DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02592-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38907216

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-21

اتجاه جديد في علاج التهاب اللثة: العلاج المناعي باستخدام المواد الحيوية المستندة إلى البلعميات

الملخص

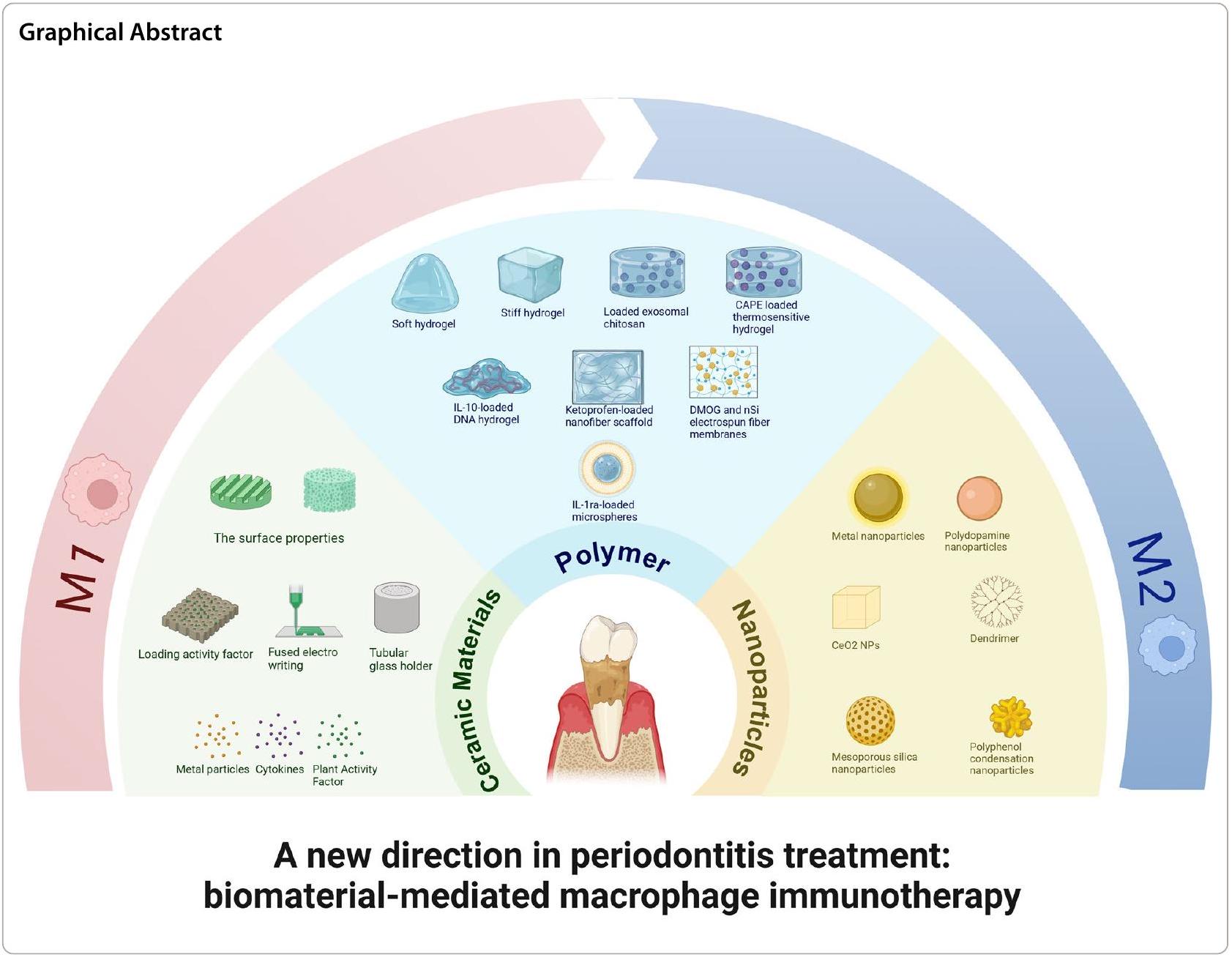

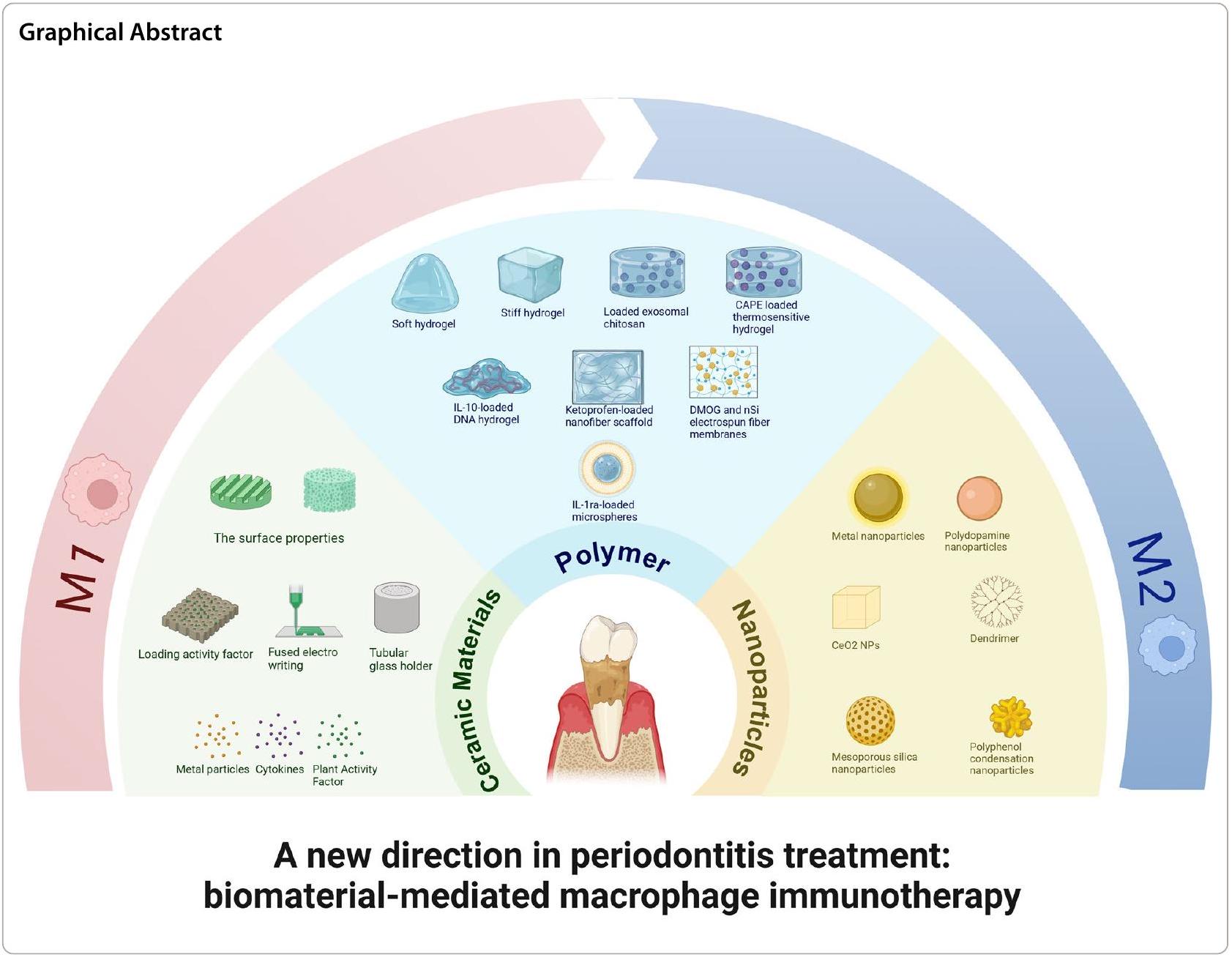

التهاب اللثة هو التهاب مزمن ناتج عن عدوى بكتيرية ويرتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا باستجابة مناعية مفرطة النشاط. يتم استخدام المواد الحيوية بشكل متزايد في علاج التهاب اللثة بسبب تصميمها ونظام توصيل الأدوية الفريد. ومع ذلك، فإن ردود الفعل المناعية المحلية والنظامية الناتجة عن زراعة المواد الحيوية يمكن أن تؤدي إلى التهاب، وتلف الأنسجة، وتليف، مما قد يؤدي إلى فشل الزراعة. لذلك، يمكن أن يقلل التعديل المناعي للمواد الحيوية من رد فعل المضيف مع القضاء على الاستجابة الالتهابية المزمنة طويلة الأمد للأنسجة اللثوية. من المهم أن نلاحظ أن البلعميات هي مكون نشط في الجهاز المناعي يمكن أن يشارك في تقدم مرض التهاب اللثة من خلال آليات استقطاب معقدة. وقد ظهر تعديل استقطاب البلعميات من خلال تصميم المواد الحيوية كتقنية جديدة لعلاج التهاب اللثة. في هذه المراجعة، نناقش دور البلعميات في التهاب اللثة والاستراتيجيات النموذجية لاستقطاب البلعميات باستخدام المواد الحيوية. بعد ذلك، نناقش التحديات والفرص المحتملة لاستخدام المواد الحيوية للتلاعب بالبلعميات اللثوية لتسهيل تجديد اللثة.

المقدمة

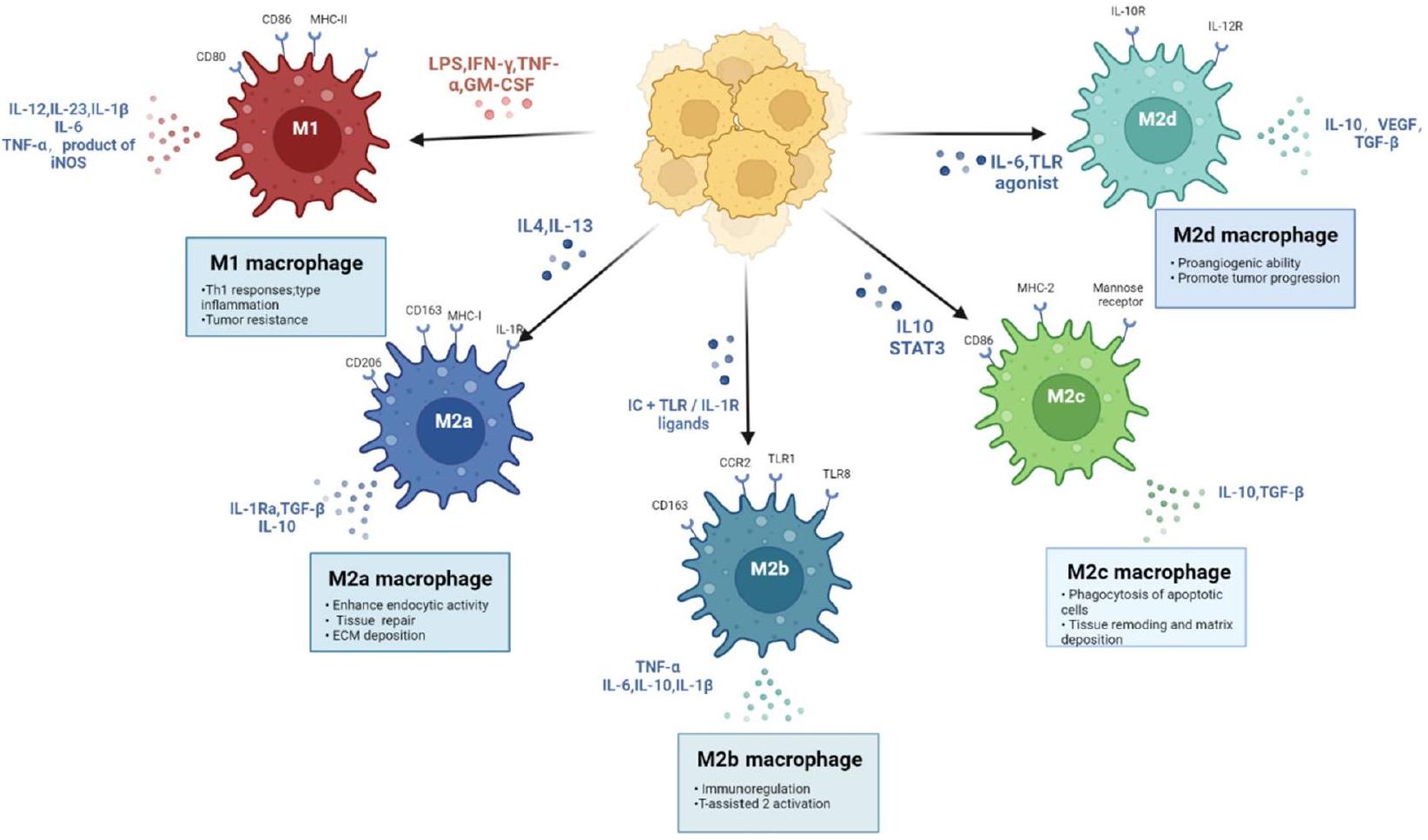

البلعميات، خلايا فعالة في الجهاز المناعي الفطري. إنها ضرورية لإزالة الميكروبات، وحل الالتهاب، واستقرار الأنسجة، وإصلاح التجديد. ترتبط العديد من الأمراض الالتهابية في الجسم، مثل الالتهاب الرئوي، والتهاب الأمعاء، والتهاب الكبد، والالتهاب أثناء شفاء الجروح، والتهاب اللثة، بالبلعميات [3]. يمكن أن تستقطب إلى نوعين، M1 و M2، وتساهم في تعزيز وتقليل الالتهاب: تتمتع بلعميات M1 بتأثيرات مؤيدة للالتهاب، وهي مسؤولة بشكل أساسي عن اكتشاف الميكروبات، والبلع،

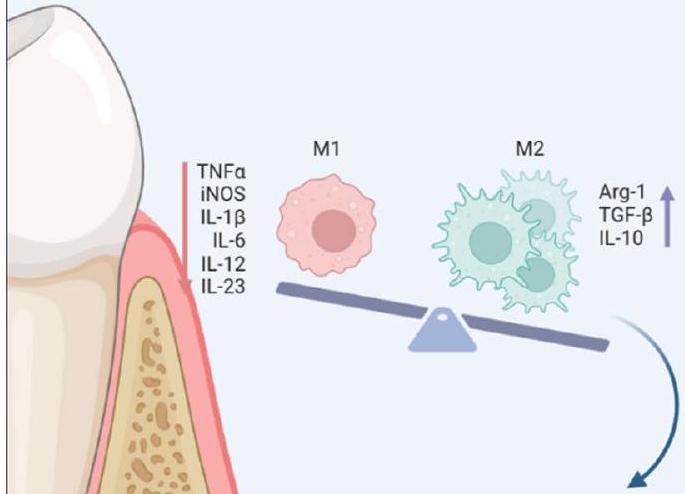

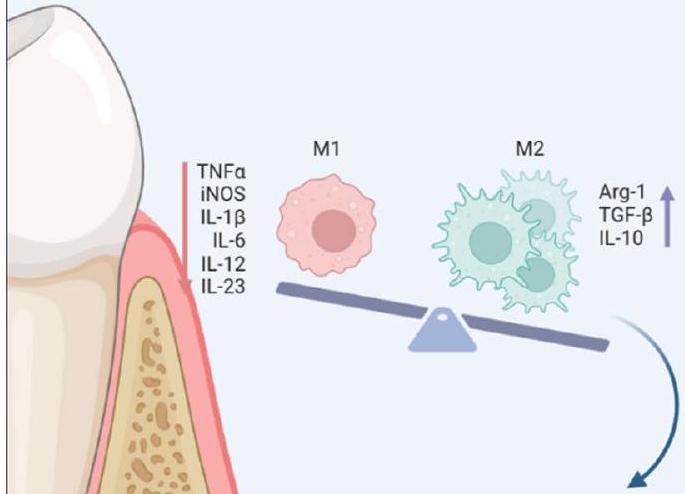

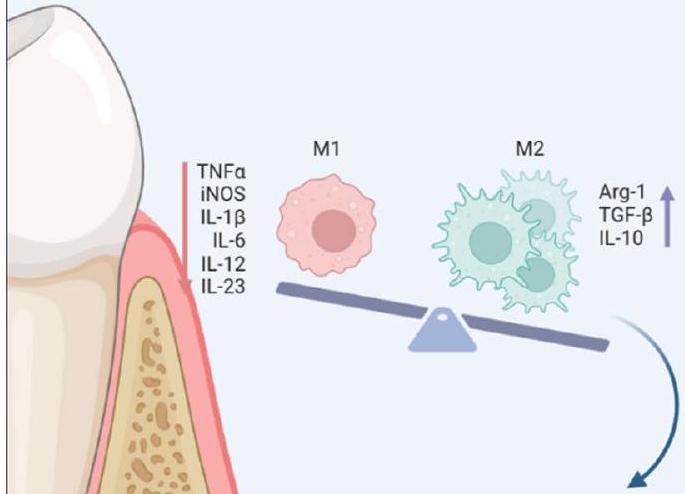

dمارها. كما أنها تفرز مستوى عالٍ من الكيموكينات والسيتوكينات المؤيدة للالتهاب، وتستقطب وتفعل الكريات البيضاء، وتساهم في تنشيط الجهاز المناعي التكيفي من خلال تقديم المستضدات وإنتاج السيتوكينات. تُعرف بلعميات M2 بأنها مضادة للالتهاب، تدعم نضوج الأوعية الدموية وترسيب المعادن على مصفوفة العظام [4]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن لـ M2 تعزيز تجديد الأنسجة وإصلاحها من خلال إفراز عوامل النمو لتنشيط الخلايا الجذعية، ودعم نضوج الأوعية، وإعادة تشكيل المصفوفة خارج الخلوية (ECM) [5]. في الدراسات المتعلقة بالتهاب اللثة، تعزز M1 تقدم التهاب اللثة، بينما تمنع M2 تقدم التهاب اللثة وتعزز استعادة اللثة. تم اكتشاف أن مستويات M1 الأعلى مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بتطور التهاب اللثة المزمن [6، 7]. علاوة على ذلك، تم إثبات أن السيتوكينات المرتبطة بـ M1، مثل MMP-9 و IL-6 و IFN-

وتقليل الالتهاب. أظهرت الأبحاث أن تنشيط M2 يوقف فقدان العظام [9، 10]. يمكن أن تؤدي حقن M2 في الأنسجة اللثوية إلى قمع نشاط الخلايا العظمية وتقليل أعراض التهاب اللثة [11]. لذلك، قد تتضمن طريقة جديدة لعلاج التهاب اللثة تعزيز تحويل M1/M2 أو الحد من التأثيرات المؤيدة للالتهاب لـ M1 اللثوي.

على الرغم من أن البلعميات قد تم تقديمها كهدف جديد في علاج التهاب اللثة، إلا أن معظم الأدوية لا تزال تعاني من مشكلات مثل عدم استقرار التأثيرات، والنشاط غير المنتظم، ونقص التخصص المستهدف [12]. لقد حظيت المواد الحيوية التي تعدل وظيفة المناعة للبلعميات باهتمام بحثي متزايد لأنها يمكن أن تعالج قيود الأدوية الحرة وحدها من خلال التصميم المدروس. يتم علاج التهاب اللثة بطريقة تدريجية، وبعد المرحلة غير الجراحية، قد تكون العيوب داخل العظام أو التفرع قابلة للجراحة التجديدية. تشمل المواد الحيوية المتاحة في العلاج البيولوجيات (تركيزات الصفائح الدموية الذاتية، الهلاميات، الجسيمات النانوية)، وزرع العظام (زرع عظام نقي أو سيراميك)، والأغشية (بوليمرات) المشاركة في علاج التهاب اللثة المساعد، واستعادة الأنسجة العظمية التجديدية، وتجديد الأنسجة الموجهة [13]. تعتبر المواد السيراميكية، والبوليمرات، والجسيمات النانوية الأنواع الرئيسية من المواد الحيوية التي تنظم بلعميات التهاب اللثة. من خلال الخصائص الفيزيائية والفيزيولوجية الفطرية للمادة أو عن طريق إضافة مكونات نشطة مثل الأدوية، وأيونات المعادن، والسيتوكينات، والإكسوزومات، وما إلى ذلك، يمكن للمواد الحيوية التحكم في حالة ونشاط البلعميات [14].

في هذه المراجعة، من أجل إنشاء أساس نظري لعلاج البلعميات المناعي لالتهاب اللثة، نناقش أولاً الوظيفة البيولوجية للبلعميات ودورها كأهداف علاجية في عملية التدمير والتعافي من التهاب اللثة. ثم، نصف المواد الحيوية (بما في ذلك السيراميك، والبوليمرات، والمواد النانوية) التي تُستخدم للتحكم في استقطاب البلعميات خلال علاج التهاب اللثة الحالي ونقدم نظرة عامة على الأساليب التي تتخذها المواد المختلفة للتحكم في البلعميات. أخيرًا، نلخص الصعوبات والاتجاهات المستقبلية المحتملة لاستخدام المواد الحيوية للتحكم في البلعميات، مما يوفر دافعًا جديدًا للعلاج المناعي لالتهاب اللثة.

الوظيفة البيولوجية لاستقطاب البلعميات وتطبيقها في علاج التهاب اللثة

نظرة عامة على التهاب اللثة

العدوى، واضطرابات الجهاز الهضمي، وأمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية، ونتائج الحمل السيئة وسرطان القولون [15]. خلال حدوث التهاب اللثة، يتشكل تفاعل بين استجابة الجهاز المناعي الالتهابية والمجتمعات الميكروبية غير المنظمة حلقة تغذية راجعة إيجابية من الاضطراب اللثوي. على وجه التحديد، تقوم مسببات الأمراض الرئيسية أولاً بزعزعة مناعة المضيف، مما يؤدي إلى تنشيط مفرط للاستجابة الالتهابية ويؤدي إلى تدمير الأنسجة. يمكن أن يؤدي الالتهاب بدوره إلى تفاقم عدم التوازن الميكروبي من خلال توفير العناصر الغذائية للبكتيريا (من منتجات تحلل الأنسجة، مثل ببتيدات الكولاجين والمركبات المحتوية على الهيم). هذه العلاقة التعزيزية بين عدم التوازن الميكروبي والالتهاب تستمر في الدائرة الجهنمية، مما يدفع مسببات الأمراض لمرض التهاب اللثة.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تشارك البلعميات في تدمير وإصلاح الأنسجة اللثوية بسبب اللدونة والتنوع في البلعميات والأدوار المختلفة التي تلعبها السيتوكينات. لذلك، من خلال فهم وصف البلعميات في الأنسجة اللثوية، من الممكن المساعدة في فهم كيفية تنظيم البلعميات وكيف تؤثر على التهاب اللثة [16، 20].

استقطاب البلعميات: نموذج M1/M2

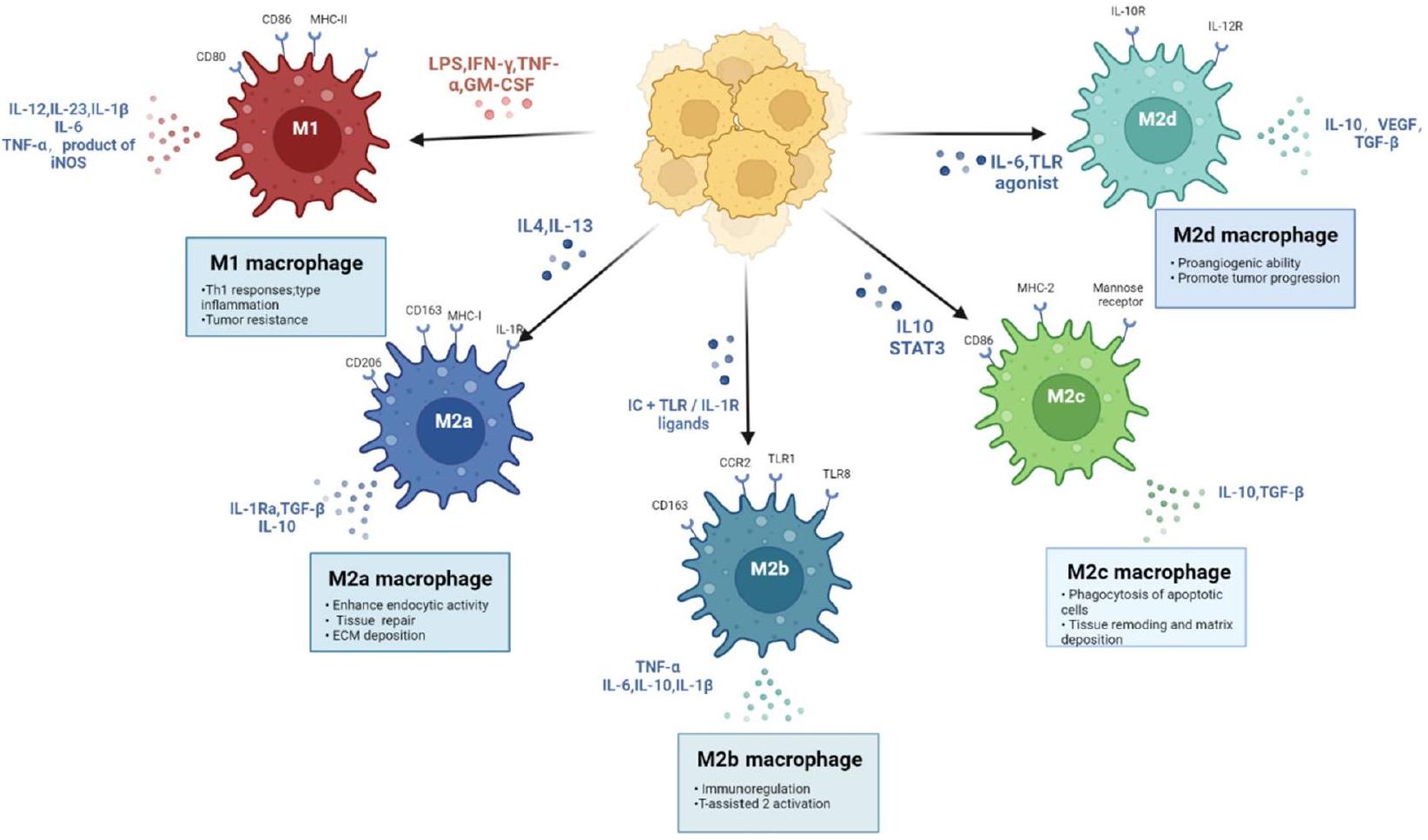

إنتاج مستويات منخفضة من IL-12 وiNOS. تتمتع هاتان المجموعتان من البلعميات بخصائص ظاهرة ووظيفية مختلفة. ومع ذلك، اعتماداً على المؤثرات المضادة للالتهاب المستخدمة في المختبر لتوليد بلعميات M2، قد تظهر هذه الخلايا تغييرات ظاهرة دقيقة [28]. تم تصنيف بلعميات M2 بشكل إضافي إلى أربعة أنماط فرعية نشطة بالتناوب (M2a، M2b، M2c، وM2d) بناءً على التمييز الوظيفي، وكلها تدعم تجديد الأنسجة وإصلاح الجروح. تحت تأثير IL-4 أو IL-13، تفرز بلعميات M2a بشكل رئيسي سيتوكينات مثل IL-1Ra، وTGF-

أنماط التوزيع وتنشيط البلعميات في التهاب اللثة

إعادة تشكيل المصفوفة خارج الخلوية [38، 39]. تعتبر البلعميات M1 هي النمط الرئيسي الملحوظ في المراحل المبكرة من الالتهاب، مع انخفاض كبير في M1 وزيادة في البلعميات M2 مع تقدم التهاب اللثة. إذا لم يحدث هذا التحول، يمكن أن يصبح التهاب اللثة ملتهبًا بشكل مزمن [40].

توسط السيتوكينات التي تنتجها خلايا المناعة المتنوعة داخل البيئة الدقيقة الالتهابية التي تنتجها مسببات الأمراض اللثوية.

وظيفة البلعميات في التهاب اللثة

تلعب البلعميات المنشطة دورًا في إفراز الوسائط الالتهابية، وإزالة البكتيريا، وتدمير وإصلاح الأنسجة اللثوية في الأنسجة اللثوية التي تطلق مجموعة من الجزيئات الفعالة في مراحل مختلفة من التهاب اللثة، بما في ذلك عوامل النمو، والإنزيمات المختلفة، والسيتوكينات المؤيدة للالتهاب (مثل بروستاجلاندين E2، TNF).

لا تطلق البلعميات فقط وسائط التهابية تساهم في العملية المرضية لـ

التهاب اللثة، لكنهم يلعبون أيضًا دورًا في القضاء على العدوى اللثوية (الشكل 3).

إصلاح وتجديد الأنسجة الداعمة للأسنان

– تعزيز إصلاح الأنسجة

إعادة تشكيل المصفوفة خارج الخلوية

التهاب اللثة التقدمي

واحدة من الآليات الحيوية لمكافحة البكتيريا بواسطة البلعميات هي أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS). يتم تمييز توليد ROS في اللثة إلى نوعين: خارجي وداخلي. البكتيريا، الديناميكا الضوئية، أيونات المعادن، والطب النانوي هي أمثلة على التأثيرات الخارجية. يرتبط تنشيط خلايا المناعة في ظروف الالتهاب والشيخوخة بتوليد ROS داخليًا في الخلايا. تشارك العديد من خلايا المناعة، بما في ذلك البلعميات، في العملية المضادة للميكروبات من خلال إنتاج كمية كبيرة من ROS عبر سلسلة التنفس الميتوكوندرية وإنزيم NADPH أوكسيداز. تشارك ROS في النشاط المضاد للميكروبات بشكل غير مباشر من خلال نقل الإشارات المناعية بينما تقتل البكتيريا بشكل مباشر عن طريق إتلاف أغشيتها الخلوية، وDNA، والبروتينات. نظرًا لأهمية أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية في النشاط المضاد للميكروبات للبلعميات، أصبح تعزيز الخصائص المضادة للميكروبات للمواد الحيوية في اللثة من خلال تعديل إطلاق أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية من البلعميات محور اهتمام للباحثين.

تسبب البلعميات أيضًا بشكل غير مباشر تدمير العظام اللثوية من خلال تنظيم الخلايا الآكلة للعظام. فقدان العظام هو أحد الأعراض الرئيسية لالتهاب اللثة. يُعتبر فقدان العظام الناتج عن الالتهاب أحد العلامات الرئيسية لالتهاب اللثة. الخلايا الوحيدة في الجسم التي يمكنها امتصاص العظام هي الخلايا الآكلة للعظام. يتم تحفيز سلف الخلايا الآكلة للعظام بواسطة عامل تحفيز مستعمرات البلعميات (M-CSF) و ligand NF-kB (RANKL) لتتطور إلى خلايا آكلة للعظام ناضجة تؤدي إلى امتصاص العظام. تسبب PAMPs الخارجية، مثل LPS المفرج عنه من تحلل البكتيريا، في تشكيل البلعميات لنمط M1 وإطلاق عدد كبير من السيتوكينات المؤيدة للالتهابات، بما في ذلك IL-1 و IL-8 و IL-12 و IL-23 و TNF-

يمكن تقليل خلايا T المنشطة السيتوبلازمية 1 (NFATc1) بواسطة TGF-

تنظم المواد الحيوية استقطاب البلعميات

تظهر التفاعلات المناعية، وتظهر أنسجة اللثة نفسها طيفًا من التفاعلات الالتهابية مع تطور التهاب اللثة. تشجع الاستجابة المناعية الخفيفة تجديد الأنسجة وشفاء الجروح، بينما يمكن أن يمنع نظام المناعة غير المنظم امتصاص أنسجة الزرع، وإنشاء الكبسولة الليفية، والإصلاح. تعتبر تقنيات هندسة الأنسجة التقليدية استجابة سلبية تهدف إلى تقليل استجابة نظام المناعة. مع تقدم هندسة الأنسجة، يتولى المزيد من الباحثين المبادرة ويستخدمون مواد حيوية مصممة بشكل جيد للتحكم في مكونات نظام المناعة الحرجة المختلفة وإنتاج بيئة مناعية تدعم تجديد الأنسجة. أصبح تصميم المواد الحيوية التي تنظم حالة استقطاب البلعميات وسيلة جديدة لعلاج التهاب اللثة.

استراتيجيات المواد الخزفية لتنظيم استقطاب البلعميات

الشحنة، المجموعات الوظيفية وقابلية البلل) وإدماج المواد الحيوية النشطة (السيتوكينات، عوامل النمو وأيونات المعادن) [116].

تؤثر خصائص سطح المواد الخزفية على استقطاب البلعميات

أثناء البحث في كيفية تأثير المحبة للماء للمواد الخزفية على استقطاب البلعميات (الجدول 1، 2).

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، ساهم تقليل IL-6 في تقليل miR-214 وزيادة مسار p38/JNK، مما قد يساهم في تعزيز تكوين العظام الناتج عن HAS-G.

الجزيئات الحيوية المدمجة في المواد الخزفية تؤثر على استقطاب البلعميات

كما أنه يؤثر على استقطاب البلعميات في الأنسجة اللثوية.

| جزيئات المؤثر | نمط الماكروفاج الأصلي | وظيفة | المراجع |

| IL-6 | M1 | 1. يتسبب IL-6 في تدمير الأنسجة من خلال زيادة ميتالوبروتيناز المصفوفة-1 (MMP-1) في الأنسجة اللثوية. 2. يحفز IL-6 تمايز الخلايا العظمية من خلايا الرباط اللثوي. 3. التثبيط المحدد لمستقبل IL-6 يقلل من فقدان العظام الالتهابي في التهاب اللثة التجريبي. | [٤٧-٤٩] |

| MMP-13 | M1 | يعزز فقدان العظام اللثوي | [50] |

| TNF-α | M1 | 1. تعزيز تجنيد كريات الدم البيضاء إلى موقع الالتهاب. 2. زيادة إنتاج IL-1

|

[51-54] |

| IL-1

|

M1 | يسبب تدمير الأنسجة عن طريق زيادة MMP-1 في الأنسجة اللثوية | [47] |

| إنترفيرون-

|

M1 | يعزز فقدان العظم السنخي وتمايز الخلايا العظمية | [55] |

| IL-12 | M1 | 1. زيادة موت الخلايا المبرمج في الخلايا العظمية. 2. زيادة التعبير عن IFN-

|

[56] |

| IL-10 | M2 | 1. يثبط إنتاج IL-6 في الخلايا الليفية اللثوية البشرية المحفزة بواسطة P.g.-LPS. 2. يثبط امتصاص العظام. 3. الفئران المعدلة وراثياً لعدم وجود IL-10 تقلل من تعبير علامات الخلايا العظمية وخلايا العظم في الأنسجة اللثوية. | [57-59] |

| TGF-

|

M2 | 1. TGF

|

[60-63] |

| IL-22 | M2 | يمنع موت الخلايا المبرمج لخلايا الظهارة اللثوية خلال التهاب اللثة | [64] |

ومع ذلك، فقد تلقت العظام بحثًا قليلًا نسبيًا. أنتج زانغ وآخرون [93] زجاجًا حيويًا نشطًا تحت الميكرون مشبعًا بالسترونتيوم (Sr-SBG) لدراسة التفاعل بين السترونتيوم واستجابة المناعة المضيفة من منظور استقطاب البلعميات من أجل التحقيق بشكل أكثر شمولاً في دور السترونتيوم في التكون العظمي المدعوم بالمواد الحيوية. وفقًا للنتائج، كان Sr-SBG قادرًا على زيادة نسب البلعميات M2 CD206 مع تقليل نسب البلعميات M1 CD11c. تم تعزيز إفراز السيتوكينات المضادة للالتهابات IL-10 وIL-1 بشكل كبير في مجموعة Sr-SBG مقارنة بمجموعة SBG، وكانت جينات BMP2 وجينات التكون العظمي في البلعميات مرتفعة نسبيًا. زاد الوسط المشروط بالبلعميات من Sr-SBG بشكل كبير من النشاط التكوني العظمي مقارنة بالمجموعة التي تفتقر إلى Sr. تعتبر السيراميك التي تحتوي على Sr خيارات واعدة لتعديل البيئة المناعية للأنسجة اللثوية لتعزيز التجديد. بالإضافة إلى المواد المعدنية، يمكن أن تؤثر الأدوية المستمدة من النباتات أيضًا على استقطاب البلعميات.

| مادة | خاصية | تقدم البحث | مرجع | ||

| الخزف | الخصائص الجسدية | محبة الماء | المواد السيراميكية المحبة للماء تعزز استقطاب البلعميات إلى M2 | [87] | |

| الهندسة | في الهياكل التي تشمل بروزات مستديرة مع إبر نانوية على السطح، تظهر البلعميات انخفاضًا كبيرًا في الجينات المؤيدة للالتهاب (iNOS، TNF-a، وCCR7) مقارنةً بالسطح الأملس. من بين الهياكل الخمسة – السطح المستوي، سطح الإبر النانوية،

|

[88] | |||

| مقارنةً بالهيكل المسامي الشائع من هيدروكسيباتيت، فإن الهيكل المسامي من هيدروكسيباتيت مع

|

[89] | ||||

| خشونة | في الهياكل الميكرو-نانوية، تزداد نسبة البلعميات M1 مع زيادة الخشونة. توجد المزيد من البلعميات M2 في المناطق ذات الخشونة المنخفضة. | [90] | |||

| عوامل حيوية نشطة | المواد الخزفية | في المجموعات الثلاث من المواد الخزفية ذات الهياكل المتطابقة HA و BCP و

|

[91] | ||

| دمج العوامل الحيوية النشطة | جزيئات معدنية | الهياكل الحيوية الزجاجية السيراميكية المحتوية على الموليبدينوم (Mo-BGC) تحفز استقطاب M2 من خلال تعزيز وظيفة الميتوكوندريا في البلعميات | [92] |

| مادة | خاصية | تقدم البحث | مرجع | ||

| تطلق البلعميات المعالجة بزجاج حيوي تحت الميكرون مشبع بالسترونتيوم (Sr-SBG) كمية ملحوظة أعلى من السيتوكينات المضادة للالتهابات IL-10 و IL-1. | [93] | ||||

| مكونات نشطة مشتقة من النباتات | نوع جديد من المواد الخزفية الحبيبية المدعمة بالبوليفينولات المستخرجة من بقايا الفاكهة قلل من تعبير الجينات المرتبطة بالالتهاب في البلعميات. | [94] | |||

| بوليمر | هيدروجيل | الخصائص الجسدية | الصلابة | عندما تُزرع البلعميات على ركائز أكثر صلابة، فإنها تتكاثر بشكل أوسع وتعبّر عن المزيد من الوسائط الالتهابية. | [95] |

| دمج العوامل الحيوية النشطة | السيتوكينات | يمكن أن تساعد الهلاميات المائية المرتبطة جسديًا بالحمض النووي في استقطاب الماكروفاج M2، حيث لديها القدرة على توزيع IL-10 لفترات طويلة. | [96] | ||

| جيلاتين مرتبط عبر الترانسجلوتاميناز (TG gel) ذو الصلابة العالية يمكن استخدامه لتعزيز استقطاب M2 للبلعميات بدلاً من استقطاب M1 بعد أن يتم تخليقه بـ IL-4 و SDF-1a. | [97] | ||||

| الإكسوزومات | الهيدروجيل المصنوع من الكيتوزان والم infused بخلايا جذعية من لب الأسنان (DPSC-Exo/ CS) يمكن أن يتسبب في إنتاج ماكروفاجات الأنسجة اللثوية لمزيد من علامة الالتهاب المضاد CD206 وأقل من علامة الالتهاب المؤيد CD86. | [98] | |||

| تسليم الإكسوزومات المستخلصة من خلايا جذر الأسنان المعالجة بـ LPS، على عكس تلك التي لم تُعالج، لديها القدرة على تحفيز استقطاب البلعميات M2 من خلال توصيل الهيدروجيل. | [99] | ||||

| المكونات النشطة المستخلصة من النباتات | الهيدروجيل المحمّل بإستر حمض الكافيك الفينيثيلي يقلل من إنتاج الوسائط الالتهابية (TNF-a، IL-1

|

[100] | |||

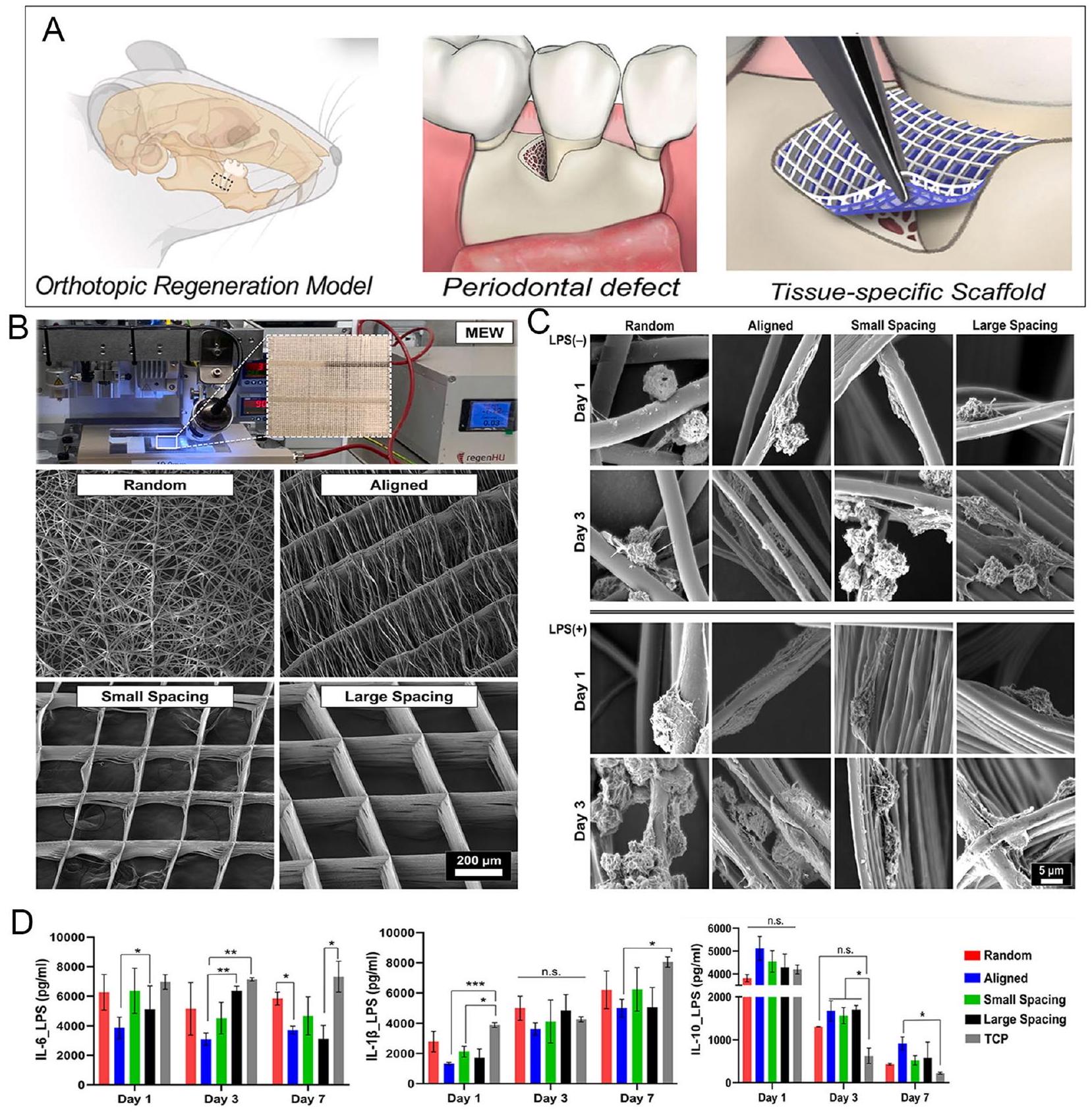

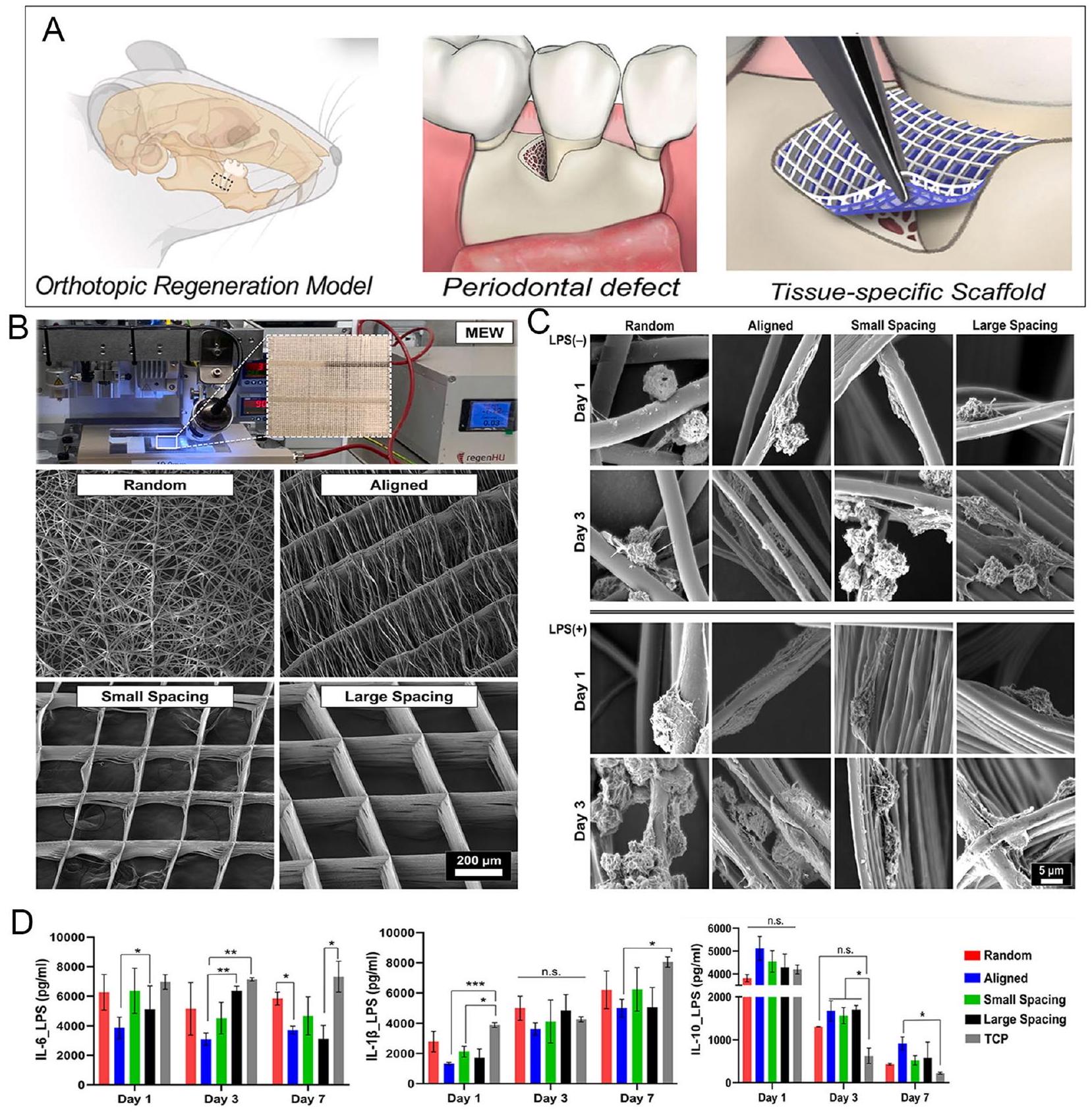

| بوليمرات الألياف | الخصائص الجسدية | الهندسة | في الهياكل الليفية التي تتكون من الطباعة الكهربائية المنصهرة، تؤدي الهياكل الليفية ذات الاتجاه العشوائي إلى استقطاب البلعميات نحو M1، بينما تؤدي الهياكل الليفية المنظمة بشكل كبير إلى استقطاب البلعميات نحو M2. | [101] | |

| مادة | خاصية | تقدم البحث | مرجع | ||

| دمج العوامل الحيوية النشطة | المخدرات | يمكن توصيل الدواء المضاد للالتهابات كيتوبروفين عبر هيكل نانوفايبر مركب يقلل بشكل كبير من MMP-9 وMMP-3 ويزيد من تعبير IL-10 في البلعميات. | [102] | ||

| تنظيمت أغشية الألياف المنسوجة بالكهرباء المحملة بـ Dimethyloxaloylglycine (DMOG) و nanosilicate (nSi) انتقال نمط ظاهرة البلعميات إلى M2 | [103] | ||||

| السيتوكينات | إطار الألياف النواة/الغلاف، الذي يتكون من ألياف بوليمرية بمعدلات تدهور متفاوتة، يدعم تحول M1/M2 للخلايا البالعة من خلال إطلاق عامل نمو الألياف الأساسية (bFGF) وBMP-2 بشكل متتابع، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة تعبير CD206 في الخلايا البالعة وتقليل إنتاج iNOS. | [104] | |||

| الميكروسفيرات | السيتوكينات | ميكروسفيرات ديكستران/PLGA المغلفة بـ IL-1 ra تثبط بشكل فعال إنتاج السيتوكينات المسببة للالتهابات من قبل البلعميات. | [105] | ||

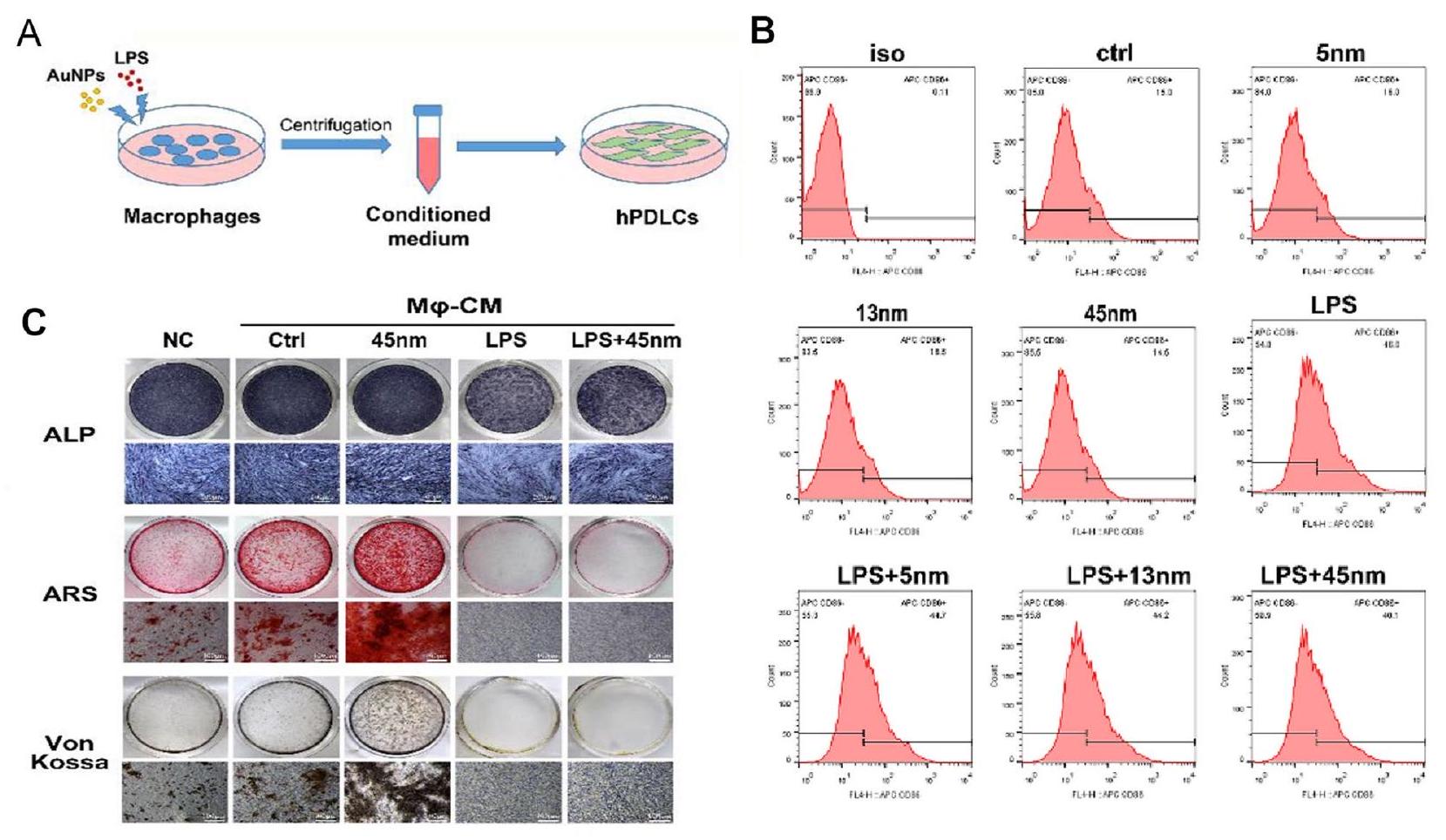

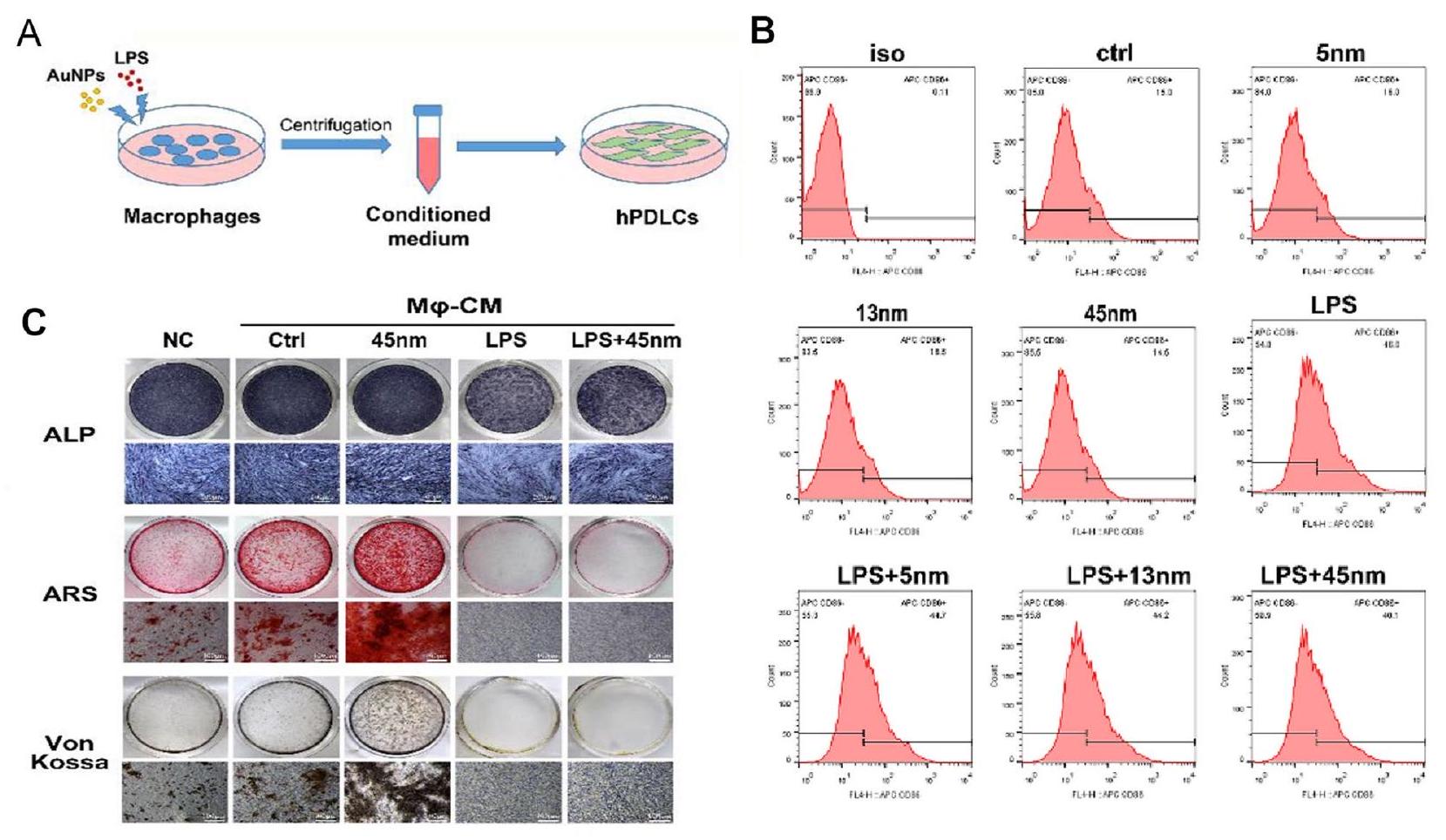

| الجسيمات النانوية | جزيئات النانو المعدنية | أو | جزيئات الذهب النانوية بحجم 45 نانومتر لديها القدرة على تحفيز البلعميات المستقطبة من النوع M2 | [106] | |

| فضة | تمكن جزيئات الفضة النانوية المرتبطة بدوائين (ميترونيدازول وكلورهيكسيدين) من تقليل مستويات التعبير عن السيتوكينات.

|

[107] | |||

| تم قمع إنتاج السيتوكينات TNF-a و IL-6 و IL-1 بواسطة المواد الحيوية الهجينة المسامية ثلاثية الأبعاد المفعلة بجزيئات الفضة النانوية. | [108] | ||||

| جزيئات البوليمر النانوية | يمكن لجزيئات البوليدوبامين النانوية (PDA-NPs) تمكين تحويل البلعميات إلى M2 | [109] | |||

| المركبات النانوية |

|

[110] | |||

| مادة | خاصية | تقدم البحث | مرجع |

| شجيري | يمكن لجزيئات PAMAM-G5 الدائرية استهداف ارتباط البلعميات وتنظيم أنماط البلعميات. | [111] | |

| مواد نانوية محملة بالأدوية | تشكل مادة الإبيغallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) التي تشبه الشاي الأخضر جزيئات نانوية (NPs) تحفز تغيير القطبية M1/M2 في البلعميات. | [112] |

استراتيجيات تنظيم البوليمر لاستقطاب البلعميات

استراتيجيات الهيدروجيل تنظم استقطاب البلعميات

تسريع إعادة بناء العظم السنخي لدى مرضى السكري. أظهرت الدراسات أن الهلام الاصطناعي ILGel قد أطال من زمن الاحتفاظ بـ IL-10 واحتفظ بالنشاط البيولوجي لـ IL-10 لمدة لا تقل عن 7 أيام وعزز من استقطاب البلعميات M2. استنادًا إلى الدراسات السابقة، وجد بينغ وزملاؤه أن دمج الهلاميات الحمض النووي مع الكتل النانوية الفضية (AgNC) والجزئيات خارج الخلوية المستمدة من البلعميات M2 يمكن أن ينظم أيضًا استقطاب البلعميات ويسرع من شفاء العظم السنخي. تشير هذه الدراسات إلى أن دمج الهلاميات الحمض النووي مع مكونات حيوية نشطة أخرى يحمل وعدًا كبيرًا في علاج إصابات العظم السنخي لدى مرضى السكري، والتهاب اللثة، وتنظيم البلعميات.

وتأثيرات إصلاح عيوب العظام. قام بن وآخرون [100] بتخليق مصفوفة هيدروجيل حرارية حساسة من الكيتوزان الميثيل أسيتيل (A-CS) وطبقوها للمرة الأولى للإدارة الموضعية في مجال اللثة. بالمقارنة مع توصيل الأدوية النظامية التقليدية، يتمتع هيدروجيل A-CS المحمّل بـ CAPE (CAPE-A-CS) بميزة تكوين خزان دوائي في الموقع، وإطلاق بطيء، وزيادة دقيقة في تركيز الدواء في موقع الإصابة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قام CAPE-A-CS بتقليل تعبير TNF-

تتحكم البوليمرات الليفية في استقطاب البلعميات

يشار إليها باسم الهياكل عالية التنظيم) (الشكل 7). تظهر النتائج أن تعبير علامة الماكروفاج M1 يكون مرتفعًا على الهياكل المصنوعة من الألياف الموجهة عشوائيًا. وقد تم الافتراض أن اتجاه هياكل الألياف المكتوبة بالكهرباء المنصهرة يؤثر على كيفية استقطاب الماكروفاجات.

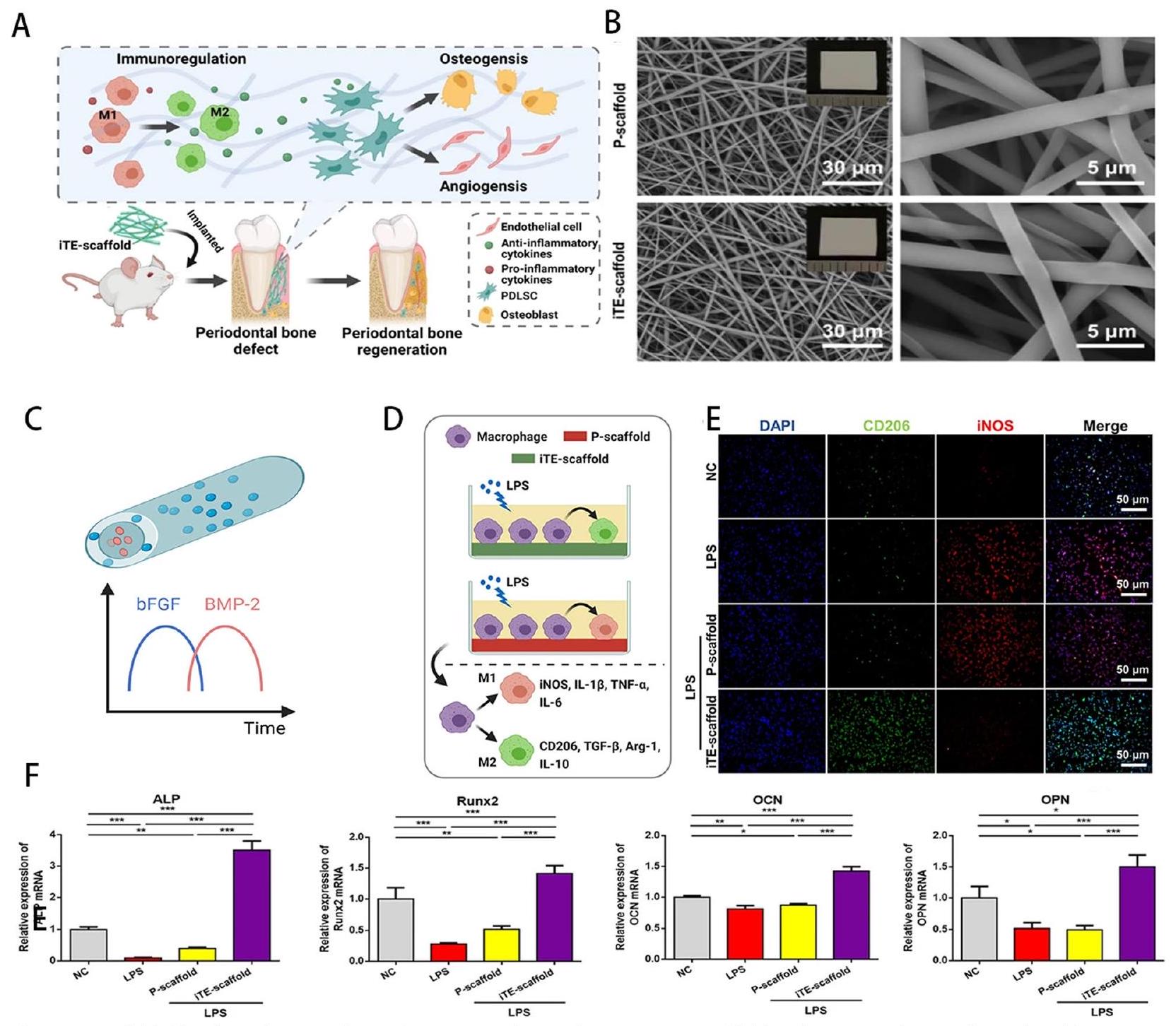

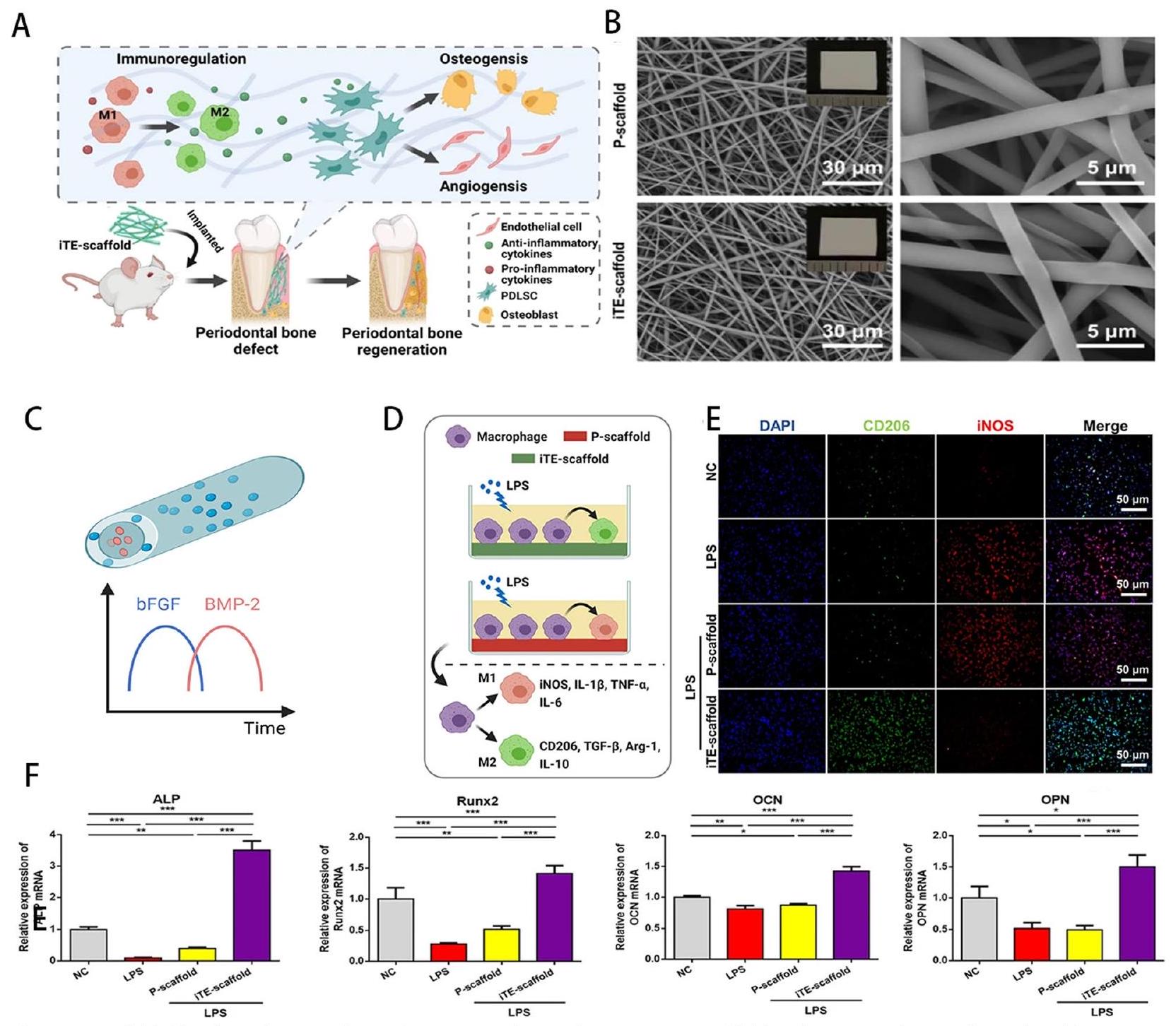

يمكن أن تعزز دمج الأدوية والسيتوكينات القدرة المناعية للبوليمرات الموجودة. البوليمر غير السام المستخدم على نطاق واسع المعروف باسم بولي (حمض اللاكتيك) (PLLA) وبولي (حمض اللاكتيك-حمض الجليكوليك) (PLGA) له توافق حيوي جيد وخصائص نقل الأدوية. قام تشاتشليوتاكي وآخرون [102] بتطوير هيكل نانوي مركب يتكون من بروتين لاصق من الحرير وPLGA ووكيل مضاد للالتهابات هو كيتوبروفين. وقد أظهر أن الهيكل المركب كان له زيادة في المحبة للماء وخصائص ميكانيكية محسنة بشكل كبير مقارنة بهيكل PLGA العادي، وأنه يمكن أن يوفر تأثيرات مضادة للالتهابات مستدامة في علاج أمراض اللثة مع وقت إطلاق دواء يصل إلى 15 يومًا. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهرت الخلايا الليفية اللثوية ارتباطًا جيدًا وتكاثرًا على الهيكل. كشفت دراسة إضافية أن MMP-9 وMMP-3 كانت منخفضة بشكل كبير وأن تعبير IL-10 كان مرتفعًا في البلعميات بعد الثقافة على الهياكل. طور ليو وآخرون [103] غشاء ألياف كهربائي قائم على PLGA لتحميل ثنائي ميثيل أوكزاليل غليسين (DMOG) ونانو سيليكات (nSi). وقد تم إثبات أنه من خلال التحكم في تحويل النمط الظاهري للبلعميات M2، قد يقلل DMOG وnSi الالتهاب أو يعزز تجديد الأنسجة. من الجدير بالذكر أن دمج ألياف البوليمر ذات معدلات تحلل مختلفة يمكن أن ينظم الإطلاق المتسلسل للسيتوكينات المدمجة فيها، مما يمكّن من تنظيم مرحلي للبلعميات. أنشأ دينغ وآخرون [104] إطار عمل قائم على الألياف بنظام نواة/قشرة قادر على الإطلاق المتسلسل لعامل نمو الخلايا الليفية الأساسي (bFGF) وBMP-2. من الجدير بالذكر أن AuNPs منعت التغيير (الشكل 8). بينما يتحلل PLLA ببطء، يتحلل PLGA بسرعة. إن الإطلاق المتسلسل لـ bFGF وBMP-2 المدمجين فيه ممكن بفضل هذا الاختلاف في معدل التحلل. أظهرت الاختبارات في المختبر أن الهيكل الهندسي للأنسجة في الموقع (iTE scaffold) قد يزيد بشكل كبير من تعبير CD206 ويقلل من إنتاج iNOS، مما يدعم البلعميات في التحول من M1 إلى M2. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن يؤدي استقطاب M2 للبلعميات الناتج عن الهيكل iTE إلى تعزيز تعبير الجينات العظمية في PDLSCs. علاوة على ذلك، يسرع الهيكل iTE من نمو الأوعية الدموية اللثوية. بشكل عام، تعتبر هياكل iTE هياكل هندسية مناسبة لتجديد العظام في التهاب اللثة المتقدم. في الختام، يمكن أن تبدأ الاستراتيجية التنظيمية لألياف البوليمرات على البلعميات من ترتيب الألياف ودمج العوامل النشطة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، الإطلاق المتسلسل

يمكن أن تلبي مجموعة من العوامل النشطة الوظيفية المختلفة من خلال دمج مواد مختلفة احتياجات آفات التهاب اللثة المعقدة بشكل أفضل، مما يحمل إمكانيات مبتكرة وعظيمة.

الكرات المجهرية تنظم استقطاب البلعميات

استراتيجية الجسيمات النانوية لتنظيم استقطاب البلعميات

جزيئات حيوية نشطة لتعديل نشاط البلعميات. تشمل هذه المواد جزيئات نانوية معدنية، ليبوزومات، دندريمرات، بوليسكريات، كبسولات، إلخ.

تنظم الجسيمات النانوية المعدنية استقطاب البلعميات

الجسيمات النانوية البوليمرية تنظم استقطاب البلعميات

تنظم المركبات النانوية استقطاب البلعميات

العلاج الضوئي المضاد للميكروبات هو علاج كيميائي ضوئي يستخدم المواد الحساسة للضوء وتفعيل الضوء لإطلاق كميات كبيرة من أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية بسرعة، مما يؤدي إلى قتل البكتيريا وتعطيل عوامل الضراوة.

تنظم الجزيئات الكبيرة الشجرية البلعميات

تنظم المواد النانوية المحملة بالأدوية استقطاب البلعميات

التحديات والآفاق

- تنظيم استقطاب البلعميات بواسطة المواد الحيوية ينطوي حاليًا بشكل رئيسي على الانتقال الكلاسيكي بين M1/M2، لكن نموذج M1/M2 ليس تمثيلاً كاملاً للوضع داخل الجسم ويواجه الاحتياجات التنظيمية المعقدة والمُحسّنة لعملية علاج التهاب اللثة، ومن الواضح أن تنظيمها يجب أن يتم تعديله من الانتقال بين M1/M2 إلى تنظيم أكثر دقة لنوع M2.

- تشمل عملية شفاء التهاب اللثة مراحل الالتهاب والإصلاح والتجديد وإعادة التشكيل، مع اختلافات دقيقة في المتطلبات الوظيفية للخلايا البالعة M1/M2 في مراحل مختلفة، مما يتطلب تصميمًا أكثر دقة للمواد الحيوية لتحقيق تنظيم ديناميكي للخلايا البالعة في المراحل، مع إزالة مبكرة للعوامل الممرضة والأنسجة التالفة، وتجنيد متوسط للخلايا الجذعية للتجديد، وفي وقت لاحق مكافحة الالتهاب وتعزيز تمايز الخلايا وتجديد الأنسجة.

- هناك عملية متسلسلة من التأثيرات المضادة للبكتيريا، والمضادة للالتهابات، وتجديد الأنسجة في شفاء التهاب اللثة، وتنظيم أحد هذه المراحل سيتداخل مع وجود ووظيفة المراحل الأخرى، ويجب تحويل استراتيجية التنظيم الكلي أو لا شيء للبلعميات إلى تنظيم معتدل لاستقطاب البلعميات.

- تنظيم عملية تجديد الأنسجة معقد. يتضمن زراعة المواد الحيوية سلسلة من الاستجابات الخلوية المتعددة، بما في ذلك خلايا المناعة، والخلايا الجذعية الميزانشيمية، وخلايا البطانة الوعائية. إن تنسيق التفاعلات الخلوية المختلفة وتحقيق التوازن بين التأثيرات المختلفة للمواد الحيوية على الخلايا المتنوعة أمر مهم لتحقيق الشفاء النهائي.

- من الصعب مطابقة حركيات شفاء التهاب اللثة مع حركيات تحلل المواد الحيوية وإطلاق المواد الفعالة. يجب دراسة منحنى تحلل المواد الحيوية، ومنحنى إطلاق المواد الفعالة، ومنحنى تجديد الأنسجة اللثوية، ومنحنى الطلب على البيئة المناعية لكل مرحلة من مراحل التهاب اللثة بعمق أكبر من أجل مطابقة متطلبات كل مرحلة بشكل أكثر ملاءمة في المستقبل.

- بالمقارنة مع شفاء الجروح، وتجديد العظام، وتجديد العضلات والأربطة، فإن البيئة الدقيقة المعقدة في اللثة خلال علاج التهاب اللثة تخلق صعوبات كبيرة للاحتفاظ طويل الأمد بالمواد الحيوية.

تجديد الأنسجة الداعمة للأسنان من خلال المواد الحيوية لا يزال مجالًا ناشئًا يحمل إمكانيات كبيرة.

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نُشر على الإنترنت: 21 يونيو 2024

References

- Du M, Bo T, Kapellas K, Peres MA. Prediction models for the incidence and progression of periodontitis: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(12):1408-20.

- Tang Y, Huang Q-X, Zheng D-W, Chen Y, Ma L, Huang C, Zhang X-Z. Engineered Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus: a countermeasure for biofilminduced periodontitis. Mater Today. 2022;53:71-83.

- Okabe Y, Medzhitov R. Tissue biology perspective on macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(1):9-17.

- Qiao W, Xie H, Fang J, Shen J, Li W, Shen D, Wu J, Wu S, Liu X, Zheng Y, Cheung KMC, Yeung KWK. Sequential activation of heterogeneous macrophage phenotypes is essential for biomaterials-induced bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 2021;276:121038.

- Franklin RA. Fibroblasts and macrophages: collaborators in tissue homeostasis. Immunol Rev. 2021;302(1):86-103.

- Almubarak A, Tanagala KKK, Papapanou PN, Lalla E, Momen-Heravi F. Disruption of monocyte and macrophage homeostasis in periodontitis. Front Immunol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00330.

- Zhang W, Guan N, Zhang X, Liu Y, Gao X, Wang L. Study on the imbalance of M1/M2 macrophage polarization in severe chronic periodontitis. Technol Health Care. 2023;31:117-24.

- Zhu L-F, Li L, Wang X-Q, Pan L, Mei Y-M, Fu Y-W, Xu Y. M1 macrophages regulate TLR4/AP1 via paracrine to promote alveolar bone destruction in periodontitis. Oral Dis. 2019;25(8):1972-82.

- Chen X, Wan Z, Yang L, Song S, Fu Z, Tang K, Chen L, Song Y. Exosomes derived from reparative M 2 -like macrophages prevent bone loss

in murine periodontitis models via IL-10 mRNA. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20(1):110. - Zhuang Z, Yoshizawa-Smith S, Glowacki A, Maltos K, Pacheco C, Shehabeldin M, Mulkeen M, Myers N, Chong R, Verdelis K, Garlet GP, Little S , Sfeir C . Induction of M 2 macrophages prevents bone loss in murine periodontitis models. J Dent Res. 2018;98(2):200-8.

- Miao Y, He L, Qi X, Lin X. Injecting immunosuppressive M2 macrophages alleviates the symptoms of periodontitis in mice. Front Mol Biosci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2020.603817.

- Li J, Li X, Pei M, Liu P. Acid-labile anhydride-linked doxorubicin-doxorubicin dimer nanoparticles as drug self-delivery system with minimized premature drug leakage and enhanced anti-tumor efficacy. Colloids Surf, B. 2020;192:111064.

- De Lauretis A, Øvrebø Ø, Romandini M, Lyngstadaas SP, Rossi F, Haugen HJ. From basic science to clinical practice: a review of current periodontal/mucogingival regenerative biomaterials. Adv Sci. 2024. https://doi. org/10.1002/advs. 202308848.

- Murray PJ. Macrophage polarization. Annu Rev Physiol. 2017;79(1):541-66.

- Slots J. Periodontitis: facts, fallacies and the future. Periodontology. 2017;75(1):7-23.

- Page RC, Schroeder HE. Pathogenesis of inflammatory periodontal disease. A summary of current work. Lab Invest. 1976;34(3):235-49.

- Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T, Hajishengallis E, Lambris JD. Neutrophil homeostasis and inflammation: novel paradigms from studying periodontitis. J Leukocyte Biol. 2014;98(4):539-48.

- Hajishengallis G, Moutsopoulos NM, Hajishengallis E, Chavakis T. Immune and regulatory functions of neutrophils in inflammatory bone loss. Semin Immunol. 2016;28(2):146-58.

- Huang Z, Zhao Q, Jiang X, Li Z. The mechanism of efferocytosis in the pathogenesis of periodontitis and its possible therapeutic strategies. J Leukocyte Biol. 2023;113(4):365-75.

- Hasan A, Palmer RM. A clinical guide to periodontology: pathology of periodontal disease. Br Dent J. 2014;216(8):457-61.

- Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, Gordon S, Hamilton JA, Ivashkiv LB, Lawrence T, Locati M, Mantovani A, Martinez FO, Mege JL, Mosser DM, Natoli G, Saeij JP, Schultze JL, Shirey KA, Sica A, Suttles J, Udalova I, van Ginderachter JA, Vogel SN, Wynn TA. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41(1):14-20.

- Mackaness GB. Cellular resistance to infection. J Exp Med. 1962;116(3):381-406.

- Nathan CF, Murray HW, Wiebe ME, Rubin BY. Identification of interferongamma as the lymphokine that activates human macrophage oxidative metabolism and antimicrobial activity. J Exp Med. 1983;158(3):670-89.

- Stein M, Keshav S, Harris N, Gordon S. Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 1992;176(1):287-92.

- Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol. 2000;164(12):6166-73.

- Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 2005;175(1):5-14.

- Martinez FO, Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:13.

- Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S, Vazini H, Taghadosi M, Esmaeili S-A, Mardani F, Seifi B, Mohammadi A, Afshari JT, Sahebkar A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(9):6425-40.

- Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):677-86.

- Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Erratum: exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(6):460-460.

- Keeler GD, Durdik JM, Stenken JA. Localized delivery of dexametha-sone-21-phosphate via microdialysis implants in rat induces M(GC) macrophage polarization and alters CCL2 concentrations. Acta Biomater. 2015;12:11-20.

- Yang J, Zhu Y, Duan D, Wang P, Xin Y, Bai L, Liu Y, Xu Y. Enhanced activity of macrophage M1/M2 phenotypes in periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2018;96:234-42.

- Viniegra A, Goldberg H, Çil Ç, Fine N, Sheikh Z, Galli M, Freire M, Wang Y, Van Dyke TE, Glogauer M, Sima C. Resolving macrophages counter osteolysis by anabolic actions on bone. Cells. 2018;97(10):1160-9.

- Chen G, Sun Q, Cai Q, Zhou H. Outer membrane vesicles from fusobacterium nucleatum switch M0-like macrophages toward the M1 phenotype to destroy periodontal tissues in mice. Front Microbiol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.815638.

- Zhuang Z, Yoshizawa-Smith S, Glowacki A, Maltos K, Pacheco C, Shehabeldin M, Mulkeen M, Myers N, Chong R, Verdelis K, Garlet GP, Little

, Sfeir C. Induction of M2 macrophages prevents bone loss in murine periodontitis models. J Dent Res. 2019;98(2):200-8. - Sun X, Gao J, Meng X, Lu X, Zhang L, Chen R. Polarized macrophages in periodontitis: characteristics function, and molecular signaling. Front Immunol. 2021;12:763334.

- Wculek SK, Dunphy G, Heras-Murillo I, Mastrangelo A, Sancho D. Metabolism of tissue macrophages in homeostasis and pathology. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19(3):384-408.

- Oishi Y, Manabe I. Macrophages in inflammation, repair and regeneration. Int Immunol. 2018;30(11):511-28.

- Chen

, Wan , Yang , Song , Fu , Tang , Chen , Song . Exosomes derived from reparative M 2 -like macrophages prevent bone loss in murine periodontitis models via IL-10 mRNA. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):110. - Kuninaka Y, Ishida Y, Ishigami A, Nosaka M, Matsuki J, Yasuda H, Kofuna A, Kimura A, Furukawa F, Kondo T. Macrophage polarity and wound age determination. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):20327.

- Kaufmann SHE, Dorhoi A. Molecular determinants in phagocyte-bacteria interactions. Immunity. 2016;44(3):476-91.

- Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1(2):135-45.

- Papadopoulos G, Weinberg EO, Massari P, Gibson FC III, Wetzler LM, Morgan EF, Genco CA. Macrophage-specific TLR2 signaling mediates pathogen-induced TNF-dependent inflammatory oral bone loss. J Immunol. 2013;190(3):1148-57.

- Lam RS, O’Brien-Simpson NM, Holden JA, Lenzo JC, Fong SB, Reynolds EC. Unprimed, M1 and M2 macrophages differentially interact with porphyromonas gingivalis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0158629.

- Makkawi H, Hoch S, Burns E, Hosur K, Hajishengallis G, Kirschning CJ, Nussbaum G. Porphyromonas gingivalis stimulates TLR2-PI3K signaling to escape immune clearance and induce bone resorption independently of MyD88. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fcimb.2017.00359.

- Wu C, Liu C, Luo K, Li Y, Jiang J, Yan F. Changes in expression of the membrane receptors CD14, MHC-II, SR-A, and TLR4 in tissue-specific monocytes/macrophages following porphyromonas gingivalis-LPS stimulation. Inflammation. 2018;41(2):418-31.

- Naruishi K, Nagata T. Biological effects of interleukin-6 on gingival fibroblasts: cytokine regulation in periodontitis. J cell Physiol. 2018;233(9):6393-400.

- Apolinário Vieira GH, Aparecida Rivas AC, Figueiredo Costa K, Ferreira Oliveira LF, Tanaka Suzuki K, Reis Messora M, Sprone Ricoldi M, de Gonçalves Almeida AL, Taba M Jr. Specific inhibition of IL-6 receptor attenuates inflammatory bone loss in experimental periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2021;92(10):1460-9.

- Iwasaki K, Komaki M, Mimori K, Leon E, Izumi Y, Ishikawa I. IL-6 induces osteoblastic differentiation of periodontal ligament cells. J Dent Res. 2008;87(10):937-42.

- Kili M, Cox SW, Chen HW, Wahlgren J, Maisi P, Eley BM, Salo T, Sorsa T. Collagenase-2 (MMP-8) and collagenase-3 (MMP-13) in adult periodontitis: molecular forms and levels in gingival crevicular fluid and immunolocalisation in gingival tissue. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(3):224-32.

- Kato Y, Hagiwara M, Ishihara Y, Isoda R, Sugiura S, Komatsu T, Ishida N, Noguchi T, Matsushita K. TNF-a augmented Porphyromonas gingivalis invasion in human gingival epithelial cells through Rab5 and ICAM-1. BMC Microbiol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-014-0229-z.

- Kato Y, Hagiwara M, Ishihara Y, Isoda R, Sugiura S, Komatsu T, Ishida N, Noguchi T, Matsushita K. TNF-a augmented Porphyromonas gingivalis

invasion in human gingival epithelial cells through Rab5 and ICAM-1. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14(1):229. - Fujihara R, Usui M, Yamamoto G, Nishii K, Tsukamoto Y, Okamatsu Y, Sato T, Asou Y, Nakashima K, Yamamoto M. Tumor necrosis factor-a enhances RANKL expression in gingival epithelial cells via protein kinase A signaling. J Periodontal Res. 2014;49(4):508-17.

- Algate K, Haynes DR, Bartold PM, Crotti TN, Cantley MD. The effects of tumour necrosis factor-a on bone cells involved in periodontal alveolar bone loss; osteoclasts, osteoblasts and osteocytes. J Periodontal Res. 2016;51(5):549-66.

- Tan J, Dai A, Pan L, Zhang L, Wang Z, Ke T, Sun W, Wu Y, Ding P-H, Chen L. Inflamm-aging-related cytokines of IL-17 and IFN-<i>

accelerate osteoclastogenesis and periodontal destruction. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021:9919024. - Issaranggun Na Ayuthaya B, Satravaha P, Pavasant P. Interleukin-12 modulates the immunomodulatory properties of human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodontal Res. 2017;52(3):546-55.

- Sasaki H, Okamatsu Y, Kawai T, Kent R, Taubman M, Stashenko P. The interleukin-10 knockout mouse is highly susceptible to Porphyromonas gingivalis-induced alveolar bone loss. J Periodontal Res. 2004;39(6):432-41.

- Claudino M, Garlet TP, Cardoso CRB, De Assis GF, Taga R, Cunha FQ, Silva JS, Garlet GP. Down-regulation of expression of osteoblast and osteocyte markers in periodontal tissues associated with the spontaneous alveolar bone loss of interleukin-10 knockout mice. Eur J Oral Sci. 2010;118(1):19-28.

- AI-Rasheed A, Scheerens H, Rennick DM, Fletcher HM, Tatakis DN. Accelerated alveolar bone loss in mice lacking interleukin-10. J Dent Res. 2003;82(8):632-5.

- Chen Y, Wang H, Ni Q, Wang T, Bao C, Geng Y, Lu Y, Cao Y, Li Y, Li L, Xu Y, Sun W. B-cell-derived TGF-

inhibits osteogenesis and contributes to bone loss in periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2023;102(7):767-76. - Um S, Lee J-H, Seo B-M. TGF-

downregulates osteogenesis under inflammatory conditions in dental follicle stem cells. Int J Oral Sci. 2018;10(3):29. - Liu Z, Guo L, Li R, Xu Q, Yang J, Chen J, Deng M. Transforming growth factor-

and hypoxia inducible factor-1 a synergistically inhibit the osteogenesis of periodontal ligament stem cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;75:105834. - Fan C, Ji Q, Zhang C, Xu S, Sun H, Li Z. TGF-

induces periodontal ligament stem cell senescence through increase of ROS production. Mol Med Rep. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2019.10580. - Huang Y, Zhang L, Tan L, Zhang C, Li X, Wang P, Gao L, Zhao C. Interleu-kin-22 inhibits apoptosis of gingival epithelial cells through TGF-

signaling pathway during periodontitis. Inflammation. 2023;46(5):1871-86. - Greene CJ, Nguyen JA, Cheung SM, Arnold CR, Balce DR, Wang YT, Soderholm A, McKenna N, Aggarwal D, Campden RI, Ewanchuk BW, Virgin HW, Yates RM. Macrophages disseminate pathogen associated molecular patterns through the direct extracellular release of the soluble content of their phagolysosomes. Nat Commun. 2022. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30654-4.

- Rasheed A, Rayner KJ. Macrophage responses to environmental stimuli during homeostasis and disease. Endocr Rev. 2021;42(4):407-35.

- Wang WZ, Zheng CX, Yang JH, Li B. Intersection between macrophages and periodontal pathogens in periodontitis. J Leukocyte Biol. 2021;110(3):577-83.

- Fleetwood AJ, Lee MKS, Singleton W, Achuthan A, Lee M-C, O’BrienSimpson NM, Cook AD, Murphy AJ, Dashper SG, Reynolds EC, Hamilton JA. Metabolic remodeling, inflammasome activation, and pyroptosis in macrophages stimulated by Porphyromonas gingivalis and its outer membrane vesicles. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fcimb.2017.00351.

- Liu Y-J, Chen J-L, Fu Z-B, Wang Y, Cao X-Z, Sun Y. Enhanced responsive formation of extracellular traps in macrophages previously exposed to Porphyromonas gingivalis. Inflammation. 2022;45(3):1174-85.

- Papadopoulos G, Shaik-Dasthagirisaheb YB, Huang N, Viglianti GA, Henderson AJ, Kantarci A, Gibson FC III. Immunologic environment influences macrophage response to Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol Oral Microbol. 2017;32(3):250-61.

- Abdal Dayem A, Hossain MK, Lee SB, Kim K, Saha SK, Yang GM, Choi HY, Cho SG. The role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the biological

activities of metallic nanoparticles. Int J Mol Sci. 2017. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms18010120. - Brand MD. The sites and topology of mitochondrial superoxide production. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45(7-8):466-72.

- Lambeth JD, Neish AS. Nox enzymes and new thinking on reactive oxygen: a double-edged sword revisited. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:119-45.

- West AP, Shadel GS, Ghosh S. Mitochondria in innate immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(6):389-402.

- Thammasitboon K, Goldring SR, Boch JA. Role of macrophages in LPSinduced osteoblast and PDL cell apoptosis. Bone. 2006;38(6):845-52.

- Liu G, Zhang L, Zhou X, Xue J, Xia R, Gan X, Lv C, Zhang Y, Mao X, Kou

, Shi , Chen . Inducing the “re-development state” of periodontal ligament cells via tuning macrophage mediated immune microenvironment. J Adv Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2023.08.009. - Liao X-M, Guan Z, Yang Z-J, Ma L-Y, Dai Y-J, Liang C, Hu J-T. Comprehensive analysis of M2 macrophage-derived exosomes facilitating osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cells. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):647.

- Sun Y, Li J, Xie X, Gu F, Sui Z, Zhang K, Yu T. Macrophage-osteoclast associations: origin polarization, and subgroups. Front Immunol. 2021;12:778078.

- Gowen M, Wood DD, Ihrie EJ, McGuire MK, Russell RG. An interleukin 1 like factor stimulates bone resorption in vitro. Nature. 1983;306(5941):378-80.

- Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(10):986-95.

- Otsuka Y, Kondo T, Aoki H, Goto Y, Kawaguchi Y, Waguri-Nagaya Y, Miyazawa K, Goto S, Aoyama M. IL-1 beta promotes osteoclastogenesis by increasing the expression of IGF2 and chemokines in non-osteoclastic cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2023;151(1):1-8.

- Tanaka K, Yamagata K, Kubo S, Nakayamada S, Sakata K, Matsui T, Yamagishi SI, Okada Y, Tanaka Y. Glycolaldehyde-modified advanced glycation end-products inhibit differentiation of human monocytes into osteoclasts via upregulation of IL-10. Bone. 2019;128:115034.

- Xu H, Zhao H, Lu C, Qiu Q, Wang G, Huang J, Guo M, Guo B, Tan Y, Xiao C. triptolide inhibits osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption in vitro via enhancing the production of IL-10 and TGF-beta1 by regulatory T cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:8048170.

- Tokunaga T, Mokuda S, Kohno H, Yukawa K, Kuranobu T, Oi K, Yoshida Y, Hirata S, Sugiyama E. TGFbeta 1 regulates human RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis via suppression of NFATc1 expression. Int J Mol Sci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21030800.

- Gao X, Ge J, Zhou W, Xu L, Geng D. IL-10 inhibits osteoclast differentiation and osteolysis through MEG3/IRF8 pathway. Cell Signal. 2022;95:110353.

- Valerio MS, Alexis F, Kirkwood KL. Functionalized nanoparticles containing MKP-1 agonists reduce periodontal bone loss. J Periodontol. 2019;90(8):894-902.

- Li W, Xu F, Dai F, Deng T, Ai Y, Xu Z, He C, Ai F, Song L. Hydrophilic surface-modified 3D printed flexible scaffolds with high ceramic particle concentrations for immunopolarization-regulation and bone regeneration. Biomater Sci. 2023;11(11):3976-97.

- Yang C, Zhao C, Wang X, Shi M, Zhu Y, Jing L, Wu C, Chang J. Stimulation of osteogenesis and angiogenesis by micro/nano hierarchical hydroxyapatite via macrophage immunomodulation. Nanoscale. 2019;11(38):17699-708.

- Li C, Yang L, Ren X, Lin M, Jiang X, Shen D, Xu T, Ren J, Huang L, Qing W, Zheng J, Mu Y. Groove structure of porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds (HAS) modulates immune environment via regulating macrophages and subsequently enhances osteogenesis. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2019;24(5):733-45.

- Wang M, Chen F, Tang Y, Wang J, Chen X, Li X, Zhang X. Regulation of macrophage polarization and functional status by modulating hydroxyapatite ceramic micro/nano-topography. Mater Des. 2022;213:110302.

- Chen X, Wang M, Chen F, Wang J, Li X, Liang J, Fan Y, Xiao Y, Zhang X. Correlations between macrophage polarization and osteoinduction of porous calcium phosphate ceramics. Acta Biomater. 2020;103:318-32.

- He X-T, Li X, Zhang M, Tian B-M, Sun L-J, Bi C-S, Deng D-K, Zhou H, Qu H-L, Wu C, Chen F-M. Role of molybdenum in material immunomodulation and periodontal wound healing: Targeting immunometabolism

and mitochondrial function for macrophage modulation. Biomaterials. 2022;283:121439. - Zhang W, Zhao F, Huang D, Fu X, Li X, Chen X. Strontium-substituted submicrometer bioactive glasses modulate macrophage responses for improved bone regeneration. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(45):30747-58.

- Iviglia G, Torre E, Cassinelli C, Morra M. Functionalization with a polyphenol-rich pomace extract empowers a ceramic bone filler with in vitro antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and pro-osteogenic properties. J Funct Biomater. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb12020031.

- Hsieh JY, Keating MT, Smith TD, Meli VS, Botvinick EL, Liu WF. Matrix crosslinking enhances macrophage adhesion, migration, and inflammatory activation. APL Bioeng. 2019;10(1063/1):5067301.

- Li W, Wang C, Wang Z, Gou L, Zhou Y, Peng G, Zhu M, Zhang J, Li R, Ni H, Wu L, Zhang W, Liu J, Tian Y, Chen Z, Han YP, Tong N, Fu X, Zheng X, Berggren PO. Physically cross-linked DNA hydrogel-based sustained cytokine delivery for in situ diabetic alveolar bone rebuilding. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(22):25173-82.

- He XT, Li X, Xia Y, Yin Y, Wu RX, Sun HH, Chen FM. Building capacity for macrophage modulation and stem cell recruitment in high-stiffness hydrogels for complex periodontal regeneration: experimental studies in vitro and in rats. Acta Biomater. 2019;88:162-80.

- Huang Y, Liu Q, Liu L, Huo F, Guo S, Tian W. Lipopolysaccharide-preconditioned dental follicle stem cells derived small extracellular vesicles treating periodontitis via reactive oxygen species/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling-mediated antioxidant effect. Int J Nanomed. 2022;17:799-819.

- Huang Y, Liu Q, Liu L, Huo F, Guo S, Tian W. Lipopolysaccharide-preconditioned dental follicle stem cells derived s mall extracellular vesicles treating periodontitis via reactive oxygen species/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling-mediated antioxida nt effect. Int J Nanomed. 2022;17:799-819.

- Peng CJ, Wang GC, Wang YX, Tang MM, Ma XD, Chang XW, Guo J, Gui SY. Thermosensitive acetylated carboxymethyl chitosan gel depot systems sustained release caffeic acid phenethyl ester for periodontitis treatment. Polym Advan Technol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/pat. 5874.

- Daghrery A, Ferreira JA, Xu J, Golafshan N, Kaigler D, Bhaduri SB, Malda J, Castilho M, Bottino MC. Tissue-specific melt electrowritten polymeric scaffolds for coordinated regeneration of soft and hard periodontal tissues. Bioact Mater. 2023;19:268-81.

- Chachlioutaki K, Karavasili C, Adamoudi E, Tsitsos A, Economou V, Beltes C, Bouropoulos N, Katsamenis OL, Doherty R, Bakopoulou A, Fatouros DG. Electrospun nanofiber films suppress inflammation in vitro and eradicate endodontic bacterial infection in an E. faecalisinfected ex vivo human tooth culture model. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022;8(5):2096-110.

- Liu ZQ , Shang LL , Ge SH. Immunomodulatory effect of dimethyloxallyl glycine/nanosilicates-loaded fibrous structure on periodontal bone remodeling. J Dent Sci. 2021;16(3):937-47.

- Ding T, Kang W, Li J, Yu L, Ge S. An in situ tissue engineering scaffold with growth factors combining angiogenesis and osteoimmunomodulatory functions for advanced periodontal bone regeneration. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19(1):247.

- Ren B, Lu J, Li M, Zou X, Liu Y, Wang C, Wang L. Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-1 ra-loaded dextran/PLGA microspheres on Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages in vitro and in vivo in a rat model of periodontitis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;134:111171.

- Ni C, Zhou J, Kong N, Bian T, Zhang Y, Huang X, Xiao Y, Yang W, Yan F. Gold nanoparticles modulate the crosstalk between macrophages and periodontal ligament cells for periodontitis treatment. Biomaterials. 2019;206:115-32.

- Steckiewicz KP, Cieciorski P, Barcinska E, Jaskiewicz M, Narajczyk M, Bauer M, Kamysz W, Megiel E, Inkielewicz-Stepniak I. Silver nanoparticles as chlorhexidine and metronidazole drug delivery platforms: their potential use in treating periodontitis. Int J Nanomed. 2022;17:495-517.

- Craciunescu O , Seciu

, Zarnescu O . In vitro and in vivo evaluation of a biomimetic scaffold embedding silver nanoparticles for improved treatment of oral lesions. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2021;123:112015. - Sun Y, Sun X, Li X, Li W, Li C, Zhou Y, Wang L, Dong B. A versatile nanocomposite based on nanoceria for antibacterial enhancement

and protection from aPDT-aggravated inflammation via modulation of macrophage polarization. Biomaterials. 2021;268:120614. - Wang Y, Li CY, Wan Y, Qi ML, Chen QH, Sun Y, Sun XL, Fang J, Fu L, Xu L, Dong BA, Wang L. Quercetin-loaded ceria nanocomposite potentiate dual-directional immunoregulation via macrophage polarization against periodontal inflammation. Small. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ smll. 202101505.

- Huang H, Pan W, Wang Y, Kim HS, Shao D, Huang B, Ho TC, Lao YH, Quek CH, Shi J, Chen Q, Shi B, Zhang S, Zhao L, Leong KW. Nanoparticulate cell-free DNA scavenger for treating inflammatory bone loss in periodontitis. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):5925.

- Tian M, Chen G, Xu J, Lin Y, Yi Z, Chen X, Li X, Chen S. Epigallocatechin gallate-based nanoparticles with reactive oxygen species scavenging property for effective chronic periodontitis treatment. Chem Eng J. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.132197.

- Noskovicova N, Hinz B, Pakshir P. Implant fibrosis and the underappreciated role of myofibroblasts in the foreign body reaction. Cells. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10071794.

- Shue L, Yufeng Z, Mony U. Biomaterials for periodontal regeneration: a review of ceramics and polymers. Biomatter. 2012;2(4):271-7.

- Zhou H, Xue Y, Dong L, Wang C. Biomaterial-based physical regulation of macrophage behaviour. J Mater Chem B. 2021;9(17):3608-21.

- Hubbell JA, Thomas SN, Swartz MA. Materials engineering for immunomodulation. Nature. 2009;462(7272):449-60.

- Hotchkiss KM, Reddy GB, Hyzy SL, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD, OlivaresNavarrete R. Titanium surface characteristics, including topography and wettability, alter macrophage activation. Acta Biomater. 2016;31:425-34.

- Chen W, Nichols L, Brinkley F, Bohna K, Tian W, Priddy MW, Priddy LB. Alkali treatment facilitates functional nano-hydroxyapatite coating of 3D printed polylactic acid scaffolds. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2021;120:111686.

- Cha B-H, Shin SR, Leijten J, Li Y-C, Singh S, Liu JC, Annabi N, Abdi R, Dokmeci MR, Vrana NE, Ghaemmaghami AM, Khademhosseini A. Integrin-mediated interactions control macrophage polarization in 3D hydrogels. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2017;6(21):1700289.

- Dalby MJ, Gadegaard N, Oreffo ROC. Harnessing nanotopography and integrin-matrix interactions to influence stem cell fate. Nat Mater. 2014;13(6):558-69.

- Wang M, Chen F, Tang Y, Wang J, Chen X, Li X, Zhang X. Regulation of macrophage polarization and functional status by modulating hydroxyapatite ceramic micro/nano-topography. Mater Des. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2021.110302.

- Nakamura J, Sugawara-Narutaki A, Ohtsuki C. Bioactive ceramics: past and future. In: Osaka A, Narayan R, editors. Bioceramics. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2021. p. 377-88.

- Haidari H, Bright R, Strudwick XL, Garg S, Vasilev K, Cowin AJ, Kopecki Z. Multifunctional ultrasmall AgNP hydrogel accelerates healing of

. aureus infected wounds. Acta Biomater. 2021;128:420-34. - Li K, Hu D, Xie Y, Huang L, Zheng X. Sr-doped nanowire modification of Ca-Si-based coatings for improved osteogenic activities and reduced inflammatory reactions. Nanotechnology. 2018;29(8):084001.

- Zhao F, Lei B, Li X, Mo Y, Wang R, Chen D, Chen X. Promoting in vivo early angiogenesis with sub-micrometer strontium-contained bioactive microspheres through modulating macrophage phenotypes. Biomaterials. 2018;178:36-47.

- Man K, Jiang LH, Foster R, Yang XB. Immunological responses to total hip arthroplasty. J Funct Biomater. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb80 30033.

- Li T, He H, Yang Z, Wang J, Zhang Y, He G, Huang J, Song D, Ni J, Zhou X, Zhu J, Ding M. Strontium-doped gelatin scaffolds promote M2 macrophage switch and angiogenesis through modulating the polarization of neutrophils. Biomater Sci. 2021;9(8):2931-46.

- Lu W, Zhou C, Ma Y, Li J, Jiang J, Chen Y, Dong L, He F. Improved osseointegration of strontium-modified titanium implants by regulating angiogenesis and macrophage polarization. Biomater Sci. 2022;10(9):2198-214.

- Chang Z, Wang Y, Liu C, Smith W, Kong L. Natural products for regulating macrophages M2 polarization. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;15(7):559-69.

- Bhattarai G, Poudel SB, Kook S-H, Lee J-C. Anti-inflammatory, anti-osteoclastic, and antioxidant activities of genistein protect against alveolar

bone loss and periodontal tissue degradation in a mouse model of periodontitis. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2017;105(9):2510-21. - Checinska K, Checinski M, Cholewa-Kowalska K, Sikora M, Chlubek D. Polyphenol-enriched composite bone regeneration materials: a systematic review of in vitro studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ijms23137473.

- Yang PM, Mu HZ, Zhang YS, Wang WC, Liu C, Zhang SY. Sequential release of immunomodulatory cytokines binding on nano-hydroxyapatite coated titanium surface for regulating macrophage polarization and bone regeneration. Med Hypotheses. 2020;144:110241.

- Gao L, Li M, Yin L, Zhao C, Chen J, Zhou J, Duan K, Feng B. Dualinflammatory cytokines on TiO(2) nanotube-coated surfaces used for regulating macrophage polarization in bone implants. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2018;106(7):1878-86.

- Ullm F, Pompe T. Fibrillar biopolymer-based scaffolds to study macrophage-fibroblast crosstalk in wound repair. Biol Chem. 2021;402(11):1309-24.

- Wu F, Dai L, Geng L, Zhu H, Jin T. Practically feasible production of sustained-release microspheres of granulocyte-macrophage colonystimulating factor (rhGM-CSF). J Control Release. 2017;259:195-202.

- Yang Z, Shen Q, Xing L, Fu X, Qiu Z, Xiang H, Huang Y, Lv F, Bai H, Huo Y, Wang S. A biophotonic device based on a conjugated polymer and a macrophage-laden hydrogel for triggering immunotherapy. Mater Horiz. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2MH01224C.

- Ryma M, Tylek T, Liebscher J, Blum C, Fernandez R, Böhm C, Kastenmüller W, Gasteiger G, Groll J. Translation of collagen ultrastructure to biomaterial fabrication for material-independent but highly efficient topographic immunomodulation. Adv Mater. 2021;33(33):2101228.

- Ahmed EM. Hydrogel: preparation, characterization, and applications: a review. J Adv Res. 2015;6(2):105-21.

- Rastogi P, Kandasubramanian B. Review of alginate-based hydrogel bioprinting for application in tissue engineering. Biofabrication. 2019;11(4):042001.

- Chen IH, Lee T-M, Huang C-L. Biopolymers hybrid particles used in dentistry. Gels. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels7010031.

- Peng G, Li W, Peng L, Li R, Wang Z, Zhou Y, Gou L, Zhu X, Xie Q, Zhang X, Shen S, Wu L, Hu L, Wang C, Zheng X, Tong N. Multifunctional DNAbased hydrogel promotes diabetic alveolar bone defect reconstruction. Small. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202305594.

- Khajouei S, Ravan H, Ebrahimi A. DNA hydrogel-empowered biosensing. Adv Coll Interface Sci. 2020;275:102060.

- Sah AK, Dewangan M, Suresh PK. Potential of chitosan-based carrier for periodontal drug delivery. Colloids Surf, B. 2019;178:185-98.

- Shen Z, Kuang S, Zhang Y, Yang M, Qin W, Shi X, Lin Z. Chitosan hydrogel incorporated with dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes alleviates periodontitis in mice via a macrophage-dependent mechanism. Bioact Mater. 2020;5(4):1113-26.

- Nakao Y, Fukuda T, Zhang Q, Sanui T, Shinjo T, Kou X, Chen C, Liu D, Watanabe Y, Hayashi C, Yamato H, Yotsumoto K, Tanaka U, Taketomi T, Uchiumi T, Le AD, Shi S, Nishimura F. Exosomes from TNF-a-treated human gingiva-derived MSCs enhance M2 macrophage polarization and inhibit periodontal bone loss. Acta Biomater. 2021;122:306-24.

- Gjoseva S, Geskovski N, Sazdovska SD, Popeski-Dimovski R, Petruševski G, Mladenovska K, Goracinova K. Design and biological response of doxycycline loaded chitosan microparticles for periodontal disease treatment. Carbohyd Polym. 2018;186:260-72.

- Lu M, Wang S, Wang H, Xue T, Cai C, Fan C, Wu F, Liu S. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate-loaded electrospun membranes for peritendinous anti-adhesion through inhibition of the nuclear factor-kB pathway. Acta Biomater. 2023;155:333-46.

- Daghrery A, Araujo IJD, Castilho M, Malda J, Bottino MC. Unveiling the potential of melt electrowriting in regenerative dental medicine. Acta Biomater. 2023;156:88-109.

- Ding T, Kang W, Li J, Yu L, Ge S. An in situ tissue engineering scaffold with growth factors combining angiogenesis and osteoimmunomodulatory functions for advanced periodontal bone regeneration. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-021-00992-4.

- Su Y, Zhang B, Sun R, Liu W, Zhu Q, Zhang X, Wang R, Chen C. PLGAbased biodegradable microspheres in drug delivery: recent advances in research and application. Drug Deliv. 2021;28(1):1397-418.

- Wang J, Toebes BJ, Plachokova AS, Liu Q, Deng D, Jansen JA, Yang F, Wilson DA. Self-propelled PLGA micromotor with chemotactic response to inflammation. Adv Healthc Mater. 2020;9(7):e1901710.

- Hussein H, Kishen A. Engineered chitosan-based nanoparticles modulate macrophage-periodontal ligament fibroblast interactions in biofilm-mediated inflammation. J Endod. 2021;47(9):1435-44.

- Zięba M, Chaber P, Duale K, Martinka Maksymiak M, Basczok M, Kowalczuk M, Adamus G. Polymeric carriers for delivery systems in the treatment of chronic periodontal disease. Polymers. 2020. https://doi. org/10.3390/polym12071574.

- Chen RX, Qiao D, Wang P, Li LJ, Zhang YH, Yan FH. Gold nanoclusters exert bactericidal activity and enhance phagocytosis of macrophage mediated killing of fusobacterium nucleatum. Front Mater. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2021.803871.

- Bruna T, Maldonado-Bravo F, Jara P, Caro N. Silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2021. https://doi.org/10. 3390/ijms22137202.

- Qian Y, Zhou X, Zhang F, Diekwisch TGH, Luan X, Yang J. Triple PLGA/PCL scaffold modification including silver impregnation, collagen coating, and electrospinning significantly improve biocompatibility, antimicrobial, and osteogenic properties for orofacial tissue regeneration. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(41):37381-96.

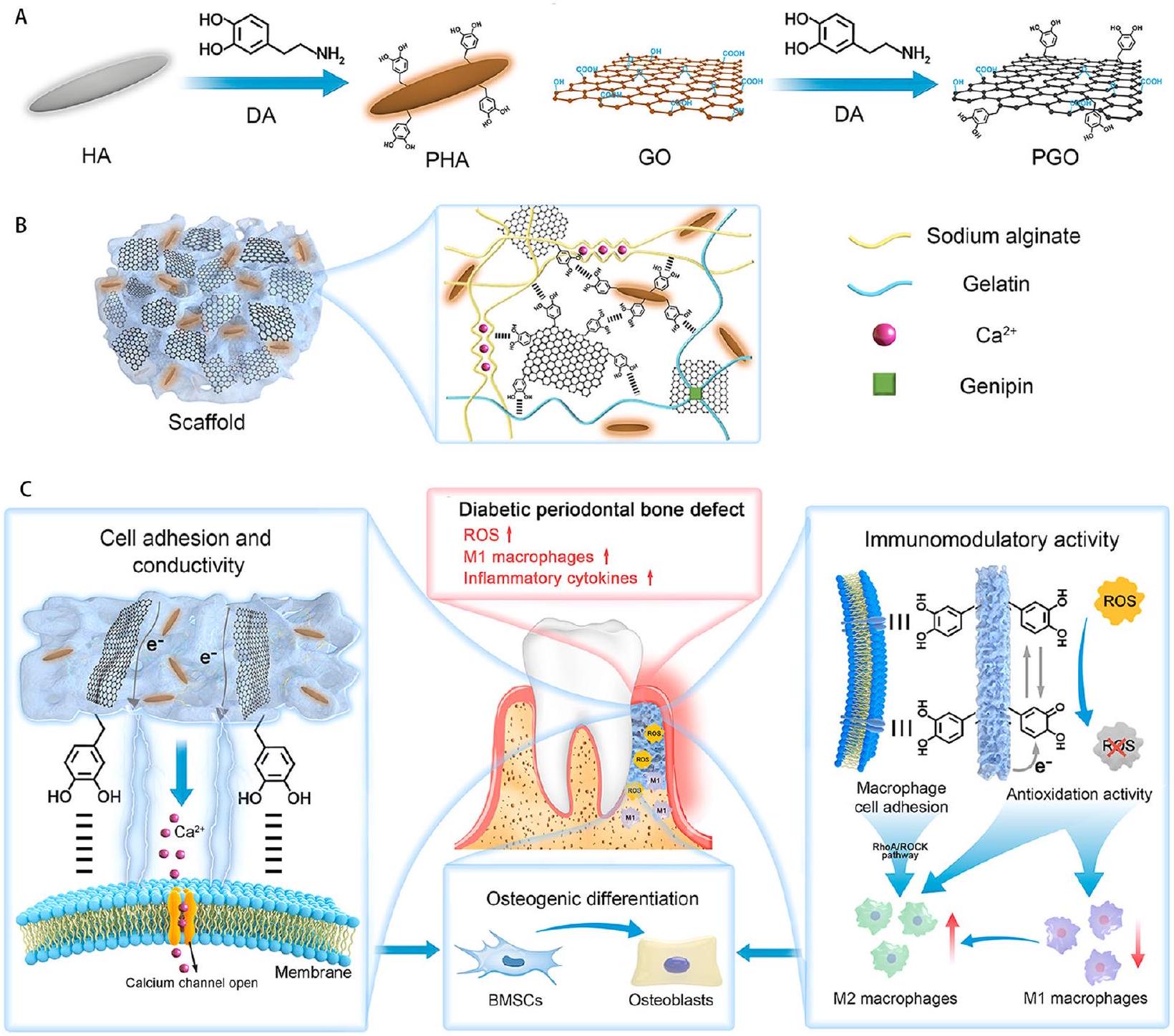

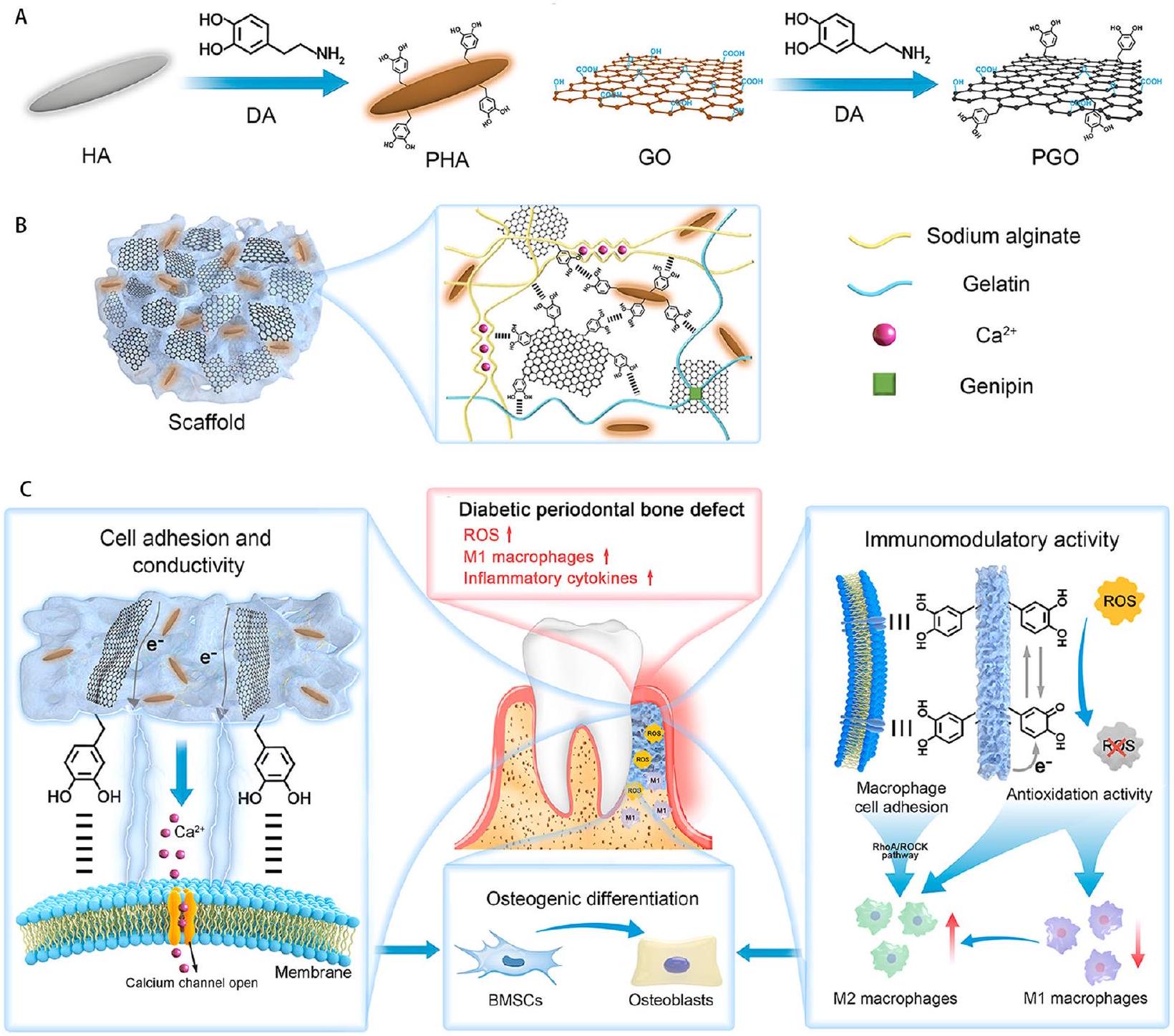

- Li Y, Yang L, Hou Y, Zhang Z, Chen M, Wang M, Liu J, Wang J, Zhao Z, Xie C, Lu X. Polydopamine-mediated graphene oxide and nanohy-droxyapatite-incorporated conductive scaffold with an immunomodulatory ability accelerates periodontal bone regeneration in diabetes. Bioact Mater. 2022;18:213-27.

- Qiao Q, Liu X, Yang T, Cui K, Kong L, Yang C, Zhang Z. Nanomedicine for acute respiratory distress syndrome: the latest application, targeting strategy, and rational design. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11(10):3060-91.

- Nelson BC, Johnson ME, Walker ML, Riley KR, Sims CM. Antioxidant cerium oxide nanoparticles in biology and medicine. Antioxidants. 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox5020015.

- Jeong H-G, Cha BG, Kang D-W, Kim DY, Yang W, Ki S-K, Kim SI, Han J, Kim CK, Kim J, Lee S-H. Ceria nanoparticles fabricated with 6-aminohexanoic acid that overcome systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2019;8(9):1801548.

- Wyszogrodzka G, Marszałek B, Gil B, Dorożyński P. Metal-organic frameworks: mechanisms of antibacterial action and potential applications. Drug Discov Today. 2016;21(6):1009-18.

- Li X, Qi ML, Li CY, Dong B, Wang J, Weir MD, Imazato S, Du LY, Lynch CD, Xu L, Zhou YM, Wang L, Xu HHK. Novel nanoparticles of cerium-doped zeolitic imidazolate frameworks with dual benefits of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory functions against periodontitis. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7(44):6955-71.

- Li Z, Pan W, Shi E, Bai L, Liu H, Li C, Wang Y, Deng J, Wang Y. a multifunctional nanosystem based on bacterial cell-penetrating photosensitizer for fighting periodontitis via combining photodynamic and antibiotic therapies. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2021;7(2):772-86.

- Wu J, Liang H, Li Y, Shi Y, Bottini M, Chen Y, Liu L. Cationic block copolymer nanoparticles with tunable DNA affinity for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Funct Mater. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 20200 0391.

- Viglianisi G, Santonocito S, Polizzi A, Troiano G, Amato M, Zhurakivska K , Pesce P, Isola G. Impact of circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) as a biomarker of the development and evolution of periodontitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(12):9981.

- Basu A, Masek E, Ebersole JL. Dietary polyphenols and periodontitis-a mini-review of literature. Molecules. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ molecules23071786.

- Tan Y, Feng J, Xiao Y, Bao C. Grafting resveratrol onto mesoporous silica nanoparticles towards efficient sustainable immunoregulation and insulin resistance alleviation for diabetic periodontitis therapy. J Mater Chem B. 2022;10(25):4840-55.

- Luan J, Li R, Xu W, Sun H, Li Q, Wang D, Dong S, Ding J. Functional biomaterials for comprehensive periodontitis therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.10.026.

ملاحظة الناشر

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02592-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38907216

Publication Date: 2024-06-21

A new direction in periodontitis treatment: biomaterial-mediated macrophage immunotherapy

Abstract

Periodontitis is a chronic inflammation caused by a bacterial infection and is intimately associated with an overactive immune response. Biomaterials are being utilized more frequently in periodontal therapy due to their designability and unique drug delivery system. However, local and systemic immune response reactions driven by the implantation of biomaterials could result in inflammation, tissue damage, and fibrosis, which could end up with the failure of the implantation. Therefore, immunological adjustment of biomaterials through precise design can reduce the host reaction while eliminating the periodontal tissue’s long-term chronic inflammation response. It is important to note that macrophages are an active immune system component that can participate in the progression of periodontal disease through intricate polarization mechanisms. And modulating macrophage polarization by designing biomaterials has emerged as a new periodontal therapy technique. In this review, we discuss the role of macrophages in periodontitis and typical strategies for polarizing macrophages with biomaterials. Subsequently, we discuss the challenges and potential opportunities of using biomaterials to manipulate periodontal macrophages to facilitate periodontal regeneration.

Introduction

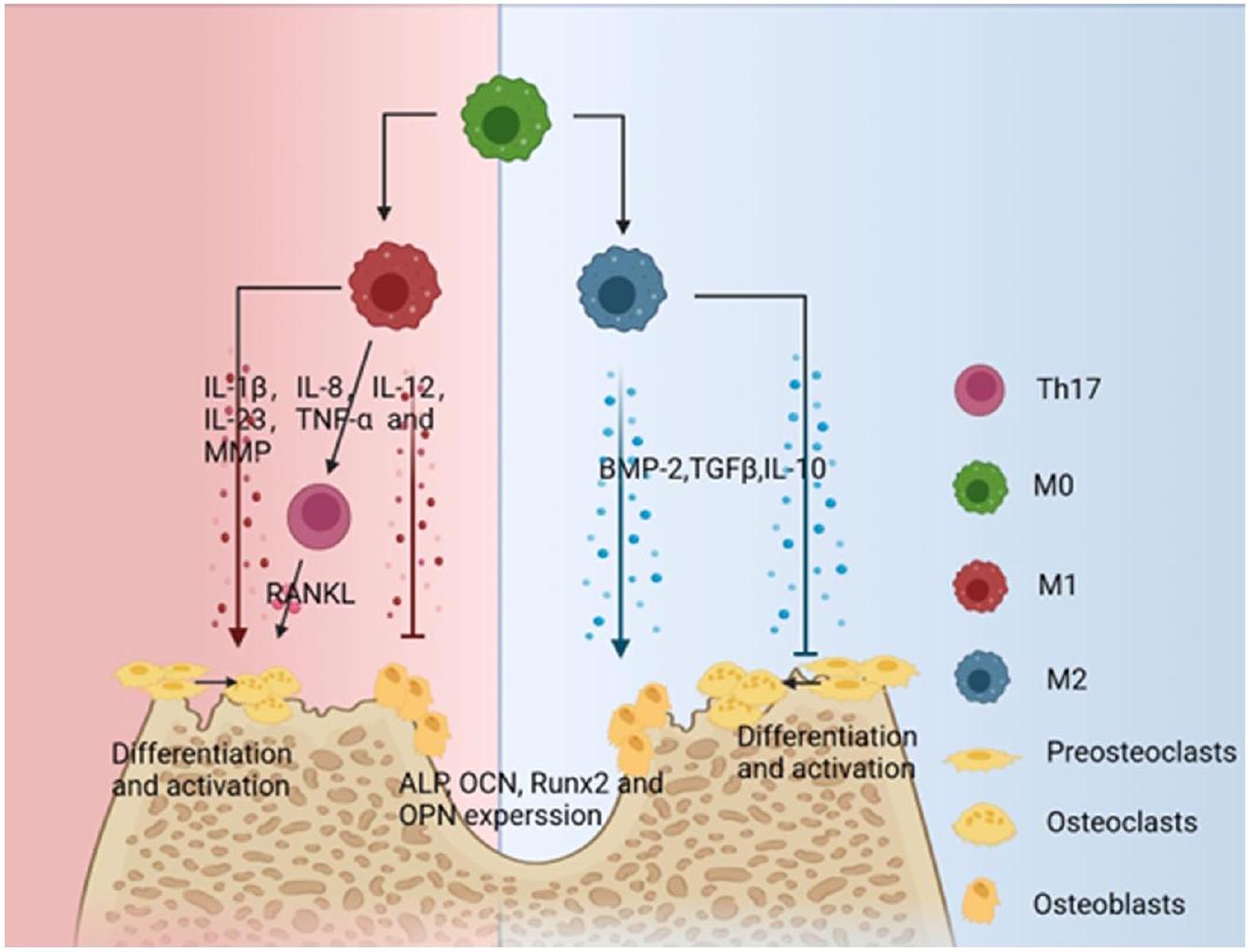

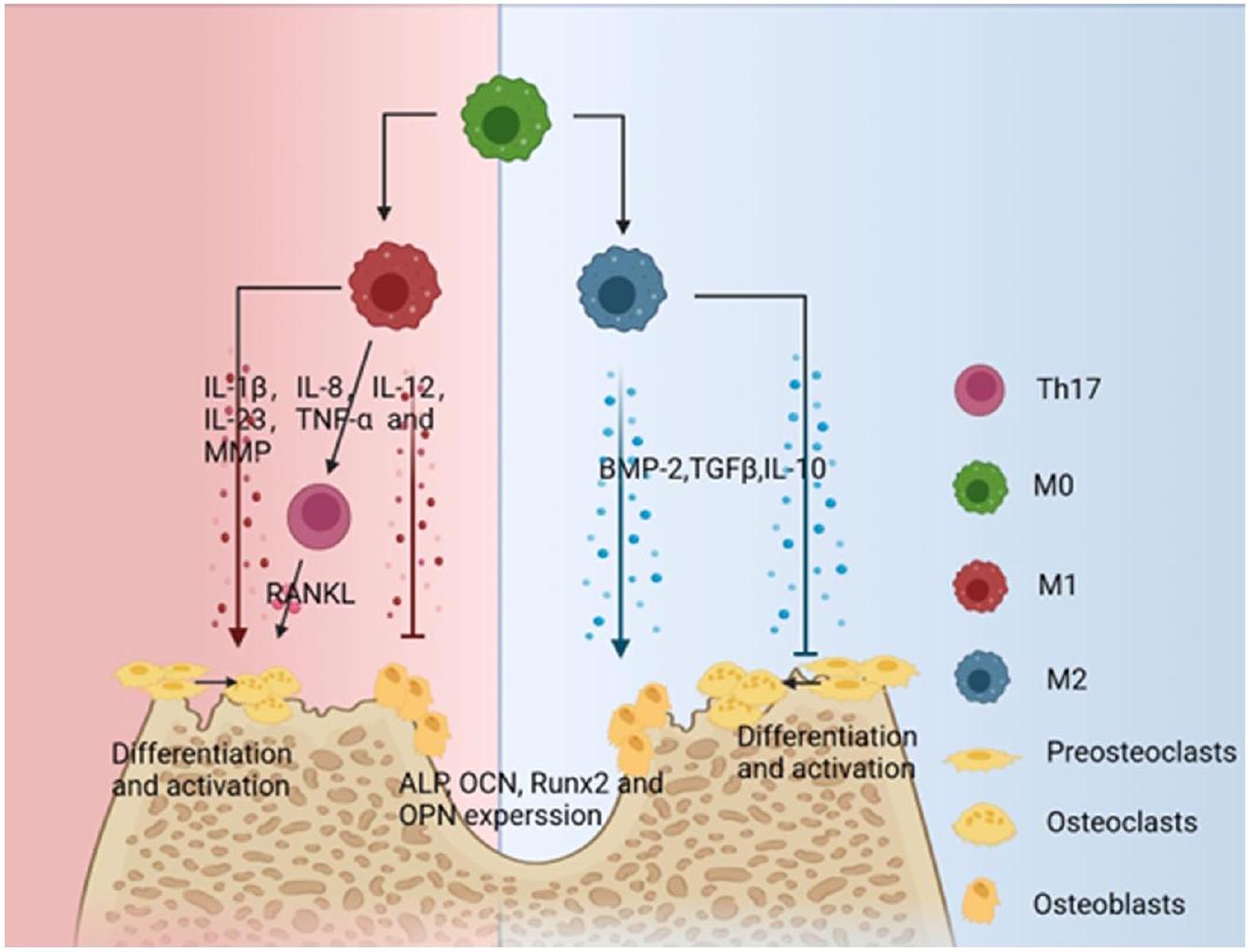

Macrophages, the innate immune system’s effector cells. They are crucial for pathogen clearance, inflammatory resolution, tissue homeostasis, and regenerative repair. Numerous inflammatory illnesses of the body, such as pneumonia, intestinal inflammation, hepatitis, inflammation during wound healing, and periodontitis, are associated with macrophages [3]. It can polarize into two phenotypes, M1 and M2, and contribute to the promotion and reduction of inflammation: M1 macrophages have pro-inflammatory effects, and are primarily responsible for pathogen detection, phagocytosis

and destruction. They also secrete a high level of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines, recruit and activate leukocytes, and contribute to the activation of the adaptive immune system by presenting antigens and producing cytokines. M2 macrophages are characterized as anti-inflammatory, support the maturation of blood vessels and the deposition of minerals on the bone matrix [4]. In addition, M2 is able to promote tissue regeneration and repair by secreting growth factors to activate stem cells, support vascular maturation, and remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) [5]. In per-iodontitis-related studies, M1 promotes the progression of periodontitis, and M2 inhibits the progression of periodontitis and promotes periodontal restoration. Higher M1 levels have been discovered to be closely linked to the development of chronic periodontitis [6, 7]. Moreover, M1-related cytokines, including as MMP-9, IL-6, and IFN-

and reducing inflammation. Research has demonstrated that activation of M2 stops bone loss [9, 10]. M2 injections into periodontal tissue have the ability to suppress osteoclast activity and lessen periodontitis symptoms [11]. Therefore, a new approach to treating periodontitis may involve promoting M1/M2 conversion or limiting the pro-inflammatory effects of periodontal M1.

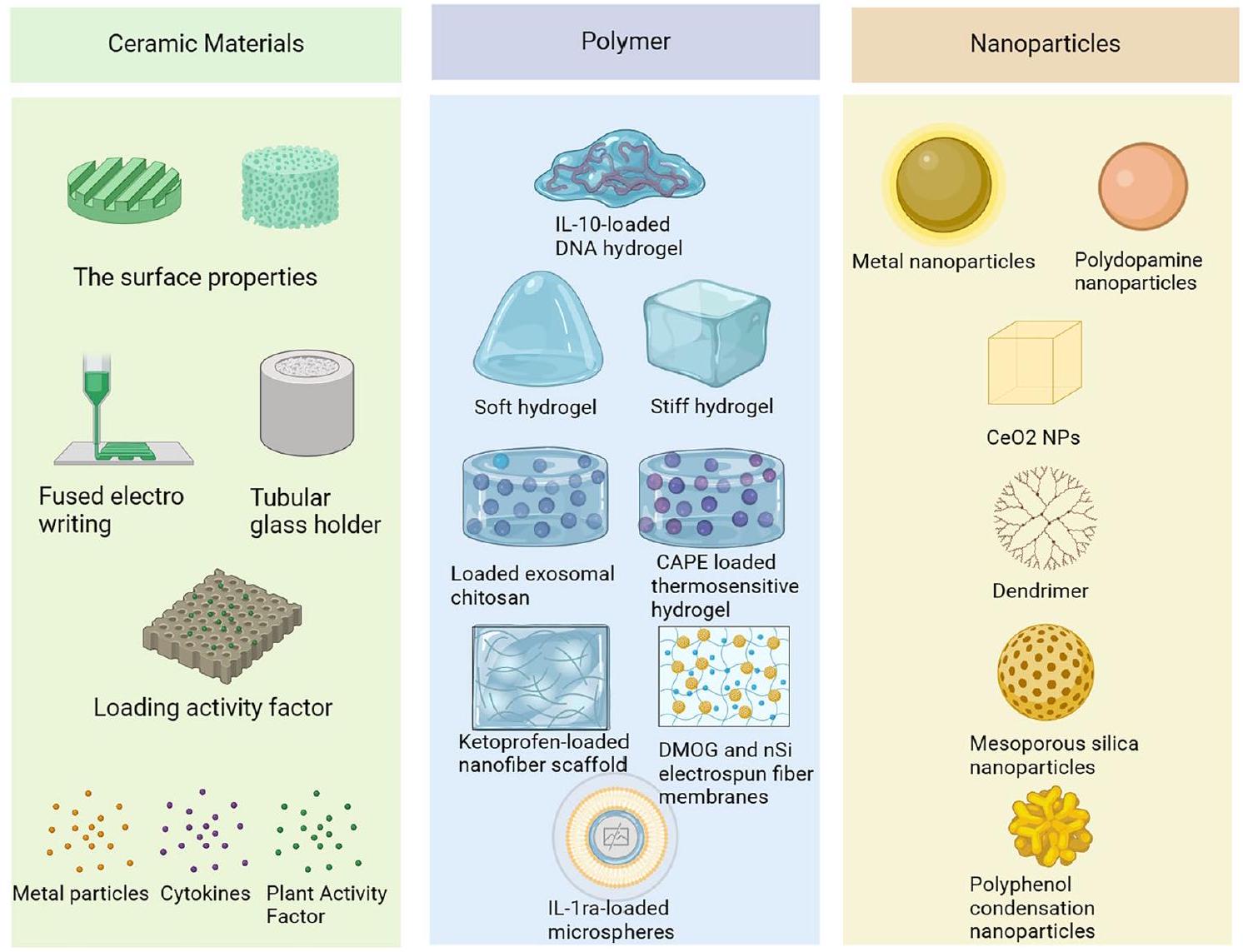

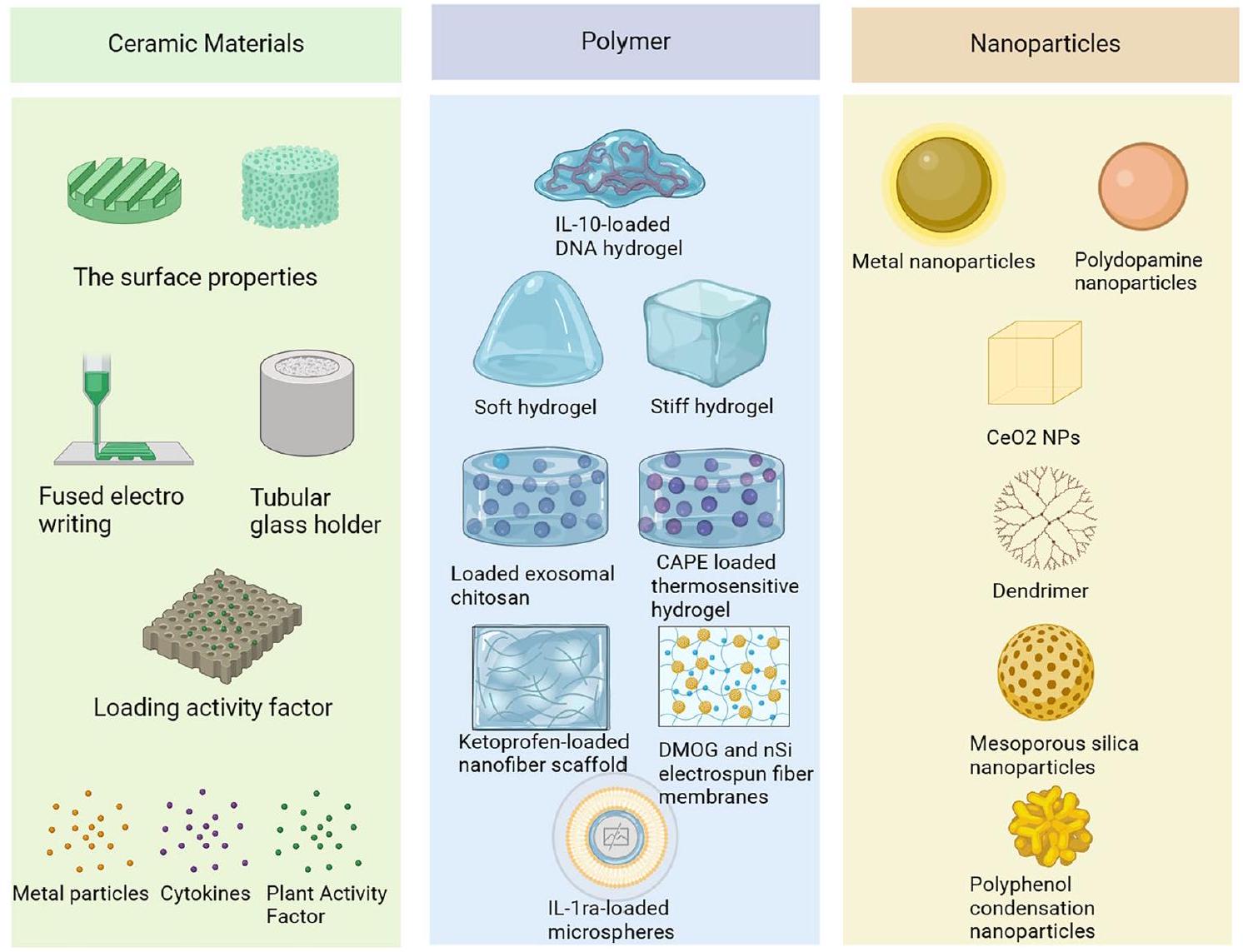

Although macrophages have been provided as a novel target in the therapy of periodontitis, most drugs still suffer from issues such as unstable effects, erratic activity, and a lack of targeting specificity [12]. Biomaterials that modulate the immune function of macrophages have gained increasing research interest because they can remedy the limitation of free drug alone through deliberate design. Periodontitis is treated with a stepwise approach, and after the non-surgical phase, intraosseous or bifurcation defects may be amenable to regenerative surgery. Biomaterials available in treatment include biologics (autologous platelet concentrates, hydrogels, nanoparticles), bone grafts (pure bone grafts or ceramics), and membranes (polymers) involved in periodontal adjuvant therapy, bone tissue regenerative restoration, and guided tissue regeneration [13]. Ceramic materials, polymers, and nanoparticles are the main types of biomaterials that regulate periodontitis macrophages. Through the material’s inherent physical and physiological characteristics or by adding active ingredients like medicines, metal ions, cytokines, exosomes, etc., biomaterials can control the state and activity of macrophages [14].

In this review, for the sake of establishing a theoretical foundation for macrophage immunotherapy for periodontitis, we first discuss the biological function of macrophages and their function as therapeutic targets in the destruction and recovery process of periodontitis. Then, we describe the biomaterials (including ceramics, polymers, and nanomaterials) that are utilized to control macrophage polarization during the present periodontitis treatment and provide an overview of the approaches taken by various materials to control macrophages. Finally, we summarize the difficulties and potential future directions of using biomaterials to control macrophages, which provide new impetus for immunotherapy of periodontitis.

The biological function of macrophage polarization and its application in the therapy of periodontitis

Overview of periodontitis

infections, gastrointestinal disorders, cardiovascular disease, and poor pregnancy outcomes and colorectal cancer [15]. During the occurrence of periodontitis, the interaction between the host immune inflammatory response and the dysregulated microbiota forms a positive feedback loop of periodontal disruption. Specifically, key pathogens initially disrupt host immunity, leading to overactivation of the inflammatory response and leading to tissue destruction. Inflammation, in turn, can exacerbate dysbiosis by providing nutrients to bacteria (from tissue breakdown products, such as collagen peptides and heme-containing compounds). This reinforcing relationship between dysbiosis and inflammation perpetuates the vicious circle, which drives the pathogenesis of periodontal disease.

In addition, macrophages are involved in the destruction and repair of periodontal tissues due to the plasticity and heterogeneity of macrophages and the various roles played by cytokines. Therefore, by understanding the description of macrophages in periodontal tissue, it is possible to help understand how macrophages are regulated and how they affect periodontitis [16, 20].

Macrophage polarization: the M1/M2 paradigm

produce low levels of IL-12 and iNOS. These two groups of macrophages have different phenotypic and functional characteristics. However, depending on the in vitro antiinflammatory stimuli used to generate M2 macrophages, these cells may exhibit subtle phenotypic changes [28]. M2 macrophages were further classified into four alternately activated subphenotypes (M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d) based on functional distinctions, all of which support tissue regeneration and wound repair. Under the induction of IL-4 or IL-13, M2a macrophages mainly secrete cytokines such as IL-1Ra, TGF-

Distribution patterns and activation of macrophages in periodontitis

remodeling of the extracellular matrix [38, 39]. M1 macrophages are the main phenotype observed in the early stages of inflammation, with a significant decrease in M1 and an increase in M2 macrophages as periodontitis progresses. If this shift does not occur, periodontitis can become chronically inflamed [40].

mediated by cytokines generated by diverse immune cells inside the inflammatory microenvironment generated by periodontal pathogens.

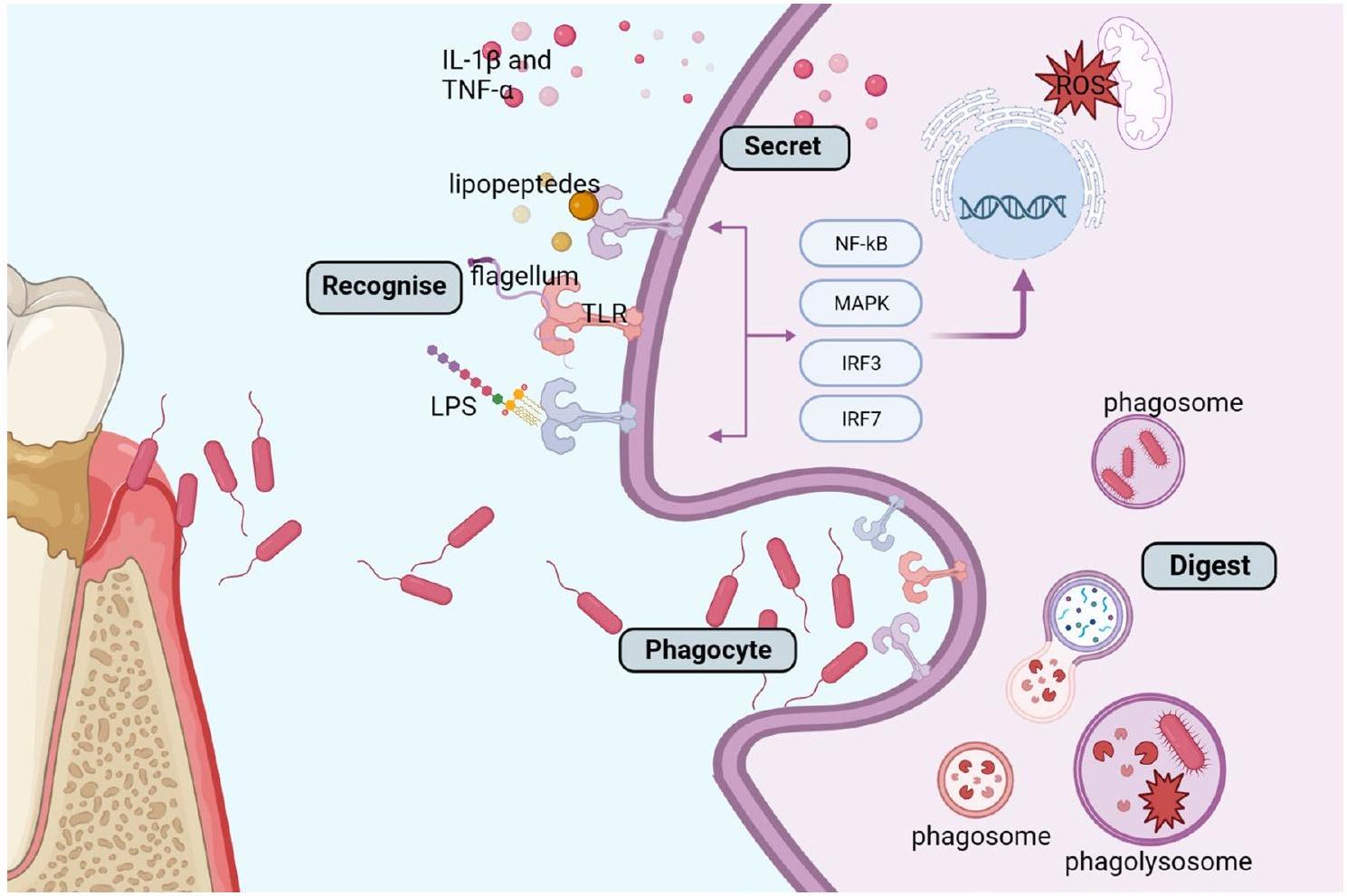

Function of macrophages in periodontitis

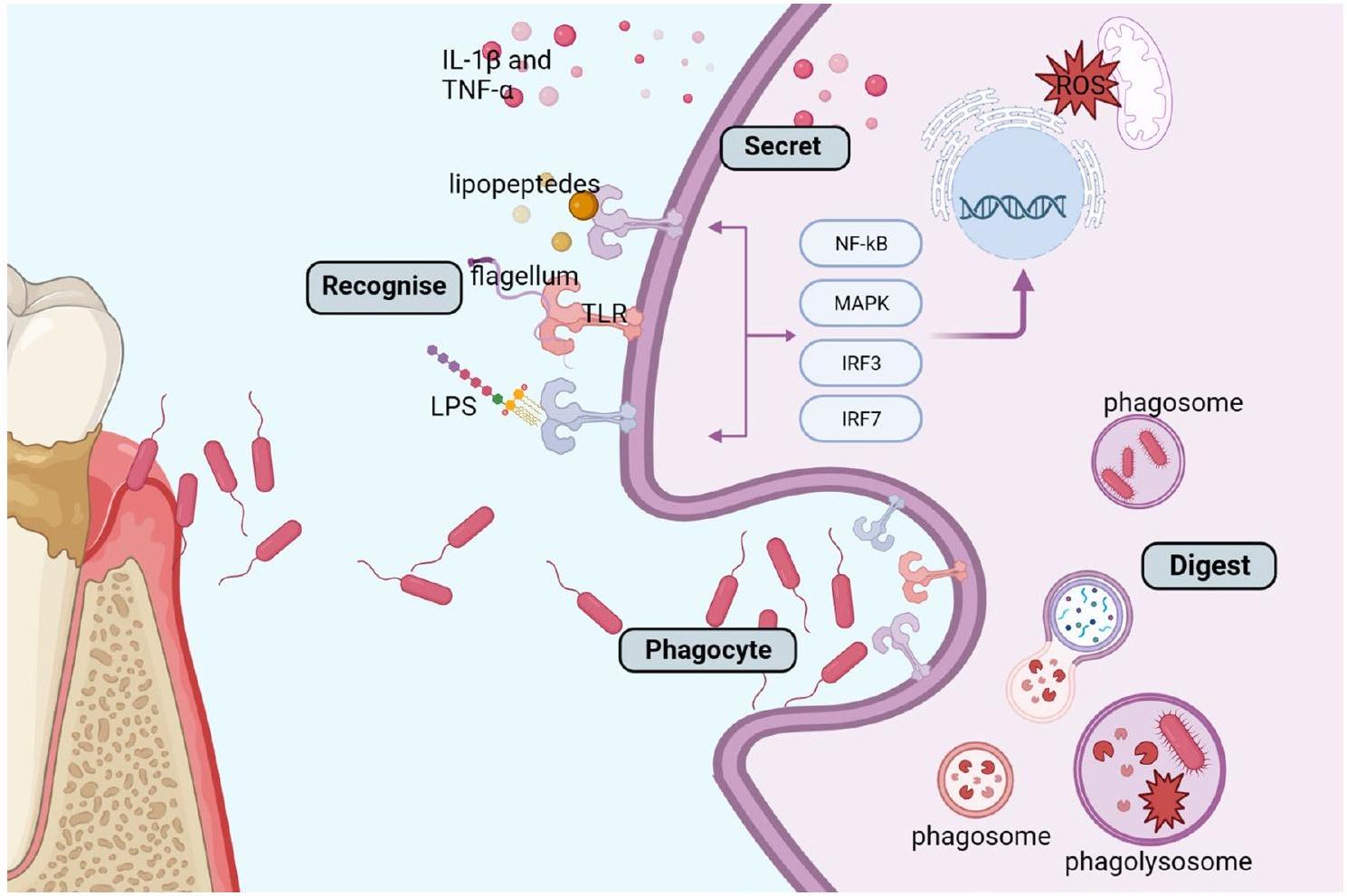

Activated macrophages play a role in the release of inflammatory mediators, bacterial clearance, and the destruction and repair of periodontal tissue in periodontal tissues which release a range of effector molecules at different stages of periodontitis, including growth factors, various enzymes, pro-inflammatory cytokines (like prostaglandin E2, TNF

Macrophages not only release inflammatory mediators that contribute to the pathological process of

periodontitis, but they also play a role in eliminating periodontal infections (Fig. 3).

Periodontal repair and regeneration

– Promoting tissue repair

– Remodeling extracellular matrix

Progressive periodontitis

One of the crucial macrophage bactericidal mechanisms is ROS. Exogenous and endogenous generation of periodontal ROS are distinguished. Bacteria, photodynamics, metal ions, and nanomedicines are illustrations for exogenous influences. Immune cell activation in inflammatory and aging circumstances is related to endogenous ROS generation in cells [71]. Many immune cells, including macrophages, engage in the antimicrobial process by producing a significant quantity of ROS via the mitochondrial respiratory chain and NADPH oxidase [72-74]. ROS participates in indirect antimicrobial activity by transferring immunological signals while directly killing bacteria by damaging their cell membranes, DNA, and proteins. Given the importance of reactive oxygen species in the antimicrobial activity of macrophages, increasing the antimicrobial properties of periodontal biomaterials by modulating the release of reactive oxygen species from macrophages has become a focus of interest for researchers (Fig. 4).

Macrophages also indirectly cause the destruction of periodontal bone by regulating osteoclasts. Bone loss is one of the main symptoms of periodontitis. Bone loss brought on by inflammation is one of the main signs of periodontitis. The only cells in the body that can absorb bone are osteoclasts. Osteoclast precursors are stimulated by the macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) and the NF-kB ligand (RANKL) to develop into mature osteoclasts which lead to bone resorption. Exogenous PAMPs, such as bacterial cleavage-released LPS, cause macrophages to form M1 and release a significant number of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-8, IL-12, IL-23, TNF-

activated T cells cytoplasmic 1 (NFATc1) can be downregulated by TGF-

Biomaterials regulate macrophage polarization

immunological reactions, and periodontal tissue itself exhibits a spectrum of inflammatory reactions as periodontitis develops. A mild immune response encourages tissue regeneration and wound healing, whereas a dysregulated immune system can prevent implant tissue resorption, fibrous capsule creation, and repair [113]. Traditional tissue engineering techniques are a passive response that aim to lessen the immune system’s response. As tissue engineering advances, more and more researchers are assuming the initiative and using well-designed biomaterials to control various critical immune system components and produce an immunological environment supportive of tissue regeneration. The design of biomaterials that regulate the polarization state of macrophages has become a new way to treat periodontitis (Table 2 Fig. 5).

Strategies of ceramic materials to regulate macrophage polarization

charge, functionalized groups and wettability) and the incorporation of bioactive substances (cytokines, growth factors and metal ions) [116].

The surface properties of ceramic materials affect the polarization of macrophages

while researching how hydrophilicity of ceramic materials affects macrophage polarization (Tables 1, 2).

of ROS compared to HAS. In addition, the reduction of IL-6 contributed to the downregulation of miR-214 and subsequent upregulation of the p38/JNK pathway, which may contribute to the osteogenesis promotion of HAS-G.

Bioactive molecules incorporated into ceramic materials affect macrophage polarization

it also affects macrophage polarization in periodontal tissue.

| Effector molecules | Macrophage phenotype of origin | Function | References |

| IL-6 | M1 | 1. IL-6 causes tissue destruction by increasing matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) in periodontal tissue. 2. IL-6 induces osteoblast differentiation of periodontal ligament cells. 3. Specific inhibition of the IL-6 receptor attenuates inflammatory bone loss in experimental periodontitis | [47-49] |

| MMP-13 | M1 | Promotes periodontal bone loss | [50] |

| TNF-a | M1 | 1. Promote the recruitment of white blood cells to the site of inflammation. 2. Upregulate the production of IL-1

|

[51-54] |

| IL-1

|

M1 | Causes tissue destruction by increasing MMP-1 in periodontal tissue | [47] |

| IFN-

|

M1 | Promotes alveolar bone loss and osteoclast differentiation | [55] |

| IL-12 | M1 | 1. Increase apoptosis of osteoclasts. 2. Up-regulate the expression of IFN-

|

[56] |

| IL-10 | M2 | 1. Inhibits IL-6 production in human gingival fibroblasts stimulated by P.g.-LPS. 2. Inhibits bone resorption.3. IL-10 knockout mice downregulate the expression of osteoblasts and osteocyte markers in periodontal tissue | [57-59] |

| TGF-

|

M2 | 1. TGF

|

[60-63] |

| IL-22 | M2 | Inhibits apoptosis of gingival epithelial cells during periodontitis | [64] |

the bones, however, has received comparatively little research. Zhang et al. [93] produced a strontium-doped submicron bioactive glass (Sr-SBG) to examine the interaction between strontium and the host immune response from the standpoint of macrophage polarization in order to more thoroughly investigate the role of strontium in biomaterial-mediated osteogenesis. According to the findings, Sr-SBG was able to boost CD206 M2 macrophage proportions while decreasing CD11c M1 macrophage proportions. The release of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-1 was considerably enhanced in the Sr-SBG group compared to the SBG group, and the genes BMP2 and osteo-genesis-related genes in macrophages were relatively elevated. Sr-SBG macrophage conditioned medium significantly increased the osteogenic activity compared to the group lacking Sr. Ceramics that include Sr are promising options for modifying the immunological environment of the periodontal tissue to encourage regeneration. In addition to metallic substances, plantderived drugs can also affect macrophage polarization.

| Material | Characteristic | Research Progress | Reference | ||

| Ceramics | Physical characteristics | Hydrophilicity | Hydrophilic ceramic materials promote macrophage polarization to M2 | [87] | |

| Geometry | In structures including rounded protrusions with nanoneedles on the surface, macrophages exhibit a considerable decrease in pro-inflammatory genes (iNOS, TNF-a, and CCR7) in comparison to the smooth plane. Out of the five struc-tures-planar, nanoneedle surface,

|

[88] | |||

| Compared with the common porous hydroxyapatite scaffold, the porous hydroxyapatite scaffold with

|

[89] | ||||

| Roughness | In micro-nano structures, the percentage of M1 macrophages increases with increasing roughness. More M2 macrophages are present in areas with reduced roughness | [90] | |||

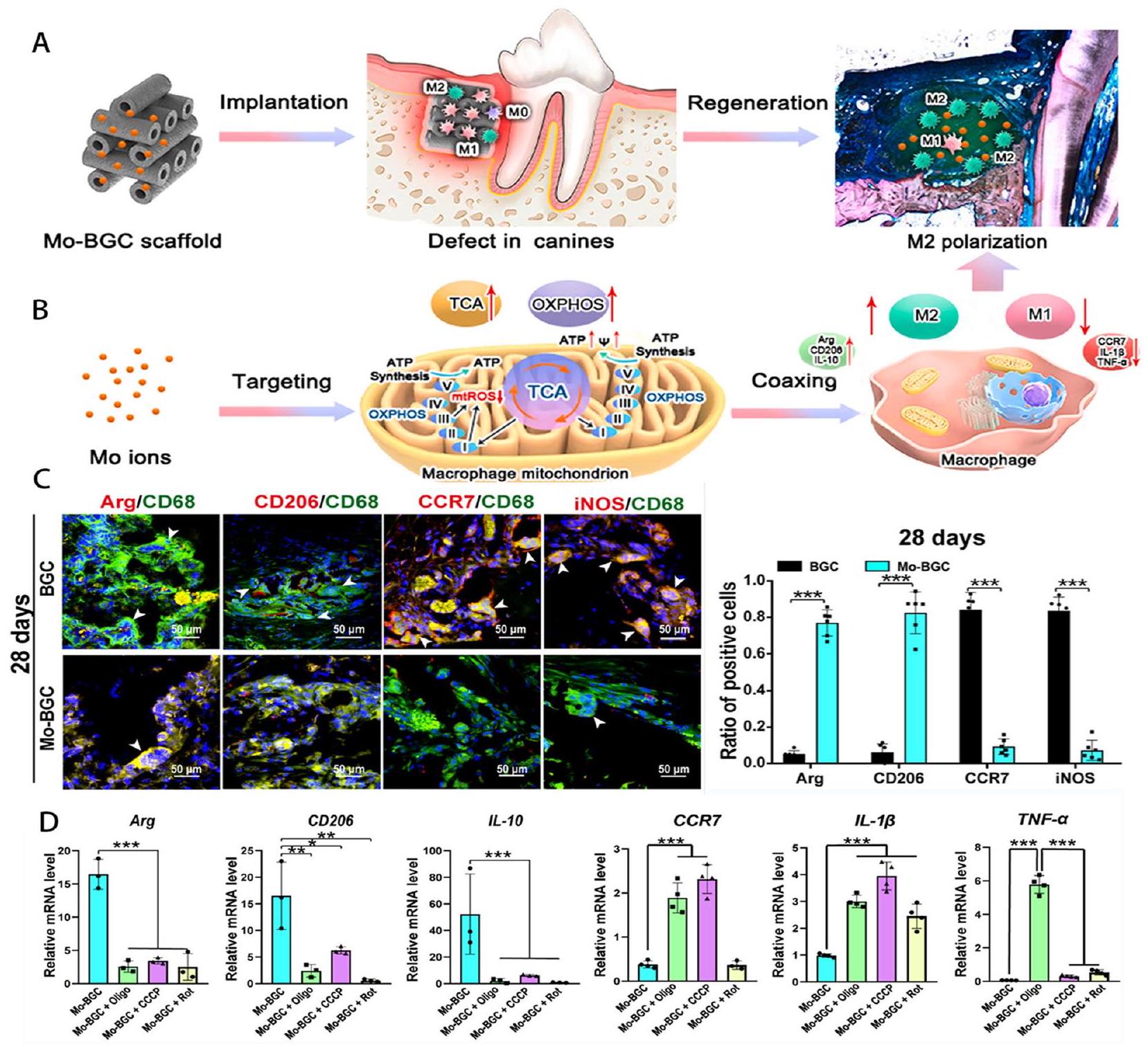

| Bioactive factors | Ceramic materials | In the three groups of ceramic materials with identical structuresHA, BCP, and

|

[91] | ||

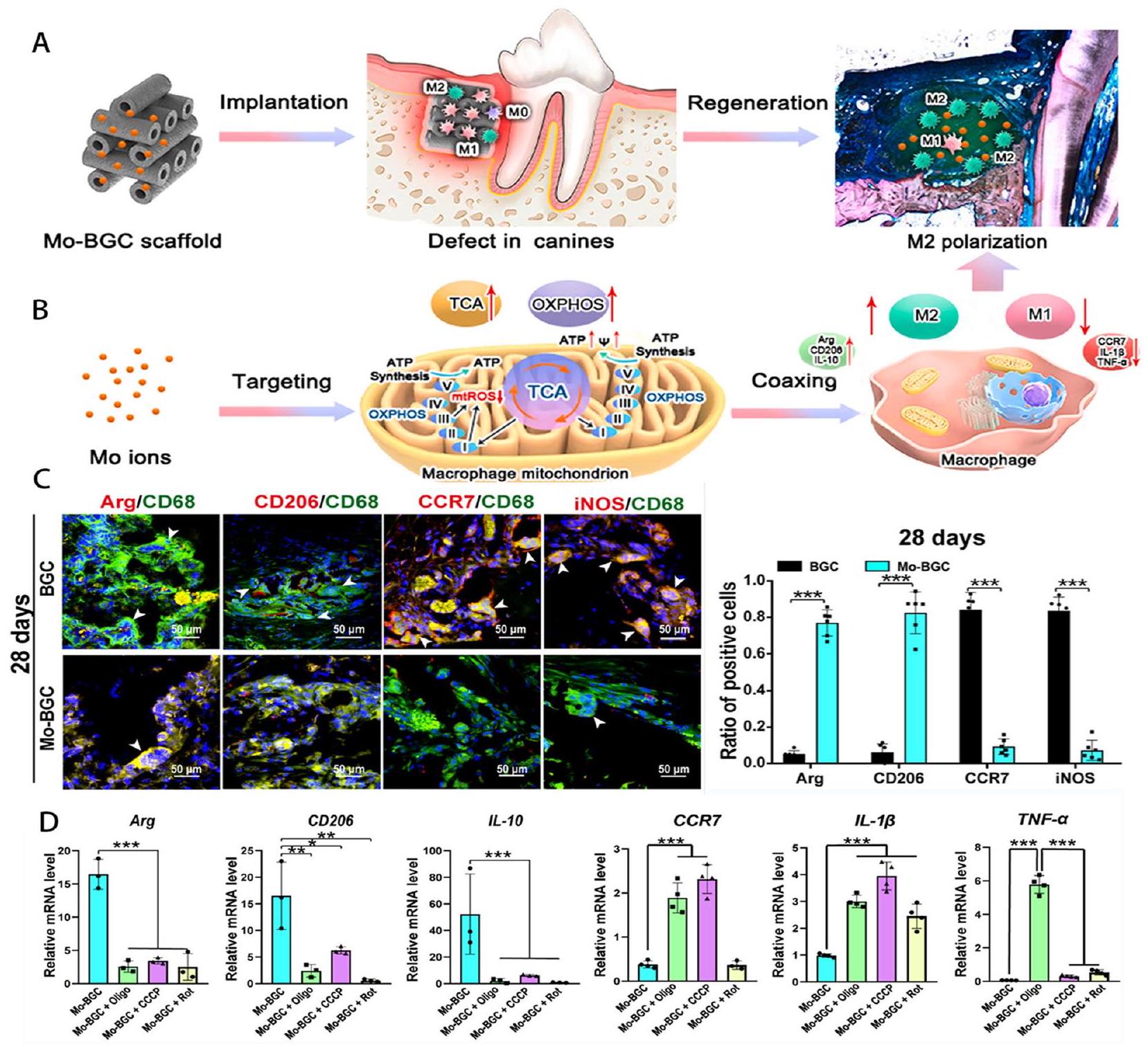

| Incorporating bioactive factors | Metallic particles | Molybdenum-containing bioactive glass-ceramic (Mo-BGC) scaffolds induce M2 polarization by enhancing mitochondrial function in macrophages | [92] |

| Material | Characteristic | Research Progress | Reference | ||

| Macrophages treated with strontium-doped submicron bioactive glass (Sr-SBG) release a notably higher amount of the antiinflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-1 | [93] | ||||

| Plant-derived active ingredients | A new type of granular ceramic material doped with polyphenols from pomace extract decreased the expression of genes linked to inflammation in macrophages | [94] | |||

| Polymer | Hydrogel | Physical characteristics | Rigidity | When macrophages are cultivated on more rigid substrates, they proliferate more widely and express more inflammatory mediators | [95] |

| Incorporating bioactive factors | Cytokines | Macrophage M2 polarization can be aided by physically cross-linked DNA hydrogels that have the capacity to distribute IL-10 for extended periods of time | [96] | ||

| Transglutaminase crosslinked gelatin (TG gel) with high hardness can be used to promote M2 polarization of macrophages instead of M1 polarization after being doped with IL-4 and SDF-1a | [97] | ||||

| Exosomes | Chitosan hydrogel infused with dental pulp stem cell exosomes (DPSC-Exo/ CS) can cause periodontal tissue macrophages to produce more of the antiinflammatory marker CD206 and less of the pro-inflammatory marker CD86 | [98] | |||

| Deliveries of LPS-pretreated dental follicle stem cell exosomes, as opposed to those without treatment, have the ability to induce M2 macrophage polarization through hydrogel delivery | [99] | ||||

| Plant-derived Active ingredients | Hydrogels laden with Caffeic acid phenethyl ester lessen the production of inflammatory mediators ((TNF-a, IL-1

|

[100] | |||

| Fiber polymers | Physical characteristics | Geometry | In the fibrous scaffolds formed by molten electrographing, randomly oriented fiber scaffolds induce macrophage polarization towards M1, and highly ordered fiber scaffolds induce macrophage polarization towards M2 | [101] | |

| Material | Characteristic | Research Progress | Reference | ||

| Incorporating bioactive factors | Drugs | The anti-inflammatory drug ketoprofen can be delivered via a composite nanofiber scaffold that dramatically reduced MMP-9 and MMP-3 and increased IL-10 expression in macrophages | [102] | ||

| Dimethyloxaloylglycine (DMOG) and nanosilicate (nSi) loaded electrospun fiber membranes regulated the transition of macrophage phenotype to M2 | [103] | ||||

| Cytokines | The core/shell fiber framework, which is made up of polymer fibers with varying rates of degradation, supports the M1/M2 transformation of macrophages by sequentially releasing basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and BMP-2, upregulating CD206 expression in macrophages, and downregulating iNOS production | [104] | |||

| Microspheres | Cytokines | Dextran/PLGA microspheres coated with IL-1 ra efficiently inhibit macrophages’ generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines | [105] | ||

| Nanoparticles | Metal nanoparticles | Au | 45 nm AuNPs have the ability to stimulate M2-polarized macrophages | [106] | |

| Ag | AgNPs coupled to two medications (metronidazole and chlorhexidine) were able to reduce the expression levels of the cytokines

|

[107] | |||

| The cytokine generation of TNF-a, IL-6, and IL-1 was suppressed by the AgNPfunctionalized 3D porous hybrid biomaterials | [108] | ||||

| Polymer nanoparticles | Polydopamine nanoparticles (PDA-NPs) can enable the conversion of macrophages to M2 | [109] | |||

| Nanocomposites |

|

[110] | |||

| Material | Characteristic | Research Progress | Reference |

| Dendritic | PAMAM-G5 dendrim macromolecules can target macrophage binding and regulate macrophage phenotypes | [111] | |

| Drug-loaded nanomaterials | The green tea-like polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) forms nanoparticles (NPs) that stimulate the M1/M2 polarity change in macrophages | [112] |

Strategies of polymer regulation of macrophage polarization

Strategies of hydrogel regulates the polarization of macrophages