DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d3fo04338j

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38414364

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-01

أنماط الأيض المعوية المرتبطة بالبوليفينولات وصحة الإنسان: تحديث

الملخص

لقد حظيت المركبات الغذائية (البوليفينول) باهتمام كبير بسبب دورها المحتمل في الوقاية من الأمراض غير المعدية وإدارتها. في السنوات الأخيرة، تم إثبات وجود تباين كبير بين الأفراد في الاستجابة البيولوجية لـ (البوليفينول)، والذي قد يكون مرتبطًا بالتباين العالي في استقلاب (البوليفينول) بواسطة الميكروبات المعوية الموجودة داخل الأفراد. هناك تفاعل بين (البوليفينول) والميكروبيوم المعوي، حيث يتم استقلاب (البوليفينول) بواسطة الميكروبات المعوية وتعديل نُوع وتكوين الميكروبات المعوية بواسطة نواتج استقلابها. تم اقتراح عدد من الأنماط الظاهرية أو الأنماط الاستقلابية التي تستقلب (البوليفينول)، ومع ذلك، لم يتم التحقيق في الأنماط الاستقلابية المحتملة لمعظم (البوليفينول)، ولا تزال العلاقة بين الأنماط الاستقلابية وصحة الإنسان غير واضحة. تقدم هذه المراجعة معرفة محدثة حول التفاعل المتبادل بين (البوليفينول) والميكروبيوم المعوي، والأنماط الاستقلابية المعوية المرتبطة، والأثر اللاحق على صحة الإنسان.

مقدمة

أيض الميكروبات المعوية للـ (بوليمر) الفينولات

البوليفينولات كمنظمات لميكروبيوم الأمعاء

نمو البكتيريا المفيدة مثل اللاكتوباسيلس والبيفيدوبكتيريوم،

تباين في استقلاب الميكروبات المعوية (البوليفينول): مفهوم أنماط استقلاب (البوليفينول)

| فئة الفينولات | النوع/السلالة | الركيزة (الركائز) | رد فعل | مرجع |

| الأنثوسيانين | بيفيدوبكتيريوم لاكتيس | أنثوسيانين |

|

٣٩ |

| لاكتوباسيلس أسيدوفيلوس | أنثوسيانين |

|

٣٩ | |

| لاكتوباسيلس كاسي | أنثوسيانين |

|

٣٩ | |

| لاكتوباسيلوس. بلانتاروم | أنثوسيانين |

|

٣٩ | |

| إيلاجي تانيين | بيفيدوبكتيريوم زيفودوكتينولاتوم | حمض الإيلاجيك | استقلاب حمض الإيلاجيك إلى يوروليثين A و B | 40 |

| أعضاء الكلوستريديوم كوكويدس | حمض الإيلاجيك | تحويل حمض الإيلاجيك إلى يوروليثينات | 41 | |

| إيلاجيباكتير إيزوروليثينيفاسيينس | حمض الإيلاجيك | استقلاب حمض الإيلاجيك إلى إيزو يوروليثين A | 42 | |

| Enterococcus faecium FUA027 | حمض الإيلاجيك | تحويل حمض الإيلاجيك إلى يوروليثين A | 43 | |

| غوردونيباكتير باميلاي | حمض الإيلاجيك | تحويل حمض الإيلاجيك إلى يوروليثينات | ٤٤ | |

| غوردونيباكتير يوروليثينفاسيينس | حمض الإيلاجيك | تحويل حمض الإيلاجيك إلى يوروليثينات | ٤٥ | |

| لاكتوكوكوس غارفيي FUA009 | حمض الإيلاجيك | تحويل حمض الإيلاجيك إلى يوروليثين A | ٤٦ | |

| ستربتوكوكوس ثيرموفيليوس FUA329 | حمض الإيلاجيك | تحويل حمض الإيلاجيك إلى يوروليثين A | ٤٧ | |

| فلافانونات | باكتيرويدس ديستاسونيس | إريوسيتري | تحلل مائي | ٤٨ |

| باكتيرويدس يونيformis | إريوسيتري | تحلل مائي | ٤٨ | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم كاتينولاتوم | هيسبيريدين | تحلل مائي | ٤٩ | |

| بيفيدوباكتيريوم زيفودوكاتينولتم | هيسبيريدين | تحلل مائي | ٤٩ | |

| كلوستريديوم بوتيريكم | إريوسيتري | انقسام حلقة C | ٤٨ | |

| فلافان-3-أول | أدليكروايتزيا إيكوليفاسيينس JCM 14793 | (-)-إيبيغالاتيكين، (-)-غالاتوكاتشين | ثنائي الهيدروكسيل | 50 |

| أسكاربكتير سيلاتوس JCM 14811 | (-)-إيبيغالاتيكين، (-)-غالاتوكاتشين | انقسام حلقة C | 50 | |

| إيجرتهيلا لنتا | (-)-إبيكاتشين، (+)-كاتشين | انقسام حلقة C | 51 | |

| سلاكية إيكوليفاسيينس JCM 16059 | (-)-إيبيغالاتشين، (-)-غالاتشين | انقسام حلقة C | 50 | |

| الفلافونات | بلاوتيا نوع MRG-PMF1 | أبيجيتري |

|

52 |

| يوبيكتيريوم سيلولوسولفنز | هومورينتين، إيزوفيتكسين | إزالة الجليكوزيل

|

53 | |

| الفلافونولات | باسيلاس سوبتيليس | كويرسيتين | انقسام حلقة C | ٥٤ |

| باكتيرويدس ديستاسونيس | روبن | تحلل الروبينين إلى كيمبفيرول | ٥٥ | |

| باكتيرويدس أوفاتوس | روتين |

|

٥٥ | |

| باكتيرويدس يونيformis | روتين |

|

٥٥ | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم أدوليسنتيس | كيمبفيرول 3-O-غلوكوزيد |

|

٥٦ | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم بيفيدوم | كيمبفيرول 3-O-غلوكوزيد |

|

٥٦ | |

| بيفيدوباكتيريوم بريف | كيمبفيرول 3-O-غلوكوزيد |

|

٥٦ | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم كاتينولاتوم | كيمبفيرول 3-O-غلوكوزيد | تحلل مائي

|

٥٦ | |

| بيفيدوباكتيريوم دينتيوم | روتين، بونسين | تحلل مائي | ٥٧ | |

| بيفيدوباكتيريوم إينفانتيس | كيمبفيرول 3-O-غلوكوزيد |

|

٥٦ | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم لونغوم | كيمبفيرول 3-O-غلوكوزيد |

|

٥٦ | |

| بيفيدوباكتيريوم زيفودوكتينولاتوم | كيمبفيرول 3-O-غلوكوزيد | تحلل مائي

|

٥٦ | |

| بلاوتيا نوع MRG-PMF1 | هيبريدين، بوليميثوكسي فلافون |

|

52 | |

| كلوستريديوم أوربيسسيندينس | كويرسيتين، تاكسيولين، لوتيولين، أبيجينين، نارينجين، فلو ريتين | انقسام حلقة C | ٥٨ | |

| إنتروكوكس أفيوم | روتين |

|

٥٩،٦٠ | |

| إنترococcus كاسيلفلافوس | كويرسيتين-3-جلوكوزيد | تحلل مائي | 61 | |

| يوبيكتيريوم رامولوس | روتين، كيرسيتين، كيمبفيرول، تاكسيولين، لوتيولين، كيرسيتين-3غلوكوزيد | انقسام الحلقة C | 61-63 | |

| فلافونيفراكتور بلوتي | كويرسيتين | انقسام الحلقة C | 64 | |

| لاكتوباسيلس أسيدوفيلوس | روتين، نيكوتيفلورين، ناريروتين |

|

65 | |

| لاكتوباسيلس بلانتاروم | روتين، نيكوتيفلورين، ناريروتين |

|

65 |

| فئة الفينولات | النوع/السلالة | الركيزة (الركائز) | رد فعل | مرجع |

| إيزوفلافونات | أدلاركروتسيا إيكوليفاسيينس | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى الإكوال | 66 |

| أسكاربكتير سيلاتوس | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى الإكوال | 67 | |

| بفيدوباكتيريوم أدوليسنتيس | دايدزين | تحلل مائي | 68 | |

| بيفيدوباكتيريوم أنيماليس | دايدزين | تحلل مائي | 69 | |

| بيفيدوباكتيريوم بيفيدوم | دايدزين | تحلل مائي | 68 | |

| بيفيدوباكتيريوم بريف | دايدزين | تحلل مائي | 68 | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم لونغوم | دايدزين | تحلل مائي | 69,70 | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم زيفودوكتينولاتوم | دايدزين | تحلل مائي | 69,70 | |

| بلاوتيا نوع MRG-PMF1 | دايدزين، جينستين، جلايسيتين | التحلل المائي، O-جلوكوز &

|

52 | |

| سلالة كلوستريديوم HGH 136 | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى ODMA | 71 | |

| سلالة كلوستريديوم SY8519 | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى ODMA | 32 | |

| سلالة كلوستريديوم TM-40 | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى دihydrodaidzein | 72 | |

| سلالة كوريوباكتيرياسيا Mt1B8 | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى الإكوال | 73 | |

| سلالة إيغرتيلا YY7918 | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى الإكوال | 74 | |

| إيجرثيلا نوع. جولونغ 732 | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى الإكوال | 75 | |

| Enterococcus sp. MRG-IFC-2 | بيورارين |

|

76 | |

| إشريشيا كولاي HGH21 | دايدزين، جينستين |

|

77 | |

| يوبيكتيريوم رامولوس | دايدزين، جينستين | انقسام حلقة C | 78 | |

| سلالة لاكنوسبيراسي CG19-1 | بيورارين | إزالة الجليكوزيل | 79 | |

| لاكتوباسيلس سب. نيو-أو16 | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى الإكوال | 75 | |

| لاكتوكوكوس سب. MRG-IFC-1 | بيورارين |

|

76 | |

| لاكتوكوكوس 20-92 | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى دihydrodaidzein | ٣٦ | |

| سلاكايا إيزوفلافونيكونفيرتنس | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايدزين إلى الإكوال | ٨٠ | |

| سلالة NATTS من Slackia sp. | دايدزين | التحويل البيولوجي للدايزين إلى الإكوال | 81 | |

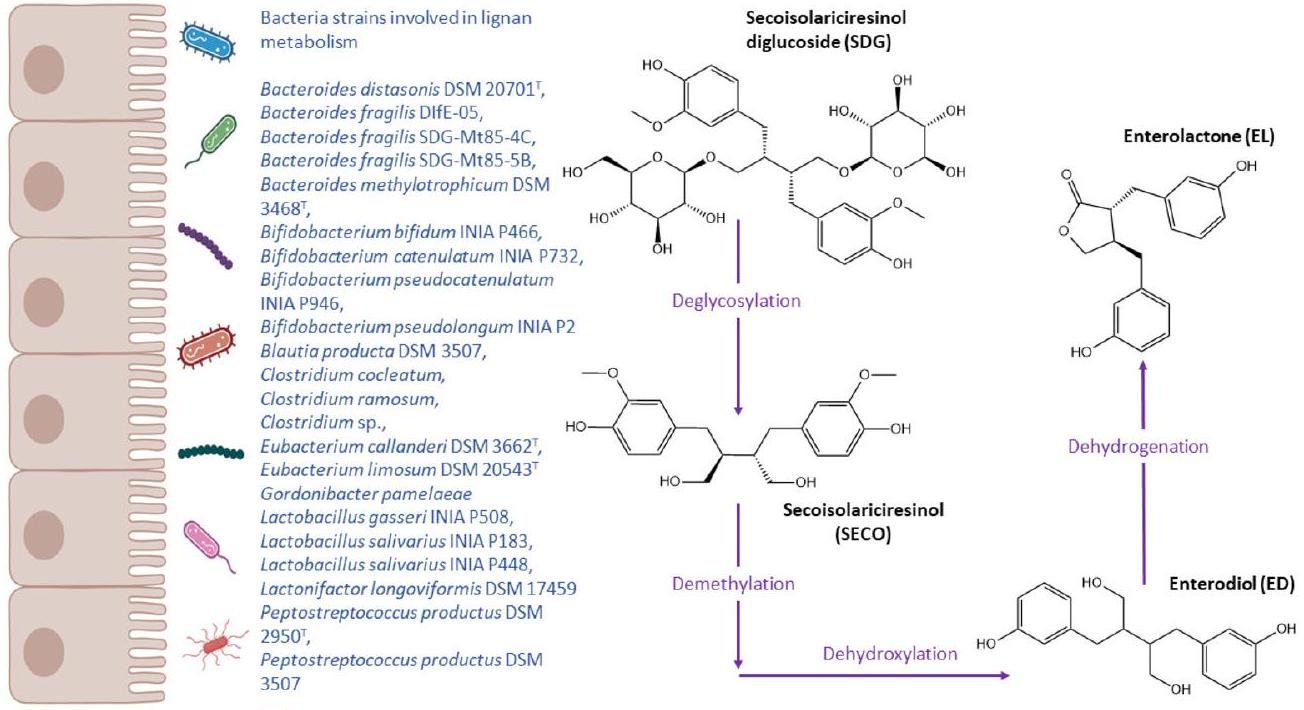

| ليغنان | باكتيرويدس ديستاسونيس DSM

|

سيكويزولاريسينول (SECO) | إزالة الجليكوزيل | 82 |

| باكتيرويدس فراجيلس DIfE-05 | سيكو | إزالة الجليكوزيل | 82 | |

| باكتيرويدس فراجيلس SDG-Mt85-4C، ب. فراجيلس SDG-Mt85-5B | سيكو | إزالة الجليكوزيل | 82 | |

| باكتيرويدس ميثيلوتروفيكوم DSM

|

سيكو | إزالة الميثيل | 82 | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم بيفيدوم INIA P466 | سيكو | تحويل SECO إلى إينتيروديو | 83 | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم كاتينولاتوم INIA P732 | سيكو | تحويل SECO إلى إينتيروديو | 83 | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم زيفودوكتينولاتوم إينيا | أهداف التنمية المستدامة | إزالة الجليكوزيل من SDG إلى SECO | 83 | |

| بيفيدوبكتيريوم زائف الطول INIA P2 | سيكو | تحويل SECO إلى إينتيروديو | 83 | |

| بلاوتيا برودكتا DSM 3507 | سيكو | إزالة الميثيل | 84 | |

| كلوستريديوم كوكليتوم | سيكويزولاريسينول ديوغلوكوزيد (SDG) | إزالة الجليكوزيل | 82 | |

| كلوستريديوم راموسوم | أهداف التنمية المستدامة | إزالة الجليكوزيل | 82 | |

| إيجرتهيلا لنتا DSM 2243 | بينوريسينول، لاريكيريسينول | تقليل | 84 | |

| يوبيكتيريوم كالاندي DSM

|

سيكو | إزالة الميثيل | 82 | |

| يوبيكتيريوم ليموسوم DSM

|

سيكو | إزالة الميثيل | 82 | |

| غوردونيباكتير باميلاي | ديديميثيل-سيكو | إزالة الهيدروكسيل | ٨٤ | |

| لاكتوباسيلس غاسيري INIA P508, | SECO | تحويل SECO إلى إنتروليغنان | ٨٣ | |

| لاكتوباسيلس ساليفاريوس INIA P183, لاكتوباسيلس ساليفاريوس INIA P448 | SECO | تحويل SECO إلى إنتروليغنان | ٨٣ | |

| لاكتونيفاكتور لونغوفيورميس DSM 17459 | إنتروديول | تحويل لاكتوني، التحويل الحيوي لإنتروديول إلى إنترولاكتون | ٨٤ | |

| غوردونيباكتير باميلاي | ديديميثيل-SECO | إزالة الهيدروكسيل | ٨٤ | |

| بيبتوستربتوكوكوس برودكتوس DSM

|

SECO | إزالة الميثيل | ٨٢ |

| فئة الفينول | النوع/السلالة | المادة (المواد) | التفاعل | المرجع. |

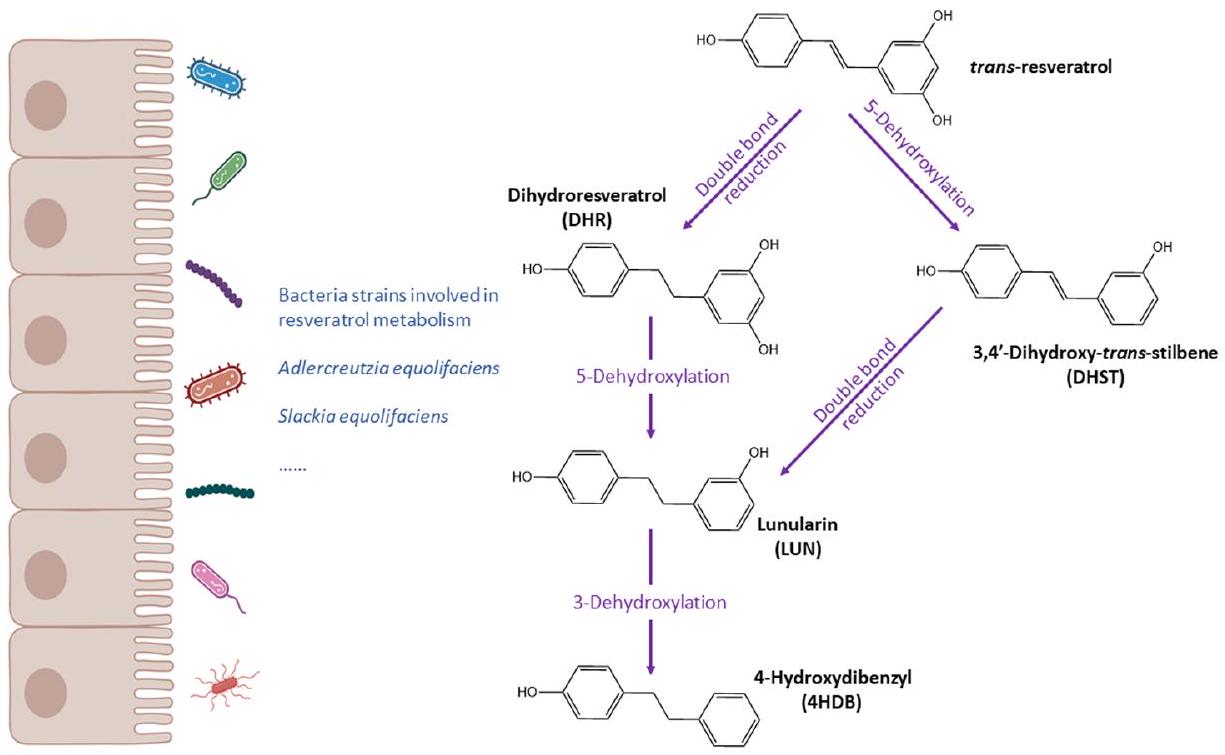

| ستيلبينات | أديلركروتسيا إيكوليفاسيينس | ريسفيراترول | تحويل ريسفيراترول إلى دihydroresveratrol | ٨٥ |

| سلاكية إيكوليفاسيينس | ريسفيراترول | تحويل ريسفيراترول إلى دihydroresveratrol | ٨٥ | |

| زانثوهومول | يوباكتيريوم رامولوس | زانثوهومول | الهدرجة | ٨٦ |

| يوباكتيريوم ليموسوم | إيزو زانثوهومول |

|

٨٦ |

(سي سي) EY-Nc هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي النسب-غير التجاري ٣.٠ غير محمي.

able to the notion of enterotype, a classification of gut microbiome composition profiles which is proposed to support the development of personalised nutrition strategies.

(البوليفينول) ميتابوتيب وصحة الإنسان: ما نعرفه حتى الآن

ميتابوتيب الإيكول وODMA

بواسطة بكتيريا الأمعاء إلى أغليكونيدات نشطة حيويًا، بما في ذلك دايدزين، جينستين وغليكيتين. استهلاك الصويا عادة ما يكون مرتفعًا في البلدان الآسيوية بينما يكون منخفضًا في السكان الغربيين.

البكتيريا البيفيدوبكتيرية في التحويل الحيوي للإيزوفلافونات في حليب الصويا قد تم إثباته جيدًا.

تم ترخيص هذه المقالة بموجب ترخيص المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام غير التجاري 3.0.

أنماط الأيض Urolithin

بين سلاكية وعوامل خطر القلب والأوعية الدموية، مثل الكوليسترول الكلي، LDL، بروتين الشحوم ب وغير HDL.

اختلفت بين UMs. خلال عام واحد بعد الولادة، أظهرت الأمهات من UMB بيئة ميكروبية معوية أكثر قوة كانت مقاومة للتغيرات، بينما كانت الأمهات من UMA لديهن ميكروبيوتا معوية متغيرة مرتبطة بانخفاض محيط الخصر. قام نفس المؤلفين لاحقًا بالتحقيق في العلاقات بين انتشار السمنة وعوامل أخرى بما في ذلك UM في مجموعة من الأطفال والمراهقين.

أنماط الأيض من اللونولارين

التأثيرات.

أنماط التمثيل الغذائي للمنتجين المنخفضين مقابل المنتجين المرتفعين

قد تكون الطبقات مفيدة لشرح التباين العالي في الاستجابة الملحوظة بعد استهلاك (البوليفينول). في هذا القسم، سنناقش بعض الأمثلة على (البوليفينول) ذات الصلة مع مستقلبات ميكروبية معوية محددة وفريدة جدًا. العديد من الفئات الأخرى الشائعة من (البوليفينول)، مثل الأحماض الفينولية، الأنثوسيانين أو الفلافونول، لديها مستقلبات ميكروبية معوية شائعة مثل الكاتيكول، الأحماض البنزويكية أو مشتقات حمض الهيبوريك التي قد تأتي من مصادر غذائية متعددة وليس فقط من (البوليفينول)، وبالتالي فهي ليست محددة بما يكفي لتصنيف الأفراد إلى أنماط استقلابية مختلفة بسهولة. ومع ذلك، يمكن استخدام مستويات تلك المستقلبات الشائعة والوفيرة كعلامات عامة لاستهلاك الأطعمة الغنية (بالبوليفينول) وجودة النظام الغذائي، وبالتالي فإن علاقاتها مع نتائج الصحة وتنوع الميكروبيوم المعوي، وتركيبه، ووظيفته هي مواضيع ذات اهتمام كبير للتحقيق في الاستجابات الفردية والجوانب الميكانيكية.

ليغنان

قد يكون ببساطة مرتبطًا بتناول اللجنات بدلاً من قدرة الأمعاء على التمثيل الغذائي. لذلك، في غياب تجارب عشوائية محكومة مصنفة حول منتجي EL وED المنخفضين والعاليين، لا يزال غير معروف ما إذا كانت التغيرات في التمثيل الغذائي الميكروبي المعوي يمكن أن تفسر التغيرات في الاستجابة لاستهلاك اللجنات.

فلافانونات

فلافان-3-أول

عن طريق إنزيمات المرحلة الثانية، ثم يتم إخراجه في البول.

فلافونويدات البرينيل من القفز

تمتلك خصائص مضادة للأكسدة، ومضادة للتكاثر، ومضادة للالتهابات، واستروجينية، وتنظيم المناعة.

تجميع الأنماط الأيضية: هل هناك نمط أيضي مشترك لعدة فئات فرعية من (البوليفينولات)؟

تبادل (البوليمر) الفينول الأيض وتأكيد التنبؤ للنماذج حول النتائج الصحية من خلال تجارب عشوائية محكومة مسبقًا.

الخاتمة

الميتاجينوميات والميتابولوميات في فهم أفضل لعمليات الأيض الخاصة بـ (البوليفينول) ودور الميكروبات المعوية. يسمح استخدام الميتابولوميات بتحديد الجوانب الوظيفية التي غالبًا ما لا يتم التقاطها من خلال تحليلات تركيب الميكروبات المعوية. تعتبر الدراسات الكبيرة مناسبة لفحص توزيع وعوامل أنماط الأيض وكذلك نطاقات تركيز المستقلبات الفريدة لـ (البوليفينول)، ولكن أيضًا المستقلبات الشائعة للعديد من (البوليفينول). سيساعد تطبيق الذكاء الاصطناعي هنا في تحديد أنماط الأيض الجديدة والأقل وضوحًا التي يتم تعريفها من خلال نطاقات تركيز المستقلبات الشائعة لـ (البوليفينول). يجب أيضًا إجراء تجارب التدخل السريرية لتحديد دور مستقلبات (البوليفينول) في تعديل تأثيرات الصحة. بشكل عام، تستحق العلاقات بين عمليات الأيض الخاصة بـ (البوليفينول) وتركيب الميكروبات المعوية وتأثيرات الصحة اللاحقة مزيدًا من البحث.

مساهمات المؤلفين

تعارض المصالح

References

2 M. I. Khan, J. H. Shin, T. S. Shin, M. Y. Kim, N. J. Cho and J. D. Kim, Anthocyanins from Cornus kousa ethanolic extract attenuate obesity in association with anti-angiogenic activities in 3T3-L1 cells by down-regulating adipogeneses and lipogenesis, PLoS One, 2018, 13, e0208556.

3 D. Esposito, A. Chen, M. H. Grace, S. Komarnytsky and M. A. Lila, Inhibitory Effects of Wild Blueberry Anthocyanins and Other Flavonoids on Biomarkers of Acute and Chronic Inflammation in Vitro, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2014, 62, 7022-7028.

4 M. M. Coman, A. M. Oancea, M. C. Verdenelli, C. Cecchini, G. E. Bahrim, C. Orpianesi, A. Cresci and S. Silvi, Polyphenol content and in vitro evaluation of antioxidant, antimicrobial and prebiotic properties of red fruit extracts, Eur. Food Res. Technol., 2018, 244, 735-745.

5 M. Inglés, J. Gambini, M. G. Miguel, V. Bonet-Costa, K. M. Abdelaziz, M. El Alami, J. Viña and C. Borrás, PTEN Mediates the Antioxidant Effect of Resveratrol at Nutritionally Relevant Concentrations, BioMed Res. Int., 2014, 2014, e580852.

7 P. Basu and C. Maier, Phytoestrogens and breast cancer: In vitro anticancer activities of isoflavones, lignans, coumestans, stilbenes and their analogs and derivatives, Biomed. Pharmacother., 2018, 107, 1648-1666.

8 M. Á. Ávila-Gálvez, A. González-Sarrías and J. C. Espín, In Vitro Research on Dietary Polyphenols and Health: A Call of Caution and a Guide on How To Proceed, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2018, 66, 7857-7858.

9 P. Mena and D. Del Rio, Gold Standards for Realistic (Poly)phenol Research, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2018, 66, 8221-8223.

10 A. Tresserra-Rimbau, E. B. Rimm, A. Medina-Remón, M. A. Martínez-González, R. de la Torre, D. Corella, J. Salas-Salvadó, E. Gómez-Gracia, J. Lapetra, F. Arós, M. Fiol, E. Ros, L. Serra-Majem, X. Pintó, G. T. Saez, J. Basora, J. V. Sorlí, J. A. Martínez, E. Vinyoles, V. RuizGutiérrez, R. Estruch and R. M. Lamuela-Raventós, Inverse association between habitual polyphenol intake and incidence of cardiovascular events in the PREDIMED study, Nutr., Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis., 2014, 24, 639-647.

11 A. A. Fallah, E. Sarmast and T. Jafari, Effect of dietary anthocyanins on biomarkers of glycemic control and glucose metabolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, Food Res. Int., 2020, 137, 109379.

12 M. Bonaccio, G. Pounis, C. Cerletti, M. B. Donati, L. Iacoviello, G. de Gaetano and on behalf of the M.-S. S. Investigators, Mediterranean diet, dietary polyphenols and low grade inflammation: results from the MOLI-SANI study, Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol., 2017, 83, 107113.

14 C. Valls-Pedret, R. M. Lamuela-Raventós, A. MedinaRemón, M. Quintana, D. Corella, X. Pintó, M. Á. MartínezGonzález, R. Estruch and E. Ros, Polyphenol-Rich Foods in the Mediterranean Diet are Associated with Better Cognitive Function in Elderly Subjects at High Cardiovascular Risk, J. Alzheimer’s Dis., 2012, 29, 773-782.

15 L. T. Fike, H. Munro, D. Yu, Q. Dai and M. J. Shrubsole, Dietary polyphenols and the risk of colorectal cancer in the prospective Southern Community Cohort Study, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2022, 115, 1155-1165.

16 N. M. Pham, V. V. Do and A. H. Lee, Polyphenol-rich foods and risk of gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Eur. J. Clin. Nutr., 2019, 73, 647-656.

17 F. Potì, D. Santi, G. Spaggiari, F. Zimetti and I. Zanotti, Polyphenol Health Effects on Cardiovascular and Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Review and MetaAnalysis, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2019, 20, 351.

19 B. de Roos, A.-M. Aura, M. Bronze, A. Cassidy, M.-T. G. Conesa, E. R. Gibney, A. Greyling, J. Kaput, Z. Kerem, N. Knežević, P. Kroon, R. Landberg, C. Manach, D. Milenkovic, A. Rodriguez-Mateos, F. A. TomásBarberán, T. van de Wiele and C. Morand, Targeting the delivery of dietary plant bioactives to those who would benefit most: from science to practical applications, Eur. J. Nutr., 2019, 58, 65-73.

20 L. Chen, H. Cao and J. Xiao, in Polyphenols: Properties, Recovery, and Applications, ed. C. M. Galanakis, Woodhead Publishing, 2018, pp. 45-67.

21 S. Mithul Aravind, S. Wichienchot, R. Tsao, S. Ramakrishnan and S. Chakkaravarthi, Role of dietary polyphenols on gut microbiota, their metabolites and health benefits, Food Res Int, 2021, 142, 110189.

22 A. González-Sarrías, J. A. Giménez-Bastida, M. Á. NúñezSánchez, M. Larrosa, M. T. García-Conesa, F. A. TomásBarberán and J. C. Espín, Phase-II metabolism limits the antiproliferative activity of urolithins in human colon cancer cells, Eur. J. Nutr., 2014, 53, 853-864.

23 L. Rubio, A. Macia and M.-J. Motilva, Impact of Various Factors on Pharmacokinetics of Bioactive Polyphenols: An Overview, Curr. Drug Metab., 2014, 15, 62-76.

24 T. Rao, Z. Tan, J. Peng, Y. Guo, Y. Chen, H. Zhou and D. Ouyang, The pharmacogenetics of natural products: A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic perspective, Pharmacol. Res., 2019, 146, 104283.

25 C. L. Frankenfeld, O-Desmethylangolensin: The Importance of Equol’s Lesser Known Cousin to Human Health, Adv. Nutr., 2011, 2, 317-324.

26 F. A. Tomás-Barberán, A. González-Sarrías, R. GarcíaVillalba, M. A. Núñez-Sánchez, M. V. Selma, M. T. GarcíaConesa and J. C. Espín, Urolithins, the rescue of “old” metabolites to understand a “new” concept: Metabotypes as a nexus among phenolic metabolism, microbiota dysbiosis, and host health status, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2017, 61, 1500901.

27 F. A. Tomás-Barberán, M. V. Selma and J. C. Espín, Interactions of gut microbiota with dietary polyphenols and consequences to human health, Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care, 2016, 19, 471-476.

28 J. C. Espín, A. González-Sarrías and F. A. Tomás-Barberán, The gut microbiota: A key factor in the therapeutic effects of (poly)phenols, Biochem. Pharmacol., 2017, 139, 82-93.

29 A. Braune and M. Blaut, Bacterial species involved in the conversion of dietary flavonoids in the human gut, Gut Microbes, 2016, 7, 216-234.

30 X. Feng, Y. Li, M. Brobbey Oppong and F. Qiu, Insights into the intestinal bacterial metabolism of flavonoids and

the bioactivities of their microbe-derived ring cleavage metabolites, Drug Metab. Rev., 2018, 50, 343-356.

31 X.-L. Wang, K.-T. Kim, J.-H. Lee, H.-G. Hur and S.-I. Kim, C-Ring Cleavage of Isoflavones Daidzein and Genistein by a Newly-Isolated Human Intestinal Bacterium Eubacterium ramulus Julong 601, J. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 2004, 14, 766771.

33 S. Yokoyama and T. Suzuki, Isolation and characterization of a novel equol-producing bacterium from human feces, Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem., 2008, 72, 2660-2666.

34 J.-S. Jin, T. Nishihata, N. Kakiuchi and M. Hattori, Biotransformation of C-glucosylisoflavone puerarin to estrogenic (3S)-equol in co-culture of two human intestinal bacteria, Biol. Pharm. Bull., 2008, 31, 1621-1625.

35 A. Matthies, M. Blaut and A. Braune, Isolation of a Human Intestinal Bacterium Capable of Daidzein and Genistein Conversion, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2009, 75, 1740-1744.

36 Y. Shimada, S. Yasuda, M. Takahashi, T. Hayashi, N. Miyazawa, I. Sato, Y. Abiru, S. Uchiyama and H. Hishigaki, Cloning and Expression of a Novel NADP (H)-Dependent Daidzein Reductase, an Enzyme Involved in the Metabolism of Daidzein, from Equol-Producing Lactococcus Strain 20-92, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2010, 76, 5892-5901.

37 J. F. Stevens and C. S. Maier, The chemistry of gut microbial metabolism of polyphenols, Phytochem. Rev., 2016, 15, 425-444.

38 R. García-Villalba, D. Beltrán, M. D. Frutos, M. V. Selma, J. C. Espín and F. A. Tomás-Barberán, Metabolism of different dietary phenolic compounds by the urolithinproducing human-gut bacteria Gordonibacter urolithinfaciens and Ellagibacter isourolithinifaciens, Food Funct., 2020, 11, 7012-7022.

39 M. Avila, M. Hidalgo, C. Sánchez-Moreno, C. Pelaez, T. Requena and S. de Pascual-Teresa, Bioconversion of anthocyanin glycosides by Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus, Food Res. Int., 2009, 42, 1453-1461.

40 P. Gaya, Á. Peirotén, M. Medina, I. Álvarez and J. M. Landete, Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum INIA P815: The first bacterium able to produce urolithins A and B from ellagic acid, J. Funct. Foods, 2018, 45, 9599.

44 M. V. Selma, F. A. Tomás-Barberán, D. Beltrán, R. GarcíaVillalba and J. C. Espín, Gordonibacter urolithinfaciens sp. nov., a urolithin-producing bacterium isolated from the human gut, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 2014, 64, 2346-2352.

45 M. V. Selma, D. Beltrán, R. García-Villalba, J. C. Espín and F. A. Tomás-Barberán, Description of urolithin production capacity from ellagic acid of two human intestinal Gordonibacter species, Food Funct., 2014, 5, 1779-1784.

46 H. Mi, S. Liu, Y. Hai, G. Yang, J. Lu, F. He, Y. Zhao, M. Xia, X. Hou and Y. Fang, Lactococcus garvieae FUA009, a Novel Intestinal Bacterium Capable of Producing the Bioactive Metabolite Urolithin A from Ellagic Acid, Foods, 2022, 11, 2621.

48 Y. Miyake, K. Yamamoto and T. Osawa, Metabolism of Antioxidant in Lemon Fruit (Citrus limon BURM. f.) by Human Intestinal Bacteria, J. Agric. Food Chem., 1997, 45, 3738-3742.

49 A. Amaretti, S. Raimondi, A. Leonardi, A. Quartieri and M. Rossi, Hydrolysis of the Rutinose-Conjugates Flavonoids Rutin and Hesperidin by the Gut Microbiota and Bifidobacteria, Nutrients, 2015, 7, 2788-2800.

50 A. Takagaki and F. Nanjo, Biotransformation of (–)-epigallocatechin and (-)-gallocatechin by intestinal bacteria involved in isoflavone metabolism, Biol. Pharm. Bull., 2015, 38, 325-330.

51 M. Kutschera, W. Engst, M. Blaut and A. Braune, Isolation of catechin-converting human intestinal bacteria, J. Appl. Microbiol., 2011, 111, 165-175.

52 M. Kim, N. Kim and J. Han, Metabolism of Kaempferia parviflora Polymethoxyflavones by Human Intestinal Bacterium Bautia sp. MRG-PMF1, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2014, 62, 12377-12383.

53 A. Braune and M. Blaut, Intestinal Bacterium Eubacterium cellulosolvens Deglycosylates Flavonoid Cand O-Glucosides, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2012, 78, 8151-8153.

54 M. R. Schaab, B. M. Barney and W. A. Francisco, Kinetic and spectroscopic studies on the quercetin 2,3-dioxygenase from Bacillus subtilis, Biochemistry, 2006, 45, 10091016.

58 L. Schoefer, R. Mohan, A. Schwiertz, A. Braune and M. Blaut, Anaerobic Degradation of Flavonoids by Clostridium orbiscindens, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2003, 69, 5849-5854.

59 Y. Liu, Y. Liu, Y. Dai, L. Xun and M. Hu, Enteric Disposition and Recycling of Flavonoids and Ginkgo Flavonoids, J. Altern. Complementary Med., 2003, 9, 631640.

61 H. Schneider, A. Schwiertz, M. D. Collins and M. Blaut, Anaerobic transformation of quercetin-3-glucoside by bacteria from the human intestinal tract, Arch. Microbiol., 1999, 171, 81-91.

62 H. Schneider and M. Blaut, Anaerobic degradation of flavonoids by Eubacterium ramulus, Arch. Microbiol., 2000, 173, 71-75.

63 A. Braune, M. Gütschow, W. Engst and M. Blaut, Degradation of Quercetin and Luteolin by Eubacterium ramulus, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2001, 67, 55585567.

65 J. Beekwilder, D. Marcozzi, S. Vecchi, R. de Vos, P. Janssen, C. Francke, J. van Hylckama Vlieg and R. D. Hall, Characterization of Rhamnosidases from Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus acidophilus, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2009, 75, 3447-3454.

66 T. Maruo, M. Sakamoto, C. Ito, T. Toda and Y. Benno, Adlercreutzia equolifaciens gen. nov., sp. nov., an equolproducing bacterium isolated from human faeces, and emended description of the genus Eggerthella, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 2008, 58, 1221-1227.

67 K. Minamida, K. Ota, M. Nishimukai, M. Tanaka, A. Abe, T. Sone, F. Tomita, H. Hara and K. Asano, Asaccharobacter celatus gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from rat caecum, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 2008, 58, 12381240.

69 D. Tsangalis, J. F. Ashton, A. E. J. Mcgill and N. P. Shah, Enzymic Transformation of Isoflavone Phytoestrogens in Soymilk by

71 H.-G. Hur, R. D. Beger, T. M. Heinze, J. O. Lay, J. P. Freeman, J. Dore and F. Rafii, Isolation of an anaerobic intestinal bacterium capable of cleaving the C-ring of the isoflavonoid daidzein, Arch. Microbiol., 2002, 178, 812.

74 S. Yokoyama, K. Oshima, I. Nomura, M. Hattori and T. Suzuki, Complete Genomic Sequence of the EquolProducing Bacterium Eggerthella sp. Strain YY7918, Isolated from Adult Human Intestine, J. Bacteriol., 2011, 193, 5570-5571.

75 X.-L. Wang, H.-J. Kim, S.-I. Kang, S.-I. Kim and H.-G. Hur, Production of phytoestrogen S-equol from daidzein in mixed culture of two anaerobic bacteria, Arch. Microbiol., 2007, 187, 155-160.

76 M. Kim, J. Lee and J. Han, Deglycosylation of isoflavone C-glycosides by newly isolated human intestinal bacteria, J. Sci. Food Agric., 2015, 95, 1925-1931.

78 L. Schoefer, R. Mohan, A. Braune, M. Birringer and M. Blaut, Anaerobic C-ring cleavage of genistein and daidzein by Eubacterium ramulus, FEMS Microbiol. Lett., 2002, 208, 197-202.

79 A. Braune and M. Blaut, Deglycosylation of puerarin and other aromatic C-glucosides by a newly isolated human intestinal bacterium, Environ. Microbiol., 2011, 13, 482494.

81 H. Tsuji, K. Moriyama, K. Nomoto and H. Akaza, Identification of an Enzyme System for Daidzein-to-Equol

82 T. Clavel, G. Henderson, W. Engst, J. Doré and M. Blaut, Phylogeny of human intestinal bacteria that activate the dietary lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 2006, 55, 471-478.

83 Á. Peirotén, P. Gaya, I. Álvarez, D. Bravo and J. M. Landete, Influence of different lignan compounds on enterolignan production by Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus strains, Int. J. Food Microbiol., 2019, 289, 17-23.

84 E. N. Bess, J. E. Bisanz, F. Yarza, A. Bustion, B. E. Rich, X. Li, S. Kitamura, E. Waligurski, Q. Y. Ang, D. L. Alba, P. Spanogiannopoulos, S. Nayfach, S. K. Koliwad, D. W. Wolan, A. A. Franke and P. J. Turnbaugh, Genetic basis for the cooperative bioactivation of plant lignans by Eggerthella lenta and other human gut bacteria, Nat. Microbiol., 2020, 5(1), 56-66.

85 L. M. Bode, D. Bunzel, M. Huch, G.-S. Cho, D. Ruhland, M. Bunzel, A. Bub, C. M. Franz and S. E. Kulling, In vivo and in vitro metabolism of trans-resveratrol by human gut microbiota, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2013, 97, 295-309.

86 I. L. Paraiso, L. S. Plagmann, L. Yang, R. Zielke, A. F. Gombart, C. S. Maier, A. E. Sikora, P. R. Blakemore and J. F. Stevens, Reductive metabolism of xanthohumol and 8-prenylnaringenin by the intestinal bacterium Eubacterium ramulus, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2019, 63, e1800923.

87 M. Moorthy, U. Sundralingam and U. D. Palanisamy, Polyphenols as Prebiotics in the Management of High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity: A Systematic Review of Animal Studies, Foods, 2021, 10, 299.

88 H. C. Lee, A. M. Jenner, C. S. Low and Y. K. Lee, Effect of tea phenolics and their aromatic fecal bacterial metabolites on intestinal microbiota, Res. Microbiol., 2006, 157, 876-884.

89 A. Duda-Chodak, T. Tarko, P. Satora and P. Sroka, Interaction of dietary compounds, especially polyphenols, with the intestinal microbiota: a review, Eur. J. Nutr., 2015, 54, 325-341.

90 M. I. Queipo-Ortuño, M. Boto-Ordóñez, M. Murri, J. M. Gomez-Zumaquero, M. Clemente-Postigo, R. Estruch, F. Cardona Diaz, C. Andrés-Lacueva and F. J. Tinahones, Influence of red wine polyphenols and ethanol on the gut microbiota ecology and biochemical biomarkers, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2012, 95, 1323-1334.

91 J.-P. Rauha, S. Remes, M. Heinonen, A. Hopia, M. Kähkönen, T. Kujala, K. Pihlaja, H. Vuorela and P. Vuorela, Antimicrobial effects of Finnish plant extracts containing flavonoids and other phenolic compounds, Int. J. Food Microbiol., 2000, 56, 3-12.

92 M. J. R. Vaquero, M. R. Alberto and M. C. M. de Nadra, Antibacterial effect of phenolic compounds from different wines, Food Control, 2007, 18, 93-101.

93 V. Gowd, N. Karim, M. R. I. Shishir, L. Xie and W. Chen, Dietary polyphenols to combat the metabolic diseases via altering gut microbiota, Trends Food Sci. Technol., 2019, 93, 81-93.

95 D. E. Roopchand, R. N. Carmody, P. Kuhn, K. Moskal, P. Rojas-Silva, P. J. Turnbaugh and I. Raskin, Dietary Polyphenols Promote Growth of the Gut Bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila and Attenuate High-Fat DietInduced Metabolic Syndrome, Diabetes, 2015, 64, 28472858.

97 C. E. Iglesias-Aguirre, A. Cortés-Martín, M. Á. Ávila-Gálvez, J. A. Giménez-Bastida, M. V. Selma, A. González-Sarrías and J. C. Espín, Main drivers of (poly)phenol effects on human health: metabolite production and/or gut micro-biota-associated metabotypes?, Food Funct., 2021, 12, 10324-10355.

98 S. Bolca, T. Van de Wiele and S. Possemiers, Gut metabotypes govern health effects of dietary polyphenols, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., 2013, 24, 220-225.

99 J. Boekhorst, N. Venlet, N. Procházková, M. L. Hansen, C. B. Lieberoth, M. I. Bahl, L. Lauritzen, O. Pedersen, T. R. Licht, M. Kleerebezem and H. M. Roager, Stool energy density is positively correlated to intestinal transit time and related to microbial enterotypes, Microbiome, 2022, 10, 223.

100 S. Hazim, P. J. Curtis, M. Y. Schär, L. M. Ostertag, C. D. Kay, A.-M. Minihane and A. Cassidy, Acute benefits of the microbial-derived isoflavone metabolite equol on arterial stiffness in men prospectively recruited according to equol producer phenotype: a double-blind randomized controlled trial, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2016, 103, 694-702.

101 K. D. R. Setchell and S. J. Cole, Method of Defining EquolProducer Status and Its Frequency among Vegetarians12, J. Nutr., 2006, 136, 2188-2193.

103 R. Yoshikata, K. Z. Myint, H. Ohta and Y. Ishigaki, Interrelationship between diet, lifestyle habits, gut microflora, and the equol-producer phenotype: baseline findings from a placebo-controlled intervention trial, Menopause, 2019, 26, 273.

104 M. Igase, K. Igase, Y. Tabara, Y. Ohyagi and K. Kohara, Cross-sectional study of equol producer status and cognitive impairment in older adults, Geriatr. Gerontol. Int., 2017, 17, 2103-2108.

105 V. Ahuja, K. Miura, A. Vishnu, A. Fujiyoshi, R. Evans, M. Zaid, N. Miyagawa, T. Hisamatsu, A. Kadota, T. Okamura, H. Ueshima and A. Sekikawa, Significant

inverse association of equol-producer status with coronary artery calcification but not dietary isoflavones in healthy Japanese men, Br. J. Nutr., 2017, 117, 260-266.

106 J. K. Aschoff, K. M. Riedl, J. L. Cooperstone, J. Högel, A. Bosy-Westphal, S. J. Schwartz, R. Carle and R. M. Schweiggert, Urinary excretion of Citrus flavanones and their major catabolites after consumption of fresh oranges and pasteurized orange juice: A randomized cross-over study, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2016, 60, 26022610.

108 C. E. Iglesias-Aguirre, F. Vallejo, D. Beltrán, E. AguilarAguilar, J. Puigcerver, M. Alajarín, J. Berná, M. V. Selma and J. C. Espín, Lunularin Producers versus Non-producers: Novel Human Metabotypes Associated with the Metabolism of Resveratrol by the Gut Microbiota, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2022, 70, 10521-10531.

109 L. Pilšáková, I. Riečanský and F. Jagla, The physiological actions of isoflavone phytoestrogens, Physiol. Res., 2010, 59, 651-664.

110 Z. Liu, W. Li, J. Sun, C. Liu, Q. Zeng, J. Huang, B. Yu and J. Huo, Intake of soy foods and soy isoflavones by rural adult women in China, Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr., 2004, 13, 204-209.

111 S. Oba, C. Nagata, N. Shimizu, H. Shimizu, M. Kametani, N. Takeyama, T. Ohnuma and S. Matsushita, Soy product consumption and the risk of colon cancer: a prospective study in Takayama, Japan, Nutr. Cancer, 2007, 57, 151-157.

112 C. L. Frankenfeld, Dairy consumption is a significant correlate of urinary equol concentration in a representative sample of US adults, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2011, 93, 11091116.

114 C. L. Frankenfeld, O-Desmethylangolensin: The Importance of Equol’s Lesser Known Cousin to Human Health, Adv. Nutr., 2011, 2, 317-324.

115 C. Atkinson, C. L. Frankenfeld and J. W. Lampe, Gut Bacterial Metabolism of the Soy Isoflavone Daidzein: Exploring the Relevance to Human Health, Exp. Biol. Med., 2005, 230, 155-170.

116 C. L. Frankenfeld, C. Atkinson, W. K. Thomas, A. Gonzalez, T. Jokela, K. Wähälä, S. M. Schwartz, S. S. Li and J. W. Lampe, High concordance of daidzein-metabolizing phenotypes in individuals measured 1 to 3 years apart, Br. J. Nutr., 2005, 94, 873-876.

117 K. B. Song, C. Atkinson, C. L. Frankenfeld, T. Jokela, K. Wähälä, W. K. Thomas and J. W. Lampe, Prevalence of Daidzein-Metabolizing Phenotypes Differs between Caucasian and Korean American Women and Girls, J. Nutr., 2006, 136, 1347-1351.

119 C. Atkinson, K. M. Newton, E. J. A. Bowles, M. Yong and J. W. Lampe, Demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors and dietary intakes in relation to daidzein-metabolizing phenotypes among premenopausal women in the United States, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2008, 87, 679-687.

120 S. Yokoyama and T. Suzuki, Isolation and characterization of a novel equol-producing bacterium from human feces, Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem., 2008, 72, 2660-2666.

121 D. Tsangalis, G. Wilcox, N. P. Shah, A. E. J. McGill and L. Stojanovska, Urinary excretion of equol by postmenopausal women consuming soymilk fermented by probiotic bifidobacteria, Eur. J. Clin. Nutr., 2007, 61, 438-441.

122 Q.-K. Wei, T.-R. Chen and J.-T. Chen, Using of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium to product the isoflavone aglycones in fermented soymilk, Int. J. Food Microbiol., 2007, 117, 120-124.

123 T. T. Pham and N. P. Shah, Biotransformation of Isoflavone Glycosides by Bifidobacterium animalis in Soymilk Supplemented with Skim Milk Powder, J. Food Sci., 2007, 72, M316-M324.

124 G. P. Rodriguez-Castaño, M. R. Dorris, X. Liu, B. W. Bolling, A. Acosta-Gonzalez and F. E. Rey, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron Starch Utilization Promotes Quercetin Degradation and Butyrate Production by Eubacterium ramulus, Front. Microbiol., 2019, 10, 1145.

125 A. Braune, W. Engst, P. W. Elsinghorst, N. Furtmann, J. Bajorath, M. Gütschow and M. Blaut, Chalcone Isomerase from Eubacterium ramulus Catalyzes the Ring Contraction of Flavanonols, J. Bacteriol., 2016, 198, 29652974.

127 M. Y. Lacourt-Ventura, B. Vilanova-Cuevas, D. RiveraRodríguez, R. Rosario-Acevedo, C. Miranda, G. Maldonado-Martínez, J. Maysonet, D. Vargas, Y. Ruiz, R. Hunter-Mellado, L. A. Cubano, S. Dharmawardhane, J. W. Lampe, A. Baerga-Ortiz, F. Godoy-Vitorino and M. M. Martínez-Montemayor, Soy and Frequent Dairy Consumption with Subsequent Equol Production Reveals Decreased Gut Health in a Cohort of Healthy Puerto Rican Women, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2021, 18, 8254.

isoflavone daidzein to O-desmethylangolensin in periand post-menopausal women, Maturitas, 2017, 99, 37-42.

129 C. L. Frankenfeld, C. Atkinson, K. Wähälä and J. W. Lampe, Obesity prevalence in relation to gut microbial environments capable of producing equol or O-desmethylangolensin from the isoflavone daidzein, Eur. J. Clin. Nutr., 2014, 68, 526-530.

130 V. Ahuja, K. Miura, A. Vishnu, A. Fujiyoshi, R. Evans, M. Zaid, N. Miyagawa, T. Hisamatsu, A. Kadota, T. Okamura, H. Ueshima and A. Sekikawa, Significant inverse association of equol-producer status with coronary artery calcification but not dietary isoflavones in healthy Japanese men, Br. J. Nutr., 2017, 117, 260-266.

131 X. Zhang, A. Fujiyoshi, V. Ahuja, A. Vishnu, E. BarinasMitchell, A. Kadota, K. Miura, D. Edmundowicz, H. Ueshima and A. Sekikawa, Association of equol producing status with aortic calcification in middle-aged Japanese men: The ERA JUMP study, Int. J. Cardiol., 2022, 352, 158-164.

132 T. Usui, M. Tochiya, Y. Sasaki, K. Muranaka, H. Yamakage, A. Himeno, A. Shimatsu, A. Inaguma, T. Ueno, S. Uchiyama and N. Satoh-Asahara, Effects of natural S-equol supplements on overweight or obesity and metabolic syndrome in the Japanese, based on sex and equol status, Clin. Endocrinol., 2013, 78, 365-372.

133 S. T. Soukup, A. K. Engelbert, B. Watzl, A. Bub and S. E. Kulling, Microbial Metabolism of the Soy Isoflavones Daidzein and Genistein in Postmenopausal Women: Human Intervention Study Reveals New Metabotypes, Nutrients, 2023, 15, 2352.

134 M. Shukla, K. Gupta, Z. Rasheed, K. A. Khan and T. M. Haqqi, Consumption of Hydrolyzable Tannins Rich Pomegranate Extract (POMx) Suppresses Inflammation and Joint Damage In Rheumatoid Arthritis, Nutrition, 2008, 24, 733-743.

135 E. Barrajón-Catalán, S. Fernández-Arroyo, D. Saura, E. Guillén, A. Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Segura-Carretero and V. Micol, Cistaceae aqueous extracts containing ellagitannins show antioxidant and antimicrobial capacity, and cytotoxic activity against human cancer cells, Food Chem. Toxicol., 2010, 48, 2273-2282.

136 V.-I. Neli, S. Ivo, J. Remi, Q. Stephane and S. G. Angel, Antiviral activities of ellagitannins against bovine herpes-virus-1, suid alphaherpesvirus-1 and caprine herpesvirus1, J. Vet. Med. Anim. Health, 2020, 12, 139-143.

137 A. González-Sarrías, M. Larrosa, F. A. Tomás-Barberán, P. Dolara and J. C. Espín, NF-кB-dependent anti-inflammatory activity of urolithins, gut microbiota ellagic acidderived metabolites, in human colonic fibroblasts, Br. J. Nutr., 2010, 104, 503-512.

138 J. A. Giménez-Bastida, A. González-Sarrías, M. Larrosa, F. Tomás-Barberán, J. C. Espín and M.-T. García-Conesa, Ellagitannin metabolites, urolithin A glucuronide and its aglycone urolithin A, ameliorate TNF-

aortic endothelial cells, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2012, 56, 784-796.

139 F. A. Tomás-Barberán, R. García-Villalba, A. GonzálezSarrías, M. V. Selma and J. C. Espín, Ellagic Acid Metabolism by Human Gut Microbiota: Consistent Observation of Three Urolithin Phenotypes in Intervention Trials, Independent of Food Source, Age, and Health Status, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2014, 62, 6535-6538.

140 A. Cortés-Martín, R. García-Villalba, A. González-Sarrías, M. Romo-Vaquero, V. Loria-Kohen, A. Ramírez-de-Molina, F. A. Tomás-Barberán, M. V. Selma and J. C. Espín, The gut microbiota urolithin metabotypes revisited: the human metabolism of ellagic acid is mainly determined by aging, Food Funct., 2018, 9, 4100-4106.

141 W. Xian, S. Yang, Y. Deng, Y. Yang, C. Chen, W. Li and R. Yang, Distribution of Urolithins Metabotypes in Healthy Chinese Youth: Difference in Gut Microbiota and Predicted Metabolic Pathways, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2021, 69, 13055-13065.

142 M. V. Selma, M. Romo-Vaquero, R. García-Villalba, A. González-Sarrías, F. A. Tomás-Barberán and J. C. Espín, The human gut microbial ecology associated with overweight and obesity determines ellagic acid metabolism, Food Funct., 2016, 7, 1769-1774.

143 M. Romo-Vaquero, E. Fernández-Villalba, A.-L. GilMartinez, L. Cuenca-Bermejo, J. C. Espín, M. T. Herrero and M. V. Selma, Urolithins: potential biomarkers of gut dysbiosis and disease stage in Parkinson’s patients, Food Funct., 2022, 13, 6306-6316.

144 M. Romo-Vaquero, A. Cortés-Martín, V. Loria-Kohen, A. Ramírez-de-Molina, I. García-Mantrana, M. C. Collado, J. C. Espín and M. V. Selma, Deciphering the Human Gut Microbiome of Urolithin Metabotypes: Association with Enterotypes and Potential Cardiometabolic Health Implications, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2019, 63, 1800958.

145 C. E. Iglesias-Aguirre, R. García-Villalba, D. Beltrán, M. D. Frutos-Lisón, J. C. Espín, F. A. Tomás-Barberán and M. V. Selma, Gut Bacteria Involved in Ellagic Acid Metabolism To Yield Human Urolithin Metabotypes Revealed, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2023, 71, 4029-4035.

146 G. Istas, R. P. Feliciano, T. Weber, R. Garcia-Villalba, F. Tomas-Barberan, C. Heiss and A. Rodriguez-Mateos, Plasma urolithin metabolites correlate with improvements in endothelial function after red raspberry consumption: A double-blind randomized controlled trial, Arch. Biochem. Biophys., 2018, 651, 43-51.

147 A. González-Sarrías, R. García-Villalba, M. Romo-Vaquero, C. Alasalvar, A. Örem, P. Zafrilla, F. A. Tomás-Barberán, M. V. Selma and J. C. Espín, Clustering according to urolithin metabotype explains the interindividual variability in the improvement of cardiovascular risk biomarkers in overweight-obese individuals consuming pomegranate: A randomized clinical trial, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2017, 61, 1600830.

149 A. Cortés-Martín, M. Romo-Vaquero, I. García-Mantrana, A. Rodríguez-Varela, M. C. Collado, J. C. Espín and M. V. Selma, Urolithin Metabotypes can Anticipate the Different Restoration of the Gut Microbiota and Anthropometric Profiles during the First Year Postpartum, Nutrients, 2019, 11, 2079.

150 A. Cortés-Martín, G. Colmenarejo, M. V. Selma and J. C. Espín, Genetic Polymorphisms, Mediterranean Diet and Microbiota-Associated Urolithin Metabotypes can Predict Obesity in Childhood-Adolescence, Sci. Rep., 2020, 10, 1-13.

151 C. E. Iglesias-Aguirre, A. González-Sarrías, A. CortésMartín, M. Romo-Vaquero, L. Osuna-Galisteo, J. J. Cerón, J. C. Espín and M. V. Selma, In vivo administration of gut bacterial consortia replicates urolithin metabotypes A and B in a non-urolithin-producing rat model, Food Funct., 2023, 14, 2657-2667.

152 D. D’Amico, P. A. Andreux, P. Valdés, A. Singh, C. Rinsch and J. Auwerx, Impact of the Natural Compound Urolithin A on Health, Disease, and Aging, Trends Mol. Med., 2021, 27, 687-699.

153 D. D’Amico, M. Olmer, A. M. Fouassier, P. Valdés, P. A. Andreux, C. Rinsch and M. Lotz, Urolithin A improves mitochondrial health, reduces cartilage degeneration, and alleviates pain in osteoarthritis, Aging Cell, 2022, 21, e13662.

154 S. Liu, D. D’Amico, E. Shankland, S. Bhayana, J. M. Garcia, P. Aebischer, C. Rinsch, A. Singh and D. J. Marcinek, Effect of Urolithin A Supplementation on Muscle Endurance and Mitochondrial Health in Older Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial, JAMA Netw. Open, 2022, 5, e2144279.

155 R. Zamora-Ros, C. Andres-Lacueva, R. M. LamuelaRaventós, T. Berenguer, P. Jakszyn, C. Martínez, M. J. Sánchez, C. Navarro, M. D. Chirlaque, M.-J. Tormo, J. R. Quirós, P. Amiano, M. Dorronsoro, N. Larrañaga, A. Barricarte, E. Ardanaz and C. A. González, Concentrations of resveratrol and derivatives in foods and estimation of dietary intake in a Spanish population: European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Spain cohort, Br. J. Nutr., 2008, 100, 188-196.

156 P. Yin, L. Yang, Q. Xue, M. Yu, F. Yao, L. Sun and Y. Liu, Identification and inhibitory activities of ellagic acid- and kaempferol-derivatives from Mongolian oak cups against

158 J. K. Bird, D. Raederstorff, P. Weber and R. E. Steinert, Cardiovascular and Antiobesity Effects of Resveratrol Mediated through the Gut Microbiota, Adv. Nutr., 2017, 8, 839-849.

159 B. N. M. Zordoky, I. M. Robertson and J. R. B. Dyck, Preclinical and clinical evidence for the role of resveratrol in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis., 2015, 1852, 1155-1177.

160 X. Huang, Y. Dai, J. Cai, N. Zhong, H. Xiao, D. J. McClements and K. Hu, Resveratrol encapsulation in core-shell biopolymer nanoparticles: Impact on antioxidant and anticancer activities, Food Hydrocolloids, 2017, 64, 157-165.

161 M. Samsami-kor, N. E. Daryani, P. R. Asl and A. Hekmatdoost, Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Resveratrol in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Randomized, DoubleBlind, Placebo-controlled Pilot Study, Arch. Med. Res., 2015, 46, 280-285.

162 C. E. Iglesias-Aguirre, F. Vallejo, D. Beltrán, J. Berná, J. Puigcerver, M. Alajarín, M. V. Selma and J. C. Espín, 4Hydroxydibenzyl: a novel metabolite from the human gut microbiota after consuming resveratrol, Food Funct., 2022, 13, 7487-7493.

163 S. V. Luca, I. Macovei, A. Bujor, A. Miron, K. SkalickaWoźniak, A. C. Aprotosoaie and A. Trifan, Bioactivity of dietary polyphenols: The role of metabolites, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., 2020, 60, 626-659.

164 S. Vogl, A. G. Atanasov, M. Binder, M. Bulusu, M. Zehl, N. Fakhrudin, E. H. Heiss, P. Picker, C. Wawrosch, J. Saukel, G. Reznicek, E. Urban, V. Bochkov, V. M. Dirsch and B. Kopp, The Herbal Drug Melampyrum pratense L. (Koch): Isolation and Identification of Its Bioactive Compounds Targeting Mediators of Inflammation, Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med., 2013, 2013, 395316.

165 T. Ito-Nagahata, C. Kurihara, M. Hasebe, A. Ishii, K. Yamashita, M. Iwabuchi, M. Sonoda, K. Fukuhara, R. Sawada, A. Matsuoka and Y. Fujiwara, Stilbene analogs of resveratrol improve insulin resistance through activation of AMPK, Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem., 2013, 77, 1229-1235.

166 F. Li, Y. Han, X. Wu, X. Cao, Z. Gao, Y. Sun, M. Wang and H. Xiao, Gut Microbiota-Derived Resveratrol Metabolites, Dihydroresveratrol and Lunularin, Significantly Contribute to the Biological Activities of Resveratrol, Front. Nutr., 2022, 9, 912591.

167 I. Günther, G. Rimbach, C. I. Mack, C. H. Weinert, N. Danylec, K. Lüersen, M. Birringer, F. Bracher, S. T. Soukup, S. E. Kulling and K. Pallauf, The Putative Caloric Restriction Mimetic Resveratrol has Moderate Impact on Insulin Sensitivity, Body Composition, and the Metabolome in Mice, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2020, 64, 1901116.

stilbene derivative dihydro-resveratrol: implication for treatment of acute pancreatitis, Sci. Rep., 2016, 6, 22859.

169 C. Rodríguez-García, C. Sánchez-Quesada, E. Toledo, M. Delgado-Rodríguez and J. J. Gaforio, Naturally LignanRich Foods: A Dietary Tool for Health Promotion?, Molecules, 2019, 24, 917.

170 R. Kiyama, Biological effects induced by estrogenic activity of lignans, Trends Food Sci. Technol., 2016, 54, 186-196.

171 J. Peterson, J. Dwyer, H. Adlercreutz, A. Scalbert, P. Jacques and M. L. McCullough, Dietary lignans: physiology and potential for cardiovascular disease risk reduction, Nutr. Rev., 2010, 68, 571-603.

172 A. K. Zaineddin, K. Buck, A. Vrieling, J. Heinz, D. FleschJanys, J. Linseisen and J. Chang-Claude, The Association Between Dietary Lignans, Phytoestrogen-Rich Foods, and Fiber Intake and Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Risk: A German Case-Control Study, Nutr. Cancer, 2012, 64, 652-665.

173 F. L. Miles, S. L. Navarro, Y. Schwarz, H. Gu, D. Djukovic, T. W. Randolph, A. Shojaie, M. Kratz, M. A. J. Hullar, P. D. Lampe, M. L. Neuhouser, D. Raftery and J. W. Lampe, Plasma metabolite abundances are associated with urinary enterolactone excretion in healthy participants on controlled diets, Food Funct., 2017, 8, 32093218.

175 A. Senizza, G. Rocchetti, J. I. Mosele, V. Patrone, M. L. Callegari, L. Morelli and L. Lucini, Lignans and Gut Microbiota: An Interplay Revealing Potential Health Implications, Molecules, 2020, 25, 5709.

176 T. Clavel, J. Doré and M. Blaut, Bioavailability of lignans in human subjects, Nutr. Res. Rev., 2006, 19, 187-196.

177 E. Eeckhaut, K. Struijs, S. Possemiers, J.-P. Vincken, D. D. Keukeleire and W. Verstraete, Metabolism of the Lignan Macromolecule into Enterolignans in the Gastrointestinal Lumen As Determined in the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2008, 56, 4806-4812.

178 Y. Hu, Y. Song, A. A. Franke, F. B. Hu, R. M. van Dam and Q. Sun, A Prospective Investigation of the Association Between Urinary Excretion of Dietary Lignan Metabolites and Weight Change in US Women, Am. J. Epidemiol., 2015, 182, 503-511.

179 C. Xu, Q. Liu, Q. Zhang, A. Gu and Z.-Y. Jiang, Urinary enterolactone is associated with obesity and metabolic alteration in men in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-10, Br. J. Nutr., 2015, 113, 683690.

182 W. Mullen, M.-A. Archeveque, C. A. Edwards, H. Matsumoto and A. Crozier, Bioavailability and Metabolism of Orange Juice Flavanones in Humans: Impact of a Full-Fat Yogurt, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2008, 56, 11157-11164.

183 I. Najmanová, M. Vopršalová, L. Saso and P. Mladěnka, The pharmacokinetics of flavanones, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., 2020, 60, 3155-3171.

184 M. Tomás-Navarro, F. Vallejo, E. Sentandreu, J. L. Navarro and F. A. Tomás-Barberán, Volunteer Stratification Is More Relevant than Technological Treatment in Orange Juice Flavanone Bioavailability, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2014, 62, 24-27.

185 F. Vallejo, M. Larrosa, E. Escudero, M. P. Zafrilla, B. Cerdá, J. Boza, M. T. García-Conesa, J. C. Espín and F. A. Tomás-Barberán, Concentration and Solubility of Flavanones in Orange Beverages Affect Their Bioavailability in Humans, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2010, 58, 6516-6524.

186 G. Pereira-Caro, G. Borges, J. van der Hooft, M. N. Clifford, D. Del Rio, M. E. Lean, S. A. Roberts, M. B. Kellerhals and A. Crozier, Orange juice (poly) phenols are highly bioavailable in humans, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2014, 100, 1378-1384.

187 A. Nishioka, E. de C. Tobaruela, L. N. Fraga, F. A. TomásBarberán, F. M. Lajolo and N. M. A. Hassimotto, Stratification of Volunteers According to Flavanone Metabolite Excretion and Phase II Metabolism Profile after Single Doses of ‘Pera’ Orange and ‘Moro’ Blood Orange Juices, Nutrients, 2021, 13, 473.

188 M. Á. Ávila-Gálvez, J. A. Giménez-Bastida, A. GonzálezSarrías and J. C. Espín, New Insights into the Metabolism of the Flavanones Eriocitrin and Hesperidin: A Comparative Human Pharmacokinetic Study, Antioxidants, 2021, 10, 435.

189 W. Lin, W. Wang, H. Yang, D. Wang and W. Ling, Influence of Intestinal Microbiota on the Catabolism of Flavonoids in Mice, J. Food Sci., 2016, 81, H3026-H3034.

190 A. Vogiatzoglou, A. A. Mulligan, R. N. Luben, M. A. H. Lentjes, C. Heiss, M. Kelm, M. W. Merx, J. P. E. Spencer, H. Schroeter and G. G. C. Kuhnle, Assessment of the dietary intake of total flavan-3-ols, monomeric flavan-3-ols, proanthocyanidins and theaflavins in the European Union, Br. J. Nutr., 2014, 111, 14631473.

ols: synthesis, analysis, bioavailability, and bioactivity, Nat. Prod. Rep., 2019, 36, 714-752.

192 A. Takagaki and F. Nanjo, Bioconversion of

193 S. Wiese, T. Esatbeyoglu, P. Winterhalter, H.-P. Kruse, S. Winkler, A. Bub and S. E. Kulling, Comparative biokinetics and metabolism of pure monomeric, dimeric, and polymeric flavan-3-ols: a randomized cross-over study in humans, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2015, 59, 610-621.

194 J. van Duynhoven, J. J. J. van der Hooft, F. A. van Dorsten, S. Peters, M. Foltz, V. Gomez-Roldan, J. Vervoort, R. C. H. de Vos and D. M. Jacobs, Rapid and sustained systemic circulation of conjugated gut microbial catabolites after single-dose black tea extract consumption, J. Proteome Res., 2014, 13, 2668-2678.

196 P. Mena, I. A. Ludwig, V. B. Tomatis, A. Acharjee, L. Calani, A. Rosi, F. Brighenti, S. Ray, J. L. Griffin, L. J. Bluck and D. Del Rio, Inter-individual variability in the production of flavan-3-ol colonic metabolites: preliminary elucidation of urinary metabotypes, Eur. J. Nutr., 2019, 58, 1529-1543.

197 F. Sánchez-Patán, C. Cueva, M. Monagas, G. E. Walton, G. R. M. Gibson, J. E. Quintanilla-López, R. LebrónAguilar, P. J. Martín-Álvarez, M. V. Moreno-Arribas and B. Bartolomé, In vitro fermentation of a red wine extract by human gut microbiota: changes in microbial groups and formation of phenolic metabolites, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2012, 60, 2136-2147.

198 P. Mena, C. Favari, A. Acharjee, S. Chernbumroong, L. Bresciani, C. Curti, F. Brighenti, C. Heiss, A. RodriguezMateos and D. Del Rio, Metabotypes of flavan-3-ol colonic metabolites after cranberry intake: elucidation and statistical approaches, Eur. J. Nutr., 2022, 61, 1299-1317.

199 A. Cortés-Martín, M. V. Selma, J. C. Espín and R. GarcíaVillalba, The Human Metabolism of Nuts Proanthocyanidins does not Reveal Urinary Metabolites Consistent with Distinctive Gut Microbiota Metabotypes, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2019, 63, 1800819.

200 N. Tosi, C. Favari, L. Bresciani, E. Flanagan, M. Hornberger, A. Narbad, D. Del Rio, D. Vauzour and P. Mena, Unravelling phenolic metabotypes in the frame of the COMBAT study, a randomized, controlled trial with cranberry supplementation, Food Res. Int., 2023, 172, 113187.

202 C. Busch, S. Noor, C. Leischner, M. Burkard, U. M. Lauer and S. Venturelli, Anti-proliferative activity of hop-derived

prenylflavonoids against human cancer cell lines, Wien. Med. Wochenschr., 2015, 165, 258-261.

203 E. Sommella, G. Verna, M. Liso, E. Salviati, T. Esposito, D. Carbone, C. Pecoraro, M. Chieppa and P. Campiglia, Hop-derived fraction rich in beta acids and prenylflavonoids regulates the inflammatory response in dendritic cells differently from quercetin: unveiling metabolic changes by mass spectrometry-based metabolomics, Food Funct., 2021, 12, 12800-12811.

204 B. Kontek, D. Jedrejek, W. Oleszek and B. Olas, Antiradical and antioxidant activity in vitro of hopsderived extracts rich in bitter acids and xanthohumol, Ind. Crops Prod., 2021, 161, 113208.

205 M. Rad, M. Hümpel, O. Schaefer, R. C. Schoemaker, W.-D. Schleuning, A. F. Cohen and J. Burggraaf, Pharmacokinetics and systemic endocrine effects of the phyto-oestrogen 8-prenylnaringenin after single oral doses to postmenopausal women, Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol., 2006, 62, 288-296.

206 L. A. Calvo-Castro, M. Burkard, N. Sus, G. Scheubeck, C. Leischner, U. M. Lauer, A. Bosy-Westphal, V. Hund, C. Busch, S. Venturelli and J. Frank, The Oral Bioavailability of 8-Prenylnaringenin from Hops (Humulus Lupulus L.) in Healthy Women and Men is Significantly Higher than that of its Positional Isomer 6-Prenylnaringenin in a Randomized Crossover Trial, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2018, 62, 1700838.

207 S. Possemiers, S. Rabot, J. C. Espín, A. Bruneau, C. Philippe, A. González-Sarrías, A. Heyerick, F. A. TomásBarberán, D. De Keukeleire and W. Verstraete, Eubacterium limosum activates isoxanthohumol from hops (Humulus lupulus L.) into the potent phytoestrogen 8 -prenylnaringenin in vitro and in rat intestine,

208 J. Guo, D. Nikolic, L. R. Chadwick, G. F. Pauli and R. B. van Breemen, Identification of Human Hepatic Cytochrome P450 Enzymes Involved in the Metabolism of 8-Prenylnaringenin and Isoxanthohumol from Hops (humulus Lupulus L.), Drug Metab. Dispos., 2006, 34, 1152-1159.

209 S. Bolca, S. Possemiers, V. Maervoet, I. Huybrechts, A. Heyerick, S. Vervarcke, H. Depypere, D. D. Keukeleire, M. Bracke, S. D. Henauw, W. Verstraete and T. V. de Wiele, Microbial and dietary factors associated with the 8-prenylnaringenin producer phenotype: a dietary intervention trial with fifty healthy post-menopausal Caucasian women, Br. J. Nutr., 2007, 98, 950-959.

210 D. Nikolic, Y. Li, L. R. Chadwick, S. Grubjesic, P. Schwab, P. Metz and R. B. van Breemen, Metabolism of 8-prenylnaringenin, a potent phytoestrogen from hops (Humulus lupulus), by human liver microsomes, Drug Metab. Dispos., 2004, 32, 272-279.

211 C. E. Iglesias-Aguirre, M. V. Selma and J. C. Espín, Unveiling metabotype clustering in resveratrol, daidzein, and ellagic acid metabolism: Prevalence, associated gut microbiomes, and their distinctive microbial networks, Food Res. Int., 2023, 173, 113470.

Department of Nutritional Sciences, School of Life Course and Population Sciences, Faculty of Life Sciences and Medicine, King’s College London, London, UK. E-mail: ana.rodriguez-mateos@kcl.ac.uk

Buchinger Wilhelmi Clinic, Überlingen, Germany

School of Food Science and Nutrition, Faculty of Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Surrey, Surrey, UK

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/d3fo04338j

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38414364

Publication Date: 2024-01-01

(Poly)phenol-related gut metabotypes and human health: an update

Abstract

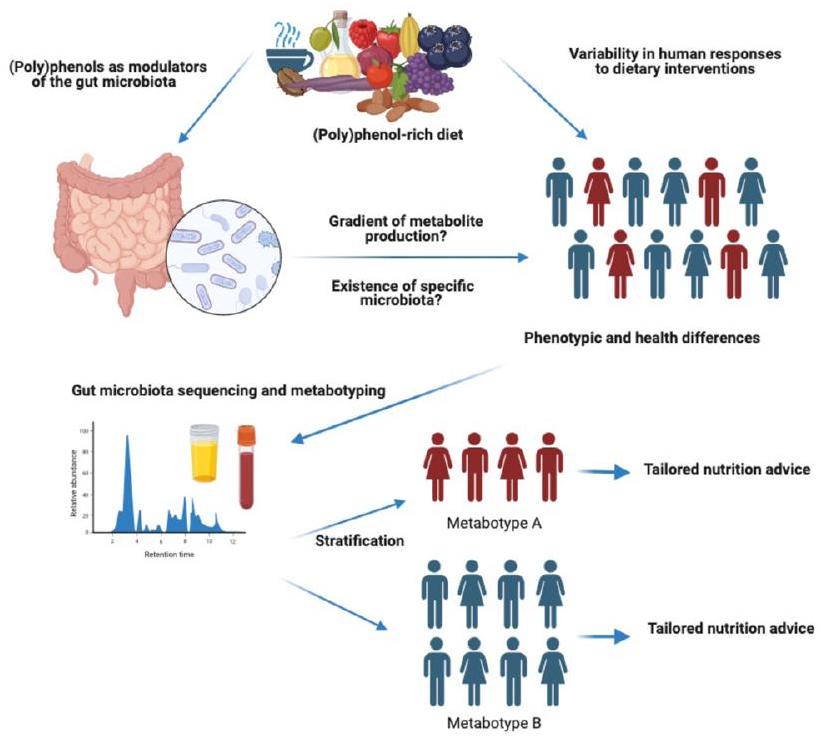

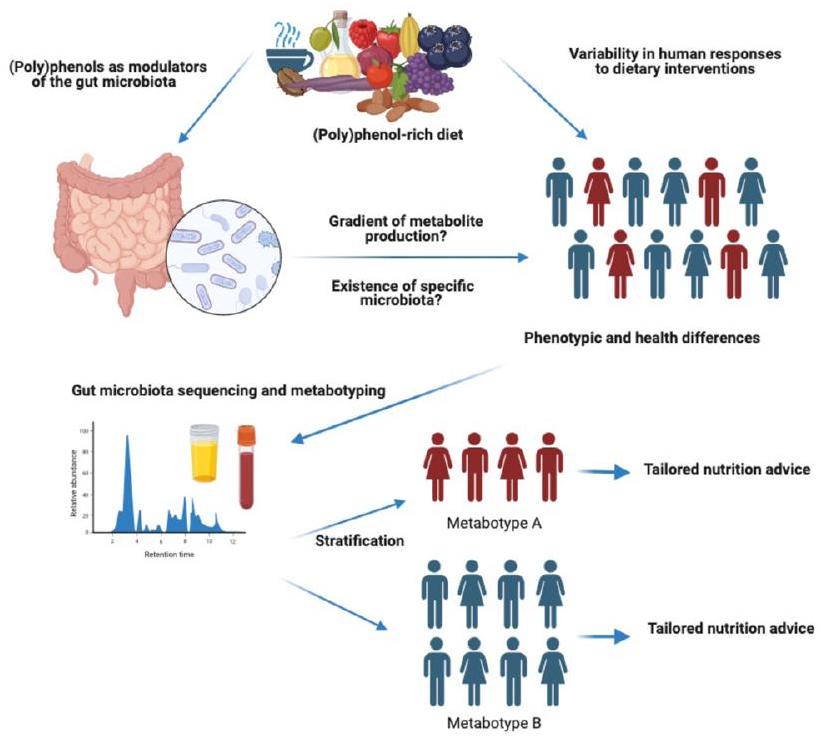

Dietary (poly)phenols have received great interest due to their potential role in the prevention and management of non-communicable diseases. In recent years, a high inter-individual variability in the biological response to (poly)phenols has been demonstrated, which could be related to the high variability in (poly)phenol gut microbial metabolism existing within individuals. An interplay between (poly)phenols and the gut microbiota exists, with (poly)phenols being metabolised by the gut microbiota and their metabolites modulating gut microbiota diversity and composition. A number of (poly)phenol metabolising phenotypes or metabotypes have been proposed, however, potential metabotypes for most (poly)phenols have not been investigated, and the relationship between metabotypes and human health remains ambiguous. This review presents updated knowledge on the reciprocal interaction between (poly)phenols and the gut microbiome, associated gut metabotypes, and subsequent impact on human health.

Introduction

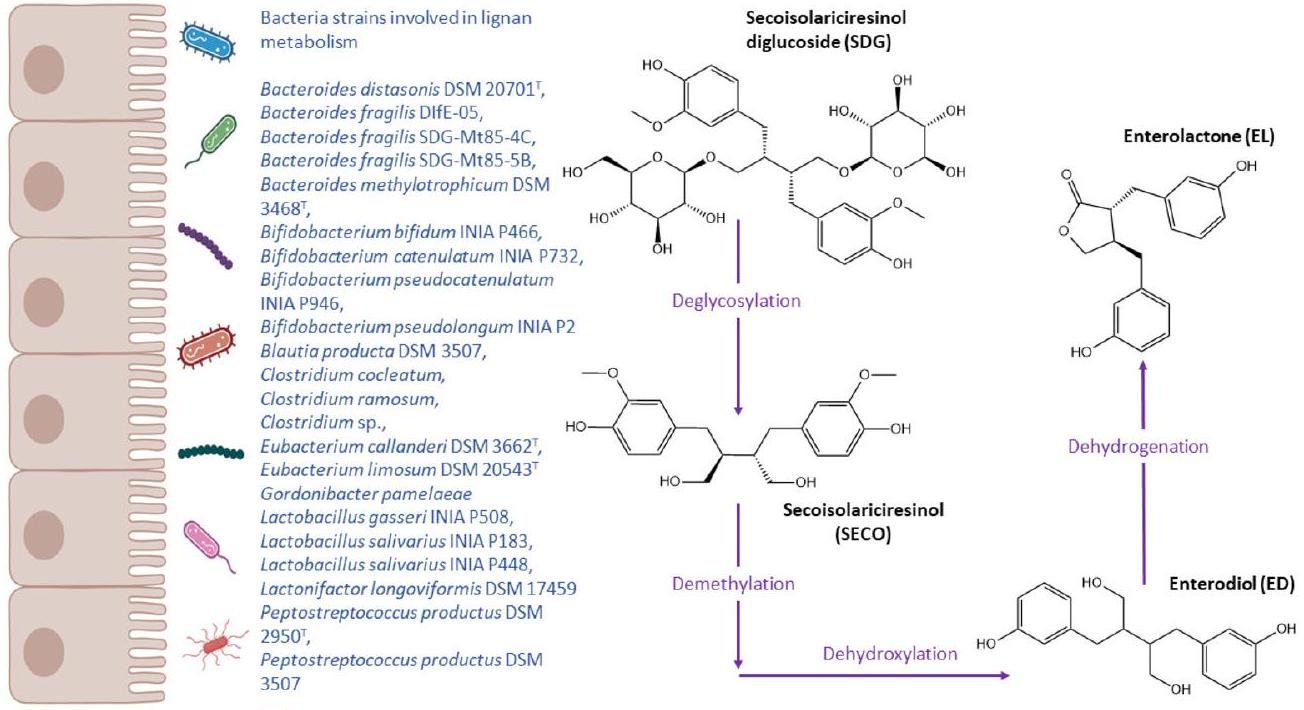

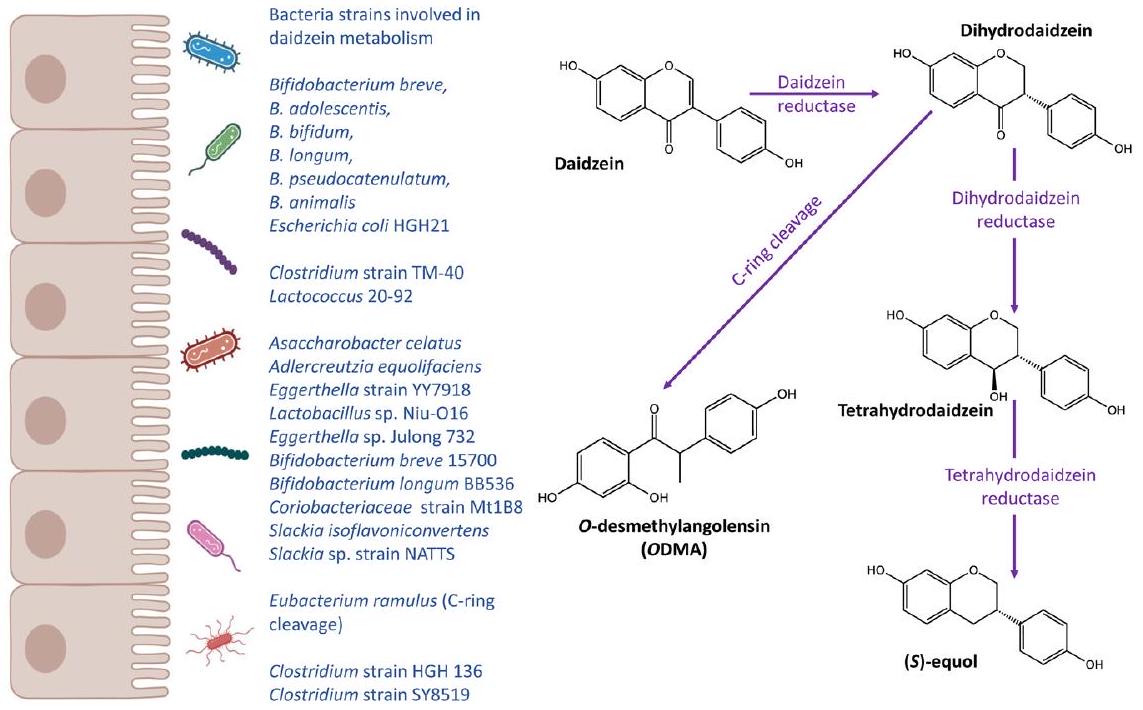

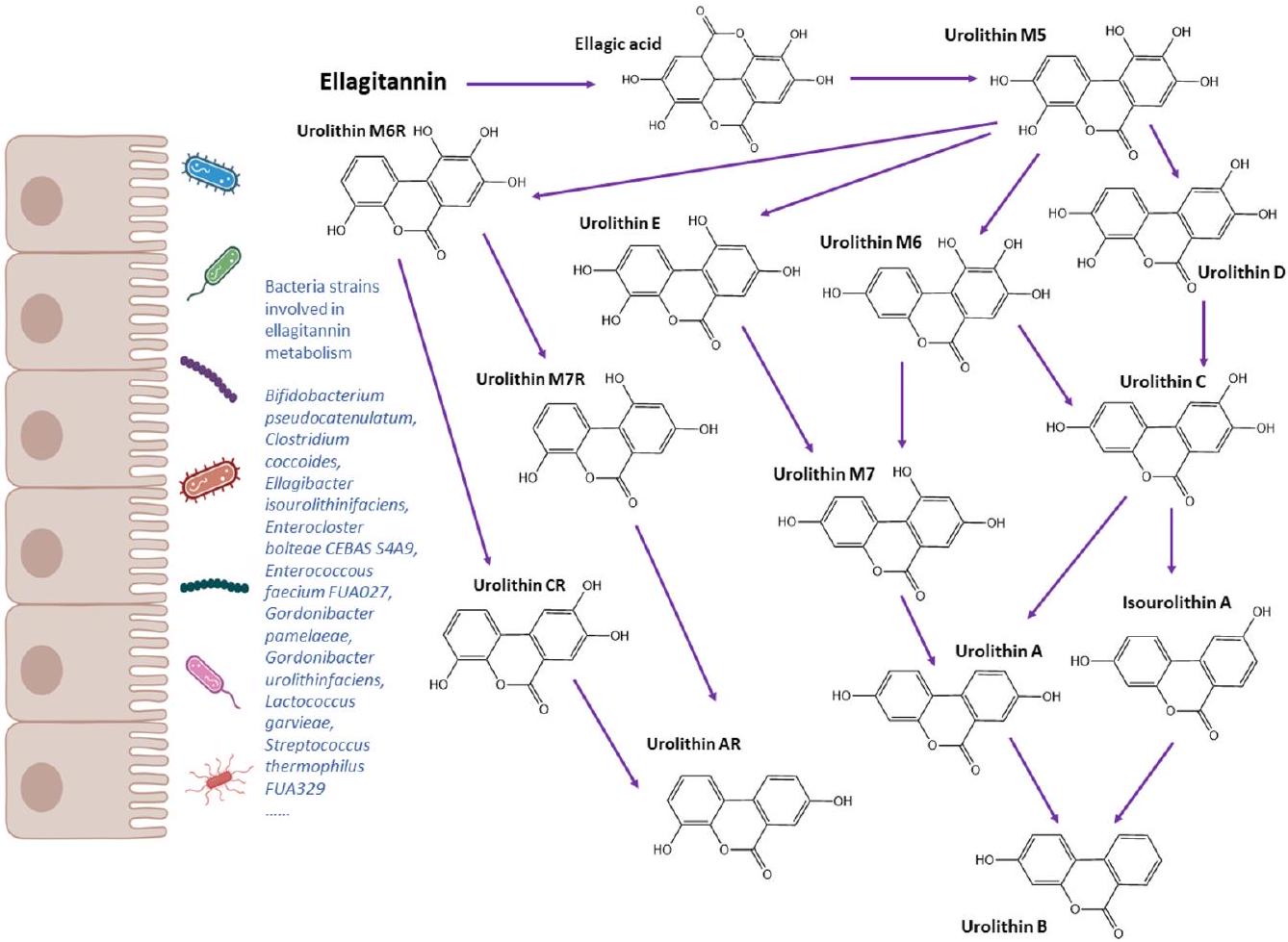

Gut microbial metabolism of (poly)phenols

(Poly)phenols as modulators of the gut microbiota

the growth of beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium,

Variability in (poly)phenol gut microbial metabolism: the concept of ( poly)phenol metabotypes

| Phenolic class | Species/strain | Substrate(s) | Reaction | Ref. |

| Anthocyanins | Bifidobacterium lactis | Anthocyanin |

|

39 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | Anthocyanin |

|

39 | |

| Lactobacillus casei | Anthocyanin |

|

39 | |

| Lactobacillus.plantarum | Anthocyanin |

|

39 | |

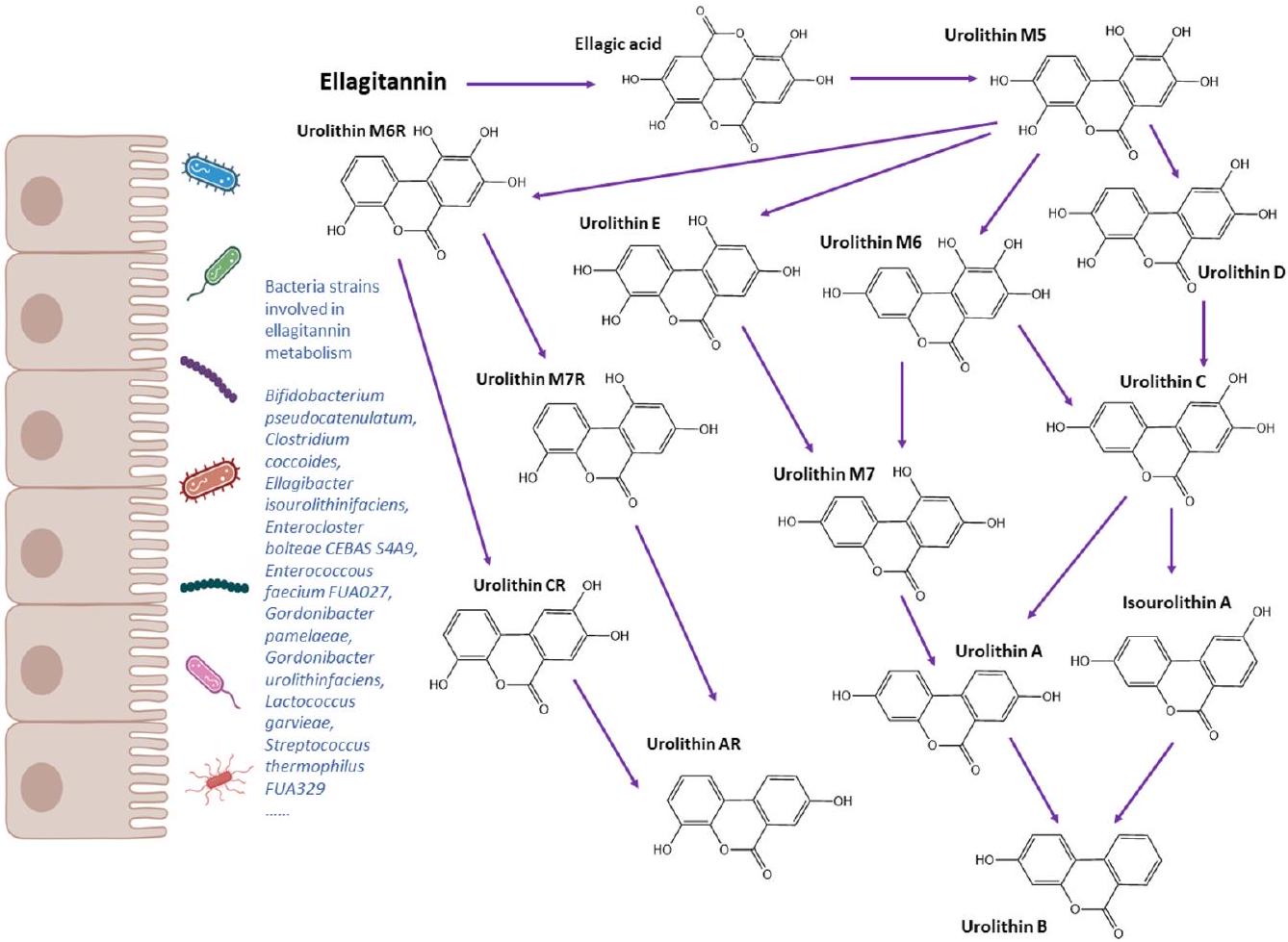

| Ellagitannins | Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum | Ellagic acid | Metabolise ellagic acid to urolithin A and B | 40 |

| Clostridium coccoides members | Ellagic acid | Metabolise ellagic acid to urolithins | 41 | |

| Ellagibacter isourolithinifaciens | Ellagic acid | Metabolise ellagic acid to isourolithin A | 42 | |

| Enterococcus faecium FUA027 | Ellagic acid | Metabolise ellagic acid to urolithin A | 43 | |

| Gordonibacter pamelaeae | Ellagic acid | Metabolise ellagic acid to urolithins | 44 | |

| Gordonibacter urolithinfaciens | Ellagic acid | Metabolise ellagic acid to urolithins | 45 | |

| Lactococcus garvieae FUA009 | Ellagic acid | Metabolise ellagic acid to urolithin A | 46 | |

| Streptococcus thermophilus FUA329 | Ellagic acid | Metabolise ellagic acid to urolithin A | 47 | |

| Flavanones | Bacteroides distasonis | Eriocitrin | Hydrolysis | 48 |

| Bacteroides uniformis | Eriocitrin | Hydrolysis | 48 | |

| Bifidobacterium catenulatum | Hesperidin | Hydrolysis | 49 | |

| Bifidobacterium pseudocatenultum | Hesperidin | Hydrolysis | 49 | |

| Clostridium butyricum | Eriocitrin | C-ring cleavage | 48 | |

| Flavan-3-ols | Adlercreutzia equolifaciens JCM 14793 | (-)-Epigallocatechin, (-)-gallocatechin | Dihydroxylation | 50 |

| Asaccharobacter celatus JCM 14811 | (-)-Epigallocatechin, (-)-gallocatechin | C-ring cleavage | 50 | |

| Eggerthella lenta | (-)-Epicatechin, (+)-catechin | C-ring cleavage | 51 | |

| Slackia equolifaciens JCM 16059 | (-)-Epigallocatechin, (-)-gallocatechin | C-ring cleavage | 50 | |

| Flavones | Blautia sp. MRG-PMF1 | Apigetrin |

|

52 |

| Eubacterium cellulosolvens | Homoorientin, isovitexin | Deglycosylation of

|

53 | |

| Flavonols | Bacillus subtilis | Quercetin | C-ring cleavage | 54 |

| Bacteroides distasonis | Robinin | Hydrolyse robinin to kaempferol | 55 | |

| Bacteroides ovatus | Rutin |

|

55 | |

| Bacteroides uniformis | Rutin |

|

55 | |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside |

|

56 | |

| Bifidobacterium bifidum | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside |

|

56 | |

| Bifidobacterium breve | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside |

|

56 | |

| Bifidobacterium catenulatum | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside | Hydrolysis,

|

56 | |

| Bifidobacterium dentium | Rutin, poncirin | Hydrolysis | 57 | |

| Bifidobacterium infantis | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside |

|

56 | |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside |

|

56 | |

| Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside | Hydrolysis,

|

56 | |

| Blautia sp. MRG-PMF1 | Hesperidin, Poylmethoxyflavones |

|

52 | |

| Clostridium orbiscindens | Quercetin, taxifolin, luteolin, apigenin, naringenin, phloretin | C-ring cleavage | 58 | |

| Enterococcus avium | Rutin |

|

59,60 | |

| Enterococcus casseliflavus | Quercetin-3-glucoside | Hydrolysis | 61 | |

| Eubacterium ramulus | Rutin, quercetin, kaempferol, taxifolin, luteolin, quercetin-3glucoside | C-ring cleavage | 61-63 | |

| Flavonifractor plautii | Quercetin | C-ring cleavage | 64 | |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | Rutin, nicotiflorin, narirutin |

|

65 | |

| Lactobacillus plantarum | Rutin, nicotiflorin, narirutin |

|

65 |

| Phenolic class | Species/strain | Substrate(s) | Reaction | Ref. |

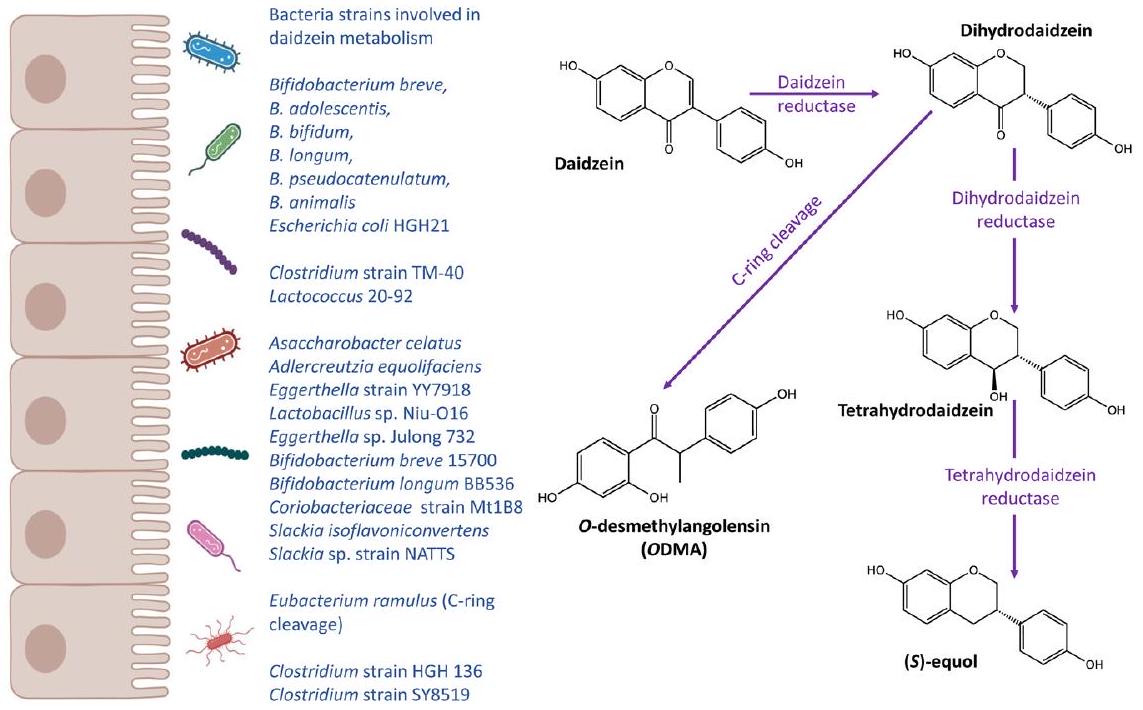

| Isoflavones | Adlercreutzia equolifaciens | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to equol | 66 |

| Asaccharobacter celatus | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to equol | 67 | |

| Bifidobacterium adolescentis | Daidzein | Hydrolysis | 68 | |

| Bifidobacterium animalis | Daidzein | Hydrolysis | 69 | |

| Bifidobacterium bifidum | Daidzein | Hydrolysis | 68 | |

| Bifidobacterium breve | Daidzein | Hydrolysis | 68 | |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Daidzein | Hydrolysis | 69,70 | |

| Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum | Daidzein | Hydrolysis | 69,70 | |

| Blautia sp. MRG-PMF1 | Daidzein, genistin, glycitin | Hydrolysis, O-glucose &

|

52 | |

| Clostridium strain HGH 136 | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to ODMA | 71 | |

| Clostridium strain SY8519 | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to ODMA | 32 | |

| Clostridium strain TM-40 | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to dihydrodaidzein | 72 | |

| Coriobacteriaceae strain Mt1B8 | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to equol | 73 | |

| Eggerthella strain YY7918 | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to equol | 74 | |

| Eggerthella sp. Julong 732 | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to equol | 75 | |

| Enterococcus sp. MRG-IFC-2 | Puerarin |

|

76 | |

| Escherichia coli HGH21 | Daidzein, genistin |

|

77 | |

| Eubacterium ramulus | Daidzein, genistin | C-ring cleavage | 78 | |

| Lachnospiraceae strain CG19-1 | Puerarin | Deglycosylation | 79 | |

| Lactobacillus sp. Niu-O16 | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to equol | 75 | |

| Lactococcus sp. MRG-IFC-1 | Puerarin |

|

76 | |

| Lactococcus 20-92 | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to dihydrodaidzein | 36 | |

| Slackia isoflavoniconvertens | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to equol | 80 | |

| Slackia sp. strain NATTS | Daidzein | Bioconversion of daidzein to equol | 81 | |

| Lignans | Bacteroides distasonis DSM

|

Secoisolariciresinol (SECO) | Deglycosylation | 82 |

| Bacteroides fragilis DIfE-05 | SECO | Deglycosylation | 82 | |

| Bacteroides fragilis SDG-Mt85-4C, B. fragilis SDG-Mt85-5B | SECO | Deglycosylation | 82 | |

| Bacteroides methylotrophicum DSM

|

SECO | Demethylation | 82 | |

| Bifidobacterium bifidum INIA P466 | SECO | Metabolise SECO to enterodiol | 83 | |

| Bifidobacterium catenulatum INIA P732 | SECO | Metabolise SECO to enterodiol | 83 | |

| Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum INIA | SDG | Deglycosylation of SDG to SECO | 83 | |

| Bifidobacterium pseudolongum INIA P2 | SECO | Metabolise SECO to enterodiol | 83 | |

| Blautia producta DSM 3507 | SECO | Demethylation | 84 | |

| Clostridium cocleatum | Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) | Deglycosylation | 82 | |

| Clostridium ramosum | SDG | Deglycosylation | 82 | |

| Eggerthella lenta DSM 2243 | Pinoresinol, lariciresinol | Reduction | 84 | |

| Eubacterium callanderi DSM

|

SECO | Demethylation | 82 | |

| Eubacterium limosum DSM

|

SECO | Demethylation | 82 | |

| Gordonibacter pamelaeae | Didemethyl-SECO | dehydroxylation | 84 | |

| Lactobacillus gasseri INIA P508, | SECO | Metabolise SECO to enterolignans | 83 | |

| Lactobacillus salivarius INIA P183, Lactobacillus salivarius INIA P448 | SECO | Metabolise SECO to enterolignans | 83 | |

| Lactonifactor longoviformis DSM 17459 | Enterodiol | Lactonization, bioconversion of enterodiol to enterolactone | 84 | |

| Gordonibacter pamelaeae | Didemethyl-SECO | dehydroxylation | 84 | |

| Peptostreptococcus productus DSM

|

SECO | Demethylation | 82 |

| Phenolic class | Species/strain | Substrate(s) | Reaction | Ref. |

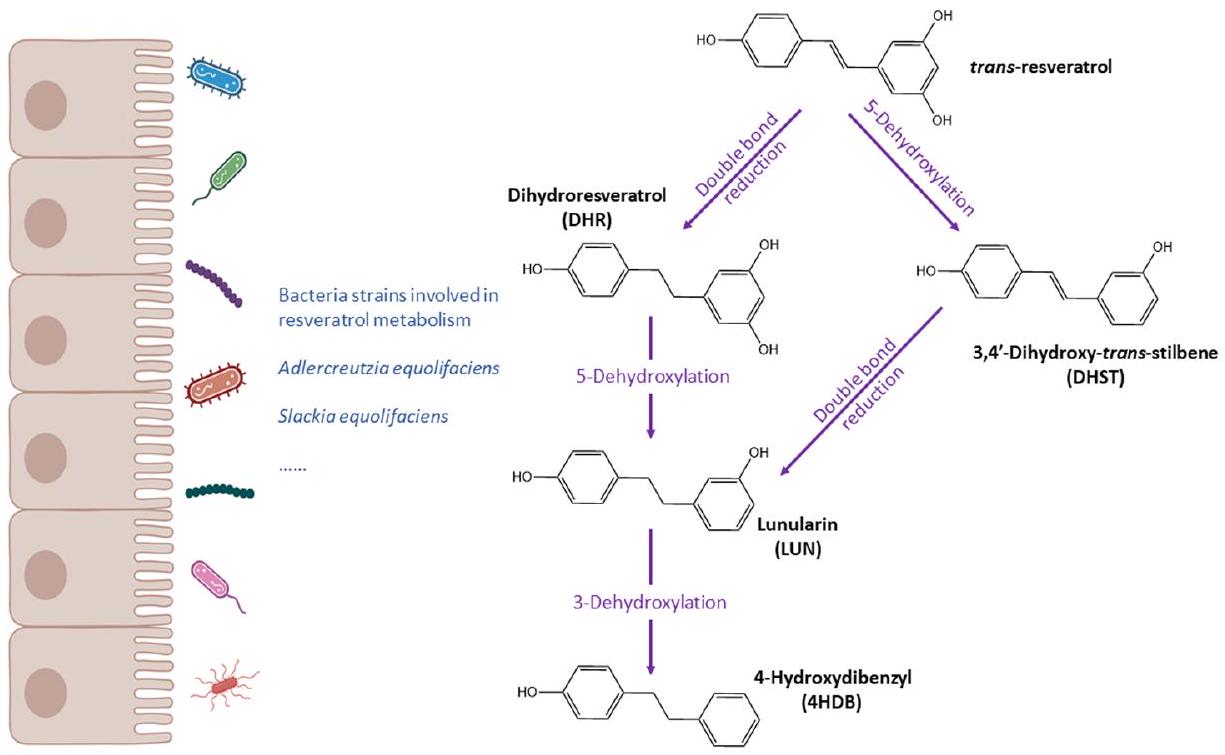

| Stilbenes | Adlercreutzia equolifaciens | Resveratrol | Metabolism resveratrol into dihydroresveratrol | 85 |

| Slackia equolifaciens | Resveratrol | Metabolism resveratrol into dihydroresveratrol | 85 | |

| Xanthohumol | Eubacterium ramulus | Xanthohumol | Hydrogenation | 86 |

| Eubacterium limosum | Isoxanthohumol |

|

86 |

(cc) EY-Nc This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence.

able to the notion of enterotype, a classification of gut microbiome composition profiles which is proposed to support the development of personalised nutrition strategies.

(Poly)phenol metabotypes and human health: what we know so far

Equol and ODMA metabotypes

by gut bacteria into bioactive aglycones, including daidzein, genistein and glycitein. Soy consumption is generally high in Asian countries whereas low in Western population.

of bifidobacterial in the biotransformation of isoflavones in soy milk has been well established.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence.

Urolithin metabotypes

correlation between Slackia and cardiometabolic risk factors, such as total cholesterol, LDL, apolipoprotein B and nonHDL.

mothers differed between UMs. During 1 year after delivery, UMB mothers showed a more robust gut microbial ecology that was resistant to changes, while UMA mothers had altered gut microbiota correlated with decreased waist circumference. The same authors later investigated associations between obesity prevalence and other factors including UM in a cohort of children and adolescents

Lunularin metabotypes

effects.

Low vs. high producer metabotypes

and stratification may be useful to explain the high variability in response observed after (poly)phenol consumption. In this section we will discuss some examples of relevant (poly) phenols with very specific and unique gut microbial metabolites. Many other abundant classes of (poly)phenols, such as phenolic acids, anthocyanins or flavonols, have common gut microbial metabolites such as catechol, benzoic acids or hippuric acid derivatives which may come from multiple dietary sources and not exclusively from (poly)phenols, and are therefore not specific enough to stratify individuals into different metabotypes easily. However, the circulating levels of those common and abundant metabolites could be used as overall markers of (poly)phenol-rich food consumption and diet quality, and therefore their relationships with health outcomes and gut microbiota diversity, composition, and functionality are of great interest to investigate individual responses and mechanistic aspects.

Lignans

may simply be related to lignan intake rather than the metabolising capacity of the gut microbiota. Therefore, in the absence of stratified randomised controlled trials into low and high EL and ED producers, whether the variability in gut microbial metabolism can explain the variability in response to lignan consumption remains unknown.

Flavanones

Flavan-3-ols

by phase-II enzymes, then excreted in urine.

Hop prenylflavonoids

possess antioxidant, anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, estrogenic and immune-regulatory properties.

Metabotype clustering: is there a common metabotype for multiple (poly)phenol subclasses?

bined (poly)phenol metabolism and further confirm the prediction for the models on health outcomes through pre-stratified randomized controlled trials.

Conclusion

metagenomics and metabolomics could contribute to a better understanding of (poly)phenol metabolism and the role of gut microbiota. Using metabolomics allows determination of functional aspects which is often not captured by gut microbiome composition analyses. Large cohort studies are a suitable means to examine the distribution and determinants of metabotypes and also concentration ranges of (poly)phenol unique marker metabolites, but also common metabolites of multiple (poly)phenols. Application of artificial intelligence here would help identify new, less obvious metabotypes defined by concentration ranges of common (poly)phenol metabolites. Clinical intervention trials should also be carried out to identify the role of (poly)phenol metabolites in the modulation of health effects. Overall, the relationships between (poly)phenol metabolism, gut microbiota composition, and subsequent health effects deserve further research.

Author contributions

Conflicts of interest

References

2 M. I. Khan, J. H. Shin, T. S. Shin, M. Y. Kim, N. J. Cho and J. D. Kim, Anthocyanins from Cornus kousa ethanolic extract attenuate obesity in association with anti-angiogenic activities in 3T3-L1 cells by down-regulating adipogeneses and lipogenesis, PLoS One, 2018, 13, e0208556.

3 D. Esposito, A. Chen, M. H. Grace, S. Komarnytsky and M. A. Lila, Inhibitory Effects of Wild Blueberry Anthocyanins and Other Flavonoids on Biomarkers of Acute and Chronic Inflammation in Vitro, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2014, 62, 7022-7028.

4 M. M. Coman, A. M. Oancea, M. C. Verdenelli, C. Cecchini, G. E. Bahrim, C. Orpianesi, A. Cresci and S. Silvi, Polyphenol content and in vitro evaluation of antioxidant, antimicrobial and prebiotic properties of red fruit extracts, Eur. Food Res. Technol., 2018, 244, 735-745.

5 M. Inglés, J. Gambini, M. G. Miguel, V. Bonet-Costa, K. M. Abdelaziz, M. El Alami, J. Viña and C. Borrás, PTEN Mediates the Antioxidant Effect of Resveratrol at Nutritionally Relevant Concentrations, BioMed Res. Int., 2014, 2014, e580852.

7 P. Basu and C. Maier, Phytoestrogens and breast cancer: In vitro anticancer activities of isoflavones, lignans, coumestans, stilbenes and their analogs and derivatives, Biomed. Pharmacother., 2018, 107, 1648-1666.

8 M. Á. Ávila-Gálvez, A. González-Sarrías and J. C. Espín, In Vitro Research on Dietary Polyphenols and Health: A Call of Caution and a Guide on How To Proceed, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2018, 66, 7857-7858.

9 P. Mena and D. Del Rio, Gold Standards for Realistic (Poly)phenol Research, J. Agric. Food Chem., 2018, 66, 8221-8223.

10 A. Tresserra-Rimbau, E. B. Rimm, A. Medina-Remón, M. A. Martínez-González, R. de la Torre, D. Corella, J. Salas-Salvadó, E. Gómez-Gracia, J. Lapetra, F. Arós, M. Fiol, E. Ros, L. Serra-Majem, X. Pintó, G. T. Saez, J. Basora, J. V. Sorlí, J. A. Martínez, E. Vinyoles, V. RuizGutiérrez, R. Estruch and R. M. Lamuela-Raventós, Inverse association between habitual polyphenol intake and incidence of cardiovascular events in the PREDIMED study, Nutr., Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis., 2014, 24, 639-647.

11 A. A. Fallah, E. Sarmast and T. Jafari, Effect of dietary anthocyanins on biomarkers of glycemic control and glucose metabolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, Food Res. Int., 2020, 137, 109379.

12 M. Bonaccio, G. Pounis, C. Cerletti, M. B. Donati, L. Iacoviello, G. de Gaetano and on behalf of the M.-S. S. Investigators, Mediterranean diet, dietary polyphenols and low grade inflammation: results from the MOLI-SANI study, Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol., 2017, 83, 107113.

14 C. Valls-Pedret, R. M. Lamuela-Raventós, A. MedinaRemón, M. Quintana, D. Corella, X. Pintó, M. Á. MartínezGonzález, R. Estruch and E. Ros, Polyphenol-Rich Foods in the Mediterranean Diet are Associated with Better Cognitive Function in Elderly Subjects at High Cardiovascular Risk, J. Alzheimer’s Dis., 2012, 29, 773-782.

15 L. T. Fike, H. Munro, D. Yu, Q. Dai and M. J. Shrubsole, Dietary polyphenols and the risk of colorectal cancer in the prospective Southern Community Cohort Study, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., 2022, 115, 1155-1165.

16 N. M. Pham, V. V. Do and A. H. Lee, Polyphenol-rich foods and risk of gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Eur. J. Clin. Nutr., 2019, 73, 647-656.

17 F. Potì, D. Santi, G. Spaggiari, F. Zimetti and I. Zanotti, Polyphenol Health Effects on Cardiovascular and Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Review and MetaAnalysis, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2019, 20, 351.

19 B. de Roos, A.-M. Aura, M. Bronze, A. Cassidy, M.-T. G. Conesa, E. R. Gibney, A. Greyling, J. Kaput, Z. Kerem, N. Knežević, P. Kroon, R. Landberg, C. Manach, D. Milenkovic, A. Rodriguez-Mateos, F. A. TomásBarberán, T. van de Wiele and C. Morand, Targeting the delivery of dietary plant bioactives to those who would benefit most: from science to practical applications, Eur. J. Nutr., 2019, 58, 65-73.

20 L. Chen, H. Cao and J. Xiao, in Polyphenols: Properties, Recovery, and Applications, ed. C. M. Galanakis, Woodhead Publishing, 2018, pp. 45-67.

21 S. Mithul Aravind, S. Wichienchot, R. Tsao, S. Ramakrishnan and S. Chakkaravarthi, Role of dietary polyphenols on gut microbiota, their metabolites and health benefits, Food Res Int, 2021, 142, 110189.

22 A. González-Sarrías, J. A. Giménez-Bastida, M. Á. NúñezSánchez, M. Larrosa, M. T. García-Conesa, F. A. TomásBarberán and J. C. Espín, Phase-II metabolism limits the antiproliferative activity of urolithins in human colon cancer cells, Eur. J. Nutr., 2014, 53, 853-864.

23 L. Rubio, A. Macia and M.-J. Motilva, Impact of Various Factors on Pharmacokinetics of Bioactive Polyphenols: An Overview, Curr. Drug Metab., 2014, 15, 62-76.

24 T. Rao, Z. Tan, J. Peng, Y. Guo, Y. Chen, H. Zhou and D. Ouyang, The pharmacogenetics of natural products: A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic perspective, Pharmacol. Res., 2019, 146, 104283.

25 C. L. Frankenfeld, O-Desmethylangolensin: The Importance of Equol’s Lesser Known Cousin to Human Health, Adv. Nutr., 2011, 2, 317-324.

26 F. A. Tomás-Barberán, A. González-Sarrías, R. GarcíaVillalba, M. A. Núñez-Sánchez, M. V. Selma, M. T. GarcíaConesa and J. C. Espín, Urolithins, the rescue of “old” metabolites to understand a “new” concept: Metabotypes as a nexus among phenolic metabolism, microbiota dysbiosis, and host health status, Mol. Nutr. Food Res., 2017, 61, 1500901.

27 F. A. Tomás-Barberán, M. V. Selma and J. C. Espín, Interactions of gut microbiota with dietary polyphenols and consequences to human health, Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care, 2016, 19, 471-476.

28 J. C. Espín, A. González-Sarrías and F. A. Tomás-Barberán, The gut microbiota: A key factor in the therapeutic effects of (poly)phenols, Biochem. Pharmacol., 2017, 139, 82-93.

29 A. Braune and M. Blaut, Bacterial species involved in the conversion of dietary flavonoids in the human gut, Gut Microbes, 2016, 7, 216-234.

30 X. Feng, Y. Li, M. Brobbey Oppong and F. Qiu, Insights into the intestinal bacterial metabolism of flavonoids and

the bioactivities of their microbe-derived ring cleavage metabolites, Drug Metab. Rev., 2018, 50, 343-356.

31 X.-L. Wang, K.-T. Kim, J.-H. Lee, H.-G. Hur and S.-I. Kim, C-Ring Cleavage of Isoflavones Daidzein and Genistein by a Newly-Isolated Human Intestinal Bacterium Eubacterium ramulus Julong 601, J. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 2004, 14, 766771.

33 S. Yokoyama and T. Suzuki, Isolation and characterization of a novel equol-producing bacterium from human feces, Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem., 2008, 72, 2660-2666.

34 J.-S. Jin, T. Nishihata, N. Kakiuchi and M. Hattori, Biotransformation of C-glucosylisoflavone puerarin to estrogenic (3S)-equol in co-culture of two human intestinal bacteria, Biol. Pharm. Bull., 2008, 31, 1621-1625.

35 A. Matthies, M. Blaut and A. Braune, Isolation of a Human Intestinal Bacterium Capable of Daidzein and Genistein Conversion, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2009, 75, 1740-1744.

36 Y. Shimada, S. Yasuda, M. Takahashi, T. Hayashi, N. Miyazawa, I. Sato, Y. Abiru, S. Uchiyama and H. Hishigaki, Cloning and Expression of a Novel NADP (H)-Dependent Daidzein Reductase, an Enzyme Involved in the Metabolism of Daidzein, from Equol-Producing Lactococcus Strain 20-92, Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2010, 76, 5892-5901.

37 J. F. Stevens and C. S. Maier, The chemistry of gut microbial metabolism of polyphenols, Phytochem. Rev., 2016, 15, 425-444.

38 R. García-Villalba, D. Beltrán, M. D. Frutos, M. V. Selma, J. C. Espín and F. A. Tomás-Barberán, Metabolism of different dietary phenolic compounds by the urolithinproducing human-gut bacteria Gordonibacter urolithinfaciens and Ellagibacter isourolithinifaciens, Food Funct., 2020, 11, 7012-7022.

39 M. Avila, M. Hidalgo, C. Sánchez-Moreno, C. Pelaez, T. Requena and S. de Pascual-Teresa, Bioconversion of anthocyanin glycosides by Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus, Food Res. Int., 2009, 42, 1453-1461.

40 P. Gaya, Á. Peirotén, M. Medina, I. Álvarez and J. M. Landete, Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum INIA P815: The first bacterium able to produce urolithins A and B from ellagic acid, J. Funct. Foods, 2018, 45, 9599.

44 M. V. Selma, F. A. Tomás-Barberán, D. Beltrán, R. GarcíaVillalba and J. C. Espín, Gordonibacter urolithinfaciens sp. nov., a urolithin-producing bacterium isolated from the human gut, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., 2014, 64, 2346-2352.

45 M. V. Selma, D. Beltrán, R. García-Villalba, J. C. Espín and F. A. Tomás-Barberán, Description of urolithin production capacity from ellagic acid of two human intestinal Gordonibacter species, Food Funct., 2014, 5, 1779-1784.

46 H. Mi, S. Liu, Y. Hai, G. Yang, J. Lu, F. He, Y. Zhao, M. Xia, X. Hou and Y. Fang, Lactococcus garvieae FUA009, a Novel Intestinal Bacterium Capable of Producing the Bioactive Metabolite Urolithin A from Ellagic Acid, Foods, 2022, 11, 2621.