DOI: https://doi.org/10.14573/altex.2403281

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38579692

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-01

توماس أ. إديسون (1847-1931)

قد لا أكون قد ذهبت إلى حيث كنت أنوي الذهاب،

لكن أعتقد أنني انتهيت حيث كنت بحاجة أن أكون.

دوغلاس آدامز (1952-2001)

طعام للتفكير …

إحداث ثورة في اختبار السمية العصبية التنموية – رحلة من نماذج الحيوانات إلى الأنظمة المتقدمة في المختبر

إي بوب 6 أبريل 2024؛

© المؤلفون، 2024.

المراسلات:

توماس هارتونغ، دكتور في الطب، دكتوراه، مركز البدائل لاختبار الحيوانات (CAAT)، جامعة جونز هوبكنز، 615 شمال شارع وولف، بالتيمور، ماريلاند، 21205، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

(THartun1 @jhu.edu)

الملخص

لقد شهد اختبار السمية العصبية التنموية (DNT) تقدمًا هائلًا على مدار العقدين الماضيين. وقبل حتى نشر إرشادات اختبار DNT المعتمدة على الحيوانات من منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية (OECD) في عام 2007، بدأت سلسلة من ورش العمل والمؤتمرات التي لا تعتمد على الحيوانات في عام 2005، مما شكل مجتمعًا قدم مجموعة شاملة من طرق الاختبار في المختبر (DNT IVB). يتم الآن تغطية تفسير بياناتها من خلال إرشادات حديثة جدًا من منظمة OECD (رقم 377). هنا، نستعرض التقدم في هذا المجال، مع التركيز على تطور استراتيجيات الاختبار، ودور التقنيات الناشئة، وتأثير إرشادات اختبار OECD على اختبار DNT. على وجه الخصوص، هذه مثال على التطوير المستهدف لنهج اختبار خالٍ من الحيوانات لأحد أكثر المخاطر تعقيدًا التي تشكلها المواد الكيميائية على صحة الإنسان. بدأت هذه التطورات حرفيًا من نقطة الصفر، دون وجود طرق بديلة مقترحة. على مدار عقدين، مكنت العلوم المتطورة من تصميم نهج اختبار يحمي الحيوانات ويتيح القدرة على معالجة هذه المخاطر الصعبة. بينما من الواضح أن هذا المجال يحتاج إلى إرشادات وتنظيم، يجب أن تكون التأثيرات الاقتصادية الضخمة الناتجة عن انخفاض القدرة المعرفية البشرية بسبب التعرض للمواد الكيميائية ذات أولوية أعلى. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن ما يميز اختبار DNT في المختبر هو التقدم العلمي الهائل الذي حققه لفهم الدماغ البشري، وتطوره، وكيف يمكن أن يتعرض للاضطراب.

ملخص بلغة بسيطة

1 المقدمة

| 1. حماية الصحة العامة (العالمية) من خلال الوقاية من الاضطرابات التنموية – الدماغ النامي عرضة بشكل خاص للمواد السامة في سياق اضطرابات طيف التوحد (ASD) واضطراب نقص الانتباه مع فرط النشاط (ADHD) والضعف الإدراكي. |

| 2. الامتثال التنظيمي |

| 3. إرشادات للنساء الحوامل |

| 4. تقليل المخاطر في التجارب السريرية للأطفال |

| 5. الآثار الاقتصادية (أ) – فقدان القدرة المعرفية (درجة الذكاء) يكلف المجتمع. |

| 6. الآثار الاقتصادية (ب) – تكلفة اختبار حيواني واحدة لا تقل عن

|

| 7. رفاهية الحيوان – يتم “استخدام” أكثر من 1000 حيوان لكل مادة كيميائية. |

| 8. التقدم العلمي |

| 9. حماية البيئة |

| 10. التطبيقات القانونية والجنائية – الأدلة في القضايا القانونية والمساهمة في جهود العدالة والتعويض |

| 11. ثقة المستهلك |

| سنة المراقبة | سنة الميلاد | عدد مواقع ADDM التي أبلغت | انتشار مجمع لكل 1,000 طفل (النطاق عبر مواقع ADDM) | هذا يعادل حوالي 1 من كل x أطفال |

| 2020 | 2012 | 11 | 27.6 (23.1-44.9) | 1 من 36 |

| 2018 | 2010 | 11 | 23.0 (16.5-38.9) | 1 من 44 |

| 2016 | 2008 | 11 | 18.5 (18.0-19.1) | 1 من 54 |

| 2014 | 2006 | 11 | 16.8 (13.1-29.3) | 1 من 59 |

| 2012 | 2004 | 11 | 14.5 (8.2-24.6) | 1 من 69 |

| 2010 | 2002 | 11 | 14.7 (5.7-21.9) | 1 من 68 |

| 2008 | 2000 | 14 | 11.3 (4.8-21.2) | 1 من 88 |

| 2006 | 1998 | 11 | 9.0 (4.2-12.1) | 1 من 110 |

| 2004 | 1996 | 8 | 8.0 (4.6-9.8) | 1 من 125 |

| 2002 | 1994 | 14 | 6.6 (3.3-10.6) | 1 من 150 |

| 2000 | 1992 | 6 | 6.7 (4.5-9.9) | 1 من 150 |

€9.59 مليار سنويًا. كان التعرض للفوسفات العضوية مرتبطًا بفرصة

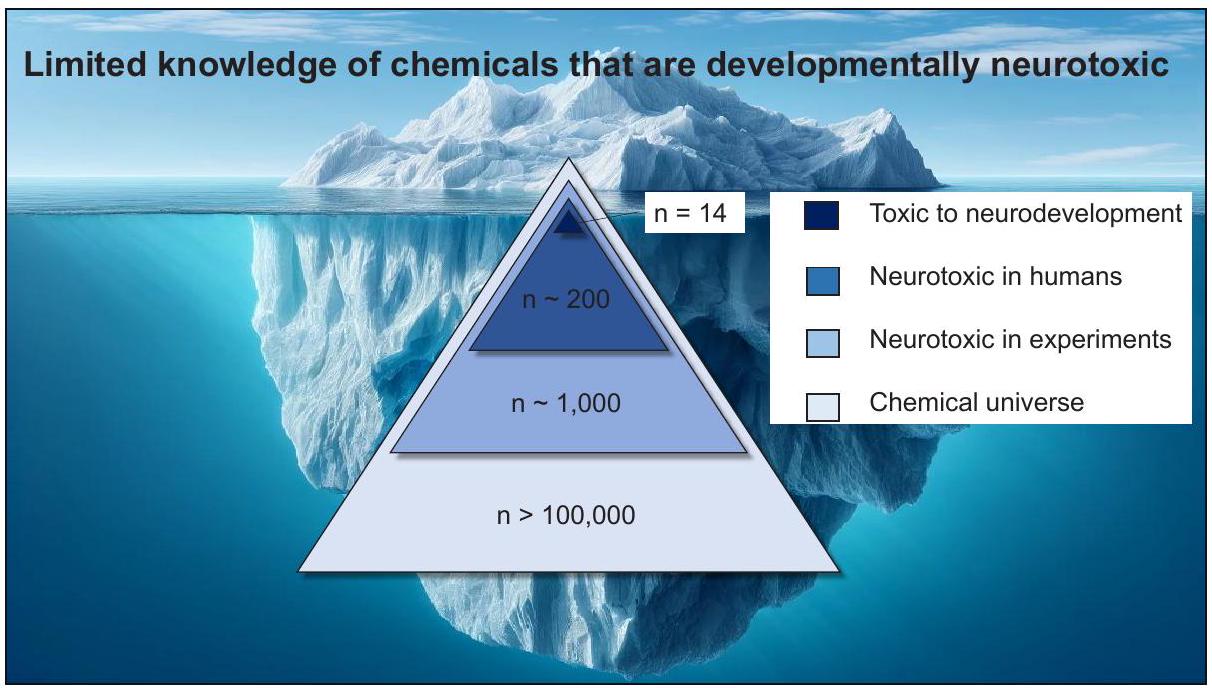

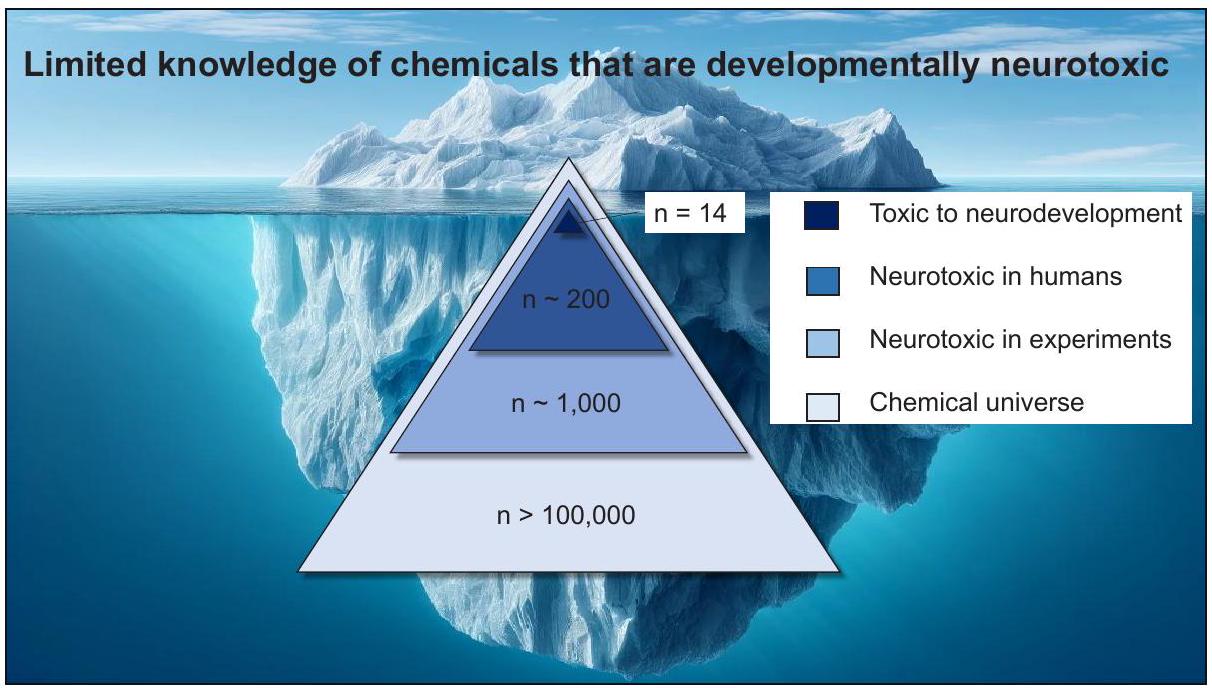

ومضافات الطعام، يبرز الحاجة الملحة لاستراتيجيات اختبار DNT موثوقة. ومع ذلك، لا يوجد متطلب قانوني لتقديم بيانات DNT لمعظم المواد الكيميائية. وبالتالي، لا توجد بيانات على الإطلاق حول

2 قيود اختبار DNT على الحيوانات

والحاجة إلى مجموعة متنوعة من طرق الاختبار لمعالجة جوانب مختلفة من DNT (ماكريس وآخرون، 2009؛ آرتس وآخرون، 2023).

للدراسة الأساسية. مدة اختبار TG 443 مقارنة بـ TG 416 هي ميزة طالما لم يتم تفعيل الجيل الثاني.

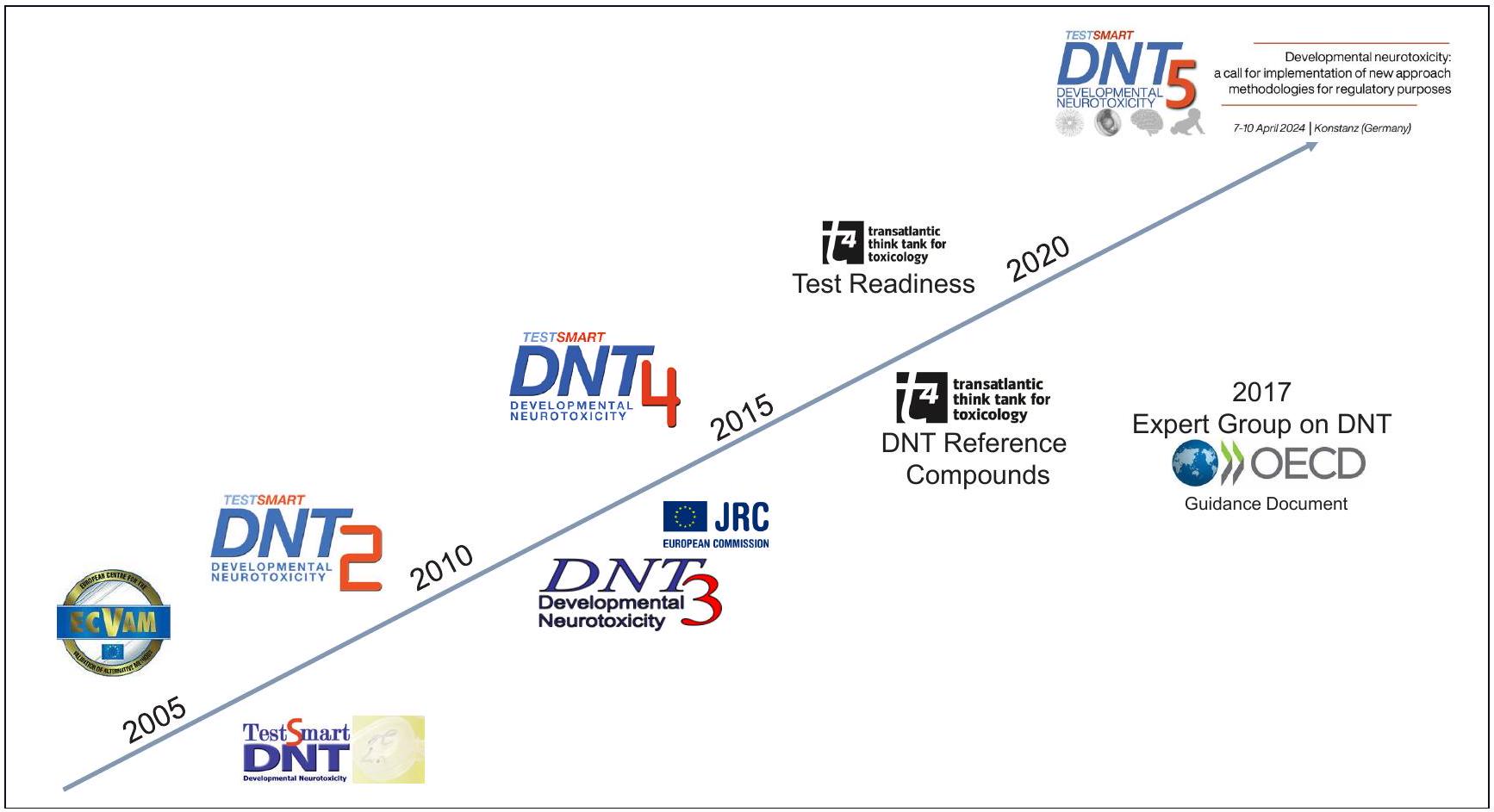

3 مسار البدائل لاختبار DNT في الجسم الحي حتى اجتماع DNT-4 في 2014

3.1 ورشة العمل الأولى حول DNT في ECVAM 2005

خلايا دماغ الجرذان، التي اعتمدناها بنجاح. وقد قادنا ذلك إلى الورقة الأولى التي تصف استخدام التسجيل الكهربائي الفيزيائي لتقييم تأثيرات السموم العصبية (فان فليت وآخرون، 2007)، وإلى الورقة الأولى حول تقييم تأثيرات السموم العصبية باستخدام الميتابولوميات (فان فليت وآخرون، 2008). ومؤخراً، سمح لنا ذلك بمعالجة الإمكانية السامة العصبية لمثبطات اللهب (هوغبرغ وآخرون، 2021).

3.2 المؤتمر الدولي الأول حول عدم تتبع DNT-1 في عام 2006

3.3 المؤتمر الدولي الثاني حول عدم تتبع DNT-2 في عام 2008

- يجب أن تتضمن طرق الاختبار نقطة أو أكثر من النقاط التي تمثل الجوانب الرئيسية لتطور الأعصاب البشرية. تقوم طريقة الاختبار بنمذجة العملية البيولوجية، ويستخدم نظام الاختبار

2. يجب إثبات القدرة على قياس نقطة النهاية المستهدفة بدقة وبدقة من خلال استخدام مجموعة من المركبات التي تُسمى “ضوابط محددة لنقطة النهاية” أو “مركبات أدوات”. يجب أن تعكس نقطة النهاية المقاسة العملية العصبية التنموية المستهدفة.

3. يجب تحديد النطاق الديناميكي لنقطة نهاية DNT لتحديد مدى التغير القابل للقياس عن قيم التحكم.

4. يجب أن يتم تحديد علاقات التركيز-الاستجابة، ويفضل اختبار ما لا يقل عن خمسة تركيزات على نطاق واسع. هذا أمر حاسم لمقارنة حساسية الطرق المختلفة.

5. يجب اختبار المواد الكيميائية الضابطة الإيجابية والسلبية التي من المعروف أنها تؤثر بشكل موثوق أو لا تؤثر على نقطة النهاية المقاسة لـ DNT من خلال آليات معروفة.

6. يجب اختبار مجموعات التدريب الأولية من المواد الكيميائية، بما في ذلك تلك المعروفة بأنها تثير أو لا تثير استجابات DNT بناءً على بيانات in vitro. هذا يقيم قدرة الطريقة على فحص أعداد معتدلة من المواد الكيميائية.

7. يجب بعد ذلك فحص مجموعات أكبر من المواد الكيميائية، بما في ذلك تلك المعروفة بأنها تسبب أو لا تسبب آثار DNT في الجسم الحي. هذا يُظهر قدرة الطريقة على اختبار أعداد أكبر من المواد الكيميائية.

8. يجب تحليل حساسية الطريقة وخصوصيتها وقدرتها التنبؤية في تحديد إمكانيات DNT للمواد الكيميائية استنادًا إلى هذه المجموعات المرجعية من المواد الكيميائية.

باختصار، كانت التوصيات تركز على إظهار الصلة والموثوقية والحساسية ومعدل الإنتاجية لطرق DNT البديلة باستخدام اختبارات نهاية محددة جيدًا ومجموعات اختبار كيميائية مرجعية كإطار لتطوير اختبارات DNT بديلة على مستوى الفحص. كان الهدف هو إثبات ملاءمة الطرق للفحص وتحديد أولويات عدد كبير من المواد الكيميائية. كانت توصيات DNT-2 تهدف إلى تسهيل الانتقال من المناقشات المفاهيمية إلى تطوير واستخدام الاختبارات العملية لأغراض تنظيمية. كان لهذه الاعتبارات والخبرة من مجال DNT تأثير مهم على تطوير مفاهيم أوسع لتطوير طرق الاختبار في المختبر ولأساليب التحقق الجديدة لمثل هذه الاختبارات (Leist et al., 2010, 2012; van Thriel et al., 2012).

3.4 المؤتمر الدولي الثالث حول DNT DNT-3 في عام 2011 في فاريزي، إيطاليا

- كان هناك توافق عام على الحاجة الملحة لتطوير استراتيجيات اختبار DNT بديلة تكون أسرع وأكثر كفاءة من حيث التكلفة، وقادرة على التنبؤ بالنتائج البشرية. هناك حاجة إلى نماذج DNT في المختبر عالية الإنتاجية لاختبار الأعداد الكبيرة من المواد الكيميائية التي لا توجد لها بيانات DNT أو تكاد تكون معدومة.

- تم الإبلاغ عن تقدم كبير في تطبيق أنظمة الاختبار في المختبر وغير الثديية على DNT، بما في ذلك الخلايا الجذعية البشرية / البروتينية.

اختبارات قائمة على خلايا الجنين، على الرغم من الحاجة إلى مزيد من العمل للتحقق من صحة هذه النماذج البديلة مقابل نتائج DNT البشرية. - تم تحديد الحاجة الملحة لتوليد بيانات عبر نماذج بديلة متعددة باستخدام مجموعة شائعة من المواد الكيميائية الاختبارية لتسهيل المقارنات وتحديد أي النماذج/النقاط النهائية هي الأكثر تنبؤًا.

- كما اعتُبر إنشاء مجموعة مرجعية من المواد الكيميائية الضابطة الإيجابية والسلبية لاختبار تأثيرات التطور العصبي أمرًا مهمًا لتقييم النماذج البديلة.

- يجب تطبيق الفحوصات المعتمدة على الخلايا التي تغطي العمليات الرئيسية في التطور العصبي مثل التكاثر، والهجرة، والتمايز، وتكوين المشابك، وتشكيل الشبكات كنقاط نهائية وظيفية لاختبار تأثيرات التطور العصبي.

- يجب استخدام النمذجة الحاسوبية وطرق المعلوماتية الحيوية لتقييم القدرة التنبؤية للنماذج/البطاريات البديلة لاختبار تأثيرات التطور العصبي.

- على الرغم من التقدم، لا تزال النماذج المختبرية غير قادرة على تكرار تعقيد الجهاز العصبي النامي. يجب تقييم صلتها بالنتائج البشرية بحذر.

باختصار، سلطت DNT-3 الضوء على التقدم في تطوير نماذج بديلة ذات إنتاجية أعلى استنادًا إلى إطار عمل DNT-2 مع تحديد الفجوات البيانية الحاسمة، مثل الحاجة إلى مزيد من المقارنات عبر النماذج باستخدام مواد كيميائية مرجعية موحدة. تم تحويل التركيز إلى التطبيق العملي لبدائل DNT للت筛ين/الأولوية، بعيدًا عن مرحلة إثبات المفهوم الأولية.

4 أول مقال غذاء للفكر … حول DNT

وتفسير الفحوصات المختبرية وفي السيليكو من حيث صلتها بالنتائج في الكائنات الحية.

5 DNT-4 – نحو AOPs واختبارات مناسبة للغرض لـ DNT

5.1 مفاهيم جديدة واستراتيجيات اختبار

أن العديد من الأطفال المصابين بـ ASD لديهم زيادة في الاتصال في الدوائر المحلية للقشرة (كيون وآخرون، 2013). يمكن أن يكون هذا النهج لربط التأثيرات الخلوية بنتيجة المرض مفيدًا للمسؤولين ويظهر استخدام بيانات in vitro لتقييم المخاطر.

5.2 الأدوات الميكانيكية والأوميكس، بالإضافة إلى نقاط النهاية الوظيفية، لزيادة محتوى معلومات الاختبار

5.3 كيفية تسريع الاختبار لـ DNT

5.4 استخدام AOPs والاختبارات البديلة لتقييم السلامة

5.5 الحدود في اختبار DNT

5.6 الاستنتاجات من DNT-4

6 التقدم المنهجي الحالي كأساس لنهج جديد لـ DNT

6.1 خلايا الجذعية

“الخزعة الحية” ونمذجة الأمراض: يمكن اعتبار الخلايا الجذعية المستحثة متعددة القدرات “خزعة حية” لحالة المريض، حيث إنها تلتقط التركيب الجيني للمريض ويمكن تمايزها إلى أنواع خلايا ذات صلة بالمرض، مما يوفر منصة لدراسة آليات المرض والعلاجات المحتملة (سميرنوفا وهارتونغ، 2024).

6.2 الثقافات العضوية والأنظمة الميكروفسيولوجية

تتعلق جوانب التطور العصبي البشري ويمكن استخدامها لدراسة العمليات البيولوجية الأساسية التي تعتبر أساسية لفهم السموم العصبية، مثل التمايز، التكاثر، الهجرة، ونمو المحاور العصبية. من خلال اختبار تأثير المواد الكيميائية على هذه الأنشطة البيولوجية، يمكننا تحديد المواد السامة المحتملة. إن الهندسة الحيوية لنظم الأعضاء المصغرة هي مهمة مهمة للغاية.

نفس المادة. كانت هذه نقطة البداية لمشروع تم تمويله من قبل وكالة حماية البيئة

6.3 مزايا الفحص عالي المحتوى في اختبار DNT

6.4 الخصائص الرئيسية للسموم العصبية التنموية

6.5 التقدم في الذكاء الاصطناعي لدعم اختبار DNT

تعزيز صلة اختبار DNT بصحة الإنسان. لقد ناقشنا سابقًا فرص نمذجة MPS من خلال الأساليب الحسابية (سميرنوفا وآخرون، 2018).

7 التقدم المفاهيمي كأساس لنهج جديد لاختبار DNT

7.1 صعود استراتيجيات الاختبار المتكاملة (ITS) المعروفة أيضًا بالأساليب المتكاملة للاختبار والتقييم (IATA)

7.2 دور AOPs

تطوير استراتيجيات الاختبار التي تكون أكثر إبلاغًا آليًا وأكثر تنبؤًا بنتائج صحة الإنسان.

8 تطوير أساليب جديدة لـ DNT كمثال على التطوير الاستراتيجي للبدائل لاختبار الحيوانات

8.1 ورش عمل مفاهيمية تعزز اختبار DNT

وإدخال الأساليب الحاسوبية في الأطر التنظيمية، مع التأكيد على الحاجة إلى نهج تعاوني بين أصحاب المصلحة لمعالجة التحديات في اختبار السموم العصبية.

- هناك حاجة ملحة لاستراتيجية اختبار DNT باستخدام طرق في المختبر ونماذج بديلة لبدء فحص وتحديد الأولويات للعدد الكبير من المواد الكيميائية غير المختبرة لتأثيراتها المحتملة على الجهاز العصبي النامي.

- مجموعة من اختبارات DNT المتاحة حاليًا في المختبر، والتي تستند إلى عمليات النمو العصبي الحرجة، جاهزة للاستخدام الآن لأغراض الفحص والتصنيف. يمكن أن يمكّن المزيد من التطوير والتوحيد لمجموعة الاختبارات من استخدامها في تقييم المخاطر ودعم قرارات إدارة المخاطر في المستقبل.

- يجب وضع خارطة طريق لتحديد الإجراءات والمعالم لتنفيذ هذا النهج الجديد لاختبار DNT. تشمل الأولويات الاختبارات الكيميائية لبناء الثقة في مجموعة الاختبارات، وتحديد معايير الأداء، وتطوير وثيقة توجيهية من منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية حول نهج متكامل لاختبار وتقييم DNT.

تم تلخيص مشروع منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية من قبل ساشانا وآخرين (2019، 2021أ). تشمل الخطوات الرئيسية: 1) إنشاء مجموعة مرجعية من المواد الكيميائية لاختبار مجموعة من اختبارات DNT في المختبر التي تغطي المجالات العصبية الرئيسية –

1) العمليات التطويرية؛ 2) اختيار مجموعة اختبارات DNT في المختبر بناءً على معايير الجاهزية؛ 3) اختبار المواد الكيميائية المرجعية في المجموعة لبناء الثقة في الأساليب البديلة؛ 4) تطوير دراسات حالة IATA باستخدام بيانات مجموعة DNT في المختبر لتطبيقات تنظيمية مختلفة؛ و 5) إعداد وثيقة توجيهية من منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية حول استخدام طرق اختبار DNT البديلة ضمن إطار IATA.

تم تقديم تقييم جاهزية اختبارات DNT الفردية في المختبر وكذلك مجموعة اختبارات DNT في المختبر (DNT IVB) لمختلف التطبيقات التنظيمية. يتيح ذلك تقييمًا كميًا لحالة تطوير الاختبارات وما هو العمل الإضافي المطلوب لزيادة الثقة التنظيمية في هذه الطرق البديلة. يوفر النهج الموضح نموذجًا لتقييم الطرق البديلة في مجالات أخرى من علم السموم. تشمل العناصر الرئيسية: 1) تحديد معايير الجاهزية بناءً على الحاجة التنظيمية وسياق الاستخدام، 2) تسجيل كمي لجاهزية الاختبار بناءً على معايير محددة متعددة، 3) تقييم مجموعة الاختبارات ككل من حيث التغطية البيولوجية، والأداء التنبؤي، والجاهزية العامة للاستخدامات التنظيمية المختلفة، و4) استخدام دراسات حالة لإظهار كيفية تطبيق الطرق البديلة في IATA. يسمح هذا الإطار بتقييم شفاف وموضوعي للطرق البديلة لتسهيل قبولها واستخدامها في التنظيم. بينما لا يزال هناك حاجة لمزيد من العمل للتحقق الكامل من DNT IVB (Juberg et al.، 2023)، كانت الاستراتيجية المقدمة خطوة مهمة إلى الأمام في تعزيز استخدام الطرق البديلة لاختبار السلامة.

- استعرضت اللجنة عدة اختبارات NAM في المختبر التي طورتها وكالة حماية البيئة والباحثون الأوروبيون لتقييم العمليات العصبية التطورية المهمة التي قد تتعطل بسبب التعرض للمواد الكيميائية. بينما وجدت اللجنة نقاط قوة في الاختبارات، لاحظت قيودًا مثل نقص أنواع الخلايا المهمة، وغياب التقييمات الوظيفية/الآلية، وصعوبات في استنتاج التأثيرات في الكائنات الحية.

- ناقشت اللجنة استخدام أساليب الاستقراء من المختبر إلى الكائن الحي (IVIVE) لمقارنة نتائج اختبارات NAM بالجرعات التي تسبب تثبيط الأستيل كولينستراز في الحيوانات بالنسبة لمبيدات الفوسفات العضوي. ووجدوا أن أسلوب IVIVE معقول، لكنهم أثاروا مخاوف بشأن افتراضات النموذج وأدائه.

- استعرضت اللجنة التحليلات التي تستمد عوامل الاستقراء بين الأنواع وداخل الأنواع من بيانات تثبيط الأستيل كولينستراز في أنسجة الجرذان والبشر. تم الإشارة إلى القيود في طرق التحليل، وتمثيل العينة، وأحجام العينات لتوصيف التباين البشري.

- بشكل عام، رأت اللجنة قيمة في نهج NAM بينما قدمت العديد من التوصيات لمعالجة القيود والشكوك في استخدام البيانات لتقييم مخاطر الصحة البشرية.

مثل هذا التقييم نقطة انطلاق مهمة للتنفيذ التنظيمي لأساليب DNT في المختبر لأهم حالة استخدام للمبيدات الزراعية. المخاوف المحددةمثلت أجندة مهمة للتطورات المستقبلية:

أ. غياب العوامل الهرمونية (هرمونات الجنس، الغدة الدرقية، هرمونات الإجهاد)

ب. تأثير إشارات الناقلات العصبية

د. تأثير العوامل الأمومية (عدوى الأم، الهرمونات، خلل في وظائف الأعضاء، سلامة المشيمة)

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم ذكر أن الاختبارات في المختبر:

أ. ستقتصر قدرتهم على اكتشاف العمليات التكيفية أو التعويضية.

ب. لا تأخذ في الاعتبار التفاعلات الخلوية الحرجة المطلوبة خلال تطور الأعصاب.

ج. يواجهون صعوبة في التمييز بين المركبات النشطة عصبيًا والمركبات السامة عصبيًا.

لا تعكس التنوع الجيني البشري عند استخدام خطوط خلايا بشرية من إنسان واحد.

8.2 إرشادات منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية والوثيقة الإرشادية

- يتضمن DNT IVB مجموعة من الاختبارات في المختبر التي تغطي العمليات الرئيسية في التطور العصبي مثل التكاثر، والهجرة، والتمايز، ونمو المحاور، وتشكيل الشبكات العصبية.

- تعتبر هذه الاختبارات أحداثًا رئيسية على المستوى الخلوي ترتبط بشكل معقول بطرق عمل السموم العصبية التنموية في الجسم.

- عند تفسير البيانات من الاختبارات الفردية، من المهم تقييم الأهمية البيولوجية لنظام الاختبار، وجودة الاختبار وقابليته للتكرار، والاختبار باستخدام مجموعة تدريب من المواد الكيميائية، وطرق تحليل البيانات، واستخدام نموذج قرار لتصنيف المواد الكيميائية.

- لتقييم DNT IVB ككل، تشمل العوامل التي يجب أخذها في الاعتبار القوة التنبؤية مقارنة بالبيانات الحية، اتساق النتائج عبر البطارية، مقارنة الفعالية مع نقاط النهاية الأخرى في المختبر، ورسم الخرائط إلى AOPs.

- يجب أن يكون استخدام بيانات DNT IVB موجهًا من خلال اتساق البيانات في المختبر، والاحتمالية البيولوجية، ودمج نماذج الاستقراء من المختبر إلى الحي، وأخذ عدم اليقين في الاعتبار في سياق الحاجة التنظيمية.

- بينما لا تمثل بديلاً كاملاً للدراسات الحيوانية، يتم استخدام بيانات DNT IVB بالفعل لإبلاغ عمليات الفحص، وتحديد الأولويات، ووزن الأدلة في تطبيقات تنظيمية مختلفة. هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من العمل لتطوير قوائم مرجعية موحدة للمواد الكيميائية، وخطوط أنابيب تحليل البيانات، واستراتيجيات اختبار متدرجة.

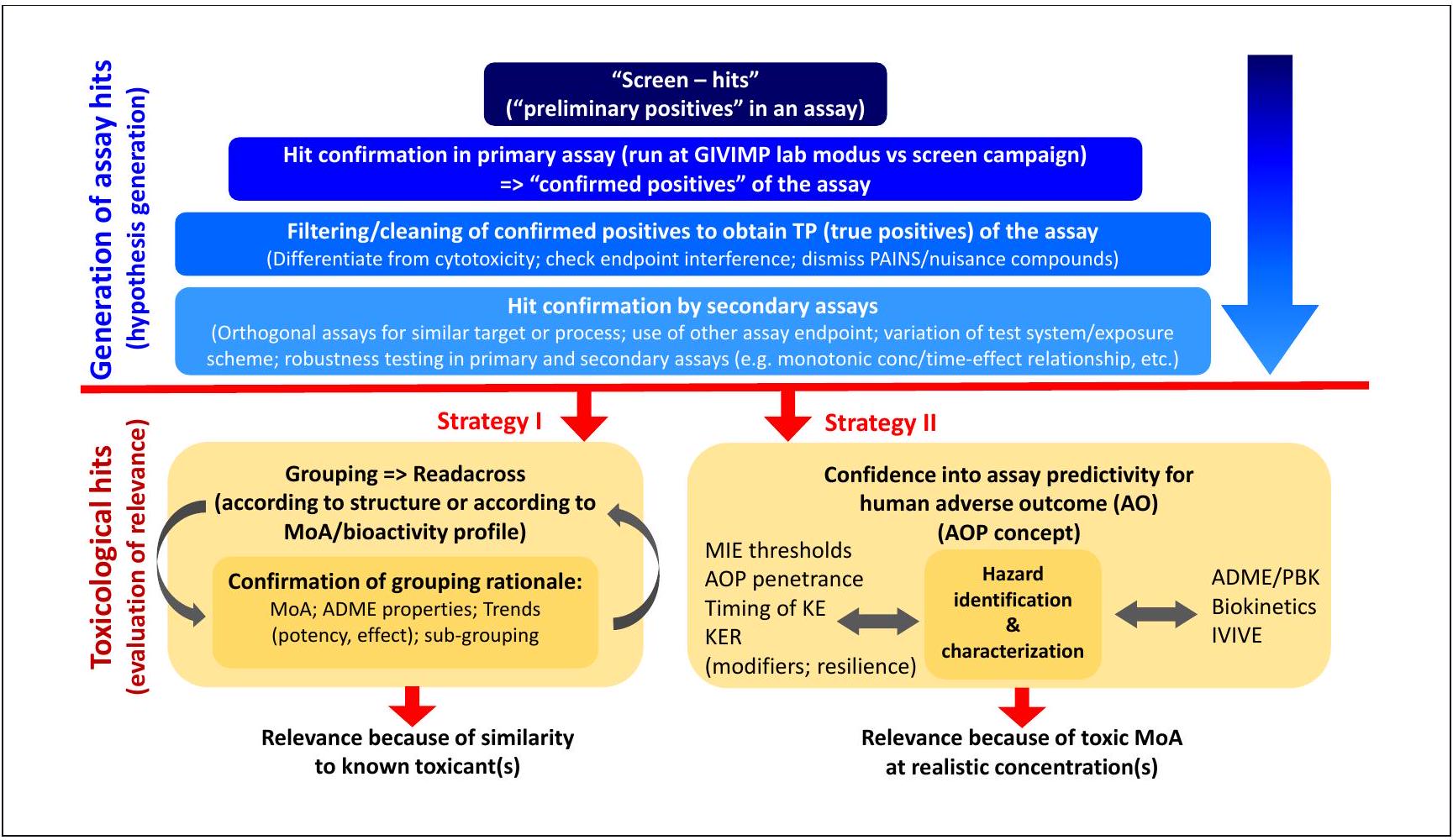

8.3 من نتائج الفحص إلى المواد السامة المحتملة DNT

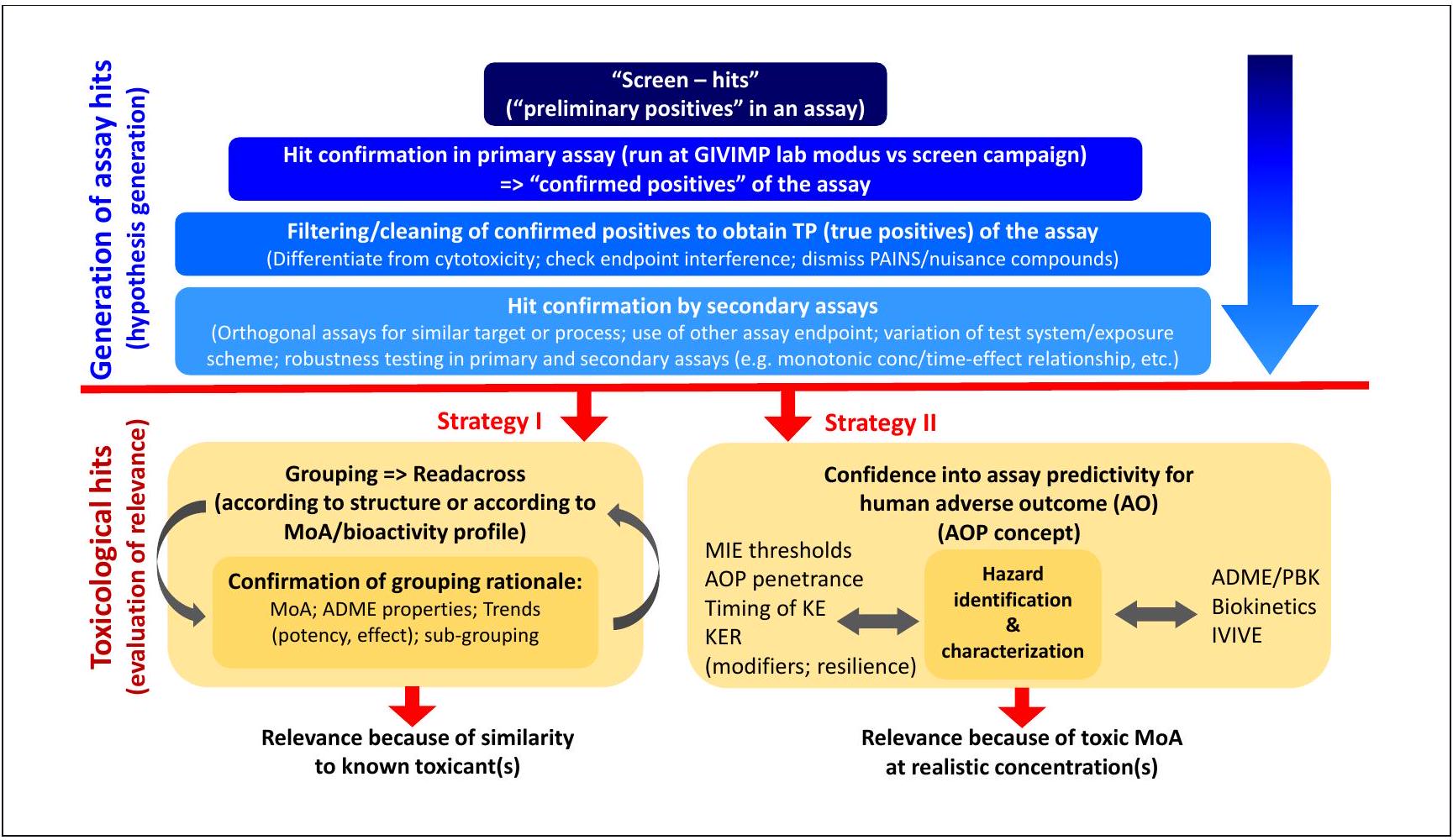

أنظمة. الفحص هو تخصص علمي تم تطويره في اكتشاف الأدوية، وتم جمع الكثير من الخبرة التي تم دمجها في ثقافة الفحص وأفضل الممارسات ضمن تخصص علم الأدوية. في علم السموم، تم اعتماد التكنولوجيا وتكييفها، لكن الثقافة متأخرة. غالبًا ما يكون التمييز بين نتيجة الفحص وسمية محتملة غير واضح ويحتاج إلى مزيد من التوضيح للاستخدام الفعال لهذا النهج في اختبار DNT. المصطلحات الصيدلانية هي كما يلي: تنتج الشاشات “إيجابيات أولية” في الاختبار المعني. بعد تأكيدها في ظروف أكثر تحكمًا، يمكن أن تُسمى “إيجابيات مؤكدة”. يجب تصفيتها، على سبيل المثال، من أجل العيوب الفنية، أو التأثيرات الثانوية بسبب السمية الخلوية. في العديد من الشاشات الصيدلانية، يؤدي ذلك إلى القضاء على

9 التحديات والاتجاهات المستقبلية

تنتج الشاشات، إذا تم تشغيلها بتقنية عالية الإنتاجية، غالبًا “إيجابيات أولية” تحتاج إلى مزيد من التأهيل والتوصيف. تتضمن الخطوة الأولى تكرار الاختبار، ربما مع نموذج تنبؤ أكثر صرامة، وضوابط إجراءات مختبرية أكثر صرامة (على سبيل المثال، وفقًا لإرشادات منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية بشأن ممارسات الطرق الجيدة في المختبر (GIVIMP)) ومع حلول جديدة، ومراقبة جيدة للمركبات. يتم الحصول على الإيجابيات الحقيقية (TP) بعد القضاء على العيوب الفنية (على سبيل المثال، المركبات الفلورية، أو المركبات التي ترتبط بشكل غير محدد بالبروتينات)، والتحكم في السمية الخلوية، وتصنيف المعلومات الكيميائية للمركبات المعروفة التي تتداخل مع الاختبارات (PAINS). يتم الحصول على اليقين بشأن النشاط البيولوجي لمثل هذه المركبات تقليديًا في اختبارات ثانوية وثالثة لمسارات أو هياكل مستهدفة مماثلة. من المثالي أن تكون هذه متعامدة بمعنى أنها تستخدم أنظمة اختبار أخرى و/أو تقنيات قراءة مختلفة. في المرحلة الثانية، يتم تقييم مثل هذه “الإيجابيات المقنعة” من حيث أهميتها السمية. تختبر الاستراتيجية الأولى الأهمية من خلال إثبات تشابه نتيجة الاختبار مع مواد سامة معروفة ومميزة. يعتمد تعريف التشابه على (ط) التشابه الهيكلي، (2) خصائص ADME المماثلة، و(3) ملف النشاط البيولوجي/طريقة العمل (MoA) المماثلة. تختبر الاستراتيجية الثانية الأهمية بناءً على MoA المتوقع أو تفعيل مسار نتيجة سلبية موثوق (AOP). القضايا الأساسية هي (ط) ما إذا كانت التركيزات التي تحفز حدث بدء جزيئي (MIE) أو حدث رئيسي (KE) يتم الوصول إليها بشكل واقعي، وما إذا كان من المحتمل أن يستمر AOP المحفز أيضًا إلى النتيجة السلبية (AO). ستستخدم تحقيقات أكثر شمولاً نماذج استقراء كمية من المختبر إلى الحي (IVIVE) وستأخذ في الاعتبار ما إذا كانت العلاقات بين الأحداث الرئيسية (KER) تأثرت بالعوامل المعدلة أو التنظيمات المضادة.

التحديات والفرص المحددة المرتبطة باختبار DNT، مثل تعقيد العمليات العصبية التنموية، وأهمية مراعاة اختلافات الأنواع (Baumann et al., 2016) وتوقيت التعرض، والحاجة إلى بطارية من الاختبارات التكميلية التي تغطي أوضاع عمل مختلفة. الوثيقة المحدثة مؤخرًا من اللجنة التنسيقية بين الوكالات بشأن التحقق من صحة الطرق البديلة (ICCVAM)، “التحقق، التأهيل، والقبول التنظيمي للطرق الجديدة”

استخدام بيانات DNT لتحديد الأنماط والعلاقات التي قد لا تكون واضحة من التحليلات الإحصائية التقليدية. يمكن بعد ذلك استخدام هذه النماذج للتنبؤ بإمكانات DNT للمواد الكيميائية الجديدة بناءً على تشابهها الهيكلي والبيولوجي مع السموم المعروفة، أو لتحديد أكثر التركيبات المعلوماتية من الاختبارات والنقاط النهائية في سياق تنظيمي معين.

9.1 التنفيذ

9.2 رؤية للمستقبل

10 استنتاجات وآفاق

تم الاستفادة منها لتطوير مجموعة واسعة من طرق الاختبار البديلة، بما في ذلك نماذج زراعة الخلايا في المختبر، ونماذج الحيوانات غير الثديية، والنهج الحاسوبية التي تقدم إمكانية تقييم أسرع وأكثر كفاءة ومعلوماتية من الناحية الميكانيكية لإمكانية التأثيرات السامة على التطور العصبي.

لاختبار DNT، مدفوعة جزئيًا بالتقدم في علم الخلايا الجذعية، وتحرير الجينوم، والفحص عالي الإنتاجية، والنمذجة الحاسوبية. كان إنشاء مجموعة خبراء DNT التابعة لمنظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية في عام 2017 ونشر “التوصيات الأولية لتقييم البيانات من بطارية اختبار DNT في المختبر” (OECD، 2023) بمثابة معالم مهمة في قبول الطرق البديلة من قبل الجهات التنظيمية.

References

Ankley, G. T., Bennett, R. S., Erickson, R. J. et al. (2010). Adverse outcome pathways: A conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Environ Toxicol Chem 29, 730-741. doi:10.1002/etc. 34

Arts, J. H. E., Faulhammer, F., Schneider, S. et al. (2023). Investigations on learning and memory function in extended one-generation reproductive toxicity studies – When considered needed and based on what? Crit Rev Toxicol 53, 372-384. doi:10. 1080/10408444.2023.2236134

Bal-Price, A., Hogberg, H. T., Buzanska, L. et al. (2010). In vitro developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) testing: Relevant models and endpoints. Neurotoxicology 31, 545-554. doi:10.1016/j. neuro.2009.11.006

Bal-Price, A. K., Coecke, S., Costa, L. et al. (2012). Advancing the science of developmental neurotoxicity (DNT): Testing for better safety evaluation. ALTEX 29, 202-215. doi:10.14573/ altex.2012.2.202

Bal-Price, A., Crofton, K. M., Sachana, M. et al. (2015a). Putative adverse outcome pathways relevant to neurotoxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol 45, 83-91. doi:10.3109/10408444.2014.981331

Bal-Price, A., Crofton, K. M., Leist, M. et al. (2015b). International STakeholder NETwork (ISTNET): Creating a developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) testing road map for regulatory purposes. Arch Toxicol 89, 269-287. doi:10.1007/s00204-015-1464-2

Bal-Price, A. and Meek, M. E. (2017). Adverse outcome pathways: Application to enhance mechanistic understanding of neurotoxicity. Pharmacol Ther 179, 84-95. doi:10.1016/j. pharmthera.2017.05.006

Bal-Price, A., Hogberg, H. T., Crofton, K. M. et al. (2018a). t

Bal-Price, A., Pistollato, F., Sachana, M. et al. (2018b). Strategies to improve the regulatory assessment of developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) using in vitro methods. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 354, 7-18. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2018.02.008

Basketter, D. A., Clewell, H., Kimber, I., et al. (2012). A roadmap for the development of alternative (non-animal) methods for systemic toxicity testing. ALTEX 29, 3-89. doi: 10.14573/altex. 2012.1.003

Bellanger, M., Demeneix, B. A., Grandjean, P. et al. (2015). Neurobehavioral deficits, diseases, and associated costs of exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the European Union. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100, 1256-1266. doi:10.1210/ jc.2014-4323

Blaauboer, B. J., Boekelheide, K., Clewell, H. J. et al. (2012). The use of biomarkers of toxicity for integrating in vitro hazard estimates into risk assessment for humans. ALTEX 29, 411-425. doi:10.14573/altex.2012.4.411

Blum, J., Masjosthusmann, S., Bartmann, K. et al. (2023). Establishment of a human cell-based in vitro battery to assess developmental neurotoxicity hazard of chemicals. Chemosphere

Boyle, J., Yeter, D., Aschner, M. et al. (2021). Estimated IQ points and lifetime earnings lost to early childhood blood lead levels in the United States. Sci Total Environ 778, 146307. doi:10.1016/j. scitotenv.2021.146307

Butera, A., Smirnova, L., Ferrando-May, E. et al. (2023). Deconvoluting gene and environment interactions to develop “epigenetic score meter” of disease. EMBO Mol Med 15, e18208. doi:10.15252/emmm. 202318208

Caloni, F., De Angelis, I. and Hartung, T. (2022). Replacement of animal testing by integrated approaches to testing and assessment (IATA): A call for in vivitrosi. Arch Toxicol 96, 1935-1950. doi:10.1007/s00204-022-03299-x

Cediel-Ulloa, A., Lupu, D. L., Johansson, Y. et al. (2022). Impact of endocrine disrupting chemicals on neurodevelopment: The need for better testing strategies for endocrine disruption-induced developmental neurotoxicity. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 17, 131-141. doi:10.1080/17446651.2022.2044788

Chesnut, M., Hartung, T., Hogberg, H. T. et al. (2021a). Human oligodendrocytes and myelin in vitro to evaluate developmental neurotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 22, 7929. doi:10.3390/ ijms22157929

Chesnut, M., Paschoud, H., Repond, C. et al. (2021b). Human 3D iPSC-derived brain model to study chemical-induced myelin disruption. Int J Mol Sci 22, 9473. doi:10.3390/ijms22179473

Coecke, S., Goldberg, A. M., Allen, S. et al. (2007). Workgroup report: Incorporating in vitro alternative methods for developmental neurotoxicity into international hazard and risk assessment strategies. Environ Health Perspect 115, 924-931. doi:10.1289/ ehp. 9427

Cohn, E. F., Clayton, B. L. L., Madhavan, M. et al. (2024). Pervasive environmental chemicals impair oligodendrocyte development. Nat Neurosci, online ahead of print. doi:10.1038/s41593-024-01599-2

Crofton, K. M., Mundy, W. R., Lein, P. J. et al. (2011). Developmental neurotoxicity testing: Recommendations for developing alternative methods for the screening and prioritization of chemicals. ALTEX 28, 9-15. doi:10.14573/altex.2011.1.009

Crofton, K., Fritsche, E., Ylikomi, T. and Bal-Price, A. (2014). International STakeholder NETwork (ISTNET) for creating a developmental neurotoxicity testing (DNT) roadmap for regulatory purposes. ALTEX 31, 223-224. doi:10.14573/altex. 1402121

Crofton, K. M. and Mundy, W. R. (2021). External scientific report on the interpretation of data from the developmental neurotoxicity in vitro testing assays for use in integrated approaches for testing and assessment. EFSA Support Publ 18, 6924E. doi:10.2903/ sp.efsa.2021.en-6924

Diemar, M. G., Vinken, M., Teunis, M. et al. (2024). Report of the First ONTOX stakeholder network meeting: Digging under the surface of ONTOX together with the stakeholders. Altern Lab Anim 52, 117-131. doi:10.1177/02611929231225730

Fritsche, E., Crofton, K. M., Hernandez, A. F. et al. (2017). OECD/ EFSA workshop on developmental neurotoxicity (DNT): The use of non-animal test methods for regulatory purposes. ALTEX 34, 311-315. doi:10.14573/altex. 1701171

Fritsche, E., Barenys, M., Klose, J. et al. (2018). Current availability of stem cell-based in vitro methods for developmental neu-

rotoxicity (DNT) testing. Toxicol Sci 165, 21-30. doi:10.1093/ toxsci/kfy178

Furxhi, I. and Murphy, F. (2020). Predicting in vitro neurotoxicity induced by nanoparticles using machine learning. Int J Mol Sci 21, 5280. doi:10.3390/ijms21155280

Gaylord, A., Osborne, G., Ghassabian, A. et al. (2020). Trends in neurodevelopmental disability burden due to early life chemical exposure in the USA from 2001 to 2016: A population-based disease burden and cost analysis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 502, 110666. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2019.110666

Grandjean, P. and Landrigan, P. J. (2006). Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. Lancet 368, 2167-2178. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69665-7

Grandjean, P. and Landrigan, P. J. (2014). Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. Lancet Neurol 13, 330-338. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70278-3

Groot, M. W. G. M., Westerink, R. H. S. and Dingemans, M. M. L. (2013). Don’t judge a neuron only by its cover: Neuronal function in in vitro developmental neurotoxicity testing. Toxicol Sci 132, 1-7. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfs269

Hartung, T., van Vliet, E., Jaworska, J. et al. (2012). Systems toxicology. ALTEX 29, 119-128. doi:10.14573/altex.2012.2.119

Hartung, T., Luechtefeld, T., Maertens, A. et al. (2013a). Integrated testing strategies for safety assessments. ALTEX 30, 3-18. doi:10.14573/altex.2013.1.003

Hartung, T., Stephens, M. and Hoffmann, S. (2013b). Mechanistic validation. ALTEX 30, 119-130. doi:10.14573/altex.2013.2.119

Hartung, T. and Tsatsakis, A. M. (2021). The state of the scientific revolution in toxicology. ALTEX 38, 379-386. doi:10.14573/ altex. 2106101

Hartung, T. (2023a). ToxAIcology – The evolving role of artificial intelligence in advancing toxicology and modernizing regulatory science. ALTEX 40, 559-570. doi:10.14573/altex. 2309191

Hartung, T. (2023b). A call for a human exposome project. ALTEX 40, 4-33. doi:10.14573/altex. 2301061

Hartung, T., Smirnova, L., Morales Pantoja, I. E. et al. (2023). The Baltimore declaration toward the exploration of organoid intelligence. Front Sci 1, 1017235. doi:10.3389/fsci.2023.1017235

Hartung, T., Morales Pantoja, I. E. and Smirnova, L. (2024). Brain organoids and organoid intelligence (OI) from ethical, legal, and social points of view. Front Artif Intell 6, 1307613. doi:10.3389/ frai.2023.1307613

Hernández-Jerez, A. F., Adriaanse, P. I., Aldrich, A. P. et al. (2021). Development of integrated approaches to testing and assessment (IATA) case studies on developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) risk assessment. EFSA J 19, e06599. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6599

Hertz-Picciotto, I. and Delwiche, L. (2009). The rise in autism and the role of age at diagnosis. Epidemiology 20, 84-90. doi:10.1097/ ede.0b013e3181902d15

Hogberg, H. T., Kinsner-Ovaskainen, A., Coecke, S. et al. (2010). mRNA expression is a relevant tool to identify developmental neurotoxicants using an in vitro approach. Toxicol Sci 113, 95115. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp175

Hogberg, H. T., Bressler, J., Christian, K. M. et al. (2013). Toward a 3D model of human brain development for studying gene/environment interactions. Stem Cell Res Ther 4, S4. doi:10.1186/scrt365

Hogberg, H. T., de Cássia da Silveira e Sá, R., Kleensang, A. et al. (2021). Organophosphorus flame retardants are developmental neurotoxicants in a rat primary BrainSphere in vitro model. Arch Toxicol 95, 207-228. doi:10.1007/s00204-020-02903-2

Hogberg, H. T. and Smirnova, L. (2022). The future of 3D brain cultures in developmental neurotoxicity testing. Front Toxicol 4, 808620. doi:10.3389/ftox.2022.808620

Huang, Q., Tang, B., Romero, J. C. et al. (2022). Shell microelectrode arrays (MEAs) for brain organoids. Sci Adv 8, eabq5031. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abq5031

Ilieva, M., Fex Svenningsen, Å., Thorsen, M. et al. (2018). Psychiatry in a dish: Stem cells and brain organoids modeling autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry 83, 558-568. doi:10.1016/j. biopsych.2017.11.011

Juberg, D. R., Fox, D. A., Forcelli, P. A. et al. (2023). A perspective on in vitro developmental neurotoxicity test assay results: An expert panel review. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 143, 105444. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2023.105444

Keown, C., Shih, P., Nair, A. et al. (2013). Local functional overconnectivity in posterior brain regions is associated with symptom severity in autism spectrum disorders. Cell Rep 5, 567-572. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.003

Kilpatrick, S., Irwin, C. and Singh, K. K. (2023). Human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) and organoid models of autism: Opportunities and limitations. Transl Psychiatry 13, 217. doi:10.1038/ s41398-023-02510-6

Kleensang, A., Maertens, A., Rosenberg, M. et al. (2014). Pathways of toxicity. ALTEX 31, 53-61. doi:10.14573/altex. 1309261

Kleinstreuer, N. and Hartung, T. (2024). Artificial intelligence (AI) – It’s the end of the tox as we know it (and I feel fine) – AI for predictive toxicology. Arch Toxicol 98, 735-754. doi:10.1007/ s00204-023-03666-2

Knight, J., Hartung, T. and Rovida, C. (2023). 4.2 million and counting… the animal toll for REACH systemic toxicity studies. ALTEX 40, 389-407. doi:10.14573/altex. 2303201

Kobolak, J., Teglasi, A., Bellak, T. et al. (2020). Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived 3D-neurospheres are suitable for neurotoxicity screening. Cells 9, 1122. doi:10.3390/cells9051122

Krewski, D., Andersen, M., Tyshenko, M. G. et al. (2020). Toxicity testing in the

Krug, A. K., Kolde, R., Gaspar, J. A. et al. (2013a). Human embryonic stem cell-derived test systems for developmental neurotoxicity: A transcriptomics approach. Arch Toxicol 87, 123-143. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0967-3

Krug, A. K., Balmer, N. V., Matt, F. et al. (2013b). Evaluation of a human neurite growth assay as specific screen for developmental neurotoxicants. Arch Toxicol 87, 2215-2231. doi:10.1007/ s00204-013-1072-y

La Merrill, M. A., Vandenberg, L. N., Smith, M. T. et al. (2020). Consensus on the key characteristics of endocrine-disrupting chemicals as a basis for hazard identification. Nat Rev Endocrinol 16, 45-57. doi:10.1038/s41574-019-0273-8

Lancaster, M., Renner, M., Martin, C. A. et al. (2013). Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 501, 373-379. doi:10.1038/nature12517

Landrigan, P. J. (2010). What causes autism? Exploring the environmental contribution. Curr Opin Pediatr 22, 219-225. doi:10.1097/mop.0b013e328336eb9a

Lee, J. and Freeman, J. L. (2014). Zebrafish as a model for developmental neurotoxicity assessment: The application of the zebrafish in defining the effects of arsenic, methylmercury, or lead on early neurodevelopment. Toxics 2, 464-495. doi:10.3390/toxics 2030464

Lein, P., Silbergeld, E., Locke, P. et al. (2005). In vitro and other alternative approaches to developmental neurotoxicity testing (DNT). Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 19, 735-744. doi:10.1016/j. etap.2004.12.035

Lein, P., Locke, P. and Goldberg, A. (2007). Meeting report: Alternatives for developmental neurotoxicity testing. Environ Health Perspect 115, 764-768. doi:10.1289/ehp. 9841

Leist, M., Efremova, L. and Karreman, C. (2010). Food for thought … considerations and guidelines for basic test method descriptions in toxicology. ALTEX 27, 309-317. doi:10.14573/ altex.2010.4.309

Leist, M., Hasiwa, N., Daneshian, M. et al. (2012). Validation and quality control of replacement alternatives – Current status and future challenges. Toxicol Res 1, 8-22. doi:10.1039/c2tx20011b

Leist, M., Hasiwa, N., Rovida, C. et al. (2014). Consensus report on the future of animal-free systemic toxicity testing. ALTEX 31, 341-356. doi:10.14573/altex. 1406091

Leist, M., Ghallab, A., Graepel, R. et al. (2017). Adverse outcome pathways: Opportunities, limitations and open questions. Arch Toxicol 91, 3477-3505. doi:10.1007/s00204-017-2045-3

Li, S. and Xia, M. (2019). Review of high-content screening applications in toxicology. Arch Toxicol 93, 3387-3396. doi:10.1007/ s00204-019-02593-5

Luderer, U., Eskenazi, B., Hauser, R. et al. (2019). Proposed key characteristics of female reproductive toxicants as an approach for organizing and evaluating mechanistic data in hazard assessment. Environ Health Perspect 127, 075001. doi:10.1289/ehp4971

Maass, C., Schaller, S., Dallmann, A. et al. (2023). Considering developmental neurotoxicity in vitro data for human health risk assessment using physiologically-based kinetic modeling: Deltamethrin case study. Toxicol Sci 192, 59-70. doi:10.1093/toxsci/ kfad007

Maenner, M. J., Warren, Z., Williams, A. R. et al. (2023). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years – Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ 72, 1-14. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1

Makris, S. L., Raffaele, K., Allen, S. et al. (2009). A retrospective performance assessment of the developmental neurotoxicity

study in support of OECD test guideline 426. Environ Health Perspect 117, 17-25. doi:10.1289/ehp. 11447

Marx, U., Andersson, T. B., Bahinski, A. et al. (2016). Biologyinspired microphysiological system approaches to solve the prediction dilemma of substance testing. ALTEX 33, 272-321. doi:10.14573/altex. 1603161

Marx, U., Akabane, T., Andersson, T. et al. (2020). Biologyinspired microphysiological systems to advance patient benefit and animal welfare in drug development. ALTEX 37, 365-394. doi:10.14573/altex. 2001241

Meigs, L., Smirnova, L., Rovida, C. et al. (2018). Animal testing and its alternatives – The most important omics is economics. ALTEX 35, 275-305. doi:10.14573/altex. 1807041

Modafferi, S., Zhong, X., Kleensang, A. et al. (2021). Gene-environment interactions in developmental neurotoxicity: A case study of synergy between chlorpyrifos and CHD8 knockout in human BrainSpheres. Environ Health Perspect 129, 77001. doi:10.1289/ehp8580

Moore, N. P., Beekhuijzen, M., Boogaard, P. J. et al. (2016). Guidance on the selection of cohorts for the extended one-generation reproduction toxicity study (OECD test guideline 443). Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 80, 32-40. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.05.036

Morales Pantoja, I. E., Smirnova, L., Muotri, A. R. et al. (2023a). First organoid intelligence (OI) workshop to form an OI community. Front ArtifIntell 6, 1116870. doi:10.3389/frai.2023.1116870

Morales Pantoja, I. E., Ding, L., Leite, P. E. C. et al. (2023b). A novel approach to increase glial cell populations in brain microphysiological systems. Adv Biol, e2300198. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/adbi. 202300198

Mundy, W. R., Padilla, S., Breier, J. M. et al. (2015). Expanding the test set: Chemicals with potential to disrupt mammalian brain development. Neurotoxicol Teratol 52, 25-35. doi:10.1016/j.ntt. 2015.10.001

NRC – National Research Council (2007). Toxicity Testing in the

Nyffeler, J., Chovancova, P., Dolde, X. et al. (2018). A structure-activity relationship linking non-planar PCBs to functional deficits of neural crest cells: New roles for connexins. Arch Toxicol 92, 1225-1247. doi:10.1007/s00204-017-2125-4

OECD (2001). Test No. 416: Two-Generation Reproduction Toxicity. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4. OECD Publishing, Paris, doi:10.1787/9789264070868-en

OECD (2007). Test No. 426: Developmental Neurotoxicity Study. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4. OECD Publishing, Paris. doi:10.1787/9789264067394-en

OECD (2018). Test No. 443: Extended One-Generation Reproductive Toxicity Study. OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4. OECD Publishing, Paris. doi:10. 1787/9789264185371-en

OECD (2023). Initial Recommendations on Evaluation of Data from the Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT) In-Vitro Testing Battery. Series on Testing and Assessment No. 377. https://one. oecd.org/document/ENV/CBC/MONO(2023)13/en/pdf

Pamies, D., Block, K., Lau, P. et al. (2018). Rotenone exerts developmental neurotoxicity in a human brain spheroid model. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 354, 101-114. doi:10.1016/j. taap.2018.02.003

Pamies. D., Leist, M., Coecke, S. et al. (2022). Guidance document on good cell and tissue culture practice 2.0 (GCCP 2.0). ALTEX 39, 30-70. doi:10.14573/altex. 2111011

Persson, M. and Hornberg, J. J. (2016). Advances in predictive toxicology for discovery safety through high content screening. Chem Res Toxicol 29, 1998-2007. doi:10.1021/acs. chemrestox.6b00248

Pessah, I. N. and Lein, P. J. (2008). Evidence for environmental susceptibility in autism – What we need to know about gene x environment interactions. In A. Zimmerman (ed.), Autism: Current Theories and Evidence (409-428). Humana Press.

Pistollato, F., de Gyves, E. M., Carpi, D. et al. (2020). Assessment of developmental neurotoxicity induced by chemical mixtures using an adverse outcome pathway concept. Environ Health 19, 23. doi:10.1186/s12940-020-00578-x

Rempel, E., Hoelting, L., Waldmann, T. et al. (2015). A transcrip-tome-based classifier to identify developmental toxicants by stem cell testing: Design, validation and optimization for histone deacetylase inhibitors. Arch Toxicol 89, 1599-1618. doi:10.1007/ s00204-015-1573-y

Rice, D. and Barone, S. Jr. (2000). Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: Evidence from humans and animal models. Environ Health Perspect 108, Suppl 3, 511-533. doi:10.1289/ehp.00108s3511

Rodier, P. M. (1995). Developing brain as a target of toxicity. Environ Health Perspect 103, Suppl 6, 73-76. doi:10.1289/ ehp.95103s673

Romero, J. C., Berlinicke, C., Chow, S. et al. (2023). Oligodendrogenesis and myelination tracing in a CRISPR/Cas9-engineered brain microphysiological system. Front Cell Neurosci 16, 1094291. doi:10.3389/fncel.2022.1094291

Roth, A. and MPS-WS Berlin 2019 (2021). Human microphysiological systems for drug development. Science 373, 1304-1306. doi:10.1126/science.abc3734

Rovida, C., Alépée, N., Api, A. M. et al. (2015). Integrated testing strategies (ITS) for safety assessment. ALTEX 32, 25-40. doi:10.14573/altex. 1411011

Rovida, C., Busquet, F., Leist, M. et al. (2023). REACH outnumbered! The future of REACH and animal numbers. ALTEX 40, 367-388. doi:10.14573/altex. 2307121

Russo, F. B., Brito, A., de Freitas, A. M. et al. (2019). The use of iPSC technology for modeling autism spectrum disorders.

Sachana, M., Bal-Price, A., Crofton, K. M. etal. (2019). International regulatory and scientific effort for improved developmental neurotoxicity testing. Toxicol Sci 167, 45-57. doi:10.1093/toxsci/ kfy211

Sachana, M., Shafer, T. J. and Terron, A. (2021a). Toward a better testing paradigm for developmental neurotoxicity: OECD efforts and regulatory considerations. Biology 10, 86. doi:10.3390/ biology10020086

Sachana, M., Willett, C., Pistollato, F. et al. (2021b). The potential of mechanistic information organised within the AOP framework to increase regulatory uptake of the developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) in vitro battery of assays. Reprod Toxicol 103, 159-170. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2021.06.006

Sagiv, S. K., Thurston, S. W., Bellinger, D. C. et al. (2010). Prenatal organochlorine exposure and behaviors associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in school-aged children.

Santos, J. L. S., Araújo, C. A., Rocha, C. A. G. et al. (2023). Modeling autism spectrum disorders with induced pluripotent stem cell-derived brain organoids. Biomolecules 13, 260. doi:10.3390/biom13020260

Schiffelers, M. W. A., Blaauboer, B. J., Bakker, W. E. et al. (2015). Regulatory acceptance and use of the extended one generation reproductive toxicity study within Europe. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 71, 114-124. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.10.012

Schmidt, B. Z., Lehmann, M., Gutbier, S. et al. (2016). In vitro acute and developmental neurotoxicity screening: An overview of cellular platforms and high-throughput technical possibilities. Arch Toxicol 91, 1-33. doi:10.1007/s00204-016-1805-9

Schmuck, M. R., Temme, T., Dach, K. et al. (2017). Omnisphero: A high-content image analysis (HCA) approach for phenotypic developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) screenings of organoid neurosphere cultures in vitro. Arch Toxicol 91, 2017-2028. doi:10.1007/s00204-016-1852-2

Schwartz, M. P., Hou, Z., Propson, N. E. et al. (2015). Human pluripotent stem cell-derived neural constructs for predicting neural toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 12516-12521. doi:10.1073/pnas. 1516645112

Shafer, T. J. (2019). Application of microelectrode array approaches to neurotoxicity testing and screening. Adv Neurobiol 22, 275297. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11135-9_12

Smirnova, L., Seiler, A. E. M. and Luch, A. (2015a). microRNA profiling as tool for developmental neurotoxicity testing (DNT). Curr Protoc Toxicol 64, 20.9.1-22. doi:10.1002/0471140856. tx2009s64

Smirnova, L., Harris, G., Leist, M. et al. (2015b). Cellular resilience. ALTEX 32, 247-260. doi:10.14573/altex. 1509271

Smirnova, L., Kleinstreuer, N., Corvi, R. et al. (2018). 3S – Systematic, systemic, and systems biology and toxicology. ALTEX 35, 139-162. doi:10.14573/altex. 1804051

Smirnova, L., Caffo, B. S., Gracias, D. H. et al. (2023a). Organoid intelligence (OI): The new frontier in biocomputing and

intelligence-in-a-dish. Front Sci 1, 1017235. doi:10.3389/ fsci.2023.1017235

Smirnova, L., Morales Pantoja, I. E. and Hartung, T. (2023b). Organoid Intelligence (OI) – The ultimate functionality of a brain microphysiological system. ALTEX 40, 191-203. doi:10.14573/ altex. 2303261

Smirnova, L. and Hartung, T. (2024). The promise and potential of brain organoids. Adv Healthc Mater, e2302745. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1002/adhm. 202302745

Spînu, N., Cronin, M. T. D., Lao, J. et al. (2022). Probabilistic modelling of developmental neurotoxicity based on a simplified adverse outcome pathway network. Comput Toxicol 21, 100206. doi:10.1016/j.comtox.2021.100206

Suciu, I., Pamies, D., Peruzzo, R. et al. (2023a). GxE interactions as a basis for toxicological uncertainty. Arch Toxicol 97, 2035-2049. doi:10.1007/s00204-023-03500-9

Suciu, I., Delp, J., Gutbier, S. et al. (2023b). Definition of the neu-rotoxicity-associated metabolic signature triggered by berberine and other respiratory chain inhibitors. Antioxidants 13, 49. doi:10.3390/antiox13010049

US EPA (1998). Health Effects Test Guidelines OPPTS 870.6300 Developmental Neurotoxicity Study. https://nepis.epa.gov/exe/ zypdf.cgi/p100irwo.pdf?dockey=p100irwo.pdf

van Thriel, C., Westerink, R. H., Beste, C. et al. (2012). Translating neurobehavioural endpoints of developmental neurotoxicity tests into in vitro assays and readouts. Neurotoxicology 33, 911-924. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2011.10.002

van Vliet, E., Stoppini, L., Balestrino, M. et al. (2007). Electrophysiological recording of re-aggregating brain cell cultures on mul-ti-electrode arrays to detect acute neurotoxic effects. Neurotoxicology 28, 1136-1146. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2007.06.004

van Vliet, E., Morath, S., Linge, J. et al. (2008). A novel in vitro metabolomics approach for neurotoxicity testing, proof of principle for methyl mercury chloride and caffeine. Neurotoxicology 29, 1-12. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2007.09.007

van Vliet, E., Daneshian, M., Beilmann, M. et al. (2014). Current approaches and future role of high content imaging in safety sciences and drug discovery. ALTEX 31, 479-493. doi:10.14573/ altex. 1405271

Villa, C., Combi, R., Conconi, D. et al. (2021). Patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and cerebral organoids for drug screening and development in autism spectrum disorder: Opportunities and challenges. Pharmaceutics 13, 280. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics13020280

Vinken, M., Benfenati, E., Busquet, F. et al. (2021). Safer chemicals using less animals: Kick-off of the European ONTOX project. Toxicology 458, 152846. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2021.152846

Wegscheid, M. L., Anastasaki, C., Hartigan, K. A. et al. (2021). Patient-derived iPSC-cerebral organoid modeling of the 17 q 11.2 microdeletion syndrome establishes CRLF3 as a critical regulator of neurogenesis. Cell Rep 36, 109315. doi:10.1016/j. celrep.2021.109315

Willett, C. E. (2018). The use of adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) to support chemical safety decisions within the context of inte-

grated approaches to testing and assessment (IATA). In H. Kojima, T. Seidle and H. Spielmann (eds), Alternatives to Animal Testing (83-90). Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-2447-5_11

Yamada, S., Hirano, Y., Kurosawa, O. et al. (2019). Evaluation of developmental neurotoxicity using neural differentiation potency in human iPS cells. Proc Annu Meet Jpn Pharmacol Soc 92. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jpssuppl/92/0/92_3-P-127/_ pdf

Yi, Z., Gao, H., Ji, X. et al. (2021). Mapping drug-induced neuropathy through in-situ motor protein tracking and machine learning. J Am Chem Soc 143, 14907-14915. doi:10.1021/ jacs.1c07312

Zablotsky, B., Black, L. I., Maenner, M. J. et al. (2019). Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the US: 2009-2017. Pediatrics 144, e20190811. doi:10.1542/ peds.2019-0811

Zhang, L., Li, M., Zhang, D. et al. (2023). Developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) QSAR combination prediction model establishment and structural characteristics interpretation. Toxicol Res 13, tfad116. doi:10.1093/toxres/tfad116

Zhong, X., Harris, G., Smirnova, L. et al. (2020). Antidepressant paroxetine exerts developmental neurotoxicity in an iPSCderived 3D human brain model. Front Cell Neurosci 14, 25. doi:10.3389/fncel.2020.00025

تعارض المصالح

توفر البيانات

الشكر والتقدير

-

الاختصارات: ADHD، اضطراب نقص الانتباه مع فرط النشاط؛ AI، الذكاء الاصطناعي؛ AO، نتيجة سلبية؛ AOP، مسار النتيجة السلبية؛ ASD، اضطراب طيف التوحد؛ DIV، أيام في المختبر؛ DNT، السمية العصبية التنموية؛ DNT IVB، بطارية اختبار DNT في المختبر؛ DRF، دراسة تحديد نطاق الجرعة؛ EDC، مادة كيميائية مدمرة للغدد الصماء؛ HCS، فحص المحتوى العالي؛ HTS، نظام عالي الإنتاجية؛ IATA، نهج متكامل للاختبار والتقييم؛ ID، إعاقة عقلية؛ iPSC، خلايا جذعية متعددة القدرات المستحثة؛ IQ، معدل الذكاء؛ ITS، استراتيجية اختبار متكاملة؛ IVIVE، من المختبر إلى الكائن الحي؛ KE، حدث رئيسي؛ KNDP، عملية تطوير عصبية رئيسية؛ MIE، حدث بدء جزيئي؛ ML، تعلم الآلة؛ MPS، أنظمة ميكروفسيولوجية؛ NAM، منهجيات جديدة؛ OECD، منظمة التعاون والتنمية الاقتصادية؛ Ol، ذكاء عضوي؛ PBDE، ثنائي الفينيل متعدد البروم؛ TG، إرشادات الاختبار

https://cefic.org; Cefic، مجلس صناعة الكيمياء الأوروبي، تأسس في عام 1972، هو صوت الشركات الكيميائية الكبيرة والمتوسطة والصغيرة في جميع أنحاء أوروبا، والتي توفر 1.2 مليون وظيفة وتمثل حوالي من إنتاج المواد الكيميائية في العالم. https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-awards-nearly-850000-johns-hopkins-university-advance-research-alternative-methods

https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/administrator-wheeler-signs-memo-reduce-animal-testing-awards-425-million-advance

https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2022/bloomberg-school-researchers-awarded-117-million-five-year-nih-grant-to-build-and-lead-autism-center-of-excellence-network - 11 https://aopwiki.org

12 مجموعة العمل للمنسقين الوطنيين لبرنامج إرشادات الاختبار (WNT) ومجموعة العمل لتقييم المخاطر (WPHA);https://one.oecd.org/ document/ENV/CBC/MONO(2021)22/en/pdf

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14573/altex.2403281

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38579692

Publication Date: 2024-01-01

Thomas A. Edison (1847-1931)

“I may not have gone where I intended to go,

but I think I have ended up where I needed to be.”

Douglas Adams (1952-2001)

Food for Thought …

Revolutionizing Developmental Neurotoxicity Testing – A Journey from Animal Models to Advanced In Vitro Systems

Epub April 6, 2024;

© The Authors, 2024.

Correspondence:

Thomas Hartung, MD, PhD, Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT), Johns Hopkins University, 615 N Wolfe St., Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA

(THartun1 @jhu.edu)

Abstract

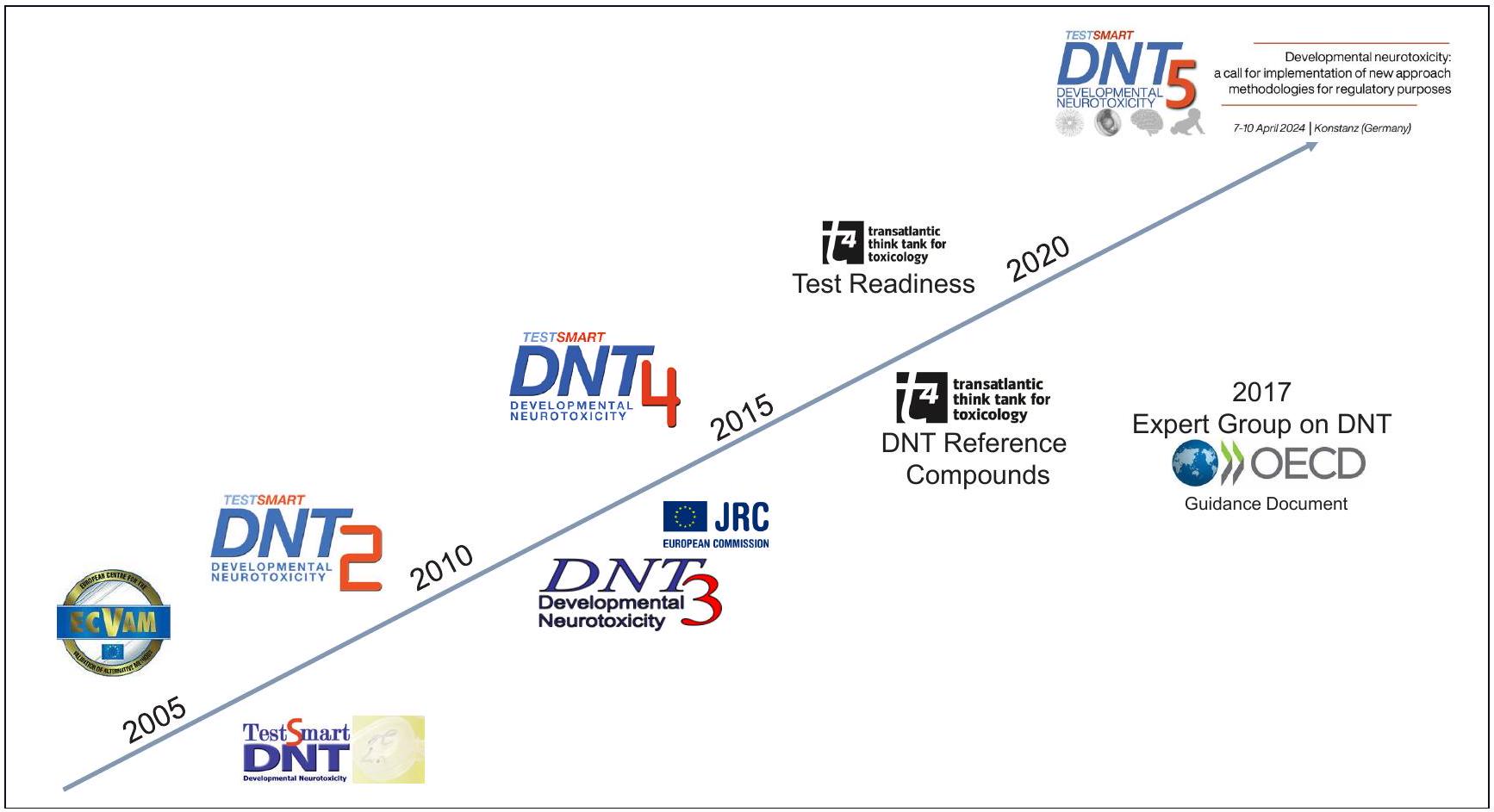

Developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) testing has seen enormous progress over the last two decades. Preceding even the publication of the animal-based OECD test guideline for DNT testing in 2007, a series of non-animal technology workshops and conferences that started in 2005 has shaped a community that has delivered a comprehensive battery of in vitro test methods (DNT IVB). Its data interpretation is now covered by a very recent OECD guidance (No. 377). Here, we overview the progress in the field, focusing on the evolution of testing strategies, the role of emerging technologies, and the impact of OECD test guidelines on DNT testing. In particular, this is an example of the targeted development of an animal-free testing approach for one of the most complex hazards of chemicals to human health. These developments started literally from a blank slate, with no proposed alternative methods available. Over two decades, cutting-edge science enabled the design of a testing approach that spares animals and enables throughput to address this challenging hazard. While it is evident that the field needs guidance and regulation, the massive economic impact of decreased human cognitive capacity caused by chemical exposure should be prioritized more highly. Beyond this, the claim to fame of DNT in vitro testing is the enormous scientific progress it has brought for understanding the human brain, its development, and how it can be perturbed.

Plain language summary

1 Introduction

| 1. (Global) public health protection by prevention of developmental disorders – The developing brain is particularly vulnerable to toxicants in the context of autism spectrum disorders (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and cognitive impairments. |

| 2. Regulatory compliance |

| 3. Guidance for pregnant women |

| 4. De-risking of pediatric clinical trials |

| 5. Economic impacts (a) – Loss of cognitive capacity (IQ score) costs society. |

| 6. Economic impacts (b) – One animal test costs at least

|

| 7. Animal welfare – More than 1000 animals are “used” for each chemical. |

| 8. Scientific advancement |

| 9. Environmental protection |

| 10. Legal and forensic applications – evidence in legal cases and contributing to justice and remediation efforts |

| 11. Consumer confidence |

| Surveillance year | Birth year | Number of ADDM sites reporting | Combined prevalence per 1,000 children (Range across ADDM sites) | This is about 1 in x children |

| 2020 | 2012 | 11 | 27.6 (23.1-44.9) | 1 in 36 |

| 2018 | 2010 | 11 | 23.0 (16.5-38.9) | 1 in 44 |

| 2016 | 2008 | 11 | 18.5 (18.0-19.1) | 1 in 54 |

| 2014 | 2006 | 11 | 16.8 (13.1-29.3) | 1 in 59 |

| 2012 | 2004 | 11 | 14.5 (8.2-24.6) | 1 in 69 |

| 2010 | 2002 | 11 | 14.7 (5.7-21.9) | 1 in 68 |

| 2008 | 2000 | 14 | 11.3 (4.8-21.2) | 1 in 88 |

| 2006 | 1998 | 11 | 9.0 (4.2-12.1) | 1 in 110 |

| 2004 | 1996 | 8 | 8.0 (4.6-9.8) | 1 in 125 |

| 2002 | 1994 | 14 | 6.6 (3.3-10.6) | 1 in 150 |

| 2000 | 1992 | 6 | 6.7 (4.5-9.9) | 1 in 150 |

€9.59 billion annually. Organophosphate exposure had a

and food additives, underscores the urgent need for reliable DNT testing strategies. However, there is no legal requirement to provide DNT data for most chemicals. Thus, there is no data at all on

2 Limitations of DNT animal testing

opment and the need for a variety of test methods to address different aspects of DNT (Makris et al., 2009; Arts et al., 2023).

for the basic study. Test duration of TG 443 compared to TG 416 is an advantage as long as the second generation is not triggered.

3 The path of alternatives to in vivo DNT testing up to the DNT-4 meeting in 2014

3.1 The first DNT workshop at ECVAM 2005

rat brain cells, which we successfully adopted. It led us to the first paper describing the use of electrophysiological recording for DNT (van Vliet et al., 2007), and to the first paper on the assessment of DNT using metabolomics (van Vliet et al., 2008). More recently, it allowed us to address the DNT potential of flame retardants (Hogberg et al., 2021).

3.2 The first international DNT conference DNT-1 in 2006

3.3 The second international DNT conference DNT-2 in 2008

- Test methods should incorporate one or more endpoints that model key aspects of human neurodevelopment. The test method models the biological process, the test system employs the

2. The ability to correctly and accurately measure the intended DNT endpoint must be demonstrated by the use of a set of compounds termed “endpoint-specific controls” or “tool compounds”. The measured endpoint should reflect the intended neurodevelopmental process.

3. The dynamic range of the DNT endpoint should be characterized to determine the measurable extent of change from control values.

4. Concentration-response relationships should be characterized, ideally testing at least five concentrations over a wide range. This is critical for comparing the sensitivity of different methods.

5. Positive and negative control chemicals should be tested that are known to reliably affect or not affect the measured DNT endpoint by known mechanisms.

6. Initial training sets of chemicals should be tested, including those known to elicit or not elicit DNT responses based on in vitro data. This evaluates the method’s ability to screen moderate numbers of chemicals.

7. Larger testing sets of chemicals should then be screened, including those known to cause or not cause DNT effects in vivo. This demonstrates the method’s ability to test larger chemical numbers.

8. The method’s sensitivity, specificity and predictivity in identifying chemicals’ DNT potential should be analyzed based on these reference chemical sets.

In summary, the recommendations focused on demonstrating the relevance, reliability, sensitivity, and throughput of alternative DNT methods using well-characterized endpoint assays and reference chemical testing sets as a framework for developing screening level alternative DNT tests. The goal was to establish the methods’ fitness for screening and prioritizing large numbers of chemicals. The DNT-2 recommendations aimed to facilitate a transition from conceptual discussions to practical assay development and use for regulatory purposes. These considerations and experience from the DNT field had an important impact on the development of broader concepts for in vitro test method development and for novel validation approaches of such assays (Leist et al., 2010, 2012; van Thriel et al., 2012).

3.4 The third international DNT conference DNT-3 in 2011 in Varese, Italy

- There was general consensus on the urgent need to develop alternative DNT testing strategies that are faster, more cost-efficient, and predictive of human outcomes. High-throughput in vitro DNT models are needed to test the large numbers of chemicals for which there is little to no DNT data.

- Significant progress was reported in applying in vitro and nonmammalian test systems to DNT, including human stem/pro-

genitor cell-based assays, though more work is needed to validate these alternative models against human DNT outcomes. - Generating data across multiple alternative models using a common set of test chemicals was identified as a critical need to facilitate comparisons and determine which models/endpoints are most predictive.

- Establishing a reference set of positive and negative control chemicals for DNT was also deemed important for evaluating alternative models.

- Cell-based assays covering key neurodevelopmental processes like proliferation, migration, differentiation, synaptogenesis, and network formation should be applied as functional DNT endpoints.

- Computational modeling and bioinformatics approaches should be utilized to evaluate the predictive capacity of alternative DNT models/batteries.

- Despite progress, in vitro models are not yet able to replicate the complexity of the developing nervous system. Their relevance to human outcomes must still be cautiously evaluated.

In summary, DNT-3 highlighted advancements in developing higher-throughput alternative models based on the DNT-2 framework while identifying crucial data gaps, such as the need for more cross-model comparisons using standardized reference chemicals. The emphasis shifted to practical application of DNT alternatives for screening/prioritization, beyond the initial proof-of-concept stage.

4 The first Food for Thought … article on DNT

and interpreting in vitro and in silico assays in terms of their relevance to in vivo outcomes.

5 DNT-4 – Toward AOPs and fit-for-purpose assays for DNT

5.1 New concepts and test strategies

that many children with ASD have increased connectivity in local circuits of the cortex (Keown et al., 2013). Such an approach to associate cellular effects with disease outcome could be informative for regulators and demonstrate the use of in vitro data for risk assessment.

5.2 Mechanistic and omics tools, as well as functional endpoints, to increase assay information content

5.3 How to accelerate testing for DNT

5.4 The use of AOPs and alternative assays for safety assessment

5.5 Frontiers in DNT testing

5.6 Conclusions from DNT-4

6 Current methodological advances as a basis for a new approach for DNT

6.1 Stem cells

“Living biopsy” and disease modeling: iPSCs can be considered a “living biopsy” of a patient’s condition, as they capture the patient’s genetic makeup and can be differentiated into disease-relevant cell types, providing a platform for studying disease mechanisms and potential treatments (Smirnova and Hartung, 2024).

6.2 Organotypic cultures and microphysiological systems

pects of human neurodevelopment and can be used to study the basic biological processes that are fundamental to understanding DNT, such as differentiation, proliferation, migration, and neurite growth. By testing the disturbance of these biological activities by chemicals, we can identify potential neurotoxicants. The bioengineering of MPS is an enormously important task.

same substance. This was the starting point for a project funded by the EPA

6.3 Advantages of high-content screening in DNT testing

6.4 Key characteristics of developmental neurotoxicants

6.5 Advances in artificial intelligence supporting DNT testing

enhancing the relevance of DNT testing to human health. We have discussed earlier the opportunities of modeling MPS by computational approaches (Smirnova et al., 2018).

7 Conceptual advances as a basis for a new approach for DNT

7.1 The rise of integrated testing strategies (ITS) aka integrated approaches to testing and assessment (IATA)

7.2 The role of AOPs

cilitating the development of testing strategies that are both more mechanistically informed and more predictive of human health outcomes.

8 The development of new approaches for DNT as an example for the strategic development of alternatives to animal testing

8.1 Conceptual workshops further advancing DNT testing

and in silico methods into regulatory frameworks, and emphasizing the need for a collaborative approach among stakeholders to address the challenges in DNT testing.

- There is an urgent need for a DNT testing strategy using in vitro methods and alternative models to begin screening and prioritizing the large number of untested chemicals for their potential effects on the developing nervous system.

- A battery of currently available in vitro DNT assays, based on critical neurodevelopmental processes, is ready for use now for screening and prioritization purposes. Further development and standardization of the testing battery can enable its use for hazard assessment and to support risk management decisions in the future.

- A roadmap should be established to define procedures and milestones for implementing this new approach to DNT testing. Priorities include chemical testing to build confidence in the testing battery, establishing performance standards, and developing an OECD guidance document on an integrated approach to DNT testing and assessment.

The OECD project was summarized by Sachana et al. (2019, 2021a). Key steps include: 1) Generating a reference set of chemicals to test a battery of in vitro DNT assays spanning key neurode-

velopmental processes; 2) selecting the battery of in vitro DNT assays based on readiness criteria; 3 ) testing the reference chemicals in the battery to build confidence in the alternative approaches; 4) developing IATA case studies using DNT in vitro battery data for different regulatory applications; and 5) drafting an OECD guidance document on the use of alternative DNT testing methods within an IATA framework.

sess the readiness of individual DNT in vitro assays as well as the overall DNT in vitro battery (DNT IVB) for various regulatory applications were put forward. This allows a quantitative assessment of the status of assay development and what further work is needed to increase regulatory confidence in these alternative methods. The approach outlined provides a role model for evaluating alternative methods in other fields of toxicology. Key elements include: 1) defining readiness criteria based on the regulatory need and context of use, 2) quantitative scoring of assay readiness based on multiple defined criteria, 3) evaluating the battery of assays as a whole in terms of biological coverage, predictive performance, and overall readiness for different regulatory uses, and 4) using case studies to demonstrate how the alternative methods can be applied in an IATA. This framework allows a transparent and objective evaluation of NAMs to facilitate their regulatory acceptance and use. While more work is needed to fully validate the DNT IVB (Juberg et al., 2023), the strategy presented was an important step forward in advancing the use of alternative methods for safety testing.

- The Panel reviewed several in vitro NAM assays developed by EPA and European researchers to evaluate important neurodevelopmental processes that may be disrupted by chemical exposure. While finding strengths in the assays, the Panel noted limitations such as the lack of important cell types, absence of functional/mechanistic assessments, and difficulties extrapolating to in vivo effects.

- The Panel considered the use of in vitro-to-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) approaches to compare NAM assay results to doses causing acetylcholinesterase inhibition in animals for organophosphate pesticides. They found the IVIVE approach reasonable but raised concerns about model assumptions and performance.

- The Panel reviewed analyses deriving interspecies and intraspecies extrapolation factors from in vitro acetylcholinesterase inhibition data in rat and human tissues. Limitations were noted in the analysis methods, sample representativeness, and sample sizes to characterize human variability.

- Overall, the Panel saw value in the NAM approaches while providing numerous recommendations to address limitations and uncertainties in using the data for human health risk assessment.

This evaluation represented an important starting point for the regulatory implementation of in vitro DNT approaches for the most important use case of agrochemicals. The specific concernsrepresented an important agenda for future developments:

“a. The absence of hormonal factors (sex hormones, thyroid, stress hormones)

b. The influence of neurotransmitter signaling

d. The influence of maternal factors (maternal infection, hormonal, organ system dysfunction, placenta integrity)

In addition, it was stated that the in vitro assays:

a. Will be limited in their ability to detect adaptive or compensatory processes.

b. Do not account for critical cell-cell interactions required during neurodevelopment.

c. Have difficulty distinguishing between neuroactive and neurotoxic compounds.

d. Do not reflect human genetic diversity when using human cell lines from one human.”

8.2 The OECD guidelines and the guidance document

- The DNT IVB includes a battery of in vitro assays that cover key neurodevelopmental processes such as proliferation, migration, differentiation, neurite outgrowth, and neural network formation.

- These assays are considered key events at the cellular level that are plausibly related to modes of action of developmental neurotoxicants in vivo.

- When interpreting data from individual assays, it’s important to evaluate the biological relevance of the test system, assay quality and reproducibility, testing with a training set of chemicals, data analysis methods, and use of a decision model to classify chemicals.

- To evaluate the DNT IVB as a whole, factors to consider include the predictive power compared to in vivo data, consistency of results across the battery, comparison of potency to other in vitro endpoints, and mapping to AOPs.

- Use of DNT IVB data should be guided by the consistency of the in vitro data, biological plausibility, incorporation of in vitro to in vivo extrapolation models, and consideration of uncertainties in the context of the regulatory need.

- While not a full replacement for animal studies, DNT IVB data is already being used to inform screening, prioritization, and weight of evidence approaches in different regulatory applications. Further work is needed to develop standardized reference chemical lists, data analysis pipelines, and tiered testing strategies.

8.3 From screening hits to potential DNT toxicants

isms. Screening is a scientific discipline developed in drug discovery, and a lot of experience has been collected that was incorporated into a screening culture and best practices within the discipline of pharmacology. In toxicology, the technology has been adopted and adapted, but the culture is lagging behind. Often, the distinction between a screen hit and a potential toxicant is not clear and needs further clarification for efficient use of this approach for DNT testing. The pharmacological terminology is as follows: screens produce “preliminary positives” in the respective assay. After a confirmation under more controlled conditions, they can be called “confirmed positives”. They need to be filtered, e.g., for technical artifacts, or secondary effects due to cytotoxicity. In many pharmacological screens this eliminates

9 Challenges and future directions

Screens, if run by high-throughput technology, often generate “preliminary positives” that need to be further qualified and characterized. A first step involves repetition of the test, possibly with a more stringent prediction model, more stringent laboratory procedure controls (e.g., according to the OECD Guidance on Good In Vitro Method Practices (GIVIMP)) and with new, well-controlled compound stock solutions. The true positives (TP) are then obtained after elimination of technical artifacts (e.g., fluorescent compounds, or compounds binding unspecifically to proteins), control for cytotoxicity, and cheminformatics filtering for known pan-assay interfering substances (PAINS). Certainty on the bioactivity of such compounds is then obtained classically in secondary and tertiary assays for similar target pathways or structures. These are ideally orthogonal in the sense that they use other test systems and/or readout technologies. In a second phase, such “convincing” assay hits are evaluated for their toxicological relevance. Strategy I tests the relevance by establishing the similarity of the assay hit to known, well-characterized toxicants. The definition of similarity relies on (i) structural similarity, (ii) similar ADME properties, and (iii) a similar bioactivity profile/mode-of-action (MoA). Strategy II tests the relevance based on the expected MoA or the activation of a reliable adverse outcome pathway (AOP). Essential issues are (i) whether the concentrations triggering an AOP molecular initiation event (MIE) or key event (KE) are realistically reached, whether it is likely that the triggered AOP also continues to the adverse outcome (AO). A more comprehensive investigation would use quantitative in vitro-to-in vivo (IVIVE) extrapolation models and would consider whether key event relationships (KER) affected by modifiers or counter-regulations.

account the specific challenges and opportunities associated with DNT testing, such as the complexity of neurodevelopmental processes, the importance of considering species differences (Baumann et al., 2016) and exposure timing, and the need for a battery of complementary assays that cover different modes of action. The recently updated document by the Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Validation of Alternative Methods (ICCVAM), “Validation, Qualification, and Regulatory Acceptance of New Approach Methodologies”

isting DNT data to identify patterns and relationships that may not be apparent from traditional statistical analyses. These models can then be used to predict the DNT potential of new chemicals based on their structural and biological similarity to known toxicants, or to identify the most informative combinations of assays and endpoints for a given regulatory context.

9.1 Implementation

9.2 Vision for the future

10 Conclusions and outlook

has been leveraged to develop a wide range of alternative testing methods, including in vitro cell culture models, non-mammalian animal models, and computational approaches that offer the potential for a more rapid, efficient, and mechanistically informative assessment of DNT potential.

for DNT testing, driven in part by advances in stem cell biology, genome editing, high-throughput screening, and computational modeling. The establishment of the OECD DNT Expert Group in 2017 and the publication of the OECD’s “Initial Recommendations on Evaluation of Data from the Developmental Neurotoxicity (DNT) In Vitro Testing Battery” (OECD, 2023) marked important milestones in the regulatory acceptance of alternative methods.

References

Ankley, G. T., Bennett, R. S., Erickson, R. J. et al. (2010). Adverse outcome pathways: A conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Environ Toxicol Chem 29, 730-741. doi:10.1002/etc. 34

Arts, J. H. E., Faulhammer, F., Schneider, S. et al. (2023). Investigations on learning and memory function in extended one-generation reproductive toxicity studies – When considered needed and based on what? Crit Rev Toxicol 53, 372-384. doi:10. 1080/10408444.2023.2236134

Bal-Price, A., Hogberg, H. T., Buzanska, L. et al. (2010). In vitro developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) testing: Relevant models and endpoints. Neurotoxicology 31, 545-554. doi:10.1016/j. neuro.2009.11.006

Bal-Price, A. K., Coecke, S., Costa, L. et al. (2012). Advancing the science of developmental neurotoxicity (DNT): Testing for better safety evaluation. ALTEX 29, 202-215. doi:10.14573/ altex.2012.2.202

Bal-Price, A., Crofton, K. M., Sachana, M. et al. (2015a). Putative adverse outcome pathways relevant to neurotoxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol 45, 83-91. doi:10.3109/10408444.2014.981331

Bal-Price, A., Crofton, K. M., Leist, M. et al. (2015b). International STakeholder NETwork (ISTNET): Creating a developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) testing road map for regulatory purposes. Arch Toxicol 89, 269-287. doi:10.1007/s00204-015-1464-2

Bal-Price, A. and Meek, M. E. (2017). Adverse outcome pathways: Application to enhance mechanistic understanding of neurotoxicity. Pharmacol Ther 179, 84-95. doi:10.1016/j. pharmthera.2017.05.006

Bal-Price, A., Hogberg, H. T., Crofton, K. M. et al. (2018a). t

Bal-Price, A., Pistollato, F., Sachana, M. et al. (2018b). Strategies to improve the regulatory assessment of developmental neurotoxicity (DNT) using in vitro methods. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 354, 7-18. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2018.02.008

Basketter, D. A., Clewell, H., Kimber, I., et al. (2012). A roadmap for the development of alternative (non-animal) methods for systemic toxicity testing. ALTEX 29, 3-89. doi: 10.14573/altex. 2012.1.003

Bellanger, M., Demeneix, B. A., Grandjean, P. et al. (2015). Neurobehavioral deficits, diseases, and associated costs of exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the European Union. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100, 1256-1266. doi:10.1210/ jc.2014-4323

Blaauboer, B. J., Boekelheide, K., Clewell, H. J. et al. (2012). The use of biomarkers of toxicity for integrating in vitro hazard estimates into risk assessment for humans. ALTEX 29, 411-425. doi:10.14573/altex.2012.4.411

Blum, J., Masjosthusmann, S., Bartmann, K. et al. (2023). Establishment of a human cell-based in vitro battery to assess developmental neurotoxicity hazard of chemicals. Chemosphere

Boyle, J., Yeter, D., Aschner, M. et al. (2021). Estimated IQ points and lifetime earnings lost to early childhood blood lead levels in the United States. Sci Total Environ 778, 146307. doi:10.1016/j. scitotenv.2021.146307

Butera, A., Smirnova, L., Ferrando-May, E. et al. (2023). Deconvoluting gene and environment interactions to develop “epigenetic score meter” of disease. EMBO Mol Med 15, e18208. doi:10.15252/emmm. 202318208

Caloni, F., De Angelis, I. and Hartung, T. (2022). Replacement of animal testing by integrated approaches to testing and assessment (IATA): A call for in vivitrosi. Arch Toxicol 96, 1935-1950. doi:10.1007/s00204-022-03299-x

Cediel-Ulloa, A., Lupu, D. L., Johansson, Y. et al. (2022). Impact of endocrine disrupting chemicals on neurodevelopment: The need for better testing strategies for endocrine disruption-induced developmental neurotoxicity. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 17, 131-141. doi:10.1080/17446651.2022.2044788

Chesnut, M., Hartung, T., Hogberg, H. T. et al. (2021a). Human oligodendrocytes and myelin in vitro to evaluate developmental neurotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 22, 7929. doi:10.3390/ ijms22157929

Chesnut, M., Paschoud, H., Repond, C. et al. (2021b). Human 3D iPSC-derived brain model to study chemical-induced myelin disruption. Int J Mol Sci 22, 9473. doi:10.3390/ijms22179473

Coecke, S., Goldberg, A. M., Allen, S. et al. (2007). Workgroup report: Incorporating in vitro alternative methods for developmental neurotoxicity into international hazard and risk assessment strategies. Environ Health Perspect 115, 924-931. doi:10.1289/ ehp. 9427

Cohn, E. F., Clayton, B. L. L., Madhavan, M. et al. (2024). Pervasive environmental chemicals impair oligodendrocyte development. Nat Neurosci, online ahead of print. doi:10.1038/s41593-024-01599-2

Crofton, K. M., Mundy, W. R., Lein, P. J. et al. (2011). Developmental neurotoxicity testing: Recommendations for developing alternative methods for the screening and prioritization of chemicals. ALTEX 28, 9-15. doi:10.14573/altex.2011.1.009

Crofton, K., Fritsche, E., Ylikomi, T. and Bal-Price, A. (2014). International STakeholder NETwork (ISTNET) for creating a developmental neurotoxicity testing (DNT) roadmap for regulatory purposes. ALTEX 31, 223-224. doi:10.14573/altex. 1402121

Crofton, K. M. and Mundy, W. R. (2021). External scientific report on the interpretation of data from the developmental neurotoxicity in vitro testing assays for use in integrated approaches for testing and assessment. EFSA Support Publ 18, 6924E. doi:10.2903/ sp.efsa.2021.en-6924

Diemar, M. G., Vinken, M., Teunis, M. et al. (2024). Report of the First ONTOX stakeholder network meeting: Digging under the surface of ONTOX together with the stakeholders. Altern Lab Anim 52, 117-131. doi:10.1177/02611929231225730

Fritsche, E., Crofton, K. M., Hernandez, A. F. et al. (2017). OECD/ EFSA workshop on developmental neurotoxicity (DNT): The use of non-animal test methods for regulatory purposes. ALTEX 34, 311-315. doi:10.14573/altex. 1701171

Fritsche, E., Barenys, M., Klose, J. et al. (2018). Current availability of stem cell-based in vitro methods for developmental neu-

rotoxicity (DNT) testing. Toxicol Sci 165, 21-30. doi:10.1093/ toxsci/kfy178

Furxhi, I. and Murphy, F. (2020). Predicting in vitro neurotoxicity induced by nanoparticles using machine learning. Int J Mol Sci 21, 5280. doi:10.3390/ijms21155280

Gaylord, A., Osborne, G., Ghassabian, A. et al. (2020). Trends in neurodevelopmental disability burden due to early life chemical exposure in the USA from 2001 to 2016: A population-based disease burden and cost analysis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 502, 110666. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2019.110666

Grandjean, P. and Landrigan, P. J. (2006). Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. Lancet 368, 2167-2178. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69665-7

Grandjean, P. and Landrigan, P. J. (2014). Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. Lancet Neurol 13, 330-338. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70278-3

Groot, M. W. G. M., Westerink, R. H. S. and Dingemans, M. M. L. (2013). Don’t judge a neuron only by its cover: Neuronal function in in vitro developmental neurotoxicity testing. Toxicol Sci 132, 1-7. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfs269