DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.23023.loh

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-01

أهمية الميزات والممثلين

الملخص

تعتمد الأساليب الرسمية نحو القواعد ثنائية اللغة ومتعددة اللغات على ادعائين مهمين: (1) يجب أن تكون البنية النحوية قادرة على التعامل مع البيانات أحادية وثنائية/متعددة اللغات دون أي قيود محددة للأخيرة، (2) تلعب الميزات دورًا محوريًا في تفسير الأنماط عبر القواعد وداخلها. في الورقة الحالية، يُدعى أن نهج الهيكل الخارجي نحو القواعد، الذي يميز بوضوح بين الميزات النحوية الأساسية وتجلياتها المورفوفونولوجية (المؤشرات)، يقدم أداة مثالية لتحليل البيانات من المتحدثين ثنائي ومتعدد اللغات. على وجه التحديد، يُظهر أن هذا الإطار يمكن أن يشمل الآلية المحددة لإعادة تجميع الميزات التي طورتها دونا لاردير منذ أواخر التسعينيات. تُقدم ثلاث دراسات حالة تتضمن لغات وتركيبات لغوية مختلفة لدعم هذا الادعاء، مما يوضح كيف يمكن استخدام نهج الهيكل الخارجي دون أي قيود أو آليات إضافية.

1. المقدمة

- هل من الممكن نمذجة القواعد اللغوية الثنائية بطريقة منهجية ومقيدة؟

- ما هي أنواع التغييرات/التعديلات المعمارية المطلوبة (إن وجدت) لتحقيق هذا الهدف مقارنةً بتلك المفترضة للقواعد اللغوية أحادية اللغة؟

آلية معقدة مثل إعادة تجميع الميزات غير ضرورية. قوة رئيسية في النهج الحالي هي أن الآليات التي تم اقتراحها كعناصر أساسية لإعادة تجميع الميزات متاحة جميعها كعناصر أولية في الهيكل الخارجي، مما يجعل إعادة تجميع الميزات زائدة عن الحاجة كنظرية أو آلية منفصلة. من وجهة النظر التي ترى أن القواعد النحوية ثنائية اللغة منظمة ومقيدة تمامًا مثل القواعد النحوية أحادية اللغة، فإن هذه نتيجة رئيسية ومرحب بها، حيث يجب أن تكون الآلات النظرية رشيقة وقابلة للتفسير قدر الإمكان (انظر تشومسكي 1995، 2005).

2. الإطار النظري

2.1 إعادة تجميع الميزات

يحدث نوع من الانفصال بين النحو والصرف بحيث يكون الصرف مفقودًا بطريقة ما، ولكن فقط على السطح.

يتطلب تجميع العناصر المعجمية الخاصة بلغة ثانية من المتعلم إعادة تكوين الميزات من الطريقة التي تم تمثيلها بها في اللغة الأولى إلى تكوينات رسمية جديدة على أنواع مختلفة من العناصر المعجمية في اللغة الثانية.

[…] تشير البيانات المتاحة إلى أن الميزات المجردة التي تحفز الحسابات النحوية معزولة بشكل وحدوي عن التفاصيل المحددة للتعبيرات المورفوفونولوجية. بدلاً من ذلك، يقوم المكون المورفولوجي بقراءة ناتج هذا الحساب، محددًا الميزات التي تشترط العمليات المورفولوجية […]

(لاردير 2000: 121-122)

على الرغم من أن أحد المكونات الرئيسية لإعادة تجميع الميزات يعتمد على فصل الميزات الدلالية والصوتية والمظاهر، إلا أن هذه الاقتراحات الناشئة لم تُدمج بالكامل في هياكل أكبر تدعو لمبادئ مشابهة. نقطة مهمة هنا لا يمكن المبالغة فيها هي التحول الذي بدأته الاقتراحات التي استخدمت بعض النسخ من إعادة تجميع الميزات لتبني معالجة قائمة على الميزات (بدلاً من المعالجة التي كانت تعتمد أكثر على المعلمات في ذلك الوقت) للتمثيلات النحوية.

- كما تذكر روبيرتا داليساندرو (ب.خ.)، هناك صلة بين التفكير الذي يقوم عليه إعادة تجميع الميزات وأعمال أخرى في اللغويات الشكلية. على سبيل المثال، مفهوم تشتت الميزات لجورجي وبيانيزي (1997)، الذي ينص على أن الرؤوس الوظيفية يمكن أن تندمج وتنقسم اعتمادًا على اللغة. أيضًا، جادل ريتزي (1994) والعديد من الأعمال المستوحاة من عمله (مثل، هاجيمان 1997؛ بريفوست 1997) بأن الهيكل الوظيفي يمكن أن يكون ‘مقصوصًا’، وهو ما يرتبط أيضًا بالأعمال الحديثة التي تجادل بأن الهياكل يمكن إزالتها أثناء الاشتقاق (مولر 2017؛ بيسيتسكي 2019). يمنعنا نقص المساحة من مناقشة هذه الصلة بشكل أعمق.

من الواضح أن تحديد مصدر التباين الصرفي في مكون صرفي (أو صوتي) متميز من القواعد يتطلب نموذجًا فصليًا للقواعد […]. أحد الأطر الممكنة لذلك هو علم الصرف الموزع، حيث يتم ‘توزيع’ تجميع العناصر المعجمية في جميع أنحاء القواعد.

2. تعالج لي (2015: 95-6) إعادة تجميع الميزات ومصفوفات الميزات مما يعطي انطباعًا بأن بعض عناصر هذا النهج تعتمد على بنية معجمية:

تدعي طريقة إعادة تجميع الميزات أن أحد أصعب جوانب اكتساب اللغة الثانية يكمن في معرفة الميزات المرتبطة بالفئات الوظيفية وإعادة رسم مصفوفات الميزات.العناصر المعجمية إلى تلك الخاصة بـ تُنسب طريقة إعادة تجميع الميزات مصدر الصعوبة ليس فقط إلى إضافة ميزات جديدة إلى مصفوفات الميزات في اللغة المستهدفة، ولكن أيضًا إلى إعادة تشكيل الميزات في تكوينات محددة للغة وبيئات شرطية قد تختلف عن اللغة الأم.

بناء البدائيات (انظر، على سبيل المثال، مناقشة سانشيز لعام 2019 حول التوافقات الثنائية اللغة). لذلك يجب أن يكون هدفًا أن نجعل أكبر قدر ممكن ينشأ من القيود من الدرجة الأولى، أي من الخصائص المتعلقة بالهيكل النحوي كما هو. هدف رئيسي من هذه المساهمة الحالية هو إحراز تقدم نحو هذا الهدف، والذي يتطلب دمج العناصر الأساسية لإعادة تجميع الميزات في نموذج يدعو إلى معجم ‘موزع’. في القسم الفرعي التالي، نقدم الهيكل العام الذي سنستخدمه، وهو ما نطلق عليه approaches exoskeletal نحو النحو، والتي يُعتبر DM واحدة من التطبيقات الممكنة.

2.2 الأساليب الخارجية نحو القواعد

[…] لقد حولت النقاش بعيدًا عن فئات الأفعال وبنية الحجة المركزية حول الأفعال إلى التحليل التفصيلي للطريقة التي تُستخدم بها هذه البنية لنقل المعنى في اللغة، حيث يتم دمج الأفعال في علاقات البنية/المعنى من خلال مساهمتها بالمحتوى الدلالي، المرتبط بشكل رئيسي بجذورها، إلى أجزاء فرعية من تمثيل المعنى المنظم.

(1) أ. تيري جرف.

ب. تيري كنس الأرض.

c. تيري جرف الفتات إلى الزاوية.

قام تيري بجرف الأوراق من الرصيف.

ن. تيري نظف الأرض.

جمع تيري الأوراق في كومة.

(2) أ. كيم صفّر.

ب. كيم صفّر للكلب.

كيم صفّر لحنًا.

د. كيم صفّر تحذيرًا.

كيم صفّر لي تحذيرًا.

ف. كيم صفقت تعبيراً عن تقديرها.

كيم صفّر للكلب ليأتي.

صوت الرصاصة كان يصفق في الهواء.

كانت الرصاصات تصفر في الهواء.

(3) أ. بات جرى.

ب. ركض بات إلى الشاطئ.

ج. باتت متعبة للغاية.

د. بات جرت حذائها حتى تمزق.

بات بعيدًا عن الصخور المتساقطة.

ف. قام المدرب بجري الرياضيين حول المضمار.

(4)

[…] على الرغم من المحاولات الطموحة لوصف كيف يمكن أن تظهر الأفعال بشكل منهجي في مجموعة متنوعة من الهياكل النحوية اعتمادًا على فئتها الدلالية، فإن مرونة الأفعال في الظهور ضمن مجموعة الإطارات المختلفة التي تربط الشكل بالمعنى قد تحدت هذه الجهود لتنظيم التغيرات الظاهرة في بنية الحجة من خلال تصنيف الأفعال.

داخل نموذج XS، فإن المعنى النهائي المحدد المرتبط بأي عبارة هو مزيج من، من جهة، هيكلها النحوي والتفسير الذي يعود لذلك الهيكل من قبل المكون الدلالي الرسمي، ومن جهة أخرى، أي قيمة تُعطى من قبل النظام المفهومي ومعرفة العالم للقوائم المحددة المدمجة داخل ذلك الهيكل. أقترح أن هذه القوائم تعمل كعوامل تعديل لذلك الهيكل.

(5) أ. التركيب يختلف عن الصرف

ب. تعمل النحو على الميزات وخصائصها

ج. هناك مكون شكلي حيث يتم التقاط الظهور والعمليات المورفوفونولوجية

د. أصغر الوحدات في القواعد هي الجذور غير المصنفة

(2015)، غريمستاد وآخرون (2018)، لاردير (1998أ، ب، 2005، 2007، 2008، 2009، 2017)، لوهندال وآخرون (2019)، لوهندال وبوتنام (2021، 2023)، لوبيز (2020، قيد النشر)، ناتفغ وآخرون (2023)، بريفوست ووايت (2000أ، ب)، بوتنام (2020)، بوتنام، بيريزكورتس وسانشيز (2019)، ريكسم (2017، 2018)، ريكسم وآخرون (2019)، سوجيموتو (2022)، سوجيموتو وبابتيستا (2022)، وفاندن وينغارد (2021). في هذه التحليلات، تلعب الهياكل المميزة المنفصلة والمظاهر المورفولوجية دورًا حاسمًا في التحقيقات حول تطور واجهة النحو-المورفولوجيا في ثنائي ومتعددي اللغات عبر مراحل الحياة.

3. إعادة تجميع الميزات ‘المذابة’: نهج خارجي للهياكل النحوية الثنائية اللغة

(7) أ. توسيع الهياكل

ب. توسيع قائمة الميزات

ج. تقسيم الميزات

د. توسيع مخزون التوسع

e. الحصول على خرائط جديدة

تتكون القواعد من ميزات وإسقاطاتها النحوية المرتبطة بها. يجب أيضًا إدراج التعيينات الفردية بين الميزات والمظاهر كجزء من المعجم، على الرغم من أن النماذج الخارجية تختلف في تصوراتها الدقيقة للمعجم. على سبيل المثال، يجادل علم الشكل الموزع بأن المعجم يتكون من ثلاث قوائم مختلفة، بينما يسمح النانو نحوي بأن يتكون المعجم من شجرات صغيرة، أي قطع صغيرة من الهيكل النحوي ومظاهرها. من الواضح أن الطفل الذي يكتسب لغته

4. دراسات حالة

4.1 اكتساب اللغة الثانية لعلامة العدد في الكورية والإندونيسية

| (8) أ. | جون اشترى ثلاثة كتب أمس. | الإندونيسية |

| جون اشترى ثلاثة كتب أمس | ||

| اشترى جون ثلاثة كتب أمس. | ||

| ب. | جون كانغاسي سي مالي لول ساس تا. | كوري |

| جو-أفضل كلب ثلاثة تم شراؤه | ||

| اشترى جون ثلاثة كلاب. |

(9) أ. اشترى جون كتابين / الكثير من الكتب.

الإندونيسية

| أ. | الأطفال يحبون تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية. | الإندونيسية | ||

| الأطفال يحبون دراسة الإنجليزية | ||||

| يحب (بعض) الأطفال دراسة اللغة الإنجليزية. | ||||

| ب. | يونان قد قابلت أصدقاءها في المدرسة أمس. | كوري | ||

|

| أ. اشتريت كتابين-كتب) / العديد من الكتب(-بُوكُو). إندونيسي |

| أشتري كتابين

|

| اشتريت كتابين / العديد من الكتب. |

| ب. توسيكوان-إي-نون مانهون تشايك-تول

|

| يوجد في المكتبة العديد من الكتب، أربعة كتب. |

| العديد من الكتب / أربعة كتب في المكتبة. |

(12) ثلاثة كلاب تلعب في الحديقة.

| (13) أ. | هاكساينغ(-تول) بايك ميونغ-ي إِي-سّتا. | كوري |

| طلاب 100 موجودين | ||

| يوجد 100 طالب. |

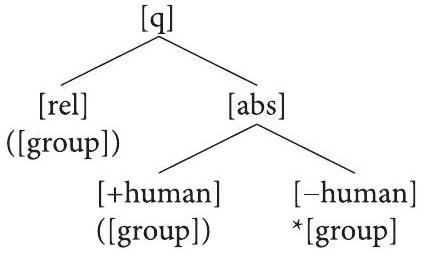

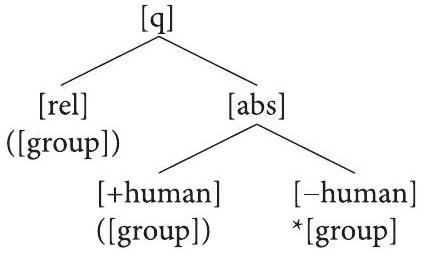

(14) ميزات تصنيف النظام العددي ونظام الكمية الكوري والإندونيسي

أ

ب. [إنسان] = إنسان

ج. [مجموعة] = جمع

د. [التخصيص]

ن.

e’. [q-rel] = ‘نسبي’ = كمي غير عددي

“e”.

ف.

| الكورية جمع: -تول | اللغة الإندونيسية: التكرار |

| [ن] | [ن] |

| [مجموعة] | [مجموعة] |

| [محدد] | [محدد] |

| [q-rel] | |

| [q-abs، إنسان] |

5. لمجموعة مختلفة من الرؤوس الوظيفية/النحوية لتفسير العدد النحوي، انظر ويلتشكو (2021).

و [q-abs] (استنادًا إلى اقتراح أولي من هوانغ ولاردير 2013). يتم تمثيل هذه التبعية في هيكل الشجرة الهرمي في (15) (المعتمد من لي ولاردير 2016:116):

6. انظر أيضًا الحاشية 1.

يتضمن ذلك دمج [q-abs] و [+human] وليس، على سبيل المثال، [q-abs] و [-human]. ثالثًا، يجب عليهم أيضًا اكتساب التوافق المناسب المرتبط بهذه العناصر المفردة. الحالات التي تتضمن “تداخل الميزات” تتطلب فقط اكتساب الارتباط مع التوافق المختلف مع حزم الميزات التي تم مشاركتها بالفعل بين اللغة الأولى واللغة الثانية. وبالتالي، فإن الاستناد إلى مفهوم “التداخل” هو موضع تساؤل، وكما نرى في مراجعة اكتساب اللغة الثانية لعلامة عدم الاكتمال الصينية في القسم التالي، يبدو أن العامل الرئيسي هو غياب الميزة بغض النظر عن موقعها الهرمي.

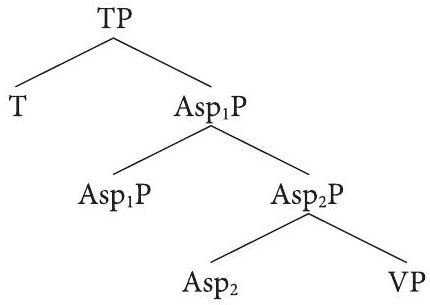

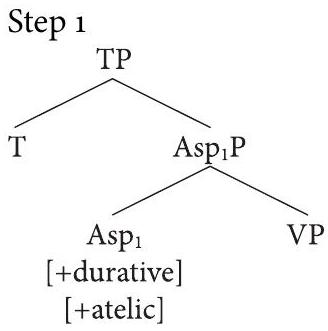

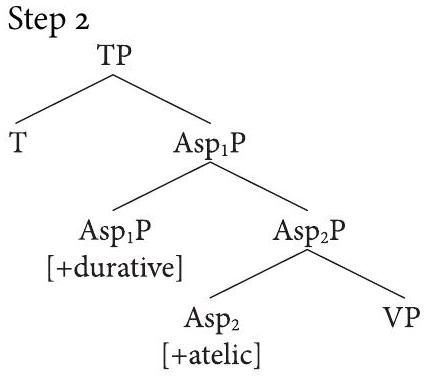

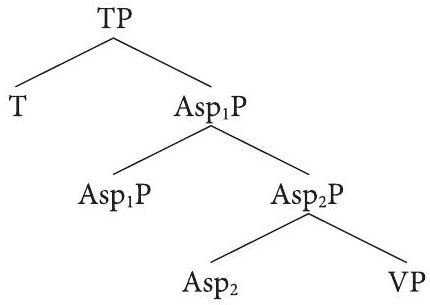

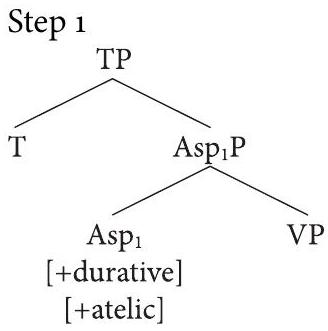

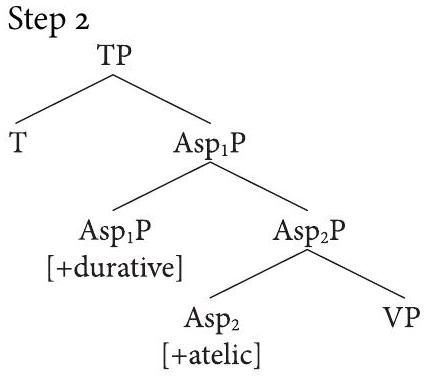

4.2 اكتساب اللغة الثانية لعلامات عدم الاكتمال الصينية

(16) علامات الاستمرارية في الإنجليزية: تراكيب be+ing

أ. إنه يأكل سمكة السيف.

[+تقدمي]

الجوارب ملقاة على الأرض.

[+نتيجة-حالة]

| علامة | ميزة | أمثلة | ||||||

| زاي | [+تقدمي] |

|

||||||

| [+مستمر] |

|

|||||||

| [+T] |

|

|||||||

| -زهي

|

[+تقدمي] |

|

||||||

| [+غير نهائي] |

|

(لين 2002) | ||||||

| -زهي

|

[+نتيجة-حالة] |

|

(18) أ. النتيجة 1: المتعلمون المتقدمون ناجحون في إعادة تجميع ميزات دلالية إضافية عندما تنتمي الفئة الوظيفية للغة الأم (L1) والفئة الوظيفية للغة الثانية (L2) التي تنتمي إليها الميزات المراد إضافتها إلى نفس الفئة الوظيفية:

- الميزة [+durative] لـ zai، و

- الميزة [+غير هدفية] لـ -زهي

البند ب: ومع ذلك، يواجه المتعلمون المتقدمون صعوبات في التمييز بين تفسيرات صيغة الاستمرار zai والحالة الناتجة.

العثور على 3: المتعلمون المتقدمون ليسوا حساسين لقراءة ‘عدم الاكتمال’ لـ

فك الارتباط بين الميزات.

4.3 التحديد في اللغة النرويجية التراثية

(21) den gaml-e hest-en

def.sg old-def horse-def.M.SG

'the old horse'

(22) a. norsk-e ordbok-a (westby_WI_o5gm)

Norwegian-DEF dictionary-DEF.F.SG

'The Norwegian dictionary' (Anderssen et al. 2018:755)

stor-e båt-en (flom_MN_o1gm)

large-def boat-DEF.M.SG

'the large boat' (van Baal 2022:9)

(23) a. den best-e gang (chicago_IL_o1g)

def.sg best-def time

'the best time' (van Baal 2022:10)

den grønn-e bil (sunburg_MN_11gk)

DEF.SG green-DEF car

'the green car' (van Baal 2022:10)

| 1942 | 1987-1992 | ALW 2018 | فان بال 2020 | |

| التحديد التركيبي | 31 (70%) | 7 (70%) | 93 (39%) | 143 (21%) |

| دمج الصفات | – | 1 (10%) | – | 47 (7%) |

| بدون أداة تعريف | 5 (11%) | 0 | 113 (48%) | ٣٣٩ (٤٩٪) |

| بدون أداة تعريف ملحقة | 7 (16%) | 0 | 31 (13%) | ٣٥ (٥٪) |

| عبارة عارية | 1 (2%) | 2 (20%) | 0 | 123 (18%) |

| إجمالي العبارات | ٤٤ | 10 | 237 | ٦٨٧ |

أ. [تعريف، مذكر/مؤنث، مفرد]

ب. [تعريف، محايد، مفرد]

ج

| أ. الحصاد – الحصاد-المعرف مذكر مفرد ‘الحصاد’ | (هاوغن 1953: 579) |

| ب. حقل – حقل معرف مؤنث مفرد ‘الحقل’ | (هاوغن 1953:575) |

| قطار-إت قطار-المحدد.م.م ‘القطار’ | (هاوغن 1953: 602) |

هذا الجبن

ب. هذه الدولة

(ديكورا_IA_o1gm)

هذا.م/ف بلد

هذا البلد

مدرسة دن (غاري_MN_o1gm)

مدرسة ذلك/تلك

تلك المدرسة

بيت الطيور ….. (كون فالي، ويسكونسن 12 جرام)

بيت الطيور

بيت الطيور ذلك

المبنى الكبير ….. (شيكاغو_إل_1غك)

مبنى كبير

المبنى الكبير

ف. الأشياء القديمة ….. (شيكاغو_إل_01غك)

تعريف.م.مأشياء قديمة

الأشياء القديمة

التسوية النرويجية ….. (albert_lea_MN_o1gk)

تعريف.م.متسوية نرويجية-دفاعية

المستوطنة النرويجية

ابن الأخ من ….. (بورتلاند_ND_o2gk)

ابن أخي

ابن أخي

خزان مياه من ….. (westby_WI_oigm)

خزانتي

خزانتي

أ. بواسطة ….. (شيكاغو_إل_1جك)

المدينة

المدينة

ب. الشباب ….. (تناغم_MN_o1gk)

الشباب

الشباب

ج. الكنيسة الجمل-إي ….. (شيكاغو_إل_01غك)

كنيسة العهد القديم

الكنيسة القديمة

د. البانجر (ألبرت ليا، مينيسوتا، o1gk)

المال – جمع غير محدد

المال

أ. أندري داج-إن (هارموني_MN_o2gk)

الثانييوم-محدد.مفرد

اليوم الثاني

| ب. الغارد-إن | (غاري_مينيسوتا_o1gm) |

| المزرعة | |

| المزرعة | |

| ب. الباقي- | |

| الباقي | |

| البقية |

5. الخاتمة

تم العثور على خصائص القواعد في القواعد الثنائية اللغة. في الواقع، إن هذه الفئات والأفراد هم بالضبط الذين يناسبهم هذا النموذج بشكل خاص. لتلخيص ذلك، فإن السمات الأساسية لنهج الهيكل الخارجي هي كما يلي:

(30) أ. العنصر البنائي في القواعد، أي النحو، يعمل على الميزات

ب. يتم تحقيق هذه الميزات شكليًا بعد الإخراج الصوتي،

ج. قد يكون الإدراك الصرفي قائمًا على ميزة واحدة – مظهر واحد (DM)، أو مظاهر متعددة،

هذه البنية مرنة بما يكفي لالتقاط التغيرات عبر فترة الحياة وعبر المتحدثين والأجيال (انظر على سبيل المثال، أيضًا لايتفوت 2020).

تدعم هذه البنية نهج النظرية الفارغة، وفقًا للذي تقترح فيه البنية المقترحة لتفسير المتحدثين أحادي اللغة،

(31) أ. بنية متكاملة متعددة الكفاءات، تجمع بين الإدراك واللغة (كرول وغولان 2014؛ بيكيرينغ وغارود 2013؛ بوتنام وكارلسون وريتر 2018)

ب. الحاجة إلى هيكل هرمي متتبع في الوقت نفسه (بريانا وهيل 2019؛ دينغ، ميلوني، تشانغ، تيان، وبوبل 2016؛ غيتز، دينغ، نيوبورت، وبوبل 2018؛ مورفي 2021)

ج. فائدة الهياكل التجريدية الهرمية في المعالجة الصرفية عبر الإنترنت (غويليامز 2019؛ مارانتز 2013ب) والتمييزات الثنائية في التمثيلات الذهنية (سيبوت ودوماهس 2023)

د. التوافق مع النماذج المودولارية، والإدراج المتأخر (Creemers 2020؛ Fruchter & Marantz 2015؛ Goodwin Davies 2018؛ Krauza & Lau 2023؛ Oseki & Marantz 2020؛ Stockall، Manouilidou، Gwilliams، Neophyton، & Marantz 2019؛ Taft 2004؛ Wu & Juffs 2022)

صراع بين التمثيلات المتنافسة (غولدريك، بوتنام، وشوارز 2016؛ هارتسويكر وبيرنوليت 2017؛ ميلينجر، برانيجان، وبيكيرينغ 2014)

تمويل

الشكر والتقدير

References

Alexiadou, A., & Lohndal, T. (in press). Grammatical gender in syntactic theory. In N. Schiller & T. Kupisch (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Classifiers. Oxford University Press.

van Baal, Y. (2020). Compositional definiteness in American heritage Norwegian. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oslo.

van Baal, Y. (2022). New Data on Language Change: Compositional Definiteness in American Norwegian. Heritage Language Journal, 19, 1-32.

| Beard, R. (1981). The Indo-European Lexicon. North-Holland. | |||

| doi | Beard, R. (1995). Lexeme-Morpheme Based Morphology. State University of New York Press. | ||

| Borer, H. (1994). The projection of arguments. In E. Benedicto & J. Runner (Eds.), University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers in Linguistics 20 (pp. 1-30). GLSA, University of Massachusetts. | |||

| Borer, H. (2003). Exo-skeletal vs. Endo-skeletal Explanations: Syntactic Projections and the Lexicon. In J. Moore & M. Polinsky (Eds.), The nature of explanation in linguistic theory (pp. 31-67). CSLI Publication. | |||

| Borer, H. (2005a). Structuring Sense, Volume 1, In Name Only. Oxford University Press. | |||

| doi | |||

| doi | Borer, H. (2013). Structuring Sense, Volume 3, Taking Form. Oxford University Press. | ||

| doi | Borer, H. (2014). The Category of Roots. In A. Alexiadou, H. Borer & F. Schäfer (Eds.), The Syntax of Roots and the Roots of Syntax (pp. 112-148). Oxford University Press. | ||

| doi | Borer, H. (2017). The Generative Word. In J. McGilvray (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Chomsky (pp. 110-133). Cambridge University Press. | ||

| doi | Brennan, J. R., & Hale, J.T. (2019). Hierarchical structure guides rapid linguistic predictions during naturalistic listening. PLOS One, 14(1), e0207741. | ||

| Caha, P. (2009). The nanosyntax of case. Doctoral dissertation, University of Tromsø. | |||

| doi | Cinque, G. (2006). Restructuring and Functional Heads: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Oxford. | ||

| Chomsky, N. (1955). The logical structure of linguistic theory. Ms., Harvard University and MIT. [Revised version published in part by Plenum, New York, 1975.] | |||

| doi |

|

||

| Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on Government and Binding. Foris. | |||

| Chomsky, N. (1995). The Minimalist Program. MIT Press. | |||

| doi | Chomsky, N. (2005). Three Factors in Language Design. Linguistic Inquiry, 36(1), 1-22. Comrie, B. (1976). Aspect. Cambridge University Press. | ||

| Creemers, A. (2020). Morphological processing and the effects of semantic transparency. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania. | |||

| doi | Ding, N., Melloni, L., Zhang, H., Tian, X., & Poeppel, D. (2016). Cortical tracking of hierarchical linguistic structures in connected speech. Nature Neuroscience, 19(1), 158-164. | ||

| di Sciullo, A., & Williams, E. (1987). On the Definition of Word. MIT Press. | |||

| doi | Embick, D. (2015). The Morpheme: A Theoretical Introduction. Mouton de Gruyter. | ||

| Embick, D., & Noyer, R. (2007). Distributed Morphology and the syntax-morphology interface. In G. Ramchand & C. Reiss (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Interfaces (pp. 289-324). Oxford University Press. | |||

| doi | Fisher, R., Natvig, D., Pretorius, E., Putnam, M.T., & Schuhmann, K.S. (2022). Why is inflectional morphology difficult to borrow? – Distributing and lexicaling plural allomorphy in Pennsylvania Dutch. Languages, 7, 86. |

doi Fruchter, J., & Marantz, A. (2015). Decomposition, lookup, and recombination: MEG evidence for the Full Decomposition model of complex visual word recognition. Brain and Language, 143, 81-96.

Gebhardt, L. (2009). Numeral classifiers and the structure of DP. Doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University.

doi Getz, H., Ding, N., Newport, E. L., & Poeppel, D. (2018). Cortical tracking of constituent structure in language acquisition. Cognition, 181, 135-140.

doi Giorgi, A., & Pianesi, F. (1997). Tense and aspect: From semantics to morphosyntax. Oxford University Press.

doi Goldrick, M., Putnam, M. T., & Schwarz, L. (2016). Coactivation in bilingual grammars: A computational account of code mixing. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19(5), 857-876.

Goodwin Davies, A.J. (2018). Morphological representations in lexical processing. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

doi Grimstad, M.B., Lohndal, T., & Åfarli, T.A. (2014). Language mixing and exoskeletal theory: A case study of word-internal mixing in American Norwegian. Nordlyd, 41, 213-237.

doi Grimstad, M. B., Riksem, B. R., Lohndal, T., & Åfarli, T.A. (2018). Lexicalist vs. Exoskeletal approaches to language mixing. The Linguistic Review, 35, 187-218.

doi Guo, Y. (2022). From a simple to a complex aspectual system: Feature reassembly in L2 acquisition of Chinese imperfective markers by English speakers. Second Language Research, 38(1), 89-116.

doi Gwilliams, L. (2019). How the brain composes morphemes into meaning. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 375: 20190311.

doi Haegeman, L. (1997). Register variation, truncation, and subject omission in English and in French. English Language and Linguistics, 1(2), 233-270.

Halle, M. (1997). Impoverishment and fission. In B. Bruening, Y. Kang, & M. McGinnis (Eds.), PF: Papers at the interface (Vol. 30 of MITWPL) (pp. 425-450). MIT Press.

doi Harley, H., & Ritter, E. (2002). Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language, 78, 482-526.

doi Hartsuiker, R. J., & Bernolet, S. (2017). The development of shared syntax in second language learning. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 20(2), 219-234.

Haugen, E. (1953). The Norwegian Language in America: A Study in Bilingual Behavior. Indiana University Press.

Haznedar, B., & Schwartz, B. D. (1997). Are there optional infinitives in child L2 acquisition? In E. Hughes, M. Hughes & A. Greenhill (Eds.), Proceedings of the 21st Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development (BUCLD) (pp. 257-268). Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

doi van Heuven, W.J. B., Schriefers, H., Dijkstra, T., & Hagoort, P. (2008). Language conflict in the brain. Cerebral Cortex, 18(11), 2706-2716.

doi Hicks, G., & Domínguez, L. (2020). A model for L1 grammatical attrition. Second Language Research, 36(2), 143-165.

doi Huang, C., Li, Y., & Li, Y. (2009). The syntax of Chinese. Cambridge University Press.

Hwang, S.H. (2012). The acquisition of Korean plural marking by native English speakers. Doctoral dissertation, Georgetown University.

doi Hwang, S.H., Lardiere, D. (2013). Plural-marking in L2 Korean: A feature-based approach. Second Language Research, 29, 57-86.

doi Jackendoff, R. (2017). In defense of theory. Cognitive Science, 41, 185-212.

Johannessen, J. B. (2015). The Corpus of American Norwegian Speech (CANS). In B. Megeysi, (Ed.), Proceedings of the 20th Nordic Conference of Computational Linguistics 23.

doi Krauzka, A., & Lau, E. (2023). Moving away from lexicalism in psycho- and neuro-linguistics. Frontiers in Language Science, 2:1125127.

Kroll, J. F., & Gollan, T.H. (2014). Speech planning in two languages: What bilinguals tell us about language production. In M. Goldrick, V. Ferriera, & M. Miozzo (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of language production (pp. 165-181). Oxford University Press.

Lapointe, S. (1980). A Theory of Grammatical Agreement. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

doi Lardiere, D. (1998a). Case and tense in the ‘fossilization’ steady state. Second Language Research, 14, 1-26.

doi Lardiere, D. (1998b). Disassociating syntax from morphology in a divergent L2 end-state grammar. Second Language Research, 14, 359-375.

Lardiere, D. (2005). On morphological competence. In L. Dekydtspotter, R.A. Sprouse & A. Liljestrand (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7 th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA 2004) (pp. 178-192). Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Lardiere, D. (2007). Ultimate attainment in second language acquisition: A case study. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Lardiere, D. (2008). Feature-assembly in second language acquisition. In J. M. Liceras, H. Zobl & H. Goodluck (Eds.), The role of formal features in second language acquisition (pp. 107-140). Lawrence Erlbaum.

doi Lardiere, D. (2009). Some thoughts on a contrastive analysis of features in second language acquisition. Second Language Research, 25, 173-227.

doi Lardiere, D. (2017). Detectability in feature reassembly. In S.M. Gass, P. Spinner, & J. Behney (Eds.), Salience in Second Language Acquisition (pp. 41-63). Routledge.

Lee, E. (2015). L2 acquisition of number marking: A bidirectional study of adult learners of Korean and Indonesian. Doctoral dissertation, Georgetown University.

Lee, E., & Lardiere, D. (2016). L2 acquisition of number marking in Korean and Indonesian: A feature-based approach. In D. Stringer (Ed.), Proceedings of the 7 th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA 2015) (pp. 113-123). Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

doi Lee, E., & Lardiere, D. (2019). Feature reassembly in the acquisition of plural marking by Korean and Indonesian bilinguals. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 9(1), 73-119.

Levin, B. (1993). English Verb Classes and Alternations. University of Chicago Press.

Liceras, J. M., Zobl, Z., & Goodluck, H. (Eds.) (2008). The role of formal features in second language acquisition. Routledge.

doi Levin, B., & Rappaport Hovav, M. (2005). Argument Realization. Cambridge University Press.

doi Lightfoot, D. (2020). Born to parse. How children select their languages. MIT Press.

Lin, J. (2002). Aspectual selection and temporal reference of the Chinese aspectual marker zhe. Tsinghua Journal of Chinese Studies, 32, 257-296.

Lohndal, T. (2012). Without specifiers: Phrase structure and argument structure. Doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland.

doi Lohndal, T. (2013). Generative grammar and language mixing. Theoretical Linguistics, 39, 215-224.

doi Lohndal, T. (2014). Phrase structure and argument structure: A case-study of the syntax semantics interface. Oxford University Press.

Lohndal, T. (2019). Neodavidsonianism in semantics and syntax. In R. Truswell (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Event Structure (pp. 287-313). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lohndal, T. (to appear). The exoskeletal model. In A. Alexiadou, R. Kramer, A. Marantz, & I. Oltra-Massuet (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Distributed Morphology. Cambridge University Press.

doi Lohndal, T., & Putnam, M.T. (2021). The Tale of Two Lexicons: Decomposing Complexity across a Distributed Lexicon. Heritage Language Journal, 18, 1-29.

Lohndal, T., & Putnam, M.T. (2023). Expanding structures while reducing mappings: Morphosyntactic complexity in agglutinating heritage languages. In M. Polinsky & M.T. Putnam (Eds.), Formal approaches to complexity in heritage languages. Language Science Press.

doi Lohndal, T., Rothman, J., Kupisch, J., & Westergaard, M. (2019). Heritage language acquisition: What it reveals and why it is important for formal linguistic theories. Language and Linguistics Compass, 13, e12357.

doi López, L. (2020). Bilingual Grammar: Toward an Integrated Model. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

López, L. (to appear). Distributed Morphology and Bilingualism. In A. Alexiadou, R. Kramer, A. Marantz, & I. Oltra-Massuet (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Distributed Morphology. Cambridge University Press.

MacSwan, J. (1999). A Minimalist Approach to Intrasentential Code Switching. Garland Press.

MacSwan, J. (2000). The architecture of the bilingual language faculty: Evidence from codeswitching. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 3(1), 37-54.

MacSwan, J. (2013). Code switching and linguistic theory. In T. K. Bhatia & W. Ritchie (Eds.), Handbook of Bilingualism and Multilingualism (pp. 223-250). Blackwell.

doi MacSwan, J. (2014). Programs and proposals in codeswitching research: Unconstraining theories of bilingual language mixing. In J. MacSwan (Ed.), Grammatical Theory and Bilingual Codeswitching (pp. 1-33). MIT Press.

Mahootian, S. (1993). A null theory of code switching. Doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University.

doi Marantz, A. (2013a). Verbal argument structure: Events and participants. Lingua, 130, 152-168.

doi Marantz, A. (2013b). No escape from morphemes in morphological processing. Language and Cognitive Processes, 28(7), 905-916.

Matthews, P.H. (1972). Inflectional Morphology: A Theoretical Study Based on Aspects of Latin Verb Conjugation. Cambridge University Press.

doi Meilinger, A., Branigan, H. P., & Pickering, M.J. (2014). Parallel processing in language production. Language, Cognition, & Neuroscience, 29, 663-683.

doi Müller, G. (2017). Structure removal: An argument for feature-driven Merge. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 2(1), 28.

Murphy, E. (2021). The oscillatory nature of language. Cambridge University Press.

doi Natvig, D.A., Putnam, M.T., & Lykke, A.K. (2023). Stability in the integrated bilingual grammar: Tense exponency in North American Norwegian. Nordic Journal of Linguistics.

Natvig, D.A., Pretorius, E., Putnam, M.T., & Carlson, M.T. (to appear). A spanning approach to bilingual representations: Initial exploration. In B. R. Page & M.T. Putnam (Eds.), Contact varieties of German: Studies in honor of William D. Keel. John Benjamins.

doi Opitz, A., Regel, S., Müller, G., & Friederici, A.D. (2013). Neurophysiological evidence for morphological underspecification in German strong adjective inflection. Language, 89(2), 231-264.

doi Oseki, Y., & Marantz, A. (2020). Modeling human morphological competence. Frontiers in Psychology, 11:513740.

Pesetsky, D. (2019). Exfoliation: towards a derivational theory of clause size. Ms., MIT. Available from https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/oo4440

doi Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2013). Forward models and their implications for production, comprehension, and dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(4), 377-392.

Pietroski, P. (2005). Events and Semantic Architecture. Oxford University Press.

doi Pietroski, P. (2018). Conjoining Meanings: Semantics Without Truth Values. Oxford University Press.

Prévost, P. (1997). Truncation in Second Language Acquisition. Doctoral dissertation, McGill University.

Prévost, P., & White, L. (2000a). Accounting for morphological variability in second language acquisition: Truncation or missing inflection? In M.-A. Friedmann & L. Rizzi (Eds.), The Acquisition of Syntax (pp. 202-235). Longman.

doi Prévost, P., & White, L. (2000b). Missing surface inflection or impairment in second language acquisition? Evidence from tense and agreement. Second Language Research, 16, 103-133.

doi Putnam, M.T. (2020). One feature – one head: Features as functional heads in language acquisition and attrition. In P. Guijaaro-Fuentes & C. Suárez-Gómez (Eds.), New trends in language acquisition within the generative perspective (pp. 3-26). Springer.

doi Putnam, M.T., Carlson, M., & Reitter, D. (2018). Integrated, not isolated: Defining typological proximity in an integrated multilingual architecture. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2212.

Putnam, M. T., Perez-Cortes, S., & Sánchez, L. (2019). Language attrition and the Feature Reassembly Hypothesis. In M.S. Schmid & B. Köpke (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Language Attrition (pp. 18-24). Oxford University Press.

doi Ramchand, G.C. (2008). Verb Meaning and the Lexicon: A First-Phase Syntax. Cambridge University Press.

doi Ramchand, G. C., & Svenonius, P. (2014). Deriving the functional hierarchy. Language Sciences, 46, 152-174.

Rappaport Hovav, M., & Levin, B. (1998). Building verb meanings. In M. Butt & W. Geuder (Eds.), The Projection of Arguments (pp. 97-134). CSLI Publications.

doi Riksem, B. R. (2017). Language Mixing and Diachronic Change: American Norwegian Noun Phrases Then and Now. Languages, 2.

doi Riksem, B.R. (2018). Language mixing in American Norwegian noun phrases: An exoskeletal analysis of synchronic and diachronic patterns. Doctoral dissertation, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

doi Riksem, B. R., Grimstad, M. B., Lohndal, T., & Åfarli, T.A. (2019). Language mixing within verbs and nouns in American Norwegian. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics, 22, 189-209.

doi Rizzi, L. (1994). Early null subjects and root null subjects. In T. Hoekstra, & B. Schwartz (Eds.), Language acquisition studies in generative grammar (pp. 151-177). John Benjamins.

doi Sánchez, L. (2019). Bilingual alignments. Languages, 4, 82:

Schein, B. (1993). Plurals and Events. MIT Press.

doi Seyboth, M., & Domahs, F. (2023). Why do he and she disagree: The role of binary morphological features in grammatical gender agreement in German. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. First view: Published online 16 January 2023.

doi Slabakova, R. (2009). Features or parameters: Which one makes second language acquisition research easier, and more interesting to study? Second Language Research, 25(2), 313-324.

Slabakova, R. (2016). Second Language Acquisition. Oxford University Press.

doi Slabakova, R. (2021). Second language acquisition. In N. Allott, T. Lohndal, & G. Rey (Eds.), A Companion to Chomsky (pp. 222-231). Wiley Blackwell.

doi Smith, C. (1997). The parameter of aspect. Kluwer Academic.

doi Song, Y., Do, Y., Thompson, A. L., Waegemaekers, E. R., & Lee, J. (2020). Second language uses exhibit shallow morphological processing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(5), 1121-1136.

doi Stockall, L., Manouilidou, C., Gwilliams, L., Neophyton, K., & Marantz, A. (2019). Prefix stripping re-re-revisited: MEG investigations of morphological decomposition and recomposition. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1964.

doi Stump, G.T. (2001). Inflectional Morphology: A Theory of Paradigm Structure. Cambridge University Press.

Sugimoto, Y. (2022). Underspecification and (Im)possible Derivations: Toward a Restrictive Theory of Grammar. Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan.

doi Sugimoto, Y., & Baptista, M. (2022). A late-insertion-based exoskeletal approach to the hybrid nature of functional features in creole languages. Languages, 7,

doi Svenonius, P. (2016). Spans and words. In H. Harley & D. Siddiqi (Eds.), Morphological metatheory (pp. 199-202). John Benjamins.

doi Taft, M. (2004). Morphological decomposition and the reverse base frequency effect. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 57(4), 745-765.

Vanden Wyngaerd, E. (2021). Bilingual Implications: Using code-switching data to inform linguistic theory. Doctoral dissertation, Université Libre de Bruxelles.

doi White, L. (2003). Second Language Acquisition and Universal Grammar. Cambridge University Press.

Williams, A. (2014). Arguments in Syntax and Semantics. Cambridge University Press.

doi Wiltschko, M. (2021). The syntax of number markers. In P.C. Hofherr & J. Doetjes (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Grammatical Number (pp. 164-196). Oxford University Press.

doi Wu, Z., & Juffs, A. (2022). Effects of L1 morphological type on L2 morphological awareness. Second Language Research, 38(4), 787-812.

doi Wood, J. (2015). Icelandic Morphosyntax and Argument Structure. Springer.

Zwicky, A.M. (1985). How to describe inflection. In M. Niepokuj, M. Van Clay, V. Nikiforidou & D. Feder (Eds.), Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 372-386). Berkeley Linguistics Society.

عنوان المراسلة

قسم اللغة والأدب

جامعة النرويج للعلوم والتكنولوجيا (NTNU)

N-7491 تروندهايم

النرويج

terje.lohndal@ntnu.no

معلومات المؤلف المشارك

تاريخ النشر

تاريخ القبول: 1 ديسمبر 2023

نشر على الإنترنت: 1 فبراير 2024

- لاحظ أن نموذج بورير غالبًا ما يُشار إليه بأنه خارجي الهيكل، ولكن كما توضح هي نفسها، فإن التنفيذ الفني لا يتبع الإطار المفاهيمي (بورير 2005ب: 10):

- فيما يلي، سأستمر في تقديم الحجج التي تدعم مكونًا وظيفيًا نحويًا غنيًا، ومكونًا معجميًا متقشفًا بشكل مت correspondingly. بدوره، سأقترح أيضًا هيكلًا وظيفيًا نحويًا محددًا جدًا لهيكل الحدث […]. ومع ذلك، فإن صحة افتراض معجم متقشف، بالمعنى المستخدم هنا، مستقلة تمامًا عن صحة أي هيكل وظيفي محدد سأقترحه.

- البيانات في هذا القسم مأخوذة مباشرة من لي ولاردير (2016: 114-5).

- هناك عدد من القضايا الداخلية للنظرية التي لا نناقشها هنا والتي تعتبر مهمة لجهود بناء النظرية المستقبلية. هنا نذكر اثنين منها: أولاً، في الوقت الحالي نتعامل مع ارتباط الميزات والشكلية المتسلسلة وغير المتسلسلة (في حالة التكرار) على أنها متطابقة. ثانيًا، مسألة ما إذا كانت الميزات التي ليست ‘نشطة’ في

(ولكنها لا تزال موجودة من الناحية الكارتوغرافية) أو يجب اكتسابها من جديد تُترك أيضًا للاعتبارات البحثية المستقبلية (انظر: سينك 2006، ورامشاند وسفينونيوس 2014).

- هناك عدد من القضايا الداخلية للنظرية التي لا نناقشها هنا والتي تعتبر مهمة لجهود بناء النظرية المستقبلية. هنا نذكر اثنين منها: أولاً، في الوقت الحالي نتعامل مع ارتباط الميزات والشكلية المتسلسلة وغير المتسلسلة (في حالة التكرار) على أنها متطابقة. ثانيًا، مسألة ما إذا كانت الميزات التي ليست ‘نشطة’ في

- بشكل أكثر تحديدًا، في الشكلية الموزعة يمكن التقاط هذه الحالة عبر العملية ما بعد النحوية “الانقسام”، وهي عملية تحول عقدة طرفية واحدة في هيكل الشجرة إلى اثنتين (مما ينتج عنه اثنين من الممثلين) (هالي 1997).

- هناك بعض الصفات الاستثنائية التي تسمح بإغفال المحدد السابق للاسم. نحن نترك هذه جانبًا هنا؛ انظر فان بال (2022) لمناقشة شاملة.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.23023.loh

Publication Date: 2024-02-01

The importance of features and exponents Dissolving Feature Reassembly

Abstract

Formal approaches to bi- and multilingual grammars rely on two important claims: (i) the grammatical architecture should be able to deal with monoand bi-/multilingual data without any specific constraints for the latter, (ii) features play a pivotal role in accounting for patterns across and within grammars. In the present paper, it is argued that an exoskeletal approach to grammar, which clearly distinguishes between the underlying syntactic features and their morphophonological realizations (exponents), offers an ideal tool to analyze data from bi- and multilingual speakers. Specifically, it is shown that this framework can subsume the specific mechanism of Feature Reassembly developed by Donna Lardiere since the late 1990’s. Three case studies involving different languages and language combinations are offered in support of this claim, demonstrating how an exoskeletal approach can be employed without any additional constraints or mechanisms.

1. Introduction

- Is it possible to model bilingual grammars in a systematic and constrained way?

- What sorts of architectural changes/adjustments from those assumed for monolingual grammars (if any) are necessary in order to achieve this goal?

icated mechanism such as Feature Reassembly is unnecessary. A major strength of the current approach is that the mechanisms that were suggested as essential components of Feature Reassembly are all available as primitives of the exoskeletal architecture, making Feature Reassembly superfluous as a separate theory or mechanism. From the point of view that bilingual grammars are just as systematic and constrained as monolingual grammars, this is a major and welcome consequence, as theoretical machinery should be as slim and explanatory as possible (cf. Chomsky 1995, 2005).

2. Theoretical framework

2.1 Feature reassembly

shell, some rupture occurs between syntax and morphology such that the morphology is somehow missing, but only on the surface.

[a]ssembling the particular lexical items of a second language requires that the learner reconfigure features from the way these are represented in the first language into new formal configurations on possibly quite different types of lexical items in the L2.

[…] the available data suggest that the abstract features which motivate syntactic computations are modularly “insulated” from the specific details of morphophonological spell-outs. Rather, the morphological component “reads” the output of this computation, identifying the features which condition morphological operations […]

(Lardiere 2000: 121-122)

Although one of the main components of Feature Reassembly is based on the separation of syn-sem features and exponents, these incipient proposals were never fully integrated into larger scale architectures that advocated for similar principles. An important point here that cannot be overstated is the shift initiated by proposals that employed some version of Feature Reassembly to adopt a featurebased (as opposed to a then more parameter-based) treatment of grammatical representations (Liceras et al. 2008; Slabakova 2009; Hicks & Domínguez 2020;

- As Roberta D’Alessandro (p.c.) reminds us, there is a link between the thinking underlying Feature Reassembly and other work in formal linguistics. For instance, Giorgi and Pianesi’s (1997) notion of feature scattering, which holds that functional heads can merge and split depending on the language. Also, Rizzi (1994) and much work inspired by his work (e.g., Haegeman 1997; Prévost 1997) has argued that the functional architecture can be ‘truncated’, which is also related to recent work which argues that structures can be removed during the derivation (Müller 2017; Pesetsky 2019). Space prevents us from discussing this link any further.

It is clear that locating the source of morphological variability in a distinct morphological (or phonological) component of the grammar requires a separationist model of grammar […]. One such possible framework is that of Distributed Morphology, in which the assembly of lexical items is ‘distributed’ throughout the grammar.

2. Lee’s (2015:95-6) treatment of Feature Reassembly and feature matrices gives the impression that some elements of this approach rely on a lexicalist architecture:

The Feature-Reassembly Approach claims that one of the most difficult aspects of L2 acquisition lies in figuring out the features associated with functional categories and remapping the feature matrices forlexical items to those of the The FeatureReassembly Approach ascribes the source of difficulty not only to the addition of new features into the feature matrices in the target language but also to remapping features into language-specific configurations and conditioning environments that may differ from the native language.

building primitives (see, i.e., Sánchez’s 2019 discussion of bilingual alignments). It should therefore be a goal to make as much as possible fall out from first-order constraints, that is, from properties related to the grammatical architecture as such. A major goal of the present contribution is to make progress towards this goal, which requires the integration of core elements of Feature Reassembly into a model that advocates for a ‘distributed’ lexicon. In the next sub-section, we present the general architecture that we will use, namely what we label exoskeletal approaches to grammar, of which DM is one possible implementation.

2.2 Exoskeletal approaches to grammar

[…] have shifted discussion away from verb classes and verb-centered argument structure to the detailed analysis of the way that structure is used to convey meaning in language, with verbs being integrated into the structure/meaning relations by contributing semantic content, mainly associated with their roots, to subparts of a structured meaning representation.

(1) a. Terry swept.

b. Terry swept the floor.

c. Terry swept the crumbs into the corner.

d. Terry swept the leaves off the sidewalk.

e. Terry swept the floor clean.

f. Terry swept the leaves into a pile.

(2) a. Kim whistled.

b. Kim whistled at the dog.

c. Kim whistled a tune.

d. Kim whistled a warning.

e. Kim whistled me a warning.

f. Kim whistled her appreciation.

g. Kim whistled to the dog to come.

h. The bullet whistled through the air.

i. The air whistled with bullets.

(3) a. Pat ran.

b. Pat ran to the beach.

c. Pat ran herself ragged.

d. Pat ran her shoes to shreds.

e. Pat ran clear of the falling rocks.

f. The coach ran the athletes around the track.

(4)

[…] despite ambitious attempts to describe how verbs might systematically appear in a variety of syntactic structures depending on their semantic category, the flexibility of verbs to appear within the various set of frames relating form and meaning has defied these efforts to regulate apparent alternations in argument structure through the classification of verbs.

Within an XS-model, then, the particular final meaning associated with any phrase is a combination of, on the one hand, its syntactic structure and the interpretation returned for that structure by the formal semantic component, and, on the other hand, by whatever value is assigned by the conceptual system and world knowledge to the particular listemes embedded within that structure. These listemes, I suggest, function as modifiers of that structure.’

(5) a. Syntax is distinct from morphology

b. Syntax operates on features and their properties

c. There is a morphological component where exponence and morphophonological operations are captured

d. The smallest units in the grammar are uncategorized roots

(2015), Grimstad et al. (2018), Lardiere (1998a, b, 2005, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2017), Lohndal et al. (2019), Lohndal & Putnam (2021, 2023), López (2020, to appear), Natvig et al. (2023), Prévost & White (2000a, b), Putnam (2020), Putnam, PerezCortes & Sánchez (2019), Riksem (2017, 2018), Riksem et al. (2019), Sugimoto (2022), Sugimoto & Baptista (2022), and Vanden Wyngaerd (2021). In these analyses, disassociated feature structures and morphonological exponents play a crucial role in investigations of the development of the syntax-morphology interface in bi- and multilinguals across the lifespan.

3. Feature reassembly ‘dissolved’: An exoskeletal approach to bilingual grammars

(7) a. Expanding structures

b. Expanding feature inventory

c. Feature splitting

d. Expanding exponency inventory

e. Acquiring new mappings

grammar consists of features and their associated syntactic projections. Individual mappings between features and exponents also have to be listed as part of the lexicon, although exoskeletal models differ in their precise conception of the lexicon. For instance, Distributed Morphology argues that the lexicon is decomposed into three different lists, whereas Nanosyntax allows the lexicon to consist of treelets, that is, small pieces of syntactic structure and their exponents. It is obvious that a child acquiring their

4. Case studies

4.1 The L2 acquisition of number marking in Korean and Indonesian

| (8) a. | John membeli tiga (buah) buku kemarin. | Indonesian |

| John buy three cl book yesterday | ||

| ‘John bought three books yesterday.’ | ||

| b. | John-un kangaci sey mali-lul sa-ss-ta. | Korean |

| Joh-TOP dog three CL-ACC buy-PAST-DECL | ||

| ‘John bought three dogs.’ |

(9) a. John membeli dua (buah) / banyak (*buah) buku. John buy two Cl many Cl book ‘John bought two / many books.’

Indonesian

| a. | Anak(-anak) senang belajar Inggris. | Indonesian | ||

| Child(-pl) like study English | ||||

| ‘(The/some specific) children like to study English.’ | ||||

| b. | Yuna-nun ecey tayhakkyo chinkwu-(tul)-ul manna-ss-ta. | Korean | ||

|

| a. Saya membeli dua buku(-buku) / banyak buku(-buku). Indonesian |

| I buy two book

|

| ‘I bought two books / many books.’ |

| b. Tosekwan-ey-nun manhun chayk-tul /

|

| library-in-TOP many book-PL four book-PL-NOM exist-DECL |

| ‘Many books / four books are in the library.’ |

(12) *Tiga ekor anjing-anging sedang bermain di kebun.

| (13) a. | Haksayng(-tul) payk myeng-i i-ss-ta. | Korean |

| student-PL 100 CL-NOM exist-PAST-DECL | ||

| ‘There are 100 students.’ |

(14) Features categorizing the Korean and Indonesian number and quantifier system

a.

b. [human] = human

c. [group] = plural

d. [individualization]

e.

e’. [q-rel] = ‘relative’ = non-numeric quantifier

e”.

f.

| Korean pl: -tul | Indonesian PL: reduplication |

| [n] | [n] |

| [group] | [group] |

| [specific] | [specific] |

| [q-rel] | |

| [q-abs, human] |

5. For a different set of functional/syntactic heads to account for grammatical number, see Wiltschko (2021).

and [q-abs] (based on an initial proposal by Hwang & Lardiere 2013). This dependency is represented in the hierarchical tree structure in (15) (adopted from Lee & Lardiere 2016:116):

6. See also footnote 1 .

tures without one another. This involves combining [q-abs] and [+human] and not, for instance, [q-abs] and [-human]. Third, they must also acquire the proper exponency associated with these Vocabulary Items. The cases involving “feature overlap” only require the acquisition of the association with different exponency with feature bundles already shared between the L1 and L2. The appeal to the notion of “embeddedness” is thus questionable, and as we see in the review of L2 acquisition of Chinese imperfective marker in the subsequent section, the primary factor at play seems to be the absence of the feature irrespective of its hierarchical position.

4.2 L2 acquisition of Chinese imperfective markers

(16) Imperfective marking in English: be+ing constructions

a. He is eating a swordfish.

[+progressive]

b. The socks are lying on the floor.

[+resultant-stative]

| Marker | Feature | Examples | ||||||

| zai | [+progressive] |

|

||||||

| [+durative] |

|

|||||||

| [+T] |

|

|||||||

| -zhe

|

[+progressive] |

|

||||||

| [+atelic] |

|

(Lin 2002) | ||||||

| -zhe

|

[+resultant-stative] |

|

(18) a. Finding 1: Advanced learners are successful in reassembling additional semantic features when the L1 and L2 functional category where the to-beadded features belong to the same functional category:

- The [+durative] feature of zai, and

- The [+atelic] feature of -zhe

b. Finding 2: Advanced learners however encounter difficulties in differentiating between the interpretations of the progressive zai and the resultantstative

c. Finding 3: Advanced learners are not sensitive to the ‘incompleteness reading’ of

de-linking of features.

4.3 Definiteness in Norwegian heritage language

(21) den gaml-e hest-en

def.sg old-def horse-def.M.SG

'the old horse'

(22) a. norsk-e ordbok-a (westby_WI_o5gm)

Norwegian-DEF dictionary-DEF.F.SG

'The Norwegian dictionary' (Anderssen et al. 2018:755)

stor-e båt-en (flom_MN_o1gm)

large-def boat-DEF.M.SG

'the large boat' (van Baal 2022:9)

(23) a. den best-e gang (chicago_IL_o1g)

def.sg best-def time

'the best time' (van Baal 2022:10)

den grønn-e bil (sunburg_MN_11gk)

DEF.SG green-DEF car

'the green car' (van Baal 2022:10)

| 1942 | 1987-1992 | ALW 2018 | van Baal 2020 | |

| Compositional definiteness | 31 (70%) | 7 (70%) | 93 (39%) | 143 (21%) |

| Adjective incorporation | – | 1 (10%) | – | 47 (7%) |

| Without determiner | 5 (11%) | 0 | 113 (48%) | 339 (49%) |

| Without suffixed article | 7 (16%) | 0 | 31 (13%) | 35 (5%) |

| Bare phrase | 1 (2%) | 2 (20%) | 0 | 123 (18%) |

| Total phrases | 44 | 10 | 237 | 687 |

a. [DEF, MASC/FEM, SG]

b. [def, neut, sg]

c.

| a. harvest-en harvest-DEF.M.SG ‘the harvest’ | (Haugen 1953: 579) |

| b. field-a field-def.f.sg ‘the field’ | (Haugen 1953:575) |

| c. train-et train-DEF.N.SG ‘the train’ | (Haugen 1953: 602) |

(26) a. denne cheese (blair_WI_o4gk) this.m/f cheese ‘this cheese’

b. denne country

(decorah_IA_o1gm)

this.m/F country

‘this country’

c. den school (gary_MN_o1gm)

that.m/f school

‘that school’

d. den birdhouse ….. (coon_valley_WI_12gm)

that.m/f birdhouse

‘that birdhouse’

e. den stor-e building ….. (chicago_IL_o1gk)

def.M/f.SG big-def building

‘the big building’

f. det gaml-e stuff ….. (chicago_IL_o1gk)

def.n.sg old-def stuff

‘the old stuff’

g. det norsk-e settlement ….. (albert_lea_MN_o1gk)

def.n.sg Norwegian-def settlement

‘the Norwegian settlement’

h. nephew min ….. (portland_ND_o2gk)

nephew my

‘my newphew’

i. cistern min ….. (westby_WI_oigm)

cistern my

‘my cistern’

a. the by ….. (chicago_IL_o1gk)

the city

‘the city’

b. the ungdom ….. (harmony_MN_o1gk)

the youth

‘the youth’

c. the gaml-e kirke ….. (chicago_IL_o1gk)

the old-def church

‘the old church’

d. the peng-er (albert_lea_MN_o1gk)

the money-INDEF.PL

‘the money’

a. the andre dag-en (harmony_MN_o2gk)

the second day-def.m.sg

‘the second day’

| b. the gård-en | (gary_MN_o1gm) |

| the farm-DEF.M.SG | |

| ‘the farm’ | |

| c. the rest-en | |

| the rest-DEF.M.SG | |

| ‘the rest’ |

5. Conclusion

cal properties found in bilingual grammars. In fact, it is exactly these populations and individuals for whom this model is particularly well-suited. To recapitulate, the fundamental attributes of an exoskeletal approach are as follows:

(30) a. The structure-building component of grammar, i.e., syntax, operates on features

b. These features are morphologically realized after Spell-Out,

c. The morphological realization may be based on a single feature – one exponent (DM), or multiple exponents,

d. This architecture is flexible enough to capture changes across the lifespan and across speakers and generations (see e.g., also Lightfoot 2020),

e. This architecture supports a null theory approach, according to which the architecture proposed to account for monolingual speakers,

(31) a. Combined multi-competent, integrated architecture of cognition and language (Kroll & Gollan 2014; Pickering & Garrod 2013; Putnam, Carlson, & Reitter 2018),

b. Need for simultaneously tracked hierarchical structure (Brenna & . Hale 2019; Ding, Melloni, Zhang, Tian, & Poeppel 2016; Getz, Ding, Newport, & Poeppel 2018; Murphy 2021),

c. Usefulness of hierarchical abstract structures in online morphological processing (Gwilliams 2019; Marantz 2013b) and binary feature distinctions in mental representations (Seyboth & Domahs 2023),

d. Compatibility with modular, late-insertion models (Creemers 2020; Fruchter & Marantz 2015; Goodwin Davies 2018; Krauza & Lau 2023; Oseki & Marantz 2020; Stockall, Manouilidou, Gwilliams, Neophyton, & Marantz 2019; Taft 2004; Wu & Juffs 2022),

e. Conflict between competing representations (Goldrick, Putnam, & Schwarz 2016; Hartsuiker & Bernolet 2017; Melinger, Branigan, & Pickering 2014)

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

Alexiadou, A., & Lohndal, T. (in press). Grammatical gender in syntactic theory. In N. Schiller & T. Kupisch (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Classifiers. Oxford University Press.

van Baal, Y. (2020). Compositional definiteness in American heritage Norwegian. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oslo.

van Baal, Y. (2022). New Data on Language Change: Compositional Definiteness in American Norwegian. Heritage Language Journal, 19, 1-32.

| Beard, R. (1981). The Indo-European Lexicon. North-Holland. | |||

| doi | Beard, R. (1995). Lexeme-Morpheme Based Morphology. State University of New York Press. | ||

| Borer, H. (1994). The projection of arguments. In E. Benedicto & J. Runner (Eds.), University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers in Linguistics 20 (pp. 1-30). GLSA, University of Massachusetts. | |||

| Borer, H. (2003). Exo-skeletal vs. Endo-skeletal Explanations: Syntactic Projections and the Lexicon. In J. Moore & M. Polinsky (Eds.), The nature of explanation in linguistic theory (pp. 31-67). CSLI Publication. | |||

| Borer, H. (2005a). Structuring Sense, Volume 1, In Name Only. Oxford University Press. | |||

| doi | |||

| doi | Borer, H. (2013). Structuring Sense, Volume 3, Taking Form. Oxford University Press. | ||

| doi | Borer, H. (2014). The Category of Roots. In A. Alexiadou, H. Borer & F. Schäfer (Eds.), The Syntax of Roots and the Roots of Syntax (pp. 112-148). Oxford University Press. | ||

| doi | Borer, H. (2017). The Generative Word. In J. McGilvray (Ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Chomsky (pp. 110-133). Cambridge University Press. | ||

| doi | Brennan, J. R., & Hale, J.T. (2019). Hierarchical structure guides rapid linguistic predictions during naturalistic listening. PLOS One, 14(1), e0207741. | ||

| Caha, P. (2009). The nanosyntax of case. Doctoral dissertation, University of Tromsø. | |||

| doi | Cinque, G. (2006). Restructuring and Functional Heads: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Oxford. | ||

| Chomsky, N. (1955). The logical structure of linguistic theory. Ms., Harvard University and MIT. [Revised version published in part by Plenum, New York, 1975.] | |||

| doi |

|

||

| Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on Government and Binding. Foris. | |||

| Chomsky, N. (1995). The Minimalist Program. MIT Press. | |||

| doi | Chomsky, N. (2005). Three Factors in Language Design. Linguistic Inquiry, 36(1), 1-22. Comrie, B. (1976). Aspect. Cambridge University Press. | ||

| Creemers, A. (2020). Morphological processing and the effects of semantic transparency. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania. | |||

| doi | Ding, N., Melloni, L., Zhang, H., Tian, X., & Poeppel, D. (2016). Cortical tracking of hierarchical linguistic structures in connected speech. Nature Neuroscience, 19(1), 158-164. | ||

| di Sciullo, A., & Williams, E. (1987). On the Definition of Word. MIT Press. | |||

| doi | Embick, D. (2015). The Morpheme: A Theoretical Introduction. Mouton de Gruyter. | ||

| Embick, D., & Noyer, R. (2007). Distributed Morphology and the syntax-morphology interface. In G. Ramchand & C. Reiss (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Interfaces (pp. 289-324). Oxford University Press. | |||

| doi | Fisher, R., Natvig, D., Pretorius, E., Putnam, M.T., & Schuhmann, K.S. (2022). Why is inflectional morphology difficult to borrow? – Distributing and lexicaling plural allomorphy in Pennsylvania Dutch. Languages, 7, 86. |

doi Fruchter, J., & Marantz, A. (2015). Decomposition, lookup, and recombination: MEG evidence for the Full Decomposition model of complex visual word recognition. Brain and Language, 143, 81-96.

Gebhardt, L. (2009). Numeral classifiers and the structure of DP. Doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University.

doi Getz, H., Ding, N., Newport, E. L., & Poeppel, D. (2018). Cortical tracking of constituent structure in language acquisition. Cognition, 181, 135-140.

doi Giorgi, A., & Pianesi, F. (1997). Tense and aspect: From semantics to morphosyntax. Oxford University Press.

doi Goldrick, M., Putnam, M. T., & Schwarz, L. (2016). Coactivation in bilingual grammars: A computational account of code mixing. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19(5), 857-876.

Goodwin Davies, A.J. (2018). Morphological representations in lexical processing. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

doi Grimstad, M.B., Lohndal, T., & Åfarli, T.A. (2014). Language mixing and exoskeletal theory: A case study of word-internal mixing in American Norwegian. Nordlyd, 41, 213-237.

doi Grimstad, M. B., Riksem, B. R., Lohndal, T., & Åfarli, T.A. (2018). Lexicalist vs. Exoskeletal approaches to language mixing. The Linguistic Review, 35, 187-218.

doi Guo, Y. (2022). From a simple to a complex aspectual system: Feature reassembly in L2 acquisition of Chinese imperfective markers by English speakers. Second Language Research, 38(1), 89-116.

doi Gwilliams, L. (2019). How the brain composes morphemes into meaning. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 375: 20190311.

doi Haegeman, L. (1997). Register variation, truncation, and subject omission in English and in French. English Language and Linguistics, 1(2), 233-270.

Halle, M. (1997). Impoverishment and fission. In B. Bruening, Y. Kang, & M. McGinnis (Eds.), PF: Papers at the interface (Vol. 30 of MITWPL) (pp. 425-450). MIT Press.

doi Harley, H., & Ritter, E. (2002). Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language, 78, 482-526.

doi Hartsuiker, R. J., & Bernolet, S. (2017). The development of shared syntax in second language learning. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 20(2), 219-234.

Haugen, E. (1953). The Norwegian Language in America: A Study in Bilingual Behavior. Indiana University Press.

Haznedar, B., & Schwartz, B. D. (1997). Are there optional infinitives in child L2 acquisition? In E. Hughes, M. Hughes & A. Greenhill (Eds.), Proceedings of the 21st Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development (BUCLD) (pp. 257-268). Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

doi van Heuven, W.J. B., Schriefers, H., Dijkstra, T., & Hagoort, P. (2008). Language conflict in the brain. Cerebral Cortex, 18(11), 2706-2716.

doi Hicks, G., & Domínguez, L. (2020). A model for L1 grammatical attrition. Second Language Research, 36(2), 143-165.

doi Huang, C., Li, Y., & Li, Y. (2009). The syntax of Chinese. Cambridge University Press.

Hwang, S.H. (2012). The acquisition of Korean plural marking by native English speakers. Doctoral dissertation, Georgetown University.

doi Hwang, S.H., Lardiere, D. (2013). Plural-marking in L2 Korean: A feature-based approach. Second Language Research, 29, 57-86.

doi Jackendoff, R. (2017). In defense of theory. Cognitive Science, 41, 185-212.

Johannessen, J. B. (2015). The Corpus of American Norwegian Speech (CANS). In B. Megeysi, (Ed.), Proceedings of the 20th Nordic Conference of Computational Linguistics 23.

doi Krauzka, A., & Lau, E. (2023). Moving away from lexicalism in psycho- and neuro-linguistics. Frontiers in Language Science, 2:1125127.

Kroll, J. F., & Gollan, T.H. (2014). Speech planning in two languages: What bilinguals tell us about language production. In M. Goldrick, V. Ferriera, & M. Miozzo (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of language production (pp. 165-181). Oxford University Press.

Lapointe, S. (1980). A Theory of Grammatical Agreement. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

doi Lardiere, D. (1998a). Case and tense in the ‘fossilization’ steady state. Second Language Research, 14, 1-26.

doi Lardiere, D. (1998b). Disassociating syntax from morphology in a divergent L2 end-state grammar. Second Language Research, 14, 359-375.

Lardiere, D. (2005). On morphological competence. In L. Dekydtspotter, R.A. Sprouse & A. Liljestrand (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7 th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA 2004) (pp. 178-192). Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Lardiere, D. (2007). Ultimate attainment in second language acquisition: A case study. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Lardiere, D. (2008). Feature-assembly in second language acquisition. In J. M. Liceras, H. Zobl & H. Goodluck (Eds.), The role of formal features in second language acquisition (pp. 107-140). Lawrence Erlbaum.

doi Lardiere, D. (2009). Some thoughts on a contrastive analysis of features in second language acquisition. Second Language Research, 25, 173-227.

doi Lardiere, D. (2017). Detectability in feature reassembly. In S.M. Gass, P. Spinner, & J. Behney (Eds.), Salience in Second Language Acquisition (pp. 41-63). Routledge.

Lee, E. (2015). L2 acquisition of number marking: A bidirectional study of adult learners of Korean and Indonesian. Doctoral dissertation, Georgetown University.

Lee, E., & Lardiere, D. (2016). L2 acquisition of number marking in Korean and Indonesian: A feature-based approach. In D. Stringer (Ed.), Proceedings of the 7 th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA 2015) (pp. 113-123). Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

doi Lee, E., & Lardiere, D. (2019). Feature reassembly in the acquisition of plural marking by Korean and Indonesian bilinguals. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 9(1), 73-119.

Levin, B. (1993). English Verb Classes and Alternations. University of Chicago Press.

Liceras, J. M., Zobl, Z., & Goodluck, H. (Eds.) (2008). The role of formal features in second language acquisition. Routledge.

doi Levin, B., & Rappaport Hovav, M. (2005). Argument Realization. Cambridge University Press.

doi Lightfoot, D. (2020). Born to parse. How children select their languages. MIT Press.

Lin, J. (2002). Aspectual selection and temporal reference of the Chinese aspectual marker zhe. Tsinghua Journal of Chinese Studies, 32, 257-296.

Lohndal, T. (2012). Without specifiers: Phrase structure and argument structure. Doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland.

doi Lohndal, T. (2013). Generative grammar and language mixing. Theoretical Linguistics, 39, 215-224.

doi Lohndal, T. (2014). Phrase structure and argument structure: A case-study of the syntax semantics interface. Oxford University Press.

Lohndal, T. (2019). Neodavidsonianism in semantics and syntax. In R. Truswell (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Event Structure (pp. 287-313). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lohndal, T. (to appear). The exoskeletal model. In A. Alexiadou, R. Kramer, A. Marantz, & I. Oltra-Massuet (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Distributed Morphology. Cambridge University Press.

doi Lohndal, T., & Putnam, M.T. (2021). The Tale of Two Lexicons: Decomposing Complexity across a Distributed Lexicon. Heritage Language Journal, 18, 1-29.

Lohndal, T., & Putnam, M.T. (2023). Expanding structures while reducing mappings: Morphosyntactic complexity in agglutinating heritage languages. In M. Polinsky & M.T. Putnam (Eds.), Formal approaches to complexity in heritage languages. Language Science Press.

doi Lohndal, T., Rothman, J., Kupisch, J., & Westergaard, M. (2019). Heritage language acquisition: What it reveals and why it is important for formal linguistic theories. Language and Linguistics Compass, 13, e12357.

doi López, L. (2020). Bilingual Grammar: Toward an Integrated Model. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

López, L. (to appear). Distributed Morphology and Bilingualism. In A. Alexiadou, R. Kramer, A. Marantz, & I. Oltra-Massuet (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Distributed Morphology. Cambridge University Press.

MacSwan, J. (1999). A Minimalist Approach to Intrasentential Code Switching. Garland Press.

MacSwan, J. (2000). The architecture of the bilingual language faculty: Evidence from codeswitching. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 3(1), 37-54.

MacSwan, J. (2013). Code switching and linguistic theory. In T. K. Bhatia & W. Ritchie (Eds.), Handbook of Bilingualism and Multilingualism (pp. 223-250). Blackwell.

doi MacSwan, J. (2014). Programs and proposals in codeswitching research: Unconstraining theories of bilingual language mixing. In J. MacSwan (Ed.), Grammatical Theory and Bilingual Codeswitching (pp. 1-33). MIT Press.

Mahootian, S. (1993). A null theory of code switching. Doctoral dissertation, Northwestern University.

doi Marantz, A. (2013a). Verbal argument structure: Events and participants. Lingua, 130, 152-168.

doi Marantz, A. (2013b). No escape from morphemes in morphological processing. Language and Cognitive Processes, 28(7), 905-916.

Matthews, P.H. (1972). Inflectional Morphology: A Theoretical Study Based on Aspects of Latin Verb Conjugation. Cambridge University Press.

doi Meilinger, A., Branigan, H. P., & Pickering, M.J. (2014). Parallel processing in language production. Language, Cognition, & Neuroscience, 29, 663-683.

doi Müller, G. (2017). Structure removal: An argument for feature-driven Merge. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics, 2(1), 28.

Murphy, E. (2021). The oscillatory nature of language. Cambridge University Press.

doi Natvig, D.A., Putnam, M.T., & Lykke, A.K. (2023). Stability in the integrated bilingual grammar: Tense exponency in North American Norwegian. Nordic Journal of Linguistics.

Natvig, D.A., Pretorius, E., Putnam, M.T., & Carlson, M.T. (to appear). A spanning approach to bilingual representations: Initial exploration. In B. R. Page & M.T. Putnam (Eds.), Contact varieties of German: Studies in honor of William D. Keel. John Benjamins.

doi Opitz, A., Regel, S., Müller, G., & Friederici, A.D. (2013). Neurophysiological evidence for morphological underspecification in German strong adjective inflection. Language, 89(2), 231-264.

doi Oseki, Y., & Marantz, A. (2020). Modeling human morphological competence. Frontiers in Psychology, 11:513740.

Pesetsky, D. (2019). Exfoliation: towards a derivational theory of clause size. Ms., MIT. Available from https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/oo4440

doi Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2013). Forward models and their implications for production, comprehension, and dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(4), 377-392.

Pietroski, P. (2005). Events and Semantic Architecture. Oxford University Press.

doi Pietroski, P. (2018). Conjoining Meanings: Semantics Without Truth Values. Oxford University Press.

Prévost, P. (1997). Truncation in Second Language Acquisition. Doctoral dissertation, McGill University.

Prévost, P., & White, L. (2000a). Accounting for morphological variability in second language acquisition: Truncation or missing inflection? In M.-A. Friedmann & L. Rizzi (Eds.), The Acquisition of Syntax (pp. 202-235). Longman.

doi Prévost, P., & White, L. (2000b). Missing surface inflection or impairment in second language acquisition? Evidence from tense and agreement. Second Language Research, 16, 103-133.

doi Putnam, M.T. (2020). One feature – one head: Features as functional heads in language acquisition and attrition. In P. Guijaaro-Fuentes & C. Suárez-Gómez (Eds.), New trends in language acquisition within the generative perspective (pp. 3-26). Springer.

doi Putnam, M.T., Carlson, M., & Reitter, D. (2018). Integrated, not isolated: Defining typological proximity in an integrated multilingual architecture. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2212.

Putnam, M. T., Perez-Cortes, S., & Sánchez, L. (2019). Language attrition and the Feature Reassembly Hypothesis. In M.S. Schmid & B. Köpke (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Language Attrition (pp. 18-24). Oxford University Press.

doi Ramchand, G.C. (2008). Verb Meaning and the Lexicon: A First-Phase Syntax. Cambridge University Press.

doi Ramchand, G. C., & Svenonius, P. (2014). Deriving the functional hierarchy. Language Sciences, 46, 152-174.

Rappaport Hovav, M., & Levin, B. (1998). Building verb meanings. In M. Butt & W. Geuder (Eds.), The Projection of Arguments (pp. 97-134). CSLI Publications.

doi Riksem, B. R. (2017). Language Mixing and Diachronic Change: American Norwegian Noun Phrases Then and Now. Languages, 2.

doi Riksem, B.R. (2018). Language mixing in American Norwegian noun phrases: An exoskeletal analysis of synchronic and diachronic patterns. Doctoral dissertation, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

doi Riksem, B. R., Grimstad, M. B., Lohndal, T., & Åfarli, T.A. (2019). Language mixing within verbs and nouns in American Norwegian. Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics, 22, 189-209.

doi Rizzi, L. (1994). Early null subjects and root null subjects. In T. Hoekstra, & B. Schwartz (Eds.), Language acquisition studies in generative grammar (pp. 151-177). John Benjamins.

doi Sánchez, L. (2019). Bilingual alignments. Languages, 4, 82:

Schein, B. (1993). Plurals and Events. MIT Press.

doi Seyboth, M., & Domahs, F. (2023). Why do he and she disagree: The role of binary morphological features in grammatical gender agreement in German. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. First view: Published online 16 January 2023.

doi Slabakova, R. (2009). Features or parameters: Which one makes second language acquisition research easier, and more interesting to study? Second Language Research, 25(2), 313-324.

Slabakova, R. (2016). Second Language Acquisition. Oxford University Press.

doi Slabakova, R. (2021). Second language acquisition. In N. Allott, T. Lohndal, & G. Rey (Eds.), A Companion to Chomsky (pp. 222-231). Wiley Blackwell.

doi Smith, C. (1997). The parameter of aspect. Kluwer Academic.

doi Song, Y., Do, Y., Thompson, A. L., Waegemaekers, E. R., & Lee, J. (2020). Second language uses exhibit shallow morphological processing. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(5), 1121-1136.

doi Stockall, L., Manouilidou, C., Gwilliams, L., Neophyton, K., & Marantz, A. (2019). Prefix stripping re-re-revisited: MEG investigations of morphological decomposition and recomposition. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1964.

doi Stump, G.T. (2001). Inflectional Morphology: A Theory of Paradigm Structure. Cambridge University Press.

Sugimoto, Y. (2022). Underspecification and (Im)possible Derivations: Toward a Restrictive Theory of Grammar. Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan.

doi Sugimoto, Y., & Baptista, M. (2022). A late-insertion-based exoskeletal approach to the hybrid nature of functional features in creole languages. Languages, 7,

doi Svenonius, P. (2016). Spans and words. In H. Harley & D. Siddiqi (Eds.), Morphological metatheory (pp. 199-202). John Benjamins.

doi Taft, M. (2004). Morphological decomposition and the reverse base frequency effect. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 57(4), 745-765.

Vanden Wyngaerd, E. (2021). Bilingual Implications: Using code-switching data to inform linguistic theory. Doctoral dissertation, Université Libre de Bruxelles.

doi White, L. (2003). Second Language Acquisition and Universal Grammar. Cambridge University Press.

Williams, A. (2014). Arguments in Syntax and Semantics. Cambridge University Press.

doi Wiltschko, M. (2021). The syntax of number markers. In P.C. Hofherr & J. Doetjes (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Grammatical Number (pp. 164-196). Oxford University Press.

doi Wu, Z., & Juffs, A. (2022). Effects of L1 morphological type on L2 morphological awareness. Second Language Research, 38(4), 787-812.

doi Wood, J. (2015). Icelandic Morphosyntax and Argument Structure. Springer.

Zwicky, A.M. (1985). How to describe inflection. In M. Niepokuj, M. Van Clay, V. Nikiforidou & D. Feder (Eds.), Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 372-386). Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Address for correspondence

Department of Language and Literature

Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU)

N-7491 Trondheim

Norway

terje.lohndal@ntnu.no

Co-author information

Pennsylvania State University

mtp12@psu.edu

(D) https://orcid.org/oooo-0002-7758-8266

Publication history

Date accepted: 1 December 2023

Published online: 1 February 2024

- Note that Borer’s model is often referred to as exoskeletal, but as she herself makes clear, the technical implementation does not follow from the conceptual framework (Borer 2005b: 10):

- In what follows, I will continue to bring forth arguments that support a rich syntactic functional component, and a correspondingly impoverished lexical component. In turn, I will also propose a very specific syntactic functional structure for event structure […]. However, the validity of postulating an impoverished lexicon, in the sense employed here, is quite independent of the validity of any specific functional structure I will propose.

- The data in this section are taken directly from Lee and Lardiere (2016:114-5).

- There are a number of theory-internal issues that we do not discuss here that are important for future theory-building efforts. Here we mention two of them: First, at the moment we are treating the association of features and concatenative and non-concatenative morphology (in the case of reduplication) as identical. Second, the question of whether or not features that are not ‘active’ in the

(but are still there in a cartographic sense) or must be acquired anew is also left for future research considerations (cf. Cinque 2006, and Ramchand & Svenonius 2014).

- There are a number of theory-internal issues that we do not discuss here that are important for future theory-building efforts. Here we mention two of them: First, at the moment we are treating the association of features and concatenative and non-concatenative morphology (in the case of reduplication) as identical. Second, the question of whether or not features that are not ‘active’ in the

- More specifically, in Distributed Morphology this situation could be captured via the postsyntactic operation Fission, which is an operation that converts one terminal node in a tree structure into two (resulting in two exponents) (Halle 1997).

- There are some exceptional adjectives that allow the omission of the prenominal determiner. We set these aside here; see van Baal (2022) for a comprehensive discussion.