DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04343-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38735940

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-13

إعادة تعريف المواد الحيوية السنية: تحسين مركب الراتنج السني المدفوع بتقنية الربط الجزيئي والديناميكا

الملخص

خلفية: تُعرف مركبات الراتنج السني المعتمدة على الراتنج بشكل واسع لجاذبيتها الجمالية وخصائصها اللاصقة، مما يجعلها جزءًا لا يتجزأ من طب الأسنان الترميمي الحديث. على الرغم من مزاياها، لا تزال تحديات الالتصاق والأداء البيوميكانيكي قائمة، مما يستدعي استراتيجيات مبتكرة للتحسين. تناولت هذه الدراسة التحديات المرتبطة بالالتصاق والخصائص البيوميكانيكية في مركبات الراتنج السني المعتمدة على الراتنج من خلال استخدام التحليل الجزيئي والمحاكاة الديناميكية. الطرق: يقيم التحليل الجزيئي طاقات الربط ويقدم رؤى قيمة حول التفاعلات بين المونومرات، والحشوات، وعوامل الربط. تعطي هذه الدراسة الأولوية لـ

المقدمة

تحسين الالتصاق بهياكل الأسنان أمر حيوي لمنع التسرب المجهري والتسوس الثانوي، وهما من المقدمات الشائعة لفشل الترميم وعدم راحة المريض [9، 10]. يلعب إدخال الحشوات غير العضوية، مثل

مقاومة أكبر لتشويه الشكل تحت ضغط القص، مما يساهم في السلامة الهيكلية العامة لمركبات الراتنج السني [19-21]. علاوة على ذلك، تعتبر قوة الانحناء مؤشرًا حاسمًا على أداء المواد السنية، حيث تحدد قدرتها على تحمل قوى الانحناء التي تواجهها أثناء المضغ [22-24].

طرق

اختيار المركبات المركبة القائمة على الراتنجات السنية للدراسة

السبب وراء هذا الاختيار متجذر في الحاجة إلى التقاط طيف واسع من المواد المستخدمة في الممارسة السريرية. يتماشى هذا النهج مع الدراسات السابقة التي تؤكد على أهمية تركيبة المواد في تحديد الخصائص الميكانيكية واللاصقة لمركبات الأسنان [1]. من خلال دراسة مجموعة متنوعة من المواد، كان الهدف من هذه الدراسة هو تقديم رؤى يمكن أن تكون قابلة للتطبيق بشكل واسع على السيناريوهات السريرية.

اختيار المحسنات المحتملة

مراجعة شاملة للأدبيات الحالية والبيانات التجريبية حول مواد الأسنان وجهت اختيار هذه المضافات. درست الدراسات السابقة مضافات متنوعة، مثل السيلاين ومواد الربط، التي يمكن أن تؤثر بشكل كبير على الالتصاق. كان تحديد هذه المضافات أمرًا حيويًا، حيث شكلت الأساس للتجارب والمحاكاة اللاحقة.

النمذجة الجزيئية لمكونات المركبات القائمة على الراتنج

الهياكل للعناصر الأساسية من المركبات المركبة القائمة على الراتنجات السنية، والتي تشمل المونومرات، والحشوات، وعوامل الربط. تشكل هذه النماذج الحاسوبية الأساس الذي نكتسب من خلاله فهماً شاملاً للتفاعلات الجزيئية المعقدة التي تحدد سلوك هذه المركبات. تم بدء هذه العملية من خلال الحصول على تمثيلات ثلاثية الأبعاد دقيقة للمكونات الأساسية للمركب. للحصول على هذه الهياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد بتنسيق بيانات الهيكل (SDF)، تم الحصول على الجزيئات التي تتكون من المونومرات، والحشوات، وعوامل الربط من قاعدة بيانات PubChem.https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). بعد ذلك، تم إخضاع كل ligand لعملية تقليل حاسمة باستخدام OpenBabel الإصدار 3.0.1. كانت هذه الخطوة ضرورية لضمان أن الهياكل الجزيئية كانت مستقرة طاقياً وت conformت لأفضل الترتيبات المكانية. باستخدام قاعدة بيانات PubChem وOpenBabel الإصدار 3.0.1، ضمنا أن نماذجنا الحاسوبية تمثل بدقة الهياكل الجزيئية الحقيقية للمكونات المركبة.

أ. المونومرات: تلعب المونومرات، وهي الكتل الأساسية لمصفوفة الراتنج، دورًا حيويًا في تحديد خصائص المركب. في هذه الخطوة، تم بناء الهياكل الجزيئية للمونومرات المختارة، بما في ذلك HEMA وBis-GMA وEBPADMA وTEGDMA وUDMA. شمل هذا العملية تحديد أطوال الروابط وزوايا الروابط وزوايا الثنائي لتكرار التكوين لهذه المونومرات في ثلاثة أبعاد بدقة.

ب. المواد المالئة: تؤثر المواد المالئة، بما في ذلك كربونات الكالسيوم وأكسيد السيريوم (IV) وجزيئات هيدروكسيباتيت وجزيئات السيليكا ونيتريد السيليكون، بشكل كبير على الخصائص الميكانيكية للمركبات. تم إنشاء الهياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد لهذه المواد المالئة بدقة باستخدام ChemDraw Ultra 12.0 (PerkinElmer Inc.) [31] لالتقاط طبيعتها البلورية أو غير البلورية. كانت هذه الجهود ضرورية لفهم كيفية توزيع المواد المالئة داخل مصفوفة الراتنج وكيف ساهمت خصائصها السطحية في الالتصاق والأداء البيوميكانيكي.

ج. عوامل الربط: عززت عوامل الربط، مثل 3-MPTS وTRIS وICPTES وAEAPTMS وVTES، الالتصاق بين المكونات العضوية وغير العضوية. مكنت برامج ChemDraw Ultra وOpenBabel من بناء هياكل ثلاثية الأبعاد لهذه العوامل، مع التركيز على مجموعاتها الوظيفية الفريدة التي سهلت الربط مع المونومرات العضوية والمواد المالئة غير العضوية.

محاكاة ربط الجزيئات

| مكون | البنية الكيميائية | الكثافة (

|

|||

| مونومرات | |||||

| 2-هيدروكسي إيثيل ميثاكريلات (HEMA) | 1.03 | ||||

| ميثاكريلات جليكيديل بيسفينول أ (Bis-GMA) | 1.16 | ||||

| ثنائي ميثاكريلات بيسفينول أ الإيثوكسيلي (EBPADMA) | 1.12 | ||||

| ثلاثي إيثيلين غليكول ثنائي الميثاكريلات (TEGDMA) | 1.07 | ||||

| ثنائي ميثاكريلات اليوريثان (UDMA) | 1.11 | ||||

| مواد مالئة | |||||

| كربونات الكالسيوم

|

2.80 | ||||

| أكسيد السيريوم (IV)

|

7.13 | ||||

| هيدروكسي أباتيت (

|

|

3.16 | |||

| جزيئات السيليكا (

|

2.58 | ||||

| نيتريد السيليكون

|

|

٣.٣٠ | |||

تم إجراء المحاكاة دون تضمين مستقبلات محددة، مما سمح باستكشاف أكثر شمولاً وانفتاحاً للتفاعلات الجزيئية. تم تحديد البقايا النشطة لكل ligand بدقة لتحديد مواقع التفاعل الحاسمة، في حين تمثل البقايا السلبية إضافية

| مكون | البنية الكيميائية | الكثافة (

|

| عوامل الربط | ||

| 3-ميثاكريلوكسيبروبيل ثلاثي إيثوكسي سيلاين (3-MPTS) | 1.04 | |

| 3-(تريميثوكسي سيلييل) بروبيل ميثاكريلات (TRIS) | 0.93 | |

| إيزوسياناتوبروبيل ثلاثي إيثوكسي سيلاين (ICPTES) | 0.99 | |

| N-(2-أمينوإيثيل)-3-أمينوبروبيل تريميثوكسي سيلاين (AEAPTMS) | 0.97 | |

| فينيل ثلاثي إيثوكسي سيلاين (VTES) | 0.90 | |

محاكاة الديناميات الجزيئية (MD)

المواد المركبة القائمة على الراتنج مع مرور الوقت وتطور التفاعلات بين الجزيئات تحت ظروف ديناميكية. تعتبر محاكاة الديناميكا الجزيئية أدوات لا غنى عنها للتحقيق في السلوك الديناميكي لمركبات الراتنج السني على مدى فترات طويلة. ركزت محاكاة الديناميكا الجزيئية على الخصائص البيوميكانيكية لمجمعات المركب السني (معامل يونغ، معامل القص، وقوة الانحناء). كما تم حساب الروابط الهيدروجينية (ك stabilizers لتفاعلات معقدات الليغاند-ليغاند). تم استخدام وحدة Forcite مع مجال القوة COMPASS II في المحاكاة لتمثيل التفاعلات داخل الجزيئات وبين الجزيئات. هذه الوحدة ومجال القوة مثاليان لمحاكاة البوليمرات والمركبات غير العضوية. في المرحلة الأولية من محاكاة الديناميكا الجزيئية، تم تقليل طاقة جميع مجمعات المركب السني (نتيجة محاكاة التوصيل) مع تقارب القوة والطاقة.

عدد الجسيمات، حجم النظام، ودرجة الحرارة (NVT) ensemble لمدة 50 نانوثانية، مع تعديل عدد الجسيمات، حجم النظام، ودرجة الحرارة. تلت ذلك محاكاة أخرى لمدة 50 نانوثانية في عدد الجسيمات، ضغط النظام، ودرجة الحرارة (NPT) ensemble، مع تنظيم عدد الجسيمات، ضغط النظام، ودرجة الحرارة عند 1.0 بار و298 كلفن. تم تسهيل التحكم في الضغط ودرجة الحرارة من خلال منظمات الحرارة Nose-Hoover ومنظمات الضغط Langevin وBerendsen، كل منها مع ثوابت تخميد تبلغ 0.1 و1.0 نانوثانية، على التوالي. بعد ذلك، خضع المركب السني لمزيد من التوازن في NVT ensemble عند 298 كلفن لمدة 50 نانوثانية. تم استخدام خوارزمية تكامل سرعة Verlet مع خطوة زمنية تبلغ 1.0 نانوثانية، وتم اختيار جودة حساب عالية لتعزيز دقة الحسابات. تم حساب تفاعلات فان der Waals والتفاعلات الكهروستاتيكية باستخدام طريقة شبكة الجسيمات Ewald. تم استخدام الهيكل الجزيئي المتوازن الناتج عن مركب الراتنج السني للتحليلات الهيكلية والميكانيكية اللاحقة.

النتائج

محاكاة ربط الجزيئات لتركيبات محتملة من المونومرات، والمواد المالئة، وعوامل الربط

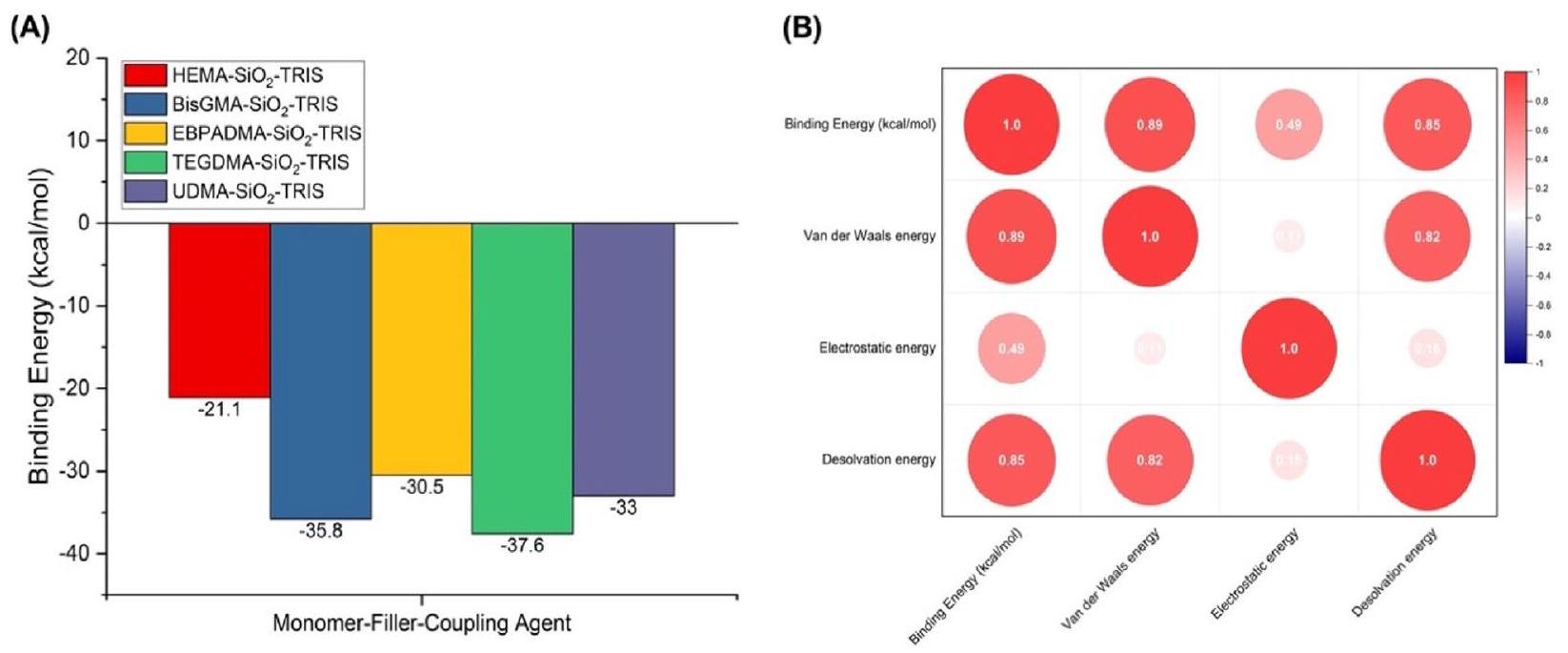

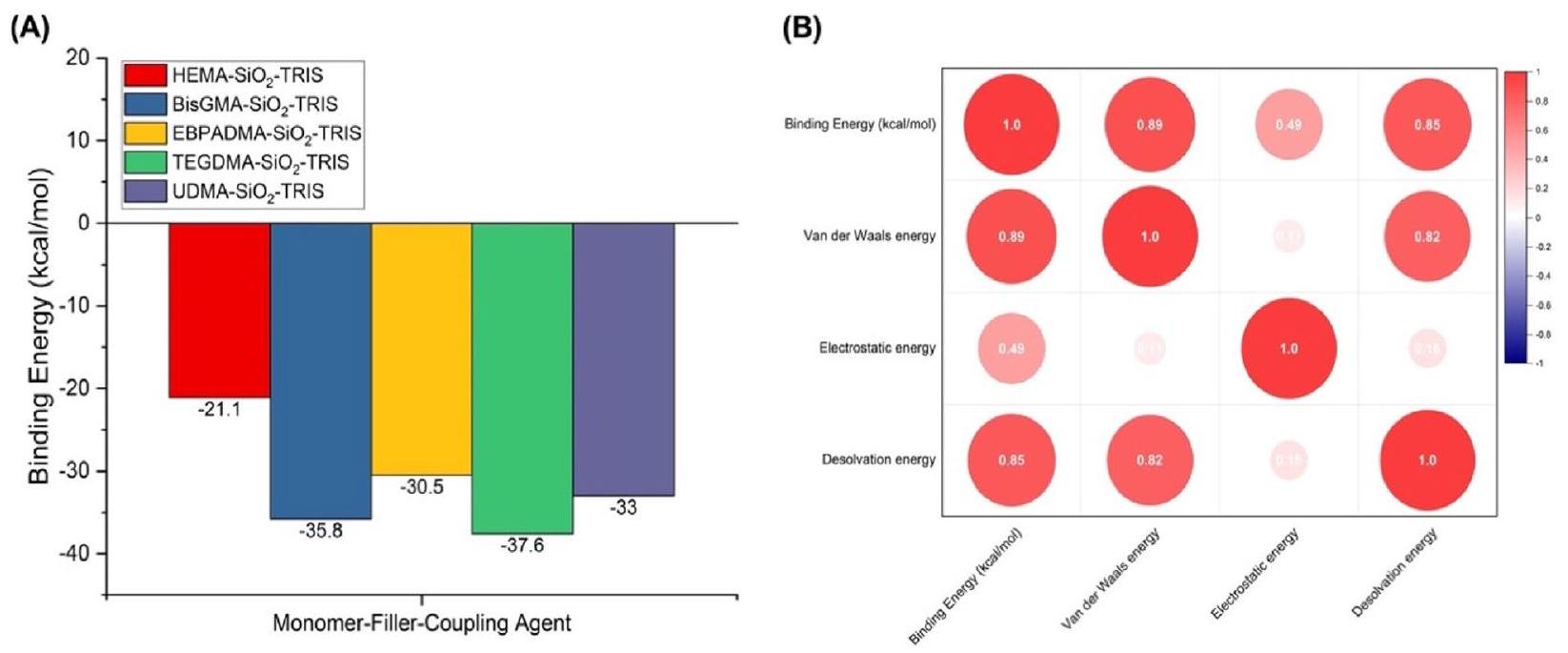

جذاب في وجود TRIS. بالنسبة لـ Bis-GMA، أشارت النتائج أيضًا إلى تفاعلات كبيرة مع TRIS. كانت أعلى طاقة ارتباط لوحظت لـ Bis-GMA هي

| مونومر | حشوة | عامل الربط | طاقة الربط (كيلو كالوري/مول) | طاقة فان دير فالس | الطاقة الكهروستاتيكية | طاقة إزالة الحلول |

| HEMA |

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

| مونومر | حشوة | عامل الربط | طاقة الربط (كيلو كالوري/مول) | طاقة فان دير فالس | الطاقة الكهروستاتيكية | طاقة إزالة الحلول |

| بيس-جي إم إيه |

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

| مونومر | حشوة | عامل الربط | طاقة الربط (كيلو كالوري/مول) | طاقة فان دير ووالس | الطاقة الكهروستاتيكية | طاقة إزالة الحلول |

| EBPADMA |

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

| مونومر | حشوة | عامل الربط | طاقة الربط (كيلو كالوري/مول) | طاقة فان دير ووالس | الطاقة الكهروستاتيكية | طاقة إزالة الحلول |

| تيغدما |

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

| مونومر | حشو | عامل الربط | طاقة الربط (كيلو كالوري/مول) | طاقة فان دير ووالس | الطاقة الكهروستاتيكية | طاقة إزالة الحلول |

| UDMA |

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| تريس |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

الطاقة المرتبطة بالطاقة المرتبطة بالربط. تشير هذه العلاقة إلى وجود ارتباط قوي بين القدرة على إزالة المذيب أو إزاحة جزيئات المذيب من موقع الربط والطاقة المرتبطة الإجمالية. تشير هذه العلاقة إلى أنه مع زيادة طاقة إزالة المذيب، هناك زيادة متCorresponding في الطاقة المرتبطة. هذه النتيجة ذات صلة خاصة بالالتصاق في سياق المركبات القائمة على الراتنجات السنية. تلعب طاقة إزالة المذيب دورًا حاسمًا في عملية الالتصاق من خلال التأثير على التفاعلات بين مكونات المواد المركبة المختلفة. عندما يتم إزاحة جزيئات المذيب بشكل فعال من موقع الربط، فإنها تعزز التفاعل وقوة الربط بين المكونات، مما يساهم في تكوين مركب أكثر استقرارًا. ترتبط طاقة إزالة المذيب الأعلى بـ

محاكاة الديناميكا الجزيئية لأفضل تركيبات المونومرات والمواد المالئة وعوامل الربط

1. معامل يونغ (E)

-

هو معامل يونغ للمركب. -

هو كسر الحجم للمكون . -

هو معامل يونغ للمكون .

2. معامل القص (G)

-

هو معامل القص للمركب. -

هو كسر الحجم للمكون . -

هو معامل القص للمكون .

3. قوة الانحناء

-

هو قوة الانحناء. -

هو قوة الشد. -

هو مقاومة الضغط.

من HEMA-

تحديد “أفضل” مركب مركب للأسنان هو قرار متعدد الأبعاد يتطلب اعتبارات دقيقة للتطبيقات المحددة ومتطلبات المواد المقابلة لها. من منظور الالتصاق، فإن الزيادة المستمرة في قوة الالتصاق من خلال

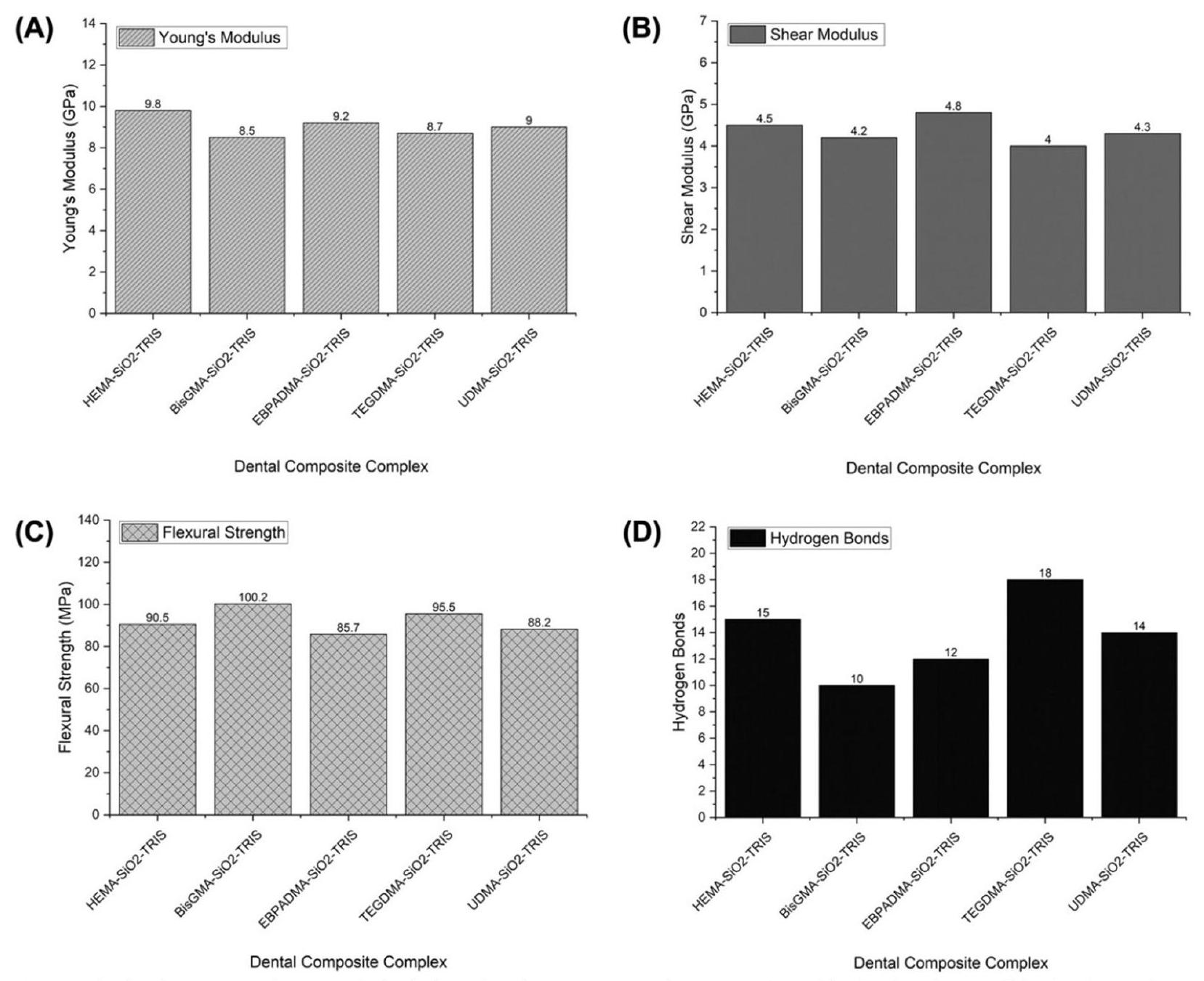

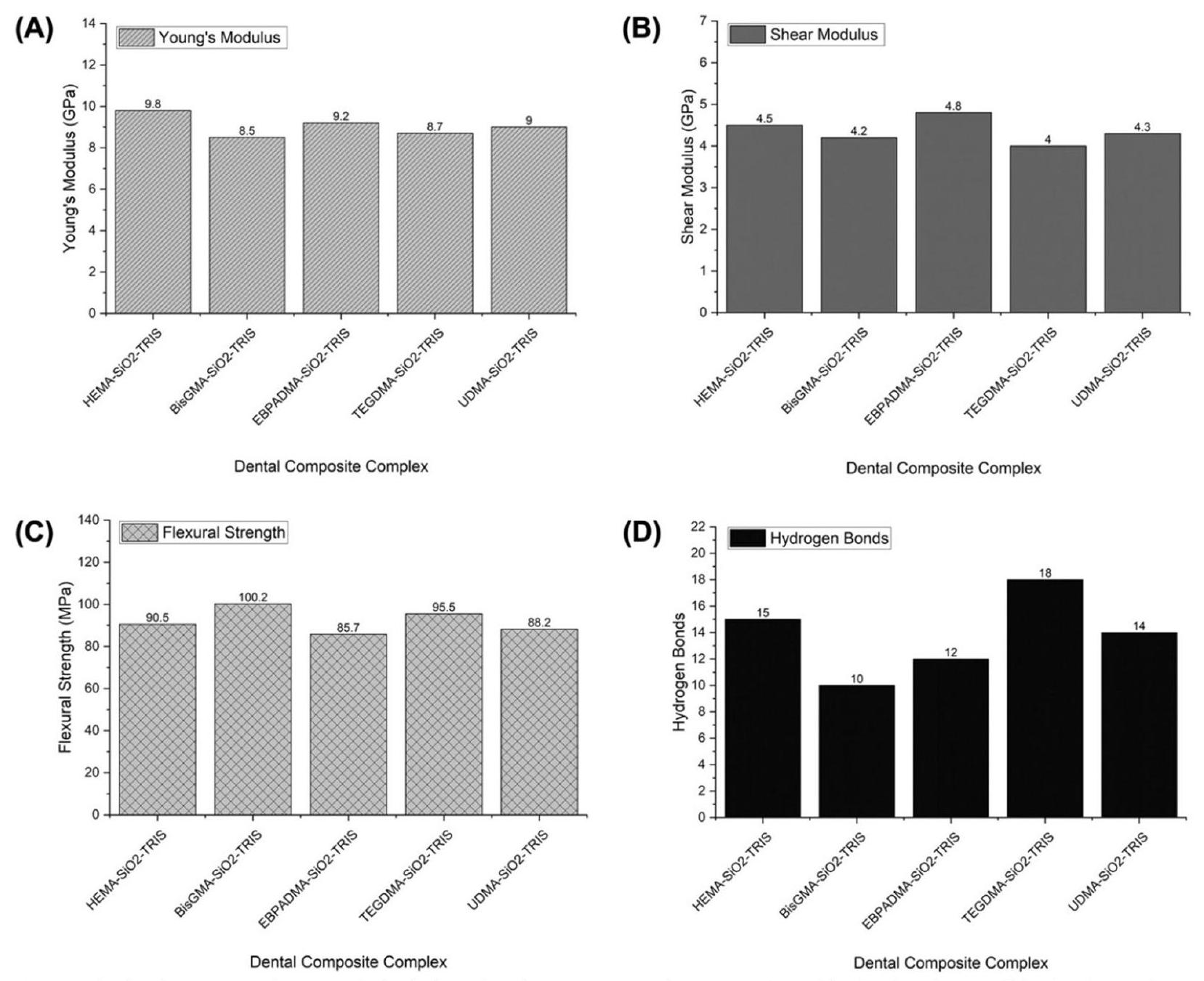

عند تحويل الانتباه إلى الخصائص البيوميكانيكية، فإن تفاصيل كل مركب مركب الموضحة في الجدول 4 تؤكد أهمية توافق الاختيار مع الاستخدام المقصود وخصائص المواد المطلوبة.

نقاش

تعزيز الخصائص البيوميكانيكية من خلال الربط الجزيئي ومحاكاة الديناميات

| مركب الراتنج السني | مودول يونغ (جيجا باسكال) | مودول القص (جيجا باسكال) | قوة الانحناء (ميجا باسكال) | روابط الهيدروجين |

| HEMA-SiO2-TRIS | 9.8 | 4.5 | 90.5 | 15 |

| BisGMA-

|

8.5 | 4.2 | 100.2 | 10 |

| EBPADMA-

|

9.2 | 4.8 | 85.7 | 12 |

| TEGDMA-

|

8.7 | 4.0 | 95.5 | 18 |

| UDMA-

|

9.0 | 4.3 | 88.2 | 14 |

نقاط القوة، والقيود، والاعتبارات السريرية نقاط القوة

تقييم خصائصها الميكانيكية تحت سيناريوهات تحميل واقعية [54، 55]. هذا الفهم الديناميكي أمر حاسم لتوقع أداء المركب في البيئة الفموية المعقدة، حيث تتعرض المواد لمجموعة من الضغوط الميكانيكية. إن دمج المحاكاة الحاسوبية مع التحقق التجريبي يحمل وعدًا كبيرًا لتسريع تطوير المواد في طب الأسنان. من خلال الجمع بين التنبؤات الحاسوبية والبيانات التجريبية، يمكن للباحثين تحسين تركيبات المركب بشكل تكراري، مما يؤدي إلى تطوير مواد محسنة ذات خصائص معززة.

القيود

الاعتبارات السريرية

نتائج سريرية أفضل وزيادة في رضا المرضى عن الترميمات السنية. علاوة على ذلك، فإن تعددية المواد المركبة المحسّنة تسمح باستخدامها في مجموعة واسعة من التطبيقات السريرية. من الحشوات البسيطة إلى الترميمات الأكثر تعقيدًا، يمكن أن توفر هذه المواد جاذبية جمالية، وتوافق حيوي، وموثوقية ميكانيكية، تلبي الاحتياجات المتنوعة للمرضى والأطباء على حد سواء. ومع ذلك، من الضروري الاعتراف بأن تحويل النتائج الحاسوبية إلى الممارسة السريرية يتطلب تحققًا دقيقًا وموافقة تنظيمية. من الضروري إجراء تحقق تجريبي لأداء المركبات في المختبر وفي الجسم الحي لتأكيد الفوائد المتوقعة وضمان سلامة وفعالية المواد الجديدة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تلعب الهيئات التنظيمية مثل إدارة الغذاء والدواء (FDA) دورًا حاسمًا في تقييم واعتماد المواد السنية للاستخدام السريري، مما يضمن أنها تلبي معايير صارمة للسلامة والأداء.

الخاتمة

الأعمال المستقبلية

المركب إلى الركائز السنية وإجراء اختبارات قوة الربط الميكروتنسيلية أو الميكروقصية باستخدام آلة اختبار عالمية. بالنسبة للخصائص البيوميكانيكية، تشمل التقييمات معامل يونغ، ومعامل القص، وقوة الانحناء، باستخدام تقنيات مثل النانو-indentations، والتحليل الميكانيكي الديناميكي، واختبارات الانحناء ثلاثية النقاط.

الاختصارات

| 3-MPTS | 3-ميثاكريلوكسيبروبيل ثلاثي إيثوكسي سيلاين |

| AEAPTMS | N-(2-أمينوإيثيل)-3-أمينوبروبيل تريميثوكسي سيلاين |

| الرس | قيود التفاعل الغامضة |

| بيس-جي إم إيه | ميثاكريلات جليكيديل بيسفينول أ |

| EBPADMA | ثنائي ميثاكريلات بيسفينول أ الإيثوكسيلي |

| إدارة الغذاء والدواء | إدارة الغذاء والدواء |

| هيما | 2-هيدروكسي إيثيل ميثاكريلات |

| ICPTES | إيزوسياناتوبروبيل ثلاثي إيثوكسي سيلاين |

| مد | ديناميكا الجزيئات |

| MTA | مركب ثلاثي أكسيد المعادن |

| NPT | عدد الجسيمات، ضغط النظام، ودرجة الحرارة |

| NVT | عدد الجسيمات، حجم النظام، ودرجة الحرارة |

| PME | إيوالد شبكة الجسيمات |

| SDF | تنسيق بيانات هيكلي |

| تيغدما | ثلاثي إيثيلين غليكول ثنائي الميثاكريلات |

| تريس | 3-(تريميثوكسي سيليل) بروبيل ميثاكريلات |

| UDMA | دي ميثاكريلات اليوريثان |

| VTES | فينيل ثلاثي إيثوكسي سيلاين |

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

وعلوم التقنية، جامعة سافيثا، تشيناي، الهند.

نُشر على الإنترنت: 13 مايو 2024

References

- Ferracane JL. Resin composite-state of the art. Dent Mater. 2011;27(1):29-38.

- Cho K , et al. Dental resin composites: A review on materials to product realizations. Compos B Eng. 2022;230:109495.

- Mousavinasab SM. Biocompatibility of composite resins. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2011;8(Suppl 1):S21-9.

- Bertassoni LE, et al. Mechanical recovery of dentin following remineralization in vitro-an indentation study. J Biomech. 2011;44(1):176-81.

- Stansbury J, et al. Conversion-dependent shrinkage stress and strain in dental resins and composites. Dental materials : official publication of the Academy of Dental Materials. 2005;21:56-67.

- Perdigão J. Current perspectives on dental adhesion: (1) Dentin adhesion – not there yet. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2020;56(1):190-207.

- Drummond JL. Degradation, fatigue, and failure of resin dental composite materials. J Dent Res. 2008;87(8):710-9.

- Mitra SB, Wu D, Holmes BN. An application of nanotechnology in advanced dental materials. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(10):1382-90.

- Jaberi Ansari Z, Kalantar Motamedi M. Microleakage of two self-adhesive cements in the enamel and dentin after 24 hours and two months. J Dent (Tehran). 2014;11(4):418-27.

- Mohanty PR, et al. Optimizing Adhesive Bonding to Caries Affected Dentin: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Dental Adhesive Strategies following Chemo-Mechanical Caries Removal. Appl Sci. 2023;13(12):7295.

- Farooq I, et al. Synergistic Effect of Bioactive Inorganic Fillers in Enhancing Properties of Dentin Adhesives-A Review. Polymers (Basel). 2021;13(13):2169.

- Akhtar K , et al. Calcium hydroxyapatite nanoparticles as a reinforcement filler in dental resin nanocomposite. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2021;32(10):129.

- Taira M , et al. Studies on radiopaque composites containing

fillers prepared by the sol-gel process. Dent Mater. 1993;9(3):167-71. - Kaur K, et al. Comparison between Restorative Materials for Pulpotomised Deciduous Molars: A Randomized Clinical Study. Children (Basel). 2023;10(2):284.

- Zhang YR , et al. Review of research on the mechanical properties of the human tooth. Int J Oral Sci. 2014;6(2):61-9.

- Galo R, et al. Hardness and modulus of elasticity of primary and permanent teeth after wear against different dental materials. Eur J Dent. 2015;9(4):587-93.

- Saini RS, Mosaddad SA, Heboyan A. Application of density functional theory for evaluating the mechanical properties and structural stability of dental implant materials. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23(1):958.

- Alshadidi AAF, et al. Investigation on the Application of Artificial Intelligence in Prosthodontics. Appl Sci. 2023;13(8):5004.

- Chiba A, et al. The influence of elastic moduli of core materials on shear stress distributions at the adhesive interface in resin built-up teeth. Dent Mater J. 2017;36(1):95-102.

- Rabelo Ribeiro JC, et al. Shear strength evaluation of composite-composite resin associations. J Dent. 2008;36:326-30.

- Zhu, H., et al. Effect of Shear Modulus on the Inflation Deformation of Parachutes Based on Fluid-Structure Interaction Simulation. Sustainability, 2023. 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065396.

- Moradi Z, et al. Fracture Toughness Comparison of Three Indirect Composite Resins Using 4-Point Flexural Strength Method. Eur J Dent. 2020;14(2):212-6.

- Moosavi H, Zeynali M, Pour ZH. Fracture Resistance of Premolars Restored by Various Types and Placement Techniques of Resin Composites. International Journal of Dentistry. 2012;2012:973641.

- Abdul-Monem M, El G, Al-Abbassy F. Effect Of Aging On The Flexural Strength And Fracture Toughness Of A Fiber Reinforced Composite Resin Versus Two Nanohybrid Composite Resins. Alex Dent J. 2016;41:328-35.

- Durrant JD, McCammon JA. Molecular dynamics simulations and drug discovery. BMC Biol. 2011;9(1):71.

- Kitchen DB, et al. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2004;3(11):935-49.

- Zhou X, et al. Development and status of resin composite as dental restorative materials. J Appl Polym Sci. 2019;136(44):48180.

- Badar MS, Shamsi S, Ahmed J, Alam MA. Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Concept, Methods, and Applications. In: Rezaei N, editor. Transdisciplinarity. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 131-51.

- Elshereksi N, et al. Review of titanate coupling agents and their application for dental composite fabrication. Dent Mater J. 2017;36(5):539-552.

- Su H-L, et al. Silica nanoparticles modified with vinyltriethoxysilane and their copolymerization with

-bismaleimide-4,4′-diphenylmethane. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;103:3600-8. - Cousins KR. Computer Review of ChemDraw Ultra 12.0. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(21):8388-8388.

- Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin AMJJ. HADDOCK: A Protein-Protein Docking Approach Based on Biochemical or Biophysical Information. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(7):1731-7.

- Sun H, et al. COMPASS II: extended coverage for polymer and drug-like molecule databases. J Mol Model. 2016;22(2):47.

- Simmonett AC, Brooks BR. A compression strategy for particle mesh Ewald theory. J Chem Phys. 2021;154(5):054112.

- Cervino G, et al. Mineral Trioxide Aggregate Applications in Endodontics: A Review. Eur J Dent. 2020;14(4):683-91.

- Zhao H, Qi N, Li Y. Interaction between polysaccharide monomer and SiO2/Al2O3/CaCO3 surfaces: A DFT theoretical study. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;466:607-14.

- Indumathy, B., et al. A Comprehensive Review on Processing, Development and Applications of Organofunctional Silanes and Silane-Based Hyperbranched Polymers. Polymers, 2023. 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ polym15112517.

- Jesionowski T, Krysztafkiewicz A. Influence of Silane Coupling Agents on Surface Properties of Precipitated Silicas. Appl Surf Sci. 2001;172:18-32.

- Dermawan D, Prabowo BA, Rakhmadina CA. In silico study of medicinal plants with cyclodextrin inclusion complex as the potential inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) and spike (S) receptor. Inform Med Unlocked. 2021;25:100645.

- Brakat, A. and H. Zhu From Forces to Assemblies: van der Waals ForcesDriven Assemblies in Anisotropic Quasi-2D Graphene and Quasi-1D Nanocellulose Heterointerfaces towards Quasi-3D Nanoarchitecture. Nanomaterials, 2023. 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13172399.

- Crouch J, et al. How van der Waals Approximation Methods Affect Activation Barriers of Cyclohexene Hydrogenation over a Pd Surface. ACS Engineering Au. 2022;2(6):547-52.

- Sahay S, et al. Role of Vander Waals and Electrostatic Energy in Binding of Drugs with GP120: Free Energy Calculation using MMGBSA Method. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Science). 2020;16:242-52.

- Erbaş A, de la Cruz MO, Marko JF. Effects of electrostatic interactions on ligand dissociation kinetics. Phys Rev E. 2018;97(2-1):022405.

- Li Z, et al. Electrostatic Contributions to the Binding Free Energy of Nicotine to the Acetylcholine Binding Protein. J Phys Chem B. 2022;126(43):8669-79.

- Browning C, et al. Critical Role of Desolvation in the Binding of 20-Hydroxyecdysone to the Ecdysone Receptor*. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(45):32924-34.

- Mondal J, Friesner R, Berne B. Role of Desolvation in Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Ligand Binding to a Kinase. J Chem Theory Comput. 2014;10:5696-705.

- Vaidya A, Pathak K. 17 – Mechanical stability of dental materials. In: Asiri AM, Inamuddin, Mohammad A, editors. Applications of Nanocomposite Materials in Dentistry: Woodhead Publishing; 2019. p. 285-305.

- Albergaria LS, et al. Effect of nanofibers as reinforcement on resin-based dental materials: A systematic review of in vitro studies. Japanese Dental Science Review. 2023;59:239-52.

- Fugolin AP, et al. Alternative monomer for BisGMA-free resin composites formulations. Dent Mater. 2020;36(7):884-92.

- Ribeiro JCR, et al. Shear strength evaluation of composite-composite resin associations. J Dent. 2008;36(5):326-30.

- Meenakumari C, et al. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Newer Nanoposterior Restorative Resin Composites: An In vitro Study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2018;9(Suppl 1):S142-s146.

- Visan, A.I. and I. Negut Integrating Artificial Intelligence for Drug Discovery in the Context of Revolutionizing Drug Delivery. Life, 2024. 14. https:// doi.org/10.3390/life14020233.

- Meng XY, et al. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structurebased drug discovery. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2011;7(2):146-57.

- Jiang, B., et al. Molecular Dynamics Simulation on the Interfacial Behavior of Over-Molded Hybrid Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Polymers, 2020. 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12061270.

- Barbhuiya S, Das BB. Molecular dynamics simulation in concrete research: A systematic review of techniques, models and future directions. Journal of Building Engineering. 2023;76: 107267.

- Gähde U, Hartmann S, Wolf J. Models, Simulations, and the Reduction of Complexity. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter; 2014. https://doi.org/10.1515/ 9783110313680.

- Marshall GR. Limiting assumptions in molecular modeling: electrostatics. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2013;27(2):107-14.

- Schmitt S, Fleckenstein F, Hasse H, Stephan S. Comparison of Force Fields for the Prediction of Thermophysical Properties of Long Linear and Branched Alkanes. J Phys Chem B. 2023;127(8):1789-1802.

- Zhou W, et al. Modifying Adhesive Materials to Improve the Longevity of Resinous Restorations. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):723.

- Carvalho RM, et al. Durability of bonds and clinical success of adhesive restorations. Dent Mater. 2012;28(1):72-86.

- Ouldyerou A, et al. Biomechanical performance of resin composite on dental tissue restoration: A finite element analysis. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(12):e0295582.

- Elleuch S , et al. Agglomeration effect on biomechanical performance of CNT-reinforced dental implant using micromechanics-based approach. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2023;145:106023.

- Chopra D, et al. Load, unload and repeat: Understanding the mechanical characteristics of zirconia in dentistry. Dent Mater. 2024;40(1):e1-17.

- Sachan S, et al. In Vitro Analysis of Outcome Differences Between Repairing and Replacing Broken Dental Restorations. Cureus. 2024;16(3):e56071.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلات:

سيد علي مصدق

mosaddad.sa@gmail.com

أرتاك هيبويان

heboyan.artak@gmail.com

قائمة كاملة بمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقال

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04343-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38735940

Publication Date: 2024-05-13

Dental biomaterials redefined: molecular docking and dynamics-driven dental resin composite optimization

Abstract

Background Dental resin-based composites are widely recognized for their aesthetic appeal and adhesive properties, which make them integral to modern restorative dentistry. Despite their advantages, adhesion and biomechanical performance challenges persist, necessitating innovative strategies for improvement. This study addressed the challenges associated with adhesion and biomechanical properties in dental resin-based composites by employing molecular docking and dynamics simulation. Methods Molecular docking assesses the binding energies and provides valuable insights into the interactions between monomers, fillers, and coupling agents. This investigation prioritizes

Introduction

Optimizing adhesion to tooth structures is pivotal to preventing microleakage and secondary caries, common precursors of restoration failure and patient discomfort [9, 10]. Incorporating inorganic fillers, such as

greater resistance to shape distortion under shear stress, contributing to the overall structural integrity of dental composites [19-21]. Furthermore, flexural strength is a critical indicator of dental material performance, dictating its ability to endure bending forces encountered during mastication [22-24].

Methods

Selection of dental resin-based composites for study

The rationale behind this selection is rooted in the need to capture a broad spectrum of materials used in clinical practice. This approach aligned with previous studies emphasizing material composition’s significance in determining dental composites’ mechanical and adhesive properties [1]. By studying a diverse set of materials, this study aimed to provide insights that could be broadly applicable to clinical scenarios.

Selection of potential modifiers

An extensive review of the existing literature and experimental data on dental materials guided the selection of these modifiers. Previous studies have explored various modifiers, such as silanes and coupling agents, that could significantly influence adhesion [29, 30]. Identifying these modifiers was crucial, as they formed the basis for subsequent simulations and experimentation.

Molecular modelling of resin-based composite components

structures for the fundamental elements of dental resin-based composites, encompassing monomers, fillers, and coupling agents. These computational models form the bedrock upon which we gain a comprehensive understanding of the complex molecular interactions that dictate the behavior of these composites. This process was initiated by procuring accurate 3D representations of the core components of the composite. To obtain these 3D structures in the structure data format (SDF), ligands consisting of monomers, fillers, and coupling agents were sourced from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Subsequently, each ligand was subjected to a crucial minimization process using OpenBabel version 3.0.1. This step was essential to ensure that the molecular structures were energetically stable and conformed to the most favorable spatial arrangements. Using the PubChem database and OpenBabel version 3.0.1, we guaranteed that our computational models accurately represented the real-world molecular structures of the composite constituents.

a. Monomers: Monomers, the primary building blocks of the resin matrix, play a pivotal role in determining the properties of the composite. In this step, the molecular structures of selected monomers, including HEMA, Bis-GMA, EBPADMA, TEGDMA, and UDMA, were constructed. This process involved defining the bond lengths, bond angles, and dihedral angles to replicate the conformation of these monomers in three dimensions faithfully.

b. Fillers: Fillers, including calcium carbonate, cerium(IV) oxide, hydroxyapatite, silica particles, and silicon nitride, significantly influence the mechanical properties of composites. The 3D structures of these fillers were meticulously created using ChemDraw Ultra 12.0 (PerkinElmer Inc.) [31] to capture their crystalline or amorphous nature. This endeavor was crucial for understanding how the fillers were dispersed within the resin matrix and how their surface properties contributed to the adhesion and biomechanical performance.

c. Coupling Agents: Coupling agents, such as 3-MPTS, TRIS, ICPTES, AEAPTMS, and VTES, enhanced the adhesion between the organic and inorganic components. ChemDraw Ultra and OpenBabel enabled the construction of 3D structures of these coupling agents, focusing on their unique functional groups that facilitated bonding with organic monomers and inorganic fillers.

Molecular docking simulations

| Component | Chemical Structure | Density (

|

|||

| Monomers | |||||

| 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) | 1.03 | ||||

| Bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate (Bis-GMA) | 1.16 | ||||

| Ethoxylated bisphenol A dimethacrylate (EBPADMA) | 1.12 | ||||

| Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA) | 1.07 | ||||

| Urethane dimethacrylate (UDMA) | 1.11 | ||||

| Fillers | |||||

| Calcium Carbonate (

|

2.80 | ||||

| Cerium(IV) Oxide (

|

7.13 | ||||

| Hydroxyapatite (

|

|

3.16 | |||

| Silica particles (

|

2.58 | ||||

| Silicon Nitride (

|

|

3.30 | |||

the simulations were carried out without including specific receptors, which allowed for a more comprehensive and open-ended exploration of the intermolecular interactions. Active residues for each ligand were meticulously specified to delineate crucial interaction sites, whereas passive residues, representing additional

| Component | Chemical Structure | Density (

|

| Coupling Agents | ||

| 3-Methacryloxypropyltriethoxysilane (3-MPTS) | 1.04 | |

| 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate (TRIS) | 0.93 | |

| Isocyanatopropyltriethoxysilane (ICPTES) | 0.99 | |

| N-(2-Aminoethyl)-3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (AEAPTMS) | 0.97 | |

| Vinyltriethoxysilane (VTES) | 0.90 | |

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

resin-based composite materials over time and the evolution of intermolecular interactions under dynamic conditions. Molecular dynamics simulations are indispensable tools for investigating the dynamic behavior of dental resin-based composites over extended periods. The MD simulation focused on the biomechanical properties of the dental composite complexes (Young’s modulus, shear modulus, and flexural strength). Hydrogen bonds (as stabilizers of ligand-ligand complex interactions) were also calculated. The Forcite module with the COMPASS II force field was used in the simulation to represent intra- and intermolecular interactions. This module and force field are ideal for simulations of polymers and inorganic compounds [33]. In the initial stage of the MD simulation, the energy of all dental composite complexes (the result of docking simulation) was minimized with a force and energy convergence of

number of particles, system volume, and temperature (NVT) ensemble for 50 ns , manipulating the particle number, system volume, and temperature. Another 50 ns simulation followed this in the number of particles, system pressure, and temperature (NPT) ensemble, regulating particle number, system pressure, and temperature at 1.0 bar and 298 K . Pressure and temperature control were facilitated through the Nose-Hoover ThermostatLangevin and Berendsen barostats, each with damping constants of 0.1 and 1.0 ns , respectively. Subsequently, the dental composite underwent additional equilibration in the NVT ensemble at 298 K for 50 ns . The Verlet velocity integration algorithm was employed with a time step of 1.0 ns , and a high calculation quality was chosen to enhance computational accuracy. Van der Waals and electrostatic interactions were computed using the particle mesh Ewald method [34]. The resulting equilibrium molecular structure of the dental resin composite was used for subsequent structural and mechanical analyses.

Results

Molecular docking simulations for possible combinations of monomers, fillers, and coupling agents

attractive in the presence of TRIS. For Bis-GMA, the results also indicated substantial interactions with TRIS. The highest binding energy observed for Bis-GMA was

| Monomer | Filler | Coupling Agent | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Van der Waals energy | Electrostatic energy | Desolvation energy |

| HEMA |

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

| Monomer | Filler | Coupling Agent | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Van der Waals energy | Electrostatic energy | Desolvation energy |

| Bis-GMA |

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

| Monomer | Filler | Coupling Agent | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Van der Waals energy | Electrostatic energy | Desolvation energy |

| EBPADMA |

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

| Monomer | Filler | Coupling Agent | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Van der Waals energy | Electrostatic energy | Desolvation energy |

| TEGDMA |

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

| Monomer | Filler | Coupling Agent | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Van der Waals energy | Electrostatic energy | Desolvation energy |

| UDMA |

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

3-MPTS |

|

|

|

|

|

| TRIS |

|

|

|

|

||

| ICPTES |

|

|

|

|

||

| AEAPTMS |

|

|

|

|

||

| VTES |

|

|

|

|

energy on binding energy [44, 45]. This correlation suggests a strong connection between the ability to desolvate or displace solvent molecules from the binding site and the overall binding energy. This correlation indicates that as the desolvation energy increases, there is a corresponding increase in the binding energy. This finding is particularly relevant to adhesion in the context of dental resin-based composites. The desolvation energy plays a crucial role in the adhesion process by influencing the interactions between different composite material components. When solvent molecules are effectively displaced from the binding site, they enhance the interaction and binding strength between the components, contributing to a more stable complex. A higher desolvation energy is associated with a

Molecular dynamics simulations for the best combinations of monomers, fillers, and coupling agents

1. Young’s modulus (E)

-

is the Young’s modulus of the composite. -

is the volume fraction of component . -

is the Young’s modulus of component .

2. Shear modulus (G)

-

is the shear modulus of the composite. -

is the volume fraction of component . -

is the Shear modulus of component .

3. Flexural strength

-

is the flexural strength. -

is the tensile strength. -

is the compressive strength.

of HEMA-

Determining the “best” dental composite complex is a multifaceted decision that requires careful consideration of specific applications and their corresponding material requirements. From the perspective of adhesion, the consistent augmentation of the adhesion power through

Turning attention to biomechanical properties, the nuances of each composite complex outlined in Table 4 underscore the importance of aligning the choice with the intended use and sought-after material properties.

Discussion

Biomechanical property enhancement through molecular docking and dynamics simulations

| Dental Composite Complex | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Shear Modulus (GPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Hydrogen Bonds |

| HEMA-SiO2-TRIS | 9.8 | 4.5 | 90.5 | 15 |

| BisGMA-

|

8.5 | 4.2 | 100.2 | 10 |

| EBPADMA-

|

9.2 | 4.8 | 85.7 | 12 |

| TEGDMA-

|

8.7 | 4.0 | 95.5 | 18 |

| UDMA-

|

9.0 | 4.3 | 88.2 | 14 |

Strengths, limitations, and clinical considerations Strengths

assess their mechanical properties under realistic loading scenarios [54, 55]. This dynamic understanding is crucial for predicting composite performance in the complex oral environment, where materials are subjected to a range of mechanical stresses. The integration of computational simulations with experimental validation holds significant promise for accelerating materials development in dentistry. By combining computational predictions with empirical data, researchers can iteratively refine composite formulations, leading to the development of optimized materials with enhanced properties.

Limitations

Clinical considerations

better clinical outcomes and increased patient satisfaction with dental restorations [63, 64]. Furthermore, the versatility of optimized composite materials allows for their use in a wide range of clinical applications. From simple fillings to more complex restorations, these materials can provide aesthetic appeal, biocompatibility, and mechanical reliability, meeting the diverse needs of patients and clinicians alike. However, it is essential to recognize that the translation of computational findings into clinical practice requires careful validation and regulatory approval. Experimental validation of composite performance in vitro and in vivo is necessary to confirm the predicted benefits and ensure the safety and efficacy of new materials. Additionally, regulatory bodies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) play a crucial role in evaluating and approving dental materials for clinical use, ensuring that they meet stringent standards for safety and performance.

Conclusion

Future works

composite to dental substrates and conducting microtensile or micro-shear bond strength tests using a universal testing machine. For biomechanical properties, evaluations include Young’s Modulus, Shear Modulus, and flexural strength, utilizing techniques such as nanoindentation, dynamic mechanical analysis, and three-point bending tests.

Abbreviations

| 3-MPTS | 3-Methacryloxypropyltriethoxysilane |

| AEAPTMS | N-(2-Aminoethyl)-3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane |

| AlRs | Ambiguous Interaction Restraints |

| Bis-GMA | Bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate |

| EBPADMA | Ethoxylated bisphenol A dimethacrylate |

| FDA | Food and drug administration |

| HEMA | 2-Hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| ICPTES | Isocyanatopropyltriethoxysilane |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| MTA | Mineral trioxide aggregate |

| NPT | Number of particles, system pressure, and temperature |

| NVT | Number of particles, system volume, and temperature |

| PME | Particle mesh Ewald |

| SDF | Structure data format |

| TEGDMA | Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate |

| TRIS | 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate |

| UDMA | Urethane dimethacrylate |

| VTES | Vinyltriethoxysilane |

Acknowledgements

Authors’ contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author details

and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, India.

Published online: 13 May 2024

References

- Ferracane JL. Resin composite-state of the art. Dent Mater. 2011;27(1):29-38.

- Cho K , et al. Dental resin composites: A review on materials to product realizations. Compos B Eng. 2022;230:109495.

- Mousavinasab SM. Biocompatibility of composite resins. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2011;8(Suppl 1):S21-9.

- Bertassoni LE, et al. Mechanical recovery of dentin following remineralization in vitro-an indentation study. J Biomech. 2011;44(1):176-81.

- Stansbury J, et al. Conversion-dependent shrinkage stress and strain in dental resins and composites. Dental materials : official publication of the Academy of Dental Materials. 2005;21:56-67.

- Perdigão J. Current perspectives on dental adhesion: (1) Dentin adhesion – not there yet. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2020;56(1):190-207.

- Drummond JL. Degradation, fatigue, and failure of resin dental composite materials. J Dent Res. 2008;87(8):710-9.

- Mitra SB, Wu D, Holmes BN. An application of nanotechnology in advanced dental materials. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134(10):1382-90.

- Jaberi Ansari Z, Kalantar Motamedi M. Microleakage of two self-adhesive cements in the enamel and dentin after 24 hours and two months. J Dent (Tehran). 2014;11(4):418-27.

- Mohanty PR, et al. Optimizing Adhesive Bonding to Caries Affected Dentin: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Dental Adhesive Strategies following Chemo-Mechanical Caries Removal. Appl Sci. 2023;13(12):7295.

- Farooq I, et al. Synergistic Effect of Bioactive Inorganic Fillers in Enhancing Properties of Dentin Adhesives-A Review. Polymers (Basel). 2021;13(13):2169.

- Akhtar K , et al. Calcium hydroxyapatite nanoparticles as a reinforcement filler in dental resin nanocomposite. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2021;32(10):129.

- Taira M , et al. Studies on radiopaque composites containing

fillers prepared by the sol-gel process. Dent Mater. 1993;9(3):167-71. - Kaur K, et al. Comparison between Restorative Materials for Pulpotomised Deciduous Molars: A Randomized Clinical Study. Children (Basel). 2023;10(2):284.

- Zhang YR , et al. Review of research on the mechanical properties of the human tooth. Int J Oral Sci. 2014;6(2):61-9.

- Galo R, et al. Hardness and modulus of elasticity of primary and permanent teeth after wear against different dental materials. Eur J Dent. 2015;9(4):587-93.

- Saini RS, Mosaddad SA, Heboyan A. Application of density functional theory for evaluating the mechanical properties and structural stability of dental implant materials. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23(1):958.

- Alshadidi AAF, et al. Investigation on the Application of Artificial Intelligence in Prosthodontics. Appl Sci. 2023;13(8):5004.

- Chiba A, et al. The influence of elastic moduli of core materials on shear stress distributions at the adhesive interface in resin built-up teeth. Dent Mater J. 2017;36(1):95-102.

- Rabelo Ribeiro JC, et al. Shear strength evaluation of composite-composite resin associations. J Dent. 2008;36:326-30.

- Zhu, H., et al. Effect of Shear Modulus on the Inflation Deformation of Parachutes Based on Fluid-Structure Interaction Simulation. Sustainability, 2023. 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065396.

- Moradi Z, et al. Fracture Toughness Comparison of Three Indirect Composite Resins Using 4-Point Flexural Strength Method. Eur J Dent. 2020;14(2):212-6.

- Moosavi H, Zeynali M, Pour ZH. Fracture Resistance of Premolars Restored by Various Types and Placement Techniques of Resin Composites. International Journal of Dentistry. 2012;2012:973641.

- Abdul-Monem M, El G, Al-Abbassy F. Effect Of Aging On The Flexural Strength And Fracture Toughness Of A Fiber Reinforced Composite Resin Versus Two Nanohybrid Composite Resins. Alex Dent J. 2016;41:328-35.

- Durrant JD, McCammon JA. Molecular dynamics simulations and drug discovery. BMC Biol. 2011;9(1):71.

- Kitchen DB, et al. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: methods and applications. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2004;3(11):935-49.

- Zhou X, et al. Development and status of resin composite as dental restorative materials. J Appl Polym Sci. 2019;136(44):48180.

- Badar MS, Shamsi S, Ahmed J, Alam MA. Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Concept, Methods, and Applications. In: Rezaei N, editor. Transdisciplinarity. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 131-51.

- Elshereksi N, et al. Review of titanate coupling agents and their application for dental composite fabrication. Dent Mater J. 2017;36(5):539-552.

- Su H-L, et al. Silica nanoparticles modified with vinyltriethoxysilane and their copolymerization with

-bismaleimide-4,4′-diphenylmethane. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;103:3600-8. - Cousins KR. Computer Review of ChemDraw Ultra 12.0. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(21):8388-8388.

- Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin AMJJ. HADDOCK: A Protein-Protein Docking Approach Based on Biochemical or Biophysical Information. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(7):1731-7.

- Sun H, et al. COMPASS II: extended coverage for polymer and drug-like molecule databases. J Mol Model. 2016;22(2):47.

- Simmonett AC, Brooks BR. A compression strategy for particle mesh Ewald theory. J Chem Phys. 2021;154(5):054112.

- Cervino G, et al. Mineral Trioxide Aggregate Applications in Endodontics: A Review. Eur J Dent. 2020;14(4):683-91.

- Zhao H, Qi N, Li Y. Interaction between polysaccharide monomer and SiO2/Al2O3/CaCO3 surfaces: A DFT theoretical study. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;466:607-14.

- Indumathy, B., et al. A Comprehensive Review on Processing, Development and Applications of Organofunctional Silanes and Silane-Based Hyperbranched Polymers. Polymers, 2023. 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ polym15112517.

- Jesionowski T, Krysztafkiewicz A. Influence of Silane Coupling Agents on Surface Properties of Precipitated Silicas. Appl Surf Sci. 2001;172:18-32.

- Dermawan D, Prabowo BA, Rakhmadina CA. In silico study of medicinal plants with cyclodextrin inclusion complex as the potential inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) and spike (S) receptor. Inform Med Unlocked. 2021;25:100645.

- Brakat, A. and H. Zhu From Forces to Assemblies: van der Waals ForcesDriven Assemblies in Anisotropic Quasi-2D Graphene and Quasi-1D Nanocellulose Heterointerfaces towards Quasi-3D Nanoarchitecture. Nanomaterials, 2023. 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13172399.

- Crouch J, et al. How van der Waals Approximation Methods Affect Activation Barriers of Cyclohexene Hydrogenation over a Pd Surface. ACS Engineering Au. 2022;2(6):547-52.

- Sahay S, et al. Role of Vander Waals and Electrostatic Energy in Binding of Drugs with GP120: Free Energy Calculation using MMGBSA Method. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Science). 2020;16:242-52.

- Erbaş A, de la Cruz MO, Marko JF. Effects of electrostatic interactions on ligand dissociation kinetics. Phys Rev E. 2018;97(2-1):022405.

- Li Z, et al. Electrostatic Contributions to the Binding Free Energy of Nicotine to the Acetylcholine Binding Protein. J Phys Chem B. 2022;126(43):8669-79.

- Browning C, et al. Critical Role of Desolvation in the Binding of 20-Hydroxyecdysone to the Ecdysone Receptor*. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(45):32924-34.

- Mondal J, Friesner R, Berne B. Role of Desolvation in Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Ligand Binding to a Kinase. J Chem Theory Comput. 2014;10:5696-705.

- Vaidya A, Pathak K. 17 – Mechanical stability of dental materials. In: Asiri AM, Inamuddin, Mohammad A, editors. Applications of Nanocomposite Materials in Dentistry: Woodhead Publishing; 2019. p. 285-305.

- Albergaria LS, et al. Effect of nanofibers as reinforcement on resin-based dental materials: A systematic review of in vitro studies. Japanese Dental Science Review. 2023;59:239-52.

- Fugolin AP, et al. Alternative monomer for BisGMA-free resin composites formulations. Dent Mater. 2020;36(7):884-92.

- Ribeiro JCR, et al. Shear strength evaluation of composite-composite resin associations. J Dent. 2008;36(5):326-30.

- Meenakumari C, et al. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Newer Nanoposterior Restorative Resin Composites: An In vitro Study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2018;9(Suppl 1):S142-s146.

- Visan, A.I. and I. Negut Integrating Artificial Intelligence for Drug Discovery in the Context of Revolutionizing Drug Delivery. Life, 2024. 14. https:// doi.org/10.3390/life14020233.

- Meng XY, et al. Molecular docking: a powerful approach for structurebased drug discovery. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2011;7(2):146-57.

- Jiang, B., et al. Molecular Dynamics Simulation on the Interfacial Behavior of Over-Molded Hybrid Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. Polymers, 2020. 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12061270.

- Barbhuiya S, Das BB. Molecular dynamics simulation in concrete research: A systematic review of techniques, models and future directions. Journal of Building Engineering. 2023;76: 107267.

- Gähde U, Hartmann S, Wolf J. Models, Simulations, and the Reduction of Complexity. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter; 2014. https://doi.org/10.1515/ 9783110313680.

- Marshall GR. Limiting assumptions in molecular modeling: electrostatics. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2013;27(2):107-14.

- Schmitt S, Fleckenstein F, Hasse H, Stephan S. Comparison of Force Fields for the Prediction of Thermophysical Properties of Long Linear and Branched Alkanes. J Phys Chem B. 2023;127(8):1789-1802.

- Zhou W, et al. Modifying Adhesive Materials to Improve the Longevity of Resinous Restorations. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):723.

- Carvalho RM, et al. Durability of bonds and clinical success of adhesive restorations. Dent Mater. 2012;28(1):72-86.

- Ouldyerou A, et al. Biomechanical performance of resin composite on dental tissue restoration: A finite element analysis. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(12):e0295582.

- Elleuch S , et al. Agglomeration effect on biomechanical performance of CNT-reinforced dental implant using micromechanics-based approach. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2023;145:106023.

- Chopra D, et al. Load, unload and repeat: Understanding the mechanical characteristics of zirconia in dentistry. Dent Mater. 2024;40(1):e1-17.

- Sachan S, et al. In Vitro Analysis of Outcome Differences Between Repairing and Replacing Broken Dental Restorations. Cureus. 2024;16(3):e56071.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Seyed Ali Mosaddad

mosaddad.sa@gmail.com

Artak Heboyan

heboyan.artak@gmail.com

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article