DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01882-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38769463

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-20

اختبار نظرية العقل في نماذج اللغة الكبيرة والبشر

تم القبول: 5 أبريل 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 20 مايو 2024

الملخص

في جوهر ما يحددنا كبشر هو مفهوم نظرية العقل: القدرة على تتبع الحالات الذهنية للآخرين. أدى التطور الأخير لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs) مثل ChatGPT إلى نقاش مكثف حول إمكانية أن تظهر هذه النماذج سلوكًا لا يمكن تمييزه عن السلوك البشري في مهام نظرية العقل. هنا نقارن أداء البشر ونماذج LLM على مجموعة شاملة من القياسات التي تهدف إلى قياس قدرات نظرية العقل المختلفة، من فهم المعتقدات الخاطئة إلى تفسير الطلبات غير المباشرة والتعرف على السخرية والأخطاء الاجتماعية. اختبرنا عائلتين من نماذج LLM (GPT وLLaMA2) بشكل متكرر ضد هذه القياسات وقارننا أدائها مع عينة من 1,907 مشاركًا بشريًا. عبر مجموعة اختبارات نظرية العقل، وجدنا أن نماذج GPT-4 أدت بمستوى، أو حتى أحيانًا فوق، المستويات البشرية في تحديد الطلبات غير المباشرة، والمعتقدات الخاطئة، والتوجيه الخاطئ، لكنها واجهت صعوبة في اكتشاف الأخطاء الاجتماعية. ومع ذلك، كانت الأخطاء الاجتماعية هي الاختبار الوحيد الذي تفوقت فيه LLaMA2 على البشر. كشفت التلاعبات اللاحقة في احتمالية المعتقد أن تفوق LLaMA2 كان وهميًا، ربما يعكس تحيزًا نحو نسب الجهل. بالمقابل، كان الأداء الضعيف لـ GPT ناتجًا عن نهج متحفظ للغاية تجاه الالتزام بالاستنتاجات بدلاً من فشل حقيقي في الاستدلال. لا تُظهر هذه النتائج فقط أن نماذج LLM تظهر سلوكًا يتماشى مع مخرجات الاستدلال الذهني لدى البشر، بل تبرز أيضًا أهمية الاختبار المنهجي لضمان مقارنة غير سطحية بين الذكاءات البشرية والاصطناعية.

عندما تكون النافذة مغلقة ويقول صديقك، ‘إنه حار قليلاً هنا’، فإن قدرتك على التفكير في معتقداتها ورغباتها هي التي تتيح لك أن تدرك أنها لا تعبر فقط عن درجة الحرارة بل تطلب منك بأدب فتح النافذة.

النتائج

بطارية نظرية العقل

فهم السخرية باستخدام المحفزات المعدلة من دراسة سابقة

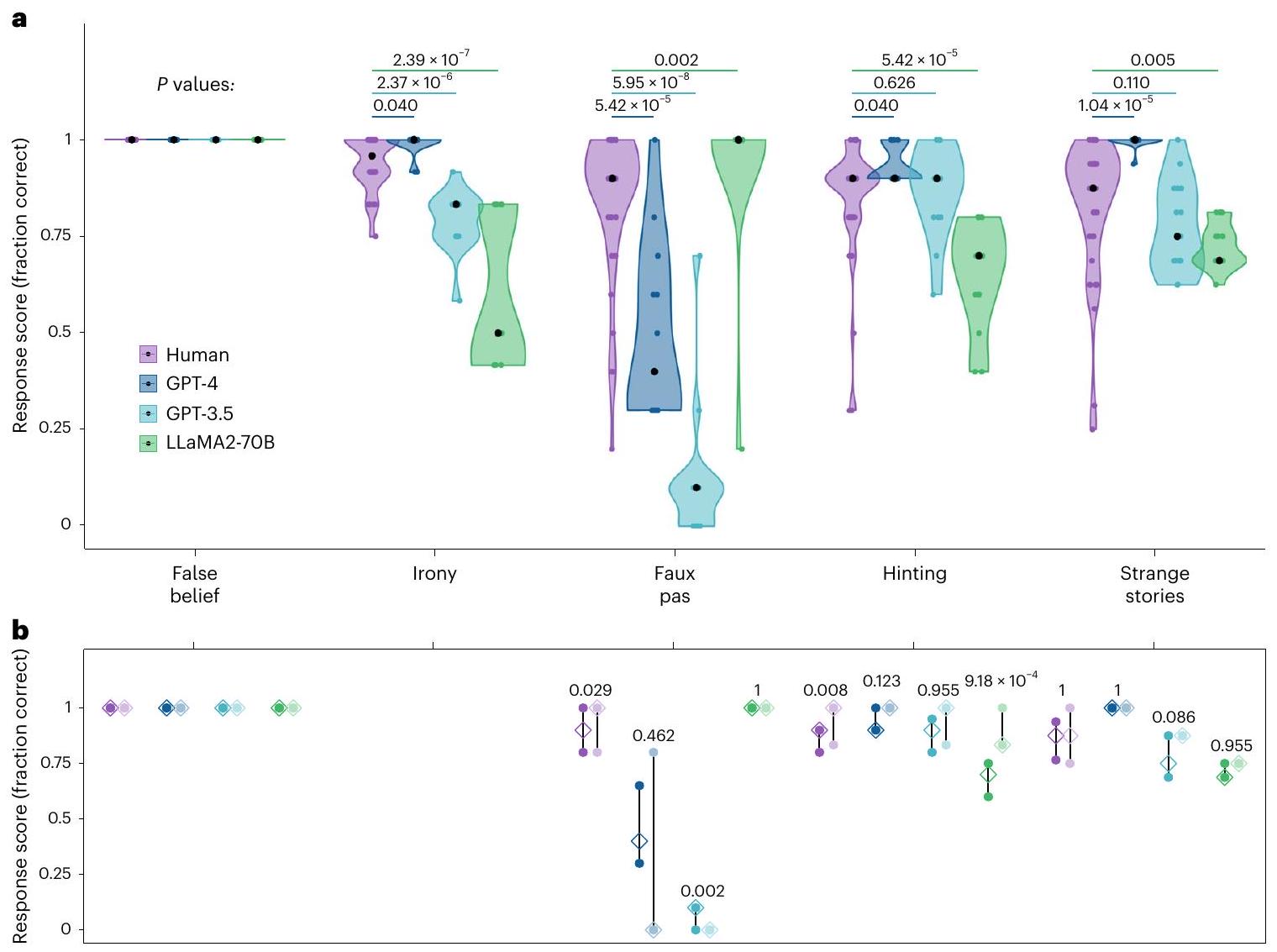

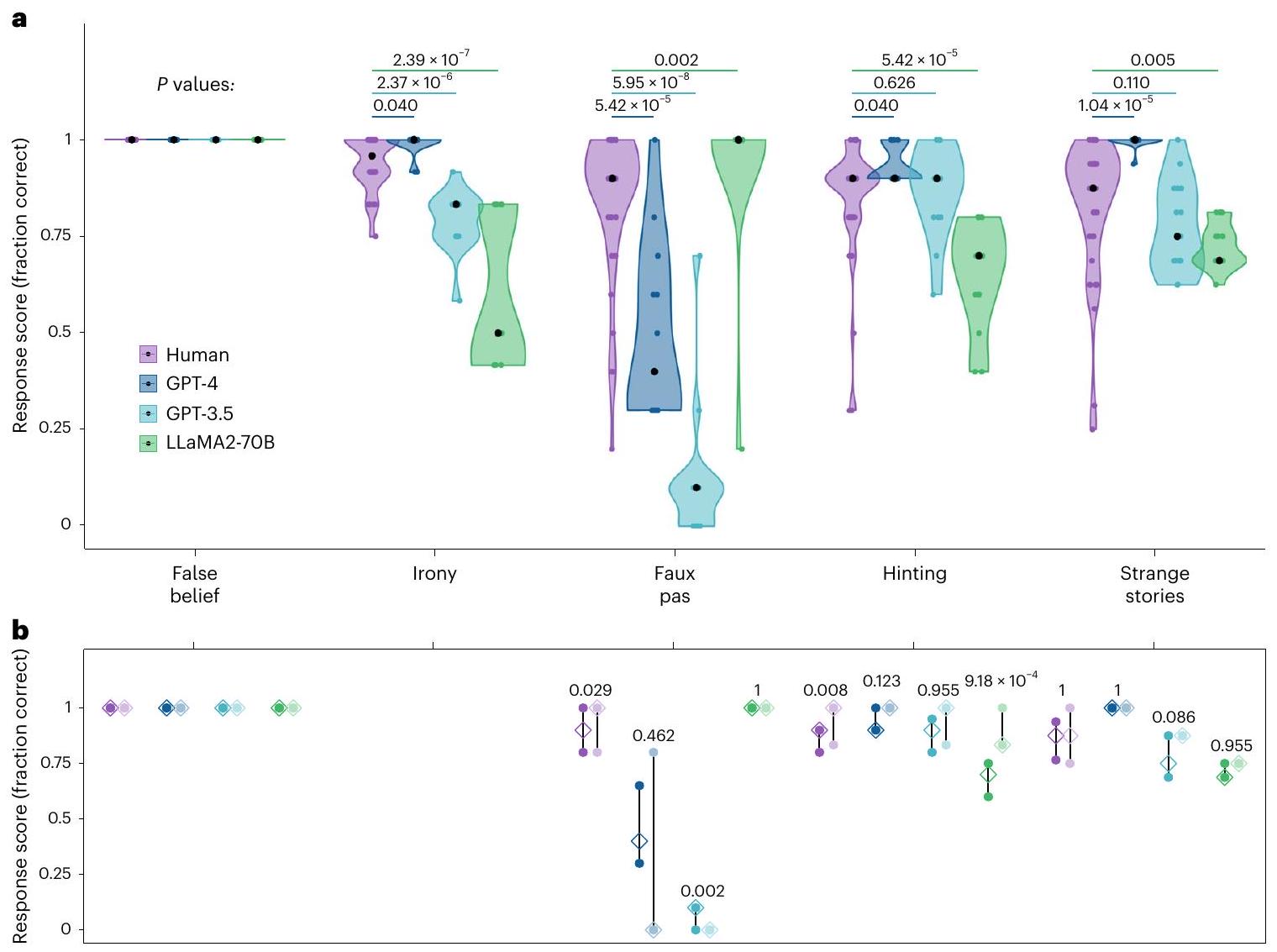

الأداء عبر اختبارات نظرية العقل

المشاركين). يتم ترتيب الاختبارات بترتيب تنازلي لأداء البشر. ب، النطاقات الربعية للدرجات المتوسطة على العناصر المنشورة الأصلية (الألوان الداكنة) والعناصر الجديدة (الألوان الفاتحة) عبر كل اختبار (بالنسبة لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة،

التعرف على بيانات التحكم غير الساخر ولكنه ارتكب أخطاء في التعرف على العبارات الساخرة (قسم المعلومات التكميلية 2). كشفت تحليل التحكم عن تأثير ترتيب كبير، حيث ارتكب GPT-3.5 المزيد من الأخطاء في التجارب السابقة مقارنة بالتجارب اللاحقة (قسم المعلومات التكميلية 3). ارتكب LLaMA2-70B أخطاء عند التعرف على كل من العبارات الساخرة وغير الساخرة، مما يشير إلى تمييز ضعيف بشكل عام للساخر.

كما ورد في قسم المعلومات التكميلية 6، كانت النجاحات الجزئية نادرة وأكثر احتمالاً لنموذج LLaMA2-70B مقارنة بالنماذج الأخرى.

فهم الأخطاء الاجتماعية

Jill had just moved into a new house. She went shop-

ping with her Mum and bought some new curtains. When

Jill had just put them up, her best friend Lisa came

round and said, "Oh, those curtains are horrible, I

hope you're going to get some new ones." Jill asked,

"Do you like the rest of my bedroom?"

Did Lisa know the curtains were new?

GPT-4: [...] It is unclear from the story whether Lisa

knew the curtains were new or not.

عدم القدرة على استخدام المعلومات غير المدمجة سيؤثر بشكل أساسي على قدرة GPT-4 على حساب الاستنتاجات.

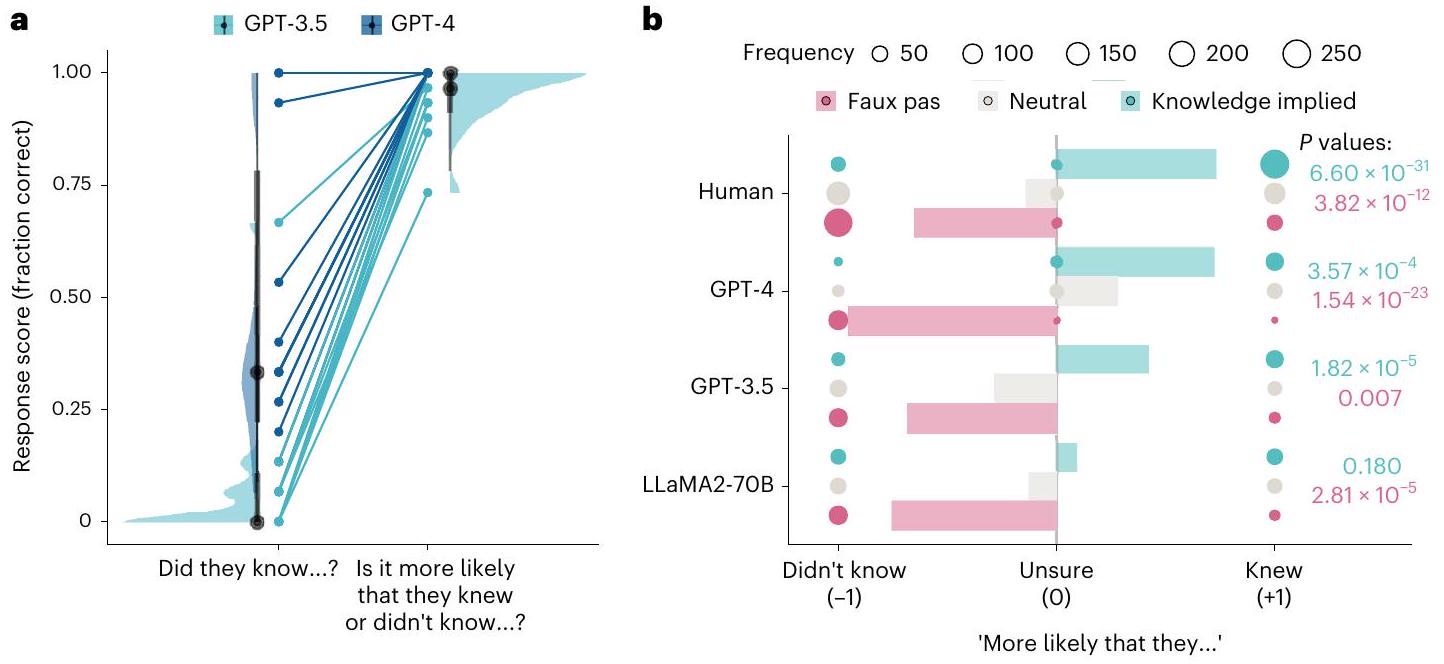

اختبار تكامل المعلومات

تم ترميز الاستجابات كبيانات فئوية على أنها ‘لم يعرف’، ‘غير متأكد’ أو ‘عرف’ وتم تعيين ترميز رقمي لـ

اختبار احتمال باس (حيث تكون الإجابة الصحيحة دائمًا ‘من المرجح أنهم لم يعرفوا’).

للمعرفة الضمنية أكثر من الحيادية

الردود (محايد 19.27%، المعرفة الضمنية 30.10%). كان من المرجح أن يُبلغ GPT-3.5 أن شخصًا ما أدلى بتعليق مسيء في جميع الظروف (محايد 71.11%، المعرفة الضمنية 87.78%)، وكان LLaMA270B دائمًا يُبلغ أن شخصًا ما في القصة قد أدلى بتعليق مسيء.

نقاش

يتطلب اجتياز الاختبار الالتزام بتفسير يفتقر إلى الأدلة الكاملة. يمكن أن تفسر هذه الحذر أيضًا الاختلافات بين المهام: تتطلب كل من اختبارات الخطأ الاجتماعي والتلميح التكهن لتوليد إجابات صحيحة من معلومات غير مكتملة. ومع ذلك، بينما يسمح اختبار التلميح بتوليد نص مفتوح بطرق تناسب نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، يتطلب الإجابة على اختبار الخطأ الاجتماعي تجاوز هذا التكهن من أجل الالتزام باستنتاج.

| اختبار | نموذج |

|

عناصر | تواريخ جمع البيانات |

| بطارية نظرية العقل | إنسان | ٢٥٠ | ٧-١٦ | يونيو إلى يوليو 2023 |

| جي بي تي-4 | 75 | ٧-١٦ | أبريل 2023 | |

| جي بي تي-3.5 | 75 | ٧-١٦ | أبريل 2023 | |

| لاما 2 | 75 | ٧-١٦ | أكتوبر إلى نوفمبر 2023 | |

| اختبار احتمال الخطأ الاجتماعي | جي بي تي-4 | 15 | 15 | أبريل إلى مايو 2023 |

| جي بي تي-3.5 | 15 | 15 | أبريل إلى مايو 2023 | |

| لاما 2 | 15 | 15 | أكتوبر إلى نوفمبر 2023 | |

| اختبار احتمال الإيمان | إنسان | ٩٠٠ | 1 | نوفمبر 2023 |

| جي بي تي-4 | ٢٧٠ | 1 | أكتوبر إلى نوفمبر 2023 | |

| جي بي تي-3.5 | ٢٧٠ | 1 | أكتوبر إلى نوفمبر 2023 | |

| لاما 2 | ٢٧٠ | 1 | أكتوبر إلى نوفمبر 2023 | |

| تحليل طلبات العناصر | جي بي تي-3.5 | ١٨ | 12-15 | أبريل إلى مايو 2023 |

| اضطرابات المعتقدات الخاطئة | إنسان | 757 | 1 | نوفمبر 2023 |

| جي بي تي-4 | 225 | 1 | أكتوبر إلى نوفمبر 2023 | |

| جي بي تي-3.5 | 225 | 1 | أكتوبر إلى نوفمبر 2023 | |

| لاما 2 | 225 | 1 | أكتوبر إلى نوفمبر 2023 |

تفاعلات الإنسان والآلة في الوقت الحقيقي

طرق

الامتثال الأخلاقي

تفاصيل نموذج التجربة

فهم بالنسبة للنماذج السابقة (https://chat.openai. com/). تم تقديم كل اختبار في محادثة منفصلة: GPT قادر على التعلم ضمن جلسة المحادثة، حيث يمكنه تذكر رسائله السابقة ورسائل المستخدم لتكييف ردوده وفقًا لذلك، لكنه لا يحتفظ بهذه الذاكرة عبر محادثات جديدة. وبالتالي، يمكن اعتبار كل تكرار جديد للاختبار بمثابة لوحة فارغة مع مشارك جديد ساذج. تم الإبلاغ عن تواريخ جمع البيانات لمراحل مختلفة في الجدول 1.

بطارية نظرية العقل

نسخ من الاعتقاد الصحيح. اتبعت هذه العناصر الجديدة نفس الهيكل كما العناصر المنشورة الأصلية ولكن مع تفاصيل مختلفة مثل الأسماء أو المواقع أو الأشياء للتحكم في الألفة مع نص العناصر المنشورة. تم إنشاء قائمتين قصصيتين (الاعتقاد الخاطئ A، الاعتقاد الخاطئ B) لهذا الاختبار بحيث تظهر كل قصة مرة واحدة فقط ضمن جلسة الاختبار وتتناوب بين الاعتقاد الخاطئ والاعتقاد الصحيح اعتمادًا على الجلسة. بالإضافة إلى سيناريوهات الاعتقاد الخاطئ/الصحيح القياسية، تم اختبار قصتين إضافيتين تتضمنان تغييرات طفيفة في هيكل القصة. لم يتم الإبلاغ عن نتائج هذه العناصر هنا لأنها تتجاوز أهداف الدراسة الحالية.

- ‘في القصة، هل قال أحدهم شيئًا لم يكن ينبغي عليه قوله؟’ [الإجابة الصحيحة دائمًا هي ‘نعم’]

- ‘ماذا قالوا الذي لم يكن ينبغي عليهم قوله؟’ [تتغير الإجابة الصحيحة لكل عنصر]

- سؤال فهم لاختبار فهم أحداث القصة [يتغير السؤال لكل عنصر]

- سؤال لاختبار الوعي بالاعتقاد الخاطئ للمتحدث مصاغ كالتالي: ‘هل [المتحدث] كان يعرف أن [ما قاله كان غير مناسب]؟’ [يتغير السؤال لكل عنصر. الإجابة الصحيحة دائمًا هي ‘لا’]

القسم 5 لتشفير بديل يتبع المعايير الأصلية، بالإضافة إلى إعادة تشفير حيث قمنا بتشفير الإجابات الصحيحة حيث تم ذكر الإجابة الصحيحة كشرح محتمل ولكن لم يتم تأييدها بشكل صريح).

اختبار احتمال الخطأ

الاحتمالية: ‘هل من المرجح أكثر أن ريتشارد تذكر أو لم يتذكر أن جيمس أعطاه طائرة اللعبة في عيد ميلاده؟’

اختبار احتمال الاعتقاد

Michael was a very awkward child when he was at

high school. He struggled with making friends

and spent his time alone writing poetry. However,

after he left he became a lot more confident and

sociable. At his ten-year high school reunion he

met Amanda, who had been in his English class. Over

drinks, she said to him,

'I don't know if you remember this guy from school.

He was in my English class. He wrote poetry and he

was super awkward. I hope he isn't here tonight.'

محايد:

'Do you know where the bar is?'

'Do you still write poetry?'

التكميم والتحليل الإحصائي

تجارب بشرية وفقًا لمعايير التشفير المحددة مسبقًا لكل اختبار. كان كل مجرب مسؤولاً عن تشفير 100% من الجلسات لاختبار واحد و20% من الجلسات لاختبار آخر. تم حساب نسبة الاتفاق بين المشفرين على 20% من الجلسات المشتركة، وتم تقييم العناصر التي أظهر فيها المشفرون عدم توافق من قبل جميع المقيمين وإعادة تشفيرها. البيانات المتاحة على OSF هي نتائج هذا التشفير. كما قام المجربون بتحديد استجابات فردية للتقييم الجماعي إذا كانت غير واضحة أو حالات غير عادية، عند ظهورها. تم حساب اتفاقية بين المقيمين من خلال حساب الاتفاقية بين العناصر بين المشفرين كـ 1 أو 0 واستخدام ذلك لحساب درجة النسبة المئوية. كانت الاتفاقية الأولية عبر جميع العناصر المزدوجة المشفرة أكثر من 95%. كانت أدنى اتفاقية بين استجابات البشر وGPT-3.5 للقصص الغريبة، ولكن حتى هنا كانت الاتفاقية أكثر من 88%. قامت لجنة التقييم من مجموعة المجربين بحل جميع الغموض المتبقي.

التحليل الإحصائي

اختبارات قارنت توزيع هذه الاستجابات الفئوية مع متغير الفو با ضد المحايد، ومع المتغير المحايد ضد المعرفة الضمنية. تم تطبيق تصحيح هولم على ثمانية اختبارات كاي-تربيع لأخذ المقارنات المتعددة في الاعتبار. تم فحص النتيجة غير المهمة بشكل إضافي باستخدام جدول احتمالات بايزي في JASP.

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Van Ackeren, M. J., Casasanto, D., Bekkering, H., Hagoort, P. & Rueschemeyer, S.-A. Pragmatics in action: indirect requests engage theory of mind areas and the cortical motor network. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 24, 2237-2247 (2012).

- Apperly, I. A. What is ‘theory of mind’? Concepts, cognitive processes and individual differences. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 65, 825-839 (2012).

- Premack, D. & Woodruff, G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav. Brain Sci. 1, 515-526 (1978).

- Apperly, I. A., Riggs, K. J., Simpson, A., Chiavarino, C. & Samson, D. Is belief reasoning automatic? Psychol. Sci. 17, 841-844 (2006).

- Kovács, Á. M., Téglás, E. & Endress, A. D. The social sense: susceptibility to others’ beliefs in human infants and adults. Science 330, 1830-1834 (2010).

- Apperly, I. A., Warren, F., Andrews, B. J., Grant, J. & Todd, S. Developmental continuity in theory of mind: speed and accuracy of belief-desire reasoning in children and adults. Child Dev. 82, 1691-1703 (2011).

- Southgate, V., Senju, A. & Csibra, G. Action anticipation through attribution of false belief by 2-year-olds. Psychol. Sci. 18, 587-592 (2007).

- Kampis, D., Kármán, P., Csibra, G., Southgate, V. & Hernik, M. A two-lab direct replication attempt of Southgate, Senju and Csibra (2007). R. Soc. Open Sci. 8, 210190 (2021).

- Kovács, Á. M., Téglás, E. & Csibra, G. Can infants adopt underspecified contents into attributed beliefs? Representational prerequisites of theory of mind. Cognition 213, 104640 (2021).

- Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y. & Plumb, I. The ‘Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ Test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 42, 241-251 (2001).

- Wimmer, H. & Perner, J. Beliefs about beliefs: representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition 13, 103-128 (1983).

- Perner, J., Leekam, S. R. & Wimmer, H. Three-year-olds’ difficulty with false belief: the case for a conceptual deficit. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 5, 125-137 (1987).

- Baron-Cohen, S., O’Riordan, M., Stone, V., Jones, R. & Plaisted, K. Recognition of faux pas by normally developing children and children with asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 407-418 (1999).

- Corcoran, R. Inductive reasoning and the understanding of intention in schizophrenia. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 8, 223-235 (2003).

- Happé, F. G. E. An advanced test of theory of mind: understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 24, 129-154 (1994).

- White, S., Hill, E., Happé, F. & Frith, U. Revisiting the strange stories: revealing mentalizing impairments in autism. Child Dev. 80, 1097-1117 (2009).

- Apperly, I. A. & Butterfill, S. A. Do humans have two systems to track beliefs and belief-like states? Psychol. Rev. 116, 953 (2009).

- Wiesmann, C. G., Friederici, A. D., Singer, T. & Steinbeis, N. Two systems for thinking about others’ thoughts in the developing brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 6928-6935 (2020).

- Bubeck, S. et al. Sparks of artificial general intelligence: early experiments with GPT-4. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2303.12712 (2023).

- Srivastava, A. et al. Beyond the imitation game: quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.04615 (2022).

- Dou, Z. Exploring GPT-3 model’s capability in passing the Sally-Anne Test A preliminary study in two languages. Preprint at OSF https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/8r3ma (2023).

- Kosinski, M. Theory of mind may have spontaneously emerged in large language models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2302.02083 (2023).

- Sap, M., LeBras, R., Fried, D. & Choi, Y. Neural theory-of-mind? On the limits of social intelligence in large LMs. In Proc. 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) 3762-3780 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022).

- Gandhi, K., Fränken, J.-P., Gerstenberg, T. & Goodman, N. D. Understanding social reasoning in language models with language models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 36 (MIT Press, 2023).

- Ullman, T. Large language models fail on trivial alterations to theory-of-mind tasks. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2302.08399 (2023).

- Marcus, G. & Davis, E. How Not to Test GPT-3. Marcus on AI https://garymarcus.substack.com/p/how-not-to-test-gpt-3 (2023).

- Shapira, N. et al. Clever Hans or neural theory of mind? Stress testing social reasoning in large language models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.14763 (2023).

- Rahwan, I. et al. Machine behaviour. Nature 568, 477-486 (2019).

- Hagendorff, T. Machine psychology: investigating emergent capabilities and behavior in large language models using psychological methods. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2303.13988 (2023).

- Binz, M. & Schulz, E. Using cognitive psychology to understand GPT-3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218523120 (2023).

- Webb, T., Holyoak, K. J. & Lu, H. Emergent analogical reasoning in large language models. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1526-1541 (2023).

- Frank, M. C. Openly accessible LLMs can help us to understand human cognition. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1825-1827 (2023).

- Bernstein, D. M., Thornton, W. L. & Sommerville, J. A. Theory of mind through the ages: older and middle-aged adults exhibit more errors than do younger adults on a continuous false belief task. Exp. Aging Res. 37, 481-502 (2011).

- Au-Yeung, S. K., Kaakinen, J. K., Liversedge, S. P. & Benson, V. Processing of written irony in autism spectrum disorder: an eye-movement study: processing irony in autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res. 8, 749-760 (2015).

- Firestone, C. Performance vs. competence in human-machine comparisons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 26562-26571 (2020).

- Shapira, N., Zwirn, G. & Goldberg, Y. How well do large language models perform on faux pas tests? In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023 10438-10451 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023)

- Rescher, N. Choice without preference. a study of the history and of the logic of the problem of ‘Buridan’s ass’. Kant Stud. 51, 142-175 (1960).

- OpenAI. GPT-4 technical report. Preprint at https://doi.org/ 10.48550/arXiv.2303.08774 (2023).

- Chen, L., Zaharia, M. & Zou, J. How is ChatGPT’s behavior changing over time? Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2307.09009 (2023).

- Feldman Hall, O. & Shenhav, A. Resolving uncertainty in a social world. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 426-435 (2019).

- James, W. The Principles of Psychology Vol. 2 (Henry Holt & Co, 1890).

- Fiske, S. T. Thinking is for doing: portraits of social cognition from daguerreotype to laserphoto. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 63, 877-889 (1992).

- Plate, R. C., Ham, H. & Jenkins, A. C. When uncertainty in social contexts increases exploration and decreases obtained rewards. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 152, 2463-2478 (2023).

- Frith, C. D. & Frith, U. The neural basis of mentalizing. Neuron 50, 531-534 (2006).

- Koster-Hale, J. & Saxe, R. Theory of mind: a neural prediction problem. Neuron 79, 836-848 (2013).

- Zhou, P. et al. How far are large language models from agents with theory-of-mind? Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2310.03051 (2023).

- Bonnefon, J.-F. & Rahwan, I. Machine thinking, fast and slow. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24, 1019-1027 (2020).

- Hanks, T. D., Mazurek, M. E., Kiani, R., Hopp, E. & Shadlen, M. N. Elapsed decision time affects the weighting of prior probability in a perceptual decision task. J. Neurosci. 31, 6339-6352 (2011).

- Pezzulo, G., Parr, T., Cisek, P., Clark, A. & Friston, K. Generating meaning: active inference and the scope and limits of passive AI. Trends Cogn. Sci. 28, 97-112 (2023).

- Chemero, A. LLMs differ from human cognition because they are not embodied. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1828-1829 (2023).

- Brunet-Gouet, E., Vidal, N. & Roux, P. In Human and Artificial Rationalities. HAR 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (eds. Baratgin, J. et al.) Vol. 14522, 107-126 (Springer, 2024).

- Kim, H. et al. FANToM: a benchmark for stress-testing machine theory of mind in interactions. In Proc. 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) 14397-14413 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023).

- Yiu, E., Kosoy, E. & Gopnik, A. Transmission versus truth, imitation versus nnovation: what children can do that large language and language-and-vision models cannot (yet). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231201401 (2023).

- Redcay, E. & Schilbach, L. Using second-person neuroscience to elucidate the mechanisms of social interaction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 495-505 (2019).

- Schilbach, L. et al. Toward a second-person neuroscience. Behav. Brain Sci. 36, 393-414 (2013).

- Gil, D., Fernández-Modamio, M., Bengochea, R. & Arrieta, M. Adaptation of the hinting task theory of the mind test to Spanish. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. Engl. Ed. 5, 79-88 (2012).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

(ج) المؤلف(ون) 2024

محفظة الطبيعة

آخر تحديث من المؤلف(ين): 05/04/2024

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

اختبار(ات) إحصائية مستخدمة وما إذا كانت أحادية أو ثنائية الجانب

يجب وصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ وصف تقنيات أكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

وصف كامل للمعلمات الإحصائية بما في ذلك الاتجاه المركزي (مثل المتوسطات) أو تقديرات أساسية أخرى (مثل معامل الانحدار) وAND التباين (مثل الانحراف المعياري) أو تقديرات عدم اليقين المرتبطة (مثل فترات الثقة)

تحتوي مجموعة الويب الخاصة بنا حول الإحصائيات لعلماء الأحياء على مقالات حول العديد من النقاط المذكورة أعلاه.

البرمجيات والرمز

معلومات السياسة حول توفر كود الكمبيوتر

تحليل البيانات

إصدار R 4.1.2

RStudio 2024.04.0-daily+368 “Chocolate Cosmos” يوميًا (605bbb38ebb4f8565e361122f6d8be3486d288e9، 2024-02-01) لنظام Ubuntu Jammy

Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML، مثل Gecko) rstudio/2024.04.0-daily+368 Chrome/120.0.6099.56

Electron/28.0.0 Safari/537.36

الرمز المستخدم لتحليل البيانات متاح كمشروع RMarkdown مستقل من: https://osf.io/j3vhq

يستخدم هذا الرمز الحزم R التالية:

DescTools_0.99.50

flextable_0.9.4

kableExtra_1.3.4

rstatix_0.7.2

cowplot_1.1.2

ggdist_3.3.1

ggpubr_0.6.0

ggplot2_3.4.4

purrr_1.0.2

Hmisc_5.1-1

tidyr_1.3.0

dplyr_1.1.4

ggtext_0.1.2

تم إخضاع النتائج الصفرية المبلغ عنها في المخطوطة الرئيسية لتحليلات بايزي متابعة لحساب عوامل باي (BF10). تم إجراء هذا التحليل باستخدام JASP v0.18.3 (فريق JASP، 2024)

البيانات

معلومات السياسة حول توفر البيانات

- رموز الوصول، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا

يمكن تنزيل النص الكامل لعناصر الأسئلة، والنص الكامل للاستجابات من نماذج GPT، ونماذج LLaMA2، والمشاركين البشريين، والدرجات المعينة لكل استجابة كملف واحد من عنوان URL التالي: https://osf.io/dbn92

ملفات البيانات مع الدرجات فقط، والتي يمكن استخدامها لإعادة إنشاء التحليل، مخزنة في مستودع OSF في المجلد scored_data/

البحث الذي يشمل المشاركين البشريين، بياناتهم، أو المواد البيولوجية

التقارير حول العرق، الإثنية، أو مجموعات اجتماعية أخرى ذات صلة

لم يتم جمع بيانات حول العرق والإثنية.

التقارير الخاصة بالمجال

X العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية

لنسخة مرجعية من الوثيقة مع جميع الأقسام، انظر nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

تصميم دراسة علوم الحياة

| حجم العينة | وصف كيف تم تحديد حجم العينة، مع توضيح أي طرق إحصائية استخدمت لتحديد حجم العينة مسبقًا أو إذا لم يتم إجراء حساب لحجم العينة، وصف كيف تم اختيار أحجام العينات وقدم مبررًا لسبب كفاية هذه الأحجام. |

| استبعاد البيانات | وصف أي استبعاد للبيانات. إذا لم يتم استبعاد أي بيانات من التحليلات، اذكر ذلك أو إذا تم استبعاد البيانات، وصف الاستبعادات والمبررات وراءها، موضحًا ما إذا كانت معايير الاستبعاد قد تم تحديدها مسبقًا. |

| التكرار | وصف التدابير المتخذة للتحقق من إمكانية إعادة إنتاج النتائج التجريبية. إذا كانت جميع محاولات التكرار ناجحة، أكد ذلك أو إذا كانت هناك أي نتائج لم يتم تكرارها أو لا يمكن إعادة إنتاجها، لاحظ ذلك ووضح السبب. |

| العشوائية | وصف كيف تم تخصيص العينات/الكائنات/المشاركين في مجموعات تجريبية. إذا لم يكن التخصيص عشوائيًا، وصف كيف تم التحكم في المتغيرات أو إذا لم يكن ذلك ذا صلة بدراستك، اشرح لماذا. |

تصميم دراسة العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية

| وصف الدراسة | تتكون البيانات من استجابات نصية كاملة للأسئلة حول مجموعة من اختبارات نظرية العقل. البيانات المبلغ عنها في المخطوطة هي درجات عددية كمية تم تعيينها لكل استجابة نصية وفقًا لمعايير الترميز المنشورة، مع أي انحرافات عن الإجراءات المعتمدة موضحة بوضوح في طرق المخطوطة الرئيسية. التصميم هو مقارنة بين العينات لثلاثة نماذج لغوية كبيرة (LLMs) مقابل عينة أساسية من المستجيبين البشريين. |

| عينة البحث | LLMs: GPT-4، GPT-3.5، LLaMA2-70B (وغيرها من نماذج LLaMA2 المبلغ عنها في المعلومات التكميلية): 15 إدارة لكل اختبار (جلسات)؛ البشر: هدف

|

| استراتيجية أخذ العينات | عينة ملائمة من خلال منصة بروليفك. تم دفع أجر للمشاركين بالجنيه الإسترليني

|

| جمع البيانات | لكل اختبار، جمعنا 15 جلسة لكل نموذج لغوي كبير وحوالي 50 موضوعًا بشريًا من خلال Prolific. تم اختبار نماذج GPT من خلال واجهة الويب ChatGPT الخاصة بـ OpenAI، وكانت الجلسة تتضمن تقديم جميع عناصر اختبار واحد ضمن نفس نافذة الدردشة. تم اختبار نماذج LLaMA باستخدام Langchain مع إعدادات محددة مع الطلب، “أنت مساعد ذكاء اصطناعي مفيد”، ودرجة حرارة 0.7، والحد الأقصى لعدد الرموز الجديدة المحدد عند 512، وعقوبة التكرار 1.1، وtop P عند 0.9. بالنسبة للبشر، تم تقديم جميع العناصر بشكل متسلسل من خلال استبيان عبر الإنترنت تم بناؤه واستضافته من خلال منصة SoSci. لم يكن الباحثون معميين عن الظروف التجريبية حيث لم يكن هناك تفاعل متبادل مع المشاركين. في حالة اختبار احتمال الخطأ، الذي شمل تقديم الباحث لطلب متابعة في حالة عدم وضوح التفكير بشأن إجابة غير صحيحة من نماذج GPT، تم تحديد معايير اتخاذ القرار لتقديم المتابعة مسبقًا وتم تقييمها لاحقًا من قبل باحثين آخرين للتحقق من صحة الطلب. |

| توقيت | تم جمع بيانات GPT حول البطارية الكاملة المبلغ عنها في المخطوطة الرئيسية وفي المواد التكميلية بين 3 أبريل و 18 أبريل 2023. تم جمع بيانات المتابعة باستخدام نسخة معدلة من اختبار Faux Pas بين 28 أبريل و 4 مايو 2023. تم جمع بيانات المتابعة مع GPT-3.5 باستخدام ترتيب تقديم عشوائي في اختبارات Irony و Strange Stories و Faux Pas بين 24 أبريل و 18 مايو 2023. تم اختبار ثلاثة نماذج LLaMA2-Chat بين أكتوبر ونوفمبر 2023. حدث اختبار المتغيرات لاختبارات False Belief و Faux Pas (اختبار احتمالية الاعتقاد) لنماذج GPT بين 25 أكتوبر و 3 نوفمبر 2023. |

| استثناءات البيانات | تم استبعاد ثلاثة عشر (13) موضوعًا بشريًا من التحليل النهائي بعد الفحص الأولي للبيانات. اختبار نظرية العقل: شخصان (2) استخدما GPT أو نموذج لغة آخر للإجابة على الأسئلة وشخص واحد (1) أجاب فقط بـ ‘نعم’ على كل سؤال؛ اختبار احتمال الاعتقاد: سبعة (7) مشاركين يُعتقد أنهم استخدموا GPT أو نموذج لغة آخر لتوليد إجاباتهم؛ اضطرابات الاعتقاد الخاطئ: ثلاثة (3) مشاركين يُعتقد أنهم استخدموا GPT أو نموذج لغة آخر لتوليد إجاباتهم. |

| عدم المشاركة | لم ينسحب أي مشارك أو يرفض المشاركة. |

| التوزيع العشوائي | لم يتم تعيين المشاركين في مجموعات تجريبية، بل تطوعوا لإجراء أحد اختبارات نظرية العقل الخمسة. كانت هذه عينة عشوائية من الفرص، وتم استبعاد الأفراد الذين شاركوا في اختبار واحد من المشاركة مرة أخرى. |

تصميم دراسة العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

| وصف الدراسة | وصف الدراسة بإيجاز. بالنسبة للبيانات الكمية، تشمل عوامل العلاج والتفاعلات، هيكل التصميم (مثل: عامل، متداخل، هرمي)، طبيعة وعدد الوحدات التجريبية والتكرارات. |

| عينة البحث | وصف عينة البحث (مثل مجموعة من طيور الدوري المنزلي المعلّمة، جميع نباتات ستينوسيريوس ثوربيري داخل نصب أنبوب الصبار الوطني)، وقدم مبررًا لاختيار العينة. عند الاقتضاء، وصف تصنيفات الكائنات، المصدر، الجنس، نطاق العمر وأي تعديلات. اذكر أي مجموعة سكانية من المفترض أن تمثلها العينة عند الاقتضاء. بالنسبة للدراسات التي تتضمن مجموعات بيانات موجودة، وصف البيانات ومصدرها. |

| استراتيجية أخذ العينات | يرجى ملاحظة إجراء أخذ العينات. وصف الطرق الإحصائية التي تم استخدامها لتحديد حجم العينة مسبقًا أو إذا لم يتم إجراء حساب لحجم العينة، يرجى وصف كيفية اختيار أحجام العينات وتقديم مبرر لسبب كفاية هذه الأحجام. |

| جمع البيانات | وصف إجراء جمع البيانات، بما في ذلك من قام بتسجيل البيانات وكيف. |

| استبعاد البيانات | إذا لم يتم استبعاد أي بيانات من التحليلات، يرجى ذكر ذلك أو إذا تم استبعاد بيانات، يرجى وصف الاستبعادات والأسباب وراءها، مع الإشارة إلى ما إذا كانت معايير الاستبعاد قد تم تحديدها مسبقًا. |

| إعادة الإنتاج | وصف التدابير المتخذة للتحقق من قابلية تكرار النتائج التجريبية. لكل تجربة، اذكر ما إذا كانت هناك أي محاولات لتكرار التجربة قد فشلت أو اذكر أن جميع المحاولات لتكرار التجربة كانت ناجحة. |

| العشوائية | وصف كيفية تخصيص العينات/الكائنات/المشاركين إلى مجموعات. إذا لم يكن التخصيص عشوائيًا، فاشرح كيف تم التحكم في المتغيرات المشتركة. إذا لم يكن هذا ذا صلة بدراستك، فاشرح لماذا. |

| مُعَمي | صف مدى استخدام التعمية أثناء جمع البيانات وتحليلها. إذا لم يكن من الممكن استخدام التعمية، فاشرح السبب أو اشرح لماذا لم تكن التعمية ذات صلة بدراستك. |

| هل شمل البحث العمل الميداني؟ |

|

العمل الميداني، الجمع والنقل

| ظروف الميدان | وصف ظروف الدراسة للعمل الميداني، مع تقديم المعايير ذات الصلة (مثل: درجة الحرارة، هطول الأمطار). |

| الموقع | حدد موقع العينة أو التجربة، مع تقديم المعلمات ذات الصلة (مثل: خط العرض وخط الطول، الارتفاع، عمق الماء). |

| الوصول والاستيراد/التصدير | صف الجهود التي بذلتها للوصول إلى المواطن وجمع عيناتك واستيرادها/تصديرها بطريقة مسؤولة وامتثالًا للقوانين المحلية والوطنية والدولية، مع الإشارة إلى أي تصاريح تم الحصول عليها (اذكر اسم الجهة المصدرة، تاريخ الإصدار، وأي معلومات تعريفية). |

| اضطراب | صف أي إزعاج ناتج عن الدراسة وكيف تم تقليله. |

التقارير عن مواد وأنظمة وطرق محددة

الأجسام المضادة

خطوط خلايا حقيقية النواة

معلومات السياسة حول خطوط الخلايا والجنس والنوع في البحث

| مصدر(s) خط الخلية | حدد مصدر كل خط خلوي مستخدم وجنس جميع الخطوط الخلوية الأولية والخلايا المشتقة من المشاركين البشريين أو النماذج الفقارية. |

| المصادقة | وصف إجراءات التحقق من الهوية لكل خط خلوي مستخدم أو إعلان أنه لم يتم التحقق من أي من خطوط الخلايا المستخدمة. |

تلوث الميكوبلازما

علم الحفريات وعلم الآثار

| أصل العينة | قدم معلومات عن مصدر العينات ووصف التصاريح التي تم الحصول عليها للعمل (بما في ذلك اسم الجهة المصدرة، تاريخ الإصدار، وأي معلومات تعريفية). يجب أن تشمل التصاريح جمع العينات، وعند الاقتضاء، التصدير. |

| إيداع العينة | حدد مكان إيداع العينات للسماح بالوصول الحر من قبل باحثين آخرين. |

| طرق التأريخ | إذا تم توفير تواريخ جديدة، يرجى وصف كيفية الحصول عليها (مثل الجمع، التخزين، معالجة العينة والقياس)، وأين تم الحصول عليها (أي اسم المختبر)، وبرنامج المعايرة وبروتوكول ضمان الجودة أو ذكر أنه لم يتم توفير تواريخ جديدة. |

الإشراف الأخلاقي

الحيوانات وغيرها من الكائنات البحثية

| الحيوانات المخبرية | بالنسبة للحيوانات المخبرية، أبلغ عن النوع والسلالة والعمر أو اذكر أن الدراسة لم تشمل حيوانات مخبرية. |

| الحيوانات البرية | قدم تفاصيل عن الحيوانات التي تم ملاحظتها أو التقاطها في الميدان؛ أبلغ عن النوع والعمر حيثما كان ذلك ممكنًا. وصف كيف تم اصطياد الحيوانات ونقلها وماذا حدث للحيوانات المحتجزة بعد الدراسة (إذا تم قتلها، اشرح لماذا ووصف الطريقة؛ إذا تم إطلاقها، قل أين ومتى) أو اذكر أن الدراسة لم تشمل حيوانات برية. |

| الإبلاغ عن الجنس | حدد ما إذا كانت النتائج تنطبق على جنس واحد فقط؛ وصف ما إذا كان الجنس قد تم أخذه في الاعتبار في تصميم الدراسة، والطرق المستخدمة لتعيين الجنس. قدم بيانات مفصلة حسب الجنس حيثما تم جمع هذه المعلومات في البيانات المصدر كما هو مناسب؛ قدم الأرقام الإجمالية في ملخص الإبلاغ هذا. يرجى الإشارة إذا لم يتم جمع هذه المعلومات. أبلغ عن التحليلات المعتمدة على الجنس حيثما تم تنفيذها، وقدم مبررات لعدم وجود تحليل معتمد على الجنس. |

| عينات تم جمعها من الميدان | بالنسبة للعمل المخبرية مع العينات التي تم جمعها من الميدان، وصف جميع المعلمات ذات الصلة مثل السكن، والصيانة، ودرجة الحرارة، وفترة الإضاءة وبروتوكول نهاية التجربة أو اذكر أن الدراسة لم تشمل عينات تم جمعها من الميدان. |

| الإشراف الأخلاقي | حدد المنظمة (المنظمات) التي وافقت أو قدمت إرشادات حول بروتوكول الدراسة، أو اذكر أنه لم يكن هناك حاجة لموافقة أخلاقية أو إرشادات واشرح لماذا. |

البيانات السريرية

يجب أن تمتثل جميع المخطوطات لإرشادات ICMJE لنشر الأبحاث السريرية ويجب تضمين قائمة مراجعة CONSORT المكتملة مع جميع التقديمات.

| تسجيل التجارب السريرية | قدم رقم تسجيل التجربة من ClinicalTrials.gov أو وكالة معادلة. |

| بروتوكول الدراسة | لاحظ أين يمكن الوصول إلى بروتوكول التجربة الكامل أو إذا لم يكن متاحًا، اشرح لماذا |

| جمع البيانات | وصف الإعدادات والأماكن لجمع البيانات، مع ملاحظة الفترات الزمنية للتجنيد وجمع البيانات. |

| النتائج | وصف كيف قمت بتعريف مقاييس النتائج الأولية والثانوية مسبقًا وكيف قمت بتقييم هذه المقاييس. |

البحث المزدوج الاستخدام المثير للقلق

المخاطر

لا

نعم

التجارب المثيرة للقلق

لا

نعم

النباتات

| مخزونات البذور | أبلغ عن مصدر جميع مخزونات البذور أو المواد النباتية الأخرى المستخدمة. إذا كان ذلك مناسبًا، اذكر مركز مخزون البذور ورقم الفهرس. إذا تم جمع عينات نباتية من الميدان، وصف موقع الجمع، التاريخ وإجراءات أخذ العينات. |

| أنماط نباتية جديدة | وصف الطرق التي تم بها إنتاج جميع الأنماط النباتية الجديدة. يشمل ذلك تلك التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة طرق نقل الجينات، وتحرير الجينات، والطفرات المعتمدة على المواد الكيميائية/الإشعاع والتزاوج. بالنسبة لخطوط النقل الجيني، وصف طريقة التحويل، عدد الخطوط المستقلة التي تم تحليلها والجيل الذي تم تنفيذ التجارب عليه. بالنسبة لخطوط تحرير الجينات، وصف المحرر المستخدم، التسلسل الداخلي المستهدف للتحرير، تسلسل RNA الدليل المستهدف (إذا كان ذلك مناسبًا) وكيف تم تطبيق المحرر. |

| التحقق | وصف أي إجراءات تحقق لكل مخزون بذور مستخدم أو نمط جديد تم إنتاجه. وصف أي تجارب استخدمت لتقييم تأثير الطفرة، وحيثما كان ذلك مناسبًا، كيف تم فحص الآثار الثانوية المحتملة (مثل إدخالات T-DNA في الموقع الثاني، التباين، تحرير الجينات خارج الهدف). |

ChIP-seq

إيداع البيانات

قد تبقى خاصة قبل النشر.

الملفات في تقديم قاعدة البيانات

جلسة متصفح الجينوم

(مثل UCSC)

قدم رابطًا لجلسة متصفح الجينوم مجهولة الهوية لوثائق “التقديم الأولي” و”الإصدار المنقح” فقط، لتمكين المراجعة من قبل الأقران. اكتب “لم يعد ينطبق” لوثائق “التقديم النهائي”.

عمق التسلسل

وصف عمق التسلسل لكل تجربة، مع تقديم العدد الإجمالي للقراءات، والقراءات المخصصة بشكل فريد، وطول القراءات وما إذا كانت مزدوجة أو مفردة النهاية.

معلمات استدعاء القمة

البرمجيات

وصف البرمجيات المستخدمة لجمع وتحليل بيانات ChIP-seq. بالنسبة للكود المخصص الذي تم إيداعه في مستودع مجتمعي، قدم تفاصيل الوصول.

تدفق السيتومتر

الرسوم البيانية

أكد أن:

المنهجية

| إعداد العينة | وصف إعداد العينة، مع توضيح المصدر البيولوجي للخلايا وأي خطوات معالجة الأنسجة المستخدمة. |

| الأداة | حدد الأداة المستخدمة لجمع البيانات، مع تحديد العلامة التجارية ورقم الطراز. |

| البرمجيات | وصف البرمجيات المستخدمة لجمع وتحليل بيانات تدفق السيتومتر. بالنسبة للكود المخصص الذي تم إيداعه في مستودع مجتمعي، قدم تفاصيل الوصول. |

| وفرة تجمعات الخلايا | وصف وفرة تجمعات الخلايا ذات الصلة ضمن الفئات بعد الفرز، مع تقديم تفاصيل حول نقاء العينات وكيف تم تحديده. |

| استراتيجية التصفية | وصف استراتيجية التصفية المستخدمة لجميع التجارب ذات الصلة، مع تحديد بوابات FSC/SSC الأولية لتجمع الخلايا البدائية، مع الإشارة إلى أين يتم تعريف الحدود بين تجمعات الخلايا “الإيجابية” و”السلبية”. |

|

|

|

التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي

تصميم التجربة

نوع التصميم

section*{مقاييس الأداء السلوكي

مقاييس الأداء السلوكي}

الاكتساب

نوع (أنواع) التصوير

قوة المجال

معلمات التسلسل والتصوير

منطقة الاكتساب

المعالجة المسبقة

برمجيات المعالجة المسبقة

حدد عدد الكتل أو التجارب أو الوحدات التجريبية لكل جلسة و/أو موضوع، وحدد طول كل تجربة أو كتلة (إذا كانت التجارب مجمعة) والفترة بين التجارب.

حدد بالتسلا

التطبيع

قالب التطبيع

إزالة الضوضاء والفن

تصفية الحجم

النمذجة الإحصائية والاستدلال

نوع النموذج والإعدادات

التأثيرات المختبرة

نوع الإحصاء للاستدلال

(انظر إكلوند وآخرون 2016)

تصحيح

حدد النوع (أحادي متغير جماعي، متعدد المتغيرات، RSA، تنبؤي، إلخ) ووضح التفاصيل الأساسية للنموذج في المستويين الأول والثاني (مثل التأثيرات الثابتة، العشوائية أو المختلطة؛ الانجراف أو الارتباط الذاتي).

1

مثل FWE، FDR، التبديل أو مونت كارلو).

النماذج والتحليل

- (W) تحقق من التحديثات

قسم الأعصاب، مركز جامعة هامبورغ-إيبندورف الطبي، هامبورغ، ألمانيا. الإدراك، الحركة وعلم الأعصاب، المعهد الإيطالي للتكنولوجيا، جنوة، إيطاليا. مركز علوم العقل/الدماغ، جامعة ترينتو، روفيريتو، إيطاليا. قسم علم النفس، جامعة تورين، تورين، إيطاليا. قسم الإدارة، ‘فالتر كانتينو’، جامعة تورين، تورين، إيطاليا. علوم الإنسان والتكنولوجيا، جامعة تورين، تورين، إيطاليا. شركة نقل التكنولوجيا الغريبة المحدودة، لندن، المملكة المتحدة. معهد معالجة المعلومات العصبية، مركز علم الأعصاب الجزيئي، مركز جامعة هامبورغ-إيبندورف الطبي، هامبورغ، ألمانيا. معهد برينستون لعلوم الأعصاب، جامعة برينستون، برينستون، نيو جيرسي، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. - البريد الإلكتروني: james.wa.strachan@gmail.com; c.becchio@uke.de

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01882-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38769463

Publication Date: 2024-05-20

Testing theory of mind in large language models and humans

Accepted: 5 April 2024

Published online: 20 May 2024

Abstract

At the core of what defines us as humans is the concept of theory of mind: the ability to track other people’s mental states. The recent development of large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT has led to intense debate about the possibility that these models exhibit behaviour that is indistinguishable from human behaviour in theory of mind tasks. Here we compare human and LLM performance on a comprehensive battery of measurements that aim to measure different theory of mind abilities, from understanding false beliefs to interpreting indirect requests and recognizing irony and faux pas. We tested two families of LLMs (GPT and LLaMA2) repeatedly against these measures and compared their performance with those from a sample of 1,907 human participants. Across the battery of theory of mind tests, we found that GPT-4 models performed at, or even sometimes above, human levels at identifying indirect requests, false beliefs and misdirection, but struggled with detecting faux pas. Faux pas, however, was the only test where LLaMA2 outperformed humans. Follow-up manipulations of the belief likelihood revealed that the superiority of LLaMA2 was illusory, possibly reflecting a bias towards attributing ignorance. By contrast, the poor performance of GPT originated from a hyperconservative approach towards committing to conclusions rather than from a genuine failure of inference. These findings not only demonstrate that LLMs exhibit behaviour that is consistent with the outputs of mentalistic inference in humans but also highlight the importance of systematic testing to ensure a non-superficial comparison between human and artificial intelligences.

closed window and a friend says, ‘It’s a bit hot in here’, it is your ability to think about her beliefs and desires that allows you to recognize that she is not just commenting on the temperature but politely asking you to open the window

Results

Theory of mind battery

irony comprehension using stimuli adapted from a previous study

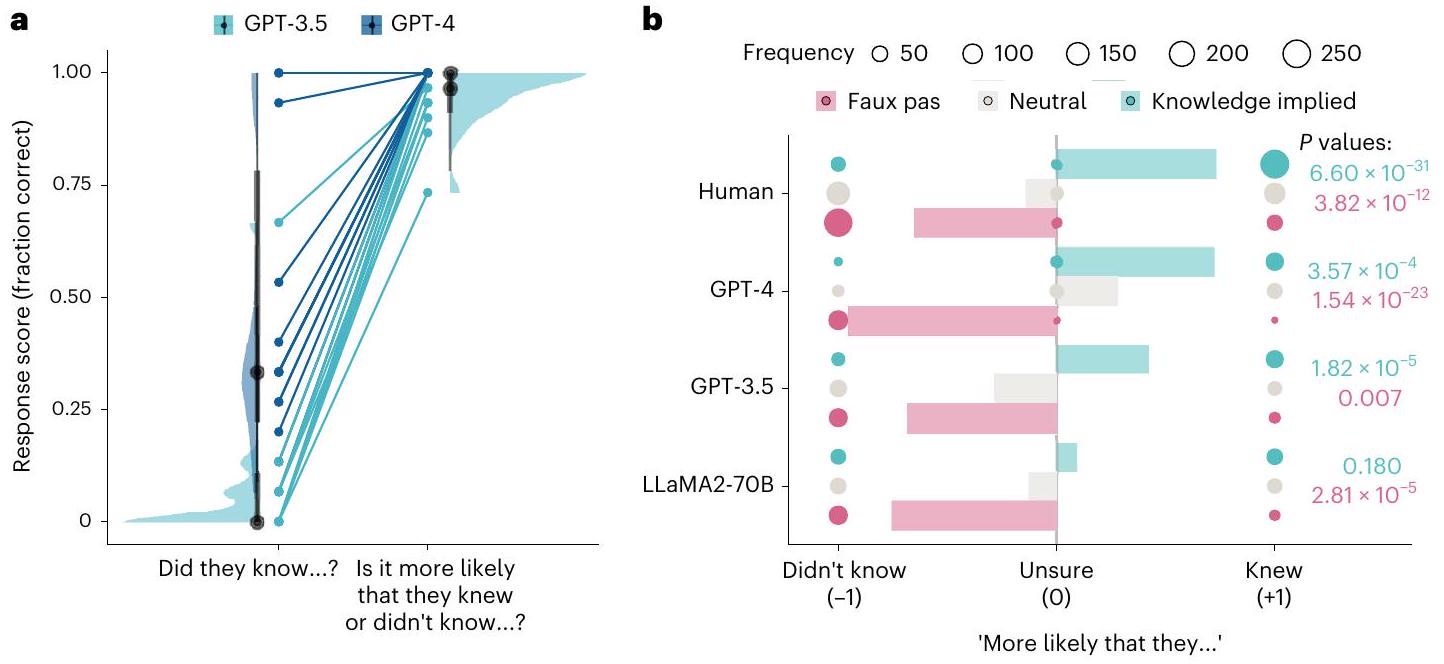

Performance across theory of mind tests

participants). Tests are ordered in descending order of human performance. b, Interquartile ranges of the average scores on the original published items (dark colours) and novel items (pale colours) across each test (for LLMs,

recognizing non-ironic control statements but made errors at recognizing ironic utterances (Supplementary Information section 2). Control analysis revealed a significant order effect, whereby GPT-3.5 made more errors on earlier trials than later ones (Supplementary Information section 3). LLaMA2-70B made errors when recognizing both ironic and non-ironic control statements, suggesting an overall poor discrimination of irony.

a Bayes factor). As reported in Supplementary Information section 6, partial successes were infrequent and more likely for LLaMA2-70B than for other models.

Understanding faux pas

Jill had just moved into a new house. She went shop-

ping with her Mum and bought some new curtains. When

Jill had just put them up, her best friend Lisa came

round and said, "Oh, those curtains are horrible, I

hope you're going to get some new ones." Jill asked,

"Do you like the rest of my bedroom?"

Did Lisa know the curtains were new?

GPT-4: [...] It is unclear from the story whether Lisa

knew the curtains were new or not.

inability to use non-embedded information would fundamentally impair the ability of GPT-4 to compute inferences.

Testing information integration

knowledge-implied variants (teal). Responses were coded as categorical data as ‘didn’t know’, ‘unsure’ or ‘knew’ and assigned a numerical coding of

pas likelihood test (where the correct answer is always ‘more likely that they didn’t know’).

for knowledge implied than for neutral (

responses (neutral 19.27%, knowledge implied 30.10%). GPT-3.5 was more likely to report that somebody made an offensive remark in all conditions (neutral 71.11%, knowledge implied 87.78%), and LLaMA270B always reported that somebody in the story had made an offensive remark.

Discussion

as passing the test requires committing to an explanation that lacks full evidence. This caution can also explain differences between tasks: both the faux pas and hinting tests require speculation to generate correct answers from incomplete information. However, while the hinting task allows for open-ended generation of text in ways to which LLMs are well suited, answering the faux pas test requires going beyond this speculation in order to commit to a conclusion.

| Test | Model |

|

Items | Dates of data collection |

| Theory of mind battery | Human | 250 | 7-16 | June to July 2023 |

| GPT-4 | 75 | 7-16 | April 2023 | |

| GPT-3.5 | 75 | 7-16 | April 2023 | |

| LLaMA2 | 75 | 7-16 | October to November 2023 | |

| Faux pas likelihood test | GPT-4 | 15 | 15 | April to May 2023 |

| GPT-3.5 | 15 | 15 | April to May 2023 | |

| LLaMA2 | 15 | 15 | October to November 2023 | |

| Belief likelihood test | Human | 900 | 1 | November 2023 |

| GPT-4 | 270 | 1 | October to November 2023 | |

| GPT-3.5 | 270 | 1 | October to November 2023 | |

| LLaMA2 | 270 | 1 | October to November 2023 | |

| Item order analysis | GPT-3.5 | 18 | 12-15 | April to May 2023 |

| False belief perturbations | Human | 757 | 1 | November 2023 |

| GPT-4 | 225 | 1 | October to November 2023 | |

| GPT-3.5 | 225 | 1 | October to November 2023 | |

| LLaMA2 | 225 | 1 | October to November 2023 |

real-time human-machine interactions

Methods

Ethical compliance

Experimental model details

comprehension relative to previous models (https://chat.openai. com/). Each test was delivered in a separate chat: GPT is capable of learning within a chat session, as it can remember both its own and the user’s previous messages to adapt its responses accordingly, but it does not retain this memory across new chats. As such, each new iteration of a test may be considered a blank slate with a new naive participant. The dates of data collection for the different stages are reported in Table1.

Theory of mind battery

true belief versions. These novel items followed the same structure as the original published items but with different details such as names, locations or objects to control for familiarity with the text of published items. Two story lists (false belief A, false belief B) were generated for this test such that each story only appeared once within a testing session and alternated between false and true belief depending on the session. In addition to the standard false/true belief scenarios, two additional catch stories were tested that involved minor alterations to the story structure. The results of these items are not reported here as they go beyond the goals of the current study.

- ‘In the story did someone say something that they should not have said?’ [The correct answer is always ‘yes’]

- ‘What did they say that they should not have said?’ [Correct answer changes for each item]

- A comprehension question to test understanding of story events [Question changes for every item]

- A question to test awareness of the speaker’s false belief phrased as, ‘Did [the speaker] know that [what they said was inappropriate]?’ [Question changes for every item. The correct answer is always ‘no’]

section 5 for an alternative coding that follows the original criteria, as well as a recoding where we coded as correct responses where the correct answer was mentioned as a possible explanation but was not explicitly endorsed).

Faux pas likelihood test

of likelihood: ‘Is it more likely that Richard remembered or did not remember that James had given him the toy aeroplane for his birthday?’

Belief likelihood test

Michael was a very awkward child when he was at

high school. He struggled with making friends

and spent his time alone writing poetry. However,

after he left he became a lot more confident and

sociable. At his ten-year high school reunion he

met Amanda, who had been in his English class. Over

drinks, she said to him,

'I don't know if you remember this guy from school.

He was in my English class. He wrote poetry and he

was super awkward. I hope he isn't here tonight.'

Neutral:

'Do you know where the bar is?'

'Do you still write poetry?'

Quantification and statistical analysis

human experimenters according to the pre-defined coding criteria for each test. Each experimenter was responsible for coding 100% of sessions for one test and 20% of sessions for another. Inter-coder per cent agreement was calculated on the 20% of shared sessions, and items where coders showed disagreement were evaluated by all raters and recoded. The data available on the OSF are the results of this recoding. Experimenters also flagged individual responses for group evaluation if they were unclear or unusual cases, as and when they arose. Inter-rater agreement was computed by calculating the item-wise agreement between coders as 1 or 0 and using this to calculate a percentage score. Initial agreement across all double-coded items was over 95%. The lowest agreement was for the human and GPT-3.5 responses of strange stories, but even here agreement was over 88%. Committee evaluation by the group of experimenters resolved all remaining ambiguities.

Statistical analysis

tests that compared the distribution of these categorical responses to the faux pas variant against the neutral, and to the neutral variant against the knowledge implied. A Holm correction was applied to the eight chi-square tests to account for multiple comparisons. The non-significant result was further examined with a Bayesian contingency table in JASP.

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Van Ackeren, M. J., Casasanto, D., Bekkering, H., Hagoort, P. & Rueschemeyer, S.-A. Pragmatics in action: indirect requests engage theory of mind areas and the cortical motor network. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 24, 2237-2247 (2012).

- Apperly, I. A. What is ‘theory of mind’? Concepts, cognitive processes and individual differences. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 65, 825-839 (2012).

- Premack, D. & Woodruff, G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav. Brain Sci. 1, 515-526 (1978).

- Apperly, I. A., Riggs, K. J., Simpson, A., Chiavarino, C. & Samson, D. Is belief reasoning automatic? Psychol. Sci. 17, 841-844 (2006).

- Kovács, Á. M., Téglás, E. & Endress, A. D. The social sense: susceptibility to others’ beliefs in human infants and adults. Science 330, 1830-1834 (2010).

- Apperly, I. A., Warren, F., Andrews, B. J., Grant, J. & Todd, S. Developmental continuity in theory of mind: speed and accuracy of belief-desire reasoning in children and adults. Child Dev. 82, 1691-1703 (2011).

- Southgate, V., Senju, A. & Csibra, G. Action anticipation through attribution of false belief by 2-year-olds. Psychol. Sci. 18, 587-592 (2007).

- Kampis, D., Kármán, P., Csibra, G., Southgate, V. & Hernik, M. A two-lab direct replication attempt of Southgate, Senju and Csibra (2007). R. Soc. Open Sci. 8, 210190 (2021).

- Kovács, Á. M., Téglás, E. & Csibra, G. Can infants adopt underspecified contents into attributed beliefs? Representational prerequisites of theory of mind. Cognition 213, 104640 (2021).

- Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Hill, J., Raste, Y. & Plumb, I. The ‘Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ Test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 42, 241-251 (2001).

- Wimmer, H. & Perner, J. Beliefs about beliefs: representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition 13, 103-128 (1983).

- Perner, J., Leekam, S. R. & Wimmer, H. Three-year-olds’ difficulty with false belief: the case for a conceptual deficit. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 5, 125-137 (1987).

- Baron-Cohen, S., O’Riordan, M., Stone, V., Jones, R. & Plaisted, K. Recognition of faux pas by normally developing children and children with asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 407-418 (1999).

- Corcoran, R. Inductive reasoning and the understanding of intention in schizophrenia. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 8, 223-235 (2003).

- Happé, F. G. E. An advanced test of theory of mind: understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 24, 129-154 (1994).

- White, S., Hill, E., Happé, F. & Frith, U. Revisiting the strange stories: revealing mentalizing impairments in autism. Child Dev. 80, 1097-1117 (2009).

- Apperly, I. A. & Butterfill, S. A. Do humans have two systems to track beliefs and belief-like states? Psychol. Rev. 116, 953 (2009).

- Wiesmann, C. G., Friederici, A. D., Singer, T. & Steinbeis, N. Two systems for thinking about others’ thoughts in the developing brain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 6928-6935 (2020).

- Bubeck, S. et al. Sparks of artificial general intelligence: early experiments with GPT-4. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2303.12712 (2023).

- Srivastava, A. et al. Beyond the imitation game: quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.04615 (2022).

- Dou, Z. Exploring GPT-3 model’s capability in passing the Sally-Anne Test A preliminary study in two languages. Preprint at OSF https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/8r3ma (2023).

- Kosinski, M. Theory of mind may have spontaneously emerged in large language models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2302.02083 (2023).

- Sap, M., LeBras, R., Fried, D. & Choi, Y. Neural theory-of-mind? On the limits of social intelligence in large LMs. In Proc. 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) 3762-3780 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022).

- Gandhi, K., Fränken, J.-P., Gerstenberg, T. & Goodman, N. D. Understanding social reasoning in language models with language models. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 36 (MIT Press, 2023).

- Ullman, T. Large language models fail on trivial alterations to theory-of-mind tasks. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2302.08399 (2023).

- Marcus, G. & Davis, E. How Not to Test GPT-3. Marcus on AI https://garymarcus.substack.com/p/how-not-to-test-gpt-3 (2023).

- Shapira, N. et al. Clever Hans or neural theory of mind? Stress testing social reasoning in large language models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.14763 (2023).

- Rahwan, I. et al. Machine behaviour. Nature 568, 477-486 (2019).

- Hagendorff, T. Machine psychology: investigating emergent capabilities and behavior in large language models using psychological methods. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2303.13988 (2023).

- Binz, M. & Schulz, E. Using cognitive psychology to understand GPT-3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218523120 (2023).

- Webb, T., Holyoak, K. J. & Lu, H. Emergent analogical reasoning in large language models. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1526-1541 (2023).

- Frank, M. C. Openly accessible LLMs can help us to understand human cognition. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1825-1827 (2023).

- Bernstein, D. M., Thornton, W. L. & Sommerville, J. A. Theory of mind through the ages: older and middle-aged adults exhibit more errors than do younger adults on a continuous false belief task. Exp. Aging Res. 37, 481-502 (2011).

- Au-Yeung, S. K., Kaakinen, J. K., Liversedge, S. P. & Benson, V. Processing of written irony in autism spectrum disorder: an eye-movement study: processing irony in autism spectrum disorders. Autism Res. 8, 749-760 (2015).

- Firestone, C. Performance vs. competence in human-machine comparisons. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 26562-26571 (2020).

- Shapira, N., Zwirn, G. & Goldberg, Y. How well do large language models perform on faux pas tests? In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023 10438-10451 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023)

- Rescher, N. Choice without preference. a study of the history and of the logic of the problem of ‘Buridan’s ass’. Kant Stud. 51, 142-175 (1960).

- OpenAI. GPT-4 technical report. Preprint at https://doi.org/ 10.48550/arXiv.2303.08774 (2023).

- Chen, L., Zaharia, M. & Zou, J. How is ChatGPT’s behavior changing over time? Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2307.09009 (2023).

- Feldman Hall, O. & Shenhav, A. Resolving uncertainty in a social world. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 426-435 (2019).

- James, W. The Principles of Psychology Vol. 2 (Henry Holt & Co, 1890).

- Fiske, S. T. Thinking is for doing: portraits of social cognition from daguerreotype to laserphoto. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 63, 877-889 (1992).

- Plate, R. C., Ham, H. & Jenkins, A. C. When uncertainty in social contexts increases exploration and decreases obtained rewards. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 152, 2463-2478 (2023).

- Frith, C. D. & Frith, U. The neural basis of mentalizing. Neuron 50, 531-534 (2006).

- Koster-Hale, J. & Saxe, R. Theory of mind: a neural prediction problem. Neuron 79, 836-848 (2013).

- Zhou, P. et al. How far are large language models from agents with theory-of-mind? Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ arXiv.2310.03051 (2023).

- Bonnefon, J.-F. & Rahwan, I. Machine thinking, fast and slow. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24, 1019-1027 (2020).

- Hanks, T. D., Mazurek, M. E., Kiani, R., Hopp, E. & Shadlen, M. N. Elapsed decision time affects the weighting of prior probability in a perceptual decision task. J. Neurosci. 31, 6339-6352 (2011).

- Pezzulo, G., Parr, T., Cisek, P., Clark, A. & Friston, K. Generating meaning: active inference and the scope and limits of passive AI. Trends Cogn. Sci. 28, 97-112 (2023).

- Chemero, A. LLMs differ from human cognition because they are not embodied. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1828-1829 (2023).

- Brunet-Gouet, E., Vidal, N. & Roux, P. In Human and Artificial Rationalities. HAR 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (eds. Baratgin, J. et al.) Vol. 14522, 107-126 (Springer, 2024).

- Kim, H. et al. FANToM: a benchmark for stress-testing machine theory of mind in interactions. In Proc. 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) 14397-14413 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023).

- Yiu, E., Kosoy, E. & Gopnik, A. Transmission versus truth, imitation versus nnovation: what children can do that large language and language-and-vision models cannot (yet). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916231201401 (2023).

- Redcay, E. & Schilbach, L. Using second-person neuroscience to elucidate the mechanisms of social interaction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 495-505 (2019).

- Schilbach, L. et al. Toward a second-person neuroscience. Behav. Brain Sci. 36, 393-414 (2013).

- Gil, D., Fernández-Modamio, M., Bengochea, R. & Arrieta, M. Adaptation of the hinting task theory of the mind test to Spanish. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. Engl. Ed. 5, 79-88 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

(c) The Author(s) 2024

natureportfolio

Last updated by author(s): 05/04/2024

Reporting Summary

Statistics

The statistical test(s) used AND whether they are one- or two-sided

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

A full description of the statistical parameters including central tendency (e.g. means) or other basic estimates (e.g. regression coefficient) AND variation (e.g. standard deviation) or associated estimates of uncertainty (e.g. confidence intervals)

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Software and code

Policy information about availability of computer code

Data analysis

R version 4.1.2

RStudio 2024.04.0-daily+368 “Chocolate Cosmos” Daily (605bbb38ebb4f8565e361122f6d8be3486d288e9, 2024-02-01) for Ubuntu Jammy

Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) rstudio/2024.04.0-daily+368 Chrome/120.0.6099.56

Electron/28.0.0 Safari/537.36

The code used for data analysis is available as a stand-alone RMarkdown project from: https://osf.io/j3vhq

This code uses the following R packages:

DescTools_0.99.50

flextable_0.9.4

kableExtra_1.3.4

rstatix_0.7.2

cowplot_1.1.2

ggdist_3.3.1

ggpubr_0.6.0

ggplot2_3.4.4

purrr_1.0.2

Hmisc_5.1-1

tidyr_1.3.0

dplyr_1.1.4

ggtext_0.1.2

Null results reported in the main manuscript were subjected to follow-up corresponding Bayesian analyses to compute Bayes Factors (BF10). This analysis was done using JASP v0.18.3 (JASP Team, 2024)

Data

Policy information about availability of data

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

The full text of question items, the full text of responses from GPT models, LLaMA2 models, and human participants, and the scores assigned to each response can be downloaded as a single file from the following URL: https://osf.io/dbn92

Data files with scores alone, which can be used to recreate the analysis, are stored in the OSF repository in the folder scored_data/

Research involving human participants, their data, or biological material

Reporting on race, ethnicity, or other socially relevant groupings

Data on race and ethnicity were not collected.

Field-specific reporting

X Behavioural & social sciences

For a reference copy of the document with all sections, see nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

Life sciences study design

| Sample size | Describe how sample size was determined, detailing any statistical methods used to predetermine sample size OR if no sample-size calculation was performed, describe how sample sizes were chosen and provide a rationale for why these sample sizes are sufficient. |

| Data exclusions | Describe any data exclusions. If no data were excluded from the analyses, state so OR if data were excluded, describe the exclusions and the rationale behind them, indicating whether exclusion criteria were pre-established. |

| Replication | Describe the measures taken to verify the reproducibility of the experimental findings. If all attempts at replication were successful, confirm this OR if there are any findings that were not replicated or cannot be reproduced, note this and describe why. |

| Randomization | Describe how samples/organisms/participants were allocated into experimental groups. If allocation was not random, describe how covariates were controlled OR if this is not relevant to your study, explain why. |

Behavioural & social sciences study design

| Study description | The data consist of full-text responses to questions on a set of Theory of Mind tests. Data reported in the manuscript are quantitative numeric scores assigned to each text response according to published coding criteria, with any deviations from validated procedures clearly highlighted in the Methods of the main manuscript. The design is a between-samples comparison of three Large Language Models (LLMs) against a baseline sample of human respondents. |

| Research sample | LLMs: GPT-4, GPT-3.5, LLaMA2-70B (and other LLaMA2 models reported in Supplementary Information): 15 administrations of each test (sessions); Humans: target

|

| Sampling strategy | Convenience sample through the Prolific platform. Participants were paid GBP

|

| Data collection | For each test we collected 15 sessions for each LLM and ~50 human subjects through Prolific. GPT models were tested through the OpenAI ChatGPT web interface, and a session involved delivering all items of a single test within the same chat window. LLaMA models were tested using Langchain using set parameters with the prompt, “You are a helpful AI assistant”, a temperature of 0.7 , the maximum number of new tokens set at 512 , a repetition penalty of 1.1 , and a top P of 0.9 . For humans, all items were presented sequentially through an online survey built and hosted through the SoSci platform. Experimenters were not blinded to the experimental conditions as there was no reciprocal interaction with the participants. In the case of the Faux Pas Likelihood test, which included the experimenter delivering a follow-up prompt in the case of unclear reasoning on an incorrect answer from GPT models, criteria for deciding to deliver the follow-up were set a priori and evaluated afterwards by other experimenters to check that the prompt had been valid. |

| Timing | The GPT data on the full battery reported in the main manuscript and in the supplementary material were collected between 3 April and 18 April 2023. The follow-up data using an adapted version of the Faux Pas test were collected between 28 April and 4 May 2023. The follow-up data with GPT-3.5 using a randomised presentation order on the Irony, Strange Stories, and Faux Pas tests were collected between 24 April and 18 May 2023. Three LLaMA2-Chat models were tested between October and November 2023. Variant testing of the False Belief and Faux Pas tests (Belief Likelihoood test) for GPT models occurred between 25 October and 3 November 2023. |

| Data exclusions | Thirteen (13) human subjects were excluded from final analysis following initial examination of the data. Theory of Mind Battery: two (2) subjects who used GPT or another LLM to answer the questions and one (1) subject who just responded ‘Yes’ to every question; Belief Likelihood Test: seven (7) participants who were believed to use GPT or another LLM to generate their responses; False Belief Perturbations: three (3) participants who were believed to use GPT or another LLM to generate their responses. |

| Non-participation | No participants dropped out or declined participation. |

| Randomization | Participants were not assigned to experimental groups, but volunteered to complete one of the five Theory of Mind tests. This was a random opportunity sample, and individuals who had participated in one test were excluded from participating again. |

Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences study design

| Study description | Briefly describe the study. For quantitative data include treatment factors and interactions, design structure (e.g. factorial, nested, hierarchical), nature and number of experimental units and replicates. |

| Research sample | Describe the research sample (e.g. a group of tagged Passer domesticus, all Stenocereus thurberi within Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument), and provide a rationale for the sample choice. When relevant, describe the organism taxa, source, sex, age range and any manipulations. State what population the sample is meant to represent when applicable. For studies involving existing datasets, describe the data and its source. |

| Sampling strategy | Note the sampling procedure. Describe the statistical methods that were used to predetermine sample size OR if no sample-size calculation was performed, describe how sample sizes were chosen and provide a rationale for why these sample sizes are sufficient. |

| Data collection | Describe the data collection procedure, including who recorded the data and how. |

| Data exclusions | If no data were excluded from the analyses, state so OR if data were excluded, describe the exclusions and the rationale behind them, indicating whether exclusion criteria were pre-established. |

| Reproducibility | Describe the measures taken to verify the reproducibility of experimental findings. For each experiment, note whether any attempts to repeat the experiment failed OR state that all attempts to repeat the experiment were successful. |

| Randomization | Describe how samples/organisms/participants were allocated into groups. If allocation was not random, describe how covariates were controlled. If this is not relevant to your study, explain why. |

| Blinding | Describe the extent of blinding used during data acquisition and analysis. If blinding was not possible, describe why OR explain why blinding was not relevant to your study. |

| Did the study involve field work |

|

Field work, collection and transport

| Field conditions | Describe the study conditions for field work, providing relevant parameters (e.g. temperature, rainfall). |

| Location | State the location of the sampling or experiment, providing relevant parameters (e.g. latitude and longitude, elevation, water depth). |

| Access & import/export | Describe the efforts you have made to access habitats and to collect and import/export your samples in a responsible manner and in compliance with local, national and international laws, noting any permits that were obtained (give the name of the issuing authority, the date of issue, and any identifying information). |

| Disturbance | Describe any disturbance caused by the study and how it was minimized. |

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

Antibodies

Eukaryotic cell lines

Policy information about cell lines and Sex and Gender in Research

| Cell line source(s) | State the source of each cell line used and the sex of all primary cell lines and cells derived from human participants or vertebrate models. |

| Authentication | Describe the authentication procedures for each cell line used OR declare that none of the cell lines used were authenticated. |

Mycoplasma contamination

Palaeontology and Archaeology

| Specimen provenance | Provide provenance information for specimens and describe permits that were obtained for the work (including the name of the issuing authority, the date of issue, and any identifying information). Permits should encompass collection and, where applicable, export. |

| Specimen deposition | Indicate where the specimens have been deposited to permit free access by other researchers. |

| Dating methods | If new dates are provided, describe how they were obtained (e.g. collection, storage, sample pretreatment and measurement), where they were obtained (i.e. lab name), the calibration program and the protocol for quality assurance OR state that no new dates are provided. |

Ethics oversight

Animals and other research organisms

| Laboratory animals | For laboratory animals, report species, strain and age OR state that the study did not involve laboratory animals. |

| Wild animals | Provide details on animals observed in or captured in the field; report species and age where possible. Describe how animals were caught and transported and what happened to captive animals after the study (if killed, explain why and describe method; if released, say where and when) OR state that the study did not involve wild animals. |

| Reporting on sex | Indicate if findings apply to only one sex; describe whether sex was considered in study design, methods used for assigning sex. Provide data disaggregated for sex where this information has been collected in the source data as appropriate; provide overall numbers in this Reporting Summary. Please state if this information has not been collected. Report sex-based analyses where performed, justify reasons for lack of sex-based analysis. |

| Field-collected samples | For laboratory work with field-collected samples, describe all relevant parameters such as housing, maintenance, temperature, photoperiod and end-of-experiment protocol OR state that the study did not involve samples collected from the field. |

| Ethics oversight | Identify the organization(s) that approved or provided guidance on the study protocol, OR state that no ethical approval or guidance was required and explain why not. |

Clinical data

All manuscripts should comply with the ICMJE guidelines for publication of clinical research and a completed CONSORT checklist must be included with all submissions.

| Clinical trial registration | Provide the trial registration number from ClinicalTrials.gov or an equivalent agency. |

| Study protocol | Note where the full trial protocol can be accessed OR if not available, explain why |

| Data collection | Describe the settings and locales of data collection, noting the time periods of recruitment and data collection. |

| Outcomes | Describe how you pre-defined primary and secondary outcome measures and how you assessed these measures. |

Dual use research of concern

Hazards

No

Yes

Experiments of concern

No

Yes

Plants

| Seed stocks | Report on the source of all seed stocks or other plant material used. If applicable, state the seed stock centre and catalogue number. If plant specimens were collected from the field, describe the collection location, date and sampling procedures. |

| Novel plant genotypes | Describe the methods by which all novel plant genotypes were produced. This includes those generated by transgenic approaches, gene editing, chemical/radiation-based mutagenesis and hybridization. For transgenic lines, describe the transformation method, the number of independent lines analyzed and the generation upon which experiments were performed. For gene-edited lines, describe the editor used, the endogenous sequence targeted for editing, the targeting guide RNA sequence (if applicable) and how the editor was applied. |

| Authentication | Describe any authentication procedures for each seed stock used or novel genotype generated. Describe any experiments used to assess the effect of a mutation and, where applicable, how potential secondary effects (e.g. second site T-DNA insertions, mosiacism, off-target gene editing) were examined. |

ChIP-seq

Data deposition

May remain private before publication.

Files in database submission

Genome browser session

(e.g. UCSC)

Provide a link to an anonymized genome browser session for “Initial submission” and “Revised version” documents only, to enable peer review. Write “no longer applicable” for “Final submission” documents.

Sequencing depth

Describe the sequencing depth for each experiment, providing the total number of reads, uniquely mapped reads, length of reads and whether they were paired- or single-end.

Peak calling parameters

Software

Describe the software used to collect and analyze the ChIP-seq data. For custom code that has been deposited into a community repository, provide accession details.

Flow Cytometry

Plots

Confirm that:

Methodology

| Sample preparation | Describe the sample preparation, detailing the biological source of the cells and any tissue processing steps used. |

| Instrument | Identify the instrument used for data collection, specifying make and model number. |

| Software | Describe the software used to collect and analyze the flow cytometry data. For custom code that has been deposited into a community repository, provide accession details. |

| Cell population abundance | Describe the abundance of the relevant cell populations within post-sort fractions, providing details on the purity of the samples and how it was determined. |

| Gating strategy | Describe the gating strategy used for all relevant experiments, specifying the preliminary FSC/SSC gates of the starting cell population, indicating where boundaries between “positive” and “negative” staining cell populations are defined. |

|

|

|

Magnetic resonance imaging

Experimental design

Design type

section*{Behavioral performance measures

Behavioral performance measures}

Acquisition

Imaging type(s)

Field strength

Sequence & imaging parameters

Area of acquisition

Preprocessing

Preprocessing software

Specify the number of blocks, trials or experimental units per session and/or subject, and specify the length of each trial or block (if trials are blocked) and interval between trials.

Specify in Tesla

Normalization

Normalization template

Noise and artifact removal

Volume censoring

Statistical modeling & inference

Model type and settings

Effect(s) tested

Statistic type for inference

(See Eklund et al. 2016)

Correction

Specify type (mass univariate, multivariate, RSA, predictive, etc.) and describe essential details of the model at the first and second levels (e.g. fixed, random or mixed effects; drift or auto-correlation).

1

.g. FWE, FDR, permutation or Monte Carlo).

Models & analysis

- (W) Check for updates

Department of Neurology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany. Cognition, Motion and Neuroscience, Italian Institute of Technology, Genoa, Italy. Center for Mind/Brain Sciences, University of Trento, Rovereto, Italy. Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy. Department of Management, ‘Valter Cantino’, University of Turin, Turin, Italy. Human Science and Technologies, University of Turin, Turin, Italy. Alien Technology Transfer Ltd, London, UK. Institute for Neural Information Processing, Center for Molecular Neurobiology, University Medical Center Hamburg- Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany. Princeton Neuroscience Institute, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA.