyrgyzstan: evidence from whole-genome sequencing-based analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2022;11(1):120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-022-01044-1.

- Akar K, Holzer K, Hoelzle LE, YIldız Öz G, Abdelmegid S, Baklan EA, et al. An evaluation of the lineage of Brucella isolates in Turkey by a whole-genome

single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis. Vet Sci. 2024;11(7). https://doi.org/ 10.3390/vetsci11070316. - Kang SI, Her M, Erdenebaataar J, Vanaabaatar B, Cho H, Sung SR, et al. Molecular epidemiological investigation of Brucella melitensis circulating in Mongolia by MLVA16. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;50:16-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2016.11.003.

- Sami Ullah TJ, Muhammad, Asif. Waqas Ahmad and Heinrich Neubauer. Brucellosis remains a neglected disease in District Muzaffargarh of Pakistani Punjab: a call for multidisciplinary collaboration. German J Veterinary Res. 2022;2(1):36-9. https://doi.org/10.51585/gjvr.2022.1.0039.

- Liu ZG, Wang M, Ta N, Fang MG, Mi JC, Yu RP, et al. Seroprevalence of human brucellosis and molecular characteristics of Brucella strains in Inner Mongolia Autonomous region of China, from 2012 to 2016. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):263-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1720528.

- Leylabadlo HE, Bialvaei AZ, Samadi Kafil H. Brucellosis in Iran: why not eradicated? Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1629-30. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ64 6.

- Ahmed F. Hikal GWaAK. Brucellosis: why is it eradicated from domestic livestock in the United States but not in the Nile River Basin countries? German J Microbiol. 2023;3(2):19-25.

- Zamri-Saad M, Kamarudin MI. Control of animal brucellosis: the Malaysian experience. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;9(12):1136-40. https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.apjtm.2016.11.007.