DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-05329-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39748344

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-02

إزالة أداة مكسورة خارج الفتحة الذروية باستخدام جراحة الميكروسكوب السنية بمساعدة الروبوت: تقرير سريري

الملخص

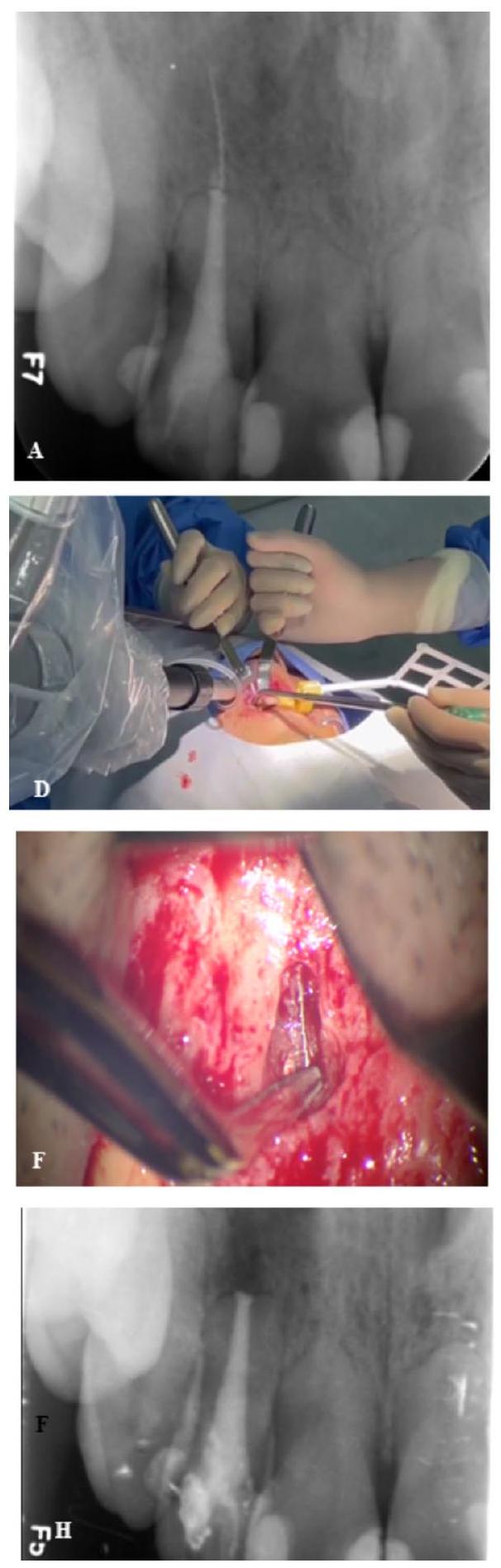

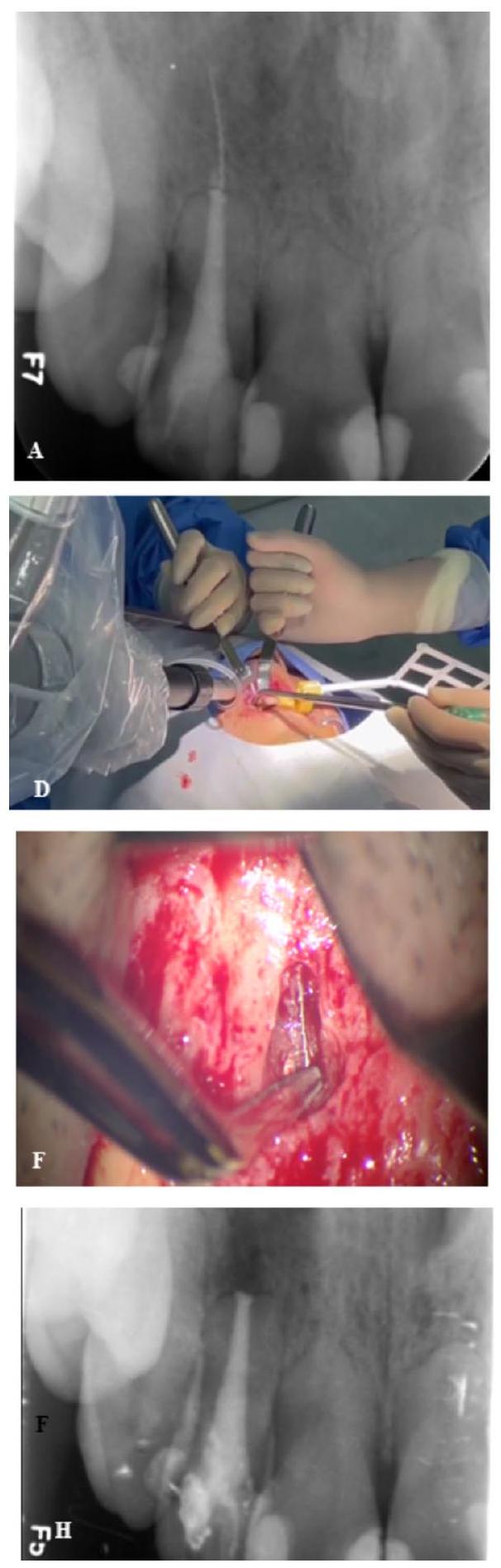

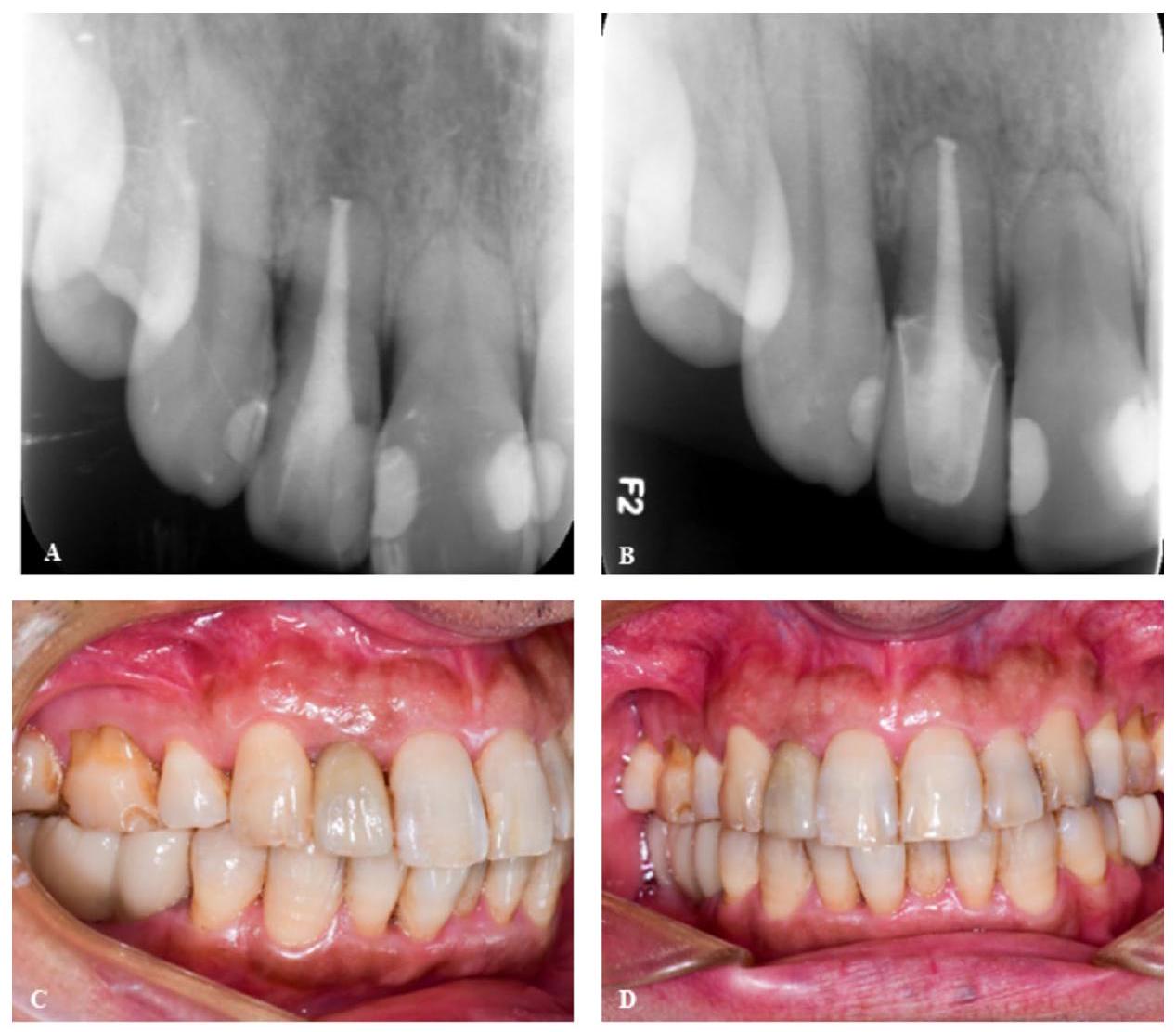

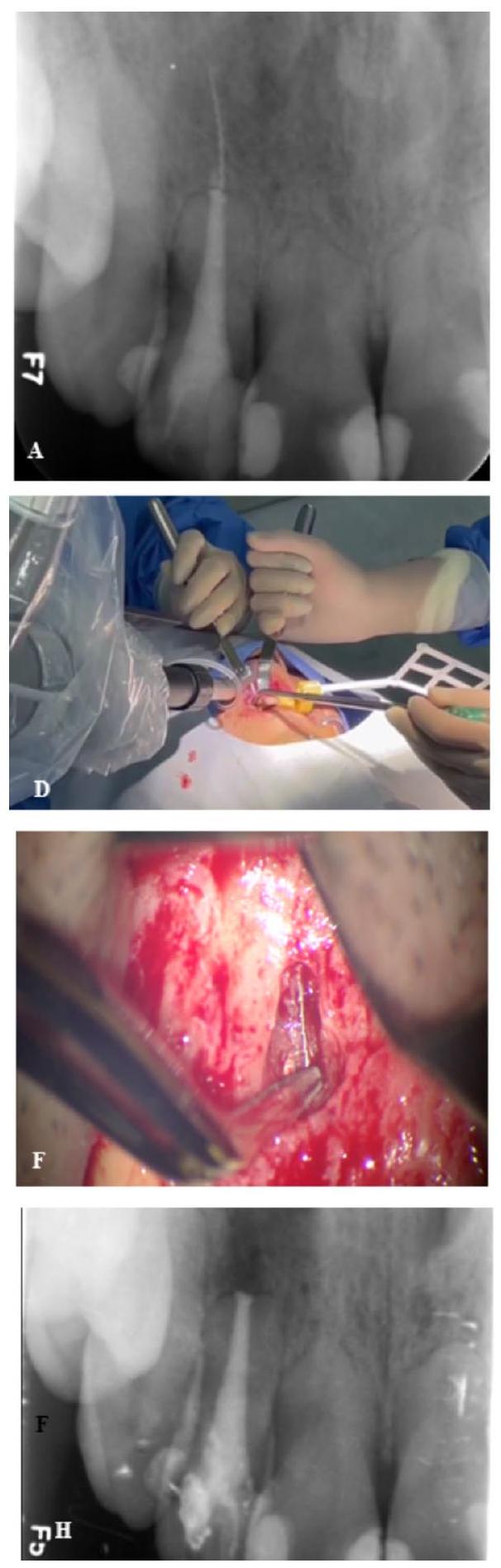

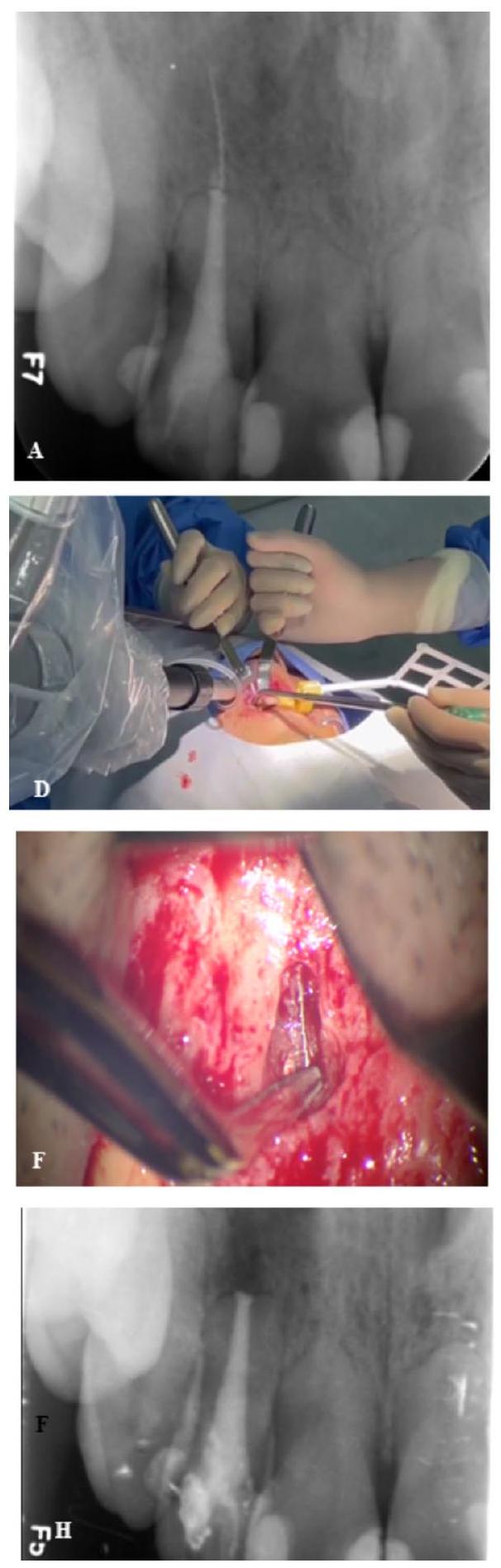

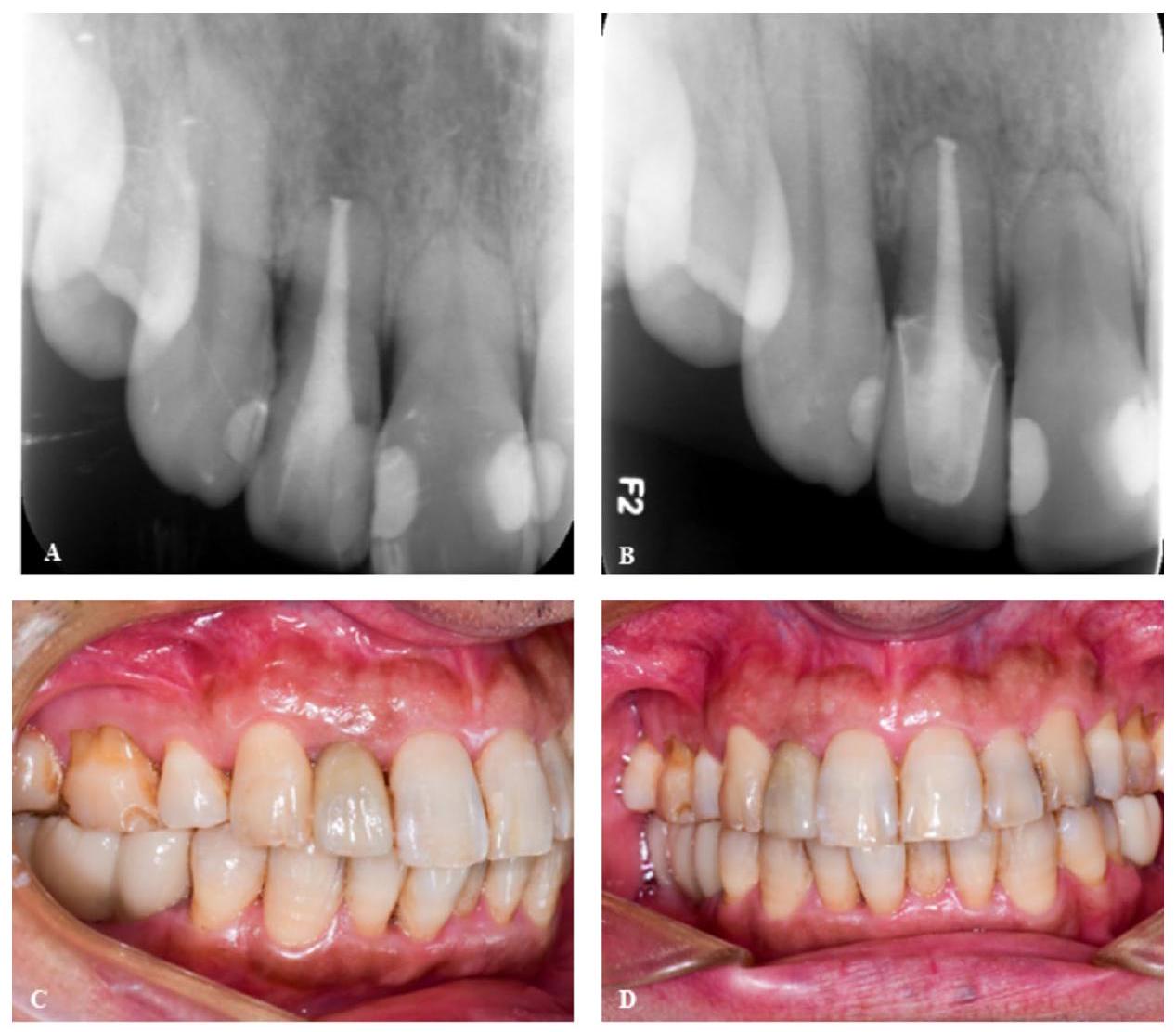

خلفية: تعتبر كسور أدوات العلاج الجذري من المضاعفات الشائعة لعلاج قناة الجذر، وتتطلب الإزالة عبر تقنيات متخصصة مثل جراحة الميكروسكوب السنية عندما يكون الملف قد تجاوز الفتحة القمية. غالبًا ما يكون من الصعب إزالة ملف مكسور بدقة وبأقل تدخل. مؤخرًا، أظهر استخدام نظام الروبوت المستقل للأسنان (ATR) وعدًا في إجراء الجراحة السنية بدقة وبأقل تدخل. لذلك، يوضح هذا الحالة تقنية لاستخدام نظام ATR لتوجيه إزالة ملف مكسور بدقة وبأقل تدخل يتجاوز الفتحة القمية. عرض الحالة: تم تشخيص مريض ذكر يبلغ من العمر 48 عامًا، دون دليل على عيوب عظمية، بوجود ملف مكسور تمامًا يتجاوز الفتحة القمية أثناء علاج قناة الجذر للسن الجانبي العلوي الأيمن. تم استخدام معلومات المريض لدمج نموذج رقمي في برنامج التخطيط قبل الجراحة لتطوير استراتيجية جراحية. يستخدم نظام ATR طرق المحاذاة المكانية للتسجيل، مما يوجه الذراع الروبوتية لتحديد موقع الملف المكسور بشكل مستقل وفقًا للخطة الجراحية. لتعظيم الجراحة الأقل تدخلاً، تمت إزالة الملف المكسور الطويل على مرحلتين. بعد إزالة العظم وملف الكسر، قام الطبيب بإجراء الخياطة تحت المجهر. لم تُلاحظ أي مضاعفات أثناء الجراحة، وبدت المعالجة ناجحة بناءً على تقييم المتابعة بعد 9 أشهر. الاستنتاجات: يمكّن نظام ATR من تحديد موقع الملف المكسور بدقة يتجاوز الفتحة القمية مع بقاء الألواح القشرية سليمة. هذه التقنية لديها القدرة على تحسين دقة التموقع، وتقليل الحاجة إلى إزالة العظم بشكل تدخلي، وتقليل الوقت الجراحي، وتسهيل إجراءات الجراحة الميكروسكوبية السنية الناجحة.

الخلفية

مع التقدم في التكنولوجيا الرقمية، يمكن استخدام كل من الألواح الدليلية الثابتة وأنظمة الملاحة الديناميكية في جراحة الميكروسكوب السني لتحديد مواقع أطراف الجذور بدقة [5،6]. الالتزام بتوجيه اللوحة الدليلية المطبوعة مسبقًا أمر ضروري عند استخدام لوحة دليل ثابتة، مما يحد من القدرة على إجراء تعديلات في الوقت الحقيقي على الخطة الجراحية. من الضروري تعقيم لوحة الدليل الراتنجية مسبقًا لتجنب تهيج محتمل للغشاء المخاطي الفموي، وقد تؤدي الأخطاء في تصميم لوحة الدليل إلى مضاعفات إضافية [5، 7]. يوفر نظام الملاحة الديناميكية توجيهًا ثلاثي الأبعاد دقيقًا في الوقت الحقيقي أثناء الإجراء الجراحي، مما يمكّن من تقنيات تحديد المواقع الأقل تدخلاً وقطع العظم لمنع الأخطاء الناتجة عن الجراحة [6]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يشارك مشغلو الملاحة الديناميكية في ممارسة متكررة لتعزيز مهارات التنسيق بين اليد والعين [8]. ومع ذلك، قد تؤدي إرهاق المشغل إلى انحراف في الموقع ثلاثي الأبعاد، ورعشة اليد الحرة، ووضعية غير صحيحة، ونقاط عمياء في مجال الرؤية أثناء الجراحة [9، 10]. نظرًا لدقة محسّنة، واستقرار، وسلامة، ومرونة، وراحة لمتخصصي الرعاية الصحية، تم استخدام الروبوتات مؤخرًا كأداة في الجراحة السنية [11]. أنظمة الروبوت المستقل للأسنان (ATR) آمنة ودقيقة [12]، وقد تم تفصيل إجراءات قطع العظم وإعادة قطع الجذر الموجهة بالروبوت [13، 14]. تستخدم أنظمة ATR الرؤية بالأشعة تحت الحمراء والتحديد في الوقت الحقيقي، مما يمكّن من التحكم دون إعادة المعايرة، مما يضمن عملية دقيقة وآمنة. تستخدم أنظمة ATR أذرع روبوتية للجراحة، وهو تحسين كبير مقارنة بالجراحة اليدوية الحرة باستخدام الألواح الدليلية أو أنظمة الملاحة [5-7، 9، 15]. بينما يمكن أن تحسن هذه التقنيات الدقة، إلا أن عوامل مثل إرهاق الطبيب ونقص المهارة يمكن أن تؤثر على دقة الجراحة [16، 17]. يمكن أن تلغي الذراع الروبوتية مثل هذه العيوب في الجراحة اليدوية الحرة باستخدام الألواح الدليلية أو أنظمة الملاحة وتؤدي جراحة دقيقة وأقل تدخلاً.

في هذه الدراسة، هدفنا إلى تحديد فعالية نظام ATR في إزالة الملفات المكسورة التي هي

موجودة خارج الفتحة القمية. في هذه الحالة، تم إجراء قطع العظم تلقائيًا تحت توجيه نظام ATR. حدد النظام بدقة الملف المكسور، مما أدى إلى تقليل تلف الأنسجة، مما أدى إلى نتيجة ناجحة للمريض الذي ظل بدون أعراض خلال فترة المتابعة التي استمرت 9 أشهر.

تقرير الحالة

قمنا بتطوير خطتي علاج: (1) ترك الملف المكسور، وإكمال علاج قناة الجذر، مع مراقبة المريض عن كثب، و (2) جراحة الميكروسكوب السني لإزالة الملف المكسور. أعرب المريض عن رغبة قوية في إزالة الملف. بعد فهم التوقعات والمخاطر والفوائد المرتبطة بخطة العلاج، قدم المريض موافقة خطية مستنيرة للخضوع لجراحة الميكروسكوب السني لإزالة الملف المكسور وإكمال العلاج الجذري. تم استخدام نظام ATR جديد (Yakebot؛ شركة Yakebot Technology Co. Ltd.، بكين، الصين) أثناء جراحة الميكروسكوب السني. قدم المريض أيضًا موافقة خطية مستنيرة لاستخدام ونشر تفاصيله الشخصية والسريرية، جنبًا إلى جنب مع أي صور تعريفية.

كانت سير العمل السريرية كما يلي: جمع البيانات والتخطيط الجراحي

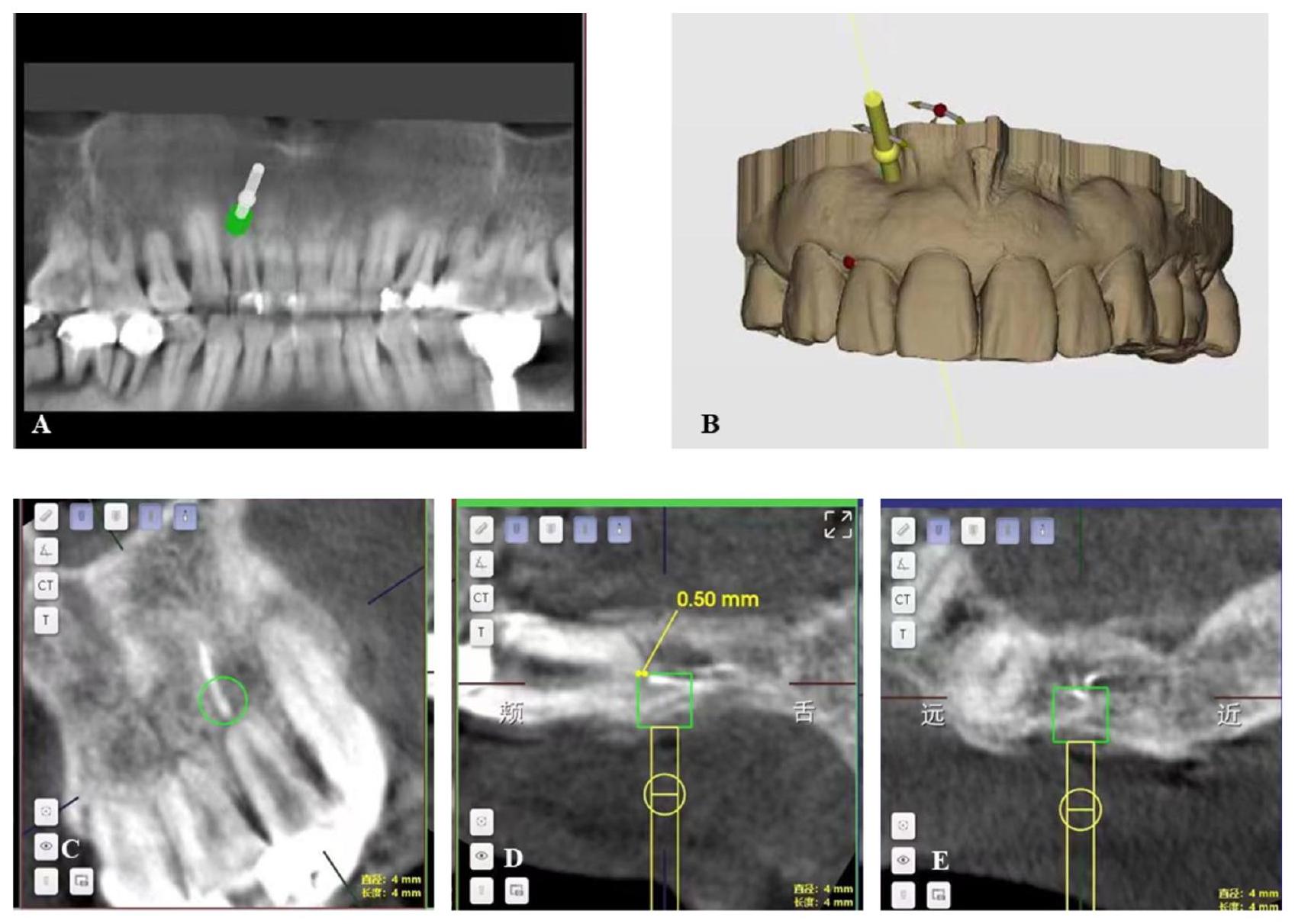

تم استخدام برنامج تخطيط ما قبل الجراحة (DentalNavi؛ Yekebot Technology Co., Ltd.، بكين، الصين) لـ

إعادة البناء ثلاثي الأبعاد والمحاذاة، مع دمج بيانات DICOM و STL المستوردة. في هذه الحالة، قام الطبيب بتحديد المحاور الطويلة للسن العلوي الأيمن باستخدام البرنامج. شمل تصميم خطط العملية تحديد طريقة إخراج الملف المكسور، وحجم وشكل نافذة العظم، والمثقب المناسب. على الرغم من جذر السن المتأثر القصير وامتصاص العظم السنخي البعيد، إلا أن السن أظهر محيطًا كبيرًا، وكان بدون أعراض ومستقر. لم يتم ملاحظة أي التهابات في الأنسجة المحيطة بالذروة للأسنان. لذلك، كان الحفاظ على السن المتأثر دون استئصال الجذر هو الخيار المناسب أثناء الجراحة. نظرًا لأن طول الملف المكسور كان حوالي 7 مم، إلى

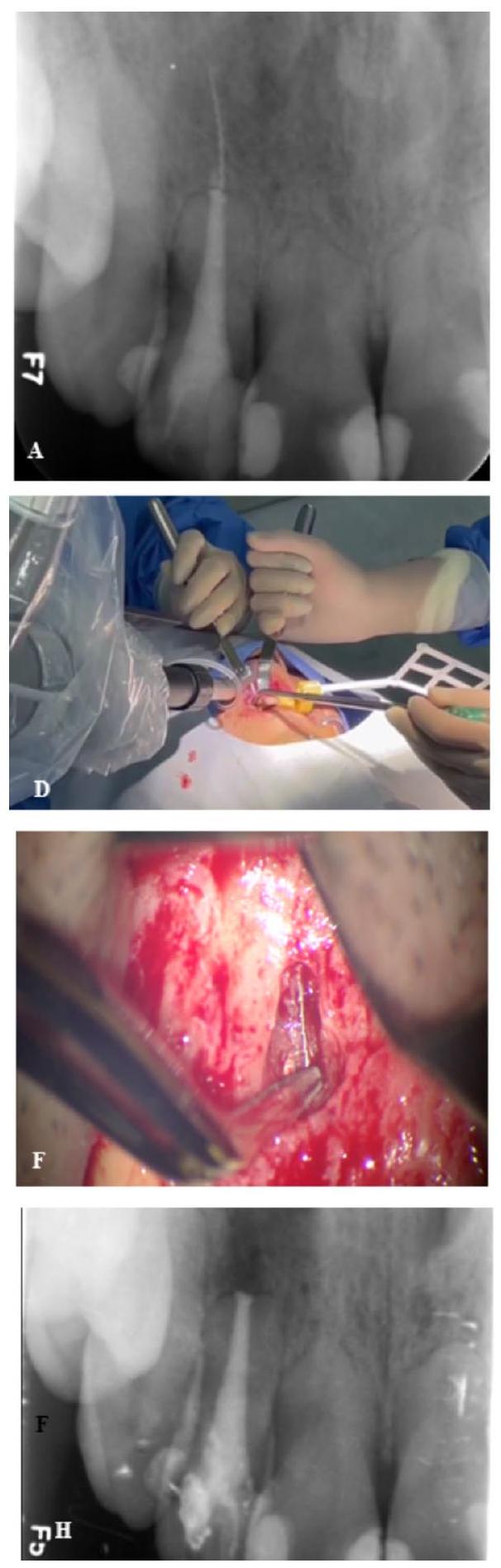

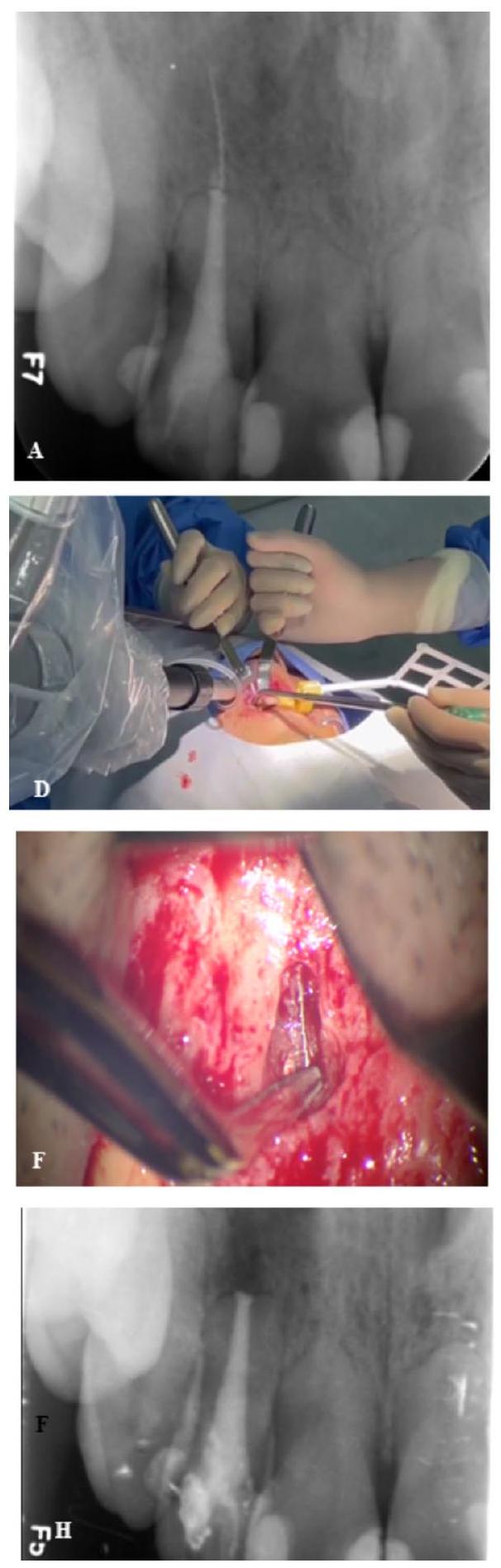

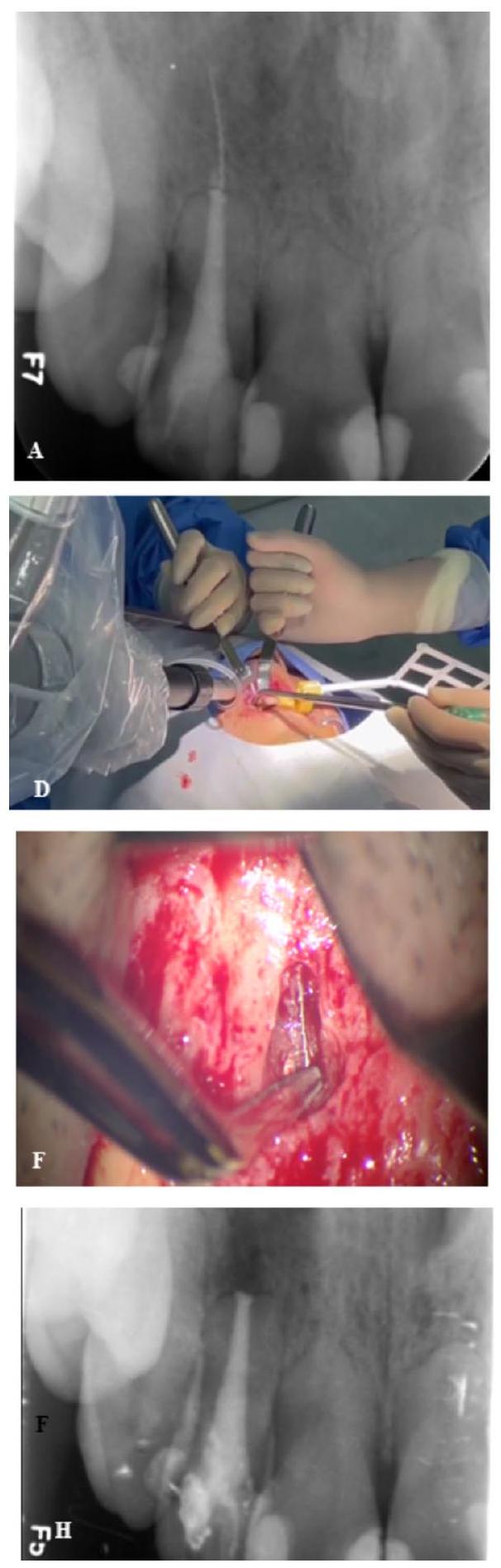

ضمان شكل نافذة العظم الحد الأدنى من التدخل، تمت إزالته على مرحلتين. بعد القياس والحساب باستخدام البرنامج، وجدنا أن قطر نافذة العظم المستديرة التي أعدها نظام ATR كان 3 مم، مما كشف مباشرة عن الجزء العلوي من الملف المكسور والذروة (0.5 مم) (الشكل 2). ثم تم إعداد نافذة العظم المستديرة، يدويًا، تحت المجهر لتشكيل ممر ضيق بطول 1.5 مم، وأخيرًا نافذة عظم على شكل ثقب المفتاح. كانت أطول نافذة عظم تم قياسها حوالي 4.5 مم. بعد قطع الجزء العلوي من الملف المكسور من نافذة العظم، تمت إزالة الجزء السفلي من بقايا الملف المكسور بطول 4.5 مم من خلال نافذة العظم بطول 4.5 مم باستخدام ملقط مجهرية. بسبب قطر نافذة العظم الصغيرة، كان من الضروري استخدام مثقاب كروي صغير (3 مم) لتحديد موقع الملف المكسور بدقة. تم تصنيع ملحقات جراحية مخصصة (الشكل S1.) باستخدام الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد (Pro S95؛ SprintRay Co.، لوس أنجلوس، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) قبل الجراحة. قام المشغل بالتدرب على استخدام الروبوت مسبقًا للتحقق مما إذا كانت خطة العملية معقولة (بما في ذلك موقع وعمق

العملية، ووضع ذراع الروبوت، والأدوات المستخدمة، وموقع العلامة). تم حفظ إعدادات الكمبيوتر.

علاج قناة الجذر للسن المتأثر

الإجراء الجراحي

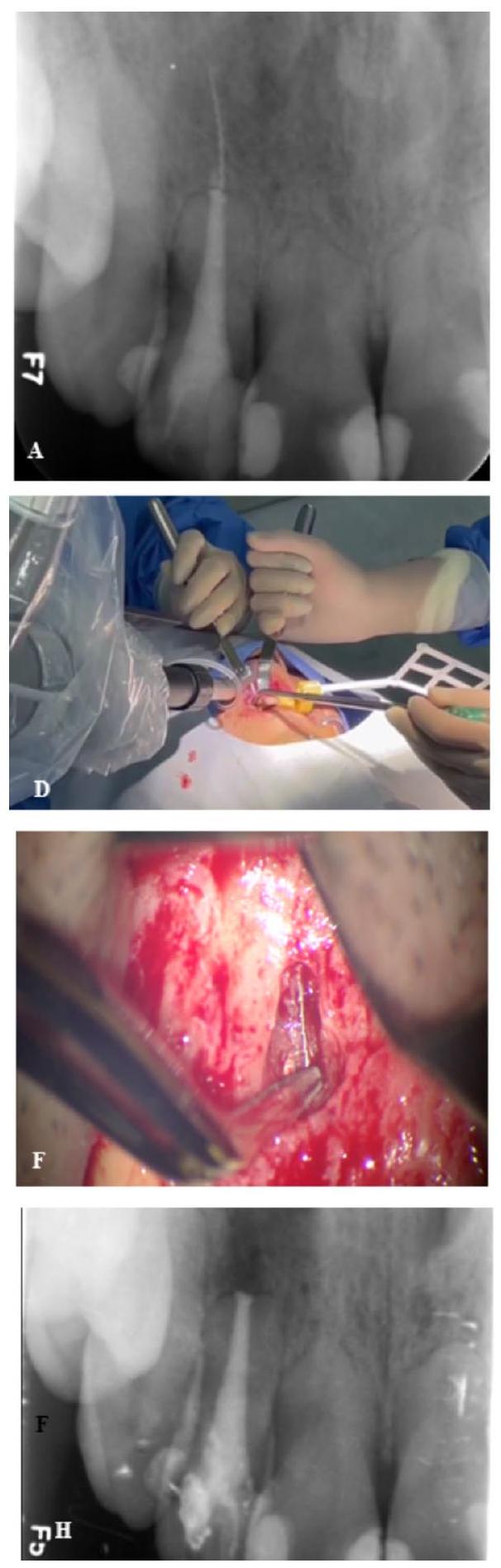

تم توجيه أداة متصلة بذراع الروبوت إلى فم المريض، بواسطة جراح، لتسجيل المسار. أثناء الجراحة، دخل نظام ATR تلقائيًا وخرج من تجويف الفم متبعًا مسارًا مسجلاً مسبقًا. تحرك ذراع الروبوت بشكل مستقل إلى المنطقة الجراحية بينما ضغط الطبيب على وحدة التحكم بالقدم. بعد ذلك، نفذ الروبوت تلقائيًا تعليمات الثقب (الشكل 3D). تم نقل ذراع الروبوت إلى الموقع المثالي وفقًا لخطة ما قبل الجراحة، وخضع المريض لعملية قطع العظم. تم استخدام محلول ملحي معقم لري وتبريد المناطق المثقوبة. قدم العرض في الوقت الحقيقي عمق وزاوية الثقب على الشاشة، بينما راقب الجراح العملية وكان بإمكانه التحكم في الروبوت في نفس الوقت باستخدام دواسات القدم.

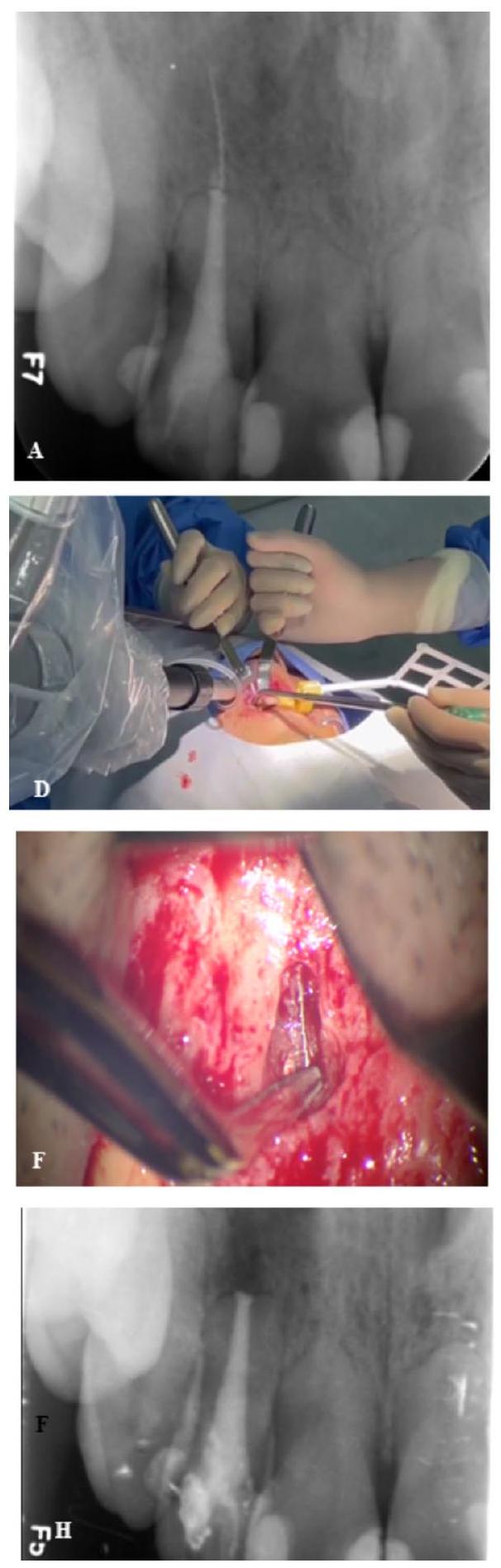

تم إعداد تجويف عظمي بمدى 3 مم مباشرة على الملف المكسور وفقًا لخطة ما قبل الجراحة. نظرًا لأن طول الملف المكسور كان 7 مم، قام الجراح بمزيد من

إعداد التجويف ليكون على شكل مفتاح بطول 4.5 مم لتسهيل إزالة الملف المكسور في شقين (الشكل 3E). كان الجزء السفلي من الملف المكسور بطول 4.5 مم كافيًا للخروج من نافذة العظم على شكل ثقب المفتاح (الشكل 3F-G). تم فحص طرف الجذر للتأكد من أن البئر محاط بـ iRoot BP Plus. تم إغلاق الشرائح بخيوط أحادية الخيط. بينما كانت الأعمال التحضيرية طويلة (حوالي 30 دقيقة)، فتح نظام ATR نافذة العظم وسمح للمشغل بالتقاط الملف المكسور في 9 دقائق فقط.

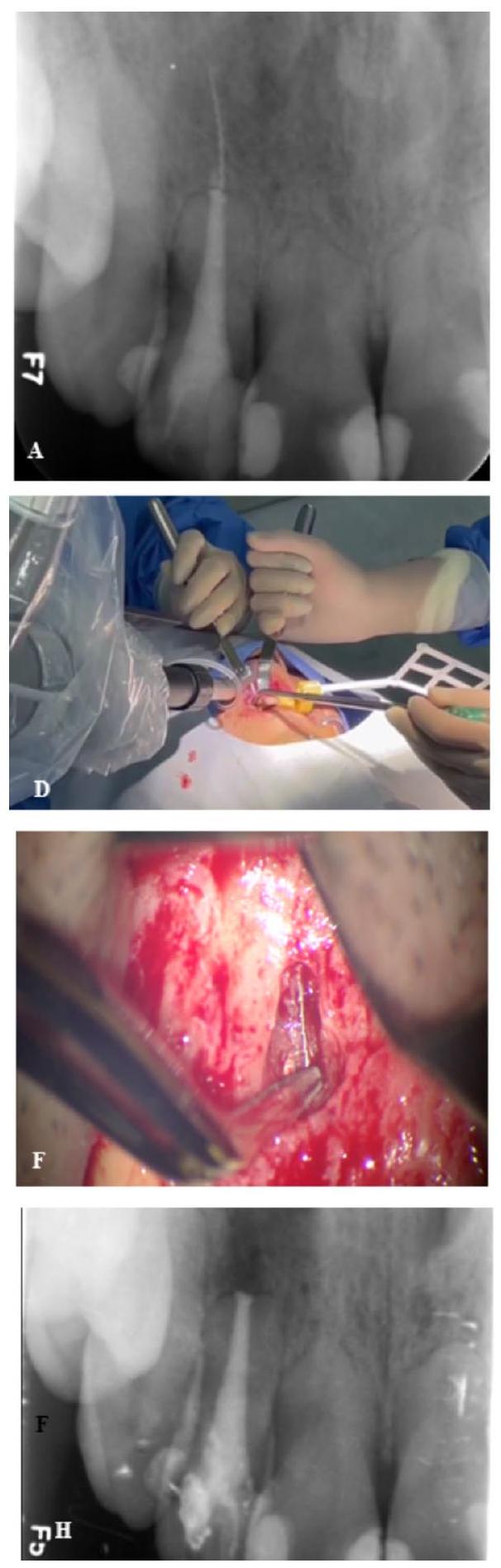

المتابعة

تم إعداد التجويف العظمي بدقة وفقًا للخطة المحددة مسبقًا، باستخدام تقنية الحد الأدنى من التدخل وفعالة من حيث الوقت بمساعدة ATR. لم تحدث أي مضاعفات أثناء الإجراء الجراحي،

وكان العلاج يبدو ناجحًا في تقييم ما بعد الجراحة بعد 9 أشهر، مما يدل على توقعات إيجابية.

المناقشة

لقد أفادت عدة دراسات باستخدام تقنية الملاحة لإزالة الملفات المكسورة الموجودة خارج الفتحة القمية. ومع ذلك، تعمل كل من الألواح الدليلية الثابتة وتقنيات الملاحة الديناميكية يدوياً، مما يؤدي إلى انحرافات ذاتية أو موضوعية لا مفر منها، خاصة عند التعامل مع الملفات المكسورة الصغيرة. بالمقابل، تضمن جراحة الأسنان المجهرية التي يتم تنفيذها بواسطة نظام ATR تحديد موضع دقيق وتكون أقل تدخلاً. يستخدم نظام ATR ذراعاً روبوتياً لتحديد الموقع بدقة وكفاءة وعمل بناءً على التخطيط قبل العملية، مما يعزز دقة أداة التحديد. تتغلب الذراع الروبوتية على القيود المرتبطة بالحركات اليدوية الحرة، وتقوم بإجراء جراحات دقيقة وأقل تدخلاً. في هذه الحالة، حدد نظام ATR بدقة الملف المكسور أثناء جراحة الأسنان المجهرية.

لزيادة دقة إجراء جراحة الأسنان المجهرية، تم استخدام نظام ATR، مصحوباً بسلسلة من الخطوات الاحترازية التي تم تنفيذها قبل العملية في الحالة الحالية. أولاً، تم التخطيط بعناية لمسار الجراحة الأمثل لنظام ATR باستخدام بيانات ما قبل العملية والتمارين التحضيرية لضمان تحديد موضع دقيق أثناء الجراحة. تعتمد دقة CBCT على جودتها؛ لذلك، فإن اختيار المعلمات المناسبة للتسجيل قبل العملية والمعايرة أمر بالغ الأهمية. في حالتنا، اخترنا CBCT واسع المجال، مما سهل التسجيل والمعايرة بسهولة لنصف أطقم الأسنان الفموية مع توفير رؤية واضحة للمنطقة الجراحية.

علاوة على ذلك، فإن دقة المسح الفموي أمر بالغ الأهمية لأن دقة التسجيل والمعايرة مهمة. أظهرت الدراسات الحديثة أن المسح داخل الفم يوفر دقة أفضل من تسجيل الأنابيب على شكل U، ويقضي على الحاجة لعدة لقطات من CBCT. في هذه الحالة، تم استخدام ماسح داخل الفم لالتقاط بيانات شاملة عن الأسنان العلوية والأنسجة الرخوة. علاوة على ذلك، قمنا بتكييف خطة التشغيل من أجل الدقة من خلال مواءمتها مع تفاصيل الحالة. حدد نظام ATR بدقة الملف المكسور داخل تجويف عظمي يبلغ 3 مم على طول المسار الجراحي، مما وضعه بدقة في مركز نافذة العظام في الحالة الحالية.

أظهرت الدراسات السابقة وتقارير الحالة أن استخدام نظام ATR أثناء جراحة الأسنان المجهرية يؤدي إلى تقليل التدخل وارتفاع الكفاءة. توضح هذه الحالة مبدأ الجراحة الأقل تدخلاً والأكثر كفاءة. تسريع الشفاء من خلال تقليل إزالة العظام أثناء الفتح. كانت الطريقة الجراحية في هذه الحالة، التي تضمنت تحديد موضع دقيق، وتقليل تعرض الأدوات، وتجنب استئصال الجذر، وإزالة الملف المكسور في قسمين، جميعها تتماشى مع مبادئ الجراحة الأقل تدخلاً. بعد 9 أشهر، شفيت نافذة العظام تماماً. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهرت إزالة الملف المكسور في 9 دقائق فقط كفاءة عالية. على عكس الطرق التقليدية التي تعتمد على خبرة المشغل، يمكن للروبوت حفر موضع محدد مسبقاً تلقائياً، مما يجعل الإجراء أكثر كفاءة.

تكشف هذه الحالة عن إمكانيات نظام ATR في تسهيل إزالة الملفات المكسورة. كان للملف المكسور في هذه الحالة قطر صغير بشكل ملحوظ؛ ومع ذلك، كان نظام ATR قادراً على تحديد موقعه ثلاثي الأبعاد بدقة. هذا يبرز دقة تحديد المواقع الروبوتية للتطبيقات الجراحية. هذا يعزز الثقة في أن الجراحة المدعومة بالروبوت ستكون مناسبة لبعض السيناريوهات السريرية في المستقبل. تشمل هذه الحالات التي تتطلب مواقع دقيقة، مثل تلك المجاورة للهياكل التشريحية الحرجة مثل الجيب الفكي، وأنبوب الأعصاب الفكي، والفتحة الذهنية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن الحالات التي يكون فيها تحديد الموضع يدوياً تحدياً، مثل الأفراد الذين لديهم لوحة عظمية سميكة وانحدار كبير في موضع الجذر، والتي ترتبط عادةً بأخطاء موضعية كبيرة، يمكن أن تستفيد أيضاً من هذه التكنولوجيا.

ومع ذلك، لا يمكن إنكار أن هناك نقصاً أو قيوداً في الحالة الحالية. على وجه التحديد، فإن وقت التحضير للعملية طويل، حيث تشير التقارير إلى أن متوسط وقت التحضير قبل العملية للروبوت هو حوالي 30 دقيقة (باستثناء وقت جمع بيانات الصور قبل العملية)، ومتوسط الوقت الإجمالي للعملية هو 25 دقيقة. علاوة على ذلك، تتماشى البيانات مع نتائجنا، ونعتقد أن هناك مجالاً لتحسين أداء ATR، وإدراكه، وقدراته على التعلم.

يمكن أن تعزز AR وAI والتعلم العميق الأداء التشغيلي.

باختصار، يمكن أن يساعد نظام ATR في تحديد وإزالة الملفات المكسورة الموجودة خارج الفتحة القمية أثناء جراحة الأسنان المجهرية. تمثل هذه الحالة الاستخدام الأول المعروف لنظام ATR لهذا الغرض، مما يوفر تحديد موضع دقيق، وتقليل إزالة العظام، وتقليل وقت الجراحة، وتوقعات إيجابية.

الخاتمة

الاختصارات

| ATR | نظام روبوتي أسنان مستقل |

| CBCT | التصوير المقطعي المحوسب باستخدام شعاع مخروط |

| STL | لغة التشكيل القياسية |

| DICOM | تصوير رقمي وتواصل في الطب |

المعلومات التكميلية

المادة التكميلية 2

المادة التكميلية 3

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2025

References

- Madarati AA, Hunter MJ, Dummer PM. Management of intracanal separated instruments. J Endod. 2013;39(5):569-81.

- Coaguila-Llerena H, Lazo-Quezada G, Teves A, Zevallos-Chávez M, Faria G. Removal of separated instruments from unfavourable locations: Case reports using the HBW ultrasonic ring or a surgical approach. Aust Endod J. 2023;49(2):358-64.

- Terauchi Y, Ali WT, Abielhassan MM. Present status and future directions: Removal of fractured instruments. Int Endod J. 2022;55(Suppl 3):685-709.

- Benjamin G, Ather A, Bueno MR, Estrela C, Diogenes A. Preserving the Neurovascular Bundle in Targeted Endodontic Microsurgery: A Case Series. J Endod. 2021;47(3):509-19.

- Strbac GD, Schnappauf A, Giannis K, Moritz A, Ulm C. Guided Modern Endodontic Surgery: A Novel Approach for Guided Osteotomy and Root Resection. J Endod. 2017;43(3):496-501.

- Gambarini G, Galli M, Stefanelli LV, Di Nardo D, Morese A, Seracchiani M, De Angelis F, Di Carlo S, Testarelli L. Endodontic Microsurgery Using Dynamic Navigation System: A Case Report. J Endod. 2019;45(11):1397-e14021396.

- Ahn SY, Kim NH, Kim S, Karabucak B, Kim E. Computer-aided Design/Com-puter-aided Manufacturing-guided Endodontic Surgery: Guided Osteotomy and Apex Localization in a Mandibular Molar with a Thick Buccal Bone Plate. J Endod. 2018;44(4):665-70.

- Bardales-Alcocer J, Ramírez-Salomón M, Vega-Lizama E, López-Villanueva M, Alvarado-Cárdenas G, Serota KS, Ramírez-Wong J. Endodontic Retreatment Using Dynamic Navigation: A Case Report. J Endod. 2021;47(6):1007-13.

- Ribeiro D, Reis E, Marques JA, Falacho RI, Palma PJ. Guided Endodontics: Static vs. Dynamic Computer-Aided Techniques-A Literature Review. J Pers Med. 2022; 12(9).

- Dianat O, Nosrat A, Tordik PA, Aldahmash SA, Romberg E, Price JB, Mostoufi B. Accuracy and Efficiency of a Dynamic Navigation System for Locating Calcified Canals. J Endod. 2020;46(11):1719-25.

- van Riet TCT, Chin Jen Sem KTH, Ho JTF, Spijker R, Kober J, de Lange J. Robot technology in dentistry, part one of a systematic review: literature characteristics. Dent Mater. 2021;37(8):1217-26.

- Liu L, Watanabe M, Ichikawa T. Robotics in Dentistry: A Narrative Review. Dent J (Basel) 2023, 11(3).

- Isufi A, Hsu TY, Chogle S. Robot-Assisted and Haptic-Guided Endodontic Surgery: A Case Report. J Endod. 2024;50(4):533-e539531.

- Liu C, Liu X, Wang X, Liu Y, Bai Y, Bai S, Zhao Y. Endodontic Microsurgery With an Autonomous Robotic System: A Clinical Report. J Endod. 2024;50(6):859-64.

- Dianat O, Gupta S, Price JB, Mostoufi B. Guided Endodontic Access in a Maxillary Molar Using a Dynamic Navigation System. J Endod. 2021;47(4):658-62.

- Vasudevan A, Santosh SS, Selvakumar RJ, Sampath DT, Natanasabapathy V. Dynamic Navigation in Guided Endodontics – A Systematic Review. Eur Endod J. 2022;7(2):81-91.

- Karim MH, Faraj BM. Comparative Evaluation of a Dynamic Navigation System versus a Three-dimensional Microscope in Retrieving Separated Endodontic Files: An In Vitro Study. J Endod. 2023;49(9):1191-8.

- Nasiri K, Wrbas KT. Management of separated instruments in root canal therapy. J Dent Sci. 2023;18(3):1433-4.

- Harada T, Harada K, Nozoe A, Tanaka S, Kogo M. A Novel Surgical Approach for the Successful Removal of Overextruded Separated Endodontic Instruments. J Endod. 2021;47(12):1942-6.

- Sukegawa S, Kanno T, Shibata A, Matsumoto K, Sukegawa-Takahashi Y, Sakaida K, Furuki Y. Use of an intraoperative navigation system for retrieving a broken dental instrument in the mandible: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11(1):14.

- Chen C, Qin L, Zhang R, Meng L. Comparison of Accuracy and Operation Time in Robotic, Dynamic, and Static-Assisted Endodontic Microsurgery: An In Vitro Study. J Endod 2024;50(10):1448-54

- Jia S, Wang G, Zhao Y, Wang X. Accuracy of an autonomous dental implant robotic system versus static guide-assisted implant surgery: A retrospective clinical study. J Prosthet Dent. 2023. Online ahead of print.

- Zhou L, Teng W, Li X, Su Y. Accuracy of an optical robotic computer-aided implant system and the trueness of virtual techniques for measuring robot accuracy evaluated with a coordinate measuring machine in vitro. J Prosthet Dent. 2023. Online ahead of print.

- Zubizarreta-Macho Á, Muñoz AP, Deglow ER, Agustín-Panadero R, Álvarez JM. Accuracy of Computer-Aided Dynamic Navigation Compared to ComputerAided Static Procedure for Endodontic Access Cavities: An in Vitro Study. J Clin Med. 2020; 9(1).

- Fu XJ, Shi JY, Lai HC. Application of machine vision image processing technology in dental implant surgery. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2024;59(6):640-5.

- Yang X, Zhang Y, Chen X, Huang L, Qiu X. Limitations and Management of Dynamic Navigation System for Locating Calcified Canals Failure. J Endod. 2024;50(1):96-105.

- Floratos S, Kim S. Modern Endodontic Microsurgery Concepts: A Clinical Update. Dent Clin North Am. 2017;61(1):81-91.

- Tian YN, Li BX, Zhang H, Jin L. Development of dental robot implantation technology. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2023;58(12):1300-6.

- Idrees W, Khalil R, Kanwal L, Fida M, Sukhia RH. Dental robotics: a groundbreaking technology with disruptive potential – review article. J Pak Med Assoc. 2024;74(4):S79-84.

- Li Y, Inamochi Y, Wang Z, Fueki K. Clinical application of robots in dentistry: A scoping review. J Prosthodont Res. 2024;68(2):193-205.

- Martinho FC, Griffin IL, Price JB, Tordik PA. Augmented Reality and 3-Dimensional Dynamic Navigation System Integration for Osteotomy and Root-end Resection. J Endod. 2023;49(10):1362-8.

- Dhopte A, Bagde H. Smart Smile: Revolutionizing Dentistry With Artificial Intelligence. Cureus. 2023;15(6):e41227.

- Setzer FC, Li J, Khan AA. The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Endodontics. J Dent Res 2024:220345241255593. Epub 2024 May 31.

ملاحظة الناشر

ساهم مي فو وشين زهاو بالتساوي في هذا العمل.

*المراسلة:

بينشيانغ هو

endohou@qq.com

تشين زانغ

endozhangchen@163.com

قسم علاج الجذور، كلية طب الأسنان، جامعة الطب الرأسمالي، بكين، الصين

مركز طب الأسنان المعزز بالميكروسكوب، كلية طب الأسنان، جامعة الطب الرأسمالي، بكين، الصين

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-05329-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39748344

Publication Date: 2025-01-02

Removal of a fractured file beyond the apical foramen using robot-assisted endodontic microsurgery: a clinical report

Abstract

Background Endodontic file fractures are common complications of root canal treatment, and requires removal via specialized techniques such as endodontic microsurgery when the file beyond the apical foramen. It is often challenging to precisely and minimally remove a fractured file. Recently the use of dental autonomous robotic system (ATR) has shown promise in precisely and minimally in dental surgery. Therefore, this case details a technique for using the ATR system to precisely and minimally guide the removal of a fractured file beyond the apical foramen. Case presentation A 48-year-old male patient, with no evidence of bone defects, was diagnosed with a file fractured completely beyond the apical foramen during root canal treatment of the right maxillary lateral incisor. Patient information was used to incorporate a digital model into preoperative planning software to develop a surgical strategy. The ATR system employs spatial alignment methods for registration, directing the robotic arm to independently locate the fractured file in accordance with the surgical plan. To maximize minimally invasive surgery, the long fractured file was removed in two stages. After removing the bone and fracture file, the clinician performed suturing under a microscope. No complications were observed during the surgery, and the treatment appeared to be successful based on the 9-month follow-up evaluation. Conclusions The ATR system enables precise localization of the fractured file beyond the apical foramen with intact cortical plates. This technology has the potential to improve positioning accuracy, minimize the need for invasive bone removal, reduce intraoperative time, and facilitate successful endodontic microsurgical procedures.

Background

With the advancements in digital technology, both static guide plates and dynamic navigation systems can be utilized in endodontic microsurgery to precisely locate root tips [5,6]. Adherence to the direction of the preprinted guide plate is essential when employing a static guide plate, which limits the ability to make realtime adjustments to the surgical plan. Pre-sterilization of the resin guide plate is necessary to avoid potential irritation of the oral mucosa, and inaccuracies in the guide plate design may result in additional complications [5, 7]. The dynamic navigation system provides real-time and precise three-dimensional guidance during the surgical procedure, enabling minimally invasive localization and osteotomy techniques to prevent iatrogenic errors [6]. In addition, dynamic navigation operators engage in repetitive practice to enhance hand-eye coordination skills [8]. However, operator fatigue may lead to three-dimensional position deviation, free hand tremors, incorrect posture, and visual field blind spots during surgery [9, 10]. Owing to enhanced accuracy, stability, safety, flexibility, and convenience for healthcare professionals, robots have recently been utilized as a tool in dental surgery [11]. Dental autonomous robotic (ATR) systems are safe and precise [12], and robot-guided osteotomy and root resection procedures have been detailed [13, 14]. ATR systems use infrared vision and real-time positioning, enabling control without recalibration, thereby ensuring precise and safe operation. ATR systems use robotic arms for surgery, which is a significant improvement over free hand surgery with guide plates or navigation systems [5-7, 9, 15]. While these techniques can improve accuracy, factors such as clinician fatigue and lack of skill can still affect surgical precision [16,17]. The robotic arm can eliminate such disadvantages of free hand using guide plate or navigation systems and perform precise and minimally invasive surgery.

In this case study, we aimed to determine the efficacy of the ATR system in removing fractured files that are

located beyond the apical foramen. In this case, the osteotomy was performed automatically under the guidance of ATR system. The system precisely located the fractured file, resulting in minimized tissue damage, leading to a successful outcome for the patient who remained asymptomatic during the 9-month follow-up period.

Case report

We developed two treatment plans: (1) leaving the fractured file, completing the root canal treatment, followed close patient monitoring, and (2) endodontic microsurgery to remove the fractured file. The patient expressed a strong desire for file removal. After understanding the prognosis, risks, and benefits associated with the treatment plan, the patient provided written informed consent to undergo endodontic microsurgery to remove the fractured file and complete the endodontic treatment. A new ATR system (Yakebot; Yakebot Technology Co. Ltd., Beijing, China) was used during endodontic microsurgery. The patient also provided written informed consent for use and publication of their personal and clinical details, along with any identifying images.

The clinical workflow was as follows Data acquisition and surgical planning

Preoperative planning software (DentalNavi; Yekebot Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was utilized for

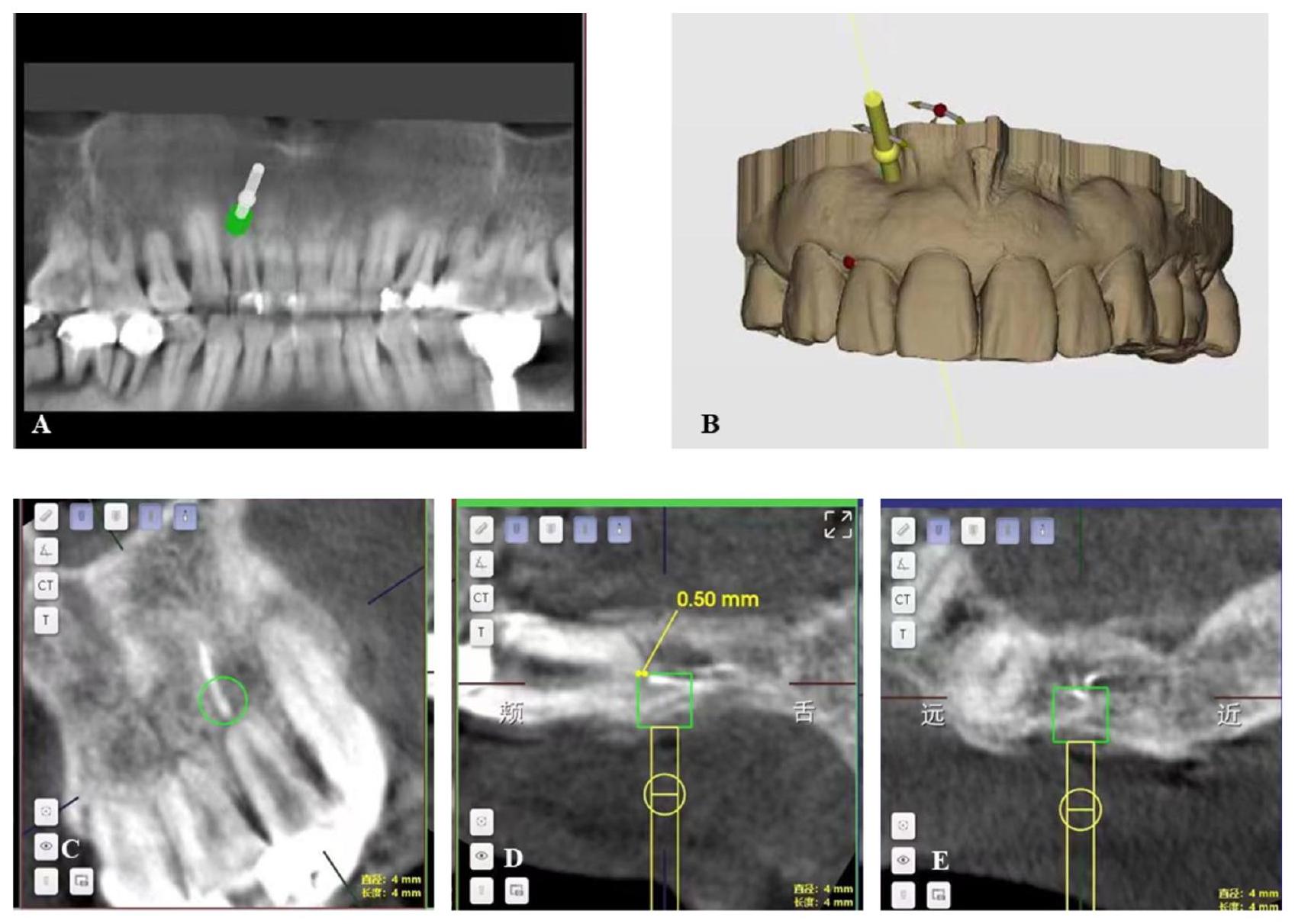

three-dimensional reconstruction and alignment, incorporating the imported DICOM and STL data. In this case, the clinician marked the long axes of the maxillary right lateral incisor using the software. The design of the operation plans included determining the fractured file took-out method, size and shape of the bone window, and appropriate drill. Despite the short root of the affected tooth and absorption of the distal alveolar bone, the tooth exhibited a large circumference, which was asymptomatic and stable. No infections were observed in the periapical tissues of the teeth. Therefore, preservation of the affected tooth without root resection was an appropriate course of action during surgery. Because the length of the fractured file was approximately 7 mm , to

ensure a minimally invasive bone window shape, it was removed in two stages. After measurement and calculation using the software, we found that the diameter of the round-shaped bone window prepared by the ATR system was 3 mm , directly exposing the upper segment of the fractured file and the apex ( 0.5 mm ) (Fig. 2). Then, the round bone window was prepared, free handedly, under a microscope to form a 1.5 mm slender isthmus, and finally a keyhole-shaped bone window. The longest measured bone window was approximately 4.5 mm . After the upper segment of the fractured file was cut off the bone window, the lower part of the 4.5 mm -length fractured file remnant was removed through the 4.5 mm -length bone window using microscopic forceps. Because of the small diameter of the bone window, a small ball drill ( 3 mm ) was required to precisely locate the fractured file. Personalized surgical accessories (Fig. S1.) were manufactured using 3D printing (Pro S95; SprintRay Co., Los Angeles, CA, USA) before surgery. The operator practiced using the robot in advance to verify if the operation plan was reasonable (including the position and depth of the

operation, posture of the robotic arm, instruments used, and position of the marker). Computer settings were saved.

Root canal treatment of affected tooth

Surgical procedure

A handpiece connected to the robotic arm was guided into the patient’s mouth, by a surgeon, to record the path. During surgery, the ATR system automatically entered and exited the oral cavity following a prerecorded path. The robotic arm moved autonomously to the surgical area while the clinician stepped on the foot controller. Subsequently, the robot automatically executed the drilling instructions (Fig. 3D). The robotic arm was moved to the ideal location according to the preoperative plan, and the patient underwent osteotomy. Sterile saline was used to irrigate and cool drilled areas. The real-time display provided the drilling depth and angle on the screen, while the surgeon monitored the operation and could simultaneously control the robot using foot pedals.

A 3 mm -ranged bone cavity was prepared directly on the fractured file as per the preoperative plan. Because the fractured file length was 7 mm , the surgeon further

prepared the cavity to a 4.5 mm -length key-like shape to facilitate the removal of the fractured file in two segments (Fig. 3E). The 4.5 mm -length lower segment of the fractured file was sufficient to exit the keyhole-shaped bone window (Fig. 3F-G). The root tip was inspected to confirm that the well was enclosed by the iRoot BP Plus. The flaps were closed with monofilament sutures. While the preparatory work was lengthy (approximately 30 min ), the ATR system opened the bone window and allowed for operator pick up of fractured file in only 9 min .

Follow-up

The bone cavity was meticulously prepared according to the pre-established plan, utilizing a minimally invasive and time-efficient technique with the assistance of ATR. No complications arose during the surgical procedure,

and the treatment appeared to be deemed successful at the 9 -month postoperative evaluation, demonstrate a favorable prognosis.

Discussion

Several studies have reported the use of navigation technology to remove fractured files located beyond the apical foramen [20]. Nevertheless, both static guide plates and dynamic navigation technologies operate manually, leading to inevitable subjective or objective deviations, particularly when dealing with diminutive fractured files. In contrast, endodontic microsurgery carried out by the ATR system ensures accurate positioning and is minimally invasive [13, 14, 21]. The ATR system employs a robotic arm for accurate and efficient localization and operation based on preoperative planning, enhancing the precision of the positioning instrument. The robotic arm overcome the limitations associated with freehand movements, and perform accurate and minimally invasive surgeries. In this case study, the ATR system accurately located the fractured file during endodontic microsurgery.

To enhance the precision of the endodontic microsurgery procedure, the ATR system was utilized, accompanied by a series of precautionary steps implemented before the operation in present case. First, the ATR system’s optimal surgical pathway was carefully planned using pre-operative data and preparatory exercises to ensure precise positioning during surgery [22-24]. The accuracy of CBCT depends on its quality; therefore, selecting appropriate parameters for preoperative registration and calibration is crucial [25]. In our case, we opted for wide field-of-view CBCT, which facilitated easy registration and calibration of half of the oral dentures while also providing clear visualization of the surgical

region. Moreover, precision of oral scanning is crucial because both registration and calibration accuracies are important [24, 25]. Recent studies have shown that intraoral scanning provides better accuracy than U-shaped tube registration, and eliminates the need for multiple CBCT shots [26]. In this case, an intraoral scanner was used to capture comprehensive data on the maxillary teeth and soft tissues. Furthermore, we tailored the operational plan for precision by aligning it with case specifics. The ATR system accurately located the fractured file within a 3 mm bone cavity along the surgical path, positioning it precisely at the center of the bone window in the present case.

Previous studies and case reports have demonstrated that the use of the ATR system during endodontic microsurgery results in minimal invasiveness and high efficiency. This case demonstrates the principle of minimally invasive and highly efficient surgery. Reduced bone removal during fenestration accelerates healing [27]. The surgical approach in this case, which included precise positioning, minimal instrument exposure, avoidance of root resection, and removal of the fractured file in two sections, all aligned with the principles of minimally invasive surgery. After 9 months, the bone window fully healed. In addition, the removal of the fractured file in just 9 min showed a high efficiency. Unlike traditional methods that rely on operator experience, the robot can automatically drill a predetermined position, making the procedure more efficient.

This case reveals the potential of the ATR system in facilitating fractured file removal. The fractured file in this case had a notably small diameter; however, the ATR system was able to precisely determine its threedimensional location. This highlighted the precision of robotic positioning for surgical applications. This instills confidence that robot-assisted surgery will be suitable for certain clinical scenarios in the future. These include cases necessitating precise locations, such as those adjacent to critical anatomical structures such as the maxillary sinus, mandibular neural tube, and mental foramen. Additionally, situations in which manual positioning is challenging, such as in individuals with a thick bone plate and significant inclination of the root position, which are typically associated with substantial positioning errors, could also benefit from this technology.

Nevertheless, it is undeniable that there are deficiencies or limitations to the current case. Specifically, the preparation time for the operation is long, with reports indicating that the average preoperative preparation time for the robot is approximately 30 min (excluding the preoperative image data collection time), and the average total operation time is 25 min [28]. Moreover, the data align with our findings, and we believe that there is room for improvement in the ATR performance, perception, and

learning abilities [12, 29, 30]. AR, AI, and deep learning can enhance operational performance [28, 31-33].

In summary, the ATR system can help locate and remove fractured files that are located beyond the apical foramen during endodontic microsurgery. This case represents the first known use of the ATR system for this purpose, offering precise positioning, minimal bone removal, shorter surgery time, and favorable prognosis.

Conclusion

Abbreviations

| ATR | Dental autonomous robotic system |

| CBCT | Cone beam computed tomography |

| STL | Standard tessellation language |

| DICOM | Digital imaging and communications in medicine |

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 2

Supplementary Material 3

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 02 January 2025

References

- Madarati AA, Hunter MJ, Dummer PM. Management of intracanal separated instruments. J Endod. 2013;39(5):569-81.

- Coaguila-Llerena H, Lazo-Quezada G, Teves A, Zevallos-Chávez M, Faria G. Removal of separated instruments from unfavourable locations: Case reports using the HBW ultrasonic ring or a surgical approach. Aust Endod J. 2023;49(2):358-64.

- Terauchi Y, Ali WT, Abielhassan MM. Present status and future directions: Removal of fractured instruments. Int Endod J. 2022;55(Suppl 3):685-709.

- Benjamin G, Ather A, Bueno MR, Estrela C, Diogenes A. Preserving the Neurovascular Bundle in Targeted Endodontic Microsurgery: A Case Series. J Endod. 2021;47(3):509-19.

- Strbac GD, Schnappauf A, Giannis K, Moritz A, Ulm C. Guided Modern Endodontic Surgery: A Novel Approach for Guided Osteotomy and Root Resection. J Endod. 2017;43(3):496-501.

- Gambarini G, Galli M, Stefanelli LV, Di Nardo D, Morese A, Seracchiani M, De Angelis F, Di Carlo S, Testarelli L. Endodontic Microsurgery Using Dynamic Navigation System: A Case Report. J Endod. 2019;45(11):1397-e14021396.

- Ahn SY, Kim NH, Kim S, Karabucak B, Kim E. Computer-aided Design/Com-puter-aided Manufacturing-guided Endodontic Surgery: Guided Osteotomy and Apex Localization in a Mandibular Molar with a Thick Buccal Bone Plate. J Endod. 2018;44(4):665-70.

- Bardales-Alcocer J, Ramírez-Salomón M, Vega-Lizama E, López-Villanueva M, Alvarado-Cárdenas G, Serota KS, Ramírez-Wong J. Endodontic Retreatment Using Dynamic Navigation: A Case Report. J Endod. 2021;47(6):1007-13.

- Ribeiro D, Reis E, Marques JA, Falacho RI, Palma PJ. Guided Endodontics: Static vs. Dynamic Computer-Aided Techniques-A Literature Review. J Pers Med. 2022; 12(9).

- Dianat O, Nosrat A, Tordik PA, Aldahmash SA, Romberg E, Price JB, Mostoufi B. Accuracy and Efficiency of a Dynamic Navigation System for Locating Calcified Canals. J Endod. 2020;46(11):1719-25.

- van Riet TCT, Chin Jen Sem KTH, Ho JTF, Spijker R, Kober J, de Lange J. Robot technology in dentistry, part one of a systematic review: literature characteristics. Dent Mater. 2021;37(8):1217-26.

- Liu L, Watanabe M, Ichikawa T. Robotics in Dentistry: A Narrative Review. Dent J (Basel) 2023, 11(3).

- Isufi A, Hsu TY, Chogle S. Robot-Assisted and Haptic-Guided Endodontic Surgery: A Case Report. J Endod. 2024;50(4):533-e539531.

- Liu C, Liu X, Wang X, Liu Y, Bai Y, Bai S, Zhao Y. Endodontic Microsurgery With an Autonomous Robotic System: A Clinical Report. J Endod. 2024;50(6):859-64.

- Dianat O, Gupta S, Price JB, Mostoufi B. Guided Endodontic Access in a Maxillary Molar Using a Dynamic Navigation System. J Endod. 2021;47(4):658-62.

- Vasudevan A, Santosh SS, Selvakumar RJ, Sampath DT, Natanasabapathy V. Dynamic Navigation in Guided Endodontics – A Systematic Review. Eur Endod J. 2022;7(2):81-91.

- Karim MH, Faraj BM. Comparative Evaluation of a Dynamic Navigation System versus a Three-dimensional Microscope in Retrieving Separated Endodontic Files: An In Vitro Study. J Endod. 2023;49(9):1191-8.

- Nasiri K, Wrbas KT. Management of separated instruments in root canal therapy. J Dent Sci. 2023;18(3):1433-4.

- Harada T, Harada K, Nozoe A, Tanaka S, Kogo M. A Novel Surgical Approach for the Successful Removal of Overextruded Separated Endodontic Instruments. J Endod. 2021;47(12):1942-6.

- Sukegawa S, Kanno T, Shibata A, Matsumoto K, Sukegawa-Takahashi Y, Sakaida K, Furuki Y. Use of an intraoperative navigation system for retrieving a broken dental instrument in the mandible: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2017;11(1):14.

- Chen C, Qin L, Zhang R, Meng L. Comparison of Accuracy and Operation Time in Robotic, Dynamic, and Static-Assisted Endodontic Microsurgery: An In Vitro Study. J Endod 2024;50(10):1448-54

- Jia S, Wang G, Zhao Y, Wang X. Accuracy of an autonomous dental implant robotic system versus static guide-assisted implant surgery: A retrospective clinical study. J Prosthet Dent. 2023. Online ahead of print.

- Zhou L, Teng W, Li X, Su Y. Accuracy of an optical robotic computer-aided implant system and the trueness of virtual techniques for measuring robot accuracy evaluated with a coordinate measuring machine in vitro. J Prosthet Dent. 2023. Online ahead of print.

- Zubizarreta-Macho Á, Muñoz AP, Deglow ER, Agustín-Panadero R, Álvarez JM. Accuracy of Computer-Aided Dynamic Navigation Compared to ComputerAided Static Procedure for Endodontic Access Cavities: An in Vitro Study. J Clin Med. 2020; 9(1).

- Fu XJ, Shi JY, Lai HC. Application of machine vision image processing technology in dental implant surgery. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2024;59(6):640-5.

- Yang X, Zhang Y, Chen X, Huang L, Qiu X. Limitations and Management of Dynamic Navigation System for Locating Calcified Canals Failure. J Endod. 2024;50(1):96-105.

- Floratos S, Kim S. Modern Endodontic Microsurgery Concepts: A Clinical Update. Dent Clin North Am. 2017;61(1):81-91.

- Tian YN, Li BX, Zhang H, Jin L. Development of dental robot implantation technology. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2023;58(12):1300-6.

- Idrees W, Khalil R, Kanwal L, Fida M, Sukhia RH. Dental robotics: a groundbreaking technology with disruptive potential – review article. J Pak Med Assoc. 2024;74(4):S79-84.

- Li Y, Inamochi Y, Wang Z, Fueki K. Clinical application of robots in dentistry: A scoping review. J Prosthodont Res. 2024;68(2):193-205.

- Martinho FC, Griffin IL, Price JB, Tordik PA. Augmented Reality and 3-Dimensional Dynamic Navigation System Integration for Osteotomy and Root-end Resection. J Endod. 2023;49(10):1362-8.

- Dhopte A, Bagde H. Smart Smile: Revolutionizing Dentistry With Artificial Intelligence. Cureus. 2023;15(6):e41227.

- Setzer FC, Li J, Khan AA. The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Endodontics. J Dent Res 2024:220345241255593. Epub 2024 May 31.

Publisher’s note

Mei Fu and Shen Zhao contributed equally to this work.

*Correspondence:

Benxiang Hou

endohou@qq.com

Chen Zhang

endozhangchen@163.com

Department of Endodontics, School of Stomatology, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

Center for Microscope Enhanced Dentistry, School of Stomatology, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China