DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-024-00335-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40021614

تاريخ النشر: 2025-02-28

إجماع الخبراء على الوقاية وعلاج إزالة المعادن من المينا في علاج تقويم الأسنان

الملخص

إزالة المعادن من المينا، وتكوين آفات البقع البيضاء، هي مشكلة شائعة في علاج تقويم الأسنان السريري. ظهور آفات البقع البيضاء لا يؤثر فقط على نسيج وصحة الأنسجة الصلبة للأسنان، بل يؤثر أيضًا على صحة وجمالية الأسنان بعد علاج تقويم الأسنان. تتضمن الوقاية والتشخيص والعلاج من آفات البقع البيضاء التي تحدث خلال عملية علاج تقويم الأسنان عدة تخصصات سنية. ستركز هذه الإجماع الخبراء على تقديم آراء توجيهية حول إدارة والوقاية من آفات البقع البيضاء خلال علاج تقويم الأسنان، داعية إلى الوقاية الاستباقية، والكشف المبكر، والعلاج في الوقت المناسب، والمتابعة العلمية، والإدارة متعددة التخصصات لآفات البقع البيضاء طوال عملية تقويم الأسنان، وبالتالي الحفاظ على صحة الأسنان للمرضى خلال علاج تقويم الأسنان.

المقدمة

| أنظمة فوسفات الكالسيوم | اختصار | الهيكل الكيميائي | Ksp |

| فوسفات الكالسيوم الهيدروجيني | DCPD |

|

6.6 |

|

|

|

|

29.5 |

| فوسفات الكالسيوم الثماني | OCP |

|

98.6 |

| هيدروكسيباتيت | HA |

|

117.2 |

| فلووروباتيتي | FA |

|

120.3 |

| فوسفات الكالسيوم غير المتبلور | ACP |

|

24.8 |

تشخيص إزالة المعادن من المينا

فحص الفم

تقييم الصور الرقمية

قيم التدرج الرمادي.

تكنولوجيا الفلورية

التحليل الضوئي عبر الألياف الضوئية – التصوير الرقمي التحليل الضوئي عبر الألياف الضوئية (FOTI-DIFOTI)

أظهرت دراسة حديثة أن هذه الطريقة التشخيصية يمكن أن تكشف بدقة أكبر عن إزالة المعادن المبكرة في مينا الأسنان والعاج المخفي في أنسجة الأسنان مقارنة بالطرق الأخرى.

قياسات المقاومة الكهربائية

التصوير المقطعي البصري

الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI)

طرق أخرى

- الطريقة المفضلة لفحص إزالة المعادن من أسطح الأسنان هي من خلال الجمع بين الفحص البصري والتنقيب، والذي يمكن أن يتم دعمه باستخدام كاميرا رقمية وعدسة ماكرو لتسجيل أسطح الأسنان المزالة المعادن. من المهم ضمان وجود ضوء كافٍ ولكن تجنب التعرض المفرط عند التقاط الصور بكاميرا رقمية لتجنب النتائج السلبية الكاذبة.

- أثناء فحص أسطح الأسنان، من المهم تنظيف الأسطح وتجفيفها بدقة وملاحظتها تحت ضوء ساطع لاكتشاف أي تغييرات في مظهر البياض الجبني.

- تم استخدام مسبار لفحص خشونة أسطح الأسنان عند إجراء الفحص وتقييم ما إذا كانت إزالة المعادن في مرحلة نشطة.

- لتحليل كمي للتغيرات الجبنية البيضاء على أسطح الأسنان، يجب استخدام طرق إضافية مثل تقنية الفلورية، والإضاءة البصرية، واختبار المقاومة. إن استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي في تفسير إزالة المعادن من الأسنان له تطبيق واعد في مساعدة الفحوصات السريرية.

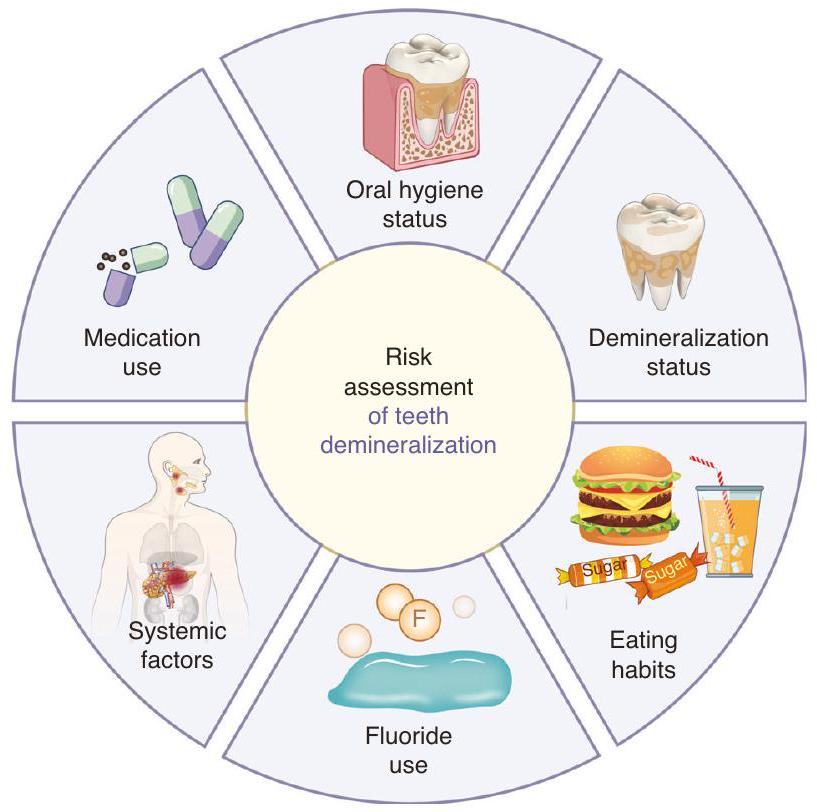

تقييم مخاطر إزالة المعادن من المينا قبل العلاج التقويمي

حالة نظافة الفم

حالة إزالة المعادن

عادات الأكل

استخدام الفلورايد

العوامل النظامية

طرق وقائية لإزالة المعادن من المينا في العلاج التقويمي

يساعد الفحص المهني المنتظم لطب الأسنان في الكشف عن البقع الجبنية البيضاء المبكرة أو التسوس على سطح الأسنان ورؤية الأخصائي في الوقت المناسب.

رعاية صحة الفم

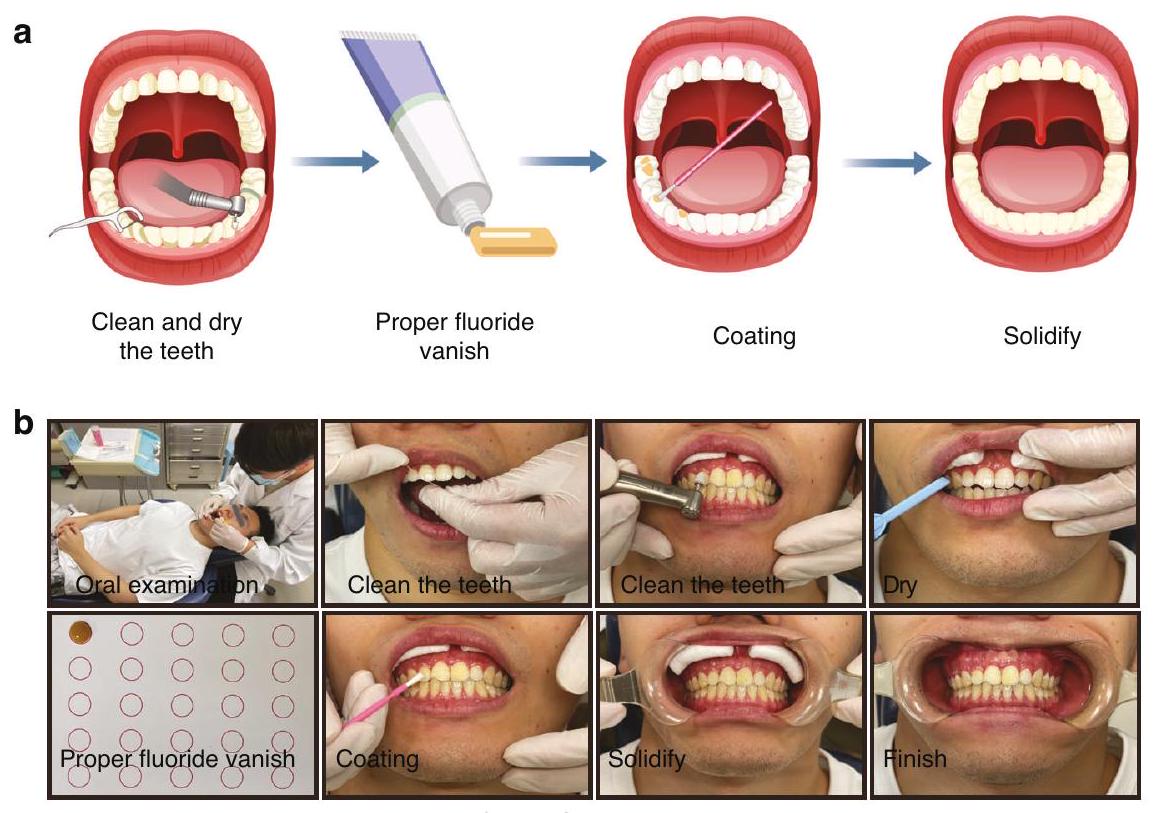

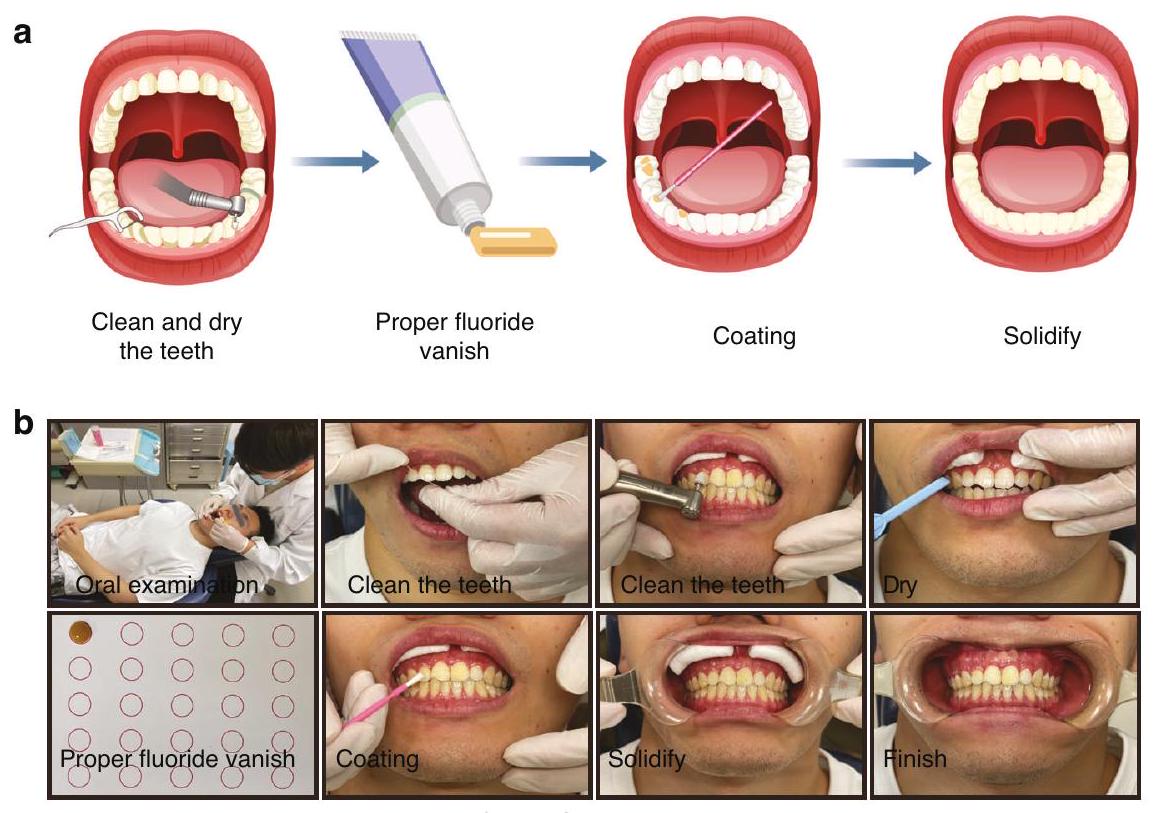

استخدام الفلورايد

بسيطة نسبيًا. باختصار، يتم أولاً تنظيف سطح السن وتجفيفه. ثم، يتم تطبيق كمية مناسبة من الفلورايد على سطح السن. من المهم ملاحظة أنه يجب عدم تناول الطعام خلال 2 إلى 4 ساعات بعد تطبيق الفلورايد، ويجب تجنب الفرشاة في تلك الليلة لضمان فعالية التطبيق.

إرشادات غذائية

استخدام الكلورهيكسيدين

تشمل علاجات تقويم الأسنان عادةً أجهزة ثابتة مثل الأقواس على الجانب الشفهي أو اللساني أو المحاذيات الشفافة. نظرًا للاختلافات في الهيكل ومكان هذه الأجهزة في تجويف الفم للمريض، تختلف طرق منع إزالة المعادن من المينا

. بالنسبة للأجهزة الثابتة الملتصقة بسطح الأسنان، مثل الأقواس، فإن وجود الأقواس والأسلاك القوسية يعيق التنظيف الذاتي لتجويف الفم والنظافة اليومية، مما يتطلب فرشاة وتنظيف بقايا الطعام حول الأقواس بعد كل وجبة لتقليل تراكم اللويحات.

- الحفاظ على نظافة الفم الجيدة هو الطريقة الأساسية لمنع إزالة المعادن من المينا في علاج تقويم الأسنان. تعتبر تعليمات نظافة الفم والتثقيف الصحي أمرًا حيويًا.

- يجب التركيز على الطريقة الصحيحة والفعالة لفرشاة الأسنان، مع ضمان كل من مدة وتكرار الفرشاة وتقليل تناول الأطعمة المسببة للتسوس.

- يجب تشجيع استخدام معجون الأسنان بالفلورايد للعناية اليومية بالأسنان لتعزيز مقاومة الحمض للمينا وتقليل إزالة المعادن.

- بعد ارتداء أجهزة تقويم الأسنان، من الضروري تنظيف تجويف الفم والمنطقة المحيطة بالأجهزة من بقايا الطعام بعد كل وجبة لمنع تكوين بيئة حمضية تؤدي إلى إزالة المعادن من المينا.

إدارة إزالة المعادن من المينا أثناء علاج تقويم الأسنان

تقييم خطر إزالة المعادن طوال عملية علاج تقويم الأسنان

إعادة التمعدن والعلاج المشترك لمكافحة الأغشية الحيوية

gيدًا لإعادة تمعدن WSL، وعند دمجه مع الفلورايد، فإنه يعزز من تأثيرات إعادة التمعدن لـ WSL.

العلاج بالليزر

استخدام الأوزون

إزالة المعادن من الأسنان.

المؤشر الرئيسي للتحبب الدقيق للأنسجة السنية الصلبة هو تغير اللون الداخلي أو تغيرات في الملمس الناتجة عن عيوب تكوين المينا أو فلوروس الأسنان.

أظهرت الدراسات في المختبر أن التبييض يمكن أن يحسن من جمالية الأسنان ذات WSL. ومع ذلك، فإن عملية التبييض تعزز فقط المظهر، مما يخفي الآفات البيضاء بدلاً من علاجها.

خلال تطور WSL، يحدث زيادة في المسامية الدقيقة في المينا. يتسرب راتنج التصلب الضوئي منخفض اللزوجة إلى منطقة المينا المسامية الدقيقة لـ WSL من خلال العمل الشعري، مما يغلق المسام ويزيد من قوة المينا، مما يوفر دعمًا ميكانيكيًا لمنع تقدم WSL.

الإدارة السريرية وعلاج WSL بعد التقويم

اعتبارات أخرى في تقويم الأسنان: إدارة إزالة المعادن من المينا في العلاج التقويمي المبكر للأطفال والمراهقين

نظافة الفم الجيدة. يجب تطبيق مواد السد المبكر للثنايا والشقوق للأضراس. خلال كل زيارة متابعة، يجب مراقبة حالة نظافة الفم، مثل اللويحات، والجير، وصحة اللثة، لمنع العوامل المسببة لـ WSL. إذا كانت WSL قد تطورت بالفعل أثناء العلاج التقويمي، يمكن اعتبار تطبيق الفلورايد الموضعي، أو استخدام عوامل إعادة التمعدن، أو تسرب الراتنج كخيارات للعلاج. التعليم الإضافي لنظافة الفم للأطفال والآباء أمر ضروري.

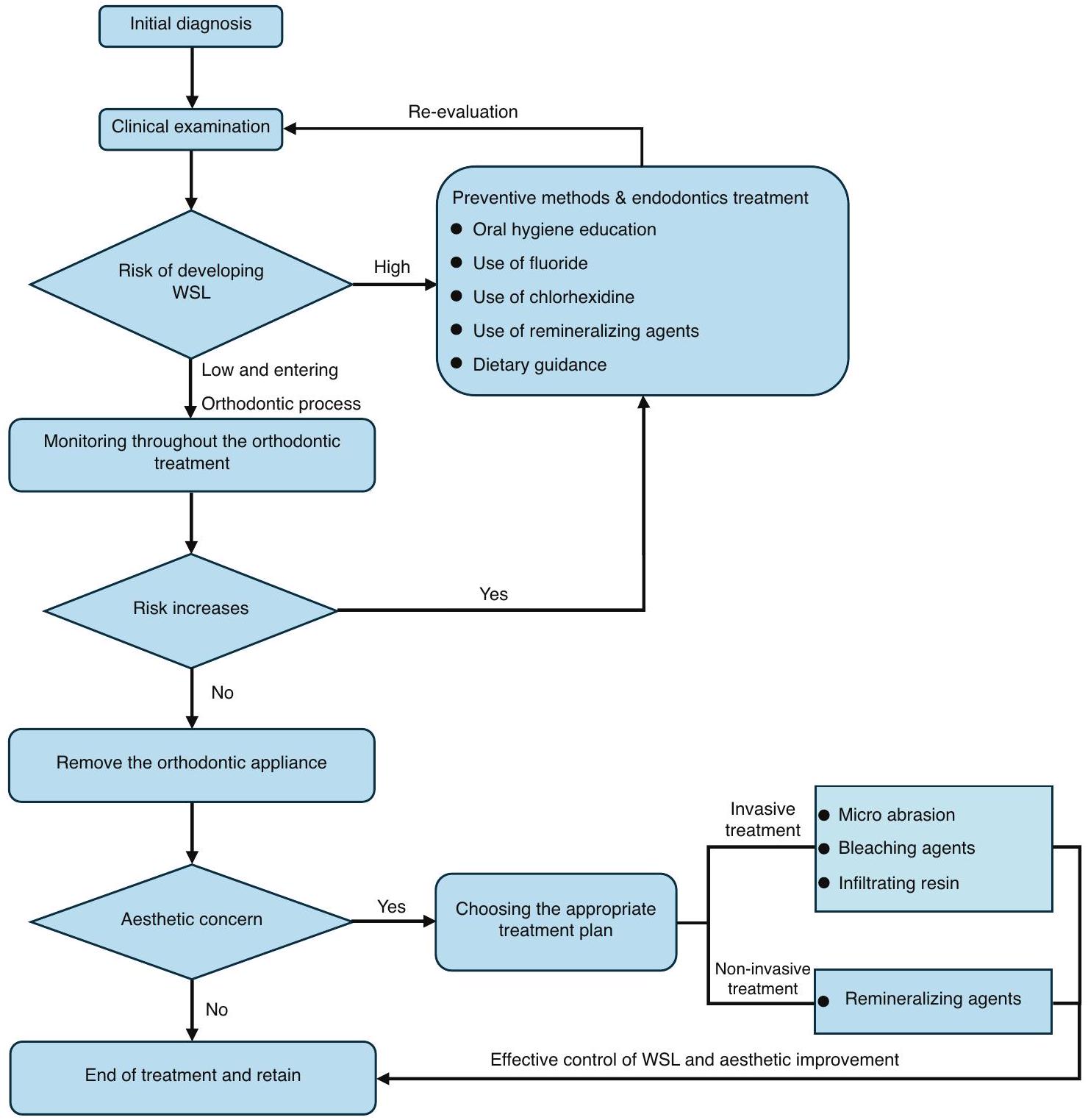

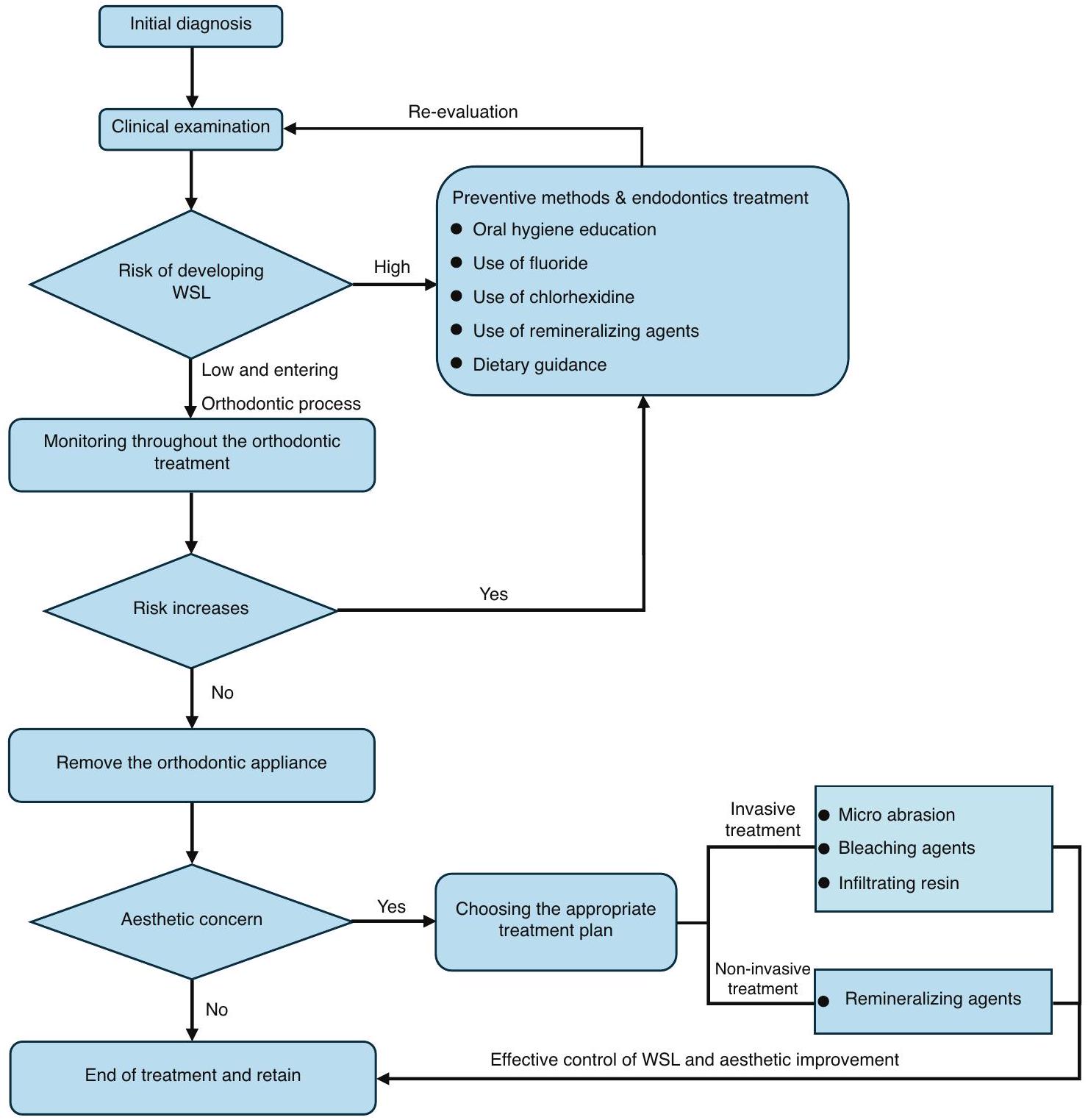

إجراءات سريرية موصى بها للوقاية والعلاج من WSL خلال عملية علاج تقويم الأسنان بالكامل

- قبل علاج تقويم الأسنان، من الضروري تقييم عوامل الخطر لتسوس الأسنان بشكل كامل. فقط عندما تكون عوامل الخطر تحت السيطرة، يمكن أن يتقدم علاج تقويم الأسنان اللاحق.

- خلال علاج تقويم الأسنان، من الضروري مراقبة حدوث WSL في كل زيارة متابعة والتدخل بسرعة. يجب أن يكون التركيز الأساسي على تعزيز التعليم حول نظافة الفم، والحفاظ على صحة الفم الجيدة، واستخدام الفلورايد ومواد إعادة التمعدن محليًا لتعزيز إعادة تمعدن WSL.

- إذا كانت تقدم WSL على سطح السن خلال علاج تقويم الأسنان غير قابل للتحكم، استبدل جهاز تقويم الأسنان بجهاز يسهل تنظيفه أو أوقف علاج تقويم الأسنان مؤقتًا حتى يتم السيطرة على WSL بشكل فعال.

- بعد علاج تقويم الأسنان، يجب اتخاذ نهج متعدد التخصصات بناءً على شدة إزالة المعادن من الأسنان بعد إزالة الجهاز.

- بالنسبة لعلاج تقويم الأسنان للأطفال والمراهقين، من الضروري تثقيف الوالدين حول نظافة الفم لضمان التزام المرضى بالعلاج وتقليل حدوث WSL.

آفاق البحث في علاج WSL

تقويم الأسنان. في المستقبل، سيكون من الممكن استخدام طرق تكنولوجية قائمة على الذكاء الاصطناعي، بالتزامن مع طرق الفحص الحالية لتشخيص WSL، لتخصيص مراقبة الأسنان خلال عمليات تقويم الأسنان. يمكن أن يتنبأ هذا بتطور وتوقع WSL في مرحلة مبكرة، وينبه المرضى إلى خطر حدوث WSL، ويقلل من تأثير WSL على عمليات تقويم الأسنان. في الوقت نفسه، يحتاج أطباء تقويم الأسنان إلى إدراك أن الذكاء الاصطناعي يلعب فقط دورًا تكميليًا في عمليات تقويم الأسنان. لا يمكن للتقنيات الناشئة المختلفة أن تحل محل دور أطباء تقويم الأسنان بالكامل في الوقاية من WSL وتشخيصه. لا يزال يتعين على أطباء تقويم الأسنان تعزيز فهمهم لـ WSL، وتحديد العلامات المبكرة للإصابات الجيرية بسرعة، والتدخل عند الضرورة.

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

معلومات إضافية

REFERENCES

- Skidmore, K. J., Brook, K. J., Thomson, W. M. & Harding, W. J. Factors influencing treatment time in orthodontic patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 129, 230-238 (2006).

- B, F., ZL, J., YX, B., L, W. & ZH, Z. Experts consensus on diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for malocclusions at early developing stage. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue 30, 449-455 (2021).

- XJ, G. Dental and endodontic basic knowledges related in orthodontic treatment. Chin. J. Orthod. 23, 167-170 (2016).

- Selwitz, R. H., Ismail, A. I. & Pitts, N. B. Dental caries. Lancet 369, 51-59 (2007).

- Marinelli, G. et al. White spot lesions in orthodontics: prevention and treatment. A descriptive review. J. Biol. Reg. Homeos Ag. 35, 227-240 (2021).

- Maxfield, B. J. et al. Development of white spot lesions during orthodontic treatment: Perceptions of patients, parents, orthodontists, and general dentists. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 141, 337-344 (2012).

- Øgaard, B., Rølla, G. & Arends, J. Orthodontic appliances and enamel demineralization: Part 1. Lesion development. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 94, 68-73 (1988).

- YX, B. Risk perception and management in orthodontic treatment. Chinese J. Stomatology. 12, 793-797 (2019).

- Julien, K. C., Buschang, P. H. & Campbell, P. M. Prevalence of white spot lesion formation during orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 83, 641-647 (2013).

- Buschang, P. H., Chastain, D., Keylor, C. L., Crosby, D. & Julien, K. C. Incidence of white spot lesions among patients treated with clear aligners and traditional braces. Angle Orthod. 89, 359-364 (2019).

- Albhaisi, Z., Al-Khateeb, S. N. & Abu Alhaija, E. S. Enamel demineralization during clear aligner orthodontic treatment compared with fixed appliance therapy, evaluated with quantitative light-induced fluorescence: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 157, 594-601 (2020).

- Gorelick, L., Geiger, A. M. & Gwinnett, A. J. Incidence of white spot formation after bonding and banding. Am. J. Orthod. 81, 93-98 (1982).

- Lucchese, A. & Gherlone, E. Prevalence of white-spot lesions before and during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur. J. Orthod. 35, 664-668 (2013).

- Heymann, G. C. & Grauer, D. A contemporary review of white spot lesions in orthodontics. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 25, 85-95 (2013).

- Chatterjee, R. & Kleinberg, I. Effect of orthodontic band placement on the chemical composition of human incisor tooth plaque. Arch. Oral. Biol. 24, 97-100 (1979).

- Mattingly, J., Sauer, G., Yancey, J. & Arnold, R. Enhancement of Streptococcus mutans colonization by direct bonded orthodontic appliances. J. Dent. Res. 62, 1209-1211 (1983).

- Rosenbloom, R. G. & Tinanoff, N. Salivary Streptococcus mutans levels in patients before, during, and after orthodontic treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 100, 35-37 (1991).

- Pitts, N. B. et al. Dental caries. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 3, 1-16 (2017).

- Lopes, P. C. et al. White spot lesions: diagnosis and treatment-a systematic review. BMC Oral. Health 24, 1-18 (2024).

- Zou, J. et al. Expert consensus on early childhood caries management. Int J. Oral. Sci. 14, 35 (2022).

- NouhzadehMalekshah, S., Fekrazad, R., Bargrizan, M. & Kalhori, K. A. Evaluation of laser fluorescence in combination with photosensitizers for detection of demineralized lesions. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 26, 300-305 (2019).

- Foros, P., Oikonomou, E., Koletsi, D. & Rahiotis, C. Detection methods for early caries diagnosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 55, 247-259 (2021).

- Pitts, N. B. & Stamm, J. W. International Consensus Workshop on Caries Clinical Trials (ICW-CCT)-Final Consensus Statements: Agreeing Where the Evidence Leads. J. Dent. Res. 83, 125-128 (2004).

- Zandoná, A. F. & Zero, D. T. Diagnostic tools for early caries detection. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 137, 1675-1684 (2006).

- Kidd, E. & Fejerskov, O. What constitutes dental caries? Histopathology of carious enamel and dentin related to the action of cariogenic biofilms. J. Dent. Res. 83, 35-38 (2004).

- Sadıkoğlu, İ. S. White spot lesions: recent detection and treatment methods. Cyprus J. Med. Sci. 5, 260-266 (2020).

- Askar, H. et al. Detecting white spot lesions on dental photography using deep learning: A pilot study. J. Dent. 107, 103615 (2021).

- Estai, M. et al. Comparison of a smartphone-based photographic method with face-to-face caries assessment: a mobile teledentistry model. Telemed. J. E-health 23, 435-440 (2017).

- Lee, H.-S., Lee, Y.-D., Kim, S.-K., Choi, J.-H. & Kim, B.-I. Assessment of tooth wear based on autofluorescence properties measured using the QLF technology in vitro. Photodiagn. Photodyn. 25, 265-270 (2019).

- Knaup, I. et al. Correlation of quantitative light-induced fluorescence and qualitative visual rating in infiltrated post-orthodontic white spot lesions. Eur. J. Orthod. 45, 133-141 (2023).

- Kim, H.-E. Red Fluorescence Intensity as a Criterion for Assessing Remineralization Efficacy in Early Carious Lesions. Photodiagn. Photodyn. 103963 (2024).

- Chandra, S. & Garg, N. Textbook of operative dentistry. (Jaypee Brothers Publishers, 2008).

- Park, S.-W. et al. Lesion activity assessment of early caries using dye-enhanced quantitative light-induced fluorescence. Sci. Rep. 12, 11848 (2022).

- Warkhankar, A., Tanpure, V. R. & Wajekar, N. A. Using light fluorescence technique as an emerging approach in treating dental caries. Int. J. Prevent. Clin. Dent. Res. 10, 69-72 (2023).

- Macey, R. et al. Fluorescence devices for the detection of dental caries. Cochrane Db. Syst. Rev. 12, CD013811 (2020).

- Sürme, K., Kara, N. B. & Yilmaz, Y. In Vitro Evaluation of Occlusal Caries Detection Methods in Primary and Permanent Teeth: A Comparison of CarieScan PRO, DIAGNOdent Pen, and DIAGNOcam Methods. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 38, 105-111 (2020).

- Hogan, R., Pretty, I. A. & Ellwood, R. P. in Detection and Assessment of Dental Caries: A Clinical Guide (eds Andrea Ferreira Zandona & Christopher Longbottom) 139-150 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

- Schwendicke, F., Elhennawy, K., Paris, S., Friebertshäuser, P. & Krois, J. Deep learning for caries lesion detection in near-infrared light transillumination images: A pilot study. J. Dent. 92, 103260 (2020).

- Fried, D., Glena, R. E., Featherstone, J. D. & Seka, W. Nature of light scattering in dental enamel and dentin at visible and near-infrared wavelengths. Appl. Opt. 34, 1278-1285 (1995).

- Stratigaki, E. et al. Clinical validation of near-infrared light transillumination for early proximal caries detection using a composite reference standard. J. Dent. 103, 100025 (2020).

- Abogazalah, N. & Ando, M. Alternative methods to visual and radiographic examinations for approximal caries detection. J. Oral. Sci. 59, 315-322 (2017).

- Y, Y., JQ, X. & JJ, S. Application progress of fiber optic transillumination in caries diagnosis. Beijing J. Stomatology 28, 118-120 (2020).

- Longbottom, C. & Huysmans, M.-C. Electrical measurements for use in caries clinical trials. J. Dent. Res. 83, 76-79 (2004).

- Wolinsky, L. E. et al. An in vitro assessment and a pilot clinical study of electrical resistance of demineralized enamel. Int. J. Clin. Dent. 10, 40-43 (1999).

- Wang, J., Someya, Y., Inaba, D., Longbottom, C. & Miyazaki, H. Relationship between electrical resistance measurements and microradiographic variables during remineralization of softened enamel lesions. Caries Res. 39, 60-64 (2005).

- Sannino, I., Angelini, E., Parvis, M., Arpaia, P. & Grassini, S. in 2022 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC). 1-5 (IEEE).

- Shimada, Y., Yoshiyama, M., Tagami, J. & Sumi, Y. Evaluation of dental caries, tooth crack, and age-related changes in tooth structure using optical coherence tomography. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 56, 109-118 (2020).

- Ibusuki, T. et al. Observation of white spot lesions using swept source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT): in vitro and in vivo study. Dent. Mater. J. 34, 545-552 (2015).

- Kühnisch, J., Meyer, O., Hesenius, M., Hickel, R. & Gruhn, V. Caries detection on intraoral images using artificial intelligence. J. Dent. Res. 101, 158-165 (2022).

- Kim, J., Shin, T. J., Kong, H. J., Hwang, J. Y. & Hyun, H. K. High-Frequency Ultrasound Imaging for Examination of Early Dental Caries. J. Dent. Res. 98, 363-367 (2019).

- Xing, H., Eckert, G. J. & Ando, M. Impact of angle on photothermal radiometry and modulated luminescence (PTR/LUM) value. J. Dent. 132, 104500 (2023).

- Liang, J. P. Research and application of new techniques for early diagnosis of caries. Chin. J. Stomatol. 56, 33-38 (2021).

- Kwon, T. H., Salem, D. M. & Levin, L. in Semin Orthod. (Elsevier).

- Bishara, S. E. & Ostby, A. W. White Spot Lesions: Formation, Prevention, and Treatment. SEMIN ORTHOD 14, 174-182 (2008).

- Ogaard, B. Enamel effects during bonding-debonding and treatment with fixed appliances. Risk Management in Orthodontics: Experts’ Guide to Malpractice Ch. 3 (Quintessence Publishing Co., 2004).

- Disney, J. A. et al. The University of North Carolina Caries Risk Assessment study: further developments in caries risk prediction. Community Dent. oral. Epidemiol. 20, 64-75 (1992).

- S, L. & M, H. A Review of Enamel Demineralization in Orthodontic Treatment with Fixed Appliances. J. Oral. Sci. Res. 37, 685-688 (2021).

- Marinho, V. Cochrane reviews of randomized trials of fluoride therapies for preventing dental caries. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 10, 183-191 (2009).

- Weyland, M. I., Jost-Brinkmann, P.-G. & Bartzela, T. Management of white spot lesions induced during orthodontic treatment with multibracket appliance: a national-based survey. Clin. Oral. Invest 26, 4871-4883 (2022).

- Sardana, D. et al. Effectiveness of professional fluorides against enamel white spot lesions during fixed orthodontic treatment: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J. Dent. 82, 1-10 (2019).

- Simmer, J. P., Hardy, N. C., Chinoy, A. F., Bartlett, J. D. & Hu, J. C. How fluoride protects dental enamel from demineralization. J. Int Soc. Prev. Commun. 10, 134 (2020).

- Song, H., Cai, M., Fu, Z. & Zou, Z. Mineralization Pathways of Amorphous Calcium Phosphate in the Presence of Fluoride. Cryst. Growth Des. 23, 7150-7158 (2023).

- Zhang, Q. et al. Application of fluoride disturbs plaque microecology and promotes remineralization of enamel initial caries. J. Oral. Microbiol. 14, 2105022 (2022).

- Øgaard, B. in Semin Orthod. 183-193 (Elsevier).

- Øgaard, B., Larsson, E., Henriksson, T., Birkhed, D. & Bishara, S. E. Effects of combined application of antimicrobial and fluoride varnishes in orthodontic patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 120, 28-35 (2001).

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride Therapy [J]. Pediatr Dent, 39, 242-245 (2017).

- Alexander, S. A. & Ripa, L. W. Effects of self-applied topical fluoride preparations in orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod. 70, 424-430 (2000).

- Hancock, S., Zinn, C. & Schofield, G. The consumption of processed sugar-and starch-containing foods, and dental caries: a systematic review. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 128, 467-475 (2020).

- Schaeken, M. J. & De Haan, P. Effects of sustained-release chlorhexidine acetate on the human dental plaque flora. J. Dent. Res. 68, 119-123 (1989).

- Sajadi, F. S., Moradi, M., Pardakhty, A., Yazdizadeh, R. & Madani, F. Effect of fluoride, chlorhexidine and fluoride-chlorhexidine mouthwashes on salivary Streptococcus mutans count and the prevalence of oral side effects. J. Dent. Res., Dent. Clin., Dent. prospects 9, 49 (2015).

- Kamarudin, Y., Skeats, M. K., Ireland, A. J. & Barbour, M. E. Chlorhexidine hexametaphosphate as a coating for elastomeric ligatures with sustained antimicrobial properties: A laboratory study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 158, e73-e82 (2020).

- Jones, C. G. Chlorhexidine: is it still the gold standard? Periodontol 2000 15, 55-62 (1997).

- Fardai, O. & Turnbull, R. S. A review of the literature on use of chlorhexidine in dentistry. Assoc. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 112, 863-869 (1986).

- Baumer, C. et al. Orthodontists’ instructions for oral hygiene in patients with removable and fixed orthodontic appliances. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. (2023).

- Raghavan, S., Abu Alhaija, E. S., Duggal, M. S., Narasimhan, S. & Al-Maweri, S. A. White spot lesions, plaque accumulation and salivary caries-associated bacteria in clear aligners compared to fixed orthodontic treatment. A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral. Health 23, 599 (2023).

- Sardana, D., Schwendicke, F., Kosan, E. & Tüfekçi, E. White spot lesions in orthodontics: consensus statements for prevention and management. Angle Orthod. 93, 621-628 (2023).

- Ten Cate, J., Buijs, M., Miller, C. C. & Exterkate, R. Elevated fluoride products enhance remineralization of advanced enamel lesions. J. Dent. Res. 87, 943-947 (2008).

- Reynolds, E. Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate: the scientific evidence. Adv. Dent. Res. 21, 25-29 (2009).

- Karabekiroğlu, S. et al. Treatment of post-orthodontic white spot lesions with CPP-ACP paste: A three year follow up study. Dent. Mater. J. 36, 791-797 (2017).

- de Oliveira, P. R. A., Barreto, L. S. D. C. & Tostes, M. A. Effectiveness of CPP-ACP and fluoride products in tooth remineralization. Int J. Dent. Hyg. 20, 635-642 (2022).

- Bourouni, S., Dritsas, K., Kloukos, D. & Wierichs, R. J. Efficacy of resin infiltration to mask post-orthodontic or non-post-orthodontic white spot lesions or fluorosis -a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral. Invest 25, 4711-4719 (2021).

- Xiaotong, W., Nanquan, R., Jing, X., Yuming, Z. & Lihong, G. Remineralization effect of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate for enamel demineralization: a system review. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 35, 629-635 (2017).

- He, J. et al. Polyzwitterion Manipulates Remineralization and Antibiofilm Functions against Dental Demineralization. ACS Nano 16, 3119-3134 (2022).

- Liao, J. et al. Stimuli-responsive graphdiyne-silver nanozymes for catalytic ion therapy of dental caries through targeted biofilms removal and remineralization. Nano Today 55, 102204 (2024).

- Tagomori, S. & Morioka, T. Combined effects of laser and fluoride on acid resistance of human dental enamel. Caries Res. 23, 225-231 (1989).

- Kuroda, S. & Fowler, B. Compositional, structural, and phase changes in in vitro laser-irradiated human tooth enamel. Calcif. Tissue Int. 36, 361-369 (1984).

- Rafiei, E., Fadaei Tehrani, P., Yassaei, S. & Haerian, A. Effect of CO 2 laser

and Remin Pro on microhardness of enamel white spot lesions. Laser Med. Sci. 35, 1193-1203 (2020). - Bevilácqua, F. M., Zezell, D. M., Magnani, R., da Ana, P. A. & Eduardo Cde, P. Fluoride uptake and acid resistance of enamel irradiated with Er:YAG laser. Lasers Med. Sci. 23, 141-147 (2008).

- Liu, Y., Hsu, C. Y., Teo, C. M. & Teoh, S. H. Potential mechanism for the laserfluoride effect on enamel demineralization. J. Dent. Res. 92, 71-75 (2013).

- Doneria, D. et al. Erbium lasers in paediatric dentistry. Int J. Healthc. Sci. 3, 604-610 (2015).

- Delbem, A. C. B., Cury, J., Nakassima, C., Gouveia, V. & Theodoro, L. H. Effect of Er: YAG laser on CaF2 formation and its anti-cariogenic action on human enamel: an in vitro study. J. clin. laser med. surg. 21, 197-201 (2003).

- Morioka, T., Tagomori, S. & Oho, T. Acid resistance of lased human enamel with Erbium: YAG laser. J. clin. laser med. surg. 9, 215-217 (1991).

- Mathew, A. et al. Acquired acid resistance of human enamel treated with laser (Er:YAG laser and Co2 laser) and acidulated phosphate fluoride treatment: An in vitro atomic emission spectrometry analysis. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 4, 170-175 (2013).

- Assarzadeh, H., Karrabi, M., Fekrazad, R. & Tabarraei, Y. Effect of Er: YAG laser irradiation and acidulated phosphate fluoride therapy on re-mineralization of white spot lesions. J. Dent. 22, 153 (2021).

- Ramezani, K. et al. Combined Effect of Fluoride Mouthwash and Sub-ablative Er: YAG Laser for Prevention of White Spot Lesions around Orthodontic Brackets. Open Dent. J. 16, (2022).

- Pinelli, C., Campos Serra, M. & de Castro Monteiro Loffredo, L. Validity and reproducibility of a laser fluorescence system for detecting the activity of whitespot lesions on free smooth surfaces in vivo. Caries Res. 36, 19-24 (2002).

- Grootveld, M., Silwood, C. J. & Lynch, E. High Resolution^ 1H NMR investigations of the oxidative consumption of salivary biomolecules by ozone: Relevance to the therapeutic applications of this agent in clinical dentistry. Biofactors 27, 5-18 (2006).

- Grocholewicz, K., Mikłasz, P., Zawiślak, A., Sobolewska, E. & Janiszewska-Olszowska, J. Fluoride varnish, ozone and octenidine reduce the incidence of white spot lesions and caries during orthodontic treatment: randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 12, 13985 (2022).

- Baysan, A., Whiley, R. & Lynch, E. Antimicrobial effect of a novel ozone-generating device on micro-organisms associated with primary root carious lesions in vitro. Caries Res. 34, 498-501 (2000).

- Sen, S. & Sen, S. Ozone therapy a new vista in dentistry: integrated review. Med. gas. Res. 10, 189 (2020).

- Liaqat, S. et al. Therapeutic effects and uses of ozone in dentistry: A systematic review. Ozone.: Sci. Eng. 45, 387-397 (2023).

- Rickard, G. D., Richardson, R. J., Johnson, T. M., McColl, D. C. & Hooper, L. Ozone therapy for the treatment of dental caries. Cochrane Db. Syst. Rev. (2004).

- Sundfeld, R. H., Croll, T. P., Briso, A. & De Alexandre, R. S. Considerations about enamel microabrasion after 18 years. Am. J. Dent. 20, 67-72 (2007).

- Shan, D. et al. A comparison of resin infiltration and microabrasion for postorthodontic white spot lesion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 160, 516-522 (2021).

- Croll, T. P. Enamel microabrasion: the technique. Quintessence Int. 20, 359-400 (1989).

- Pini, N. I. et al. Enamel microabrasion: An overview of clinical and scientific considerations. World J. Clin. Cases 3, 34-41 (2015).

- Gu, X. et al. Esthetic improvements of postorthodontic white-spot lesions treated with resin infiltration and microabrasion: A split-mouth, randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod. 89, 372-377 (2019).

- Paris, S., Meyer-Lueckel, H., Cölfen, H. & Kielbassa, A. M. Penetration coefficients of commercially available and experimental composites intended to infiltrate enamel carious lesions. Dent. Mater. 23, 742-748 (2007).

- Kim, Y., Son, H. H., Yi, K., Ahn, J. S. & Chang, J. Bleaching Effects on Color, Chemical, and Mechanical Properties of White Spot Lesions. Oper. Dent. 41, 318-326 (2016).

- Gizani, S., Kloukos, D., Papadimitriou, A., Roumani, T. & Twetman, S. Is bleaching effective in managing post-orthodontic white-spot lesions? A systematic review. Oral. Health Prev. Dent. 18, 1-10 (2020).

- Sawaf, H., Kassem, H. E. & Enany, N. M. TOOTH COLOR UNIFORMITY FOLLOWING WHITE SPOT LESION TREATMENT WITH RESIN INFILTRATION OR BLEACHING IN VITRO STUDY. Egypt. Orthodontic J. 56, 51-60 (2019).

- Meyer-Lueckel, H. & Paris, S. Improved resin infiltration of natural caries lesions. J. Dent. Res. 87, 1112-1116 (2008).

- Chatzimarkou, S., Koletsi, D. & Kavvadia, K. The effect of resin infiltration on proximal caries lesions in primary and permanent teeth. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J. Dent. 77, 8-17 (2018).

- Roberson, T., Heymann, H. & Swift, E. (Elsevier, 2006).

- Meyer-Lueckel, H., Chatzidakis, A., Naumann, M., Dörfer, C. E. & Paris, S. Influence of application time on penetration of an infiltrant into natural enamel caries. J. Dent. 39, 465-469 (2011).

- Perdigão, J. Resin infiltration of enamel white spot lesions: An ultramorphological analysis. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 32, 317-324 (2020).

- Kim, S., Kim, E. Y., Jeong, T. S. & Kim, J. W. The evaluation of resin infiltration for masking labial enamel white spot lesions. Int J. Paediatr. Dent. 21, 241-248 (2011).

- Rocha Gomes Torres, C., Borges, A. B., Torres, L. M., Gomes, I. S. & de Oliveira, R. S. Effect of caries infiltration technique and fluoride therapy on the colour masking of white spot lesions. J. Dent. 39, 202-207 (2011).

- Zhou, C. et al. Expert consensus on pediatric orthodontic therapies of malocclusions in children. Int J. Oral. Sci. 16, 32 (2024).

- Ozgur, B., Unverdi, G. E., Ertan, A. & Cehreli, Z. Effectiveness and color stability of resin infiltration on demineralized and hypomineralized (MIH) enamel in children: six-month results of a prospective trial. Oper. Dent. 48, 258-267 (2023).

- Abdullah, Z. & John, J. Minimally Invasive Treatment of White Spot Lesions-A Systematic Review. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 14, (2016).

- Paula, A. B. P. et al. Therapies for white spot lesions-A systematic review. J. Evid.-Based Dent. Pr. 17, 23-38 (2017).

- Lopatiene, K., Borisovaite, M. & Lapenaite, E. Prevention and treatment of white spot lesions during and after treatment with fixed orthodontic appliances: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Oral Max. Surg. 7, (2016).

- Akin, M. & Basciftci, F. A. Can white spot lesions be treated effectively? Angle Orthod. 82, 770-775 (2012).

- Philip, N. State of the Art Enamel Remineralization Systems: The Next Frontier in Caries Management. Caries Res. 53, 284-295 (2018).

- Cochrane, N., Cai, F., Huq, N., Burrow, M. & Reynolds, E. New approaches to enhanced remineralization of tooth enamel. J. Dent. Res. 89, 1187-1197 (2010).

- Fredrick, C., Krithikadatta, J., Abarajithan, M. & Kandaswamy, D. Remineralisation of Occlusal White Spot Lesions with a Combination of 10% CPP-ACP and 0.2% Sodium Fluoride Evaluated Using Diagnodent: A Pilot Study. Oral HIth. Prev. Dent. 11, (2013).

- Ismail, A. I. et al. Caries management pathways preserve dental tissues and promote oral health. Community Dent. Oral. 41, e12-e40 (2013).

- Dai, Z. et al. Novel nanostructured resin infiltrant containing calcium phosphate nanoparticles to prevent enamel white spot lesions. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 126, 104990 (2022).

© The Author(s) 2025

Department of Orthodontics, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, College of Stomatology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, National Center for Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Shanghai Research Institute of Stomatology, Shanghai, China; State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases & National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases & Department of Pediatric Dentistry, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China; State Key Laboratory of Military Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shaanxi Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Department of Orthodontics, School of Stomatology, Air Force Medical University, Xi’an, China; Department of Orthodontics, Hubei-MOST KLOS and KLOBM, School & Hospital of Stomatology, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China; Department of Orthodontics, Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Jiangsu Province Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, Nanjing, China; Department of Orthodontics, Capital Medical University School of Stomatology, Beijing, China; Department of Stomatology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, School of Stomatology, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Hubei Province Key Laboratory of Oral and Maxillofacial Development and Regeneration, Wuhan, China; Department of Orthodontics, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology, National Center of Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, National Engineering Research Center of Oral Biomaterials and Digital Medical Devices, Beijing Key Laboratory of Digital Stomatology, Beijing, China; State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases & National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases & Department of Orthodontics, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China; Department of Orthodontics, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun, China; Department of Orthodontics, Stomatological Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases and Biomedical Sciences, Chongqing Municipal Key Laboratory of Oral Biomedical Engineering of Higher Education, Chongqing, China; Department of Orthodontics, Hospital of Stomatology, Guanghua School of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Guangzhou, China; Department of Orthodontics, Shanghai Stomatological Hospital, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Craniomaxillofacial Development and Diseases, Fudan University, Shanghai, China; Center for Microscope Enhanced Dentistry, Capital Medical University School of Stomatology, Beijing, China; Department of Operative Dentistry and Endodontics, Hospital of Stomatology, Guanghua School of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Guangzhou, China; Department of Prosthodontics, School of Stomatology, Air Force Medical University, State Key Laboratory of Oral & Maxillofacial Reconstruction and Regeneration, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Xi’an, China; Department of Preventive Dentistry, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, College of Stomatology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, National Center of Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Shanghai Research Institute of Stomatology, Shanghai, China; Tianjin Stomatological Hospital, School of Medicine, Nankai University, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Oral and Maxillofacial Function Reconstruction, Tianjin, China; Department of Orthodontics, School of Stomatology, Harbin Medical University, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China; Department of Orthodontics, Shenyang Stomatological Hospital, Shenyang, China; Department of Orthodontics, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Shandong University, Jinan, China; Department of Orthodontics, Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Nanchang University, Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Oral Biomedicine, Nanchang, China; Department of Orthodontics, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Hebei Medical University, Hebei Provincial Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Hebei Provincial Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shijiazhuang, China; School of Stomatology, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China; Department of Orthodontics, Fujian Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, Stomatological Key Lab of Fujian College and University, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China; Department of Orthodontics, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Shanxi Medical University, Shanxi Province Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases Prevention and New Materials, Taiyuan, China; Department of Orthodontics, Xiangya Stomatology Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China; Department of Orthodontics, Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China; Department of Cariology and Endodontology, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology, National Center for Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, National Engineering Research Center of Oral Biomaterials and Digital Medical Devices, Beijing Key Laboratory of Digital Stomatology, Beijing, China and School and Hospital of Stomatology, Institute of Stomatology, Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Oral Soft and Hard Tissues Restoration and Regeneration, Tianjin, China

Correspondence: Lin Yue (kqlinyue@bjmu.edu.cn) or Xu Zhang (zhangxu@tmu.edu.cn) or Bing Fang (fangbing@sjtu.edu.cn)

These authors contributed equally: Lunguo Xia, Chenchen Zhou, Peng Mei.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41368-024-00335-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40021614

Publication Date: 2025-02-28

Expert consensus on the prevention and treatment of enamel demineralization in orthodontic treatment

Abstract

Enamel demineralization, the formation of white spot lesions, is a common issue in clinical orthodontic treatment. The appearance of white spot lesions not only affects the texture and health of dental hard tissues but also impacts the health and aesthetics of teeth after orthodontic treatment. The prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of white spot lesions that occur throughout the orthodontic treatment process involve multiple dental specialties. This expert consensus will focus on providing guiding opinions on the management and prevention of white spot lesions during orthodontic treatment, advocating for proactive prevention, early detection, timely treatment, scientific follow-up, and multidisciplinary management of white spot lesions throughout the orthodontic process, thereby maintaining the dental health of patients during orthodontic treatment.

INTRODUCTION

| Calcium Phosphate Systems | Abbreviation | Chemical structure | Ksp |

| Calcium Hydrogen Phosphate | DCPD |

|

6.6 |

|

|

|

|

29.5 |

| Octacalcium phosphate | OCP |

|

98.6 |

| Hydroxyapatite | HA |

|

117.2 |

| Fluorapatite | FA |

|

120.3 |

| Amorphous calcium phosphate | ACP |

|

24.8 |

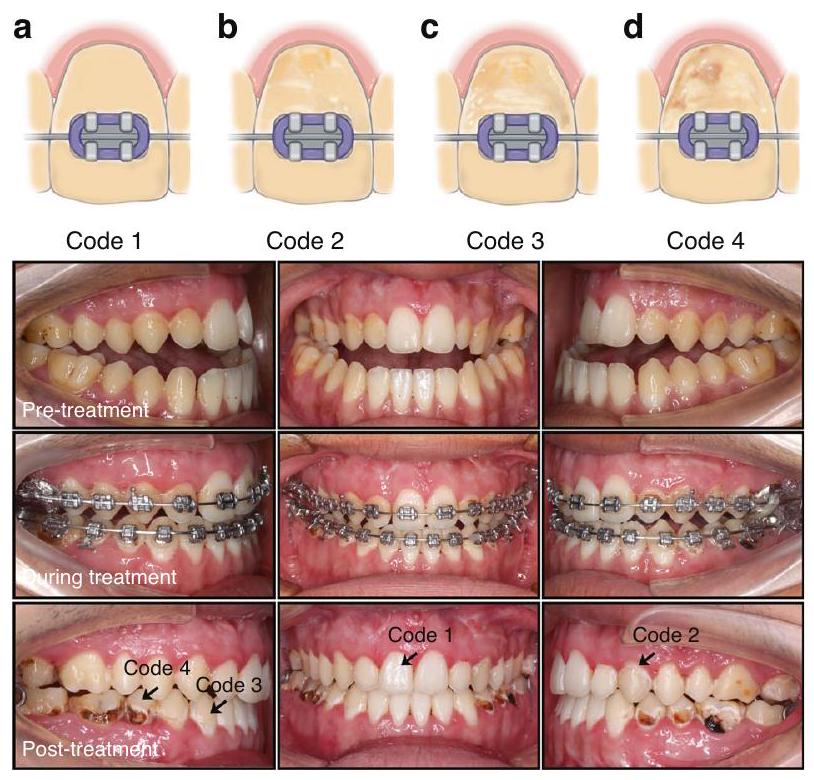

DIAGNOSIS OF ENAMEL DEMINERALIZATION

Oral examination

Digital photo evaluation

grayscale values.

Fluorescence technology

Fiber-optic transillumination-digital imaging fiber-optic transillumination (FOTI-DIFOTI)

recent study showed that this diagnostic method can more accurately detect early demineralization of dental enamel and dentin hidden in dental tissue than other methods.

Electrical resistance measurements

Optical coherence tomography

Artificial intelligence (AI)

Other methods

- The preferred method for examining the demineralization of tooth surfaces is through a combination of visual and probing examination, which can be supplemented by using a digital camera and a macro lens to record the demineralized tooth surfaces. It is important to ensure sufficient light but avoid overexposure when taking photos with a digital camera to prevent false-negatives.

- During the examination of tooth surfaces, it is important to thoroughly clean and dry the surfaces and observe them under bright light to detect any changes in the appearance of white chalkiness.

- A probe was used to examine the roughness of the tooth surfaces when conducting the examination and to assess whether demineralization was in an active stage.

- For quantitative analysis of white chalky changes on tooth surfaces, supplementary methods such as fluorescence technology, fiber optic transillumination, and resistance testing should be used. The use of artificial intelligence for interpreting tooth demineralization has a promising application in assisting chair-side examinations.

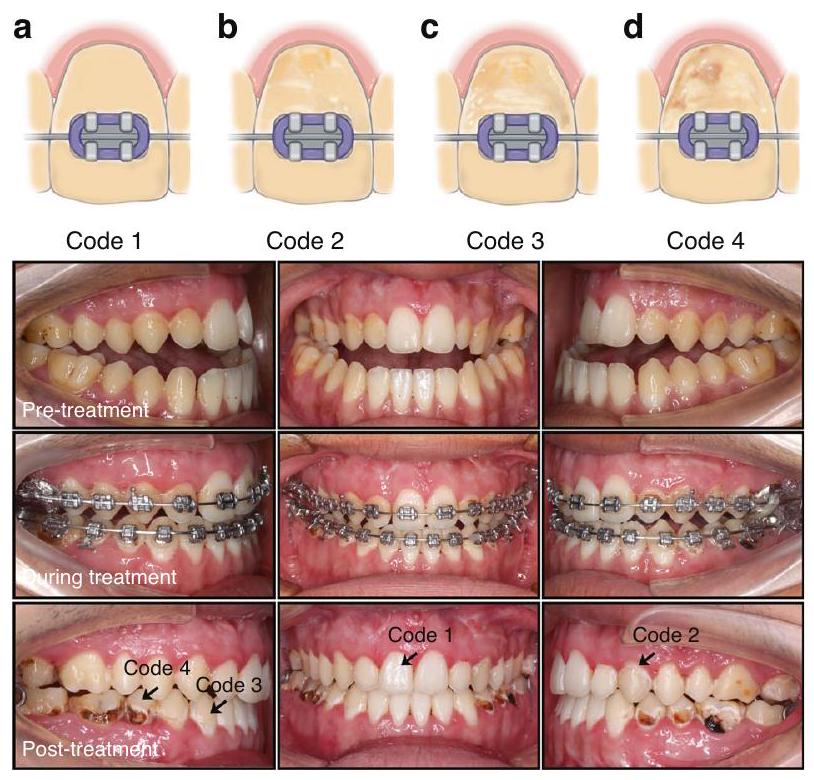

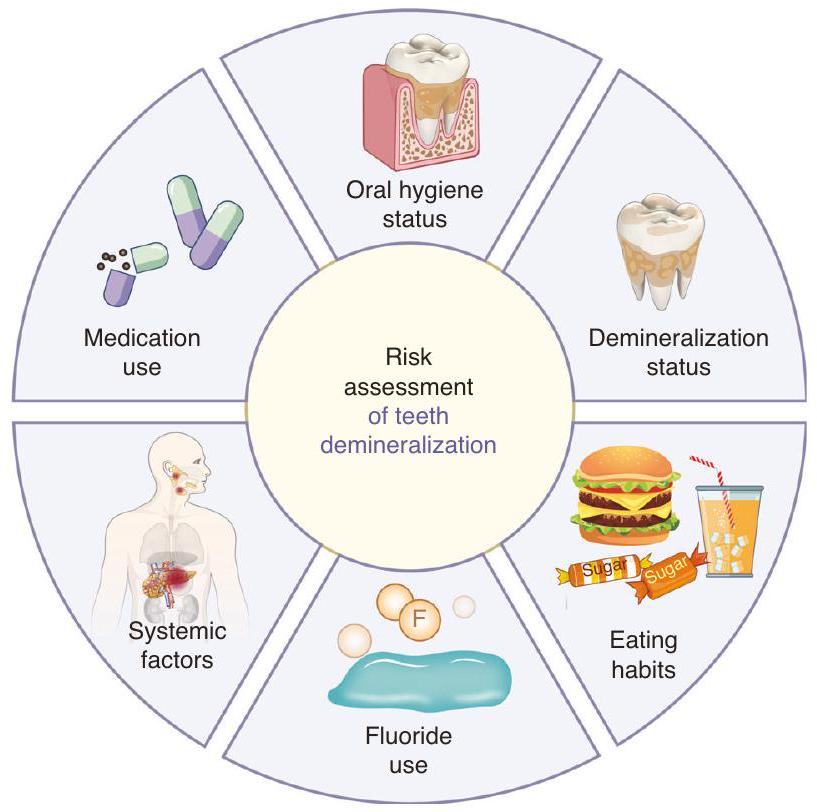

RISK ASSESSMENT OF ENAMEL DEMINERALIZATION BEFORE ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT

Oral hygiene status

Demineralization status

Eating habits

Fluoride use

Systemic factors

PREVENTIVE METHODS FOR ENAMEL DEMINERALIZATION IN ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT

Regular professional endodontic examination helps to detect early white chalky spots or caries on the tooth surface and to see the specialist in time.

Oral health care

Use of fluoride

relatively simple. Briefly, the tooth surface is first cleaned and dried. Then, an appropriate amount of fluoride is applied to the tooth surface. It is important to note that no eating should occur within 2 to 4 h after the fluoride application, and brushing should be avoided that evening to ensure the effectiveness of the application.

Dietary guidance

Use of chlorhexidine

Orthodontic treatments typically involve fixed appliances such as brackets on the labial or lingual side or clear aligners. Due to differences in the structure and placement of these appliances in the patient’s oral cavity, methods to prevent enamel demineralization

vary. For fixed appliances bonded to the tooth surface, such as brackets, the presence of brackets and archwires hinders self-cleaning of the oral cavity and daily hygiene, requiring brushing and cleaning of food debris around the brackets after every meal to reduce plaque accumulation.

- Maintaining good oral hygiene is the primary method for preventing enamel demineralization in orthodontic treatment. Oral hygiene instructions and health education are crucial.

- Emphasis should be placed on the correct and effective toothbrushing method, ensuring both the duration and frequency of brushing and reducing the intake of cariogenic foods.

- The use of fluoride toothpaste for daily dental care should be encouraged to enhance the acid resistance of enamel and reduce demineralization.

- After wearing orthodontic appliances, it is essential to clean the oral cavity and the area around the appliances for food residue after each meal to prevent the formation of an acidic environment leading to enamel demineralization.

MANAGEMENT OF ENAMEL DEMINERALIZATION DURING ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT

Assess demineralization risk throughout the process of orthodontic treatment

Remineralization and antibiofilm combined therapy

good choice for WSL remineralization, and when combined with fluoride, it enhances the remineralizing effects of WSL.

Laser therapy

Ozone use

demineralization of the teeth.

The main indication for microabrasion of dental hard tissues is intrinsic discoloration or texture changes caused byamelogenesis imperfecta or dental fluorosis.

In vitro studies have shown that bleaching can improve the aesthetics of teeth with WSL. However, the bleaching process only enhances the appearance, disguising white spot lesions instead of treating them.

During WSL development, there is an increase in microporosity in the enamel. Low-viscosity light-curing resin infiltrates the microporous enamel area of WSL through capillary action, sealing the micropores and increasing the strength of the enamel, providing mechanical support to inhibit the progression of WSL.

CLINICAL MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT OF POSTORTHODONTIC WSL

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS IN ORTHODONTICS: MANAGEMENT OF ENAMEL DEMINERALIZATION IN EARLY ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

good oral hygiene. Early pit and fissure sealants for molars should be applied. During each follow-up visit, monitoring of oral hygiene status, such as plaque, calculus, and gum health, should be conducted to prevent the causative factors of WSL. If WSL has already developed during orthodontic treatment, localized fluoride application, the use of remineralizing agents, or resin infiltration can be considered for treatment. Further oral hygiene education for children and parents is essential.

RECOMMENDED CLINICAL PROCEDURES FOR THE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF WSL DURING THE WHOLE ORTHODONTIC TREATMENT PROCESS

- Before orthodontic treatment, it is necessary to fully evaluate the risk factors for dental caries. Only when the risk factors are under control, the subsequent orthodontic treatment could proceed.

- During orthodontic treatment, it is essential to monitor the occurrence of WSL at each follow-up visit and intervene promptly. The primary focus should be on enhancing oral hygiene education, maintaining good oral health, and using fluoride and remineralizing agents locally to promote WSL remineralization.

- If the progression of WSL on the tooth surface during orthodontic treatment is uncontrollable, replace the orthodontic appliance with an easier-to-clean appliance or temporarily suspend orthodontic treatment until the WSL is effectively controlled.

- After orthodontic treatment, a multidisciplinary approach should be taken based on the severity of tooth demineralization after appliance removal.

- For orthodontic treatment in children and adolescents, oral hygiene education is necessary for guardians to ensure patient compliance with treatment and reduce the occurrence of WSL.

THE RESEARCH PROSPECTS OF WSL TREATMENT

orthodontics. In the future, it will be possible to utilize Al-based technological methods, in conjunction with existing examination methods for WSL, to personalize the monitoring of teeth during orthodontic processes. This can predict the development and prognosis of WSL at an early stage, alert patients to the risk of WSL occurrence, and further reduce the impact of WSL on orthodontic processes. At the same time, orthodontists need to realize that artificial intelligence only plays a supplementary role in orthodontic processes. Various emerging technologies cannot fully replace the role of orthodontists in preventing and diagnosing WSL. Orthodontists still need to enhance their understanding of WSL, identify early signs of chalky lesions promptly, and intervene when necessary.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

REFERENCES

- Skidmore, K. J., Brook, K. J., Thomson, W. M. & Harding, W. J. Factors influencing treatment time in orthodontic patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 129, 230-238 (2006).

- B, F., ZL, J., YX, B., L, W. & ZH, Z. Experts consensus on diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for malocclusions at early developing stage. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue 30, 449-455 (2021).

- XJ, G. Dental and endodontic basic knowledges related in orthodontic treatment. Chin. J. Orthod. 23, 167-170 (2016).

- Selwitz, R. H., Ismail, A. I. & Pitts, N. B. Dental caries. Lancet 369, 51-59 (2007).

- Marinelli, G. et al. White spot lesions in orthodontics: prevention and treatment. A descriptive review. J. Biol. Reg. Homeos Ag. 35, 227-240 (2021).

- Maxfield, B. J. et al. Development of white spot lesions during orthodontic treatment: Perceptions of patients, parents, orthodontists, and general dentists. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 141, 337-344 (2012).

- Øgaard, B., Rølla, G. & Arends, J. Orthodontic appliances and enamel demineralization: Part 1. Lesion development. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 94, 68-73 (1988).

- YX, B. Risk perception and management in orthodontic treatment. Chinese J. Stomatology. 12, 793-797 (2019).

- Julien, K. C., Buschang, P. H. & Campbell, P. M. Prevalence of white spot lesion formation during orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 83, 641-647 (2013).

- Buschang, P. H., Chastain, D., Keylor, C. L., Crosby, D. & Julien, K. C. Incidence of white spot lesions among patients treated with clear aligners and traditional braces. Angle Orthod. 89, 359-364 (2019).

- Albhaisi, Z., Al-Khateeb, S. N. & Abu Alhaija, E. S. Enamel demineralization during clear aligner orthodontic treatment compared with fixed appliance therapy, evaluated with quantitative light-induced fluorescence: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 157, 594-601 (2020).

- Gorelick, L., Geiger, A. M. & Gwinnett, A. J. Incidence of white spot formation after bonding and banding. Am. J. Orthod. 81, 93-98 (1982).

- Lucchese, A. & Gherlone, E. Prevalence of white-spot lesions before and during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur. J. Orthod. 35, 664-668 (2013).

- Heymann, G. C. & Grauer, D. A contemporary review of white spot lesions in orthodontics. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 25, 85-95 (2013).

- Chatterjee, R. & Kleinberg, I. Effect of orthodontic band placement on the chemical composition of human incisor tooth plaque. Arch. Oral. Biol. 24, 97-100 (1979).

- Mattingly, J., Sauer, G., Yancey, J. & Arnold, R. Enhancement of Streptococcus mutans colonization by direct bonded orthodontic appliances. J. Dent. Res. 62, 1209-1211 (1983).

- Rosenbloom, R. G. & Tinanoff, N. Salivary Streptococcus mutans levels in patients before, during, and after orthodontic treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 100, 35-37 (1991).

- Pitts, N. B. et al. Dental caries. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 3, 1-16 (2017).

- Lopes, P. C. et al. White spot lesions: diagnosis and treatment-a systematic review. BMC Oral. Health 24, 1-18 (2024).

- Zou, J. et al. Expert consensus on early childhood caries management. Int J. Oral. Sci. 14, 35 (2022).

- NouhzadehMalekshah, S., Fekrazad, R., Bargrizan, M. & Kalhori, K. A. Evaluation of laser fluorescence in combination with photosensitizers for detection of demineralized lesions. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 26, 300-305 (2019).

- Foros, P., Oikonomou, E., Koletsi, D. & Rahiotis, C. Detection methods for early caries diagnosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 55, 247-259 (2021).

- Pitts, N. B. & Stamm, J. W. International Consensus Workshop on Caries Clinical Trials (ICW-CCT)-Final Consensus Statements: Agreeing Where the Evidence Leads. J. Dent. Res. 83, 125-128 (2004).

- Zandoná, A. F. & Zero, D. T. Diagnostic tools for early caries detection. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 137, 1675-1684 (2006).

- Kidd, E. & Fejerskov, O. What constitutes dental caries? Histopathology of carious enamel and dentin related to the action of cariogenic biofilms. J. Dent. Res. 83, 35-38 (2004).

- Sadıkoğlu, İ. S. White spot lesions: recent detection and treatment methods. Cyprus J. Med. Sci. 5, 260-266 (2020).

- Askar, H. et al. Detecting white spot lesions on dental photography using deep learning: A pilot study. J. Dent. 107, 103615 (2021).

- Estai, M. et al. Comparison of a smartphone-based photographic method with face-to-face caries assessment: a mobile teledentistry model. Telemed. J. E-health 23, 435-440 (2017).

- Lee, H.-S., Lee, Y.-D., Kim, S.-K., Choi, J.-H. & Kim, B.-I. Assessment of tooth wear based on autofluorescence properties measured using the QLF technology in vitro. Photodiagn. Photodyn. 25, 265-270 (2019).

- Knaup, I. et al. Correlation of quantitative light-induced fluorescence and qualitative visual rating in infiltrated post-orthodontic white spot lesions. Eur. J. Orthod. 45, 133-141 (2023).

- Kim, H.-E. Red Fluorescence Intensity as a Criterion for Assessing Remineralization Efficacy in Early Carious Lesions. Photodiagn. Photodyn. 103963 (2024).

- Chandra, S. & Garg, N. Textbook of operative dentistry. (Jaypee Brothers Publishers, 2008).

- Park, S.-W. et al. Lesion activity assessment of early caries using dye-enhanced quantitative light-induced fluorescence. Sci. Rep. 12, 11848 (2022).

- Warkhankar, A., Tanpure, V. R. & Wajekar, N. A. Using light fluorescence technique as an emerging approach in treating dental caries. Int. J. Prevent. Clin. Dent. Res. 10, 69-72 (2023).

- Macey, R. et al. Fluorescence devices for the detection of dental caries. Cochrane Db. Syst. Rev. 12, CD013811 (2020).

- Sürme, K., Kara, N. B. & Yilmaz, Y. In Vitro Evaluation of Occlusal Caries Detection Methods in Primary and Permanent Teeth: A Comparison of CarieScan PRO, DIAGNOdent Pen, and DIAGNOcam Methods. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 38, 105-111 (2020).

- Hogan, R., Pretty, I. A. & Ellwood, R. P. in Detection and Assessment of Dental Caries: A Clinical Guide (eds Andrea Ferreira Zandona & Christopher Longbottom) 139-150 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).

- Schwendicke, F., Elhennawy, K., Paris, S., Friebertshäuser, P. & Krois, J. Deep learning for caries lesion detection in near-infrared light transillumination images: A pilot study. J. Dent. 92, 103260 (2020).

- Fried, D., Glena, R. E., Featherstone, J. D. & Seka, W. Nature of light scattering in dental enamel and dentin at visible and near-infrared wavelengths. Appl. Opt. 34, 1278-1285 (1995).

- Stratigaki, E. et al. Clinical validation of near-infrared light transillumination for early proximal caries detection using a composite reference standard. J. Dent. 103, 100025 (2020).

- Abogazalah, N. & Ando, M. Alternative methods to visual and radiographic examinations for approximal caries detection. J. Oral. Sci. 59, 315-322 (2017).

- Y, Y., JQ, X. & JJ, S. Application progress of fiber optic transillumination in caries diagnosis. Beijing J. Stomatology 28, 118-120 (2020).

- Longbottom, C. & Huysmans, M.-C. Electrical measurements for use in caries clinical trials. J. Dent. Res. 83, 76-79 (2004).

- Wolinsky, L. E. et al. An in vitro assessment and a pilot clinical study of electrical resistance of demineralized enamel. Int. J. Clin. Dent. 10, 40-43 (1999).

- Wang, J., Someya, Y., Inaba, D., Longbottom, C. & Miyazaki, H. Relationship between electrical resistance measurements and microradiographic variables during remineralization of softened enamel lesions. Caries Res. 39, 60-64 (2005).

- Sannino, I., Angelini, E., Parvis, M., Arpaia, P. & Grassini, S. in 2022 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC). 1-5 (IEEE).

- Shimada, Y., Yoshiyama, M., Tagami, J. & Sumi, Y. Evaluation of dental caries, tooth crack, and age-related changes in tooth structure using optical coherence tomography. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 56, 109-118 (2020).

- Ibusuki, T. et al. Observation of white spot lesions using swept source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT): in vitro and in vivo study. Dent. Mater. J. 34, 545-552 (2015).

- Kühnisch, J., Meyer, O., Hesenius, M., Hickel, R. & Gruhn, V. Caries detection on intraoral images using artificial intelligence. J. Dent. Res. 101, 158-165 (2022).

- Kim, J., Shin, T. J., Kong, H. J., Hwang, J. Y. & Hyun, H. K. High-Frequency Ultrasound Imaging for Examination of Early Dental Caries. J. Dent. Res. 98, 363-367 (2019).

- Xing, H., Eckert, G. J. & Ando, M. Impact of angle on photothermal radiometry and modulated luminescence (PTR/LUM) value. J. Dent. 132, 104500 (2023).

- Liang, J. P. Research and application of new techniques for early diagnosis of caries. Chin. J. Stomatol. 56, 33-38 (2021).

- Kwon, T. H., Salem, D. M. & Levin, L. in Semin Orthod. (Elsevier).

- Bishara, S. E. & Ostby, A. W. White Spot Lesions: Formation, Prevention, and Treatment. SEMIN ORTHOD 14, 174-182 (2008).

- Ogaard, B. Enamel effects during bonding-debonding and treatment with fixed appliances. Risk Management in Orthodontics: Experts’ Guide to Malpractice Ch. 3 (Quintessence Publishing Co., 2004).

- Disney, J. A. et al. The University of North Carolina Caries Risk Assessment study: further developments in caries risk prediction. Community Dent. oral. Epidemiol. 20, 64-75 (1992).

- S, L. & M, H. A Review of Enamel Demineralization in Orthodontic Treatment with Fixed Appliances. J. Oral. Sci. Res. 37, 685-688 (2021).

- Marinho, V. Cochrane reviews of randomized trials of fluoride therapies for preventing dental caries. Eur. J. Paediatr. Dent. 10, 183-191 (2009).

- Weyland, M. I., Jost-Brinkmann, P.-G. & Bartzela, T. Management of white spot lesions induced during orthodontic treatment with multibracket appliance: a national-based survey. Clin. Oral. Invest 26, 4871-4883 (2022).

- Sardana, D. et al. Effectiveness of professional fluorides against enamel white spot lesions during fixed orthodontic treatment: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J. Dent. 82, 1-10 (2019).

- Simmer, J. P., Hardy, N. C., Chinoy, A. F., Bartlett, J. D. & Hu, J. C. How fluoride protects dental enamel from demineralization. J. Int Soc. Prev. Commun. 10, 134 (2020).

- Song, H., Cai, M., Fu, Z. & Zou, Z. Mineralization Pathways of Amorphous Calcium Phosphate in the Presence of Fluoride. Cryst. Growth Des. 23, 7150-7158 (2023).

- Zhang, Q. et al. Application of fluoride disturbs plaque microecology and promotes remineralization of enamel initial caries. J. Oral. Microbiol. 14, 2105022 (2022).

- Øgaard, B. in Semin Orthod. 183-193 (Elsevier).

- Øgaard, B., Larsson, E., Henriksson, T., Birkhed, D. & Bishara, S. E. Effects of combined application of antimicrobial and fluoride varnishes in orthodontic patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 120, 28-35 (2001).

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Fluoride Therapy [J]. Pediatr Dent, 39, 242-245 (2017).

- Alexander, S. A. & Ripa, L. W. Effects of self-applied topical fluoride preparations in orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod. 70, 424-430 (2000).

- Hancock, S., Zinn, C. & Schofield, G. The consumption of processed sugar-and starch-containing foods, and dental caries: a systematic review. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 128, 467-475 (2020).

- Schaeken, M. J. & De Haan, P. Effects of sustained-release chlorhexidine acetate on the human dental plaque flora. J. Dent. Res. 68, 119-123 (1989).

- Sajadi, F. S., Moradi, M., Pardakhty, A., Yazdizadeh, R. & Madani, F. Effect of fluoride, chlorhexidine and fluoride-chlorhexidine mouthwashes on salivary Streptococcus mutans count and the prevalence of oral side effects. J. Dent. Res., Dent. Clin., Dent. prospects 9, 49 (2015).

- Kamarudin, Y., Skeats, M. K., Ireland, A. J. & Barbour, M. E. Chlorhexidine hexametaphosphate as a coating for elastomeric ligatures with sustained antimicrobial properties: A laboratory study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 158, e73-e82 (2020).

- Jones, C. G. Chlorhexidine: is it still the gold standard? Periodontol 2000 15, 55-62 (1997).

- Fardai, O. & Turnbull, R. S. A review of the literature on use of chlorhexidine in dentistry. Assoc. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 112, 863-869 (1986).

- Baumer, C. et al. Orthodontists’ instructions for oral hygiene in patients with removable and fixed orthodontic appliances. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. (2023).

- Raghavan, S., Abu Alhaija, E. S., Duggal, M. S., Narasimhan, S. & Al-Maweri, S. A. White spot lesions, plaque accumulation and salivary caries-associated bacteria in clear aligners compared to fixed orthodontic treatment. A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral. Health 23, 599 (2023).

- Sardana, D., Schwendicke, F., Kosan, E. & Tüfekçi, E. White spot lesions in orthodontics: consensus statements for prevention and management. Angle Orthod. 93, 621-628 (2023).

- Ten Cate, J., Buijs, M., Miller, C. C. & Exterkate, R. Elevated fluoride products enhance remineralization of advanced enamel lesions. J. Dent. Res. 87, 943-947 (2008).

- Reynolds, E. Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate: the scientific evidence. Adv. Dent. Res. 21, 25-29 (2009).

- Karabekiroğlu, S. et al. Treatment of post-orthodontic white spot lesions with CPP-ACP paste: A three year follow up study. Dent. Mater. J. 36, 791-797 (2017).

- de Oliveira, P. R. A., Barreto, L. S. D. C. & Tostes, M. A. Effectiveness of CPP-ACP and fluoride products in tooth remineralization. Int J. Dent. Hyg. 20, 635-642 (2022).

- Bourouni, S., Dritsas, K., Kloukos, D. & Wierichs, R. J. Efficacy of resin infiltration to mask post-orthodontic or non-post-orthodontic white spot lesions or fluorosis -a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral. Invest 25, 4711-4719 (2021).

- Xiaotong, W., Nanquan, R., Jing, X., Yuming, Z. & Lihong, G. Remineralization effect of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate for enamel demineralization: a system review. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 35, 629-635 (2017).

- He, J. et al. Polyzwitterion Manipulates Remineralization and Antibiofilm Functions against Dental Demineralization. ACS Nano 16, 3119-3134 (2022).

- Liao, J. et al. Stimuli-responsive graphdiyne-silver nanozymes for catalytic ion therapy of dental caries through targeted biofilms removal and remineralization. Nano Today 55, 102204 (2024).

- Tagomori, S. & Morioka, T. Combined effects of laser and fluoride on acid resistance of human dental enamel. Caries Res. 23, 225-231 (1989).

- Kuroda, S. & Fowler, B. Compositional, structural, and phase changes in in vitro laser-irradiated human tooth enamel. Calcif. Tissue Int. 36, 361-369 (1984).

- Rafiei, E., Fadaei Tehrani, P., Yassaei, S. & Haerian, A. Effect of CO 2 laser

and Remin Pro on microhardness of enamel white spot lesions. Laser Med. Sci. 35, 1193-1203 (2020). - Bevilácqua, F. M., Zezell, D. M., Magnani, R., da Ana, P. A. & Eduardo Cde, P. Fluoride uptake and acid resistance of enamel irradiated with Er:YAG laser. Lasers Med. Sci. 23, 141-147 (2008).

- Liu, Y., Hsu, C. Y., Teo, C. M. & Teoh, S. H. Potential mechanism for the laserfluoride effect on enamel demineralization. J. Dent. Res. 92, 71-75 (2013).

- Doneria, D. et al. Erbium lasers in paediatric dentistry. Int J. Healthc. Sci. 3, 604-610 (2015).

- Delbem, A. C. B., Cury, J., Nakassima, C., Gouveia, V. & Theodoro, L. H. Effect of Er: YAG laser on CaF2 formation and its anti-cariogenic action on human enamel: an in vitro study. J. clin. laser med. surg. 21, 197-201 (2003).

- Morioka, T., Tagomori, S. & Oho, T. Acid resistance of lased human enamel with Erbium: YAG laser. J. clin. laser med. surg. 9, 215-217 (1991).

- Mathew, A. et al. Acquired acid resistance of human enamel treated with laser (Er:YAG laser and Co2 laser) and acidulated phosphate fluoride treatment: An in vitro atomic emission spectrometry analysis. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 4, 170-175 (2013).

- Assarzadeh, H., Karrabi, M., Fekrazad, R. & Tabarraei, Y. Effect of Er: YAG laser irradiation and acidulated phosphate fluoride therapy on re-mineralization of white spot lesions. J. Dent. 22, 153 (2021).

- Ramezani, K. et al. Combined Effect of Fluoride Mouthwash and Sub-ablative Er: YAG Laser for Prevention of White Spot Lesions around Orthodontic Brackets. Open Dent. J. 16, (2022).

- Pinelli, C., Campos Serra, M. & de Castro Monteiro Loffredo, L. Validity and reproducibility of a laser fluorescence system for detecting the activity of whitespot lesions on free smooth surfaces in vivo. Caries Res. 36, 19-24 (2002).

- Grootveld, M., Silwood, C. J. & Lynch, E. High Resolution^ 1H NMR investigations of the oxidative consumption of salivary biomolecules by ozone: Relevance to the therapeutic applications of this agent in clinical dentistry. Biofactors 27, 5-18 (2006).

- Grocholewicz, K., Mikłasz, P., Zawiślak, A., Sobolewska, E. & Janiszewska-Olszowska, J. Fluoride varnish, ozone and octenidine reduce the incidence of white spot lesions and caries during orthodontic treatment: randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 12, 13985 (2022).

- Baysan, A., Whiley, R. & Lynch, E. Antimicrobial effect of a novel ozone-generating device on micro-organisms associated with primary root carious lesions in vitro. Caries Res. 34, 498-501 (2000).

- Sen, S. & Sen, S. Ozone therapy a new vista in dentistry: integrated review. Med. gas. Res. 10, 189 (2020).

- Liaqat, S. et al. Therapeutic effects and uses of ozone in dentistry: A systematic review. Ozone.: Sci. Eng. 45, 387-397 (2023).

- Rickard, G. D., Richardson, R. J., Johnson, T. M., McColl, D. C. & Hooper, L. Ozone therapy for the treatment of dental caries. Cochrane Db. Syst. Rev. (2004).

- Sundfeld, R. H., Croll, T. P., Briso, A. & De Alexandre, R. S. Considerations about enamel microabrasion after 18 years. Am. J. Dent. 20, 67-72 (2007).

- Shan, D. et al. A comparison of resin infiltration and microabrasion for postorthodontic white spot lesion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. 160, 516-522 (2021).

- Croll, T. P. Enamel microabrasion: the technique. Quintessence Int. 20, 359-400 (1989).

- Pini, N. I. et al. Enamel microabrasion: An overview of clinical and scientific considerations. World J. Clin. Cases 3, 34-41 (2015).

- Gu, X. et al. Esthetic improvements of postorthodontic white-spot lesions treated with resin infiltration and microabrasion: A split-mouth, randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod. 89, 372-377 (2019).

- Paris, S., Meyer-Lueckel, H., Cölfen, H. & Kielbassa, A. M. Penetration coefficients of commercially available and experimental composites intended to infiltrate enamel carious lesions. Dent. Mater. 23, 742-748 (2007).

- Kim, Y., Son, H. H., Yi, K., Ahn, J. S. & Chang, J. Bleaching Effects on Color, Chemical, and Mechanical Properties of White Spot Lesions. Oper. Dent. 41, 318-326 (2016).

- Gizani, S., Kloukos, D., Papadimitriou, A., Roumani, T. & Twetman, S. Is bleaching effective in managing post-orthodontic white-spot lesions? A systematic review. Oral. Health Prev. Dent. 18, 1-10 (2020).

- Sawaf, H., Kassem, H. E. & Enany, N. M. TOOTH COLOR UNIFORMITY FOLLOWING WHITE SPOT LESION TREATMENT WITH RESIN INFILTRATION OR BLEACHING IN VITRO STUDY. Egypt. Orthodontic J. 56, 51-60 (2019).

- Meyer-Lueckel, H. & Paris, S. Improved resin infiltration of natural caries lesions. J. Dent. Res. 87, 1112-1116 (2008).

- Chatzimarkou, S., Koletsi, D. & Kavvadia, K. The effect of resin infiltration on proximal caries lesions in primary and permanent teeth. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J. Dent. 77, 8-17 (2018).

- Roberson, T., Heymann, H. & Swift, E. (Elsevier, 2006).

- Meyer-Lueckel, H., Chatzidakis, A., Naumann, M., Dörfer, C. E. & Paris, S. Influence of application time on penetration of an infiltrant into natural enamel caries. J. Dent. 39, 465-469 (2011).

- Perdigão, J. Resin infiltration of enamel white spot lesions: An ultramorphological analysis. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 32, 317-324 (2020).

- Kim, S., Kim, E. Y., Jeong, T. S. & Kim, J. W. The evaluation of resin infiltration for masking labial enamel white spot lesions. Int J. Paediatr. Dent. 21, 241-248 (2011).

- Rocha Gomes Torres, C., Borges, A. B., Torres, L. M., Gomes, I. S. & de Oliveira, R. S. Effect of caries infiltration technique and fluoride therapy on the colour masking of white spot lesions. J. Dent. 39, 202-207 (2011).

- Zhou, C. et al. Expert consensus on pediatric orthodontic therapies of malocclusions in children. Int J. Oral. Sci. 16, 32 (2024).

- Ozgur, B., Unverdi, G. E., Ertan, A. & Cehreli, Z. Effectiveness and color stability of resin infiltration on demineralized and hypomineralized (MIH) enamel in children: six-month results of a prospective trial. Oper. Dent. 48, 258-267 (2023).

- Abdullah, Z. & John, J. Minimally Invasive Treatment of White Spot Lesions-A Systematic Review. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 14, (2016).

- Paula, A. B. P. et al. Therapies for white spot lesions-A systematic review. J. Evid.-Based Dent. Pr. 17, 23-38 (2017).

- Lopatiene, K., Borisovaite, M. & Lapenaite, E. Prevention and treatment of white spot lesions during and after treatment with fixed orthodontic appliances: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Oral Max. Surg. 7, (2016).

- Akin, M. & Basciftci, F. A. Can white spot lesions be treated effectively? Angle Orthod. 82, 770-775 (2012).

- Philip, N. State of the Art Enamel Remineralization Systems: The Next Frontier in Caries Management. Caries Res. 53, 284-295 (2018).

- Cochrane, N., Cai, F., Huq, N., Burrow, M. & Reynolds, E. New approaches to enhanced remineralization of tooth enamel. J. Dent. Res. 89, 1187-1197 (2010).

- Fredrick, C., Krithikadatta, J., Abarajithan, M. & Kandaswamy, D. Remineralisation of Occlusal White Spot Lesions with a Combination of 10% CPP-ACP and 0.2% Sodium Fluoride Evaluated Using Diagnodent: A Pilot Study. Oral HIth. Prev. Dent. 11, (2013).

- Ismail, A. I. et al. Caries management pathways preserve dental tissues and promote oral health. Community Dent. Oral. 41, e12-e40 (2013).

- Dai, Z. et al. Novel nanostructured resin infiltrant containing calcium phosphate nanoparticles to prevent enamel white spot lesions. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 126, 104990 (2022).

© The Author(s) 2025

Department of Orthodontics, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, College of Stomatology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, National Center for Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Shanghai Research Institute of Stomatology, Shanghai, China; State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases & National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases & Department of Pediatric Dentistry, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China; State Key Laboratory of Military Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shaanxi Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Department of Orthodontics, School of Stomatology, Air Force Medical University, Xi’an, China; Department of Orthodontics, Hubei-MOST KLOS and KLOBM, School & Hospital of Stomatology, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China; Department of Orthodontics, Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Jiangsu Province Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, Nanjing, China; Department of Orthodontics, Capital Medical University School of Stomatology, Beijing, China; Department of Stomatology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, School of Stomatology, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Hubei Province Key Laboratory of Oral and Maxillofacial Development and Regeneration, Wuhan, China; Department of Orthodontics, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology, National Center of Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, National Engineering Research Center of Oral Biomaterials and Digital Medical Devices, Beijing Key Laboratory of Digital Stomatology, Beijing, China; State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases & National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases & Department of Orthodontics, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China; Department of Orthodontics, Hospital of Stomatology, Jilin University, Changchun, China; Department of Orthodontics, Stomatological Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases and Biomedical Sciences, Chongqing Municipal Key Laboratory of Oral Biomedical Engineering of Higher Education, Chongqing, China; Department of Orthodontics, Hospital of Stomatology, Guanghua School of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Guangzhou, China; Department of Orthodontics, Shanghai Stomatological Hospital, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Craniomaxillofacial Development and Diseases, Fudan University, Shanghai, China; Center for Microscope Enhanced Dentistry, Capital Medical University School of Stomatology, Beijing, China; Department of Operative Dentistry and Endodontics, Hospital of Stomatology, Guanghua School of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Guangzhou, China; Department of Prosthodontics, School of Stomatology, Air Force Medical University, State Key Laboratory of Oral & Maxillofacial Reconstruction and Regeneration, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Xi’an, China; Department of Preventive Dentistry, Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, College of Stomatology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, National Center of Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Shanghai Research Institute of Stomatology, Shanghai, China; Tianjin Stomatological Hospital, School of Medicine, Nankai University, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Oral and Maxillofacial Function Reconstruction, Tianjin, China; Department of Orthodontics, School of Stomatology, Harbin Medical University, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China; Department of Orthodontics, Shenyang Stomatological Hospital, Shenyang, China; Department of Orthodontics, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Shandong University, Jinan, China; Department of Orthodontics, Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Nanchang University, Jiangxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Oral Biomedicine, Nanchang, China; Department of Orthodontics, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Hebei Medical University, Hebei Provincial Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Hebei Provincial Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, Shijiazhuang, China; School of Stomatology, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China; Department of Orthodontics, Fujian Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, Stomatological Key Lab of Fujian College and University, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China; Department of Orthodontics, School and Hospital of Stomatology, Shanxi Medical University, Shanxi Province Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases Prevention and New Materials, Taiyuan, China; Department of Orthodontics, Xiangya Stomatology Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China; Department of Orthodontics, Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming, China; Department of Cariology and Endodontology, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology, National Center for Stomatology, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, National Engineering Research Center of Oral Biomaterials and Digital Medical Devices, Beijing Key Laboratory of Digital Stomatology, Beijing, China and School and Hospital of Stomatology, Institute of Stomatology, Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin Key Laboratory of Oral Soft and Hard Tissues Restoration and Regeneration, Tianjin, China

Correspondence: Lin Yue (kqlinyue@bjmu.edu.cn) or Xu Zhang (zhangxu@tmu.edu.cn) or Bing Fang (fangbing@sjtu.edu.cn)

These authors contributed equally: Lunguo Xia, Chenchen Zhou, Peng Mei.