DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101822

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-26

إطار متكامل لعمليات صيانة المباني المستدامة والفعالة يتماشى مع تغير المناخ وأهداف التنمية المستدامة والتكنولوجيا الناشئة

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

أهداف التنمية المستدامة

انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة

بIM

صيانة المباني

الملخص

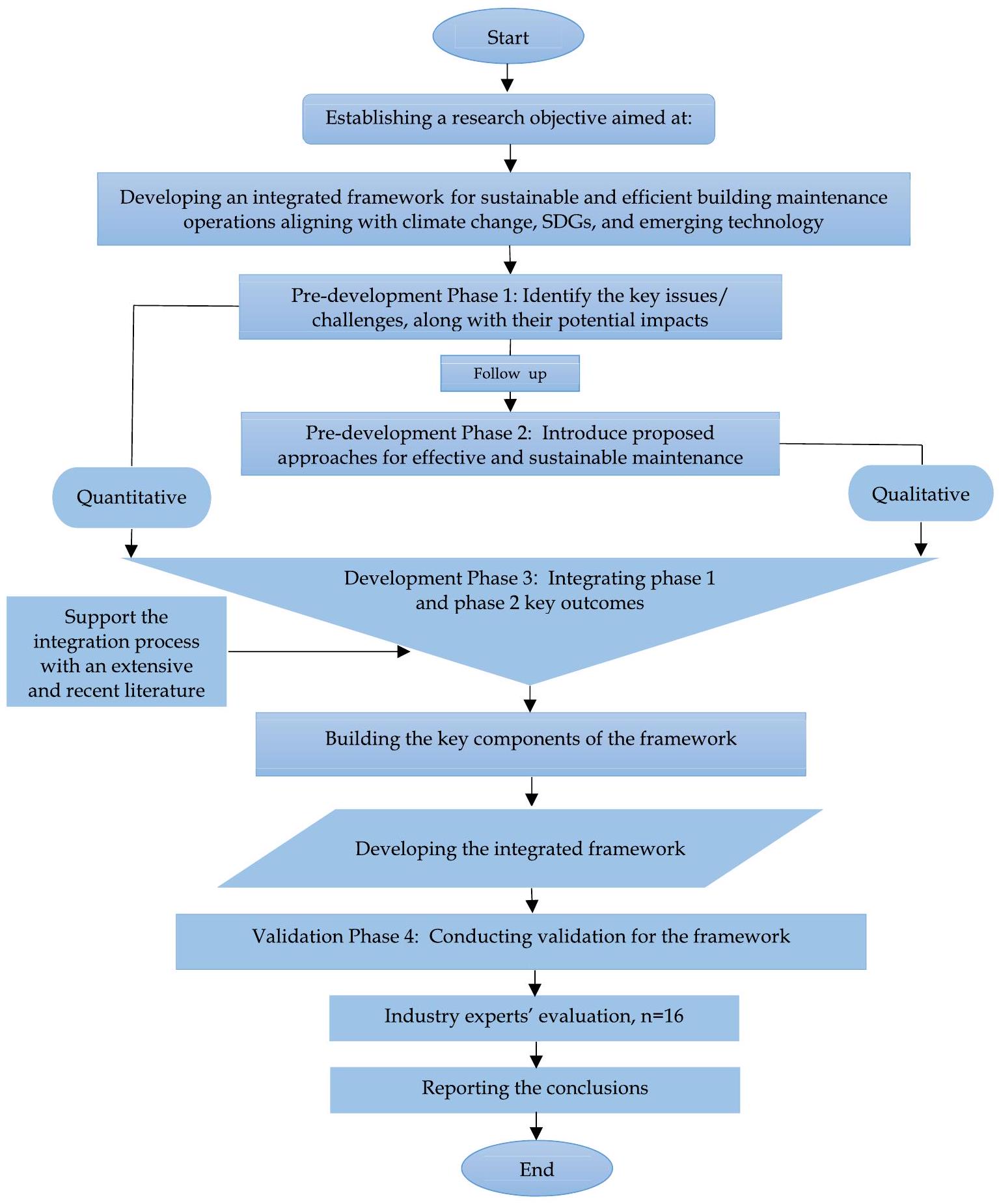

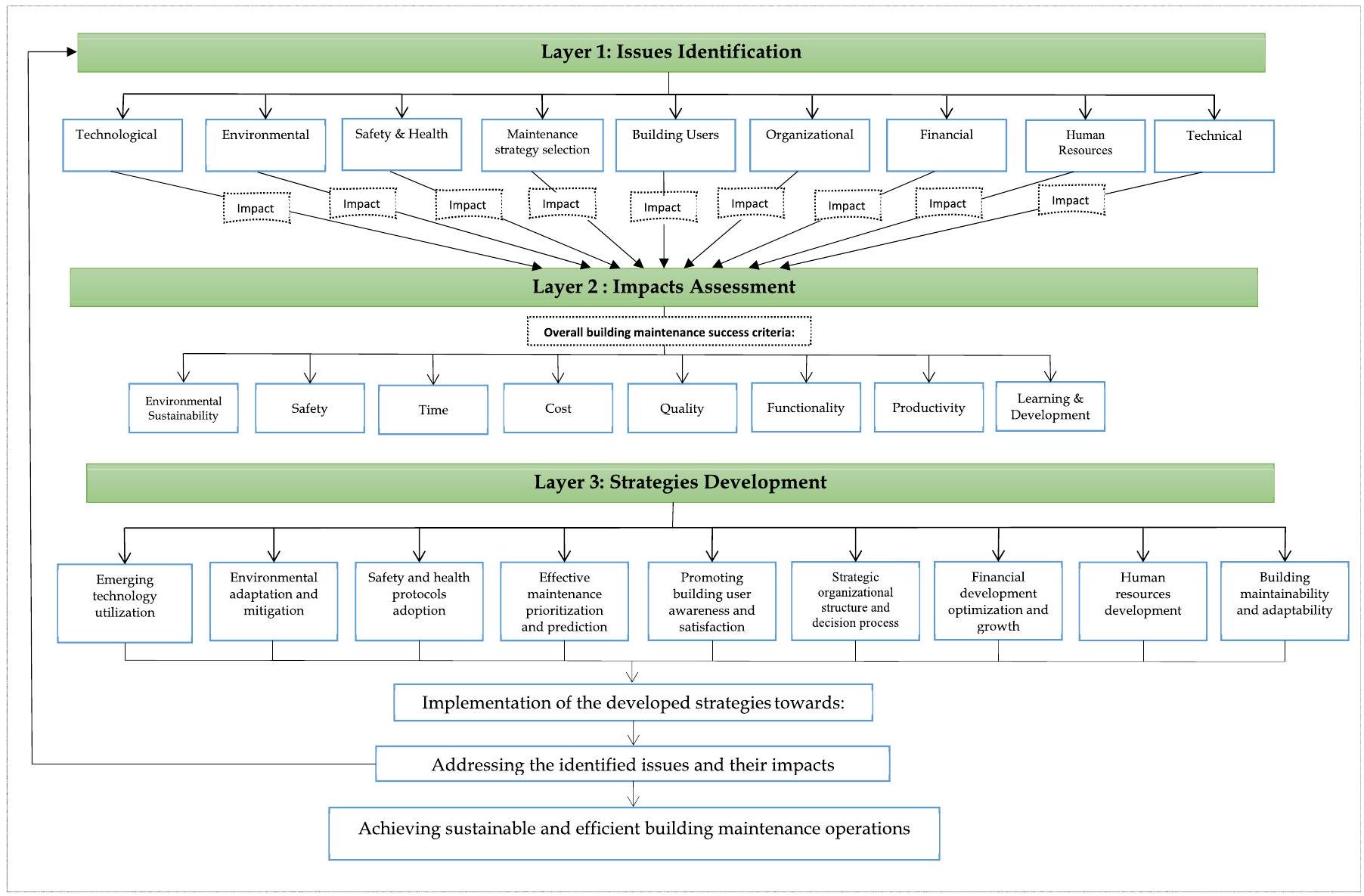

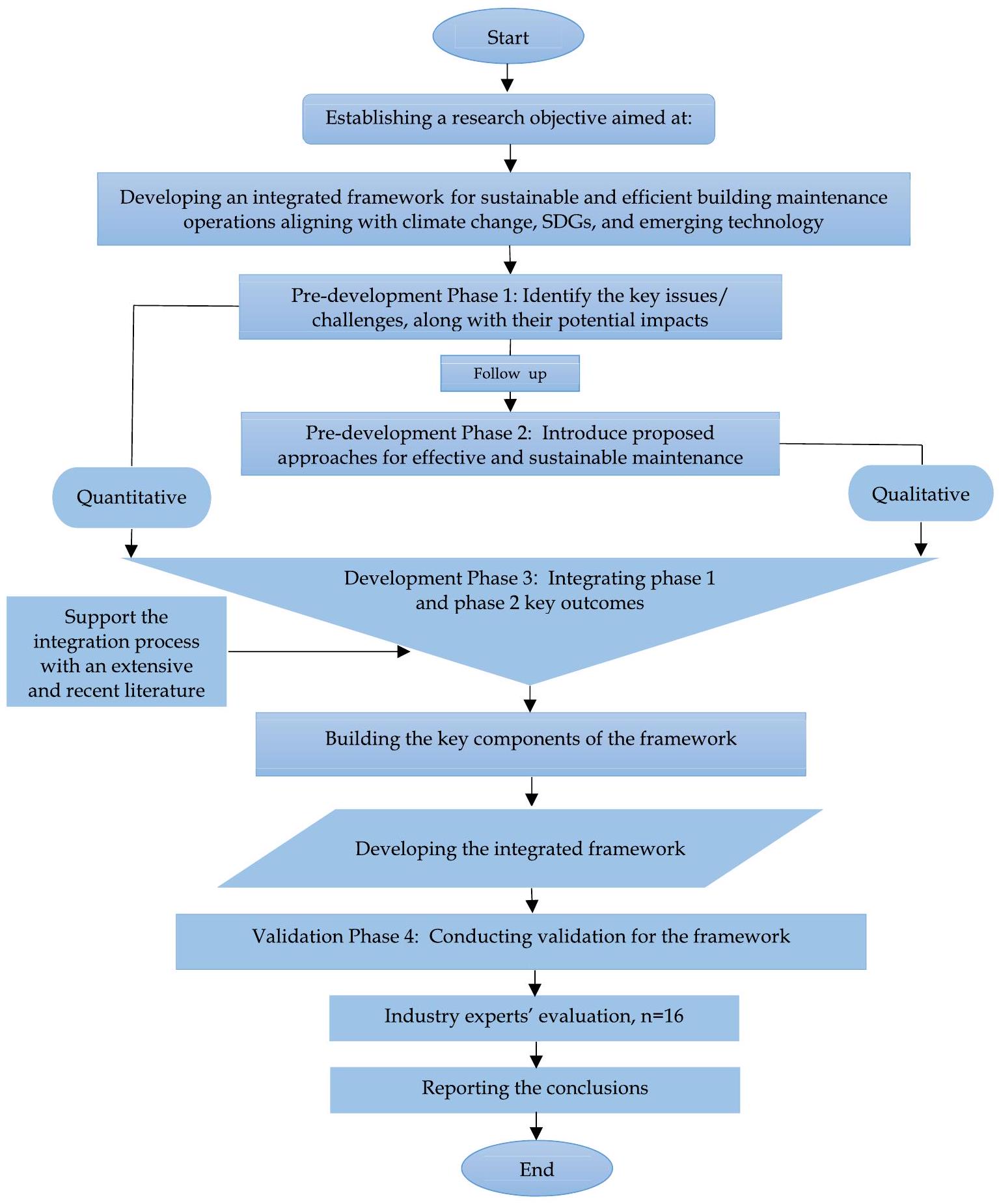

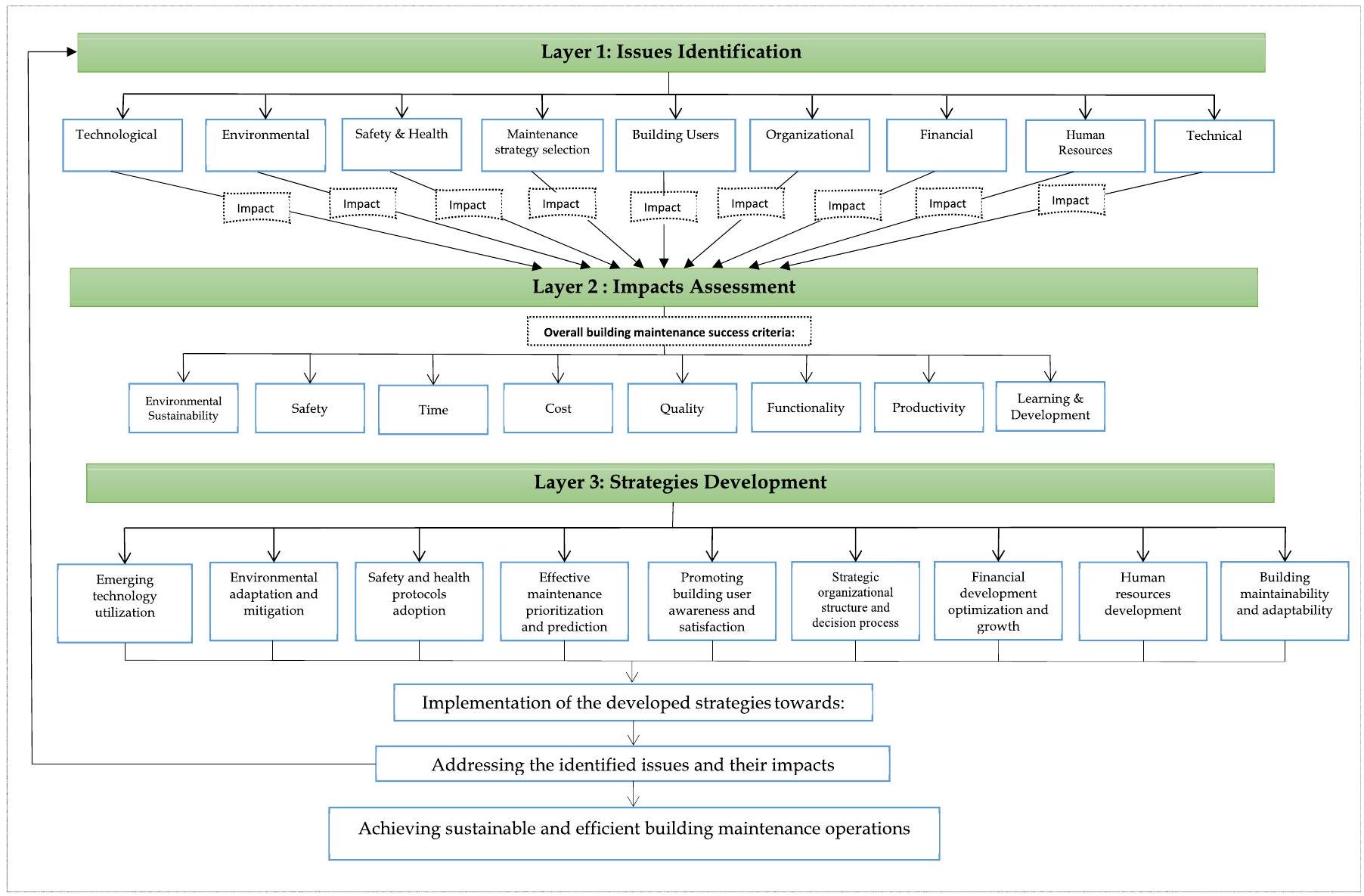

يمكن أن يؤدي تحسين تشغيل وصيانة المباني إلى تقليل انبعاثات الكربون واستهلاك الطاقة والتحديات البيئية الأخرى بشكل كبير، مع تعزيز الاستدامة. بينما تقدم الأدبيات الحالية أطرًا متنوعة، فإنها تركز بشكل أساسي على إجراءات صيانة المباني التقليدية وتتجاهل أهمية دمج الاستدامة وتغير المناخ والعوامل البيئية والتقنيات الناشئة. لمعالجة هذه الفجوة، طورت هذه الدراسة إطارًا شاملاً يلبي الاحتياجات الحالية والتحديات والأولويات المستقبلية. يتماشى الإطار المتكامل لعمليات صيانة المباني مع أهداف التنمية المستدامة (SDGs) والتخفيف من تغير المناخ والتكيف معه، واعتماد التكنولوجيا الناشئة، والحفاظ على الطاقة، فضلاً عن السلامة والمرونة والفعالية. شمل تطوير الإطار أربع مراحل: مراحل ما قبل التطوير 1 و2، مرحلة التطوير 3، ومرحلة التحقق 4. خلال هذه العملية، تم تحديد القضايا والتحديات الحالية، وتم تقييم الآثار، وتطوير الاستراتيجيات. يعمل الإطار كخريطة طريق لمعالجة هذه التحديات والمتطلبات في عمليات صيانة المباني المستقبلية، مما يساهم بشكل كبير في الأبعاد الثلاثة للاستدامة: البيئية والاجتماعية والاقتصادية. باختصار، تقدم هذه الدراسة تحليلًا شاملاً وعميقًا للقضايا الحالية والتحديات والتحسينات والفوائد المحتملة في عمليات صيانة المباني، مما يوفر دليلًا عمليًا لأصحاب المصلحة في الصناعة ويقدم مساهمة كبيرة في المعرفة الحالية.

1. المقدمة

تقليل الآثار البيئية [1]. في الواقع، فإن قطاع البناء مسؤول عن جزء كبير من استهلاك الطاقة، وانبعاثات غازات الدفيئة (GHG)، واستخدام الموارد. وفقًا لدراسات مختلفة ودوائر الطاقة، فإن المباني مسؤولة عن استهلاك ما يقرب من 40% من إجمالي الطاقة المستخدمة وإنتاج

| قائمة الاختصارات | دي تي | التوأم الرقمي | |

| التقييم البيئي | تقييم الأثر البيئي | ||

| أهداف التنمية المستدامة | أهداف التنمية المستدامة | إنترنت الأشياء | إنترنت الأشياء |

| الهدف 13 من أهداف التنمية المستدامة | العمل المناخي | تعلم الآلة | تعلم الآلة |

| الهدف 12 من أهداف التنمية المستدامة | الاستهلاك والإنتاج المسؤول | الذكاء الاصطناعي | الذكاء الاصطناعي |

| الهدف 11 من أهداف التنمية المستدامة | المدن والمجتمعات المستدامة | لCA | تقييم دورة الحياة |

| الهدف 9 من أهداف التنمية المستدامة | الصناعة والابتكار والبنية التحتية | عربي | الواقع المعزز |

| الهدف السابع من أهداف التنمية المستدامة | طاقة نظيفة وبأسعار معقولة | الواقع الافتراضي | الواقع الافتراضي |

| غازات الدفيئة | غازات الدفيئة | السيد | الواقع المختلط |

| تكييف الهواء | التدفئة والتهوية وتكييف الهواء | FDD | كشف الأعطال والتشخيص |

| نظام إدارة الصيانة المحوسب | أنظمة إدارة الصيانة المحوسبة | تحليل أنماط الفشل وتأثيراته | تحليل أنماط الفشل وآثاره |

| نموذج معلومات البناء | نمذجة معلومات البناء | SD | الانحراف المعياري |

في الأبعاد البيئية والاقتصادية والاجتماعية [3,15,19].

لذلك، يمكن استنتاج من الجوانب المذكورة أعلاه أن المباني القائمة تلعب دورًا حاسمًا في التنمية البيئية والاقتصادية والاجتماعية. بينما يمكن أن يؤدي تحسين استراتيجيات الصيانة إلى تقليل انبعاثات الكربون بشكل كبير، ومعالجة التحديات البيئية المختلفة، وإطالة عمرها [7,10]، فإن ممارسات الصيانة غير الفعالة يمكن أن يكون لها تأثيرات سلبية كبيرة على البيئة، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة، وزيادة استهلاك الطاقة، والاستخدام غير الفعال للمواد والموارد [3,8,9]. لذلك، يجب تحديث الأطر والنماذج التشغيلية التي تعمل عليها الصيانة لتكون استجابة للاحتياجات الحالية وقادرة على معالجة التحديات الحالية، بما في ذلك دمج أهداف التنمية المستدامة، وأبعاد الاستدامة، والقضايا البيئية.

a) دمج تغير المناخ، وأهداف التنمية المستدامة، والتكنولوجيا الناشئة بالكامل في إطار عمليات صيانة المباني.

b) تقديم إطار تشغيلي لصيانة المباني، لا سيما في سياق إجراءات الصيانة المنظمة،

تحقيق عمليات صيانة مباني مستدامة وفعالة. تقدم هذه الدراسة فهمًا جديدًا للترابطات بين عمليات صيانة المباني، والاعتبارات المناخية، وأهداف التنمية المستدامة، مما يوفر منظورًا شاملًا يعزز المعرفة في كل من صناعة البناء ومجالات التنمية المستدامة. وهذا يساهم في تعزيز فهمنا لكيفية مواءمة عمليات صيانة المباني بشكل استراتيجي مع القضايا الحالية، والتحديات، والتطورات، والجهود العالمية للاستدامة، لا سيما بالنسبة لمنظمات الصيانة، وأصحاب المصلحة، وغيرها من المنظمات البيئية ذات الصلة المعنية بصناعة البناء. من خلال تقديم خارطة طريق تمكن صناعة صيانة المباني من تحقيق تأثير إيجابي على ثلاثة أبعاد حاسمة من

الاستدامة – البيئية، والاجتماعية، والاقتصادية – وهذا يتضح من حقيقة أن الإطار المقترح لعمليات صيانة المباني في هذه الدراسة يتناول مجموعة من العوامل البيئية والاقتصادية والاجتماعية التي لها تأثير كبير على عالمنا. باختصار، تقدم هذه الدراسة إطارًا لا يعالج فقط الفجوة الحرجة في الدراسات الحالية، بل يوفر أيضًا خارطة طريق لعمليات صيانة المباني التي تستجيب للتحديات والتطورات الحالية، وتلبي الاحتياجات الحالية والمستقبلية، وتعزز استدامة المباني وسلامتها.

2. الأساليب

2.1. تطوير الإطار

2.2. التحقق من فعالية الإطار

وجهات نظرهم حول فعالية الإطار المقترح في تحقيق صيانة مباني مستدامة وفعالة تتماشى مع تغير المناخ، وأهداف التنمية المستدامة، والتقنيات الناشئة. استخدم الاستبيان مقياس ليكرت من خمس نقاط، حيث يمثل 1 “موافق بشدة”، و2 يمثل “موافق”، و3 يمثل “موافق قليلاً”، و4 يمثل “موافق”، و5 يمثل “موافق بشدة”، لجمع آراء الخبراء والحصول على رؤى قيمة. تم أخذ الأدوار الوظيفية، والخبرة المهنية، والمؤهلات، والخبرة الواسعة ذات الصلة لـ 16 خبيرًا يعملون في 16 منظمة/شركة صيانة في الصناعة الماليزية بعين الاعتبار بعناية خلال مشاركتهم. تم اختيار هؤلاء الخبراء، بما في ذلك رؤساء الأقسام/رؤساء الوحدات، ومستشاري الاستدامة، ومديري الصيانة، والمهندسين الكبار، ومديري المنظمات، والمهندسين المحترفين، وخبراء التكنولوجيا المحترفين، ومديري المرافق، ومقدري الكميات الكبار، ونواب مديري المنظمات، ومديري الإدارة، كمطلعين رئيسيين بناءً على خصائصهم الموثوقة، كما أوصى سوبياكتو وآخرون [29].

3. المكونات الرئيسية للإطار

3.1. الطبقة 1: تحديد القضايا

3.1.1. القضايا التكنولوجية

3.1.1.1. تنفيذ نمذجة معلومات المباني (BIM). على الرغم من أن BIM يوفر تمثيلًا رقميًا شاملاً للمبنى وأنظمته، والتي يمكن استخدامها لتتبع وإدارة بيانات الأصول، وجداول الصيانة، وأوامر العمل، إلا أن اعتماد واستخدام BIM خلال عمليات الصيانة لا يزال بطيئًا بسبب العديد من التحديات. للبدء، فإن غياب احتياجات المعلومات الواضحة التي تدعم استخدام BIM، بالإضافة إلى مشكلات التوافق بين BIM والأنظمة المختلفة المستخدمة في المراحل السابقة من بناء مثل التصميم والبناء. لذلك، فإن استخدام BIM خلال عمليات الصيانة في مبنى قائم حيث لم يتم استخدامه خلال مرحلة البناء والتصميم يمثل تحديًا. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن المقاييس الرئيسية التي يمكن

3.1.1.2. تنفيذ التوأم الرقمي (DT). تم تعريف DT من قبل رادزي وآخرون [35] بأنه “مفهوم يتضمن جمع بيانات في الوقت الحقيقي لمراقبة أصل مادي وتحسين الكفاءة التشغيلية، مما يمكّن من الصيانة التنبؤية واتخاذ قرارات أفضل”. بعض الباحثين والممارسين في عمليات صيانة المباني لديهم فكرة استخدام BIM كأساس لإنشاء DT لمبنى. DT لديه

إمكانية تعزيز أداء المباني بشكل فعال ضمن نطاق عمليات الصيانة. ومع ذلك، فإن تنفيذ تقنية التوأم الرقمي في عمليات صيانة المباني يمكن أن يكون تحديًا نظرًا لعدم وجود أساسات نمذجة معلومات المباني في عدد كبير من المباني الحالية. وبالتالي، فإن المباني التي لديها أدوات جمع البيانات وتحليلها اللازمة ستكون لديها القدرة على دعم إنشاء وصيانة التوأم الرقمي. كما تحتاج أيضًا إلى التأكد من أن التوأم الرقمي متكامل بشكل صحيح مع أنظمة المباني الأخرى وأن الأفراد المعنيين مدربون على استخدام التكنولوجيا بشكل فعال. أشار رادزي وآخرون [35] إلى أن دمج نماذج نمذجة معلومات المباني كما هو مصمم وكما هو مبني في أنظمة معلومات التوأم الرقمي من شأنه تحسين عمليات الصيانة. بينما أشار زهاو وآخرون [11] إلى أن إنترنت الأشياء، وتعلم الآلة، والذكاء الاصطناعي، وتقنية البلوك تشين، وتحليلات البيانات الضخمة يمكن استخدامها لبناء التوأم الرقمي وأن مكون التصور للتوأم الرقمي يعتمد على نموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد غني بالمعلومات تم إنشاؤه من عملية نمذجة معلومات المباني، بينما يتم الحصول على الحالة الفعلية للمبنى من شبكات المستشعرات الذكية المختلفة في عمليات تشغيل وصيانة المباني. ومع ذلك، فإن استخدام تقنية التوأم الرقمي في عمليات صيانة المباني لا يزال في مراحله الأولى، ولكن هناك إمكانيات كبيرة للتطبيقات المستقبلية. على سبيل المثال، يمكن استخدام تقنية التوأم الرقمي لمراقبة أداء أنظمة المباني في الوقت الفعلي وتوليد أوامر العمل للصيانة والإصلاحات تلقائيًا. يمكن أيضًا استخدامها لمحاكاة تأثير أنشطة الصيانة والإصلاح على أنظمة المباني قبل تنفيذها، مما قد يساعد في تقليل الاضطراب على شاغلي المبنى. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن تقنيات مثل إنترنت الأشياء، وتعلم الآلة، والذكاء الاصطناعي يمكن استخدامها بشكل منفصل أو متكامل مع نمذجة معلومات المباني لتحسين مهام الصيانة بشكل كبير، وليس فقط محدودًا لبناء التوأم الرقمي.

3.1.1.3. تنفيذ أدوات الكشف عن الأعطال والتشخيص. الكشف

عن الأعطال أمر أساسي في عمليات صيانة المباني، حيث يسمح الكشف المبكر عن المشكلات المحتملة باتخاذ إجراءات تصحيحية سريعة لتجنب تعطل أجزاء المبنى والمواد والمعدات، وتقليل وقت التوقف، وتعزيز الأداء العام للمبنى [16]. في هذا السياق، تم تقديم تكنولوجيا متقدمة لأدوات الكشف عن العيوب أو الأعطال في المباني. في السنوات الأخيرة، كانت هناك تقدمات كبيرة في أساليب الكشف عن العيوب في المباني والتشخيص والتفتيش [3]، وأهمية تقدم هذه الأساليب واضحة في كيفية استخدام هذه التكنولوجيا لتحديد العيوب في جميع المباني الحالية ودفعها نحو طريقة أكثر أتمتة وأمانًا للكشف عن العيوب وتقييمها. على سبيل المثال، تعتبر التصوير الحراري أداة وتقنية غير مدمرة يمكن استخدامها للمساعدة في تحديد المصادر الشائعة لفقدان الحرارة في المباني الحالية والجديدة بالإضافة إلى الكشف عن العيوب في الواجهات، وخاصة عيب التشقق، مثل تلك الناتجة عن التهوية والتوصيل [36،37].

3.1.2. القضايا البيئية

مثل 55% في المملكة المتحدة، و48% في الولايات المتحدة، و52% في إسبانيا. لذلك، فإن مراقبة سلوك أنظمة التكييف بعد الإشغال أمر بالغ الأهمية [10]. يمكن أن تؤدي الصيانة السيئة لأنظمة التكييف إلى زيادة استهلاك الطاقة، والذي غالبًا ما يكون مصحوبًا بارتفاع انبعاثات الكربون، بينما يمكن أن تؤدي الصيانة الفعالة المنتظمة لأنظمة التكييف إلى تقليل استهلاك الطاقة بشكل كبير، مما يؤدي إلى انخفاض تكاليف التشغيل وتقليل انبعاثات الكربون.

3.1.2.2. شيخوخة المباني. يواجه عدد كبير من مخزون المباني الحالية حول العالم مشكلات شيخوخة. على سبيل المثال، في هونغ كونغ، فإن الغالبية العظمى من المباني تزيد أعمارها عن 30 عامًا، مع أكثر من 5000 مبنى سكني ومركب تزيد أعمارها عن 50 عامًا [15]. واحدة من الأسباب الرئيسية لشيخوخة مخزون المباني هي أن العديد من المباني تم بناؤها خلال طفرة بناء حدثت في العقود الخمسة الماضية. غالبًا ما تم بناء هذه المباني باستخدام مواد وتقنيات أصبحت الآن قديمة، وقد لا تكون قادرة على تحمل التآكل الناتج عن الاستخدام اليومي على المدى الطويل [9]. نتيجة لذلك، تتطلب هذه المباني القديمة المزيد من أعمال الصيانة، وتميل إلى استهلاك المزيد من الطاقة، وتوليد كميات أكبر من نفايات الصيانة

3.1.2.3. غياب تقييم دورة الحياة (LCA). يمكن أن يؤدي غياب تقييم دورة الحياة عند التعامل مع الصيانة في المباني القديمة إلى اتخاذ قرارات خاطئة تؤدي إلى زيادة استهلاك الطاقة والنفايات والمشاكل البيئية [1]. على سبيل المثال، اختيار استراتيجية صيانة للحفاظ على المباني دون تقييم الأثر البيئي لن تكون الخيار الأكثر كفاءة على المدى القصير، لكنها قد تؤدي إلى زيادة استهلاك الطاقة ونفايات الصيانة على المدى الطويل. في الوقت الحالي، هناك نقص في القرارات الصحيحة بشأن صيانة أو تجديد المباني القديمة بناءً على نتائج تقييم الأثر البيئي. ومع ذلك، يمكن أن يساعد إجراء تقييم دورة الحياة في تحديد استراتيجية الصيانة الأكثر ملاءمة أو قرار آخر مثل التجديد للمباني القديمة التي تأخذ في الاعتبار دورة حياة المبنى بالكامل وتأثيره على البيئة [44]. مع تقييم دورة الحياة، سيصبح من الواضح أن الأساليب الوقائية أو التصحيحية للصيانة، بالإضافة إلى التجديد، ضرورية في تقليل الآثار البيئية للمباني.

3.1.2.4. تأثير تغير المناخ على صيانة المباني. لقد كان لتغير المناخ أو من المتوقع أن يكون له تأثيرات كبيرة على قطاع المباني، لا سيما من حيث صيانة وإصلاح المباني، بما في ذلك مرونة مواد المباني ومكوناتها، فضلاً عن رفاهية وسلامة مستخدمي المباني. لقد تأثرت صيانة وإصلاح المباني بشكل كبير بتغير المناخ، بما في ذلك ارتفاع درجات الحرارة العالمية وأنماط الطقس المتطرفة، حيث أصبحت المباني أكثر عرضة للتلف نتيجة أحداث مثل الأمطار الغزيرة، والفيضانات، والعواصف، وموجات الحرارة، والحرائق البرية. على سبيل المثال، مع ارتفاع درجات الحرارة، سيكون هناك طلب أكبر على أنظمة التكييف والتبريد، ومن المتوقع أن يرتفع استخدام الطاقة للتبريد.

زيادة بمقدار

3.1.3. قضايا السلامة والصحة

3.1.3.2. خطر الصيانة المؤجلة. يمكن أن يكون لتأخير صيانة عيوب المباني تأثيرات كبيرة على سلامة وصحة شاغلي المباني وكذلك على البيئة. يمكن أن تؤدي الفشل الهيكلي بسبب الإهمال في الفحص والصيانة إلى إصابات خطيرة أو وفاة مستخدمي المبنى، بينما يمكن أن تنشأ مخاطر كهربائية أيضًا بسبب أنظمة كهربائية غير مُصانة بشكل جيد. أيضًا، التأثير السلبي على البيئة هو مصدر قلق آخر. على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن يؤدي تلف المياه الناتج عن تسرب الأسطح أو أنظمة السباكة إلى نمو العفن، مما يمكن أن يكون له آثار سلبية على الجهاز التنفسي ويؤدي إلى أمراض خطيرة بالإضافة إلى جودة الهواء الداخلي السيئة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن تنتشر هذه المواد الخطرة في جميع أنحاء المبنى إذا لم يتم التعامل معها في الوقت المناسب، مما يؤثر على عدد أكبر من الشاغلين. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن يؤدي تأخير الصيانة إلى تفاقم

عيوب البناء مع مرور الوقت، مما يؤدي إلى إصلاحات أكثر شمولاً تكون مكلفة وتسبب ضرراً للبيئة

3.1.4. قضايا اختيار استراتيجية الصيانة

3.1.4.2. نقص اعتماد الصيانة الوقائية. حاليًا، تميل معظم منظمات الصيانة إلى الاعتماد بشكل كبير على الصيانة التصحيحية كنهجها الأساسي. يمكن أن يؤدي هذا النهج إلى تقديم خدمة رديئة، وانخفاض رضا المستخدمين، وتراكم متأخرات الصيانة المستمرة [3]. أيضًا، هذا النهج تفاعلي ومكلف لأنه يتطلب إصلاحات عاجلة بعد تعطل عنصر ما، مما قد يتسبب في مزيد من الأضرار للمبنى، وقد يجلب أيضًا مخاطر للمستخدمين لأنه يعالج فقط المشكلة المحددة دون معالجة السبب الجذري. بينما يُعتبر النهج الأكثر فعالية والذي يتم تشجيعه على نطاق واسع هو الصيانة الوقائية، حيث يتضمن الفحوصات الروتينية وأنشطة الصيانة لتحديد وإصلاح المشكلات قبل أن تصبح مشاكل كبيرة، خاصة في أنظمة التدفئة والتهوية وتكييف الهواء (HVAC) التي يجب أن تكون دائمًا في حالة ممتازة لتجنب استهلاك الطاقة [3]. بينما تتضمن الصيانة المعتمدة على الحالة تخطيط الفحص، فإن الطبيعة التنبؤية لهذه الاستراتيجية للصيانة تقدم إمكانيات كبيرة لتحسين الدقة. إنها مناسبة بشكل خاص لعناصر المبنى التي يمكن مراقبة حالتها وأدائها بشكل فعال [53]. وبالتالي، يجب أن يستند اختيار استراتيجية الصيانة المثلى إلى أداة فعالة يمكن أن تحلل معايير متنوعة، بما في ذلك السلامة، والتكلفة، والأثر على المبنى، والمستخدمين، والبيئة.

3.1.5. قضايا مستخدمي المباني

عند النظر في فحص التفاعلات بين المستخدمين وصيانة المباني، على الرغم من أن الصيانة المناسبة لأنظمة المباني تلعب دورًا حاسمًا في كفاءتها الطاقية واستدامة المبنى ككل [13،57]. ومع ذلك، عندما يفتقر مستخدمو المباني إلى الوعي أو المعرفة حول أهمية صيانة المباني، بما في ذلك أهمية الإبلاغ عن مشكلات الصيانة على الفور أو الالتزام بإجراءات الصيانة، يمكن أن يؤدي ذلك إلى إهمال أو تجاهل لاحتياجات الصيانة، مما يؤدي إلى تأخير أو عدم كفاية إجراءات الصيانة وفي النهاية يؤثر على الحالة العامة وأداء المبنى. لاحظ هاوشده وآخرون [3] أن المستخدمين الذين لديهم مستوى عالٍ من الوعي حول صيانة المباني يظهرون سلوكًا مسؤولًا من خلال الحفاظ على سلامة المباني للاحتلال، والحفاظ على المباني من التدهور، والإبلاغ عن الأعطال على الفور، مهما كانت صغيرة. من ناحية أخرى، يميل المستخدمون الذين يفتقرون إلى الوعي بأهمية صيانة المباني والحفاظ على المبنى ومرافقه في حالة جيدة إلى الفشل في اتباع جداول الصيانة، أو إساءة استخدام أو استخدام مرافق المبنى بشكل غير صحيح، أو تجاهل تعليمات الصيانة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن يؤدي عدم الامتثال لبروتوكولات الصيانة إلى تسريع عمر مكونات المبنى، وزيادة استهلاك الطاقة، وتقليل كفاءة النظام. لذلك، يمكن أن تؤثر سلوكيات المستخدمين، مثل الاستخدام غير المبالي للمرافق، أو التعامل غير الصحيح مع المعدات، أو عدم مراعاة احتياجات الصيانة، بشكل كبير على حالة وأداء أنظمة المباني. وفقًا لأو-يونغ وآخرون [58]، قد تشير مكونات المبنى المتدهورة إلى مستوى العناية الممنوحة للمرافق من قبل مستخدمي المباني بدلاً من فعالية عمليات الصيانة. في الواقع، قد يظهر مستخدمو المباني إهمالًا أو عدم مبالاة تجاه صيانة المباني، معتبرين أنها مسؤولية تعود فقط إلى فريق الصيانة. يمكن أن يؤدي ذلك إلى نقص في الإبلاغ عن مشكلات الصيانة وفشل في التواصل حول احتياجات الصيانة. بينما يمكن أن يمنع الإبلاغ في الوقت المناسب عن عيوب المباني من تفاقم العيوب، وتجنب تكاليف صيانة إضافية بسبب مزيد من الأضرار، وتعزيز استدامة المباني [16].

3.1.5.2. فجوة التواصل بين إدارة الصيانة والمستخدمين. التواصل الضعيف بين مستخدمي المباني وفريق إدارة الصيانة، مما قد يؤدي إلى تقارير غير كافية وحل مشكلات الصيانة [19]. قد يواجه المستخدمون فجوات في التواصل تعيق إجراءات الصيانة الفعالة وفي الوقت المناسب، خاصة في الإبلاغ عن العيوب إلى إدارة صيانة المباني والوقت المطلوب للإصلاحات [59]. يمكن أن تؤدي الانهيارات في التواصل والتحديات في التنسيق بين مستخدمي المباني/الشاغلين وموظفي الصيانة إلى تأخيرات في معالجة احتياجات الصيانة وقد تؤدي إلى مزيد من الأضرار للمبنى. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن نقص ملاحظات مستخدمي المباني المقدمة من قبل منظمات الصيانة أو إدارة المباني هو تحدٍ آخر. في الواقع، تعتبر ملاحظات مستخدمي المباني ضرورية لممارسات الصيانة المناسبة حيث تتيح للمستخدمين تقديم اقتراحات، وملاحظات، واهتمامات، بينما توفر أيضًا وسيلة لإدارة الصيانة لتحسين خدماتها [16]. تحدٍ آخر قد يواجهه مستخدمو المباني في المشاركة الإيجابية في عمليات صيانة المباني هو تعقيد عملية الصيانة نفسها [50]. يمكن أن تكون تعقيدات عملية الصيانة ومتطلباتها تحديات للمستخدمين الجدد، مما يؤدي إلى الارتباك، وسوء الفهم، وعدم الامتثال لإجراءات الصيانة. لذلك، يواجه مستخدمو المباني أنفسهم بعض التحديات التي تحد من تفاعلهم الإيجابي نحو تنفيذ صيانة المباني بنجاح.

3.1.6. قضايا تنظيمية

المسؤوليات، التي تعتبر ضرورية لتقليل الفوضى وضمان النجاح في صيانة المباني. في الواقع، بدون هيكل محدد جيدًا، قد يواجه الموظفون صعوبات في فهم أدوارهم ومسؤولياتهم، مما يؤدي إلى الارتباك وعدم الكفاءة، ونتائج سلبية محتملة. يمكن أن يؤدي ذلك أيضًا إلى جدولة غير صحيحة لأوامر صيانة العمل، خاصة مع زيادة الطلب على صيانة المباني. في الواقع، كان هناك ارتفاع كبير في الطلب على أعمال صيانة المباني، المباني المتوسطة الحجم (بين 464.5 و

3.1.6.2. اختيار مقاولين صيانة غير مؤهلين. تعتبر قدرات اتخاذ القرار والمعالجة لدى منظمة الصيانة في اختيار مقاولين صيانة مؤهلين عندما تقدم المنظمة عطاءات للمقاولين قضايا حاسمة. يؤكد هاوشده وآخرون [19] أن اتخاذ قرارات صيانة مناسبة ومستنيرة يجب أن يكون أولوية. ومع ذلك، عندما يتم اختيار مقاولين غير مؤهلين، يمكن أن يؤدي ذلك إلى أعمال صيانة دون المستوى وعواقب سلبية. لذلك، من الضروري أن تمتلك منظمات الصيانة عملية شاملة لتقييم المقاولين في عملياتها لضمان منح العقود فقط للمقاولين المؤهلين. في معظم الحالات، يعتمد تفضيل المنظمة في منح العقود فقط على أقل سعر للعطاء، مما لا يتماشى مع أفضل الممارسات لصيانة المباني المستدامة والفعالة والآمنة [3،19]. على الرغم من أنه يُقترح أن تُمنح العقود لمقاولين مؤهلين يستوفون معايير مهمة أخرى، مثل وجود سجل جيد في تنفيذ صيانة مستدامة وآمنة في المباني. ستعزز هذه الآلية أن الاستدامة والسلامة هما عاملان حاسمان في صيانة المباني ويجب أن يؤخذوا في الاعتبار جنبًا إلى جنب مع التكلفة. بالإضافة إلى المخاوف المتعلقة باستخدام مواد دون المستوى، يمكن أن تؤدي ممارسة اختيار أقل مزايد مع التركيز على السعر أيضًا إلى توظيف المقاولين لعمال غير مهرة بأجور منخفضة. يمكن أن يؤثر ذلك بشكل كبير على جودة واستدامة وسلامة صيانة المباني.

3.1.6.3. نقص في حفظ السجلات والتوثيق بشكل صحيح. إن حفظ السجلات والتوثيق بشكل صحيح مهم لتتبع أنشطة الصيانة، ومراقبة الأداء، واتخاذ قرارات مستنيرة [50]. يمكن أن تؤدي سجلات الصيانة والتوثيق التي لا يتم الحفاظ عليها بدقة أو التي تكون غير مكتملة إلى صعوبات في تتبع تاريخ الصيانة وتقييم فعالية عمليات الصيانة. على وجه الخصوص، يمكن أن تؤدي السجلات غير الدقيقة لممارسات معلومات أنظمة المباني إلى تكاليف غير ضرورية وعدم كفاءة [13،60]. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تؤدي هذه الممارسة إلى عمليات شاقة، وانخفاض فعالية الصيانة، وارتفاع تكاليف الصيانة. لأن منظمات الصيانة لا تزال تعتمد على توثيق ورقي واسع، مما يجلب تحديات من حيث الحفظ ولا يوفر المعلومات اللازمة بشكل فعال لفرق الصيانة، كما أشار إليه تشين وآخرون [61]. علاوة على ذلك، فإن نقص نظام اتصال رقمي موحد بين موظفي الصيانة ومديري الصيانة وغيرهم من أصحاب المصلحة يؤدي إلى سجلات غير صحيحة أو مفقودة لعمليات الصيانة [3،50]. في الواقع، إن التواصل بين أصحاب المصلحة في صيانة المباني طوال عملية الصيانة يولد كميات هائلة من مصادر البيانات التي غالبًا ما تكون غير مرتبة وغير منظمة وصعبة الإدارة، مما يمكن أن يعيق أعمال الصيانة [11،19]. ومع ذلك، فإن عددًا كبيرًا من الصيانة

لم تقم المنظمات بعد باستخدام التكنولوجيا بشكل كامل لإدارة البيانات بفعالية من أجل تحسين التوافق وتقديم رؤى قيمة لتعزيز عمليات صيانة المباني، مما يؤدي إلى مهام يدوية تستغرق وقتًا طويلاً، وزيادة احتمالية حدوث أخطاء بشرية، وانخفاض الكفاءة في تقديم الصيانة.

3.1.6.4. غياب أقسام مخصصة للاستدامة والبيئة. على الرغم من وجود العديد من الأقسام/الوحدات تحت منظمات صيانة المباني، مثل الشراء، والعقود، والهندسة المعمارية، وضمان الجودة، ومراقبة الجودة. إلا أنه يفتقر إلى أقسام/وحدات مخصصة للاستدامة والبيئة، فضلاً عن السلامة والصحة، وهي جوانب حاسمة في عمليات صيانة المباني. وبالتالي، فإن دمج تقييم الاستدامة والبيئة في عمليات صيانة المباني يفتقر حالياً، كما أشار أديغوريولا وآخرون [20] وونغ وزو [62]، وهو أيضاً مفقود بين الأقسام الداخلية لمنظمات الصيانة، كما أشار هاوشده وآخرون [16]. يمكن أن تركز قسم الاستدامة والبيئة على تقييم ومراقبة تنفيذ الممارسات المستدامة في صيانة المباني، مثل كفاءة الطاقة، والحفاظ على المياه، وتقليل النفايات، وإعادة الاستخدام والتدوير. يمكن أن يكون قسم السلامة والصحة مسؤولاً عن ضمان الامتثال للوائح الصحة والسلامة المهنية، وتطوير وتنفيذ بروتوكولات السلامة، وإجراء فحوصات السلامة، وتقديم التدريب لطاقم الصيانة حول إجراءات السلامة.

3.1.7. قضايا الموارد البشرية

3.1.7.2. نقص مبادئ التكامل للتنمية المستدامة في إدارة الموارد البشرية. يمكن أن يؤدي نقص الوعي بممارسات الصيانة المستدامة ومبادئ التنمية المستدامة إلى

فرص ضائعة لدمج الممارسات البيئية المستدامة خلال أعمال الصيانة. يمكن أن يؤثر ذلك على المستوى العام للاستدامة البيئية أثناء تنفيذ مهام الصيانة، خاصة عندما يكون هناك نقص في الاعتبار للتنمية المستدامة ضمن إدارة الموارد البشرية [3،64]. يمكن أن يؤدي ذلك إلى تنفيذ غير مثالي للممارسات المستدامة، مثل تقليل النفايات، والمشتريات الخضراء، مما يمكن أن يؤثر على معايير تقييم نجاح الصيانة، مثل الاستدامة البيئية وأهداف الاستدامة على المدى الطويل [10،13]. وبالتالي، يمكن أن يؤدي غياب دمج مبادئ الاستدامة في إدارة الموارد البشرية إلى تدريب غير كافٍ وفرص تطوير مهني محدودة تتعلق بممارسات صيانة المباني المستدامة. في النهاية، يمكن أن يقيّد ذلك قدرة موظفي الصيانة على تنفيذ ممارسات الصيانة المستدامة بفعالية والبقاء على اطلاع بأحدث التطورات في الاستدامة.

3.1.8. القضايا المالية

3.1.8.2. تخصيص ميزانية غير فعالة وفعالية التكلفة. عادةً ما يكون نقص تخصيص الميزانيات المناسبة أمرًا حاسمًا لصيانة المباني الفعالة [13،20]. لا يزال تخصيص ميزانية الصيانة يمثل تحديًا لأنه لا يوجد معيار شامل للتكلفة وغالبًا ما يكون من الصعب تحديد التكلفة الدقيقة لأعمال الصيانة، مثل الإصلاحات، والاستبدالات، والأنشطة الداخلية للصيانة، مما يجعل من الصعب تخصيص الأموال لكل مبنى بشكل متساوٍ [19]. نتيجة لذلك، تواجه بعض المباني الإهمال من قبل منظمات الصيانة بسبب قيود الميزانية ونقص التوزيع النظامي لميزانيات الصيانة [54]. في الواقع، تكون معظم منظمات صيانة المباني عادةً مسؤولة عن صيانة عدة مباني، مع ميزانية واحدة مخصصة لجميعها [3]. ومع ذلك، في العديد من الحالات، ينتهي الأمر ببعض المباني إلى الإهمال بسبب تخصيص الميزانية غير الفعال للصيانة. علاوة على ذلك، فإن نقص أهمية عمليات الشراء المناسبة، بما في ذلك الحصول على عروض تنافسية والتفاوض على العقود، لضمان خدمات صيانة فعالة من حيث التكلفة وجودة. يمكن أن يؤدي نقص النزاهة والشفافية في ممارسات النفقات إلى مشكلات مثل سوء استخدام الأموال، ونقص المساءلة، ومخاطر عدم الامتثال القانوني والتنظيمي. أيضًا، نقص التقارير والتحليلات المالية، مما يمكن أن يؤثر على اتخاذ القرار وتخصيص الموارد لصيانة المباني. أبرز أديغوريولا وآخرون [20]، وبوكوń وتشارنيغوفسكا [66]، وهاواشده وآخرون [3] أهمية دقة تقارير النفقات

والتحليل في تقييم تكاليف الصيانة، وتحديد اتجاهات التكاليف، واتخاذ قرارات مستنيرة بشأن تخصيص الميزانية، مما يساهم جميعه في تحقيق فعالية تكاليف الصيانة.

3.1.9. القضايا التقنية

3.1.9.2. فشل أنظمة المباني بسبب مواصفات التصميم والتركيب غير السليمة. قضية مهمة يمكن أن تنشأ أثناء عملية صيانة المباني هي فشل أنظمة المباني، والذي يمكن أن يحدث بسبب عوامل مثل تعطل التحكم في نظام التدفئة والتهوية وتكييف الهواء (HVAC) والمواصفات غير السليمة للاحتياجات المستقبلية خلال مرحلة تصميم أو بناء المبنى [69]. يمكن أن يؤدي هذا الفشل إلى تحديات كبيرة خلال مرحلة التشغيل والصيانة، مما يتطلب تعديلات أو إصلاحات مكلفة. وبالتالي، يمكن أن تؤدي أنظمة المباني التي لم يتم تصميمها أو تحديدها بشكل صحيح خلال مرحلة البناء الأولية إلى عدم الكفاءة أثناء ممارسات الصيانة، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة التكاليف وتمديد فترة التعطل. علاوة على ذلك، فإن عدم مراعاة الاستخدام أو المتطلبات المستقبلية للمبنى خلال المراحل المبكرة يمكن أن يؤثر أيضًا على عمليات الصيانة، مما يؤدي إلى ممارسات صيانة غير فعالة وزيادة التكاليف عندما تكون التعديلات أو الترقيات مطلوبة لاحقًا [16]. وهذا يبرز أهمية اعتماد نهج شامل لتصميم المباني ومواد البناء، والذي يأخذ في الاعتبار الاحتياجات طويلة الأجل لمرحلة صيانة المبنى فضلاً عن رفاهية شاغليه.

3.2. الطبقة 2: تقييم الآثار

استنادًا إلى ثمانية معايير شاملة كما حددها هاوشده وآخرون [13]. تأخذ هذه المعايير في الاعتبار الاحتياجات المستقبلية والاتجاهات الحالية، بما في ذلك جوانب الاستدامة، وتنسق الجهود مع الأهداف التنموية القصيرة والطويلة الأجل، والتي تشمل الاستدامة البيئية، والسلامة، والوقت، والتكلفة، والجودة، والوظائف، والإنتاجية، والتعلم والتطوير. تكشف النتائج عن تأثير سلبي كبير للقضايا المتعلقة بالمنظمات على نجاح صيانة المباني بشكل عام، مع تأثيرات كبيرة. أيضًا، كان هناك تأثير سلبي للقضايا المتعلقة بالتكنولوجيا، والقضايا التقنية، والقضايا المتعلقة بالموارد البشرية على نجاح صيانة المباني بشكل عام، مع تأثيرات صغيرة. بينما هناك تأثير سلبي كبير لسمات مستخدمي المباني والتمويل على نجاح صيانة المباني بشكل عام، هناك أيضًا تأثيرات متوسطة. من المهم أيضًا ملاحظة أن أهمية وحجم تأثير هذه القضايا أو العوامل على نجاح الصيانة لا يزال يعتمد على مستوى القدرات التكنولوجية، والموارد البشرية والمالية، وثقافة المستخدم، والإعداد البيئي، لذا يمكن تكرار تقييم نجاح صيانة المباني في إعدادات أخرى لتقييم مدى تأثير تلك القضايا المحددة على تقديم نجاح صيانة المباني ضمن تلك الإعدادات، لا سيما بالنسبة للقضايا البيئية والسلامة والصحة.

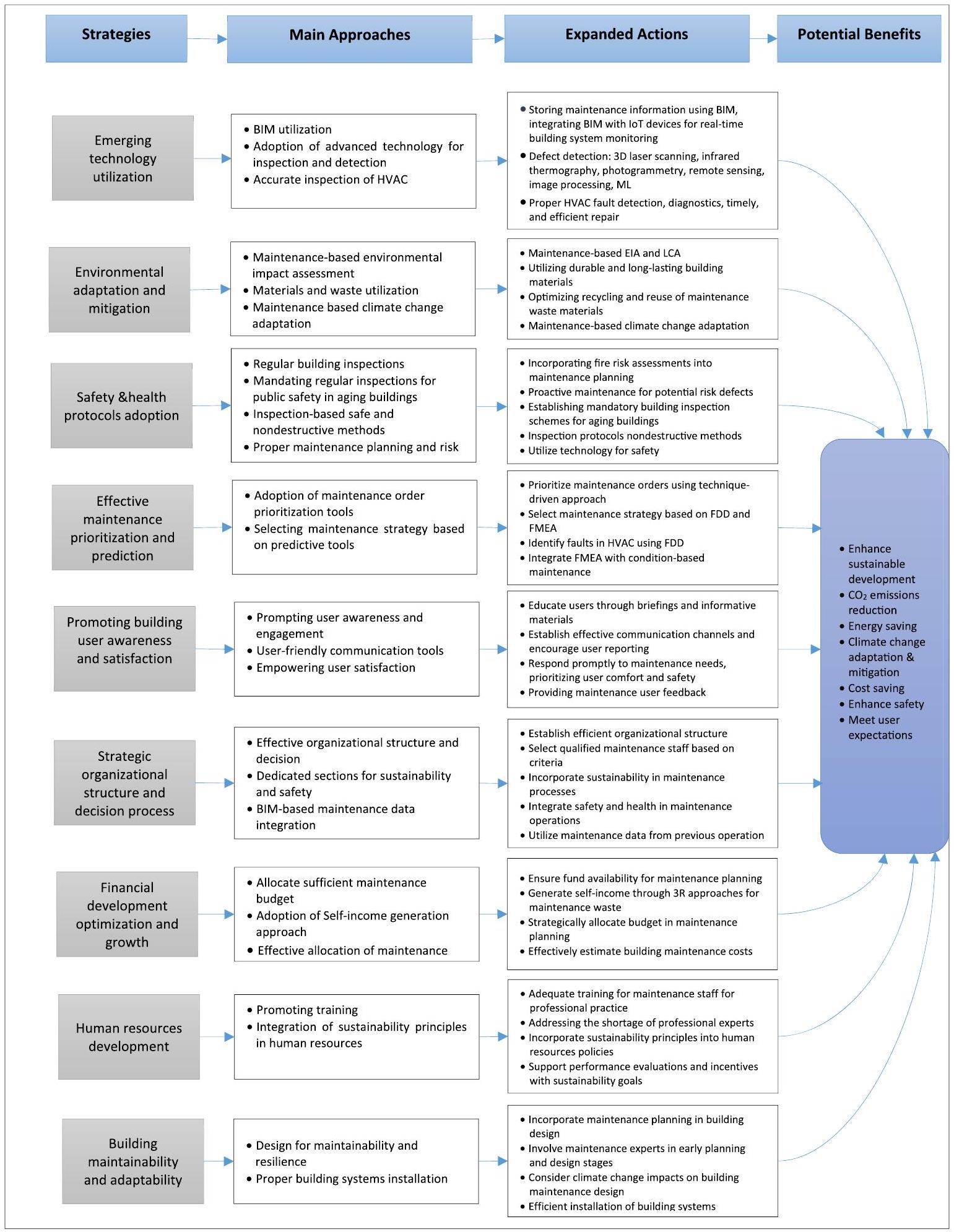

3.3. الطبقة 3: تطوير الاستراتيجيات

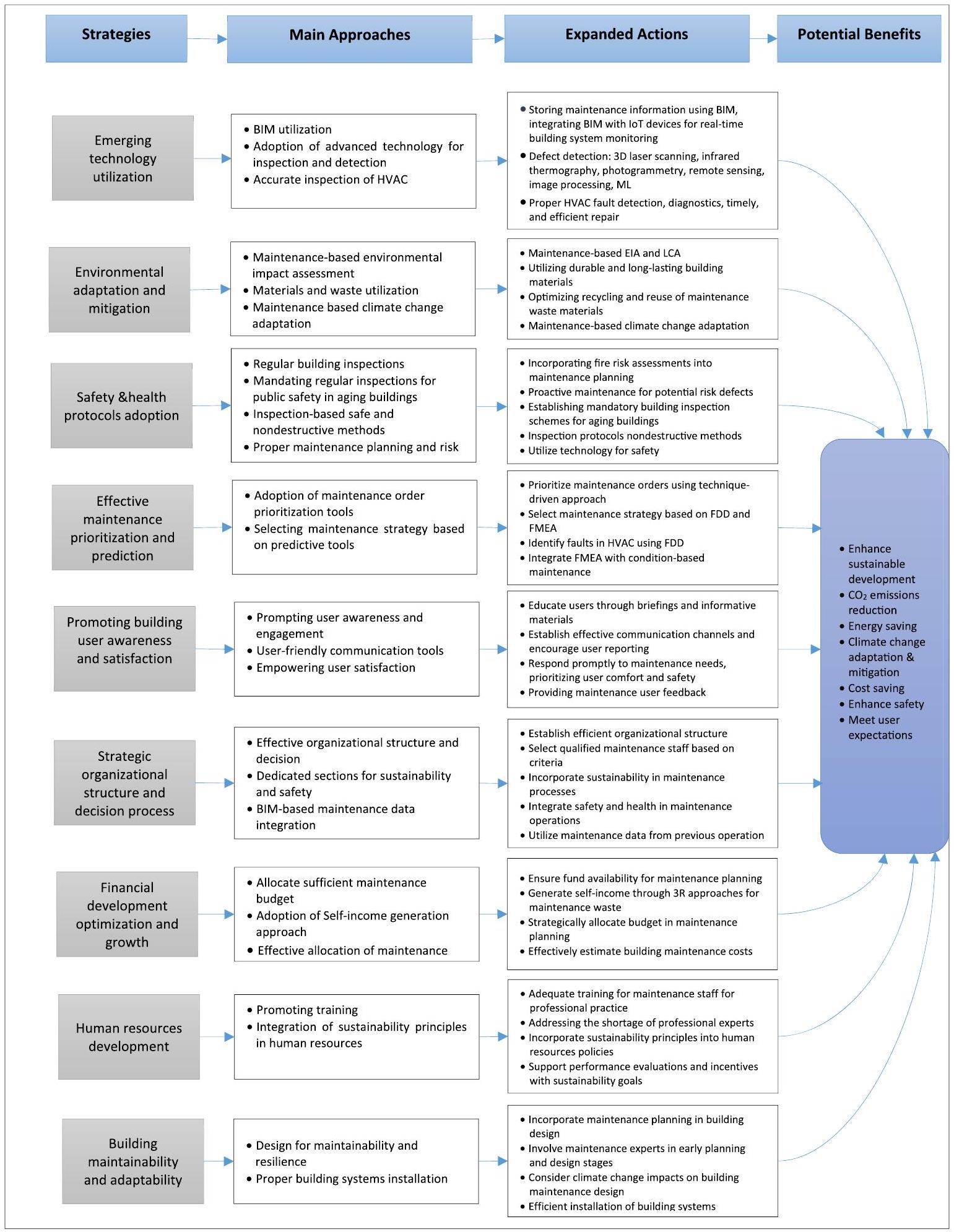

3.3.1. استخدام التكنولوجيا الناشئة

3.3.1.2. اعتماد التكنولوجيا المتقدمة للتفتيش والكشف.

يمكن أن يكون له القدرة على تحسين دقة وفعالية فحص المباني بشكل كبير مع تقليل التكاليف وتقليل مخاطر الأضرار. تشمل هذه التقنيات الطائرات بدون طيار، والمسح بالليزر ثلاثي الأبعاد، والتصوير الحراري، والقياس التصويري، والاستشعار عن بعد، ومعالجة الصور الرقمية، وتعلم الآلة. أظهر راخة وآخرون [75] إمكانية استخدام الطائرات بدون طيار المزودة بكاميرات حرارية لفحص غلاف المبنى (السقف والجدران)، مما سيقلل من وقت وتكاليف الفحص بالإضافة إلى تحسين الدقة. أيضًا، اقترح دايس وآخرون [76] وبيريز وآخرون [38] استخدام التعلم العميق للكشف الآلي عن عيوب المباني وتصنيفها، مثل الشقوق والبقع والدهانات. أظهرت تقنية التعلم العميق دقة وكفاءة عالية مقارنة بالطرق التقليدية التي تعمل بناءً على تقنيات تحليل الصور للكشف عن العيوب، والتي تم اقتراحها كبديل لطرق الفحص اليدوي في الموقع. علاوة على ذلك، تم استخدام شبكات الاستشعار القائمة على إنترنت الأشياء لمراقبة ظروف معدات المباني وبيئة المبنى [77]. أيضًا، ستكون البيانات التي ستجمعها هذه المستشعرات هي المصدر الرئيسي لتخطيط وصيانة التنبؤ. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن للمفتشين استخدام نظارات الواقع المختلط لتحديد المشكلات، مثل الشقوق، أثناء وجودهم في الموقع للتدخلات المستقبلية. يمكنهم وضع علامة رقمية على كل مشكلة، وترتبط هذه العلامات بنموذج ثلاثي الأبعاد للمساحة، ويمكنهم استخدام نفس سماعة الرأس للواقع المختلط في وقت لاحق لتحديد وتحديد وتشخيص وتتبع وإصلاح المشكلات في النهاية [72]. لقد مكنت التطورات السريعة في تكنولوجيا الذكاء الاصطناعي وإنترنت الأشياء من تحويل فحص عيوب المباني من يدوي إلى آلي وذكي، مما أدى إلى تحسين الكفاءة والجودة وتقليل التكاليف [12]. على الرغم من أن هذه الدراسات تركز على الفوائد المحتملة لاعتماد التقنيات الحديثة للكشف عن المباني وفحصها، إلا أن هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من البحث للتغلب على الحواجز أمام الاعتماد وضمان أن تكون هذه التقنيات متاحة وميسورة التكلفة لمفتشي المباني.

3.3.1.3. فحص دقيق لأنظمة التدفئة والتهوية وتكييف الهواء. يعد الفحص السليم والدقيق لأنظمة التدفئة والتهوية وتكييف الهواء أمرًا حيويًا نظرًا لمساهمتها الكبيرة وتأثيرها على استهلاك الطاقة و

وتحتاج إلى مزيد من التحقق. وهذا يبرز الحاجة إلى البحث والتطوير المستمرين للتحقق من فعالية هذه النماذج في السيناريوهات الواقعية ولضمان موثوقيتها في التنبؤ والكشف بدقة عن عيوب نظام التدفئة والتهوية وتكييف الهواء. وبالتالي، يجب إجراء مزيد من التحقيق لتقييم أداء هذه الطرق المقترحة في التطبيقات العملية وكذلك مزاياها المحتملة.

3.3.2. التكيف البيئي والتخفيف

3.3.2.2. استخدام المواد والنفايات. تحتوي مهام الصيانة على آثار بيئية متنوعة، بما في ذلك استهلاك المواد وتوليد النفايات [3،9]. وهذا أمر مقلق بشكل خاص عندما تكون المواد الخطرة متورطة، حيث يمكن أن تشكل خطرًا على صحة الإنسان والبيئة [42]. لذلك، من الضروري إدارة عمليات الصيانة بكفاءة لتقليل هذه الآثار، مما يتضمن الحد من استخدام المواد الخطرة، والحفاظ على الموارد، و

ضمان بيئة عمل آمنة ومنتجة. يمكن أن تحسن أساليب الصيانة الفعالة بشكل كبير من استخدام الموارد من حيث الاستدامة الاقتصادية والبيئية والاجتماعية، وهي الأعمدة الثلاثة للاستدامة [3،22]. لتقليل استهلاك المواد وتحسين استخدام النفايات ضمن عمليات الصيانة، وتعزيز ممارسات البناء المستدامة والواعية بيئيًا، يمكن استخدام عدة استراتيجيات. أحد الأساليب هو تقليل استهلاك المواد وكمية النفايات الناتجة من خلال طرق تقليل المصدر، مثل استخدام مواد بناء متينة وطويلة الأمد.

3.3.2.3. التكيف مع تغير المناخ في الصيانة. لتحسين تخطيط صيانة المباني، من الضروري تحديد آثار تغير المناخ على المباني، خاصة فيما يتعلق بالقدرة الوظيفية وتدهور المواد والمكونات [3،46]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن تكييف أدوات مكملة مثل أنظمة التفتيش ومنهجيات توقع عمر الخدمة للاستخدام ضمن سياق تغير المناخ. علاوة على ذلك، يجب أن يكون تخطيط الصيانة جزءًا من استراتيجية أوسع تأخذ في الاعتبار تعرض المباني لآثار تغير المناخ على المدى القصير والطويل [46]. أيضًا، يجب على فرق الصيانة إجراء تقييم شامل لعرض مبانيهم لآثار تغير المناخ والاستجابة لذلك في عمليات الصيانة المستقبلية [3،47]. من خلال معالجة أي مشكلات أو نقاط ضعف محتملة بشكل استباقي، تساعد الصيانة الوقائية في تقليل الاضطرابات، وتحسين كفاءة الطاقة، وتعزيز المرونة العامة للمباني في مواجهة تحديات تغير المناخ. للتخفيف من آثار تغير المناخ على المباني، يجب إعطاء الأولوية لاستخدام مواد بناء مستدامة ومرنة يمكن أن تتحمل مثل هذه الآثار خلال مراحل البناء والصيانة. من خلال استخدام مواد مقاومة للرياح القوية، والأمطار الغزيرة، ودرجات الحرارة القصوى، والتي يمكن أن تساعد في التخفيف من الأضرار الناجمة عن تغير المناخ. علاوة على ذلك، سيسمح تطوير أدوات مثل تصنيف معلمات المناخ ومؤشرات التعرض للمواد والمكونات في عمليات اتخاذ القرار بتوفير معلومات حيوية حول تعرض المواد والمكونات لمعايير المناخ المحددة. سيساعد اعتماد هذه الأدوات في تحديد مجالات القلق، وتحديد أولويات جهود الصيانة، وتوجيه اختيار المواد والمكونات الأكثر ملاءمة لتحمل آثار تغير المناخ، مما يدعم في النهاية إنشاء مباني أكثر استدامة ومرونة يمكنها الاستجابة بفعالية للتحديات التي يطرحها تغير المناخ [3]. في الواقع، يعد النظر في معلمات المناخ ومؤشرات التعرض المحددة للمواد والمكونات خلال عمليات اتخاذ القرار أمرًا ضروريًا للاستجابة بفعالية للتحديات المتعلقة بالمناخ [3،44،46]. في النهاية، سيسمح ذلك لمتخصصي الصيانة باتخاذ خيارات مستنيرة بشأن استراتيجيات الصيانة واختيار المواد [46]، مما يساهم في اتخاذ قرارات أكثر فعالية من حيث صيانة المباني، والتكيف، والمرونة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن متابعة النتائج المناخية الفعلية والمتوقعة تمكن محترفي الصيانة من تنفيذ التغييرات المناسبة، مثل الإصلاحات

والتعديلات، لضمان قدرة المباني على التحمل والازدهار في ظروف المناخ المتغيرة.

3.3.3. اعتماد تدابير السلامة والصحة

3.3.3.1. الفحوصات الدورية للمباني. يمكن أن تساعد الفحوصات الدورية للمباني في تحديد المخاطر المحتملة للحرائق وضمان وجود تدابير السلامة [30]. وبالتالي، من خلال دمج تقييمات مخاطر الحرائق في تخطيط الصيانة والعمليات، يمكن لفرق الصيانة تحديد المخاطر المحتملة للحرائق وتنفيذ تدابير وقائية مناسبة [30]. في الواقع، تعتبر الفحوصات الدورية لأنظمة المباني، مثل الأنظمة الكهربائية والميكانيكية وأنظمة الحماية من الحرائق، ضرورية لاكتشاف العيوب والأعطال التي قد تؤدي إلى حوادث حرائق. أيضًا، تضمن الصيانة الاستباقية، بما في ذلك التنظيف والاختبار والإصلاحات، أن تكون تدابير السلامة من الحرائق مثل أجهزة الإنذار ورشاشات المياه ومخارج الطوارئ في حالة عمل مناسبة. علاوة على ذلك، يجب على فرق الصيانة أيضًا إعطاء الأولوية لصيانة المخارج الواضحة وطرق الهروب، بالإضافة إلى التركيب والصيانة المناسبة للأبواب المقاومة للحريق وتدابير الحماية من الحرائق السلبية، لمنع انتشار الحريق وضمان سلامة شاغلي المباني [52]، حيث أن الفشل في صيانة هذه الأنظمة يمكن أن يؤدي إلى عواقب وخيمة في حالة حدوث حريق. من خلال ربط الصيانة بتقييمات مخاطر الحرائق، يمكن لفرق صيانة المباني اتخاذ خطوات استباقية للسيطرة على مخاطر الحرائق وخلق بيئة أكثر أمانًا لمستخدمي المباني [30]. لذلك، فإن إعطاء الأولوية للفحص والصيانة المناسبة للمباني أمر ضروري للتخفيف من آثار الحرائق وضمان سلامة وراحة الشاغلين [32].

3.3.3.2. فرض الفحوصات الدورية للسلامة العامة في المباني القديمة. من الضروري وضع تشريعات تفرض الفحوصات الدورية، خاصة للمباني العالية القديمة. يجب تنفيذ تدابير تشريعية محددة، مثل أنظمة الفحص الإلزامي للمباني، مما يتطلب من إدارة المباني أو مستخدمي المباني الخاصة إجراء فحوصات دورية للمكونات مثل النوافذ، بالإضافة إلى التركيبات الخارجية مثل الوحدات الخارجية لمكيفات الهواء [3,9,84]. سيساعد ذلك في تحديد العيوب والمخاطر التي قد تهدد سلامة المشاة في الشارع أو مستخدمي المباني ويجب تحديدها ومعالجتها بسرعة لضمان سلامة هذه المباني وامتثالها [9].

3.3.3.3. طريقة آمنة وغير مدمرة تعتمد على الفحص. من خلال استخدام طرق غير مدمرة، يمكن تقليل المخاطر المرتبطة بالأضرار المحتملة ومخاطر السلامة لفرق الصيانة والشاغلين [16, 37]. على سبيل المثال، استخدام التصوير الحراري بالأشعة تحت الحمراء للكشف عن تسرب الهواء من خلال غلاف المبنى [85]. لذلك، فإن التخطيط الدقيق، والالتزام ببروتوكولات السلامة، والتدريب المناسب للموظفين أمر ضروري لتقليل المخاطر المرتبطة بالاختبارات المدمرة وضمان رفاهية جميع الأفراد المعنيين. ومع ذلك، يجب تجنب الاختبارات المدمرة من قبل فرق الصيانة كلما كان ذلك ممكنًا؛ وعندما يصبح ذلك غير ممكن، من الضروري التعامل معه بحذر والالتزام بأعلى معايير السلوك المهني وبروتوكولات السلامة. علاوة على ذلك، تحتاج منظمات ومديرو الصيانة إلى مراعاة الآثار السلبية المحتملة لفحوصات الاختبارات المدمرة على كل من مستخدمي المباني وموظفي الصيانة. يمكن أن تشكل مثل هذه الفحوصات الجسدية مخاطر على سلامة شاغلي المباني بسبب احتمال حدوث أضرار غير مخطط لها للمبنى، مما قد يهدد استقراره الهيكلي ويؤدي إلى مخاطر سلامة كبيرة. من خلال تحقيق توازن بين الحاجة إلى معلومات قيمة وسلامة شاغلي المباني، يمكن تقليل الآثار السلبية المحتملة للاختبارات المدمرة من خلال استخدام الفحص غير المدمر. وبالتالي، لضمان سلامة ورفاهية مستخدمي المباني، يتطلب الأمر اعتبارات تخطيط قبل التنفيذ [19,71].

3.3.3.4. تخطيط الصيانة المناسب وتقييم المخاطر. الطبيعة الديناميكية والمعقدة لعمل صيانة المباني، جنبًا إلى جنب مع التعقيد المتزايد للمباني، قد أدت بشكل كبير إلى زيادة المخاوف المتعلقة بالسلامة في السنوات الأخيرة [14]. وبالتالي، يجب على منظمات صيانة المباني والشركات والمقاولين أيضًا إعطاء الأولوية للسلامة في جميع عمليات الصيانة الخاصة بهم ويجب أن يأخذوا في الاعتبار هذه التحديات [32]. يمكن تحقيق ذلك من خلال توفير بيئة عمل آمنة، وضمان تدريب عمال الصيانة وتجهيزهم بتكنولوجيا المباني، ومراجعة وتحديث إجراءات السلامة بانتظام، وتزويد عمال الصيانة بمعدات الحماية الشخصية المناسبة [86]، وتنفيذ إجراءات السلامة، وتوفير التدريب للعمال. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد تخضع أعمال صيانة المباني لمتطلبات ومعايير تنظيمية لضمان السلامة مثل إدارة السلامة والصحة المهنية. في الواقع، فإن ضمان السلامة أثناء أعمال صيانة المباني أمر حاسم لحماية العمال ومنع الحوادث والإصابات [14]. لضمان السلامة أثناء أعمال صيانة المباني، من الضروري أن يكون هناك تخطيط مناسب وتقييم للمخاطر، مثل تحديد المخاطر المحتملة، وتقييم المخاطر المرتبطة بكل خطر، وتنفيذ تدابير للسيطرة على تلك المخاطر أو القضاء عليها. وقد لخص وانغ وآخرون [49]، استنادًا إلى دراسات سابقة، أن تخطيط تقييم مخاطر صيانة المباني يجب أن يأخذ في الاعتبار تحديد وتقييم المخاطر، وتخطيط الصيانة، والصيانة التصحيحية للسلامة، وفحص أنظمة الحماية من الحرائق والطوارئ. ومع ذلك، فإن هذه التدابير قابلة للتكيف ومرنة للغاية، مما يعزز الأداء في مجال السلامة. من خلال أخذ تحديد ومعالجة المخاطر المحتملة قبل أن تصبح مشاكل كبيرة كمثال، يمكن تحقيق هذه التدابير من خلال الفحوصات الدورية للأسلاك الكهربائية والسباكة والأنظمة الأخرى التي قد تشكل خطرًا على الشاغلين. هذه هي نهج رئيسي تساهم من خلاله صيانة المباني بشكل إيجابي في السلامة، بينما قد لا تعمل تدابير أخرى على هذا المستوى [3,54]. لذلك، يجب تطوير تخطيط الصيانة وتقييم المخاطر بناءً على نطاق عمل منظمة الصيانة، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار هذه العوامل الحاسمة. هذا النهج ضروري لتحقيق تخطيط فعال للصيانة وتقييم المخاطر، مما يضمن في النهاية سلامة موظفي الصيانة والمباني ومستخدمي المباني.

3.3.3.5. استخدام التكنولوجيا من أجل السلامة. يجب استخدام التكنولوجيا الناشئة الحالية لتعزيز سلامة عمليات تفتيش المباني ونتائجها، مما سيساهم في سلامة عمال الصيانة وعمليات الصيانة وسلامة المباني والجمهور. في الواقع، لقد ثبت أن النظام الجوي غير المأهول، المعروف عادةً بالطائرة بدون طيار، والذي يمكن تزويده بأجهزة ذات صلة مثل الكاميرات، هو أداة بديلة فعالة وواعدة لدعم تفتيش أغلفة المباني والأسطح، مما سيساعد في مسح المباني والتأكد من وجود مخاطر محتملة [87،88،89]. تعتبر هذه المجالات حاسمة للحفاظ على سلامة المبنى وللحصول على الوصول لأغراض التفتيش، بينما يمكن للطائرات بدون طيار أن تفحص عن كثب حالة هذه الأسطح وتحدد مشكلات مثل الشقوق، التسريبات، أو الأضرار في مواد التسقيف، مما قد يعزز سلامة المباني والجمهور، وسلامة المساحين معرضة للخطر باستمرار [90]. في الواقع، يمكن أن يكون فحص وتحليل الجزء العلوي من الواجهة، بالإضافة إلى تقييم الشذوذ في مواقع محددة، تحديًا للمساح دون وسائل وصول مناسبة وفي ظروف جوية غير مواتية [91]، مما يجعل استخدام الطائرات بدون طيار قابلاً للتطبيق ومفيدًا. أيضًا، من حيث السلامة الشخصية، يمكن أن يكون إجراء تفتيش فعلي على سطح المبنى تحديًا ومخاطرة، بينما يمكن أن يوفر استخدام الطائرات بدون طيار المجهزة بالكاميرات نتائج أكثر دقة وبديلًا أكثر أمانًا للتفتيشات التقليدية الفعلية والبصرية [16،40،90]. على الرغم من أن استخدام الطائرات بدون طيار يجعل عملية تفتيش المباني أكثر قابلية للتطبيق وأتمتة بشكل كبير، من المهم الإشارة إلى أنه لا يزال هناك حاجة لوضع إجراءات واضحة يجب اتباعها من خلال التفتيش باستخدام الطائرات بدون طيار. يمكن أن تكون هذه الإجراءات شرطًا أساسيًا لضمان أن النزاهة والسلامة مضمونة [87،88].

3.3.4. تحديد أولويات الصيانة الفعالة والتنبؤ بها

3.3.4.2. اختيار استراتيجية الصيانة بناءً على الأدوات التنبؤية. إن

اختيار استراتيجيات الصيانة الفعالة يمكن أن يقلل من تكاليف صيانة المباني وحتى يمدد عمر مكونات المباني [3،77]. من خلال الكشف عن المشكلات المحتملة والتنبؤ بها مبكرًا، يمكن اتخاذ الإجراءات الصحيحة في الصيانة لمنع فشل المباني، وتقليل فترة التوقف، وتحسين الأداء العام للمبنى [69]. أولاً، يمكن التنبؤ بالصيانة التنبؤية باستخدام اكتشاف الأعطال والتشخيص (FDD). يستخدم FDD أجهزة استشعار متقدمة لجمع البيانات في الوقت الحقيقي، ومعالجة الإشارات، وتصنيف الأعطال. يتضمن عنصرين رئيسيين: الكشف والتشخيص. الهدف الأساسي من FDD هو تحديد الوظيفة السليمة لأنظمة المباني (الكشف) وفي حالة الأداء غير الكافي، تحديد السبب الجذري (التشخيص). يُعرف نهج FDD للصيانة التنبؤية الذي يركز على تحديد الأعطال في أنظمة التدفئة والتهوية وتكييف الهواء قبل حدوث الفشل [10]. بينما يمكن أن يساعد تحليل أنماط الفشل (FMEA) في تحديد متى يجب استخدام الصيانة المعتمدة على الحالة، والتي تتضمن مراقبة حالة أنظمة ومكونات المباني من خلال أجهزة الاستشعار والتقنيات الأخرى، يمكن استخدام FMEA عندما تظهر أنماط الفشل المحددة مؤشرات أو علامات تحذيرية معينة. إنها أداة قيمة لتحديد أنماط الفشل المحتملة وتأثيراتها على أنظمة المباني. من خلال إجراء تحليل FMEA، يمكن لمشغلي المباني الحصول على رؤى حول أهمية وشدة أنماط الفشل المختلفة. ثم، استنادًا إلى نتائج FMEA، يمكن للمشغلين تحديد أولويات جهودهم في الصيانة وتحديد أي نهج صيانة هو الأكثر ملاءمة [17]. من خلال دمج FMEA مع الصيانة المعتمدة على الحالة، يمكن للمشغلين مراقبة حالة المكونات الحرجة بشكل استباقي، وجمع البيانات في الوقت الحقيقي، واستخدام تلك المعلومات لتحفيز إجراءات الصيانة عند اكتشاف أنماط الفشل أو التدهورات المحددة.

3.3.5. تعزيز وعي المستخدمين ورضاهم

3.3.5.2. أدوات التواصل سهلة الاستخدام. تعتبر قنوات الاتصال الفعالة بين إدارة صيانة المباني والمستخدمين ضرورية للإبلاغ الفوري عن مشكلات الصيانة والإصلاحات في الوقت المناسب، مما يؤدي إلى تحسين حالة المبنى [3,58,96]. لذلك، يجب على منظمات الصيانة دائمًا أن تهدف إلى توفير قنوات اتصال فعالة، وتشجيع المستخدمين على الإبلاغ عن عيوب المباني، والحفاظ على المبنى في حالة ممتازة. ولتحقيق ذلك، يمكن القيام بذلك من خلال تبسيط عملية الصيانة، وتوفير إرشادات وتعليمات واضحة للمستخدمين، وإشراكهم في صيانة المبنى، و

تعزيز مشاركتهم النشطة. في الواقع، ست empower قنوات الاتصال سهلة الاستخدام للإبلاغ عن مشكلات الصيانة، جنبًا إلى جنب مع تعليمات سهلة الفهم لمهام الصيانة الأساسية، المستخدمين على المساهمة بنشاط في صيانة المبنى بنجاح [3].

3.3.5.3. تعزيز رضا المستخدمين. لقد ارتبط رضا المستخدمين دائمًا بحالة المبنى [54]، حيث إن المستخدمين الراضين هم أكثر احتمالًا للمشاركة بنشاط في جهود الصيانة، مما يؤدي إلى تحسين حالة المبنى. ومن ثم، فإن صيانة المباني الفعالة أمر حيوي لتلبية احتياجات وتوقعات شاغلي المباني، وضمان وصولهم وإنتاجيتهم وصحتهم وراحتهم. ومع ذلك، ليس من المؤكد دائمًا أن جهود صيانة المباني تلبي هذه المتطلبات بنجاح لرضا مستخدمي المبنى [69]. قد يكون لدى المستخدمين توقعات متفاوتة بشأن حالة المباني، وأوقات الاستجابة لطلبات الصيانة، وجودة تدخلات الصيانة. وبناءً عليه، قد يكون تلبية توقعات المستخدمين وضمان رضاهم تحديًا في سياق صيانة المباني. ومع ذلك، يمكن أن تلعب ملاحظات المستخدمين دورًا حيويًا في تحديد المشكلات وحلها، مما يعزز الرضا العام لمستخدمي المباني حول عمليات صيانة المباني. من الضروري فهم توقعات وملاحظات مستخدمي المباني حيث يلعبون دورًا كبيرًا في تحسين الحالة العامة للمباني [64]. التواصل الفعال، والاستجابة السريعة لاحتياجات الصيانة، والمباني الآمنة والوظيفية والمصانة جيدًا ضرورية لإدارة توقعات المستخدمين وضمان رضاهم [3,58].

3.3.6. الهيكل التنظيمي الاستراتيجي وعملية اتخاذ القرار

3.3.6.2. أقسام مخصصة للاستدامة والسلامة. جانب آخر مهم من منظمات صيانة المباني هو إنشاء قسم أو قسم مخصص للاستدامة والمخاوف البيئية. توصي هذه الدراسة بشدة منظمات الصيانة بدمج ممارسات الاستدامة ضمن عملياتها. وفقًا لهاوشده وآخرون [3]، فإن دمج الاستدامة في صناعة صيانة المباني أمر حيوي لتحقيق التنمية المستدامة. يجب أن يركز هذا القسم على دمج الممارسات المستدامة، والمبادرات البيئية، والامتثال للوائح، وتخصيص الموارد، وتطوير الاستراتيجيات، وإجراء التقييمات، ومراقبة الطاقة لمعالجة الاستدامة والأثر البيئي في عمليات الصيانة. أيضًا، من خلال تعزيز المواد المستدامة وتوفير التدريب على مفهوم وأبعاد الاستدامة، تظهر هذه المنظمات نهجًا استباقيًا في إعطاء الأولوية ودمج الاعتبارات البيئية في جميع عملياتها [3,9]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن دمج قسم أو قسم مخصص للسلامة والصحة داخل منظمات الصيانة أمر أساسي لضمان

رفاهية الموظفين ومستخدمي المباني والمباني، فضلاً عن الامتثال للوائح السلامة. يجب أن يركز هذا القسم على تنفيذ تدابير السلامة، والبروتوكولات، وبرامج التدريب لإنشاء بيئة عمل آمنة. يشمل ذلك إجراء تقييمات المخاطر، وتطوير إجراءات السلامة، ومراقبة الامتثال لإرشادات الصحة والسلامة. من خلال إعطاء الأولوية للسلامة والصحة، تظهر منظمات الصيانة التزامها بتنفيذ عمليات صيانة آمنة وتقليل المخاطر المحتملة على الموظفين ومستخدمي المباني والمبنى ككل [14]. سيلعب هذا القسم المخصص دورًا استباقيًا في دمج اعتبارات السلامة والصحة في جميع عمليات الصيانة، مما يساهم في ثقافة السلامة داخل المنظمة. علاوة على ذلك، فإن وجود مناخ سلامة قوي داخل منظمة صيانة المباني أمر حيوي لإعطاء الأولوية للسلامة ودمجها في جميع جوانب العمليات [48].

3.3.6.3. دمج بيانات الصيانة المعتمدة على نمذجة معلومات البناء. إن الاستخدام الفعال لبيانات الصيانة من قبل منظمات الصيانة من العمليات السابقة أمر حاسم لتحسين آليات الصيانة المستقبلية، حيث تعتمد أداء آليات الصيانة المستقبلية على الاستخدام الفعال لمعلومات المباني وبيانات الصيانة السابقة من العمليات السابقة. في الواقع، فتحت التطورات في رقمنة المباني، وتقنيات الاستشعار الذكي، والقياس إمكانيات جديدة للتحكم في صيانة المباني المعتمدة على البيانات. إن توفر كميات هائلة من البيانات، إلى جانب التحليلات المتقدمة والتحكم في الوقت الحقيقي، يمكّن مشغلي المباني من اتخاذ قرارات مستنيرة، وتحسين الأداء، وخلق بيئات مبنية مستدامة وذكية. ومع ذلك، فإن نقص تكامل البيانات يؤدي إلى إهدار كبير في الوقت، مع أكثر من

3.3.7. تحسين وتطوير النمو المالي

3.3.7.2. اعتماد نهج توليد الدخل الذاتي. هناك ارتفاع

عدد منظمات الصيانة التي لديها القدرة على توليد دخل ذاتي من خلال تنفيذ أساليب 3R (التقليل، إعادة الاستخدام، إعادة التدوير) لنفايات الصيانة، مما يمكن أن يساعد إلى جانب الميزانية المخصصة. لا تساعد هذه الطريقة فقط في تقليل التكاليف، بل تفيد أيضًا البيئة من خلال تقليل التخلص من النفايات. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن لبعض منظمات الصيانة إنشاء مراكز تدريب، والتي يمكن أن تكون مصدرًا لتوليد الدخل. من خلال تقديم خدمات التدريب للأطراف الخارجية، يمكنهم توليد إيرادات مع الاستفادة من خبراتهم في مجال الصيانة. يمكن أن تساهم هذه المصادر الإضافية للدخل في الاستدامة المالية لمنظمات الصيانة ودعم عملياتها بشكل أكبر.

3.3.7.3. التخصيص الفعال لميزانية الصيانة وتقدير التكاليف. يتيح التخصيص الفعال للميزانية في تخطيط الصيانة للمنظمات معالجة القضايا المحتملة بشكل استباقي، وتقليل مخاطر الفشل غير المتوقع، وإطالة عمر مكونات وأنظمة المباني، مما يسمح بإجراء الفحوصات في الوقت المناسب، والمهام الروتينية للصيانة، وتنفيذ تدابير كفاءة الطاقة، وكل ذلك يساهم في الأداء المستدام وتوفير التكاليف التشغيلية. علاوة على ذلك، يساعد التخصيص الاستراتيجي للميزانية في تخطيط الصيانة المنظمات على تحديد الأولويات في المجالات الحرجة التي تتطلب اهتمامًا فوريًا، مثل أنظمة السلامة، والامتثال للوائح، مما يضمن بيئة آمنة وصحية للسكان مع تقليل التأثير المحتمل للاضطرابات المتعلقة بالصيانة على وظائف المباني وإنتاجيتها. وبالتالي، فإن التقدير الفعال لتكاليف صيانة المباني (التكاليف المباشرة) أمر بالغ الأهمية للمنظمات المعنية بالصيانة، حيث إنه أساسي لميزانية الصيانة، بالإضافة إلى النفقات التشغيلية (التكاليف غير المباشرة). ولتحقيق ذلك، يجب على المنظمات استخدام استراتيجيات مثل توقع التكاليف، وإنشاء ميزانيات واقعية، وتطوير خطط مالية سليمة، باستخدام بيانات موثوقة ومعلومات تاريخية لإنشاء نماذج تقدّر التكاليف بدقة لعمليات الصيانة المختلفة، مما يسمح بتخصيص الموارد بكفاءة، وتخطيط الصيانة المستقبلية، وضمان التمويل الكافي، مما يحسن في النهاية تخطيطهم المالي. إن التنبؤ الدقيق بتكاليف الصيانة والتكاليف التشغيلية له أهمية قصوى لتخطيط الميزانية الفعال ومعالجة التحديات المتعلقة بالصيانة. وقد أجريت دراسة بواسطة كوان وآخرين طورت نموذجًا استخدم التفكير القائم على الحالة وخوارزمية جينية لتوقع تكاليف الصيانة. من خلال الحصول على تقدير دقيق لهذه التكاليف، يمكن للمنظمات المعنية بالصيانة تخصيص مواردها بشكل أفضل، والتخطيط لعمليات الصيانة المستقبلية، وضمان أن لديها تمويلًا كافيًا لتلبية احتياجاتها من الصيانة. علاوة على ذلك، فإن تخصيص ميزانية الصيانة لكل مبنى ضمن الفترة المحددة أمر بالغ الأهمية لاستخدام الموارد بكفاءة وضمان أن أعمال الصيانة مخططة ومجدولة ومنفذة بشكل مناسب في كل مبنى، مما يؤدي إلى أداء مثالي للمباني طوال دورة حياتها.

3.3.8. تطوير الموارد البشرية

يمكن للموظفين تعزيز قدراتهم على تحديد المشكلات وحلها، وتنفيذ مهام الصيانة الروتينية، وتحسين أداء النظام. يركز هذا على توفير التدريب الكافي لأعضاء الفريق المعنيين بصيانة النظام لضمان التشغيل الفعال.

3.3.8.2. دمج مبادئ الاستدامة في الموارد البشرية. لمعالجة نقص دمج مبادئ الاستدامة في إدارة الموارد البشرية خلال عمليات صيانة المباني، من الضروري تعزيز ثقافة الاستدامة وتنفيذ ممارسات صيانة مستدامة بشكل فعال [3,64]. من خلال دمج مبادئ الاستدامة البيئية في سياسات واستراتيجيات وممارسات الموارد البشرية، يمكن للمنظمات تعزيز المبادرات الخضراء. يشمل ذلك دمج ممارسات الشراء الأخضر/المستدام، مثل الحصول على مواد ومعدات صديقة للبيئة، في عمليات الصيانة. أيضًا، فإن توفير فرص تعليمية وتطوير مهني كافية تتعلق بممارسات الصيانة المستدامة أمر حاسم لتعزيز معرفة ومهارات الموظفين [100]. دعم تقييمات الأداء والحوافز بأهداف الاستدامة يمكن أن يحفز الأفراد بشكل أكبر على اعتماد وتفضيل التخطيط المستدام للصيانة للمباني، مما يؤدي بالمنظمات إلى تحسين أدائها البيئي وتحقيق أهداف الاستدامة.

3.3.9. قابلية صيانة المباني وقابليتها للتكيف

3.3.9.2. التركيب الصحيح لأنظمة المباني. إن تنفيذ إجراءات تركيب موحدة ودقيقة، وإجراء فحوصات منتظمة وصيانة لأنظمة التحكم، وضمان وجود حساسات دقيقة سيتناول القضايا الفنية التي قد تنشأ بسبب عوامل مثل التركيب الخاطئ، وأنظمة التحكم المعطلة، والتحديات التشغيلية [16,97]. أيضًا، فإن اعتماد تسميات موحدة لنقاط البيانات، وضمان التركيب الصحيح للحساسات، وإقامة منطق تحكم موحد هي خطوات أساسية لتحسين الأداء [3,53,97]. في الواقع، لا تزال الفحوصات المنتظمة وصيانة أنظمة التحكم تلعب دورًا حاسمًا في تحديد الأعطال أو مشاكل المعايرة وضمان عملها بشكل صحيح [3,53]. من خلال معالجة هذه القضايا الفنية، يمكن تحقيق تحسينات كبيرة في كفاءة وموثوقية أنظمة المباني، وخاصة أنظمة التدفئة والتهوية وتكييف الهواء، مما يؤدي إلى تحسين الراحة الداخلية، وتوفير الطاقة،

والفعالية التشغيلية العامة.

في نهاية هذا القسم، توضح الشكل 3 تمثيلًا بصريًا ملخصًا للاستراتيجيات المطورة نحو تحقيق عمليات صيانة مستدامة وفعالة تتماشى مع تغير المناخ، وأهداف التنمية المستدامة، واستخدام التكنولوجيا الناشئة.

4. نتائج التحقق من فعالية الإطار

5. تداعيات الدراسة

5.1. التداعيات العملية

الخصائص الرئيسية للمقيمين.

| رقم س/ن | المسمى الوظيفي الحالي | المؤهل | الخلفية التعليمية | سنوات الخبرة |

| 1 | مدير الصيانة | درجة الماجستير | الهندسة | 11-15 سنة |

| 2 | مدير المنظمة | درجة الماجستير | الهندسة | أكثر من 15 سنة |

| 3 | خبير التكنولوجيا المهنية | درجة الماجستير | تكنولوجيا البناء | أكثر من 15 سنة |

| 4 | نائب مدير المنظمة | درجة الماجستير | الهندسة | 11-15 سنة |

| 5 | مدير المنشأة | درجة البكالوريوس | الهندسة | أقل من 5 سنوات |

| 6 | مهندس أول | درجة البكالوريوس | الهندسة | أكثر من 15 سنة |

| 7 | رئيس القسم/رئيس الوحدة | درجة الماجستير | الهندسة المعمارية | أكثر من 15 سنة |

| 8 | مدير الإدارة | درجة الماجستير | إدارة المشاريع | أكثر من 15 سنة |

| 9 | استشاري الاستدامة | درجة الماجستير | البيئة | 6-10 سنوات |

| 10 | مساح كميات أول | درجة الماجستير | مسح الكميات | 11-15 سنة |

| 11 | رئيس القسم/رئيس الوحدة | درجة الماجستير | مسح الكميات | أكثر من 15 سنة |

| 12 | استشاري الاستدامة | درجة الماجستير | البيئة | 11-15 سنة |

| 13 | مهندس محترف | درجة الماجستير | الهندسة | 11-15 سنة |

| 14 | رئيس القسم/رئيس الوحدة | درجة الماجستير | إدارة المنشآت | 11-15 سنة |

| 15 | مدير الصيانة | درجة البكالوريوس | الهندسة | 11-15 سنة |

| 16 | استشاري الاستدامة | درجة الماجستير | البيئة | أكثر من 15 سنة |

نتائج التحقق من فعالية الإطار.

| العناصر | ن | المتوسط | الانحراف المعياري | مستوى الاتفاق |

| لقد عالج الإطار المتكامل، جنبًا إلى جنب مع السمات الرئيسية تحت كل عنصر من عناصر هذا الإطار المطور، القضايا والتحديات والاحتياجات الحالية والمستقبلية بشكل فعال | 16 | 4.25 | 1.183 | إلى حد كبير جدًا |

| يساهم الإطار المتكامل، جنبًا إلى جنب مع السمات الرئيسية تحت كل عنصر من عناصر هذا الإطار المطور، بشكل كبير في تحقيق أهداف التنمية المستدامة ذات الصلة | 16 | 4.13 | 1.147 | إلى حد كبير |

| لقد أخذ الإطار المتكامل، جنبًا إلى جنب مع السمات الرئيسية تحت كل عنصر من عناصر هذا الإطار المطور، أبعاد الاستدامة في الاعتبار على جميع عمليات الصيانة | 16 | 4.38 | 1.025 | إلى حد كبير جدًا |

| يتماشى الإطار المتكامل، جنبًا إلى جنب مع السمات الرئيسية تحت كل عنصر من عناصر هذا الإطار المطور، مع جهود التخفيف من تغير المناخ والتكيف معه. | 16 | 4.25 | 0.931 | إلى حد كبير جدًا |

| يدمج الإطار المتكامل، جنبًا إلى جنب مع السمات الرئيسية تحت كل عنصر من عناصر هذا الإطار المطور، استهلاك الطاقة و

|

16 | 4.19 | 0.750 | إلى حد كبير |

| يدمج الإطار المتكامل، جنبًا إلى جنب مع السمات الرئيسية تحت كل عنصر من عناصر هذا الإطار المطور، التقنيات الناشئة بما في ذلك نمذجة معلومات البناء وإنترنت الأشياء على جميع عمليات صيانة المباني | 16 | 4.13 | 0.957 | إلى حد كبير |

| يعزز الإطار المتكامل، جنبًا إلى جنب مع السمات الرئيسية تحت كل عنصر من عناصر هذا الإطار المطور، السلامة والصحة على جميع عمليات صيانة المباني | 16 | 4.13 | 0.957 | إلى حد كبير |

| يمتلك الإطار المتكامل، جنبًا إلى جنب مع السمات الرئيسية تحت كل عنصر من عناصر هذا الإطار المطور، القدرة على تحسين استدامة المباني | 16 | 4.13 | 1.147 | إلى حد كبير |

| بشكل عام، يمتلك الإطار المتكامل، جنبًا إلى جنب مع السمات الرئيسية تحت كل عنصر من عناصر هذا الإطار المطور، القدرة على تقديم صيانة مستدامة وفعالة | 16 | 4.13 | 0.806 | إلى حد كبير |

5.2. التداعيات النظرية

دراسات لاستكشاف كيف يمكن أن تمكّن استراتيجيات مختلفة، عند تطبيقها في سياقات متنوعة، استراتيجيات فعالة ومستدامة، وتساهم في تحقيق أهداف التنمية المستدامة المقابلة. أيضًا، تعتبر مكونات الإطار وعناصرها أساسًا للدراسات المستقبلية في مجال صيانة المباني وعملياتها.

6. الاستنتاجات

- تغير المناخ: كشفت هذه الدراسة كيف يمكن لصيانة المباني أن تستجيب لتغير المناخ وتتكيف مع آثاره. كما أوضحت أهمية الصيانة الفعالة لأنظمة التدفئة والتهوية وتكييف الهواء في تحقيق وفورات كبيرة في الطاقة وتقليل

الانبعاثات. علاوة على ذلك، فقد أبرزت الفوائد المحتملة لترقية أنظمة المباني لتعزيز كفاءة وأداء طاقة المباني. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فقد شرحت كيف تأثرت أو ستتأثر صيانة المباني بتأثيرات تغير المناخ من خلال تحديد التأثيرات المحتملة وسبل التكيف مع هذا التحدي. - أهداف التنمية المستدامة: لقد أظهرت هذه الدراسة الدور الحيوي لعمليات صيانة المباني المستدامة والفعالة في المباني القائمة في المساهمة في تحقيق عدد من أهداف التنمية المستدامة التابعة للأمم المتحدة. للبدء، فإن تنفيذ صيانة فعالة للمباني القديمة التي تستهلك كميات كبيرة من الطاقة وتؤثر على البيئة المحيطة من خلال قرارات الصيانة المستندة إلى تقييمات الأثر البيئي يتماشى مع الهدف 13: العمل المناخي. كما أنه يدعم الهدف 11 من خلال التأكيد على أهمية المباني التي تتم صيانتها بشكل جيد والتي تساهم في التنمية الحضرية المستدامة، مما يتماشى مع الهدف 11: المدن والمجتمعات المستدامة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن استخدام التقنيات الناشئة في عمليات صيانة المباني يعزز الهدف 9 من خلال تعزيز التقنيات المبتكرة التي تعزز السلامة، وتقلل من الأضرار البيئية، وتستخدم أدوات الأتمتة مثل فحص الاختبارات غير التدميرية، مما يتماشى مع الهدف 9: الصناعة والابتكار والبنية التحتية. أخيرًا، فإنه يعزز الاستخدام الفعال للموارد طوال عملية الصيانة بأكملها، مما يتماشى مع الهدف 12: الاستهلاك والإنتاج المسؤولين.

- التكنولوجيا الناشئة: لقد أظهرت هذه الدراسة بفعالية كيف يمكن استخدام التكنولوجيا الناشئة كأدوات لمعالجة مختلف القضايا المتعلقة بالصيانة. وقدمت تطبيقًا عمليًا محتملاً لنموذج معلومات البناء (BIM) في عمليات الصيانة. من خلال تسليط الضوء على كيفية استخدامها مع معظم القضايا المحددة كأداة قيمة في معالجة القضايا المعقدة للصيانة من خلال تنفيذها في تخطيط الصيانة، وإدارة معلومات المباني، وإدارة البيانات، ومنصات التعاون بين أصحاب المصلحة في الصيانة، ومراقبة أنظمة المباني من خلال دمج BIM في DT و

دمجها مع إنترنت الأشياء. كما أظهرت قدرة التكنولوجيا المتقدمة، بما في ذلك المسح بالليزر ثلاثي الأبعاد، التصوير الحراري بالأشعة تحت الحمراء، التصوير الفوتوغرافي، الاستشعار عن بعد، معالجة الصور الرقمية، وتعلم الآلة، في اكتشاف وتقييم عيوب المباني. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يستكشف هذا البحث كيف يمكن للذكاء الاصطناعي، وإنترنت الأشياء، والواقع المختلط، تمكين أتمتة بعض المهام في صيانة المباني، وتحويلها من عمليات يدوية إلى عمليات آلية.

بيان مساهمة مؤلفي CRediT

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

توفر البيانات

شكر وتقدير

References

[2] H. Feng, D.R. Liyanage, H. Karunathilake, R. Sadiq, K. Hewage, BIM-based life cycle environmental performance assessment of single-family houses: renovation and reconstruction strategies for aging building stock in British Columbia, J. Clean. Prod. 250 (2020) 119543, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jclepro.2019.119543.

[3] A. Hauashdh, J. Jailani, I.A. Rahman, N. AL-fadhali, Strategic approaches towards achieving sustainable and effective building maintenance practices in maintenance-managed buildings: a combination of expert interviews and a literature review, J. Build. Eng. 45 (2022) 103490, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jobe.2021.103490.

[4] J. Langevin, C.B. Harris, J.L. Reyna, Assessing the potential to reduce U.S. Building CO2 emissions

[5] B.K. Oh, B. Glisic, S.H. Lee, T. Cho, H.S. Park, Comprehensive investigation of embodied carbon emissions, costs, design parameters, and serviceability in

optimum green construction of two-way slabs in buildings, J. Clean. Prod. 222 (2019) 111-128, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.003.

[6] S. Tae, C. Baek, S. Shin, Life cycle CO2 evaluation on reinforced concrete structures with high-strength concrete, Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 31 (2011) 253-260, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2010.07.002.

[7] M. Lin, A. Afshari, E. Azar, A data-driven analysis of building energy use with emphasis on operation and maintenance: a case study from the UAE, J. Clean. Prod. 192 (2018) 169-178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.270.

[8] R. Ruparathna, K. Hewage, R. Sadiq, Improving the energy efficiency of the existing building stock: a critical review of commercial and institutional buildings, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 53 (2016) 1032-1045, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.rser.2015.09.084.

[9] Y.H. Chiang, J. Li, L. Zhou, F.K.W. Wong, P.T.I. Lam, The nexus among employment opportunities, life-cycle costs, and carbon emissions: a case study of sustainable building maintenance in Hong Kong, J. Clean. Prod. 109 (2015) 326-335, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.07.069.

[10] A. Alghanmi, A. Yunusa-Kaltungo, R.E. Edwards, Investigating the influence of maintenance strategies on building energy performance: a systematic literature review, Energy Rep. 8 (2022) 14673-14698, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. egyr.2022.10.441.

[11] J. Zhao, H. Feng, Q. Chen, B. Garcia de Soto, Developing a conceptual framework for the application of digital twin technologies to revamp building operation and maintenance processes, J. Build. Eng. 49 (2022) 104028, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104028.

[12] J. Wang, X. Wang, Y. Shen, X. Xiong, W. Zheng, P. Li, X. Fang, Building operation and maintenance scheme based on sharding blockchain, Heliyon 9 (2023) e13186, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13186.

[13] A. Hauashdh, J. Jailani, I.A. Rahman, N. AL-fadhali, Structural equation model for assessing factors affecting building maintenance success, J. Build. Eng. 44 (2021) 102680, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102680.

[14] N.M. Pilanawithana, Y. Feng, K. London, P. Zhang, Developing resilience for safety management systems in building repair and maintenance: a conceptual model, Saf. Sci. 152 (2022) 105768, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ssci.2022.105768.

[15] A.T.W. Yu, K.S.H. Mok, I. Wong, Minimisation and management strategies for refurbishment and renovation waste in Hong Kong, Eng. Construct. Architect. Manag. 30 (2021) 869-888, https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-02-2021-0113.

[16] A. Hauashdh, J. Jailani, I. Abdul Rahman, N. Al-Fadhali, Factors affecting the number of building defects and the approaches to reduce their negative impacts in Malaysian public universities’ buildings, J. Facil. Manag. 20 (2022) 145-171, https://doi.org/10.1108/JFM-11-2020-0079.

[17] C. Yang, W. Shen, Q. Chen, B. Gunay, A practical solution for HVAC prognostics: failure mode and effects analysis in building maintenance, J. Build. Eng. (2018), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2017.10.013.

[18] J. García-Sanz-Calcedo, M. Gómez-Chaparro, Quantitative analysis of the impact of maintenance management on the energy consumption of a hospital in Extremadura (Spain), Sustain. Cities Soc. 30 (2017) 217-222, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.scs.2017.01.019.

[19] A. Hauashdh, J. Jailani, I. Abdul Rahman, N. AL-fadhali, Building maintenance practices in Malaysia: a systematic review of issues, effects and the way forward, Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 38 (2020) 653-672, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBPA-10-2019-0093.

[20] M.I. Adegoriola, J.H.K. Lai, E.H. Chan, A. Darko, Heritage building maintenance management (HBMM): a bibliometric-qualitative analysis of literature, J. Build. Eng. 42 (2021) 102416, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102416.

[21] C. Jiménez-Pulido, A. Jiménez-Rivero, J. García-Navarro, Improved sustainability certification systems to respond to building renovation challenges based on a literature review, J. Build. Eng. (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jobe.2021.103575.

[22] A. Saihi, M. Ben-Daya, R.A. As’ad, Maintenance and sustainability: a systematic review of modeling-based literature, J. Qual. Mainten. Eng. 29 (2022) 155-187, https://doi.org/10.1108/JQME-07-2021-0058.

[23] L.F. Cabeza, M. Chàfer, Technological options and strategies towards zero energy buildings contributing to climate change mitigation: a systematic review, Energy Build. 219 (2020) 110009, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110009.

[24] M.H. Salaheldin, M.A. Hassanain, A.M. Ibrahim, A systematic conduct of POE for polyclinic facilities in Saudi Arabia, Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 15 (2021) 344-363, https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-08-2020-0156.

[25] J.W. Creswell, V.L. Plano-Clark, Choosing a mixed methods design, in: Des. Conduct. Mix. Method Res., SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, California, 2011, pp. 53-106.

[26] T.C. Guetterman, M.D. Fetters, J.W. Creswell, Integrating quantitative and qualitative results in health science mixed methods research through joint displays, Ann. Fam. Med. 13 (2015) 554-561, https://doi.org/10.1370/ afm. 1865.

[27] Y. Jabareen, Building a conceptual framework: philosophy, definitions, and procedure, Int. J. Qual. Methods (2009), https://doi.org/10.1177/ 160940690900800406.

[28] N. Al-Fadhali, D. Mansir, R. Zainal, Validation of an integrated influential factors (IIFs) model as a panacea to curb projects completion delay in Yemen, J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 10 (2019) 793-811, https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTPM-08-2018-0080.

[29] A. Subiyakto, A.R. Ahlan, S.J. Putra, M. Kartiwi, Validation of Information System Project Success Model, vol. 5, SAGE Open, 2015215824401558165 , https://doi. org/10.1177/2158244015581650.

[30] L. Wang, W. Li, W. Feng, R. Yang, Fire risk assessment for building operation and maintenance based on BIM technology, Build. Environ. 205 (2021) 108188, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.108188.

[31] R. Volk, J. Stengel, F. Schultmann, Building Information Modeling (BIM) for existing buildings – literature review and future needs, Autom. ConStruct. 38 (2014) 109-127, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2013.10.023.

[32] X. Gao, P. Pishdad-Bozorgi, BIM-enabled facilities operation and maintenance: a review, Adv. Eng. Inf. 39 (2019) 227-247, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. aei.2019.01.005.

[33] S. Durdyev, M. Ashour, S. Connelly, A. Mahdiyar, Barriers to the implementation of building information modelling (BIM) for facility management, J. Build. Eng. (2022), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103736.

[34] A. Waqar, I. Othman, N. Shafiq, A. Deifalla, A.E. Ragab, M. Khan, Impediments in BIM implementation for the risk management of tall buildings, Results Eng 20 (2023) 101401, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101401.

[35] A.R. Radzi, N.F. Azmi, S.N. Kamaruzzaman, R.A. Rahman, E. Papadonikolaki, Relationship between digital twin and building information modeling: a systematic review and future directions, Construct. Innovat. (2023), https://doi. org/10.1108/ci-07-2022-0183.

[36] M. Fox, D. Coley, S. Goodhew, P. de Wilde, Thermography methodologies for detecting energy related building defects, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 40 (2014) 296-310, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.07.188.

[37] M. Fox, S. Goodhew, P. De Wilde, Building defect detection: external versus internal thermography, Build. Environ. (2016), https://doi.org/10.1016/j. buildenv.2016.06.011.

[38] H. Perez, J.H.M. Tah, A. Mosavi, Deep learning for detecting building defects using convolutional neural networks, Sensors 19 (2019) 3556, https://doi.org/ 10.3390/s19163556.

[39] E. Valero, A. Forster, F. Bosché, E. Hyslop, L. Wilson, A. Turmel, Automated defect detection and classification in ashlar masonry walls using machine learning, Autom. ConStruct. 106 (2019) 102846, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. autcon.2019.102846.

[40] M. Choi, S. Kim, S. Kim, Semi-automated visualization method for visual inspection of buildings on BIM using 3D point cloud, J. Build. Eng. (2023) 108017, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.108017.

[41] U.S.D. of Energy., Preventative Maintenance for Commercial HVAC Equipment. Better Buildings Solution Center. https://betterbuildingssolutioncenter.energy. gov/technology-info-suite/preventative-maintenance-commercial-hvac-equip ment..

[42] F. Jalaei, M. Zoghi, A. Khoshand, Life cycle environmental impact assessment to manage and optimize construction waste using Building Information Modeling (BIM), Int. J. Constr. Manag. 21 (2021) 784-801, https://doi.org/10.1080/ 15623599.2019.1583850.

[43] F. Setaki, A. van Timmeren, Disruptive technologies for a circular building industry, Build. Environ. 223 (2022) 109394, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. buildenv.2022.109394.

[44] V. Apostolopoulos, I. Mamounakis, A. Seitaridis, N. Tagkoulis, D.S. Kourkoumpas, P. Iliadis, K. Angelakoglou, N. Nikolopoulos, An integrated life cycle assessment and life cycle costing approach towards sustainable building renovation via a dynamic online tool, Appl. Energy 334 (2023) 120710, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.120710.

[45] C. De Wolf, M. Cordella, N. Dodd, B. Byers, S. Donatello, Whole life cycle environmental impact assessment of buildings: developing software tool and database support for the EU framework Level(s), Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 188 (2023) 106642, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106642.

[46] J. Barrelas, Q. Ren, C. Pereira, Implications of climate change in the implementation of maintenance planning and use of building inspection systems, J. Build. Eng. 40 (2021) 102777, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102777.

[47] S. Soudian, U. Berardi, Experimental performance evaluation of a climateresponsive ventilated building façade, J. Build. Eng. 61 (2022) 105233, https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105233.

[48] C.K.H. Hon, A.P.C. Chan, M.C.H. Yam, Relationships between safety climate and safety performance of building repair, maintenance, minor alteration, and addition (RMAA) works, Saf. Sci. 65 (2014) 10-19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ssci.2013.12.012.

[49] K.C. Wang, R. Almassy, H.H. Wei, I.M. Shohet, Integrated building maintenance and safety framework: educational and public facilities case study, Buildings 12 (2022), https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12060770.

[50] M. Ensafi, W. Thabet, K. Afsari, E. Yang, Challenges and gaps with user-led decision-making for prioritizing maintenance work orders, J. Build. Eng. 66 (2023) 105840, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.105840.

[51] D. Qin, P. Gao, F. Aslam, M. Sufian, H. Alabduljabbar, A comprehensive review on fire damage assessment of reinforced concrete structures, Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16 (2022) e00843, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00843.

[52] V. Kodur, P. Kumar, M.M. Rafi, Fire hazard in buildings: review, assessment and strategies for improving fire safety, PSU Res. Rev. 4 (2019) 1-23, https://doi.org/ 10.1108/PRR-12-2018-0033.

[53] C. Ferreira, A. Silva, J. de Brito, I.S. Dias, I. Flores-Colen, The impact of imperfect maintenance actions on the degradation of buildings’ envelope components, J. Build. Eng. 33 (2021) 101571, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101571.

[54] R. Bortolini, N. Forcada, Analysis of building maintenance requests using a text mining approach: building services evaluation, Build. Res. Inf. 48 (2020) 207-217, https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2019.1609291.

[55] Y. Mo, D. Zhao, J. Du, M. Syal, A. Aziz, H. Li, Automated staff assignment for building maintenance using natural language processing, Autom. ConStruct. 113 (2020) 103150, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103150.

[56] M. Jia, A. Komeily, Y. Wang, R.S. Srinivasan, Adopting Internet of Things for the development of smart buildings: a review of enabling technologies and applications, Autom. ConStruct. 101 (2019) 111-126, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. autcon.2019.01.023.

[57] Y. Cao, T. Wang, X. Song, An energy-aware, agent-based maintenance-scheduling framework to improve occupant satisfaction, Autom. ConStruct. (2015), https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2015.09.002.

[58] C.P. Au-Yong, A.-S. Ali, F. Ahmad, S.J.L. Chua, Influences of key stakeholders’ involvement in maintenance management, Property Manag. 35 (2017) 217-231, https://doi.org/10.1108/PM-01-2016-0004.

[59] E.A. Pärn, D.J. Edwards, M.C.P. Sing, The building information modelling trajectory in facilities management: a review, Autom. ConStruct. 75 (2017) 45-55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2016.12.003.

[60] W. Chen, K. Chen, J.C.P. Cheng, Q. Wang, V.J.L. Gan, BIM-based framework for automatic scheduling of facility maintenance work orders, Autom. ConStruct. (2018), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2018.03.007.

[61] Y.-J. Chen, Y.-S. Lai, Y.-H. Lin, BIM-based augmented reality inspection and maintenance of fire safety equipment, Autom. ConStruct. 110 (2020) 103041, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.103041.

[62] J.K.W. Wong, J. Zhou, Enhancing environmental sustainability over building life cycles through green BIM: a review, Autom. ConStruct. 57 (2015) 156-165, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2015.06.003.

[63] D.E. Ighravwe, S.A. Oke, A multi-criteria decision-making framework for selecting a suitable maintenance strategy for public buildings using sustainability criteria, J. Build. Eng. 24 (2019) 100753, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jobe.2019.100753.

[64] C.P. Au-Yong, N.F. Azmi, N.E. Myeda, Promoting employee participation in operation and maintenance of green office building by adopting the total productive maintenance (TPM) concept, J. Clean. Prod. 352 (2022) 131608, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131608.

[65] V. Villa, G. Bruno, K. Aliev, P. Piantanida, A. Corneli, D. Antonelli, Machine learning framework for the sustainable maintenance of building facilities, Sustain. Times 14 (2022) 1-17, https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020681.

[66] R. Bucoń, A. Czarnigowska, A model to support long-term building maintenance planning for multifamily housing, J. Build. Eng. 44 (2021) 103000, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103000.

[67] R. Islam, T.H. Nazifa, S.F. Mohammed, M.A. Zishan, Z.M. Yusof, S.G. Mong, Impacts of design deficiencies on maintenance cost of high-rise residential buildings and mitigation measures, J. Build. Eng. 39 (2021) 102215, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102215.

[68] A.A. Akanmu, J. Olayiwola, O.A. Olatunji, Automated checking of building component accessibility for maintenance, Autom. ConStruct. 114 (2020) 103196, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103196.

[69] H.H. Hosamo, H.K. Nielsen, D. Kraniotis, P.R. Svennevig, K. Svidt, Improving building occupant comfort through a digital twin approach: a Bayesian network model and predictive maintenance method, Energy Build. 288 (2023) 112992, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.112992.

[70] Y. Li, L. Fan, Z. Zhang, Z. Wei, Z. Qin, Exploring the design risks affecting operation performance of green commercial buildings in China, J. Build. Eng. 64 (2023) 105711, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105711.

[71] Q. Lu, X. Xie, A.K. Parlikad, J.M. Schooling, Digital twin-enabled anomaly detection for built asset monitoring in operation and maintenance, Autom. ConStruct. 118 (2020) 103277, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103277.

[72] M. Casini, Extended reality for smart building operation and maintenance: a review, Energies 15 (2022) 3785, https://doi.org/10.3390/en15103785.

[73] Y. Peng, J.R. Lin, J.P. Zhang, Z.Z. Hu, A hybrid data mining approach on BIMbased building operation and maintenance, Build. Environ. 126 (2017) 483-495, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2017.09.030.

[74] S. Tang, D.R. Shelden, C.M. Eastman, P. Pishdad-Bozorgi, X. Gao, A review of building information modeling (BIM) and the internet of things (IoT) devices integration: present status and future trends, Autom. ConStruct. 101 (2019) 127-139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2019.01.020.

[75] T. Rakha, Y. El Masri, K. Chen, E. Panagoulia, P. De Wilde, Building envelope anomaly characterization and simulation using drone time-lapse thermography, Energy Build. 259 (2022) 111754, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. enbuild.2021.111754.

[76] D. Dais, İ.E. Bal, E. Smyrou, V. Sarhosis, Automatic crack classification and segmentation on masonry surfaces using convolutional neural networks and transfer learning, Autom. ConStruct. 125 (2021) 103606, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.autcon.2021.103606.

[77] J.C.P. Cheng, W. Chen, K. Chen, Q. Wang, Data-driven predictive maintenance planning framework for MEP components based on BIM and IoT using machine learning algorithms, Autom. ConStruct. 112 (2020) 103087, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103087.

[78] H.H. Hosamo, P.R. Svennevig, K. Svidt, D. Han, H.K. Nielsen, A Digital Twin predictive maintenance framework of air handling units based on automatic fault

detection and diagnostics, Energy Build. 261 (2022) 111988, https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.enbuild.2022.111988.

[79] D. Daly, C. Carr, M. Daly, P. McGuirk, E. Stanes, I. Santala, Extending urban energy transitions to the mid-tier: insights into energy efficiency from the management of HVAC maintenance in ‘mid-tier’ office buildings, Energy Pol. 174 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.113415.

[80] M.S. Piscitelli, D.M. Mazzarelli, A. Capozzoli, Enhancing operational performance of AHUs through an advanced fault detection and diagnosis process based on temporal association and decision rules, Energy Build. 226 (2020) 110369, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110369.

[81] K. Yan, J. Huang, W. Shen, Z. Ji, Unsupervised learning for fault detection and diagnosis of air handling units, Energy Build. 210 (2020) 109689, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.109689.

[82] A. Gallego-Schmid, H.-M. Chen, M. Sharmina, J.M.F. Mendoza, Links between circular economy and climate change mitigation in the built environment, J. Clean. Prod. 260 (2020) 121115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jclepro.2020.121115.

[83] A.P.M. Velenturf, P. Purnell, Principles for a sustainable circular economy, Sustain. Prod. Consum. 27 (2021) 1437-1457, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. spc.2021.02.018.

[84] D.W.M. Chan, Sustainable building maintenance for safer and healthier cities: effective strategies for implementing the Mandatory Building Inspection Scheme (MBIS) in Hong Kong, J. Build. Eng. (2019), https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jobe.2019.100737.

[85] E. Barreira, R.M.S.F. Almeida, M. Moreira, An infrared thermography passive approach to assess the effect of leakage points in buildings, Energy Build. 140 (2017) 224-235, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.02.009.

[86] N.D. Nath, A.H. Behzadan, S.G. Paal, Deep learning for site safety: real-time detection of personal protective equipment, Autom. ConStruct. (2020), https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103085.

[87] J.F. Falorca, J.C.G. Lanzinha, Facade inspections with drones-theoretical analysis and exploratory tests, Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 39 (2020) 235-258, https:// doi.org/10.1108/IJBPA-07-2019-0063.

[88] T. Rakha, A. Gorodetsky, Review of Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) applications in the built environment: towards automated building inspection procedures using drones, Autom. ConStruct. (2018), https://doi.org/10.1016/j. autcon.2018.05.002.

[89] M. Gheisari, B. Esmaeili, Applications and requirements of unmanned aerial systems (UASs) for construction safety, Saf. Sci. 118 (2019) 230-240, https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.05.015.

[90] M.-T. Cao, Drone-assisted segmentation of tile peeling on building façades using a deep learning model, J. Build. Eng. (2023) 108063, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jobe.2023.108063.

[91] I. Dias, I. Flores-Colen, A. Silva, Critical analysis about emerging technologies for building’s façade inspection, Buildings 11 (2021) 53, https://doi.org/10.3390/ buildings11020053.

[92] C. Okonkwo, I. Okpala, I. Awolusi, C. Nnaji, Overcoming barriers to smart safety management system implementation in the construction industry, Results Eng 20 (2023) 101503, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101503.

[93] Y. Pan, L. Zhang, Roles of artificial intelligence in construction engineering and management: a critical review and future trends, Autom. ConStruct. 122 (2021) 103517, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103517.

[94] X. Li, W. Yi, H.L. Chi, X. Wang, A.P.C. Chan, A critical review of virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR) applications in construction safety, Autom. ConStruct. (2018), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2017.11.003.

[95] C. Nnaji, A.A. Karakhan, Technologies for safety and health management in construction: current use, implementation benefits and limitations, and adoption barriers, J. Build. Eng. 29 (2020) 101212, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jobe.2020.101212.

[96] A.W.Y. Lai, W.M. Lai, Users’ satisfaction survey on building maintenance in public housing, Eng. Construct. Architect. Manag. 20 (2013) 420-440, https:// doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-06-2011-0057.

[97] Z. Chen, Z. O’Neill, J. Wen, O. Pradhan, T. Yang, X. Lu, G. Lin, S. Miyata, S. Lee, C. Shen, R. Chiosa, M.S. Piscitelli, A. Capozzoli, F. Hengel, A. Kührer, M. Pritoni, W. Liu, J. Clauß, Y. Chen, T. Herr, A review of data-driven fault detection and diagnostics for building HVAC systems, Appl. Energy 339 (2023) 121030, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.121030.

[98] Ö. Çimen, Development of a circular building lifecycle framework: inception to circulation, Results Eng 17 (2023) 100861, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. rineng.2022.100861.

[99] N. Kwon, K. Song, Y. Ahn, M. Park, Y. Jang, Maintenance cost prediction for aging residential buildings based on case-based reasoning and genetic algorithm, J. Build. Eng. 28 (2020) 101006, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2019.101006.

[100] M. Shoaib, A. Nawal, R. Zámečník, R. Korsakienė, A.U. Rehman, Go green! Measuring the factors that influence sustainable performance, J. Clean. Prod. 366 (2022) 132959, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132959.

- Corresponding author.

** Corresponding author. Faculty of Civil Engineering and Built Environment, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Batu Pahat, Johor, 86400, Malaysia

*** Corresponding author. Department of Civil, Environmental and Natural Resources Engineering, Luleå University of Technology, Sweden.

E-mail addresses: alihauashdh@gmail.com (A. Hauashdh), sasitharan@uthm.edu.my (S. Nagapan), yaser.gamil@ltu.se (Y. Gamil).

- Corresponding author.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.101822

Publication Date: 2024-01-26

An integrated framework for sustainable and efficient building maintenance operations aligning with climate change, SDGs, and emerging technology

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

SDGs

GHG emissions

BIM

Building maintenance

Abstract

Improving the operation and maintenance of buildings can significantly reduce carbon emissions, energy consumption, and other environmental challenges while promoting sustainability. While existing literature offers various frameworks, they primarily focus on traditional building maintenance procedures and overlook the importance of integrating sustainability, climate change, environmental factors, and emerging technologies. To address this gap, this research has developed a comprehensive framework that caters to current needs, challenges, and future priorities. The integrated framework for building maintenance operations aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), climate change mitigation and adaptation, the adoption of emerging technology, energy conservation, as well as safety, resilience, and effectiveness. The development of the framework encompassed four phases: pre-development phases 1 and 2 , development phase 3 , and validation phase 4. During this process, current issues and challenges were identified, impacts were assessed, and strategies were developed. The framework serves as a roadmap to address these challenges and requirements in future building maintenance operations, making significant contributions to all three dimensions of sustainability: environmental, social, and economic. In summary, this study offers a comprehensive and in-depth analysis of the current issues, challenges, and potential improvements and benefits in building maintenance operations, providing a practical guide for industry stakeholders and making a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge.

1. Introduction

reducing environmental impacts [1]. In fact, the building sector is responsible for a significant portion of energy consumption, Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, and resource use. According to various studies and energy departments, buildings are responsible for consuming almost 40 % of the total energy used and producing

| List of abbreviations | DT | Digital Twin | |